User login

CAR T-cell start-up launched

Dr. Siddhartha Mukherjee has partnered with Puretech Health to launch a new biotechnology and immuno-oncology company to broaden the use of chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy. Dr. Mukherjee, a Columbia University researcher, hematologist, oncologist, and Pulitzer Prize–winning author of “The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of Cancer,” (New York: Scribner, a division of Simon & Schuster, 2011) is licensing his CAR T-cell technology to the joint venture, called Vor BioPharma.

Vor BioPharma will focus on advancing and expanding CAR T-cell therapy, a relatively new cancer treatment where T cells are first collected from a patient’s blood and then genetically engineered to produce CAR proteins on their surface. The CAR proteins are designed to bind specific antigens found on the patient’s cancer cells. These genetically engineered T cells are grown in a laboratory and then infused into the patient. As of now, CAR T-cell therapy is primarily used to treat B-cell leukemias and other chronic lymphocytic leukemia.

“We continue to make great strides in developing new ways to treat cancer using the body’s immune system,” said Dr. Mukherjee in a written statement announcing the partnership. “The positive clinical response researchers have achieved with CAR T-cell therapies in B-cell leukemias has led to great interest within the oncology community and is something we hope to achieve in other cancers over time,” he said.

“CAR T-cell therapies have shown remarkable progress in the clinic, yet their applicability beyond a small subset of cancers is currently very limited,” said Dr. Sanjiv Sam Gambhir of Stanford University and a member of the Vor Scientific Advisory Board. “This technology seeks to address bottlenecks that prevent CAR T-cell therapy from becoming more broadly useful in treating cancers outside of B-cell cancers.”

Other Vor BioPharma employees and Scientific Advisory Board members include Dr. Joseph Bolen, former President and Chief Scientific Officer of Moderna Therapeutics; Dr. Dan Littman of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute; and Dr. Derrick Rossi of Harvard University.

On Twitter @jess_craig94

Dr. Siddhartha Mukherjee has partnered with Puretech Health to launch a new biotechnology and immuno-oncology company to broaden the use of chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy. Dr. Mukherjee, a Columbia University researcher, hematologist, oncologist, and Pulitzer Prize–winning author of “The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of Cancer,” (New York: Scribner, a division of Simon & Schuster, 2011) is licensing his CAR T-cell technology to the joint venture, called Vor BioPharma.

Vor BioPharma will focus on advancing and expanding CAR T-cell therapy, a relatively new cancer treatment where T cells are first collected from a patient’s blood and then genetically engineered to produce CAR proteins on their surface. The CAR proteins are designed to bind specific antigens found on the patient’s cancer cells. These genetically engineered T cells are grown in a laboratory and then infused into the patient. As of now, CAR T-cell therapy is primarily used to treat B-cell leukemias and other chronic lymphocytic leukemia.

“We continue to make great strides in developing new ways to treat cancer using the body’s immune system,” said Dr. Mukherjee in a written statement announcing the partnership. “The positive clinical response researchers have achieved with CAR T-cell therapies in B-cell leukemias has led to great interest within the oncology community and is something we hope to achieve in other cancers over time,” he said.

“CAR T-cell therapies have shown remarkable progress in the clinic, yet their applicability beyond a small subset of cancers is currently very limited,” said Dr. Sanjiv Sam Gambhir of Stanford University and a member of the Vor Scientific Advisory Board. “This technology seeks to address bottlenecks that prevent CAR T-cell therapy from becoming more broadly useful in treating cancers outside of B-cell cancers.”

Other Vor BioPharma employees and Scientific Advisory Board members include Dr. Joseph Bolen, former President and Chief Scientific Officer of Moderna Therapeutics; Dr. Dan Littman of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute; and Dr. Derrick Rossi of Harvard University.

On Twitter @jess_craig94

Dr. Siddhartha Mukherjee has partnered with Puretech Health to launch a new biotechnology and immuno-oncology company to broaden the use of chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy. Dr. Mukherjee, a Columbia University researcher, hematologist, oncologist, and Pulitzer Prize–winning author of “The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of Cancer,” (New York: Scribner, a division of Simon & Schuster, 2011) is licensing his CAR T-cell technology to the joint venture, called Vor BioPharma.

Vor BioPharma will focus on advancing and expanding CAR T-cell therapy, a relatively new cancer treatment where T cells are first collected from a patient’s blood and then genetically engineered to produce CAR proteins on their surface. The CAR proteins are designed to bind specific antigens found on the patient’s cancer cells. These genetically engineered T cells are grown in a laboratory and then infused into the patient. As of now, CAR T-cell therapy is primarily used to treat B-cell leukemias and other chronic lymphocytic leukemia.

“We continue to make great strides in developing new ways to treat cancer using the body’s immune system,” said Dr. Mukherjee in a written statement announcing the partnership. “The positive clinical response researchers have achieved with CAR T-cell therapies in B-cell leukemias has led to great interest within the oncology community and is something we hope to achieve in other cancers over time,” he said.

“CAR T-cell therapies have shown remarkable progress in the clinic, yet their applicability beyond a small subset of cancers is currently very limited,” said Dr. Sanjiv Sam Gambhir of Stanford University and a member of the Vor Scientific Advisory Board. “This technology seeks to address bottlenecks that prevent CAR T-cell therapy from becoming more broadly useful in treating cancers outside of B-cell cancers.”

Other Vor BioPharma employees and Scientific Advisory Board members include Dr. Joseph Bolen, former President and Chief Scientific Officer of Moderna Therapeutics; Dr. Dan Littman of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute; and Dr. Derrick Rossi of Harvard University.

On Twitter @jess_craig94

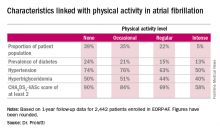

Exercise is protective but underutilized in atrial fib patients

CHICAGO – Efforts to encourage even modest amounts of physical activity in sedentary patients with atrial fibrillation are likely to pay off in reduced risks of cardiovascular and all-cause mortality, according to a report from the EurObservational Research Program Pilot Survey on Atrial Fibrillation General Registry.

“Clearly we would recommend regular physical activity for patients with atrial fibrillation on the basis of the mortality benefit we see in the registry. If we give patients with atrial fibrillation oral anticoagulation, they are protected against stroke risk, but clearly they are still dying a lot,” Dr. Marco Proietti said at the annual meeting of the American College of Cardiology.

He presented 1-year follow-up data on 2,442 “real world” patients enrolled in the nine-country, observational, prospective registry, known as EORP-AF, shortly after being diagnosed with AF. One of the goals of EORP-AF is to learn whether physical exercise protects against cardiovascular events and all-cause mortality in AF patients, as has been well established in the general population and in patients at high cardiovascular risk.

One striking finding was that nearly 40% of patients in EORP-AF reported engaging in no physical activity, defined for study purposes as zero to less than 3 hours of physical activity per week for less than 2 years.

The other three categories employed by investigators were “occasional,” meaning less than 3 hours per week but for 2 years or more; “regular,” defined as at least 3 hours weekly for at least 2 years; and “intense,” which required more than 7 hours of physical activity per week for at least 2 years. Levels of cardiovascular and stroke risk factors decreased progressively with increasing levels of physical activity. Only 5% of the AF patients met the ‘intense’ standard, noted Dr. Proietti of the University of Birmingham (England).

The 1-year cardiovascular mortality rate approached 6% in the no physical activity group and hovered around 1% in the other three groups. The 1-year all-cause mortality rate exceeded 12% in the no-exercise group, was 4%% in the occasional exercisers, and 1%-2% in the groups reporting regular or intense physical activity.

The 1-year composite endpoint of cardiovascular death, any thromboembolism, or a bleeding event occurred in 12% of the sedentary patients, a rate two-to-three times higher than in the others.

Updated outcomes are to be reported from the EORP-AF pilot registry after 2 and 3 years of follow-up. Meanwhile, on the basis of the success of the pilot registry, more than 10,000 patients with AF have been enrolled in the EORP-AF main registry, according to Dr. Proietti.

A study limitation, he conceded, is that the registry includes no objective measure of physical capacity, such as METS.

Session co-chair Dr. Brian Olshansky, emeritus professor of internal medicine at the University of Iowa, Iowa City, observed that the registry data raise a classic chicken-versus-egg issue: Do the sedentary patients do worse because they’re inactive, or are they inactive because they are sicker and hence have worse outcomes?

Dr. Proietti said the registry data provide some support for the latter idea, since the no-physical-activity group had higher prevalences of coronary artery disease and heart failure.

Dr. Olshansky raised another point: “It’s interesting to me that there’s a whole bunch of literature showing that elite endurance athletes – bike racers, cross country skiers – have a very high incidence of atrial fibrillation. It seems to be either an inflammatory or an autonomic issue.”

Dr. Proietti replied that he’s familiar with that extensive literature, but the EORP-AF data through 1 year don’t provide validation. While the intense physical activity group tended to have more symptomatic AF than the other groups, they were no more likely to show progression from paroxysmal to permanent AF. The much larger main registry now underway may be able to better clarify the relationship between physical activity and incidence and progression of AF, including the possibility of a U-shaped dose-response curve.

The EORP-AF registry is supported by the European Society of Cardiology. Dr. Proietti reported having no financial conflicts of interest.

CHICAGO – Efforts to encourage even modest amounts of physical activity in sedentary patients with atrial fibrillation are likely to pay off in reduced risks of cardiovascular and all-cause mortality, according to a report from the EurObservational Research Program Pilot Survey on Atrial Fibrillation General Registry.

“Clearly we would recommend regular physical activity for patients with atrial fibrillation on the basis of the mortality benefit we see in the registry. If we give patients with atrial fibrillation oral anticoagulation, they are protected against stroke risk, but clearly they are still dying a lot,” Dr. Marco Proietti said at the annual meeting of the American College of Cardiology.

He presented 1-year follow-up data on 2,442 “real world” patients enrolled in the nine-country, observational, prospective registry, known as EORP-AF, shortly after being diagnosed with AF. One of the goals of EORP-AF is to learn whether physical exercise protects against cardiovascular events and all-cause mortality in AF patients, as has been well established in the general population and in patients at high cardiovascular risk.

One striking finding was that nearly 40% of patients in EORP-AF reported engaging in no physical activity, defined for study purposes as zero to less than 3 hours of physical activity per week for less than 2 years.

The other three categories employed by investigators were “occasional,” meaning less than 3 hours per week but for 2 years or more; “regular,” defined as at least 3 hours weekly for at least 2 years; and “intense,” which required more than 7 hours of physical activity per week for at least 2 years. Levels of cardiovascular and stroke risk factors decreased progressively with increasing levels of physical activity. Only 5% of the AF patients met the ‘intense’ standard, noted Dr. Proietti of the University of Birmingham (England).

The 1-year cardiovascular mortality rate approached 6% in the no physical activity group and hovered around 1% in the other three groups. The 1-year all-cause mortality rate exceeded 12% in the no-exercise group, was 4%% in the occasional exercisers, and 1%-2% in the groups reporting regular or intense physical activity.

The 1-year composite endpoint of cardiovascular death, any thromboembolism, or a bleeding event occurred in 12% of the sedentary patients, a rate two-to-three times higher than in the others.

Updated outcomes are to be reported from the EORP-AF pilot registry after 2 and 3 years of follow-up. Meanwhile, on the basis of the success of the pilot registry, more than 10,000 patients with AF have been enrolled in the EORP-AF main registry, according to Dr. Proietti.

A study limitation, he conceded, is that the registry includes no objective measure of physical capacity, such as METS.

Session co-chair Dr. Brian Olshansky, emeritus professor of internal medicine at the University of Iowa, Iowa City, observed that the registry data raise a classic chicken-versus-egg issue: Do the sedentary patients do worse because they’re inactive, or are they inactive because they are sicker and hence have worse outcomes?

Dr. Proietti said the registry data provide some support for the latter idea, since the no-physical-activity group had higher prevalences of coronary artery disease and heart failure.

Dr. Olshansky raised another point: “It’s interesting to me that there’s a whole bunch of literature showing that elite endurance athletes – bike racers, cross country skiers – have a very high incidence of atrial fibrillation. It seems to be either an inflammatory or an autonomic issue.”

Dr. Proietti replied that he’s familiar with that extensive literature, but the EORP-AF data through 1 year don’t provide validation. While the intense physical activity group tended to have more symptomatic AF than the other groups, they were no more likely to show progression from paroxysmal to permanent AF. The much larger main registry now underway may be able to better clarify the relationship between physical activity and incidence and progression of AF, including the possibility of a U-shaped dose-response curve.

The EORP-AF registry is supported by the European Society of Cardiology. Dr. Proietti reported having no financial conflicts of interest.

CHICAGO – Efforts to encourage even modest amounts of physical activity in sedentary patients with atrial fibrillation are likely to pay off in reduced risks of cardiovascular and all-cause mortality, according to a report from the EurObservational Research Program Pilot Survey on Atrial Fibrillation General Registry.

“Clearly we would recommend regular physical activity for patients with atrial fibrillation on the basis of the mortality benefit we see in the registry. If we give patients with atrial fibrillation oral anticoagulation, they are protected against stroke risk, but clearly they are still dying a lot,” Dr. Marco Proietti said at the annual meeting of the American College of Cardiology.

He presented 1-year follow-up data on 2,442 “real world” patients enrolled in the nine-country, observational, prospective registry, known as EORP-AF, shortly after being diagnosed with AF. One of the goals of EORP-AF is to learn whether physical exercise protects against cardiovascular events and all-cause mortality in AF patients, as has been well established in the general population and in patients at high cardiovascular risk.

One striking finding was that nearly 40% of patients in EORP-AF reported engaging in no physical activity, defined for study purposes as zero to less than 3 hours of physical activity per week for less than 2 years.

The other three categories employed by investigators were “occasional,” meaning less than 3 hours per week but for 2 years or more; “regular,” defined as at least 3 hours weekly for at least 2 years; and “intense,” which required more than 7 hours of physical activity per week for at least 2 years. Levels of cardiovascular and stroke risk factors decreased progressively with increasing levels of physical activity. Only 5% of the AF patients met the ‘intense’ standard, noted Dr. Proietti of the University of Birmingham (England).

The 1-year cardiovascular mortality rate approached 6% in the no physical activity group and hovered around 1% in the other three groups. The 1-year all-cause mortality rate exceeded 12% in the no-exercise group, was 4%% in the occasional exercisers, and 1%-2% in the groups reporting regular or intense physical activity.

The 1-year composite endpoint of cardiovascular death, any thromboembolism, or a bleeding event occurred in 12% of the sedentary patients, a rate two-to-three times higher than in the others.

Updated outcomes are to be reported from the EORP-AF pilot registry after 2 and 3 years of follow-up. Meanwhile, on the basis of the success of the pilot registry, more than 10,000 patients with AF have been enrolled in the EORP-AF main registry, according to Dr. Proietti.

A study limitation, he conceded, is that the registry includes no objective measure of physical capacity, such as METS.

Session co-chair Dr. Brian Olshansky, emeritus professor of internal medicine at the University of Iowa, Iowa City, observed that the registry data raise a classic chicken-versus-egg issue: Do the sedentary patients do worse because they’re inactive, or are they inactive because they are sicker and hence have worse outcomes?

Dr. Proietti said the registry data provide some support for the latter idea, since the no-physical-activity group had higher prevalences of coronary artery disease and heart failure.

Dr. Olshansky raised another point: “It’s interesting to me that there’s a whole bunch of literature showing that elite endurance athletes – bike racers, cross country skiers – have a very high incidence of atrial fibrillation. It seems to be either an inflammatory or an autonomic issue.”

Dr. Proietti replied that he’s familiar with that extensive literature, but the EORP-AF data through 1 year don’t provide validation. While the intense physical activity group tended to have more symptomatic AF than the other groups, they were no more likely to show progression from paroxysmal to permanent AF. The much larger main registry now underway may be able to better clarify the relationship between physical activity and incidence and progression of AF, including the possibility of a U-shaped dose-response curve.

The EORP-AF registry is supported by the European Society of Cardiology. Dr. Proietti reported having no financial conflicts of interest.

AT ACC 16

Key clinical point: Atrial fibrillation patients who report engaging in even occasional physical activity have a markedly lower risk of all-cause mortality than those who are sedentary.

Major finding: The 1-year composite outcome of cardiovascular death, any thromboembolism, or a bleeding event occurred in 12% in patients with atrial fibrillation who were sedentary, a rate two to three times greater than in those who engaged in various amounts of physical activity.

Data source: An analysis of 1-year outcomes in 2,442 patients with AF enrolled in the prospective, observational EORP-AF pilot registry.

Disclosures: The EORP-AF registry is supported by the European Society of Cardiology. The presenter reported having no financial conflicts of interest.

Optimal timing of CRC postop colonoscopy studied

LOS ANGELES – The detection rate of significant polyps was highest for the first postoperative surveillance colonoscopies performed at 1 year following curative resection for colorectal cancer, results from a single-center study demonstrated.

“There’s no consensus on when to perform the first surveillance colonoscopy post curative resection for colorectal cancer,” lead study author Dr. Noura Alhassan said at the annual meeting of the American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons. For example, the American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons and National Carcinoma Comprehensive Network guidelines recommend a colonoscopy at 1 year, while the Canadian Association of Gastroenterology recommends surveillance at 3 years postoperatively.

In an effort to determine the optimal timing of the first surveillance colonoscopy following curative colorectal carcinoma resection, Dr. Alhassan and her associates retrospectively reviewed the charts of all patients who underwent colorectal resection from 2007 to 2012 at Jewish General Hospital, a tertiary care center affiliated with McGill University, Montreal. The study included patients who had a complete preoperative colonoscopy, those who had a complete postoperative colonoscopy performed by one of the Jewish General Hospital colorectal surgeons, and those who had colorectal cancer resection with curative intent. Excluded from the study were patients with stage IV colorectal cancer, those with a prior history of colorectal cancer, those who underwent total abdominal colectomies or proctocolectomies, those who underwent local excision, and those with familial cancer syndromes and inflammatory bowel disease.

Dr. Alhassan, a fourth-year resident in the division of general surgery at McGill University, said that the researchers classified the colonoscopic findings as normal, nonsignificant polyps, significant polyps, and recurrence. Significant polyps consisted of adenomas 1 cm or greater in size, villous or tubulovillous adenoma, adenoma with high-grade dysplasia, three or more adenomas, or sessile serrated polyps at least 1 cm in size or with dysplasia. Of the 857 colorectal resections performed during the study period, 181 met inclusion criteria. The tumor stage was evenly distributed among study participants and 57% of the resections were colon operations, while the remaining 43% were proctectomies.

The preoperative colonoscopy was done by one of the Jewish General Hospital gastroenterologists 43% of the time, by one of the Jewish General Hospital colorectal surgeons 41% of the time, and by an outside hospital 16% of the time. The median time to postoperative colonoscopy was 421 days (1.1 years). Specifically, 25.90% of patients underwent their first surveillance colonoscopy in the first postoperative year, 48.10% in the second year, 14.40% in the third year, 8.5% in the fourth year, and 2.7% in the fifth year.

Dr. Alhassan reported that the all-polyp detection rate was 30.1%; 21.3% were detected in postoperative year 1, 33.3% in year 2, and 34.6% in year 3.

The overall significant polyp detection rate was 10.5%, but the detection rate was 12.8% in postoperative year 1, 8% in postoperative year 2, and 7.7% in postoperative year 3. There were two anastomotic recurrences: one in year 1 (2.1%) and one in year 3 (3.8%).

On univariate analysis, factors associated with significant polyp detection were male gender, poor bowel preparation on preoperative colonoscopy, and concomitant use of metformin, while having stage III disease was associated with a lower significant polyp detection rate.

On multivariate analysis only male gender was associated with a higher significant polyp detection rate, while stage III disease was associated with a lower significant polyp detection rate.

“Significant polyp detection rate of 12.8% at postoperative year 1 justifies surveillance colonoscopy at 1 year post curative colon cancer resection,” Dr. Alhassan concluded. She reported having no financial disclosures.

LOS ANGELES – The detection rate of significant polyps was highest for the first postoperative surveillance colonoscopies performed at 1 year following curative resection for colorectal cancer, results from a single-center study demonstrated.

“There’s no consensus on when to perform the first surveillance colonoscopy post curative resection for colorectal cancer,” lead study author Dr. Noura Alhassan said at the annual meeting of the American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons. For example, the American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons and National Carcinoma Comprehensive Network guidelines recommend a colonoscopy at 1 year, while the Canadian Association of Gastroenterology recommends surveillance at 3 years postoperatively.

In an effort to determine the optimal timing of the first surveillance colonoscopy following curative colorectal carcinoma resection, Dr. Alhassan and her associates retrospectively reviewed the charts of all patients who underwent colorectal resection from 2007 to 2012 at Jewish General Hospital, a tertiary care center affiliated with McGill University, Montreal. The study included patients who had a complete preoperative colonoscopy, those who had a complete postoperative colonoscopy performed by one of the Jewish General Hospital colorectal surgeons, and those who had colorectal cancer resection with curative intent. Excluded from the study were patients with stage IV colorectal cancer, those with a prior history of colorectal cancer, those who underwent total abdominal colectomies or proctocolectomies, those who underwent local excision, and those with familial cancer syndromes and inflammatory bowel disease.

Dr. Alhassan, a fourth-year resident in the division of general surgery at McGill University, said that the researchers classified the colonoscopic findings as normal, nonsignificant polyps, significant polyps, and recurrence. Significant polyps consisted of adenomas 1 cm or greater in size, villous or tubulovillous adenoma, adenoma with high-grade dysplasia, three or more adenomas, or sessile serrated polyps at least 1 cm in size or with dysplasia. Of the 857 colorectal resections performed during the study period, 181 met inclusion criteria. The tumor stage was evenly distributed among study participants and 57% of the resections were colon operations, while the remaining 43% were proctectomies.

The preoperative colonoscopy was done by one of the Jewish General Hospital gastroenterologists 43% of the time, by one of the Jewish General Hospital colorectal surgeons 41% of the time, and by an outside hospital 16% of the time. The median time to postoperative colonoscopy was 421 days (1.1 years). Specifically, 25.90% of patients underwent their first surveillance colonoscopy in the first postoperative year, 48.10% in the second year, 14.40% in the third year, 8.5% in the fourth year, and 2.7% in the fifth year.

Dr. Alhassan reported that the all-polyp detection rate was 30.1%; 21.3% were detected in postoperative year 1, 33.3% in year 2, and 34.6% in year 3.

The overall significant polyp detection rate was 10.5%, but the detection rate was 12.8% in postoperative year 1, 8% in postoperative year 2, and 7.7% in postoperative year 3. There were two anastomotic recurrences: one in year 1 (2.1%) and one in year 3 (3.8%).

On univariate analysis, factors associated with significant polyp detection were male gender, poor bowel preparation on preoperative colonoscopy, and concomitant use of metformin, while having stage III disease was associated with a lower significant polyp detection rate.

On multivariate analysis only male gender was associated with a higher significant polyp detection rate, while stage III disease was associated with a lower significant polyp detection rate.

“Significant polyp detection rate of 12.8% at postoperative year 1 justifies surveillance colonoscopy at 1 year post curative colon cancer resection,” Dr. Alhassan concluded. She reported having no financial disclosures.

LOS ANGELES – The detection rate of significant polyps was highest for the first postoperative surveillance colonoscopies performed at 1 year following curative resection for colorectal cancer, results from a single-center study demonstrated.

“There’s no consensus on when to perform the first surveillance colonoscopy post curative resection for colorectal cancer,” lead study author Dr. Noura Alhassan said at the annual meeting of the American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons. For example, the American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons and National Carcinoma Comprehensive Network guidelines recommend a colonoscopy at 1 year, while the Canadian Association of Gastroenterology recommends surveillance at 3 years postoperatively.

In an effort to determine the optimal timing of the first surveillance colonoscopy following curative colorectal carcinoma resection, Dr. Alhassan and her associates retrospectively reviewed the charts of all patients who underwent colorectal resection from 2007 to 2012 at Jewish General Hospital, a tertiary care center affiliated with McGill University, Montreal. The study included patients who had a complete preoperative colonoscopy, those who had a complete postoperative colonoscopy performed by one of the Jewish General Hospital colorectal surgeons, and those who had colorectal cancer resection with curative intent. Excluded from the study were patients with stage IV colorectal cancer, those with a prior history of colorectal cancer, those who underwent total abdominal colectomies or proctocolectomies, those who underwent local excision, and those with familial cancer syndromes and inflammatory bowel disease.

Dr. Alhassan, a fourth-year resident in the division of general surgery at McGill University, said that the researchers classified the colonoscopic findings as normal, nonsignificant polyps, significant polyps, and recurrence. Significant polyps consisted of adenomas 1 cm or greater in size, villous or tubulovillous adenoma, adenoma with high-grade dysplasia, three or more adenomas, or sessile serrated polyps at least 1 cm in size or with dysplasia. Of the 857 colorectal resections performed during the study period, 181 met inclusion criteria. The tumor stage was evenly distributed among study participants and 57% of the resections were colon operations, while the remaining 43% were proctectomies.

The preoperative colonoscopy was done by one of the Jewish General Hospital gastroenterologists 43% of the time, by one of the Jewish General Hospital colorectal surgeons 41% of the time, and by an outside hospital 16% of the time. The median time to postoperative colonoscopy was 421 days (1.1 years). Specifically, 25.90% of patients underwent their first surveillance colonoscopy in the first postoperative year, 48.10% in the second year, 14.40% in the third year, 8.5% in the fourth year, and 2.7% in the fifth year.

Dr. Alhassan reported that the all-polyp detection rate was 30.1%; 21.3% were detected in postoperative year 1, 33.3% in year 2, and 34.6% in year 3.

The overall significant polyp detection rate was 10.5%, but the detection rate was 12.8% in postoperative year 1, 8% in postoperative year 2, and 7.7% in postoperative year 3. There were two anastomotic recurrences: one in year 1 (2.1%) and one in year 3 (3.8%).

On univariate analysis, factors associated with significant polyp detection were male gender, poor bowel preparation on preoperative colonoscopy, and concomitant use of metformin, while having stage III disease was associated with a lower significant polyp detection rate.

On multivariate analysis only male gender was associated with a higher significant polyp detection rate, while stage III disease was associated with a lower significant polyp detection rate.

“Significant polyp detection rate of 12.8% at postoperative year 1 justifies surveillance colonoscopy at 1 year post curative colon cancer resection,” Dr. Alhassan concluded. She reported having no financial disclosures.

AT THE ASCRS ANNUAL MEETING

Key clinical point: The highest proportion of significant polyps on surveillance colonoscopy after curative resection was detected in postoperative year 1.

Major finding: The overall significant polyp detection rate was 10.5%, but 12.8% were detected in postoperative year 1, 8% in postoperative year 2, and 7.7% in postoperative year 3.

Data source: A retrospective study of 181 patients who underwent colorectal resection from 2007 to 2012 at Jewish General Hospital, Montreal.

Disclosures: Dr. Alhassan reported having no financial disclosures.

Anticoagulation therapy after VT ablation yields fewer thrombotic events

San Francisco – Anticoagulation therapy is probably a good idea after ventricular tachycardia ablation in patients with risk factors or stroke, even if they don’t have atrial fibrillation, according to investigators from the University of Kansas Medical Center in Kansas City.

The advice comes from a review of 2,235 ventricular tachycardia (VT) ablation cases from the university and other members of the International VT Ablation Center Collaborative; about a quarter of the patients (604) were prescribed oral anticoagulation therapy at baseline and at discharge, nearly all for atrial fibrillation (AF) and most with warfarin. Over the next year, just 0.3% (2) had a subsequent thromboembolic complication, one of which was an ischemic stroke.

The remaining patients (1,631) did not have a diagnosis of AF and were not on anticoagulants at baseline or after discharge. They were more likely to have New York Heart Association class I or II heart failure and higher ejection fractions, and to otherwise be in better shape compared with the patients who received anticoagulation therapy. Even so, within a year, 1.3% (21) had a thromboembolic event, almost half of which were ischemic strokes, a substantial increase in relative risk (P = .05).

Maybe those patients had undiagnosed AF at baseline, or perhaps a clot formed over the ablation scar, Dr. Rizwan Afzal said at the annual scientific sessions of the Heart Rhythm Society. Regardless, “this observation has changed our practice. If VT ablation patients have low ejection fractions, if they’re elderly, or have other risk factors for stroke, we put them on blood thinners [afterward] “even if they don’t have atrial fibrillation. We are not sure how long they should be on anticoagulation [therapy] to counteract the increased risk of stroke,” but probably at least for a few weeks, he said.

Dr. Afzal and his colleagues generally opt for warfarin; the use is off label for newer oral anticoagulants, and a tough sell to insurance companies.

There were no predictors of increased thromboembolic risk in the group that was not on anticoagulation therapy. During follow-up, about 2.2% (13) of patients on anticoagulation therapy had bleeding complications, including one intracranial hemorrhage, compared with 2.5% (41) of the patients not treated with an anticoagulant; most of them were on aspirin after the procedure, and the rest were on dual antiplatelet therapy (P = .7), reported Dr. Afzal, a cardiology fellow at the University of Kansas.

The median age of the study patients was 65 years, and 87% were men. In the group on anticoagulation therapy, the mean baseline left ventricular ejection fraction was 31%; 35% had prior cardiac surgery, 29% were on cardiac resynchronization therapy, and 44% had NYHA class III or IV heart failure. The mean baseline ejection fraction among patients who were not on anticoagulation therapy was 35%; 29% had prior heart surgery, 24% were on CRT, and 32.5% had NYHA class III or IV heart failure.

There was no industry funding for the work, and the investigators had no disclosures.

San Francisco – Anticoagulation therapy is probably a good idea after ventricular tachycardia ablation in patients with risk factors or stroke, even if they don’t have atrial fibrillation, according to investigators from the University of Kansas Medical Center in Kansas City.

The advice comes from a review of 2,235 ventricular tachycardia (VT) ablation cases from the university and other members of the International VT Ablation Center Collaborative; about a quarter of the patients (604) were prescribed oral anticoagulation therapy at baseline and at discharge, nearly all for atrial fibrillation (AF) and most with warfarin. Over the next year, just 0.3% (2) had a subsequent thromboembolic complication, one of which was an ischemic stroke.

The remaining patients (1,631) did not have a diagnosis of AF and were not on anticoagulants at baseline or after discharge. They were more likely to have New York Heart Association class I or II heart failure and higher ejection fractions, and to otherwise be in better shape compared with the patients who received anticoagulation therapy. Even so, within a year, 1.3% (21) had a thromboembolic event, almost half of which were ischemic strokes, a substantial increase in relative risk (P = .05).

Maybe those patients had undiagnosed AF at baseline, or perhaps a clot formed over the ablation scar, Dr. Rizwan Afzal said at the annual scientific sessions of the Heart Rhythm Society. Regardless, “this observation has changed our practice. If VT ablation patients have low ejection fractions, if they’re elderly, or have other risk factors for stroke, we put them on blood thinners [afterward] “even if they don’t have atrial fibrillation. We are not sure how long they should be on anticoagulation [therapy] to counteract the increased risk of stroke,” but probably at least for a few weeks, he said.

Dr. Afzal and his colleagues generally opt for warfarin; the use is off label for newer oral anticoagulants, and a tough sell to insurance companies.

There were no predictors of increased thromboembolic risk in the group that was not on anticoagulation therapy. During follow-up, about 2.2% (13) of patients on anticoagulation therapy had bleeding complications, including one intracranial hemorrhage, compared with 2.5% (41) of the patients not treated with an anticoagulant; most of them were on aspirin after the procedure, and the rest were on dual antiplatelet therapy (P = .7), reported Dr. Afzal, a cardiology fellow at the University of Kansas.

The median age of the study patients was 65 years, and 87% were men. In the group on anticoagulation therapy, the mean baseline left ventricular ejection fraction was 31%; 35% had prior cardiac surgery, 29% were on cardiac resynchronization therapy, and 44% had NYHA class III or IV heart failure. The mean baseline ejection fraction among patients who were not on anticoagulation therapy was 35%; 29% had prior heart surgery, 24% were on CRT, and 32.5% had NYHA class III or IV heart failure.

There was no industry funding for the work, and the investigators had no disclosures.

San Francisco – Anticoagulation therapy is probably a good idea after ventricular tachycardia ablation in patients with risk factors or stroke, even if they don’t have atrial fibrillation, according to investigators from the University of Kansas Medical Center in Kansas City.

The advice comes from a review of 2,235 ventricular tachycardia (VT) ablation cases from the university and other members of the International VT Ablation Center Collaborative; about a quarter of the patients (604) were prescribed oral anticoagulation therapy at baseline and at discharge, nearly all for atrial fibrillation (AF) and most with warfarin. Over the next year, just 0.3% (2) had a subsequent thromboembolic complication, one of which was an ischemic stroke.

The remaining patients (1,631) did not have a diagnosis of AF and were not on anticoagulants at baseline or after discharge. They were more likely to have New York Heart Association class I or II heart failure and higher ejection fractions, and to otherwise be in better shape compared with the patients who received anticoagulation therapy. Even so, within a year, 1.3% (21) had a thromboembolic event, almost half of which were ischemic strokes, a substantial increase in relative risk (P = .05).

Maybe those patients had undiagnosed AF at baseline, or perhaps a clot formed over the ablation scar, Dr. Rizwan Afzal said at the annual scientific sessions of the Heart Rhythm Society. Regardless, “this observation has changed our practice. If VT ablation patients have low ejection fractions, if they’re elderly, or have other risk factors for stroke, we put them on blood thinners [afterward] “even if they don’t have atrial fibrillation. We are not sure how long they should be on anticoagulation [therapy] to counteract the increased risk of stroke,” but probably at least for a few weeks, he said.

Dr. Afzal and his colleagues generally opt for warfarin; the use is off label for newer oral anticoagulants, and a tough sell to insurance companies.

There were no predictors of increased thromboembolic risk in the group that was not on anticoagulation therapy. During follow-up, about 2.2% (13) of patients on anticoagulation therapy had bleeding complications, including one intracranial hemorrhage, compared with 2.5% (41) of the patients not treated with an anticoagulant; most of them were on aspirin after the procedure, and the rest were on dual antiplatelet therapy (P = .7), reported Dr. Afzal, a cardiology fellow at the University of Kansas.

The median age of the study patients was 65 years, and 87% were men. In the group on anticoagulation therapy, the mean baseline left ventricular ejection fraction was 31%; 35% had prior cardiac surgery, 29% were on cardiac resynchronization therapy, and 44% had NYHA class III or IV heart failure. The mean baseline ejection fraction among patients who were not on anticoagulation therapy was 35%; 29% had prior heart surgery, 24% were on CRT, and 32.5% had NYHA class III or IV heart failure.

There was no industry funding for the work, and the investigators had no disclosures.

AT HEART RHYTHM 2016

Key clinical point: Anticoagulant therapy may be a good idea after ventricular tachycardia ablation in patients with risk factors for stroke, even if they don’t have atrial fibrillation.

Major finding: About 0.3% of patients on oral anticoagulant therapy after VT ablation had a thromboembolic event within a year, compared with 1.3% of those who were not on such therapy.

Data source: Review of 2,245 VT ablation cases.

Disclosures: There was no industry funding for the work, and the investigators had no disclosures.

Low vasculitis risk with TNF inhibitors

GLASGOW – Treatment with tumor necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitors for rheumatoid arthritis is associated with a low risk of vasculitis-like events, according to a large analysis of data from the United Kingdom.

Investigators using data from the British Society for Rheumatology Biologics Register for Rheumatoid Arthritis (BSRBR-RA) found that the crude incidence rate was 16 cases per 10,000 person-years among TNF-inhibitor users versus seven cases per 10,000 person-years among users of nonbiologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (nbDMARDs) such as methotrexate and sulfasalazine.

Although the risk was slightly higher among anti-TNF than nbDMARD users, the propensity score fully adjusted hazard ratio for a first vasculitis-like event was 1.27, comparing the anti-TNF drugs with nbDMARDs, with a 95% confidence interval of 0.40-4.04.

“This is the first prospective observational study to systematically look at the risk of vasculitis-like events” in patients with RA treated with anti-TNF agents, Dr. Meghna Jani said at the British Society for Rheumatology annual conference.

Dr. Jani of the Arthritis Research UK Centre for Epidemiology at the University of Manchester (England) explained that the reason for looking at this topic was that vasculitis-like events had been reported in case series and single-center studies, but these prior reports were too small to be able to estimate exactly how big a problem this was.

“Anti-TNF agents are associated with the development of a number of autoantibodies, including antinuclear antibodies and antidrug antibodies, and ANCA [antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody],” she observed.

“We know that a small proportion of these patients may then go on to develop autoimmune diseases, some independent of autoantibodies,” she added. The most common of these is vasculitis, including cutaneous vasculitis.

Vasculitis is a somewhat paradoxical adverse event, she noted, in that it has been associated with anti-TNF therapy, but these drugs can also be used to treat it.

Now in its 15th year, the BSRBR-RA is the largest ongoing cohort of patients treated with biologic agents for rheumatic disease and provides one of the best sources of data to examine the risk for vasculitis-like events Dr. Jani observed. The aims were to look at the respective risks as well as to see if there were any particular predictive factors.

The current analysis included more than 16,000 patients enrolled in the BSRBR-RA between 2001 and 2015, of whom 12,745 were newly started on an anti-TNF drug and 3,640 were receiving nbDMARDs and were also biologic naive. The mean age of patients in the two groups was 56 and 60 years, 76% and 72% were female, with a mean Disease Activity Score (DAS28) of 6.5 and 5.1 and median disease duration of 11 and 6 years, respectively.

After more than 52,428 person-years of exposure and a median of 5.1 years of follow-up, 81 vasculitis-like events occurred in the anti-TNF therapy group. Vasculitis-like events were attributed to treatment only if they had occurred within 90 days of starting the drug. Follow-up stopped after a first event; if there was a switch to another biologic drug; and at death, the last clinical follow-up, or the end of the analysis period (May 31, 2015).

In comparison, there were 20,635 person-years of exposure and 6.5 years’ follow-up in the nbDMARD group, with 14 vasculitis-like events reported during this time.

A sensitivity analysis was performed excluding patients who had nail-fold vasculitis at baseline, had vasculitis due to a possible secondary cause such as infection, and were taking any other medications associated with vasculitis-like events. Results showed a similar risk for a first vasculitis event between anti-TNF and nbDMARD users (aHR = 1.05; 95% CI, 0.32-3.45).

Looking at the risk of vasculitis events for individual anti-TNF drugs, there initially appeared to be a higher risk for patients taking infliximab (n = 3,292) and etanercept (n = 4,450) but not for those taking adalimumab (n = 4,312) versus nbDMARDs, with crude incidence rates of 10, 17, and 11 per 10,000 person-years; after adjustment, these differences were not significant (aHRs of 1.55, 1.72, and 0.77, respectively, with 95% CIs crossing 1.0). A crude rate for certolizumab could not be calculated as there were no vasculitis events reported but there were only 691 patients enrolled in the BSRBR-RA at the time of the analysis who had been exposed to the drug.

“The risk of the event was highest in the first year of treatment, followed by reduction over time,” Dr. Jani reported. “Reassuringly, up to two-thirds of patients in both cohorts had manifestations that were just limited to cutaneous involvement,” she said.

The most common systemic presentation was digital ischemia, affecting 14% of patients treated with anti-TNFs and 14% of those given nbDMARDs. Neurologic involvement was also seen in both groups of patients (7% vs. 7%), but new nail-fold vasculitis (17% vs. 0%), respiratory involvement (4% vs. 0%), associated thrombotic events (5% vs. 0%), and renal involvement (2.5% vs. 0%) were seen in TNF inhibitor-treated patients only.

Ten anti-TNF–treated patients and one nbDMARD-treated patient needed treatment for the vasculitis-like event, and three patients in the anti-TNF cohort died as a result of the event, all of whom had multisystem organ involvement and one of whom had cytoplasmic ANCA-positive vasculitis.

Treatment with methotrexate or sulfasalazine at baseline was associated with a lower risk for vasculitis-like events, while seropositive status, disease duration, DAS28, and HAQ scores were associated with an increased risk for such events.

The BSRBR-RA receives restricted income financial support from Abbvie, Amgen, Swedish Orphan Biovitram (SOBI), Merck, Pfizer, Roche, and UCB Pharma. Dr. Jani disclosed she has received honoraria from Pfizer, Abbvie, and UCB Pharma.

GLASGOW – Treatment with tumor necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitors for rheumatoid arthritis is associated with a low risk of vasculitis-like events, according to a large analysis of data from the United Kingdom.

Investigators using data from the British Society for Rheumatology Biologics Register for Rheumatoid Arthritis (BSRBR-RA) found that the crude incidence rate was 16 cases per 10,000 person-years among TNF-inhibitor users versus seven cases per 10,000 person-years among users of nonbiologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (nbDMARDs) such as methotrexate and sulfasalazine.

Although the risk was slightly higher among anti-TNF than nbDMARD users, the propensity score fully adjusted hazard ratio for a first vasculitis-like event was 1.27, comparing the anti-TNF drugs with nbDMARDs, with a 95% confidence interval of 0.40-4.04.

“This is the first prospective observational study to systematically look at the risk of vasculitis-like events” in patients with RA treated with anti-TNF agents, Dr. Meghna Jani said at the British Society for Rheumatology annual conference.

Dr. Jani of the Arthritis Research UK Centre for Epidemiology at the University of Manchester (England) explained that the reason for looking at this topic was that vasculitis-like events had been reported in case series and single-center studies, but these prior reports were too small to be able to estimate exactly how big a problem this was.

“Anti-TNF agents are associated with the development of a number of autoantibodies, including antinuclear antibodies and antidrug antibodies, and ANCA [antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody],” she observed.

“We know that a small proportion of these patients may then go on to develop autoimmune diseases, some independent of autoantibodies,” she added. The most common of these is vasculitis, including cutaneous vasculitis.

Vasculitis is a somewhat paradoxical adverse event, she noted, in that it has been associated with anti-TNF therapy, but these drugs can also be used to treat it.

Now in its 15th year, the BSRBR-RA is the largest ongoing cohort of patients treated with biologic agents for rheumatic disease and provides one of the best sources of data to examine the risk for vasculitis-like events Dr. Jani observed. The aims were to look at the respective risks as well as to see if there were any particular predictive factors.

The current analysis included more than 16,000 patients enrolled in the BSRBR-RA between 2001 and 2015, of whom 12,745 were newly started on an anti-TNF drug and 3,640 were receiving nbDMARDs and were also biologic naive. The mean age of patients in the two groups was 56 and 60 years, 76% and 72% were female, with a mean Disease Activity Score (DAS28) of 6.5 and 5.1 and median disease duration of 11 and 6 years, respectively.

After more than 52,428 person-years of exposure and a median of 5.1 years of follow-up, 81 vasculitis-like events occurred in the anti-TNF therapy group. Vasculitis-like events were attributed to treatment only if they had occurred within 90 days of starting the drug. Follow-up stopped after a first event; if there was a switch to another biologic drug; and at death, the last clinical follow-up, or the end of the analysis period (May 31, 2015).

In comparison, there were 20,635 person-years of exposure and 6.5 years’ follow-up in the nbDMARD group, with 14 vasculitis-like events reported during this time.

A sensitivity analysis was performed excluding patients who had nail-fold vasculitis at baseline, had vasculitis due to a possible secondary cause such as infection, and were taking any other medications associated with vasculitis-like events. Results showed a similar risk for a first vasculitis event between anti-TNF and nbDMARD users (aHR = 1.05; 95% CI, 0.32-3.45).

Looking at the risk of vasculitis events for individual anti-TNF drugs, there initially appeared to be a higher risk for patients taking infliximab (n = 3,292) and etanercept (n = 4,450) but not for those taking adalimumab (n = 4,312) versus nbDMARDs, with crude incidence rates of 10, 17, and 11 per 10,000 person-years; after adjustment, these differences were not significant (aHRs of 1.55, 1.72, and 0.77, respectively, with 95% CIs crossing 1.0). A crude rate for certolizumab could not be calculated as there were no vasculitis events reported but there were only 691 patients enrolled in the BSRBR-RA at the time of the analysis who had been exposed to the drug.

“The risk of the event was highest in the first year of treatment, followed by reduction over time,” Dr. Jani reported. “Reassuringly, up to two-thirds of patients in both cohorts had manifestations that were just limited to cutaneous involvement,” she said.

The most common systemic presentation was digital ischemia, affecting 14% of patients treated with anti-TNFs and 14% of those given nbDMARDs. Neurologic involvement was also seen in both groups of patients (7% vs. 7%), but new nail-fold vasculitis (17% vs. 0%), respiratory involvement (4% vs. 0%), associated thrombotic events (5% vs. 0%), and renal involvement (2.5% vs. 0%) were seen in TNF inhibitor-treated patients only.

Ten anti-TNF–treated patients and one nbDMARD-treated patient needed treatment for the vasculitis-like event, and three patients in the anti-TNF cohort died as a result of the event, all of whom had multisystem organ involvement and one of whom had cytoplasmic ANCA-positive vasculitis.

Treatment with methotrexate or sulfasalazine at baseline was associated with a lower risk for vasculitis-like events, while seropositive status, disease duration, DAS28, and HAQ scores were associated with an increased risk for such events.

The BSRBR-RA receives restricted income financial support from Abbvie, Amgen, Swedish Orphan Biovitram (SOBI), Merck, Pfizer, Roche, and UCB Pharma. Dr. Jani disclosed she has received honoraria from Pfizer, Abbvie, and UCB Pharma.

GLASGOW – Treatment with tumor necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitors for rheumatoid arthritis is associated with a low risk of vasculitis-like events, according to a large analysis of data from the United Kingdom.

Investigators using data from the British Society for Rheumatology Biologics Register for Rheumatoid Arthritis (BSRBR-RA) found that the crude incidence rate was 16 cases per 10,000 person-years among TNF-inhibitor users versus seven cases per 10,000 person-years among users of nonbiologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (nbDMARDs) such as methotrexate and sulfasalazine.

Although the risk was slightly higher among anti-TNF than nbDMARD users, the propensity score fully adjusted hazard ratio for a first vasculitis-like event was 1.27, comparing the anti-TNF drugs with nbDMARDs, with a 95% confidence interval of 0.40-4.04.

“This is the first prospective observational study to systematically look at the risk of vasculitis-like events” in patients with RA treated with anti-TNF agents, Dr. Meghna Jani said at the British Society for Rheumatology annual conference.

Dr. Jani of the Arthritis Research UK Centre for Epidemiology at the University of Manchester (England) explained that the reason for looking at this topic was that vasculitis-like events had been reported in case series and single-center studies, but these prior reports were too small to be able to estimate exactly how big a problem this was.

“Anti-TNF agents are associated with the development of a number of autoantibodies, including antinuclear antibodies and antidrug antibodies, and ANCA [antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody],” she observed.

“We know that a small proportion of these patients may then go on to develop autoimmune diseases, some independent of autoantibodies,” she added. The most common of these is vasculitis, including cutaneous vasculitis.

Vasculitis is a somewhat paradoxical adverse event, she noted, in that it has been associated with anti-TNF therapy, but these drugs can also be used to treat it.

Now in its 15th year, the BSRBR-RA is the largest ongoing cohort of patients treated with biologic agents for rheumatic disease and provides one of the best sources of data to examine the risk for vasculitis-like events Dr. Jani observed. The aims were to look at the respective risks as well as to see if there were any particular predictive factors.

The current analysis included more than 16,000 patients enrolled in the BSRBR-RA between 2001 and 2015, of whom 12,745 were newly started on an anti-TNF drug and 3,640 were receiving nbDMARDs and were also biologic naive. The mean age of patients in the two groups was 56 and 60 years, 76% and 72% were female, with a mean Disease Activity Score (DAS28) of 6.5 and 5.1 and median disease duration of 11 and 6 years, respectively.

After more than 52,428 person-years of exposure and a median of 5.1 years of follow-up, 81 vasculitis-like events occurred in the anti-TNF therapy group. Vasculitis-like events were attributed to treatment only if they had occurred within 90 days of starting the drug. Follow-up stopped after a first event; if there was a switch to another biologic drug; and at death, the last clinical follow-up, or the end of the analysis period (May 31, 2015).

In comparison, there were 20,635 person-years of exposure and 6.5 years’ follow-up in the nbDMARD group, with 14 vasculitis-like events reported during this time.

A sensitivity analysis was performed excluding patients who had nail-fold vasculitis at baseline, had vasculitis due to a possible secondary cause such as infection, and were taking any other medications associated with vasculitis-like events. Results showed a similar risk for a first vasculitis event between anti-TNF and nbDMARD users (aHR = 1.05; 95% CI, 0.32-3.45).

Looking at the risk of vasculitis events for individual anti-TNF drugs, there initially appeared to be a higher risk for patients taking infliximab (n = 3,292) and etanercept (n = 4,450) but not for those taking adalimumab (n = 4,312) versus nbDMARDs, with crude incidence rates of 10, 17, and 11 per 10,000 person-years; after adjustment, these differences were not significant (aHRs of 1.55, 1.72, and 0.77, respectively, with 95% CIs crossing 1.0). A crude rate for certolizumab could not be calculated as there were no vasculitis events reported but there were only 691 patients enrolled in the BSRBR-RA at the time of the analysis who had been exposed to the drug.

“The risk of the event was highest in the first year of treatment, followed by reduction over time,” Dr. Jani reported. “Reassuringly, up to two-thirds of patients in both cohorts had manifestations that were just limited to cutaneous involvement,” she said.

The most common systemic presentation was digital ischemia, affecting 14% of patients treated with anti-TNFs and 14% of those given nbDMARDs. Neurologic involvement was also seen in both groups of patients (7% vs. 7%), but new nail-fold vasculitis (17% vs. 0%), respiratory involvement (4% vs. 0%), associated thrombotic events (5% vs. 0%), and renal involvement (2.5% vs. 0%) were seen in TNF inhibitor-treated patients only.

Ten anti-TNF–treated patients and one nbDMARD-treated patient needed treatment for the vasculitis-like event, and three patients in the anti-TNF cohort died as a result of the event, all of whom had multisystem organ involvement and one of whom had cytoplasmic ANCA-positive vasculitis.

Treatment with methotrexate or sulfasalazine at baseline was associated with a lower risk for vasculitis-like events, while seropositive status, disease duration, DAS28, and HAQ scores were associated with an increased risk for such events.

The BSRBR-RA receives restricted income financial support from Abbvie, Amgen, Swedish Orphan Biovitram (SOBI), Merck, Pfizer, Roche, and UCB Pharma. Dr. Jani disclosed she has received honoraria from Pfizer, Abbvie, and UCB Pharma.

AT RHEUMATOLOGY 2016

Key clinical point: There is a low risk of vasculitis-like events with tumor necrosis factor inhibitors.

Major finding: Crude incidence rates for vasculitis-like events were 16/10,000 person-years with TNF-inhibitor therapy and 7/10,000 person-years with nonbiologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs.

Data source: British Society for Rheumatology Biologics Register for Rheumatoid Arthritis of 12,745 TNF-inhibitor and 3,640 nbDMARD users.

Disclosures: The BSRBR-RA receives restricted income financial support from Abbvie, Amgen, Swedish Orphan Biovitram (SOBI), Merck, Pfizer, Roche, and UCB Pharma. Dr. Jani disclosed she has received honoraria from Pfizer, Abbvie, and UCB Pharma.

Erythematous Atrophic Plaque in the Inguinal Fold

The Diagnosis: Granulomatous Slack Skin Disease

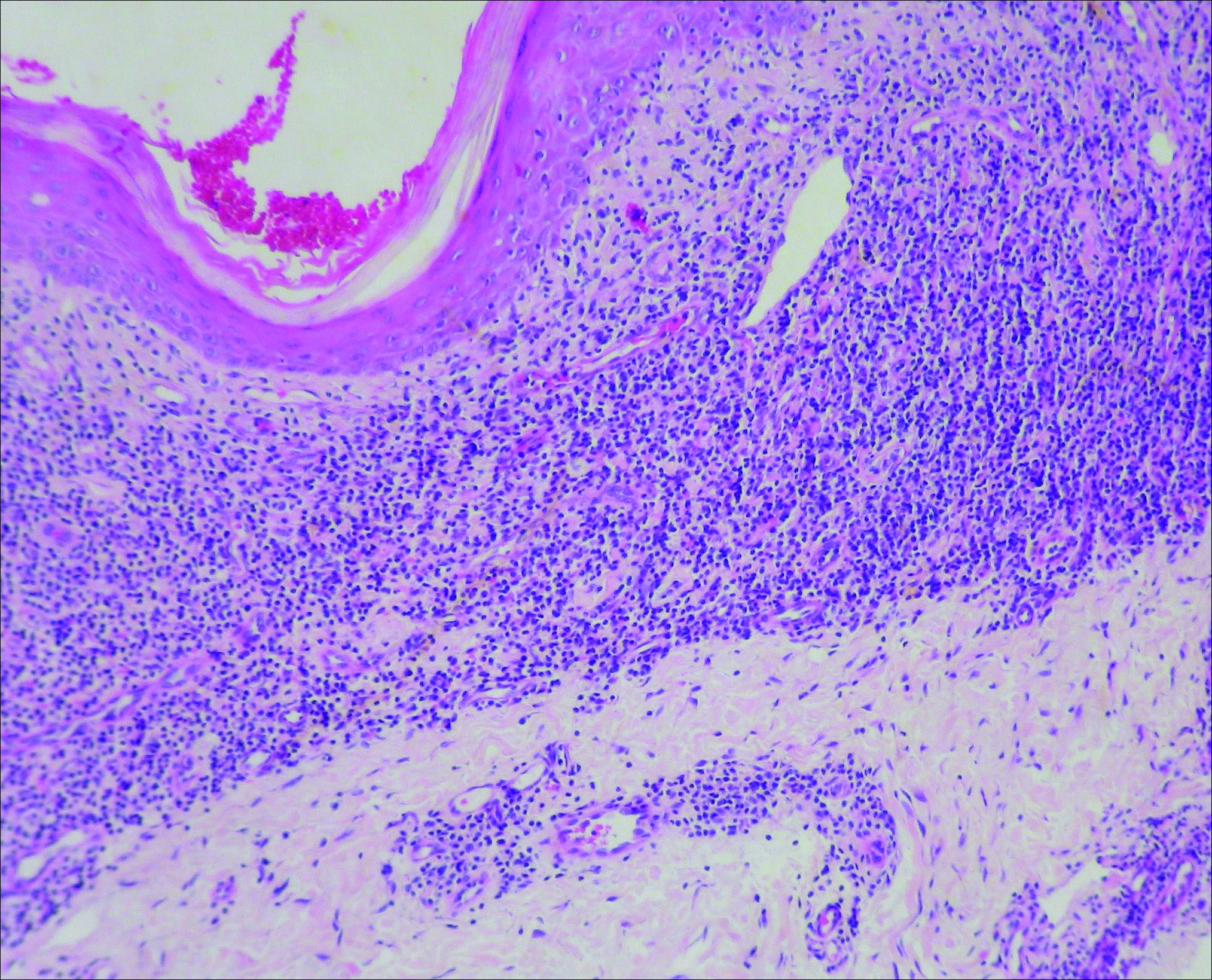

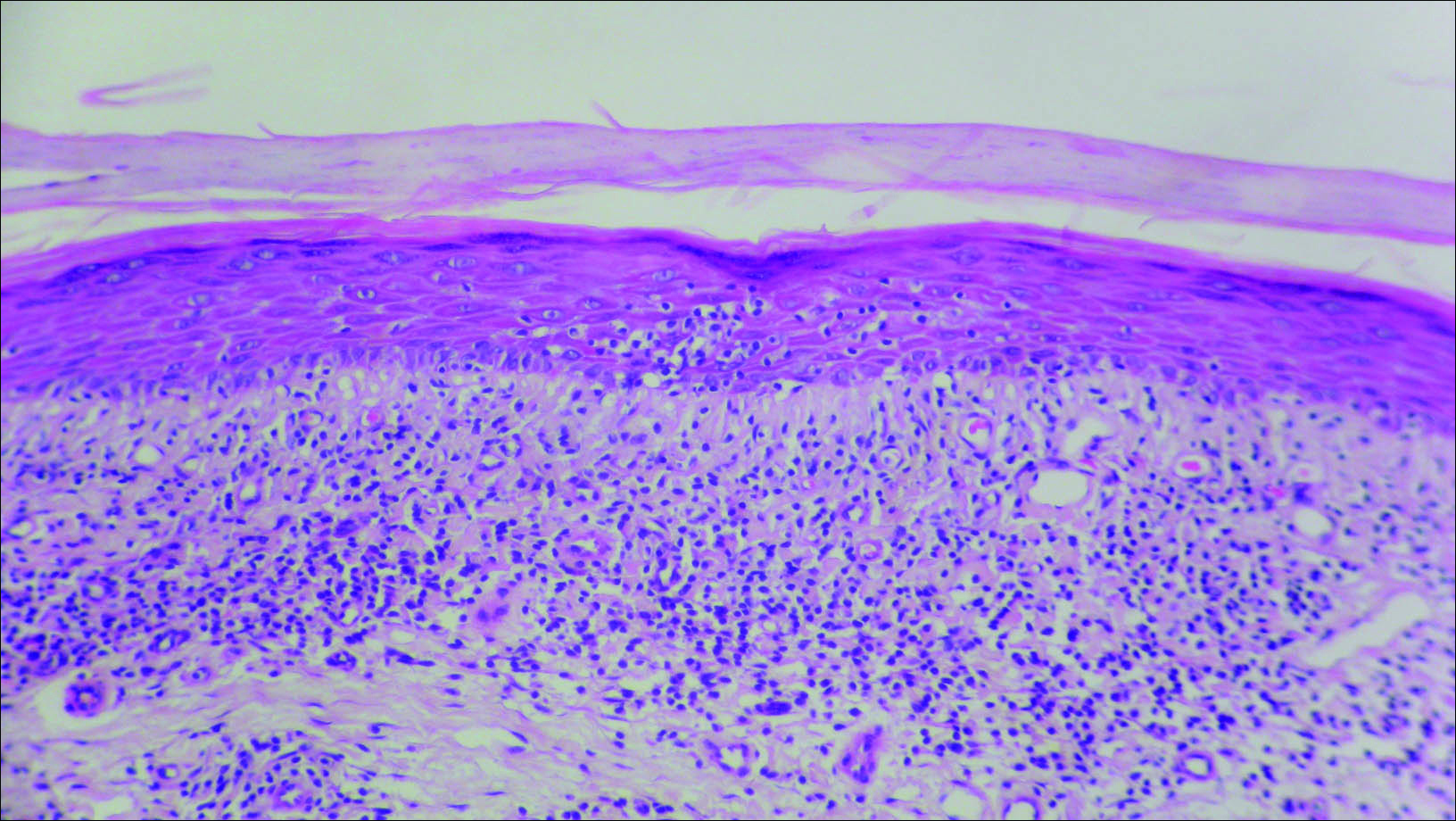

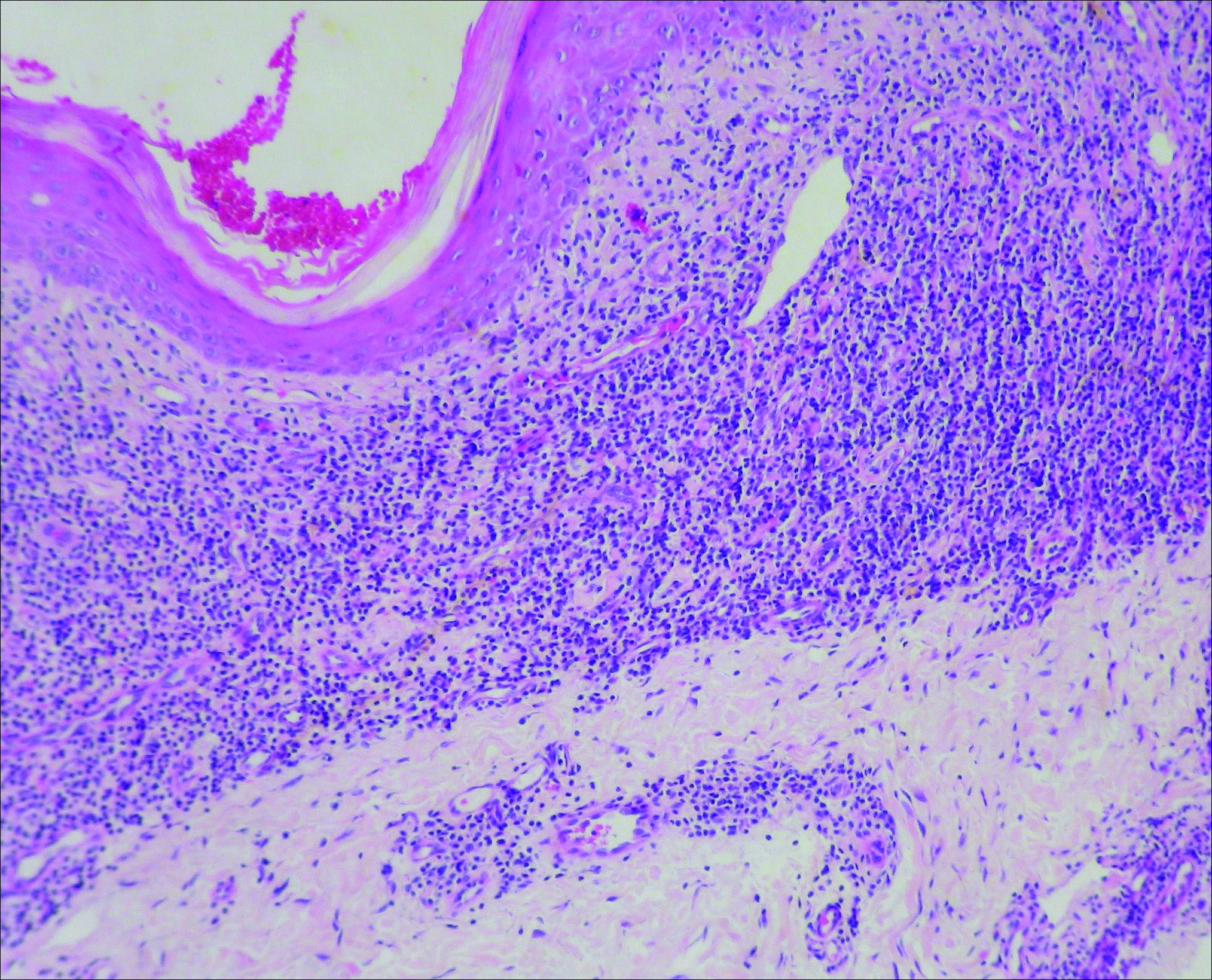

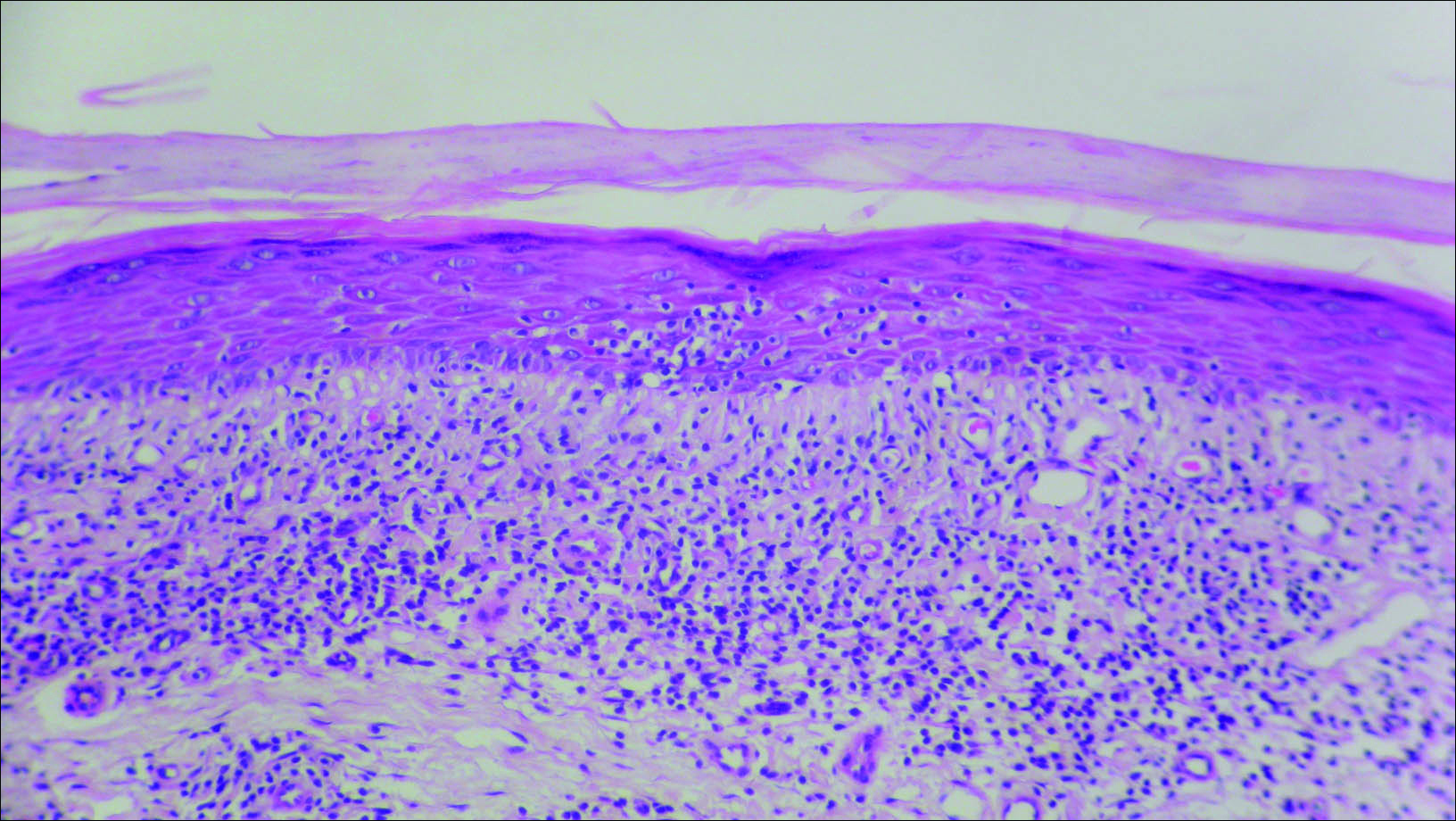

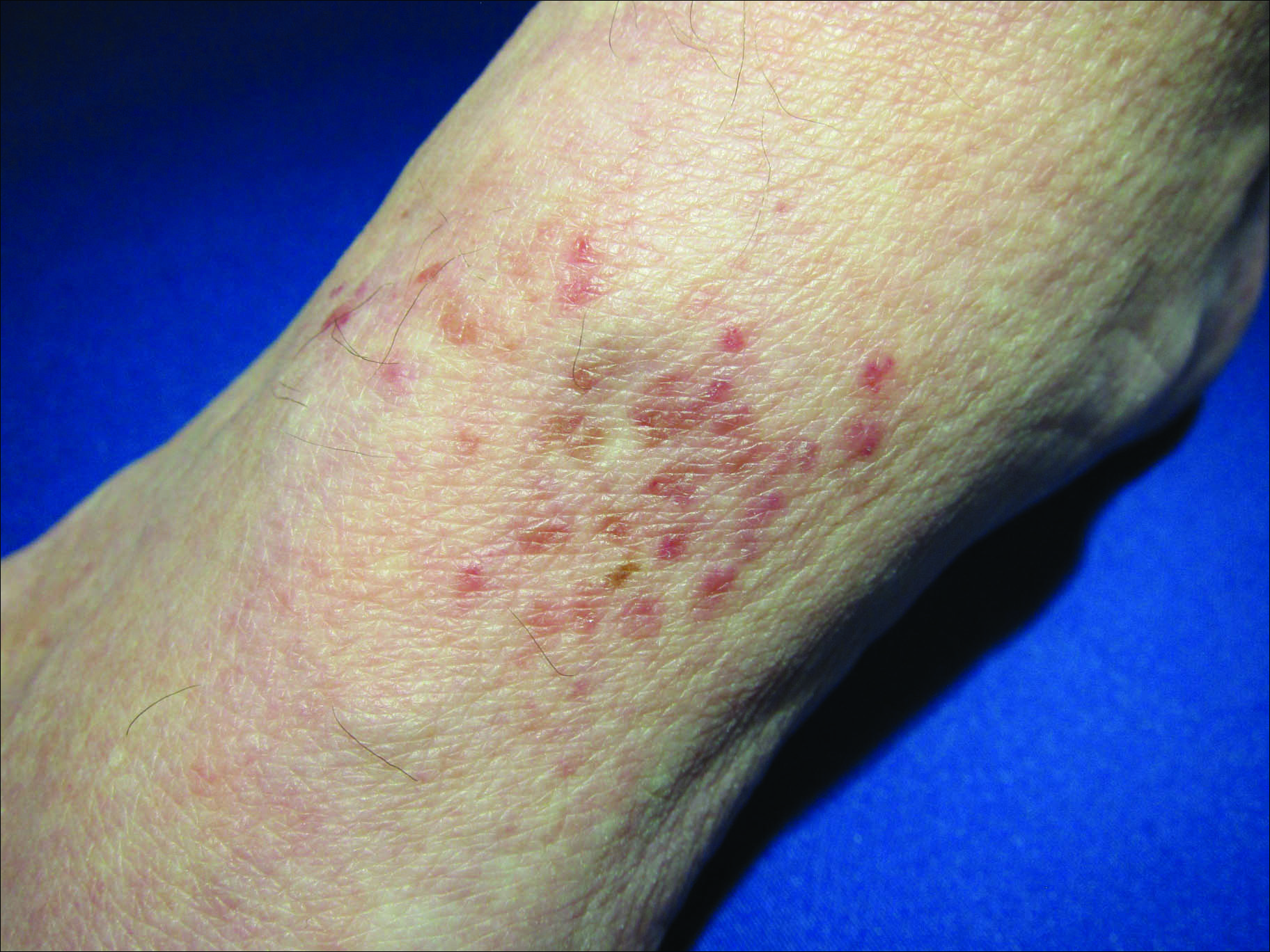

Initial biopsy revealed a lichenoid lymphohistiocytic infiltrate with scattered epidermotropism, papillary dermal sclerosis, and lymphocyte atypia (Figure 1). A repeat biopsy showed a lichenoid granulomatous infiltrate with histiocytes and rare giant cells, superficially located in the dermis, without a deeper dense infiltration. Focal lymphocytic epidermotropism also was present (Figure 2). The infiltrate was CD3+CD4+ with a minority of cells also staining for CD8. An elastin stain demonstrated diminished elastin fibers in the superficial dermis. A clonal T-cell receptor gene rearrangement was identified by polymerase chain reaction. One group of pink and brown papules was present on the dorsal aspect of the right foot (Figure 3). A biopsy of this area showed similar findings. The patient was treated with a trial of carmustine 20-mg% ointment over the following year with some improvement of the mild pruritus but without notable change in the clinical findings.

Granulomatous slack skin disease (GSSD) is a rare form of mycosis fungoides–type cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. It usually presents as well-demarcated, atrophic, poikilodermatous patches and plaques with a predilection for the inguinal and axillary regions.1 The affected areas tend to be asymptomatic and enlarge gradually over years to become pendulous with lax skin and wrinkles. In contrast to other forms of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma, extracutaneous spread is rare. The disease shows a slow progression over many years and by itself is not life threatening. However, affected patients have a risk for developing secondary lymphoproliferative neoplasms, which have been documented in approximately 50% of reported cases.2 These lymphoproliferative neoplasms may arise concurrently, precede, or follow the development of GSSD lesions. Hodgkin lymphoma, seen in 33% of cases, is the most common association, with others being non-Hodgkin lymphoma, mycosis fungoides, acute myeloid leukemia, and Langerhans cell histiocytosis.1-3

Histologically, GSSD is characterized by a dense, dermal, granulomatous proliferation of atypical T lymphocytes with scattered multinucleated giant cells.1,4 There is a loss of elastin fibers in the infiltrated areas, and occasional elastophagocytosis can be seen.1,2,4 Immunoprofiling of the infiltrate has shown CD3+CD4+CD45RO+ T-helper cells with occasional loss of CD5 and CD7.3 A clonal T-cell receptor rearrangement of the g and b genes frequently is described.1,4,5

At this time no treatment has been found to be reliably curative. Varying success in treating GSSD has been achieved with topical nitrogen mustard, carmustine, topical and systemic corticosteroids, psoralen plus UVA, radiotherapy, azathioprine, IFN-g, and combinations of these agents.1-3,6-9 Excision of the diseased skin has been performed for cosmetically or functionally disturbing lesions, but in all but one case the lesions recurred within months.1,10 A consistently reliable treatment of GSSD has not been established; treatment should be tailored to the individual patient.

- Shah A, Safaya A. Granulomatous slack skin disease: a review, in comparison with mycosis fungoides. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2012;26:1472-1478.

- Teixeira M, Alves R, Lima M, et al. Granulomatous slack skin. Eur J Dermatol. 2007;17:435-438.

- van Haselen CW, Toonstra J, van der Putte SJ, et al. Granulomatous slack skin: report of three patients with an updated review of the literature. Dermatology. 1998;196:382-391.

- Kempf W, Ostheeren-Michaelis S, Paulli M, et al. Granulomatous mycosis fungoides and granulomatous slack skin: a multicenter study of the Cutaneous Lymphoma Histopathology Task Force Group of the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC). Arch Dermatol. 2008;144:1609-1617.

- LeBoit PE, Zackheim HS, White CR Jr. Granulomatous variants of cutaneous t-cell lymphoma: the histopathology of granulomatous mycosis fungoides and granulomatous slack skin. Am J Surg Pathol. 1988;12:83-95.

- Hultgren TL, Jones D, Duvic M. Topical nitrogen mustard for the treatment of granulomatous slack skin. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2007;8:51-54.

- Camacho FM, Burg G, Moreno JC, et al. Granulomatous slack skin in childhood. Pediatr Dermatol. 1997;14:204-208.

- Liu Z, Huang C, Li J. Prednisone combined with interferon for the treatment of one case of generalized granulomatous slack skin. J Huazhong Univ Sci Technolo Med Sci. 2005;25:617-618.

- Oberholzer PA, Cozzio A, Dummer R, et al. Granulomatous slack skin responds to UVA1 phototherapy. Dermatology. 2009;219:268-271.

- Clarijis M, Poot F, Laka A, et al. Granulomatous slack skin: treatment with extensive surgery and review of the literature. Dermatology. 2003;206:393-397.

The Diagnosis: Granulomatous Slack Skin Disease

Initial biopsy revealed a lichenoid lymphohistiocytic infiltrate with scattered epidermotropism, papillary dermal sclerosis, and lymphocyte atypia (Figure 1). A repeat biopsy showed a lichenoid granulomatous infiltrate with histiocytes and rare giant cells, superficially located in the dermis, without a deeper dense infiltration. Focal lymphocytic epidermotropism also was present (Figure 2). The infiltrate was CD3+CD4+ with a minority of cells also staining for CD8. An elastin stain demonstrated diminished elastin fibers in the superficial dermis. A clonal T-cell receptor gene rearrangement was identified by polymerase chain reaction. One group of pink and brown papules was present on the dorsal aspect of the right foot (Figure 3). A biopsy of this area showed similar findings. The patient was treated with a trial of carmustine 20-mg% ointment over the following year with some improvement of the mild pruritus but without notable change in the clinical findings.

Granulomatous slack skin disease (GSSD) is a rare form of mycosis fungoides–type cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. It usually presents as well-demarcated, atrophic, poikilodermatous patches and plaques with a predilection for the inguinal and axillary regions.1 The affected areas tend to be asymptomatic and enlarge gradually over years to become pendulous with lax skin and wrinkles. In contrast to other forms of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma, extracutaneous spread is rare. The disease shows a slow progression over many years and by itself is not life threatening. However, affected patients have a risk for developing secondary lymphoproliferative neoplasms, which have been documented in approximately 50% of reported cases.2 These lymphoproliferative neoplasms may arise concurrently, precede, or follow the development of GSSD lesions. Hodgkin lymphoma, seen in 33% of cases, is the most common association, with others being non-Hodgkin lymphoma, mycosis fungoides, acute myeloid leukemia, and Langerhans cell histiocytosis.1-3

Histologically, GSSD is characterized by a dense, dermal, granulomatous proliferation of atypical T lymphocytes with scattered multinucleated giant cells.1,4 There is a loss of elastin fibers in the infiltrated areas, and occasional elastophagocytosis can be seen.1,2,4 Immunoprofiling of the infiltrate has shown CD3+CD4+CD45RO+ T-helper cells with occasional loss of CD5 and CD7.3 A clonal T-cell receptor rearrangement of the g and b genes frequently is described.1,4,5

At this time no treatment has been found to be reliably curative. Varying success in treating GSSD has been achieved with topical nitrogen mustard, carmustine, topical and systemic corticosteroids, psoralen plus UVA, radiotherapy, azathioprine, IFN-g, and combinations of these agents.1-3,6-9 Excision of the diseased skin has been performed for cosmetically or functionally disturbing lesions, but in all but one case the lesions recurred within months.1,10 A consistently reliable treatment of GSSD has not been established; treatment should be tailored to the individual patient.

The Diagnosis: Granulomatous Slack Skin Disease

Initial biopsy revealed a lichenoid lymphohistiocytic infiltrate with scattered epidermotropism, papillary dermal sclerosis, and lymphocyte atypia (Figure 1). A repeat biopsy showed a lichenoid granulomatous infiltrate with histiocytes and rare giant cells, superficially located in the dermis, without a deeper dense infiltration. Focal lymphocytic epidermotropism also was present (Figure 2). The infiltrate was CD3+CD4+ with a minority of cells also staining for CD8. An elastin stain demonstrated diminished elastin fibers in the superficial dermis. A clonal T-cell receptor gene rearrangement was identified by polymerase chain reaction. One group of pink and brown papules was present on the dorsal aspect of the right foot (Figure 3). A biopsy of this area showed similar findings. The patient was treated with a trial of carmustine 20-mg% ointment over the following year with some improvement of the mild pruritus but without notable change in the clinical findings.

Granulomatous slack skin disease (GSSD) is a rare form of mycosis fungoides–type cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. It usually presents as well-demarcated, atrophic, poikilodermatous patches and plaques with a predilection for the inguinal and axillary regions.1 The affected areas tend to be asymptomatic and enlarge gradually over years to become pendulous with lax skin and wrinkles. In contrast to other forms of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma, extracutaneous spread is rare. The disease shows a slow progression over many years and by itself is not life threatening. However, affected patients have a risk for developing secondary lymphoproliferative neoplasms, which have been documented in approximately 50% of reported cases.2 These lymphoproliferative neoplasms may arise concurrently, precede, or follow the development of GSSD lesions. Hodgkin lymphoma, seen in 33% of cases, is the most common association, with others being non-Hodgkin lymphoma, mycosis fungoides, acute myeloid leukemia, and Langerhans cell histiocytosis.1-3

Histologically, GSSD is characterized by a dense, dermal, granulomatous proliferation of atypical T lymphocytes with scattered multinucleated giant cells.1,4 There is a loss of elastin fibers in the infiltrated areas, and occasional elastophagocytosis can be seen.1,2,4 Immunoprofiling of the infiltrate has shown CD3+CD4+CD45RO+ T-helper cells with occasional loss of CD5 and CD7.3 A clonal T-cell receptor rearrangement of the g and b genes frequently is described.1,4,5

At this time no treatment has been found to be reliably curative. Varying success in treating GSSD has been achieved with topical nitrogen mustard, carmustine, topical and systemic corticosteroids, psoralen plus UVA, radiotherapy, azathioprine, IFN-g, and combinations of these agents.1-3,6-9 Excision of the diseased skin has been performed for cosmetically or functionally disturbing lesions, but in all but one case the lesions recurred within months.1,10 A consistently reliable treatment of GSSD has not been established; treatment should be tailored to the individual patient.

- Shah A, Safaya A. Granulomatous slack skin disease: a review, in comparison with mycosis fungoides. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2012;26:1472-1478.

- Teixeira M, Alves R, Lima M, et al. Granulomatous slack skin. Eur J Dermatol. 2007;17:435-438.

- van Haselen CW, Toonstra J, van der Putte SJ, et al. Granulomatous slack skin: report of three patients with an updated review of the literature. Dermatology. 1998;196:382-391.

- Kempf W, Ostheeren-Michaelis S, Paulli M, et al. Granulomatous mycosis fungoides and granulomatous slack skin: a multicenter study of the Cutaneous Lymphoma Histopathology Task Force Group of the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC). Arch Dermatol. 2008;144:1609-1617.

- LeBoit PE, Zackheim HS, White CR Jr. Granulomatous variants of cutaneous t-cell lymphoma: the histopathology of granulomatous mycosis fungoides and granulomatous slack skin. Am J Surg Pathol. 1988;12:83-95.

- Hultgren TL, Jones D, Duvic M. Topical nitrogen mustard for the treatment of granulomatous slack skin. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2007;8:51-54.

- Camacho FM, Burg G, Moreno JC, et al. Granulomatous slack skin in childhood. Pediatr Dermatol. 1997;14:204-208.

- Liu Z, Huang C, Li J. Prednisone combined with interferon for the treatment of one case of generalized granulomatous slack skin. J Huazhong Univ Sci Technolo Med Sci. 2005;25:617-618.

- Oberholzer PA, Cozzio A, Dummer R, et al. Granulomatous slack skin responds to UVA1 phototherapy. Dermatology. 2009;219:268-271.

- Clarijis M, Poot F, Laka A, et al. Granulomatous slack skin: treatment with extensive surgery and review of the literature. Dermatology. 2003;206:393-397.

- Shah A, Safaya A. Granulomatous slack skin disease: a review, in comparison with mycosis fungoides. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2012;26:1472-1478.

- Teixeira M, Alves R, Lima M, et al. Granulomatous slack skin. Eur J Dermatol. 2007;17:435-438.

- van Haselen CW, Toonstra J, van der Putte SJ, et al. Granulomatous slack skin: report of three patients with an updated review of the literature. Dermatology. 1998;196:382-391.

- Kempf W, Ostheeren-Michaelis S, Paulli M, et al. Granulomatous mycosis fungoides and granulomatous slack skin: a multicenter study of the Cutaneous Lymphoma Histopathology Task Force Group of the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC). Arch Dermatol. 2008;144:1609-1617.

- LeBoit PE, Zackheim HS, White CR Jr. Granulomatous variants of cutaneous t-cell lymphoma: the histopathology of granulomatous mycosis fungoides and granulomatous slack skin. Am J Surg Pathol. 1988;12:83-95.

- Hultgren TL, Jones D, Duvic M. Topical nitrogen mustard for the treatment of granulomatous slack skin. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2007;8:51-54.

- Camacho FM, Burg G, Moreno JC, et al. Granulomatous slack skin in childhood. Pediatr Dermatol. 1997;14:204-208.

- Liu Z, Huang C, Li J. Prednisone combined with interferon for the treatment of one case of generalized granulomatous slack skin. J Huazhong Univ Sci Technolo Med Sci. 2005;25:617-618.

- Oberholzer PA, Cozzio A, Dummer R, et al. Granulomatous slack skin responds to UVA1 phototherapy. Dermatology. 2009;219:268-271.

- Clarijis M, Poot F, Laka A, et al. Granulomatous slack skin: treatment with extensive surgery and review of the literature. Dermatology. 2003;206:393-397.

A 66-year-old man presented with a rash on the groin of more than 6 years’ duration. The eruption was asymptomatic, except for occasional pruritus during the summer months. Numerous over-the-counter ointments, creams, and powders, as well as prescription topical corticosteroids, had failed to provide improvement. An outside biopsy performed 1 year earlier was considered nondiagnostic. Physical examination revealed a pink to violaceous, pendulous, atrophic plaque with slight scale on the right side of the lower abdomen running just superior to the right inguinal fold; the left inguinal fold was unaffected. Inguinal lymph nodes were not palpable. A 4-mm punch biopsy of the plaque in the inguinal fold was performed.

Summer colds

Most viral infections in summer months are caused by enteroviruses. We studied illnesses in about 400 kids aged 4-18 years seen in private pediatric practice and were surprised by what we found.

Our impression was that summer colds lasted for a shorter time span than winter colds. What we found was that the median duration of illness was about 8 days. Among the various syndromes, the most common was stomatitis (viral blisters in the throat), accounting for 58% of all cases seen. A flulike illness with fever, myalgias, and malaise was second most common (28% of cases), followed by hand/foot/mouth syndrome (8%), pleurodynia (3%), fever with viral rash (3%), and aseptic meningitis (1%). Most of the cases occurred among children 4-12 years old.

The most prevalent symptoms were fever, headache, sore throat, tiredness, muscle aches, and crankiness. Fever was present in about 85% of cases of children with stomatitis, in 95% of cases with myalgias and malaise, but in only 50% of cases of hand/foot/mouth. Headache was very common as well, occurring in about 40% of children with stomatitis, 70% of children with myalgias and malaise, and in 30% of children with hand/foot/mouth.

Illness within a household was quite common. About 50% of the children who came for care had a sibling or parent ill with a summer cold. However, while the symptoms of the family members often were the same as the child who presented for care, that was not always the case. As anticipated, most illness within a household occurred within a 2-week time span. Hand/foot/mouth was most easily recognized by parents to have spread among their children. When a parent became ill, it was almost always the mother because she was almost always the primary parent caretaker.