User login

Catching up on the latest USPSTF recommendations

In 2014, the United States Preventive Services Task Force released 24 recommendations on 14 topics.1 There were no level A recommendations, 10 B recommendations, 1 C recommendation, 3 D recommendations, and 10 I statements. A and B recommendations require that commercial insurance plans offer the recommended services at no cost to patients. This Practice Alert focuses on last year’s B and D recommendations (TABLE 11).

Cardiovascular disease

When to screen for abdominal aortic aneurism. The Task Force (TF) reaffirmed a previous B recommendation for a one-time abdominal ultrasound (US) screening for abdominal aortic aneurism (AAA) in men ages 65 to 75 years who have ever smoked. This screening and follow-up of abnormal findings results in decreased AAA rupture and AAA-related mortality, although it appears to have no effect on all-cause mortality.2 The value of screening men who have never smoked is very small and should be considered selectively for men who have a family history of AAA, or a personal history of cardiovascular risk factors or disease. The prevalence of AAA in men in the target age group is 6% to 7% (it is 0.8% for women overall in the same age range).2

The recommended screening modality, abdominal US, matches the sensitivity and specificity of abdominal CT but at lower cost and with no radiation exposure. Refer patients with AAAs ≥5.5 cm for surgical repair.2

Patients with smaller aneurysms (3.0 to 5.4 cm) can be managed conservatively with repeated US every 3 to 12 months. Patients with AAAs <3 cm that exhibit rapid growth (>1 cm/year) or that cross the threshold of 5.5 cm on repeated US should undergo surgical consultation.2

The TF also looked at the value of AAA screening for women in the same age group who have ever smoked, and it could not find enough evidence to make a recommendation. However, in women who have never smoked, the TF concluded that, largely due to the low prevalence of AAA, potential harms of screening outweigh its benefits.2

General screening for carotid artery stenosis is unhelpful. For asymptomatic adults, the TF gave a thumbs-down D recommendation on screening for carotid artery stenosis.3 Carotid artery screening is conducted with US, followed by, if findings indicate the need, confirmatory testing with angiography. US has reasonable sensitivity (90%) for finding the most significant lesions, but the specificity of 94% often leads to false-positive results that can bring about unnecessary surgery and serious harms, including death, stroke, and myocardial infarction. There is no evidence of any benefit from screening by auscultation of the neck.

The TF believes it is better to focus on primary prevention of stroke, including screening for hypertension and dyslipidemia, counseling on smoking cessation, encouraging healthful diet and physical activity, and recommending aspirin use for those at increased risk for cardiovascular disease.3

Focus on CVD prevention. For adults who are overweight or obese and have additional cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk factors, the TF recommends offering, or referring patients for, intensive behavioral counseling interventions to promote a healthy diet and increased physical activity. A previous Practice Alert discussed the rationale behind this selective intensive approach to CVD prevention, as well as the lack of endorsement of vitamins to prevent CVD or cancer.4

Sexually transmitted infections

When to screen for gonorrhea and chlamydia. The TF recommends screening for chlamydial and gonorrheal infections in all sexually active women ages 24 years and younger, and for women older than 24 years who are at high risk.5 The TF could not find adequate evidence to make a recommendation for or against screening men for either disease.

Risk is defined rather broadly to include having a new sex partner, more than one sex partner, or a sex partner with concurrent partners or a sexually transmitted infection (STI); inconsistent condom use among individuals who are not in mutually monogamous relationships; having a previous or coexisting STI; and exchanging sex for money or drugs. The TF also points out that physicians should know the prevalence of these infections in their community and be aware of particular groups that are at higher risk.

Chlamydia and gonorrhea are the most commonly reported STIs in the United States. In 2012, more than 1.4 million cases of chlamydial infection were reported to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).5 This is an underestimate of true prevalence because most infections are asymptomatic and not detected. The rate of chlamydial infection in females was 643.3 cases per 100,000 (more than twice that seen in males—262.6 cases per 100,000), with most infections occurring in females ages 15 to 24 years.5

In 2012, more than 330,000 cases of gonococcal infection were reported to the CDC. The rate of gonorrhea infection was similar for females and males (108.7 vs. 105.8 cases per 100,000, respectively), but while most infections in females occurred between the ages of 15 and 24 years, men most often affected were ages 20 to 24 years.5

Chlamydial and gonococcal infections can be diagnosed by nucleic acid amplification tests conducted on specimens collected in a number of ways: urine; endocervical, vaginal, and male urethral specimens; and self-collected vaginal specimens in clinical settings. Treatment recommendations for both infections can be found on the CDC STI treatment Web site.6

Intensive behavioral counseling as a means of preventing STIs is recommended for all sexually active adolescents and adults at elevated risk—ie, those with current STIs or infected within the past year, those who have multiple sex partners, and those who do not consistently use condoms.7

Intensive intervention ranges from 30 minutes to 2 hours or more of contact time. All counseling within this range is beneficial, with more time being more effective.7 These interventions can be delivered by primary care clinicians or behavioral counselors. The most successful approaches provide basic information about STIs (and STI transmission) and train patients in important skills, such as condom use, communication about safe sex, problem solving, and goal setting.

Hepatitis B screening: A change

The TF changed its previous position on screening for chronic hepatitis B virus (HBV) in those at high risk from an I statement to a B recommendation. Previously, the TF opposed screening of low-risk populations; the new recommendation is silent on this issue. Those at high risk for HBV include:8

• individuals born in countries and regions with a prevalence of HBV infection ≥2%

• US-born individuals not vaccinated as infants, whose parents are from regions with a very high prevalence of HBV infection (≥8%)—eg, sub-Saharan Africa or southeast or central Asia

• HIV-positive individuals

• injection drug users

• men who have sex with men

• household contacts or sexual partners of individuals with HBV infection.

Information on countries and regions with a high prevalence of HBV infection can be found at: www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/rr5708a1.htm.

The TF notes that approximately 700,000 to 2.2 million individuals in the United States have chronic HBV infection.8 However, HBV vaccine has been a recommended child vaccine for more than 20 years and the pool of those at risk shrinks annually.

Chronic HBV infection can lead to cirrhosis, hepatic failure, and hepatocellular carcinoma. An estimated 15% to 25% of individuals with chronic HBV infection die of cirrhosis or hepatocellular carcinoma.8 Those with chronic infection can also infect others. Screening for HBV infection could identify chronically infected people who may benefit from treatment and be counseled to prevent transmission.

In screening, test for hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg), which has a reported sensitivity and specificity of >98%.8 While the TF did not find direct evidence of screening benefits on mortality, it found convincing evidence that antiviral treatment in patients with chronic HBV infection improves intermediate outcomes (virologic or histologic improvement or clearance of hepatitis B e antigen [HBeAg]) and adequate evidence that antiviral regimens improve health outcomes (such as reduced risk for hepatocellular carcinoma).8

Prevention of tooth decay in kids

The TF recommends that primary care physicians implement 2 interventions to prevent tooth decay in infants and children: prescribing oral fluoride supplementation starting at age 6 months in areas where the local water supply is deficient in fluoride (defined as <0.6 ppm F); and periodically applying fluoride varnish to primary teeth starting at the age of tooth eruption through age 5 years. The TF emphasizes, however, that the most effective way to prevent dental decay in children is to maintain recommended levels of fluoride in community water supplies.9

Both recommended interventions are supported by good evidence, although no study directly assessed the appropriate ages at which to start and stop the application of fluoride varnish or the optimal frequency of applications. Most studies looked at children ages 3 to 5 years, but the TF believes that benefits are likely to begin at the time of primary tooth eruption.

Limited evidence found no clear difference in benefit between performing a single fluoride varnish once every 6 months vs once a year or between a single application every 6 months vs multiple applications once a year or every 6 months.9

Pregnancy

Screen for gestational diabetes. The previous TF statement on gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) found insufficient evidence to screen for this condition. The new recommendation advises screening starting at 24 weeks gestation using the 50-g oral glucose challenge test.10 Other screening options, such as the use of fasting plasma glucose testing or basing decisions to screen on risk factors, have not been studied as extensively. The USPSTF found inadequate evidence to compare the effectiveness of different screening tests or thresholds in determining positive screen results.

Treating those with GDM with diet, glucose monitoring, and insulin (if needed) can significantly reduce the risk of preeclampsia, fetal macrosomia, and shoulder dystocia, which, according to the TF, adds up to a moderate net benefit for both mother and infant. There is no evidence that treatment will improve long-term metabolic outcomes in women.

The TF found inadequate evidence to determine whether there are benefits to screening for GDM in women before 24 weeks of gestation.

Give low-dose aspirin to prevent preeclampsia. In a new recommendation, the TF endorses low-dose aspirin (81 mg/d) to reduce rates of preeclampsia, preterm birth, and intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR) in women at increased risk for preeclampsia—defined as those with kidney disease, diabetes (type 1 or 2), hypertension, autoimmune disease, a history of preeclampsia, or a current multifetal pregnancy.11

Aspirin should be started after 12 weeks and before 28 weeks of gestation, which has been shown to reduce the risk of preeclampsia by 24%, preterm birth by 14%, and IUGR by 20%.11 The number needed to treat to prevent one case of preeclampsia was 42; 71 for IUGR, and 65 for preterm birth.11 (For more on the evidence behind this recommendation, see “Another good reason to recommend lowdose aspirin” on page 301.)

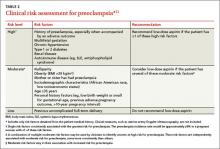

TABLE 211 lists risk factors for preeclampsia and recommendations for those in high-, moderate-, and low-risk groups.

Screenings/interventions with insufficient supporting evidence

Three conditions that cause significant morbidity or mortality were looked at by the TF last year, and insufficient evidence was found to make a recommendation—screening for cognitive impairment (early Alzheimer’s); primary care interventions to prevent or reduce illicit drug or nonmedical pharmaceutical use in children and adolescents; and screening for suicide risk in adolescents, adults, and older adults in primary care. In addition, no evidence could be found for the benefit of screening for vitamin D deficiency in adults.

1. US Preventive Services Task Force. Published recommendations. US Preventive Services Task Force Web site. Available at: http://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/BrowseRec/Index. Accessed March 24, 2015.

2. US Preventive Services Task Force. Abdominal aortic aneurism: screening. US Preventive Services Task Force Web site. Available at: http://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/RecommendationStatementFinal/abdominal-aortic-aneurysm-screening. Accessed March 24, 2015.

3. US Preventive Services Task Force. Carotid artery stenosis: screening. US Preventive Services Task Force Web site. Available at: http://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/RecommendationStatementFinal/carotid-artery-stenosis-screening. Accessed March 24, 2015.

4. Campos-Outcalt D. Diet, exercise, and CVD: When counseling makes the most sense. J Fam Pract. 2014;63:458-460.

5. US Preventive Services Task Force. Chlamydia and gonorrhea screening. US Preventive Services Task Force Web site. Available at: http://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/RecommendationStatementFinal/chlamydia-and-gonorrhea-screening. Accessed March 24, 2015.

6. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2010 STD treatment guidelines. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Web site. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/std/treatment/2010/default.htm. Accessed March 24, 2015.

7. US Preventive Services Task Force. Sexually transmitted infections: behavioral counseling. US Preventive Services Task Force Web site. Available at: http://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/RecommendationStatementFinal/sexually-transmitted-infections-behavioral-counseling1. Accessed March 24, 2015.

8. US Preventive Services Task Force. Hepatitis B virus infection: screening, 2014. US Preventive Services Task Force Web site. Available at: http://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/RecommendationStatementFinal/hepatitis-bvirus-infection-screening-2014. Accessed March 24, 2015.

9. US Preventive Services Task Force. Dental caries in children from birth through age 5 years: screening. US Preventive Services Task Force Web site. Available at: http://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/RecommendationStatementFinal/dental-caries-in-children-from-birth-through-age-5-years-screening. Accessed March 24, 2015.

10. US Preventive Services Task Force. Gestational diabetes mellitus, screening. US Preventive Services Task Force Web site. Available at: http://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/RecommendationStatementFinal/gestational-diabetesmellitus-screening. Accessed March 24, 2015.

11. US Preventive Services Task Force. Low-dose aspirin use for the prevention of morbidity and mortality from preeclampsia: preventive medication. US Preventive Services Task Force Web site. Available at: http://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/RecommendationStatementFinal/low-dose-aspirin-use-for-the-prevention-of-morbidity-and-mortality-frompreeclampsia-preventive-medication. Accessed March 24, 2015.

In 2014, the United States Preventive Services Task Force released 24 recommendations on 14 topics.1 There were no level A recommendations, 10 B recommendations, 1 C recommendation, 3 D recommendations, and 10 I statements. A and B recommendations require that commercial insurance plans offer the recommended services at no cost to patients. This Practice Alert focuses on last year’s B and D recommendations (TABLE 11).

Cardiovascular disease

When to screen for abdominal aortic aneurism. The Task Force (TF) reaffirmed a previous B recommendation for a one-time abdominal ultrasound (US) screening for abdominal aortic aneurism (AAA) in men ages 65 to 75 years who have ever smoked. This screening and follow-up of abnormal findings results in decreased AAA rupture and AAA-related mortality, although it appears to have no effect on all-cause mortality.2 The value of screening men who have never smoked is very small and should be considered selectively for men who have a family history of AAA, or a personal history of cardiovascular risk factors or disease. The prevalence of AAA in men in the target age group is 6% to 7% (it is 0.8% for women overall in the same age range).2

The recommended screening modality, abdominal US, matches the sensitivity and specificity of abdominal CT but at lower cost and with no radiation exposure. Refer patients with AAAs ≥5.5 cm for surgical repair.2

Patients with smaller aneurysms (3.0 to 5.4 cm) can be managed conservatively with repeated US every 3 to 12 months. Patients with AAAs <3 cm that exhibit rapid growth (>1 cm/year) or that cross the threshold of 5.5 cm on repeated US should undergo surgical consultation.2

The TF also looked at the value of AAA screening for women in the same age group who have ever smoked, and it could not find enough evidence to make a recommendation. However, in women who have never smoked, the TF concluded that, largely due to the low prevalence of AAA, potential harms of screening outweigh its benefits.2

General screening for carotid artery stenosis is unhelpful. For asymptomatic adults, the TF gave a thumbs-down D recommendation on screening for carotid artery stenosis.3 Carotid artery screening is conducted with US, followed by, if findings indicate the need, confirmatory testing with angiography. US has reasonable sensitivity (90%) for finding the most significant lesions, but the specificity of 94% often leads to false-positive results that can bring about unnecessary surgery and serious harms, including death, stroke, and myocardial infarction. There is no evidence of any benefit from screening by auscultation of the neck.

The TF believes it is better to focus on primary prevention of stroke, including screening for hypertension and dyslipidemia, counseling on smoking cessation, encouraging healthful diet and physical activity, and recommending aspirin use for those at increased risk for cardiovascular disease.3

Focus on CVD prevention. For adults who are overweight or obese and have additional cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk factors, the TF recommends offering, or referring patients for, intensive behavioral counseling interventions to promote a healthy diet and increased physical activity. A previous Practice Alert discussed the rationale behind this selective intensive approach to CVD prevention, as well as the lack of endorsement of vitamins to prevent CVD or cancer.4

Sexually transmitted infections

When to screen for gonorrhea and chlamydia. The TF recommends screening for chlamydial and gonorrheal infections in all sexually active women ages 24 years and younger, and for women older than 24 years who are at high risk.5 The TF could not find adequate evidence to make a recommendation for or against screening men for either disease.

Risk is defined rather broadly to include having a new sex partner, more than one sex partner, or a sex partner with concurrent partners or a sexually transmitted infection (STI); inconsistent condom use among individuals who are not in mutually monogamous relationships; having a previous or coexisting STI; and exchanging sex for money or drugs. The TF also points out that physicians should know the prevalence of these infections in their community and be aware of particular groups that are at higher risk.

Chlamydia and gonorrhea are the most commonly reported STIs in the United States. In 2012, more than 1.4 million cases of chlamydial infection were reported to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).5 This is an underestimate of true prevalence because most infections are asymptomatic and not detected. The rate of chlamydial infection in females was 643.3 cases per 100,000 (more than twice that seen in males—262.6 cases per 100,000), with most infections occurring in females ages 15 to 24 years.5

In 2012, more than 330,000 cases of gonococcal infection were reported to the CDC. The rate of gonorrhea infection was similar for females and males (108.7 vs. 105.8 cases per 100,000, respectively), but while most infections in females occurred between the ages of 15 and 24 years, men most often affected were ages 20 to 24 years.5

Chlamydial and gonococcal infections can be diagnosed by nucleic acid amplification tests conducted on specimens collected in a number of ways: urine; endocervical, vaginal, and male urethral specimens; and self-collected vaginal specimens in clinical settings. Treatment recommendations for both infections can be found on the CDC STI treatment Web site.6

Intensive behavioral counseling as a means of preventing STIs is recommended for all sexually active adolescents and adults at elevated risk—ie, those with current STIs or infected within the past year, those who have multiple sex partners, and those who do not consistently use condoms.7

Intensive intervention ranges from 30 minutes to 2 hours or more of contact time. All counseling within this range is beneficial, with more time being more effective.7 These interventions can be delivered by primary care clinicians or behavioral counselors. The most successful approaches provide basic information about STIs (and STI transmission) and train patients in important skills, such as condom use, communication about safe sex, problem solving, and goal setting.

Hepatitis B screening: A change

The TF changed its previous position on screening for chronic hepatitis B virus (HBV) in those at high risk from an I statement to a B recommendation. Previously, the TF opposed screening of low-risk populations; the new recommendation is silent on this issue. Those at high risk for HBV include:8

• individuals born in countries and regions with a prevalence of HBV infection ≥2%

• US-born individuals not vaccinated as infants, whose parents are from regions with a very high prevalence of HBV infection (≥8%)—eg, sub-Saharan Africa or southeast or central Asia

• HIV-positive individuals

• injection drug users

• men who have sex with men

• household contacts or sexual partners of individuals with HBV infection.

Information on countries and regions with a high prevalence of HBV infection can be found at: www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/rr5708a1.htm.

The TF notes that approximately 700,000 to 2.2 million individuals in the United States have chronic HBV infection.8 However, HBV vaccine has been a recommended child vaccine for more than 20 years and the pool of those at risk shrinks annually.

Chronic HBV infection can lead to cirrhosis, hepatic failure, and hepatocellular carcinoma. An estimated 15% to 25% of individuals with chronic HBV infection die of cirrhosis or hepatocellular carcinoma.8 Those with chronic infection can also infect others. Screening for HBV infection could identify chronically infected people who may benefit from treatment and be counseled to prevent transmission.

In screening, test for hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg), which has a reported sensitivity and specificity of >98%.8 While the TF did not find direct evidence of screening benefits on mortality, it found convincing evidence that antiviral treatment in patients with chronic HBV infection improves intermediate outcomes (virologic or histologic improvement or clearance of hepatitis B e antigen [HBeAg]) and adequate evidence that antiviral regimens improve health outcomes (such as reduced risk for hepatocellular carcinoma).8

Prevention of tooth decay in kids

The TF recommends that primary care physicians implement 2 interventions to prevent tooth decay in infants and children: prescribing oral fluoride supplementation starting at age 6 months in areas where the local water supply is deficient in fluoride (defined as <0.6 ppm F); and periodically applying fluoride varnish to primary teeth starting at the age of tooth eruption through age 5 years. The TF emphasizes, however, that the most effective way to prevent dental decay in children is to maintain recommended levels of fluoride in community water supplies.9

Both recommended interventions are supported by good evidence, although no study directly assessed the appropriate ages at which to start and stop the application of fluoride varnish or the optimal frequency of applications. Most studies looked at children ages 3 to 5 years, but the TF believes that benefits are likely to begin at the time of primary tooth eruption.

Limited evidence found no clear difference in benefit between performing a single fluoride varnish once every 6 months vs once a year or between a single application every 6 months vs multiple applications once a year or every 6 months.9

Pregnancy

Screen for gestational diabetes. The previous TF statement on gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) found insufficient evidence to screen for this condition. The new recommendation advises screening starting at 24 weeks gestation using the 50-g oral glucose challenge test.10 Other screening options, such as the use of fasting plasma glucose testing or basing decisions to screen on risk factors, have not been studied as extensively. The USPSTF found inadequate evidence to compare the effectiveness of different screening tests or thresholds in determining positive screen results.

Treating those with GDM with diet, glucose monitoring, and insulin (if needed) can significantly reduce the risk of preeclampsia, fetal macrosomia, and shoulder dystocia, which, according to the TF, adds up to a moderate net benefit for both mother and infant. There is no evidence that treatment will improve long-term metabolic outcomes in women.

The TF found inadequate evidence to determine whether there are benefits to screening for GDM in women before 24 weeks of gestation.

Give low-dose aspirin to prevent preeclampsia. In a new recommendation, the TF endorses low-dose aspirin (81 mg/d) to reduce rates of preeclampsia, preterm birth, and intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR) in women at increased risk for preeclampsia—defined as those with kidney disease, diabetes (type 1 or 2), hypertension, autoimmune disease, a history of preeclampsia, or a current multifetal pregnancy.11

Aspirin should be started after 12 weeks and before 28 weeks of gestation, which has been shown to reduce the risk of preeclampsia by 24%, preterm birth by 14%, and IUGR by 20%.11 The number needed to treat to prevent one case of preeclampsia was 42; 71 for IUGR, and 65 for preterm birth.11 (For more on the evidence behind this recommendation, see “Another good reason to recommend lowdose aspirin” on page 301.)

TABLE 211 lists risk factors for preeclampsia and recommendations for those in high-, moderate-, and low-risk groups.

Screenings/interventions with insufficient supporting evidence

Three conditions that cause significant morbidity or mortality were looked at by the TF last year, and insufficient evidence was found to make a recommendation—screening for cognitive impairment (early Alzheimer’s); primary care interventions to prevent or reduce illicit drug or nonmedical pharmaceutical use in children and adolescents; and screening for suicide risk in adolescents, adults, and older adults in primary care. In addition, no evidence could be found for the benefit of screening for vitamin D deficiency in adults.

In 2014, the United States Preventive Services Task Force released 24 recommendations on 14 topics.1 There were no level A recommendations, 10 B recommendations, 1 C recommendation, 3 D recommendations, and 10 I statements. A and B recommendations require that commercial insurance plans offer the recommended services at no cost to patients. This Practice Alert focuses on last year’s B and D recommendations (TABLE 11).

Cardiovascular disease

When to screen for abdominal aortic aneurism. The Task Force (TF) reaffirmed a previous B recommendation for a one-time abdominal ultrasound (US) screening for abdominal aortic aneurism (AAA) in men ages 65 to 75 years who have ever smoked. This screening and follow-up of abnormal findings results in decreased AAA rupture and AAA-related mortality, although it appears to have no effect on all-cause mortality.2 The value of screening men who have never smoked is very small and should be considered selectively for men who have a family history of AAA, or a personal history of cardiovascular risk factors or disease. The prevalence of AAA in men in the target age group is 6% to 7% (it is 0.8% for women overall in the same age range).2

The recommended screening modality, abdominal US, matches the sensitivity and specificity of abdominal CT but at lower cost and with no radiation exposure. Refer patients with AAAs ≥5.5 cm for surgical repair.2

Patients with smaller aneurysms (3.0 to 5.4 cm) can be managed conservatively with repeated US every 3 to 12 months. Patients with AAAs <3 cm that exhibit rapid growth (>1 cm/year) or that cross the threshold of 5.5 cm on repeated US should undergo surgical consultation.2

The TF also looked at the value of AAA screening for women in the same age group who have ever smoked, and it could not find enough evidence to make a recommendation. However, in women who have never smoked, the TF concluded that, largely due to the low prevalence of AAA, potential harms of screening outweigh its benefits.2

General screening for carotid artery stenosis is unhelpful. For asymptomatic adults, the TF gave a thumbs-down D recommendation on screening for carotid artery stenosis.3 Carotid artery screening is conducted with US, followed by, if findings indicate the need, confirmatory testing with angiography. US has reasonable sensitivity (90%) for finding the most significant lesions, but the specificity of 94% often leads to false-positive results that can bring about unnecessary surgery and serious harms, including death, stroke, and myocardial infarction. There is no evidence of any benefit from screening by auscultation of the neck.

The TF believes it is better to focus on primary prevention of stroke, including screening for hypertension and dyslipidemia, counseling on smoking cessation, encouraging healthful diet and physical activity, and recommending aspirin use for those at increased risk for cardiovascular disease.3

Focus on CVD prevention. For adults who are overweight or obese and have additional cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk factors, the TF recommends offering, or referring patients for, intensive behavioral counseling interventions to promote a healthy diet and increased physical activity. A previous Practice Alert discussed the rationale behind this selective intensive approach to CVD prevention, as well as the lack of endorsement of vitamins to prevent CVD or cancer.4

Sexually transmitted infections

When to screen for gonorrhea and chlamydia. The TF recommends screening for chlamydial and gonorrheal infections in all sexually active women ages 24 years and younger, and for women older than 24 years who are at high risk.5 The TF could not find adequate evidence to make a recommendation for or against screening men for either disease.

Risk is defined rather broadly to include having a new sex partner, more than one sex partner, or a sex partner with concurrent partners or a sexually transmitted infection (STI); inconsistent condom use among individuals who are not in mutually monogamous relationships; having a previous or coexisting STI; and exchanging sex for money or drugs. The TF also points out that physicians should know the prevalence of these infections in their community and be aware of particular groups that are at higher risk.

Chlamydia and gonorrhea are the most commonly reported STIs in the United States. In 2012, more than 1.4 million cases of chlamydial infection were reported to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).5 This is an underestimate of true prevalence because most infections are asymptomatic and not detected. The rate of chlamydial infection in females was 643.3 cases per 100,000 (more than twice that seen in males—262.6 cases per 100,000), with most infections occurring in females ages 15 to 24 years.5

In 2012, more than 330,000 cases of gonococcal infection were reported to the CDC. The rate of gonorrhea infection was similar for females and males (108.7 vs. 105.8 cases per 100,000, respectively), but while most infections in females occurred between the ages of 15 and 24 years, men most often affected were ages 20 to 24 years.5

Chlamydial and gonococcal infections can be diagnosed by nucleic acid amplification tests conducted on specimens collected in a number of ways: urine; endocervical, vaginal, and male urethral specimens; and self-collected vaginal specimens in clinical settings. Treatment recommendations for both infections can be found on the CDC STI treatment Web site.6

Intensive behavioral counseling as a means of preventing STIs is recommended for all sexually active adolescents and adults at elevated risk—ie, those with current STIs or infected within the past year, those who have multiple sex partners, and those who do not consistently use condoms.7

Intensive intervention ranges from 30 minutes to 2 hours or more of contact time. All counseling within this range is beneficial, with more time being more effective.7 These interventions can be delivered by primary care clinicians or behavioral counselors. The most successful approaches provide basic information about STIs (and STI transmission) and train patients in important skills, such as condom use, communication about safe sex, problem solving, and goal setting.

Hepatitis B screening: A change

The TF changed its previous position on screening for chronic hepatitis B virus (HBV) in those at high risk from an I statement to a B recommendation. Previously, the TF opposed screening of low-risk populations; the new recommendation is silent on this issue. Those at high risk for HBV include:8

• individuals born in countries and regions with a prevalence of HBV infection ≥2%

• US-born individuals not vaccinated as infants, whose parents are from regions with a very high prevalence of HBV infection (≥8%)—eg, sub-Saharan Africa or southeast or central Asia

• HIV-positive individuals

• injection drug users

• men who have sex with men

• household contacts or sexual partners of individuals with HBV infection.

Information on countries and regions with a high prevalence of HBV infection can be found at: www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/rr5708a1.htm.

The TF notes that approximately 700,000 to 2.2 million individuals in the United States have chronic HBV infection.8 However, HBV vaccine has been a recommended child vaccine for more than 20 years and the pool of those at risk shrinks annually.

Chronic HBV infection can lead to cirrhosis, hepatic failure, and hepatocellular carcinoma. An estimated 15% to 25% of individuals with chronic HBV infection die of cirrhosis or hepatocellular carcinoma.8 Those with chronic infection can also infect others. Screening for HBV infection could identify chronically infected people who may benefit from treatment and be counseled to prevent transmission.

In screening, test for hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg), which has a reported sensitivity and specificity of >98%.8 While the TF did not find direct evidence of screening benefits on mortality, it found convincing evidence that antiviral treatment in patients with chronic HBV infection improves intermediate outcomes (virologic or histologic improvement or clearance of hepatitis B e antigen [HBeAg]) and adequate evidence that antiviral regimens improve health outcomes (such as reduced risk for hepatocellular carcinoma).8

Prevention of tooth decay in kids

The TF recommends that primary care physicians implement 2 interventions to prevent tooth decay in infants and children: prescribing oral fluoride supplementation starting at age 6 months in areas where the local water supply is deficient in fluoride (defined as <0.6 ppm F); and periodically applying fluoride varnish to primary teeth starting at the age of tooth eruption through age 5 years. The TF emphasizes, however, that the most effective way to prevent dental decay in children is to maintain recommended levels of fluoride in community water supplies.9

Both recommended interventions are supported by good evidence, although no study directly assessed the appropriate ages at which to start and stop the application of fluoride varnish or the optimal frequency of applications. Most studies looked at children ages 3 to 5 years, but the TF believes that benefits are likely to begin at the time of primary tooth eruption.

Limited evidence found no clear difference in benefit between performing a single fluoride varnish once every 6 months vs once a year or between a single application every 6 months vs multiple applications once a year or every 6 months.9

Pregnancy

Screen for gestational diabetes. The previous TF statement on gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) found insufficient evidence to screen for this condition. The new recommendation advises screening starting at 24 weeks gestation using the 50-g oral glucose challenge test.10 Other screening options, such as the use of fasting plasma glucose testing or basing decisions to screen on risk factors, have not been studied as extensively. The USPSTF found inadequate evidence to compare the effectiveness of different screening tests or thresholds in determining positive screen results.

Treating those with GDM with diet, glucose monitoring, and insulin (if needed) can significantly reduce the risk of preeclampsia, fetal macrosomia, and shoulder dystocia, which, according to the TF, adds up to a moderate net benefit for both mother and infant. There is no evidence that treatment will improve long-term metabolic outcomes in women.

The TF found inadequate evidence to determine whether there are benefits to screening for GDM in women before 24 weeks of gestation.

Give low-dose aspirin to prevent preeclampsia. In a new recommendation, the TF endorses low-dose aspirin (81 mg/d) to reduce rates of preeclampsia, preterm birth, and intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR) in women at increased risk for preeclampsia—defined as those with kidney disease, diabetes (type 1 or 2), hypertension, autoimmune disease, a history of preeclampsia, or a current multifetal pregnancy.11

Aspirin should be started after 12 weeks and before 28 weeks of gestation, which has been shown to reduce the risk of preeclampsia by 24%, preterm birth by 14%, and IUGR by 20%.11 The number needed to treat to prevent one case of preeclampsia was 42; 71 for IUGR, and 65 for preterm birth.11 (For more on the evidence behind this recommendation, see “Another good reason to recommend lowdose aspirin” on page 301.)

TABLE 211 lists risk factors for preeclampsia and recommendations for those in high-, moderate-, and low-risk groups.

Screenings/interventions with insufficient supporting evidence

Three conditions that cause significant morbidity or mortality were looked at by the TF last year, and insufficient evidence was found to make a recommendation—screening for cognitive impairment (early Alzheimer’s); primary care interventions to prevent or reduce illicit drug or nonmedical pharmaceutical use in children and adolescents; and screening for suicide risk in adolescents, adults, and older adults in primary care. In addition, no evidence could be found for the benefit of screening for vitamin D deficiency in adults.

1. US Preventive Services Task Force. Published recommendations. US Preventive Services Task Force Web site. Available at: http://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/BrowseRec/Index. Accessed March 24, 2015.

2. US Preventive Services Task Force. Abdominal aortic aneurism: screening. US Preventive Services Task Force Web site. Available at: http://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/RecommendationStatementFinal/abdominal-aortic-aneurysm-screening. Accessed March 24, 2015.

3. US Preventive Services Task Force. Carotid artery stenosis: screening. US Preventive Services Task Force Web site. Available at: http://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/RecommendationStatementFinal/carotid-artery-stenosis-screening. Accessed March 24, 2015.

4. Campos-Outcalt D. Diet, exercise, and CVD: When counseling makes the most sense. J Fam Pract. 2014;63:458-460.

5. US Preventive Services Task Force. Chlamydia and gonorrhea screening. US Preventive Services Task Force Web site. Available at: http://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/RecommendationStatementFinal/chlamydia-and-gonorrhea-screening. Accessed March 24, 2015.

6. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2010 STD treatment guidelines. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Web site. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/std/treatment/2010/default.htm. Accessed March 24, 2015.

7. US Preventive Services Task Force. Sexually transmitted infections: behavioral counseling. US Preventive Services Task Force Web site. Available at: http://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/RecommendationStatementFinal/sexually-transmitted-infections-behavioral-counseling1. Accessed March 24, 2015.

8. US Preventive Services Task Force. Hepatitis B virus infection: screening, 2014. US Preventive Services Task Force Web site. Available at: http://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/RecommendationStatementFinal/hepatitis-bvirus-infection-screening-2014. Accessed March 24, 2015.

9. US Preventive Services Task Force. Dental caries in children from birth through age 5 years: screening. US Preventive Services Task Force Web site. Available at: http://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/RecommendationStatementFinal/dental-caries-in-children-from-birth-through-age-5-years-screening. Accessed March 24, 2015.

10. US Preventive Services Task Force. Gestational diabetes mellitus, screening. US Preventive Services Task Force Web site. Available at: http://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/RecommendationStatementFinal/gestational-diabetesmellitus-screening. Accessed March 24, 2015.

11. US Preventive Services Task Force. Low-dose aspirin use for the prevention of morbidity and mortality from preeclampsia: preventive medication. US Preventive Services Task Force Web site. Available at: http://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/RecommendationStatementFinal/low-dose-aspirin-use-for-the-prevention-of-morbidity-and-mortality-frompreeclampsia-preventive-medication. Accessed March 24, 2015.

1. US Preventive Services Task Force. Published recommendations. US Preventive Services Task Force Web site. Available at: http://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/BrowseRec/Index. Accessed March 24, 2015.

2. US Preventive Services Task Force. Abdominal aortic aneurism: screening. US Preventive Services Task Force Web site. Available at: http://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/RecommendationStatementFinal/abdominal-aortic-aneurysm-screening. Accessed March 24, 2015.

3. US Preventive Services Task Force. Carotid artery stenosis: screening. US Preventive Services Task Force Web site. Available at: http://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/RecommendationStatementFinal/carotid-artery-stenosis-screening. Accessed March 24, 2015.

4. Campos-Outcalt D. Diet, exercise, and CVD: When counseling makes the most sense. J Fam Pract. 2014;63:458-460.

5. US Preventive Services Task Force. Chlamydia and gonorrhea screening. US Preventive Services Task Force Web site. Available at: http://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/RecommendationStatementFinal/chlamydia-and-gonorrhea-screening. Accessed March 24, 2015.

6. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2010 STD treatment guidelines. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Web site. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/std/treatment/2010/default.htm. Accessed March 24, 2015.

7. US Preventive Services Task Force. Sexually transmitted infections: behavioral counseling. US Preventive Services Task Force Web site. Available at: http://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/RecommendationStatementFinal/sexually-transmitted-infections-behavioral-counseling1. Accessed March 24, 2015.

8. US Preventive Services Task Force. Hepatitis B virus infection: screening, 2014. US Preventive Services Task Force Web site. Available at: http://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/RecommendationStatementFinal/hepatitis-bvirus-infection-screening-2014. Accessed March 24, 2015.

9. US Preventive Services Task Force. Dental caries in children from birth through age 5 years: screening. US Preventive Services Task Force Web site. Available at: http://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/RecommendationStatementFinal/dental-caries-in-children-from-birth-through-age-5-years-screening. Accessed March 24, 2015.

10. US Preventive Services Task Force. Gestational diabetes mellitus, screening. US Preventive Services Task Force Web site. Available at: http://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/RecommendationStatementFinal/gestational-diabetesmellitus-screening. Accessed March 24, 2015.

11. US Preventive Services Task Force. Low-dose aspirin use for the prevention of morbidity and mortality from preeclampsia: preventive medication. US Preventive Services Task Force Web site. Available at: http://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/RecommendationStatementFinal/low-dose-aspirin-use-for-the-prevention-of-morbidity-and-mortality-frompreeclampsia-preventive-medication. Accessed March 24, 2015.

Epithelial Ovarian Cancer: Management of Advanced Disease

Edited by: Arthur T. Skarin, MD, FACP, FCCP

Epithelial ovarian cancer is the fifth leading cause of cancer death among women in the United States. Most women with ovarian cancer present at an advanced stage (International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics stage III), for which the standard treatment remains cytoreductive surgery followed by platinum- and taxane-based combination chemotherapy. Although this treatment frequently is curative for patients with early-stage disease, more than 60% of women with advanced disease will develop recurrent disease with progressively shorter disease-free intervals. However, there are many clinical trials in progress that are aimed at refining current therapy and evaluating different approaches to postoperative therapy, with the goal of improving prognosis and quality of life.

To read the full article in PDF:

Edited by: Arthur T. Skarin, MD, FACP, FCCP

Epithelial ovarian cancer is the fifth leading cause of cancer death among women in the United States. Most women with ovarian cancer present at an advanced stage (International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics stage III), for which the standard treatment remains cytoreductive surgery followed by platinum- and taxane-based combination chemotherapy. Although this treatment frequently is curative for patients with early-stage disease, more than 60% of women with advanced disease will develop recurrent disease with progressively shorter disease-free intervals. However, there are many clinical trials in progress that are aimed at refining current therapy and evaluating different approaches to postoperative therapy, with the goal of improving prognosis and quality of life.

To read the full article in PDF:

Edited by: Arthur T. Skarin, MD, FACP, FCCP

Epithelial ovarian cancer is the fifth leading cause of cancer death among women in the United States. Most women with ovarian cancer present at an advanced stage (International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics stage III), for which the standard treatment remains cytoreductive surgery followed by platinum- and taxane-based combination chemotherapy. Although this treatment frequently is curative for patients with early-stage disease, more than 60% of women with advanced disease will develop recurrent disease with progressively shorter disease-free intervals. However, there are many clinical trials in progress that are aimed at refining current therapy and evaluating different approaches to postoperative therapy, with the goal of improving prognosis and quality of life.

To read the full article in PDF:

Mind the Gap: Case Study in Toxicology

Case

An 8-month-old boy with a history of hypotonia, developmental delay, and seizure disorder refractory to multiple anticonvulsant medications, was presented to the ED with a 2-week history of intermittent fever and poor oral intake. His current medications included sodium bromide 185 mg orally twice daily for his seizure disorder.

On physical examination, the boy appeared small for his age, with diffuse hypotonia and diminished reflexes. He was able to track with his eyes but was otherwise unresponsive. No rash was present. Results of initial laboratory studies were: sodium 144 mEq/L; potassium, 4.8 mEq/L; chloride, 179 mEq/L; bicarbonate, 21 mEq/L; blood urea nitrogen, 6 mg/dL; creatinine, 0.1 mg/dL; and glucose, 63 mg/dL. His anion gap (AG) was −56.

What does the anion gap represent?

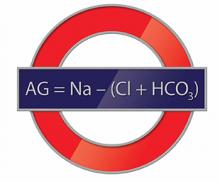

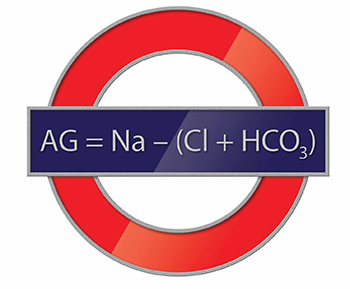

The AG is a valuable clinical calculation derived from the measured extracellular electrolytes and provides an index of acid-base status.1 Due to the necessity of electroneutrality, the sum of positive charges (cations) in the extracellular fluid must be balanced exactly with the sum of negative charges (anions). However, to routinely measure all of the cations and anions in the serum would be time-consuming and is also unnecessary. Because most clinical laboratories commonly only measure one relevant cation (sodium) and two anions (chloride and bicarbonate), the positive and negative sums are not completely balanced. The AG therefore refers to this difference (ie, AG = Na – [Cl + HCO3]).

Of course, electroneutrality exists in vivo, and is accomplished by the presence of unmeasured anions (UA) (eg, lactate and phosphate) and unmeasured cations (UC) (eg, potassium and calcium) not accounted for in the AG (ie, AG = UA – UC). In other words, the sum of measured plus the unmeasured anions must equal the sum of the measured plus unmeasured cations.

What causes a low or negative anion gap?

While most healthcare providers are well versed in the clinical significance of an elevated AG (eg, MUDPILES [methanol, uremia, diabetic ketoacidosis, propylene glycol or phenformin, iron or isoniazid, lactate, ethylene glycol, salicylates]), the meaning of a low or negative AG is underappreciated. There are several scenarios that could potentially yield a low or negative AG, including decreased concentration of UA, increased concentrations of nonsodium cations (UC), and overestimation of serum chloride.

Decreased Concentration of Unmeasured Anions. This most commonly occurs by two mechanisms: dilution of the extracellular fluid or hypoalbuminemia. The addition of water to the extracellular fluid will cause a proportionate dilution of all the measured electrolytes. Since the concentration of measured cations is higher than the measured anions, there is a small and relatively insignificant decrease in the AG.

Alternatively, hypoalbuminemia results in a low AG due to the change in UA; albumin is negatively charged. At physiologic pH, the overwhelming majority of serum proteins are anionic and counter-balanced by the positive charge of sodium. Albumin, the most abundant serum protein, accounts for approximately 75% of the normal AG. Hypoalbuminemic states, such as cirrhosis or nephrotic syndrome, can therefore cause low AG due to the retention of chloride to replace the lost negative charge. The albumin concentration can be corrected to calculate the AG.2

Nonsodium Cations. There are a number of clinical conditions that result in the retention of nonsodium cations. For example, the excess positively charged paraproteins associated with IgG myeloma raise the UC concentration, resulting in a low AG. Similarly, elevations of unmeasured cationic electrolytes, such as calcium and magnesium, may also result in a lower AG. Significant changes in AG, though, are caused only by profound (and often life-threatening) hypercalcemia or hypermagnesemia.

Overestimation of Serum Chloride. Overestimation of serum chloride most commonly occurs in the clinical scenario of bromide exposure. In normal physiologic conditions, chloride is the only halide present in the extracellular fluid. With intake of brominated products, chloride may be partially replaced by bromide. As there is greater renal tubular avidity for bromide, chronic ingestion of bromide results in a gradual rise in serum bromide concentrations with a proportional fall in chloride. However, and more importantly, bromide interferes with a number of laboratory techniques measuring chloride concentrations, resulting in a spuriously elevated chloride, or pseudohyperchloremia. Because the measured sodium and bicarbonate concentrations will remain unchanged, this falsely elevated chloride measurement will result in a negative AG.

What causes the falsely elevated chloride?

All of the current laboratory techniques for measurement of serum chloride concentration can potentially result in a falsely elevated value. However, the degree of pseudohyperchloremia will depend on the specific assay used for measurement. The ion-selective electrode method used by many common laboratory analyzers appears to have the greatest interference on chloride measurement in the presence of bromide. This is simply due to the molecular similarity of bromide and chloride. Conversely, the coulometry method, often used as a reference standard, has the least interference of current laboratory methods.3 This is because coulometry does not completely rely on molecular structure to measure concentration, but rather it measures the amount of energy produced or consumed in an electrolysis reaction. Iodide, another halide compound, has also been described as a cause of pseudohyperchloremia, whereas fluoride does not seem to have significant interference.4

How are patients exposed to bromide salts?

Bromide salts, specifically sodium bromide, are infrequently used to treat seizure disorders, but are generally reserved for patients with epilepsy refractory to other, less toxic anticonvulsant medications. During the era when bromide salts were more commonly used to treat epilepsy, bromide intoxication, or bromism, was frequently observed.

Bromism may manifest as a constellation of nonspecific neurological and psychiatric symptoms. These most commonly include headache, weakness, agitation, confusion, and hallucinations. In more severe cases of bromism, stupor and coma may occur.3,5

Although bromide salts are no longer commonly prescribed, a number of products still contain brominated ingredients. Symptoms of bromide intoxication can occur with chronic use of a cough syrup containing dextromethorphan hydrobromide as well as the brominated vegetable oils found in some soft drinks.5

How is bromism treated?

The treatment of bromism involves preventing further exposure to bromide and promoting bromide excretion. Bromide has a long half-life (10-12 days), and in patients with normal renal function, it is possible to reduce this half-life to approximately 3 days with hydration and diuresis with sodium chloride.3 Alternatively, in patients with impaired renal function or severe intoxication, hemodialysis has been used effectively.5

Case Conclusion

The patient was admitted for observation and treated with intravenous sodium chloride. After consultation with his neurologist, he was discharged home in the care of his parents, who were advised to continue him on sodium bromide 185 mg orally twice daily since his seizures were refractory to other anticonvulsant medications.

Dr Repplinger is a medical toxicology fellow in the department of emergency medicine at New York University Langone Medical Center. Dr Nelson, editor of “Case Studies in Toxicology,” is a professor in the department of emergency medicine and director of the medical toxicology fellowship program at the New York University School of Medicine and the New York City Poison Control Center. He is also associate editor, toxicology, of the EMERGENCY MEDICINE editorial board.

- Emmett M, Narins RG. Clinical use of the anion gap. Medicine (Baltimore). 1977;56(1):38-54.

- Figge J, Jabor A, Kazda A, Fencl V. Anion gap and hypoalbuminemia. Crit Care Med. 1998;26(11):1807-1810.

- Vasuyattakul S, Lertpattanasuwan N, Vareesangthip K, Nimmannit S, Nilwarangkur S. A negative aniongap as a clue to diagnose bromide intoxication.Nephron. 1995;69(3):311-313.

- Yamamoto K, Kobayashi H, Kobayashi T, MurakamiS. False hyperchloremia in bromism. J Anesth.1991;5(1):88-91.

- Ng YY, Lin WL, Chen TW. Spurious hyperchloremiaand decreased anion gap in a patient with dextromethorphan bromide. Am J Nephrol. 1992;12(4):268-270.

Case

An 8-month-old boy with a history of hypotonia, developmental delay, and seizure disorder refractory to multiple anticonvulsant medications, was presented to the ED with a 2-week history of intermittent fever and poor oral intake. His current medications included sodium bromide 185 mg orally twice daily for his seizure disorder.

On physical examination, the boy appeared small for his age, with diffuse hypotonia and diminished reflexes. He was able to track with his eyes but was otherwise unresponsive. No rash was present. Results of initial laboratory studies were: sodium 144 mEq/L; potassium, 4.8 mEq/L; chloride, 179 mEq/L; bicarbonate, 21 mEq/L; blood urea nitrogen, 6 mg/dL; creatinine, 0.1 mg/dL; and glucose, 63 mg/dL. His anion gap (AG) was −56.

What does the anion gap represent?

The AG is a valuable clinical calculation derived from the measured extracellular electrolytes and provides an index of acid-base status.1 Due to the necessity of electroneutrality, the sum of positive charges (cations) in the extracellular fluid must be balanced exactly with the sum of negative charges (anions). However, to routinely measure all of the cations and anions in the serum would be time-consuming and is also unnecessary. Because most clinical laboratories commonly only measure one relevant cation (sodium) and two anions (chloride and bicarbonate), the positive and negative sums are not completely balanced. The AG therefore refers to this difference (ie, AG = Na – [Cl + HCO3]).

Of course, electroneutrality exists in vivo, and is accomplished by the presence of unmeasured anions (UA) (eg, lactate and phosphate) and unmeasured cations (UC) (eg, potassium and calcium) not accounted for in the AG (ie, AG = UA – UC). In other words, the sum of measured plus the unmeasured anions must equal the sum of the measured plus unmeasured cations.

What causes a low or negative anion gap?

While most healthcare providers are well versed in the clinical significance of an elevated AG (eg, MUDPILES [methanol, uremia, diabetic ketoacidosis, propylene glycol or phenformin, iron or isoniazid, lactate, ethylene glycol, salicylates]), the meaning of a low or negative AG is underappreciated. There are several scenarios that could potentially yield a low or negative AG, including decreased concentration of UA, increased concentrations of nonsodium cations (UC), and overestimation of serum chloride.

Decreased Concentration of Unmeasured Anions. This most commonly occurs by two mechanisms: dilution of the extracellular fluid or hypoalbuminemia. The addition of water to the extracellular fluid will cause a proportionate dilution of all the measured electrolytes. Since the concentration of measured cations is higher than the measured anions, there is a small and relatively insignificant decrease in the AG.

Alternatively, hypoalbuminemia results in a low AG due to the change in UA; albumin is negatively charged. At physiologic pH, the overwhelming majority of serum proteins are anionic and counter-balanced by the positive charge of sodium. Albumin, the most abundant serum protein, accounts for approximately 75% of the normal AG. Hypoalbuminemic states, such as cirrhosis or nephrotic syndrome, can therefore cause low AG due to the retention of chloride to replace the lost negative charge. The albumin concentration can be corrected to calculate the AG.2

Nonsodium Cations. There are a number of clinical conditions that result in the retention of nonsodium cations. For example, the excess positively charged paraproteins associated with IgG myeloma raise the UC concentration, resulting in a low AG. Similarly, elevations of unmeasured cationic electrolytes, such as calcium and magnesium, may also result in a lower AG. Significant changes in AG, though, are caused only by profound (and often life-threatening) hypercalcemia or hypermagnesemia.

Overestimation of Serum Chloride. Overestimation of serum chloride most commonly occurs in the clinical scenario of bromide exposure. In normal physiologic conditions, chloride is the only halide present in the extracellular fluid. With intake of brominated products, chloride may be partially replaced by bromide. As there is greater renal tubular avidity for bromide, chronic ingestion of bromide results in a gradual rise in serum bromide concentrations with a proportional fall in chloride. However, and more importantly, bromide interferes with a number of laboratory techniques measuring chloride concentrations, resulting in a spuriously elevated chloride, or pseudohyperchloremia. Because the measured sodium and bicarbonate concentrations will remain unchanged, this falsely elevated chloride measurement will result in a negative AG.

What causes the falsely elevated chloride?

All of the current laboratory techniques for measurement of serum chloride concentration can potentially result in a falsely elevated value. However, the degree of pseudohyperchloremia will depend on the specific assay used for measurement. The ion-selective electrode method used by many common laboratory analyzers appears to have the greatest interference on chloride measurement in the presence of bromide. This is simply due to the molecular similarity of bromide and chloride. Conversely, the coulometry method, often used as a reference standard, has the least interference of current laboratory methods.3 This is because coulometry does not completely rely on molecular structure to measure concentration, but rather it measures the amount of energy produced or consumed in an electrolysis reaction. Iodide, another halide compound, has also been described as a cause of pseudohyperchloremia, whereas fluoride does not seem to have significant interference.4

How are patients exposed to bromide salts?

Bromide salts, specifically sodium bromide, are infrequently used to treat seizure disorders, but are generally reserved for patients with epilepsy refractory to other, less toxic anticonvulsant medications. During the era when bromide salts were more commonly used to treat epilepsy, bromide intoxication, or bromism, was frequently observed.

Bromism may manifest as a constellation of nonspecific neurological and psychiatric symptoms. These most commonly include headache, weakness, agitation, confusion, and hallucinations. In more severe cases of bromism, stupor and coma may occur.3,5

Although bromide salts are no longer commonly prescribed, a number of products still contain brominated ingredients. Symptoms of bromide intoxication can occur with chronic use of a cough syrup containing dextromethorphan hydrobromide as well as the brominated vegetable oils found in some soft drinks.5

How is bromism treated?

The treatment of bromism involves preventing further exposure to bromide and promoting bromide excretion. Bromide has a long half-life (10-12 days), and in patients with normal renal function, it is possible to reduce this half-life to approximately 3 days with hydration and diuresis with sodium chloride.3 Alternatively, in patients with impaired renal function or severe intoxication, hemodialysis has been used effectively.5

Case Conclusion

The patient was admitted for observation and treated with intravenous sodium chloride. After consultation with his neurologist, he was discharged home in the care of his parents, who were advised to continue him on sodium bromide 185 mg orally twice daily since his seizures were refractory to other anticonvulsant medications.

Dr Repplinger is a medical toxicology fellow in the department of emergency medicine at New York University Langone Medical Center. Dr Nelson, editor of “Case Studies in Toxicology,” is a professor in the department of emergency medicine and director of the medical toxicology fellowship program at the New York University School of Medicine and the New York City Poison Control Center. He is also associate editor, toxicology, of the EMERGENCY MEDICINE editorial board.

Case

An 8-month-old boy with a history of hypotonia, developmental delay, and seizure disorder refractory to multiple anticonvulsant medications, was presented to the ED with a 2-week history of intermittent fever and poor oral intake. His current medications included sodium bromide 185 mg orally twice daily for his seizure disorder.

On physical examination, the boy appeared small for his age, with diffuse hypotonia and diminished reflexes. He was able to track with his eyes but was otherwise unresponsive. No rash was present. Results of initial laboratory studies were: sodium 144 mEq/L; potassium, 4.8 mEq/L; chloride, 179 mEq/L; bicarbonate, 21 mEq/L; blood urea nitrogen, 6 mg/dL; creatinine, 0.1 mg/dL; and glucose, 63 mg/dL. His anion gap (AG) was −56.

What does the anion gap represent?

The AG is a valuable clinical calculation derived from the measured extracellular electrolytes and provides an index of acid-base status.1 Due to the necessity of electroneutrality, the sum of positive charges (cations) in the extracellular fluid must be balanced exactly with the sum of negative charges (anions). However, to routinely measure all of the cations and anions in the serum would be time-consuming and is also unnecessary. Because most clinical laboratories commonly only measure one relevant cation (sodium) and two anions (chloride and bicarbonate), the positive and negative sums are not completely balanced. The AG therefore refers to this difference (ie, AG = Na – [Cl + HCO3]).

Of course, electroneutrality exists in vivo, and is accomplished by the presence of unmeasured anions (UA) (eg, lactate and phosphate) and unmeasured cations (UC) (eg, potassium and calcium) not accounted for in the AG (ie, AG = UA – UC). In other words, the sum of measured plus the unmeasured anions must equal the sum of the measured plus unmeasured cations.

What causes a low or negative anion gap?

While most healthcare providers are well versed in the clinical significance of an elevated AG (eg, MUDPILES [methanol, uremia, diabetic ketoacidosis, propylene glycol or phenformin, iron or isoniazid, lactate, ethylene glycol, salicylates]), the meaning of a low or negative AG is underappreciated. There are several scenarios that could potentially yield a low or negative AG, including decreased concentration of UA, increased concentrations of nonsodium cations (UC), and overestimation of serum chloride.

Decreased Concentration of Unmeasured Anions. This most commonly occurs by two mechanisms: dilution of the extracellular fluid or hypoalbuminemia. The addition of water to the extracellular fluid will cause a proportionate dilution of all the measured electrolytes. Since the concentration of measured cations is higher than the measured anions, there is a small and relatively insignificant decrease in the AG.

Alternatively, hypoalbuminemia results in a low AG due to the change in UA; albumin is negatively charged. At physiologic pH, the overwhelming majority of serum proteins are anionic and counter-balanced by the positive charge of sodium. Albumin, the most abundant serum protein, accounts for approximately 75% of the normal AG. Hypoalbuminemic states, such as cirrhosis or nephrotic syndrome, can therefore cause low AG due to the retention of chloride to replace the lost negative charge. The albumin concentration can be corrected to calculate the AG.2

Nonsodium Cations. There are a number of clinical conditions that result in the retention of nonsodium cations. For example, the excess positively charged paraproteins associated with IgG myeloma raise the UC concentration, resulting in a low AG. Similarly, elevations of unmeasured cationic electrolytes, such as calcium and magnesium, may also result in a lower AG. Significant changes in AG, though, are caused only by profound (and often life-threatening) hypercalcemia or hypermagnesemia.

Overestimation of Serum Chloride. Overestimation of serum chloride most commonly occurs in the clinical scenario of bromide exposure. In normal physiologic conditions, chloride is the only halide present in the extracellular fluid. With intake of brominated products, chloride may be partially replaced by bromide. As there is greater renal tubular avidity for bromide, chronic ingestion of bromide results in a gradual rise in serum bromide concentrations with a proportional fall in chloride. However, and more importantly, bromide interferes with a number of laboratory techniques measuring chloride concentrations, resulting in a spuriously elevated chloride, or pseudohyperchloremia. Because the measured sodium and bicarbonate concentrations will remain unchanged, this falsely elevated chloride measurement will result in a negative AG.

What causes the falsely elevated chloride?

All of the current laboratory techniques for measurement of serum chloride concentration can potentially result in a falsely elevated value. However, the degree of pseudohyperchloremia will depend on the specific assay used for measurement. The ion-selective electrode method used by many common laboratory analyzers appears to have the greatest interference on chloride measurement in the presence of bromide. This is simply due to the molecular similarity of bromide and chloride. Conversely, the coulometry method, often used as a reference standard, has the least interference of current laboratory methods.3 This is because coulometry does not completely rely on molecular structure to measure concentration, but rather it measures the amount of energy produced or consumed in an electrolysis reaction. Iodide, another halide compound, has also been described as a cause of pseudohyperchloremia, whereas fluoride does not seem to have significant interference.4

How are patients exposed to bromide salts?

Bromide salts, specifically sodium bromide, are infrequently used to treat seizure disorders, but are generally reserved for patients with epilepsy refractory to other, less toxic anticonvulsant medications. During the era when bromide salts were more commonly used to treat epilepsy, bromide intoxication, or bromism, was frequently observed.

Bromism may manifest as a constellation of nonspecific neurological and psychiatric symptoms. These most commonly include headache, weakness, agitation, confusion, and hallucinations. In more severe cases of bromism, stupor and coma may occur.3,5

Although bromide salts are no longer commonly prescribed, a number of products still contain brominated ingredients. Symptoms of bromide intoxication can occur with chronic use of a cough syrup containing dextromethorphan hydrobromide as well as the brominated vegetable oils found in some soft drinks.5

How is bromism treated?

The treatment of bromism involves preventing further exposure to bromide and promoting bromide excretion. Bromide has a long half-life (10-12 days), and in patients with normal renal function, it is possible to reduce this half-life to approximately 3 days with hydration and diuresis with sodium chloride.3 Alternatively, in patients with impaired renal function or severe intoxication, hemodialysis has been used effectively.5

Case Conclusion

The patient was admitted for observation and treated with intravenous sodium chloride. After consultation with his neurologist, he was discharged home in the care of his parents, who were advised to continue him on sodium bromide 185 mg orally twice daily since his seizures were refractory to other anticonvulsant medications.

Dr Repplinger is a medical toxicology fellow in the department of emergency medicine at New York University Langone Medical Center. Dr Nelson, editor of “Case Studies in Toxicology,” is a professor in the department of emergency medicine and director of the medical toxicology fellowship program at the New York University School of Medicine and the New York City Poison Control Center. He is also associate editor, toxicology, of the EMERGENCY MEDICINE editorial board.

- Emmett M, Narins RG. Clinical use of the anion gap. Medicine (Baltimore). 1977;56(1):38-54.

- Figge J, Jabor A, Kazda A, Fencl V. Anion gap and hypoalbuminemia. Crit Care Med. 1998;26(11):1807-1810.

- Vasuyattakul S, Lertpattanasuwan N, Vareesangthip K, Nimmannit S, Nilwarangkur S. A negative aniongap as a clue to diagnose bromide intoxication.Nephron. 1995;69(3):311-313.

- Yamamoto K, Kobayashi H, Kobayashi T, MurakamiS. False hyperchloremia in bromism. J Anesth.1991;5(1):88-91.

- Ng YY, Lin WL, Chen TW. Spurious hyperchloremiaand decreased anion gap in a patient with dextromethorphan bromide. Am J Nephrol. 1992;12(4):268-270.

- Emmett M, Narins RG. Clinical use of the anion gap. Medicine (Baltimore). 1977;56(1):38-54.

- Figge J, Jabor A, Kazda A, Fencl V. Anion gap and hypoalbuminemia. Crit Care Med. 1998;26(11):1807-1810.

- Vasuyattakul S, Lertpattanasuwan N, Vareesangthip K, Nimmannit S, Nilwarangkur S. A negative aniongap as a clue to diagnose bromide intoxication.Nephron. 1995;69(3):311-313.

- Yamamoto K, Kobayashi H, Kobayashi T, MurakamiS. False hyperchloremia in bromism. J Anesth.1991;5(1):88-91.

- Ng YY, Lin WL, Chen TW. Spurious hyperchloremiaand decreased anion gap in a patient with dextromethorphan bromide. Am J Nephrol. 1992;12(4):268-270.

Malpractice Counsel

Sepsis Following Vaginal Hysterectomy

| A 45-year-old woman presented to the ED complaining of lower abdominal pain, which she described as gradual, aching, and intermittent. The patient stated that she had undergone a vaginal hysterectomy a few days prior and that the pain started less than 24 hours after discharge from the hospital. She denied fever or chills, nausea, or vomiting, and said that she had a bowel movement earlier that day. She also denied any urinary symptoms. Her medical history was significant only for hypothyroidism, for which she was taking levothyroxine. The patient denied cigarette smoking or alcohol consumption. She said she had been taking acetaminophen-hydrocodone for postoperative pain, but that it did not provide any relief. |

The patient’s vital signs were: temperature, 98.6˚F; blood pressure, 112/65 mm Hg; heart rate, 98 beats/minute; and respiratory rate, 20 breaths/minute. The head, eyes, ears, nose, and throat examination was normal, as were the heart and lung examinations. The patient’s abdomen was soft, with mild diffuse lower abdominal tenderness. There was no guarding, rebound, or mass present. A gross nonspeculum examination of the vaginal area did not reveal any discharge or erythema; a rectal examination was not performed.

The EP ordered a complete blood count (CBC), lipase evaluation, and urinalysis. All test results were normal. The emergency physician (EP) then contacted the obstetrician-gynecologist (OB/GYN) who had performed the hysterectomy. The OB/GYN recommended the EP change the analgesic agent to acetaminophen-oxycodone and to encourage the patient to keep her follow-up postoperative appointment in 1 week. The EP followed these instructions and discharged the patient home with a prescription for the new analgesic.

Three days later, however, the patient presented back to the same ED complaining of increased and now generalized abdominal pain, nausea, and vomiting. She was noted to be febrile, tachycardic, and hypotensive. On physical examination, her abdomen was diffusely tender with guarding and rebound. She was given a 2-L bolus of intravenous (IV) normal saline and started on broad spectrum IV antibiotics. After another consultation with the patient’s OB/GYN surgeon, the patient was taken immediately to the operating room. On exploration, she was found to have a segment of perforated bowel and peritonitis. A portion of the bowel was resected, but her postoperative course was complicated by sepsis. After a 1-month stay in the hospital, she was discharged home.

The patient sued the EP—but not her OB/GYN—for failure to obtain a CT scan of the abdomen/pelvis on her initial ED visit, or at least to admit her to the hospital for observation. The EP argued that even if a computed tomography (CT) scan had been performed on the initial visit, it probably would have been normal, since the bowel had not yet perforated. After trial, a defense verdict was returned.

Discussion

This case illustrates two important points. First, not every patient with abdominal pain requires a CT scan of the abdomen/pelvis. So many malpractice cases against EPs involve the failure to perform advanced imaging. Unfortunately, that is usually only through the benefit of hindsight. For a patient with mild abdominal pain, only minimal tenderness on examination, and a negative laboratory workup, it can be perfectly appropriate to treat him or her symptomatically with close follow-up and specific instructions to return to the ED if his or her condition worsens (as was the case with this patient).

The second important point is to not over-rely on a consultant(s), especially if she or he has not independently examined the patient. When calling a consultant, it is best to have a specific question (ie, “Can you see the patient in the morning?”) or action (ie, “I would like to admit the patient to your service”). In general, the EP should not rely on the consultant to give “permission” to discharge the patient. As the physician seeing the patient, the EP is the most well-equipped to work up the patient and determine the needed disposition. Rare is the consultant that can arrive at a better disposition than the EP who performed the history and physical examination on the patient.