User login

Ceramic Femoral Heads for All Patients? An Argument for Cost Containment in Hip Surgery

Total hip arthroplasty (THA) has revolutionized the practice of orthopedic surgery. The number of primary THAs performed in the United States alone is predicted to rise to 572,000 per year by 2030.1 Increasing demand requires a tighter focus on cost-effectiveness, particularly with regard to expensive postoperative complications. Trunnionosis and taper corrosion have recently emerged as problems in THA.2-7 No longer restricted to metal-on-metal bearings, these phenomena now affect an increasing number of metal-on-polyethylene THAs and are exacerbated by modularity.8 The emergence of these complications adds complexity to the diagnostic algorithm in patients who present with painful THAs. Furthermore, the diagnosis of either trunnionosis or taper corrosion calls for revision surgery. In response to the increase in these complications, a group of orthopedic professional societies developed an algorithm for managing suspected metal toxicity issues.9 However, increases in toxicity and patient morbidity, and the added costs of toxicity surveillance and revision surgery, will place a substantial economic burden on many health systems at a time when policy makers are implementing substantial changes to health delivery in an effort to contain costs while improving patient outcomes.

Although they are more expensive than cobalt-chrome heads, ceramic femoral heads make metal toxicity a nonissue and eliminate the need for toxicity surveillance protocols. Furthermore, ceramic femoral heads are thought to have longevity advantages (this relationship needs to be confirmed in long-term studies).

In this article, we provide a theoretical framework for debating whether use of ceramic femoral heads in all THA patients could represent a more cost-effective option over the long term.

Materials and Methods

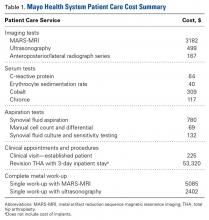

Guidelines for the diagnostic algorithm for painful THA with suspected metal toxicity were obtained from a recent orthopedic professional society consensus statement.9 The cost of this work-up was obtained from the finance department at our institution (Table 1).

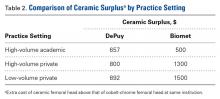

We created 2 metrics to analyze the cost difference between ceramic and cobalt-chrome femoral heads. The first metric was “ceramic surplus,” the extra cost of a ceramic femoral head above that of a cobalt-chrome femoral head, and the second was “maximum ceramic surplus,” the ceramic surplus cutoff value for which using ceramic femoral heads in all patients becomes more cost-effective than using cobalt-chrome heads.

The cost of a metal work-up was determined for a single round of imaging tests (stratified by MRI and US), serum tests, aspiration tests, and clinic visit. These data were then combined with the cost of revision THA (Table 1) to create a series of maximum ceramic surplus models. In all these simulations, we assumed that about 7% of patients with metal-on-polyethylene THA would present with groin pain 1 to 2 years after surgery,10 and, working on this assumption, we applied a series of theoretical incidence ratios (12.5%, 25%, 50%) to both the percentage of patients who presented with a painful THA and received a metal toxicity work-up and the percentage of those who received the toxicity work-up and eventually needed revision surgery. For example, in the best-case scenario, the model assumes that 7% of THA patients present with pain and that 12.5% of the painful cohort receives a single work-up for metal toxicity (0.875% of all THAs). The best-case scenario then assumes that 12.5% of patients who receive a work-up for metal toxicity are eventually revised (0.11% of all THAs). By contrast, in the worst-case scenario, the model continues to assume that 7% of THA patients present with pain, but it also assumes that 50% of the painful cohort receives a single work-up for metal toxicity (3.5% of all THAs).

The lowest maximum ceramic surplus values were calculated from the best-case scenario, and the highest from the worst-case scenario. These steps were taken in keeping with the fact that a lower incidence of metal toxicity work-ups and revisions would require the price difference between ceramic and cobalt-chrome heads (ceramic surplus) to be small in order for ceramic heads in all patients to be cost-effective. The inverse is true for a high incidence of metal toxicity work-ups and revisions: A larger price difference between ceramic and cobalt-chrome femoral heads would be tolerable to still be cost-effective.

Results

A single metal toxicity work-up cost $5085 with MARS-MRI and $2402 with US (Table 1). Revision THA with a 3-day inpatient stay cost $53,320, and that figure does not include the cost of surgical implants or perioperative medications and devices, all of which have highly variable cost structures (Table 1). Ceramic surplus was as low as $500 in a high-volume academic practice and as high as $1500 in a low-volume private practice (Table 2). Maximum ceramic surplus ranged from $511 to $2044 in the models integrating MARS-MRI and from $488 to $1950 in the models integrating US (Table 3).

Discussion

Trunnionosis, corrosion, and metal toxicity are of increasing concern in hip implants that incorporate a cobalt-chrome femoral head, regardless of the counterpart articulation surface (metal, ceramic, polyethylene).2-8 In response to the added diagnostic challenge raised by these phenomena, a group of orthopedic professional societies developed an algorithm that can guide surgeons in the management of suspected corrosion or metal toxicity.9 In this protocol, toxicity surveillance in conjunction with potential revision surgery for metal-associated complications has the potential to increase patient morbidity and place a significant economic burden on many health systems. Given the recent emergence of trunnionosis, epidemiologic data on this complication are lacking.10 However, there is a substantial body of evidence showing devastating complications associated with adverse reactions to metal debris.11-17

Given the potential complications specific to cobalt-chrome femoral heads, we wanted to provide a theoretical framework for debating whether use of ceramic heads in all patients has the potential to be a more cost-effective option over the long term. Ceramic femoral heads are premium implants, certainly more expensive at initial point of care. One study based on a large community registry showed premium implants (eg, ceramic femoral heads) add a surplus averaging $1000.18 In our investigation, ceramic surplus varied with practice setting, from $500 to $1500. Lower costs were discovered in high-volume practice settings, indicating that a shift to increased use of ceramic femoral heads would likely decrease ceramic surplus for most institutions.

We used a series of simulations to predict maximum ceramic surplus after manipulation of theoretical incidence ratios. The main limitation of this study was our use of 7% as the incidence of painful THA within 1- to 2-year follow-up. This point estimate was derived from a manuscript that to our knowledge provides the most realistic estimate of this complication10; with use of more complete data in upcoming studies, however, the 7% figure could certainly change. As data are also lacking on the proportion of painful THAs that receive a metal work-up and on the proportion of metal work-ups that indicate revision surgery, we modeled values of 12.5%, 25%, and 50% for each of these metrics to cover a wide range of possibilities.

It is also true the model did not incorporate scenarios to account for the law of unintended consequences, which would caution that using ceramics for all patients may bring a new set of complications. Zirconia ceramic bearings have tended to fracture, with the vast majority of fractures occurring in the liner of ceramic-on-ceramic articulations. Midterm reports and laboratory data suggest this issue has largely been solved with the advent of delta ceramics, a composite containing only a small fraction of zirconia.19,20 Nevertheless, longer term in vivo data are needed to confirm the stability, longevity, and complication profile of these materials.

A final limitation of the present study is that the cost of a single metal toxicity work-up was based on just one institution. Grossly differing cost structures in other markets could alter the economic risk–benefit analysis we have described. However, we should note that the costs of tests, procedures, and appointments at our institution were uniform across a wide variety of practice settings in multiple regions of the United States, and thus are likely similar to the costs at a majority of practices.

Although our model took some liberties by necessity, it was also quite conservative in many respects. Many patients who undergo surveillance for metal toxicity undergo serial follow-ups; for this analysis, however, we considered the cost of only a single work-up. In addition, our proposed cost of revision surgery accounts only for facility and personnel costs during a 3-day inpatient stay and does not include the costs of implants, perioperative medications and devices, follow-up care, and potentially longer hospital stays or subsequent procedures, all of which can be highly variable and add considerable cost. Had any or all of these factors been incorporated into more complex modeling, the potential economic benefits of ceramic femoral heads would have been significantly greater.

After taking all these factors into account, our model found that maximum ceramic surplus ranged from $488 to $2044, depending on theoretical incidence ratio and imaging modality (Table 3). The lowest maximum ceramic surplus values ($511 for MARS-MRI protocol, $488 for US protocol) were based on the assumption that only 12.5% of patients who present with a painful THA receive a single metal work-up (0.875% of all THAs) and that only 12.5% of those patients are eventually revised (0.11% of all THAs). This outcome suggests ceramic femoral heads could be more cost-effective than cobalt-chrome femoral heads under these conservative projections when considering ceramic surplus is already as low as $500 at some high-volume centers. This figure would likely decline further in parallel with widespread growth in demand. Further study on the epidemiology of trunnionosis, corrosion, and metal toxicity in metal-on-polyethylene THA is needed to evaluate the economic validity of this proposal. Nevertheless, the superior safety profile of ceramic femoral heads with regard to metal toxicity indicates that wholesale use in THAs may in fact provide the most economical option on a societal scale.

Am J Orthop. 2016;45(6):E362-E366. Copyright Frontline Medical Communications Inc. 2016. All rights reserved.

1. Kurtz S, Ong K, Lau E, Mowat F, Halpern M. Projections of primary and revision hip and knee arthroplasty in the United States from 2005 to 2030. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89(4):780-785.

2. Cooper HJ. The local effects of metal corrosion in total hip arthroplasty. Orthop Clin North Am. 2014;45(1):9-18.

3. Cooper HJ, Della Valle CJ, Berger RA, et al. Corrosion at the head-neck taper as a cause for adverse local tissue reactions after total hip arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2012;94(18):1655-1661.

4. Cooper HJ, Urban RM, Wixson RL, Meneghini RM, Jacobs JJ. Adverse local tissue reaction arising from corrosion at the femoral neck-body junction in a dual-taper stem with a cobalt-chromium modular neck. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2013;95(10):865-872.

5. Jacobs JJ, Cooper HJ, Urban RM, Wixson RL, Della Valle CJ. What do we know about taper corrosion in total hip arthroplasty? J Arthroplasty. 2014;29(4):668-669.

6. Pastides PS, Dodd M, Sarraf KM, Willis-Owen CA. Trunnionosis: a pain in the neck. World J Orthop. 2013;4(4):161-166.

7. Shulman RM, Zywiel MG, Gandhi R, Davey JR, Salonen DC. Trunnionosis: the latest culprit in adverse reactions to metal debris following hip arthroplasty. Skeletal Radiol. 2015;44(3):433-440.

8. Mihalko WM, Wimmer MA, Pacione CA, Laurent MP, Murphy RF, Rider C. How have alternative bearings and modularity affected revision rates in total hip arthroplasty? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2014;472(12):3747-3758.

9. Kwon YM, Lombardi AV, Jacobs JJ, Fehring TK, Lewis CG, Cabanela ME. Risk stratification algorithm for management of patients with metal-on-metal hip arthroplasty: consensus statement of the American Association of Hip and Knee Surgeons, the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons, and the Hip Society. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2014;96(1):e4.

10. Bartelt RB, Yuan BJ, Trousdale RT, Sierra RJ. The prevalence of groin pain after metal-on-metal total hip arthroplasty and total hip resurfacing. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2010;468(9):2346-2356.

11. Bozic KJ, Lau EC, Ong KL, Vail TP, Rubash HE, Berry DJ. Comparative effectiveness of metal-on-metal and metal-on-polyethylene bearings in Medicare total hip arthroplasty patients. J Arthroplasty. 2012;27(8 suppl):37-40.

12. Cuckler JM. Metal-on-metal surface replacement: a triumph of hope over reason: affirms. Orthopedics. 2011;34(9):e439-e441.

13. de Steiger RN, Hang JR, Miller LN, Graves SE, Davidson DC. Five-year results of the ASR XL Acetabular System and the ASR Hip Resurfacing System: an analysis from the Australian Orthopaedic Association National Joint Replacement Registry. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2011;93(24):2287-2293.

14. Fehring TK, Odum S, Sproul R, Weathersbee J. High frequency of adverse local tissue reactions in asymptomatic patients with metal-on-metal THA. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2014;472(2):517-522.

15. Hasegawa M, Yoshida K, Wakabayashi H, Sudo A. Prevalence of adverse reactions to metal debris following metal-on-metal THA. Orthopedics. 2013;36(5):e606-e612.

16. Melvin JS, Karthikeyan T, Cope R, Fehring TK. Early failures in total hip arthroplasty—a changing paradigm. J Arthroplasty. 2014;29(6):1285-1288.

17. Wyles CC, Van Demark RE 3rd, Sierra RJ, Trousdale RT. High rate of infection after aseptic revision of failed metal-on-metal total hip arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2014;472(2):509-516.

18. Gioe TJ, Sharma A, Tatman P, Mehle S. Do “premium” joint implants add value?: Analysis of high cost joint implants in a community registry. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2011;469(1):48-54.

19. D’Antonio JA, Capello WN, Naughton M. Ceramic bearings for total hip arthroplasty have high survivorship at 10 years. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2012;470(2):373-381.

20. D’Antonio JA, Capello WN, Naughton M. High survivorship with a titanium-encased alumina ceramic bearing for total hip arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2014;472(2):611-616.

Total hip arthroplasty (THA) has revolutionized the practice of orthopedic surgery. The number of primary THAs performed in the United States alone is predicted to rise to 572,000 per year by 2030.1 Increasing demand requires a tighter focus on cost-effectiveness, particularly with regard to expensive postoperative complications. Trunnionosis and taper corrosion have recently emerged as problems in THA.2-7 No longer restricted to metal-on-metal bearings, these phenomena now affect an increasing number of metal-on-polyethylene THAs and are exacerbated by modularity.8 The emergence of these complications adds complexity to the diagnostic algorithm in patients who present with painful THAs. Furthermore, the diagnosis of either trunnionosis or taper corrosion calls for revision surgery. In response to the increase in these complications, a group of orthopedic professional societies developed an algorithm for managing suspected metal toxicity issues.9 However, increases in toxicity and patient morbidity, and the added costs of toxicity surveillance and revision surgery, will place a substantial economic burden on many health systems at a time when policy makers are implementing substantial changes to health delivery in an effort to contain costs while improving patient outcomes.

Although they are more expensive than cobalt-chrome heads, ceramic femoral heads make metal toxicity a nonissue and eliminate the need for toxicity surveillance protocols. Furthermore, ceramic femoral heads are thought to have longevity advantages (this relationship needs to be confirmed in long-term studies).

In this article, we provide a theoretical framework for debating whether use of ceramic femoral heads in all THA patients could represent a more cost-effective option over the long term.

Materials and Methods

Guidelines for the diagnostic algorithm for painful THA with suspected metal toxicity were obtained from a recent orthopedic professional society consensus statement.9 The cost of this work-up was obtained from the finance department at our institution (Table 1).

We created 2 metrics to analyze the cost difference between ceramic and cobalt-chrome femoral heads. The first metric was “ceramic surplus,” the extra cost of a ceramic femoral head above that of a cobalt-chrome femoral head, and the second was “maximum ceramic surplus,” the ceramic surplus cutoff value for which using ceramic femoral heads in all patients becomes more cost-effective than using cobalt-chrome heads.

The cost of a metal work-up was determined for a single round of imaging tests (stratified by MRI and US), serum tests, aspiration tests, and clinic visit. These data were then combined with the cost of revision THA (Table 1) to create a series of maximum ceramic surplus models. In all these simulations, we assumed that about 7% of patients with metal-on-polyethylene THA would present with groin pain 1 to 2 years after surgery,10 and, working on this assumption, we applied a series of theoretical incidence ratios (12.5%, 25%, 50%) to both the percentage of patients who presented with a painful THA and received a metal toxicity work-up and the percentage of those who received the toxicity work-up and eventually needed revision surgery. For example, in the best-case scenario, the model assumes that 7% of THA patients present with pain and that 12.5% of the painful cohort receives a single work-up for metal toxicity (0.875% of all THAs). The best-case scenario then assumes that 12.5% of patients who receive a work-up for metal toxicity are eventually revised (0.11% of all THAs). By contrast, in the worst-case scenario, the model continues to assume that 7% of THA patients present with pain, but it also assumes that 50% of the painful cohort receives a single work-up for metal toxicity (3.5% of all THAs).

The lowest maximum ceramic surplus values were calculated from the best-case scenario, and the highest from the worst-case scenario. These steps were taken in keeping with the fact that a lower incidence of metal toxicity work-ups and revisions would require the price difference between ceramic and cobalt-chrome heads (ceramic surplus) to be small in order for ceramic heads in all patients to be cost-effective. The inverse is true for a high incidence of metal toxicity work-ups and revisions: A larger price difference between ceramic and cobalt-chrome femoral heads would be tolerable to still be cost-effective.

Results

A single metal toxicity work-up cost $5085 with MARS-MRI and $2402 with US (Table 1). Revision THA with a 3-day inpatient stay cost $53,320, and that figure does not include the cost of surgical implants or perioperative medications and devices, all of which have highly variable cost structures (Table 1). Ceramic surplus was as low as $500 in a high-volume academic practice and as high as $1500 in a low-volume private practice (Table 2). Maximum ceramic surplus ranged from $511 to $2044 in the models integrating MARS-MRI and from $488 to $1950 in the models integrating US (Table 3).

Discussion

Trunnionosis, corrosion, and metal toxicity are of increasing concern in hip implants that incorporate a cobalt-chrome femoral head, regardless of the counterpart articulation surface (metal, ceramic, polyethylene).2-8 In response to the added diagnostic challenge raised by these phenomena, a group of orthopedic professional societies developed an algorithm that can guide surgeons in the management of suspected corrosion or metal toxicity.9 In this protocol, toxicity surveillance in conjunction with potential revision surgery for metal-associated complications has the potential to increase patient morbidity and place a significant economic burden on many health systems. Given the recent emergence of trunnionosis, epidemiologic data on this complication are lacking.10 However, there is a substantial body of evidence showing devastating complications associated with adverse reactions to metal debris.11-17

Given the potential complications specific to cobalt-chrome femoral heads, we wanted to provide a theoretical framework for debating whether use of ceramic heads in all patients has the potential to be a more cost-effective option over the long term. Ceramic femoral heads are premium implants, certainly more expensive at initial point of care. One study based on a large community registry showed premium implants (eg, ceramic femoral heads) add a surplus averaging $1000.18 In our investigation, ceramic surplus varied with practice setting, from $500 to $1500. Lower costs were discovered in high-volume practice settings, indicating that a shift to increased use of ceramic femoral heads would likely decrease ceramic surplus for most institutions.

We used a series of simulations to predict maximum ceramic surplus after manipulation of theoretical incidence ratios. The main limitation of this study was our use of 7% as the incidence of painful THA within 1- to 2-year follow-up. This point estimate was derived from a manuscript that to our knowledge provides the most realistic estimate of this complication10; with use of more complete data in upcoming studies, however, the 7% figure could certainly change. As data are also lacking on the proportion of painful THAs that receive a metal work-up and on the proportion of metal work-ups that indicate revision surgery, we modeled values of 12.5%, 25%, and 50% for each of these metrics to cover a wide range of possibilities.

It is also true the model did not incorporate scenarios to account for the law of unintended consequences, which would caution that using ceramics for all patients may bring a new set of complications. Zirconia ceramic bearings have tended to fracture, with the vast majority of fractures occurring in the liner of ceramic-on-ceramic articulations. Midterm reports and laboratory data suggest this issue has largely been solved with the advent of delta ceramics, a composite containing only a small fraction of zirconia.19,20 Nevertheless, longer term in vivo data are needed to confirm the stability, longevity, and complication profile of these materials.

A final limitation of the present study is that the cost of a single metal toxicity work-up was based on just one institution. Grossly differing cost structures in other markets could alter the economic risk–benefit analysis we have described. However, we should note that the costs of tests, procedures, and appointments at our institution were uniform across a wide variety of practice settings in multiple regions of the United States, and thus are likely similar to the costs at a majority of practices.

Although our model took some liberties by necessity, it was also quite conservative in many respects. Many patients who undergo surveillance for metal toxicity undergo serial follow-ups; for this analysis, however, we considered the cost of only a single work-up. In addition, our proposed cost of revision surgery accounts only for facility and personnel costs during a 3-day inpatient stay and does not include the costs of implants, perioperative medications and devices, follow-up care, and potentially longer hospital stays or subsequent procedures, all of which can be highly variable and add considerable cost. Had any or all of these factors been incorporated into more complex modeling, the potential economic benefits of ceramic femoral heads would have been significantly greater.

After taking all these factors into account, our model found that maximum ceramic surplus ranged from $488 to $2044, depending on theoretical incidence ratio and imaging modality (Table 3). The lowest maximum ceramic surplus values ($511 for MARS-MRI protocol, $488 for US protocol) were based on the assumption that only 12.5% of patients who present with a painful THA receive a single metal work-up (0.875% of all THAs) and that only 12.5% of those patients are eventually revised (0.11% of all THAs). This outcome suggests ceramic femoral heads could be more cost-effective than cobalt-chrome femoral heads under these conservative projections when considering ceramic surplus is already as low as $500 at some high-volume centers. This figure would likely decline further in parallel with widespread growth in demand. Further study on the epidemiology of trunnionosis, corrosion, and metal toxicity in metal-on-polyethylene THA is needed to evaluate the economic validity of this proposal. Nevertheless, the superior safety profile of ceramic femoral heads with regard to metal toxicity indicates that wholesale use in THAs may in fact provide the most economical option on a societal scale.

Am J Orthop. 2016;45(6):E362-E366. Copyright Frontline Medical Communications Inc. 2016. All rights reserved.

Total hip arthroplasty (THA) has revolutionized the practice of orthopedic surgery. The number of primary THAs performed in the United States alone is predicted to rise to 572,000 per year by 2030.1 Increasing demand requires a tighter focus on cost-effectiveness, particularly with regard to expensive postoperative complications. Trunnionosis and taper corrosion have recently emerged as problems in THA.2-7 No longer restricted to metal-on-metal bearings, these phenomena now affect an increasing number of metal-on-polyethylene THAs and are exacerbated by modularity.8 The emergence of these complications adds complexity to the diagnostic algorithm in patients who present with painful THAs. Furthermore, the diagnosis of either trunnionosis or taper corrosion calls for revision surgery. In response to the increase in these complications, a group of orthopedic professional societies developed an algorithm for managing suspected metal toxicity issues.9 However, increases in toxicity and patient morbidity, and the added costs of toxicity surveillance and revision surgery, will place a substantial economic burden on many health systems at a time when policy makers are implementing substantial changes to health delivery in an effort to contain costs while improving patient outcomes.

Although they are more expensive than cobalt-chrome heads, ceramic femoral heads make metal toxicity a nonissue and eliminate the need for toxicity surveillance protocols. Furthermore, ceramic femoral heads are thought to have longevity advantages (this relationship needs to be confirmed in long-term studies).

In this article, we provide a theoretical framework for debating whether use of ceramic femoral heads in all THA patients could represent a more cost-effective option over the long term.

Materials and Methods

Guidelines for the diagnostic algorithm for painful THA with suspected metal toxicity were obtained from a recent orthopedic professional society consensus statement.9 The cost of this work-up was obtained from the finance department at our institution (Table 1).

We created 2 metrics to analyze the cost difference between ceramic and cobalt-chrome femoral heads. The first metric was “ceramic surplus,” the extra cost of a ceramic femoral head above that of a cobalt-chrome femoral head, and the second was “maximum ceramic surplus,” the ceramic surplus cutoff value for which using ceramic femoral heads in all patients becomes more cost-effective than using cobalt-chrome heads.

The cost of a metal work-up was determined for a single round of imaging tests (stratified by MRI and US), serum tests, aspiration tests, and clinic visit. These data were then combined with the cost of revision THA (Table 1) to create a series of maximum ceramic surplus models. In all these simulations, we assumed that about 7% of patients with metal-on-polyethylene THA would present with groin pain 1 to 2 years after surgery,10 and, working on this assumption, we applied a series of theoretical incidence ratios (12.5%, 25%, 50%) to both the percentage of patients who presented with a painful THA and received a metal toxicity work-up and the percentage of those who received the toxicity work-up and eventually needed revision surgery. For example, in the best-case scenario, the model assumes that 7% of THA patients present with pain and that 12.5% of the painful cohort receives a single work-up for metal toxicity (0.875% of all THAs). The best-case scenario then assumes that 12.5% of patients who receive a work-up for metal toxicity are eventually revised (0.11% of all THAs). By contrast, in the worst-case scenario, the model continues to assume that 7% of THA patients present with pain, but it also assumes that 50% of the painful cohort receives a single work-up for metal toxicity (3.5% of all THAs).

The lowest maximum ceramic surplus values were calculated from the best-case scenario, and the highest from the worst-case scenario. These steps were taken in keeping with the fact that a lower incidence of metal toxicity work-ups and revisions would require the price difference between ceramic and cobalt-chrome heads (ceramic surplus) to be small in order for ceramic heads in all patients to be cost-effective. The inverse is true for a high incidence of metal toxicity work-ups and revisions: A larger price difference between ceramic and cobalt-chrome femoral heads would be tolerable to still be cost-effective.

Results

A single metal toxicity work-up cost $5085 with MARS-MRI and $2402 with US (Table 1). Revision THA with a 3-day inpatient stay cost $53,320, and that figure does not include the cost of surgical implants or perioperative medications and devices, all of which have highly variable cost structures (Table 1). Ceramic surplus was as low as $500 in a high-volume academic practice and as high as $1500 in a low-volume private practice (Table 2). Maximum ceramic surplus ranged from $511 to $2044 in the models integrating MARS-MRI and from $488 to $1950 in the models integrating US (Table 3).

Discussion

Trunnionosis, corrosion, and metal toxicity are of increasing concern in hip implants that incorporate a cobalt-chrome femoral head, regardless of the counterpart articulation surface (metal, ceramic, polyethylene).2-8 In response to the added diagnostic challenge raised by these phenomena, a group of orthopedic professional societies developed an algorithm that can guide surgeons in the management of suspected corrosion or metal toxicity.9 In this protocol, toxicity surveillance in conjunction with potential revision surgery for metal-associated complications has the potential to increase patient morbidity and place a significant economic burden on many health systems. Given the recent emergence of trunnionosis, epidemiologic data on this complication are lacking.10 However, there is a substantial body of evidence showing devastating complications associated with adverse reactions to metal debris.11-17

Given the potential complications specific to cobalt-chrome femoral heads, we wanted to provide a theoretical framework for debating whether use of ceramic heads in all patients has the potential to be a more cost-effective option over the long term. Ceramic femoral heads are premium implants, certainly more expensive at initial point of care. One study based on a large community registry showed premium implants (eg, ceramic femoral heads) add a surplus averaging $1000.18 In our investigation, ceramic surplus varied with practice setting, from $500 to $1500. Lower costs were discovered in high-volume practice settings, indicating that a shift to increased use of ceramic femoral heads would likely decrease ceramic surplus for most institutions.

We used a series of simulations to predict maximum ceramic surplus after manipulation of theoretical incidence ratios. The main limitation of this study was our use of 7% as the incidence of painful THA within 1- to 2-year follow-up. This point estimate was derived from a manuscript that to our knowledge provides the most realistic estimate of this complication10; with use of more complete data in upcoming studies, however, the 7% figure could certainly change. As data are also lacking on the proportion of painful THAs that receive a metal work-up and on the proportion of metal work-ups that indicate revision surgery, we modeled values of 12.5%, 25%, and 50% for each of these metrics to cover a wide range of possibilities.

It is also true the model did not incorporate scenarios to account for the law of unintended consequences, which would caution that using ceramics for all patients may bring a new set of complications. Zirconia ceramic bearings have tended to fracture, with the vast majority of fractures occurring in the liner of ceramic-on-ceramic articulations. Midterm reports and laboratory data suggest this issue has largely been solved with the advent of delta ceramics, a composite containing only a small fraction of zirconia.19,20 Nevertheless, longer term in vivo data are needed to confirm the stability, longevity, and complication profile of these materials.

A final limitation of the present study is that the cost of a single metal toxicity work-up was based on just one institution. Grossly differing cost structures in other markets could alter the economic risk–benefit analysis we have described. However, we should note that the costs of tests, procedures, and appointments at our institution were uniform across a wide variety of practice settings in multiple regions of the United States, and thus are likely similar to the costs at a majority of practices.

Although our model took some liberties by necessity, it was also quite conservative in many respects. Many patients who undergo surveillance for metal toxicity undergo serial follow-ups; for this analysis, however, we considered the cost of only a single work-up. In addition, our proposed cost of revision surgery accounts only for facility and personnel costs during a 3-day inpatient stay and does not include the costs of implants, perioperative medications and devices, follow-up care, and potentially longer hospital stays or subsequent procedures, all of which can be highly variable and add considerable cost. Had any or all of these factors been incorporated into more complex modeling, the potential economic benefits of ceramic femoral heads would have been significantly greater.

After taking all these factors into account, our model found that maximum ceramic surplus ranged from $488 to $2044, depending on theoretical incidence ratio and imaging modality (Table 3). The lowest maximum ceramic surplus values ($511 for MARS-MRI protocol, $488 for US protocol) were based on the assumption that only 12.5% of patients who present with a painful THA receive a single metal work-up (0.875% of all THAs) and that only 12.5% of those patients are eventually revised (0.11% of all THAs). This outcome suggests ceramic femoral heads could be more cost-effective than cobalt-chrome femoral heads under these conservative projections when considering ceramic surplus is already as low as $500 at some high-volume centers. This figure would likely decline further in parallel with widespread growth in demand. Further study on the epidemiology of trunnionosis, corrosion, and metal toxicity in metal-on-polyethylene THA is needed to evaluate the economic validity of this proposal. Nevertheless, the superior safety profile of ceramic femoral heads with regard to metal toxicity indicates that wholesale use in THAs may in fact provide the most economical option on a societal scale.

Am J Orthop. 2016;45(6):E362-E366. Copyright Frontline Medical Communications Inc. 2016. All rights reserved.

1. Kurtz S, Ong K, Lau E, Mowat F, Halpern M. Projections of primary and revision hip and knee arthroplasty in the United States from 2005 to 2030. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89(4):780-785.

2. Cooper HJ. The local effects of metal corrosion in total hip arthroplasty. Orthop Clin North Am. 2014;45(1):9-18.

3. Cooper HJ, Della Valle CJ, Berger RA, et al. Corrosion at the head-neck taper as a cause for adverse local tissue reactions after total hip arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2012;94(18):1655-1661.

4. Cooper HJ, Urban RM, Wixson RL, Meneghini RM, Jacobs JJ. Adverse local tissue reaction arising from corrosion at the femoral neck-body junction in a dual-taper stem with a cobalt-chromium modular neck. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2013;95(10):865-872.

5. Jacobs JJ, Cooper HJ, Urban RM, Wixson RL, Della Valle CJ. What do we know about taper corrosion in total hip arthroplasty? J Arthroplasty. 2014;29(4):668-669.

6. Pastides PS, Dodd M, Sarraf KM, Willis-Owen CA. Trunnionosis: a pain in the neck. World J Orthop. 2013;4(4):161-166.

7. Shulman RM, Zywiel MG, Gandhi R, Davey JR, Salonen DC. Trunnionosis: the latest culprit in adverse reactions to metal debris following hip arthroplasty. Skeletal Radiol. 2015;44(3):433-440.

8. Mihalko WM, Wimmer MA, Pacione CA, Laurent MP, Murphy RF, Rider C. How have alternative bearings and modularity affected revision rates in total hip arthroplasty? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2014;472(12):3747-3758.

9. Kwon YM, Lombardi AV, Jacobs JJ, Fehring TK, Lewis CG, Cabanela ME. Risk stratification algorithm for management of patients with metal-on-metal hip arthroplasty: consensus statement of the American Association of Hip and Knee Surgeons, the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons, and the Hip Society. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2014;96(1):e4.

10. Bartelt RB, Yuan BJ, Trousdale RT, Sierra RJ. The prevalence of groin pain after metal-on-metal total hip arthroplasty and total hip resurfacing. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2010;468(9):2346-2356.

11. Bozic KJ, Lau EC, Ong KL, Vail TP, Rubash HE, Berry DJ. Comparative effectiveness of metal-on-metal and metal-on-polyethylene bearings in Medicare total hip arthroplasty patients. J Arthroplasty. 2012;27(8 suppl):37-40.

12. Cuckler JM. Metal-on-metal surface replacement: a triumph of hope over reason: affirms. Orthopedics. 2011;34(9):e439-e441.

13. de Steiger RN, Hang JR, Miller LN, Graves SE, Davidson DC. Five-year results of the ASR XL Acetabular System and the ASR Hip Resurfacing System: an analysis from the Australian Orthopaedic Association National Joint Replacement Registry. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2011;93(24):2287-2293.

14. Fehring TK, Odum S, Sproul R, Weathersbee J. High frequency of adverse local tissue reactions in asymptomatic patients with metal-on-metal THA. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2014;472(2):517-522.

15. Hasegawa M, Yoshida K, Wakabayashi H, Sudo A. Prevalence of adverse reactions to metal debris following metal-on-metal THA. Orthopedics. 2013;36(5):e606-e612.

16. Melvin JS, Karthikeyan T, Cope R, Fehring TK. Early failures in total hip arthroplasty—a changing paradigm. J Arthroplasty. 2014;29(6):1285-1288.

17. Wyles CC, Van Demark RE 3rd, Sierra RJ, Trousdale RT. High rate of infection after aseptic revision of failed metal-on-metal total hip arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2014;472(2):509-516.

18. Gioe TJ, Sharma A, Tatman P, Mehle S. Do “premium” joint implants add value?: Analysis of high cost joint implants in a community registry. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2011;469(1):48-54.

19. D’Antonio JA, Capello WN, Naughton M. Ceramic bearings for total hip arthroplasty have high survivorship at 10 years. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2012;470(2):373-381.

20. D’Antonio JA, Capello WN, Naughton M. High survivorship with a titanium-encased alumina ceramic bearing for total hip arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2014;472(2):611-616.

1. Kurtz S, Ong K, Lau E, Mowat F, Halpern M. Projections of primary and revision hip and knee arthroplasty in the United States from 2005 to 2030. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89(4):780-785.

2. Cooper HJ. The local effects of metal corrosion in total hip arthroplasty. Orthop Clin North Am. 2014;45(1):9-18.

3. Cooper HJ, Della Valle CJ, Berger RA, et al. Corrosion at the head-neck taper as a cause for adverse local tissue reactions after total hip arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2012;94(18):1655-1661.

4. Cooper HJ, Urban RM, Wixson RL, Meneghini RM, Jacobs JJ. Adverse local tissue reaction arising from corrosion at the femoral neck-body junction in a dual-taper stem with a cobalt-chromium modular neck. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2013;95(10):865-872.

5. Jacobs JJ, Cooper HJ, Urban RM, Wixson RL, Della Valle CJ. What do we know about taper corrosion in total hip arthroplasty? J Arthroplasty. 2014;29(4):668-669.

6. Pastides PS, Dodd M, Sarraf KM, Willis-Owen CA. Trunnionosis: a pain in the neck. World J Orthop. 2013;4(4):161-166.

7. Shulman RM, Zywiel MG, Gandhi R, Davey JR, Salonen DC. Trunnionosis: the latest culprit in adverse reactions to metal debris following hip arthroplasty. Skeletal Radiol. 2015;44(3):433-440.

8. Mihalko WM, Wimmer MA, Pacione CA, Laurent MP, Murphy RF, Rider C. How have alternative bearings and modularity affected revision rates in total hip arthroplasty? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2014;472(12):3747-3758.

9. Kwon YM, Lombardi AV, Jacobs JJ, Fehring TK, Lewis CG, Cabanela ME. Risk stratification algorithm for management of patients with metal-on-metal hip arthroplasty: consensus statement of the American Association of Hip and Knee Surgeons, the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons, and the Hip Society. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2014;96(1):e4.

10. Bartelt RB, Yuan BJ, Trousdale RT, Sierra RJ. The prevalence of groin pain after metal-on-metal total hip arthroplasty and total hip resurfacing. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2010;468(9):2346-2356.

11. Bozic KJ, Lau EC, Ong KL, Vail TP, Rubash HE, Berry DJ. Comparative effectiveness of metal-on-metal and metal-on-polyethylene bearings in Medicare total hip arthroplasty patients. J Arthroplasty. 2012;27(8 suppl):37-40.

12. Cuckler JM. Metal-on-metal surface replacement: a triumph of hope over reason: affirms. Orthopedics. 2011;34(9):e439-e441.

13. de Steiger RN, Hang JR, Miller LN, Graves SE, Davidson DC. Five-year results of the ASR XL Acetabular System and the ASR Hip Resurfacing System: an analysis from the Australian Orthopaedic Association National Joint Replacement Registry. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2011;93(24):2287-2293.

14. Fehring TK, Odum S, Sproul R, Weathersbee J. High frequency of adverse local tissue reactions in asymptomatic patients with metal-on-metal THA. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2014;472(2):517-522.

15. Hasegawa M, Yoshida K, Wakabayashi H, Sudo A. Prevalence of adverse reactions to metal debris following metal-on-metal THA. Orthopedics. 2013;36(5):e606-e612.

16. Melvin JS, Karthikeyan T, Cope R, Fehring TK. Early failures in total hip arthroplasty—a changing paradigm. J Arthroplasty. 2014;29(6):1285-1288.

17. Wyles CC, Van Demark RE 3rd, Sierra RJ, Trousdale RT. High rate of infection after aseptic revision of failed metal-on-metal total hip arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2014;472(2):509-516.

18. Gioe TJ, Sharma A, Tatman P, Mehle S. Do “premium” joint implants add value?: Analysis of high cost joint implants in a community registry. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2011;469(1):48-54.

19. D’Antonio JA, Capello WN, Naughton M. Ceramic bearings for total hip arthroplasty have high survivorship at 10 years. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2012;470(2):373-381.

20. D’Antonio JA, Capello WN, Naughton M. High survivorship with a titanium-encased alumina ceramic bearing for total hip arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2014;472(2):611-616.

Fluoxetine fails to slow progressive multiple sclerosis

LONDON – Contrary to expectation of a neuroprotective benefit, fluoxetine does not slow down the progressive phase of multiple sclerosis, according to the results of a randomized, double-blind, multicenter trial.

The first results of the FLUOX-PMS trial, reported by Melissa Cambron, MD, of University Hospital Brussels (Belgium), showed no statistically significant difference between fluoxetine and placebo for improving the primary endpoint of the time to confirmed disease progression.

“The progressive phase of MS remains an ill-understood part of the disease and it is a holy grail to find a drug that can stop this progression,” Dr. Cambron said at the annual congress of the European Committee for Treatment and Research in Multiple Sclerosis (ECTRIMS).

The rationale for looking at whether fluoxetine, a well-studied antidepressant drug, could be such a drug, was that it had several neuroprotective features – it has been shown to stimulate the release of brain-derived neurotrophic factor, stimulate metabolism in astrocytes, and lower glutamatergic toxicity, she said. All of these could potentially help prevent axonal degeneration.

The FLUOX-PMS (Fluoxetine in Progressive Multiple Sclerosis) trial (Trials. 2014;15:37) ran from 2012 to June 2016 and enrolled patients with primary progressive MS (PPMS) or secondary progressive MS (SPMS), as defined by the 2010 McDonald criteria. A total of 137 patients were enrolled, and 69 were randomized to treatment with fluoxetine 40 mg/day and 68 were randomized to placebo. Fluoxetine treatment was started at a dose of 20 mg and titrated to the full 40-mg dose by 12 weeks.

Patient demographics were mostly similar between the groups. Around 44% of patients in the fluoxetine and placebo groups were female; roughly 40% had PPMS and 60% had SPMS in both groups; the mean Expanded Disability Status Scale score was 5.2 in both groups; the mean age was 54 and 51 years, respectively; and the disease duration was between 18 and 20 years.

Dr. Cambron also reported that the trials’ secondary endpoints showed no advantage of using fluoxetine over placebo. The proportion of patients without sustained progression during the trial was similar among the fluoxetine- and placebo-treated patients, at a respective 69.6% and 61.8% (P = .434). The proportion of patients with a stable Hauser Ambulation Index was also similar (P = .371).

The primary and secondary endpoints were assessed every 3 months in the trial. Patients also underwent cognitive testing, completed the Beck Depression Inventory-II, and Modified Fatigue Impact Scale before treatment and at 48 and 108 weeks after treatment with fluoxetine or placebo. Brain MRI was also performed at baseline and at week 108. The results of these measurements have yet to be analyzed.

Although patients in the fluoxetine group versus the placebo arm experienced more side effects, there was no evidence of an excess of severe adverse events.

“Unfortunately, our study was inconclusive because we failed to show a statistical significant difference between the placebo arm and the fluoxetine group, although I’m convinced that there’s a trend that can certainly not be ignored,” Dr. Cambron maintained. “Probably there was not enough progression in the study and possibly the study duration was too short, she suggested, “but it remains challenging to study these patients for a long period of time, especially with a placebo-controlled design.”

The trial was funded by IWT, the Government Agency for Innovation by Science and Technology in Flanders (Belgium). Dr. Cambron had no relevant financial disclosures.

LONDON – Contrary to expectation of a neuroprotective benefit, fluoxetine does not slow down the progressive phase of multiple sclerosis, according to the results of a randomized, double-blind, multicenter trial.

The first results of the FLUOX-PMS trial, reported by Melissa Cambron, MD, of University Hospital Brussels (Belgium), showed no statistically significant difference between fluoxetine and placebo for improving the primary endpoint of the time to confirmed disease progression.

“The progressive phase of MS remains an ill-understood part of the disease and it is a holy grail to find a drug that can stop this progression,” Dr. Cambron said at the annual congress of the European Committee for Treatment and Research in Multiple Sclerosis (ECTRIMS).

The rationale for looking at whether fluoxetine, a well-studied antidepressant drug, could be such a drug, was that it had several neuroprotective features – it has been shown to stimulate the release of brain-derived neurotrophic factor, stimulate metabolism in astrocytes, and lower glutamatergic toxicity, she said. All of these could potentially help prevent axonal degeneration.

The FLUOX-PMS (Fluoxetine in Progressive Multiple Sclerosis) trial (Trials. 2014;15:37) ran from 2012 to June 2016 and enrolled patients with primary progressive MS (PPMS) or secondary progressive MS (SPMS), as defined by the 2010 McDonald criteria. A total of 137 patients were enrolled, and 69 were randomized to treatment with fluoxetine 40 mg/day and 68 were randomized to placebo. Fluoxetine treatment was started at a dose of 20 mg and titrated to the full 40-mg dose by 12 weeks.

Patient demographics were mostly similar between the groups. Around 44% of patients in the fluoxetine and placebo groups were female; roughly 40% had PPMS and 60% had SPMS in both groups; the mean Expanded Disability Status Scale score was 5.2 in both groups; the mean age was 54 and 51 years, respectively; and the disease duration was between 18 and 20 years.

Dr. Cambron also reported that the trials’ secondary endpoints showed no advantage of using fluoxetine over placebo. The proportion of patients without sustained progression during the trial was similar among the fluoxetine- and placebo-treated patients, at a respective 69.6% and 61.8% (P = .434). The proportion of patients with a stable Hauser Ambulation Index was also similar (P = .371).

The primary and secondary endpoints were assessed every 3 months in the trial. Patients also underwent cognitive testing, completed the Beck Depression Inventory-II, and Modified Fatigue Impact Scale before treatment and at 48 and 108 weeks after treatment with fluoxetine or placebo. Brain MRI was also performed at baseline and at week 108. The results of these measurements have yet to be analyzed.

Although patients in the fluoxetine group versus the placebo arm experienced more side effects, there was no evidence of an excess of severe adverse events.

“Unfortunately, our study was inconclusive because we failed to show a statistical significant difference between the placebo arm and the fluoxetine group, although I’m convinced that there’s a trend that can certainly not be ignored,” Dr. Cambron maintained. “Probably there was not enough progression in the study and possibly the study duration was too short, she suggested, “but it remains challenging to study these patients for a long period of time, especially with a placebo-controlled design.”

The trial was funded by IWT, the Government Agency for Innovation by Science and Technology in Flanders (Belgium). Dr. Cambron had no relevant financial disclosures.

LONDON – Contrary to expectation of a neuroprotective benefit, fluoxetine does not slow down the progressive phase of multiple sclerosis, according to the results of a randomized, double-blind, multicenter trial.

The first results of the FLUOX-PMS trial, reported by Melissa Cambron, MD, of University Hospital Brussels (Belgium), showed no statistically significant difference between fluoxetine and placebo for improving the primary endpoint of the time to confirmed disease progression.

“The progressive phase of MS remains an ill-understood part of the disease and it is a holy grail to find a drug that can stop this progression,” Dr. Cambron said at the annual congress of the European Committee for Treatment and Research in Multiple Sclerosis (ECTRIMS).

The rationale for looking at whether fluoxetine, a well-studied antidepressant drug, could be such a drug, was that it had several neuroprotective features – it has been shown to stimulate the release of brain-derived neurotrophic factor, stimulate metabolism in astrocytes, and lower glutamatergic toxicity, she said. All of these could potentially help prevent axonal degeneration.

The FLUOX-PMS (Fluoxetine in Progressive Multiple Sclerosis) trial (Trials. 2014;15:37) ran from 2012 to June 2016 and enrolled patients with primary progressive MS (PPMS) or secondary progressive MS (SPMS), as defined by the 2010 McDonald criteria. A total of 137 patients were enrolled, and 69 were randomized to treatment with fluoxetine 40 mg/day and 68 were randomized to placebo. Fluoxetine treatment was started at a dose of 20 mg and titrated to the full 40-mg dose by 12 weeks.

Patient demographics were mostly similar between the groups. Around 44% of patients in the fluoxetine and placebo groups were female; roughly 40% had PPMS and 60% had SPMS in both groups; the mean Expanded Disability Status Scale score was 5.2 in both groups; the mean age was 54 and 51 years, respectively; and the disease duration was between 18 and 20 years.

Dr. Cambron also reported that the trials’ secondary endpoints showed no advantage of using fluoxetine over placebo. The proportion of patients without sustained progression during the trial was similar among the fluoxetine- and placebo-treated patients, at a respective 69.6% and 61.8% (P = .434). The proportion of patients with a stable Hauser Ambulation Index was also similar (P = .371).

The primary and secondary endpoints were assessed every 3 months in the trial. Patients also underwent cognitive testing, completed the Beck Depression Inventory-II, and Modified Fatigue Impact Scale before treatment and at 48 and 108 weeks after treatment with fluoxetine or placebo. Brain MRI was also performed at baseline and at week 108. The results of these measurements have yet to be analyzed.

Although patients in the fluoxetine group versus the placebo arm experienced more side effects, there was no evidence of an excess of severe adverse events.

“Unfortunately, our study was inconclusive because we failed to show a statistical significant difference between the placebo arm and the fluoxetine group, although I’m convinced that there’s a trend that can certainly not be ignored,” Dr. Cambron maintained. “Probably there was not enough progression in the study and possibly the study duration was too short, she suggested, “but it remains challenging to study these patients for a long period of time, especially with a placebo-controlled design.”

The trial was funded by IWT, the Government Agency for Innovation by Science and Technology in Flanders (Belgium). Dr. Cambron had no relevant financial disclosures.

Key clinical point:

Major finding: There was no difference in the time to confirmed disease progression between fluoxetine- and placebo-treated patients (P = .07).

Data source: FLUOX-PMS, a multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical study of 137 patients with primary or secondary progressive multiple sclerosis treated with fluoxetine or placebo.

Disclosures: The trial was funded by IWT, the Government Agency for Innovation by Science and Technology in Flanders (Belgium). Dr. Cambron had no relevant financial disclosures.

Zika virus shows no signs of slowing down

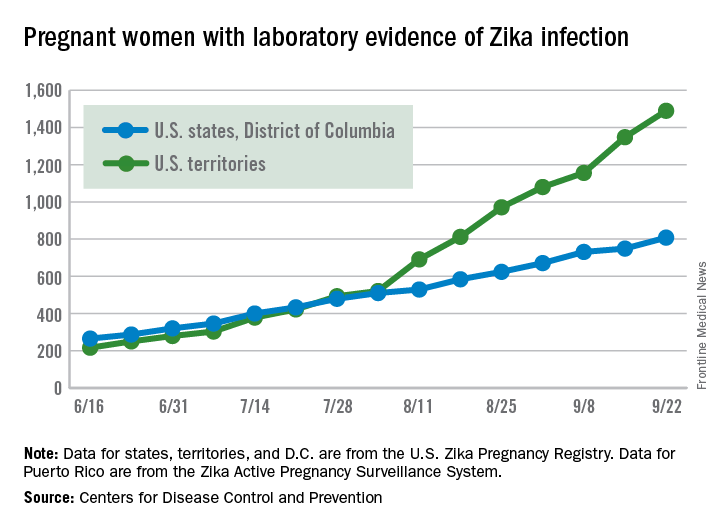

Zika virus transmission continues at a rapid clip as the number of new cases among pregnant women topped 200 again for the week ending Sept. 22, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

After setting a new high of 210 the previous week, there were 201 new cases of pregnant women with laboratory-confirmed Zika infection for the week ending Sept. 22. There were 59 new cases in the 50 states and the District of Columbia and 142 new cases in the U.S. territories, the CDC reported Sept. 29. In the United States this year, there have been 2,298 reported cases of Zika-infected pregnant women: 808 in the states and D.C. and 1,490 in the territories.

Among all Americans, there were 2,559 new cases of Zika infection as of Sept. 28 – 267 in the states/D.C. and 2,292 in the territories – although Puerto Rico continues to retroactively report cases, which has been pushing the numbers higher in recent weeks. There have been 25,694 total cases of Zika infection in 2015-2016, the CDC reported.

Zika-related birth defects reported by the CDC could include microcephaly, calcium deposits in the brain indicating possible brain damage, excess fluid in the brain cavities and surrounding the brain, absent or poorly formed brain structures, abnormal eye development, or other problems resulting from brain damage that affect nerves, muscles, and bones. The pregnancy losses encompass any miscarriage, stillbirth, and termination with evidence of birth defects.

The figures for states, territories, and D.C. reflect reporting to the U.S. Zika Pregnancy Registry; data for Puerto Rico are reported to the U.S. Zika Active Pregnancy Surveillance System.

Zika virus transmission continues at a rapid clip as the number of new cases among pregnant women topped 200 again for the week ending Sept. 22, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

After setting a new high of 210 the previous week, there were 201 new cases of pregnant women with laboratory-confirmed Zika infection for the week ending Sept. 22. There were 59 new cases in the 50 states and the District of Columbia and 142 new cases in the U.S. territories, the CDC reported Sept. 29. In the United States this year, there have been 2,298 reported cases of Zika-infected pregnant women: 808 in the states and D.C. and 1,490 in the territories.

Among all Americans, there were 2,559 new cases of Zika infection as of Sept. 28 – 267 in the states/D.C. and 2,292 in the territories – although Puerto Rico continues to retroactively report cases, which has been pushing the numbers higher in recent weeks. There have been 25,694 total cases of Zika infection in 2015-2016, the CDC reported.

Zika-related birth defects reported by the CDC could include microcephaly, calcium deposits in the brain indicating possible brain damage, excess fluid in the brain cavities and surrounding the brain, absent or poorly formed brain structures, abnormal eye development, or other problems resulting from brain damage that affect nerves, muscles, and bones. The pregnancy losses encompass any miscarriage, stillbirth, and termination with evidence of birth defects.

The figures for states, territories, and D.C. reflect reporting to the U.S. Zika Pregnancy Registry; data for Puerto Rico are reported to the U.S. Zika Active Pregnancy Surveillance System.

Zika virus transmission continues at a rapid clip as the number of new cases among pregnant women topped 200 again for the week ending Sept. 22, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

After setting a new high of 210 the previous week, there were 201 new cases of pregnant women with laboratory-confirmed Zika infection for the week ending Sept. 22. There were 59 new cases in the 50 states and the District of Columbia and 142 new cases in the U.S. territories, the CDC reported Sept. 29. In the United States this year, there have been 2,298 reported cases of Zika-infected pregnant women: 808 in the states and D.C. and 1,490 in the territories.

Among all Americans, there were 2,559 new cases of Zika infection as of Sept. 28 – 267 in the states/D.C. and 2,292 in the territories – although Puerto Rico continues to retroactively report cases, which has been pushing the numbers higher in recent weeks. There have been 25,694 total cases of Zika infection in 2015-2016, the CDC reported.

Zika-related birth defects reported by the CDC could include microcephaly, calcium deposits in the brain indicating possible brain damage, excess fluid in the brain cavities and surrounding the brain, absent or poorly formed brain structures, abnormal eye development, or other problems resulting from brain damage that affect nerves, muscles, and bones. The pregnancy losses encompass any miscarriage, stillbirth, and termination with evidence of birth defects.

The figures for states, territories, and D.C. reflect reporting to the U.S. Zika Pregnancy Registry; data for Puerto Rico are reported to the U.S. Zika Active Pregnancy Surveillance System.

Sentinel lymph node technique in endometrial cancer, Part 2

As reviewed in Part 1, surgery is indicated for the staging and treatment of endometrial cancer. Lymph node status is one of the most important factors in determining prognosis and the need for adjuvant treatment. The extent of lymph node evaluation is controversial as full lymphadenectomy carries risks, including increased operative time, blood loss, nerve injury, and lymphedema.

Two trials have found no survival benefit from lymphadenectomy for endometrial cancer; however, other evidence suggests that women without known nodal status may be more likely to receive radiotherapy.1,2,3

Given these issues, the sentinel lymph node technique strikes a balance between the risks and benefits of lymph node evaluation in endometrial cancer.

Sentinel lymph nodes (SLN) are the first nodes to drain a tumor site, and thus, are typically the first to demonstrate occult malignancy. The use of the SLN technique as an alternative to complete lymphadenectomy in endometrial cancer has been well described, although its accuracy and the validity of its use are still debated.

The viability of the SLN technique is predicated on the ability to achieve mapping of dye or tracer from the tumor to the first lymph node to drain the tumor. The lymphatic drainage of the endometrium is complex and unlike vulvar or breast cancer, endometrial cancer is less accessible for peritumoral injection. Several injection techniques have been described; cervical injection is the easiest to achieve and has been found to have similar or higher SLN detection than hysteroscopic or fundal injections.4,5

There are a number of techniques for SLN detection, each with unique benefits and risks. Visual identification of blue dye, most frequently isosulfan blue, is the “colorimetric method” and has been used most commonly with cervical injection for endometrial cancer. Injection of isosulfan blue does not require specialized equipment, however visualization in obese patients is inferior.6

Technetium sulfur colloid (Tc) is a radioactive tracer that can be detected by gamma probes. A preoperative lymphoscintigraphy and a handheld gamma probe are used to map lymphatics. This technique has limitations, including the additional time and coordination of procedures, as well as some evidence of poor correlation between lymphoscintigraphy and surgical SLN mapping.7

Indocyanine green (ICG) is a fluorescent dye that has excellent signal penetration and allows for real-time visual identification using near-infrared fluorescence imaging. The bilateral detection rate with ICG appears comparable or better than blue dye.8 Combinations of dye, either ICG plus Tc or Tc plus blue dye, may be also used to increase SLN detection.

The accuracy of the SLN technique is the cornerstone to its success. In a prospective multicenter study – Senti-Endo – patients with early-stage disease underwent pelvic SLN assessment with cervical injection of a combination of dyes followed by systematic pelvic node dissection. The overall negative predictive value was 97% with three patients who had positive lymph nodes that were not detected, all of whom had a type 2 endometrial cancer.9

With the uptake of the SLN technique, many institutions have protocols surrounding the technique to ensure appropriate SLN detection and evaluation. Physicians using this technique should adhere to protocols supported by National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines, taking care to remove any suspicious lymph nodes and perform a full side-specific lymphadenectomy if bilateral mapping is not achieved.

The extent of lymphadenectomy and application of the SLN technique in high-risk endometrial cancer remains controversial. These patients are at higher risk for unsuccessful mapping and isolated para-aortic metastasis. Retrospective series have suggested equivalent oncologic outcomes for women with high-grade cancers who have been staged by SLN biopsy, compared with selective or complete lymphadenectomy.10,11

We await the results of a large prospective trial in which patients undergo comprehensive lymphadenectomy in addition to SLN biopsy to assess the accuracy of the technique (NCT01673022).

Pathologic evaluation of SLNs is frequently done with ultrastaging, which describes additional sectioning and staining of the node. This technique frequently identifies isolated tumor cells and micrometastasis (collectively called low-volume disease) in addition to macrometastasis. The clinical and prognostic significance of low-volume disease is unknown and additional investigation is urgently needed to determine appropriate adjuvant therapy and follow-up for these patients.

The SLN technique is an acceptable approach to assess clinical stage I endometrial cancer. Physicians should consider adding the SLN biopsy to their routine staging techniques prior to exclusively adopting the new technique. They should take care to adhere to SLN algorithms and monitor outcomes.

References

1. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2008;100(23):1707-16.

2. Lancet. 2009 Jan;373(9658):125-36.

3. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2011 Dec;205(6):562.e1–9.

4. Gynecol Oncol. 2013 Nov;131(2):299-303.

5. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2013 Nov;23(9):1704-11.

6. Gynecol Oncol 2014 Aug;134(2):281-6.

7. Gynecol Oncol. 2009 Feb;112(2):348-352.

8. Gynecol Oncol. 2014 May;133(2):274-7.

9. Lancet Oncol. 2011 May;12(5):469-76.

10. Ann Surg Oncol. 2016 Jan;23(1):196-202.

11. Gynecol Oncol. 2016 Mar;140(3):394-9.

Dr. Rossi is an assistant professor in the division of gynecologic oncology at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill. Dr. Sullivan is a clinical fellow in the division of gynecologic oncology at UNC, Chapel Hill. Dr. Rossi and Dr. Sullivan reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

As reviewed in Part 1, surgery is indicated for the staging and treatment of endometrial cancer. Lymph node status is one of the most important factors in determining prognosis and the need for adjuvant treatment. The extent of lymph node evaluation is controversial as full lymphadenectomy carries risks, including increased operative time, blood loss, nerve injury, and lymphedema.

Two trials have found no survival benefit from lymphadenectomy for endometrial cancer; however, other evidence suggests that women without known nodal status may be more likely to receive radiotherapy.1,2,3

Given these issues, the sentinel lymph node technique strikes a balance between the risks and benefits of lymph node evaluation in endometrial cancer.

Sentinel lymph nodes (SLN) are the first nodes to drain a tumor site, and thus, are typically the first to demonstrate occult malignancy. The use of the SLN technique as an alternative to complete lymphadenectomy in endometrial cancer has been well described, although its accuracy and the validity of its use are still debated.

The viability of the SLN technique is predicated on the ability to achieve mapping of dye or tracer from the tumor to the first lymph node to drain the tumor. The lymphatic drainage of the endometrium is complex and unlike vulvar or breast cancer, endometrial cancer is less accessible for peritumoral injection. Several injection techniques have been described; cervical injection is the easiest to achieve and has been found to have similar or higher SLN detection than hysteroscopic or fundal injections.4,5

There are a number of techniques for SLN detection, each with unique benefits and risks. Visual identification of blue dye, most frequently isosulfan blue, is the “colorimetric method” and has been used most commonly with cervical injection for endometrial cancer. Injection of isosulfan blue does not require specialized equipment, however visualization in obese patients is inferior.6

Technetium sulfur colloid (Tc) is a radioactive tracer that can be detected by gamma probes. A preoperative lymphoscintigraphy and a handheld gamma probe are used to map lymphatics. This technique has limitations, including the additional time and coordination of procedures, as well as some evidence of poor correlation between lymphoscintigraphy and surgical SLN mapping.7

Indocyanine green (ICG) is a fluorescent dye that has excellent signal penetration and allows for real-time visual identification using near-infrared fluorescence imaging. The bilateral detection rate with ICG appears comparable or better than blue dye.8 Combinations of dye, either ICG plus Tc or Tc plus blue dye, may be also used to increase SLN detection.

The accuracy of the SLN technique is the cornerstone to its success. In a prospective multicenter study – Senti-Endo – patients with early-stage disease underwent pelvic SLN assessment with cervical injection of a combination of dyes followed by systematic pelvic node dissection. The overall negative predictive value was 97% with three patients who had positive lymph nodes that were not detected, all of whom had a type 2 endometrial cancer.9

With the uptake of the SLN technique, many institutions have protocols surrounding the technique to ensure appropriate SLN detection and evaluation. Physicians using this technique should adhere to protocols supported by National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines, taking care to remove any suspicious lymph nodes and perform a full side-specific lymphadenectomy if bilateral mapping is not achieved.

The extent of lymphadenectomy and application of the SLN technique in high-risk endometrial cancer remains controversial. These patients are at higher risk for unsuccessful mapping and isolated para-aortic metastasis. Retrospective series have suggested equivalent oncologic outcomes for women with high-grade cancers who have been staged by SLN biopsy, compared with selective or complete lymphadenectomy.10,11

We await the results of a large prospective trial in which patients undergo comprehensive lymphadenectomy in addition to SLN biopsy to assess the accuracy of the technique (NCT01673022).

Pathologic evaluation of SLNs is frequently done with ultrastaging, which describes additional sectioning and staining of the node. This technique frequently identifies isolated tumor cells and micrometastasis (collectively called low-volume disease) in addition to macrometastasis. The clinical and prognostic significance of low-volume disease is unknown and additional investigation is urgently needed to determine appropriate adjuvant therapy and follow-up for these patients.

The SLN technique is an acceptable approach to assess clinical stage I endometrial cancer. Physicians should consider adding the SLN biopsy to their routine staging techniques prior to exclusively adopting the new technique. They should take care to adhere to SLN algorithms and monitor outcomes.

References

1. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2008;100(23):1707-16.

2. Lancet. 2009 Jan;373(9658):125-36.

3. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2011 Dec;205(6):562.e1–9.

4. Gynecol Oncol. 2013 Nov;131(2):299-303.

5. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2013 Nov;23(9):1704-11.

6. Gynecol Oncol 2014 Aug;134(2):281-6.

7. Gynecol Oncol. 2009 Feb;112(2):348-352.

8. Gynecol Oncol. 2014 May;133(2):274-7.

9. Lancet Oncol. 2011 May;12(5):469-76.

10. Ann Surg Oncol. 2016 Jan;23(1):196-202.

11. Gynecol Oncol. 2016 Mar;140(3):394-9.

Dr. Rossi is an assistant professor in the division of gynecologic oncology at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill. Dr. Sullivan is a clinical fellow in the division of gynecologic oncology at UNC, Chapel Hill. Dr. Rossi and Dr. Sullivan reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

As reviewed in Part 1, surgery is indicated for the staging and treatment of endometrial cancer. Lymph node status is one of the most important factors in determining prognosis and the need for adjuvant treatment. The extent of lymph node evaluation is controversial as full lymphadenectomy carries risks, including increased operative time, blood loss, nerve injury, and lymphedema.

Two trials have found no survival benefit from lymphadenectomy for endometrial cancer; however, other evidence suggests that women without known nodal status may be more likely to receive radiotherapy.1,2,3

Given these issues, the sentinel lymph node technique strikes a balance between the risks and benefits of lymph node evaluation in endometrial cancer.

Sentinel lymph nodes (SLN) are the first nodes to drain a tumor site, and thus, are typically the first to demonstrate occult malignancy. The use of the SLN technique as an alternative to complete lymphadenectomy in endometrial cancer has been well described, although its accuracy and the validity of its use are still debated.

The viability of the SLN technique is predicated on the ability to achieve mapping of dye or tracer from the tumor to the first lymph node to drain the tumor. The lymphatic drainage of the endometrium is complex and unlike vulvar or breast cancer, endometrial cancer is less accessible for peritumoral injection. Several injection techniques have been described; cervical injection is the easiest to achieve and has been found to have similar or higher SLN detection than hysteroscopic or fundal injections.4,5

There are a number of techniques for SLN detection, each with unique benefits and risks. Visual identification of blue dye, most frequently isosulfan blue, is the “colorimetric method” and has been used most commonly with cervical injection for endometrial cancer. Injection of isosulfan blue does not require specialized equipment, however visualization in obese patients is inferior.6

Technetium sulfur colloid (Tc) is a radioactive tracer that can be detected by gamma probes. A preoperative lymphoscintigraphy and a handheld gamma probe are used to map lymphatics. This technique has limitations, including the additional time and coordination of procedures, as well as some evidence of poor correlation between lymphoscintigraphy and surgical SLN mapping.7

Indocyanine green (ICG) is a fluorescent dye that has excellent signal penetration and allows for real-time visual identification using near-infrared fluorescence imaging. The bilateral detection rate with ICG appears comparable or better than blue dye.8 Combinations of dye, either ICG plus Tc or Tc plus blue dye, may be also used to increase SLN detection.

The accuracy of the SLN technique is the cornerstone to its success. In a prospective multicenter study – Senti-Endo – patients with early-stage disease underwent pelvic SLN assessment with cervical injection of a combination of dyes followed by systematic pelvic node dissection. The overall negative predictive value was 97% with three patients who had positive lymph nodes that were not detected, all of whom had a type 2 endometrial cancer.9

With the uptake of the SLN technique, many institutions have protocols surrounding the technique to ensure appropriate SLN detection and evaluation. Physicians using this technique should adhere to protocols supported by National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines, taking care to remove any suspicious lymph nodes and perform a full side-specific lymphadenectomy if bilateral mapping is not achieved.

The extent of lymphadenectomy and application of the SLN technique in high-risk endometrial cancer remains controversial. These patients are at higher risk for unsuccessful mapping and isolated para-aortic metastasis. Retrospective series have suggested equivalent oncologic outcomes for women with high-grade cancers who have been staged by SLN biopsy, compared with selective or complete lymphadenectomy.10,11

We await the results of a large prospective trial in which patients undergo comprehensive lymphadenectomy in addition to SLN biopsy to assess the accuracy of the technique (NCT01673022).

Pathologic evaluation of SLNs is frequently done with ultrastaging, which describes additional sectioning and staining of the node. This technique frequently identifies isolated tumor cells and micrometastasis (collectively called low-volume disease) in addition to macrometastasis. The clinical and prognostic significance of low-volume disease is unknown and additional investigation is urgently needed to determine appropriate adjuvant therapy and follow-up for these patients.

The SLN technique is an acceptable approach to assess clinical stage I endometrial cancer. Physicians should consider adding the SLN biopsy to their routine staging techniques prior to exclusively adopting the new technique. They should take care to adhere to SLN algorithms and monitor outcomes.

References

1. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2008;100(23):1707-16.

2. Lancet. 2009 Jan;373(9658):125-36.

3. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2011 Dec;205(6):562.e1–9.

4. Gynecol Oncol. 2013 Nov;131(2):299-303.

5. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2013 Nov;23(9):1704-11.

6. Gynecol Oncol 2014 Aug;134(2):281-6.

7. Gynecol Oncol. 2009 Feb;112(2):348-352.

8. Gynecol Oncol. 2014 May;133(2):274-7.

9. Lancet Oncol. 2011 May;12(5):469-76.

10. Ann Surg Oncol. 2016 Jan;23(1):196-202.

11. Gynecol Oncol. 2016 Mar;140(3):394-9.

Dr. Rossi is an assistant professor in the division of gynecologic oncology at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill. Dr. Sullivan is a clinical fellow in the division of gynecologic oncology at UNC, Chapel Hill. Dr. Rossi and Dr. Sullivan reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

Well-woman care: Reshaping the routine visit

From her vantage point in medical education, Christine M. Peterson, MD, is acutely aware that well-woman care is at a turning point.

“We’re at an interesting crossroads between tradition and evidence-based practice,” said Dr. Peterson, who practiced obstetrics and gynecology in the 1980s and now serves as associate professor of ob.gyn. and assistant dean for student affairs at the University of Virginia’s School of Medicine in Charlottesville.

“Even young trainees are aware of the traditions for the annual well-woman visit – the Pap, the pelvic, the breast exam,” she said. “But the evidence is pointing us in a different direction ... toward doing only those things that are effective for prevention and early detection of disease, or that have [demonstrated] value in one way or another.”