User login

Anticipating Growth in Medical Costs, U.S Health Insurers Will Receive Higher Government Payments in 2017

NEW YORK (Reuters) - U.S. health insurers that provide Medicare Advantage plans to elderly and disabled Americans will receive government payments in 2017 that are 0.85 percent higher on average than in 2016, reflecting small anticipated growth in medical costs, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services said on Monday.

Health and Human Services' final plan to raise payments is a bit lower than the 1.35 percent increase the agency had proposed in February. It said the lower figure reflects revisions to medical services cost calculations.

In addition, the agency said it planned to introduce a two-year transition period to implement reductions in payments to insurers that offer employer-sponsored prescription drug plans for retirees. After it proposed the cuts to 2017 payments in February, insurers and other lobbying groups said the agency was too aggressive.

Insurers including UnitedHealth Group Inc, Aetna Inc and Anthem Inc manage health benefits for more than 17 million Americans enrolled in Medicare Advantage plans.

The other more than 30 million people eligible for Medicare coverage are part of the government-run fee-for-service program.

Each year the government sets out how it will reimburse insurers for the healthcare services their members use. Payments vary by region, the quality rating earned by the plan, and the relative health of the members.

NEW YORK (Reuters) - U.S. health insurers that provide Medicare Advantage plans to elderly and disabled Americans will receive government payments in 2017 that are 0.85 percent higher on average than in 2016, reflecting small anticipated growth in medical costs, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services said on Monday.

Health and Human Services' final plan to raise payments is a bit lower than the 1.35 percent increase the agency had proposed in February. It said the lower figure reflects revisions to medical services cost calculations.

In addition, the agency said it planned to introduce a two-year transition period to implement reductions in payments to insurers that offer employer-sponsored prescription drug plans for retirees. After it proposed the cuts to 2017 payments in February, insurers and other lobbying groups said the agency was too aggressive.

Insurers including UnitedHealth Group Inc, Aetna Inc and Anthem Inc manage health benefits for more than 17 million Americans enrolled in Medicare Advantage plans.

The other more than 30 million people eligible for Medicare coverage are part of the government-run fee-for-service program.

Each year the government sets out how it will reimburse insurers for the healthcare services their members use. Payments vary by region, the quality rating earned by the plan, and the relative health of the members.

NEW YORK (Reuters) - U.S. health insurers that provide Medicare Advantage plans to elderly and disabled Americans will receive government payments in 2017 that are 0.85 percent higher on average than in 2016, reflecting small anticipated growth in medical costs, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services said on Monday.

Health and Human Services' final plan to raise payments is a bit lower than the 1.35 percent increase the agency had proposed in February. It said the lower figure reflects revisions to medical services cost calculations.

In addition, the agency said it planned to introduce a two-year transition period to implement reductions in payments to insurers that offer employer-sponsored prescription drug plans for retirees. After it proposed the cuts to 2017 payments in February, insurers and other lobbying groups said the agency was too aggressive.

Insurers including UnitedHealth Group Inc, Aetna Inc and Anthem Inc manage health benefits for more than 17 million Americans enrolled in Medicare Advantage plans.

The other more than 30 million people eligible for Medicare coverage are part of the government-run fee-for-service program.

Each year the government sets out how it will reimburse insurers for the healthcare services their members use. Payments vary by region, the quality rating earned by the plan, and the relative health of the members.

Change in T-cell distribution predicts LFS, OS in AML

NEW ORLEANS—A phase 4 study has revealed biomarkers that appear to predict the efficacy of treatment with histamine dihydrochloride (HDC) and interleukin-2 (IL-2) in patients with acute myeloid leukemia (AML).

Researchers found that patients who remained in complete remission after 1 cycle of HDC/IL-2 experienced a significant reduction in effector memory T cells (TEM) and a concomitant increase in effector T cells (Teff) during therapy.

This “TEM to Teff transition” was associated with favorable leukemia-free survival (LFS) and overall survival (OS), especially among patients older than 60.

Frida Ewald Sander, PhD, of University of Gothenburg in Sweden, and her colleagues presented this research at the 2016 AACR Annual Meeting (abstract CT116*).

The study was supported by The Swedish Research Council, The Swedish Cancer Society, The Swedish Society for Medical Research, Meda Pharma, and Immune Pharmaceuticals, which markets HDC as Ceplene®.

The combination of HDC and IL-2 is currently approved in more than 30 countries to prevent relapse in AML patients. In this phase 4 study (Re:MISSION), the researchers set out to assess the immunomodulatory properties of this treatment and correlate potential biomarkers with clinical outcomes.

The study included 84 non-transplanted AML patients (ages 18 to 79) in first complete remission. The patients received HDC (0.5 mg SC BID) and human recombinant IL-2 (1MIU SC BID) in 3-week cycles for 18 months. The patients were followed for at least 2 years from the start of immunotherapy to evaluate survival.

The researchers collected blood from the patients before they began HDC/IL-2 therapy and at the end of the first treatment cycle. From these samples, the team assessed the frequency of CD8+ T cells, including naïve T cells (CD45RA+CCR7+), central memory T cells (CD45RO+CCR7+), TEM cells (CD45RO+CCR7-), and Teff cells (CD45RA+CCR7-).

The researchers found that non-relapsing patients experienced a significant reduction in TEM cells (P=0.001) and a significant increase in Teff cells (P=0.007) during cycle 1. However, this effect was not observed in patients who did relapse.

Further analysis revealed that the reduction in TEM cells was significantly associated with favorable LFS and OS in the entire cohort (P=0.0007 and P=0.005, respectively) and among patients over 60 (P<0.0001 and P=0.002, respectively).

Likewise, the increase in Teff cells was associated with favorable LFS and OS in the entire cohort (P=0.07 and P=0.04, respectively) and among patients over 60 (P=0.004 and P=0.0001, respectively).

The concomitant reduction of TEM cells and induction of Teff cells—the TEM to Teff transition—was associated with superior LFS and OS in the overall cohort (P=0.0002 and P=0.002, respectively) and in the over-60 population (P<0.0001 for LFS and OS).

The researchers said these predictors of outcome remained significant when they adjusted for potential confounders (age, risk group classification, number of induction courses required to achieve complete response, and number of consolidation courses).

Therefore, the team concluded that the altered distribution of cytotoxic T cells during treatment with HDC/IL-2 can prognosticate LFS and OS in AML patients, particularly those over 60.

“We believe that the new data may allow a personalized approach to selection of patients who are most likely to benefit from Ceplene/IL-2 treatment in AML—in particular, the older patient population, who have demonstrated almost 100% survival when positive for the T-cell transition biomarkers,” said Miri Ben-Ami, MD, executive vice president of oncology at Immune Pharmaceuticals.

“In addition, current research is revealing the potential synergy between immune checkpoint inhibitors and Ceplene, which could open the possibility of additional therapeutic indications for this combination.” ![]()

*Information in the abstract differs from that presented at the meeting.

NEW ORLEANS—A phase 4 study has revealed biomarkers that appear to predict the efficacy of treatment with histamine dihydrochloride (HDC) and interleukin-2 (IL-2) in patients with acute myeloid leukemia (AML).

Researchers found that patients who remained in complete remission after 1 cycle of HDC/IL-2 experienced a significant reduction in effector memory T cells (TEM) and a concomitant increase in effector T cells (Teff) during therapy.

This “TEM to Teff transition” was associated with favorable leukemia-free survival (LFS) and overall survival (OS), especially among patients older than 60.

Frida Ewald Sander, PhD, of University of Gothenburg in Sweden, and her colleagues presented this research at the 2016 AACR Annual Meeting (abstract CT116*).

The study was supported by The Swedish Research Council, The Swedish Cancer Society, The Swedish Society for Medical Research, Meda Pharma, and Immune Pharmaceuticals, which markets HDC as Ceplene®.

The combination of HDC and IL-2 is currently approved in more than 30 countries to prevent relapse in AML patients. In this phase 4 study (Re:MISSION), the researchers set out to assess the immunomodulatory properties of this treatment and correlate potential biomarkers with clinical outcomes.

The study included 84 non-transplanted AML patients (ages 18 to 79) in first complete remission. The patients received HDC (0.5 mg SC BID) and human recombinant IL-2 (1MIU SC BID) in 3-week cycles for 18 months. The patients were followed for at least 2 years from the start of immunotherapy to evaluate survival.

The researchers collected blood from the patients before they began HDC/IL-2 therapy and at the end of the first treatment cycle. From these samples, the team assessed the frequency of CD8+ T cells, including naïve T cells (CD45RA+CCR7+), central memory T cells (CD45RO+CCR7+), TEM cells (CD45RO+CCR7-), and Teff cells (CD45RA+CCR7-).

The researchers found that non-relapsing patients experienced a significant reduction in TEM cells (P=0.001) and a significant increase in Teff cells (P=0.007) during cycle 1. However, this effect was not observed in patients who did relapse.

Further analysis revealed that the reduction in TEM cells was significantly associated with favorable LFS and OS in the entire cohort (P=0.0007 and P=0.005, respectively) and among patients over 60 (P<0.0001 and P=0.002, respectively).

Likewise, the increase in Teff cells was associated with favorable LFS and OS in the entire cohort (P=0.07 and P=0.04, respectively) and among patients over 60 (P=0.004 and P=0.0001, respectively).

The concomitant reduction of TEM cells and induction of Teff cells—the TEM to Teff transition—was associated with superior LFS and OS in the overall cohort (P=0.0002 and P=0.002, respectively) and in the over-60 population (P<0.0001 for LFS and OS).

The researchers said these predictors of outcome remained significant when they adjusted for potential confounders (age, risk group classification, number of induction courses required to achieve complete response, and number of consolidation courses).

Therefore, the team concluded that the altered distribution of cytotoxic T cells during treatment with HDC/IL-2 can prognosticate LFS and OS in AML patients, particularly those over 60.

“We believe that the new data may allow a personalized approach to selection of patients who are most likely to benefit from Ceplene/IL-2 treatment in AML—in particular, the older patient population, who have demonstrated almost 100% survival when positive for the T-cell transition biomarkers,” said Miri Ben-Ami, MD, executive vice president of oncology at Immune Pharmaceuticals.

“In addition, current research is revealing the potential synergy between immune checkpoint inhibitors and Ceplene, which could open the possibility of additional therapeutic indications for this combination.” ![]()

*Information in the abstract differs from that presented at the meeting.

NEW ORLEANS—A phase 4 study has revealed biomarkers that appear to predict the efficacy of treatment with histamine dihydrochloride (HDC) and interleukin-2 (IL-2) in patients with acute myeloid leukemia (AML).

Researchers found that patients who remained in complete remission after 1 cycle of HDC/IL-2 experienced a significant reduction in effector memory T cells (TEM) and a concomitant increase in effector T cells (Teff) during therapy.

This “TEM to Teff transition” was associated with favorable leukemia-free survival (LFS) and overall survival (OS), especially among patients older than 60.

Frida Ewald Sander, PhD, of University of Gothenburg in Sweden, and her colleagues presented this research at the 2016 AACR Annual Meeting (abstract CT116*).

The study was supported by The Swedish Research Council, The Swedish Cancer Society, The Swedish Society for Medical Research, Meda Pharma, and Immune Pharmaceuticals, which markets HDC as Ceplene®.

The combination of HDC and IL-2 is currently approved in more than 30 countries to prevent relapse in AML patients. In this phase 4 study (Re:MISSION), the researchers set out to assess the immunomodulatory properties of this treatment and correlate potential biomarkers with clinical outcomes.

The study included 84 non-transplanted AML patients (ages 18 to 79) in first complete remission. The patients received HDC (0.5 mg SC BID) and human recombinant IL-2 (1MIU SC BID) in 3-week cycles for 18 months. The patients were followed for at least 2 years from the start of immunotherapy to evaluate survival.

The researchers collected blood from the patients before they began HDC/IL-2 therapy and at the end of the first treatment cycle. From these samples, the team assessed the frequency of CD8+ T cells, including naïve T cells (CD45RA+CCR7+), central memory T cells (CD45RO+CCR7+), TEM cells (CD45RO+CCR7-), and Teff cells (CD45RA+CCR7-).

The researchers found that non-relapsing patients experienced a significant reduction in TEM cells (P=0.001) and a significant increase in Teff cells (P=0.007) during cycle 1. However, this effect was not observed in patients who did relapse.

Further analysis revealed that the reduction in TEM cells was significantly associated with favorable LFS and OS in the entire cohort (P=0.0007 and P=0.005, respectively) and among patients over 60 (P<0.0001 and P=0.002, respectively).

Likewise, the increase in Teff cells was associated with favorable LFS and OS in the entire cohort (P=0.07 and P=0.04, respectively) and among patients over 60 (P=0.004 and P=0.0001, respectively).

The concomitant reduction of TEM cells and induction of Teff cells—the TEM to Teff transition—was associated with superior LFS and OS in the overall cohort (P=0.0002 and P=0.002, respectively) and in the over-60 population (P<0.0001 for LFS and OS).

The researchers said these predictors of outcome remained significant when they adjusted for potential confounders (age, risk group classification, number of induction courses required to achieve complete response, and number of consolidation courses).

Therefore, the team concluded that the altered distribution of cytotoxic T cells during treatment with HDC/IL-2 can prognosticate LFS and OS in AML patients, particularly those over 60.

“We believe that the new data may allow a personalized approach to selection of patients who are most likely to benefit from Ceplene/IL-2 treatment in AML—in particular, the older patient population, who have demonstrated almost 100% survival when positive for the T-cell transition biomarkers,” said Miri Ben-Ami, MD, executive vice president of oncology at Immune Pharmaceuticals.

“In addition, current research is revealing the potential synergy between immune checkpoint inhibitors and Ceplene, which could open the possibility of additional therapeutic indications for this combination.” ![]()

*Information in the abstract differs from that presented at the meeting.

Gene therapy benefits older patients with SCID-X1

Photo courtesy of St. Jude

Children’s Research Hospital

Lentiviral gene therapy with reduced-intensity conditioning can provide long-term benefits for older patients with X-linked severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID-X1), according to a small study.

All 5 patients who received this therapy exhibited selective expansion of gene-marked B, T, and natural killer (NK) cells.

In 2 of the older patients, the treatment restored normal immune function, an effect that lasted 2 and 3 years, respectively.

“This study demonstrates that lentivirus gene therapy, when combined with busulfan conditioning, can rebuild the immune system and lead to broad immunity in young adults with this devastating disorder,” said Brian Sorrentino, MD, of St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital in Memphis, Tennessee.

Dr Sorrentino and his colleagues described this research in Science Translational Medicine.

The researchers explained that SCID-X1 is a profound deficiency of T, B, and NK cell immunity caused by mutations in IL2RG encoding the common chain (γc) of several interleukin receptors. And gammaretroviral gene therapy given without conditioning can restore T-cell immunity in young children with SCID-X1 but fails in older patients.

With this in mind, the team developed a lentiviral vector γc transduced autologous hematopoietic stem cell (HSC) gene therapy and tested it with nonmyeloablative busulfan conditioning in 5 SCID-X1 patients.

The patients were 7 to 23 years old. They all had chronic viral infections and other health problems related to SCID-X1, despite having received 1 or more haploidentical HSC transplants.

More than 2 years after undergoing gene therapy, the first 2 patients (ages 22 and 23) were producing a greater percentage of T, B, and NK cells with the corrected gene. The therapy had also restored antibody production in response to vaccination.

Furthermore, the patients’ health improved as their chronic viral infections resolved, and they put on weight as their protein absorption improved. One patient’s disfiguring warts were eased, and both patients ended life-long immune globulin therapy.

However, one of these patients died from pre-existing lung damage more than 2 years after receiving gene therapy.

Like the 2 older patients, the 3 younger patients (ages 7, 10, and 15) began producing a greater percentage of T, B, and NK cells with the corrected gene after therapy. But the younger patients have only been followed for several months.

The researchers said the safety results in this study were reassuring. There were no adverse events associated with the gene therapy and no indication of possible precancer cell proliferation.

As expected, patients experienced busulfan-related neutropenia and thrombocytopenia but recovered without any intervention. And 3 patients developed febrile neutropenia that responded to empiric antimicrobial therapy.

“While additional clinical experience and follow-up is needed, these promising results suggest gene therapy should be considered as an early treatment for patients in order to minimize or prevent the life-threatening organ damage that occurs when bone marrow transplant therapy fails to provide a sufficient immune response,” Dr Sorrentino said.

To that end, St. Jude has opened a gene therapy trial using the same lentiviral vector and busulfan conditioning for newly identified infants with SCID-X1 who lack a genetically matched sibling HSC donor.

“Based on the safety and health benefits for older patients reported in this study, we hope this novel gene therapy will help improve immune functioning and transform the lives of younger patients with this devastating disease,” Dr Sorrentino said. ![]()

Photo courtesy of St. Jude

Children’s Research Hospital

Lentiviral gene therapy with reduced-intensity conditioning can provide long-term benefits for older patients with X-linked severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID-X1), according to a small study.

All 5 patients who received this therapy exhibited selective expansion of gene-marked B, T, and natural killer (NK) cells.

In 2 of the older patients, the treatment restored normal immune function, an effect that lasted 2 and 3 years, respectively.

“This study demonstrates that lentivirus gene therapy, when combined with busulfan conditioning, can rebuild the immune system and lead to broad immunity in young adults with this devastating disorder,” said Brian Sorrentino, MD, of St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital in Memphis, Tennessee.

Dr Sorrentino and his colleagues described this research in Science Translational Medicine.

The researchers explained that SCID-X1 is a profound deficiency of T, B, and NK cell immunity caused by mutations in IL2RG encoding the common chain (γc) of several interleukin receptors. And gammaretroviral gene therapy given without conditioning can restore T-cell immunity in young children with SCID-X1 but fails in older patients.

With this in mind, the team developed a lentiviral vector γc transduced autologous hematopoietic stem cell (HSC) gene therapy and tested it with nonmyeloablative busulfan conditioning in 5 SCID-X1 patients.

The patients were 7 to 23 years old. They all had chronic viral infections and other health problems related to SCID-X1, despite having received 1 or more haploidentical HSC transplants.

More than 2 years after undergoing gene therapy, the first 2 patients (ages 22 and 23) were producing a greater percentage of T, B, and NK cells with the corrected gene. The therapy had also restored antibody production in response to vaccination.

Furthermore, the patients’ health improved as their chronic viral infections resolved, and they put on weight as their protein absorption improved. One patient’s disfiguring warts were eased, and both patients ended life-long immune globulin therapy.

However, one of these patients died from pre-existing lung damage more than 2 years after receiving gene therapy.

Like the 2 older patients, the 3 younger patients (ages 7, 10, and 15) began producing a greater percentage of T, B, and NK cells with the corrected gene after therapy. But the younger patients have only been followed for several months.

The researchers said the safety results in this study were reassuring. There were no adverse events associated with the gene therapy and no indication of possible precancer cell proliferation.

As expected, patients experienced busulfan-related neutropenia and thrombocytopenia but recovered without any intervention. And 3 patients developed febrile neutropenia that responded to empiric antimicrobial therapy.

“While additional clinical experience and follow-up is needed, these promising results suggest gene therapy should be considered as an early treatment for patients in order to minimize or prevent the life-threatening organ damage that occurs when bone marrow transplant therapy fails to provide a sufficient immune response,” Dr Sorrentino said.

To that end, St. Jude has opened a gene therapy trial using the same lentiviral vector and busulfan conditioning for newly identified infants with SCID-X1 who lack a genetically matched sibling HSC donor.

“Based on the safety and health benefits for older patients reported in this study, we hope this novel gene therapy will help improve immune functioning and transform the lives of younger patients with this devastating disease,” Dr Sorrentino said. ![]()

Photo courtesy of St. Jude

Children’s Research Hospital

Lentiviral gene therapy with reduced-intensity conditioning can provide long-term benefits for older patients with X-linked severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID-X1), according to a small study.

All 5 patients who received this therapy exhibited selective expansion of gene-marked B, T, and natural killer (NK) cells.

In 2 of the older patients, the treatment restored normal immune function, an effect that lasted 2 and 3 years, respectively.

“This study demonstrates that lentivirus gene therapy, when combined with busulfan conditioning, can rebuild the immune system and lead to broad immunity in young adults with this devastating disorder,” said Brian Sorrentino, MD, of St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital in Memphis, Tennessee.

Dr Sorrentino and his colleagues described this research in Science Translational Medicine.

The researchers explained that SCID-X1 is a profound deficiency of T, B, and NK cell immunity caused by mutations in IL2RG encoding the common chain (γc) of several interleukin receptors. And gammaretroviral gene therapy given without conditioning can restore T-cell immunity in young children with SCID-X1 but fails in older patients.

With this in mind, the team developed a lentiviral vector γc transduced autologous hematopoietic stem cell (HSC) gene therapy and tested it with nonmyeloablative busulfan conditioning in 5 SCID-X1 patients.

The patients were 7 to 23 years old. They all had chronic viral infections and other health problems related to SCID-X1, despite having received 1 or more haploidentical HSC transplants.

More than 2 years after undergoing gene therapy, the first 2 patients (ages 22 and 23) were producing a greater percentage of T, B, and NK cells with the corrected gene. The therapy had also restored antibody production in response to vaccination.

Furthermore, the patients’ health improved as their chronic viral infections resolved, and they put on weight as their protein absorption improved. One patient’s disfiguring warts were eased, and both patients ended life-long immune globulin therapy.

However, one of these patients died from pre-existing lung damage more than 2 years after receiving gene therapy.

Like the 2 older patients, the 3 younger patients (ages 7, 10, and 15) began producing a greater percentage of T, B, and NK cells with the corrected gene after therapy. But the younger patients have only been followed for several months.

The researchers said the safety results in this study were reassuring. There were no adverse events associated with the gene therapy and no indication of possible precancer cell proliferation.

As expected, patients experienced busulfan-related neutropenia and thrombocytopenia but recovered without any intervention. And 3 patients developed febrile neutropenia that responded to empiric antimicrobial therapy.

“While additional clinical experience and follow-up is needed, these promising results suggest gene therapy should be considered as an early treatment for patients in order to minimize or prevent the life-threatening organ damage that occurs when bone marrow transplant therapy fails to provide a sufficient immune response,” Dr Sorrentino said.

To that end, St. Jude has opened a gene therapy trial using the same lentiviral vector and busulfan conditioning for newly identified infants with SCID-X1 who lack a genetically matched sibling HSC donor.

“Based on the safety and health benefits for older patients reported in this study, we hope this novel gene therapy will help improve immune functioning and transform the lives of younger patients with this devastating disease,” Dr Sorrentino said. ![]()

Low risk of complications with well-managed warfarin

Photo courtesy of NIGMS

Results of a retrospective study suggest that well-managed warfarin therapy confers a low risk of complications in patients with non-valvular atrial fibrillation (NVAF).

However, certain patients require close monitoring, including those with renal failure, those taking aspirin concomitantly, and those with an individual time in therapeutic range (iTTR) less than 70% or high international normalized ratio (INR) variability.

Fredrik Björck, MD, of Umea University in Umea, Sweden, and his colleagues conducted this research and reported the results in JAMA Cardiology.

The researchers noted that warfarin has been compared to non-vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulants for stroke prevention in NVAF, but these studies were based on comparisons with warfarin arms that had TTRs of 55.2% to 64.9%, which makes the results less credible in healthcare systems with higher TTRs.

So the team wanted to evaluate the efficacy and safety of well-managed warfarin therapy in patients with NVAF. They analyzed data from Swedish registries to identify 40,449 patients who were starting warfarin due to NVAF.

The patients’ mean age was 72.5, 40% (n=16,201) were women, and their mean CHA2DS2-VASc score at baseline was 3.3. They were monitored until they stopped treatment, died, or the study ended.

Overall results

The annual incidence of all-cause mortality was 2.19%. The annual incidence of any major bleeding was 2.23%—0.76% gastrointestinal, 0.44% intracranial, and 1.23% other bleeding.

The annual incidence of any thromboembolism was 2.95%—1.73% arterial thromboembolism, 1.23% myocardial infarction, and 0.13% venous thromboembolism.

Aspirin and intracranial bleeding

When compared to patients who were only taking warfarin, those who were also taking aspirin had significantly higher rates of any major bleeding (2.04% vs 3.07%), gastrointestinal bleeding (0.67% vs 1.18%), and other major bleeding (1.13% vs 1.67%).

But there was no significant difference in intracranial bleeding (0.41% vs 0.62%).

Overall, patients had an increased risk of intracranial bleeding if they had renal failure (hazard ratio [HR]=2.25, P=0.003), stroke (HR=1.58, P=0.002), or hypertension (HR=1.37, P=0.03).

In addition, the risk of intracranial bleeding increased significantly with age (HR=1.03, P=0.002), and women had a lower risk than men (HR=0.71, P=0.01).

INR and iTTR

Patients with an iTTR of less than 70% had a significantly higher incidence of treatment complications than patients with an iTTR of 70% or greater.

This includes all-cause mortality (4.35% vs 1.29%), any major bleeding (3.81% vs 1.61%), intracranial bleeding (0.72% vs 0.34%), gastrointestinal bleeding (1.26% vs 0.56%), other bleeding (2.17% vs 0.84), any thromboembolism (4.41% vs 2.37%), arterial thromboembolism (2.52% vs 1.41%), myocardial infarction (1.90% vs 0.98%), and venous thromboembolism (0.24% vs 0.09%).

Similarly, patients with high INR variability had a significantly higher incidence of nearly all events when compared to patients with low INR variability (below the mean value of 0.83).

This includes all-cause mortality (2.94% vs 1.50%), any major bleeding (3.04% vs 1.47%), gastrointestinal bleeding (1.05% vs 0.50%), other bleeding (1.79% vs 0.71), any thromboembolism (3.48% vs 2.46%), arterial thromboembolism (1.98% vs 1.51%), and myocardial infarction (1.53% vs 0.96%).

The exceptions were intracranial bleeding (0.51% vs 0.38%) and venous thromboembolism (0.16% vs 0.11%).

For patients with an iTTR of 70% or greater, there was no significant difference in the cumulative incidence of complications when comparing groups according to INR variability. ![]()

Photo courtesy of NIGMS

Results of a retrospective study suggest that well-managed warfarin therapy confers a low risk of complications in patients with non-valvular atrial fibrillation (NVAF).

However, certain patients require close monitoring, including those with renal failure, those taking aspirin concomitantly, and those with an individual time in therapeutic range (iTTR) less than 70% or high international normalized ratio (INR) variability.

Fredrik Björck, MD, of Umea University in Umea, Sweden, and his colleagues conducted this research and reported the results in JAMA Cardiology.

The researchers noted that warfarin has been compared to non-vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulants for stroke prevention in NVAF, but these studies were based on comparisons with warfarin arms that had TTRs of 55.2% to 64.9%, which makes the results less credible in healthcare systems with higher TTRs.

So the team wanted to evaluate the efficacy and safety of well-managed warfarin therapy in patients with NVAF. They analyzed data from Swedish registries to identify 40,449 patients who were starting warfarin due to NVAF.

The patients’ mean age was 72.5, 40% (n=16,201) were women, and their mean CHA2DS2-VASc score at baseline was 3.3. They were monitored until they stopped treatment, died, or the study ended.

Overall results

The annual incidence of all-cause mortality was 2.19%. The annual incidence of any major bleeding was 2.23%—0.76% gastrointestinal, 0.44% intracranial, and 1.23% other bleeding.

The annual incidence of any thromboembolism was 2.95%—1.73% arterial thromboembolism, 1.23% myocardial infarction, and 0.13% venous thromboembolism.

Aspirin and intracranial bleeding

When compared to patients who were only taking warfarin, those who were also taking aspirin had significantly higher rates of any major bleeding (2.04% vs 3.07%), gastrointestinal bleeding (0.67% vs 1.18%), and other major bleeding (1.13% vs 1.67%).

But there was no significant difference in intracranial bleeding (0.41% vs 0.62%).

Overall, patients had an increased risk of intracranial bleeding if they had renal failure (hazard ratio [HR]=2.25, P=0.003), stroke (HR=1.58, P=0.002), or hypertension (HR=1.37, P=0.03).

In addition, the risk of intracranial bleeding increased significantly with age (HR=1.03, P=0.002), and women had a lower risk than men (HR=0.71, P=0.01).

INR and iTTR

Patients with an iTTR of less than 70% had a significantly higher incidence of treatment complications than patients with an iTTR of 70% or greater.

This includes all-cause mortality (4.35% vs 1.29%), any major bleeding (3.81% vs 1.61%), intracranial bleeding (0.72% vs 0.34%), gastrointestinal bleeding (1.26% vs 0.56%), other bleeding (2.17% vs 0.84), any thromboembolism (4.41% vs 2.37%), arterial thromboembolism (2.52% vs 1.41%), myocardial infarction (1.90% vs 0.98%), and venous thromboembolism (0.24% vs 0.09%).

Similarly, patients with high INR variability had a significantly higher incidence of nearly all events when compared to patients with low INR variability (below the mean value of 0.83).

This includes all-cause mortality (2.94% vs 1.50%), any major bleeding (3.04% vs 1.47%), gastrointestinal bleeding (1.05% vs 0.50%), other bleeding (1.79% vs 0.71), any thromboembolism (3.48% vs 2.46%), arterial thromboembolism (1.98% vs 1.51%), and myocardial infarction (1.53% vs 0.96%).

The exceptions were intracranial bleeding (0.51% vs 0.38%) and venous thromboembolism (0.16% vs 0.11%).

For patients with an iTTR of 70% or greater, there was no significant difference in the cumulative incidence of complications when comparing groups according to INR variability. ![]()

Photo courtesy of NIGMS

Results of a retrospective study suggest that well-managed warfarin therapy confers a low risk of complications in patients with non-valvular atrial fibrillation (NVAF).

However, certain patients require close monitoring, including those with renal failure, those taking aspirin concomitantly, and those with an individual time in therapeutic range (iTTR) less than 70% or high international normalized ratio (INR) variability.

Fredrik Björck, MD, of Umea University in Umea, Sweden, and his colleagues conducted this research and reported the results in JAMA Cardiology.

The researchers noted that warfarin has been compared to non-vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulants for stroke prevention in NVAF, but these studies were based on comparisons with warfarin arms that had TTRs of 55.2% to 64.9%, which makes the results less credible in healthcare systems with higher TTRs.

So the team wanted to evaluate the efficacy and safety of well-managed warfarin therapy in patients with NVAF. They analyzed data from Swedish registries to identify 40,449 patients who were starting warfarin due to NVAF.

The patients’ mean age was 72.5, 40% (n=16,201) were women, and their mean CHA2DS2-VASc score at baseline was 3.3. They were monitored until they stopped treatment, died, or the study ended.

Overall results

The annual incidence of all-cause mortality was 2.19%. The annual incidence of any major bleeding was 2.23%—0.76% gastrointestinal, 0.44% intracranial, and 1.23% other bleeding.

The annual incidence of any thromboembolism was 2.95%—1.73% arterial thromboembolism, 1.23% myocardial infarction, and 0.13% venous thromboembolism.

Aspirin and intracranial bleeding

When compared to patients who were only taking warfarin, those who were also taking aspirin had significantly higher rates of any major bleeding (2.04% vs 3.07%), gastrointestinal bleeding (0.67% vs 1.18%), and other major bleeding (1.13% vs 1.67%).

But there was no significant difference in intracranial bleeding (0.41% vs 0.62%).

Overall, patients had an increased risk of intracranial bleeding if they had renal failure (hazard ratio [HR]=2.25, P=0.003), stroke (HR=1.58, P=0.002), or hypertension (HR=1.37, P=0.03).

In addition, the risk of intracranial bleeding increased significantly with age (HR=1.03, P=0.002), and women had a lower risk than men (HR=0.71, P=0.01).

INR and iTTR

Patients with an iTTR of less than 70% had a significantly higher incidence of treatment complications than patients with an iTTR of 70% or greater.

This includes all-cause mortality (4.35% vs 1.29%), any major bleeding (3.81% vs 1.61%), intracranial bleeding (0.72% vs 0.34%), gastrointestinal bleeding (1.26% vs 0.56%), other bleeding (2.17% vs 0.84), any thromboembolism (4.41% vs 2.37%), arterial thromboembolism (2.52% vs 1.41%), myocardial infarction (1.90% vs 0.98%), and venous thromboembolism (0.24% vs 0.09%).

Similarly, patients with high INR variability had a significantly higher incidence of nearly all events when compared to patients with low INR variability (below the mean value of 0.83).

This includes all-cause mortality (2.94% vs 1.50%), any major bleeding (3.04% vs 1.47%), gastrointestinal bleeding (1.05% vs 0.50%), other bleeding (1.79% vs 0.71), any thromboembolism (3.48% vs 2.46%), arterial thromboembolism (1.98% vs 1.51%), and myocardial infarction (1.53% vs 0.96%).

The exceptions were intracranial bleeding (0.51% vs 0.38%) and venous thromboembolism (0.16% vs 0.11%).

For patients with an iTTR of 70% or greater, there was no significant difference in the cumulative incidence of complications when comparing groups according to INR variability. ![]()

Drug bests placebo in kids with chronic ITP

Photo by Bill Branson

The thrombopoietin receptor agonist romiplostim can produce durable platelet responses in children with symptomatic chronic immune thrombocytopenia (ITP), according to a phase 3 study.

Fifty-two percent of patients who received romiplostim achieved a durable platelet response, compared to 10% of placebo-treated patients.

Investigators said these results suggest romiplostim may be a treatment option for this patient population.

“The results of this study suggest that romiplostim could reduce the frequency and severity of bleeding events for children suffering from symptomatic ITP, thus providing them with another potential treatment option,” said Michael D. Tarantino, MD, of the University of Illinois College of Medicine-Peoria.

Dr Tarantino and his colleagues reported the results in The Lancet. The study was supported by Amgen, which markets romiplostim (Nplate) as a treatment for adults with chronic ITP.

This double-blind study included 62 children (ages 6 to 14) who had ITP for more than 6 months and were randomized to weekly romiplostim (n=42) or placebo (n=20) for 24 weeks. Baseline characteristics were well-balanced between the treatment arms.

The median time since ITP diagnosis was about 2 years for both arms, and the median age at diagnosis was about 7. The median baseline platelet counts were 17.8 x 109/L in the romiplostim arm and 17.7 x 109/L in the placebo arm.

Durable platelet response, the primary endpoint of the study, was defined as achieving weekly platelet responses without rescue medication in at least 6 of the final 8 weeks of the study.

The rates of durable platelet response were 52% (22/42) in the romiplostim arm and 10% (2/20) in the placebo arm (P=0.002, odds ratio 9.1, 95% CI: 1.9, 43.2).

The rates of overall platelet response were 71% (30/42) in the romiplostim arm and 20% in the placebo arm (P=0.0002, odds ratio 9.0, 95% CI: 2.5, 32.3), and the rates of any platelet response were 81% (34/42) and 55% (11/20), respectively (P=0.0313).

The most frequently reported adverse events (AEs) observed in patients receiving romiplostim were contusion (50%), epistaxis (48%), headache (43%), and upper respiratory tract infection (38%).

Oropharyngeal pain occurred more frequently with romiplostim than placebo—26.2% (11/42) and 5.3% (1/19), respectively.

In the 11 romiplostim-treated patients with oropharyngeal pain, streptococcal pharyngitis (n=2), allergic rhinitis (n=2), gastroesophageal reflux (n=1), and serum sickness from IVIg (n=1) were also reported. No oropharyngeal pain AEs were serious or considered treatment-related.

Serious AEs occurred in 23.8% of romiplostim-treated patients and 5.3% of placebo-treated patients.

Serious AEs in the romiplostim arm included epistaxis (n=2), contusion (n=2), headache (n=2), bronchiolitis (n=1), nausea (n=1), petechiae (n=1), epilepsy (n=1), fever (n=1), thrombocytosis (n=1), urinary tract infection (n=1), and vomiting (n=1).

One subject with treatment-related serious AEs experienced headache and thrombocytosis, which did not recur when romiplostim was restarted.

There were no thrombotic events, none of the patients withdrew due to AEs, and none died.

“These data are important in understanding how Nplate may play a role in helping children manage this disease,” said Sean E. Harper, MD, executive vice president of research and development at Amgen.

“We will work with regulatory authorities towards an approval for Nplate for pediatric patients.” ![]()

Photo by Bill Branson

The thrombopoietin receptor agonist romiplostim can produce durable platelet responses in children with symptomatic chronic immune thrombocytopenia (ITP), according to a phase 3 study.

Fifty-two percent of patients who received romiplostim achieved a durable platelet response, compared to 10% of placebo-treated patients.

Investigators said these results suggest romiplostim may be a treatment option for this patient population.

“The results of this study suggest that romiplostim could reduce the frequency and severity of bleeding events for children suffering from symptomatic ITP, thus providing them with another potential treatment option,” said Michael D. Tarantino, MD, of the University of Illinois College of Medicine-Peoria.

Dr Tarantino and his colleagues reported the results in The Lancet. The study was supported by Amgen, which markets romiplostim (Nplate) as a treatment for adults with chronic ITP.

This double-blind study included 62 children (ages 6 to 14) who had ITP for more than 6 months and were randomized to weekly romiplostim (n=42) or placebo (n=20) for 24 weeks. Baseline characteristics were well-balanced between the treatment arms.

The median time since ITP diagnosis was about 2 years for both arms, and the median age at diagnosis was about 7. The median baseline platelet counts were 17.8 x 109/L in the romiplostim arm and 17.7 x 109/L in the placebo arm.

Durable platelet response, the primary endpoint of the study, was defined as achieving weekly platelet responses without rescue medication in at least 6 of the final 8 weeks of the study.

The rates of durable platelet response were 52% (22/42) in the romiplostim arm and 10% (2/20) in the placebo arm (P=0.002, odds ratio 9.1, 95% CI: 1.9, 43.2).

The rates of overall platelet response were 71% (30/42) in the romiplostim arm and 20% in the placebo arm (P=0.0002, odds ratio 9.0, 95% CI: 2.5, 32.3), and the rates of any platelet response were 81% (34/42) and 55% (11/20), respectively (P=0.0313).

The most frequently reported adverse events (AEs) observed in patients receiving romiplostim were contusion (50%), epistaxis (48%), headache (43%), and upper respiratory tract infection (38%).

Oropharyngeal pain occurred more frequently with romiplostim than placebo—26.2% (11/42) and 5.3% (1/19), respectively.

In the 11 romiplostim-treated patients with oropharyngeal pain, streptococcal pharyngitis (n=2), allergic rhinitis (n=2), gastroesophageal reflux (n=1), and serum sickness from IVIg (n=1) were also reported. No oropharyngeal pain AEs were serious or considered treatment-related.

Serious AEs occurred in 23.8% of romiplostim-treated patients and 5.3% of placebo-treated patients.

Serious AEs in the romiplostim arm included epistaxis (n=2), contusion (n=2), headache (n=2), bronchiolitis (n=1), nausea (n=1), petechiae (n=1), epilepsy (n=1), fever (n=1), thrombocytosis (n=1), urinary tract infection (n=1), and vomiting (n=1).

One subject with treatment-related serious AEs experienced headache and thrombocytosis, which did not recur when romiplostim was restarted.

There were no thrombotic events, none of the patients withdrew due to AEs, and none died.

“These data are important in understanding how Nplate may play a role in helping children manage this disease,” said Sean E. Harper, MD, executive vice president of research and development at Amgen.

“We will work with regulatory authorities towards an approval for Nplate for pediatric patients.” ![]()

Photo by Bill Branson

The thrombopoietin receptor agonist romiplostim can produce durable platelet responses in children with symptomatic chronic immune thrombocytopenia (ITP), according to a phase 3 study.

Fifty-two percent of patients who received romiplostim achieved a durable platelet response, compared to 10% of placebo-treated patients.

Investigators said these results suggest romiplostim may be a treatment option for this patient population.

“The results of this study suggest that romiplostim could reduce the frequency and severity of bleeding events for children suffering from symptomatic ITP, thus providing them with another potential treatment option,” said Michael D. Tarantino, MD, of the University of Illinois College of Medicine-Peoria.

Dr Tarantino and his colleagues reported the results in The Lancet. The study was supported by Amgen, which markets romiplostim (Nplate) as a treatment for adults with chronic ITP.

This double-blind study included 62 children (ages 6 to 14) who had ITP for more than 6 months and were randomized to weekly romiplostim (n=42) or placebo (n=20) for 24 weeks. Baseline characteristics were well-balanced between the treatment arms.

The median time since ITP diagnosis was about 2 years for both arms, and the median age at diagnosis was about 7. The median baseline platelet counts were 17.8 x 109/L in the romiplostim arm and 17.7 x 109/L in the placebo arm.

Durable platelet response, the primary endpoint of the study, was defined as achieving weekly platelet responses without rescue medication in at least 6 of the final 8 weeks of the study.

The rates of durable platelet response were 52% (22/42) in the romiplostim arm and 10% (2/20) in the placebo arm (P=0.002, odds ratio 9.1, 95% CI: 1.9, 43.2).

The rates of overall platelet response were 71% (30/42) in the romiplostim arm and 20% in the placebo arm (P=0.0002, odds ratio 9.0, 95% CI: 2.5, 32.3), and the rates of any platelet response were 81% (34/42) and 55% (11/20), respectively (P=0.0313).

The most frequently reported adverse events (AEs) observed in patients receiving romiplostim were contusion (50%), epistaxis (48%), headache (43%), and upper respiratory tract infection (38%).

Oropharyngeal pain occurred more frequently with romiplostim than placebo—26.2% (11/42) and 5.3% (1/19), respectively.

In the 11 romiplostim-treated patients with oropharyngeal pain, streptococcal pharyngitis (n=2), allergic rhinitis (n=2), gastroesophageal reflux (n=1), and serum sickness from IVIg (n=1) were also reported. No oropharyngeal pain AEs were serious or considered treatment-related.

Serious AEs occurred in 23.8% of romiplostim-treated patients and 5.3% of placebo-treated patients.

Serious AEs in the romiplostim arm included epistaxis (n=2), contusion (n=2), headache (n=2), bronchiolitis (n=1), nausea (n=1), petechiae (n=1), epilepsy (n=1), fever (n=1), thrombocytosis (n=1), urinary tract infection (n=1), and vomiting (n=1).

One subject with treatment-related serious AEs experienced headache and thrombocytosis, which did not recur when romiplostim was restarted.

There were no thrombotic events, none of the patients withdrew due to AEs, and none died.

“These data are important in understanding how Nplate may play a role in helping children manage this disease,” said Sean E. Harper, MD, executive vice president of research and development at Amgen.

“We will work with regulatory authorities towards an approval for Nplate for pediatric patients.” ![]()

Review of the BRIDGE Trial

In the United States, it is estimated that 2.7 to 6.1 million people have atrial fibrillation (AF).[1] This number is projected to increase to 12.1 million in 2030.[2] Despite the advent of direct oral anticoagulants (DOAC), roughly half of patients with AF on anticoagulation are treated with vitamin K antagonists (VKA), warfarin being the most widely used.[3]

Every year at least 250,000 individuals will require anticoagulation interruption for an elective procedure.[4] Clinicians, especially in hospitalized settings, are faced with the need to balance the risk of procedural bleeding with the potential for arterial thromboembolic (ATE) events. This is further complicated by warfarin's long half‐life (3660 hours).[5] The slow weaning off and restoration of warfarin's anticoagulant effect expose patients, in theory, to a higher risk of ATE in the perioperative period. Heparin bridging therapy with unfractionated heparin (UFH) or low‐molecular‐weight heparin (LMWH) was believed to be a solution to provide continuous anticoagulant effect during temporary interruption of warfarin. Perioperative bridging therapy remains widely used by hospitalists, despite uncertainties about whether it meets its premise of conferring a clinically meaningful reduction of ATE's risk that overweighs the likely higher incidence of major bleeding associated with its use over a no‐bridging strategy. Up until recently, no randomized clinical trials have evaluated the fundamental question of should we bridge. The landmark BRIDGE (Perioperative Bridging Anticoagulation in Patients with Atrial Fibrillation) trial published in August 2015 greatly contributed to answering this question.[6]

In this article we perform a narrative review of the literature on the perioperative anticoagulation management of patients with AF on chronic warfarin needing an elective procedure or surgery that led to the BRIDGE trial. We also examine the most recent 9th Edition Guidelines from the American College of Chest Physicians (ACCP) on perioperative management of anticoagulation in this population.[4] We then discuss in detail findings from the BRIDGE trial along with its implications for the hospitalist. Further, we suggest a practical treatment algorithm to the perioperative anticoagulation management of patients with AF on warfarin who are undergoing an elective procedure or surgery. We opt to focus on warfarin and to omit DOAC and antiplatelet therapies in our suggested practical approach. We lastly evaluate ongoing trials in this field.

RECENT STUDIES ON HEPARIN BRIDGING IN ATRIAL FIBRILLATION USING CONTROL GROUPS

In the last five years a body of evidence has progressively questioned the value of perioperative bridging therapy in preventing ATEs. The ORBIT‐AF (Outcomes Registry for Better Informed Treatment of Atrial Fibrillation) study examined data on oral anticoagulation (OAC) interruption among 2200 patients in the United States.[7] Patients who received bridging therapy accounted for 24% of interruptions and had a slightly higher CHADS2 score than non‐bridged groups (2.53 vs 2.34, P = 0.004). Overall, no significant differences in the rate of stroke or systemic embolism were detected between the bridged and nonbridged groups (0.6% vs 0.3%, P = 0.3). In multivariate analysis, bridging was associated with an odds ratio (OR) of 3.84 of major bleeding within 30 days (P 0.0001), along with a higher 30‐day composite incidence of myocardial infarction, stroke or systemic embolism, bleeding, hospitalization, or death (OR: 1.94, P = 0.0001). The increased adverse events with bridging therapy were independent of the baseline OAC (warfarin or dabigatran). Although the study argued against the routine use of bridging in AF patients, the authors could not exclude the potential impact of measured (CHADS2) and unmeasured confounding variables.[7]

The open‐label RE‐LY (Randomized Evaluation of Long Term Anticoagulant Therapy With Dabigatran Etexilate) trial compared dabigatran to warfarin in nonvalvular AF. Its dataset provided prospective information on 1424 warfarin interruptions for an elective procedure or surgery. The interruptions, of which 27.5% were treated with bridging therapy, were analyzed in a substudy of the trial.[8] The CHADS2 or CHA2DS2‐VASC scores were similar in the bridged and nonbridged warfarin groups. Relatively higher rates of major bleeding were observed in the bridged group (6.8% vs 1.6%, P 0.001) with no statistically significant difference in stroke and systemic embolism (0.5% vs 0.2%, P = 0.32) compared to the nonbridged group. Paradoxically, bridging therapy was associated with a 6‐fold increase in the risk of any thromboembolic event among patients on warfarin (P = 0.007). As in the ORBIT‐AF study, it was difficult to determine whether this increase was secondary to unmeasured confounding variables associated with higher baseline risk of ATE.[8]

The problem of unmeasured variables was common to the previous studies of perioperative bridging therapy. The heterogeneity of event definitions, bridging regimens, and per‐protocol adherence rates were additional limitations to the studies' clinical implications, despite the consistency of a 3‐ to 4‐fold increase in the major bleeding risk among bridged patients with no accompanying protection against ATE. From this perspective, the absence of high‐quality data was the motivating force behind the BRIDGE trial.

THE BRIDGE TRIAL

The BRIDGE trial[6] attempted to answer a simple yet fundamental question: in patients with AF on warfarin who need temporary interruption for an elective procedure or surgery, is perioperative heparin bridging necessary?

Adult patients (18 years of age) were eligible for the study if they had chronic AF treated with warfarin for 3 months or more with a target International Normalized Ratio (INR) range of 2.0 to 3.0, CHADS2 score 1, and were undergoing an elective invasive procedure or nonurgent surgery. The study excluded patients planned for a cardiac, intracranial, or intraspinal surgery. A history of stroke, ATE, or TIA in the preceding 3 months; a major bleed in the previous 6 weeks; or a mechanical heart valve precluded study participation. Further, those with a platelet count 100,000/mm[3] or creatinine clearance less than 30 mL per minute were also excluded.

Patients were randomly assigned to receive LMWH (dalteparin 100 IU/kg of body weight) or placebo subcutaneously twice daily in a double‐blind fashion. In all patients, warfarin was withheld 5 days before the invasive procedure or elective surgery and restarted within 24 hours afterward. The bridging arm received therapeutic‐dose LMWH starting 3 days before the procedure with matching placebo in the nonbridged arm. The last dose of LMWH or placebo was given around 24 hours before the procedure and then withheld. LMWH or placebo was restarted 12 to 24 hours after the procedure for defined low bleeding‐risk procedures and 48 to 72 hours for high bleeding‐risk procedures. The study drug was continued for 5 to 10 days and stopped when the INR was in the therapeutic range. The coprimary outcomes were ATE (stroke, TIA, or systemic embolism) and major bleeding using a standardized definition. These outcomes were assessed in the 30 days following the procedure.

Out of 1884 recruited patients in the United States and Canada, 934 patients were assigned to the bridging arm and 950 to the nonbridging arm. Study participants had a mean age of 71.7 years, a CHADS2 score of 2.3, and 3 out of 4 were men. The 2 arms had similar baseline characteristics. Adherence to the study‐drug protocol was high, with an 86.5% rate of adherence before the procedure to 96.5% after the procedure. At 30 days, the rate of ATE in the bridging group (0.4%) was noninferior to the nonbridging one (0.3%) (95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.6 to 0.8; P value for noninferiority = 0.01). The mean CHADS2 score in patients who sustained an ATE event was 2.6 (range, 14). The median time to an ATE event was 19.0 days (interquartile range [IQR], 6.023.0 days). The bridging group had a significantly higher rate of major bleeding compared to the nonbridging one (3.2% vs 1.3%, P = 0.005). The median time to a major bleeding event after a procedure was 7.0 days (IQR, 4.018.0 days). The 2 arms did not differ in their rates of venous thromboembolic (VTE) events and death in the study period. Yet, there was a significantly greater rate of minor bleeding in the bridging group (20.9% vs 12.0%, P 0.001) and a trend toward more episodes of myocardial infarction in the bridging group as well (1.6% vs 0.8%, P = 0.10).

The BRIDGE trial was a proof of concept that the average AF patient may safely undergo commonly performed elective procedures or surgeries in which warfarin is simply withheld 5 days before and reinitiated within a day of the procedure without the need for periprocedural heparin bridging. Perioperative ATE rates, previously thought to be around 1%, have been overestimated. The ATE rate was low in the BRIDGE trial (0.4%), especially given a representative AF study population. The classical concern that warfarin interruption leads to a rebound hypercoagulable state was not supported by the trial.

The 9th Edition 2012 ACCP Guidelines on perioperative management of anticoagulation had suggested bridging in AF patients at high thrombotic risk and no bridging in the low risk group (Table 1).[4] For patients at moderate risk, the ACCP Guidelines called for an individualized assessment of risk versus benefits of bridging, a recommendation that was not based on high‐quality data. The BRIDGE trial findings are likely to change practice by providing level 1 evidence to forgo bridging in the vast majority of represented AF patients. For the hospitalist, this should greatly simplify periprocedural anticoagulant management for the AF patient on chronic warfarin in a hospitalized setting.

| Risk Category | Mechanical Heart Valve | Atrial Fibrillation | Venous Thromboembolism |

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| High | Mitral valve prosthesis | CHADS2 score of 5 or 6 | Recent (3 month) VTE |

| Caged‐ball or tilting‐disc aortic valve prosthesis | Recent (3 months) stroke or TIA | Severe thrombophilia | |

| Recent (6 months) stroke or TIA | Rheumatic valvular heart disease | Deficiency of protein C, protein S, or antithrombin | |

| Antiphospholipid antibodies | |||

| Multiple thrombophilias | |||

| Intermediate | Bileaflet aortic valve prosthesis with a major risk factor for stroke | CHADS2 score of 3 or 4 | VTE within past 312 months |

| Nonsevere thrombophilia | |||

| Recurrent VTE | |||

| Active cancer | |||

| Low | Bileaflet aortic valve prosthesis without a major risk factor for stroke | CHADS2 score of 0 to 2 with no prior stroke or TIA | VTE >12 months previous |

Limitations of the BRIDGE trial include the exclusion of surgeries that have an inherent high risk of postoperative thrombosis as well as bleeding, such as cardiac and vascular surgeries. Also, the trial had an under‐representation of patients with a CHADS2 score of 5 or 6 and excluded those with a mechanical heart valve. Both of these groups carry a high risk of ATE. However, it would be expected that the increase in postprocedural bleed risk seen with therapeutic‐dose bridging therapy in the BRIDGE trial would only be magnified in high bleeding‐risk procedures, with either no effect on postoperative ATE risk reduction, or the potential to cause an increase in downstream ATE events by the withholding of anticoagulant therapy for a bleed event. The ongoing placebo‐controlled PERIOP‐2 trial (

PRACTICAL APPROACH TO PERIOPERATIVE MANAGEMENT OF WARFARIN ANTICOAGULATION IN ATRIAL FIBRILLATION

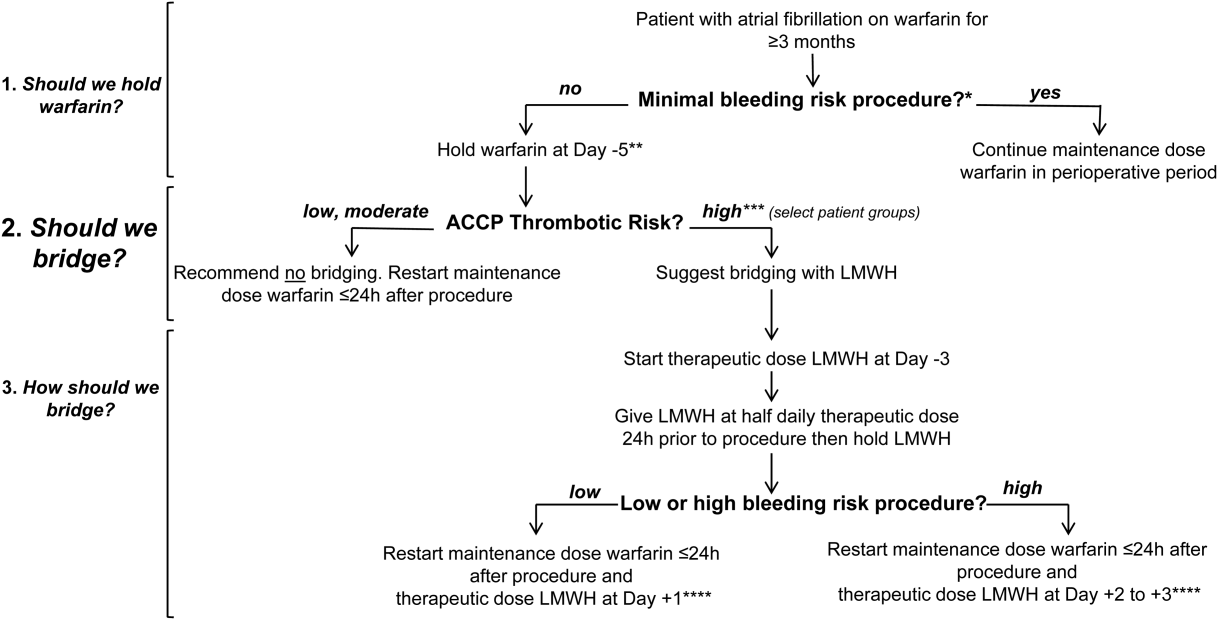

In Figure 1 we suggest a practical 3‐step framework for the perioperative anticoagulation management of patients on chronic warfarin for AF. First, if the planned invasive procedure or surgery falls under the minimal bleeding‐risk group in Table 2, we propose continuing warfarin in the perioperative period. Notably, implantation of a pacemaker or cardioverter‐defibrillator device is included in this group based on recently completed randomized trials in this patient group. In fact, the BRUISE CONTROL trial showed a markedly reduced incidence of device‐pocket hematoma when warfarin was continued in the perioperative period as compared to its temporary interruption and use of bridging (3.5% vs 16%, P 0.001). Other surgical complications including ATE events were similar in the 2 groups.[10] The COMPARE trial demonstrated that warfarin can also be continued in the periprocedural period in patients undergoing catheter ablation of AF. Warfarin's continuation among 1584 AF patients who had this procedure was associated with significantly fewer thromboembolic events(0.25% vs 4.9%, P 0.001) and minor bleeding complications (4.1% vs 22%, P 0.001) compared to its temporary interruption and use of bridging.[11] We recognize that the clinical distinction between minimal and low bleeding risk can be difficult, yet the former is increasingly recognized as a group in which anticoagulation can be safely continued in the perioperative period.[12]

| Minimal Bleeding‐Risk Procedures | Low Bleeding‐Risk Procedures | High Bleeding‐Risk Procedures |

|---|---|---|

| Implantation of pacemaker or cardioverter‐defibrillator device;* catheter ablation of atrial fibrillation* | Coronary angiography | Cardiac, intracranial, or spinal surgery; any major procedure lasting 45 minutes |

| Minor cutaneous excision (actinic keratosis, premalignant/malignant skin nevi, basal and squamous cell skin carcinoma) | Cutaneous or lymph node biopsy | Major surgery with extensive tissue resection; cancer surgery |

| Cataract surgery | Arthroscopy; surgery of hand, foot, or shoulder | Major orthopedic surgery |

| Minor dental procedure (cleaning, filling, extraction, endodontic, prosthetic) | Endoscopy/colonoscopy biopsy, laparoscopic cholecystectomy, hemorrhoidal surgery, abdominal hernia repair | Liver or spleen surgery, bowel resection, colonic polyp resection, percutaneous endoscopic gastrotomy placement, endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography |

| Bronchosopy | Nephrectomy, kidney biopsy, transurethral prostate resection, bladder resection, or tumor ablation | |

Second, if the decision was made to hold warfarin, the next step is to estimate the patient's perioperative thrombotic risk based on the 9th Edition ACCP Guidelines shown in Table 1. Whereas patients may have additional comorbidities, a theoretical framework for an individual patient's ATE risk stratification as seen in the ACCP Guidelines is determined by the CHADS2 score, a history of rheumatic heart disease, and a recent ATE event (within 3 months). In the low ATE risk group, recommendations from the ACCP,[4] the American Heart Association, and the American College of Cardiology[13] are in agreement against the use of perioperative bridging. Level 1 evidence from the BRIDGE trial now supports that bridging may be forgone in patients in the moderate ATE risk group and likely many patients in the high ATE risk group (although patients with a CHADS2 score of 5 and 6 were under‐represented in the BRIDGE trial). In certain high ATE risk patient groups with AF, especially those with a recent ATE event, mechanical heart valves, or severe rheumatic heart disease, it may be prudent to bridge those patients with UFH/LMWH.

Third, assuming adequate hemostasis is achieved after the procedure, warfarin can be restarted within 24 hours at its usual maintenance dose regardless of bridging. For patients among whom bridging is chosen, we suggest that the timing of resumption of LMWH bridging be based on the procedural risk of bleeding (Table 2): 1‐day postprocedurally in the low bleeding‐risk groups or 2 to 3 days postprocedurally in the high bleeding‐risk groups. For the latter group, a stepwise use of prophylactic‐dose LMWH, especially after a major surgery for the prevention of VTE, may be resumed earlier at the discretion of the surgeon or interventionist. For both groups, therapeutic‐dose LMWH may be stopped once the INR is 2.

A number of challenges are associated with the proposed framework. Real‐world data show that nonindicated OAC interruptions and bridging are commonplace. This may defer the hospitalist's readiness to change practice.[7] Although the CHADS2/CHA2DS2‐VASc scores are widely used to estimate the perioperative ATE risk, there is scant evidence from validation studies,[14, 15] whereas the CHADS2 score has been used in guideline recommendations.[4] Also, as previously discussed, this framework excludes patients with a recent stroke or a mechanical heart valve, patients on warfarin for VTE, and patients on DOACs.

RETHINKING HEPARIN BRIDGING THERAPY IN NONATRIAL FIBRILLATION PATIENT GROUPS

There is now mounting recent evidence from over 12,000 patients that any heparin‐based bridging strategy does not reduce the risk of ATE events but confers an over 2‐ to 3‐fold increased risk of major bleeding.[16] Thus, in our view, the BRIDGE trial was a proof of concept that calls to question the premise of heparin bridging therapy in preventing ATE beyond the AF population. Retrospective studies provide evidence of the lack of treatment effect with heparin bridging even in perceived high thromboembolic risk populations, including those with mechanical heart valves and VTE (2 patient groups for whom there are currently no level 1 data on perioperative management of anticoagulation and bridging therapy).

In their systematic review and meta‐analysis, Siegal et al. evaluated periprocedural rates of bleeding and thromboembolic events in more than 12,000 patients on VKA based on whether they were bridged with control groups.[16] Thirty out of 34 studies reported the indication for anticoagulation, with AF being the most common (44%). Bridging was associated with an OR of 5.4 for overall bleeding (95% CI: 3.0 to 9.7) and an OR of 3.6 for major bleeding (95% CI: 1.5 to 8.5). ATE and VTE events were rare, with no statistically significant differences between the bridged (0.9%) and nonbridged patients (0.6%) (OR: 0.8, 95% CI: 0.42 to 1.54). The authors suggested that bridging might better be reserved to patients who are at high risk of thromboembolism. Nonetheless, the implications of the findings were limited by the poor quality of included studies and their heterogeneity in reporting outcomes, especially bleeding events.[16]

In a retrospective cohort study of 1777 patients who underwent mechanical heart valve replacement (56% aortic, 34% mitral, 9% combined aortic and mitral), 923 patients who received therapeutic‐dose bridging therapy in the immediate postvalve implantation period had a 2.5 to 3 times more major bleeding (5.4% vs 1.9%, P = 0.001) and a longer hospital stay compared to those who received prophylactic‐dose bridging anticoagulation. The two groups had comparable thromboembolic complications at 30 days (2%, P = 0.81).[17] Another study retrospectively analyzed data from 1178 patients on warfarin for prevention of secondary VTE who had anticoagulation interruption for an invasive procedure or surgery. About one‐third received bridging therapy, the majority with therapeutic‐dose LMWH. Of the bridged patients, 2.7% had a clinically relevant bleeding at 30 days compared to 0.2% in the nonbridged groups (P = 0.01). The incidence of a recurrent VTE was low across all thrombotic risk groups, with no differences between bridged and nonbridged patients (0.0% vs 0.2%, P = 0.56).[18]

There are a number of factors as to why heparin bridging appears ineffective in preventing periprocedural ATE events. It is possible that rebound hypercoagulability and a postoperative thrombotic state have been overestimated. Older analyses supporting postoperative ATE rates of 1.6% to 4.0% and a 10‐fold increased risk of ATE by major surgery are not supported by recent perioperative anticoagulant studies with control arms, including the BRIDGE trial, where the ATE event rate was closer to 0.5% to 1.0%.[6, 7, 8, 19] The mechanisms of perioperative ATE may be more related to other factors than anticoagulant‐related factors, such as the vascular milieu,[14] alterations in blood pressure,[20] improvements in surgical and anesthetic techniques (including increasing use of neuraxial anesthesia),[21] and earlier patient mobilization. Indeed, the occurrence of ATE events in the BRIDGE trial did not appear to be influenced by a patient's underlying CHADS2 score (mean CHADS2 score of 2.6). There is a growing body of evidence that suggests perioperative heparin bridging has the opposite effect to that assumed by its use: there are trends toward an increase in postoperative ATE events in patients who receive bridging therapy.[8]

In the BRIDGE trial, there was a trend toward an increase in myocardial infarction in the bridging arm. This can be explained by a number of factors, but the most obvious includes an increase in bleeding events as may be expected by the use of therapeutic‐dose heparin bridging over a no‐bridging approach, which then predisposes a patient to downstream ATE events after withholding of anticoagulant therapy. The median time to a major bleed in BRIDGE was 7 days, whereas the mean time to an ATE event was 19 days, suggesting that bleeding is front‐loaded and that withholding of anticoagulant therapy after a bleed event may potentially place a patient at risk for later ATE events. This is consistent with an earlier single‐arm prospective cohort study of 224 high ATE risk patients on warfarin who were treated with perioperative LMWH bridging therapy. Among patients who had a thromboembolic event in the 90 postoperative days, 75% (6 out of 8) had their warfarin therapy withdrawn or deferred because of bleeding.[22] Last, if prophylactic doses of heparin were used as bridging therapy, there is no evidence that this would be protective of ATE events, which is the premise of using heparin bridging. Both of these concepts will be assessed when results of the PERIOP‐2 trial are made available.

An emerging body of evidence suggests an unfavorable risk versus benefit balance of heparin bridging, regardless of the underlying thrombotic risk. Overall, if bridging therapy is effective in protecting against ATE (which has yet to be demonstrated), recent studies show that its number needed to treat (NNT) would be very large and far larger than its number needed to harm (NNH). If more patients undergoing high bleeding‐risk procedures were included in the BRIDGE trial, these effects of unfavorable NNT to NNH would be magnified. While awaiting more definite answers from future trials, we believe clinicians should be critical of heparin bridging. We also suggest that they reserve it for patients who are at a significantly high risk of ATE complications until uncertainties around its use are clarified.

CONCLUSION

The BRIDGE trial provided high‐quality evidence that routine perioperative heparin bridging of patients on chronic warfarin for AF needing an elective procedure or surgery is both unnecessary and harmful. The trial is practice changing for patients with AF, and its results will likely be implemented in future international guidelines on the topic, including those of the ACCP. The hospitalist should be aware that the current large body of evidence points to more harm than benefit associated with heparin bridging in preventing ATE for any patient group, including those at high risk of ATE. Ongoing and future trials may clarify the role of heparin bridgingif anyin patients on chronic warfarin at high risk of ATE, including those with mechanical heart valves.

Disclosures: Alex C. Spyropoulos, MD, has served as a consultant for Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Daiichi Sankyo, and Janssen. He also has served on advisory committees for Bristol‐Myers Squibb and Pfizer.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Atrial fibrillation fact sheet. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/dhdsp/data_statistics/fact_sheets/fs_atrial_fibrillation.htm. Updated August 13, 2015. Accessed November 22, 2015.

- , , , , , . Estimates of current and future incidence and prevalence of atrial fibrillation in the U.S. adult population. Am J Cardiol. 2013;112(8):1142–1147.

- , , , . National trends in ambulatory oral anticoagulant use. Am J Med. 2015;128(12):1300–1305.e2.

- , , , et al. Perioperative management of antithrombotic therapy: Antithrombotic Therapy and Prevention of Thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians evidence‐based clinical practice guidelines. Chest. 2012;141(2 suppl):e326S–e350S.

- , , , et al. Pharmacology and management of the vitamin K antagonists: American College of Chest Physicians evidence‐based clinical practice guidelines (8th edition). Chest. 2008;133(6 suppl):160S–198S.

- , , , et al. Perioperative Bridging Anticoagulation in Patients with Atrial Fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(9):823–833.

- , , , et al. Use and outcomes associated with bridging during anticoagulation interruptions in patients with atrial fibrillation: findings from the Outcomes Registry for Better Informed Treatment of Atrial Fibrillation (ORBIT‐AF). Circulation. 2015;131(5):488–494.

- , , , et al. Perioperative bridging anticoagulation during dabigatran or warfarin interruption among patients who had an elective surgery or procedure. Substudy of the RE‐LY trial. Thromb Haemost. 2015;113(3):625–632.

- PERIOP 2—A Safety and Effectiveness Study of LMWH Bridging Therapy Versus Placebo Bridging Therapy for Patients on Long Term Warfarin and Require Temporary Interruption of Their Warfarin. ClinicalTrials.gov. Available at: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT00432796. Accessed December 9, 2015.

- , , , et al. Pacemaker or defibrillator surgery without interruption of anticoagulation. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(22):2084–2093.

- , , , et al. Periprocedural stroke and bleeding complications in patients undergoing catheter ablation of atrial fibrillation with different anticoagulation management: results from the Role of Coumadin in Preventing Thromboembolism in Atrial Fibrillation (AF) Patients Undergoing Catheter Ablation (COMPARE) randomized trial. Circulation. 2014;129(25):2638–2644.

- , , , . Risk factors for bleeding after oral surgery in patients who continued using oral anticoagulant therapy. J Am Dent Assoc. 2015;146(6):375–381.

- , , , et al. 2014 ACC/AHA guideline on perioperative cardiovascular evaluation and management of patients undergoing noncardiac surgery: executive summary: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2014;130(24):2215–2245.

- , , , , . Risk of stroke after surgery in patients with and without chronic atrial fibrillation. J Thromb Haemost. 2010;8(5):884–890.

- . Peri‐procedural management of patients taking oral anticoagulants. BMJ. 2015;351:h2391.

- , , , , , . Periprocedural heparin bridging in patients receiving vitamin K antagonists: systematic review and meta‐analysis of bleeding and thromboembolic rates. Circulation. 2012;126(13):1630–1639.

- , , , et al. Efficacy and safety of early parenteral anticoagulation as a bridge to warfarin after mechanical valve replacement. Thromb Haemost. 2014;112(6):1120–1128.

- , , , et al. Bleeding, recurrent venous thromboembolism, and mortality risks during warfarin interruption for invasive procedures. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(7):1163–1168.

- , . Perioperative management of patients receiving oral anticoagulants: a systematic review. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163(8):901–908.

- , , , et al. Predictors of intraoperative hypotension and bradycardia. Am J Med. 2015;128(5):532–538.

- . Perioperative stroke. N Engl J Med. 2007;356(7):706–713.

- , , , et al. Single‐arm study of bridging therapy with low‐molecular‐weight heparin for patients at risk of arterial embolism who require temporary interruption of warfarin. Circulation. 2004;110(12):1658–1663.

In the United States, it is estimated that 2.7 to 6.1 million people have atrial fibrillation (AF).[1] This number is projected to increase to 12.1 million in 2030.[2] Despite the advent of direct oral anticoagulants (DOAC), roughly half of patients with AF on anticoagulation are treated with vitamin K antagonists (VKA), warfarin being the most widely used.[3]