User login

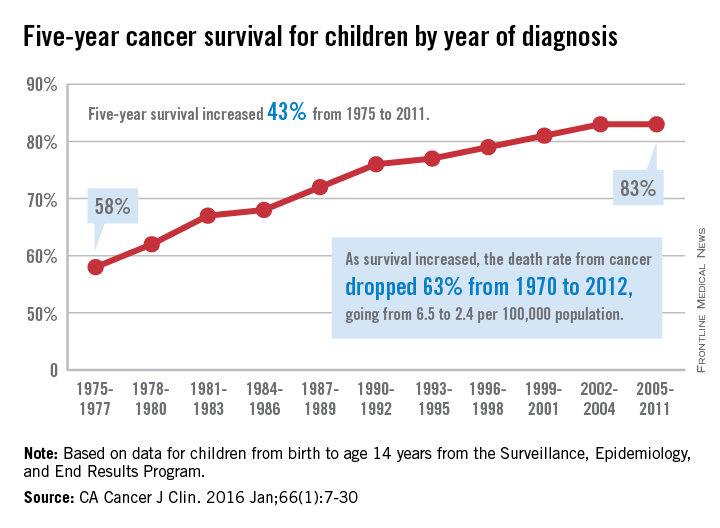

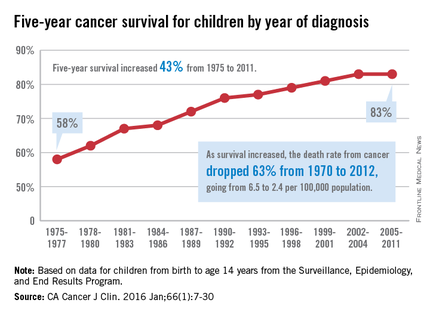

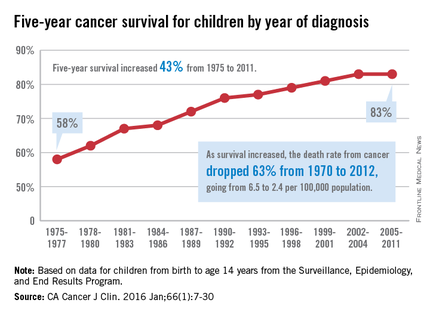

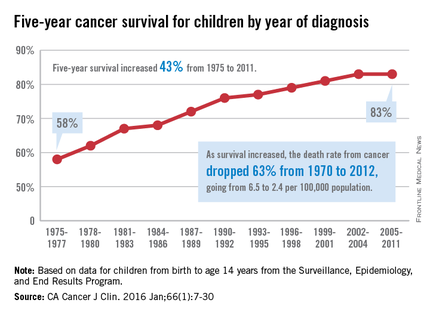

Children’s cancer survival steadily increasing

The 5-year cancer survival rate for children younger than 15 years old is up by 43% since 1975, according to investigators from the American Cancer Society.

The 5-year survival rate for all cancers showed a statistically significant rise from 58% in 1975 to 83% in 2011, said Rebecca L. Siegel and her associates at the ACS (CA Cancer J Clin. 2016 Jan;66[1]:7-30).

“The substantial progress for all of the major childhood cancers reflects both improvements in treatment and high levels of participation in clinical trials,” they wrote.

Survival for cancers of the brain and nervous system – now the leading cause of cancer death for those younger than 20 years old – increased from 57% in 1975 to 74% in 2011. The next-most-common cause of cancer death in children and adolescents is leukemia, and 5-year survival for acute myeloid leukemia went from 19% in 1975 to 67% in 2011, while 5-year survival for acute lymphocytic leukemia rose from 57% to 91% over that time period, the investigators reported.

The authors reported no conflicts of interest.

The 5-year cancer survival rate for children younger than 15 years old is up by 43% since 1975, according to investigators from the American Cancer Society.

The 5-year survival rate for all cancers showed a statistically significant rise from 58% in 1975 to 83% in 2011, said Rebecca L. Siegel and her associates at the ACS (CA Cancer J Clin. 2016 Jan;66[1]:7-30).

“The substantial progress for all of the major childhood cancers reflects both improvements in treatment and high levels of participation in clinical trials,” they wrote.

Survival for cancers of the brain and nervous system – now the leading cause of cancer death for those younger than 20 years old – increased from 57% in 1975 to 74% in 2011. The next-most-common cause of cancer death in children and adolescents is leukemia, and 5-year survival for acute myeloid leukemia went from 19% in 1975 to 67% in 2011, while 5-year survival for acute lymphocytic leukemia rose from 57% to 91% over that time period, the investigators reported.

The authors reported no conflicts of interest.

The 5-year cancer survival rate for children younger than 15 years old is up by 43% since 1975, according to investigators from the American Cancer Society.

The 5-year survival rate for all cancers showed a statistically significant rise from 58% in 1975 to 83% in 2011, said Rebecca L. Siegel and her associates at the ACS (CA Cancer J Clin. 2016 Jan;66[1]:7-30).

“The substantial progress for all of the major childhood cancers reflects both improvements in treatment and high levels of participation in clinical trials,” they wrote.

Survival for cancers of the brain and nervous system – now the leading cause of cancer death for those younger than 20 years old – increased from 57% in 1975 to 74% in 2011. The next-most-common cause of cancer death in children and adolescents is leukemia, and 5-year survival for acute myeloid leukemia went from 19% in 1975 to 67% in 2011, while 5-year survival for acute lymphocytic leukemia rose from 57% to 91% over that time period, the investigators reported.

The authors reported no conflicts of interest.

FROM CA: A CANCER JOURNAL FOR CLINICIANS

Chestnut extract

Known as sweet chestnut, Castanea sativa is a member of the Fagaceae family, and is found in abundance in Southern and Southeastern Europe and Asia.1 In traditional medicine, chestnut tree flower preparations have been used for various indications.2 Chestnut has been used in French folk medicine as a tea to treat severe cough, colds, and bronchitis as well as diarrhea.2-6 In modern times, C. sativa leaf extract has been described as having the capacity to scavenge various free radicals associated with oxidative stress induced by ultraviolet exposure.7

Traditional uses

A 2014 study of the therapeutic and traditional uses of the plants native to the Western Italian Alps revealed that C. sativa has long been important in the region, typically for food and wood.8 But medical uses have been uncovered in that region as well. In fact, ancient Romans found C. sativa to exhibit antibacterial, astringent, antitoxic, and tonic qualities, with chestnut honey used then to dress chronic wounds, burns, and skin ulcers.9 A 2014 study by Carocho et al. of the phytochemical profile and antioxidant activity of C. sativa flowers is noteworthy for buttressing the reported health benefits of the use of chestnut flower infusions and decoctions in traditional medicine.2

Antioxidant activity

In 2005, Calliste et al. investigated the antioxidant potential of C. sativa leaf to act against the stable free radical 2,2-diphenyl-1-pycrylhydrazyl, superoxide anion, and hydroxyl radical. Using electronic spin resonance, the investigators showed that C. sativa exhibited high antioxidant potential equivalent to reference antioxidants quercetin and vitamin E.3

Three years later, Almeida et al. conducted an in vitro assessment of an ethanol/water (7:3) extract from C. sativa leaves and an ethanol/water (2:3) extract from Quercus robur (English oak) leaves, finding that both plants demonstrated a high potency to scavenge various reactive oxygen and nitrogen species. The researchers concluded that these findings supported the burgeoning interest in these extracts for use in topical antioxidant formulations.4 An in vivo investigation using an ethanol/water (7:3) extract from C. sativa conducted by the same team later in the year yielded similar results, with the researchers concluding that chestnut extract has the potential to confer benefits against photoaging and other oxidative stress–mediated conditions when included in an appropriately formulated topical antioxidant preparation.6 Subsequently, Barreira et al. demonstrated that chestnut skin and leaves exhibited sufficient antioxidant potency to warrant use in novel antioxidant formulations.10

In 2015, Almeida et al. characterized an antioxidant semisolid surfactant-free topical formulation featuring C. sativa leaf extract. In the process of ascertaining the physical, functional, and microbiologic stability of the antioxidant formulation, the investigators identified a hydrating effect and good skin tolerance, which they concluded suggested a capacity to prevent or treat cutaneous conditions in which oxidative stress plays a role.11

Photoprotective potential

In 2010, Sapkota et al. evaluated the antioxidant and antimelanogenic characteristics of several prebloom and full-bloom chestnut flower extracts, finding that a prebloom methanol extract and an ethanol extract evinced the greatest levels of phenolic and flavonoid compounds. These extracts also displayed the best radical scavenging and mushroom tyrosinase–inhibiting activities. Notably, the prebloom extract was effective in protecting the skin from the deleterious impact of UV radiation. The investigators also observed that all of the tested extracts lowered the tyrosinase activity and melanin formation of SK-MEL-2 cells similarly to arbutin. They ascribed the antimelanogenic effects of chestnut flower extracts to their antioxidant-mediated inhibitory effects on tyrosinase. They concluded that chestnut flower extracts have considerable potential as cosmetic agents.12

Recently, Almeida et al. studied the protective effects in a human keratinocyte cell line of C. sativa extract at various concentrations (0.001-, 0.01-, 0.05-, and 0.1-mcg/mL) against UV-induced DNA damage. They found that the chestnut extract concentration dependently protected against UV-mediated DNA damage, with the 0.1-mcg/mL concentration affording maximum protection (66.4%). This result was considered to be a direct antioxidant effect attributed to various phenolic antioxidants present in C. sativa. In addition, the investigators observed no phototoxic or genotoxic effects on HaCaT cells incubated with up to 0.1 mcg/mL of chestnut leaf extract. They concluded that C. sativa leaf extract has the potential to prevent or mitigate UV-induced harm to the skin.7

Other benefits and bioactivity

Assessments of C. sativa by-products have shown a favorable profile of bioactive constituents that demonstrate antioxidant, anticarcinogenic, and cardioprotective activity. Braga et al. conducted a 2015 review that concluded these compounds, as part of agro-industrial waste, offer value to the pharmaceutical, cosmetics, and food industries, with the potential to lower pollution costs and raise profits while enhancing social, economic, and environmental sustainability in growing regions.1

A related chestnut species also has been linked to dermatologic uses. In East Asia, a skin firming/antiwrinkle formulation features the inner shell of Castanea crenata as an active ingredient.13 In 2002, Chi et al. showed that the chestnut inner shell extract improved cell-associated expression of the adhesion molecules fibronectin and vitronectin. They also found that scoparone (6,7-dimethoxycoumarin) isolated from the chestnut extract exhibited comparable qualities. The investigators concluded that the enhanced expression of adhesion molecules imparted by the chestnut inner shell extract may account for the prevention of cell detachment and the manifestation of antiaging effects.13

Allergy

It is worth noting that chestnut is one of the many allergens associated with the latex-fruit syndrome.14 However, in a patch test investigation of the skin irritation potential of C. sativa leaf extract in 20 volunteers, Almeida et al. identified five phenolic compounds in the extract (chlorogenic acid, ellagic acid, rutin, isoquercitrin, and hyperoside) and found it safe for topical application.6 Chestnut is considered to pose a low to moderate risk of inducing allergic reactions.9

Conclusion

Recent research appears to suggest the in vitro antioxidant activity of sweet chestnut and potential for use in topical formulations. There remains a paucity of in vivo evidence, however. While much more research is necessary to determine whether it has a place in the dermatologic armamentarium, current data are intriguing.

References

1. Nat Prod Res. 2015;29(1):1-18

2. Biomed Res Int. 2014;2014:232956

3. J Agric Food Chem. 2005 Jan 26;53(2):282-8

4. J Photochem Photobiol B. 2008 May 29;91(2-3):87-95

5. A Modern Herbal (vol. I). New York: Dover Publications, 1971, p. 195

6. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol. 2008 Nov;103(5):461-7

7. J Photochem Photobiol B. 2015 Mar;144C:28-34

8. J Ethnopharmacol. 2014 Aug 8;155(1):463-84

9. J Sci Food Agric. 2010 Aug 15;90(10):1578-89

10. Food Sci Technol Int. 2010 June;16(3):209-16

11. Drug Dev Ind Pharm. 2015 Jan;41(1):148-55

12. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 2010;74(8):1527-33

13. Arch Pharm Res. 2002 Aug;25(4):469-74

14. Allergy. 2007 Nov;62(11):1277-81

Dr. Baumann is chief executive officer of the Baumann Cosmetic & Research Institute in the Design District in Miami. She founded the Cosmetic Dermatology Center at the University of Miami in 1997. Dr. Baumann wrote the textbook “Cosmetic Dermatology: Principles and Practice” (New York: McGraw-Hill, 2002), and a book for consumers, “The Skin Type Solution” (New York: Bantam Dell, 2006). Her latest book, “Cosmeceuticals and Cosmetic Ingredients,” was published in November 2014. Dr. Baumann has received funding for clinical grants from Allergan, Aveeno, Avon Products, Evolus, Galderma, GlaxoSmithKline, Kythera Biopharmaceuticals, Mary Kay, Medicis Pharmaceuticals, Neutrogena, Philosophy, Topix Pharmaceuticals, and Unilever.

Known as sweet chestnut, Castanea sativa is a member of the Fagaceae family, and is found in abundance in Southern and Southeastern Europe and Asia.1 In traditional medicine, chestnut tree flower preparations have been used for various indications.2 Chestnut has been used in French folk medicine as a tea to treat severe cough, colds, and bronchitis as well as diarrhea.2-6 In modern times, C. sativa leaf extract has been described as having the capacity to scavenge various free radicals associated with oxidative stress induced by ultraviolet exposure.7

Traditional uses

A 2014 study of the therapeutic and traditional uses of the plants native to the Western Italian Alps revealed that C. sativa has long been important in the region, typically for food and wood.8 But medical uses have been uncovered in that region as well. In fact, ancient Romans found C. sativa to exhibit antibacterial, astringent, antitoxic, and tonic qualities, with chestnut honey used then to dress chronic wounds, burns, and skin ulcers.9 A 2014 study by Carocho et al. of the phytochemical profile and antioxidant activity of C. sativa flowers is noteworthy for buttressing the reported health benefits of the use of chestnut flower infusions and decoctions in traditional medicine.2

Antioxidant activity

In 2005, Calliste et al. investigated the antioxidant potential of C. sativa leaf to act against the stable free radical 2,2-diphenyl-1-pycrylhydrazyl, superoxide anion, and hydroxyl radical. Using electronic spin resonance, the investigators showed that C. sativa exhibited high antioxidant potential equivalent to reference antioxidants quercetin and vitamin E.3

Three years later, Almeida et al. conducted an in vitro assessment of an ethanol/water (7:3) extract from C. sativa leaves and an ethanol/water (2:3) extract from Quercus robur (English oak) leaves, finding that both plants demonstrated a high potency to scavenge various reactive oxygen and nitrogen species. The researchers concluded that these findings supported the burgeoning interest in these extracts for use in topical antioxidant formulations.4 An in vivo investigation using an ethanol/water (7:3) extract from C. sativa conducted by the same team later in the year yielded similar results, with the researchers concluding that chestnut extract has the potential to confer benefits against photoaging and other oxidative stress–mediated conditions when included in an appropriately formulated topical antioxidant preparation.6 Subsequently, Barreira et al. demonstrated that chestnut skin and leaves exhibited sufficient antioxidant potency to warrant use in novel antioxidant formulations.10

In 2015, Almeida et al. characterized an antioxidant semisolid surfactant-free topical formulation featuring C. sativa leaf extract. In the process of ascertaining the physical, functional, and microbiologic stability of the antioxidant formulation, the investigators identified a hydrating effect and good skin tolerance, which they concluded suggested a capacity to prevent or treat cutaneous conditions in which oxidative stress plays a role.11

Photoprotective potential

In 2010, Sapkota et al. evaluated the antioxidant and antimelanogenic characteristics of several prebloom and full-bloom chestnut flower extracts, finding that a prebloom methanol extract and an ethanol extract evinced the greatest levels of phenolic and flavonoid compounds. These extracts also displayed the best radical scavenging and mushroom tyrosinase–inhibiting activities. Notably, the prebloom extract was effective in protecting the skin from the deleterious impact of UV radiation. The investigators also observed that all of the tested extracts lowered the tyrosinase activity and melanin formation of SK-MEL-2 cells similarly to arbutin. They ascribed the antimelanogenic effects of chestnut flower extracts to their antioxidant-mediated inhibitory effects on tyrosinase. They concluded that chestnut flower extracts have considerable potential as cosmetic agents.12

Recently, Almeida et al. studied the protective effects in a human keratinocyte cell line of C. sativa extract at various concentrations (0.001-, 0.01-, 0.05-, and 0.1-mcg/mL) against UV-induced DNA damage. They found that the chestnut extract concentration dependently protected against UV-mediated DNA damage, with the 0.1-mcg/mL concentration affording maximum protection (66.4%). This result was considered to be a direct antioxidant effect attributed to various phenolic antioxidants present in C. sativa. In addition, the investigators observed no phototoxic or genotoxic effects on HaCaT cells incubated with up to 0.1 mcg/mL of chestnut leaf extract. They concluded that C. sativa leaf extract has the potential to prevent or mitigate UV-induced harm to the skin.7

Other benefits and bioactivity

Assessments of C. sativa by-products have shown a favorable profile of bioactive constituents that demonstrate antioxidant, anticarcinogenic, and cardioprotective activity. Braga et al. conducted a 2015 review that concluded these compounds, as part of agro-industrial waste, offer value to the pharmaceutical, cosmetics, and food industries, with the potential to lower pollution costs and raise profits while enhancing social, economic, and environmental sustainability in growing regions.1

A related chestnut species also has been linked to dermatologic uses. In East Asia, a skin firming/antiwrinkle formulation features the inner shell of Castanea crenata as an active ingredient.13 In 2002, Chi et al. showed that the chestnut inner shell extract improved cell-associated expression of the adhesion molecules fibronectin and vitronectin. They also found that scoparone (6,7-dimethoxycoumarin) isolated from the chestnut extract exhibited comparable qualities. The investigators concluded that the enhanced expression of adhesion molecules imparted by the chestnut inner shell extract may account for the prevention of cell detachment and the manifestation of antiaging effects.13

Allergy

It is worth noting that chestnut is one of the many allergens associated with the latex-fruit syndrome.14 However, in a patch test investigation of the skin irritation potential of C. sativa leaf extract in 20 volunteers, Almeida et al. identified five phenolic compounds in the extract (chlorogenic acid, ellagic acid, rutin, isoquercitrin, and hyperoside) and found it safe for topical application.6 Chestnut is considered to pose a low to moderate risk of inducing allergic reactions.9

Conclusion

Recent research appears to suggest the in vitro antioxidant activity of sweet chestnut and potential for use in topical formulations. There remains a paucity of in vivo evidence, however. While much more research is necessary to determine whether it has a place in the dermatologic armamentarium, current data are intriguing.

References

1. Nat Prod Res. 2015;29(1):1-18

2. Biomed Res Int. 2014;2014:232956

3. J Agric Food Chem. 2005 Jan 26;53(2):282-8

4. J Photochem Photobiol B. 2008 May 29;91(2-3):87-95

5. A Modern Herbal (vol. I). New York: Dover Publications, 1971, p. 195

6. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol. 2008 Nov;103(5):461-7

7. J Photochem Photobiol B. 2015 Mar;144C:28-34

8. J Ethnopharmacol. 2014 Aug 8;155(1):463-84

9. J Sci Food Agric. 2010 Aug 15;90(10):1578-89

10. Food Sci Technol Int. 2010 June;16(3):209-16

11. Drug Dev Ind Pharm. 2015 Jan;41(1):148-55

12. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 2010;74(8):1527-33

13. Arch Pharm Res. 2002 Aug;25(4):469-74

14. Allergy. 2007 Nov;62(11):1277-81

Dr. Baumann is chief executive officer of the Baumann Cosmetic & Research Institute in the Design District in Miami. She founded the Cosmetic Dermatology Center at the University of Miami in 1997. Dr. Baumann wrote the textbook “Cosmetic Dermatology: Principles and Practice” (New York: McGraw-Hill, 2002), and a book for consumers, “The Skin Type Solution” (New York: Bantam Dell, 2006). Her latest book, “Cosmeceuticals and Cosmetic Ingredients,” was published in November 2014. Dr. Baumann has received funding for clinical grants from Allergan, Aveeno, Avon Products, Evolus, Galderma, GlaxoSmithKline, Kythera Biopharmaceuticals, Mary Kay, Medicis Pharmaceuticals, Neutrogena, Philosophy, Topix Pharmaceuticals, and Unilever.

Known as sweet chestnut, Castanea sativa is a member of the Fagaceae family, and is found in abundance in Southern and Southeastern Europe and Asia.1 In traditional medicine, chestnut tree flower preparations have been used for various indications.2 Chestnut has been used in French folk medicine as a tea to treat severe cough, colds, and bronchitis as well as diarrhea.2-6 In modern times, C. sativa leaf extract has been described as having the capacity to scavenge various free radicals associated with oxidative stress induced by ultraviolet exposure.7

Traditional uses

A 2014 study of the therapeutic and traditional uses of the plants native to the Western Italian Alps revealed that C. sativa has long been important in the region, typically for food and wood.8 But medical uses have been uncovered in that region as well. In fact, ancient Romans found C. sativa to exhibit antibacterial, astringent, antitoxic, and tonic qualities, with chestnut honey used then to dress chronic wounds, burns, and skin ulcers.9 A 2014 study by Carocho et al. of the phytochemical profile and antioxidant activity of C. sativa flowers is noteworthy for buttressing the reported health benefits of the use of chestnut flower infusions and decoctions in traditional medicine.2

Antioxidant activity

In 2005, Calliste et al. investigated the antioxidant potential of C. sativa leaf to act against the stable free radical 2,2-diphenyl-1-pycrylhydrazyl, superoxide anion, and hydroxyl radical. Using electronic spin resonance, the investigators showed that C. sativa exhibited high antioxidant potential equivalent to reference antioxidants quercetin and vitamin E.3

Three years later, Almeida et al. conducted an in vitro assessment of an ethanol/water (7:3) extract from C. sativa leaves and an ethanol/water (2:3) extract from Quercus robur (English oak) leaves, finding that both plants demonstrated a high potency to scavenge various reactive oxygen and nitrogen species. The researchers concluded that these findings supported the burgeoning interest in these extracts for use in topical antioxidant formulations.4 An in vivo investigation using an ethanol/water (7:3) extract from C. sativa conducted by the same team later in the year yielded similar results, with the researchers concluding that chestnut extract has the potential to confer benefits against photoaging and other oxidative stress–mediated conditions when included in an appropriately formulated topical antioxidant preparation.6 Subsequently, Barreira et al. demonstrated that chestnut skin and leaves exhibited sufficient antioxidant potency to warrant use in novel antioxidant formulations.10

In 2015, Almeida et al. characterized an antioxidant semisolid surfactant-free topical formulation featuring C. sativa leaf extract. In the process of ascertaining the physical, functional, and microbiologic stability of the antioxidant formulation, the investigators identified a hydrating effect and good skin tolerance, which they concluded suggested a capacity to prevent or treat cutaneous conditions in which oxidative stress plays a role.11

Photoprotective potential

In 2010, Sapkota et al. evaluated the antioxidant and antimelanogenic characteristics of several prebloom and full-bloom chestnut flower extracts, finding that a prebloom methanol extract and an ethanol extract evinced the greatest levels of phenolic and flavonoid compounds. These extracts also displayed the best radical scavenging and mushroom tyrosinase–inhibiting activities. Notably, the prebloom extract was effective in protecting the skin from the deleterious impact of UV radiation. The investigators also observed that all of the tested extracts lowered the tyrosinase activity and melanin formation of SK-MEL-2 cells similarly to arbutin. They ascribed the antimelanogenic effects of chestnut flower extracts to their antioxidant-mediated inhibitory effects on tyrosinase. They concluded that chestnut flower extracts have considerable potential as cosmetic agents.12

Recently, Almeida et al. studied the protective effects in a human keratinocyte cell line of C. sativa extract at various concentrations (0.001-, 0.01-, 0.05-, and 0.1-mcg/mL) against UV-induced DNA damage. They found that the chestnut extract concentration dependently protected against UV-mediated DNA damage, with the 0.1-mcg/mL concentration affording maximum protection (66.4%). This result was considered to be a direct antioxidant effect attributed to various phenolic antioxidants present in C. sativa. In addition, the investigators observed no phototoxic or genotoxic effects on HaCaT cells incubated with up to 0.1 mcg/mL of chestnut leaf extract. They concluded that C. sativa leaf extract has the potential to prevent or mitigate UV-induced harm to the skin.7

Other benefits and bioactivity

Assessments of C. sativa by-products have shown a favorable profile of bioactive constituents that demonstrate antioxidant, anticarcinogenic, and cardioprotective activity. Braga et al. conducted a 2015 review that concluded these compounds, as part of agro-industrial waste, offer value to the pharmaceutical, cosmetics, and food industries, with the potential to lower pollution costs and raise profits while enhancing social, economic, and environmental sustainability in growing regions.1

A related chestnut species also has been linked to dermatologic uses. In East Asia, a skin firming/antiwrinkle formulation features the inner shell of Castanea crenata as an active ingredient.13 In 2002, Chi et al. showed that the chestnut inner shell extract improved cell-associated expression of the adhesion molecules fibronectin and vitronectin. They also found that scoparone (6,7-dimethoxycoumarin) isolated from the chestnut extract exhibited comparable qualities. The investigators concluded that the enhanced expression of adhesion molecules imparted by the chestnut inner shell extract may account for the prevention of cell detachment and the manifestation of antiaging effects.13

Allergy

It is worth noting that chestnut is one of the many allergens associated with the latex-fruit syndrome.14 However, in a patch test investigation of the skin irritation potential of C. sativa leaf extract in 20 volunteers, Almeida et al. identified five phenolic compounds in the extract (chlorogenic acid, ellagic acid, rutin, isoquercitrin, and hyperoside) and found it safe for topical application.6 Chestnut is considered to pose a low to moderate risk of inducing allergic reactions.9

Conclusion

Recent research appears to suggest the in vitro antioxidant activity of sweet chestnut and potential for use in topical formulations. There remains a paucity of in vivo evidence, however. While much more research is necessary to determine whether it has a place in the dermatologic armamentarium, current data are intriguing.

References

1. Nat Prod Res. 2015;29(1):1-18

2. Biomed Res Int. 2014;2014:232956

3. J Agric Food Chem. 2005 Jan 26;53(2):282-8

4. J Photochem Photobiol B. 2008 May 29;91(2-3):87-95

5. A Modern Herbal (vol. I). New York: Dover Publications, 1971, p. 195

6. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol. 2008 Nov;103(5):461-7

7. J Photochem Photobiol B. 2015 Mar;144C:28-34

8. J Ethnopharmacol. 2014 Aug 8;155(1):463-84

9. J Sci Food Agric. 2010 Aug 15;90(10):1578-89

10. Food Sci Technol Int. 2010 June;16(3):209-16

11. Drug Dev Ind Pharm. 2015 Jan;41(1):148-55

12. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 2010;74(8):1527-33

13. Arch Pharm Res. 2002 Aug;25(4):469-74

14. Allergy. 2007 Nov;62(11):1277-81

Dr. Baumann is chief executive officer of the Baumann Cosmetic & Research Institute in the Design District in Miami. She founded the Cosmetic Dermatology Center at the University of Miami in 1997. Dr. Baumann wrote the textbook “Cosmetic Dermatology: Principles and Practice” (New York: McGraw-Hill, 2002), and a book for consumers, “The Skin Type Solution” (New York: Bantam Dell, 2006). Her latest book, “Cosmeceuticals and Cosmetic Ingredients,” was published in November 2014. Dr. Baumann has received funding for clinical grants from Allergan, Aveeno, Avon Products, Evolus, Galderma, GlaxoSmithKline, Kythera Biopharmaceuticals, Mary Kay, Medicis Pharmaceuticals, Neutrogena, Philosophy, Topix Pharmaceuticals, and Unilever.

FDA approves new treatment for chronic HCV genotypes 1 and 4

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved Zepatier (elbasvir and grazoprevir) with or without ribavirin for the treatment of chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV) genotypes 1 and 4 infections in adults.

Zepatier, marketed by Merck, was granted breakthrough therapy designation for the treatment of chronic HCV genotype 1 infection in patients with end stage renal disease on hemodialysis and for the treatment of chronic HCV genotype 4 infection. This designation expedites the development and review of drugs that are intended to treat a serious condition when preliminary evidence indicates that the drug may demonstrate substantial improvement over an available therapy.

For more on Zepatier, see GI & Hepatology News: http://www.gihepnews.com/specialty-focus/liver-disease/single-article-page/fda-approves-new-treatment-for-chronic-hcv-genotypes-1-and-4/174b52697cbe2b7f82ce4ae71c9128b8.html.

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved Zepatier (elbasvir and grazoprevir) with or without ribavirin for the treatment of chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV) genotypes 1 and 4 infections in adults.

Zepatier, marketed by Merck, was granted breakthrough therapy designation for the treatment of chronic HCV genotype 1 infection in patients with end stage renal disease on hemodialysis and for the treatment of chronic HCV genotype 4 infection. This designation expedites the development and review of drugs that are intended to treat a serious condition when preliminary evidence indicates that the drug may demonstrate substantial improvement over an available therapy.

For more on Zepatier, see GI & Hepatology News: http://www.gihepnews.com/specialty-focus/liver-disease/single-article-page/fda-approves-new-treatment-for-chronic-hcv-genotypes-1-and-4/174b52697cbe2b7f82ce4ae71c9128b8.html.

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved Zepatier (elbasvir and grazoprevir) with or without ribavirin for the treatment of chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV) genotypes 1 and 4 infections in adults.

Zepatier, marketed by Merck, was granted breakthrough therapy designation for the treatment of chronic HCV genotype 1 infection in patients with end stage renal disease on hemodialysis and for the treatment of chronic HCV genotype 4 infection. This designation expedites the development and review of drugs that are intended to treat a serious condition when preliminary evidence indicates that the drug may demonstrate substantial improvement over an available therapy.

For more on Zepatier, see GI & Hepatology News: http://www.gihepnews.com/specialty-focus/liver-disease/single-article-page/fda-approves-new-treatment-for-chronic-hcv-genotypes-1-and-4/174b52697cbe2b7f82ce4ae71c9128b8.html.

The intersection of obstructive lung disease and sleep apnea

Many patients who have chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) or asthma also have obstructive sleep apnea (OSA)—and vice versa. This review from Cleveland Clinic Journal of Medicine, available at http://www.ccjm.org/topics/obesity-weight-management/single-article-page/the-intersection-of-obstructive-lung-disease-and-sleep-apnea/dff50621172ad1329c163560b7f1b19b.html, explores the shared risk factors for sleep-disordered breathing and obstructive lung diseases, describes potential pathophysiologic mechanisms explaining these associations, and highlights the importance of recognizing and individually treating the overlaps of OSA and COPD or asthma.

Many patients who have chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) or asthma also have obstructive sleep apnea (OSA)—and vice versa. This review from Cleveland Clinic Journal of Medicine, available at http://www.ccjm.org/topics/obesity-weight-management/single-article-page/the-intersection-of-obstructive-lung-disease-and-sleep-apnea/dff50621172ad1329c163560b7f1b19b.html, explores the shared risk factors for sleep-disordered breathing and obstructive lung diseases, describes potential pathophysiologic mechanisms explaining these associations, and highlights the importance of recognizing and individually treating the overlaps of OSA and COPD or asthma.

Many patients who have chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) or asthma also have obstructive sleep apnea (OSA)—and vice versa. This review from Cleveland Clinic Journal of Medicine, available at http://www.ccjm.org/topics/obesity-weight-management/single-article-page/the-intersection-of-obstructive-lung-disease-and-sleep-apnea/dff50621172ad1329c163560b7f1b19b.html, explores the shared risk factors for sleep-disordered breathing and obstructive lung diseases, describes potential pathophysiologic mechanisms explaining these associations, and highlights the importance of recognizing and individually treating the overlaps of OSA and COPD or asthma.

Make the Diagnosis - March 2016

Diagnosis: Eruptive keratoacanthomas

Keratoacanthomas (KAs) most commonly affect people between the ages of 50 and 69 years old, although there have been reports in all age groups, including children. Studies have additionally revealed an equal distribution in prevalence between the sexes.

KAs are common, frequently self-limiting, epidermal tumors that consist of keratinizing squamous cells, thought to arise from the seboglandular part of the hair follicle. KAs have been divided into two general categories consisting of solitary and multiple types. Although the solitary type is most commonly observed, the multiple KAs category may be further subdivided to include the Ferguson-Smith type, which involves multiple self-healing KAs, generalized eruptive KA, which involves both skin and mucosa, multiple familial KA, multiple KA in association with Muir-Torre syndrome, and multiple KA centrifugum marginatum.

There are numerous factors implicated in the development of KAs, including trauma, light, exogenous carcinogens, impaired cell-mediated immunity, and immunosuppressive medications. A KA, which may be asymptomatic, slightly tender, or pruritic, initially forms as a small red macule and then evolves into a rapidly-growing (2 to 8 weeks) firm papule with scale. The papule then becomes a round, firm and raised skin-colored to pink nodule with a central keratin plug at the peak.

Histopathology varies depending upon the developmental stage of the lesion when biopsied. KA formation is comprised of 3 stages that may be recognized clinically and histologically, including the early-growing phase, the fully developed (stationary) phase and the senescent phase. Although not unique to KAs, histology may commonly show reactive proliferation of eccrine gland ducts beneath the tumor lobules. The ducts may adopt an adenomatoid appearance, as they lose their two-layer cellular construct.

The controversy regarding KA’s benign or malignant nature remains. Therefore, diagnosis is frequently confirmed through biopsy, in order to rule out squamous cell carcinoma. Although most KAs may resolve spontaneously, patients who find the lesions cosmetically unacceptable or painful may seek treatment. Nonsurgical modalities should be utilized before surgery, as surgical removal may leave scarring. Nonsurgical treatment options include local and systemic therapies, as well as electrodessication and curettage and laser therapy. A promising agent emerging in the treatment of KAs is 5-fluorouracil, which may be used as an intralesional injection, topically, or combined with lasers, leading to optimal cosmetic results with rapid clearance. The patient and family reported a noticeable improvement in appearance two weeks after discontinuing the new therapy.

Dr. Bilu Martin is in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at edermatologynews.com. To submit your case for possible publication, send an email to [email protected].

Diagnosis: Eruptive keratoacanthomas

Keratoacanthomas (KAs) most commonly affect people between the ages of 50 and 69 years old, although there have been reports in all age groups, including children. Studies have additionally revealed an equal distribution in prevalence between the sexes.

KAs are common, frequently self-limiting, epidermal tumors that consist of keratinizing squamous cells, thought to arise from the seboglandular part of the hair follicle. KAs have been divided into two general categories consisting of solitary and multiple types. Although the solitary type is most commonly observed, the multiple KAs category may be further subdivided to include the Ferguson-Smith type, which involves multiple self-healing KAs, generalized eruptive KA, which involves both skin and mucosa, multiple familial KA, multiple KA in association with Muir-Torre syndrome, and multiple KA centrifugum marginatum.

There are numerous factors implicated in the development of KAs, including trauma, light, exogenous carcinogens, impaired cell-mediated immunity, and immunosuppressive medications. A KA, which may be asymptomatic, slightly tender, or pruritic, initially forms as a small red macule and then evolves into a rapidly-growing (2 to 8 weeks) firm papule with scale. The papule then becomes a round, firm and raised skin-colored to pink nodule with a central keratin plug at the peak.

Histopathology varies depending upon the developmental stage of the lesion when biopsied. KA formation is comprised of 3 stages that may be recognized clinically and histologically, including the early-growing phase, the fully developed (stationary) phase and the senescent phase. Although not unique to KAs, histology may commonly show reactive proliferation of eccrine gland ducts beneath the tumor lobules. The ducts may adopt an adenomatoid appearance, as they lose their two-layer cellular construct.

The controversy regarding KA’s benign or malignant nature remains. Therefore, diagnosis is frequently confirmed through biopsy, in order to rule out squamous cell carcinoma. Although most KAs may resolve spontaneously, patients who find the lesions cosmetically unacceptable or painful may seek treatment. Nonsurgical modalities should be utilized before surgery, as surgical removal may leave scarring. Nonsurgical treatment options include local and systemic therapies, as well as electrodessication and curettage and laser therapy. A promising agent emerging in the treatment of KAs is 5-fluorouracil, which may be used as an intralesional injection, topically, or combined with lasers, leading to optimal cosmetic results with rapid clearance. The patient and family reported a noticeable improvement in appearance two weeks after discontinuing the new therapy.

Dr. Bilu Martin is in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at edermatologynews.com. To submit your case for possible publication, send an email to [email protected].

Diagnosis: Eruptive keratoacanthomas

Keratoacanthomas (KAs) most commonly affect people between the ages of 50 and 69 years old, although there have been reports in all age groups, including children. Studies have additionally revealed an equal distribution in prevalence between the sexes.

KAs are common, frequently self-limiting, epidermal tumors that consist of keratinizing squamous cells, thought to arise from the seboglandular part of the hair follicle. KAs have been divided into two general categories consisting of solitary and multiple types. Although the solitary type is most commonly observed, the multiple KAs category may be further subdivided to include the Ferguson-Smith type, which involves multiple self-healing KAs, generalized eruptive KA, which involves both skin and mucosa, multiple familial KA, multiple KA in association with Muir-Torre syndrome, and multiple KA centrifugum marginatum.

There are numerous factors implicated in the development of KAs, including trauma, light, exogenous carcinogens, impaired cell-mediated immunity, and immunosuppressive medications. A KA, which may be asymptomatic, slightly tender, or pruritic, initially forms as a small red macule and then evolves into a rapidly-growing (2 to 8 weeks) firm papule with scale. The papule then becomes a round, firm and raised skin-colored to pink nodule with a central keratin plug at the peak.

Histopathology varies depending upon the developmental stage of the lesion when biopsied. KA formation is comprised of 3 stages that may be recognized clinically and histologically, including the early-growing phase, the fully developed (stationary) phase and the senescent phase. Although not unique to KAs, histology may commonly show reactive proliferation of eccrine gland ducts beneath the tumor lobules. The ducts may adopt an adenomatoid appearance, as they lose their two-layer cellular construct.

The controversy regarding KA’s benign or malignant nature remains. Therefore, diagnosis is frequently confirmed through biopsy, in order to rule out squamous cell carcinoma. Although most KAs may resolve spontaneously, patients who find the lesions cosmetically unacceptable or painful may seek treatment. Nonsurgical modalities should be utilized before surgery, as surgical removal may leave scarring. Nonsurgical treatment options include local and systemic therapies, as well as electrodessication and curettage and laser therapy. A promising agent emerging in the treatment of KAs is 5-fluorouracil, which may be used as an intralesional injection, topically, or combined with lasers, leading to optimal cosmetic results with rapid clearance. The patient and family reported a noticeable improvement in appearance two weeks after discontinuing the new therapy.

Dr. Bilu Martin is in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at edermatologynews.com. To submit your case for possible publication, send an email to [email protected].

A 67 year-old female with a past medical history significant for metastatic carcinoma of the lung and synovial sarcoma presented with a 6 week history of multiple verrucous scaly and acneiform papules scattered diffusely across her face and trunk. The lesions began one month post cancer treatment with a Notch inhibitor.

Pediatric Dermatology Consult - March 2016

BY ELLEN S. HADDOCK AND LAWRENCE F. EICHENFIELD, M.D.

Pediatric Dermatology Consult: Pernio

Itchy localized areas of swelling on the bilateral hands with erythematous papules and crusting is consistent with pernio, as seen in the presentation of the teen boy described on p. 2. Pernio is a localized abnormal inflammatory response to cold and damp conditions, also known as chilblains, derived from the old English words for chill and sore.1 Damp air is thought to enhance the air conductivity of cold.2 Pernio typically presents with erythematous to blue-violet macules, papules, and nodules on the bilateral fingers and toes. When occurring on the feet, it is sometimes called trench foot or kibes.1 The nose and ears also can be affected.3 Lesions may develop 12-24 hours after exposure to damp or chilly weather, typically at temperatures above freezing.4

This patient’s pernio may have been triggered by recent stormy winter weather; being from within San Diego County, he had no exposure to snow. Lesions often are tender and may be accompanied by pruritus, pain, or a burning sensation, but they can be asymptomatic.3 Lesions may blister and ulcerate, and can become secondarily infected.5 Brownish or yellowish discoloration may be seen.1 Proposed diagnostic criteria requires localized erythema and swelling of the acral sites for more than 24 hours, as well as either onset during the cool months of the year or improvement with warming the affected area.3

Pernio is most common in adults, with a mean age of 38 years in one series.3 It also occurs in children but is uncommon, with only eight cases diagnosed at the University of Colorado over a 10-year period.6 Adult patients are primarily female,3 while the gender distribution in children is equal.6 Because pernio is triggered by cold and damp weather, it is not surprising that pernio occurs more often in cold climates.3 Raynaud’s phenomenon, smoking, and anorexia nervosa (due to lack of insulating fat) seem to be risk factors.1,3

Pernio typically is a benign primary disorder thought to result from cold-induced vasospasm, which leads to hypoxia and triggers a localized inflammatory reaction.7 Lesions of primary pernio usually resolve in a few weeks to months.4,6 However, pernio can be secondarily associated with systemic diseases including lupus (5% of patients in one of the largest series), non-lupus connective tissue disorders (4%), hematologic malignancy (3%), solid organ malignancy (2%), hepatitis, and Epstein-Barr virus.3 In these cases, pernio may be more persistent and hyperviscosity may contribute to its pathogenesis.8,9

Approximately a third of patients have laboratory abnormalities such as anemia, abnormal blood smear, autoantibodies, or serum monoclonal proteins,3 which may facilitate diagnosis of an underlying systemic disease. Not all pernio patients with connective tissue disease autoantibodies have clinical features of connective tissue disease, but these may manifest later.3,9 Laboratory abnormalities including cryoglobulinemia, cold agglutinins, rheumatoid factor, and antineutrophilic antibody also are seen in children;6,10 however, there are no reports of childhood pernio being associated with connective tissue disease or other systemic illness, although long-term studies are lacking.

When lesions are biopsied, histopathology shows nonspecific dermal edema with superficial and deep perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate.3,4

Differential diagnosis

The differential diagnosis for pernio includes Raynaud’s phenomenon, frostbite, herpetic whitlow, and purpura caused by cryoproteinemia. In Raynaud’s, pallor and cyanosis are followed by erythema, but the discoloration is more sharply demarcated and episodes are typically shorter, lasting hours rather than days.1,8 In this case, progression of the lesions over weeks and the lack of sudden skin color change when holding a cold drink make Raynaud’s unlikely. Frostbite, in which the tissue freezes and necroses, can be distinguished by history.11

When lesions have blistered, herpetic whitlow also may be on the differential, but herpetic whitlow vesicles typically cluster or coalesce into a single bulla while pernio lesions are more discrete. Cryoproteinemia causes lesions on acral sites exposed to the cold, but its onset is sudden and lesions are purpuric with a reticular (net-like) pattern.12 In adults, cutaneous thromboemboli also can present similarly to pernio,13 but thromboemboli are unlikely in children.

Clinical findings of pernio in the setting of lupus erythematosus is called chilblains lupus erythematosus. Confusingly, the condition called lupus pernio is actually a cutaneous manifestation of sarcoidosis, not lupus, and its erythematous or violaceous lesions occur on the nose and central face, not the hands and feet.13

Work-up

For pernio patients without systemic symptoms or signs of underlying systemic disease, laboratory workup or skin biopsy are not necessary.3,4 When history or physical exam is concerning for a systemic condition, preliminary workup should include complete blood count, peripheral blood smear, serum protein electrophoresis, cold agglutinins, and antinuclear antibody.3 Rheumatoid factor, antiphospholipid antibodies, and cryoglobulins also can be considered. Laboratory workup should be performed if pernio persists beyond the cold season, as persistent pernio may be associated with systemic illness.4,9

This patient’s recent weight loss was concerning for underlying systemic disease, so a laboratory workup including complete blood count, serum protein electrophoresis, cold agglutinins, antinuclear antibody, rheumatoid factor, and cryoglobulins was performed. Cryoglobulinemia was detected. All other lab values were within normal limits. Although cryoglobulinemia is rare in adults,3,14 it was detected in approximately 40% of the children in two pediatric series.6,10 Cryoglobulins, which can be produced in response to viral infection, may suggest a precipitating viral illness, with transient cryoproteinemia amplifying cold injury.6 Although the significance of laboratory abnormalities in pediatric pernio is unclear, because associated systemic disease has not been reported in children, some practitioners recommend long-term monitoring in light of the association between lab abnormalities and systemic disease in adults.10

Treatment

Most pernio (82% in one series) resolves when affected skin is warmed and dried, without additional treatment required.3 Corticosteroids, such as 0.1% triamcinolone cream, sometimes are given to hasten the healing of the lesions, but their benefit is unproven.6 The second-line treatment for persistent pernio is calcium channel blockers such as nifedipine.3,15 This patient’s pernio quickly improved after he began wearing gloves to keep his hands warm. On re-examination 2 weeks later, his hands were warm and the erythematous nodules had resolved, leaving only some scale at the sites of prior lesions (Figure 3). Some patients relapse annually during the cool months.11

References

- Pediatrics. 2005 Sep;116(3):e472-5. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-2681.

- Journal of Medical Case Reports. 2014 Nov;8:381. doi: 10.1186/1752-1947-8-381.

- Mayo Clin Proc. 2014 Feb;89(2):207-15.

- Clin Exp Dermatol. 2012 Dec;37(8):844-9.

- J Paediatr Child Health. 2013 Feb;49(2):144-7.

- Pediatr Dermatol. 2000 Mar-Apr;17(2):97-9.

- Am J Med. 2009 Dec;122(12):1152-5.

- J Amer Acad Dermatol. 1990 Aug;23(Part 1):257-62.

- Medicine (Baltimore). 2001 May;80(3):180-8.

- Arch Dis Child. 2010 Jul;95(7):567-8.

- Br J Dermatol. 2010 Sep;163(3):645-6.

- Cutaneous manifestations of microvascular occlusion syndromes, in “Dermatology,” 3rd ed. (Philadelphia, 2012, pp 373-4).

- Environmental and sports-related skin diseases, in “Dermatology,” 3rd ed. (Philadelphia, 2012).

- J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010 Jun;62(6):e21-2.

- Br J Dermatol. 1989 Feb;120(2):267-75.

Ms. Haddock is a medical student at the University of California, San Diego, and a research associate at Rady Children’s Hospital, San Diego. Dr. Eichenfield is chief of pediatric and adolescent dermatology at Rady Children’s Hospital, San Diego, and Professor of Medicine and Pediatrics at the University of California, San Diego. Dr. Eichenfield and Ms. Haddock said they have no relevant financial disclosures.

BY ELLEN S. HADDOCK AND LAWRENCE F. EICHENFIELD, M.D.

Pediatric Dermatology Consult: Pernio

Itchy localized areas of swelling on the bilateral hands with erythematous papules and crusting is consistent with pernio, as seen in the presentation of the teen boy described on p. 2. Pernio is a localized abnormal inflammatory response to cold and damp conditions, also known as chilblains, derived from the old English words for chill and sore.1 Damp air is thought to enhance the air conductivity of cold.2 Pernio typically presents with erythematous to blue-violet macules, papules, and nodules on the bilateral fingers and toes. When occurring on the feet, it is sometimes called trench foot or kibes.1 The nose and ears also can be affected.3 Lesions may develop 12-24 hours after exposure to damp or chilly weather, typically at temperatures above freezing.4

This patient’s pernio may have been triggered by recent stormy winter weather; being from within San Diego County, he had no exposure to snow. Lesions often are tender and may be accompanied by pruritus, pain, or a burning sensation, but they can be asymptomatic.3 Lesions may blister and ulcerate, and can become secondarily infected.5 Brownish or yellowish discoloration may be seen.1 Proposed diagnostic criteria requires localized erythema and swelling of the acral sites for more than 24 hours, as well as either onset during the cool months of the year or improvement with warming the affected area.3

Pernio is most common in adults, with a mean age of 38 years in one series.3 It also occurs in children but is uncommon, with only eight cases diagnosed at the University of Colorado over a 10-year period.6 Adult patients are primarily female,3 while the gender distribution in children is equal.6 Because pernio is triggered by cold and damp weather, it is not surprising that pernio occurs more often in cold climates.3 Raynaud’s phenomenon, smoking, and anorexia nervosa (due to lack of insulating fat) seem to be risk factors.1,3

Pernio typically is a benign primary disorder thought to result from cold-induced vasospasm, which leads to hypoxia and triggers a localized inflammatory reaction.7 Lesions of primary pernio usually resolve in a few weeks to months.4,6 However, pernio can be secondarily associated with systemic diseases including lupus (5% of patients in one of the largest series), non-lupus connective tissue disorders (4%), hematologic malignancy (3%), solid organ malignancy (2%), hepatitis, and Epstein-Barr virus.3 In these cases, pernio may be more persistent and hyperviscosity may contribute to its pathogenesis.8,9

Approximately a third of patients have laboratory abnormalities such as anemia, abnormal blood smear, autoantibodies, or serum monoclonal proteins,3 which may facilitate diagnosis of an underlying systemic disease. Not all pernio patients with connective tissue disease autoantibodies have clinical features of connective tissue disease, but these may manifest later.3,9 Laboratory abnormalities including cryoglobulinemia, cold agglutinins, rheumatoid factor, and antineutrophilic antibody also are seen in children;6,10 however, there are no reports of childhood pernio being associated with connective tissue disease or other systemic illness, although long-term studies are lacking.

When lesions are biopsied, histopathology shows nonspecific dermal edema with superficial and deep perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate.3,4

Differential diagnosis

The differential diagnosis for pernio includes Raynaud’s phenomenon, frostbite, herpetic whitlow, and purpura caused by cryoproteinemia. In Raynaud’s, pallor and cyanosis are followed by erythema, but the discoloration is more sharply demarcated and episodes are typically shorter, lasting hours rather than days.1,8 In this case, progression of the lesions over weeks and the lack of sudden skin color change when holding a cold drink make Raynaud’s unlikely. Frostbite, in which the tissue freezes and necroses, can be distinguished by history.11

When lesions have blistered, herpetic whitlow also may be on the differential, but herpetic whitlow vesicles typically cluster or coalesce into a single bulla while pernio lesions are more discrete. Cryoproteinemia causes lesions on acral sites exposed to the cold, but its onset is sudden and lesions are purpuric with a reticular (net-like) pattern.12 In adults, cutaneous thromboemboli also can present similarly to pernio,13 but thromboemboli are unlikely in children.

Clinical findings of pernio in the setting of lupus erythematosus is called chilblains lupus erythematosus. Confusingly, the condition called lupus pernio is actually a cutaneous manifestation of sarcoidosis, not lupus, and its erythematous or violaceous lesions occur on the nose and central face, not the hands and feet.13

Work-up

For pernio patients without systemic symptoms or signs of underlying systemic disease, laboratory workup or skin biopsy are not necessary.3,4 When history or physical exam is concerning for a systemic condition, preliminary workup should include complete blood count, peripheral blood smear, serum protein electrophoresis, cold agglutinins, and antinuclear antibody.3 Rheumatoid factor, antiphospholipid antibodies, and cryoglobulins also can be considered. Laboratory workup should be performed if pernio persists beyond the cold season, as persistent pernio may be associated with systemic illness.4,9

This patient’s recent weight loss was concerning for underlying systemic disease, so a laboratory workup including complete blood count, serum protein electrophoresis, cold agglutinins, antinuclear antibody, rheumatoid factor, and cryoglobulins was performed. Cryoglobulinemia was detected. All other lab values were within normal limits. Although cryoglobulinemia is rare in adults,3,14 it was detected in approximately 40% of the children in two pediatric series.6,10 Cryoglobulins, which can be produced in response to viral infection, may suggest a precipitating viral illness, with transient cryoproteinemia amplifying cold injury.6 Although the significance of laboratory abnormalities in pediatric pernio is unclear, because associated systemic disease has not been reported in children, some practitioners recommend long-term monitoring in light of the association between lab abnormalities and systemic disease in adults.10

Treatment

Most pernio (82% in one series) resolves when affected skin is warmed and dried, without additional treatment required.3 Corticosteroids, such as 0.1% triamcinolone cream, sometimes are given to hasten the healing of the lesions, but their benefit is unproven.6 The second-line treatment for persistent pernio is calcium channel blockers such as nifedipine.3,15 This patient’s pernio quickly improved after he began wearing gloves to keep his hands warm. On re-examination 2 weeks later, his hands were warm and the erythematous nodules had resolved, leaving only some scale at the sites of prior lesions (Figure 3). Some patients relapse annually during the cool months.11

References

- Pediatrics. 2005 Sep;116(3):e472-5. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-2681.

- Journal of Medical Case Reports. 2014 Nov;8:381. doi: 10.1186/1752-1947-8-381.

- Mayo Clin Proc. 2014 Feb;89(2):207-15.

- Clin Exp Dermatol. 2012 Dec;37(8):844-9.

- J Paediatr Child Health. 2013 Feb;49(2):144-7.

- Pediatr Dermatol. 2000 Mar-Apr;17(2):97-9.

- Am J Med. 2009 Dec;122(12):1152-5.

- J Amer Acad Dermatol. 1990 Aug;23(Part 1):257-62.

- Medicine (Baltimore). 2001 May;80(3):180-8.

- Arch Dis Child. 2010 Jul;95(7):567-8.

- Br J Dermatol. 2010 Sep;163(3):645-6.

- Cutaneous manifestations of microvascular occlusion syndromes, in “Dermatology,” 3rd ed. (Philadelphia, 2012, pp 373-4).

- Environmental and sports-related skin diseases, in “Dermatology,” 3rd ed. (Philadelphia, 2012).

- J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010 Jun;62(6):e21-2.

- Br J Dermatol. 1989 Feb;120(2):267-75.

Ms. Haddock is a medical student at the University of California, San Diego, and a research associate at Rady Children’s Hospital, San Diego. Dr. Eichenfield is chief of pediatric and adolescent dermatology at Rady Children’s Hospital, San Diego, and Professor of Medicine and Pediatrics at the University of California, San Diego. Dr. Eichenfield and Ms. Haddock said they have no relevant financial disclosures.

BY ELLEN S. HADDOCK AND LAWRENCE F. EICHENFIELD, M.D.

Pediatric Dermatology Consult: Pernio

Itchy localized areas of swelling on the bilateral hands with erythematous papules and crusting is consistent with pernio, as seen in the presentation of the teen boy described on p. 2. Pernio is a localized abnormal inflammatory response to cold and damp conditions, also known as chilblains, derived from the old English words for chill and sore.1 Damp air is thought to enhance the air conductivity of cold.2 Pernio typically presents with erythematous to blue-violet macules, papules, and nodules on the bilateral fingers and toes. When occurring on the feet, it is sometimes called trench foot or kibes.1 The nose and ears also can be affected.3 Lesions may develop 12-24 hours after exposure to damp or chilly weather, typically at temperatures above freezing.4

This patient’s pernio may have been triggered by recent stormy winter weather; being from within San Diego County, he had no exposure to snow. Lesions often are tender and may be accompanied by pruritus, pain, or a burning sensation, but they can be asymptomatic.3 Lesions may blister and ulcerate, and can become secondarily infected.5 Brownish or yellowish discoloration may be seen.1 Proposed diagnostic criteria requires localized erythema and swelling of the acral sites for more than 24 hours, as well as either onset during the cool months of the year or improvement with warming the affected area.3

Pernio is most common in adults, with a mean age of 38 years in one series.3 It also occurs in children but is uncommon, with only eight cases diagnosed at the University of Colorado over a 10-year period.6 Adult patients are primarily female,3 while the gender distribution in children is equal.6 Because pernio is triggered by cold and damp weather, it is not surprising that pernio occurs more often in cold climates.3 Raynaud’s phenomenon, smoking, and anorexia nervosa (due to lack of insulating fat) seem to be risk factors.1,3

Pernio typically is a benign primary disorder thought to result from cold-induced vasospasm, which leads to hypoxia and triggers a localized inflammatory reaction.7 Lesions of primary pernio usually resolve in a few weeks to months.4,6 However, pernio can be secondarily associated with systemic diseases including lupus (5% of patients in one of the largest series), non-lupus connective tissue disorders (4%), hematologic malignancy (3%), solid organ malignancy (2%), hepatitis, and Epstein-Barr virus.3 In these cases, pernio may be more persistent and hyperviscosity may contribute to its pathogenesis.8,9

Approximately a third of patients have laboratory abnormalities such as anemia, abnormal blood smear, autoantibodies, or serum monoclonal proteins,3 which may facilitate diagnosis of an underlying systemic disease. Not all pernio patients with connective tissue disease autoantibodies have clinical features of connective tissue disease, but these may manifest later.3,9 Laboratory abnormalities including cryoglobulinemia, cold agglutinins, rheumatoid factor, and antineutrophilic antibody also are seen in children;6,10 however, there are no reports of childhood pernio being associated with connective tissue disease or other systemic illness, although long-term studies are lacking.

When lesions are biopsied, histopathology shows nonspecific dermal edema with superficial and deep perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate.3,4

Differential diagnosis

The differential diagnosis for pernio includes Raynaud’s phenomenon, frostbite, herpetic whitlow, and purpura caused by cryoproteinemia. In Raynaud’s, pallor and cyanosis are followed by erythema, but the discoloration is more sharply demarcated and episodes are typically shorter, lasting hours rather than days.1,8 In this case, progression of the lesions over weeks and the lack of sudden skin color change when holding a cold drink make Raynaud’s unlikely. Frostbite, in which the tissue freezes and necroses, can be distinguished by history.11

When lesions have blistered, herpetic whitlow also may be on the differential, but herpetic whitlow vesicles typically cluster or coalesce into a single bulla while pernio lesions are more discrete. Cryoproteinemia causes lesions on acral sites exposed to the cold, but its onset is sudden and lesions are purpuric with a reticular (net-like) pattern.12 In adults, cutaneous thromboemboli also can present similarly to pernio,13 but thromboemboli are unlikely in children.

Clinical findings of pernio in the setting of lupus erythematosus is called chilblains lupus erythematosus. Confusingly, the condition called lupus pernio is actually a cutaneous manifestation of sarcoidosis, not lupus, and its erythematous or violaceous lesions occur on the nose and central face, not the hands and feet.13

Work-up

For pernio patients without systemic symptoms or signs of underlying systemic disease, laboratory workup or skin biopsy are not necessary.3,4 When history or physical exam is concerning for a systemic condition, preliminary workup should include complete blood count, peripheral blood smear, serum protein electrophoresis, cold agglutinins, and antinuclear antibody.3 Rheumatoid factor, antiphospholipid antibodies, and cryoglobulins also can be considered. Laboratory workup should be performed if pernio persists beyond the cold season, as persistent pernio may be associated with systemic illness.4,9

This patient’s recent weight loss was concerning for underlying systemic disease, so a laboratory workup including complete blood count, serum protein electrophoresis, cold agglutinins, antinuclear antibody, rheumatoid factor, and cryoglobulins was performed. Cryoglobulinemia was detected. All other lab values were within normal limits. Although cryoglobulinemia is rare in adults,3,14 it was detected in approximately 40% of the children in two pediatric series.6,10 Cryoglobulins, which can be produced in response to viral infection, may suggest a precipitating viral illness, with transient cryoproteinemia amplifying cold injury.6 Although the significance of laboratory abnormalities in pediatric pernio is unclear, because associated systemic disease has not been reported in children, some practitioners recommend long-term monitoring in light of the association between lab abnormalities and systemic disease in adults.10

Treatment

Most pernio (82% in one series) resolves when affected skin is warmed and dried, without additional treatment required.3 Corticosteroids, such as 0.1% triamcinolone cream, sometimes are given to hasten the healing of the lesions, but their benefit is unproven.6 The second-line treatment for persistent pernio is calcium channel blockers such as nifedipine.3,15 This patient’s pernio quickly improved after he began wearing gloves to keep his hands warm. On re-examination 2 weeks later, his hands were warm and the erythematous nodules had resolved, leaving only some scale at the sites of prior lesions (Figure 3). Some patients relapse annually during the cool months.11

References

- Pediatrics. 2005 Sep;116(3):e472-5. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-2681.

- Journal of Medical Case Reports. 2014 Nov;8:381. doi: 10.1186/1752-1947-8-381.

- Mayo Clin Proc. 2014 Feb;89(2):207-15.

- Clin Exp Dermatol. 2012 Dec;37(8):844-9.

- J Paediatr Child Health. 2013 Feb;49(2):144-7.

- Pediatr Dermatol. 2000 Mar-Apr;17(2):97-9.

- Am J Med. 2009 Dec;122(12):1152-5.

- J Amer Acad Dermatol. 1990 Aug;23(Part 1):257-62.

- Medicine (Baltimore). 2001 May;80(3):180-8.

- Arch Dis Child. 2010 Jul;95(7):567-8.

- Br J Dermatol. 2010 Sep;163(3):645-6.

- Cutaneous manifestations of microvascular occlusion syndromes, in “Dermatology,” 3rd ed. (Philadelphia, 2012, pp 373-4).

- Environmental and sports-related skin diseases, in “Dermatology,” 3rd ed. (Philadelphia, 2012).

- J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010 Jun;62(6):e21-2.

- Br J Dermatol. 1989 Feb;120(2):267-75.

Ms. Haddock is a medical student at the University of California, San Diego, and a research associate at Rady Children’s Hospital, San Diego. Dr. Eichenfield is chief of pediatric and adolescent dermatology at Rady Children’s Hospital, San Diego, and Professor of Medicine and Pediatrics at the University of California, San Diego. Dr. Eichenfield and Ms. Haddock said they have no relevant financial disclosures.

A 13-year-old male presents with a rash that began as purplish spots on several fingers of the right hand and progressed over 2 months to involve all ten fingers. No other parts of his body are affected, and he had never experienced anything like this before. The fingers are intermittently painful and swollen. He is otherwise well, playing video games regularly and playing soccer with normal energy, although he states that a few of his soccer games have been canceled due to winter rains. He denies any sudden changes in the color of his hands with exposure to cold or holding cold drink bottles or cans (no “white, blue, and red changes”). He does not have any muscle or joint aches, but his mom reports that he has lost several pounds over the past 3 months. On physical exam, he has fifteen red, violaceous papules with surrounding swelling and erythema scattered on his dorsal fingers (Figure 1) and several similar lesions on his volar fingers. A few of the lesions are crusted. The skin of his volar fingers is dry, with some fine scale and several thickened, yellow-brown areas (Figure 2). His hands are very cold. His fingernails and feet are normal, and he has no lymphadenopathy.

New and Noteworthy Information—March 2016

Adults with a diagnosis of concussion have an increased long-term risk of suicide, particularly after concussions on weekends, according to a study published online ahead of print February 8 in the Canadian Medical Association Journal. Researchers performed a longitudinal cohort analysis of adults with a diagnosis of concussion from April 1, 1992 to March 31, 2012. Concussions that resulted in hospital admission were excluded. Investigators identified 235,110 patients with concussion, and 667 subsequent suicides occurring over a median follow-up of 9.3 years, which was three times the expected rate. Weekend concussions were associated with a one-third further increased risk of suicide, compared with weekday concussions. According to the researchers, the increased risk applied regardless of patients’ demographic characteristics, was independent of past psychiatric conditions, became accentuated with time, and exceeded the risk among military personnel.

Imaging with 3-T T2-weighted brain MRI distinguishes perivenous multiple sclerosis (MS) lesions from microangiopathic lesions, according to a study of 40 patients published online ahead of print December 10, 2015, in the Multiple Sclerosis Journal. Initially, a test cohort of 10 patients with MS and 10 patients with microangiopathic white matter lesions underwent T2-weighted brain imaging on a 3T MRI. Anonymized scans were analyzed blind to clinical data, and simple diagnostic rules were devised. These rules were applied to a validation cohort of 20 patients by a blinded observer. Within the test cohort, all patients with MS had central veins visible in more than 45% of brain lesions, while the rest had central veins visible in less than 45% of lesions. By applying diagnostic rules to the validation cohort, all remaining patients were correctly categorized.

In asymptomatic patients with severe carotid stenosis who are not at high risk for surgical complications, stenting is noninferior to endarterectomy with regard to the rates of stroke, death, or myocardial infarction at one year, according to a study published online ahead of print February 17 in the New England Journal of Medicine. Researchers compared carotid-artery stenting with embolic protection and carotid endarterectomy in 1,453 patients age 79 or younger. The rate of stroke or death within 30 days was 2.9% in the stenting group and 1.7% in the endarterectomy group. From 30 days to five years after the procedure, the rate of freedom from ipsilateral stroke was 97.8% in the stenting group and 97.3% in the endarterectomy group, and the overall survival rates were 87.1% and 89.4%, respectively.

Past exposure to marijuana is associated with worsened verbal memory, but does not appear to affect other domains of cognitive function, according to a study published online ahead of print February 1 in JAMA Internal Medicine. Researchers examined data for 5,115 African American and Caucasian men and women ages 18 to 30 at baseline. Participants were followed for 26 years to estimate cumulative exposure to marijuana. Among 3,385 participants with cognitive function measurements at the year 25 visit, 2,852 reported past marijuana use, and 392 continued to use marijuana into middle age. After excluding current users and adjusting for potential confounders, cumulative lifetime exposure to marijuana remained significantly associated with worsened verbal memory. For each five years of past exposure, verbal memory was 0.13 standardized units lower.

Frequent shifts in sleep timing may impair metabolic health among non-shift-working women of middle age, according to a study published in the February issue of Sleep. A total of 338 Caucasian, African American, and Chinese non-shift-working women ages 48 through 58 who were not taking insulin-related medications participated in the Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation Sleep Study and were examined approximately 5.39 years later. Daily diary-reported bedtimes were used to calculate four measures of sleep timing. BMI and insulin resistance were measured at two time points. In cross-sectional models, greater variability in bedtime and greater bedtime delay were associated with higher homeostatic model assessment-insulin resistance, and greater bedtime advance was associated with higher BMI. Prospectively, greater bedtime delay predicted increased homeostatic model assessment-insulin resistance.

Elderly people with high levels of depressive symptoms on several occasions over a 10-year period have substantially increased risk of coronary heart disease and stroke, according to a study published in the January issue of Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. Researchers examined 9,294 participants at baseline between 1999 and 2001, and during repeated study visits. There were 7,313 participants with an average age of 73.8, with no history of coronary heart disease, stroke, or dementia at baseline. After a median follow-up of 8.4 years, 629 first coronary heart disease or stroke events occurred. After adjustment for sociodemographic characteristics and vascular risk factors, the risk of coronary heart disease and stroke combined increased 1.15-fold per each additional study visit with high levels of depressive symptoms.

Submandibular gland needle biopsies identify phosphorylated alpha-synuclein staining in 74% of patients with early Parkinson’s disease, according to a study published in the February issue of Movement Disorders. Twenty-five patients with early Parkinson’s disease and 10 controls underwent transcutaneous needle core biopsies of the submandibular gland. Tissue was stained for phosphorylated alpha-synuclein and reviewed blind to clinical diagnosis. Only nerve element staining was considered positive. Mean age was 69.5 for the Parkinson’s disease group and 64.8 for controls, and disease duration was 2.6 years. Six people with Parkinson’s disease and one control subject had inadequate glandular tissue. Positive staining was found in 14 of 19 patients with Parkinson’s disease and two out of nine control subjects. Parkinson’s disease-positive and -negative cases did not differ clinically.

Lower cardiovascular fitness and exaggerated exercise blood pressure heart-rate responses in middle-aged adults are associated with smaller brain volume nearly two decades later, according to a study published online ahead of print February 10 in Neurology. In all, 1,094 people without dementia and cardiovascular disease underwent an exercise treadmill test at a mean age of 40. A second treadmill test and MRI scans of the brain were administered two decades later. Poor cardiovascular fitness and greater diastolic blood pressure and heart-rate response to exercise at baseline were associated with a smaller total cerebral brain volume almost two decades later in multivariable adjusted models. The effect of one standard deviation of lower fitness was equivalent to approximately one additional year of brain aging in individuals free of cardiovascular disease.

The increased risks of falling and hip fracture before the diagnosis of Parkinson’s disease may suggest the presence of clinically relevant neurodegenerative impairment years before the diagnosis of the disease, according to a study published February 2 in PLOS Medicine. Researchers compiled two nested case–control cohorts: In cohort one were individuals diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease; cohort two included individuals with an injurious fall. In cohort one, 18.0% of cases had at least one injurious fall before Parkinson’s disease diagnosis, whereas 11.5% of controls had an injurious fall. In cohort two, 0.7% of individuals with an injurious fall and 0.5% of controls were diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease during follow-up. The risk of Parkinson’s disease was increased for as long as 10 years after an injurious fall.

Increased amyloid β burden is observed in traumatic brain injury (TBI), according to a study published online ahead of print February 3 in Neurology. Patients age 11 months to 17 years with moderate to severe TBI underwent 11C-Pittsburgh compound B (11C-PiB)-PET, structural and diffusion MRI, and neuropsychologic examination. Healthy controls and patients with Alzheimer’s disease underwent PET and structural MRI. In TBI, fractional anisotropy was estimated and correlated with 11C-PiB binding potential. Increased 11C-PiB binding potential was found in TBI versus controls in the posterior cingulate cortex and cerebellum. Binding in the posterior cingulate cortex increased with decreasing fractional anisotropy of associated white matter tracts and increased with time since injury. Compared with Alzheimer’s disease, binding after TBI was lower in neocortical regions, but increased in the cerebellum.

Among participants in the Framingham Heart Study, the incidence of dementia has declined over three decades, according to a study published February 11 in the New England Journal of Medicine. In this analysis, which included 5,205 people age 60 and older, researchers used Cox proportional-hazards models adjusted for age and sex to determine the five-year incidence of dementia during each of four epochs. The five-year age- and sex-adjusted cumulative hazard rates for dementia were 3.6 per 100 persons during the first epoch, 2.8 per 100 persons during the second epoch, 2.2 per 100 persons during the third epoch, and 2.0 per 100 persons during the fourth epoch. During the second through fourth epochs, the incidence of dementia declined by 22%, 38%, and 44%, respectively, compared with the first epoch.