User login

HIPAA enforcement in 2016: Is your practice ready?

Two reports from the Office of the Inspector General (OIG) have attracted a lot of attention in recent weeks: The Office for Civil Rights (OCR), OIG said, needs to improve and expand its enforcement of the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA). In response, the OCR announced that it plans to identify a pool of potential audit targets and launch a permanent audit program this year. That, combined with the substantial fine levied against a dermatology group last year for violating one of the new rules, signals the importance of reviewing your practice’s HIPAA compliance as soon as possible.

You can compare your office’s compliance status against the recommendations listed on the OCR website, but pay particular attention to your agreements with Business Associates (BAs). Those are the individuals or businesses, other than your employees, who perform “functions or activities” on behalf of your practice that involve “creating, receiving, maintaining, or transmitting” personal health information.

First, make sure that all individuals and enterprises fitting that definition have a signed agreement in place. Typical BAs include answering and billing services, independent transcriptionists, hardware and software companies, and any other vendors involved in creating or maintaining your medical records. Practice management consultants, attorneys, specialty pharmacies, and record storage, microfilming, and shredding services are BAs if they must have direct access to confidential information in order to do their job.

The revised rules place additional onus on physicians for confidentiality breaches committed by their BAs. It’s not enough to simply have a BA contract; you are expected to use “reasonable diligence” in monitoring their work. BAs and their subcontractors are directly responsible for their own actions, but the primary responsibility is yours. Furthermore, you must now assume the worst-case scenario: Previously, when protected health information (PHI) was compromised, you would have to notify only affected patients (and the government) if there was a “significant risk of financial or reputational harm,” but now, any incident involving patient records is assumed to be a breach, and must be reported.

Failure to do so could subject your practice, as well as the contractor, to significant fines. That is where the Massachusetts dermatology group ran into trouble: It lost a thumb drive containing unencrypted patient records, and was forced to pay a $150,000 fine, even though there was no evidence that the information was found or exploited.

Had the lost drive been encrypted, the incident would not have been considered a breach, according to the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, because its contents would not have been viewable by the finder. The biggest vulnerability in most practices is probably mobile devices carrying patient data. There is no longer any excuse for not encrypting HIPAA-protected information; encryption software is cheap, readily available, and easy to use.

Patients have new rights under the new rules as well; they may now restrict any PHI shared with third-party insurers and health plans, if they pay for the services themselves. They also have the right to request copies of their electronic health records (EHRs). You can bill the costs of responding to such requests. If you have EHRs, work out a system for doing this, because the response time has been decreased from 90 days to 30 days – even shorter in some states.

If you haven’t yet revised your Notice of Privacy Practices (NPP) to explain your relationships with BAs, and their status under the new rules, do it now. (You should have done it last year.) You need to explain the breach notification process too, as well as the new patient rights mentioned above. You must post your revised NPP in your office, and make copies available there, but you need not mail a copy to every patient.

You also should examine every part of your office where patient information is handled to identify potential violations. Examples include computer screens in your reception area that are visible to patients; laptops not locked up after hours; unencrypted emails or texts that might reveal confidential information; and documents designated for shredding that sit, unshredded, in the “to shred” bin for days.

And make sure you correct any problems you find before the OCR auditors come calling.

To view the recommendations at the OCR website so you can check your office’s compliance status, go to: www.hhs.gov/hipaa/index.html.

Dr. Eastern practices dermatology and dermatologic surgery in Belleville, N.J. He is the author of numerous articles and textbook chapters, and is a longtime monthly columnist for Dermatology News.

Two reports from the Office of the Inspector General (OIG) have attracted a lot of attention in recent weeks: The Office for Civil Rights (OCR), OIG said, needs to improve and expand its enforcement of the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA). In response, the OCR announced that it plans to identify a pool of potential audit targets and launch a permanent audit program this year. That, combined with the substantial fine levied against a dermatology group last year for violating one of the new rules, signals the importance of reviewing your practice’s HIPAA compliance as soon as possible.

You can compare your office’s compliance status against the recommendations listed on the OCR website, but pay particular attention to your agreements with Business Associates (BAs). Those are the individuals or businesses, other than your employees, who perform “functions or activities” on behalf of your practice that involve “creating, receiving, maintaining, or transmitting” personal health information.

First, make sure that all individuals and enterprises fitting that definition have a signed agreement in place. Typical BAs include answering and billing services, independent transcriptionists, hardware and software companies, and any other vendors involved in creating or maintaining your medical records. Practice management consultants, attorneys, specialty pharmacies, and record storage, microfilming, and shredding services are BAs if they must have direct access to confidential information in order to do their job.

The revised rules place additional onus on physicians for confidentiality breaches committed by their BAs. It’s not enough to simply have a BA contract; you are expected to use “reasonable diligence” in monitoring their work. BAs and their subcontractors are directly responsible for their own actions, but the primary responsibility is yours. Furthermore, you must now assume the worst-case scenario: Previously, when protected health information (PHI) was compromised, you would have to notify only affected patients (and the government) if there was a “significant risk of financial or reputational harm,” but now, any incident involving patient records is assumed to be a breach, and must be reported.

Failure to do so could subject your practice, as well as the contractor, to significant fines. That is where the Massachusetts dermatology group ran into trouble: It lost a thumb drive containing unencrypted patient records, and was forced to pay a $150,000 fine, even though there was no evidence that the information was found or exploited.

Had the lost drive been encrypted, the incident would not have been considered a breach, according to the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, because its contents would not have been viewable by the finder. The biggest vulnerability in most practices is probably mobile devices carrying patient data. There is no longer any excuse for not encrypting HIPAA-protected information; encryption software is cheap, readily available, and easy to use.

Patients have new rights under the new rules as well; they may now restrict any PHI shared with third-party insurers and health plans, if they pay for the services themselves. They also have the right to request copies of their electronic health records (EHRs). You can bill the costs of responding to such requests. If you have EHRs, work out a system for doing this, because the response time has been decreased from 90 days to 30 days – even shorter in some states.

If you haven’t yet revised your Notice of Privacy Practices (NPP) to explain your relationships with BAs, and their status under the new rules, do it now. (You should have done it last year.) You need to explain the breach notification process too, as well as the new patient rights mentioned above. You must post your revised NPP in your office, and make copies available there, but you need not mail a copy to every patient.

You also should examine every part of your office where patient information is handled to identify potential violations. Examples include computer screens in your reception area that are visible to patients; laptops not locked up after hours; unencrypted emails or texts that might reveal confidential information; and documents designated for shredding that sit, unshredded, in the “to shred” bin for days.

And make sure you correct any problems you find before the OCR auditors come calling.

To view the recommendations at the OCR website so you can check your office’s compliance status, go to: www.hhs.gov/hipaa/index.html.

Dr. Eastern practices dermatology and dermatologic surgery in Belleville, N.J. He is the author of numerous articles and textbook chapters, and is a longtime monthly columnist for Dermatology News.

Two reports from the Office of the Inspector General (OIG) have attracted a lot of attention in recent weeks: The Office for Civil Rights (OCR), OIG said, needs to improve and expand its enforcement of the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA). In response, the OCR announced that it plans to identify a pool of potential audit targets and launch a permanent audit program this year. That, combined with the substantial fine levied against a dermatology group last year for violating one of the new rules, signals the importance of reviewing your practice’s HIPAA compliance as soon as possible.

You can compare your office’s compliance status against the recommendations listed on the OCR website, but pay particular attention to your agreements with Business Associates (BAs). Those are the individuals or businesses, other than your employees, who perform “functions or activities” on behalf of your practice that involve “creating, receiving, maintaining, or transmitting” personal health information.

First, make sure that all individuals and enterprises fitting that definition have a signed agreement in place. Typical BAs include answering and billing services, independent transcriptionists, hardware and software companies, and any other vendors involved in creating or maintaining your medical records. Practice management consultants, attorneys, specialty pharmacies, and record storage, microfilming, and shredding services are BAs if they must have direct access to confidential information in order to do their job.

The revised rules place additional onus on physicians for confidentiality breaches committed by their BAs. It’s not enough to simply have a BA contract; you are expected to use “reasonable diligence” in monitoring their work. BAs and their subcontractors are directly responsible for their own actions, but the primary responsibility is yours. Furthermore, you must now assume the worst-case scenario: Previously, when protected health information (PHI) was compromised, you would have to notify only affected patients (and the government) if there was a “significant risk of financial or reputational harm,” but now, any incident involving patient records is assumed to be a breach, and must be reported.

Failure to do so could subject your practice, as well as the contractor, to significant fines. That is where the Massachusetts dermatology group ran into trouble: It lost a thumb drive containing unencrypted patient records, and was forced to pay a $150,000 fine, even though there was no evidence that the information was found or exploited.

Had the lost drive been encrypted, the incident would not have been considered a breach, according to the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, because its contents would not have been viewable by the finder. The biggest vulnerability in most practices is probably mobile devices carrying patient data. There is no longer any excuse for not encrypting HIPAA-protected information; encryption software is cheap, readily available, and easy to use.

Patients have new rights under the new rules as well; they may now restrict any PHI shared with third-party insurers and health plans, if they pay for the services themselves. They also have the right to request copies of their electronic health records (EHRs). You can bill the costs of responding to such requests. If you have EHRs, work out a system for doing this, because the response time has been decreased from 90 days to 30 days – even shorter in some states.

If you haven’t yet revised your Notice of Privacy Practices (NPP) to explain your relationships with BAs, and their status under the new rules, do it now. (You should have done it last year.) You need to explain the breach notification process too, as well as the new patient rights mentioned above. You must post your revised NPP in your office, and make copies available there, but you need not mail a copy to every patient.

You also should examine every part of your office where patient information is handled to identify potential violations. Examples include computer screens in your reception area that are visible to patients; laptops not locked up after hours; unencrypted emails or texts that might reveal confidential information; and documents designated for shredding that sit, unshredded, in the “to shred” bin for days.

And make sure you correct any problems you find before the OCR auditors come calling.

To view the recommendations at the OCR website so you can check your office’s compliance status, go to: www.hhs.gov/hipaa/index.html.

Dr. Eastern practices dermatology and dermatologic surgery in Belleville, N.J. He is the author of numerous articles and textbook chapters, and is a longtime monthly columnist for Dermatology News.

Obesity

Emily is a 15-year-old girl who was referred by her pediatrician because of cutting behavior and conflict with her parents. Her parents reported that she has had a high body weight in the obese range since early in life. She had tried various diets without success, and her parents were frustrated with the pediatrician’s emphasis on weight over the years.

Mood problems had begun when she was in the sixth grade when she began to be severely bullied about her weight. Emily said this time was so difficult that she did not have clear memories of it. She described feeling numb. She began experiencing intense anxiety about school, and she was sometimes reluctant to attend and started cutting herself as a means of managing her emotions. In middle school, she began to fight back and associated herself with a group of “mean girls” who drank. She began having increasing conflict with her parents over the drinking and the cutting.

Discussion

Obesity is an extremely complex issue without simple answers. Severe obesity is correlated with numerous health risks including not only cardiovascular disease, type 2 diabetes, hypertension, and cancer, but also psychiatric problems such as depression, anxiety, body dissatisfaction, eating disorders, and unhealthy weight control behaviors. While some of these issues relate directly to the weight itself, many of the psychiatric concerns stem from society’s extremely harsh response to obesity.

We are all aware that the percentage of overweight and obese children, teens, and adults has increased in the past 50 years, although with some recent stabilization.1 The rise in obesity is related to societal factors – the prevalence and advertising of nutrient-poor/high-calorie processed foods in the marketplace, the rise of technologies that have decreased the need for movement, increases in portion sizes in restaurants, especially fast food settings, as well as the subsidizing of unhealthy foods, limited access to and greater cost of more nutritious foods, and limited access to exercise opportunities in poorer areas. This is the “obesogenic environment.” As in numerous aspects of health, weight is also influenced by genetics. Those who are genetically more likely to gain weight are the ones who suffer most from these social changes.

The problem is that, except for bariatric surgery, the interventions prescribed for individuals with obesity don’t work for the vast majority of people in the long run. There is an assumption that if the obese would just eat and exercise the way a thin person does, then they would be thin. While there is evidence that lifestyle strategies that induce a negative energy balance through cutting calories (often by 500-1,000) and “programmed exercise” can help some people lose weight over the course of 6 months to a year, longer-term follow-up suggests that most people regain this weight in the long run, at 5 years out. Even the most optimistic estimates suggest that only about one out of five people can maintain weight losses of 10% in the long term with current standard lifestyle interventions.2

There is evidence that someone attaining a particular body mass index (BMI) through dieting is not able to consume as many calories as another person who has always been at that BMI, requiring constant dietary restraint and a very high level of exercise to maintain the weight loss.3 The great majority of people who are unable to lose the weight, or briefly succeed and then gain the weight back or more, are seen as failing by society, by many medical professionals, and by themselves. There is clearly a need to focus more of our efforts on making changes on a societal level.

There also are alternative individual approaches that take the emphasis away from dieting and weight loss and instead focus on body acceptance and self-care. These interventions go by several names including mindful eating, intuitive eating, weight neutral, and “Health at Every Size.” This approach acknowledges the environmental and genetic factors beyond personal control and discusses how society pressures people to be thin. Instead of emphasizing repeated restrictive dieting, these programs stress maximizing health through making sustainable changes to increase activity and nutrition. These programs encourage people to care for themselves now rather than focusing on dieting toward a future weight where one can start enjoying life. Enjoyment of food, taking time to savor food, and being aware of when one is hungry and when not are central. For physical activity, the emphasis is on discovering something that is pleasurable and sustainable, rather than an onerous duty, as a means to an end of weight loss.4

Management

For Emily, struggling on the individual level, there is not a neat resolution. Psychotherapy to address anxiety, trauma, and substance abuse is indicated. Psychotherapy also should address Emily’s relationship with her body, as this is at the heart of many of these issues. Acknowledging the powerful stigma that society places on the obese while tolerating and even promoting an obesogenic environment, and the reality that weight loss is in fact extremely difficult, would open the door to a discussion with Emily and her family about what she wants and all her options to find the healthiest and most enjoyable way for her to live her life.

1. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2015 Oct;62(5):1241-61.

2. Annu Rev Nutr. 2001;21:323-41.

3. Am J Clin Nutr. 2005 Jul;82(1 Suppl):222S-225S.

4. Tylka TL, Annunziato RA, Burgard D, et al. “The Weight-Inclusive versus Weight-Normative Approach to Health: Evaluating the Evidence for Prioritizing Well-Being over Weight Loss.” J Obes. 2014;2014:983495. doi: 10.1155/2014/983495.

Dr. Hall is an assistant professor of psychiatry and pediatrics at the University of Vermont, Burlington.

Emily is a 15-year-old girl who was referred by her pediatrician because of cutting behavior and conflict with her parents. Her parents reported that she has had a high body weight in the obese range since early in life. She had tried various diets without success, and her parents were frustrated with the pediatrician’s emphasis on weight over the years.

Mood problems had begun when she was in the sixth grade when she began to be severely bullied about her weight. Emily said this time was so difficult that she did not have clear memories of it. She described feeling numb. She began experiencing intense anxiety about school, and she was sometimes reluctant to attend and started cutting herself as a means of managing her emotions. In middle school, she began to fight back and associated herself with a group of “mean girls” who drank. She began having increasing conflict with her parents over the drinking and the cutting.

Discussion

Obesity is an extremely complex issue without simple answers. Severe obesity is correlated with numerous health risks including not only cardiovascular disease, type 2 diabetes, hypertension, and cancer, but also psychiatric problems such as depression, anxiety, body dissatisfaction, eating disorders, and unhealthy weight control behaviors. While some of these issues relate directly to the weight itself, many of the psychiatric concerns stem from society’s extremely harsh response to obesity.

We are all aware that the percentage of overweight and obese children, teens, and adults has increased in the past 50 years, although with some recent stabilization.1 The rise in obesity is related to societal factors – the prevalence and advertising of nutrient-poor/high-calorie processed foods in the marketplace, the rise of technologies that have decreased the need for movement, increases in portion sizes in restaurants, especially fast food settings, as well as the subsidizing of unhealthy foods, limited access to and greater cost of more nutritious foods, and limited access to exercise opportunities in poorer areas. This is the “obesogenic environment.” As in numerous aspects of health, weight is also influenced by genetics. Those who are genetically more likely to gain weight are the ones who suffer most from these social changes.

The problem is that, except for bariatric surgery, the interventions prescribed for individuals with obesity don’t work for the vast majority of people in the long run. There is an assumption that if the obese would just eat and exercise the way a thin person does, then they would be thin. While there is evidence that lifestyle strategies that induce a negative energy balance through cutting calories (often by 500-1,000) and “programmed exercise” can help some people lose weight over the course of 6 months to a year, longer-term follow-up suggests that most people regain this weight in the long run, at 5 years out. Even the most optimistic estimates suggest that only about one out of five people can maintain weight losses of 10% in the long term with current standard lifestyle interventions.2

There is evidence that someone attaining a particular body mass index (BMI) through dieting is not able to consume as many calories as another person who has always been at that BMI, requiring constant dietary restraint and a very high level of exercise to maintain the weight loss.3 The great majority of people who are unable to lose the weight, or briefly succeed and then gain the weight back or more, are seen as failing by society, by many medical professionals, and by themselves. There is clearly a need to focus more of our efforts on making changes on a societal level.

There also are alternative individual approaches that take the emphasis away from dieting and weight loss and instead focus on body acceptance and self-care. These interventions go by several names including mindful eating, intuitive eating, weight neutral, and “Health at Every Size.” This approach acknowledges the environmental and genetic factors beyond personal control and discusses how society pressures people to be thin. Instead of emphasizing repeated restrictive dieting, these programs stress maximizing health through making sustainable changes to increase activity and nutrition. These programs encourage people to care for themselves now rather than focusing on dieting toward a future weight where one can start enjoying life. Enjoyment of food, taking time to savor food, and being aware of when one is hungry and when not are central. For physical activity, the emphasis is on discovering something that is pleasurable and sustainable, rather than an onerous duty, as a means to an end of weight loss.4

Management

For Emily, struggling on the individual level, there is not a neat resolution. Psychotherapy to address anxiety, trauma, and substance abuse is indicated. Psychotherapy also should address Emily’s relationship with her body, as this is at the heart of many of these issues. Acknowledging the powerful stigma that society places on the obese while tolerating and even promoting an obesogenic environment, and the reality that weight loss is in fact extremely difficult, would open the door to a discussion with Emily and her family about what she wants and all her options to find the healthiest and most enjoyable way for her to live her life.

1. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2015 Oct;62(5):1241-61.

2. Annu Rev Nutr. 2001;21:323-41.

3. Am J Clin Nutr. 2005 Jul;82(1 Suppl):222S-225S.

4. Tylka TL, Annunziato RA, Burgard D, et al. “The Weight-Inclusive versus Weight-Normative Approach to Health: Evaluating the Evidence for Prioritizing Well-Being over Weight Loss.” J Obes. 2014;2014:983495. doi: 10.1155/2014/983495.

Dr. Hall is an assistant professor of psychiatry and pediatrics at the University of Vermont, Burlington.

Emily is a 15-year-old girl who was referred by her pediatrician because of cutting behavior and conflict with her parents. Her parents reported that she has had a high body weight in the obese range since early in life. She had tried various diets without success, and her parents were frustrated with the pediatrician’s emphasis on weight over the years.

Mood problems had begun when she was in the sixth grade when she began to be severely bullied about her weight. Emily said this time was so difficult that she did not have clear memories of it. She described feeling numb. She began experiencing intense anxiety about school, and she was sometimes reluctant to attend and started cutting herself as a means of managing her emotions. In middle school, she began to fight back and associated herself with a group of “mean girls” who drank. She began having increasing conflict with her parents over the drinking and the cutting.

Discussion

Obesity is an extremely complex issue without simple answers. Severe obesity is correlated with numerous health risks including not only cardiovascular disease, type 2 diabetes, hypertension, and cancer, but also psychiatric problems such as depression, anxiety, body dissatisfaction, eating disorders, and unhealthy weight control behaviors. While some of these issues relate directly to the weight itself, many of the psychiatric concerns stem from society’s extremely harsh response to obesity.

We are all aware that the percentage of overweight and obese children, teens, and adults has increased in the past 50 years, although with some recent stabilization.1 The rise in obesity is related to societal factors – the prevalence and advertising of nutrient-poor/high-calorie processed foods in the marketplace, the rise of technologies that have decreased the need for movement, increases in portion sizes in restaurants, especially fast food settings, as well as the subsidizing of unhealthy foods, limited access to and greater cost of more nutritious foods, and limited access to exercise opportunities in poorer areas. This is the “obesogenic environment.” As in numerous aspects of health, weight is also influenced by genetics. Those who are genetically more likely to gain weight are the ones who suffer most from these social changes.

The problem is that, except for bariatric surgery, the interventions prescribed for individuals with obesity don’t work for the vast majority of people in the long run. There is an assumption that if the obese would just eat and exercise the way a thin person does, then they would be thin. While there is evidence that lifestyle strategies that induce a negative energy balance through cutting calories (often by 500-1,000) and “programmed exercise” can help some people lose weight over the course of 6 months to a year, longer-term follow-up suggests that most people regain this weight in the long run, at 5 years out. Even the most optimistic estimates suggest that only about one out of five people can maintain weight losses of 10% in the long term with current standard lifestyle interventions.2

There is evidence that someone attaining a particular body mass index (BMI) through dieting is not able to consume as many calories as another person who has always been at that BMI, requiring constant dietary restraint and a very high level of exercise to maintain the weight loss.3 The great majority of people who are unable to lose the weight, or briefly succeed and then gain the weight back or more, are seen as failing by society, by many medical professionals, and by themselves. There is clearly a need to focus more of our efforts on making changes on a societal level.

There also are alternative individual approaches that take the emphasis away from dieting and weight loss and instead focus on body acceptance and self-care. These interventions go by several names including mindful eating, intuitive eating, weight neutral, and “Health at Every Size.” This approach acknowledges the environmental and genetic factors beyond personal control and discusses how society pressures people to be thin. Instead of emphasizing repeated restrictive dieting, these programs stress maximizing health through making sustainable changes to increase activity and nutrition. These programs encourage people to care for themselves now rather than focusing on dieting toward a future weight where one can start enjoying life. Enjoyment of food, taking time to savor food, and being aware of when one is hungry and when not are central. For physical activity, the emphasis is on discovering something that is pleasurable and sustainable, rather than an onerous duty, as a means to an end of weight loss.4

Management

For Emily, struggling on the individual level, there is not a neat resolution. Psychotherapy to address anxiety, trauma, and substance abuse is indicated. Psychotherapy also should address Emily’s relationship with her body, as this is at the heart of many of these issues. Acknowledging the powerful stigma that society places on the obese while tolerating and even promoting an obesogenic environment, and the reality that weight loss is in fact extremely difficult, would open the door to a discussion with Emily and her family about what she wants and all her options to find the healthiest and most enjoyable way for her to live her life.

1. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2015 Oct;62(5):1241-61.

2. Annu Rev Nutr. 2001;21:323-41.

3. Am J Clin Nutr. 2005 Jul;82(1 Suppl):222S-225S.

4. Tylka TL, Annunziato RA, Burgard D, et al. “The Weight-Inclusive versus Weight-Normative Approach to Health: Evaluating the Evidence for Prioritizing Well-Being over Weight Loss.” J Obes. 2014;2014:983495. doi: 10.1155/2014/983495.

Dr. Hall is an assistant professor of psychiatry and pediatrics at the University of Vermont, Burlington.

Make Room on Your Shelves

As orthopedic surgeons, we’ve made a commitment to lifelong learning. I can’t think of a single surgery that I perform the same way I did when I was in training. With rapidly evolving technology, continuously advancing procedures, and ever-increasing documentation requirements, it’s hard to stay on top of it all. We know your time is precious and that you have less of it than ever before. What little time you have that is not dedicated to work is reserved for your family or your hobbies. There’s no time to read every orthopedic journal, many filled with articles that have no practical value to your practice. That’s why we’ve created the new AJO. Our goal, as an editorial staff, is to provide a journal where every article, column, and feature contains information that directly benefits your practice, your patients, or your bottom line, and keeps you informed of the latest techniques, procedures, and products. We will help surgeons “work smarter, not harder,” implement new technologies into their practices, and find creative revenue streams that are both legal and compliant.

We’ve assembled a team of talented editors to accomplish this task, and will introduce them throughout the coming year. In this issue, you will meet our Deputy Editors-in-Chief and some of our new Associate Editors who’ve collaborated to bring you the “new AJO”.

At this year’s Academy, the AJO launched an extensive rebranding. We have a new look, a new logo, and a new creative directive. The journal will now feature new columns, invited articles, and innovative surgical techniques. We will publish 5 issues for the remainder of 2016. Our March/April issue is a special edition dedicated to baseball. In time for Spring Training/Opening Day, this issue includes articles from Major League Baseball’s physicians and trainers, a “Codes to Know” segment, “Tips of the Trade,” and a “Tools of the Trade” feature. “The Baseball Issue” will set the tone for what readers can expect from the “new AJO”.

Our first feature article, written by Jed Kuhn, takes a philosophical look at the evolution of the throwing shoulder, and invites the reader to help unlock some of the great shoulder anatomy mysteries by viewing them from a time when throwing was an activity of daily living. In ancient times, if you couldn’t throw, you couldn’t eat. We know that children who play baseball remodel their shoulder to allow for increased external rotation. Read Dr. Kuhn’s article and imagine when a shoulder optimized for throwing was a competitive advantage for survival.

Our second feature article is written by Stan Conte, a legend of the game and longtime trainer for the Los Angeles Dodgers. Dr. Conte studied injury trends in baseball over the past 18 seasons and provides an analysis of the staggering cost of placing players on the disabled list.

A baseball issue could not be complete without an article on Tommy John surgery. In this issue, AJO shares a revolutionary new technique for treating players with MUCL tears by author Jeffrey Dugas. Named the “Internal Brace”, Dr. Dugas shares his technique for augmenting the injured MUCL and we are proud to bring it to you first.

A recurring feature in the new AJO will be a section we refer to as “Codes to Know.” In partnership with Karen Zupko, AJO will present little-known coding secrets and proper coding techniques to help you get reimbursed appropriately for your work. This month, in the first article of a 3-part series, Alan Hirahara teaches us how to properly code for a diagnostic ultrasound examination of the shoulder. The article includes templates available for download to assist you with proper documentation. Parts 2 and 3 will provide a tutorial on the proper technique for examinations and injections.

While shoulder and elbow injuries get more attention, Major League Baseball’s Injury Panel has produced a look at the staggering amount of knee injuries over the 2011-2014 seasons, inspiring us to feature the knee in our 2 “Trade” Columns.

The “Tips of the Trade” column will continue, featuring this month a guide to identifying and treating meniscal root tears. A new segment, referred to as “Tools of the Trade,” reviews the latest products for all-inside meniscal repair. Our “Tools” section will feature announcements and reviews of the hottest new products, with a buying guide and surgical pearls from the surgeons who know them best.

While we are discussing the lower extremity, we should point out that we plan to do the “leg work” for you. Each AJO issue will have handouts that can be downloaded from our website and utilized in your practice. Read Robin West’s article entitled “Interval Throwing and Hitting Programs in Baseball: Biomechanics and Rehabilitation,” and download Return to Throwing and Hitting programs your patients and therapists can use.

Finally, I’d like to thank our previous Editor-in-Chief Dr. Peter McCann for his stewardship the last 10 years and recognize him for his dedication to the journal.

Thank you for reading AJO and for continuing to do so in the future. I know that collectively, we can turn AJO into a product worthy of its title. We know our past reputation. We are no longer that journal. Spend some time to get to know the “new AJO”, and make some room on your shelves, because the information between the covers will provide a template to implement new technologies and revenue streams into your practice and help fulfill your commitment to learning.

As orthopedic surgeons, we’ve made a commitment to lifelong learning. I can’t think of a single surgery that I perform the same way I did when I was in training. With rapidly evolving technology, continuously advancing procedures, and ever-increasing documentation requirements, it’s hard to stay on top of it all. We know your time is precious and that you have less of it than ever before. What little time you have that is not dedicated to work is reserved for your family or your hobbies. There’s no time to read every orthopedic journal, many filled with articles that have no practical value to your practice. That’s why we’ve created the new AJO. Our goal, as an editorial staff, is to provide a journal where every article, column, and feature contains information that directly benefits your practice, your patients, or your bottom line, and keeps you informed of the latest techniques, procedures, and products. We will help surgeons “work smarter, not harder,” implement new technologies into their practices, and find creative revenue streams that are both legal and compliant.

We’ve assembled a team of talented editors to accomplish this task, and will introduce them throughout the coming year. In this issue, you will meet our Deputy Editors-in-Chief and some of our new Associate Editors who’ve collaborated to bring you the “new AJO”.

At this year’s Academy, the AJO launched an extensive rebranding. We have a new look, a new logo, and a new creative directive. The journal will now feature new columns, invited articles, and innovative surgical techniques. We will publish 5 issues for the remainder of 2016. Our March/April issue is a special edition dedicated to baseball. In time for Spring Training/Opening Day, this issue includes articles from Major League Baseball’s physicians and trainers, a “Codes to Know” segment, “Tips of the Trade,” and a “Tools of the Trade” feature. “The Baseball Issue” will set the tone for what readers can expect from the “new AJO”.

Our first feature article, written by Jed Kuhn, takes a philosophical look at the evolution of the throwing shoulder, and invites the reader to help unlock some of the great shoulder anatomy mysteries by viewing them from a time when throwing was an activity of daily living. In ancient times, if you couldn’t throw, you couldn’t eat. We know that children who play baseball remodel their shoulder to allow for increased external rotation. Read Dr. Kuhn’s article and imagine when a shoulder optimized for throwing was a competitive advantage for survival.

Our second feature article is written by Stan Conte, a legend of the game and longtime trainer for the Los Angeles Dodgers. Dr. Conte studied injury trends in baseball over the past 18 seasons and provides an analysis of the staggering cost of placing players on the disabled list.

A baseball issue could not be complete without an article on Tommy John surgery. In this issue, AJO shares a revolutionary new technique for treating players with MUCL tears by author Jeffrey Dugas. Named the “Internal Brace”, Dr. Dugas shares his technique for augmenting the injured MUCL and we are proud to bring it to you first.

A recurring feature in the new AJO will be a section we refer to as “Codes to Know.” In partnership with Karen Zupko, AJO will present little-known coding secrets and proper coding techniques to help you get reimbursed appropriately for your work. This month, in the first article of a 3-part series, Alan Hirahara teaches us how to properly code for a diagnostic ultrasound examination of the shoulder. The article includes templates available for download to assist you with proper documentation. Parts 2 and 3 will provide a tutorial on the proper technique for examinations and injections.

While shoulder and elbow injuries get more attention, Major League Baseball’s Injury Panel has produced a look at the staggering amount of knee injuries over the 2011-2014 seasons, inspiring us to feature the knee in our 2 “Trade” Columns.

The “Tips of the Trade” column will continue, featuring this month a guide to identifying and treating meniscal root tears. A new segment, referred to as “Tools of the Trade,” reviews the latest products for all-inside meniscal repair. Our “Tools” section will feature announcements and reviews of the hottest new products, with a buying guide and surgical pearls from the surgeons who know them best.

While we are discussing the lower extremity, we should point out that we plan to do the “leg work” for you. Each AJO issue will have handouts that can be downloaded from our website and utilized in your practice. Read Robin West’s article entitled “Interval Throwing and Hitting Programs in Baseball: Biomechanics and Rehabilitation,” and download Return to Throwing and Hitting programs your patients and therapists can use.

Finally, I’d like to thank our previous Editor-in-Chief Dr. Peter McCann for his stewardship the last 10 years and recognize him for his dedication to the journal.

Thank you for reading AJO and for continuing to do so in the future. I know that collectively, we can turn AJO into a product worthy of its title. We know our past reputation. We are no longer that journal. Spend some time to get to know the “new AJO”, and make some room on your shelves, because the information between the covers will provide a template to implement new technologies and revenue streams into your practice and help fulfill your commitment to learning.

As orthopedic surgeons, we’ve made a commitment to lifelong learning. I can’t think of a single surgery that I perform the same way I did when I was in training. With rapidly evolving technology, continuously advancing procedures, and ever-increasing documentation requirements, it’s hard to stay on top of it all. We know your time is precious and that you have less of it than ever before. What little time you have that is not dedicated to work is reserved for your family or your hobbies. There’s no time to read every orthopedic journal, many filled with articles that have no practical value to your practice. That’s why we’ve created the new AJO. Our goal, as an editorial staff, is to provide a journal where every article, column, and feature contains information that directly benefits your practice, your patients, or your bottom line, and keeps you informed of the latest techniques, procedures, and products. We will help surgeons “work smarter, not harder,” implement new technologies into their practices, and find creative revenue streams that are both legal and compliant.

We’ve assembled a team of talented editors to accomplish this task, and will introduce them throughout the coming year. In this issue, you will meet our Deputy Editors-in-Chief and some of our new Associate Editors who’ve collaborated to bring you the “new AJO”.

At this year’s Academy, the AJO launched an extensive rebranding. We have a new look, a new logo, and a new creative directive. The journal will now feature new columns, invited articles, and innovative surgical techniques. We will publish 5 issues for the remainder of 2016. Our March/April issue is a special edition dedicated to baseball. In time for Spring Training/Opening Day, this issue includes articles from Major League Baseball’s physicians and trainers, a “Codes to Know” segment, “Tips of the Trade,” and a “Tools of the Trade” feature. “The Baseball Issue” will set the tone for what readers can expect from the “new AJO”.

Our first feature article, written by Jed Kuhn, takes a philosophical look at the evolution of the throwing shoulder, and invites the reader to help unlock some of the great shoulder anatomy mysteries by viewing them from a time when throwing was an activity of daily living. In ancient times, if you couldn’t throw, you couldn’t eat. We know that children who play baseball remodel their shoulder to allow for increased external rotation. Read Dr. Kuhn’s article and imagine when a shoulder optimized for throwing was a competitive advantage for survival.

Our second feature article is written by Stan Conte, a legend of the game and longtime trainer for the Los Angeles Dodgers. Dr. Conte studied injury trends in baseball over the past 18 seasons and provides an analysis of the staggering cost of placing players on the disabled list.

A baseball issue could not be complete without an article on Tommy John surgery. In this issue, AJO shares a revolutionary new technique for treating players with MUCL tears by author Jeffrey Dugas. Named the “Internal Brace”, Dr. Dugas shares his technique for augmenting the injured MUCL and we are proud to bring it to you first.

A recurring feature in the new AJO will be a section we refer to as “Codes to Know.” In partnership with Karen Zupko, AJO will present little-known coding secrets and proper coding techniques to help you get reimbursed appropriately for your work. This month, in the first article of a 3-part series, Alan Hirahara teaches us how to properly code for a diagnostic ultrasound examination of the shoulder. The article includes templates available for download to assist you with proper documentation. Parts 2 and 3 will provide a tutorial on the proper technique for examinations and injections.

While shoulder and elbow injuries get more attention, Major League Baseball’s Injury Panel has produced a look at the staggering amount of knee injuries over the 2011-2014 seasons, inspiring us to feature the knee in our 2 “Trade” Columns.

The “Tips of the Trade” column will continue, featuring this month a guide to identifying and treating meniscal root tears. A new segment, referred to as “Tools of the Trade,” reviews the latest products for all-inside meniscal repair. Our “Tools” section will feature announcements and reviews of the hottest new products, with a buying guide and surgical pearls from the surgeons who know them best.

While we are discussing the lower extremity, we should point out that we plan to do the “leg work” for you. Each AJO issue will have handouts that can be downloaded from our website and utilized in your practice. Read Robin West’s article entitled “Interval Throwing and Hitting Programs in Baseball: Biomechanics and Rehabilitation,” and download Return to Throwing and Hitting programs your patients and therapists can use.

Finally, I’d like to thank our previous Editor-in-Chief Dr. Peter McCann for his stewardship the last 10 years and recognize him for his dedication to the journal.

Thank you for reading AJO and for continuing to do so in the future. I know that collectively, we can turn AJO into a product worthy of its title. We know our past reputation. We are no longer that journal. Spend some time to get to know the “new AJO”, and make some room on your shelves, because the information between the covers will provide a template to implement new technologies and revenue streams into your practice and help fulfill your commitment to learning.

Piebaldism in Children

Case Report

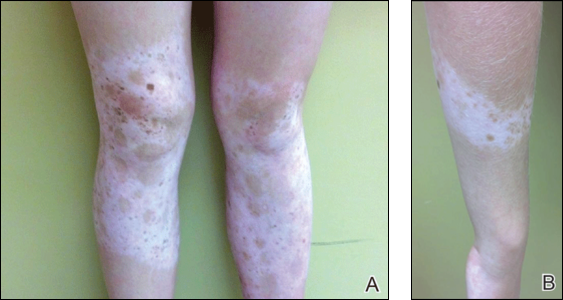

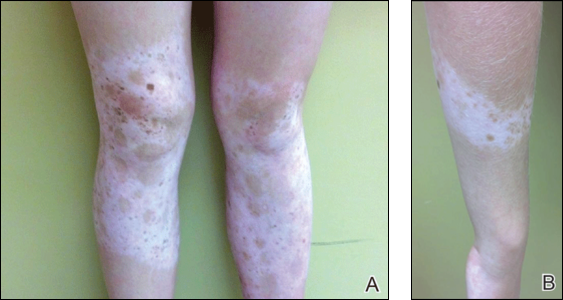

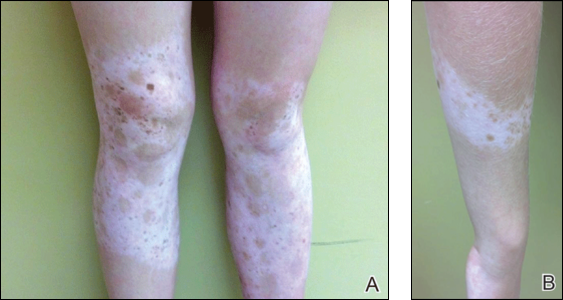

A 14-year-old adolescent girl presented with multiple asymptomatic light-colored patches on the forehead, bilateral arms, and legs that had been present since birth. The patient reported that the size of the patches had increased in proportion to her overall growth and that “brown spots” had gradually started to form within and around the patches. She noted that her father and paternal grandfather also had similar clinical findings. A review of systems was negative for hearing impairment, ocular abnormalities, and recurrent infections.

Physical examination revealed an otherwise healthy adolescent girl with Fitzpatrick skin type I and homogeneous blue eyes. Large symmetric depigmented patches were noted on the extensor surfaces of the mid legs and mid forearms (Figure). Macules of baseline pigment and hyperpigmentation were irregularly scattered within and at the periphery of the patches. A triangular hypopigmented patch at the hairline on the mid frontal scalp hairline was accompanied by depigmentation of terminal hairs in this region.

A clinical diagnosis of piebaldism was made and was discussed at length with the patient. Due to the benign nature of the condition and patient preference, no therapeutic intervention was pursued. It was recommended that she apply sunscreen daily for protection of the depigmented areas.

Comment

Piebaldism is a rare hereditary disorder of melanocyte development characterized clinically by the presence of congenital poliosis and leukoderma.1 The exact prevalence of piebaldism is unknown, but it has been estimated that less than 1 in 20,000 children are born with this condition.2 Poliosis circumscripta, traditionally known as white forelock, may be the only manifestation in 80% to 90% of cases and is present at birth.3 The white forelock typically appears in a triangular shape and the underlying skin of the scalp also is amelanotic. The eyebrows and eyelashes also may be involved.3

Characteristically, lesions of leukoderma are well-circumscribed, irregular, white patches that are often accompanied by hyperpigmented macules noted on both depigmented and unaffected adjacent skin.1 The lesions are classically distributed on the central forehead and anterior trunk, with extension to the flanks, anterior mid arms, and mid legs. Sparing of the dorsal midline, hands, feet, and periorificial area is characteristic.1

Depigmented patches typically are nonprogressive and persist into adulthood. Additional hyperpigmented macules may develop at or within the margins of the white patches. Partial or complete repigmentation may occur spontaneously or after trauma in some patients.2 Some children may develop café au lait lesions and may be misdiagnosed as concurrently having neurofibromatosis type I and piebaldism. If neurofibromatosis type I is suspected, patients should be thoroughly evaluated for other diagnostic criteria of this syndrome, as there may be cases of coexistence and overlap with piebaldism.4

Piebaldism is an autosomal-dominant inherited disorder and most commonly develops as a consequence of a mutation in the c-kit proto-oncogene (located on chromosome arm 14q12), which affects melanoblast migration, proliferation, differentiation, and survival.2 In piebaldism, the site of mutation within the gene correlates with the severity of the phenotype.5 Melanocytes are histologically and ultrastructurally absent or considerably reduced in depigmented patches but are normal in number in the hyperpigmented areas.2

Rare cases of piebaldism have been reported in association with other diseases, including congenital megacolon, congenital dyserythropoietic anemia type II, Diamond-Blackfan anemia, Grover disease (transient acantholytic dermatosis), and glycogen-storage disease type 1a.1,6 Poliosis alone may be the initial presentation of certain genetic syndromes, including Waardenburg syndrome (WS) and tuberous sclerosis; it also may be acquired in the setting of several conditions, including vitiligo, Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada syndrome, Alezzandrini syndrome, alopecia areata, and sarcoidosis.3

Notably, the diagnosis of piebaldism should alert the clinician to the possibility of WS, an autosomal-dominant disease characterized by a congenital white forelock, leukoderma in a piebaldlike distribution, lateral displacement of the medial canthi, a hypertrophic nasal root, heterochromia iridis, and progressive sensorineural hearing loss.7 Four clinical subtypes of WS have been described, with various gene mutations implicated: type 1 is the classic form, type 2 lacks dystopia canthorum and has a stonger association with deafness, type 3 is associated with limb abnormalities, and type 4 is associated with congenital megacolon. A case of WS type 1 has been described in association with facial nerve palsy and lingua plicata, 2 main features of Melkerson-Rosenthal syndrome.8 Depigmentation in WS is caused by the absence of melanocytes in the affected areas as well as failed migration of melanocytes to the ears and eyes.3 Waardenburg syndrome may be distinguished from piebaldism by characteristic facial features of the disease and should prompt a thorough ocular and auditory examination in affected patients.9

Although not a diagnostic criterion, poliosis rarely has been reported as one of the earliest associated findings of tuberous sclerosis.3,10 Major cutaneous features of this disease include facial angiofibromas, hypomelanotic macules, shagreen patches (connective tissue nevi), periungual fibromas, molluscum pendulum, and café au lait macules.

Vitiligo also may be considered in the differential diagnosis of piebaldism and can be distinguished by the presence of depigmented patches in a typical acral and periorificial distribution, lack of congential presentation, and relatively progressive course. Vitiligo is characterized by an acquired loss of epidermal melanocytes, leading to depigmented macules and patches.1,3

Vitiligo, poliosis, and alopecia areata usually are late clinical manifestations of Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada syndrome, a rare condition characterized by an autoimmune response to melanocyte-associated antigens. This condition initially presents with neurologic and ocular manifestations including headache, muscle weakness, tinnitus, uveitis, and choroiditis prior to dermatologic manifestations.11

Alezzandrini syndrome, a rare and closely related disorder, is distinctly characterized by whitening of scalp hair, eyebrows, and eyelashes, along with unilateral depigmentation of facial skin. This presentation is associated with ipsilateral visual changes and hearing abnormalities.12

The absence of abnormal ocular, auditory, and neurologic examinations, along with lack of characteristic cutaneous features indicating any of the aforementioned disorders, highly suggests a diagnosis of piebaldism.

Piebaldism is considered a relatively benign disorder but can be highly socially disabling, which presents a therapeutic challenge in affected children. Depigmented skin in piebaldism generally is considered unresponsive to medical or light therapy.1 Topical treatments with makeup or artificial pigmenting agents (eg, dihydroxyacetone [an ingredient used in sunless tanning products]) are useful but temporary. Sunscreen should be used judiciously to avoid sunburn and reduce carcinogenic potential.13

Several surgical techniques have been reported for treatment of leukoderma but with variable success. Of those reported, micropunch transplantation (minigrafting) using epidermal donor sites of 1 to 1.25 mm is a relatively inexpensive and effective method but is limited by scarring at the donor site.14 Autologous cultured epidermal cellular grafting with a controlled number of melanocytes is reported to achieve greater than 75% repigmentation. It requires fewer donor sites and, therefore, results in less scarring.15 Additionally, use of the erbium-doped:YAG laser aids in deepithelialization of the recipient site, allowing for treatment of large piebald lesions during a single operation.16 Despite these advances, additional studies are needed to improve quality of life in those affected.

- Janjua SA, Khachemoune A, Guldbakke KK. Piebaldism: a case report and a concise review of the literature. Cutis. 2007;80:411-414.

- Agarwal S, Ojha A. Piebaldism: a brief report and review of the literature. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2012;3:144-147.

- Sleiman R, Kurban M, Succaria F, et al. Poliosis circumscripta: overview and underlying causes. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69:625-633.

- Oiso N, Fukai K, Kawada A, et al. Piebaldism. J Dermatol. 2013;40:330-355.

- López V, Jordá E. Piebaldism in a 2-year-old girl. Dermatol Online J. 2011;17:13.

- Ghoshal B, Sarkar N, Bhattacharjee M, et al. Glycogen storage disease 1a with piebaldism. Indian Pediatr. 2012;49:235-236.

- Salvatore S, Carnevale C, Infussi R, et al. Waardenburg syndrome: a review of literature and case reports. Clin Ter. 2012;163:e85-e94.

- Dourmishev AL, Dourmishev LA, Schwartz RA, et al. Waardenburg syndrome. Int J Dermatol. 1999;38:656-663.

- Fistarol SK, Itin PH. Disorders of pigmentation. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2010;8:187-201.

- McWilliam RC, Stephenson JB. Depigmented hair. the earliest sign of tuberous sclerosis. Arch Dis Child. 1978;53:961-963.

- Chan EW, Sanjay S, Chang BC. Headache, red eyes, blurred vision and hearing loss. diagnosis: Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada syndrome. CMAJ. 2010;182:1205-1209.

- Andrade A, Pithon M. Alezzandrini syndrome: report of a sixth clinical case. Dermatology (Basel). 2011;222:8-9.

- Suga Y, Ikejima A, Matsuba S, et al. Medical pearl: DHA application for camouflaging segmental vitiligo and piebald lesions. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;47:436-438.

- Neves DR, Régis Júnior JR, Oliveira PJ, et al. Melanocyte transplant in piebaldism: case report. An Bras Dermatol. 2010;85:384-388.

- Van geel N, Wallaeys E, Goh BK, et al. Long-term results of noncultured epidermal cellular grafting in vitiligo, halo naevi, piebaldism and naevus depigmentosus. Br J Dermatol. 2010;163:1186-1193.

- Guerra L, Primavera G, Raskovic D, et al. Permanent repigmentation of piebaldism by erbium:YAG laser and autologous cultured epidermis. Br J Dermatol. 2004;150:715-721.

Case Report

A 14-year-old adolescent girl presented with multiple asymptomatic light-colored patches on the forehead, bilateral arms, and legs that had been present since birth. The patient reported that the size of the patches had increased in proportion to her overall growth and that “brown spots” had gradually started to form within and around the patches. She noted that her father and paternal grandfather also had similar clinical findings. A review of systems was negative for hearing impairment, ocular abnormalities, and recurrent infections.

Physical examination revealed an otherwise healthy adolescent girl with Fitzpatrick skin type I and homogeneous blue eyes. Large symmetric depigmented patches were noted on the extensor surfaces of the mid legs and mid forearms (Figure). Macules of baseline pigment and hyperpigmentation were irregularly scattered within and at the periphery of the patches. A triangular hypopigmented patch at the hairline on the mid frontal scalp hairline was accompanied by depigmentation of terminal hairs in this region.

A clinical diagnosis of piebaldism was made and was discussed at length with the patient. Due to the benign nature of the condition and patient preference, no therapeutic intervention was pursued. It was recommended that she apply sunscreen daily for protection of the depigmented areas.

Comment

Piebaldism is a rare hereditary disorder of melanocyte development characterized clinically by the presence of congenital poliosis and leukoderma.1 The exact prevalence of piebaldism is unknown, but it has been estimated that less than 1 in 20,000 children are born with this condition.2 Poliosis circumscripta, traditionally known as white forelock, may be the only manifestation in 80% to 90% of cases and is present at birth.3 The white forelock typically appears in a triangular shape and the underlying skin of the scalp also is amelanotic. The eyebrows and eyelashes also may be involved.3

Characteristically, lesions of leukoderma are well-circumscribed, irregular, white patches that are often accompanied by hyperpigmented macules noted on both depigmented and unaffected adjacent skin.1 The lesions are classically distributed on the central forehead and anterior trunk, with extension to the flanks, anterior mid arms, and mid legs. Sparing of the dorsal midline, hands, feet, and periorificial area is characteristic.1

Depigmented patches typically are nonprogressive and persist into adulthood. Additional hyperpigmented macules may develop at or within the margins of the white patches. Partial or complete repigmentation may occur spontaneously or after trauma in some patients.2 Some children may develop café au lait lesions and may be misdiagnosed as concurrently having neurofibromatosis type I and piebaldism. If neurofibromatosis type I is suspected, patients should be thoroughly evaluated for other diagnostic criteria of this syndrome, as there may be cases of coexistence and overlap with piebaldism.4

Piebaldism is an autosomal-dominant inherited disorder and most commonly develops as a consequence of a mutation in the c-kit proto-oncogene (located on chromosome arm 14q12), which affects melanoblast migration, proliferation, differentiation, and survival.2 In piebaldism, the site of mutation within the gene correlates with the severity of the phenotype.5 Melanocytes are histologically and ultrastructurally absent or considerably reduced in depigmented patches but are normal in number in the hyperpigmented areas.2

Rare cases of piebaldism have been reported in association with other diseases, including congenital megacolon, congenital dyserythropoietic anemia type II, Diamond-Blackfan anemia, Grover disease (transient acantholytic dermatosis), and glycogen-storage disease type 1a.1,6 Poliosis alone may be the initial presentation of certain genetic syndromes, including Waardenburg syndrome (WS) and tuberous sclerosis; it also may be acquired in the setting of several conditions, including vitiligo, Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada syndrome, Alezzandrini syndrome, alopecia areata, and sarcoidosis.3

Notably, the diagnosis of piebaldism should alert the clinician to the possibility of WS, an autosomal-dominant disease characterized by a congenital white forelock, leukoderma in a piebaldlike distribution, lateral displacement of the medial canthi, a hypertrophic nasal root, heterochromia iridis, and progressive sensorineural hearing loss.7 Four clinical subtypes of WS have been described, with various gene mutations implicated: type 1 is the classic form, type 2 lacks dystopia canthorum and has a stonger association with deafness, type 3 is associated with limb abnormalities, and type 4 is associated with congenital megacolon. A case of WS type 1 has been described in association with facial nerve palsy and lingua plicata, 2 main features of Melkerson-Rosenthal syndrome.8 Depigmentation in WS is caused by the absence of melanocytes in the affected areas as well as failed migration of melanocytes to the ears and eyes.3 Waardenburg syndrome may be distinguished from piebaldism by characteristic facial features of the disease and should prompt a thorough ocular and auditory examination in affected patients.9

Although not a diagnostic criterion, poliosis rarely has been reported as one of the earliest associated findings of tuberous sclerosis.3,10 Major cutaneous features of this disease include facial angiofibromas, hypomelanotic macules, shagreen patches (connective tissue nevi), periungual fibromas, molluscum pendulum, and café au lait macules.

Vitiligo also may be considered in the differential diagnosis of piebaldism and can be distinguished by the presence of depigmented patches in a typical acral and periorificial distribution, lack of congential presentation, and relatively progressive course. Vitiligo is characterized by an acquired loss of epidermal melanocytes, leading to depigmented macules and patches.1,3

Vitiligo, poliosis, and alopecia areata usually are late clinical manifestations of Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada syndrome, a rare condition characterized by an autoimmune response to melanocyte-associated antigens. This condition initially presents with neurologic and ocular manifestations including headache, muscle weakness, tinnitus, uveitis, and choroiditis prior to dermatologic manifestations.11

Alezzandrini syndrome, a rare and closely related disorder, is distinctly characterized by whitening of scalp hair, eyebrows, and eyelashes, along with unilateral depigmentation of facial skin. This presentation is associated with ipsilateral visual changes and hearing abnormalities.12

The absence of abnormal ocular, auditory, and neurologic examinations, along with lack of characteristic cutaneous features indicating any of the aforementioned disorders, highly suggests a diagnosis of piebaldism.

Piebaldism is considered a relatively benign disorder but can be highly socially disabling, which presents a therapeutic challenge in affected children. Depigmented skin in piebaldism generally is considered unresponsive to medical or light therapy.1 Topical treatments with makeup or artificial pigmenting agents (eg, dihydroxyacetone [an ingredient used in sunless tanning products]) are useful but temporary. Sunscreen should be used judiciously to avoid sunburn and reduce carcinogenic potential.13

Several surgical techniques have been reported for treatment of leukoderma but with variable success. Of those reported, micropunch transplantation (minigrafting) using epidermal donor sites of 1 to 1.25 mm is a relatively inexpensive and effective method but is limited by scarring at the donor site.14 Autologous cultured epidermal cellular grafting with a controlled number of melanocytes is reported to achieve greater than 75% repigmentation. It requires fewer donor sites and, therefore, results in less scarring.15 Additionally, use of the erbium-doped:YAG laser aids in deepithelialization of the recipient site, allowing for treatment of large piebald lesions during a single operation.16 Despite these advances, additional studies are needed to improve quality of life in those affected.

Case Report

A 14-year-old adolescent girl presented with multiple asymptomatic light-colored patches on the forehead, bilateral arms, and legs that had been present since birth. The patient reported that the size of the patches had increased in proportion to her overall growth and that “brown spots” had gradually started to form within and around the patches. She noted that her father and paternal grandfather also had similar clinical findings. A review of systems was negative for hearing impairment, ocular abnormalities, and recurrent infections.

Physical examination revealed an otherwise healthy adolescent girl with Fitzpatrick skin type I and homogeneous blue eyes. Large symmetric depigmented patches were noted on the extensor surfaces of the mid legs and mid forearms (Figure). Macules of baseline pigment and hyperpigmentation were irregularly scattered within and at the periphery of the patches. A triangular hypopigmented patch at the hairline on the mid frontal scalp hairline was accompanied by depigmentation of terminal hairs in this region.

A clinical diagnosis of piebaldism was made and was discussed at length with the patient. Due to the benign nature of the condition and patient preference, no therapeutic intervention was pursued. It was recommended that she apply sunscreen daily for protection of the depigmented areas.

Comment

Piebaldism is a rare hereditary disorder of melanocyte development characterized clinically by the presence of congenital poliosis and leukoderma.1 The exact prevalence of piebaldism is unknown, but it has been estimated that less than 1 in 20,000 children are born with this condition.2 Poliosis circumscripta, traditionally known as white forelock, may be the only manifestation in 80% to 90% of cases and is present at birth.3 The white forelock typically appears in a triangular shape and the underlying skin of the scalp also is amelanotic. The eyebrows and eyelashes also may be involved.3

Characteristically, lesions of leukoderma are well-circumscribed, irregular, white patches that are often accompanied by hyperpigmented macules noted on both depigmented and unaffected adjacent skin.1 The lesions are classically distributed on the central forehead and anterior trunk, with extension to the flanks, anterior mid arms, and mid legs. Sparing of the dorsal midline, hands, feet, and periorificial area is characteristic.1

Depigmented patches typically are nonprogressive and persist into adulthood. Additional hyperpigmented macules may develop at or within the margins of the white patches. Partial or complete repigmentation may occur spontaneously or after trauma in some patients.2 Some children may develop café au lait lesions and may be misdiagnosed as concurrently having neurofibromatosis type I and piebaldism. If neurofibromatosis type I is suspected, patients should be thoroughly evaluated for other diagnostic criteria of this syndrome, as there may be cases of coexistence and overlap with piebaldism.4

Piebaldism is an autosomal-dominant inherited disorder and most commonly develops as a consequence of a mutation in the c-kit proto-oncogene (located on chromosome arm 14q12), which affects melanoblast migration, proliferation, differentiation, and survival.2 In piebaldism, the site of mutation within the gene correlates with the severity of the phenotype.5 Melanocytes are histologically and ultrastructurally absent or considerably reduced in depigmented patches but are normal in number in the hyperpigmented areas.2

Rare cases of piebaldism have been reported in association with other diseases, including congenital megacolon, congenital dyserythropoietic anemia type II, Diamond-Blackfan anemia, Grover disease (transient acantholytic dermatosis), and glycogen-storage disease type 1a.1,6 Poliosis alone may be the initial presentation of certain genetic syndromes, including Waardenburg syndrome (WS) and tuberous sclerosis; it also may be acquired in the setting of several conditions, including vitiligo, Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada syndrome, Alezzandrini syndrome, alopecia areata, and sarcoidosis.3

Notably, the diagnosis of piebaldism should alert the clinician to the possibility of WS, an autosomal-dominant disease characterized by a congenital white forelock, leukoderma in a piebaldlike distribution, lateral displacement of the medial canthi, a hypertrophic nasal root, heterochromia iridis, and progressive sensorineural hearing loss.7 Four clinical subtypes of WS have been described, with various gene mutations implicated: type 1 is the classic form, type 2 lacks dystopia canthorum and has a stonger association with deafness, type 3 is associated with limb abnormalities, and type 4 is associated with congenital megacolon. A case of WS type 1 has been described in association with facial nerve palsy and lingua plicata, 2 main features of Melkerson-Rosenthal syndrome.8 Depigmentation in WS is caused by the absence of melanocytes in the affected areas as well as failed migration of melanocytes to the ears and eyes.3 Waardenburg syndrome may be distinguished from piebaldism by characteristic facial features of the disease and should prompt a thorough ocular and auditory examination in affected patients.9

Although not a diagnostic criterion, poliosis rarely has been reported as one of the earliest associated findings of tuberous sclerosis.3,10 Major cutaneous features of this disease include facial angiofibromas, hypomelanotic macules, shagreen patches (connective tissue nevi), periungual fibromas, molluscum pendulum, and café au lait macules.

Vitiligo also may be considered in the differential diagnosis of piebaldism and can be distinguished by the presence of depigmented patches in a typical acral and periorificial distribution, lack of congential presentation, and relatively progressive course. Vitiligo is characterized by an acquired loss of epidermal melanocytes, leading to depigmented macules and patches.1,3

Vitiligo, poliosis, and alopecia areata usually are late clinical manifestations of Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada syndrome, a rare condition characterized by an autoimmune response to melanocyte-associated antigens. This condition initially presents with neurologic and ocular manifestations including headache, muscle weakness, tinnitus, uveitis, and choroiditis prior to dermatologic manifestations.11

Alezzandrini syndrome, a rare and closely related disorder, is distinctly characterized by whitening of scalp hair, eyebrows, and eyelashes, along with unilateral depigmentation of facial skin. This presentation is associated with ipsilateral visual changes and hearing abnormalities.12

The absence of abnormal ocular, auditory, and neurologic examinations, along with lack of characteristic cutaneous features indicating any of the aforementioned disorders, highly suggests a diagnosis of piebaldism.

Piebaldism is considered a relatively benign disorder but can be highly socially disabling, which presents a therapeutic challenge in affected children. Depigmented skin in piebaldism generally is considered unresponsive to medical or light therapy.1 Topical treatments with makeup or artificial pigmenting agents (eg, dihydroxyacetone [an ingredient used in sunless tanning products]) are useful but temporary. Sunscreen should be used judiciously to avoid sunburn and reduce carcinogenic potential.13

Several surgical techniques have been reported for treatment of leukoderma but with variable success. Of those reported, micropunch transplantation (minigrafting) using epidermal donor sites of 1 to 1.25 mm is a relatively inexpensive and effective method but is limited by scarring at the donor site.14 Autologous cultured epidermal cellular grafting with a controlled number of melanocytes is reported to achieve greater than 75% repigmentation. It requires fewer donor sites and, therefore, results in less scarring.15 Additionally, use of the erbium-doped:YAG laser aids in deepithelialization of the recipient site, allowing for treatment of large piebald lesions during a single operation.16 Despite these advances, additional studies are needed to improve quality of life in those affected.

- Janjua SA, Khachemoune A, Guldbakke KK. Piebaldism: a case report and a concise review of the literature. Cutis. 2007;80:411-414.

- Agarwal S, Ojha A. Piebaldism: a brief report and review of the literature. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2012;3:144-147.

- Sleiman R, Kurban M, Succaria F, et al. Poliosis circumscripta: overview and underlying causes. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69:625-633.

- Oiso N, Fukai K, Kawada A, et al. Piebaldism. J Dermatol. 2013;40:330-355.

- López V, Jordá E. Piebaldism in a 2-year-old girl. Dermatol Online J. 2011;17:13.

- Ghoshal B, Sarkar N, Bhattacharjee M, et al. Glycogen storage disease 1a with piebaldism. Indian Pediatr. 2012;49:235-236.

- Salvatore S, Carnevale C, Infussi R, et al. Waardenburg syndrome: a review of literature and case reports. Clin Ter. 2012;163:e85-e94.

- Dourmishev AL, Dourmishev LA, Schwartz RA, et al. Waardenburg syndrome. Int J Dermatol. 1999;38:656-663.

- Fistarol SK, Itin PH. Disorders of pigmentation. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2010;8:187-201.

- McWilliam RC, Stephenson JB. Depigmented hair. the earliest sign of tuberous sclerosis. Arch Dis Child. 1978;53:961-963.

- Chan EW, Sanjay S, Chang BC. Headache, red eyes, blurred vision and hearing loss. diagnosis: Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada syndrome. CMAJ. 2010;182:1205-1209.

- Andrade A, Pithon M. Alezzandrini syndrome: report of a sixth clinical case. Dermatology (Basel). 2011;222:8-9.

- Suga Y, Ikejima A, Matsuba S, et al. Medical pearl: DHA application for camouflaging segmental vitiligo and piebald lesions. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;47:436-438.

- Neves DR, Régis Júnior JR, Oliveira PJ, et al. Melanocyte transplant in piebaldism: case report. An Bras Dermatol. 2010;85:384-388.

- Van geel N, Wallaeys E, Goh BK, et al. Long-term results of noncultured epidermal cellular grafting in vitiligo, halo naevi, piebaldism and naevus depigmentosus. Br J Dermatol. 2010;163:1186-1193.

- Guerra L, Primavera G, Raskovic D, et al. Permanent repigmentation of piebaldism by erbium:YAG laser and autologous cultured epidermis. Br J Dermatol. 2004;150:715-721.

- Janjua SA, Khachemoune A, Guldbakke KK. Piebaldism: a case report and a concise review of the literature. Cutis. 2007;80:411-414.

- Agarwal S, Ojha A. Piebaldism: a brief report and review of the literature. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2012;3:144-147.

- Sleiman R, Kurban M, Succaria F, et al. Poliosis circumscripta: overview and underlying causes. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69:625-633.

- Oiso N, Fukai K, Kawada A, et al. Piebaldism. J Dermatol. 2013;40:330-355.

- López V, Jordá E. Piebaldism in a 2-year-old girl. Dermatol Online J. 2011;17:13.

- Ghoshal B, Sarkar N, Bhattacharjee M, et al. Glycogen storage disease 1a with piebaldism. Indian Pediatr. 2012;49:235-236.

- Salvatore S, Carnevale C, Infussi R, et al. Waardenburg syndrome: a review of literature and case reports. Clin Ter. 2012;163:e85-e94.

- Dourmishev AL, Dourmishev LA, Schwartz RA, et al. Waardenburg syndrome. Int J Dermatol. 1999;38:656-663.

- Fistarol SK, Itin PH. Disorders of pigmentation. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2010;8:187-201.

- McWilliam RC, Stephenson JB. Depigmented hair. the earliest sign of tuberous sclerosis. Arch Dis Child. 1978;53:961-963.

- Chan EW, Sanjay S, Chang BC. Headache, red eyes, blurred vision and hearing loss. diagnosis: Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada syndrome. CMAJ. 2010;182:1205-1209.

- Andrade A, Pithon M. Alezzandrini syndrome: report of a sixth clinical case. Dermatology (Basel). 2011;222:8-9.

- Suga Y, Ikejima A, Matsuba S, et al. Medical pearl: DHA application for camouflaging segmental vitiligo and piebald lesions. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;47:436-438.

- Neves DR, Régis Júnior JR, Oliveira PJ, et al. Melanocyte transplant in piebaldism: case report. An Bras Dermatol. 2010;85:384-388.

- Van geel N, Wallaeys E, Goh BK, et al. Long-term results of noncultured epidermal cellular grafting in vitiligo, halo naevi, piebaldism and naevus depigmentosus. Br J Dermatol. 2010;163:1186-1193.