User login

Catching up with our past presidents

Where are they now? What have they been up to? CHEST’s Past Presidents each forged the way for the many successes of the American College of Chest Physicians (CHEST), leading to enhanced patient care around the globe. Their outstanding leadership and vision are evidenced today in many of CHEST’s current initiatives, and now it is time to check in with these past leaders to give us a look at what’s new in their lives.

Kalpalatha K. Guntupalli, MD, Master FCCP, MACP, FCCM

Frances K. Friedman and Oscar Friedman, MD ’36 Endowed Professor for Pulmonary Disorders; and Chief, Section of Pulmonary, Critical Care, and Sleep Medicine, Department of Medicine, Baylor College of Medicine.

President 2009-2010

November 1, 2009, is clearly etched into my memory. I was sworn in as the 73rd President, and 3rd woman President, of the American College of Chest Physicians during CHEST Annual Meeting 2009 in San Diego.

I consider the 2 years leading up to the presidency and the year following my term as the best years of my professional career. They were action packed, full of excitement that gave immense satisfaction. During my year, the longtime EVP/CEO, Al Lever, retired, and we welcomed the new EVP/CEO Mr. Paul Markowski.

To make the transition easier, I started the “4 Ps” call of the 4 Presidents (President-Designate, President-Elect, President, and the Past President), a weekly call to catch up and keep everyone in the loop. This has since become a tradition in the organization.

My theme for the year was “Act local, Think global.” We started many international initiatives, in the Middle East, India, China, and South America, that have since evolved into successful programs. In 2010, as members of the Federation of International Respiratory Societies (FIRS), we celebrated the “Year of the Lung.” We participated in the “world spirometry day” (102,487 spirometries were done globally) and did many other programs to increase awareness of lung disease. We held a long-term strategic retreat developing goals for the College. We implemented many other process-driven initiatives under the new CEO’s leadership.

Land was acquired where the new beautiful headquarters building now stands.

What is life like after CHEST Presidency?

I was very honored in 2012 to receive the “Pravasi Bharatiya Samman,” the highest award bestowed on a nonresident Indian by the President of India or distinguished members of the Indian Diaspora to “honor exceptional and meritorious contributions in their chosen field/profession and enhancing the image of India.” In 2013, I spent 4 months as a Fulbright Scholar forming an ARDS network in India, and in 2015, I was honored as a Master FCCP by our own organization.

As the Section Chief, I have been busy building a “Lung Institute” and ICU services along with many new initiatives in our very active Pulmonary/CC/Sleep section at Baylor College of Medicine.

Where are they now? What have they been up to? CHEST’s Past Presidents each forged the way for the many successes of the American College of Chest Physicians (CHEST), leading to enhanced patient care around the globe. Their outstanding leadership and vision are evidenced today in many of CHEST’s current initiatives, and now it is time to check in with these past leaders to give us a look at what’s new in their lives.

Kalpalatha K. Guntupalli, MD, Master FCCP, MACP, FCCM

Frances K. Friedman and Oscar Friedman, MD ’36 Endowed Professor for Pulmonary Disorders; and Chief, Section of Pulmonary, Critical Care, and Sleep Medicine, Department of Medicine, Baylor College of Medicine.

President 2009-2010

November 1, 2009, is clearly etched into my memory. I was sworn in as the 73rd President, and 3rd woman President, of the American College of Chest Physicians during CHEST Annual Meeting 2009 in San Diego.

I consider the 2 years leading up to the presidency and the year following my term as the best years of my professional career. They were action packed, full of excitement that gave immense satisfaction. During my year, the longtime EVP/CEO, Al Lever, retired, and we welcomed the new EVP/CEO Mr. Paul Markowski.

To make the transition easier, I started the “4 Ps” call of the 4 Presidents (President-Designate, President-Elect, President, and the Past President), a weekly call to catch up and keep everyone in the loop. This has since become a tradition in the organization.

My theme for the year was “Act local, Think global.” We started many international initiatives, in the Middle East, India, China, and South America, that have since evolved into successful programs. In 2010, as members of the Federation of International Respiratory Societies (FIRS), we celebrated the “Year of the Lung.” We participated in the “world spirometry day” (102,487 spirometries were done globally) and did many other programs to increase awareness of lung disease. We held a long-term strategic retreat developing goals for the College. We implemented many other process-driven initiatives under the new CEO’s leadership.

Land was acquired where the new beautiful headquarters building now stands.

What is life like after CHEST Presidency?

I was very honored in 2012 to receive the “Pravasi Bharatiya Samman,” the highest award bestowed on a nonresident Indian by the President of India or distinguished members of the Indian Diaspora to “honor exceptional and meritorious contributions in their chosen field/profession and enhancing the image of India.” In 2013, I spent 4 months as a Fulbright Scholar forming an ARDS network in India, and in 2015, I was honored as a Master FCCP by our own organization.

As the Section Chief, I have been busy building a “Lung Institute” and ICU services along with many new initiatives in our very active Pulmonary/CC/Sleep section at Baylor College of Medicine.

Where are they now? What have they been up to? CHEST’s Past Presidents each forged the way for the many successes of the American College of Chest Physicians (CHEST), leading to enhanced patient care around the globe. Their outstanding leadership and vision are evidenced today in many of CHEST’s current initiatives, and now it is time to check in with these past leaders to give us a look at what’s new in their lives.

Kalpalatha K. Guntupalli, MD, Master FCCP, MACP, FCCM

Frances K. Friedman and Oscar Friedman, MD ’36 Endowed Professor for Pulmonary Disorders; and Chief, Section of Pulmonary, Critical Care, and Sleep Medicine, Department of Medicine, Baylor College of Medicine.

President 2009-2010

November 1, 2009, is clearly etched into my memory. I was sworn in as the 73rd President, and 3rd woman President, of the American College of Chest Physicians during CHEST Annual Meeting 2009 in San Diego.

I consider the 2 years leading up to the presidency and the year following my term as the best years of my professional career. They were action packed, full of excitement that gave immense satisfaction. During my year, the longtime EVP/CEO, Al Lever, retired, and we welcomed the new EVP/CEO Mr. Paul Markowski.

To make the transition easier, I started the “4 Ps” call of the 4 Presidents (President-Designate, President-Elect, President, and the Past President), a weekly call to catch up and keep everyone in the loop. This has since become a tradition in the organization.

My theme for the year was “Act local, Think global.” We started many international initiatives, in the Middle East, India, China, and South America, that have since evolved into successful programs. In 2010, as members of the Federation of International Respiratory Societies (FIRS), we celebrated the “Year of the Lung.” We participated in the “world spirometry day” (102,487 spirometries were done globally) and did many other programs to increase awareness of lung disease. We held a long-term strategic retreat developing goals for the College. We implemented many other process-driven initiatives under the new CEO’s leadership.

Land was acquired where the new beautiful headquarters building now stands.

What is life like after CHEST Presidency?

I was very honored in 2012 to receive the “Pravasi Bharatiya Samman,” the highest award bestowed on a nonresident Indian by the President of India or distinguished members of the Indian Diaspora to “honor exceptional and meritorious contributions in their chosen field/profession and enhancing the image of India.” In 2013, I spent 4 months as a Fulbright Scholar forming an ARDS network in India, and in 2015, I was honored as a Master FCCP by our own organization.

As the Section Chief, I have been busy building a “Lung Institute” and ICU services along with many new initiatives in our very active Pulmonary/CC/Sleep section at Baylor College of Medicine.

Predictors of abnormal longitudinal patterns of lung-function growth and decline

When it comes to predictive demographic and clinical factors associated with abnormal patterns of lung growth and decline in those with persistent, mild-to-moderate asthma in childhood, male sex and childhood levels of lung function as assessed by the forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) make all the difference, according to the results of a study published in the New England Journal of Medicine.

“Determinants of abnormal patterns of FEV1 growth and decline are multifactorial and complex, and identification of factors associated with the timing of a decline from the maximal level requires longitudinal data,” said author Michael McGeachie, Ph.D., of Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, and his colleagues.

To identify these determinants, particularly in those with asthma, Dr. McGeachie and colleagues analyzed longitudinal data from a subset of participants from the Childhood Asthma Management Program (CAMP) cohort who were followed from enrollment at the age of 5 to 12 years, into the third decade of life. The trajectory of lung growth and the decline from maximum growth in this large cohort of persons who had persistent, mild-to-moderate asthma in childhood were compared against those from persons without asthma who were participants in the third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. (N Engl J Med. 2016;374:1842-52).

Data from 684 participants from the CAMP cohort were assessed and 25% had normal lung-function growth without an early decline, 26% had normal growth and an early decline, 23% had reduced growth without an early decline, and 26% had reduced growth and an early decline. Results of the multinomial logistic-regression analysis of risk factors for abnormal patterns of lung growth and decline showed that the 26% of participants with reduced growth and an early decline had lower FEV1 lung function at enrollment and were more likely to be male, compared with those who had normal growth.

Additional study results indicated that 18% of the participants who had reduced lung-function growth, with or without an early decline, met the case definition for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) based on the postbronchodilator spirometric criteria at an age of less than 30 years.

Based on their data, Dr. McGeachie and his colleagues said that detection of an abnormal trajectory by means of early and ongoing serial FEV1 monitoring may help identify children and young adults at risk for abnormal lung-function growth that could lead to chronic airflow obstruction in adulthood.

Funding for this project was provided by grants from the Parker B. Francis Foundation, the National Institutes of Health, the National Human Genome Research Institute, and the Human Frontier Science Program Organization. Dr. McGeachie reported grant support from one of the funding sources during the conduct of the study. Nineteen coauthors reported they had nothing to disclose and the remainder either reported grant support or ties to industry sources.

When it comes to predictive demographic and clinical factors associated with abnormal patterns of lung growth and decline in those with persistent, mild-to-moderate asthma in childhood, male sex and childhood levels of lung function as assessed by the forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) make all the difference, according to the results of a study published in the New England Journal of Medicine.

“Determinants of abnormal patterns of FEV1 growth and decline are multifactorial and complex, and identification of factors associated with the timing of a decline from the maximal level requires longitudinal data,” said author Michael McGeachie, Ph.D., of Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, and his colleagues.

To identify these determinants, particularly in those with asthma, Dr. McGeachie and colleagues analyzed longitudinal data from a subset of participants from the Childhood Asthma Management Program (CAMP) cohort who were followed from enrollment at the age of 5 to 12 years, into the third decade of life. The trajectory of lung growth and the decline from maximum growth in this large cohort of persons who had persistent, mild-to-moderate asthma in childhood were compared against those from persons without asthma who were participants in the third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. (N Engl J Med. 2016;374:1842-52).

Data from 684 participants from the CAMP cohort were assessed and 25% had normal lung-function growth without an early decline, 26% had normal growth and an early decline, 23% had reduced growth without an early decline, and 26% had reduced growth and an early decline. Results of the multinomial logistic-regression analysis of risk factors for abnormal patterns of lung growth and decline showed that the 26% of participants with reduced growth and an early decline had lower FEV1 lung function at enrollment and were more likely to be male, compared with those who had normal growth.

Additional study results indicated that 18% of the participants who had reduced lung-function growth, with or without an early decline, met the case definition for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) based on the postbronchodilator spirometric criteria at an age of less than 30 years.

Based on their data, Dr. McGeachie and his colleagues said that detection of an abnormal trajectory by means of early and ongoing serial FEV1 monitoring may help identify children and young adults at risk for abnormal lung-function growth that could lead to chronic airflow obstruction in adulthood.

Funding for this project was provided by grants from the Parker B. Francis Foundation, the National Institutes of Health, the National Human Genome Research Institute, and the Human Frontier Science Program Organization. Dr. McGeachie reported grant support from one of the funding sources during the conduct of the study. Nineteen coauthors reported they had nothing to disclose and the remainder either reported grant support or ties to industry sources.

When it comes to predictive demographic and clinical factors associated with abnormal patterns of lung growth and decline in those with persistent, mild-to-moderate asthma in childhood, male sex and childhood levels of lung function as assessed by the forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) make all the difference, according to the results of a study published in the New England Journal of Medicine.

“Determinants of abnormal patterns of FEV1 growth and decline are multifactorial and complex, and identification of factors associated with the timing of a decline from the maximal level requires longitudinal data,” said author Michael McGeachie, Ph.D., of Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, and his colleagues.

To identify these determinants, particularly in those with asthma, Dr. McGeachie and colleagues analyzed longitudinal data from a subset of participants from the Childhood Asthma Management Program (CAMP) cohort who were followed from enrollment at the age of 5 to 12 years, into the third decade of life. The trajectory of lung growth and the decline from maximum growth in this large cohort of persons who had persistent, mild-to-moderate asthma in childhood were compared against those from persons without asthma who were participants in the third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. (N Engl J Med. 2016;374:1842-52).

Data from 684 participants from the CAMP cohort were assessed and 25% had normal lung-function growth without an early decline, 26% had normal growth and an early decline, 23% had reduced growth without an early decline, and 26% had reduced growth and an early decline. Results of the multinomial logistic-regression analysis of risk factors for abnormal patterns of lung growth and decline showed that the 26% of participants with reduced growth and an early decline had lower FEV1 lung function at enrollment and were more likely to be male, compared with those who had normal growth.

Additional study results indicated that 18% of the participants who had reduced lung-function growth, with or without an early decline, met the case definition for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) based on the postbronchodilator spirometric criteria at an age of less than 30 years.

Based on their data, Dr. McGeachie and his colleagues said that detection of an abnormal trajectory by means of early and ongoing serial FEV1 monitoring may help identify children and young adults at risk for abnormal lung-function growth that could lead to chronic airflow obstruction in adulthood.

Funding for this project was provided by grants from the Parker B. Francis Foundation, the National Institutes of Health, the National Human Genome Research Institute, and the Human Frontier Science Program Organization. Dr. McGeachie reported grant support from one of the funding sources during the conduct of the study. Nineteen coauthors reported they had nothing to disclose and the remainder either reported grant support or ties to industry sources.

Key clinical point: Abnormal longitudinal patterns of lung-function growth in young asthma patients are associated with specific risk factors and may be related to development of COPD.

Major finding: Those with reduced lung growth and an early decline had a lower forced expiratory volume in 1 second lung function in childhood and were more likely to be male.

Data sources: A subset of participants from the Childhood Asthma Management Program cohort.

Disclosures: Funding for this project was provided by grants from the Parker B. Francis Foundation, the National Institutes of Health, the National Human Genome Research Institute, and the Human Frontier Science Program Organization. Dr. McGeachie reported grant support from one of the funding sources during the conduct of the study. Nineteen coauthors reported they had nothing to disclose and the remainder either reported grant support or ties to industry sources.

Fresh Press: ACS Surgery News May issue is live on the website!

The digital May issue of ACS Surgery News is available online. Use the mobile app to download or view as a pdf.

The growing problem with reproducibility and sloppy use of statistical tools in biomedical research is the topic of this month’s feature. Even lab mice can be the sources of misleading research results. Dr. Peter Angelos reflects on what all this can mean for surgical research.

Don’t miss Dr. Tyler Hughes’s lighthearted look at a fictional surgeon of the future, Dr. ‘Bones’ McCoy, and how some of Dr. McCoy’s challenges are all too familiar to today’s surgeons.

This issue has news from on-site coverage of the annual meetings of the American Association of Endocrine Surgeons, the American Surgical Association, and the Central Surgical Association.

The digital May issue of ACS Surgery News is available online. Use the mobile app to download or view as a pdf.

The growing problem with reproducibility and sloppy use of statistical tools in biomedical research is the topic of this month’s feature. Even lab mice can be the sources of misleading research results. Dr. Peter Angelos reflects on what all this can mean for surgical research.

Don’t miss Dr. Tyler Hughes’s lighthearted look at a fictional surgeon of the future, Dr. ‘Bones’ McCoy, and how some of Dr. McCoy’s challenges are all too familiar to today’s surgeons.

This issue has news from on-site coverage of the annual meetings of the American Association of Endocrine Surgeons, the American Surgical Association, and the Central Surgical Association.

The digital May issue of ACS Surgery News is available online. Use the mobile app to download or view as a pdf.

The growing problem with reproducibility and sloppy use of statistical tools in biomedical research is the topic of this month’s feature. Even lab mice can be the sources of misleading research results. Dr. Peter Angelos reflects on what all this can mean for surgical research.

Don’t miss Dr. Tyler Hughes’s lighthearted look at a fictional surgeon of the future, Dr. ‘Bones’ McCoy, and how some of Dr. McCoy’s challenges are all too familiar to today’s surgeons.

This issue has news from on-site coverage of the annual meetings of the American Association of Endocrine Surgeons, the American Surgical Association, and the Central Surgical Association.

Alastair Noyce, MBBS, PhD

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

Rhythm control may be best for atrial fib in HFpEF

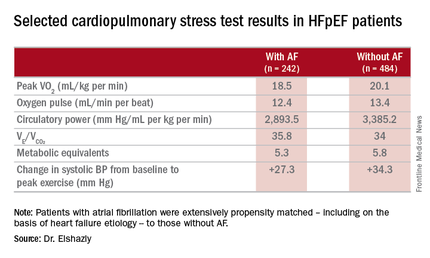

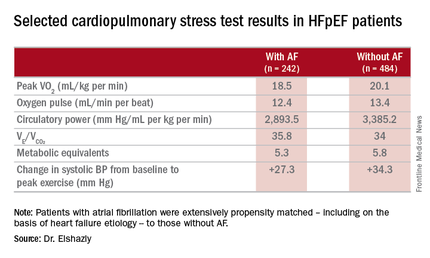

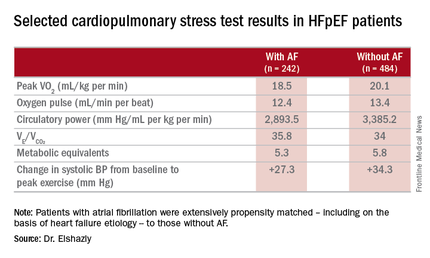

CHICAGO – Atrial fibrillation with good heart rate control in patients who have heart failure with preserved ejection fraction is independently associated with exercise intolerance, impaired contractile reserve, and a sharply higher mortality rate than in matched HFpEF patients without the arrhythmia, a retrospective analysis showed.

“Our study, the largest of its kind, provides mechanistic evidence from cardiopulmonary testing that a rhythm control strategy may potentially improve peak exercise capacity and survival in this patient population, a finding that of course requires future prospective appraisal in randomized trials comparing rate and rhythm control of atrial fibrillation in HFpEF,” Dr. Mohamed Badreldin Elshazly reported at the annual meeting of the American College of Cardiology.

In the meantime, his study also shows the useful role cardiopulmonary stress testing can play in the setting of atrial fibrillation (AF) in HFpEF, he added.

“Cardiopulmonary stress tests are cheap and easy to do. They’re a big asset for personalized medicine. Using an objective measure like cardiopulmonary stress testing to define the physiologic and hemodynamic consequences of atrial fibrillation in individual patients may help identify those in whom rhythm control may improve exercise tolerance and quality of life, and those who may be okay with rate control,” according to Dr. Elshazly of the Cleveland Clinic.

He noted that while it’s well established that atrial fibrillation is associated with exercise intolerance in patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) and that restoration of sinus rhythm in such patients has a positive impact on exercise hemodynamics, symptom severity, and quality of life, the situation is murkier regarding AF in patients with HFpEF. Prior studies were generally small and unable to establish whether AF was independently associated with exercise intolerance or if HFpEF patients who developed AF were sicker and higher risk.

He presented a retrospective, case-control study in a cohort of 1,825 patients with HFpEF referred for maximal, symptom-limited cardiopulmonary stress testing at the Cleveland Clinic. Among these were 242 patients with AF. They were extensively propensity matched – including on the basis of heart failure etiology – to 484 HFpEF patients without AF.

“That’s what makes our study strong. We were the first to be able to do propensity matching and therefore account for other risk factors in our analysis,” Dr. Elshazly explained.

The investigators measured peak oxygen uptake (VO2), the minute ventilation–carbon dioxide production relationship (VE/VCO2) as an indicator of ventilatory efficiency, metabolic equivalents (METS), ventilatory anaerobic threshold, circulatory power as a proxy for cardiac power, peak oxygen pulse as a surrogate for stroke volume, and resting and peak heart rate and systolic blood pressure. The patients with AF were in fibrillation at the time of their cardiopulmonary stress testing.

The HFpEF patients with AF had a mean resting heart rate of 70 beats per minute and a peak rate of 130 bpm. This group showed evidence of impaired peak exercise tolerance as reflected in lower peak VO2, oxygen pulse, and circulatory power at peak exercise. Their VE/VCO2 was higher, indicating impaired ventilatory efficiency. Notably, however, their submaximal exercise capacity was similar to the non-AF controls.

“Atrial fibrillation in these patients is really more of a disease that shows itself in patients when you take them to their peak exercise capacity,” he observed.

All-cause mortality was significantly higher in the AF as compared with no-AF patients with HFpEF. The mortality curves separated early and the divergence grew larger over the course of 8 years of follow-up.

One audience member pointed out that the large mortality difference between the two groups seems disproportionate to the rather modest differences in exercise capacity.

“It brings up an interesting point,” Dr. Elshazly replied. “Maybe the increase in total mortality that we see is being driven by other things besides cardiovascular mortality. Our data doesn’t capture the specific cause of death, be it cancer, for example, but it does raise the idea that this mortality difference is not all driven by cardiovascular mortality, but by atrial fibrillation.”

Dr. Elshazly reported having no financial conflicts of interest regarding his institutionally supported study.

CHICAGO – Atrial fibrillation with good heart rate control in patients who have heart failure with preserved ejection fraction is independently associated with exercise intolerance, impaired contractile reserve, and a sharply higher mortality rate than in matched HFpEF patients without the arrhythmia, a retrospective analysis showed.

“Our study, the largest of its kind, provides mechanistic evidence from cardiopulmonary testing that a rhythm control strategy may potentially improve peak exercise capacity and survival in this patient population, a finding that of course requires future prospective appraisal in randomized trials comparing rate and rhythm control of atrial fibrillation in HFpEF,” Dr. Mohamed Badreldin Elshazly reported at the annual meeting of the American College of Cardiology.

In the meantime, his study also shows the useful role cardiopulmonary stress testing can play in the setting of atrial fibrillation (AF) in HFpEF, he added.

“Cardiopulmonary stress tests are cheap and easy to do. They’re a big asset for personalized medicine. Using an objective measure like cardiopulmonary stress testing to define the physiologic and hemodynamic consequences of atrial fibrillation in individual patients may help identify those in whom rhythm control may improve exercise tolerance and quality of life, and those who may be okay with rate control,” according to Dr. Elshazly of the Cleveland Clinic.

He noted that while it’s well established that atrial fibrillation is associated with exercise intolerance in patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) and that restoration of sinus rhythm in such patients has a positive impact on exercise hemodynamics, symptom severity, and quality of life, the situation is murkier regarding AF in patients with HFpEF. Prior studies were generally small and unable to establish whether AF was independently associated with exercise intolerance or if HFpEF patients who developed AF were sicker and higher risk.

He presented a retrospective, case-control study in a cohort of 1,825 patients with HFpEF referred for maximal, symptom-limited cardiopulmonary stress testing at the Cleveland Clinic. Among these were 242 patients with AF. They were extensively propensity matched – including on the basis of heart failure etiology – to 484 HFpEF patients without AF.

“That’s what makes our study strong. We were the first to be able to do propensity matching and therefore account for other risk factors in our analysis,” Dr. Elshazly explained.

The investigators measured peak oxygen uptake (VO2), the minute ventilation–carbon dioxide production relationship (VE/VCO2) as an indicator of ventilatory efficiency, metabolic equivalents (METS), ventilatory anaerobic threshold, circulatory power as a proxy for cardiac power, peak oxygen pulse as a surrogate for stroke volume, and resting and peak heart rate and systolic blood pressure. The patients with AF were in fibrillation at the time of their cardiopulmonary stress testing.

The HFpEF patients with AF had a mean resting heart rate of 70 beats per minute and a peak rate of 130 bpm. This group showed evidence of impaired peak exercise tolerance as reflected in lower peak VO2, oxygen pulse, and circulatory power at peak exercise. Their VE/VCO2 was higher, indicating impaired ventilatory efficiency. Notably, however, their submaximal exercise capacity was similar to the non-AF controls.

“Atrial fibrillation in these patients is really more of a disease that shows itself in patients when you take them to their peak exercise capacity,” he observed.

All-cause mortality was significantly higher in the AF as compared with no-AF patients with HFpEF. The mortality curves separated early and the divergence grew larger over the course of 8 years of follow-up.

One audience member pointed out that the large mortality difference between the two groups seems disproportionate to the rather modest differences in exercise capacity.

“It brings up an interesting point,” Dr. Elshazly replied. “Maybe the increase in total mortality that we see is being driven by other things besides cardiovascular mortality. Our data doesn’t capture the specific cause of death, be it cancer, for example, but it does raise the idea that this mortality difference is not all driven by cardiovascular mortality, but by atrial fibrillation.”

Dr. Elshazly reported having no financial conflicts of interest regarding his institutionally supported study.

CHICAGO – Atrial fibrillation with good heart rate control in patients who have heart failure with preserved ejection fraction is independently associated with exercise intolerance, impaired contractile reserve, and a sharply higher mortality rate than in matched HFpEF patients without the arrhythmia, a retrospective analysis showed.

“Our study, the largest of its kind, provides mechanistic evidence from cardiopulmonary testing that a rhythm control strategy may potentially improve peak exercise capacity and survival in this patient population, a finding that of course requires future prospective appraisal in randomized trials comparing rate and rhythm control of atrial fibrillation in HFpEF,” Dr. Mohamed Badreldin Elshazly reported at the annual meeting of the American College of Cardiology.

In the meantime, his study also shows the useful role cardiopulmonary stress testing can play in the setting of atrial fibrillation (AF) in HFpEF, he added.

“Cardiopulmonary stress tests are cheap and easy to do. They’re a big asset for personalized medicine. Using an objective measure like cardiopulmonary stress testing to define the physiologic and hemodynamic consequences of atrial fibrillation in individual patients may help identify those in whom rhythm control may improve exercise tolerance and quality of life, and those who may be okay with rate control,” according to Dr. Elshazly of the Cleveland Clinic.

He noted that while it’s well established that atrial fibrillation is associated with exercise intolerance in patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) and that restoration of sinus rhythm in such patients has a positive impact on exercise hemodynamics, symptom severity, and quality of life, the situation is murkier regarding AF in patients with HFpEF. Prior studies were generally small and unable to establish whether AF was independently associated with exercise intolerance or if HFpEF patients who developed AF were sicker and higher risk.

He presented a retrospective, case-control study in a cohort of 1,825 patients with HFpEF referred for maximal, symptom-limited cardiopulmonary stress testing at the Cleveland Clinic. Among these were 242 patients with AF. They were extensively propensity matched – including on the basis of heart failure etiology – to 484 HFpEF patients without AF.

“That’s what makes our study strong. We were the first to be able to do propensity matching and therefore account for other risk factors in our analysis,” Dr. Elshazly explained.

The investigators measured peak oxygen uptake (VO2), the minute ventilation–carbon dioxide production relationship (VE/VCO2) as an indicator of ventilatory efficiency, metabolic equivalents (METS), ventilatory anaerobic threshold, circulatory power as a proxy for cardiac power, peak oxygen pulse as a surrogate for stroke volume, and resting and peak heart rate and systolic blood pressure. The patients with AF were in fibrillation at the time of their cardiopulmonary stress testing.

The HFpEF patients with AF had a mean resting heart rate of 70 beats per minute and a peak rate of 130 bpm. This group showed evidence of impaired peak exercise tolerance as reflected in lower peak VO2, oxygen pulse, and circulatory power at peak exercise. Their VE/VCO2 was higher, indicating impaired ventilatory efficiency. Notably, however, their submaximal exercise capacity was similar to the non-AF controls.

“Atrial fibrillation in these patients is really more of a disease that shows itself in patients when you take them to their peak exercise capacity,” he observed.

All-cause mortality was significantly higher in the AF as compared with no-AF patients with HFpEF. The mortality curves separated early and the divergence grew larger over the course of 8 years of follow-up.

One audience member pointed out that the large mortality difference between the two groups seems disproportionate to the rather modest differences in exercise capacity.

“It brings up an interesting point,” Dr. Elshazly replied. “Maybe the increase in total mortality that we see is being driven by other things besides cardiovascular mortality. Our data doesn’t capture the specific cause of death, be it cancer, for example, but it does raise the idea that this mortality difference is not all driven by cardiovascular mortality, but by atrial fibrillation.”

Dr. Elshazly reported having no financial conflicts of interest regarding his institutionally supported study.

AT ACC 16

Key clinical point: Atrial fibrillation in patients with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction is associated with exercise intolerance and increased mortality.

Major finding: Mean peak VO2 was 18.5 mL/kg per minute in patients with HFpEF and atrial fibrillation, significantly less than the 20.1 mL/kg per minute in controls.

Data source: A retrospective, single-institution study of cardiopulmonary stress test findings and 8-year mortality in 242 patients with HFpEF and atrial fibrillation and 484 propensity-matched controls with HFpEF and no arrhythmia.

Disclosures: The presenter reported having no financial conflicts of interest regarding his institutionally supported study.

Refined technique eliminates phrenic nerve palsy with second-generation cryoablation device

SAN FRANCISCO – Lower doses and conservative applications eliminated phrenic nerve palsy with Medtronic’s Arctic Front Advance cryoballoon ablation catheter at the University of Florida, Gainesville.

Cardiologists there were accustomed to performing atrial fibrillation pulmonary vein isolation with the first-generation device – the Arctic Front – when they switched to the second-generation Advance catheter in 2012; they had 2 phrenic nerve palsies in the first 33 patients (6%), a doubling from the 2 cases in 74 patients (2.7%) with the first-generation device.

The second-generation catheter is more powerful, with a cooling jet in the front of the balloon that delivers colder temperatures deeper into pulmonary veins. “We realized we needed to change the way we were using these catheters. You can use them safely, but you have to respect” their power, said lead investigator Dr. Robert Gibson.

“We reduced freezing times from 240 seconds to 180 seconds, and made that a hard rule. We limited the number of ablations” to two complete occlusions per vein, down from four to seven with the first-generation Arctic Front. “We also implemented a nadir cutoff to stop ablation when catheter temperatures fell below –55° C, and we tried to stay as proximal as possible to the pulmonary vein antra while still maintaining complete occlusion.” To help with that, cardiologists stopped using the 23-mm catheter, opting instead for the 28-mm catheter, Dr. Gibson said at the Heart Rhythm Society annual meeting.

Since making the changes, the team has performed 140 ablations, and there has not been a single phrenic nerve palsy. “We haven’t experienced a diaphragm paralysis” with the new approach. “We are very happy with these results. The changes make physiologic sense. You stay back; you use fewer freezes,” he said.

Phrenic nerve injury also decreased, from 3 cases in the first 33 second-generation patients (9%) to 9 in the 140 (6.4%) with the refined technique. Total phrenic nerve complications are now fewer in Gainesville than with the original, less powerful first-generation Arctic Front.

The team didn’t report ablation success with their new approach, but a 2015 review of Arctic Front Advance in more than 3,000 patients suggested long-term success with similar refinements (Heart Rhythm. 2015 Jul;12[7]:1658-66).

Patients in the University of Florida review were in their early 60s, on average, and about two-thirds were men. About 30% had prior ablations. Phrenic nerve injury was determined by continuous phrenic nerve stimulation and manual diaphragm palpation during cryoablation.

The investigators had no relevant financial disclosures. Medtronic helped with the statistical analysis.

SAN FRANCISCO – Lower doses and conservative applications eliminated phrenic nerve palsy with Medtronic’s Arctic Front Advance cryoballoon ablation catheter at the University of Florida, Gainesville.

Cardiologists there were accustomed to performing atrial fibrillation pulmonary vein isolation with the first-generation device – the Arctic Front – when they switched to the second-generation Advance catheter in 2012; they had 2 phrenic nerve palsies in the first 33 patients (6%), a doubling from the 2 cases in 74 patients (2.7%) with the first-generation device.

The second-generation catheter is more powerful, with a cooling jet in the front of the balloon that delivers colder temperatures deeper into pulmonary veins. “We realized we needed to change the way we were using these catheters. You can use them safely, but you have to respect” their power, said lead investigator Dr. Robert Gibson.

“We reduced freezing times from 240 seconds to 180 seconds, and made that a hard rule. We limited the number of ablations” to two complete occlusions per vein, down from four to seven with the first-generation Arctic Front. “We also implemented a nadir cutoff to stop ablation when catheter temperatures fell below –55° C, and we tried to stay as proximal as possible to the pulmonary vein antra while still maintaining complete occlusion.” To help with that, cardiologists stopped using the 23-mm catheter, opting instead for the 28-mm catheter, Dr. Gibson said at the Heart Rhythm Society annual meeting.

Since making the changes, the team has performed 140 ablations, and there has not been a single phrenic nerve palsy. “We haven’t experienced a diaphragm paralysis” with the new approach. “We are very happy with these results. The changes make physiologic sense. You stay back; you use fewer freezes,” he said.

Phrenic nerve injury also decreased, from 3 cases in the first 33 second-generation patients (9%) to 9 in the 140 (6.4%) with the refined technique. Total phrenic nerve complications are now fewer in Gainesville than with the original, less powerful first-generation Arctic Front.

The team didn’t report ablation success with their new approach, but a 2015 review of Arctic Front Advance in more than 3,000 patients suggested long-term success with similar refinements (Heart Rhythm. 2015 Jul;12[7]:1658-66).

Patients in the University of Florida review were in their early 60s, on average, and about two-thirds were men. About 30% had prior ablations. Phrenic nerve injury was determined by continuous phrenic nerve stimulation and manual diaphragm palpation during cryoablation.

The investigators had no relevant financial disclosures. Medtronic helped with the statistical analysis.

SAN FRANCISCO – Lower doses and conservative applications eliminated phrenic nerve palsy with Medtronic’s Arctic Front Advance cryoballoon ablation catheter at the University of Florida, Gainesville.

Cardiologists there were accustomed to performing atrial fibrillation pulmonary vein isolation with the first-generation device – the Arctic Front – when they switched to the second-generation Advance catheter in 2012; they had 2 phrenic nerve palsies in the first 33 patients (6%), a doubling from the 2 cases in 74 patients (2.7%) with the first-generation device.

The second-generation catheter is more powerful, with a cooling jet in the front of the balloon that delivers colder temperatures deeper into pulmonary veins. “We realized we needed to change the way we were using these catheters. You can use them safely, but you have to respect” their power, said lead investigator Dr. Robert Gibson.

“We reduced freezing times from 240 seconds to 180 seconds, and made that a hard rule. We limited the number of ablations” to two complete occlusions per vein, down from four to seven with the first-generation Arctic Front. “We also implemented a nadir cutoff to stop ablation when catheter temperatures fell below –55° C, and we tried to stay as proximal as possible to the pulmonary vein antra while still maintaining complete occlusion.” To help with that, cardiologists stopped using the 23-mm catheter, opting instead for the 28-mm catheter, Dr. Gibson said at the Heart Rhythm Society annual meeting.

Since making the changes, the team has performed 140 ablations, and there has not been a single phrenic nerve palsy. “We haven’t experienced a diaphragm paralysis” with the new approach. “We are very happy with these results. The changes make physiologic sense. You stay back; you use fewer freezes,” he said.

Phrenic nerve injury also decreased, from 3 cases in the first 33 second-generation patients (9%) to 9 in the 140 (6.4%) with the refined technique. Total phrenic nerve complications are now fewer in Gainesville than with the original, less powerful first-generation Arctic Front.

The team didn’t report ablation success with their new approach, but a 2015 review of Arctic Front Advance in more than 3,000 patients suggested long-term success with similar refinements (Heart Rhythm. 2015 Jul;12[7]:1658-66).

Patients in the University of Florida review were in their early 60s, on average, and about two-thirds were men. About 30% had prior ablations. Phrenic nerve injury was determined by continuous phrenic nerve stimulation and manual diaphragm palpation during cryoablation.

The investigators had no relevant financial disclosures. Medtronic helped with the statistical analysis.

AT HEART RHYTHM 2016

Key clinical point: Second-generation cryoablation devices require a lighter touch to avoid phrenic nerve palsy.

Major finding: A conservative approach dropped the phrenic nerve palsy rate from 6% to 0% (P = .025).

Data source: A review of 247 cryoballoon ablations for paroxysmal atrial fibrillation

Disclosures: The investigators had no relevant financial disclosures. Medtronic helped with the statistical analysis.

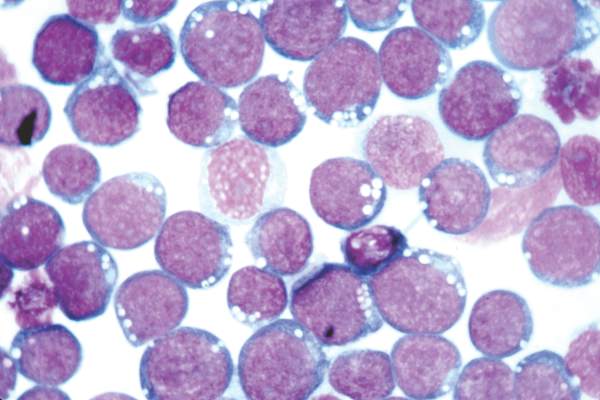

Epstein-Barr virus DNA in plasma reliably detects EBV-positive lymphoproliferative disorders

Detection of Epstein-Barr virus DNA in plasma reliably signaled “a broad range” of EBV+ diseases, according to investigators.

In contrast, the presence of EBV DNA in peripheral blood mononuclear cells did not reliably predict EBV diseases, said Dr. Jennifer A. Kanakry and her associates at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore. Patients without EBV diseases can have EBV DNA in their PBMCs, particularly if they are immunocompromised, the researchers observed.

Latent EBV infection is associated with lymphomas, lymphoproliferative disorders, hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis, solid tumors, and other diseases. To characterize the relationship between these diseases and EBV DNA, the researchers studied viral quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction assays of plasma and PBMCs from 2,146 patients tested at Johns Hopkins over 5 years. Patients were usually immunocompromised and hospitalized, the investigators noted (Blood 2016;127:2007-17).

A total of 535 patients (25%) had EBV detected in plasma or PBMCs. Notably, 69% of patients who did not have EBV diseases had EBV in PBMCs, but not in plasma. Among 105 patients with active systemic EBV+ diseases, 99% had EBV DNA in plasma, but only 54% had EBV in PBMCs. Furthermore, the number of copies of EBV DNA distinguished untreated EBV+ lymphoma, remitted EBV+ lymphoma, and EBV- lymphoma, and also distinguished untreated, EBV+ post-transplantation lymphoproliferative disorder (PTLD), EBV+ PTLD in remission, and EBV– PTLD.

“Cell-free (plasma) EBV DNA performs better than cellular EBV DNA as a marker of a broad range of EBV+ diseases,” the investigators concluded. “Within a largely immunocompromised and hospitalized cohort, detection of EBV DNA in plasma is uncommon in the absence of EBV+ disease.”

The National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, and Center for AIDS Research funded the study. The researchers had no disclosures.

Detection of Epstein-Barr virus DNA in plasma reliably signaled “a broad range” of EBV+ diseases, according to investigators.

In contrast, the presence of EBV DNA in peripheral blood mononuclear cells did not reliably predict EBV diseases, said Dr. Jennifer A. Kanakry and her associates at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore. Patients without EBV diseases can have EBV DNA in their PBMCs, particularly if they are immunocompromised, the researchers observed.

Latent EBV infection is associated with lymphomas, lymphoproliferative disorders, hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis, solid tumors, and other diseases. To characterize the relationship between these diseases and EBV DNA, the researchers studied viral quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction assays of plasma and PBMCs from 2,146 patients tested at Johns Hopkins over 5 years. Patients were usually immunocompromised and hospitalized, the investigators noted (Blood 2016;127:2007-17).

A total of 535 patients (25%) had EBV detected in plasma or PBMCs. Notably, 69% of patients who did not have EBV diseases had EBV in PBMCs, but not in plasma. Among 105 patients with active systemic EBV+ diseases, 99% had EBV DNA in plasma, but only 54% had EBV in PBMCs. Furthermore, the number of copies of EBV DNA distinguished untreated EBV+ lymphoma, remitted EBV+ lymphoma, and EBV- lymphoma, and also distinguished untreated, EBV+ post-transplantation lymphoproliferative disorder (PTLD), EBV+ PTLD in remission, and EBV– PTLD.

“Cell-free (plasma) EBV DNA performs better than cellular EBV DNA as a marker of a broad range of EBV+ diseases,” the investigators concluded. “Within a largely immunocompromised and hospitalized cohort, detection of EBV DNA in plasma is uncommon in the absence of EBV+ disease.”

The National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, and Center for AIDS Research funded the study. The researchers had no disclosures.

Detection of Epstein-Barr virus DNA in plasma reliably signaled “a broad range” of EBV+ diseases, according to investigators.

In contrast, the presence of EBV DNA in peripheral blood mononuclear cells did not reliably predict EBV diseases, said Dr. Jennifer A. Kanakry and her associates at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore. Patients without EBV diseases can have EBV DNA in their PBMCs, particularly if they are immunocompromised, the researchers observed.

Latent EBV infection is associated with lymphomas, lymphoproliferative disorders, hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis, solid tumors, and other diseases. To characterize the relationship between these diseases and EBV DNA, the researchers studied viral quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction assays of plasma and PBMCs from 2,146 patients tested at Johns Hopkins over 5 years. Patients were usually immunocompromised and hospitalized, the investigators noted (Blood 2016;127:2007-17).

A total of 535 patients (25%) had EBV detected in plasma or PBMCs. Notably, 69% of patients who did not have EBV diseases had EBV in PBMCs, but not in plasma. Among 105 patients with active systemic EBV+ diseases, 99% had EBV DNA in plasma, but only 54% had EBV in PBMCs. Furthermore, the number of copies of EBV DNA distinguished untreated EBV+ lymphoma, remitted EBV+ lymphoma, and EBV- lymphoma, and also distinguished untreated, EBV+ post-transplantation lymphoproliferative disorder (PTLD), EBV+ PTLD in remission, and EBV– PTLD.

“Cell-free (plasma) EBV DNA performs better than cellular EBV DNA as a marker of a broad range of EBV+ diseases,” the investigators concluded. “Within a largely immunocompromised and hospitalized cohort, detection of EBV DNA in plasma is uncommon in the absence of EBV+ disease.”

The National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, and Center for AIDS Research funded the study. The researchers had no disclosures.

FROM BLOOD

Key clinical point: Epstein-Barr virus DNA was a more specific indicator of EBV+ diseases when detected in plasma, as opposed to peripheral blood mononuclear cells.

Major finding: Among 105 patients with active systemic EBV+ diseases, 99% had EBV DNA in plasma, but 54% had EBV in PBMCs.

Data source: Viral quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction assays of plasma and PBMCs from 2,146 patients.

Disclosures: The National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, and Center for AIDS Research funded the study. The researchers had no disclosures.

FDA: Olanzapine can cause serious skin reaction

Olanzapine can cause a rare but serious skin reaction that can affect other parts of the body, according to a Food and Drug Administration safety alert released May 10.

The condition linked to all products containing the second-generation antipsychotic is called Drug Reaction with Eosinophilia and Systemic Symptoms, or DRESS. Symptoms of DRESS include a rash that can spread to all parts of the body, fever, swollen lymph nodes, and swelling. In addition, DRESS can result in injury to the liver, kidneys, lungs, heart, or pancreas, and it also can lead to death. The mortality tied to DRESS can reach 10%, the FDA said.

The FDA Adverse Event Reporting System database has identified 23 cases worldwide of DRESS resulting from olanzapine since 1996, including one patient who died. Currently, the only way to treat DRESS is to withdraw the drug promptly. “Health care professionals should immediately stop treatment with olanzapine if DRESS is suspected,” the safety alert states. “The important ways to manage DRESS are early recognition of the syndrome, discontinuation of the offending agent as soon as possible, and supportive care.”

Olanzapine, used to treat schizophrenia and manic episodes of bipolar disorder, is available in generic versions. The medication also is available under the brand names Zyprexa, Zyprexa Zydis, Zyprexa Relprevv, and Symbyax. The agency said it would add a warning describing DRESS to the labels of drugs containing olanzapine.

Read the full safety alert on the FDA website.

Olanzapine can cause a rare but serious skin reaction that can affect other parts of the body, according to a Food and Drug Administration safety alert released May 10.

The condition linked to all products containing the second-generation antipsychotic is called Drug Reaction with Eosinophilia and Systemic Symptoms, or DRESS. Symptoms of DRESS include a rash that can spread to all parts of the body, fever, swollen lymph nodes, and swelling. In addition, DRESS can result in injury to the liver, kidneys, lungs, heart, or pancreas, and it also can lead to death. The mortality tied to DRESS can reach 10%, the FDA said.

The FDA Adverse Event Reporting System database has identified 23 cases worldwide of DRESS resulting from olanzapine since 1996, including one patient who died. Currently, the only way to treat DRESS is to withdraw the drug promptly. “Health care professionals should immediately stop treatment with olanzapine if DRESS is suspected,” the safety alert states. “The important ways to manage DRESS are early recognition of the syndrome, discontinuation of the offending agent as soon as possible, and supportive care.”

Olanzapine, used to treat schizophrenia and manic episodes of bipolar disorder, is available in generic versions. The medication also is available under the brand names Zyprexa, Zyprexa Zydis, Zyprexa Relprevv, and Symbyax. The agency said it would add a warning describing DRESS to the labels of drugs containing olanzapine.

Read the full safety alert on the FDA website.

Olanzapine can cause a rare but serious skin reaction that can affect other parts of the body, according to a Food and Drug Administration safety alert released May 10.

The condition linked to all products containing the second-generation antipsychotic is called Drug Reaction with Eosinophilia and Systemic Symptoms, or DRESS. Symptoms of DRESS include a rash that can spread to all parts of the body, fever, swollen lymph nodes, and swelling. In addition, DRESS can result in injury to the liver, kidneys, lungs, heart, or pancreas, and it also can lead to death. The mortality tied to DRESS can reach 10%, the FDA said.

The FDA Adverse Event Reporting System database has identified 23 cases worldwide of DRESS resulting from olanzapine since 1996, including one patient who died. Currently, the only way to treat DRESS is to withdraw the drug promptly. “Health care professionals should immediately stop treatment with olanzapine if DRESS is suspected,” the safety alert states. “The important ways to manage DRESS are early recognition of the syndrome, discontinuation of the offending agent as soon as possible, and supportive care.”

Olanzapine, used to treat schizophrenia and manic episodes of bipolar disorder, is available in generic versions. The medication also is available under the brand names Zyprexa, Zyprexa Zydis, Zyprexa Relprevv, and Symbyax. The agency said it would add a warning describing DRESS to the labels of drugs containing olanzapine.

Read the full safety alert on the FDA website.

Red Facial Lesions Are No Day at the Beach

A 70-year-old man is seen for “broken blood vessels” on his face. The lesions were recently noted by a relative who had not seen him in years.

The patient has a pronounced history of sun overexposure as a result of his job and his hobbies, which include fishing and hunting. As a younger man, he enjoyed waterskiing and going to the lake almost every weekend during the warmer months.

He is in decent health apart from the lesions and has no other skin complaints.

EXAMINATION

The sides of the patient’s face are covered with linear, red, dilated blood vessels running in jagged patterns. The lesions are asymptomatic and range from 0.5 to 1.0 mm in diameter; some are several centimeters long. They are readily blanchable with digital pressure, though none are palpable.

Far more blood vessels are seen on the patient’s left side than on his right. The underlying skin is quite fair and thin. In some locations (eg, the lateral forehead), there are patches of white skin free of surface adnexa (ie pores, skin lines, or hair follicles).

His dorsal arms are very rough, with hundreds of solar lentigines, while the skin on his volar arms is relatively unaffected.

What is the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

This collection of findings is called dermatoheliosis (DHe), literally “sun-skin condition,” caused by overexposure to UV light. Telangiectasias, one manifestation, have many potential causes, but sun exposure is the most common—especially in those whose skin burns easily and frequently.

These blood vessels are simply normal surface vasculature made more obvious by two factors: First, chronic sun exposure overheats the skin for prolonged periods, leading to persistent vasodilatation that eventually becomes fixed. Second, solar atrophy may occur when the skin thins from sun overexposure, making typically invisible structures apparent.

DHe can also manifest as actinic keratosis, weathering of the skin, solar elastosis, and sun-caused skin cancers (basal and squamous cell carcinomas, melanoma, etc). The condition is incredibly common.

Many causes of telangiectasias are unrelated to sun exposure. Other processes that thin the skin—such as radiation therapy or injudicious use of topical steroids—may produce telangiectasias. Further examples include spider vessels on legs due to venous insufficiency and newly acquired vascular lesions resulting from pregnancy or liver cirrhosis. There are also two unusual but significant conditions that involve telangiectasias: a variant of systemic sclerosis called CREST syndrome (calcinosis, Raynaud’s, esophageal dysmotility, sclerodactyly, and telangiectasias) and hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasias (also known eponymically as Osler-Weber-Rendu syndrome).

Treatment for sun-caused telangiectasias includes laser and electrodessication.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

• Telangiectasias are permanently dilated surface vasculature usually seen on the most prominently sun-exposed areas of the skin. The left face and arm are often more heavily affected than the right, since they are closer to the car window during driving.

• Telangiectasias are only one of a number of sun-caused skin changes that are collectively termed dermatoheliosis (DHe).

• Telangiectasias are important because they identify patients at risk for sun-caused skin cancers, such as basal or squamous cell carcinomas and melanoma.

• Other potential causes of telangiectasias include injudicious use of topical steroids, focal radiation therapy, pregnancy, liver disease, and rare conditions such as CREST syndrome and hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasias.

A 70-year-old man is seen for “broken blood vessels” on his face. The lesions were recently noted by a relative who had not seen him in years.

The patient has a pronounced history of sun overexposure as a result of his job and his hobbies, which include fishing and hunting. As a younger man, he enjoyed waterskiing and going to the lake almost every weekend during the warmer months.

He is in decent health apart from the lesions and has no other skin complaints.

EXAMINATION

The sides of the patient’s face are covered with linear, red, dilated blood vessels running in jagged patterns. The lesions are asymptomatic and range from 0.5 to 1.0 mm in diameter; some are several centimeters long. They are readily blanchable with digital pressure, though none are palpable.

Far more blood vessels are seen on the patient’s left side than on his right. The underlying skin is quite fair and thin. In some locations (eg, the lateral forehead), there are patches of white skin free of surface adnexa (ie pores, skin lines, or hair follicles).

His dorsal arms are very rough, with hundreds of solar lentigines, while the skin on his volar arms is relatively unaffected.

What is the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

This collection of findings is called dermatoheliosis (DHe), literally “sun-skin condition,” caused by overexposure to UV light. Telangiectasias, one manifestation, have many potential causes, but sun exposure is the most common—especially in those whose skin burns easily and frequently.

These blood vessels are simply normal surface vasculature made more obvious by two factors: First, chronic sun exposure overheats the skin for prolonged periods, leading to persistent vasodilatation that eventually becomes fixed. Second, solar atrophy may occur when the skin thins from sun overexposure, making typically invisible structures apparent.

DHe can also manifest as actinic keratosis, weathering of the skin, solar elastosis, and sun-caused skin cancers (basal and squamous cell carcinomas, melanoma, etc). The condition is incredibly common.

Many causes of telangiectasias are unrelated to sun exposure. Other processes that thin the skin—such as radiation therapy or injudicious use of topical steroids—may produce telangiectasias. Further examples include spider vessels on legs due to venous insufficiency and newly acquired vascular lesions resulting from pregnancy or liver cirrhosis. There are also two unusual but significant conditions that involve telangiectasias: a variant of systemic sclerosis called CREST syndrome (calcinosis, Raynaud’s, esophageal dysmotility, sclerodactyly, and telangiectasias) and hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasias (also known eponymically as Osler-Weber-Rendu syndrome).

Treatment for sun-caused telangiectasias includes laser and electrodessication.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

• Telangiectasias are permanently dilated surface vasculature usually seen on the most prominently sun-exposed areas of the skin. The left face and arm are often more heavily affected than the right, since they are closer to the car window during driving.

• Telangiectasias are only one of a number of sun-caused skin changes that are collectively termed dermatoheliosis (DHe).

• Telangiectasias are important because they identify patients at risk for sun-caused skin cancers, such as basal or squamous cell carcinomas and melanoma.

• Other potential causes of telangiectasias include injudicious use of topical steroids, focal radiation therapy, pregnancy, liver disease, and rare conditions such as CREST syndrome and hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasias.

A 70-year-old man is seen for “broken blood vessels” on his face. The lesions were recently noted by a relative who had not seen him in years.

The patient has a pronounced history of sun overexposure as a result of his job and his hobbies, which include fishing and hunting. As a younger man, he enjoyed waterskiing and going to the lake almost every weekend during the warmer months.

He is in decent health apart from the lesions and has no other skin complaints.

EXAMINATION

The sides of the patient’s face are covered with linear, red, dilated blood vessels running in jagged patterns. The lesions are asymptomatic and range from 0.5 to 1.0 mm in diameter; some are several centimeters long. They are readily blanchable with digital pressure, though none are palpable.

Far more blood vessels are seen on the patient’s left side than on his right. The underlying skin is quite fair and thin. In some locations (eg, the lateral forehead), there are patches of white skin free of surface adnexa (ie pores, skin lines, or hair follicles).

His dorsal arms are very rough, with hundreds of solar lentigines, while the skin on his volar arms is relatively unaffected.

What is the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

This collection of findings is called dermatoheliosis (DHe), literally “sun-skin condition,” caused by overexposure to UV light. Telangiectasias, one manifestation, have many potential causes, but sun exposure is the most common—especially in those whose skin burns easily and frequently.

These blood vessels are simply normal surface vasculature made more obvious by two factors: First, chronic sun exposure overheats the skin for prolonged periods, leading to persistent vasodilatation that eventually becomes fixed. Second, solar atrophy may occur when the skin thins from sun overexposure, making typically invisible structures apparent.

DHe can also manifest as actinic keratosis, weathering of the skin, solar elastosis, and sun-caused skin cancers (basal and squamous cell carcinomas, melanoma, etc). The condition is incredibly common.

Many causes of telangiectasias are unrelated to sun exposure. Other processes that thin the skin—such as radiation therapy or injudicious use of topical steroids—may produce telangiectasias. Further examples include spider vessels on legs due to venous insufficiency and newly acquired vascular lesions resulting from pregnancy or liver cirrhosis. There are also two unusual but significant conditions that involve telangiectasias: a variant of systemic sclerosis called CREST syndrome (calcinosis, Raynaud’s, esophageal dysmotility, sclerodactyly, and telangiectasias) and hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasias (also known eponymically as Osler-Weber-Rendu syndrome).

Treatment for sun-caused telangiectasias includes laser and electrodessication.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

• Telangiectasias are permanently dilated surface vasculature usually seen on the most prominently sun-exposed areas of the skin. The left face and arm are often more heavily affected than the right, since they are closer to the car window during driving.

• Telangiectasias are only one of a number of sun-caused skin changes that are collectively termed dermatoheliosis (DHe).

• Telangiectasias are important because they identify patients at risk for sun-caused skin cancers, such as basal or squamous cell carcinomas and melanoma.

• Other potential causes of telangiectasias include injudicious use of topical steroids, focal radiation therapy, pregnancy, liver disease, and rare conditions such as CREST syndrome and hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasias.

PIANO study provides insight on safety of biologics in pregnancy

MAUI, HAWAII – The consensus among gastroenterologists with expertise in inflammatory bowel disease is that continuation of biologics or immunomodulators in affected women throughout pregnancy and breastfeeding poses no increased risks to the fetus – and therein lies a message for rheumatologists and obstetricians, Dr. Uma Mahadevan said at the 2016 Rheumatology Winter Clinical Symposium.

“The risk of uncontrolled disease must be weighed against the risk of medical therapy. And this is something that is often missed,” according to Dr. Mahadevan, professor of medicine and co–medical director of the Center for Colitis and Crohn’s Disease at the University of California, San Francisco.

Gastroenterologists – at least, those whose practices focus on inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) – have led the way within medicine in terms of establishing the safety of biologics and immunomodulators such as azathioprine in pregnant women with chronic inflammatory diseases and their babies. And having accomplished that, they have been ahead of the curve in terms of continuing such therapy throughout pregnancy and breastfeeding. That’s because active Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis are particularly common in women during their childbearing years. And a disease flare during pregnancy is associated with a markedly increased risk of preterm birth and other adverse outcomes.

Gastroenterologists’ longstanding interest in the safety to mother and fetus of continued use of effective, potent medications throughout pregnancy was the impetus for the ongoing prospective U.S. Pregnancy in Inflammatory Bowel Disease and Neonatal Outcomes (PIANO) study, now in its ninth year, with an enrollment of roughly 1,500 women with IBD. The study has included comparisons of outcomes of women on different medications during pregnancy versus unmedicated women.

In multiple publications, Dr. Mahadevan and other PIANO investigators have established that increased IBD activity adversely affects pregnancy outcomes, and that stabilization of disease and effective maintenance therapy throughout pregnancy is important. The PIANO group has demonstrated that IBD medication exposure well into the third trimester in patients in sustained remission was not associated with an increase in congenital anomalies, spontaneous abortions, intrauterine growth restriction, or low birth weight.

To the surprise of many gastroenterologists, the PIANO study has shown that women with Crohn’s disease generally have smoother pregnancies than do those with ulcerative colitis, who tend to get sicker and have more complications.

Since PIANO data show an increased rate of preterm birth and low birth weight in IBD patients on combination therapy with azathioprine plus a biologic throughout pregnancy, Dr. Mahadevan and others try to discontinue the azathioprine, even though the need for combination therapy is a marker for patients with more severe disease.

Anti-TNF-alpha use during third trimester

Of particular interest to rheumatologists, who rely heavily on many of the same biologic agents gastroenterologists use to treat IBD, the use of anti–tumor necrosis factor–alpha biologics in the third trimester was not associated with an increase in preterm birth or maternal disease activity in the third trimester or the first 4 months post partum. When women on certolizumab pegol (Cimzia) during the third trimester were excluded from the analysis, since this biologic uniquely does not cross the placenta at all, the most recent PIANO data show a modest yet statistically significant 35% increase in infections in infants at age 12 months whose mothers were on other biologics in the third trimester. But Dr. Mahadevan said she doesn’t yet consider this finding definitive.

“It’s still a small group of patients, and every year when we update the results the infant infection risk goes back and forth from statistically significant to nonsignificant. I think there’s a signal here; we just need to keep collecting more data,” she said.

Particularly reassuring is the finding that the offspring of PIANO participants who had in utero exposure to biologics and immunomodulators didn’t have any developmental delay, compared with unexposed babies, according to the validated Ages and Stages Questionnaire at ages 1, 2, 3, and 4 years and Denver Childhood Developmental Score at months 4, 9, and 12.

“These kids do great later in life. Actually, they have better scores than unexposed kids. Not to say that biologics make your kid smarter. It probably has to do with better IBD control,” Dr. Mahadevan said.

Effects while breastfeeding

Breastfeeding while on biologics or azathioprine didn’t adversely affect infant growth, infection rate, or developmental milestones. More specifically, levels of biologics in the mothers, babies, or cord serum were not associated with the likelihood of a neonatal intensive care unit stay, an increase in infant infections, or achievement of developmental milestones.

“Almost all the agents are detectable in breast milk, but only at the nanogram level. We tell all our patients on biologics they can breastfeed. It doesn’t matter when their last dose was, don’t worry about it,” the gastroenterologist said.

Importance of preconception counseling

Key practical lessons she has learned in taking care of large numbers of patients with severe IBD referred to her tertiary center include the importance of preconception counseling. A woman should stop methotrexate at least 3 months prior to conception. Providing information on medication safety and the risks of poorly controlled disease helps in adherence.

It’s best to communicate with the patient’s obstetrician about the importance of continuing her IBD therapy during pregnancy before she becomes pregnant.

“It’s better to have this discussion ahead of time and have a plan in place. Once a patient is pregnant it’s very difficult if her doula or someone else has told them to stop a medication to convince them to continue it,” said Dr. Mahadevan.

All women with IBD should be followed as high-risk pregnancies. Mode of delivery is at the discretion of the obstetrician unless the patient has an open rectovaginal fistula; even if it’s inactive, cesarean delivery is preferable in that situation, she said.

Steps taken in the third trimester

In the third trimester, she routinely sends a letter to the patient’s pediatrician requesting no live virus vaccines in the coming baby’s first 6 months – in the United States, that’s the rotavirus vaccine – if the infant was exposed in utero to a biologic other than certolizumab pegol, but that all other vaccines can be given on schedule. She also asks that the pediatrician monitor an exposed baby for infections.

“That being said, there have been 20-plus exposures to rotavirus vaccine in the first 6 months of life recorded in the PIANO registry in the infants of mothers on biologics and we haven’t seen any adverse events. So maybe the CDC is overstating the risk, but at this point the rule is still no live virus vaccines,” she said.

She tries to time her last dose of biologic agents during pregnancy as follows: at week 30-32 for infliximab or vedolizumab and week 36-38 for adalimumab or golimumab. As for certolizumab pegol, “they can take that on their way to labor and delivery,” she quipped.

“I give the next dose of a biologic agent soon after delivery, often while the patient is still in the hospital, 24 hours after vaginal delivery and 48 hours after a C-section, assuming no infection,” Dr. Mahadevan said.

The elements of her approach to management of the pregnant patient with IBD are in accord with a recent report, The Toronto Consensus Statements for the Management of Inflammatory Bowel Disease in Pregnancy, in which she participated (Gastroenterology. 2016 Mar;150[3]:734-57).

Rheumatologists’ habits with biologics in pregnancy

Dr. John J. Cush rose from the audience to observe that the situation in rheumatology with regard to biologics in pregnancy is quite a bit different from what’s going on in gastroenterology.

“I think a lot of rheumatologists don’t let their patients get pregnant on biologics for fear of what may happen. And that’s because they don’t know the data. I think you’ve shown very clearly that you can get pregnant on biologics and do well. But for many of us who do allow our patients to get pregnant on biologic monotherapy, the practice is to stop it once they get pregnant. The idea is we want them to be in a very deep remission to increase the odds of getting pregnant and having a successful pregnancy, but then we stop the drug and we assume the disease state is going to stay the same. Often, though, it doesn’t stay the same, it gets worse. Yet this is a common practice in rheumatology. What’s your response?” asked Dr. Cush, professor of medicine and rheumatology at Baylor University Medical Center, Dallas, and director of clinical rheumatology at the Baylor Research Institute.

“I think in IBD it’s very clear that patients with active disease in pregnancy do much, much worse,” Dr. Mahadevan replied. “They have preterm birth, they get very sick, they’re hospitalized and placed on steroids. So for us, the benefit is very clear. I don’t know the data in rheumatoid arthritis – whether active disease leads to increased complication rates – but I do know from colleagues that in the postpartum period women with poorly controlled rheumatoid arthritis can’t take care of their baby because their hands are so damaged. And that’s a big deal.

“So when you see that the drugs are not associated with an increased risk of birth defects and on monotherapy there’s no increase in infections and other complications, you’d think that in the right patient continuing treatment until the late third trimester would be the way to go, especially since if you’ve put the patient on a biologic it must mean she has severe disease,” the gastroenterologist observed.

Dr. Roy Fleischmann of the University of Texas, Dallas, asked why gastroenterologists don’t put all IBD patients of childbearing age on certolizumab pegol if they need biologic therapy, since it doesn’t cross the placenta.

“Maybe IBD is different, but our biologics don’t necessarily have the longest persistence,” Dr. Mahadevan replied. “If you start a woman on certolizumab pegol at age 20 the chances of her still being on it at 28 are probably pretty low.”

Conference director Dr. Arthur Kavanaugh, professor of medicine at the University of California, San Diego, asked if the message regarding management of IBD in pregnancy being put forth by Dr. Mahadevan and the IBD in Pregnancy Consensus Group has gained wide acceptance by gastroenterologists across the country.

“I think the people who do IBD as a concentrated practice, whether in private or academic practice, are very aware of this literature,” she said.

“In general, IBD has become more and more centered among a group of people who want to take care of IBD. If you look at the big private practices, they have a hepatitis C person, an IBD person, and everyone else just wants to scope. I think the message is getting across to non-IBD gastroenterologists, but there is some confusion because the Europeans are very firm about stopping biologics at 22 weeks’ gestation if the patient is in deep remission and we in North America continue treatment,” said Dr. Mahadevan.

Her work with the PIANO study is funded by the Crohn’s and Colitis Foundation of America. In addition, Dr. Mahadevan disclosed ties to more than half a dozen pharmaceutical companies.

MAUI, HAWAII – The consensus among gastroenterologists with expertise in inflammatory bowel disease is that continuation of biologics or immunomodulators in affected women throughout pregnancy and breastfeeding poses no increased risks to the fetus – and therein lies a message for rheumatologists and obstetricians, Dr. Uma Mahadevan said at the 2016 Rheumatology Winter Clinical Symposium.