User login

Drug could reduce morbidity, mortality in aTTP, doc says

Photo courtesy of ASH

THE HAGUE—Caplacizumab has the potential to reduce morbidity and mortality associated with acquired thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura (aTTP), according to the principal investigator of the phase 2 TITAN study.

Post-hoc analyses of data from this study suggested that adding caplacizumab to standard therapy can reduce major thromboembolic complications and aTTP-related death, as well as refractoriness to standard treatment.

These findings were recently presented at the European Congress on Thrombosis and Haemostasis (ECTH). The study was sponsored by Ablynx, the company developing caplacizumab.

Caplacizumab is an anti-von Willebrand factor nanobody that works by blocking the interaction of ultra-large von Willebrand factor multimers with platelets.

According to Ablynx, the nanobody has an immediate effect on platelet aggregation and the ensuing formation and accumulation of the micro-clots that cause severe thrombocytopenia and organ and tissue damage in patients with aTTP. This immediate effect protects the patient from the manifestations of the disease while the underlying disease process resolves.

Previous results from TITAN

TITAN was a single-blinded study that enrolled 75 aTTP patients. They all received the current standard of care for aTTP—daily plasma exchange and immunosuppressive therapy. Thirty-six patients were randomized to receive caplacizumab as well, and 39 were randomized to placebo.

The study’s primary endpoint was time to response (platelet count normalization). Patients in the caplacizumab arm had a 39% reduction in the median time to response compared to patients in the placebo arm (P=0.005).

The rate of confirmed response was 86.1% (n=31) in the caplacizumab arm and 71.8% (n=28) in the placebo arm.

There were more relapses in the caplacizumab arm than the placebo arm—8 (22.2%) and 0, respectively. Relapse was defined as a TTP event occurring more than 30 days after the end of daily plasma exchange.

There were fewer exacerbations in the caplacizumab arm than the placebo arm—3 (8.3%) and 11 (28.2%), respectively. Exacerbation was defined as recurrent thrombocytopenia within 30 days of the end of daily plasma exchange that required reinitiation of daily exchange.

The rate of adverse events thought to be related to the study drug was 17% in the caplacizumab arm and 11% in the placebo arm. The rate of events that were possibly related was 54% and 8%, respectively.

These and other results from TITAN were published in NEJM earlier this year.

Post-hoc analyses

Investigators performed post-hoc analyses of TITAN data to assess the impact of caplacizumab on a composite endpoint of major thromboembolic complications and aTTP-related mortality, as well as on refractoriness to standard treatment.

The proportion of patients who died or had at least 1 major thromboembolic event was lower in the caplacizumab arm than the placebo arm—11.4% and 43.2%, respectively.

There were 4 major thromboembolic events in the caplacizumab arm—3 recurrences of TTP during the treatment period and 1 pulmonary embolism.

There were 20 major thromboembolic events in the placebo arm—13 recurrences of TTP during the treatment period (in 11 patients), 2 acute myocardial infarctions, 1 deep vein thrombosis, 1 venous thrombosis, 1 pulmonary embolism, 1 ischemic stroke, and 1 hemorrhagic stroke.

There were no deaths in the caplacizumab arm, but there were 2 deaths in the placebo arm. Both of those patients were refractory to treatment.

Fewer patients in the caplacizumab arm than the placebo arm were refractory to treatment.

When refractoriness was defined as “failure of platelet response after 7 days despite daily plasma exchange treatment,” the rates of refractoriness were 5.7% in the caplacizumab arm and 21.6% in the placebo arm.

When refractoriness was defined as “absence of platelet count doubling after 4 days of standard treatment and lactate dehydrogenase greater than the upper limit of normal,” the rates of refractoriness were 0% in the caplacizumab arm and 10.8% in the placebo arm.

“Acquired TTP is a very severe disease with high unmet medical need,” said TITAN’s principal investigator Flora Peyvandi, MD, PhD, of the University of Milan in Italy.

“Any new treatment option would need to act fast to immediately inhibit the formation of micro-clots in order to protect the patient during the acute phase of the disease and so have the potential to avoid the resulting complications.”

“The top-line results and the subsequent post-hoc analyses of the phase 2 TITAN data demonstrate that caplacizumab has the potential to reduce the major morbidity and mortality associated with acquired TTP, and confirm our conviction that it should become an important pillar in the management of acquired TTP.” ![]()

Photo courtesy of ASH

THE HAGUE—Caplacizumab has the potential to reduce morbidity and mortality associated with acquired thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura (aTTP), according to the principal investigator of the phase 2 TITAN study.

Post-hoc analyses of data from this study suggested that adding caplacizumab to standard therapy can reduce major thromboembolic complications and aTTP-related death, as well as refractoriness to standard treatment.

These findings were recently presented at the European Congress on Thrombosis and Haemostasis (ECTH). The study was sponsored by Ablynx, the company developing caplacizumab.

Caplacizumab is an anti-von Willebrand factor nanobody that works by blocking the interaction of ultra-large von Willebrand factor multimers with platelets.

According to Ablynx, the nanobody has an immediate effect on platelet aggregation and the ensuing formation and accumulation of the micro-clots that cause severe thrombocytopenia and organ and tissue damage in patients with aTTP. This immediate effect protects the patient from the manifestations of the disease while the underlying disease process resolves.

Previous results from TITAN

TITAN was a single-blinded study that enrolled 75 aTTP patients. They all received the current standard of care for aTTP—daily plasma exchange and immunosuppressive therapy. Thirty-six patients were randomized to receive caplacizumab as well, and 39 were randomized to placebo.

The study’s primary endpoint was time to response (platelet count normalization). Patients in the caplacizumab arm had a 39% reduction in the median time to response compared to patients in the placebo arm (P=0.005).

The rate of confirmed response was 86.1% (n=31) in the caplacizumab arm and 71.8% (n=28) in the placebo arm.

There were more relapses in the caplacizumab arm than the placebo arm—8 (22.2%) and 0, respectively. Relapse was defined as a TTP event occurring more than 30 days after the end of daily plasma exchange.

There were fewer exacerbations in the caplacizumab arm than the placebo arm—3 (8.3%) and 11 (28.2%), respectively. Exacerbation was defined as recurrent thrombocytopenia within 30 days of the end of daily plasma exchange that required reinitiation of daily exchange.

The rate of adverse events thought to be related to the study drug was 17% in the caplacizumab arm and 11% in the placebo arm. The rate of events that were possibly related was 54% and 8%, respectively.

These and other results from TITAN were published in NEJM earlier this year.

Post-hoc analyses

Investigators performed post-hoc analyses of TITAN data to assess the impact of caplacizumab on a composite endpoint of major thromboembolic complications and aTTP-related mortality, as well as on refractoriness to standard treatment.

The proportion of patients who died or had at least 1 major thromboembolic event was lower in the caplacizumab arm than the placebo arm—11.4% and 43.2%, respectively.

There were 4 major thromboembolic events in the caplacizumab arm—3 recurrences of TTP during the treatment period and 1 pulmonary embolism.

There were 20 major thromboembolic events in the placebo arm—13 recurrences of TTP during the treatment period (in 11 patients), 2 acute myocardial infarctions, 1 deep vein thrombosis, 1 venous thrombosis, 1 pulmonary embolism, 1 ischemic stroke, and 1 hemorrhagic stroke.

There were no deaths in the caplacizumab arm, but there were 2 deaths in the placebo arm. Both of those patients were refractory to treatment.

Fewer patients in the caplacizumab arm than the placebo arm were refractory to treatment.

When refractoriness was defined as “failure of platelet response after 7 days despite daily plasma exchange treatment,” the rates of refractoriness were 5.7% in the caplacizumab arm and 21.6% in the placebo arm.

When refractoriness was defined as “absence of platelet count doubling after 4 days of standard treatment and lactate dehydrogenase greater than the upper limit of normal,” the rates of refractoriness were 0% in the caplacizumab arm and 10.8% in the placebo arm.

“Acquired TTP is a very severe disease with high unmet medical need,” said TITAN’s principal investigator Flora Peyvandi, MD, PhD, of the University of Milan in Italy.

“Any new treatment option would need to act fast to immediately inhibit the formation of micro-clots in order to protect the patient during the acute phase of the disease and so have the potential to avoid the resulting complications.”

“The top-line results and the subsequent post-hoc analyses of the phase 2 TITAN data demonstrate that caplacizumab has the potential to reduce the major morbidity and mortality associated with acquired TTP, and confirm our conviction that it should become an important pillar in the management of acquired TTP.” ![]()

Photo courtesy of ASH

THE HAGUE—Caplacizumab has the potential to reduce morbidity and mortality associated with acquired thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura (aTTP), according to the principal investigator of the phase 2 TITAN study.

Post-hoc analyses of data from this study suggested that adding caplacizumab to standard therapy can reduce major thromboembolic complications and aTTP-related death, as well as refractoriness to standard treatment.

These findings were recently presented at the European Congress on Thrombosis and Haemostasis (ECTH). The study was sponsored by Ablynx, the company developing caplacizumab.

Caplacizumab is an anti-von Willebrand factor nanobody that works by blocking the interaction of ultra-large von Willebrand factor multimers with platelets.

According to Ablynx, the nanobody has an immediate effect on platelet aggregation and the ensuing formation and accumulation of the micro-clots that cause severe thrombocytopenia and organ and tissue damage in patients with aTTP. This immediate effect protects the patient from the manifestations of the disease while the underlying disease process resolves.

Previous results from TITAN

TITAN was a single-blinded study that enrolled 75 aTTP patients. They all received the current standard of care for aTTP—daily plasma exchange and immunosuppressive therapy. Thirty-six patients were randomized to receive caplacizumab as well, and 39 were randomized to placebo.

The study’s primary endpoint was time to response (platelet count normalization). Patients in the caplacizumab arm had a 39% reduction in the median time to response compared to patients in the placebo arm (P=0.005).

The rate of confirmed response was 86.1% (n=31) in the caplacizumab arm and 71.8% (n=28) in the placebo arm.

There were more relapses in the caplacizumab arm than the placebo arm—8 (22.2%) and 0, respectively. Relapse was defined as a TTP event occurring more than 30 days after the end of daily plasma exchange.

There were fewer exacerbations in the caplacizumab arm than the placebo arm—3 (8.3%) and 11 (28.2%), respectively. Exacerbation was defined as recurrent thrombocytopenia within 30 days of the end of daily plasma exchange that required reinitiation of daily exchange.

The rate of adverse events thought to be related to the study drug was 17% in the caplacizumab arm and 11% in the placebo arm. The rate of events that were possibly related was 54% and 8%, respectively.

These and other results from TITAN were published in NEJM earlier this year.

Post-hoc analyses

Investigators performed post-hoc analyses of TITAN data to assess the impact of caplacizumab on a composite endpoint of major thromboembolic complications and aTTP-related mortality, as well as on refractoriness to standard treatment.

The proportion of patients who died or had at least 1 major thromboembolic event was lower in the caplacizumab arm than the placebo arm—11.4% and 43.2%, respectively.

There were 4 major thromboembolic events in the caplacizumab arm—3 recurrences of TTP during the treatment period and 1 pulmonary embolism.

There were 20 major thromboembolic events in the placebo arm—13 recurrences of TTP during the treatment period (in 11 patients), 2 acute myocardial infarctions, 1 deep vein thrombosis, 1 venous thrombosis, 1 pulmonary embolism, 1 ischemic stroke, and 1 hemorrhagic stroke.

There were no deaths in the caplacizumab arm, but there were 2 deaths in the placebo arm. Both of those patients were refractory to treatment.

Fewer patients in the caplacizumab arm than the placebo arm were refractory to treatment.

When refractoriness was defined as “failure of platelet response after 7 days despite daily plasma exchange treatment,” the rates of refractoriness were 5.7% in the caplacizumab arm and 21.6% in the placebo arm.

When refractoriness was defined as “absence of platelet count doubling after 4 days of standard treatment and lactate dehydrogenase greater than the upper limit of normal,” the rates of refractoriness were 0% in the caplacizumab arm and 10.8% in the placebo arm.

“Acquired TTP is a very severe disease with high unmet medical need,” said TITAN’s principal investigator Flora Peyvandi, MD, PhD, of the University of Milan in Italy.

“Any new treatment option would need to act fast to immediately inhibit the formation of micro-clots in order to protect the patient during the acute phase of the disease and so have the potential to avoid the resulting complications.”

“The top-line results and the subsequent post-hoc analyses of the phase 2 TITAN data demonstrate that caplacizumab has the potential to reduce the major morbidity and mortality associated with acquired TTP, and confirm our conviction that it should become an important pillar in the management of acquired TTP.” ![]()

Scientist awarded Nobel Prize for autophagy research

Photo by Mari Honda

The 2016 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine has been awarded to Yoshinori Ohsumi, PhD, for his discoveries related to autophagy.

The concept of autophagy emerged during the 1960s, but little was known about the process until the early 1990s.

That’s when Dr Ohsumi used yeast cells to identify genes essential for autophagy. He cloned several of these genes in yeast and mammalian cells and described the function of the encoded proteins.

According to The Nobel Assembly at Karolinska Institutet, Dr Ohsumi’s discoveries opened the path to understanding the fundamental importance of autophagy in many physiological processes.

The man

Dr Ohsumi was born in 1945 in Fukuoka, Japan. He received a PhD from University of Tokyo in 1974.

After spending 3 years at Rockefeller University in New York, he returned to the University of Tokyo, where he established his research group in 1988. Since 2009, he has been a professor at the Tokyo Institute of Technology.

The research

The Belgian scientist Christian de Duve coined the term autophagy in 1963. However, the process was still not well understood when Dr Ohsumi began his research on autophagy.

In the early 1990s, Dr Ohsumi decided to study autophagy using the budding yeast Saccharomyces cerevisae as a model system.

He was not sure whether autophagy existed in this organism. However, he reasoned that, if it did, and he could disrupt the degradation process in the vacuole while autophagy was active, autophagosomes should accumulate within the vacuole.

Dr Ohsumi cultured mutated yeast lacking vacuolar degradation enzymes and simultaneously stimulated autophagy by starving the cells.

Within hours, the vacuoles were filled with small vesicles that had not been degraded. The vesicles were autophagosomes, and the experiment proved that autophagy exists in yeast cells.

The experiment also provided a method to identify and characterize genes involved in autophagy.

Dr Ohsumi noted that the accumulation of autophagosomes should not occur if genes important for autophagy were inactivated.

So he exposed the yeast cells to a chemical that randomly introduced mutations in many genes, and then he induced autophagy. In this way, he identified 15 genes essential for autophagy in budding yeast.

In his subsequent studies, Dr Ohsumi cloned several of these genes in yeast and mammalian cells and characterized the function of the proteins encoded by these genes.

He found that autophagy is controlled by a cascade of proteins and protein complexes, each regulating a distinct stage of autophagosome initiation and formation.

Insights provided by Dr Ohsumi’s work enabled subsequent research that has revealed the role of autophagy in human physiology and disease.

For more information on Dr Ohsumi and his work, visit the Nobel Prize website. ![]()

Photo by Mari Honda

The 2016 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine has been awarded to Yoshinori Ohsumi, PhD, for his discoveries related to autophagy.

The concept of autophagy emerged during the 1960s, but little was known about the process until the early 1990s.

That’s when Dr Ohsumi used yeast cells to identify genes essential for autophagy. He cloned several of these genes in yeast and mammalian cells and described the function of the encoded proteins.

According to The Nobel Assembly at Karolinska Institutet, Dr Ohsumi’s discoveries opened the path to understanding the fundamental importance of autophagy in many physiological processes.

The man

Dr Ohsumi was born in 1945 in Fukuoka, Japan. He received a PhD from University of Tokyo in 1974.

After spending 3 years at Rockefeller University in New York, he returned to the University of Tokyo, where he established his research group in 1988. Since 2009, he has been a professor at the Tokyo Institute of Technology.

The research

The Belgian scientist Christian de Duve coined the term autophagy in 1963. However, the process was still not well understood when Dr Ohsumi began his research on autophagy.

In the early 1990s, Dr Ohsumi decided to study autophagy using the budding yeast Saccharomyces cerevisae as a model system.

He was not sure whether autophagy existed in this organism. However, he reasoned that, if it did, and he could disrupt the degradation process in the vacuole while autophagy was active, autophagosomes should accumulate within the vacuole.

Dr Ohsumi cultured mutated yeast lacking vacuolar degradation enzymes and simultaneously stimulated autophagy by starving the cells.

Within hours, the vacuoles were filled with small vesicles that had not been degraded. The vesicles were autophagosomes, and the experiment proved that autophagy exists in yeast cells.

The experiment also provided a method to identify and characterize genes involved in autophagy.

Dr Ohsumi noted that the accumulation of autophagosomes should not occur if genes important for autophagy were inactivated.

So he exposed the yeast cells to a chemical that randomly introduced mutations in many genes, and then he induced autophagy. In this way, he identified 15 genes essential for autophagy in budding yeast.

In his subsequent studies, Dr Ohsumi cloned several of these genes in yeast and mammalian cells and characterized the function of the proteins encoded by these genes.

He found that autophagy is controlled by a cascade of proteins and protein complexes, each regulating a distinct stage of autophagosome initiation and formation.

Insights provided by Dr Ohsumi’s work enabled subsequent research that has revealed the role of autophagy in human physiology and disease.

For more information on Dr Ohsumi and his work, visit the Nobel Prize website. ![]()

Photo by Mari Honda

The 2016 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine has been awarded to Yoshinori Ohsumi, PhD, for his discoveries related to autophagy.

The concept of autophagy emerged during the 1960s, but little was known about the process until the early 1990s.

That’s when Dr Ohsumi used yeast cells to identify genes essential for autophagy. He cloned several of these genes in yeast and mammalian cells and described the function of the encoded proteins.

According to The Nobel Assembly at Karolinska Institutet, Dr Ohsumi’s discoveries opened the path to understanding the fundamental importance of autophagy in many physiological processes.

The man

Dr Ohsumi was born in 1945 in Fukuoka, Japan. He received a PhD from University of Tokyo in 1974.

After spending 3 years at Rockefeller University in New York, he returned to the University of Tokyo, where he established his research group in 1988. Since 2009, he has been a professor at the Tokyo Institute of Technology.

The research

The Belgian scientist Christian de Duve coined the term autophagy in 1963. However, the process was still not well understood when Dr Ohsumi began his research on autophagy.

In the early 1990s, Dr Ohsumi decided to study autophagy using the budding yeast Saccharomyces cerevisae as a model system.

He was not sure whether autophagy existed in this organism. However, he reasoned that, if it did, and he could disrupt the degradation process in the vacuole while autophagy was active, autophagosomes should accumulate within the vacuole.

Dr Ohsumi cultured mutated yeast lacking vacuolar degradation enzymes and simultaneously stimulated autophagy by starving the cells.

Within hours, the vacuoles were filled with small vesicles that had not been degraded. The vesicles were autophagosomes, and the experiment proved that autophagy exists in yeast cells.

The experiment also provided a method to identify and characterize genes involved in autophagy.

Dr Ohsumi noted that the accumulation of autophagosomes should not occur if genes important for autophagy were inactivated.

So he exposed the yeast cells to a chemical that randomly introduced mutations in many genes, and then he induced autophagy. In this way, he identified 15 genes essential for autophagy in budding yeast.

In his subsequent studies, Dr Ohsumi cloned several of these genes in yeast and mammalian cells and characterized the function of the proteins encoded by these genes.

He found that autophagy is controlled by a cascade of proteins and protein complexes, each regulating a distinct stage of autophagosome initiation and formation.

Insights provided by Dr Ohsumi’s work enabled subsequent research that has revealed the role of autophagy in human physiology and disease.

For more information on Dr Ohsumi and his work, visit the Nobel Prize website. ![]()

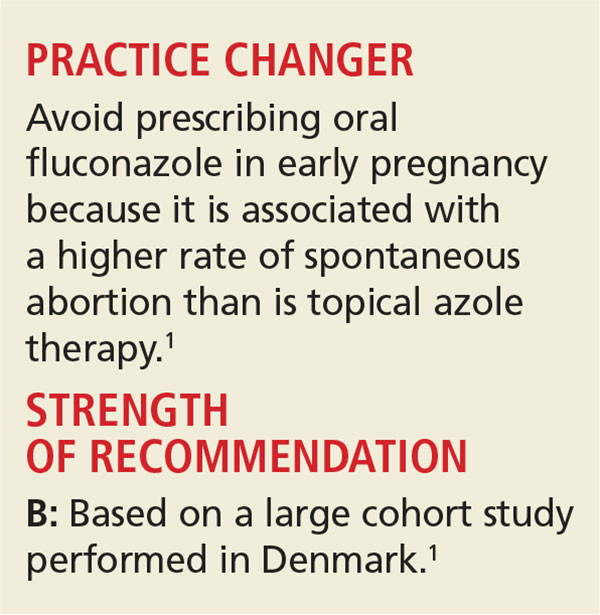

Yeast Infection in Pregnancy? Think Twice About Fluconazole

A 25-year-old woman who is 16 weeks pregnant with her first child is experiencing increased vaginal discharge associated with vaginal itching. A microscopic examination of the discharge confirms your suspicions of vaginal candidiasis. Is oral fluconazole or a topical azole your treatment of choice?

Because of the increased production of sex hormones, vaginal candidiasis is common during pregnancy, affecting up to 10% of pregnant women in the United States.1,2 Treatment options include oral fluconazole and a variety of topical azoles. Although the latter are recommended as firstline therapy, the ease of oral therapy makes it an attractive option.3,4

However, the safety of oral fluconazole during pregnancy has recently come under scrutiny. Case reports have linked high-dose use with congenital malformation.5,6 These case reports led to epidemiologic studies in which no such association was found.7,8

A large cohort study involving 1,079 fluconazole-exposed pregnancies and 170,453 unexposed pregnancies found no increased risk for congenital malformation or stillbirth; rates of spontaneous abortion and miscarriage were not evaluated.9 A prospective cohort study of 226 pregnant women found no association between fluconazole use during the first trimester and miscarriage.10 However, the validity of both studies’ findings was limited by small numbers of participants.

The current study is the largest to date to evaluate whether use of fluconazole in early pregnancy is associated with increased rates of spontaneous abortion and stillbirth, compared to topical azoles.

STUDY SUMMARY

Increased risk for miscarriage, but not stillbirth

This nationwide cohort study, conducted using the Medical Birth Register in Denmark, evaluated more than 1.4 million pregnancies occurring from 1997 to 2013 for exposure to oral fluconazole between 7 and 22 weeks’ gestation. Each oral fluconazole–exposed pregnancy was matched with up to four unexposed pregnancies (based on propensity score, maternal age, calendar year, and gestational age) and to pregnancies exposed to intravaginal formulations of topical azoles. Exposure to fluconazole was documented by filled prescriptions from the National Prescription Register. Primary outcomes were rates of spontaneous abortion (loss before 22 weeks) and stillbirth (loss after 23 weeks).

Rates of spontaneous abortion. Of the total cohort, 3,315 pregnancies were exposed to oral fluconazole between 7 and 22 weeks’ gestation. Spontaneous abortion occurred in 147 of these pregnancies and in 563 of 13,246 unexposed, matched pregnancies (hazard ratio [HR], 1.48).

Rates of stillbirth. Of 5,382 pregnancies exposed to fluconazole from week 7 to birth, 21 resulted in stillbirth; 77 stillbirths occurred in the 21,506 unexposed matched pregnancies (HR, 1.32). In a sensitivity analysis, however, higher doses of fluconazole (350 mg) were four times more likely than lower doses (150 mg) to be associated with stillbirth (HRs, 4.10 and 0.99, respectively).

Oral fluconazole vs topical azole. Use of oral fluconazole in pregnancy was associated with an increased risk for spontaneous abortion, compared to topical azole use (130 of 2,823 pregnancies vs 118 of 2,823 pregnancies; HR, 1.62)—but not an increased risk for stillbirth (20 of 4,301 pregnancies vs 22 of 4,301 pregnancies; HR, 1.18).

WHAT'S NEW

A sizeable study with a treatment comparison

The authors found that exposure in early pregnancy to oral fluconazole, as compared to topical azoles, increases the risk for spontaneous abortion. By comparing treatments in a sensitivity analysis, the researchers were able to eliminate Candida infections causing spontaneous abortion as a confounding factor. In addition, this study challenges the balance between ease of use and safety.

CAVEATS

A skewed population?

This cohort study using a Danish hospital registry may not be generalizable to a larger, non-Scandinavian population. Those not seeking care through a hospital were likely missed; if those seeking care through the hospital had a higher risk for abortion, the results could be biased. However, this would not have affected the results of the comparison between the two active treatments.

In addition, the study focused on women exposed from 7 to 22 weeks’ gestation; the findings may not be generalizable to fluconazole exposure prior to 7 weeks. Likewise, the registry is unlikely to capture very early spontaneous abortions that are not recognized clinically.

In all, given the large sample size and the care taken to match each exposed pregnancy with up to four unexposed pregnancies, these limitations likely had little influence on the overall findings.

CHALLENGES TO IMPLEMENTATION

Balancing ease of use with safety

Given the ease of using oral fluconazole, compared with daily topical azole therapy, many clinicians and patients may still opt for oral treatment.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The PURLs Surveillance System was supported in part by Grant Number UL1RR024999 from the National Center For Research Resources, a Clinical Translational Science Award to the University of Chicago. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Center For Research Resources or the National Institutes of Health.

Copyright © 2016. The Family Physicians Inquiries Network. All rights reserved.

Reprinted with permission from the Family Physicians Inquiries Network and The Journal of Family Practice. 2016;65(9):624-626.

1. Mølgaard-Nielsen D, Svanström H, Melbye M, et al. Association between use of oral fluconazole during pregnancy and risk of spontaneous abortion and stillbirth. JAMA. 2016;315:58-67.

2. Cotch MF, Hillier SL, Gibbs RS, et al; Vaginal Infections and Prematurity Study Group. Epidemiology and outcomes associated with moderate to heavy Candida colonization during pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1998;178:374-380.

3. Workowski KA, Bolan GA, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2015. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2015;64:1-137.

4. Tooley PJ. Patient and doctor preferences in the treatment of vaginal candidiasis. Practitioner. 1985;229:655-660.

5. Aleck KA, Bartley DL. Multiple malformation syndrome following fluconazole use in pregnancy: report of an additional patient. Am J Med Genet. 1997;72:253-256.

6. Lee BE, Feinberg M, Abraham JJ, et al. Congenital malformations in an infant born to a woman treated with fluconazole. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1992;11:1062-1064.

7. Jick SS. Pregnancy outcomes after maternal exposure to fluconazole. Pharmacotherapy. 1999;19:221-222.

8. Mølgaard-Nielsen D, Pasternak B, Hviid A. Use of oral fluconazole during pregnancy and the risk of birth defects. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:830-839.

9. Nørgaard M, Pedersen L, Gislum M, et al. Maternal use of fluconazole and risk of congenital malformations: a Danish population-based cohort study. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2008;62:172-176.

10. Mastroiacovo P, Mazzone T, Botto LD, et al. Prospective assessment of pregnancy outcomes after first-trimester exposure to fluconazole. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1996;175:1645-1650.

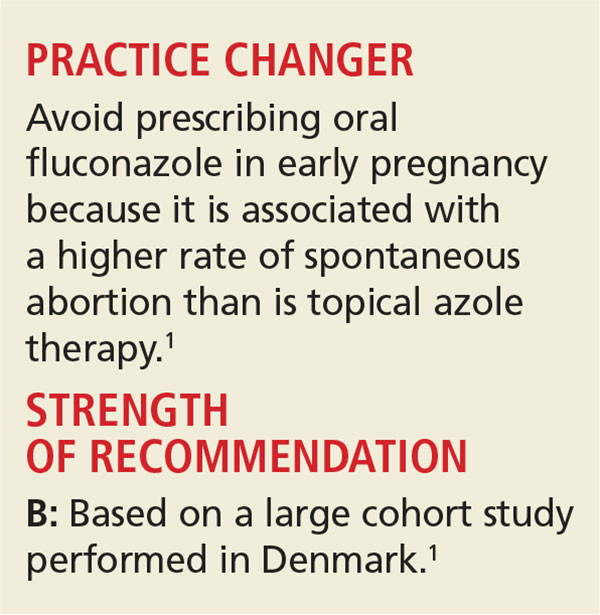

A 25-year-old woman who is 16 weeks pregnant with her first child is experiencing increased vaginal discharge associated with vaginal itching. A microscopic examination of the discharge confirms your suspicions of vaginal candidiasis. Is oral fluconazole or a topical azole your treatment of choice?

Because of the increased production of sex hormones, vaginal candidiasis is common during pregnancy, affecting up to 10% of pregnant women in the United States.1,2 Treatment options include oral fluconazole and a variety of topical azoles. Although the latter are recommended as firstline therapy, the ease of oral therapy makes it an attractive option.3,4

However, the safety of oral fluconazole during pregnancy has recently come under scrutiny. Case reports have linked high-dose use with congenital malformation.5,6 These case reports led to epidemiologic studies in which no such association was found.7,8

A large cohort study involving 1,079 fluconazole-exposed pregnancies and 170,453 unexposed pregnancies found no increased risk for congenital malformation or stillbirth; rates of spontaneous abortion and miscarriage were not evaluated.9 A prospective cohort study of 226 pregnant women found no association between fluconazole use during the first trimester and miscarriage.10 However, the validity of both studies’ findings was limited by small numbers of participants.

The current study is the largest to date to evaluate whether use of fluconazole in early pregnancy is associated with increased rates of spontaneous abortion and stillbirth, compared to topical azoles.

STUDY SUMMARY

Increased risk for miscarriage, but not stillbirth

This nationwide cohort study, conducted using the Medical Birth Register in Denmark, evaluated more than 1.4 million pregnancies occurring from 1997 to 2013 for exposure to oral fluconazole between 7 and 22 weeks’ gestation. Each oral fluconazole–exposed pregnancy was matched with up to four unexposed pregnancies (based on propensity score, maternal age, calendar year, and gestational age) and to pregnancies exposed to intravaginal formulations of topical azoles. Exposure to fluconazole was documented by filled prescriptions from the National Prescription Register. Primary outcomes were rates of spontaneous abortion (loss before 22 weeks) and stillbirth (loss after 23 weeks).

Rates of spontaneous abortion. Of the total cohort, 3,315 pregnancies were exposed to oral fluconazole between 7 and 22 weeks’ gestation. Spontaneous abortion occurred in 147 of these pregnancies and in 563 of 13,246 unexposed, matched pregnancies (hazard ratio [HR], 1.48).

Rates of stillbirth. Of 5,382 pregnancies exposed to fluconazole from week 7 to birth, 21 resulted in stillbirth; 77 stillbirths occurred in the 21,506 unexposed matched pregnancies (HR, 1.32). In a sensitivity analysis, however, higher doses of fluconazole (350 mg) were four times more likely than lower doses (150 mg) to be associated with stillbirth (HRs, 4.10 and 0.99, respectively).

Oral fluconazole vs topical azole. Use of oral fluconazole in pregnancy was associated with an increased risk for spontaneous abortion, compared to topical azole use (130 of 2,823 pregnancies vs 118 of 2,823 pregnancies; HR, 1.62)—but not an increased risk for stillbirth (20 of 4,301 pregnancies vs 22 of 4,301 pregnancies; HR, 1.18).

WHAT'S NEW

A sizeable study with a treatment comparison

The authors found that exposure in early pregnancy to oral fluconazole, as compared to topical azoles, increases the risk for spontaneous abortion. By comparing treatments in a sensitivity analysis, the researchers were able to eliminate Candida infections causing spontaneous abortion as a confounding factor. In addition, this study challenges the balance between ease of use and safety.

CAVEATS

A skewed population?

This cohort study using a Danish hospital registry may not be generalizable to a larger, non-Scandinavian population. Those not seeking care through a hospital were likely missed; if those seeking care through the hospital had a higher risk for abortion, the results could be biased. However, this would not have affected the results of the comparison between the two active treatments.

In addition, the study focused on women exposed from 7 to 22 weeks’ gestation; the findings may not be generalizable to fluconazole exposure prior to 7 weeks. Likewise, the registry is unlikely to capture very early spontaneous abortions that are not recognized clinically.

In all, given the large sample size and the care taken to match each exposed pregnancy with up to four unexposed pregnancies, these limitations likely had little influence on the overall findings.

CHALLENGES TO IMPLEMENTATION

Balancing ease of use with safety

Given the ease of using oral fluconazole, compared with daily topical azole therapy, many clinicians and patients may still opt for oral treatment.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The PURLs Surveillance System was supported in part by Grant Number UL1RR024999 from the National Center For Research Resources, a Clinical Translational Science Award to the University of Chicago. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Center For Research Resources or the National Institutes of Health.

Copyright © 2016. The Family Physicians Inquiries Network. All rights reserved.

Reprinted with permission from the Family Physicians Inquiries Network and The Journal of Family Practice. 2016;65(9):624-626.

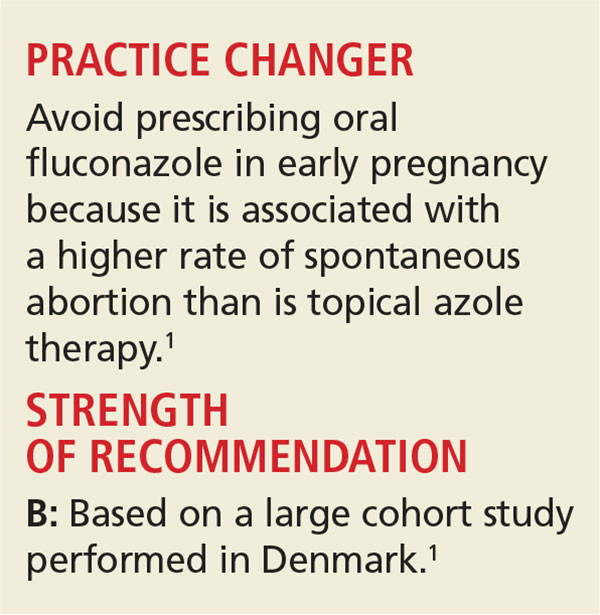

A 25-year-old woman who is 16 weeks pregnant with her first child is experiencing increased vaginal discharge associated with vaginal itching. A microscopic examination of the discharge confirms your suspicions of vaginal candidiasis. Is oral fluconazole or a topical azole your treatment of choice?

Because of the increased production of sex hormones, vaginal candidiasis is common during pregnancy, affecting up to 10% of pregnant women in the United States.1,2 Treatment options include oral fluconazole and a variety of topical azoles. Although the latter are recommended as firstline therapy, the ease of oral therapy makes it an attractive option.3,4

However, the safety of oral fluconazole during pregnancy has recently come under scrutiny. Case reports have linked high-dose use with congenital malformation.5,6 These case reports led to epidemiologic studies in which no such association was found.7,8

A large cohort study involving 1,079 fluconazole-exposed pregnancies and 170,453 unexposed pregnancies found no increased risk for congenital malformation or stillbirth; rates of spontaneous abortion and miscarriage were not evaluated.9 A prospective cohort study of 226 pregnant women found no association between fluconazole use during the first trimester and miscarriage.10 However, the validity of both studies’ findings was limited by small numbers of participants.

The current study is the largest to date to evaluate whether use of fluconazole in early pregnancy is associated with increased rates of spontaneous abortion and stillbirth, compared to topical azoles.

STUDY SUMMARY

Increased risk for miscarriage, but not stillbirth

This nationwide cohort study, conducted using the Medical Birth Register in Denmark, evaluated more than 1.4 million pregnancies occurring from 1997 to 2013 for exposure to oral fluconazole between 7 and 22 weeks’ gestation. Each oral fluconazole–exposed pregnancy was matched with up to four unexposed pregnancies (based on propensity score, maternal age, calendar year, and gestational age) and to pregnancies exposed to intravaginal formulations of topical azoles. Exposure to fluconazole was documented by filled prescriptions from the National Prescription Register. Primary outcomes were rates of spontaneous abortion (loss before 22 weeks) and stillbirth (loss after 23 weeks).

Rates of spontaneous abortion. Of the total cohort, 3,315 pregnancies were exposed to oral fluconazole between 7 and 22 weeks’ gestation. Spontaneous abortion occurred in 147 of these pregnancies and in 563 of 13,246 unexposed, matched pregnancies (hazard ratio [HR], 1.48).

Rates of stillbirth. Of 5,382 pregnancies exposed to fluconazole from week 7 to birth, 21 resulted in stillbirth; 77 stillbirths occurred in the 21,506 unexposed matched pregnancies (HR, 1.32). In a sensitivity analysis, however, higher doses of fluconazole (350 mg) were four times more likely than lower doses (150 mg) to be associated with stillbirth (HRs, 4.10 and 0.99, respectively).

Oral fluconazole vs topical azole. Use of oral fluconazole in pregnancy was associated with an increased risk for spontaneous abortion, compared to topical azole use (130 of 2,823 pregnancies vs 118 of 2,823 pregnancies; HR, 1.62)—but not an increased risk for stillbirth (20 of 4,301 pregnancies vs 22 of 4,301 pregnancies; HR, 1.18).

WHAT'S NEW

A sizeable study with a treatment comparison

The authors found that exposure in early pregnancy to oral fluconazole, as compared to topical azoles, increases the risk for spontaneous abortion. By comparing treatments in a sensitivity analysis, the researchers were able to eliminate Candida infections causing spontaneous abortion as a confounding factor. In addition, this study challenges the balance between ease of use and safety.

CAVEATS

A skewed population?

This cohort study using a Danish hospital registry may not be generalizable to a larger, non-Scandinavian population. Those not seeking care through a hospital were likely missed; if those seeking care through the hospital had a higher risk for abortion, the results could be biased. However, this would not have affected the results of the comparison between the two active treatments.

In addition, the study focused on women exposed from 7 to 22 weeks’ gestation; the findings may not be generalizable to fluconazole exposure prior to 7 weeks. Likewise, the registry is unlikely to capture very early spontaneous abortions that are not recognized clinically.

In all, given the large sample size and the care taken to match each exposed pregnancy with up to four unexposed pregnancies, these limitations likely had little influence on the overall findings.

CHALLENGES TO IMPLEMENTATION

Balancing ease of use with safety

Given the ease of using oral fluconazole, compared with daily topical azole therapy, many clinicians and patients may still opt for oral treatment.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The PURLs Surveillance System was supported in part by Grant Number UL1RR024999 from the National Center For Research Resources, a Clinical Translational Science Award to the University of Chicago. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Center For Research Resources or the National Institutes of Health.

Copyright © 2016. The Family Physicians Inquiries Network. All rights reserved.

Reprinted with permission from the Family Physicians Inquiries Network and The Journal of Family Practice. 2016;65(9):624-626.

1. Mølgaard-Nielsen D, Svanström H, Melbye M, et al. Association between use of oral fluconazole during pregnancy and risk of spontaneous abortion and stillbirth. JAMA. 2016;315:58-67.

2. Cotch MF, Hillier SL, Gibbs RS, et al; Vaginal Infections and Prematurity Study Group. Epidemiology and outcomes associated with moderate to heavy Candida colonization during pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1998;178:374-380.

3. Workowski KA, Bolan GA, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2015. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2015;64:1-137.

4. Tooley PJ. Patient and doctor preferences in the treatment of vaginal candidiasis. Practitioner. 1985;229:655-660.

5. Aleck KA, Bartley DL. Multiple malformation syndrome following fluconazole use in pregnancy: report of an additional patient. Am J Med Genet. 1997;72:253-256.

6. Lee BE, Feinberg M, Abraham JJ, et al. Congenital malformations in an infant born to a woman treated with fluconazole. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1992;11:1062-1064.

7. Jick SS. Pregnancy outcomes after maternal exposure to fluconazole. Pharmacotherapy. 1999;19:221-222.

8. Mølgaard-Nielsen D, Pasternak B, Hviid A. Use of oral fluconazole during pregnancy and the risk of birth defects. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:830-839.

9. Nørgaard M, Pedersen L, Gislum M, et al. Maternal use of fluconazole and risk of congenital malformations: a Danish population-based cohort study. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2008;62:172-176.

10. Mastroiacovo P, Mazzone T, Botto LD, et al. Prospective assessment of pregnancy outcomes after first-trimester exposure to fluconazole. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1996;175:1645-1650.

1. Mølgaard-Nielsen D, Svanström H, Melbye M, et al. Association between use of oral fluconazole during pregnancy and risk of spontaneous abortion and stillbirth. JAMA. 2016;315:58-67.

2. Cotch MF, Hillier SL, Gibbs RS, et al; Vaginal Infections and Prematurity Study Group. Epidemiology and outcomes associated with moderate to heavy Candida colonization during pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1998;178:374-380.

3. Workowski KA, Bolan GA, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2015. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2015;64:1-137.

4. Tooley PJ. Patient and doctor preferences in the treatment of vaginal candidiasis. Practitioner. 1985;229:655-660.

5. Aleck KA, Bartley DL. Multiple malformation syndrome following fluconazole use in pregnancy: report of an additional patient. Am J Med Genet. 1997;72:253-256.

6. Lee BE, Feinberg M, Abraham JJ, et al. Congenital malformations in an infant born to a woman treated with fluconazole. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1992;11:1062-1064.

7. Jick SS. Pregnancy outcomes after maternal exposure to fluconazole. Pharmacotherapy. 1999;19:221-222.

8. Mølgaard-Nielsen D, Pasternak B, Hviid A. Use of oral fluconazole during pregnancy and the risk of birth defects. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:830-839.

9. Nørgaard M, Pedersen L, Gislum M, et al. Maternal use of fluconazole and risk of congenital malformations: a Danish population-based cohort study. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2008;62:172-176.

10. Mastroiacovo P, Mazzone T, Botto LD, et al. Prospective assessment of pregnancy outcomes after first-trimester exposure to fluconazole. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1996;175:1645-1650.

Zika funding slated for prevention, vaccine development

Federal health officials are wasting no time in putting to use long-awaited congressional funding aimed at strengthening Zika prevention and advancing research efforts.

The country’s health care agencies will split the $1.1 billion in funding approved by Congress on Sept. 28, dividing the money among Zika vaccine development, mosquito control, and response to virus outbreaks in the United States and globally, Sylvia Burwell, Health and Human Services secretary, said during an Oct. 3 press conference.

“At HHS, we’ll put this funding to use quickly and wisely,” Secretary Burwell said during the press conference. “It will support essential strategies to combat this virus, like expanding mosquito surveillance and control programs. It will also help us further accelerate the development of tests to detect Zika treatment and vaccines, including beginning human testing of additional vaccine candidates. It will also fund vital research as we continue to learn about the virus and monitor the progress of babies born with Zika-related birth defects.”

Of the $1.1 billion included in the final package to fight Zika, $15 million will go to the state of Florida and $60 million to the territory of Puerto Rico to respond to Zika outbreaks in those areas.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention will receive $394 million, of which $44 million will go toward replenishing funds pulled from the Public Health Emergency Preparedness (PHEP) cooperative agreement to address the Zika crisis, said CDC Director Tom Frieden, MD. The CDC’s remaining $350 million will allow the agency to extend existing responses to Zika outbreaks and grow partnerships with state and local authorities.

The National Institutes of Health will use its portion of the Zika funding – $152 million – to further vaccine development and move forward clinical trials already in the works, said Anthony Fauci, MD, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. The NIH is well on its way with a phase I vaccine trial, having enrolled 80 patients thus far, Dr. Fauci said during the press call. The agency will soon have enough information to determine to move onto phase II, he said.

Meanwhile, HHS will use its portion of the funding – $245 million – to support advanced vaccine development and ensure the drug manufacturing process runs smoothly and quickly, said Nicole Lurie, MD, HHS assistant secretary for preparedness and response. Agency officials also plan to support more clinical trials that will be integrated with the ongoing NIH trials, she said.

The remaining funds from the bill will go toward global health programs, operating costs, and other expenses.

Despite the positives from the supplemental funding, Secretary Burwell noted that Congress’ delay in approving the extra money has caused irreparable harm to other health care programs and initiatives. HHS diverted funds from other departments, such as the Administration for Children and Families and the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration to address Zika outbreaks and begin research. Vaccine and diagnostic developments are also behind because of funding delays, according to officials.

“The damage that occurred because we took those funds will continue,” Secretary Burwell said. “The time and energy that was spent in seeking and working to get the funding instead of working to use the funding [was detrimental]. That money would be out the door if we were in a situation where we had received that money at the point at which we had asked for it.”

[email protected]

On Twitter @legal_med

Federal health officials are wasting no time in putting to use long-awaited congressional funding aimed at strengthening Zika prevention and advancing research efforts.

The country’s health care agencies will split the $1.1 billion in funding approved by Congress on Sept. 28, dividing the money among Zika vaccine development, mosquito control, and response to virus outbreaks in the United States and globally, Sylvia Burwell, Health and Human Services secretary, said during an Oct. 3 press conference.

“At HHS, we’ll put this funding to use quickly and wisely,” Secretary Burwell said during the press conference. “It will support essential strategies to combat this virus, like expanding mosquito surveillance and control programs. It will also help us further accelerate the development of tests to detect Zika treatment and vaccines, including beginning human testing of additional vaccine candidates. It will also fund vital research as we continue to learn about the virus and monitor the progress of babies born with Zika-related birth defects.”

Of the $1.1 billion included in the final package to fight Zika, $15 million will go to the state of Florida and $60 million to the territory of Puerto Rico to respond to Zika outbreaks in those areas.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention will receive $394 million, of which $44 million will go toward replenishing funds pulled from the Public Health Emergency Preparedness (PHEP) cooperative agreement to address the Zika crisis, said CDC Director Tom Frieden, MD. The CDC’s remaining $350 million will allow the agency to extend existing responses to Zika outbreaks and grow partnerships with state and local authorities.

The National Institutes of Health will use its portion of the Zika funding – $152 million – to further vaccine development and move forward clinical trials already in the works, said Anthony Fauci, MD, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. The NIH is well on its way with a phase I vaccine trial, having enrolled 80 patients thus far, Dr. Fauci said during the press call. The agency will soon have enough information to determine to move onto phase II, he said.

Meanwhile, HHS will use its portion of the funding – $245 million – to support advanced vaccine development and ensure the drug manufacturing process runs smoothly and quickly, said Nicole Lurie, MD, HHS assistant secretary for preparedness and response. Agency officials also plan to support more clinical trials that will be integrated with the ongoing NIH trials, she said.

The remaining funds from the bill will go toward global health programs, operating costs, and other expenses.

Despite the positives from the supplemental funding, Secretary Burwell noted that Congress’ delay in approving the extra money has caused irreparable harm to other health care programs and initiatives. HHS diverted funds from other departments, such as the Administration for Children and Families and the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration to address Zika outbreaks and begin research. Vaccine and diagnostic developments are also behind because of funding delays, according to officials.

“The damage that occurred because we took those funds will continue,” Secretary Burwell said. “The time and energy that was spent in seeking and working to get the funding instead of working to use the funding [was detrimental]. That money would be out the door if we were in a situation where we had received that money at the point at which we had asked for it.”

[email protected]

On Twitter @legal_med

Federal health officials are wasting no time in putting to use long-awaited congressional funding aimed at strengthening Zika prevention and advancing research efforts.

The country’s health care agencies will split the $1.1 billion in funding approved by Congress on Sept. 28, dividing the money among Zika vaccine development, mosquito control, and response to virus outbreaks in the United States and globally, Sylvia Burwell, Health and Human Services secretary, said during an Oct. 3 press conference.

“At HHS, we’ll put this funding to use quickly and wisely,” Secretary Burwell said during the press conference. “It will support essential strategies to combat this virus, like expanding mosquito surveillance and control programs. It will also help us further accelerate the development of tests to detect Zika treatment and vaccines, including beginning human testing of additional vaccine candidates. It will also fund vital research as we continue to learn about the virus and monitor the progress of babies born with Zika-related birth defects.”

Of the $1.1 billion included in the final package to fight Zika, $15 million will go to the state of Florida and $60 million to the territory of Puerto Rico to respond to Zika outbreaks in those areas.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention will receive $394 million, of which $44 million will go toward replenishing funds pulled from the Public Health Emergency Preparedness (PHEP) cooperative agreement to address the Zika crisis, said CDC Director Tom Frieden, MD. The CDC’s remaining $350 million will allow the agency to extend existing responses to Zika outbreaks and grow partnerships with state and local authorities.

The National Institutes of Health will use its portion of the Zika funding – $152 million – to further vaccine development and move forward clinical trials already in the works, said Anthony Fauci, MD, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. The NIH is well on its way with a phase I vaccine trial, having enrolled 80 patients thus far, Dr. Fauci said during the press call. The agency will soon have enough information to determine to move onto phase II, he said.

Meanwhile, HHS will use its portion of the funding – $245 million – to support advanced vaccine development and ensure the drug manufacturing process runs smoothly and quickly, said Nicole Lurie, MD, HHS assistant secretary for preparedness and response. Agency officials also plan to support more clinical trials that will be integrated with the ongoing NIH trials, she said.

The remaining funds from the bill will go toward global health programs, operating costs, and other expenses.

Despite the positives from the supplemental funding, Secretary Burwell noted that Congress’ delay in approving the extra money has caused irreparable harm to other health care programs and initiatives. HHS diverted funds from other departments, such as the Administration for Children and Families and the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration to address Zika outbreaks and begin research. Vaccine and diagnostic developments are also behind because of funding delays, according to officials.

“The damage that occurred because we took those funds will continue,” Secretary Burwell said. “The time and energy that was spent in seeking and working to get the funding instead of working to use the funding [was detrimental]. That money would be out the door if we were in a situation where we had received that money at the point at which we had asked for it.”

[email protected]

On Twitter @legal_med

Absorbable suture performs well in sacrocolpopexy with mesh

DENVER – Using absorbable polydioxanone suture during laparoscopic sacrocolpopexy was associated with a mesh erosion rate of just 1.6%, according to a single-center, 1-year prospective study of 64 patients.

That is substantially less than typical erosion rates of about 5% when permanent suture is used, Danielle Taylor, DO, of Akron (Ohio ) General Medical Center said at Pelvic Floor Disorders Week sponsored by the American Urogynecologic Society.

The researchers observed no anatomic failures or suture extrusions, and patients reported significant postoperative improvements on several validated measures of quality of life.

“Larger samples and longer follow-up may be needed,” said Dr. Taylor. “But our study suggests that permanent, nondissolving suture material may not be necessary for sacrocolpopexy.”

Sacrocolpopexy with mesh usually involves using nonabsorbable suture to attach its anterior and posterior arms to the vaginal mucosa. Instead, Dr. Taylor and colleagues used 90-day delayed absorbable 2.0 V-Loc (Covidien) suture during laparoscopic sacrocolpopexy for patients with baseline Pelvic Organ Prolapse Quantification (POP-Q) scores of at least 2 and symptomatic uterovaginal prolapse.

Two permanent Gore-Tex sutures were also placed at the apex of the cervix in each of the 64 patients, said Dr. Taylor, a urogynecology fellow at the University of Massachusetts, Worcester, who worked on the study as a resident at the Cleveland Clinic Akron General, in Ohio. She and her colleagues rechecked patients at postoperative weeks 2 and 6, and at months 6 and 12. They lost two patients to follow-up, both after week 2.

At baseline, 37 patients (58%) were in stage II pelvic organ prolapse, 27% were in stage III, and 14% were in stage IV. At 6 months after surgery, 85% had no detectable prolapse, 8% had stage I, and 6% had stage II. At 1 year, 82% remained in pelvic organ prolapse stage 0 and the rest were in stage I or II. All stage II patients remained asymptomatic, Dr. Taylor said.

At baseline, the median value for POP-Q point C was -3 (range, –8 to +6). At 6 months and 1 year later, the median value had improved to –8, and patients ranged between –10 and –8.

Quality of life surveys of 54 patients reflected these outcomes, Dr. Taylor said. A year after surgery, average scores on the Pelvic Floor Distress Index (PFDI) dropped by 67 points, from 103 to 35 (P less than .0001). Likewise, average scores on the Pelvic Floor Impact Questionnaire (PFIQ) dropped by 29 points (P less than .0001), and scores on the Pelvic Organ Prolapse/Urinary Incontinence Sexual Function Questionnaire (PISQ) indicated a significant decrease in the effects of pelvic organ prolapse on sexual functioning (P = .008).

In addition to a single case of mesh erosion, one patient developed postoperative ileus and one experienced small bowel obstruction, both of which resolved, Dr. Taylor reported. The researchers aim to continue the study with longer follow-up intervals and detailed analyses of postoperative pain.

Dr. Taylor reported no funding sources and had no disclosures. One coauthor disclosed ties to Coloplast Corp.

DENVER – Using absorbable polydioxanone suture during laparoscopic sacrocolpopexy was associated with a mesh erosion rate of just 1.6%, according to a single-center, 1-year prospective study of 64 patients.

That is substantially less than typical erosion rates of about 5% when permanent suture is used, Danielle Taylor, DO, of Akron (Ohio ) General Medical Center said at Pelvic Floor Disorders Week sponsored by the American Urogynecologic Society.

The researchers observed no anatomic failures or suture extrusions, and patients reported significant postoperative improvements on several validated measures of quality of life.

“Larger samples and longer follow-up may be needed,” said Dr. Taylor. “But our study suggests that permanent, nondissolving suture material may not be necessary for sacrocolpopexy.”

Sacrocolpopexy with mesh usually involves using nonabsorbable suture to attach its anterior and posterior arms to the vaginal mucosa. Instead, Dr. Taylor and colleagues used 90-day delayed absorbable 2.0 V-Loc (Covidien) suture during laparoscopic sacrocolpopexy for patients with baseline Pelvic Organ Prolapse Quantification (POP-Q) scores of at least 2 and symptomatic uterovaginal prolapse.

Two permanent Gore-Tex sutures were also placed at the apex of the cervix in each of the 64 patients, said Dr. Taylor, a urogynecology fellow at the University of Massachusetts, Worcester, who worked on the study as a resident at the Cleveland Clinic Akron General, in Ohio. She and her colleagues rechecked patients at postoperative weeks 2 and 6, and at months 6 and 12. They lost two patients to follow-up, both after week 2.

At baseline, 37 patients (58%) were in stage II pelvic organ prolapse, 27% were in stage III, and 14% were in stage IV. At 6 months after surgery, 85% had no detectable prolapse, 8% had stage I, and 6% had stage II. At 1 year, 82% remained in pelvic organ prolapse stage 0 and the rest were in stage I or II. All stage II patients remained asymptomatic, Dr. Taylor said.

At baseline, the median value for POP-Q point C was -3 (range, –8 to +6). At 6 months and 1 year later, the median value had improved to –8, and patients ranged between –10 and –8.

Quality of life surveys of 54 patients reflected these outcomes, Dr. Taylor said. A year after surgery, average scores on the Pelvic Floor Distress Index (PFDI) dropped by 67 points, from 103 to 35 (P less than .0001). Likewise, average scores on the Pelvic Floor Impact Questionnaire (PFIQ) dropped by 29 points (P less than .0001), and scores on the Pelvic Organ Prolapse/Urinary Incontinence Sexual Function Questionnaire (PISQ) indicated a significant decrease in the effects of pelvic organ prolapse on sexual functioning (P = .008).

In addition to a single case of mesh erosion, one patient developed postoperative ileus and one experienced small bowel obstruction, both of which resolved, Dr. Taylor reported. The researchers aim to continue the study with longer follow-up intervals and detailed analyses of postoperative pain.

Dr. Taylor reported no funding sources and had no disclosures. One coauthor disclosed ties to Coloplast Corp.

DENVER – Using absorbable polydioxanone suture during laparoscopic sacrocolpopexy was associated with a mesh erosion rate of just 1.6%, according to a single-center, 1-year prospective study of 64 patients.

That is substantially less than typical erosion rates of about 5% when permanent suture is used, Danielle Taylor, DO, of Akron (Ohio ) General Medical Center said at Pelvic Floor Disorders Week sponsored by the American Urogynecologic Society.

The researchers observed no anatomic failures or suture extrusions, and patients reported significant postoperative improvements on several validated measures of quality of life.

“Larger samples and longer follow-up may be needed,” said Dr. Taylor. “But our study suggests that permanent, nondissolving suture material may not be necessary for sacrocolpopexy.”

Sacrocolpopexy with mesh usually involves using nonabsorbable suture to attach its anterior and posterior arms to the vaginal mucosa. Instead, Dr. Taylor and colleagues used 90-day delayed absorbable 2.0 V-Loc (Covidien) suture during laparoscopic sacrocolpopexy for patients with baseline Pelvic Organ Prolapse Quantification (POP-Q) scores of at least 2 and symptomatic uterovaginal prolapse.

Two permanent Gore-Tex sutures were also placed at the apex of the cervix in each of the 64 patients, said Dr. Taylor, a urogynecology fellow at the University of Massachusetts, Worcester, who worked on the study as a resident at the Cleveland Clinic Akron General, in Ohio. She and her colleagues rechecked patients at postoperative weeks 2 and 6, and at months 6 and 12. They lost two patients to follow-up, both after week 2.

At baseline, 37 patients (58%) were in stage II pelvic organ prolapse, 27% were in stage III, and 14% were in stage IV. At 6 months after surgery, 85% had no detectable prolapse, 8% had stage I, and 6% had stage II. At 1 year, 82% remained in pelvic organ prolapse stage 0 and the rest were in stage I or II. All stage II patients remained asymptomatic, Dr. Taylor said.

At baseline, the median value for POP-Q point C was -3 (range, –8 to +6). At 6 months and 1 year later, the median value had improved to –8, and patients ranged between –10 and –8.

Quality of life surveys of 54 patients reflected these outcomes, Dr. Taylor said. A year after surgery, average scores on the Pelvic Floor Distress Index (PFDI) dropped by 67 points, from 103 to 35 (P less than .0001). Likewise, average scores on the Pelvic Floor Impact Questionnaire (PFIQ) dropped by 29 points (P less than .0001), and scores on the Pelvic Organ Prolapse/Urinary Incontinence Sexual Function Questionnaire (PISQ) indicated a significant decrease in the effects of pelvic organ prolapse on sexual functioning (P = .008).

In addition to a single case of mesh erosion, one patient developed postoperative ileus and one experienced small bowel obstruction, both of which resolved, Dr. Taylor reported. The researchers aim to continue the study with longer follow-up intervals and detailed analyses of postoperative pain.

Dr. Taylor reported no funding sources and had no disclosures. One coauthor disclosed ties to Coloplast Corp.

Key clinical point:

Major finding: When 90-day delayed absorbable polydioxanone suture was used, the mesh erosion rate was 1.6%. There were no anatomic failures or cases of suture extrusion.

Data source: A single-center prospective case series of 64 patients.

Disclosures: Dr. Taylor reported having no financial disclosures. One coauthor reported ties to Coloplast Corp.

The EHR time suck gets quantified

How many hours a day do you typically work?

I’m not just talking about seeing patients, although that’s included. I’m also thinking about all the time spent reviewing tests, filling out forms, returning calls, refilling meds, talking to your staff about what needs to be done for the patients who called with questions or problems, and (a big one) dictating and charting notes for the day.

Sadly, the issue appears to be getting worse. A recent study in Annals of Internal Medicine found that for every hour you spend seeing patients, you’re spending another 2 hours working on the computer EHR doing ancillary stuff for the visits. I’m pretty sure insurance companies aren’t paying for that time.

That’s just in the office. The same study found most of us spend another 1-2 hours of our home time each night doing more office work to finish up what we didn’t get done during the day. So much for that work-life balance we hear so much about.

Ready for the breakdown? Here it is:

• Percentage of the total office day spent with patients = 27%

• Percentage of the total office day spent on charting and other EHR-related tasks = 49%

That’s just overall. Now let’s look at the time you’re actually with the patient in an exam room:

• Face-to-face with patient = 53%

• Time on the computer = 37%

So even in a room with a patient in front of you, over one-third of the time is still spent on the computer.

The degree of drudgery is surprising, too. How many mouse clicks are needed, in one system, to order and record a flu shot? Take a guess. 5? 10? 15? How about 32. Yeah, you read that right. No wonder your index finger hurts.

But let’s go back to the main point here, that 1 hour of patient time equals 2 hours of computer time ratio. At its core, it suggests that in order to get everything done, you should only be seeing patients for 3 hours a day because you’ll need at least another 6 hours to get all the computer stuff for them done. You think you can make a living, or even pay your overhead, billing for 3 hours of patient time a day? Me neither. I need to put in at least 8 hours of patient time, which means another 16 hours or so of computer time crammed in somewhere, overflowing into evenings and weekends. There are, quite literally, not enough hours in the day to practice good medicine and still get all the ancillary work done quickly and correctly.

With this kind of formula it’s only a matter of time before people get hurt. And the bean counters who run many medical practices these days will never see that aspect of medicine. The more patients, the more revenue, in their minds.

Rather than making life easier for us, EHRs have taken things the opposite way. In a profession where face-to-face time is the most critical part of what we do and the center of the doctor-patient relationship, it’s now second to face-to-screen time. That can’t be good for those who need our help.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

How many hours a day do you typically work?

I’m not just talking about seeing patients, although that’s included. I’m also thinking about all the time spent reviewing tests, filling out forms, returning calls, refilling meds, talking to your staff about what needs to be done for the patients who called with questions or problems, and (a big one) dictating and charting notes for the day.

Sadly, the issue appears to be getting worse. A recent study in Annals of Internal Medicine found that for every hour you spend seeing patients, you’re spending another 2 hours working on the computer EHR doing ancillary stuff for the visits. I’m pretty sure insurance companies aren’t paying for that time.

That’s just in the office. The same study found most of us spend another 1-2 hours of our home time each night doing more office work to finish up what we didn’t get done during the day. So much for that work-life balance we hear so much about.

Ready for the breakdown? Here it is:

• Percentage of the total office day spent with patients = 27%

• Percentage of the total office day spent on charting and other EHR-related tasks = 49%

That’s just overall. Now let’s look at the time you’re actually with the patient in an exam room:

• Face-to-face with patient = 53%

• Time on the computer = 37%

So even in a room with a patient in front of you, over one-third of the time is still spent on the computer.

The degree of drudgery is surprising, too. How many mouse clicks are needed, in one system, to order and record a flu shot? Take a guess. 5? 10? 15? How about 32. Yeah, you read that right. No wonder your index finger hurts.

But let’s go back to the main point here, that 1 hour of patient time equals 2 hours of computer time ratio. At its core, it suggests that in order to get everything done, you should only be seeing patients for 3 hours a day because you’ll need at least another 6 hours to get all the computer stuff for them done. You think you can make a living, or even pay your overhead, billing for 3 hours of patient time a day? Me neither. I need to put in at least 8 hours of patient time, which means another 16 hours or so of computer time crammed in somewhere, overflowing into evenings and weekends. There are, quite literally, not enough hours in the day to practice good medicine and still get all the ancillary work done quickly and correctly.

With this kind of formula it’s only a matter of time before people get hurt. And the bean counters who run many medical practices these days will never see that aspect of medicine. The more patients, the more revenue, in their minds.

Rather than making life easier for us, EHRs have taken things the opposite way. In a profession where face-to-face time is the most critical part of what we do and the center of the doctor-patient relationship, it’s now second to face-to-screen time. That can’t be good for those who need our help.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

How many hours a day do you typically work?

I’m not just talking about seeing patients, although that’s included. I’m also thinking about all the time spent reviewing tests, filling out forms, returning calls, refilling meds, talking to your staff about what needs to be done for the patients who called with questions or problems, and (a big one) dictating and charting notes for the day.

Sadly, the issue appears to be getting worse. A recent study in Annals of Internal Medicine found that for every hour you spend seeing patients, you’re spending another 2 hours working on the computer EHR doing ancillary stuff for the visits. I’m pretty sure insurance companies aren’t paying for that time.

That’s just in the office. The same study found most of us spend another 1-2 hours of our home time each night doing more office work to finish up what we didn’t get done during the day. So much for that work-life balance we hear so much about.

Ready for the breakdown? Here it is:

• Percentage of the total office day spent with patients = 27%

• Percentage of the total office day spent on charting and other EHR-related tasks = 49%

That’s just overall. Now let’s look at the time you’re actually with the patient in an exam room:

• Face-to-face with patient = 53%

• Time on the computer = 37%

So even in a room with a patient in front of you, over one-third of the time is still spent on the computer.

The degree of drudgery is surprising, too. How many mouse clicks are needed, in one system, to order and record a flu shot? Take a guess. 5? 10? 15? How about 32. Yeah, you read that right. No wonder your index finger hurts.

But let’s go back to the main point here, that 1 hour of patient time equals 2 hours of computer time ratio. At its core, it suggests that in order to get everything done, you should only be seeing patients for 3 hours a day because you’ll need at least another 6 hours to get all the computer stuff for them done. You think you can make a living, or even pay your overhead, billing for 3 hours of patient time a day? Me neither. I need to put in at least 8 hours of patient time, which means another 16 hours or so of computer time crammed in somewhere, overflowing into evenings and weekends. There are, quite literally, not enough hours in the day to practice good medicine and still get all the ancillary work done quickly and correctly.

With this kind of formula it’s only a matter of time before people get hurt. And the bean counters who run many medical practices these days will never see that aspect of medicine. The more patients, the more revenue, in their minds.

Rather than making life easier for us, EHRs have taken things the opposite way. In a profession where face-to-face time is the most critical part of what we do and the center of the doctor-patient relationship, it’s now second to face-to-screen time. That can’t be good for those who need our help.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

Conference News Roundup—European Society of Cardiology

Low Socioeconomic Status Associated With Higher Risk of Second Heart Attack or Stroke

Low socioeconomic status is associated with a higher risk of a second heart attack or stroke, according to Joel Ohm, MD, a physician at the Karolinska University Hospital and Karolinska Institute in Stockholm. The study of nearly 30,000 patients with a prior heart attack revealed that the risk of a second event was 36% lower for those in the highest income quintile, compared with the lowest, and increased by 14% in divorced patients, compared with married patients.

"Are you rich or poor? Married or divorced? That might affect your risk of a second heart attack or stroke," said Dr. Ohm. "Advances in prevention and acute treatment have increased survival after heart attack and stroke over the past several decades. The result is that more people live with cardiovascular disease in Sweden. Almost one-fifth of the total population is in this group."

Most research on cardiovascular prevention is based on healthy people, and it is unclear whether the findings apply to patients with established disease. An association between socioeconomic status in healthy individuals and future cardiovascular disease was found in the 1950s. This study investigated the link between socioeconomic status in patients who had survived a first heart attack and the risk of a second heart attack or a stroke.

The study included 29,953 patients from the Swedish nationwide registry, Secondary Prevention after Heart Intensive Care Admission (SEPHIA), who had been discharged approximately one year previously from a cardiac intensive care unit after treatment for a first myocardial infarction. Data on outcome over time and socioeconomic status (defined as disposable income, marital status, and level of education) was obtained from Statistics Sweden and the National Board of Health and Welfare.

During an average follow-up of four years, 2,405 patients (8%) had a heart attack or stroke. After adjustments for age, gender, smoking status, and the defined measures of socioeconomic status, being divorced was independently associated with a 14% greater risk of a second event, compared with being married. There was an independent and linear relationship between disposable income and the risk of a second event, with those in the highest quintile of income having a 36% lower risk than those in the lowest quintile. A higher level of education was associated with a lower risk of events, but the association was not significant after adjustment for income.

"Our study shows that in the years following a first myocardial infarction, men and women with low socioeconomic status have a higher risk of suffering another heart attack or stroke. This is a new finding and suggests that socioeconomic status should be included in risk assessment for secondary prevention after a heart attack," said Dr Ohm. "Even though health care providers are unlikely to keep track of their patients' yearly salary, simple questions about other socioeconomic variables such as marital status and educational level could make a difference."

According to the widely used assessment tools for cardiovascular risk, survivors of heart attacks are at the highest possible risk for subsequent events, regardless of other risk factors. There is, for example, no difference in the estimated risk level between a previously healthy 40-year old female from Spain and a heavily smoking, obese, elderly man with diabetes and high blood pressure from Finland.