User login

No need to restrict hep C DAA therapy based on alcohol use

TOPLINE:

Alcohol use at any level, including alcohol use disorder (AUD), is not associated with decreased odds of a sustained virologic response (SVR) to direct-acting antiviral (DAA) therapy for chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection. Therefore, DAA therapy should not be withheld from patients who consume alcohol.

METHODOLOGY:

- The researchers examined electronic health records for 69,229 patients (mean age, 63 years; 97% men; 50% non-Hispanic White) who started DAA therapy through the Department of Veterans Affairs between 2014 and 2018.

- Alcohol use categories were abstinent without history of AUD, abstinent with history of AUD, lower-risk consumption, moderate-risk consumption, and high-risk consumption or AUD.

- The primary outcome was SVR, which was defined as undetectable HCV RNA for 12 weeks to 6 months after completion of DAA treatment.

TAKEAWAY:

- Close to half (46.6%) of patients were abstinent without AUD, 13.3% were abstinent with AUD, 19.4% had lower-risk consumption, 4.5% had moderate-risk consumption, and 16.2% had high-risk consumption or AUD.

- Overall, 94.4% of those who started on DAA treatment achieved SVR.

- After adjustment, there was no evidence that any alcohol category was significantly associated with decreased odds of achieving SVR. The odds ratios were 1.09 for abstinent without AUD history, 0.92 for abstinent with AUD history, 0.96 for moderate-risk consumption, and 0.95 for high-risk consumption or AUD.

- SVR did not differ by baseline stage of hepatic fibrosis, as measured by Fibrosis-4 score of 3.25 or less versus greater than 3.25.

IN PRACTICE:

“Achieving SVR has been shown to be associated with reduced risk of post-SVR outcomes, including hepatocellular carcinoma, liver-related mortality, and all-cause mortality. Our findings suggest that DAA therapy should be provided and reimbursed despite alcohol consumption or history of AUD. Restricting access to DAA therapy according to alcohol consumption or AUD creates an unnecessary barrier to patients accessing DAA therapy and challenges HCV elimination goals,” the investigators wrote.

SOURCE:

Emily J. Cartwright, MD, of Emory University, Atlanta, led the study, which was published online in JAMA Network Open.

LIMITATIONS:

The study was observational and subject to potential residual confounding. To define SVR, HCV RNA was measured 6 months after DAA treatment ended, which may have resulted in a misclassification of patients who experienced viral relapse. Most participants were men born between 1945 and 1965, and the results may not be generalizable to women and/or older and younger patients.

DISCLOSURES:

The study was supported by grants from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. Dr. Cartwright reported no disclosures. Two coauthors disclosed fees from pharmaceutical companies outside the submitted work.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

Alcohol use at any level, including alcohol use disorder (AUD), is not associated with decreased odds of a sustained virologic response (SVR) to direct-acting antiviral (DAA) therapy for chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection. Therefore, DAA therapy should not be withheld from patients who consume alcohol.

METHODOLOGY:

- The researchers examined electronic health records for 69,229 patients (mean age, 63 years; 97% men; 50% non-Hispanic White) who started DAA therapy through the Department of Veterans Affairs between 2014 and 2018.

- Alcohol use categories were abstinent without history of AUD, abstinent with history of AUD, lower-risk consumption, moderate-risk consumption, and high-risk consumption or AUD.

- The primary outcome was SVR, which was defined as undetectable HCV RNA for 12 weeks to 6 months after completion of DAA treatment.

TAKEAWAY:

- Close to half (46.6%) of patients were abstinent without AUD, 13.3% were abstinent with AUD, 19.4% had lower-risk consumption, 4.5% had moderate-risk consumption, and 16.2% had high-risk consumption or AUD.

- Overall, 94.4% of those who started on DAA treatment achieved SVR.

- After adjustment, there was no evidence that any alcohol category was significantly associated with decreased odds of achieving SVR. The odds ratios were 1.09 for abstinent without AUD history, 0.92 for abstinent with AUD history, 0.96 for moderate-risk consumption, and 0.95 for high-risk consumption or AUD.

- SVR did not differ by baseline stage of hepatic fibrosis, as measured by Fibrosis-4 score of 3.25 or less versus greater than 3.25.

IN PRACTICE:

“Achieving SVR has been shown to be associated with reduced risk of post-SVR outcomes, including hepatocellular carcinoma, liver-related mortality, and all-cause mortality. Our findings suggest that DAA therapy should be provided and reimbursed despite alcohol consumption or history of AUD. Restricting access to DAA therapy according to alcohol consumption or AUD creates an unnecessary barrier to patients accessing DAA therapy and challenges HCV elimination goals,” the investigators wrote.

SOURCE:

Emily J. Cartwright, MD, of Emory University, Atlanta, led the study, which was published online in JAMA Network Open.

LIMITATIONS:

The study was observational and subject to potential residual confounding. To define SVR, HCV RNA was measured 6 months after DAA treatment ended, which may have resulted in a misclassification of patients who experienced viral relapse. Most participants were men born between 1945 and 1965, and the results may not be generalizable to women and/or older and younger patients.

DISCLOSURES:

The study was supported by grants from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. Dr. Cartwright reported no disclosures. Two coauthors disclosed fees from pharmaceutical companies outside the submitted work.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

Alcohol use at any level, including alcohol use disorder (AUD), is not associated with decreased odds of a sustained virologic response (SVR) to direct-acting antiviral (DAA) therapy for chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection. Therefore, DAA therapy should not be withheld from patients who consume alcohol.

METHODOLOGY:

- The researchers examined electronic health records for 69,229 patients (mean age, 63 years; 97% men; 50% non-Hispanic White) who started DAA therapy through the Department of Veterans Affairs between 2014 and 2018.

- Alcohol use categories were abstinent without history of AUD, abstinent with history of AUD, lower-risk consumption, moderate-risk consumption, and high-risk consumption or AUD.

- The primary outcome was SVR, which was defined as undetectable HCV RNA for 12 weeks to 6 months after completion of DAA treatment.

TAKEAWAY:

- Close to half (46.6%) of patients were abstinent without AUD, 13.3% were abstinent with AUD, 19.4% had lower-risk consumption, 4.5% had moderate-risk consumption, and 16.2% had high-risk consumption or AUD.

- Overall, 94.4% of those who started on DAA treatment achieved SVR.

- After adjustment, there was no evidence that any alcohol category was significantly associated with decreased odds of achieving SVR. The odds ratios were 1.09 for abstinent without AUD history, 0.92 for abstinent with AUD history, 0.96 for moderate-risk consumption, and 0.95 for high-risk consumption or AUD.

- SVR did not differ by baseline stage of hepatic fibrosis, as measured by Fibrosis-4 score of 3.25 or less versus greater than 3.25.

IN PRACTICE:

“Achieving SVR has been shown to be associated with reduced risk of post-SVR outcomes, including hepatocellular carcinoma, liver-related mortality, and all-cause mortality. Our findings suggest that DAA therapy should be provided and reimbursed despite alcohol consumption or history of AUD. Restricting access to DAA therapy according to alcohol consumption or AUD creates an unnecessary barrier to patients accessing DAA therapy and challenges HCV elimination goals,” the investigators wrote.

SOURCE:

Emily J. Cartwright, MD, of Emory University, Atlanta, led the study, which was published online in JAMA Network Open.

LIMITATIONS:

The study was observational and subject to potential residual confounding. To define SVR, HCV RNA was measured 6 months after DAA treatment ended, which may have resulted in a misclassification of patients who experienced viral relapse. Most participants were men born between 1945 and 1965, and the results may not be generalizable to women and/or older and younger patients.

DISCLOSURES:

The study was supported by grants from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. Dr. Cartwright reported no disclosures. Two coauthors disclosed fees from pharmaceutical companies outside the submitted work.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM JAMA NETWORK OPEN

No benefit of EC/IC bypass versus meds in large-artery stroke

in the latest randomized trial comparing the two interventions.

However, subgroup analyses suggest a potential benefit of surgery for certain patients, such as those with MCA vs. ICA occlusion, mean transit time greater than 6 seconds, or regional blood flow of 0.8 or less.

“We were disappointed by the results,” Liqun Jiao, MD, of the National Center for Neurological Disorders in Beijing, told this news organization. “We were expecting to demonstrate a benefit from EC-IC bypass surgery over medical treatment alone in symptomatic patients with ICA or MCA occlusion and hemodynamic insufficiency, per our original hypothesis.”

Although the study showed improved efficacy and safety for the surgical procedure, he said, “The progress of medical treatment is even better.”

The study was published online in JAMA.

Subgroup analyses promising

Previous randomized clinical trials, including the EC/IC Bypass Study and the Carotid Occlusion Surgery Study (COSS), showed no benefit in stroke prevention for patients with atherosclerotic occlusion of the ICA or MCA.

However, in light of improvements over the years in surgical techniques and patient selection, the authors conducted the Carotid and Middle Cerebral Artery Occlusion Surgery Study (CMOSS), a multicenter, randomized, open-label trial comparing EC-IC bypass surgery plus medical therapy, consisting of antiplatelet therapy and control of stroke risk factors, with medical therapy alone in symptomatic patients with ICA or MCA occlusion and hemodynamic insufficiency, with refined patient and operator selection.

A total of 324 patients (median age, 52.7 years; 79% men) in 13 centers in China were included; 309 patients (95%) completed the study.

The primary outcome was a composite of stroke or death within 30 days or ipsilateral ischemic stroke beyond 30 days through 2 years after randomization.

Secondary outcomes included, among others, any stroke or death within 2 years and fatal stroke within 2 years.

No significant difference was found for the primary outcome between the surgical group (8.6%) and the medical group (12.3%).

The 30-day risk of stroke or death was 6.2% in the surgery group, versus 1.8% (3/163) for the medical group. The risk of ipsilateral ischemic stroke beyond 30 days through 2 years was 2%, versus 10.3% – nonsignificant differences.

Furthermore, none of the prespecified secondary endpoints showed a significant difference, including any stroke or death within 2 years (9.9% vs. 15.3%; hazard ratio, 0.69) and fatal stroke within 2 years (2% vs. none).

Despite the findings, “We are encouraged by the subgroup analysis and the trend of long-term outcomes,” Dr. Jiao said. “We will continue to finish 5-10 years of follow-up to see whether the benefit of bypass surgery can be identified.”

The team has also launched the CMOSS-2 trial with a refined study design based on the results of subgroup analysis of the CMOSS study.

CMOSS-2 is recruiting patients with symptomatic chronic occlusion of the MCA and severe hemodynamic insufficiency in 13 sites in China. The primary outcome is ischemic stroke in the territory of the target artery within 24 months after randomization.

Can’t exclude benefit

Thomas Jeerakathil, MD, a professor at the University of Alberta and Northern Stroke Lead, Cardiovascular and Stroke Strategic Clinical Network, Alberta Health Services, Edmonton, commented on the study for this news organization. Like the authors, he said, “I don’t consider this study to definitively exclude the benefit of EC/IC bypass. More studies are required.”

Dr. Jeerakathil would like to see a study of a higher-risk group based on both clinical and hemodynamic blood flow criteria. In the current study, he said, “The trial group overall may not have been at high enough stroke risk to justify the up-front risks of the EC-IC bypass procedure.”

In addition, “The analysis method of Cox proportional hazards regression for the primary outcome did not fit the data when the perioperative period was combined with the period beyond 30 days,” he noted. “The researchers were open about this and did pivot and included a post hoc relative risk-based analysis, but the validity of their primary analysis is questionable.”

Furthermore, the study was “somewhat underpowered with a relatively small sample size and had the potential to miss clinically significant differences between groups,” he said. “It would be good to see a longer follow-up period of at least 5 years added to this trial and used in future trials, rather than 2 years.”

“Lastly,” he said, “it’s difficult to ignore the reduction in recurrent stroke events over the 30-day to 2-year time period associated with EC-IC bypass (from 10.3% down to 2%). This reduction alone shows the procedure has some potential to prevent stroke and would argue for more trials.”

EC-IC could be considered for patients who have failed other medical therapies and have more substantial evidence of compromised blood flow to the brain than those in the CMOSS trial, he noted, as many of these patients have few other options. “In our center and many other centers, the approach to EC-IC bypass is probably much more selective than used in the trial.”

Dr. Jeerakathil concluded, “Clinicians should be cautious about offering the procedure to patients with just mildly delayed blood flow in the hemisphere affected by the occluded artery and those who have not yet failed maximal medical therapy.”

But Seemant Chaturvedi, MD, and J. Marc Simard, MD, PhD, both of the University of Maryland, Baltimore, are not as optimistic about the potential for EC-IC.

Writing in a related editorial, they conclude that the results with EC-IC bypass surgery in randomized trials “remain unimpressive. Until a better understanding of the unique hemodynamic features of the brain is achieved, it will be difficult for neurosurgeons to continue offering this procedure to patients with ICA or MCA occlusion. Intensive, multifaceted medical therapy remains the first-line treatment for [these] patients.”

The study was supported by a research grant from the National Health Commission of the People’s Republic of China. Dr. Jiao, Dr. Jeerakathil, Dr. Chaturvedi, and Dr. Simard reported no conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

in the latest randomized trial comparing the two interventions.

However, subgroup analyses suggest a potential benefit of surgery for certain patients, such as those with MCA vs. ICA occlusion, mean transit time greater than 6 seconds, or regional blood flow of 0.8 or less.

“We were disappointed by the results,” Liqun Jiao, MD, of the National Center for Neurological Disorders in Beijing, told this news organization. “We were expecting to demonstrate a benefit from EC-IC bypass surgery over medical treatment alone in symptomatic patients with ICA or MCA occlusion and hemodynamic insufficiency, per our original hypothesis.”

Although the study showed improved efficacy and safety for the surgical procedure, he said, “The progress of medical treatment is even better.”

The study was published online in JAMA.

Subgroup analyses promising

Previous randomized clinical trials, including the EC/IC Bypass Study and the Carotid Occlusion Surgery Study (COSS), showed no benefit in stroke prevention for patients with atherosclerotic occlusion of the ICA or MCA.

However, in light of improvements over the years in surgical techniques and patient selection, the authors conducted the Carotid and Middle Cerebral Artery Occlusion Surgery Study (CMOSS), a multicenter, randomized, open-label trial comparing EC-IC bypass surgery plus medical therapy, consisting of antiplatelet therapy and control of stroke risk factors, with medical therapy alone in symptomatic patients with ICA or MCA occlusion and hemodynamic insufficiency, with refined patient and operator selection.

A total of 324 patients (median age, 52.7 years; 79% men) in 13 centers in China were included; 309 patients (95%) completed the study.

The primary outcome was a composite of stroke or death within 30 days or ipsilateral ischemic stroke beyond 30 days through 2 years after randomization.

Secondary outcomes included, among others, any stroke or death within 2 years and fatal stroke within 2 years.

No significant difference was found for the primary outcome between the surgical group (8.6%) and the medical group (12.3%).

The 30-day risk of stroke or death was 6.2% in the surgery group, versus 1.8% (3/163) for the medical group. The risk of ipsilateral ischemic stroke beyond 30 days through 2 years was 2%, versus 10.3% – nonsignificant differences.

Furthermore, none of the prespecified secondary endpoints showed a significant difference, including any stroke or death within 2 years (9.9% vs. 15.3%; hazard ratio, 0.69) and fatal stroke within 2 years (2% vs. none).

Despite the findings, “We are encouraged by the subgroup analysis and the trend of long-term outcomes,” Dr. Jiao said. “We will continue to finish 5-10 years of follow-up to see whether the benefit of bypass surgery can be identified.”

The team has also launched the CMOSS-2 trial with a refined study design based on the results of subgroup analysis of the CMOSS study.

CMOSS-2 is recruiting patients with symptomatic chronic occlusion of the MCA and severe hemodynamic insufficiency in 13 sites in China. The primary outcome is ischemic stroke in the territory of the target artery within 24 months after randomization.

Can’t exclude benefit

Thomas Jeerakathil, MD, a professor at the University of Alberta and Northern Stroke Lead, Cardiovascular and Stroke Strategic Clinical Network, Alberta Health Services, Edmonton, commented on the study for this news organization. Like the authors, he said, “I don’t consider this study to definitively exclude the benefit of EC/IC bypass. More studies are required.”

Dr. Jeerakathil would like to see a study of a higher-risk group based on both clinical and hemodynamic blood flow criteria. In the current study, he said, “The trial group overall may not have been at high enough stroke risk to justify the up-front risks of the EC-IC bypass procedure.”

In addition, “The analysis method of Cox proportional hazards regression for the primary outcome did not fit the data when the perioperative period was combined with the period beyond 30 days,” he noted. “The researchers were open about this and did pivot and included a post hoc relative risk-based analysis, but the validity of their primary analysis is questionable.”

Furthermore, the study was “somewhat underpowered with a relatively small sample size and had the potential to miss clinically significant differences between groups,” he said. “It would be good to see a longer follow-up period of at least 5 years added to this trial and used in future trials, rather than 2 years.”

“Lastly,” he said, “it’s difficult to ignore the reduction in recurrent stroke events over the 30-day to 2-year time period associated with EC-IC bypass (from 10.3% down to 2%). This reduction alone shows the procedure has some potential to prevent stroke and would argue for more trials.”

EC-IC could be considered for patients who have failed other medical therapies and have more substantial evidence of compromised blood flow to the brain than those in the CMOSS trial, he noted, as many of these patients have few other options. “In our center and many other centers, the approach to EC-IC bypass is probably much more selective than used in the trial.”

Dr. Jeerakathil concluded, “Clinicians should be cautious about offering the procedure to patients with just mildly delayed blood flow in the hemisphere affected by the occluded artery and those who have not yet failed maximal medical therapy.”

But Seemant Chaturvedi, MD, and J. Marc Simard, MD, PhD, both of the University of Maryland, Baltimore, are not as optimistic about the potential for EC-IC.

Writing in a related editorial, they conclude that the results with EC-IC bypass surgery in randomized trials “remain unimpressive. Until a better understanding of the unique hemodynamic features of the brain is achieved, it will be difficult for neurosurgeons to continue offering this procedure to patients with ICA or MCA occlusion. Intensive, multifaceted medical therapy remains the first-line treatment for [these] patients.”

The study was supported by a research grant from the National Health Commission of the People’s Republic of China. Dr. Jiao, Dr. Jeerakathil, Dr. Chaturvedi, and Dr. Simard reported no conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

in the latest randomized trial comparing the two interventions.

However, subgroup analyses suggest a potential benefit of surgery for certain patients, such as those with MCA vs. ICA occlusion, mean transit time greater than 6 seconds, or regional blood flow of 0.8 or less.

“We were disappointed by the results,” Liqun Jiao, MD, of the National Center for Neurological Disorders in Beijing, told this news organization. “We were expecting to demonstrate a benefit from EC-IC bypass surgery over medical treatment alone in symptomatic patients with ICA or MCA occlusion and hemodynamic insufficiency, per our original hypothesis.”

Although the study showed improved efficacy and safety for the surgical procedure, he said, “The progress of medical treatment is even better.”

The study was published online in JAMA.

Subgroup analyses promising

Previous randomized clinical trials, including the EC/IC Bypass Study and the Carotid Occlusion Surgery Study (COSS), showed no benefit in stroke prevention for patients with atherosclerotic occlusion of the ICA or MCA.

However, in light of improvements over the years in surgical techniques and patient selection, the authors conducted the Carotid and Middle Cerebral Artery Occlusion Surgery Study (CMOSS), a multicenter, randomized, open-label trial comparing EC-IC bypass surgery plus medical therapy, consisting of antiplatelet therapy and control of stroke risk factors, with medical therapy alone in symptomatic patients with ICA or MCA occlusion and hemodynamic insufficiency, with refined patient and operator selection.

A total of 324 patients (median age, 52.7 years; 79% men) in 13 centers in China were included; 309 patients (95%) completed the study.

The primary outcome was a composite of stroke or death within 30 days or ipsilateral ischemic stroke beyond 30 days through 2 years after randomization.

Secondary outcomes included, among others, any stroke or death within 2 years and fatal stroke within 2 years.

No significant difference was found for the primary outcome between the surgical group (8.6%) and the medical group (12.3%).

The 30-day risk of stroke or death was 6.2% in the surgery group, versus 1.8% (3/163) for the medical group. The risk of ipsilateral ischemic stroke beyond 30 days through 2 years was 2%, versus 10.3% – nonsignificant differences.

Furthermore, none of the prespecified secondary endpoints showed a significant difference, including any stroke or death within 2 years (9.9% vs. 15.3%; hazard ratio, 0.69) and fatal stroke within 2 years (2% vs. none).

Despite the findings, “We are encouraged by the subgroup analysis and the trend of long-term outcomes,” Dr. Jiao said. “We will continue to finish 5-10 years of follow-up to see whether the benefit of bypass surgery can be identified.”

The team has also launched the CMOSS-2 trial with a refined study design based on the results of subgroup analysis of the CMOSS study.

CMOSS-2 is recruiting patients with symptomatic chronic occlusion of the MCA and severe hemodynamic insufficiency in 13 sites in China. The primary outcome is ischemic stroke in the territory of the target artery within 24 months after randomization.

Can’t exclude benefit

Thomas Jeerakathil, MD, a professor at the University of Alberta and Northern Stroke Lead, Cardiovascular and Stroke Strategic Clinical Network, Alberta Health Services, Edmonton, commented on the study for this news organization. Like the authors, he said, “I don’t consider this study to definitively exclude the benefit of EC/IC bypass. More studies are required.”

Dr. Jeerakathil would like to see a study of a higher-risk group based on both clinical and hemodynamic blood flow criteria. In the current study, he said, “The trial group overall may not have been at high enough stroke risk to justify the up-front risks of the EC-IC bypass procedure.”

In addition, “The analysis method of Cox proportional hazards regression for the primary outcome did not fit the data when the perioperative period was combined with the period beyond 30 days,” he noted. “The researchers were open about this and did pivot and included a post hoc relative risk-based analysis, but the validity of their primary analysis is questionable.”

Furthermore, the study was “somewhat underpowered with a relatively small sample size and had the potential to miss clinically significant differences between groups,” he said. “It would be good to see a longer follow-up period of at least 5 years added to this trial and used in future trials, rather than 2 years.”

“Lastly,” he said, “it’s difficult to ignore the reduction in recurrent stroke events over the 30-day to 2-year time period associated with EC-IC bypass (from 10.3% down to 2%). This reduction alone shows the procedure has some potential to prevent stroke and would argue for more trials.”

EC-IC could be considered for patients who have failed other medical therapies and have more substantial evidence of compromised blood flow to the brain than those in the CMOSS trial, he noted, as many of these patients have few other options. “In our center and many other centers, the approach to EC-IC bypass is probably much more selective than used in the trial.”

Dr. Jeerakathil concluded, “Clinicians should be cautious about offering the procedure to patients with just mildly delayed blood flow in the hemisphere affected by the occluded artery and those who have not yet failed maximal medical therapy.”

But Seemant Chaturvedi, MD, and J. Marc Simard, MD, PhD, both of the University of Maryland, Baltimore, are not as optimistic about the potential for EC-IC.

Writing in a related editorial, they conclude that the results with EC-IC bypass surgery in randomized trials “remain unimpressive. Until a better understanding of the unique hemodynamic features of the brain is achieved, it will be difficult for neurosurgeons to continue offering this procedure to patients with ICA or MCA occlusion. Intensive, multifaceted medical therapy remains the first-line treatment for [these] patients.”

The study was supported by a research grant from the National Health Commission of the People’s Republic of China. Dr. Jiao, Dr. Jeerakathil, Dr. Chaturvedi, and Dr. Simard reported no conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM JAMA

Study: Antiviral med linked to COVID mutations that can spread

published in the online journal Nature.

There’s no evidence that molnupiravir, sold under the brand name Lagevrio, has caused the creation of more transmissible or severe variants of COVID, the study says, but researchers called for more scrutiny of the drug.

Researchers looked at 15 million COVID genomes and discovered that hallmark mutations linked to molnupiravir increased in 2022, especially in places where the drug was widely used, such as the United States and the United Kingdom. Levels of the mutations were also found in populations where the drug was heavily prescribed, such as seniors.

Molnupiravir is an antiviral given to people after they show signs of having COVID-19. It interferes with the COVID-19 virus’s ability to make copies of itself, thus stopping the spread of the virus throughout the body and keeping the virus level low.

The study found the virus can sometimes survive molnupiravir, resulting in mutations that have spread to other people.

Theo Sanderson, PhD, the lead author on the study and a postdoctoral researcher at the Francis Crick Institute in London, told The Guardian that the implications of the mutations were unclear.

“The signature is very clear, but there aren’t any widely circulating variants that have the signature. At the moment there’s nothing that’s transmitted very widely that’s due to molnupiravir,” he said.

The study doesn’t say people should not use molnupiravir but calls for public health officials to scrutinize it.

“The observation that molnupiravir treatment has left a visible trace in global sequencing databases, including onwards transmission of molnupiravir-derived sequences, will be an important consideration for assessing the effects and evolutionary safety of this drug,” the researchers concluded.

When reached for comment, Merck questioned the evidence.

“The authors assume these mutations were associated with viral spread from molnupiravir-treated patients without documented evidence of that transmission. Instead, the authors rely on circumstantial associations between the region from which the sequence was identified and time frame of sequence collection in countries where molnupiravir is available to draw their conclusions,” the company said.

The Food and Drug Administration authorized the use of molnupiravir for the treatment of mild to moderate COVID-19 in adults in December 2021. The FDA has also authorized the use of nirmatrelvir/ritonavir (Paxlovid), an antiviral made by Pfizer.

A version of this article appeared on WebMD.com.

published in the online journal Nature.

There’s no evidence that molnupiravir, sold under the brand name Lagevrio, has caused the creation of more transmissible or severe variants of COVID, the study says, but researchers called for more scrutiny of the drug.

Researchers looked at 15 million COVID genomes and discovered that hallmark mutations linked to molnupiravir increased in 2022, especially in places where the drug was widely used, such as the United States and the United Kingdom. Levels of the mutations were also found in populations where the drug was heavily prescribed, such as seniors.

Molnupiravir is an antiviral given to people after they show signs of having COVID-19. It interferes with the COVID-19 virus’s ability to make copies of itself, thus stopping the spread of the virus throughout the body and keeping the virus level low.

The study found the virus can sometimes survive molnupiravir, resulting in mutations that have spread to other people.

Theo Sanderson, PhD, the lead author on the study and a postdoctoral researcher at the Francis Crick Institute in London, told The Guardian that the implications of the mutations were unclear.

“The signature is very clear, but there aren’t any widely circulating variants that have the signature. At the moment there’s nothing that’s transmitted very widely that’s due to molnupiravir,” he said.

The study doesn’t say people should not use molnupiravir but calls for public health officials to scrutinize it.

“The observation that molnupiravir treatment has left a visible trace in global sequencing databases, including onwards transmission of molnupiravir-derived sequences, will be an important consideration for assessing the effects and evolutionary safety of this drug,” the researchers concluded.

When reached for comment, Merck questioned the evidence.

“The authors assume these mutations were associated with viral spread from molnupiravir-treated patients without documented evidence of that transmission. Instead, the authors rely on circumstantial associations between the region from which the sequence was identified and time frame of sequence collection in countries where molnupiravir is available to draw their conclusions,” the company said.

The Food and Drug Administration authorized the use of molnupiravir for the treatment of mild to moderate COVID-19 in adults in December 2021. The FDA has also authorized the use of nirmatrelvir/ritonavir (Paxlovid), an antiviral made by Pfizer.

A version of this article appeared on WebMD.com.

published in the online journal Nature.

There’s no evidence that molnupiravir, sold under the brand name Lagevrio, has caused the creation of more transmissible or severe variants of COVID, the study says, but researchers called for more scrutiny of the drug.

Researchers looked at 15 million COVID genomes and discovered that hallmark mutations linked to molnupiravir increased in 2022, especially in places where the drug was widely used, such as the United States and the United Kingdom. Levels of the mutations were also found in populations where the drug was heavily prescribed, such as seniors.

Molnupiravir is an antiviral given to people after they show signs of having COVID-19. It interferes with the COVID-19 virus’s ability to make copies of itself, thus stopping the spread of the virus throughout the body and keeping the virus level low.

The study found the virus can sometimes survive molnupiravir, resulting in mutations that have spread to other people.

Theo Sanderson, PhD, the lead author on the study and a postdoctoral researcher at the Francis Crick Institute in London, told The Guardian that the implications of the mutations were unclear.

“The signature is very clear, but there aren’t any widely circulating variants that have the signature. At the moment there’s nothing that’s transmitted very widely that’s due to molnupiravir,” he said.

The study doesn’t say people should not use molnupiravir but calls for public health officials to scrutinize it.

“The observation that molnupiravir treatment has left a visible trace in global sequencing databases, including onwards transmission of molnupiravir-derived sequences, will be an important consideration for assessing the effects and evolutionary safety of this drug,” the researchers concluded.

When reached for comment, Merck questioned the evidence.

“The authors assume these mutations were associated with viral spread from molnupiravir-treated patients without documented evidence of that transmission. Instead, the authors rely on circumstantial associations between the region from which the sequence was identified and time frame of sequence collection in countries where molnupiravir is available to draw their conclusions,” the company said.

The Food and Drug Administration authorized the use of molnupiravir for the treatment of mild to moderate COVID-19 in adults in December 2021. The FDA has also authorized the use of nirmatrelvir/ritonavir (Paxlovid), an antiviral made by Pfizer.

A version of this article appeared on WebMD.com.

FROM NATURE

Long COVID and the Gastrointestinal System: Emerging Evidence

- Lutchmansingh DD et al. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2023;44(1):130-142. doi:10.1055/s-0042-1759568

- Choudhury A et al. Therap Adv Gastroenterol. 2022;15:17562848221118403. doi:10.1177/17562848221118403

- Xu E et al. Nat Commun. 2023;14(1):983. doi:10.1038/s41467-023-36223-7

- Freedberg DE, Chang L. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2022;38(6):555-561. doi:10.1097/MOG.0000000000000876

- Blackett JW et al. Gastroenterology. 2022;162(2):648-650.e2. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2021.10.040

- Chey WD et al. Gastroenterology. 2021;160(1):47-62. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2020.06.099

- Líška D et al. Front Public Health. 2022;10:975992. doi:10.3389/fpubh.2022.975992

- Moens M et al. Front Public Health. 2022;10:991572. doi:10.3389/fpubh.2022.991572

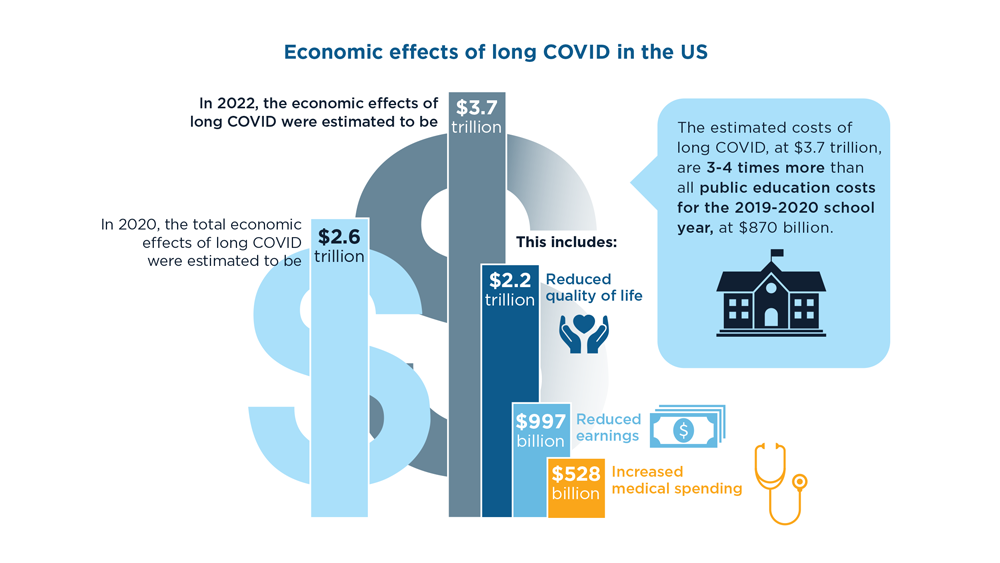

- Cutler DM. The economic cost of long COVID: an update. Scholars at Harvard. Published July 2022. Accessed July 20, 2023. https://scholar.harvard.edu/sites/scholar.harvard.edu/files/cutler/files/long_covid_update_7-22.pdf

- National Center for Education Statistics (2023). Public School Expenditures. Condition of Education. US Department of Education, Institute of Education Sciences. Accessed August 4, 2023. https://nces.ed.gov/programs/coe/indicator/cmb

- Lutchmansingh DD et al. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2023;44(1):130-142. doi:10.1055/s-0042-1759568

- Choudhury A et al. Therap Adv Gastroenterol. 2022;15:17562848221118403. doi:10.1177/17562848221118403

- Xu E et al. Nat Commun. 2023;14(1):983. doi:10.1038/s41467-023-36223-7

- Freedberg DE, Chang L. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2022;38(6):555-561. doi:10.1097/MOG.0000000000000876

- Blackett JW et al. Gastroenterology. 2022;162(2):648-650.e2. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2021.10.040

- Chey WD et al. Gastroenterology. 2021;160(1):47-62. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2020.06.099

- Líška D et al. Front Public Health. 2022;10:975992. doi:10.3389/fpubh.2022.975992

- Moens M et al. Front Public Health. 2022;10:991572. doi:10.3389/fpubh.2022.991572

- Cutler DM. The economic cost of long COVID: an update. Scholars at Harvard. Published July 2022. Accessed July 20, 2023. https://scholar.harvard.edu/sites/scholar.harvard.edu/files/cutler/files/long_covid_update_7-22.pdf

- National Center for Education Statistics (2023). Public School Expenditures. Condition of Education. US Department of Education, Institute of Education Sciences. Accessed August 4, 2023. https://nces.ed.gov/programs/coe/indicator/cmb

- Lutchmansingh DD et al. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2023;44(1):130-142. doi:10.1055/s-0042-1759568

- Choudhury A et al. Therap Adv Gastroenterol. 2022;15:17562848221118403. doi:10.1177/17562848221118403

- Xu E et al. Nat Commun. 2023;14(1):983. doi:10.1038/s41467-023-36223-7

- Freedberg DE, Chang L. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2022;38(6):555-561. doi:10.1097/MOG.0000000000000876

- Blackett JW et al. Gastroenterology. 2022;162(2):648-650.e2. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2021.10.040

- Chey WD et al. Gastroenterology. 2021;160(1):47-62. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2020.06.099

- Líška D et al. Front Public Health. 2022;10:975992. doi:10.3389/fpubh.2022.975992

- Moens M et al. Front Public Health. 2022;10:991572. doi:10.3389/fpubh.2022.991572

- Cutler DM. The economic cost of long COVID: an update. Scholars at Harvard. Published July 2022. Accessed July 20, 2023. https://scholar.harvard.edu/sites/scholar.harvard.edu/files/cutler/files/long_covid_update_7-22.pdf

- National Center for Education Statistics (2023). Public School Expenditures. Condition of Education. US Department of Education, Institute of Education Sciences. Accessed August 4, 2023. https://nces.ed.gov/programs/coe/indicator/cmb

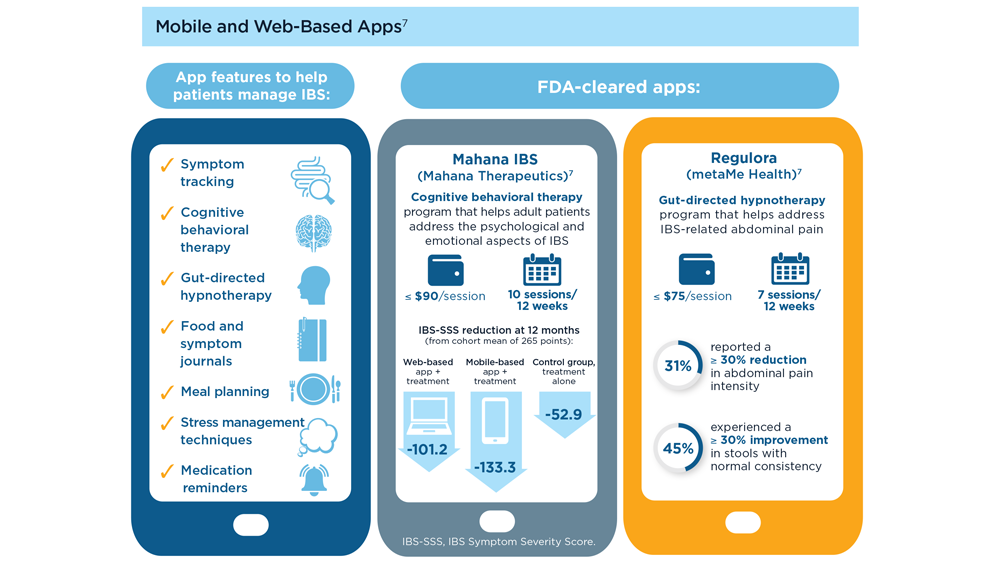

Digital Tools in the Management of IBS/ Functional GI Disorders

- Hasan SS et al. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2023;35(4):e14554. doi:10.1111/nmo.14554

- Peters SL et al. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2023;35(4):e14533. doi:10.1111/nmo.14533

- Zhou C et al. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2019;31(2):e13461. doi:10.1111/nmo.13461

- Staudacher HM et al. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2023;1-15. doi:10.1038/s41575-023-00794-z

- Qin HY et al. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20(39):14126-14131. doi:10.3748/wjg.v20.i39.14126

- Varjú P et al. PLoS One. 2017;12(8):e0182942. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0182942

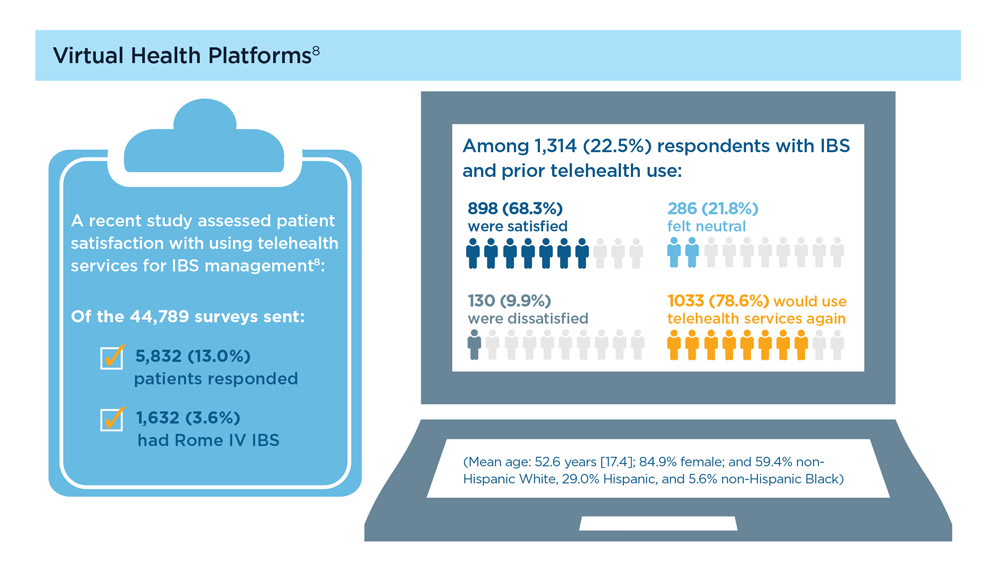

- Saleh ZM et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2023. doi:10.14309/ajg.0000000000002220

- Yu C et al. Clin Transl Gastroenterol. 2022;13(9):e00515. doi:10.14309/ctg.0000000000000515

- Jagannath B et al. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2020;26(10):1533-1542. doi:10.1093/ibd/izaa191

- Zhang H et al. J Nutr. 2023;153(4):924-939. doi:10.1016/j.tjnut.2023.01.026

- Karakan T et al. Gut Microbes. 2022;14(1):2138672. doi:10.1080/19490976.2022.2138672

- Kordi M et al. Inform Med Unlocked. 2022;29:100891. doi:10.1016/j.imu.2022.100891

- Gubatan J et al. World J Gastroenterol. 2021;27(17):1920-1935. doi:10.3748/wjg.v27.i17.1920

- Boucher EM et al. Expert Rev Med Devices. 2021;18(suppl 1):37-49. doi:10.1080/17434440.2021.2013200

- Babel A et al. Front Digit Health. 2021;3:669869. doi:10.3389/fdgth.2021.669869

- Hasan SS et al. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2023;35(4):e14554. doi:10.1111/nmo.14554

- Peters SL et al. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2023;35(4):e14533. doi:10.1111/nmo.14533

- Zhou C et al. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2019;31(2):e13461. doi:10.1111/nmo.13461

- Staudacher HM et al. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2023;1-15. doi:10.1038/s41575-023-00794-z

- Qin HY et al. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20(39):14126-14131. doi:10.3748/wjg.v20.i39.14126

- Varjú P et al. PLoS One. 2017;12(8):e0182942. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0182942

- Saleh ZM et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2023. doi:10.14309/ajg.0000000000002220

- Yu C et al. Clin Transl Gastroenterol. 2022;13(9):e00515. doi:10.14309/ctg.0000000000000515

- Jagannath B et al. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2020;26(10):1533-1542. doi:10.1093/ibd/izaa191

- Zhang H et al. J Nutr. 2023;153(4):924-939. doi:10.1016/j.tjnut.2023.01.026

- Karakan T et al. Gut Microbes. 2022;14(1):2138672. doi:10.1080/19490976.2022.2138672

- Kordi M et al. Inform Med Unlocked. 2022;29:100891. doi:10.1016/j.imu.2022.100891

- Gubatan J et al. World J Gastroenterol. 2021;27(17):1920-1935. doi:10.3748/wjg.v27.i17.1920

- Boucher EM et al. Expert Rev Med Devices. 2021;18(suppl 1):37-49. doi:10.1080/17434440.2021.2013200

- Babel A et al. Front Digit Health. 2021;3:669869. doi:10.3389/fdgth.2021.669869

- Hasan SS et al. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2023;35(4):e14554. doi:10.1111/nmo.14554

- Peters SL et al. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2023;35(4):e14533. doi:10.1111/nmo.14533

- Zhou C et al. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2019;31(2):e13461. doi:10.1111/nmo.13461

- Staudacher HM et al. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2023;1-15. doi:10.1038/s41575-023-00794-z

- Qin HY et al. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20(39):14126-14131. doi:10.3748/wjg.v20.i39.14126

- Varjú P et al. PLoS One. 2017;12(8):e0182942. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0182942

- Saleh ZM et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2023. doi:10.14309/ajg.0000000000002220

- Yu C et al. Clin Transl Gastroenterol. 2022;13(9):e00515. doi:10.14309/ctg.0000000000000515

- Jagannath B et al. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2020;26(10):1533-1542. doi:10.1093/ibd/izaa191

- Zhang H et al. J Nutr. 2023;153(4):924-939. doi:10.1016/j.tjnut.2023.01.026

- Karakan T et al. Gut Microbes. 2022;14(1):2138672. doi:10.1080/19490976.2022.2138672

- Kordi M et al. Inform Med Unlocked. 2022;29:100891. doi:10.1016/j.imu.2022.100891

- Gubatan J et al. World J Gastroenterol. 2021;27(17):1920-1935. doi:10.3748/wjg.v27.i17.1920

- Boucher EM et al. Expert Rev Med Devices. 2021;18(suppl 1):37-49. doi:10.1080/17434440.2021.2013200

- Babel A et al. Front Digit Health. 2021;3:669869. doi:10.3389/fdgth.2021.669869

‘Old school’ laser resurfacing remains an effective option for rejuvenation

SAN DIEGO – , according to Arisa E. Ortiz, MD.

“Fractional resurfacing is great because there is less downtime, but the results are not as dramatic as with fully ablative resurfacing,” Dr. Ortiz, director of laser and cosmetic dermatology at the University of California, San Diego, said at the annual Masters of Aesthetics Symposium. In her practice, she said, “we do a combination,” which can include “fully ablative around the mouth and eyes and fractional everywhere else.”

Key drawbacks to fully ablative laser resurfacing include significant downtime and extensive wound care, “so it’s not for everybody,” she said. Prolonged erythema following treatment is expected, “so patients need to plan for this. It can last 3-4 months, and it will continue to fade and can be covered up with makeup, but it does last a while,” she noted. “One of the things that made ablative resurfacing fall out of favor was the delayed and permanent hypopigmentation where there’s a stark line of demarcation because you can’t treat the neck [with this modality], so patients have this pearly white looking face that appears 6 months after the treatment,” she added.

Preoperatively, Dr. Ortiz asks patients what other cosmetic procedures they have had in the past. For example, if they have had a facelift, they might have neck skin on their jawline, which will react differently to fully ablative resurfacing than facial skin. “I don’t perform fully ablative resurfacing on the neck or body, or in patients with darker skin types,” she said.

To optimize results, she recommends pretreatment of the area with a neuromodulator a week or 2 before the procedure, “so that they’re not actively contracting and recreating creases,” she said. Studies, she noted, have shown that this approach results in better outcomes. She also asks patients to apply a tripeptide serum daily a week or 2 prior to their procedure to stimulate wound healing and collagen remodeling.

For antibiotic and antiviral prophylaxis, Dr. Ortiz typically prescribes doxycycline 100 mg b.i.d. for 7 days and valacyclovir 500 mg b.i.d. for 7 days and asks patients to start the course the night before the procedure. “If they break through the antiviral, I increase to zoster dosing,” she said. “I make sure they have my cell phone number and call me right away if that happens. I don’t routinely prescribe an antifungal, but you can if you want to.”

For anesthesia, Dr. Ortiz applies lidocaine 23%/tetracaine 7% an hour before the procedure and performs nerve blocks at the mentalis, infraorbital, supraorbital, and nasalis muscles. “I also do local infiltration with a three-pronged Mesoram adapter,” she said. “That has changed the comfort level for these patients. I don’t offer any sedation in my practice but that is an option if you have it available. If you’re going to be resurfacing within the orbital rim you need to know how to place corneal shields. Only use injectable lidocaine in this area because if topical lidocaine gets into the eye, it can cause a chemical corneal abrasion. Nothing happens to their vision permanently, but it’s extremely painful for 24-48 hours.”

Dr. Ortiz described postoperative wound care as “the hardest part” of fully ablative laser resurfacing treatments. The treated area will look “bloody and crusty” for 1-2 weeks. She instructs patients to do vinegar soaks four times per day for 2-3 weeks, “depending on how quickly they heal,” she said. She also counsels patients to apply petrolatum ointment to the area and provides them with a bottle of hypochlorous acid spray, an antiseptic – which also helps with the itching they may experience. “They need to avoid the sun, so I recommend full face visors,” she added.

In her clinical experience, postoperative pain medications are not required. “If the patient calls you on day 3 with increased pain, that’s usually a sign of infection; don’t ignore that,” said Dr. Ortiz, who is also president-elect of the American Society for Laser Medicine and Surgery. In a case of suspected infection, she asks the patient to come in right away, and obtains a bacterial culture. “If they break through the doxycycline, it’s usually a gram-negative infection, so I’ll treat them prophylactically for that,” she said.

“Significant itching may be a sign of Candida infection,” she noted. “Because the epidermis has been disrupted, if they have systemic symptoms then you want to consider IV antibiotics because the infection can spread rapidly.”

Dr. Ortiz disclosed having financial relationships with several pharmaceutical and device companies. She is also cochair of the MOAS.

SAN DIEGO – , according to Arisa E. Ortiz, MD.

“Fractional resurfacing is great because there is less downtime, but the results are not as dramatic as with fully ablative resurfacing,” Dr. Ortiz, director of laser and cosmetic dermatology at the University of California, San Diego, said at the annual Masters of Aesthetics Symposium. In her practice, she said, “we do a combination,” which can include “fully ablative around the mouth and eyes and fractional everywhere else.”

Key drawbacks to fully ablative laser resurfacing include significant downtime and extensive wound care, “so it’s not for everybody,” she said. Prolonged erythema following treatment is expected, “so patients need to plan for this. It can last 3-4 months, and it will continue to fade and can be covered up with makeup, but it does last a while,” she noted. “One of the things that made ablative resurfacing fall out of favor was the delayed and permanent hypopigmentation where there’s a stark line of demarcation because you can’t treat the neck [with this modality], so patients have this pearly white looking face that appears 6 months after the treatment,” she added.

Preoperatively, Dr. Ortiz asks patients what other cosmetic procedures they have had in the past. For example, if they have had a facelift, they might have neck skin on their jawline, which will react differently to fully ablative resurfacing than facial skin. “I don’t perform fully ablative resurfacing on the neck or body, or in patients with darker skin types,” she said.

To optimize results, she recommends pretreatment of the area with a neuromodulator a week or 2 before the procedure, “so that they’re not actively contracting and recreating creases,” she said. Studies, she noted, have shown that this approach results in better outcomes. She also asks patients to apply a tripeptide serum daily a week or 2 prior to their procedure to stimulate wound healing and collagen remodeling.

For antibiotic and antiviral prophylaxis, Dr. Ortiz typically prescribes doxycycline 100 mg b.i.d. for 7 days and valacyclovir 500 mg b.i.d. for 7 days and asks patients to start the course the night before the procedure. “If they break through the antiviral, I increase to zoster dosing,” she said. “I make sure they have my cell phone number and call me right away if that happens. I don’t routinely prescribe an antifungal, but you can if you want to.”

For anesthesia, Dr. Ortiz applies lidocaine 23%/tetracaine 7% an hour before the procedure and performs nerve blocks at the mentalis, infraorbital, supraorbital, and nasalis muscles. “I also do local infiltration with a three-pronged Mesoram adapter,” she said. “That has changed the comfort level for these patients. I don’t offer any sedation in my practice but that is an option if you have it available. If you’re going to be resurfacing within the orbital rim you need to know how to place corneal shields. Only use injectable lidocaine in this area because if topical lidocaine gets into the eye, it can cause a chemical corneal abrasion. Nothing happens to their vision permanently, but it’s extremely painful for 24-48 hours.”

Dr. Ortiz described postoperative wound care as “the hardest part” of fully ablative laser resurfacing treatments. The treated area will look “bloody and crusty” for 1-2 weeks. She instructs patients to do vinegar soaks four times per day for 2-3 weeks, “depending on how quickly they heal,” she said. She also counsels patients to apply petrolatum ointment to the area and provides them with a bottle of hypochlorous acid spray, an antiseptic – which also helps with the itching they may experience. “They need to avoid the sun, so I recommend full face visors,” she added.

In her clinical experience, postoperative pain medications are not required. “If the patient calls you on day 3 with increased pain, that’s usually a sign of infection; don’t ignore that,” said Dr. Ortiz, who is also president-elect of the American Society for Laser Medicine and Surgery. In a case of suspected infection, she asks the patient to come in right away, and obtains a bacterial culture. “If they break through the doxycycline, it’s usually a gram-negative infection, so I’ll treat them prophylactically for that,” she said.

“Significant itching may be a sign of Candida infection,” she noted. “Because the epidermis has been disrupted, if they have systemic symptoms then you want to consider IV antibiotics because the infection can spread rapidly.”

Dr. Ortiz disclosed having financial relationships with several pharmaceutical and device companies. She is also cochair of the MOAS.

SAN DIEGO – , according to Arisa E. Ortiz, MD.

“Fractional resurfacing is great because there is less downtime, but the results are not as dramatic as with fully ablative resurfacing,” Dr. Ortiz, director of laser and cosmetic dermatology at the University of California, San Diego, said at the annual Masters of Aesthetics Symposium. In her practice, she said, “we do a combination,” which can include “fully ablative around the mouth and eyes and fractional everywhere else.”

Key drawbacks to fully ablative laser resurfacing include significant downtime and extensive wound care, “so it’s not for everybody,” she said. Prolonged erythema following treatment is expected, “so patients need to plan for this. It can last 3-4 months, and it will continue to fade and can be covered up with makeup, but it does last a while,” she noted. “One of the things that made ablative resurfacing fall out of favor was the delayed and permanent hypopigmentation where there’s a stark line of demarcation because you can’t treat the neck [with this modality], so patients have this pearly white looking face that appears 6 months after the treatment,” she added.

Preoperatively, Dr. Ortiz asks patients what other cosmetic procedures they have had in the past. For example, if they have had a facelift, they might have neck skin on their jawline, which will react differently to fully ablative resurfacing than facial skin. “I don’t perform fully ablative resurfacing on the neck or body, or in patients with darker skin types,” she said.

To optimize results, she recommends pretreatment of the area with a neuromodulator a week or 2 before the procedure, “so that they’re not actively contracting and recreating creases,” she said. Studies, she noted, have shown that this approach results in better outcomes. She also asks patients to apply a tripeptide serum daily a week or 2 prior to their procedure to stimulate wound healing and collagen remodeling.

For antibiotic and antiviral prophylaxis, Dr. Ortiz typically prescribes doxycycline 100 mg b.i.d. for 7 days and valacyclovir 500 mg b.i.d. for 7 days and asks patients to start the course the night before the procedure. “If they break through the antiviral, I increase to zoster dosing,” she said. “I make sure they have my cell phone number and call me right away if that happens. I don’t routinely prescribe an antifungal, but you can if you want to.”

For anesthesia, Dr. Ortiz applies lidocaine 23%/tetracaine 7% an hour before the procedure and performs nerve blocks at the mentalis, infraorbital, supraorbital, and nasalis muscles. “I also do local infiltration with a three-pronged Mesoram adapter,” she said. “That has changed the comfort level for these patients. I don’t offer any sedation in my practice but that is an option if you have it available. If you’re going to be resurfacing within the orbital rim you need to know how to place corneal shields. Only use injectable lidocaine in this area because if topical lidocaine gets into the eye, it can cause a chemical corneal abrasion. Nothing happens to their vision permanently, but it’s extremely painful for 24-48 hours.”

Dr. Ortiz described postoperative wound care as “the hardest part” of fully ablative laser resurfacing treatments. The treated area will look “bloody and crusty” for 1-2 weeks. She instructs patients to do vinegar soaks four times per day for 2-3 weeks, “depending on how quickly they heal,” she said. She also counsels patients to apply petrolatum ointment to the area and provides them with a bottle of hypochlorous acid spray, an antiseptic – which also helps with the itching they may experience. “They need to avoid the sun, so I recommend full face visors,” she added.

In her clinical experience, postoperative pain medications are not required. “If the patient calls you on day 3 with increased pain, that’s usually a sign of infection; don’t ignore that,” said Dr. Ortiz, who is also president-elect of the American Society for Laser Medicine and Surgery. In a case of suspected infection, she asks the patient to come in right away, and obtains a bacterial culture. “If they break through the doxycycline, it’s usually a gram-negative infection, so I’ll treat them prophylactically for that,” she said.

“Significant itching may be a sign of Candida infection,” she noted. “Because the epidermis has been disrupted, if they have systemic symptoms then you want to consider IV antibiotics because the infection can spread rapidly.”

Dr. Ortiz disclosed having financial relationships with several pharmaceutical and device companies. She is also cochair of the MOAS.

AT MOAS 2023

Anxiety and panic attacks

Given the patient's insidious cognitive decline, as well as increased agitation, irritability, anxiety, social isolation, inability to fully manage finances, loss of routine hygienic practices, and loss of interest in regular meals, this patient is diagnosed with probable Alzheimer's disease (AD) dementia and is referred to a specialist for further testing.

AD is one of the most common forms of dementia. More than 6 million people in the United States have clinical AD or mild cognitive impairment because of AD. By 2060, the incidence of AD is expected to grow to 15 million people. AD is classified into four stages: preclinical, mild, moderate, and severe. Patients with preclinical AD — a relatively new classification currently only used for research — do not yet show abnormal results on physical exam or mental status testing, but areas of the brain are undergoing pathologic changes. Mild AD signs and symptoms include memory loss, compromised judgment, trouble handling money and paying bills, mood and personality changes, and increased anxiety. People with moderate AD show increasing signs of memory loss and confusion, problems with recognizing family and friends, and difficulty with organizing thoughts and thinking logically, and they repeat themselves in conversation, among other symptoms. Severe AD is generally described as a complete loss of self, with the inability to recognize family and friends, inability to communicate effectively, and complete dependence on others for care.

Diagnosing AD currently relies on a clinical approach. A complete physical examination, with a detailed neurologic examination and a mental status examination, is used to evaluate disease stage and rule out comorbid conditions. Initial mental status testing should evaluate attention and concentration, recent and remote memory, language, praxis, executive function, and visuospatial function. Imaging studies may be performed to rule out other treatable causes of cognitive decline. In addition, volumetric studies of the hippocampus and 2-[18F]fluoro-2-deoxy-D-glucose PET with or without amyloid imaging can be used for early detection and differentiating dementia etiologies. Lumbar puncture as a diagnostic measure for levels of tau (which is often elevated in AD) and amyloid (which is often reduced in AD) is currently reserved for research settings.

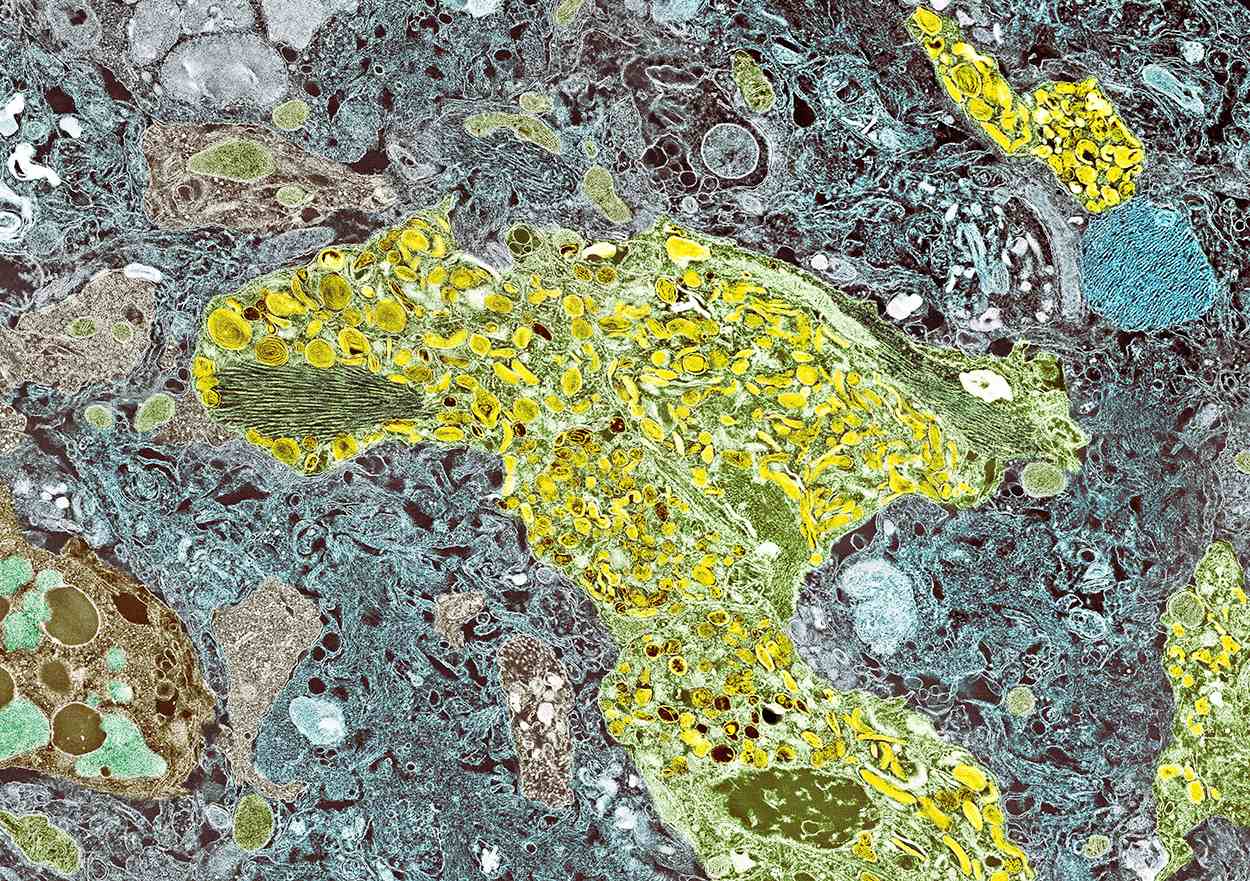

Although the cause of AD is unknown, experts believe that environmental and genetic risk factors trigger a pathophysiologic cascade that, over decades, leads to Alzheimer's pathology and dementia. Universally accepted pathologic hallmarks of AD are beta-amyloid plaques and neurofibrillary tangles (NFTs). NFTs result from changes in the tau protein, a key chemical in neuronal support structures, and are associated with malfunctions in communication between neurons as well as cell death. Beta-amyloid plaques are dense, mostly insoluble deposits that develop around neurons in the hippocampus and other regions in the cerebral cortex used for decision-making, disrupting function and leading to brain atrophy. Risk factors for AD include advancing age, family history, APOE e4 genotype, insulin resistance, hypertension, depression, and traumatic brain injury.

After an AD diagnosis, physicians should encourage the involvement of family and friends who agree to become more involved in the patient's care as the disease progresses. These individuals need to understand the patient's wishes around care, especially for the future, when the patient is no longer able to make decisions. The patient may also consider establishing medical advance directives and durable power of attorney for medical and financial decision-making. Caregivers supporting the patient are encouraged to help balance the physical needs of the patient while maintaining respect for them as a competent adult to the extent allowed by the progression of their disease.

Currently, AD treatments are focused on symptomatic therapies that modulate neurotransmitters — either acetylcholine or glutamate. The standard medical treatment includes cholinesterase inhibitors and a partial N-methyl-D-aspartate antagonist. Two amyloid-directed antibodies (aducanumab, lecanemab) are currently available in the US for individuals with AD exhibiting mild cognitive impairment or mild dementia. A third agent currently in clinical trials (donanemab) has shown significantly slowed clinical progression after 1.5 years among clinical trial participants with early symptomatic AD and amyloid and tau pathology.

Jasvinder Chawla, MD, Professor of Neurology, Loyola University Medical Center, Maywood; Director, Clinical Neurophysiology Lab, Department of Neurology, Hines VA Hospital, Hines, IL.

Jasvinder Chawla, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

Given the patient's insidious cognitive decline, as well as increased agitation, irritability, anxiety, social isolation, inability to fully manage finances, loss of routine hygienic practices, and loss of interest in regular meals, this patient is diagnosed with probable Alzheimer's disease (AD) dementia and is referred to a specialist for further testing.

AD is one of the most common forms of dementia. More than 6 million people in the United States have clinical AD or mild cognitive impairment because of AD. By 2060, the incidence of AD is expected to grow to 15 million people. AD is classified into four stages: preclinical, mild, moderate, and severe. Patients with preclinical AD — a relatively new classification currently only used for research — do not yet show abnormal results on physical exam or mental status testing, but areas of the brain are undergoing pathologic changes. Mild AD signs and symptoms include memory loss, compromised judgment, trouble handling money and paying bills, mood and personality changes, and increased anxiety. People with moderate AD show increasing signs of memory loss and confusion, problems with recognizing family and friends, and difficulty with organizing thoughts and thinking logically, and they repeat themselves in conversation, among other symptoms. Severe AD is generally described as a complete loss of self, with the inability to recognize family and friends, inability to communicate effectively, and complete dependence on others for care.

Diagnosing AD currently relies on a clinical approach. A complete physical examination, with a detailed neurologic examination and a mental status examination, is used to evaluate disease stage and rule out comorbid conditions. Initial mental status testing should evaluate attention and concentration, recent and remote memory, language, praxis, executive function, and visuospatial function. Imaging studies may be performed to rule out other treatable causes of cognitive decline. In addition, volumetric studies of the hippocampus and 2-[18F]fluoro-2-deoxy-D-glucose PET with or without amyloid imaging can be used for early detection and differentiating dementia etiologies. Lumbar puncture as a diagnostic measure for levels of tau (which is often elevated in AD) and amyloid (which is often reduced in AD) is currently reserved for research settings.

Although the cause of AD is unknown, experts believe that environmental and genetic risk factors trigger a pathophysiologic cascade that, over decades, leads to Alzheimer's pathology and dementia. Universally accepted pathologic hallmarks of AD are beta-amyloid plaques and neurofibrillary tangles (NFTs). NFTs result from changes in the tau protein, a key chemical in neuronal support structures, and are associated with malfunctions in communication between neurons as well as cell death. Beta-amyloid plaques are dense, mostly insoluble deposits that develop around neurons in the hippocampus and other regions in the cerebral cortex used for decision-making, disrupting function and leading to brain atrophy. Risk factors for AD include advancing age, family history, APOE e4 genotype, insulin resistance, hypertension, depression, and traumatic brain injury.

After an AD diagnosis, physicians should encourage the involvement of family and friends who agree to become more involved in the patient's care as the disease progresses. These individuals need to understand the patient's wishes around care, especially for the future, when the patient is no longer able to make decisions. The patient may also consider establishing medical advance directives and durable power of attorney for medical and financial decision-making. Caregivers supporting the patient are encouraged to help balance the physical needs of the patient while maintaining respect for them as a competent adult to the extent allowed by the progression of their disease.

Currently, AD treatments are focused on symptomatic therapies that modulate neurotransmitters — either acetylcholine or glutamate. The standard medical treatment includes cholinesterase inhibitors and a partial N-methyl-D-aspartate antagonist. Two amyloid-directed antibodies (aducanumab, lecanemab) are currently available in the US for individuals with AD exhibiting mild cognitive impairment or mild dementia. A third agent currently in clinical trials (donanemab) has shown significantly slowed clinical progression after 1.5 years among clinical trial participants with early symptomatic AD and amyloid and tau pathology.

Jasvinder Chawla, MD, Professor of Neurology, Loyola University Medical Center, Maywood; Director, Clinical Neurophysiology Lab, Department of Neurology, Hines VA Hospital, Hines, IL.

Jasvinder Chawla, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

Given the patient's insidious cognitive decline, as well as increased agitation, irritability, anxiety, social isolation, inability to fully manage finances, loss of routine hygienic practices, and loss of interest in regular meals, this patient is diagnosed with probable Alzheimer's disease (AD) dementia and is referred to a specialist for further testing.

AD is one of the most common forms of dementia. More than 6 million people in the United States have clinical AD or mild cognitive impairment because of AD. By 2060, the incidence of AD is expected to grow to 15 million people. AD is classified into four stages: preclinical, mild, moderate, and severe. Patients with preclinical AD — a relatively new classification currently only used for research — do not yet show abnormal results on physical exam or mental status testing, but areas of the brain are undergoing pathologic changes. Mild AD signs and symptoms include memory loss, compromised judgment, trouble handling money and paying bills, mood and personality changes, and increased anxiety. People with moderate AD show increasing signs of memory loss and confusion, problems with recognizing family and friends, and difficulty with organizing thoughts and thinking logically, and they repeat themselves in conversation, among other symptoms. Severe AD is generally described as a complete loss of self, with the inability to recognize family and friends, inability to communicate effectively, and complete dependence on others for care.

Diagnosing AD currently relies on a clinical approach. A complete physical examination, with a detailed neurologic examination and a mental status examination, is used to evaluate disease stage and rule out comorbid conditions. Initial mental status testing should evaluate attention and concentration, recent and remote memory, language, praxis, executive function, and visuospatial function. Imaging studies may be performed to rule out other treatable causes of cognitive decline. In addition, volumetric studies of the hippocampus and 2-[18F]fluoro-2-deoxy-D-glucose PET with or without amyloid imaging can be used for early detection and differentiating dementia etiologies. Lumbar puncture as a diagnostic measure for levels of tau (which is often elevated in AD) and amyloid (which is often reduced in AD) is currently reserved for research settings.

Although the cause of AD is unknown, experts believe that environmental and genetic risk factors trigger a pathophysiologic cascade that, over decades, leads to Alzheimer's pathology and dementia. Universally accepted pathologic hallmarks of AD are beta-amyloid plaques and neurofibrillary tangles (NFTs). NFTs result from changes in the tau protein, a key chemical in neuronal support structures, and are associated with malfunctions in communication between neurons as well as cell death. Beta-amyloid plaques are dense, mostly insoluble deposits that develop around neurons in the hippocampus and other regions in the cerebral cortex used for decision-making, disrupting function and leading to brain atrophy. Risk factors for AD include advancing age, family history, APOE e4 genotype, insulin resistance, hypertension, depression, and traumatic brain injury.

After an AD diagnosis, physicians should encourage the involvement of family and friends who agree to become more involved in the patient's care as the disease progresses. These individuals need to understand the patient's wishes around care, especially for the future, when the patient is no longer able to make decisions. The patient may also consider establishing medical advance directives and durable power of attorney for medical and financial decision-making. Caregivers supporting the patient are encouraged to help balance the physical needs of the patient while maintaining respect for them as a competent adult to the extent allowed by the progression of their disease.

Currently, AD treatments are focused on symptomatic therapies that modulate neurotransmitters — either acetylcholine or glutamate. The standard medical treatment includes cholinesterase inhibitors and a partial N-methyl-D-aspartate antagonist. Two amyloid-directed antibodies (aducanumab, lecanemab) are currently available in the US for individuals with AD exhibiting mild cognitive impairment or mild dementia. A third agent currently in clinical trials (donanemab) has shown significantly slowed clinical progression after 1.5 years among clinical trial participants with early symptomatic AD and amyloid and tau pathology.

Jasvinder Chawla, MD, Professor of Neurology, Loyola University Medical Center, Maywood; Director, Clinical Neurophysiology Lab, Department of Neurology, Hines VA Hospital, Hines, IL.

Jasvinder Chawla, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

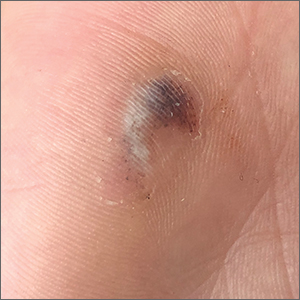

A 73-year-old man who lives independently presents to his primary care physician (PCP) with irritability, anxiety, and panic attacks. Last year, he saw his PCP at the urging of his brother, who noticed that the patient was becoming more forgetful and agitated. At that time, the brother reported concerns that the patient, who normally enjoyed spending time with his extended family, was beginning to regularly forget to show up at family functions. When asked why he hadn't attended, the patient would become irate, saying it was his family who failed to invite him. The patient wouldn't have agreed to seeing the PCP except he was having issues with insomnia that he wanted to address. During last year's visit, the physician conducted a complete physical examination, as well as detailed neurologic and mental status examinations; all came back normal.

At today's visit, in addition to patient-reported mood fluctuations, the brother tells the physician that the patient has become reclusive, skipping nearly all family functions as well as daily walks with friends. His daily hygiene has suffered, and he has stopped eating regularly. The brother also mentions to the doctor that the patient has received some late-payment notices for utilities that he normally meticulously paid on time. The PCP orders another round of cognitive, behavioral, and functional assessments, which reveal a decline in all areas from last year's results, as well as a complete neurologic examination that reveals mild hyposmia.

MASLD/MASH and Weight Loss

- Younossi ZM et al. Gastroenterology. 2021;160(3):912-918. doi:10.1053/j.astro.2020.11.051

- Cusi K et al. Endocr Pract. 2022;28(5):528-562. doi:10.1016/j.eprac.2022.03.010

- Rinella ME et al. Hepatology. 2023;77(5):1797-1835. doi:10.1097/HEP.0000000000000323

- World obesity atlas 2023. World Obesity Day. Published March 2023. Accessed July 23, 2023. https://www.worldobesityday.org/assets/downloads/World_Obesity_Atlas_2023_Report.pdf

- Le MH et al. Clin Mol Hepatol. 2022;28(4):841-850. doi:10.3350/cmh.2022.0239

- Vilar-Gomez E et al. Gastroenterology. 2015;149(2):367-78.e5. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2015.04.005

- Koutoukidis DA et al. Metabolism. 2021;115:154455. doi:10.1016/j.metabol.2020.154455

- Ma J et al. Gastroenterology. 2018;155(1):107-117. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2018.03.038

- Ahern AL et al. Lancet. 2017;389(10085):2214-2225. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30647-5

- Newsome PN et al; NN9931-4296 Investigators. N Engl J Med. 2021;384(12):1113-1124. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2028395

- Armstrong MJ et al. Lancet. 2016;387(10019):679-690. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00803-X

- Gastaldelli A et al. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2022;10(6):393-406. doi:10.1016/S2213-8587(22)00070-5

- Kahl S et al. Diabetes Care. 2020;43(2):298-305. doi:10.2337/dc19-0641

- Younossi ZM et al. Gastroenterology. 2021;160(3):912-918. doi:10.1053/j.astro.2020.11.051

- Cusi K et al. Endocr Pract. 2022;28(5):528-562. doi:10.1016/j.eprac.2022.03.010

- Rinella ME et al. Hepatology. 2023;77(5):1797-1835. doi:10.1097/HEP.0000000000000323

- World obesity atlas 2023. World Obesity Day. Published March 2023. Accessed July 23, 2023. https://www.worldobesityday.org/assets/downloads/World_Obesity_Atlas_2023_Report.pdf

- Le MH et al. Clin Mol Hepatol. 2022;28(4):841-850. doi:10.3350/cmh.2022.0239

- Vilar-Gomez E et al. Gastroenterology. 2015;149(2):367-78.e5. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2015.04.005

- Koutoukidis DA et al. Metabolism. 2021;115:154455. doi:10.1016/j.metabol.2020.154455

- Ma J et al. Gastroenterology. 2018;155(1):107-117. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2018.03.038

- Ahern AL et al. Lancet. 2017;389(10085):2214-2225. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30647-5

- Newsome PN et al; NN9931-4296 Investigators. N Engl J Med. 2021;384(12):1113-1124. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2028395

- Armstrong MJ et al. Lancet. 2016;387(10019):679-690. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00803-X

- Gastaldelli A et al. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2022;10(6):393-406. doi:10.1016/S2213-8587(22)00070-5

- Kahl S et al. Diabetes Care. 2020;43(2):298-305. doi:10.2337/dc19-0641

- Younossi ZM et al. Gastroenterology. 2021;160(3):912-918. doi:10.1053/j.astro.2020.11.051

- Cusi K et al. Endocr Pract. 2022;28(5):528-562. doi:10.1016/j.eprac.2022.03.010

- Rinella ME et al. Hepatology. 2023;77(5):1797-1835. doi:10.1097/HEP.0000000000000323

- World obesity atlas 2023. World Obesity Day. Published March 2023. Accessed July 23, 2023. https://www.worldobesityday.org/assets/downloads/World_Obesity_Atlas_2023_Report.pdf

- Le MH et al. Clin Mol Hepatol. 2022;28(4):841-850. doi:10.3350/cmh.2022.0239

- Vilar-Gomez E et al. Gastroenterology. 2015;149(2):367-78.e5. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2015.04.005

- Koutoukidis DA et al. Metabolism. 2021;115:154455. doi:10.1016/j.metabol.2020.154455

- Ma J et al. Gastroenterology. 2018;155(1):107-117. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2018.03.038

- Ahern AL et al. Lancet. 2017;389(10085):2214-2225. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30647-5

- Newsome PN et al; NN9931-4296 Investigators. N Engl J Med. 2021;384(12):1113-1124. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2028395

- Armstrong MJ et al. Lancet. 2016;387(10019):679-690. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00803-X

- Gastaldelli A et al. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2022;10(6):393-406. doi:10.1016/S2213-8587(22)00070-5

- Kahl S et al. Diabetes Care. 2020;43(2):298-305. doi:10.2337/dc19-0641

The Evolving Role of Surgery for IBD

- Gul F et al. Ann Med Surg (Lond). 2022;81:104476. doi:10.1016/j.amsu.2022.104476

- Kotze PG et al. Clin Colon Rectal Surg. 2021;34(3):172-180. doi:10.1055/s-0040-1718685

- Bemelman WA; S-ECCO collaborators. J Crohns Colitis. 2018;12(8):1005-1007. doi:10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjy056

- Ricci C et al. Dig Liver Dis. 2008;40(suppl 2):S285-S288. doi:10.1016/S1590-8658(08)60539-3

- Lin X et al. Therap Adv Gastroenterol. 2022;15:17562848221104951. doi:10.1177/17562848221104951

- Parigi TL et al. Dis Colon Rectum. 2022;65(suppl 1):S119-S128. doi:10.1097/DCR.0000000000002548

- Pilonis ND et al. Transl Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;7:7. doi:10.21037/tgh.2020.04.02