User login

Letters to the Editor: Rectal misoprostol for postpartum hemorrhage

“STOP USING RECTAL MISOPROSTOL FOR THE TREATMENT OF POSTPARTUM HEMORRHAGE CAUSED BY UTERINE ATONY”

ROBERT L. BARBIERI, MD (JULY 2016)

More on rectal misoprostol for postpartum hemorrhage

We applaud Dr. Barbieri’s July Editorial urging providers to stop administering misoprostol rectally for the treatment of postpartum hemorrhage (PPH) given the well-documented evidence and pharmacokinetics that recommend the sublingual route. Confusion among providers may derive from the fact that not all international guidelines, including the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists clinical guidelines on the management of PPH, have been updated to reflect the latest evidence.1 Guidelines from the World Health Organization and the International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics reflect the latest evidence and clearly recommend the evidence-based regimen of 800 μg misoprostol sublingually for treatment of PPH,2 which has been shown to be comparable to 40 IU oxytocin intravenously in women who receive oxytocin for PPH prophylaxis.3

Although oxytocin remains the first-line treatment for PPH, evidence suggests that sublingual misoprostol should be considered a viable first alternative if oxytocin is not available or fails. There is little evidence on the benefit of methergine or carboprost over misoprostol for PPH treatment, and inclusion of these drugs in treatment guidelines and practice is based on extrapolations from studies on PPH prevention.4 As Dr. Barbieri noted, pyrexia from misoprostol has been cited in the literature; however, contrary to contraindications for methergine, for example, this rare event does not pose serious risks to women, is self-limiting, and appears to be most acute among certain populations.5

It is paramount that safe, effective, and evidence-based PPH treatments be available and known to providers both in the United States and globally in order to provide women with timely treatment. Greater discussion and research is warranted about the hierarchy of use for these drugs and the possible impact of routine use of uterotonics before and during delivery, given that overexposure to uterotonics may in fact be making PPH harder to treat.6

Gillian Burkhardt, MD, and Rasha Dabash, MPH

New York, New York

Dr. Barbieri responds

I thank Drs. Burkhardt and Dabash for sharing their expert perspective with our readers. They advocate for the use of sublingual misoprostol for the treatment of PPH “if oxytocin is not available or fails.” I agree that at a home birth, if oxytocin is not available, sublingual misoprostol would be of great benefit. I remain concerned that misoprostol has little clinical utility for the treatment of PPH in the hospital setting in which oxytocin, methergine, and carboprost are available alternatives. Misoprostol causes fever in many women, and women who develop a postpartum fever due to misoprostol will receive unnecessary antibiotic treatment. I recommend that our readers stop using misoprostol for the treatment of PPH in the hospital setting.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- ACOG Committee on Practice Bulletins–Obstetrics. ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 76: Postpartum hemorrhage. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;108(4):1039–1048. Reaffirmed 2015.

- World Health Organization. WHO recommendations for the prevention and treatment of postpartum haemorrhage. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2012.

- Blum J, Winikoff B, Raghavan S, et al. Treatment of post-partum haemorrhage with sublingual misoprostol versus oxytocin in women receiving prophylactic oxytocin: a double-blind placebo-controlled randomized non-inferiority trial. Lancet. 2010;375(9710):217–223.

- Weeks A. The prevention and treatment of postpartum haemorrhage: what do we know, and where do we go to next? BJOG. 2015;122(2):202–210.

- Durocher J, Bynum J, León W, Barrera G, Winikoff B. High fever following postpartum administration of sublingual misoprostol. BJOG. 2010;117(7):845–852.

- Balki M, Erik-Soussi M, Kingdom J, Carvalho JC. Oxytocin pretreatment attenuates oxytocin-induced contractions in human myometrium in vitro. Anesthesiology. 2013;119(3):552–561.

“STOP USING RECTAL MISOPROSTOL FOR THE TREATMENT OF POSTPARTUM HEMORRHAGE CAUSED BY UTERINE ATONY”

ROBERT L. BARBIERI, MD (JULY 2016)

More on rectal misoprostol for postpartum hemorrhage

We applaud Dr. Barbieri’s July Editorial urging providers to stop administering misoprostol rectally for the treatment of postpartum hemorrhage (PPH) given the well-documented evidence and pharmacokinetics that recommend the sublingual route. Confusion among providers may derive from the fact that not all international guidelines, including the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists clinical guidelines on the management of PPH, have been updated to reflect the latest evidence.1 Guidelines from the World Health Organization and the International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics reflect the latest evidence and clearly recommend the evidence-based regimen of 800 μg misoprostol sublingually for treatment of PPH,2 which has been shown to be comparable to 40 IU oxytocin intravenously in women who receive oxytocin for PPH prophylaxis.3

Although oxytocin remains the first-line treatment for PPH, evidence suggests that sublingual misoprostol should be considered a viable first alternative if oxytocin is not available or fails. There is little evidence on the benefit of methergine or carboprost over misoprostol for PPH treatment, and inclusion of these drugs in treatment guidelines and practice is based on extrapolations from studies on PPH prevention.4 As Dr. Barbieri noted, pyrexia from misoprostol has been cited in the literature; however, contrary to contraindications for methergine, for example, this rare event does not pose serious risks to women, is self-limiting, and appears to be most acute among certain populations.5

It is paramount that safe, effective, and evidence-based PPH treatments be available and known to providers both in the United States and globally in order to provide women with timely treatment. Greater discussion and research is warranted about the hierarchy of use for these drugs and the possible impact of routine use of uterotonics before and during delivery, given that overexposure to uterotonics may in fact be making PPH harder to treat.6

Gillian Burkhardt, MD, and Rasha Dabash, MPH

New York, New York

Dr. Barbieri responds

I thank Drs. Burkhardt and Dabash for sharing their expert perspective with our readers. They advocate for the use of sublingual misoprostol for the treatment of PPH “if oxytocin is not available or fails.” I agree that at a home birth, if oxytocin is not available, sublingual misoprostol would be of great benefit. I remain concerned that misoprostol has little clinical utility for the treatment of PPH in the hospital setting in which oxytocin, methergine, and carboprost are available alternatives. Misoprostol causes fever in many women, and women who develop a postpartum fever due to misoprostol will receive unnecessary antibiotic treatment. I recommend that our readers stop using misoprostol for the treatment of PPH in the hospital setting.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

“STOP USING RECTAL MISOPROSTOL FOR THE TREATMENT OF POSTPARTUM HEMORRHAGE CAUSED BY UTERINE ATONY”

ROBERT L. BARBIERI, MD (JULY 2016)

More on rectal misoprostol for postpartum hemorrhage

We applaud Dr. Barbieri’s July Editorial urging providers to stop administering misoprostol rectally for the treatment of postpartum hemorrhage (PPH) given the well-documented evidence and pharmacokinetics that recommend the sublingual route. Confusion among providers may derive from the fact that not all international guidelines, including the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists clinical guidelines on the management of PPH, have been updated to reflect the latest evidence.1 Guidelines from the World Health Organization and the International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics reflect the latest evidence and clearly recommend the evidence-based regimen of 800 μg misoprostol sublingually for treatment of PPH,2 which has been shown to be comparable to 40 IU oxytocin intravenously in women who receive oxytocin for PPH prophylaxis.3

Although oxytocin remains the first-line treatment for PPH, evidence suggests that sublingual misoprostol should be considered a viable first alternative if oxytocin is not available or fails. There is little evidence on the benefit of methergine or carboprost over misoprostol for PPH treatment, and inclusion of these drugs in treatment guidelines and practice is based on extrapolations from studies on PPH prevention.4 As Dr. Barbieri noted, pyrexia from misoprostol has been cited in the literature; however, contrary to contraindications for methergine, for example, this rare event does not pose serious risks to women, is self-limiting, and appears to be most acute among certain populations.5

It is paramount that safe, effective, and evidence-based PPH treatments be available and known to providers both in the United States and globally in order to provide women with timely treatment. Greater discussion and research is warranted about the hierarchy of use for these drugs and the possible impact of routine use of uterotonics before and during delivery, given that overexposure to uterotonics may in fact be making PPH harder to treat.6

Gillian Burkhardt, MD, and Rasha Dabash, MPH

New York, New York

Dr. Barbieri responds

I thank Drs. Burkhardt and Dabash for sharing their expert perspective with our readers. They advocate for the use of sublingual misoprostol for the treatment of PPH “if oxytocin is not available or fails.” I agree that at a home birth, if oxytocin is not available, sublingual misoprostol would be of great benefit. I remain concerned that misoprostol has little clinical utility for the treatment of PPH in the hospital setting in which oxytocin, methergine, and carboprost are available alternatives. Misoprostol causes fever in many women, and women who develop a postpartum fever due to misoprostol will receive unnecessary antibiotic treatment. I recommend that our readers stop using misoprostol for the treatment of PPH in the hospital setting.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- ACOG Committee on Practice Bulletins–Obstetrics. ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 76: Postpartum hemorrhage. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;108(4):1039–1048. Reaffirmed 2015.

- World Health Organization. WHO recommendations for the prevention and treatment of postpartum haemorrhage. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2012.

- Blum J, Winikoff B, Raghavan S, et al. Treatment of post-partum haemorrhage with sublingual misoprostol versus oxytocin in women receiving prophylactic oxytocin: a double-blind placebo-controlled randomized non-inferiority trial. Lancet. 2010;375(9710):217–223.

- Weeks A. The prevention and treatment of postpartum haemorrhage: what do we know, and where do we go to next? BJOG. 2015;122(2):202–210.

- Durocher J, Bynum J, León W, Barrera G, Winikoff B. High fever following postpartum administration of sublingual misoprostol. BJOG. 2010;117(7):845–852.

- Balki M, Erik-Soussi M, Kingdom J, Carvalho JC. Oxytocin pretreatment attenuates oxytocin-induced contractions in human myometrium in vitro. Anesthesiology. 2013;119(3):552–561.

- ACOG Committee on Practice Bulletins–Obstetrics. ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 76: Postpartum hemorrhage. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;108(4):1039–1048. Reaffirmed 2015.

- World Health Organization. WHO recommendations for the prevention and treatment of postpartum haemorrhage. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2012.

- Blum J, Winikoff B, Raghavan S, et al. Treatment of post-partum haemorrhage with sublingual misoprostol versus oxytocin in women receiving prophylactic oxytocin: a double-blind placebo-controlled randomized non-inferiority trial. Lancet. 2010;375(9710):217–223.

- Weeks A. The prevention and treatment of postpartum haemorrhage: what do we know, and where do we go to next? BJOG. 2015;122(2):202–210.

- Durocher J, Bynum J, León W, Barrera G, Winikoff B. High fever following postpartum administration of sublingual misoprostol. BJOG. 2010;117(7):845–852.

- Balki M, Erik-Soussi M, Kingdom J, Carvalho JC. Oxytocin pretreatment attenuates oxytocin-induced contractions in human myometrium in vitro. Anesthesiology. 2013;119(3):552–561.

Product Update: JUST…Love, pjur med

MASSAGE AND MOISTURING OIL

Just Pure Essentials suggests that JUST…Love be used to moisturize the face and body and for facial cleansing and shaving. It has been recommended by women’s health professionals as a lubricant and moisturizer to relieve vaginal dryness, says the manufacturer.

Just Pure Essentials products are 100% vegan; chemical and preservative free; and without alcohols, additives, or phytoestrogens. The base of each product is coconut medium-chain triglyceride (MCT) oil pressed from nongenetically modified coconut oil by a steam distillation process. The oil is blended with other organic oils and botanical ingredients, including green tea see oil, French plum oil, argan, and marshmallow leaf. It does not contain dyes, perfumes, or artificial flavors. Just Pure Essentials says its formulas do not dry up and turn sticky.

FOR MORE INFORMATION, VISIT: www.justpureessentials.com

SEXUAL HEALTH AND WELLBEING

pjur med says that PREMIUM glide is specially formulated for dry or highly sensitive genital mucous membranes and is made of non–pore-blocking, high-quality silicones. SENSITIVE glide is specifically developed for those with very sensitive genital mucous membranes, according to the manufacturer. Both products are available in 3.4 fl oz bottles. pjur med suggests its products are suitable for every skin type and maintains that they are dermatologically tested and paraben-, glycerin-, and preservative-free. In addition, pjur med says its formulas have been kept as neutral as possible and the ingredients have been put together in a way that microbial growth cannot occur.

FOR MORE INFORMATION, VISIT: www.pjurmed.com

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

MASSAGE AND MOISTURING OIL

Just Pure Essentials suggests that JUST…Love be used to moisturize the face and body and for facial cleansing and shaving. It has been recommended by women’s health professionals as a lubricant and moisturizer to relieve vaginal dryness, says the manufacturer.

Just Pure Essentials products are 100% vegan; chemical and preservative free; and without alcohols, additives, or phytoestrogens. The base of each product is coconut medium-chain triglyceride (MCT) oil pressed from nongenetically modified coconut oil by a steam distillation process. The oil is blended with other organic oils and botanical ingredients, including green tea see oil, French plum oil, argan, and marshmallow leaf. It does not contain dyes, perfumes, or artificial flavors. Just Pure Essentials says its formulas do not dry up and turn sticky.

FOR MORE INFORMATION, VISIT: www.justpureessentials.com

SEXUAL HEALTH AND WELLBEING

pjur med says that PREMIUM glide is specially formulated for dry or highly sensitive genital mucous membranes and is made of non–pore-blocking, high-quality silicones. SENSITIVE glide is specifically developed for those with very sensitive genital mucous membranes, according to the manufacturer. Both products are available in 3.4 fl oz bottles. pjur med suggests its products are suitable for every skin type and maintains that they are dermatologically tested and paraben-, glycerin-, and preservative-free. In addition, pjur med says its formulas have been kept as neutral as possible and the ingredients have been put together in a way that microbial growth cannot occur.

FOR MORE INFORMATION, VISIT: www.pjurmed.com

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

MASSAGE AND MOISTURING OIL

Just Pure Essentials suggests that JUST…Love be used to moisturize the face and body and for facial cleansing and shaving. It has been recommended by women’s health professionals as a lubricant and moisturizer to relieve vaginal dryness, says the manufacturer.

Just Pure Essentials products are 100% vegan; chemical and preservative free; and without alcohols, additives, or phytoestrogens. The base of each product is coconut medium-chain triglyceride (MCT) oil pressed from nongenetically modified coconut oil by a steam distillation process. The oil is blended with other organic oils and botanical ingredients, including green tea see oil, French plum oil, argan, and marshmallow leaf. It does not contain dyes, perfumes, or artificial flavors. Just Pure Essentials says its formulas do not dry up and turn sticky.

FOR MORE INFORMATION, VISIT: www.justpureessentials.com

SEXUAL HEALTH AND WELLBEING

pjur med says that PREMIUM glide is specially formulated for dry or highly sensitive genital mucous membranes and is made of non–pore-blocking, high-quality silicones. SENSITIVE glide is specifically developed for those with very sensitive genital mucous membranes, according to the manufacturer. Both products are available in 3.4 fl oz bottles. pjur med suggests its products are suitable for every skin type and maintains that they are dermatologically tested and paraben-, glycerin-, and preservative-free. In addition, pjur med says its formulas have been kept as neutral as possible and the ingredients have been put together in a way that microbial growth cannot occur.

FOR MORE INFORMATION, VISIT: www.pjurmed.com

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

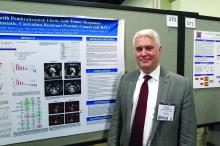

Vaccine/PD-1 inhibitor combo shows early promise against mCRPC

NATIONAL HARBOR, MD. – To date, checkpoint inhibitors have shown little clinical activity as single agents against metastatic, castration-resistant prostate cancer, but a combination of a DNA vaccine and a programmed-death 1 inhibitor shows promise for enhancing anti-tumor immune responses, report investigators in a phase I trial.

“If you vaccinate animals, PD-1 expression transiently goes up, and if you block it at that point you get a better anti-tumor response, and that was in models where anti PD-1 therapy alone didn’t do anything. So we thought this could be a good approach for prostate cancer,” Douglas G. McNeel, MD, PhD, of the University of Wisconsin, Madison, said in an interview at the annual meeting of the Society for Immunotherapy of Cancer.

Dr. McNeel and colleagues are exploring the therapeutic potential of combining the PD-1 inhibitor pembrolizumab (Keytruda) with an investigational DNA vaccine targeted against prostatic acid phosphatase (PAP), the same antigen targeted by sipuleucel-T (Provenge).

They presented data in a scientific poster from a pilot study of the combination in patients with metastatic, castration-resistant prostate cancer (mCRPC).

Vaccine ramps up PD-1 expression

The investigators had previously shown that patients immunized with a DNA vaccine encoding PAP (pTVG-HP; currently in phase II clinical trials) developed PD-1-regulated, PAP-specific T cells and had increased PD-L1 expression in circulating tumor cells. They also demonstrated in preclinical studies with mouse models that increased PD-1 expression on vaccine-induced CD8-positive T cells led to inferior anti-tumor immune responses, and that blocking PD-1 at the time of T-cell activation with vaccine improved anti-tumor responses.

“The current pilot trial was designed to evaluate whether delivery of PD-1 blockade after immunization (when PD-1-regulated T cells are elicited and when PD-L1 expression is induced with vaccination on tumor cells) or with immunization (when PD-1 expression increases on antigen-specific CD8+ T cells with activation) results in anti-tumor responses in patients with advanced, metastatic, castration-resistant prostate cancer,” Dr. McNeel and his colleagues wrote.

They reported preliminary impressions of the efficacy and safety of the combination in 12 patients with mCRPC. The patients all had evidence of progressive disease and were at least 6 months out from chemotherapy. Patients could have previously been treated with enzalutamide (Xtandi) or abiraterone (Zytiga), but were excluded if they had received sipuleucel-T vaccine.

Patients in the ongoing trial are randomized to receive six doses of pTVG-HP over 10 weeks with either four doses of concurrent pembrolizumab, or four doses of pembrolizumab delivered every 3 weeks beginning 2 weeks after the last vaccine dose.

The authors reported that treatment with the combination evokes changes in serum prostate-specific antigen (PSA) that are associated with objective radiographic changes, and “elicits robust and persistent PAP-specific Th1-based immunity.”

They also found evidence to suggest that concurrent administration of the vaccine and the PD-1 inhibitor may be more effective than sequential administration, based on differences in serum PSA and PAP.

Adverse events were generally mild and similar to those seen in other studies of pembrolizumab and DNA vaccine, with only three grade 3 events and no grade 4 events.

The investigators hope to expand the pilot study beyond the 12 weeks originally scheduled, and plan to explore potential biomarkers for vaccine response based on T-cell proliferation in tumors and in regional lymph nodes as seen on imaging modalities.

The study is funded by a 2014 Movember Prostate Cancer Foundation Challenge Award and Madison Vaccines Inc. Dr. McNeel reports an ownership interest and funding support from Madison Vaccines. All other coauthors reported no conflicts of interest.

NATIONAL HARBOR, MD. – To date, checkpoint inhibitors have shown little clinical activity as single agents against metastatic, castration-resistant prostate cancer, but a combination of a DNA vaccine and a programmed-death 1 inhibitor shows promise for enhancing anti-tumor immune responses, report investigators in a phase I trial.

“If you vaccinate animals, PD-1 expression transiently goes up, and if you block it at that point you get a better anti-tumor response, and that was in models where anti PD-1 therapy alone didn’t do anything. So we thought this could be a good approach for prostate cancer,” Douglas G. McNeel, MD, PhD, of the University of Wisconsin, Madison, said in an interview at the annual meeting of the Society for Immunotherapy of Cancer.

Dr. McNeel and colleagues are exploring the therapeutic potential of combining the PD-1 inhibitor pembrolizumab (Keytruda) with an investigational DNA vaccine targeted against prostatic acid phosphatase (PAP), the same antigen targeted by sipuleucel-T (Provenge).

They presented data in a scientific poster from a pilot study of the combination in patients with metastatic, castration-resistant prostate cancer (mCRPC).

Vaccine ramps up PD-1 expression

The investigators had previously shown that patients immunized with a DNA vaccine encoding PAP (pTVG-HP; currently in phase II clinical trials) developed PD-1-regulated, PAP-specific T cells and had increased PD-L1 expression in circulating tumor cells. They also demonstrated in preclinical studies with mouse models that increased PD-1 expression on vaccine-induced CD8-positive T cells led to inferior anti-tumor immune responses, and that blocking PD-1 at the time of T-cell activation with vaccine improved anti-tumor responses.

“The current pilot trial was designed to evaluate whether delivery of PD-1 blockade after immunization (when PD-1-regulated T cells are elicited and when PD-L1 expression is induced with vaccination on tumor cells) or with immunization (when PD-1 expression increases on antigen-specific CD8+ T cells with activation) results in anti-tumor responses in patients with advanced, metastatic, castration-resistant prostate cancer,” Dr. McNeel and his colleagues wrote.

They reported preliminary impressions of the efficacy and safety of the combination in 12 patients with mCRPC. The patients all had evidence of progressive disease and were at least 6 months out from chemotherapy. Patients could have previously been treated with enzalutamide (Xtandi) or abiraterone (Zytiga), but were excluded if they had received sipuleucel-T vaccine.

Patients in the ongoing trial are randomized to receive six doses of pTVG-HP over 10 weeks with either four doses of concurrent pembrolizumab, or four doses of pembrolizumab delivered every 3 weeks beginning 2 weeks after the last vaccine dose.

The authors reported that treatment with the combination evokes changes in serum prostate-specific antigen (PSA) that are associated with objective radiographic changes, and “elicits robust and persistent PAP-specific Th1-based immunity.”

They also found evidence to suggest that concurrent administration of the vaccine and the PD-1 inhibitor may be more effective than sequential administration, based on differences in serum PSA and PAP.

Adverse events were generally mild and similar to those seen in other studies of pembrolizumab and DNA vaccine, with only three grade 3 events and no grade 4 events.

The investigators hope to expand the pilot study beyond the 12 weeks originally scheduled, and plan to explore potential biomarkers for vaccine response based on T-cell proliferation in tumors and in regional lymph nodes as seen on imaging modalities.

The study is funded by a 2014 Movember Prostate Cancer Foundation Challenge Award and Madison Vaccines Inc. Dr. McNeel reports an ownership interest and funding support from Madison Vaccines. All other coauthors reported no conflicts of interest.

NATIONAL HARBOR, MD. – To date, checkpoint inhibitors have shown little clinical activity as single agents against metastatic, castration-resistant prostate cancer, but a combination of a DNA vaccine and a programmed-death 1 inhibitor shows promise for enhancing anti-tumor immune responses, report investigators in a phase I trial.

“If you vaccinate animals, PD-1 expression transiently goes up, and if you block it at that point you get a better anti-tumor response, and that was in models where anti PD-1 therapy alone didn’t do anything. So we thought this could be a good approach for prostate cancer,” Douglas G. McNeel, MD, PhD, of the University of Wisconsin, Madison, said in an interview at the annual meeting of the Society for Immunotherapy of Cancer.

Dr. McNeel and colleagues are exploring the therapeutic potential of combining the PD-1 inhibitor pembrolizumab (Keytruda) with an investigational DNA vaccine targeted against prostatic acid phosphatase (PAP), the same antigen targeted by sipuleucel-T (Provenge).

They presented data in a scientific poster from a pilot study of the combination in patients with metastatic, castration-resistant prostate cancer (mCRPC).

Vaccine ramps up PD-1 expression

The investigators had previously shown that patients immunized with a DNA vaccine encoding PAP (pTVG-HP; currently in phase II clinical trials) developed PD-1-regulated, PAP-specific T cells and had increased PD-L1 expression in circulating tumor cells. They also demonstrated in preclinical studies with mouse models that increased PD-1 expression on vaccine-induced CD8-positive T cells led to inferior anti-tumor immune responses, and that blocking PD-1 at the time of T-cell activation with vaccine improved anti-tumor responses.

“The current pilot trial was designed to evaluate whether delivery of PD-1 blockade after immunization (when PD-1-regulated T cells are elicited and when PD-L1 expression is induced with vaccination on tumor cells) or with immunization (when PD-1 expression increases on antigen-specific CD8+ T cells with activation) results in anti-tumor responses in patients with advanced, metastatic, castration-resistant prostate cancer,” Dr. McNeel and his colleagues wrote.

They reported preliminary impressions of the efficacy and safety of the combination in 12 patients with mCRPC. The patients all had evidence of progressive disease and were at least 6 months out from chemotherapy. Patients could have previously been treated with enzalutamide (Xtandi) or abiraterone (Zytiga), but were excluded if they had received sipuleucel-T vaccine.

Patients in the ongoing trial are randomized to receive six doses of pTVG-HP over 10 weeks with either four doses of concurrent pembrolizumab, or four doses of pembrolizumab delivered every 3 weeks beginning 2 weeks after the last vaccine dose.

The authors reported that treatment with the combination evokes changes in serum prostate-specific antigen (PSA) that are associated with objective radiographic changes, and “elicits robust and persistent PAP-specific Th1-based immunity.”

They also found evidence to suggest that concurrent administration of the vaccine and the PD-1 inhibitor may be more effective than sequential administration, based on differences in serum PSA and PAP.

Adverse events were generally mild and similar to those seen in other studies of pembrolizumab and DNA vaccine, with only three grade 3 events and no grade 4 events.

The investigators hope to expand the pilot study beyond the 12 weeks originally scheduled, and plan to explore potential biomarkers for vaccine response based on T-cell proliferation in tumors and in regional lymph nodes as seen on imaging modalities.

The study is funded by a 2014 Movember Prostate Cancer Foundation Challenge Award and Madison Vaccines Inc. Dr. McNeel reports an ownership interest and funding support from Madison Vaccines. All other coauthors reported no conflicts of interest.

AT SITC 2016

Key clinical point:. Adding the PD-1 inhibitor pembrolizumab to a DNA vaccine may enhance vaccine-induced immunity against metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (mCRPC).

Major finding: Treatment with a vaccine targeted to prostatic acid phosphatase and pembrolizumab elicited changes in PAP that are associated with objective radiographic responses.

Data source: Ongoing open-label, randomized pilot study in men with mCRPC.

Disclosures: The study is funded by a 2014 Movember Prostate Cancer Foundation Challenge Award and Madison Vaccines Inc. Dr. McNeel reports an ownership interest and funding support from Madison Vaccines. All other coauthors reported no conflicts of interest.

The art of persuasion

With the advent of the Internet, many parents and teen patients come in armed with information and sometimes even a diagnosis. Much of our time is spent dispelling falsehoods that were posted on the Internet or clarifying information that was misinterpreted. Although generally more information is a good thing, too much false information can result in limiting health care.

Vaccine administration has suffered significantly because of this. With a simple Google search, you can find articles that do everything just short of proving that vaccines are harmful, and tear-jerking stories about children who were harmed by the administration of vaccines. Many sites – Vaxtruth.org, healthwyze.org, naturalnews.com – all present convincing data that would scare any concerned parent to not vaccinate their child. So how do medical professionals regain the trust of their parents and/or patients?

The strategies put forth by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention for talking to parents about vaccines begin with listening.1 Many parents come with fears that are unfounded and unrealistic that can simply be discussed and resolved. Others present with information from the Internet that discourages vaccines or life experiences such as another family member who was thought to be harmed by vaccines; this discussion is more complex.

It is imperative to become familiar with the most popular information sources on the Internet so that you can speak directly to the validity of the source. As well, countering with a more reliable source will substantiate your position. Healthychildren.org2 is an excellent reference for the AAP recommendations and further references. Vaccinesafety.edu is an independent source that reviews vaccine safety and current research.

Being proactive also builds trust. Provide families with the list of ingredients (vaccinesafety.edu), what their role is in keeping vaccines safe (tell them to go to cdc.gov and search under “vaccines for parents”), and help them understand how vaccines work. Parents then see that you are well informed and are passionate about the health of their children. The AAP provides physicians with a tool kit for the HPV vaccine, and the CDC has an HPV tipsheet entitled “Addressing Parents’ Top Questions about HPV Vaccine” that gives suggestions for what you can say or that can save you time if you provide it while the family waits to be seen.

Probably the most important strategy is believing in what you’re doing. No matter what you’re promoting, if you truly believe in it, then you will encourage others to believe in it as well. This requires educating yourself on current research and recommendations, as well as what is being reported in the news so you can be armed with factual data when parents have questions.

Today, health care is a partnership, and we must embrace our role as educators to empower patients to make good choices for themselves as well as their families.

References

1. http://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/hcp/conversations/conv-materials.html

2. https://www.healthychildren.org/English/safety-prevention/immunizations/Pages/Vaccine-Safety-The-Facts.aspx

3. http://www.immunize.org

Dr. Pearce is a pediatrician in Frankfort, Ill. Email her at [email protected].

With the advent of the Internet, many parents and teen patients come in armed with information and sometimes even a diagnosis. Much of our time is spent dispelling falsehoods that were posted on the Internet or clarifying information that was misinterpreted. Although generally more information is a good thing, too much false information can result in limiting health care.

Vaccine administration has suffered significantly because of this. With a simple Google search, you can find articles that do everything just short of proving that vaccines are harmful, and tear-jerking stories about children who were harmed by the administration of vaccines. Many sites – Vaxtruth.org, healthwyze.org, naturalnews.com – all present convincing data that would scare any concerned parent to not vaccinate their child. So how do medical professionals regain the trust of their parents and/or patients?

The strategies put forth by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention for talking to parents about vaccines begin with listening.1 Many parents come with fears that are unfounded and unrealistic that can simply be discussed and resolved. Others present with information from the Internet that discourages vaccines or life experiences such as another family member who was thought to be harmed by vaccines; this discussion is more complex.

It is imperative to become familiar with the most popular information sources on the Internet so that you can speak directly to the validity of the source. As well, countering with a more reliable source will substantiate your position. Healthychildren.org2 is an excellent reference for the AAP recommendations and further references. Vaccinesafety.edu is an independent source that reviews vaccine safety and current research.

Being proactive also builds trust. Provide families with the list of ingredients (vaccinesafety.edu), what their role is in keeping vaccines safe (tell them to go to cdc.gov and search under “vaccines for parents”), and help them understand how vaccines work. Parents then see that you are well informed and are passionate about the health of their children. The AAP provides physicians with a tool kit for the HPV vaccine, and the CDC has an HPV tipsheet entitled “Addressing Parents’ Top Questions about HPV Vaccine” that gives suggestions for what you can say or that can save you time if you provide it while the family waits to be seen.

Probably the most important strategy is believing in what you’re doing. No matter what you’re promoting, if you truly believe in it, then you will encourage others to believe in it as well. This requires educating yourself on current research and recommendations, as well as what is being reported in the news so you can be armed with factual data when parents have questions.

Today, health care is a partnership, and we must embrace our role as educators to empower patients to make good choices for themselves as well as their families.

References

1. http://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/hcp/conversations/conv-materials.html

2. https://www.healthychildren.org/English/safety-prevention/immunizations/Pages/Vaccine-Safety-The-Facts.aspx

3. http://www.immunize.org

Dr. Pearce is a pediatrician in Frankfort, Ill. Email her at [email protected].

With the advent of the Internet, many parents and teen patients come in armed with information and sometimes even a diagnosis. Much of our time is spent dispelling falsehoods that were posted on the Internet or clarifying information that was misinterpreted. Although generally more information is a good thing, too much false information can result in limiting health care.

Vaccine administration has suffered significantly because of this. With a simple Google search, you can find articles that do everything just short of proving that vaccines are harmful, and tear-jerking stories about children who were harmed by the administration of vaccines. Many sites – Vaxtruth.org, healthwyze.org, naturalnews.com – all present convincing data that would scare any concerned parent to not vaccinate their child. So how do medical professionals regain the trust of their parents and/or patients?

The strategies put forth by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention for talking to parents about vaccines begin with listening.1 Many parents come with fears that are unfounded and unrealistic that can simply be discussed and resolved. Others present with information from the Internet that discourages vaccines or life experiences such as another family member who was thought to be harmed by vaccines; this discussion is more complex.

It is imperative to become familiar with the most popular information sources on the Internet so that you can speak directly to the validity of the source. As well, countering with a more reliable source will substantiate your position. Healthychildren.org2 is an excellent reference for the AAP recommendations and further references. Vaccinesafety.edu is an independent source that reviews vaccine safety and current research.

Being proactive also builds trust. Provide families with the list of ingredients (vaccinesafety.edu), what their role is in keeping vaccines safe (tell them to go to cdc.gov and search under “vaccines for parents”), and help them understand how vaccines work. Parents then see that you are well informed and are passionate about the health of their children. The AAP provides physicians with a tool kit for the HPV vaccine, and the CDC has an HPV tipsheet entitled “Addressing Parents’ Top Questions about HPV Vaccine” that gives suggestions for what you can say or that can save you time if you provide it while the family waits to be seen.

Probably the most important strategy is believing in what you’re doing. No matter what you’re promoting, if you truly believe in it, then you will encourage others to believe in it as well. This requires educating yourself on current research and recommendations, as well as what is being reported in the news so you can be armed with factual data when parents have questions.

Today, health care is a partnership, and we must embrace our role as educators to empower patients to make good choices for themselves as well as their families.

References

1. http://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/hcp/conversations/conv-materials.html

2. https://www.healthychildren.org/English/safety-prevention/immunizations/Pages/Vaccine-Safety-The-Facts.aspx

3. http://www.immunize.org

Dr. Pearce is a pediatrician in Frankfort, Ill. Email her at [email protected].

HCV patients with early-stage hepatocellular carcinoma can achieve SVR

BOSTON – Among patients with hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), rates of sustained viral response (SVR) to direct-acting regimens for hepatitis C virus were 79% for genotype 1, 69% for genotype 2, and 47% for genotype 3 infections, reported George N. Ioannou, MD.

“These rates are lower than in patients who do not have hepatocellular carcinoma [HCC], but are still remarkably high,” Dr. Ioannou said during an oral presentation at the annual meeting of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. “Antiviral therapy should be considered in patients with early-stage hepatocellular carcinoma, ideally after adequate locoregional treatments.”

The study included Veterans Affairs Health Care System data on 17,487 recipients of direct-acting anti-HCV regimens. When patients did not have HCC, SVR rates were 93% for genotype 1 infection, 87% for genotype 2 (GT2), and 76% for GT3. Among the 624 (3.6%) patients with a history of HCC, 142 underwent antiviral treatment after transplantation and 482 received other types of cancer therapy.

Why HCC is associated with lower SVR in HCV patients remains unclear, Dr. Ioannou noted. Age does not seem to explain the effect, and neither does sex, race, or ethnicity; cirrhosis or decompensated cirrhosis; renal disease; diabetes; HCV viral load; genotype or subgenotype; HCV regimen; or treatment experience, he said.

Dr. Ioannou noted several study limitations. Nine percent of patients lacked data on SVR, and the imputation to correct for this lowered SVR rates by about 1%-2%. The dataset also did not include information on HCC tumor size or number, and the researchers have not yet examined how antiviral therapy affects the likelihood of de novo HCC, recurrent HCC, or progression of cirrhosis and liver dysfunction.

The Veterans Affairs Office of Research and Development sponsored the study. Dr. Ioannou had no disclosures.

BOSTON – Among patients with hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), rates of sustained viral response (SVR) to direct-acting regimens for hepatitis C virus were 79% for genotype 1, 69% for genotype 2, and 47% for genotype 3 infections, reported George N. Ioannou, MD.

“These rates are lower than in patients who do not have hepatocellular carcinoma [HCC], but are still remarkably high,” Dr. Ioannou said during an oral presentation at the annual meeting of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. “Antiviral therapy should be considered in patients with early-stage hepatocellular carcinoma, ideally after adequate locoregional treatments.”

The study included Veterans Affairs Health Care System data on 17,487 recipients of direct-acting anti-HCV regimens. When patients did not have HCC, SVR rates were 93% for genotype 1 infection, 87% for genotype 2 (GT2), and 76% for GT3. Among the 624 (3.6%) patients with a history of HCC, 142 underwent antiviral treatment after transplantation and 482 received other types of cancer therapy.

Why HCC is associated with lower SVR in HCV patients remains unclear, Dr. Ioannou noted. Age does not seem to explain the effect, and neither does sex, race, or ethnicity; cirrhosis or decompensated cirrhosis; renal disease; diabetes; HCV viral load; genotype or subgenotype; HCV regimen; or treatment experience, he said.

Dr. Ioannou noted several study limitations. Nine percent of patients lacked data on SVR, and the imputation to correct for this lowered SVR rates by about 1%-2%. The dataset also did not include information on HCC tumor size or number, and the researchers have not yet examined how antiviral therapy affects the likelihood of de novo HCC, recurrent HCC, or progression of cirrhosis and liver dysfunction.

The Veterans Affairs Office of Research and Development sponsored the study. Dr. Ioannou had no disclosures.

BOSTON – Among patients with hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), rates of sustained viral response (SVR) to direct-acting regimens for hepatitis C virus were 79% for genotype 1, 69% for genotype 2, and 47% for genotype 3 infections, reported George N. Ioannou, MD.

“These rates are lower than in patients who do not have hepatocellular carcinoma [HCC], but are still remarkably high,” Dr. Ioannou said during an oral presentation at the annual meeting of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. “Antiviral therapy should be considered in patients with early-stage hepatocellular carcinoma, ideally after adequate locoregional treatments.”

The study included Veterans Affairs Health Care System data on 17,487 recipients of direct-acting anti-HCV regimens. When patients did not have HCC, SVR rates were 93% for genotype 1 infection, 87% for genotype 2 (GT2), and 76% for GT3. Among the 624 (3.6%) patients with a history of HCC, 142 underwent antiviral treatment after transplantation and 482 received other types of cancer therapy.

Why HCC is associated with lower SVR in HCV patients remains unclear, Dr. Ioannou noted. Age does not seem to explain the effect, and neither does sex, race, or ethnicity; cirrhosis or decompensated cirrhosis; renal disease; diabetes; HCV viral load; genotype or subgenotype; HCV regimen; or treatment experience, he said.

Dr. Ioannou noted several study limitations. Nine percent of patients lacked data on SVR, and the imputation to correct for this lowered SVR rates by about 1%-2%. The dataset also did not include information on HCC tumor size or number, and the researchers have not yet examined how antiviral therapy affects the likelihood of de novo HCC, recurrent HCC, or progression of cirrhosis and liver dysfunction.

The Veterans Affairs Office of Research and Development sponsored the study. Dr. Ioannou had no disclosures.

AT THE LIVER MEETING

Key clinical point: Consider direct-acting antiviral therapy in HCV-infected patients with early-stage HCC.

Major finding: Rates of sustained viral response were 79% in HCC patients with GT1 HCV infection, 69% in GT2 patients, and 47% in GT3 patients.

Data source: An analysis of Veterans Affairs Health Care System data on 17,487 recipients of direct-acting antiviral regimens, including 624 patients with HCC.

Disclosures: The Veterans Affairs Office of Research and Development sponsored the study.

Early TIPS effective in high-risk cirrhosis patients, but still underutilized

BOSTON – High-risk cirrhosis patients treated early with a transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) showed increased survival rates and reduced rates of adverse events, according to a study.

The data were presented at the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases by Virginia Hernandez-Gea, MD, a hepatologist at the Hospital Clinic in Barcelona.

In each study arm, three-quarters were men in their mid-50s. Cirrhosis in the non-TIPS group was alcohol-related in 57.4% of the cohort, compared with 71.2% of the group given early TIPS; roughly half of each group mentioned alcohol use in the past 3 months.

Also similar were Model for End-stage Liver Disease (MELD) scores: an average of 15.5 in the non-TIPS group, compared with 15 on average in the TIPS group. Nearly three-quarters of the TIPS group had a Child-Pugh C score, compared with 64% in the non-TIPS group. A Child-Pugh score with active bleeding was recorded in 28.8% of the TIPS group, compared with 36% in the non-TIPS group.

The transplant-free survival rate at 1 year in the standard care group was 61%, compared with 76% in the early TIPS group (P = .0175). The failure and bleeding rate at 1 year was significantly higher in the standard care group: 91%, compared with 68% in the early TIPS group (P = .004). Failure and bleeding rates in the Child-Pugh B and C groups across the study were similar.

Ascites at 1 year was seen in 88% of the standard care group, compared with in 64% of the study group. Rates of hepatic encephalopathy were similar in those with Child-Pugh B with active bleeding, and Child-Pugh C across both groups: 22% in the standard care group vs. 25% in the early TIPS group.

That there was no associated significant risk of hepatic encephalopathy in persons with acute variceal bleeding who were given early TIPS “strongly suggests that early TIPS should be included in clinical practice,” Dr. Hernandez-Gea said, noting that only 10% of the 34 sites in the study had used early TIPS. “We don’t really know why centers are not using this, since it is very difficult to find treatments that extend survival rates in this population.”

[email protected]

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

BOSTON – High-risk cirrhosis patients treated early with a transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) showed increased survival rates and reduced rates of adverse events, according to a study.

The data were presented at the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases by Virginia Hernandez-Gea, MD, a hepatologist at the Hospital Clinic in Barcelona.

In each study arm, three-quarters were men in their mid-50s. Cirrhosis in the non-TIPS group was alcohol-related in 57.4% of the cohort, compared with 71.2% of the group given early TIPS; roughly half of each group mentioned alcohol use in the past 3 months.

Also similar were Model for End-stage Liver Disease (MELD) scores: an average of 15.5 in the non-TIPS group, compared with 15 on average in the TIPS group. Nearly three-quarters of the TIPS group had a Child-Pugh C score, compared with 64% in the non-TIPS group. A Child-Pugh score with active bleeding was recorded in 28.8% of the TIPS group, compared with 36% in the non-TIPS group.

The transplant-free survival rate at 1 year in the standard care group was 61%, compared with 76% in the early TIPS group (P = .0175). The failure and bleeding rate at 1 year was significantly higher in the standard care group: 91%, compared with 68% in the early TIPS group (P = .004). Failure and bleeding rates in the Child-Pugh B and C groups across the study were similar.

Ascites at 1 year was seen in 88% of the standard care group, compared with in 64% of the study group. Rates of hepatic encephalopathy were similar in those with Child-Pugh B with active bleeding, and Child-Pugh C across both groups: 22% in the standard care group vs. 25% in the early TIPS group.

That there was no associated significant risk of hepatic encephalopathy in persons with acute variceal bleeding who were given early TIPS “strongly suggests that early TIPS should be included in clinical practice,” Dr. Hernandez-Gea said, noting that only 10% of the 34 sites in the study had used early TIPS. “We don’t really know why centers are not using this, since it is very difficult to find treatments that extend survival rates in this population.”

[email protected]

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

BOSTON – High-risk cirrhosis patients treated early with a transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) showed increased survival rates and reduced rates of adverse events, according to a study.

The data were presented at the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases by Virginia Hernandez-Gea, MD, a hepatologist at the Hospital Clinic in Barcelona.

In each study arm, three-quarters were men in their mid-50s. Cirrhosis in the non-TIPS group was alcohol-related in 57.4% of the cohort, compared with 71.2% of the group given early TIPS; roughly half of each group mentioned alcohol use in the past 3 months.

Also similar were Model for End-stage Liver Disease (MELD) scores: an average of 15.5 in the non-TIPS group, compared with 15 on average in the TIPS group. Nearly three-quarters of the TIPS group had a Child-Pugh C score, compared with 64% in the non-TIPS group. A Child-Pugh score with active bleeding was recorded in 28.8% of the TIPS group, compared with 36% in the non-TIPS group.

The transplant-free survival rate at 1 year in the standard care group was 61%, compared with 76% in the early TIPS group (P = .0175). The failure and bleeding rate at 1 year was significantly higher in the standard care group: 91%, compared with 68% in the early TIPS group (P = .004). Failure and bleeding rates in the Child-Pugh B and C groups across the study were similar.

Ascites at 1 year was seen in 88% of the standard care group, compared with in 64% of the study group. Rates of hepatic encephalopathy were similar in those with Child-Pugh B with active bleeding, and Child-Pugh C across both groups: 22% in the standard care group vs. 25% in the early TIPS group.

That there was no associated significant risk of hepatic encephalopathy in persons with acute variceal bleeding who were given early TIPS “strongly suggests that early TIPS should be included in clinical practice,” Dr. Hernandez-Gea said, noting that only 10% of the 34 sites in the study had used early TIPS. “We don’t really know why centers are not using this, since it is very difficult to find treatments that extend survival rates in this population.”

[email protected]

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

AT THE LIVER MEETING

Key clinical point:

Major finding: At 1 year post procedure, early TIPS was associated with better rates of survival and lower rates of adverse events, compared with those who did not receive early TIPS.

Data source: Multicenter, international observational study between 2011 and 2015 of 671 high-risk patients with cirrhosis managed according to current guidelines.

Disclosures: Dr. Hernandez-Gea did not have any relevant disclosures.

Texas reports local Zika transmission

On Nov. 28, public health officials there reported a case of Zika virus in a Brownsville woman who hadn’t traveled to Mexico or any other area with active Zika transmission. Brownsville sits on the border of Mexico at the state’s southern tip, and is home to Aedes species mosquitoes known to carry the virus. The area had recently been sprayed for mosquitoes.

Zika’s telltale genetic thumbprint was found in the woman’s urine, but her blood was negative, so the virus could no longer be spread from her by mosquito. She was not pregnant. There are no other suspected cases of local transmission, according to Texas officials.

“We knew it was only a matter of time before we saw a Zika case spread by a mosquito in Texas,” John Hellerstedt, MD, commissioner of the Texas Department of State Health Services, said in a statement. “We still don’t believe the virus will become widespread in Texas, but there could be more cases, so people need to protect themselves from mosquito bites, especially in parts of the state that stay relatively warm in the fall and winter.”

The state public health officials recommend testing all pregnant women who have traveled – or who have sexual partners who have traveled – to areas with active Zika transmission. In addition to Mexico, the list includes Southeast Asia, Central and South America, the Caribbean, Cape Verde, and Pacific islands including Tonga, Samoa, and Papua New Guinea.

Texas officials also recommend antibody testing of pregnant women in southern Texas if they have two or more symptoms – fever, itchy rash, joint pain, and eye redness – and anyone statewide with at least three symptoms.

As of Nov. 23, a total of 4,444 Zika cases have been reported to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in U.S. states and the District of Columbia. Just 182 of those cases were the result of local spread by mosquitoes in Florida. Puerto Rico has reported nearly 32,000 locally-transmitted cases.

The 257 previously confirmed cases in Texas were all associated with travel. Most were in the Houston and Dallas–Fort Worth areas.

Local and state health officials are working with the CDC to pinpoint how and where the Brownsville infection occurred. Mosquitoes are being trapped, and workers are going door to door to educate people about Zika and request urine samples to screen for infection.

On Nov. 28, public health officials there reported a case of Zika virus in a Brownsville woman who hadn’t traveled to Mexico or any other area with active Zika transmission. Brownsville sits on the border of Mexico at the state’s southern tip, and is home to Aedes species mosquitoes known to carry the virus. The area had recently been sprayed for mosquitoes.

Zika’s telltale genetic thumbprint was found in the woman’s urine, but her blood was negative, so the virus could no longer be spread from her by mosquito. She was not pregnant. There are no other suspected cases of local transmission, according to Texas officials.

“We knew it was only a matter of time before we saw a Zika case spread by a mosquito in Texas,” John Hellerstedt, MD, commissioner of the Texas Department of State Health Services, said in a statement. “We still don’t believe the virus will become widespread in Texas, but there could be more cases, so people need to protect themselves from mosquito bites, especially in parts of the state that stay relatively warm in the fall and winter.”

The state public health officials recommend testing all pregnant women who have traveled – or who have sexual partners who have traveled – to areas with active Zika transmission. In addition to Mexico, the list includes Southeast Asia, Central and South America, the Caribbean, Cape Verde, and Pacific islands including Tonga, Samoa, and Papua New Guinea.

Texas officials also recommend antibody testing of pregnant women in southern Texas if they have two or more symptoms – fever, itchy rash, joint pain, and eye redness – and anyone statewide with at least three symptoms.

As of Nov. 23, a total of 4,444 Zika cases have been reported to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in U.S. states and the District of Columbia. Just 182 of those cases were the result of local spread by mosquitoes in Florida. Puerto Rico has reported nearly 32,000 locally-transmitted cases.

The 257 previously confirmed cases in Texas were all associated with travel. Most were in the Houston and Dallas–Fort Worth areas.

Local and state health officials are working with the CDC to pinpoint how and where the Brownsville infection occurred. Mosquitoes are being trapped, and workers are going door to door to educate people about Zika and request urine samples to screen for infection.

On Nov. 28, public health officials there reported a case of Zika virus in a Brownsville woman who hadn’t traveled to Mexico or any other area with active Zika transmission. Brownsville sits on the border of Mexico at the state’s southern tip, and is home to Aedes species mosquitoes known to carry the virus. The area had recently been sprayed for mosquitoes.

Zika’s telltale genetic thumbprint was found in the woman’s urine, but her blood was negative, so the virus could no longer be spread from her by mosquito. She was not pregnant. There are no other suspected cases of local transmission, according to Texas officials.

“We knew it was only a matter of time before we saw a Zika case spread by a mosquito in Texas,” John Hellerstedt, MD, commissioner of the Texas Department of State Health Services, said in a statement. “We still don’t believe the virus will become widespread in Texas, but there could be more cases, so people need to protect themselves from mosquito bites, especially in parts of the state that stay relatively warm in the fall and winter.”

The state public health officials recommend testing all pregnant women who have traveled – or who have sexual partners who have traveled – to areas with active Zika transmission. In addition to Mexico, the list includes Southeast Asia, Central and South America, the Caribbean, Cape Verde, and Pacific islands including Tonga, Samoa, and Papua New Guinea.

Texas officials also recommend antibody testing of pregnant women in southern Texas if they have two or more symptoms – fever, itchy rash, joint pain, and eye redness – and anyone statewide with at least three symptoms.

As of Nov. 23, a total of 4,444 Zika cases have been reported to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in U.S. states and the District of Columbia. Just 182 of those cases were the result of local spread by mosquitoes in Florida. Puerto Rico has reported nearly 32,000 locally-transmitted cases.

The 257 previously confirmed cases in Texas were all associated with travel. Most were in the Houston and Dallas–Fort Worth areas.

Local and state health officials are working with the CDC to pinpoint how and where the Brownsville infection occurred. Mosquitoes are being trapped, and workers are going door to door to educate people about Zika and request urine samples to screen for infection.

Survey finds high rate of misdiagnosed fungal infections

Fungal skin infections may be missed or misdiagnosed by many dermatologists, according to the results of a survey published online in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology.

For the interactive survey, conducted during a session on fungal infections at the 2016 Orlando Dermatology Aesthetic and Clinical Conference, board-certified dermatologists viewed 13 clinical images (which included other conditions such as secondary syphilis and pityriasis rosea) and were asked via an audience response system whether or not they thought the case was a fungal skin infection. In only 1 of the 13 cases presented did 90% of the dermatologists correctly categorize the case as either a dermatomycosis or not, reported Ramsin Joseph Yadgar of George Washington University in Washington, D.C., and colleagues.

Although most cases (8 of 13) “were appropriately categorized by more than 50% of the audience, this percentage decreased as accuracy of categorization increased,” they wrote. “For example, in only 4 of the 13 cases did audience members accurately categorize the cases with more than 75% accuracy,” they said (J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016 Nov 11. pii: S0190-9622[16]30883-0. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2016.09.041).

“Dermatology is full of doppelgangers,” Dr. Friedman, director of the residency program and of translational research in the department of dermatology at George Washington University, said in an interview.

“While we [dermatologists] pride ourselves on our visual prowess, there are many skin diseases which do not follow the textbook and can be quite protean in their presentations,” he said.

The variability in presentation makes diagnosing fungal infections especially challenging, he noted. “Fungal infections of the skin can have many clinical flavors and can infect skin, hair and nails. Also, inappropriate treatment can obscure the appearance of the infection, and the fact that there are multiple other conditions that can look like these [fungal] infections makes proper identification difficult.”

Although the results were limited by several factors including possible selection bias, lack of measurable response rate, and small sample size, the findings highlight how easy it can be to miss a diagnosis of fungal infection, “which can result in inappropriate therapy, worsening of symptoms, and even additional skin and soft-tissue infections,” the researchers wrote.

“Keep an open mind and cast a wider differential,” to help catch fungal infections, and use all the dermatologic tools, including slide preps, cultures, and biopsies, Dr. Friedman said. Better diagnostic tools and improved training for clinicians outside of dermatology also could reduce the misdiagnosis of fungal infections, he added. “Many of these patients are misdiagnosed in the emergency department, urgent care, or primary care settings,” and delayed treatment increases associated morbidity, he said.

Mr. Yadgar, Dr. Friedman, and another coauthor, Neal Bhatia, MD, of Therapeutics Clinical Research, San Diego, Calif., had no financial conflicts to disclose. There was no funding source.

Fungal skin infections may be missed or misdiagnosed by many dermatologists, according to the results of a survey published online in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology.

For the interactive survey, conducted during a session on fungal infections at the 2016 Orlando Dermatology Aesthetic and Clinical Conference, board-certified dermatologists viewed 13 clinical images (which included other conditions such as secondary syphilis and pityriasis rosea) and were asked via an audience response system whether or not they thought the case was a fungal skin infection. In only 1 of the 13 cases presented did 90% of the dermatologists correctly categorize the case as either a dermatomycosis or not, reported Ramsin Joseph Yadgar of George Washington University in Washington, D.C., and colleagues.

Although most cases (8 of 13) “were appropriately categorized by more than 50% of the audience, this percentage decreased as accuracy of categorization increased,” they wrote. “For example, in only 4 of the 13 cases did audience members accurately categorize the cases with more than 75% accuracy,” they said (J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016 Nov 11. pii: S0190-9622[16]30883-0. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2016.09.041).

“Dermatology is full of doppelgangers,” Dr. Friedman, director of the residency program and of translational research in the department of dermatology at George Washington University, said in an interview.

“While we [dermatologists] pride ourselves on our visual prowess, there are many skin diseases which do not follow the textbook and can be quite protean in their presentations,” he said.

The variability in presentation makes diagnosing fungal infections especially challenging, he noted. “Fungal infections of the skin can have many clinical flavors and can infect skin, hair and nails. Also, inappropriate treatment can obscure the appearance of the infection, and the fact that there are multiple other conditions that can look like these [fungal] infections makes proper identification difficult.”

Although the results were limited by several factors including possible selection bias, lack of measurable response rate, and small sample size, the findings highlight how easy it can be to miss a diagnosis of fungal infection, “which can result in inappropriate therapy, worsening of symptoms, and even additional skin and soft-tissue infections,” the researchers wrote.

“Keep an open mind and cast a wider differential,” to help catch fungal infections, and use all the dermatologic tools, including slide preps, cultures, and biopsies, Dr. Friedman said. Better diagnostic tools and improved training for clinicians outside of dermatology also could reduce the misdiagnosis of fungal infections, he added. “Many of these patients are misdiagnosed in the emergency department, urgent care, or primary care settings,” and delayed treatment increases associated morbidity, he said.

Mr. Yadgar, Dr. Friedman, and another coauthor, Neal Bhatia, MD, of Therapeutics Clinical Research, San Diego, Calif., had no financial conflicts to disclose. There was no funding source.

Fungal skin infections may be missed or misdiagnosed by many dermatologists, according to the results of a survey published online in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology.

For the interactive survey, conducted during a session on fungal infections at the 2016 Orlando Dermatology Aesthetic and Clinical Conference, board-certified dermatologists viewed 13 clinical images (which included other conditions such as secondary syphilis and pityriasis rosea) and were asked via an audience response system whether or not they thought the case was a fungal skin infection. In only 1 of the 13 cases presented did 90% of the dermatologists correctly categorize the case as either a dermatomycosis or not, reported Ramsin Joseph Yadgar of George Washington University in Washington, D.C., and colleagues.

Although most cases (8 of 13) “were appropriately categorized by more than 50% of the audience, this percentage decreased as accuracy of categorization increased,” they wrote. “For example, in only 4 of the 13 cases did audience members accurately categorize the cases with more than 75% accuracy,” they said (J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016 Nov 11. pii: S0190-9622[16]30883-0. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2016.09.041).

“Dermatology is full of doppelgangers,” Dr. Friedman, director of the residency program and of translational research in the department of dermatology at George Washington University, said in an interview.

“While we [dermatologists] pride ourselves on our visual prowess, there are many skin diseases which do not follow the textbook and can be quite protean in their presentations,” he said.

The variability in presentation makes diagnosing fungal infections especially challenging, he noted. “Fungal infections of the skin can have many clinical flavors and can infect skin, hair and nails. Also, inappropriate treatment can obscure the appearance of the infection, and the fact that there are multiple other conditions that can look like these [fungal] infections makes proper identification difficult.”

Although the results were limited by several factors including possible selection bias, lack of measurable response rate, and small sample size, the findings highlight how easy it can be to miss a diagnosis of fungal infection, “which can result in inappropriate therapy, worsening of symptoms, and even additional skin and soft-tissue infections,” the researchers wrote.

“Keep an open mind and cast a wider differential,” to help catch fungal infections, and use all the dermatologic tools, including slide preps, cultures, and biopsies, Dr. Friedman said. Better diagnostic tools and improved training for clinicians outside of dermatology also could reduce the misdiagnosis of fungal infections, he added. “Many of these patients are misdiagnosed in the emergency department, urgent care, or primary care settings,” and delayed treatment increases associated morbidity, he said.

Mr. Yadgar, Dr. Friedman, and another coauthor, Neal Bhatia, MD, of Therapeutics Clinical Research, San Diego, Calif., had no financial conflicts to disclose. There was no funding source.

FROM JAAD

Key clinical point: Fungal infections may often be missed or misdiagnosed by dermatologists.

Major finding: In 1 of 13 cases did 90% of an audience of dermatologists correctly categorize the condition.

Data source: A survey of board-certified dermatologists, asked whether or not 13 clinical images were a fungal infection or not, during a session on fungal infections at a dermatology meeting.

Disclosures: The research team had no relevant financial conflicts to disclose.

Comparing Cost, Efficacy, and Safety of Intravenous and Topical Tranexamic Acid in Total Hip and Knee Arthroplasty

Total hip arthroplasty (THA) and total knee arthroplasty (TKA) can be associated with significant blood loss that in some cases requires transfusion. The incidence of transfusion ranges from 16% to 37% in patients who undergo THA and from 11% to 21% in patients who undergo TKA.1-3 Allogeneic blood transfusions have been associated with several risks (transfusion-related acute lung injury, hemolytic reactions, immunologic reactions, fluid overload, renal failure, infections), increased cost, and longer hospital length of stay (LOS).4-7 With improved patient outcomes the ultimate goal, blood-conserving strategies designed to decrease blood loss and transfusions have been adopted as a standard in successful joint replacement programs.

Tranexamic acid (TXA), an antifibrinolytic agent, has become a major component of blood conservation management after THA and TKA. TXA stabilizes clots at the surgical site by inhibiting plasminogen activation and thereby blocking fibrinolysis.8 The literature supports intravenous (IV) TXA as effective in significantly reducing blood loss and transfusion rates in elective THA and TKA.9,10 However, data on increased risk of thrombotic events with IV TXA in both THA and TKA are conflicting.11,12 Topical TXA is thought to have an advantage over IV TXA in that it provides a higher concentration of drug at the surgical site and is associated with little systemic absorption.2,13Recent prospective randomized studies have compared the efficacy and safety of IV and topical TXA in THA and TKA.9,14 However, controversy remains because relatively few studies have compared these 2 routes of administration. In addition, healthcare–associated costs have come under increased scrutiny, and the cost of these treatments should be considered. More research is needed to determine which application is most efficacious and cost-conscious and poses the least risk to patients. Therefore, we conducted a study to compare the cost, efficacy, and safety of IV and topical TXA in primary THA and TKA.

Materials and Methods

Our Institutional Review Board approved this study. Patients who were age 18 years or older, underwent primary THA or TKA, and received IV or topical TXA between August 2013 and September 2014 were considered eligible for the study. For both groups, exclusion criteria were trauma service admission, TXA hypersensitivity, pregnancy, and concomitant use of IV and topical TXA.

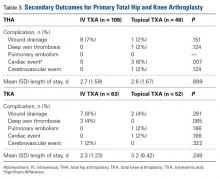

We collected demographic data (age, sex, weight, height, body mass index), noted all transfusions of packed red blood cells, and recorded preoperative and postoperative hemoglobin (Hgb) levels and surgical drain outputs. We also recorded any complications that occurred within 90 days after surgery: deep vein thrombosis (DVT), pulmonary embolism (PE), cardiac events, cerebrovascular events, and wound drainage. Wound drainage was defined as readmission to hospital or return to operating room for wound drainage caused by infection or hematoma. Postoperative care (disposition, LOS, follow-up) was documented. Average cost of both IV and topical TXA administration was calculated using average wholesale price.

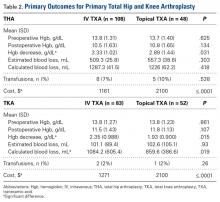

Use of IV TXA and use of topical TXA were compared in both THA and TKA. Patients in the IV TXA group received TXA in two 10-mg/kg doses with a maximum of 1 g per dose. The first IV dose was given before the incision, and the second was given 3 hours after the first. Patients in the topical TXA group underwent direct irrigation with 3 g of TXA in 100 mL of normal saline at the surgical site after closure of the deep fascia in THA and after closure of the knee arthrotomy in TKA. The drain remained occluded for 30 minutes after surgery. The wound was irrigated with topical TXA before wound closure in the THA group and before tourniquet release in the TKA group. TXA dosing was based on institutional formulary dosing restrictions and was consistent with best practices and current literature.3,9,14,15Primary outcomes measured for each cohort and treatment arm were Hgb levels (difference between preoperative levels and lowest postoperative levels 24 hours after surgery), blood loss, transfusion rates, and cost. Secondary outcomes were LOS and complications that occurred within 90 days after surgery (DVT, PE, cardiac events, cerebrovascular events, wound drainage).

Calculated blood loss was determined with equations described by Konig and colleagues,3 Good and colleagues,16 and Nadler and colleagues.17 Total calculated blood loss was based on the difference in Hgb levels before surgery and the lowest Hgb levels 24 hours after surgery:

Blood loss (mL) = 100 mL/dL × Hgbloss/Hgbi

Hgbloss = BV × (Hgbi – Hgbe) × 10 dL/L + Hgbt

= 0.3669 × Height3 (m) + 0.03219 × Weight (kg) + 0.6041 (for men)

= 0.3561 × Height3 (m) + 0.03308 × Weight (kg) + 0.1833 (for women)

where Hgbi is the Hgb concentration (g/dL) before surgery, Hgbe is the lowest Hgb concentration (g/dL) 24 hours after surgery, Hgbt is the total amount (g) of allogeneic Hgb transfused, and BV is the estimated total body blood volume (L).17 As Hgb concentrations after blood transfusions were compared in this study, the Hgbt variable was removed from the equation. Based on Hgb decrease data in a study that compared IV and topical TXA in TKA,14 we determined that a sample size of least 140 patients (70 in each cohort) was needed in order to have 80% power to detect a difference in Hgb decrease of 0.36 g/dL in IV and topical TXA.

All data were reported with descriptive statistics. Frequencies and percentages were reported for categorical variables. Means and standard deviations were reported for continuous variables. The groups of continuous data were compared with unpaired Student t tests and 1-way analysis of variance. Comparisons among groups of categorical data were analyzed with Fisher exact tests. Statistical significance was set at P < .05.

Results

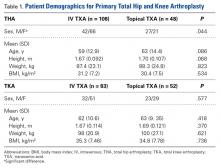

Data were collected on 291 patients (156 THA, 135 TKA). There was a significant (P = .044) sex difference in the THA group: more men in the topical TXA subgroup and more women in the IV TXA subgroup. Other patient demographics were similarly matched with respect to age, height, weight, and body mass index (Table 1).

The secondary outcomes (differences in complications and LOS) are listed in Table 3.

Discussion