User login

Study finds inflammatory bowel disease risk higher in children, adults with atopic dermatitis

The published recently in JAMA Dermatology.

The study also found an increased risk for Crohn’s disease (CD) in adults and children with AD, as well as an increased risk for ulcerative colitis (UC) in adults with AD and in children with severe AD, researchers reported.

“It is imperative for clinicians to understand atopic dermatitis and the trajectory of our patients with it in order to provide the best standard of care,” senior author Joel M. Gelfand, MD, MSCE, professor in clinical investigation with the department of dermatology at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, said in a news release.

“There are new and better treatments for AD today, and there will likely continue to be more,” continued Dr. Gelfand. “But providers have to understand how those treatments could impact other autoimmune diseases. For patients with AD and another autoimmune disease, some currently available medications can exacerbate symptoms of their other disease or can help treat two immune diseases at the same time.”

The study results support the idea that AD and IBD may have some common underlying causes, said Sheilagh Maguiness, MD, pediatric dermatologist and associate professor in the department of dermatology at the University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, who was asked to comment on the findings.

“As the pathogenesis of AD is becoming better understood, we are recognizing that, rather than simply a cutaneous disease, the underlying inflammation and immune dysregulation that leads to AD best categorizes it as a systemic inflammatory disease with significant comorbidities,” she told this news organization. “I will be more likely to ask patients and families about GI symptoms, and if positive, may plan to refer to GI more readily than in the past,” added Dr. Maguiness, who was not involved in the study.

UK general practice cohort

AD has been associated with an increasing number of comorbidities, including IBD, but studies linking AD with IBD, including UC, have had mixed results, the authors wrote. And few studies have separately examined how AD or AD severity may be linked with UC or CD risk.

To examine the risk for new-onset IBD, UC, and CD in children and adults with atopic dermatitis, the researchers conducted a population-based cohort study using the THIN (The Health Improvement Network) electronic medical record database of patients registered with United Kingdom general practices. They used 21 years of data collected from January 1994 to February 2015.

The researchers matched each patient who had AD with up to five controls based on age, practice, and index date. Because THIN does not capture AD severity, they used treatment exposure assessed by dermatologic referrals and treatments patients received as proxy for severity. The authors used logistic regression to examine the risks for IBD, UC, and CD in children (aged 1-10) with AD, and in adults (aged 30-68) with AD, and they compared their outcomes with the outcomes for controls.

In the pediatric cohort, the team compared 409,431 children who had AD with 1.8 million children without AD. Slightly more than half were boys. In the adult cohort, they compared 625,083 people who had AD with 2.68 million controls, and slightly more than half were women. Data on race or ethnicity were not available, the authors wrote, but the THIN database is considered to be representative of the UK population.

AD severity linked with IBD risk

The risk for new-onset inflammatory bowel disease appears to be higher in children and adults with AD, and the risk varies based on age, AD severity, and subtype of inflammatory bowel disease, the authors reported.

Overall, AD in children was associated with a 44% increased risk for IBD (adjusted hazard ratio (HR), 1.44; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.31-1.58) compared with controls, the authors reported. They found a 74% increased risk for CD in children with AD compared with controls (HR, 1.74; 95% CI, 1.54-1.97). More severe AD was linked with increased risk for both IBD and CD.

AD did not appear to increase risk for UC in children, except those with severe AD (HR, 1.65; 95% CI, 1.02-2.67).

Overall, adults with AD had a 34% (HR, 1.34; 95% CI, 1.27-1.40) increased risk for IBD, a 36% (HR, 1.36; 95% CI, 1.26-1.47) increased risk for CD, and a 32% (HR, 1.32; 95% CI, 1.24-1.41) increased risk for UC, with risk increasing with increased AD severity.

Robust data with cautionary note

“This study provides the most robust data to date on the association between IBD and AD. It provides clear evidence for an association that most dermatologists or primary care providers are not typically taught in training,” Kelly Scarberry, MD, assistant professor of dermatology at Case Western Reserve University in Cleveland, told this news organization. “I will be much more likely to pursue diagnostic workup in my AD patients who have GI complaints.”

However, AD severity was measured by proxy, added Dr. Scarberry, who was not involved in the study, and the study lacked important racial and ethnic data.

Lindsay C. Strowd, MD, associate professor of dermatology at Wake Forest University, Winston-Salem, N.C., also not involved in the study, said in an interview that she found the size of the cohort and the longitudinal data to be strengths of the study.

But, she added, the “lack of family IBD history, race and ethnicity, and comorbidities, are limitations, as is treatment exposure used as a proxy for disease severity, given that physician treatment practices differ.”

For Steven R. Feldman, MD, PhD, professor of dermatology at Wake Forest, “the most important conclusion, and it is a definitive finding, [is] that IBD is uncommon, even in patients with AD.

“The findings could be misinterpreted,” cautioned Dr. Feldman, who was not involved in the study. “While there is an increased relative risk, the absolute risk is small.” The study found that “the highest relative risk group is children with severe AD, who have a roughly fivefold increased risk for CD.” However, he added, the incidence rates of CD were 0.68 per 1,000 person-years in children with severe AD and 0.08 per 1,000 person-years in controls.

“Basically, because Crohn’s disease and IBD don’t happen very often, the modest increase in relative risk the investigators found doesn’t amount to much we’d have to worry about,” he said. “The findings do not show any need to screen patients with atopic dermatitis for IBD any more than we’d need to screen patients without atopic dermatitis.”

The increased relative risk “could be a clue to possible genetic connections between diseases,” he added. “But when we’re making clinical decisions, those decisions should be based on the absolute risk that some event may occur.”

Susan Massick, MD, dermatologist and associate professor at The Ohio State University in Columbus, who was not involved with the study, said in an interview, “We are still scratching the surface of the complexity of the immune and inflammatory pathways in AD and IBD.

“It is important to remember that correlation does not mean causation,” Dr. Massick said. “It would be premature to draw direct conclusions based on this study alone.”

The authors recommend future related studies in more diverse populations.

Dr. Gelfand and two coauthors reported ties with Pfizer, which supported the study. Dr. Gelfand and three coauthors reported ties with other pharmaceutical companies. Dr. Maguiness, Dr. Scarberry, Dr. Strowd, and Dr. Massick reported having no relevant disclosures. Dr. Feldman reported ties with Pfizer and other pharmaceutical companies.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

The published recently in JAMA Dermatology.

The study also found an increased risk for Crohn’s disease (CD) in adults and children with AD, as well as an increased risk for ulcerative colitis (UC) in adults with AD and in children with severe AD, researchers reported.

“It is imperative for clinicians to understand atopic dermatitis and the trajectory of our patients with it in order to provide the best standard of care,” senior author Joel M. Gelfand, MD, MSCE, professor in clinical investigation with the department of dermatology at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, said in a news release.

“There are new and better treatments for AD today, and there will likely continue to be more,” continued Dr. Gelfand. “But providers have to understand how those treatments could impact other autoimmune diseases. For patients with AD and another autoimmune disease, some currently available medications can exacerbate symptoms of their other disease or can help treat two immune diseases at the same time.”

The study results support the idea that AD and IBD may have some common underlying causes, said Sheilagh Maguiness, MD, pediatric dermatologist and associate professor in the department of dermatology at the University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, who was asked to comment on the findings.

“As the pathogenesis of AD is becoming better understood, we are recognizing that, rather than simply a cutaneous disease, the underlying inflammation and immune dysregulation that leads to AD best categorizes it as a systemic inflammatory disease with significant comorbidities,” she told this news organization. “I will be more likely to ask patients and families about GI symptoms, and if positive, may plan to refer to GI more readily than in the past,” added Dr. Maguiness, who was not involved in the study.

UK general practice cohort

AD has been associated with an increasing number of comorbidities, including IBD, but studies linking AD with IBD, including UC, have had mixed results, the authors wrote. And few studies have separately examined how AD or AD severity may be linked with UC or CD risk.

To examine the risk for new-onset IBD, UC, and CD in children and adults with atopic dermatitis, the researchers conducted a population-based cohort study using the THIN (The Health Improvement Network) electronic medical record database of patients registered with United Kingdom general practices. They used 21 years of data collected from January 1994 to February 2015.

The researchers matched each patient who had AD with up to five controls based on age, practice, and index date. Because THIN does not capture AD severity, they used treatment exposure assessed by dermatologic referrals and treatments patients received as proxy for severity. The authors used logistic regression to examine the risks for IBD, UC, and CD in children (aged 1-10) with AD, and in adults (aged 30-68) with AD, and they compared their outcomes with the outcomes for controls.

In the pediatric cohort, the team compared 409,431 children who had AD with 1.8 million children without AD. Slightly more than half were boys. In the adult cohort, they compared 625,083 people who had AD with 2.68 million controls, and slightly more than half were women. Data on race or ethnicity were not available, the authors wrote, but the THIN database is considered to be representative of the UK population.

AD severity linked with IBD risk

The risk for new-onset inflammatory bowel disease appears to be higher in children and adults with AD, and the risk varies based on age, AD severity, and subtype of inflammatory bowel disease, the authors reported.

Overall, AD in children was associated with a 44% increased risk for IBD (adjusted hazard ratio (HR), 1.44; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.31-1.58) compared with controls, the authors reported. They found a 74% increased risk for CD in children with AD compared with controls (HR, 1.74; 95% CI, 1.54-1.97). More severe AD was linked with increased risk for both IBD and CD.

AD did not appear to increase risk for UC in children, except those with severe AD (HR, 1.65; 95% CI, 1.02-2.67).

Overall, adults with AD had a 34% (HR, 1.34; 95% CI, 1.27-1.40) increased risk for IBD, a 36% (HR, 1.36; 95% CI, 1.26-1.47) increased risk for CD, and a 32% (HR, 1.32; 95% CI, 1.24-1.41) increased risk for UC, with risk increasing with increased AD severity.

Robust data with cautionary note

“This study provides the most robust data to date on the association between IBD and AD. It provides clear evidence for an association that most dermatologists or primary care providers are not typically taught in training,” Kelly Scarberry, MD, assistant professor of dermatology at Case Western Reserve University in Cleveland, told this news organization. “I will be much more likely to pursue diagnostic workup in my AD patients who have GI complaints.”

However, AD severity was measured by proxy, added Dr. Scarberry, who was not involved in the study, and the study lacked important racial and ethnic data.

Lindsay C. Strowd, MD, associate professor of dermatology at Wake Forest University, Winston-Salem, N.C., also not involved in the study, said in an interview that she found the size of the cohort and the longitudinal data to be strengths of the study.

But, she added, the “lack of family IBD history, race and ethnicity, and comorbidities, are limitations, as is treatment exposure used as a proxy for disease severity, given that physician treatment practices differ.”

For Steven R. Feldman, MD, PhD, professor of dermatology at Wake Forest, “the most important conclusion, and it is a definitive finding, [is] that IBD is uncommon, even in patients with AD.

“The findings could be misinterpreted,” cautioned Dr. Feldman, who was not involved in the study. “While there is an increased relative risk, the absolute risk is small.” The study found that “the highest relative risk group is children with severe AD, who have a roughly fivefold increased risk for CD.” However, he added, the incidence rates of CD were 0.68 per 1,000 person-years in children with severe AD and 0.08 per 1,000 person-years in controls.

“Basically, because Crohn’s disease and IBD don’t happen very often, the modest increase in relative risk the investigators found doesn’t amount to much we’d have to worry about,” he said. “The findings do not show any need to screen patients with atopic dermatitis for IBD any more than we’d need to screen patients without atopic dermatitis.”

The increased relative risk “could be a clue to possible genetic connections between diseases,” he added. “But when we’re making clinical decisions, those decisions should be based on the absolute risk that some event may occur.”

Susan Massick, MD, dermatologist and associate professor at The Ohio State University in Columbus, who was not involved with the study, said in an interview, “We are still scratching the surface of the complexity of the immune and inflammatory pathways in AD and IBD.

“It is important to remember that correlation does not mean causation,” Dr. Massick said. “It would be premature to draw direct conclusions based on this study alone.”

The authors recommend future related studies in more diverse populations.

Dr. Gelfand and two coauthors reported ties with Pfizer, which supported the study. Dr. Gelfand and three coauthors reported ties with other pharmaceutical companies. Dr. Maguiness, Dr. Scarberry, Dr. Strowd, and Dr. Massick reported having no relevant disclosures. Dr. Feldman reported ties with Pfizer and other pharmaceutical companies.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

The published recently in JAMA Dermatology.

The study also found an increased risk for Crohn’s disease (CD) in adults and children with AD, as well as an increased risk for ulcerative colitis (UC) in adults with AD and in children with severe AD, researchers reported.

“It is imperative for clinicians to understand atopic dermatitis and the trajectory of our patients with it in order to provide the best standard of care,” senior author Joel M. Gelfand, MD, MSCE, professor in clinical investigation with the department of dermatology at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, said in a news release.

“There are new and better treatments for AD today, and there will likely continue to be more,” continued Dr. Gelfand. “But providers have to understand how those treatments could impact other autoimmune diseases. For patients with AD and another autoimmune disease, some currently available medications can exacerbate symptoms of their other disease or can help treat two immune diseases at the same time.”

The study results support the idea that AD and IBD may have some common underlying causes, said Sheilagh Maguiness, MD, pediatric dermatologist and associate professor in the department of dermatology at the University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, who was asked to comment on the findings.

“As the pathogenesis of AD is becoming better understood, we are recognizing that, rather than simply a cutaneous disease, the underlying inflammation and immune dysregulation that leads to AD best categorizes it as a systemic inflammatory disease with significant comorbidities,” she told this news organization. “I will be more likely to ask patients and families about GI symptoms, and if positive, may plan to refer to GI more readily than in the past,” added Dr. Maguiness, who was not involved in the study.

UK general practice cohort

AD has been associated with an increasing number of comorbidities, including IBD, but studies linking AD with IBD, including UC, have had mixed results, the authors wrote. And few studies have separately examined how AD or AD severity may be linked with UC or CD risk.

To examine the risk for new-onset IBD, UC, and CD in children and adults with atopic dermatitis, the researchers conducted a population-based cohort study using the THIN (The Health Improvement Network) electronic medical record database of patients registered with United Kingdom general practices. They used 21 years of data collected from January 1994 to February 2015.

The researchers matched each patient who had AD with up to five controls based on age, practice, and index date. Because THIN does not capture AD severity, they used treatment exposure assessed by dermatologic referrals and treatments patients received as proxy for severity. The authors used logistic regression to examine the risks for IBD, UC, and CD in children (aged 1-10) with AD, and in adults (aged 30-68) with AD, and they compared their outcomes with the outcomes for controls.

In the pediatric cohort, the team compared 409,431 children who had AD with 1.8 million children without AD. Slightly more than half were boys. In the adult cohort, they compared 625,083 people who had AD with 2.68 million controls, and slightly more than half were women. Data on race or ethnicity were not available, the authors wrote, but the THIN database is considered to be representative of the UK population.

AD severity linked with IBD risk

The risk for new-onset inflammatory bowel disease appears to be higher in children and adults with AD, and the risk varies based on age, AD severity, and subtype of inflammatory bowel disease, the authors reported.

Overall, AD in children was associated with a 44% increased risk for IBD (adjusted hazard ratio (HR), 1.44; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.31-1.58) compared with controls, the authors reported. They found a 74% increased risk for CD in children with AD compared with controls (HR, 1.74; 95% CI, 1.54-1.97). More severe AD was linked with increased risk for both IBD and CD.

AD did not appear to increase risk for UC in children, except those with severe AD (HR, 1.65; 95% CI, 1.02-2.67).

Overall, adults with AD had a 34% (HR, 1.34; 95% CI, 1.27-1.40) increased risk for IBD, a 36% (HR, 1.36; 95% CI, 1.26-1.47) increased risk for CD, and a 32% (HR, 1.32; 95% CI, 1.24-1.41) increased risk for UC, with risk increasing with increased AD severity.

Robust data with cautionary note

“This study provides the most robust data to date on the association between IBD and AD. It provides clear evidence for an association that most dermatologists or primary care providers are not typically taught in training,” Kelly Scarberry, MD, assistant professor of dermatology at Case Western Reserve University in Cleveland, told this news organization. “I will be much more likely to pursue diagnostic workup in my AD patients who have GI complaints.”

However, AD severity was measured by proxy, added Dr. Scarberry, who was not involved in the study, and the study lacked important racial and ethnic data.

Lindsay C. Strowd, MD, associate professor of dermatology at Wake Forest University, Winston-Salem, N.C., also not involved in the study, said in an interview that she found the size of the cohort and the longitudinal data to be strengths of the study.

But, she added, the “lack of family IBD history, race and ethnicity, and comorbidities, are limitations, as is treatment exposure used as a proxy for disease severity, given that physician treatment practices differ.”

For Steven R. Feldman, MD, PhD, professor of dermatology at Wake Forest, “the most important conclusion, and it is a definitive finding, [is] that IBD is uncommon, even in patients with AD.

“The findings could be misinterpreted,” cautioned Dr. Feldman, who was not involved in the study. “While there is an increased relative risk, the absolute risk is small.” The study found that “the highest relative risk group is children with severe AD, who have a roughly fivefold increased risk for CD.” However, he added, the incidence rates of CD were 0.68 per 1,000 person-years in children with severe AD and 0.08 per 1,000 person-years in controls.

“Basically, because Crohn’s disease and IBD don’t happen very often, the modest increase in relative risk the investigators found doesn’t amount to much we’d have to worry about,” he said. “The findings do not show any need to screen patients with atopic dermatitis for IBD any more than we’d need to screen patients without atopic dermatitis.”

The increased relative risk “could be a clue to possible genetic connections between diseases,” he added. “But when we’re making clinical decisions, those decisions should be based on the absolute risk that some event may occur.”

Susan Massick, MD, dermatologist and associate professor at The Ohio State University in Columbus, who was not involved with the study, said in an interview, “We are still scratching the surface of the complexity of the immune and inflammatory pathways in AD and IBD.

“It is important to remember that correlation does not mean causation,” Dr. Massick said. “It would be premature to draw direct conclusions based on this study alone.”

The authors recommend future related studies in more diverse populations.

Dr. Gelfand and two coauthors reported ties with Pfizer, which supported the study. Dr. Gelfand and three coauthors reported ties with other pharmaceutical companies. Dr. Maguiness, Dr. Scarberry, Dr. Strowd, and Dr. Massick reported having no relevant disclosures. Dr. Feldman reported ties with Pfizer and other pharmaceutical companies.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM JAMA DERMATOLOGY

FDA OKs subcutaneous vedolizumab for UC maintenance therapy

The Food and Drug Administration has approved the subcutaneous administration of vedolizumab (Entyvio SC, Takeda) for maintenance therapy in adults with moderately to severely active ulcerative colitis (UC) following induction therapy with intravenous administration of vedolizumab.

The FDA approved the intravenous formulation of the biologic in 2014 for patients with moderate to severe UC and Crohn’s disease who failed or cannot tolerate other therapies.

The approval of subcutaneous (SC) vedolizumab was based on results from the phase 3, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled VISIBLE 1 trial.

The trial assessed the safety and efficacy of maintenance therapy with SC vedolizumab in adult patients with moderately to severely active UC who achieved clinical response at week 6 following two doses of intravenous vedolizumab.

At week 6, 162 patients were randomly allocated (2:1) to vedolizumab or placebo by subcutaneous injection every 2 weeks. The primary endpoint was clinical remission at week 52, defined as a total Mayo score of 2 or less and no individual subscore greater than 1.

At week 52, nearly half (46%) of patients who received vedolizumab SC maintenance therapy achieved clinical remission, compared with 14% of those who received placebo SC (P < .001).

The safety profile of SC vedolizumab was “generally consistent” with that of intravenous vedolizumab, with the addition of injection-site reactions, the drugmaker, Takeda, said in a news release.

The most common adverse reactions with intravenous vedolizumab are nasopharyngitis, headache, arthralgia, nausea, pyrexia (fever), upper respiratory tract infection, fatigue, cough, bronchitis, influenza, back pain, rash, pruritus, sinusitis, oropharyngeal pain, and pain in the extremities.

SC vedolizumab “can provide physicians with an additional administration option for achieving remission in their moderate to severe ulcerative colitis patients,” according to Bruce E. Sands, MD, AGAF, chief of gastroenterology at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York. He provided a statement in the Takeda news release.

“I appreciate now having a subcutaneous administration option that provides a clinical profile consistent with Entyvio intravenous while also giving me and my appropriate UC patients a choice of how they receive their maintenance therapy,” Dr. Sands said.

The FDA is currently reviewing Takeda’s biologics license application for subcutaneous administration of vedolizumab in the treatment of adults with moderately to severely active Crohn’s disease.

Dr. Sands is a paid consultant of Takeda.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The Food and Drug Administration has approved the subcutaneous administration of vedolizumab (Entyvio SC, Takeda) for maintenance therapy in adults with moderately to severely active ulcerative colitis (UC) following induction therapy with intravenous administration of vedolizumab.

The FDA approved the intravenous formulation of the biologic in 2014 for patients with moderate to severe UC and Crohn’s disease who failed or cannot tolerate other therapies.

The approval of subcutaneous (SC) vedolizumab was based on results from the phase 3, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled VISIBLE 1 trial.

The trial assessed the safety and efficacy of maintenance therapy with SC vedolizumab in adult patients with moderately to severely active UC who achieved clinical response at week 6 following two doses of intravenous vedolizumab.

At week 6, 162 patients were randomly allocated (2:1) to vedolizumab or placebo by subcutaneous injection every 2 weeks. The primary endpoint was clinical remission at week 52, defined as a total Mayo score of 2 or less and no individual subscore greater than 1.

At week 52, nearly half (46%) of patients who received vedolizumab SC maintenance therapy achieved clinical remission, compared with 14% of those who received placebo SC (P < .001).

The safety profile of SC vedolizumab was “generally consistent” with that of intravenous vedolizumab, with the addition of injection-site reactions, the drugmaker, Takeda, said in a news release.

The most common adverse reactions with intravenous vedolizumab are nasopharyngitis, headache, arthralgia, nausea, pyrexia (fever), upper respiratory tract infection, fatigue, cough, bronchitis, influenza, back pain, rash, pruritus, sinusitis, oropharyngeal pain, and pain in the extremities.

SC vedolizumab “can provide physicians with an additional administration option for achieving remission in their moderate to severe ulcerative colitis patients,” according to Bruce E. Sands, MD, AGAF, chief of gastroenterology at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York. He provided a statement in the Takeda news release.

“I appreciate now having a subcutaneous administration option that provides a clinical profile consistent with Entyvio intravenous while also giving me and my appropriate UC patients a choice of how they receive their maintenance therapy,” Dr. Sands said.

The FDA is currently reviewing Takeda’s biologics license application for subcutaneous administration of vedolizumab in the treatment of adults with moderately to severely active Crohn’s disease.

Dr. Sands is a paid consultant of Takeda.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The Food and Drug Administration has approved the subcutaneous administration of vedolizumab (Entyvio SC, Takeda) for maintenance therapy in adults with moderately to severely active ulcerative colitis (UC) following induction therapy with intravenous administration of vedolizumab.

The FDA approved the intravenous formulation of the biologic in 2014 for patients with moderate to severe UC and Crohn’s disease who failed or cannot tolerate other therapies.

The approval of subcutaneous (SC) vedolizumab was based on results from the phase 3, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled VISIBLE 1 trial.

The trial assessed the safety and efficacy of maintenance therapy with SC vedolizumab in adult patients with moderately to severely active UC who achieved clinical response at week 6 following two doses of intravenous vedolizumab.

At week 6, 162 patients were randomly allocated (2:1) to vedolizumab or placebo by subcutaneous injection every 2 weeks. The primary endpoint was clinical remission at week 52, defined as a total Mayo score of 2 or less and no individual subscore greater than 1.

At week 52, nearly half (46%) of patients who received vedolizumab SC maintenance therapy achieved clinical remission, compared with 14% of those who received placebo SC (P < .001).

The safety profile of SC vedolizumab was “generally consistent” with that of intravenous vedolizumab, with the addition of injection-site reactions, the drugmaker, Takeda, said in a news release.

The most common adverse reactions with intravenous vedolizumab are nasopharyngitis, headache, arthralgia, nausea, pyrexia (fever), upper respiratory tract infection, fatigue, cough, bronchitis, influenza, back pain, rash, pruritus, sinusitis, oropharyngeal pain, and pain in the extremities.

SC vedolizumab “can provide physicians with an additional administration option for achieving remission in their moderate to severe ulcerative colitis patients,” according to Bruce E. Sands, MD, AGAF, chief of gastroenterology at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York. He provided a statement in the Takeda news release.

“I appreciate now having a subcutaneous administration option that provides a clinical profile consistent with Entyvio intravenous while also giving me and my appropriate UC patients a choice of how they receive their maintenance therapy,” Dr. Sands said.

The FDA is currently reviewing Takeda’s biologics license application for subcutaneous administration of vedolizumab in the treatment of adults with moderately to severely active Crohn’s disease.

Dr. Sands is a paid consultant of Takeda.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

ChatGPT may aid decision-making in the ED for acute ulcerative colitis

(UC).

In a small study, ChatGPT version 4 (GPT-4) accurately gauged disease severity and made decisions about the need for hospitalization that were largely in line with expert gastroenterologists.

“Our findings suggest that GPT-4 has potential as a clinical decision-support tool in assessing UC severity and recommending suitable settings for further treatment,” say the authors, led by Asaf Levartovsky, MD, department of gastroenterology, Sheba Medical Center, Tel Aviv University.

The study was published online in the American Journal of Gastroenterology.

Assessing its potential

UC is a chronic inflammatory bowel disease known for episodes of flare-ups and remissions. Flare-ups often result in a trip to the ED, where staff must rapidly assess disease severity and need for hospital admission.

Dr. Levartovsky and colleagues explored how helpful GPT-4 could be in 20 distinct presentations of acute UC in the ED. They assessed the chatbot’s ability to determine the severity of disease and whether a specific presentation warranted hospital admission for further treatment.

They fed GPT-4 case summaries that included crucial data such as symptoms, vital signs, and laboratory results. For each case, they asked the chatbot to assess disease severity based on established criteria and recommend hospital admission or outpatient care.

The GPT-4 answers were compared with assessments made by gastroenterologists and the actual decision regarding hospitalization made by the physician in the ED.

Overall, ChatGPT categorized acute UC as severe in 12 patients, as moderate in 7, and as mild in 1. In each case, the chatbot provided a detailed answer depicting severity of every variable of the criteria and an overall severity classification.

ChatGPT’s assessments were consistent with gastroenterologists’ assessments 80% of the time, with a “high degree of reliability” between the two assessments, the study team reports.

The average correlation between ChatGPT and physician ratings was 0.839 (P < .001). Inconsistencies in four cases stemmed largely from inaccurate cut-off values for systemic variables (such as hemoglobin and tachycardia).

Following severity assessment, ChatGPT leaned toward hospital admission for 16 patients, whereas in actual clinical practice, only 12 patients were hospitalized. In one patient with moderate UC who was discharged, ChatGPT was in favor of hospitalization, based on the patient’s age and comorbid conditions. For two moderate UC cases, the chatbot recommended consultation with a health care professional for further evaluation and management, which the researchers deemed to be an indecisive response.

Based on their findings, the researchers say ChatGPT could serve as a real-time decision support tool – one that is not meant to replace physicians but rather enhance human decision-making.

They note that the small sample size is a limitation and that ChatGPT’s accuracy rate requires further validation across larger samples and diverse clinical scenarios.

The study had no specific funding. The authors report no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

(UC).

In a small study, ChatGPT version 4 (GPT-4) accurately gauged disease severity and made decisions about the need for hospitalization that were largely in line with expert gastroenterologists.

“Our findings suggest that GPT-4 has potential as a clinical decision-support tool in assessing UC severity and recommending suitable settings for further treatment,” say the authors, led by Asaf Levartovsky, MD, department of gastroenterology, Sheba Medical Center, Tel Aviv University.

The study was published online in the American Journal of Gastroenterology.

Assessing its potential

UC is a chronic inflammatory bowel disease known for episodes of flare-ups and remissions. Flare-ups often result in a trip to the ED, where staff must rapidly assess disease severity and need for hospital admission.

Dr. Levartovsky and colleagues explored how helpful GPT-4 could be in 20 distinct presentations of acute UC in the ED. They assessed the chatbot’s ability to determine the severity of disease and whether a specific presentation warranted hospital admission for further treatment.

They fed GPT-4 case summaries that included crucial data such as symptoms, vital signs, and laboratory results. For each case, they asked the chatbot to assess disease severity based on established criteria and recommend hospital admission or outpatient care.

The GPT-4 answers were compared with assessments made by gastroenterologists and the actual decision regarding hospitalization made by the physician in the ED.

Overall, ChatGPT categorized acute UC as severe in 12 patients, as moderate in 7, and as mild in 1. In each case, the chatbot provided a detailed answer depicting severity of every variable of the criteria and an overall severity classification.

ChatGPT’s assessments were consistent with gastroenterologists’ assessments 80% of the time, with a “high degree of reliability” between the two assessments, the study team reports.

The average correlation between ChatGPT and physician ratings was 0.839 (P < .001). Inconsistencies in four cases stemmed largely from inaccurate cut-off values for systemic variables (such as hemoglobin and tachycardia).

Following severity assessment, ChatGPT leaned toward hospital admission for 16 patients, whereas in actual clinical practice, only 12 patients were hospitalized. In one patient with moderate UC who was discharged, ChatGPT was in favor of hospitalization, based on the patient’s age and comorbid conditions. For two moderate UC cases, the chatbot recommended consultation with a health care professional for further evaluation and management, which the researchers deemed to be an indecisive response.

Based on their findings, the researchers say ChatGPT could serve as a real-time decision support tool – one that is not meant to replace physicians but rather enhance human decision-making.

They note that the small sample size is a limitation and that ChatGPT’s accuracy rate requires further validation across larger samples and diverse clinical scenarios.

The study had no specific funding. The authors report no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

(UC).

In a small study, ChatGPT version 4 (GPT-4) accurately gauged disease severity and made decisions about the need for hospitalization that were largely in line with expert gastroenterologists.

“Our findings suggest that GPT-4 has potential as a clinical decision-support tool in assessing UC severity and recommending suitable settings for further treatment,” say the authors, led by Asaf Levartovsky, MD, department of gastroenterology, Sheba Medical Center, Tel Aviv University.

The study was published online in the American Journal of Gastroenterology.

Assessing its potential

UC is a chronic inflammatory bowel disease known for episodes of flare-ups and remissions. Flare-ups often result in a trip to the ED, where staff must rapidly assess disease severity and need for hospital admission.

Dr. Levartovsky and colleagues explored how helpful GPT-4 could be in 20 distinct presentations of acute UC in the ED. They assessed the chatbot’s ability to determine the severity of disease and whether a specific presentation warranted hospital admission for further treatment.

They fed GPT-4 case summaries that included crucial data such as symptoms, vital signs, and laboratory results. For each case, they asked the chatbot to assess disease severity based on established criteria and recommend hospital admission or outpatient care.

The GPT-4 answers were compared with assessments made by gastroenterologists and the actual decision regarding hospitalization made by the physician in the ED.

Overall, ChatGPT categorized acute UC as severe in 12 patients, as moderate in 7, and as mild in 1. In each case, the chatbot provided a detailed answer depicting severity of every variable of the criteria and an overall severity classification.

ChatGPT’s assessments were consistent with gastroenterologists’ assessments 80% of the time, with a “high degree of reliability” between the two assessments, the study team reports.

The average correlation between ChatGPT and physician ratings was 0.839 (P < .001). Inconsistencies in four cases stemmed largely from inaccurate cut-off values for systemic variables (such as hemoglobin and tachycardia).

Following severity assessment, ChatGPT leaned toward hospital admission for 16 patients, whereas in actual clinical practice, only 12 patients were hospitalized. In one patient with moderate UC who was discharged, ChatGPT was in favor of hospitalization, based on the patient’s age and comorbid conditions. For two moderate UC cases, the chatbot recommended consultation with a health care professional for further evaluation and management, which the researchers deemed to be an indecisive response.

Based on their findings, the researchers say ChatGPT could serve as a real-time decision support tool – one that is not meant to replace physicians but rather enhance human decision-making.

They note that the small sample size is a limitation and that ChatGPT’s accuracy rate requires further validation across larger samples and diverse clinical scenarios.

The study had no specific funding. The authors report no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM THE AMERICAN JOURNAL OF GASTROENTEROLOGY

Real-world data confirm efficacy of dupilumab in severe EoE

TOPLINE:

Dupilumab provides histologic, endoscopic, and symptomatic improvement in patients with severe, treatment-refractory, fibrostenotic eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE), new research shows.

METHODOLOGY:

- The researchers conducted a retrospective cohort study of 46 patients with severe, treatment-refractory fibrostenotic EoE who were prescribed dupilumab 300 mg subcutaneously every other week or weekly.

- Histologic response, endoscopic severity, and symptom improvement were assessed using the results of esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) conducted before and after dupilumab therapy.

TAKEAWAY:

- Most patients demonstrated endoscopic, histologic, and symptomatic improvement on dupilumab, compared with predupilumab EGD results.

- The average peak eosinophil count improved from 70 eosinophils/high-power field to 9 eosinophils/HPF while on dupilumab, and 80% of patients achieved histologic remission (< 15 eosinophils/HPF), compared with 11% before dupilumab.

- Endoscopic features also improved on dupilumab, with a significant reduction in exudates, rings, edema, and furrows. The total EoE Endoscopic Reference Score decreased from 4.62 to 1.89 (P < .001).

- With dupilumab, a significant increase in predilation esophageal diameter (from 13.9 to 16 mm; P < .001) was observed, with no change in the proportion of strictures.

- Global symptom improvement was reported in 91% of patients while on dupilumab versus 2% before dupilumab.

IN PRACTICE:

“These results echo the results from the prior phase 3 study, but in a population where most subjects would likely have been excluded due to stricture severity and need for dilation,” the authors wrote. “ Further studies are needed to determine not only long-term efficacy of dupilumab for this group of EoE patients, but whether dupilumab could be moved earlier in the treatment algorithm for this severe subgroup.”

SOURCE:

The study, by Christopher Lee, MD, and Evan Dellon, MD, MPH, with the Center for Esophageal Diseases and Swallowing, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, was published online in Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology.

LIMITATIONS:

The study involved a single tertiary care center, which could limit the generalizability of the findings. The patients were primarily adults, so the results may not be able to be extended to younger children.

DISCLOSURES:

The study had no specific funding. Dr. Dellon has received research funding and consulting fees from multiple pharmaceutical companies. Dr. Lee has no relevant disclosures.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

Dupilumab provides histologic, endoscopic, and symptomatic improvement in patients with severe, treatment-refractory, fibrostenotic eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE), new research shows.

METHODOLOGY:

- The researchers conducted a retrospective cohort study of 46 patients with severe, treatment-refractory fibrostenotic EoE who were prescribed dupilumab 300 mg subcutaneously every other week or weekly.

- Histologic response, endoscopic severity, and symptom improvement were assessed using the results of esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) conducted before and after dupilumab therapy.

TAKEAWAY:

- Most patients demonstrated endoscopic, histologic, and symptomatic improvement on dupilumab, compared with predupilumab EGD results.

- The average peak eosinophil count improved from 70 eosinophils/high-power field to 9 eosinophils/HPF while on dupilumab, and 80% of patients achieved histologic remission (< 15 eosinophils/HPF), compared with 11% before dupilumab.

- Endoscopic features also improved on dupilumab, with a significant reduction in exudates, rings, edema, and furrows. The total EoE Endoscopic Reference Score decreased from 4.62 to 1.89 (P < .001).

- With dupilumab, a significant increase in predilation esophageal diameter (from 13.9 to 16 mm; P < .001) was observed, with no change in the proportion of strictures.

- Global symptom improvement was reported in 91% of patients while on dupilumab versus 2% before dupilumab.

IN PRACTICE:

“These results echo the results from the prior phase 3 study, but in a population where most subjects would likely have been excluded due to stricture severity and need for dilation,” the authors wrote. “ Further studies are needed to determine not only long-term efficacy of dupilumab for this group of EoE patients, but whether dupilumab could be moved earlier in the treatment algorithm for this severe subgroup.”

SOURCE:

The study, by Christopher Lee, MD, and Evan Dellon, MD, MPH, with the Center for Esophageal Diseases and Swallowing, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, was published online in Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology.

LIMITATIONS:

The study involved a single tertiary care center, which could limit the generalizability of the findings. The patients were primarily adults, so the results may not be able to be extended to younger children.

DISCLOSURES:

The study had no specific funding. Dr. Dellon has received research funding and consulting fees from multiple pharmaceutical companies. Dr. Lee has no relevant disclosures.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

Dupilumab provides histologic, endoscopic, and symptomatic improvement in patients with severe, treatment-refractory, fibrostenotic eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE), new research shows.

METHODOLOGY:

- The researchers conducted a retrospective cohort study of 46 patients with severe, treatment-refractory fibrostenotic EoE who were prescribed dupilumab 300 mg subcutaneously every other week or weekly.

- Histologic response, endoscopic severity, and symptom improvement were assessed using the results of esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) conducted before and after dupilumab therapy.

TAKEAWAY:

- Most patients demonstrated endoscopic, histologic, and symptomatic improvement on dupilumab, compared with predupilumab EGD results.

- The average peak eosinophil count improved from 70 eosinophils/high-power field to 9 eosinophils/HPF while on dupilumab, and 80% of patients achieved histologic remission (< 15 eosinophils/HPF), compared with 11% before dupilumab.

- Endoscopic features also improved on dupilumab, with a significant reduction in exudates, rings, edema, and furrows. The total EoE Endoscopic Reference Score decreased from 4.62 to 1.89 (P < .001).

- With dupilumab, a significant increase in predilation esophageal diameter (from 13.9 to 16 mm; P < .001) was observed, with no change in the proportion of strictures.

- Global symptom improvement was reported in 91% of patients while on dupilumab versus 2% before dupilumab.

IN PRACTICE:

“These results echo the results from the prior phase 3 study, but in a population where most subjects would likely have been excluded due to stricture severity and need for dilation,” the authors wrote. “ Further studies are needed to determine not only long-term efficacy of dupilumab for this group of EoE patients, but whether dupilumab could be moved earlier in the treatment algorithm for this severe subgroup.”

SOURCE:

The study, by Christopher Lee, MD, and Evan Dellon, MD, MPH, with the Center for Esophageal Diseases and Swallowing, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, was published online in Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology.

LIMITATIONS:

The study involved a single tertiary care center, which could limit the generalizability of the findings. The patients were primarily adults, so the results may not be able to be extended to younger children.

DISCLOSURES:

The study had no specific funding. Dr. Dellon has received research funding and consulting fees from multiple pharmaceutical companies. Dr. Lee has no relevant disclosures.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM CLINICAL GASTROENTEROLOGY AND HEPATOLOGY

Palpable mass on exam

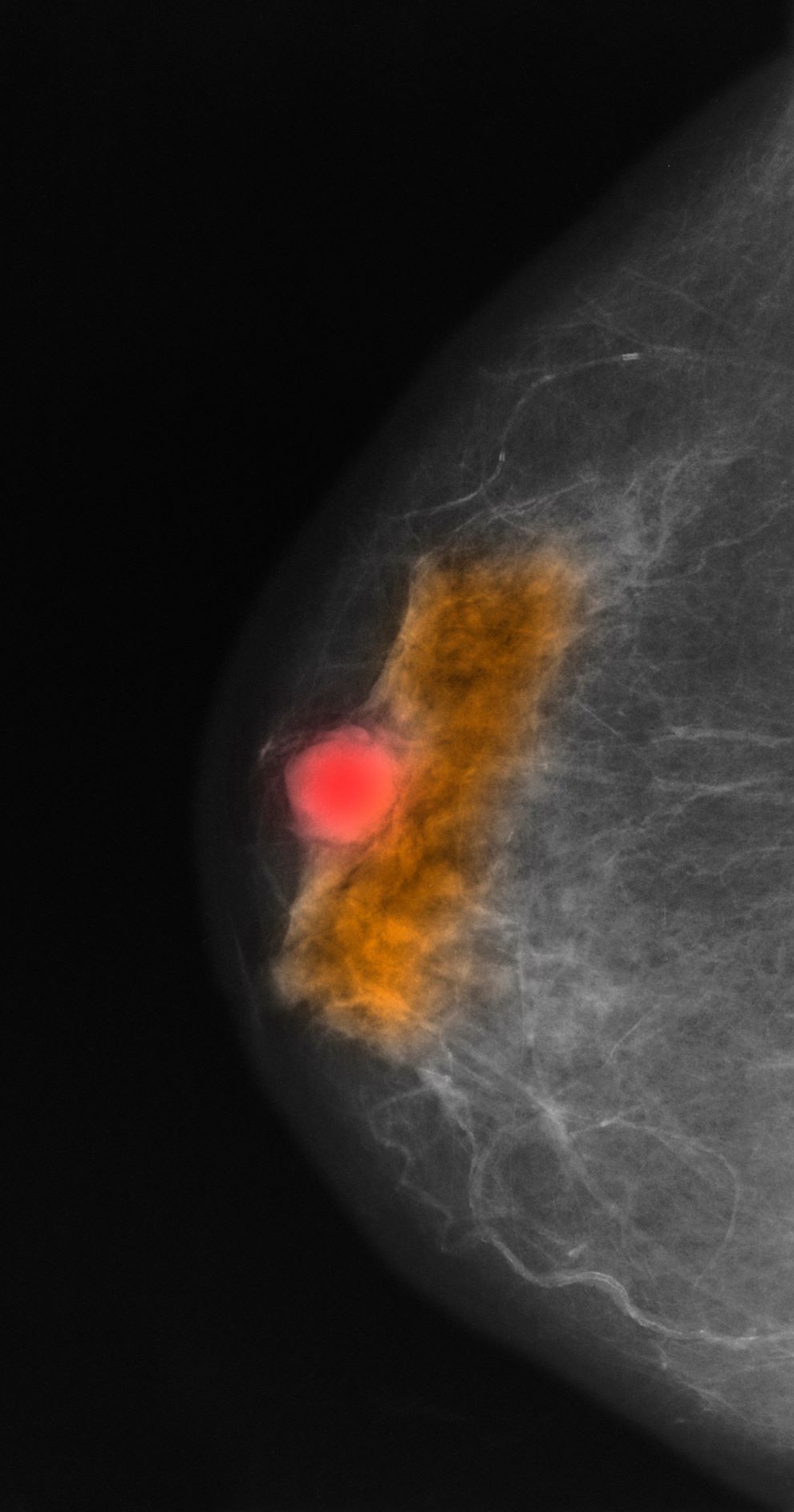

Given the age of the patient and the results of imaging, histology, and immunohistochemistry, the diagnosis is mucinous (colloid) carcinoma. The patient and oncologist discuss prognosis and discuss treatment options, such as breast-conserving surgery, local radiation, and possible adjuvant endocrine therapy.

Mucinous (colloid) carcinoma is a rare histologic subtype of invasive breast cancer that occurs in < 5% of patients and generally develops in those who are ≥ 60 years old. Patients with mucinous (colloid) carcinoma generally present with a palpable mass or, on imaging, a poorly defined tumor with rare calcifications. The histologic hallmark of mucinous (colloid) carcinoma is mucin production. There are two subtypes of mucinous breast carcinoma: pure and mixed. A pure mucinous tumor is defined as a carcinoma consisting of ≥ 90% intracellular or extracellular mucin. This pure subtype occurs more frequently than mixed mucinous breast carcinoma and is also less likely to metastasize to the lymph nodes.

Differential diagnosis can be challenging because mucinous (colloid) carcinoma can mimic a benign tumor on imaging, which is why it is important to include multiple factors when diagnosing in daily practice. According to the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN), diagnosing nonmetastatic invasive breast cancer like mucinous (colloid) carcinoma involves patient history and physical exam, diagnostic bilateral mammography (ultrasound and breast MRI, as needed), pathology review, tumor estrogen/progesterone receptor status, HER2 status, and genetic counseling for those with a family history. In most cases of mucinous (colloid) carcinoma, tumors are ER- and PR-positive and HER2-negative.

A pure mucinous histologic subtype is generally associated with a favorable prognosis; 10-year survival rates of mucinous (colloid) carcinoma are > 80%. The tumor is generally not high grade and is most often classified on surgical excision. Two main types of lesions exist — A and B — as does a combination of AB. Type A has larger quantities of extracellular mucin and is considered the classic form of mucinous carcinoma. Type B is a distinct variant with endocrine differentiation. In addition, glycoproteins MUC2 and MUC6 are predominantly expressed in mucinous (colloid) carcinoma; ductal carcinoma in situ is not often found in this setting.

NCCN recommends multidisciplinary care and development of a personalized survivorship treatment plan, which includes a customized summary of possible long-term treatment toxicities. In addition, multidisciplinary care coordination encourages close follow-up that helps patients adhere to their medications and stay current with ongoing screening.

Breast-conserving surgery and local radiation therapy are often the two modalities used to treat mucinous (colloid) carcinoma, especially because prognosis is so favorable. NCCN recommends the consideration of adjuvant endocrine treatment for patients with pure mucinous tumors that are HER2-negative and ER-positive and/or PR-positive; staged at pT1, pT2, or pT3, and pN0 or pN1mi; and ≤ 2.9 cm. Adjuvant endocrine therapy is recommended for patients with the same disease characteristics whose tumor is ≥ 3 cm.

Avan J. Armaghani, MD, Assistant Member, Department of Breast Oncology, Moffitt Cancer Center, University of South Florida, Tampa, FL.

Avan J. Armaghani, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

Given the age of the patient and the results of imaging, histology, and immunohistochemistry, the diagnosis is mucinous (colloid) carcinoma. The patient and oncologist discuss prognosis and discuss treatment options, such as breast-conserving surgery, local radiation, and possible adjuvant endocrine therapy.

Mucinous (colloid) carcinoma is a rare histologic subtype of invasive breast cancer that occurs in < 5% of patients and generally develops in those who are ≥ 60 years old. Patients with mucinous (colloid) carcinoma generally present with a palpable mass or, on imaging, a poorly defined tumor with rare calcifications. The histologic hallmark of mucinous (colloid) carcinoma is mucin production. There are two subtypes of mucinous breast carcinoma: pure and mixed. A pure mucinous tumor is defined as a carcinoma consisting of ≥ 90% intracellular or extracellular mucin. This pure subtype occurs more frequently than mixed mucinous breast carcinoma and is also less likely to metastasize to the lymph nodes.

Differential diagnosis can be challenging because mucinous (colloid) carcinoma can mimic a benign tumor on imaging, which is why it is important to include multiple factors when diagnosing in daily practice. According to the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN), diagnosing nonmetastatic invasive breast cancer like mucinous (colloid) carcinoma involves patient history and physical exam, diagnostic bilateral mammography (ultrasound and breast MRI, as needed), pathology review, tumor estrogen/progesterone receptor status, HER2 status, and genetic counseling for those with a family history. In most cases of mucinous (colloid) carcinoma, tumors are ER- and PR-positive and HER2-negative.

A pure mucinous histologic subtype is generally associated with a favorable prognosis; 10-year survival rates of mucinous (colloid) carcinoma are > 80%. The tumor is generally not high grade and is most often classified on surgical excision. Two main types of lesions exist — A and B — as does a combination of AB. Type A has larger quantities of extracellular mucin and is considered the classic form of mucinous carcinoma. Type B is a distinct variant with endocrine differentiation. In addition, glycoproteins MUC2 and MUC6 are predominantly expressed in mucinous (colloid) carcinoma; ductal carcinoma in situ is not often found in this setting.

NCCN recommends multidisciplinary care and development of a personalized survivorship treatment plan, which includes a customized summary of possible long-term treatment toxicities. In addition, multidisciplinary care coordination encourages close follow-up that helps patients adhere to their medications and stay current with ongoing screening.

Breast-conserving surgery and local radiation therapy are often the two modalities used to treat mucinous (colloid) carcinoma, especially because prognosis is so favorable. NCCN recommends the consideration of adjuvant endocrine treatment for patients with pure mucinous tumors that are HER2-negative and ER-positive and/or PR-positive; staged at pT1, pT2, or pT3, and pN0 or pN1mi; and ≤ 2.9 cm. Adjuvant endocrine therapy is recommended for patients with the same disease characteristics whose tumor is ≥ 3 cm.

Avan J. Armaghani, MD, Assistant Member, Department of Breast Oncology, Moffitt Cancer Center, University of South Florida, Tampa, FL.

Avan J. Armaghani, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

Given the age of the patient and the results of imaging, histology, and immunohistochemistry, the diagnosis is mucinous (colloid) carcinoma. The patient and oncologist discuss prognosis and discuss treatment options, such as breast-conserving surgery, local radiation, and possible adjuvant endocrine therapy.

Mucinous (colloid) carcinoma is a rare histologic subtype of invasive breast cancer that occurs in < 5% of patients and generally develops in those who are ≥ 60 years old. Patients with mucinous (colloid) carcinoma generally present with a palpable mass or, on imaging, a poorly defined tumor with rare calcifications. The histologic hallmark of mucinous (colloid) carcinoma is mucin production. There are two subtypes of mucinous breast carcinoma: pure and mixed. A pure mucinous tumor is defined as a carcinoma consisting of ≥ 90% intracellular or extracellular mucin. This pure subtype occurs more frequently than mixed mucinous breast carcinoma and is also less likely to metastasize to the lymph nodes.

Differential diagnosis can be challenging because mucinous (colloid) carcinoma can mimic a benign tumor on imaging, which is why it is important to include multiple factors when diagnosing in daily practice. According to the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN), diagnosing nonmetastatic invasive breast cancer like mucinous (colloid) carcinoma involves patient history and physical exam, diagnostic bilateral mammography (ultrasound and breast MRI, as needed), pathology review, tumor estrogen/progesterone receptor status, HER2 status, and genetic counseling for those with a family history. In most cases of mucinous (colloid) carcinoma, tumors are ER- and PR-positive and HER2-negative.

A pure mucinous histologic subtype is generally associated with a favorable prognosis; 10-year survival rates of mucinous (colloid) carcinoma are > 80%. The tumor is generally not high grade and is most often classified on surgical excision. Two main types of lesions exist — A and B — as does a combination of AB. Type A has larger quantities of extracellular mucin and is considered the classic form of mucinous carcinoma. Type B is a distinct variant with endocrine differentiation. In addition, glycoproteins MUC2 and MUC6 are predominantly expressed in mucinous (colloid) carcinoma; ductal carcinoma in situ is not often found in this setting.

NCCN recommends multidisciplinary care and development of a personalized survivorship treatment plan, which includes a customized summary of possible long-term treatment toxicities. In addition, multidisciplinary care coordination encourages close follow-up that helps patients adhere to their medications and stay current with ongoing screening.

Breast-conserving surgery and local radiation therapy are often the two modalities used to treat mucinous (colloid) carcinoma, especially because prognosis is so favorable. NCCN recommends the consideration of adjuvant endocrine treatment for patients with pure mucinous tumors that are HER2-negative and ER-positive and/or PR-positive; staged at pT1, pT2, or pT3, and pN0 or pN1mi; and ≤ 2.9 cm. Adjuvant endocrine therapy is recommended for patients with the same disease characteristics whose tumor is ≥ 3 cm.

Avan J. Armaghani, MD, Assistant Member, Department of Breast Oncology, Moffitt Cancer Center, University of South Florida, Tampa, FL.

Avan J. Armaghani, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

A 64-year-old woman with no prior history of cancer presents to an oncologist after referral from her primary care physician (PCP). The referral came after the patient reported feeling a lump in her left breast during self-examination. She made an appointment with her PCP, who confirmed a palpable mass on physical examination and ordered mammography. Bilateral mammography revealed a poorly defined tumor with rare calcifications in the left breast. Size of the tumor was 1.8 cm. Now, the oncologist orders a percutaneous vacuum-assisted large-gauge core-needle biopsy with image guidance. Results show the tumor is pure mucinous, ER-positive and PR-positive, and HER2-negative; staging is pT2/pN0. Immunohistochemistry reveals that the predominantly expressed glycoproteins are MUC2 and MUC6.

AMA funds standardized BP training for medical, PA, and nursing schools

according to the American Medical Association. Hypertension affects about half of U.S. adults and is a leading contributor to cardiovascular disease.

First-year medical students typically read about BP measurement in a textbook and possibly attend a lecture before practicing using a manual cuff a few times on classmates, said Martha Gulati, MD, professor and director of preventive cardiology at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles.

The dearth of BP instruction is alarming because inaccurate readings contribute to under- and overtreatment of hypertension, she said in an interview.

The AMA hopes $100,000 in grants to five health education schools will help improve BP instruction. The group recently announced it would give $20,000 each to five schools that train health professionals, expanding on a 2021 program to improve BP measurement training.

The new grants for interactive lessons will benefit nearly 5,000 students from Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore; Nova Southeastern University, Fort Lauderdale, Fla.; University of Washington, Seattle; Stony Brook (N.Y.) University; and the University of Pittsburgh.

In a 2021 survey of 571 clinicians, most of whom were cardiologists, Dr. Gulati found that only 23% performed accurate BP measurements despite the majority saying they trusted BP readings taken in their clinic. Accurate readings were defined as routinely checking BP in both arms, checking BP at least twice each visit, and waiting 5 minutes before taking the reading.

Med students fare no better when it comes to BP skills. In a 2017 study of 159 students from medical schools in 37 states, only one student demonstrated proficiency in all 11 elements necessary to measure BP accurately. Students, on average, performed just four of them correctly.

The elements of proper BP measurement include patients resting for 5 minutes before the measurement with legs uncrossed, feet on floor, and arm supported, not talking, reading, or using cell phone; BP taken in both arms with correct size of cuff placed over bare arm; and identifying BP from the arm with the higher reading as clinically more important and as the one to use for future readings.

Manual BP readings require an appropriately sized BP cuff, a sphygmomanometer, and a clinician skilled in using a stethoscope and auscultatory method. Meanwhile, automated readings require a clinician to place the cuff, but a digital device collects the measurement. Though preference depends on the setting and clinician, automated readings are more common. In Dr. Gulati’s study, automated BP assessment was used by 58% of respondents.

Depending on the BP device and technique, significant variations in readings can occur. In a 2021 study, Current Hypertension Reports found that automated readings may more closely reflect the patient’s baseline BP and produce results similar to ambulatory monitoring by a medical professional. An earlier JAMA Internal Medicine analysis found that clinicians’ manual readings reflect higher BP measurements than automated readings.

Though the AMA offers a free online series on BP measurement for students, making the training available to more health care team members can help prevent hypertension, said Kate Kirley, MD, director of the AMA’s chronic disease prevention and programs.

Concern over the lack of standardized BP techniques isn’t new. In 2019, the American Heart Association and the AMA created an online BP course for health care workers. Two years later, the AMA offered grants to five medical schools for training courses.

Most of the new training sessions already on the AMA website take students about 15 minutes to complete. Dr. Kirley says because equipment varies across settings, participants will learn how to conduct manual, semi-automated, and automated office BP readings and identify workarounds for less-than-ideal room setups that can skew results. They will also explore how to guide patients in performing BP readings at home.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

according to the American Medical Association. Hypertension affects about half of U.S. adults and is a leading contributor to cardiovascular disease.

First-year medical students typically read about BP measurement in a textbook and possibly attend a lecture before practicing using a manual cuff a few times on classmates, said Martha Gulati, MD, professor and director of preventive cardiology at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles.

The dearth of BP instruction is alarming because inaccurate readings contribute to under- and overtreatment of hypertension, she said in an interview.

The AMA hopes $100,000 in grants to five health education schools will help improve BP instruction. The group recently announced it would give $20,000 each to five schools that train health professionals, expanding on a 2021 program to improve BP measurement training.

The new grants for interactive lessons will benefit nearly 5,000 students from Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore; Nova Southeastern University, Fort Lauderdale, Fla.; University of Washington, Seattle; Stony Brook (N.Y.) University; and the University of Pittsburgh.

In a 2021 survey of 571 clinicians, most of whom were cardiologists, Dr. Gulati found that only 23% performed accurate BP measurements despite the majority saying they trusted BP readings taken in their clinic. Accurate readings were defined as routinely checking BP in both arms, checking BP at least twice each visit, and waiting 5 minutes before taking the reading.

Med students fare no better when it comes to BP skills. In a 2017 study of 159 students from medical schools in 37 states, only one student demonstrated proficiency in all 11 elements necessary to measure BP accurately. Students, on average, performed just four of them correctly.

The elements of proper BP measurement include patients resting for 5 minutes before the measurement with legs uncrossed, feet on floor, and arm supported, not talking, reading, or using cell phone; BP taken in both arms with correct size of cuff placed over bare arm; and identifying BP from the arm with the higher reading as clinically more important and as the one to use for future readings.

Manual BP readings require an appropriately sized BP cuff, a sphygmomanometer, and a clinician skilled in using a stethoscope and auscultatory method. Meanwhile, automated readings require a clinician to place the cuff, but a digital device collects the measurement. Though preference depends on the setting and clinician, automated readings are more common. In Dr. Gulati’s study, automated BP assessment was used by 58% of respondents.

Depending on the BP device and technique, significant variations in readings can occur. In a 2021 study, Current Hypertension Reports found that automated readings may more closely reflect the patient’s baseline BP and produce results similar to ambulatory monitoring by a medical professional. An earlier JAMA Internal Medicine analysis found that clinicians’ manual readings reflect higher BP measurements than automated readings.

Though the AMA offers a free online series on BP measurement for students, making the training available to more health care team members can help prevent hypertension, said Kate Kirley, MD, director of the AMA’s chronic disease prevention and programs.

Concern over the lack of standardized BP techniques isn’t new. In 2019, the American Heart Association and the AMA created an online BP course for health care workers. Two years later, the AMA offered grants to five medical schools for training courses.

Most of the new training sessions already on the AMA website take students about 15 minutes to complete. Dr. Kirley says because equipment varies across settings, participants will learn how to conduct manual, semi-automated, and automated office BP readings and identify workarounds for less-than-ideal room setups that can skew results. They will also explore how to guide patients in performing BP readings at home.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

according to the American Medical Association. Hypertension affects about half of U.S. adults and is a leading contributor to cardiovascular disease.

First-year medical students typically read about BP measurement in a textbook and possibly attend a lecture before practicing using a manual cuff a few times on classmates, said Martha Gulati, MD, professor and director of preventive cardiology at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles.

The dearth of BP instruction is alarming because inaccurate readings contribute to under- and overtreatment of hypertension, she said in an interview.

The AMA hopes $100,000 in grants to five health education schools will help improve BP instruction. The group recently announced it would give $20,000 each to five schools that train health professionals, expanding on a 2021 program to improve BP measurement training.

The new grants for interactive lessons will benefit nearly 5,000 students from Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore; Nova Southeastern University, Fort Lauderdale, Fla.; University of Washington, Seattle; Stony Brook (N.Y.) University; and the University of Pittsburgh.

In a 2021 survey of 571 clinicians, most of whom were cardiologists, Dr. Gulati found that only 23% performed accurate BP measurements despite the majority saying they trusted BP readings taken in their clinic. Accurate readings were defined as routinely checking BP in both arms, checking BP at least twice each visit, and waiting 5 minutes before taking the reading.

Med students fare no better when it comes to BP skills. In a 2017 study of 159 students from medical schools in 37 states, only one student demonstrated proficiency in all 11 elements necessary to measure BP accurately. Students, on average, performed just four of them correctly.

The elements of proper BP measurement include patients resting for 5 minutes before the measurement with legs uncrossed, feet on floor, and arm supported, not talking, reading, or using cell phone; BP taken in both arms with correct size of cuff placed over bare arm; and identifying BP from the arm with the higher reading as clinically more important and as the one to use for future readings.

Manual BP readings require an appropriately sized BP cuff, a sphygmomanometer, and a clinician skilled in using a stethoscope and auscultatory method. Meanwhile, automated readings require a clinician to place the cuff, but a digital device collects the measurement. Though preference depends on the setting and clinician, automated readings are more common. In Dr. Gulati’s study, automated BP assessment was used by 58% of respondents.

Depending on the BP device and technique, significant variations in readings can occur. In a 2021 study, Current Hypertension Reports found that automated readings may more closely reflect the patient’s baseline BP and produce results similar to ambulatory monitoring by a medical professional. An earlier JAMA Internal Medicine analysis found that clinicians’ manual readings reflect higher BP measurements than automated readings.

Though the AMA offers a free online series on BP measurement for students, making the training available to more health care team members can help prevent hypertension, said Kate Kirley, MD, director of the AMA’s chronic disease prevention and programs.

Concern over the lack of standardized BP techniques isn’t new. In 2019, the American Heart Association and the AMA created an online BP course for health care workers. Two years later, the AMA offered grants to five medical schools for training courses.

Most of the new training sessions already on the AMA website take students about 15 minutes to complete. Dr. Kirley says because equipment varies across settings, participants will learn how to conduct manual, semi-automated, and automated office BP readings and identify workarounds for less-than-ideal room setups that can skew results. They will also explore how to guide patients in performing BP readings at home.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FDA gives semaglutide two drug safety–related label changes

The FDA added a warning to the drug-interaction section of the Ozempiclabel that reiterates a warning that is already in place in other label sections, reinforcing the message that the glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonist Ozempiccan potentially interact with the action of certain other agents to increase a person’s risk for hypoglycemia.

The added text says: “Ozempic stimulates insulin release in the presence of elevated blood glucose concentrations. Patients receiving Ozempic in combination with an insulin secretagogue (for instance, sulfonylurea) or insulin may have an increased risk of hypoglycemia, including severe hypoglycemia.”

This text was already included in both the “Warning and Precautions” and the “Adverse Reactions” sections of the label. The warning also advises, “The risk of hypoglycemia may be lowered by a reduction in the dose of sulfonylurea (or other concomitantly administered insulin secretagogue) or insulin. Inform patients using these concomitant medications of the risk of hypoglycemia and educate them on the signs and symptoms of hypoglycemia.”

Reports of ileus episodes after approval

The second addition concerns a new adverse reaction that was identified during the postmarketing experience.

The FDA has received more than 8,500 reports of gastrointestinal issues among patients prescribed glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonists. Ileus is mentioned in 33 cases, including two deaths, associated with semaglutide. The FDA stopped short of saying there is a direct link between the drug and intestinal blockages.

“Because these reactions are reported voluntarily from a population of uncertain size, it is not always possible to reliably estimate their frequency or establish a causal relationship to drug exposure,” the FDA stated in its approval of the label update.

The same warning for the risk of intestinal blockages is already listed on the labels for tirzepatide (Mounjaro, Lilly) and semaglutide injection 2.4 mg (Wegovy, Novo Nordisk).

The label change comes after a Louisiana woman filed a lawsuit in August that claims she was “severely injured” after using Mounjaro and Ozempic. She claimed the drug makers failed to disclose risks of vomiting and diarrhea due to inflammation of the stomach lining, as well as the risk of gastroparesis.

*Correction, 10/3/23: An earlier version of this article misstated the semaglutide formulation that received the updates.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The FDA added a warning to the drug-interaction section of the Ozempiclabel that reiterates a warning that is already in place in other label sections, reinforcing the message that the glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonist Ozempiccan potentially interact with the action of certain other agents to increase a person’s risk for hypoglycemia.

The added text says: “Ozempic stimulates insulin release in the presence of elevated blood glucose concentrations. Patients receiving Ozempic in combination with an insulin secretagogue (for instance, sulfonylurea) or insulin may have an increased risk of hypoglycemia, including severe hypoglycemia.”

This text was already included in both the “Warning and Precautions” and the “Adverse Reactions” sections of the label. The warning also advises, “The risk of hypoglycemia may be lowered by a reduction in the dose of sulfonylurea (or other concomitantly administered insulin secretagogue) or insulin. Inform patients using these concomitant medications of the risk of hypoglycemia and educate them on the signs and symptoms of hypoglycemia.”

Reports of ileus episodes after approval

The second addition concerns a new adverse reaction that was identified during the postmarketing experience.

The FDA has received more than 8,500 reports of gastrointestinal issues among patients prescribed glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonists. Ileus is mentioned in 33 cases, including two deaths, associated with semaglutide. The FDA stopped short of saying there is a direct link between the drug and intestinal blockages.

“Because these reactions are reported voluntarily from a population of uncertain size, it is not always possible to reliably estimate their frequency or establish a causal relationship to drug exposure,” the FDA stated in its approval of the label update.

The same warning for the risk of intestinal blockages is already listed on the labels for tirzepatide (Mounjaro, Lilly) and semaglutide injection 2.4 mg (Wegovy, Novo Nordisk).

The label change comes after a Louisiana woman filed a lawsuit in August that claims she was “severely injured” after using Mounjaro and Ozempic. She claimed the drug makers failed to disclose risks of vomiting and diarrhea due to inflammation of the stomach lining, as well as the risk of gastroparesis.

*Correction, 10/3/23: An earlier version of this article misstated the semaglutide formulation that received the updates.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The FDA added a warning to the drug-interaction section of the Ozempiclabel that reiterates a warning that is already in place in other label sections, reinforcing the message that the glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonist Ozempiccan potentially interact with the action of certain other agents to increase a person’s risk for hypoglycemia.

The added text says: “Ozempic stimulates insulin release in the presence of elevated blood glucose concentrations. Patients receiving Ozempic in combination with an insulin secretagogue (for instance, sulfonylurea) or insulin may have an increased risk of hypoglycemia, including severe hypoglycemia.”