User login

Pediatric pill swallowing interventions effective

For children as young as 2 years old, interventions such as behavioral therapy, flavored throat spray, a specialized pill cup, simple verbal instructions, and head-posture training were successful in improving pill swallowing abilities for more than half of the study population, according to the results of a data review published in Pediatrics.

Amee Patel, M.P.H., and her associates at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, examined data from 211 articles identified in a PubMed search published between December 1986 and December 2013. Four cohort studies and one case series met the criteria for inclusion. Each of the studies concluded that pill acceptance rates were improved shortly after their intervention, with three studies reporting pill acceptance continuing for 3-6 months after the intervention.

“A major reason for the success of all the interventions is that every study recognized and specifically addressed problems with pill swallowing. As a result, there was a conscious effort to help children with their difficulties in swallowing pills,” the investigators wrote.

Read the entire article here: Pediatrics 2015 (doi: 10.1542/peds.2014-2114).

For children as young as 2 years old, interventions such as behavioral therapy, flavored throat spray, a specialized pill cup, simple verbal instructions, and head-posture training were successful in improving pill swallowing abilities for more than half of the study population, according to the results of a data review published in Pediatrics.

Amee Patel, M.P.H., and her associates at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, examined data from 211 articles identified in a PubMed search published between December 1986 and December 2013. Four cohort studies and one case series met the criteria for inclusion. Each of the studies concluded that pill acceptance rates were improved shortly after their intervention, with three studies reporting pill acceptance continuing for 3-6 months after the intervention.

“A major reason for the success of all the interventions is that every study recognized and specifically addressed problems with pill swallowing. As a result, there was a conscious effort to help children with their difficulties in swallowing pills,” the investigators wrote.

Read the entire article here: Pediatrics 2015 (doi: 10.1542/peds.2014-2114).

For children as young as 2 years old, interventions such as behavioral therapy, flavored throat spray, a specialized pill cup, simple verbal instructions, and head-posture training were successful in improving pill swallowing abilities for more than half of the study population, according to the results of a data review published in Pediatrics.

Amee Patel, M.P.H., and her associates at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, examined data from 211 articles identified in a PubMed search published between December 1986 and December 2013. Four cohort studies and one case series met the criteria for inclusion. Each of the studies concluded that pill acceptance rates were improved shortly after their intervention, with three studies reporting pill acceptance continuing for 3-6 months after the intervention.

“A major reason for the success of all the interventions is that every study recognized and specifically addressed problems with pill swallowing. As a result, there was a conscious effort to help children with their difficulties in swallowing pills,” the investigators wrote.

Read the entire article here: Pediatrics 2015 (doi: 10.1542/peds.2014-2114).

VTE risk tied to natural anticoagulant deficiency

Deficiency of the endogenous anticoagulant proteins antithrombin, protein C, and protein S are significantly associated with an increased risk of a first episode of venous thromboembolism, according to a study published in Thrombosis Research.

To determine the impact of inherited deficiency of natural anticoagulants on VTE risk, the authors performed a systematic review and meta-analysis of 21 studies comprising a total of 3,452 cases and 11,562 controls. The investigation showed a significantly increased risk of first VTE in antithrombin deficient subjects compared to controls (OR 16.26), as well as an in protein C (OR 7.51) and protein S deficient patients (OR 5.37). For VTE recurrence, they found a significant association with antithrombin (OR 3.61) and protein C deficiencies (OR 2.94), but not with protein S deficiency.

“The strength of association between the deficiency of these natural anticoagulants and the risk of a first episode of VTE . . . may justify the research of these uncommon anticoagulant deficiencies, in particular in patients with unprovoked events,” wrote Dr. Matteo Nicola Dario Di Minno of Federico II University in Naples, Italy and his associates.

Read the full article in Thrombosis Research here: (DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.thromres.2015.03.010)

Deficiency of the endogenous anticoagulant proteins antithrombin, protein C, and protein S are significantly associated with an increased risk of a first episode of venous thromboembolism, according to a study published in Thrombosis Research.

To determine the impact of inherited deficiency of natural anticoagulants on VTE risk, the authors performed a systematic review and meta-analysis of 21 studies comprising a total of 3,452 cases and 11,562 controls. The investigation showed a significantly increased risk of first VTE in antithrombin deficient subjects compared to controls (OR 16.26), as well as an in protein C (OR 7.51) and protein S deficient patients (OR 5.37). For VTE recurrence, they found a significant association with antithrombin (OR 3.61) and protein C deficiencies (OR 2.94), but not with protein S deficiency.

“The strength of association between the deficiency of these natural anticoagulants and the risk of a first episode of VTE . . . may justify the research of these uncommon anticoagulant deficiencies, in particular in patients with unprovoked events,” wrote Dr. Matteo Nicola Dario Di Minno of Federico II University in Naples, Italy and his associates.

Read the full article in Thrombosis Research here: (DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.thromres.2015.03.010)

Deficiency of the endogenous anticoagulant proteins antithrombin, protein C, and protein S are significantly associated with an increased risk of a first episode of venous thromboembolism, according to a study published in Thrombosis Research.

To determine the impact of inherited deficiency of natural anticoagulants on VTE risk, the authors performed a systematic review and meta-analysis of 21 studies comprising a total of 3,452 cases and 11,562 controls. The investigation showed a significantly increased risk of first VTE in antithrombin deficient subjects compared to controls (OR 16.26), as well as an in protein C (OR 7.51) and protein S deficient patients (OR 5.37). For VTE recurrence, they found a significant association with antithrombin (OR 3.61) and protein C deficiencies (OR 2.94), but not with protein S deficiency.

“The strength of association between the deficiency of these natural anticoagulants and the risk of a first episode of VTE . . . may justify the research of these uncommon anticoagulant deficiencies, in particular in patients with unprovoked events,” wrote Dr. Matteo Nicola Dario Di Minno of Federico II University in Naples, Italy and his associates.

Read the full article in Thrombosis Research here: (DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.thromres.2015.03.010)

Fondaparinux safe for VTE prophylaxis in ischemic stroke

Fondaparinux was just as safe as unfractionated heparin for venous thromboembolism prophylaxis in ischemic stroke, report Dr. C.T. Hackett and co-authors of the department of neurology and Allegheny General Hospital Comprehensive Stroke Center at the University of South Carolina.

In an analysis of 644 acute ischemic stroke patients receiving either fondaparinux or unfractionated heparin (UFH) for venous thromboembolism (VTE) prophylaxis, major hemorrhages occurred in just 1.2% of patients in the fondaparinux group, compared with 3.7% in the UFH group. This difference was not statistically significant (P = .08). Additionally, there was no significant difference in total hemorrhage (P = .15), intracranial hemorrhage (P = .48), major extracranial hemorrhage, (P = .18) or symptomatic VTE (P = 1.00) between the two groups.

The findings “provide supportive safety data for a prospective trial of extended VTE prophylaxis with fondaparinux in acute ischemic stroke,” the authors wrote.

Read the full article in Thrombosis Research: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.thromres.2014.11.041.

Fondaparinux was just as safe as unfractionated heparin for venous thromboembolism prophylaxis in ischemic stroke, report Dr. C.T. Hackett and co-authors of the department of neurology and Allegheny General Hospital Comprehensive Stroke Center at the University of South Carolina.

In an analysis of 644 acute ischemic stroke patients receiving either fondaparinux or unfractionated heparin (UFH) for venous thromboembolism (VTE) prophylaxis, major hemorrhages occurred in just 1.2% of patients in the fondaparinux group, compared with 3.7% in the UFH group. This difference was not statistically significant (P = .08). Additionally, there was no significant difference in total hemorrhage (P = .15), intracranial hemorrhage (P = .48), major extracranial hemorrhage, (P = .18) or symptomatic VTE (P = 1.00) between the two groups.

The findings “provide supportive safety data for a prospective trial of extended VTE prophylaxis with fondaparinux in acute ischemic stroke,” the authors wrote.

Read the full article in Thrombosis Research: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.thromres.2014.11.041.

Fondaparinux was just as safe as unfractionated heparin for venous thromboembolism prophylaxis in ischemic stroke, report Dr. C.T. Hackett and co-authors of the department of neurology and Allegheny General Hospital Comprehensive Stroke Center at the University of South Carolina.

In an analysis of 644 acute ischemic stroke patients receiving either fondaparinux or unfractionated heparin (UFH) for venous thromboembolism (VTE) prophylaxis, major hemorrhages occurred in just 1.2% of patients in the fondaparinux group, compared with 3.7% in the UFH group. This difference was not statistically significant (P = .08). Additionally, there was no significant difference in total hemorrhage (P = .15), intracranial hemorrhage (P = .48), major extracranial hemorrhage, (P = .18) or symptomatic VTE (P = 1.00) between the two groups.

The findings “provide supportive safety data for a prospective trial of extended VTE prophylaxis with fondaparinux in acute ischemic stroke,” the authors wrote.

Read the full article in Thrombosis Research: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.thromres.2014.11.041.

Illicit drug use highest in accommodations and food service workers

Workers in mining, construction, and the accommodations and food services industries report the highest rates of alcohol and substance abuse across a wide range of industries, according to the latest analysis of data from the National Survey on Drug Use and Health.

The survey, published April 16 in The CBHSQ Report, showed that the prevalence of heavy alcohol use in the previous month ranged from a high of 17.5% in the mining industry to 4.4% among workers in health care and social assistance. A total of 19.1% of accommodations and food services workers reported illicit drug use in the past month, compared with 4.3% in public administration.

A comparison of data from 2003-2007 and 2008-2012 also revealed that illicit drug use has increased in the accommodations and food services industries, and in educational services, but decreased in construction workers (The CBHSQ Report 2015, April 16).

“An extension of this research could examine whether the changes in use rates correspond to either changes in climate in the industries (e.g., attitudes towards substance use, distribution of prevention messages) or shifts in the demographic compositions of the industries across these time periods,” wrote Dr. Donna M. Bush and Dr. Rachel N. Lipari from the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration.

The annual National Survey on Drug Use and Health is sponsored by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. No conflicts of interest were declared.

Workers in mining, construction, and the accommodations and food services industries report the highest rates of alcohol and substance abuse across a wide range of industries, according to the latest analysis of data from the National Survey on Drug Use and Health.

The survey, published April 16 in The CBHSQ Report, showed that the prevalence of heavy alcohol use in the previous month ranged from a high of 17.5% in the mining industry to 4.4% among workers in health care and social assistance. A total of 19.1% of accommodations and food services workers reported illicit drug use in the past month, compared with 4.3% in public administration.

A comparison of data from 2003-2007 and 2008-2012 also revealed that illicit drug use has increased in the accommodations and food services industries, and in educational services, but decreased in construction workers (The CBHSQ Report 2015, April 16).

“An extension of this research could examine whether the changes in use rates correspond to either changes in climate in the industries (e.g., attitudes towards substance use, distribution of prevention messages) or shifts in the demographic compositions of the industries across these time periods,” wrote Dr. Donna M. Bush and Dr. Rachel N. Lipari from the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration.

The annual National Survey on Drug Use and Health is sponsored by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. No conflicts of interest were declared.

Workers in mining, construction, and the accommodations and food services industries report the highest rates of alcohol and substance abuse across a wide range of industries, according to the latest analysis of data from the National Survey on Drug Use and Health.

The survey, published April 16 in The CBHSQ Report, showed that the prevalence of heavy alcohol use in the previous month ranged from a high of 17.5% in the mining industry to 4.4% among workers in health care and social assistance. A total of 19.1% of accommodations and food services workers reported illicit drug use in the past month, compared with 4.3% in public administration.

A comparison of data from 2003-2007 and 2008-2012 also revealed that illicit drug use has increased in the accommodations and food services industries, and in educational services, but decreased in construction workers (The CBHSQ Report 2015, April 16).

“An extension of this research could examine whether the changes in use rates correspond to either changes in climate in the industries (e.g., attitudes towards substance use, distribution of prevention messages) or shifts in the demographic compositions of the industries across these time periods,” wrote Dr. Donna M. Bush and Dr. Rachel N. Lipari from the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration.

The annual National Survey on Drug Use and Health is sponsored by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. No conflicts of interest were declared.

Key clinical point: Mining, construction, and accommodations and food services workers report the highest rates of alcohol and illicit drug use across a wide range of industries.

Major finding: Nearly one in five accommodations and food services workers reported illicit drug use in the past month.

Data source: National Survey on Drug Use and Health.

Disclosures: The annual National Survey on Drug Use and Health is sponsored by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. No conflicts of interest were declared.

Mutation linked to drug-resistant malaria in Africa

Image by Ute Frevert

and Margaret Shear

New research provides genetic evidence that malaria parasites in Africa are developing resistance to antimalarial drugs.

Researchers found that Plasmodium falciparum parasites with a mutation in the gene ap2mu were less sensitive to both artemisinin and quinine.

A study published in 2013 suggested a link between a mutation in ap2mu and low levels of malaria parasites remaining in the blood of Kenyan children after treatment with artemisinin.

However, further research was needed to confirm that these genetic characteristics represented an early step toward resistance.

In the new study, published in Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy, researchers genetically altered the malaria parasite to mutate ap2mu in the same way that had been observed in Kenya.

The team found the altered parasite was significantly less susceptible to treatment, requiring 32% more drug to be killed by artemisinin. The genetically altered parasite was also 42.4% less susceptible to quinine.

Earlier this year, a different research group discovered mutations in the gene kelch13, which were linked to reduced susceptibility to artemisinin combination treatment in South East Asia.

Historically, resistance to antimalarial medicines has emerged in South East Asia and then spread to Africa. But these new findings suggest a different route to drug resistance may be developing independently in Africa.

“Our findings could be a sign of much worse things to come for malaria in Africa,” said study author Colin Sutherland, PhD, of the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine in the UK.

“The malaria parasite is constantly evolving to evade our control efforts. We’ve already moved away from using quinine to treat cases as the malaria parasite has become more resistant to it, but if further drug resistance were to develop against our most valuable malaria drug, artemisinin, we would be facing a grave situation.”

“We now know that the gene ap2mu is an important factor in determining how well our drugs kill malaria parasites. We will be conducting laboratory and field studies to more accurately measure the impact of mutations in the ap2mu gene. We hope our findings will help [us] understand resistance of malaria to drugs and potentially be an important tool for monitoring malaria treatment in the future.” ![]()

Image by Ute Frevert

and Margaret Shear

New research provides genetic evidence that malaria parasites in Africa are developing resistance to antimalarial drugs.

Researchers found that Plasmodium falciparum parasites with a mutation in the gene ap2mu were less sensitive to both artemisinin and quinine.

A study published in 2013 suggested a link between a mutation in ap2mu and low levels of malaria parasites remaining in the blood of Kenyan children after treatment with artemisinin.

However, further research was needed to confirm that these genetic characteristics represented an early step toward resistance.

In the new study, published in Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy, researchers genetically altered the malaria parasite to mutate ap2mu in the same way that had been observed in Kenya.

The team found the altered parasite was significantly less susceptible to treatment, requiring 32% more drug to be killed by artemisinin. The genetically altered parasite was also 42.4% less susceptible to quinine.

Earlier this year, a different research group discovered mutations in the gene kelch13, which were linked to reduced susceptibility to artemisinin combination treatment in South East Asia.

Historically, resistance to antimalarial medicines has emerged in South East Asia and then spread to Africa. But these new findings suggest a different route to drug resistance may be developing independently in Africa.

“Our findings could be a sign of much worse things to come for malaria in Africa,” said study author Colin Sutherland, PhD, of the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine in the UK.

“The malaria parasite is constantly evolving to evade our control efforts. We’ve already moved away from using quinine to treat cases as the malaria parasite has become more resistant to it, but if further drug resistance were to develop against our most valuable malaria drug, artemisinin, we would be facing a grave situation.”

“We now know that the gene ap2mu is an important factor in determining how well our drugs kill malaria parasites. We will be conducting laboratory and field studies to more accurately measure the impact of mutations in the ap2mu gene. We hope our findings will help [us] understand resistance of malaria to drugs and potentially be an important tool for monitoring malaria treatment in the future.” ![]()

Image by Ute Frevert

and Margaret Shear

New research provides genetic evidence that malaria parasites in Africa are developing resistance to antimalarial drugs.

Researchers found that Plasmodium falciparum parasites with a mutation in the gene ap2mu were less sensitive to both artemisinin and quinine.

A study published in 2013 suggested a link between a mutation in ap2mu and low levels of malaria parasites remaining in the blood of Kenyan children after treatment with artemisinin.

However, further research was needed to confirm that these genetic characteristics represented an early step toward resistance.

In the new study, published in Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy, researchers genetically altered the malaria parasite to mutate ap2mu in the same way that had been observed in Kenya.

The team found the altered parasite was significantly less susceptible to treatment, requiring 32% more drug to be killed by artemisinin. The genetically altered parasite was also 42.4% less susceptible to quinine.

Earlier this year, a different research group discovered mutations in the gene kelch13, which were linked to reduced susceptibility to artemisinin combination treatment in South East Asia.

Historically, resistance to antimalarial medicines has emerged in South East Asia and then spread to Africa. But these new findings suggest a different route to drug resistance may be developing independently in Africa.

“Our findings could be a sign of much worse things to come for malaria in Africa,” said study author Colin Sutherland, PhD, of the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine in the UK.

“The malaria parasite is constantly evolving to evade our control efforts. We’ve already moved away from using quinine to treat cases as the malaria parasite has become more resistant to it, but if further drug resistance were to develop against our most valuable malaria drug, artemisinin, we would be facing a grave situation.”

“We now know that the gene ap2mu is an important factor in determining how well our drugs kill malaria parasites. We will be conducting laboratory and field studies to more accurately measure the impact of mutations in the ap2mu gene. We hope our findings will help [us] understand resistance of malaria to drugs and potentially be an important tool for monitoring malaria treatment in the future.” ![]()

Novel oral anticoagulants best warfarin for AF in heart failure

SAN DIEGO – The novel oral anticoagulants clearly outperformed warfarin for stroke prevention and safety endpoints in patients with atrial fibrillation and comorbid heart failure in a meta-analysis of four recent landmark Phase 3 clinical trials.

Collectively the four novel oral anticoagulants (NOACs) approved for stroke prophylaxis in nonvalvular atrial fibrillation (AF) reduced the risk of stroke and systemic embolism by 14%, compared with patients randomized to warfarin. Moreover, the NOACs decreased the risks of major bleeding and intracranial bleeding by 23% and 45%, respectively, Dr. Gianluigi Savarese reported at the annual meeting of the American College of Cardiology.

“NOACs represent a valuable therapeutic option in patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation and heart failure,” concluded Dr. Savarese of Federico II University, Naples.

There has never been a randomized trial comparing a NOAC to warfarin specifically in patients with these dual diagnoses. In the absence of such a definitive study, the next best thing is a meta-analysis of the pivotal Phase 3 trials in which warfarin was compared to dabigatran (Pradaxa, the RE-LY study), apixaban (Eliquis, ARISTOTLE), rivaroxaban (Xarelto, ROCKET AF), and edoxaban (Savaysa, ENGAGE AF-TIMI 48).

The meta-analysis focused on a subset population of 26,384 randomized patients with AF and heart failure. It’s important to know how the NOACs stack up against warfarin in this population because symptomatic heart failure is common: indeed, it’s present in 30% of patients with AF. Patients with AF and comorbid heart failure are generally older, frailer, have more comorbidities, and are at higher risk of both stroke and bleeding, compared with AF patients without heart failure. Since heart failure is a recognized risk factor for reduced time in the therapeutic international normalized ratio (INR) range for patients on warfarin, it’s likely that warfarin-treated dual diagnosis patients would be exposed to further increased risks of stroke and bleeding, according to Dr. Savarese.

In the meta-analysis, in addition to the NOAC-treated patients’ significantly reduced risks of stroke, major bleeding, and intracranial bleeding, they showed a 12% decrease in total bleeding and an 8% reduction in cardiovascular death, compared with warfarin-treated controls, although neither of those latter two favorable trends achieved statistical significance.

The four NOACs didn’t differ significantly on any of the prespecified outcomes in the meta-analysis.

One audience member noted that while the relative risk reductions for stroke and major bleeding seen with the NOACs in the meta-analysis were large and impressive, the absolute risk reductions were actually quite small. For example, warfarin-treated controls in RE-LY, the first of the major trials, had a stroke/systemic embolism rate of 1.69%/year and a major bleeding rate of 3.4%/year (N. Engl. J. Med. 2009;361:1139-51), while controls in ENGAGE AF-TIMI 48 had annualized stroke and major bleeding rates of 1.5% and 3.4%, respectively (N. Engl. J. Med. 2013;369:2093-2104).

Dr. Savarese replied that he and his coinvestigators consider those absolute risk reductions to be clinically meaningful, especially in light of the enormous and rapidly growing number of patients with both AF and heart failure.

He reported having no financial conflicts regarding this meta-analysis, which was carried out free of commercial support.

SAN DIEGO – The novel oral anticoagulants clearly outperformed warfarin for stroke prevention and safety endpoints in patients with atrial fibrillation and comorbid heart failure in a meta-analysis of four recent landmark Phase 3 clinical trials.

Collectively the four novel oral anticoagulants (NOACs) approved for stroke prophylaxis in nonvalvular atrial fibrillation (AF) reduced the risk of stroke and systemic embolism by 14%, compared with patients randomized to warfarin. Moreover, the NOACs decreased the risks of major bleeding and intracranial bleeding by 23% and 45%, respectively, Dr. Gianluigi Savarese reported at the annual meeting of the American College of Cardiology.

“NOACs represent a valuable therapeutic option in patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation and heart failure,” concluded Dr. Savarese of Federico II University, Naples.

There has never been a randomized trial comparing a NOAC to warfarin specifically in patients with these dual diagnoses. In the absence of such a definitive study, the next best thing is a meta-analysis of the pivotal Phase 3 trials in which warfarin was compared to dabigatran (Pradaxa, the RE-LY study), apixaban (Eliquis, ARISTOTLE), rivaroxaban (Xarelto, ROCKET AF), and edoxaban (Savaysa, ENGAGE AF-TIMI 48).

The meta-analysis focused on a subset population of 26,384 randomized patients with AF and heart failure. It’s important to know how the NOACs stack up against warfarin in this population because symptomatic heart failure is common: indeed, it’s present in 30% of patients with AF. Patients with AF and comorbid heart failure are generally older, frailer, have more comorbidities, and are at higher risk of both stroke and bleeding, compared with AF patients without heart failure. Since heart failure is a recognized risk factor for reduced time in the therapeutic international normalized ratio (INR) range for patients on warfarin, it’s likely that warfarin-treated dual diagnosis patients would be exposed to further increased risks of stroke and bleeding, according to Dr. Savarese.

In the meta-analysis, in addition to the NOAC-treated patients’ significantly reduced risks of stroke, major bleeding, and intracranial bleeding, they showed a 12% decrease in total bleeding and an 8% reduction in cardiovascular death, compared with warfarin-treated controls, although neither of those latter two favorable trends achieved statistical significance.

The four NOACs didn’t differ significantly on any of the prespecified outcomes in the meta-analysis.

One audience member noted that while the relative risk reductions for stroke and major bleeding seen with the NOACs in the meta-analysis were large and impressive, the absolute risk reductions were actually quite small. For example, warfarin-treated controls in RE-LY, the first of the major trials, had a stroke/systemic embolism rate of 1.69%/year and a major bleeding rate of 3.4%/year (N. Engl. J. Med. 2009;361:1139-51), while controls in ENGAGE AF-TIMI 48 had annualized stroke and major bleeding rates of 1.5% and 3.4%, respectively (N. Engl. J. Med. 2013;369:2093-2104).

Dr. Savarese replied that he and his coinvestigators consider those absolute risk reductions to be clinically meaningful, especially in light of the enormous and rapidly growing number of patients with both AF and heart failure.

He reported having no financial conflicts regarding this meta-analysis, which was carried out free of commercial support.

SAN DIEGO – The novel oral anticoagulants clearly outperformed warfarin for stroke prevention and safety endpoints in patients with atrial fibrillation and comorbid heart failure in a meta-analysis of four recent landmark Phase 3 clinical trials.

Collectively the four novel oral anticoagulants (NOACs) approved for stroke prophylaxis in nonvalvular atrial fibrillation (AF) reduced the risk of stroke and systemic embolism by 14%, compared with patients randomized to warfarin. Moreover, the NOACs decreased the risks of major bleeding and intracranial bleeding by 23% and 45%, respectively, Dr. Gianluigi Savarese reported at the annual meeting of the American College of Cardiology.

“NOACs represent a valuable therapeutic option in patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation and heart failure,” concluded Dr. Savarese of Federico II University, Naples.

There has never been a randomized trial comparing a NOAC to warfarin specifically in patients with these dual diagnoses. In the absence of such a definitive study, the next best thing is a meta-analysis of the pivotal Phase 3 trials in which warfarin was compared to dabigatran (Pradaxa, the RE-LY study), apixaban (Eliquis, ARISTOTLE), rivaroxaban (Xarelto, ROCKET AF), and edoxaban (Savaysa, ENGAGE AF-TIMI 48).

The meta-analysis focused on a subset population of 26,384 randomized patients with AF and heart failure. It’s important to know how the NOACs stack up against warfarin in this population because symptomatic heart failure is common: indeed, it’s present in 30% of patients with AF. Patients with AF and comorbid heart failure are generally older, frailer, have more comorbidities, and are at higher risk of both stroke and bleeding, compared with AF patients without heart failure. Since heart failure is a recognized risk factor for reduced time in the therapeutic international normalized ratio (INR) range for patients on warfarin, it’s likely that warfarin-treated dual diagnosis patients would be exposed to further increased risks of stroke and bleeding, according to Dr. Savarese.

In the meta-analysis, in addition to the NOAC-treated patients’ significantly reduced risks of stroke, major bleeding, and intracranial bleeding, they showed a 12% decrease in total bleeding and an 8% reduction in cardiovascular death, compared with warfarin-treated controls, although neither of those latter two favorable trends achieved statistical significance.

The four NOACs didn’t differ significantly on any of the prespecified outcomes in the meta-analysis.

One audience member noted that while the relative risk reductions for stroke and major bleeding seen with the NOACs in the meta-analysis were large and impressive, the absolute risk reductions were actually quite small. For example, warfarin-treated controls in RE-LY, the first of the major trials, had a stroke/systemic embolism rate of 1.69%/year and a major bleeding rate of 3.4%/year (N. Engl. J. Med. 2009;361:1139-51), while controls in ENGAGE AF-TIMI 48 had annualized stroke and major bleeding rates of 1.5% and 3.4%, respectively (N. Engl. J. Med. 2013;369:2093-2104).

Dr. Savarese replied that he and his coinvestigators consider those absolute risk reductions to be clinically meaningful, especially in light of the enormous and rapidly growing number of patients with both AF and heart failure.

He reported having no financial conflicts regarding this meta-analysis, which was carried out free of commercial support.

AT ACC 15

Key clinical point: Patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation and heart failure clearly fare better on any of the novel oral anticoagulants than with warfarin for stroke prophylaxis.

Major finding: Dual diagnosis patients randomized to a novel oral anticoagulant had a 14% reduction in stroke/systemic embolism and a 23% decrease in major bleeding compared with those on warfarin.

Data source: This was a meta-analysis of the 26,384 patients with both atrial fibrillation and heart failure who were included in four pivotal Phase 3 clinical trials that led to approval of dabigatran, apixaban, rivaroxaban, and edoxaban.

Disclosures: The presenter reported having no financial conflicts regarding this meta-analysis, which was carried out free of commercial support.

Platelet indexes flag suspected pulmonary embolism

Levels of platelet distribution width (PDW) and mean platelet volume (MPV) were significantly higher in patients with pulmonary embolism, Dr. Jianqiang Huang and co-authors at the Department of Cardiovascular Medicine, Shantou Central Hospital in Guangdong Province, China, have reported.

A study of platelet indexes in 70 PE patients and 75 controls showed that PDW (16.40% vs. 16.00%) and MPV (9.91±1.40 fL vs. 8.84±1.68) values were significantly higher in those with PE, compared with controls. There were no significant differences in platelet count, the investigators reported.

The results indicate that measuring “MPV can increase the specificity and [positive predictive value] to improve the diagnostic value of D-dimer for PE,” the authors wrote. “Because platelet indexes are convenient to detect, clinical physicians may increase their vigilance to identify suspected PE,” they added.

Read the full article at the American Journal of Emergency Medicine: 10.1016/j.ajem.2015.02.043.

Levels of platelet distribution width (PDW) and mean platelet volume (MPV) were significantly higher in patients with pulmonary embolism, Dr. Jianqiang Huang and co-authors at the Department of Cardiovascular Medicine, Shantou Central Hospital in Guangdong Province, China, have reported.

A study of platelet indexes in 70 PE patients and 75 controls showed that PDW (16.40% vs. 16.00%) and MPV (9.91±1.40 fL vs. 8.84±1.68) values were significantly higher in those with PE, compared with controls. There were no significant differences in platelet count, the investigators reported.

The results indicate that measuring “MPV can increase the specificity and [positive predictive value] to improve the diagnostic value of D-dimer for PE,” the authors wrote. “Because platelet indexes are convenient to detect, clinical physicians may increase their vigilance to identify suspected PE,” they added.

Read the full article at the American Journal of Emergency Medicine: 10.1016/j.ajem.2015.02.043.

Levels of platelet distribution width (PDW) and mean platelet volume (MPV) were significantly higher in patients with pulmonary embolism, Dr. Jianqiang Huang and co-authors at the Department of Cardiovascular Medicine, Shantou Central Hospital in Guangdong Province, China, have reported.

A study of platelet indexes in 70 PE patients and 75 controls showed that PDW (16.40% vs. 16.00%) and MPV (9.91±1.40 fL vs. 8.84±1.68) values were significantly higher in those with PE, compared with controls. There were no significant differences in platelet count, the investigators reported.

The results indicate that measuring “MPV can increase the specificity and [positive predictive value] to improve the diagnostic value of D-dimer for PE,” the authors wrote. “Because platelet indexes are convenient to detect, clinical physicians may increase their vigilance to identify suspected PE,” they added.

Read the full article at the American Journal of Emergency Medicine: 10.1016/j.ajem.2015.02.043.

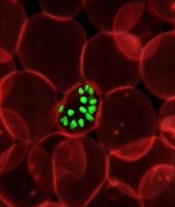

Explaining drug-resistant malaria

infecting a red blood cell

Image courtesy of St. Jude

Children’s Research Hospital

Researchers say they have identified a molecular mechanism responsible for making malaria parasites resistant to artemisinins, the leading class of antimalarial drugs.

The team found that a kinase, Plasmodium falciparum phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase (PfPI3K), and its lipid product, phosphatidylinositol-3-phosphate (PI3P), play key roles in artemisinin resistance.

So targeting PfPI3K or PI3P could potentially treat resistant Plasmodium falciparum malaria.

Alassane Mbengue, PhD, of the University of Notre Dame in Indiana, and his colleagues described this research in a letter to Nature.

“We observed that levels of [PI3P] were higher in artemisinin-resistant P falciparum than artemisinin-sensitive strains,” Dr Mbengue said. “This lipid is produced by an enzyme called PfPI3K. We found that artemisinins block this kinase from producing PI3P lipids. We also discovered that the amount of the kinase present in the parasite is controlled by the gene PfKelch13.”

“Mutation in the gene increases the kinase levels, which, in turn, increases PI3P lipid levels. The higher the level of PI3P lipids present in the parasite, the greater the level of artemisinin resistance. We also studied the lipid levels in parasites without the gene mutation and observed that when PI3P lipid levels were increased artificially, the parasites still became proportionately resistant.”

Specifically, the researchers found that increased PfPI3K was associated with the C580Y mutation in PfKelch13. The mutation reduced polyubiquitination of PfPI3K and its binding to PfKelch13, which limited proteolysis of PfPI3K and led to increased levels of both PfPI3K and PI3P.

The team found that PI3P levels were predictive of artemisinin resistance in clinical and engineered parasites. And although increases in PI3P levels induced artemisinin resistance in the absence of PfKelch13 mutations, PI3P levels were still responsive to regulation by PfKelch13.

Dr Mbengue and his colleagues said the next step for this research is to identify drugs that can kill P falciparum by preventing PfPI3K from making PI3P or disrupting the production of the kinase itself. ![]()

infecting a red blood cell

Image courtesy of St. Jude

Children’s Research Hospital

Researchers say they have identified a molecular mechanism responsible for making malaria parasites resistant to artemisinins, the leading class of antimalarial drugs.

The team found that a kinase, Plasmodium falciparum phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase (PfPI3K), and its lipid product, phosphatidylinositol-3-phosphate (PI3P), play key roles in artemisinin resistance.

So targeting PfPI3K or PI3P could potentially treat resistant Plasmodium falciparum malaria.

Alassane Mbengue, PhD, of the University of Notre Dame in Indiana, and his colleagues described this research in a letter to Nature.

“We observed that levels of [PI3P] were higher in artemisinin-resistant P falciparum than artemisinin-sensitive strains,” Dr Mbengue said. “This lipid is produced by an enzyme called PfPI3K. We found that artemisinins block this kinase from producing PI3P lipids. We also discovered that the amount of the kinase present in the parasite is controlled by the gene PfKelch13.”

“Mutation in the gene increases the kinase levels, which, in turn, increases PI3P lipid levels. The higher the level of PI3P lipids present in the parasite, the greater the level of artemisinin resistance. We also studied the lipid levels in parasites without the gene mutation and observed that when PI3P lipid levels were increased artificially, the parasites still became proportionately resistant.”

Specifically, the researchers found that increased PfPI3K was associated with the C580Y mutation in PfKelch13. The mutation reduced polyubiquitination of PfPI3K and its binding to PfKelch13, which limited proteolysis of PfPI3K and led to increased levels of both PfPI3K and PI3P.

The team found that PI3P levels were predictive of artemisinin resistance in clinical and engineered parasites. And although increases in PI3P levels induced artemisinin resistance in the absence of PfKelch13 mutations, PI3P levels were still responsive to regulation by PfKelch13.

Dr Mbengue and his colleagues said the next step for this research is to identify drugs that can kill P falciparum by preventing PfPI3K from making PI3P or disrupting the production of the kinase itself. ![]()

infecting a red blood cell

Image courtesy of St. Jude

Children’s Research Hospital

Researchers say they have identified a molecular mechanism responsible for making malaria parasites resistant to artemisinins, the leading class of antimalarial drugs.

The team found that a kinase, Plasmodium falciparum phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase (PfPI3K), and its lipid product, phosphatidylinositol-3-phosphate (PI3P), play key roles in artemisinin resistance.

So targeting PfPI3K or PI3P could potentially treat resistant Plasmodium falciparum malaria.

Alassane Mbengue, PhD, of the University of Notre Dame in Indiana, and his colleagues described this research in a letter to Nature.

“We observed that levels of [PI3P] were higher in artemisinin-resistant P falciparum than artemisinin-sensitive strains,” Dr Mbengue said. “This lipid is produced by an enzyme called PfPI3K. We found that artemisinins block this kinase from producing PI3P lipids. We also discovered that the amount of the kinase present in the parasite is controlled by the gene PfKelch13.”

“Mutation in the gene increases the kinase levels, which, in turn, increases PI3P lipid levels. The higher the level of PI3P lipids present in the parasite, the greater the level of artemisinin resistance. We also studied the lipid levels in parasites without the gene mutation and observed that when PI3P lipid levels were increased artificially, the parasites still became proportionately resistant.”

Specifically, the researchers found that increased PfPI3K was associated with the C580Y mutation in PfKelch13. The mutation reduced polyubiquitination of PfPI3K and its binding to PfKelch13, which limited proteolysis of PfPI3K and led to increased levels of both PfPI3K and PI3P.

The team found that PI3P levels were predictive of artemisinin resistance in clinical and engineered parasites. And although increases in PI3P levels induced artemisinin resistance in the absence of PfKelch13 mutations, PI3P levels were still responsive to regulation by PfKelch13.

Dr Mbengue and his colleagues said the next step for this research is to identify drugs that can kill P falciparum by preventing PfPI3K from making PI3P or disrupting the production of the kinase itself. ![]()

Point/Counterpoint: Covered stent grafts vs. drug-eluting stents for treating long superficial femoral artery occlusions

Head-to-head comparisons are lacking, but similar results have been reported

BY MICHAEL D. DAKE, M.D.

Well, at least one thing is for sure – we would not have been having this discussion a mere 10 years ago.

I remained sheepishly silent for most of my early career as well-intentioned invasive and noninvasive specialists criticized the state of evidence supporting the legitimacy of endovascular interventions as a competitive strategy to manage infrainguinal peripheral arterial disease. Good data from well-controlled randomized clinical trials were not available to make a case for endovascular therapies.

Over the recent decade and a half, however, a number of contributing factors have influenced thinking and what we now consider standard of care for symptomatic disease of the superficial femoral artery (SFA). The proposal of an “endovascular first” interventional approach has evolved to a consensually agreed upon management strategy by all interested disciplines.

This did not occur on a whim. Rather, out of the shadows of relative ignorance there slowly emerged a welcomed accumulation of a large number of publications that detail the outcomes of a wide variety of randomized trials with a range of endovascular devices. This has allowed us to enter an era where valid comparisons between interventional therapies is not only possible, but allows us to more appropriately offer care to vascular patients with more nuanced strategies. These are strategies that recognize subtleties between subgroups of individuals stratified on the basis of patient demographics and lesion characteristics in a way not appreciated prior to the recent spate of endovascular device studies.

Thus, thanks to the dedication and hard work of many, we are now at a stage where we can have meaningful dialogues on a variety of endovascular topics, such as the one at hand, and proponents can argue their perspectives armed with objective evidence to support their positions. In this discussion regarding covered stent grafts and drug-eluting stents, we wish we had even more data.

Specifically, we are missing direct head-to-head comparisons between the two devices in patients with long SFA lesions. So, what do we know?

Here are some fundamental facts: The most commonly used covered stent graft for management of femoropopliteal occlusive disease is the Viabahn endoprosthesis (W. L. Gore and Associates, Flagstaff, Ariz.). The prosthesis is composed of a self-expanding nitinol stent framework and expanded polytetrafluoroethylene (ePTFE) graft with its surface lined with a coating of covalently bound heparin (Propaten bioactive surface).The only approved drug-eluting stent with significant safety and effectiveness data available is the Zilver PTX paclitaxel-eluting, self-expanding nitinol stent (Cook Medical Inc., Bloomington, Ind.).

Now in terms of the proposition, we need to discuss the meaning of the word “long” with reference to the SFA. Just what do we consider a long SFA lesion? I think all of us could agree that an arterial stenosis or occlusion of 6 cm or less is short. Lesions between 5 cm or 6 cm to 10 cm or 12 cm in length are moderately long, and disease greater than 10 cm or 12 cm is commonly characterized as long. Segments of disease greater than 20 cm long are typically considered very long or extremely long lesions from an endovascular interventional perspective.

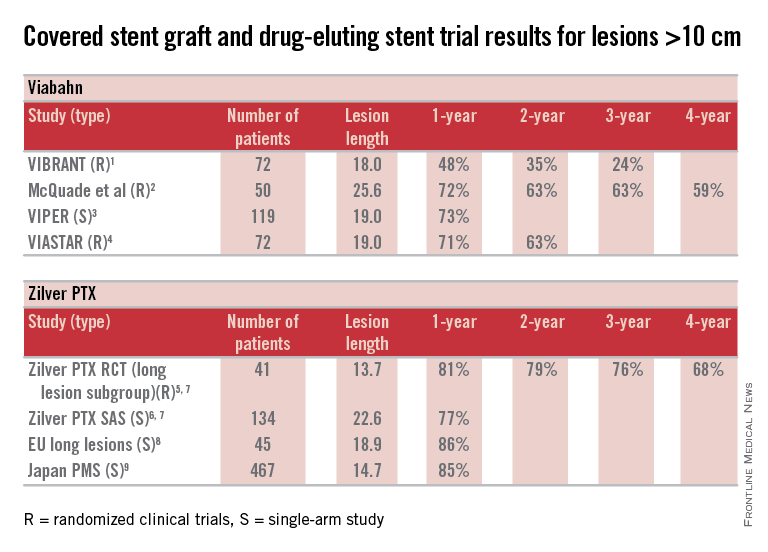

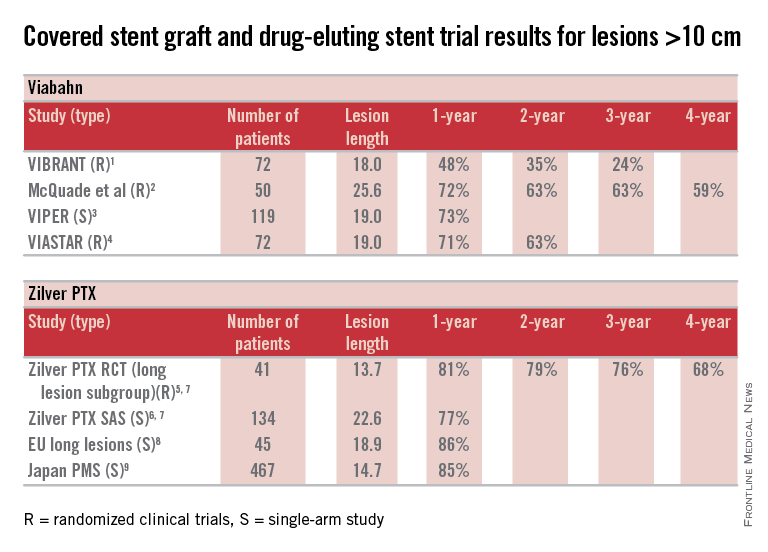

So, how can currently available trial outcomes help us? Below, I have compiled a table that includes most of the recent clinical trial data for Viabahn and Zilver PTX in patients with long SFA occlusive disease.

OK, what can we honestly say about these data besides recognizing that we are at risk when we make any conclusions based upon cross-trial comparisons? Such an accounting of results is fraught with problems, but what we can say is that the table grossly confirms the current consensus that both devices enhance the standard of care for long lesions over traditional balloon angioplasty (PTA) and bare metal stent technologies.

Beyond this, however, it is accepted that patency results with Viabahn are lesion-length immune – that is, outcomes in long and extremely long segments of disease are not very different from the patency achieved in short lesions. This is clearly different than what is traditionally found for interventions with PTA or bare metal stents. There is not enough controlled data for extremely long lesions to reach a conclusion on drug-eluting stents; however, there is an initial suggestion that they behave in a manner more similar to stent grafts than traditional devices.

Grossly, the table suggests that the midterm and available greater than 1-year patency results with Viabahn and Zilver PTX are relatively comparable. What about the price of the device? What role does it play in our selection of the current most cost-effective endovascular strategy for long SFA lesions?

In my institution Viabahn is more expensive than Zilver PTX with a relative cost premium of about 30%-50% depending on the treatment length. Of course, when treating long TASC C and D lesions any up-front difference in the costs of the devices used initially is more than made up for by any relative reduction in subsequent reinterventions.

So, there you have it. Look at the table as simply a current snapshot. In the future, we will benefit from additional trials and comparisons, not to mention better endovascular technologies to address symptomatic long SFA lesions.

Dr. Dake is the Thelma and Henry Doelger Professor of Cardiovascular Surgery at the Stanford (Calif.) School of Medicine. He disclosed that he is a member of the Peripheral Scientific Advisory Board: Abbott Vascular Member, is on the Aortic Medical Advisory Board: W. L. Gore, is a consultant for Cook Medical, Medtronic, and Surmodics Research, and receives grants/clinical trial support from W. L. Gore, Medtronic, and Novate.

References for table

1. J. Vasc. Surg. 2013;58:386-95.

2. J. Vasc. Surg. 2010;52:584-90.

3. J. Vasc. Interv. Radiol. 2013;24:165-73.

4. Cardiovasc. Interv. Radiol. 2015;38:25-32.

5. Circ. Cardiovasc. Interv. 2011;4:495-504.

6. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2013;61:2417-27.

7. J. Endovasc. Ther. 2011;18:613-23.

8. Zeller T. Oral presentations. 2014.

9. Yokoi H. Oral presentations. 2014.

Covered stent grafts in the SFA are still the endovascular champion in long lesions

BY DENNIS GABLE, M.D.

There remains a continued debate among investigators as to the best modality for treatment of stenosis/occlusion of the SFA especially with the recent advent of drug-eluting technology. However, I suggest that for long lesions over 15 cm only covered stent grafts continue to outperform the competition.

If we review the numerous studies available on treatment of SFA disease, the Viabahn-covered stent device (W. L. Gore & Associates, Flagstaff, Ariz.) is by far the most studied modality. There are currently 22 independent studies available providing data on 1,473 limbs. Several of these reports are multicenter studies and many of them are prospective randomized trials. Two of the most recent are the VIPER (J. Vasc. Intervent. Radiol. 2013;24:165-73) and VIASTAR study (JACC 2013;62:1320-27).

The VIPER study prospectively enrolled 119 patients (72 with TASC II C/D disease; mean lesion length 190 mm). Primary patency was reported at 73% at 1 year but in patients with less than 20% oversizing, as is recommended by the IFU, patency as high as 88% was noted. Additionally, there was no difference in patency in smaller-diameter vessels (5 mm) versus larger-diameter vessels (6-7 mm).

In a head-to-head randomized controlled trial of Viabahn to bare metal stents (BMS), the VIASTAR study enrolled 141 patients (72 in covered stent arm; mean lesion length 190 mm). On a per protocol evaluation, the patency at 1 year was 78% and 71% on an intention-to-treat evaluation with a patency of 70% and 63% respectively at 2 years. There was no statistical difference between the two evaluations on intention to treat vs. per protocol but there was clear superiority demonstrated against BMS.

Furthermore, in a prospective, randomized, head-to-head comparison of Viabahn to prosthetic above knee femoral popliteal bypass, it was shown that there was no difference in primary or secondary patency between the two groups out to 4 years follow-up (J. Vasc. Surg. 2010;52:584-91). This included an average lesion length of 25.6 cm with a primary and secondary patency of 59% and 74% in the Viabahn group and 58% and 71% in the surgery group. When compared to a large meta-analysis for femoral popliteal bypass outcomes reported on by Bates and AbuRahma in 2004 (J. Endovasc. Ther. 2004;11[suppl. II]:II-107–27), the patency for the surgical arm with prosthetic bypass in the above Viabahn study was similar at 4 years to the 38 peer-reviewed articles Bates et al. reviewed with over 4,000 limbs. The reported primary and secondary patency at 4 years for prosthetic femoral above knee popliteal bypass was 51% and 61%, respectively in his review. Although the above Viabahn study was not powered to formally demonstrate noninferiority to surgical bypass with prosthetic, it did strongly suggest and show just that.

How do we put these data together with the Zilver data and how do we decide what is best for our patients? Some operators have expressed concern over a perceived risk for a “higher rate of amputation” or “a worse Rutherford level of ischemia on presentation” if patients with the Viabahn stent graft occlude post procedure. Commonly, this results from extrapolation of prior studies looking at results of occlusion with an ePTFE bypass. In fact, review of peer-reviewed data reveal none of the prospective studies outlined above, or those currently available, demonstrate that either of these perceptions are true and there are no published prospective data that support these fears either. In the studies listed above as well as all current prospective studies available evaluating Viabahn usage, the highest rate of amputation reported was 5% by Fisher in 2006 with all of the remaining studies reporting an amputation rate of 2% or less (when reported). Moreover, it has not been demonstrated that patients with this device present with an increased level of ischemia secondary to sudden occlusion.

There is one report used to argue against the use of the Viabahn stent graft (J. Vasc. Surg. 2008;47:967-74). This study evaluated prospectively 109 patients (71 for claudication; 38 for critical limb ischemia) treated for SFA occlusive disease (mean lesion length 15.7 cm). Only 19 of the 109 patients (17%) were treated with Viabahn (17 for claudication; 2 for critical limb ischemia). The remaining limbs were treated with various other BMS devices (n=10). The authors concluded that patients initially treated with Viabahn who presented back with occlusion had a higher chance of presenting with acute symptoms (i.e., a worse Rutherford score). The lesion length treated in the Viabahn group, however, was nearly twice as long as all the other stent platforms combined (25.4 cm vs. 13.7 cm) and there was a higher level of tibial artery deterioration with thrombosis of the BMS group, compared with the Viabahn group (7.7% vs. 5.3%). The number of Viabahn patients presenting with acute thrombosis was not defined. With the small number of limbs treated in the Viabahn group, the conclusions expressed cannot be statistically supported.

What about the in-vogue DES device?

Dr. Dake and his colleagues recently presented 5-year data on the Zilver DES platform at VIVA 2014. He reported a primary patency at 5 years of 66.4% showing superiority to angioplasty alone as well as angioplasty with provisional stenting. This study enrolled 479 patients into the randomization arm and also had a registry arm that although often included in reporting of patency, does not stand up to the scrutiny of peer review. Even though there were some patients with longer lesions, the randomized arm mean lesion length was only 66 mm, which does not compare to the published longer mean lesion length of the Viabahn device. Bosiers et al. (J. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2013 54:115-222) reviewed 135 patients treated with the Zilver device (a subgroup derived from the 787 patients enrolled in the registry data of the Zilver trial) with a mean lesion length of 226 mm. They reported 77.6% primary patency but only at 1 year. Again, however, this is registry derived data and does not have the scientific validity of a randomized trial.

So what can I conclude from these experiences? We know today that covered stent grafts have been widely used and reported on, including by Dr. Dake himself (Radiology 2000 October;217:95-104) and all appear to have had similar conclusions.

The mean lesion length treated in these studies of Viabahn is often longer than 15 cm and nearly all studies report primary patency outcomes. Zilver supporters on the other hand are prone to quote TLR which is an inferior endpoint (as recently noted in an editorial by Dr. Russell Samson (Vasc. Spec. 2015;11:2). Costs of both devices are an issue but may vary by region and institution. However, Viabahn does have the advantage of longer devices, compared with the Zilver (15 and 25 cm vs. 10 cm) so fewer devices may be required to treat long lesions. Although short lesions may be better addressed with BMS or DES, for longer SFA lesions over 12-15 cm there are very few truly comparable data that argue against the use of Viabahn.

Dr. Gable is chief of vascular and endovascular surgery at The Heart Hospital Baylor Plano (Tex.). He is also an associate medical editor for Vascular Specialist. He disclosed that he is a consultant, speaker, and receives research support from W. L. Gore and Medtronic.

Head-to-head comparisons are lacking, but similar results have been reported

BY MICHAEL D. DAKE, M.D.

Well, at least one thing is for sure – we would not have been having this discussion a mere 10 years ago.

I remained sheepishly silent for most of my early career as well-intentioned invasive and noninvasive specialists criticized the state of evidence supporting the legitimacy of endovascular interventions as a competitive strategy to manage infrainguinal peripheral arterial disease. Good data from well-controlled randomized clinical trials were not available to make a case for endovascular therapies.

Over the recent decade and a half, however, a number of contributing factors have influenced thinking and what we now consider standard of care for symptomatic disease of the superficial femoral artery (SFA). The proposal of an “endovascular first” interventional approach has evolved to a consensually agreed upon management strategy by all interested disciplines.

This did not occur on a whim. Rather, out of the shadows of relative ignorance there slowly emerged a welcomed accumulation of a large number of publications that detail the outcomes of a wide variety of randomized trials with a range of endovascular devices. This has allowed us to enter an era where valid comparisons between interventional therapies is not only possible, but allows us to more appropriately offer care to vascular patients with more nuanced strategies. These are strategies that recognize subtleties between subgroups of individuals stratified on the basis of patient demographics and lesion characteristics in a way not appreciated prior to the recent spate of endovascular device studies.

Thus, thanks to the dedication and hard work of many, we are now at a stage where we can have meaningful dialogues on a variety of endovascular topics, such as the one at hand, and proponents can argue their perspectives armed with objective evidence to support their positions. In this discussion regarding covered stent grafts and drug-eluting stents, we wish we had even more data.

Specifically, we are missing direct head-to-head comparisons between the two devices in patients with long SFA lesions. So, what do we know?

Here are some fundamental facts: The most commonly used covered stent graft for management of femoropopliteal occlusive disease is the Viabahn endoprosthesis (W. L. Gore and Associates, Flagstaff, Ariz.). The prosthesis is composed of a self-expanding nitinol stent framework and expanded polytetrafluoroethylene (ePTFE) graft with its surface lined with a coating of covalently bound heparin (Propaten bioactive surface).The only approved drug-eluting stent with significant safety and effectiveness data available is the Zilver PTX paclitaxel-eluting, self-expanding nitinol stent (Cook Medical Inc., Bloomington, Ind.).

Now in terms of the proposition, we need to discuss the meaning of the word “long” with reference to the SFA. Just what do we consider a long SFA lesion? I think all of us could agree that an arterial stenosis or occlusion of 6 cm or less is short. Lesions between 5 cm or 6 cm to 10 cm or 12 cm in length are moderately long, and disease greater than 10 cm or 12 cm is commonly characterized as long. Segments of disease greater than 20 cm long are typically considered very long or extremely long lesions from an endovascular interventional perspective.

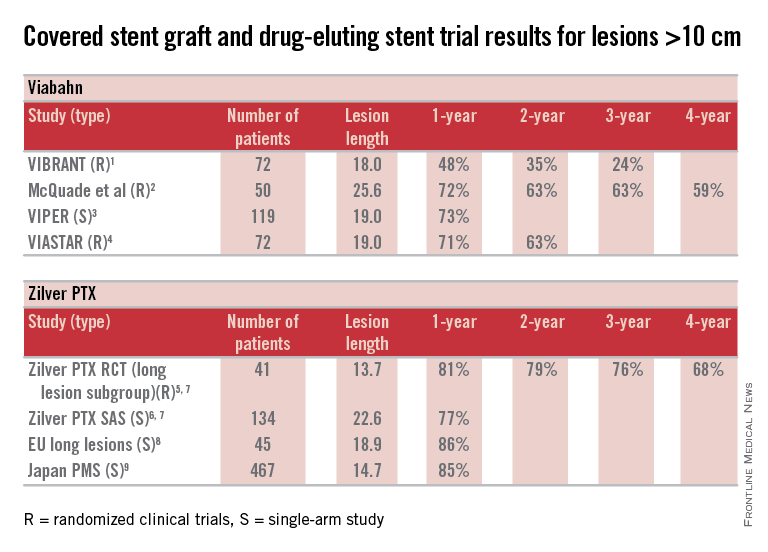

So, how can currently available trial outcomes help us? Below, I have compiled a table that includes most of the recent clinical trial data for Viabahn and Zilver PTX in patients with long SFA occlusive disease.

OK, what can we honestly say about these data besides recognizing that we are at risk when we make any conclusions based upon cross-trial comparisons? Such an accounting of results is fraught with problems, but what we can say is that the table grossly confirms the current consensus that both devices enhance the standard of care for long lesions over traditional balloon angioplasty (PTA) and bare metal stent technologies.

Beyond this, however, it is accepted that patency results with Viabahn are lesion-length immune – that is, outcomes in long and extremely long segments of disease are not very different from the patency achieved in short lesions. This is clearly different than what is traditionally found for interventions with PTA or bare metal stents. There is not enough controlled data for extremely long lesions to reach a conclusion on drug-eluting stents; however, there is an initial suggestion that they behave in a manner more similar to stent grafts than traditional devices.

Grossly, the table suggests that the midterm and available greater than 1-year patency results with Viabahn and Zilver PTX are relatively comparable. What about the price of the device? What role does it play in our selection of the current most cost-effective endovascular strategy for long SFA lesions?

In my institution Viabahn is more expensive than Zilver PTX with a relative cost premium of about 30%-50% depending on the treatment length. Of course, when treating long TASC C and D lesions any up-front difference in the costs of the devices used initially is more than made up for by any relative reduction in subsequent reinterventions.

So, there you have it. Look at the table as simply a current snapshot. In the future, we will benefit from additional trials and comparisons, not to mention better endovascular technologies to address symptomatic long SFA lesions.

Dr. Dake is the Thelma and Henry Doelger Professor of Cardiovascular Surgery at the Stanford (Calif.) School of Medicine. He disclosed that he is a member of the Peripheral Scientific Advisory Board: Abbott Vascular Member, is on the Aortic Medical Advisory Board: W. L. Gore, is a consultant for Cook Medical, Medtronic, and Surmodics Research, and receives grants/clinical trial support from W. L. Gore, Medtronic, and Novate.

References for table

1. J. Vasc. Surg. 2013;58:386-95.

2. J. Vasc. Surg. 2010;52:584-90.

3. J. Vasc. Interv. Radiol. 2013;24:165-73.

4. Cardiovasc. Interv. Radiol. 2015;38:25-32.

5. Circ. Cardiovasc. Interv. 2011;4:495-504.

6. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2013;61:2417-27.

7. J. Endovasc. Ther. 2011;18:613-23.

8. Zeller T. Oral presentations. 2014.

9. Yokoi H. Oral presentations. 2014.

Covered stent grafts in the SFA are still the endovascular champion in long lesions

BY DENNIS GABLE, M.D.

There remains a continued debate among investigators as to the best modality for treatment of stenosis/occlusion of the SFA especially with the recent advent of drug-eluting technology. However, I suggest that for long lesions over 15 cm only covered stent grafts continue to outperform the competition.

If we review the numerous studies available on treatment of SFA disease, the Viabahn-covered stent device (W. L. Gore & Associates, Flagstaff, Ariz.) is by far the most studied modality. There are currently 22 independent studies available providing data on 1,473 limbs. Several of these reports are multicenter studies and many of them are prospective randomized trials. Two of the most recent are the VIPER (J. Vasc. Intervent. Radiol. 2013;24:165-73) and VIASTAR study (JACC 2013;62:1320-27).

The VIPER study prospectively enrolled 119 patients (72 with TASC II C/D disease; mean lesion length 190 mm). Primary patency was reported at 73% at 1 year but in patients with less than 20% oversizing, as is recommended by the IFU, patency as high as 88% was noted. Additionally, there was no difference in patency in smaller-diameter vessels (5 mm) versus larger-diameter vessels (6-7 mm).

In a head-to-head randomized controlled trial of Viabahn to bare metal stents (BMS), the VIASTAR study enrolled 141 patients (72 in covered stent arm; mean lesion length 190 mm). On a per protocol evaluation, the patency at 1 year was 78% and 71% on an intention-to-treat evaluation with a patency of 70% and 63% respectively at 2 years. There was no statistical difference between the two evaluations on intention to treat vs. per protocol but there was clear superiority demonstrated against BMS.

Furthermore, in a prospective, randomized, head-to-head comparison of Viabahn to prosthetic above knee femoral popliteal bypass, it was shown that there was no difference in primary or secondary patency between the two groups out to 4 years follow-up (J. Vasc. Surg. 2010;52:584-91). This included an average lesion length of 25.6 cm with a primary and secondary patency of 59% and 74% in the Viabahn group and 58% and 71% in the surgery group. When compared to a large meta-analysis for femoral popliteal bypass outcomes reported on by Bates and AbuRahma in 2004 (J. Endovasc. Ther. 2004;11[suppl. II]:II-107–27), the patency for the surgical arm with prosthetic bypass in the above Viabahn study was similar at 4 years to the 38 peer-reviewed articles Bates et al. reviewed with over 4,000 limbs. The reported primary and secondary patency at 4 years for prosthetic femoral above knee popliteal bypass was 51% and 61%, respectively in his review. Although the above Viabahn study was not powered to formally demonstrate noninferiority to surgical bypass with prosthetic, it did strongly suggest and show just that.

How do we put these data together with the Zilver data and how do we decide what is best for our patients? Some operators have expressed concern over a perceived risk for a “higher rate of amputation” or “a worse Rutherford level of ischemia on presentation” if patients with the Viabahn stent graft occlude post procedure. Commonly, this results from extrapolation of prior studies looking at results of occlusion with an ePTFE bypass. In fact, review of peer-reviewed data reveal none of the prospective studies outlined above, or those currently available, demonstrate that either of these perceptions are true and there are no published prospective data that support these fears either. In the studies listed above as well as all current prospective studies available evaluating Viabahn usage, the highest rate of amputation reported was 5% by Fisher in 2006 with all of the remaining studies reporting an amputation rate of 2% or less (when reported). Moreover, it has not been demonstrated that patients with this device present with an increased level of ischemia secondary to sudden occlusion.

There is one report used to argue against the use of the Viabahn stent graft (J. Vasc. Surg. 2008;47:967-74). This study evaluated prospectively 109 patients (71 for claudication; 38 for critical limb ischemia) treated for SFA occlusive disease (mean lesion length 15.7 cm). Only 19 of the 109 patients (17%) were treated with Viabahn (17 for claudication; 2 for critical limb ischemia). The remaining limbs were treated with various other BMS devices (n=10). The authors concluded that patients initially treated with Viabahn who presented back with occlusion had a higher chance of presenting with acute symptoms (i.e., a worse Rutherford score). The lesion length treated in the Viabahn group, however, was nearly twice as long as all the other stent platforms combined (25.4 cm vs. 13.7 cm) and there was a higher level of tibial artery deterioration with thrombosis of the BMS group, compared with the Viabahn group (7.7% vs. 5.3%). The number of Viabahn patients presenting with acute thrombosis was not defined. With the small number of limbs treated in the Viabahn group, the conclusions expressed cannot be statistically supported.

What about the in-vogue DES device?

Dr. Dake and his colleagues recently presented 5-year data on the Zilver DES platform at VIVA 2014. He reported a primary patency at 5 years of 66.4% showing superiority to angioplasty alone as well as angioplasty with provisional stenting. This study enrolled 479 patients into the randomization arm and also had a registry arm that although often included in reporting of patency, does not stand up to the scrutiny of peer review. Even though there were some patients with longer lesions, the randomized arm mean lesion length was only 66 mm, which does not compare to the published longer mean lesion length of the Viabahn device. Bosiers et al. (J. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2013 54:115-222) reviewed 135 patients treated with the Zilver device (a subgroup derived from the 787 patients enrolled in the registry data of the Zilver trial) with a mean lesion length of 226 mm. They reported 77.6% primary patency but only at 1 year. Again, however, this is registry derived data and does not have the scientific validity of a randomized trial.

So what can I conclude from these experiences? We know today that covered stent grafts have been widely used and reported on, including by Dr. Dake himself (Radiology 2000 October;217:95-104) and all appear to have had similar conclusions.

The mean lesion length treated in these studies of Viabahn is often longer than 15 cm and nearly all studies report primary patency outcomes. Zilver supporters on the other hand are prone to quote TLR which is an inferior endpoint (as recently noted in an editorial by Dr. Russell Samson (Vasc. Spec. 2015;11:2). Costs of both devices are an issue but may vary by region and institution. However, Viabahn does have the advantage of longer devices, compared with the Zilver (15 and 25 cm vs. 10 cm) so fewer devices may be required to treat long lesions. Although short lesions may be better addressed with BMS or DES, for longer SFA lesions over 12-15 cm there are very few truly comparable data that argue against the use of Viabahn.

Dr. Gable is chief of vascular and endovascular surgery at The Heart Hospital Baylor Plano (Tex.). He is also an associate medical editor for Vascular Specialist. He disclosed that he is a consultant, speaker, and receives research support from W. L. Gore and Medtronic.

Head-to-head comparisons are lacking, but similar results have been reported

BY MICHAEL D. DAKE, M.D.

Well, at least one thing is for sure – we would not have been having this discussion a mere 10 years ago.

I remained sheepishly silent for most of my early career as well-intentioned invasive and noninvasive specialists criticized the state of evidence supporting the legitimacy of endovascular interventions as a competitive strategy to manage infrainguinal peripheral arterial disease. Good data from well-controlled randomized clinical trials were not available to make a case for endovascular therapies.

Over the recent decade and a half, however, a number of contributing factors have influenced thinking and what we now consider standard of care for symptomatic disease of the superficial femoral artery (SFA). The proposal of an “endovascular first” interventional approach has evolved to a consensually agreed upon management strategy by all interested disciplines.

This did not occur on a whim. Rather, out of the shadows of relative ignorance there slowly emerged a welcomed accumulation of a large number of publications that detail the outcomes of a wide variety of randomized trials with a range of endovascular devices. This has allowed us to enter an era where valid comparisons between interventional therapies is not only possible, but allows us to more appropriately offer care to vascular patients with more nuanced strategies. These are strategies that recognize subtleties between subgroups of individuals stratified on the basis of patient demographics and lesion characteristics in a way not appreciated prior to the recent spate of endovascular device studies.

Thus, thanks to the dedication and hard work of many, we are now at a stage where we can have meaningful dialogues on a variety of endovascular topics, such as the one at hand, and proponents can argue their perspectives armed with objective evidence to support their positions. In this discussion regarding covered stent grafts and drug-eluting stents, we wish we had even more data.

Specifically, we are missing direct head-to-head comparisons between the two devices in patients with long SFA lesions. So, what do we know?

Here are some fundamental facts: The most commonly used covered stent graft for management of femoropopliteal occlusive disease is the Viabahn endoprosthesis (W. L. Gore and Associates, Flagstaff, Ariz.). The prosthesis is composed of a self-expanding nitinol stent framework and expanded polytetrafluoroethylene (ePTFE) graft with its surface lined with a coating of covalently bound heparin (Propaten bioactive surface).The only approved drug-eluting stent with significant safety and effectiveness data available is the Zilver PTX paclitaxel-eluting, self-expanding nitinol stent (Cook Medical Inc., Bloomington, Ind.).

Now in terms of the proposition, we need to discuss the meaning of the word “long” with reference to the SFA. Just what do we consider a long SFA lesion? I think all of us could agree that an arterial stenosis or occlusion of 6 cm or less is short. Lesions between 5 cm or 6 cm to 10 cm or 12 cm in length are moderately long, and disease greater than 10 cm or 12 cm is commonly characterized as long. Segments of disease greater than 20 cm long are typically considered very long or extremely long lesions from an endovascular interventional perspective.

So, how can currently available trial outcomes help us? Below, I have compiled a table that includes most of the recent clinical trial data for Viabahn and Zilver PTX in patients with long SFA occlusive disease.

OK, what can we honestly say about these data besides recognizing that we are at risk when we make any conclusions based upon cross-trial comparisons? Such an accounting of results is fraught with problems, but what we can say is that the table grossly confirms the current consensus that both devices enhance the standard of care for long lesions over traditional balloon angioplasty (PTA) and bare metal stent technologies.

Beyond this, however, it is accepted that patency results with Viabahn are lesion-length immune – that is, outcomes in long and extremely long segments of disease are not very different from the patency achieved in short lesions. This is clearly different than what is traditionally found for interventions with PTA or bare metal stents. There is not enough controlled data for extremely long lesions to reach a conclusion on drug-eluting stents; however, there is an initial suggestion that they behave in a manner more similar to stent grafts than traditional devices.

Grossly, the table suggests that the midterm and available greater than 1-year patency results with Viabahn and Zilver PTX are relatively comparable. What about the price of the device? What role does it play in our selection of the current most cost-effective endovascular strategy for long SFA lesions?

In my institution Viabahn is more expensive than Zilver PTX with a relative cost premium of about 30%-50% depending on the treatment length. Of course, when treating long TASC C and D lesions any up-front difference in the costs of the devices used initially is more than made up for by any relative reduction in subsequent reinterventions.

So, there you have it. Look at the table as simply a current snapshot. In the future, we will benefit from additional trials and comparisons, not to mention better endovascular technologies to address symptomatic long SFA lesions.

Dr. Dake is the Thelma and Henry Doelger Professor of Cardiovascular Surgery at the Stanford (Calif.) School of Medicine. He disclosed that he is a member of the Peripheral Scientific Advisory Board: Abbott Vascular Member, is on the Aortic Medical Advisory Board: W. L. Gore, is a consultant for Cook Medical, Medtronic, and Surmodics Research, and receives grants/clinical trial support from W. L. Gore, Medtronic, and Novate.

References for table

1. J. Vasc. Surg. 2013;58:386-95.

2. J. Vasc. Surg. 2010;52:584-90.

3. J. Vasc. Interv. Radiol. 2013;24:165-73.

4. Cardiovasc. Interv. Radiol. 2015;38:25-32.

5. Circ. Cardiovasc. Interv. 2011;4:495-504.

6. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2013;61:2417-27.

7. J. Endovasc. Ther. 2011;18:613-23.

8. Zeller T. Oral presentations. 2014.

9. Yokoi H. Oral presentations. 2014.

Covered stent grafts in the SFA are still the endovascular champion in long lesions

BY DENNIS GABLE, M.D.