User login

A second-degree burn after MRI

A 48-year-old Nicaraguan man underwent mag netic resonance imaging (MRI) 3 days after admission to a South Florida hospital for treatment of cellulitis of the right thigh with vancomycin. MRI had been ordered to evaluate for a possible drainable source of infection, as the clinical picture and duration of illness was worsening and longer than expected for typical uncomplicated cellulitis despite intravenous antibiotic therapy. The MRI showed multiple enlarged inguinal lymph nodes and cellulitis of the superficial soft tissues of the thigh without discrete drainable collections.

After the procedure, the patient was noted to have a bullous lesion on each thigh, each lesion roughly 1 cm in diameter and filled with clear serous fluid (Figure 1). He reported that his legs had been pressed together before entering the MRI machine and that he had felt a burning sensation in both thighs during the test. Examination confirmed that the lesions indeed aligned with each other when he pressed his thighs together.

Study of a biopsy of one of the lesions revealed subepidermal cell blisters with focal epidermal necrosis and coagulative changes in the superficial dermis, consistent with a thermal injury (Figure 2).

HOW BURNS CAN OCCUR DURING MRI

Thermal burns are a potential cause of injury during MRI. Most have been observed in patients connected to external metal-containing monitoring devices, such as electrocardiogram leads and pulse oximeters.1,2 Thermal burns in patients unconnected to external devices have occurred when the patient’s body was touching radiofrequency coils3 or, as with our patient, when skin touches skin.2,4,5 Skin-to-skin contact during MRI can cause the scanner to emit high-power electromagnetic radiofrequency pulses that are conducted through the body, creating heat. Tissue loops are created at points of skin-to-skin contact, thus forming a closed conducting circuit. The current flowing through this circuit can produce second-degree burns.4

We believe that during placement in the scanner, our patient inadvertently moved his thighs together, forming a closed loop conduction circuit and resulting in a thermal burn.

This case illustrates the importance of correct positioning during MRI. The MRI technicians had taken standard precautions, placing a sheet over the patient and ensuring no direct contact with the radiofrequency transmitter receiver (MR unit). However, precautions against skin-to-skin contact were not taken, and the patient’s legs were not separated.

LESSONS LEARNED

Appropriate positioning prevents closed skin-to-skin loops, but this may be more challenging in a larger patient.6 While the patient is in the scanner, a “squeeze ball” alert system allows the patient to signal the technologist should unexpected distress or heating occur.6,7 A patient’s inability to utilize the squeeze ball contributes to the risk of a severe injury. Further, in this instance, there may have been a language barrier. Also, proximity of the anatomic skin-to-skin loop to the imaged body part (and therefore the center of the MRI coil) may have conferred risk related to field strength in this patient.

The MRI technologist, under supervision of a radiologist, is primarily responsible for positioning the patient to decrease the risk of this complication and for following institutional MRI safety protocols and professional guidelines.6–8 MRI technologist certification training highlights all aspects of safety, including skin-to-skin conducting loop prevention.7,8

- Dempsey MF, Condon B. Thermal injuries associated with MRI. Clin Radiol 2001; 56:457–465.

- Haik J, Daniel S, Tessone A, Orenstein A, Winkler E. MRI induced fourth-degree burn in an extremity, leading to amputation. Burns 2009; 35:294–296.

- Friedstat J, Moore ME, Goverman J, Fagan SP. An unusual burn during routine magnetic resonance imaging. J Burn Care Res 2013; 34: e110–e111.

- Eising EG, Hughes J, Nolte F, Jentzen W, Bockisch A. Burn injury by nuclear magnetic resonance imaging. Clin Imaging 2010; 34:293–297.

- Landman A, Goldfarb S. Magnetic resonance-induced thermal burn. Ann Emerg Med 2008; 52:308–309.

- Expert Panel on MR Safety; Kanal E, Barkovich AJ, Bell C, et al. ACR guidance document on MR safe practices: 2013. J Magn Reson Imaging 2013; 37:501–530.

- Magnetic resonance safety. Radiol Technol 2010; 81:615–616.

- Shellock FG, Crues JV. MR procedures: biologic effects, safety, and patient care. Radiology 2004; 232:635–652.

A 48-year-old Nicaraguan man underwent mag netic resonance imaging (MRI) 3 days after admission to a South Florida hospital for treatment of cellulitis of the right thigh with vancomycin. MRI had been ordered to evaluate for a possible drainable source of infection, as the clinical picture and duration of illness was worsening and longer than expected for typical uncomplicated cellulitis despite intravenous antibiotic therapy. The MRI showed multiple enlarged inguinal lymph nodes and cellulitis of the superficial soft tissues of the thigh without discrete drainable collections.

After the procedure, the patient was noted to have a bullous lesion on each thigh, each lesion roughly 1 cm in diameter and filled with clear serous fluid (Figure 1). He reported that his legs had been pressed together before entering the MRI machine and that he had felt a burning sensation in both thighs during the test. Examination confirmed that the lesions indeed aligned with each other when he pressed his thighs together.

Study of a biopsy of one of the lesions revealed subepidermal cell blisters with focal epidermal necrosis and coagulative changes in the superficial dermis, consistent with a thermal injury (Figure 2).

HOW BURNS CAN OCCUR DURING MRI

Thermal burns are a potential cause of injury during MRI. Most have been observed in patients connected to external metal-containing monitoring devices, such as electrocardiogram leads and pulse oximeters.1,2 Thermal burns in patients unconnected to external devices have occurred when the patient’s body was touching radiofrequency coils3 or, as with our patient, when skin touches skin.2,4,5 Skin-to-skin contact during MRI can cause the scanner to emit high-power electromagnetic radiofrequency pulses that are conducted through the body, creating heat. Tissue loops are created at points of skin-to-skin contact, thus forming a closed conducting circuit. The current flowing through this circuit can produce second-degree burns.4

We believe that during placement in the scanner, our patient inadvertently moved his thighs together, forming a closed loop conduction circuit and resulting in a thermal burn.

This case illustrates the importance of correct positioning during MRI. The MRI technicians had taken standard precautions, placing a sheet over the patient and ensuring no direct contact with the radiofrequency transmitter receiver (MR unit). However, precautions against skin-to-skin contact were not taken, and the patient’s legs were not separated.

LESSONS LEARNED

Appropriate positioning prevents closed skin-to-skin loops, but this may be more challenging in a larger patient.6 While the patient is in the scanner, a “squeeze ball” alert system allows the patient to signal the technologist should unexpected distress or heating occur.6,7 A patient’s inability to utilize the squeeze ball contributes to the risk of a severe injury. Further, in this instance, there may have been a language barrier. Also, proximity of the anatomic skin-to-skin loop to the imaged body part (and therefore the center of the MRI coil) may have conferred risk related to field strength in this patient.

The MRI technologist, under supervision of a radiologist, is primarily responsible for positioning the patient to decrease the risk of this complication and for following institutional MRI safety protocols and professional guidelines.6–8 MRI technologist certification training highlights all aspects of safety, including skin-to-skin conducting loop prevention.7,8

A 48-year-old Nicaraguan man underwent mag netic resonance imaging (MRI) 3 days after admission to a South Florida hospital for treatment of cellulitis of the right thigh with vancomycin. MRI had been ordered to evaluate for a possible drainable source of infection, as the clinical picture and duration of illness was worsening and longer than expected for typical uncomplicated cellulitis despite intravenous antibiotic therapy. The MRI showed multiple enlarged inguinal lymph nodes and cellulitis of the superficial soft tissues of the thigh without discrete drainable collections.

After the procedure, the patient was noted to have a bullous lesion on each thigh, each lesion roughly 1 cm in diameter and filled with clear serous fluid (Figure 1). He reported that his legs had been pressed together before entering the MRI machine and that he had felt a burning sensation in both thighs during the test. Examination confirmed that the lesions indeed aligned with each other when he pressed his thighs together.

Study of a biopsy of one of the lesions revealed subepidermal cell blisters with focal epidermal necrosis and coagulative changes in the superficial dermis, consistent with a thermal injury (Figure 2).

HOW BURNS CAN OCCUR DURING MRI

Thermal burns are a potential cause of injury during MRI. Most have been observed in patients connected to external metal-containing monitoring devices, such as electrocardiogram leads and pulse oximeters.1,2 Thermal burns in patients unconnected to external devices have occurred when the patient’s body was touching radiofrequency coils3 or, as with our patient, when skin touches skin.2,4,5 Skin-to-skin contact during MRI can cause the scanner to emit high-power electromagnetic radiofrequency pulses that are conducted through the body, creating heat. Tissue loops are created at points of skin-to-skin contact, thus forming a closed conducting circuit. The current flowing through this circuit can produce second-degree burns.4

We believe that during placement in the scanner, our patient inadvertently moved his thighs together, forming a closed loop conduction circuit and resulting in a thermal burn.

This case illustrates the importance of correct positioning during MRI. The MRI technicians had taken standard precautions, placing a sheet over the patient and ensuring no direct contact with the radiofrequency transmitter receiver (MR unit). However, precautions against skin-to-skin contact were not taken, and the patient’s legs were not separated.

LESSONS LEARNED

Appropriate positioning prevents closed skin-to-skin loops, but this may be more challenging in a larger patient.6 While the patient is in the scanner, a “squeeze ball” alert system allows the patient to signal the technologist should unexpected distress or heating occur.6,7 A patient’s inability to utilize the squeeze ball contributes to the risk of a severe injury. Further, in this instance, there may have been a language barrier. Also, proximity of the anatomic skin-to-skin loop to the imaged body part (and therefore the center of the MRI coil) may have conferred risk related to field strength in this patient.

The MRI technologist, under supervision of a radiologist, is primarily responsible for positioning the patient to decrease the risk of this complication and for following institutional MRI safety protocols and professional guidelines.6–8 MRI technologist certification training highlights all aspects of safety, including skin-to-skin conducting loop prevention.7,8

- Dempsey MF, Condon B. Thermal injuries associated with MRI. Clin Radiol 2001; 56:457–465.

- Haik J, Daniel S, Tessone A, Orenstein A, Winkler E. MRI induced fourth-degree burn in an extremity, leading to amputation. Burns 2009; 35:294–296.

- Friedstat J, Moore ME, Goverman J, Fagan SP. An unusual burn during routine magnetic resonance imaging. J Burn Care Res 2013; 34: e110–e111.

- Eising EG, Hughes J, Nolte F, Jentzen W, Bockisch A. Burn injury by nuclear magnetic resonance imaging. Clin Imaging 2010; 34:293–297.

- Landman A, Goldfarb S. Magnetic resonance-induced thermal burn. Ann Emerg Med 2008; 52:308–309.

- Expert Panel on MR Safety; Kanal E, Barkovich AJ, Bell C, et al. ACR guidance document on MR safe practices: 2013. J Magn Reson Imaging 2013; 37:501–530.

- Magnetic resonance safety. Radiol Technol 2010; 81:615–616.

- Shellock FG, Crues JV. MR procedures: biologic effects, safety, and patient care. Radiology 2004; 232:635–652.

- Dempsey MF, Condon B. Thermal injuries associated with MRI. Clin Radiol 2001; 56:457–465.

- Haik J, Daniel S, Tessone A, Orenstein A, Winkler E. MRI induced fourth-degree burn in an extremity, leading to amputation. Burns 2009; 35:294–296.

- Friedstat J, Moore ME, Goverman J, Fagan SP. An unusual burn during routine magnetic resonance imaging. J Burn Care Res 2013; 34: e110–e111.

- Eising EG, Hughes J, Nolte F, Jentzen W, Bockisch A. Burn injury by nuclear magnetic resonance imaging. Clin Imaging 2010; 34:293–297.

- Landman A, Goldfarb S. Magnetic resonance-induced thermal burn. Ann Emerg Med 2008; 52:308–309.

- Expert Panel on MR Safety; Kanal E, Barkovich AJ, Bell C, et al. ACR guidance document on MR safe practices: 2013. J Magn Reson Imaging 2013; 37:501–530.

- Magnetic resonance safety. Radiol Technol 2010; 81:615–616.

- Shellock FG, Crues JV. MR procedures: biologic effects, safety, and patient care. Radiology 2004; 232:635–652.

Serotonin syndrome

To the Editor: I enjoyed the article “Serotonin syndrome: Preventing, recognizing, and treating it.”1 I am a relatively new internal medicine physician, out of residency only 1 year, and sadly I felt that the psychiatric training I received was minimal at best. Therefore, I was very excited to read more about serotonin syndrome since such a large percentage of my patients are on selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) or serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors.

Could you speak to the time frame it takes for serotonin syndrome to develop? For instance, if someone is taking an SSRI and develops a terrible yeast infection, would 3 doses of fluconazole be enough to tip the scales? Or as-needed sumatriptan, with some ondansetron for migraine? The problem I have is that patients often require short doses of many medications that can interact, and I routinely sigh, briefly explain the possibility of serotonin syndrome, and then click through the flashing red warning signs on the electronic medical record and send patients out with their meds—though in honesty I do not know the likelihood of developing even mild symptoms of serotonin syndrome with short courses of interacting medications.

- Wang RZ, Vashistha V, Kaur S, Houchens NW. Serotonin syndrome: preventing, recognizing, and treating it. Cleve Clin J Med 2016; 83:810–817.

To the Editor: I enjoyed the article “Serotonin syndrome: Preventing, recognizing, and treating it.”1 I am a relatively new internal medicine physician, out of residency only 1 year, and sadly I felt that the psychiatric training I received was minimal at best. Therefore, I was very excited to read more about serotonin syndrome since such a large percentage of my patients are on selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) or serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors.

Could you speak to the time frame it takes for serotonin syndrome to develop? For instance, if someone is taking an SSRI and develops a terrible yeast infection, would 3 doses of fluconazole be enough to tip the scales? Or as-needed sumatriptan, with some ondansetron for migraine? The problem I have is that patients often require short doses of many medications that can interact, and I routinely sigh, briefly explain the possibility of serotonin syndrome, and then click through the flashing red warning signs on the electronic medical record and send patients out with their meds—though in honesty I do not know the likelihood of developing even mild symptoms of serotonin syndrome with short courses of interacting medications.

To the Editor: I enjoyed the article “Serotonin syndrome: Preventing, recognizing, and treating it.”1 I am a relatively new internal medicine physician, out of residency only 1 year, and sadly I felt that the psychiatric training I received was minimal at best. Therefore, I was very excited to read more about serotonin syndrome since such a large percentage of my patients are on selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) or serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors.

Could you speak to the time frame it takes for serotonin syndrome to develop? For instance, if someone is taking an SSRI and develops a terrible yeast infection, would 3 doses of fluconazole be enough to tip the scales? Or as-needed sumatriptan, with some ondansetron for migraine? The problem I have is that patients often require short doses of many medications that can interact, and I routinely sigh, briefly explain the possibility of serotonin syndrome, and then click through the flashing red warning signs on the electronic medical record and send patients out with their meds—though in honesty I do not know the likelihood of developing even mild symptoms of serotonin syndrome with short courses of interacting medications.

- Wang RZ, Vashistha V, Kaur S, Houchens NW. Serotonin syndrome: preventing, recognizing, and treating it. Cleve Clin J Med 2016; 83:810–817.

- Wang RZ, Vashistha V, Kaur S, Houchens NW. Serotonin syndrome: preventing, recognizing, and treating it. Cleve Clin J Med 2016; 83:810–817.

In reply: Serotonin syndrome

In Reply: The questions posed by Dr. Rose reflect critical issues primary care physicians encounter when prescribing medications for patients who are taking serotonergic agents. “Switching strategies” have been described for starting or discontinuing serotonergic antidepressants.1 Options range from conservative exchanges requiring 5 half-lives between discontinuation of 1 antidepressant and initiation of another vs a direct cross-taper exchange. Decisions regarding specific patients should take into account previous adverse effects from serotonergic medications and half-lives of discontinued antidepressants. To our knowledge, switching strategies have not been validated and are based on expert opinion. Scenarios are complicated further if patients have already been prescribed 2 or more antidepressants and 1 medication is exchanged or dose-adjusted while another is added. With this degree of complexity, we recommend referral to a psychiatrist.

Dr. Rose’s questions on prescribing nonpsychiatric serotonergic drugs concurrently with antidepressants broaches a topic with even less evidence. Some data exist about nonpsychiatric serotonergic drugs given in combination with triptans. Soldin et al2 reviewed the US Food and Drug Administration’s Adverse Event Reporting System and discovered 38 cases of serotonin syndrome in patients using triptans. Eleven of these patients were using triptans without concomitant antidepressants. Though definitive evidence is lacking for safe prescribing practice with triptans, the authors noted that most cases of triptan-induced serotonin toxicity occur within hours of triptan ingestion.2

The evidence on the risk of serotonin syndrome with other medications is limited to case reports. In regard to linezolid, a review suggested that when linezolid was administered to a patient on long-term citalopram, a prolonged serotonin syndrome was precipitated, which is not an issue with other antidepressants.3 The World Health Organization has issued warnings for serotonin toxicity with ondansetron and other 5-HT3 receptor antagonists based on case reports.4,5 No data are available for the appropriate prescribing of 5-HT3 antagonists with antidepressants. A review of cases suggests a link between fluconazole and severe serotonin toxicity in patients taking citalopram; however, no prescribing guidelines have been established for fluconazole either.6

Dr. Rose asks important clinical questions, but evidence-based answers are not available. We can only recommend that patients be advised to report symptoms immediately after starting any medication associated with serotonin syndrome. For patients on multiple antidepressants, psychiatric assistance is advised. An observational cohort study of patients using antidepressants while exposed to other suspect drugs may better delineate effects of several pharmaceuticals on the serotonergic axis. Only then may safe prescribing practices be validated with evidence.

- Keks N, Hope J, Keogh S. Switching and stopping antidepressants. Aust Prescr 2016; 39:76–83.

- Soldin OP, Tonning JM; Obstetric-Fetal Pharmacology Research Unit Network. Serotonin syndrome associated with triptan monotherapy (letter). N Engl J Med 2008; 15:2185–2186.

- Morales-Molina JA, Mateu-de Antonio J, Marín-Casino M, Grau S. Linezolid-associated serotonin syndrome: what we can learn from cases reported so far. J Antimicrob Chemother 2005; 56:1176–1178.

- World Health Organization. Ondansetron and serotonin syndrome. WHO Pharmaceuticals Newsletter 2012; 3:16–21.

- Rojas-Fernandez CH. Can 5-HT3 antagonists really contribute to serotonin toxicity? A call for clarity and pharmacological law and order. Drugs Real World Outcomes 2014; 1:3–5.

- Levin TT, Cortes-Ladino A, Weiss M, Palomba ML. Life-threatening serotonin toxicity due to a citalopram-fluconazole drug interaction: case reports and discussion. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 2008; 30:372–377.

In Reply: The questions posed by Dr. Rose reflect critical issues primary care physicians encounter when prescribing medications for patients who are taking serotonergic agents. “Switching strategies” have been described for starting or discontinuing serotonergic antidepressants.1 Options range from conservative exchanges requiring 5 half-lives between discontinuation of 1 antidepressant and initiation of another vs a direct cross-taper exchange. Decisions regarding specific patients should take into account previous adverse effects from serotonergic medications and half-lives of discontinued antidepressants. To our knowledge, switching strategies have not been validated and are based on expert opinion. Scenarios are complicated further if patients have already been prescribed 2 or more antidepressants and 1 medication is exchanged or dose-adjusted while another is added. With this degree of complexity, we recommend referral to a psychiatrist.

Dr. Rose’s questions on prescribing nonpsychiatric serotonergic drugs concurrently with antidepressants broaches a topic with even less evidence. Some data exist about nonpsychiatric serotonergic drugs given in combination with triptans. Soldin et al2 reviewed the US Food and Drug Administration’s Adverse Event Reporting System and discovered 38 cases of serotonin syndrome in patients using triptans. Eleven of these patients were using triptans without concomitant antidepressants. Though definitive evidence is lacking for safe prescribing practice with triptans, the authors noted that most cases of triptan-induced serotonin toxicity occur within hours of triptan ingestion.2

The evidence on the risk of serotonin syndrome with other medications is limited to case reports. In regard to linezolid, a review suggested that when linezolid was administered to a patient on long-term citalopram, a prolonged serotonin syndrome was precipitated, which is not an issue with other antidepressants.3 The World Health Organization has issued warnings for serotonin toxicity with ondansetron and other 5-HT3 receptor antagonists based on case reports.4,5 No data are available for the appropriate prescribing of 5-HT3 antagonists with antidepressants. A review of cases suggests a link between fluconazole and severe serotonin toxicity in patients taking citalopram; however, no prescribing guidelines have been established for fluconazole either.6

Dr. Rose asks important clinical questions, but evidence-based answers are not available. We can only recommend that patients be advised to report symptoms immediately after starting any medication associated with serotonin syndrome. For patients on multiple antidepressants, psychiatric assistance is advised. An observational cohort study of patients using antidepressants while exposed to other suspect drugs may better delineate effects of several pharmaceuticals on the serotonergic axis. Only then may safe prescribing practices be validated with evidence.

In Reply: The questions posed by Dr. Rose reflect critical issues primary care physicians encounter when prescribing medications for patients who are taking serotonergic agents. “Switching strategies” have been described for starting or discontinuing serotonergic antidepressants.1 Options range from conservative exchanges requiring 5 half-lives between discontinuation of 1 antidepressant and initiation of another vs a direct cross-taper exchange. Decisions regarding specific patients should take into account previous adverse effects from serotonergic medications and half-lives of discontinued antidepressants. To our knowledge, switching strategies have not been validated and are based on expert opinion. Scenarios are complicated further if patients have already been prescribed 2 or more antidepressants and 1 medication is exchanged or dose-adjusted while another is added. With this degree of complexity, we recommend referral to a psychiatrist.

Dr. Rose’s questions on prescribing nonpsychiatric serotonergic drugs concurrently with antidepressants broaches a topic with even less evidence. Some data exist about nonpsychiatric serotonergic drugs given in combination with triptans. Soldin et al2 reviewed the US Food and Drug Administration’s Adverse Event Reporting System and discovered 38 cases of serotonin syndrome in patients using triptans. Eleven of these patients were using triptans without concomitant antidepressants. Though definitive evidence is lacking for safe prescribing practice with triptans, the authors noted that most cases of triptan-induced serotonin toxicity occur within hours of triptan ingestion.2

The evidence on the risk of serotonin syndrome with other medications is limited to case reports. In regard to linezolid, a review suggested that when linezolid was administered to a patient on long-term citalopram, a prolonged serotonin syndrome was precipitated, which is not an issue with other antidepressants.3 The World Health Organization has issued warnings for serotonin toxicity with ondansetron and other 5-HT3 receptor antagonists based on case reports.4,5 No data are available for the appropriate prescribing of 5-HT3 antagonists with antidepressants. A review of cases suggests a link between fluconazole and severe serotonin toxicity in patients taking citalopram; however, no prescribing guidelines have been established for fluconazole either.6

Dr. Rose asks important clinical questions, but evidence-based answers are not available. We can only recommend that patients be advised to report symptoms immediately after starting any medication associated with serotonin syndrome. For patients on multiple antidepressants, psychiatric assistance is advised. An observational cohort study of patients using antidepressants while exposed to other suspect drugs may better delineate effects of several pharmaceuticals on the serotonergic axis. Only then may safe prescribing practices be validated with evidence.

- Keks N, Hope J, Keogh S. Switching and stopping antidepressants. Aust Prescr 2016; 39:76–83.

- Soldin OP, Tonning JM; Obstetric-Fetal Pharmacology Research Unit Network. Serotonin syndrome associated with triptan monotherapy (letter). N Engl J Med 2008; 15:2185–2186.

- Morales-Molina JA, Mateu-de Antonio J, Marín-Casino M, Grau S. Linezolid-associated serotonin syndrome: what we can learn from cases reported so far. J Antimicrob Chemother 2005; 56:1176–1178.

- World Health Organization. Ondansetron and serotonin syndrome. WHO Pharmaceuticals Newsletter 2012; 3:16–21.

- Rojas-Fernandez CH. Can 5-HT3 antagonists really contribute to serotonin toxicity? A call for clarity and pharmacological law and order. Drugs Real World Outcomes 2014; 1:3–5.

- Levin TT, Cortes-Ladino A, Weiss M, Palomba ML. Life-threatening serotonin toxicity due to a citalopram-fluconazole drug interaction: case reports and discussion. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 2008; 30:372–377.

- Keks N, Hope J, Keogh S. Switching and stopping antidepressants. Aust Prescr 2016; 39:76–83.

- Soldin OP, Tonning JM; Obstetric-Fetal Pharmacology Research Unit Network. Serotonin syndrome associated with triptan monotherapy (letter). N Engl J Med 2008; 15:2185–2186.

- Morales-Molina JA, Mateu-de Antonio J, Marín-Casino M, Grau S. Linezolid-associated serotonin syndrome: what we can learn from cases reported so far. J Antimicrob Chemother 2005; 56:1176–1178.

- World Health Organization. Ondansetron and serotonin syndrome. WHO Pharmaceuticals Newsletter 2012; 3:16–21.

- Rojas-Fernandez CH. Can 5-HT3 antagonists really contribute to serotonin toxicity? A call for clarity and pharmacological law and order. Drugs Real World Outcomes 2014; 1:3–5.

- Levin TT, Cortes-Ladino A, Weiss M, Palomba ML. Life-threatening serotonin toxicity due to a citalopram-fluconazole drug interaction: case reports and discussion. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 2008; 30:372–377.

May 2017 Digital Edition

Click here to access the May 2017 Digital Edition.

Table of Contents

- Providing Mental Health Care to All Veterans Regardless of Discharge Status

- Need for Mental Health Providers in Progressive Tinnitus Management

- Blood Loss and Need for Blood Transfusions in Total Knee and Total Hip Arthroplasty

- Peripheral Exudative Hemorrhagic Chorioretinopathy in Patients With Nonexudative Age-Related Macular Degeneration

- The Personal Health Inventory: Current Use, Perceived Barriers, and Benefits

- Dependence of Elevated Eosinophil Levels on Geographic Location

- The Design and Implementation of a Home-Based Cardiac Rehabilitation Program

- FRAX Prediction With and Without Bone Mineral Density Testing

- Improved Access to Drug Safety Labeling Changes Information

- Defining Pharmacy Leadership in the VA

- VA Nurses Advocate for Best Care

Click here to access the May 2017 Digital Edition.

Table of Contents

- Providing Mental Health Care to All Veterans Regardless of Discharge Status

- Need for Mental Health Providers in Progressive Tinnitus Management

- Blood Loss and Need for Blood Transfusions in Total Knee and Total Hip Arthroplasty

- Peripheral Exudative Hemorrhagic Chorioretinopathy in Patients With Nonexudative Age-Related Macular Degeneration

- The Personal Health Inventory: Current Use, Perceived Barriers, and Benefits

- Dependence of Elevated Eosinophil Levels on Geographic Location

- The Design and Implementation of a Home-Based Cardiac Rehabilitation Program

- FRAX Prediction With and Without Bone Mineral Density Testing

- Improved Access to Drug Safety Labeling Changes Information

- Defining Pharmacy Leadership in the VA

- VA Nurses Advocate for Best Care

Click here to access the May 2017 Digital Edition.

Table of Contents

- Providing Mental Health Care to All Veterans Regardless of Discharge Status

- Need for Mental Health Providers in Progressive Tinnitus Management

- Blood Loss and Need for Blood Transfusions in Total Knee and Total Hip Arthroplasty

- Peripheral Exudative Hemorrhagic Chorioretinopathy in Patients With Nonexudative Age-Related Macular Degeneration

- The Personal Health Inventory: Current Use, Perceived Barriers, and Benefits

- Dependence of Elevated Eosinophil Levels on Geographic Location

- The Design and Implementation of a Home-Based Cardiac Rehabilitation Program

- FRAX Prediction With and Without Bone Mineral Density Testing

- Improved Access to Drug Safety Labeling Changes Information

- Defining Pharmacy Leadership in the VA

- VA Nurses Advocate for Best Care

Caution patients about common food–drug interactions

Many individuals read about the health benefits of certain foods, such as coffee, grapefruit, and red wine, but psychiatrists might neglect to inform their patients that these common foods could interact with drugs, thereby preventing certain psychotropics from achieving maximum benefit or causing toxicity. Educate your patients about food–drug interactions and to refrain from alcohol and specific foods when taking psychotropics. Although far from comprehensive, we present a discussion of the most frequently encountered and preventable food/nutrient–drug interactions.

Grapefruit juice may alter bioavailability of many psychotropics by inhibiting cytochrome P450 (CYP) 3A4 and 1A2 isoforms, interfering with prehepatic metabolism, and enteric absorption. Common medications affected by this interaction include alprazolam, buspirone, sertraline, carbamazepine, and methadone.1 Patients should be advised about eating grapefruit or drinking grapefruit juice as it could require dose adjustment to avoid drug toxicity.

Table salt. Lithium is a salt, and less table salt intake could cause lithium levels to rise and vice versa. Lithium and other salts compete for absorption and secretion in the renal tubules, which are responsible for this interaction. Therefore, it is advisable to keep a stable salt intake throughout treatment. Patients should be cautioned about eating salty foods during the summer because excessive sweating could lead to lithium intoxication.

Caffeine is a widely used stimulant; however, it can decrease blood lithium levels and block clozapine clearance via inhibition of the CYP1A2 enzyme. Excessive caffeine intake can lead to clozapine toxicity.2

Beef liver, aged sausage and cheese, and wine contain tyramine. Tyramine is broken down by monoamine oxidase (MAO) enzymes in the body, which are inhibited by MAO inhibitors (MAOI) such as phenelzine and selegiline. A patient taking a MAOI cannot catabolize tyramine and other amines. These exogenous amines could cause a life-threatening hyperadrenergic crisis. Physicians should educate their patients about the MAOI diet and monitor adherence to the food avoidance list.

St. John’s wort is a herb commonly used for treating mild depression. It is a strong inducer of the CYP3A4 enzyme and reduces plasma concentrations and could decrease clinical effectiveness of aripiprazole, quetiapine, alprazolam, and oxycodone.3 It could interact with serotonin reuptake inhibitors causing serotonin syndrome.

Full vs empty stomach. Food is known to affect bioavailability and enteral absorption of different psychotropics. Some medications are best taken on a full stomach and some on an empty one. For example, the antipsychotic ziprasidone should be taken with meals of at least 500 calories for optimal and consistent bioavailability. Benzodiazepines are rapidly absorbed when taken on an empty stomach.

Discuss dietary habits with patients to encourage a healthy lifestyle and provide valuable direction about potential food/nutrient–drug interactions.

1. Pawełczyk T, Kłoszewska I. Grapefruit juice interactions with psychotropic drugs: advantages and potential risk [in Polish]. Przegl Lek. 2008;62(2):92-95.

2. Hägg S, Spigset O, Mjörndal T, et al. Effect of caffeine on clozapine pharmacokinetics in healthy volunteers. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2000;49(1):59-63.

3. Markowitz JS, Donovan JL, DeVane CL, et al. Effect of St John’s wort on drug metabolism by induction of cytochrome P450 3A4 enzyme. JAMA. 2003;290(11):1500-1504.

Many individuals read about the health benefits of certain foods, such as coffee, grapefruit, and red wine, but psychiatrists might neglect to inform their patients that these common foods could interact with drugs, thereby preventing certain psychotropics from achieving maximum benefit or causing toxicity. Educate your patients about food–drug interactions and to refrain from alcohol and specific foods when taking psychotropics. Although far from comprehensive, we present a discussion of the most frequently encountered and preventable food/nutrient–drug interactions.

Grapefruit juice may alter bioavailability of many psychotropics by inhibiting cytochrome P450 (CYP) 3A4 and 1A2 isoforms, interfering with prehepatic metabolism, and enteric absorption. Common medications affected by this interaction include alprazolam, buspirone, sertraline, carbamazepine, and methadone.1 Patients should be advised about eating grapefruit or drinking grapefruit juice as it could require dose adjustment to avoid drug toxicity.

Table salt. Lithium is a salt, and less table salt intake could cause lithium levels to rise and vice versa. Lithium and other salts compete for absorption and secretion in the renal tubules, which are responsible for this interaction. Therefore, it is advisable to keep a stable salt intake throughout treatment. Patients should be cautioned about eating salty foods during the summer because excessive sweating could lead to lithium intoxication.

Caffeine is a widely used stimulant; however, it can decrease blood lithium levels and block clozapine clearance via inhibition of the CYP1A2 enzyme. Excessive caffeine intake can lead to clozapine toxicity.2

Beef liver, aged sausage and cheese, and wine contain tyramine. Tyramine is broken down by monoamine oxidase (MAO) enzymes in the body, which are inhibited by MAO inhibitors (MAOI) such as phenelzine and selegiline. A patient taking a MAOI cannot catabolize tyramine and other amines. These exogenous amines could cause a life-threatening hyperadrenergic crisis. Physicians should educate their patients about the MAOI diet and monitor adherence to the food avoidance list.

St. John’s wort is a herb commonly used for treating mild depression. It is a strong inducer of the CYP3A4 enzyme and reduces plasma concentrations and could decrease clinical effectiveness of aripiprazole, quetiapine, alprazolam, and oxycodone.3 It could interact with serotonin reuptake inhibitors causing serotonin syndrome.

Full vs empty stomach. Food is known to affect bioavailability and enteral absorption of different psychotropics. Some medications are best taken on a full stomach and some on an empty one. For example, the antipsychotic ziprasidone should be taken with meals of at least 500 calories for optimal and consistent bioavailability. Benzodiazepines are rapidly absorbed when taken on an empty stomach.

Discuss dietary habits with patients to encourage a healthy lifestyle and provide valuable direction about potential food/nutrient–drug interactions.

Many individuals read about the health benefits of certain foods, such as coffee, grapefruit, and red wine, but psychiatrists might neglect to inform their patients that these common foods could interact with drugs, thereby preventing certain psychotropics from achieving maximum benefit or causing toxicity. Educate your patients about food–drug interactions and to refrain from alcohol and specific foods when taking psychotropics. Although far from comprehensive, we present a discussion of the most frequently encountered and preventable food/nutrient–drug interactions.

Grapefruit juice may alter bioavailability of many psychotropics by inhibiting cytochrome P450 (CYP) 3A4 and 1A2 isoforms, interfering with prehepatic metabolism, and enteric absorption. Common medications affected by this interaction include alprazolam, buspirone, sertraline, carbamazepine, and methadone.1 Patients should be advised about eating grapefruit or drinking grapefruit juice as it could require dose adjustment to avoid drug toxicity.

Table salt. Lithium is a salt, and less table salt intake could cause lithium levels to rise and vice versa. Lithium and other salts compete for absorption and secretion in the renal tubules, which are responsible for this interaction. Therefore, it is advisable to keep a stable salt intake throughout treatment. Patients should be cautioned about eating salty foods during the summer because excessive sweating could lead to lithium intoxication.

Caffeine is a widely used stimulant; however, it can decrease blood lithium levels and block clozapine clearance via inhibition of the CYP1A2 enzyme. Excessive caffeine intake can lead to clozapine toxicity.2

Beef liver, aged sausage and cheese, and wine contain tyramine. Tyramine is broken down by monoamine oxidase (MAO) enzymes in the body, which are inhibited by MAO inhibitors (MAOI) such as phenelzine and selegiline. A patient taking a MAOI cannot catabolize tyramine and other amines. These exogenous amines could cause a life-threatening hyperadrenergic crisis. Physicians should educate their patients about the MAOI diet and monitor adherence to the food avoidance list.

St. John’s wort is a herb commonly used for treating mild depression. It is a strong inducer of the CYP3A4 enzyme and reduces plasma concentrations and could decrease clinical effectiveness of aripiprazole, quetiapine, alprazolam, and oxycodone.3 It could interact with serotonin reuptake inhibitors causing serotonin syndrome.

Full vs empty stomach. Food is known to affect bioavailability and enteral absorption of different psychotropics. Some medications are best taken on a full stomach and some on an empty one. For example, the antipsychotic ziprasidone should be taken with meals of at least 500 calories for optimal and consistent bioavailability. Benzodiazepines are rapidly absorbed when taken on an empty stomach.

Discuss dietary habits with patients to encourage a healthy lifestyle and provide valuable direction about potential food/nutrient–drug interactions.

1. Pawełczyk T, Kłoszewska I. Grapefruit juice interactions with psychotropic drugs: advantages and potential risk [in Polish]. Przegl Lek. 2008;62(2):92-95.

2. Hägg S, Spigset O, Mjörndal T, et al. Effect of caffeine on clozapine pharmacokinetics in healthy volunteers. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2000;49(1):59-63.

3. Markowitz JS, Donovan JL, DeVane CL, et al. Effect of St John’s wort on drug metabolism by induction of cytochrome P450 3A4 enzyme. JAMA. 2003;290(11):1500-1504.

1. Pawełczyk T, Kłoszewska I. Grapefruit juice interactions with psychotropic drugs: advantages and potential risk [in Polish]. Przegl Lek. 2008;62(2):92-95.

2. Hägg S, Spigset O, Mjörndal T, et al. Effect of caffeine on clozapine pharmacokinetics in healthy volunteers. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2000;49(1):59-63.

3. Markowitz JS, Donovan JL, DeVane CL, et al. Effect of St John’s wort on drug metabolism by induction of cytochrome P450 3A4 enzyme. JAMA. 2003;290(11):1500-1504.

Subjected to sexually inappropriate behavior? Set LIMITS

Everyone needs love, companionship, and intimacy. Unfortunately, mental illness often results in interpersonal dysfunction, thereby frustrating these desires. Patients might exhibit sexually inappropriate behavior (SIB), consisting of comments, requests, or actions. The causes of SIB include confusion, predation, loneliness, psychosis, social impairment, character pathology, and/or mania.

Such attention poses an issue for mental health providers; trainees could be particularly vulnerable. The impact can be disheartening and cause practitioners to withdraw from patients or question their work, which could be detrimental to both providers and patients. While maintaining their personal safety, it is important that clinicians approach patients with compassion. To help clinicians manage SIB, we propose setting LIMITS.

Look after personal safety. Clinicians are trained to care for all patients, but situations can arise where it is no longer safe to work with an individual. A clinician who feels threatened is less likely to help the patient, especially if real danger is posed. Such situations could necessitate transferring the patient’s care to another provider. Clinicians also can choose to interact with a patient exhibiting SIB while colleagues are present.

Identify the etiology. SIB arises from a variety of underlying states, and the clinician’s response can vary depending on the cause. Questions to consider before reacting include:

- What is the origin of the behavior?

- What form is the behavior taking?

- In what context is it occurring?

- How frequent is it occurring?

- What factors are contributing?

- What are the risks to all parties?1

Maintain a professional role. Although SIB can undermine the provider–patient relationship, the behavior could be unintended. To remain professional, practitioners should pause before reacting and consider how to respond. A particular concern is countertransference, meaning that the provider might react to a patient’s behavior based on personal bias. This could result in amorous, hateful, or angry responses from the provider, which could put the treatment relationship at risk, harm the patient, or result in medical–legal repercussions.

Implement appropriate boundaries. In man

Talk with a Supervisor. These scenarios often produce many emotions. Residents could be experiencing them for the first time, but even seasoned clinicians can find them challenging. When in doubt, seek guidance from colleagues, supervisors, or mentors to help you clarify the situation.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Kristina Zdanys, MD, David Schmidt, DO, Joanna Chaurette, MD, PhD, and Shilpa Lad, MD, for their input.

1. Series H, Dégano P. Hypersexuality in dementia. Adv Psychiatr Treat. 2005; 11(6):424-431.

Everyone needs love, companionship, and intimacy. Unfortunately, mental illness often results in interpersonal dysfunction, thereby frustrating these desires. Patients might exhibit sexually inappropriate behavior (SIB), consisting of comments, requests, or actions. The causes of SIB include confusion, predation, loneliness, psychosis, social impairment, character pathology, and/or mania.

Such attention poses an issue for mental health providers; trainees could be particularly vulnerable. The impact can be disheartening and cause practitioners to withdraw from patients or question their work, which could be detrimental to both providers and patients. While maintaining their personal safety, it is important that clinicians approach patients with compassion. To help clinicians manage SIB, we propose setting LIMITS.

Look after personal safety. Clinicians are trained to care for all patients, but situations can arise where it is no longer safe to work with an individual. A clinician who feels threatened is less likely to help the patient, especially if real danger is posed. Such situations could necessitate transferring the patient’s care to another provider. Clinicians also can choose to interact with a patient exhibiting SIB while colleagues are present.

Identify the etiology. SIB arises from a variety of underlying states, and the clinician’s response can vary depending on the cause. Questions to consider before reacting include:

- What is the origin of the behavior?

- What form is the behavior taking?

- In what context is it occurring?

- How frequent is it occurring?

- What factors are contributing?

- What are the risks to all parties?1

Maintain a professional role. Although SIB can undermine the provider–patient relationship, the behavior could be unintended. To remain professional, practitioners should pause before reacting and consider how to respond. A particular concern is countertransference, meaning that the provider might react to a patient’s behavior based on personal bias. This could result in amorous, hateful, or angry responses from the provider, which could put the treatment relationship at risk, harm the patient, or result in medical–legal repercussions.

Implement appropriate boundaries. In man

Talk with a Supervisor. These scenarios often produce many emotions. Residents could be experiencing them for the first time, but even seasoned clinicians can find them challenging. When in doubt, seek guidance from colleagues, supervisors, or mentors to help you clarify the situation.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Kristina Zdanys, MD, David Schmidt, DO, Joanna Chaurette, MD, PhD, and Shilpa Lad, MD, for their input.

Everyone needs love, companionship, and intimacy. Unfortunately, mental illness often results in interpersonal dysfunction, thereby frustrating these desires. Patients might exhibit sexually inappropriate behavior (SIB), consisting of comments, requests, or actions. The causes of SIB include confusion, predation, loneliness, psychosis, social impairment, character pathology, and/or mania.

Such attention poses an issue for mental health providers; trainees could be particularly vulnerable. The impact can be disheartening and cause practitioners to withdraw from patients or question their work, which could be detrimental to both providers and patients. While maintaining their personal safety, it is important that clinicians approach patients with compassion. To help clinicians manage SIB, we propose setting LIMITS.

Look after personal safety. Clinicians are trained to care for all patients, but situations can arise where it is no longer safe to work with an individual. A clinician who feels threatened is less likely to help the patient, especially if real danger is posed. Such situations could necessitate transferring the patient’s care to another provider. Clinicians also can choose to interact with a patient exhibiting SIB while colleagues are present.

Identify the etiology. SIB arises from a variety of underlying states, and the clinician’s response can vary depending on the cause. Questions to consider before reacting include:

- What is the origin of the behavior?

- What form is the behavior taking?

- In what context is it occurring?

- How frequent is it occurring?

- What factors are contributing?

- What are the risks to all parties?1

Maintain a professional role. Although SIB can undermine the provider–patient relationship, the behavior could be unintended. To remain professional, practitioners should pause before reacting and consider how to respond. A particular concern is countertransference, meaning that the provider might react to a patient’s behavior based on personal bias. This could result in amorous, hateful, or angry responses from the provider, which could put the treatment relationship at risk, harm the patient, or result in medical–legal repercussions.

Implement appropriate boundaries. In man

Talk with a Supervisor. These scenarios often produce many emotions. Residents could be experiencing them for the first time, but even seasoned clinicians can find them challenging. When in doubt, seek guidance from colleagues, supervisors, or mentors to help you clarify the situation.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Kristina Zdanys, MD, David Schmidt, DO, Joanna Chaurette, MD, PhD, and Shilpa Lad, MD, for their input.

1. Series H, Dégano P. Hypersexuality in dementia. Adv Psychiatr Treat. 2005; 11(6):424-431.

1. Series H, Dégano P. Hypersexuality in dementia. Adv Psychiatr Treat. 2005; 11(6):424-431.

Benefits and costs of accepting credit cards in your practice

Are you tired of waiting for checks in the mail? Do patients leave without paying their balance? Streamlining revenue collection by taking credit cards is a tantalizing antidote to these ills, but it has downsides. Weighing the value for you and your patients is necessary before you decide on this important practice management policy.

Clinical and practical advantages

Many patients prefer that their health care practitioners take credit cards, because it simplifies their busy lives—and who carries a checkbook anymore? Patients can put the whole session to good use without sacrificing time taking care of payment. They also can receive credit card rewards for their payment, or use health savings accounts, health reimbursement accounts, or flexible spending debit cards, making treatment more affordable.

Benefits of credit cards

Accepting credit cards has many benefits:

- Allows more time in a session to focus on clinical matters because you do not have to allocate time to collect payment, which might include dealing with a forgotten checkbook or a request for a change in your payment policies.

- Easier to collect payment for no-shows. This could result in a reduced no-show rate, because a patient might feel more accountable to show up knowing that his (her) credit card is on file.

- Saves time recording and depositing checks.

- Avoids bounced checks and collection agencies.

Money doesn’t grow on trees

Although there are advantages to accepting credit cards, several costs should be considered. Some practitioners feel that accepting credit cards makes their practice seem like a commercial business. There also is an expense of accepting credit cards, and understanding these costs can be confusing because there are different processing systems of rates. Whether the rate is flat, tiered, or wholesale, you always will pay a percentage of the transaction, plus a transaction fee.

Here are some general guidelines on rates:

- Debit cards are the least expensive to process but often have low spending limits.

- Rewards cards, such as frequent flyer cards, are the most expensive to process. Have you ever wondered who foots the bill for those frequent flyer miles? It’s not the airline; it’s the merchant (you).

- For tiered rates, swiping cards is typically cheaper than typing in the credit card info. Tiered rates often have low rates, known as “teaser” rates, because they are applicable in far fewer cases.

- For flat or wholesale rates, securely saving credit card numbers is not any more expensive than swiping a card, and saves time in the long run and potential awkwardness at the end of a session.

- A higher volume of processed credit cards might allow you to negotiate your rates.

- Check if your bank offers a less expensive option. Some banks offer preferred rates for their customers.

Also consider the time and possible expense of ensuring that you are Payment Card Industry Data Security Standard compliant (information security standards that aim to keep cardholder data secure).

Different methods of processing transactions have varying levels of requirements:

- A swiping reader with a terminal connected to a telephone line is more secure than through the Internet and carries fewer compliance burdens. Use a reader that can handle chip-cards, because you could be liable for fraudulent transactions.

- Do not save or store credit card numbers you typed yourself. Compliance is less burdensome if patients input credit card data into a secure portal.

- Store credit card data securely via your credit card processing partner, although the partner is still at risk of a data breach. Practitioners should weigh the value of convenience vs security.

- If there is a data breach and you are found negligent you could be fined $5,000 to $100,000 per month, depending on whether you are a large company or solo practice.

Bottom dollar

Credit card processing has significant advantages from both a practice management and clinical standpoint. Because prices for services vary, shop around to find the best rates and educate yourself about security requirements. Taking the time to research these matters can pay off in the long term.

Are you tired of waiting for checks in the mail? Do patients leave without paying their balance? Streamlining revenue collection by taking credit cards is a tantalizing antidote to these ills, but it has downsides. Weighing the value for you and your patients is necessary before you decide on this important practice management policy.

Clinical and practical advantages

Many patients prefer that their health care practitioners take credit cards, because it simplifies their busy lives—and who carries a checkbook anymore? Patients can put the whole session to good use without sacrificing time taking care of payment. They also can receive credit card rewards for their payment, or use health savings accounts, health reimbursement accounts, or flexible spending debit cards, making treatment more affordable.

Benefits of credit cards

Accepting credit cards has many benefits:

- Allows more time in a session to focus on clinical matters because you do not have to allocate time to collect payment, which might include dealing with a forgotten checkbook or a request for a change in your payment policies.

- Easier to collect payment for no-shows. This could result in a reduced no-show rate, because a patient might feel more accountable to show up knowing that his (her) credit card is on file.

- Saves time recording and depositing checks.

- Avoids bounced checks and collection agencies.

Money doesn’t grow on trees

Although there are advantages to accepting credit cards, several costs should be considered. Some practitioners feel that accepting credit cards makes their practice seem like a commercial business. There also is an expense of accepting credit cards, and understanding these costs can be confusing because there are different processing systems of rates. Whether the rate is flat, tiered, or wholesale, you always will pay a percentage of the transaction, plus a transaction fee.

Here are some general guidelines on rates:

- Debit cards are the least expensive to process but often have low spending limits.

- Rewards cards, such as frequent flyer cards, are the most expensive to process. Have you ever wondered who foots the bill for those frequent flyer miles? It’s not the airline; it’s the merchant (you).

- For tiered rates, swiping cards is typically cheaper than typing in the credit card info. Tiered rates often have low rates, known as “teaser” rates, because they are applicable in far fewer cases.

- For flat or wholesale rates, securely saving credit card numbers is not any more expensive than swiping a card, and saves time in the long run and potential awkwardness at the end of a session.

- A higher volume of processed credit cards might allow you to negotiate your rates.

- Check if your bank offers a less expensive option. Some banks offer preferred rates for their customers.

Also consider the time and possible expense of ensuring that you are Payment Card Industry Data Security Standard compliant (information security standards that aim to keep cardholder data secure).

Different methods of processing transactions have varying levels of requirements:

- A swiping reader with a terminal connected to a telephone line is more secure than through the Internet and carries fewer compliance burdens. Use a reader that can handle chip-cards, because you could be liable for fraudulent transactions.

- Do not save or store credit card numbers you typed yourself. Compliance is less burdensome if patients input credit card data into a secure portal.

- Store credit card data securely via your credit card processing partner, although the partner is still at risk of a data breach. Practitioners should weigh the value of convenience vs security.

- If there is a data breach and you are found negligent you could be fined $5,000 to $100,000 per month, depending on whether you are a large company or solo practice.

Bottom dollar

Credit card processing has significant advantages from both a practice management and clinical standpoint. Because prices for services vary, shop around to find the best rates and educate yourself about security requirements. Taking the time to research these matters can pay off in the long term.

Are you tired of waiting for checks in the mail? Do patients leave without paying their balance? Streamlining revenue collection by taking credit cards is a tantalizing antidote to these ills, but it has downsides. Weighing the value for you and your patients is necessary before you decide on this important practice management policy.

Clinical and practical advantages

Many patients prefer that their health care practitioners take credit cards, because it simplifies their busy lives—and who carries a checkbook anymore? Patients can put the whole session to good use without sacrificing time taking care of payment. They also can receive credit card rewards for their payment, or use health savings accounts, health reimbursement accounts, or flexible spending debit cards, making treatment more affordable.

Benefits of credit cards

Accepting credit cards has many benefits:

- Allows more time in a session to focus on clinical matters because you do not have to allocate time to collect payment, which might include dealing with a forgotten checkbook or a request for a change in your payment policies.

- Easier to collect payment for no-shows. This could result in a reduced no-show rate, because a patient might feel more accountable to show up knowing that his (her) credit card is on file.

- Saves time recording and depositing checks.

- Avoids bounced checks and collection agencies.

Money doesn’t grow on trees

Although there are advantages to accepting credit cards, several costs should be considered. Some practitioners feel that accepting credit cards makes their practice seem like a commercial business. There also is an expense of accepting credit cards, and understanding these costs can be confusing because there are different processing systems of rates. Whether the rate is flat, tiered, or wholesale, you always will pay a percentage of the transaction, plus a transaction fee.

Here are some general guidelines on rates:

- Debit cards are the least expensive to process but often have low spending limits.

- Rewards cards, such as frequent flyer cards, are the most expensive to process. Have you ever wondered who foots the bill for those frequent flyer miles? It’s not the airline; it’s the merchant (you).

- For tiered rates, swiping cards is typically cheaper than typing in the credit card info. Tiered rates often have low rates, known as “teaser” rates, because they are applicable in far fewer cases.

- For flat or wholesale rates, securely saving credit card numbers is not any more expensive than swiping a card, and saves time in the long run and potential awkwardness at the end of a session.

- A higher volume of processed credit cards might allow you to negotiate your rates.

- Check if your bank offers a less expensive option. Some banks offer preferred rates for their customers.

Also consider the time and possible expense of ensuring that you are Payment Card Industry Data Security Standard compliant (information security standards that aim to keep cardholder data secure).

Different methods of processing transactions have varying levels of requirements:

- A swiping reader with a terminal connected to a telephone line is more secure than through the Internet and carries fewer compliance burdens. Use a reader that can handle chip-cards, because you could be liable for fraudulent transactions.

- Do not save or store credit card numbers you typed yourself. Compliance is less burdensome if patients input credit card data into a secure portal.

- Store credit card data securely via your credit card processing partner, although the partner is still at risk of a data breach. Practitioners should weigh the value of convenience vs security.

- If there is a data breach and you are found negligent you could be fined $5,000 to $100,000 per month, depending on whether you are a large company or solo practice.

Bottom dollar

Credit card processing has significant advantages from both a practice management and clinical standpoint. Because prices for services vary, shop around to find the best rates and educate yourself about security requirements. Taking the time to research these matters can pay off in the long term.

How you can simplify your patient’s medication regimen to enhance adherence

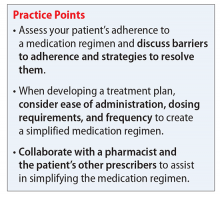

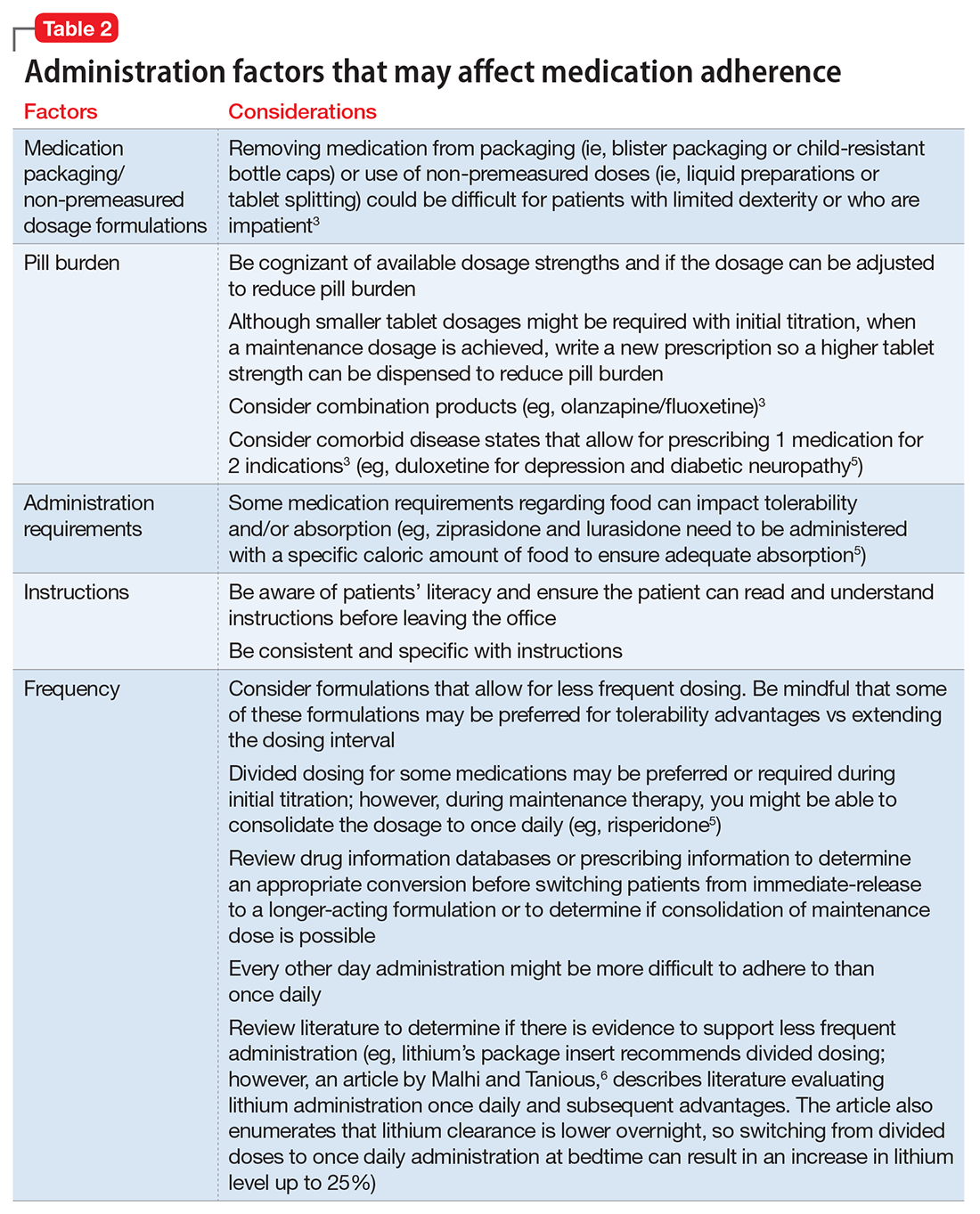

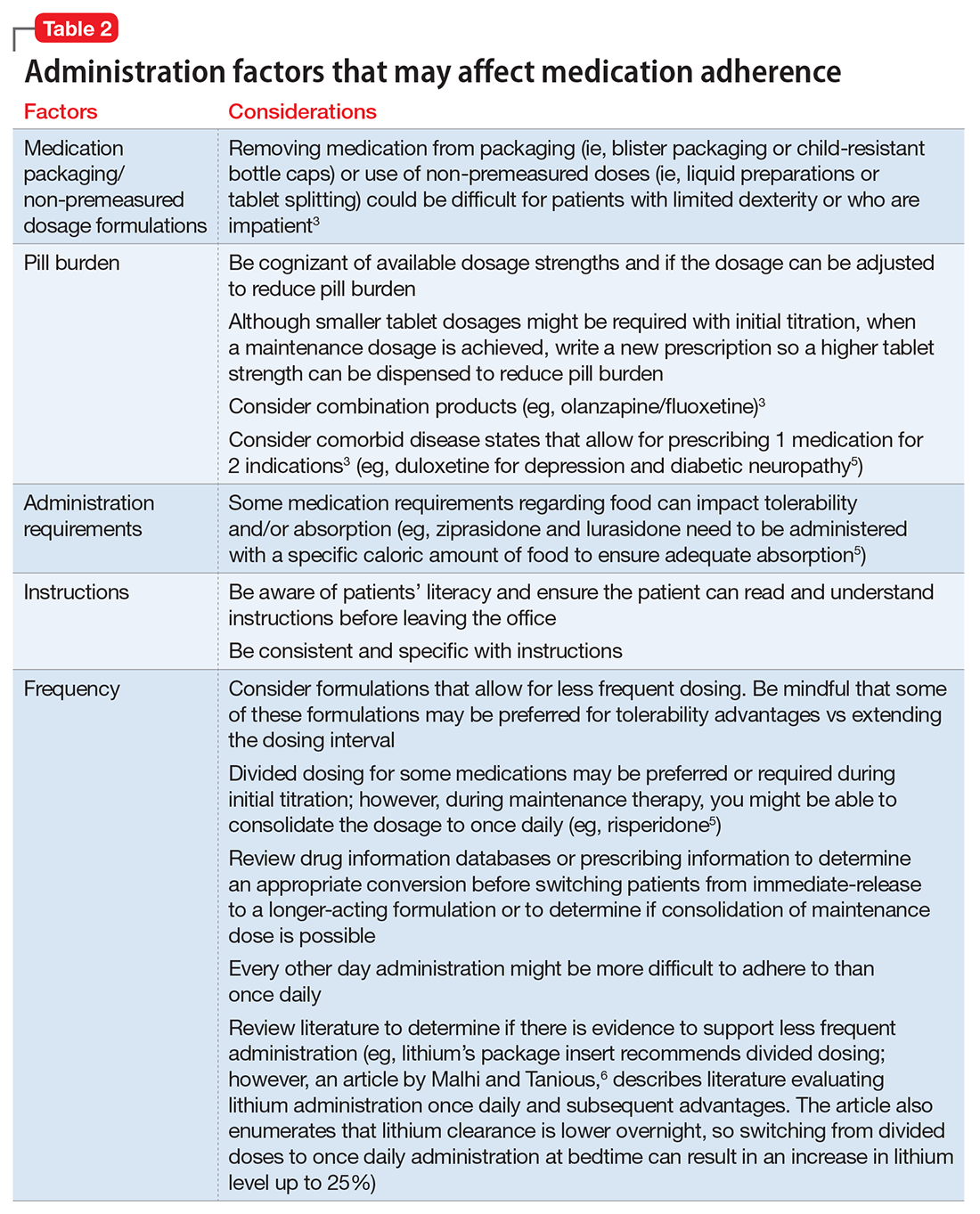

Ms. S, age 53, has bipolar disorder, dyslipidemia, and drug-induced tremor and presents to the clinic complaining of increasing depressive symptoms despite a history of response to her current medication regimen (Table 1). When informed that her lithium and divalproex levels are subtherapeutic, Ms. S admits that she doesn’t always take her medication. She understands her psychiatric and medical conditions and rationale for her current medications; however, she recently changed jobs, which has affected her ability to adhere to her regimen. Ms. S says the only thing preventing her from adhering to her medication is the frequency of administration.

Only approximately one-half of patients with chronic illness adhere to their medication regimen.1 Nonadherence has been reported in 20% to 72% of patients with schizophrenia, 20% to 50% of those with bipolar disorder, and 28% to 52% with major depressive disorder.2 Medication nonadherence can impact a patient’s health outcomes1 and could lead to increased hospitalizations, homelessness, substance use, decreased quality of life, and suicide; however, it is difficult to fully determine the extent of medication nonadherence due to lack of standard measurement methodology.2

Factors that affect medication adherence in patients with psychiatric diagnoses include:

- patient-related (ie, demographic factors)

- psychological (eg, lack of insight into illness, negative emotions toward medications)

- social and environmental (eg, therapeutic alliance with the physician, housing stability and support, and discharge planning)

- medication-related (eg, complex dosing schedule).2

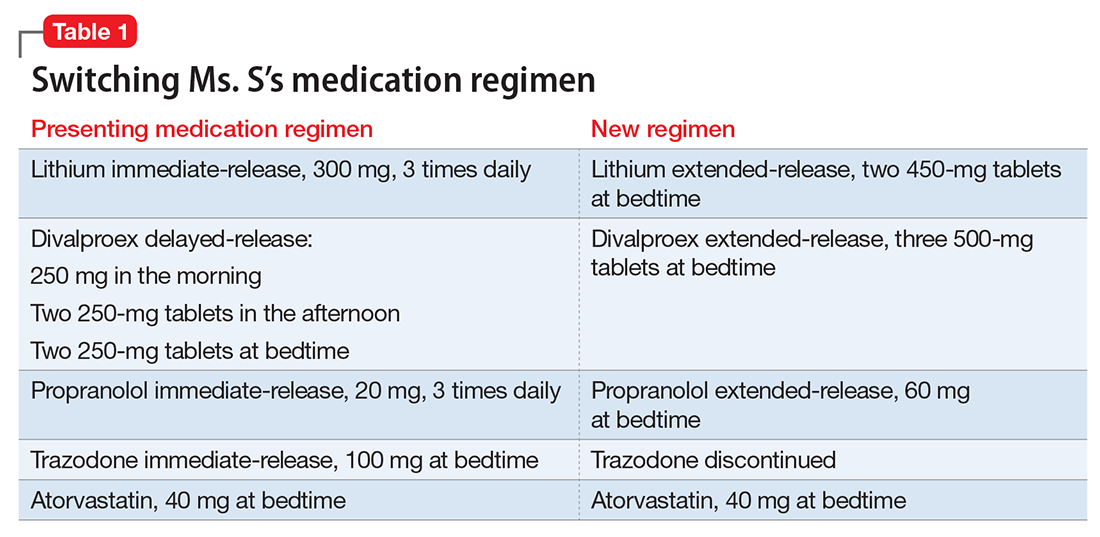

Medication regimen tolerability, complexity, and cost; patient understanding of medication indications and onset of therapeutic effect; and patient’s view of benefits can impact adherence.1,3 Assessing medication adherence and identifying barriers specific to the patient is essential when developing a treatment plan. If complexity is a barrier, simplify the medication regimen.

Claxton et al4 found an inverse relationship between medication dosing and adherence. Reviewing data from 76 studies that used electronic monitoring (records the time and date of actual dosing events) the overall rate of medication adherence was 71% ± 17%. Adherence rates were significantly higher with once daily (79% ± 14%) vs 3 times daily (65% ± 16%) or 4 times daily (51% ± 20%), and twice daily (69% ± 15%) was significantly better than 4 times daily dosing. Adherence between once daily and twice daily or twice daily and 3 times daily did not result in a significant difference. The authors noted that electronic monitoring has limitations; patients could have opened the medication bottle but not ingested the drug.4

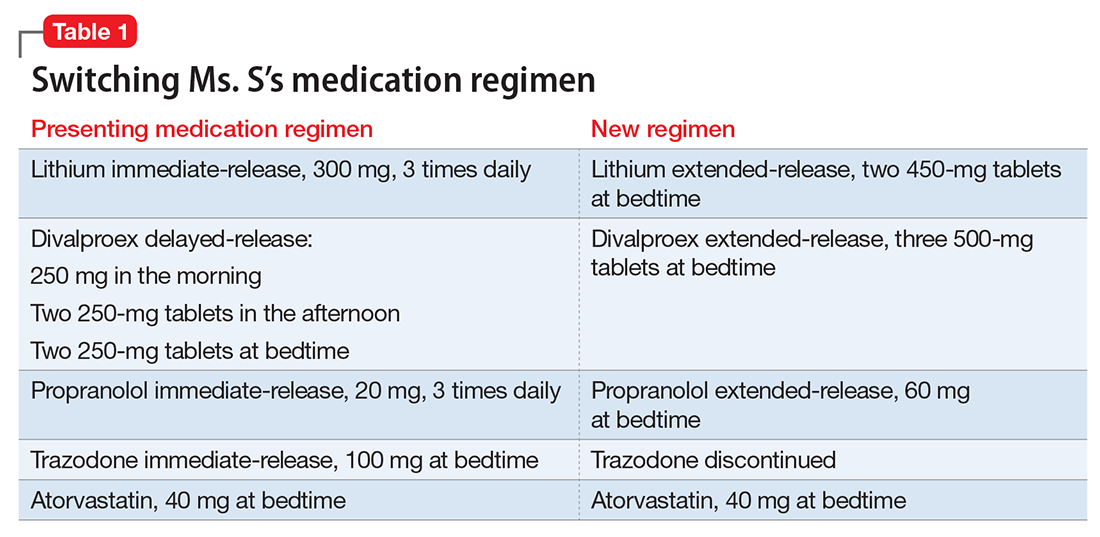

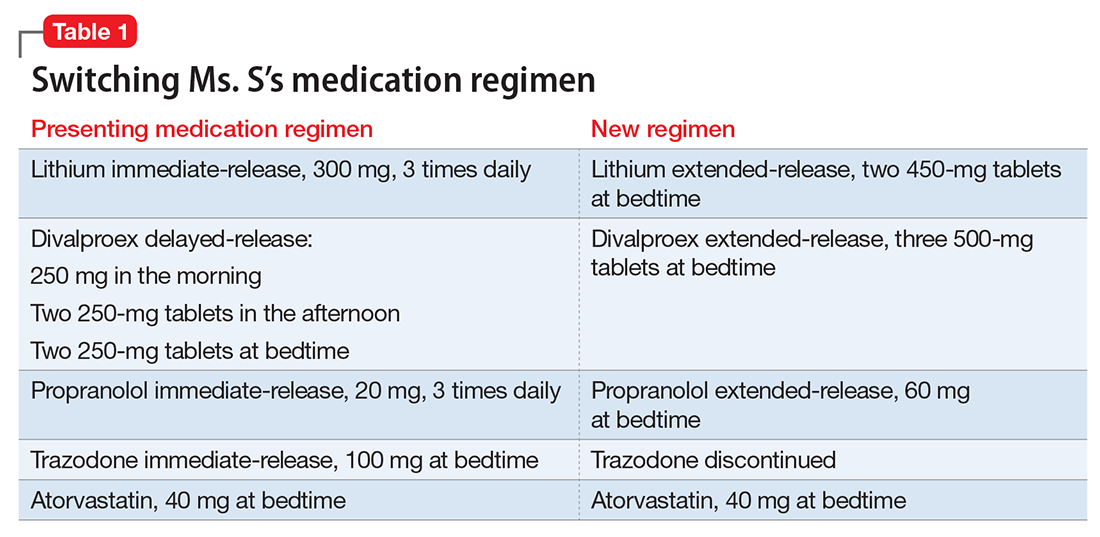

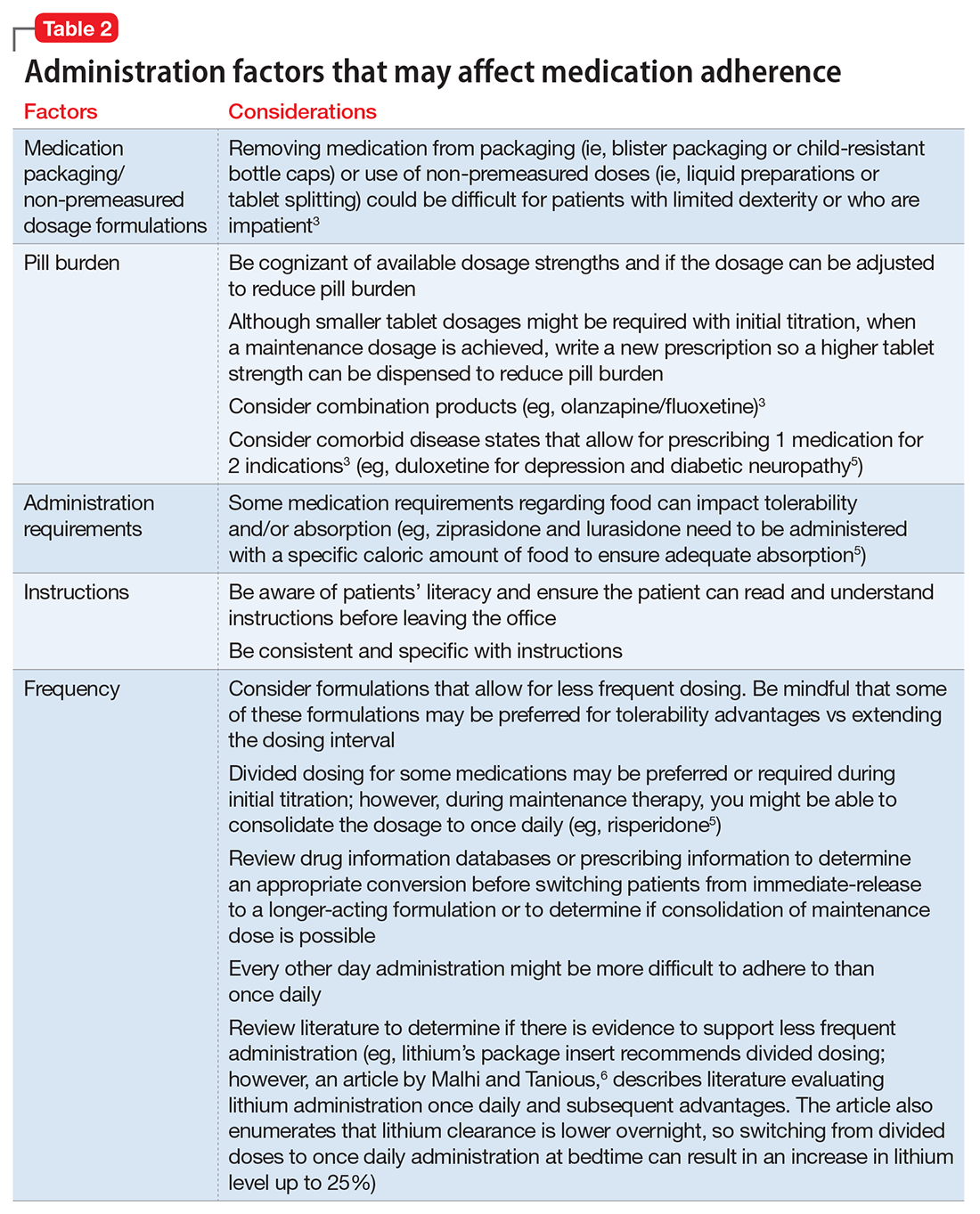

Consider these factors and strategies when developing a treatment plan (Table 2).3,5,6

Ease of administration

Medication packaging. Patients with limited dexterity might not be able to remove the medication from blister packaging or child-proof cap, measure non-unit dose liquid preparations, or split tablets in half.3 Patients with limited patience could get frustrated and skip medications that take longer to remove from packaging or have to be measured. Consult a pharmacist about medication packaging options or formulations that might be appropriate for some patients (ie, individuals with dysphagia), such as oral-disintegrating or sublingual tablets.

Assess pill burden. Although it might not be appropriate when titrating medications, consider adjusting the maintenance dosage to reduce the number of tablets (eg, a patient prescribed divalproex delayed-release, 2,750 mg/d, will take eleven 250-mg tablets vs taking divalproex delayed-release, 2,500 mg/d, which is five 500-mg tablets).

Keep in mind availability of combination medications (eg, olanzapine/fluoxetine) to reduce pill burden. Also, if possible, consider comorbid disease states that allow for prescribing 1 medication that can treat 2 conditions to reduce pill burden (eg, duloxetine for depression and diabetic neuropathy).3

Food recommendations. Review food requirements (ie, administration on an empty stomach vs the need for a specific caloric amount) and whether these are recommendations to improve tolerability or required to ensure adequate absorption. Nonadherence with dietary recommendations that can affect absorption may result in reduced effectiveness despite taking the medication.

Administration instructions

Keep administration instructions simple and be consistent with instructions and terminology.3 For example, if all medications are to be administered once daily in the morning, provide specific instructions (ie, “every morning”) because it may be confusing for patients if some medications are written for “once daily” and others for “every morning.” Some patients might prefer to have the medication indication noted in the administration instructions. Additionally, be aware of the patient’s literacy, and ensure the patient is able to read and understand instructions before leaving the office.

Administration frequency

Consider the required administration frequency and the patient’s self-reported ability to adhere to that frequency before initiating a new medication. Ask the patient what frequencies he (she) can best manage and evaluate his (her) regimen to determine if a less frequent schedule is possible. Consider formulations that may allow for less frequent dosing (eg, controlled-release, sustained-release, long-acting, or extended-release formulations) or consolidating divided doses to once daily if possible.3 Some of these formulations may be preferred for tolerability advantages vs extending the dosing interval (eg, regular-release and extended-release lithium tablets have the same half-life of approximately 18 to 36 hours; however, the extended-release formulation has a longer time to peak serum concentration, approximately 2 to 6 hours vs 0.5 to 3 hours, respectively. As a result, the extended-release formulation may offer improved tolerability in terms of peak-related side effects,5,7 which may be advantageous, especially when dosing lithium once daily). Keep in mind, for some patients every other day administration is more difficult to adhere to than once daily.

Review drug or prescribing information to determine an appropriate conversion before switching from an immediate-release to a longer-acting formulation. The switch may result in different drug serum concentrations (eg, propranolol sustained-release has different pharmacokinetics and produces lower blood levels than the immediate-release formulation). When switching between formulations, monitor patients to ensure the desired therapeutic effect is maintained.8

Consider collaborating with pharmacists, primary care providers, and other prescribers to simplify medical and psychiatric medications.

Other considerations

Lab monitoring requirements for drugs, such as clozapine, lithium, or divalproex, could affect a patient’s willingness to adhere. Use of weekly or monthly medication organizers, mobile apps, alarms (on cell phones or clocks), medication check-off sheets or calendars, and family or friend support could help improve medication adherence.

Case continued

After reviewing the medication regimen and consulting with a pharmacist, Ms. S’s regimen is simplified to once-daily administration, and pill burden is reduced by using extended-release formulations and consolidating doses at bedtime (Table 1). Additionally, trazodone is discontinued because divalproex, now taken once daily at bedtime, is sedating and aids in sleep.

For medications that require therapeutic blood monitoring such as lithium and divalproex, check drug levels when switching formulations. In the case of Ms. S, lithium, propranolol, and divalproex dosages were switched to extended-release preparations and consolidated to once daily at bedtime; the divalproex dosage was increased because an increase in total daily dose between 8% to 20% may be required to maintain similar serum concentrations.5 Lithium immediate-release was switched to the extended-release, which reduced the pill burden and could help tolerability if Ms. S experiences peak concentration-related side effects. Consolidating the lithium dosage from divided to once daily at bedtime can increase the lithium serum level by up to 25%.6

With a change in formulation, monitor tolerability and effectiveness of the medication regimen in regard to mood stabilization and tremor control, as well as check serum lithium and divalproex levels, creatinine, and sodium after 5 days, unless signs and symptoms of toxicity occur.

1. World Health Organization. Adherence to long-term therapies: evidence for action. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/42682/1/9241545992.pdf. Published 2003. Accessed November 29, 2015.

2. Julius RJ, Novitsky MA, Dubin WR. Medication adherence: a review of the literature and implications for clinical practice. J Psychiatr Pract. 2009;15(1):34-44.

3. Atreja A, Bellam N, Levy SR. Strategies to enhance patient adherence: making it simple. MedGenMed. 2005;7(1):4.

4. Claxton AJ, Cramer J, Pierce C. A systematic review of the associations between dose regimens and medication compliance. Clin Ther. 2001;23(8):1296-1310.

5. Lexicomp Online, Lexi-Drugs, Hudson, Ohio: Lexi-Comp, Inc.; February 28, 2016.

6. Malhi GS, Tanious M. Optimal frequency of lithium administration in the treatment of bipolar disorder: clinical and dosing considerations. CNS Drugs. 2011;25(4):289-298.

7. Jefferson JW, Greist JH, Ackerman DL, et al. Lithium: an overview. In: Lithium encyclopedia for clinical practice. 2nd ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press; 1987.

8. Inderal LA (propranolol extended release) [package insert]. Cranford, NJ: Akrimax Pharmaceuticals; November 2015.

Ms. S, age 53, has bipolar disorder, dyslipidemia, and drug-induced tremor and presents to the clinic complaining of increasing depressive symptoms despite a history of response to her current medication regimen (Table 1). When informed that her lithium and divalproex levels are subtherapeutic, Ms. S admits that she doesn’t always take her medication. She understands her psychiatric and medical conditions and rationale for her current medications; however, she recently changed jobs, which has affected her ability to adhere to her regimen. Ms. S says the only thing preventing her from adhering to her medication is the frequency of administration.

Only approximately one-half of patients with chronic illness adhere to their medication regimen.1 Nonadherence has been reported in 20% to 72% of patients with schizophrenia, 20% to 50% of those with bipolar disorder, and 28% to 52% with major depressive disorder.2 Medication nonadherence can impact a patient’s health outcomes1 and could lead to increased hospitalizations, homelessness, substance use, decreased quality of life, and suicide; however, it is difficult to fully determine the extent of medication nonadherence due to lack of standard measurement methodology.2

Factors that affect medication adherence in patients with psychiatric diagnoses include:

- patient-related (ie, demographic factors)

- psychological (eg, lack of insight into illness, negative emotions toward medications)

- social and environmental (eg, therapeutic alliance with the physician, housing stability and support, and discharge planning)

- medication-related (eg, complex dosing schedule).2

Medication regimen tolerability, complexity, and cost; patient understanding of medication indications and onset of therapeutic effect; and patient’s view of benefits can impact adherence.1,3 Assessing medication adherence and identifying barriers specific to the patient is essential when developing a treatment plan. If complexity is a barrier, simplify the medication regimen.

Claxton et al4 found an inverse relationship between medication dosing and adherence. Reviewing data from 76 studies that used electronic monitoring (records the time and date of actual dosing events) the overall rate of medication adherence was 71% ± 17%. Adherence rates were significantly higher with once daily (79% ± 14%) vs 3 times daily (65% ± 16%) or 4 times daily (51% ± 20%), and twice daily (69% ± 15%) was significantly better than 4 times daily dosing. Adherence between once daily and twice daily or twice daily and 3 times daily did not result in a significant difference. The authors noted that electronic monitoring has limitations; patients could have opened the medication bottle but not ingested the drug.4

Consider these factors and strategies when developing a treatment plan (Table 2).3,5,6

Ease of administration

Medication packaging. Patients with limited dexterity might not be able to remove the medication from blister packaging or child-proof cap, measure non-unit dose liquid preparations, or split tablets in half.3 Patients with limited patience could get frustrated and skip medications that take longer to remove from packaging or have to be measured. Consult a pharmacist about medication packaging options or formulations that might be appropriate for some patients (ie, individuals with dysphagia), such as oral-disintegrating or sublingual tablets.

Assess pill burden. Although it might not be appropriate when titrating medications, consider adjusting the maintenance dosage to reduce the number of tablets (eg, a patient prescribed divalproex delayed-release, 2,750 mg/d, will take eleven 250-mg tablets vs taking divalproex delayed-release, 2,500 mg/d, which is five 500-mg tablets).

Keep in mind availability of combination medications (eg, olanzapine/fluoxetine) to reduce pill burden. Also, if possible, consider comorbid disease states that allow for prescribing 1 medication that can treat 2 conditions to reduce pill burden (eg, duloxetine for depression and diabetic neuropathy).3

Food recommendations. Review food requirements (ie, administration on an empty stomach vs the need for a specific caloric amount) and whether these are recommendations to improve tolerability or required to ensure adequate absorption. Nonadherence with dietary recommendations that can affect absorption may result in reduced effectiveness despite taking the medication.

Administration instructions