User login

Switzerland approves drug to treat MCL

Credit: CDC

Swissmedic, the regulatory authority for Switzerland, has granted

approval for lenalidomide (Revlimid) to treat patients with

relapsed or refractory mantle cell lymphoma (MCL) after prior therapy

that included bortezomib and chemotherapy or rituximab.

This is the third approval of lenalidomide for MCL worldwide. The drug is also approved for this indication in the US and Israel.

Swissmedic’s decision to approve the drug was based on results of the phase 2 EMERGE study (MCL-001).

In this trial, researchers evaluated lenalidomide (25 mg once a day on days 1-21 of each 28-day cycle) in 134 MCL patients who had received prior treatment with rituximab, cyclophosphamide, an anthracycline (or mitoxantrone), and bortezomib alone or in combination.

The overall response rate (the primary endpoint) was 28% (37/134), and the complete response rate was 7% (10/134). The median duration of response was 16.6 months (95% CI, 7.7-26.7).

The most common grade 3/4 adverse events reported in at least 5% of patients were neutropenia (43%), thrombocytopenia (28%), anemia (11%), pneumonia (9%), fatigue (7%), leukopenia (7%), febrile neutropenia (6%), diarrhea (6%), and dyspnea (6%).

“MCL is a rare B-cell lymphoma of the elderly that usually responds quite well to first-line treatment,” said Christoph Renner, MD, of Onkozentrum Hirslanden Zürich.

“However, even intensive treatment does not prevent relapse in the majority of patients, and new therapeutic options are needed. Therefore, having access to lenalidomide, an immunomodulatory drug with a well-known safety profile, will definitely enrich our therapeutic armamentarium.”

Lenalidomide is already approved in Switzerland for use in combination

with dexamethasone to treat patients with multiple myeloma who have

received at least one previous treatment.

The drug is also

approved to treat patients with transfusion-dependent anemia due to low-

or intermediate-risk-1 myelodysplastic syndrome associated with a 5q

deletion, with or without additional cytogenetic abnormalities.

Lenalidomide is under development by Celgene International Sàrl, a wholly owned subsidiary of Celgene Corporation. ![]()

Credit: CDC

Swissmedic, the regulatory authority for Switzerland, has granted

approval for lenalidomide (Revlimid) to treat patients with

relapsed or refractory mantle cell lymphoma (MCL) after prior therapy

that included bortezomib and chemotherapy or rituximab.

This is the third approval of lenalidomide for MCL worldwide. The drug is also approved for this indication in the US and Israel.

Swissmedic’s decision to approve the drug was based on results of the phase 2 EMERGE study (MCL-001).

In this trial, researchers evaluated lenalidomide (25 mg once a day on days 1-21 of each 28-day cycle) in 134 MCL patients who had received prior treatment with rituximab, cyclophosphamide, an anthracycline (or mitoxantrone), and bortezomib alone or in combination.

The overall response rate (the primary endpoint) was 28% (37/134), and the complete response rate was 7% (10/134). The median duration of response was 16.6 months (95% CI, 7.7-26.7).

The most common grade 3/4 adverse events reported in at least 5% of patients were neutropenia (43%), thrombocytopenia (28%), anemia (11%), pneumonia (9%), fatigue (7%), leukopenia (7%), febrile neutropenia (6%), diarrhea (6%), and dyspnea (6%).

“MCL is a rare B-cell lymphoma of the elderly that usually responds quite well to first-line treatment,” said Christoph Renner, MD, of Onkozentrum Hirslanden Zürich.

“However, even intensive treatment does not prevent relapse in the majority of patients, and new therapeutic options are needed. Therefore, having access to lenalidomide, an immunomodulatory drug with a well-known safety profile, will definitely enrich our therapeutic armamentarium.”

Lenalidomide is already approved in Switzerland for use in combination

with dexamethasone to treat patients with multiple myeloma who have

received at least one previous treatment.

The drug is also

approved to treat patients with transfusion-dependent anemia due to low-

or intermediate-risk-1 myelodysplastic syndrome associated with a 5q

deletion, with or without additional cytogenetic abnormalities.

Lenalidomide is under development by Celgene International Sàrl, a wholly owned subsidiary of Celgene Corporation. ![]()

Credit: CDC

Swissmedic, the regulatory authority for Switzerland, has granted

approval for lenalidomide (Revlimid) to treat patients with

relapsed or refractory mantle cell lymphoma (MCL) after prior therapy

that included bortezomib and chemotherapy or rituximab.

This is the third approval of lenalidomide for MCL worldwide. The drug is also approved for this indication in the US and Israel.

Swissmedic’s decision to approve the drug was based on results of the phase 2 EMERGE study (MCL-001).

In this trial, researchers evaluated lenalidomide (25 mg once a day on days 1-21 of each 28-day cycle) in 134 MCL patients who had received prior treatment with rituximab, cyclophosphamide, an anthracycline (or mitoxantrone), and bortezomib alone or in combination.

The overall response rate (the primary endpoint) was 28% (37/134), and the complete response rate was 7% (10/134). The median duration of response was 16.6 months (95% CI, 7.7-26.7).

The most common grade 3/4 adverse events reported in at least 5% of patients were neutropenia (43%), thrombocytopenia (28%), anemia (11%), pneumonia (9%), fatigue (7%), leukopenia (7%), febrile neutropenia (6%), diarrhea (6%), and dyspnea (6%).

“MCL is a rare B-cell lymphoma of the elderly that usually responds quite well to first-line treatment,” said Christoph Renner, MD, of Onkozentrum Hirslanden Zürich.

“However, even intensive treatment does not prevent relapse in the majority of patients, and new therapeutic options are needed. Therefore, having access to lenalidomide, an immunomodulatory drug with a well-known safety profile, will definitely enrich our therapeutic armamentarium.”

Lenalidomide is already approved in Switzerland for use in combination

with dexamethasone to treat patients with multiple myeloma who have

received at least one previous treatment.

The drug is also

approved to treat patients with transfusion-dependent anemia due to low-

or intermediate-risk-1 myelodysplastic syndrome associated with a 5q

deletion, with or without additional cytogenetic abnormalities.

Lenalidomide is under development by Celgene International Sàrl, a wholly owned subsidiary of Celgene Corporation. ![]()

FDA grants drug orphan designation for aHUS

Credit: Kevin MacKenzie

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has granted orphan drug designation for CCX168, an oral inhibitor targeting the receptor for the complement protein C5a, to treat atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome (aHUS).

This rare but life-threatening disease causes inflammation of the blood vessels and thrombus formation throughout the body.

Patients with aHUS are at constant risk of sudden and progressive damage to, and failure of, vital organs. Roughly 10% to 15% of patients die in the initial, acute phase of aHUS.

The majority of patients—up to 70%—develop end-stage kidney failure requiring dialysis. And 1 in 5 patients has aHUS affecting organs other than the kidneys, most commonly the brain or heart.

“Given the life-threatening nature of aHUS, we are very pleased with the granting of orphan drug designation for CCX168 in this disease,” said Thomas J. Schall, PhD, president and chief executive officer of ChemoCentryx, Inc., the company developing CCX168.

ChemoCentryx has generated positive preclinical data that suggest an important role of C5a receptor inhibition in reducing microvasculature thrombosis formation in aHUS.

The company plans to initiate a phase 2 proof-of-concept study in patients with aHUS by the end of 2014.

CCX168 is also in phase 2 development for the treatment of anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody-associated vasculitis.

The orphan designation for CCX168 will provide ChemoCentryx with a 7-year period of US marketing exclusivity if the drug is approved to treat aHUS, tax credits for clinical research costs, the ability to apply for annual grant funding, clinical research trial design assistance, and the waiver of prescription drug user fees. ![]()

Credit: Kevin MacKenzie

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has granted orphan drug designation for CCX168, an oral inhibitor targeting the receptor for the complement protein C5a, to treat atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome (aHUS).

This rare but life-threatening disease causes inflammation of the blood vessels and thrombus formation throughout the body.

Patients with aHUS are at constant risk of sudden and progressive damage to, and failure of, vital organs. Roughly 10% to 15% of patients die in the initial, acute phase of aHUS.

The majority of patients—up to 70%—develop end-stage kidney failure requiring dialysis. And 1 in 5 patients has aHUS affecting organs other than the kidneys, most commonly the brain or heart.

“Given the life-threatening nature of aHUS, we are very pleased with the granting of orphan drug designation for CCX168 in this disease,” said Thomas J. Schall, PhD, president and chief executive officer of ChemoCentryx, Inc., the company developing CCX168.

ChemoCentryx has generated positive preclinical data that suggest an important role of C5a receptor inhibition in reducing microvasculature thrombosis formation in aHUS.

The company plans to initiate a phase 2 proof-of-concept study in patients with aHUS by the end of 2014.

CCX168 is also in phase 2 development for the treatment of anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody-associated vasculitis.

The orphan designation for CCX168 will provide ChemoCentryx with a 7-year period of US marketing exclusivity if the drug is approved to treat aHUS, tax credits for clinical research costs, the ability to apply for annual grant funding, clinical research trial design assistance, and the waiver of prescription drug user fees. ![]()

Credit: Kevin MacKenzie

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has granted orphan drug designation for CCX168, an oral inhibitor targeting the receptor for the complement protein C5a, to treat atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome (aHUS).

This rare but life-threatening disease causes inflammation of the blood vessels and thrombus formation throughout the body.

Patients with aHUS are at constant risk of sudden and progressive damage to, and failure of, vital organs. Roughly 10% to 15% of patients die in the initial, acute phase of aHUS.

The majority of patients—up to 70%—develop end-stage kidney failure requiring dialysis. And 1 in 5 patients has aHUS affecting organs other than the kidneys, most commonly the brain or heart.

“Given the life-threatening nature of aHUS, we are very pleased with the granting of orphan drug designation for CCX168 in this disease,” said Thomas J. Schall, PhD, president and chief executive officer of ChemoCentryx, Inc., the company developing CCX168.

ChemoCentryx has generated positive preclinical data that suggest an important role of C5a receptor inhibition in reducing microvasculature thrombosis formation in aHUS.

The company plans to initiate a phase 2 proof-of-concept study in patients with aHUS by the end of 2014.

CCX168 is also in phase 2 development for the treatment of anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody-associated vasculitis.

The orphan designation for CCX168 will provide ChemoCentryx with a 7-year period of US marketing exclusivity if the drug is approved to treat aHUS, tax credits for clinical research costs, the ability to apply for annual grant funding, clinical research trial design assistance, and the waiver of prescription drug user fees. ![]()

Public Quality Reporting

Few consumers would choose to dine at a restaurant if they knew the kitchen was infested with cockroaches. Few patients would choose to undergo a liver transplant in a hospital that was performing the procedure for the first time. In most sectors, consumers gather information about quality (and price) from the marketplace, where economic theory predicts that rational behavior and competition will lead to continuous improvement over time. However, for some goods and services, information is sparse and asymmetric between consumers and suppliers. In sectors where consumer health is at risk, society has often intervened to assure minimum standards. Yet sometimes these efforts have fallen short. In healthcare, physician licensure and hospital accreditation (eg, through the Joint Commission), although providing an important foundation to assure safety, have not come close to solving the widespread quality problems.[1] Basic regulatory requirements for restaurants have also proven inadequate to prevent food‐borne illness. Consumer trust, without information, can be a recipe (or prescription) for trouble.

In response, high‐profile efforts have been introduced to publicize the quality and safety of service providers. One example is Hospital Compare, Medicare's national quality reporting program for US hospitals.[2] The New York City sanitary grade inspection program is a parallel effort for restaurants. Although customers can judge how much they like the food from a restaurantor look up reviews at

The aims of Hospital Compare and the New York City sanitary inspection program are fundamentally similar. Both initiatives seek to address a common market failure resulting in the consumer's lack of information on quality and safety. By infusing the market with information, these programs enable consumers to make better choices and encourage service providers to improve quality and safety.[3] Despite the promise of these programs, a copious literature about the effects of public quality reporting in healthcare has found mixed results.[4, 5] Although the performance measures in any public reporting program must be valid and reliable, good measures are not sufficient to achieve the goals of public reporting. To engage patients, reported results must also be accessible, understandable, and meaningful. Both patients' lack of knowledge about the reports[6] and patients' inability to effectively use these data to make better decisions[7] are some reasons why public quality reporting has fallen short of its expectations. This article argues that the New York City program is much better structured to positively affect patient choice, and holds important lessons for public quality reporting in US hospitals.

CONTRASTS BETWEEN HOSPITAL COMPARE AND THE NEW YORK CITY RESTAURANT SANITARY INSPECTION PROGRAM

Hospital Compare reports performance for 108 separate quality indicators related to quality and patient safety for US hospitals (Table 1). These are a combination of structure measures (eg, hospital participation in a systematic database for cardiac surgery), process of care measures (eg, acute myocardial infarction patients receiving fibrinolytic therapy within 30 minutes of hospital arrival), outcomes (eg, 30‐day mortality and readmission), and patient experience measures (eg, how you would rate your communication with your physician). Hospital Compare data, frequently based on hospital quality performance 1 to 3 years prior to publication, are displayed on a website. Hospitals do not receive a summary measure of quality or safety.[8] Hospitals face financial incentives that are tied to measure reporting[9] and performance for some of the measures on Hospital Compare.[10, 11] Hospital accreditation is only loosely related to performance on these measures.

| Attribute | Hospital Compare | New York City Sanitary Inspection Program |

|---|---|---|

| Display of information | On a website ( |

On the front of the restaurant, with additional information also available on a website ( |

| Frequency of information update | Quarterly; data often lag by between 1 and 3 years. | Unannounced inspections occur at least annually. Grades are posted immediately after inspection. |

| Quality measures | Mix of measures pertaining to quality improvement activities (eg, hospital participation in a cardiac surgery registry or a quality improvement initiative), rates of adherence with evidence‐based medicine (eg, heart failure patients receiving discharge instructions, acute myocardial infarction patients receiving ‐blocker at arrival), and patient outcomes (eg, 30‐day mortality and 30‐day readmission for acute myocardial infarction, heart failure, and pneumonia). | Mix of measures pertaining to conditions of the facility (eg, improper sewage disposal system, improper food contact surface, evidence of live rats in the facility) and the treatment and handling of food (eg, food is unwrapped, appropriate thermometer not used to measure temperature of potentially hazardous foods, food not prepared to sufficiently high temperature). |

| Clarity and simplicity of information | 108 individual measures. No summary measure. | Single summary letter grade displayed on front of restaurant. Detailed data on individual violations (ie, measures) available on website. |

| Consequences of poor performance and mechanisms for enforcement | Hospitals are subject to financial penalties for not reporting certain measures and face financial incentives for performance on a subset of measures. | Restaurants are fined for violations, are subject to repeated inspections for poor performance, and are subject to closure for severe violations. |

| Consumer awareness | Limited | Widespread |

The New York City sanitation program regularly inspects restaurants and scores them on a standard set of indicators that correspond to critical violations (eg, food is contaminated by mouse droppings) or general violations (eg, garbage is not adequately covered).[12] Points are assigned to each type and severity of violation, and the sum of the points are converted into a summary grade of A, B, or C. Restaurants can dispute the grades, receiving a grade pending designation until the dispute is adjudicated. After inspection, sanitation grades are immediately posted on restaurants' front door or window, providing current information that is clearly visible to consumers before entering. More detailed information on sanitation violations is also available on a website. If restaurants receive an A grade, they face no additional inspections for 1 year, but poorly graded restaurants may receive monthly inspections. Restaurants face fines from violations and are subject to closure from severe violations. Recently proposed changes would decrease fines and give restaurants greater opportunities to appeal grades, but leave the program otherwise intact.[13]

IMPLICATIONS FOR PUBLIC QUALITY REPORTING IN HOSPITALS

Along with value‐based payment reforms, public quality reporting is one of the few major system‐level approaches that is being implemented in the US to improve quality and safety in healthcare. However, without a simple and understandable display of information that is available when a patient needs it, quality and safety information will likely go unused.[14] Hospital Compare leaves it up the patient to find the quality and safety information and does little to help patients understand and use the information effectively. Hospital Compare asks patients to do far more work, which is perhaps why it has been largely ignored by patients.[2, 15] The New York City sanitation inspection program evaluates restaurants, prominently displays an understandable summary result, and puts the scoring details in the background. Although peer‐reviewed evaluations of the New York City sanitation inspection program have not yet been published, internal data show that the program has decreased customer concern about getting sick, improved sanitary practices, and decreased salmonella.[16] Evidence from a similar program in Los Angeles County found that hygiene grades steered consumers toward restaurants with better sanitary conditions and decreased food‐borne illness.[17]

The nature of choice in healthcare, particularly the choice of hospital, is much different than it is for restaurants. In some areas, a single hospital may serve a large geographical area, severely limiting choice. Even when patients have the ability to receive care at different hospitals, choice may be limited because patients are referred to a specific hospital by their outpatient physician or are brought to a hospital during an emergency.[18] In these cases, quality grades on the front doors of hospitals would not affect patient decisions, at least for that admission. Nonetheless, if quality grades were posted on the front doors of hospitals, patients receiving both inpatient and outpatient care would see the grades, and could use the information to make future decisions. Posted grades may also lead patients to review more in‐depth quality information related to their condition on the Hospital Compare website. Posted quality grades would also increase the visibility of the grades for other stakeholdersincluding the media and boards of directorsmagnifying their salience and impact.

How quality information is displayed and summarized can make or break public reporting programs. The New York City sanitation inspection program displays summarized, composite measures in the form of widely understood letter grades. Hospital Compare, however, displays myriad, unrelated performance measures that are not summarized into a global quality or safety measure. This information display is at odds with best practice. Patients find it difficult to synthesize data from multiple performance indicators to determine the relative quality of healthcare providers or insurance plans.7 In many cases, more information can lead to worse decision making.[19] Patients' difficulty making optimal choices has been noted in numerous healthcare settings, including purchasing Medicare Part D plans[20] and choosing health plans.[21] Recent evidence suggests that Nursing Home Compare's shift from an unsummarized collection of disparate performance measures to a 5‐star rating system has led patients to choose higher‐ranked facilities.[22] The fact that commercial providers of product quality information, such as Consumer Reports[23] and US News and World Report,[24] publish global summary scores, in addition to component scores, is a hint that this style of reporting is more appealing to consumers. Reports suggest that Medicare is moving toward a 5‐star quality rating system for hospitals,[8] which is a welcome development.

Different types of patients may demand different types of quality information, and a single summary measure for Hospital Compare may not meet the needs of a diverse set of patients. Nonetheless, the benefits from an actionable, understandable, comprehensive, and appropriate summary measure likely outweigh the costs of a potential mismatch for certain types of patients. Many of the performance measures on Hospital Compare already apply broadly to diverse sets of patients (eg, the structure measures, patient experience, and surgical safety) and are not specific to certain disease areas. Global summary measures could be complemented by separate component scores (eg, by disease area or domain of quality) for patients who wanted information on different aspects of care.

The inspection regime that underlies the New York City sanitary inspection program has parallels in healthcare that could be extended to Hospital Compare. For instance, the Joint Commission performs surprise inspections of hospitals as part of its accreditation process. The publicly reported 5‐star ratings for nursing homes are also based, in part, on inspection results.[25] Results from these types of inspections can capture up‐to‐date information on important dimensions of quality and safety that are not available in standard administrative data sources. Incorporating inspection results into Hospital Compare could increase both the timeliness and validity of the reporting.

The New York City sanitation inspection program is not a panacea: the indicators may not capture all relevant aspects of restaurant sanitation, some research suggests that past sanitary grades do not predict future grades,[26] and sanitary grade inflation over time has the potential to mask meaningful differences in sanitary conditions that are related to food‐borne illness.[16, 26] However, by providing understandable and meaningful reports at the point of service, the New York City program is well designed to encourage sanitation improvement through both consumer and supplier behavior.

Where the New York City sanitation inspection program succeeds, Hospital Compare fails. Hospital Compare is not patient centered, and it is not working for patients. Medicare can learn from the New York City restaurant sanitation inspection program to enhance the effects of public reporting by presenting information to consumers that is relevant, easy to access and interpret, and up to date. The greater complexity of hospital product lines should not deter these efforts. Patients' lives, not just the health of their gastrointestinal tracts, are at stake.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors thank Kaveh G. Shojania, MD, and Edward E. Etchells, MD, MSc, University of Toronto, and Martin Roland, DM, University of Oxford and RAND Europe for their comments on an earlier draft of the manuscript. None were compensated for their contributions.

Disclosures: Nothing to report.

- Institute of Medicine. Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 2001.

- , , . Medicare's public reporting initiative on hospital quality had modest or no impact on mortality from three key conditions. Health Aff (Millwood). 2012;31(3):585–592.

- , . Public reporting of hospital hand hygiene compliance—helpful or harmful? JAMA. 2010;304(10):1116–1117.

- . Do cardiac surgery report cards reduce mortality? Assessing the evidence. Med Care Res Rev. 2006;63(4):403–426.

- , . Quality and consumer decision making in the market for health insurance and health care services. Med Care Res Rev. 2009;66(1 suppl):28S–52S.

- , . Use of public performance reports: a survey of patients undergoing cardiac surgery. JAMA. 1998;279(20):1638–1642.

- , , . Informing consumer decisions in health care: implications from decision‐making research. Milbank Q. 1997;75(3):395–414.

- Centers for Medicare hospital inpatient prospective payment systems for acute care hospitals and the long‐term care hospital prospective payment system and proposed fiscal year 2014 rates; quality reporting requirements for specific providers; hospital conditions of participation. Fed Regist. 2013:27486–27823.

- , . Relationship between Medicare's hospital compare performance measures and mortality rates. JAMA. 2006;296(22):2694–2702.

- . Will value‐based purchasing increase disparities in care? N Engl J Med. 2013;369(26):2472–2474.

- , . A path forward on Medicare readmissions. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(13):1175–1177.

- New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene. What to expect when you're inspected: a guide for food service operators. New York, NY: New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene; 2010.

- . In reprieve for restaurant industry, New York proposes changes to grading system. New York Times. March 22, 2014:A15.

- . Thinking, Fast and Slow. New York, NY: Farrar, Straus and Giroux; 2011.

- , , . Public hospital quality report awareness: evidence from National and Californian Internet searches and social media mentions, 2012. BMJ Open. 2014;4(3):e004417.

- New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene. Restaurant Grading in New York City at 18 Months. New York, NY: New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene; 2013.

- , . The effect of information on product quality: evidence from restaurant hygiene grade cards. Q J Econ. 2003;118(2):409–451.

- , , , . Do high‐cost hospitals deliver better care? Evidence from ambulance referral patterns. National Bureau of Economic Research. Working paper no. 17936. Available at: http://www.nber.org/papers/w17936.pdf. Published March 2012. Accessed November 18, 2014.

- , , , , . Less is more in presenting quality information to consumers. Med Care Res Rev. 2007;64(2)169–190.

- and . Choice inconsistencies among the elderly: evidence from plan choice in the Medicare Part D program. Amer Econ Rev. 2011;101(4)1180–1210.

- , , , . Strategies for reporting health plan performance information to consumers: evidence from controlled studies. Health Serv Res. 2002;37(2):291–313.

- , . Quality reporting and private prices: evidence from the nursing home industry. Paper presented at: American Society of Health Economists Annual Meeting; June 23, 2014; Los Angeles, CA.

- Consumer Reports. Best new care values. Available at: http://consumerreports.org/cro/2012/05/best-new-car-values/index.htm. Updated February 2014. Accessed November 18, 2014.

- . Best value schools methodology. US News and World Report. September 8, 2014. Available at: http://www.usnews.com/education/best-colleges/articles/2013/09/09/best-value-schools-methodology. Accessed November 18, 2014.

- Centers for Medicare 122:574–677.

Few consumers would choose to dine at a restaurant if they knew the kitchen was infested with cockroaches. Few patients would choose to undergo a liver transplant in a hospital that was performing the procedure for the first time. In most sectors, consumers gather information about quality (and price) from the marketplace, where economic theory predicts that rational behavior and competition will lead to continuous improvement over time. However, for some goods and services, information is sparse and asymmetric between consumers and suppliers. In sectors where consumer health is at risk, society has often intervened to assure minimum standards. Yet sometimes these efforts have fallen short. In healthcare, physician licensure and hospital accreditation (eg, through the Joint Commission), although providing an important foundation to assure safety, have not come close to solving the widespread quality problems.[1] Basic regulatory requirements for restaurants have also proven inadequate to prevent food‐borne illness. Consumer trust, without information, can be a recipe (or prescription) for trouble.

In response, high‐profile efforts have been introduced to publicize the quality and safety of service providers. One example is Hospital Compare, Medicare's national quality reporting program for US hospitals.[2] The New York City sanitary grade inspection program is a parallel effort for restaurants. Although customers can judge how much they like the food from a restaurantor look up reviews at

The aims of Hospital Compare and the New York City sanitary inspection program are fundamentally similar. Both initiatives seek to address a common market failure resulting in the consumer's lack of information on quality and safety. By infusing the market with information, these programs enable consumers to make better choices and encourage service providers to improve quality and safety.[3] Despite the promise of these programs, a copious literature about the effects of public quality reporting in healthcare has found mixed results.[4, 5] Although the performance measures in any public reporting program must be valid and reliable, good measures are not sufficient to achieve the goals of public reporting. To engage patients, reported results must also be accessible, understandable, and meaningful. Both patients' lack of knowledge about the reports[6] and patients' inability to effectively use these data to make better decisions[7] are some reasons why public quality reporting has fallen short of its expectations. This article argues that the New York City program is much better structured to positively affect patient choice, and holds important lessons for public quality reporting in US hospitals.

CONTRASTS BETWEEN HOSPITAL COMPARE AND THE NEW YORK CITY RESTAURANT SANITARY INSPECTION PROGRAM

Hospital Compare reports performance for 108 separate quality indicators related to quality and patient safety for US hospitals (Table 1). These are a combination of structure measures (eg, hospital participation in a systematic database for cardiac surgery), process of care measures (eg, acute myocardial infarction patients receiving fibrinolytic therapy within 30 minutes of hospital arrival), outcomes (eg, 30‐day mortality and readmission), and patient experience measures (eg, how you would rate your communication with your physician). Hospital Compare data, frequently based on hospital quality performance 1 to 3 years prior to publication, are displayed on a website. Hospitals do not receive a summary measure of quality or safety.[8] Hospitals face financial incentives that are tied to measure reporting[9] and performance for some of the measures on Hospital Compare.[10, 11] Hospital accreditation is only loosely related to performance on these measures.

| Attribute | Hospital Compare | New York City Sanitary Inspection Program |

|---|---|---|

| Display of information | On a website ( |

On the front of the restaurant, with additional information also available on a website ( |

| Frequency of information update | Quarterly; data often lag by between 1 and 3 years. | Unannounced inspections occur at least annually. Grades are posted immediately after inspection. |

| Quality measures | Mix of measures pertaining to quality improvement activities (eg, hospital participation in a cardiac surgery registry or a quality improvement initiative), rates of adherence with evidence‐based medicine (eg, heart failure patients receiving discharge instructions, acute myocardial infarction patients receiving ‐blocker at arrival), and patient outcomes (eg, 30‐day mortality and 30‐day readmission for acute myocardial infarction, heart failure, and pneumonia). | Mix of measures pertaining to conditions of the facility (eg, improper sewage disposal system, improper food contact surface, evidence of live rats in the facility) and the treatment and handling of food (eg, food is unwrapped, appropriate thermometer not used to measure temperature of potentially hazardous foods, food not prepared to sufficiently high temperature). |

| Clarity and simplicity of information | 108 individual measures. No summary measure. | Single summary letter grade displayed on front of restaurant. Detailed data on individual violations (ie, measures) available on website. |

| Consequences of poor performance and mechanisms for enforcement | Hospitals are subject to financial penalties for not reporting certain measures and face financial incentives for performance on a subset of measures. | Restaurants are fined for violations, are subject to repeated inspections for poor performance, and are subject to closure for severe violations. |

| Consumer awareness | Limited | Widespread |

The New York City sanitation program regularly inspects restaurants and scores them on a standard set of indicators that correspond to critical violations (eg, food is contaminated by mouse droppings) or general violations (eg, garbage is not adequately covered).[12] Points are assigned to each type and severity of violation, and the sum of the points are converted into a summary grade of A, B, or C. Restaurants can dispute the grades, receiving a grade pending designation until the dispute is adjudicated. After inspection, sanitation grades are immediately posted on restaurants' front door or window, providing current information that is clearly visible to consumers before entering. More detailed information on sanitation violations is also available on a website. If restaurants receive an A grade, they face no additional inspections for 1 year, but poorly graded restaurants may receive monthly inspections. Restaurants face fines from violations and are subject to closure from severe violations. Recently proposed changes would decrease fines and give restaurants greater opportunities to appeal grades, but leave the program otherwise intact.[13]

IMPLICATIONS FOR PUBLIC QUALITY REPORTING IN HOSPITALS

Along with value‐based payment reforms, public quality reporting is one of the few major system‐level approaches that is being implemented in the US to improve quality and safety in healthcare. However, without a simple and understandable display of information that is available when a patient needs it, quality and safety information will likely go unused.[14] Hospital Compare leaves it up the patient to find the quality and safety information and does little to help patients understand and use the information effectively. Hospital Compare asks patients to do far more work, which is perhaps why it has been largely ignored by patients.[2, 15] The New York City sanitation inspection program evaluates restaurants, prominently displays an understandable summary result, and puts the scoring details in the background. Although peer‐reviewed evaluations of the New York City sanitation inspection program have not yet been published, internal data show that the program has decreased customer concern about getting sick, improved sanitary practices, and decreased salmonella.[16] Evidence from a similar program in Los Angeles County found that hygiene grades steered consumers toward restaurants with better sanitary conditions and decreased food‐borne illness.[17]

The nature of choice in healthcare, particularly the choice of hospital, is much different than it is for restaurants. In some areas, a single hospital may serve a large geographical area, severely limiting choice. Even when patients have the ability to receive care at different hospitals, choice may be limited because patients are referred to a specific hospital by their outpatient physician or are brought to a hospital during an emergency.[18] In these cases, quality grades on the front doors of hospitals would not affect patient decisions, at least for that admission. Nonetheless, if quality grades were posted on the front doors of hospitals, patients receiving both inpatient and outpatient care would see the grades, and could use the information to make future decisions. Posted grades may also lead patients to review more in‐depth quality information related to their condition on the Hospital Compare website. Posted quality grades would also increase the visibility of the grades for other stakeholdersincluding the media and boards of directorsmagnifying their salience and impact.

How quality information is displayed and summarized can make or break public reporting programs. The New York City sanitation inspection program displays summarized, composite measures in the form of widely understood letter grades. Hospital Compare, however, displays myriad, unrelated performance measures that are not summarized into a global quality or safety measure. This information display is at odds with best practice. Patients find it difficult to synthesize data from multiple performance indicators to determine the relative quality of healthcare providers or insurance plans.7 In many cases, more information can lead to worse decision making.[19] Patients' difficulty making optimal choices has been noted in numerous healthcare settings, including purchasing Medicare Part D plans[20] and choosing health plans.[21] Recent evidence suggests that Nursing Home Compare's shift from an unsummarized collection of disparate performance measures to a 5‐star rating system has led patients to choose higher‐ranked facilities.[22] The fact that commercial providers of product quality information, such as Consumer Reports[23] and US News and World Report,[24] publish global summary scores, in addition to component scores, is a hint that this style of reporting is more appealing to consumers. Reports suggest that Medicare is moving toward a 5‐star quality rating system for hospitals,[8] which is a welcome development.

Different types of patients may demand different types of quality information, and a single summary measure for Hospital Compare may not meet the needs of a diverse set of patients. Nonetheless, the benefits from an actionable, understandable, comprehensive, and appropriate summary measure likely outweigh the costs of a potential mismatch for certain types of patients. Many of the performance measures on Hospital Compare already apply broadly to diverse sets of patients (eg, the structure measures, patient experience, and surgical safety) and are not specific to certain disease areas. Global summary measures could be complemented by separate component scores (eg, by disease area or domain of quality) for patients who wanted information on different aspects of care.

The inspection regime that underlies the New York City sanitary inspection program has parallels in healthcare that could be extended to Hospital Compare. For instance, the Joint Commission performs surprise inspections of hospitals as part of its accreditation process. The publicly reported 5‐star ratings for nursing homes are also based, in part, on inspection results.[25] Results from these types of inspections can capture up‐to‐date information on important dimensions of quality and safety that are not available in standard administrative data sources. Incorporating inspection results into Hospital Compare could increase both the timeliness and validity of the reporting.

The New York City sanitation inspection program is not a panacea: the indicators may not capture all relevant aspects of restaurant sanitation, some research suggests that past sanitary grades do not predict future grades,[26] and sanitary grade inflation over time has the potential to mask meaningful differences in sanitary conditions that are related to food‐borne illness.[16, 26] However, by providing understandable and meaningful reports at the point of service, the New York City program is well designed to encourage sanitation improvement through both consumer and supplier behavior.

Where the New York City sanitation inspection program succeeds, Hospital Compare fails. Hospital Compare is not patient centered, and it is not working for patients. Medicare can learn from the New York City restaurant sanitation inspection program to enhance the effects of public reporting by presenting information to consumers that is relevant, easy to access and interpret, and up to date. The greater complexity of hospital product lines should not deter these efforts. Patients' lives, not just the health of their gastrointestinal tracts, are at stake.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors thank Kaveh G. Shojania, MD, and Edward E. Etchells, MD, MSc, University of Toronto, and Martin Roland, DM, University of Oxford and RAND Europe for their comments on an earlier draft of the manuscript. None were compensated for their contributions.

Disclosures: Nothing to report.

Few consumers would choose to dine at a restaurant if they knew the kitchen was infested with cockroaches. Few patients would choose to undergo a liver transplant in a hospital that was performing the procedure for the first time. In most sectors, consumers gather information about quality (and price) from the marketplace, where economic theory predicts that rational behavior and competition will lead to continuous improvement over time. However, for some goods and services, information is sparse and asymmetric between consumers and suppliers. In sectors where consumer health is at risk, society has often intervened to assure minimum standards. Yet sometimes these efforts have fallen short. In healthcare, physician licensure and hospital accreditation (eg, through the Joint Commission), although providing an important foundation to assure safety, have not come close to solving the widespread quality problems.[1] Basic regulatory requirements for restaurants have also proven inadequate to prevent food‐borne illness. Consumer trust, without information, can be a recipe (or prescription) for trouble.

In response, high‐profile efforts have been introduced to publicize the quality and safety of service providers. One example is Hospital Compare, Medicare's national quality reporting program for US hospitals.[2] The New York City sanitary grade inspection program is a parallel effort for restaurants. Although customers can judge how much they like the food from a restaurantor look up reviews at

The aims of Hospital Compare and the New York City sanitary inspection program are fundamentally similar. Both initiatives seek to address a common market failure resulting in the consumer's lack of information on quality and safety. By infusing the market with information, these programs enable consumers to make better choices and encourage service providers to improve quality and safety.[3] Despite the promise of these programs, a copious literature about the effects of public quality reporting in healthcare has found mixed results.[4, 5] Although the performance measures in any public reporting program must be valid and reliable, good measures are not sufficient to achieve the goals of public reporting. To engage patients, reported results must also be accessible, understandable, and meaningful. Both patients' lack of knowledge about the reports[6] and patients' inability to effectively use these data to make better decisions[7] are some reasons why public quality reporting has fallen short of its expectations. This article argues that the New York City program is much better structured to positively affect patient choice, and holds important lessons for public quality reporting in US hospitals.

CONTRASTS BETWEEN HOSPITAL COMPARE AND THE NEW YORK CITY RESTAURANT SANITARY INSPECTION PROGRAM

Hospital Compare reports performance for 108 separate quality indicators related to quality and patient safety for US hospitals (Table 1). These are a combination of structure measures (eg, hospital participation in a systematic database for cardiac surgery), process of care measures (eg, acute myocardial infarction patients receiving fibrinolytic therapy within 30 minutes of hospital arrival), outcomes (eg, 30‐day mortality and readmission), and patient experience measures (eg, how you would rate your communication with your physician). Hospital Compare data, frequently based on hospital quality performance 1 to 3 years prior to publication, are displayed on a website. Hospitals do not receive a summary measure of quality or safety.[8] Hospitals face financial incentives that are tied to measure reporting[9] and performance for some of the measures on Hospital Compare.[10, 11] Hospital accreditation is only loosely related to performance on these measures.

| Attribute | Hospital Compare | New York City Sanitary Inspection Program |

|---|---|---|

| Display of information | On a website ( |

On the front of the restaurant, with additional information also available on a website ( |

| Frequency of information update | Quarterly; data often lag by between 1 and 3 years. | Unannounced inspections occur at least annually. Grades are posted immediately after inspection. |

| Quality measures | Mix of measures pertaining to quality improvement activities (eg, hospital participation in a cardiac surgery registry or a quality improvement initiative), rates of adherence with evidence‐based medicine (eg, heart failure patients receiving discharge instructions, acute myocardial infarction patients receiving ‐blocker at arrival), and patient outcomes (eg, 30‐day mortality and 30‐day readmission for acute myocardial infarction, heart failure, and pneumonia). | Mix of measures pertaining to conditions of the facility (eg, improper sewage disposal system, improper food contact surface, evidence of live rats in the facility) and the treatment and handling of food (eg, food is unwrapped, appropriate thermometer not used to measure temperature of potentially hazardous foods, food not prepared to sufficiently high temperature). |

| Clarity and simplicity of information | 108 individual measures. No summary measure. | Single summary letter grade displayed on front of restaurant. Detailed data on individual violations (ie, measures) available on website. |

| Consequences of poor performance and mechanisms for enforcement | Hospitals are subject to financial penalties for not reporting certain measures and face financial incentives for performance on a subset of measures. | Restaurants are fined for violations, are subject to repeated inspections for poor performance, and are subject to closure for severe violations. |

| Consumer awareness | Limited | Widespread |

The New York City sanitation program regularly inspects restaurants and scores them on a standard set of indicators that correspond to critical violations (eg, food is contaminated by mouse droppings) or general violations (eg, garbage is not adequately covered).[12] Points are assigned to each type and severity of violation, and the sum of the points are converted into a summary grade of A, B, or C. Restaurants can dispute the grades, receiving a grade pending designation until the dispute is adjudicated. After inspection, sanitation grades are immediately posted on restaurants' front door or window, providing current information that is clearly visible to consumers before entering. More detailed information on sanitation violations is also available on a website. If restaurants receive an A grade, they face no additional inspections for 1 year, but poorly graded restaurants may receive monthly inspections. Restaurants face fines from violations and are subject to closure from severe violations. Recently proposed changes would decrease fines and give restaurants greater opportunities to appeal grades, but leave the program otherwise intact.[13]

IMPLICATIONS FOR PUBLIC QUALITY REPORTING IN HOSPITALS

Along with value‐based payment reforms, public quality reporting is one of the few major system‐level approaches that is being implemented in the US to improve quality and safety in healthcare. However, without a simple and understandable display of information that is available when a patient needs it, quality and safety information will likely go unused.[14] Hospital Compare leaves it up the patient to find the quality and safety information and does little to help patients understand and use the information effectively. Hospital Compare asks patients to do far more work, which is perhaps why it has been largely ignored by patients.[2, 15] The New York City sanitation inspection program evaluates restaurants, prominently displays an understandable summary result, and puts the scoring details in the background. Although peer‐reviewed evaluations of the New York City sanitation inspection program have not yet been published, internal data show that the program has decreased customer concern about getting sick, improved sanitary practices, and decreased salmonella.[16] Evidence from a similar program in Los Angeles County found that hygiene grades steered consumers toward restaurants with better sanitary conditions and decreased food‐borne illness.[17]

The nature of choice in healthcare, particularly the choice of hospital, is much different than it is for restaurants. In some areas, a single hospital may serve a large geographical area, severely limiting choice. Even when patients have the ability to receive care at different hospitals, choice may be limited because patients are referred to a specific hospital by their outpatient physician or are brought to a hospital during an emergency.[18] In these cases, quality grades on the front doors of hospitals would not affect patient decisions, at least for that admission. Nonetheless, if quality grades were posted on the front doors of hospitals, patients receiving both inpatient and outpatient care would see the grades, and could use the information to make future decisions. Posted grades may also lead patients to review more in‐depth quality information related to their condition on the Hospital Compare website. Posted quality grades would also increase the visibility of the grades for other stakeholdersincluding the media and boards of directorsmagnifying their salience and impact.

How quality information is displayed and summarized can make or break public reporting programs. The New York City sanitation inspection program displays summarized, composite measures in the form of widely understood letter grades. Hospital Compare, however, displays myriad, unrelated performance measures that are not summarized into a global quality or safety measure. This information display is at odds with best practice. Patients find it difficult to synthesize data from multiple performance indicators to determine the relative quality of healthcare providers or insurance plans.7 In many cases, more information can lead to worse decision making.[19] Patients' difficulty making optimal choices has been noted in numerous healthcare settings, including purchasing Medicare Part D plans[20] and choosing health plans.[21] Recent evidence suggests that Nursing Home Compare's shift from an unsummarized collection of disparate performance measures to a 5‐star rating system has led patients to choose higher‐ranked facilities.[22] The fact that commercial providers of product quality information, such as Consumer Reports[23] and US News and World Report,[24] publish global summary scores, in addition to component scores, is a hint that this style of reporting is more appealing to consumers. Reports suggest that Medicare is moving toward a 5‐star quality rating system for hospitals,[8] which is a welcome development.

Different types of patients may demand different types of quality information, and a single summary measure for Hospital Compare may not meet the needs of a diverse set of patients. Nonetheless, the benefits from an actionable, understandable, comprehensive, and appropriate summary measure likely outweigh the costs of a potential mismatch for certain types of patients. Many of the performance measures on Hospital Compare already apply broadly to diverse sets of patients (eg, the structure measures, patient experience, and surgical safety) and are not specific to certain disease areas. Global summary measures could be complemented by separate component scores (eg, by disease area or domain of quality) for patients who wanted information on different aspects of care.

The inspection regime that underlies the New York City sanitary inspection program has parallels in healthcare that could be extended to Hospital Compare. For instance, the Joint Commission performs surprise inspections of hospitals as part of its accreditation process. The publicly reported 5‐star ratings for nursing homes are also based, in part, on inspection results.[25] Results from these types of inspections can capture up‐to‐date information on important dimensions of quality and safety that are not available in standard administrative data sources. Incorporating inspection results into Hospital Compare could increase both the timeliness and validity of the reporting.

The New York City sanitation inspection program is not a panacea: the indicators may not capture all relevant aspects of restaurant sanitation, some research suggests that past sanitary grades do not predict future grades,[26] and sanitary grade inflation over time has the potential to mask meaningful differences in sanitary conditions that are related to food‐borne illness.[16, 26] However, by providing understandable and meaningful reports at the point of service, the New York City program is well designed to encourage sanitation improvement through both consumer and supplier behavior.

Where the New York City sanitation inspection program succeeds, Hospital Compare fails. Hospital Compare is not patient centered, and it is not working for patients. Medicare can learn from the New York City restaurant sanitation inspection program to enhance the effects of public reporting by presenting information to consumers that is relevant, easy to access and interpret, and up to date. The greater complexity of hospital product lines should not deter these efforts. Patients' lives, not just the health of their gastrointestinal tracts, are at stake.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors thank Kaveh G. Shojania, MD, and Edward E. Etchells, MD, MSc, University of Toronto, and Martin Roland, DM, University of Oxford and RAND Europe for their comments on an earlier draft of the manuscript. None were compensated for their contributions.

Disclosures: Nothing to report.

- Institute of Medicine. Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 2001.

- , , . Medicare's public reporting initiative on hospital quality had modest or no impact on mortality from three key conditions. Health Aff (Millwood). 2012;31(3):585–592.

- , . Public reporting of hospital hand hygiene compliance—helpful or harmful? JAMA. 2010;304(10):1116–1117.

- . Do cardiac surgery report cards reduce mortality? Assessing the evidence. Med Care Res Rev. 2006;63(4):403–426.

- , . Quality and consumer decision making in the market for health insurance and health care services. Med Care Res Rev. 2009;66(1 suppl):28S–52S.

- , . Use of public performance reports: a survey of patients undergoing cardiac surgery. JAMA. 1998;279(20):1638–1642.

- , , . Informing consumer decisions in health care: implications from decision‐making research. Milbank Q. 1997;75(3):395–414.

- Centers for Medicare hospital inpatient prospective payment systems for acute care hospitals and the long‐term care hospital prospective payment system and proposed fiscal year 2014 rates; quality reporting requirements for specific providers; hospital conditions of participation. Fed Regist. 2013:27486–27823.

- , . Relationship between Medicare's hospital compare performance measures and mortality rates. JAMA. 2006;296(22):2694–2702.

- . Will value‐based purchasing increase disparities in care? N Engl J Med. 2013;369(26):2472–2474.

- , . A path forward on Medicare readmissions. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(13):1175–1177.

- New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene. What to expect when you're inspected: a guide for food service operators. New York, NY: New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene; 2010.

- . In reprieve for restaurant industry, New York proposes changes to grading system. New York Times. March 22, 2014:A15.

- . Thinking, Fast and Slow. New York, NY: Farrar, Straus and Giroux; 2011.

- , , . Public hospital quality report awareness: evidence from National and Californian Internet searches and social media mentions, 2012. BMJ Open. 2014;4(3):e004417.

- New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene. Restaurant Grading in New York City at 18 Months. New York, NY: New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene; 2013.

- , . The effect of information on product quality: evidence from restaurant hygiene grade cards. Q J Econ. 2003;118(2):409–451.

- , , , . Do high‐cost hospitals deliver better care? Evidence from ambulance referral patterns. National Bureau of Economic Research. Working paper no. 17936. Available at: http://www.nber.org/papers/w17936.pdf. Published March 2012. Accessed November 18, 2014.

- , , , , . Less is more in presenting quality information to consumers. Med Care Res Rev. 2007;64(2)169–190.

- and . Choice inconsistencies among the elderly: evidence from plan choice in the Medicare Part D program. Amer Econ Rev. 2011;101(4)1180–1210.

- , , , . Strategies for reporting health plan performance information to consumers: evidence from controlled studies. Health Serv Res. 2002;37(2):291–313.

- , . Quality reporting and private prices: evidence from the nursing home industry. Paper presented at: American Society of Health Economists Annual Meeting; June 23, 2014; Los Angeles, CA.

- Consumer Reports. Best new care values. Available at: http://consumerreports.org/cro/2012/05/best-new-car-values/index.htm. Updated February 2014. Accessed November 18, 2014.

- . Best value schools methodology. US News and World Report. September 8, 2014. Available at: http://www.usnews.com/education/best-colleges/articles/2013/09/09/best-value-schools-methodology. Accessed November 18, 2014.

- Centers for Medicare 122:574–677.

- Institute of Medicine. Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 2001.

- , , . Medicare's public reporting initiative on hospital quality had modest or no impact on mortality from three key conditions. Health Aff (Millwood). 2012;31(3):585–592.

- , . Public reporting of hospital hand hygiene compliance—helpful or harmful? JAMA. 2010;304(10):1116–1117.

- . Do cardiac surgery report cards reduce mortality? Assessing the evidence. Med Care Res Rev. 2006;63(4):403–426.

- , . Quality and consumer decision making in the market for health insurance and health care services. Med Care Res Rev. 2009;66(1 suppl):28S–52S.

- , . Use of public performance reports: a survey of patients undergoing cardiac surgery. JAMA. 1998;279(20):1638–1642.

- , , . Informing consumer decisions in health care: implications from decision‐making research. Milbank Q. 1997;75(3):395–414.

- Centers for Medicare hospital inpatient prospective payment systems for acute care hospitals and the long‐term care hospital prospective payment system and proposed fiscal year 2014 rates; quality reporting requirements for specific providers; hospital conditions of participation. Fed Regist. 2013:27486–27823.

- , . Relationship between Medicare's hospital compare performance measures and mortality rates. JAMA. 2006;296(22):2694–2702.

- . Will value‐based purchasing increase disparities in care? N Engl J Med. 2013;369(26):2472–2474.

- , . A path forward on Medicare readmissions. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(13):1175–1177.

- New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene. What to expect when you're inspected: a guide for food service operators. New York, NY: New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene; 2010.

- . In reprieve for restaurant industry, New York proposes changes to grading system. New York Times. March 22, 2014:A15.

- . Thinking, Fast and Slow. New York, NY: Farrar, Straus and Giroux; 2011.

- , , . Public hospital quality report awareness: evidence from National and Californian Internet searches and social media mentions, 2012. BMJ Open. 2014;4(3):e004417.

- New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene. Restaurant Grading in New York City at 18 Months. New York, NY: New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene; 2013.

- , . The effect of information on product quality: evidence from restaurant hygiene grade cards. Q J Econ. 2003;118(2):409–451.

- , , , . Do high‐cost hospitals deliver better care? Evidence from ambulance referral patterns. National Bureau of Economic Research. Working paper no. 17936. Available at: http://www.nber.org/papers/w17936.pdf. Published March 2012. Accessed November 18, 2014.

- , , , , . Less is more in presenting quality information to consumers. Med Care Res Rev. 2007;64(2)169–190.

- and . Choice inconsistencies among the elderly: evidence from plan choice in the Medicare Part D program. Amer Econ Rev. 2011;101(4)1180–1210.

- , , , . Strategies for reporting health plan performance information to consumers: evidence from controlled studies. Health Serv Res. 2002;37(2):291–313.

- , . Quality reporting and private prices: evidence from the nursing home industry. Paper presented at: American Society of Health Economists Annual Meeting; June 23, 2014; Los Angeles, CA.

- Consumer Reports. Best new care values. Available at: http://consumerreports.org/cro/2012/05/best-new-car-values/index.htm. Updated February 2014. Accessed November 18, 2014.

- . Best value schools methodology. US News and World Report. September 8, 2014. Available at: http://www.usnews.com/education/best-colleges/articles/2013/09/09/best-value-schools-methodology. Accessed November 18, 2014.

- Centers for Medicare 122:574–677.

Improving Notes in the EHR

There are described advantages to documenting in an electronic health record (EHR).[1, 2, 3, 4, 5] There has been, however, an unanticipated decline in certain aspects of documentation quality after implementing EHRs,[6, 7, 8] for example, the overinclusion of data (note clutter) and inappropriate use of copy‐paste.[6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17]

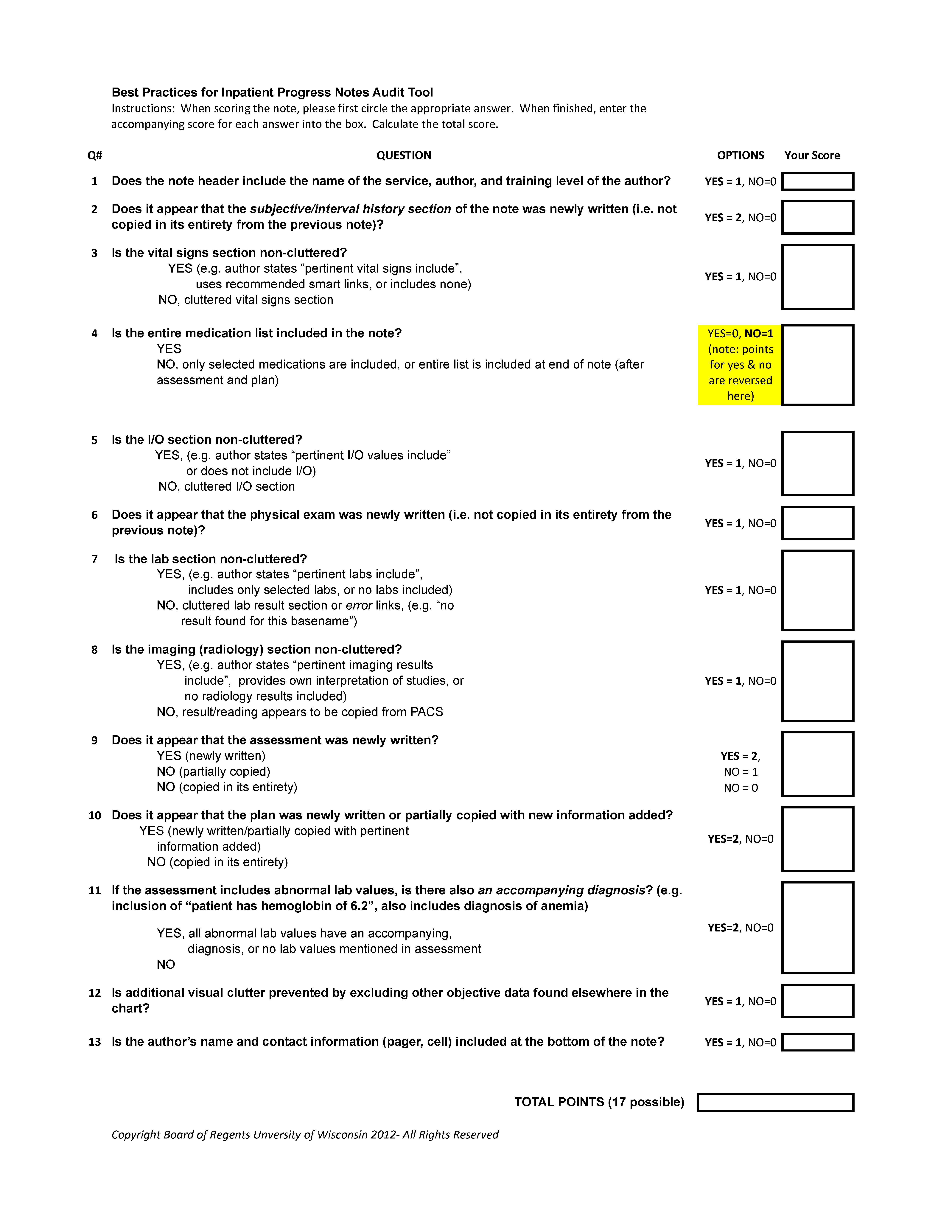

The objectives of this pilot study were to examine the effectiveness of an intervention bundle designed to improve resident progress notes written in an EHR (Epic Systems Corp., Verona, WI) and to establish the reliability of an audit tool used to assess the notes. Prior to this intervention, we provided no formal education for our residents about documentation in the EHR and had no policy governing format or content. The institutional review board at the University of Wisconsin approved this study.

METHODS

The Intervention Bundle

A multidisciplinary task force developed a set of Best Practice Guidelines for Writing Progress Notes in the EHR (see Supporting Information, Appendix 1, in the online version of this article). They were designed to promote cognitive review of data, reduce note clutter, promote synthesis of data, and discourage copy‐paste. For example, the guidelines recommended either the phrase, Vital signs from the last 24 hours have been reviewed and are pertinent for or a link that included minimum/maximum values rather than including multiple sets of data. We next developed a note template aligned with these guidelines (see Supporting Information, Appendix 2, in the online version of this article) using features and links that already existed within the EHR. Interns received classroom teaching about the best practices and instruction in use of the template.

Study Design

The study was a retrospective pre‐/postintervention. An audit tool designed to assess compliance with the guidelines was used to score 25 progress notes written by pediatric interns in August 2010 and August 2011 during the pre‐ and postintervention periods, respectively (see Supporting Information, Appendix 3, in the online version of this article).

Progress notes were eligible based on the following criteria: (1) written on any day subsequent to the admission date, (2) written by a pediatric intern, and (3) progress note from the previous day available for comparison. It was not required that 2 consecutive notes be written by the same resident. Eligible notes were identified using a computer‐generated report, reviewed by a study member to ensure eligibility, and assigned a number.

Notes were scored on a scale of 0 to 17, with each question having a range of possible scores from 0 to 2. Some questions related to inappropriate copy‐paste (questions 2, 9, 10) and a question related to discrete diagnostic language for abnormal labs (question 11) were weighted more heavily in the tool, as compliance with these components of the guideline was felt to be of greater importance. Several questions within the audit tool refer to clutter. We defined clutter as any additional data not endorsed by the guidelines or not explicitly stated as relevant to the patient's care for that day.

Raters were trained to score notes through practice sessions, during which they all scored the same note and compared findings. To rectify inter‐rater scoring discrepancies identified during these sessions, a reference manual was created to assist raters in scoring notes (see Supporting Information, Appendix 4, in the online version of this article). Each preintervention note was then systematically assigned to 2 raters, comprised of a physician and 3 staff from health information management. Each rater scored the note individually without discussion. The inter‐rater reliability was determined to be excellent, with kappa indices ranging from 88% to 100% for the 13 questions; each note in the postintervention period was therefore assigned to only 1 rater. Total and individual questions' scores were sent to the statistician for analysis.

Statistical Analysis

Inter‐rater reliability of the audit tool was evaluated by calculating the intraclass correlation (ICC) coefficient using a multilevel random intercept model to account for the rater effect.[18] The study was powered to detect an anticipated ICC of at least 0.75 at the 1‐sided 0.05 significance level, assuming a null hypothesis that the ICC is 0.4 or less. The total score was summarized in terms of means and standard deviation. Individual item responses were summarized using percentages and compared between the pre‐ and postintervention assessment using the Fisher exact test. The analysis of response patterns for individual item scores was considered exploratory. The Benjamini‐Hochberg false discovery rate method was utilized to control the false‐positive rate when comparing individual item scores.[19] All P values were 2‐sided and considered statistically significant at 0.05. Statistical analyses were conducted using SAS software version 9.2 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC).

RESULTS

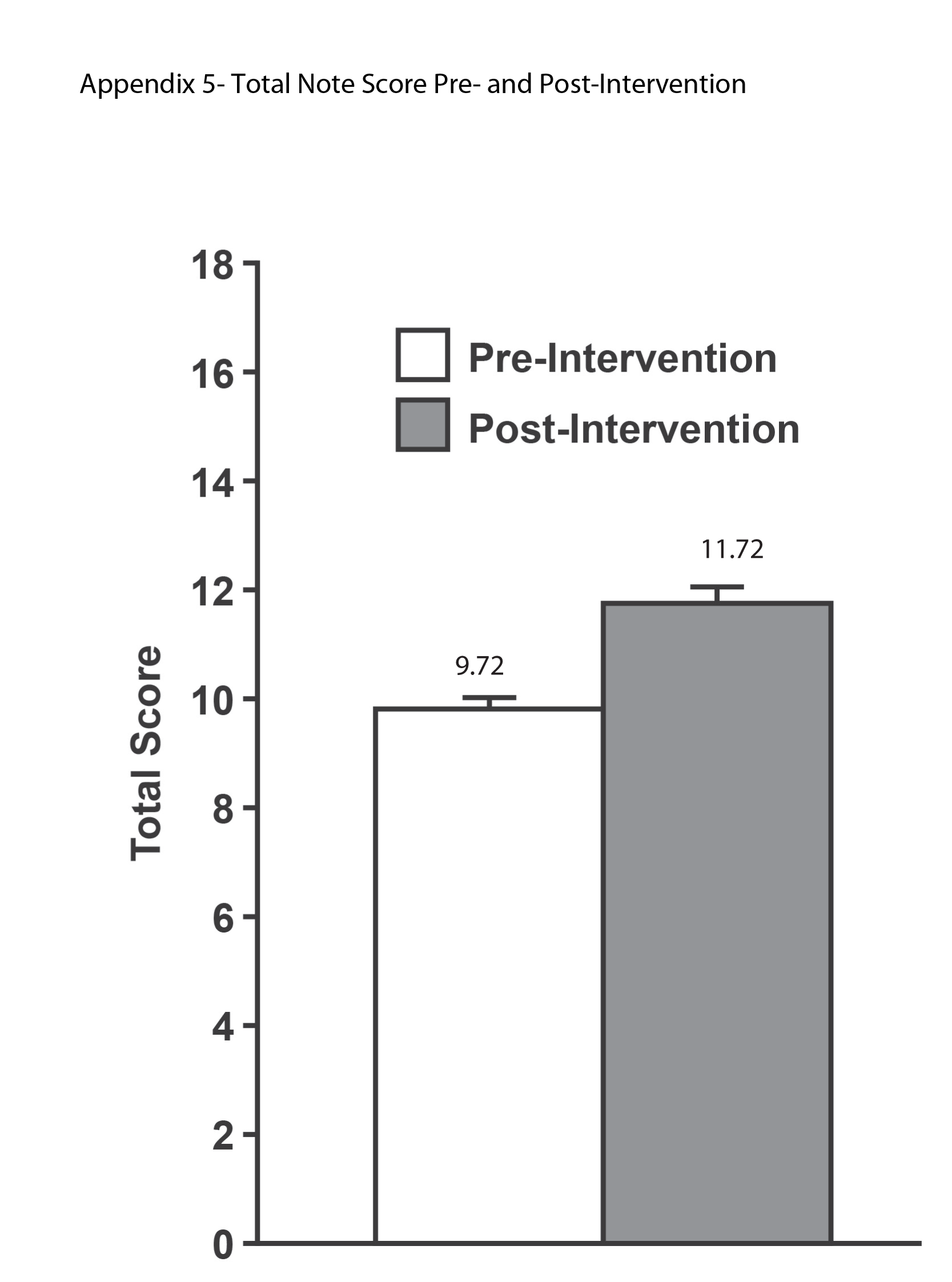

The ICC was 0.96 (95% confidence interval: 0.91‐0.98), indicating an excellent level of inter‐rater reliability. There was a significant improvement in the total score (see Supporting Information, Appendix 5, in the online version of this article) between the preintervention (mean 9.72, standard deviation [SD] 1.52) and postintervention (mean 11.72, SD 1.62) periods (P0.0001).

Table 1 shows the percentage of yes responses to each individual item in the pre‐ and postintervention periods. Our intervention had a significant impact on reducing vital sign clutter (4% preintervention, 84% postintervention, P0.0001) and other visual clutter within the note (0% preintervention, 28% postintervention, P=0.0035). We did not observe a significant impact on the reduction of input/output or lab clutter. There was no significant difference observed in the inclusion of the medication list. No significant improvements were seen in questions related to copy‐paste. The intervention had no significant impact on areas with an already high baseline performance: newly written interval histories, newly written physical exams, newly written plans, and the inclusion of discrete diagnostic language for abnormal labs.

| Question | Preintervention, N=25* | Postintervention, N=25 | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| 1. Does the note header include the name of the service, author, and training level of the author? | 0% | 68% | 0.0001 |

| 2. Does it appear that the subjective/emnterval history section of the note was newly written? (ie, not copied in its entirety from the previous note) | 100% | 96% | 0.9999 |

| 3. Is the vital sign section noncluttered? | 4% | 84% | 0.0001 |

| 4. Is the entire medication list included in the note? | 96% | 96% | 0.9999 |

| 5. Is the intake/output section noncluttered? | 0% | 16% | 0.3076 |

| 6. Does it appear that the physical exam was newly written? (ie, not copied in its entirety from the previous note) | 80% | 68% | 0.9103 |

| 7. Is the lab section noncluttered? | 64% | 44% | 0.5125 |

| 8. Is the imaging section noncluttered? | 100% | 100% | 0.9999 |

| 9. Does it appear that the assessment was newly written? | 48% | 28% | 0.5121 |

| 48% partial | 52% partial | 0.9999 | |

| 10. Does it appear that the plan was newly written or partially copied with new information added? | 88% | 96% | 0.9477 |

| 11. If the assessment includes abnormal lab values, is there also an accompanying diagnosis? (eg, inclusion of patient has hemoglobin of 6.2, also includes diagnosis of anemia) | 96% | 96% | 0.9999 |

| 12. Is additional visual clutter prevented by excluding other objective data found elsewhere in the chart? | 0% | 28% | 0.0035 |

| 13. Is the author's name and contact information (pager, cell) included at the bottom of the note? | 0% | 72% | 0.0001 |

DISCUSSION

Principal Findings

Improvements in electronic note writing, particularly in reducing note clutter, were achieved after the implementation of a bundled intervention. Because the intervention is a bundle, we cannot definitively identify which component had the greatest impact. Given the improvements seen in some areas with very low baseline performance, we hypothesize that these are most attributable to the creation of a compliant note template that (1) guided authors in using data links that were less cluttered and (2) eliminated the use of unnecessary links (eg, pain scores and daily weights). The lack of similar improvements in reducing input/output and lab clutter may be due to the fact that even with changes to the template suggesting a more narrative approach to these components, residents still felt compelled to use data links. Because our EHR does not easily allow for the inclusion of individual data elements, such as specific drain output or hemoglobin as opposed to a complete blood count, residents continued to use links that included more data than necessary. Although not significant findings, there was an observed decline in the proportion of notes containing a physical exam not entirely copied from the previous day and containing an assessment that was entirely new. These findings may be attributable to having a small sample of authors, a few of whom in the postintervention period were particularly prone to using copy‐paste.

Relationship to Other Evidence

The observed decline in quality of provider documentation after implementation of the EHR has led to a robust discussion in the literature about what really constitutes a quality provider note.[7, 8, 9, 10, 20] The absence of a defined gold standard makes research in this area challenging. It is our observation that when physicians refer to a decline in quality documentation in the EHR, they are frequently referring to the fact that electronically generated notes are often unattractive, difficult to read, and seem to lack clinical narrative.

Several publications have attempted to define note quality. Payne et al. described physical characteristics of electronically generated notes that were deemed more attractive to a reader, including a large proportion of narrative free text.[15] Hanson performed a qualitative study to describe outpatient clinical notes from the perspective of multiple stakeholders, resulting in a description of the characteristics of a quality note.[21] This formed the basis for the QNOTE, a validated tool to measure the quality of outpatient notes.[22] Similar work has not been done to rigorously define quality for inpatient documentation. Stetson did develop an instrument, the Physician Documentation Quality Instrument (PDQI‐9) to assess inpatient notes across 9 attributes; however, the validation method relied on a gold standard of a general impression score of 7 physician leaders.[23, 24]

Although these tools aim to address overall note quality, an advantage provided by our audit tool is that it directly addresses the problems most attributable to documenting in an EHR, namely note clutter and copy‐paste. A second advantage is that clinicians and nonclinicians can score notes objectively. The QNOTE and PDQI‐9 still rely on subjective assessment and require that the evaluator be a clinician.

There has also been little published about how to achieve notes of high quality. In 2013, Shoolin et al. did publish a consensus statement from the Association of Medical Directors of Information Systems outlining some guidelines for inpatient EHR documentation.[25] Optimal strategies for implementing such guidelines, however, and the overall impact such an implementation would have on improving note writing has not previously been studied. This study, therefore, adds to the existing body of literature by providing an example of an intervention that may lead to improvements in note writing.

Limitations

Our study has several limitations. The sample size of notes and authors was small. The short duration of the study and the assessment of notes soon after the intervention prevented an assessment of whether improvements were sustained over time.

Unfortunately, we were not evaluating the same group of interns in the pre‐ and postintervention periods. Interns were chosen as subjects as there was an existing opportunity to do large group training during new intern orientation. Furthermore, we were concerned that more note‐writing experience alone would influence the outcome if we examined the same interns later in the year.

The audit tool was also a first attempt at measuring compliance with the guidelines. Determination of an optimal score/weight for each item requires further investigation as part of a larger scale validation study. In addition, the cognitive review and synthesis of data encouraged in our guideline were more difficult to measure using the audit tool, as they require some clinical knowledge about the patient and an assessment of the author's medical decision making. We do not assert, therefore, that compliance with the guidelines or a higher total score necessarily translates into overall note quality, as we recognize these limitations of the tool.

Future Directions

In conclusion, this report is a first effort to improve the quality of note writing in the EHR. Much more work is necessary, particularly in improving the clinical narrative and inappropriate copy‐paste. The examination of other interventions, such as the impact of structured feedback to the note author, whether by way of a validated scoring tool and/or narrative comments, is a logical next step for investigation.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors acknowledge and appreciate the support of Joel Buchanan, MD, Ellen Wald, MD, and Ann Boyer, MD, for their contributions to this study and manuscript preparation. We also acknowledge the members of the auditing team: Linda Brickert, Jane Duckert, and Jeannine Strunk.

Disclosure: Nothing to report.

- , , . Use of computer‐based records, completeness of documentation, and appropriateness of documented clinical decisions. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 1999;6(3):245–251.

- , , , et al. An automated model to identify heart failure patients at risk for 30‐day readmission or death using electronic medical record data. Med Care. 2010;48(11):981–988.