User login

Women with ACS showed improved outcomes, but remain underrepresented in trials

Though acute coronary syndromes are the leading cause of death in U.S. women, an analysis of clinical trials showed that enrollment among women remained disproportionately low from 1994 to 2010, reported Dr. Kristian Kragholm and coauthors at Duke Clinical Research Institute.

An analysis of data in 76,148 non–ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndrome patients from 11 phase III clinical trials found that women comprised just 33.3% of participants, which did not change significantly over the 17-year period. Women consistently had higher incidence of diabetes, hypertension, and heart failure, the authors reported.

Use of ACE inhibitors/angiotensin II receptor blockers, thienopyridines, beta-blockers, and lipid-lowering drugs significantly increased over time for both sexes, as did use of coronary angiography and percutaneous coronary intervention. Observed in-hospital, 30-day, and 6-month mortality decreased significantly in both men and women, Dr. Kragholm and colleagues said.

The findings suggest that “current efforts to representatively enroll women in NSTE ACS trials are insufficient,” the authors wrote. “Because safety and efficacy findings may differ according to sex, this disparity could undermine generalizability of clinical trial results to treatment of the overall NSTE ACS population.”

Read the full article here.

Though acute coronary syndromes are the leading cause of death in U.S. women, an analysis of clinical trials showed that enrollment among women remained disproportionately low from 1994 to 2010, reported Dr. Kristian Kragholm and coauthors at Duke Clinical Research Institute.

An analysis of data in 76,148 non–ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndrome patients from 11 phase III clinical trials found that women comprised just 33.3% of participants, which did not change significantly over the 17-year period. Women consistently had higher incidence of diabetes, hypertension, and heart failure, the authors reported.

Use of ACE inhibitors/angiotensin II receptor blockers, thienopyridines, beta-blockers, and lipid-lowering drugs significantly increased over time for both sexes, as did use of coronary angiography and percutaneous coronary intervention. Observed in-hospital, 30-day, and 6-month mortality decreased significantly in both men and women, Dr. Kragholm and colleagues said.

The findings suggest that “current efforts to representatively enroll women in NSTE ACS trials are insufficient,” the authors wrote. “Because safety and efficacy findings may differ according to sex, this disparity could undermine generalizability of clinical trial results to treatment of the overall NSTE ACS population.”

Read the full article here.

Though acute coronary syndromes are the leading cause of death in U.S. women, an analysis of clinical trials showed that enrollment among women remained disproportionately low from 1994 to 2010, reported Dr. Kristian Kragholm and coauthors at Duke Clinical Research Institute.

An analysis of data in 76,148 non–ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndrome patients from 11 phase III clinical trials found that women comprised just 33.3% of participants, which did not change significantly over the 17-year period. Women consistently had higher incidence of diabetes, hypertension, and heart failure, the authors reported.

Use of ACE inhibitors/angiotensin II receptor blockers, thienopyridines, beta-blockers, and lipid-lowering drugs significantly increased over time for both sexes, as did use of coronary angiography and percutaneous coronary intervention. Observed in-hospital, 30-day, and 6-month mortality decreased significantly in both men and women, Dr. Kragholm and colleagues said.

The findings suggest that “current efforts to representatively enroll women in NSTE ACS trials are insufficient,” the authors wrote. “Because safety and efficacy findings may differ according to sex, this disparity could undermine generalizability of clinical trial results to treatment of the overall NSTE ACS population.”

Read the full article here.

Three Cheers for B3?

At the recent American Society of Clinical Oncology Annual Meeting, Martin et al presented data from the Australian Oral Nicotinamide to Reduce Actinic Cancer (ONTRAC) study. This prospective double-blind, randomized, controlled trial examined 386 immunocompetent patients with 2 or more nonmelanoma skin cancers (NMSCs) in the last 5 years (average, 8). The patients were randomized to receive oral nicotinamide 500 mg twice daily or placebo for 1 year, resulting in significant reduction of new NMSCs (average rate 1.77 vs 2.42; relative rate reduction, 23%; P=.02), with similar results for basal and squamous cell carcinomas. Actinic keratosis counts were reduced throughout the year by up to 20%, peaking at 9 months. No differences in adverse events were noted between the treatment and placebo groups.

What’s the issue?

High-risk NMSC patients present a challenge to dermatologists, as their need for constant surveillance, field therapy for actinic keratoses, and revolving visits between skin examinations and procedural modalities such as Mohs micrographic surgery can be staggering. Chemopreventive strategies pose difficulties, especially for elderly patients, due to tolerability and adherence, skin irritation and cosmetic limitations of topical therapies such as 5-fluorouracil, and inadequacy or financial inaccessibility of oral therapies such as acitretin.

Nicotinamide is a confusing supplement, as it is also called niacinamide. One of the 2 forms of vitamin B3, nicotinic acid (or niacin) is the other form and can be converted to nicotinamide in the body. It has cholesterol and vasodilatory/flushing effects that nicotinamide itself does not. Therefore, these supplement subtypes are not generally interchangeable.

Nicotinamide is postulated to enhance DNA repair and reverse UV immunosuppression in NMSC patients and is a well-tolerated and inexpensive supplement (approximately $10 a month for the dosage in this study). Although the decrease in skin cancer number per year seems modest in this study, my patients would likely welcome at least 1 fewer surgery per year and much less cryotherapy or 5-fluorouracil cream, especially if it is as simple as buying the supplement at the grocery store as they do for their fish oil capsules and probiotics. Does vitamin B3 hold promise for your high-risk NMSC patients?

At the recent American Society of Clinical Oncology Annual Meeting, Martin et al presented data from the Australian Oral Nicotinamide to Reduce Actinic Cancer (ONTRAC) study. This prospective double-blind, randomized, controlled trial examined 386 immunocompetent patients with 2 or more nonmelanoma skin cancers (NMSCs) in the last 5 years (average, 8). The patients were randomized to receive oral nicotinamide 500 mg twice daily or placebo for 1 year, resulting in significant reduction of new NMSCs (average rate 1.77 vs 2.42; relative rate reduction, 23%; P=.02), with similar results for basal and squamous cell carcinomas. Actinic keratosis counts were reduced throughout the year by up to 20%, peaking at 9 months. No differences in adverse events were noted between the treatment and placebo groups.

What’s the issue?

High-risk NMSC patients present a challenge to dermatologists, as their need for constant surveillance, field therapy for actinic keratoses, and revolving visits between skin examinations and procedural modalities such as Mohs micrographic surgery can be staggering. Chemopreventive strategies pose difficulties, especially for elderly patients, due to tolerability and adherence, skin irritation and cosmetic limitations of topical therapies such as 5-fluorouracil, and inadequacy or financial inaccessibility of oral therapies such as acitretin.

Nicotinamide is a confusing supplement, as it is also called niacinamide. One of the 2 forms of vitamin B3, nicotinic acid (or niacin) is the other form and can be converted to nicotinamide in the body. It has cholesterol and vasodilatory/flushing effects that nicotinamide itself does not. Therefore, these supplement subtypes are not generally interchangeable.

Nicotinamide is postulated to enhance DNA repair and reverse UV immunosuppression in NMSC patients and is a well-tolerated and inexpensive supplement (approximately $10 a month for the dosage in this study). Although the decrease in skin cancer number per year seems modest in this study, my patients would likely welcome at least 1 fewer surgery per year and much less cryotherapy or 5-fluorouracil cream, especially if it is as simple as buying the supplement at the grocery store as they do for their fish oil capsules and probiotics. Does vitamin B3 hold promise for your high-risk NMSC patients?

At the recent American Society of Clinical Oncology Annual Meeting, Martin et al presented data from the Australian Oral Nicotinamide to Reduce Actinic Cancer (ONTRAC) study. This prospective double-blind, randomized, controlled trial examined 386 immunocompetent patients with 2 or more nonmelanoma skin cancers (NMSCs) in the last 5 years (average, 8). The patients were randomized to receive oral nicotinamide 500 mg twice daily or placebo for 1 year, resulting in significant reduction of new NMSCs (average rate 1.77 vs 2.42; relative rate reduction, 23%; P=.02), with similar results for basal and squamous cell carcinomas. Actinic keratosis counts were reduced throughout the year by up to 20%, peaking at 9 months. No differences in adverse events were noted between the treatment and placebo groups.

What’s the issue?

High-risk NMSC patients present a challenge to dermatologists, as their need for constant surveillance, field therapy for actinic keratoses, and revolving visits between skin examinations and procedural modalities such as Mohs micrographic surgery can be staggering. Chemopreventive strategies pose difficulties, especially for elderly patients, due to tolerability and adherence, skin irritation and cosmetic limitations of topical therapies such as 5-fluorouracil, and inadequacy or financial inaccessibility of oral therapies such as acitretin.

Nicotinamide is a confusing supplement, as it is also called niacinamide. One of the 2 forms of vitamin B3, nicotinic acid (or niacin) is the other form and can be converted to nicotinamide in the body. It has cholesterol and vasodilatory/flushing effects that nicotinamide itself does not. Therefore, these supplement subtypes are not generally interchangeable.

Nicotinamide is postulated to enhance DNA repair and reverse UV immunosuppression in NMSC patients and is a well-tolerated and inexpensive supplement (approximately $10 a month for the dosage in this study). Although the decrease in skin cancer number per year seems modest in this study, my patients would likely welcome at least 1 fewer surgery per year and much less cryotherapy or 5-fluorouracil cream, especially if it is as simple as buying the supplement at the grocery store as they do for their fish oil capsules and probiotics. Does vitamin B3 hold promise for your high-risk NMSC patients?

Heroin use up across demographic groups from 2002 to 2013

Heroin use is rising across all demographic groups in the United States, and is gaining traction among groups that previously have been associated with lower use, doubling among women and more than doubling among non-Hispanic whites, Dr. Thomas Frieden, director of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, said in a July 7 telebriefing.

Between 2002 and 2013, the rate of heroin-related overdose deaths nearly quadrupled, and more than 8,200 people died in 2013, according to the latest Vital Signs report, a combined project from the CDC and the Food and Drug Administration that analyzed data from the 2002-2013 National Survey on Drug Use and Health.

In addition, the gaps between men and women, low and higher incomes, and people with Medicaid and private insurance have narrowed in the past decade, although the most at-risk groups are still non-Hispanic whites, men, 18- to 25-year-olds, people with an annual household incomes of less than $20,000, Medicaid recipients, and the uninsured.

Although people who are addicted to prescription opioid painkillers were 40 times more likely to abuse heroin, the general idea that people gravitating to heroin abuse are doing so because opiates have become harder to get is not true, Dr. Frieden noted. The study identified two factors that were likely responsible for the increase in heroin users – the combination of the increased supply of heroin and higher demand, as well as the number of people already addicted to opioids who are “primed” for a heroin addiction.

However, state agencies have a central role to play in curbing heroin abuse, and will need to increase support for drug monitoring and surveillance programs to make tracking opiate abusers easier and more efficient, Dr. Frieden said.

The CDC is addressing the epidemic by helping to create federal guidelines for pain management, and supporting research and development for less addictive pain medications, he said.

“Improving prescribing practices is part of the solution, not part of the cause,” Dr. Frieden said.

Individual health care providers can help by following best practices for responsible painkiller prescribing to reduce opioid painkiller addiction, and by providing training for ways to adequately and comprehensively address pain beyond simply prescribing painkillers.

“Opiates are very good at curbing severe pain ... But for chronic, noncancer pain, you really need to look at the risks and benefits,” said Christopher M. Jones, Pharm.D., the study’s coauthor and a senior adviser at the FDA.

Heroin use is rising across all demographic groups in the United States, and is gaining traction among groups that previously have been associated with lower use, doubling among women and more than doubling among non-Hispanic whites, Dr. Thomas Frieden, director of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, said in a July 7 telebriefing.

Between 2002 and 2013, the rate of heroin-related overdose deaths nearly quadrupled, and more than 8,200 people died in 2013, according to the latest Vital Signs report, a combined project from the CDC and the Food and Drug Administration that analyzed data from the 2002-2013 National Survey on Drug Use and Health.

In addition, the gaps between men and women, low and higher incomes, and people with Medicaid and private insurance have narrowed in the past decade, although the most at-risk groups are still non-Hispanic whites, men, 18- to 25-year-olds, people with an annual household incomes of less than $20,000, Medicaid recipients, and the uninsured.

Although people who are addicted to prescription opioid painkillers were 40 times more likely to abuse heroin, the general idea that people gravitating to heroin abuse are doing so because opiates have become harder to get is not true, Dr. Frieden noted. The study identified two factors that were likely responsible for the increase in heroin users – the combination of the increased supply of heroin and higher demand, as well as the number of people already addicted to opioids who are “primed” for a heroin addiction.

However, state agencies have a central role to play in curbing heroin abuse, and will need to increase support for drug monitoring and surveillance programs to make tracking opiate abusers easier and more efficient, Dr. Frieden said.

The CDC is addressing the epidemic by helping to create federal guidelines for pain management, and supporting research and development for less addictive pain medications, he said.

“Improving prescribing practices is part of the solution, not part of the cause,” Dr. Frieden said.

Individual health care providers can help by following best practices for responsible painkiller prescribing to reduce opioid painkiller addiction, and by providing training for ways to adequately and comprehensively address pain beyond simply prescribing painkillers.

“Opiates are very good at curbing severe pain ... But for chronic, noncancer pain, you really need to look at the risks and benefits,” said Christopher M. Jones, Pharm.D., the study’s coauthor and a senior adviser at the FDA.

Heroin use is rising across all demographic groups in the United States, and is gaining traction among groups that previously have been associated with lower use, doubling among women and more than doubling among non-Hispanic whites, Dr. Thomas Frieden, director of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, said in a July 7 telebriefing.

Between 2002 and 2013, the rate of heroin-related overdose deaths nearly quadrupled, and more than 8,200 people died in 2013, according to the latest Vital Signs report, a combined project from the CDC and the Food and Drug Administration that analyzed data from the 2002-2013 National Survey on Drug Use and Health.

In addition, the gaps between men and women, low and higher incomes, and people with Medicaid and private insurance have narrowed in the past decade, although the most at-risk groups are still non-Hispanic whites, men, 18- to 25-year-olds, people with an annual household incomes of less than $20,000, Medicaid recipients, and the uninsured.

Although people who are addicted to prescription opioid painkillers were 40 times more likely to abuse heroin, the general idea that people gravitating to heroin abuse are doing so because opiates have become harder to get is not true, Dr. Frieden noted. The study identified two factors that were likely responsible for the increase in heroin users – the combination of the increased supply of heroin and higher demand, as well as the number of people already addicted to opioids who are “primed” for a heroin addiction.

However, state agencies have a central role to play in curbing heroin abuse, and will need to increase support for drug monitoring and surveillance programs to make tracking opiate abusers easier and more efficient, Dr. Frieden said.

The CDC is addressing the epidemic by helping to create federal guidelines for pain management, and supporting research and development for less addictive pain medications, he said.

“Improving prescribing practices is part of the solution, not part of the cause,” Dr. Frieden said.

Individual health care providers can help by following best practices for responsible painkiller prescribing to reduce opioid painkiller addiction, and by providing training for ways to adequately and comprehensively address pain beyond simply prescribing painkillers.

“Opiates are very good at curbing severe pain ... But for chronic, noncancer pain, you really need to look at the risks and benefits,” said Christopher M. Jones, Pharm.D., the study’s coauthor and a senior adviser at the FDA.

FROM A CDC TELEBRIEFING

Extended warfarin delays return of unprovoked pulmonary embolism

Adding an extra 18 months of warfarin therapy to the standard 6 months of anticoagulation delays the recurrence of venous thrombosis in patients who have a first episode of unprovoked pulmonary embolism – but the risk of recurrence resumes as soon as the warfarin is discontinued, according to a report published online July 7 in JAMA.

“Our results suggest that patients such as those who participated in our study require long-term secondary prophylaxis measures. Whether these should include systematic treatment with vitamin K antagonists, new anticoagulants, or aspirin, or be tailored according to patient risk factors (including elevated D-dimer levels) needs further investigation,” said Dr. Francis Couturaud of the department of internal medicine and chest diseases, University of Brest (France) Hospital, and his associates (JAMA 2015;314:31-40).

Adults with a first episode of unprovoked VT are at much greater risk of recurrence when the standard 6 months of anticoagulation runs out, compared with those whose VT is provoked by a known, transient risk factor such as lengthy surgery, trauma with immobilization of the lower limbs, or bed rest extending longer than 72 hours.

Some experts have advocated extending anticoagulation further in such patients; but whether this is actually beneficial remains uncertain, the investigators said, because most studies have not pursued follow-up beyond the end of treatment.

The researchers performed a multicenter, double-blind trial in which 371 consecutive patients with a first episode of unprovoked PE completed 6 months of anticoagulation and then were randomly assigned to a further 18 months on either warfarin or matching placebo.

During this 18-month treatment period, the primary outcome – a composite of recurrent VT (including PE) and major bleeding – occurred in 3.3% of the warfarin group and 13.5% of the placebo group. That significant difference translated to a 78% reduction in favor of warfarin (hazard ratio, 0.22), Dr. Couturaud and his associates said.

However, after the treatment period ended, the composite outcome occurred in 17.7% of the warfarin group and 10.3% of the placebo group. Thus, the risk of recurrence returned to its normal high level once warfarin was discontinued, the study authors noted.

The study was supported by the Programme Hospitalier de Recherche Clinique (the French Department of Health) and the University Hospital of Brest (France). Dr. Couturaud reported receiving research grants, honoraria, and travel pay from Actelion, AstraZeneca, Bayer, Daiichi Sankyo, Intermune, Leo Pharma, and Pfizer, and his associates reported ties to numerous industry sources.

Related Information

- Computed tomographic pulmonary angiography (CTPA) may be useful in the diagnosis of suspected PE, wrote Dr. Gregoire Le Gal and co-authors from the University of Ottawa. Alternately, a V/Q scan may be performed. The complete accompanying article on diagnostic testing methods for suspected pulmonary embolism can be found here.

- The recently approved anticoagulant edoxaban is similar to warfarin in its ability to treat acute VTE, according to a report published in the Medical Letter on Drugs and Therapeutics in the same issue. However, further study is needed to evaluate its safety and efficacy compared with dabigatran, rivaroxaban, and apixaban, the three other oral anticoagulant drugs currently FDA-approved for acute VTE.

- A meta-analysis of 3,716 patients with VTE found that long-term treatment with Vitamin K antagonists was associated with lower rates of thromboembolic events (relative risk = 0.20) and higher rates of bleeding complications (RR = 3.44), compared with short-term therapy, Dr. Saskia Middeldorp and Dr. Barbara A. Hutten of the University of Amsterdam reported in the same issue. There was no difference in mortality between the two groups.

- Currently, recommended treatment duration for PE can range from three months to lifelong treatment, wrote Dr. Jill Jin in a clinical synopsis for patients published with the study.

- Read the full article and listen to the related podcast: http://jama.jamanetwork.com/article.aspx?doi=10.1001/jama.2015.7046

Madhu Rajaraman contributed to this report.

Adding an extra 18 months of warfarin therapy to the standard 6 months of anticoagulation delays the recurrence of venous thrombosis in patients who have a first episode of unprovoked pulmonary embolism – but the risk of recurrence resumes as soon as the warfarin is discontinued, according to a report published online July 7 in JAMA.

“Our results suggest that patients such as those who participated in our study require long-term secondary prophylaxis measures. Whether these should include systematic treatment with vitamin K antagonists, new anticoagulants, or aspirin, or be tailored according to patient risk factors (including elevated D-dimer levels) needs further investigation,” said Dr. Francis Couturaud of the department of internal medicine and chest diseases, University of Brest (France) Hospital, and his associates (JAMA 2015;314:31-40).

Adults with a first episode of unprovoked VT are at much greater risk of recurrence when the standard 6 months of anticoagulation runs out, compared with those whose VT is provoked by a known, transient risk factor such as lengthy surgery, trauma with immobilization of the lower limbs, or bed rest extending longer than 72 hours.

Some experts have advocated extending anticoagulation further in such patients; but whether this is actually beneficial remains uncertain, the investigators said, because most studies have not pursued follow-up beyond the end of treatment.

The researchers performed a multicenter, double-blind trial in which 371 consecutive patients with a first episode of unprovoked PE completed 6 months of anticoagulation and then were randomly assigned to a further 18 months on either warfarin or matching placebo.

During this 18-month treatment period, the primary outcome – a composite of recurrent VT (including PE) and major bleeding – occurred in 3.3% of the warfarin group and 13.5% of the placebo group. That significant difference translated to a 78% reduction in favor of warfarin (hazard ratio, 0.22), Dr. Couturaud and his associates said.

However, after the treatment period ended, the composite outcome occurred in 17.7% of the warfarin group and 10.3% of the placebo group. Thus, the risk of recurrence returned to its normal high level once warfarin was discontinued, the study authors noted.

The study was supported by the Programme Hospitalier de Recherche Clinique (the French Department of Health) and the University Hospital of Brest (France). Dr. Couturaud reported receiving research grants, honoraria, and travel pay from Actelion, AstraZeneca, Bayer, Daiichi Sankyo, Intermune, Leo Pharma, and Pfizer, and his associates reported ties to numerous industry sources.

Related Information

- Computed tomographic pulmonary angiography (CTPA) may be useful in the diagnosis of suspected PE, wrote Dr. Gregoire Le Gal and co-authors from the University of Ottawa. Alternately, a V/Q scan may be performed. The complete accompanying article on diagnostic testing methods for suspected pulmonary embolism can be found here.

- The recently approved anticoagulant edoxaban is similar to warfarin in its ability to treat acute VTE, according to a report published in the Medical Letter on Drugs and Therapeutics in the same issue. However, further study is needed to evaluate its safety and efficacy compared with dabigatran, rivaroxaban, and apixaban, the three other oral anticoagulant drugs currently FDA-approved for acute VTE.

- A meta-analysis of 3,716 patients with VTE found that long-term treatment with Vitamin K antagonists was associated with lower rates of thromboembolic events (relative risk = 0.20) and higher rates of bleeding complications (RR = 3.44), compared with short-term therapy, Dr. Saskia Middeldorp and Dr. Barbara A. Hutten of the University of Amsterdam reported in the same issue. There was no difference in mortality between the two groups.

- Currently, recommended treatment duration for PE can range from three months to lifelong treatment, wrote Dr. Jill Jin in a clinical synopsis for patients published with the study.

- Read the full article and listen to the related podcast: http://jama.jamanetwork.com/article.aspx?doi=10.1001/jama.2015.7046

Madhu Rajaraman contributed to this report.

Adding an extra 18 months of warfarin therapy to the standard 6 months of anticoagulation delays the recurrence of venous thrombosis in patients who have a first episode of unprovoked pulmonary embolism – but the risk of recurrence resumes as soon as the warfarin is discontinued, according to a report published online July 7 in JAMA.

“Our results suggest that patients such as those who participated in our study require long-term secondary prophylaxis measures. Whether these should include systematic treatment with vitamin K antagonists, new anticoagulants, or aspirin, or be tailored according to patient risk factors (including elevated D-dimer levels) needs further investigation,” said Dr. Francis Couturaud of the department of internal medicine and chest diseases, University of Brest (France) Hospital, and his associates (JAMA 2015;314:31-40).

Adults with a first episode of unprovoked VT are at much greater risk of recurrence when the standard 6 months of anticoagulation runs out, compared with those whose VT is provoked by a known, transient risk factor such as lengthy surgery, trauma with immobilization of the lower limbs, or bed rest extending longer than 72 hours.

Some experts have advocated extending anticoagulation further in such patients; but whether this is actually beneficial remains uncertain, the investigators said, because most studies have not pursued follow-up beyond the end of treatment.

The researchers performed a multicenter, double-blind trial in which 371 consecutive patients with a first episode of unprovoked PE completed 6 months of anticoagulation and then were randomly assigned to a further 18 months on either warfarin or matching placebo.

During this 18-month treatment period, the primary outcome – a composite of recurrent VT (including PE) and major bleeding – occurred in 3.3% of the warfarin group and 13.5% of the placebo group. That significant difference translated to a 78% reduction in favor of warfarin (hazard ratio, 0.22), Dr. Couturaud and his associates said.

However, after the treatment period ended, the composite outcome occurred in 17.7% of the warfarin group and 10.3% of the placebo group. Thus, the risk of recurrence returned to its normal high level once warfarin was discontinued, the study authors noted.

The study was supported by the Programme Hospitalier de Recherche Clinique (the French Department of Health) and the University Hospital of Brest (France). Dr. Couturaud reported receiving research grants, honoraria, and travel pay from Actelion, AstraZeneca, Bayer, Daiichi Sankyo, Intermune, Leo Pharma, and Pfizer, and his associates reported ties to numerous industry sources.

Related Information

- Computed tomographic pulmonary angiography (CTPA) may be useful in the diagnosis of suspected PE, wrote Dr. Gregoire Le Gal and co-authors from the University of Ottawa. Alternately, a V/Q scan may be performed. The complete accompanying article on diagnostic testing methods for suspected pulmonary embolism can be found here.

- The recently approved anticoagulant edoxaban is similar to warfarin in its ability to treat acute VTE, according to a report published in the Medical Letter on Drugs and Therapeutics in the same issue. However, further study is needed to evaluate its safety and efficacy compared with dabigatran, rivaroxaban, and apixaban, the three other oral anticoagulant drugs currently FDA-approved for acute VTE.

- A meta-analysis of 3,716 patients with VTE found that long-term treatment with Vitamin K antagonists was associated with lower rates of thromboembolic events (relative risk = 0.20) and higher rates of bleeding complications (RR = 3.44), compared with short-term therapy, Dr. Saskia Middeldorp and Dr. Barbara A. Hutten of the University of Amsterdam reported in the same issue. There was no difference in mortality between the two groups.

- Currently, recommended treatment duration for PE can range from three months to lifelong treatment, wrote Dr. Jill Jin in a clinical synopsis for patients published with the study.

- Read the full article and listen to the related podcast: http://jama.jamanetwork.com/article.aspx?doi=10.1001/jama.2015.7046

Madhu Rajaraman contributed to this report.

FROM JAMA

Key clinical point: Eighteen additional months of warfarin therapy delays the recurrence of unprovoked pulmonary embolism.

Major finding: During treatment, the primary outcome – a composite of recurrent venous thromboembolism and major bleeding – occurred in 3.3% of the warfarin group and 13.5% of the placebo group, a significant difference that translated to a 78% reduction in favor of warfarin (hazard ratio, 0.22).

Data source: A multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial involving 371 patients followed for a mean of 41 months.

Disclosures: This study was supported by the Programme Hospitalier de Recherche Clinique (the French Department of Health) and the University Hospital of Brest (France). Dr. Couturaud reported receiving research grants, honoraria, and travel pay from Actelion, AstraZeneca, Bayer, Daiichi Sankyo, Intermune, Leo Pharma, and Pfizer, and his associates reported ties to numerous industry sources.

Madelung Deformity and Extensor Tendon Rupture

Extensor tendon rupture in chronic Madelung deformity, as a result of tendon attrition on the dislocated distal ulna, occurs infrequently. However, it is often seen in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. This issue has been reported in only a few English-language case reports. Here we report a case of multiple tendon ruptures in a previously undiagnosed Madelung deformity. The patient provided written informed consent for print and electronic publication of this case report.

Case Report

A 56-year-old active woman presented with 50 days’ inability to extend the fourth and fifth fingers of her dominant right hand. The loss of finger extension progressed, over several weeks, to involve the third finger as well. The first 2 tendon ruptures had been triggered by lifting a light grocery bag, when she noticed a sharp sudden pain and “pop.” The third rupture occurred spontaneously with a snapping sound the night before surgery.

The patient had observed some prominence on the ulnar side of her right wrist since childhood but had never experienced any pain or functional disability. There was neither history of trauma, inflammatory disease, diabetes mellitus, or infection, nor positive family history of similar wrist deformity.

The physical examination showed a dorsally subluxated distal radioulnar joint, prominent ulnar styloid, and mild ulnar and volar deviation of the wrist along with limitation of wrist dorsiflexion. Complete loss of active extension of the 3 ulnar fingers was demonstrated, while neurovascular status and all other hand evaluations were normal. The wrist radiographs confirmed the typical findings of Madelung deformity (Figure 1).

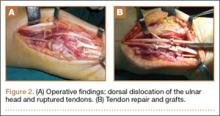

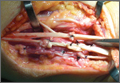

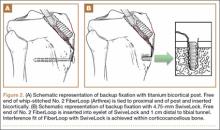

Repair of the ruptured tendons and resection of the prominent distal ulna (Darrach procedure) was planned. (Given the patient’s age and evidence of degenerative changes in the radiocarpal joint, correction of the Madelung deformity did not seem necessary). At time of surgery, the recently ruptured third finger extensor tendon was easily found and approximated, and end-to-end repair was performed. The fourth and fifth fingers, however, had to be fished out more proximally from dense granulation tissue. After the distal ulna was resected for a distance of 1.5 cm, meticulous repair of the ulnar collateral ligament and the capsule and periosteum over the end of the ulna was performed. Then, for grafting of the ruptured tendons, the extensor indicis proprius tendon was isolated and transected at the second metacarpophalangeal joint level. A piece of this tendon was used as interpositional graft for the fourth extensor tendon, and the main tendon unit was transferred to the fifth finger extensor. The extensor digiti quinti tendon, which was about to rupture, was further reinforced by suturing it side to side to the muscle and tendon of the extensor indicis proprius (Figure 2).

Postoperatively, the wrist was kept in extension in a cast for 3 weeks while the fingers were free for active movement. A removable wrist splint was used for an additional month. At 3-month follow-up, the patient had regained full and strong finger extension and wrist motion.

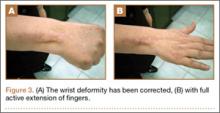

At 3-year follow-up, the patient was pain-free, and had full extension of all fingers, full forearm rotation, and near-normal motion (better than her preoperative motion). The grip power on the operated right hand was 215 N, and pinch power was 93 N. (The values for the left side were 254 N and 83 N, respectively, using the Jamar hydraulic hand dynamometer [Patterson Medical].) The patient has had no additional tendon rupture (Figure 3).

Discussion

Madelung deformity was first described by Madelung in 1878 and several cases have reported this deformity. However, extensor tendon rupture caused by Madelung deformity is very rare, reported in few cases.1

Extensor tendon rupture caused by chronic Madelung deformity has been reported few times in the English literature. Goodwin1 apparently published the first report of such an occurrence in 1979. Ducloyer and colleagues2 from France reported 6 cases of extensor tendon rupture as a result of inferior distal radioulnar joint deformity of Madelung. Jebson and colleagues3 reported bilateral spontaneous extensor tendon ruptures in Madelung deformity in 1992.

The mechanism of tendon rupture seems to be mechanical, resulting from continuous rubbing and erosion of tendons over the deformed ulnar head, which has a rough irregular surface4 and leads to fraying of the tendons and eventual rupture and retraction of the severed tendon ends. This rupture usually progresses stepwise from more medial to the lateral tendons.2 Older patients are, therefore, subject to chronic repetitive attritional trauma leading to tendon rupture.

Tendons may rupture as a result of a variety of conditions, such as chronic synovitis in rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus, mixed connective tissue disease, or crystal deposition in gout.5-8 Some other metabolic or endocrine conditions that involve tendon ruptures include diabetes mellitus, chronic renal failure, and hyperparathyroidism. Steroid injection into the tendons also has a detrimental effect on tendon integrity and may cause tendon tear.9 Mechanical factors, such as erosion on bony prominences, are well-known etiologies for tendon rupture, as commonly seen in rheumatoid arthritis, and have been reported in Kienböck disease,10 thumb carpometacarpal arthritis,11 Colles fracture, scaphoid fracture nonunion,12 and Madelung deformity.

Conclusion

Our case reflects the usual middle-aged female presentation of such a tendon rupture. The tendon ruptures were spontaneous in the reported order of ulnar to radial, beginning with the little and ring fingers, and progressed radially. The patient had isolated Madelung deformity with no other sign of dyschondrosteosis13 or dwarfism, conditions commonly mentioned in association with Madelung deformity. This case report should raise awareness about possible tendon rupture in any chronic case of Madelung deformity.

1. Goodwin DR, Michels CH, Weissman SL. Spontaneous rupture of extensor tendons in Madelung’s deformity. Hand. 1979;11(1):72-75.

2. Ducloyer P, Leclercq C, Lisfrance R, Saffar P. Spontaneous rupture of the extensor tendons of the fingers in Madelung’s deformity. J Hand Surg Br. 1991;16(3):329-333.

3. Jebson PJ, Blair WF. Bilateral spontaneous extensor tendon ruptures in Madelung’s deformity. J Hand Surg Am. 1992;17(2):277-280.

4. Schulstad I. Madelung’s deformity with extensor tendon rupture. Case report. Scand J Plast Reconstr Surg. 1971;5(2):153-155.

5. Gong HS, Lee JO, Baek GH, et al. Extensor tendon rupture in rheumatoid arthritis: a survey of patients between 2005 and 2010 at five Korean hospitals. Hand Surg. 2012;17(1):43-47.

6. Oishi H, Oda R, Morisaki S, Fujiwara H, Tokunaga D, Kubo T. Spontaneous tendon rupture of the extensor digitrum communis in systemic lupus erythematosus. Mod Rheumatol. 2013;23(3);608-610.

7. Kobayashi A, Futami T, Tadano I, Fujita M. Spontaneous rupture of extensor tendons at the wrist in a patient with mixed connective tissue disease. Mod Rheumatol. 2002;12(3):256-258.

8. Iwamoto T, Toki H, Ikari K, Yamanaka H, Momohara S. Multiple extensor tendon ruptures caused by tophaceous gout. Mod Rheumatol. 2010;20(2):210-212.

9. Nquyen ML, Jones NF. Rupture of both abductor pollicis longus and extensor pollicis brevis tendon after steroid injection for de quervain tenosynovitis. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2012;129(5):883e-886e.

10. Hernández-Cortés P, Pajares-López M, Gómez-Sánchez R, Garrido-Gómez, Lara-Garcia F. Rupture of extensor tendon secondary to previously undiagnosed Kienböck disease. J Plast Surg Hand Surg. 2012;46(3-4):291-293.

11. Apard T, Marcucci L, Jarriges J. Spontaneous rupture of extensor pollicis longus in isolated trapeziometacarpal arthritis. Chir Main. 2011;30(5):349-351.

12. Harvey FJ, Harvey PM. Three rare causes of extensor tendon rupture. J Hand Surg Am. 1989;14(6):957-962.

13. Duro EA, Prado GS. Clinical variations in Léri-Weill dyschondrosteosis. An Esp Pediatr. 1990;33(5):461-463.

Extensor tendon rupture in chronic Madelung deformity, as a result of tendon attrition on the dislocated distal ulna, occurs infrequently. However, it is often seen in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. This issue has been reported in only a few English-language case reports. Here we report a case of multiple tendon ruptures in a previously undiagnosed Madelung deformity. The patient provided written informed consent for print and electronic publication of this case report.

Case Report

A 56-year-old active woman presented with 50 days’ inability to extend the fourth and fifth fingers of her dominant right hand. The loss of finger extension progressed, over several weeks, to involve the third finger as well. The first 2 tendon ruptures had been triggered by lifting a light grocery bag, when she noticed a sharp sudden pain and “pop.” The third rupture occurred spontaneously with a snapping sound the night before surgery.

The patient had observed some prominence on the ulnar side of her right wrist since childhood but had never experienced any pain or functional disability. There was neither history of trauma, inflammatory disease, diabetes mellitus, or infection, nor positive family history of similar wrist deformity.

The physical examination showed a dorsally subluxated distal radioulnar joint, prominent ulnar styloid, and mild ulnar and volar deviation of the wrist along with limitation of wrist dorsiflexion. Complete loss of active extension of the 3 ulnar fingers was demonstrated, while neurovascular status and all other hand evaluations were normal. The wrist radiographs confirmed the typical findings of Madelung deformity (Figure 1).

Repair of the ruptured tendons and resection of the prominent distal ulna (Darrach procedure) was planned. (Given the patient’s age and evidence of degenerative changes in the radiocarpal joint, correction of the Madelung deformity did not seem necessary). At time of surgery, the recently ruptured third finger extensor tendon was easily found and approximated, and end-to-end repair was performed. The fourth and fifth fingers, however, had to be fished out more proximally from dense granulation tissue. After the distal ulna was resected for a distance of 1.5 cm, meticulous repair of the ulnar collateral ligament and the capsule and periosteum over the end of the ulna was performed. Then, for grafting of the ruptured tendons, the extensor indicis proprius tendon was isolated and transected at the second metacarpophalangeal joint level. A piece of this tendon was used as interpositional graft for the fourth extensor tendon, and the main tendon unit was transferred to the fifth finger extensor. The extensor digiti quinti tendon, which was about to rupture, was further reinforced by suturing it side to side to the muscle and tendon of the extensor indicis proprius (Figure 2).

Postoperatively, the wrist was kept in extension in a cast for 3 weeks while the fingers were free for active movement. A removable wrist splint was used for an additional month. At 3-month follow-up, the patient had regained full and strong finger extension and wrist motion.

At 3-year follow-up, the patient was pain-free, and had full extension of all fingers, full forearm rotation, and near-normal motion (better than her preoperative motion). The grip power on the operated right hand was 215 N, and pinch power was 93 N. (The values for the left side were 254 N and 83 N, respectively, using the Jamar hydraulic hand dynamometer [Patterson Medical].) The patient has had no additional tendon rupture (Figure 3).

Discussion

Madelung deformity was first described by Madelung in 1878 and several cases have reported this deformity. However, extensor tendon rupture caused by Madelung deformity is very rare, reported in few cases.1

Extensor tendon rupture caused by chronic Madelung deformity has been reported few times in the English literature. Goodwin1 apparently published the first report of such an occurrence in 1979. Ducloyer and colleagues2 from France reported 6 cases of extensor tendon rupture as a result of inferior distal radioulnar joint deformity of Madelung. Jebson and colleagues3 reported bilateral spontaneous extensor tendon ruptures in Madelung deformity in 1992.

The mechanism of tendon rupture seems to be mechanical, resulting from continuous rubbing and erosion of tendons over the deformed ulnar head, which has a rough irregular surface4 and leads to fraying of the tendons and eventual rupture and retraction of the severed tendon ends. This rupture usually progresses stepwise from more medial to the lateral tendons.2 Older patients are, therefore, subject to chronic repetitive attritional trauma leading to tendon rupture.

Tendons may rupture as a result of a variety of conditions, such as chronic synovitis in rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus, mixed connective tissue disease, or crystal deposition in gout.5-8 Some other metabolic or endocrine conditions that involve tendon ruptures include diabetes mellitus, chronic renal failure, and hyperparathyroidism. Steroid injection into the tendons also has a detrimental effect on tendon integrity and may cause tendon tear.9 Mechanical factors, such as erosion on bony prominences, are well-known etiologies for tendon rupture, as commonly seen in rheumatoid arthritis, and have been reported in Kienböck disease,10 thumb carpometacarpal arthritis,11 Colles fracture, scaphoid fracture nonunion,12 and Madelung deformity.

Conclusion

Our case reflects the usual middle-aged female presentation of such a tendon rupture. The tendon ruptures were spontaneous in the reported order of ulnar to radial, beginning with the little and ring fingers, and progressed radially. The patient had isolated Madelung deformity with no other sign of dyschondrosteosis13 or dwarfism, conditions commonly mentioned in association with Madelung deformity. This case report should raise awareness about possible tendon rupture in any chronic case of Madelung deformity.

Extensor tendon rupture in chronic Madelung deformity, as a result of tendon attrition on the dislocated distal ulna, occurs infrequently. However, it is often seen in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. This issue has been reported in only a few English-language case reports. Here we report a case of multiple tendon ruptures in a previously undiagnosed Madelung deformity. The patient provided written informed consent for print and electronic publication of this case report.

Case Report

A 56-year-old active woman presented with 50 days’ inability to extend the fourth and fifth fingers of her dominant right hand. The loss of finger extension progressed, over several weeks, to involve the third finger as well. The first 2 tendon ruptures had been triggered by lifting a light grocery bag, when she noticed a sharp sudden pain and “pop.” The third rupture occurred spontaneously with a snapping sound the night before surgery.

The patient had observed some prominence on the ulnar side of her right wrist since childhood but had never experienced any pain or functional disability. There was neither history of trauma, inflammatory disease, diabetes mellitus, or infection, nor positive family history of similar wrist deformity.

The physical examination showed a dorsally subluxated distal radioulnar joint, prominent ulnar styloid, and mild ulnar and volar deviation of the wrist along with limitation of wrist dorsiflexion. Complete loss of active extension of the 3 ulnar fingers was demonstrated, while neurovascular status and all other hand evaluations were normal. The wrist radiographs confirmed the typical findings of Madelung deformity (Figure 1).

Repair of the ruptured tendons and resection of the prominent distal ulna (Darrach procedure) was planned. (Given the patient’s age and evidence of degenerative changes in the radiocarpal joint, correction of the Madelung deformity did not seem necessary). At time of surgery, the recently ruptured third finger extensor tendon was easily found and approximated, and end-to-end repair was performed. The fourth and fifth fingers, however, had to be fished out more proximally from dense granulation tissue. After the distal ulna was resected for a distance of 1.5 cm, meticulous repair of the ulnar collateral ligament and the capsule and periosteum over the end of the ulna was performed. Then, for grafting of the ruptured tendons, the extensor indicis proprius tendon was isolated and transected at the second metacarpophalangeal joint level. A piece of this tendon was used as interpositional graft for the fourth extensor tendon, and the main tendon unit was transferred to the fifth finger extensor. The extensor digiti quinti tendon, which was about to rupture, was further reinforced by suturing it side to side to the muscle and tendon of the extensor indicis proprius (Figure 2).

Postoperatively, the wrist was kept in extension in a cast for 3 weeks while the fingers were free for active movement. A removable wrist splint was used for an additional month. At 3-month follow-up, the patient had regained full and strong finger extension and wrist motion.

At 3-year follow-up, the patient was pain-free, and had full extension of all fingers, full forearm rotation, and near-normal motion (better than her preoperative motion). The grip power on the operated right hand was 215 N, and pinch power was 93 N. (The values for the left side were 254 N and 83 N, respectively, using the Jamar hydraulic hand dynamometer [Patterson Medical].) The patient has had no additional tendon rupture (Figure 3).

Discussion

Madelung deformity was first described by Madelung in 1878 and several cases have reported this deformity. However, extensor tendon rupture caused by Madelung deformity is very rare, reported in few cases.1

Extensor tendon rupture caused by chronic Madelung deformity has been reported few times in the English literature. Goodwin1 apparently published the first report of such an occurrence in 1979. Ducloyer and colleagues2 from France reported 6 cases of extensor tendon rupture as a result of inferior distal radioulnar joint deformity of Madelung. Jebson and colleagues3 reported bilateral spontaneous extensor tendon ruptures in Madelung deformity in 1992.

The mechanism of tendon rupture seems to be mechanical, resulting from continuous rubbing and erosion of tendons over the deformed ulnar head, which has a rough irregular surface4 and leads to fraying of the tendons and eventual rupture and retraction of the severed tendon ends. This rupture usually progresses stepwise from more medial to the lateral tendons.2 Older patients are, therefore, subject to chronic repetitive attritional trauma leading to tendon rupture.

Tendons may rupture as a result of a variety of conditions, such as chronic synovitis in rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus, mixed connective tissue disease, or crystal deposition in gout.5-8 Some other metabolic or endocrine conditions that involve tendon ruptures include diabetes mellitus, chronic renal failure, and hyperparathyroidism. Steroid injection into the tendons also has a detrimental effect on tendon integrity and may cause tendon tear.9 Mechanical factors, such as erosion on bony prominences, are well-known etiologies for tendon rupture, as commonly seen in rheumatoid arthritis, and have been reported in Kienböck disease,10 thumb carpometacarpal arthritis,11 Colles fracture, scaphoid fracture nonunion,12 and Madelung deformity.

Conclusion

Our case reflects the usual middle-aged female presentation of such a tendon rupture. The tendon ruptures were spontaneous in the reported order of ulnar to radial, beginning with the little and ring fingers, and progressed radially. The patient had isolated Madelung deformity with no other sign of dyschondrosteosis13 or dwarfism, conditions commonly mentioned in association with Madelung deformity. This case report should raise awareness about possible tendon rupture in any chronic case of Madelung deformity.

1. Goodwin DR, Michels CH, Weissman SL. Spontaneous rupture of extensor tendons in Madelung’s deformity. Hand. 1979;11(1):72-75.

2. Ducloyer P, Leclercq C, Lisfrance R, Saffar P. Spontaneous rupture of the extensor tendons of the fingers in Madelung’s deformity. J Hand Surg Br. 1991;16(3):329-333.

3. Jebson PJ, Blair WF. Bilateral spontaneous extensor tendon ruptures in Madelung’s deformity. J Hand Surg Am. 1992;17(2):277-280.

4. Schulstad I. Madelung’s deformity with extensor tendon rupture. Case report. Scand J Plast Reconstr Surg. 1971;5(2):153-155.

5. Gong HS, Lee JO, Baek GH, et al. Extensor tendon rupture in rheumatoid arthritis: a survey of patients between 2005 and 2010 at five Korean hospitals. Hand Surg. 2012;17(1):43-47.

6. Oishi H, Oda R, Morisaki S, Fujiwara H, Tokunaga D, Kubo T. Spontaneous tendon rupture of the extensor digitrum communis in systemic lupus erythematosus. Mod Rheumatol. 2013;23(3);608-610.

7. Kobayashi A, Futami T, Tadano I, Fujita M. Spontaneous rupture of extensor tendons at the wrist in a patient with mixed connective tissue disease. Mod Rheumatol. 2002;12(3):256-258.

8. Iwamoto T, Toki H, Ikari K, Yamanaka H, Momohara S. Multiple extensor tendon ruptures caused by tophaceous gout. Mod Rheumatol. 2010;20(2):210-212.

9. Nquyen ML, Jones NF. Rupture of both abductor pollicis longus and extensor pollicis brevis tendon after steroid injection for de quervain tenosynovitis. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2012;129(5):883e-886e.

10. Hernández-Cortés P, Pajares-López M, Gómez-Sánchez R, Garrido-Gómez, Lara-Garcia F. Rupture of extensor tendon secondary to previously undiagnosed Kienböck disease. J Plast Surg Hand Surg. 2012;46(3-4):291-293.

11. Apard T, Marcucci L, Jarriges J. Spontaneous rupture of extensor pollicis longus in isolated trapeziometacarpal arthritis. Chir Main. 2011;30(5):349-351.

12. Harvey FJ, Harvey PM. Three rare causes of extensor tendon rupture. J Hand Surg Am. 1989;14(6):957-962.

13. Duro EA, Prado GS. Clinical variations in Léri-Weill dyschondrosteosis. An Esp Pediatr. 1990;33(5):461-463.

1. Goodwin DR, Michels CH, Weissman SL. Spontaneous rupture of extensor tendons in Madelung’s deformity. Hand. 1979;11(1):72-75.

2. Ducloyer P, Leclercq C, Lisfrance R, Saffar P. Spontaneous rupture of the extensor tendons of the fingers in Madelung’s deformity. J Hand Surg Br. 1991;16(3):329-333.

3. Jebson PJ, Blair WF. Bilateral spontaneous extensor tendon ruptures in Madelung’s deformity. J Hand Surg Am. 1992;17(2):277-280.

4. Schulstad I. Madelung’s deformity with extensor tendon rupture. Case report. Scand J Plast Reconstr Surg. 1971;5(2):153-155.

5. Gong HS, Lee JO, Baek GH, et al. Extensor tendon rupture in rheumatoid arthritis: a survey of patients between 2005 and 2010 at five Korean hospitals. Hand Surg. 2012;17(1):43-47.

6. Oishi H, Oda R, Morisaki S, Fujiwara H, Tokunaga D, Kubo T. Spontaneous tendon rupture of the extensor digitrum communis in systemic lupus erythematosus. Mod Rheumatol. 2013;23(3);608-610.

7. Kobayashi A, Futami T, Tadano I, Fujita M. Spontaneous rupture of extensor tendons at the wrist in a patient with mixed connective tissue disease. Mod Rheumatol. 2002;12(3):256-258.

8. Iwamoto T, Toki H, Ikari K, Yamanaka H, Momohara S. Multiple extensor tendon ruptures caused by tophaceous gout. Mod Rheumatol. 2010;20(2):210-212.

9. Nquyen ML, Jones NF. Rupture of both abductor pollicis longus and extensor pollicis brevis tendon after steroid injection for de quervain tenosynovitis. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2012;129(5):883e-886e.

10. Hernández-Cortés P, Pajares-López M, Gómez-Sánchez R, Garrido-Gómez, Lara-Garcia F. Rupture of extensor tendon secondary to previously undiagnosed Kienböck disease. J Plast Surg Hand Surg. 2012;46(3-4):291-293.

11. Apard T, Marcucci L, Jarriges J. Spontaneous rupture of extensor pollicis longus in isolated trapeziometacarpal arthritis. Chir Main. 2011;30(5):349-351.

12. Harvey FJ, Harvey PM. Three rare causes of extensor tendon rupture. J Hand Surg Am. 1989;14(6):957-962.

13. Duro EA, Prado GS. Clinical variations in Léri-Weill dyschondrosteosis. An Esp Pediatr. 1990;33(5):461-463.

Septic Arthritis and Osteomyelitis Caused by Pasteurella multocida

A few days after an incidental cat bite, a patient presented to the emergency department for treatment of poison sumac exposure. He was discharged with oral methylprednisolone for the dermatitis and returned 1 week later with symptoms, examination findings, and laboratory results consistent with sepsis and bilateral upper extremity necrotizing soft-tissue infections. After administering multiple irrigation and débridement procedures, hyperbaric oxygen treatments, and an antibiotic regimen, the patient’s status greatly improved. However, the patient returned 1 month later with a new sternoclavicular joint prominence that was associated with painful crepitus. Additionally, he noted that his wrists were gradually becoming more swollen and painful. Imaging studies showed a lytic destruction of the sternoclavicular joint and erosive changes throughout the carpus and radiocarpal joint bilaterally, consistent with osteomyelitis. The patient was treated with ertapenem for 6 weeks, and his polyarthropathy resolved. The patient provided written informed consent for print and electronic publication of this case report.

Case Report

A 73-year-old, right-hand–dominant man with no notable medical history presented to the emergency department for treatment of poison sumac exposure, incidentally, a few days after being bitten by a cat on the bilateral distal upper extremities. He was prescribed a course of oral methylprednisolone for dermatitis. A week later, the patient returned to the emergency department with altered mental status, fevers, diaphoresis, lethargy, and polyarthralgia. At the time of presentation, the patient’s vital signs were labile, and he was found to have extensive bilateral upper extremity erythema, blistering, petechiae, purpuric lesions, and exquisite pain with passive range of motion of his fingers and wrists. His leukocyte count was 25.1 × 109/L, and he had elevated C-reactive protein level and erythrocyte sedimentation rate of 150 mg/L and 120 mm/h, respectively. He was admitted for management of sepsis and presumed bilateral upper extremity necrotizing soft-tissue infection.

Broad-spectrum intravenous (IV) antibiotics (vancomycin, piperacillin, tazobactam) were initiated after blood cultures were obtained, and the patient was taken emergently to the operating theatre for irrigation and débridement of his hands and wrists bilaterally. Arthrotomy of the wrist and débridement of the distal extensor compartment and its tenosynovium were performed on the right forearm, in addition to a decompressive fasciotomy of the left forearm. Postoperatively, the patient’s mental status improved and his vital signs gradually normalized. He received multiple hyperbaric oxygen treatments and underwent several additional operative débridement procedures with eventual closure of his wounds. At initial presentation, the differential diagnosis for the severe soft-tissue infection included necrotizing fasciitis or myositis caused by any of a variety of bacterial pathogens. Most notably, it was important to elicit the history of a cat bite to include and consider Pasteurella multocida as a potential pathogen. Initial cultures supported the diagnosis of acute P multocida necrotizing skin and soft-tissue infection, in addition to septic arthritis. The patient’s blood and intraoperative wound cultures grew P multocida. The antibiotic treatment was tailored initially to ampicillin and sulbactam and then to a final regimen of orally administered ciprofloxacin (750 mg twice a day), once susceptibility testing was performed on the cultures. On hospital day 10, the patient was discharged home, receiving a 6-week course of ciprofloxacin to complete the 8-week course of treatment.

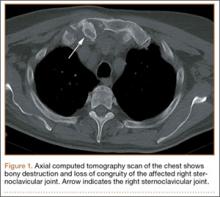

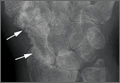

At follow-up, approximately 1 month after discharge, the patient noted that he had developed a new right sternoclavicular joint prominence that was associated with painful crepitus. He also noted that his wrists were gradually becoming more swollen and painful bilaterally. Computed tomography scans of the chest were obtained to evaluate the sternoclavicular joint (Figure 1). Repeat radiographs of the wrists were also obtained (Figure 2). Imaging showed lytic destruction of the sternoclavicular joint and erosive changes throughout the carpus and radiocarpal joint, consistent with osteomyelitis. The C-reactive protein level and erythrocyte sedimentation rate at this time were 34 mg/L and 124 mm/h, respectively.

The patient returned to the operating room for débridement and biopsy of the right sternoclavicular joint and left wrist. This patient’s delayed presentation was characterized by a subacute worsening of isolated musculoskeletal complaints. The differential diagnosis then included infection with the same bacterial pathogen versus reactive or inflammatory arthritis. Several intraoperative cultures failed to grow any bacteria, including P multocida, although P multocida was the presumptive cause of the erosive polyarthropathy, considering that symptoms eventually resolved with a repeated course of IV-administered ertapenem for 6 weeks. The patient experienced complete resolution of his joint pain and swelling. He was able to resume his activities of daily living and had no further recurrence of symptoms at follow-up 3 months later.

Discussion

Cat bites often are the source of Pasteurella species infections because the bacteria are carried by more than 90% of cats.1 These types of infections can cause septic arthritis, osteomyelitis, and deep subcutaneous and myofascial infections because of the sharp and narrow morphology of cat teeth. The infections can progress to necrotizing fasciitis and myositis if not recognized early, as was the case with our patient. Prophylactic antibiotic administration for animal bites is controversial and is not a universal practice.1,2Pasteurella bacteremia is an atypical progression that occurs more often in patients with pneumonia, septic arthritis, or meningitis. Cases of Pasteurella sepsis, necrotizing fasciitis, and septic arthritis have been reported.3-7 However, associated progressive septic arthritis and osteomyelitis, despite initial clinical improvement, have not been reported. Severe infection (ie, sepsis and septic shock) can occur in infants, pregnant women, and other immunocompromised patients.7 Immune suppression of our patient with steroid medication for poison sumac dermatitis likely contributed to the progression and systemic spread of an initially benign cat bite. Before prescribing steroids, it is imperative to ask about exposures and encourage patients to seek prompt medical attention with worsening or new symptoms. Healthy individuals rarely develop bacteremia; however, in these cases, mortality remains high at approximately 25%.4,6

The clinical course of this case emphasizes the need for vigilance and thoroughness in obtaining histories from patients presenting with seemingly benign complaints, especially in vulnerable populations, such as infants, pregnant women, and immunocompromised adults. In this case, the progression of symptoms might have been avoided if the patient’s dermatitis had been treated conservatively or with topical rather than systemic steroids.

1. Esposito S, Picciolli I, Semino M, Principi N. Dog and cat bite-associated infections in children. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2013;32(8):971-976.

2. Medeiros I, Saconato H. Antibiotic prophylaxis for mammalian bites. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2001;(2):CD001738.

3. Haybaeck J, Schindler C, Braza P, Willinger B, Drlicek M. Rapidly progressive and lethal septicemia due to infection with Pasteurella multocida in an infant. Wien Klin Wochenschr. 2009;121(5-6):216-219.

4. Migliore E, Serraino C, Brignone C, et al. Pasteurella multocida infection in a cirrhotic patient: case report, microbiological aspects and a review of the literature. Adv Med Sci. 2009;54(1):109-112.

5. Mugambi SM, Ullian ME. Bacteremia, sepsis, and peritonitis with Pasteurella multocida in a peritoneal dialysis patient. Perit Dial Int. 2010;30(3):381-383.

6. Weber DJ, Wolfson JS, Swartz MN, Hooper DC. Pasteurella multocida infections. Report of 34 cases and review of the literature. Medicine (Baltimore). 1984;63(3):133-154.

7. Oehler RL, Velez AP, Mizrachi M, Lamarche J, Gompf S. Bite-related and septic syndromes caused by cats and dogs. Lancet Infect Dis. 2009;9(7):439-447.

A few days after an incidental cat bite, a patient presented to the emergency department for treatment of poison sumac exposure. He was discharged with oral methylprednisolone for the dermatitis and returned 1 week later with symptoms, examination findings, and laboratory results consistent with sepsis and bilateral upper extremity necrotizing soft-tissue infections. After administering multiple irrigation and débridement procedures, hyperbaric oxygen treatments, and an antibiotic regimen, the patient’s status greatly improved. However, the patient returned 1 month later with a new sternoclavicular joint prominence that was associated with painful crepitus. Additionally, he noted that his wrists were gradually becoming more swollen and painful. Imaging studies showed a lytic destruction of the sternoclavicular joint and erosive changes throughout the carpus and radiocarpal joint bilaterally, consistent with osteomyelitis. The patient was treated with ertapenem for 6 weeks, and his polyarthropathy resolved. The patient provided written informed consent for print and electronic publication of this case report.

Case Report

A 73-year-old, right-hand–dominant man with no notable medical history presented to the emergency department for treatment of poison sumac exposure, incidentally, a few days after being bitten by a cat on the bilateral distal upper extremities. He was prescribed a course of oral methylprednisolone for dermatitis. A week later, the patient returned to the emergency department with altered mental status, fevers, diaphoresis, lethargy, and polyarthralgia. At the time of presentation, the patient’s vital signs were labile, and he was found to have extensive bilateral upper extremity erythema, blistering, petechiae, purpuric lesions, and exquisite pain with passive range of motion of his fingers and wrists. His leukocyte count was 25.1 × 109/L, and he had elevated C-reactive protein level and erythrocyte sedimentation rate of 150 mg/L and 120 mm/h, respectively. He was admitted for management of sepsis and presumed bilateral upper extremity necrotizing soft-tissue infection.

Broad-spectrum intravenous (IV) antibiotics (vancomycin, piperacillin, tazobactam) were initiated after blood cultures were obtained, and the patient was taken emergently to the operating theatre for irrigation and débridement of his hands and wrists bilaterally. Arthrotomy of the wrist and débridement of the distal extensor compartment and its tenosynovium were performed on the right forearm, in addition to a decompressive fasciotomy of the left forearm. Postoperatively, the patient’s mental status improved and his vital signs gradually normalized. He received multiple hyperbaric oxygen treatments and underwent several additional operative débridement procedures with eventual closure of his wounds. At initial presentation, the differential diagnosis for the severe soft-tissue infection included necrotizing fasciitis or myositis caused by any of a variety of bacterial pathogens. Most notably, it was important to elicit the history of a cat bite to include and consider Pasteurella multocida as a potential pathogen. Initial cultures supported the diagnosis of acute P multocida necrotizing skin and soft-tissue infection, in addition to septic arthritis. The patient’s blood and intraoperative wound cultures grew P multocida. The antibiotic treatment was tailored initially to ampicillin and sulbactam and then to a final regimen of orally administered ciprofloxacin (750 mg twice a day), once susceptibility testing was performed on the cultures. On hospital day 10, the patient was discharged home, receiving a 6-week course of ciprofloxacin to complete the 8-week course of treatment.

At follow-up, approximately 1 month after discharge, the patient noted that he had developed a new right sternoclavicular joint prominence that was associated with painful crepitus. He also noted that his wrists were gradually becoming more swollen and painful bilaterally. Computed tomography scans of the chest were obtained to evaluate the sternoclavicular joint (Figure 1). Repeat radiographs of the wrists were also obtained (Figure 2). Imaging showed lytic destruction of the sternoclavicular joint and erosive changes throughout the carpus and radiocarpal joint, consistent with osteomyelitis. The C-reactive protein level and erythrocyte sedimentation rate at this time were 34 mg/L and 124 mm/h, respectively.

The patient returned to the operating room for débridement and biopsy of the right sternoclavicular joint and left wrist. This patient’s delayed presentation was characterized by a subacute worsening of isolated musculoskeletal complaints. The differential diagnosis then included infection with the same bacterial pathogen versus reactive or inflammatory arthritis. Several intraoperative cultures failed to grow any bacteria, including P multocida, although P multocida was the presumptive cause of the erosive polyarthropathy, considering that symptoms eventually resolved with a repeated course of IV-administered ertapenem for 6 weeks. The patient experienced complete resolution of his joint pain and swelling. He was able to resume his activities of daily living and had no further recurrence of symptoms at follow-up 3 months later.

Discussion

Cat bites often are the source of Pasteurella species infections because the bacteria are carried by more than 90% of cats.1 These types of infections can cause septic arthritis, osteomyelitis, and deep subcutaneous and myofascial infections because of the sharp and narrow morphology of cat teeth. The infections can progress to necrotizing fasciitis and myositis if not recognized early, as was the case with our patient. Prophylactic antibiotic administration for animal bites is controversial and is not a universal practice.1,2Pasteurella bacteremia is an atypical progression that occurs more often in patients with pneumonia, septic arthritis, or meningitis. Cases of Pasteurella sepsis, necrotizing fasciitis, and septic arthritis have been reported.3-7 However, associated progressive septic arthritis and osteomyelitis, despite initial clinical improvement, have not been reported. Severe infection (ie, sepsis and septic shock) can occur in infants, pregnant women, and other immunocompromised patients.7 Immune suppression of our patient with steroid medication for poison sumac dermatitis likely contributed to the progression and systemic spread of an initially benign cat bite. Before prescribing steroids, it is imperative to ask about exposures and encourage patients to seek prompt medical attention with worsening or new symptoms. Healthy individuals rarely develop bacteremia; however, in these cases, mortality remains high at approximately 25%.4,6

The clinical course of this case emphasizes the need for vigilance and thoroughness in obtaining histories from patients presenting with seemingly benign complaints, especially in vulnerable populations, such as infants, pregnant women, and immunocompromised adults. In this case, the progression of symptoms might have been avoided if the patient’s dermatitis had been treated conservatively or with topical rather than systemic steroids.

A few days after an incidental cat bite, a patient presented to the emergency department for treatment of poison sumac exposure. He was discharged with oral methylprednisolone for the dermatitis and returned 1 week later with symptoms, examination findings, and laboratory results consistent with sepsis and bilateral upper extremity necrotizing soft-tissue infections. After administering multiple irrigation and débridement procedures, hyperbaric oxygen treatments, and an antibiotic regimen, the patient’s status greatly improved. However, the patient returned 1 month later with a new sternoclavicular joint prominence that was associated with painful crepitus. Additionally, he noted that his wrists were gradually becoming more swollen and painful. Imaging studies showed a lytic destruction of the sternoclavicular joint and erosive changes throughout the carpus and radiocarpal joint bilaterally, consistent with osteomyelitis. The patient was treated with ertapenem for 6 weeks, and his polyarthropathy resolved. The patient provided written informed consent for print and electronic publication of this case report.

Case Report

A 73-year-old, right-hand–dominant man with no notable medical history presented to the emergency department for treatment of poison sumac exposure, incidentally, a few days after being bitten by a cat on the bilateral distal upper extremities. He was prescribed a course of oral methylprednisolone for dermatitis. A week later, the patient returned to the emergency department with altered mental status, fevers, diaphoresis, lethargy, and polyarthralgia. At the time of presentation, the patient’s vital signs were labile, and he was found to have extensive bilateral upper extremity erythema, blistering, petechiae, purpuric lesions, and exquisite pain with passive range of motion of his fingers and wrists. His leukocyte count was 25.1 × 109/L, and he had elevated C-reactive protein level and erythrocyte sedimentation rate of 150 mg/L and 120 mm/h, respectively. He was admitted for management of sepsis and presumed bilateral upper extremity necrotizing soft-tissue infection.

Broad-spectrum intravenous (IV) antibiotics (vancomycin, piperacillin, tazobactam) were initiated after blood cultures were obtained, and the patient was taken emergently to the operating theatre for irrigation and débridement of his hands and wrists bilaterally. Arthrotomy of the wrist and débridement of the distal extensor compartment and its tenosynovium were performed on the right forearm, in addition to a decompressive fasciotomy of the left forearm. Postoperatively, the patient’s mental status improved and his vital signs gradually normalized. He received multiple hyperbaric oxygen treatments and underwent several additional operative débridement procedures with eventual closure of his wounds. At initial presentation, the differential diagnosis for the severe soft-tissue infection included necrotizing fasciitis or myositis caused by any of a variety of bacterial pathogens. Most notably, it was important to elicit the history of a cat bite to include and consider Pasteurella multocida as a potential pathogen. Initial cultures supported the diagnosis of acute P multocida necrotizing skin and soft-tissue infection, in addition to septic arthritis. The patient’s blood and intraoperative wound cultures grew P multocida. The antibiotic treatment was tailored initially to ampicillin and sulbactam and then to a final regimen of orally administered ciprofloxacin (750 mg twice a day), once susceptibility testing was performed on the cultures. On hospital day 10, the patient was discharged home, receiving a 6-week course of ciprofloxacin to complete the 8-week course of treatment.

At follow-up, approximately 1 month after discharge, the patient noted that he had developed a new right sternoclavicular joint prominence that was associated with painful crepitus. He also noted that his wrists were gradually becoming more swollen and painful bilaterally. Computed tomography scans of the chest were obtained to evaluate the sternoclavicular joint (Figure 1). Repeat radiographs of the wrists were also obtained (Figure 2). Imaging showed lytic destruction of the sternoclavicular joint and erosive changes throughout the carpus and radiocarpal joint, consistent with osteomyelitis. The C-reactive protein level and erythrocyte sedimentation rate at this time were 34 mg/L and 124 mm/h, respectively.

The patient returned to the operating room for débridement and biopsy of the right sternoclavicular joint and left wrist. This patient’s delayed presentation was characterized by a subacute worsening of isolated musculoskeletal complaints. The differential diagnosis then included infection with the same bacterial pathogen versus reactive or inflammatory arthritis. Several intraoperative cultures failed to grow any bacteria, including P multocida, although P multocida was the presumptive cause of the erosive polyarthropathy, considering that symptoms eventually resolved with a repeated course of IV-administered ertapenem for 6 weeks. The patient experienced complete resolution of his joint pain and swelling. He was able to resume his activities of daily living and had no further recurrence of symptoms at follow-up 3 months later.

Discussion