User login

Religion and LGBTQ identities

JB is a 15-year-old female who presents to your office for a wellness check. Mom is concerned because she has seemed more depressed and withdrawn over the past few months. During the confidential portion of your visit, JB discloses that, while she has had boyfriends in the past, she is realizing that she is romantically and sexually attracted to females. Many members of her religious faith, which she is strongly connected to, believe that homosexuality is a sin. She has been secretly researching therapies to help her “not be gay” and asks you for advice.

Adolescence is a time of rapid growth and development. Two important developmental tasks of adolescence are to establish key aspects of identity and identify meaningful moral standards, values, and belief systems.1 For some LGBTQ adolescents, these tasks can become more complicated when the value system or religious faith in which they were raised views homosexuality or gender nonconformity as a sin.

- Identifying as lesbian, gay, bisexual, or transgender is normal, just different.

- LGBT people exist in almost every faith group across the country.

- Many religious groups have wrestled with homosexuality, gender identity, and religion and decided to be more welcoming to LGBT communities.

- Within most faiths, there are many interpretations of religious texts, such as the Bible and the Koran, on all issues, including homosexuality.

- While every religion has different teachings, almost all religions advocate love and compassion.

- Clergy and other faith leaders can be a source of support. However, every faith community is different and may not always be supportive. Safely investigate your individual community’s approach. You have the right to question and explore your faith, sexuality, and/or gender identity and reconcile these in a way that is true to you.

- Remember this is your journey. You get to decide the path and the pace.

- Recognize that this may involve working for change within your community or it may mean leaving it.

- Referral for “conversion” or “reparative therapy” is never indicated. Such therapy is not effective and may be harmful to LGBTQ individuals by increasing internalized stigma, distress, and depression.

Dr. Chelvakumar is an attending physician in the division of adolescent medicine at Nationwide Children’s Hospital and an assistant professor of clinical pediatrics at the Ohio State University, both in Columbus. She has no relevant financial disclosures. Email her at [email protected].

Spirituality resources

- LGBTQ and Religion: Your Relationship with Religion is Completely Up to You, the FAQ Page by the Trevor Project, a national organization that provides crisis intervention and suicide prevention resources to LGBTQ young people ages 13-24 years. www.thetrevorproject.org/pages/lgbtq-and-religion

- Faith in Our Families: Parents, Families and Friends Talk About Religion and Homosexuality, a resource from PFLAG (Parents, Families, and Friends of Lesbians and Gays). www.pflag.org/sites/default/files/Faith%20In%20Our%20Families.pdf

- LGBT Center UNC Chapel Hill: Religion and Spirituality, a page with a link to nondenominational and denomination-specific resources with various religious and spiritual communities’ beliefs regarding faith and LGBTQIA+ (Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, Queer, Intersex, Asexual). lgbtq.unc.edu/resources/exploring-identities/religion-and-spirituality

- HRC: Explore Religion and Faith, a Human Rights Campaign page containing links to resources on religion and faith. It also has links to the Coming Home Series, guides aimed at those who hope to lead their faith communities toward a more welcoming stance and those seeking a path back to beloved traditions. www.hrc.org/explore/topic/religion-faith

References

1. Raising teens: A synthesis or research and a foundation for action. (Boston: Center for Health Communication, Harvard School of Public Health, 2001).

2. Faith in Our Families: Parents, Families and Friends Talk About Religion and Homosexuality (Washington, D.C.: Parents, Families and Friends of Lesbians and Gays, 1997)

3. Pediatrics. 2013 Jul;132(1):198-203.

4. The Health of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender People: Building a Foundation for Better Understanding. (Washington, D.C.: National Academies Press, 2011)

5. Coming Home: To Faith, to Spirit, to Self. Pamphlet by the Human Rights Campaign.

JB is a 15-year-old female who presents to your office for a wellness check. Mom is concerned because she has seemed more depressed and withdrawn over the past few months. During the confidential portion of your visit, JB discloses that, while she has had boyfriends in the past, she is realizing that she is romantically and sexually attracted to females. Many members of her religious faith, which she is strongly connected to, believe that homosexuality is a sin. She has been secretly researching therapies to help her “not be gay” and asks you for advice.

Adolescence is a time of rapid growth and development. Two important developmental tasks of adolescence are to establish key aspects of identity and identify meaningful moral standards, values, and belief systems.1 For some LGBTQ adolescents, these tasks can become more complicated when the value system or religious faith in which they were raised views homosexuality or gender nonconformity as a sin.

- Identifying as lesbian, gay, bisexual, or transgender is normal, just different.

- LGBT people exist in almost every faith group across the country.

- Many religious groups have wrestled with homosexuality, gender identity, and religion and decided to be more welcoming to LGBT communities.

- Within most faiths, there are many interpretations of religious texts, such as the Bible and the Koran, on all issues, including homosexuality.

- While every religion has different teachings, almost all religions advocate love and compassion.

- Clergy and other faith leaders can be a source of support. However, every faith community is different and may not always be supportive. Safely investigate your individual community’s approach. You have the right to question and explore your faith, sexuality, and/or gender identity and reconcile these in a way that is true to you.

- Remember this is your journey. You get to decide the path and the pace.

- Recognize that this may involve working for change within your community or it may mean leaving it.

- Referral for “conversion” or “reparative therapy” is never indicated. Such therapy is not effective and may be harmful to LGBTQ individuals by increasing internalized stigma, distress, and depression.

Dr. Chelvakumar is an attending physician in the division of adolescent medicine at Nationwide Children’s Hospital and an assistant professor of clinical pediatrics at the Ohio State University, both in Columbus. She has no relevant financial disclosures. Email her at [email protected].

Spirituality resources

- LGBTQ and Religion: Your Relationship with Religion is Completely Up to You, the FAQ Page by the Trevor Project, a national organization that provides crisis intervention and suicide prevention resources to LGBTQ young people ages 13-24 years. www.thetrevorproject.org/pages/lgbtq-and-religion

- Faith in Our Families: Parents, Families and Friends Talk About Religion and Homosexuality, a resource from PFLAG (Parents, Families, and Friends of Lesbians and Gays). www.pflag.org/sites/default/files/Faith%20In%20Our%20Families.pdf

- LGBT Center UNC Chapel Hill: Religion and Spirituality, a page with a link to nondenominational and denomination-specific resources with various religious and spiritual communities’ beliefs regarding faith and LGBTQIA+ (Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, Queer, Intersex, Asexual). lgbtq.unc.edu/resources/exploring-identities/religion-and-spirituality

- HRC: Explore Religion and Faith, a Human Rights Campaign page containing links to resources on religion and faith. It also has links to the Coming Home Series, guides aimed at those who hope to lead their faith communities toward a more welcoming stance and those seeking a path back to beloved traditions. www.hrc.org/explore/topic/religion-faith

References

1. Raising teens: A synthesis or research and a foundation for action. (Boston: Center for Health Communication, Harvard School of Public Health, 2001).

2. Faith in Our Families: Parents, Families and Friends Talk About Religion and Homosexuality (Washington, D.C.: Parents, Families and Friends of Lesbians and Gays, 1997)

3. Pediatrics. 2013 Jul;132(1):198-203.

4. The Health of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender People: Building a Foundation for Better Understanding. (Washington, D.C.: National Academies Press, 2011)

5. Coming Home: To Faith, to Spirit, to Self. Pamphlet by the Human Rights Campaign.

JB is a 15-year-old female who presents to your office for a wellness check. Mom is concerned because she has seemed more depressed and withdrawn over the past few months. During the confidential portion of your visit, JB discloses that, while she has had boyfriends in the past, she is realizing that she is romantically and sexually attracted to females. Many members of her religious faith, which she is strongly connected to, believe that homosexuality is a sin. She has been secretly researching therapies to help her “not be gay” and asks you for advice.

Adolescence is a time of rapid growth and development. Two important developmental tasks of adolescence are to establish key aspects of identity and identify meaningful moral standards, values, and belief systems.1 For some LGBTQ adolescents, these tasks can become more complicated when the value system or religious faith in which they were raised views homosexuality or gender nonconformity as a sin.

- Identifying as lesbian, gay, bisexual, or transgender is normal, just different.

- LGBT people exist in almost every faith group across the country.

- Many religious groups have wrestled with homosexuality, gender identity, and religion and decided to be more welcoming to LGBT communities.

- Within most faiths, there are many interpretations of religious texts, such as the Bible and the Koran, on all issues, including homosexuality.

- While every religion has different teachings, almost all religions advocate love and compassion.

- Clergy and other faith leaders can be a source of support. However, every faith community is different and may not always be supportive. Safely investigate your individual community’s approach. You have the right to question and explore your faith, sexuality, and/or gender identity and reconcile these in a way that is true to you.

- Remember this is your journey. You get to decide the path and the pace.

- Recognize that this may involve working for change within your community or it may mean leaving it.

- Referral for “conversion” or “reparative therapy” is never indicated. Such therapy is not effective and may be harmful to LGBTQ individuals by increasing internalized stigma, distress, and depression.

Dr. Chelvakumar is an attending physician in the division of adolescent medicine at Nationwide Children’s Hospital and an assistant professor of clinical pediatrics at the Ohio State University, both in Columbus. She has no relevant financial disclosures. Email her at [email protected].

Spirituality resources

- LGBTQ and Religion: Your Relationship with Religion is Completely Up to You, the FAQ Page by the Trevor Project, a national organization that provides crisis intervention and suicide prevention resources to LGBTQ young people ages 13-24 years. www.thetrevorproject.org/pages/lgbtq-and-religion

- Faith in Our Families: Parents, Families and Friends Talk About Religion and Homosexuality, a resource from PFLAG (Parents, Families, and Friends of Lesbians and Gays). www.pflag.org/sites/default/files/Faith%20In%20Our%20Families.pdf

- LGBT Center UNC Chapel Hill: Religion and Spirituality, a page with a link to nondenominational and denomination-specific resources with various religious and spiritual communities’ beliefs regarding faith and LGBTQIA+ (Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, Queer, Intersex, Asexual). lgbtq.unc.edu/resources/exploring-identities/religion-and-spirituality

- HRC: Explore Religion and Faith, a Human Rights Campaign page containing links to resources on religion and faith. It also has links to the Coming Home Series, guides aimed at those who hope to lead their faith communities toward a more welcoming stance and those seeking a path back to beloved traditions. www.hrc.org/explore/topic/religion-faith

References

1. Raising teens: A synthesis or research and a foundation for action. (Boston: Center for Health Communication, Harvard School of Public Health, 2001).

2. Faith in Our Families: Parents, Families and Friends Talk About Religion and Homosexuality (Washington, D.C.: Parents, Families and Friends of Lesbians and Gays, 1997)

3. Pediatrics. 2013 Jul;132(1):198-203.

4. The Health of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender People: Building a Foundation for Better Understanding. (Washington, D.C.: National Academies Press, 2011)

5. Coming Home: To Faith, to Spirit, to Self. Pamphlet by the Human Rights Campaign.

Sleep Duration Affects Likelihood of Insomnia and Depression Remission

BOSTON—Objective sleep duration moderates the probability of remission among patients with comorbid depression and insomnia, according to research presented at the 31st Annual Meeting of the Associated Professional Sleep Societies. Sleep durations of greater than five to six hours increase the likelihood that these patients will achieve insomnia remission with cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia (CBT-I), but do not affect the likelihood of depression remission. Sleep durations of seven or more hours optimize the likelihood of insomnia remission and depression remission in response to CBT-I.

In a 2015 consensus statement, the Sleep Research Society recommended seven or more hours of sleep per night for adults younger than 60. Investigations by Vgontzas and colleagues indicate that sleep durations of less than five hours and less than six hours are associated with increased morbidity and poor treatment response among patients with insomnia. “We wanted to know what [sleep-duration] cutoffs … might be better predictors of eventual insomnia and depression remission through treatment,” said Jack Edinger, PhD, Professor of Medicine at National Jewish Health in Denver.

An Analysis of the TRIAD Study

Dr. Edinger and colleagues conducted a secondary analysis of the TRIAD study, which examined whether combined treatment of depression and insomnia improves depression and sleep outcomes in participants with both disorders. Eligible participants met Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (4th ed.) criteria for major depression and primary insomnia, had a Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HAMD-17) score of 16 or greater, and had an Insomnia Severity Index (ISI) score of 11 or greater. People who had had psychotherapy in the previous four months, or had failed or could not tolerate previous adequate trials of the study medications, were excluded. Participants completed one night of baseline polysomnography before entering the treatment phase of the study.

The study population included 104 participants (75 women) with a mean age of 47. Mean baseline HAMD-17 score was 22, and mean baseline ISI score was 20.6. All participants received antidepressant medication (ie, citalopram, sertraline, or venlafaxine). Patients were randomized to CBT-I or sham (ie, a pseudo desensitization condition with sleep education). The investigators assessed participants biweekly with the HAMD-17 and the ISI. The treatment period lasted for 16 weeks.

CBT-I Provided Benefits

Participants with five or more hours of sleep were more likely to respond to CBT-I than participants with fewer than five hours of sleep. Among participants with sleep duration of five or more hours, insomnia remission was more likely with CBT-I than with the control condition. The five-hour cutoff had no association with depression remission.

Among participants with six or more hours of sleep, those who received CBT-I were more likely to achieve insomnia remission than controls. The six-hour cutoff did not affect the likelihood of depression remission, however.

Among participants with seven or more hours of sleep, those randomized to CBT-I were more likely to achieve insomnia remission and depression remission than controls.

“More research is needed to determine how best to achieve depression remission in those patients with less than seven hours of objective sleep duration prior to starting treatment,” Dr. Edinger concluded.

—Erik Greb

Suggested Reading

Bathgate CJ, Edinger JD, Krystal AD. Insomnia patients with objective short sleep duration have a blunted response to cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia. Sleep. 2017;40(1).

Vgontzas AN, Liao D, Bixler EO, et al. Insomnia with objective short sleep duration is associated with a high risk for hypertension. Sleep. 2009;32(4):491-497.

Watson NF, Badr MS, Belenky G, et al. Recommended amount of sleep for a healthy adult: A joint consensus statement of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine and Sleep Research Society. Sleep. 2015;38(6):843-844.

BOSTON—Objective sleep duration moderates the probability of remission among patients with comorbid depression and insomnia, according to research presented at the 31st Annual Meeting of the Associated Professional Sleep Societies. Sleep durations of greater than five to six hours increase the likelihood that these patients will achieve insomnia remission with cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia (CBT-I), but do not affect the likelihood of depression remission. Sleep durations of seven or more hours optimize the likelihood of insomnia remission and depression remission in response to CBT-I.

In a 2015 consensus statement, the Sleep Research Society recommended seven or more hours of sleep per night for adults younger than 60. Investigations by Vgontzas and colleagues indicate that sleep durations of less than five hours and less than six hours are associated with increased morbidity and poor treatment response among patients with insomnia. “We wanted to know what [sleep-duration] cutoffs … might be better predictors of eventual insomnia and depression remission through treatment,” said Jack Edinger, PhD, Professor of Medicine at National Jewish Health in Denver.

An Analysis of the TRIAD Study

Dr. Edinger and colleagues conducted a secondary analysis of the TRIAD study, which examined whether combined treatment of depression and insomnia improves depression and sleep outcomes in participants with both disorders. Eligible participants met Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (4th ed.) criteria for major depression and primary insomnia, had a Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HAMD-17) score of 16 or greater, and had an Insomnia Severity Index (ISI) score of 11 or greater. People who had had psychotherapy in the previous four months, or had failed or could not tolerate previous adequate trials of the study medications, were excluded. Participants completed one night of baseline polysomnography before entering the treatment phase of the study.

The study population included 104 participants (75 women) with a mean age of 47. Mean baseline HAMD-17 score was 22, and mean baseline ISI score was 20.6. All participants received antidepressant medication (ie, citalopram, sertraline, or venlafaxine). Patients were randomized to CBT-I or sham (ie, a pseudo desensitization condition with sleep education). The investigators assessed participants biweekly with the HAMD-17 and the ISI. The treatment period lasted for 16 weeks.

CBT-I Provided Benefits

Participants with five or more hours of sleep were more likely to respond to CBT-I than participants with fewer than five hours of sleep. Among participants with sleep duration of five or more hours, insomnia remission was more likely with CBT-I than with the control condition. The five-hour cutoff had no association with depression remission.

Among participants with six or more hours of sleep, those who received CBT-I were more likely to achieve insomnia remission than controls. The six-hour cutoff did not affect the likelihood of depression remission, however.

Among participants with seven or more hours of sleep, those randomized to CBT-I were more likely to achieve insomnia remission and depression remission than controls.

“More research is needed to determine how best to achieve depression remission in those patients with less than seven hours of objective sleep duration prior to starting treatment,” Dr. Edinger concluded.

—Erik Greb

Suggested Reading

Bathgate CJ, Edinger JD, Krystal AD. Insomnia patients with objective short sleep duration have a blunted response to cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia. Sleep. 2017;40(1).

Vgontzas AN, Liao D, Bixler EO, et al. Insomnia with objective short sleep duration is associated with a high risk for hypertension. Sleep. 2009;32(4):491-497.

Watson NF, Badr MS, Belenky G, et al. Recommended amount of sleep for a healthy adult: A joint consensus statement of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine and Sleep Research Society. Sleep. 2015;38(6):843-844.

BOSTON—Objective sleep duration moderates the probability of remission among patients with comorbid depression and insomnia, according to research presented at the 31st Annual Meeting of the Associated Professional Sleep Societies. Sleep durations of greater than five to six hours increase the likelihood that these patients will achieve insomnia remission with cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia (CBT-I), but do not affect the likelihood of depression remission. Sleep durations of seven or more hours optimize the likelihood of insomnia remission and depression remission in response to CBT-I.

In a 2015 consensus statement, the Sleep Research Society recommended seven or more hours of sleep per night for adults younger than 60. Investigations by Vgontzas and colleagues indicate that sleep durations of less than five hours and less than six hours are associated with increased morbidity and poor treatment response among patients with insomnia. “We wanted to know what [sleep-duration] cutoffs … might be better predictors of eventual insomnia and depression remission through treatment,” said Jack Edinger, PhD, Professor of Medicine at National Jewish Health in Denver.

An Analysis of the TRIAD Study

Dr. Edinger and colleagues conducted a secondary analysis of the TRIAD study, which examined whether combined treatment of depression and insomnia improves depression and sleep outcomes in participants with both disorders. Eligible participants met Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (4th ed.) criteria for major depression and primary insomnia, had a Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HAMD-17) score of 16 or greater, and had an Insomnia Severity Index (ISI) score of 11 or greater. People who had had psychotherapy in the previous four months, or had failed or could not tolerate previous adequate trials of the study medications, were excluded. Participants completed one night of baseline polysomnography before entering the treatment phase of the study.

The study population included 104 participants (75 women) with a mean age of 47. Mean baseline HAMD-17 score was 22, and mean baseline ISI score was 20.6. All participants received antidepressant medication (ie, citalopram, sertraline, or venlafaxine). Patients were randomized to CBT-I or sham (ie, a pseudo desensitization condition with sleep education). The investigators assessed participants biweekly with the HAMD-17 and the ISI. The treatment period lasted for 16 weeks.

CBT-I Provided Benefits

Participants with five or more hours of sleep were more likely to respond to CBT-I than participants with fewer than five hours of sleep. Among participants with sleep duration of five or more hours, insomnia remission was more likely with CBT-I than with the control condition. The five-hour cutoff had no association with depression remission.

Among participants with six or more hours of sleep, those who received CBT-I were more likely to achieve insomnia remission than controls. The six-hour cutoff did not affect the likelihood of depression remission, however.

Among participants with seven or more hours of sleep, those randomized to CBT-I were more likely to achieve insomnia remission and depression remission than controls.

“More research is needed to determine how best to achieve depression remission in those patients with less than seven hours of objective sleep duration prior to starting treatment,” Dr. Edinger concluded.

—Erik Greb

Suggested Reading

Bathgate CJ, Edinger JD, Krystal AD. Insomnia patients with objective short sleep duration have a blunted response to cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia. Sleep. 2017;40(1).

Vgontzas AN, Liao D, Bixler EO, et al. Insomnia with objective short sleep duration is associated with a high risk for hypertension. Sleep. 2009;32(4):491-497.

Watson NF, Badr MS, Belenky G, et al. Recommended amount of sleep for a healthy adult: A joint consensus statement of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine and Sleep Research Society. Sleep. 2015;38(6):843-844.

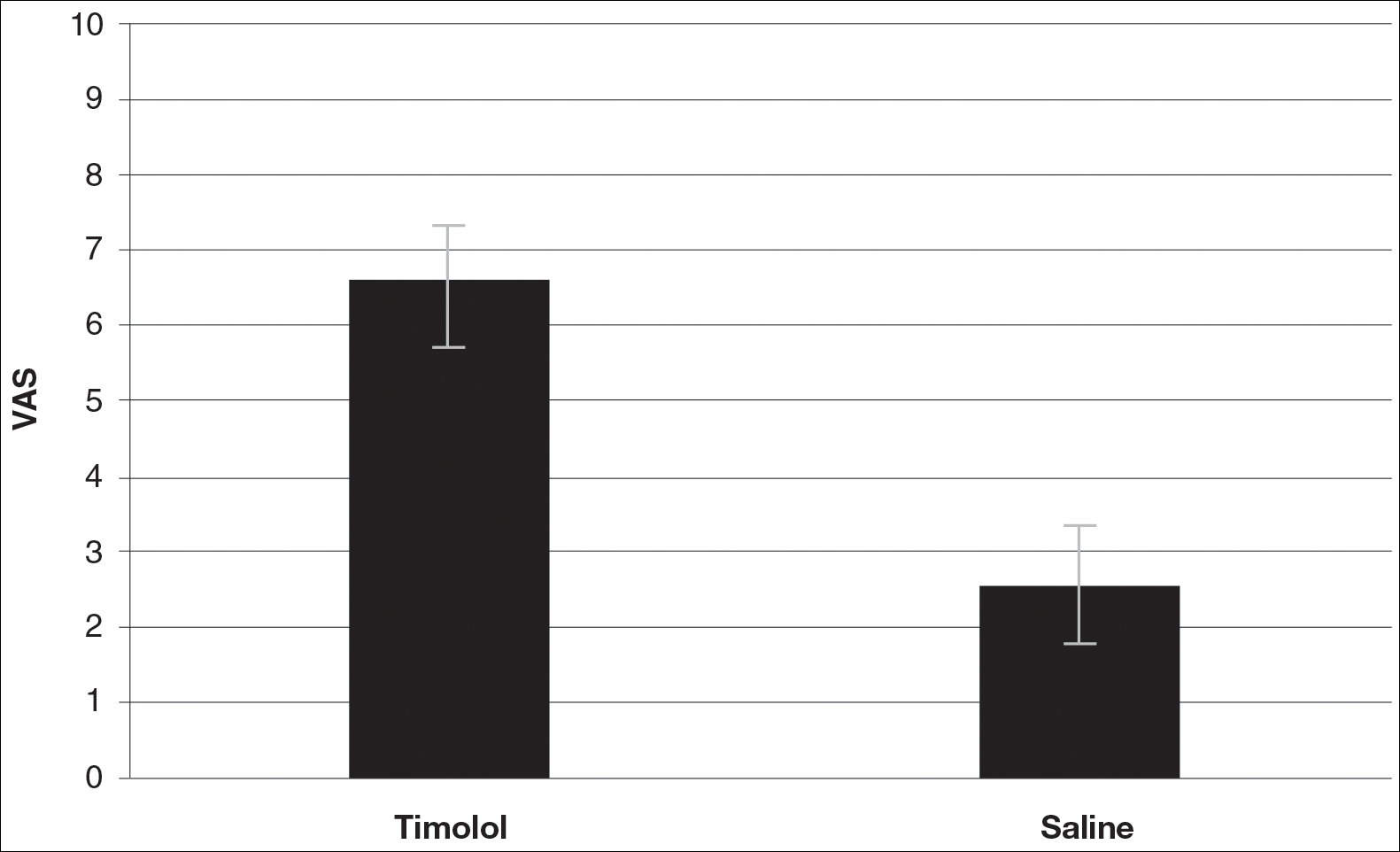

Topical Timolol May Improve Overall Scar Cosmesis in Acute Surgical Wounds

Timolol is a nonselective β-adrenergic receptor antagonist indicated for treating glaucoma, heart attacks, hypertension, and migraine headaches. It is made in both an oral and ophthalmic form. In dermatology, the beta-blocker propranolol is approved for the treatment of infantile hemangiomas (IHs). The exact mechanism of action of beta-blockers for the treatment of IHs is not yet completely understood, but it is postulated that they inhibit growth by at least 4 distinct mechanisms: (1) vasoconstriction, (2) inhibition of angiogenesis or vasculogenesis, (3) induction of apoptosis, and (4) recruitment of endothelial progenitor cells to the site of the hemangioma.1

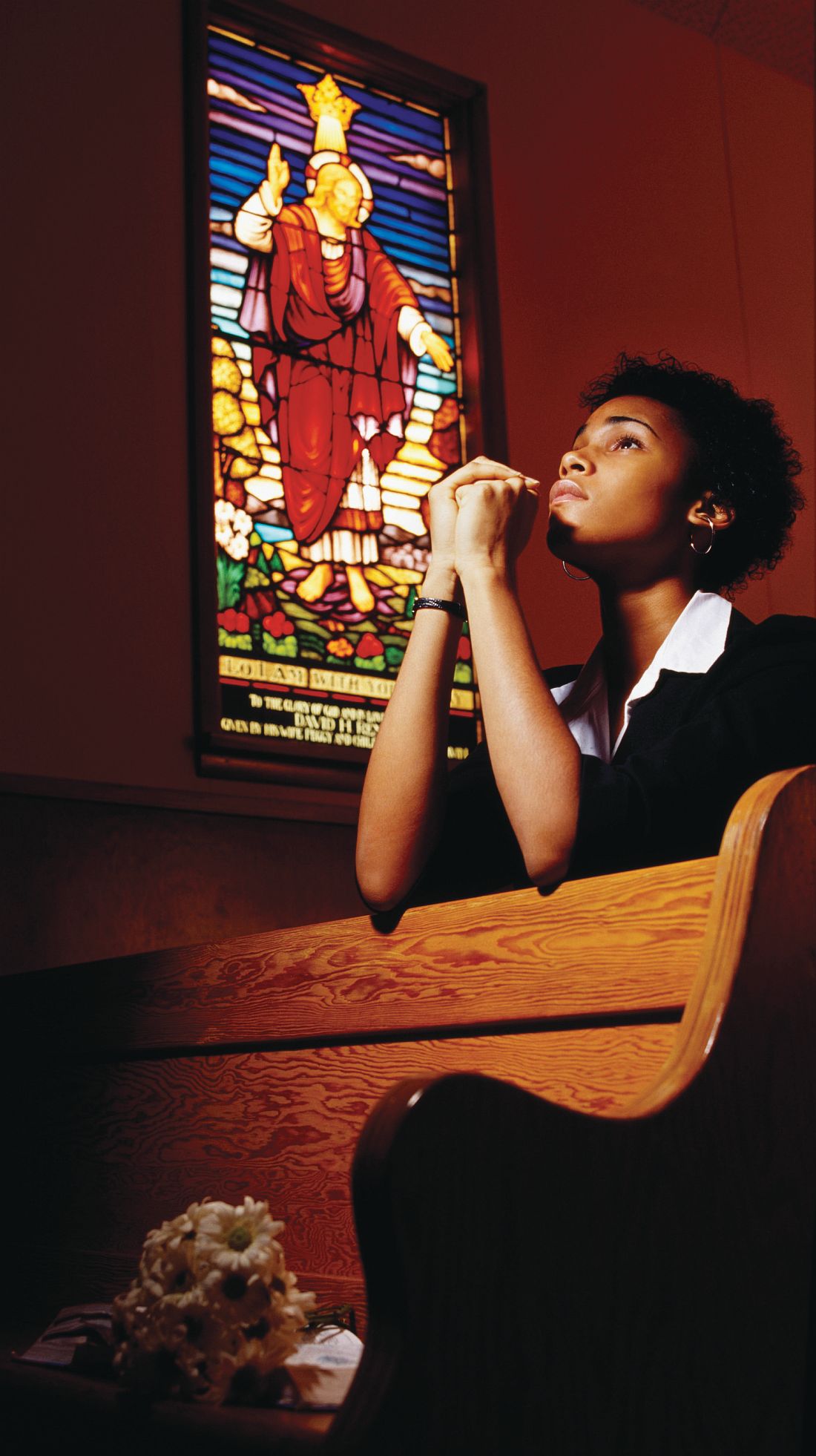

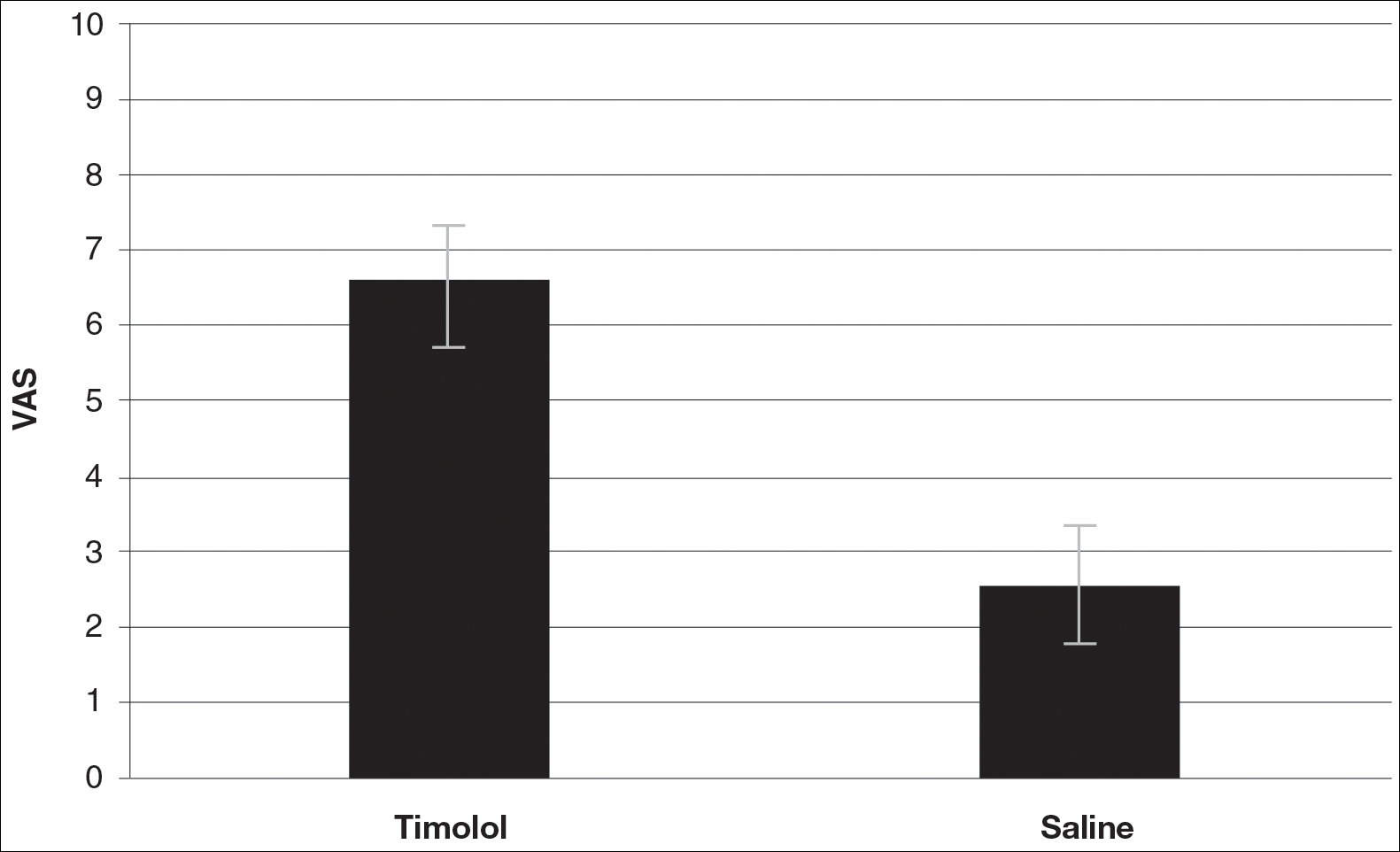

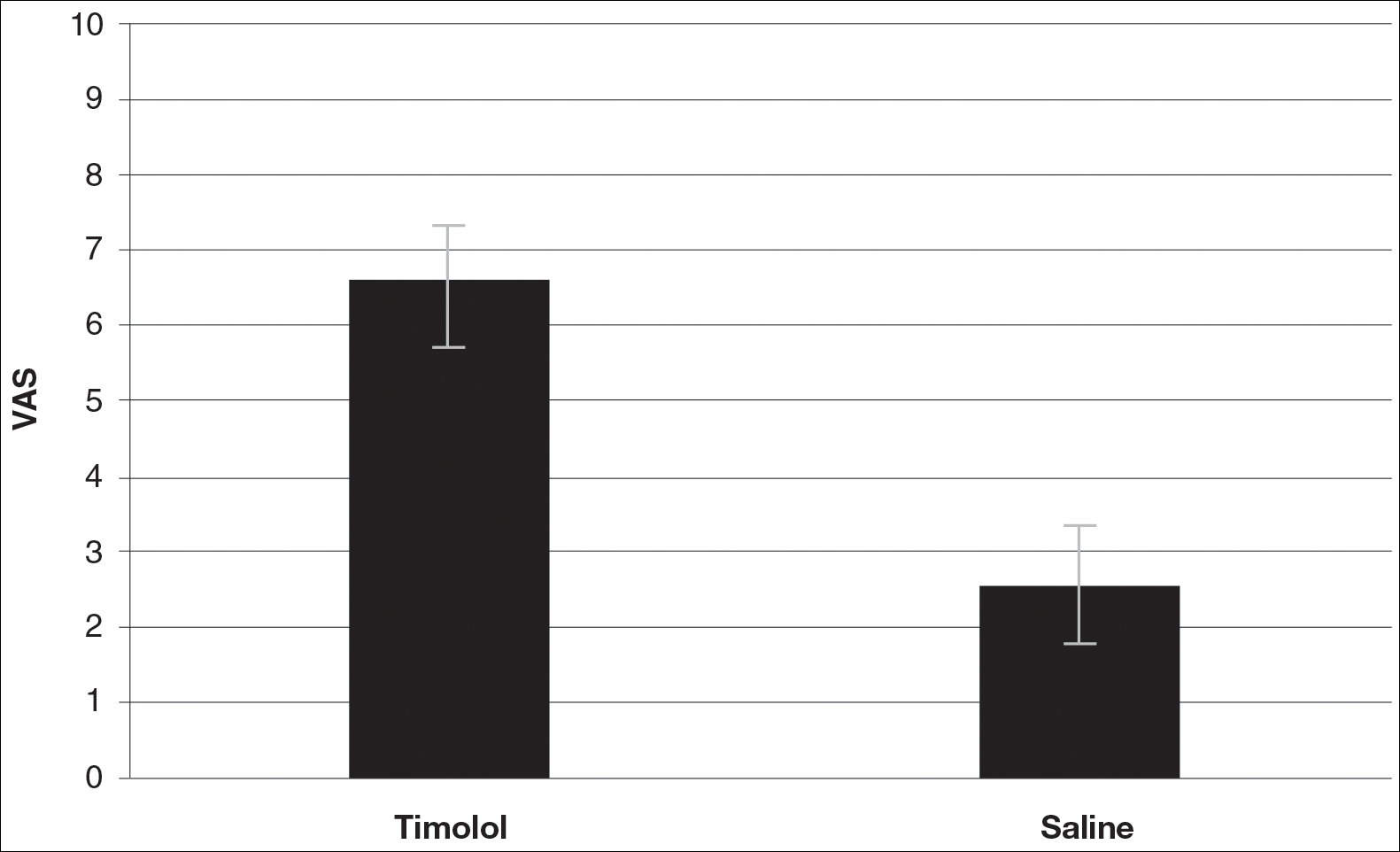

Scar cosmesis can be calculated using the visual analog scale (VAS), which is a subjective scar assessment scored from poor to excellent. The multidimensional VAS is a photograph-based scale derived from evaluating standardized digital photographs in 4 dimensions—pigmentation, vascularity, acceptability, and observer comfort—plus contour. It uses the sum of the individual scores to obtain a single overall score ranging from excellent to poor.2 In this study, we sought to determine if the use of topical timolol after excision or Mohs micrographic surgery (MMS) treatment of nonmelanoma skin cancers improved the overall cosmesis of the scar.

Methods

The study protocol was approved by the institutional review board at Roger Williams Medical Center (Providence, Rhode Island). Eligibility criteria included patients who required excision or MMS for their nonmelanoma skin cancer located below the patella and those who agreed to allow their wounds to heal by secondary intention when given options for closure of their wounds. Patients were randomized to either the timolol (study medication) group or the saline (placebo) group. The initial defects were measured and photographed. Patients were educated on how to apply the study medication. All patients were prescribed 40 mm Hg compression stockings to wear following application of the study medication. Patients were asked to return at 1 and 5 weeks postsurgery and then every 1 to 2 weeks for wound assessment and measurement until their wounds had healed or at 13 weeks, depending on which came first. A healed wound was defined as having no exudate, exhibiting complete reepithelialization, and being stable for 1 week.

Healed wounds were assessed by a blinded outside dermatologist who examined photographs of the wounds and then completed the VAS for each participant’s scar.

Results

A total of 9 participants were enrolled in the study. Three participants were lost to follow-up; 6 completed the study (4 females, 2 males). The mean age was 70 years (age range, 46–89 years). The average wound size was 2×2 cm with a depth of 1 mm. Three participants were in the active medication group and 3 were in the control group.

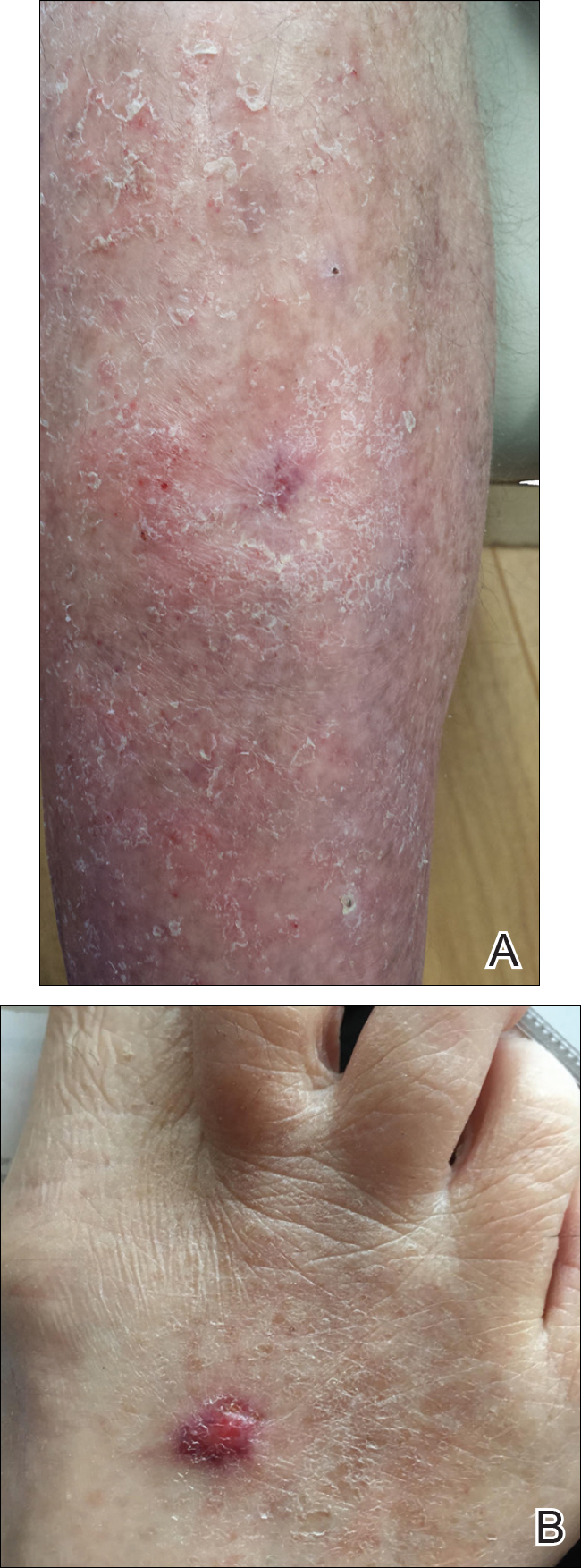

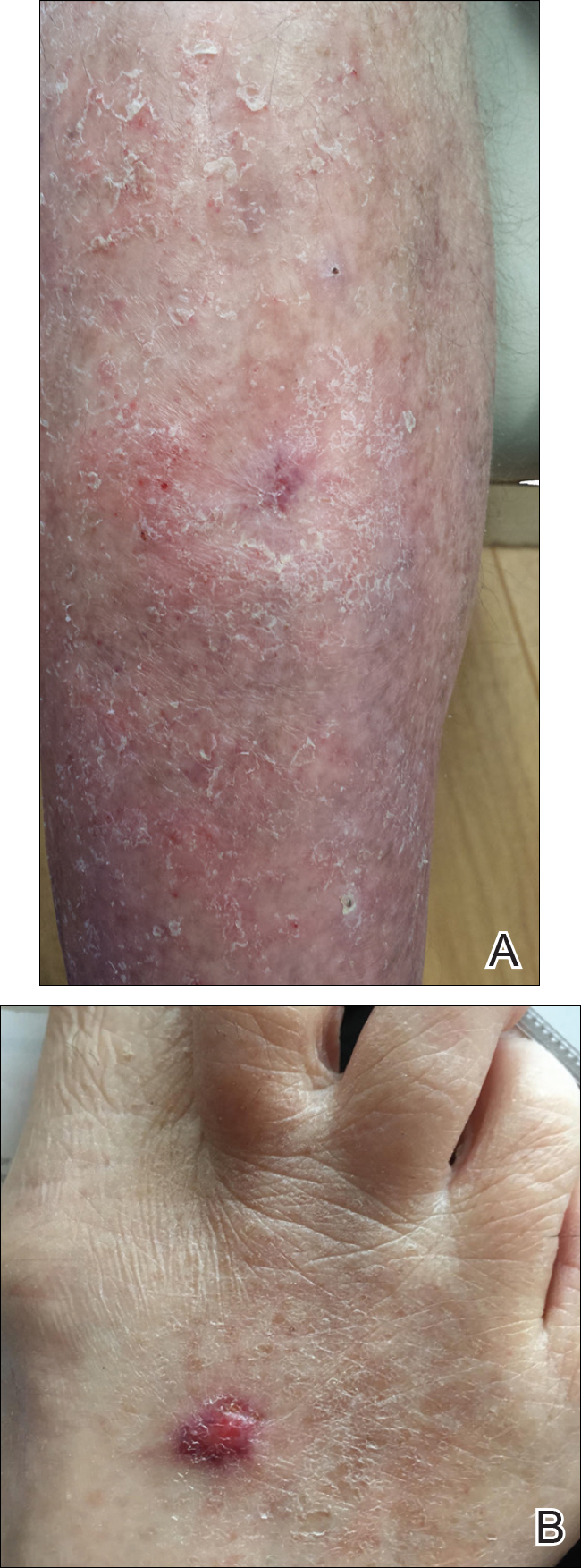

A VAS was completed for each participant’s scar by an outside blinded dermatologist. Based on the VAS, wounds treated with timolol resulted in more cosmetically favorable scars (scored higher on the VAS) compared to control (mean [SD]: 6.5±0.9 vs 2.5±0.7; P<0.05). See Figures 1 and 2 for representative results.

Comment

Dermatologists create acute wounds in patients on a daily basis. Ensuring that patients achieve the most desirable cosmetic outcome is a primary goal for dermatologists and an important component of patient satisfaction. A number of studies have examined patient satisfaction following MMS.3,4 Patient satisfaction is an especially important outcome measure in dermatology, as dermatologic diseases affect cosmetic appearance and are related to quality of life.3,4

Timolol is a nonselective β-adrenergic receptor antagonist that is used in dermatology to treat IHs. In this preliminary study, the authors sought to determine if topical timolol applied to acute wounds following surgical removal of nonmelanoma skin cancers could improve the overall cosmetic outcome of acute surgical scars. The results showed that compared to control, topical timolol resulted in a more cosmetically favorable scar. The results are preliminary, and it would be of future interest to further study the effects of topical timolol on acute surgical wounds from a wound-healing standpoint as well as to further test its effects on the cosmesis of these wounds.

- Chisholm KM, Chang KW, Truong MT, et al. β-Adrenergic receptor expression in vascular tumors [published online June 29, 2012]. Mod Pathol. 2012;25:1446-1451.

- Fearmonti R, Bond J, Erdmann D, et al. A review of scar scales and scar measuring devices. Eplasty. 2010;10:e43.

- Asgari MM, Warton EM, Neugebauer R, et al. Predictors of patient satisfaction with Mohs surgery: analysis of preoperative, intraoperative, and postoperative factors in a prospective cohort. Arch Dermatol. 2011;147:1387-1394.

- Asgari MM, Bertenthal D, Sen S, et al. Patient satisfaction after treatment of nonmelanoma skin cancer. Dermatol Surg. 2009;35:1041-1049.

Timolol is a nonselective β-adrenergic receptor antagonist indicated for treating glaucoma, heart attacks, hypertension, and migraine headaches. It is made in both an oral and ophthalmic form. In dermatology, the beta-blocker propranolol is approved for the treatment of infantile hemangiomas (IHs). The exact mechanism of action of beta-blockers for the treatment of IHs is not yet completely understood, but it is postulated that they inhibit growth by at least 4 distinct mechanisms: (1) vasoconstriction, (2) inhibition of angiogenesis or vasculogenesis, (3) induction of apoptosis, and (4) recruitment of endothelial progenitor cells to the site of the hemangioma.1

Scar cosmesis can be calculated using the visual analog scale (VAS), which is a subjective scar assessment scored from poor to excellent. The multidimensional VAS is a photograph-based scale derived from evaluating standardized digital photographs in 4 dimensions—pigmentation, vascularity, acceptability, and observer comfort—plus contour. It uses the sum of the individual scores to obtain a single overall score ranging from excellent to poor.2 In this study, we sought to determine if the use of topical timolol after excision or Mohs micrographic surgery (MMS) treatment of nonmelanoma skin cancers improved the overall cosmesis of the scar.

Methods

The study protocol was approved by the institutional review board at Roger Williams Medical Center (Providence, Rhode Island). Eligibility criteria included patients who required excision or MMS for their nonmelanoma skin cancer located below the patella and those who agreed to allow their wounds to heal by secondary intention when given options for closure of their wounds. Patients were randomized to either the timolol (study medication) group or the saline (placebo) group. The initial defects were measured and photographed. Patients were educated on how to apply the study medication. All patients were prescribed 40 mm Hg compression stockings to wear following application of the study medication. Patients were asked to return at 1 and 5 weeks postsurgery and then every 1 to 2 weeks for wound assessment and measurement until their wounds had healed or at 13 weeks, depending on which came first. A healed wound was defined as having no exudate, exhibiting complete reepithelialization, and being stable for 1 week.

Healed wounds were assessed by a blinded outside dermatologist who examined photographs of the wounds and then completed the VAS for each participant’s scar.

Results

A total of 9 participants were enrolled in the study. Three participants were lost to follow-up; 6 completed the study (4 females, 2 males). The mean age was 70 years (age range, 46–89 years). The average wound size was 2×2 cm with a depth of 1 mm. Three participants were in the active medication group and 3 were in the control group.

A VAS was completed for each participant’s scar by an outside blinded dermatologist. Based on the VAS, wounds treated with timolol resulted in more cosmetically favorable scars (scored higher on the VAS) compared to control (mean [SD]: 6.5±0.9 vs 2.5±0.7; P<0.05). See Figures 1 and 2 for representative results.

Comment

Dermatologists create acute wounds in patients on a daily basis. Ensuring that patients achieve the most desirable cosmetic outcome is a primary goal for dermatologists and an important component of patient satisfaction. A number of studies have examined patient satisfaction following MMS.3,4 Patient satisfaction is an especially important outcome measure in dermatology, as dermatologic diseases affect cosmetic appearance and are related to quality of life.3,4

Timolol is a nonselective β-adrenergic receptor antagonist that is used in dermatology to treat IHs. In this preliminary study, the authors sought to determine if topical timolol applied to acute wounds following surgical removal of nonmelanoma skin cancers could improve the overall cosmetic outcome of acute surgical scars. The results showed that compared to control, topical timolol resulted in a more cosmetically favorable scar. The results are preliminary, and it would be of future interest to further study the effects of topical timolol on acute surgical wounds from a wound-healing standpoint as well as to further test its effects on the cosmesis of these wounds.

Timolol is a nonselective β-adrenergic receptor antagonist indicated for treating glaucoma, heart attacks, hypertension, and migraine headaches. It is made in both an oral and ophthalmic form. In dermatology, the beta-blocker propranolol is approved for the treatment of infantile hemangiomas (IHs). The exact mechanism of action of beta-blockers for the treatment of IHs is not yet completely understood, but it is postulated that they inhibit growth by at least 4 distinct mechanisms: (1) vasoconstriction, (2) inhibition of angiogenesis or vasculogenesis, (3) induction of apoptosis, and (4) recruitment of endothelial progenitor cells to the site of the hemangioma.1

Scar cosmesis can be calculated using the visual analog scale (VAS), which is a subjective scar assessment scored from poor to excellent. The multidimensional VAS is a photograph-based scale derived from evaluating standardized digital photographs in 4 dimensions—pigmentation, vascularity, acceptability, and observer comfort—plus contour. It uses the sum of the individual scores to obtain a single overall score ranging from excellent to poor.2 In this study, we sought to determine if the use of topical timolol after excision or Mohs micrographic surgery (MMS) treatment of nonmelanoma skin cancers improved the overall cosmesis of the scar.

Methods

The study protocol was approved by the institutional review board at Roger Williams Medical Center (Providence, Rhode Island). Eligibility criteria included patients who required excision or MMS for their nonmelanoma skin cancer located below the patella and those who agreed to allow their wounds to heal by secondary intention when given options for closure of their wounds. Patients were randomized to either the timolol (study medication) group or the saline (placebo) group. The initial defects were measured and photographed. Patients were educated on how to apply the study medication. All patients were prescribed 40 mm Hg compression stockings to wear following application of the study medication. Patients were asked to return at 1 and 5 weeks postsurgery and then every 1 to 2 weeks for wound assessment and measurement until their wounds had healed or at 13 weeks, depending on which came first. A healed wound was defined as having no exudate, exhibiting complete reepithelialization, and being stable for 1 week.

Healed wounds were assessed by a blinded outside dermatologist who examined photographs of the wounds and then completed the VAS for each participant’s scar.

Results

A total of 9 participants were enrolled in the study. Three participants were lost to follow-up; 6 completed the study (4 females, 2 males). The mean age was 70 years (age range, 46–89 years). The average wound size was 2×2 cm with a depth of 1 mm. Three participants were in the active medication group and 3 were in the control group.

A VAS was completed for each participant’s scar by an outside blinded dermatologist. Based on the VAS, wounds treated with timolol resulted in more cosmetically favorable scars (scored higher on the VAS) compared to control (mean [SD]: 6.5±0.9 vs 2.5±0.7; P<0.05). See Figures 1 and 2 for representative results.

Comment

Dermatologists create acute wounds in patients on a daily basis. Ensuring that patients achieve the most desirable cosmetic outcome is a primary goal for dermatologists and an important component of patient satisfaction. A number of studies have examined patient satisfaction following MMS.3,4 Patient satisfaction is an especially important outcome measure in dermatology, as dermatologic diseases affect cosmetic appearance and are related to quality of life.3,4

Timolol is a nonselective β-adrenergic receptor antagonist that is used in dermatology to treat IHs. In this preliminary study, the authors sought to determine if topical timolol applied to acute wounds following surgical removal of nonmelanoma skin cancers could improve the overall cosmetic outcome of acute surgical scars. The results showed that compared to control, topical timolol resulted in a more cosmetically favorable scar. The results are preliminary, and it would be of future interest to further study the effects of topical timolol on acute surgical wounds from a wound-healing standpoint as well as to further test its effects on the cosmesis of these wounds.

- Chisholm KM, Chang KW, Truong MT, et al. β-Adrenergic receptor expression in vascular tumors [published online June 29, 2012]. Mod Pathol. 2012;25:1446-1451.

- Fearmonti R, Bond J, Erdmann D, et al. A review of scar scales and scar measuring devices. Eplasty. 2010;10:e43.

- Asgari MM, Warton EM, Neugebauer R, et al. Predictors of patient satisfaction with Mohs surgery: analysis of preoperative, intraoperative, and postoperative factors in a prospective cohort. Arch Dermatol. 2011;147:1387-1394.

- Asgari MM, Bertenthal D, Sen S, et al. Patient satisfaction after treatment of nonmelanoma skin cancer. Dermatol Surg. 2009;35:1041-1049.

- Chisholm KM, Chang KW, Truong MT, et al. β-Adrenergic receptor expression in vascular tumors [published online June 29, 2012]. Mod Pathol. 2012;25:1446-1451.

- Fearmonti R, Bond J, Erdmann D, et al. A review of scar scales and scar measuring devices. Eplasty. 2010;10:e43.

- Asgari MM, Warton EM, Neugebauer R, et al. Predictors of patient satisfaction with Mohs surgery: analysis of preoperative, intraoperative, and postoperative factors in a prospective cohort. Arch Dermatol. 2011;147:1387-1394.

- Asgari MM, Bertenthal D, Sen S, et al. Patient satisfaction after treatment of nonmelanoma skin cancer. Dermatol Surg. 2009;35:1041-1049.

Resident Pearl

- Dermatologists create acute surgical wounds on a daily basis. We should strive for excellent patient outcomes as well as the most desirable cosmetic result. This research article points to a possible new application of a longstanding medication to improve the cosmetic outcome in acute surgical wounds.

Better bariatric surgery outcomes with lower preoperative BMI

Delaying bariatric surgery until body mass index is highly elevated may reduce the likelihood of achieving a BMI of less than 30 within a year, according to a paper published online July 26 in JAMA Surgery.

A retrospective study using prospectively gathered clinical data of 27,320 adults who underwent bariatric surgery in Michigan showed around one in three (36%) achieved a BMI below 30 within a year after surgery (JAMA Surgery 2017, July 26. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2017.2348). But obese patients with a body mass index of less than 40 kg/m2 before undergoing bariatric surgery are significantly more likely to achieve a postoperative BMI of under 30.

Individuals who had a preoperative BMI of less than 40 had a 12-fold higher chance of getting their BMI below 30, compared to those whose preoperative BMI was 40 or above (95% confidence interval 1.71-14.16, P less than .001). Only 8.5% of individuals with a BMI at or above 50 achieved a postoperative BMI below 30.

The likelihood of getting below 30 within a year was eightfold higher in patients who had a sleeve gastrectomy, 21 times greater in those who underwent Roux-en-Y bypass, and 82 times higher in those who had a duodenal switch, compared with patients who had adjustable gastric banding (P less than .001).

The researchers also compared other outcomes in individuals whose BMI dropped below 30 and in those who did not achieve this degree of weight loss. The analysis showed that those with a BMI below 30 after 1 year had at least a twofold greater chance of discontinuing cholesterol-lowering medications, insulin, diabetes medications, antihypertensives, and CPAP for sleep apnea, compared with those whose BMI remained at 30 or above. They were also more than three times more likely to report being ‘very satisfied’ with the outcomes of surgery.

The authors noted that the cohort’s mean BMI was 48, which was above the established threshold for bariatric surgery, namely a BMI of 40, or 35 with weight-related comorbidities.

“Our results suggest that patients with morbid obesity should be targeted for surgery when their BMI is still less than 40, as these patients are more likely to achieve a target BMI that results in substantial reduction in weight-related comorbidities,” the authors wrote.

However, they stressed that their findings should not be taken as a reason to exclude patients with a BMI above 40 from surgery, pointing out that even for patients with higher preoperative BMIs, bariatric surgery offered substantial health and quality of life benefits.

They also acknowledged that 1-year weight data was available for around 50% of patients in the registry, which may have led to selection bias.

“Policies and practice patterns that delay or incentivize patients to pursue bariatric surgery only once the BMI is highly elevated can result in inferior outcomes,” the investigators concluded.

Blue Cross Blue Shield of Michigan/Blue Care Network funded the study. Three authors had received salary support from Blue Cross Blue Shield. No other conflicts of interest were declared.

Patients with obesity need a multidisciplinary approach to achieve a healthy weight, and AGA believes that gastroenterologists are in a unique position to lead the care team.

To provide gastroenterologists with a comprehensive, multi-disciplinary process to guide and personalize innovative obesity care for safe and effective weight management, including a model for how to operationalize business issues, AGA has created an Obesity Practice Guide. The program includes an obesity program to help gastroenterologists manage their patients with obesity, as well as a framework focused on the business operational issues related to the management of obese patients. Learn more at www.gastro.org/obesity.

The authors’ conclusion that bariatric surgery should be more liberally applied to patients with less severe obesity is consistent with multiple reports of improved control of type 2 diabetes, if not remission, among lower-BMI patient populations following MBS [metabolic and bariatric surgery]. However, these reports generally do not refute the importance of weight loss in achieving important clinical benefit among patients with obesity-related comorbid disease.

One strength of the present study is that it is a clinical database. However, 50% attrition of the follow-up weight loss data at 1 year is potentially problematic.

Bruce M. Wolfe, MD, FACS, and Elizaveta Walker, MPH, are in the division of bariatric surgery, department of surgery, at Oregon Health & Science University, Portland. These comments are taken from an accompanying editorial (JAMA Surgery 2017 Jul 26. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2017.2349). No conflicts of interest were declared.

The authors’ conclusion that bariatric surgery should be more liberally applied to patients with less severe obesity is consistent with multiple reports of improved control of type 2 diabetes, if not remission, among lower-BMI patient populations following MBS [metabolic and bariatric surgery]. However, these reports generally do not refute the importance of weight loss in achieving important clinical benefit among patients with obesity-related comorbid disease.

One strength of the present study is that it is a clinical database. However, 50% attrition of the follow-up weight loss data at 1 year is potentially problematic.

Bruce M. Wolfe, MD, FACS, and Elizaveta Walker, MPH, are in the division of bariatric surgery, department of surgery, at Oregon Health & Science University, Portland. These comments are taken from an accompanying editorial (JAMA Surgery 2017 Jul 26. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2017.2349). No conflicts of interest were declared.

The authors’ conclusion that bariatric surgery should be more liberally applied to patients with less severe obesity is consistent with multiple reports of improved control of type 2 diabetes, if not remission, among lower-BMI patient populations following MBS [metabolic and bariatric surgery]. However, these reports generally do not refute the importance of weight loss in achieving important clinical benefit among patients with obesity-related comorbid disease.

One strength of the present study is that it is a clinical database. However, 50% attrition of the follow-up weight loss data at 1 year is potentially problematic.

Bruce M. Wolfe, MD, FACS, and Elizaveta Walker, MPH, are in the division of bariatric surgery, department of surgery, at Oregon Health & Science University, Portland. These comments are taken from an accompanying editorial (JAMA Surgery 2017 Jul 26. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2017.2349). No conflicts of interest were declared.

Delaying bariatric surgery until body mass index is highly elevated may reduce the likelihood of achieving a BMI of less than 30 within a year, according to a paper published online July 26 in JAMA Surgery.

A retrospective study using prospectively gathered clinical data of 27,320 adults who underwent bariatric surgery in Michigan showed around one in three (36%) achieved a BMI below 30 within a year after surgery (JAMA Surgery 2017, July 26. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2017.2348). But obese patients with a body mass index of less than 40 kg/m2 before undergoing bariatric surgery are significantly more likely to achieve a postoperative BMI of under 30.

Individuals who had a preoperative BMI of less than 40 had a 12-fold higher chance of getting their BMI below 30, compared to those whose preoperative BMI was 40 or above (95% confidence interval 1.71-14.16, P less than .001). Only 8.5% of individuals with a BMI at or above 50 achieved a postoperative BMI below 30.

The likelihood of getting below 30 within a year was eightfold higher in patients who had a sleeve gastrectomy, 21 times greater in those who underwent Roux-en-Y bypass, and 82 times higher in those who had a duodenal switch, compared with patients who had adjustable gastric banding (P less than .001).

The researchers also compared other outcomes in individuals whose BMI dropped below 30 and in those who did not achieve this degree of weight loss. The analysis showed that those with a BMI below 30 after 1 year had at least a twofold greater chance of discontinuing cholesterol-lowering medications, insulin, diabetes medications, antihypertensives, and CPAP for sleep apnea, compared with those whose BMI remained at 30 or above. They were also more than three times more likely to report being ‘very satisfied’ with the outcomes of surgery.

The authors noted that the cohort’s mean BMI was 48, which was above the established threshold for bariatric surgery, namely a BMI of 40, or 35 with weight-related comorbidities.

“Our results suggest that patients with morbid obesity should be targeted for surgery when their BMI is still less than 40, as these patients are more likely to achieve a target BMI that results in substantial reduction in weight-related comorbidities,” the authors wrote.

However, they stressed that their findings should not be taken as a reason to exclude patients with a BMI above 40 from surgery, pointing out that even for patients with higher preoperative BMIs, bariatric surgery offered substantial health and quality of life benefits.

They also acknowledged that 1-year weight data was available for around 50% of patients in the registry, which may have led to selection bias.

“Policies and practice patterns that delay or incentivize patients to pursue bariatric surgery only once the BMI is highly elevated can result in inferior outcomes,” the investigators concluded.

Blue Cross Blue Shield of Michigan/Blue Care Network funded the study. Three authors had received salary support from Blue Cross Blue Shield. No other conflicts of interest were declared.

Patients with obesity need a multidisciplinary approach to achieve a healthy weight, and AGA believes that gastroenterologists are in a unique position to lead the care team.

To provide gastroenterologists with a comprehensive, multi-disciplinary process to guide and personalize innovative obesity care for safe and effective weight management, including a model for how to operationalize business issues, AGA has created an Obesity Practice Guide. The program includes an obesity program to help gastroenterologists manage their patients with obesity, as well as a framework focused on the business operational issues related to the management of obese patients. Learn more at www.gastro.org/obesity.

Delaying bariatric surgery until body mass index is highly elevated may reduce the likelihood of achieving a BMI of less than 30 within a year, according to a paper published online July 26 in JAMA Surgery.

A retrospective study using prospectively gathered clinical data of 27,320 adults who underwent bariatric surgery in Michigan showed around one in three (36%) achieved a BMI below 30 within a year after surgery (JAMA Surgery 2017, July 26. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2017.2348). But obese patients with a body mass index of less than 40 kg/m2 before undergoing bariatric surgery are significantly more likely to achieve a postoperative BMI of under 30.

Individuals who had a preoperative BMI of less than 40 had a 12-fold higher chance of getting their BMI below 30, compared to those whose preoperative BMI was 40 or above (95% confidence interval 1.71-14.16, P less than .001). Only 8.5% of individuals with a BMI at or above 50 achieved a postoperative BMI below 30.

The likelihood of getting below 30 within a year was eightfold higher in patients who had a sleeve gastrectomy, 21 times greater in those who underwent Roux-en-Y bypass, and 82 times higher in those who had a duodenal switch, compared with patients who had adjustable gastric banding (P less than .001).

The researchers also compared other outcomes in individuals whose BMI dropped below 30 and in those who did not achieve this degree of weight loss. The analysis showed that those with a BMI below 30 after 1 year had at least a twofold greater chance of discontinuing cholesterol-lowering medications, insulin, diabetes medications, antihypertensives, and CPAP for sleep apnea, compared with those whose BMI remained at 30 or above. They were also more than three times more likely to report being ‘very satisfied’ with the outcomes of surgery.

The authors noted that the cohort’s mean BMI was 48, which was above the established threshold for bariatric surgery, namely a BMI of 40, or 35 with weight-related comorbidities.

“Our results suggest that patients with morbid obesity should be targeted for surgery when their BMI is still less than 40, as these patients are more likely to achieve a target BMI that results in substantial reduction in weight-related comorbidities,” the authors wrote.

However, they stressed that their findings should not be taken as a reason to exclude patients with a BMI above 40 from surgery, pointing out that even for patients with higher preoperative BMIs, bariatric surgery offered substantial health and quality of life benefits.

They also acknowledged that 1-year weight data was available for around 50% of patients in the registry, which may have led to selection bias.

“Policies and practice patterns that delay or incentivize patients to pursue bariatric surgery only once the BMI is highly elevated can result in inferior outcomes,” the investigators concluded.

Blue Cross Blue Shield of Michigan/Blue Care Network funded the study. Three authors had received salary support from Blue Cross Blue Shield. No other conflicts of interest were declared.

Patients with obesity need a multidisciplinary approach to achieve a healthy weight, and AGA believes that gastroenterologists are in a unique position to lead the care team.

To provide gastroenterologists with a comprehensive, multi-disciplinary process to guide and personalize innovative obesity care for safe and effective weight management, including a model for how to operationalize business issues, AGA has created an Obesity Practice Guide. The program includes an obesity program to help gastroenterologists manage their patients with obesity, as well as a framework focused on the business operational issues related to the management of obese patients. Learn more at www.gastro.org/obesity.

FROM JAMA SURGERY

Key clinical point: A BMI below 40 prior to undergoing bariatric surgery gives patients a significantly better chance of achieving a 1-year postoperative BMI under 30.

Major finding: Obese patients with a BMI less than 40 before undergoing bariatric surgery are more than 12 times more likely to achieve a postoperative BMI of under 30.

Data source: A retrospective study using prospectively gathered clinical data of 27, 320 adults who underwent bariatric surgery.

Disclosures: Blue Cross Blue Shield of Michigan/Blue Care Network funded the study. Three authors had received salary support from Blue Cross Blue Shield. No other conflicts of interest were declared.

Elective open conversion after failed EVAR safer than emergent

Emergency open conversion after failed endovascular aortic aneurysm repair shows significantly higher mortality and morbidity, compared with elective conversion, according to the results of a retrospective, observational study of 31 patients at a single institution.

The primary endpoints of the study were 30-day and in-hospital mortality. Secondary endpoints included moderate to severe complications, secondary interventions, length of ICU stay, and length of hospital stay (LOS), according to I. Ben Abdallah, MD, of the Hôpital Européen Georges Pompidou and his colleagues.

During the study period, a total of 338 patients received EVAR at the institution. Of these, 31 patients underwent open conversion (19 elective, 12 emergent) after EVAR between August 2008 and September 2016. The median time from the index EVAR to the open conversion was 35 months, with the most common indications for intervention being endoleaks (24 patients, 77%), stent graft infection (3, 10%), thrombosis (3, 10%) and kinking (1, 3%). Stents removed were manufactured by various device makers, according to the report (Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2017;53:831-6).

The patient population had a mean age of 73 years and comprised 84% men. The two groups, elective and emergent, were highly similar in numerous comorbidities, with the only significant difference between them being a greater incidence of chronic renal disease among the emergent group, as compared with the elective (42% vs. 5%).

Overall in-hospital mortality was 10%, and significantly greater in emergent vs. elective conversion (25% vs. 0%). Renal and pulmonary complications were significantly higher in the emergency group (42% vs. 5% and 42% vs. 0%, respectively). There was no significant difference between elective and emergent hospital stay (14 days vs. 20 days), but ICU stay was significantly shorter for elective conversion (2 days vs. 7 days).

There were no late complications or death seen in either group after a mean follow-up of 18 months.

“In this series, open conversion seems to be significantly safer and more effective when performed electively with no mortality, a lower incidence of morbidity (renal and pulmonary), and shorter ICU stay. These results underline that close surveillance, allowing planned elective open conversion, is the key to better outcomes after failed EVAR,” the researchers concluded.

The authors reported that they had no conflicts of interest, and the study received no outside funding.

Emergency open conversion after failed endovascular aortic aneurysm repair shows significantly higher mortality and morbidity, compared with elective conversion, according to the results of a retrospective, observational study of 31 patients at a single institution.

The primary endpoints of the study were 30-day and in-hospital mortality. Secondary endpoints included moderate to severe complications, secondary interventions, length of ICU stay, and length of hospital stay (LOS), according to I. Ben Abdallah, MD, of the Hôpital Européen Georges Pompidou and his colleagues.

During the study period, a total of 338 patients received EVAR at the institution. Of these, 31 patients underwent open conversion (19 elective, 12 emergent) after EVAR between August 2008 and September 2016. The median time from the index EVAR to the open conversion was 35 months, with the most common indications for intervention being endoleaks (24 patients, 77%), stent graft infection (3, 10%), thrombosis (3, 10%) and kinking (1, 3%). Stents removed were manufactured by various device makers, according to the report (Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2017;53:831-6).

The patient population had a mean age of 73 years and comprised 84% men. The two groups, elective and emergent, were highly similar in numerous comorbidities, with the only significant difference between them being a greater incidence of chronic renal disease among the emergent group, as compared with the elective (42% vs. 5%).

Overall in-hospital mortality was 10%, and significantly greater in emergent vs. elective conversion (25% vs. 0%). Renal and pulmonary complications were significantly higher in the emergency group (42% vs. 5% and 42% vs. 0%, respectively). There was no significant difference between elective and emergent hospital stay (14 days vs. 20 days), but ICU stay was significantly shorter for elective conversion (2 days vs. 7 days).

There were no late complications or death seen in either group after a mean follow-up of 18 months.

“In this series, open conversion seems to be significantly safer and more effective when performed electively with no mortality, a lower incidence of morbidity (renal and pulmonary), and shorter ICU stay. These results underline that close surveillance, allowing planned elective open conversion, is the key to better outcomes after failed EVAR,” the researchers concluded.

The authors reported that they had no conflicts of interest, and the study received no outside funding.

Emergency open conversion after failed endovascular aortic aneurysm repair shows significantly higher mortality and morbidity, compared with elective conversion, according to the results of a retrospective, observational study of 31 patients at a single institution.

The primary endpoints of the study were 30-day and in-hospital mortality. Secondary endpoints included moderate to severe complications, secondary interventions, length of ICU stay, and length of hospital stay (LOS), according to I. Ben Abdallah, MD, of the Hôpital Européen Georges Pompidou and his colleagues.

During the study period, a total of 338 patients received EVAR at the institution. Of these, 31 patients underwent open conversion (19 elective, 12 emergent) after EVAR between August 2008 and September 2016. The median time from the index EVAR to the open conversion was 35 months, with the most common indications for intervention being endoleaks (24 patients, 77%), stent graft infection (3, 10%), thrombosis (3, 10%) and kinking (1, 3%). Stents removed were manufactured by various device makers, according to the report (Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2017;53:831-6).

The patient population had a mean age of 73 years and comprised 84% men. The two groups, elective and emergent, were highly similar in numerous comorbidities, with the only significant difference between them being a greater incidence of chronic renal disease among the emergent group, as compared with the elective (42% vs. 5%).

Overall in-hospital mortality was 10%, and significantly greater in emergent vs. elective conversion (25% vs. 0%). Renal and pulmonary complications were significantly higher in the emergency group (42% vs. 5% and 42% vs. 0%, respectively). There was no significant difference between elective and emergent hospital stay (14 days vs. 20 days), but ICU stay was significantly shorter for elective conversion (2 days vs. 7 days).

There were no late complications or death seen in either group after a mean follow-up of 18 months.

“In this series, open conversion seems to be significantly safer and more effective when performed electively with no mortality, a lower incidence of morbidity (renal and pulmonary), and shorter ICU stay. These results underline that close surveillance, allowing planned elective open conversion, is the key to better outcomes after failed EVAR,” the researchers concluded.

The authors reported that they had no conflicts of interest, and the study received no outside funding.

FROM THE EUROPEAN JOURNAL OF VASCULAR AND ENDOVASCULAR SURGERY

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Overall in-hospital mortality was 10% and significantly greater in emergent vs. elective conversion (25% vs. 0%).

Data source: A retrospective database analysis of 31 patients undergoing EVAR open conversion at a single institution.

Disclosures: The authors reported that they had no conflicts of interest, and the study received no outside funding.

Fujifilm issues recall to update ED-530XT duodenoscopes

Fujifilm has issued an Urgent Medical Device Correction and Removal notification for all ED-530XT duodenoscopes, according to a Safety Alert from the Food and Drug Administration.

The recall, initiated voluntarily by Fujifilm, includes replacement of the ED-530XT forceps elevator mechanism including the O-ring seal, replacement of the distal end cap, and new operation manuals. The FDA authorized the changes on July 21, 2017.

“Reprocessing is a detailed, multistep process to clean and disinfect or sterilize reusable devices. The FDA has been working with duodenoscope manufacturers as they modify and validate their reprocessing instructions to further enhance the safety margin of their devices and show with a high degree of assurance that their reprocessing instructions, when followed correctly, effectively clean and disinfect the duodenoscopes,” the FDA said in the press release.

Find the full Safety Alert on the FDA website.

The AGA Center for GI Innovation and Technology is committed to working towards zero device-associated infections and will keep you apprised of any future updates. Learn more at www.gastro.org/CGIT.

Fujifilm has issued an Urgent Medical Device Correction and Removal notification for all ED-530XT duodenoscopes, according to a Safety Alert from the Food and Drug Administration.

The recall, initiated voluntarily by Fujifilm, includes replacement of the ED-530XT forceps elevator mechanism including the O-ring seal, replacement of the distal end cap, and new operation manuals. The FDA authorized the changes on July 21, 2017.

“Reprocessing is a detailed, multistep process to clean and disinfect or sterilize reusable devices. The FDA has been working with duodenoscope manufacturers as they modify and validate their reprocessing instructions to further enhance the safety margin of their devices and show with a high degree of assurance that their reprocessing instructions, when followed correctly, effectively clean and disinfect the duodenoscopes,” the FDA said in the press release.

Find the full Safety Alert on the FDA website.

The AGA Center for GI Innovation and Technology is committed to working towards zero device-associated infections and will keep you apprised of any future updates. Learn more at www.gastro.org/CGIT.

Fujifilm has issued an Urgent Medical Device Correction and Removal notification for all ED-530XT duodenoscopes, according to a Safety Alert from the Food and Drug Administration.

The recall, initiated voluntarily by Fujifilm, includes replacement of the ED-530XT forceps elevator mechanism including the O-ring seal, replacement of the distal end cap, and new operation manuals. The FDA authorized the changes on July 21, 2017.

“Reprocessing is a detailed, multistep process to clean and disinfect or sterilize reusable devices. The FDA has been working with duodenoscope manufacturers as they modify and validate their reprocessing instructions to further enhance the safety margin of their devices and show with a high degree of assurance that their reprocessing instructions, when followed correctly, effectively clean and disinfect the duodenoscopes,” the FDA said in the press release.

Find the full Safety Alert on the FDA website.

The AGA Center for GI Innovation and Technology is committed to working towards zero device-associated infections and will keep you apprised of any future updates. Learn more at www.gastro.org/CGIT.

Student Hospitalist Scholars: Discovering a passion for research

Editor’s Note: The Society of Hospital Medicine’s (SHM’s) Physician in Training Committee launched a scholarship program in 2015 for medical students to help transform health care and revolutionize patient care. The program has been expanded for the 2017-2018 year, offering two options for students to receive funding and engage in scholarly work during their first, second, and third years of medical school. As a part of the program, recipients are required to write about their experience on a biweekly basis.

When I decided to leave the business world to pursue a career in medicine, I envisioned myself in a clinic or an operating room helping the people in my community with the knowledge and skills acquired in my medical training. The thought of becoming a researcher had never even crossed my mind.

I grew up in Scottsdale, Arizona, a city which has no major academic medical centers. Prior to entering medical school, I was enrolled in a postbaccalaureate program at Johns Hopkins University, where I took the basic science classes necessary to apply. I was quite surprised to learn that, even at this level of education, I was required to participate in a research project. This experience changed the way I envisioned my entire career as a physician.

I am now a fourth year medical student and a pioneer of the “new curriculum” at Weill Cornell Medical College. In contrast to the traditional medical school curriculum, Cornell carved out 6 months of protected research time for all medical students by condensing the preclinical curriculum from 2 years to 1.5 years. I learned how much I enjoyed research at Johns Hopkins, which is one of the main reasons I applied here.

Despite my interest in research, I still struggled with the ultimate career question: What kind of doctor do I want to be?

After completing my medicine clerkship, I remember feeling intellectually stimulated in a way I hadn’t experienced in the previous years. While this may have had to do with the subject matter, I attribute much of this feeling to my clerkship director whose passion for medicine and teaching was contagious. I ultimately chose Ernie Esquivel, MD, to be my research mentor because of how much he impacted my education.

Together we came up with a project to study the utility of bone biopsies in the management of osteomyelitis. We are doing this by analyzing changes from empiric to final antibiotics after bone biopsy results become available to determine how clinicians use this information to guide their management of the disease. We were also interested in analyzing predictors of positive bone cultures in this population. The success of this project will mostly be based on our ability to perform these analyses, regardless of what the results may be. We hypothesize that, in fact, bone biopsy results are not likely to have a significant impact on antibiotic management of osteomyelitis in nonvertebral bones.

I was one of the lucky few to be awarded a grant from the Society of Hospital Medicine, which will be instrumental in the success of the project. This grant will not only support my ongoing research efforts but will also afford me the opportunity to attend the annual SHM conference and become integrated into the medical community in a way that would otherwise never be possible.

Cole Hirschfeld is originally from Phoenix, Ariz. He received undergraduate degrees in finance and entrepreneurship from the University of Arizona and went on to work in the finance industry for 2 years before deciding to change careers and attend medical school. He is now a fourth year medical student at Weill Cornell Medical College and plans to apply for residency in internal medicine.

Editor’s Note: The Society of Hospital Medicine’s (SHM’s) Physician in Training Committee launched a scholarship program in 2015 for medical students to help transform health care and revolutionize patient care. The program has been expanded for the 2017-2018 year, offering two options for students to receive funding and engage in scholarly work during their first, second, and third years of medical school. As a part of the program, recipients are required to write about their experience on a biweekly basis.

When I decided to leave the business world to pursue a career in medicine, I envisioned myself in a clinic or an operating room helping the people in my community with the knowledge and skills acquired in my medical training. The thought of becoming a researcher had never even crossed my mind.

I grew up in Scottsdale, Arizona, a city which has no major academic medical centers. Prior to entering medical school, I was enrolled in a postbaccalaureate program at Johns Hopkins University, where I took the basic science classes necessary to apply. I was quite surprised to learn that, even at this level of education, I was required to participate in a research project. This experience changed the way I envisioned my entire career as a physician.

I am now a fourth year medical student and a pioneer of the “new curriculum” at Weill Cornell Medical College. In contrast to the traditional medical school curriculum, Cornell carved out 6 months of protected research time for all medical students by condensing the preclinical curriculum from 2 years to 1.5 years. I learned how much I enjoyed research at Johns Hopkins, which is one of the main reasons I applied here.

Despite my interest in research, I still struggled with the ultimate career question: What kind of doctor do I want to be?

After completing my medicine clerkship, I remember feeling intellectually stimulated in a way I hadn’t experienced in the previous years. While this may have had to do with the subject matter, I attribute much of this feeling to my clerkship director whose passion for medicine and teaching was contagious. I ultimately chose Ernie Esquivel, MD, to be my research mentor because of how much he impacted my education.

Together we came up with a project to study the utility of bone biopsies in the management of osteomyelitis. We are doing this by analyzing changes from empiric to final antibiotics after bone biopsy results become available to determine how clinicians use this information to guide their management of the disease. We were also interested in analyzing predictors of positive bone cultures in this population. The success of this project will mostly be based on our ability to perform these analyses, regardless of what the results may be. We hypothesize that, in fact, bone biopsy results are not likely to have a significant impact on antibiotic management of osteomyelitis in nonvertebral bones.

I was one of the lucky few to be awarded a grant from the Society of Hospital Medicine, which will be instrumental in the success of the project. This grant will not only support my ongoing research efforts but will also afford me the opportunity to attend the annual SHM conference and become integrated into the medical community in a way that would otherwise never be possible.

Cole Hirschfeld is originally from Phoenix, Ariz. He received undergraduate degrees in finance and entrepreneurship from the University of Arizona and went on to work in the finance industry for 2 years before deciding to change careers and attend medical school. He is now a fourth year medical student at Weill Cornell Medical College and plans to apply for residency in internal medicine.

Editor’s Note: The Society of Hospital Medicine’s (SHM’s) Physician in Training Committee launched a scholarship program in 2015 for medical students to help transform health care and revolutionize patient care. The program has been expanded for the 2017-2018 year, offering two options for students to receive funding and engage in scholarly work during their first, second, and third years of medical school. As a part of the program, recipients are required to write about their experience on a biweekly basis.

When I decided to leave the business world to pursue a career in medicine, I envisioned myself in a clinic or an operating room helping the people in my community with the knowledge and skills acquired in my medical training. The thought of becoming a researcher had never even crossed my mind.

I grew up in Scottsdale, Arizona, a city which has no major academic medical centers. Prior to entering medical school, I was enrolled in a postbaccalaureate program at Johns Hopkins University, where I took the basic science classes necessary to apply. I was quite surprised to learn that, even at this level of education, I was required to participate in a research project. This experience changed the way I envisioned my entire career as a physician.

I am now a fourth year medical student and a pioneer of the “new curriculum” at Weill Cornell Medical College. In contrast to the traditional medical school curriculum, Cornell carved out 6 months of protected research time for all medical students by condensing the preclinical curriculum from 2 years to 1.5 years. I learned how much I enjoyed research at Johns Hopkins, which is one of the main reasons I applied here.

Despite my interest in research, I still struggled with the ultimate career question: What kind of doctor do I want to be?

After completing my medicine clerkship, I remember feeling intellectually stimulated in a way I hadn’t experienced in the previous years. While this may have had to do with the subject matter, I attribute much of this feeling to my clerkship director whose passion for medicine and teaching was contagious. I ultimately chose Ernie Esquivel, MD, to be my research mentor because of how much he impacted my education.

Together we came up with a project to study the utility of bone biopsies in the management of osteomyelitis. We are doing this by analyzing changes from empiric to final antibiotics after bone biopsy results become available to determine how clinicians use this information to guide their management of the disease. We were also interested in analyzing predictors of positive bone cultures in this population. The success of this project will mostly be based on our ability to perform these analyses, regardless of what the results may be. We hypothesize that, in fact, bone biopsy results are not likely to have a significant impact on antibiotic management of osteomyelitis in nonvertebral bones.

I was one of the lucky few to be awarded a grant from the Society of Hospital Medicine, which will be instrumental in the success of the project. This grant will not only support my ongoing research efforts but will also afford me the opportunity to attend the annual SHM conference and become integrated into the medical community in a way that would otherwise never be possible.

Cole Hirschfeld is originally from Phoenix, Ariz. He received undergraduate degrees in finance and entrepreneurship from the University of Arizona and went on to work in the finance industry for 2 years before deciding to change careers and attend medical school. He is now a fourth year medical student at Weill Cornell Medical College and plans to apply for residency in internal medicine.

Less lenalidomide may be more in frail elderly multiple myeloma patients