User login

Broad-spectrum antibiotics may worsen GVHD

Broad-spectrum antibiotics may increase the severity of graft-versus-host disease (GVHD), according to research published in Science Translational Medicine.

Researchers evaluated the relationship between antibiotics and GVHD using data from more than 850 transplant patients and by conducting experiments in mice.

Their results suggested that selecting antibiotics that spare “good” bacteria may help protect patients from GVHD.

Results in patients

Yusuke Shono, MD, PhD, of Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York, New York, and his colleagues conducted this study, first mining the clinical records of 857 patients who underwent allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplant

(HSCT).

The team found that patients who received imipenem-cilastatin and piperacillin-tazobactam antibiotics to treat neutropenic fever had a higher incidence of GVHD-related mortality at 5 years than patients who did not receive these drugs.

The incidence of GVHD-related death was 21.5% in patients who received imipenem-cilastatin and 13.1% in those who did not (P=0.025). The incidence was 19.8% in patients who received piperacillin-tazobactam and 11.9% in those who did not (P=0.007).

Two other antibiotics used to treat neutropenic fever, aztreonam and cefepime, were not associated with an increased risk of GVHD-related mortality.

The incidence of GVHD-related death was 13.8% in patients who received cefepime and 14.6% in those who did not (P=0.98). The incidence was 17.5% in patients who received aztreonam and 14.2% in those who did not (P=0.78).

The researchers also found that piperacillin-tazobactam and imipenem-cilastatin were both associated with an increased incidence of grade 2-4 GVHD (P=0.0167 and P=0.0165, respectively), upper gastrointestinal GVHD (P=0.002 and P=0.045, respectively), and lower gastrointestinal GVHD (P=0.019 and P=0.036, respectively).

When the team analyzed patients’ stool samples, they found that piperacillin-tazobactam perturbed the gut microbiome, killing off protective bacteria. The therapy was associated with a greater loss of Bacteroidetes and Lactobacillus, when compared to treatment with aztreonam or cefepime.

The change in abundance of Enterococcus, Akkermansia, and Erysipelotrichia was similar with the 3 therapies. But there was a trend toward a decrease in Clostridia and Actinobacteria with piperacillin-tazobactam.

The researchers said they could not assess the effects of imipenem-cilastatin on bacterial populations because, at their center, imipenem-cilastatin is almost always given to HSCT patients as second-line therapy for neutropenic fever.

Results in mice

In mice treated with various antibiotic regimens following HSCT, those given broad-spectrum antibiotics developed more severe GVHD.

Specifically, the researchers observed aggravated GVHD mortality with imipenem-cilastatin or piperacillin-tazobactam compared to aztreonam (P<0.01 and P<0.05, respectively).

They also found evidence of increased GVHD pathology localized in the colon of mice that received imipenem-cilastatin (P<0.05). Mice with GVHD that received imipenem-cilastatin experienced loss of the protective mucus lining of the colon (P<0.01) and compromised intestinal barrier function (P<0.05).

When the researchers sequenced stool samples from mice with GVHD that received imipenem-cilastatin, they saw an increase in Akkermansia muciniphila (P<0.001), a commensal bacterium with mucus-degrading capabilities. They said this raises the possibility that mucus degradation may contribute to murine GVHD.

The researchers noted that these findings must be confirmed in clinical trials, but they caution against the use of broad-spectrum antibiotics in HSCT patients at risk of GVHD. ![]()

Broad-spectrum antibiotics may increase the severity of graft-versus-host disease (GVHD), according to research published in Science Translational Medicine.

Researchers evaluated the relationship between antibiotics and GVHD using data from more than 850 transplant patients and by conducting experiments in mice.

Their results suggested that selecting antibiotics that spare “good” bacteria may help protect patients from GVHD.

Results in patients

Yusuke Shono, MD, PhD, of Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York, New York, and his colleagues conducted this study, first mining the clinical records of 857 patients who underwent allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplant

(HSCT).

The team found that patients who received imipenem-cilastatin and piperacillin-tazobactam antibiotics to treat neutropenic fever had a higher incidence of GVHD-related mortality at 5 years than patients who did not receive these drugs.

The incidence of GVHD-related death was 21.5% in patients who received imipenem-cilastatin and 13.1% in those who did not (P=0.025). The incidence was 19.8% in patients who received piperacillin-tazobactam and 11.9% in those who did not (P=0.007).

Two other antibiotics used to treat neutropenic fever, aztreonam and cefepime, were not associated with an increased risk of GVHD-related mortality.

The incidence of GVHD-related death was 13.8% in patients who received cefepime and 14.6% in those who did not (P=0.98). The incidence was 17.5% in patients who received aztreonam and 14.2% in those who did not (P=0.78).

The researchers also found that piperacillin-tazobactam and imipenem-cilastatin were both associated with an increased incidence of grade 2-4 GVHD (P=0.0167 and P=0.0165, respectively), upper gastrointestinal GVHD (P=0.002 and P=0.045, respectively), and lower gastrointestinal GVHD (P=0.019 and P=0.036, respectively).

When the team analyzed patients’ stool samples, they found that piperacillin-tazobactam perturbed the gut microbiome, killing off protective bacteria. The therapy was associated with a greater loss of Bacteroidetes and Lactobacillus, when compared to treatment with aztreonam or cefepime.

The change in abundance of Enterococcus, Akkermansia, and Erysipelotrichia was similar with the 3 therapies. But there was a trend toward a decrease in Clostridia and Actinobacteria with piperacillin-tazobactam.

The researchers said they could not assess the effects of imipenem-cilastatin on bacterial populations because, at their center, imipenem-cilastatin is almost always given to HSCT patients as second-line therapy for neutropenic fever.

Results in mice

In mice treated with various antibiotic regimens following HSCT, those given broad-spectrum antibiotics developed more severe GVHD.

Specifically, the researchers observed aggravated GVHD mortality with imipenem-cilastatin or piperacillin-tazobactam compared to aztreonam (P<0.01 and P<0.05, respectively).

They also found evidence of increased GVHD pathology localized in the colon of mice that received imipenem-cilastatin (P<0.05). Mice with GVHD that received imipenem-cilastatin experienced loss of the protective mucus lining of the colon (P<0.01) and compromised intestinal barrier function (P<0.05).

When the researchers sequenced stool samples from mice with GVHD that received imipenem-cilastatin, they saw an increase in Akkermansia muciniphila (P<0.001), a commensal bacterium with mucus-degrading capabilities. They said this raises the possibility that mucus degradation may contribute to murine GVHD.

The researchers noted that these findings must be confirmed in clinical trials, but they caution against the use of broad-spectrum antibiotics in HSCT patients at risk of GVHD. ![]()

Broad-spectrum antibiotics may increase the severity of graft-versus-host disease (GVHD), according to research published in Science Translational Medicine.

Researchers evaluated the relationship between antibiotics and GVHD using data from more than 850 transplant patients and by conducting experiments in mice.

Their results suggested that selecting antibiotics that spare “good” bacteria may help protect patients from GVHD.

Results in patients

Yusuke Shono, MD, PhD, of Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York, New York, and his colleagues conducted this study, first mining the clinical records of 857 patients who underwent allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplant

(HSCT).

The team found that patients who received imipenem-cilastatin and piperacillin-tazobactam antibiotics to treat neutropenic fever had a higher incidence of GVHD-related mortality at 5 years than patients who did not receive these drugs.

The incidence of GVHD-related death was 21.5% in patients who received imipenem-cilastatin and 13.1% in those who did not (P=0.025). The incidence was 19.8% in patients who received piperacillin-tazobactam and 11.9% in those who did not (P=0.007).

Two other antibiotics used to treat neutropenic fever, aztreonam and cefepime, were not associated with an increased risk of GVHD-related mortality.

The incidence of GVHD-related death was 13.8% in patients who received cefepime and 14.6% in those who did not (P=0.98). The incidence was 17.5% in patients who received aztreonam and 14.2% in those who did not (P=0.78).

The researchers also found that piperacillin-tazobactam and imipenem-cilastatin were both associated with an increased incidence of grade 2-4 GVHD (P=0.0167 and P=0.0165, respectively), upper gastrointestinal GVHD (P=0.002 and P=0.045, respectively), and lower gastrointestinal GVHD (P=0.019 and P=0.036, respectively).

When the team analyzed patients’ stool samples, they found that piperacillin-tazobactam perturbed the gut microbiome, killing off protective bacteria. The therapy was associated with a greater loss of Bacteroidetes and Lactobacillus, when compared to treatment with aztreonam or cefepime.

The change in abundance of Enterococcus, Akkermansia, and Erysipelotrichia was similar with the 3 therapies. But there was a trend toward a decrease in Clostridia and Actinobacteria with piperacillin-tazobactam.

The researchers said they could not assess the effects of imipenem-cilastatin on bacterial populations because, at their center, imipenem-cilastatin is almost always given to HSCT patients as second-line therapy for neutropenic fever.

Results in mice

In mice treated with various antibiotic regimens following HSCT, those given broad-spectrum antibiotics developed more severe GVHD.

Specifically, the researchers observed aggravated GVHD mortality with imipenem-cilastatin or piperacillin-tazobactam compared to aztreonam (P<0.01 and P<0.05, respectively).

They also found evidence of increased GVHD pathology localized in the colon of mice that received imipenem-cilastatin (P<0.05). Mice with GVHD that received imipenem-cilastatin experienced loss of the protective mucus lining of the colon (P<0.01) and compromised intestinal barrier function (P<0.05).

When the researchers sequenced stool samples from mice with GVHD that received imipenem-cilastatin, they saw an increase in Akkermansia muciniphila (P<0.001), a commensal bacterium with mucus-degrading capabilities. They said this raises the possibility that mucus degradation may contribute to murine GVHD.

The researchers noted that these findings must be confirmed in clinical trials, but they caution against the use of broad-spectrum antibiotics in HSCT patients at risk of GVHD. ![]()

Prevalence, Characteristics of Physicians Prone to Malpractice Claims

Clinical question: Do claim-prone physicians account for a substantial share of all paid malpractice claims?

Background: Many studies have compared physicians who have multiple malpractice claims against them with colleagues who have few or no claims against them and have identified systemic differences in their age, sex, and specialty. However, only a few published studies have analyzed the nature of maldistribution itself.

Study design: Retrospective cohort study.

Setting: Using data from the National Practitioner Data Bank (NPDB).

Synopsis: The NPDB is a confidential data repository created by Congress in 1986. Information was obtained on all payments reported to the NPDB against physicians in the U.S. between January 1, 2005, and December 31, 2014. The study sample consisted of 66,426 paid claims against 54,099 physicians.

Physicians in four specialty groups accounted for more than half the claims: internal medicine (15%), obstetrics and gynecology (13%), general surgery (12%), and family medicine (11%). One percent of all physicians accounted for 32% of paid claims. Physicians’ risk of future paid claims increased monotonically with their number of previous paid claims. Physicians who had two paid claims had almost twice the risk of having another one (HR, 1.97; 95% CI, 1.86–2.07).

Risk also varied widely according to specialty. Compared with internal medicine physicians, neurosurgeons had approximately double the risk of recurrence (HR, 2.32; 95% CI, 1.77–3.03).

The study has some limitations. Some malpractice payments do not reach the NPDB. The study also focused on paid claims only.

Bottom line: A small group of U.S. physicians accounted for a disproportionately large share of paid malpractice claims. Several physician characteristics, most notably the number of previous claims and physician specialty, were significantly associated with recurrence of claims.

Citation: Studdert DM, Bismark MM, Mello MM, Singh H, Spittal MJ. Prevalence and characteristics of physicians prone to malpractice claims. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(4):354-362. doi:10.1056/nejmsa1506137.

Clinical question: Do claim-prone physicians account for a substantial share of all paid malpractice claims?

Background: Many studies have compared physicians who have multiple malpractice claims against them with colleagues who have few or no claims against them and have identified systemic differences in their age, sex, and specialty. However, only a few published studies have analyzed the nature of maldistribution itself.

Study design: Retrospective cohort study.

Setting: Using data from the National Practitioner Data Bank (NPDB).

Synopsis: The NPDB is a confidential data repository created by Congress in 1986. Information was obtained on all payments reported to the NPDB against physicians in the U.S. between January 1, 2005, and December 31, 2014. The study sample consisted of 66,426 paid claims against 54,099 physicians.

Physicians in four specialty groups accounted for more than half the claims: internal medicine (15%), obstetrics and gynecology (13%), general surgery (12%), and family medicine (11%). One percent of all physicians accounted for 32% of paid claims. Physicians’ risk of future paid claims increased monotonically with their number of previous paid claims. Physicians who had two paid claims had almost twice the risk of having another one (HR, 1.97; 95% CI, 1.86–2.07).

Risk also varied widely according to specialty. Compared with internal medicine physicians, neurosurgeons had approximately double the risk of recurrence (HR, 2.32; 95% CI, 1.77–3.03).

The study has some limitations. Some malpractice payments do not reach the NPDB. The study also focused on paid claims only.

Bottom line: A small group of U.S. physicians accounted for a disproportionately large share of paid malpractice claims. Several physician characteristics, most notably the number of previous claims and physician specialty, were significantly associated with recurrence of claims.

Citation: Studdert DM, Bismark MM, Mello MM, Singh H, Spittal MJ. Prevalence and characteristics of physicians prone to malpractice claims. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(4):354-362. doi:10.1056/nejmsa1506137.

Clinical question: Do claim-prone physicians account for a substantial share of all paid malpractice claims?

Background: Many studies have compared physicians who have multiple malpractice claims against them with colleagues who have few or no claims against them and have identified systemic differences in their age, sex, and specialty. However, only a few published studies have analyzed the nature of maldistribution itself.

Study design: Retrospective cohort study.

Setting: Using data from the National Practitioner Data Bank (NPDB).

Synopsis: The NPDB is a confidential data repository created by Congress in 1986. Information was obtained on all payments reported to the NPDB against physicians in the U.S. between January 1, 2005, and December 31, 2014. The study sample consisted of 66,426 paid claims against 54,099 physicians.

Physicians in four specialty groups accounted for more than half the claims: internal medicine (15%), obstetrics and gynecology (13%), general surgery (12%), and family medicine (11%). One percent of all physicians accounted for 32% of paid claims. Physicians’ risk of future paid claims increased monotonically with their number of previous paid claims. Physicians who had two paid claims had almost twice the risk of having another one (HR, 1.97; 95% CI, 1.86–2.07).

Risk also varied widely according to specialty. Compared with internal medicine physicians, neurosurgeons had approximately double the risk of recurrence (HR, 2.32; 95% CI, 1.77–3.03).

The study has some limitations. Some malpractice payments do not reach the NPDB. The study also focused on paid claims only.

Bottom line: A small group of U.S. physicians accounted for a disproportionately large share of paid malpractice claims. Several physician characteristics, most notably the number of previous claims and physician specialty, were significantly associated with recurrence of claims.

Citation: Studdert DM, Bismark MM, Mello MM, Singh H, Spittal MJ. Prevalence and characteristics of physicians prone to malpractice claims. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(4):354-362. doi:10.1056/nejmsa1506137.

Association of Frailty on One-Year Postoperative Mortality Following Major Elective Non-Cardiac Surgery

Clinical question: What is the association of preoperative frailty on one-year postoperative mortality?

Background: Frailty is an aggregate expression of susceptibility to poor outcomes owing to age and disease-related deficits that accumulate with multiple domains. Frailty in this study was defined by the Johns Hopkins Adjusted Clinical Groups (ACG) frailty-defining diagnoses indicator. It is a binary variable that uses 12 clusters of frailty-defining diagnoses.

Study design: Population-based retrospective cohort study.

Setting: All hospital and physician services funded through the public health care system in Toronto.

Synopsis: The study had 202,980 patients who underwent major elective non-cardiac surgery. Frailty-defining diagnoses were present in 6,289 patients (3.1%). Mean age for the frail population was about 77 years. Joint replacements were the most common procedures for the frail and non-frail groups. Knee replacements were more prevalent in the non-frail group. One year after surgery, 855 frail patients (13.6%) and 9,433 non-frail patients (4.8%) died (unadjusted hazard ratio [HR], 2.98; 95% CI, 2.78–3.20). When adjusted for age, sex, neighborhood income quintile, and procedure, one-year mortality risk remained significantly higher in the frail group. One-year risk of death was significantly higher in frail patients for all surgical procedures, especially with total joint arthroplasty.

The relative hazard ratio of mortality in frail versus non-frail was extremely high in the early postoperative period, most notably at postoperative day three.

One major weakness of the study is that there is no universal definition of frailty, plus the results are difficult to generalize across populations.

Bottom line: Presence of preoperative frailty-defining diagnoses is associated with increased risk for one-year postoperative mortality; the risk appears to be very high in the early postoperative period.

Citation: McIsaac D, Bryson G, van Walraven C. Association of frailty and 1-year postoperative mortality following major elective noncardiac surgery: a population-based cohort study [published online ahead of print January 20, 2016]. JAMA Surg. doi:10.1001/jamasurg.2015.5085.

Short Take

Early Discharge Associated with Longer Length of Stay

Retrospective analysis showed early discharge before noon was associated with longer length of stay, especially among emergent admissions. However, multiple metrics should be used to measure true effectiveness of an early discharge program.

Citation: Rajkomar A, Valencia V, Novelero M, Mourad M, Auerbach A. The association between discharge before noon and length of stay in medical and surgical patients [published online ahead of print December 30, 2015]. J Hosp Med. doi:10.1002/jhm.2529.

Clinical question: What is the association of preoperative frailty on one-year postoperative mortality?

Background: Frailty is an aggregate expression of susceptibility to poor outcomes owing to age and disease-related deficits that accumulate with multiple domains. Frailty in this study was defined by the Johns Hopkins Adjusted Clinical Groups (ACG) frailty-defining diagnoses indicator. It is a binary variable that uses 12 clusters of frailty-defining diagnoses.

Study design: Population-based retrospective cohort study.

Setting: All hospital and physician services funded through the public health care system in Toronto.

Synopsis: The study had 202,980 patients who underwent major elective non-cardiac surgery. Frailty-defining diagnoses were present in 6,289 patients (3.1%). Mean age for the frail population was about 77 years. Joint replacements were the most common procedures for the frail and non-frail groups. Knee replacements were more prevalent in the non-frail group. One year after surgery, 855 frail patients (13.6%) and 9,433 non-frail patients (4.8%) died (unadjusted hazard ratio [HR], 2.98; 95% CI, 2.78–3.20). When adjusted for age, sex, neighborhood income quintile, and procedure, one-year mortality risk remained significantly higher in the frail group. One-year risk of death was significantly higher in frail patients for all surgical procedures, especially with total joint arthroplasty.

The relative hazard ratio of mortality in frail versus non-frail was extremely high in the early postoperative period, most notably at postoperative day three.

One major weakness of the study is that there is no universal definition of frailty, plus the results are difficult to generalize across populations.

Bottom line: Presence of preoperative frailty-defining diagnoses is associated with increased risk for one-year postoperative mortality; the risk appears to be very high in the early postoperative period.

Citation: McIsaac D, Bryson G, van Walraven C. Association of frailty and 1-year postoperative mortality following major elective noncardiac surgery: a population-based cohort study [published online ahead of print January 20, 2016]. JAMA Surg. doi:10.1001/jamasurg.2015.5085.

Short Take

Early Discharge Associated with Longer Length of Stay

Retrospective analysis showed early discharge before noon was associated with longer length of stay, especially among emergent admissions. However, multiple metrics should be used to measure true effectiveness of an early discharge program.

Citation: Rajkomar A, Valencia V, Novelero M, Mourad M, Auerbach A. The association between discharge before noon and length of stay in medical and surgical patients [published online ahead of print December 30, 2015]. J Hosp Med. doi:10.1002/jhm.2529.

Clinical question: What is the association of preoperative frailty on one-year postoperative mortality?

Background: Frailty is an aggregate expression of susceptibility to poor outcomes owing to age and disease-related deficits that accumulate with multiple domains. Frailty in this study was defined by the Johns Hopkins Adjusted Clinical Groups (ACG) frailty-defining diagnoses indicator. It is a binary variable that uses 12 clusters of frailty-defining diagnoses.

Study design: Population-based retrospective cohort study.

Setting: All hospital and physician services funded through the public health care system in Toronto.

Synopsis: The study had 202,980 patients who underwent major elective non-cardiac surgery. Frailty-defining diagnoses were present in 6,289 patients (3.1%). Mean age for the frail population was about 77 years. Joint replacements were the most common procedures for the frail and non-frail groups. Knee replacements were more prevalent in the non-frail group. One year after surgery, 855 frail patients (13.6%) and 9,433 non-frail patients (4.8%) died (unadjusted hazard ratio [HR], 2.98; 95% CI, 2.78–3.20). When adjusted for age, sex, neighborhood income quintile, and procedure, one-year mortality risk remained significantly higher in the frail group. One-year risk of death was significantly higher in frail patients for all surgical procedures, especially with total joint arthroplasty.

The relative hazard ratio of mortality in frail versus non-frail was extremely high in the early postoperative period, most notably at postoperative day three.

One major weakness of the study is that there is no universal definition of frailty, plus the results are difficult to generalize across populations.

Bottom line: Presence of preoperative frailty-defining diagnoses is associated with increased risk for one-year postoperative mortality; the risk appears to be very high in the early postoperative period.

Citation: McIsaac D, Bryson G, van Walraven C. Association of frailty and 1-year postoperative mortality following major elective noncardiac surgery: a population-based cohort study [published online ahead of print January 20, 2016]. JAMA Surg. doi:10.1001/jamasurg.2015.5085.

Short Take

Early Discharge Associated with Longer Length of Stay

Retrospective analysis showed early discharge before noon was associated with longer length of stay, especially among emergent admissions. However, multiple metrics should be used to measure true effectiveness of an early discharge program.

Citation: Rajkomar A, Valencia V, Novelero M, Mourad M, Auerbach A. The association between discharge before noon and length of stay in medical and surgical patients [published online ahead of print December 30, 2015]. J Hosp Med. doi:10.1002/jhm.2529.

Method could make injectable drugs safer

Photo by Bill Branson

A new drug-making technique could reduce the risk of hemolysis, thrombosis, and other serious side effects that can occur with injectable drugs, according to researchers.

The team used the technique to remove potentially harmful additives—surfactants—from 12 common injectable drugs.

Jonathan F. Lovell, PhD, of University at Buffalo in New York, and his colleagues described the technique in Nature Communications.

Pharmaceutical companies use surfactants to dissolve a medicine into a liquid solution, making it suitable for injection. Unfortunately, solutions loaded with surfactants and other nonessential ingredients may increase the risk of thrombosis, hemolysis, anaphylactic shock, and other side effects.

Researchers have tried to address this problem in two ways, each with varying degrees of success.

Some have taken the “top-down” approach, in which they shrink drug particles to nanoscale sizes to eliminate excess additives. While promising, the method doesn’t work well with injectable medicine because the drug particles are still too large to safely inject.

Other researchers have worked from the “bottom up,” using nanotechnology to build new drugs from scratch. This can yield the desired results, but developing new drug formulations takes years, and drugs are coupled with new additives that can produce new side effects.

The technique described in Nature Communications differs from both of these approaches.

Dr Lovell and his colleagues dissolved 12 drugs—vitamin K1, cyclosporine, cabazitaxel, and others—one at a time into a surfactant called Pluronic. Then, by lowering the solution’s temperature to 4° C, they were able to remove the excess Pluronic via a membrane.

The end result was drugs that contain 100 to 1000 times less excess additives.

“For the drugs we looked at, this is as close as anyone has gotten to introducing pure, injectable medicine into the body,” Dr Lovell said. “Essentially, it’s a new way to package drugs.”

The findings are significant, he said, because they show that many injectable drug formulations may be improved through an easy-to-adopt process. He and his colleagues are now working to refine the method further. ![]()

Photo by Bill Branson

A new drug-making technique could reduce the risk of hemolysis, thrombosis, and other serious side effects that can occur with injectable drugs, according to researchers.

The team used the technique to remove potentially harmful additives—surfactants—from 12 common injectable drugs.

Jonathan F. Lovell, PhD, of University at Buffalo in New York, and his colleagues described the technique in Nature Communications.

Pharmaceutical companies use surfactants to dissolve a medicine into a liquid solution, making it suitable for injection. Unfortunately, solutions loaded with surfactants and other nonessential ingredients may increase the risk of thrombosis, hemolysis, anaphylactic shock, and other side effects.

Researchers have tried to address this problem in two ways, each with varying degrees of success.

Some have taken the “top-down” approach, in which they shrink drug particles to nanoscale sizes to eliminate excess additives. While promising, the method doesn’t work well with injectable medicine because the drug particles are still too large to safely inject.

Other researchers have worked from the “bottom up,” using nanotechnology to build new drugs from scratch. This can yield the desired results, but developing new drug formulations takes years, and drugs are coupled with new additives that can produce new side effects.

The technique described in Nature Communications differs from both of these approaches.

Dr Lovell and his colleagues dissolved 12 drugs—vitamin K1, cyclosporine, cabazitaxel, and others—one at a time into a surfactant called Pluronic. Then, by lowering the solution’s temperature to 4° C, they were able to remove the excess Pluronic via a membrane.

The end result was drugs that contain 100 to 1000 times less excess additives.

“For the drugs we looked at, this is as close as anyone has gotten to introducing pure, injectable medicine into the body,” Dr Lovell said. “Essentially, it’s a new way to package drugs.”

The findings are significant, he said, because they show that many injectable drug formulations may be improved through an easy-to-adopt process. He and his colleagues are now working to refine the method further. ![]()

Photo by Bill Branson

A new drug-making technique could reduce the risk of hemolysis, thrombosis, and other serious side effects that can occur with injectable drugs, according to researchers.

The team used the technique to remove potentially harmful additives—surfactants—from 12 common injectable drugs.

Jonathan F. Lovell, PhD, of University at Buffalo in New York, and his colleagues described the technique in Nature Communications.

Pharmaceutical companies use surfactants to dissolve a medicine into a liquid solution, making it suitable for injection. Unfortunately, solutions loaded with surfactants and other nonessential ingredients may increase the risk of thrombosis, hemolysis, anaphylactic shock, and other side effects.

Researchers have tried to address this problem in two ways, each with varying degrees of success.

Some have taken the “top-down” approach, in which they shrink drug particles to nanoscale sizes to eliminate excess additives. While promising, the method doesn’t work well with injectable medicine because the drug particles are still too large to safely inject.

Other researchers have worked from the “bottom up,” using nanotechnology to build new drugs from scratch. This can yield the desired results, but developing new drug formulations takes years, and drugs are coupled with new additives that can produce new side effects.

The technique described in Nature Communications differs from both of these approaches.

Dr Lovell and his colleagues dissolved 12 drugs—vitamin K1, cyclosporine, cabazitaxel, and others—one at a time into a surfactant called Pluronic. Then, by lowering the solution’s temperature to 4° C, they were able to remove the excess Pluronic via a membrane.

The end result was drugs that contain 100 to 1000 times less excess additives.

“For the drugs we looked at, this is as close as anyone has gotten to introducing pure, injectable medicine into the body,” Dr Lovell said. “Essentially, it’s a new way to package drugs.”

The findings are significant, he said, because they show that many injectable drug formulations may be improved through an easy-to-adopt process. He and his colleagues are now working to refine the method further. ![]()

Mutation in mice may have affected research results

Researchers say they have discovered a mutation in a subline of C57BL/6 mice that could compromise results from previous studies.

“We found an unexpected mutation with potentially important consequences in strains of mice that had been separately engineered in labs in California and Japan,” said Shiv Pillai, MD, PhD, of The Ragon Institute of MGH, MIT and Harvard in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

“[W]e traced the problem to a subline of B6 mice from one specific company that have been sold in Asia, North America, Europe, and Israel. We have notified this company—Harlan Laboratories, which is now part of Envigo—of our findings, and they have been very responsive and will use approaches we have provided to check all of their colonies.”

Dr Pillai and his colleagues described their discovery of the mutation in Cell Reports.

The team noted that, in immunological studies, mutant mice are backcrossed for many generations into B6 mice so that all genes other than the mutant gene are derived from the B6 strain. This allows the comparison of data from laboratories in different parts of the world and simplifies creating mice with mutations in several genes.

A 2009 study out of Dr Pillai’s lab showed that 2 strains of mice engineered to lack the Siae or Cmah genes—both of which code for enzymes involved with sialic acid proteins—also had significant defects in the development of B cells, which were assumed to be the result of the knockout genes.

However, when Siae-deficient mice were further backcrossed with a different group of C57BL/6 mice, the result was a strain of Siae-knockout mice that did not have the B-cell development defects. A newly engineered strain of mice with a different Siae mutation also had normal B-cell development.

Detailed genetic sequencing of the first knockout line revealed a previously unsuspected mutation in a gene called Dock2, located on a chromosome 11, instead of chromosome 9 where Siae is located.

The same mutation was previously reported in 2 colonies of a different knockout mouse developed in Japan.

Dr Pillai’s team also found the Dock2 mutation in a completely different group of mice from the University of California, San Diego—where their Siae-mutant strain had been developed—and realized that 3 different engineered strains with the same unwanted mutation had probably acquired it from a common source. The team eventually traced it back to a subline of C57BL/6 mice from Harlan/Envigo.

Since most research papers using C57BL/6 mice or other such “background” strains do not indicate the specific subline, the researchers said they have no way of knowing how many studies might be affected by their findings.

But they hope the publication of these results will alert other research teams to the potential need to review their results.

“While embryonic stem cells from C57BL/6 mice have recently become available, which allows the generation of knockout strains with less backcrossing, B6 mice are used for many different kinds of experiments, including as controls,” Dr Pillai said.

“Researchers who have used them need to re-genotype the mice to look for the Dock2 mutation and, if they find it, check to see whether their results are preserved if the Dock2 mutation is bred out.” ![]()

Researchers say they have discovered a mutation in a subline of C57BL/6 mice that could compromise results from previous studies.

“We found an unexpected mutation with potentially important consequences in strains of mice that had been separately engineered in labs in California and Japan,” said Shiv Pillai, MD, PhD, of The Ragon Institute of MGH, MIT and Harvard in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

“[W]e traced the problem to a subline of B6 mice from one specific company that have been sold in Asia, North America, Europe, and Israel. We have notified this company—Harlan Laboratories, which is now part of Envigo—of our findings, and they have been very responsive and will use approaches we have provided to check all of their colonies.”

Dr Pillai and his colleagues described their discovery of the mutation in Cell Reports.

The team noted that, in immunological studies, mutant mice are backcrossed for many generations into B6 mice so that all genes other than the mutant gene are derived from the B6 strain. This allows the comparison of data from laboratories in different parts of the world and simplifies creating mice with mutations in several genes.

A 2009 study out of Dr Pillai’s lab showed that 2 strains of mice engineered to lack the Siae or Cmah genes—both of which code for enzymes involved with sialic acid proteins—also had significant defects in the development of B cells, which were assumed to be the result of the knockout genes.

However, when Siae-deficient mice were further backcrossed with a different group of C57BL/6 mice, the result was a strain of Siae-knockout mice that did not have the B-cell development defects. A newly engineered strain of mice with a different Siae mutation also had normal B-cell development.

Detailed genetic sequencing of the first knockout line revealed a previously unsuspected mutation in a gene called Dock2, located on a chromosome 11, instead of chromosome 9 where Siae is located.

The same mutation was previously reported in 2 colonies of a different knockout mouse developed in Japan.

Dr Pillai’s team also found the Dock2 mutation in a completely different group of mice from the University of California, San Diego—where their Siae-mutant strain had been developed—and realized that 3 different engineered strains with the same unwanted mutation had probably acquired it from a common source. The team eventually traced it back to a subline of C57BL/6 mice from Harlan/Envigo.

Since most research papers using C57BL/6 mice or other such “background” strains do not indicate the specific subline, the researchers said they have no way of knowing how many studies might be affected by their findings.

But they hope the publication of these results will alert other research teams to the potential need to review their results.

“While embryonic stem cells from C57BL/6 mice have recently become available, which allows the generation of knockout strains with less backcrossing, B6 mice are used for many different kinds of experiments, including as controls,” Dr Pillai said.

“Researchers who have used them need to re-genotype the mice to look for the Dock2 mutation and, if they find it, check to see whether their results are preserved if the Dock2 mutation is bred out.” ![]()

Researchers say they have discovered a mutation in a subline of C57BL/6 mice that could compromise results from previous studies.

“We found an unexpected mutation with potentially important consequences in strains of mice that had been separately engineered in labs in California and Japan,” said Shiv Pillai, MD, PhD, of The Ragon Institute of MGH, MIT and Harvard in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

“[W]e traced the problem to a subline of B6 mice from one specific company that have been sold in Asia, North America, Europe, and Israel. We have notified this company—Harlan Laboratories, which is now part of Envigo—of our findings, and they have been very responsive and will use approaches we have provided to check all of their colonies.”

Dr Pillai and his colleagues described their discovery of the mutation in Cell Reports.

The team noted that, in immunological studies, mutant mice are backcrossed for many generations into B6 mice so that all genes other than the mutant gene are derived from the B6 strain. This allows the comparison of data from laboratories in different parts of the world and simplifies creating mice with mutations in several genes.

A 2009 study out of Dr Pillai’s lab showed that 2 strains of mice engineered to lack the Siae or Cmah genes—both of which code for enzymes involved with sialic acid proteins—also had significant defects in the development of B cells, which were assumed to be the result of the knockout genes.

However, when Siae-deficient mice were further backcrossed with a different group of C57BL/6 mice, the result was a strain of Siae-knockout mice that did not have the B-cell development defects. A newly engineered strain of mice with a different Siae mutation also had normal B-cell development.

Detailed genetic sequencing of the first knockout line revealed a previously unsuspected mutation in a gene called Dock2, located on a chromosome 11, instead of chromosome 9 where Siae is located.

The same mutation was previously reported in 2 colonies of a different knockout mouse developed in Japan.

Dr Pillai’s team also found the Dock2 mutation in a completely different group of mice from the University of California, San Diego—where their Siae-mutant strain had been developed—and realized that 3 different engineered strains with the same unwanted mutation had probably acquired it from a common source. The team eventually traced it back to a subline of C57BL/6 mice from Harlan/Envigo.

Since most research papers using C57BL/6 mice or other such “background” strains do not indicate the specific subline, the researchers said they have no way of knowing how many studies might be affected by their findings.

But they hope the publication of these results will alert other research teams to the potential need to review their results.

“While embryonic stem cells from C57BL/6 mice have recently become available, which allows the generation of knockout strains with less backcrossing, B6 mice are used for many different kinds of experiments, including as controls,” Dr Pillai said.

“Researchers who have used them need to re-genotype the mice to look for the Dock2 mutation and, if they find it, check to see whether their results are preserved if the Dock2 mutation is bred out.” ![]()

Breast cancer drug could treat AML

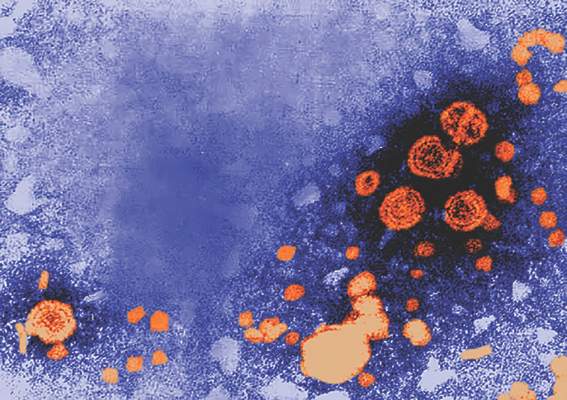

(below) palbociclib treatment

Images courtesy of Iris Uras

and Vetmeduni Vienna

Palbociclib, a CDK4/6 kinase inhibitor approved to treat breast cancer, could also be used to treat acute myeloid leukemia (AML), according to research published in Blood.

The drug induced apoptosis in FLT3-mutant AML cells and inhibited tumor growth in mouse models of FLT3-ITD+ AML.

Palbociclib also demonstrated synergy with a range of FLT3 inhibitors.

The researchers said these results can be explained by the fact that CDK6 is “absolutely required” for the viability of FLT3-dependent leukemic cells and FLT3-ITD-induced leukemogenesis.

“We found a novel therapeutic window that attacks the dependency of a cancer cell on its growth regulator,” said study author Iris Uras, PhD, of Vetmeduni Vienna in Austria.

Dr Uras and her colleagues first found that palbociclib acts specifically on FLT3-ITD+ AML cells, inhibiting their viability in a dose-dependent manner. Palbociclib induced cell-cycle arrest and apoptosis in these cells.

Palbociclib also arrested tumor growth in mouse models of FLT3-ITD+ AML, significantly decreasing tumor size when compared to untreated controls (P<0.05).

Further investigation revealed that CDK6—but not CDK4—directly regulates FLT3 expression.

CDK6 acts as a transcriptional regulator of FLT3 and the serine threonine kinase PIM1, which also plays a role in leukemogenesis. As palbociclib inhibits CDK6, it downregulates FLT3 and reduces PIM1 transcription.

To build upon these findings, the researchers tested palbociclib in combination with FLT3 inhibitors.

They observed “pronounced in vitro synergy” between palbociclib and TCS-359, tandutinib, and quizartinib in FLT3-ITD+ AML cell lines and samples from patients with FLT3-ITD+ AML.

“We are attacking FLT3 from two sides there—blocking its expression and inhibiting its activity,” Dr Uras said. “A combination therapy could be a breakthrough for many patients suffering from leukemia.” ![]()

(below) palbociclib treatment

Images courtesy of Iris Uras

and Vetmeduni Vienna

Palbociclib, a CDK4/6 kinase inhibitor approved to treat breast cancer, could also be used to treat acute myeloid leukemia (AML), according to research published in Blood.

The drug induced apoptosis in FLT3-mutant AML cells and inhibited tumor growth in mouse models of FLT3-ITD+ AML.

Palbociclib also demonstrated synergy with a range of FLT3 inhibitors.

The researchers said these results can be explained by the fact that CDK6 is “absolutely required” for the viability of FLT3-dependent leukemic cells and FLT3-ITD-induced leukemogenesis.

“We found a novel therapeutic window that attacks the dependency of a cancer cell on its growth regulator,” said study author Iris Uras, PhD, of Vetmeduni Vienna in Austria.

Dr Uras and her colleagues first found that palbociclib acts specifically on FLT3-ITD+ AML cells, inhibiting their viability in a dose-dependent manner. Palbociclib induced cell-cycle arrest and apoptosis in these cells.

Palbociclib also arrested tumor growth in mouse models of FLT3-ITD+ AML, significantly decreasing tumor size when compared to untreated controls (P<0.05).

Further investigation revealed that CDK6—but not CDK4—directly regulates FLT3 expression.

CDK6 acts as a transcriptional regulator of FLT3 and the serine threonine kinase PIM1, which also plays a role in leukemogenesis. As palbociclib inhibits CDK6, it downregulates FLT3 and reduces PIM1 transcription.

To build upon these findings, the researchers tested palbociclib in combination with FLT3 inhibitors.

They observed “pronounced in vitro synergy” between palbociclib and TCS-359, tandutinib, and quizartinib in FLT3-ITD+ AML cell lines and samples from patients with FLT3-ITD+ AML.

“We are attacking FLT3 from two sides there—blocking its expression and inhibiting its activity,” Dr Uras said. “A combination therapy could be a breakthrough for many patients suffering from leukemia.” ![]()

(below) palbociclib treatment

Images courtesy of Iris Uras

and Vetmeduni Vienna

Palbociclib, a CDK4/6 kinase inhibitor approved to treat breast cancer, could also be used to treat acute myeloid leukemia (AML), according to research published in Blood.

The drug induced apoptosis in FLT3-mutant AML cells and inhibited tumor growth in mouse models of FLT3-ITD+ AML.

Palbociclib also demonstrated synergy with a range of FLT3 inhibitors.

The researchers said these results can be explained by the fact that CDK6 is “absolutely required” for the viability of FLT3-dependent leukemic cells and FLT3-ITD-induced leukemogenesis.

“We found a novel therapeutic window that attacks the dependency of a cancer cell on its growth regulator,” said study author Iris Uras, PhD, of Vetmeduni Vienna in Austria.

Dr Uras and her colleagues first found that palbociclib acts specifically on FLT3-ITD+ AML cells, inhibiting their viability in a dose-dependent manner. Palbociclib induced cell-cycle arrest and apoptosis in these cells.

Palbociclib also arrested tumor growth in mouse models of FLT3-ITD+ AML, significantly decreasing tumor size when compared to untreated controls (P<0.05).

Further investigation revealed that CDK6—but not CDK4—directly regulates FLT3 expression.

CDK6 acts as a transcriptional regulator of FLT3 and the serine threonine kinase PIM1, which also plays a role in leukemogenesis. As palbociclib inhibits CDK6, it downregulates FLT3 and reduces PIM1 transcription.

To build upon these findings, the researchers tested palbociclib in combination with FLT3 inhibitors.

They observed “pronounced in vitro synergy” between palbociclib and TCS-359, tandutinib, and quizartinib in FLT3-ITD+ AML cell lines and samples from patients with FLT3-ITD+ AML.

“We are attacking FLT3 from two sides there—blocking its expression and inhibiting its activity,” Dr Uras said. “A combination therapy could be a breakthrough for many patients suffering from leukemia.” ![]()

FDA: No oral ketoconazole for skin, nail fungus

The Food and Drug Administration is warning health care professionals not to prescribe oral ketoconazole for patients with fungal infections of the skin and nails, because of "the risks of serious liver damage, adrenal gland problems, and harmful interactions with other medicines that outweigh its benefit in treating these conditions."

The advisory, issued on May 19, points out that oral ketoconazole (Nizoral) is no longer approved for treating nail or skin fungal infections. Topical forms of ketoconazole have not been associated with liver damage, adrenal problems, or drug interactions, the advisory adds.

"Health care professionals should use ketoconazole tablets only to treat serious fungal infections when no other antifungal therapies are available," according to the FDA. "Skin and nail fungal infections in otherwise healthy persons are not life-threatening, and so the risks associated with oral ketoconazole outweigh the benefits. Other treatment options are available over-the-counter and by prescription, but are also associated with risks that should be weighed against their benefits."

The advisory updates one issued in July 2013 when the drug's label was changed to reflect these safety concerns, including dropping the nail and skin infections from the approved indications. Since then, the FDA has received one report of a patient who died of liver failure associated with oral ketoconazole used to treat nail fungus. Furthermore, a survey of office-based physicians found that in the 18 months ending in June 2015, "skin and nail fungal infections were the only diagnoses cited for the use of oral ketoconazole."

Serious adverse events associated with oral ketoconazole should be reported to the FDA's MedWatch program online or call 800-332-1088.

The Food and Drug Administration is warning health care professionals not to prescribe oral ketoconazole for patients with fungal infections of the skin and nails, because of "the risks of serious liver damage, adrenal gland problems, and harmful interactions with other medicines that outweigh its benefit in treating these conditions."

The advisory, issued on May 19, points out that oral ketoconazole (Nizoral) is no longer approved for treating nail or skin fungal infections. Topical forms of ketoconazole have not been associated with liver damage, adrenal problems, or drug interactions, the advisory adds.

"Health care professionals should use ketoconazole tablets only to treat serious fungal infections when no other antifungal therapies are available," according to the FDA. "Skin and nail fungal infections in otherwise healthy persons are not life-threatening, and so the risks associated with oral ketoconazole outweigh the benefits. Other treatment options are available over-the-counter and by prescription, but are also associated with risks that should be weighed against their benefits."

The advisory updates one issued in July 2013 when the drug's label was changed to reflect these safety concerns, including dropping the nail and skin infections from the approved indications. Since then, the FDA has received one report of a patient who died of liver failure associated with oral ketoconazole used to treat nail fungus. Furthermore, a survey of office-based physicians found that in the 18 months ending in June 2015, "skin and nail fungal infections were the only diagnoses cited for the use of oral ketoconazole."

Serious adverse events associated with oral ketoconazole should be reported to the FDA's MedWatch program online or call 800-332-1088.

The Food and Drug Administration is warning health care professionals not to prescribe oral ketoconazole for patients with fungal infections of the skin and nails, because of "the risks of serious liver damage, adrenal gland problems, and harmful interactions with other medicines that outweigh its benefit in treating these conditions."

The advisory, issued on May 19, points out that oral ketoconazole (Nizoral) is no longer approved for treating nail or skin fungal infections. Topical forms of ketoconazole have not been associated with liver damage, adrenal problems, or drug interactions, the advisory adds.

"Health care professionals should use ketoconazole tablets only to treat serious fungal infections when no other antifungal therapies are available," according to the FDA. "Skin and nail fungal infections in otherwise healthy persons are not life-threatening, and so the risks associated with oral ketoconazole outweigh the benefits. Other treatment options are available over-the-counter and by prescription, but are also associated with risks that should be weighed against their benefits."

The advisory updates one issued in July 2013 when the drug's label was changed to reflect these safety concerns, including dropping the nail and skin infections from the approved indications. Since then, the FDA has received one report of a patient who died of liver failure associated with oral ketoconazole used to treat nail fungus. Furthermore, a survey of office-based physicians found that in the 18 months ending in June 2015, "skin and nail fungal infections were the only diagnoses cited for the use of oral ketoconazole."

Serious adverse events associated with oral ketoconazole should be reported to the FDA's MedWatch program online or call 800-332-1088.

Hepatitis A and B combo vaccinations remain effective after 15 years

Young adults who received a combined hepatitis A and B vaccination at age 12-15 years maintained immunity after 15 years, making a booster shot unnecessary, according to Dr. Jiri Beran of the Vaccination and Travel Medicine Centre, Hradec Kralove, Czech Republic, and associates.

Study participants received either a 2-dose adult formulation or a 3-dose pediatric formulation. Of the 162 participants included in the 15-year follow-up, all were seropositive for anti–hepatitis A vaccine antibodies, 81.1% of those who received the two-dose vaccination had anti–hepatitis B antibodies, and 81.8% of those who received the three-dose vaccination had anti–hepatitis B antibodies.

In a subsequent hepatitis B vaccine challenge, all of 8 participants who received the two-dose vaccination and 10 of 11 participants who received the three-dose vaccination developed an anamnastic response. No side effects inconsistent with previous experience were observed.

“The present study confirms that the combined hepatitis A and B vaccine is equally immunogenic and safe in adolescents when administered as the standard three-dose pediatric regimen or as two doses of the adult strength vacciwne,” the investigators said.

Find the full study in Vaccine (doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2016.04.033).

Young adults who received a combined hepatitis A and B vaccination at age 12-15 years maintained immunity after 15 years, making a booster shot unnecessary, according to Dr. Jiri Beran of the Vaccination and Travel Medicine Centre, Hradec Kralove, Czech Republic, and associates.

Study participants received either a 2-dose adult formulation or a 3-dose pediatric formulation. Of the 162 participants included in the 15-year follow-up, all were seropositive for anti–hepatitis A vaccine antibodies, 81.1% of those who received the two-dose vaccination had anti–hepatitis B antibodies, and 81.8% of those who received the three-dose vaccination had anti–hepatitis B antibodies.

In a subsequent hepatitis B vaccine challenge, all of 8 participants who received the two-dose vaccination and 10 of 11 participants who received the three-dose vaccination developed an anamnastic response. No side effects inconsistent with previous experience were observed.

“The present study confirms that the combined hepatitis A and B vaccine is equally immunogenic and safe in adolescents when administered as the standard three-dose pediatric regimen or as two doses of the adult strength vacciwne,” the investigators said.

Find the full study in Vaccine (doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2016.04.033).

Young adults who received a combined hepatitis A and B vaccination at age 12-15 years maintained immunity after 15 years, making a booster shot unnecessary, according to Dr. Jiri Beran of the Vaccination and Travel Medicine Centre, Hradec Kralove, Czech Republic, and associates.

Study participants received either a 2-dose adult formulation or a 3-dose pediatric formulation. Of the 162 participants included in the 15-year follow-up, all were seropositive for anti–hepatitis A vaccine antibodies, 81.1% of those who received the two-dose vaccination had anti–hepatitis B antibodies, and 81.8% of those who received the three-dose vaccination had anti–hepatitis B antibodies.

In a subsequent hepatitis B vaccine challenge, all of 8 participants who received the two-dose vaccination and 10 of 11 participants who received the three-dose vaccination developed an anamnastic response. No side effects inconsistent with previous experience were observed.

“The present study confirms that the combined hepatitis A and B vaccine is equally immunogenic and safe in adolescents when administered as the standard three-dose pediatric regimen or as two doses of the adult strength vacciwne,” the investigators said.

Find the full study in Vaccine (doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2016.04.033).

FROM VACCINE

Hepatitis B vaccine in infancy provides long-term protection into adolescence

Pediatric doses of hepatitis B vaccine can provide long-term protection against hepatitis B up to 15-16 years, and also can produce strong immune memory, according to Dr. Olivier Van Der Meeren of GlaxoSmithKline Vaccines, Wavre, Belgium, and his associates.

The researchers looked at 303 healthy adolescents who had received three doses of monovalent pediatric hepatitis B vaccine (containing 10 mcg hepatitis B surface antigen, HBsAg) in infancy. Of the 293 patients analyzed, 71% were seropositive (anti-HBs antibodies greater than or equal to 6.2 mIU/mL) before the challenge dose and 65% remained seroprotected (anti-HBs antibodies greater than or equal to 10 mIU/mL) after challenge. One month after the challenge dose, the percentage of seroprotected subjects increased to 99%, and 91% of those patients had anti-HBs antibody concentrations greater than or equal to 100 mIU/mL.

The study also looked at safety and reactogenicity. The researchers stated that it was well tolerated, with pain and fatigue the most frequently reported adverse effects.

“Despite declining levels of circulating anti-HBs antibodies, the vast majority of subjects in our study were able to mount a rapid and robust anamnestic response after a challenge dose (more than 150-fold increase in GMC [geometric mean concentration]) regardless of their pre-challenge serostatus,” the researchers concluded. “This confirms that maintaining anti-HBs antibody concentrations greater than 10 mIU/mL may not be essential for protection against clinically significant breakthrough hepatitis B infection.”

Find the study in Vaccine (doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2016.04.013).

Pediatric doses of hepatitis B vaccine can provide long-term protection against hepatitis B up to 15-16 years, and also can produce strong immune memory, according to Dr. Olivier Van Der Meeren of GlaxoSmithKline Vaccines, Wavre, Belgium, and his associates.

The researchers looked at 303 healthy adolescents who had received three doses of monovalent pediatric hepatitis B vaccine (containing 10 mcg hepatitis B surface antigen, HBsAg) in infancy. Of the 293 patients analyzed, 71% were seropositive (anti-HBs antibodies greater than or equal to 6.2 mIU/mL) before the challenge dose and 65% remained seroprotected (anti-HBs antibodies greater than or equal to 10 mIU/mL) after challenge. One month after the challenge dose, the percentage of seroprotected subjects increased to 99%, and 91% of those patients had anti-HBs antibody concentrations greater than or equal to 100 mIU/mL.

The study also looked at safety and reactogenicity. The researchers stated that it was well tolerated, with pain and fatigue the most frequently reported adverse effects.

“Despite declining levels of circulating anti-HBs antibodies, the vast majority of subjects in our study were able to mount a rapid and robust anamnestic response after a challenge dose (more than 150-fold increase in GMC [geometric mean concentration]) regardless of their pre-challenge serostatus,” the researchers concluded. “This confirms that maintaining anti-HBs antibody concentrations greater than 10 mIU/mL may not be essential for protection against clinically significant breakthrough hepatitis B infection.”

Find the study in Vaccine (doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2016.04.013).

Pediatric doses of hepatitis B vaccine can provide long-term protection against hepatitis B up to 15-16 years, and also can produce strong immune memory, according to Dr. Olivier Van Der Meeren of GlaxoSmithKline Vaccines, Wavre, Belgium, and his associates.

The researchers looked at 303 healthy adolescents who had received three doses of monovalent pediatric hepatitis B vaccine (containing 10 mcg hepatitis B surface antigen, HBsAg) in infancy. Of the 293 patients analyzed, 71% were seropositive (anti-HBs antibodies greater than or equal to 6.2 mIU/mL) before the challenge dose and 65% remained seroprotected (anti-HBs antibodies greater than or equal to 10 mIU/mL) after challenge. One month after the challenge dose, the percentage of seroprotected subjects increased to 99%, and 91% of those patients had anti-HBs antibody concentrations greater than or equal to 100 mIU/mL.

The study also looked at safety and reactogenicity. The researchers stated that it was well tolerated, with pain and fatigue the most frequently reported adverse effects.

“Despite declining levels of circulating anti-HBs antibodies, the vast majority of subjects in our study were able to mount a rapid and robust anamnestic response after a challenge dose (more than 150-fold increase in GMC [geometric mean concentration]) regardless of their pre-challenge serostatus,” the researchers concluded. “This confirms that maintaining anti-HBs antibody concentrations greater than 10 mIU/mL may not be essential for protection against clinically significant breakthrough hepatitis B infection.”

Find the study in Vaccine (doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2016.04.013).

FROM VACCINE