User login

Hospitalists' Role in the Ebola Response

Concern and fear over an infection and how best to contain its spread is a well‐known storyline dating back centuries before the germ theory was hypothesized. During the Plague of Athens in the fourth century bc, upon noticing that physicians and caregivers of the sick were most at risk of dying, the Greek historian and philosopher Thucydides wrote that thwarting the disease likely required more practical measures than simple prayer to the gods.[1] To this day, the fears of contracting disease often outstripor worse, overrideour practical or scientific understanding.

Ebola has rekindled past concerns about disease transmission, whether real or imagined. In this article we will describe the history of Ebola outside the United States as well as recent events in US hospitals. We will review guidelines for how to prepare hospitals to treat potential Ebola patients and highlight the key role that hospitalists can have in ensuring the safety of their patients and coworkers. We will also describe the emerging role of global health hospitalists, whose numbers are growing and whose expertise is ideally suited to improving hospital care in developing countries.

EBOLA EPIDEMICS AND HEALTH EQUITY

In the first identified Ebola outbreak in 1976 in Zaire, now the Democratic Republic of the Congo, patients arrived at local hospitals with symptoms that resembled common endemic illnesses like malaria, typhoid, and yellow fever. The ensuing deaths of 11 of the 17 staff members at 1 hospital were only an introduction to the deadly consequences of Ebola and the necessity of vigilant infection control. Unfortunately, not much has changed with each subsequent outbreak; to this day the heralding of an Ebola outbreak denotes the death of healthcare workers. Since the discovery of the Ebola virus 38 years ago, there have been nearly 30 recorded Ebola outbreaks. The mortality rates of prior outbreaks range widely between 25% and 90%; reports of the current outbreak's mortality falls within that range, between 50% and 70%. It is important to note that despite this high mortality, there had been no more than 1600 Ebola deaths worldwide before the 2014 West African pandemic.[2] In comparison, the number of deaths in Guinea, Sierra Leone, and Liberia approaches 6000.[3]

Although these disturbing figures have fueled public fear and panic in the United States, we wonder how many of these deaths were actually preventable. At the epicenter of the current Ebola virus disease (EVD) outbreak are 3 countries especially vulnerable to epidemics, with armed conflict recently crippling the health systems that have now just started to rebuild. When Liberia emerged from its second civil war in 2003, they had barely 50 physicians caring for a country of nearly 4 million.[4] In contrast with the devastating death toll in Liberia, it perhaps should not come as a surprise that out of the 10 known cases of Ebola that were treated in the United States and caught early, none have resulted in death. With an advanced healthcare infrastructure in place, the mortality rate for EVD in the United States has been close to zero. Although the true unpreventable case fatality rate in West Africa is unknown, the positive outcomes in the United States cases illustrate that hospitals can treat EVD successfully, provided that they are well staffed, supplied, and prepared.

Furthermore, the stark difference in access to quality healthcare between nations suggests that combating the virus should not be our only concern. In fact, EVD itself is only an acute symptom of a much larger, chronic problem with the health systems in Guinea, Sierra Leone, and Liberia. Western countries must direct more resources and attention to improving the overall quality of care in these countries, for although the underlying inequities may be limited to places like Guinea, Liberia, and Sierra Leone, the resulting threat is a global one.

PREPARING FOR THE FIGHT AGAINST EBOLA IN THE UNITED STATES

On September 25, 2014, Thomas Eric Duncan presented to Texas Health Presbyterian Hospital with fever, abdominal pain, and headache 11 days after transporting a pregnant neighbor in his home country of Liberia who later died of EVD. Duncan was discharged from the emergency room without admission. Three days later, on September 28, 2014, an ambulance was called and transported him to Texas Health where he was admitted. He was isolated and the hospital followed existing Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) guidelines for infection control. He was confirmed to have EVD on September 30, 2014. He was cared for by the healthcare providers at Texas Health Presbyterian Hospital, but despite their care, his condition deteriorated. Eric Duncan died on October 8, 2014. About 120 healthcare workers came into contact with the patient. None of his 48 contacts prior to admission to the hospital contracted the disease. However, 2 nurses who cared for him during his admission developed symptoms and were confirmed to have Ebola. An alarm was sounded across the United States, awakening hospitals to the reality of their vulnerability and need for preparedness.[5]

For any healthcare worker treating EVD, whether working in a hospital here in the United States or an Ebola treatment unit (ETU) in West Africa, intensive training is necessary to keep oneself safe. Although infection control is not a novel concept, the stakes have undoubtedly been raised, as even the smallest misstep can be deadly when dealing with the Ebola virus. We were participants in a 3‐day infection control training program conducted by the CDC in Anniston, Alabama, which aimed to prepare healthcare workers to assist with the Ebola response in West Africa. Throughout the training, we repeatedly donned and doffed personal protective equipment (PPE), following protocols established by the World Health Organization and Doctors Without Borders (Mdecins Sans Frontires):

- Use a combination of contact, droplet, and standard precautions, ensuring no area of skin is left uncovered.

- Enter and exit with a buddy; inspect one another for breaches at each step of donning, caring for the patient, and doffing.

- Wash gloved hands with 0.5% chlorine bleach between tasks and patients.

- Exit at the slightest breach of infection protocol.

- Doff PPE per protocol and under supervision; take great care not to contaminate oneself.

Doffing is considered the most difficult and also the most important part, with 7 pieces to remove and no less than 20 steps to do so. After 3 full days of training, although we felt more confident with the carefully choreographed movements of donning and doffing, we were also more aware of the many opportunities during which a breach could occur. Despite our repeated practice, the training staff was firm in telling us that we were still not prepared to work in an ETU. We had only undergone what could be called a cold training. To work in the hot zone of the ETUs, it is essential to undergo additional mentorship and training once in the field. We believe a similar approach to extensive training should be employed for all healthcare workers on the front lines of an Ebola response, both in the United States and abroad.

Given the complexity of the infection control practices above, questions have appropriately been raised about US healthcare facilities' aptitude at providing care for patients with EVD. Although hospitals have historically been focal point(s) for dissemination of infection of Ebola, this does not have to be the case.[6] With appropriate preparedness, training, and understanding of facility limitations, hospitals can also be places of confidence and healing.

Both Emory University and the University of Nebraska have successfully treated multiple Ebola patients without incurring further transmission.[7, 8] Much of their success comes from the work of longitudinal teams that are trained in infectious disease response on a regular basis, despite the rare occurrence of a serious outbreak. When Emory scaled up this team upon receiving a confirmed EVD patient, new members were required to pass a proficiency test prior to providing care. Emory's strict adherence to infection control and advanced preparation serve as a model for other institutions.

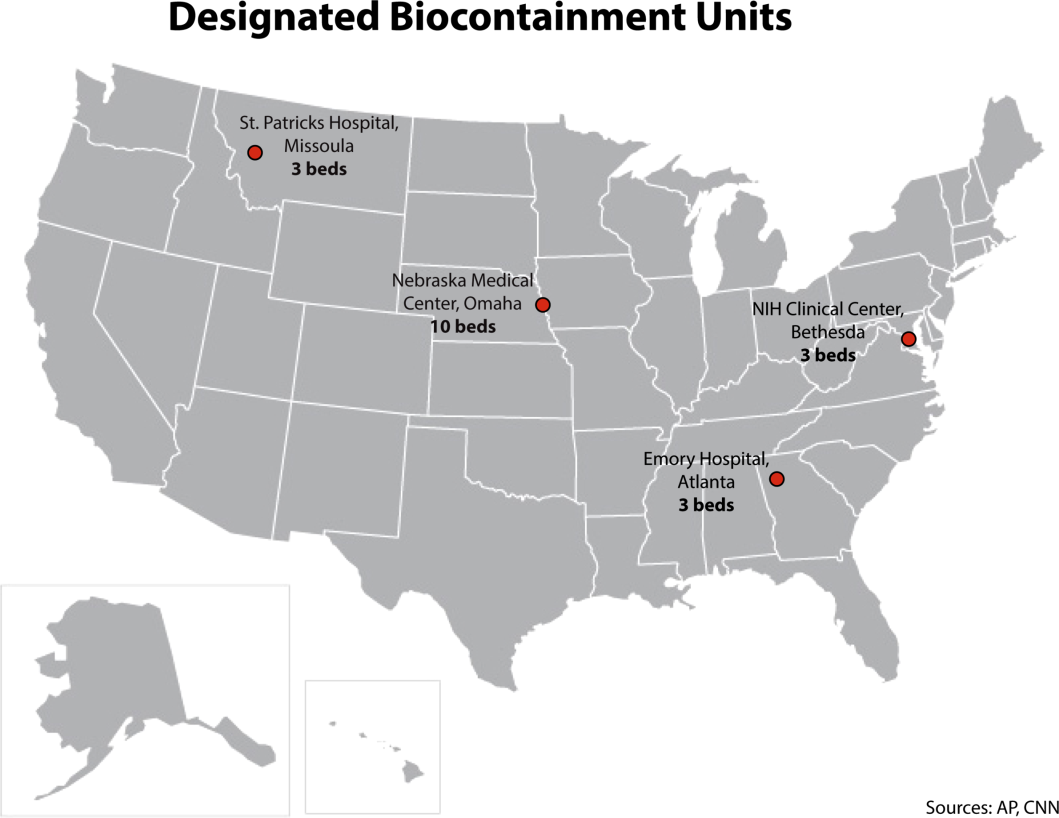

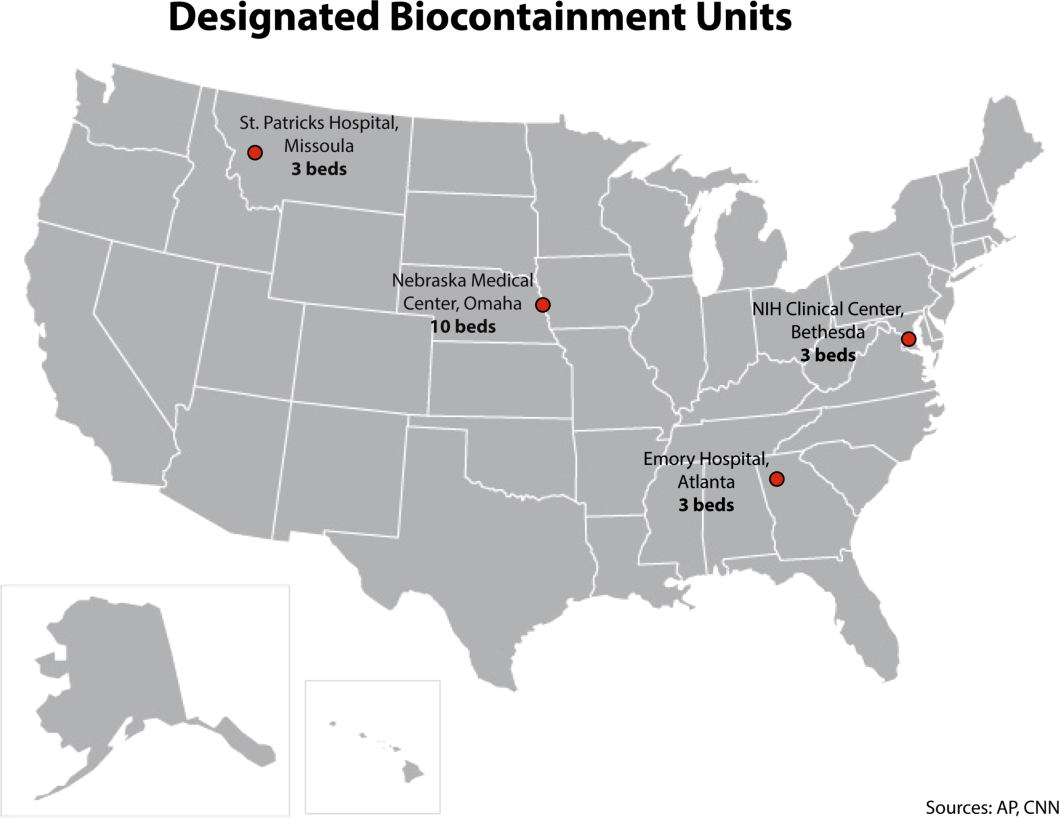

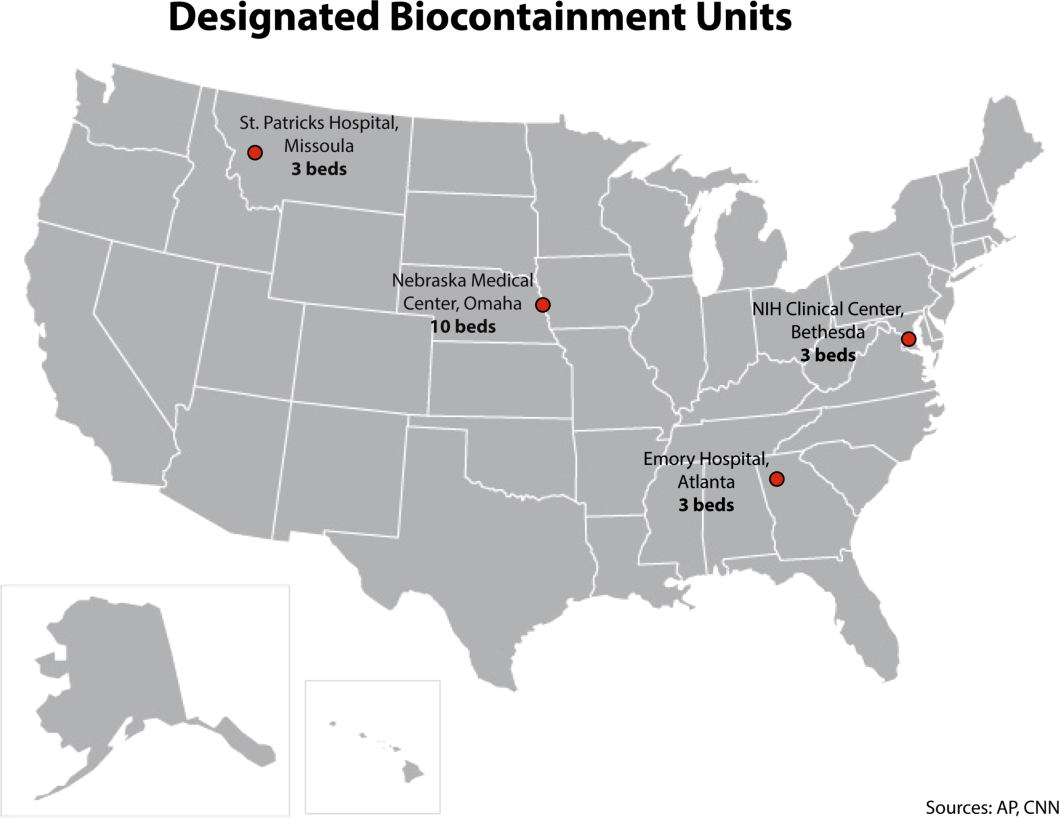

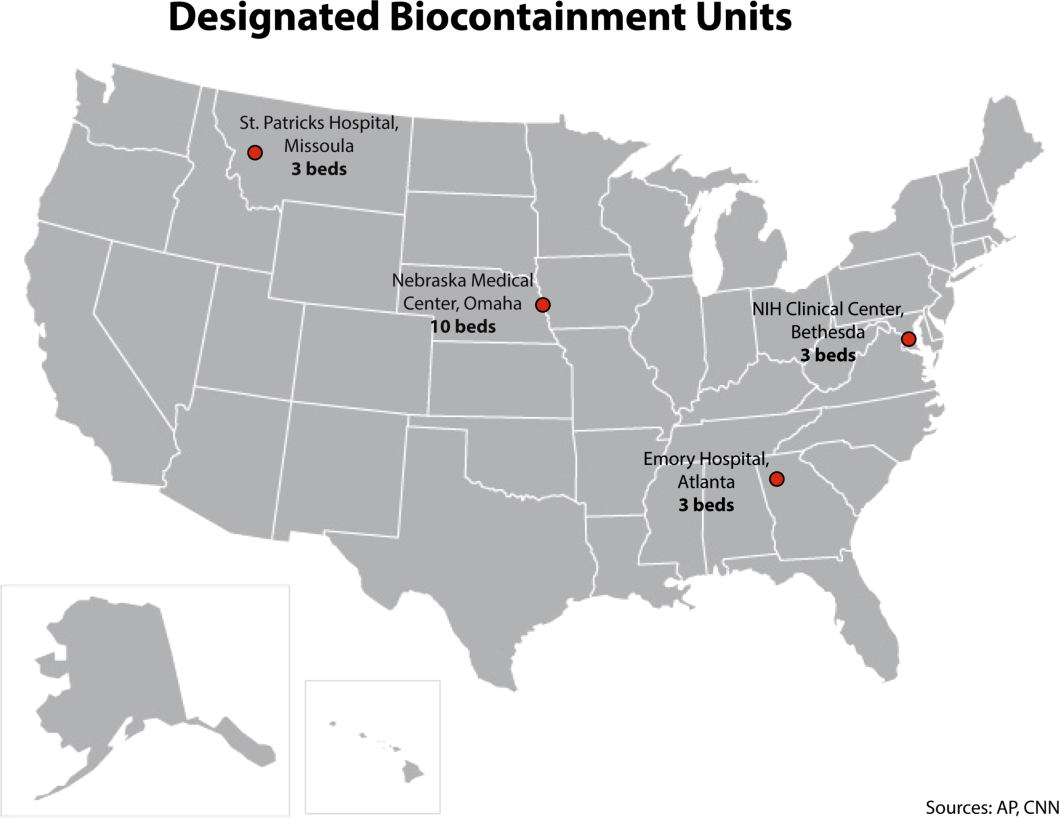

It is important to recognize that not all hospitals should be fully equipped and staffed for safe care of a patient with EVD. Much like in cases of high‐level trauma, regional centers should be identified, prepared, and available to be called upon in a time of need (Figure 1). At the writing of this article, guidelines for hospitals are evolving; most states, with input from federal and local officials, are moving toward designating regional referral centers. Although the number of designated facilities and standards for each vary by state, general preparedness for care of a patient with suspected or confirmed EVD should include: (1) a designated and trained care team, (2) appropriate and vetted operational protocols, (3) an assigned isolation unit with adequate space for the necessary specialized precautions, (4) separate laboratory and diagnostic capabilities, and (5) a working waste management plan.[9] Although not all facilities throughout the United States will have the capability to care for a patient with EVD, all hospitals must have an action plan.

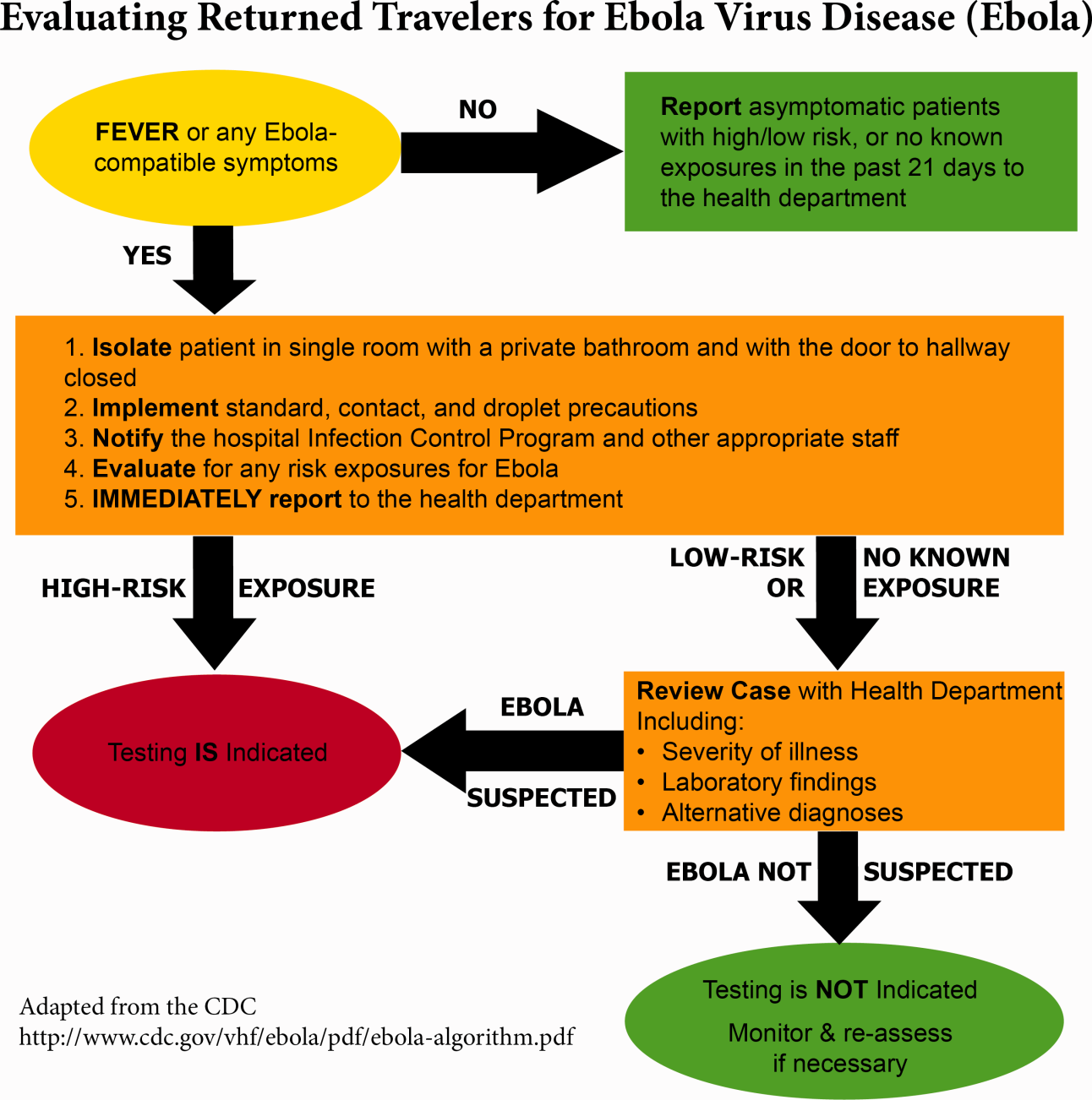

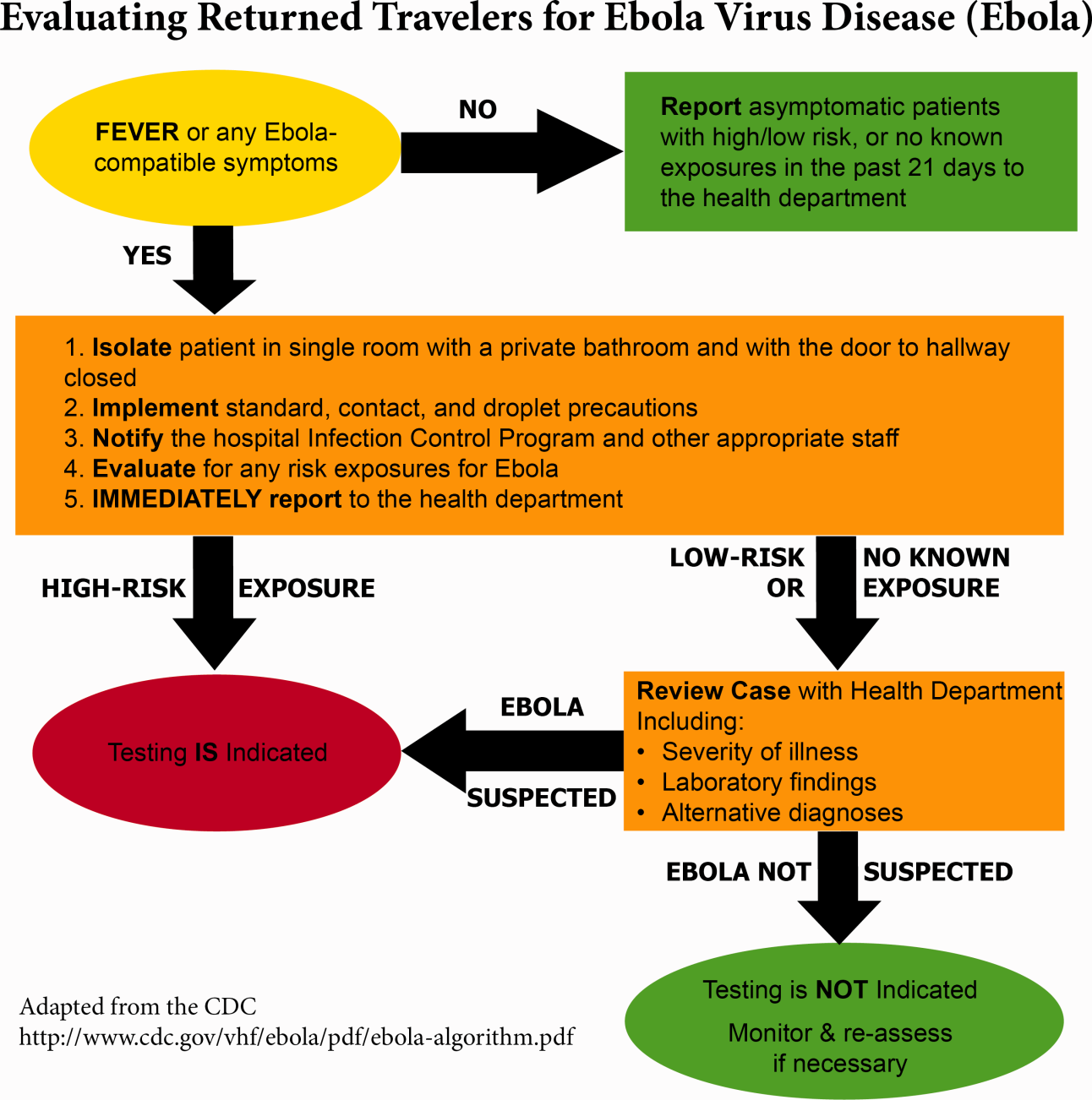

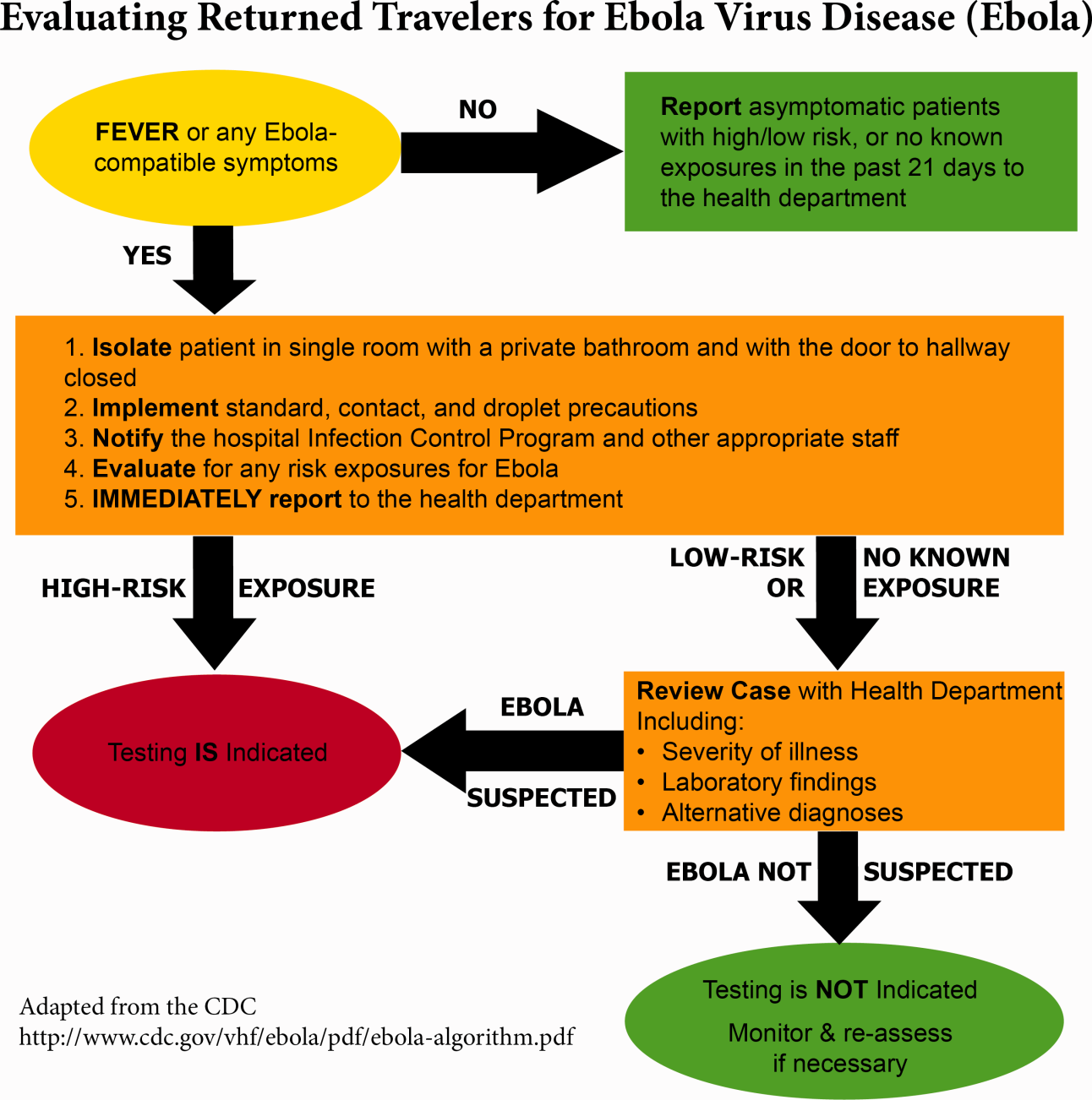

Triage is the first step; facilities should have well‐informed and trained staff prepared to perform assessments of potential cases safely (Figure 2). The ability to temporarily isolate and then efficiently transfer suspected or confirmed EVD patients to an appropriate facility also requires careful planning. Prompt identification, constant vigilance, and accurate histories all serve as stepping stones to a successful outcome and can protect employees and other patients in the process.

Within this proposed structure, hospitalists are uniquely equipped to play a leading role in EVD response. First, hospitalists are frequently responsible for interfacility transfer. Their intimate knowledge of this process and the collegiality they have fostered through its use are both assets in navigating the tiered referral system outlined above. Furthermore, as point people in the acute‐care setting who accept patients from emergency medicine colleagues, discuss cases with various consultants, and coordinate discharges with multidisciplinary teams on a daily basis, hospitalists have honed communication and leadership skills that are highly valuable in collaborative efforts. Finally, many hospitalists are also champions of quality and safety in their institutions. The focus on the process of continuous improvement is critical in the face of evolving challenges such as EVD.

GLOBAL HEALTH HOSPITALISTS

The Ebola outbreak is a global crisis that clearly illustrates the challenges of addressing highly infectious diseases in modern times. We have outlined the role of hospitalists and defined the steps toward adequate preparedness within our facilities. By following the measured and practical actions Thucydides advised, we can further strengthen our health systems and work toward the control of this outbreak in the United States. The important role of hospitalists can and should be extended to serve those in poor countries.

Over the last decade, health systems strengthening, health workforce training, and patient safety have come to the forefront of global health priorities, the same priorities that are also at the forefront of many hospitalists' aspirations. Shoeb et al. recently conducted a survey of global health hospitalists. They found that within the framework of global health, hospitalists are uniquely positioned to contribute to this growing field, particularly in areas such as quality improvement, safety, systems thinking, and medical education, all strengths of the hospital medicine model that could be translated to resource‐limited settings.[10]

We believe that hospitalists, with their unique positions and skills, are natural and necessary agents of action in this time of need. Our ultimate aim is for hospitalists to become actively engaged in addressing not only the current Ebola outbreak, but also the extreme inequity of healthcare globallyan inequity that lies at the heart of the current devastation in West Africa. We call upon hospital medicine leaders, from division chiefs to chairs of medicine to chief medical officers to support, encourage, and incentivize their staff and faculty to join the ranks of global health hospitalists as they work to both end gross inequities in healthcare abroad and protect our patients and ourselves back home.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful for Brett Lewis' assistance in the preparation of this article.

Disclosure

Nothing to report.

- . Infection control throughout history. Lancet Infect Dis. 2014;14(4):280.

- , . Ebola then and now. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:1663–1666.

- World Health Organization. Ebola response roadmap—situation report. Available at: http://www.who.int/csr/disease/ebola/situation‐reports/en/. Accessed November 2014.

- , . Effect of civil war on medical education in Liberia. Int J Emerg Med. 2011;4:6.

- , . Is the U.S. prepared for an Ebola outbreak? New York Times. October 10, 2014. Available at: http://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2014/10/09/us/is-the-us-prepared-for-an-ebola-outbreak.html?module=Search61(6):997–1003.

- . With good hospital practices, Emory rises to Ebola challenge. Kaiser Health News. U.S. News 8(3):162–163.

Concern and fear over an infection and how best to contain its spread is a well‐known storyline dating back centuries before the germ theory was hypothesized. During the Plague of Athens in the fourth century bc, upon noticing that physicians and caregivers of the sick were most at risk of dying, the Greek historian and philosopher Thucydides wrote that thwarting the disease likely required more practical measures than simple prayer to the gods.[1] To this day, the fears of contracting disease often outstripor worse, overrideour practical or scientific understanding.

Ebola has rekindled past concerns about disease transmission, whether real or imagined. In this article we will describe the history of Ebola outside the United States as well as recent events in US hospitals. We will review guidelines for how to prepare hospitals to treat potential Ebola patients and highlight the key role that hospitalists can have in ensuring the safety of their patients and coworkers. We will also describe the emerging role of global health hospitalists, whose numbers are growing and whose expertise is ideally suited to improving hospital care in developing countries.

EBOLA EPIDEMICS AND HEALTH EQUITY

In the first identified Ebola outbreak in 1976 in Zaire, now the Democratic Republic of the Congo, patients arrived at local hospitals with symptoms that resembled common endemic illnesses like malaria, typhoid, and yellow fever. The ensuing deaths of 11 of the 17 staff members at 1 hospital were only an introduction to the deadly consequences of Ebola and the necessity of vigilant infection control. Unfortunately, not much has changed with each subsequent outbreak; to this day the heralding of an Ebola outbreak denotes the death of healthcare workers. Since the discovery of the Ebola virus 38 years ago, there have been nearly 30 recorded Ebola outbreaks. The mortality rates of prior outbreaks range widely between 25% and 90%; reports of the current outbreak's mortality falls within that range, between 50% and 70%. It is important to note that despite this high mortality, there had been no more than 1600 Ebola deaths worldwide before the 2014 West African pandemic.[2] In comparison, the number of deaths in Guinea, Sierra Leone, and Liberia approaches 6000.[3]

Although these disturbing figures have fueled public fear and panic in the United States, we wonder how many of these deaths were actually preventable. At the epicenter of the current Ebola virus disease (EVD) outbreak are 3 countries especially vulnerable to epidemics, with armed conflict recently crippling the health systems that have now just started to rebuild. When Liberia emerged from its second civil war in 2003, they had barely 50 physicians caring for a country of nearly 4 million.[4] In contrast with the devastating death toll in Liberia, it perhaps should not come as a surprise that out of the 10 known cases of Ebola that were treated in the United States and caught early, none have resulted in death. With an advanced healthcare infrastructure in place, the mortality rate for EVD in the United States has been close to zero. Although the true unpreventable case fatality rate in West Africa is unknown, the positive outcomes in the United States cases illustrate that hospitals can treat EVD successfully, provided that they are well staffed, supplied, and prepared.

Furthermore, the stark difference in access to quality healthcare between nations suggests that combating the virus should not be our only concern. In fact, EVD itself is only an acute symptom of a much larger, chronic problem with the health systems in Guinea, Sierra Leone, and Liberia. Western countries must direct more resources and attention to improving the overall quality of care in these countries, for although the underlying inequities may be limited to places like Guinea, Liberia, and Sierra Leone, the resulting threat is a global one.

PREPARING FOR THE FIGHT AGAINST EBOLA IN THE UNITED STATES

On September 25, 2014, Thomas Eric Duncan presented to Texas Health Presbyterian Hospital with fever, abdominal pain, and headache 11 days after transporting a pregnant neighbor in his home country of Liberia who later died of EVD. Duncan was discharged from the emergency room without admission. Three days later, on September 28, 2014, an ambulance was called and transported him to Texas Health where he was admitted. He was isolated and the hospital followed existing Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) guidelines for infection control. He was confirmed to have EVD on September 30, 2014. He was cared for by the healthcare providers at Texas Health Presbyterian Hospital, but despite their care, his condition deteriorated. Eric Duncan died on October 8, 2014. About 120 healthcare workers came into contact with the patient. None of his 48 contacts prior to admission to the hospital contracted the disease. However, 2 nurses who cared for him during his admission developed symptoms and were confirmed to have Ebola. An alarm was sounded across the United States, awakening hospitals to the reality of their vulnerability and need for preparedness.[5]

For any healthcare worker treating EVD, whether working in a hospital here in the United States or an Ebola treatment unit (ETU) in West Africa, intensive training is necessary to keep oneself safe. Although infection control is not a novel concept, the stakes have undoubtedly been raised, as even the smallest misstep can be deadly when dealing with the Ebola virus. We were participants in a 3‐day infection control training program conducted by the CDC in Anniston, Alabama, which aimed to prepare healthcare workers to assist with the Ebola response in West Africa. Throughout the training, we repeatedly donned and doffed personal protective equipment (PPE), following protocols established by the World Health Organization and Doctors Without Borders (Mdecins Sans Frontires):

- Use a combination of contact, droplet, and standard precautions, ensuring no area of skin is left uncovered.

- Enter and exit with a buddy; inspect one another for breaches at each step of donning, caring for the patient, and doffing.

- Wash gloved hands with 0.5% chlorine bleach between tasks and patients.

- Exit at the slightest breach of infection protocol.

- Doff PPE per protocol and under supervision; take great care not to contaminate oneself.

Doffing is considered the most difficult and also the most important part, with 7 pieces to remove and no less than 20 steps to do so. After 3 full days of training, although we felt more confident with the carefully choreographed movements of donning and doffing, we were also more aware of the many opportunities during which a breach could occur. Despite our repeated practice, the training staff was firm in telling us that we were still not prepared to work in an ETU. We had only undergone what could be called a cold training. To work in the hot zone of the ETUs, it is essential to undergo additional mentorship and training once in the field. We believe a similar approach to extensive training should be employed for all healthcare workers on the front lines of an Ebola response, both in the United States and abroad.

Given the complexity of the infection control practices above, questions have appropriately been raised about US healthcare facilities' aptitude at providing care for patients with EVD. Although hospitals have historically been focal point(s) for dissemination of infection of Ebola, this does not have to be the case.[6] With appropriate preparedness, training, and understanding of facility limitations, hospitals can also be places of confidence and healing.

Both Emory University and the University of Nebraska have successfully treated multiple Ebola patients without incurring further transmission.[7, 8] Much of their success comes from the work of longitudinal teams that are trained in infectious disease response on a regular basis, despite the rare occurrence of a serious outbreak. When Emory scaled up this team upon receiving a confirmed EVD patient, new members were required to pass a proficiency test prior to providing care. Emory's strict adherence to infection control and advanced preparation serve as a model for other institutions.

It is important to recognize that not all hospitals should be fully equipped and staffed for safe care of a patient with EVD. Much like in cases of high‐level trauma, regional centers should be identified, prepared, and available to be called upon in a time of need (Figure 1). At the writing of this article, guidelines for hospitals are evolving; most states, with input from federal and local officials, are moving toward designating regional referral centers. Although the number of designated facilities and standards for each vary by state, general preparedness for care of a patient with suspected or confirmed EVD should include: (1) a designated and trained care team, (2) appropriate and vetted operational protocols, (3) an assigned isolation unit with adequate space for the necessary specialized precautions, (4) separate laboratory and diagnostic capabilities, and (5) a working waste management plan.[9] Although not all facilities throughout the United States will have the capability to care for a patient with EVD, all hospitals must have an action plan.

Triage is the first step; facilities should have well‐informed and trained staff prepared to perform assessments of potential cases safely (Figure 2). The ability to temporarily isolate and then efficiently transfer suspected or confirmed EVD patients to an appropriate facility also requires careful planning. Prompt identification, constant vigilance, and accurate histories all serve as stepping stones to a successful outcome and can protect employees and other patients in the process.

Within this proposed structure, hospitalists are uniquely equipped to play a leading role in EVD response. First, hospitalists are frequently responsible for interfacility transfer. Their intimate knowledge of this process and the collegiality they have fostered through its use are both assets in navigating the tiered referral system outlined above. Furthermore, as point people in the acute‐care setting who accept patients from emergency medicine colleagues, discuss cases with various consultants, and coordinate discharges with multidisciplinary teams on a daily basis, hospitalists have honed communication and leadership skills that are highly valuable in collaborative efforts. Finally, many hospitalists are also champions of quality and safety in their institutions. The focus on the process of continuous improvement is critical in the face of evolving challenges such as EVD.

GLOBAL HEALTH HOSPITALISTS

The Ebola outbreak is a global crisis that clearly illustrates the challenges of addressing highly infectious diseases in modern times. We have outlined the role of hospitalists and defined the steps toward adequate preparedness within our facilities. By following the measured and practical actions Thucydides advised, we can further strengthen our health systems and work toward the control of this outbreak in the United States. The important role of hospitalists can and should be extended to serve those in poor countries.

Over the last decade, health systems strengthening, health workforce training, and patient safety have come to the forefront of global health priorities, the same priorities that are also at the forefront of many hospitalists' aspirations. Shoeb et al. recently conducted a survey of global health hospitalists. They found that within the framework of global health, hospitalists are uniquely positioned to contribute to this growing field, particularly in areas such as quality improvement, safety, systems thinking, and medical education, all strengths of the hospital medicine model that could be translated to resource‐limited settings.[10]

We believe that hospitalists, with their unique positions and skills, are natural and necessary agents of action in this time of need. Our ultimate aim is for hospitalists to become actively engaged in addressing not only the current Ebola outbreak, but also the extreme inequity of healthcare globallyan inequity that lies at the heart of the current devastation in West Africa. We call upon hospital medicine leaders, from division chiefs to chairs of medicine to chief medical officers to support, encourage, and incentivize their staff and faculty to join the ranks of global health hospitalists as they work to both end gross inequities in healthcare abroad and protect our patients and ourselves back home.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful for Brett Lewis' assistance in the preparation of this article.

Disclosure

Nothing to report.

Concern and fear over an infection and how best to contain its spread is a well‐known storyline dating back centuries before the germ theory was hypothesized. During the Plague of Athens in the fourth century bc, upon noticing that physicians and caregivers of the sick were most at risk of dying, the Greek historian and philosopher Thucydides wrote that thwarting the disease likely required more practical measures than simple prayer to the gods.[1] To this day, the fears of contracting disease often outstripor worse, overrideour practical or scientific understanding.

Ebola has rekindled past concerns about disease transmission, whether real or imagined. In this article we will describe the history of Ebola outside the United States as well as recent events in US hospitals. We will review guidelines for how to prepare hospitals to treat potential Ebola patients and highlight the key role that hospitalists can have in ensuring the safety of their patients and coworkers. We will also describe the emerging role of global health hospitalists, whose numbers are growing and whose expertise is ideally suited to improving hospital care in developing countries.

EBOLA EPIDEMICS AND HEALTH EQUITY

In the first identified Ebola outbreak in 1976 in Zaire, now the Democratic Republic of the Congo, patients arrived at local hospitals with symptoms that resembled common endemic illnesses like malaria, typhoid, and yellow fever. The ensuing deaths of 11 of the 17 staff members at 1 hospital were only an introduction to the deadly consequences of Ebola and the necessity of vigilant infection control. Unfortunately, not much has changed with each subsequent outbreak; to this day the heralding of an Ebola outbreak denotes the death of healthcare workers. Since the discovery of the Ebola virus 38 years ago, there have been nearly 30 recorded Ebola outbreaks. The mortality rates of prior outbreaks range widely between 25% and 90%; reports of the current outbreak's mortality falls within that range, between 50% and 70%. It is important to note that despite this high mortality, there had been no more than 1600 Ebola deaths worldwide before the 2014 West African pandemic.[2] In comparison, the number of deaths in Guinea, Sierra Leone, and Liberia approaches 6000.[3]

Although these disturbing figures have fueled public fear and panic in the United States, we wonder how many of these deaths were actually preventable. At the epicenter of the current Ebola virus disease (EVD) outbreak are 3 countries especially vulnerable to epidemics, with armed conflict recently crippling the health systems that have now just started to rebuild. When Liberia emerged from its second civil war in 2003, they had barely 50 physicians caring for a country of nearly 4 million.[4] In contrast with the devastating death toll in Liberia, it perhaps should not come as a surprise that out of the 10 known cases of Ebola that were treated in the United States and caught early, none have resulted in death. With an advanced healthcare infrastructure in place, the mortality rate for EVD in the United States has been close to zero. Although the true unpreventable case fatality rate in West Africa is unknown, the positive outcomes in the United States cases illustrate that hospitals can treat EVD successfully, provided that they are well staffed, supplied, and prepared.

Furthermore, the stark difference in access to quality healthcare between nations suggests that combating the virus should not be our only concern. In fact, EVD itself is only an acute symptom of a much larger, chronic problem with the health systems in Guinea, Sierra Leone, and Liberia. Western countries must direct more resources and attention to improving the overall quality of care in these countries, for although the underlying inequities may be limited to places like Guinea, Liberia, and Sierra Leone, the resulting threat is a global one.

PREPARING FOR THE FIGHT AGAINST EBOLA IN THE UNITED STATES

On September 25, 2014, Thomas Eric Duncan presented to Texas Health Presbyterian Hospital with fever, abdominal pain, and headache 11 days after transporting a pregnant neighbor in his home country of Liberia who later died of EVD. Duncan was discharged from the emergency room without admission. Three days later, on September 28, 2014, an ambulance was called and transported him to Texas Health where he was admitted. He was isolated and the hospital followed existing Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) guidelines for infection control. He was confirmed to have EVD on September 30, 2014. He was cared for by the healthcare providers at Texas Health Presbyterian Hospital, but despite their care, his condition deteriorated. Eric Duncan died on October 8, 2014. About 120 healthcare workers came into contact with the patient. None of his 48 contacts prior to admission to the hospital contracted the disease. However, 2 nurses who cared for him during his admission developed symptoms and were confirmed to have Ebola. An alarm was sounded across the United States, awakening hospitals to the reality of their vulnerability and need for preparedness.[5]

For any healthcare worker treating EVD, whether working in a hospital here in the United States or an Ebola treatment unit (ETU) in West Africa, intensive training is necessary to keep oneself safe. Although infection control is not a novel concept, the stakes have undoubtedly been raised, as even the smallest misstep can be deadly when dealing with the Ebola virus. We were participants in a 3‐day infection control training program conducted by the CDC in Anniston, Alabama, which aimed to prepare healthcare workers to assist with the Ebola response in West Africa. Throughout the training, we repeatedly donned and doffed personal protective equipment (PPE), following protocols established by the World Health Organization and Doctors Without Borders (Mdecins Sans Frontires):

- Use a combination of contact, droplet, and standard precautions, ensuring no area of skin is left uncovered.

- Enter and exit with a buddy; inspect one another for breaches at each step of donning, caring for the patient, and doffing.

- Wash gloved hands with 0.5% chlorine bleach between tasks and patients.

- Exit at the slightest breach of infection protocol.

- Doff PPE per protocol and under supervision; take great care not to contaminate oneself.

Doffing is considered the most difficult and also the most important part, with 7 pieces to remove and no less than 20 steps to do so. After 3 full days of training, although we felt more confident with the carefully choreographed movements of donning and doffing, we were also more aware of the many opportunities during which a breach could occur. Despite our repeated practice, the training staff was firm in telling us that we were still not prepared to work in an ETU. We had only undergone what could be called a cold training. To work in the hot zone of the ETUs, it is essential to undergo additional mentorship and training once in the field. We believe a similar approach to extensive training should be employed for all healthcare workers on the front lines of an Ebola response, both in the United States and abroad.

Given the complexity of the infection control practices above, questions have appropriately been raised about US healthcare facilities' aptitude at providing care for patients with EVD. Although hospitals have historically been focal point(s) for dissemination of infection of Ebola, this does not have to be the case.[6] With appropriate preparedness, training, and understanding of facility limitations, hospitals can also be places of confidence and healing.

Both Emory University and the University of Nebraska have successfully treated multiple Ebola patients without incurring further transmission.[7, 8] Much of their success comes from the work of longitudinal teams that are trained in infectious disease response on a regular basis, despite the rare occurrence of a serious outbreak. When Emory scaled up this team upon receiving a confirmed EVD patient, new members were required to pass a proficiency test prior to providing care. Emory's strict adherence to infection control and advanced preparation serve as a model for other institutions.

It is important to recognize that not all hospitals should be fully equipped and staffed for safe care of a patient with EVD. Much like in cases of high‐level trauma, regional centers should be identified, prepared, and available to be called upon in a time of need (Figure 1). At the writing of this article, guidelines for hospitals are evolving; most states, with input from federal and local officials, are moving toward designating regional referral centers. Although the number of designated facilities and standards for each vary by state, general preparedness for care of a patient with suspected or confirmed EVD should include: (1) a designated and trained care team, (2) appropriate and vetted operational protocols, (3) an assigned isolation unit with adequate space for the necessary specialized precautions, (4) separate laboratory and diagnostic capabilities, and (5) a working waste management plan.[9] Although not all facilities throughout the United States will have the capability to care for a patient with EVD, all hospitals must have an action plan.

Triage is the first step; facilities should have well‐informed and trained staff prepared to perform assessments of potential cases safely (Figure 2). The ability to temporarily isolate and then efficiently transfer suspected or confirmed EVD patients to an appropriate facility also requires careful planning. Prompt identification, constant vigilance, and accurate histories all serve as stepping stones to a successful outcome and can protect employees and other patients in the process.

Within this proposed structure, hospitalists are uniquely equipped to play a leading role in EVD response. First, hospitalists are frequently responsible for interfacility transfer. Their intimate knowledge of this process and the collegiality they have fostered through its use are both assets in navigating the tiered referral system outlined above. Furthermore, as point people in the acute‐care setting who accept patients from emergency medicine colleagues, discuss cases with various consultants, and coordinate discharges with multidisciplinary teams on a daily basis, hospitalists have honed communication and leadership skills that are highly valuable in collaborative efforts. Finally, many hospitalists are also champions of quality and safety in their institutions. The focus on the process of continuous improvement is critical in the face of evolving challenges such as EVD.

GLOBAL HEALTH HOSPITALISTS

The Ebola outbreak is a global crisis that clearly illustrates the challenges of addressing highly infectious diseases in modern times. We have outlined the role of hospitalists and defined the steps toward adequate preparedness within our facilities. By following the measured and practical actions Thucydides advised, we can further strengthen our health systems and work toward the control of this outbreak in the United States. The important role of hospitalists can and should be extended to serve those in poor countries.

Over the last decade, health systems strengthening, health workforce training, and patient safety have come to the forefront of global health priorities, the same priorities that are also at the forefront of many hospitalists' aspirations. Shoeb et al. recently conducted a survey of global health hospitalists. They found that within the framework of global health, hospitalists are uniquely positioned to contribute to this growing field, particularly in areas such as quality improvement, safety, systems thinking, and medical education, all strengths of the hospital medicine model that could be translated to resource‐limited settings.[10]

We believe that hospitalists, with their unique positions and skills, are natural and necessary agents of action in this time of need. Our ultimate aim is for hospitalists to become actively engaged in addressing not only the current Ebola outbreak, but also the extreme inequity of healthcare globallyan inequity that lies at the heart of the current devastation in West Africa. We call upon hospital medicine leaders, from division chiefs to chairs of medicine to chief medical officers to support, encourage, and incentivize their staff and faculty to join the ranks of global health hospitalists as they work to both end gross inequities in healthcare abroad and protect our patients and ourselves back home.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful for Brett Lewis' assistance in the preparation of this article.

Disclosure

Nothing to report.

- . Infection control throughout history. Lancet Infect Dis. 2014;14(4):280.

- , . Ebola then and now. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:1663–1666.

- World Health Organization. Ebola response roadmap—situation report. Available at: http://www.who.int/csr/disease/ebola/situation‐reports/en/. Accessed November 2014.

- , . Effect of civil war on medical education in Liberia. Int J Emerg Med. 2011;4:6.

- , . Is the U.S. prepared for an Ebola outbreak? New York Times. October 10, 2014. Available at: http://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2014/10/09/us/is-the-us-prepared-for-an-ebola-outbreak.html?module=Search61(6):997–1003.

- . With good hospital practices, Emory rises to Ebola challenge. Kaiser Health News. U.S. News 8(3):162–163.

- . Infection control throughout history. Lancet Infect Dis. 2014;14(4):280.

- , . Ebola then and now. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:1663–1666.

- World Health Organization. Ebola response roadmap—situation report. Available at: http://www.who.int/csr/disease/ebola/situation‐reports/en/. Accessed November 2014.

- , . Effect of civil war on medical education in Liberia. Int J Emerg Med. 2011;4:6.

- , . Is the U.S. prepared for an Ebola outbreak? New York Times. October 10, 2014. Available at: http://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2014/10/09/us/is-the-us-prepared-for-an-ebola-outbreak.html?module=Search61(6):997–1003.

- . With good hospital practices, Emory rises to Ebola challenge. Kaiser Health News. U.S. News 8(3):162–163.

© 2014 Society of Hospital Medicine

69%: hospitals with perfect hand-hygiene compliance

69%: the percentage of hospitals that had perfect compliance with the Leapfrog Group employer coalition’s safe practices for hand hygiene in its 2013 annual quality survey of 1,437 U.S. hospitals.

The CDC estimates 2 million patients annually acquire hospital-acquired infections (HAIs), often spread by contaminated hands of healthcare workers.

Urban hospitals performed better than rural hospitals in compliance with Leapfrog’s standard.

69%: the percentage of hospitals that had perfect compliance with the Leapfrog Group employer coalition’s safe practices for hand hygiene in its 2013 annual quality survey of 1,437 U.S. hospitals.

The CDC estimates 2 million patients annually acquire hospital-acquired infections (HAIs), often spread by contaminated hands of healthcare workers.

Urban hospitals performed better than rural hospitals in compliance with Leapfrog’s standard.

69%: the percentage of hospitals that had perfect compliance with the Leapfrog Group employer coalition’s safe practices for hand hygiene in its 2013 annual quality survey of 1,437 U.S. hospitals.

The CDC estimates 2 million patients annually acquire hospital-acquired infections (HAIs), often spread by contaminated hands of healthcare workers.

Urban hospitals performed better than rural hospitals in compliance with Leapfrog’s standard.

FDA issues new pregnancy/lactation drug label standards

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration has issued a final rule requiring content and format changes to pregnancy and lactation labeling information for prescription drugs and biologic products.

The long-awaited “Content and Format of Labeling for Human Prescription Drug and Biological Products; Requirements for Pregnancy and Lactation Labeling, or the Pregnancy and Lactation Labeling Rule”(PLLR) is part of broad effort by the FDA to improve the content and format of prescription drug labeling. The PLLR, which finalizes many of the provisions in a proposed rule issued in May 2008 after input from numerous stakeholders, calls for replacement of the current A, B, C, D, and X drug classification system with more detailed information about the risks and benefits of use during pregnancy and breastfeeding.

The rule will take effect June 30, 2015.

Under the PLLR, labels will be required to include three detailed subsections entitled Pregnancy, Lactation, and Females and Males of Reproductive Potential. Each will include a risk summary, a discussion of the supporting data, and relevant information to help providers make prescribing and counseling decisions, according to the FDA. If no data are available to guide decision making, this must be stated.

The Pregnancy subsection combines the existing Pregnancy and Labor and Delivery subsections, and will address use of the drug during pregnancy as well as provide information about relevant registries that collect and maintain data on the use of the product in pregnant women. The Lactation subsection replaces the existing Nursing Mothers subsection, and will include information about use of the product during breastfeeding, including the amount of drug in breast milk and potential effects on the breastfed child. The new Females and Males of Reproductive Potential subsection will address pregnancy testing, contraception, and fertility issues as they relate to use of the product.

The existing A, B, C, D, and X categories were frequently misinterpreted as a grading system, giving an over simplified view of product risk, according to Dr. Sandra Kweder, deputy director of the Office of New Drugs in the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research.

The new, more detailed approach to labeling will better address the complex risk-benefit considerations inherent in prescribing decisions during pregnancy and lactation, she said during a press briefing.

“I’m excited because clinicians will, going forward, be able to rely on FDA-approved drug labeling for comprehensive, chronically relevant, and user-friendly information in this part of labeling – something that has been missing for many years,” she said, noting that the changes are particularly important, given that the more than 6 million women who become pregnant each year in the United States take an average of 3-5 different prescription products during the course of their pregnancy and while breastfeeding.

“It is our hope that this new system will help their health care professionals and these women as they discuss treatment options,” she said.

Importantly, the PLLR ensures that more robust and informative data about drugs will be provided than ever before – and in a manner that speaks directly to the concerns that are common among providers, she said.

In addition to the elimination of the letter categories and the addition of the three new subsections, the use of standardized risk statement also was eliminated, as these had the same limitations as the letter categories. A section on inadvertent exposure also was eliminated due to redundancy, as the risk would be the same as with intentional exposure.

The rule also requires that labels be updated as they become outdated.

Much of the information that will be included on the new labels, which will be phased in for existing drugs and required immediately for drugs approved after June 30, 2015, was already included, but was scattered and difficult to find. The new formatting requirements provides for consistency across labels by pulling this information together in one place, Dr. Kweder said.

In an official statement, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists applauded the rule for “taking needed steps to increase understanding about the effect of prescription medicine on women during pregnancy and lactation.”

“The FDA’s updated method of presenting information about both risk and benefit will improve the ability of all physicians to treat their pregnant and breastfeeding patients, as well as women who may become pregnant. It will also help more women to understand and take part in their health care decision making,” according to the ACOG statement, which also noted that the organization hopes the new content on prescription drug and biological product labels will “provide added incentives for clinical research as well as participation in patient registries.”

Christina Chambers, Ph.D., professor of pediatrics and director of clinical research for the department of pediatrics at the University of California, San Diego, also praised the new labeling rule, noting in an interview that “the final rule has been long awaited by many who work in the field of counseling pregnant and breastfeeding women about risks and safety of prescription medications, such as counselors with organizations like MotherToBaby, a service of the Organization of Teratology Information Specialists, which provides information about medication and other exposures during pregnancy and breastfeeding, and which was involved in development of the final rule.

“The MotherToBaby counselors located throughout the United States who answer questions about medication exposures for hundreds of women every day, have struggled for years with trying to explain the not-so-useful A, B, C, D, X pregnancy categories to patients and providers alike who commonly misinterpret their meaning. The new label format is much more content rich and evidence-based, and encompasses the larger picture of the safety data in the context of treatment (or lack of treatment) of the maternal condition. This is a huge step forward – and will make even more clear how critical the need is for more human pregnancy data for all medications likely to be used by women of reproductive age,” she said.

Dr. Chambers is the program director for MotherToBaby California, and director of the MotherToBaby research center at the University of California, San Diego. She reported having no relevant disclosures.

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration has issued a final rule requiring content and format changes to pregnancy and lactation labeling information for prescription drugs and biologic products.

The long-awaited “Content and Format of Labeling for Human Prescription Drug and Biological Products; Requirements for Pregnancy and Lactation Labeling, or the Pregnancy and Lactation Labeling Rule”(PLLR) is part of broad effort by the FDA to improve the content and format of prescription drug labeling. The PLLR, which finalizes many of the provisions in a proposed rule issued in May 2008 after input from numerous stakeholders, calls for replacement of the current A, B, C, D, and X drug classification system with more detailed information about the risks and benefits of use during pregnancy and breastfeeding.

The rule will take effect June 30, 2015.

Under the PLLR, labels will be required to include three detailed subsections entitled Pregnancy, Lactation, and Females and Males of Reproductive Potential. Each will include a risk summary, a discussion of the supporting data, and relevant information to help providers make prescribing and counseling decisions, according to the FDA. If no data are available to guide decision making, this must be stated.

The Pregnancy subsection combines the existing Pregnancy and Labor and Delivery subsections, and will address use of the drug during pregnancy as well as provide information about relevant registries that collect and maintain data on the use of the product in pregnant women. The Lactation subsection replaces the existing Nursing Mothers subsection, and will include information about use of the product during breastfeeding, including the amount of drug in breast milk and potential effects on the breastfed child. The new Females and Males of Reproductive Potential subsection will address pregnancy testing, contraception, and fertility issues as they relate to use of the product.

The existing A, B, C, D, and X categories were frequently misinterpreted as a grading system, giving an over simplified view of product risk, according to Dr. Sandra Kweder, deputy director of the Office of New Drugs in the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research.

The new, more detailed approach to labeling will better address the complex risk-benefit considerations inherent in prescribing decisions during pregnancy and lactation, she said during a press briefing.

“I’m excited because clinicians will, going forward, be able to rely on FDA-approved drug labeling for comprehensive, chronically relevant, and user-friendly information in this part of labeling – something that has been missing for many years,” she said, noting that the changes are particularly important, given that the more than 6 million women who become pregnant each year in the United States take an average of 3-5 different prescription products during the course of their pregnancy and while breastfeeding.

“It is our hope that this new system will help their health care professionals and these women as they discuss treatment options,” she said.

Importantly, the PLLR ensures that more robust and informative data about drugs will be provided than ever before – and in a manner that speaks directly to the concerns that are common among providers, she said.

In addition to the elimination of the letter categories and the addition of the three new subsections, the use of standardized risk statement also was eliminated, as these had the same limitations as the letter categories. A section on inadvertent exposure also was eliminated due to redundancy, as the risk would be the same as with intentional exposure.

The rule also requires that labels be updated as they become outdated.

Much of the information that will be included on the new labels, which will be phased in for existing drugs and required immediately for drugs approved after June 30, 2015, was already included, but was scattered and difficult to find. The new formatting requirements provides for consistency across labels by pulling this information together in one place, Dr. Kweder said.

In an official statement, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists applauded the rule for “taking needed steps to increase understanding about the effect of prescription medicine on women during pregnancy and lactation.”

“The FDA’s updated method of presenting information about both risk and benefit will improve the ability of all physicians to treat their pregnant and breastfeeding patients, as well as women who may become pregnant. It will also help more women to understand and take part in their health care decision making,” according to the ACOG statement, which also noted that the organization hopes the new content on prescription drug and biological product labels will “provide added incentives for clinical research as well as participation in patient registries.”

Christina Chambers, Ph.D., professor of pediatrics and director of clinical research for the department of pediatrics at the University of California, San Diego, also praised the new labeling rule, noting in an interview that “the final rule has been long awaited by many who work in the field of counseling pregnant and breastfeeding women about risks and safety of prescription medications, such as counselors with organizations like MotherToBaby, a service of the Organization of Teratology Information Specialists, which provides information about medication and other exposures during pregnancy and breastfeeding, and which was involved in development of the final rule.

“The MotherToBaby counselors located throughout the United States who answer questions about medication exposures for hundreds of women every day, have struggled for years with trying to explain the not-so-useful A, B, C, D, X pregnancy categories to patients and providers alike who commonly misinterpret their meaning. The new label format is much more content rich and evidence-based, and encompasses the larger picture of the safety data in the context of treatment (or lack of treatment) of the maternal condition. This is a huge step forward – and will make even more clear how critical the need is for more human pregnancy data for all medications likely to be used by women of reproductive age,” she said.

Dr. Chambers is the program director for MotherToBaby California, and director of the MotherToBaby research center at the University of California, San Diego. She reported having no relevant disclosures.

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration has issued a final rule requiring content and format changes to pregnancy and lactation labeling information for prescription drugs and biologic products.

The long-awaited “Content and Format of Labeling for Human Prescription Drug and Biological Products; Requirements for Pregnancy and Lactation Labeling, or the Pregnancy and Lactation Labeling Rule”(PLLR) is part of broad effort by the FDA to improve the content and format of prescription drug labeling. The PLLR, which finalizes many of the provisions in a proposed rule issued in May 2008 after input from numerous stakeholders, calls for replacement of the current A, B, C, D, and X drug classification system with more detailed information about the risks and benefits of use during pregnancy and breastfeeding.

The rule will take effect June 30, 2015.

Under the PLLR, labels will be required to include three detailed subsections entitled Pregnancy, Lactation, and Females and Males of Reproductive Potential. Each will include a risk summary, a discussion of the supporting data, and relevant information to help providers make prescribing and counseling decisions, according to the FDA. If no data are available to guide decision making, this must be stated.

The Pregnancy subsection combines the existing Pregnancy and Labor and Delivery subsections, and will address use of the drug during pregnancy as well as provide information about relevant registries that collect and maintain data on the use of the product in pregnant women. The Lactation subsection replaces the existing Nursing Mothers subsection, and will include information about use of the product during breastfeeding, including the amount of drug in breast milk and potential effects on the breastfed child. The new Females and Males of Reproductive Potential subsection will address pregnancy testing, contraception, and fertility issues as they relate to use of the product.

The existing A, B, C, D, and X categories were frequently misinterpreted as a grading system, giving an over simplified view of product risk, according to Dr. Sandra Kweder, deputy director of the Office of New Drugs in the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research.

The new, more detailed approach to labeling will better address the complex risk-benefit considerations inherent in prescribing decisions during pregnancy and lactation, she said during a press briefing.

“I’m excited because clinicians will, going forward, be able to rely on FDA-approved drug labeling for comprehensive, chronically relevant, and user-friendly information in this part of labeling – something that has been missing for many years,” she said, noting that the changes are particularly important, given that the more than 6 million women who become pregnant each year in the United States take an average of 3-5 different prescription products during the course of their pregnancy and while breastfeeding.

“It is our hope that this new system will help their health care professionals and these women as they discuss treatment options,” she said.

Importantly, the PLLR ensures that more robust and informative data about drugs will be provided than ever before – and in a manner that speaks directly to the concerns that are common among providers, she said.

In addition to the elimination of the letter categories and the addition of the three new subsections, the use of standardized risk statement also was eliminated, as these had the same limitations as the letter categories. A section on inadvertent exposure also was eliminated due to redundancy, as the risk would be the same as with intentional exposure.

The rule also requires that labels be updated as they become outdated.

Much of the information that will be included on the new labels, which will be phased in for existing drugs and required immediately for drugs approved after June 30, 2015, was already included, but was scattered and difficult to find. The new formatting requirements provides for consistency across labels by pulling this information together in one place, Dr. Kweder said.

In an official statement, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists applauded the rule for “taking needed steps to increase understanding about the effect of prescription medicine on women during pregnancy and lactation.”

“The FDA’s updated method of presenting information about both risk and benefit will improve the ability of all physicians to treat their pregnant and breastfeeding patients, as well as women who may become pregnant. It will also help more women to understand and take part in their health care decision making,” according to the ACOG statement, which also noted that the organization hopes the new content on prescription drug and biological product labels will “provide added incentives for clinical research as well as participation in patient registries.”

Christina Chambers, Ph.D., professor of pediatrics and director of clinical research for the department of pediatrics at the University of California, San Diego, also praised the new labeling rule, noting in an interview that “the final rule has been long awaited by many who work in the field of counseling pregnant and breastfeeding women about risks and safety of prescription medications, such as counselors with organizations like MotherToBaby, a service of the Organization of Teratology Information Specialists, which provides information about medication and other exposures during pregnancy and breastfeeding, and which was involved in development of the final rule.

“The MotherToBaby counselors located throughout the United States who answer questions about medication exposures for hundreds of women every day, have struggled for years with trying to explain the not-so-useful A, B, C, D, X pregnancy categories to patients and providers alike who commonly misinterpret their meaning. The new label format is much more content rich and evidence-based, and encompasses the larger picture of the safety data in the context of treatment (or lack of treatment) of the maternal condition. This is a huge step forward – and will make even more clear how critical the need is for more human pregnancy data for all medications likely to be used by women of reproductive age,” she said.

Dr. Chambers is the program director for MotherToBaby California, and director of the MotherToBaby research center at the University of California, San Diego. She reported having no relevant disclosures.

$167 billion: hospital payments forfeited for choosing not to expand Medicaid

$167 billion: Amount of federal Medicaid reimbursement payments that hospitals will forego between 2013 and 2022 in states that have opted not to expand their state programs under the 2010 Affordable Care Act.

For every $1 a state spends on expanding Medicaid, $13.41 in federal funding flows into the state, according to a new report from the Urban Institute and Robert Wood Johnson Foundation.

$167 billion: Amount of federal Medicaid reimbursement payments that hospitals will forego between 2013 and 2022 in states that have opted not to expand their state programs under the 2010 Affordable Care Act.

For every $1 a state spends on expanding Medicaid, $13.41 in federal funding flows into the state, according to a new report from the Urban Institute and Robert Wood Johnson Foundation.

$167 billion: Amount of federal Medicaid reimbursement payments that hospitals will forego between 2013 and 2022 in states that have opted not to expand their state programs under the 2010 Affordable Care Act.

For every $1 a state spends on expanding Medicaid, $13.41 in federal funding flows into the state, according to a new report from the Urban Institute and Robert Wood Johnson Foundation.

UpToDate Adds Palliative Care

UpToDate, a leading clinical decision support resource for physicians, in July added palliative care as the newest of its 22 medical specialties. The palliative care section covers a variety of topics focused on improving symptoms and providing best quality of life for patients with serious illnesses. The new service resulted from two years of extensive collaboration by a team of 100 leading palliative care specialists from around the world, led by Harvard Medical School palliative care physicians J. Andrew Billings, MD, and Susan D. Block, MD, reviewing and grading the body of research and scientific literature on palliative care.

UpToDate, a leading clinical decision support resource for physicians, in July added palliative care as the newest of its 22 medical specialties. The palliative care section covers a variety of topics focused on improving symptoms and providing best quality of life for patients with serious illnesses. The new service resulted from two years of extensive collaboration by a team of 100 leading palliative care specialists from around the world, led by Harvard Medical School palliative care physicians J. Andrew Billings, MD, and Susan D. Block, MD, reviewing and grading the body of research and scientific literature on palliative care.

UpToDate, a leading clinical decision support resource for physicians, in July added palliative care as the newest of its 22 medical specialties. The palliative care section covers a variety of topics focused on improving symptoms and providing best quality of life for patients with serious illnesses. The new service resulted from two years of extensive collaboration by a team of 100 leading palliative care specialists from around the world, led by Harvard Medical School palliative care physicians J. Andrew Billings, MD, and Susan D. Block, MD, reviewing and grading the body of research and scientific literature on palliative care.

Preventing recurrent staphylococcal skin and soft tissue infection

A frequent referral to our pediatric infectious disease outpatient program at Boston Medical Center is the child with recurrent skin and soft tissue infection. Most often, the child is an infant, toddler, or adolescent; the child is otherwise well but has had two or three prior episodes of skin infection; the infections are typically peri-inguinal including the buttocks, but may involve the face, back, thighs, or scalp. The families are often frustrated and hoping for a solution. Are there effective strategies for reducing recurrences?

Several recent studies provide insights and can be helpful in forming an evidence-based approach that offers modest benefit for reducing the risk of recurrence. Most recently, Kaplan et al. (Clin. Inf. Dis. 2014;58:679-82) reported on a clinical trial of sodium hypochlorite bleach baths combined with hygienic measures (frequent hand washing with soap, cutting fingernails short, using towels or washcloths and clothing without sharing, and daily bathing or showering), compared with hygienic measures alone. The treatment group received twice-weekly hypochlorite baths with 5 mL household bleach (Clorox-Regular 6.0% hypochlorite) per gallon of bath water, followed by moisturizer. Most children were colonized with methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA)(approximately 70%) or methicillin-susceptible S. aureus (MSSA)(approximately 30%). In the 12-month follow-up, 20% of children had recurrent skin or soft tissue infection (SSTI). Risk factors for recurrence were young age (<6 years) and burden of colonization (number of colonized sites). A small, nonstatistically significant benefit was observed in the treatment group with a 17% incidence of SSTI, compared with 20.9% in controls (P = 0.15). The authors concluded a bleach bath plus hygiene measures was associated with about a 20% nonstatistically significant decrease in recurrent community-acquired SSTI. No adverse effects of bleach baths were identified.

A second open-label, randomized study by Fritz et al. (Clin. Inf. Dis. 2012;54:743-51) evaluated the value of individual decolonization, compared with household decolonization, in children 6 months through 20 years of age with prior community-acquired SSTI. Cases were randomized to individual decolonization regimens (hygiene, 2% mupirocin for 5 days and 4% chlorhexidine daily body washes) or to household decolonization. Staphylococcal colonization was evaluated at 1, 3, 6, and 12 months. No differences in the rate of eradication of S. aureus were observed between the two strategies, except at 3 months where a greater proportion of children randomized to household decolonization were culture negative. Despite the lack of impact on colonization, SSTI documented by a physician was less common in children where decolonization was householdwide. After 12 months, 36% of children in the household decolonization sites had recurrent SSTI, compared with 55% in the individual decolonization stratum (P = .03). The authors concluded that household decolonization reduces SSTI in both the individual and household contacts.

Another approach to decolonization has been the use of oral antibiotics in combination with mupirocin and hexachloradine. Although data are limited, Miller et al. (Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2012;56:1084-6) reported on a small cohort of 31 prospectively evaluated patients with recurrent community-acquired MRSA skin infections. Individuals received nasal mupirocin, topical hexachlorophene body wash, and an oral antibiotic based on susceptibility testing (doxycycline, minocycline, or trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole). In the 6 months prior to enrollment, the mean rate of SSTI was three infections per person (range, 2-30). The mean number of MRSA infections after the intervention decreased significantly from 0.84 infections per month to 0.03 infections per month during the 5.2-month follow-up. In general, the regimens were well tolerated with minor gastrointestinal complaints. The authors concluded that the combination of systemic and topical antimicrobials was associated with subsequent decreases in community-acquired MRSA SSTI; however, they acknowledged that without a control group, they were unable to be certain that the decrease was due to the prescribed regimen.

Our current approach for children referred with recurrent SSTI is household decolonization with nasal mupirocin and daily hexachloradine baths or showers or hypochlorite baths. The mupirocin is prescribed for 5-10 days; the hexachloradine/hypochlorite baths, for several months. We also stress the need for hygiene, including washing towels and linens in hot water, and cleaning surfaces and items such as remote controls with hypochlorite solutions. Although the value of environmental decontamination is unknown, studies by Uhlemann et al. (PLOS ONE 2011;6: e22407) demonstrated excess contamination of household surfaces in homes of SSTI cases. If recurrences continue, the addition of an antimicrobial agent is considered. We reserve doxycycline for children over 8 years of age and prescribe trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole for those younger than 8 years. We also will ask about pets although we are aware of only anecdotal reports where treating the family dog or cat has aborted recurrent disease in the patients.

In summary, recurrent SSTI is common, especially among young children. The burden of colonization appears related to both the risk for recurrent disease and the risk for transmission within the household. Reducing colonization is valuable for decreasing the incidence of recurrent SSTI both for the individual as well as the household members. The current strategies demonstrate modest success, but as many as 30%-40% of patients will continue to have recurrent SSTI. Education about the early signs of infection, early evaluation of SSTI, and appropriate management (topical treatment, incision and drainage, or systemic antibiotics) are successful strategies for limiting progression to invasive staphylococcal disease.

Dr. Pelton is chief of pediatric infectious disease and coordinator of the maternal-child HIV program at Boston Medical Center. Dr. Yildirim is a fellow in pediatric infectious disease and an epidemiologist, at Boston Medical Center. To comment, e-mail Dr. Pelton and Dr. Yildirim at [email protected].

A frequent referral to our pediatric infectious disease outpatient program at Boston Medical Center is the child with recurrent skin and soft tissue infection. Most often, the child is an infant, toddler, or adolescent; the child is otherwise well but has had two or three prior episodes of skin infection; the infections are typically peri-inguinal including the buttocks, but may involve the face, back, thighs, or scalp. The families are often frustrated and hoping for a solution. Are there effective strategies for reducing recurrences?

Several recent studies provide insights and can be helpful in forming an evidence-based approach that offers modest benefit for reducing the risk of recurrence. Most recently, Kaplan et al. (Clin. Inf. Dis. 2014;58:679-82) reported on a clinical trial of sodium hypochlorite bleach baths combined with hygienic measures (frequent hand washing with soap, cutting fingernails short, using towels or washcloths and clothing without sharing, and daily bathing or showering), compared with hygienic measures alone. The treatment group received twice-weekly hypochlorite baths with 5 mL household bleach (Clorox-Regular 6.0% hypochlorite) per gallon of bath water, followed by moisturizer. Most children were colonized with methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA)(approximately 70%) or methicillin-susceptible S. aureus (MSSA)(approximately 30%). In the 12-month follow-up, 20% of children had recurrent skin or soft tissue infection (SSTI). Risk factors for recurrence were young age (<6 years) and burden of colonization (number of colonized sites). A small, nonstatistically significant benefit was observed in the treatment group with a 17% incidence of SSTI, compared with 20.9% in controls (P = 0.15). The authors concluded a bleach bath plus hygiene measures was associated with about a 20% nonstatistically significant decrease in recurrent community-acquired SSTI. No adverse effects of bleach baths were identified.

A second open-label, randomized study by Fritz et al. (Clin. Inf. Dis. 2012;54:743-51) evaluated the value of individual decolonization, compared with household decolonization, in children 6 months through 20 years of age with prior community-acquired SSTI. Cases were randomized to individual decolonization regimens (hygiene, 2% mupirocin for 5 days and 4% chlorhexidine daily body washes) or to household decolonization. Staphylococcal colonization was evaluated at 1, 3, 6, and 12 months. No differences in the rate of eradication of S. aureus were observed between the two strategies, except at 3 months where a greater proportion of children randomized to household decolonization were culture negative. Despite the lack of impact on colonization, SSTI documented by a physician was less common in children where decolonization was householdwide. After 12 months, 36% of children in the household decolonization sites had recurrent SSTI, compared with 55% in the individual decolonization stratum (P = .03). The authors concluded that household decolonization reduces SSTI in both the individual and household contacts.

Another approach to decolonization has been the use of oral antibiotics in combination with mupirocin and hexachloradine. Although data are limited, Miller et al. (Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2012;56:1084-6) reported on a small cohort of 31 prospectively evaluated patients with recurrent community-acquired MRSA skin infections. Individuals received nasal mupirocin, topical hexachlorophene body wash, and an oral antibiotic based on susceptibility testing (doxycycline, minocycline, or trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole). In the 6 months prior to enrollment, the mean rate of SSTI was three infections per person (range, 2-30). The mean number of MRSA infections after the intervention decreased significantly from 0.84 infections per month to 0.03 infections per month during the 5.2-month follow-up. In general, the regimens were well tolerated with minor gastrointestinal complaints. The authors concluded that the combination of systemic and topical antimicrobials was associated with subsequent decreases in community-acquired MRSA SSTI; however, they acknowledged that without a control group, they were unable to be certain that the decrease was due to the prescribed regimen.

Our current approach for children referred with recurrent SSTI is household decolonization with nasal mupirocin and daily hexachloradine baths or showers or hypochlorite baths. The mupirocin is prescribed for 5-10 days; the hexachloradine/hypochlorite baths, for several months. We also stress the need for hygiene, including washing towels and linens in hot water, and cleaning surfaces and items such as remote controls with hypochlorite solutions. Although the value of environmental decontamination is unknown, studies by Uhlemann et al. (PLOS ONE 2011;6: e22407) demonstrated excess contamination of household surfaces in homes of SSTI cases. If recurrences continue, the addition of an antimicrobial agent is considered. We reserve doxycycline for children over 8 years of age and prescribe trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole for those younger than 8 years. We also will ask about pets although we are aware of only anecdotal reports where treating the family dog or cat has aborted recurrent disease in the patients.

In summary, recurrent SSTI is common, especially among young children. The burden of colonization appears related to both the risk for recurrent disease and the risk for transmission within the household. Reducing colonization is valuable for decreasing the incidence of recurrent SSTI both for the individual as well as the household members. The current strategies demonstrate modest success, but as many as 30%-40% of patients will continue to have recurrent SSTI. Education about the early signs of infection, early evaluation of SSTI, and appropriate management (topical treatment, incision and drainage, or systemic antibiotics) are successful strategies for limiting progression to invasive staphylococcal disease.

Dr. Pelton is chief of pediatric infectious disease and coordinator of the maternal-child HIV program at Boston Medical Center. Dr. Yildirim is a fellow in pediatric infectious disease and an epidemiologist, at Boston Medical Center. To comment, e-mail Dr. Pelton and Dr. Yildirim at [email protected].

A frequent referral to our pediatric infectious disease outpatient program at Boston Medical Center is the child with recurrent skin and soft tissue infection. Most often, the child is an infant, toddler, or adolescent; the child is otherwise well but has had two or three prior episodes of skin infection; the infections are typically peri-inguinal including the buttocks, but may involve the face, back, thighs, or scalp. The families are often frustrated and hoping for a solution. Are there effective strategies for reducing recurrences?