User login

Medicare Rankings Favor Small, For-Profit Hospitals

In April, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) publicly revealed for the first time which hospitals achieved five stars and which had room for improvement based on patient experience per the Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (HCAHPS) survey.

Although these measures are not new, this year CMS assembled the star ratings from HCAHPS survey results and made them available on its consumer-facing website, in an effort to increase transparency.

The decision has not been met without controversy, particularly given the fact that just 251 hospitals out of more than 3,500 received five stars, and only two major teaching hospitals achieved the highest rating. Some professional groups, like the American Hospital Association (AHA), which issued a statement the day CMS released its ratings, believe the rankings risk “oversimplifying the complexity of quality care or misinterpreting what is important to a particular patient, especially since patients seek care for many different reasons.”

Others argue that there is a disconnect between what hospital leaders perceive as important drivers of patient experience and what patients really want. For instance, a 2013 Harvard Business Review article cites a 2012 survey in which C-suite leaders suggested new facilities, private rooms, on-demand food, bedside electronics, and more amenities were necessary to improve patient experience in the hospital.1

“I am surprised at how much controversy there is on this,” says Ashish Jha, MD, MPH, hospitalist at the VA Boston Healthcare System and professor of health policy at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health. “Modestly good evidence suggests that hospitals that do well on patient experience scores are also the hospitals that have better patient outcomes on more hard measures, like mortality and evidence-based guidelines.”

Dr. Jha cites a February 2015 study, published in the Journal of Hospital Medicine, in which patients were moved from one clinical building to a newer one with more patient-centered features.2 The care team remained the same. The study concluded that patients were able to differentiate between satisfactory clinical care and their surroundings, and that clinical care had a greater impact on patient experience than any other factor.

“Was your pain controlled adequately? Were people responsive to your needs? Were you treated with dignity and respect?” Dr. Jha says. “I think it’s disrespectful to say patients can’t tell the difference between high thread-count bed sheets and being treated with disrespect.”

The HCAHPS survey, Dr. Jha notes, reflects important aspects of healthcare that only patients can report. It encompasses 11 measures that gauge, for example, how well patients felt nurses and physicians communicated with them. It also asks patients to provide an overall hospital rank on a 10-point scale (counting only those that receive a nine or 10), according to Kaiser Health News, and to rate the cleanliness and quietness of the rooms.

Hospitals must send surveys to a random sample of adult patients monthly, including those not on Medicare, within six weeks of discharge, and Inpatient Prospective Payment System hospitals should collect at least 300 surveys every four years, CMS says.

“I think one of the most important things for a hospital to understand is [that] the methodology behind creating the star ratings and the way CMS structures the ratings does make it challenging to achieve the very highest score,” says Akin Demehin, AHA senior associate director of policy.

While CMS applies adjustments to account for sampling methods and patient characteristics of hospitals, an analysis by Dr. Jha’s team showed significant disparities between the rankings of large, academic medical centers and those of small, for-profit hospitals, as well as a substantial difference between hospitals that provide for the greatest number of poor patients and those that serve the fewest.3

However, he writes on his blog, "An Ounce of Evidence," that survey methodology is not the problem and that he believes star ratings are a good idea. Although some hospitals might find themselves at score cut-offs—a one-point difference can translate to a full star change—it’s a “small price to pay to make data more accessible to patients,” he writes.

“There is pretty good evidence hospitals are paying attention, and one that gets a one or two-star rating may be motivated to be better,” Dr. Jha says.

“Every hospital is interested in this because it’s part of value-based purchasing,” says Trina Dorrah, MD, MPH, a hospitalist and director of quality at Baylor Scott & White Health in Round Rock, Texas.

Dr. Dorrah has authored two books focused on patient experience, and she suggests simple ways hospitals can work toward improving their HCAHPS scores, and potentially their star ratings, from having nurses round with physicians to installing communication-facilitating whiteboards in every room.

Her hospital also awards bonuses to the hospitalist group for achieving set goals. Some hospitalist programs around the country are also adding questions to their surveys to link individual providers to patient rankings, she said, though many also do it in aggregate, because linking patients to individual physicians can get “very messy.”

CMS advises caution in interpreting star rankings, acknowledging that they are not the only valuable measures of care quality. Despite the concern over the contextual value of the new rankings, Demehin says AHA supports use of the HCAHPS survey and the value of patient experience measures and believes they should be consulted in conjunction with other quality improvement efforts.

“When I’m really sick and I go to the hospital, I want to be treated with dignity and respect and I want my pain treated quickly, but I also want to survive and not develop an infection,” Dr. Jha says. “That’s obviously not in the star ratings.”

Kelly April Tyrrell is a freelance writer in Madison, Wis.

References

- Merlino J, Raman A. Understanding the drivers of the patient experience. Harvard Business Review. Sept. 17, 2013. Accessed May 14, 2015.

- Siddiqui Z, Zuccarelli R, Durkin N, Wu AW, Brotman DJ. Changes in patient satisfaction related to hospital renovation: Experience with a new clinical building. J Hosp Med. 2015;10(3):165-171.

- Jha A. Finding the stars of hospital care in the U.S. An Ounce of Evidence blog. April 20, 2015. Accessed June 4, 2015.

In April, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) publicly revealed for the first time which hospitals achieved five stars and which had room for improvement based on patient experience per the Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (HCAHPS) survey.

Although these measures are not new, this year CMS assembled the star ratings from HCAHPS survey results and made them available on its consumer-facing website, in an effort to increase transparency.

The decision has not been met without controversy, particularly given the fact that just 251 hospitals out of more than 3,500 received five stars, and only two major teaching hospitals achieved the highest rating. Some professional groups, like the American Hospital Association (AHA), which issued a statement the day CMS released its ratings, believe the rankings risk “oversimplifying the complexity of quality care or misinterpreting what is important to a particular patient, especially since patients seek care for many different reasons.”

Others argue that there is a disconnect between what hospital leaders perceive as important drivers of patient experience and what patients really want. For instance, a 2013 Harvard Business Review article cites a 2012 survey in which C-suite leaders suggested new facilities, private rooms, on-demand food, bedside electronics, and more amenities were necessary to improve patient experience in the hospital.1

“I am surprised at how much controversy there is on this,” says Ashish Jha, MD, MPH, hospitalist at the VA Boston Healthcare System and professor of health policy at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health. “Modestly good evidence suggests that hospitals that do well on patient experience scores are also the hospitals that have better patient outcomes on more hard measures, like mortality and evidence-based guidelines.”

Dr. Jha cites a February 2015 study, published in the Journal of Hospital Medicine, in which patients were moved from one clinical building to a newer one with more patient-centered features.2 The care team remained the same. The study concluded that patients were able to differentiate between satisfactory clinical care and their surroundings, and that clinical care had a greater impact on patient experience than any other factor.

“Was your pain controlled adequately? Were people responsive to your needs? Were you treated with dignity and respect?” Dr. Jha says. “I think it’s disrespectful to say patients can’t tell the difference between high thread-count bed sheets and being treated with disrespect.”

The HCAHPS survey, Dr. Jha notes, reflects important aspects of healthcare that only patients can report. It encompasses 11 measures that gauge, for example, how well patients felt nurses and physicians communicated with them. It also asks patients to provide an overall hospital rank on a 10-point scale (counting only those that receive a nine or 10), according to Kaiser Health News, and to rate the cleanliness and quietness of the rooms.

Hospitals must send surveys to a random sample of adult patients monthly, including those not on Medicare, within six weeks of discharge, and Inpatient Prospective Payment System hospitals should collect at least 300 surveys every four years, CMS says.

“I think one of the most important things for a hospital to understand is [that] the methodology behind creating the star ratings and the way CMS structures the ratings does make it challenging to achieve the very highest score,” says Akin Demehin, AHA senior associate director of policy.

While CMS applies adjustments to account for sampling methods and patient characteristics of hospitals, an analysis by Dr. Jha’s team showed significant disparities between the rankings of large, academic medical centers and those of small, for-profit hospitals, as well as a substantial difference between hospitals that provide for the greatest number of poor patients and those that serve the fewest.3

However, he writes on his blog, "An Ounce of Evidence," that survey methodology is not the problem and that he believes star ratings are a good idea. Although some hospitals might find themselves at score cut-offs—a one-point difference can translate to a full star change—it’s a “small price to pay to make data more accessible to patients,” he writes.

“There is pretty good evidence hospitals are paying attention, and one that gets a one or two-star rating may be motivated to be better,” Dr. Jha says.

“Every hospital is interested in this because it’s part of value-based purchasing,” says Trina Dorrah, MD, MPH, a hospitalist and director of quality at Baylor Scott & White Health in Round Rock, Texas.

Dr. Dorrah has authored two books focused on patient experience, and she suggests simple ways hospitals can work toward improving their HCAHPS scores, and potentially their star ratings, from having nurses round with physicians to installing communication-facilitating whiteboards in every room.

Her hospital also awards bonuses to the hospitalist group for achieving set goals. Some hospitalist programs around the country are also adding questions to their surveys to link individual providers to patient rankings, she said, though many also do it in aggregate, because linking patients to individual physicians can get “very messy.”

CMS advises caution in interpreting star rankings, acknowledging that they are not the only valuable measures of care quality. Despite the concern over the contextual value of the new rankings, Demehin says AHA supports use of the HCAHPS survey and the value of patient experience measures and believes they should be consulted in conjunction with other quality improvement efforts.

“When I’m really sick and I go to the hospital, I want to be treated with dignity and respect and I want my pain treated quickly, but I also want to survive and not develop an infection,” Dr. Jha says. “That’s obviously not in the star ratings.”

Kelly April Tyrrell is a freelance writer in Madison, Wis.

References

- Merlino J, Raman A. Understanding the drivers of the patient experience. Harvard Business Review. Sept. 17, 2013. Accessed May 14, 2015.

- Siddiqui Z, Zuccarelli R, Durkin N, Wu AW, Brotman DJ. Changes in patient satisfaction related to hospital renovation: Experience with a new clinical building. J Hosp Med. 2015;10(3):165-171.

- Jha A. Finding the stars of hospital care in the U.S. An Ounce of Evidence blog. April 20, 2015. Accessed June 4, 2015.

In April, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) publicly revealed for the first time which hospitals achieved five stars and which had room for improvement based on patient experience per the Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (HCAHPS) survey.

Although these measures are not new, this year CMS assembled the star ratings from HCAHPS survey results and made them available on its consumer-facing website, in an effort to increase transparency.

The decision has not been met without controversy, particularly given the fact that just 251 hospitals out of more than 3,500 received five stars, and only two major teaching hospitals achieved the highest rating. Some professional groups, like the American Hospital Association (AHA), which issued a statement the day CMS released its ratings, believe the rankings risk “oversimplifying the complexity of quality care or misinterpreting what is important to a particular patient, especially since patients seek care for many different reasons.”

Others argue that there is a disconnect between what hospital leaders perceive as important drivers of patient experience and what patients really want. For instance, a 2013 Harvard Business Review article cites a 2012 survey in which C-suite leaders suggested new facilities, private rooms, on-demand food, bedside electronics, and more amenities were necessary to improve patient experience in the hospital.1

“I am surprised at how much controversy there is on this,” says Ashish Jha, MD, MPH, hospitalist at the VA Boston Healthcare System and professor of health policy at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health. “Modestly good evidence suggests that hospitals that do well on patient experience scores are also the hospitals that have better patient outcomes on more hard measures, like mortality and evidence-based guidelines.”

Dr. Jha cites a February 2015 study, published in the Journal of Hospital Medicine, in which patients were moved from one clinical building to a newer one with more patient-centered features.2 The care team remained the same. The study concluded that patients were able to differentiate between satisfactory clinical care and their surroundings, and that clinical care had a greater impact on patient experience than any other factor.

“Was your pain controlled adequately? Were people responsive to your needs? Were you treated with dignity and respect?” Dr. Jha says. “I think it’s disrespectful to say patients can’t tell the difference between high thread-count bed sheets and being treated with disrespect.”

The HCAHPS survey, Dr. Jha notes, reflects important aspects of healthcare that only patients can report. It encompasses 11 measures that gauge, for example, how well patients felt nurses and physicians communicated with them. It also asks patients to provide an overall hospital rank on a 10-point scale (counting only those that receive a nine or 10), according to Kaiser Health News, and to rate the cleanliness and quietness of the rooms.

Hospitals must send surveys to a random sample of adult patients monthly, including those not on Medicare, within six weeks of discharge, and Inpatient Prospective Payment System hospitals should collect at least 300 surveys every four years, CMS says.

“I think one of the most important things for a hospital to understand is [that] the methodology behind creating the star ratings and the way CMS structures the ratings does make it challenging to achieve the very highest score,” says Akin Demehin, AHA senior associate director of policy.

While CMS applies adjustments to account for sampling methods and patient characteristics of hospitals, an analysis by Dr. Jha’s team showed significant disparities between the rankings of large, academic medical centers and those of small, for-profit hospitals, as well as a substantial difference between hospitals that provide for the greatest number of poor patients and those that serve the fewest.3

However, he writes on his blog, "An Ounce of Evidence," that survey methodology is not the problem and that he believes star ratings are a good idea. Although some hospitals might find themselves at score cut-offs—a one-point difference can translate to a full star change—it’s a “small price to pay to make data more accessible to patients,” he writes.

“There is pretty good evidence hospitals are paying attention, and one that gets a one or two-star rating may be motivated to be better,” Dr. Jha says.

“Every hospital is interested in this because it’s part of value-based purchasing,” says Trina Dorrah, MD, MPH, a hospitalist and director of quality at Baylor Scott & White Health in Round Rock, Texas.

Dr. Dorrah has authored two books focused on patient experience, and she suggests simple ways hospitals can work toward improving their HCAHPS scores, and potentially their star ratings, from having nurses round with physicians to installing communication-facilitating whiteboards in every room.

Her hospital also awards bonuses to the hospitalist group for achieving set goals. Some hospitalist programs around the country are also adding questions to their surveys to link individual providers to patient rankings, she said, though many also do it in aggregate, because linking patients to individual physicians can get “very messy.”

CMS advises caution in interpreting star rankings, acknowledging that they are not the only valuable measures of care quality. Despite the concern over the contextual value of the new rankings, Demehin says AHA supports use of the HCAHPS survey and the value of patient experience measures and believes they should be consulted in conjunction with other quality improvement efforts.

“When I’m really sick and I go to the hospital, I want to be treated with dignity and respect and I want my pain treated quickly, but I also want to survive and not develop an infection,” Dr. Jha says. “That’s obviously not in the star ratings.”

Kelly April Tyrrell is a freelance writer in Madison, Wis.

References

- Merlino J, Raman A. Understanding the drivers of the patient experience. Harvard Business Review. Sept. 17, 2013. Accessed May 14, 2015.

- Siddiqui Z, Zuccarelli R, Durkin N, Wu AW, Brotman DJ. Changes in patient satisfaction related to hospital renovation: Experience with a new clinical building. J Hosp Med. 2015;10(3):165-171.

- Jha A. Finding the stars of hospital care in the U.S. An Ounce of Evidence blog. April 20, 2015. Accessed June 4, 2015.

The Hospital Leader Explores Ways Hospitalists Can Tackle Healthcare Costs

EDITOR’S NOTE: A version of this article originally appeared on Medpage Today on May 5, 2015.

By now, we have all heard the stories about unconscionable medical bills causing financial harm for patients. We have read about more Americans than ever before on high-deductible health insurance plans. Some of us have even helped our parents navigate the deceptively simple-looking bronze, silver, and gold tiers of the insurance exchanges, weighing the gamble of increasingly unaffordable monthly premiums against catastrophically high deductibles and out-of-pocket costs.

We have accepted the fact that healthcare costs are out of control and causing real constraints on every level, from individuals to communities to businesses to states to our nation.

OK, but now what are we supposed to do about it?

“Remarkably, given the importance of this issue, until now, we lacked a roadmap to attack it,” wrote Bob Wachter, MD, in the foreword to our new book, Understanding Value-Based Healthcare. “Now we have one.”

For starters, we can supply a pipeline for change by embedding the principles of value-based care in the apprenticeship of health professional education. Recently, the leaders of the soon-to-open Dell Medical School at University of Texas-Austin articulated their plan to build their entire curriculum around teaching students to root out waste and to care for the health of the community. This is the clearest example that medical educators are taking seriously the calls to action coming from the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME), the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC), the American College of Physicians (ACP), and other leaders to address healthcare value in training very seriously. However, the front lines are not waiting for new medical schools to open up or for massive curricular overhauls. The Second Annual Teaching Value and Choosing Wisely Challenge that we organized resulted in 80 submissions spanning the country (and Canada). The authors, including five students, 30 residents or fellows, and at least 41 faculty members, described their bright ideas and innovations for integrating healthcare value into education.

Education is fundamental but will not be enough. We must also practice what we preach. Practicing clinicians can deflate medical bills for their patients by advocating for appropriate care, considering patient affordability in customizing treatments, and leading local initiatives to improve value of care.

Clinicians can advocate for appropriate care by avoiding low-value services at the point of care. Specific targets for improving appropriate resource utilization may be identified from resources such as Choosing Wisely lists, guidelines, and appropriateness criteria. Physicians will need to understand the true risks and benefits of recommended therapies and learn ways to communicate this balance with patients.

Patient affordability is increasingly important, with more patients now facing astronomically high out-of-pocket bills, even for simple medical treatments or procedures. A December 2014 CBS/New York Times poll found that 80% of Americans now think their doctor should discuss the cost of recommended medical treatment with them ahead of time. Clinicians can screen their patients for financial harm and can help them navigate the trade-offs of lower cost options. Physicians should seek to provide high-value prescribing, which entails recommending the simplest medication regimen that minimizes physical and financial risk to the patient while achieving the best outcome. In other words, decreasing either cost, complexity, or risk of medications can improve value—and clinicians should aim to improve all three simultaneously.

In addition to reducing waste and considering patient affordability, clinicians are ideal leaders of local value initiatives, whether they accomplish this by running value improvement projects or by launching formal high-value care programs. Our framework to guide value improvement project design is “COST”: culture, oversight accountability, system support, and training. This approach leverages principles from implementation science to ensure that value improvement projects successfully provide multi-pronged tactics for overcoming the many barriers to high-value care delivery. At some locations across the country, individual efforts have matured into entire groups dedicated to designing and implementing value-improvement initiatives, including the UCSF High Value Care Committee, the Johns Hopkins High-Value Care Committee, Johns Hopkins Bayview Physicians for Responsible Ordering (PRO), and “High-Value Carolina” in North Carolina.

Health professionals are faced with a responsibility to help deflate medical bills. To achieve this goal, clinicians can advocate for appropriate care, consider patient affordability, and lead local value improvement initiatives. For those ready to tackle this challenge, we elaborate on and explain some of these necessary tools in our book, Understanding Value-Based Healthcare.

EDITOR’S NOTE: A version of this article originally appeared on Medpage Today on May 5, 2015.

By now, we have all heard the stories about unconscionable medical bills causing financial harm for patients. We have read about more Americans than ever before on high-deductible health insurance plans. Some of us have even helped our parents navigate the deceptively simple-looking bronze, silver, and gold tiers of the insurance exchanges, weighing the gamble of increasingly unaffordable monthly premiums against catastrophically high deductibles and out-of-pocket costs.

We have accepted the fact that healthcare costs are out of control and causing real constraints on every level, from individuals to communities to businesses to states to our nation.

OK, but now what are we supposed to do about it?

“Remarkably, given the importance of this issue, until now, we lacked a roadmap to attack it,” wrote Bob Wachter, MD, in the foreword to our new book, Understanding Value-Based Healthcare. “Now we have one.”

For starters, we can supply a pipeline for change by embedding the principles of value-based care in the apprenticeship of health professional education. Recently, the leaders of the soon-to-open Dell Medical School at University of Texas-Austin articulated their plan to build their entire curriculum around teaching students to root out waste and to care for the health of the community. This is the clearest example that medical educators are taking seriously the calls to action coming from the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME), the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC), the American College of Physicians (ACP), and other leaders to address healthcare value in training very seriously. However, the front lines are not waiting for new medical schools to open up or for massive curricular overhauls. The Second Annual Teaching Value and Choosing Wisely Challenge that we organized resulted in 80 submissions spanning the country (and Canada). The authors, including five students, 30 residents or fellows, and at least 41 faculty members, described their bright ideas and innovations for integrating healthcare value into education.

Education is fundamental but will not be enough. We must also practice what we preach. Practicing clinicians can deflate medical bills for their patients by advocating for appropriate care, considering patient affordability in customizing treatments, and leading local initiatives to improve value of care.

Clinicians can advocate for appropriate care by avoiding low-value services at the point of care. Specific targets for improving appropriate resource utilization may be identified from resources such as Choosing Wisely lists, guidelines, and appropriateness criteria. Physicians will need to understand the true risks and benefits of recommended therapies and learn ways to communicate this balance with patients.

Patient affordability is increasingly important, with more patients now facing astronomically high out-of-pocket bills, even for simple medical treatments or procedures. A December 2014 CBS/New York Times poll found that 80% of Americans now think their doctor should discuss the cost of recommended medical treatment with them ahead of time. Clinicians can screen their patients for financial harm and can help them navigate the trade-offs of lower cost options. Physicians should seek to provide high-value prescribing, which entails recommending the simplest medication regimen that minimizes physical and financial risk to the patient while achieving the best outcome. In other words, decreasing either cost, complexity, or risk of medications can improve value—and clinicians should aim to improve all three simultaneously.

In addition to reducing waste and considering patient affordability, clinicians are ideal leaders of local value initiatives, whether they accomplish this by running value improvement projects or by launching formal high-value care programs. Our framework to guide value improvement project design is “COST”: culture, oversight accountability, system support, and training. This approach leverages principles from implementation science to ensure that value improvement projects successfully provide multi-pronged tactics for overcoming the many barriers to high-value care delivery. At some locations across the country, individual efforts have matured into entire groups dedicated to designing and implementing value-improvement initiatives, including the UCSF High Value Care Committee, the Johns Hopkins High-Value Care Committee, Johns Hopkins Bayview Physicians for Responsible Ordering (PRO), and “High-Value Carolina” in North Carolina.

Health professionals are faced with a responsibility to help deflate medical bills. To achieve this goal, clinicians can advocate for appropriate care, consider patient affordability, and lead local value improvement initiatives. For those ready to tackle this challenge, we elaborate on and explain some of these necessary tools in our book, Understanding Value-Based Healthcare.

EDITOR’S NOTE: A version of this article originally appeared on Medpage Today on May 5, 2015.

By now, we have all heard the stories about unconscionable medical bills causing financial harm for patients. We have read about more Americans than ever before on high-deductible health insurance plans. Some of us have even helped our parents navigate the deceptively simple-looking bronze, silver, and gold tiers of the insurance exchanges, weighing the gamble of increasingly unaffordable monthly premiums against catastrophically high deductibles and out-of-pocket costs.

We have accepted the fact that healthcare costs are out of control and causing real constraints on every level, from individuals to communities to businesses to states to our nation.

OK, but now what are we supposed to do about it?

“Remarkably, given the importance of this issue, until now, we lacked a roadmap to attack it,” wrote Bob Wachter, MD, in the foreword to our new book, Understanding Value-Based Healthcare. “Now we have one.”

For starters, we can supply a pipeline for change by embedding the principles of value-based care in the apprenticeship of health professional education. Recently, the leaders of the soon-to-open Dell Medical School at University of Texas-Austin articulated their plan to build their entire curriculum around teaching students to root out waste and to care for the health of the community. This is the clearest example that medical educators are taking seriously the calls to action coming from the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME), the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC), the American College of Physicians (ACP), and other leaders to address healthcare value in training very seriously. However, the front lines are not waiting for new medical schools to open up or for massive curricular overhauls. The Second Annual Teaching Value and Choosing Wisely Challenge that we organized resulted in 80 submissions spanning the country (and Canada). The authors, including five students, 30 residents or fellows, and at least 41 faculty members, described their bright ideas and innovations for integrating healthcare value into education.

Education is fundamental but will not be enough. We must also practice what we preach. Practicing clinicians can deflate medical bills for their patients by advocating for appropriate care, considering patient affordability in customizing treatments, and leading local initiatives to improve value of care.

Clinicians can advocate for appropriate care by avoiding low-value services at the point of care. Specific targets for improving appropriate resource utilization may be identified from resources such as Choosing Wisely lists, guidelines, and appropriateness criteria. Physicians will need to understand the true risks and benefits of recommended therapies and learn ways to communicate this balance with patients.

Patient affordability is increasingly important, with more patients now facing astronomically high out-of-pocket bills, even for simple medical treatments or procedures. A December 2014 CBS/New York Times poll found that 80% of Americans now think their doctor should discuss the cost of recommended medical treatment with them ahead of time. Clinicians can screen their patients for financial harm and can help them navigate the trade-offs of lower cost options. Physicians should seek to provide high-value prescribing, which entails recommending the simplest medication regimen that minimizes physical and financial risk to the patient while achieving the best outcome. In other words, decreasing either cost, complexity, or risk of medications can improve value—and clinicians should aim to improve all three simultaneously.

In addition to reducing waste and considering patient affordability, clinicians are ideal leaders of local value initiatives, whether they accomplish this by running value improvement projects or by launching formal high-value care programs. Our framework to guide value improvement project design is “COST”: culture, oversight accountability, system support, and training. This approach leverages principles from implementation science to ensure that value improvement projects successfully provide multi-pronged tactics for overcoming the many barriers to high-value care delivery. At some locations across the country, individual efforts have matured into entire groups dedicated to designing and implementing value-improvement initiatives, including the UCSF High Value Care Committee, the Johns Hopkins High-Value Care Committee, Johns Hopkins Bayview Physicians for Responsible Ordering (PRO), and “High-Value Carolina” in North Carolina.

Health professionals are faced with a responsibility to help deflate medical bills. To achieve this goal, clinicians can advocate for appropriate care, consider patient affordability, and lead local value improvement initiatives. For those ready to tackle this challenge, we elaborate on and explain some of these necessary tools in our book, Understanding Value-Based Healthcare.

SGR Repeal: What It Means for Hospitalists

On April 16, President Obama signed into law a bipartisan, bicameral piece of legislation that not only fully repealed the sustainable growth rate (SGR) but also permanently eliminated the recurring threat of physician payment cuts in Medicare.

Along with the SGR repeal, the Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act, or MACRA, institutes the Merit-based Incentive Payment System (MIPS). Starting in 2019, the MIPS will consolidate all of Medicare’s current quality reporting programs: the Physician Quality Reporting System (PQRS), the Value-Based Payment Modifier (VBPM) Program, and the meaningful use (MU) requirements, and will restructure their associated penalties.

Under current law, however, physicians are still required to participate in PQRS, VBPM, and MU, or face their associated penalties until the MIPS is fully implemented in 2019. MACRA also incentivizes the adoption of alternative payment models (APMs). APMs are broadly defined within the law as models that involve both upside and downside financial risk (e.g. ACOs or bundled payments) or patient-centered medical homes, provided they improve quality without increasing costs or lower costs without decreasing quality. Those participating in and deriving substantial revenue from an approved APM will not only be exempt from reporting within the MIPS, but will also receive an automatic 5% bonus in their Medicare billing.

Pay-for-performance programs lack relevant quality metrics and are structured in ways that do not account for the realities of providing inpatient care, which increasingly result in headaches for hospitalists. MACRA has the potential to alleviate this burden and reshape the way in which hospitalists are measured.

SHM worked closely with key Congressional committees, as they were developing the SGR repeal legislation, to include flexible language that could better align quality measures for hospitalists. As a result, buried deep in the text of MACRA lies a two-sentence section that makes this goal possible. The law authorizes the “use [of] measures used for a payment system other than for physicians, such as measures for inpatient hospitals, for the purposes of the performance categories [quality and resource use].” Permitting the use of measures from other payment systems allows hospitalists to have the opportunity to align their quality and resource use performance with that of their institutions. As this alignment is not allowed under current law, it brings new potential to level the playing field and increase the relevance of hospitalist quality reporting in the future.

SHM has been pressing CMS to pursue this concept for the last three years, and MACRA finally gives CMS clear authority to move ahead.

The law is not overly specific, so it is not exactly clear how this provision will be implemented. SHM will remain vigilant, working with CMS to ensure that the MIPS-related regulations set the stage for more fair assessment of hospitalists when the MIPS goes into effect in 2019.

Although hospitalists face an uphill battle in terms of current PQRS reporting, the flexibility contained in MACRA provides an important first step toward a better pathway to reporting quality measures that are fair and relevant for hospitalists.

Ellen Boyer is SHM’s government relations project coordinator.

On April 16, President Obama signed into law a bipartisan, bicameral piece of legislation that not only fully repealed the sustainable growth rate (SGR) but also permanently eliminated the recurring threat of physician payment cuts in Medicare.

Along with the SGR repeal, the Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act, or MACRA, institutes the Merit-based Incentive Payment System (MIPS). Starting in 2019, the MIPS will consolidate all of Medicare’s current quality reporting programs: the Physician Quality Reporting System (PQRS), the Value-Based Payment Modifier (VBPM) Program, and the meaningful use (MU) requirements, and will restructure their associated penalties.

Under current law, however, physicians are still required to participate in PQRS, VBPM, and MU, or face their associated penalties until the MIPS is fully implemented in 2019. MACRA also incentivizes the adoption of alternative payment models (APMs). APMs are broadly defined within the law as models that involve both upside and downside financial risk (e.g. ACOs or bundled payments) or patient-centered medical homes, provided they improve quality without increasing costs or lower costs without decreasing quality. Those participating in and deriving substantial revenue from an approved APM will not only be exempt from reporting within the MIPS, but will also receive an automatic 5% bonus in their Medicare billing.

Pay-for-performance programs lack relevant quality metrics and are structured in ways that do not account for the realities of providing inpatient care, which increasingly result in headaches for hospitalists. MACRA has the potential to alleviate this burden and reshape the way in which hospitalists are measured.

SHM worked closely with key Congressional committees, as they were developing the SGR repeal legislation, to include flexible language that could better align quality measures for hospitalists. As a result, buried deep in the text of MACRA lies a two-sentence section that makes this goal possible. The law authorizes the “use [of] measures used for a payment system other than for physicians, such as measures for inpatient hospitals, for the purposes of the performance categories [quality and resource use].” Permitting the use of measures from other payment systems allows hospitalists to have the opportunity to align their quality and resource use performance with that of their institutions. As this alignment is not allowed under current law, it brings new potential to level the playing field and increase the relevance of hospitalist quality reporting in the future.

SHM has been pressing CMS to pursue this concept for the last three years, and MACRA finally gives CMS clear authority to move ahead.

The law is not overly specific, so it is not exactly clear how this provision will be implemented. SHM will remain vigilant, working with CMS to ensure that the MIPS-related regulations set the stage for more fair assessment of hospitalists when the MIPS goes into effect in 2019.

Although hospitalists face an uphill battle in terms of current PQRS reporting, the flexibility contained in MACRA provides an important first step toward a better pathway to reporting quality measures that are fair and relevant for hospitalists.

Ellen Boyer is SHM’s government relations project coordinator.

On April 16, President Obama signed into law a bipartisan, bicameral piece of legislation that not only fully repealed the sustainable growth rate (SGR) but also permanently eliminated the recurring threat of physician payment cuts in Medicare.

Along with the SGR repeal, the Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act, or MACRA, institutes the Merit-based Incentive Payment System (MIPS). Starting in 2019, the MIPS will consolidate all of Medicare’s current quality reporting programs: the Physician Quality Reporting System (PQRS), the Value-Based Payment Modifier (VBPM) Program, and the meaningful use (MU) requirements, and will restructure their associated penalties.

Under current law, however, physicians are still required to participate in PQRS, VBPM, and MU, or face their associated penalties until the MIPS is fully implemented in 2019. MACRA also incentivizes the adoption of alternative payment models (APMs). APMs are broadly defined within the law as models that involve both upside and downside financial risk (e.g. ACOs or bundled payments) or patient-centered medical homes, provided they improve quality without increasing costs or lower costs without decreasing quality. Those participating in and deriving substantial revenue from an approved APM will not only be exempt from reporting within the MIPS, but will also receive an automatic 5% bonus in their Medicare billing.

Pay-for-performance programs lack relevant quality metrics and are structured in ways that do not account for the realities of providing inpatient care, which increasingly result in headaches for hospitalists. MACRA has the potential to alleviate this burden and reshape the way in which hospitalists are measured.

SHM worked closely with key Congressional committees, as they were developing the SGR repeal legislation, to include flexible language that could better align quality measures for hospitalists. As a result, buried deep in the text of MACRA lies a two-sentence section that makes this goal possible. The law authorizes the “use [of] measures used for a payment system other than for physicians, such as measures for inpatient hospitals, for the purposes of the performance categories [quality and resource use].” Permitting the use of measures from other payment systems allows hospitalists to have the opportunity to align their quality and resource use performance with that of their institutions. As this alignment is not allowed under current law, it brings new potential to level the playing field and increase the relevance of hospitalist quality reporting in the future.

SHM has been pressing CMS to pursue this concept for the last three years, and MACRA finally gives CMS clear authority to move ahead.

The law is not overly specific, so it is not exactly clear how this provision will be implemented. SHM will remain vigilant, working with CMS to ensure that the MIPS-related regulations set the stage for more fair assessment of hospitalists when the MIPS goes into effect in 2019.

Although hospitalists face an uphill battle in terms of current PQRS reporting, the flexibility contained in MACRA provides an important first step toward a better pathway to reporting quality measures that are fair and relevant for hospitalists.

Ellen Boyer is SHM’s government relations project coordinator.

Hospitalists Play Key Role Developing Electronic Health Records

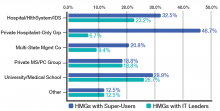

If you are a hospitalist, you know this to be true: Electronic health records (EHRs) run more smoothly because of our input. According to the 2014 State of Hospital Medicine (SOHM) report, hospitalists played a significant role in implementing their hospitals’ EHR systems; 34% of respondent hospital medicine groups (HMGs) serving adults only develop order sets, protocols, and decision support, while 28.3% of HMGs serve as super users. As super users, hospitalists are role models who help other physicians work successfully with the computerized systems and set the tone for acceptance within their medical staff and the larger hospital staff.

When EHRs were implemented a decade ago at Allina Health, a 14-hospital system headquartered in Minneapolis, hospitalists acted as super users and were able to interface closely with IT staff, quickly fixing computer troubles that physicians encountered. We partnered with IT to help them prioritize their work by letting them know which computer issues involved patient safety, which were high frequency, irksome issues, and which EHR quirks could be queued farther down the line for repair.

Although successful EHR implementation is a mammoth accomplishment, it is just the tip of the iceberg. Once a system is implemented, an unending amount of work is needed to make sure EHRs deliver, through data analysis and standardization of care, all the efficiency, safety, and cost containment we hoped for at their inception.

When hospitalists at Allina were asked to be the first group of physicians to convert to professional fee billing using the EHR, we found that we needed to create a check-and-balance reporting system to ensure that our charges were indeed being captured. All of our health system physicians now use the hospitalist-developed reporting system.

Hospitalists in our system also forged the way to getting meaningful data out of the EHR system. When we first implemented our EHR, we found it difficult to get hospitalist-specific data. We worked closely with data analytics staff to develop a hospitalist “flag” that would differentiate hospitalists from other physicians providing inpatient care.

Because hospitalists are involved with patients through all phases of their care, from admission to discharge, they encounter firsthand the benefits and glitches of EHRs. By the very nature of our work, we are positioned to help improve EHRs. Hospitalist input ranges from informal feedback to the IT department to participation in focused work groups dedicated to specific aspects of improving patient care. Not surprisingly, 18.4% of adults-only HMGs who participated in the last SOHM survey have hospitalists serving in an IT leadership role for their organizations.

When looked at by ownership/employment models (see Table 1), this number is higher for the “University, Medical School, or Faculty Practice Plan” (26.7%) and for the “Hospital, Health System, or Integrated Delivery System” (23.2%) and lower for the “Private Local/Regional Hospitalist-Only Medical Groups” (6.7%).

Interestingly, the “Private Local/Regional Hospitalist-Only” employment model has the highest percentage of super users (46.7%).

Although most hospitalists across the nation spend a majority of their time interfacing with EHRs, 4.5% of HMGs in the most recent SOHM responded that their hospitals or health systems have not yet begun EHR implementation. I’m guessing the hospitalists in those organizations have a lot of work ahead of them in the next year or two!

Dr. Stephan is a hospitalist at Abbott Northwestern Hospital in Minneapolis and a member of the SHM Practice Analysis Committee.

If you are a hospitalist, you know this to be true: Electronic health records (EHRs) run more smoothly because of our input. According to the 2014 State of Hospital Medicine (SOHM) report, hospitalists played a significant role in implementing their hospitals’ EHR systems; 34% of respondent hospital medicine groups (HMGs) serving adults only develop order sets, protocols, and decision support, while 28.3% of HMGs serve as super users. As super users, hospitalists are role models who help other physicians work successfully with the computerized systems and set the tone for acceptance within their medical staff and the larger hospital staff.

When EHRs were implemented a decade ago at Allina Health, a 14-hospital system headquartered in Minneapolis, hospitalists acted as super users and were able to interface closely with IT staff, quickly fixing computer troubles that physicians encountered. We partnered with IT to help them prioritize their work by letting them know which computer issues involved patient safety, which were high frequency, irksome issues, and which EHR quirks could be queued farther down the line for repair.

Although successful EHR implementation is a mammoth accomplishment, it is just the tip of the iceberg. Once a system is implemented, an unending amount of work is needed to make sure EHRs deliver, through data analysis and standardization of care, all the efficiency, safety, and cost containment we hoped for at their inception.

When hospitalists at Allina were asked to be the first group of physicians to convert to professional fee billing using the EHR, we found that we needed to create a check-and-balance reporting system to ensure that our charges were indeed being captured. All of our health system physicians now use the hospitalist-developed reporting system.

Hospitalists in our system also forged the way to getting meaningful data out of the EHR system. When we first implemented our EHR, we found it difficult to get hospitalist-specific data. We worked closely with data analytics staff to develop a hospitalist “flag” that would differentiate hospitalists from other physicians providing inpatient care.

Because hospitalists are involved with patients through all phases of their care, from admission to discharge, they encounter firsthand the benefits and glitches of EHRs. By the very nature of our work, we are positioned to help improve EHRs. Hospitalist input ranges from informal feedback to the IT department to participation in focused work groups dedicated to specific aspects of improving patient care. Not surprisingly, 18.4% of adults-only HMGs who participated in the last SOHM survey have hospitalists serving in an IT leadership role for their organizations.

When looked at by ownership/employment models (see Table 1), this number is higher for the “University, Medical School, or Faculty Practice Plan” (26.7%) and for the “Hospital, Health System, or Integrated Delivery System” (23.2%) and lower for the “Private Local/Regional Hospitalist-Only Medical Groups” (6.7%).

Interestingly, the “Private Local/Regional Hospitalist-Only” employment model has the highest percentage of super users (46.7%).

Although most hospitalists across the nation spend a majority of their time interfacing with EHRs, 4.5% of HMGs in the most recent SOHM responded that their hospitals or health systems have not yet begun EHR implementation. I’m guessing the hospitalists in those organizations have a lot of work ahead of them in the next year or two!

Dr. Stephan is a hospitalist at Abbott Northwestern Hospital in Minneapolis and a member of the SHM Practice Analysis Committee.

If you are a hospitalist, you know this to be true: Electronic health records (EHRs) run more smoothly because of our input. According to the 2014 State of Hospital Medicine (SOHM) report, hospitalists played a significant role in implementing their hospitals’ EHR systems; 34% of respondent hospital medicine groups (HMGs) serving adults only develop order sets, protocols, and decision support, while 28.3% of HMGs serve as super users. As super users, hospitalists are role models who help other physicians work successfully with the computerized systems and set the tone for acceptance within their medical staff and the larger hospital staff.

When EHRs were implemented a decade ago at Allina Health, a 14-hospital system headquartered in Minneapolis, hospitalists acted as super users and were able to interface closely with IT staff, quickly fixing computer troubles that physicians encountered. We partnered with IT to help them prioritize their work by letting them know which computer issues involved patient safety, which were high frequency, irksome issues, and which EHR quirks could be queued farther down the line for repair.

Although successful EHR implementation is a mammoth accomplishment, it is just the tip of the iceberg. Once a system is implemented, an unending amount of work is needed to make sure EHRs deliver, through data analysis and standardization of care, all the efficiency, safety, and cost containment we hoped for at their inception.

When hospitalists at Allina were asked to be the first group of physicians to convert to professional fee billing using the EHR, we found that we needed to create a check-and-balance reporting system to ensure that our charges were indeed being captured. All of our health system physicians now use the hospitalist-developed reporting system.

Hospitalists in our system also forged the way to getting meaningful data out of the EHR system. When we first implemented our EHR, we found it difficult to get hospitalist-specific data. We worked closely with data analytics staff to develop a hospitalist “flag” that would differentiate hospitalists from other physicians providing inpatient care.

Because hospitalists are involved with patients through all phases of their care, from admission to discharge, they encounter firsthand the benefits and glitches of EHRs. By the very nature of our work, we are positioned to help improve EHRs. Hospitalist input ranges from informal feedback to the IT department to participation in focused work groups dedicated to specific aspects of improving patient care. Not surprisingly, 18.4% of adults-only HMGs who participated in the last SOHM survey have hospitalists serving in an IT leadership role for their organizations.

When looked at by ownership/employment models (see Table 1), this number is higher for the “University, Medical School, or Faculty Practice Plan” (26.7%) and for the “Hospital, Health System, or Integrated Delivery System” (23.2%) and lower for the “Private Local/Regional Hospitalist-Only Medical Groups” (6.7%).

Interestingly, the “Private Local/Regional Hospitalist-Only” employment model has the highest percentage of super users (46.7%).

Although most hospitalists across the nation spend a majority of their time interfacing with EHRs, 4.5% of HMGs in the most recent SOHM responded that their hospitals or health systems have not yet begun EHR implementation. I’m guessing the hospitalists in those organizations have a lot of work ahead of them in the next year or two!

Dr. Stephan is a hospitalist at Abbott Northwestern Hospital in Minneapolis and a member of the SHM Practice Analysis Committee.

Job Search Tips for First-Time Hospitalists

The best strategy for landing that first job is to start your search early, says Cheryl DeVita, senior search consultant at Cejka Search, Inc., in St. Louis, Mo.

“Many hospital organizations planning to add to their staff are willing to consider candidates six or 12 months out,” DeVita explains. Required licensing and credentialing “don’t happen fast,” she adds, and you will not be the only applicant. To preserve your range of choices, explore options early, preferably in the fall before your residency concludes.

Tom Baudendistel, MD, FACP, program director of internal medicine residency at Kaiser Permanente in Oakland, Calif., encourages his senior residents to “at least interview at new settings, and test the waters a bit.

“Too often, I see residents trying to find the absolute perfect position for the next 30 years of their career,” he says, “when in reality they are likely to change jobs in a few years for a variety of reasons, from personal to geographic to the job itself. Even if they decide to remain with Kaiser—as many do—they’ll have some perspective on what other systems are up to, which they can file away for future reference.”

At Stake? More than Money

Salary and benefits are important, but they aren’t the only factors to evaluate during a job search. Dr. Baudendistel offers a few “don’ts” to help guide the job search journey:

- Don’t forget to consider how you will stay up to date: “Residents sometimes take for granted the amount of didactic learning going on every day in the academic environment of residency, only to become disenchanted to take a job at a hospital where there may only be one grand rounds a week [if that], and the group meetings center primarily on business items, such as contracts, coding, and RVUs.”

- Don’t be lured by the money: Debt-ridden residents may be drawn to the quick fix of a nice salary, but this can cloud the fact that the salary might not increase much over the next five to 10 years, that the benefits/retirement/home loan packages are thin, or that there is very little growth potential within the group. To assess the potential for professional growth—a better predictor of job satisfaction—ask the attendings who have been with the group for five to 10 years: “How has your job evolved since you first started?” Be wary if the answer is, “I’ve been doing the same full-time clinical job since I started.”

- Don’t forget to look critically at group happiness. What is the turnover of the group? How is leadership viewed by the rank-and-file attendings? What is the relationship between the HM group and the hospital administration and nurses? A good question to ask is, “Does the group go to lunch?”

- Don’t forget to consider who your mentors will be. Who will help you grow and thrive in your job? Is there a formal mentoring program? If not, how does the group leader mentor the attendings?

The Nuts and Bolts

Once you’ve been offered a contract, it’s not just a simple matter of whether you will be salaried with benefits or a contract employee and have to purchase your own benefits. Legal counsel might be appropriate, DeVita says, to ensure you understand the ramifications of malpractice insurance.

Importantly, find out who pays for “tail insurance” for when you leave a job. This is vital, because physicians remain liable for malpractice acts performed when they were a part of the previous medical group.

You’re In, Now What?

Dr. Baudendistel and DeVita agree that honing your clinical skills will be “job one” once you start to work.

“If you’re averaging 12 patients and your peers are averaging 17, you will be in a position of jeopardy,” DeVita cautions.

For that reason, Baudendistel advises young hospitalists not to overcommit to nonclinical duties.

“There is a temptation to say ‘yes’ to every opportunity that arises in your first job. There will be plenty of time over the years to get involved in committee work, QI [quality improvement], and the like. Sometimes saying ‘no’ is the right approach in your early years,” he says.

Once you’re maintaining the same productivity level as your peers, DeVita points out, then it may be appropriate to participate in committee work—and there may be bonus components for citizenship work.

Gretchen Henkel is a freelance writer in California.

The best strategy for landing that first job is to start your search early, says Cheryl DeVita, senior search consultant at Cejka Search, Inc., in St. Louis, Mo.

“Many hospital organizations planning to add to their staff are willing to consider candidates six or 12 months out,” DeVita explains. Required licensing and credentialing “don’t happen fast,” she adds, and you will not be the only applicant. To preserve your range of choices, explore options early, preferably in the fall before your residency concludes.

Tom Baudendistel, MD, FACP, program director of internal medicine residency at Kaiser Permanente in Oakland, Calif., encourages his senior residents to “at least interview at new settings, and test the waters a bit.

“Too often, I see residents trying to find the absolute perfect position for the next 30 years of their career,” he says, “when in reality they are likely to change jobs in a few years for a variety of reasons, from personal to geographic to the job itself. Even if they decide to remain with Kaiser—as many do—they’ll have some perspective on what other systems are up to, which they can file away for future reference.”

At Stake? More than Money

Salary and benefits are important, but they aren’t the only factors to evaluate during a job search. Dr. Baudendistel offers a few “don’ts” to help guide the job search journey:

- Don’t forget to consider how you will stay up to date: “Residents sometimes take for granted the amount of didactic learning going on every day in the academic environment of residency, only to become disenchanted to take a job at a hospital where there may only be one grand rounds a week [if that], and the group meetings center primarily on business items, such as contracts, coding, and RVUs.”

- Don’t be lured by the money: Debt-ridden residents may be drawn to the quick fix of a nice salary, but this can cloud the fact that the salary might not increase much over the next five to 10 years, that the benefits/retirement/home loan packages are thin, or that there is very little growth potential within the group. To assess the potential for professional growth—a better predictor of job satisfaction—ask the attendings who have been with the group for five to 10 years: “How has your job evolved since you first started?” Be wary if the answer is, “I’ve been doing the same full-time clinical job since I started.”

- Don’t forget to look critically at group happiness. What is the turnover of the group? How is leadership viewed by the rank-and-file attendings? What is the relationship between the HM group and the hospital administration and nurses? A good question to ask is, “Does the group go to lunch?”

- Don’t forget to consider who your mentors will be. Who will help you grow and thrive in your job? Is there a formal mentoring program? If not, how does the group leader mentor the attendings?

The Nuts and Bolts

Once you’ve been offered a contract, it’s not just a simple matter of whether you will be salaried with benefits or a contract employee and have to purchase your own benefits. Legal counsel might be appropriate, DeVita says, to ensure you understand the ramifications of malpractice insurance.

Importantly, find out who pays for “tail insurance” for when you leave a job. This is vital, because physicians remain liable for malpractice acts performed when they were a part of the previous medical group.

You’re In, Now What?

Dr. Baudendistel and DeVita agree that honing your clinical skills will be “job one” once you start to work.

“If you’re averaging 12 patients and your peers are averaging 17, you will be in a position of jeopardy,” DeVita cautions.

For that reason, Baudendistel advises young hospitalists not to overcommit to nonclinical duties.

“There is a temptation to say ‘yes’ to every opportunity that arises in your first job. There will be plenty of time over the years to get involved in committee work, QI [quality improvement], and the like. Sometimes saying ‘no’ is the right approach in your early years,” he says.

Once you’re maintaining the same productivity level as your peers, DeVita points out, then it may be appropriate to participate in committee work—and there may be bonus components for citizenship work.

Gretchen Henkel is a freelance writer in California.

The best strategy for landing that first job is to start your search early, says Cheryl DeVita, senior search consultant at Cejka Search, Inc., in St. Louis, Mo.

“Many hospital organizations planning to add to their staff are willing to consider candidates six or 12 months out,” DeVita explains. Required licensing and credentialing “don’t happen fast,” she adds, and you will not be the only applicant. To preserve your range of choices, explore options early, preferably in the fall before your residency concludes.

Tom Baudendistel, MD, FACP, program director of internal medicine residency at Kaiser Permanente in Oakland, Calif., encourages his senior residents to “at least interview at new settings, and test the waters a bit.

“Too often, I see residents trying to find the absolute perfect position for the next 30 years of their career,” he says, “when in reality they are likely to change jobs in a few years for a variety of reasons, from personal to geographic to the job itself. Even if they decide to remain with Kaiser—as many do—they’ll have some perspective on what other systems are up to, which they can file away for future reference.”

At Stake? More than Money

Salary and benefits are important, but they aren’t the only factors to evaluate during a job search. Dr. Baudendistel offers a few “don’ts” to help guide the job search journey:

- Don’t forget to consider how you will stay up to date: “Residents sometimes take for granted the amount of didactic learning going on every day in the academic environment of residency, only to become disenchanted to take a job at a hospital where there may only be one grand rounds a week [if that], and the group meetings center primarily on business items, such as contracts, coding, and RVUs.”

- Don’t be lured by the money: Debt-ridden residents may be drawn to the quick fix of a nice salary, but this can cloud the fact that the salary might not increase much over the next five to 10 years, that the benefits/retirement/home loan packages are thin, or that there is very little growth potential within the group. To assess the potential for professional growth—a better predictor of job satisfaction—ask the attendings who have been with the group for five to 10 years: “How has your job evolved since you first started?” Be wary if the answer is, “I’ve been doing the same full-time clinical job since I started.”

- Don’t forget to look critically at group happiness. What is the turnover of the group? How is leadership viewed by the rank-and-file attendings? What is the relationship between the HM group and the hospital administration and nurses? A good question to ask is, “Does the group go to lunch?”

- Don’t forget to consider who your mentors will be. Who will help you grow and thrive in your job? Is there a formal mentoring program? If not, how does the group leader mentor the attendings?

The Nuts and Bolts

Once you’ve been offered a contract, it’s not just a simple matter of whether you will be salaried with benefits or a contract employee and have to purchase your own benefits. Legal counsel might be appropriate, DeVita says, to ensure you understand the ramifications of malpractice insurance.

Importantly, find out who pays for “tail insurance” for when you leave a job. This is vital, because physicians remain liable for malpractice acts performed when they were a part of the previous medical group.

You’re In, Now What?

Dr. Baudendistel and DeVita agree that honing your clinical skills will be “job one” once you start to work.

“If you’re averaging 12 patients and your peers are averaging 17, you will be in a position of jeopardy,” DeVita cautions.

For that reason, Baudendistel advises young hospitalists not to overcommit to nonclinical duties.

“There is a temptation to say ‘yes’ to every opportunity that arises in your first job. There will be plenty of time over the years to get involved in committee work, QI [quality improvement], and the like. Sometimes saying ‘no’ is the right approach in your early years,” he says.

Once you’re maintaining the same productivity level as your peers, DeVita points out, then it may be appropriate to participate in committee work—and there may be bonus components for citizenship work.

Gretchen Henkel is a freelance writer in California.

Hospital Medicine’s Challenges, Rewards Lure Healthcare Administrator

As a child, Courtney, director of operations for a multi-site hospitalist program at Baptist Health System in Birmingham, Ala., knew a boy who was diagnosed with leukemia.

“I often visited him in the hospital,” she says. “Those visits made me want to be in medicine. As I grew up, I knew I had more of a business mindset verses clinical, but my passion for healthcare remained.”

She’s not kidding. In 2000, she earned a bachelor of science degree in business administration from Mississippi University for Women in Columbus. Five years later, she earned an MBA in healthcare administration from the University of Phoenix. Her career started in marketing in North Carolina, but after five years in her current role, she has been involved in developing new hospitalist programs at three hospital sites.

Courtney is an active SHM member and is in her second year as a member of SHM’s Practice Administrators Committee. Now she is bringing that nonphysician perspective to Team Hospitalist. She is one of seven new members of The Hospitalist’s volunteer editorial advisory board.

Question: Was there a specific person/mentor who steered you to hospital medicine?

Answer: I was over operations of outpatient clinics and one hospitalist location when the opportunity to help start our system-wide hospitalist program became available. My boss approached me with the opportunity. She had once helped start a hospital medicine program and thought I would enjoy the challenge it would bring.

Q: What do you like most about working in hospital medicine?

A: My favorite part of hospital medicine is working with my medical directors, physicians, and hospital leadership to improve quality and outcomes for our patients. It’s great to see initiatives start from the group up and then watch the improved outcomes take place.

Q: What do you dislike most?

A: Navigating the staffing challenges is the least enjoyable part of my job.

Q: What’s the best advice you ever received?

A: My father always was kind to everyone and [was] respected because of his character. I was taught a person’s character is more important than any professional achievement.

Q: What’s the biggest change you’ve seen in HM in your career?

A: It seems I’ve seen an uptick of specialists wanting to model their practice after hospitalists. I’ve seen neurologists and nephrologists who only want to do inpatient care. I believe this stems from the [interest in] work-/home life balance that is more important to the newest generation of physicians.

Q: What is your biggest professional challenge?

A: Helping start our system hospitalist program has been both my biggest professional challenge and biggest professional reward. It was tough. With one established program already in place, it was decided to bring our two largest hospital medicine programs in-house. The programs were literally starting over from scratch within one month of each other. We started with six (full-time) FT physicians, two office managers, and me between the two locations. There was lots of locum usage, heavy recruiting, physicians working crazy hours to help out, and sleepless nights.

Q: And since then?

A: We have maintained good staffing/quality physicians at our initial location, fully staffed with 28 full-time physicians, four nurse practitioners, and several other support staff at our two startup locations, and have started a program at the fourth hospital. The hospital medicine group and the hospitals have worked together on clinical documentation improvement [and] geographic interdisciplinary rounding and have gone through an EPIC EHR install. It’s been a very challenging but rewarding road to be on.

Q: What SHM event (i.e., Leadership Academy, annual meeting) made the most lasting impression on you?

A: The “Leadership Essentials” course [part of SHM’s three-course Leadership Academy] was very important to me. I look forward to continuing the Leadership Academy courses.

Q: Where do you see yourself in 10 years?

A: I love the organization I currently work for. I hope to continue on my current career path and grow as a leader within the organization.

Q: When you aren’t working, what is important to you?

Answer: My family life is very important. I’m married, and we have one son who is nine. My off time revolves around traveling and sports my son participates in.

Q: Apple or Android?

A: As much as I hate to admit it, I’m an Apple fan. It took me a long time to make the switch, but I’m like the masses and addicted.

Q: What show is sitting in your Netflix queue that you can’t wait to binge watch?

A: I’m a “Walking Dead” fan and am working my way through all of the seasons now. I’ve made it up to last season.

As a child, Courtney, director of operations for a multi-site hospitalist program at Baptist Health System in Birmingham, Ala., knew a boy who was diagnosed with leukemia.

“I often visited him in the hospital,” she says. “Those visits made me want to be in medicine. As I grew up, I knew I had more of a business mindset verses clinical, but my passion for healthcare remained.”

She’s not kidding. In 2000, she earned a bachelor of science degree in business administration from Mississippi University for Women in Columbus. Five years later, she earned an MBA in healthcare administration from the University of Phoenix. Her career started in marketing in North Carolina, but after five years in her current role, she has been involved in developing new hospitalist programs at three hospital sites.

Courtney is an active SHM member and is in her second year as a member of SHM’s Practice Administrators Committee. Now she is bringing that nonphysician perspective to Team Hospitalist. She is one of seven new members of The Hospitalist’s volunteer editorial advisory board.

Question: Was there a specific person/mentor who steered you to hospital medicine?

Answer: I was over operations of outpatient clinics and one hospitalist location when the opportunity to help start our system-wide hospitalist program became available. My boss approached me with the opportunity. She had once helped start a hospital medicine program and thought I would enjoy the challenge it would bring.

Q: What do you like most about working in hospital medicine?

A: My favorite part of hospital medicine is working with my medical directors, physicians, and hospital leadership to improve quality and outcomes for our patients. It’s great to see initiatives start from the group up and then watch the improved outcomes take place.

Q: What do you dislike most?

A: Navigating the staffing challenges is the least enjoyable part of my job.

Q: What’s the best advice you ever received?

A: My father always was kind to everyone and [was] respected because of his character. I was taught a person’s character is more important than any professional achievement.

Q: What’s the biggest change you’ve seen in HM in your career?

A: It seems I’ve seen an uptick of specialists wanting to model their practice after hospitalists. I’ve seen neurologists and nephrologists who only want to do inpatient care. I believe this stems from the [interest in] work-/home life balance that is more important to the newest generation of physicians.

Q: What is your biggest professional challenge?

A: Helping start our system hospitalist program has been both my biggest professional challenge and biggest professional reward. It was tough. With one established program already in place, it was decided to bring our two largest hospital medicine programs in-house. The programs were literally starting over from scratch within one month of each other. We started with six (full-time) FT physicians, two office managers, and me between the two locations. There was lots of locum usage, heavy recruiting, physicians working crazy hours to help out, and sleepless nights.

Q: And since then?

A: We have maintained good staffing/quality physicians at our initial location, fully staffed with 28 full-time physicians, four nurse practitioners, and several other support staff at our two startup locations, and have started a program at the fourth hospital. The hospital medicine group and the hospitals have worked together on clinical documentation improvement [and] geographic interdisciplinary rounding and have gone through an EPIC EHR install. It’s been a very challenging but rewarding road to be on.

Q: What SHM event (i.e., Leadership Academy, annual meeting) made the most lasting impression on you?

A: The “Leadership Essentials” course [part of SHM’s three-course Leadership Academy] was very important to me. I look forward to continuing the Leadership Academy courses.

Q: Where do you see yourself in 10 years?

A: I love the organization I currently work for. I hope to continue on my current career path and grow as a leader within the organization.

Q: When you aren’t working, what is important to you?

Answer: My family life is very important. I’m married, and we have one son who is nine. My off time revolves around traveling and sports my son participates in.

Q: Apple or Android?

A: As much as I hate to admit it, I’m an Apple fan. It took me a long time to make the switch, but I’m like the masses and addicted.

Q: What show is sitting in your Netflix queue that you can’t wait to binge watch?

A: I’m a “Walking Dead” fan and am working my way through all of the seasons now. I’ve made it up to last season.

As a child, Courtney, director of operations for a multi-site hospitalist program at Baptist Health System in Birmingham, Ala., knew a boy who was diagnosed with leukemia.