User login

Trends in Blood‐Product Transfusion

Although potentially life saving, blood‐product transfusion is costly and associated with transfusion‐related adverse events, including death on rare occasions. Studies in varied patient populations have demonstrated that a restrictive red blood cell transfusion strategy reduces the number of transfusion‐related adverse effects and can result in improved short‐term survival.[1, 2, 3] In 2011, more than 20 million blood products were transfused in the United States, which resulted in more than 50,000 transfusion‐related adverse reactions (0.24%).[4] With a mean cost of greater than $50 per unit of plasma and $500 per unit of apheresis platelets,[4] the cost of blood transfusion is well in excess of $1 billion per year. Blood‐product transfusion is the most frequent inpatient procedure,[5] and inpatient blood‐product transfusion contributes to the bulk of transfusions nationwide. To study the utilization of blood‐product transfusion in the inpatient population, we studied the temporal trend of inpatient blood‐product transfusions in the United States from 2002 to 2011 using data from the Nationwide Inpatient Sample (NIS), Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.[4] The NIS, the largest inpatient care database in the United States, includes approximately a 20% stratified sample of US community hospital admissions and is weighted at discharge level to permit population‐level estimates.[6] We utilized this database to identify the total number of blood‐product transfusions and discharges between 2002 and 2011. We calculated the rate of all blood‐product transfusions, which include packed red blood cell, platelets, and other blood components, using the International Classification of DiseasesNinth Revision, Clinical Modification Procedural Clinical Classification Software code 222.[7] Trend analysis and calculation of average annual percent change were done using the Joinpoint Regression Program version 4.0.4 (National Cancer Institute, Bethesda, MD).[8] This software uses trend data and calculates the best fit lines to create the simplest joinpoint model that the data allow. The model can be expressed as a figure where several different multisegmented trend lines are connected together at the joinpoints. Trend over a fixed prespecified interval was computed as average annual percent change, and the Monte Carlo permutation method was used to test for apparent change in the trends.[9, 10] The study was exempted by the institutional review board of the University of Nebraska Medical Center.

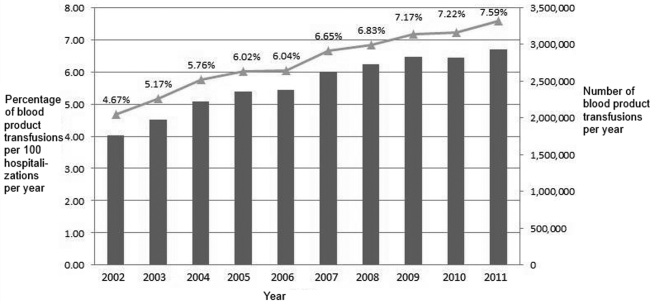

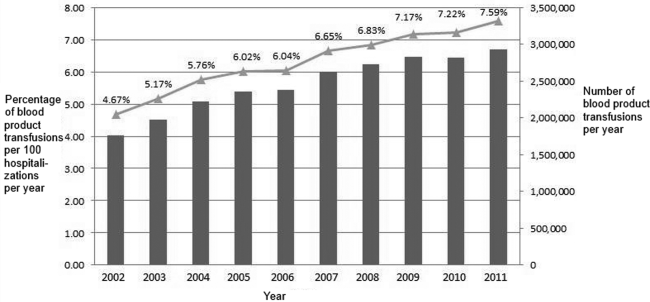

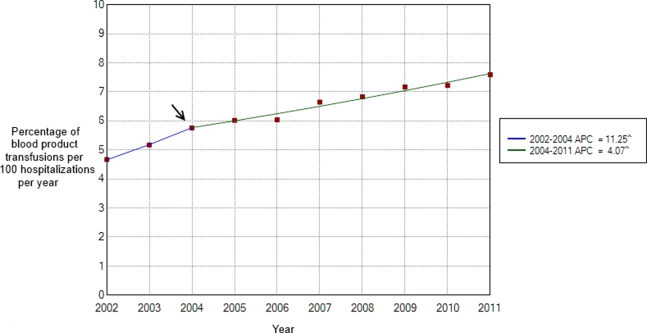

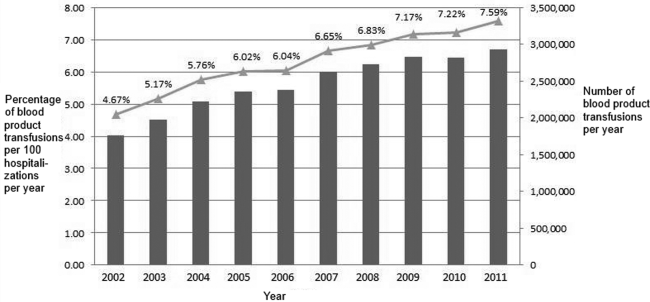

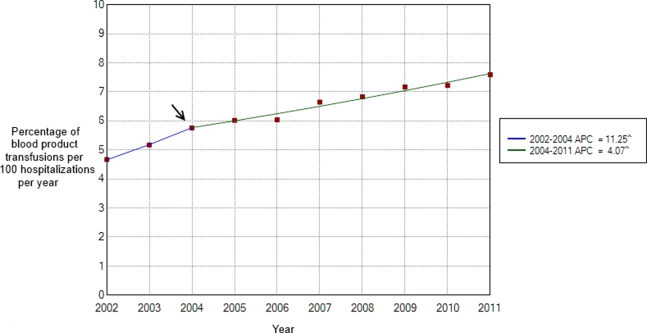

Between 2002 and 2011, there were a total of 24,641,581 blood‐product transfusions among 389,761,571 hospitalizations. The rate of transfusion per 100 hospitalizations increased by 2.9% from 2002 to 2011 (4.6% in 2002 [n=1,767,111] to 7.5% in 2011 [n=2,929,312]) (Figure 1). The average annual percent change from 2002 to 2011 was 5.6% (95% confidence interval [CI]: 3.7‐7.6), which was statistically significant at P0.05. A statistically significant change in trend (joinpoint) was observed in 2004. The annual percent change was 11.2% (95% CI: 0.323.4) from 2002 to 2004 and 4.1% (95% CI: 3.05.1) from 2004 to 2011, both of which were statistically significant at P0.05 (Figure 2).

Our study demonstrates an overall increasing trend in the inpatient blood‐product transfusions over the past decade. However, the rate of increase seems to have slowed down since 2004. The National Blood Collection and Utilization Survey[4] demonstrated a decrease of 11.6% in the total number of all components transfused in the United States between 2008 and 2011. Our data are different from the survey, which also included blood transfusions in outpatient settings, emergency departments, and pediatric patients. The rising proportion of aging population with multiple comorbidities and cancers, increases in hematopoietic stem cell/solid organ transplants and chemotherapy, as well as widespread availability of blood products presumably contributed to the continued increase observed in our inpatient data after 2004. Nevertheless, the declining trend in the rate of the increased blood‐product transfusion usage seen after 2004 is encouraging. Increased awareness of restrictive transfusion strategy, coupled with efforts by professional bodies to improve the adoption of restrictive strategies, is most likely responsible for this.[3, 11, 12] As the clinical classification software procedure code 222 lumps together all the different types of blood products, we were unable to study the transfusion trend among each different type of blood products. In conclusion, further efforts need to be directed at increasing the awareness of clinicians, especially hospitalists, about the benefits of a restrictive transfusion policy and decreasing the rate of blood product use in the inpatient service. Furthermore, studies elaborating the patient population who are being transfused and the factors influencing the transfusion trends can provide useful insights to optimize blood‐product utilization and control resource consumption.

Disclosure

Nothing to report.

- , , . Outcomes using lower vs higher hemoglobin thresholds for red blood cell transfusion. JAMA. 2013;309(1):83–84.

- , , , et al. Transfusion strategies for acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(1):11–21.

- , , , . Evidence review: periprocedural use of blood products. J Hosp Med. 2013;8(11):647–652.

- The 2011 National Blood Collection and Utilization Survey Report. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of the Assistant Secretary for Health; 2013.

- , , , et al. HCUP facts and figures: statistics on hospital‐based care in the United States. 2009. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Rockville, MD. Available at: http://www.hcup‐us.ahrq.gov/reports.jsp. Accessed January 2, 2014.

- HCUP Nationwide Inpatient Sample (NIS). Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project. 2009–2011. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Rockville, MD. Available at: www.hcup‐us.ahrq.gov/nisoverview.jsp. Accessed December 15, 2013.

- HCUP Clinical Classifications Software (CCS) for ICD‐9‐CM. Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project. 2009–2011. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Rockville, MD. Available at: www.hcup‐us.ahrq.gov/toolssoftware/ccs/ccs.jsp. Accessed December 15, 2013.

- Joinpoint Regression Program, Version 4.0.4, December, 2014. Statistical Methodology and Applications Branch, Surveillance Research Program, National Cancer Institute. Available at: https://surveillance.cancer.gov/joinpoint/download. Accessed December 25, 2013.

- , , , , . Estimating average annual per cent change in trend analysis. Stat Med. 2009;28(29):3670–3682.

- , , , . Permutation tests for joinpoint regression with applications to cancer rates. Stat Med. 2000;19(3):335–351.

- , , , et al. Choosing wisely in adult hospital medicine: five opportunities for improved healthcare value. J Hosp Med. 2013;8(9):486–492.

- , , , . Patient‐centered blood management. J Hosp Med. 2014;9(1):60–65.

Although potentially life saving, blood‐product transfusion is costly and associated with transfusion‐related adverse events, including death on rare occasions. Studies in varied patient populations have demonstrated that a restrictive red blood cell transfusion strategy reduces the number of transfusion‐related adverse effects and can result in improved short‐term survival.[1, 2, 3] In 2011, more than 20 million blood products were transfused in the United States, which resulted in more than 50,000 transfusion‐related adverse reactions (0.24%).[4] With a mean cost of greater than $50 per unit of plasma and $500 per unit of apheresis platelets,[4] the cost of blood transfusion is well in excess of $1 billion per year. Blood‐product transfusion is the most frequent inpatient procedure,[5] and inpatient blood‐product transfusion contributes to the bulk of transfusions nationwide. To study the utilization of blood‐product transfusion in the inpatient population, we studied the temporal trend of inpatient blood‐product transfusions in the United States from 2002 to 2011 using data from the Nationwide Inpatient Sample (NIS), Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.[4] The NIS, the largest inpatient care database in the United States, includes approximately a 20% stratified sample of US community hospital admissions and is weighted at discharge level to permit population‐level estimates.[6] We utilized this database to identify the total number of blood‐product transfusions and discharges between 2002 and 2011. We calculated the rate of all blood‐product transfusions, which include packed red blood cell, platelets, and other blood components, using the International Classification of DiseasesNinth Revision, Clinical Modification Procedural Clinical Classification Software code 222.[7] Trend analysis and calculation of average annual percent change were done using the Joinpoint Regression Program version 4.0.4 (National Cancer Institute, Bethesda, MD).[8] This software uses trend data and calculates the best fit lines to create the simplest joinpoint model that the data allow. The model can be expressed as a figure where several different multisegmented trend lines are connected together at the joinpoints. Trend over a fixed prespecified interval was computed as average annual percent change, and the Monte Carlo permutation method was used to test for apparent change in the trends.[9, 10] The study was exempted by the institutional review board of the University of Nebraska Medical Center.

Between 2002 and 2011, there were a total of 24,641,581 blood‐product transfusions among 389,761,571 hospitalizations. The rate of transfusion per 100 hospitalizations increased by 2.9% from 2002 to 2011 (4.6% in 2002 [n=1,767,111] to 7.5% in 2011 [n=2,929,312]) (Figure 1). The average annual percent change from 2002 to 2011 was 5.6% (95% confidence interval [CI]: 3.7‐7.6), which was statistically significant at P0.05. A statistically significant change in trend (joinpoint) was observed in 2004. The annual percent change was 11.2% (95% CI: 0.323.4) from 2002 to 2004 and 4.1% (95% CI: 3.05.1) from 2004 to 2011, both of which were statistically significant at P0.05 (Figure 2).

Our study demonstrates an overall increasing trend in the inpatient blood‐product transfusions over the past decade. However, the rate of increase seems to have slowed down since 2004. The National Blood Collection and Utilization Survey[4] demonstrated a decrease of 11.6% in the total number of all components transfused in the United States between 2008 and 2011. Our data are different from the survey, which also included blood transfusions in outpatient settings, emergency departments, and pediatric patients. The rising proportion of aging population with multiple comorbidities and cancers, increases in hematopoietic stem cell/solid organ transplants and chemotherapy, as well as widespread availability of blood products presumably contributed to the continued increase observed in our inpatient data after 2004. Nevertheless, the declining trend in the rate of the increased blood‐product transfusion usage seen after 2004 is encouraging. Increased awareness of restrictive transfusion strategy, coupled with efforts by professional bodies to improve the adoption of restrictive strategies, is most likely responsible for this.[3, 11, 12] As the clinical classification software procedure code 222 lumps together all the different types of blood products, we were unable to study the transfusion trend among each different type of blood products. In conclusion, further efforts need to be directed at increasing the awareness of clinicians, especially hospitalists, about the benefits of a restrictive transfusion policy and decreasing the rate of blood product use in the inpatient service. Furthermore, studies elaborating the patient population who are being transfused and the factors influencing the transfusion trends can provide useful insights to optimize blood‐product utilization and control resource consumption.

Disclosure

Nothing to report.

Although potentially life saving, blood‐product transfusion is costly and associated with transfusion‐related adverse events, including death on rare occasions. Studies in varied patient populations have demonstrated that a restrictive red blood cell transfusion strategy reduces the number of transfusion‐related adverse effects and can result in improved short‐term survival.[1, 2, 3] In 2011, more than 20 million blood products were transfused in the United States, which resulted in more than 50,000 transfusion‐related adverse reactions (0.24%).[4] With a mean cost of greater than $50 per unit of plasma and $500 per unit of apheresis platelets,[4] the cost of blood transfusion is well in excess of $1 billion per year. Blood‐product transfusion is the most frequent inpatient procedure,[5] and inpatient blood‐product transfusion contributes to the bulk of transfusions nationwide. To study the utilization of blood‐product transfusion in the inpatient population, we studied the temporal trend of inpatient blood‐product transfusions in the United States from 2002 to 2011 using data from the Nationwide Inpatient Sample (NIS), Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.[4] The NIS, the largest inpatient care database in the United States, includes approximately a 20% stratified sample of US community hospital admissions and is weighted at discharge level to permit population‐level estimates.[6] We utilized this database to identify the total number of blood‐product transfusions and discharges between 2002 and 2011. We calculated the rate of all blood‐product transfusions, which include packed red blood cell, platelets, and other blood components, using the International Classification of DiseasesNinth Revision, Clinical Modification Procedural Clinical Classification Software code 222.[7] Trend analysis and calculation of average annual percent change were done using the Joinpoint Regression Program version 4.0.4 (National Cancer Institute, Bethesda, MD).[8] This software uses trend data and calculates the best fit lines to create the simplest joinpoint model that the data allow. The model can be expressed as a figure where several different multisegmented trend lines are connected together at the joinpoints. Trend over a fixed prespecified interval was computed as average annual percent change, and the Monte Carlo permutation method was used to test for apparent change in the trends.[9, 10] The study was exempted by the institutional review board of the University of Nebraska Medical Center.

Between 2002 and 2011, there were a total of 24,641,581 blood‐product transfusions among 389,761,571 hospitalizations. The rate of transfusion per 100 hospitalizations increased by 2.9% from 2002 to 2011 (4.6% in 2002 [n=1,767,111] to 7.5% in 2011 [n=2,929,312]) (Figure 1). The average annual percent change from 2002 to 2011 was 5.6% (95% confidence interval [CI]: 3.7‐7.6), which was statistically significant at P0.05. A statistically significant change in trend (joinpoint) was observed in 2004. The annual percent change was 11.2% (95% CI: 0.323.4) from 2002 to 2004 and 4.1% (95% CI: 3.05.1) from 2004 to 2011, both of which were statistically significant at P0.05 (Figure 2).

Our study demonstrates an overall increasing trend in the inpatient blood‐product transfusions over the past decade. However, the rate of increase seems to have slowed down since 2004. The National Blood Collection and Utilization Survey[4] demonstrated a decrease of 11.6% in the total number of all components transfused in the United States between 2008 and 2011. Our data are different from the survey, which also included blood transfusions in outpatient settings, emergency departments, and pediatric patients. The rising proportion of aging population with multiple comorbidities and cancers, increases in hematopoietic stem cell/solid organ transplants and chemotherapy, as well as widespread availability of blood products presumably contributed to the continued increase observed in our inpatient data after 2004. Nevertheless, the declining trend in the rate of the increased blood‐product transfusion usage seen after 2004 is encouraging. Increased awareness of restrictive transfusion strategy, coupled with efforts by professional bodies to improve the adoption of restrictive strategies, is most likely responsible for this.[3, 11, 12] As the clinical classification software procedure code 222 lumps together all the different types of blood products, we were unable to study the transfusion trend among each different type of blood products. In conclusion, further efforts need to be directed at increasing the awareness of clinicians, especially hospitalists, about the benefits of a restrictive transfusion policy and decreasing the rate of blood product use in the inpatient service. Furthermore, studies elaborating the patient population who are being transfused and the factors influencing the transfusion trends can provide useful insights to optimize blood‐product utilization and control resource consumption.

Disclosure

Nothing to report.

- , , . Outcomes using lower vs higher hemoglobin thresholds for red blood cell transfusion. JAMA. 2013;309(1):83–84.

- , , , et al. Transfusion strategies for acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(1):11–21.

- , , , . Evidence review: periprocedural use of blood products. J Hosp Med. 2013;8(11):647–652.

- The 2011 National Blood Collection and Utilization Survey Report. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of the Assistant Secretary for Health; 2013.

- , , , et al. HCUP facts and figures: statistics on hospital‐based care in the United States. 2009. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Rockville, MD. Available at: http://www.hcup‐us.ahrq.gov/reports.jsp. Accessed January 2, 2014.

- HCUP Nationwide Inpatient Sample (NIS). Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project. 2009–2011. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Rockville, MD. Available at: www.hcup‐us.ahrq.gov/nisoverview.jsp. Accessed December 15, 2013.

- HCUP Clinical Classifications Software (CCS) for ICD‐9‐CM. Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project. 2009–2011. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Rockville, MD. Available at: www.hcup‐us.ahrq.gov/toolssoftware/ccs/ccs.jsp. Accessed December 15, 2013.

- Joinpoint Regression Program, Version 4.0.4, December, 2014. Statistical Methodology and Applications Branch, Surveillance Research Program, National Cancer Institute. Available at: https://surveillance.cancer.gov/joinpoint/download. Accessed December 25, 2013.

- , , , , . Estimating average annual per cent change in trend analysis. Stat Med. 2009;28(29):3670–3682.

- , , , . Permutation tests for joinpoint regression with applications to cancer rates. Stat Med. 2000;19(3):335–351.

- , , , et al. Choosing wisely in adult hospital medicine: five opportunities for improved healthcare value. J Hosp Med. 2013;8(9):486–492.

- , , , . Patient‐centered blood management. J Hosp Med. 2014;9(1):60–65.

- , , . Outcomes using lower vs higher hemoglobin thresholds for red blood cell transfusion. JAMA. 2013;309(1):83–84.

- , , , et al. Transfusion strategies for acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(1):11–21.

- , , , . Evidence review: periprocedural use of blood products. J Hosp Med. 2013;8(11):647–652.

- The 2011 National Blood Collection and Utilization Survey Report. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of the Assistant Secretary for Health; 2013.

- , , , et al. HCUP facts and figures: statistics on hospital‐based care in the United States. 2009. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Rockville, MD. Available at: http://www.hcup‐us.ahrq.gov/reports.jsp. Accessed January 2, 2014.

- HCUP Nationwide Inpatient Sample (NIS). Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project. 2009–2011. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Rockville, MD. Available at: www.hcup‐us.ahrq.gov/nisoverview.jsp. Accessed December 15, 2013.

- HCUP Clinical Classifications Software (CCS) for ICD‐9‐CM. Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project. 2009–2011. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Rockville, MD. Available at: www.hcup‐us.ahrq.gov/toolssoftware/ccs/ccs.jsp. Accessed December 15, 2013.

- Joinpoint Regression Program, Version 4.0.4, December, 2014. Statistical Methodology and Applications Branch, Surveillance Research Program, National Cancer Institute. Available at: https://surveillance.cancer.gov/joinpoint/download. Accessed December 25, 2013.

- , , , , . Estimating average annual per cent change in trend analysis. Stat Med. 2009;28(29):3670–3682.

- , , , . Permutation tests for joinpoint regression with applications to cancer rates. Stat Med. 2000;19(3):335–351.

- , , , et al. Choosing wisely in adult hospital medicine: five opportunities for improved healthcare value. J Hosp Med. 2013;8(9):486–492.

- , , , . Patient‐centered blood management. J Hosp Med. 2014;9(1):60–65.

Bedside Interprofessional Rounds

Interprofessional collaborative care (IPCC) involves members from different professions working together to enhance communication, coordination, and healthcare quality.[1, 2, 3] Because several current healthcare policy initiatives include financial incentives for increased quality of care, there has been resultant interest in the implementation of IPCC in healthcare systems.[4, 5] Unfortunately, many hospitals have found IPCC difficult to achieve. Hospital‐based medicine units are complex, time‐constrained environments requiring a high degree of collaboration and mutual decision‐making between nurses, physicians, therapists, pharmacists, care coordinators, and patients. In addition, despite recommendations for interprofessional collaborative care, the implementation and assessment of IPCC within this environment has not been well studied.[6, 7]

On academic internal medicine services, the majority of care decisions occur during rounds. Although rounds provide a common structure, the participants, length, location, and agenda of rounds tend to vary by institution and individual physician preference.[8, 9, 10, 11] Traditionally, ward rounds occur mostly in hallways and conference rooms rather than the patient's bedside.[12] Additionally, during rounds, nurse‐physician collaboration occurs infrequently, estimated at <10% of rounding time.[13] Recently, an increased focus on quality, safety, and collaboration has inspired the investigation and implementation of new methods to increase interprofessional collaboration during rounds, but many of these interventions occurred away from the patient's bedside.[14, 15] One trial of bedside interprofessional rounds (BIRs) by Curley et al. suggested improvements in patient‐level outcomes (cost and length of stay) versus traditional physician‐based rounds.[16] Although interprofessional nurse‐physician rounds at patients' bedsides may represent an ideal process, limited work has investigated this activity.[17]

A prerequisite for successful and sustained integration of BIRs is a shared conceptualization among physicians and nurses regarding the process. Such a shared conceptualization would include perceptions of benefits and barriers to implementation.[18] Currently, such perceptions have not been measured. In this study, we sought to evaluate perceptions of front‐line care providers on inpatient units, specifically nursing staff, attending physicians, and housestaff physicians, regarding the benefits and barriers to BIRs.

METHODS

Study Design and Participants

In June 2013, we performed a cross‐sectional assessment of front‐line providers caring for patients on the internal medicine services in our academic hospital. Participants included medicine nursing staff in acute care and intermediate care units, medicine and combined medicine‐pediatrics housestaff physicians, and general internal medicine faculty physicians who supervised the housestaff physicians.

Study Setting

The study was conducted at a 378‐bed, university‐based, acute care teaching hospital in central Pennsylvania. There are a total of 64 internal medicine beds located in2 units, a general medicine unit (44 beds, staffed by 60 nurses, nurse‐to‐patient ratio 1:4) and an intermediate care unit (20 beds, staffed by 41 nurses, nurse‐to‐patient ratio 1:3). Both units are staffed by the general internal medicine physician teams. The academic medicine residency program consists of 69 internal medicine housestaff and 14 combined internal medicine‐pediatrics housestaff. Five teams, organized into 3 academic teaching teams and 2 nonteaching teams, provide care for all patients admitted to the medicine units. Teaching teams consist of 1 junior (postgraduate year [PGY]2) or senior (PGY34) housestaff member, 2 interns (PGY1), 2 medical students, and 1 attending physician.

There are several main features of BIRs in our medicine units. The rounding team of physicians alerts the assigned nurse about the start of rounds. In our main medicine unit, each doorway is equipped with a light that allows the physician team to indicate the start of the BIRs encounter. Case presentations by trainees occur either in the hallway or bedside, at the discretion of the attending physician. During bedside encounters, nurses typically contribute to the discussion about clinical status, decision making, patient concerns, and disposition. Patients are encouraged to contribute to the discussion and are provided the opportunity to ask questions.

For the purposes of this study, we specifically defined BIRs as: encounters that include the team of providers, at least 2 physicians plus a nurse or other care provider, discussing the case at the patient's bedside. In our prior work performed during the same time period as this study, we used the same definition to examine the incidence of and time spent in BIRs in both of our medicine units.[19] We found that 63% to 81% of patients in both units received BIRs. As a result, we assumed all nursing staff, attending physicians, and housestaff physicians had experienced this process, and their responses to this survey were contextualized in these experiences.

Survey Instrument

We developed a survey instrument specifically for this study. We derived items primarily from our prior qualitative work on physician‐based team bedside rounds and a literature review.[20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25] For the benefits to BIRs, we developed items related to 5 domains, including factors related to the patient, education, communication/coordination/teamwork, efficiency and process, and outcomes.[20, 26] For the barriers to BIRs, we developed items related to 4 domains, including factors related to the patient, time, systems issues, and providers (nurses, attending physicians, and housestaff physicians).[22, 24, 25] We included our definition of BIRs into the survey instructions. We pilot tested the survey with 3 medicine faculty and 3 nursing staff and, based on our pilot, modified several questions to improve clarity. Primary demographic items in the survey included identification of provider role (nurses, attending physicians, or housestaff physicians) and years in the current role. Respondent preference for the benefits and barriers were investigated on a 7‐point scale (1=lowest response and 7=high response possible). Descriptive text was provided at the extremes (choice 1 and 7), but intermediary values (26) did not have descriptive cues.[27] As an incentive, the end of the survey provided respondents with an option for submitting their name to be entered into a raffle to win 1 of 50, $5 gift certificates to a coffee shop.

Prior to the end of the academic year in June 2013, we sent a survey link via e‐mail to all medicine nursing staff, housestaff physicians, and attending physicians. The email described the study and explained the voluntary nature of the work, and that informed consent would be implied by survey completion. Following the initial e‐mail, 3 additional weekly e‐mail reminders were sent by the lead investigator. The study was approved by the institutional review board at the Pennsylvania State College of Medicine.

Data Analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to examine the characteristics of the 3 respondent groups and combined totals for each survey item. The nonparametric Wilcoxon rank sum test was used to compare the average values between groups (nursing staff vs all physicians, attending physicians vs housestaff physicians) for both sets of survey variables (benefits and barriers). The nonparametric correlation statistical test Spearman rank was used to assess the degree of correlation between respondent groups for both survey variables. The data were analyzed using SAS 9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) and Stata/IC‐8 (StataCorp, College Station, Texas).

RESULTS

Of the 171 surveys sent, 149 participants completed surveys (response rate 87%). Responses were received from 53/58 nursing staff (91% response), 21/28 attending physicians (75% response), and 75/85 housestaff physicians (88% response). Table 1 describes the participant response demographics.

| Variable | Value |

|---|---|

| |

| Nursing staff, n=58, n (%) | 53 (36) |

| Intermediate care unit, n (%) | 14 (26) |

| General medicine ward, n (%) | 39 (74) |

| All day shifts, n (%) | 25 (47) |

| Mix of day and night shifts, n (%) | 32 (60) |

| Years of experience, mean (SD) | 7.4 (9) |

| Attending physicians, n=28, n (%) | 21 (14) |

| Years since residency graduation, mean (SD) | 10.5 (8) |

| No. of weeks in past year serving as teaching attending, mean (SD) | 9.1(8) |

| Housestaff physicians (n=85), n (%) | 75 (50) |

| Intern, n (%) | 28 (37) |

| Junior resident, n (%) | 25 (33) |

| Senior resident, n (%)a | 22 (29) |

Benefits of BIRs

Respondents' perceptions of the benefits of BIRs are shown by mean value (between 1 and 7) for the total respondent pool and by each participant group (Table 2). Six of the 7 highest‐ranked benefits were related to communication, coordination, and teamwork, including improves communication between nurses and physicians, improves awareness of clinical issues that need to be addressed, and improves team‐building between nurses and physicians. Lowest‐ranked benefits were related to efficiency, process, and outcomes, including decreases patients' hospital length‐of‐stay, improves timeliness of consultations, and reduces ordering of unnecessary tests and treatments. Comparing mean values among the 3 groups, all 18 items showed statistical differences in response rates (all P values <0.05). Nursing staff reported more favorable ratings than both attending physicians and housestaff physicians for each of the 18 items, whereas attending physicians reported more favorable ratings than housestaff physicians in 16/18 items. The rank order among provider groups showed a high degree of correlation (r=0.92, P<0.001).

| Survey Itema | Item Domain | Total, N=149, Mean (SD) | Nurses, N=53, Mean (SD) | Attending Physicians, N=21, Mean (SD) | House staff Physicians, N=75, Mean (SD)b |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||

| Improves communication between nurses and physicians. | CCT | 6.26 (1.11) | 6.74 (0.59)c | 6.52 (1.03)d | 5.85 (1.26) |

| Improves awareness of clinical issues needing to be addressed. | CCT | 6.05 (1.12) | 6.57 (0.64)c | 5.95 (1.07) | 5.71 (1.26) |

| Improves team‐building between nurses and physicians. | CCT | 6.03 (1.32) | 6.72 (0.60)c | 6.14 (1.11) | 5.52 (1.51) |

| Improves coordination of the patient's care. | CCT | 5.98 (1.34) | 6.60 (0.72)c | 6.00 (1.18) | 5.53 (1.55) |

| Improves nursing contributions to a patient's care plan. | CCT | 5.91 (1.25) | 6.47 (0.77)c | 6.14 (0.85) | 5.44 (1.43) |

| Improves quality of care delivered in our unit. | O | 5.72 (1.42) | 6.34 (0.83)c | 5.81 (1.33) | 5.25 (1.61) |

| Improves appreciation of the roles/contributions of other providers. | CCT | 5.69 (1.49) | 6.36 (0.86)c | 5.90 (1.04) | 5.16 (1.73) |

| Promotes shared decision making between patients and providers. | P | 5.62 (1.51) | 6.43 (0.77)c | 5.57 (1.40) | 5.05 (1.68) |

| Improves patients' satisfaction with their hospitalization. | P, O | 5.53 (1.40) | 6.15 (0.95)c | 5.38 (1.12) | 5.13 (1.58) |

| Provides more respect/dignity to patients. | P | 5.31 (1.55) | 6.23 (0.89)c | 5.10 (1.18) | 4.72 (1.71) |

| Decreases number of pages/phone calls between nurses and physicians. | EP | 5.28 (1.82) | 6.28 (0.93)c | 5.24 (1.30) | 4.57 (2.09) |

| Improves educational opportunities for housestaff/students. | E | 5.07 (1.77) | 6.08 (0.98)c | 4.81 (1.60) | 4.43 (1.93) |

| Improves the efficiency of your work. | EP | 5.01 (1.77) | 6.04 (1.13)c | 4.90 (1.30) | 4.31 (1.92) |

| Improves adherence to evidence‐based guidelines or interventions. | EP | 4.89 (1.79) | 6.06 (0.91)c | 4.00 (1.18) | 4.31 (1.97) |

| Improves the accuracy of your sign‐outs (or reports) to the next shift. | EP | 4.80 (1.99) | 6.30 (0.93)c | 4.05 (1.66) | 3.95 (2.01) |

| Reduces ordering of unnecessary tests and treatments. | O | 4.51 (1.86) | 5.77 (1.15)c | 3.86 (1.11) | 3.8 (1.97) |

| Improves the timeliness of consultations. | EP | 4.28 (1.99) | 5.66 (1.22)c | 3.24 (1.48) | 3.59 (2.02) |

| Decreases patients' hospital length of stay. | O | 4.15 (1.68) | 5.04 (1.24)c | 3.95 (1.16) | 3.57 (1.81) |

Barriers to BIRs

Respondents' perceptions of barriers to BIRs are shown by mean value (between 1 and 7) for the total respondent pool and by each participant group (Table 3). The 6 highest‐ranked barriers were related to time, including nursing staff have limited time, the time required for bedside nurse‐physician encounters, and coordinating the start time of encounters with arrival of both physicians and nursing. The lowest‐ranked barriers were related to provider‐ and patient‐related factors, including patient lack of comfort with bedside nurse‐physician encounters, attending physicians/housestaff lack bedside skills, and attending physicians lack comfort with bedside nurse‐physician encounters. Comparing mean values between groups, 10 of 21 items showed statistical differences (P<0.05). The rank order among groups showed moderate correlation (nurses‐attending physicians r=0.62, nurses‐housestaff physicians r=0.76, attending physicians‐housestaff physicians r=0.82). A qualitative inspection of disparities among respondent groups highlighted that nursing staff were more likely to rank bedside rounds are not part of the unit's culture lower than physician groups.

| Survey Itema | Item Domain | Total, N=149, Mean (SD) | Nurses, n=53, Mean (SD) | Attending Physicians, n=21, Mean (SD) | Housestaff Physicians, n=75,b Mean (SD) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||

| Nursing staff have limited time. | T | 4.89 (1.34) | 4.96 (1.27) | 4.86 (1.65) | 4.85 (1.30) |

| Coordinating start time of encounters with arrival of physicians and nursing. | T | 4.80 (1.50) | 4.58 (1.43) | 5.24 (1.45) | 4.84 (1.55) |

| Housestaff have limited time. | T | 4.68 (1.47) | 4.56 (1.26) | 4.24 (1.81) | 4.89 (1.48) |

| Attending physicians have limited time. | T | 4.50 (1.49) | 4.81 (1.34) | 4.33 (1.65) | 4.34 (1.53) |

| Other acutely sick patients in unit. | T | 4.39 (1.42) | 4.79 (1.30)c | 4.52 (1.21) | 4.08 (1.49) |

| Time required for bedside nurse‐physician encounters. | T | 4.32 (1.55) | 4.85 (1.38)c | 3.62 (1.80) | 4.15 (1.49) |

| Lack of use of the pink‐rounding light to alert nursing staff. | S | 3.77 (1.75) | 4.71 (1.70)c | 3.48 (1.86) | 3.19 (1.46) |

| Patient not available (eg, off to test, getting bathed) | S | 3.74 (1.40) | 3.98 (1.28) | 4.52 (1.36)d | 3.35 (1.37) |

| Large team size. | S | 3.64 (1.74) | 3.12 (1.58)c | 3.95 (1.83) | 3.92 (1.77) |

| Patients in dispersed locations (eg, other units or in different hallways). | S | 3.64 (1.77) | 2.77 (1.55)c | 4.52 (1.83) | 4.00 (1.66) |

| Bedside nurse‐physician rounds are not part of the unit's culture. | S | 3.35 (1.94) | 2.25 (1.47)c | 4.76 (1.92) | 3.72 (1.85) |

| Limitations in physical facilities (eg, rooms too small, limited chairs). | S | 3.25 (1.71) | 2.71 (1.72) | 3.33 (1.71) | 3.59 (1.62) |

| Insufficient nurse engagement during bedside nurse‐physician encounters. | PR | 3.24 (1.63) | 2.71 (1.47)c | 3.67 (1.68) | 3.49 (1.65) |

| Patient on contact or respiratory isolation. | S | 3.20 (1.82) | 2.42 (1.67)c | 3.43 (1.63) | 3.69 (1.80) |

| Language barrier between providers and patients. | P | 2.69 (1.37) | 2.77 (1.39) | 2.57 (1.08) | 2.68 (1.43) |

| Privacy/sensitive patient issues. | P | 2.65 (1.45) | 2.27 (1.24) | 2.57 (1.33) | 2.93 (1.56) |

| Housestaff lack comfort with bedside nurse‐physician encounters. | PR | 2.55 (1.49) | 2.48 (1.15) | 2.67 (1.68) | 2.57 (1.65) |

| Nurses lack comfort with bedside nurse‐physician encounters. | PR | 2.45 (1.45) | 2.35 (1.27) | 2.48 (1.66) | 2.51 (1.53) |

| Attending physicians lack comfort with bedside nurse‐physician encounters. | PR | 2.35 (1.38) | 2.33 (1.25) | 2.33 (1.62) | 2.36 (1.41) |

| Attending physician/housestaff lack bedside skills (eg, history, exam). | PR | 2.34 (1.34) | 2.19 (1.19) | 2.85 (1.69) | 2.30 (1.32) |

| Patient lack of comfort with bedside nurse‐physician encounters. | P | 2.33 (1.48) | 2.23 (1.37) | 1.95 (1.32) | 2.5 (1.59) |

DISCUSSION

In this study, we sought to compare perceptions of nurses and physicians on the benefits and barriers to BIRs. Nursing staff ranked each benefit higher than physicians, though rank orders of specific benefits were highly correlated. Highest‐ranked benefits related to coordination and communication more than quality or process benefits. Across groups, the highest‐ranked barriers to BIRs were related to time, whereas the lowest‐ranked factors were related to provider and patient discomfort. These results highlight important similarities and differences in perceptions between front‐line providers.

The highest‐ranked benefits were related to improved interprofessional communication and coordination. Combining interprofessional team members during care delivery allows for integrated understanding of daily care plans and clinical issues, and fosters collaboration and a team‐based atmosphere.[1, 20, 26] The lowest‐ranked benefits were related to more tangible measures, including length of stay, timely consultations, and judicious laboratory ordering. This finding contrasts with the limited literature demonstrating increased efficiency in general medicine units practicing IPCC.[16] These rankings may reflect a poor understanding or self‐assessment of outcome measures by healthcare providers, representing a potential focus for educational initiatives. Future investigations using objective assessment methods of outcomes and collaboration will provide a more accurate understanding of these findings.

The highest‐ranked barriers were related to time and systems issues. Several studies of physician‐based bedside rounds have identified systems‐ and time‐related issues as primary limiting barriers.[22, 24] In units without colocalization of patients and providers, finding receptive times for BIRs can be difficult. Although time‐related issues could be addressed by decreasing patient‐provider ratios, these changes require substantial investment in resources. A reasonable degree of improvement in efficiency and coordination is expected following acclimation to BIRs or by addressing modifiable systems factors to increase this activity. Less costly interventions, such as tailoring provider schedules, prescheduling patient rounding times, and geographic colocalization of patients and providers may be more feasible. However, the clinical microsystems within which medicine patients are cared for are often chaotic and disorganized at the infrastructural and cultural levels, which may be less influenced by surface‐level interventions. Such interventions may be ward specific and require customization to individual team needs.

The lowest‐ranked barriers to BIRs were related to provider‐ and patient‐related factors, including comfort level of patients and providers. Prior work on bedside rounds has identified physicians who are apprehensive about performing bedside rounds, but those who experience this activity are more likely to be comfortable with it.[12, 28] Our results from a culture where BIRs occur on nearly two‐thirds of patients suggest provider discomfort is not a predominant barrier.[22, 29] Additionally, educators have raised concerns about patient discomfort with bedside rounds, but nearly all studies evaluating patients' perspectives reveal patient preference for bedside case presentations over activities occurring in alternative locations.[30, 31, 32] Little work has investigated patient preference for BIRs as per our definition; our participants do not believe patients are discomforted by BIRs, building upon evidence in the literature for patient preferences regarding bedside activities.

Nursing staff perceptions of the benefits and culture related to BIRs were more positive than physicians. We hypothesize several reasons for this disparity. First, nursing staff may have more experience with observing and understanding the positive impact of BIRs and therefore are more likely to understand the positive ramifications. Alternatively, nursing staff may be satisfied with active integration into traditional physician‐centric decisions. Additionally, the professional culture and educational foundation of the nursing culture is based upon a patient‐centered approach and therefore may be more aligned with the goals of BIRs. Last, physicians may have competing priorities, favoring productivity and didactic learning rather than interprofessional collaboration. Further investigation is required to understand differences between nurses and physicians, in addition to other providers integral to BIRs (eg, care coordinators, pharmacists). Regardless, during the implementation of interprofessional collaborative care models, our findings suggest initial challenges, and the focus of educational initiatives may necessitate acclimating physician groups to benefits identified by front‐line nursing staff.

There are several limitations to our study. We investigated the perceptions of medicine nurses and physicians in 1 teaching hospital, limiting generalizability to other specialties, other vital professional groups, and nonteaching hospitals. Additionally, BIRs has been a focus of our hospital for several years. Therefore, perceived barriers may differ in BIRs‐nave hospitals. Second, although pilot‐tested for content, the construct validity of the instrument was not rigorously assessed, and the instrument was not designed to measure benefits and barriers not explicitly identified during pilot testing. Last, although surveys were anonymous, the possibility of social desirability bias exists, thereby limiting accuracy.

For over a century, physician‐led rounds have been the preferred modality for point‐of‐care decision making.[10, 15, 32, 33] BIRs address our growing understanding of patient‐centered care. Future efforts should address the quality of collaboration and current hospital and unit structures hindering patient‐centered IPCC and patient outcomes.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the medicine nursing staff and physicians for their dedication to patient‐centered care and willingness to participate in this study.

Disclosures: The Department of Medicine at the Penn State Hershey Medical Center provided funding for this project. There are no conflicts of interest to report.

- , , . Interprofessional collaboration: effects of practice‐based interventions on professional practice and healthcare outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009(3):CD000072.

- . Teamswork! Hosp Health Netw. 2012;86(3):24–27, 21.

- , , , . The coming of age for interprofessional education and practice. Am J Med. 2013;126(4):284–288.

- , . Payment incentives and integrated care delivery: levers for health system reform and cost containment. Inquiry. 2011;48(4):277–287.

- . Payment reform and the mission of academic medical centers. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(19):1784–1786.

- Josiah Macy Jr. Foundation. Transforming patient care: aligning interprofessional education and clinical practice redesign. In: Proceedings of the Josiah Macy Jr. Foundation Conference; January 17–20, 2013; Atlanta, GA.

- , , , . Bridging the quality chasm: interprofessional teams to the rescue? Am J Med. 2013;126(4):276–277.

- . Attending rounds: guidelines for teaching on the wards. J Gen Intern Med. 1992;7(1):68–75.

- , . Teaching at the bedside: a new model. Med Teach. 2003;25(2):127–130.

- . On bedside teaching. Ann Intern Med. 1997;126(3):217–220.

- , , , . Relationships of the location and content of rounds to specialty, institution, patient‐census, and team size. PloS One. 2010;5(6):e11246.

- , , , . Attending rounds and bedside case presentations: medical student and medicine resident experiences and attitudes. Teach Learn Med. 2009;21(2):105–110.

- , , , et al. Attending rounds in the current era: what is and is not happening. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173(12):1084–1089.

- , , , et al. Structured interdisciplinary rounds in a medical teaching unit: improving patient safety. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171(7):678–684.

- , , , , . Use of multidisciplinary rounds to simultaneously improve quality outcomes, enhance resident education, and shorten length of stay. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22(8):1073–1079.

- , , . A firm trial of interdisciplinary rounds on the inpatient medical wards: an intervention designed using continuous quality improvement. Med Care. 1998;36(8 suppl):AS4–AS12.

- , , , . A randomized, controlled trial of bedside versus conference‐room case presentation in a pediatric intensive care unit. Pediatrics. 2007;120(2):275–280.

- , . The challenge of innovation implementation. Acad Manage Rev. 1996;21(4):1055–1080.

- , , , . Ocular dipping in creutzfeldt‐jakob disease. J Clin Neurol. 2014;10(2):162–165.

- , , , et al. The value of bedside rounds: a multicenter qualitative study. Teach Learn Med. 2013;25(4):326–333.

- , , , et al. The art of bedside rounds: a multi‐center qualitative study of strategies used by experienced bedside teachers. J Gen Intern Med. 2013;28(3):412–420.

- , , , et al. Identifying and overcoming the barriers to bedside rounds: a multicenter qualitative study. Acad Med. 2014;89(2):326–334.

- , . Bedside teaching in medical education: a literature review. Perspec Med Educ. 2014;3(2):76–88.

- , , . Impediments to bed‐side teaching. Med Educ. 1998;32(2):159–162.

- , , , . Whither bedside teaching? A focus‐group study of clinical teachers. Acad Med. 2003;78(4):384–390.

- , . Staff preference for multidisciplinary rounding practices in the critical care setting. 2011. Paper presented at: Design July 6–10, 2011. Boston, MA. Available at: http://www.designandhealth.com/uploaded/documents/Awards‐and‐events/WCDH2011/Presentations/Friday/Session‐8/DianaAnderson.pdf. Accessed July 6, 2014.

- , . Health Measurement Scales: A Practical Guide to Their Development and Use. 2nd ed. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 1995.

- , , . Student and patient perspectives on bedside teaching. Med Educ. 1997;31(5):341–346.

- , , , , , . The positive impact of portfolios on health care assistants' clinical practice. J Eval Clin Pract. 2008;14(1):172–174.

- , , , . The physiologic and psychological effects of the bedside presentation. N Engl J Med. 1989;321(18):1273–1275.

- , , , , . The effect of bedside case presentations on patients' perceptions of their medical care. N Engl J Med. 1997;336(16):1150–1155.

- , , , . The return of bedside rounds: an educational intervention. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25(8):792–798.

- . Bedside rounds revisited. N Engl J Med. 1997;336(16):1174–1175.

Interprofessional collaborative care (IPCC) involves members from different professions working together to enhance communication, coordination, and healthcare quality.[1, 2, 3] Because several current healthcare policy initiatives include financial incentives for increased quality of care, there has been resultant interest in the implementation of IPCC in healthcare systems.[4, 5] Unfortunately, many hospitals have found IPCC difficult to achieve. Hospital‐based medicine units are complex, time‐constrained environments requiring a high degree of collaboration and mutual decision‐making between nurses, physicians, therapists, pharmacists, care coordinators, and patients. In addition, despite recommendations for interprofessional collaborative care, the implementation and assessment of IPCC within this environment has not been well studied.[6, 7]

On academic internal medicine services, the majority of care decisions occur during rounds. Although rounds provide a common structure, the participants, length, location, and agenda of rounds tend to vary by institution and individual physician preference.[8, 9, 10, 11] Traditionally, ward rounds occur mostly in hallways and conference rooms rather than the patient's bedside.[12] Additionally, during rounds, nurse‐physician collaboration occurs infrequently, estimated at <10% of rounding time.[13] Recently, an increased focus on quality, safety, and collaboration has inspired the investigation and implementation of new methods to increase interprofessional collaboration during rounds, but many of these interventions occurred away from the patient's bedside.[14, 15] One trial of bedside interprofessional rounds (BIRs) by Curley et al. suggested improvements in patient‐level outcomes (cost and length of stay) versus traditional physician‐based rounds.[16] Although interprofessional nurse‐physician rounds at patients' bedsides may represent an ideal process, limited work has investigated this activity.[17]

A prerequisite for successful and sustained integration of BIRs is a shared conceptualization among physicians and nurses regarding the process. Such a shared conceptualization would include perceptions of benefits and barriers to implementation.[18] Currently, such perceptions have not been measured. In this study, we sought to evaluate perceptions of front‐line care providers on inpatient units, specifically nursing staff, attending physicians, and housestaff physicians, regarding the benefits and barriers to BIRs.

METHODS

Study Design and Participants

In June 2013, we performed a cross‐sectional assessment of front‐line providers caring for patients on the internal medicine services in our academic hospital. Participants included medicine nursing staff in acute care and intermediate care units, medicine and combined medicine‐pediatrics housestaff physicians, and general internal medicine faculty physicians who supervised the housestaff physicians.

Study Setting

The study was conducted at a 378‐bed, university‐based, acute care teaching hospital in central Pennsylvania. There are a total of 64 internal medicine beds located in2 units, a general medicine unit (44 beds, staffed by 60 nurses, nurse‐to‐patient ratio 1:4) and an intermediate care unit (20 beds, staffed by 41 nurses, nurse‐to‐patient ratio 1:3). Both units are staffed by the general internal medicine physician teams. The academic medicine residency program consists of 69 internal medicine housestaff and 14 combined internal medicine‐pediatrics housestaff. Five teams, organized into 3 academic teaching teams and 2 nonteaching teams, provide care for all patients admitted to the medicine units. Teaching teams consist of 1 junior (postgraduate year [PGY]2) or senior (PGY34) housestaff member, 2 interns (PGY1), 2 medical students, and 1 attending physician.

There are several main features of BIRs in our medicine units. The rounding team of physicians alerts the assigned nurse about the start of rounds. In our main medicine unit, each doorway is equipped with a light that allows the physician team to indicate the start of the BIRs encounter. Case presentations by trainees occur either in the hallway or bedside, at the discretion of the attending physician. During bedside encounters, nurses typically contribute to the discussion about clinical status, decision making, patient concerns, and disposition. Patients are encouraged to contribute to the discussion and are provided the opportunity to ask questions.

For the purposes of this study, we specifically defined BIRs as: encounters that include the team of providers, at least 2 physicians plus a nurse or other care provider, discussing the case at the patient's bedside. In our prior work performed during the same time period as this study, we used the same definition to examine the incidence of and time spent in BIRs in both of our medicine units.[19] We found that 63% to 81% of patients in both units received BIRs. As a result, we assumed all nursing staff, attending physicians, and housestaff physicians had experienced this process, and their responses to this survey were contextualized in these experiences.

Survey Instrument

We developed a survey instrument specifically for this study. We derived items primarily from our prior qualitative work on physician‐based team bedside rounds and a literature review.[20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25] For the benefits to BIRs, we developed items related to 5 domains, including factors related to the patient, education, communication/coordination/teamwork, efficiency and process, and outcomes.[20, 26] For the barriers to BIRs, we developed items related to 4 domains, including factors related to the patient, time, systems issues, and providers (nurses, attending physicians, and housestaff physicians).[22, 24, 25] We included our definition of BIRs into the survey instructions. We pilot tested the survey with 3 medicine faculty and 3 nursing staff and, based on our pilot, modified several questions to improve clarity. Primary demographic items in the survey included identification of provider role (nurses, attending physicians, or housestaff physicians) and years in the current role. Respondent preference for the benefits and barriers were investigated on a 7‐point scale (1=lowest response and 7=high response possible). Descriptive text was provided at the extremes (choice 1 and 7), but intermediary values (26) did not have descriptive cues.[27] As an incentive, the end of the survey provided respondents with an option for submitting their name to be entered into a raffle to win 1 of 50, $5 gift certificates to a coffee shop.

Prior to the end of the academic year in June 2013, we sent a survey link via e‐mail to all medicine nursing staff, housestaff physicians, and attending physicians. The email described the study and explained the voluntary nature of the work, and that informed consent would be implied by survey completion. Following the initial e‐mail, 3 additional weekly e‐mail reminders were sent by the lead investigator. The study was approved by the institutional review board at the Pennsylvania State College of Medicine.

Data Analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to examine the characteristics of the 3 respondent groups and combined totals for each survey item. The nonparametric Wilcoxon rank sum test was used to compare the average values between groups (nursing staff vs all physicians, attending physicians vs housestaff physicians) for both sets of survey variables (benefits and barriers). The nonparametric correlation statistical test Spearman rank was used to assess the degree of correlation between respondent groups for both survey variables. The data were analyzed using SAS 9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) and Stata/IC‐8 (StataCorp, College Station, Texas).

RESULTS

Of the 171 surveys sent, 149 participants completed surveys (response rate 87%). Responses were received from 53/58 nursing staff (91% response), 21/28 attending physicians (75% response), and 75/85 housestaff physicians (88% response). Table 1 describes the participant response demographics.

| Variable | Value |

|---|---|

| |

| Nursing staff, n=58, n (%) | 53 (36) |

| Intermediate care unit, n (%) | 14 (26) |

| General medicine ward, n (%) | 39 (74) |

| All day shifts, n (%) | 25 (47) |

| Mix of day and night shifts, n (%) | 32 (60) |

| Years of experience, mean (SD) | 7.4 (9) |

| Attending physicians, n=28, n (%) | 21 (14) |

| Years since residency graduation, mean (SD) | 10.5 (8) |

| No. of weeks in past year serving as teaching attending, mean (SD) | 9.1(8) |

| Housestaff physicians (n=85), n (%) | 75 (50) |

| Intern, n (%) | 28 (37) |

| Junior resident, n (%) | 25 (33) |

| Senior resident, n (%)a | 22 (29) |

Benefits of BIRs

Respondents' perceptions of the benefits of BIRs are shown by mean value (between 1 and 7) for the total respondent pool and by each participant group (Table 2). Six of the 7 highest‐ranked benefits were related to communication, coordination, and teamwork, including improves communication between nurses and physicians, improves awareness of clinical issues that need to be addressed, and improves team‐building between nurses and physicians. Lowest‐ranked benefits were related to efficiency, process, and outcomes, including decreases patients' hospital length‐of‐stay, improves timeliness of consultations, and reduces ordering of unnecessary tests and treatments. Comparing mean values among the 3 groups, all 18 items showed statistical differences in response rates (all P values <0.05). Nursing staff reported more favorable ratings than both attending physicians and housestaff physicians for each of the 18 items, whereas attending physicians reported more favorable ratings than housestaff physicians in 16/18 items. The rank order among provider groups showed a high degree of correlation (r=0.92, P<0.001).

| Survey Itema | Item Domain | Total, N=149, Mean (SD) | Nurses, N=53, Mean (SD) | Attending Physicians, N=21, Mean (SD) | House staff Physicians, N=75, Mean (SD)b |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||

| Improves communication between nurses and physicians. | CCT | 6.26 (1.11) | 6.74 (0.59)c | 6.52 (1.03)d | 5.85 (1.26) |

| Improves awareness of clinical issues needing to be addressed. | CCT | 6.05 (1.12) | 6.57 (0.64)c | 5.95 (1.07) | 5.71 (1.26) |

| Improves team‐building between nurses and physicians. | CCT | 6.03 (1.32) | 6.72 (0.60)c | 6.14 (1.11) | 5.52 (1.51) |

| Improves coordination of the patient's care. | CCT | 5.98 (1.34) | 6.60 (0.72)c | 6.00 (1.18) | 5.53 (1.55) |

| Improves nursing contributions to a patient's care plan. | CCT | 5.91 (1.25) | 6.47 (0.77)c | 6.14 (0.85) | 5.44 (1.43) |

| Improves quality of care delivered in our unit. | O | 5.72 (1.42) | 6.34 (0.83)c | 5.81 (1.33) | 5.25 (1.61) |

| Improves appreciation of the roles/contributions of other providers. | CCT | 5.69 (1.49) | 6.36 (0.86)c | 5.90 (1.04) | 5.16 (1.73) |

| Promotes shared decision making between patients and providers. | P | 5.62 (1.51) | 6.43 (0.77)c | 5.57 (1.40) | 5.05 (1.68) |

| Improves patients' satisfaction with their hospitalization. | P, O | 5.53 (1.40) | 6.15 (0.95)c | 5.38 (1.12) | 5.13 (1.58) |

| Provides more respect/dignity to patients. | P | 5.31 (1.55) | 6.23 (0.89)c | 5.10 (1.18) | 4.72 (1.71) |

| Decreases number of pages/phone calls between nurses and physicians. | EP | 5.28 (1.82) | 6.28 (0.93)c | 5.24 (1.30) | 4.57 (2.09) |

| Improves educational opportunities for housestaff/students. | E | 5.07 (1.77) | 6.08 (0.98)c | 4.81 (1.60) | 4.43 (1.93) |

| Improves the efficiency of your work. | EP | 5.01 (1.77) | 6.04 (1.13)c | 4.90 (1.30) | 4.31 (1.92) |

| Improves adherence to evidence‐based guidelines or interventions. | EP | 4.89 (1.79) | 6.06 (0.91)c | 4.00 (1.18) | 4.31 (1.97) |

| Improves the accuracy of your sign‐outs (or reports) to the next shift. | EP | 4.80 (1.99) | 6.30 (0.93)c | 4.05 (1.66) | 3.95 (2.01) |

| Reduces ordering of unnecessary tests and treatments. | O | 4.51 (1.86) | 5.77 (1.15)c | 3.86 (1.11) | 3.8 (1.97) |

| Improves the timeliness of consultations. | EP | 4.28 (1.99) | 5.66 (1.22)c | 3.24 (1.48) | 3.59 (2.02) |

| Decreases patients' hospital length of stay. | O | 4.15 (1.68) | 5.04 (1.24)c | 3.95 (1.16) | 3.57 (1.81) |

Barriers to BIRs

Respondents' perceptions of barriers to BIRs are shown by mean value (between 1 and 7) for the total respondent pool and by each participant group (Table 3). The 6 highest‐ranked barriers were related to time, including nursing staff have limited time, the time required for bedside nurse‐physician encounters, and coordinating the start time of encounters with arrival of both physicians and nursing. The lowest‐ranked barriers were related to provider‐ and patient‐related factors, including patient lack of comfort with bedside nurse‐physician encounters, attending physicians/housestaff lack bedside skills, and attending physicians lack comfort with bedside nurse‐physician encounters. Comparing mean values between groups, 10 of 21 items showed statistical differences (P<0.05). The rank order among groups showed moderate correlation (nurses‐attending physicians r=0.62, nurses‐housestaff physicians r=0.76, attending physicians‐housestaff physicians r=0.82). A qualitative inspection of disparities among respondent groups highlighted that nursing staff were more likely to rank bedside rounds are not part of the unit's culture lower than physician groups.

| Survey Itema | Item Domain | Total, N=149, Mean (SD) | Nurses, n=53, Mean (SD) | Attending Physicians, n=21, Mean (SD) | Housestaff Physicians, n=75,b Mean (SD) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||

| Nursing staff have limited time. | T | 4.89 (1.34) | 4.96 (1.27) | 4.86 (1.65) | 4.85 (1.30) |

| Coordinating start time of encounters with arrival of physicians and nursing. | T | 4.80 (1.50) | 4.58 (1.43) | 5.24 (1.45) | 4.84 (1.55) |

| Housestaff have limited time. | T | 4.68 (1.47) | 4.56 (1.26) | 4.24 (1.81) | 4.89 (1.48) |

| Attending physicians have limited time. | T | 4.50 (1.49) | 4.81 (1.34) | 4.33 (1.65) | 4.34 (1.53) |

| Other acutely sick patients in unit. | T | 4.39 (1.42) | 4.79 (1.30)c | 4.52 (1.21) | 4.08 (1.49) |

| Time required for bedside nurse‐physician encounters. | T | 4.32 (1.55) | 4.85 (1.38)c | 3.62 (1.80) | 4.15 (1.49) |

| Lack of use of the pink‐rounding light to alert nursing staff. | S | 3.77 (1.75) | 4.71 (1.70)c | 3.48 (1.86) | 3.19 (1.46) |

| Patient not available (eg, off to test, getting bathed) | S | 3.74 (1.40) | 3.98 (1.28) | 4.52 (1.36)d | 3.35 (1.37) |

| Large team size. | S | 3.64 (1.74) | 3.12 (1.58)c | 3.95 (1.83) | 3.92 (1.77) |

| Patients in dispersed locations (eg, other units or in different hallways). | S | 3.64 (1.77) | 2.77 (1.55)c | 4.52 (1.83) | 4.00 (1.66) |

| Bedside nurse‐physician rounds are not part of the unit's culture. | S | 3.35 (1.94) | 2.25 (1.47)c | 4.76 (1.92) | 3.72 (1.85) |

| Limitations in physical facilities (eg, rooms too small, limited chairs). | S | 3.25 (1.71) | 2.71 (1.72) | 3.33 (1.71) | 3.59 (1.62) |

| Insufficient nurse engagement during bedside nurse‐physician encounters. | PR | 3.24 (1.63) | 2.71 (1.47)c | 3.67 (1.68) | 3.49 (1.65) |

| Patient on contact or respiratory isolation. | S | 3.20 (1.82) | 2.42 (1.67)c | 3.43 (1.63) | 3.69 (1.80) |

| Language barrier between providers and patients. | P | 2.69 (1.37) | 2.77 (1.39) | 2.57 (1.08) | 2.68 (1.43) |

| Privacy/sensitive patient issues. | P | 2.65 (1.45) | 2.27 (1.24) | 2.57 (1.33) | 2.93 (1.56) |

| Housestaff lack comfort with bedside nurse‐physician encounters. | PR | 2.55 (1.49) | 2.48 (1.15) | 2.67 (1.68) | 2.57 (1.65) |

| Nurses lack comfort with bedside nurse‐physician encounters. | PR | 2.45 (1.45) | 2.35 (1.27) | 2.48 (1.66) | 2.51 (1.53) |

| Attending physicians lack comfort with bedside nurse‐physician encounters. | PR | 2.35 (1.38) | 2.33 (1.25) | 2.33 (1.62) | 2.36 (1.41) |

| Attending physician/housestaff lack bedside skills (eg, history, exam). | PR | 2.34 (1.34) | 2.19 (1.19) | 2.85 (1.69) | 2.30 (1.32) |

| Patient lack of comfort with bedside nurse‐physician encounters. | P | 2.33 (1.48) | 2.23 (1.37) | 1.95 (1.32) | 2.5 (1.59) |

DISCUSSION

In this study, we sought to compare perceptions of nurses and physicians on the benefits and barriers to BIRs. Nursing staff ranked each benefit higher than physicians, though rank orders of specific benefits were highly correlated. Highest‐ranked benefits related to coordination and communication more than quality or process benefits. Across groups, the highest‐ranked barriers to BIRs were related to time, whereas the lowest‐ranked factors were related to provider and patient discomfort. These results highlight important similarities and differences in perceptions between front‐line providers.

The highest‐ranked benefits were related to improved interprofessional communication and coordination. Combining interprofessional team members during care delivery allows for integrated understanding of daily care plans and clinical issues, and fosters collaboration and a team‐based atmosphere.[1, 20, 26] The lowest‐ranked benefits were related to more tangible measures, including length of stay, timely consultations, and judicious laboratory ordering. This finding contrasts with the limited literature demonstrating increased efficiency in general medicine units practicing IPCC.[16] These rankings may reflect a poor understanding or self‐assessment of outcome measures by healthcare providers, representing a potential focus for educational initiatives. Future investigations using objective assessment methods of outcomes and collaboration will provide a more accurate understanding of these findings.

The highest‐ranked barriers were related to time and systems issues. Several studies of physician‐based bedside rounds have identified systems‐ and time‐related issues as primary limiting barriers.[22, 24] In units without colocalization of patients and providers, finding receptive times for BIRs can be difficult. Although time‐related issues could be addressed by decreasing patient‐provider ratios, these changes require substantial investment in resources. A reasonable degree of improvement in efficiency and coordination is expected following acclimation to BIRs or by addressing modifiable systems factors to increase this activity. Less costly interventions, such as tailoring provider schedules, prescheduling patient rounding times, and geographic colocalization of patients and providers may be more feasible. However, the clinical microsystems within which medicine patients are cared for are often chaotic and disorganized at the infrastructural and cultural levels, which may be less influenced by surface‐level interventions. Such interventions may be ward specific and require customization to individual team needs.

The lowest‐ranked barriers to BIRs were related to provider‐ and patient‐related factors, including comfort level of patients and providers. Prior work on bedside rounds has identified physicians who are apprehensive about performing bedside rounds, but those who experience this activity are more likely to be comfortable with it.[12, 28] Our results from a culture where BIRs occur on nearly two‐thirds of patients suggest provider discomfort is not a predominant barrier.[22, 29] Additionally, educators have raised concerns about patient discomfort with bedside rounds, but nearly all studies evaluating patients' perspectives reveal patient preference for bedside case presentations over activities occurring in alternative locations.[30, 31, 32] Little work has investigated patient preference for BIRs as per our definition; our participants do not believe patients are discomforted by BIRs, building upon evidence in the literature for patient preferences regarding bedside activities.

Nursing staff perceptions of the benefits and culture related to BIRs were more positive than physicians. We hypothesize several reasons for this disparity. First, nursing staff may have more experience with observing and understanding the positive impact of BIRs and therefore are more likely to understand the positive ramifications. Alternatively, nursing staff may be satisfied with active integration into traditional physician‐centric decisions. Additionally, the professional culture and educational foundation of the nursing culture is based upon a patient‐centered approach and therefore may be more aligned with the goals of BIRs. Last, physicians may have competing priorities, favoring productivity and didactic learning rather than interprofessional collaboration. Further investigation is required to understand differences between nurses and physicians, in addition to other providers integral to BIRs (eg, care coordinators, pharmacists). Regardless, during the implementation of interprofessional collaborative care models, our findings suggest initial challenges, and the focus of educational initiatives may necessitate acclimating physician groups to benefits identified by front‐line nursing staff.

There are several limitations to our study. We investigated the perceptions of medicine nurses and physicians in 1 teaching hospital, limiting generalizability to other specialties, other vital professional groups, and nonteaching hospitals. Additionally, BIRs has been a focus of our hospital for several years. Therefore, perceived barriers may differ in BIRs‐nave hospitals. Second, although pilot‐tested for content, the construct validity of the instrument was not rigorously assessed, and the instrument was not designed to measure benefits and barriers not explicitly identified during pilot testing. Last, although surveys were anonymous, the possibility of social desirability bias exists, thereby limiting accuracy.

For over a century, physician‐led rounds have been the preferred modality for point‐of‐care decision making.[10, 15, 32, 33] BIRs address our growing understanding of patient‐centered care. Future efforts should address the quality of collaboration and current hospital and unit structures hindering patient‐centered IPCC and patient outcomes.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the medicine nursing staff and physicians for their dedication to patient‐centered care and willingness to participate in this study.

Disclosures: The Department of Medicine at the Penn State Hershey Medical Center provided funding for this project. There are no conflicts of interest to report.

Interprofessional collaborative care (IPCC) involves members from different professions working together to enhance communication, coordination, and healthcare quality.[1, 2, 3] Because several current healthcare policy initiatives include financial incentives for increased quality of care, there has been resultant interest in the implementation of IPCC in healthcare systems.[4, 5] Unfortunately, many hospitals have found IPCC difficult to achieve. Hospital‐based medicine units are complex, time‐constrained environments requiring a high degree of collaboration and mutual decision‐making between nurses, physicians, therapists, pharmacists, care coordinators, and patients. In addition, despite recommendations for interprofessional collaborative care, the implementation and assessment of IPCC within this environment has not been well studied.[6, 7]

On academic internal medicine services, the majority of care decisions occur during rounds. Although rounds provide a common structure, the participants, length, location, and agenda of rounds tend to vary by institution and individual physician preference.[8, 9, 10, 11] Traditionally, ward rounds occur mostly in hallways and conference rooms rather than the patient's bedside.[12] Additionally, during rounds, nurse‐physician collaboration occurs infrequently, estimated at <10% of rounding time.[13] Recently, an increased focus on quality, safety, and collaboration has inspired the investigation and implementation of new methods to increase interprofessional collaboration during rounds, but many of these interventions occurred away from the patient's bedside.[14, 15] One trial of bedside interprofessional rounds (BIRs) by Curley et al. suggested improvements in patient‐level outcomes (cost and length of stay) versus traditional physician‐based rounds.[16] Although interprofessional nurse‐physician rounds at patients' bedsides may represent an ideal process, limited work has investigated this activity.[17]

A prerequisite for successful and sustained integration of BIRs is a shared conceptualization among physicians and nurses regarding the process. Such a shared conceptualization would include perceptions of benefits and barriers to implementation.[18] Currently, such perceptions have not been measured. In this study, we sought to evaluate perceptions of front‐line care providers on inpatient units, specifically nursing staff, attending physicians, and housestaff physicians, regarding the benefits and barriers to BIRs.

METHODS

Study Design and Participants

In June 2013, we performed a cross‐sectional assessment of front‐line providers caring for patients on the internal medicine services in our academic hospital. Participants included medicine nursing staff in acute care and intermediate care units, medicine and combined medicine‐pediatrics housestaff physicians, and general internal medicine faculty physicians who supervised the housestaff physicians.

Study Setting

The study was conducted at a 378‐bed, university‐based, acute care teaching hospital in central Pennsylvania. There are a total of 64 internal medicine beds located in2 units, a general medicine unit (44 beds, staffed by 60 nurses, nurse‐to‐patient ratio 1:4) and an intermediate care unit (20 beds, staffed by 41 nurses, nurse‐to‐patient ratio 1:3). Both units are staffed by the general internal medicine physician teams. The academic medicine residency program consists of 69 internal medicine housestaff and 14 combined internal medicine‐pediatrics housestaff. Five teams, organized into 3 academic teaching teams and 2 nonteaching teams, provide care for all patients admitted to the medicine units. Teaching teams consist of 1 junior (postgraduate year [PGY]2) or senior (PGY34) housestaff member, 2 interns (PGY1), 2 medical students, and 1 attending physician.

There are several main features of BIRs in our medicine units. The rounding team of physicians alerts the assigned nurse about the start of rounds. In our main medicine unit, each doorway is equipped with a light that allows the physician team to indicate the start of the BIRs encounter. Case presentations by trainees occur either in the hallway or bedside, at the discretion of the attending physician. During bedside encounters, nurses typically contribute to the discussion about clinical status, decision making, patient concerns, and disposition. Patients are encouraged to contribute to the discussion and are provided the opportunity to ask questions.

For the purposes of this study, we specifically defined BIRs as: encounters that include the team of providers, at least 2 physicians plus a nurse or other care provider, discussing the case at the patient's bedside. In our prior work performed during the same time period as this study, we used the same definition to examine the incidence of and time spent in BIRs in both of our medicine units.[19] We found that 63% to 81% of patients in both units received BIRs. As a result, we assumed all nursing staff, attending physicians, and housestaff physicians had experienced this process, and their responses to this survey were contextualized in these experiences.

Survey Instrument

We developed a survey instrument specifically for this study. We derived items primarily from our prior qualitative work on physician‐based team bedside rounds and a literature review.[20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25] For the benefits to BIRs, we developed items related to 5 domains, including factors related to the patient, education, communication/coordination/teamwork, efficiency and process, and outcomes.[20, 26] For the barriers to BIRs, we developed items related to 4 domains, including factors related to the patient, time, systems issues, and providers (nurses, attending physicians, and housestaff physicians).[22, 24, 25] We included our definition of BIRs into the survey instructions. We pilot tested the survey with 3 medicine faculty and 3 nursing staff and, based on our pilot, modified several questions to improve clarity. Primary demographic items in the survey included identification of provider role (nurses, attending physicians, or housestaff physicians) and years in the current role. Respondent preference for the benefits and barriers were investigated on a 7‐point scale (1=lowest response and 7=high response possible). Descriptive text was provided at the extremes (choice 1 and 7), but intermediary values (26) did not have descriptive cues.[27] As an incentive, the end of the survey provided respondents with an option for submitting their name to be entered into a raffle to win 1 of 50, $5 gift certificates to a coffee shop.

Prior to the end of the academic year in June 2013, we sent a survey link via e‐mail to all medicine nursing staff, housestaff physicians, and attending physicians. The email described the study and explained the voluntary nature of the work, and that informed consent would be implied by survey completion. Following the initial e‐mail, 3 additional weekly e‐mail reminders were sent by the lead investigator. The study was approved by the institutional review board at the Pennsylvania State College of Medicine.

Data Analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to examine the characteristics of the 3 respondent groups and combined totals for each survey item. The nonparametric Wilcoxon rank sum test was used to compare the average values between groups (nursing staff vs all physicians, attending physicians vs housestaff physicians) for both sets of survey variables (benefits and barriers). The nonparametric correlation statistical test Spearman rank was used to assess the degree of correlation between respondent groups for both survey variables. The data were analyzed using SAS 9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) and Stata/IC‐8 (StataCorp, College Station, Texas).

RESULTS