User login

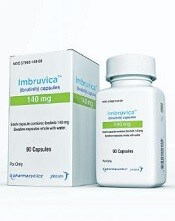

Health Canada approves ibrutinib for WM

Photo from Janssen Biotech

Health Canada has approved the BTK inhibitor ibrutinib (Imbruvica) as a treatment for patients with Waldenström’s macroglobulinemia (WM).

Ibrutinib was first approved in Canada in November 2014 for the treatment of patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL), including those with 17p deletion, who have received at least one prior therapy, or for the frontline treatment of patients with CLL and 17p deletion.

In July 2015, ibrutinib was granted conditional approval for the treatment of patients with relapsed or refractory mantle cell lymphoma.

Health Canada’s approval of ibrutinib for WM was based on results of a multicenter, phase 2 study in which researchers tested the drug (given at 420 mg once daily) in 63 patients with previously treated WM.

The patients’ median age was 63 (range, 44-86), and their median number of prior therapies was 2 (range, 1-11).

Initial data showed an overall response rate of 87.3% in patients who received ibrutinib for a median of 11.7 months.

Updated results from the study were published in NEJM in April 2015. After a median treatment duration of 19.1 months, the overall response rate was 91%.

At 24 months, the estimated rate of progression-free survival was 69%, and the estimated rate of overall survival was 95%.

The most common grade 2-4 adverse events were neutropenia (22%) and thrombocytopenia (14%). Ibrutinib-related neutropenia and thrombocytopenia were reversible but required a dose reduction in 3 patients and treatment discontinuation in 4 patients.

Grade 2 or higher bleeding events occurred in 4 patients, and there were 15 infections considered possibly related to ibrutinib.

Treatment-related atrial fibrillation (AFib) occurred in 3 patients, all of whom had a prior history of paroxysmal AFib. AFib resolved when treatment was withheld, and all 3 patients were able to continue on therapy per protocol without an additional event.

Ibrutinib is co-developed by Cilag GmbH International (a member of the Janssen Pharmaceutical Companies) and Pharmacyclics LLC, an AbbVie company. Janssen Inc. markets ibrutinib as Imbruvica in Canada. ![]()

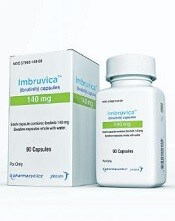

Photo from Janssen Biotech

Health Canada has approved the BTK inhibitor ibrutinib (Imbruvica) as a treatment for patients with Waldenström’s macroglobulinemia (WM).

Ibrutinib was first approved in Canada in November 2014 for the treatment of patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL), including those with 17p deletion, who have received at least one prior therapy, or for the frontline treatment of patients with CLL and 17p deletion.

In July 2015, ibrutinib was granted conditional approval for the treatment of patients with relapsed or refractory mantle cell lymphoma.

Health Canada’s approval of ibrutinib for WM was based on results of a multicenter, phase 2 study in which researchers tested the drug (given at 420 mg once daily) in 63 patients with previously treated WM.

The patients’ median age was 63 (range, 44-86), and their median number of prior therapies was 2 (range, 1-11).

Initial data showed an overall response rate of 87.3% in patients who received ibrutinib for a median of 11.7 months.

Updated results from the study were published in NEJM in April 2015. After a median treatment duration of 19.1 months, the overall response rate was 91%.

At 24 months, the estimated rate of progression-free survival was 69%, and the estimated rate of overall survival was 95%.

The most common grade 2-4 adverse events were neutropenia (22%) and thrombocytopenia (14%). Ibrutinib-related neutropenia and thrombocytopenia were reversible but required a dose reduction in 3 patients and treatment discontinuation in 4 patients.

Grade 2 or higher bleeding events occurred in 4 patients, and there were 15 infections considered possibly related to ibrutinib.

Treatment-related atrial fibrillation (AFib) occurred in 3 patients, all of whom had a prior history of paroxysmal AFib. AFib resolved when treatment was withheld, and all 3 patients were able to continue on therapy per protocol without an additional event.

Ibrutinib is co-developed by Cilag GmbH International (a member of the Janssen Pharmaceutical Companies) and Pharmacyclics LLC, an AbbVie company. Janssen Inc. markets ibrutinib as Imbruvica in Canada. ![]()

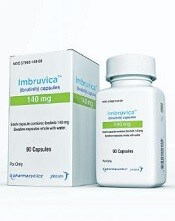

Photo from Janssen Biotech

Health Canada has approved the BTK inhibitor ibrutinib (Imbruvica) as a treatment for patients with Waldenström’s macroglobulinemia (WM).

Ibrutinib was first approved in Canada in November 2014 for the treatment of patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL), including those with 17p deletion, who have received at least one prior therapy, or for the frontline treatment of patients with CLL and 17p deletion.

In July 2015, ibrutinib was granted conditional approval for the treatment of patients with relapsed or refractory mantle cell lymphoma.

Health Canada’s approval of ibrutinib for WM was based on results of a multicenter, phase 2 study in which researchers tested the drug (given at 420 mg once daily) in 63 patients with previously treated WM.

The patients’ median age was 63 (range, 44-86), and their median number of prior therapies was 2 (range, 1-11).

Initial data showed an overall response rate of 87.3% in patients who received ibrutinib for a median of 11.7 months.

Updated results from the study were published in NEJM in April 2015. After a median treatment duration of 19.1 months, the overall response rate was 91%.

At 24 months, the estimated rate of progression-free survival was 69%, and the estimated rate of overall survival was 95%.

The most common grade 2-4 adverse events were neutropenia (22%) and thrombocytopenia (14%). Ibrutinib-related neutropenia and thrombocytopenia were reversible but required a dose reduction in 3 patients and treatment discontinuation in 4 patients.

Grade 2 or higher bleeding events occurred in 4 patients, and there were 15 infections considered possibly related to ibrutinib.

Treatment-related atrial fibrillation (AFib) occurred in 3 patients, all of whom had a prior history of paroxysmal AFib. AFib resolved when treatment was withheld, and all 3 patients were able to continue on therapy per protocol without an additional event.

Ibrutinib is co-developed by Cilag GmbH International (a member of the Janssen Pharmaceutical Companies) and Pharmacyclics LLC, an AbbVie company. Janssen Inc. markets ibrutinib as Imbruvica in Canada. ![]()

Drug may reduce severity of AEs from dexamethasone

Photo by Bill Branson

Adding a physiologic dose of hydrocortisone to treatment with dexamethasone can reduce the severity of certain adverse effects (AEs) in pediatric patients with acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL), according to researchers.

Hydrocortisone did not decrease the incidence of psychosocial problems or sleep-related issues in these patients, but the drug did reduce the severity of these problems among patients who experienced them.

Lidewij T. Warris, MD, of Erasmus MC-Sophia Children’s Hospital in Rotterdam, the Netherlands, and her colleagues reported these results in the Journal of Clinical Oncology.

The team conducted this study to determine whether a physiologic dose of hydrocortisone could reduce neuropsychologic and metabolic AEs in children with ALL who were receiving dexamethasone.

The study enrolled 50 patients (ages 3 to 16) who were set to receive 2 consecutive courses of dexamethasone in accordance with Dutch Childhood Oncology Group ALL protocols.

The patients were randomized to receive either hydrocortisone or placebo in a circadian rhythm (10 mg/m2/d) during their first dexamethasone course. During their second course, the patients were assigned to the opposite arm.

The treatment groups were similar with regard to age, type of leukemia, treatment protocol, and CNS status at diagnosis.

Psychosocial problems

The researchers assessed psychosocial problems by having parents complete the Strength and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ). Forty-six parents completed the questionnaire at all 4 time points tested.

The results showed that 4 days of dexamethasone treatment significantly increased patient problems, as reported by all SDQ scales and subscales. However, one-third of the population did not have any increase in SDQ total difficulties with dexamethasone.

The addition of hydrocortisone did not affect patients’ total difficulties score (mean difference, -0.8 ± 5.5; P=0.33), emotional symptoms (mean difference, -0.6 ± 2.3; P=0.08), conduct problems (mean difference, 0.0 ± 1.5; P=1.00), or other SDQ subscales.

However, hydrocortisone did have a clinically significant effect in the subset of 16 patients who had clinically relevant dexamethasone-related AEs. This was defined as an increase of ≥5 in their SDQ total difficulties score.

In these patients, hydrocortisone improved the total difficulties delta-score (median difference, -5.0; IQR, -7.8 to -3.0), emotional symptoms score (median difference, -1.5; IQR, -4.0 to -1.0), conduct problems score (median difference, -1.0; IQR, -2.0 to 0.0), and impact of stress score (median difference, -1.0; IQR, -2.0 to 0.0).

Sleep issues

The researchers used the Sleep Disturbance Scale for Children (SDSC) to assess sleep quality and sleep disturbances. Forty-seven parents completed the questionnaire at all 4 time points tested.

Results showed that dexamethasone significantly increased disorders of arousal (P=0.04), sleep-wake transition disorders (P=0.01), and disorders of excessive somnolence (P=0.01).

The addition of hydrocortisone had no significant effect on patients’ total SDSC score (P=0.84), disorders of initiating and maintaining sleep (P=0.74), disorders of excessive somnolence (P=0.29), or sleep-wake transition disorder (P=0.29).

However, hydrocortisone did have a clinically significant effect in the subset of 9 children who had clinically relevant dexamethasone-induced sleeping problems, which were defined as a change of ≥7 in SDSC total score.

Hydrocortisone reduced SDSC total scores (median difference, -11.0; IQR, -16.0 to 0.0) and disorders of initiating and maintaining sleep scores (median difference, -3.0; IQR, -7.0 to –0.5).

Other outcomes

The researchers also found that dexamethasone treatment alone did not affect patients’ attention, visual-spatial functions, memory, or processing speed.

However, the addition of hydrocortisone significantly improved patients’ long-term visual memory (P=0.01).

Hydrocortisone did not have any effect on other neuropsychological tests or on metabolic parameters. ![]()

Photo by Bill Branson

Adding a physiologic dose of hydrocortisone to treatment with dexamethasone can reduce the severity of certain adverse effects (AEs) in pediatric patients with acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL), according to researchers.

Hydrocortisone did not decrease the incidence of psychosocial problems or sleep-related issues in these patients, but the drug did reduce the severity of these problems among patients who experienced them.

Lidewij T. Warris, MD, of Erasmus MC-Sophia Children’s Hospital in Rotterdam, the Netherlands, and her colleagues reported these results in the Journal of Clinical Oncology.

The team conducted this study to determine whether a physiologic dose of hydrocortisone could reduce neuropsychologic and metabolic AEs in children with ALL who were receiving dexamethasone.

The study enrolled 50 patients (ages 3 to 16) who were set to receive 2 consecutive courses of dexamethasone in accordance with Dutch Childhood Oncology Group ALL protocols.

The patients were randomized to receive either hydrocortisone or placebo in a circadian rhythm (10 mg/m2/d) during their first dexamethasone course. During their second course, the patients were assigned to the opposite arm.

The treatment groups were similar with regard to age, type of leukemia, treatment protocol, and CNS status at diagnosis.

Psychosocial problems

The researchers assessed psychosocial problems by having parents complete the Strength and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ). Forty-six parents completed the questionnaire at all 4 time points tested.

The results showed that 4 days of dexamethasone treatment significantly increased patient problems, as reported by all SDQ scales and subscales. However, one-third of the population did not have any increase in SDQ total difficulties with dexamethasone.

The addition of hydrocortisone did not affect patients’ total difficulties score (mean difference, -0.8 ± 5.5; P=0.33), emotional symptoms (mean difference, -0.6 ± 2.3; P=0.08), conduct problems (mean difference, 0.0 ± 1.5; P=1.00), or other SDQ subscales.

However, hydrocortisone did have a clinically significant effect in the subset of 16 patients who had clinically relevant dexamethasone-related AEs. This was defined as an increase of ≥5 in their SDQ total difficulties score.

In these patients, hydrocortisone improved the total difficulties delta-score (median difference, -5.0; IQR, -7.8 to -3.0), emotional symptoms score (median difference, -1.5; IQR, -4.0 to -1.0), conduct problems score (median difference, -1.0; IQR, -2.0 to 0.0), and impact of stress score (median difference, -1.0; IQR, -2.0 to 0.0).

Sleep issues

The researchers used the Sleep Disturbance Scale for Children (SDSC) to assess sleep quality and sleep disturbances. Forty-seven parents completed the questionnaire at all 4 time points tested.

Results showed that dexamethasone significantly increased disorders of arousal (P=0.04), sleep-wake transition disorders (P=0.01), and disorders of excessive somnolence (P=0.01).

The addition of hydrocortisone had no significant effect on patients’ total SDSC score (P=0.84), disorders of initiating and maintaining sleep (P=0.74), disorders of excessive somnolence (P=0.29), or sleep-wake transition disorder (P=0.29).

However, hydrocortisone did have a clinically significant effect in the subset of 9 children who had clinically relevant dexamethasone-induced sleeping problems, which were defined as a change of ≥7 in SDSC total score.

Hydrocortisone reduced SDSC total scores (median difference, -11.0; IQR, -16.0 to 0.0) and disorders of initiating and maintaining sleep scores (median difference, -3.0; IQR, -7.0 to –0.5).

Other outcomes

The researchers also found that dexamethasone treatment alone did not affect patients’ attention, visual-spatial functions, memory, or processing speed.

However, the addition of hydrocortisone significantly improved patients’ long-term visual memory (P=0.01).

Hydrocortisone did not have any effect on other neuropsychological tests or on metabolic parameters. ![]()

Photo by Bill Branson

Adding a physiologic dose of hydrocortisone to treatment with dexamethasone can reduce the severity of certain adverse effects (AEs) in pediatric patients with acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL), according to researchers.

Hydrocortisone did not decrease the incidence of psychosocial problems or sleep-related issues in these patients, but the drug did reduce the severity of these problems among patients who experienced them.

Lidewij T. Warris, MD, of Erasmus MC-Sophia Children’s Hospital in Rotterdam, the Netherlands, and her colleagues reported these results in the Journal of Clinical Oncology.

The team conducted this study to determine whether a physiologic dose of hydrocortisone could reduce neuropsychologic and metabolic AEs in children with ALL who were receiving dexamethasone.

The study enrolled 50 patients (ages 3 to 16) who were set to receive 2 consecutive courses of dexamethasone in accordance with Dutch Childhood Oncology Group ALL protocols.

The patients were randomized to receive either hydrocortisone or placebo in a circadian rhythm (10 mg/m2/d) during their first dexamethasone course. During their second course, the patients were assigned to the opposite arm.

The treatment groups were similar with regard to age, type of leukemia, treatment protocol, and CNS status at diagnosis.

Psychosocial problems

The researchers assessed psychosocial problems by having parents complete the Strength and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ). Forty-six parents completed the questionnaire at all 4 time points tested.

The results showed that 4 days of dexamethasone treatment significantly increased patient problems, as reported by all SDQ scales and subscales. However, one-third of the population did not have any increase in SDQ total difficulties with dexamethasone.

The addition of hydrocortisone did not affect patients’ total difficulties score (mean difference, -0.8 ± 5.5; P=0.33), emotional symptoms (mean difference, -0.6 ± 2.3; P=0.08), conduct problems (mean difference, 0.0 ± 1.5; P=1.00), or other SDQ subscales.

However, hydrocortisone did have a clinically significant effect in the subset of 16 patients who had clinically relevant dexamethasone-related AEs. This was defined as an increase of ≥5 in their SDQ total difficulties score.

In these patients, hydrocortisone improved the total difficulties delta-score (median difference, -5.0; IQR, -7.8 to -3.0), emotional symptoms score (median difference, -1.5; IQR, -4.0 to -1.0), conduct problems score (median difference, -1.0; IQR, -2.0 to 0.0), and impact of stress score (median difference, -1.0; IQR, -2.0 to 0.0).

Sleep issues

The researchers used the Sleep Disturbance Scale for Children (SDSC) to assess sleep quality and sleep disturbances. Forty-seven parents completed the questionnaire at all 4 time points tested.

Results showed that dexamethasone significantly increased disorders of arousal (P=0.04), sleep-wake transition disorders (P=0.01), and disorders of excessive somnolence (P=0.01).

The addition of hydrocortisone had no significant effect on patients’ total SDSC score (P=0.84), disorders of initiating and maintaining sleep (P=0.74), disorders of excessive somnolence (P=0.29), or sleep-wake transition disorder (P=0.29).

However, hydrocortisone did have a clinically significant effect in the subset of 9 children who had clinically relevant dexamethasone-induced sleeping problems, which were defined as a change of ≥7 in SDSC total score.

Hydrocortisone reduced SDSC total scores (median difference, -11.0; IQR, -16.0 to 0.0) and disorders of initiating and maintaining sleep scores (median difference, -3.0; IQR, -7.0 to –0.5).

Other outcomes

The researchers also found that dexamethasone treatment alone did not affect patients’ attention, visual-spatial functions, memory, or processing speed.

However, the addition of hydrocortisone significantly improved patients’ long-term visual memory (P=0.01).

Hydrocortisone did not have any effect on other neuropsychological tests or on metabolic parameters. ![]()

EEG Basics

ACO Insider: MACRA – don’t let indecision be your biggest decision

By now, most of us have heard of accountable care organizations and bundled payment. But for many of you, the shift to value-based population health management or compensation based on performance hasn’t affected your practice.

You still get paid fee for service. You’ve seen “the next big thing” in health care come and go; you don’t have the capital or spare intellectual bandwidth to make the transformation to value-based care – and as many of you have told me, at the end of the day, you just want to see patients.

There are a lot of reasons to sit on the sidelines a while longer. I get it. But that indecision could result in the biggest decision of your career. But it won’t be your decision – it will be defaulted to others. Why?

Welcome to MACRA – the Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act. On April 16, 2015, President Obama signed sweeping legislation irrevocably moving the American health care system to value-based payment. The United States Senate and House – Republicans and Democrats – came together to replace the Sustainable Growth Rate formula (SGR) with MACRA.

MACRA represents the end of a long history of perpetually delayed Medicare physician fee schedule cuts that were to be automatically triggered under the punitive SGR formula absent Congress’ annual postponement ritual. After providing for a series of annual physician payment increases, MACRA’s reimbursement methodology transitions to a value-based model that includes two pathways: 1) the Alternative Payment Model (APM), and 2) the Merit-Based Incentive Payment System (MIPS).

APMs include organizations that are focused on providing high-quality and cost-effective care, while also taking on significant financial risk (for example, an ACO).

MACRA highly incentivizes provider participation in APMs. For example, APM participants will receive 5% bonus payments from 2019 to 2024, if they receive a certain percentage of their Medicare revenue through APMs. In addition, providers qualifying as APM participants are excluded from participating in the MIPS model and are subject only to their own quality standards.

Under the MIPS model, provider performance will be evaluated according to established performance standards and used to calculate an adjustment factor that will then determine a provider’s payment for the year.

The performance standards will include the following weighted categories: 1. quality, 2. resource use, 3. clinical practice improvement activities, and 4. meaningful use. Depending on their performance in these categories, providers will receive either a positive adjustment, no adjustment, or a negative adjustment.

In 2022, these adjustments will range from a 9% negative adjustment to a similar positive adjustment. MIPS will apply to all Medicare services and items provided on or after Jan. 1, 2019.

What does this mean to you?

You are going to be reimbursed as if you have embraced value-based population health management, whether you really do or not. The MIPS formula could deny you north of 9% of your payments. Conversely, if you decide to get into an ACO or something similar, you not only don’t get dinged, you receive a 5% bump in fee-for-service compensation and the chance for additional savings payments. Of course, you have to decide to actually engage and lead this care improvement from your medical home. A fake ACO that lets costs rise will be responsible for those increases.

Readers of this column know that the statistics are bearing out the fact that primary care–led ACOs are the best model. The whole premise has changed. Instead of paying for volume and expensive procedures for very sick people, it rewards value – that is the highest quality at the lowest costs – through things in primary care’s wheelhouse: prevention, wellness, care coordination, complex patient management, and medical home care transition management.

In fact, CMS has recognized this by making primary care subspecialties the only ones required to be in the Medicare ACO program and the Medicare Shared Savings Program (MSSP), and recently with its ACO Investment Model, which prioritized ACO advanced infrastructure payments to physician- or small hospital-led ACOs in rural areas.

There are more physician-owned ACOs today than any other kind. If you are part of another type of ACO, such as one driven by a health system or multispecialty practice, don’t despair. They can work, too. But you need to step up and make sure they do.

The price of passivity

MACRA’s shifting of the annual flow of $3 trillion from rewarding volume to rewarding value will, in this author’s estimation, have MACRA easily eclipse the Affordable Care Act in significance. Indecision will not stop your placement in the value-based payment system. Why not control your destiny to achieve your professional and financial goals as leaders of health care? Through indecision, you will be both unprepared and defaulted into the quality and efficiency compensation measurements of MIPS.

MACRA has changed everything. You’ve been asked to lead American health care and get paid to do it. This is not a hard question. Please feel free to contact me directly with questions or comments on how to prepare.

Mr. Bobbitt is a head of the Health Law Group at the Smith Anderson law firm in Raleigh, N.C. He is president of Value Health Partners, LLC, a health care strategic consulting company. He has years of experience assisting physicians form integrated delivery systems. He has spoken and written nationally to primary care physicians on the strategies and practicalities of forming or joining ACOs. This article is meant to be educational and does not constitute legal advice. For additional information, readers may contact the author at [email protected] or 919-821-6612.

By now, most of us have heard of accountable care organizations and bundled payment. But for many of you, the shift to value-based population health management or compensation based on performance hasn’t affected your practice.

You still get paid fee for service. You’ve seen “the next big thing” in health care come and go; you don’t have the capital or spare intellectual bandwidth to make the transformation to value-based care – and as many of you have told me, at the end of the day, you just want to see patients.

There are a lot of reasons to sit on the sidelines a while longer. I get it. But that indecision could result in the biggest decision of your career. But it won’t be your decision – it will be defaulted to others. Why?

Welcome to MACRA – the Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act. On April 16, 2015, President Obama signed sweeping legislation irrevocably moving the American health care system to value-based payment. The United States Senate and House – Republicans and Democrats – came together to replace the Sustainable Growth Rate formula (SGR) with MACRA.

MACRA represents the end of a long history of perpetually delayed Medicare physician fee schedule cuts that were to be automatically triggered under the punitive SGR formula absent Congress’ annual postponement ritual. After providing for a series of annual physician payment increases, MACRA’s reimbursement methodology transitions to a value-based model that includes two pathways: 1) the Alternative Payment Model (APM), and 2) the Merit-Based Incentive Payment System (MIPS).

APMs include organizations that are focused on providing high-quality and cost-effective care, while also taking on significant financial risk (for example, an ACO).

MACRA highly incentivizes provider participation in APMs. For example, APM participants will receive 5% bonus payments from 2019 to 2024, if they receive a certain percentage of their Medicare revenue through APMs. In addition, providers qualifying as APM participants are excluded from participating in the MIPS model and are subject only to their own quality standards.

Under the MIPS model, provider performance will be evaluated according to established performance standards and used to calculate an adjustment factor that will then determine a provider’s payment for the year.

The performance standards will include the following weighted categories: 1. quality, 2. resource use, 3. clinical practice improvement activities, and 4. meaningful use. Depending on their performance in these categories, providers will receive either a positive adjustment, no adjustment, or a negative adjustment.

In 2022, these adjustments will range from a 9% negative adjustment to a similar positive adjustment. MIPS will apply to all Medicare services and items provided on or after Jan. 1, 2019.

What does this mean to you?

You are going to be reimbursed as if you have embraced value-based population health management, whether you really do or not. The MIPS formula could deny you north of 9% of your payments. Conversely, if you decide to get into an ACO or something similar, you not only don’t get dinged, you receive a 5% bump in fee-for-service compensation and the chance for additional savings payments. Of course, you have to decide to actually engage and lead this care improvement from your medical home. A fake ACO that lets costs rise will be responsible for those increases.

Readers of this column know that the statistics are bearing out the fact that primary care–led ACOs are the best model. The whole premise has changed. Instead of paying for volume and expensive procedures for very sick people, it rewards value – that is the highest quality at the lowest costs – through things in primary care’s wheelhouse: prevention, wellness, care coordination, complex patient management, and medical home care transition management.

In fact, CMS has recognized this by making primary care subspecialties the only ones required to be in the Medicare ACO program and the Medicare Shared Savings Program (MSSP), and recently with its ACO Investment Model, which prioritized ACO advanced infrastructure payments to physician- or small hospital-led ACOs in rural areas.

There are more physician-owned ACOs today than any other kind. If you are part of another type of ACO, such as one driven by a health system or multispecialty practice, don’t despair. They can work, too. But you need to step up and make sure they do.

The price of passivity

MACRA’s shifting of the annual flow of $3 trillion from rewarding volume to rewarding value will, in this author’s estimation, have MACRA easily eclipse the Affordable Care Act in significance. Indecision will not stop your placement in the value-based payment system. Why not control your destiny to achieve your professional and financial goals as leaders of health care? Through indecision, you will be both unprepared and defaulted into the quality and efficiency compensation measurements of MIPS.

MACRA has changed everything. You’ve been asked to lead American health care and get paid to do it. This is not a hard question. Please feel free to contact me directly with questions or comments on how to prepare.

Mr. Bobbitt is a head of the Health Law Group at the Smith Anderson law firm in Raleigh, N.C. He is president of Value Health Partners, LLC, a health care strategic consulting company. He has years of experience assisting physicians form integrated delivery systems. He has spoken and written nationally to primary care physicians on the strategies and practicalities of forming or joining ACOs. This article is meant to be educational and does not constitute legal advice. For additional information, readers may contact the author at [email protected] or 919-821-6612.

By now, most of us have heard of accountable care organizations and bundled payment. But for many of you, the shift to value-based population health management or compensation based on performance hasn’t affected your practice.

You still get paid fee for service. You’ve seen “the next big thing” in health care come and go; you don’t have the capital or spare intellectual bandwidth to make the transformation to value-based care – and as many of you have told me, at the end of the day, you just want to see patients.

There are a lot of reasons to sit on the sidelines a while longer. I get it. But that indecision could result in the biggest decision of your career. But it won’t be your decision – it will be defaulted to others. Why?

Welcome to MACRA – the Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act. On April 16, 2015, President Obama signed sweeping legislation irrevocably moving the American health care system to value-based payment. The United States Senate and House – Republicans and Democrats – came together to replace the Sustainable Growth Rate formula (SGR) with MACRA.

MACRA represents the end of a long history of perpetually delayed Medicare physician fee schedule cuts that were to be automatically triggered under the punitive SGR formula absent Congress’ annual postponement ritual. After providing for a series of annual physician payment increases, MACRA’s reimbursement methodology transitions to a value-based model that includes two pathways: 1) the Alternative Payment Model (APM), and 2) the Merit-Based Incentive Payment System (MIPS).

APMs include organizations that are focused on providing high-quality and cost-effective care, while also taking on significant financial risk (for example, an ACO).

MACRA highly incentivizes provider participation in APMs. For example, APM participants will receive 5% bonus payments from 2019 to 2024, if they receive a certain percentage of their Medicare revenue through APMs. In addition, providers qualifying as APM participants are excluded from participating in the MIPS model and are subject only to their own quality standards.

Under the MIPS model, provider performance will be evaluated according to established performance standards and used to calculate an adjustment factor that will then determine a provider’s payment for the year.

The performance standards will include the following weighted categories: 1. quality, 2. resource use, 3. clinical practice improvement activities, and 4. meaningful use. Depending on their performance in these categories, providers will receive either a positive adjustment, no adjustment, or a negative adjustment.

In 2022, these adjustments will range from a 9% negative adjustment to a similar positive adjustment. MIPS will apply to all Medicare services and items provided on or after Jan. 1, 2019.

What does this mean to you?

You are going to be reimbursed as if you have embraced value-based population health management, whether you really do or not. The MIPS formula could deny you north of 9% of your payments. Conversely, if you decide to get into an ACO or something similar, you not only don’t get dinged, you receive a 5% bump in fee-for-service compensation and the chance for additional savings payments. Of course, you have to decide to actually engage and lead this care improvement from your medical home. A fake ACO that lets costs rise will be responsible for those increases.

Readers of this column know that the statistics are bearing out the fact that primary care–led ACOs are the best model. The whole premise has changed. Instead of paying for volume and expensive procedures for very sick people, it rewards value – that is the highest quality at the lowest costs – through things in primary care’s wheelhouse: prevention, wellness, care coordination, complex patient management, and medical home care transition management.

In fact, CMS has recognized this by making primary care subspecialties the only ones required to be in the Medicare ACO program and the Medicare Shared Savings Program (MSSP), and recently with its ACO Investment Model, which prioritized ACO advanced infrastructure payments to physician- or small hospital-led ACOs in rural areas.

There are more physician-owned ACOs today than any other kind. If you are part of another type of ACO, such as one driven by a health system or multispecialty practice, don’t despair. They can work, too. But you need to step up and make sure they do.

The price of passivity

MACRA’s shifting of the annual flow of $3 trillion from rewarding volume to rewarding value will, in this author’s estimation, have MACRA easily eclipse the Affordable Care Act in significance. Indecision will not stop your placement in the value-based payment system. Why not control your destiny to achieve your professional and financial goals as leaders of health care? Through indecision, you will be both unprepared and defaulted into the quality and efficiency compensation measurements of MIPS.

MACRA has changed everything. You’ve been asked to lead American health care and get paid to do it. This is not a hard question. Please feel free to contact me directly with questions or comments on how to prepare.

Mr. Bobbitt is a head of the Health Law Group at the Smith Anderson law firm in Raleigh, N.C. He is president of Value Health Partners, LLC, a health care strategic consulting company. He has years of experience assisting physicians form integrated delivery systems. He has spoken and written nationally to primary care physicians on the strategies and practicalities of forming or joining ACOs. This article is meant to be educational and does not constitute legal advice. For additional information, readers may contact the author at [email protected] or 919-821-6612.

National Harbor - Gateway to Washington, D.C.

For things to see and do while at the Vascular Annual Meeting, consider National Harbor as a gateway port to Washington, D.C., situated just across the Potomac. The famous sights, monuments, museums, and cultural icons in the nation’s capitol are a given for any visitor (visit www.washington.org for a full rundown).

But there are also a lot of lesser known tourist attractions unavailable anywhere else in the country. Medical history buffs, for example, may want to visit the National Musuem of American History, which houses collections of medical science and biotechnology artifacts. And Civil War buffs with access to a car can visit the National Museum of Civil War Medicine in Frederick, Md., about an hour’s drive from National Harbor. Frederick was the site of three Confederate invasions and two major battles.

Cultural events abound during the annual meeting period. Theater goers can attend Shakespeare’s “Taming of the Shrew” or the musical “La Cage aux Folles.” You can attend the DC Jazz Festival or the National Symphony Orchestra’s performance of pieces by Bruckner and Mahler. For more cultural events, visit www.culturalcapitol.com.

For sports lovers, baseball season will be just getting underway and the Washington Nationals will be playing the Philadelphia Phillies on Saturday and Sunday at Nationals Park.

And National Harbor has its own attractions. Hardest to miss is the Capitol Wheel, a giant ferris wheel that soars 180 feet above the Potomac River waterfront, with views of the White House and Capitol, the National Mall, and all the surrounding DC metro area.

To plan your visit, check out www.nationalharbor.com/consumer/entertainment.

For things to see and do while at the Vascular Annual Meeting, consider National Harbor as a gateway port to Washington, D.C., situated just across the Potomac. The famous sights, monuments, museums, and cultural icons in the nation’s capitol are a given for any visitor (visit www.washington.org for a full rundown).

But there are also a lot of lesser known tourist attractions unavailable anywhere else in the country. Medical history buffs, for example, may want to visit the National Musuem of American History, which houses collections of medical science and biotechnology artifacts. And Civil War buffs with access to a car can visit the National Museum of Civil War Medicine in Frederick, Md., about an hour’s drive from National Harbor. Frederick was the site of three Confederate invasions and two major battles.

Cultural events abound during the annual meeting period. Theater goers can attend Shakespeare’s “Taming of the Shrew” or the musical “La Cage aux Folles.” You can attend the DC Jazz Festival or the National Symphony Orchestra’s performance of pieces by Bruckner and Mahler. For more cultural events, visit www.culturalcapitol.com.

For sports lovers, baseball season will be just getting underway and the Washington Nationals will be playing the Philadelphia Phillies on Saturday and Sunday at Nationals Park.

And National Harbor has its own attractions. Hardest to miss is the Capitol Wheel, a giant ferris wheel that soars 180 feet above the Potomac River waterfront, with views of the White House and Capitol, the National Mall, and all the surrounding DC metro area.

To plan your visit, check out www.nationalharbor.com/consumer/entertainment.

For things to see and do while at the Vascular Annual Meeting, consider National Harbor as a gateway port to Washington, D.C., situated just across the Potomac. The famous sights, monuments, museums, and cultural icons in the nation’s capitol are a given for any visitor (visit www.washington.org for a full rundown).

But there are also a lot of lesser known tourist attractions unavailable anywhere else in the country. Medical history buffs, for example, may want to visit the National Musuem of American History, which houses collections of medical science and biotechnology artifacts. And Civil War buffs with access to a car can visit the National Museum of Civil War Medicine in Frederick, Md., about an hour’s drive from National Harbor. Frederick was the site of three Confederate invasions and two major battles.

Cultural events abound during the annual meeting period. Theater goers can attend Shakespeare’s “Taming of the Shrew” or the musical “La Cage aux Folles.” You can attend the DC Jazz Festival or the National Symphony Orchestra’s performance of pieces by Bruckner and Mahler. For more cultural events, visit www.culturalcapitol.com.

For sports lovers, baseball season will be just getting underway and the Washington Nationals will be playing the Philadelphia Phillies on Saturday and Sunday at Nationals Park.

And National Harbor has its own attractions. Hardest to miss is the Capitol Wheel, a giant ferris wheel that soars 180 feet above the Potomac River waterfront, with views of the White House and Capitol, the National Mall, and all the surrounding DC metro area.

To plan your visit, check out www.nationalharbor.com/consumer/entertainment.

What Matters: Fasting and cancer

We are a product of our environment. But we shan’t forget that we are a product of the critical interaction between our environment and our evolutionary biology.

Back when we were roaming the plains searching for food, we likely experienced “forced fasts” (that is, we had no food). Our ancestors who were the best at surviving these periods of scarcity lived to bear us into our current period of staggering abundance. Now, we are the unhealthiest humans in history.

Is part of the answer to our current health problems to return to our roots and ... fast?

In a recent article by Catherine Marinac and her colleagues, patients aged 27-70 years with breast cancer in the Women’s Healthy Eating and Living study were analyzed to uncover the relationship between nightly fasting duration and new primary breast tumors and death (JAMA Oncol. 2016 Mar 31. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2016.0164). Fasting was assessed through use of 24-hour dietary recall.

Fasting less than 13 hours per night was associated with an increased risk of breast cancer, compared with fasting at least 13 hours (hazard ratio, 1.36; 95% confidence interval, 1.05-1.76). Different fasting durations were not associated with breast cancer mortality.

Additional analyses demonstrated that each 2-hour increase in fasting duration was associated with significantly lower hemoglobin A1c levels and a longer duration of nighttime sleep.

The positive health benefits of fasting have become increasingly “discussed,” albeit commonly on websites advertising for fasting cookbooks. Benefits of fasting include weight loss, improved insulin sensitivity, reductions in inflammation, improved cardiovascular risk factors, enhanced brain function, reductions in Alzheimer’s disease symptoms, and extended life span.

Many of these data are preliminary, and some are based upon animal models, such as the prolonged lifespan. In one study, rats undergoing alternate-day fasting lived 83% longer than rats who were not fasted. Interestingly, human data suggest that food consumption on the nonfasting days does not result in caloric consumption to cover the caloric deficit on the fasted day.

I have to admit that I am intrigued. I am not hearing much discussion about fasting among my colleagues – although a lot them skip meals, I know. But nobody is discussing it as a recommendation to appropriately selected patients (for example, not on insulin) to combat obesity and other diseases. I tried to suggest it to a patient the other day, who had a staggering amount of central adiposity, and he laughed at me. Is the thought of skipping eating for a day so anathema to our modern consumptive culture that we can’t even consider it?

Depending on the type of fasting that one is doing, one does not have to count calories on the fasting days, because there aren’t any. That makes it easy.

In a world of abundance and limitless food options, it may seem strange (self-indulgent?) to fast. But perhaps it will be a key to help us continue the species for a couple more generations.

Dr. Ebbert is professor of medicine, a general internist at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., and a diplomate of the American Board of Addiction Medicine. The opinions expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views and opinions of the Mayo Clinic. The opinions expressed in this article should not be used to diagnose or treat any medical condition nor should they be used as a substitute for medical advice from a qualified, board-certified practicing clinician. Dr. Ebbert has no relevant financial disclosures about this article.

We are a product of our environment. But we shan’t forget that we are a product of the critical interaction between our environment and our evolutionary biology.

Back when we were roaming the plains searching for food, we likely experienced “forced fasts” (that is, we had no food). Our ancestors who were the best at surviving these periods of scarcity lived to bear us into our current period of staggering abundance. Now, we are the unhealthiest humans in history.

Is part of the answer to our current health problems to return to our roots and ... fast?

In a recent article by Catherine Marinac and her colleagues, patients aged 27-70 years with breast cancer in the Women’s Healthy Eating and Living study were analyzed to uncover the relationship between nightly fasting duration and new primary breast tumors and death (JAMA Oncol. 2016 Mar 31. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2016.0164). Fasting was assessed through use of 24-hour dietary recall.

Fasting less than 13 hours per night was associated with an increased risk of breast cancer, compared with fasting at least 13 hours (hazard ratio, 1.36; 95% confidence interval, 1.05-1.76). Different fasting durations were not associated with breast cancer mortality.

Additional analyses demonstrated that each 2-hour increase in fasting duration was associated with significantly lower hemoglobin A1c levels and a longer duration of nighttime sleep.

The positive health benefits of fasting have become increasingly “discussed,” albeit commonly on websites advertising for fasting cookbooks. Benefits of fasting include weight loss, improved insulin sensitivity, reductions in inflammation, improved cardiovascular risk factors, enhanced brain function, reductions in Alzheimer’s disease symptoms, and extended life span.

Many of these data are preliminary, and some are based upon animal models, such as the prolonged lifespan. In one study, rats undergoing alternate-day fasting lived 83% longer than rats who were not fasted. Interestingly, human data suggest that food consumption on the nonfasting days does not result in caloric consumption to cover the caloric deficit on the fasted day.

I have to admit that I am intrigued. I am not hearing much discussion about fasting among my colleagues – although a lot them skip meals, I know. But nobody is discussing it as a recommendation to appropriately selected patients (for example, not on insulin) to combat obesity and other diseases. I tried to suggest it to a patient the other day, who had a staggering amount of central adiposity, and he laughed at me. Is the thought of skipping eating for a day so anathema to our modern consumptive culture that we can’t even consider it?

Depending on the type of fasting that one is doing, one does not have to count calories on the fasting days, because there aren’t any. That makes it easy.

In a world of abundance and limitless food options, it may seem strange (self-indulgent?) to fast. But perhaps it will be a key to help us continue the species for a couple more generations.

Dr. Ebbert is professor of medicine, a general internist at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., and a diplomate of the American Board of Addiction Medicine. The opinions expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views and opinions of the Mayo Clinic. The opinions expressed in this article should not be used to diagnose or treat any medical condition nor should they be used as a substitute for medical advice from a qualified, board-certified practicing clinician. Dr. Ebbert has no relevant financial disclosures about this article.

We are a product of our environment. But we shan’t forget that we are a product of the critical interaction between our environment and our evolutionary biology.

Back when we were roaming the plains searching for food, we likely experienced “forced fasts” (that is, we had no food). Our ancestors who were the best at surviving these periods of scarcity lived to bear us into our current period of staggering abundance. Now, we are the unhealthiest humans in history.

Is part of the answer to our current health problems to return to our roots and ... fast?

In a recent article by Catherine Marinac and her colleagues, patients aged 27-70 years with breast cancer in the Women’s Healthy Eating and Living study were analyzed to uncover the relationship between nightly fasting duration and new primary breast tumors and death (JAMA Oncol. 2016 Mar 31. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2016.0164). Fasting was assessed through use of 24-hour dietary recall.

Fasting less than 13 hours per night was associated with an increased risk of breast cancer, compared with fasting at least 13 hours (hazard ratio, 1.36; 95% confidence interval, 1.05-1.76). Different fasting durations were not associated with breast cancer mortality.

Additional analyses demonstrated that each 2-hour increase in fasting duration was associated with significantly lower hemoglobin A1c levels and a longer duration of nighttime sleep.

The positive health benefits of fasting have become increasingly “discussed,” albeit commonly on websites advertising for fasting cookbooks. Benefits of fasting include weight loss, improved insulin sensitivity, reductions in inflammation, improved cardiovascular risk factors, enhanced brain function, reductions in Alzheimer’s disease symptoms, and extended life span.

Many of these data are preliminary, and some are based upon animal models, such as the prolonged lifespan. In one study, rats undergoing alternate-day fasting lived 83% longer than rats who were not fasted. Interestingly, human data suggest that food consumption on the nonfasting days does not result in caloric consumption to cover the caloric deficit on the fasted day.

I have to admit that I am intrigued. I am not hearing much discussion about fasting among my colleagues – although a lot them skip meals, I know. But nobody is discussing it as a recommendation to appropriately selected patients (for example, not on insulin) to combat obesity and other diseases. I tried to suggest it to a patient the other day, who had a staggering amount of central adiposity, and he laughed at me. Is the thought of skipping eating for a day so anathema to our modern consumptive culture that we can’t even consider it?

Depending on the type of fasting that one is doing, one does not have to count calories on the fasting days, because there aren’t any. That makes it easy.

In a world of abundance and limitless food options, it may seem strange (self-indulgent?) to fast. But perhaps it will be a key to help us continue the species for a couple more generations.

Dr. Ebbert is professor of medicine, a general internist at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., and a diplomate of the American Board of Addiction Medicine. The opinions expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views and opinions of the Mayo Clinic. The opinions expressed in this article should not be used to diagnose or treat any medical condition nor should they be used as a substitute for medical advice from a qualified, board-certified practicing clinician. Dr. Ebbert has no relevant financial disclosures about this article.

Ambulatory blood pressure rules hypertension diagnosis and follow-up

Evidence is becoming overwhelming that ambulatory blood pressure monitoring is the only reliable way to measure blood pressure for both diagnosing hypertension and following patients once they are diagnosed.

Office-based blood pressure measurement is out, be it a one-off reading or a cluster of sequential readings during a single office visit. Ambulatory blood pressure monitoring (ABPM) increasingly is the standard of care.

One recent nail in the coffin of office-based measurement came in a modestly-sized but revealing study reported by Dr. Joyce P. Samuel, a pediatric hypertension specialist at the University of Texas in Houston. She reported her experience directly comparing ambulatory and carefully-done office-based blood pressure measurement in a presentation at the annual meeting of the Pediatric Academic Societies in Baltimore.

Dr. Samuel followed 40 patients age 9-21 years whom she had previously diagnosed with essential hypertension (children with a systolic blood pressure at or above the 95th percentile for sex, age, and height), and repeatedly measured their blood pressures by both ambulatory and office-based readings at 2-week intervals as she searched for the best combination of antihypertensive drugs for each patient. She sent patients home for 24 hours of blood-pressure monitoring with an ambulatory device, and when they returned to her office the next day, she performed an office-based measurement using meticulous technique: Each child was seated and calm, measured on the right arm, with four measurements taken sequentially at about 1 minute intervals with the first reading discarded and the remaining three averaged.

Over the course of several months, she collected 173 paired ambulatory and office-based systolic blood pressure readings from individual patients. Substantial differences between the two forms of measurement were remarkably common. In 20% of the pairs, the ambulatory systolic reading was at least 10 mm Hg higher than the office-based reading, and for some pairs the differences ran as high as 30 mm Hg. In an additional 32% of the paired readings, office-based systolic pressure ran at least 10 mm Hg higher and in some cases as much as 35 mm Hg higher than the ambulatory reading.

Dr. Samuel also analyzed her findings a different way to assess the clinical consequences of these differences based on whether a child’s systolic pressure identified the patient as normotensive, hypertensive, or prehypertensive (a systolic pressure at the 90-94th percentile for the child’s age, sex and height). She found that the diagnoses matched for only 49% of the paired measurements. In 24% of the paired readings, ABPM identified children with hypertension that was not seen with concurrent office-based measurement, cases of masked hypertension. In 17% of the pairs, office-based measurement diagnosed hypertension that was not confirmed by ABPM, cases of white-coat hypertension. The remaining 10% of pairs were mismatched by showing normotensive with one method and prehypertensive with the other method. Dr. Samuel searched for any consistent patterns in these differences and found none. The disparate results with ambulatory and office-based measurements seemed almost random, with no correlation with age, sex, race, the medications patients received, or how many times a patient had already undergone dual blood-pressure monitoring. Individual patients had no meaningful differences between some of their paired measurements but had a meaningful disparity for others.

“We were unable to predict discrepancies,” said Dr. Samuels.

“You can’t get around it, you need ambulatory blood pressure monitoring to make the best diagnosis” of hypertension, she told me. “We need to push to make ambulatory monitoring more available. I am moving toward believing that ambulatory blood pressure monitoring must be routinely done on everyone. This is what the data suggest.”

It’s also where medicine is headed. In 2015, the U.S. Preventative Services Task Force (USPSTF) issued new recommendations for hypertension screening in adults aged 18 years or older, indicating that there was “convincing evidence that ABPM is the best method for diagnosing hypertension,” and the agency further recommended that ABPM is “the reference standard for confirming the diagnosis of hypertension.” Another endorsement of ambulatory blood pressure monitoring came out last year from the International Society for Chronobiology.

Recommendations are not yet as evolved for children. The USPSTF last weighed in on screening kids for hypertension in 2013, and said the evidence as of then was “insufficient” to assess the benefits and harms of screening for hypertension in children and adolescents. That document endorsed careful office-based blood pressure measurement, which highlights how recently expert sentiment has shifted on the issue of measurement. In response to the USPSTF 2013 statement, the American Academy of Pediatrics noted that it continued to back recommendations that are more than a decade old from the National High Blood Pressure Education Program that called for hypertension screening in children starting when they are 3 years old. Neither of these two groups has made any recent statement about the preferred method to measure blood pressure.

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

Evidence is becoming overwhelming that ambulatory blood pressure monitoring is the only reliable way to measure blood pressure for both diagnosing hypertension and following patients once they are diagnosed.

Office-based blood pressure measurement is out, be it a one-off reading or a cluster of sequential readings during a single office visit. Ambulatory blood pressure monitoring (ABPM) increasingly is the standard of care.

One recent nail in the coffin of office-based measurement came in a modestly-sized but revealing study reported by Dr. Joyce P. Samuel, a pediatric hypertension specialist at the University of Texas in Houston. She reported her experience directly comparing ambulatory and carefully-done office-based blood pressure measurement in a presentation at the annual meeting of the Pediatric Academic Societies in Baltimore.

Dr. Samuel followed 40 patients age 9-21 years whom she had previously diagnosed with essential hypertension (children with a systolic blood pressure at or above the 95th percentile for sex, age, and height), and repeatedly measured their blood pressures by both ambulatory and office-based readings at 2-week intervals as she searched for the best combination of antihypertensive drugs for each patient. She sent patients home for 24 hours of blood-pressure monitoring with an ambulatory device, and when they returned to her office the next day, she performed an office-based measurement using meticulous technique: Each child was seated and calm, measured on the right arm, with four measurements taken sequentially at about 1 minute intervals with the first reading discarded and the remaining three averaged.

Over the course of several months, she collected 173 paired ambulatory and office-based systolic blood pressure readings from individual patients. Substantial differences between the two forms of measurement were remarkably common. In 20% of the pairs, the ambulatory systolic reading was at least 10 mm Hg higher than the office-based reading, and for some pairs the differences ran as high as 30 mm Hg. In an additional 32% of the paired readings, office-based systolic pressure ran at least 10 mm Hg higher and in some cases as much as 35 mm Hg higher than the ambulatory reading.

Dr. Samuel also analyzed her findings a different way to assess the clinical consequences of these differences based on whether a child’s systolic pressure identified the patient as normotensive, hypertensive, or prehypertensive (a systolic pressure at the 90-94th percentile for the child’s age, sex and height). She found that the diagnoses matched for only 49% of the paired measurements. In 24% of the paired readings, ABPM identified children with hypertension that was not seen with concurrent office-based measurement, cases of masked hypertension. In 17% of the pairs, office-based measurement diagnosed hypertension that was not confirmed by ABPM, cases of white-coat hypertension. The remaining 10% of pairs were mismatched by showing normotensive with one method and prehypertensive with the other method. Dr. Samuel searched for any consistent patterns in these differences and found none. The disparate results with ambulatory and office-based measurements seemed almost random, with no correlation with age, sex, race, the medications patients received, or how many times a patient had already undergone dual blood-pressure monitoring. Individual patients had no meaningful differences between some of their paired measurements but had a meaningful disparity for others.

“We were unable to predict discrepancies,” said Dr. Samuels.

“You can’t get around it, you need ambulatory blood pressure monitoring to make the best diagnosis” of hypertension, she told me. “We need to push to make ambulatory monitoring more available. I am moving toward believing that ambulatory blood pressure monitoring must be routinely done on everyone. This is what the data suggest.”

It’s also where medicine is headed. In 2015, the U.S. Preventative Services Task Force (USPSTF) issued new recommendations for hypertension screening in adults aged 18 years or older, indicating that there was “convincing evidence that ABPM is the best method for diagnosing hypertension,” and the agency further recommended that ABPM is “the reference standard for confirming the diagnosis of hypertension.” Another endorsement of ambulatory blood pressure monitoring came out last year from the International Society for Chronobiology.

Recommendations are not yet as evolved for children. The USPSTF last weighed in on screening kids for hypertension in 2013, and said the evidence as of then was “insufficient” to assess the benefits and harms of screening for hypertension in children and adolescents. That document endorsed careful office-based blood pressure measurement, which highlights how recently expert sentiment has shifted on the issue of measurement. In response to the USPSTF 2013 statement, the American Academy of Pediatrics noted that it continued to back recommendations that are more than a decade old from the National High Blood Pressure Education Program that called for hypertension screening in children starting when they are 3 years old. Neither of these two groups has made any recent statement about the preferred method to measure blood pressure.

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

Evidence is becoming overwhelming that ambulatory blood pressure monitoring is the only reliable way to measure blood pressure for both diagnosing hypertension and following patients once they are diagnosed.

Office-based blood pressure measurement is out, be it a one-off reading or a cluster of sequential readings during a single office visit. Ambulatory blood pressure monitoring (ABPM) increasingly is the standard of care.

One recent nail in the coffin of office-based measurement came in a modestly-sized but revealing study reported by Dr. Joyce P. Samuel, a pediatric hypertension specialist at the University of Texas in Houston. She reported her experience directly comparing ambulatory and carefully-done office-based blood pressure measurement in a presentation at the annual meeting of the Pediatric Academic Societies in Baltimore.

Dr. Samuel followed 40 patients age 9-21 years whom she had previously diagnosed with essential hypertension (children with a systolic blood pressure at or above the 95th percentile for sex, age, and height), and repeatedly measured their blood pressures by both ambulatory and office-based readings at 2-week intervals as she searched for the best combination of antihypertensive drugs for each patient. She sent patients home for 24 hours of blood-pressure monitoring with an ambulatory device, and when they returned to her office the next day, she performed an office-based measurement using meticulous technique: Each child was seated and calm, measured on the right arm, with four measurements taken sequentially at about 1 minute intervals with the first reading discarded and the remaining three averaged.

Over the course of several months, she collected 173 paired ambulatory and office-based systolic blood pressure readings from individual patients. Substantial differences between the two forms of measurement were remarkably common. In 20% of the pairs, the ambulatory systolic reading was at least 10 mm Hg higher than the office-based reading, and for some pairs the differences ran as high as 30 mm Hg. In an additional 32% of the paired readings, office-based systolic pressure ran at least 10 mm Hg higher and in some cases as much as 35 mm Hg higher than the ambulatory reading.

Dr. Samuel also analyzed her findings a different way to assess the clinical consequences of these differences based on whether a child’s systolic pressure identified the patient as normotensive, hypertensive, or prehypertensive (a systolic pressure at the 90-94th percentile for the child’s age, sex and height). She found that the diagnoses matched for only 49% of the paired measurements. In 24% of the paired readings, ABPM identified children with hypertension that was not seen with concurrent office-based measurement, cases of masked hypertension. In 17% of the pairs, office-based measurement diagnosed hypertension that was not confirmed by ABPM, cases of white-coat hypertension. The remaining 10% of pairs were mismatched by showing normotensive with one method and prehypertensive with the other method. Dr. Samuel searched for any consistent patterns in these differences and found none. The disparate results with ambulatory and office-based measurements seemed almost random, with no correlation with age, sex, race, the medications patients received, or how many times a patient had already undergone dual blood-pressure monitoring. Individual patients had no meaningful differences between some of their paired measurements but had a meaningful disparity for others.

“We were unable to predict discrepancies,” said Dr. Samuels.

“You can’t get around it, you need ambulatory blood pressure monitoring to make the best diagnosis” of hypertension, she told me. “We need to push to make ambulatory monitoring more available. I am moving toward believing that ambulatory blood pressure monitoring must be routinely done on everyone. This is what the data suggest.”

It’s also where medicine is headed. In 2015, the U.S. Preventative Services Task Force (USPSTF) issued new recommendations for hypertension screening in adults aged 18 years or older, indicating that there was “convincing evidence that ABPM is the best method for diagnosing hypertension,” and the agency further recommended that ABPM is “the reference standard for confirming the diagnosis of hypertension.” Another endorsement of ambulatory blood pressure monitoring came out last year from the International Society for Chronobiology.

Recommendations are not yet as evolved for children. The USPSTF last weighed in on screening kids for hypertension in 2013, and said the evidence as of then was “insufficient” to assess the benefits and harms of screening for hypertension in children and adolescents. That document endorsed careful office-based blood pressure measurement, which highlights how recently expert sentiment has shifted on the issue of measurement. In response to the USPSTF 2013 statement, the American Academy of Pediatrics noted that it continued to back recommendations that are more than a decade old from the National High Blood Pressure Education Program that called for hypertension screening in children starting when they are 3 years old. Neither of these two groups has made any recent statement about the preferred method to measure blood pressure.

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

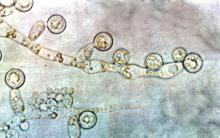

Candida linked to sex-specific schizophrenia symptoms

Exposure to Candida albicans significantly increased the odds of a schizophrenia diagnosis in men, according to case-control data from two cohorts of 947 adults.

“Fungal pathogens have not been extensively evaluated in studies of psychiatric disorders,” wrote Dr. Emily G. Severance of Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, and her colleagues, in njp (Nature Partner Journals) Schizophrenia.

The researchers compared C. albicans IgG levels of individuals with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder with controls and found no diagnostic differences. However, stratification by sex showed a significantly increased risk of schizophrenia in men with elevated C. albicans IgG levels, with a ninefold increase in risk at the highest of three levels of seropositivity (odds ratio, 9.53). Elevated C. albicans levels in males with bipolar disorder were attributed to a history of homelessness.

C. albicans antibodies in women were not significantly different between groups. However, C. albicans was significantly associated with cognitive impairment in women with schizophrenia vs. control women (OR, 1.12), but no such difference was noted in men.

High levels of C. albicans antibodies were associated with comorbid gastrointestinal, genitourinary, and neoplastic conditions among individuals with psychiatric disorders overall.

“It may be premature to list this pathogen as a risk factor for disease causation, but its status as a comorbidity requires clinical attention,” the researchers wrote. “In the long term, more research is required to understand the mechanisms that trigger pathogenicity of fungal commensals and how this might impact brain function in psychiatric disorders.”

The findings were published in npj Schizophrenia. Read the full study here (npj Schizophrenia 2016 May 4. doi: 10.1038/npjschz.2016.18).

Exposure to Candida albicans significantly increased the odds of a schizophrenia diagnosis in men, according to case-control data from two cohorts of 947 adults.

“Fungal pathogens have not been extensively evaluated in studies of psychiatric disorders,” wrote Dr. Emily G. Severance of Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, and her colleagues, in njp (Nature Partner Journals) Schizophrenia.

The researchers compared C. albicans IgG levels of individuals with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder with controls and found no diagnostic differences. However, stratification by sex showed a significantly increased risk of schizophrenia in men with elevated C. albicans IgG levels, with a ninefold increase in risk at the highest of three levels of seropositivity (odds ratio, 9.53). Elevated C. albicans levels in males with bipolar disorder were attributed to a history of homelessness.

C. albicans antibodies in women were not significantly different between groups. However, C. albicans was significantly associated with cognitive impairment in women with schizophrenia vs. control women (OR, 1.12), but no such difference was noted in men.

High levels of C. albicans antibodies were associated with comorbid gastrointestinal, genitourinary, and neoplastic conditions among individuals with psychiatric disorders overall.

“It may be premature to list this pathogen as a risk factor for disease causation, but its status as a comorbidity requires clinical attention,” the researchers wrote. “In the long term, more research is required to understand the mechanisms that trigger pathogenicity of fungal commensals and how this might impact brain function in psychiatric disorders.”

The findings were published in npj Schizophrenia. Read the full study here (npj Schizophrenia 2016 May 4. doi: 10.1038/npjschz.2016.18).

Exposure to Candida albicans significantly increased the odds of a schizophrenia diagnosis in men, according to case-control data from two cohorts of 947 adults.

“Fungal pathogens have not been extensively evaluated in studies of psychiatric disorders,” wrote Dr. Emily G. Severance of Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, and her colleagues, in njp (Nature Partner Journals) Schizophrenia.

The researchers compared C. albicans IgG levels of individuals with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder with controls and found no diagnostic differences. However, stratification by sex showed a significantly increased risk of schizophrenia in men with elevated C. albicans IgG levels, with a ninefold increase in risk at the highest of three levels of seropositivity (odds ratio, 9.53). Elevated C. albicans levels in males with bipolar disorder were attributed to a history of homelessness.

C. albicans antibodies in women were not significantly different between groups. However, C. albicans was significantly associated with cognitive impairment in women with schizophrenia vs. control women (OR, 1.12), but no such difference was noted in men.

High levels of C. albicans antibodies were associated with comorbid gastrointestinal, genitourinary, and neoplastic conditions among individuals with psychiatric disorders overall.

“It may be premature to list this pathogen as a risk factor for disease causation, but its status as a comorbidity requires clinical attention,” the researchers wrote. “In the long term, more research is required to understand the mechanisms that trigger pathogenicity of fungal commensals and how this might impact brain function in psychiatric disorders.”

The findings were published in npj Schizophrenia. Read the full study here (npj Schizophrenia 2016 May 4. doi: 10.1038/npjschz.2016.18).

FROM NPJ SCHIZOPHRENIA

Welcome from the Vascular Quality Initiative

I am pleased to welcome you to the first Vascular Quality Initiative (VQI) Annual Meeting (VQI@VAM), which will be held on June 8th, in conjunction with this year’s Vascular Annual Meeting at Gaylord National Resort & Convention Center. We have scheduled a full day program of practical QI sessions, including presentations from both QI leaders and VQI members who will be sharing their experiences in sessions designed to benefit both vascular specialists and quality improvement professionals.

We are very fortunate to have two QI experts joining us – Dr. Michael Englesbe from the Michigan Surgical Quality Collaborative and Dr. Ted James from the University of Vermont – who will provide their perspectives on how we can drive quality with the VQI registries. Dr. Englesbe, as our keynote speaker, and Dr. James, our quality expert, will be addressing the practicalities, opportunities, and challenges of using registry data for quality improvement. Dr. James will also be moderating case study discussion with centers from across the country to help VQI members use the QI tools and VQI data effectively in their own practices. All the sessions are geared to demonstrating practical QI skills so that attendees can leverage their own VQI data and reporting, and discuss solutions. Registration and a $100 fee are required.

Overall, I believe that the Annual Meeting will create a valuable opportunity for both vascular specialists and quality improvement staff to see how participation in VQI can help improve the day-to-day quality of vascular care for patients. By taking a team approach, those who attend will be able to share a combination of best practice, collaboration, and benchmarking. Data managers will gain deeper insights into the value of reporting and analytics, and practitioners will able to compare their experiences with others.

This inaugural VQI Annual Meeting is an important part of our road map to the next level for the Vascular Quality Initiative’s development. It allows us to directly reach our base of over 2,800 physicians to introduce new approaches, such as tracking long-term follow-up and better measurement of the quality of vascular care, which will increase our effectiveness as practitioners.

Over the years of development of the VQI, we’ve seen the value of quality improvement data and analytics for the VQI in our practices. Now we’ve developed a valuable body of VQI-based real world experience to draw upon, which we will demonstrate at this event and going forward. I look forward to seeing you at the Gaylord National Resort & Convention Center on June 8th for VQI@VAM.

Dr. Larry Kraiss

Chair, SVS PSO Governing Council

I am pleased to welcome you to the first Vascular Quality Initiative (VQI) Annual Meeting (VQI@VAM), which will be held on June 8th, in conjunction with this year’s Vascular Annual Meeting at Gaylord National Resort & Convention Center. We have scheduled a full day program of practical QI sessions, including presentations from both QI leaders and VQI members who will be sharing their experiences in sessions designed to benefit both vascular specialists and quality improvement professionals.

We are very fortunate to have two QI experts joining us – Dr. Michael Englesbe from the Michigan Surgical Quality Collaborative and Dr. Ted James from the University of Vermont – who will provide their perspectives on how we can drive quality with the VQI registries. Dr. Englesbe, as our keynote speaker, and Dr. James, our quality expert, will be addressing the practicalities, opportunities, and challenges of using registry data for quality improvement. Dr. James will also be moderating case study discussion with centers from across the country to help VQI members use the QI tools and VQI data effectively in their own practices. All the sessions are geared to demonstrating practical QI skills so that attendees can leverage their own VQI data and reporting, and discuss solutions. Registration and a $100 fee are required.

Overall, I believe that the Annual Meeting will create a valuable opportunity for both vascular specialists and quality improvement staff to see how participation in VQI can help improve the day-to-day quality of vascular care for patients. By taking a team approach, those who attend will be able to share a combination of best practice, collaboration, and benchmarking. Data managers will gain deeper insights into the value of reporting and analytics, and practitioners will able to compare their experiences with others.