User login

The Death of a Dream: Closing an NP Practice

For many nurse practitioners, having your own practice is the culmination of many years of planning and anticipation. I worked as an NP for 14 years in practices operated by others—hospitals and physicians—before I opened my own practice. During those years, I had observed which ways of doing things appeared productive and healing to me and which did not.

When the time came, having seen a need for more affordable health care that was not predicated on the assumption that every patient had health insurance, I opened a cash-only practice in the town where I resided. By eliminating the need for personnel and apparatus dedicated to insurance filing, I was able to charge about half of what other practices in the same location did for identical services. My chief goal was to be of service to the community, not to make the most money possible. I anticipated that volume would make up for the lower prices in the long run.

For about four years, our revenue grew slowly. I decided to risk all and stop teaching part-time in order to focus exclusively on my practice. This proved to be a good decision—for about one year. Then the recession hit my part of the country. Suddenly, the operation of a “cash-only” practice became an oxymoron, as many of the patients with already limited funds lost their jobs. These patients started to seek “free” care at area emergency departments, and the practice income plummeted. My revenue fell by one-half the first year and then one-half of that the next year.

In what would turn out to be my final year of practice ownership, I decided to accept a full-time position as faculty of a distance FNP program. I was practicing “on the side,” although in reality I was in my office full-time and teaching from there. I was already recognizing the difficulties of juggling my roles and responsibilities when a student in one of my classes asked what it would take for me to decide to close my practice, since I was (by this point) making no money from it.

As I pondered that question (my initial response was a quite honest “I don’t know”), I stepped onto the road toward closing my practice. From a business perspective, there was little point in keeping the practice open. However, from an emotional point of view, I had invested so much in building my dream—and, by extension, so had my family—that closing the practice seemed unthinkable.

THE DECISION

Opening a practice is a time of joy, pride, and a sense of accomplishment; closing that same practice induces a period of reflection, sadness, and even anger that circumstances did not allow continued operation. While financial considerations play a significant role in the decision to close a practice, they may not be the only, or the deciding, factor.

In my case, the financial shortfall of the practice led me to accept a teaching position in order to earn living expenses. The result of that decision was that my attention became divided: Sometimes I was in meetings or interacting with students—and for a few weeks per year, I was out of town—which meant less time devoted to seeing patients. Conversely, if I was with a patient, I of course could not be available to my students. Over time, I started to feel that I was not giving my all to either role as I shifted back and forth. Having given 100% to each of these roles at previous points in my career, I now felt that I was cheating my patients and my students.

The decision to close a practice may take months or even years before the actual process is started. I lived with my conundrum for about a year before I made the decision to close. I was exhausted—and while I was relieved to have the burden of deciding off my shoulders, it was now time to do the work of closing a practice.

NOTIFYING YOUR STAKEHOLDERS

Once the decision to close a practice is reached, the provider/owner ceases to exist in a vacuum. There are stakeholders who need to be notified—some obvious, some less so.

I started by breaking the news to my family, the people who had supported me in opening my practice (and even helped me find and refurbish furniture for my waiting room!). Although they had been aware of my internal debate, they had not lived with the decision process as I had. Having resolved at least some of my own emotions, I now had to watch others experience many of those same feelings.

Next, I had to tell my employees of the decision. Through attrition, my staff had already shrunk to two: a receptionist and a part-time licensed vocational nurse (LVN). Like my family, they had to process their own emotions about the closure. I had anticipated that the people who worked for me, concerned about their future, might choose to accept another job before we officially closed. My LVN—who had observed the practice dwindling in the preceding two years—seemed prepared for my decision. She stuck it out with me until the end and was a huge help with the influx of patients requesting records. (My MD—required by Texas law to delegate prescriptive authority to me—had already relocated his practice and was ill, so he was content with my decision.)

Of course, the biggest stakeholders in a practice are the patients. Notifying them of the impending closure is the most important action you will take (aside from making the decision to close). Although you can place notices in the local media (newspapers, TV, radio) to announce the closure of your practice to the community, you should send a notification letter directly to your patients. It should be sent at least 60 to 90 days before the closure date—and certainly not less than 30 days in any case—giving patients adequate time to find new providers and arrange for their records to be transferred.1,2 The letter should include

- A statement of gratitude for the patient’s business

- The dates of the transition period

- What is expected of the patient (eg, does he/she need to come and pick up his/her records?)

- An explanation for the closure3

I composed a letter to be sent to all patients who had been seen within the past 18 months. In it, I thanked them for being a part of the practice and gave them 60 days’ notice of the intent to close. For many patients, this was an emotional time; many understandably worried how their health care needs would be met in the future. Some responded with sadness that I had not been able to make the practice a success.

AVOIDING “ABANDONMENT”

Ideally, a provider who wants to get out of the business should seek to sell the practice—but this is not always feasible.3,4 When closure is the best (or only) option, it is important to avoid even the appearance of abandonment.

Besides giving adequate notice of practice closure, providers must have a plan for the dispersal of patients.1 Be prepared to give recommendations for new providers. Depending on the practice location (rural or urban), options may vary.

I made a concerted effort to refer patients to new providers, with the caveat that if the patient did not feel a particular provider was a good match, he/she should seek another provider of his/her choosing. Unlike in a purchased practice, where patients “go with” the practice, patients from a closed practice may be referred to one, several, or even many other providers.5

Provisions must be made to store patient records so that they are retrievable for a specified period of time. The requirements vary by state, so consultation of the state board’s rules and regulations—and/or an attorney—is in order.3 In general, the proscribed time period is seven to 10 years for adults and seven to 10 years after the patient turns 18 for pediatric patients.2 In some states, the retention time may be as short as three years for adults.1

OTHER PRACTICAL CONSIDERATIONS

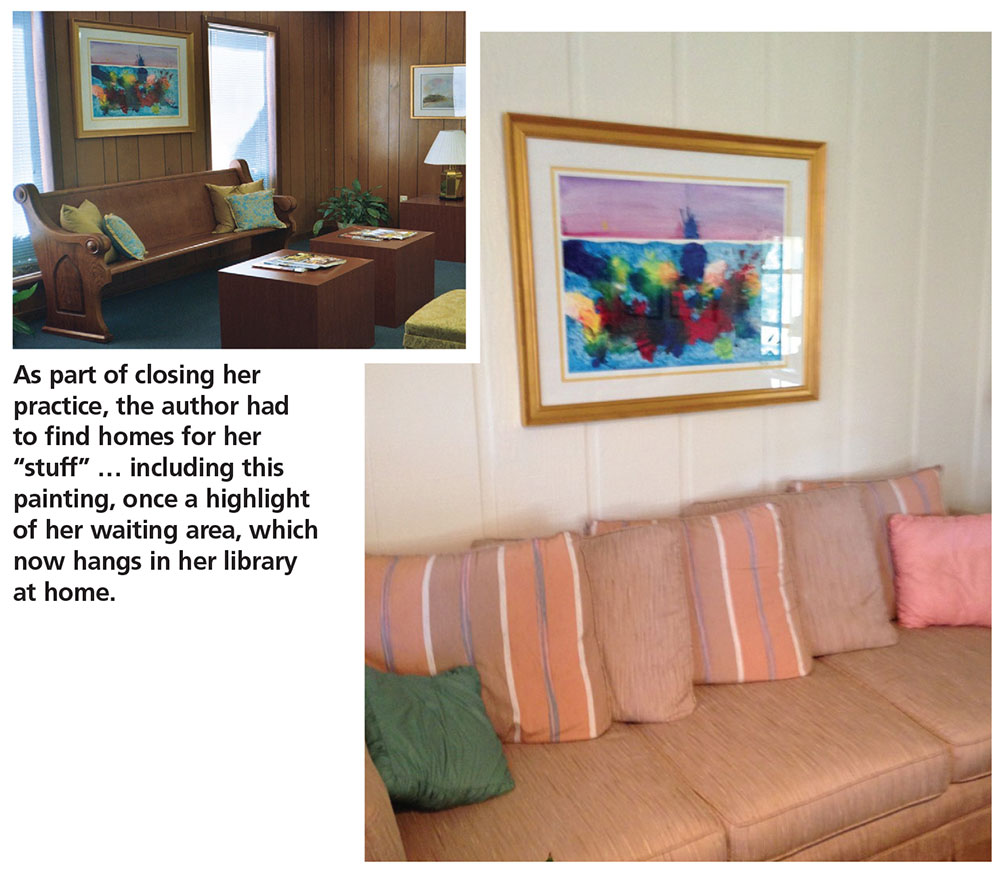

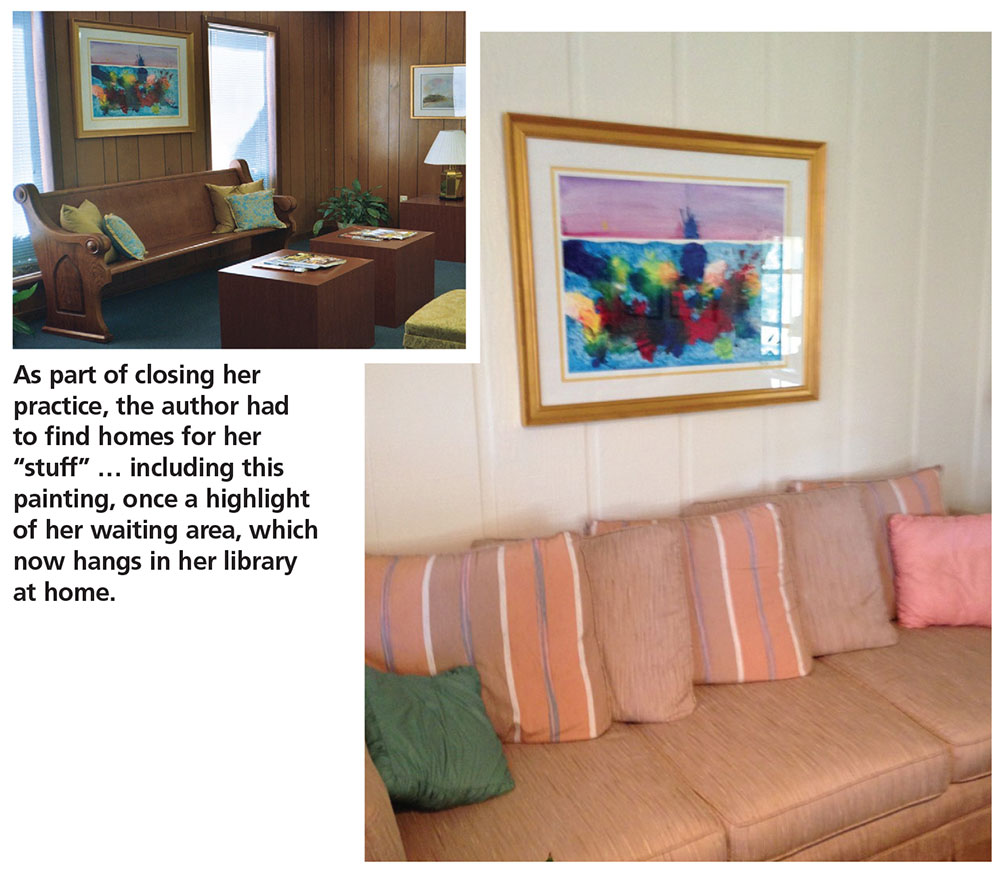

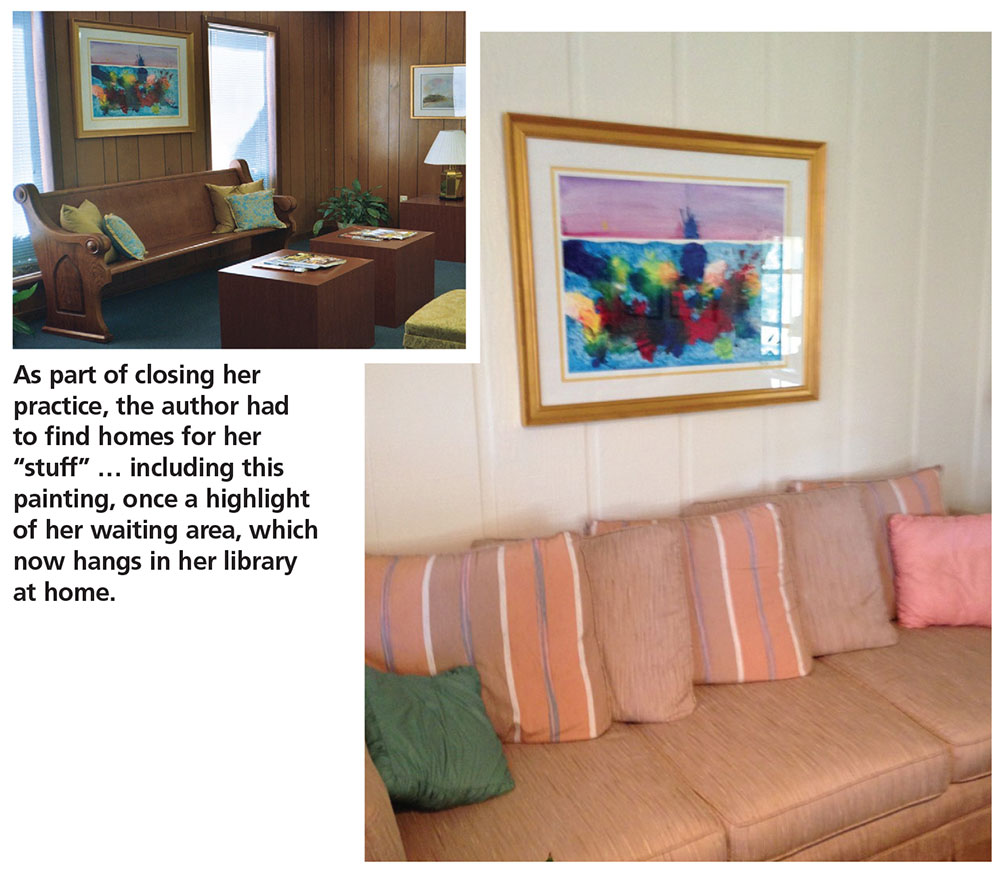

While people will be your priority as you work through the process of closing, you will have “stuff” to deal with. What will you do with the furnishings and equipment? Obviously, anything that was borrowed can be returned. Beyond that, your options are to sell (to another provider or even a patient), donate, or repurpose items.

The orthopedic exam table from my practice went to a private school for their athletic training facility. Screens went to my neighbor, a chiropractor. My preschool-aged grandsons were thrilled to be given the children’s art supplies and books that had once graced my waiting area. One of my patients bought some decorative vases and a bookcase. The painting that had been carefully chosen to pull together my waiting room now hangs in my library at home.

As the closure date approaches, the practice environment may begin to look bare as furnishings are sold or moved. One item you will want to buy, however, is a fresh ink cartridge for your copier/printer. As patients request documents, you’ll use it!

RESPONSE AND AFTERMATH

The practice may be very busy immediately following the receipt of notification letters—but don’t be fooled into thinking you have made the wrong decision. The first month after the letters went out advising of the closure, my practice was busier than it had ever been! This tapered off in the second month, though.

Most patients, once they’ve heard the news, will want prescription refills and/or their records. Some may just want to know what happened to result in the closure. Remember that to the patient, this seems like a sudden decision—no matter how long you have deliberated about it.

What surprised me most, however, was that new patients continued to present to the practice, seeking care for acute issues. While I did provide this, I made them aware from the beginning that the practice was in the process of closing and that I could not assume the responsibility of being their primary provider. I made sure to provide these patients with recommendations for other providers.

Slowly the rush will settle down, as patients start to move on to other providers. A few may drop in to see you socially. On the day I closed my practice, several patients came in just to say goodbye and wish me well.

The last things I did in my practice were turn off the lights and leave a sign on the door stating that the practice was now closed.

RECOVERY

The time needed to recover from the closure of a practice will differ. Factors include how long the practice was open and how the clinician normally deals with a setback.6 For some, relief that the pressures of ownership are over may be the predominant emotion. Having a steady, stable salary in a new position goes a long way toward making the transition easier! Although if possible, take some time between closing the practice and starting a new job.

Do not be surprised if negative emotions manifest at odd times, as feelings of sadness, regret, and even a sense of failure are worked through. Life does go on—and nurse practitioners are resilient. Find a way to use the knowledge gained from your practice in your new endeavors, whatever they may be.

For me, the healing process would have started sooner if I had acknowledged how difficult giving up the dream of having my own practice was. If I had sought out others with similar experience or even talked with a counselor, my journey through this process could have been expedited. When I started to share my story, one frequently asked question was “How did you get through this?” This showed me that others could learn from my experience.

1. Tatooles JJ, Brunell A. What you need to know before leaving a medical practice: a primer for moving on. AAOS NOW. 2015;22-23.

2. Kern SI. Take these steps if selling or closing a practice. Med Econ. 2010;87(20):66.

3. Weiss GG. How to close a practice. Med Econ. 2004;81:69.

4. Zaumeyer C. How to Start an Independent Practice: The Nurse Practitioner’s Guide to Success. Philadelphia: F. A. Davis, Publishers; 2003.

5. Barrett W. The legal corner: Eleven essential steps to purchasing or selling a medical practice. J Med Pract Manage. 2014;29(5):275-277.

6. McBride JL. Personal issues to consider before leaving independent practice. Fam Pract Manag. 2013;20(4):9-12.

For many nurse practitioners, having your own practice is the culmination of many years of planning and anticipation. I worked as an NP for 14 years in practices operated by others—hospitals and physicians—before I opened my own practice. During those years, I had observed which ways of doing things appeared productive and healing to me and which did not.

When the time came, having seen a need for more affordable health care that was not predicated on the assumption that every patient had health insurance, I opened a cash-only practice in the town where I resided. By eliminating the need for personnel and apparatus dedicated to insurance filing, I was able to charge about half of what other practices in the same location did for identical services. My chief goal was to be of service to the community, not to make the most money possible. I anticipated that volume would make up for the lower prices in the long run.

For about four years, our revenue grew slowly. I decided to risk all and stop teaching part-time in order to focus exclusively on my practice. This proved to be a good decision—for about one year. Then the recession hit my part of the country. Suddenly, the operation of a “cash-only” practice became an oxymoron, as many of the patients with already limited funds lost their jobs. These patients started to seek “free” care at area emergency departments, and the practice income plummeted. My revenue fell by one-half the first year and then one-half of that the next year.

In what would turn out to be my final year of practice ownership, I decided to accept a full-time position as faculty of a distance FNP program. I was practicing “on the side,” although in reality I was in my office full-time and teaching from there. I was already recognizing the difficulties of juggling my roles and responsibilities when a student in one of my classes asked what it would take for me to decide to close my practice, since I was (by this point) making no money from it.

As I pondered that question (my initial response was a quite honest “I don’t know”), I stepped onto the road toward closing my practice. From a business perspective, there was little point in keeping the practice open. However, from an emotional point of view, I had invested so much in building my dream—and, by extension, so had my family—that closing the practice seemed unthinkable.

THE DECISION

Opening a practice is a time of joy, pride, and a sense of accomplishment; closing that same practice induces a period of reflection, sadness, and even anger that circumstances did not allow continued operation. While financial considerations play a significant role in the decision to close a practice, they may not be the only, or the deciding, factor.

In my case, the financial shortfall of the practice led me to accept a teaching position in order to earn living expenses. The result of that decision was that my attention became divided: Sometimes I was in meetings or interacting with students—and for a few weeks per year, I was out of town—which meant less time devoted to seeing patients. Conversely, if I was with a patient, I of course could not be available to my students. Over time, I started to feel that I was not giving my all to either role as I shifted back and forth. Having given 100% to each of these roles at previous points in my career, I now felt that I was cheating my patients and my students.

The decision to close a practice may take months or even years before the actual process is started. I lived with my conundrum for about a year before I made the decision to close. I was exhausted—and while I was relieved to have the burden of deciding off my shoulders, it was now time to do the work of closing a practice.

NOTIFYING YOUR STAKEHOLDERS

Once the decision to close a practice is reached, the provider/owner ceases to exist in a vacuum. There are stakeholders who need to be notified—some obvious, some less so.

I started by breaking the news to my family, the people who had supported me in opening my practice (and even helped me find and refurbish furniture for my waiting room!). Although they had been aware of my internal debate, they had not lived with the decision process as I had. Having resolved at least some of my own emotions, I now had to watch others experience many of those same feelings.

Next, I had to tell my employees of the decision. Through attrition, my staff had already shrunk to two: a receptionist and a part-time licensed vocational nurse (LVN). Like my family, they had to process their own emotions about the closure. I had anticipated that the people who worked for me, concerned about their future, might choose to accept another job before we officially closed. My LVN—who had observed the practice dwindling in the preceding two years—seemed prepared for my decision. She stuck it out with me until the end and was a huge help with the influx of patients requesting records. (My MD—required by Texas law to delegate prescriptive authority to me—had already relocated his practice and was ill, so he was content with my decision.)

Of course, the biggest stakeholders in a practice are the patients. Notifying them of the impending closure is the most important action you will take (aside from making the decision to close). Although you can place notices in the local media (newspapers, TV, radio) to announce the closure of your practice to the community, you should send a notification letter directly to your patients. It should be sent at least 60 to 90 days before the closure date—and certainly not less than 30 days in any case—giving patients adequate time to find new providers and arrange for their records to be transferred.1,2 The letter should include

- A statement of gratitude for the patient’s business

- The dates of the transition period

- What is expected of the patient (eg, does he/she need to come and pick up his/her records?)

- An explanation for the closure3

I composed a letter to be sent to all patients who had been seen within the past 18 months. In it, I thanked them for being a part of the practice and gave them 60 days’ notice of the intent to close. For many patients, this was an emotional time; many understandably worried how their health care needs would be met in the future. Some responded with sadness that I had not been able to make the practice a success.

AVOIDING “ABANDONMENT”

Ideally, a provider who wants to get out of the business should seek to sell the practice—but this is not always feasible.3,4 When closure is the best (or only) option, it is important to avoid even the appearance of abandonment.

Besides giving adequate notice of practice closure, providers must have a plan for the dispersal of patients.1 Be prepared to give recommendations for new providers. Depending on the practice location (rural or urban), options may vary.

I made a concerted effort to refer patients to new providers, with the caveat that if the patient did not feel a particular provider was a good match, he/she should seek another provider of his/her choosing. Unlike in a purchased practice, where patients “go with” the practice, patients from a closed practice may be referred to one, several, or even many other providers.5

Provisions must be made to store patient records so that they are retrievable for a specified period of time. The requirements vary by state, so consultation of the state board’s rules and regulations—and/or an attorney—is in order.3 In general, the proscribed time period is seven to 10 years for adults and seven to 10 years after the patient turns 18 for pediatric patients.2 In some states, the retention time may be as short as three years for adults.1

OTHER PRACTICAL CONSIDERATIONS

While people will be your priority as you work through the process of closing, you will have “stuff” to deal with. What will you do with the furnishings and equipment? Obviously, anything that was borrowed can be returned. Beyond that, your options are to sell (to another provider or even a patient), donate, or repurpose items.

The orthopedic exam table from my practice went to a private school for their athletic training facility. Screens went to my neighbor, a chiropractor. My preschool-aged grandsons were thrilled to be given the children’s art supplies and books that had once graced my waiting area. One of my patients bought some decorative vases and a bookcase. The painting that had been carefully chosen to pull together my waiting room now hangs in my library at home.

As the closure date approaches, the practice environment may begin to look bare as furnishings are sold or moved. One item you will want to buy, however, is a fresh ink cartridge for your copier/printer. As patients request documents, you’ll use it!

RESPONSE AND AFTERMATH

The practice may be very busy immediately following the receipt of notification letters—but don’t be fooled into thinking you have made the wrong decision. The first month after the letters went out advising of the closure, my practice was busier than it had ever been! This tapered off in the second month, though.

Most patients, once they’ve heard the news, will want prescription refills and/or their records. Some may just want to know what happened to result in the closure. Remember that to the patient, this seems like a sudden decision—no matter how long you have deliberated about it.

What surprised me most, however, was that new patients continued to present to the practice, seeking care for acute issues. While I did provide this, I made them aware from the beginning that the practice was in the process of closing and that I could not assume the responsibility of being their primary provider. I made sure to provide these patients with recommendations for other providers.

Slowly the rush will settle down, as patients start to move on to other providers. A few may drop in to see you socially. On the day I closed my practice, several patients came in just to say goodbye and wish me well.

The last things I did in my practice were turn off the lights and leave a sign on the door stating that the practice was now closed.

RECOVERY

The time needed to recover from the closure of a practice will differ. Factors include how long the practice was open and how the clinician normally deals with a setback.6 For some, relief that the pressures of ownership are over may be the predominant emotion. Having a steady, stable salary in a new position goes a long way toward making the transition easier! Although if possible, take some time between closing the practice and starting a new job.

Do not be surprised if negative emotions manifest at odd times, as feelings of sadness, regret, and even a sense of failure are worked through. Life does go on—and nurse practitioners are resilient. Find a way to use the knowledge gained from your practice in your new endeavors, whatever they may be.

For me, the healing process would have started sooner if I had acknowledged how difficult giving up the dream of having my own practice was. If I had sought out others with similar experience or even talked with a counselor, my journey through this process could have been expedited. When I started to share my story, one frequently asked question was “How did you get through this?” This showed me that others could learn from my experience.

For many nurse practitioners, having your own practice is the culmination of many years of planning and anticipation. I worked as an NP for 14 years in practices operated by others—hospitals and physicians—before I opened my own practice. During those years, I had observed which ways of doing things appeared productive and healing to me and which did not.

When the time came, having seen a need for more affordable health care that was not predicated on the assumption that every patient had health insurance, I opened a cash-only practice in the town where I resided. By eliminating the need for personnel and apparatus dedicated to insurance filing, I was able to charge about half of what other practices in the same location did for identical services. My chief goal was to be of service to the community, not to make the most money possible. I anticipated that volume would make up for the lower prices in the long run.

For about four years, our revenue grew slowly. I decided to risk all and stop teaching part-time in order to focus exclusively on my practice. This proved to be a good decision—for about one year. Then the recession hit my part of the country. Suddenly, the operation of a “cash-only” practice became an oxymoron, as many of the patients with already limited funds lost their jobs. These patients started to seek “free” care at area emergency departments, and the practice income plummeted. My revenue fell by one-half the first year and then one-half of that the next year.

In what would turn out to be my final year of practice ownership, I decided to accept a full-time position as faculty of a distance FNP program. I was practicing “on the side,” although in reality I was in my office full-time and teaching from there. I was already recognizing the difficulties of juggling my roles and responsibilities when a student in one of my classes asked what it would take for me to decide to close my practice, since I was (by this point) making no money from it.

As I pondered that question (my initial response was a quite honest “I don’t know”), I stepped onto the road toward closing my practice. From a business perspective, there was little point in keeping the practice open. However, from an emotional point of view, I had invested so much in building my dream—and, by extension, so had my family—that closing the practice seemed unthinkable.

THE DECISION

Opening a practice is a time of joy, pride, and a sense of accomplishment; closing that same practice induces a period of reflection, sadness, and even anger that circumstances did not allow continued operation. While financial considerations play a significant role in the decision to close a practice, they may not be the only, or the deciding, factor.

In my case, the financial shortfall of the practice led me to accept a teaching position in order to earn living expenses. The result of that decision was that my attention became divided: Sometimes I was in meetings or interacting with students—and for a few weeks per year, I was out of town—which meant less time devoted to seeing patients. Conversely, if I was with a patient, I of course could not be available to my students. Over time, I started to feel that I was not giving my all to either role as I shifted back and forth. Having given 100% to each of these roles at previous points in my career, I now felt that I was cheating my patients and my students.

The decision to close a practice may take months or even years before the actual process is started. I lived with my conundrum for about a year before I made the decision to close. I was exhausted—and while I was relieved to have the burden of deciding off my shoulders, it was now time to do the work of closing a practice.

NOTIFYING YOUR STAKEHOLDERS

Once the decision to close a practice is reached, the provider/owner ceases to exist in a vacuum. There are stakeholders who need to be notified—some obvious, some less so.

I started by breaking the news to my family, the people who had supported me in opening my practice (and even helped me find and refurbish furniture for my waiting room!). Although they had been aware of my internal debate, they had not lived with the decision process as I had. Having resolved at least some of my own emotions, I now had to watch others experience many of those same feelings.

Next, I had to tell my employees of the decision. Through attrition, my staff had already shrunk to two: a receptionist and a part-time licensed vocational nurse (LVN). Like my family, they had to process their own emotions about the closure. I had anticipated that the people who worked for me, concerned about their future, might choose to accept another job before we officially closed. My LVN—who had observed the practice dwindling in the preceding two years—seemed prepared for my decision. She stuck it out with me until the end and was a huge help with the influx of patients requesting records. (My MD—required by Texas law to delegate prescriptive authority to me—had already relocated his practice and was ill, so he was content with my decision.)

Of course, the biggest stakeholders in a practice are the patients. Notifying them of the impending closure is the most important action you will take (aside from making the decision to close). Although you can place notices in the local media (newspapers, TV, radio) to announce the closure of your practice to the community, you should send a notification letter directly to your patients. It should be sent at least 60 to 90 days before the closure date—and certainly not less than 30 days in any case—giving patients adequate time to find new providers and arrange for their records to be transferred.1,2 The letter should include

- A statement of gratitude for the patient’s business

- The dates of the transition period

- What is expected of the patient (eg, does he/she need to come and pick up his/her records?)

- An explanation for the closure3

I composed a letter to be sent to all patients who had been seen within the past 18 months. In it, I thanked them for being a part of the practice and gave them 60 days’ notice of the intent to close. For many patients, this was an emotional time; many understandably worried how their health care needs would be met in the future. Some responded with sadness that I had not been able to make the practice a success.

AVOIDING “ABANDONMENT”

Ideally, a provider who wants to get out of the business should seek to sell the practice—but this is not always feasible.3,4 When closure is the best (or only) option, it is important to avoid even the appearance of abandonment.

Besides giving adequate notice of practice closure, providers must have a plan for the dispersal of patients.1 Be prepared to give recommendations for new providers. Depending on the practice location (rural or urban), options may vary.

I made a concerted effort to refer patients to new providers, with the caveat that if the patient did not feel a particular provider was a good match, he/she should seek another provider of his/her choosing. Unlike in a purchased practice, where patients “go with” the practice, patients from a closed practice may be referred to one, several, or even many other providers.5

Provisions must be made to store patient records so that they are retrievable for a specified period of time. The requirements vary by state, so consultation of the state board’s rules and regulations—and/or an attorney—is in order.3 In general, the proscribed time period is seven to 10 years for adults and seven to 10 years after the patient turns 18 for pediatric patients.2 In some states, the retention time may be as short as three years for adults.1

OTHER PRACTICAL CONSIDERATIONS

While people will be your priority as you work through the process of closing, you will have “stuff” to deal with. What will you do with the furnishings and equipment? Obviously, anything that was borrowed can be returned. Beyond that, your options are to sell (to another provider or even a patient), donate, or repurpose items.

The orthopedic exam table from my practice went to a private school for their athletic training facility. Screens went to my neighbor, a chiropractor. My preschool-aged grandsons were thrilled to be given the children’s art supplies and books that had once graced my waiting area. One of my patients bought some decorative vases and a bookcase. The painting that had been carefully chosen to pull together my waiting room now hangs in my library at home.

As the closure date approaches, the practice environment may begin to look bare as furnishings are sold or moved. One item you will want to buy, however, is a fresh ink cartridge for your copier/printer. As patients request documents, you’ll use it!

RESPONSE AND AFTERMATH

The practice may be very busy immediately following the receipt of notification letters—but don’t be fooled into thinking you have made the wrong decision. The first month after the letters went out advising of the closure, my practice was busier than it had ever been! This tapered off in the second month, though.

Most patients, once they’ve heard the news, will want prescription refills and/or their records. Some may just want to know what happened to result in the closure. Remember that to the patient, this seems like a sudden decision—no matter how long you have deliberated about it.

What surprised me most, however, was that new patients continued to present to the practice, seeking care for acute issues. While I did provide this, I made them aware from the beginning that the practice was in the process of closing and that I could not assume the responsibility of being their primary provider. I made sure to provide these patients with recommendations for other providers.

Slowly the rush will settle down, as patients start to move on to other providers. A few may drop in to see you socially. On the day I closed my practice, several patients came in just to say goodbye and wish me well.

The last things I did in my practice were turn off the lights and leave a sign on the door stating that the practice was now closed.

RECOVERY

The time needed to recover from the closure of a practice will differ. Factors include how long the practice was open and how the clinician normally deals with a setback.6 For some, relief that the pressures of ownership are over may be the predominant emotion. Having a steady, stable salary in a new position goes a long way toward making the transition easier! Although if possible, take some time between closing the practice and starting a new job.

Do not be surprised if negative emotions manifest at odd times, as feelings of sadness, regret, and even a sense of failure are worked through. Life does go on—and nurse practitioners are resilient. Find a way to use the knowledge gained from your practice in your new endeavors, whatever they may be.

For me, the healing process would have started sooner if I had acknowledged how difficult giving up the dream of having my own practice was. If I had sought out others with similar experience or even talked with a counselor, my journey through this process could have been expedited. When I started to share my story, one frequently asked question was “How did you get through this?” This showed me that others could learn from my experience.

1. Tatooles JJ, Brunell A. What you need to know before leaving a medical practice: a primer for moving on. AAOS NOW. 2015;22-23.

2. Kern SI. Take these steps if selling or closing a practice. Med Econ. 2010;87(20):66.

3. Weiss GG. How to close a practice. Med Econ. 2004;81:69.

4. Zaumeyer C. How to Start an Independent Practice: The Nurse Practitioner’s Guide to Success. Philadelphia: F. A. Davis, Publishers; 2003.

5. Barrett W. The legal corner: Eleven essential steps to purchasing or selling a medical practice. J Med Pract Manage. 2014;29(5):275-277.

6. McBride JL. Personal issues to consider before leaving independent practice. Fam Pract Manag. 2013;20(4):9-12.

1. Tatooles JJ, Brunell A. What you need to know before leaving a medical practice: a primer for moving on. AAOS NOW. 2015;22-23.

2. Kern SI. Take these steps if selling or closing a practice. Med Econ. 2010;87(20):66.

3. Weiss GG. How to close a practice. Med Econ. 2004;81:69.

4. Zaumeyer C. How to Start an Independent Practice: The Nurse Practitioner’s Guide to Success. Philadelphia: F. A. Davis, Publishers; 2003.

5. Barrett W. The legal corner: Eleven essential steps to purchasing or selling a medical practice. J Med Pract Manage. 2014;29(5):275-277.

6. McBride JL. Personal issues to consider before leaving independent practice. Fam Pract Manag. 2013;20(4):9-12.

Do fellowship programs help prepare general surgery residents for board exams?

WASHINGTON – Pass rates on the general surgery board exams were significantly higher for programs in which residents trained alongside surgical fellows, according to a retrospective study presented at the annual clinical congress of the American College of Surgeons.

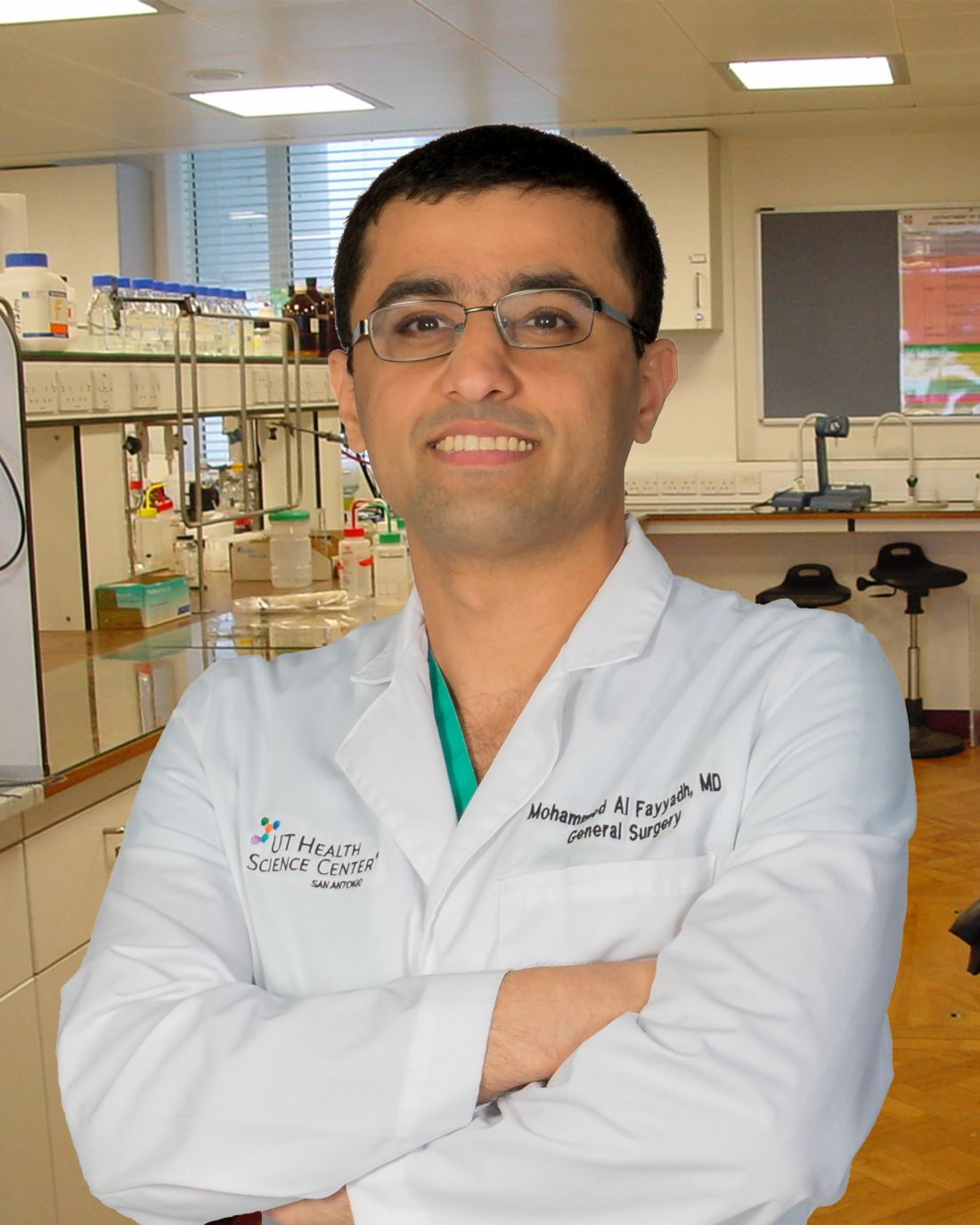

The study adds another perspective to the ongoing debate about the impact of fellowships on general surgery residency and residency programs. Mohammed J. Al Fayyadh, MD, of the University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio and his associates investigated the impact of fellowships on program pass rates for general surgery boards. They reviewed American Board of Surgery exam data for the classes of 2010-2014, which included 242 programs (a total of 5,191 resident examinees), of which 148 had fellows participating (3,767 resident examinees).

The findings suggest that having fellows in a program has a positive impact on the pass rates of those taking the ABS general surgery exam. Pass rates were significantly higher for general surgery programs with fellows. This trend held for all measures studied: Qualifying (written) exam (88% vs. 86%), certifying (oral) exam (83% vs. 80%), and combined exams (74% vs. 69%). Differences between the groups were statistically significant.

The pass rates tended to be higher in programs with higher Fel:Res ratios. For example, programs with a 1.5:1 Fel:Res ratio had the highest pass rates for the qualifying, certifying, and combined exams.

The impact of subspecialty fellowships on general surgery residencies has been the subject of research and debate in recent years. Some studies have suggested that subspecialty training for fellows has meant that general surgery residents have less opportunity to operate in areas such as trauma (“Trauma operative training declining for general surgery residents,” ACS Surgery News, Oct. 4, 2016) and vascular surgery (Ann Vasc Surg. 2016;33;98-102).

Taken in this context, it is possible that the programs with more fellows simply recruit more competitive residents who tend to do better on exams. However, this could also reflect more resources in fellowship programs that are available to all trainees or better mentorship opportunities, said Dr. Al Fayyadh. He concluded that more research is needed to tease out the impact of fellowship programs on general surgery resident education.

Dr. Al Fayyadh had no disclosures.

WASHINGTON – Pass rates on the general surgery board exams were significantly higher for programs in which residents trained alongside surgical fellows, according to a retrospective study presented at the annual clinical congress of the American College of Surgeons.

The study adds another perspective to the ongoing debate about the impact of fellowships on general surgery residency and residency programs. Mohammed J. Al Fayyadh, MD, of the University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio and his associates investigated the impact of fellowships on program pass rates for general surgery boards. They reviewed American Board of Surgery exam data for the classes of 2010-2014, which included 242 programs (a total of 5,191 resident examinees), of which 148 had fellows participating (3,767 resident examinees).

The findings suggest that having fellows in a program has a positive impact on the pass rates of those taking the ABS general surgery exam. Pass rates were significantly higher for general surgery programs with fellows. This trend held for all measures studied: Qualifying (written) exam (88% vs. 86%), certifying (oral) exam (83% vs. 80%), and combined exams (74% vs. 69%). Differences between the groups were statistically significant.

The pass rates tended to be higher in programs with higher Fel:Res ratios. For example, programs with a 1.5:1 Fel:Res ratio had the highest pass rates for the qualifying, certifying, and combined exams.

The impact of subspecialty fellowships on general surgery residencies has been the subject of research and debate in recent years. Some studies have suggested that subspecialty training for fellows has meant that general surgery residents have less opportunity to operate in areas such as trauma (“Trauma operative training declining for general surgery residents,” ACS Surgery News, Oct. 4, 2016) and vascular surgery (Ann Vasc Surg. 2016;33;98-102).

Taken in this context, it is possible that the programs with more fellows simply recruit more competitive residents who tend to do better on exams. However, this could also reflect more resources in fellowship programs that are available to all trainees or better mentorship opportunities, said Dr. Al Fayyadh. He concluded that more research is needed to tease out the impact of fellowship programs on general surgery resident education.

Dr. Al Fayyadh had no disclosures.

WASHINGTON – Pass rates on the general surgery board exams were significantly higher for programs in which residents trained alongside surgical fellows, according to a retrospective study presented at the annual clinical congress of the American College of Surgeons.

The study adds another perspective to the ongoing debate about the impact of fellowships on general surgery residency and residency programs. Mohammed J. Al Fayyadh, MD, of the University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio and his associates investigated the impact of fellowships on program pass rates for general surgery boards. They reviewed American Board of Surgery exam data for the classes of 2010-2014, which included 242 programs (a total of 5,191 resident examinees), of which 148 had fellows participating (3,767 resident examinees).

The findings suggest that having fellows in a program has a positive impact on the pass rates of those taking the ABS general surgery exam. Pass rates were significantly higher for general surgery programs with fellows. This trend held for all measures studied: Qualifying (written) exam (88% vs. 86%), certifying (oral) exam (83% vs. 80%), and combined exams (74% vs. 69%). Differences between the groups were statistically significant.

The pass rates tended to be higher in programs with higher Fel:Res ratios. For example, programs with a 1.5:1 Fel:Res ratio had the highest pass rates for the qualifying, certifying, and combined exams.

The impact of subspecialty fellowships on general surgery residencies has been the subject of research and debate in recent years. Some studies have suggested that subspecialty training for fellows has meant that general surgery residents have less opportunity to operate in areas such as trauma (“Trauma operative training declining for general surgery residents,” ACS Surgery News, Oct. 4, 2016) and vascular surgery (Ann Vasc Surg. 2016;33;98-102).

Taken in this context, it is possible that the programs with more fellows simply recruit more competitive residents who tend to do better on exams. However, this could also reflect more resources in fellowship programs that are available to all trainees or better mentorship opportunities, said Dr. Al Fayyadh. He concluded that more research is needed to tease out the impact of fellowship programs on general surgery resident education.

Dr. Al Fayyadh had no disclosures.

AT THE ACS CLINICAL CONGRESS

It’s elementary: Watson aids in breast cancer decisions

SAN ANTONIO – When oncologists at Manipal Hospitals in Bangalore, India, need help with a breast cancer conundrum, they can make the electronic equivalent of the famous cry for help “Watson, come here, I want you!”

In this case, Watson is not the real-life sidekick of Alexander Graham Bell or the fictional companion of Sherlock Holmes, but Watson for Oncology (WFO), an IBM-created artificial intelligence platform being developed in the United States and used in clinical practice in India to help guide clinical decision making but not to replace clinicians’ judgment, explained S.P. Somashekhar, MBBS, MS, MCH, FRCS, chairman of the Manipal Comprehensive Cancer Center.

This is no game

WFO is the clinical cousin of the artificial intelligence platform, also named Watson, that beat all-time champion Ken Jennings on the television game show “Jeopardy!” The system was named after Thomas J. Watson, IBM’s first chief executive officer.

The version of Watson used in India was developed by physicians and investigators at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (MSKCC) in New York and by IBM. Watson for Oncology is fed national treatment guidelines, more than 1,000 training cases, MSKCC internal guidelines, and medical literature curated by MSKCC; it then chews over the data and spits out evidence-based recommendations.

At Manipal Hospitals, the electronic medical record contains an “Ask Watson” button that allows clinicians to interrogate the artificial entity’s vast stores of medical data to offer recommendations that clinicians can then use, modify, or reject at their discretion.

The system analyzes more than 100 patient attributes and then offers options with a green label for “recommended,” amber label “for consideration,” or a red label for “not recommended.”

Concordance study

At SABCS, Dr. Somashekhar presented results of a study evaluating the concordance of treatment recommendations between WFO and the members of the Manipal Multidisciplinary Tumor Board (MTB).

They looked at data on 638 patients treated in their hospital system over the three prior years, assessing the MTBs initial, best joint decision at the time of the original treatment decision (T1), and compared it with WFO’s recommendation made in 2016 (T2) and with a blinded MTB re-review of nonconcordant cases, also made in 2016.

Evaluating concordance by stage, they found that, for 514 cases of nonmetastatic disease, there was 79% concordance between the original MTB decisions and WFO’s recommendations for therapies in the combined “for consideration” and “recommended” categories.

For 124 cases of metastatic disease, however, Watson and its human counterparts were more frequently at odds, with only a 46% concordance.

In a subset analysis by receptor status, the investigators found that Watson was best – that is, most highly concordant – in triple-negative disease, with a 67.9% concordance in regard to MTB choices. In contrast, for patients with metastatic disease negative for the human epidermal growth factor receptor-2 (HER2), the concordance rate was a low 35%.

Dr. Somashekhar commented that part of the explanation for the discordant concordance rates by tumor subtype can be attributed to the fact that patients with triple-negative breast cancers have fewer treatment options than patients with HER2 negative–only tumors, who have a much broader array of possibilities.

One area where WFO has its two-legged colleagues beaten hands down, however, is in the time it takes to capture and analyze data: humans took a mean of 20 minutes, Watson a median of 40 seconds.

The investigators acknowledged that WFO represents a further step toward personalized medicine, but emphasized that software will never replace the doctor-patient relationship or override the treating physician’s decisions.

‘This one would actually help’

At the briefing, moderator C. Kent Osborne, MD, from Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, commented, “I guess this not going to put us out of business as physicians – at least I hope not.”

Asked whether WFO could be a useful clinical tool or just another nuisance task added to an already overcrowded clinic schedule, Dr. Osborne responded, “I think this one would actually help.”

This study was investigative and received no external funding. Dr. Somashekhar, Dr. Osborne, and Dr. Blaes reported no conflicts of interest.

SAN ANTONIO – When oncologists at Manipal Hospitals in Bangalore, India, need help with a breast cancer conundrum, they can make the electronic equivalent of the famous cry for help “Watson, come here, I want you!”

In this case, Watson is not the real-life sidekick of Alexander Graham Bell or the fictional companion of Sherlock Holmes, but Watson for Oncology (WFO), an IBM-created artificial intelligence platform being developed in the United States and used in clinical practice in India to help guide clinical decision making but not to replace clinicians’ judgment, explained S.P. Somashekhar, MBBS, MS, MCH, FRCS, chairman of the Manipal Comprehensive Cancer Center.

This is no game

WFO is the clinical cousin of the artificial intelligence platform, also named Watson, that beat all-time champion Ken Jennings on the television game show “Jeopardy!” The system was named after Thomas J. Watson, IBM’s first chief executive officer.

The version of Watson used in India was developed by physicians and investigators at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (MSKCC) in New York and by IBM. Watson for Oncology is fed national treatment guidelines, more than 1,000 training cases, MSKCC internal guidelines, and medical literature curated by MSKCC; it then chews over the data and spits out evidence-based recommendations.

At Manipal Hospitals, the electronic medical record contains an “Ask Watson” button that allows clinicians to interrogate the artificial entity’s vast stores of medical data to offer recommendations that clinicians can then use, modify, or reject at their discretion.

The system analyzes more than 100 patient attributes and then offers options with a green label for “recommended,” amber label “for consideration,” or a red label for “not recommended.”

Concordance study

At SABCS, Dr. Somashekhar presented results of a study evaluating the concordance of treatment recommendations between WFO and the members of the Manipal Multidisciplinary Tumor Board (MTB).

They looked at data on 638 patients treated in their hospital system over the three prior years, assessing the MTBs initial, best joint decision at the time of the original treatment decision (T1), and compared it with WFO’s recommendation made in 2016 (T2) and with a blinded MTB re-review of nonconcordant cases, also made in 2016.

Evaluating concordance by stage, they found that, for 514 cases of nonmetastatic disease, there was 79% concordance between the original MTB decisions and WFO’s recommendations for therapies in the combined “for consideration” and “recommended” categories.

For 124 cases of metastatic disease, however, Watson and its human counterparts were more frequently at odds, with only a 46% concordance.

In a subset analysis by receptor status, the investigators found that Watson was best – that is, most highly concordant – in triple-negative disease, with a 67.9% concordance in regard to MTB choices. In contrast, for patients with metastatic disease negative for the human epidermal growth factor receptor-2 (HER2), the concordance rate was a low 35%.

Dr. Somashekhar commented that part of the explanation for the discordant concordance rates by tumor subtype can be attributed to the fact that patients with triple-negative breast cancers have fewer treatment options than patients with HER2 negative–only tumors, who have a much broader array of possibilities.

One area where WFO has its two-legged colleagues beaten hands down, however, is in the time it takes to capture and analyze data: humans took a mean of 20 minutes, Watson a median of 40 seconds.

The investigators acknowledged that WFO represents a further step toward personalized medicine, but emphasized that software will never replace the doctor-patient relationship or override the treating physician’s decisions.

‘This one would actually help’

At the briefing, moderator C. Kent Osborne, MD, from Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, commented, “I guess this not going to put us out of business as physicians – at least I hope not.”

Asked whether WFO could be a useful clinical tool or just another nuisance task added to an already overcrowded clinic schedule, Dr. Osborne responded, “I think this one would actually help.”

This study was investigative and received no external funding. Dr. Somashekhar, Dr. Osborne, and Dr. Blaes reported no conflicts of interest.

SAN ANTONIO – When oncologists at Manipal Hospitals in Bangalore, India, need help with a breast cancer conundrum, they can make the electronic equivalent of the famous cry for help “Watson, come here, I want you!”

In this case, Watson is not the real-life sidekick of Alexander Graham Bell or the fictional companion of Sherlock Holmes, but Watson for Oncology (WFO), an IBM-created artificial intelligence platform being developed in the United States and used in clinical practice in India to help guide clinical decision making but not to replace clinicians’ judgment, explained S.P. Somashekhar, MBBS, MS, MCH, FRCS, chairman of the Manipal Comprehensive Cancer Center.

This is no game

WFO is the clinical cousin of the artificial intelligence platform, also named Watson, that beat all-time champion Ken Jennings on the television game show “Jeopardy!” The system was named after Thomas J. Watson, IBM’s first chief executive officer.

The version of Watson used in India was developed by physicians and investigators at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (MSKCC) in New York and by IBM. Watson for Oncology is fed national treatment guidelines, more than 1,000 training cases, MSKCC internal guidelines, and medical literature curated by MSKCC; it then chews over the data and spits out evidence-based recommendations.

At Manipal Hospitals, the electronic medical record contains an “Ask Watson” button that allows clinicians to interrogate the artificial entity’s vast stores of medical data to offer recommendations that clinicians can then use, modify, or reject at their discretion.

The system analyzes more than 100 patient attributes and then offers options with a green label for “recommended,” amber label “for consideration,” or a red label for “not recommended.”

Concordance study

At SABCS, Dr. Somashekhar presented results of a study evaluating the concordance of treatment recommendations between WFO and the members of the Manipal Multidisciplinary Tumor Board (MTB).

They looked at data on 638 patients treated in their hospital system over the three prior years, assessing the MTBs initial, best joint decision at the time of the original treatment decision (T1), and compared it with WFO’s recommendation made in 2016 (T2) and with a blinded MTB re-review of nonconcordant cases, also made in 2016.

Evaluating concordance by stage, they found that, for 514 cases of nonmetastatic disease, there was 79% concordance between the original MTB decisions and WFO’s recommendations for therapies in the combined “for consideration” and “recommended” categories.

For 124 cases of metastatic disease, however, Watson and its human counterparts were more frequently at odds, with only a 46% concordance.

In a subset analysis by receptor status, the investigators found that Watson was best – that is, most highly concordant – in triple-negative disease, with a 67.9% concordance in regard to MTB choices. In contrast, for patients with metastatic disease negative for the human epidermal growth factor receptor-2 (HER2), the concordance rate was a low 35%.

Dr. Somashekhar commented that part of the explanation for the discordant concordance rates by tumor subtype can be attributed to the fact that patients with triple-negative breast cancers have fewer treatment options than patients with HER2 negative–only tumors, who have a much broader array of possibilities.

One area where WFO has its two-legged colleagues beaten hands down, however, is in the time it takes to capture and analyze data: humans took a mean of 20 minutes, Watson a median of 40 seconds.

The investigators acknowledged that WFO represents a further step toward personalized medicine, but emphasized that software will never replace the doctor-patient relationship or override the treating physician’s decisions.

‘This one would actually help’

At the briefing, moderator C. Kent Osborne, MD, from Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, commented, “I guess this not going to put us out of business as physicians – at least I hope not.”

Asked whether WFO could be a useful clinical tool or just another nuisance task added to an already overcrowded clinic schedule, Dr. Osborne responded, “I think this one would actually help.”

This study was investigative and received no external funding. Dr. Somashekhar, Dr. Osborne, and Dr. Blaes reported no conflicts of interest.

AT SABCS 2016

Key clinical point: There was good, if imperfect, concordance in breast cancer treatment decisions between the software platform Watson for Oncology and human tumor board members.

Major finding: Concordance on treatment decisions for nonmetastatic breast cancers was 79%; concordance for metastatic cancers was 46%.

Data source: Single-institution study comparing treatment-decision concordance rates between a computerized decision tool and human reviewers.

Disclosures: This study was investigative and received no external funding. Dr. Somashekhar, Dr. Osborne, and Dr. Blaes reported no conflicts of interest.

VIDEO: Watson for Oncology offers electronic curbside consults in breast cancer

SAN ANTONIO – Watson for Oncology or WFO, is the clinical cousin of the IBM-created cognitive computing system best known as the machine that defeated all-time champions on the TV quiz show “Jeopardy!”

WFO, however, has the much more important function of providing oncologists with evidence-based support for clinical decisions. Data being presented here at the San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium show that in Bangalore, India, where WFO is used in a large hospital system, there is good concordance between tumor board recommendations and WFO’s recommendations about the treatment of breast cancer, although much more work needs to be done. The investigators emphasize that WFO is a highly useful tool that can augment but will not replace clinical judgment, and can never replace the physician-patient relationship.

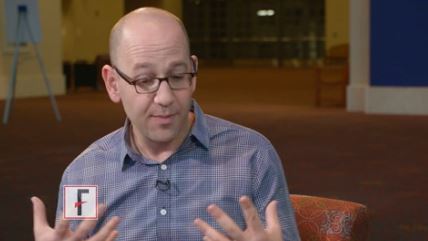

In this video interview, Andrew Norden, MD, deputy chief health officer for the IBM Watson project, based in Cambridge, Mass., describes how Watson for Oncology works, and how different versions of the Watson platform are being used in medicine throughout the world.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

SAN ANTONIO – Watson for Oncology or WFO, is the clinical cousin of the IBM-created cognitive computing system best known as the machine that defeated all-time champions on the TV quiz show “Jeopardy!”

WFO, however, has the much more important function of providing oncologists with evidence-based support for clinical decisions. Data being presented here at the San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium show that in Bangalore, India, where WFO is used in a large hospital system, there is good concordance between tumor board recommendations and WFO’s recommendations about the treatment of breast cancer, although much more work needs to be done. The investigators emphasize that WFO is a highly useful tool that can augment but will not replace clinical judgment, and can never replace the physician-patient relationship.

In this video interview, Andrew Norden, MD, deputy chief health officer for the IBM Watson project, based in Cambridge, Mass., describes how Watson for Oncology works, and how different versions of the Watson platform are being used in medicine throughout the world.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

SAN ANTONIO – Watson for Oncology or WFO, is the clinical cousin of the IBM-created cognitive computing system best known as the machine that defeated all-time champions on the TV quiz show “Jeopardy!”

WFO, however, has the much more important function of providing oncologists with evidence-based support for clinical decisions. Data being presented here at the San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium show that in Bangalore, India, where WFO is used in a large hospital system, there is good concordance between tumor board recommendations and WFO’s recommendations about the treatment of breast cancer, although much more work needs to be done. The investigators emphasize that WFO is a highly useful tool that can augment but will not replace clinical judgment, and can never replace the physician-patient relationship.

In this video interview, Andrew Norden, MD, deputy chief health officer for the IBM Watson project, based in Cambridge, Mass., describes how Watson for Oncology works, and how different versions of the Watson platform are being used in medicine throughout the world.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

AT SABCS 2016

VIDEO: Abemaciclib reduces Ki67 expression in early HR+/HER2– breast cancer

SAN ANTONIO – Abemaciclib, both alone and in combination with anastrozole, significantly reduced Ki67 expression vs. anastrozole monotherapy after 2 weeks of treatment in the NeoMONARCH phase II neoadjuvant clinical trial of postmenopausal patients with hormone receptor–positive, HER2-negative early-stage breast cancer.

The findings, given that a change in Ki67 at 2 weeks in neoadjuvant studies appears to predict improved disease-free survival in adjuvant studies, support continued evaluation of the cyclin-dependent kinase-4 (CDK4) inhibitor for the treatment of patients with early-stage breast cancer, Sara Hurvitz, MD, reported at the San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium.

“In hormone receptor–positive breast cancers, estrogen stimulates D-type cyclins, resulting in increased activity of CDK4 and CDK6, and then phosphorylate RB – the tumor suppressor protein retinoblastoma – which releases the E2F transcription factor,” explained Dr. Hurvitz of the University of California, Los Angeles.

This in turn ultimately leads to cell cycle progression from G1 to S.

“This increased rate of proliferation can be observed in tumor tissue samples by measuring the expression of Ki67. Blocking CDK4 and CDK6 should lead to a decrease in E2F expression, as well as a drop in the cell cycling and a drop in Ki67,” she said, adding that cell cycle arrest may induce senescence, which may also induce a phenotype that’s characterized by an immune cell infiltrate.

Indeed, in study subjects randomized to receive abemaciclib, treatment was shown to induce profound cell cycle arrest defined by decreased Ki67 and E2F targeted proliferation messenger RNAs, and reduction of expression of genes associated with senescence.

“Abemaciclib alone or in combination with anastrozole significantly reduced the Ki67 expression compared to anastrozole alone after 2 weeks of therapy, based on the geometric mean change and complete cell cycle arrest, and the study did meet its primary endpoint,” she said.

In a video interview, Dr. Hurvitz discussed the study methodology, results, and safety findings, as well as an intriguing observation regarding the effects of treatment on tumor differentiation and immune infiltrates over time.

This study was sponsored by Eli Lilly. Dr. Hurvitz has received renumeration for research and/or travel from Amgen, Bayer, BioMarin, Boehringer Ingelheim, Dignitana, Eli Lilly, Genentech, GSK, Medivation, Merrimack, Novartis, OBI Pharma, Pfizer, Puma Biotechnology, and Roche.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

SAN ANTONIO – Abemaciclib, both alone and in combination with anastrozole, significantly reduced Ki67 expression vs. anastrozole monotherapy after 2 weeks of treatment in the NeoMONARCH phase II neoadjuvant clinical trial of postmenopausal patients with hormone receptor–positive, HER2-negative early-stage breast cancer.

The findings, given that a change in Ki67 at 2 weeks in neoadjuvant studies appears to predict improved disease-free survival in adjuvant studies, support continued evaluation of the cyclin-dependent kinase-4 (CDK4) inhibitor for the treatment of patients with early-stage breast cancer, Sara Hurvitz, MD, reported at the San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium.

“In hormone receptor–positive breast cancers, estrogen stimulates D-type cyclins, resulting in increased activity of CDK4 and CDK6, and then phosphorylate RB – the tumor suppressor protein retinoblastoma – which releases the E2F transcription factor,” explained Dr. Hurvitz of the University of California, Los Angeles.

This in turn ultimately leads to cell cycle progression from G1 to S.

“This increased rate of proliferation can be observed in tumor tissue samples by measuring the expression of Ki67. Blocking CDK4 and CDK6 should lead to a decrease in E2F expression, as well as a drop in the cell cycling and a drop in Ki67,” she said, adding that cell cycle arrest may induce senescence, which may also induce a phenotype that’s characterized by an immune cell infiltrate.

Indeed, in study subjects randomized to receive abemaciclib, treatment was shown to induce profound cell cycle arrest defined by decreased Ki67 and E2F targeted proliferation messenger RNAs, and reduction of expression of genes associated with senescence.

“Abemaciclib alone or in combination with anastrozole significantly reduced the Ki67 expression compared to anastrozole alone after 2 weeks of therapy, based on the geometric mean change and complete cell cycle arrest, and the study did meet its primary endpoint,” she said.

In a video interview, Dr. Hurvitz discussed the study methodology, results, and safety findings, as well as an intriguing observation regarding the effects of treatment on tumor differentiation and immune infiltrates over time.

This study was sponsored by Eli Lilly. Dr. Hurvitz has received renumeration for research and/or travel from Amgen, Bayer, BioMarin, Boehringer Ingelheim, Dignitana, Eli Lilly, Genentech, GSK, Medivation, Merrimack, Novartis, OBI Pharma, Pfizer, Puma Biotechnology, and Roche.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

SAN ANTONIO – Abemaciclib, both alone and in combination with anastrozole, significantly reduced Ki67 expression vs. anastrozole monotherapy after 2 weeks of treatment in the NeoMONARCH phase II neoadjuvant clinical trial of postmenopausal patients with hormone receptor–positive, HER2-negative early-stage breast cancer.

The findings, given that a change in Ki67 at 2 weeks in neoadjuvant studies appears to predict improved disease-free survival in adjuvant studies, support continued evaluation of the cyclin-dependent kinase-4 (CDK4) inhibitor for the treatment of patients with early-stage breast cancer, Sara Hurvitz, MD, reported at the San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium.

“In hormone receptor–positive breast cancers, estrogen stimulates D-type cyclins, resulting in increased activity of CDK4 and CDK6, and then phosphorylate RB – the tumor suppressor protein retinoblastoma – which releases the E2F transcription factor,” explained Dr. Hurvitz of the University of California, Los Angeles.

This in turn ultimately leads to cell cycle progression from G1 to S.

“This increased rate of proliferation can be observed in tumor tissue samples by measuring the expression of Ki67. Blocking CDK4 and CDK6 should lead to a decrease in E2F expression, as well as a drop in the cell cycling and a drop in Ki67,” she said, adding that cell cycle arrest may induce senescence, which may also induce a phenotype that’s characterized by an immune cell infiltrate.

Indeed, in study subjects randomized to receive abemaciclib, treatment was shown to induce profound cell cycle arrest defined by decreased Ki67 and E2F targeted proliferation messenger RNAs, and reduction of expression of genes associated with senescence.

“Abemaciclib alone or in combination with anastrozole significantly reduced the Ki67 expression compared to anastrozole alone after 2 weeks of therapy, based on the geometric mean change and complete cell cycle arrest, and the study did meet its primary endpoint,” she said.

In a video interview, Dr. Hurvitz discussed the study methodology, results, and safety findings, as well as an intriguing observation regarding the effects of treatment on tumor differentiation and immune infiltrates over time.

This study was sponsored by Eli Lilly. Dr. Hurvitz has received renumeration for research and/or travel from Amgen, Bayer, BioMarin, Boehringer Ingelheim, Dignitana, Eli Lilly, Genentech, GSK, Medivation, Merrimack, Novartis, OBI Pharma, Pfizer, Puma Biotechnology, and Roche.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

AT SABCS 2016

Study reinforces lenalidomide maintenance in newly diagnosed multiple myeloma

SAN DIEGO – Maintenance therapy with lenalidomide significantly improved progression-free survival in patients of all ages with myeloma, regardless of their risk or response status at the end of induction, Gareth Morgan, MD, PhD, said during an oral session at the annual meeting of the American Society of Hematology.

“The very important point is that maintenance therapy with lenalidomide worked across a range of different risk groups,” said Dr. Morgan, director of the Myeloma Institute at the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences in Little Rock. “It worked independent of gender, age, [International Staging System] disease stage, and response at baseline,” he added. ‘It also worked irrespective of genetic risk status, which is contrary to what you hear very frequently. All of the curves are consistent with better outcomes if you continue lenalidomide long-term.”

In the overall cohort analysis, half of the patients who received lenalidomide (Revlimid) maintenance were alive and progression-free after 36 months (95% confidence interval, 31-39 months), twice the median PFS of observation-only patients, for a hazard ratio of 0.45 (95% CI, 0.39-0.52; P less than .0001).

This effect held up across numerous subgroups. For example, among 828 transplant-eligible patients, median PFS was 50 months with lenalidomide maintenance and 28 months with observation only (HR, 0.47; P less than .0001). Among 724 transplant-ineligible patients, median PFS was 24 months with lenalidomide and 11 months with observation only (HR, 0.42; P less than .0001), Dr. Morgan reported.

Lenalidomide maintenance did not fully overcome the effects of high-risk cytogenetics but still increased PFS by a median of 10 months, compared with no maintenance (median PFS, 23 months vs. 13 months, respectively; P less than .0001). For patients with standard-risk cytogenetics, median PFS was 44 months on lenalidomide maintenance and 25 months otherwise (P less than .0001).

When patients had minimal residual disease after induction, their median PFS on lenalidomide was 17 months longer if they received maintenance lenalidomide (30 vs. 13 months; P less than .0001). Not surprisingly, the best overall outcomes occurred in MRD-negative patients who received lenalidomide maintenance (median PFS, 44 months, vs. 31 months without lenalidomide; P less than .0001), he said.

Responses also were more likely to deepen over time if patients received lenalidomide maintenance (HR, 1.74; 95% CI, 1.2-2.6; P = .004). “This continued down to about 24 months, which is compatible with conventional response rates,” Dr. Morgan noted.

Safety results reflected prior studies and were unremarkable, he added. “I treat a lot of people with lenalidomide for long periods of time, and the worst thing I usually see is some fatigue.” About one-third of patients developed grade 3-4 neutropenia on lenalidomide maintenance, but less than 5% developed grade 3-4 thrombocytopenia, anemia, deep vein thromboses, or neuropathies. Rates of primary and second malignancies were no worse with maintenance than without it. “All investigators are now in agreement on this finding,” Dr. Morgan emphasized.

The researchers also performed a whole exosome study of 70 paired specimens collected when patients were randomized and again when they relapsed. They found no evidence that lenalidomide induced excess mutations and no significant difference between groups in mutational patterns or genomic copy number variants that alter risk status.

Dr. Morgan and his associates will present overall survival data when the number of events reaches 458, he said. For now, the PFS data reinforce lenalidomide as the standard of care for patients of all ages with newly diagnosed multiple myeloma, he concluded.

The Myeloma XI trial is funded by Cancer Research UK, the Experimental Cancer Medicine Centre, NIHR Clinical Research Network: Cancer, and the University of Leeds. Dr. Morgan disclosed consulting and other relationships with Celgene, the maker of lenalidomide.

SAN DIEGO – Maintenance therapy with lenalidomide significantly improved progression-free survival in patients of all ages with myeloma, regardless of their risk or response status at the end of induction, Gareth Morgan, MD, PhD, said during an oral session at the annual meeting of the American Society of Hematology.

“The very important point is that maintenance therapy with lenalidomide worked across a range of different risk groups,” said Dr. Morgan, director of the Myeloma Institute at the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences in Little Rock. “It worked independent of gender, age, [International Staging System] disease stage, and response at baseline,” he added. ‘It also worked irrespective of genetic risk status, which is contrary to what you hear very frequently. All of the curves are consistent with better outcomes if you continue lenalidomide long-term.”

In the overall cohort analysis, half of the patients who received lenalidomide (Revlimid) maintenance were alive and progression-free after 36 months (95% confidence interval, 31-39 months), twice the median PFS of observation-only patients, for a hazard ratio of 0.45 (95% CI, 0.39-0.52; P less than .0001).

This effect held up across numerous subgroups. For example, among 828 transplant-eligible patients, median PFS was 50 months with lenalidomide maintenance and 28 months with observation only (HR, 0.47; P less than .0001). Among 724 transplant-ineligible patients, median PFS was 24 months with lenalidomide and 11 months with observation only (HR, 0.42; P less than .0001), Dr. Morgan reported.

Lenalidomide maintenance did not fully overcome the effects of high-risk cytogenetics but still increased PFS by a median of 10 months, compared with no maintenance (median PFS, 23 months vs. 13 months, respectively; P less than .0001). For patients with standard-risk cytogenetics, median PFS was 44 months on lenalidomide maintenance and 25 months otherwise (P less than .0001).

When patients had minimal residual disease after induction, their median PFS on lenalidomide was 17 months longer if they received maintenance lenalidomide (30 vs. 13 months; P less than .0001). Not surprisingly, the best overall outcomes occurred in MRD-negative patients who received lenalidomide maintenance (median PFS, 44 months, vs. 31 months without lenalidomide; P less than .0001), he said.

Responses also were more likely to deepen over time if patients received lenalidomide maintenance (HR, 1.74; 95% CI, 1.2-2.6; P = .004). “This continued down to about 24 months, which is compatible with conventional response rates,” Dr. Morgan noted.

Safety results reflected prior studies and were unremarkable, he added. “I treat a lot of people with lenalidomide for long periods of time, and the worst thing I usually see is some fatigue.” About one-third of patients developed grade 3-4 neutropenia on lenalidomide maintenance, but less than 5% developed grade 3-4 thrombocytopenia, anemia, deep vein thromboses, or neuropathies. Rates of primary and second malignancies were no worse with maintenance than without it. “All investigators are now in agreement on this finding,” Dr. Morgan emphasized.

The researchers also performed a whole exosome study of 70 paired specimens collected when patients were randomized and again when they relapsed. They found no evidence that lenalidomide induced excess mutations and no significant difference between groups in mutational patterns or genomic copy number variants that alter risk status.

Dr. Morgan and his associates will present overall survival data when the number of events reaches 458, he said. For now, the PFS data reinforce lenalidomide as the standard of care for patients of all ages with newly diagnosed multiple myeloma, he concluded.

The Myeloma XI trial is funded by Cancer Research UK, the Experimental Cancer Medicine Centre, NIHR Clinical Research Network: Cancer, and the University of Leeds. Dr. Morgan disclosed consulting and other relationships with Celgene, the maker of lenalidomide.

SAN DIEGO – Maintenance therapy with lenalidomide significantly improved progression-free survival in patients of all ages with myeloma, regardless of their risk or response status at the end of induction, Gareth Morgan, MD, PhD, said during an oral session at the annual meeting of the American Society of Hematology.

“The very important point is that maintenance therapy with lenalidomide worked across a range of different risk groups,” said Dr. Morgan, director of the Myeloma Institute at the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences in Little Rock. “It worked independent of gender, age, [International Staging System] disease stage, and response at baseline,” he added. ‘It also worked irrespective of genetic risk status, which is contrary to what you hear very frequently. All of the curves are consistent with better outcomes if you continue lenalidomide long-term.”

In the overall cohort analysis, half of the patients who received lenalidomide (Revlimid) maintenance were alive and progression-free after 36 months (95% confidence interval, 31-39 months), twice the median PFS of observation-only patients, for a hazard ratio of 0.45 (95% CI, 0.39-0.52; P less than .0001).