User login

Light and heavy mesh deliver similar outcomes and QOL for lap inguinal repair

WASHINGTON – The weight of mesh used in laparoscopic inguinal hernia repairs was not a significant factor in postoperative outcomes and quality of life, in a large, long-term study.

“There are approximately 700,000 inguinal hernia repairs annually,” said Steve Groene, MD, of the Carolinas Medical Center, Charlotte, N.C. “The goal of our study was to utilize a large sample size of long-term follow-up and compare surgical and quality of life outcomes between light-weight and heavy-weight mesh in laparoscopic inguinal hernia repairs.”

The rates of postoperative complications such as surgical infection, urinary retention, and recurrence in the two groups were similar. Although the LW mesh group had a significantly higher rate of hematoma and seroma, that difference vanished with a multivariate analysis that accounted for confounding factors such as smoking, elective vs. emergent surgery, and surgical technique, Dr. Groene said at the annual clinical congress of the American College of Surgeons.

Quality of life (QOL) was measured with the Carolina Comfort Scale before surgery and at the 2-week, 1-month, 6-month, 12-month, 24-month, and 36-month follow-ups. The investigators looked at pain, movement limitation, and mesh sensation for outcomes and symptoms. There were no other statistically significant differences in QOL between the groups at any of the follow-up time points.

When asked during the discussion about the experience of the investigators in getting patients to continue through a 36-month follow-up, Dr. Groene said that “at 1 month, we were about 60%, [and] at 1 year about 40%; having about 40%-42% of people following up at 1 month is very good.”

Dr. Groene concluded that surgeons should continue to use the type of mesh they feel most comfortable with for laparoscopic inguinal hernia repair and expect to have similar outcomes.

He reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

WASHINGTON – The weight of mesh used in laparoscopic inguinal hernia repairs was not a significant factor in postoperative outcomes and quality of life, in a large, long-term study.

“There are approximately 700,000 inguinal hernia repairs annually,” said Steve Groene, MD, of the Carolinas Medical Center, Charlotte, N.C. “The goal of our study was to utilize a large sample size of long-term follow-up and compare surgical and quality of life outcomes between light-weight and heavy-weight mesh in laparoscopic inguinal hernia repairs.”

The rates of postoperative complications such as surgical infection, urinary retention, and recurrence in the two groups were similar. Although the LW mesh group had a significantly higher rate of hematoma and seroma, that difference vanished with a multivariate analysis that accounted for confounding factors such as smoking, elective vs. emergent surgery, and surgical technique, Dr. Groene said at the annual clinical congress of the American College of Surgeons.

Quality of life (QOL) was measured with the Carolina Comfort Scale before surgery and at the 2-week, 1-month, 6-month, 12-month, 24-month, and 36-month follow-ups. The investigators looked at pain, movement limitation, and mesh sensation for outcomes and symptoms. There were no other statistically significant differences in QOL between the groups at any of the follow-up time points.

When asked during the discussion about the experience of the investigators in getting patients to continue through a 36-month follow-up, Dr. Groene said that “at 1 month, we were about 60%, [and] at 1 year about 40%; having about 40%-42% of people following up at 1 month is very good.”

Dr. Groene concluded that surgeons should continue to use the type of mesh they feel most comfortable with for laparoscopic inguinal hernia repair and expect to have similar outcomes.

He reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

WASHINGTON – The weight of mesh used in laparoscopic inguinal hernia repairs was not a significant factor in postoperative outcomes and quality of life, in a large, long-term study.

“There are approximately 700,000 inguinal hernia repairs annually,” said Steve Groene, MD, of the Carolinas Medical Center, Charlotte, N.C. “The goal of our study was to utilize a large sample size of long-term follow-up and compare surgical and quality of life outcomes between light-weight and heavy-weight mesh in laparoscopic inguinal hernia repairs.”

The rates of postoperative complications such as surgical infection, urinary retention, and recurrence in the two groups were similar. Although the LW mesh group had a significantly higher rate of hematoma and seroma, that difference vanished with a multivariate analysis that accounted for confounding factors such as smoking, elective vs. emergent surgery, and surgical technique, Dr. Groene said at the annual clinical congress of the American College of Surgeons.

Quality of life (QOL) was measured with the Carolina Comfort Scale before surgery and at the 2-week, 1-month, 6-month, 12-month, 24-month, and 36-month follow-ups. The investigators looked at pain, movement limitation, and mesh sensation for outcomes and symptoms. There were no other statistically significant differences in QOL between the groups at any of the follow-up time points.

When asked during the discussion about the experience of the investigators in getting patients to continue through a 36-month follow-up, Dr. Groene said that “at 1 month, we were about 60%, [and] at 1 year about 40%; having about 40%-42% of people following up at 1 month is very good.”

Dr. Groene concluded that surgeons should continue to use the type of mesh they feel most comfortable with for laparoscopic inguinal hernia repair and expect to have similar outcomes.

He reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

FROM ACS CLINICAL CONGRESS

Key clinical point:

Major finding: For laparoscopic inguinal hernia repair, mesh weight was not a significant factor in postoperative complications or quality of life, as measured by the Carolinas Comfort Scale.

Data source: A prospective study of 1,270 laparoscopic inguinal hernia repair patients from a hernia-specific database.

Disclosures: Dr. Groene reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

Risk models for hernia recurrence don’t hold up to external validation

Five common variable selection strategies failed to produce a statistical model that accurately predicted ventral hernia recurrence in an investigation published in the Journal of Surgical Research.

The finding matters because those five techniques – expert opinion and various multivariate regression and bootstrapping strategies – have been widely used in previous studies to create risk scores for ventral hernia recurrence. The new study calls the value of existing scoring systems into question (J Surg Res. 2016 Nov;206[1]:159-67. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2016.07.042).

The lack of external validation in many studies leads to medical findings that often can’t be confirmed by subsequent studies. It’s a problem that has contributed to skepticism about research results in both the medical community and the general public, they said.

“This study demonstrates the importance of true external validation on an external data set. Simply splitting a data set and validating [internally] does not appear to be an adequate assessment of predictive accuracy. … We recommend that future researchers consider using and presenting the results of multiple variable selection strategies [and] focus on presenting predictive accuracy on external data sets to validate their model,” the team concluded.

The original goal of the project was to identify the best predictors of ventral hernia recurrence since suggestions from past studies have varied. The team first used a prospective database of 790 ventral hernia repair patients to identify predictors of recurrence. Of that group, 526 patients – 173 (32.9%) of whom had a recurrence after a median follow-up of 20 months – were used to identify risk variables using expert opinion, selective stepwise regression, liberal stepwise regression, and bootstrapping with both restrictive and liberal internal resampling.

The team used the remaining 264 patients to confirm the findings. As in previous studies, internal validation worked: all five models had a Harrell’s C-statistic of about 0.76, which is considered reasonable, Dr. Holihan and her associates reported.

However, when the investigators applied their models to a second database of 1,225 patients followed for a median of 9 months – with 155 recurrences (12.7%) – they were not much better at predicting recurrence than a coin toss, with C-statistic values of about 0.56.

Some variables made the cut with all five selection techniques, including hernia type, wound class, and albumin levels, which are related to how well the wound heals. Other variables were significant in some selection strategies but not others, including smoking status, open versus laparoscopic approach, and mesh use.

At least for now, clinical intuition remains important for assessing rerupture risk, they said.

The National Institutes of Health funded the work. Author disclosures were not reported.

Five common variable selection strategies failed to produce a statistical model that accurately predicted ventral hernia recurrence in an investigation published in the Journal of Surgical Research.

The finding matters because those five techniques – expert opinion and various multivariate regression and bootstrapping strategies – have been widely used in previous studies to create risk scores for ventral hernia recurrence. The new study calls the value of existing scoring systems into question (J Surg Res. 2016 Nov;206[1]:159-67. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2016.07.042).

The lack of external validation in many studies leads to medical findings that often can’t be confirmed by subsequent studies. It’s a problem that has contributed to skepticism about research results in both the medical community and the general public, they said.

“This study demonstrates the importance of true external validation on an external data set. Simply splitting a data set and validating [internally] does not appear to be an adequate assessment of predictive accuracy. … We recommend that future researchers consider using and presenting the results of multiple variable selection strategies [and] focus on presenting predictive accuracy on external data sets to validate their model,” the team concluded.

The original goal of the project was to identify the best predictors of ventral hernia recurrence since suggestions from past studies have varied. The team first used a prospective database of 790 ventral hernia repair patients to identify predictors of recurrence. Of that group, 526 patients – 173 (32.9%) of whom had a recurrence after a median follow-up of 20 months – were used to identify risk variables using expert opinion, selective stepwise regression, liberal stepwise regression, and bootstrapping with both restrictive and liberal internal resampling.

The team used the remaining 264 patients to confirm the findings. As in previous studies, internal validation worked: all five models had a Harrell’s C-statistic of about 0.76, which is considered reasonable, Dr. Holihan and her associates reported.

However, when the investigators applied their models to a second database of 1,225 patients followed for a median of 9 months – with 155 recurrences (12.7%) – they were not much better at predicting recurrence than a coin toss, with C-statistic values of about 0.56.

Some variables made the cut with all five selection techniques, including hernia type, wound class, and albumin levels, which are related to how well the wound heals. Other variables were significant in some selection strategies but not others, including smoking status, open versus laparoscopic approach, and mesh use.

At least for now, clinical intuition remains important for assessing rerupture risk, they said.

The National Institutes of Health funded the work. Author disclosures were not reported.

Five common variable selection strategies failed to produce a statistical model that accurately predicted ventral hernia recurrence in an investigation published in the Journal of Surgical Research.

The finding matters because those five techniques – expert opinion and various multivariate regression and bootstrapping strategies – have been widely used in previous studies to create risk scores for ventral hernia recurrence. The new study calls the value of existing scoring systems into question (J Surg Res. 2016 Nov;206[1]:159-67. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2016.07.042).

The lack of external validation in many studies leads to medical findings that often can’t be confirmed by subsequent studies. It’s a problem that has contributed to skepticism about research results in both the medical community and the general public, they said.

“This study demonstrates the importance of true external validation on an external data set. Simply splitting a data set and validating [internally] does not appear to be an adequate assessment of predictive accuracy. … We recommend that future researchers consider using and presenting the results of multiple variable selection strategies [and] focus on presenting predictive accuracy on external data sets to validate their model,” the team concluded.

The original goal of the project was to identify the best predictors of ventral hernia recurrence since suggestions from past studies have varied. The team first used a prospective database of 790 ventral hernia repair patients to identify predictors of recurrence. Of that group, 526 patients – 173 (32.9%) of whom had a recurrence after a median follow-up of 20 months – were used to identify risk variables using expert opinion, selective stepwise regression, liberal stepwise regression, and bootstrapping with both restrictive and liberal internal resampling.

The team used the remaining 264 patients to confirm the findings. As in previous studies, internal validation worked: all five models had a Harrell’s C-statistic of about 0.76, which is considered reasonable, Dr. Holihan and her associates reported.

However, when the investigators applied their models to a second database of 1,225 patients followed for a median of 9 months – with 155 recurrences (12.7%) – they were not much better at predicting recurrence than a coin toss, with C-statistic values of about 0.56.

Some variables made the cut with all five selection techniques, including hernia type, wound class, and albumin levels, which are related to how well the wound heals. Other variables were significant in some selection strategies but not others, including smoking status, open versus laparoscopic approach, and mesh use.

At least for now, clinical intuition remains important for assessing rerupture risk, they said.

The National Institutes of Health funded the work. Author disclosures were not reported.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF SURGICAL RESEARCH

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Risk models developed from the five strategies weren’t much better at predicting recurrence than a coin toss, with C-statistic values of about 0.56.

Data source: Analysis of two datasets containing a total of 2,015 ventral hernia repair patients.

Disclosures: The National Institutes of Health funded the work. Author disclosures were not reported.

Tenotomy, Tenodesis, Transfer: A Review of Treatment Options for Biceps-Labrum Complex Disease

Pathology of the biceps-labrum complex (BLC) can be an important source of shoulder pain. Discussion of pathoanatomy, imaging, and surgical intervention is facilitated by distinguishing the anatomical zones of the BLC: inside, junction, and bicipital tunnel (extra-articular), parts of which cannot be visualized with standard diagnostic arthroscopy.

The recent literature indicates that bicipital tunnel lesions are common and perhaps overlooked. Systematic reviews suggest improvement in outcomes of BLC operations when the bicipital tunnel is decompressed. Higher-level clinical and basic science studies are needed to fully elucidate the role of the bicipital tunnel, but it is evident that a comprehensive physical examination and an understanding of the limits of advanced imaging are necessary to correctly diagnose and treat BLC-related shoulder pain.

Anatomy of Biceps-Labrum Complex

The long head of the biceps tendon (LHBT) and the glenoid labrum work as an interdependent functional unit, the biceps-labrum complex (BLC). The BLC is divided into 3 distinct anatomical zones: inside, junction, and bicipital tunnel.1,2

Inside

The inside includes the superior labrum and biceps attachment. The LHBT most commonly originates in the superior labrum.3-5 Vangsness and colleagues3 described 4 types of LHBT origins: Type I biceps attaches solely to the posterior labrum, type II predominantly posterior, type III equally to the anterior and posterior labrum, and type IV mostly to the anterior labrum. The LHBT can also originate in the supraglenoid tubercle or the inferior border of the supraspinatus.3,6

Junction

Junction is the intra-articular segment of the LHBT and the biceps pulley. The LHBT traverses the glenohumeral joint en route to the extra-articular bicipital tunnel.2 The LHBT is enveloped in synovium that extends into part of the bicipital tunnel.2 The intra-articular segment of the LHBT is about 25 mm in length7 and has a diameter of 5 mm to 6 mm.8

A cadaveric study found that the average length of the LHBT that can be arthroscopically visualized at rest is 35.6 mm, or only 40% of the total length of the LHBT with respect to the proximal margin of the pectoralis major tendon.1 When the LHBT was pulled into the joint, more tendon (another 14 mm) was visualized.1 Therefore, diagnostic arthroscopy of the glenohumeral joint visualizes about 50% of the LHBT.9The morphology of the LHBT varies by location. The intra-articular portion of the LHBT is wide and flat, whereas the extra-articular portion is round.8 The tendon becomes smoother and more avascular as it exits the joint to promote gliding within its sheath in the bicipital groove.10 The proximal LHBT receives its vascular supply from superior labrum tributaries, and distally the LHBT is supplied by ascending branches of the anterior humeral circumflex artery.4 There is a hypovascular zone, created by this dual blood supply, about 12 mm to 30 mm from the LHBT origin, predisposing the tendon to rupture or fray in this region.11The LHBT makes a 30° turn into the biceps pulley system as it exits the glenohumeral joint. The fibrous pulley system that stabilizes the LHBT in this region has contributions from the coracohumeral ligament, the superior glenohumeral ligament, and the supraspinatus tendon.12-14

Bicipital Tunnel

The bicipital tunnel, the third portion of the BLC, remains largely hidden from standard diagnostic glenohumeral arthroscopy. The bicipital tunnel is an extra-articular, closed space that constrains the LHBT from the articular margin through the subpectoral region.2

Zone 1 is the traditional bicipital groove or “bony groove” that extends from the articular margin to the distal margin of the subscapularis tendon. The floor consists of a deep osseous groove covered by a continuation of subscapularis tendon fibers and periosteum.2Zone 2, “no man’s land,” extends from the distal margin of the subscapularis tendon to the proximal margin of the pectoralis major (PMPM). The LHBT in this zone cannot be visualized during a pull test at arthroscopy, yet lesions commonly occur here.1 Zones 1 and 2 have a similar histology and contain synovium.2Zone 3 is the subpectoral region distal to the PMPM. Fibers of the latissimus dorsi form the flat floor of zone 3, and the pectoralis major inserts lateral to the LHBT on the humerus in this zone. The synovium encapsulating the LHBT in zones 1 and 2 rarely extends past the PMPM. Taylor and colleagues2 found a higher percentage of unoccupied tunnel space in zone 3 than in zones 1 and 2, which results in a “functional bottleneck” between zones 2 and 3 represented by the PMPM.

Pathoanatomy

BLC lesions may occur in isolation or concomitantly across multiple anatomical zones. In a series of 277 chronically symptomatic shoulders that underwent transfer of the LHBT to the conjoint tendon with subdeltoid arthroscopy, Taylor and colleagues1 found 47% incidence of bicipital tunnel lesions, 44% incidence of junctional lesions, and 35% incidence of inside lesions. In their series, 37% of patients had concomitant lesions involving more than 1 anatomical zone.

Inside Lesions

Inside lesions involve the superior labrum, the LHBT origin, or both. Superior labrum anterior-posterior (SLAP) tears are included as inside BLC lesions. Snyder and colleagues16 originally identified 4 broad categories of SLAP tears, but Powell and colleagues17 described up to 10 variations. Type II lesions, which are the most common, destabilize the biceps anchor.

Dynamic incarceration of the biceps between the humeral head and the glenoid labrum is another inside lesion that can be identified during routine diagnostic glenohumeral arthroscopy. The arthroscopic active compression test, as described by Verma and colleagues,18 can be used during surgery to demonstrate incarceration of the biceps tendon.

Medial biceps chondromalacia, attritional chondral wear along the anteromedial aspect of the humeral head, occurs secondary to a windshield wiper effect of the LHBT in the setting of an incarcerating LHBT or may be associated with destabilization of the biceps pulley.

Junctional Lesions

Junctional lesions, which include lesions that affect the intra-articular LHBT, can be visualized during routine glenohumeral arthroscopy. They include partial and complete biceps tears, biceps pulley lesions, and junctional biceps chondromalacia.

Biceps pulley injuries and/or tears of the upper subscapularis tendon can destabilize the biceps as it exits the joint, and this destabilization may result in medial subluxation of the tendon and the aforementioned medial biceps chondromalacia.10,19 Junctional biceps chondromalacia is attritional chondral wear of the humeral head from abnormal tracking of the LHBT deep to the LHBT near the articular margin.

Recently elucidated is the limited ability of diagnostic glenohumeral arthroscopy to fully identify the extent of BLC pathology.1,20-22 Gilmer and colleagues20 found that diagnostic arthroscopy identified only 67% of biceps pathology and underestimated its extent in 56% of patients in their series. Similarly, Moon and colleagues21 found that 79% of proximal LHBT tears propagated distally into the bicipital tunnel and were incompletely visualized with standard arthroscopy.

Bicipital Tunnel Lesions

Recent evidence indicates that the bicipital tunnel is a closed space that often conceals space-occupying lesions, including scar, synovitis, loose bodies, and osteophytes, which can become trapped in the tunnel. The functional bottleneck between zones 2 and 3 of the bicipital tunnel explains the aggregation of loose bodies in this region.2 Similarly, as the percentage of free space within the bicipital tunnel increases, space-occupying lesions (eg scar, loose bodies, osteophytes) may exude a compressive and/or abrasive force within zones 1 and 2, but not as commonly within zone 3.2

Physical Examination of Biceps-Labrum Complex

Accurate diagnosis of BLC disease is crucial in selecting an optimal intervention, but challenging. Beyond identifying biceps pathology, specific examination maneuvers may help distinguish between lesions of the intra-articular BLC and lesions of the extra-articular bicipital tunnel.23

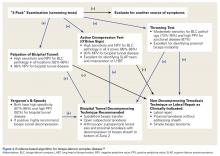

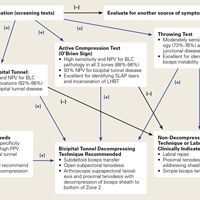

Traditional examination maneuvers for biceps-related shoulder pain include the Speed test, the full can test, and the Yergason test.24,25 For the Speed test, the patient forward-flexes the shoulder to 60° to 90°, extends the arm at the elbow, and supinates the forearm. The clinician applies a downward force as the patient resists. The reported sensitivity of the Speed test ranges from 37% to 63%, and specificity is 60% to 88%.25,26 In the full can test, with the patient’s arm in the plane of the scapula, the shoulder abducted to 90°, and the forearm in neutral rotation, a downward force is applied against resistance. Sensitivity of the full can test is 60% to 67%, and specificity is 76% to 84%.24 The Yergason test is performed with the patient’s arm at his or her side, the elbow flexed to 90°, and the forearm pronated. The patient supinates the forearm against the clinician’s resistance. Sensitivity of the Yergason test is 19% to 32%, and specificity is 70% to 100%.25,26 The Yergason test has a positive predictive value of 92% for bicipital tunnel disease.

O’Brien and colleagues23,26 introduced a “3-pack” physical examination designed to elicit BLC symptoms. In this examination, the LHBT is palpated along its course within the bicipital tunnel. Reproduction of the patient’s pain by palpation had a sensitivity of 98% for bicipital tunnel disease but was less specific (70%). Gill and colleagues27 reported low sensitivity (53%) and low specificity (54%) for biceps palpation, and they used arthroscopy as a gold standard. Since then, multiple studies have demonstrated that glenohumeral arthroscopy fails to identify lesions concealed within the bicipital tunnel.20-22The second part of the 3-pack examination is the active compression test. A downward force is applied as the patient resists with his or her arm forward-flexed to 90° and adducted 10° to 15° with the thumb pointing downward.28 This action is repeated with the humerus externally rotated and the forearm supinated. A positive test is indicated by reproduction of symptoms with the thumb down, and elimination or reduction of symptoms with the palm up. Test sensitivity is 88% to 96%, and specificity is 46% to 64% for BLC lesions, but for bicipital tunnel disease sensitivity is higher (96%), and the negative predictive value is 93%.26The third component of the 3-pack examination is the throwing test. A late-cocking throwing position is re-created with the shoulder externally rotated and abducted to 90° and the elbow flexed to 90°. The patient steps forward with the contralateral leg and moves into the acceleration phase of throwing while the clinician provides isometric resistance. If this maneuver reproduces pain, the test is positive. As Taylor and colleagues26 reported, the throwing test has sensitivity of 73% to 77% and specificity of 65% to 79% for BLC pathology. This test has moderate sensitivity and negative predictive value for bicipital tunnel disease but may be the only positive test on physical examination in the setting of LHBT instability.

Imaging of Biceps-Labrum Complex

Plain anteroposterior, lateral, and axillary radiographs of the shoulder should be obtained for all patients having an orthopedic examination for shoulder pain. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and ultrasound are the advanced modalities most commonly used for diagnostic imaging. These modalities should be considered in conjunction with, not in place of, a comprehensive history and physical examination.

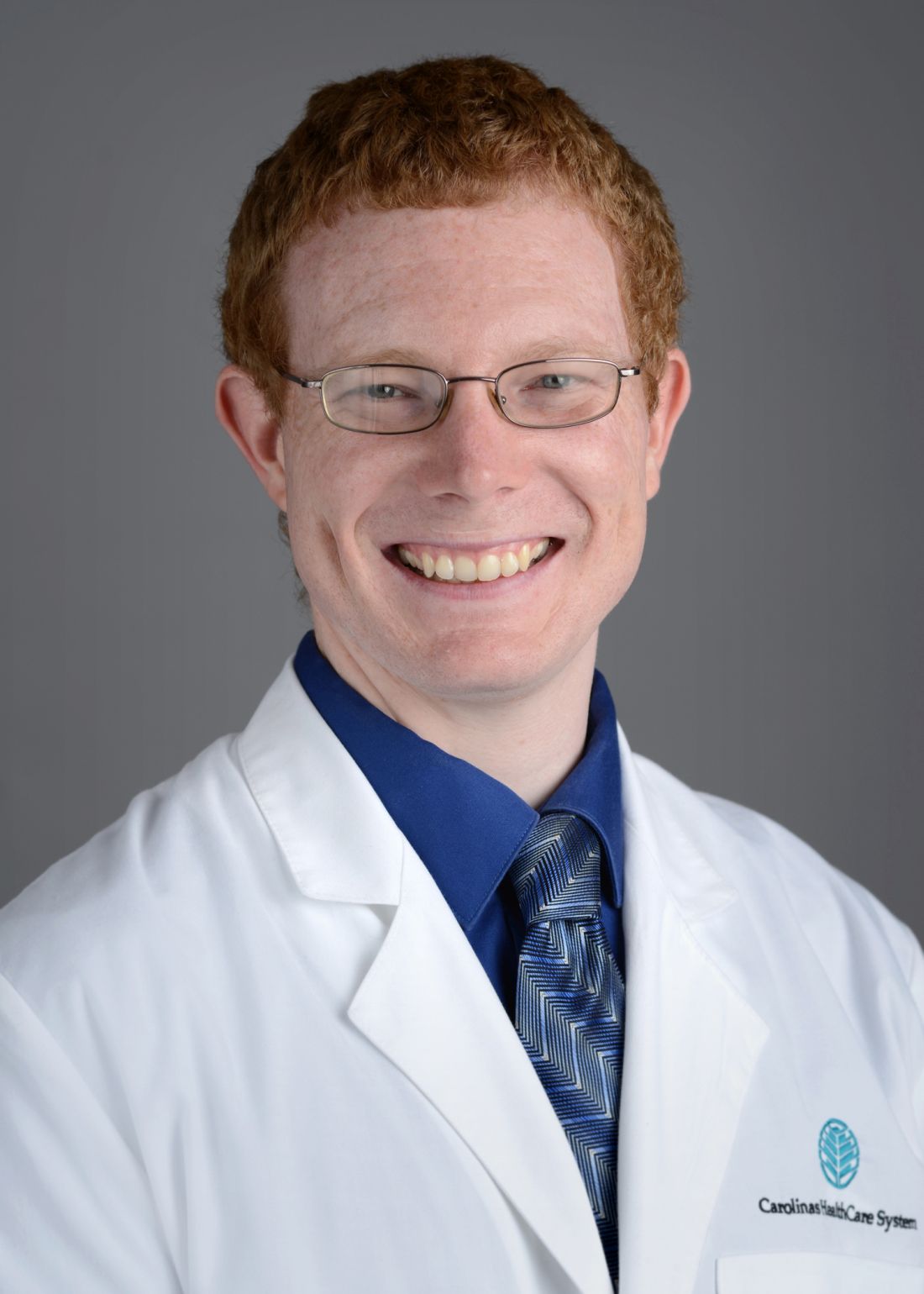

MRI has sensitivity of 9% to 89% for LHBT pathology29-37 and 38% to 98% for SLAP pathology.35,38-41 The wide range of reported sensitivity and specificity might be attributed to the varying criteria for what constitutes a BLC lesion. Some authors include biceps chondromalacia, dynamic incarceration of LHBT, and extra-articular bicipital tunnel lesions, while others historically have included only intra-articular LHBT lesions that can be directly visualized arthroscopically.

In their retrospective review of 277 shoulders with chronic refractory BLC symptoms treated with subdeltoid transfer of the LHBT to the conjoint tendon, Taylor and colleagues30 reported MRI was more sensitive for inside BLC lesions than for junctional or bicipital tunnel lesions (77% vs 43% and 50%, respectively).

Treatment Options for Biceps-Labrum Complex Lesions

A diagnosis of BLC disease warrants a trial of conservative (nonoperative) management for at least 3 months. Many patients improve with activity modification, use of oral anti-inflammatory medication, and structured physical therapy focused on dynamic stabilizers and range of motion. If pain persists, local anesthetic and corticosteroid can be injected under ultrasound guidance into the bicipital tunnel; this injection has the advantage of being both diagnostic and therapeutic. Hashiuchi and colleagues42 found ultrasound-guided injections are 87% successful in achieving intra-sheath placement (injections without ultrasound guidance are only 27% successful).

If the 3-month trial of conservative management fails, surgical intervention should be considered. The goal in treating BLC pain is to maximize clinical function and alleviate pain in a predictable manner while minimizing technical demands and morbidity. A singular solution has not been identified. Furthermore, 3 systematic reviews failed to identify a difference between the most commonly used techniques, biceps tenodesis and tenotomy.43-45 These reviews grouped all tenotomy procedures together and compared them with all tenodesis procedures. A limitation of these systematic reviews is that they did not differentiate tenodesis techniques. We prefer to classify techniques according to whether or not they decompress zones 1 and 2 of the bicipital tunnel.

Bicipital Tunnel Nondecompressing Techniques

Release of the biceps tendon, a biceps tenotomy, is a simple procedure that potentially avoids open surgery and provides patients with a quick return to activity. Disadvantages of tenotomy include cosmetic (Popeye) deformity after surgery, potential cramping and fatigue, and biomechanical changes in the humeral head,46-48 particularly among patients younger than 65 years. High rates of revision after tenotomy have been reported.43,49 Incomplete retraction of the LHBT and/or residual synovium may be responsible for refractory pain following biceps tenotomy.49 We hypothesize that failure of tenotomy may be related to unaddressed bicipital tunnel disease.

Proximal nondecompressing tenodesis techniques may be performed either on soft tissue in the interval or rotator cuff or on bone at the articular margin or within zone 1 of the bicipital tunnel.50-52 These techniques can be performed with standard glenohumeral arthroscopy and generally are fast and well tolerated and have limited operative morbidity. Advantages of these techniques over simple tenotomy are lower rates of cosmetic deformity and lower rates of cramping and fatigue pain, likely resulting from maintenance of the muscle tension relationship of the LHBT. Disadvantages of proximal tenodesis techniques include introduction of hardware for bony fixation, longer postoperative rehabilitation to protect repairs, and failure to address hidden bicipital tunnel disease. Furthermore, the rate of stiffness in patients who undergo proximal tenodesis without decompression of the bicipital tunnel may be as high as 18%.53

Bicipital Tunnel Decompressing Techniques

Surgical techniques that decompress the bicipital tunnel include proximal techniques that release the bicipital sheath within zones 1 and 2 of the bicipital tunnel (to the level of the proximal margin of the pectoralis major tendon) and certain arthroscopic suprapectoral techniques,54 open subpectoral tenodeses,55-57 and arthroscopic transfer of the LHBT to the conjoint tendon.58,59

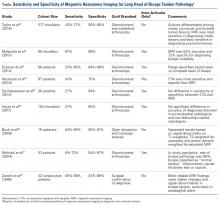

Open subpectoral tenodesis techniques have the advantage of maintaining the length-tension relationship of the LHBT and preventing Popeye deformity. However, these techniques require making an incision near the axilla, which may introduce an unnecessary source of infection. Furthermore, open subpectoral tenodesis requires drilling the humerus and placing a screw for bony fixation of the LHBT, which can create a risk of neurovascular injury, given the proximity of neurovascular structures,60-62 and humeral shaft fracture, particularly in athletes.63,64Our preferred method is transfer of the LHBT to the conjoint tendon (Figure 3).59

Am J Orthop. 2016;45(7):E503-E511. Copyright Frontline Medical Communications Inc. 2016. All rights reserved.

1. Taylor SA, Khair MM, Gulotta LV, et al. Diagnostic glenohumeral arthroscopy fails to fully evaluate the biceps-labral complex. Arthroscopy. 2015;31(2):215-224.

2. Taylor SA, Fabricant PD, Bansal M, et al. The anatomy and histology of the bicipital tunnel of the shoulder. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2015;24(4):511-519.

3. Vangsness CT Jr, Jorgenson SS, Watson T, Johnson DL. The origin of the long head of the biceps from the scapula and glenoid labrum. An anatomical study of 100 shoulders. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1994;76(6):951-954.

4. Cooper DE, Arnoczky SP, O’Brien SJ, Warren RF, DiCarlo E, Allen AA. Anatomy, histology, and vascularity of the glenoid labrum. an anatomical study. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1992;74(1):46-52.

5. Tuoheti Y, Itoi E, Minagawa H, et al. Attachment types of the long head of the biceps tendon to the glenoid labrum and their relationships with the glenohumeral ligaments. Arthroscopy. 2005;21(10):1242-1249.

6. Dierickx C, Ceccarelli E, Conti M, Vanlommel J, Castagna A. Variations of the intra-articular portion of the long head of the biceps tendon: a classification of embryologically explained variations. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2009;18(4):556-565.

7. Denard PJ, Dai X, Hanypsiak BT, Burkhart SS. Anatomy of the biceps tendon: implications for restoring physiological length-tension relation during biceps tenodesis with interference screw fixation. Arthroscopy. 2012;28(10):1352-1358.

8. Ahrens PM, Boileau P. The long head of biceps and associated tendinopathy. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2007;89(8):1001-1009.

9. Hart ND, Golish SR, Dragoo JL. Effects of arm position on maximizing intra-articular visualization of the biceps tendon: a cadaveric study. Arthroscopy. 2012;28(4):481-485.

10. Elser F, Braun S, Dewing CB, Giphart JE, Millett PJ. Anatomy, function, injuries, and treatment of the long head of the biceps brachii tendon. Arthroscopy. 2011;27(4):581-592.

11. Cheng NM, Pan WR, Vally F, Le Roux CM, Richardson MD. The arterial supply of the long head of biceps tendon: anatomical study with implications for tendon rupture. Clin Anat. 2010;23(6):683-692.

12. Habermeyer P, Magosch P, Pritsch M, Scheibel MT, Lichtenberg S. Anterosuperior impingement of the shoulder as a result of pulley lesions: a prospective arthroscopic study. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2004;13(1):5-12.

13. Gohlke F, Daum P, Bushe C. The stabilizing function of the glenohumeral joint capsule. Current aspects of the biomechanics of instability [in German]. Z Orthop Ihre Grenzgeb. 1994;132(2):112-119.

14. Arai R, Mochizuki T, Yamaguchi K, et al. Functional anatomy of the superior glenohumeral and coracohumeral ligaments and the subscapularis tendon in view of stabilization of the long head of the biceps tendon. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2010;19(1):58-64.

15. Busconi BB, DeAngelis N, Guerrero PE. The proximal biceps tendon: tricks and pearls. Sports Med Arthrosc. 2008;16(3):187-194.

16. Snyder SJ, Karzel RP, Del Pizzo W, Ferkel RD, Friedman MJ. SLAP lesions of the shoulder. Arthroscopy. 1990;6(4):274-279.

17. Powell SE, Nord KD, Ryu RKN. The diagnosis, classification, and treatment of SLAP lesions. Oper Tech Sports Med. 2004;12(2):99-110.

18. Verma NN, Drakos M, O’Brien SJ. The arthroscopic active compression test. Arthroscopy. 2005;21(5):634.

19. Walch G, Nove-Josserand L, Levigne C, Renaud E. Tears of the supraspinatus tendon associated with “hidden” lesions of the rotator interval. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 1994;3(6):353-360.

20. Gilmer BB, DeMers AM, Guerrero D, Reid JB 3rd, Lubowitz JH, Guttmann D. Arthroscopic versus open comparison of long head of biceps tendon visualization and pathology in patients requiring tenodesis. Arthroscopy. 2015;31(1):29-34.

21. Moon SC, Cho NS, Rhee YG. Analysis of “hidden lesions” of the extra-articular biceps after subpectoral biceps tenodesis: the subpectoral portion as the optimal tenodesis site. Am J Sports Med. 2015;43(1):63-68.

22. Festa A, Allert J, Issa K, Tasto JP, Myer JJ. Visualization of the extra-articular portion of the long head of the biceps tendon during intra-articular shoulder arthroscopy. Arthroscopy. 2014;30(11):1413-1417.

23. O’Brien SJ, Newman AM, Taylor SA, et al. The accurate diagnosis of biceps-labral complex lesions with MRI and “3-pack” physical examination: a retrospective analysis with prospective validation. Orthop J Sports Med. 2013;1(4 suppl). doi:10.1177/2325967113S00018.

24. Hegedus EJ, Goode AP, Cook CE, et al. Which physical examination tests provide clinicians with the most value when examining the shoulder? Update of a systematic review with meta-analysis of individual tests. Br J Sports Med. 2012;46(14):964-978.

25. Chen HS, Lin SH, Hsu YH, Chen SC, Kang JH. A comparison of physical examinations with musculoskeletal ultrasound in the diagnosis of biceps long head tendinitis. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2011;37(9):1392-1398.

26. Taylor SA, Newman AM, Dawson C, et al. The “3-Pack” examination is critical for comprehensive evaluation of the biceps-labrum complex and the bicipital tunnel: a prospective study. Arthroscopy. 2016 Jul 20. [Epub ahead of print]

27. Gill HS, El Rassi G, Bahk MS, Castillo RC, McFarland EG. Physical examination for partial tears of the biceps tendon. Am J Sports Med. 2007;35(8):1334-1340.

28. O’Brien SJ, Pagnani MJ, Fealy S, McGlynn SR, Wilson JB. The active compression test: a new and effective test for diagnosing labral tears and acromioclavicular joint abnormality. Am J Sports Med. 1998;26(5):610-613.

29. Zanetti M, Weishaupt D, Gerber C, Hodler J. Tendinopathy and rupture of the tendon of the long head of the biceps brachii muscle: evaluation with MR arthrography. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1998;170(6):1557-1561.

30. Taylor SA, Newman AM, Nguyen J, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging currently fails to fully evaluate the biceps-labrum complex and bicipital tunnel. Arthroscopy. 2016;32(2):238-244.

31. Malavolta EA, Assunção JH, Guglielmetti CL, de Souza FF, Gracitelli ME, Ferreira Neto AA. Accuracy of preoperative MRI in the diagnosis of disorders of the long head of the biceps tendon. Eur J Radiol. 2015;84(11):2250-2254.

32. Dubrow SA, Streit JJ, Shishani Y, Robbin MR, Gobezie R. Diagnostic accuracy in detecting tears in the proximal biceps tendon using standard nonenhancing shoulder MRI. Open Access J Sports Med. 2014;5:81-87.

33. Nourissat G, Tribot-Laspiere Q, Aim F, Radier C. Contribution of MRI and CT arthrography to the diagnosis of intra-articular tendinopathy of the long head of the biceps. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res. 2014;100(8 suppl):S391-S394.

34. De Maeseneer M, Boulet C, Pouliart N, et al. Assessment of the long head of the biceps tendon of the shoulder with 3T magnetic resonance arthrography and CT arthrography. Eur J Radiol. 2012;81(5):934-939.

35. Houtz CG, Schwartzberg RS, Barry JA, Reuss BL, Papa L. Shoulder MRI accuracy in the community setting. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2011;20(4):537-542.

36. Buck FM, Grehn H, Hilbe M, Pfirrmann CW, Manzanell S, Hodler J. Degeneration of the long biceps tendon: comparison of MRI with gross anatomy and histology. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2009;193(5):1367-1375.

37. Mohtadi NG, Vellet AD, Clark ML, et al. A prospective, double-blind comparison of magnetic resonance imaging and arthroscopy in the evaluation of patients presenting with shoulder pain. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2004;13(3):258-265.

38. Sheridan K, Kreulen C, Kim S, Mak W, Lewis K, Marder R. Accuracy of magnetic resonance imaging to diagnose superior labrum anterior-posterior tears. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2015;23(9):2645-2650.

39. Connolly KP, Schwartzberg RS, Reuss B, Crumbie D Jr, Homan BM. Sensitivity and specificity of noncontrast magnetic resonance imaging reports in the diagnosis of type-II superior labral anterior-posterior lesions in the community setting. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2013;95(4):308-313.

40. Reuss BL, Schwartzberg R, Zlatkin MB, Cooperman A, Dixon JR. Magnetic resonance imaging accuracy for the diagnosis of superior labrum anterior-posterior lesions in the community setting: eighty-three arthroscopically confirmed cases. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2006;15(5):580-585.

41. Connell DA, Potter HG, Wickiewicz TL, Altchek DW, Warren RF. Noncontrast magnetic resonance imaging of superior labral lesions. 102 cases confirmed at arthroscopic surgery. Am J Sports Med. 1999;27(2):208-213.

42. Hashiuchi T, Sakurai G, Morimoto M, Komei T, Takakura Y, Tanaka Y. Accuracy of the biceps tendon sheath injection: ultrasound-guided or unguided injection? A randomized controlled trial. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2011;20(7):1069-1073.

43. Hsu AR, Ghodadra NS, Provencher MT, Lewis PB, Bach BR. Biceps tenotomy versus tenodesis: a review of clinical outcomes and biomechanical results. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2011;20(2):326-332.

44. Slenker NR, Lawson K, Ciccotti MG, Dodson CC, Cohen SB. Biceps tenotomy versus tenodesis: clinical outcomes. Arthroscopy. 2012;28(4):576-582.

45. Frost A, Zafar MS, Maffulli N. Tenotomy versus tenodesis in the management of pathologic lesions of the tendon of the long head of the biceps brachii. Am J Sports Med. 2009;37(4):828-833.

46. Kelly AM, Drakos MC, Fealy S, Taylor SA, O’Brien SJ. Arthroscopic release of the long head of the biceps tendon: functional outcome and clinical results. Am J Sports Med. 2005;33(2):208-213.

47. Berlemann U, Bayley I. Tenodesis of the long head of biceps brachii in the painful shoulder: improving results in the long term. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 1995;4(6):429-435.

48. Gill TJ, McIrvin E, Mair SD, Hawkins RJ. Results of biceps tenotomy for treatment of pathology of the long head of the biceps brachii. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2001;10(3):247-249.

49. Sanders B, Lavery KP, Pennington S, Warner JJ. Clinical success of biceps tenodesis with and without release of the transverse humeral ligament. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2012;21(1):66-71.

50. Gartsman GM, Hammerman SM. Arthroscopic biceps tenodesis: operative technique. Arthroscopy. 2000;16(5):550-552.

51. Richards DP, Burkhart SS. Arthroscopic-assisted biceps tenodesis for ruptures of the long head of biceps brachii: the cobra procedure. Arthroscopy. 2004;20(suppl 2):201-207.

52. Klepps S, Hazrati Y, Flatow E. Arthroscopic biceps tenodesis. Arthroscopy. 2002;18(9):1040-1045.

53. Werner BC, Pehlivan HC, Hart JM, et al. Increased incidence of postoperative stiffness after arthroscopic compared with open biceps tenodesis. Arthroscopy. 2014;30(9):1075-1084.54. Werner BC, Lyons ML, Evans CL, et al. Arthroscopic suprapectoral and open subpectoral biceps tenodesis: a comparison of restoration of length-tension and mechanical strength between techniques. Arthroscopy. 2015;31(4):620-627.

55. Nho SJ, Reiff SN, Verma NN, Slabaugh MA, Mazzocca AD, Romeo AA. Complications associated with subpectoral biceps tenodesis: low rates of incidence following surgery. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2010;19(5):764-768.

56. Mazzocca AD, Cote MP, Arciero CL, Romeo AA, Arciero RA. Clinical outcomes after subpectoral biceps tenodesis with an interference screw. Am J Sports Med. 2008;36(10):1922-1929.

57. Provencher MT, LeClere LE, Romeo AA. Subpectoral biceps tenodesis. Sports Med Arthrosc. 2008;16(3):170-176.

58. Taylor SA, Fabricant PD, Baret NJ, et al. Midterm clinical outcomes for arthroscopic subdeltoid transfer of the long head of the biceps tendon to the conjoint tendon. Arthroscopy. 2014;30(12):1574-1581.

59. Drakos MC, Verma NN, Gulotta LV, et al. Arthroscopic transfer of the long head of the biceps tendon: functional outcome and clinical results. Arthroscopy. 2008;24(2):217-223.

60. Ding DY, Gupta A, Snir N, Wolfson T, Meislin RJ. Nerve proximity during bicortical drilling for subpectoral biceps tenodesis: a cadaveric study. Arthroscopy. 2014;30(8):942-946.

61. Dickens JF, Kilcoyne KG, Tintle SM, Giuliani J, Schaefer RA, Rue JP. Subpectoral biceps tenodesis: an anatomic study and evaluation of at-risk structures. Am J Sports Med. 2012;40(10):2337-2341.

62. Ma H, Van Heest A, Glisson C, Patel S. Musculocutaneous nerve entrapment: an unusual complication after biceps tenodesis. Am J Sports Med. 2009;37(12):2467-2469.

63. Dein EJ, Huri G, Gordon JC, McFarland EG. A humerus fracture in a baseball pitcher after biceps tenodesis. Am J Sports Med. 2014;42(4):877-879.

64. Sears BW, Spencer EE, Getz CL. Humeral fracture following subpectoral biceps tenodesis in 2 active, healthy patients. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2011;20(6):e7-e11.

65. O’Brien SJ, Taylor SA, DiPietro JR, Newman AM, Drakos MC, Voos JE. The arthroscopic “subdeltoid approach” to the anterior shoulder. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2013;22(4):e6-e10.

66. Urch E, Taylor SA, Ramkumar PN, et al. Biceps tenodesis: a comparison of tendon-to-bone and tendon-to-tendon healing in a rat model. Paper presented at: Closed Meeting of the American Shoulder and Elbow Surgeons; October 10, 2015; Asheville, NC. Paper 26.

67. Taylor SA, Ramkumar PN, Fabricant PD, et al. The clinical impact of bicipital tunnel decompression during long head of the biceps tendon surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Arthroscopy. 2016;32(6):1155-1164.

Pathology of the biceps-labrum complex (BLC) can be an important source of shoulder pain. Discussion of pathoanatomy, imaging, and surgical intervention is facilitated by distinguishing the anatomical zones of the BLC: inside, junction, and bicipital tunnel (extra-articular), parts of which cannot be visualized with standard diagnostic arthroscopy.

The recent literature indicates that bicipital tunnel lesions are common and perhaps overlooked. Systematic reviews suggest improvement in outcomes of BLC operations when the bicipital tunnel is decompressed. Higher-level clinical and basic science studies are needed to fully elucidate the role of the bicipital tunnel, but it is evident that a comprehensive physical examination and an understanding of the limits of advanced imaging are necessary to correctly diagnose and treat BLC-related shoulder pain.

Anatomy of Biceps-Labrum Complex

The long head of the biceps tendon (LHBT) and the glenoid labrum work as an interdependent functional unit, the biceps-labrum complex (BLC). The BLC is divided into 3 distinct anatomical zones: inside, junction, and bicipital tunnel.1,2

Inside

The inside includes the superior labrum and biceps attachment. The LHBT most commonly originates in the superior labrum.3-5 Vangsness and colleagues3 described 4 types of LHBT origins: Type I biceps attaches solely to the posterior labrum, type II predominantly posterior, type III equally to the anterior and posterior labrum, and type IV mostly to the anterior labrum. The LHBT can also originate in the supraglenoid tubercle or the inferior border of the supraspinatus.3,6

Junction

Junction is the intra-articular segment of the LHBT and the biceps pulley. The LHBT traverses the glenohumeral joint en route to the extra-articular bicipital tunnel.2 The LHBT is enveloped in synovium that extends into part of the bicipital tunnel.2 The intra-articular segment of the LHBT is about 25 mm in length7 and has a diameter of 5 mm to 6 mm.8

A cadaveric study found that the average length of the LHBT that can be arthroscopically visualized at rest is 35.6 mm, or only 40% of the total length of the LHBT with respect to the proximal margin of the pectoralis major tendon.1 When the LHBT was pulled into the joint, more tendon (another 14 mm) was visualized.1 Therefore, diagnostic arthroscopy of the glenohumeral joint visualizes about 50% of the LHBT.9The morphology of the LHBT varies by location. The intra-articular portion of the LHBT is wide and flat, whereas the extra-articular portion is round.8 The tendon becomes smoother and more avascular as it exits the joint to promote gliding within its sheath in the bicipital groove.10 The proximal LHBT receives its vascular supply from superior labrum tributaries, and distally the LHBT is supplied by ascending branches of the anterior humeral circumflex artery.4 There is a hypovascular zone, created by this dual blood supply, about 12 mm to 30 mm from the LHBT origin, predisposing the tendon to rupture or fray in this region.11The LHBT makes a 30° turn into the biceps pulley system as it exits the glenohumeral joint. The fibrous pulley system that stabilizes the LHBT in this region has contributions from the coracohumeral ligament, the superior glenohumeral ligament, and the supraspinatus tendon.12-14

Bicipital Tunnel

The bicipital tunnel, the third portion of the BLC, remains largely hidden from standard diagnostic glenohumeral arthroscopy. The bicipital tunnel is an extra-articular, closed space that constrains the LHBT from the articular margin through the subpectoral region.2

Zone 1 is the traditional bicipital groove or “bony groove” that extends from the articular margin to the distal margin of the subscapularis tendon. The floor consists of a deep osseous groove covered by a continuation of subscapularis tendon fibers and periosteum.2Zone 2, “no man’s land,” extends from the distal margin of the subscapularis tendon to the proximal margin of the pectoralis major (PMPM). The LHBT in this zone cannot be visualized during a pull test at arthroscopy, yet lesions commonly occur here.1 Zones 1 and 2 have a similar histology and contain synovium.2Zone 3 is the subpectoral region distal to the PMPM. Fibers of the latissimus dorsi form the flat floor of zone 3, and the pectoralis major inserts lateral to the LHBT on the humerus in this zone. The synovium encapsulating the LHBT in zones 1 and 2 rarely extends past the PMPM. Taylor and colleagues2 found a higher percentage of unoccupied tunnel space in zone 3 than in zones 1 and 2, which results in a “functional bottleneck” between zones 2 and 3 represented by the PMPM.

Pathoanatomy

BLC lesions may occur in isolation or concomitantly across multiple anatomical zones. In a series of 277 chronically symptomatic shoulders that underwent transfer of the LHBT to the conjoint tendon with subdeltoid arthroscopy, Taylor and colleagues1 found 47% incidence of bicipital tunnel lesions, 44% incidence of junctional lesions, and 35% incidence of inside lesions. In their series, 37% of patients had concomitant lesions involving more than 1 anatomical zone.

Inside Lesions

Inside lesions involve the superior labrum, the LHBT origin, or both. Superior labrum anterior-posterior (SLAP) tears are included as inside BLC lesions. Snyder and colleagues16 originally identified 4 broad categories of SLAP tears, but Powell and colleagues17 described up to 10 variations. Type II lesions, which are the most common, destabilize the biceps anchor.

Dynamic incarceration of the biceps between the humeral head and the glenoid labrum is another inside lesion that can be identified during routine diagnostic glenohumeral arthroscopy. The arthroscopic active compression test, as described by Verma and colleagues,18 can be used during surgery to demonstrate incarceration of the biceps tendon.

Medial biceps chondromalacia, attritional chondral wear along the anteromedial aspect of the humeral head, occurs secondary to a windshield wiper effect of the LHBT in the setting of an incarcerating LHBT or may be associated with destabilization of the biceps pulley.

Junctional Lesions

Junctional lesions, which include lesions that affect the intra-articular LHBT, can be visualized during routine glenohumeral arthroscopy. They include partial and complete biceps tears, biceps pulley lesions, and junctional biceps chondromalacia.

Biceps pulley injuries and/or tears of the upper subscapularis tendon can destabilize the biceps as it exits the joint, and this destabilization may result in medial subluxation of the tendon and the aforementioned medial biceps chondromalacia.10,19 Junctional biceps chondromalacia is attritional chondral wear of the humeral head from abnormal tracking of the LHBT deep to the LHBT near the articular margin.

Recently elucidated is the limited ability of diagnostic glenohumeral arthroscopy to fully identify the extent of BLC pathology.1,20-22 Gilmer and colleagues20 found that diagnostic arthroscopy identified only 67% of biceps pathology and underestimated its extent in 56% of patients in their series. Similarly, Moon and colleagues21 found that 79% of proximal LHBT tears propagated distally into the bicipital tunnel and were incompletely visualized with standard arthroscopy.

Bicipital Tunnel Lesions

Recent evidence indicates that the bicipital tunnel is a closed space that often conceals space-occupying lesions, including scar, synovitis, loose bodies, and osteophytes, which can become trapped in the tunnel. The functional bottleneck between zones 2 and 3 of the bicipital tunnel explains the aggregation of loose bodies in this region.2 Similarly, as the percentage of free space within the bicipital tunnel increases, space-occupying lesions (eg scar, loose bodies, osteophytes) may exude a compressive and/or abrasive force within zones 1 and 2, but not as commonly within zone 3.2

Physical Examination of Biceps-Labrum Complex

Accurate diagnosis of BLC disease is crucial in selecting an optimal intervention, but challenging. Beyond identifying biceps pathology, specific examination maneuvers may help distinguish between lesions of the intra-articular BLC and lesions of the extra-articular bicipital tunnel.23

Traditional examination maneuvers for biceps-related shoulder pain include the Speed test, the full can test, and the Yergason test.24,25 For the Speed test, the patient forward-flexes the shoulder to 60° to 90°, extends the arm at the elbow, and supinates the forearm. The clinician applies a downward force as the patient resists. The reported sensitivity of the Speed test ranges from 37% to 63%, and specificity is 60% to 88%.25,26 In the full can test, with the patient’s arm in the plane of the scapula, the shoulder abducted to 90°, and the forearm in neutral rotation, a downward force is applied against resistance. Sensitivity of the full can test is 60% to 67%, and specificity is 76% to 84%.24 The Yergason test is performed with the patient’s arm at his or her side, the elbow flexed to 90°, and the forearm pronated. The patient supinates the forearm against the clinician’s resistance. Sensitivity of the Yergason test is 19% to 32%, and specificity is 70% to 100%.25,26 The Yergason test has a positive predictive value of 92% for bicipital tunnel disease.

O’Brien and colleagues23,26 introduced a “3-pack” physical examination designed to elicit BLC symptoms. In this examination, the LHBT is palpated along its course within the bicipital tunnel. Reproduction of the patient’s pain by palpation had a sensitivity of 98% for bicipital tunnel disease but was less specific (70%). Gill and colleagues27 reported low sensitivity (53%) and low specificity (54%) for biceps palpation, and they used arthroscopy as a gold standard. Since then, multiple studies have demonstrated that glenohumeral arthroscopy fails to identify lesions concealed within the bicipital tunnel.20-22The second part of the 3-pack examination is the active compression test. A downward force is applied as the patient resists with his or her arm forward-flexed to 90° and adducted 10° to 15° with the thumb pointing downward.28 This action is repeated with the humerus externally rotated and the forearm supinated. A positive test is indicated by reproduction of symptoms with the thumb down, and elimination or reduction of symptoms with the palm up. Test sensitivity is 88% to 96%, and specificity is 46% to 64% for BLC lesions, but for bicipital tunnel disease sensitivity is higher (96%), and the negative predictive value is 93%.26The third component of the 3-pack examination is the throwing test. A late-cocking throwing position is re-created with the shoulder externally rotated and abducted to 90° and the elbow flexed to 90°. The patient steps forward with the contralateral leg and moves into the acceleration phase of throwing while the clinician provides isometric resistance. If this maneuver reproduces pain, the test is positive. As Taylor and colleagues26 reported, the throwing test has sensitivity of 73% to 77% and specificity of 65% to 79% for BLC pathology. This test has moderate sensitivity and negative predictive value for bicipital tunnel disease but may be the only positive test on physical examination in the setting of LHBT instability.

Imaging of Biceps-Labrum Complex

Plain anteroposterior, lateral, and axillary radiographs of the shoulder should be obtained for all patients having an orthopedic examination for shoulder pain. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and ultrasound are the advanced modalities most commonly used for diagnostic imaging. These modalities should be considered in conjunction with, not in place of, a comprehensive history and physical examination.

MRI has sensitivity of 9% to 89% for LHBT pathology29-37 and 38% to 98% for SLAP pathology.35,38-41 The wide range of reported sensitivity and specificity might be attributed to the varying criteria for what constitutes a BLC lesion. Some authors include biceps chondromalacia, dynamic incarceration of LHBT, and extra-articular bicipital tunnel lesions, while others historically have included only intra-articular LHBT lesions that can be directly visualized arthroscopically.

In their retrospective review of 277 shoulders with chronic refractory BLC symptoms treated with subdeltoid transfer of the LHBT to the conjoint tendon, Taylor and colleagues30 reported MRI was more sensitive for inside BLC lesions than for junctional or bicipital tunnel lesions (77% vs 43% and 50%, respectively).

Treatment Options for Biceps-Labrum Complex Lesions

A diagnosis of BLC disease warrants a trial of conservative (nonoperative) management for at least 3 months. Many patients improve with activity modification, use of oral anti-inflammatory medication, and structured physical therapy focused on dynamic stabilizers and range of motion. If pain persists, local anesthetic and corticosteroid can be injected under ultrasound guidance into the bicipital tunnel; this injection has the advantage of being both diagnostic and therapeutic. Hashiuchi and colleagues42 found ultrasound-guided injections are 87% successful in achieving intra-sheath placement (injections without ultrasound guidance are only 27% successful).

If the 3-month trial of conservative management fails, surgical intervention should be considered. The goal in treating BLC pain is to maximize clinical function and alleviate pain in a predictable manner while minimizing technical demands and morbidity. A singular solution has not been identified. Furthermore, 3 systematic reviews failed to identify a difference between the most commonly used techniques, biceps tenodesis and tenotomy.43-45 These reviews grouped all tenotomy procedures together and compared them with all tenodesis procedures. A limitation of these systematic reviews is that they did not differentiate tenodesis techniques. We prefer to classify techniques according to whether or not they decompress zones 1 and 2 of the bicipital tunnel.

Bicipital Tunnel Nondecompressing Techniques

Release of the biceps tendon, a biceps tenotomy, is a simple procedure that potentially avoids open surgery and provides patients with a quick return to activity. Disadvantages of tenotomy include cosmetic (Popeye) deformity after surgery, potential cramping and fatigue, and biomechanical changes in the humeral head,46-48 particularly among patients younger than 65 years. High rates of revision after tenotomy have been reported.43,49 Incomplete retraction of the LHBT and/or residual synovium may be responsible for refractory pain following biceps tenotomy.49 We hypothesize that failure of tenotomy may be related to unaddressed bicipital tunnel disease.

Proximal nondecompressing tenodesis techniques may be performed either on soft tissue in the interval or rotator cuff or on bone at the articular margin or within zone 1 of the bicipital tunnel.50-52 These techniques can be performed with standard glenohumeral arthroscopy and generally are fast and well tolerated and have limited operative morbidity. Advantages of these techniques over simple tenotomy are lower rates of cosmetic deformity and lower rates of cramping and fatigue pain, likely resulting from maintenance of the muscle tension relationship of the LHBT. Disadvantages of proximal tenodesis techniques include introduction of hardware for bony fixation, longer postoperative rehabilitation to protect repairs, and failure to address hidden bicipital tunnel disease. Furthermore, the rate of stiffness in patients who undergo proximal tenodesis without decompression of the bicipital tunnel may be as high as 18%.53

Bicipital Tunnel Decompressing Techniques

Surgical techniques that decompress the bicipital tunnel include proximal techniques that release the bicipital sheath within zones 1 and 2 of the bicipital tunnel (to the level of the proximal margin of the pectoralis major tendon) and certain arthroscopic suprapectoral techniques,54 open subpectoral tenodeses,55-57 and arthroscopic transfer of the LHBT to the conjoint tendon.58,59

Open subpectoral tenodesis techniques have the advantage of maintaining the length-tension relationship of the LHBT and preventing Popeye deformity. However, these techniques require making an incision near the axilla, which may introduce an unnecessary source of infection. Furthermore, open subpectoral tenodesis requires drilling the humerus and placing a screw for bony fixation of the LHBT, which can create a risk of neurovascular injury, given the proximity of neurovascular structures,60-62 and humeral shaft fracture, particularly in athletes.63,64Our preferred method is transfer of the LHBT to the conjoint tendon (Figure 3).59

Am J Orthop. 2016;45(7):E503-E511. Copyright Frontline Medical Communications Inc. 2016. All rights reserved.

Pathology of the biceps-labrum complex (BLC) can be an important source of shoulder pain. Discussion of pathoanatomy, imaging, and surgical intervention is facilitated by distinguishing the anatomical zones of the BLC: inside, junction, and bicipital tunnel (extra-articular), parts of which cannot be visualized with standard diagnostic arthroscopy.

The recent literature indicates that bicipital tunnel lesions are common and perhaps overlooked. Systematic reviews suggest improvement in outcomes of BLC operations when the bicipital tunnel is decompressed. Higher-level clinical and basic science studies are needed to fully elucidate the role of the bicipital tunnel, but it is evident that a comprehensive physical examination and an understanding of the limits of advanced imaging are necessary to correctly diagnose and treat BLC-related shoulder pain.

Anatomy of Biceps-Labrum Complex

The long head of the biceps tendon (LHBT) and the glenoid labrum work as an interdependent functional unit, the biceps-labrum complex (BLC). The BLC is divided into 3 distinct anatomical zones: inside, junction, and bicipital tunnel.1,2

Inside

The inside includes the superior labrum and biceps attachment. The LHBT most commonly originates in the superior labrum.3-5 Vangsness and colleagues3 described 4 types of LHBT origins: Type I biceps attaches solely to the posterior labrum, type II predominantly posterior, type III equally to the anterior and posterior labrum, and type IV mostly to the anterior labrum. The LHBT can also originate in the supraglenoid tubercle or the inferior border of the supraspinatus.3,6

Junction

Junction is the intra-articular segment of the LHBT and the biceps pulley. The LHBT traverses the glenohumeral joint en route to the extra-articular bicipital tunnel.2 The LHBT is enveloped in synovium that extends into part of the bicipital tunnel.2 The intra-articular segment of the LHBT is about 25 mm in length7 and has a diameter of 5 mm to 6 mm.8

A cadaveric study found that the average length of the LHBT that can be arthroscopically visualized at rest is 35.6 mm, or only 40% of the total length of the LHBT with respect to the proximal margin of the pectoralis major tendon.1 When the LHBT was pulled into the joint, more tendon (another 14 mm) was visualized.1 Therefore, diagnostic arthroscopy of the glenohumeral joint visualizes about 50% of the LHBT.9The morphology of the LHBT varies by location. The intra-articular portion of the LHBT is wide and flat, whereas the extra-articular portion is round.8 The tendon becomes smoother and more avascular as it exits the joint to promote gliding within its sheath in the bicipital groove.10 The proximal LHBT receives its vascular supply from superior labrum tributaries, and distally the LHBT is supplied by ascending branches of the anterior humeral circumflex artery.4 There is a hypovascular zone, created by this dual blood supply, about 12 mm to 30 mm from the LHBT origin, predisposing the tendon to rupture or fray in this region.11The LHBT makes a 30° turn into the biceps pulley system as it exits the glenohumeral joint. The fibrous pulley system that stabilizes the LHBT in this region has contributions from the coracohumeral ligament, the superior glenohumeral ligament, and the supraspinatus tendon.12-14

Bicipital Tunnel

The bicipital tunnel, the third portion of the BLC, remains largely hidden from standard diagnostic glenohumeral arthroscopy. The bicipital tunnel is an extra-articular, closed space that constrains the LHBT from the articular margin through the subpectoral region.2

Zone 1 is the traditional bicipital groove or “bony groove” that extends from the articular margin to the distal margin of the subscapularis tendon. The floor consists of a deep osseous groove covered by a continuation of subscapularis tendon fibers and periosteum.2Zone 2, “no man’s land,” extends from the distal margin of the subscapularis tendon to the proximal margin of the pectoralis major (PMPM). The LHBT in this zone cannot be visualized during a pull test at arthroscopy, yet lesions commonly occur here.1 Zones 1 and 2 have a similar histology and contain synovium.2Zone 3 is the subpectoral region distal to the PMPM. Fibers of the latissimus dorsi form the flat floor of zone 3, and the pectoralis major inserts lateral to the LHBT on the humerus in this zone. The synovium encapsulating the LHBT in zones 1 and 2 rarely extends past the PMPM. Taylor and colleagues2 found a higher percentage of unoccupied tunnel space in zone 3 than in zones 1 and 2, which results in a “functional bottleneck” between zones 2 and 3 represented by the PMPM.

Pathoanatomy

BLC lesions may occur in isolation or concomitantly across multiple anatomical zones. In a series of 277 chronically symptomatic shoulders that underwent transfer of the LHBT to the conjoint tendon with subdeltoid arthroscopy, Taylor and colleagues1 found 47% incidence of bicipital tunnel lesions, 44% incidence of junctional lesions, and 35% incidence of inside lesions. In their series, 37% of patients had concomitant lesions involving more than 1 anatomical zone.

Inside Lesions

Inside lesions involve the superior labrum, the LHBT origin, or both. Superior labrum anterior-posterior (SLAP) tears are included as inside BLC lesions. Snyder and colleagues16 originally identified 4 broad categories of SLAP tears, but Powell and colleagues17 described up to 10 variations. Type II lesions, which are the most common, destabilize the biceps anchor.

Dynamic incarceration of the biceps between the humeral head and the glenoid labrum is another inside lesion that can be identified during routine diagnostic glenohumeral arthroscopy. The arthroscopic active compression test, as described by Verma and colleagues,18 can be used during surgery to demonstrate incarceration of the biceps tendon.

Medial biceps chondromalacia, attritional chondral wear along the anteromedial aspect of the humeral head, occurs secondary to a windshield wiper effect of the LHBT in the setting of an incarcerating LHBT or may be associated with destabilization of the biceps pulley.

Junctional Lesions

Junctional lesions, which include lesions that affect the intra-articular LHBT, can be visualized during routine glenohumeral arthroscopy. They include partial and complete biceps tears, biceps pulley lesions, and junctional biceps chondromalacia.

Biceps pulley injuries and/or tears of the upper subscapularis tendon can destabilize the biceps as it exits the joint, and this destabilization may result in medial subluxation of the tendon and the aforementioned medial biceps chondromalacia.10,19 Junctional biceps chondromalacia is attritional chondral wear of the humeral head from abnormal tracking of the LHBT deep to the LHBT near the articular margin.

Recently elucidated is the limited ability of diagnostic glenohumeral arthroscopy to fully identify the extent of BLC pathology.1,20-22 Gilmer and colleagues20 found that diagnostic arthroscopy identified only 67% of biceps pathology and underestimated its extent in 56% of patients in their series. Similarly, Moon and colleagues21 found that 79% of proximal LHBT tears propagated distally into the bicipital tunnel and were incompletely visualized with standard arthroscopy.

Bicipital Tunnel Lesions

Recent evidence indicates that the bicipital tunnel is a closed space that often conceals space-occupying lesions, including scar, synovitis, loose bodies, and osteophytes, which can become trapped in the tunnel. The functional bottleneck between zones 2 and 3 of the bicipital tunnel explains the aggregation of loose bodies in this region.2 Similarly, as the percentage of free space within the bicipital tunnel increases, space-occupying lesions (eg scar, loose bodies, osteophytes) may exude a compressive and/or abrasive force within zones 1 and 2, but not as commonly within zone 3.2

Physical Examination of Biceps-Labrum Complex

Accurate diagnosis of BLC disease is crucial in selecting an optimal intervention, but challenging. Beyond identifying biceps pathology, specific examination maneuvers may help distinguish between lesions of the intra-articular BLC and lesions of the extra-articular bicipital tunnel.23

Traditional examination maneuvers for biceps-related shoulder pain include the Speed test, the full can test, and the Yergason test.24,25 For the Speed test, the patient forward-flexes the shoulder to 60° to 90°, extends the arm at the elbow, and supinates the forearm. The clinician applies a downward force as the patient resists. The reported sensitivity of the Speed test ranges from 37% to 63%, and specificity is 60% to 88%.25,26 In the full can test, with the patient’s arm in the plane of the scapula, the shoulder abducted to 90°, and the forearm in neutral rotation, a downward force is applied against resistance. Sensitivity of the full can test is 60% to 67%, and specificity is 76% to 84%.24 The Yergason test is performed with the patient’s arm at his or her side, the elbow flexed to 90°, and the forearm pronated. The patient supinates the forearm against the clinician’s resistance. Sensitivity of the Yergason test is 19% to 32%, and specificity is 70% to 100%.25,26 The Yergason test has a positive predictive value of 92% for bicipital tunnel disease.

O’Brien and colleagues23,26 introduced a “3-pack” physical examination designed to elicit BLC symptoms. In this examination, the LHBT is palpated along its course within the bicipital tunnel. Reproduction of the patient’s pain by palpation had a sensitivity of 98% for bicipital tunnel disease but was less specific (70%). Gill and colleagues27 reported low sensitivity (53%) and low specificity (54%) for biceps palpation, and they used arthroscopy as a gold standard. Since then, multiple studies have demonstrated that glenohumeral arthroscopy fails to identify lesions concealed within the bicipital tunnel.20-22The second part of the 3-pack examination is the active compression test. A downward force is applied as the patient resists with his or her arm forward-flexed to 90° and adducted 10° to 15° with the thumb pointing downward.28 This action is repeated with the humerus externally rotated and the forearm supinated. A positive test is indicated by reproduction of symptoms with the thumb down, and elimination or reduction of symptoms with the palm up. Test sensitivity is 88% to 96%, and specificity is 46% to 64% for BLC lesions, but for bicipital tunnel disease sensitivity is higher (96%), and the negative predictive value is 93%.26The third component of the 3-pack examination is the throwing test. A late-cocking throwing position is re-created with the shoulder externally rotated and abducted to 90° and the elbow flexed to 90°. The patient steps forward with the contralateral leg and moves into the acceleration phase of throwing while the clinician provides isometric resistance. If this maneuver reproduces pain, the test is positive. As Taylor and colleagues26 reported, the throwing test has sensitivity of 73% to 77% and specificity of 65% to 79% for BLC pathology. This test has moderate sensitivity and negative predictive value for bicipital tunnel disease but may be the only positive test on physical examination in the setting of LHBT instability.

Imaging of Biceps-Labrum Complex

Plain anteroposterior, lateral, and axillary radiographs of the shoulder should be obtained for all patients having an orthopedic examination for shoulder pain. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and ultrasound are the advanced modalities most commonly used for diagnostic imaging. These modalities should be considered in conjunction with, not in place of, a comprehensive history and physical examination.

MRI has sensitivity of 9% to 89% for LHBT pathology29-37 and 38% to 98% for SLAP pathology.35,38-41 The wide range of reported sensitivity and specificity might be attributed to the varying criteria for what constitutes a BLC lesion. Some authors include biceps chondromalacia, dynamic incarceration of LHBT, and extra-articular bicipital tunnel lesions, while others historically have included only intra-articular LHBT lesions that can be directly visualized arthroscopically.

In their retrospective review of 277 shoulders with chronic refractory BLC symptoms treated with subdeltoid transfer of the LHBT to the conjoint tendon, Taylor and colleagues30 reported MRI was more sensitive for inside BLC lesions than for junctional or bicipital tunnel lesions (77% vs 43% and 50%, respectively).

Treatment Options for Biceps-Labrum Complex Lesions

A diagnosis of BLC disease warrants a trial of conservative (nonoperative) management for at least 3 months. Many patients improve with activity modification, use of oral anti-inflammatory medication, and structured physical therapy focused on dynamic stabilizers and range of motion. If pain persists, local anesthetic and corticosteroid can be injected under ultrasound guidance into the bicipital tunnel; this injection has the advantage of being both diagnostic and therapeutic. Hashiuchi and colleagues42 found ultrasound-guided injections are 87% successful in achieving intra-sheath placement (injections without ultrasound guidance are only 27% successful).

If the 3-month trial of conservative management fails, surgical intervention should be considered. The goal in treating BLC pain is to maximize clinical function and alleviate pain in a predictable manner while minimizing technical demands and morbidity. A singular solution has not been identified. Furthermore, 3 systematic reviews failed to identify a difference between the most commonly used techniques, biceps tenodesis and tenotomy.43-45 These reviews grouped all tenotomy procedures together and compared them with all tenodesis procedures. A limitation of these systematic reviews is that they did not differentiate tenodesis techniques. We prefer to classify techniques according to whether or not they decompress zones 1 and 2 of the bicipital tunnel.

Bicipital Tunnel Nondecompressing Techniques

Release of the biceps tendon, a biceps tenotomy, is a simple procedure that potentially avoids open surgery and provides patients with a quick return to activity. Disadvantages of tenotomy include cosmetic (Popeye) deformity after surgery, potential cramping and fatigue, and biomechanical changes in the humeral head,46-48 particularly among patients younger than 65 years. High rates of revision after tenotomy have been reported.43,49 Incomplete retraction of the LHBT and/or residual synovium may be responsible for refractory pain following biceps tenotomy.49 We hypothesize that failure of tenotomy may be related to unaddressed bicipital tunnel disease.

Proximal nondecompressing tenodesis techniques may be performed either on soft tissue in the interval or rotator cuff or on bone at the articular margin or within zone 1 of the bicipital tunnel.50-52 These techniques can be performed with standard glenohumeral arthroscopy and generally are fast and well tolerated and have limited operative morbidity. Advantages of these techniques over simple tenotomy are lower rates of cosmetic deformity and lower rates of cramping and fatigue pain, likely resulting from maintenance of the muscle tension relationship of the LHBT. Disadvantages of proximal tenodesis techniques include introduction of hardware for bony fixation, longer postoperative rehabilitation to protect repairs, and failure to address hidden bicipital tunnel disease. Furthermore, the rate of stiffness in patients who undergo proximal tenodesis without decompression of the bicipital tunnel may be as high as 18%.53

Bicipital Tunnel Decompressing Techniques

Surgical techniques that decompress the bicipital tunnel include proximal techniques that release the bicipital sheath within zones 1 and 2 of the bicipital tunnel (to the level of the proximal margin of the pectoralis major tendon) and certain arthroscopic suprapectoral techniques,54 open subpectoral tenodeses,55-57 and arthroscopic transfer of the LHBT to the conjoint tendon.58,59