User login

The Importance of Lymph Node Retrieval and Lymph Node Ratio in Male Patients With Colorectal Cancer: A 5-Year Retrospective Single Institution Study

Background: The National Comprehensive Cancer Network and the American Joint Committee on Cancer recommend retrieving > 12 lymph nodes for adequate colorectal cancer (CRC) staging. Nodal status and presence of metastasis is an important prognostic factor and may guide decision making for adjuvant chemotherapy. Recent data have shown variable results for survival based on the number of lymph nodes sampled and the ratio of positive lymph nodes of the total sampled. In our study, we aimed to assess the influence of lymph node retrieval and positive lymph node status on overall survival of male veteran patients with CRC.

Methods: A retrospective chart review study at a VA medical center in a large metropolitan area was conducted. Charts of patients diagnosed with colon cancer from January 1, 2008, to January 1, 2012, were reviewed, and data on age, diagnosis of cancer, symptoms, histologic type of tumor, stage, number of lymph nodes harvested, number of lymph nodes positive for cancer, tumor invasion, date of diagnosis, and date of death were recorded. Descriptive statistics, including average/median, range, and standard deviation were calculated. Lymph node ratio (LNR) was calculated from the number of lymph nodes positive for cancer of the total number of lymph nodes harvested. Survival was calculated from date of diagnosis to date of death. Differences in survival were assessed through t tests for different groups. Pearson’s correlations and regression analysis were carried out for survival for the 4 groups of interest (< 12 nodes harvested, ≥ 12 nodes harvested. Lymph node ratio < 0.2, and LNR > 0.2)

Results: Data from 84 patients were obtained with a median survival of 299 days. On diagnosis, 26 (31%) were stage I, 21 (25%) were stage II, 16 (18%) were stage III, and 21 (25%) were stage IV. Twenty-three (27.3%) patients had local invasion at time of diagnosis. An average of 14.5 lymph nodes (range 4-29) were sampled per patient. Twenty-two (26%) patients had < 12 nodes sampled, and 42 (50%) had ≥ 12 nodes sampled. The average LNR for the whole group was 0.07 (SD ± 0.15). There was no significant difference in sur-vival between the patient groups who had < 12 LNs sampled vs those who had 12 or more LNs sampled (mean 316.6 days vs 543.6 days, t = 0.82, df 11, P = .42). There was no significant difference in survival between the patient groups who had LNR < 0.2 vs those who had LNR > 0.2 (mean 450.7 days vs 580.0 days, t = 0.50, df 9, P = .62).There were no significant differences in survival based on mode of diagnosis (screening colonoscopy vs presence of symptoms) or presence of local invasion at diagnosis.

Conclusion: This study did not find that number of harvested LNs as well as LNR had an impact on survival.

Background: The National Comprehensive Cancer Network and the American Joint Committee on Cancer recommend retrieving > 12 lymph nodes for adequate colorectal cancer (CRC) staging. Nodal status and presence of metastasis is an important prognostic factor and may guide decision making for adjuvant chemotherapy. Recent data have shown variable results for survival based on the number of lymph nodes sampled and the ratio of positive lymph nodes of the total sampled. In our study, we aimed to assess the influence of lymph node retrieval and positive lymph node status on overall survival of male veteran patients with CRC.

Methods: A retrospective chart review study at a VA medical center in a large metropolitan area was conducted. Charts of patients diagnosed with colon cancer from January 1, 2008, to January 1, 2012, were reviewed, and data on age, diagnosis of cancer, symptoms, histologic type of tumor, stage, number of lymph nodes harvested, number of lymph nodes positive for cancer, tumor invasion, date of diagnosis, and date of death were recorded. Descriptive statistics, including average/median, range, and standard deviation were calculated. Lymph node ratio (LNR) was calculated from the number of lymph nodes positive for cancer of the total number of lymph nodes harvested. Survival was calculated from date of diagnosis to date of death. Differences in survival were assessed through t tests for different groups. Pearson’s correlations and regression analysis were carried out for survival for the 4 groups of interest (< 12 nodes harvested, ≥ 12 nodes harvested. Lymph node ratio < 0.2, and LNR > 0.2)

Results: Data from 84 patients were obtained with a median survival of 299 days. On diagnosis, 26 (31%) were stage I, 21 (25%) were stage II, 16 (18%) were stage III, and 21 (25%) were stage IV. Twenty-three (27.3%) patients had local invasion at time of diagnosis. An average of 14.5 lymph nodes (range 4-29) were sampled per patient. Twenty-two (26%) patients had < 12 nodes sampled, and 42 (50%) had ≥ 12 nodes sampled. The average LNR for the whole group was 0.07 (SD ± 0.15). There was no significant difference in sur-vival between the patient groups who had < 12 LNs sampled vs those who had 12 or more LNs sampled (mean 316.6 days vs 543.6 days, t = 0.82, df 11, P = .42). There was no significant difference in survival between the patient groups who had LNR < 0.2 vs those who had LNR > 0.2 (mean 450.7 days vs 580.0 days, t = 0.50, df 9, P = .62).There were no significant differences in survival based on mode of diagnosis (screening colonoscopy vs presence of symptoms) or presence of local invasion at diagnosis.

Conclusion: This study did not find that number of harvested LNs as well as LNR had an impact on survival.

Background: The National Comprehensive Cancer Network and the American Joint Committee on Cancer recommend retrieving > 12 lymph nodes for adequate colorectal cancer (CRC) staging. Nodal status and presence of metastasis is an important prognostic factor and may guide decision making for adjuvant chemotherapy. Recent data have shown variable results for survival based on the number of lymph nodes sampled and the ratio of positive lymph nodes of the total sampled. In our study, we aimed to assess the influence of lymph node retrieval and positive lymph node status on overall survival of male veteran patients with CRC.

Methods: A retrospective chart review study at a VA medical center in a large metropolitan area was conducted. Charts of patients diagnosed with colon cancer from January 1, 2008, to January 1, 2012, were reviewed, and data on age, diagnosis of cancer, symptoms, histologic type of tumor, stage, number of lymph nodes harvested, number of lymph nodes positive for cancer, tumor invasion, date of diagnosis, and date of death were recorded. Descriptive statistics, including average/median, range, and standard deviation were calculated. Lymph node ratio (LNR) was calculated from the number of lymph nodes positive for cancer of the total number of lymph nodes harvested. Survival was calculated from date of diagnosis to date of death. Differences in survival were assessed through t tests for different groups. Pearson’s correlations and regression analysis were carried out for survival for the 4 groups of interest (< 12 nodes harvested, ≥ 12 nodes harvested. Lymph node ratio < 0.2, and LNR > 0.2)

Results: Data from 84 patients were obtained with a median survival of 299 days. On diagnosis, 26 (31%) were stage I, 21 (25%) were stage II, 16 (18%) were stage III, and 21 (25%) were stage IV. Twenty-three (27.3%) patients had local invasion at time of diagnosis. An average of 14.5 lymph nodes (range 4-29) were sampled per patient. Twenty-two (26%) patients had < 12 nodes sampled, and 42 (50%) had ≥ 12 nodes sampled. The average LNR for the whole group was 0.07 (SD ± 0.15). There was no significant difference in sur-vival between the patient groups who had < 12 LNs sampled vs those who had 12 or more LNs sampled (mean 316.6 days vs 543.6 days, t = 0.82, df 11, P = .42). There was no significant difference in survival between the patient groups who had LNR < 0.2 vs those who had LNR > 0.2 (mean 450.7 days vs 580.0 days, t = 0.50, df 9, P = .62).There were no significant differences in survival based on mode of diagnosis (screening colonoscopy vs presence of symptoms) or presence of local invasion at diagnosis.

Conclusion: This study did not find that number of harvested LNs as well as LNR had an impact on survival.

LISTEN NOW: Pediatric Hospital Medicine and the “Right Care” Movement

Three pediatric hospitalists – Dr. Ricardo Quiñonez of San Antonio Children’s Hospital, Dr. Shawn Ralston of Dartmouth-Hitchcock, and Dr. Alan Schroeder of Santa Clara Valley Medical Center – talk about the concept of “right care” in hospital medicine, and their participation in the Lown Institute’s Right Care movement.

Three pediatric hospitalists – Dr. Ricardo Quiñonez of San Antonio Children’s Hospital, Dr. Shawn Ralston of Dartmouth-Hitchcock, and Dr. Alan Schroeder of Santa Clara Valley Medical Center – talk about the concept of “right care” in hospital medicine, and their participation in the Lown Institute’s Right Care movement.

Three pediatric hospitalists – Dr. Ricardo Quiñonez of San Antonio Children’s Hospital, Dr. Shawn Ralston of Dartmouth-Hitchcock, and Dr. Alan Schroeder of Santa Clara Valley Medical Center – talk about the concept of “right care” in hospital medicine, and their participation in the Lown Institute’s Right Care movement.

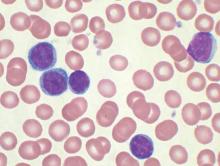

No evidence for CLL transmission via blood transfusion

Analysis of data from blood transfusions that took place in Sweden and Denmark over a 30-year period showed no indication that chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) risk is higher among recipients of blood from donors who subsequently developed CLL, according to researchers.

The study compared 7,413 recipients of blood from 796 donors who subsequently developed CLL (exposed group), with 80,431 recipients from 7,477 donors free of CLL (unexposed group). In total, 12 recipients in the exposed group and 107 in the unexposed group were later diagnosed with CLL, for an incidence rate ratio of 0.94 (95% confidence interval, 0.52-1.71). When defining “exposed” as receiving blood less than 10 years before donor CLL diagnosis, the incidence rate ratio was 0.46 (95% CI, 0.12-1.85).

“The analyses provided little evidence that donor MBL [monoclonal B-cell lymphocytosis]/CLL transmission in blood products influences recipient CLL risk,” wrote Dr. Henrik Hjalgrim of the department of epidemiology research at Statens Serum Institut, Copenhagen, and his colleagues (Blood 2015 doi: 10.1182/blood-2015-03-632844).

MBL is fairly common in healthy individuals (estimated at 7.1% in a study of American blood donors aged 45-91 years) and may progress to CLL at various rates depending on the MBL cell count. Results from previous studies investigating the association between transfusion and risk of CLL or small lymphocytic lymphoma have been mixed, they noted.

Using a retrospective approach, Dr. Hjalgrim and his associates first identified donors subsequently diagnosed with CLL, then identified control donors free from CLL who were matched for age, sex, county, number of donations, and blood type.

In case MBL may have progressed in the recipient but not the donor, investigators also examined whether CLL clustered among recipients from an individual donor, regardless of donor CLL status, but found no such clusters.

Limiting the analysis was the lack of donor MBL status, for which postdonation CLL diagnosis substituted. Some recipients in the exposed group may have received blood drawn before the donor developed MBL.

Dr. Hjalgrim and his coauthors reported having no disclosures.

Analysis of data from blood transfusions that took place in Sweden and Denmark over a 30-year period showed no indication that chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) risk is higher among recipients of blood from donors who subsequently developed CLL, according to researchers.

The study compared 7,413 recipients of blood from 796 donors who subsequently developed CLL (exposed group), with 80,431 recipients from 7,477 donors free of CLL (unexposed group). In total, 12 recipients in the exposed group and 107 in the unexposed group were later diagnosed with CLL, for an incidence rate ratio of 0.94 (95% confidence interval, 0.52-1.71). When defining “exposed” as receiving blood less than 10 years before donor CLL diagnosis, the incidence rate ratio was 0.46 (95% CI, 0.12-1.85).

“The analyses provided little evidence that donor MBL [monoclonal B-cell lymphocytosis]/CLL transmission in blood products influences recipient CLL risk,” wrote Dr. Henrik Hjalgrim of the department of epidemiology research at Statens Serum Institut, Copenhagen, and his colleagues (Blood 2015 doi: 10.1182/blood-2015-03-632844).

MBL is fairly common in healthy individuals (estimated at 7.1% in a study of American blood donors aged 45-91 years) and may progress to CLL at various rates depending on the MBL cell count. Results from previous studies investigating the association between transfusion and risk of CLL or small lymphocytic lymphoma have been mixed, they noted.

Using a retrospective approach, Dr. Hjalgrim and his associates first identified donors subsequently diagnosed with CLL, then identified control donors free from CLL who were matched for age, sex, county, number of donations, and blood type.

In case MBL may have progressed in the recipient but not the donor, investigators also examined whether CLL clustered among recipients from an individual donor, regardless of donor CLL status, but found no such clusters.

Limiting the analysis was the lack of donor MBL status, for which postdonation CLL diagnosis substituted. Some recipients in the exposed group may have received blood drawn before the donor developed MBL.

Dr. Hjalgrim and his coauthors reported having no disclosures.

Analysis of data from blood transfusions that took place in Sweden and Denmark over a 30-year period showed no indication that chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) risk is higher among recipients of blood from donors who subsequently developed CLL, according to researchers.

The study compared 7,413 recipients of blood from 796 donors who subsequently developed CLL (exposed group), with 80,431 recipients from 7,477 donors free of CLL (unexposed group). In total, 12 recipients in the exposed group and 107 in the unexposed group were later diagnosed with CLL, for an incidence rate ratio of 0.94 (95% confidence interval, 0.52-1.71). When defining “exposed” as receiving blood less than 10 years before donor CLL diagnosis, the incidence rate ratio was 0.46 (95% CI, 0.12-1.85).

“The analyses provided little evidence that donor MBL [monoclonal B-cell lymphocytosis]/CLL transmission in blood products influences recipient CLL risk,” wrote Dr. Henrik Hjalgrim of the department of epidemiology research at Statens Serum Institut, Copenhagen, and his colleagues (Blood 2015 doi: 10.1182/blood-2015-03-632844).

MBL is fairly common in healthy individuals (estimated at 7.1% in a study of American blood donors aged 45-91 years) and may progress to CLL at various rates depending on the MBL cell count. Results from previous studies investigating the association between transfusion and risk of CLL or small lymphocytic lymphoma have been mixed, they noted.

Using a retrospective approach, Dr. Hjalgrim and his associates first identified donors subsequently diagnosed with CLL, then identified control donors free from CLL who were matched for age, sex, county, number of donations, and blood type.

In case MBL may have progressed in the recipient but not the donor, investigators also examined whether CLL clustered among recipients from an individual donor, regardless of donor CLL status, but found no such clusters.

Limiting the analysis was the lack of donor MBL status, for which postdonation CLL diagnosis substituted. Some recipients in the exposed group may have received blood drawn before the donor developed MBL.

Dr. Hjalgrim and his coauthors reported having no disclosures.

FROM BLOOD

Key clinical point: There is no evidence for higher risk of chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) among recipients of blood products from donors who subsequently were diagnosed with CLL.

Major finding: Among exposed recipients (7,413 who received blood from 796 donors who subsequently developed CLL), 12 were diagnosed with CLL. Among unexposed recipients (80,431 who received blood from 7,477 donors free of CLL), 107 were diagnosed with CLL, for an incidence rate ratio of 0.94 (95% CI, 0.52-1.71).

Data source: The Scandinavian Donations and Transfusions (SCANDAT2) database comprises information, including donor and recipient health outcomes, for more than 20 million blood products handled by blood banks from 1968 to 2010.

Disclosures: Dr. Hjalgrim and his coauthors reported having no disclosures.

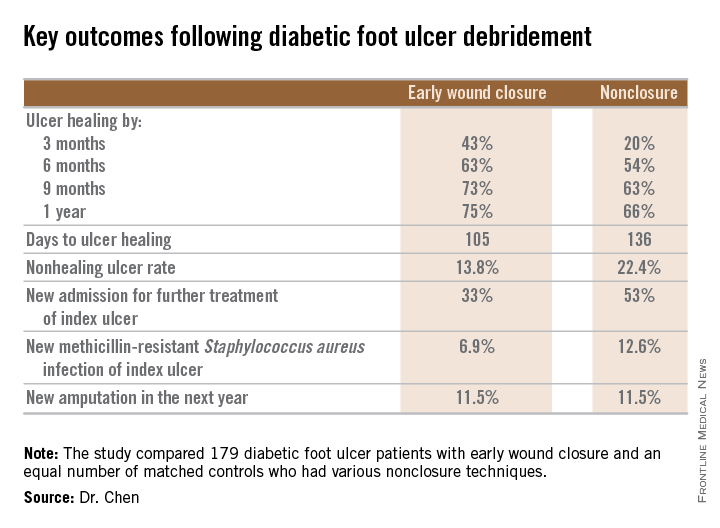

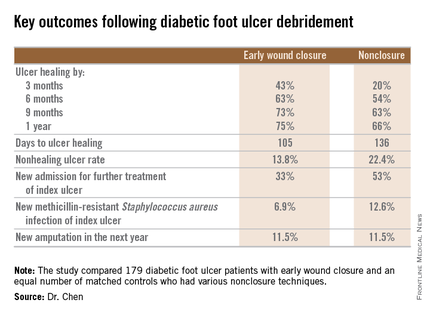

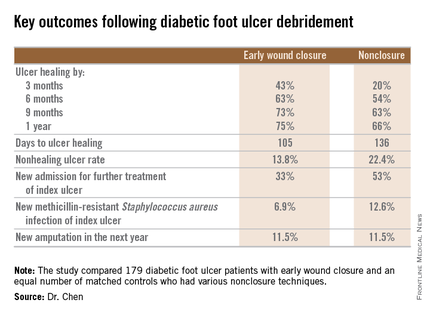

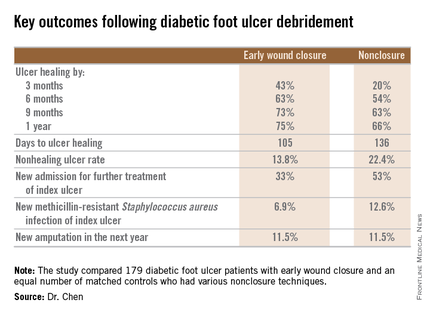

Diabetic foot ulcer: Early closure post debridement best

SAN DIEGO – Early wound closure prior to hospital discharge after surgical debridement of infected diabetic foot ulcers yields higher ulcer healing rates and a shorter time to healing, compared with various nonclosure wound management methods, according to a propensity-matched study.

How best to manage the open wound following nonamputative surgery of infected diabetic foot ulcers has been controversial. But early wound closure during the index hospitalization was the clear winner in this comparative study, Dr. Shey-Ying Chen reported at the annual Interscience Conference on Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy.

He presented a retrospective comparison between 179 diabetic foot ulcer (DFU) patients with early wound closure after surgical debridement and an equal number of matched controls treated with various nonclosure techniques, including negative pressure wound therapy and the repeated application of moist dressings. The two study groups were matched first on the basis of DFU location – toe, forefoot, midfoot, or rear foot – and then further propensity matched based on demographics, comorbid conditions, the presence of neuropathy, ulcer status by Wagner classification, infection severity, revascularization procedures, and other variables.

During 1 year of follow-up post discharge, ulcer healing occurred in 75% of the early wound closure group, compared with 66% of the nonclosure patients. Readmission for further treatment of the index ulcer occurred in 33% of the early closure group and 52% of the nonclosure group. Other outcomes were also superior in the early wound closure group, noted Dr. Chen of Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston.

Two independent predictors of DFU healing during the follow-up period emerged from a Cox regression analysis: early wound closure, with an adjusted odds ratio of 1.63, and acute as opposed to chronic DFU, with an OR of 1.35.

Ulcer healing was significantly less likely in patients with peripheral vascular disease, with an OR of 0.62; neuropathy, with an OR of 0.53; and methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus wound infection, with an OR of 0.59, he continued.

Underscoring the longer-term difficulties faced by patients with DFUs, it’s noteworthy that 11.5% of patients in both study arms underwent new amputations during the year of follow-up. Moreover, a new diagnosis of osteomyelitis was made in 20% of the early wound closure group and 26% of the nonclosure group, a nonsignificant difference.

Dr. Adolf W. Karchmer, Dr. Chen’s senior coinvestigator, said the outcome data are too new to be able to gauge how vascular, orthopedic, and podiatric surgeons will react.

The investigators reported having no financial conflicts with regard to this study, conducted without commercial sponsorship.

SAN DIEGO – Early wound closure prior to hospital discharge after surgical debridement of infected diabetic foot ulcers yields higher ulcer healing rates and a shorter time to healing, compared with various nonclosure wound management methods, according to a propensity-matched study.

How best to manage the open wound following nonamputative surgery of infected diabetic foot ulcers has been controversial. But early wound closure during the index hospitalization was the clear winner in this comparative study, Dr. Shey-Ying Chen reported at the annual Interscience Conference on Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy.

He presented a retrospective comparison between 179 diabetic foot ulcer (DFU) patients with early wound closure after surgical debridement and an equal number of matched controls treated with various nonclosure techniques, including negative pressure wound therapy and the repeated application of moist dressings. The two study groups were matched first on the basis of DFU location – toe, forefoot, midfoot, or rear foot – and then further propensity matched based on demographics, comorbid conditions, the presence of neuropathy, ulcer status by Wagner classification, infection severity, revascularization procedures, and other variables.

During 1 year of follow-up post discharge, ulcer healing occurred in 75% of the early wound closure group, compared with 66% of the nonclosure patients. Readmission for further treatment of the index ulcer occurred in 33% of the early closure group and 52% of the nonclosure group. Other outcomes were also superior in the early wound closure group, noted Dr. Chen of Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston.

Two independent predictors of DFU healing during the follow-up period emerged from a Cox regression analysis: early wound closure, with an adjusted odds ratio of 1.63, and acute as opposed to chronic DFU, with an OR of 1.35.

Ulcer healing was significantly less likely in patients with peripheral vascular disease, with an OR of 0.62; neuropathy, with an OR of 0.53; and methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus wound infection, with an OR of 0.59, he continued.

Underscoring the longer-term difficulties faced by patients with DFUs, it’s noteworthy that 11.5% of patients in both study arms underwent new amputations during the year of follow-up. Moreover, a new diagnosis of osteomyelitis was made in 20% of the early wound closure group and 26% of the nonclosure group, a nonsignificant difference.

Dr. Adolf W. Karchmer, Dr. Chen’s senior coinvestigator, said the outcome data are too new to be able to gauge how vascular, orthopedic, and podiatric surgeons will react.

The investigators reported having no financial conflicts with regard to this study, conducted without commercial sponsorship.

SAN DIEGO – Early wound closure prior to hospital discharge after surgical debridement of infected diabetic foot ulcers yields higher ulcer healing rates and a shorter time to healing, compared with various nonclosure wound management methods, according to a propensity-matched study.

How best to manage the open wound following nonamputative surgery of infected diabetic foot ulcers has been controversial. But early wound closure during the index hospitalization was the clear winner in this comparative study, Dr. Shey-Ying Chen reported at the annual Interscience Conference on Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy.

He presented a retrospective comparison between 179 diabetic foot ulcer (DFU) patients with early wound closure after surgical debridement and an equal number of matched controls treated with various nonclosure techniques, including negative pressure wound therapy and the repeated application of moist dressings. The two study groups were matched first on the basis of DFU location – toe, forefoot, midfoot, or rear foot – and then further propensity matched based on demographics, comorbid conditions, the presence of neuropathy, ulcer status by Wagner classification, infection severity, revascularization procedures, and other variables.

During 1 year of follow-up post discharge, ulcer healing occurred in 75% of the early wound closure group, compared with 66% of the nonclosure patients. Readmission for further treatment of the index ulcer occurred in 33% of the early closure group and 52% of the nonclosure group. Other outcomes were also superior in the early wound closure group, noted Dr. Chen of Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston.

Two independent predictors of DFU healing during the follow-up period emerged from a Cox regression analysis: early wound closure, with an adjusted odds ratio of 1.63, and acute as opposed to chronic DFU, with an OR of 1.35.

Ulcer healing was significantly less likely in patients with peripheral vascular disease, with an OR of 0.62; neuropathy, with an OR of 0.53; and methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus wound infection, with an OR of 0.59, he continued.

Underscoring the longer-term difficulties faced by patients with DFUs, it’s noteworthy that 11.5% of patients in both study arms underwent new amputations during the year of follow-up. Moreover, a new diagnosis of osteomyelitis was made in 20% of the early wound closure group and 26% of the nonclosure group, a nonsignificant difference.

Dr. Adolf W. Karchmer, Dr. Chen’s senior coinvestigator, said the outcome data are too new to be able to gauge how vascular, orthopedic, and podiatric surgeons will react.

The investigators reported having no financial conflicts with regard to this study, conducted without commercial sponsorship.

AT ICAAC 2015

Key clinical point: Diabetic foot ulcers are more likely to heal with early wound closure following surgical debridement than with nonclosure techniques.

Major finding: Healing of diabetic foot ulcers after surgical debridement took an average of 105 days in patients who underwent early wound closure prior to hospital discharge, compared with 136 days in those whose wounds were managed with nonclosure techniques.

Data source: A retrospective, nonrandomized study featuring two propensity score–matched groups, with 179 patients in each, who were followed for 1 year post discharge for surgical debridement of a diabetic foot ulcer.

Disclosures: The presenter reported having no financial conflicts regarding this study, conducted free of commercial support.

Travel Burden and Distress in Veterans With Head and Neck Cancer

Purpose: To investigate whether traveling long distances to a cancer treatment facility increases self-reported distress among veterans with head and neck cancer.

Background: Veterans within VISN 20 receive radiation therapy for head and neck cancer in Portland, Oregon, or Seattle, Washington. Given the geography, many travel and stay in lodging for the duration of treatment. As they cannot access usual sources of support within their communities, these veterans may be at risk for greater distress while undergoing cancer treatment.

Methods: The National Comprehensive Cancer Network Distress Thermometer (DT) is a validated tool for self-reported distress by cancer patients. Respondents report distress on a 0 to 10 scale and answer 28 questions regarding physical, emotional, and practical problems. In Seattle, the DT is completed shortly before starting treatment. Patient demographics, treatment plan (chemoradiation vs radiation alone), and DT data for veterans with head and neck cancer were abstracted from the Computerized Patient Record System. A DT score of 7 or higher was considered significant distress. Distance to the VA was calculated by zip code from the veteran’s address. Data were analyzed with logistic regression to control for possible effects of cancer stage, age category, or treatment plan.

Results: Sixty veterans with head and neck cancer completed the DT between April 2014 and April 2015. The average age was 65.4 years (range 39-91), all were male, 77% were white, 77% had stage III or IV cancer at diagnosis, and 47% traveled > 50 miles. The average DT score was 5.4. Veterans traveling > 50 miles were more likely to report significant distress compared with those who traveled < 50 miles (odds ratio (OR) = 1.6, P = .02). Sleep was the only problem significantly more likely for veterans traveling > 50 miles (OR = 1.71, P = .01).

Implications: Veterans with head and neck cancer traveling > 50 miles for cancer care are more likely to report significant distress or distress related to sleep. This small study suggests travel burden may be an underappreciated source of distress for veterans with cancer. Further research is warranted to better understand how travel burden affects distress and identify opportunities for intervention

Purpose: To investigate whether traveling long distances to a cancer treatment facility increases self-reported distress among veterans with head and neck cancer.

Background: Veterans within VISN 20 receive radiation therapy for head and neck cancer in Portland, Oregon, or Seattle, Washington. Given the geography, many travel and stay in lodging for the duration of treatment. As they cannot access usual sources of support within their communities, these veterans may be at risk for greater distress while undergoing cancer treatment.

Methods: The National Comprehensive Cancer Network Distress Thermometer (DT) is a validated tool for self-reported distress by cancer patients. Respondents report distress on a 0 to 10 scale and answer 28 questions regarding physical, emotional, and practical problems. In Seattle, the DT is completed shortly before starting treatment. Patient demographics, treatment plan (chemoradiation vs radiation alone), and DT data for veterans with head and neck cancer were abstracted from the Computerized Patient Record System. A DT score of 7 or higher was considered significant distress. Distance to the VA was calculated by zip code from the veteran’s address. Data were analyzed with logistic regression to control for possible effects of cancer stage, age category, or treatment plan.

Results: Sixty veterans with head and neck cancer completed the DT between April 2014 and April 2015. The average age was 65.4 years (range 39-91), all were male, 77% were white, 77% had stage III or IV cancer at diagnosis, and 47% traveled > 50 miles. The average DT score was 5.4. Veterans traveling > 50 miles were more likely to report significant distress compared with those who traveled < 50 miles (odds ratio (OR) = 1.6, P = .02). Sleep was the only problem significantly more likely for veterans traveling > 50 miles (OR = 1.71, P = .01).

Implications: Veterans with head and neck cancer traveling > 50 miles for cancer care are more likely to report significant distress or distress related to sleep. This small study suggests travel burden may be an underappreciated source of distress for veterans with cancer. Further research is warranted to better understand how travel burden affects distress and identify opportunities for intervention

Purpose: To investigate whether traveling long distances to a cancer treatment facility increases self-reported distress among veterans with head and neck cancer.

Background: Veterans within VISN 20 receive radiation therapy for head and neck cancer in Portland, Oregon, or Seattle, Washington. Given the geography, many travel and stay in lodging for the duration of treatment. As they cannot access usual sources of support within their communities, these veterans may be at risk for greater distress while undergoing cancer treatment.

Methods: The National Comprehensive Cancer Network Distress Thermometer (DT) is a validated tool for self-reported distress by cancer patients. Respondents report distress on a 0 to 10 scale and answer 28 questions regarding physical, emotional, and practical problems. In Seattle, the DT is completed shortly before starting treatment. Patient demographics, treatment plan (chemoradiation vs radiation alone), and DT data for veterans with head and neck cancer were abstracted from the Computerized Patient Record System. A DT score of 7 or higher was considered significant distress. Distance to the VA was calculated by zip code from the veteran’s address. Data were analyzed with logistic regression to control for possible effects of cancer stage, age category, or treatment plan.

Results: Sixty veterans with head and neck cancer completed the DT between April 2014 and April 2015. The average age was 65.4 years (range 39-91), all were male, 77% were white, 77% had stage III or IV cancer at diagnosis, and 47% traveled > 50 miles. The average DT score was 5.4. Veterans traveling > 50 miles were more likely to report significant distress compared with those who traveled < 50 miles (odds ratio (OR) = 1.6, P = .02). Sleep was the only problem significantly more likely for veterans traveling > 50 miles (OR = 1.71, P = .01).

Implications: Veterans with head and neck cancer traveling > 50 miles for cancer care are more likely to report significant distress or distress related to sleep. This small study suggests travel burden may be an underappreciated source of distress for veterans with cancer. Further research is warranted to better understand how travel burden affects distress and identify opportunities for intervention

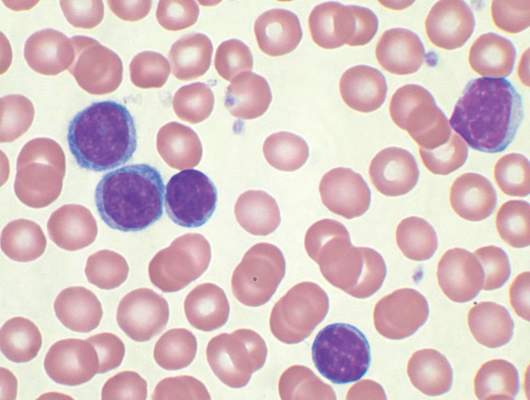

Patterns of Initial Treatment in Veteran Patients With Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia: A National VA Tumor Registry Study

Background: Chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) is the most common leukemia in adults, including elderly veterans, with many new treatment options now available. Data on patterns of treatment in elderly veteran patients with CLL is limited. We sought to assess initial treatment patterns over a 13-year period among veteran patients in the Minneapolis VA Health Care System.

Methods: We identified 6,756 CLL cases diagnosed from 2000 to 2013 and are presenting interim data on 2015. We reviewed clinical data from 2,015 patients with CLL diagnosed from 2000 to 2013 and identified through the National VA Tumor Registry. Baseline demographics and treatment information were collected. The objective of this study was to assess initial treatment patterns, time to initial treatment, and variation of these parameters by age.

Results: At diagnosis, median age was 69 years (range, 37-96 years); 98% were male (1,979); Rai stage was 0 (n = 1,331, 66%), 1 (n = 317, 16%), 2 (n = 156, 8%), 3 (n = 91, 5%), 4 (n = 113, 6%). The majority of patients were white (n = 1,752, 87%); followed by African American (n = 203, 10%); and Hispanic (n = 33, 2%). Of the 2,015 patients, 751 (37%) received therapy over this period of follow-up. Median time from diagnosis to initial treatment was 1.3 years (range, 0-13 years). The most common initial therapies utilized were chlorambucil (39.4%); fludarabine/cyclophosphamide/ritux-imab (FCR) (12.4%); and single-agent fludarabine (10.5%). When examining these parameters by age in decades, we found that there were no differences in Rai stage at diagnosis by age-decade. There was a progressive increase in initial chlorambucil usage by advancing age. Likewise, the majority of FCR usage was in patients aged < 70 years.

Conclusions: In this veteran population, including many elderly patients, the majority of patients requiring therapy initiated it within 2 years of diagnosis. These patients were most commonly treated with chlorambucil. These patterns of care will be changing with the introduction of newer oral agents, such as ibrutinib and idelalisib, but at a significantly higher cost. The National VA Tumor Registry data will allow future opportunity to examine evolving treatment patterns in both an elderly as well as a veteran population. Updated data will be presented at the AVAHO annual meeting.

Background: Chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) is the most common leukemia in adults, including elderly veterans, with many new treatment options now available. Data on patterns of treatment in elderly veteran patients with CLL is limited. We sought to assess initial treatment patterns over a 13-year period among veteran patients in the Minneapolis VA Health Care System.

Methods: We identified 6,756 CLL cases diagnosed from 2000 to 2013 and are presenting interim data on 2015. We reviewed clinical data from 2,015 patients with CLL diagnosed from 2000 to 2013 and identified through the National VA Tumor Registry. Baseline demographics and treatment information were collected. The objective of this study was to assess initial treatment patterns, time to initial treatment, and variation of these parameters by age.

Results: At diagnosis, median age was 69 years (range, 37-96 years); 98% were male (1,979); Rai stage was 0 (n = 1,331, 66%), 1 (n = 317, 16%), 2 (n = 156, 8%), 3 (n = 91, 5%), 4 (n = 113, 6%). The majority of patients were white (n = 1,752, 87%); followed by African American (n = 203, 10%); and Hispanic (n = 33, 2%). Of the 2,015 patients, 751 (37%) received therapy over this period of follow-up. Median time from diagnosis to initial treatment was 1.3 years (range, 0-13 years). The most common initial therapies utilized were chlorambucil (39.4%); fludarabine/cyclophosphamide/ritux-imab (FCR) (12.4%); and single-agent fludarabine (10.5%). When examining these parameters by age in decades, we found that there were no differences in Rai stage at diagnosis by age-decade. There was a progressive increase in initial chlorambucil usage by advancing age. Likewise, the majority of FCR usage was in patients aged < 70 years.

Conclusions: In this veteran population, including many elderly patients, the majority of patients requiring therapy initiated it within 2 years of diagnosis. These patients were most commonly treated with chlorambucil. These patterns of care will be changing with the introduction of newer oral agents, such as ibrutinib and idelalisib, but at a significantly higher cost. The National VA Tumor Registry data will allow future opportunity to examine evolving treatment patterns in both an elderly as well as a veteran population. Updated data will be presented at the AVAHO annual meeting.

Background: Chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) is the most common leukemia in adults, including elderly veterans, with many new treatment options now available. Data on patterns of treatment in elderly veteran patients with CLL is limited. We sought to assess initial treatment patterns over a 13-year period among veteran patients in the Minneapolis VA Health Care System.

Methods: We identified 6,756 CLL cases diagnosed from 2000 to 2013 and are presenting interim data on 2015. We reviewed clinical data from 2,015 patients with CLL diagnosed from 2000 to 2013 and identified through the National VA Tumor Registry. Baseline demographics and treatment information were collected. The objective of this study was to assess initial treatment patterns, time to initial treatment, and variation of these parameters by age.

Results: At diagnosis, median age was 69 years (range, 37-96 years); 98% were male (1,979); Rai stage was 0 (n = 1,331, 66%), 1 (n = 317, 16%), 2 (n = 156, 8%), 3 (n = 91, 5%), 4 (n = 113, 6%). The majority of patients were white (n = 1,752, 87%); followed by African American (n = 203, 10%); and Hispanic (n = 33, 2%). Of the 2,015 patients, 751 (37%) received therapy over this period of follow-up. Median time from diagnosis to initial treatment was 1.3 years (range, 0-13 years). The most common initial therapies utilized were chlorambucil (39.4%); fludarabine/cyclophosphamide/ritux-imab (FCR) (12.4%); and single-agent fludarabine (10.5%). When examining these parameters by age in decades, we found that there were no differences in Rai stage at diagnosis by age-decade. There was a progressive increase in initial chlorambucil usage by advancing age. Likewise, the majority of FCR usage was in patients aged < 70 years.

Conclusions: In this veteran population, including many elderly patients, the majority of patients requiring therapy initiated it within 2 years of diagnosis. These patients were most commonly treated with chlorambucil. These patterns of care will be changing with the introduction of newer oral agents, such as ibrutinib and idelalisib, but at a significantly higher cost. The National VA Tumor Registry data will allow future opportunity to examine evolving treatment patterns in both an elderly as well as a veteran population. Updated data will be presented at the AVAHO annual meeting.

Initial Cytogenetic Features of Veteran Patients With Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia: A National VA Tumor Registry Study

Background: Chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) is the most common leukemia in adults, including elderly veterans. Some veterans have a history of Agent Orange exposure, which may potentially impact their presentation and disease course. We sought to assess initial patterns of cytogenetic aberrations among patients with CLL within the Minneapolis VA Health Care System (MVAHCS).

Methods: For this interim analysis, we evaluated a subset (30%) of a larger sample (6,756). We reviewed clinical data from 2,015 patients with CLL diagnosed from 2000 to 2013 and identified through the National VA Tumor Registry. Baseline demographics, including bone marrow/cytogenetic findings and treatment information were collected. The objective of this study was to assess initial cytogenetic patterns and variation of these parameters by age and Agent Orange exposure.

Results: Median age at diagnosis was 69 years (range, 37-96 years); 98% were male (1,979); Rai stage was 0 (n = 1,331, 66%), 1 (n = 317, 16%), 2 (n = 156, 8%), 3 (n = 91, 5%), 4 (n = 113, 6%). Cytogenetic data were available on 590 of 2,015 (29%) patients. Cytogenetic findings were normal in 258 (44%) patients. Abnormal cytogenetic findings in the remaining 330 cases included del 13q (28%); trisomy 12 (15%); del 11q (11%); del 17p (6%); and other abnor-malities (13%). Of 330 patients with noted abnormalities, 191 (58%) had 1 abnormality; 60 (18%) had 2; and 79 (24%) had > 2 abnormalities. Out of 2,015 patients, 283 (14%) had a reported exposure to Agent Orange; cytogenetic information was available in 130 (46%). Chromosomal abnormalities were detected in 80 of 130 cases (62%). The most frequent abnormality was del 13q (40%); trisomy 12 (19%); other abnormalities (18%); and del 11q (17%). Of the 80 pa-tients with noted abnormalities, 44 (55%) had 1 abnormality;14 (18%) had 2; and 22 (28%) had > 2 abnormalities.

Conclusions: Cytogenetic abnormalities in CLL play an important role in predicting disease progression and survival. These abnormalities paired with Agent Orange exposure have yet to be explored. Utilization of the National VA Tumor Registry data will allow the opportunity to examine the impact, if any, of Agent Orange exposure on the presentation and disease course of veterans with CLL. Updated cytogenetic findings will be presented at the AVAHO annual meeting.

Background: Chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) is the most common leukemia in adults, including elderly veterans. Some veterans have a history of Agent Orange exposure, which may potentially impact their presentation and disease course. We sought to assess initial patterns of cytogenetic aberrations among patients with CLL within the Minneapolis VA Health Care System (MVAHCS).

Methods: For this interim analysis, we evaluated a subset (30%) of a larger sample (6,756). We reviewed clinical data from 2,015 patients with CLL diagnosed from 2000 to 2013 and identified through the National VA Tumor Registry. Baseline demographics, including bone marrow/cytogenetic findings and treatment information were collected. The objective of this study was to assess initial cytogenetic patterns and variation of these parameters by age and Agent Orange exposure.

Results: Median age at diagnosis was 69 years (range, 37-96 years); 98% were male (1,979); Rai stage was 0 (n = 1,331, 66%), 1 (n = 317, 16%), 2 (n = 156, 8%), 3 (n = 91, 5%), 4 (n = 113, 6%). Cytogenetic data were available on 590 of 2,015 (29%) patients. Cytogenetic findings were normal in 258 (44%) patients. Abnormal cytogenetic findings in the remaining 330 cases included del 13q (28%); trisomy 12 (15%); del 11q (11%); del 17p (6%); and other abnor-malities (13%). Of 330 patients with noted abnormalities, 191 (58%) had 1 abnormality; 60 (18%) had 2; and 79 (24%) had > 2 abnormalities. Out of 2,015 patients, 283 (14%) had a reported exposure to Agent Orange; cytogenetic information was available in 130 (46%). Chromosomal abnormalities were detected in 80 of 130 cases (62%). The most frequent abnormality was del 13q (40%); trisomy 12 (19%); other abnormalities (18%); and del 11q (17%). Of the 80 pa-tients with noted abnormalities, 44 (55%) had 1 abnormality;14 (18%) had 2; and 22 (28%) had > 2 abnormalities.

Conclusions: Cytogenetic abnormalities in CLL play an important role in predicting disease progression and survival. These abnormalities paired with Agent Orange exposure have yet to be explored. Utilization of the National VA Tumor Registry data will allow the opportunity to examine the impact, if any, of Agent Orange exposure on the presentation and disease course of veterans with CLL. Updated cytogenetic findings will be presented at the AVAHO annual meeting.

Background: Chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) is the most common leukemia in adults, including elderly veterans. Some veterans have a history of Agent Orange exposure, which may potentially impact their presentation and disease course. We sought to assess initial patterns of cytogenetic aberrations among patients with CLL within the Minneapolis VA Health Care System (MVAHCS).

Methods: For this interim analysis, we evaluated a subset (30%) of a larger sample (6,756). We reviewed clinical data from 2,015 patients with CLL diagnosed from 2000 to 2013 and identified through the National VA Tumor Registry. Baseline demographics, including bone marrow/cytogenetic findings and treatment information were collected. The objective of this study was to assess initial cytogenetic patterns and variation of these parameters by age and Agent Orange exposure.

Results: Median age at diagnosis was 69 years (range, 37-96 years); 98% were male (1,979); Rai stage was 0 (n = 1,331, 66%), 1 (n = 317, 16%), 2 (n = 156, 8%), 3 (n = 91, 5%), 4 (n = 113, 6%). Cytogenetic data were available on 590 of 2,015 (29%) patients. Cytogenetic findings were normal in 258 (44%) patients. Abnormal cytogenetic findings in the remaining 330 cases included del 13q (28%); trisomy 12 (15%); del 11q (11%); del 17p (6%); and other abnor-malities (13%). Of 330 patients with noted abnormalities, 191 (58%) had 1 abnormality; 60 (18%) had 2; and 79 (24%) had > 2 abnormalities. Out of 2,015 patients, 283 (14%) had a reported exposure to Agent Orange; cytogenetic information was available in 130 (46%). Chromosomal abnormalities were detected in 80 of 130 cases (62%). The most frequent abnormality was del 13q (40%); trisomy 12 (19%); other abnormalities (18%); and del 11q (17%). Of the 80 pa-tients with noted abnormalities, 44 (55%) had 1 abnormality;14 (18%) had 2; and 22 (28%) had > 2 abnormalities.

Conclusions: Cytogenetic abnormalities in CLL play an important role in predicting disease progression and survival. These abnormalities paired with Agent Orange exposure have yet to be explored. Utilization of the National VA Tumor Registry data will allow the opportunity to examine the impact, if any, of Agent Orange exposure on the presentation and disease course of veterans with CLL. Updated cytogenetic findings will be presented at the AVAHO annual meeting.

Prevalence of Undiagnosed Diabetes in US

Diabetes affects up to 14 percent of the U.S. population - an increase from nearly 10 percent in the early 1990s - yet over a third of cases still go undiagnosed, according to a new analysis.

Screening seems to be catching more cases, accounting for the general rise over two decades, the study authors say, but mainly whites have benefited; for Hispanic and Asian people in particular, more than half of cases go undetected.

"We need to better educate people on the risk factors for diabetes - including older age, family history and obesity - and improve screening for those at high risk," lead study author Andy Menke, an epidemiologist at Social and Scientific Systems in Silver Spring, Maryland, said by email.

Globally, about one in nine adults has diagnosed diabetes, and the disease will be the seventh leading cause of death by 2030, according to the World Health Organization.

Most of these people have Type 2, or adult-onset, diabetes, which happens when the body can't properly use or make enough of the hormone insulin to convert blood sugar into energy. Left untreated, diabetes can lead to nerve damage, amputations, blindness, heart disease and strokes.

Average blood sugar levels over the course of several months can be estimated by measuring changes to the hemoglobin molecule in red blood cells. The hemoglobin A1c test measures the percentage of hemoglobin - the protein in red blood cells that

carries oxygen - that is coated with sugar, with readings of 6.5 percent or above signaling diabetes.

People with A1c levels between 5.7 percent and 6.4 percent aren't diabetic, but because this is considered elevated it is sometimes called "pre-diabetes" and considered a risk factor for going on to develop full-blown diabetes.

Menke and colleagues estimated the prevalence of diabetes and pre-diabetes using data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) collected on 2,781 adults in 2011 to 2012 and an additional 23,634 adults from 1988 to 2010.

While the prevalence of diabetes increased over time in the overall population, gains were more pronounced among racial and ethnic minorities, the study found.

About 11 percent of white people have diabetes, the researchers calculated, compared with 22 percent of non-Hispanic black participants, 21 percent of Asians and 23 percent of Hispanics.

Among Asians, 51 percent of those with diabetes were unaware of it, and the same was true for 49 percent of Hispanic people with the condition.

An additional 38 percent of adults fell into the pre-diabetes category. Added to the prevalence of diabetes, that means more than half of the U.S. population has diabetes or is at increased risk for it, the authors point out.

The good news, however, is fewer people are undiagnosed than in the past, Dr. William Herman and Dr. Amy Rothberg of the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor note in commentary accompanying the study in JAMA.

In it, they note that the increase in diabetes prevalence between 1988 and 2012 seen in the study was due to an increase in diagnosed cases, and that overall undiagnosed cases fell from 40 percent in 1988-1994 to 31 percent in 2008-2012.

This "likely reflects increased awareness of the problem of undiagnosed diabetes and increased testing," they said by email.

The drop in undiagnosed cases, they added, may be due in part to the newer, simpler A1c test, which doesn't require fasting or any advance preparation.

It's also possible that new cases of diabetes are starting to fall for the first time in decades because more people are getting the message about lifestyle choices that can contribute to diabetes, noted Dr. David Nathan, director of the diabetes center at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston and a professor at Harvard Medical School.

In particular, more patients now understand that being overweight or obese increases the risk for diabetes, Nathan, author of a separate report in JAMA on advances in diagnosis and treatment, said by email.

"Behavioral changes, including healthy eating and more activity can prevent, or at least ameliorate, the diabetes epidemic," Nathan said.

Diabetes affects up to 14 percent of the U.S. population - an increase from nearly 10 percent in the early 1990s - yet over a third of cases still go undiagnosed, according to a new analysis.

Screening seems to be catching more cases, accounting for the general rise over two decades, the study authors say, but mainly whites have benefited; for Hispanic and Asian people in particular, more than half of cases go undetected.

"We need to better educate people on the risk factors for diabetes - including older age, family history and obesity - and improve screening for those at high risk," lead study author Andy Menke, an epidemiologist at Social and Scientific Systems in Silver Spring, Maryland, said by email.

Globally, about one in nine adults has diagnosed diabetes, and the disease will be the seventh leading cause of death by 2030, according to the World Health Organization.

Most of these people have Type 2, or adult-onset, diabetes, which happens when the body can't properly use or make enough of the hormone insulin to convert blood sugar into energy. Left untreated, diabetes can lead to nerve damage, amputations, blindness, heart disease and strokes.

Average blood sugar levels over the course of several months can be estimated by measuring changes to the hemoglobin molecule in red blood cells. The hemoglobin A1c test measures the percentage of hemoglobin - the protein in red blood cells that

carries oxygen - that is coated with sugar, with readings of 6.5 percent or above signaling diabetes.

People with A1c levels between 5.7 percent and 6.4 percent aren't diabetic, but because this is considered elevated it is sometimes called "pre-diabetes" and considered a risk factor for going on to develop full-blown diabetes.

Menke and colleagues estimated the prevalence of diabetes and pre-diabetes using data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) collected on 2,781 adults in 2011 to 2012 and an additional 23,634 adults from 1988 to 2010.

While the prevalence of diabetes increased over time in the overall population, gains were more pronounced among racial and ethnic minorities, the study found.

About 11 percent of white people have diabetes, the researchers calculated, compared with 22 percent of non-Hispanic black participants, 21 percent of Asians and 23 percent of Hispanics.

Among Asians, 51 percent of those with diabetes were unaware of it, and the same was true for 49 percent of Hispanic people with the condition.

An additional 38 percent of adults fell into the pre-diabetes category. Added to the prevalence of diabetes, that means more than half of the U.S. population has diabetes or is at increased risk for it, the authors point out.

The good news, however, is fewer people are undiagnosed than in the past, Dr. William Herman and Dr. Amy Rothberg of the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor note in commentary accompanying the study in JAMA.

In it, they note that the increase in diabetes prevalence between 1988 and 2012 seen in the study was due to an increase in diagnosed cases, and that overall undiagnosed cases fell from 40 percent in 1988-1994 to 31 percent in 2008-2012.

This "likely reflects increased awareness of the problem of undiagnosed diabetes and increased testing," they said by email.

The drop in undiagnosed cases, they added, may be due in part to the newer, simpler A1c test, which doesn't require fasting or any advance preparation.

It's also possible that new cases of diabetes are starting to fall for the first time in decades because more people are getting the message about lifestyle choices that can contribute to diabetes, noted Dr. David Nathan, director of the diabetes center at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston and a professor at Harvard Medical School.

In particular, more patients now understand that being overweight or obese increases the risk for diabetes, Nathan, author of a separate report in JAMA on advances in diagnosis and treatment, said by email.

"Behavioral changes, including healthy eating and more activity can prevent, or at least ameliorate, the diabetes epidemic," Nathan said.

Diabetes affects up to 14 percent of the U.S. population - an increase from nearly 10 percent in the early 1990s - yet over a third of cases still go undiagnosed, according to a new analysis.

Screening seems to be catching more cases, accounting for the general rise over two decades, the study authors say, but mainly whites have benefited; for Hispanic and Asian people in particular, more than half of cases go undetected.

"We need to better educate people on the risk factors for diabetes - including older age, family history and obesity - and improve screening for those at high risk," lead study author Andy Menke, an epidemiologist at Social and Scientific Systems in Silver Spring, Maryland, said by email.

Globally, about one in nine adults has diagnosed diabetes, and the disease will be the seventh leading cause of death by 2030, according to the World Health Organization.

Most of these people have Type 2, or adult-onset, diabetes, which happens when the body can't properly use or make enough of the hormone insulin to convert blood sugar into energy. Left untreated, diabetes can lead to nerve damage, amputations, blindness, heart disease and strokes.

Average blood sugar levels over the course of several months can be estimated by measuring changes to the hemoglobin molecule in red blood cells. The hemoglobin A1c test measures the percentage of hemoglobin - the protein in red blood cells that

carries oxygen - that is coated with sugar, with readings of 6.5 percent or above signaling diabetes.

People with A1c levels between 5.7 percent and 6.4 percent aren't diabetic, but because this is considered elevated it is sometimes called "pre-diabetes" and considered a risk factor for going on to develop full-blown diabetes.

Menke and colleagues estimated the prevalence of diabetes and pre-diabetes using data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) collected on 2,781 adults in 2011 to 2012 and an additional 23,634 adults from 1988 to 2010.

While the prevalence of diabetes increased over time in the overall population, gains were more pronounced among racial and ethnic minorities, the study found.

About 11 percent of white people have diabetes, the researchers calculated, compared with 22 percent of non-Hispanic black participants, 21 percent of Asians and 23 percent of Hispanics.

Among Asians, 51 percent of those with diabetes were unaware of it, and the same was true for 49 percent of Hispanic people with the condition.

An additional 38 percent of adults fell into the pre-diabetes category. Added to the prevalence of diabetes, that means more than half of the U.S. population has diabetes or is at increased risk for it, the authors point out.

The good news, however, is fewer people are undiagnosed than in the past, Dr. William Herman and Dr. Amy Rothberg of the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor note in commentary accompanying the study in JAMA.

In it, they note that the increase in diabetes prevalence between 1988 and 2012 seen in the study was due to an increase in diagnosed cases, and that overall undiagnosed cases fell from 40 percent in 1988-1994 to 31 percent in 2008-2012.

This "likely reflects increased awareness of the problem of undiagnosed diabetes and increased testing," they said by email.

The drop in undiagnosed cases, they added, may be due in part to the newer, simpler A1c test, which doesn't require fasting or any advance preparation.

It's also possible that new cases of diabetes are starting to fall for the first time in decades because more people are getting the message about lifestyle choices that can contribute to diabetes, noted Dr. David Nathan, director of the diabetes center at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston and a professor at Harvard Medical School.

In particular, more patients now understand that being overweight or obese increases the risk for diabetes, Nathan, author of a separate report in JAMA on advances in diagnosis and treatment, said by email.

"Behavioral changes, including healthy eating and more activity can prevent, or at least ameliorate, the diabetes epidemic," Nathan said.

Respiratory problems make adenotonsillectomy recovery worse for kids

Respiratory compromise and secondary hemorrhage were the most common early side effects in children who had adenotonsillectomies; children with obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) have nearly five times more respiratory complications after surgery than children without OSA, a multistudy review concluded.

Graziela De Luca Canto, Ph.D., of the Federal University of Santa Catarina, Brazil, and her associates performed a data review by identifying 1,254 different citations found via electronic database searches; after eliminations, only 23 studies were included in the final analysis. Although children with OSA have nearly five times more respiratory complications after adenotonsillectomy than their peers, (odds ratio, 4.90), they are less likely to have postoperative bleeding, compared with children without OSA (OR, 0.41). Among both groups, the most frequent complication was respiratory compromise (9.4%), followed by secondary hemorrhage (2.6%).

Because children with OSA are more likely to require supplemental oxygen, oral or nasal airway insertion, or assisted ventilation in the immediate postoperative period than their peers, the authors suggested that anesthesiologists would be wise to screen patients for snoring, airway dysfunction, and other airway anatomic disorders before performing surgery.

“Children with OSA are clearly at higher anesthetic risk than are patients with normal upper airway function. … Despite the pressure to reduce costs, both surgeons and anesthesiologists should improve screening procedures, perhaps develop alternate surgical approaches, to decrease the risks,” the investigators wrote.

Read the full article in Pediatrics 2015 (doi: 10.1542/peds.2015-1283).

Respiratory compromise and secondary hemorrhage were the most common early side effects in children who had adenotonsillectomies; children with obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) have nearly five times more respiratory complications after surgery than children without OSA, a multistudy review concluded.

Graziela De Luca Canto, Ph.D., of the Federal University of Santa Catarina, Brazil, and her associates performed a data review by identifying 1,254 different citations found via electronic database searches; after eliminations, only 23 studies were included in the final analysis. Although children with OSA have nearly five times more respiratory complications after adenotonsillectomy than their peers, (odds ratio, 4.90), they are less likely to have postoperative bleeding, compared with children without OSA (OR, 0.41). Among both groups, the most frequent complication was respiratory compromise (9.4%), followed by secondary hemorrhage (2.6%).

Because children with OSA are more likely to require supplemental oxygen, oral or nasal airway insertion, or assisted ventilation in the immediate postoperative period than their peers, the authors suggested that anesthesiologists would be wise to screen patients for snoring, airway dysfunction, and other airway anatomic disorders before performing surgery.

“Children with OSA are clearly at higher anesthetic risk than are patients with normal upper airway function. … Despite the pressure to reduce costs, both surgeons and anesthesiologists should improve screening procedures, perhaps develop alternate surgical approaches, to decrease the risks,” the investigators wrote.

Read the full article in Pediatrics 2015 (doi: 10.1542/peds.2015-1283).

Respiratory compromise and secondary hemorrhage were the most common early side effects in children who had adenotonsillectomies; children with obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) have nearly five times more respiratory complications after surgery than children without OSA, a multistudy review concluded.

Graziela De Luca Canto, Ph.D., of the Federal University of Santa Catarina, Brazil, and her associates performed a data review by identifying 1,254 different citations found via electronic database searches; after eliminations, only 23 studies were included in the final analysis. Although children with OSA have nearly five times more respiratory complications after adenotonsillectomy than their peers, (odds ratio, 4.90), they are less likely to have postoperative bleeding, compared with children without OSA (OR, 0.41). Among both groups, the most frequent complication was respiratory compromise (9.4%), followed by secondary hemorrhage (2.6%).

Because children with OSA are more likely to require supplemental oxygen, oral or nasal airway insertion, or assisted ventilation in the immediate postoperative period than their peers, the authors suggested that anesthesiologists would be wise to screen patients for snoring, airway dysfunction, and other airway anatomic disorders before performing surgery.

“Children with OSA are clearly at higher anesthetic risk than are patients with normal upper airway function. … Despite the pressure to reduce costs, both surgeons and anesthesiologists should improve screening procedures, perhaps develop alternate surgical approaches, to decrease the risks,” the investigators wrote.

Read the full article in Pediatrics 2015 (doi: 10.1542/peds.2015-1283).

FROM PEDIATRICS

Reducing SCD patients’ wait time for pain meds

Photo courtesy of St. Jude

Children’s Research Hospital

A quality improvement initiative may help reduce the amount of time pediatric patients with sickle cell disease (SCD) wait for pain medication when visiting the emergency department (ED) for a vaso-occlusive episode (VOE).

In a single-center study, the initiative cut patients’ average wait time from triage to the first dose of pain medication by more than 50%—from 56 minutes to 23 minutes.

The researchers described this study in Pediatrics.

The National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute recommends that a pediatric SCD patient experiencing a VOE be triaged and treated as quickly as possible in the ED. However, previous US studies have indicated that patients often wait, on average, between 65 and 90 minutes for their first dose of pain medication.

“When a child with sickle cell disease comes to the emergency room with pain from a VOE, they likely have been in tremendous pain for hours,” said study author Patricia Kavanagh, MD, of Boston Medical Center (BMC) in Massachusetts.

“The goal of this initiative was to treat the pain episode as quickly and aggressively as possible so that these children could return to their usual activities, including school and time with family and friends.”

Implementing the initiative

From September 2010 to April 2014, a team at BMC implemented the following interventions in the pediatric ED:

- Using a standardized, time-specific protocol that guides care when the patient is in the ED

- Using intranasal fentanyl as a first-line pain medication, as placing intravenous lines (IVs) can be difficult in children with SCD

- Using an online calculator to determine appropriate pain medication doses in line with what is used nationally for children in the ED

- Providing education on this work to emergency providers and families.

The team implemented these interventions in phases. From September 2010 to May 2011 (baseline), they collected data on the timing of first and subsequent pain medications for children with SCD who presented to the ED with VOEs.

From May to November 2011 (phase 1), the team introduced intranasal fentanyl as the first-line parenteral opioid.

From December 2011 to November 2012 (phase 2), the goal was to streamline VOE care from triage to disposition decision. The team revised the VOE algorithm to recommend 2 doses of intranasal fentanyl, 2 doses of IV opioids, and then a disposition decision. Then, they introduced the pain medication calculator.

From December 2012 to April 2014 (phase 3), the team assessed the sustainability of the interventions from phase 2. The team also revised the VOE algorithm in May 2013 to initiate patient-controlled analgesics after the first dose of IV opioid for patients with severe pain.

Results

The team observed a reduction in the average time from triage to the first dose of a pain medication—either through the nose or IV—from 56 minutes at baseline to 23 minutes in phase 3. The time to the second IV pain medication dose decreased as well—from 106 minutes to 83 minutes.

There was also a reduction in the time it took for the physician to determine whether the patient would be admitted—from 163 minutes to 109 minutes—or discharged—from 271 minutes to 178 minutes.

In addition, patients who were admitted were given patient-controlled analgesics to control their pain, and the time to its initiation decreased from 216 minutes to 141 minutes.

“While future studies are necessary to determine if these results can be replicated at other hospitals, our data indicates that these initiatives could have a tremendous impact on care for kids with SCD across the country,” said James Moses, MD, of BMC. ![]()

Photo courtesy of St. Jude

Children’s Research Hospital

A quality improvement initiative may help reduce the amount of time pediatric patients with sickle cell disease (SCD) wait for pain medication when visiting the emergency department (ED) for a vaso-occlusive episode (VOE).

In a single-center study, the initiative cut patients’ average wait time from triage to the first dose of pain medication by more than 50%—from 56 minutes to 23 minutes.

The researchers described this study in Pediatrics.

The National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute recommends that a pediatric SCD patient experiencing a VOE be triaged and treated as quickly as possible in the ED. However, previous US studies have indicated that patients often wait, on average, between 65 and 90 minutes for their first dose of pain medication.

“When a child with sickle cell disease comes to the emergency room with pain from a VOE, they likely have been in tremendous pain for hours,” said study author Patricia Kavanagh, MD, of Boston Medical Center (BMC) in Massachusetts.

“The goal of this initiative was to treat the pain episode as quickly and aggressively as possible so that these children could return to their usual activities, including school and time with family and friends.”

Implementing the initiative

From September 2010 to April 2014, a team at BMC implemented the following interventions in the pediatric ED:

- Using a standardized, time-specific protocol that guides care when the patient is in the ED

- Using intranasal fentanyl as a first-line pain medication, as placing intravenous lines (IVs) can be difficult in children with SCD

- Using an online calculator to determine appropriate pain medication doses in line with what is used nationally for children in the ED

- Providing education on this work to emergency providers and families.

The team implemented these interventions in phases. From September 2010 to May 2011 (baseline), they collected data on the timing of first and subsequent pain medications for children with SCD who presented to the ED with VOEs.

From May to November 2011 (phase 1), the team introduced intranasal fentanyl as the first-line parenteral opioid.

From December 2011 to November 2012 (phase 2), the goal was to streamline VOE care from triage to disposition decision. The team revised the VOE algorithm to recommend 2 doses of intranasal fentanyl, 2 doses of IV opioids, and then a disposition decision. Then, they introduced the pain medication calculator.

From December 2012 to April 2014 (phase 3), the team assessed the sustainability of the interventions from phase 2. The team also revised the VOE algorithm in May 2013 to initiate patient-controlled analgesics after the first dose of IV opioid for patients with severe pain.

Results

The team observed a reduction in the average time from triage to the first dose of a pain medication—either through the nose or IV—from 56 minutes at baseline to 23 minutes in phase 3. The time to the second IV pain medication dose decreased as well—from 106 minutes to 83 minutes.

There was also a reduction in the time it took for the physician to determine whether the patient would be admitted—from 163 minutes to 109 minutes—or discharged—from 271 minutes to 178 minutes.

In addition, patients who were admitted were given patient-controlled analgesics to control their pain, and the time to its initiation decreased from 216 minutes to 141 minutes.

“While future studies are necessary to determine if these results can be replicated at other hospitals, our data indicates that these initiatives could have a tremendous impact on care for kids with SCD across the country,” said James Moses, MD, of BMC. ![]()

Photo courtesy of St. Jude

Children’s Research Hospital

A quality improvement initiative may help reduce the amount of time pediatric patients with sickle cell disease (SCD) wait for pain medication when visiting the emergency department (ED) for a vaso-occlusive episode (VOE).

In a single-center study, the initiative cut patients’ average wait time from triage to the first dose of pain medication by more than 50%—from 56 minutes to 23 minutes.

The researchers described this study in Pediatrics.

The National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute recommends that a pediatric SCD patient experiencing a VOE be triaged and treated as quickly as possible in the ED. However, previous US studies have indicated that patients often wait, on average, between 65 and 90 minutes for their first dose of pain medication.

“When a child with sickle cell disease comes to the emergency room with pain from a VOE, they likely have been in tremendous pain for hours,” said study author Patricia Kavanagh, MD, of Boston Medical Center (BMC) in Massachusetts.

“The goal of this initiative was to treat the pain episode as quickly and aggressively as possible so that these children could return to their usual activities, including school and time with family and friends.”

Implementing the initiative

From September 2010 to April 2014, a team at BMC implemented the following interventions in the pediatric ED:

- Using a standardized, time-specific protocol that guides care when the patient is in the ED

- Using intranasal fentanyl as a first-line pain medication, as placing intravenous lines (IVs) can be difficult in children with SCD

- Using an online calculator to determine appropriate pain medication doses in line with what is used nationally for children in the ED

- Providing education on this work to emergency providers and families.

The team implemented these interventions in phases. From September 2010 to May 2011 (baseline), they collected data on the timing of first and subsequent pain medications for children with SCD who presented to the ED with VOEs.

From May to November 2011 (phase 1), the team introduced intranasal fentanyl as the first-line parenteral opioid.

From December 2011 to November 2012 (phase 2), the goal was to streamline VOE care from triage to disposition decision. The team revised the VOE algorithm to recommend 2 doses of intranasal fentanyl, 2 doses of IV opioids, and then a disposition decision. Then, they introduced the pain medication calculator.

From December 2012 to April 2014 (phase 3), the team assessed the sustainability of the interventions from phase 2. The team also revised the VOE algorithm in May 2013 to initiate patient-controlled analgesics after the first dose of IV opioid for patients with severe pain.

Results

The team observed a reduction in the average time from triage to the first dose of a pain medication—either through the nose or IV—from 56 minutes at baseline to 23 minutes in phase 3. The time to the second IV pain medication dose decreased as well—from 106 minutes to 83 minutes.

There was also a reduction in the time it took for the physician to determine whether the patient would be admitted—from 163 minutes to 109 minutes—or discharged—from 271 minutes to 178 minutes.

In addition, patients who were admitted were given patient-controlled analgesics to control their pain, and the time to its initiation decreased from 216 minutes to 141 minutes.

“While future studies are necessary to determine if these results can be replicated at other hospitals, our data indicates that these initiatives could have a tremendous impact on care for kids with SCD across the country,” said James Moses, MD, of BMC. ![]()