User login

Latest ixekizumab safety data called ‘very reassuring’

VIENNA – Updated longer-term safety data for ixekizumab in patients with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis continue to show no new safety signals, Alexa B. Kimball, MD, reported at the annual congress of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology.

The safety database now includes 4,213 psoriasis patients on ixekizumab (Taltz) for a total of 7,843 patient-years of regular ongoing follow-up in seven different phase I-III clinical trials. And with a large group of patients now having been on the novel humanized monoclonal antibody targeting interleukin-17A for 2 years and smaller numbers out to 5 years, there have been no surprises, according to Dr. Kimball, professor of dermatology at Harvard Medical School, Boston.

The key trends in the safety analysis are that the number of patients with an adverse event resulting in ixekizumab discontinuation is very low, yet adverse event rates are declining over time.

“This is pretty common in clinical trials,” according to the dermatologist. “In those first 12 weeks of a study you are seeing the patients very frequently, asking them very detailed questions, and we often pick up adverse events more frequently as a result. Upper respiratory infections are a good example: In the first month a patient will remember what happened last week. But if you haven’t seen a patient in 3 months they might not remember that 10 weeks ago they had a little cold. That’s why we tend to see URI rates go down over time. Now, if you see adverse events go up over time – especially for things like malignancy – then there is certainly cause for concern that there’s a cumulative problem with toxicity. That is clearly not a problem with this drug.”

Turning to selected adverse events of interest, Dr. Kimball noted that 2.1% of patients have experienced oral candidiasis while on ixekizumab.

“Oral Candida infection is one of the known side effects with this drug. It doesn’t happen very frequently, and to date, the infections have been very manageable, but it is something you want to have in your mind because it does happen,” she noted.

Serious infections have occurred in 105 patients, 2.5% of those on ixekizumab. Major adverse cardiovascular events have occurred in 1.0%, nonmelanoma skin cancers in 0.7%, and other cancers in 1.1%. Of note, only 5 patients (0.1%) have developed Crohn’s disease, 10 have been diagnosed with ulcerative colitis, and there have been no completed suicides.

The safety follow-up is ongoing.

The safety registry is supported by Eli Lilly, which markets ixekizumab. Dr. Kimball reported receiving research funding from and serving as a consultant to Eli Lilly and numerous other pharmaceutical companies.

VIENNA – Updated longer-term safety data for ixekizumab in patients with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis continue to show no new safety signals, Alexa B. Kimball, MD, reported at the annual congress of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology.

The safety database now includes 4,213 psoriasis patients on ixekizumab (Taltz) for a total of 7,843 patient-years of regular ongoing follow-up in seven different phase I-III clinical trials. And with a large group of patients now having been on the novel humanized monoclonal antibody targeting interleukin-17A for 2 years and smaller numbers out to 5 years, there have been no surprises, according to Dr. Kimball, professor of dermatology at Harvard Medical School, Boston.

The key trends in the safety analysis are that the number of patients with an adverse event resulting in ixekizumab discontinuation is very low, yet adverse event rates are declining over time.

“This is pretty common in clinical trials,” according to the dermatologist. “In those first 12 weeks of a study you are seeing the patients very frequently, asking them very detailed questions, and we often pick up adverse events more frequently as a result. Upper respiratory infections are a good example: In the first month a patient will remember what happened last week. But if you haven’t seen a patient in 3 months they might not remember that 10 weeks ago they had a little cold. That’s why we tend to see URI rates go down over time. Now, if you see adverse events go up over time – especially for things like malignancy – then there is certainly cause for concern that there’s a cumulative problem with toxicity. That is clearly not a problem with this drug.”

Turning to selected adverse events of interest, Dr. Kimball noted that 2.1% of patients have experienced oral candidiasis while on ixekizumab.

“Oral Candida infection is one of the known side effects with this drug. It doesn’t happen very frequently, and to date, the infections have been very manageable, but it is something you want to have in your mind because it does happen,” she noted.

Serious infections have occurred in 105 patients, 2.5% of those on ixekizumab. Major adverse cardiovascular events have occurred in 1.0%, nonmelanoma skin cancers in 0.7%, and other cancers in 1.1%. Of note, only 5 patients (0.1%) have developed Crohn’s disease, 10 have been diagnosed with ulcerative colitis, and there have been no completed suicides.

The safety follow-up is ongoing.

The safety registry is supported by Eli Lilly, which markets ixekizumab. Dr. Kimball reported receiving research funding from and serving as a consultant to Eli Lilly and numerous other pharmaceutical companies.

VIENNA – Updated longer-term safety data for ixekizumab in patients with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis continue to show no new safety signals, Alexa B. Kimball, MD, reported at the annual congress of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology.

The safety database now includes 4,213 psoriasis patients on ixekizumab (Taltz) for a total of 7,843 patient-years of regular ongoing follow-up in seven different phase I-III clinical trials. And with a large group of patients now having been on the novel humanized monoclonal antibody targeting interleukin-17A for 2 years and smaller numbers out to 5 years, there have been no surprises, according to Dr. Kimball, professor of dermatology at Harvard Medical School, Boston.

The key trends in the safety analysis are that the number of patients with an adverse event resulting in ixekizumab discontinuation is very low, yet adverse event rates are declining over time.

“This is pretty common in clinical trials,” according to the dermatologist. “In those first 12 weeks of a study you are seeing the patients very frequently, asking them very detailed questions, and we often pick up adverse events more frequently as a result. Upper respiratory infections are a good example: In the first month a patient will remember what happened last week. But if you haven’t seen a patient in 3 months they might not remember that 10 weeks ago they had a little cold. That’s why we tend to see URI rates go down over time. Now, if you see adverse events go up over time – especially for things like malignancy – then there is certainly cause for concern that there’s a cumulative problem with toxicity. That is clearly not a problem with this drug.”

Turning to selected adverse events of interest, Dr. Kimball noted that 2.1% of patients have experienced oral candidiasis while on ixekizumab.

“Oral Candida infection is one of the known side effects with this drug. It doesn’t happen very frequently, and to date, the infections have been very manageable, but it is something you want to have in your mind because it does happen,” she noted.

Serious infections have occurred in 105 patients, 2.5% of those on ixekizumab. Major adverse cardiovascular events have occurred in 1.0%, nonmelanoma skin cancers in 0.7%, and other cancers in 1.1%. Of note, only 5 patients (0.1%) have developed Crohn’s disease, 10 have been diagnosed with ulcerative colitis, and there have been no completed suicides.

The safety follow-up is ongoing.

The safety registry is supported by Eli Lilly, which markets ixekizumab. Dr. Kimball reported receiving research funding from and serving as a consultant to Eli Lilly and numerous other pharmaceutical companies.

THE EADV CONGRESS

Unshackle American medicine

Physician pay has been flat for years, and my crystal ball doesn’t show that changing any time soon. But the American people just elected a regulatory wrecking ball, so let’s look at some changes we can hope the Trump administration will make.

Let’s start by eliminating the regulations that interfere with patient care and degrade the quality of care. Does the Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act (MACRA) and its Merit-based Incentive Payment System (MIPS) really have anything to do with the quality of care? No, the regulations that will implement the coming MACRA reforms were written contrary to congressional intent by the Department of Health & Human Services as a last-ditch attempt to impose the Affordable Care Act on American physicians. Let’s repeal it! At a minimum, let’s exempt physician practices of 9 or less, rather than 15, as the regulations call for. Where did 15 come from?

What about electronic medical records? I’ve heard some emergency physicians and hospitalists like them. Well OK, they can keep them. Many of the rest of us believe it has seriously degraded the physician-patient encounter and that the preprogrammed nature of many systems makes the medical record much less useful for providers. Let’s repeal any financial penalties for not adopting electronic medical records.

Let’s eliminate the pay differential for office-based physician services when provided in the office and when they are provided – and better paid – in the hospital. Office services are provided more efficiently, and at lower risk, in the office than in the hospital. This is an anomaly in the payment system that potentially injures patients and dramatically increases costs.

Let’s repeal the ability of nurses and physician assistants to bill independently for surgical procedures. Congress never dreamed that this could happen when they passed independent payment authority for these providers. This subjects patients to unnecessary procedures by inadequately trained providers and and generates unnecessary costs.

How about HIPAA? How many lives has HIPAA protected and how much useless paperwork and legal mumbo jumbo has it created?

Let’s eliminate the Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments (CLIA). Has this legislation really saved any lives or increased the quality of care? Show me the data!

Let’s eliminate most of the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) medical office requirements. It is hard to argue against hepatitis vaccinations, but the rest of the regulations are regulatory overkill. Do you really need a metal container with a lockable lid to carry instruments to the lab to be autoclaved? Do you really need two pairs of long leather gloves to fill a cryo gun? Do you really need material safety data sheets for every liquid in the office, including the solumedrol for injection in your cabinet?

Which medical regulations would you like to see repealed? President-elect Trump has stated he wants two regulations repealed for every new one enacted. Let’s give him a wish list from dermatologists. This is a major opportunity to increase the efficiency and productivity of American medicine. If Congress refuses to reimburse physicians at rates pacing the cost of living, the least they can do is unshackle us!

Dr. Coldiron is past president of the American Academy of Dermatology. He is currently in private practice but maintains a clinical assistant professorship at the University of Cincinnati. He cares for patients, teaches medical students and residents, and has several active clinical research projects. Dr. Coldiron is the author of more than 80 scientific letters, papers, and several book chapters, and he speaks frequently on a variety of topics. Write to him at [email protected].

Physician pay has been flat for years, and my crystal ball doesn’t show that changing any time soon. But the American people just elected a regulatory wrecking ball, so let’s look at some changes we can hope the Trump administration will make.

Let’s start by eliminating the regulations that interfere with patient care and degrade the quality of care. Does the Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act (MACRA) and its Merit-based Incentive Payment System (MIPS) really have anything to do with the quality of care? No, the regulations that will implement the coming MACRA reforms were written contrary to congressional intent by the Department of Health & Human Services as a last-ditch attempt to impose the Affordable Care Act on American physicians. Let’s repeal it! At a minimum, let’s exempt physician practices of 9 or less, rather than 15, as the regulations call for. Where did 15 come from?

What about electronic medical records? I’ve heard some emergency physicians and hospitalists like them. Well OK, they can keep them. Many of the rest of us believe it has seriously degraded the physician-patient encounter and that the preprogrammed nature of many systems makes the medical record much less useful for providers. Let’s repeal any financial penalties for not adopting electronic medical records.

Let’s eliminate the pay differential for office-based physician services when provided in the office and when they are provided – and better paid – in the hospital. Office services are provided more efficiently, and at lower risk, in the office than in the hospital. This is an anomaly in the payment system that potentially injures patients and dramatically increases costs.

Let’s repeal the ability of nurses and physician assistants to bill independently for surgical procedures. Congress never dreamed that this could happen when they passed independent payment authority for these providers. This subjects patients to unnecessary procedures by inadequately trained providers and and generates unnecessary costs.

How about HIPAA? How many lives has HIPAA protected and how much useless paperwork and legal mumbo jumbo has it created?

Let’s eliminate the Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments (CLIA). Has this legislation really saved any lives or increased the quality of care? Show me the data!

Let’s eliminate most of the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) medical office requirements. It is hard to argue against hepatitis vaccinations, but the rest of the regulations are regulatory overkill. Do you really need a metal container with a lockable lid to carry instruments to the lab to be autoclaved? Do you really need two pairs of long leather gloves to fill a cryo gun? Do you really need material safety data sheets for every liquid in the office, including the solumedrol for injection in your cabinet?

Which medical regulations would you like to see repealed? President-elect Trump has stated he wants two regulations repealed for every new one enacted. Let’s give him a wish list from dermatologists. This is a major opportunity to increase the efficiency and productivity of American medicine. If Congress refuses to reimburse physicians at rates pacing the cost of living, the least they can do is unshackle us!

Dr. Coldiron is past president of the American Academy of Dermatology. He is currently in private practice but maintains a clinical assistant professorship at the University of Cincinnati. He cares for patients, teaches medical students and residents, and has several active clinical research projects. Dr. Coldiron is the author of more than 80 scientific letters, papers, and several book chapters, and he speaks frequently on a variety of topics. Write to him at [email protected].

Physician pay has been flat for years, and my crystal ball doesn’t show that changing any time soon. But the American people just elected a regulatory wrecking ball, so let’s look at some changes we can hope the Trump administration will make.

Let’s start by eliminating the regulations that interfere with patient care and degrade the quality of care. Does the Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act (MACRA) and its Merit-based Incentive Payment System (MIPS) really have anything to do with the quality of care? No, the regulations that will implement the coming MACRA reforms were written contrary to congressional intent by the Department of Health & Human Services as a last-ditch attempt to impose the Affordable Care Act on American physicians. Let’s repeal it! At a minimum, let’s exempt physician practices of 9 or less, rather than 15, as the regulations call for. Where did 15 come from?

What about electronic medical records? I’ve heard some emergency physicians and hospitalists like them. Well OK, they can keep them. Many of the rest of us believe it has seriously degraded the physician-patient encounter and that the preprogrammed nature of many systems makes the medical record much less useful for providers. Let’s repeal any financial penalties for not adopting electronic medical records.

Let’s eliminate the pay differential for office-based physician services when provided in the office and when they are provided – and better paid – in the hospital. Office services are provided more efficiently, and at lower risk, in the office than in the hospital. This is an anomaly in the payment system that potentially injures patients and dramatically increases costs.

Let’s repeal the ability of nurses and physician assistants to bill independently for surgical procedures. Congress never dreamed that this could happen when they passed independent payment authority for these providers. This subjects patients to unnecessary procedures by inadequately trained providers and and generates unnecessary costs.

How about HIPAA? How many lives has HIPAA protected and how much useless paperwork and legal mumbo jumbo has it created?

Let’s eliminate the Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments (CLIA). Has this legislation really saved any lives or increased the quality of care? Show me the data!

Let’s eliminate most of the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) medical office requirements. It is hard to argue against hepatitis vaccinations, but the rest of the regulations are regulatory overkill. Do you really need a metal container with a lockable lid to carry instruments to the lab to be autoclaved? Do you really need two pairs of long leather gloves to fill a cryo gun? Do you really need material safety data sheets for every liquid in the office, including the solumedrol for injection in your cabinet?

Which medical regulations would you like to see repealed? President-elect Trump has stated he wants two regulations repealed for every new one enacted. Let’s give him a wish list from dermatologists. This is a major opportunity to increase the efficiency and productivity of American medicine. If Congress refuses to reimburse physicians at rates pacing the cost of living, the least they can do is unshackle us!

Dr. Coldiron is past president of the American Academy of Dermatology. He is currently in private practice but maintains a clinical assistant professorship at the University of Cincinnati. He cares for patients, teaches medical students and residents, and has several active clinical research projects. Dr. Coldiron is the author of more than 80 scientific letters, papers, and several book chapters, and he speaks frequently on a variety of topics. Write to him at [email protected].

Primary Cutaneous Mycobacterium avium Complex Infection Following Squamous Cell Carcinoma Excision

Case Report

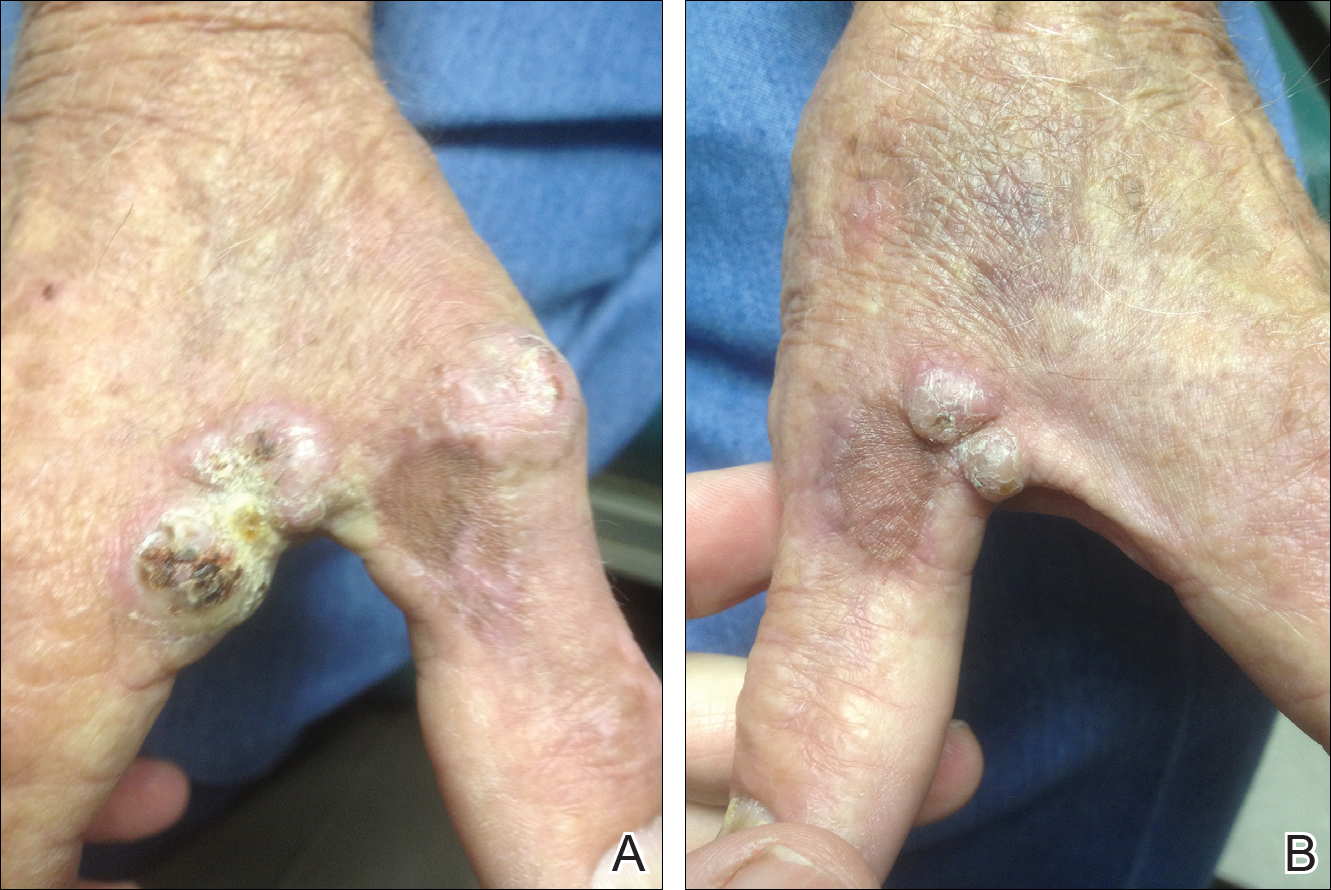

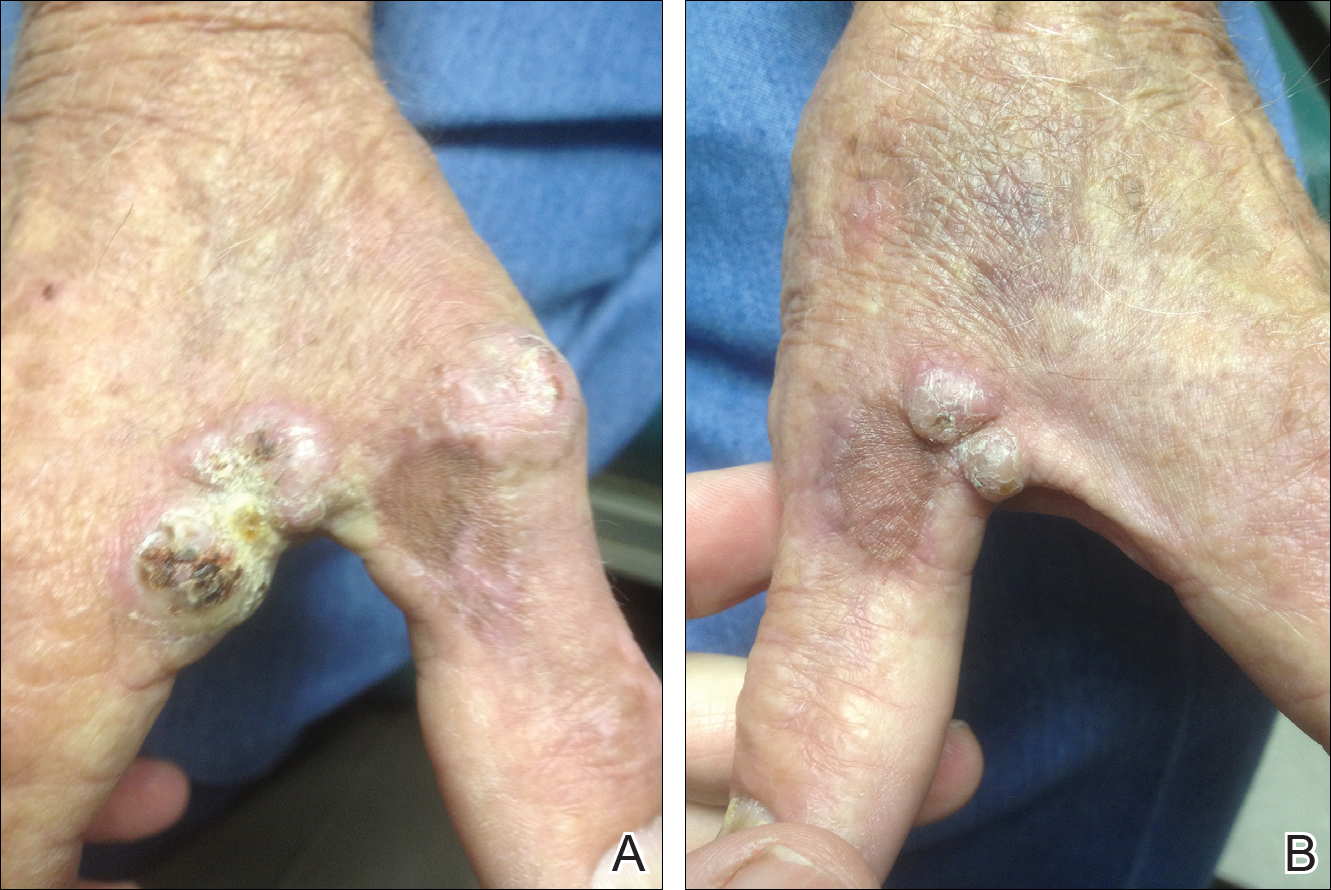

A 78-year-old man presented for evaluation of 4 painful keratotic nodules that had appeared on the dorsal aspect of the right thumb, the first web space of the right hand, and the first web space of the left hand. The nodules developed in pericicatricial skin following Mohs micrographic surgery to the affected areas for treatment of invasive squamous cell carcinomas (SCCs) 2 months prior. The patient had worked in lawn maintenance for decades and continued to garden on an avocational basis. He denied exposure to angling or aquariums.

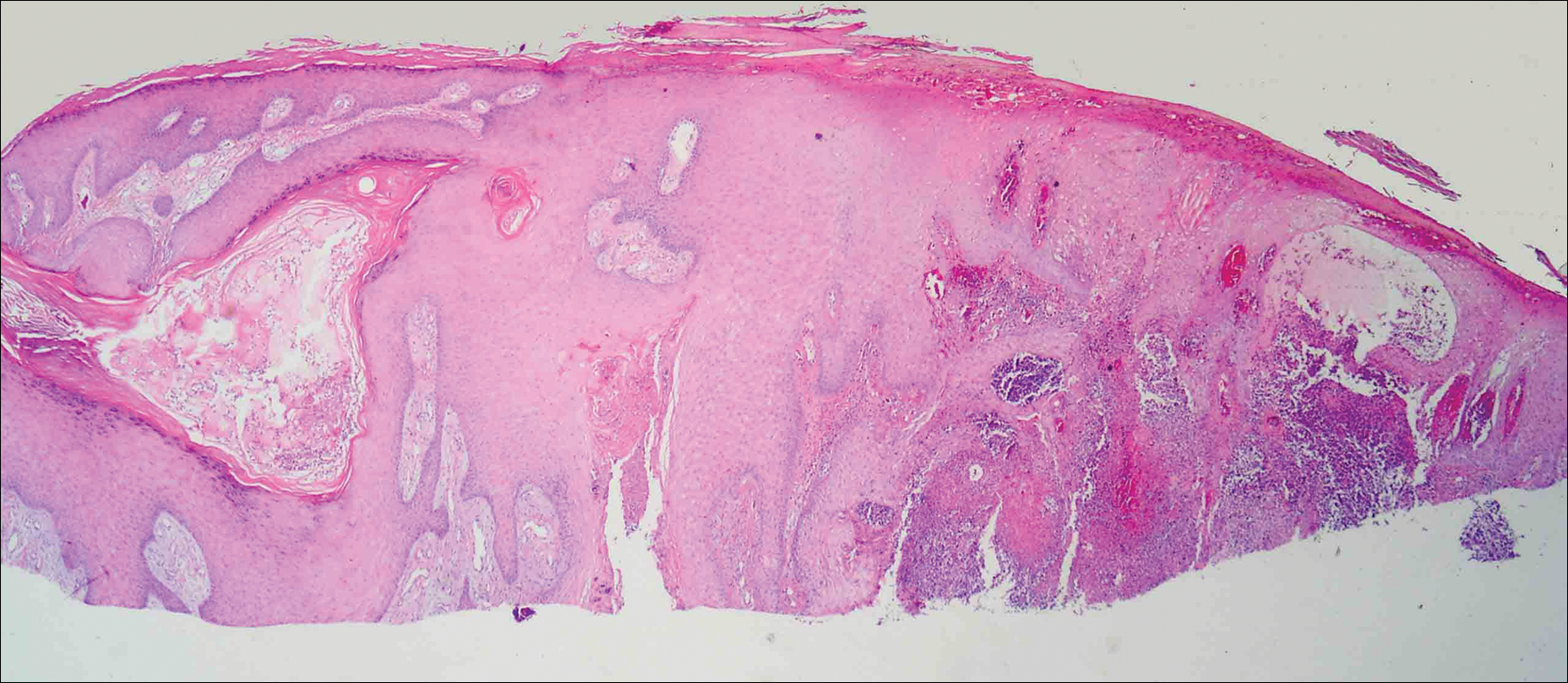

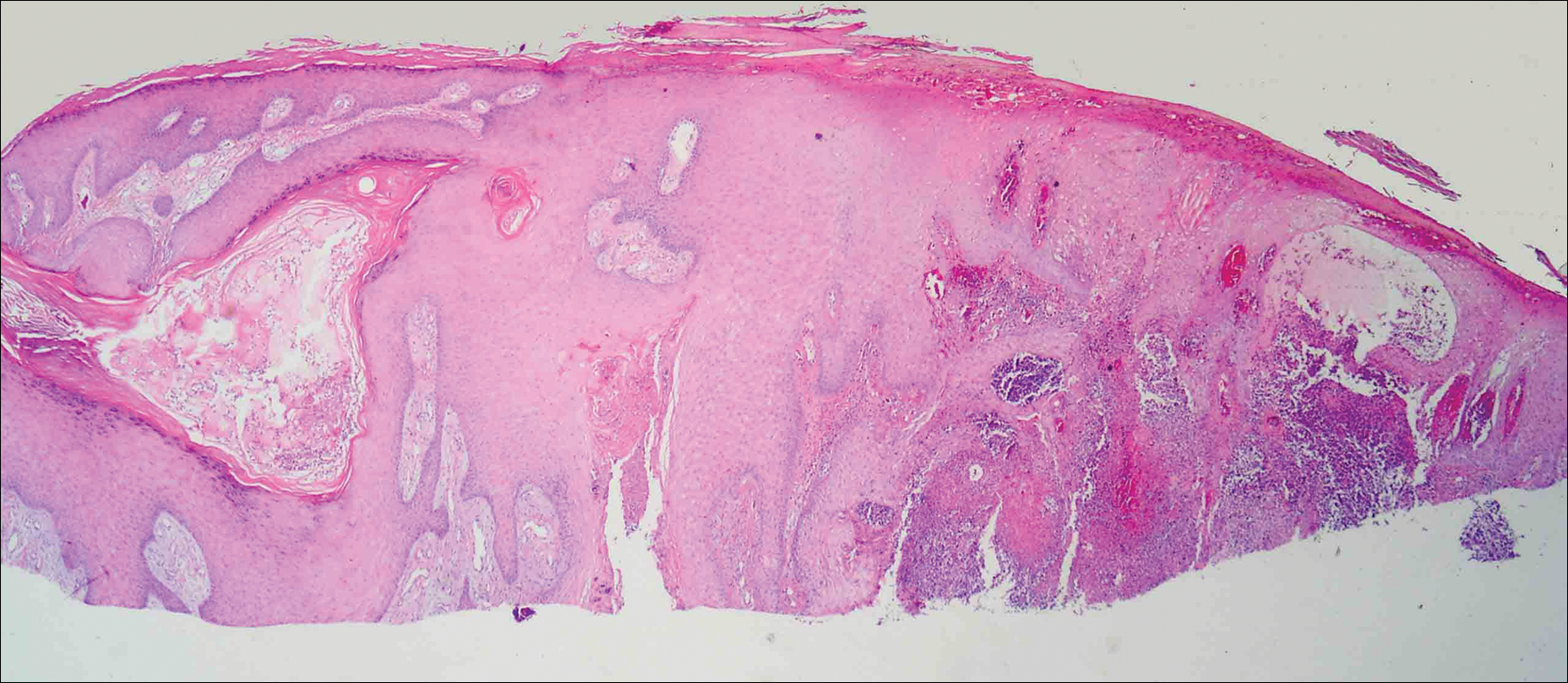

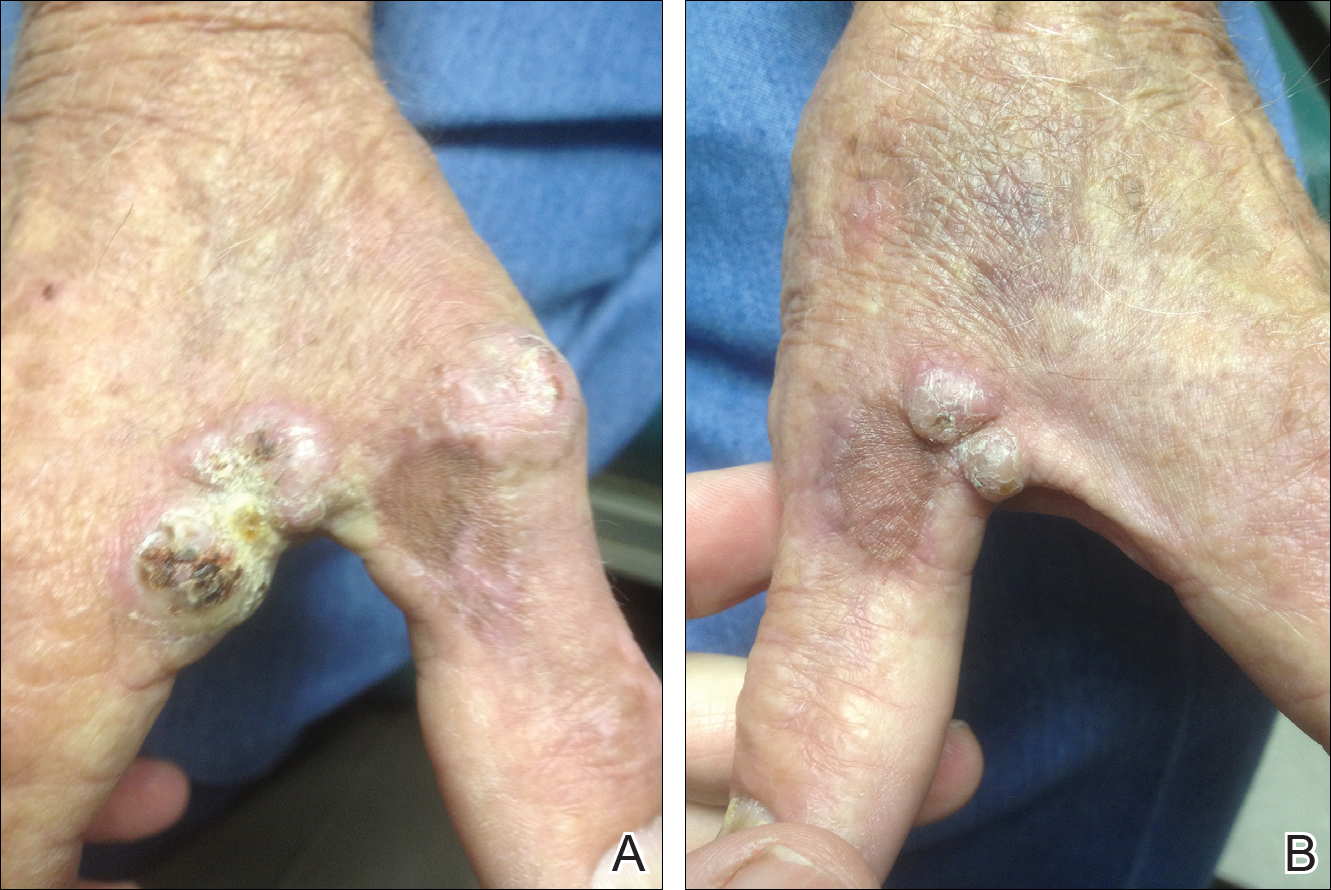

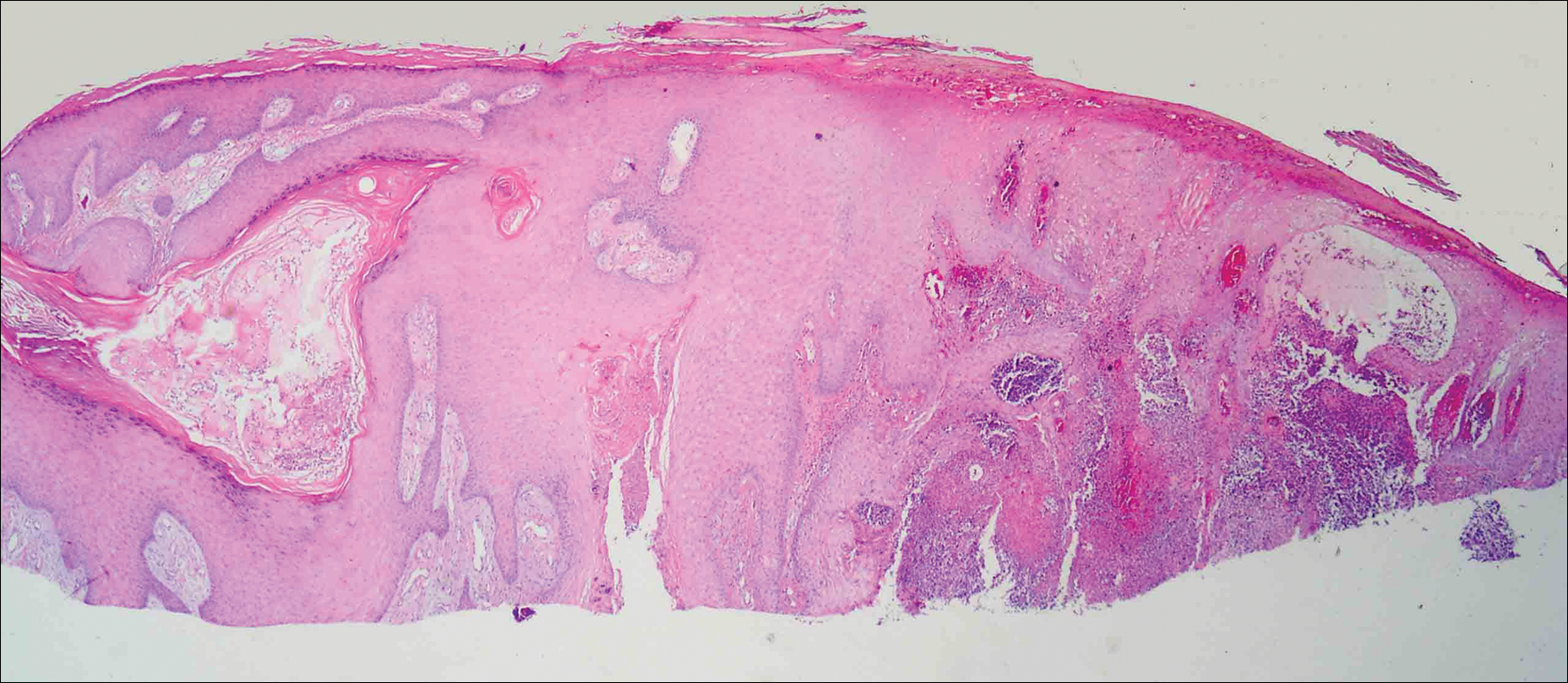

On physical examination the lesions appeared as firm, dusky-violaceous, crusted nodules (Figure 1). Brown patches of hyperpigmentation or characteristic cornlike elevations of the palm were not present to implicate arsenic exposure. Extensive sun damage to the face, neck, forearms, and dorsal aspect of the hands was noted. Epitrochlear lymphadenopathy or lymphangitic streaking were not appreciated. Routine hematologic parameters including leukocyte count were normal, except for chronic thrombocytopenia. Computerized tomography of the abdomen demonstrated no hepatosplenomegaly or enlarged lymph nodes. Hematoxylin and eosin staining of biopsy specimens from the right thumb showed irregular squamous epithelial hyperplasia with an impetiginized scale crust and pustular tissue reaction, including suppurative abscess formation in the dermis (Figure 2). Initial acid-fast staining performed on the biopsy from the right thumb was negative for microorganisms. Given the concerning histologic features indicating infection, a tissue culture was performed. Subsequent growth on Lowenstein-Jensen culture medium confirmed infection with Mycobacterium avium complex (MAC). The patient was started on clarithromycin 500 mg twice daily in accordance with laboratory susceptibilities, and the cutaneous nodules improved. Unfortunately, the patient died 6 months later secondary to cardiac arrest.

Comment

The genus Mycobacterium comprises more than 130 described bacteria, including the precipitants of tuberculosis and leprosy. Mycobacterium avium complex--an umbrella term for M avium, Mycobacterium intracellulare, and other close relatives--is a member of the genus that maintains a low pathogenicity for healthy individuals.1,2 Nonetheless, MAC accounts for more than 70% of cases of nontuberculous mycobacterial disease in the United States.3 Mycobacterium avium complex typically acts as a respiratory pathogen, but infection may manifest with lymphadenitis, osteomyelitis, hepatosplenomegaly, or skin involvement. Disseminated MAC infection can occur in patients with defective immune systems, including those with conditions such as AIDS or hairy cell leukemia and those undergoing immunosuppressive therapy.1,4 Although uncommon, cutaneous infection with MAC occurs via 3 possible mechanisms: (1) primary inoculation, (2) lymphogenous extension, or (3) hematologic dissemination.4 According to a PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms primary cutaneous Mycobacterium avium complex and MAC skin infection, only 11 known cases of primary cutaneous MAC infection have been reported in the English-language literature,4-14 the most recent being a report by Landriscina et al.11

A Runyon group III bacillus, MAC is a slow-growing nonchromogen that is ubiquitous in nature.15 It has been isolated from soil, water, house dust, vegetables, eggs, and milk. According to Reed et al,3 occupational exposure to soil is an independent risk factor for MAC infection, with individuals reporting more than 6 years of cumulative participation in lawn and landscaping services, farming, or other occupations involving substantial exposure to dirt or dust most likely to be MAC-positive. Cutaneous MAC infection may be associated with water exposure, as Sugita et al2 described one familial outbreak of cutaneous MAC infection linked to use of a circulating, constantly heated bathwater system. With respect to US geography, individuals living in rural areas of the South seem most prone to MAC infection.3

Primary cutaneous infection with MAC occurs after a breach in the skin surface, though this fact may not be elicited by history. Modes of entry include minor abrasions after falling,1 small wounds,2 traumatic inoculation,15 and intramuscular injection.16 Clinically, cutaneous lesions of MAC are protean. In the literature, clinical presentation is described as a polymorphous appearance with scaling plaques, verrucous nodules, crusted ulcers, inflammatory nodules, dermatitis, panniculitis, draining sinuses, ecthymatous lesions, sporotrichoid growth patterns, or rosacealike papulopustules.1,15,17 Lesions may affect the arms and legs, trunk, buttocks, and face.18

The differential diagnosis of MAC infection includes lupus vulgaris, Mycobacterium marinum infection (also known as swimming pool granuloma), sporotrichosis, nocardiosis, sarcoidosis, neutrophilic dermatosis, pyoderma gangrenosum, and cutaneous blastomycosis. Given its rarity and variability, diagnosis of MAC infection requires a high index of suspicion. Cutaneous MAC infection should be considered if a nodule, plaque, or ulcer fails to respond to conventional treatment, especially in patients with a history of environmental exposure and possible injury to the skin.

We report a rare case of primary cutaneous MAC infection arising in SCC excision sites in a patient without known immune deficiency. This presentation may have occurred for several reasons. First, the surgical excision sites coupled with the substantial occupational and recreational exposure to soil experienced by our patient may have served as portals for infection. Although SCCs are common on the hands, Mohs micrographic surgery is not always performed for excision; in our patient's case, this approach allowed for maximum tissue conservation and preserved manual function given the number and location of the lesions. Second, despite an overtly intact immune system, our patient may have harbored an occult immune deficiency, predisposing him to dermatologic infection with a microorganism of low intrinsic virulence and recurrent malignant neoplasms. This presentation may have been the first clinical indication of subtle immune compromise. For example, inadequate proinflammatory cytokines may contribute to both mycobacterial and malignant disease. A potential risk of inhibition of tumor necrosis factor α is the unmasking of tuberculosis or lymphoma.19,20 Likewise, IFN-γ is vital in suppressing mycobacteria and malignancy. Yonekura et al21 found that IFN-γ induces apoptosis in oral SCC lines. It follows that a paucity of IFN-γ could allow neoplastic growth. Normal function of IFN-γ prompts microbicidal activity in macrophages and stimulates granuloma formation, both of which combat mycobacterial infection.19 A final postulation is that a simmering cutaneous MAC infection precipitated neoplastic degeneration into SCC, much the same way that the human papillomavirus has been correlated in the carcinogenesis of cervical cancer. As an intracellular microbe, MAC could cause the genetic machinery of skin cells to go awry. Kullavanijaya et al18 described a patient with cutaneous MAC in association with cervical cancer.

Conclusion

This association of primary cutaneous MAC infection and cutaneous malignancy in a reportedly immunocompetent patient is rare. Cancer patients, as noted by Feld et al,22 are 3 times more likely to develop infections with mycobacteria, with SCC, lymphoma, and leukemia being most commonly indicated. A specific immune deficit in the IFN-γ receptor is known to confer a selective predisposition to mycobacterial infection.23,24 Toyoda et al25 outlined the case of a pediatric patient with IFN-γ receptor 2 deficiency who presented with disseminated MAC infection and later succumbed to multiple SCCs of the hands and face. The authors' assertion was that inherited disorders of IFN-γ-mediated immunity may be associated with SCCs.25 Unfortunately, our patient died before more specific immunological testing could be conducted. This case highlights the remarkable singularity of primary cutaneous MAC infection in association with multiple SCCs with seemingly intact immune status and offers some intriguing hypotheses regarding its occurrence.

- Hong BK, Kumar C, Marottoli RA. "MAC" attack. Am J Med. 2009;122:1096-1098.

- Sugita Y, Ishii N, Katsuno M, et al. Familial cluster of cutaneous Mycobacterium avium infection resulting from use of a circulating, constantly heated bath water system. Br J Dermatol. 2000;142:789-793.

- Reed C, von Reyn CF, Chamblee S, et al. Environmental risk factors for infection with Mycobacterium avium complex [published online May 4, 2006]. Am J Epidemiol. 2006;164:32-40.

- Ichiki Y, Hirose M, Akiyama T, et al. Skin infection caused by Mycobacterium avium. Br J Dermatol. 1997;136:260-263.

- Aboutalebi A, Shen A, Katta R, et al. Primary cutaneous infection by Mycobacterium avium: a case report and literature review. Cutis. 2012;89:175-179.

- Nassar D, Ortonne N, Grégoire-Krikorian B, et al. Chronic granulomatous Mycobacterium avium skin pseudotumor. Lancet Infect Dis. 2009;9:136.

- Escalonilla P, Esteban J, Soriano ML, et al. Cutaneous manifestations of infection by nontuberculous mycobacteria. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1998;23:214-221.

- Lugo-Janer G, Cruz A, Sanchez JL. Disseminated cutaneous infection caused by Mycobacterium avium complex. Arch Dermatol. 1990;126:1108-1110.

- Schmidt JD, Yeager H Jr, Smith EB, et al. Cutaneous infection due to a Runyon group 3 atypical Mycobacterium. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1972;106:469-471.

- Carlos C, Tang YW, Adler DJ, et al. Mycobacterial infection identified with broad-range PCR amplification and suspension array identification. J Clin Pathol. 2012;39:795-797.

- Landriscina A, Musaev T, Amin B, et al. A surprising case of Mycobacterium avium complex skin infection in an immunocompetent patient. J Drugs Dermatol. 2014;13:1491-1493.

- Zhou L, Wang HS, Feng SY, et al. Cutaneous Mycobacterium intracellulare infection in an immunocompetent person. Acta Derm Venereol. 2013;93:711-714.

- Cox S, Strausbaugh L. Chronic cutaneous infection caused by Mycobacterium intracellulare. Arch Dermatol. 1981;117:794-796.

- Sachs M, Fraimow HF, Staros EB, et al. Mycobacterium intracellulare soft tissue infection. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1992;27:1019-1021.

- Jogi R, Tyring SK. Therapy of nontuberculous mycobacterial infections. Dermatol Ther. 2004;17:491-498.

- Meadows JR, Carter R, Katner HP. Cutaneous Mycobacterium avium complex infection at an intramuscular injection site in a patient with AIDS. Clin Infect Dis. 1997;24:1273-1274.

- Kayal JD, McCall CO. Sporotrichoid cutaneous Mycobacterium avium complex infection. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;47(5 suppl):S249-S250.

- Kullavanijaya P, Sirimachan S, Surarak S. Primary cutaneous infection with Mycobacterium avium intracellulare complex resembling lupus vulgaris. Br J Dermatol. 1997;136:264-266.

- Netea MG, Kullberg BJ, Van der Meer JW. Proinflammatory cytokines in the treatment of bacterial and fungal infections. BioDrugs. 2004;18:9-22.

- Dommasch E, Gelfand JM. Is there truly a risk of lymphoma from biologic therapies? Dermatol Ther. 2009;22:418-430.

- Yonekura N, Yokota S, Yonekura K, et al. Interferon-γ downregulates Hsp27 expression and suppresses the negative regulation of cell death in oral squamous cell carcinoma lines. Cell Death Differ. 2003;10:313-322.

- Feld R, Bodey GP, Groschel D. Mycobacteriosis in patients with malignant disease. Arch Intern Med. 1976;136:67-70.

- Dorman S, Picard C, Lammas D, et al. Clinical features of dominant and recessive interferon γ receptor 1 deficiencies. Lancet. 2004;364:2113-2121.

- Storgaard M, Varming K, Herlin T, et al. Novel mutation in the interferon-γ receptor gene and susceptibility to mycobacterial infections. Scand J Immunol. 2006;64:137-139.

- Toyoda H, Ido M, Nakanishi K, et al. Multiple cutaneous squamous cell carcinomas in a patient with interferon γ receptor 2 (IFNγR2) deficiency [published online June 18, 2010]. J Med Genet. 2010;47:631-634.

Case Report

A 78-year-old man presented for evaluation of 4 painful keratotic nodules that had appeared on the dorsal aspect of the right thumb, the first web space of the right hand, and the first web space of the left hand. The nodules developed in pericicatricial skin following Mohs micrographic surgery to the affected areas for treatment of invasive squamous cell carcinomas (SCCs) 2 months prior. The patient had worked in lawn maintenance for decades and continued to garden on an avocational basis. He denied exposure to angling or aquariums.

On physical examination the lesions appeared as firm, dusky-violaceous, crusted nodules (Figure 1). Brown patches of hyperpigmentation or characteristic cornlike elevations of the palm were not present to implicate arsenic exposure. Extensive sun damage to the face, neck, forearms, and dorsal aspect of the hands was noted. Epitrochlear lymphadenopathy or lymphangitic streaking were not appreciated. Routine hematologic parameters including leukocyte count were normal, except for chronic thrombocytopenia. Computerized tomography of the abdomen demonstrated no hepatosplenomegaly or enlarged lymph nodes. Hematoxylin and eosin staining of biopsy specimens from the right thumb showed irregular squamous epithelial hyperplasia with an impetiginized scale crust and pustular tissue reaction, including suppurative abscess formation in the dermis (Figure 2). Initial acid-fast staining performed on the biopsy from the right thumb was negative for microorganisms. Given the concerning histologic features indicating infection, a tissue culture was performed. Subsequent growth on Lowenstein-Jensen culture medium confirmed infection with Mycobacterium avium complex (MAC). The patient was started on clarithromycin 500 mg twice daily in accordance with laboratory susceptibilities, and the cutaneous nodules improved. Unfortunately, the patient died 6 months later secondary to cardiac arrest.

Comment

The genus Mycobacterium comprises more than 130 described bacteria, including the precipitants of tuberculosis and leprosy. Mycobacterium avium complex--an umbrella term for M avium, Mycobacterium intracellulare, and other close relatives--is a member of the genus that maintains a low pathogenicity for healthy individuals.1,2 Nonetheless, MAC accounts for more than 70% of cases of nontuberculous mycobacterial disease in the United States.3 Mycobacterium avium complex typically acts as a respiratory pathogen, but infection may manifest with lymphadenitis, osteomyelitis, hepatosplenomegaly, or skin involvement. Disseminated MAC infection can occur in patients with defective immune systems, including those with conditions such as AIDS or hairy cell leukemia and those undergoing immunosuppressive therapy.1,4 Although uncommon, cutaneous infection with MAC occurs via 3 possible mechanisms: (1) primary inoculation, (2) lymphogenous extension, or (3) hematologic dissemination.4 According to a PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms primary cutaneous Mycobacterium avium complex and MAC skin infection, only 11 known cases of primary cutaneous MAC infection have been reported in the English-language literature,4-14 the most recent being a report by Landriscina et al.11

A Runyon group III bacillus, MAC is a slow-growing nonchromogen that is ubiquitous in nature.15 It has been isolated from soil, water, house dust, vegetables, eggs, and milk. According to Reed et al,3 occupational exposure to soil is an independent risk factor for MAC infection, with individuals reporting more than 6 years of cumulative participation in lawn and landscaping services, farming, or other occupations involving substantial exposure to dirt or dust most likely to be MAC-positive. Cutaneous MAC infection may be associated with water exposure, as Sugita et al2 described one familial outbreak of cutaneous MAC infection linked to use of a circulating, constantly heated bathwater system. With respect to US geography, individuals living in rural areas of the South seem most prone to MAC infection.3

Primary cutaneous infection with MAC occurs after a breach in the skin surface, though this fact may not be elicited by history. Modes of entry include minor abrasions after falling,1 small wounds,2 traumatic inoculation,15 and intramuscular injection.16 Clinically, cutaneous lesions of MAC are protean. In the literature, clinical presentation is described as a polymorphous appearance with scaling plaques, verrucous nodules, crusted ulcers, inflammatory nodules, dermatitis, panniculitis, draining sinuses, ecthymatous lesions, sporotrichoid growth patterns, or rosacealike papulopustules.1,15,17 Lesions may affect the arms and legs, trunk, buttocks, and face.18

The differential diagnosis of MAC infection includes lupus vulgaris, Mycobacterium marinum infection (also known as swimming pool granuloma), sporotrichosis, nocardiosis, sarcoidosis, neutrophilic dermatosis, pyoderma gangrenosum, and cutaneous blastomycosis. Given its rarity and variability, diagnosis of MAC infection requires a high index of suspicion. Cutaneous MAC infection should be considered if a nodule, plaque, or ulcer fails to respond to conventional treatment, especially in patients with a history of environmental exposure and possible injury to the skin.

We report a rare case of primary cutaneous MAC infection arising in SCC excision sites in a patient without known immune deficiency. This presentation may have occurred for several reasons. First, the surgical excision sites coupled with the substantial occupational and recreational exposure to soil experienced by our patient may have served as portals for infection. Although SCCs are common on the hands, Mohs micrographic surgery is not always performed for excision; in our patient's case, this approach allowed for maximum tissue conservation and preserved manual function given the number and location of the lesions. Second, despite an overtly intact immune system, our patient may have harbored an occult immune deficiency, predisposing him to dermatologic infection with a microorganism of low intrinsic virulence and recurrent malignant neoplasms. This presentation may have been the first clinical indication of subtle immune compromise. For example, inadequate proinflammatory cytokines may contribute to both mycobacterial and malignant disease. A potential risk of inhibition of tumor necrosis factor α is the unmasking of tuberculosis or lymphoma.19,20 Likewise, IFN-γ is vital in suppressing mycobacteria and malignancy. Yonekura et al21 found that IFN-γ induces apoptosis in oral SCC lines. It follows that a paucity of IFN-γ could allow neoplastic growth. Normal function of IFN-γ prompts microbicidal activity in macrophages and stimulates granuloma formation, both of which combat mycobacterial infection.19 A final postulation is that a simmering cutaneous MAC infection precipitated neoplastic degeneration into SCC, much the same way that the human papillomavirus has been correlated in the carcinogenesis of cervical cancer. As an intracellular microbe, MAC could cause the genetic machinery of skin cells to go awry. Kullavanijaya et al18 described a patient with cutaneous MAC in association with cervical cancer.

Conclusion

This association of primary cutaneous MAC infection and cutaneous malignancy in a reportedly immunocompetent patient is rare. Cancer patients, as noted by Feld et al,22 are 3 times more likely to develop infections with mycobacteria, with SCC, lymphoma, and leukemia being most commonly indicated. A specific immune deficit in the IFN-γ receptor is known to confer a selective predisposition to mycobacterial infection.23,24 Toyoda et al25 outlined the case of a pediatric patient with IFN-γ receptor 2 deficiency who presented with disseminated MAC infection and later succumbed to multiple SCCs of the hands and face. The authors' assertion was that inherited disorders of IFN-γ-mediated immunity may be associated with SCCs.25 Unfortunately, our patient died before more specific immunological testing could be conducted. This case highlights the remarkable singularity of primary cutaneous MAC infection in association with multiple SCCs with seemingly intact immune status and offers some intriguing hypotheses regarding its occurrence.

Case Report

A 78-year-old man presented for evaluation of 4 painful keratotic nodules that had appeared on the dorsal aspect of the right thumb, the first web space of the right hand, and the first web space of the left hand. The nodules developed in pericicatricial skin following Mohs micrographic surgery to the affected areas for treatment of invasive squamous cell carcinomas (SCCs) 2 months prior. The patient had worked in lawn maintenance for decades and continued to garden on an avocational basis. He denied exposure to angling or aquariums.

On physical examination the lesions appeared as firm, dusky-violaceous, crusted nodules (Figure 1). Brown patches of hyperpigmentation or characteristic cornlike elevations of the palm were not present to implicate arsenic exposure. Extensive sun damage to the face, neck, forearms, and dorsal aspect of the hands was noted. Epitrochlear lymphadenopathy or lymphangitic streaking were not appreciated. Routine hematologic parameters including leukocyte count were normal, except for chronic thrombocytopenia. Computerized tomography of the abdomen demonstrated no hepatosplenomegaly or enlarged lymph nodes. Hematoxylin and eosin staining of biopsy specimens from the right thumb showed irregular squamous epithelial hyperplasia with an impetiginized scale crust and pustular tissue reaction, including suppurative abscess formation in the dermis (Figure 2). Initial acid-fast staining performed on the biopsy from the right thumb was negative for microorganisms. Given the concerning histologic features indicating infection, a tissue culture was performed. Subsequent growth on Lowenstein-Jensen culture medium confirmed infection with Mycobacterium avium complex (MAC). The patient was started on clarithromycin 500 mg twice daily in accordance with laboratory susceptibilities, and the cutaneous nodules improved. Unfortunately, the patient died 6 months later secondary to cardiac arrest.

Comment

The genus Mycobacterium comprises more than 130 described bacteria, including the precipitants of tuberculosis and leprosy. Mycobacterium avium complex--an umbrella term for M avium, Mycobacterium intracellulare, and other close relatives--is a member of the genus that maintains a low pathogenicity for healthy individuals.1,2 Nonetheless, MAC accounts for more than 70% of cases of nontuberculous mycobacterial disease in the United States.3 Mycobacterium avium complex typically acts as a respiratory pathogen, but infection may manifest with lymphadenitis, osteomyelitis, hepatosplenomegaly, or skin involvement. Disseminated MAC infection can occur in patients with defective immune systems, including those with conditions such as AIDS or hairy cell leukemia and those undergoing immunosuppressive therapy.1,4 Although uncommon, cutaneous infection with MAC occurs via 3 possible mechanisms: (1) primary inoculation, (2) lymphogenous extension, or (3) hematologic dissemination.4 According to a PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms primary cutaneous Mycobacterium avium complex and MAC skin infection, only 11 known cases of primary cutaneous MAC infection have been reported in the English-language literature,4-14 the most recent being a report by Landriscina et al.11

A Runyon group III bacillus, MAC is a slow-growing nonchromogen that is ubiquitous in nature.15 It has been isolated from soil, water, house dust, vegetables, eggs, and milk. According to Reed et al,3 occupational exposure to soil is an independent risk factor for MAC infection, with individuals reporting more than 6 years of cumulative participation in lawn and landscaping services, farming, or other occupations involving substantial exposure to dirt or dust most likely to be MAC-positive. Cutaneous MAC infection may be associated with water exposure, as Sugita et al2 described one familial outbreak of cutaneous MAC infection linked to use of a circulating, constantly heated bathwater system. With respect to US geography, individuals living in rural areas of the South seem most prone to MAC infection.3

Primary cutaneous infection with MAC occurs after a breach in the skin surface, though this fact may not be elicited by history. Modes of entry include minor abrasions after falling,1 small wounds,2 traumatic inoculation,15 and intramuscular injection.16 Clinically, cutaneous lesions of MAC are protean. In the literature, clinical presentation is described as a polymorphous appearance with scaling plaques, verrucous nodules, crusted ulcers, inflammatory nodules, dermatitis, panniculitis, draining sinuses, ecthymatous lesions, sporotrichoid growth patterns, or rosacealike papulopustules.1,15,17 Lesions may affect the arms and legs, trunk, buttocks, and face.18

The differential diagnosis of MAC infection includes lupus vulgaris, Mycobacterium marinum infection (also known as swimming pool granuloma), sporotrichosis, nocardiosis, sarcoidosis, neutrophilic dermatosis, pyoderma gangrenosum, and cutaneous blastomycosis. Given its rarity and variability, diagnosis of MAC infection requires a high index of suspicion. Cutaneous MAC infection should be considered if a nodule, plaque, or ulcer fails to respond to conventional treatment, especially in patients with a history of environmental exposure and possible injury to the skin.

We report a rare case of primary cutaneous MAC infection arising in SCC excision sites in a patient without known immune deficiency. This presentation may have occurred for several reasons. First, the surgical excision sites coupled with the substantial occupational and recreational exposure to soil experienced by our patient may have served as portals for infection. Although SCCs are common on the hands, Mohs micrographic surgery is not always performed for excision; in our patient's case, this approach allowed for maximum tissue conservation and preserved manual function given the number and location of the lesions. Second, despite an overtly intact immune system, our patient may have harbored an occult immune deficiency, predisposing him to dermatologic infection with a microorganism of low intrinsic virulence and recurrent malignant neoplasms. This presentation may have been the first clinical indication of subtle immune compromise. For example, inadequate proinflammatory cytokines may contribute to both mycobacterial and malignant disease. A potential risk of inhibition of tumor necrosis factor α is the unmasking of tuberculosis or lymphoma.19,20 Likewise, IFN-γ is vital in suppressing mycobacteria and malignancy. Yonekura et al21 found that IFN-γ induces apoptosis in oral SCC lines. It follows that a paucity of IFN-γ could allow neoplastic growth. Normal function of IFN-γ prompts microbicidal activity in macrophages and stimulates granuloma formation, both of which combat mycobacterial infection.19 A final postulation is that a simmering cutaneous MAC infection precipitated neoplastic degeneration into SCC, much the same way that the human papillomavirus has been correlated in the carcinogenesis of cervical cancer. As an intracellular microbe, MAC could cause the genetic machinery of skin cells to go awry. Kullavanijaya et al18 described a patient with cutaneous MAC in association with cervical cancer.

Conclusion

This association of primary cutaneous MAC infection and cutaneous malignancy in a reportedly immunocompetent patient is rare. Cancer patients, as noted by Feld et al,22 are 3 times more likely to develop infections with mycobacteria, with SCC, lymphoma, and leukemia being most commonly indicated. A specific immune deficit in the IFN-γ receptor is known to confer a selective predisposition to mycobacterial infection.23,24 Toyoda et al25 outlined the case of a pediatric patient with IFN-γ receptor 2 deficiency who presented with disseminated MAC infection and later succumbed to multiple SCCs of the hands and face. The authors' assertion was that inherited disorders of IFN-γ-mediated immunity may be associated with SCCs.25 Unfortunately, our patient died before more specific immunological testing could be conducted. This case highlights the remarkable singularity of primary cutaneous MAC infection in association with multiple SCCs with seemingly intact immune status and offers some intriguing hypotheses regarding its occurrence.

- Hong BK, Kumar C, Marottoli RA. "MAC" attack. Am J Med. 2009;122:1096-1098.

- Sugita Y, Ishii N, Katsuno M, et al. Familial cluster of cutaneous Mycobacterium avium infection resulting from use of a circulating, constantly heated bath water system. Br J Dermatol. 2000;142:789-793.

- Reed C, von Reyn CF, Chamblee S, et al. Environmental risk factors for infection with Mycobacterium avium complex [published online May 4, 2006]. Am J Epidemiol. 2006;164:32-40.

- Ichiki Y, Hirose M, Akiyama T, et al. Skin infection caused by Mycobacterium avium. Br J Dermatol. 1997;136:260-263.

- Aboutalebi A, Shen A, Katta R, et al. Primary cutaneous infection by Mycobacterium avium: a case report and literature review. Cutis. 2012;89:175-179.

- Nassar D, Ortonne N, Grégoire-Krikorian B, et al. Chronic granulomatous Mycobacterium avium skin pseudotumor. Lancet Infect Dis. 2009;9:136.

- Escalonilla P, Esteban J, Soriano ML, et al. Cutaneous manifestations of infection by nontuberculous mycobacteria. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1998;23:214-221.

- Lugo-Janer G, Cruz A, Sanchez JL. Disseminated cutaneous infection caused by Mycobacterium avium complex. Arch Dermatol. 1990;126:1108-1110.

- Schmidt JD, Yeager H Jr, Smith EB, et al. Cutaneous infection due to a Runyon group 3 atypical Mycobacterium. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1972;106:469-471.

- Carlos C, Tang YW, Adler DJ, et al. Mycobacterial infection identified with broad-range PCR amplification and suspension array identification. J Clin Pathol. 2012;39:795-797.

- Landriscina A, Musaev T, Amin B, et al. A surprising case of Mycobacterium avium complex skin infection in an immunocompetent patient. J Drugs Dermatol. 2014;13:1491-1493.

- Zhou L, Wang HS, Feng SY, et al. Cutaneous Mycobacterium intracellulare infection in an immunocompetent person. Acta Derm Venereol. 2013;93:711-714.

- Cox S, Strausbaugh L. Chronic cutaneous infection caused by Mycobacterium intracellulare. Arch Dermatol. 1981;117:794-796.

- Sachs M, Fraimow HF, Staros EB, et al. Mycobacterium intracellulare soft tissue infection. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1992;27:1019-1021.

- Jogi R, Tyring SK. Therapy of nontuberculous mycobacterial infections. Dermatol Ther. 2004;17:491-498.

- Meadows JR, Carter R, Katner HP. Cutaneous Mycobacterium avium complex infection at an intramuscular injection site in a patient with AIDS. Clin Infect Dis. 1997;24:1273-1274.

- Kayal JD, McCall CO. Sporotrichoid cutaneous Mycobacterium avium complex infection. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;47(5 suppl):S249-S250.

- Kullavanijaya P, Sirimachan S, Surarak S. Primary cutaneous infection with Mycobacterium avium intracellulare complex resembling lupus vulgaris. Br J Dermatol. 1997;136:264-266.

- Netea MG, Kullberg BJ, Van der Meer JW. Proinflammatory cytokines in the treatment of bacterial and fungal infections. BioDrugs. 2004;18:9-22.

- Dommasch E, Gelfand JM. Is there truly a risk of lymphoma from biologic therapies? Dermatol Ther. 2009;22:418-430.

- Yonekura N, Yokota S, Yonekura K, et al. Interferon-γ downregulates Hsp27 expression and suppresses the negative regulation of cell death in oral squamous cell carcinoma lines. Cell Death Differ. 2003;10:313-322.

- Feld R, Bodey GP, Groschel D. Mycobacteriosis in patients with malignant disease. Arch Intern Med. 1976;136:67-70.

- Dorman S, Picard C, Lammas D, et al. Clinical features of dominant and recessive interferon γ receptor 1 deficiencies. Lancet. 2004;364:2113-2121.

- Storgaard M, Varming K, Herlin T, et al. Novel mutation in the interferon-γ receptor gene and susceptibility to mycobacterial infections. Scand J Immunol. 2006;64:137-139.

- Toyoda H, Ido M, Nakanishi K, et al. Multiple cutaneous squamous cell carcinomas in a patient with interferon γ receptor 2 (IFNγR2) deficiency [published online June 18, 2010]. J Med Genet. 2010;47:631-634.

- Hong BK, Kumar C, Marottoli RA. "MAC" attack. Am J Med. 2009;122:1096-1098.

- Sugita Y, Ishii N, Katsuno M, et al. Familial cluster of cutaneous Mycobacterium avium infection resulting from use of a circulating, constantly heated bath water system. Br J Dermatol. 2000;142:789-793.

- Reed C, von Reyn CF, Chamblee S, et al. Environmental risk factors for infection with Mycobacterium avium complex [published online May 4, 2006]. Am J Epidemiol. 2006;164:32-40.

- Ichiki Y, Hirose M, Akiyama T, et al. Skin infection caused by Mycobacterium avium. Br J Dermatol. 1997;136:260-263.

- Aboutalebi A, Shen A, Katta R, et al. Primary cutaneous infection by Mycobacterium avium: a case report and literature review. Cutis. 2012;89:175-179.

- Nassar D, Ortonne N, Grégoire-Krikorian B, et al. Chronic granulomatous Mycobacterium avium skin pseudotumor. Lancet Infect Dis. 2009;9:136.

- Escalonilla P, Esteban J, Soriano ML, et al. Cutaneous manifestations of infection by nontuberculous mycobacteria. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1998;23:214-221.

- Lugo-Janer G, Cruz A, Sanchez JL. Disseminated cutaneous infection caused by Mycobacterium avium complex. Arch Dermatol. 1990;126:1108-1110.

- Schmidt JD, Yeager H Jr, Smith EB, et al. Cutaneous infection due to a Runyon group 3 atypical Mycobacterium. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1972;106:469-471.

- Carlos C, Tang YW, Adler DJ, et al. Mycobacterial infection identified with broad-range PCR amplification and suspension array identification. J Clin Pathol. 2012;39:795-797.

- Landriscina A, Musaev T, Amin B, et al. A surprising case of Mycobacterium avium complex skin infection in an immunocompetent patient. J Drugs Dermatol. 2014;13:1491-1493.

- Zhou L, Wang HS, Feng SY, et al. Cutaneous Mycobacterium intracellulare infection in an immunocompetent person. Acta Derm Venereol. 2013;93:711-714.

- Cox S, Strausbaugh L. Chronic cutaneous infection caused by Mycobacterium intracellulare. Arch Dermatol. 1981;117:794-796.

- Sachs M, Fraimow HF, Staros EB, et al. Mycobacterium intracellulare soft tissue infection. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1992;27:1019-1021.

- Jogi R, Tyring SK. Therapy of nontuberculous mycobacterial infections. Dermatol Ther. 2004;17:491-498.

- Meadows JR, Carter R, Katner HP. Cutaneous Mycobacterium avium complex infection at an intramuscular injection site in a patient with AIDS. Clin Infect Dis. 1997;24:1273-1274.

- Kayal JD, McCall CO. Sporotrichoid cutaneous Mycobacterium avium complex infection. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;47(5 suppl):S249-S250.

- Kullavanijaya P, Sirimachan S, Surarak S. Primary cutaneous infection with Mycobacterium avium intracellulare complex resembling lupus vulgaris. Br J Dermatol. 1997;136:264-266.

- Netea MG, Kullberg BJ, Van der Meer JW. Proinflammatory cytokines in the treatment of bacterial and fungal infections. BioDrugs. 2004;18:9-22.

- Dommasch E, Gelfand JM. Is there truly a risk of lymphoma from biologic therapies? Dermatol Ther. 2009;22:418-430.

- Yonekura N, Yokota S, Yonekura K, et al. Interferon-γ downregulates Hsp27 expression and suppresses the negative regulation of cell death in oral squamous cell carcinoma lines. Cell Death Differ. 2003;10:313-322.

- Feld R, Bodey GP, Groschel D. Mycobacteriosis in patients with malignant disease. Arch Intern Med. 1976;136:67-70.

- Dorman S, Picard C, Lammas D, et al. Clinical features of dominant and recessive interferon γ receptor 1 deficiencies. Lancet. 2004;364:2113-2121.

- Storgaard M, Varming K, Herlin T, et al. Novel mutation in the interferon-γ receptor gene and susceptibility to mycobacterial infections. Scand J Immunol. 2006;64:137-139.

- Toyoda H, Ido M, Nakanishi K, et al. Multiple cutaneous squamous cell carcinomas in a patient with interferon γ receptor 2 (IFNγR2) deficiency [published online June 18, 2010]. J Med Genet. 2010;47:631-634.

Practice Points

- Mycobacterium avium complex (MAC) is a ubiquitous bacterium that commonly infects the lungs and less commonly infects the skin.

- Clinically, cutaneous MAC infection is polymorphous and may present as a nodule, plaque, or ulcer.

- Standard treatment of primary cutaneous MAC includes systemic antibiotics with or without surgical excision.

VIDEO: AIs associated with endothelial dysfunction, a predictor of CVD

SAN ANTONIO – Aromatase inhibitors (AIs) appear to be associated with declines in vascular endothelial function, which in turn have been associated with the development of cardiovascular disease, suggests a small study presented at the San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium.

In this video interview, Anne Blaes, MD, from the Masonic Cancer Center at the University of Minnesota in Minneapolis, talks about the study, which compared endothelial function between postmenopausal women with hormone receptor–positive breast cancers treated with AIs and healthy postmenopausal controls.

Those treated with AIs, independent of the duration of therapy, had significantly worse endothelial function than healthy postmenopausal controls, as measured by the EndoPAT ratio.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

SAN ANTONIO – Aromatase inhibitors (AIs) appear to be associated with declines in vascular endothelial function, which in turn have been associated with the development of cardiovascular disease, suggests a small study presented at the San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium.

In this video interview, Anne Blaes, MD, from the Masonic Cancer Center at the University of Minnesota in Minneapolis, talks about the study, which compared endothelial function between postmenopausal women with hormone receptor–positive breast cancers treated with AIs and healthy postmenopausal controls.

Those treated with AIs, independent of the duration of therapy, had significantly worse endothelial function than healthy postmenopausal controls, as measured by the EndoPAT ratio.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

SAN ANTONIO – Aromatase inhibitors (AIs) appear to be associated with declines in vascular endothelial function, which in turn have been associated with the development of cardiovascular disease, suggests a small study presented at the San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium.

In this video interview, Anne Blaes, MD, from the Masonic Cancer Center at the University of Minnesota in Minneapolis, talks about the study, which compared endothelial function between postmenopausal women with hormone receptor–positive breast cancers treated with AIs and healthy postmenopausal controls.

Those treated with AIs, independent of the duration of therapy, had significantly worse endothelial function than healthy postmenopausal controls, as measured by the EndoPAT ratio.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

AT SABCS 2016

Trump administration to focus on ACA reform, tort reform

Look for three things from the Trump administration: significant changes to the Affordable Care Act, few changes to MACRA’s Quality Payment Program, and a conservative swing in the courts.

Republicans have had their sights on the Affordable Care Act since its passage in 2010; with majorities in both the House and the Senate, the question is not if, but when President Obama’s signature piece of legislation will be dismantled.

President-elect Donald Trump ran on the promise of ACA repeal. Health policy priorities on his transition website focus on greater use of health savings accounts, the ability to purchase insurance across state lines, and the reestablishment of high-risk pools.

Health policy experts differ in how they see ACA reform coming about, with some predicting a quick repeal coupled with an immediate legislative replacement, while others envision repeal with more time to craft replacement legislation. Reform also could come as a series of smaller bills rather than one comprehensive package.

Using budget reconciliation would not allow for full ACA repeal since only provisions that involve revenue generation or spending could be altered. However, since budget reconciliation bills cannot be filibustered, only a simple majority is needed for Senate passage. With their razor-thin majority – 51 seats – Republicans will need some support from outside of their own party.

“Twenty-some Democrats, many in very-deep ‘red states’ including North Dakota, are up for reelection in 2018,” Ms. Turner said. “They saw what happened to the candidates who supported Obamacare in 2016 – many of them went down. It happened with Evan Bayh in Indiana, who was running again to reclaim the Senate seat he left in 2010. And the Republican candidate [Todd Young] reminded the voters over and over that Evan Bayh voted for Obamacare. Same thing happened in Wisconsin with [Republican] Sen. Ron Johnson being challenged by Russ Feingold, who also was in the Senate when Obamacare passed. Feingold went down to defeat again. I think the lot of Democratic senators are going to be looking at what happened to those people and think ‘Maybe I better participate in coming up with a more sensible solution.’ ”

More importantly, the GOP may be looking for bipartisan support, especially since the ACA passed on a strict party-line vote. To that end, it could make more sense to delay reform efforts until a broader coalition can be formed and simultaneous repeal/replace package could be brought to both the House and the Senate floors.

In the new Congress, Senate Republicans might face some of the same obstructionist tactics they used during the Obama administration, which could complicate efforts to get bipartisan support.

“When you have people like Sen. [Bernie] Sanders (I-Vt.) and Sen. [Elizabeth] Warren (D-Mass.) saying they are going to adapt a scorched earth approach going forward, they and their followers don’t have any intention of doing anything that would in any way appear to cooperate with the Republicans,” Dr. Wilensky said. “Of course, there are other Democrats, especially some of the ones who will be up in 2018, who might not be quite so adamant.”

“Repeal without a clear idea of what the replacement would be would really throw that market into chaos, where right now we are at a place where the markets are relatively stable,” Dr. Collins said in an interview.“The best way to think about the ACA, and particularly on the marketplaces and what repeal means, is this image of the three-legged stool. The individual market is the seat and the legs include consumer protections, particularly guaranteed issue; the individual requirement to have insurance; and the subsidies to make that coverage affordable – Medicaid expansion is part of that as well. If you start to remove any one of those legs, the market becomes extremely unstable.”

Repealing the individual mandate is problematic as it goes hand in hand with the ban on coverage denial because of preexisting conditions, something President-elect Trump has signaled he is looking to maintain, Ms. Turner said, adding that free market solutions with appropriate incentives could be a different way to encourage healthy people to get coverage to help generate premium revenue to cover patients with preexisting conditions.

While the ACA will be in the crosshairs, experts expect MACRA to remain more or less intact, maybe with some minor tweaks, at least early on.

While the Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act of 2015 passed with overwhelming support from both parties, “the [implementing regulations] are just a nightmare and I think the Trump administration is going to have to take a look at them,” Ms. Turner said. She added that physicians are weary of the ever-growing federal administrative hassles. “You do not want doctors to leave private practice in droves, and they are looking at this cost of compliance.”

“I think that [MACRA] is just way too much of an in-the-weeds policy thing for the Trump administration to have addressed yet,” Ms. Turner continued. “But this certainly is going to have to be on the agenda because they are going to hear from a lot of doctors that this is not acceptable.”

Mr. Trump also has called for Medicaid reform, with block grants to the states.

“Everyone keeps talking about a block grant, but that is a clumsy way of doing it,” Ms. Turner said, suggesting the program be even more refined to cover people in different baskets, including dual-eligibles, healthy adults that were part of the ACA Medicaid expansion, mothers and infants, and disabled individuals. “A capitated allotment [allows the government to provide more support to] the people who need it.”

Dr. Wilensky suggested that the Trump administration could revisit the 1332 waiver process, another provision of the ACA.

“The current administration has taken a very-rigid view on that you have to keep savings from Medicaid and the ACA separate and any changes have to be budget neutral to each, which is an extremely rigid set of requirements,” she said. Instead “Medicaid and ACA savings could count together and it just needs to be budget neutral over a 3- or 5-year period. That would then allow states to come in and request a lot of flexibility that the current administration hasn’t been inclined to give them.”

Likewise, the Children’s Health Insurance Plan (CHIP) is up for reauthorization. While the program remains relatively popular, it could be due for some reforms as well. Dr. Wilensky said it might be time for the program to go away, though doing that would face resistance from congressional Democrats.

Likewise, Ms. Turner suggested it could be time to fold CHIP into another program like Medicaid.

“Does it really make sense for a mother who is overwhelmed, maybe even with two jobs, to have her kids on a different health insurance program than she’s on?” Ms. Turner said. “It just adds to the burden and the paperwork. Would it make more sense to blend some of these programs together, making sure the people get the health coverage they need, but without all these artificial silos that really make it much more difficult for the user at the other end. I think they are going to take a look at that.”

Whether the ACA is amended or repealed may affect some – but not all – of the ACA-related cases lingering in the courts.

Zubik v. Burwell for instance, may become irrelevant if President-elect Trump eliminates the ACA’s birth control mandate or its accommodation clause. Zubik centers on an exception to the birth control mandate for organizations that oppose coverage for contraceptives but are not exempted entities, such as churches. The plaintiffs argue that the government’s opt-out process makes them complicit in offering contraception coverage indirectly.

The Trump administration could choose to broaden the mandate’s exemption to include the religious organizations, thus satisfying the plaintiffs, said Timothy S. Jost, a health law professor at Washington and Lee University in Lexington, Va., who added that the case would become moot if the ACA is repealed wholesale.

“Millions of women [currently] get access to birth control without cost sharing through the Affordable Care Act,” he said in an interview. “That’s an issue [the new administration] is going to have to confront.”

In March, U.S. Supreme Court justices requested that both sides provide new briefs that outlined how contraception could be provided without requiring notice on the part of the suing employers. Then, in light of the briefs, the high court vacated the lower court rulings related to Zubik and remanded the case to the four appeals courts that had originally ruled on the issue.

If the case makes its way back to the Supreme Court, the ultimate ruling will largely depend on the makeup of the court at the time, said Eric D. Fader, a New York–based health law attorney.

“As long as we have a 4-4 Supreme Court, everything is up in the air,” Mr. Fader said in an interview. “As soon as that ninth slot is filled, I think we’re going to see some decisions that are going to be in line with traditional Republican conservative positions.”

However, a set of ACA-related cases that involve payments to insurers will continue litigating, regardless of actions by the new administration, analysts said. A half-dozen health insurers have sued the Health & Human Services department over alleged underpayments under the ACA’s risk corridor program.

“Even if you do away with the ACA, these cases all pertain to conduct that has already occurred, so they’re not going to be automatically moot,” Mr. Fader said in an interview. “They may struggle along for a while.”

The cases stem from the ACA’s risk corridor program, which requires HHS to collect funds from excessively profitable insurers that offer qualified health plans under the exchanges, while paying out funds to QHP insurers that have excessive losses. Collections from profitable insurers under the program fell short in 2014 and again in 2015, resulting in HHS paying about 12 cents on the dollar in payments to insurers.

The plaintiffs allege they’ve been shortchanged and that the government must reimburse them full payments for 2014. The Department of Justice (DOJ) argues the cases are premature because the full amount owed under the program is not due until 2016, after the program runs its course.

The Trump administration may surrender another ACA-linked challenge that questions billions in payments made to insurers, Mr. Jost said in an interview. In House v. Burwell, the House of Representatives accuses HHS of wrongly spending billions to repay insurers for health insurance provided to certain low-income patients under the ACA. The House claims HHS is illegally spending monies that Congress never appropriated. HHS argues that other statutory provisions of the ACA authorize expenditures for cost-sharing reimbursements. In May, the U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia decided in favor of the House, ruling that Congress never appropriated money for the payments and that no public money can be spent without an appropriation.

There is speculation that the Trump administration may not pursue an appeal, Mr. Jost said. “I think they better think long and hard about that because I don’t know why any president would want court precedent saying one house of Congress can sue the president whenever it disagrees,” he said. “If the Trump administration would give in on the lawsuit or the House would win … there would be some very large losses and some very large premium increases next year. There could be some very significant disruption of insurance markets.”

Again, if the ACA is repealed, the case may become irrelevant, Mr. Fader said. “If you get rid of the ACA and eliminate the cost sharing structure, than House v. Burwell is going to just be moot.”

“We have seen a substantial uptick in antitrust enforcement activity in health care over the last several years,” he said in an interview. “The Trump administration has said that one of its themes is reducing the regulatory burden on businesses. People will be watching to see if that means an attempt to back off of some of the more-aggressive antitrust enforcement activities in health care and other industries.”

The Obama administration is currently fighting to block two mega-mergers among four of the largest health insurers in the nation. The DOJ filed legal challenges earlier this year seeking to ban Anthem’s proposed acquisition of Cigna and Aetna’s proposed acquisition of Humana. The lawsuits allege the mergers – valued at $54 billion and $37 billion respectively – would negatively affect doctors, patients, and employers by limiting price competition, reducing benefits, and lowering quality of care. A majority of physician associations and patient groups oppose the mergers. But experts said the new administration could drop the challenges.

Similarly, the Trump administration could be more lax in its enforcement of the Stark Law. “You could certainly say if the administration is committed to reducing regulatory burden, one thing the administration might push forward is reducing some of the enforcement with respect to technical violations of Stark,” Mr. Horton said, noting that the Senate recently questioned if the government is going too far in regulating physician relationships under Stark. “If your theme is ‘Let’s cut back on regulation,’ that would be an area that you would think the administration would look at.”

Meanwhile, stronger medical malpractice reforms could be on the horizon in light of a Republican-controlled Congress. Tort reform advocates have a good chance at passing federal medical liability reforms that were left out of the ACA’s passage in 2010, said Dennis A. Cardoza, public affairs director and cochair of the federal public affairs practice at a national health law firm.

Earlier versions of the ACA included amendments that mandated lawsuits go through a state or federal alternative dispute resolution system prior to being filed in court. Another provision that failed would have provided federal grants to states that created special health courts for medical malpractice claims. The amendment would have allowed states to create expert panels, administrative health care tribunals, or a combination of the two.

“There’s much stronger support for tort reform among the Republicans in Congress,” Mr. Cardoza said in an interview. “There’s a shot [now]. If the reforms don’t go too far where they would penalize injured patients, I think they could get additional support and be well received by the Congress.”

Tougher abortion restrictions are likely under the Trump administration, experts said. President-elect Trump has said he is committed to nominating a ninth Supreme Court justice who opposes Roe v. Wade.

Vice President-elect Mike Pence, who is considered a strong voice for the religious right, will likely influence who Mr. Trump nominates for the high court, said Rep-elect Raskin, who added that if ever there was time that abortion rights are in jeopardy, it’s now.

“This really puts the Republicans to the test,” he said in an interview. “For decades now, they have been calling for the overruling of Roe v. Wade. The religious right will never forgive them if it doesn’t happen now. [Republicans] control the House, the Senate, and the White House. They have it within their reach to create a five-justice majority on the court.”

[email protected]

[email protected]

On Twitter @legal_med

Look for three things from the Trump administration: significant changes to the Affordable Care Act, few changes to MACRA’s Quality Payment Program, and a conservative swing in the courts.

Republicans have had their sights on the Affordable Care Act since its passage in 2010; with majorities in both the House and the Senate, the question is not if, but when President Obama’s signature piece of legislation will be dismantled.

President-elect Donald Trump ran on the promise of ACA repeal. Health policy priorities on his transition website focus on greater use of health savings accounts, the ability to purchase insurance across state lines, and the reestablishment of high-risk pools.

Health policy experts differ in how they see ACA reform coming about, with some predicting a quick repeal coupled with an immediate legislative replacement, while others envision repeal with more time to craft replacement legislation. Reform also could come as a series of smaller bills rather than one comprehensive package.

Using budget reconciliation would not allow for full ACA repeal since only provisions that involve revenue generation or spending could be altered. However, since budget reconciliation bills cannot be filibustered, only a simple majority is needed for Senate passage. With their razor-thin majority – 51 seats – Republicans will need some support from outside of their own party.

“Twenty-some Democrats, many in very-deep ‘red states’ including North Dakota, are up for reelection in 2018,” Ms. Turner said. “They saw what happened to the candidates who supported Obamacare in 2016 – many of them went down. It happened with Evan Bayh in Indiana, who was running again to reclaim the Senate seat he left in 2010. And the Republican candidate [Todd Young] reminded the voters over and over that Evan Bayh voted for Obamacare. Same thing happened in Wisconsin with [Republican] Sen. Ron Johnson being challenged by Russ Feingold, who also was in the Senate when Obamacare passed. Feingold went down to defeat again. I think the lot of Democratic senators are going to be looking at what happened to those people and think ‘Maybe I better participate in coming up with a more sensible solution.’ ”

More importantly, the GOP may be looking for bipartisan support, especially since the ACA passed on a strict party-line vote. To that end, it could make more sense to delay reform efforts until a broader coalition can be formed and simultaneous repeal/replace package could be brought to both the House and the Senate floors.

In the new Congress, Senate Republicans might face some of the same obstructionist tactics they used during the Obama administration, which could complicate efforts to get bipartisan support.

“When you have people like Sen. [Bernie] Sanders (I-Vt.) and Sen. [Elizabeth] Warren (D-Mass.) saying they are going to adapt a scorched earth approach going forward, they and their followers don’t have any intention of doing anything that would in any way appear to cooperate with the Republicans,” Dr. Wilensky said. “Of course, there are other Democrats, especially some of the ones who will be up in 2018, who might not be quite so adamant.”

“Repeal without a clear idea of what the replacement would be would really throw that market into chaos, where right now we are at a place where the markets are relatively stable,” Dr. Collins said in an interview.“The best way to think about the ACA, and particularly on the marketplaces and what repeal means, is this image of the three-legged stool. The individual market is the seat and the legs include consumer protections, particularly guaranteed issue; the individual requirement to have insurance; and the subsidies to make that coverage affordable – Medicaid expansion is part of that as well. If you start to remove any one of those legs, the market becomes extremely unstable.”