User login

Antibiotic Overprescribing Sparks Call for Stronger Stewardship

Antibiotic overprescription remains a problem in the U.S. and abroad and shows no signs of slowing. A study published in the October 2014 issue of JAMA reports that nearly half of all hospitalized patients receive antibiotics, and the drugs most commonly prescribed are broad-spectrum antibiotics, which have been linked with promoting the spread of antibiotic-resistant bacteria. Based on a one-day prevalence survey of more than 11,000 patients in 183 U.S. hospitals in 2011, the study notes that half of inpatients prescribed antibiotics received two or more of them. The CDC estimates that 20% to 50% of all antibiotics prescribed in U.S. hospitals are either unnecessary or inappropriate, and many of them count adverse drug reactions among their side effects .

While a growing body of evidence suggests that hospital-based antibiotic stewardship programs can optimize treatment, reduce antibacterial side effects, and save money, a study published September 2014 in JAMA says those benefits may be lost post-discharge. Results of a randomized trial of an outpatient antimicrobial stewardship intervention found that an initial 50% reduction in antibiotic prescriptions was lost when their targeted interventions ceased.

“These data suggest that audit and feedback was a vital element of this intervention and that antimicrobial stewardship requires continued, active efforts to sustain initial improvements,” says lead author Jeffrey S. Gerber, MD, PhD, CHCP, attending physician in infectious diseases at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia.

The federal government has taken a three-pronged approach to the problem: a report from the President’s Council of Advisors on Science and Technology with recommendations for monitoring superbugs and slowing their spread; an executive order issued by President Obama on September 18, 2014 with a commitment to “accelerate scientific research and facilitate the development of new antibacterial drugs;” and the creation of a national task force charged with designing a national strategy to combat antibiotic overuse by February 2015.

The President’s Council report notes that bacteria are becoming resistant to antibiotics in large part because these drugs are overprescribed to patients and overused in animals raised for food. The report recommends the CDC develop rules by 2017 requiring hospitals and nursing homes to implement best practices for antibiotic use.

Antibiotic overprescription remains a problem in the U.S. and abroad and shows no signs of slowing. A study published in the October 2014 issue of JAMA reports that nearly half of all hospitalized patients receive antibiotics, and the drugs most commonly prescribed are broad-spectrum antibiotics, which have been linked with promoting the spread of antibiotic-resistant bacteria. Based on a one-day prevalence survey of more than 11,000 patients in 183 U.S. hospitals in 2011, the study notes that half of inpatients prescribed antibiotics received two or more of them. The CDC estimates that 20% to 50% of all antibiotics prescribed in U.S. hospitals are either unnecessary or inappropriate, and many of them count adverse drug reactions among their side effects .

While a growing body of evidence suggests that hospital-based antibiotic stewardship programs can optimize treatment, reduce antibacterial side effects, and save money, a study published September 2014 in JAMA says those benefits may be lost post-discharge. Results of a randomized trial of an outpatient antimicrobial stewardship intervention found that an initial 50% reduction in antibiotic prescriptions was lost when their targeted interventions ceased.

“These data suggest that audit and feedback was a vital element of this intervention and that antimicrobial stewardship requires continued, active efforts to sustain initial improvements,” says lead author Jeffrey S. Gerber, MD, PhD, CHCP, attending physician in infectious diseases at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia.

The federal government has taken a three-pronged approach to the problem: a report from the President’s Council of Advisors on Science and Technology with recommendations for monitoring superbugs and slowing their spread; an executive order issued by President Obama on September 18, 2014 with a commitment to “accelerate scientific research and facilitate the development of new antibacterial drugs;” and the creation of a national task force charged with designing a national strategy to combat antibiotic overuse by February 2015.

The President’s Council report notes that bacteria are becoming resistant to antibiotics in large part because these drugs are overprescribed to patients and overused in animals raised for food. The report recommends the CDC develop rules by 2017 requiring hospitals and nursing homes to implement best practices for antibiotic use.

Antibiotic overprescription remains a problem in the U.S. and abroad and shows no signs of slowing. A study published in the October 2014 issue of JAMA reports that nearly half of all hospitalized patients receive antibiotics, and the drugs most commonly prescribed are broad-spectrum antibiotics, which have been linked with promoting the spread of antibiotic-resistant bacteria. Based on a one-day prevalence survey of more than 11,000 patients in 183 U.S. hospitals in 2011, the study notes that half of inpatients prescribed antibiotics received two or more of them. The CDC estimates that 20% to 50% of all antibiotics prescribed in U.S. hospitals are either unnecessary or inappropriate, and many of them count adverse drug reactions among their side effects .

While a growing body of evidence suggests that hospital-based antibiotic stewardship programs can optimize treatment, reduce antibacterial side effects, and save money, a study published September 2014 in JAMA says those benefits may be lost post-discharge. Results of a randomized trial of an outpatient antimicrobial stewardship intervention found that an initial 50% reduction in antibiotic prescriptions was lost when their targeted interventions ceased.

“These data suggest that audit and feedback was a vital element of this intervention and that antimicrobial stewardship requires continued, active efforts to sustain initial improvements,” says lead author Jeffrey S. Gerber, MD, PhD, CHCP, attending physician in infectious diseases at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia.

The federal government has taken a three-pronged approach to the problem: a report from the President’s Council of Advisors on Science and Technology with recommendations for monitoring superbugs and slowing their spread; an executive order issued by President Obama on September 18, 2014 with a commitment to “accelerate scientific research and facilitate the development of new antibacterial drugs;” and the creation of a national task force charged with designing a national strategy to combat antibiotic overuse by February 2015.

The President’s Council report notes that bacteria are becoming resistant to antibiotics in large part because these drugs are overprescribed to patients and overused in animals raised for food. The report recommends the CDC develop rules by 2017 requiring hospitals and nursing homes to implement best practices for antibiotic use.

A Practice Resolution

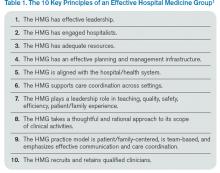

In the heart of the holiday season’s gluttony (and the challenges of staffing the holidays), we need something to get us excited for 2015. Let me suggest that you resolve to use “The Key Principles and Characteristics of an Effective Hospital Medicine Group: An Assessment Guide for Hospitals and Hospitalists” to trim those holiday pounds and make your hospitalist group (HMG) fitter than ever.1

When we published the “Key Principles and Characteristics” in the Journal of Hospital Medicine in February, we intended it to be “aspirational, helping to raise the bar for the specialty of hospital medicine.”1 The author group’s intent was to provide a framework for quality improvement at the HMG level. One can use the 10 principles and 47 characteristics as a basis for self-assessment within the cycle of quality improvement. I will provide an illustration of how a group might utilize the guide to improve its performance using an example and W. Edward Deming’s classic plan-do-study-act (PDSA) cycle.

Principle 6: The HMG supports care coordination across settings.

Characteristic 6.1: The HMG has systems in place to ensure effective and reliable communication with the patient’s primary care provider and/or other providers involved in the patient’s care in the nonacute care setting.

Plan

This phase involves identifying a goal, setting success metrics, and putting a plan into action.

Example: 90% of primary care providers (PCPs) will receive a discharge summary within 24 hours of discharge.

Do

Here the key components of the plan are implemented.

Example: All referring PCPs’ preferred methods of communication and contact information are documented. The HMG has the ability to utilize such communication, e.g. electronic health record (EHR) e-mail or electronic fax. All hospitalists prepare a discharge summary in real time.

Study

In this phase, outcomes are assessed for success and barriers.

Example: Although 97% of discharge summaries are transmitted according to the PCPs’ preferred communication, PCPs state that they received it only 78% of the time.

Act

This is where the lessons learned throughout the process are integrated to adjust the methods, the goal, or the approach in general. Then the entire cycle is repeated.

Example: Even though most PCPs are on the same EHR system as the hospitalists, they don’t check their EHR e-mail (even though during the Plan phase they said they did). Their office staff uses electronic fax, so that will be the method of communication for the PCPs who do not check their EHR e-mail inbox.

In this example, the next time the PDSA cycle is completed, the new approach—using electronic fax for PCPs who don’t check their EHR e-mail while using e-mail for those who check it—will be employed, measured, and further improved in iterative cycles.

Gap Analysis

Another way you can use the “Key Principles and Characteristics” is to do a gap analysis of your HMG. You can assess the current state of your HMG against the “Key Principles and Characteristics,” which can be viewed as an ideal state. The gap between the current and the ideal state can be a roadmap to improvement for your HMG.

For an example of a large HMG’s gap analysis, see “TeamHealth Hospital Medicine Shares Performance Stats” in the August 2014 issue of The Hospitalist.

Strategic Planning

You may be thinking about taking a block of time to devote to your group’s strategic planning. The “Key Principles and Characteristics” is the ideal framework for such planning. You can use the document as a backdrop to your SWOT (strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats) analysis, which forms the basis of your HMG strategic planning activities.

Keep Your Resolution

One of the best ways to maintain your new habit in the New Year is to let others know of your resolution. In the case of your “Key Principles and Characteristics” resolution, announce your plans at the next monthly meeting of your HMG, and find a way to involve other group members in the project. You might assign a single principle or characteristic to each group member, who is tasked with doing a QI project and reporting on the results at a future date. Or, group members can engage in a portion of a gap analysis or SWOT analysis.

No matter how you use the “Key Principles and Characteristics,” I hope they will guide your HMG to a happy, healthy, and effective 2015!

Reference

In the heart of the holiday season’s gluttony (and the challenges of staffing the holidays), we need something to get us excited for 2015. Let me suggest that you resolve to use “The Key Principles and Characteristics of an Effective Hospital Medicine Group: An Assessment Guide for Hospitals and Hospitalists” to trim those holiday pounds and make your hospitalist group (HMG) fitter than ever.1

When we published the “Key Principles and Characteristics” in the Journal of Hospital Medicine in February, we intended it to be “aspirational, helping to raise the bar for the specialty of hospital medicine.”1 The author group’s intent was to provide a framework for quality improvement at the HMG level. One can use the 10 principles and 47 characteristics as a basis for self-assessment within the cycle of quality improvement. I will provide an illustration of how a group might utilize the guide to improve its performance using an example and W. Edward Deming’s classic plan-do-study-act (PDSA) cycle.

Principle 6: The HMG supports care coordination across settings.

Characteristic 6.1: The HMG has systems in place to ensure effective and reliable communication with the patient’s primary care provider and/or other providers involved in the patient’s care in the nonacute care setting.

Plan

This phase involves identifying a goal, setting success metrics, and putting a plan into action.

Example: 90% of primary care providers (PCPs) will receive a discharge summary within 24 hours of discharge.

Do

Here the key components of the plan are implemented.

Example: All referring PCPs’ preferred methods of communication and contact information are documented. The HMG has the ability to utilize such communication, e.g. electronic health record (EHR) e-mail or electronic fax. All hospitalists prepare a discharge summary in real time.

Study

In this phase, outcomes are assessed for success and barriers.

Example: Although 97% of discharge summaries are transmitted according to the PCPs’ preferred communication, PCPs state that they received it only 78% of the time.

Act

This is where the lessons learned throughout the process are integrated to adjust the methods, the goal, or the approach in general. Then the entire cycle is repeated.

Example: Even though most PCPs are on the same EHR system as the hospitalists, they don’t check their EHR e-mail (even though during the Plan phase they said they did). Their office staff uses electronic fax, so that will be the method of communication for the PCPs who do not check their EHR e-mail inbox.

In this example, the next time the PDSA cycle is completed, the new approach—using electronic fax for PCPs who don’t check their EHR e-mail while using e-mail for those who check it—will be employed, measured, and further improved in iterative cycles.

Gap Analysis

Another way you can use the “Key Principles and Characteristics” is to do a gap analysis of your HMG. You can assess the current state of your HMG against the “Key Principles and Characteristics,” which can be viewed as an ideal state. The gap between the current and the ideal state can be a roadmap to improvement for your HMG.

For an example of a large HMG’s gap analysis, see “TeamHealth Hospital Medicine Shares Performance Stats” in the August 2014 issue of The Hospitalist.

Strategic Planning

You may be thinking about taking a block of time to devote to your group’s strategic planning. The “Key Principles and Characteristics” is the ideal framework for such planning. You can use the document as a backdrop to your SWOT (strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats) analysis, which forms the basis of your HMG strategic planning activities.

Keep Your Resolution

One of the best ways to maintain your new habit in the New Year is to let others know of your resolution. In the case of your “Key Principles and Characteristics” resolution, announce your plans at the next monthly meeting of your HMG, and find a way to involve other group members in the project. You might assign a single principle or characteristic to each group member, who is tasked with doing a QI project and reporting on the results at a future date. Or, group members can engage in a portion of a gap analysis or SWOT analysis.

No matter how you use the “Key Principles and Characteristics,” I hope they will guide your HMG to a happy, healthy, and effective 2015!

Reference

In the heart of the holiday season’s gluttony (and the challenges of staffing the holidays), we need something to get us excited for 2015. Let me suggest that you resolve to use “The Key Principles and Characteristics of an Effective Hospital Medicine Group: An Assessment Guide for Hospitals and Hospitalists” to trim those holiday pounds and make your hospitalist group (HMG) fitter than ever.1

When we published the “Key Principles and Characteristics” in the Journal of Hospital Medicine in February, we intended it to be “aspirational, helping to raise the bar for the specialty of hospital medicine.”1 The author group’s intent was to provide a framework for quality improvement at the HMG level. One can use the 10 principles and 47 characteristics as a basis for self-assessment within the cycle of quality improvement. I will provide an illustration of how a group might utilize the guide to improve its performance using an example and W. Edward Deming’s classic plan-do-study-act (PDSA) cycle.

Principle 6: The HMG supports care coordination across settings.

Characteristic 6.1: The HMG has systems in place to ensure effective and reliable communication with the patient’s primary care provider and/or other providers involved in the patient’s care in the nonacute care setting.

Plan

This phase involves identifying a goal, setting success metrics, and putting a plan into action.

Example: 90% of primary care providers (PCPs) will receive a discharge summary within 24 hours of discharge.

Do

Here the key components of the plan are implemented.

Example: All referring PCPs’ preferred methods of communication and contact information are documented. The HMG has the ability to utilize such communication, e.g. electronic health record (EHR) e-mail or electronic fax. All hospitalists prepare a discharge summary in real time.

Study

In this phase, outcomes are assessed for success and barriers.

Example: Although 97% of discharge summaries are transmitted according to the PCPs’ preferred communication, PCPs state that they received it only 78% of the time.

Act

This is where the lessons learned throughout the process are integrated to adjust the methods, the goal, or the approach in general. Then the entire cycle is repeated.

Example: Even though most PCPs are on the same EHR system as the hospitalists, they don’t check their EHR e-mail (even though during the Plan phase they said they did). Their office staff uses electronic fax, so that will be the method of communication for the PCPs who do not check their EHR e-mail inbox.

In this example, the next time the PDSA cycle is completed, the new approach—using electronic fax for PCPs who don’t check their EHR e-mail while using e-mail for those who check it—will be employed, measured, and further improved in iterative cycles.

Gap Analysis

Another way you can use the “Key Principles and Characteristics” is to do a gap analysis of your HMG. You can assess the current state of your HMG against the “Key Principles and Characteristics,” which can be viewed as an ideal state. The gap between the current and the ideal state can be a roadmap to improvement for your HMG.

For an example of a large HMG’s gap analysis, see “TeamHealth Hospital Medicine Shares Performance Stats” in the August 2014 issue of The Hospitalist.

Strategic Planning

You may be thinking about taking a block of time to devote to your group’s strategic planning. The “Key Principles and Characteristics” is the ideal framework for such planning. You can use the document as a backdrop to your SWOT (strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats) analysis, which forms the basis of your HMG strategic planning activities.

Keep Your Resolution

One of the best ways to maintain your new habit in the New Year is to let others know of your resolution. In the case of your “Key Principles and Characteristics” resolution, announce your plans at the next monthly meeting of your HMG, and find a way to involve other group members in the project. You might assign a single principle or characteristic to each group member, who is tasked with doing a QI project and reporting on the results at a future date. Or, group members can engage in a portion of a gap analysis or SWOT analysis.

No matter how you use the “Key Principles and Characteristics,” I hope they will guide your HMG to a happy, healthy, and effective 2015!

Reference

Palliative Care Patient Transitions Challenging For Hospitalists, Oncologists

When should treating a cancer patient become more about controlling symptoms and making the patient comfortable than about trying to slow the cancer itself?

Hospitalists, who often care for patients in the worst stages of health, regularly make important observations that result in a patient transitioning to hospice care. When such a case is suspected, careful discussions with the treating oncologist, the patient, and the patient’s family should be held.

Determining how and when to have those discussions can be tricky, experts say.

“You have to understand the family dynamic before anything else,” Dr. Sahitya Gadiraju, DO, says. “You have to understand the patient, how mentally and emotionally ready they are to have that conversation. And how ready [the family] is to have that conversation.”

“The best treatment, regardless of anything else, is really symptom control, palliative care, taking care of the anxiety, the pain, the sleep, the constipation, the nausea. When you do those things well, everything falls in place.”—Dr. Halm

One treatment course to question, according to the American Society of Clinical Oncology’s Choosing Wisely list, is the use of cancer treatments at the end of life. The society recommends that patients with advanced, solid tumors be shifted to palliative care when previous treatments haven’t worked and no additional, evidence-based treatments are available; when patients can’t care for themselves and spend most of their time in a chair or a bed; and when they aren’t eligible for a clinical trial.

Dr. Lowell Schnipper, MD, who led the group that created the list, says this guidance can be helpful to hospitalists. He says hospitalists should be aware of the patient’s “trajectory” and should only call in consultants when “something clearly suggests that this situation is reversible.”

Dr. Suresh Ramalingam, MD says conferring with the oncologist before talking to a patient about hospice care is crucial, because new treatments are available that can bring about remarkable turnarounds, even in patients in dire condition.

“For certain subsets of patients with cancer, there are specific, molecularly targeted therapies that produce so-called ‘Lazarus responses,’ he explains. “They are bed-bound, totally crippled one day, and a few days after you give them the drug, they’re like a new person walking into your clinic.”

Dr. Josiah Halm, MD, says that, working at a comprehensive cancer center like M.D. Anderson Cancer Center in Houston, he sometimes sees patients who won’t accept the initial determination that aggressive treatment is not a good option when they have poor performance status. They sometimes still demand “small chemo,” or “a little chemo,” from their oncologist.

“Sometimes these patients would have gone elsewhere. They’ve been told, ‘Look, what you need is hospice; there’s nothing else we can do.’ And they’ll come here,” he says. “Either we’re telling them the same thing and that’s when they accept it or [they are] still demanding treatment. Sometimes they may be eligible for cancer treatment after being reviewed by our oncologists.

“The best treatment, regardless of anything else, is really symptom control, palliative care, taking care of the anxiety, the pain, the sleep, the constipation, the nausea,” he adds. “When you do those things well, everything falls in place.”

Dr. Halm sometimes asks patients what he can do to make them feel better “today,” with emphasis on the moment. In this way, he gets patients to focus on one main symptom that is causing them the most discomfort.

When patients don’t want to accept palliative-only care, Dr. Gadiraju says, it’s helpful to get them to realize they are still getting treatment, even if the nature of the treatment is different.

“We don’t want the patient to ever feel like we’re giving up on them,” he says.

When should treating a cancer patient become more about controlling symptoms and making the patient comfortable than about trying to slow the cancer itself?

Hospitalists, who often care for patients in the worst stages of health, regularly make important observations that result in a patient transitioning to hospice care. When such a case is suspected, careful discussions with the treating oncologist, the patient, and the patient’s family should be held.

Determining how and when to have those discussions can be tricky, experts say.

“You have to understand the family dynamic before anything else,” Dr. Sahitya Gadiraju, DO, says. “You have to understand the patient, how mentally and emotionally ready they are to have that conversation. And how ready [the family] is to have that conversation.”

“The best treatment, regardless of anything else, is really symptom control, palliative care, taking care of the anxiety, the pain, the sleep, the constipation, the nausea. When you do those things well, everything falls in place.”—Dr. Halm

One treatment course to question, according to the American Society of Clinical Oncology’s Choosing Wisely list, is the use of cancer treatments at the end of life. The society recommends that patients with advanced, solid tumors be shifted to palliative care when previous treatments haven’t worked and no additional, evidence-based treatments are available; when patients can’t care for themselves and spend most of their time in a chair or a bed; and when they aren’t eligible for a clinical trial.

Dr. Lowell Schnipper, MD, who led the group that created the list, says this guidance can be helpful to hospitalists. He says hospitalists should be aware of the patient’s “trajectory” and should only call in consultants when “something clearly suggests that this situation is reversible.”

Dr. Suresh Ramalingam, MD says conferring with the oncologist before talking to a patient about hospice care is crucial, because new treatments are available that can bring about remarkable turnarounds, even in patients in dire condition.

“For certain subsets of patients with cancer, there are specific, molecularly targeted therapies that produce so-called ‘Lazarus responses,’ he explains. “They are bed-bound, totally crippled one day, and a few days after you give them the drug, they’re like a new person walking into your clinic.”

Dr. Josiah Halm, MD, says that, working at a comprehensive cancer center like M.D. Anderson Cancer Center in Houston, he sometimes sees patients who won’t accept the initial determination that aggressive treatment is not a good option when they have poor performance status. They sometimes still demand “small chemo,” or “a little chemo,” from their oncologist.

“Sometimes these patients would have gone elsewhere. They’ve been told, ‘Look, what you need is hospice; there’s nothing else we can do.’ And they’ll come here,” he says. “Either we’re telling them the same thing and that’s when they accept it or [they are] still demanding treatment. Sometimes they may be eligible for cancer treatment after being reviewed by our oncologists.

“The best treatment, regardless of anything else, is really symptom control, palliative care, taking care of the anxiety, the pain, the sleep, the constipation, the nausea,” he adds. “When you do those things well, everything falls in place.”

Dr. Halm sometimes asks patients what he can do to make them feel better “today,” with emphasis on the moment. In this way, he gets patients to focus on one main symptom that is causing them the most discomfort.

When patients don’t want to accept palliative-only care, Dr. Gadiraju says, it’s helpful to get them to realize they are still getting treatment, even if the nature of the treatment is different.

“We don’t want the patient to ever feel like we’re giving up on them,” he says.

When should treating a cancer patient become more about controlling symptoms and making the patient comfortable than about trying to slow the cancer itself?

Hospitalists, who often care for patients in the worst stages of health, regularly make important observations that result in a patient transitioning to hospice care. When such a case is suspected, careful discussions with the treating oncologist, the patient, and the patient’s family should be held.

Determining how and when to have those discussions can be tricky, experts say.

“You have to understand the family dynamic before anything else,” Dr. Sahitya Gadiraju, DO, says. “You have to understand the patient, how mentally and emotionally ready they are to have that conversation. And how ready [the family] is to have that conversation.”

“The best treatment, regardless of anything else, is really symptom control, palliative care, taking care of the anxiety, the pain, the sleep, the constipation, the nausea. When you do those things well, everything falls in place.”—Dr. Halm

One treatment course to question, according to the American Society of Clinical Oncology’s Choosing Wisely list, is the use of cancer treatments at the end of life. The society recommends that patients with advanced, solid tumors be shifted to palliative care when previous treatments haven’t worked and no additional, evidence-based treatments are available; when patients can’t care for themselves and spend most of their time in a chair or a bed; and when they aren’t eligible for a clinical trial.

Dr. Lowell Schnipper, MD, who led the group that created the list, says this guidance can be helpful to hospitalists. He says hospitalists should be aware of the patient’s “trajectory” and should only call in consultants when “something clearly suggests that this situation is reversible.”

Dr. Suresh Ramalingam, MD says conferring with the oncologist before talking to a patient about hospice care is crucial, because new treatments are available that can bring about remarkable turnarounds, even in patients in dire condition.

“For certain subsets of patients with cancer, there are specific, molecularly targeted therapies that produce so-called ‘Lazarus responses,’ he explains. “They are bed-bound, totally crippled one day, and a few days after you give them the drug, they’re like a new person walking into your clinic.”

Dr. Josiah Halm, MD, says that, working at a comprehensive cancer center like M.D. Anderson Cancer Center in Houston, he sometimes sees patients who won’t accept the initial determination that aggressive treatment is not a good option when they have poor performance status. They sometimes still demand “small chemo,” or “a little chemo,” from their oncologist.

“Sometimes these patients would have gone elsewhere. They’ve been told, ‘Look, what you need is hospice; there’s nothing else we can do.’ And they’ll come here,” he says. “Either we’re telling them the same thing and that’s when they accept it or [they are] still demanding treatment. Sometimes they may be eligible for cancer treatment after being reviewed by our oncologists.

“The best treatment, regardless of anything else, is really symptom control, palliative care, taking care of the anxiety, the pain, the sleep, the constipation, the nausea,” he adds. “When you do those things well, everything falls in place.”

Dr. Halm sometimes asks patients what he can do to make them feel better “today,” with emphasis on the moment. In this way, he gets patients to focus on one main symptom that is causing them the most discomfort.

When patients don’t want to accept palliative-only care, Dr. Gadiraju says, it’s helpful to get them to realize they are still getting treatment, even if the nature of the treatment is different.

“We don’t want the patient to ever feel like we’re giving up on them,” he says.

For Patients in Clinical Trials, Health, Safety Top Concerns for Hospitalists

Patients might come into a hospitalist’s care when they are in the middle of a clinical trial. What then?

The first step for a hospitalist is to find out whether a patient is enrolled in a trial.

“The safety and health of a patient obviously are more important than anything else,” Dr. Khuri says, “but simply asking about participation in a trial can avert doing something that unnecessarily forces the removal of the patient from the trial, in which they might have been receiving a beneficial treatment.

“What they [hospitalists] don’t want to do, unless they have to, is something that forces the patient to come off a clinical trial. Unfortunately, that’s a relatively easy thing to do.”

Hospitalists should ask their cancer patients if they are part of a cancer clinical trial. If the answer is yes, hospitalists “need to be very careful to obtain information about that trial, to understand if the trial is in any way contributing to the illness, or is it helping improve the acute illness,” Dr. Khuri says. Hospitalists also need to know if they are “going to do something that could potentially force the patient to be ineligible to continue that treatment.”

Treatments being explored in trials are often metabolized in the liver or excreted in the kidneys, and the hospitalist might have a choice between two treatment options—one of which might interfere with how the drug is metabolized and another that does not. The steps taken by hospitalists could determine whether the patient would have to be taken off treatment they were being given in the trial.

“If that treatment option on the clinical trial constitutes the best option for the patient, I don’t need to tell you that intervening in a way that forces the patient off that experimental treatment is undesirable in all but the most important, life-saving situations,” Dr. Khuri says.

But it all starts with asking the question.

“You couldn’t even process that information,” he says, “if you didn’t know in the first place that the patient was on a clinical trial.”

Patients might come into a hospitalist’s care when they are in the middle of a clinical trial. What then?

The first step for a hospitalist is to find out whether a patient is enrolled in a trial.

“The safety and health of a patient obviously are more important than anything else,” Dr. Khuri says, “but simply asking about participation in a trial can avert doing something that unnecessarily forces the removal of the patient from the trial, in which they might have been receiving a beneficial treatment.

“What they [hospitalists] don’t want to do, unless they have to, is something that forces the patient to come off a clinical trial. Unfortunately, that’s a relatively easy thing to do.”

Hospitalists should ask their cancer patients if they are part of a cancer clinical trial. If the answer is yes, hospitalists “need to be very careful to obtain information about that trial, to understand if the trial is in any way contributing to the illness, or is it helping improve the acute illness,” Dr. Khuri says. Hospitalists also need to know if they are “going to do something that could potentially force the patient to be ineligible to continue that treatment.”

Treatments being explored in trials are often metabolized in the liver or excreted in the kidneys, and the hospitalist might have a choice between two treatment options—one of which might interfere with how the drug is metabolized and another that does not. The steps taken by hospitalists could determine whether the patient would have to be taken off treatment they were being given in the trial.

“If that treatment option on the clinical trial constitutes the best option for the patient, I don’t need to tell you that intervening in a way that forces the patient off that experimental treatment is undesirable in all but the most important, life-saving situations,” Dr. Khuri says.

But it all starts with asking the question.

“You couldn’t even process that information,” he says, “if you didn’t know in the first place that the patient was on a clinical trial.”

Patients might come into a hospitalist’s care when they are in the middle of a clinical trial. What then?

The first step for a hospitalist is to find out whether a patient is enrolled in a trial.

“The safety and health of a patient obviously are more important than anything else,” Dr. Khuri says, “but simply asking about participation in a trial can avert doing something that unnecessarily forces the removal of the patient from the trial, in which they might have been receiving a beneficial treatment.

“What they [hospitalists] don’t want to do, unless they have to, is something that forces the patient to come off a clinical trial. Unfortunately, that’s a relatively easy thing to do.”

Hospitalists should ask their cancer patients if they are part of a cancer clinical trial. If the answer is yes, hospitalists “need to be very careful to obtain information about that trial, to understand if the trial is in any way contributing to the illness, or is it helping improve the acute illness,” Dr. Khuri says. Hospitalists also need to know if they are “going to do something that could potentially force the patient to be ineligible to continue that treatment.”

Treatments being explored in trials are often metabolized in the liver or excreted in the kidneys, and the hospitalist might have a choice between two treatment options—one of which might interfere with how the drug is metabolized and another that does not. The steps taken by hospitalists could determine whether the patient would have to be taken off treatment they were being given in the trial.

“If that treatment option on the clinical trial constitutes the best option for the patient, I don’t need to tell you that intervening in a way that forces the patient off that experimental treatment is undesirable in all but the most important, life-saving situations,” Dr. Khuri says.

But it all starts with asking the question.

“You couldn’t even process that information,” he says, “if you didn’t know in the first place that the patient was on a clinical trial.”

Cut Costs, Improve Quality and Patient Experience

“Now that’s a fire!”

—Eddie Murphy

This is the final column in my five-part series tracing the history of the hospitalist movement and the factors that propelled it into becoming the fastest growing medical specialty in history and the mainstay of American medicine that it has become.

In the first column, “Tinder & Spark,” economic forces of the early 1990s pushed Baby Boomer physicians into creative ways of working in the hospital; a seminal article in the most famous journal in the world then sparked a revolution. In part two, “Fuel,” Generation X physicians aligned with the values of the HM movement and joined the field in record numbers. In part three, “Oxygen,” I explained how the patient safety and quality movement propelled hospitalist growth, through both inspiration and funding, to new heights throughout the late 90s and early 2000s. And in the October 2014 issue, I continued my journey through the first 20 years of hospital medicine as a field with the fourth installment, “Heat,” a focus on the rise in importance of patient experience and the Millennial generation’s arrival in our hospitalist workforce.

That brings us to the present and back to a factor that started our rise and is becoming more important than ever, both for us as a specialty and for our success as a country.

The Affordability Crisis

We have known for a long time how expensive healthcare is. If it wasn’t for managed care trying to control costs in the 80s and 90s, hospitalists might very well not even exist. But now, it isn’t just costly. It is unaffordable for the average family.

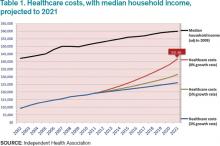

Table 1 shows projected healthcare costs and growth curves through 2021, with a median four-person household income overlaid.

In most scenarios, the two lines, income and healthcare costs, continue to get closer and closer—with healthcare costs almost $42,000 per family by 2021 in the most aggressive projection (8% growth). I am sure many of you have heard the phrase “bending the curve.” That simply means to try and bend that red line down to something approximating the blue line. It is slowing the growth, not actually decreasing the cost.

But it’s a step.

Only at that slowest healthcare growth rate projection (3%) does household income maintain pace. At the highest projection, two-thirds of family income will go toward healthcare. It simply won’t work. Affordability must be addressed.

Hospitalists are at the center of this storm. If you look at the various factors contributing to costs, we (and our keyboards) have great control and influence over inpatient, professional services, and pharmacy costs. To our credit, and to the credit of our teammates in the hospital, we actually seem to be bending the curve down toward the 5% range in inpatient care and professional services. Nevertheless, even at that level it is outpacing income growth.

In 2013, total healthcare costs for a family of four finally caught up with college costs. It is now just north of $22,000 per year for both healthcare costs and the annual cost of attending an in-state public college. Let’s not catch the private colleges as the biggest family budget buster.

The Triple Aim

So, over the course of five articles, I have talked about how we as hospitalists have faced and learned about key aspects of delivering care in a modern healthcare system. First, it was economics, then patient safety and quality, then patient experience, and now we’re back to economics as we consider patient affordability.

Wouldn’t it be great just to focus on one thing at a time? Unfortunately, life doesn’t work that way. In today’s world, hospitalists must give the best quality care while giving a great experience to their patients, all at an affordable cost. This concept of triple focus has given rise to a new term, “Triple Aim.”

The Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI) developed the phrase—and the idea—in 2006. It symbolizes an understanding that all three areas of quality MUST be joined together to achieve true success for our patients. As physicians and hospitalists, we have been taught to focus on health as the cornerstone of our profession. We know about cost pressures, and we now appreciate how important patient experience is. The problem has been that we tend to bounce back and forth in addressing these, silo to silo, depending on the circumstance—JCAHO [Joint Council on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations] visit, publication of CMS core measures, Press-Ganey scores.

Payers and public data sites already have moved away from just reporting health measures. Experience is nearly as prominent in the discussion now. Affordability measures and transparent pricing are on the verge, especially as we arrive in a world with value-based purchasing and cost bundling.

It is easy to focus on just the crisis of the moment. Today, that might very well be the affordability crisis, but it’s important to understand that when delivering healthcare to real live human beings, with all their complexities and vulnerabilities, we have to tune in to our most creative selves to come up with solutions that don’t just address individual areas of care but that also integrate and synergize.

Into the Future

So why this long, five-column preamble into our history, our grand social movement? Because our society and specialty, even with almost 20 years under our belts, are still in the early days. Our members know this and stay connected and coordinated, either in person, at our annual meeting, or virtually using HMX, to better face the many challenges today and those coming down the road. When SHM surveyed its members last year about why they had attended the annual meeting, the overwhelming response was to “be part of the hospital medicine movement.”

Our specialty started out as a group of one-offs and experiments and then coalesced into a social movement, and although it has changed directions and gathered new areas of focus, we are charging ahead. Much social, cultural, and medical change is to come. It’s why our members have told us they keep coming back—to share in this great and glorious social movement called hospital medicine.

Dr. Kealey is SHM president and medical director of hospital specialties at HealthPartners Medical Group in St. Paul, Minn.

“Now that’s a fire!”

—Eddie Murphy

This is the final column in my five-part series tracing the history of the hospitalist movement and the factors that propelled it into becoming the fastest growing medical specialty in history and the mainstay of American medicine that it has become.

In the first column, “Tinder & Spark,” economic forces of the early 1990s pushed Baby Boomer physicians into creative ways of working in the hospital; a seminal article in the most famous journal in the world then sparked a revolution. In part two, “Fuel,” Generation X physicians aligned with the values of the HM movement and joined the field in record numbers. In part three, “Oxygen,” I explained how the patient safety and quality movement propelled hospitalist growth, through both inspiration and funding, to new heights throughout the late 90s and early 2000s. And in the October 2014 issue, I continued my journey through the first 20 years of hospital medicine as a field with the fourth installment, “Heat,” a focus on the rise in importance of patient experience and the Millennial generation’s arrival in our hospitalist workforce.

That brings us to the present and back to a factor that started our rise and is becoming more important than ever, both for us as a specialty and for our success as a country.

The Affordability Crisis

We have known for a long time how expensive healthcare is. If it wasn’t for managed care trying to control costs in the 80s and 90s, hospitalists might very well not even exist. But now, it isn’t just costly. It is unaffordable for the average family.

Table 1 shows projected healthcare costs and growth curves through 2021, with a median four-person household income overlaid.

In most scenarios, the two lines, income and healthcare costs, continue to get closer and closer—with healthcare costs almost $42,000 per family by 2021 in the most aggressive projection (8% growth). I am sure many of you have heard the phrase “bending the curve.” That simply means to try and bend that red line down to something approximating the blue line. It is slowing the growth, not actually decreasing the cost.

But it’s a step.

Only at that slowest healthcare growth rate projection (3%) does household income maintain pace. At the highest projection, two-thirds of family income will go toward healthcare. It simply won’t work. Affordability must be addressed.

Hospitalists are at the center of this storm. If you look at the various factors contributing to costs, we (and our keyboards) have great control and influence over inpatient, professional services, and pharmacy costs. To our credit, and to the credit of our teammates in the hospital, we actually seem to be bending the curve down toward the 5% range in inpatient care and professional services. Nevertheless, even at that level it is outpacing income growth.

In 2013, total healthcare costs for a family of four finally caught up with college costs. It is now just north of $22,000 per year for both healthcare costs and the annual cost of attending an in-state public college. Let’s not catch the private colleges as the biggest family budget buster.

The Triple Aim

So, over the course of five articles, I have talked about how we as hospitalists have faced and learned about key aspects of delivering care in a modern healthcare system. First, it was economics, then patient safety and quality, then patient experience, and now we’re back to economics as we consider patient affordability.

Wouldn’t it be great just to focus on one thing at a time? Unfortunately, life doesn’t work that way. In today’s world, hospitalists must give the best quality care while giving a great experience to their patients, all at an affordable cost. This concept of triple focus has given rise to a new term, “Triple Aim.”

The Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI) developed the phrase—and the idea—in 2006. It symbolizes an understanding that all three areas of quality MUST be joined together to achieve true success for our patients. As physicians and hospitalists, we have been taught to focus on health as the cornerstone of our profession. We know about cost pressures, and we now appreciate how important patient experience is. The problem has been that we tend to bounce back and forth in addressing these, silo to silo, depending on the circumstance—JCAHO [Joint Council on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations] visit, publication of CMS core measures, Press-Ganey scores.

Payers and public data sites already have moved away from just reporting health measures. Experience is nearly as prominent in the discussion now. Affordability measures and transparent pricing are on the verge, especially as we arrive in a world with value-based purchasing and cost bundling.

It is easy to focus on just the crisis of the moment. Today, that might very well be the affordability crisis, but it’s important to understand that when delivering healthcare to real live human beings, with all their complexities and vulnerabilities, we have to tune in to our most creative selves to come up with solutions that don’t just address individual areas of care but that also integrate and synergize.

Into the Future

So why this long, five-column preamble into our history, our grand social movement? Because our society and specialty, even with almost 20 years under our belts, are still in the early days. Our members know this and stay connected and coordinated, either in person, at our annual meeting, or virtually using HMX, to better face the many challenges today and those coming down the road. When SHM surveyed its members last year about why they had attended the annual meeting, the overwhelming response was to “be part of the hospital medicine movement.”

Our specialty started out as a group of one-offs and experiments and then coalesced into a social movement, and although it has changed directions and gathered new areas of focus, we are charging ahead. Much social, cultural, and medical change is to come. It’s why our members have told us they keep coming back—to share in this great and glorious social movement called hospital medicine.

Dr. Kealey is SHM president and medical director of hospital specialties at HealthPartners Medical Group in St. Paul, Minn.

“Now that’s a fire!”

—Eddie Murphy

This is the final column in my five-part series tracing the history of the hospitalist movement and the factors that propelled it into becoming the fastest growing medical specialty in history and the mainstay of American medicine that it has become.

In the first column, “Tinder & Spark,” economic forces of the early 1990s pushed Baby Boomer physicians into creative ways of working in the hospital; a seminal article in the most famous journal in the world then sparked a revolution. In part two, “Fuel,” Generation X physicians aligned with the values of the HM movement and joined the field in record numbers. In part three, “Oxygen,” I explained how the patient safety and quality movement propelled hospitalist growth, through both inspiration and funding, to new heights throughout the late 90s and early 2000s. And in the October 2014 issue, I continued my journey through the first 20 years of hospital medicine as a field with the fourth installment, “Heat,” a focus on the rise in importance of patient experience and the Millennial generation’s arrival in our hospitalist workforce.

That brings us to the present and back to a factor that started our rise and is becoming more important than ever, both for us as a specialty and for our success as a country.

The Affordability Crisis

We have known for a long time how expensive healthcare is. If it wasn’t for managed care trying to control costs in the 80s and 90s, hospitalists might very well not even exist. But now, it isn’t just costly. It is unaffordable for the average family.

Table 1 shows projected healthcare costs and growth curves through 2021, with a median four-person household income overlaid.

In most scenarios, the two lines, income and healthcare costs, continue to get closer and closer—with healthcare costs almost $42,000 per family by 2021 in the most aggressive projection (8% growth). I am sure many of you have heard the phrase “bending the curve.” That simply means to try and bend that red line down to something approximating the blue line. It is slowing the growth, not actually decreasing the cost.

But it’s a step.

Only at that slowest healthcare growth rate projection (3%) does household income maintain pace. At the highest projection, two-thirds of family income will go toward healthcare. It simply won’t work. Affordability must be addressed.

Hospitalists are at the center of this storm. If you look at the various factors contributing to costs, we (and our keyboards) have great control and influence over inpatient, professional services, and pharmacy costs. To our credit, and to the credit of our teammates in the hospital, we actually seem to be bending the curve down toward the 5% range in inpatient care and professional services. Nevertheless, even at that level it is outpacing income growth.

In 2013, total healthcare costs for a family of four finally caught up with college costs. It is now just north of $22,000 per year for both healthcare costs and the annual cost of attending an in-state public college. Let’s not catch the private colleges as the biggest family budget buster.

The Triple Aim

So, over the course of five articles, I have talked about how we as hospitalists have faced and learned about key aspects of delivering care in a modern healthcare system. First, it was economics, then patient safety and quality, then patient experience, and now we’re back to economics as we consider patient affordability.

Wouldn’t it be great just to focus on one thing at a time? Unfortunately, life doesn’t work that way. In today’s world, hospitalists must give the best quality care while giving a great experience to their patients, all at an affordable cost. This concept of triple focus has given rise to a new term, “Triple Aim.”

The Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI) developed the phrase—and the idea—in 2006. It symbolizes an understanding that all three areas of quality MUST be joined together to achieve true success for our patients. As physicians and hospitalists, we have been taught to focus on health as the cornerstone of our profession. We know about cost pressures, and we now appreciate how important patient experience is. The problem has been that we tend to bounce back and forth in addressing these, silo to silo, depending on the circumstance—JCAHO [Joint Council on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations] visit, publication of CMS core measures, Press-Ganey scores.

Payers and public data sites already have moved away from just reporting health measures. Experience is nearly as prominent in the discussion now. Affordability measures and transparent pricing are on the verge, especially as we arrive in a world with value-based purchasing and cost bundling.

It is easy to focus on just the crisis of the moment. Today, that might very well be the affordability crisis, but it’s important to understand that when delivering healthcare to real live human beings, with all their complexities and vulnerabilities, we have to tune in to our most creative selves to come up with solutions that don’t just address individual areas of care but that also integrate and synergize.

Into the Future

So why this long, five-column preamble into our history, our grand social movement? Because our society and specialty, even with almost 20 years under our belts, are still in the early days. Our members know this and stay connected and coordinated, either in person, at our annual meeting, or virtually using HMX, to better face the many challenges today and those coming down the road. When SHM surveyed its members last year about why they had attended the annual meeting, the overwhelming response was to “be part of the hospital medicine movement.”

Our specialty started out as a group of one-offs and experiments and then coalesced into a social movement, and although it has changed directions and gathered new areas of focus, we are charging ahead. Much social, cultural, and medical change is to come. It’s why our members have told us they keep coming back—to share in this great and glorious social movement called hospital medicine.

Dr. Kealey is SHM president and medical director of hospital specialties at HealthPartners Medical Group in St. Paul, Minn.

Ebola Spurs Better Infection Prevention Practices for U.S.-based Hospitalists

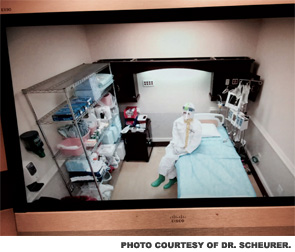

In the beginning phases of the Ebola evolution in the U.S., when Thomas Duncan was declared the first probable case on U.S. soil, many American hospitals were left scared and wondering if they could adequately care for a patient with such a highly contagious infectious disease. Uneasy thoughts swirled around individual practitioners’ minds about whether they would be willing and able to safely provide care to a patient with a devastating, highly infectious disease that has a touted 50% to 70% mortality rate.

Although a handful of biohazard units in the U.S. had undertaken such care, they had done so in a true biohazard unit, which had been meticulously planned and funded for years and featured a highly trained and skilled staff of physicians, nurses, and others. Nonetheless, with the realization that U.S. hospitals would not get to choose whether or not a patient with Ebola was presented to them, massive planning ensued in thousands of U.S. hospitals.

Within days, hospitals quickly rolled out visible signage and appropriate screening tools to quickly and efficiently identify and isolate the next contagious patient on U.S. soil. As the healthcare workers at Texas Presbyterian Hospital diligently cared for Thomas Duncan, U.S. hospitals and healthcare providers were faced with the sobering reality that a healthcare worker had been infected with the deadly virus.

This was not a case of a medical missionary working in a third world country with limited protective equipment and in unsanitary conditions. This was a highly skilled nurse, with (what was at the time considered to be) adequate protective equipment, who was stricken with a highly lethal disease in the course of nursing care in a U.S. hospital.

Ebola became the leading headline for every news organization in the U.S. and beyond, causing confusion and concern among the lay public. Within U.S. healthcare systems, the signs and symptoms of Ebola began to roll easily off the tongues of both clinical and nonclinical staff, all of whom quickly became well versed on the geography of West Africa.

What happened next in the U.S. healthcare system was a dizzying series of recommendations and changes at the local, regional, and national level. This was accompanied by another sobering realization: Most U.S. hospitals are not able and should not attempt to handle patients infected with Ebola.

The concept of regionalization of Ebola care was quickly accepted as a viable model, as many U.S. hospitals did not have the volunteer workforce, facilities, disaster preparedness infrastructure, protective equipment, or training infrastructure to safely care for such a patient, even if only short-term care was required.

These regionalization efforts required unparalleled cooperation among U.S. hospital systems and created the need for complex interdependencies among federal and state agencies across the nation. Many hospitals, including my own, invested thousands of man-hours and significant fiscal resources in preparing for the possibility of an infected patient.

These efforts also prompted a series of uncomfortable conversations, especially among clinicians and bioethicists, about what level of care can be safely provided to an Ebola patient in the U.S. Clinicians and bioethicists came to the realization that an Ebola patient in the U.S. may receive a different standard of care than a patient with a different blood-borne infectious disease. The guiding principle of “staff safety first” made for further difficult conversations among clinicians, who are accustomed to putting their safety second.

With all these perturbations to the system and anxiety-laden clinical discussions, the question is, has any good occurred as a result of this viral penetration into the U.S.? I believe the answer is yes, as the rapid anticipation and planning for this level of care has spurned efforts that otherwise would have remained dormant, including:

- Unparalleled cooperation among U.S. hospitals for aiding and assisting each others’ readiness to screen accurately and safely provide first responder care;

- Remarkable cooperation and assistance from state and federal agencies in guidance, communication, and preparedness for the centers designated as regional referral centers;

- Enhanced planning and capabilities for U.S. hospitals to respond and adapt to changes in the external environment, which makes them that much more prepared to respond and adapt to the next contagious disease crisis, one that will undoubtedly occur; and

- A renewed sense of volunteerism among many clinicians, despite the possibility of personal threat.

Current estimates predict the Ebola outbreak will expand from hundreds to thousands of new cases (and deaths) per month.1 As this situation evolves, individual regionalized centers in the U.S. become more prepared (logistically and psychologically) to handle Ebola as each day passes.

The foundational structure of care designed during this outbreak can and should put the U.S. in a very good position to resiliently and effectively care for any highly contagious agent in the future. So in the face of this disruptive adversity, we should all be able to keep calm and Ebola on.

Dr. Scheurer is a hospitalist and chief quality officer at the Medical University of South Carolina in Charleston. She is physician editor of The Hospitalist. Email her at [email protected].

Reference

In the beginning phases of the Ebola evolution in the U.S., when Thomas Duncan was declared the first probable case on U.S. soil, many American hospitals were left scared and wondering if they could adequately care for a patient with such a highly contagious infectious disease. Uneasy thoughts swirled around individual practitioners’ minds about whether they would be willing and able to safely provide care to a patient with a devastating, highly infectious disease that has a touted 50% to 70% mortality rate.

Although a handful of biohazard units in the U.S. had undertaken such care, they had done so in a true biohazard unit, which had been meticulously planned and funded for years and featured a highly trained and skilled staff of physicians, nurses, and others. Nonetheless, with the realization that U.S. hospitals would not get to choose whether or not a patient with Ebola was presented to them, massive planning ensued in thousands of U.S. hospitals.

Within days, hospitals quickly rolled out visible signage and appropriate screening tools to quickly and efficiently identify and isolate the next contagious patient on U.S. soil. As the healthcare workers at Texas Presbyterian Hospital diligently cared for Thomas Duncan, U.S. hospitals and healthcare providers were faced with the sobering reality that a healthcare worker had been infected with the deadly virus.

This was not a case of a medical missionary working in a third world country with limited protective equipment and in unsanitary conditions. This was a highly skilled nurse, with (what was at the time considered to be) adequate protective equipment, who was stricken with a highly lethal disease in the course of nursing care in a U.S. hospital.

Ebola became the leading headline for every news organization in the U.S. and beyond, causing confusion and concern among the lay public. Within U.S. healthcare systems, the signs and symptoms of Ebola began to roll easily off the tongues of both clinical and nonclinical staff, all of whom quickly became well versed on the geography of West Africa.

What happened next in the U.S. healthcare system was a dizzying series of recommendations and changes at the local, regional, and national level. This was accompanied by another sobering realization: Most U.S. hospitals are not able and should not attempt to handle patients infected with Ebola.

The concept of regionalization of Ebola care was quickly accepted as a viable model, as many U.S. hospitals did not have the volunteer workforce, facilities, disaster preparedness infrastructure, protective equipment, or training infrastructure to safely care for such a patient, even if only short-term care was required.

These regionalization efforts required unparalleled cooperation among U.S. hospital systems and created the need for complex interdependencies among federal and state agencies across the nation. Many hospitals, including my own, invested thousands of man-hours and significant fiscal resources in preparing for the possibility of an infected patient.

These efforts also prompted a series of uncomfortable conversations, especially among clinicians and bioethicists, about what level of care can be safely provided to an Ebola patient in the U.S. Clinicians and bioethicists came to the realization that an Ebola patient in the U.S. may receive a different standard of care than a patient with a different blood-borne infectious disease. The guiding principle of “staff safety first” made for further difficult conversations among clinicians, who are accustomed to putting their safety second.

With all these perturbations to the system and anxiety-laden clinical discussions, the question is, has any good occurred as a result of this viral penetration into the U.S.? I believe the answer is yes, as the rapid anticipation and planning for this level of care has spurned efforts that otherwise would have remained dormant, including:

- Unparalleled cooperation among U.S. hospitals for aiding and assisting each others’ readiness to screen accurately and safely provide first responder care;

- Remarkable cooperation and assistance from state and federal agencies in guidance, communication, and preparedness for the centers designated as regional referral centers;

- Enhanced planning and capabilities for U.S. hospitals to respond and adapt to changes in the external environment, which makes them that much more prepared to respond and adapt to the next contagious disease crisis, one that will undoubtedly occur; and

- A renewed sense of volunteerism among many clinicians, despite the possibility of personal threat.

Current estimates predict the Ebola outbreak will expand from hundreds to thousands of new cases (and deaths) per month.1 As this situation evolves, individual regionalized centers in the U.S. become more prepared (logistically and psychologically) to handle Ebola as each day passes.

The foundational structure of care designed during this outbreak can and should put the U.S. in a very good position to resiliently and effectively care for any highly contagious agent in the future. So in the face of this disruptive adversity, we should all be able to keep calm and Ebola on.

Dr. Scheurer is a hospitalist and chief quality officer at the Medical University of South Carolina in Charleston. She is physician editor of The Hospitalist. Email her at [email protected].

Reference

In the beginning phases of the Ebola evolution in the U.S., when Thomas Duncan was declared the first probable case on U.S. soil, many American hospitals were left scared and wondering if they could adequately care for a patient with such a highly contagious infectious disease. Uneasy thoughts swirled around individual practitioners’ minds about whether they would be willing and able to safely provide care to a patient with a devastating, highly infectious disease that has a touted 50% to 70% mortality rate.

Although a handful of biohazard units in the U.S. had undertaken such care, they had done so in a true biohazard unit, which had been meticulously planned and funded for years and featured a highly trained and skilled staff of physicians, nurses, and others. Nonetheless, with the realization that U.S. hospitals would not get to choose whether or not a patient with Ebola was presented to them, massive planning ensued in thousands of U.S. hospitals.

Within days, hospitals quickly rolled out visible signage and appropriate screening tools to quickly and efficiently identify and isolate the next contagious patient on U.S. soil. As the healthcare workers at Texas Presbyterian Hospital diligently cared for Thomas Duncan, U.S. hospitals and healthcare providers were faced with the sobering reality that a healthcare worker had been infected with the deadly virus.

This was not a case of a medical missionary working in a third world country with limited protective equipment and in unsanitary conditions. This was a highly skilled nurse, with (what was at the time considered to be) adequate protective equipment, who was stricken with a highly lethal disease in the course of nursing care in a U.S. hospital.

Ebola became the leading headline for every news organization in the U.S. and beyond, causing confusion and concern among the lay public. Within U.S. healthcare systems, the signs and symptoms of Ebola began to roll easily off the tongues of both clinical and nonclinical staff, all of whom quickly became well versed on the geography of West Africa.

What happened next in the U.S. healthcare system was a dizzying series of recommendations and changes at the local, regional, and national level. This was accompanied by another sobering realization: Most U.S. hospitals are not able and should not attempt to handle patients infected with Ebola.

The concept of regionalization of Ebola care was quickly accepted as a viable model, as many U.S. hospitals did not have the volunteer workforce, facilities, disaster preparedness infrastructure, protective equipment, or training infrastructure to safely care for such a patient, even if only short-term care was required.

These regionalization efforts required unparalleled cooperation among U.S. hospital systems and created the need for complex interdependencies among federal and state agencies across the nation. Many hospitals, including my own, invested thousands of man-hours and significant fiscal resources in preparing for the possibility of an infected patient.

These efforts also prompted a series of uncomfortable conversations, especially among clinicians and bioethicists, about what level of care can be safely provided to an Ebola patient in the U.S. Clinicians and bioethicists came to the realization that an Ebola patient in the U.S. may receive a different standard of care than a patient with a different blood-borne infectious disease. The guiding principle of “staff safety first” made for further difficult conversations among clinicians, who are accustomed to putting their safety second.

With all these perturbations to the system and anxiety-laden clinical discussions, the question is, has any good occurred as a result of this viral penetration into the U.S.? I believe the answer is yes, as the rapid anticipation and planning for this level of care has spurned efforts that otherwise would have remained dormant, including:

- Unparalleled cooperation among U.S. hospitals for aiding and assisting each others’ readiness to screen accurately and safely provide first responder care;

- Remarkable cooperation and assistance from state and federal agencies in guidance, communication, and preparedness for the centers designated as regional referral centers;

- Enhanced planning and capabilities for U.S. hospitals to respond and adapt to changes in the external environment, which makes them that much more prepared to respond and adapt to the next contagious disease crisis, one that will undoubtedly occur; and

- A renewed sense of volunteerism among many clinicians, despite the possibility of personal threat.

Current estimates predict the Ebola outbreak will expand from hundreds to thousands of new cases (and deaths) per month.1 As this situation evolves, individual regionalized centers in the U.S. become more prepared (logistically and psychologically) to handle Ebola as each day passes.

The foundational structure of care designed during this outbreak can and should put the U.S. in a very good position to resiliently and effectively care for any highly contagious agent in the future. So in the face of this disruptive adversity, we should all be able to keep calm and Ebola on.

Dr. Scheurer is a hospitalist and chief quality officer at the Medical University of South Carolina in Charleston. She is physician editor of The Hospitalist. Email her at [email protected].

Reference

When is a biopsy not a biopsy?

“When I use a word, it means just what I choose it to mean…” – Humpty Dumpty

Even after all these years, I’m still surprised to learn new ways the words we use every day can mean different things to patients to whom we say them.

Take the word “biopsy.” To a dermatologist, it means “a test of a piece of tissue” (in our case, of skin), to help find out what the problem is.

I’ve always known that to many patients, the word “biopsy” suggests cancer, or at least the concern that there may be cancer, because cancer is the context in which most people hear the word: breast biopsy, prostate biopsy, and so on. It can therefore be useful to point out to patients when a biopsy is performed for diagnostic purposes and cancer is not even on the list of possibilities.

Lately, though, I’ve had a few encounters that highlighted other interesting ways the word “biopsy” can be misunderstood.

Case 1: Arnold the Irritated

“Arnold,” I say. “I need to biopsy this. Based on the results, it may need further treatment, but I doubt it.”

“I thought you were taking it off now,” says Arnold.

“No, I’m testing it, “I say.

“But I want it off,” says Arnold. “It gets irritated when I shave over it, so I want it off.”

“Yes,” I say, “but in order to remove it properly, I need to know what it is.”

“What?”

We have to go around a few more times before Arnold catches on.

Case 2: Gaetano the Outraged

“Gaetano is on the phone,” says my billing clerk. “He says you told him you weren’t going to biopsy his spot, and then he got a bill from the pathology lab.”

I call Gaetano. “You said you weren’t going to biopsy this,” he says. “You said you were sure you knew what it was, so you didn’t have to biopsy it.”

“First of all,” I explain, “I’m never totally sure. Your spot looked like a basal cell skin cancer, and that’s what it turned out to be. But I’ve had cases where the pathology results surprised me, and it turned out to be something less – or something more. So I have to check the biopsy.”

“I understand, Doctor” says Gaetano.

“In addition,” I go on, “what I actually meant to say was that I was not going to only take a biopsy of the spot. I was going to remove it completely, so that if my diagnosis was confirmed, you wouldn’t have to come back and have more done. Sorry if I didn’t make that clear.”

“So you biopsied it,” says Gaetano, but you didn’t just biopsy it. I get it. I think.”

Good for you, Gaetano. Next time I am going to – actually, next time I don’t know what I’ll do.

Case 3: Melvin the Clueless

“I understand your former dermatologist removed something from your arm,” I say to Melvin.

“Yes, they took a biopsy, and then they removed it,” says Melvin. “I just have one question.”

“What is that?” I ask.

“Which was the biopsy?” asks Melvin, “the first or the second?”

I didn’t let on, but inside I was shaking my head.

Even with the best will on both sides – and even if both are native speakers of the same language – there are just so many ways people can misunderstand each other. Humpty Dumpty was wrong. Words can mean what both the talker and the listener think they mean. Humpty Dumpty probably didn’t get out much.

Never biopsy an egg.

Dr. Rockoff practices dermatology in Brookline, Mass., and is a longtime contributor to Skin & Allergy News. He serves on the clinical faculty at Tufts University, Boston, and has taught senior medical students and other trainees for 30 years.

“When I use a word, it means just what I choose it to mean…” – Humpty Dumpty

Even after all these years, I’m still surprised to learn new ways the words we use every day can mean different things to patients to whom we say them.

Take the word “biopsy.” To a dermatologist, it means “a test of a piece of tissue” (in our case, of skin), to help find out what the problem is.

I’ve always known that to many patients, the word “biopsy” suggests cancer, or at least the concern that there may be cancer, because cancer is the context in which most people hear the word: breast biopsy, prostate biopsy, and so on. It can therefore be useful to point out to patients when a biopsy is performed for diagnostic purposes and cancer is not even on the list of possibilities.

Lately, though, I’ve had a few encounters that highlighted other interesting ways the word “biopsy” can be misunderstood.

Case 1: Arnold the Irritated

“Arnold,” I say. “I need to biopsy this. Based on the results, it may need further treatment, but I doubt it.”

“I thought you were taking it off now,” says Arnold.

“No, I’m testing it, “I say.

“But I want it off,” says Arnold. “It gets irritated when I shave over it, so I want it off.”

“Yes,” I say, “but in order to remove it properly, I need to know what it is.”

“What?”