User login

Is immediate-release topiramate an effective treatment for adult obesity?

EVIDENCE-BASED ANSWER:

Yes. Topiramate (at daily doses of 64-400 mg) produces an average 5.34 kg of additional weight loss compared with placebo (95% confidence interval [CI], -6.12 to -4.56) in overweight to obese adults for periods of 16 to 60 weeks (strength of recommendation [SOR]: A, meta-analyses of randomized controlled trials [RCTs]).

Topiramate increases the chances of losing 5% or more of baseline body weight (BBW) with a number needed to treat (NNT) of 3 (95% CI, 2-3) and 10% or more of BBW with an NNT of 4 (95% CI, 3-4). However, approximately 17% of patients discontinue the drug because of adverse effects, including paresthesia, hypoesthesia, taste perversion, and psychomotor impairment (SOR: A, meta-analyses of RCTs).

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

A meta-analysis of 10 well-done RCTs with a total of 3320 patients found that topiramate produced more weight loss than placebo.1 Studies included men and women ages 18 to 75 years, with a body mass index (BMI) of 27 to 50. Several studies included patients with hypertension, dyslipidemia, and diabetes mellitus; one study included patients with binge eating disorder. Investigators recruited subjects from sites in Europe, North America, Australia, and South Africa. The studies lasted 16 to 60 weeks and used variable doses of topiramate (64-400 mg daily). Most incorporated a structured lifestyle intervention program for both the treatment and control groups.

Patients taking topiramate lost 5.34 kg (95% CI, -6.12 to -4.56) more than subjects taking placebo. All studies showed significantly greater weight loss in the topiramate groups, regardless of dose and duration, although there was some heterogeneity among the results. The NNTs to achieve weight loss of 5% or more of BBW and 10% or more of BBW were 3 (95% CI, 2-3) and 4 (95% CI, 3-4), respectively.

No major adverse events, but some unpleasant effects

A safety analysis on 6620 subjects found no major adverse events.1 Subjects in the topiramate group were more likely to withdraw because of adverse effects (odds ratio=1.97; 95% CI, 1.64-2.29; number needed to harm=14; 95% CI, 11-18). The most common adverse effects were paresthesia, hypoesthesia, taste perversion, and psychomotor impairment, and these effects were most likely to lead to discontinuation at daily doses >96 mg.

Two formulas are effective in patients with diabetes

Investigators stopped 6 studies early because the sponsor wanted to pursue development of a controlled-release formulation of topiramate. The meta-analysis includes a single study of controlled-release topiramate, 175 mg daily in patients with diabetes, that showed equivalent efficacy and similar tolerability to immediate-release topiramate.2

Three other RCTs included in the meta-analysis specifically examined obese patients with type 2 diabetes, a population deemed more resistant to typical weight loss regimens, treated with immediate-release topiramate in dosages of 96 mg and 192 mg daily.3-5 These patients also experienced greater weight loss than patients taking placebo, comparable to what was seen in the overall meta-analysis.

FDA approval and cost of therapy

Topiramate monotherapy isn’t approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for obesity treatment. In 2012, the FDA approved phentermine/topiramate extended-release (Qsymia) for long-term treatment of obesity; the monthly cost for a maintenance dose of 7.5 mg/46 mg daily is approximately $185.6 Topiramate immediate-release tablets cost approximately $25 per month for twice daily doses of 50 to 100 mg.7

RECOMMENDATIONS

The US Preventive Services Task Force recommends screening all adults for obesity by measuring BMI and referring patients with a BMI ≥30 for high-intensity, comprehensive behavioral interventions. It makes no recommendation for pharmacologic management.8

The Institute for Clinical Systems Improvement concludes that pharmacotherapy should be used only as part of a comprehensive obesity treatment plan. Pharmacotherapy should be considered if obese patients are unable to lose 1 pound per week with diet, physical activity, and behavior modification.9

1. Kramer CK, Leitão CB, Pinto LC, et al. Efficacy and safety of topiramate on weight loss: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Obes Rev. 2011;12:e338-e347.

2. Rosenstock J, Hollander P, Gadde KM, et al; OBD-202 Study Group. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicenter study to assess the efficacy and safety of topiramate controlled release in the treatment of obese type 2 diabetic patients. Diabetes Care. 2007;30:1480-1486.

3. Stenlöf K, Rössner S, Vercruysse F, et al. Topiramate in the treatment of obese subjects with drug-naive type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2007;9:360-368.

4. Toplak H, Hamann A, Moore R, et al. Efficacy and safety of topiramate in combination with metformin in the treatment of obese subjects with type 2 diabetes: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Int J Obes (Lond). 2007;31:138-146.

5. Eliasson B, Gudbjörnsdottir S, Cederholm J, et al. Weight loss and metabolic effects of topiramate in overweight and obese type 2 diabetic patients: randomized double-blind placebo-controlled trial. Int J Obes (Lond). 2007;31: 1140-1147.

6. Drugs.com. Qsymia. Drugs.com Web site. Available at: www.drugs.com/pro/qsymia.html. Accessed September 26, 2014.

7. Drugs.com. Topirimate prices, coupons and patient assistance programs. Drugs.com Web site. Available at: www.drugs.com/price-guide/topiramate. Accessed September 26, 2014.

8. US Preventive Services Task Force. Obesity in Adults: Screening and management. US Preventive Services Task Force Web site. Available at: www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf11/obeseadult/obesers.htm. Accessed September 30, 2014.

9. Fitch A, Everling L, Fox C, et al. Prevention and management of obesity for adults. Institute for Clinical Systems Improvement Web site. Available at: www.icsi.org/_asset/s935hy/Obesity-Adults.pdf. Accessed September 30, 2014.

EVIDENCE-BASED ANSWER:

Yes. Topiramate (at daily doses of 64-400 mg) produces an average 5.34 kg of additional weight loss compared with placebo (95% confidence interval [CI], -6.12 to -4.56) in overweight to obese adults for periods of 16 to 60 weeks (strength of recommendation [SOR]: A, meta-analyses of randomized controlled trials [RCTs]).

Topiramate increases the chances of losing 5% or more of baseline body weight (BBW) with a number needed to treat (NNT) of 3 (95% CI, 2-3) and 10% or more of BBW with an NNT of 4 (95% CI, 3-4). However, approximately 17% of patients discontinue the drug because of adverse effects, including paresthesia, hypoesthesia, taste perversion, and psychomotor impairment (SOR: A, meta-analyses of RCTs).

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

A meta-analysis of 10 well-done RCTs with a total of 3320 patients found that topiramate produced more weight loss than placebo.1 Studies included men and women ages 18 to 75 years, with a body mass index (BMI) of 27 to 50. Several studies included patients with hypertension, dyslipidemia, and diabetes mellitus; one study included patients with binge eating disorder. Investigators recruited subjects from sites in Europe, North America, Australia, and South Africa. The studies lasted 16 to 60 weeks and used variable doses of topiramate (64-400 mg daily). Most incorporated a structured lifestyle intervention program for both the treatment and control groups.

Patients taking topiramate lost 5.34 kg (95% CI, -6.12 to -4.56) more than subjects taking placebo. All studies showed significantly greater weight loss in the topiramate groups, regardless of dose and duration, although there was some heterogeneity among the results. The NNTs to achieve weight loss of 5% or more of BBW and 10% or more of BBW were 3 (95% CI, 2-3) and 4 (95% CI, 3-4), respectively.

No major adverse events, but some unpleasant effects

A safety analysis on 6620 subjects found no major adverse events.1 Subjects in the topiramate group were more likely to withdraw because of adverse effects (odds ratio=1.97; 95% CI, 1.64-2.29; number needed to harm=14; 95% CI, 11-18). The most common adverse effects were paresthesia, hypoesthesia, taste perversion, and psychomotor impairment, and these effects were most likely to lead to discontinuation at daily doses >96 mg.

Two formulas are effective in patients with diabetes

Investigators stopped 6 studies early because the sponsor wanted to pursue development of a controlled-release formulation of topiramate. The meta-analysis includes a single study of controlled-release topiramate, 175 mg daily in patients with diabetes, that showed equivalent efficacy and similar tolerability to immediate-release topiramate.2

Three other RCTs included in the meta-analysis specifically examined obese patients with type 2 diabetes, a population deemed more resistant to typical weight loss regimens, treated with immediate-release topiramate in dosages of 96 mg and 192 mg daily.3-5 These patients also experienced greater weight loss than patients taking placebo, comparable to what was seen in the overall meta-analysis.

FDA approval and cost of therapy

Topiramate monotherapy isn’t approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for obesity treatment. In 2012, the FDA approved phentermine/topiramate extended-release (Qsymia) for long-term treatment of obesity; the monthly cost for a maintenance dose of 7.5 mg/46 mg daily is approximately $185.6 Topiramate immediate-release tablets cost approximately $25 per month for twice daily doses of 50 to 100 mg.7

RECOMMENDATIONS

The US Preventive Services Task Force recommends screening all adults for obesity by measuring BMI and referring patients with a BMI ≥30 for high-intensity, comprehensive behavioral interventions. It makes no recommendation for pharmacologic management.8

The Institute for Clinical Systems Improvement concludes that pharmacotherapy should be used only as part of a comprehensive obesity treatment plan. Pharmacotherapy should be considered if obese patients are unable to lose 1 pound per week with diet, physical activity, and behavior modification.9

EVIDENCE-BASED ANSWER:

Yes. Topiramate (at daily doses of 64-400 mg) produces an average 5.34 kg of additional weight loss compared with placebo (95% confidence interval [CI], -6.12 to -4.56) in overweight to obese adults for periods of 16 to 60 weeks (strength of recommendation [SOR]: A, meta-analyses of randomized controlled trials [RCTs]).

Topiramate increases the chances of losing 5% or more of baseline body weight (BBW) with a number needed to treat (NNT) of 3 (95% CI, 2-3) and 10% or more of BBW with an NNT of 4 (95% CI, 3-4). However, approximately 17% of patients discontinue the drug because of adverse effects, including paresthesia, hypoesthesia, taste perversion, and psychomotor impairment (SOR: A, meta-analyses of RCTs).

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

A meta-analysis of 10 well-done RCTs with a total of 3320 patients found that topiramate produced more weight loss than placebo.1 Studies included men and women ages 18 to 75 years, with a body mass index (BMI) of 27 to 50. Several studies included patients with hypertension, dyslipidemia, and diabetes mellitus; one study included patients with binge eating disorder. Investigators recruited subjects from sites in Europe, North America, Australia, and South Africa. The studies lasted 16 to 60 weeks and used variable doses of topiramate (64-400 mg daily). Most incorporated a structured lifestyle intervention program for both the treatment and control groups.

Patients taking topiramate lost 5.34 kg (95% CI, -6.12 to -4.56) more than subjects taking placebo. All studies showed significantly greater weight loss in the topiramate groups, regardless of dose and duration, although there was some heterogeneity among the results. The NNTs to achieve weight loss of 5% or more of BBW and 10% or more of BBW were 3 (95% CI, 2-3) and 4 (95% CI, 3-4), respectively.

No major adverse events, but some unpleasant effects

A safety analysis on 6620 subjects found no major adverse events.1 Subjects in the topiramate group were more likely to withdraw because of adverse effects (odds ratio=1.97; 95% CI, 1.64-2.29; number needed to harm=14; 95% CI, 11-18). The most common adverse effects were paresthesia, hypoesthesia, taste perversion, and psychomotor impairment, and these effects were most likely to lead to discontinuation at daily doses >96 mg.

Two formulas are effective in patients with diabetes

Investigators stopped 6 studies early because the sponsor wanted to pursue development of a controlled-release formulation of topiramate. The meta-analysis includes a single study of controlled-release topiramate, 175 mg daily in patients with diabetes, that showed equivalent efficacy and similar tolerability to immediate-release topiramate.2

Three other RCTs included in the meta-analysis specifically examined obese patients with type 2 diabetes, a population deemed more resistant to typical weight loss regimens, treated with immediate-release topiramate in dosages of 96 mg and 192 mg daily.3-5 These patients also experienced greater weight loss than patients taking placebo, comparable to what was seen in the overall meta-analysis.

FDA approval and cost of therapy

Topiramate monotherapy isn’t approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for obesity treatment. In 2012, the FDA approved phentermine/topiramate extended-release (Qsymia) for long-term treatment of obesity; the monthly cost for a maintenance dose of 7.5 mg/46 mg daily is approximately $185.6 Topiramate immediate-release tablets cost approximately $25 per month for twice daily doses of 50 to 100 mg.7

RECOMMENDATIONS

The US Preventive Services Task Force recommends screening all adults for obesity by measuring BMI and referring patients with a BMI ≥30 for high-intensity, comprehensive behavioral interventions. It makes no recommendation for pharmacologic management.8

The Institute for Clinical Systems Improvement concludes that pharmacotherapy should be used only as part of a comprehensive obesity treatment plan. Pharmacotherapy should be considered if obese patients are unable to lose 1 pound per week with diet, physical activity, and behavior modification.9

1. Kramer CK, Leitão CB, Pinto LC, et al. Efficacy and safety of topiramate on weight loss: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Obes Rev. 2011;12:e338-e347.

2. Rosenstock J, Hollander P, Gadde KM, et al; OBD-202 Study Group. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicenter study to assess the efficacy and safety of topiramate controlled release in the treatment of obese type 2 diabetic patients. Diabetes Care. 2007;30:1480-1486.

3. Stenlöf K, Rössner S, Vercruysse F, et al. Topiramate in the treatment of obese subjects with drug-naive type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2007;9:360-368.

4. Toplak H, Hamann A, Moore R, et al. Efficacy and safety of topiramate in combination with metformin in the treatment of obese subjects with type 2 diabetes: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Int J Obes (Lond). 2007;31:138-146.

5. Eliasson B, Gudbjörnsdottir S, Cederholm J, et al. Weight loss and metabolic effects of topiramate in overweight and obese type 2 diabetic patients: randomized double-blind placebo-controlled trial. Int J Obes (Lond). 2007;31: 1140-1147.

6. Drugs.com. Qsymia. Drugs.com Web site. Available at: www.drugs.com/pro/qsymia.html. Accessed September 26, 2014.

7. Drugs.com. Topirimate prices, coupons and patient assistance programs. Drugs.com Web site. Available at: www.drugs.com/price-guide/topiramate. Accessed September 26, 2014.

8. US Preventive Services Task Force. Obesity in Adults: Screening and management. US Preventive Services Task Force Web site. Available at: www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf11/obeseadult/obesers.htm. Accessed September 30, 2014.

9. Fitch A, Everling L, Fox C, et al. Prevention and management of obesity for adults. Institute for Clinical Systems Improvement Web site. Available at: www.icsi.org/_asset/s935hy/Obesity-Adults.pdf. Accessed September 30, 2014.

1. Kramer CK, Leitão CB, Pinto LC, et al. Efficacy and safety of topiramate on weight loss: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Obes Rev. 2011;12:e338-e347.

2. Rosenstock J, Hollander P, Gadde KM, et al; OBD-202 Study Group. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicenter study to assess the efficacy and safety of topiramate controlled release in the treatment of obese type 2 diabetic patients. Diabetes Care. 2007;30:1480-1486.

3. Stenlöf K, Rössner S, Vercruysse F, et al. Topiramate in the treatment of obese subjects with drug-naive type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2007;9:360-368.

4. Toplak H, Hamann A, Moore R, et al. Efficacy and safety of topiramate in combination with metformin in the treatment of obese subjects with type 2 diabetes: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Int J Obes (Lond). 2007;31:138-146.

5. Eliasson B, Gudbjörnsdottir S, Cederholm J, et al. Weight loss and metabolic effects of topiramate in overweight and obese type 2 diabetic patients: randomized double-blind placebo-controlled trial. Int J Obes (Lond). 2007;31: 1140-1147.

6. Drugs.com. Qsymia. Drugs.com Web site. Available at: www.drugs.com/pro/qsymia.html. Accessed September 26, 2014.

7. Drugs.com. Topirimate prices, coupons and patient assistance programs. Drugs.com Web site. Available at: www.drugs.com/price-guide/topiramate. Accessed September 26, 2014.

8. US Preventive Services Task Force. Obesity in Adults: Screening and management. US Preventive Services Task Force Web site. Available at: www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf11/obeseadult/obesers.htm. Accessed September 30, 2014.

9. Fitch A, Everling L, Fox C, et al. Prevention and management of obesity for adults. Institute for Clinical Systems Improvement Web site. Available at: www.icsi.org/_asset/s935hy/Obesity-Adults.pdf. Accessed September 30, 2014.

Evidence-based answers from the Family Physicians Inquiries Network

High failure rate seen with limited parathyroidectomy in patients with MEN-1

SAN FRANCISCO – Patients with hyperparathyroidism due to multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1 (MEN-1) have a 4 in 10 chance of persistent hyperparathyroidism if they undergo surgery that leaves at least one gland in place, according to a retrospective cohort study presented at the annual clinical congress of the American College of Surgeons.

“Limited initial parathyroidectomy in patients with MEN-1–associated primary hyperparathyroidism results in a high failure rate. Additional enlarged contralateral parathyroid glands are frequently missed by preoperative localizing studies,” commented lead investigator Dr. Naris Nilubol, a staff clinician with the endocrine oncology branch of the Center for Cancer Research, National Cancer Institute, Bethesda, Md.

“We conclude that limited parathyroidectomy in MEN-1 guided by preoperative localizing studies is associated with high failure rates and therefore should not be performed,” he maintained.

In an interview, session comoderator Dr. Marybeth S. Hughes, a staff clinician with the thoracic and gastrointestinal oncology branch, Center for Cancer Research, National Cancer Institute, commented, “In general, I would say that the data presented just reiterates the standard of care, that MEN-1 patients should have bilateral neck exploration with [removal of] three and half glands, or four glands with autotransplantation. So it just basically solidifies what is being done standardly. I don’t think there is a compelling argument to change the standard.”

Dr. Nilubol and colleagues reviewed the charts of 99 patients with MEN-1 who underwent at least one parathyroidectomy at the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

Of the 64 patients who had initial surgery at NIH and had preoperative localizing studies done, 32 had only a single enlarged gland identified by the tests, suggesting they would be good candidates for limited surgery, according to Dr. Nilubol. Bilateral neck dissection at the time of parathyroidectomy showed that in 22 (69%) of these 32 patients, the studies had correctly identified the largest gland; however, in 19 (87%) of those 22, it missed another enlarged gland on the contralateral side. Furthermore, in 5 (16%) of the 32, the largest gland was found on the contralateral side.

With a median follow-up of 23 months, the risk of persistent hyperparathyroidism was 41% for patients who had limited parathyroidectomy (three or fewer glands removed) at initial surgery, significantly and sharply higher than the 6% seen in patients who had subtotal parathyroidectomy or more extensive surgery (at least three and a half glands removed).

Looking at the cumulative number of glands removed during initial and subsequent surgeries, 57% of patients having two or fewer glands removed and 45% of those having two and a half to three glands removed had persistent hyperparathyroidism – both significantly higher than the 5% of patients having at least three and a half glands removed.

Regarding complications, 10% of the patients who had their initial surgery at NIH developed permanent hypoparathyroidism, reported Dr. Nilubol, who disclosed that he had no relevant conflicts of interest.

Session attendees asked about the use of parathyroid hormone levels intraoperatively to guide surgery and what strategy surgeons follow at his institution in this patient population.

Previous research has suggested that intraoperative parathyroid hormone levels do not add any information that would change the operative plan, Dr. Nilubol replied. “Everybody at NIH has preop localizing studies as part of the clinical investigation, but it doesn’t change the way we approach it. Everybody gets a bilateral neck exploration and three and a half–gland removal,” provided all glands can be found, he said.

Session attendee Dr. Michael J. Campbell, a surgeon at the University California, Davis, commented, “A 10% permanent hypoparathyroidism rate in these patients – and they have a tendency to be young, most of them in their late teens, early 20s – that’s a major complication. So could you take your data and make exactly the opposite argument, that maybe you should be doing less to these patients to limit that fairly life-altering complication?” Permanent hypothyroidism at that age is “a significant medical problem,” Dr. Nilubol agreed. However, “at the NIH, we don’t operate on everybody just because they have primary hyperparathyroidism. They have to fulfill metabolic complications before we choose to operate on them. We want to delay the surgeries and [time] between the surgeries because if they live long enough, it will recur, so we want to operate when we can make the most difference, meaning [addressing] kidney stone, bone loss, etc. The most common reason for young patients is they have kidney stones, which leads to surgery.”

SAN FRANCISCO – Patients with hyperparathyroidism due to multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1 (MEN-1) have a 4 in 10 chance of persistent hyperparathyroidism if they undergo surgery that leaves at least one gland in place, according to a retrospective cohort study presented at the annual clinical congress of the American College of Surgeons.

“Limited initial parathyroidectomy in patients with MEN-1–associated primary hyperparathyroidism results in a high failure rate. Additional enlarged contralateral parathyroid glands are frequently missed by preoperative localizing studies,” commented lead investigator Dr. Naris Nilubol, a staff clinician with the endocrine oncology branch of the Center for Cancer Research, National Cancer Institute, Bethesda, Md.

“We conclude that limited parathyroidectomy in MEN-1 guided by preoperative localizing studies is associated with high failure rates and therefore should not be performed,” he maintained.

In an interview, session comoderator Dr. Marybeth S. Hughes, a staff clinician with the thoracic and gastrointestinal oncology branch, Center for Cancer Research, National Cancer Institute, commented, “In general, I would say that the data presented just reiterates the standard of care, that MEN-1 patients should have bilateral neck exploration with [removal of] three and half glands, or four glands with autotransplantation. So it just basically solidifies what is being done standardly. I don’t think there is a compelling argument to change the standard.”

Dr. Nilubol and colleagues reviewed the charts of 99 patients with MEN-1 who underwent at least one parathyroidectomy at the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

Of the 64 patients who had initial surgery at NIH and had preoperative localizing studies done, 32 had only a single enlarged gland identified by the tests, suggesting they would be good candidates for limited surgery, according to Dr. Nilubol. Bilateral neck dissection at the time of parathyroidectomy showed that in 22 (69%) of these 32 patients, the studies had correctly identified the largest gland; however, in 19 (87%) of those 22, it missed another enlarged gland on the contralateral side. Furthermore, in 5 (16%) of the 32, the largest gland was found on the contralateral side.

With a median follow-up of 23 months, the risk of persistent hyperparathyroidism was 41% for patients who had limited parathyroidectomy (three or fewer glands removed) at initial surgery, significantly and sharply higher than the 6% seen in patients who had subtotal parathyroidectomy or more extensive surgery (at least three and a half glands removed).

Looking at the cumulative number of glands removed during initial and subsequent surgeries, 57% of patients having two or fewer glands removed and 45% of those having two and a half to three glands removed had persistent hyperparathyroidism – both significantly higher than the 5% of patients having at least three and a half glands removed.

Regarding complications, 10% of the patients who had their initial surgery at NIH developed permanent hypoparathyroidism, reported Dr. Nilubol, who disclosed that he had no relevant conflicts of interest.

Session attendees asked about the use of parathyroid hormone levels intraoperatively to guide surgery and what strategy surgeons follow at his institution in this patient population.

Previous research has suggested that intraoperative parathyroid hormone levels do not add any information that would change the operative plan, Dr. Nilubol replied. “Everybody at NIH has preop localizing studies as part of the clinical investigation, but it doesn’t change the way we approach it. Everybody gets a bilateral neck exploration and three and a half–gland removal,” provided all glands can be found, he said.

Session attendee Dr. Michael J. Campbell, a surgeon at the University California, Davis, commented, “A 10% permanent hypoparathyroidism rate in these patients – and they have a tendency to be young, most of them in their late teens, early 20s – that’s a major complication. So could you take your data and make exactly the opposite argument, that maybe you should be doing less to these patients to limit that fairly life-altering complication?” Permanent hypothyroidism at that age is “a significant medical problem,” Dr. Nilubol agreed. However, “at the NIH, we don’t operate on everybody just because they have primary hyperparathyroidism. They have to fulfill metabolic complications before we choose to operate on them. We want to delay the surgeries and [time] between the surgeries because if they live long enough, it will recur, so we want to operate when we can make the most difference, meaning [addressing] kidney stone, bone loss, etc. The most common reason for young patients is they have kidney stones, which leads to surgery.”

SAN FRANCISCO – Patients with hyperparathyroidism due to multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1 (MEN-1) have a 4 in 10 chance of persistent hyperparathyroidism if they undergo surgery that leaves at least one gland in place, according to a retrospective cohort study presented at the annual clinical congress of the American College of Surgeons.

“Limited initial parathyroidectomy in patients with MEN-1–associated primary hyperparathyroidism results in a high failure rate. Additional enlarged contralateral parathyroid glands are frequently missed by preoperative localizing studies,” commented lead investigator Dr. Naris Nilubol, a staff clinician with the endocrine oncology branch of the Center for Cancer Research, National Cancer Institute, Bethesda, Md.

“We conclude that limited parathyroidectomy in MEN-1 guided by preoperative localizing studies is associated with high failure rates and therefore should not be performed,” he maintained.

In an interview, session comoderator Dr. Marybeth S. Hughes, a staff clinician with the thoracic and gastrointestinal oncology branch, Center for Cancer Research, National Cancer Institute, commented, “In general, I would say that the data presented just reiterates the standard of care, that MEN-1 patients should have bilateral neck exploration with [removal of] three and half glands, or four glands with autotransplantation. So it just basically solidifies what is being done standardly. I don’t think there is a compelling argument to change the standard.”

Dr. Nilubol and colleagues reviewed the charts of 99 patients with MEN-1 who underwent at least one parathyroidectomy at the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

Of the 64 patients who had initial surgery at NIH and had preoperative localizing studies done, 32 had only a single enlarged gland identified by the tests, suggesting they would be good candidates for limited surgery, according to Dr. Nilubol. Bilateral neck dissection at the time of parathyroidectomy showed that in 22 (69%) of these 32 patients, the studies had correctly identified the largest gland; however, in 19 (87%) of those 22, it missed another enlarged gland on the contralateral side. Furthermore, in 5 (16%) of the 32, the largest gland was found on the contralateral side.

With a median follow-up of 23 months, the risk of persistent hyperparathyroidism was 41% for patients who had limited parathyroidectomy (three or fewer glands removed) at initial surgery, significantly and sharply higher than the 6% seen in patients who had subtotal parathyroidectomy or more extensive surgery (at least three and a half glands removed).

Looking at the cumulative number of glands removed during initial and subsequent surgeries, 57% of patients having two or fewer glands removed and 45% of those having two and a half to three glands removed had persistent hyperparathyroidism – both significantly higher than the 5% of patients having at least three and a half glands removed.

Regarding complications, 10% of the patients who had their initial surgery at NIH developed permanent hypoparathyroidism, reported Dr. Nilubol, who disclosed that he had no relevant conflicts of interest.

Session attendees asked about the use of parathyroid hormone levels intraoperatively to guide surgery and what strategy surgeons follow at his institution in this patient population.

Previous research has suggested that intraoperative parathyroid hormone levels do not add any information that would change the operative plan, Dr. Nilubol replied. “Everybody at NIH has preop localizing studies as part of the clinical investigation, but it doesn’t change the way we approach it. Everybody gets a bilateral neck exploration and three and a half–gland removal,” provided all glands can be found, he said.

Session attendee Dr. Michael J. Campbell, a surgeon at the University California, Davis, commented, “A 10% permanent hypoparathyroidism rate in these patients – and they have a tendency to be young, most of them in their late teens, early 20s – that’s a major complication. So could you take your data and make exactly the opposite argument, that maybe you should be doing less to these patients to limit that fairly life-altering complication?” Permanent hypothyroidism at that age is “a significant medical problem,” Dr. Nilubol agreed. However, “at the NIH, we don’t operate on everybody just because they have primary hyperparathyroidism. They have to fulfill metabolic complications before we choose to operate on them. We want to delay the surgeries and [time] between the surgeries because if they live long enough, it will recur, so we want to operate when we can make the most difference, meaning [addressing] kidney stone, bone loss, etc. The most common reason for young patients is they have kidney stones, which leads to surgery.”

AT THE ACS CLINICAL CONGRESS

Key clinical point: Patients are more likely to have persistent hyperparathyroidism if a gland is left behind.

Major finding: The failure rate after initial parathyroidectomy was 41% with limited surgery versus 6% with subtotal or more extensive surgery.

Data source: A retrospective chart review of 99 patients with MEN-1–associated hyperparathyroidism.

Disclosures: Dr. Nilubol disclosed that he had no relevant conflicts of interest.

Diabetes therapy and cancer risk

To the Editor: I would like to add three points to the excellent review of diabetes therapy and cancer risk by Drs. Sun, Kashyap, and Nasr in the October 2014 issue of Cleveland Clinic Journal of Medicine.1

First, a recent 10-year prospective observational study of more than 190,000 patients showed no increase in bladder cancer with exposure to or long-term use of pioglitazone vs comparator when smoking status was controlled. Although publicly released, these 10-year data have not yet been published.

Second, a recent paper2 from the US Food and Drug Administration and European Medicine Agency reviewed the pancreatic safety of incretin-based therapies. They concluded that there is no evidence that these agents increase the risk of pancreatitis or of pancreatic cancer. So I believe that the authors’ comment that pancreatitis is a “potential side effect” of these agents is not quite accurate.

Lastly, the authors cite no substantial evidence that would support their statement to avoid using glucagon-like protein 1 (GLP-1) receptor agonists in those with a personal history of differentiated thyroid cancer. Indeed these patients, if adequately treated, should have no remnant thyroid tissue. The rodent data indicate an effect of GLP-1 agonists on rodent C cells, not thyroid follicular cells.3 In addition, the prescribing information for these agents does not advise such a limitation on their use.

- Ching Sun GE, Kashyap SR, Nasr C. Diabetes therapy and cancer risk: where do we stand when treating patients? Cleve Clin J Med 2014; 81:620–628.

- Egan AG, Blind E, Dunder K, et al. Pancreatic safety of incretin-based drugs—FDA and EMA assessment. N Engl J Med 2014; 370:794–797.

- Knudsen L, Madsen LW, Andersen S, et al. Glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists activate rodent thyroid C-cells causing calcitonin release and C-cell proliferation. Endocrinology 2010; 151:1473–1486.

To the Editor: I would like to add three points to the excellent review of diabetes therapy and cancer risk by Drs. Sun, Kashyap, and Nasr in the October 2014 issue of Cleveland Clinic Journal of Medicine.1

First, a recent 10-year prospective observational study of more than 190,000 patients showed no increase in bladder cancer with exposure to or long-term use of pioglitazone vs comparator when smoking status was controlled. Although publicly released, these 10-year data have not yet been published.

Second, a recent paper2 from the US Food and Drug Administration and European Medicine Agency reviewed the pancreatic safety of incretin-based therapies. They concluded that there is no evidence that these agents increase the risk of pancreatitis or of pancreatic cancer. So I believe that the authors’ comment that pancreatitis is a “potential side effect” of these agents is not quite accurate.

Lastly, the authors cite no substantial evidence that would support their statement to avoid using glucagon-like protein 1 (GLP-1) receptor agonists in those with a personal history of differentiated thyroid cancer. Indeed these patients, if adequately treated, should have no remnant thyroid tissue. The rodent data indicate an effect of GLP-1 agonists on rodent C cells, not thyroid follicular cells.3 In addition, the prescribing information for these agents does not advise such a limitation on their use.

To the Editor: I would like to add three points to the excellent review of diabetes therapy and cancer risk by Drs. Sun, Kashyap, and Nasr in the October 2014 issue of Cleveland Clinic Journal of Medicine.1

First, a recent 10-year prospective observational study of more than 190,000 patients showed no increase in bladder cancer with exposure to or long-term use of pioglitazone vs comparator when smoking status was controlled. Although publicly released, these 10-year data have not yet been published.

Second, a recent paper2 from the US Food and Drug Administration and European Medicine Agency reviewed the pancreatic safety of incretin-based therapies. They concluded that there is no evidence that these agents increase the risk of pancreatitis or of pancreatic cancer. So I believe that the authors’ comment that pancreatitis is a “potential side effect” of these agents is not quite accurate.

Lastly, the authors cite no substantial evidence that would support their statement to avoid using glucagon-like protein 1 (GLP-1) receptor agonists in those with a personal history of differentiated thyroid cancer. Indeed these patients, if adequately treated, should have no remnant thyroid tissue. The rodent data indicate an effect of GLP-1 agonists on rodent C cells, not thyroid follicular cells.3 In addition, the prescribing information for these agents does not advise such a limitation on their use.

- Ching Sun GE, Kashyap SR, Nasr C. Diabetes therapy and cancer risk: where do we stand when treating patients? Cleve Clin J Med 2014; 81:620–628.

- Egan AG, Blind E, Dunder K, et al. Pancreatic safety of incretin-based drugs—FDA and EMA assessment. N Engl J Med 2014; 370:794–797.

- Knudsen L, Madsen LW, Andersen S, et al. Glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists activate rodent thyroid C-cells causing calcitonin release and C-cell proliferation. Endocrinology 2010; 151:1473–1486.

- Ching Sun GE, Kashyap SR, Nasr C. Diabetes therapy and cancer risk: where do we stand when treating patients? Cleve Clin J Med 2014; 81:620–628.

- Egan AG, Blind E, Dunder K, et al. Pancreatic safety of incretin-based drugs—FDA and EMA assessment. N Engl J Med 2014; 370:794–797.

- Knudsen L, Madsen LW, Andersen S, et al. Glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists activate rodent thyroid C-cells causing calcitonin release and C-cell proliferation. Endocrinology 2010; 151:1473–1486.

In reply: Diabetes therapy and cancer risk

In Reply: In regard to Dr. Weiss’s first point, the Kaiser Permanente Northern California diabetes registry study aimed to assess the association between bladder cancer and pioglitazone in 193,099 patients. In their 2011 interim 5-year analysis, Lewis et al reported a modest but statistically significant increased risk of bladder cancer in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus who used pioglitazone for 2 or more years.1

We appreciate Dr. Weiss’s comment on the 10-year study conclusion data. As Dr. Weiss has indicated, the recent Takeda news release2 showed that the primary analysis found no association between pioglitazone use and bladder cancer risk. Furthermore, no association was found between bladder cancer risk and duration of use, higher cumulative doses, or time since initiation of pioglitazone.2

Regarding Dr. Weiss’s second point, we agree that at this time the cumulative data are not supportive of pancreatitis as per Egan et al.3 Recent publication of the SAVOR-TIMI trial4 of saxagliptin documented no increased risk of pancreatitis or pancreatic cancer over 2.1 years of follow-up in more than 16,000 patients over the age of 40 with type 2 diabetes. However, since amylase and lipase levels were not routinely checked in study participants, subclinical and asymptomatic cases may not have been recognized.4 Therefore, we stand by our statement that pancreatitis is a potential side effect.

It is important to recognize that although the observational data reviewed by both agencies (the US Food and Drug Administration and European Medicine Agency) in the publication by Egan et al3 are reassuring, we cannot yet say with absolute certainty that there is no associated risk. In fact, the concluding statements of the publication are as follows: “Although the totality of the data that have been reviewed provides reassurance, pancreatitis will continue to be considered a risk associated with these drugs until more data are available; both agencies continue to investigate this safety signal.”3

On September 18, 2014, the newest approved GLP-1 receptor agonist, dulaglutide, was approved with a boxed warning that it causes thyroid C-cell tumors in rats, that whether it causes thyroid C-cell tumors including medullary thyroid carcinoma (MTC) in humans is unknown, and that since relevance to humans could not be determined from clinical or nonclinical studies, dulaglutide is contraindicated in patients with a personal or family history of MTC, as well as in patients with multiple endocrine neoplasia syndrome type 2.5

It is important to recognize that despite these controversies, which have not been well-supported to date, incretin-based therapies have numerous metabolic benefits, including favorable glycemic and weight effects.

In regard to Dr. Weiss’s last point, we would like to point out the study by Gier et al6 in which GLP-1 receptor expression was found in 3 of 17 cases of human papillary thyroid cancer. The implication is that abnormal thyroid tissue does not behave the same way as normal tissue.

Furthermore, Dr. Weiss brings up the point that patients with thyroid cancer, if it is adequately treated, should have no remnant thyroid tissue. Certainly, adequate treatment would be an easy call to make if a stimulated thyroglobulin level is below the assay’s detection limit and there is no imaging evidence of residual thyroid cancer. For example, in someone with a history of thyroid cancer diagnosed more than 10 years ago without biochemical or imaging evidence of disease, any potential concerns of GLP-1 receptor agonist use in regards to thyroid cancer would be nominal. But not everyone with thyroid cancer falls into this category.

We do not suggest that these potential risks preclude the use of these agents in all patients, but rather that a discussion should occur between physician and patient. Diabetes therapy, as in treatment of other medical conditions, should be tailored to the individual patient, and all potential risk and benefits should be disclosed and considered.

- Lewis JD, Ferrara A, Peng T, et al. Risk of bladder cancer among diabetic patients treated with pioglitazone: interim report of a longitudinal cohort study. Diabetes Care 2011; 34:916–922.

- Takeda Pharmaceuticals. 2014. Takeda announces completion of the post-marketing commitment to submit data to the FDA, the EMA and the PMDA for pioglitazone containing medicines including ACTOS. [Press release]. Accessed 19 October 2014. www.takeda.us/newsroom/press_release_detail.aspx?year=2014&id=314. Accessed November 3, 2014.

- Egan AG, Blind E, Dunder K, et al. Pancreatic safety of incretin-based drugs—FDA and EMA assessment. N Engl J Med 2014; 370:794–797.

- Raz I, Bhatt DL, Hirshberg B, et al. Incidence of pancreatitis and pancreatic cancer in a randomized controlled multicenter trial (SAVOR-TIMI 53) of the dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitor saxagliptin. Diabetes Care 2014; 37:2435–2441.

- Trulicity [package insert]. Indianapolis, IN: Eli Lilly & Company; 2014.

- Gier B, Butler PC, Lai CK, Kirakossian D, DeNicola MM, Yeh MW. Glucagon like peptide-1 receptor expression in the human thyroid gland. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2012; 97:121–131.

In Reply: In regard to Dr. Weiss’s first point, the Kaiser Permanente Northern California diabetes registry study aimed to assess the association between bladder cancer and pioglitazone in 193,099 patients. In their 2011 interim 5-year analysis, Lewis et al reported a modest but statistically significant increased risk of bladder cancer in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus who used pioglitazone for 2 or more years.1

We appreciate Dr. Weiss’s comment on the 10-year study conclusion data. As Dr. Weiss has indicated, the recent Takeda news release2 showed that the primary analysis found no association between pioglitazone use and bladder cancer risk. Furthermore, no association was found between bladder cancer risk and duration of use, higher cumulative doses, or time since initiation of pioglitazone.2

Regarding Dr. Weiss’s second point, we agree that at this time the cumulative data are not supportive of pancreatitis as per Egan et al.3 Recent publication of the SAVOR-TIMI trial4 of saxagliptin documented no increased risk of pancreatitis or pancreatic cancer over 2.1 years of follow-up in more than 16,000 patients over the age of 40 with type 2 diabetes. However, since amylase and lipase levels were not routinely checked in study participants, subclinical and asymptomatic cases may not have been recognized.4 Therefore, we stand by our statement that pancreatitis is a potential side effect.

It is important to recognize that although the observational data reviewed by both agencies (the US Food and Drug Administration and European Medicine Agency) in the publication by Egan et al3 are reassuring, we cannot yet say with absolute certainty that there is no associated risk. In fact, the concluding statements of the publication are as follows: “Although the totality of the data that have been reviewed provides reassurance, pancreatitis will continue to be considered a risk associated with these drugs until more data are available; both agencies continue to investigate this safety signal.”3

On September 18, 2014, the newest approved GLP-1 receptor agonist, dulaglutide, was approved with a boxed warning that it causes thyroid C-cell tumors in rats, that whether it causes thyroid C-cell tumors including medullary thyroid carcinoma (MTC) in humans is unknown, and that since relevance to humans could not be determined from clinical or nonclinical studies, dulaglutide is contraindicated in patients with a personal or family history of MTC, as well as in patients with multiple endocrine neoplasia syndrome type 2.5

It is important to recognize that despite these controversies, which have not been well-supported to date, incretin-based therapies have numerous metabolic benefits, including favorable glycemic and weight effects.

In regard to Dr. Weiss’s last point, we would like to point out the study by Gier et al6 in which GLP-1 receptor expression was found in 3 of 17 cases of human papillary thyroid cancer. The implication is that abnormal thyroid tissue does not behave the same way as normal tissue.

Furthermore, Dr. Weiss brings up the point that patients with thyroid cancer, if it is adequately treated, should have no remnant thyroid tissue. Certainly, adequate treatment would be an easy call to make if a stimulated thyroglobulin level is below the assay’s detection limit and there is no imaging evidence of residual thyroid cancer. For example, in someone with a history of thyroid cancer diagnosed more than 10 years ago without biochemical or imaging evidence of disease, any potential concerns of GLP-1 receptor agonist use in regards to thyroid cancer would be nominal. But not everyone with thyroid cancer falls into this category.

We do not suggest that these potential risks preclude the use of these agents in all patients, but rather that a discussion should occur between physician and patient. Diabetes therapy, as in treatment of other medical conditions, should be tailored to the individual patient, and all potential risk and benefits should be disclosed and considered.

In Reply: In regard to Dr. Weiss’s first point, the Kaiser Permanente Northern California diabetes registry study aimed to assess the association between bladder cancer and pioglitazone in 193,099 patients. In their 2011 interim 5-year analysis, Lewis et al reported a modest but statistically significant increased risk of bladder cancer in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus who used pioglitazone for 2 or more years.1

We appreciate Dr. Weiss’s comment on the 10-year study conclusion data. As Dr. Weiss has indicated, the recent Takeda news release2 showed that the primary analysis found no association between pioglitazone use and bladder cancer risk. Furthermore, no association was found between bladder cancer risk and duration of use, higher cumulative doses, or time since initiation of pioglitazone.2

Regarding Dr. Weiss’s second point, we agree that at this time the cumulative data are not supportive of pancreatitis as per Egan et al.3 Recent publication of the SAVOR-TIMI trial4 of saxagliptin documented no increased risk of pancreatitis or pancreatic cancer over 2.1 years of follow-up in more than 16,000 patients over the age of 40 with type 2 diabetes. However, since amylase and lipase levels were not routinely checked in study participants, subclinical and asymptomatic cases may not have been recognized.4 Therefore, we stand by our statement that pancreatitis is a potential side effect.

It is important to recognize that although the observational data reviewed by both agencies (the US Food and Drug Administration and European Medicine Agency) in the publication by Egan et al3 are reassuring, we cannot yet say with absolute certainty that there is no associated risk. In fact, the concluding statements of the publication are as follows: “Although the totality of the data that have been reviewed provides reassurance, pancreatitis will continue to be considered a risk associated with these drugs until more data are available; both agencies continue to investigate this safety signal.”3

On September 18, 2014, the newest approved GLP-1 receptor agonist, dulaglutide, was approved with a boxed warning that it causes thyroid C-cell tumors in rats, that whether it causes thyroid C-cell tumors including medullary thyroid carcinoma (MTC) in humans is unknown, and that since relevance to humans could not be determined from clinical or nonclinical studies, dulaglutide is contraindicated in patients with a personal or family history of MTC, as well as in patients with multiple endocrine neoplasia syndrome type 2.5

It is important to recognize that despite these controversies, which have not been well-supported to date, incretin-based therapies have numerous metabolic benefits, including favorable glycemic and weight effects.

In regard to Dr. Weiss’s last point, we would like to point out the study by Gier et al6 in which GLP-1 receptor expression was found in 3 of 17 cases of human papillary thyroid cancer. The implication is that abnormal thyroid tissue does not behave the same way as normal tissue.

Furthermore, Dr. Weiss brings up the point that patients with thyroid cancer, if it is adequately treated, should have no remnant thyroid tissue. Certainly, adequate treatment would be an easy call to make if a stimulated thyroglobulin level is below the assay’s detection limit and there is no imaging evidence of residual thyroid cancer. For example, in someone with a history of thyroid cancer diagnosed more than 10 years ago without biochemical or imaging evidence of disease, any potential concerns of GLP-1 receptor agonist use in regards to thyroid cancer would be nominal. But not everyone with thyroid cancer falls into this category.

We do not suggest that these potential risks preclude the use of these agents in all patients, but rather that a discussion should occur between physician and patient. Diabetes therapy, as in treatment of other medical conditions, should be tailored to the individual patient, and all potential risk and benefits should be disclosed and considered.

- Lewis JD, Ferrara A, Peng T, et al. Risk of bladder cancer among diabetic patients treated with pioglitazone: interim report of a longitudinal cohort study. Diabetes Care 2011; 34:916–922.

- Takeda Pharmaceuticals. 2014. Takeda announces completion of the post-marketing commitment to submit data to the FDA, the EMA and the PMDA for pioglitazone containing medicines including ACTOS. [Press release]. Accessed 19 October 2014. www.takeda.us/newsroom/press_release_detail.aspx?year=2014&id=314. Accessed November 3, 2014.

- Egan AG, Blind E, Dunder K, et al. Pancreatic safety of incretin-based drugs—FDA and EMA assessment. N Engl J Med 2014; 370:794–797.

- Raz I, Bhatt DL, Hirshberg B, et al. Incidence of pancreatitis and pancreatic cancer in a randomized controlled multicenter trial (SAVOR-TIMI 53) of the dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitor saxagliptin. Diabetes Care 2014; 37:2435–2441.

- Trulicity [package insert]. Indianapolis, IN: Eli Lilly & Company; 2014.

- Gier B, Butler PC, Lai CK, Kirakossian D, DeNicola MM, Yeh MW. Glucagon like peptide-1 receptor expression in the human thyroid gland. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2012; 97:121–131.

- Lewis JD, Ferrara A, Peng T, et al. Risk of bladder cancer among diabetic patients treated with pioglitazone: interim report of a longitudinal cohort study. Diabetes Care 2011; 34:916–922.

- Takeda Pharmaceuticals. 2014. Takeda announces completion of the post-marketing commitment to submit data to the FDA, the EMA and the PMDA for pioglitazone containing medicines including ACTOS. [Press release]. Accessed 19 October 2014. www.takeda.us/newsroom/press_release_detail.aspx?year=2014&id=314. Accessed November 3, 2014.

- Egan AG, Blind E, Dunder K, et al. Pancreatic safety of incretin-based drugs—FDA and EMA assessment. N Engl J Med 2014; 370:794–797.

- Raz I, Bhatt DL, Hirshberg B, et al. Incidence of pancreatitis and pancreatic cancer in a randomized controlled multicenter trial (SAVOR-TIMI 53) of the dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitor saxagliptin. Diabetes Care 2014; 37:2435–2441.

- Trulicity [package insert]. Indianapolis, IN: Eli Lilly & Company; 2014.

- Gier B, Butler PC, Lai CK, Kirakossian D, DeNicola MM, Yeh MW. Glucagon like peptide-1 receptor expression in the human thyroid gland. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2012; 97:121–131.

Mutations indicate predisposition to blood cancers

Credit: Graham Colm

Two teams of researchers have identified somatic mutations that increase the likelihood a person will develop a hematologic malignancy.

This “pre-malignant” stage was detected simply by sequencing DNA from blood samples.

The researchers found that subjects carrying certain mutations had more than 10 times the risk of developing a hematologic malignancy than individuals without the mutations. And the risk increased with age.

Steven McCarroll, PhD, of Harvard Medical School in Boston, Massachusetts, and Benjamin Ebert, MD, PhD, also of Harvard Medical School, reported these findings in NEJM.

Both research teams looked at somatic mutations in DNA samples collected from the blood of subjects who had not been diagnosed with cancer or blood disorders.

Taking two very different approaches, the teams found that a surprising percentage of individuals had acquired a subset of the somatic mutations present in hematologic malignancies. And subjects with the mutations were more likely to develop these cancers.

This pre-malignant state was rare in individuals under the age of 40. But it appeared with increasing frequency with each decade of life, ultimately appearing in more than 10% of individuals over the age of 70.

The researchers believe these early mutations lie in wait for follow-on, cooperating mutations that, when they occur in the same cells as the earlier mutations, drive the cells toward cancer. The majority of mutations occurred in just 3 genes: DNMT3A, TET2, and ASXL1.

Dr Ebert’s group

Dr Ebert and his colleagues had hypothesized that, since hematologic malignancies increase with age, it might be possible to detect early somatic mutations that could be initiating the disease process, and these mutations might increase with age.

The researchers looked specifically at 160 genes known to be recurrently mutated in hematologic malignancies, using genetic data derived from approximately 17,000 blood samples originally obtained for studies on the genetics of type 2 diabetes.

The team found a roughly 11-fold increase in the risk of hematologic malignancy among subjects with the subset of somatic mutations linked to blood cancers. And there was a clear association between age and the frequency of these mutations.

Men were slightly more likely to have the mutations than women, and Hispanics were slightly less likely to have the mutations than other racial/ethnic groups.

The researchers also found an association between the presence of this pre-malignant state and the risk of overall mortality independent of malignancy. Individuals with the mutations had a higher risk of type 2 diabetes, coronary heart disease, and ischemic stroke as well.

However, additional research will be needed to determine the nature of these associations.

Dr McCarroll’s group

Dr McCarroll and his colleagues discovered the same phenomenon while trying to determine whether somatic mutations contribute to the risk of developing schizophrenia.

The team studied roughly 12,000 DNA samples from patients with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder, as well as healthy controls, searching across the whole genome at all of the protein-coding genes for patterns in somatic mutations.

The somatic mutations were concentrated in a handful of genes that turned out to be cancer genes.

So the researchers used electronic medical records to follow the patients’ medical histories, finding that subjects with these acquired mutations had a nearly 13-fold higher risk of developing a hematologic malignancy than subjects without the mutations.

The team conducted follow-up analyses on tumor samples from 2 patients who had progressed from this pre-malignant state to cancer. In both cases, the cancer developed from the same cells that had harbored the initiating mutations years earlier.

“The fact that both teams converged on strikingly similar findings, using very different approaches and looking at DNA from very different sets of patients, has given us great confidence in the results,” said study author Giulio Genovese, PhD, of the Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

Next steps

The researchers emphasized that there is no clinical benefit today for testing for this pre-malignant state, as there are no treatments currently available that would address this condition in otherwise healthy people.

However, they said the results open the door to entirely new directions for research, toward early detection and even prevention of hematologic malignancies.

“The results demonstrate a way to identify high-risk cohorts—people who are at much higher than average risk of progressing to cancer—which could be a population for clinical trials of future prevention strategies,” Dr McCarroll said. “The abundance of these mutated cells could also serve as a biomarker—like LDL cholesterol is for cardiovascular disease—to test the effects of potential prevention therapies in clinical trials.”

Dr Ebert added, “A new focus of investigation will now be to develop interventions that might decrease the likelihood that individuals with these mutations will go on to develop overt malignancies, or therapeutic strategies to decrease mortality from other conditions that may be instigated by these mutations.”

This research is set to be presented on December 9 at the 56th ASH Annual Meeting in San Francisco. ![]()

Credit: Graham Colm

Two teams of researchers have identified somatic mutations that increase the likelihood a person will develop a hematologic malignancy.

This “pre-malignant” stage was detected simply by sequencing DNA from blood samples.

The researchers found that subjects carrying certain mutations had more than 10 times the risk of developing a hematologic malignancy than individuals without the mutations. And the risk increased with age.

Steven McCarroll, PhD, of Harvard Medical School in Boston, Massachusetts, and Benjamin Ebert, MD, PhD, also of Harvard Medical School, reported these findings in NEJM.

Both research teams looked at somatic mutations in DNA samples collected from the blood of subjects who had not been diagnosed with cancer or blood disorders.

Taking two very different approaches, the teams found that a surprising percentage of individuals had acquired a subset of the somatic mutations present in hematologic malignancies. And subjects with the mutations were more likely to develop these cancers.

This pre-malignant state was rare in individuals under the age of 40. But it appeared with increasing frequency with each decade of life, ultimately appearing in more than 10% of individuals over the age of 70.

The researchers believe these early mutations lie in wait for follow-on, cooperating mutations that, when they occur in the same cells as the earlier mutations, drive the cells toward cancer. The majority of mutations occurred in just 3 genes: DNMT3A, TET2, and ASXL1.

Dr Ebert’s group

Dr Ebert and his colleagues had hypothesized that, since hematologic malignancies increase with age, it might be possible to detect early somatic mutations that could be initiating the disease process, and these mutations might increase with age.

The researchers looked specifically at 160 genes known to be recurrently mutated in hematologic malignancies, using genetic data derived from approximately 17,000 blood samples originally obtained for studies on the genetics of type 2 diabetes.

The team found a roughly 11-fold increase in the risk of hematologic malignancy among subjects with the subset of somatic mutations linked to blood cancers. And there was a clear association between age and the frequency of these mutations.

Men were slightly more likely to have the mutations than women, and Hispanics were slightly less likely to have the mutations than other racial/ethnic groups.

The researchers also found an association between the presence of this pre-malignant state and the risk of overall mortality independent of malignancy. Individuals with the mutations had a higher risk of type 2 diabetes, coronary heart disease, and ischemic stroke as well.

However, additional research will be needed to determine the nature of these associations.

Dr McCarroll’s group

Dr McCarroll and his colleagues discovered the same phenomenon while trying to determine whether somatic mutations contribute to the risk of developing schizophrenia.

The team studied roughly 12,000 DNA samples from patients with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder, as well as healthy controls, searching across the whole genome at all of the protein-coding genes for patterns in somatic mutations.

The somatic mutations were concentrated in a handful of genes that turned out to be cancer genes.

So the researchers used electronic medical records to follow the patients’ medical histories, finding that subjects with these acquired mutations had a nearly 13-fold higher risk of developing a hematologic malignancy than subjects without the mutations.

The team conducted follow-up analyses on tumor samples from 2 patients who had progressed from this pre-malignant state to cancer. In both cases, the cancer developed from the same cells that had harbored the initiating mutations years earlier.

“The fact that both teams converged on strikingly similar findings, using very different approaches and looking at DNA from very different sets of patients, has given us great confidence in the results,” said study author Giulio Genovese, PhD, of the Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

Next steps

The researchers emphasized that there is no clinical benefit today for testing for this pre-malignant state, as there are no treatments currently available that would address this condition in otherwise healthy people.

However, they said the results open the door to entirely new directions for research, toward early detection and even prevention of hematologic malignancies.

“The results demonstrate a way to identify high-risk cohorts—people who are at much higher than average risk of progressing to cancer—which could be a population for clinical trials of future prevention strategies,” Dr McCarroll said. “The abundance of these mutated cells could also serve as a biomarker—like LDL cholesterol is for cardiovascular disease—to test the effects of potential prevention therapies in clinical trials.”

Dr Ebert added, “A new focus of investigation will now be to develop interventions that might decrease the likelihood that individuals with these mutations will go on to develop overt malignancies, or therapeutic strategies to decrease mortality from other conditions that may be instigated by these mutations.”

This research is set to be presented on December 9 at the 56th ASH Annual Meeting in San Francisco. ![]()

Credit: Graham Colm

Two teams of researchers have identified somatic mutations that increase the likelihood a person will develop a hematologic malignancy.

This “pre-malignant” stage was detected simply by sequencing DNA from blood samples.

The researchers found that subjects carrying certain mutations had more than 10 times the risk of developing a hematologic malignancy than individuals without the mutations. And the risk increased with age.

Steven McCarroll, PhD, of Harvard Medical School in Boston, Massachusetts, and Benjamin Ebert, MD, PhD, also of Harvard Medical School, reported these findings in NEJM.

Both research teams looked at somatic mutations in DNA samples collected from the blood of subjects who had not been diagnosed with cancer or blood disorders.

Taking two very different approaches, the teams found that a surprising percentage of individuals had acquired a subset of the somatic mutations present in hematologic malignancies. And subjects with the mutations were more likely to develop these cancers.

This pre-malignant state was rare in individuals under the age of 40. But it appeared with increasing frequency with each decade of life, ultimately appearing in more than 10% of individuals over the age of 70.

The researchers believe these early mutations lie in wait for follow-on, cooperating mutations that, when they occur in the same cells as the earlier mutations, drive the cells toward cancer. The majority of mutations occurred in just 3 genes: DNMT3A, TET2, and ASXL1.

Dr Ebert’s group

Dr Ebert and his colleagues had hypothesized that, since hematologic malignancies increase with age, it might be possible to detect early somatic mutations that could be initiating the disease process, and these mutations might increase with age.

The researchers looked specifically at 160 genes known to be recurrently mutated in hematologic malignancies, using genetic data derived from approximately 17,000 blood samples originally obtained for studies on the genetics of type 2 diabetes.

The team found a roughly 11-fold increase in the risk of hematologic malignancy among subjects with the subset of somatic mutations linked to blood cancers. And there was a clear association between age and the frequency of these mutations.

Men were slightly more likely to have the mutations than women, and Hispanics were slightly less likely to have the mutations than other racial/ethnic groups.

The researchers also found an association between the presence of this pre-malignant state and the risk of overall mortality independent of malignancy. Individuals with the mutations had a higher risk of type 2 diabetes, coronary heart disease, and ischemic stroke as well.

However, additional research will be needed to determine the nature of these associations.

Dr McCarroll’s group

Dr McCarroll and his colleagues discovered the same phenomenon while trying to determine whether somatic mutations contribute to the risk of developing schizophrenia.

The team studied roughly 12,000 DNA samples from patients with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder, as well as healthy controls, searching across the whole genome at all of the protein-coding genes for patterns in somatic mutations.

The somatic mutations were concentrated in a handful of genes that turned out to be cancer genes.

So the researchers used electronic medical records to follow the patients’ medical histories, finding that subjects with these acquired mutations had a nearly 13-fold higher risk of developing a hematologic malignancy than subjects without the mutations.

The team conducted follow-up analyses on tumor samples from 2 patients who had progressed from this pre-malignant state to cancer. In both cases, the cancer developed from the same cells that had harbored the initiating mutations years earlier.

“The fact that both teams converged on strikingly similar findings, using very different approaches and looking at DNA from very different sets of patients, has given us great confidence in the results,” said study author Giulio Genovese, PhD, of the Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

Next steps

The researchers emphasized that there is no clinical benefit today for testing for this pre-malignant state, as there are no treatments currently available that would address this condition in otherwise healthy people.

However, they said the results open the door to entirely new directions for research, toward early detection and even prevention of hematologic malignancies.

“The results demonstrate a way to identify high-risk cohorts—people who are at much higher than average risk of progressing to cancer—which could be a population for clinical trials of future prevention strategies,” Dr McCarroll said. “The abundance of these mutated cells could also serve as a biomarker—like LDL cholesterol is for cardiovascular disease—to test the effects of potential prevention therapies in clinical trials.”

Dr Ebert added, “A new focus of investigation will now be to develop interventions that might decrease the likelihood that individuals with these mutations will go on to develop overt malignancies, or therapeutic strategies to decrease mortality from other conditions that may be instigated by these mutations.”

This research is set to be presented on December 9 at the 56th ASH Annual Meeting in San Francisco. ![]()

Management of Bleeding Complications in Patients with Cancer

Patients with cancer can have many hematologic complications. One of the most serious is bleeding, which can range in severity from laboratory abnormalities to life-threatening hemorrhage. The bleeding can be due to complications of the cancer, its therapy, or treatment for complications of cancer such as thrombosis. This manual discusses an approach to the cancer patient with bleeding, with a specific focus on issues such as coagulation defects, thrombocytopenia, and platelet dysfunction. Bleeding complications of specific cancers and their treatment will be discussed as well.

To read the full article in PDF:

Patients with cancer can have many hematologic complications. One of the most serious is bleeding, which can range in severity from laboratory abnormalities to life-threatening hemorrhage. The bleeding can be due to complications of the cancer, its therapy, or treatment for complications of cancer such as thrombosis. This manual discusses an approach to the cancer patient with bleeding, with a specific focus on issues such as coagulation defects, thrombocytopenia, and platelet dysfunction. Bleeding complications of specific cancers and their treatment will be discussed as well.

To read the full article in PDF:

Patients with cancer can have many hematologic complications. One of the most serious is bleeding, which can range in severity from laboratory abnormalities to life-threatening hemorrhage. The bleeding can be due to complications of the cancer, its therapy, or treatment for complications of cancer such as thrombosis. This manual discusses an approach to the cancer patient with bleeding, with a specific focus on issues such as coagulation defects, thrombocytopenia, and platelet dysfunction. Bleeding complications of specific cancers and their treatment will be discussed as well.

To read the full article in PDF:

Metastatic Prostate Cancer: A Case Study

Prostate cancer remains the second leading cause of death in men in the United States as of 2012. It is estimated that prostate cancer affected more than 241,000 new men in 2012, with 15% of these patients presenting with advanced disease. As one would expect, compared to localized prostate cancer, metastatic disease remains the more challenging type to treat. In 1941 Huggins and Hodges demonstrated the dependence of prostatic tissues on androgens and from this work hormonal therapy was developed as the primary treatment for metastatic prostate cancer. Since then, significant progress has been made in the treatment of metastatic prostate cancer, including advances in androgen deprivation therapy and in the treatment of castrationresistant prostate cancer (CRPC), with many advances yet to come. CPRC has been an exciting topic for recent research and advancement, as our understanding of how prostate cancer utilizes very low levels of androgen has evolved considerably.

To read the full article in PDF:

Prostate cancer remains the second leading cause of death in men in the United States as of 2012. It is estimated that prostate cancer affected more than 241,000 new men in 2012, with 15% of these patients presenting with advanced disease. As one would expect, compared to localized prostate cancer, metastatic disease remains the more challenging type to treat. In 1941 Huggins and Hodges demonstrated the dependence of prostatic tissues on androgens and from this work hormonal therapy was developed as the primary treatment for metastatic prostate cancer. Since then, significant progress has been made in the treatment of metastatic prostate cancer, including advances in androgen deprivation therapy and in the treatment of castrationresistant prostate cancer (CRPC), with many advances yet to come. CPRC has been an exciting topic for recent research and advancement, as our understanding of how prostate cancer utilizes very low levels of androgen has evolved considerably.

To read the full article in PDF:

Prostate cancer remains the second leading cause of death in men in the United States as of 2012. It is estimated that prostate cancer affected more than 241,000 new men in 2012, with 15% of these patients presenting with advanced disease. As one would expect, compared to localized prostate cancer, metastatic disease remains the more challenging type to treat. In 1941 Huggins and Hodges demonstrated the dependence of prostatic tissues on androgens and from this work hormonal therapy was developed as the primary treatment for metastatic prostate cancer. Since then, significant progress has been made in the treatment of metastatic prostate cancer, including advances in androgen deprivation therapy and in the treatment of castrationresistant prostate cancer (CRPC), with many advances yet to come. CPRC has been an exciting topic for recent research and advancement, as our understanding of how prostate cancer utilizes very low levels of androgen has evolved considerably.

To read the full article in PDF:

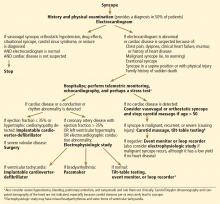

Syncope: Etiology and diagnostic approach

Syncope is a transient loss of consciousness and postural tone with spontaneous, complete recovery. There are three major types: neurally mediated, orthostatic, and cardiac (Table 1).

NEURALLY MEDIATED SYNCOPE

Neurally mediated (reflex) syncope is the most common type, accounting for two-thirds of cases.1–3 It results from autonomic reflexes that respond inappropriately, leading to vasodilation and bradycardia.

See related patient-education handout

Neurally mediated syncope is usually preceded by premonitory symptoms such as lightheadedness, diaphoresis, nausea, malaise, abdominal discomfort, and tunnel vision. However, this may not be the case in one-third of patients, especially in elderly patients, who may not recognize or remember the warning symptoms. Palpitations are frequently reported with neurally mediated syncope and do not necessarily imply that the syncope is due to an arrhythmia.4,5 Neurally mediated syncope does not usually occur in the supine position4,5 but can occur in the seated position.6

Subtypes of neurally mediated syncope are as follows:

Vasovagal syncope

Vasovagal syncope is usually triggered by sudden emotional stress, prolonged sitting or standing, dehydration, or a warm environment, but it can also occur without a trigger. It is the most common type of syncope in young patients (more so in females than in males), but contrary to a common misconception, it can also occur in the elderly.7 Usually, it is not only preceded by but also followed by nausea, malaise, fatigue, and diaphoresis4,5,8; full recovery may be slow. If the syncope lasts longer than 30 to 60 seconds, clonic movements and loss of bladder control are common.9

Mechanism. Vasovagal syncope is initiated by anything that leads to strong myocardial contractions in an "empty" heart. Emotional stress, reduced venous return (from dehydration or prolonged standing), or vasodilation (caused by a hot environment) stimulates the sympathetic nervous system and reduces the left ventricular cavity size, which leads to strong hyperdynamic contractions in a relatively empty heart. This hyperdynamic cavity obliteration activates myocardial mechanoreceptors, initiating a paradoxical vagal reflex with vasodilation and relative bradycardia.10 Vasodilation is usually the predominant mechanism (vasodepressor response), particularly in older patients, but severe bradycardia is also possible (cardioinhibitory response), particularly in younger patients.7 Diuretic and vasodilator therapies increase the predisposition to vasovagal syncope, particularly in the elderly.