User login

Presenting Treatment Safety Data: Subjective Interpretations of Objective Information

The Nuremberg Code in 1947,1 the Declaration of Helsinki in 1964,2 and the Belmont Report in 19793 were cornerstones in the establishment of ethical principles in the medical field. These documents specifically highlight the concept of informed consent, which maintains that to practice ethical medicine, physicians must fully inform patients of all therapeutic benefits and especially risks as well as treatment alternatives before they consent to therapeutic intervention. Educating patients about risks of treatment is obligatory. Risk communication involves a mutual exchange of information between physicians and patients; the physician presents risk information in an understandable manner that adequately conveys pertinent data that is critical for the patient to make an informed therapeutic decision.4

An inherent problem with risk education is that patients may be terrified about risks associated with treatment. Some patients will refuse needed treatment because of fear.5 When patients have concerns about the safety profile of a treatment regimen and potential adverse effects, they may be less compliant with treatment.6 The intelligent noncompliance phenomenon occurs when a patient knowingly makes the choice to not adhere to treatment, and concern regarding treatment risks relative to benefits is a common reason underlying this phenomenon.7,8

Behavioral economists have studied how individuals weigh risks. Kahneman and Tversky’s9 prospect theory asserts that individuals tend to overweigh unlikely risks and underweigh more certain risks, which they call the certainty effect; it is the basis of the human tendency to avoid risks in situations of likely gain and to pursue risks in situations of likely loss. The tendency to overweigh rare risks is even more pronounced for affect-rich events such as serious side effects.10 The way data are presented can affect how patients interpret the information. Context and framing of data affect patients’ perceptions.11 We describe several ways to present safety data using graphical presentation of psoriasis treatment safety data as an example and explain how each one can affect patients’ perception of treatment risks.

Approaches to Presenting Safety Data

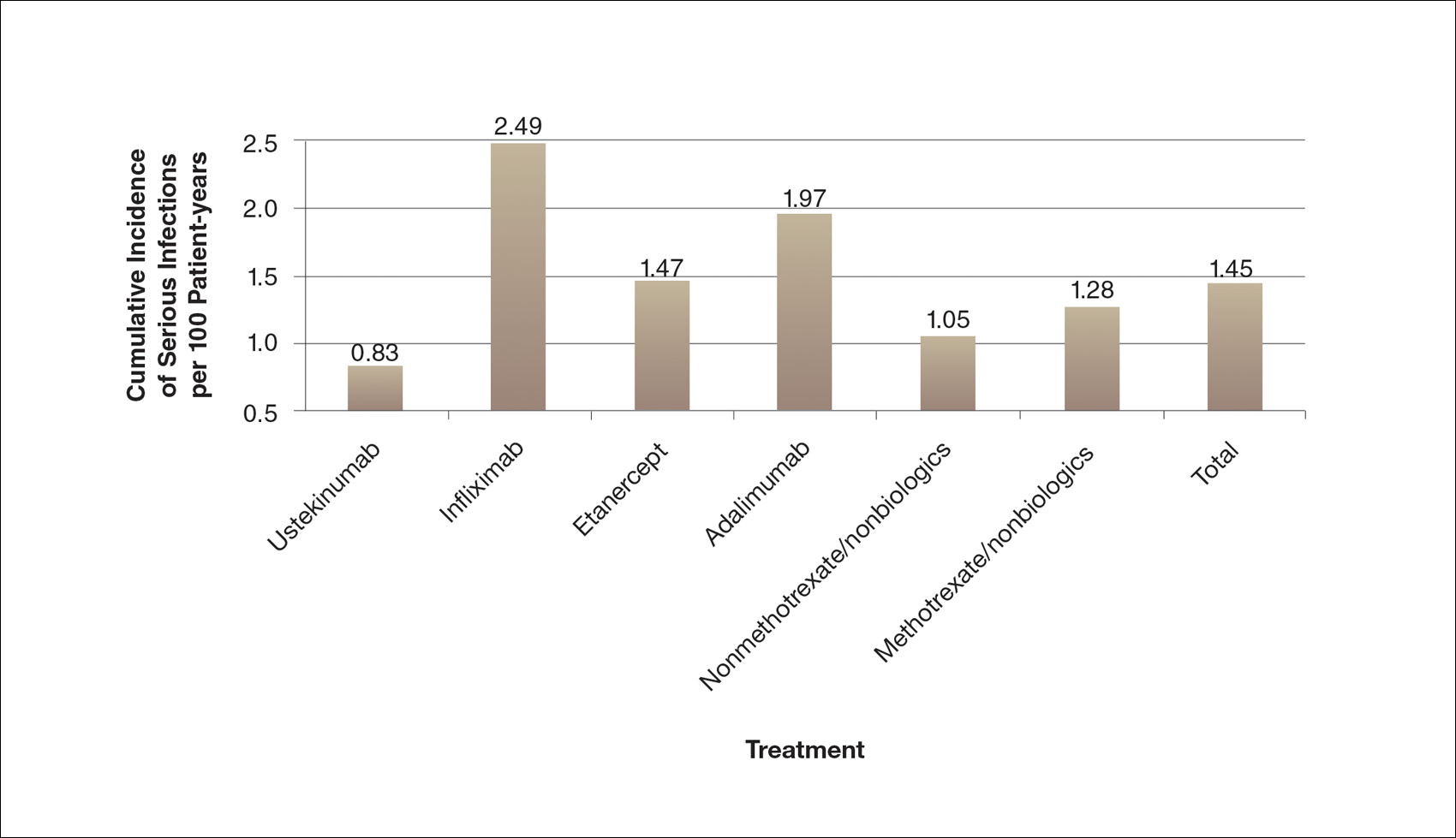

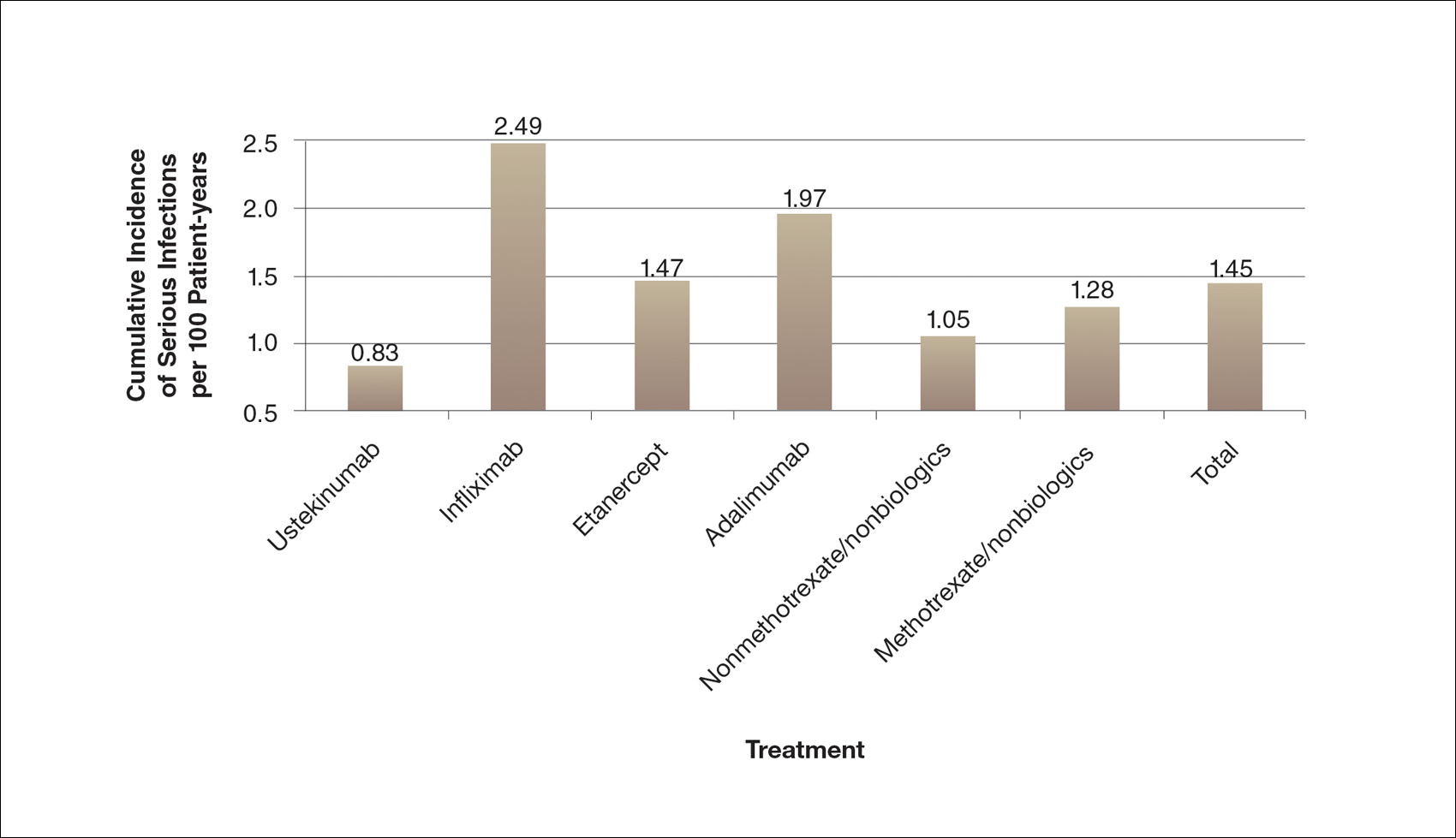

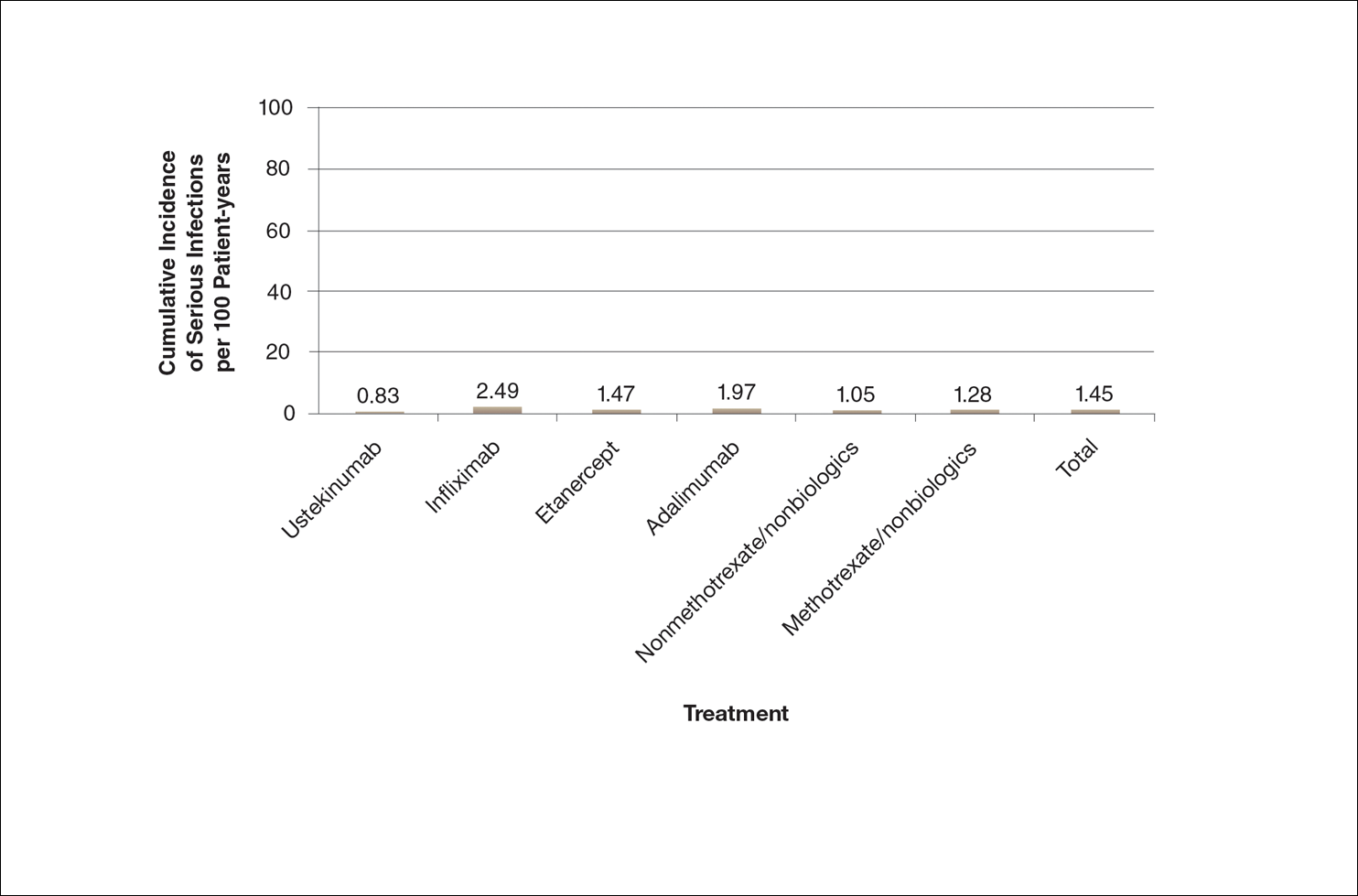

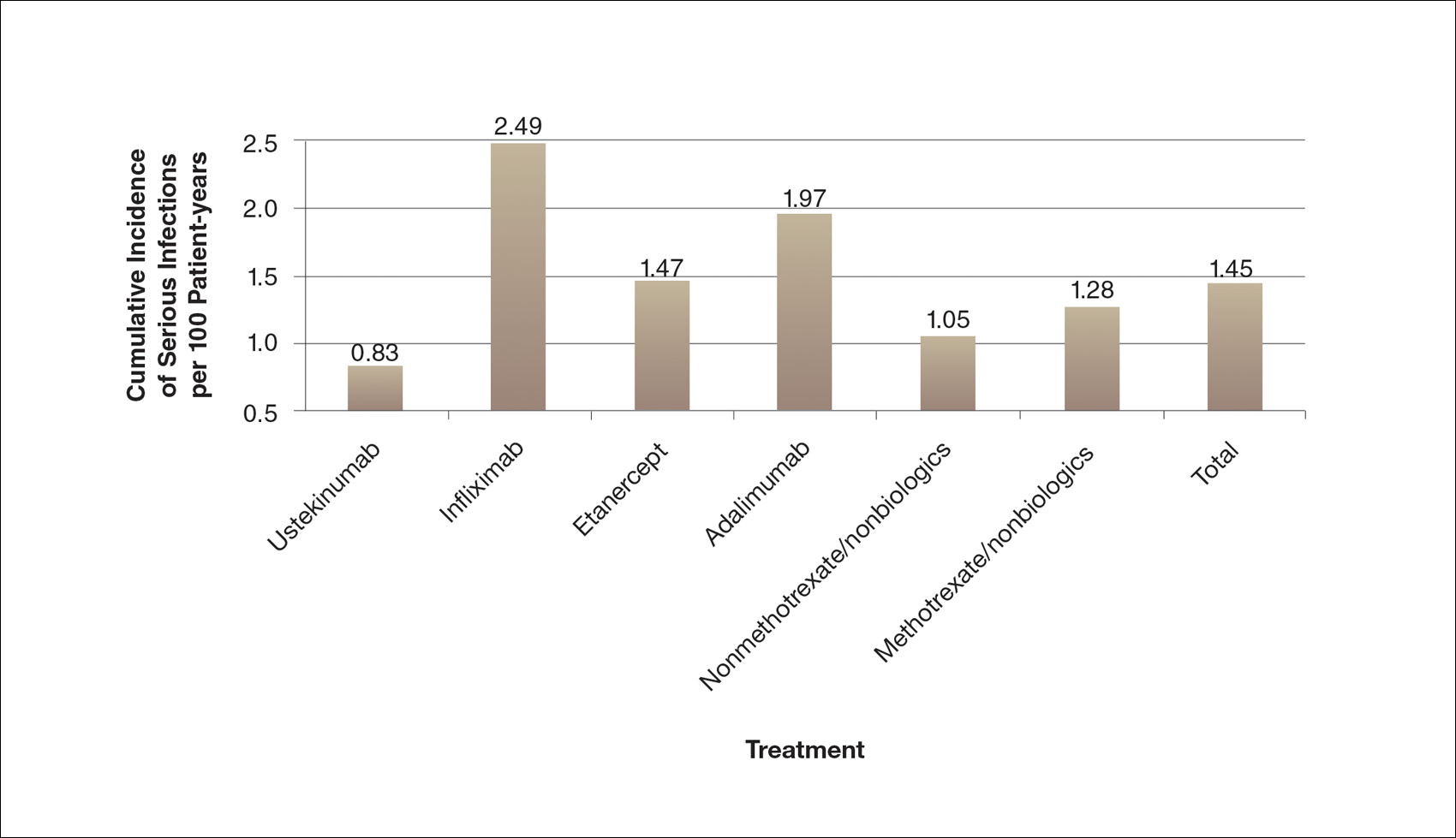

There are numerous ways to present safety data to patients, including verbal, numeric, and visual strategies.12 Many methods of presentation are a combination of these strategies. Graphs are visual strategies to further categorize and present numeric data, and physicians may choose to incorporate these aids when presenting safety information to patients. Graphical presentations give the patient a mental picture of the data. Numerous types of graphs can be constructed. Kalb et al13 determined the effect of psoriasis treatment on the risk of serious infection from the Psoriasis Longitudinal Assessment and Registry (PSOLAR). We used the results from this study to demonstrate multiple ways of presenting safety data (Figures 1–3).

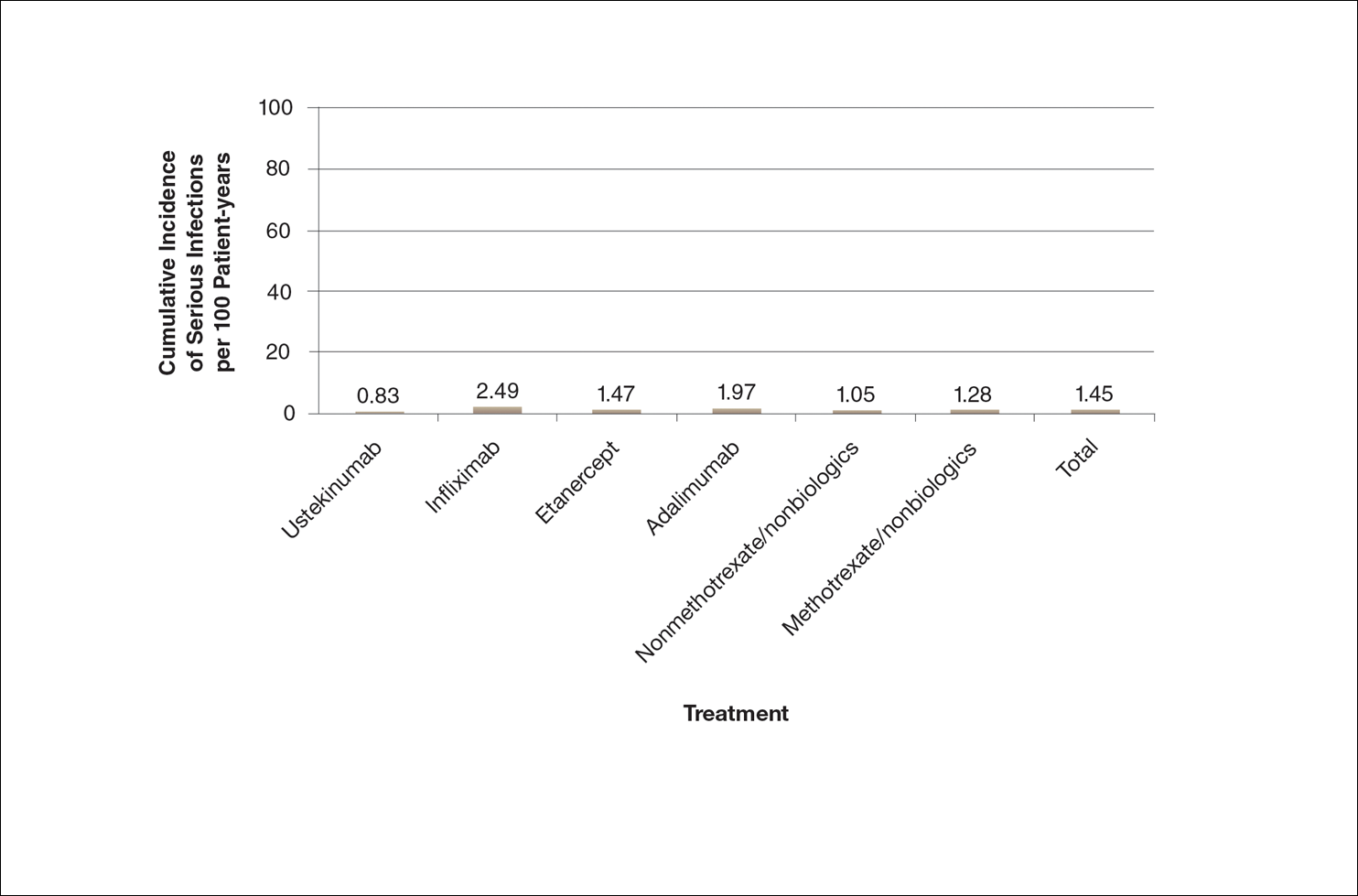

A graphical presentation with a truncated y-axis is a common approach (Figure 1). Graphs with truncated axes are sometimes used to conserve space or to accentuate certain differences in the graph that would otherwise be less obvious without the zoomed in y-axis.14 These graphs present quantitatively accurate information that can be visually misleading at the same time. Truncated axes accentuate differences, creating mental impressions that are not reflective of the magnitude of the numeric differences. Alternatively, a graph with a full y-axis includes both the maximum and minimum data values on the y-axis (Figure 2). The y-axis also extends maximally to the total number of patients or patient-years studied. This type of graph presents all of the numeric data without distortion.

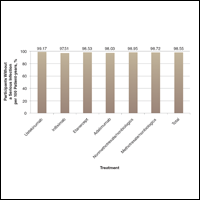

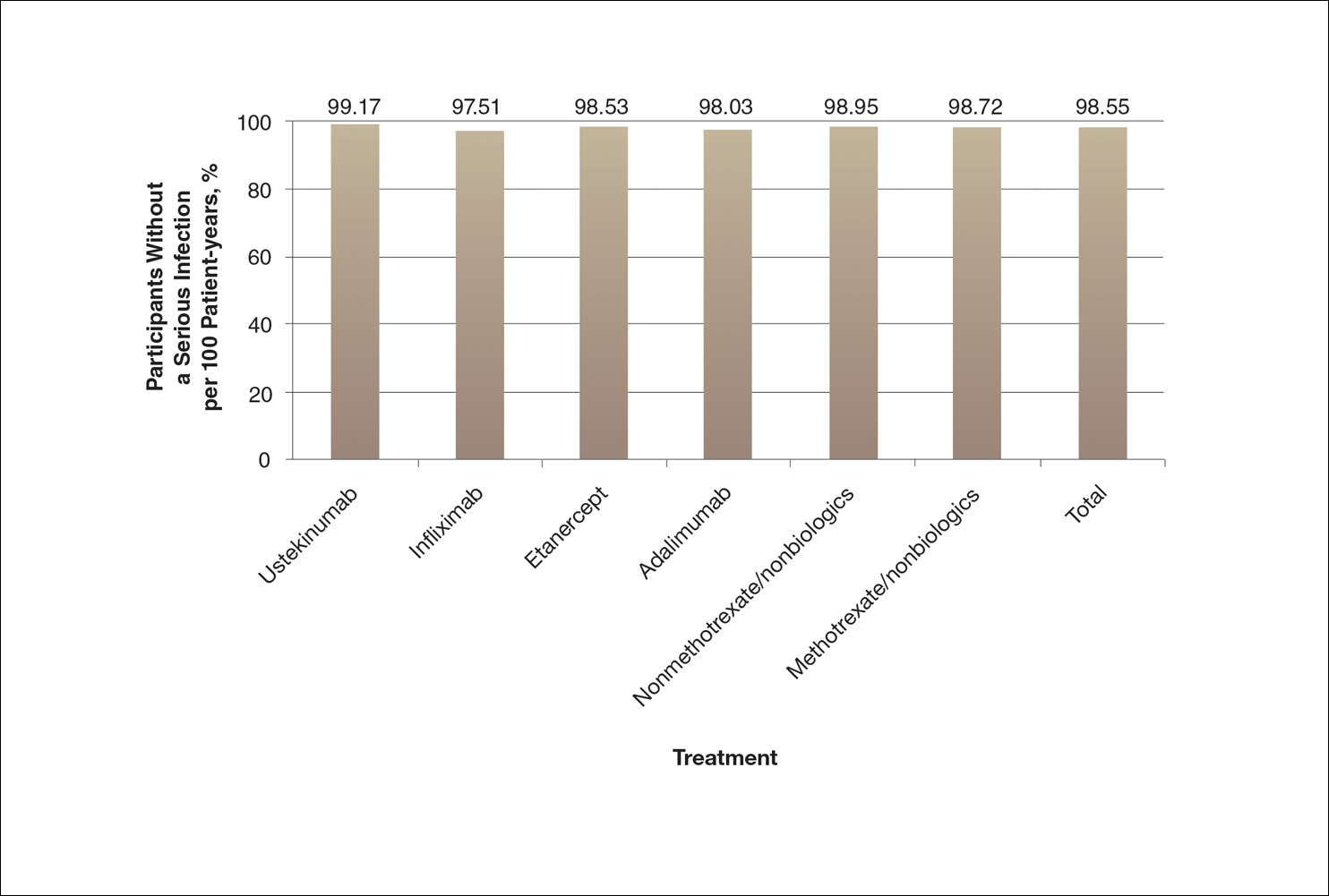

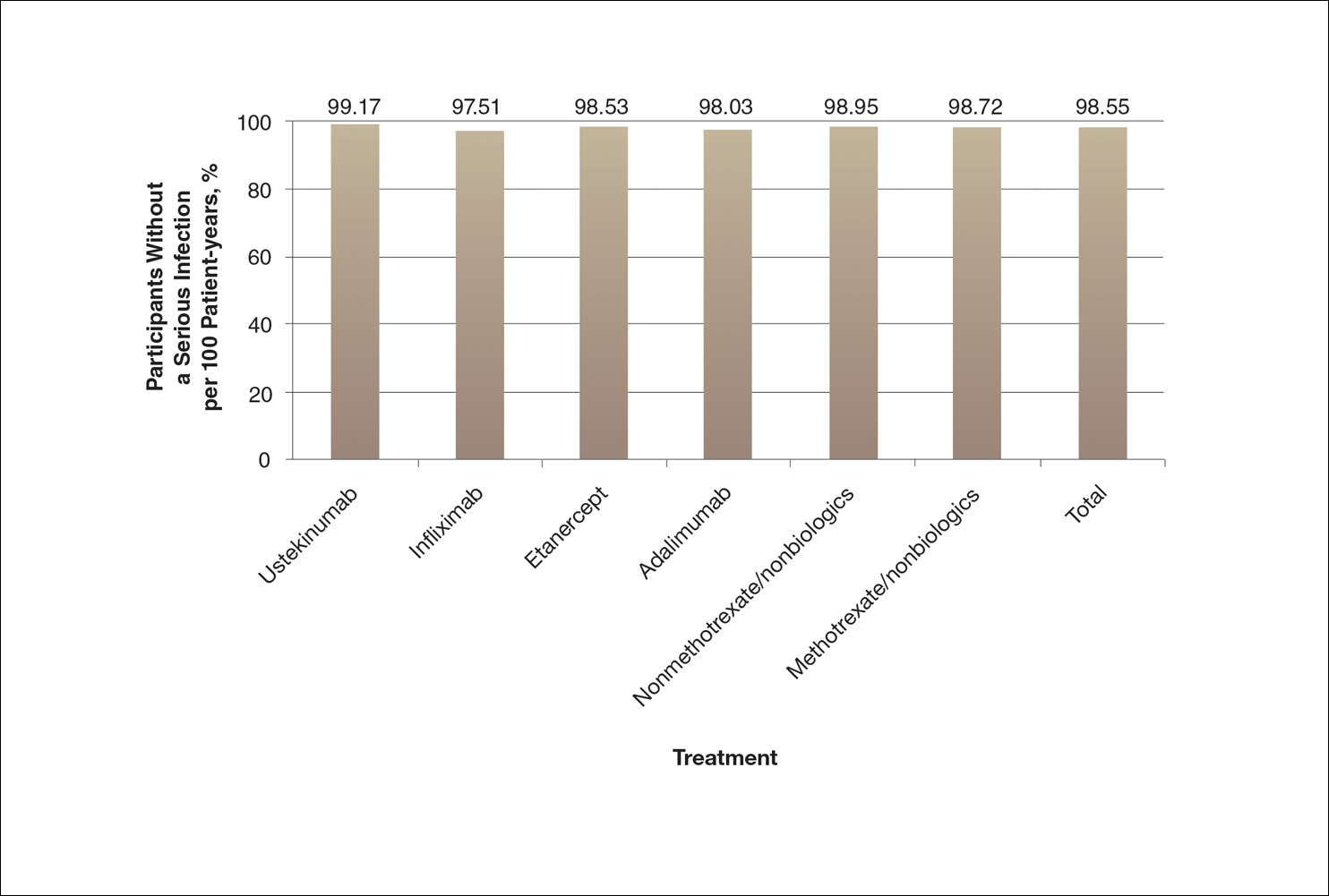

A graph also can present the percentage of patients or patient-years that do not have an adverse effect (Figure 3). This inverse presentation of the data does not emphasize rare cases of patients who have had adverse effects; instead, it emphasizes the large percentage of patients who did not have adverse effects and presents a far more reassuring perspective, even though mathematically the information is identical.

Focus on the Patients Who Do Not Have Adverse Effects of Treatments

Fear of adverse effects is one of the most commonly reported causes of poor treatment adherence.15 New therapies for psoriasis are highly effective and safe, but as with all treatments, they also are associated with some risks. Patients may latch onto those risks too tightly or perhaps, in other circumstances, not tightly enough. The method used by a physician to present safety data to a patient may determine the patient’s perception about treatments.

When trying to give patients an accurate impression of treatment risks, it may be helpful to avoid approaches that focus on presenting the (few) cases of severe adverse drug effects since patients (and physicians) are likely to overweigh the unlikely risk of having an adverse effect if presented with this information. It may be more reassuring to focus on presenting information about the chance of not having an adverse drug effect, assuming the physician’s goal is to be reassuring.

Poor communication with patients when presenting safety data can foster exaggerated fears of an unlikely consequence to the point that patients can be left undertreated and sustaining disease symptoms.16 Physicians may strive to do no harm to their patients, but without careful presentation of safety data in the process of helping the patient make an informed decision, it is possible to do mental harm to patients in the form of fear or even, in the case of nonadherence or treatment refusal, physical harm in the form of continued disease symptoms.

One limitation of this review is that we only used graphical presentation of data as an example. Similar concerns apply to numerical data presentation. Telling a patient the risk of a severe adverse reaction is doubled by a certain treatment may be terrifying, though if the baseline risk is rare, doubling the baseline risk may represent only a minimal increase in the absolute risk. Telling a patient the risk is only 1 in 1000 may still be alarming because many patients tend to focus on the 1, but telling a patient that 999 of 1000 patients do not have a problem can be much more reassuring.

The physician’s goal—to help patients make informed decisions about their treatment—calls for him/her to assimilate safety data into useful information that the patient can use to make an informed decision.17 Overly comforting or alarming, confusing, and inaccurate information can misguide the patient, violating the ethical principle of nonmaleficence. Although there is an obligation to educate patients about risks, there may not be a purely objective way to do it. When physicians present objective data to patients, whether in numerical or graphical form, there will be an unavoidable subjective interpretation of the data. The form of presentation will have a critical effect on patients’ subjective perceptions. Physicians can present objective data in such a way as to be reassuring or frightening.

Conclusion

Despite physicians’ best-intentioned efforts, it may be impossible to avoid presenting safety data in a way that will be subjectively interpreted by patients. Physicians have a choice in how they present data to patients; their best judgment should be used in how they present data to inform patients, guide them, and offer them the best treatment outcomes.

Acknowledgment

We thank Scott Jaros, BA (Winston-Salem, North Carolina), for his assistance in the revision of the manuscript.

- Freyhofer HH. The Nuremberg Medical Trial: The Holocaust and the Origin of the Nuremberg Medical Code. New York, NY: Peter Lang Publishing; 2004.

- Carlson R, Boyd KM, Webb DJ. The revision of the Declaration of Helsinki: past, present and future. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2004;57:695-713.

- Office for Human Research Protections. The Belmont Report. Rockville, MD: US Department of Health and Human Services; 1979.

- Edwards A, Elwyn G, Mulley A. Explaining risks: turning numerical data into meaningful pictures. BMJ. 2002;324:827-830.

- Hayden C, Neame R, Tarrant C. Patients’ adherence-related beliefs about methotrexate: a qualitative study of the role of written patient information. BMJ Open. 2015;5:e006918.

- Horne R, Weinman J. Patients’ beliefs about prescribed medicines and their role in adherence to treatment in chronic physical illness. J Psychosom Res. 1999;47:555-567.

- Weintraub M. Intelligent noncompliance with special emphasis on the elderly. Contemp Pharm Pract. 1981;4:8-11.

- Horne R. Representations of medication and treatment: advances in theory and measurement. In: Petrie KJ, Weinman JA, eds. Perceptions of Health and Illness: Current Research and Applications. London, England: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group; 1997:155-188.

- Kahneman D, Tversky A. Prospect theory: an analysis of decision under risk. Econometrica. 1979;47:263-291.

- Rottenstreich Y, Hsee CK. Money, kisses, and electric shocks: on the affective psychology of risk. Psychol Sci. 2001;12:185-190.

- Kessler JB, Zhang CY. Behavioural economics and health. In: Detels R, Gulliford M, Abdool Karim Q, et al, eds. Oxford Textbook of Global Public Health. 6th ed. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; 2015:775-789.

- Lipkus IM. Numeric, verbal, and visual formats of conveying health risks: suggested best practices and future recommendations [published online September 14, 2007]. Med Decis Making. 2007;27:696-713.

- Kalb RE, Fiorentino DF, Lebwohl MG, et al. Risk of serious infection with biologic and systemic treatment of psoriasis: results from the Psoriasis Longitudinal Assessment and Registry (PSOLAR). JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151:961-969.

- Rensberger B. Slanting the slopes of graphs. The Washington Post. May 10, 1995. http://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/1995/05/10/slanting-the-slope-of-graphs/08a34412-60a2-4719-86e5-d7433938c166/. Accessed September 21, 2016.

- Horne R, Weinman J. Patients’ beliefs about prescribed medicines and their role in adherence to treatment in chronic physical illness. J Psychosom Res. 1999;47:555-567.

- Hahn RA. The nocebo phenomenon: concept, evidence, and implications for public health. Prev Med. 1997;26(5, pt 1):607-611.

- Paling J. Strategies to help patients understand risks. BMJ. 2003;327:745-748.

The Nuremberg Code in 1947,1 the Declaration of Helsinki in 1964,2 and the Belmont Report in 19793 were cornerstones in the establishment of ethical principles in the medical field. These documents specifically highlight the concept of informed consent, which maintains that to practice ethical medicine, physicians must fully inform patients of all therapeutic benefits and especially risks as well as treatment alternatives before they consent to therapeutic intervention. Educating patients about risks of treatment is obligatory. Risk communication involves a mutual exchange of information between physicians and patients; the physician presents risk information in an understandable manner that adequately conveys pertinent data that is critical for the patient to make an informed therapeutic decision.4

An inherent problem with risk education is that patients may be terrified about risks associated with treatment. Some patients will refuse needed treatment because of fear.5 When patients have concerns about the safety profile of a treatment regimen and potential adverse effects, they may be less compliant with treatment.6 The intelligent noncompliance phenomenon occurs when a patient knowingly makes the choice to not adhere to treatment, and concern regarding treatment risks relative to benefits is a common reason underlying this phenomenon.7,8

Behavioral economists have studied how individuals weigh risks. Kahneman and Tversky’s9 prospect theory asserts that individuals tend to overweigh unlikely risks and underweigh more certain risks, which they call the certainty effect; it is the basis of the human tendency to avoid risks in situations of likely gain and to pursue risks in situations of likely loss. The tendency to overweigh rare risks is even more pronounced for affect-rich events such as serious side effects.10 The way data are presented can affect how patients interpret the information. Context and framing of data affect patients’ perceptions.11 We describe several ways to present safety data using graphical presentation of psoriasis treatment safety data as an example and explain how each one can affect patients’ perception of treatment risks.

Approaches to Presenting Safety Data

There are numerous ways to present safety data to patients, including verbal, numeric, and visual strategies.12 Many methods of presentation are a combination of these strategies. Graphs are visual strategies to further categorize and present numeric data, and physicians may choose to incorporate these aids when presenting safety information to patients. Graphical presentations give the patient a mental picture of the data. Numerous types of graphs can be constructed. Kalb et al13 determined the effect of psoriasis treatment on the risk of serious infection from the Psoriasis Longitudinal Assessment and Registry (PSOLAR). We used the results from this study to demonstrate multiple ways of presenting safety data (Figures 1–3).

A graphical presentation with a truncated y-axis is a common approach (Figure 1). Graphs with truncated axes are sometimes used to conserve space or to accentuate certain differences in the graph that would otherwise be less obvious without the zoomed in y-axis.14 These graphs present quantitatively accurate information that can be visually misleading at the same time. Truncated axes accentuate differences, creating mental impressions that are not reflective of the magnitude of the numeric differences. Alternatively, a graph with a full y-axis includes both the maximum and minimum data values on the y-axis (Figure 2). The y-axis also extends maximally to the total number of patients or patient-years studied. This type of graph presents all of the numeric data without distortion.

A graph also can present the percentage of patients or patient-years that do not have an adverse effect (Figure 3). This inverse presentation of the data does not emphasize rare cases of patients who have had adverse effects; instead, it emphasizes the large percentage of patients who did not have adverse effects and presents a far more reassuring perspective, even though mathematically the information is identical.

Focus on the Patients Who Do Not Have Adverse Effects of Treatments

Fear of adverse effects is one of the most commonly reported causes of poor treatment adherence.15 New therapies for psoriasis are highly effective and safe, but as with all treatments, they also are associated with some risks. Patients may latch onto those risks too tightly or perhaps, in other circumstances, not tightly enough. The method used by a physician to present safety data to a patient may determine the patient’s perception about treatments.

When trying to give patients an accurate impression of treatment risks, it may be helpful to avoid approaches that focus on presenting the (few) cases of severe adverse drug effects since patients (and physicians) are likely to overweigh the unlikely risk of having an adverse effect if presented with this information. It may be more reassuring to focus on presenting information about the chance of not having an adverse drug effect, assuming the physician’s goal is to be reassuring.

Poor communication with patients when presenting safety data can foster exaggerated fears of an unlikely consequence to the point that patients can be left undertreated and sustaining disease symptoms.16 Physicians may strive to do no harm to their patients, but without careful presentation of safety data in the process of helping the patient make an informed decision, it is possible to do mental harm to patients in the form of fear or even, in the case of nonadherence or treatment refusal, physical harm in the form of continued disease symptoms.

One limitation of this review is that we only used graphical presentation of data as an example. Similar concerns apply to numerical data presentation. Telling a patient the risk of a severe adverse reaction is doubled by a certain treatment may be terrifying, though if the baseline risk is rare, doubling the baseline risk may represent only a minimal increase in the absolute risk. Telling a patient the risk is only 1 in 1000 may still be alarming because many patients tend to focus on the 1, but telling a patient that 999 of 1000 patients do not have a problem can be much more reassuring.

The physician’s goal—to help patients make informed decisions about their treatment—calls for him/her to assimilate safety data into useful information that the patient can use to make an informed decision.17 Overly comforting or alarming, confusing, and inaccurate information can misguide the patient, violating the ethical principle of nonmaleficence. Although there is an obligation to educate patients about risks, there may not be a purely objective way to do it. When physicians present objective data to patients, whether in numerical or graphical form, there will be an unavoidable subjective interpretation of the data. The form of presentation will have a critical effect on patients’ subjective perceptions. Physicians can present objective data in such a way as to be reassuring or frightening.

Conclusion

Despite physicians’ best-intentioned efforts, it may be impossible to avoid presenting safety data in a way that will be subjectively interpreted by patients. Physicians have a choice in how they present data to patients; their best judgment should be used in how they present data to inform patients, guide them, and offer them the best treatment outcomes.

Acknowledgment

We thank Scott Jaros, BA (Winston-Salem, North Carolina), for his assistance in the revision of the manuscript.

The Nuremberg Code in 1947,1 the Declaration of Helsinki in 1964,2 and the Belmont Report in 19793 were cornerstones in the establishment of ethical principles in the medical field. These documents specifically highlight the concept of informed consent, which maintains that to practice ethical medicine, physicians must fully inform patients of all therapeutic benefits and especially risks as well as treatment alternatives before they consent to therapeutic intervention. Educating patients about risks of treatment is obligatory. Risk communication involves a mutual exchange of information between physicians and patients; the physician presents risk information in an understandable manner that adequately conveys pertinent data that is critical for the patient to make an informed therapeutic decision.4

An inherent problem with risk education is that patients may be terrified about risks associated with treatment. Some patients will refuse needed treatment because of fear.5 When patients have concerns about the safety profile of a treatment regimen and potential adverse effects, they may be less compliant with treatment.6 The intelligent noncompliance phenomenon occurs when a patient knowingly makes the choice to not adhere to treatment, and concern regarding treatment risks relative to benefits is a common reason underlying this phenomenon.7,8

Behavioral economists have studied how individuals weigh risks. Kahneman and Tversky’s9 prospect theory asserts that individuals tend to overweigh unlikely risks and underweigh more certain risks, which they call the certainty effect; it is the basis of the human tendency to avoid risks in situations of likely gain and to pursue risks in situations of likely loss. The tendency to overweigh rare risks is even more pronounced for affect-rich events such as serious side effects.10 The way data are presented can affect how patients interpret the information. Context and framing of data affect patients’ perceptions.11 We describe several ways to present safety data using graphical presentation of psoriasis treatment safety data as an example and explain how each one can affect patients’ perception of treatment risks.

Approaches to Presenting Safety Data

There are numerous ways to present safety data to patients, including verbal, numeric, and visual strategies.12 Many methods of presentation are a combination of these strategies. Graphs are visual strategies to further categorize and present numeric data, and physicians may choose to incorporate these aids when presenting safety information to patients. Graphical presentations give the patient a mental picture of the data. Numerous types of graphs can be constructed. Kalb et al13 determined the effect of psoriasis treatment on the risk of serious infection from the Psoriasis Longitudinal Assessment and Registry (PSOLAR). We used the results from this study to demonstrate multiple ways of presenting safety data (Figures 1–3).

A graphical presentation with a truncated y-axis is a common approach (Figure 1). Graphs with truncated axes are sometimes used to conserve space or to accentuate certain differences in the graph that would otherwise be less obvious without the zoomed in y-axis.14 These graphs present quantitatively accurate information that can be visually misleading at the same time. Truncated axes accentuate differences, creating mental impressions that are not reflective of the magnitude of the numeric differences. Alternatively, a graph with a full y-axis includes both the maximum and minimum data values on the y-axis (Figure 2). The y-axis also extends maximally to the total number of patients or patient-years studied. This type of graph presents all of the numeric data without distortion.

A graph also can present the percentage of patients or patient-years that do not have an adverse effect (Figure 3). This inverse presentation of the data does not emphasize rare cases of patients who have had adverse effects; instead, it emphasizes the large percentage of patients who did not have adverse effects and presents a far more reassuring perspective, even though mathematically the information is identical.

Focus on the Patients Who Do Not Have Adverse Effects of Treatments

Fear of adverse effects is one of the most commonly reported causes of poor treatment adherence.15 New therapies for psoriasis are highly effective and safe, but as with all treatments, they also are associated with some risks. Patients may latch onto those risks too tightly or perhaps, in other circumstances, not tightly enough. The method used by a physician to present safety data to a patient may determine the patient’s perception about treatments.

When trying to give patients an accurate impression of treatment risks, it may be helpful to avoid approaches that focus on presenting the (few) cases of severe adverse drug effects since patients (and physicians) are likely to overweigh the unlikely risk of having an adverse effect if presented with this information. It may be more reassuring to focus on presenting information about the chance of not having an adverse drug effect, assuming the physician’s goal is to be reassuring.

Poor communication with patients when presenting safety data can foster exaggerated fears of an unlikely consequence to the point that patients can be left undertreated and sustaining disease symptoms.16 Physicians may strive to do no harm to their patients, but without careful presentation of safety data in the process of helping the patient make an informed decision, it is possible to do mental harm to patients in the form of fear or even, in the case of nonadherence or treatment refusal, physical harm in the form of continued disease symptoms.

One limitation of this review is that we only used graphical presentation of data as an example. Similar concerns apply to numerical data presentation. Telling a patient the risk of a severe adverse reaction is doubled by a certain treatment may be terrifying, though if the baseline risk is rare, doubling the baseline risk may represent only a minimal increase in the absolute risk. Telling a patient the risk is only 1 in 1000 may still be alarming because many patients tend to focus on the 1, but telling a patient that 999 of 1000 patients do not have a problem can be much more reassuring.

The physician’s goal—to help patients make informed decisions about their treatment—calls for him/her to assimilate safety data into useful information that the patient can use to make an informed decision.17 Overly comforting or alarming, confusing, and inaccurate information can misguide the patient, violating the ethical principle of nonmaleficence. Although there is an obligation to educate patients about risks, there may not be a purely objective way to do it. When physicians present objective data to patients, whether in numerical or graphical form, there will be an unavoidable subjective interpretation of the data. The form of presentation will have a critical effect on patients’ subjective perceptions. Physicians can present objective data in such a way as to be reassuring or frightening.

Conclusion

Despite physicians’ best-intentioned efforts, it may be impossible to avoid presenting safety data in a way that will be subjectively interpreted by patients. Physicians have a choice in how they present data to patients; their best judgment should be used in how they present data to inform patients, guide them, and offer them the best treatment outcomes.

Acknowledgment

We thank Scott Jaros, BA (Winston-Salem, North Carolina), for his assistance in the revision of the manuscript.

- Freyhofer HH. The Nuremberg Medical Trial: The Holocaust and the Origin of the Nuremberg Medical Code. New York, NY: Peter Lang Publishing; 2004.

- Carlson R, Boyd KM, Webb DJ. The revision of the Declaration of Helsinki: past, present and future. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2004;57:695-713.

- Office for Human Research Protections. The Belmont Report. Rockville, MD: US Department of Health and Human Services; 1979.

- Edwards A, Elwyn G, Mulley A. Explaining risks: turning numerical data into meaningful pictures. BMJ. 2002;324:827-830.

- Hayden C, Neame R, Tarrant C. Patients’ adherence-related beliefs about methotrexate: a qualitative study of the role of written patient information. BMJ Open. 2015;5:e006918.

- Horne R, Weinman J. Patients’ beliefs about prescribed medicines and their role in adherence to treatment in chronic physical illness. J Psychosom Res. 1999;47:555-567.

- Weintraub M. Intelligent noncompliance with special emphasis on the elderly. Contemp Pharm Pract. 1981;4:8-11.

- Horne R. Representations of medication and treatment: advances in theory and measurement. In: Petrie KJ, Weinman JA, eds. Perceptions of Health and Illness: Current Research and Applications. London, England: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group; 1997:155-188.

- Kahneman D, Tversky A. Prospect theory: an analysis of decision under risk. Econometrica. 1979;47:263-291.

- Rottenstreich Y, Hsee CK. Money, kisses, and electric shocks: on the affective psychology of risk. Psychol Sci. 2001;12:185-190.

- Kessler JB, Zhang CY. Behavioural economics and health. In: Detels R, Gulliford M, Abdool Karim Q, et al, eds. Oxford Textbook of Global Public Health. 6th ed. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; 2015:775-789.

- Lipkus IM. Numeric, verbal, and visual formats of conveying health risks: suggested best practices and future recommendations [published online September 14, 2007]. Med Decis Making. 2007;27:696-713.

- Kalb RE, Fiorentino DF, Lebwohl MG, et al. Risk of serious infection with biologic and systemic treatment of psoriasis: results from the Psoriasis Longitudinal Assessment and Registry (PSOLAR). JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151:961-969.

- Rensberger B. Slanting the slopes of graphs. The Washington Post. May 10, 1995. http://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/1995/05/10/slanting-the-slope-of-graphs/08a34412-60a2-4719-86e5-d7433938c166/. Accessed September 21, 2016.

- Horne R, Weinman J. Patients’ beliefs about prescribed medicines and their role in adherence to treatment in chronic physical illness. J Psychosom Res. 1999;47:555-567.

- Hahn RA. The nocebo phenomenon: concept, evidence, and implications for public health. Prev Med. 1997;26(5, pt 1):607-611.

- Paling J. Strategies to help patients understand risks. BMJ. 2003;327:745-748.

- Freyhofer HH. The Nuremberg Medical Trial: The Holocaust and the Origin of the Nuremberg Medical Code. New York, NY: Peter Lang Publishing; 2004.

- Carlson R, Boyd KM, Webb DJ. The revision of the Declaration of Helsinki: past, present and future. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2004;57:695-713.

- Office for Human Research Protections. The Belmont Report. Rockville, MD: US Department of Health and Human Services; 1979.

- Edwards A, Elwyn G, Mulley A. Explaining risks: turning numerical data into meaningful pictures. BMJ. 2002;324:827-830.

- Hayden C, Neame R, Tarrant C. Patients’ adherence-related beliefs about methotrexate: a qualitative study of the role of written patient information. BMJ Open. 2015;5:e006918.

- Horne R, Weinman J. Patients’ beliefs about prescribed medicines and their role in adherence to treatment in chronic physical illness. J Psychosom Res. 1999;47:555-567.

- Weintraub M. Intelligent noncompliance with special emphasis on the elderly. Contemp Pharm Pract. 1981;4:8-11.

- Horne R. Representations of medication and treatment: advances in theory and measurement. In: Petrie KJ, Weinman JA, eds. Perceptions of Health and Illness: Current Research and Applications. London, England: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group; 1997:155-188.

- Kahneman D, Tversky A. Prospect theory: an analysis of decision under risk. Econometrica. 1979;47:263-291.

- Rottenstreich Y, Hsee CK. Money, kisses, and electric shocks: on the affective psychology of risk. Psychol Sci. 2001;12:185-190.

- Kessler JB, Zhang CY. Behavioural economics and health. In: Detels R, Gulliford M, Abdool Karim Q, et al, eds. Oxford Textbook of Global Public Health. 6th ed. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; 2015:775-789.

- Lipkus IM. Numeric, verbal, and visual formats of conveying health risks: suggested best practices and future recommendations [published online September 14, 2007]. Med Decis Making. 2007;27:696-713.

- Kalb RE, Fiorentino DF, Lebwohl MG, et al. Risk of serious infection with biologic and systemic treatment of psoriasis: results from the Psoriasis Longitudinal Assessment and Registry (PSOLAR). JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151:961-969.

- Rensberger B. Slanting the slopes of graphs. The Washington Post. May 10, 1995. http://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/1995/05/10/slanting-the-slope-of-graphs/08a34412-60a2-4719-86e5-d7433938c166/. Accessed September 21, 2016.

- Horne R, Weinman J. Patients’ beliefs about prescribed medicines and their role in adherence to treatment in chronic physical illness. J Psychosom Res. 1999;47:555-567.

- Hahn RA. The nocebo phenomenon: concept, evidence, and implications for public health. Prev Med. 1997;26(5, pt 1):607-611.

- Paling J. Strategies to help patients understand risks. BMJ. 2003;327:745-748.

Practice Points

- Physicians can guide patients’ perceptions of drug safety by the way safety data are presented.

- For patients who are concerned about rare treatment risks, presenting data on the patients who have not experienced adverse effects can be reassuring.

Psoriasis not consistently linked to adverse pregnancy outcomes

Psoriasis was not consistently associated with adverse pregnancy outcomes across nine studies in a systematic review of the literature, but four of the studies reported significant increases in at least one adverse outcome among women with psoriasis, according to a report in the British Journal of Dermatology.

Many women with psoriasis develop the disorder during their reproductive years, and more than 100,000 births to such patients are estimated to occur in the United States each year. Other autoimmune diseases are known to adversely affect pregnancy outcomes, but the issue has not been well studied among women with psoriasis, said Robert Bobotsis, a medical student at Western University, London (Ont.), and his associates.

They performed a systematic review of the literature to examine a possible link, but were only able to find nine fair- or good-quality studies involving a total of 4,756 pregnancies from which to extract data concerning a possible association. This small sample size may have been underpowered to detect the uncommon adverse pregnancy outcomes being assessed. Moreover, the investigators were unable to conduct a meta-analysis pooling the data because the effect measures were inconsistent across the nine studies, Mr. Bobotsis and his associates noted.

The review included a retrospective case series, a retrospective case control study, three retrospective cohort studies, two prospective cohort studies, one cross-sectional study, and one study combining prospective and retrospective cohorts. It “did not demonstrate an increased risk of poor outcomes in pregnant women with psoriasis” (Br J Dermatol. 2016 Jul 24;175:464-72).

However, four studies showed that compared with women who didn’t have psoriasis, those who did were at significantly increased risk for spontaneous abortion, cesarean delivery, low birth weight, macrosomia, large for gestational age, and prematurity, with odds ratios as high as 5.6. “Our results should be viewed as an opportunity to further research pregnancy outcomes in psoriasis,” the investigators said.

Psoriasis was not consistently associated with adverse pregnancy outcomes across nine studies in a systematic review of the literature, but four of the studies reported significant increases in at least one adverse outcome among women with psoriasis, according to a report in the British Journal of Dermatology.

Many women with psoriasis develop the disorder during their reproductive years, and more than 100,000 births to such patients are estimated to occur in the United States each year. Other autoimmune diseases are known to adversely affect pregnancy outcomes, but the issue has not been well studied among women with psoriasis, said Robert Bobotsis, a medical student at Western University, London (Ont.), and his associates.

They performed a systematic review of the literature to examine a possible link, but were only able to find nine fair- or good-quality studies involving a total of 4,756 pregnancies from which to extract data concerning a possible association. This small sample size may have been underpowered to detect the uncommon adverse pregnancy outcomes being assessed. Moreover, the investigators were unable to conduct a meta-analysis pooling the data because the effect measures were inconsistent across the nine studies, Mr. Bobotsis and his associates noted.

The review included a retrospective case series, a retrospective case control study, three retrospective cohort studies, two prospective cohort studies, one cross-sectional study, and one study combining prospective and retrospective cohorts. It “did not demonstrate an increased risk of poor outcomes in pregnant women with psoriasis” (Br J Dermatol. 2016 Jul 24;175:464-72).

However, four studies showed that compared with women who didn’t have psoriasis, those who did were at significantly increased risk for spontaneous abortion, cesarean delivery, low birth weight, macrosomia, large for gestational age, and prematurity, with odds ratios as high as 5.6. “Our results should be viewed as an opportunity to further research pregnancy outcomes in psoriasis,” the investigators said.

Psoriasis was not consistently associated with adverse pregnancy outcomes across nine studies in a systematic review of the literature, but four of the studies reported significant increases in at least one adverse outcome among women with psoriasis, according to a report in the British Journal of Dermatology.

Many women with psoriasis develop the disorder during their reproductive years, and more than 100,000 births to such patients are estimated to occur in the United States each year. Other autoimmune diseases are known to adversely affect pregnancy outcomes, but the issue has not been well studied among women with psoriasis, said Robert Bobotsis, a medical student at Western University, London (Ont.), and his associates.

They performed a systematic review of the literature to examine a possible link, but were only able to find nine fair- or good-quality studies involving a total of 4,756 pregnancies from which to extract data concerning a possible association. This small sample size may have been underpowered to detect the uncommon adverse pregnancy outcomes being assessed. Moreover, the investigators were unable to conduct a meta-analysis pooling the data because the effect measures were inconsistent across the nine studies, Mr. Bobotsis and his associates noted.

The review included a retrospective case series, a retrospective case control study, three retrospective cohort studies, two prospective cohort studies, one cross-sectional study, and one study combining prospective and retrospective cohorts. It “did not demonstrate an increased risk of poor outcomes in pregnant women with psoriasis” (Br J Dermatol. 2016 Jul 24;175:464-72).

However, four studies showed that compared with women who didn’t have psoriasis, those who did were at significantly increased risk for spontaneous abortion, cesarean delivery, low birth weight, macrosomia, large for gestational age, and prematurity, with odds ratios as high as 5.6. “Our results should be viewed as an opportunity to further research pregnancy outcomes in psoriasis,” the investigators said.

Key clinical point: Psoriasis is not consistently associated with adverse pregnancy outcomes across studies, but individual studies reported such links.

Major finding: Four of nine studies showed that compared with women who did not have psoriasis, those who did were at significantly increased risk for spontaneous abortion, cesarean delivery, low birth weight, macrosomia, large for gestational age, and prematurity, with odds ratios as high as 5.6.

Data source: A systematic review of nine reports in the literature concerning adverse outcomes in 4,756 pregnancies among women with psoriasis.

Disclosures: The authors reported that this work had no funding sources. Mr. Bobotsis reported having no relevant financial disclosures; two of his associates reported ties to AbbVie, Actelion, Amgen, Bio-K, Celgene, Eli Lilly, Galderma, Janssen, LEO Pharma, Merck, Novartis, Pfizer, Roche, and Valeant.

Pediatricians partner with hospitals for value-based models

When Jason Vargas, MD, first moved to the Phoenix area 13 years ago, he found an atmosphere of distant relationships between general pediatricians like him, subspecialists, and hospitals. Getting patients a referral to a subspecialist could take months, and communication among providers was often weak, Dr. Vargas said.

Today, things are vastly different thanks in large part to the clinically integrated network of which Dr. Vargas and 950 area providers are a part.

Phoenix Children’s Care Network (PCCN), established in 2014, coordinates health care across multiple providers and settings in the Phoenix area, including half of all general pediatricians and 80% of pediatric subspecialists practicing in Maricopa County. The network is a value- and risk-based system that provides financial incentives to participating providers and health systems that meet established quality metrics. Patients have access to 950 providers within the network, including primary and specialty care sites of service, urgent care locations, surgery centers, and Phoenix Children’s Hospital.

Meanwhile, 2,000 miles away, another unique payment model is changing the way pediatric care is delivered in the Columbus, Ohio area. Partners For Kids (PFK) is a pediatric accountable care organization (ACO) that coordinates care between Nationwide Children’s Hospital and more than 1,000 doctors. Through its 20-year evolution, PFK has successfully assumed full financial and clinical risk for children under age 19 enrolled in Medicaid managed care. This means PFK is responsible for paying for the costs of all patient care, no matter how much or where that care occurs.

The two models illustrate how pediatricians are affiliating with value-centric networks while keeping their independence, said Timothy Johnson, senior vice president of pediatrics at Valence Health, a consulting firm that helps health providers transition to value-based care.

With MACRA (the Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act of 2015) “it’s going to be difficult for individual pediatricians to do what is required in a value-based medical system because they just don’t have the resources,” Mr. Johnson said in an interview. “That doesn’t mean they can’t be independent. It means they are going to have to band together in some way, whether with a health system, with other practices. It is extremely important for pediatricians to start thinking about how to do that.”

Going from splintered to unified

Like most communities, care delivery in the Phoenix area was relatively fractured prior to 2014. To bring everyone together, Phoenix Children’s started with community outreach and education.

Along with building trust among providers, project leaders had to overcome operational hurdles. This included creating a process for 110 practices to collectively negotiate contracts, operate under a new structure, and adhere to quality metrics, he said.

“Operationally, you have to take 110 different ways of doing things and try merge them into one common way as you develop these new contractual risk-based models,” he said. “At the same time, we had to transition people away from what they were used to as a purely fee-for-service model. It was a very big operational transition.”

To bolster engagement by community pediatricians, PCCN developed a physician-governance approach, assigning participating providers leadership responsibilities. Participating physicians then worked to create the benchmarks by which doctors are measured against. To date, provider performance is tracked against 14 primary care and 34 specialist metrics encompassing engagement, safety, quality, and transparency.

PCCN leaders also had to ensure that participating in such a network was beneficial for busy doctors, said Dr. Vargas, who is chair of the PCCN Network and Utilization committee and a member of the network’s board of managers.

Asking physicians to change their framework, track patient data, and meet metrics, all while potentially losing money if they fail to hit benchmarks is not the most popular proposition, he said. So PCCN created advantages for member doctors, such as nighttime pediatric triage, a negotiated discount for professional services, IT support, streamlined access to specialists, and more avenues to communicate with subspecialists.

“With so many schedules, professional, and academic pressures on our daily professional lives, we have wanted to make sure that there were practical value added benefits to members,” he said. “I think right now that the benefits outweigh the administrative burdens.”

A changing payer relationship

As a network, PCCN works with payers to assume the risk that insurers have historically taken. Payers continue to handle the administrative and billing side of the equation, while the network controls the medical management and care coordination of the patient population, Mr. Johnson said.

“We feel we can do it much more efficiently, much more effectively, and we feel it’s better care for the patient when we’re the one controlling that,” he said. “The insurance companies don’t disagree.”

The network partners with Medicaid and commercial payers and has a direct-to-employer agreement with a major employer in conjunction with an adult partner system/network. Early performance efforts by the PCCN have been rewarded by shared savings disbursements from two payers, according to PCCN officials. The network has also met or exceeded state Medicaid pediatric quality targets and consistently contained medical expenses below expected medical cost trends for its managed pediatric populations.

Building a population health model

For more than 2 decades, PFK in Ohio has taken a novel care delivery approach that has focused on value and community partnerships.

Back in 1994, Nationwide Children’s Hospital partnered with community pediatricians to create PFK, a physician/hospital organization with governance shared equally. Today, PFK has assumed full financial and clinical risk for pediatric managed Medicaid enrollees, and is the largest and oldest known pediatric ACO.

A key hurdle was collecting timely, complete, and accurate data for the patient population, Dr. Gleeson said, adding that working with data and understanding changing trends is an everyday challenge. Interacting with busy physicians and securing their time and cooperation also has been an obstacle.

“The lessons learned for us is that we really need to approach them understanding that there is a limited amount of time that practices can invest in infrastructure or invest in the processes of care,” he said. “We have to approach things knowing that [doctors] are going to struggle with the amount of time necessary to engage in large projects, so it needs to be chopped up into bite-sized pieces that they can consume on the run, so they can keep their practices running well.”

PFK efforts have paid off in terms of lowering costs and improving care. Between 2008 and 2013, PFK achieved lower cost growth than Medicaid fee-for-service programs and managed care plans in the Columbus, Ohio, area (Pediatrics. 2015 Mar;135[3];e582-9).

Fundamentally, the model has remained the same over the years, Dr. Gleeson said, but in 2005, PFK made the decision to expand and take responsibility for all the Medicaid-enrolled children in the region.

“It really gives a much broader field of view and perspective on patients in the region,” he said. “We know that they are all our responsibility so we take more of a population health type of approach, working with any physician who is caring for those children.”

Guidance for other practices

Dr. Gleeson encouraged other pediatricians interested in transitioning to value-based care to start by evaluating their data. Take a hard look at the quality of care you provide and begin to measure it, he said. For smaller practices, consider joining a larger group or network that will allow pediatricians to engage in collaborative work, he added.

Dr. Vargas stressed that change is coming whether pediatricians are prepared or not. Aligning with the right partners will be the difference between sinking or staying afloat in the value-based landscape.

“Payers are moving toward value-based models and it is not practical for the general pediatrician to be able to provide the infrastructure and professional resources necessary,” he said. “To maintain our professional livelihood as independent pediatricians, and to continue to provide the individually crafted, quality care our families are accustomed to, we will have to align ourselves with organizations that value the experience and insight of the independent pediatrician to deliver that care.”

[email protected]

On Twitter @legal_med

When Jason Vargas, MD, first moved to the Phoenix area 13 years ago, he found an atmosphere of distant relationships between general pediatricians like him, subspecialists, and hospitals. Getting patients a referral to a subspecialist could take months, and communication among providers was often weak, Dr. Vargas said.

Today, things are vastly different thanks in large part to the clinically integrated network of which Dr. Vargas and 950 area providers are a part.

Phoenix Children’s Care Network (PCCN), established in 2014, coordinates health care across multiple providers and settings in the Phoenix area, including half of all general pediatricians and 80% of pediatric subspecialists practicing in Maricopa County. The network is a value- and risk-based system that provides financial incentives to participating providers and health systems that meet established quality metrics. Patients have access to 950 providers within the network, including primary and specialty care sites of service, urgent care locations, surgery centers, and Phoenix Children’s Hospital.

Meanwhile, 2,000 miles away, another unique payment model is changing the way pediatric care is delivered in the Columbus, Ohio area. Partners For Kids (PFK) is a pediatric accountable care organization (ACO) that coordinates care between Nationwide Children’s Hospital and more than 1,000 doctors. Through its 20-year evolution, PFK has successfully assumed full financial and clinical risk for children under age 19 enrolled in Medicaid managed care. This means PFK is responsible for paying for the costs of all patient care, no matter how much or where that care occurs.

The two models illustrate how pediatricians are affiliating with value-centric networks while keeping their independence, said Timothy Johnson, senior vice president of pediatrics at Valence Health, a consulting firm that helps health providers transition to value-based care.

With MACRA (the Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act of 2015) “it’s going to be difficult for individual pediatricians to do what is required in a value-based medical system because they just don’t have the resources,” Mr. Johnson said in an interview. “That doesn’t mean they can’t be independent. It means they are going to have to band together in some way, whether with a health system, with other practices. It is extremely important for pediatricians to start thinking about how to do that.”

Going from splintered to unified

Like most communities, care delivery in the Phoenix area was relatively fractured prior to 2014. To bring everyone together, Phoenix Children’s started with community outreach and education.

Along with building trust among providers, project leaders had to overcome operational hurdles. This included creating a process for 110 practices to collectively negotiate contracts, operate under a new structure, and adhere to quality metrics, he said.

“Operationally, you have to take 110 different ways of doing things and try merge them into one common way as you develop these new contractual risk-based models,” he said. “At the same time, we had to transition people away from what they were used to as a purely fee-for-service model. It was a very big operational transition.”

To bolster engagement by community pediatricians, PCCN developed a physician-governance approach, assigning participating providers leadership responsibilities. Participating physicians then worked to create the benchmarks by which doctors are measured against. To date, provider performance is tracked against 14 primary care and 34 specialist metrics encompassing engagement, safety, quality, and transparency.

PCCN leaders also had to ensure that participating in such a network was beneficial for busy doctors, said Dr. Vargas, who is chair of the PCCN Network and Utilization committee and a member of the network’s board of managers.

Asking physicians to change their framework, track patient data, and meet metrics, all while potentially losing money if they fail to hit benchmarks is not the most popular proposition, he said. So PCCN created advantages for member doctors, such as nighttime pediatric triage, a negotiated discount for professional services, IT support, streamlined access to specialists, and more avenues to communicate with subspecialists.

“With so many schedules, professional, and academic pressures on our daily professional lives, we have wanted to make sure that there were practical value added benefits to members,” he said. “I think right now that the benefits outweigh the administrative burdens.”

A changing payer relationship

As a network, PCCN works with payers to assume the risk that insurers have historically taken. Payers continue to handle the administrative and billing side of the equation, while the network controls the medical management and care coordination of the patient population, Mr. Johnson said.

“We feel we can do it much more efficiently, much more effectively, and we feel it’s better care for the patient when we’re the one controlling that,” he said. “The insurance companies don’t disagree.”

The network partners with Medicaid and commercial payers and has a direct-to-employer agreement with a major employer in conjunction with an adult partner system/network. Early performance efforts by the PCCN have been rewarded by shared savings disbursements from two payers, according to PCCN officials. The network has also met or exceeded state Medicaid pediatric quality targets and consistently contained medical expenses below expected medical cost trends for its managed pediatric populations.

Building a population health model

For more than 2 decades, PFK in Ohio has taken a novel care delivery approach that has focused on value and community partnerships.

Back in 1994, Nationwide Children’s Hospital partnered with community pediatricians to create PFK, a physician/hospital organization with governance shared equally. Today, PFK has assumed full financial and clinical risk for pediatric managed Medicaid enrollees, and is the largest and oldest known pediatric ACO.

A key hurdle was collecting timely, complete, and accurate data for the patient population, Dr. Gleeson said, adding that working with data and understanding changing trends is an everyday challenge. Interacting with busy physicians and securing their time and cooperation also has been an obstacle.

“The lessons learned for us is that we really need to approach them understanding that there is a limited amount of time that practices can invest in infrastructure or invest in the processes of care,” he said. “We have to approach things knowing that [doctors] are going to struggle with the amount of time necessary to engage in large projects, so it needs to be chopped up into bite-sized pieces that they can consume on the run, so they can keep their practices running well.”

PFK efforts have paid off in terms of lowering costs and improving care. Between 2008 and 2013, PFK achieved lower cost growth than Medicaid fee-for-service programs and managed care plans in the Columbus, Ohio, area (Pediatrics. 2015 Mar;135[3];e582-9).

Fundamentally, the model has remained the same over the years, Dr. Gleeson said, but in 2005, PFK made the decision to expand and take responsibility for all the Medicaid-enrolled children in the region.

“It really gives a much broader field of view and perspective on patients in the region,” he said. “We know that they are all our responsibility so we take more of a population health type of approach, working with any physician who is caring for those children.”

Guidance for other practices

Dr. Gleeson encouraged other pediatricians interested in transitioning to value-based care to start by evaluating their data. Take a hard look at the quality of care you provide and begin to measure it, he said. For smaller practices, consider joining a larger group or network that will allow pediatricians to engage in collaborative work, he added.

Dr. Vargas stressed that change is coming whether pediatricians are prepared or not. Aligning with the right partners will be the difference between sinking or staying afloat in the value-based landscape.

“Payers are moving toward value-based models and it is not practical for the general pediatrician to be able to provide the infrastructure and professional resources necessary,” he said. “To maintain our professional livelihood as independent pediatricians, and to continue to provide the individually crafted, quality care our families are accustomed to, we will have to align ourselves with organizations that value the experience and insight of the independent pediatrician to deliver that care.”

[email protected]

On Twitter @legal_med

When Jason Vargas, MD, first moved to the Phoenix area 13 years ago, he found an atmosphere of distant relationships between general pediatricians like him, subspecialists, and hospitals. Getting patients a referral to a subspecialist could take months, and communication among providers was often weak, Dr. Vargas said.

Today, things are vastly different thanks in large part to the clinically integrated network of which Dr. Vargas and 950 area providers are a part.

Phoenix Children’s Care Network (PCCN), established in 2014, coordinates health care across multiple providers and settings in the Phoenix area, including half of all general pediatricians and 80% of pediatric subspecialists practicing in Maricopa County. The network is a value- and risk-based system that provides financial incentives to participating providers and health systems that meet established quality metrics. Patients have access to 950 providers within the network, including primary and specialty care sites of service, urgent care locations, surgery centers, and Phoenix Children’s Hospital.

Meanwhile, 2,000 miles away, another unique payment model is changing the way pediatric care is delivered in the Columbus, Ohio area. Partners For Kids (PFK) is a pediatric accountable care organization (ACO) that coordinates care between Nationwide Children’s Hospital and more than 1,000 doctors. Through its 20-year evolution, PFK has successfully assumed full financial and clinical risk for children under age 19 enrolled in Medicaid managed care. This means PFK is responsible for paying for the costs of all patient care, no matter how much or where that care occurs.

The two models illustrate how pediatricians are affiliating with value-centric networks while keeping their independence, said Timothy Johnson, senior vice president of pediatrics at Valence Health, a consulting firm that helps health providers transition to value-based care.

With MACRA (the Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act of 2015) “it’s going to be difficult for individual pediatricians to do what is required in a value-based medical system because they just don’t have the resources,” Mr. Johnson said in an interview. “That doesn’t mean they can’t be independent. It means they are going to have to band together in some way, whether with a health system, with other practices. It is extremely important for pediatricians to start thinking about how to do that.”

Going from splintered to unified

Like most communities, care delivery in the Phoenix area was relatively fractured prior to 2014. To bring everyone together, Phoenix Children’s started with community outreach and education.

Along with building trust among providers, project leaders had to overcome operational hurdles. This included creating a process for 110 practices to collectively negotiate contracts, operate under a new structure, and adhere to quality metrics, he said.

“Operationally, you have to take 110 different ways of doing things and try merge them into one common way as you develop these new contractual risk-based models,” he said. “At the same time, we had to transition people away from what they were used to as a purely fee-for-service model. It was a very big operational transition.”

To bolster engagement by community pediatricians, PCCN developed a physician-governance approach, assigning participating providers leadership responsibilities. Participating physicians then worked to create the benchmarks by which doctors are measured against. To date, provider performance is tracked against 14 primary care and 34 specialist metrics encompassing engagement, safety, quality, and transparency.

PCCN leaders also had to ensure that participating in such a network was beneficial for busy doctors, said Dr. Vargas, who is chair of the PCCN Network and Utilization committee and a member of the network’s board of managers.

Asking physicians to change their framework, track patient data, and meet metrics, all while potentially losing money if they fail to hit benchmarks is not the most popular proposition, he said. So PCCN created advantages for member doctors, such as nighttime pediatric triage, a negotiated discount for professional services, IT support, streamlined access to specialists, and more avenues to communicate with subspecialists.

“With so many schedules, professional, and academic pressures on our daily professional lives, we have wanted to make sure that there were practical value added benefits to members,” he said. “I think right now that the benefits outweigh the administrative burdens.”

A changing payer relationship

As a network, PCCN works with payers to assume the risk that insurers have historically taken. Payers continue to handle the administrative and billing side of the equation, while the network controls the medical management and care coordination of the patient population, Mr. Johnson said.

“We feel we can do it much more efficiently, much more effectively, and we feel it’s better care for the patient when we’re the one controlling that,” he said. “The insurance companies don’t disagree.”

The network partners with Medicaid and commercial payers and has a direct-to-employer agreement with a major employer in conjunction with an adult partner system/network. Early performance efforts by the PCCN have been rewarded by shared savings disbursements from two payers, according to PCCN officials. The network has also met or exceeded state Medicaid pediatric quality targets and consistently contained medical expenses below expected medical cost trends for its managed pediatric populations.

Building a population health model

For more than 2 decades, PFK in Ohio has taken a novel care delivery approach that has focused on value and community partnerships.

Back in 1994, Nationwide Children’s Hospital partnered with community pediatricians to create PFK, a physician/hospital organization with governance shared equally. Today, PFK has assumed full financial and clinical risk for pediatric managed Medicaid enrollees, and is the largest and oldest known pediatric ACO.

A key hurdle was collecting timely, complete, and accurate data for the patient population, Dr. Gleeson said, adding that working with data and understanding changing trends is an everyday challenge. Interacting with busy physicians and securing their time and cooperation also has been an obstacle.

“The lessons learned for us is that we really need to approach them understanding that there is a limited amount of time that practices can invest in infrastructure or invest in the processes of care,” he said. “We have to approach things knowing that [doctors] are going to struggle with the amount of time necessary to engage in large projects, so it needs to be chopped up into bite-sized pieces that they can consume on the run, so they can keep their practices running well.”

PFK efforts have paid off in terms of lowering costs and improving care. Between 2008 and 2013, PFK achieved lower cost growth than Medicaid fee-for-service programs and managed care plans in the Columbus, Ohio, area (Pediatrics. 2015 Mar;135[3];e582-9).

Fundamentally, the model has remained the same over the years, Dr. Gleeson said, but in 2005, PFK made the decision to expand and take responsibility for all the Medicaid-enrolled children in the region.

“It really gives a much broader field of view and perspective on patients in the region,” he said. “We know that they are all our responsibility so we take more of a population health type of approach, working with any physician who is caring for those children.”

Guidance for other practices

Dr. Gleeson encouraged other pediatricians interested in transitioning to value-based care to start by evaluating their data. Take a hard look at the quality of care you provide and begin to measure it, he said. For smaller practices, consider joining a larger group or network that will allow pediatricians to engage in collaborative work, he added.

Dr. Vargas stressed that change is coming whether pediatricians are prepared or not. Aligning with the right partners will be the difference between sinking or staying afloat in the value-based landscape.

“Payers are moving toward value-based models and it is not practical for the general pediatrician to be able to provide the infrastructure and professional resources necessary,” he said. “To maintain our professional livelihood as independent pediatricians, and to continue to provide the individually crafted, quality care our families are accustomed to, we will have to align ourselves with organizations that value the experience and insight of the independent pediatrician to deliver that care.”

[email protected]

On Twitter @legal_med

Occupational Complexity May Protect Cognition in People at Risk for Alzheimer’s Disease

TORONTO—High levels of occupational complexity, specifically related to work with people, enable individuals to maintain normal cognition despite white matter pathology in the brain, according to research described at the Alzheimer’s Association International Conference. The results “could have potential implications for preventing or maybe delaying Alzheimer’s disease onset in the future,” said Elizabeth Boots, research specialist at Wisconsin Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center in Madison.

According to one estimate, about 30% of cognitively healthy elderly adults may have widespread Alzheimer’s disease pathology. Cognitive reserve may allow these individuals to perform at a normal level of cognition despite this pathology. Because many people spend the majority of their lives at work, Ms. Boots and colleagues chose to examine occupational complexity as a measure of cognitive reserve. The investigators also focused on white matter hyperintensities, which increase the risk for cognitive decline and are common in Alzheimer’s disease. “The objective of our study was to determine whether occupational complexity is associated with more white matter hyperintensities when participants are matched for cognitive function, which would support the cognitive reserve hypothesis,” said Ms. Boots.

Examining Cognitive Testing and Imaging

She and her colleagues, led by senior author Ozioma Okonkwo, PhD, Assistant Professor of Geriatrics at the University of Wisconsin School of Medicine in Madison, selected 284 participants in the Wisconsin Registry for Alzheimer’s Prevention, a group of approximately 1,500 cognitively healthy people with increased risk for Alzheimer’s disease because of parental family history. Participants underwent extensive cognitive testing, and the researchers looked at the average of four cognitive domains—verbal learning and memory, immediate memory, working memory, and speed and flexibility—to match individuals on cognitive function. Participants also underwent a brain scan for white matter hyperintensities.

In addition, study participants described as many as three occupations that they had performed, including the number of years spent on each occupation. Ms. Boots and her colleagues rated each job for three categories of occupational complexity (ie, complexity of work with data, people, and things). In the domain of work with people, for example, the researchers considered taking instructions as the least complex occupation, and mentoring the most complex. They weighted the scores by the number of years on the job and summed the scores to create a total occupational complexity measure.

Social Interaction May Be Crucial

Average age in the study cohort was 60, and 67% of participants were female. Study participants had an average of 16.67 years of education. When the investigators controlled the data for cognitive function, they found that higher levels of occupational complexity were associated with increased white matter hyperintensities in the brain. “Those with higher levels of occupational complexity are able to tolerate more white matter pathology in the brain and still perform at the same cognitive level as their peers,” said Ms. Boots. The association did not change when the researchers controlled for potential confounders such as education, socioeconomic status, and vascular risk. Furthermore, Ms. Boots and colleagues found that complexity of work with people, but not complexity of work with data or things, had the greatest effect on preserving cognitive performance.

The results support the cognitive reserve hypothesis and suggest that social interaction plays a unique role in cognitive reserve, according to Dr. Okonkwo. “These analyses underscore the importance of social engagement in the work setting for building resilience to Alzheimer’s disease,” he added. The Alzheimer’s Association, the NIH, and the Extendicare Foundation funded the study.

Suggested Reading

Boots EA, Schultz SA, Almeida RP, et al. Occupational complexity and cognitive reserve in a middle-aged cohort at risk for Alzheimer’s disease. Arch Clin

Lo RY, Jagust WJ; Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative. Effect of cognitive reserve markers on Alzheimer pathologic progression. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2013;27(4):343-350.

Pool LR, Weuve J, Wilson RS, et al. Occupational cognitive requirements and late-life cognitive aging. Neurology. 2016;86(15):1386-1392.

Stern Y. Cognitive reserve in ageing and Alzheimer’s disease. Lancet Neurol. 2012; 11(11):1006-1012.

TORONTO—High levels of occupational complexity, specifically related to work with people, enable individuals to maintain normal cognition despite white matter pathology in the brain, according to research described at the Alzheimer’s Association International Conference. The results “could have potential implications for preventing or maybe delaying Alzheimer’s disease onset in the future,” said Elizabeth Boots, research specialist at Wisconsin Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center in Madison.

According to one estimate, about 30% of cognitively healthy elderly adults may have widespread Alzheimer’s disease pathology. Cognitive reserve may allow these individuals to perform at a normal level of cognition despite this pathology. Because many people spend the majority of their lives at work, Ms. Boots and colleagues chose to examine occupational complexity as a measure of cognitive reserve. The investigators also focused on white matter hyperintensities, which increase the risk for cognitive decline and are common in Alzheimer’s disease. “The objective of our study was to determine whether occupational complexity is associated with more white matter hyperintensities when participants are matched for cognitive function, which would support the cognitive reserve hypothesis,” said Ms. Boots.

Examining Cognitive Testing and Imaging

She and her colleagues, led by senior author Ozioma Okonkwo, PhD, Assistant Professor of Geriatrics at the University of Wisconsin School of Medicine in Madison, selected 284 participants in the Wisconsin Registry for Alzheimer’s Prevention, a group of approximately 1,500 cognitively healthy people with increased risk for Alzheimer’s disease because of parental family history. Participants underwent extensive cognitive testing, and the researchers looked at the average of four cognitive domains—verbal learning and memory, immediate memory, working memory, and speed and flexibility—to match individuals on cognitive function. Participants also underwent a brain scan for white matter hyperintensities.

In addition, study participants described as many as three occupations that they had performed, including the number of years spent on each occupation. Ms. Boots and her colleagues rated each job for three categories of occupational complexity (ie, complexity of work with data, people, and things). In the domain of work with people, for example, the researchers considered taking instructions as the least complex occupation, and mentoring the most complex. They weighted the scores by the number of years on the job and summed the scores to create a total occupational complexity measure.

Social Interaction May Be Crucial

Average age in the study cohort was 60, and 67% of participants were female. Study participants had an average of 16.67 years of education. When the investigators controlled the data for cognitive function, they found that higher levels of occupational complexity were associated with increased white matter hyperintensities in the brain. “Those with higher levels of occupational complexity are able to tolerate more white matter pathology in the brain and still perform at the same cognitive level as their peers,” said Ms. Boots. The association did not change when the researchers controlled for potential confounders such as education, socioeconomic status, and vascular risk. Furthermore, Ms. Boots and colleagues found that complexity of work with people, but not complexity of work with data or things, had the greatest effect on preserving cognitive performance.

The results support the cognitive reserve hypothesis and suggest that social interaction plays a unique role in cognitive reserve, according to Dr. Okonkwo. “These analyses underscore the importance of social engagement in the work setting for building resilience to Alzheimer’s disease,” he added. The Alzheimer’s Association, the NIH, and the Extendicare Foundation funded the study.

Suggested Reading

Boots EA, Schultz SA, Almeida RP, et al. Occupational complexity and cognitive reserve in a middle-aged cohort at risk for Alzheimer’s disease. Arch Clin

Lo RY, Jagust WJ; Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative. Effect of cognitive reserve markers on Alzheimer pathologic progression. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2013;27(4):343-350.

Pool LR, Weuve J, Wilson RS, et al. Occupational cognitive requirements and late-life cognitive aging. Neurology. 2016;86(15):1386-1392.

Stern Y. Cognitive reserve in ageing and Alzheimer’s disease. Lancet Neurol. 2012; 11(11):1006-1012.

TORONTO—High levels of occupational complexity, specifically related to work with people, enable individuals to maintain normal cognition despite white matter pathology in the brain, according to research described at the Alzheimer’s Association International Conference. The results “could have potential implications for preventing or maybe delaying Alzheimer’s disease onset in the future,” said Elizabeth Boots, research specialist at Wisconsin Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center in Madison.

According to one estimate, about 30% of cognitively healthy elderly adults may have widespread Alzheimer’s disease pathology. Cognitive reserve may allow these individuals to perform at a normal level of cognition despite this pathology. Because many people spend the majority of their lives at work, Ms. Boots and colleagues chose to examine occupational complexity as a measure of cognitive reserve. The investigators also focused on white matter hyperintensities, which increase the risk for cognitive decline and are common in Alzheimer’s disease. “The objective of our study was to determine whether occupational complexity is associated with more white matter hyperintensities when participants are matched for cognitive function, which would support the cognitive reserve hypothesis,” said Ms. Boots.

Examining Cognitive Testing and Imaging

She and her colleagues, led by senior author Ozioma Okonkwo, PhD, Assistant Professor of Geriatrics at the University of Wisconsin School of Medicine in Madison, selected 284 participants in the Wisconsin Registry for Alzheimer’s Prevention, a group of approximately 1,500 cognitively healthy people with increased risk for Alzheimer’s disease because of parental family history. Participants underwent extensive cognitive testing, and the researchers looked at the average of four cognitive domains—verbal learning and memory, immediate memory, working memory, and speed and flexibility—to match individuals on cognitive function. Participants also underwent a brain scan for white matter hyperintensities.

In addition, study participants described as many as three occupations that they had performed, including the number of years spent on each occupation. Ms. Boots and her colleagues rated each job for three categories of occupational complexity (ie, complexity of work with data, people, and things). In the domain of work with people, for example, the researchers considered taking instructions as the least complex occupation, and mentoring the most complex. They weighted the scores by the number of years on the job and summed the scores to create a total occupational complexity measure.

Social Interaction May Be Crucial

Average age in the study cohort was 60, and 67% of participants were female. Study participants had an average of 16.67 years of education. When the investigators controlled the data for cognitive function, they found that higher levels of occupational complexity were associated with increased white matter hyperintensities in the brain. “Those with higher levels of occupational complexity are able to tolerate more white matter pathology in the brain and still perform at the same cognitive level as their peers,” said Ms. Boots. The association did not change when the researchers controlled for potential confounders such as education, socioeconomic status, and vascular risk. Furthermore, Ms. Boots and colleagues found that complexity of work with people, but not complexity of work with data or things, had the greatest effect on preserving cognitive performance.

The results support the cognitive reserve hypothesis and suggest that social interaction plays a unique role in cognitive reserve, according to Dr. Okonkwo. “These analyses underscore the importance of social engagement in the work setting for building resilience to Alzheimer’s disease,” he added. The Alzheimer’s Association, the NIH, and the Extendicare Foundation funded the study.

Suggested Reading

Boots EA, Schultz SA, Almeida RP, et al. Occupational complexity and cognitive reserve in a middle-aged cohort at risk for Alzheimer’s disease. Arch Clin

Lo RY, Jagust WJ; Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative. Effect of cognitive reserve markers on Alzheimer pathologic progression. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2013;27(4):343-350.

Pool LR, Weuve J, Wilson RS, et al. Occupational cognitive requirements and late-life cognitive aging. Neurology. 2016;86(15):1386-1392.