User login

Check out AGA’s Offerings at DDW®

If you’re planning to attend Digestive Disease Week® (DDW), make sure to take advantage of all AGA has to offer, including the 2016 AGA Postgraduate Course: Cognitive and Technical Skills for the Gastroenterologist.

This year’s course will host more than 60 expert presenters – the best in the world – including five AGA Governing Board members.

You won’t want to miss these talks:

• Michael Camilleri, M.D., AGAF

“Overlooked, Overused, and Emerging Therapies for Common Gastrointestinal Disorders”

• Sheila Crowe, M.D., AGAF

“Bloating, Functional Bowel Disease and Food Sensitivity: Non-Celiac Gluten-Sensitivity, the Low-FODMAP Diet and Beyond”

• Gregory Gores, M.D., AGAF

“Managing the Possibly Malignant Biliary Stricture”

• John Inadomi, M.D., AGAF

“Colon Cancer Screening”

• Rajeev Jain, M.D., AGAF

“A Primer on Performance Measures and Bundled Payment: Volume to Value”

The course takes place May 21 and 22, 2016. Learn more at http://www.gastro.org/pgc.

Also, make sure to check out the AGA Institute Council Highlights at DDW 2016 booklet and online tool to find out about section programming, committee-sponsored and joint society sessions, as well as a plethora of basic science offerings.

We look forward to seeing you in San Diego.

If you’re planning to attend Digestive Disease Week® (DDW), make sure to take advantage of all AGA has to offer, including the 2016 AGA Postgraduate Course: Cognitive and Technical Skills for the Gastroenterologist.

This year’s course will host more than 60 expert presenters – the best in the world – including five AGA Governing Board members.

You won’t want to miss these talks:

• Michael Camilleri, M.D., AGAF

“Overlooked, Overused, and Emerging Therapies for Common Gastrointestinal Disorders”

• Sheila Crowe, M.D., AGAF

“Bloating, Functional Bowel Disease and Food Sensitivity: Non-Celiac Gluten-Sensitivity, the Low-FODMAP Diet and Beyond”

• Gregory Gores, M.D., AGAF

“Managing the Possibly Malignant Biliary Stricture”

• John Inadomi, M.D., AGAF

“Colon Cancer Screening”

• Rajeev Jain, M.D., AGAF

“A Primer on Performance Measures and Bundled Payment: Volume to Value”

The course takes place May 21 and 22, 2016. Learn more at http://www.gastro.org/pgc.

Also, make sure to check out the AGA Institute Council Highlights at DDW 2016 booklet and online tool to find out about section programming, committee-sponsored and joint society sessions, as well as a plethora of basic science offerings.

We look forward to seeing you in San Diego.

If you’re planning to attend Digestive Disease Week® (DDW), make sure to take advantage of all AGA has to offer, including the 2016 AGA Postgraduate Course: Cognitive and Technical Skills for the Gastroenterologist.

This year’s course will host more than 60 expert presenters – the best in the world – including five AGA Governing Board members.

You won’t want to miss these talks:

• Michael Camilleri, M.D., AGAF

“Overlooked, Overused, and Emerging Therapies for Common Gastrointestinal Disorders”

• Sheila Crowe, M.D., AGAF

“Bloating, Functional Bowel Disease and Food Sensitivity: Non-Celiac Gluten-Sensitivity, the Low-FODMAP Diet and Beyond”

• Gregory Gores, M.D., AGAF

“Managing the Possibly Malignant Biliary Stricture”

• John Inadomi, M.D., AGAF

“Colon Cancer Screening”

• Rajeev Jain, M.D., AGAF

“A Primer on Performance Measures and Bundled Payment: Volume to Value”

The course takes place May 21 and 22, 2016. Learn more at http://www.gastro.org/pgc.

Also, make sure to check out the AGA Institute Council Highlights at DDW 2016 booklet and online tool to find out about section programming, committee-sponsored and joint society sessions, as well as a plethora of basic science offerings.

We look forward to seeing you in San Diego.

Allogeneic cell therapy fares well in phase III osteoarthritis trial

AMSTERDAM – A novel intra-articular allogeneic cell therapy improved knee osteoarthritis pain, physical activity, and patients’ quality of life in a randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind, phase III trial reported at the World Congress on Osteoarthritis.

During a 1-year follow up, single-dose treatment with TissueGene C (Invossa) in patients with degenerative knee osteoarthritis (OA) led to significantly greater improvements in International Knee Documentation Committee (IKDC) knee pain, Likert visual analog scale (VAS) pain score, and Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index (WOMAC) scores than in those given a saline placebo.

The positive results of the trial, which was conducted exclusively in Korea, now pave the way for a similar phase III clinical trial to be run in the United States. The study design is being finalized and will follow the usual criteria for a phase III trial, but it will add one refinement on the design used in the Korean trial in that the TissueGene C (TG-C) will be given by image-guided intra-articular injection.

TG-C consists of two different populations of chondrocytes derived from a single human subject with polydactyly finger, of which one cell population has been genetically modified to express the gene for transforming growth factor-beta 1 (TGF-B1). It is a single-dose treatment that is intended to provide symptomatic relief and delay the structural progression of knee OA.

The proposed mode of action is that it targets cartilage degradation by enhancing chondrocyte proliferation, essentially improving cartilage structure by redirecting immune responses via effects on interleukin-10 and on M2 macrophages.

The target population is patients with with Kellgren-Lawrence grade II and III knee OA, Dr. Bumsup Lee of Kolon Life Science said during a company-sponsored symposium held during the congress, which was sponsored by Osteoarthritis Research Society International. Dr. Lee is chief operating officer of TissueGene Inc. in the United States, which is collaborating with Kolon Life Science, the Korean-based biochemical company that developed the novel OA therapy.

The aim is to develop a disease-modifying osteoarthritis drug (DMOAD) that fits criteria suggested by the Food and Drug Administration and the European Medicines Agency, Dr. Lee said. The clinical development program started in 2006, with phase I, II, and III studies now completed in Korea and phase II and III studies underway in the United States.

The results of the phase III Korean trial, which involved 163 patients, were presented during a poster session and during the industry-sponsored symposium. These showed that IKDC scores progressively increased (improved) for TG-C–treated patients from baseline through months 1, 3, 6, 9, and 12 with scores of 40.3, 42.9, 48.9, 53.2, 53.6, and 55.4, respectively, versus placebo scores at the same time points of 39.6, 44.6, 45.2, 36.5, 47.1, and 44.6. The differences became significant at 6 months. Changes in IKDC scores from baseline were also only significantly in favor of TG-C versus placebo starting at 6 months (12.9 vs. 6.9), then extending to 9 months (13.3 vs. 7.5) and 12 months (15.1 vs. 5.0).

TG-C proved superior to placebo in improving VAS pain scores at 6, 9, and 12 months, and changes in WOMAC scores were significant after 12 months with a mean change of –13.9 with TG-C and –6.2 with placebo.

The OMERACT-OARSI response rate was also assessed. A responder was identified as someone with an improvement in VAS pain score of 50% or more and an absolute change in score of at least 10 points and at least a 50% improvement in IKDC score with an absolute change of at least 20 points. The response rate for TG-C and placebo was 70% versus 52% (P = .02) at 6 months, 77% versus 52% at 9 months (P = .0011), and 84% versus 45% (P less than .001) at 12 months.

The most common adverse events seen were related to the intra-articular injection, Dr. Lee noted. Two serious adverse events – arthralgia and joint swelling – occurred in one subject who received the novel treatment, but this resolved within 10 days of administration.

Biomarker analyses have been performed and it appears that patients with greater joint space width, and higher baseline levels of CTX-II and C3M may be more likely to respond to TG-C. Some changes in CTX-I and CTX-II were clinically meaningful, and although the MRI data are still being evaluated, there was one striking feature: Patients treated with TG-C did not grow any osteophytes, compared with patients on placebo.

“Invossa holds great potential for a disease-modifying osteoarthritis drug,” said Dr. Gurdyal Kalsi, chief medical officer of TissueGene Inc. Based on the evidence today, which includes a phase II trial conducted in the United States (Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2015;23:2109-18), he said that the novel treatment “offers sustained improvement of pain and function over 2 years with a single injection.” OMERACT-OARSI response rates were 81%-86% in patients not responding to conservative therapies in the phase II study.

It is envisioned that the phase III U.S. trial will start enrolling patients from the start of next year, with the last patient enrolled around May 2018 and the first results appearing around the summer of 2019. TissueGene Inc. would then expect to have the full trial results by 2020 and make a Biologics License Application to the FDA in early 2021.

“We believe we truly have something that we hope would fulfill a DMOAD application,” Dr. Kalsi said.

Kolon Life Science and TissueGene Inc. sponsored the studies. Dr. Lee and Dr. Kalsi are employees of TissueGene Inc.

AMSTERDAM – A novel intra-articular allogeneic cell therapy improved knee osteoarthritis pain, physical activity, and patients’ quality of life in a randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind, phase III trial reported at the World Congress on Osteoarthritis.

During a 1-year follow up, single-dose treatment with TissueGene C (Invossa) in patients with degenerative knee osteoarthritis (OA) led to significantly greater improvements in International Knee Documentation Committee (IKDC) knee pain, Likert visual analog scale (VAS) pain score, and Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index (WOMAC) scores than in those given a saline placebo.

The positive results of the trial, which was conducted exclusively in Korea, now pave the way for a similar phase III clinical trial to be run in the United States. The study design is being finalized and will follow the usual criteria for a phase III trial, but it will add one refinement on the design used in the Korean trial in that the TissueGene C (TG-C) will be given by image-guided intra-articular injection.

TG-C consists of two different populations of chondrocytes derived from a single human subject with polydactyly finger, of which one cell population has been genetically modified to express the gene for transforming growth factor-beta 1 (TGF-B1). It is a single-dose treatment that is intended to provide symptomatic relief and delay the structural progression of knee OA.

The proposed mode of action is that it targets cartilage degradation by enhancing chondrocyte proliferation, essentially improving cartilage structure by redirecting immune responses via effects on interleukin-10 and on M2 macrophages.

The target population is patients with with Kellgren-Lawrence grade II and III knee OA, Dr. Bumsup Lee of Kolon Life Science said during a company-sponsored symposium held during the congress, which was sponsored by Osteoarthritis Research Society International. Dr. Lee is chief operating officer of TissueGene Inc. in the United States, which is collaborating with Kolon Life Science, the Korean-based biochemical company that developed the novel OA therapy.

The aim is to develop a disease-modifying osteoarthritis drug (DMOAD) that fits criteria suggested by the Food and Drug Administration and the European Medicines Agency, Dr. Lee said. The clinical development program started in 2006, with phase I, II, and III studies now completed in Korea and phase II and III studies underway in the United States.

The results of the phase III Korean trial, which involved 163 patients, were presented during a poster session and during the industry-sponsored symposium. These showed that IKDC scores progressively increased (improved) for TG-C–treated patients from baseline through months 1, 3, 6, 9, and 12 with scores of 40.3, 42.9, 48.9, 53.2, 53.6, and 55.4, respectively, versus placebo scores at the same time points of 39.6, 44.6, 45.2, 36.5, 47.1, and 44.6. The differences became significant at 6 months. Changes in IKDC scores from baseline were also only significantly in favor of TG-C versus placebo starting at 6 months (12.9 vs. 6.9), then extending to 9 months (13.3 vs. 7.5) and 12 months (15.1 vs. 5.0).

TG-C proved superior to placebo in improving VAS pain scores at 6, 9, and 12 months, and changes in WOMAC scores were significant after 12 months with a mean change of –13.9 with TG-C and –6.2 with placebo.

The OMERACT-OARSI response rate was also assessed. A responder was identified as someone with an improvement in VAS pain score of 50% or more and an absolute change in score of at least 10 points and at least a 50% improvement in IKDC score with an absolute change of at least 20 points. The response rate for TG-C and placebo was 70% versus 52% (P = .02) at 6 months, 77% versus 52% at 9 months (P = .0011), and 84% versus 45% (P less than .001) at 12 months.

The most common adverse events seen were related to the intra-articular injection, Dr. Lee noted. Two serious adverse events – arthralgia and joint swelling – occurred in one subject who received the novel treatment, but this resolved within 10 days of administration.

Biomarker analyses have been performed and it appears that patients with greater joint space width, and higher baseline levels of CTX-II and C3M may be more likely to respond to TG-C. Some changes in CTX-I and CTX-II were clinically meaningful, and although the MRI data are still being evaluated, there was one striking feature: Patients treated with TG-C did not grow any osteophytes, compared with patients on placebo.

“Invossa holds great potential for a disease-modifying osteoarthritis drug,” said Dr. Gurdyal Kalsi, chief medical officer of TissueGene Inc. Based on the evidence today, which includes a phase II trial conducted in the United States (Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2015;23:2109-18), he said that the novel treatment “offers sustained improvement of pain and function over 2 years with a single injection.” OMERACT-OARSI response rates were 81%-86% in patients not responding to conservative therapies in the phase II study.

It is envisioned that the phase III U.S. trial will start enrolling patients from the start of next year, with the last patient enrolled around May 2018 and the first results appearing around the summer of 2019. TissueGene Inc. would then expect to have the full trial results by 2020 and make a Biologics License Application to the FDA in early 2021.

“We believe we truly have something that we hope would fulfill a DMOAD application,” Dr. Kalsi said.

Kolon Life Science and TissueGene Inc. sponsored the studies. Dr. Lee and Dr. Kalsi are employees of TissueGene Inc.

AMSTERDAM – A novel intra-articular allogeneic cell therapy improved knee osteoarthritis pain, physical activity, and patients’ quality of life in a randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind, phase III trial reported at the World Congress on Osteoarthritis.

During a 1-year follow up, single-dose treatment with TissueGene C (Invossa) in patients with degenerative knee osteoarthritis (OA) led to significantly greater improvements in International Knee Documentation Committee (IKDC) knee pain, Likert visual analog scale (VAS) pain score, and Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index (WOMAC) scores than in those given a saline placebo.

The positive results of the trial, which was conducted exclusively in Korea, now pave the way for a similar phase III clinical trial to be run in the United States. The study design is being finalized and will follow the usual criteria for a phase III trial, but it will add one refinement on the design used in the Korean trial in that the TissueGene C (TG-C) will be given by image-guided intra-articular injection.

TG-C consists of two different populations of chondrocytes derived from a single human subject with polydactyly finger, of which one cell population has been genetically modified to express the gene for transforming growth factor-beta 1 (TGF-B1). It is a single-dose treatment that is intended to provide symptomatic relief and delay the structural progression of knee OA.

The proposed mode of action is that it targets cartilage degradation by enhancing chondrocyte proliferation, essentially improving cartilage structure by redirecting immune responses via effects on interleukin-10 and on M2 macrophages.

The target population is patients with with Kellgren-Lawrence grade II and III knee OA, Dr. Bumsup Lee of Kolon Life Science said during a company-sponsored symposium held during the congress, which was sponsored by Osteoarthritis Research Society International. Dr. Lee is chief operating officer of TissueGene Inc. in the United States, which is collaborating with Kolon Life Science, the Korean-based biochemical company that developed the novel OA therapy.

The aim is to develop a disease-modifying osteoarthritis drug (DMOAD) that fits criteria suggested by the Food and Drug Administration and the European Medicines Agency, Dr. Lee said. The clinical development program started in 2006, with phase I, II, and III studies now completed in Korea and phase II and III studies underway in the United States.

The results of the phase III Korean trial, which involved 163 patients, were presented during a poster session and during the industry-sponsored symposium. These showed that IKDC scores progressively increased (improved) for TG-C–treated patients from baseline through months 1, 3, 6, 9, and 12 with scores of 40.3, 42.9, 48.9, 53.2, 53.6, and 55.4, respectively, versus placebo scores at the same time points of 39.6, 44.6, 45.2, 36.5, 47.1, and 44.6. The differences became significant at 6 months. Changes in IKDC scores from baseline were also only significantly in favor of TG-C versus placebo starting at 6 months (12.9 vs. 6.9), then extending to 9 months (13.3 vs. 7.5) and 12 months (15.1 vs. 5.0).

TG-C proved superior to placebo in improving VAS pain scores at 6, 9, and 12 months, and changes in WOMAC scores were significant after 12 months with a mean change of –13.9 with TG-C and –6.2 with placebo.

The OMERACT-OARSI response rate was also assessed. A responder was identified as someone with an improvement in VAS pain score of 50% or more and an absolute change in score of at least 10 points and at least a 50% improvement in IKDC score with an absolute change of at least 20 points. The response rate for TG-C and placebo was 70% versus 52% (P = .02) at 6 months, 77% versus 52% at 9 months (P = .0011), and 84% versus 45% (P less than .001) at 12 months.

The most common adverse events seen were related to the intra-articular injection, Dr. Lee noted. Two serious adverse events – arthralgia and joint swelling – occurred in one subject who received the novel treatment, but this resolved within 10 days of administration.

Biomarker analyses have been performed and it appears that patients with greater joint space width, and higher baseline levels of CTX-II and C3M may be more likely to respond to TG-C. Some changes in CTX-I and CTX-II were clinically meaningful, and although the MRI data are still being evaluated, there was one striking feature: Patients treated with TG-C did not grow any osteophytes, compared with patients on placebo.

“Invossa holds great potential for a disease-modifying osteoarthritis drug,” said Dr. Gurdyal Kalsi, chief medical officer of TissueGene Inc. Based on the evidence today, which includes a phase II trial conducted in the United States (Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2015;23:2109-18), he said that the novel treatment “offers sustained improvement of pain and function over 2 years with a single injection.” OMERACT-OARSI response rates were 81%-86% in patients not responding to conservative therapies in the phase II study.

It is envisioned that the phase III U.S. trial will start enrolling patients from the start of next year, with the last patient enrolled around May 2018 and the first results appearing around the summer of 2019. TissueGene Inc. would then expect to have the full trial results by 2020 and make a Biologics License Application to the FDA in early 2021.

“We believe we truly have something that we hope would fulfill a DMOAD application,” Dr. Kalsi said.

Kolon Life Science and TissueGene Inc. sponsored the studies. Dr. Lee and Dr. Kalsi are employees of TissueGene Inc.

AT OARSI 2016

Key clinical point: A single intra-articular injection of TissueGene C provided symptomatic relief and could be the first disease-modifying osteoarthritis drug.

Major finding: Changes in IKDC, VAS pain, and WOMAC scores at 1 year of follow-up with TG-C and saline placebo were a respective 15.1 and 5.0 points (P less than .05), –24.5 and –0.3 points (P less than .05), and –13.9 and –6.2 points (P less than .05).

Data source: Phase III, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial conducted in Korea in 163 patients with knee osteoarthritis.

Disclosures: Kolon Life Science and TissueGene Inc. sponsored the studies. Dr. Lee and Dr. Kalsi are employees of TissueGene Inc.

Military sexual trauma tied to homelessness risk among veterans

A positive screen for military sexual trauma among recently discharged male and female veterans may be a predictive factor for homelessness. In addition, the association between military sexual trauma and homelessness is stronger among male veterans, results of a retrospective study published April 20 show.

Emily Brignone, Dr. Adi V. Gundlapalli, and their associates examined health care data from the Veterans Health Administration’s 2011 Operation Enduring Freedom and Operation Iraqi Freedom official roster of veterans. All of the veterans separated from the military between fiscal years 2001 and 2011, and used Veterans Health Administration (VHA) services between fiscal years 2004 and 2013 (JAMA Psychiatry. 2016 Apr 20. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2016.0101).

The total study population included 601,892, 590,989, and 262,589 U.S. veterans who screened positive for military sexual trauma at 30 days, 1 year, and 5 years, respectively, after their initial VHA visit, reported Ms. Brignone and Dr. Gundlapalli, both of whom are affiliated with the Informatics, Decision Enhancement, and Analytic Sciences Center at the VA Salt Lake City Health Care System.

They found that the incidence of homelessness in this population was 1.6%, 4.4%, and 9.6% within 30 days, 1 year, and 5 years, respectively. The rates for male veterans were higher than for their female counterparts, as evidenced by 30-day, 1-year, and 5-year homelessness rates of 2.3%, 6.2%, and 11.8%, respectively, compared with 1.3%, 3.9%, and 8.9%. About 25% of female veterans report experiencing sexual trauma during their military service, compared with 1% of male veterans, research shows (Am J Public Health. 2007;97[12]:2160-6).

Meanwhile, the rates of positive military sexual trauma screens among homeless veterans were almost twice as high, compared with the rates of veterans who were not homeless (0.7%, 1.8%, and 4.3%, respectively).

Logistic regression analysis models adjusted for mental health and substance use diagnoses showed that military sexual trauma screen status remained significantly associated with homelessness, such that veterans with a positive military sexual trauma screen were roughly 1.5-fold more likely to be homelessness than those with a negative screen. The adjusted models also showed that the interaction between military sexual trauma status and sex remained significant for the 30-day and 1-year cohorts.

Ms. Brignone, Dr. Gundlapalli, and their associates cited several limitations. For example, a positive screen for military sexual trauma is a self-reported marker rather than a diagnosis. “Because a positive screen for [military sexual trauma] is associated with increased service use, there may be more opportunities to detect homelessness among veterans with a positive screen,” they wrote.

The investigators said further research is needed to understand the temporal associations between sexual trauma, mental health diagnoses, and sex-dependent differences. Understanding those associations might be useful in attempts at prevention and intervention of postdeployment homelessness, they wrote.

A U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs grant funded this project. The authors disclosed no conflicts of interest.

The results of the study by Emily Brignone, Dr. Adi V. Gundlapalli, and their associates should promote zero tolerance for the perpetration of sexual trauma in the military, Natalie Mota, Ph.D., and her associates wrote in an accompanying editorial. “Education and awareness about the widespread deleterious effects of [military sexual trauma] on mental and physical health as well as military cohesion and productivity could help to advance this aim,” they wrote.

Ms. Brignone’s study also should prompt efforts to identify veterans with military sexual trauma in order to facilitate timely connections to evidence-based interventions such as Housing First approaches. Also, continued research focused on personalizing screening and outreach efforts specifically targeted to this population will be required to identify veterans at increased risk for postdeployment homelessness, they wrote.

Other possible solutions to reducing postdeployment homelessness are facilitated, supported, and encouraged reporting of military sexual trauma, sensitive and effective assessment of military sexual trauma, and facilitated access to evidence-based interventions for military sexual trauma–related mental health problems across health care systems.

Dr. Mota is affiliated with the department of clinical health psychology at the University of Manitoba in Winnipeg (JAMA Psychiatry. 2016 Apr 20. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2016.0136).

The results of the study by Emily Brignone, Dr. Adi V. Gundlapalli, and their associates should promote zero tolerance for the perpetration of sexual trauma in the military, Natalie Mota, Ph.D., and her associates wrote in an accompanying editorial. “Education and awareness about the widespread deleterious effects of [military sexual trauma] on mental and physical health as well as military cohesion and productivity could help to advance this aim,” they wrote.

Ms. Brignone’s study also should prompt efforts to identify veterans with military sexual trauma in order to facilitate timely connections to evidence-based interventions such as Housing First approaches. Also, continued research focused on personalizing screening and outreach efforts specifically targeted to this population will be required to identify veterans at increased risk for postdeployment homelessness, they wrote.

Other possible solutions to reducing postdeployment homelessness are facilitated, supported, and encouraged reporting of military sexual trauma, sensitive and effective assessment of military sexual trauma, and facilitated access to evidence-based interventions for military sexual trauma–related mental health problems across health care systems.

Dr. Mota is affiliated with the department of clinical health psychology at the University of Manitoba in Winnipeg (JAMA Psychiatry. 2016 Apr 20. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2016.0136).

The results of the study by Emily Brignone, Dr. Adi V. Gundlapalli, and their associates should promote zero tolerance for the perpetration of sexual trauma in the military, Natalie Mota, Ph.D., and her associates wrote in an accompanying editorial. “Education and awareness about the widespread deleterious effects of [military sexual trauma] on mental and physical health as well as military cohesion and productivity could help to advance this aim,” they wrote.

Ms. Brignone’s study also should prompt efforts to identify veterans with military sexual trauma in order to facilitate timely connections to evidence-based interventions such as Housing First approaches. Also, continued research focused on personalizing screening and outreach efforts specifically targeted to this population will be required to identify veterans at increased risk for postdeployment homelessness, they wrote.

Other possible solutions to reducing postdeployment homelessness are facilitated, supported, and encouraged reporting of military sexual trauma, sensitive and effective assessment of military sexual trauma, and facilitated access to evidence-based interventions for military sexual trauma–related mental health problems across health care systems.

Dr. Mota is affiliated with the department of clinical health psychology at the University of Manitoba in Winnipeg (JAMA Psychiatry. 2016 Apr 20. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2016.0136).

A positive screen for military sexual trauma among recently discharged male and female veterans may be a predictive factor for homelessness. In addition, the association between military sexual trauma and homelessness is stronger among male veterans, results of a retrospective study published April 20 show.

Emily Brignone, Dr. Adi V. Gundlapalli, and their associates examined health care data from the Veterans Health Administration’s 2011 Operation Enduring Freedom and Operation Iraqi Freedom official roster of veterans. All of the veterans separated from the military between fiscal years 2001 and 2011, and used Veterans Health Administration (VHA) services between fiscal years 2004 and 2013 (JAMA Psychiatry. 2016 Apr 20. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2016.0101).

The total study population included 601,892, 590,989, and 262,589 U.S. veterans who screened positive for military sexual trauma at 30 days, 1 year, and 5 years, respectively, after their initial VHA visit, reported Ms. Brignone and Dr. Gundlapalli, both of whom are affiliated with the Informatics, Decision Enhancement, and Analytic Sciences Center at the VA Salt Lake City Health Care System.

They found that the incidence of homelessness in this population was 1.6%, 4.4%, and 9.6% within 30 days, 1 year, and 5 years, respectively. The rates for male veterans were higher than for their female counterparts, as evidenced by 30-day, 1-year, and 5-year homelessness rates of 2.3%, 6.2%, and 11.8%, respectively, compared with 1.3%, 3.9%, and 8.9%. About 25% of female veterans report experiencing sexual trauma during their military service, compared with 1% of male veterans, research shows (Am J Public Health. 2007;97[12]:2160-6).

Meanwhile, the rates of positive military sexual trauma screens among homeless veterans were almost twice as high, compared with the rates of veterans who were not homeless (0.7%, 1.8%, and 4.3%, respectively).

Logistic regression analysis models adjusted for mental health and substance use diagnoses showed that military sexual trauma screen status remained significantly associated with homelessness, such that veterans with a positive military sexual trauma screen were roughly 1.5-fold more likely to be homelessness than those with a negative screen. The adjusted models also showed that the interaction between military sexual trauma status and sex remained significant for the 30-day and 1-year cohorts.

Ms. Brignone, Dr. Gundlapalli, and their associates cited several limitations. For example, a positive screen for military sexual trauma is a self-reported marker rather than a diagnosis. “Because a positive screen for [military sexual trauma] is associated with increased service use, there may be more opportunities to detect homelessness among veterans with a positive screen,” they wrote.

The investigators said further research is needed to understand the temporal associations between sexual trauma, mental health diagnoses, and sex-dependent differences. Understanding those associations might be useful in attempts at prevention and intervention of postdeployment homelessness, they wrote.

A U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs grant funded this project. The authors disclosed no conflicts of interest.

A positive screen for military sexual trauma among recently discharged male and female veterans may be a predictive factor for homelessness. In addition, the association between military sexual trauma and homelessness is stronger among male veterans, results of a retrospective study published April 20 show.

Emily Brignone, Dr. Adi V. Gundlapalli, and their associates examined health care data from the Veterans Health Administration’s 2011 Operation Enduring Freedom and Operation Iraqi Freedom official roster of veterans. All of the veterans separated from the military between fiscal years 2001 and 2011, and used Veterans Health Administration (VHA) services between fiscal years 2004 and 2013 (JAMA Psychiatry. 2016 Apr 20. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2016.0101).

The total study population included 601,892, 590,989, and 262,589 U.S. veterans who screened positive for military sexual trauma at 30 days, 1 year, and 5 years, respectively, after their initial VHA visit, reported Ms. Brignone and Dr. Gundlapalli, both of whom are affiliated with the Informatics, Decision Enhancement, and Analytic Sciences Center at the VA Salt Lake City Health Care System.

They found that the incidence of homelessness in this population was 1.6%, 4.4%, and 9.6% within 30 days, 1 year, and 5 years, respectively. The rates for male veterans were higher than for their female counterparts, as evidenced by 30-day, 1-year, and 5-year homelessness rates of 2.3%, 6.2%, and 11.8%, respectively, compared with 1.3%, 3.9%, and 8.9%. About 25% of female veterans report experiencing sexual trauma during their military service, compared with 1% of male veterans, research shows (Am J Public Health. 2007;97[12]:2160-6).

Meanwhile, the rates of positive military sexual trauma screens among homeless veterans were almost twice as high, compared with the rates of veterans who were not homeless (0.7%, 1.8%, and 4.3%, respectively).

Logistic regression analysis models adjusted for mental health and substance use diagnoses showed that military sexual trauma screen status remained significantly associated with homelessness, such that veterans with a positive military sexual trauma screen were roughly 1.5-fold more likely to be homelessness than those with a negative screen. The adjusted models also showed that the interaction between military sexual trauma status and sex remained significant for the 30-day and 1-year cohorts.

Ms. Brignone, Dr. Gundlapalli, and their associates cited several limitations. For example, a positive screen for military sexual trauma is a self-reported marker rather than a diagnosis. “Because a positive screen for [military sexual trauma] is associated with increased service use, there may be more opportunities to detect homelessness among veterans with a positive screen,” they wrote.

The investigators said further research is needed to understand the temporal associations between sexual trauma, mental health diagnoses, and sex-dependent differences. Understanding those associations might be useful in attempts at prevention and intervention of postdeployment homelessness, they wrote.

A U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs grant funded this project. The authors disclosed no conflicts of interest.

FROM JAMA PSYCHIATRY

Key clinical point: Male and female U.S. veterans who screen positive for military sexual trauma have an increased risk of homelessness postdeployment.

Major finding: The primary outcome – the incidence of homelessness among veterans with a positive screen for military sexual trauma – was 1.6% within 30 days, 4.4% within 1 year, and 9.6% within 5 years.

Data source: Health care data on three cohorts (30 days, 1 year, and 5 years) of veterans who separated from the military between fiscal years 2001 and 2011 from the Veterans Health Administration’s 2011 Operation Enduring Freedom and Operation Iraqi Freedom official roster.

Disclosures: A U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs grant funded this project. The authors disclosed no conflicts of interest.

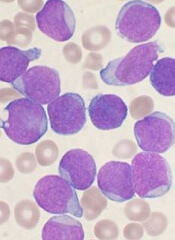

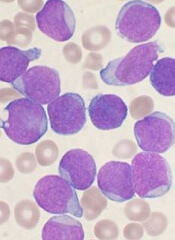

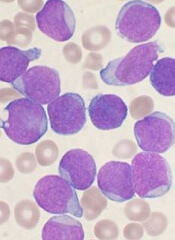

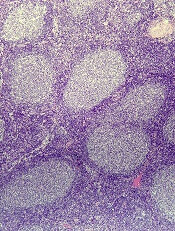

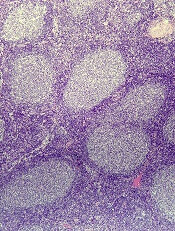

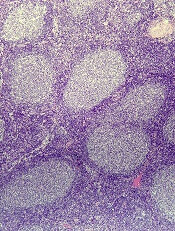

Painful Lesions on the Tongue

The Diagnosis: Herpetic Glossitis

Oral lesions of the tongue are common during primary herpetic gingivostomatitis, though most primary oral herpes simplex virus (HSV) infections occur during childhood or early adulthood. Reactivation of HSV type 1 most commonly manifests as herpes labialis.1 When recurrent HSV involves intraoral lesions, they are typically confined to the gingiva and palate, sparing the tongue.

Clinical presentation of herpetic glossitis varies. Recurrent herpetic glossitis has been described in immunocompromised patients, particularly those with hematologic malignancies and organ transplants.2 In addition, immunocompromised and human immunodeficiency virus–infected patients may present with deep and/or broad ulcers. A case of herpes infection presenting with nodules on the tongue has been reported in Hodgkin disease.3 Herpetic geometric glossitis also has been described, which is a linear, crosshatched, or sharply angled branching with painful fissuring of the tongue. Herpetic geometric glossitis has been reported to occur in both immunocompetent and immunocompromised individuals.4 Tongue involvement during oral reactivation of HSV is exceedingly rare and the pathogenesis remains elusive, though one hypothesis proposes a protective role of salivary-specific IgA and lysozyme.5 Here, we report a case in which a patient developed similar lingual HSV lesions following recent immunosuppression.

1. Arduino PG, Porter SR. Herpes simplex virus type 1 infection: overview on relevant clinico-pathological features. J Oral Pathol Med. 2008;37:107-121.

2. Nikkels AF, Piérard GE. Chronic herpes simplex virus type I glossitis in an immunocompromised man. Br J Dermatol. 1999;140:343-346.

3. Leming PD, Martin SE, Zwelling LA. Atypical herpes simplex (HSV) infection in a patient with Hodgkin’s disease. Cancer. 1984;54:3043-3047.

4. Mirowski GW, Goddard A. Herpetic geometric glossitis in an immunocompetent patient with pneumonia. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;61:139-142.

5. Heineman HS, Greenberg MS. Cell protective effect of human saliva specific for herpes simplex virus. Arch Oral Biol. 1980;25:257-261.

The Diagnosis: Herpetic Glossitis

Oral lesions of the tongue are common during primary herpetic gingivostomatitis, though most primary oral herpes simplex virus (HSV) infections occur during childhood or early adulthood. Reactivation of HSV type 1 most commonly manifests as herpes labialis.1 When recurrent HSV involves intraoral lesions, they are typically confined to the gingiva and palate, sparing the tongue.

Clinical presentation of herpetic glossitis varies. Recurrent herpetic glossitis has been described in immunocompromised patients, particularly those with hematologic malignancies and organ transplants.2 In addition, immunocompromised and human immunodeficiency virus–infected patients may present with deep and/or broad ulcers. A case of herpes infection presenting with nodules on the tongue has been reported in Hodgkin disease.3 Herpetic geometric glossitis also has been described, which is a linear, crosshatched, or sharply angled branching with painful fissuring of the tongue. Herpetic geometric glossitis has been reported to occur in both immunocompetent and immunocompromised individuals.4 Tongue involvement during oral reactivation of HSV is exceedingly rare and the pathogenesis remains elusive, though one hypothesis proposes a protective role of salivary-specific IgA and lysozyme.5 Here, we report a case in which a patient developed similar lingual HSV lesions following recent immunosuppression.

The Diagnosis: Herpetic Glossitis

Oral lesions of the tongue are common during primary herpetic gingivostomatitis, though most primary oral herpes simplex virus (HSV) infections occur during childhood or early adulthood. Reactivation of HSV type 1 most commonly manifests as herpes labialis.1 When recurrent HSV involves intraoral lesions, they are typically confined to the gingiva and palate, sparing the tongue.

Clinical presentation of herpetic glossitis varies. Recurrent herpetic glossitis has been described in immunocompromised patients, particularly those with hematologic malignancies and organ transplants.2 In addition, immunocompromised and human immunodeficiency virus–infected patients may present with deep and/or broad ulcers. A case of herpes infection presenting with nodules on the tongue has been reported in Hodgkin disease.3 Herpetic geometric glossitis also has been described, which is a linear, crosshatched, or sharply angled branching with painful fissuring of the tongue. Herpetic geometric glossitis has been reported to occur in both immunocompetent and immunocompromised individuals.4 Tongue involvement during oral reactivation of HSV is exceedingly rare and the pathogenesis remains elusive, though one hypothesis proposes a protective role of salivary-specific IgA and lysozyme.5 Here, we report a case in which a patient developed similar lingual HSV lesions following recent immunosuppression.

1. Arduino PG, Porter SR. Herpes simplex virus type 1 infection: overview on relevant clinico-pathological features. J Oral Pathol Med. 2008;37:107-121.

2. Nikkels AF, Piérard GE. Chronic herpes simplex virus type I glossitis in an immunocompromised man. Br J Dermatol. 1999;140:343-346.

3. Leming PD, Martin SE, Zwelling LA. Atypical herpes simplex (HSV) infection in a patient with Hodgkin’s disease. Cancer. 1984;54:3043-3047.

4. Mirowski GW, Goddard A. Herpetic geometric glossitis in an immunocompetent patient with pneumonia. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;61:139-142.

5. Heineman HS, Greenberg MS. Cell protective effect of human saliva specific for herpes simplex virus. Arch Oral Biol. 1980;25:257-261.

1. Arduino PG, Porter SR. Herpes simplex virus type 1 infection: overview on relevant clinico-pathological features. J Oral Pathol Med. 2008;37:107-121.

2. Nikkels AF, Piérard GE. Chronic herpes simplex virus type I glossitis in an immunocompromised man. Br J Dermatol. 1999;140:343-346.

3. Leming PD, Martin SE, Zwelling LA. Atypical herpes simplex (HSV) infection in a patient with Hodgkin’s disease. Cancer. 1984;54:3043-3047.

4. Mirowski GW, Goddard A. Herpetic geometric glossitis in an immunocompetent patient with pneumonia. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;61:139-142.

5. Heineman HS, Greenberg MS. Cell protective effect of human saliva specific for herpes simplex virus. Arch Oral Biol. 1980;25:257-261.

A 77-year-old man with a history of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and recent pneumonia was treated with oral prednisone 40 mg daily, antibiotics, and a fluticasone-salmeterol inhaler. One week into treatment, the patient developed painful lesions limited to the oral cavity. Physical examination revealed many fixed, umbilicated, white-tan plaques on the lower lips, tongue, and posterior aspect of the oropharynx. The dermatology department was consulted because the lesions failed to respond to nystatin oral suspension.

In rosacea, flushing and inflammation need to be addressed

WAIKOLOA, HAWAII – The topical vasoconstrictor brimonidine 0.33% gel brings impressive improvement in the facial redness component of rosacea, but it does nothing to address the inflammatory lesions of the disease, Dr. Joseph F. Fowler, Jr., said at the Hawaii Dermatology Seminar provided by the Global Academy for Medical Education/Skin Disease Education Foundation.

Rebound flushing wasn’t seen in the 52-week, large, open-label safety study of brimonidine gel, but has been anecdotally reported since its approval. Flushing occurs 12-24 hours after application, and usually lasts a day or two, according to Dr. Fowler, who was the first author of several multicenter randomized trials of the therapy.

“The rebound phenomenon is not something that frightens me or others I know who use the medication routinely, because it’s not something that’s going to cause a long-term problem,” he declared. Indeed, once brimonidine gel (Mirvaso) has quelled the erythema, the inflammatory lesions will stand out even more prominently, noted Dr. Fowler, the conference co-director and a dermatologist at the University of Louisville. “You’ve got to do something about the inflammatory component.”

Two topical therapies that address the inflammatory component include ivermectin 1% cream (Soolantra), shown to reduce counts of papules and pustules in two 40-week extension studies of phase III trials (J Drugs Dermatol. 2014 Nov;13[11]:1380-6), and azelaic acid 15% foam (Finacea), which also achieved an impressive reduction in inflammatory lesion counts in a phase III trial (Cutis. 2015 Jul;96[1]:54-61).

Both agents were well tolerated in those studies. That’s a major treatment consideration because rosacea patients have elevated facial skin sensitivity and often can’t tolerate older off-label topical therapies because of stinging and burning, according to Dr. Fowler.

Some rosacea patients are so intolerant of topicals that they prefer oral therapy. For those patients, subantimicrobial-dose doxycycline is a good option, Dr. Fowler said.

In addition to its anti-inflammatory effects, topical ivermectin kills Demodex. While rosacea is an inflammatory disorder, not an infection, drugs like ivermectin and crotamiton 10% cream (Eurax) that kill Demodex also improve rosacea, he observed.

The initial irritation event rate with azelaic acid 15% foam in the phase III trial was in the 2%-5% range, and those events were short lived. Irritation is a much bigger problem with the older azelaic acid 15% gel, with event rates in the 15%-25% range.

Dr. Fowler has also had good results using topical calcineurin inhibitors off-label for rosacea. Pimecrolimus cream (Elidel) is in ongoing studies for treatment of seborrheic dermatitis, which often coexists with rosacea, he noted.

He reported serving as a consultant to half a dozen pharmaceutical companies, including Galderma, which markets ivermectin cream and brimonidine gel, and Bayer, which markets azelaic acid foam.

SDEF and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

WAIKOLOA, HAWAII – The topical vasoconstrictor brimonidine 0.33% gel brings impressive improvement in the facial redness component of rosacea, but it does nothing to address the inflammatory lesions of the disease, Dr. Joseph F. Fowler, Jr., said at the Hawaii Dermatology Seminar provided by the Global Academy for Medical Education/Skin Disease Education Foundation.

Rebound flushing wasn’t seen in the 52-week, large, open-label safety study of brimonidine gel, but has been anecdotally reported since its approval. Flushing occurs 12-24 hours after application, and usually lasts a day or two, according to Dr. Fowler, who was the first author of several multicenter randomized trials of the therapy.

“The rebound phenomenon is not something that frightens me or others I know who use the medication routinely, because it’s not something that’s going to cause a long-term problem,” he declared. Indeed, once brimonidine gel (Mirvaso) has quelled the erythema, the inflammatory lesions will stand out even more prominently, noted Dr. Fowler, the conference co-director and a dermatologist at the University of Louisville. “You’ve got to do something about the inflammatory component.”

Two topical therapies that address the inflammatory component include ivermectin 1% cream (Soolantra), shown to reduce counts of papules and pustules in two 40-week extension studies of phase III trials (J Drugs Dermatol. 2014 Nov;13[11]:1380-6), and azelaic acid 15% foam (Finacea), which also achieved an impressive reduction in inflammatory lesion counts in a phase III trial (Cutis. 2015 Jul;96[1]:54-61).

Both agents were well tolerated in those studies. That’s a major treatment consideration because rosacea patients have elevated facial skin sensitivity and often can’t tolerate older off-label topical therapies because of stinging and burning, according to Dr. Fowler.

Some rosacea patients are so intolerant of topicals that they prefer oral therapy. For those patients, subantimicrobial-dose doxycycline is a good option, Dr. Fowler said.

In addition to its anti-inflammatory effects, topical ivermectin kills Demodex. While rosacea is an inflammatory disorder, not an infection, drugs like ivermectin and crotamiton 10% cream (Eurax) that kill Demodex also improve rosacea, he observed.

The initial irritation event rate with azelaic acid 15% foam in the phase III trial was in the 2%-5% range, and those events were short lived. Irritation is a much bigger problem with the older azelaic acid 15% gel, with event rates in the 15%-25% range.

Dr. Fowler has also had good results using topical calcineurin inhibitors off-label for rosacea. Pimecrolimus cream (Elidel) is in ongoing studies for treatment of seborrheic dermatitis, which often coexists with rosacea, he noted.

He reported serving as a consultant to half a dozen pharmaceutical companies, including Galderma, which markets ivermectin cream and brimonidine gel, and Bayer, which markets azelaic acid foam.

SDEF and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

WAIKOLOA, HAWAII – The topical vasoconstrictor brimonidine 0.33% gel brings impressive improvement in the facial redness component of rosacea, but it does nothing to address the inflammatory lesions of the disease, Dr. Joseph F. Fowler, Jr., said at the Hawaii Dermatology Seminar provided by the Global Academy for Medical Education/Skin Disease Education Foundation.

Rebound flushing wasn’t seen in the 52-week, large, open-label safety study of brimonidine gel, but has been anecdotally reported since its approval. Flushing occurs 12-24 hours after application, and usually lasts a day or two, according to Dr. Fowler, who was the first author of several multicenter randomized trials of the therapy.

“The rebound phenomenon is not something that frightens me or others I know who use the medication routinely, because it’s not something that’s going to cause a long-term problem,” he declared. Indeed, once brimonidine gel (Mirvaso) has quelled the erythema, the inflammatory lesions will stand out even more prominently, noted Dr. Fowler, the conference co-director and a dermatologist at the University of Louisville. “You’ve got to do something about the inflammatory component.”

Two topical therapies that address the inflammatory component include ivermectin 1% cream (Soolantra), shown to reduce counts of papules and pustules in two 40-week extension studies of phase III trials (J Drugs Dermatol. 2014 Nov;13[11]:1380-6), and azelaic acid 15% foam (Finacea), which also achieved an impressive reduction in inflammatory lesion counts in a phase III trial (Cutis. 2015 Jul;96[1]:54-61).

Both agents were well tolerated in those studies. That’s a major treatment consideration because rosacea patients have elevated facial skin sensitivity and often can’t tolerate older off-label topical therapies because of stinging and burning, according to Dr. Fowler.

Some rosacea patients are so intolerant of topicals that they prefer oral therapy. For those patients, subantimicrobial-dose doxycycline is a good option, Dr. Fowler said.

In addition to its anti-inflammatory effects, topical ivermectin kills Demodex. While rosacea is an inflammatory disorder, not an infection, drugs like ivermectin and crotamiton 10% cream (Eurax) that kill Demodex also improve rosacea, he observed.

The initial irritation event rate with azelaic acid 15% foam in the phase III trial was in the 2%-5% range, and those events were short lived. Irritation is a much bigger problem with the older azelaic acid 15% gel, with event rates in the 15%-25% range.

Dr. Fowler has also had good results using topical calcineurin inhibitors off-label for rosacea. Pimecrolimus cream (Elidel) is in ongoing studies for treatment of seborrheic dermatitis, which often coexists with rosacea, he noted.

He reported serving as a consultant to half a dozen pharmaceutical companies, including Galderma, which markets ivermectin cream and brimonidine gel, and Bayer, which markets azelaic acid foam.

SDEF and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM THE SDEF HAWAII DERMATOLOGY SEMINAR

U.S. Surgeon General Encourages Hospitalists to Remain Hopeful, Motivated

Hopefully, many of you were able to attend the Society of Hospital Medicine’s annual meeting this year in San Diego. (I know at least 4,000 of you made it!) Each year, the annual meeting is a time of catching up with hospitalists from around the country (many of whom I only see once a year) and catching up on what is going on in the medical industry.

This year was not particularly unique in that many sessions focused on the myriad challenges we should expect to see in the medical industry in the coming years. There was much discussion about future payment models; although there is ongoing ambiguity about exactly how these models are going to be operationalized, there is certainly no ambiguity that the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) is hard driving the amount of payments that will be tied to some form of alternative payment model (50% by 2018).

We also heard about ongoing challenges in quality and safety, where a stunning number of patients continue to suffer preventable harm on a daily basis within our hospital walls. And we heard much about the ongoing and mounting opiate abuse epidemic. All of these are monumentally difficult challenges that remain unsolved and without a clear path forward to resolution.

Contrast that with the message from the U.S. Surgeon General during the opening plenary of the annual meeting. Vivek Murthy, MD, was named Surgeon General at a time in the U.S. when all of the above challenges are being added to the abounding issues of chronic disease, mental illness, and extraordinary healthcare costs. He is the highest leader in the nation ordained with trying to improve the health of all Americans at a time when we have never been unhealthier. But despite these monumental challenges, his message was not about the average American body mass index (BMI), smoking status, or heroin addiction. Much different, his message was chock full of amazing stories of community engagement and resilience, focused on innovation and fresh thinking, and about creative problem-solving despite lean and unforgiving budgets.

What Dr. Murthy offered were endless stories of hope and goodness, which he was able to find in each and every city he has visited in his short time as the nation’s “top doc.”

During his tenure, he has visited innumerable communities and engaged with locals in listening sessions. His takeaway from these sessions is “you wouldn’t believe how much good is out there.” One of his many stories was of a hospital and a YMCA that joined forces to improve the health and well-being of the hospital patients, employees, and entire community. This was at a time when both were struggling with lean budgets and stagnant progress in healthy living.

This pragmatic optimism reminds me a bit of one of my life mentors, my Aunt Karen. She is extremely realistic and grounded and knows in great detail the trials and tribulations of being alive for 66 years (including being a 10-year survivor of recurrent ovarian rhabdomyosarcoma). What Aunt Karen does that is so uniquely different than anyone else I know is that she creates goodness. I did not fully understand this until a few years ago, but I noticed that she goes out of her way to create extreme goodness out of extreme ordinariness. I have often joked that she purposely befriends pregnant women just to have an excuse to host a baby shower. She goes overboard to make any and every excuse to celebrate relatively ordinary life milestones (anniversaries, Valentine’s Day, St. Patrick’s Day). In her words, “you have to have a buffer for the funerals.”

Flip Your Switch

And so while Dr. Murthy and Aunt Karen have little else in common, they do share the priceless ability to help others see the goodness in everything around them even when surrounded by remarkable challenges and uncertainty. What a unique gift they have.

But are there simple ways we can all incorporate such goodness into our lives and start to routinely build in these buffers?

In your own personal life and work life, what are your buffers? How could you routinely and repeatedly “find the good” in all things around you?

A few months ago, I started searching for what I call “inbox buffers” as I noticed my email inbox was routinely chock full of requests for time, advice, or resources (all of which can be limited). I found a daily email called “The Daily Good.” It comes into my inbox early each morning and typically covers a human-interest story that is short, interesting, and inspiring. I have found these help me reset my mindset and attitude toward one that is more resilient and forgiving; in other words, it helps me find the good even within the crevices of a cranky email inbox. I have many other buffers, but I cite this one as it is simple, easy, free, predictable, dependable, and routinely inspiring!

So in this time when hospitalists are facing monumental change, unpredictable conflict, and unending challenges, we all need to purposely and repeatedly build in buffers to keep us hopeful and motivated and to seamlessly and routinely find the good in all we do. TH

Hopefully, many of you were able to attend the Society of Hospital Medicine’s annual meeting this year in San Diego. (I know at least 4,000 of you made it!) Each year, the annual meeting is a time of catching up with hospitalists from around the country (many of whom I only see once a year) and catching up on what is going on in the medical industry.

This year was not particularly unique in that many sessions focused on the myriad challenges we should expect to see in the medical industry in the coming years. There was much discussion about future payment models; although there is ongoing ambiguity about exactly how these models are going to be operationalized, there is certainly no ambiguity that the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) is hard driving the amount of payments that will be tied to some form of alternative payment model (50% by 2018).

We also heard about ongoing challenges in quality and safety, where a stunning number of patients continue to suffer preventable harm on a daily basis within our hospital walls. And we heard much about the ongoing and mounting opiate abuse epidemic. All of these are monumentally difficult challenges that remain unsolved and without a clear path forward to resolution.

Contrast that with the message from the U.S. Surgeon General during the opening plenary of the annual meeting. Vivek Murthy, MD, was named Surgeon General at a time in the U.S. when all of the above challenges are being added to the abounding issues of chronic disease, mental illness, and extraordinary healthcare costs. He is the highest leader in the nation ordained with trying to improve the health of all Americans at a time when we have never been unhealthier. But despite these monumental challenges, his message was not about the average American body mass index (BMI), smoking status, or heroin addiction. Much different, his message was chock full of amazing stories of community engagement and resilience, focused on innovation and fresh thinking, and about creative problem-solving despite lean and unforgiving budgets.

What Dr. Murthy offered were endless stories of hope and goodness, which he was able to find in each and every city he has visited in his short time as the nation’s “top doc.”

During his tenure, he has visited innumerable communities and engaged with locals in listening sessions. His takeaway from these sessions is “you wouldn’t believe how much good is out there.” One of his many stories was of a hospital and a YMCA that joined forces to improve the health and well-being of the hospital patients, employees, and entire community. This was at a time when both were struggling with lean budgets and stagnant progress in healthy living.

This pragmatic optimism reminds me a bit of one of my life mentors, my Aunt Karen. She is extremely realistic and grounded and knows in great detail the trials and tribulations of being alive for 66 years (including being a 10-year survivor of recurrent ovarian rhabdomyosarcoma). What Aunt Karen does that is so uniquely different than anyone else I know is that she creates goodness. I did not fully understand this until a few years ago, but I noticed that she goes out of her way to create extreme goodness out of extreme ordinariness. I have often joked that she purposely befriends pregnant women just to have an excuse to host a baby shower. She goes overboard to make any and every excuse to celebrate relatively ordinary life milestones (anniversaries, Valentine’s Day, St. Patrick’s Day). In her words, “you have to have a buffer for the funerals.”

Flip Your Switch

And so while Dr. Murthy and Aunt Karen have little else in common, they do share the priceless ability to help others see the goodness in everything around them even when surrounded by remarkable challenges and uncertainty. What a unique gift they have.

But are there simple ways we can all incorporate such goodness into our lives and start to routinely build in these buffers?

In your own personal life and work life, what are your buffers? How could you routinely and repeatedly “find the good” in all things around you?

A few months ago, I started searching for what I call “inbox buffers” as I noticed my email inbox was routinely chock full of requests for time, advice, or resources (all of which can be limited). I found a daily email called “The Daily Good.” It comes into my inbox early each morning and typically covers a human-interest story that is short, interesting, and inspiring. I have found these help me reset my mindset and attitude toward one that is more resilient and forgiving; in other words, it helps me find the good even within the crevices of a cranky email inbox. I have many other buffers, but I cite this one as it is simple, easy, free, predictable, dependable, and routinely inspiring!

So in this time when hospitalists are facing monumental change, unpredictable conflict, and unending challenges, we all need to purposely and repeatedly build in buffers to keep us hopeful and motivated and to seamlessly and routinely find the good in all we do. TH

Hopefully, many of you were able to attend the Society of Hospital Medicine’s annual meeting this year in San Diego. (I know at least 4,000 of you made it!) Each year, the annual meeting is a time of catching up with hospitalists from around the country (many of whom I only see once a year) and catching up on what is going on in the medical industry.

This year was not particularly unique in that many sessions focused on the myriad challenges we should expect to see in the medical industry in the coming years. There was much discussion about future payment models; although there is ongoing ambiguity about exactly how these models are going to be operationalized, there is certainly no ambiguity that the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) is hard driving the amount of payments that will be tied to some form of alternative payment model (50% by 2018).

We also heard about ongoing challenges in quality and safety, where a stunning number of patients continue to suffer preventable harm on a daily basis within our hospital walls. And we heard much about the ongoing and mounting opiate abuse epidemic. All of these are monumentally difficult challenges that remain unsolved and without a clear path forward to resolution.

Contrast that with the message from the U.S. Surgeon General during the opening plenary of the annual meeting. Vivek Murthy, MD, was named Surgeon General at a time in the U.S. when all of the above challenges are being added to the abounding issues of chronic disease, mental illness, and extraordinary healthcare costs. He is the highest leader in the nation ordained with trying to improve the health of all Americans at a time when we have never been unhealthier. But despite these monumental challenges, his message was not about the average American body mass index (BMI), smoking status, or heroin addiction. Much different, his message was chock full of amazing stories of community engagement and resilience, focused on innovation and fresh thinking, and about creative problem-solving despite lean and unforgiving budgets.

What Dr. Murthy offered were endless stories of hope and goodness, which he was able to find in each and every city he has visited in his short time as the nation’s “top doc.”

During his tenure, he has visited innumerable communities and engaged with locals in listening sessions. His takeaway from these sessions is “you wouldn’t believe how much good is out there.” One of his many stories was of a hospital and a YMCA that joined forces to improve the health and well-being of the hospital patients, employees, and entire community. This was at a time when both were struggling with lean budgets and stagnant progress in healthy living.

This pragmatic optimism reminds me a bit of one of my life mentors, my Aunt Karen. She is extremely realistic and grounded and knows in great detail the trials and tribulations of being alive for 66 years (including being a 10-year survivor of recurrent ovarian rhabdomyosarcoma). What Aunt Karen does that is so uniquely different than anyone else I know is that she creates goodness. I did not fully understand this until a few years ago, but I noticed that she goes out of her way to create extreme goodness out of extreme ordinariness. I have often joked that she purposely befriends pregnant women just to have an excuse to host a baby shower. She goes overboard to make any and every excuse to celebrate relatively ordinary life milestones (anniversaries, Valentine’s Day, St. Patrick’s Day). In her words, “you have to have a buffer for the funerals.”

Flip Your Switch

And so while Dr. Murthy and Aunt Karen have little else in common, they do share the priceless ability to help others see the goodness in everything around them even when surrounded by remarkable challenges and uncertainty. What a unique gift they have.

But are there simple ways we can all incorporate such goodness into our lives and start to routinely build in these buffers?

In your own personal life and work life, what are your buffers? How could you routinely and repeatedly “find the good” in all things around you?

A few months ago, I started searching for what I call “inbox buffers” as I noticed my email inbox was routinely chock full of requests for time, advice, or resources (all of which can be limited). I found a daily email called “The Daily Good.” It comes into my inbox early each morning and typically covers a human-interest story that is short, interesting, and inspiring. I have found these help me reset my mindset and attitude toward one that is more resilient and forgiving; in other words, it helps me find the good even within the crevices of a cranky email inbox. I have many other buffers, but I cite this one as it is simple, easy, free, predictable, dependable, and routinely inspiring!

So in this time when hospitalists are facing monumental change, unpredictable conflict, and unending challenges, we all need to purposely and repeatedly build in buffers to keep us hopeful and motivated and to seamlessly and routinely find the good in all we do. TH

Climate Change is Expected to Boost the Number of Annual Premature U.S Deaths

WASHINGTON (Reuters) - Climate change can be expected to boost the number of annual premature U.S. deaths from heat waves in coming decades and to increase mental health problems from extreme weather like hurricanes and floods, a U.S. study said on Monday.

"I don't know that we've seen something like this before, where we have a force that has such a multitude of effects," Surgeon General Vivek Murthy told reporters at the White House about the study. "There's not one single source that we can target with climate change, there are multiple paths that we have to address."

Heat waves were estimated to cause 670 to 1,300 U.S. deaths annually in recent years. Premature U.S. deaths from heat waves can be expected to rise more than 27,000 per year by 2100, from a 1990 baseline, one scenario in the study said. The rise outpaced projected decreases in deaths from extreme cold.

Extreme heat can cause more forest fires and increase pollen counts and the resulting poor air quality threatens people with asthma and other lung conditions. The report said poor air quality will likely lead to hundreds of thousands of premature deaths, hospital visits, and acute respiratory illness each year by 2030.

Climate change also threatens mental health, the study found. Post traumatic stress disorder, depression, and general anxiety can all result in places that suffer extreme weather linked to climate change, such as hurricanes and floods. More study needs to be done on assessing the risks to mental health, it said.

The peer-reviewed study by eight federal agencies can be found at: https://health2016.globalchange.gov/

Cases of mosquito and tick-borne diseases can also be expected to increase, though the study, completed over three years, did not look at whether locally-transmitted Zika virus cases would be more likely to hit the U.S.

President Barack Obama's administration has taken steps to cut carbon emissions by speeding a switch from coal and oil to cleaner energy sources. In February, the Supreme Court dealt a blow to the White House's climate ambitions by putting a hold on Obama's plan to cut emissions from power plants. Administration officials say the plan is on safe legal footing.John Holdren, Obama's senior science adviser, said steps the world agreed to in Paris last year to curb emissions through 2030 can help fight the risks to health.

"We will need a big encore after 2030 . . . in order to avoid the bulk of the worst impacts described in this report,"he said.

WASHINGTON (Reuters) - Climate change can be expected to boost the number of annual premature U.S. deaths from heat waves in coming decades and to increase mental health problems from extreme weather like hurricanes and floods, a U.S. study said on Monday.

"I don't know that we've seen something like this before, where we have a force that has such a multitude of effects," Surgeon General Vivek Murthy told reporters at the White House about the study. "There's not one single source that we can target with climate change, there are multiple paths that we have to address."

Heat waves were estimated to cause 670 to 1,300 U.S. deaths annually in recent years. Premature U.S. deaths from heat waves can be expected to rise more than 27,000 per year by 2100, from a 1990 baseline, one scenario in the study said. The rise outpaced projected decreases in deaths from extreme cold.

Extreme heat can cause more forest fires and increase pollen counts and the resulting poor air quality threatens people with asthma and other lung conditions. The report said poor air quality will likely lead to hundreds of thousands of premature deaths, hospital visits, and acute respiratory illness each year by 2030.

Climate change also threatens mental health, the study found. Post traumatic stress disorder, depression, and general anxiety can all result in places that suffer extreme weather linked to climate change, such as hurricanes and floods. More study needs to be done on assessing the risks to mental health, it said.

The peer-reviewed study by eight federal agencies can be found at: https://health2016.globalchange.gov/

Cases of mosquito and tick-borne diseases can also be expected to increase, though the study, completed over three years, did not look at whether locally-transmitted Zika virus cases would be more likely to hit the U.S.

President Barack Obama's administration has taken steps to cut carbon emissions by speeding a switch from coal and oil to cleaner energy sources. In February, the Supreme Court dealt a blow to the White House's climate ambitions by putting a hold on Obama's plan to cut emissions from power plants. Administration officials say the plan is on safe legal footing.John Holdren, Obama's senior science adviser, said steps the world agreed to in Paris last year to curb emissions through 2030 can help fight the risks to health.

"We will need a big encore after 2030 . . . in order to avoid the bulk of the worst impacts described in this report,"he said.

WASHINGTON (Reuters) - Climate change can be expected to boost the number of annual premature U.S. deaths from heat waves in coming decades and to increase mental health problems from extreme weather like hurricanes and floods, a U.S. study said on Monday.

"I don't know that we've seen something like this before, where we have a force that has such a multitude of effects," Surgeon General Vivek Murthy told reporters at the White House about the study. "There's not one single source that we can target with climate change, there are multiple paths that we have to address."

Heat waves were estimated to cause 670 to 1,300 U.S. deaths annually in recent years. Premature U.S. deaths from heat waves can be expected to rise more than 27,000 per year by 2100, from a 1990 baseline, one scenario in the study said. The rise outpaced projected decreases in deaths from extreme cold.

Extreme heat can cause more forest fires and increase pollen counts and the resulting poor air quality threatens people with asthma and other lung conditions. The report said poor air quality will likely lead to hundreds of thousands of premature deaths, hospital visits, and acute respiratory illness each year by 2030.

Climate change also threatens mental health, the study found. Post traumatic stress disorder, depression, and general anxiety can all result in places that suffer extreme weather linked to climate change, such as hurricanes and floods. More study needs to be done on assessing the risks to mental health, it said.

The peer-reviewed study by eight federal agencies can be found at: https://health2016.globalchange.gov/

Cases of mosquito and tick-borne diseases can also be expected to increase, though the study, completed over three years, did not look at whether locally-transmitted Zika virus cases would be more likely to hit the U.S.

President Barack Obama's administration has taken steps to cut carbon emissions by speeding a switch from coal and oil to cleaner energy sources. In February, the Supreme Court dealt a blow to the White House's climate ambitions by putting a hold on Obama's plan to cut emissions from power plants. Administration officials say the plan is on safe legal footing.John Holdren, Obama's senior science adviser, said steps the world agreed to in Paris last year to curb emissions through 2030 can help fight the risks to health.

"We will need a big encore after 2030 . . . in order to avoid the bulk of the worst impacts described in this report,"he said.

Treatment can produce durable responses in NHL

2016 AACR Annual Meeting

© AACR/Todd Buchanan

NEW ORLEANS—Administering an antibody-radionuclide conjugate after B-cell depletion with rituximab can produce lasting responses in patients with relapsed non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL), according to a phase 1/2 study.

The conjugate, 177Lu-DOTA-HH1 (Betalutin), consists of the tumor-specific antibody HH1, which targets the CD37 antigen on the surface of NHL cells, conjugated to the β-emitting isotope lutetium-177 (Lu-177) via the chemical linker DOTA.

In an ongoing phase 1/2 study, Betalutin given after rituximab produced an overall response rate of 63.2%.

The median duration of response has not yet been reached, and 1 patient has maintained a response for more than 36 months.

In addition, the researchers said Betalutin was well tolerated, with a predictable and manageable safety profile. Most adverse events were hematologic, and all have been transient and reversible.

These results were presented at the 2016 AACR Annual Meeting (abstract LB-252*). The study is sponsored by Nordic Nanovector ASA.

Patients and study design

The researchers presented data on 21 patients—19 with follicular lymphoma and 2 with mantle cell lymphoma. All tumors were positive for CD37.

The patients’ median age was 68 (range, 41-78). Sixty-seven percent were male, and they had received 1 to 8 prior treatment regimens.

In this dose-escalation study, patients received Betalutin at 3 different doses, but they were also divided into 2 arms according to predosing with cold HH1 antibody.

In Arm 1 (n=12), patients received rituximab (at 375 mg/m2) on day -28 and -21 to deplete circulating B cells. On day 0, predosing with 50 mg HH1 was given before Betalutin injection. Then, patients received Betalutin at 10 MBq/kg (n=3), 15 MBq/kg (n=6), or 20 MBq/kg (n=3).

In Arm 2 (n=4), patients received rituximab at the same dose and schedule as Arm 1, but Betalutin was administered without HH1 predosing on day 0 at either 10 MBq/kg (n=2) or 15 MBq/kg (n=2).

The first patient treated on this trial received 250 mg/m2 of rituximab on day -7 and day 0 prior to Betalutin administration and was included in the 10 MBq/kg group in Arm 2.

The 15 MBq/kg dose level of Arm 1 has been expanded into the phase 2 portion of the study, as dose-limiting toxicities occurred at the 20 MBq/kg dose. Five patients have been treated in the phase 2 portion.

Safety

Adverse events (AEs) from the phase 2 portion of the study were not reported, as the data are still being collected.

In the phase 1 portion, grade 3/4 AEs were hematologic in nature and included decreases in platelet counts (3 grade 3 and 6 grade 4) and neutrophil counts (5 grade 3 and 4 grade 4).