User login

FDA approves elranatamab for multiple myeloma

The B-cell maturation antigen (BCMA) CD3-targeted bispecific antibody (BsAb) was given Priority Review in February and had previously received Breakthrough Therapy Designation for relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma (RRMM), according to Pfizer.

FDA approval was based on favorable response and duration of response rates in the single-arm, phase 2 MagnetisMM-3 trial. The trial showed meaningful responses in heavily pretreated patients with RRMM who received elranatamab as their first BCMA-directed therapy.

The overall response rate in 97 BCMA-naive patients (cohort A) who previously received at least four lines of therapy, including a proteasome inhibitor, an immunomodulatory agent, and an anti-CD38 monoclonal antibody, was 58%, with an estimated 82% maintaining the response for 9 months or longer. Median time to first response was 1.2 months.

In 63 patients who received at least four prior lines of therapy, which also included a BCMA-directed therapy, the overall response rate was 33% after median follow-up of 10.2 months. An estimated 84% maintained a response for at least 9 months.

Elranatamab was given subcutaneously at a dose of 76 mg weekly on a 28-day cycle with a step-up priming dose regimen. The priming regimen included 12 mg and 32 mg doses on days 1 and 4, respectively, during cycle 1. Patients who received at least six cycles and showed at least a partial response for 2 or more months had a biweekly dosing interval.

Elranatamab carries a boxed warning for cytokine release syndrome (CRS) and neurologic toxicity, as well as warnings and precautions for infections, neutropenia, hepatotoxicity, and embryo–fetal toxicity. Therefore, the agent is available only through a restricted Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy (REMS).

The boxed warning is included in the full prescribing information.

A confirmatory trial to gather additional safety and efficacy data was launched in 2022. Continued FDA approval is contingent on confirmed safety and efficacy data.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The B-cell maturation antigen (BCMA) CD3-targeted bispecific antibody (BsAb) was given Priority Review in February and had previously received Breakthrough Therapy Designation for relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma (RRMM), according to Pfizer.

FDA approval was based on favorable response and duration of response rates in the single-arm, phase 2 MagnetisMM-3 trial. The trial showed meaningful responses in heavily pretreated patients with RRMM who received elranatamab as their first BCMA-directed therapy.

The overall response rate in 97 BCMA-naive patients (cohort A) who previously received at least four lines of therapy, including a proteasome inhibitor, an immunomodulatory agent, and an anti-CD38 monoclonal antibody, was 58%, with an estimated 82% maintaining the response for 9 months or longer. Median time to first response was 1.2 months.

In 63 patients who received at least four prior lines of therapy, which also included a BCMA-directed therapy, the overall response rate was 33% after median follow-up of 10.2 months. An estimated 84% maintained a response for at least 9 months.

Elranatamab was given subcutaneously at a dose of 76 mg weekly on a 28-day cycle with a step-up priming dose regimen. The priming regimen included 12 mg and 32 mg doses on days 1 and 4, respectively, during cycle 1. Patients who received at least six cycles and showed at least a partial response for 2 or more months had a biweekly dosing interval.

Elranatamab carries a boxed warning for cytokine release syndrome (CRS) and neurologic toxicity, as well as warnings and precautions for infections, neutropenia, hepatotoxicity, and embryo–fetal toxicity. Therefore, the agent is available only through a restricted Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy (REMS).

The boxed warning is included in the full prescribing information.

A confirmatory trial to gather additional safety and efficacy data was launched in 2022. Continued FDA approval is contingent on confirmed safety and efficacy data.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The B-cell maturation antigen (BCMA) CD3-targeted bispecific antibody (BsAb) was given Priority Review in February and had previously received Breakthrough Therapy Designation for relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma (RRMM), according to Pfizer.

FDA approval was based on favorable response and duration of response rates in the single-arm, phase 2 MagnetisMM-3 trial. The trial showed meaningful responses in heavily pretreated patients with RRMM who received elranatamab as their first BCMA-directed therapy.

The overall response rate in 97 BCMA-naive patients (cohort A) who previously received at least four lines of therapy, including a proteasome inhibitor, an immunomodulatory agent, and an anti-CD38 monoclonal antibody, was 58%, with an estimated 82% maintaining the response for 9 months or longer. Median time to first response was 1.2 months.

In 63 patients who received at least four prior lines of therapy, which also included a BCMA-directed therapy, the overall response rate was 33% after median follow-up of 10.2 months. An estimated 84% maintained a response for at least 9 months.

Elranatamab was given subcutaneously at a dose of 76 mg weekly on a 28-day cycle with a step-up priming dose regimen. The priming regimen included 12 mg and 32 mg doses on days 1 and 4, respectively, during cycle 1. Patients who received at least six cycles and showed at least a partial response for 2 or more months had a biweekly dosing interval.

Elranatamab carries a boxed warning for cytokine release syndrome (CRS) and neurologic toxicity, as well as warnings and precautions for infections, neutropenia, hepatotoxicity, and embryo–fetal toxicity. Therefore, the agent is available only through a restricted Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy (REMS).

The boxed warning is included in the full prescribing information.

A confirmatory trial to gather additional safety and efficacy data was launched in 2022. Continued FDA approval is contingent on confirmed safety and efficacy data.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Advancements help guide achalasia management, experts say

at a pace that has left the line-tracing technology considered to have debatable merit just 15 years ago “now as obsolete as a typewriter,” experts said recently in a review in Gastro Hep Advances.

“We have come to conceptualize esophageal motility disorders by specific aspects of physiological dysfunction,” wrote a trio of experts – Peter Kahrilas, MD, professor of medicine; Dustin Carlson, MD, MS, assistant professor of medicine, and John Pandolfino, MD, chief of gastroenterology and hepatology, all at Northwestern University, Chicago. “A major implication of this approach is a shift in management strategy toward rendering treatment in a phenotype-specific manner.”

High-resolution manometry (HRM) was trail-blazing, they said, as it replaced line-tracing manometry in evaluating the motility of the esophagus. HRM led to the subtyping of achalasia based on the three patterns of pressurization in the esophagus that are associated with obstruction at the esophagogastric junction. But the field has continued to advance.

“It has since become clear that obstructive physiology also occurs in syndromes besides achalasia involving the esophagogastric junction and/or distal esophagus,” Dr. Kahrilas, Dr. Carlson, and Dr. Pandolfino said. “In fact, obstructive physiology is increasingly recognized as the fundamental abnormality leading to the perception of dysphagia with esophageal motility disorders. This concept of obstructive physiology as the fundamental abnormality has substantially morphed the clinical management of esophageal motility disorders.”

HRM, has many limitations, but in cases of an uncertain achalasia diagnosis, functional luminal imaging probe (FLIP) technology can help, they said. FLIP can also help surgeons tailor myotomy procedures.

In FLIP, a probe is carefully filled with fluid, causing distension of the esophagus. In the test, the distensibility of the esophagogastric junction is measured. The procedure allows a more refined assessment of the movement of the esophagus, and the subtypes of achalasia.

Identifying the achalasia subtype is crucial to choosing the right treatment, data suggests. There have been no randomized controlled trials on achalasia management that prospectively consider achalasia subtype, but retrospective analysis of RCT data “suggests that achalasia subtypes are of great relevance in forecasting treatment effectiveness,” they said.

In one trial, pneumatic dilation was effective in 100% of type II achalasia, which involves panesophageal pressurization, significantly better than laparoscopic Heller myotomy (LHM). But it was much less effective than LHM in type III achalasia, the spastic form, although a significance couldn’t be established because of the number of cases. Data from a meta-analysis showed that peroral endoscopic myotomy, which allows for a longer myotomy if needed, was better than LHM for classic achalasia and spastic achalasia and was most efficacious overall.

The writers said that the diagnostic classifications for achalasia are likely to continue to evolve, pointing to the dynamic nature of the Chicago Classification for the disorder.

“The fact that it has now gone through four iterations since 2008 emphasizes that this is a work in progress and that no classification scheme of esophageal motility disorders based on a single test will ever be perfect,” they said. “After all, there are no biomarkers of esophageal motility disorders and, in the absence of a biomarker, there can be no ‘gold standard’ for diagnosis.”

Dr. Pandolfino, Dr. Kahrilas, and Northwestern University hold shared intellectual property rights and ownership surrounding FLIP Panometry systems, methods, and apparatus with Medtronic. Dr. Kahrilas reported consulting with Ironwood, Reckitt, and Phathom. Dr. Carlson reported conflicts of interest with Medtronic and Phathom Pharmaceuticals. Dr. Pandolfino reported conflicts of interest with Sandhill Scientific/Diversatek, Takeda, AstraZeneca, Medtronic, Torax, and Ironwood.

16% of the U.S. population experience dysphagia, only half of whom seek medical care and the others manage their symptoms by modifying diet.

X-ray barium swallow and endoscopy with biopsy to exclude eosinophilic esophagitis are the initial tests for dysphagia diagnosis. If the above are normal, a high-resolution esophageal manometry impedance (HRMZ) is recommended to diagnose primary and secondary esophageal motility disorder.

However, only in a minority of patients is it likely to cause dysphagia because uncontrolled studies show that therapeutic strategies to address EGJOO (botox, dilation, and myotomy) relieve dysphagia symptoms in a minority of patients. Hence, in significant number of patients the cause of dysphagia symptoms remains obscure. It might be that our testing is inadequate, or possibly, patients have functional dysphagia (sensory dysfunction of the esophagus). My opinion is that it is the former.

The esophagus has only one simple function, that is, to transfer the pharyngeal pump driven, that is, swallowed contents to the stomach, for which its luminal cross-sectional area must be larger than that of the swallowed bolus and contraction (measured by manometry) behind the bolus must be of adequate strength. The latter is likely less relevant because humans eat in the upright position and gravity provides propulsion for the bolus. Stated simply, as long as esophagus can distend well and there is no resistance to the outflow at the EGJ, esophagus can achieve its goal. However, until recently, there was no single test to determine the distension and contraction, the two essential elements of primary esophageal peristalsis.

Endoscopy and x-ray barium swallow are tests to determine the luminal diameter but have limitations. Endoflip measures the opening function of the EGJ and is useful when the HRM is normal. However, pressures that are currently being used to measure the EGJ distensibility by Endoflip are not physiological. Furthermore, esophageal body motor function assessed by a bag that distends a long segment of the esophagus under high pressure is unphysiological. The distension-contraction plots, which determines the luminal CSA and contraction simultaneously during primary peristalsis is ideally suited to study the pathophysiology of esophageal motility disorders. Several studies from my laboratory show that in patients with nutcracker esophagus, EGJOO and normal HRM, the esophagus distends significantly less than that of normal subjects during primary peristalsis. I suspect that an esophageal contraction pushing bolus through a narrow lumen esophagus is the cause of dysphagia sensation in many patients that have been labeled as functional dysphagia.

The last 2 decades have seen significant progress in the diagnosis of esophageal motility disorders using HRM, Endoflip, and distension-contraction plots of peristalsis. Furthermore, endoscopic treatment of achalasia and “achalasia-like syndromes” is revolutionary. What is desperately needed is an understanding of the pathogenesis of esophageal motor disorders, pharmacotherapy of esophageal symptoms, such as chest pain, proton pump inhibitor–resistant heartburn, and others because dysfunctional esophagus is a huge burden on health care expenditures worldwide.

Ravinder K. Mittal, MD, is a professor of medicine and gastroenterologist with UC San Diego Health. He has patent application pending on the computer software Dplots.

16% of the U.S. population experience dysphagia, only half of whom seek medical care and the others manage their symptoms by modifying diet.

X-ray barium swallow and endoscopy with biopsy to exclude eosinophilic esophagitis are the initial tests for dysphagia diagnosis. If the above are normal, a high-resolution esophageal manometry impedance (HRMZ) is recommended to diagnose primary and secondary esophageal motility disorder.

However, only in a minority of patients is it likely to cause dysphagia because uncontrolled studies show that therapeutic strategies to address EGJOO (botox, dilation, and myotomy) relieve dysphagia symptoms in a minority of patients. Hence, in significant number of patients the cause of dysphagia symptoms remains obscure. It might be that our testing is inadequate, or possibly, patients have functional dysphagia (sensory dysfunction of the esophagus). My opinion is that it is the former.

The esophagus has only one simple function, that is, to transfer the pharyngeal pump driven, that is, swallowed contents to the stomach, for which its luminal cross-sectional area must be larger than that of the swallowed bolus and contraction (measured by manometry) behind the bolus must be of adequate strength. The latter is likely less relevant because humans eat in the upright position and gravity provides propulsion for the bolus. Stated simply, as long as esophagus can distend well and there is no resistance to the outflow at the EGJ, esophagus can achieve its goal. However, until recently, there was no single test to determine the distension and contraction, the two essential elements of primary esophageal peristalsis.

Endoscopy and x-ray barium swallow are tests to determine the luminal diameter but have limitations. Endoflip measures the opening function of the EGJ and is useful when the HRM is normal. However, pressures that are currently being used to measure the EGJ distensibility by Endoflip are not physiological. Furthermore, esophageal body motor function assessed by a bag that distends a long segment of the esophagus under high pressure is unphysiological. The distension-contraction plots, which determines the luminal CSA and contraction simultaneously during primary peristalsis is ideally suited to study the pathophysiology of esophageal motility disorders. Several studies from my laboratory show that in patients with nutcracker esophagus, EGJOO and normal HRM, the esophagus distends significantly less than that of normal subjects during primary peristalsis. I suspect that an esophageal contraction pushing bolus through a narrow lumen esophagus is the cause of dysphagia sensation in many patients that have been labeled as functional dysphagia.

The last 2 decades have seen significant progress in the diagnosis of esophageal motility disorders using HRM, Endoflip, and distension-contraction plots of peristalsis. Furthermore, endoscopic treatment of achalasia and “achalasia-like syndromes” is revolutionary. What is desperately needed is an understanding of the pathogenesis of esophageal motor disorders, pharmacotherapy of esophageal symptoms, such as chest pain, proton pump inhibitor–resistant heartburn, and others because dysfunctional esophagus is a huge burden on health care expenditures worldwide.

Ravinder K. Mittal, MD, is a professor of medicine and gastroenterologist with UC San Diego Health. He has patent application pending on the computer software Dplots.

16% of the U.S. population experience dysphagia, only half of whom seek medical care and the others manage their symptoms by modifying diet.

X-ray barium swallow and endoscopy with biopsy to exclude eosinophilic esophagitis are the initial tests for dysphagia diagnosis. If the above are normal, a high-resolution esophageal manometry impedance (HRMZ) is recommended to diagnose primary and secondary esophageal motility disorder.

However, only in a minority of patients is it likely to cause dysphagia because uncontrolled studies show that therapeutic strategies to address EGJOO (botox, dilation, and myotomy) relieve dysphagia symptoms in a minority of patients. Hence, in significant number of patients the cause of dysphagia symptoms remains obscure. It might be that our testing is inadequate, or possibly, patients have functional dysphagia (sensory dysfunction of the esophagus). My opinion is that it is the former.

The esophagus has only one simple function, that is, to transfer the pharyngeal pump driven, that is, swallowed contents to the stomach, for which its luminal cross-sectional area must be larger than that of the swallowed bolus and contraction (measured by manometry) behind the bolus must be of adequate strength. The latter is likely less relevant because humans eat in the upright position and gravity provides propulsion for the bolus. Stated simply, as long as esophagus can distend well and there is no resistance to the outflow at the EGJ, esophagus can achieve its goal. However, until recently, there was no single test to determine the distension and contraction, the two essential elements of primary esophageal peristalsis.

Endoscopy and x-ray barium swallow are tests to determine the luminal diameter but have limitations. Endoflip measures the opening function of the EGJ and is useful when the HRM is normal. However, pressures that are currently being used to measure the EGJ distensibility by Endoflip are not physiological. Furthermore, esophageal body motor function assessed by a bag that distends a long segment of the esophagus under high pressure is unphysiological. The distension-contraction plots, which determines the luminal CSA and contraction simultaneously during primary peristalsis is ideally suited to study the pathophysiology of esophageal motility disorders. Several studies from my laboratory show that in patients with nutcracker esophagus, EGJOO and normal HRM, the esophagus distends significantly less than that of normal subjects during primary peristalsis. I suspect that an esophageal contraction pushing bolus through a narrow lumen esophagus is the cause of dysphagia sensation in many patients that have been labeled as functional dysphagia.

The last 2 decades have seen significant progress in the diagnosis of esophageal motility disorders using HRM, Endoflip, and distension-contraction plots of peristalsis. Furthermore, endoscopic treatment of achalasia and “achalasia-like syndromes” is revolutionary. What is desperately needed is an understanding of the pathogenesis of esophageal motor disorders, pharmacotherapy of esophageal symptoms, such as chest pain, proton pump inhibitor–resistant heartburn, and others because dysfunctional esophagus is a huge burden on health care expenditures worldwide.

Ravinder K. Mittal, MD, is a professor of medicine and gastroenterologist with UC San Diego Health. He has patent application pending on the computer software Dplots.

at a pace that has left the line-tracing technology considered to have debatable merit just 15 years ago “now as obsolete as a typewriter,” experts said recently in a review in Gastro Hep Advances.

“We have come to conceptualize esophageal motility disorders by specific aspects of physiological dysfunction,” wrote a trio of experts – Peter Kahrilas, MD, professor of medicine; Dustin Carlson, MD, MS, assistant professor of medicine, and John Pandolfino, MD, chief of gastroenterology and hepatology, all at Northwestern University, Chicago. “A major implication of this approach is a shift in management strategy toward rendering treatment in a phenotype-specific manner.”

High-resolution manometry (HRM) was trail-blazing, they said, as it replaced line-tracing manometry in evaluating the motility of the esophagus. HRM led to the subtyping of achalasia based on the three patterns of pressurization in the esophagus that are associated with obstruction at the esophagogastric junction. But the field has continued to advance.

“It has since become clear that obstructive physiology also occurs in syndromes besides achalasia involving the esophagogastric junction and/or distal esophagus,” Dr. Kahrilas, Dr. Carlson, and Dr. Pandolfino said. “In fact, obstructive physiology is increasingly recognized as the fundamental abnormality leading to the perception of dysphagia with esophageal motility disorders. This concept of obstructive physiology as the fundamental abnormality has substantially morphed the clinical management of esophageal motility disorders.”

HRM, has many limitations, but in cases of an uncertain achalasia diagnosis, functional luminal imaging probe (FLIP) technology can help, they said. FLIP can also help surgeons tailor myotomy procedures.

In FLIP, a probe is carefully filled with fluid, causing distension of the esophagus. In the test, the distensibility of the esophagogastric junction is measured. The procedure allows a more refined assessment of the movement of the esophagus, and the subtypes of achalasia.

Identifying the achalasia subtype is crucial to choosing the right treatment, data suggests. There have been no randomized controlled trials on achalasia management that prospectively consider achalasia subtype, but retrospective analysis of RCT data “suggests that achalasia subtypes are of great relevance in forecasting treatment effectiveness,” they said.

In one trial, pneumatic dilation was effective in 100% of type II achalasia, which involves panesophageal pressurization, significantly better than laparoscopic Heller myotomy (LHM). But it was much less effective than LHM in type III achalasia, the spastic form, although a significance couldn’t be established because of the number of cases. Data from a meta-analysis showed that peroral endoscopic myotomy, which allows for a longer myotomy if needed, was better than LHM for classic achalasia and spastic achalasia and was most efficacious overall.

The writers said that the diagnostic classifications for achalasia are likely to continue to evolve, pointing to the dynamic nature of the Chicago Classification for the disorder.

“The fact that it has now gone through four iterations since 2008 emphasizes that this is a work in progress and that no classification scheme of esophageal motility disorders based on a single test will ever be perfect,” they said. “After all, there are no biomarkers of esophageal motility disorders and, in the absence of a biomarker, there can be no ‘gold standard’ for diagnosis.”

Dr. Pandolfino, Dr. Kahrilas, and Northwestern University hold shared intellectual property rights and ownership surrounding FLIP Panometry systems, methods, and apparatus with Medtronic. Dr. Kahrilas reported consulting with Ironwood, Reckitt, and Phathom. Dr. Carlson reported conflicts of interest with Medtronic and Phathom Pharmaceuticals. Dr. Pandolfino reported conflicts of interest with Sandhill Scientific/Diversatek, Takeda, AstraZeneca, Medtronic, Torax, and Ironwood.

at a pace that has left the line-tracing technology considered to have debatable merit just 15 years ago “now as obsolete as a typewriter,” experts said recently in a review in Gastro Hep Advances.

“We have come to conceptualize esophageal motility disorders by specific aspects of physiological dysfunction,” wrote a trio of experts – Peter Kahrilas, MD, professor of medicine; Dustin Carlson, MD, MS, assistant professor of medicine, and John Pandolfino, MD, chief of gastroenterology and hepatology, all at Northwestern University, Chicago. “A major implication of this approach is a shift in management strategy toward rendering treatment in a phenotype-specific manner.”

High-resolution manometry (HRM) was trail-blazing, they said, as it replaced line-tracing manometry in evaluating the motility of the esophagus. HRM led to the subtyping of achalasia based on the three patterns of pressurization in the esophagus that are associated with obstruction at the esophagogastric junction. But the field has continued to advance.

“It has since become clear that obstructive physiology also occurs in syndromes besides achalasia involving the esophagogastric junction and/or distal esophagus,” Dr. Kahrilas, Dr. Carlson, and Dr. Pandolfino said. “In fact, obstructive physiology is increasingly recognized as the fundamental abnormality leading to the perception of dysphagia with esophageal motility disorders. This concept of obstructive physiology as the fundamental abnormality has substantially morphed the clinical management of esophageal motility disorders.”

HRM, has many limitations, but in cases of an uncertain achalasia diagnosis, functional luminal imaging probe (FLIP) technology can help, they said. FLIP can also help surgeons tailor myotomy procedures.

In FLIP, a probe is carefully filled with fluid, causing distension of the esophagus. In the test, the distensibility of the esophagogastric junction is measured. The procedure allows a more refined assessment of the movement of the esophagus, and the subtypes of achalasia.

Identifying the achalasia subtype is crucial to choosing the right treatment, data suggests. There have been no randomized controlled trials on achalasia management that prospectively consider achalasia subtype, but retrospective analysis of RCT data “suggests that achalasia subtypes are of great relevance in forecasting treatment effectiveness,” they said.

In one trial, pneumatic dilation was effective in 100% of type II achalasia, which involves panesophageal pressurization, significantly better than laparoscopic Heller myotomy (LHM). But it was much less effective than LHM in type III achalasia, the spastic form, although a significance couldn’t be established because of the number of cases. Data from a meta-analysis showed that peroral endoscopic myotomy, which allows for a longer myotomy if needed, was better than LHM for classic achalasia and spastic achalasia and was most efficacious overall.

The writers said that the diagnostic classifications for achalasia are likely to continue to evolve, pointing to the dynamic nature of the Chicago Classification for the disorder.

“The fact that it has now gone through four iterations since 2008 emphasizes that this is a work in progress and that no classification scheme of esophageal motility disorders based on a single test will ever be perfect,” they said. “After all, there are no biomarkers of esophageal motility disorders and, in the absence of a biomarker, there can be no ‘gold standard’ for diagnosis.”

Dr. Pandolfino, Dr. Kahrilas, and Northwestern University hold shared intellectual property rights and ownership surrounding FLIP Panometry systems, methods, and apparatus with Medtronic. Dr. Kahrilas reported consulting with Ironwood, Reckitt, and Phathom. Dr. Carlson reported conflicts of interest with Medtronic and Phathom Pharmaceuticals. Dr. Pandolfino reported conflicts of interest with Sandhill Scientific/Diversatek, Takeda, AstraZeneca, Medtronic, Torax, and Ironwood.

FROM GASTRO HEP ADVANCES

News & Perspectives from Ob.Gyn. News

NEWS FROM THE FDA/CDC

FDA approves first over-the-counter birth control pill

The Food and Drug Administration’s approval today of the first birth control pill for women to be available without a prescription is being hailed by many as a long-needed development, but there remain questions to be resolved, including how much the drug will cost and how it will be used.

The drug, Opill, is expected to be available early next year, and its maker has yet to reveal a retail price. It is the same birth control pill that has been available by prescription for 50 years. But for the first time, women will be able to buy the contraception at a local pharmacy, other retail locations, or online without having to see a doctor first.

Likely to drive debate

Contraception in the United States is not without controversy. The FDA’s approval spurred reactions both for and against making hormonal birth control for women available without a prescription.

“It’s an exciting time, especially right now when reproductive rights are being curtailed in a lot of states. Giving people an additional option for contraception will change people’s lives,” said Beverly Gray, MD, division director of Women’s Community and Population Health at Duke University Medical Center in Durham, N.C.

https://www.mdedge.com/obgyn/news-fda/cdc

FEATURE

U.S. mammogram update sparks concern, reignites debates

A recent update to the U.S. recommendations for breast cancer screening is raising concerns about the costs associated with potential follow-up tests, while also renewing debates about the timing of these tests and the screening approaches used.

The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force is currently finalizing an update to its recommendations on breast cancer screening. In May, the task force released a proposed update that dropped the initial age for routine mammogram screening from 50 to 40.

The task force intends to give a “B” rating to this recommendation, which covers screening every other year up to age 74 for women deemed average risk for breast cancer.

The task force’s rating carries clout, A. Mark Fendrick, MD, director of the Value-Based Insurance Design at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, said in an interview.

For one, the Affordable Care Act requires that private insurers cover services that get top A or B marks from USPSTF without charging copays.

However, Dr. Fendrick noted, such coverage does not necessarily apply to follow-up testing when a routine mammogram comes back with a positive finding. The expense of follow-up testing may deter some women from seeking follow-up diagnostic imaging or biopsies after an abnormal result on a screen-ing mammogram.

A recent analysis in JAMA Network Open found that women facing higher anticipated out-of-pocket costs for breast cancer diagnostic tests, based on their health insurance plan, were less likely to get that follow-up screening. For instance, the use of breast MRI decreased by nearly 24% between patients undergoing subsequent diagnostic testing in plans with the lowest out-of-pocket costs vs. those with the highest.

https://www.mdedge.com/obgyn/article/264198/breast-cancer/us-mammogram-update-sparks-concern-reignites-debates

Continue to: GENDER-AFFIRMING GYNECOLOGY...

GENDER-AFFIRMING GYNECOLOGY

Updates on pregnancy outcomes in transgender men

Despite increased societal gains, transgender individuals are still a medically and socially underserved group. The historic rise of antitransgender legislation and the overturning of Roe v. Wade, further compound existing health care disparities, particularly in the realm of contraception and pregnancy. Obstetrician-gynecologistsand midwives are typically first-line providers when discussing family planning and fertility options for all patients assigned female at birth. Unfortunately, compared with the surgical, hormonal, and mental health aspects of gender-affirming care, fertility and pregnancy in transgender men is still a relatively new and under-researched topic.

Only individuals who are assigned female at birth and have a uterus are capable of pregnancy. This can include both cisgender women and nonbinary/transgender men. However, societal and medical institutions are struggling with this shift in perspective from a traditionally gendered role to a more inclusive one. Obstetrician-gynecologists and midwives can serve to bridge this gap between these patients and societal misconceptions surrounding transgender men who desire and experience pregnancy.

Providers need to remember that many transmasculine individuals will still retain their uterus and are therefore capable of getting pregnant. While testosterone causes amenorrhea, if patients are engaging in penile-vaginal intercourse, conception is still possible. If a patient does not desire pregnancy, all contraceptive options available for cisgender women, which also include combined oral contraceptives, should be offered.

https://www.mdedge.com/obgyn/gender-affirming-gynecology

REPRODUCTIVE ROUNDS

Affordable IVF—Are we there yet?

The price for an in vitro fertilization (IVF) cycle continues to increase annually by many clinics, particularly because of “add-ons” of dubious value.

The initial application of IVF was for tubal factor infertility. Over the decades since 1981, the year of the first successful live birth in the United States, indications for IVF have dramatically expanded—ovulation dysfunction, unexplained infertility, male factor, advanced stage endometriosis, unexplained infertility, embryo testing to avoid an inherited genetic disease from the intended parents carrying the same mutation, and family balancing for gender, along with fertility preservation, including before potentially gonadotoxic treatment and “elective” planned oocyte cryopreservation.

The cost of IVF remains a significant, and possibly leading, stumbling block for women, couples, and men who lack insurance coverage. From RESOLVE.org, the National Infertility Association: “As of June 2022, 20 states have passed fertility insurance coverage laws, 14 of those laws include IVF coverage, and 12 states have fertility preservation laws for iatrogenic (medically induced) infertility.” Consequently, “affordable IVF” is paramount to providing equal access for patients.

https://www.mdedge.com/obgyn/reproductive-rounds

CONFERENCE COVERAGE

‘Artificial pancreas’ for all type 1 diabetes pregnancies?

In the largest randomized controlled trial of an automated insulin delivery (AID) system (hybrid closed-loop) versus standard insulin delivery in pregnant women with type 1 diabetes, the automated CamAPS FX system prevailed.

The percentage of time spent in the pregnancy-specific target blood glucose range of 63-140 mg/dL (3.5-7.8 mmol/L) from 16 weeks’ gestation to delivery was significantly higher in women in the AID group.

Helen R. Murphy, MD, presented these topline findings from the Automated Insulin Delivery Amongst Pregnant Women With Type 1 Diabetes (AiDAPT) trial during an e-poster session at the annual scientific sessions of the American Diabetes Association.

The “hybrid closed-loop significantly improved maternal glucose and should be offered to all pregnant women with type 1 diabetes,” concluded Dr. Murphy, professor of medicine at the University of East Anglia and a clinician at Norfolk and Norwich University Hospital in the United Kingdom.

CamAPS FX is the only AID system approved in Europe and the United Kingdom for type 1 diabetes from age 1 and during pregnancy. The hybrid closed-loop system is not available in the United States but other systems are available and sometimes used off label in pregnancy. Such systems are sometimes known colloquially as an “artificial pancreas.”

The researchers said their findings provide evidence for the UK National Institute of Clinical Excellence (NICE) to recommend that all pregnant women with type 1 diabetes should be offered the CamAPS FX system.

NEWS FROM THE FDA/CDC

FDA approves first over-the-counter birth control pill

The Food and Drug Administration’s approval today of the first birth control pill for women to be available without a prescription is being hailed by many as a long-needed development, but there remain questions to be resolved, including how much the drug will cost and how it will be used.

The drug, Opill, is expected to be available early next year, and its maker has yet to reveal a retail price. It is the same birth control pill that has been available by prescription for 50 years. But for the first time, women will be able to buy the contraception at a local pharmacy, other retail locations, or online without having to see a doctor first.

Likely to drive debate

Contraception in the United States is not without controversy. The FDA’s approval spurred reactions both for and against making hormonal birth control for women available without a prescription.

“It’s an exciting time, especially right now when reproductive rights are being curtailed in a lot of states. Giving people an additional option for contraception will change people’s lives,” said Beverly Gray, MD, division director of Women’s Community and Population Health at Duke University Medical Center in Durham, N.C.

https://www.mdedge.com/obgyn/news-fda/cdc

FEATURE

U.S. mammogram update sparks concern, reignites debates

A recent update to the U.S. recommendations for breast cancer screening is raising concerns about the costs associated with potential follow-up tests, while also renewing debates about the timing of these tests and the screening approaches used.

The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force is currently finalizing an update to its recommendations on breast cancer screening. In May, the task force released a proposed update that dropped the initial age for routine mammogram screening from 50 to 40.

The task force intends to give a “B” rating to this recommendation, which covers screening every other year up to age 74 for women deemed average risk for breast cancer.

The task force’s rating carries clout, A. Mark Fendrick, MD, director of the Value-Based Insurance Design at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, said in an interview.

For one, the Affordable Care Act requires that private insurers cover services that get top A or B marks from USPSTF without charging copays.

However, Dr. Fendrick noted, such coverage does not necessarily apply to follow-up testing when a routine mammogram comes back with a positive finding. The expense of follow-up testing may deter some women from seeking follow-up diagnostic imaging or biopsies after an abnormal result on a screen-ing mammogram.

A recent analysis in JAMA Network Open found that women facing higher anticipated out-of-pocket costs for breast cancer diagnostic tests, based on their health insurance plan, were less likely to get that follow-up screening. For instance, the use of breast MRI decreased by nearly 24% between patients undergoing subsequent diagnostic testing in plans with the lowest out-of-pocket costs vs. those with the highest.

https://www.mdedge.com/obgyn/article/264198/breast-cancer/us-mammogram-update-sparks-concern-reignites-debates

Continue to: GENDER-AFFIRMING GYNECOLOGY...

GENDER-AFFIRMING GYNECOLOGY

Updates on pregnancy outcomes in transgender men

Despite increased societal gains, transgender individuals are still a medically and socially underserved group. The historic rise of antitransgender legislation and the overturning of Roe v. Wade, further compound existing health care disparities, particularly in the realm of contraception and pregnancy. Obstetrician-gynecologistsand midwives are typically first-line providers when discussing family planning and fertility options for all patients assigned female at birth. Unfortunately, compared with the surgical, hormonal, and mental health aspects of gender-affirming care, fertility and pregnancy in transgender men is still a relatively new and under-researched topic.

Only individuals who are assigned female at birth and have a uterus are capable of pregnancy. This can include both cisgender women and nonbinary/transgender men. However, societal and medical institutions are struggling with this shift in perspective from a traditionally gendered role to a more inclusive one. Obstetrician-gynecologists and midwives can serve to bridge this gap between these patients and societal misconceptions surrounding transgender men who desire and experience pregnancy.

Providers need to remember that many transmasculine individuals will still retain their uterus and are therefore capable of getting pregnant. While testosterone causes amenorrhea, if patients are engaging in penile-vaginal intercourse, conception is still possible. If a patient does not desire pregnancy, all contraceptive options available for cisgender women, which also include combined oral contraceptives, should be offered.

https://www.mdedge.com/obgyn/gender-affirming-gynecology

REPRODUCTIVE ROUNDS

Affordable IVF—Are we there yet?

The price for an in vitro fertilization (IVF) cycle continues to increase annually by many clinics, particularly because of “add-ons” of dubious value.

The initial application of IVF was for tubal factor infertility. Over the decades since 1981, the year of the first successful live birth in the United States, indications for IVF have dramatically expanded—ovulation dysfunction, unexplained infertility, male factor, advanced stage endometriosis, unexplained infertility, embryo testing to avoid an inherited genetic disease from the intended parents carrying the same mutation, and family balancing for gender, along with fertility preservation, including before potentially gonadotoxic treatment and “elective” planned oocyte cryopreservation.

The cost of IVF remains a significant, and possibly leading, stumbling block for women, couples, and men who lack insurance coverage. From RESOLVE.org, the National Infertility Association: “As of June 2022, 20 states have passed fertility insurance coverage laws, 14 of those laws include IVF coverage, and 12 states have fertility preservation laws for iatrogenic (medically induced) infertility.” Consequently, “affordable IVF” is paramount to providing equal access for patients.

https://www.mdedge.com/obgyn/reproductive-rounds

CONFERENCE COVERAGE

‘Artificial pancreas’ for all type 1 diabetes pregnancies?

In the largest randomized controlled trial of an automated insulin delivery (AID) system (hybrid closed-loop) versus standard insulin delivery in pregnant women with type 1 diabetes, the automated CamAPS FX system prevailed.

The percentage of time spent in the pregnancy-specific target blood glucose range of 63-140 mg/dL (3.5-7.8 mmol/L) from 16 weeks’ gestation to delivery was significantly higher in women in the AID group.

Helen R. Murphy, MD, presented these topline findings from the Automated Insulin Delivery Amongst Pregnant Women With Type 1 Diabetes (AiDAPT) trial during an e-poster session at the annual scientific sessions of the American Diabetes Association.

The “hybrid closed-loop significantly improved maternal glucose and should be offered to all pregnant women with type 1 diabetes,” concluded Dr. Murphy, professor of medicine at the University of East Anglia and a clinician at Norfolk and Norwich University Hospital in the United Kingdom.

CamAPS FX is the only AID system approved in Europe and the United Kingdom for type 1 diabetes from age 1 and during pregnancy. The hybrid closed-loop system is not available in the United States but other systems are available and sometimes used off label in pregnancy. Such systems are sometimes known colloquially as an “artificial pancreas.”

The researchers said their findings provide evidence for the UK National Institute of Clinical Excellence (NICE) to recommend that all pregnant women with type 1 diabetes should be offered the CamAPS FX system.

NEWS FROM THE FDA/CDC

FDA approves first over-the-counter birth control pill

The Food and Drug Administration’s approval today of the first birth control pill for women to be available without a prescription is being hailed by many as a long-needed development, but there remain questions to be resolved, including how much the drug will cost and how it will be used.

The drug, Opill, is expected to be available early next year, and its maker has yet to reveal a retail price. It is the same birth control pill that has been available by prescription for 50 years. But for the first time, women will be able to buy the contraception at a local pharmacy, other retail locations, or online without having to see a doctor first.

Likely to drive debate

Contraception in the United States is not without controversy. The FDA’s approval spurred reactions both for and against making hormonal birth control for women available without a prescription.

“It’s an exciting time, especially right now when reproductive rights are being curtailed in a lot of states. Giving people an additional option for contraception will change people’s lives,” said Beverly Gray, MD, division director of Women’s Community and Population Health at Duke University Medical Center in Durham, N.C.

https://www.mdedge.com/obgyn/news-fda/cdc

FEATURE

U.S. mammogram update sparks concern, reignites debates

A recent update to the U.S. recommendations for breast cancer screening is raising concerns about the costs associated with potential follow-up tests, while also renewing debates about the timing of these tests and the screening approaches used.

The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force is currently finalizing an update to its recommendations on breast cancer screening. In May, the task force released a proposed update that dropped the initial age for routine mammogram screening from 50 to 40.

The task force intends to give a “B” rating to this recommendation, which covers screening every other year up to age 74 for women deemed average risk for breast cancer.

The task force’s rating carries clout, A. Mark Fendrick, MD, director of the Value-Based Insurance Design at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, said in an interview.

For one, the Affordable Care Act requires that private insurers cover services that get top A or B marks from USPSTF without charging copays.

However, Dr. Fendrick noted, such coverage does not necessarily apply to follow-up testing when a routine mammogram comes back with a positive finding. The expense of follow-up testing may deter some women from seeking follow-up diagnostic imaging or biopsies after an abnormal result on a screen-ing mammogram.

A recent analysis in JAMA Network Open found that women facing higher anticipated out-of-pocket costs for breast cancer diagnostic tests, based on their health insurance plan, were less likely to get that follow-up screening. For instance, the use of breast MRI decreased by nearly 24% between patients undergoing subsequent diagnostic testing in plans with the lowest out-of-pocket costs vs. those with the highest.

https://www.mdedge.com/obgyn/article/264198/breast-cancer/us-mammogram-update-sparks-concern-reignites-debates

Continue to: GENDER-AFFIRMING GYNECOLOGY...

GENDER-AFFIRMING GYNECOLOGY

Updates on pregnancy outcomes in transgender men

Despite increased societal gains, transgender individuals are still a medically and socially underserved group. The historic rise of antitransgender legislation and the overturning of Roe v. Wade, further compound existing health care disparities, particularly in the realm of contraception and pregnancy. Obstetrician-gynecologistsand midwives are typically first-line providers when discussing family planning and fertility options for all patients assigned female at birth. Unfortunately, compared with the surgical, hormonal, and mental health aspects of gender-affirming care, fertility and pregnancy in transgender men is still a relatively new and under-researched topic.

Only individuals who are assigned female at birth and have a uterus are capable of pregnancy. This can include both cisgender women and nonbinary/transgender men. However, societal and medical institutions are struggling with this shift in perspective from a traditionally gendered role to a more inclusive one. Obstetrician-gynecologists and midwives can serve to bridge this gap between these patients and societal misconceptions surrounding transgender men who desire and experience pregnancy.

Providers need to remember that many transmasculine individuals will still retain their uterus and are therefore capable of getting pregnant. While testosterone causes amenorrhea, if patients are engaging in penile-vaginal intercourse, conception is still possible. If a patient does not desire pregnancy, all contraceptive options available for cisgender women, which also include combined oral contraceptives, should be offered.

https://www.mdedge.com/obgyn/gender-affirming-gynecology

REPRODUCTIVE ROUNDS

Affordable IVF—Are we there yet?

The price for an in vitro fertilization (IVF) cycle continues to increase annually by many clinics, particularly because of “add-ons” of dubious value.

The initial application of IVF was for tubal factor infertility. Over the decades since 1981, the year of the first successful live birth in the United States, indications for IVF have dramatically expanded—ovulation dysfunction, unexplained infertility, male factor, advanced stage endometriosis, unexplained infertility, embryo testing to avoid an inherited genetic disease from the intended parents carrying the same mutation, and family balancing for gender, along with fertility preservation, including before potentially gonadotoxic treatment and “elective” planned oocyte cryopreservation.

The cost of IVF remains a significant, and possibly leading, stumbling block for women, couples, and men who lack insurance coverage. From RESOLVE.org, the National Infertility Association: “As of June 2022, 20 states have passed fertility insurance coverage laws, 14 of those laws include IVF coverage, and 12 states have fertility preservation laws for iatrogenic (medically induced) infertility.” Consequently, “affordable IVF” is paramount to providing equal access for patients.

https://www.mdedge.com/obgyn/reproductive-rounds

CONFERENCE COVERAGE

‘Artificial pancreas’ for all type 1 diabetes pregnancies?

In the largest randomized controlled trial of an automated insulin delivery (AID) system (hybrid closed-loop) versus standard insulin delivery in pregnant women with type 1 diabetes, the automated CamAPS FX system prevailed.

The percentage of time spent in the pregnancy-specific target blood glucose range of 63-140 mg/dL (3.5-7.8 mmol/L) from 16 weeks’ gestation to delivery was significantly higher in women in the AID group.

Helen R. Murphy, MD, presented these topline findings from the Automated Insulin Delivery Amongst Pregnant Women With Type 1 Diabetes (AiDAPT) trial during an e-poster session at the annual scientific sessions of the American Diabetes Association.

The “hybrid closed-loop significantly improved maternal glucose and should be offered to all pregnant women with type 1 diabetes,” concluded Dr. Murphy, professor of medicine at the University of East Anglia and a clinician at Norfolk and Norwich University Hospital in the United Kingdom.

CamAPS FX is the only AID system approved in Europe and the United Kingdom for type 1 diabetes from age 1 and during pregnancy. The hybrid closed-loop system is not available in the United States but other systems are available and sometimes used off label in pregnancy. Such systems are sometimes known colloquially as an “artificial pancreas.”

The researchers said their findings provide evidence for the UK National Institute of Clinical Excellence (NICE) to recommend that all pregnant women with type 1 diabetes should be offered the CamAPS FX system.

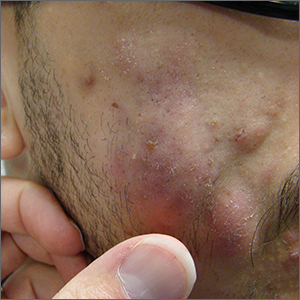

Fluctuant facial lesions

This patient had more than cystic acne; he had acne conglobata. AC is a severe form of inflammatory acne leading to coalescing lesions with purulent sinus tracts under the skin. It can be seen as part of the follicular tetrad syndrome of cystic acne, hidradenitis suppurativa, dissecting cellulitis, and pilonidal disease. AC is thought to be an elevated tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-alpha response to Propionibacterium acnes (now known as Cutibacterium acnes) that leads to excessive inflammation and sterile abscesses.1 Acne fulminans (AF) can also manifest as a purulent form of acne, but AF has associated systemic signs and symptoms that include fevers, chills, and malaise.

Due to the depth of the inflammation, AC is treated with systemic medications, most commonly isotretinoin. Isotretinoin can be started at 0.5 mg/kg (divided twice daily to enhance tolerability) and then increased to 1 mg/kg (divided twice daily) for 5 months. There is some variation in dosing regimens in practice; the target goal is 120 to 150 mg/kg over the course of treatment. In AF, the patient is pretreated with systemic steroids, and in AC, some clinicians will even prescribe systemic steroids (prednisone 0.5 mg/kg daily for the first month) along with isotretinoin.

Second-line medications include dapsone (50-150 mg/d).2 Case reports describe the successful use of the TNF-alpha antagonist adalimumab, although this is not a usual practice in AC treatment.1 Note that all of these medications have the potential for severe adverse effects and require laboratory evaluation prior to initiation.

This patient was counseled, prescribed isotretinoin (dose as above), and enrolled in the IPledge prescribing and monitoring system for isotretinoin. At 20 weeks of use, the purulent drainage ceased. The pus-filled sinus tracts and redness had resolved, although he still had thickened tissue and scarring where the tracts had been. In time, the scars will usually get flatter and softer.

If the patient’s AC were to flare, another 20-week course of isotretinoin could be prescribed after a 2-month hiatus or he could be switched to a second-line medication. Referral for any cosmetic therapy is typically delayed for another 6 months in case there is a need to treat a recurrence.

Photo and text courtesy of Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Professor and Chair, Department of Family and Community Medicine, Western Michigan University Homer Stryker, MD School of Medicine, Kalamazoo.

1. Yiu ZZ, Madan V, Griffiths CE. Acne conglobata and adalimumab: use of tumour necrosis factor-α antagonists in treatment-resistant acne conglobata, and review of the literature. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2015;40:383-386. doi: 10.1111/ced.12540

2. Hafsi W, Arnold DL, Kassardjian M. Acne Conglobata. StatPearls Publishing; 2023.

This patient had more than cystic acne; he had acne conglobata. AC is a severe form of inflammatory acne leading to coalescing lesions with purulent sinus tracts under the skin. It can be seen as part of the follicular tetrad syndrome of cystic acne, hidradenitis suppurativa, dissecting cellulitis, and pilonidal disease. AC is thought to be an elevated tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-alpha response to Propionibacterium acnes (now known as Cutibacterium acnes) that leads to excessive inflammation and sterile abscesses.1 Acne fulminans (AF) can also manifest as a purulent form of acne, but AF has associated systemic signs and symptoms that include fevers, chills, and malaise.

Due to the depth of the inflammation, AC is treated with systemic medications, most commonly isotretinoin. Isotretinoin can be started at 0.5 mg/kg (divided twice daily to enhance tolerability) and then increased to 1 mg/kg (divided twice daily) for 5 months. There is some variation in dosing regimens in practice; the target goal is 120 to 150 mg/kg over the course of treatment. In AF, the patient is pretreated with systemic steroids, and in AC, some clinicians will even prescribe systemic steroids (prednisone 0.5 mg/kg daily for the first month) along with isotretinoin.

Second-line medications include dapsone (50-150 mg/d).2 Case reports describe the successful use of the TNF-alpha antagonist adalimumab, although this is not a usual practice in AC treatment.1 Note that all of these medications have the potential for severe adverse effects and require laboratory evaluation prior to initiation.

This patient was counseled, prescribed isotretinoin (dose as above), and enrolled in the IPledge prescribing and monitoring system for isotretinoin. At 20 weeks of use, the purulent drainage ceased. The pus-filled sinus tracts and redness had resolved, although he still had thickened tissue and scarring where the tracts had been. In time, the scars will usually get flatter and softer.

If the patient’s AC were to flare, another 20-week course of isotretinoin could be prescribed after a 2-month hiatus or he could be switched to a second-line medication. Referral for any cosmetic therapy is typically delayed for another 6 months in case there is a need to treat a recurrence.

Photo and text courtesy of Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Professor and Chair, Department of Family and Community Medicine, Western Michigan University Homer Stryker, MD School of Medicine, Kalamazoo.

This patient had more than cystic acne; he had acne conglobata. AC is a severe form of inflammatory acne leading to coalescing lesions with purulent sinus tracts under the skin. It can be seen as part of the follicular tetrad syndrome of cystic acne, hidradenitis suppurativa, dissecting cellulitis, and pilonidal disease. AC is thought to be an elevated tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-alpha response to Propionibacterium acnes (now known as Cutibacterium acnes) that leads to excessive inflammation and sterile abscesses.1 Acne fulminans (AF) can also manifest as a purulent form of acne, but AF has associated systemic signs and symptoms that include fevers, chills, and malaise.

Due to the depth of the inflammation, AC is treated with systemic medications, most commonly isotretinoin. Isotretinoin can be started at 0.5 mg/kg (divided twice daily to enhance tolerability) and then increased to 1 mg/kg (divided twice daily) for 5 months. There is some variation in dosing regimens in practice; the target goal is 120 to 150 mg/kg over the course of treatment. In AF, the patient is pretreated with systemic steroids, and in AC, some clinicians will even prescribe systemic steroids (prednisone 0.5 mg/kg daily for the first month) along with isotretinoin.

Second-line medications include dapsone (50-150 mg/d).2 Case reports describe the successful use of the TNF-alpha antagonist adalimumab, although this is not a usual practice in AC treatment.1 Note that all of these medications have the potential for severe adverse effects and require laboratory evaluation prior to initiation.

This patient was counseled, prescribed isotretinoin (dose as above), and enrolled in the IPledge prescribing and monitoring system for isotretinoin. At 20 weeks of use, the purulent drainage ceased. The pus-filled sinus tracts and redness had resolved, although he still had thickened tissue and scarring where the tracts had been. In time, the scars will usually get flatter and softer.

If the patient’s AC were to flare, another 20-week course of isotretinoin could be prescribed after a 2-month hiatus or he could be switched to a second-line medication. Referral for any cosmetic therapy is typically delayed for another 6 months in case there is a need to treat a recurrence.

Photo and text courtesy of Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Professor and Chair, Department of Family and Community Medicine, Western Michigan University Homer Stryker, MD School of Medicine, Kalamazoo.

1. Yiu ZZ, Madan V, Griffiths CE. Acne conglobata and adalimumab: use of tumour necrosis factor-α antagonists in treatment-resistant acne conglobata, and review of the literature. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2015;40:383-386. doi: 10.1111/ced.12540

2. Hafsi W, Arnold DL, Kassardjian M. Acne Conglobata. StatPearls Publishing; 2023.

1. Yiu ZZ, Madan V, Griffiths CE. Acne conglobata and adalimumab: use of tumour necrosis factor-α antagonists in treatment-resistant acne conglobata, and review of the literature. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2015;40:383-386. doi: 10.1111/ced.12540

2. Hafsi W, Arnold DL, Kassardjian M. Acne Conglobata. StatPearls Publishing; 2023.

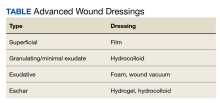

Leathery plaque on thigh

The necrotic eschar on this patient’s thigh is calciphylaxis, also known as calcific uremic arteriolopathy (CUA). Most cases are seen in ESRD and start as painful erythematous, firm lesions that progress to necrotic eschars. Up to 4% of patients with ESRD who are on dialysis develop CUA.1

The exact pathology of CUA is unknown. Calcification of the arterioles leads to ischemia and necrosis of tissue, which is not limited to the skin and can affect tissue elsewhere (eg, muscles, central nervous system, internal organs).2

Morbidity and mortality of CUA is often due to bacterial infections and sepsis related to the necrotic tissue. CUA can be treated with sodium thiosulfate (25 g in 100 mL of normal saline) infused intravenously during the last 30 minutes of dialysis treatment 3 times per week.3 Sodium thiosulfate (which acts as a calcium binder) and cinacalcet (a calcimimetic that leads to lower parathyroid hormone levels) have been used, but evidence of efficacy is limited. In a multicenter observational study involving 89 patients with chronic kidney disease and CUA, 17% of patients experienced complete wound healing, while 56% died over a median follow-up period of 5.8 months.1 (No cause of death data were available; sodium thiosulfate and a calcimimetic were the most widely used treatment strategies.) This extrapolated to a mortality rate of 72 patients per 100 individuals over the course of 1 year (the 100 patient-years rate).1

This patient continued her dialysis regimen and general care. She was seen by the wound care team and treated with topical wound care, including moist dressings for her open lesions. The eschars were not debrided because they showed no sign of active infection. Unfortunately, she was in extremely frail condition and died 1 month after evaluation.

Photo and text courtesy of Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Professor and Chair, Department of Family and Community Medicine, Western Michigan University Homer Stryker, MD School of Medicine, Kalamazoo.

1. Chinnadurai R, Huckle A, Hegarty J, et al. Calciphylaxis in end-stage kidney disease: outcome data from the United Kingdom Calciphylaxis Study. J Nephrol. 2021;34:1537-1545. doi: 10.1007/s40620-020-00908-9

2. Nigwekar SU, Kroshinsky D, Nazarian RM, et al. Calciphylaxis: risk factors, diagnosis, and treatment. Am J Kidney Dis. 2015;66:133-146. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2015.01.034

3. Nigwekar SU, Kroshinsky D, Nazarian RM, et al. Calciphylaxis: risk factors, diagnosis, and treatment. Am J Kidney Dis. 2015;66:133-146. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2015.01.034

The necrotic eschar on this patient’s thigh is calciphylaxis, also known as calcific uremic arteriolopathy (CUA). Most cases are seen in ESRD and start as painful erythematous, firm lesions that progress to necrotic eschars. Up to 4% of patients with ESRD who are on dialysis develop CUA.1

The exact pathology of CUA is unknown. Calcification of the arterioles leads to ischemia and necrosis of tissue, which is not limited to the skin and can affect tissue elsewhere (eg, muscles, central nervous system, internal organs).2

Morbidity and mortality of CUA is often due to bacterial infections and sepsis related to the necrotic tissue. CUA can be treated with sodium thiosulfate (25 g in 100 mL of normal saline) infused intravenously during the last 30 minutes of dialysis treatment 3 times per week.3 Sodium thiosulfate (which acts as a calcium binder) and cinacalcet (a calcimimetic that leads to lower parathyroid hormone levels) have been used, but evidence of efficacy is limited. In a multicenter observational study involving 89 patients with chronic kidney disease and CUA, 17% of patients experienced complete wound healing, while 56% died over a median follow-up period of 5.8 months.1 (No cause of death data were available; sodium thiosulfate and a calcimimetic were the most widely used treatment strategies.) This extrapolated to a mortality rate of 72 patients per 100 individuals over the course of 1 year (the 100 patient-years rate).1

This patient continued her dialysis regimen and general care. She was seen by the wound care team and treated with topical wound care, including moist dressings for her open lesions. The eschars were not debrided because they showed no sign of active infection. Unfortunately, she was in extremely frail condition and died 1 month after evaluation.

Photo and text courtesy of Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Professor and Chair, Department of Family and Community Medicine, Western Michigan University Homer Stryker, MD School of Medicine, Kalamazoo.

The necrotic eschar on this patient’s thigh is calciphylaxis, also known as calcific uremic arteriolopathy (CUA). Most cases are seen in ESRD and start as painful erythematous, firm lesions that progress to necrotic eschars. Up to 4% of patients with ESRD who are on dialysis develop CUA.1

The exact pathology of CUA is unknown. Calcification of the arterioles leads to ischemia and necrosis of tissue, which is not limited to the skin and can affect tissue elsewhere (eg, muscles, central nervous system, internal organs).2

Morbidity and mortality of CUA is often due to bacterial infections and sepsis related to the necrotic tissue. CUA can be treated with sodium thiosulfate (25 g in 100 mL of normal saline) infused intravenously during the last 30 minutes of dialysis treatment 3 times per week.3 Sodium thiosulfate (which acts as a calcium binder) and cinacalcet (a calcimimetic that leads to lower parathyroid hormone levels) have been used, but evidence of efficacy is limited. In a multicenter observational study involving 89 patients with chronic kidney disease and CUA, 17% of patients experienced complete wound healing, while 56% died over a median follow-up period of 5.8 months.1 (No cause of death data were available; sodium thiosulfate and a calcimimetic were the most widely used treatment strategies.) This extrapolated to a mortality rate of 72 patients per 100 individuals over the course of 1 year (the 100 patient-years rate).1

This patient continued her dialysis regimen and general care. She was seen by the wound care team and treated with topical wound care, including moist dressings for her open lesions. The eschars were not debrided because they showed no sign of active infection. Unfortunately, she was in extremely frail condition and died 1 month after evaluation.

Photo and text courtesy of Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Professor and Chair, Department of Family and Community Medicine, Western Michigan University Homer Stryker, MD School of Medicine, Kalamazoo.

1. Chinnadurai R, Huckle A, Hegarty J, et al. Calciphylaxis in end-stage kidney disease: outcome data from the United Kingdom Calciphylaxis Study. J Nephrol. 2021;34:1537-1545. doi: 10.1007/s40620-020-00908-9

2. Nigwekar SU, Kroshinsky D, Nazarian RM, et al. Calciphylaxis: risk factors, diagnosis, and treatment. Am J Kidney Dis. 2015;66:133-146. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2015.01.034

3. Nigwekar SU, Kroshinsky D, Nazarian RM, et al. Calciphylaxis: risk factors, diagnosis, and treatment. Am J Kidney Dis. 2015;66:133-146. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2015.01.034

1. Chinnadurai R, Huckle A, Hegarty J, et al. Calciphylaxis in end-stage kidney disease: outcome data from the United Kingdom Calciphylaxis Study. J Nephrol. 2021;34:1537-1545. doi: 10.1007/s40620-020-00908-9

2. Nigwekar SU, Kroshinsky D, Nazarian RM, et al. Calciphylaxis: risk factors, diagnosis, and treatment. Am J Kidney Dis. 2015;66:133-146. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2015.01.034

3. Nigwekar SU, Kroshinsky D, Nazarian RM, et al. Calciphylaxis: risk factors, diagnosis, and treatment. Am J Kidney Dis. 2015;66:133-146. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2015.01.034

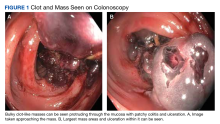

Gastrointestinal Bleeding Caused by Large Intestine Amyloidosis

Gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding is a common cause of hospital admissions. The yearly incidence of upper GI bleeding is 80 to 150/100,000 people and lower GI bleeding is 87/100,000 people.1,2 The differential tends to initially be broad but narrows with good history followed by endoscopic findings. Getting an appropriate history can be difficult at times, which leads health care practitioners to rely more on interventional results.

Amyloidosis is a rare disorder of abnormal protein folding, leading to the deposition of insoluble fibrils that disrupt normal tissues and cause disease.3 There are 2 main types of amyloidosis, systemic and transthyretin, and 4 subtypes. Systemic amyloidosis includes amyloid light-chain (AL) deposition, caused by plasma cell dyscrasia, and amyloid A (AA) protein deposition, caused by systemic autoimmune illness or infections. Transthyretin amyloidosis is caused by changes and deposition of the transthyretin protein consisting of either unstable, mutant protein or wild type protein. Biopsy-proven amyloidosis of the GI tract is rare.4 About 60% of patients with AA amyloidosis and 8% with AL amyloidosis have GI involvement.5

We present a case of nonspecific symptoms that ultimately lined up perfectly with the official histologic confirmation of intestinal amyloidosis.

Case Presentation

A 79-year-old man with a history of type 2 diabetes mellitus, congestive heart failure, hyperlipidemia, obstructive sleep apnea, hypothyroidism, hypertension, coronary artery disease status postcoronary artery bypass grafting, and stent placements presented for 3 episodes of large, bright red bowel movements. He reported past bleeding and straining with stools, but bleeding of this amount had not been noted prior. He also reported dry heaves, lower abdominal pain, constipation with straining, early satiety with dysphagia, weakness, and decreased appetite. Lastly, he mentioned intentionally losing about 35 to 40 pounds in the past 3 to 4 months and over the past several months increased abdominal distention. However, he stated he had no history of alcohol misuse, liver or intestinal disease, cirrhosis, or other autoimmune diseases. His most recent colonoscopy was more than a decade prior and showed no acute process. The patient never had an esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD).

On initial presentation, the patient’s vital signs showed no acute findings. His physical examination noted a chronically ill–appearing male with decreased breath sounds to the bases bilaterally and noted abdominal distention with mild generalized tenderness. Laboratory findings were significant for a hemoglobin level, 9.4 g/dL (reference range, 11.6-15.3); iron, 23 ug/dL (reference range, 45-160); transferrin saturation, 8% (reference range, 15-50); ferritin level, 80 ng/mL (reference range, 30-300); and carcinoembryonic antigen level, 1.5 ng/mL (reference range, 0-2.9). Aspartate aminotransferase level was 54 IU/L (reference range, 0-40); alanine transaminase, 24 IU/L (reference range, 7-52); albumin, 2.7 g/dL (reference range, 3.4-5.7); international normalized ratio, 1.3 (reference range, 0-1.1); creatinine, 1.74 mg/dL (reference range, 0.44-1.27); alkaline phosphatase, 369 IU/L (reference range, 39-117). White blood cell count was 15.5 × 109/L (reference range, 3.5-10.3), and lactic acid was 2.5 mmol/L (reference range, 0.5-2.2). He was started on piperacillin/tazobactam in the emergency department and transitioned to ciprofloxacin and metronidazole for presumed intra-abdominal infection. Paracentesis showed a serum ascites albumin gradient of > 1.1 g/dL with no signs of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis. Computed tomography of the abdomen and pelvis with contrast was suspicious for colitis involving the proximal colon, and colonic mass could not be excluded. Also noted was hepatosplenomegaly with abdominopelvic ascites.

Based on these findings, an EGD and colonoscopy were done. The EGD showed mild portal hypertensive gastropathy.

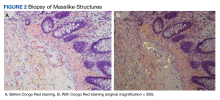

After the biopsy results, the patient was officially diagnosed with intestinal amyloidosis (Figure 2).

He returned to the gastroenterology clinic 2 months later. At that point, he had worsening symptoms, liver function test results, and international normalized ratio. He was admitted for further investigation. A bone biopsy was done to confirm the histology and define the underlying disorder. The biopsy returned showing Waldenstrom macroglobulinemia, and he was started on bortezomib. Unfortunately, his clinical status rapidly worsened, leading to acute renal and hepatic failure and the development of encephalopathy. He eventually died under palliative care services.

Discussion

Amyloidosis is a rare disorder of abnormal protein folding, leading to the deposition of insoluble fibrils that disrupt normal tissues and cause disease.3 There are several variations of amyloid, but the most common type is AL amyloidosis, which affects several organs, including the heart, kidney, liver, nervous system, and GI tract. When AL amyloidosis involves the liver, the median survival time is about 8.5 months.6 There are different ways to diagnose the disease, but a tissue biopsy and Congo Red staining can confirm specific organ involvement as seen in our case.

This case adds another layer to our constantly expanding differential as health care practitioners and proves that atypical patient presentations may not be atypical after all. GI amyloidosis tends to present similarly to our patient with bleeding, malabsorption, dysmotility, and protein-losing gastroenteropathy as ascites, edema, pericardial effusions, and laboratory evidence of hypoalbuminemia.7 Because amyloidosis is a systemic illness, early recognition is important as intestinal complications tend to present as symptoms, but mortality is more often caused by renal failure, cardiomyopathy, or ischemic heart disease, making early multispecialty involvement very important.8

Conclusions

Health care practitioners in all specialties should be aware of and include intestinal amyloidosis in their differential diagnosis when working up GI bleeds with the hope of identifying the disease early. With early recognition, rapid biopsy identification, and early specialist involvement, patients will get the opportunity for expedited multidisciplinary treatment and potentially delay rapid decompensation as shown by the evidence in this case.

1. Antunes C, Copelin II EL. Upper gastrointestinal bleeding. StatPearls [internet]. Updated July 18, 2022. Accessed May 25, 2023. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK470300

2. Almaghrabi M, Gandhi M, Guizzetti L, et al. Comparison of risk scores for lower gastrointestinal bleeding: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5(5):e2214253. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.14253

3. Pepys MB. Pathogenesis, diagnosis and treatment of systemic amyloidosis. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2001;356(1406):203-211. doi:10.1098/rstb.2000.0766

4. Cowan AJ, Skinner M, Seldin DC, et al. Amyloidosis of the gastrointestinal tract: a 13-year, single-center, referral experience. Haematologica. 2013;98(1):141-146. doi:10.3324/haematol.2012.068155

5. Lee BS, Chudasama Y, Chen AI, Lim BS, Taira MT. Colonoscopy leading to the diagnosis of AL amyloidosis in the gastrointestinal tract mimicking an acute ulcerative colitis flare. ACG Case Rep J. 2019;6(11):e00289. doi:10.14309/crj.0000000000000289

6. Zhao L, Ren G, Guo J, Chen W, Xu W, Huang X. The clinical features and outcomes of systemic light chain amyloidosis with hepatic involvement. Ann Med. 2022;54(1):1226-1232. doi:10.1080/07853890.2022.2069281

7. Rowe K, Pankow J, Nehme F, Salyers W. Gastrointestinal amyloidosis: review of the literature. Cureus. 2017;9(5):e1228. doi:10.7759/cureus.1228

8. Kyle RA, Greipp PR, O’Fallon WM. Primary systemic amyloidosis: multivariate analysis for prognostic factors in 168 cases. Blood. 1986;68(1):220-224.

Gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding is a common cause of hospital admissions. The yearly incidence of upper GI bleeding is 80 to 150/100,000 people and lower GI bleeding is 87/100,000 people.1,2 The differential tends to initially be broad but narrows with good history followed by endoscopic findings. Getting an appropriate history can be difficult at times, which leads health care practitioners to rely more on interventional results.

Amyloidosis is a rare disorder of abnormal protein folding, leading to the deposition of insoluble fibrils that disrupt normal tissues and cause disease.3 There are 2 main types of amyloidosis, systemic and transthyretin, and 4 subtypes. Systemic amyloidosis includes amyloid light-chain (AL) deposition, caused by plasma cell dyscrasia, and amyloid A (AA) protein deposition, caused by systemic autoimmune illness or infections. Transthyretin amyloidosis is caused by changes and deposition of the transthyretin protein consisting of either unstable, mutant protein or wild type protein. Biopsy-proven amyloidosis of the GI tract is rare.4 About 60% of patients with AA amyloidosis and 8% with AL amyloidosis have GI involvement.5

We present a case of nonspecific symptoms that ultimately lined up perfectly with the official histologic confirmation of intestinal amyloidosis.

Case Presentation