User login

When is an answer not an answer?

When your beloved authors were studying research and statistics, around the time that Methuselah was celebrating his first birthday, we thought we knew the difference between hypothesis testing and hypothesis generating. With the former, you begin with a question, design a study to answer it, carry it out, and then do some statistical mumbo-jumbo on the data to determine if you have reasonable evidence to answer the question. With the latter, usually done after you’ve answered the main questions, you don’t have any preconceived idea of what’s going on, so you analyze anything that moves. We know that’s not really kosher, because the probability of finding something just by chance (a Type I error) increases astronomically as you do more tests.1 So, in the hypothesis generating phase, you don’t come to any conclusions; you just say, “That’s an interesting finding. Now we’ll have to do a real study to see if our observation holds up.”

Click on the PDF icon at the top of this introduction to read the full article.

When your beloved authors were studying research and statistics, around the time that Methuselah was celebrating his first birthday, we thought we knew the difference between hypothesis testing and hypothesis generating. With the former, you begin with a question, design a study to answer it, carry it out, and then do some statistical mumbo-jumbo on the data to determine if you have reasonable evidence to answer the question. With the latter, usually done after you’ve answered the main questions, you don’t have any preconceived idea of what’s going on, so you analyze anything that moves. We know that’s not really kosher, because the probability of finding something just by chance (a Type I error) increases astronomically as you do more tests.1 So, in the hypothesis generating phase, you don’t come to any conclusions; you just say, “That’s an interesting finding. Now we’ll have to do a real study to see if our observation holds up.”

Click on the PDF icon at the top of this introduction to read the full article.

When your beloved authors were studying research and statistics, around the time that Methuselah was celebrating his first birthday, we thought we knew the difference between hypothesis testing and hypothesis generating. With the former, you begin with a question, design a study to answer it, carry it out, and then do some statistical mumbo-jumbo on the data to determine if you have reasonable evidence to answer the question. With the latter, usually done after you’ve answered the main questions, you don’t have any preconceived idea of what’s going on, so you analyze anything that moves. We know that’s not really kosher, because the probability of finding something just by chance (a Type I error) increases astronomically as you do more tests.1 So, in the hypothesis generating phase, you don’t come to any conclusions; you just say, “That’s an interesting finding. Now we’ll have to do a real study to see if our observation holds up.”

Click on the PDF icon at the top of this introduction to read the full article.

Adaptability and Resiliency of Military Families During Reunification: Results of a Longitudinal Study

Medicare Beneficiaries Likely Readmitted

For at least 25 years, approximately 20% of Medicare fee‐for‐service discharges have been followed by a hospital readmission within 30 days.[1, 2] Section 3025 of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA)[3] created escalating penalties for hospitals with higher than expected 30‐day readmission rates, and the Congressional Budget Office estimated this will reduce Medicare spending by over $7 billion between 2010 and 2019.[4]

Hospitals and physicians have begun developing strategies to identify which Medicare beneficiaries are most likely to be readmitted and use this information to design programs to reduce their readmission rate. Initially, penalties will be based on readmission rates after an index discharge with heart failure, myocardial infarction, and pneumonia.[5] Recently, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) released the Inpatient Prospective Payment System FY2014 proposed rule, which proposes to add 2 new readmission penalties beginning in FY2015: readmissions for hip/knee arthroplasty and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.[6] Other countries are already penalizing hospitals with high readmission rates; for example, Germany is penalizing all readmissions that occur within a 30‐day period following admission.[7] In this brief report, we examine the characteristics of Medicare beneficiaries most likely to be readmitted within 30 days. We focus on readmission rates for all discharge conditions and all patient readmission rates, because we believe the language in the ACA ultimately points to an all‐inclusive approach.

METHODS

We used a nationally random 5% sample of all Medicare beneficiaries for the period between January 1, 2008 and September 30, 2008. To be included, beneficiaries must have both Part A and B coverage and live within the United States. Medicare Advantage patients were excluded because Medicare Advantage plans do not report the data in the same way as fee for service. We calculated the readmission rate as the number of admissions that were preceded by an at‐risk discharge within 30 days divided by the total number of at‐risk discharges. This definition included admissions to and discharges from sole community providers, Medicare‐dependent small rural hospitals, and critical access hospitals. We counted as at risk all live discharges from short‐term acute care hospitals that were not discharged against medical advice, discharged to a rehabilitation unit within an acute care hospital, or readmitted on day 0 (due to inconsistency with use of transfer coding). We only included discharges and readmissions to acute care hospitals and excluded hospitalizations in long‐term care facilities, rehabilitation facilities, skilled nursing homes, and other non‐acute care hospital facilities from being an index hospitalization. However, if the beneficiary was discharged to 1 of these facilities and then readmitted to an acute care hospital, the readmission was counted.

Each discharge was recorded as an independent event and we reset the readmission clock for a fresh 30‐day count each time the beneficiary was discharged. We examined the admission and readmission rate to determine if the rates varied by age, gender, reason for entitlement, racial characteristics, region of the country, number of chronic conditions, and whether the beneficiary is also enrolled in Medicaid (dual eligibles). We calculated the mean readmission rate for each diagnosis‐related group (DRG) and then used the probability of having a readmission for each DRG to calculate a case mix adjustment for each hospital. To calculate the chronic illness burden, we used a previously developed methodology for counting the number of chronic disease categories reported for the patient in the preceding year (2007).[8, 9] The classification system is maintained by the Agency for Health Care Research and Quality. We then used logistic regression to calculate the odds ratio of a discharge being readmitted based on these factors. We preformed statistical analysis using SAS version 9.1.3 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC).

RESULTS

There were 434,999 hospital discharges that occurred in the first 9 months of 2008 in the 5% sample. There were 20.6% of Medicare beneficiaries hospitalized, and the overall readmission rate was 19.5%. Table 1 shows the odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals for the probability that a Medicare beneficiary will be readmitted within 30 days for variables including: age, sex, race, dual‐eligibility status, number of comorbid conditions, geographic region, and reason for entitlement. Of note, beneficiaries with 10 or more chronic conditions were more than 6 times more likely, and beneficiaries with 5 to 9 chronic conditions were more than 2.5 times more likely, to be readmitted than beneficiaries with 1 to 4 chronic conditions.

| Variable | Estimate | 95% Confidence Limits |

|---|---|---|

| ||

| Age 144 years | 1.634 | 1.5071.771 |

| Age 4564 years | 1.231 | 1.1421.327 |

| Age 7584 years | 1.048 | 1.0271.069 |

| Age 85+ years | 1.141 | 1.1151.168 |

| Age 6574 years | REF | |

| Male | 1.201 | 1.1831.220 |

| Black | 1.250 | 1.2211.280 |

| Other race | 1.071 | 1.0331.111 |

| White | REF | |

| Dual eligibles | 1.173 | 1.1511.195 |

| Northeast region | 1.146 | 1.1151.178 |

| Midwest region | 1.092 | 1.0631.122 |

| South region | 1.037 | 1.0111.063 |

| West region | REF | |

| 0 comorbidities | 0.255 | 0.1480.441 |

| 59 comorbidities | 2.533 | 2.4492.621 |

| 10+ comorbidities | 6.119 | 5.9136.332 |

| 14 comorbidities | REF | |

| Disabled | 0.817 | 0.7570.880 |

| ESRD | 1.327 | 1.2231.440 |

| Age >64 years | REF | |

DISCUSSION

The most interesting finding is that beneficiaries with 10 or more chronic conditions were more than 6 times more likely to be readmitted than beneficiaries with 1 to 4 chronic conditions. Beneficiaries with 10 or more chronic conditions represent only 8.9% of all Medicare beneficiaries (31.0% of all hospitalizations), but they were responsible for 50.2% of all readmissions. The 31.8% of beneficiaries with 5 to 9 chronic conditions (55.5% of all hospitalizations) had the second highest odds ratio (2.5) and were responsible for 45% of all readmissions. The 59.3% of beneficiaries with 5 comorbidities (13.6% of all hospitalizations) were associated with only 4.7% of all readmissions. This strongly suggests that hospitals focus their attention on beneficiaries with 10 or more comorbidities. These results were despite correction for DRG diagnosis in the model.

We recognize that the number of chronic conditions is a crude measure of health status because it weighs hundreds of different clinical conditions equally; however, it seems a good proxy for 3 closely allied concepts: (1) the overall burden of chronic illness carried by the patient, (2) the patient's level of engagement with the healthcare system (including number of unique providers), and (3) the number of conditions being treated. By providing a 1‐year window of a patient's health status, it is a more complete picture than any single hospital claim submission or indices based solely on hospital discharge data.

The other variables are less predictive of 30‐day readmissions. Beneficiaries over 85 years old are only 14% more likely, whereas disabled Medicare beneficiaries 44 years old are 63% more likely to be readmitted than beneficiaries between 65 and 74 years old. Men are 20% more likely to be readmitted than women. Black race and dual‐eligibility slightly increase rates of readmission. Beneficiaries located in the West have the lowest readmission rates. In comparison to those who are aged, those with end‐stage renal disease (ESRD) have a higher rate of readmission, and those with a disability have a lower rate of readmission. In considering the age and reason for entitlement findings, one would assume that ESRD was the driver of higher readmission rates in the younger Medicare population.

CMS will need to analyze which hospitals have higher than expected readmission rates, and this will require risk adjustment at each hospital. In addition to the number of chronic conditions and other variables shown in Table 1, other factors CMS might want to include when it starts doing readmissions for all discharges is the discharge diagnosis (because our results suggest there are significant differences in the probability of a readmission across DRGs). In addition, CMS will need to consider how to capture additional data not currently in the claims data, such as social factors like homelessness.

We recognize significant limitations to these findings. First, this analysis uses only information that is available from Medicare claims and administrative data. Claims give almost no information on how well the hospital planned the discharge, instructed the patient and family, or engaged follow‐up providers. Also, claims data tell us virtually nothing about a patient's health literacy or social situation. Second, the analysis relies on claims data, but this has little clinical detail. Third, these data are limited to persons enrolled in fee‐for‐service Medicare. Fourth, we included all readmissions, including some readmissions (such as chemotherapy and staged percutaneous coronary interventions) that were part of a planned treatment protocol.[10] Fifth, we were unable to distinguish same‐day readmissions versus transfers, and therefore excluded all same‐day readmissions from measurement.

As hospitals and physicians begin to plan for the regulations that will penalize hospitals with high readmission rates, they will need to strongly consider targeting beneficiaries with more than 10 chronic conditions.

Acknowledgments

The Commonwealth Fund provided a grant to Dr. Anderson to help support this work. The authors report no conflicts of interest.

- , . Hospital readmissions in the Medicare population. N Engl J Med. 1984;311:1349–1353.

- , , . Rehospitalizations among patients in the Medicare fee‐for‐service program. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:1418–1428.

- Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act. Section 3025. Available at: http://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/PLAW‐111publ148/pdf/PLAW‐111publ148.pdf. Accessed April 8, 2013.

- Congressional Budget Office.Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act. Available at: http://www.cbo.gov/doc.cfm?index=10868. Accessed April 8, 2013.

- , , , et al.2012 measures maintenance technical report: acute myocardial infarction, heart failure, and pneumonia 30‐day risk‐standardized readmission measures. Available at: http://www.qualitynet.org/dcs/ContentServer?c=Page78:27597–27599.

- , , , , . Hospital payment based on diagnosis‐related groups differs in Europe and holds lessons for the United States. Health Aff (Millwood). 2013;32:713–723.

- , , , . Out‐of‐pocket medical spending for care of chronic conditions. Health Aff (Millwood). 2001;20:267–278.

- MEPS data documentation HC‐006: 1996 medical conditions. Pub. no. 99‐DP06. Rockville, MD: AHRQ; 1999.

- , . Planned readmissions: a potential solution. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172:269–270.

For at least 25 years, approximately 20% of Medicare fee‐for‐service discharges have been followed by a hospital readmission within 30 days.[1, 2] Section 3025 of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA)[3] created escalating penalties for hospitals with higher than expected 30‐day readmission rates, and the Congressional Budget Office estimated this will reduce Medicare spending by over $7 billion between 2010 and 2019.[4]

Hospitals and physicians have begun developing strategies to identify which Medicare beneficiaries are most likely to be readmitted and use this information to design programs to reduce their readmission rate. Initially, penalties will be based on readmission rates after an index discharge with heart failure, myocardial infarction, and pneumonia.[5] Recently, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) released the Inpatient Prospective Payment System FY2014 proposed rule, which proposes to add 2 new readmission penalties beginning in FY2015: readmissions for hip/knee arthroplasty and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.[6] Other countries are already penalizing hospitals with high readmission rates; for example, Germany is penalizing all readmissions that occur within a 30‐day period following admission.[7] In this brief report, we examine the characteristics of Medicare beneficiaries most likely to be readmitted within 30 days. We focus on readmission rates for all discharge conditions and all patient readmission rates, because we believe the language in the ACA ultimately points to an all‐inclusive approach.

METHODS

We used a nationally random 5% sample of all Medicare beneficiaries for the period between January 1, 2008 and September 30, 2008. To be included, beneficiaries must have both Part A and B coverage and live within the United States. Medicare Advantage patients were excluded because Medicare Advantage plans do not report the data in the same way as fee for service. We calculated the readmission rate as the number of admissions that were preceded by an at‐risk discharge within 30 days divided by the total number of at‐risk discharges. This definition included admissions to and discharges from sole community providers, Medicare‐dependent small rural hospitals, and critical access hospitals. We counted as at risk all live discharges from short‐term acute care hospitals that were not discharged against medical advice, discharged to a rehabilitation unit within an acute care hospital, or readmitted on day 0 (due to inconsistency with use of transfer coding). We only included discharges and readmissions to acute care hospitals and excluded hospitalizations in long‐term care facilities, rehabilitation facilities, skilled nursing homes, and other non‐acute care hospital facilities from being an index hospitalization. However, if the beneficiary was discharged to 1 of these facilities and then readmitted to an acute care hospital, the readmission was counted.

Each discharge was recorded as an independent event and we reset the readmission clock for a fresh 30‐day count each time the beneficiary was discharged. We examined the admission and readmission rate to determine if the rates varied by age, gender, reason for entitlement, racial characteristics, region of the country, number of chronic conditions, and whether the beneficiary is also enrolled in Medicaid (dual eligibles). We calculated the mean readmission rate for each diagnosis‐related group (DRG) and then used the probability of having a readmission for each DRG to calculate a case mix adjustment for each hospital. To calculate the chronic illness burden, we used a previously developed methodology for counting the number of chronic disease categories reported for the patient in the preceding year (2007).[8, 9] The classification system is maintained by the Agency for Health Care Research and Quality. We then used logistic regression to calculate the odds ratio of a discharge being readmitted based on these factors. We preformed statistical analysis using SAS version 9.1.3 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC).

RESULTS

There were 434,999 hospital discharges that occurred in the first 9 months of 2008 in the 5% sample. There were 20.6% of Medicare beneficiaries hospitalized, and the overall readmission rate was 19.5%. Table 1 shows the odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals for the probability that a Medicare beneficiary will be readmitted within 30 days for variables including: age, sex, race, dual‐eligibility status, number of comorbid conditions, geographic region, and reason for entitlement. Of note, beneficiaries with 10 or more chronic conditions were more than 6 times more likely, and beneficiaries with 5 to 9 chronic conditions were more than 2.5 times more likely, to be readmitted than beneficiaries with 1 to 4 chronic conditions.

| Variable | Estimate | 95% Confidence Limits |

|---|---|---|

| ||

| Age 144 years | 1.634 | 1.5071.771 |

| Age 4564 years | 1.231 | 1.1421.327 |

| Age 7584 years | 1.048 | 1.0271.069 |

| Age 85+ years | 1.141 | 1.1151.168 |

| Age 6574 years | REF | |

| Male | 1.201 | 1.1831.220 |

| Black | 1.250 | 1.2211.280 |

| Other race | 1.071 | 1.0331.111 |

| White | REF | |

| Dual eligibles | 1.173 | 1.1511.195 |

| Northeast region | 1.146 | 1.1151.178 |

| Midwest region | 1.092 | 1.0631.122 |

| South region | 1.037 | 1.0111.063 |

| West region | REF | |

| 0 comorbidities | 0.255 | 0.1480.441 |

| 59 comorbidities | 2.533 | 2.4492.621 |

| 10+ comorbidities | 6.119 | 5.9136.332 |

| 14 comorbidities | REF | |

| Disabled | 0.817 | 0.7570.880 |

| ESRD | 1.327 | 1.2231.440 |

| Age >64 years | REF | |

DISCUSSION

The most interesting finding is that beneficiaries with 10 or more chronic conditions were more than 6 times more likely to be readmitted than beneficiaries with 1 to 4 chronic conditions. Beneficiaries with 10 or more chronic conditions represent only 8.9% of all Medicare beneficiaries (31.0% of all hospitalizations), but they were responsible for 50.2% of all readmissions. The 31.8% of beneficiaries with 5 to 9 chronic conditions (55.5% of all hospitalizations) had the second highest odds ratio (2.5) and were responsible for 45% of all readmissions. The 59.3% of beneficiaries with 5 comorbidities (13.6% of all hospitalizations) were associated with only 4.7% of all readmissions. This strongly suggests that hospitals focus their attention on beneficiaries with 10 or more comorbidities. These results were despite correction for DRG diagnosis in the model.

We recognize that the number of chronic conditions is a crude measure of health status because it weighs hundreds of different clinical conditions equally; however, it seems a good proxy for 3 closely allied concepts: (1) the overall burden of chronic illness carried by the patient, (2) the patient's level of engagement with the healthcare system (including number of unique providers), and (3) the number of conditions being treated. By providing a 1‐year window of a patient's health status, it is a more complete picture than any single hospital claim submission or indices based solely on hospital discharge data.

The other variables are less predictive of 30‐day readmissions. Beneficiaries over 85 years old are only 14% more likely, whereas disabled Medicare beneficiaries 44 years old are 63% more likely to be readmitted than beneficiaries between 65 and 74 years old. Men are 20% more likely to be readmitted than women. Black race and dual‐eligibility slightly increase rates of readmission. Beneficiaries located in the West have the lowest readmission rates. In comparison to those who are aged, those with end‐stage renal disease (ESRD) have a higher rate of readmission, and those with a disability have a lower rate of readmission. In considering the age and reason for entitlement findings, one would assume that ESRD was the driver of higher readmission rates in the younger Medicare population.

CMS will need to analyze which hospitals have higher than expected readmission rates, and this will require risk adjustment at each hospital. In addition to the number of chronic conditions and other variables shown in Table 1, other factors CMS might want to include when it starts doing readmissions for all discharges is the discharge diagnosis (because our results suggest there are significant differences in the probability of a readmission across DRGs). In addition, CMS will need to consider how to capture additional data not currently in the claims data, such as social factors like homelessness.

We recognize significant limitations to these findings. First, this analysis uses only information that is available from Medicare claims and administrative data. Claims give almost no information on how well the hospital planned the discharge, instructed the patient and family, or engaged follow‐up providers. Also, claims data tell us virtually nothing about a patient's health literacy or social situation. Second, the analysis relies on claims data, but this has little clinical detail. Third, these data are limited to persons enrolled in fee‐for‐service Medicare. Fourth, we included all readmissions, including some readmissions (such as chemotherapy and staged percutaneous coronary interventions) that were part of a planned treatment protocol.[10] Fifth, we were unable to distinguish same‐day readmissions versus transfers, and therefore excluded all same‐day readmissions from measurement.

As hospitals and physicians begin to plan for the regulations that will penalize hospitals with high readmission rates, they will need to strongly consider targeting beneficiaries with more than 10 chronic conditions.

Acknowledgments

The Commonwealth Fund provided a grant to Dr. Anderson to help support this work. The authors report no conflicts of interest.

For at least 25 years, approximately 20% of Medicare fee‐for‐service discharges have been followed by a hospital readmission within 30 days.[1, 2] Section 3025 of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA)[3] created escalating penalties for hospitals with higher than expected 30‐day readmission rates, and the Congressional Budget Office estimated this will reduce Medicare spending by over $7 billion between 2010 and 2019.[4]

Hospitals and physicians have begun developing strategies to identify which Medicare beneficiaries are most likely to be readmitted and use this information to design programs to reduce their readmission rate. Initially, penalties will be based on readmission rates after an index discharge with heart failure, myocardial infarction, and pneumonia.[5] Recently, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) released the Inpatient Prospective Payment System FY2014 proposed rule, which proposes to add 2 new readmission penalties beginning in FY2015: readmissions for hip/knee arthroplasty and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.[6] Other countries are already penalizing hospitals with high readmission rates; for example, Germany is penalizing all readmissions that occur within a 30‐day period following admission.[7] In this brief report, we examine the characteristics of Medicare beneficiaries most likely to be readmitted within 30 days. We focus on readmission rates for all discharge conditions and all patient readmission rates, because we believe the language in the ACA ultimately points to an all‐inclusive approach.

METHODS

We used a nationally random 5% sample of all Medicare beneficiaries for the period between January 1, 2008 and September 30, 2008. To be included, beneficiaries must have both Part A and B coverage and live within the United States. Medicare Advantage patients were excluded because Medicare Advantage plans do not report the data in the same way as fee for service. We calculated the readmission rate as the number of admissions that were preceded by an at‐risk discharge within 30 days divided by the total number of at‐risk discharges. This definition included admissions to and discharges from sole community providers, Medicare‐dependent small rural hospitals, and critical access hospitals. We counted as at risk all live discharges from short‐term acute care hospitals that were not discharged against medical advice, discharged to a rehabilitation unit within an acute care hospital, or readmitted on day 0 (due to inconsistency with use of transfer coding). We only included discharges and readmissions to acute care hospitals and excluded hospitalizations in long‐term care facilities, rehabilitation facilities, skilled nursing homes, and other non‐acute care hospital facilities from being an index hospitalization. However, if the beneficiary was discharged to 1 of these facilities and then readmitted to an acute care hospital, the readmission was counted.

Each discharge was recorded as an independent event and we reset the readmission clock for a fresh 30‐day count each time the beneficiary was discharged. We examined the admission and readmission rate to determine if the rates varied by age, gender, reason for entitlement, racial characteristics, region of the country, number of chronic conditions, and whether the beneficiary is also enrolled in Medicaid (dual eligibles). We calculated the mean readmission rate for each diagnosis‐related group (DRG) and then used the probability of having a readmission for each DRG to calculate a case mix adjustment for each hospital. To calculate the chronic illness burden, we used a previously developed methodology for counting the number of chronic disease categories reported for the patient in the preceding year (2007).[8, 9] The classification system is maintained by the Agency for Health Care Research and Quality. We then used logistic regression to calculate the odds ratio of a discharge being readmitted based on these factors. We preformed statistical analysis using SAS version 9.1.3 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC).

RESULTS

There were 434,999 hospital discharges that occurred in the first 9 months of 2008 in the 5% sample. There were 20.6% of Medicare beneficiaries hospitalized, and the overall readmission rate was 19.5%. Table 1 shows the odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals for the probability that a Medicare beneficiary will be readmitted within 30 days for variables including: age, sex, race, dual‐eligibility status, number of comorbid conditions, geographic region, and reason for entitlement. Of note, beneficiaries with 10 or more chronic conditions were more than 6 times more likely, and beneficiaries with 5 to 9 chronic conditions were more than 2.5 times more likely, to be readmitted than beneficiaries with 1 to 4 chronic conditions.

| Variable | Estimate | 95% Confidence Limits |

|---|---|---|

| ||

| Age 144 years | 1.634 | 1.5071.771 |

| Age 4564 years | 1.231 | 1.1421.327 |

| Age 7584 years | 1.048 | 1.0271.069 |

| Age 85+ years | 1.141 | 1.1151.168 |

| Age 6574 years | REF | |

| Male | 1.201 | 1.1831.220 |

| Black | 1.250 | 1.2211.280 |

| Other race | 1.071 | 1.0331.111 |

| White | REF | |

| Dual eligibles | 1.173 | 1.1511.195 |

| Northeast region | 1.146 | 1.1151.178 |

| Midwest region | 1.092 | 1.0631.122 |

| South region | 1.037 | 1.0111.063 |

| West region | REF | |

| 0 comorbidities | 0.255 | 0.1480.441 |

| 59 comorbidities | 2.533 | 2.4492.621 |

| 10+ comorbidities | 6.119 | 5.9136.332 |

| 14 comorbidities | REF | |

| Disabled | 0.817 | 0.7570.880 |

| ESRD | 1.327 | 1.2231.440 |

| Age >64 years | REF | |

DISCUSSION

The most interesting finding is that beneficiaries with 10 or more chronic conditions were more than 6 times more likely to be readmitted than beneficiaries with 1 to 4 chronic conditions. Beneficiaries with 10 or more chronic conditions represent only 8.9% of all Medicare beneficiaries (31.0% of all hospitalizations), but they were responsible for 50.2% of all readmissions. The 31.8% of beneficiaries with 5 to 9 chronic conditions (55.5% of all hospitalizations) had the second highest odds ratio (2.5) and were responsible for 45% of all readmissions. The 59.3% of beneficiaries with 5 comorbidities (13.6% of all hospitalizations) were associated with only 4.7% of all readmissions. This strongly suggests that hospitals focus their attention on beneficiaries with 10 or more comorbidities. These results were despite correction for DRG diagnosis in the model.

We recognize that the number of chronic conditions is a crude measure of health status because it weighs hundreds of different clinical conditions equally; however, it seems a good proxy for 3 closely allied concepts: (1) the overall burden of chronic illness carried by the patient, (2) the patient's level of engagement with the healthcare system (including number of unique providers), and (3) the number of conditions being treated. By providing a 1‐year window of a patient's health status, it is a more complete picture than any single hospital claim submission or indices based solely on hospital discharge data.

The other variables are less predictive of 30‐day readmissions. Beneficiaries over 85 years old are only 14% more likely, whereas disabled Medicare beneficiaries 44 years old are 63% more likely to be readmitted than beneficiaries between 65 and 74 years old. Men are 20% more likely to be readmitted than women. Black race and dual‐eligibility slightly increase rates of readmission. Beneficiaries located in the West have the lowest readmission rates. In comparison to those who are aged, those with end‐stage renal disease (ESRD) have a higher rate of readmission, and those with a disability have a lower rate of readmission. In considering the age and reason for entitlement findings, one would assume that ESRD was the driver of higher readmission rates in the younger Medicare population.

CMS will need to analyze which hospitals have higher than expected readmission rates, and this will require risk adjustment at each hospital. In addition to the number of chronic conditions and other variables shown in Table 1, other factors CMS might want to include when it starts doing readmissions for all discharges is the discharge diagnosis (because our results suggest there are significant differences in the probability of a readmission across DRGs). In addition, CMS will need to consider how to capture additional data not currently in the claims data, such as social factors like homelessness.

We recognize significant limitations to these findings. First, this analysis uses only information that is available from Medicare claims and administrative data. Claims give almost no information on how well the hospital planned the discharge, instructed the patient and family, or engaged follow‐up providers. Also, claims data tell us virtually nothing about a patient's health literacy or social situation. Second, the analysis relies on claims data, but this has little clinical detail. Third, these data are limited to persons enrolled in fee‐for‐service Medicare. Fourth, we included all readmissions, including some readmissions (such as chemotherapy and staged percutaneous coronary interventions) that were part of a planned treatment protocol.[10] Fifth, we were unable to distinguish same‐day readmissions versus transfers, and therefore excluded all same‐day readmissions from measurement.

As hospitals and physicians begin to plan for the regulations that will penalize hospitals with high readmission rates, they will need to strongly consider targeting beneficiaries with more than 10 chronic conditions.

Acknowledgments

The Commonwealth Fund provided a grant to Dr. Anderson to help support this work. The authors report no conflicts of interest.

- , . Hospital readmissions in the Medicare population. N Engl J Med. 1984;311:1349–1353.

- , , . Rehospitalizations among patients in the Medicare fee‐for‐service program. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:1418–1428.

- Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act. Section 3025. Available at: http://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/PLAW‐111publ148/pdf/PLAW‐111publ148.pdf. Accessed April 8, 2013.

- Congressional Budget Office.Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act. Available at: http://www.cbo.gov/doc.cfm?index=10868. Accessed April 8, 2013.

- , , , et al.2012 measures maintenance technical report: acute myocardial infarction, heart failure, and pneumonia 30‐day risk‐standardized readmission measures. Available at: http://www.qualitynet.org/dcs/ContentServer?c=Page78:27597–27599.

- , , , , . Hospital payment based on diagnosis‐related groups differs in Europe and holds lessons for the United States. Health Aff (Millwood). 2013;32:713–723.

- , , , . Out‐of‐pocket medical spending for care of chronic conditions. Health Aff (Millwood). 2001;20:267–278.

- MEPS data documentation HC‐006: 1996 medical conditions. Pub. no. 99‐DP06. Rockville, MD: AHRQ; 1999.

- , . Planned readmissions: a potential solution. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172:269–270.

- , . Hospital readmissions in the Medicare population. N Engl J Med. 1984;311:1349–1353.

- , , . Rehospitalizations among patients in the Medicare fee‐for‐service program. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:1418–1428.

- Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act. Section 3025. Available at: http://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/PLAW‐111publ148/pdf/PLAW‐111publ148.pdf. Accessed April 8, 2013.

- Congressional Budget Office.Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act. Available at: http://www.cbo.gov/doc.cfm?index=10868. Accessed April 8, 2013.

- , , , et al.2012 measures maintenance technical report: acute myocardial infarction, heart failure, and pneumonia 30‐day risk‐standardized readmission measures. Available at: http://www.qualitynet.org/dcs/ContentServer?c=Page78:27597–27599.

- , , , , . Hospital payment based on diagnosis‐related groups differs in Europe and holds lessons for the United States. Health Aff (Millwood). 2013;32:713–723.

- , , , . Out‐of‐pocket medical spending for care of chronic conditions. Health Aff (Millwood). 2001;20:267–278.

- MEPS data documentation HC‐006: 1996 medical conditions. Pub. no. 99‐DP06. Rockville, MD: AHRQ; 1999.

- , . Planned readmissions: a potential solution. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172:269–270.

Dear Doctor: A Patient‐Centered Tool

In their seminal report Crossing the Quality Chasm, the Institute of Medicine outlined patient‐centered care as 1 of its 6 aims to improve the healthcare delivery system.[1] Patients who are more involved in their diagnosis and treatment plan are more likely to feel respected, be satisfied with their healthcare experience, and ultimately have better outcomes.[2, 3] In a study of hospitalized patients, only 42% were able to state their diagnosis at the time of discharge, suggesting that hospital providers could communicate better with patients about their hospital care.[4] Additionally, only 28% of hospitalized patients were able to list their medications, and only 37% were able to state the purpose of their medications. Although hospitals have taken great strides to improve the quality of patient care, publicly reported patient care surveys, such as the Hospital Consumer Assessment of Hospitals and Health Systems (HCAHPS), suggest that physician communication with patients could be further improved.[1, 5] Furthermore, a recent report by the Institute of Medicine stresses the need to get patients and families involved in their care.[6] Thus, hospital‐based providers should seek to enhance the quality of their communication with patients.

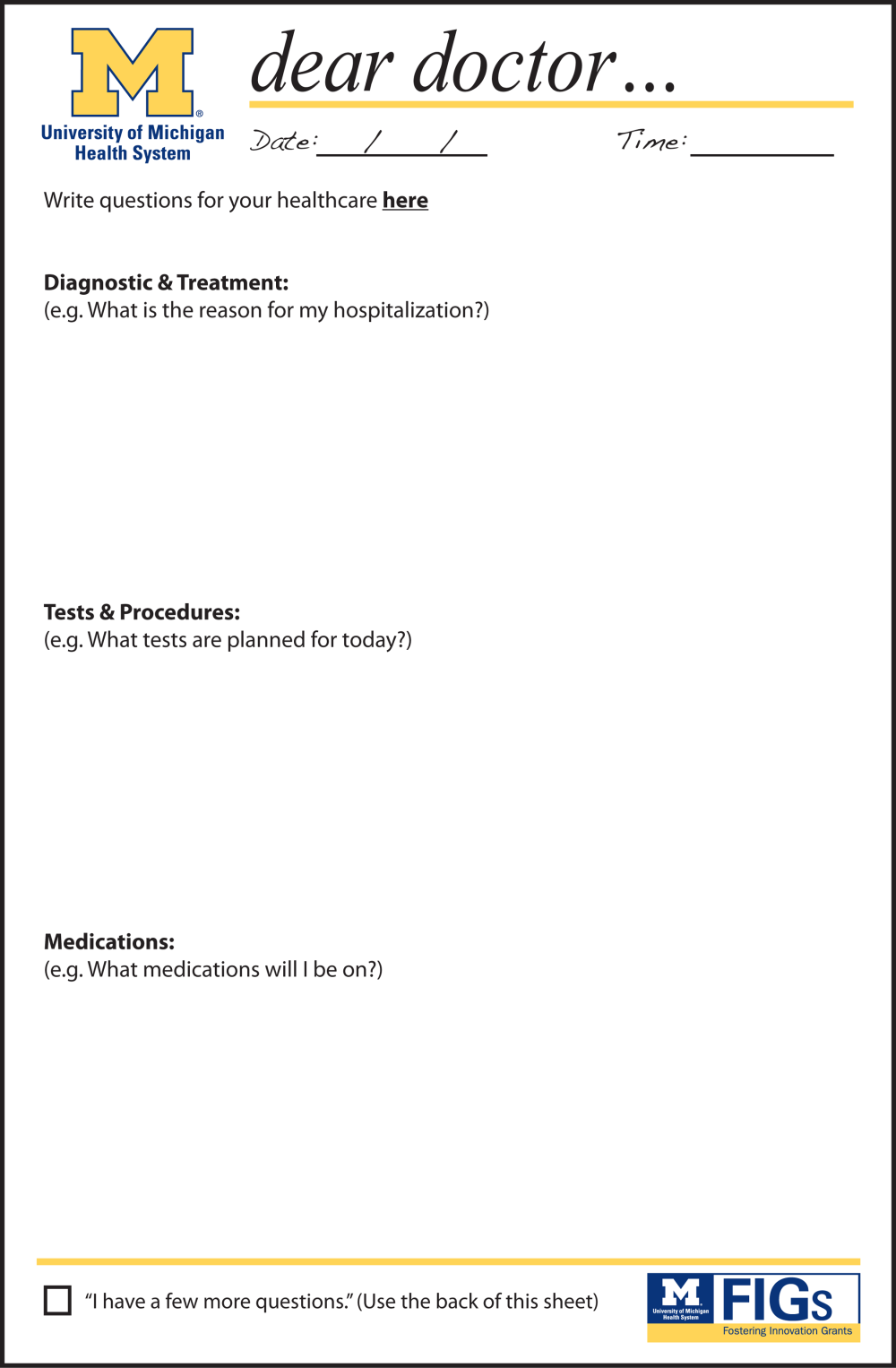

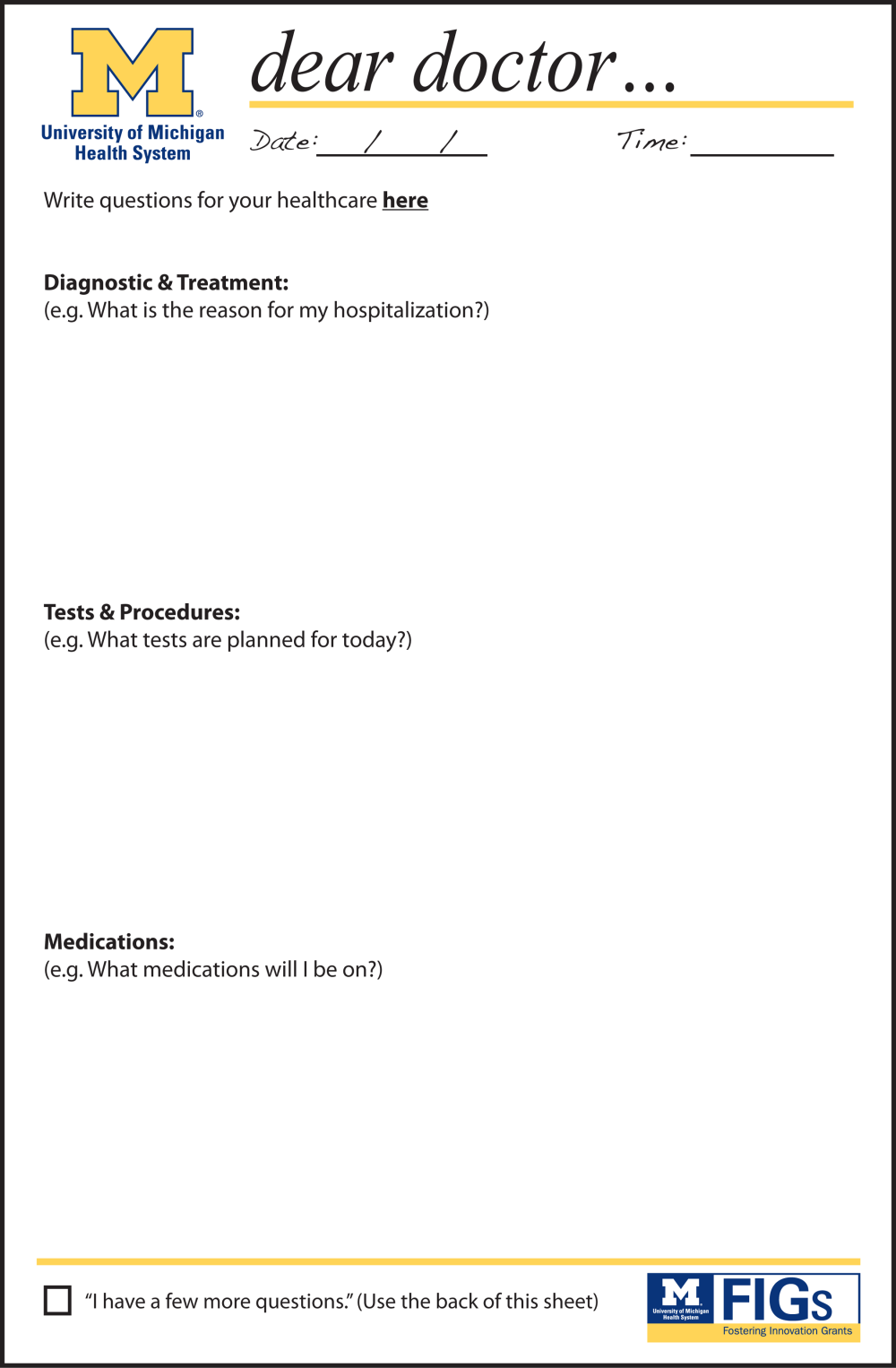

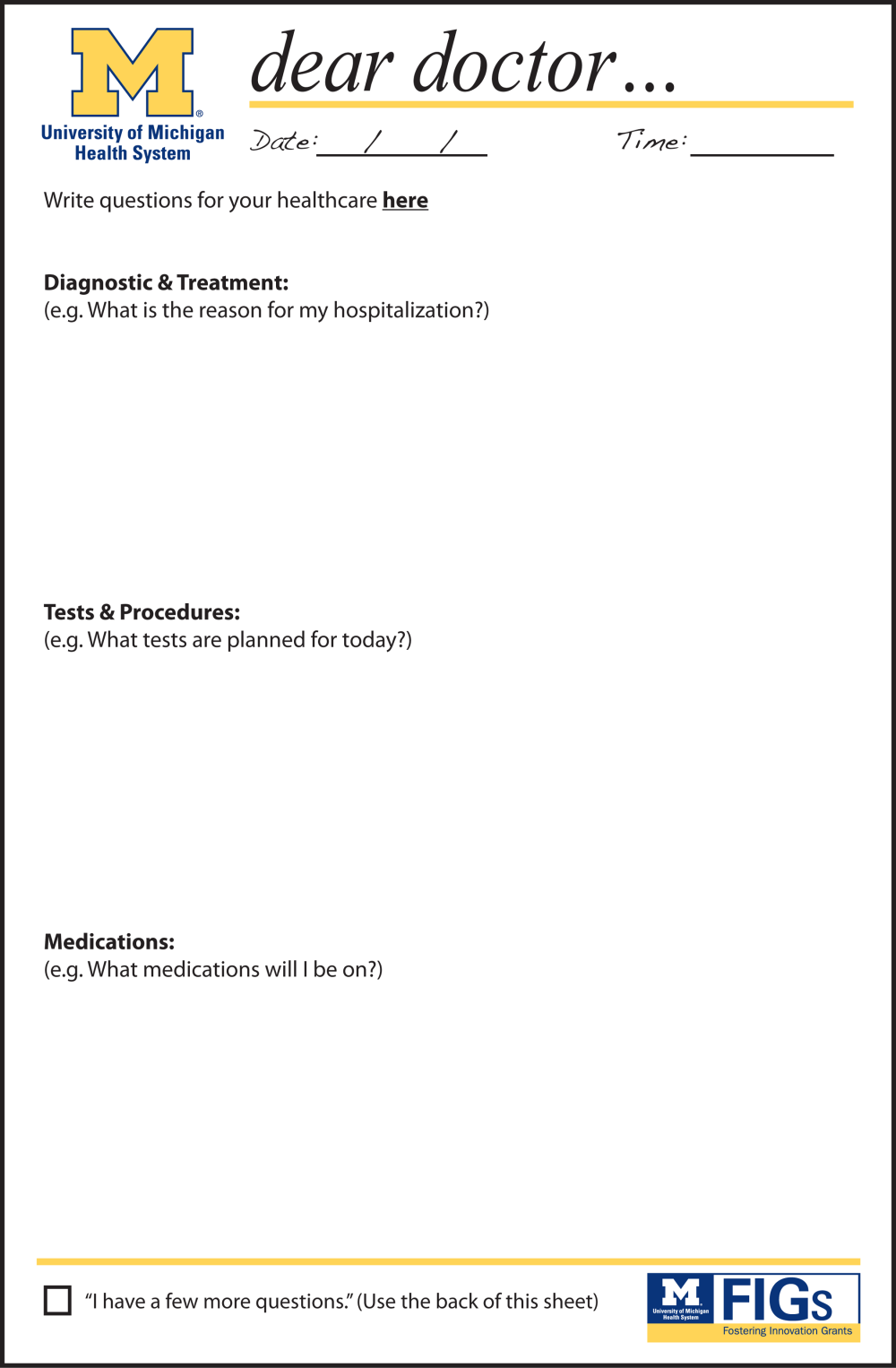

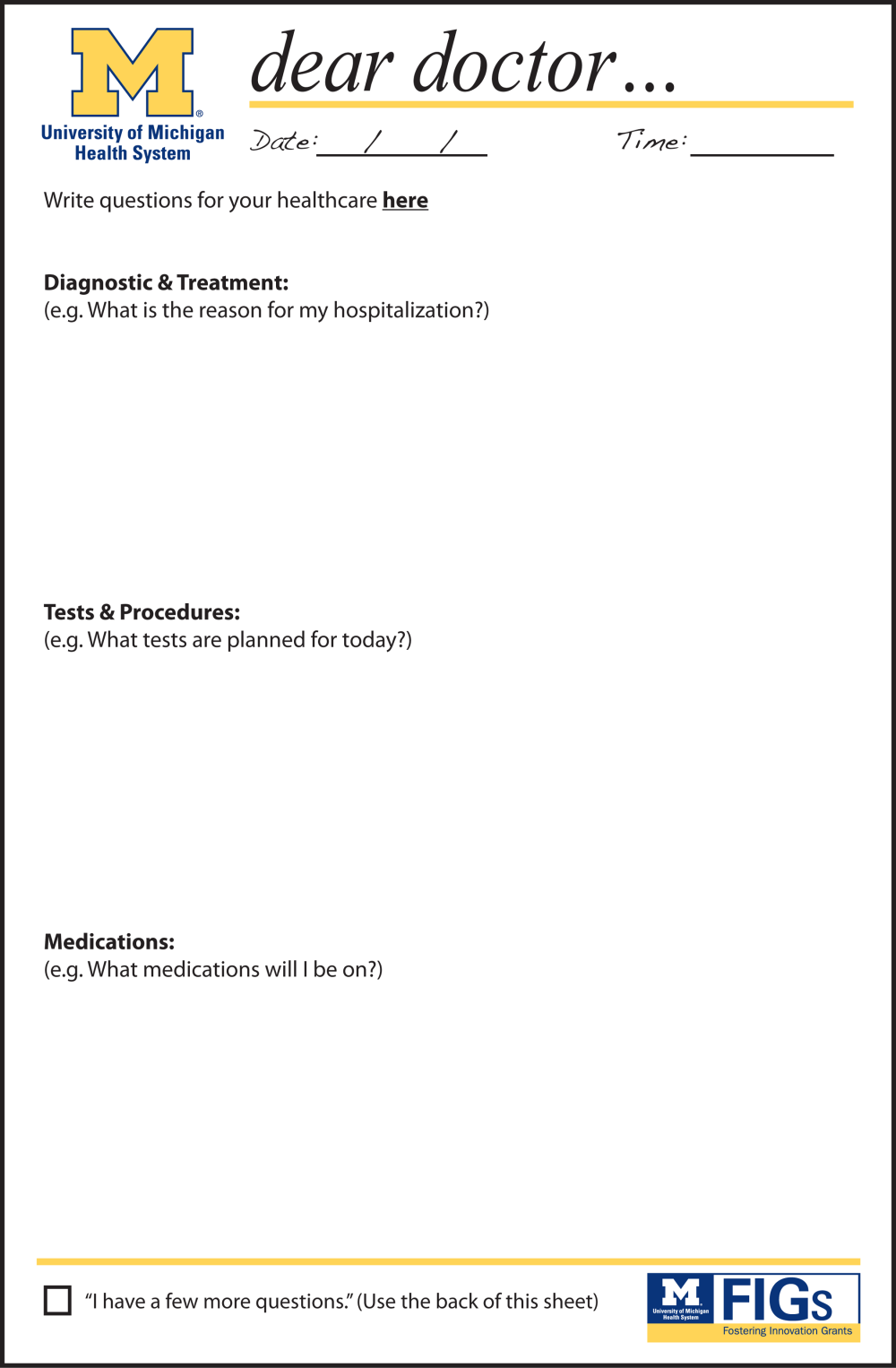

With greater emphasis placed on patient‐ and family‐centered care at many health systems, simple and easy‐to‐implement strategies to improve communication with patients need to be developed and tested.[7, 8] Patients who actively participate in their healthcare by asking questions of their doctor are able to control the focus of their interaction and adjust the amount of information provided.[9] Simply asking questions can have a critical impact, as 1 study found that the frequency with which patients asked questions was significantly related to the amount of information received about general and specific medical matters.[10] The notepad is a common tool for reminders and personal interactions that is used in everyday life, but has not been formalized in the hospital. We introduced Dear Doctor (DD) notes, a bedside notepad designed to prompt patient questions, with the goal of facilitating patient communication with their hospitalist physicians (Figure 1). As hospitalists provide direct and indirect care to a growing number of hospitalized patients, they are likely to be asked questions and opinions about the patients' diagnoses and plans. Furthermore, hospitalists are poised to lead institutional quality, safety, efficiency, and service improvement efforts in the inpatient setting. Becoming familiar with communication‐enhancing tools, such as the DD notes, may help hospitalists in their improvement team roles.

METHODS

Setting

We conducted a study between July 2009 and September 2009 on inpatient medical wards at a large academic medical center with 610 beds and over 44,000 annual discharges.[11] The internal medicine services served by attending physicians and residents comprise a large proportion of hospitalized patients, accounting for over 17,000 discharges per year. Each medical unit includes 32 beds.

Population

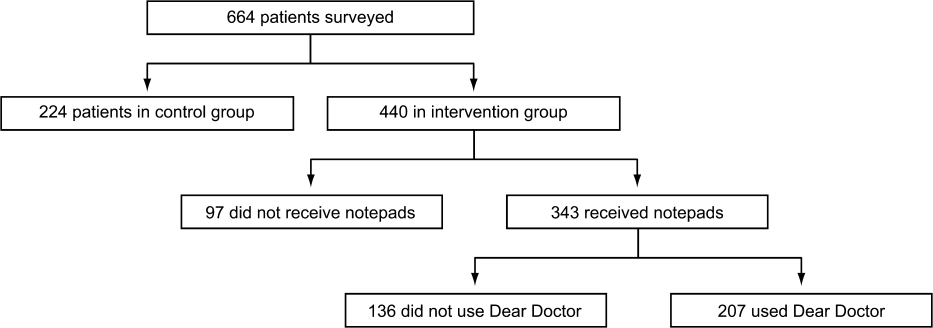

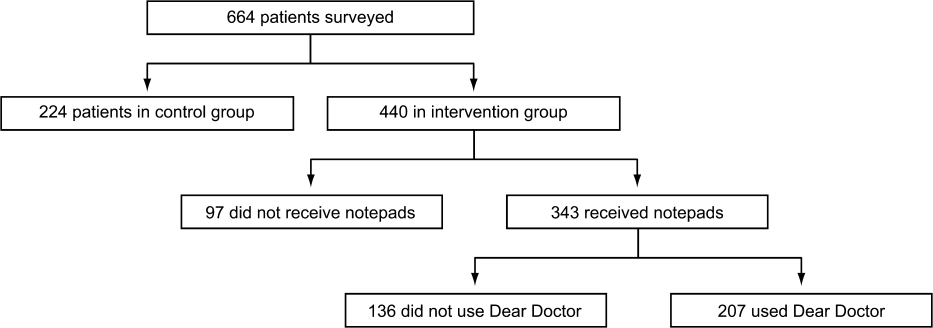

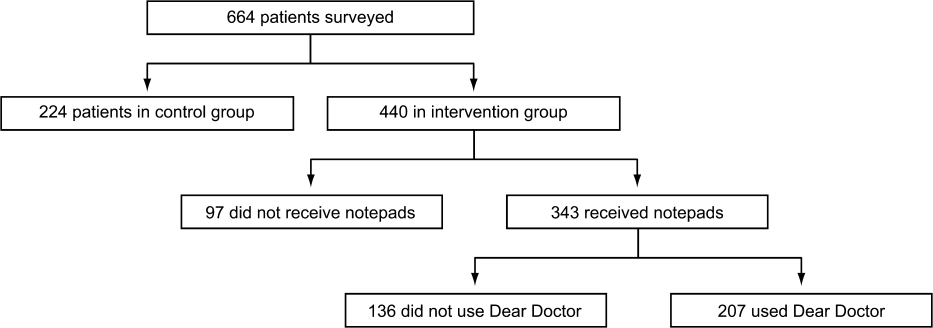

Patients over the age of 18 years admitted to a general medicine or cardiology unit and who were able to verbally communicate in English were eligible to be surveyed in the study. Patients with a length of stay <24 hours were excluded. A total of 664 patients were surveyed for inclusion in the study, 440 patients in the intervention group and 224 patients in the control group.

Intervention

The DD notepad included sample questions and informational prompts derived with input from a community focus group. The community focus group consisted of current and formerly hospitalized patients and family members who were asked by members of the study group what they thought would be important to include on a notepad provided to patients. From their answers the study team developed the DD notepad prototype. The DD notepad included 3 general categories of questions: (1) diagnosis and treatment, (2) tests and procedures, and (3) medications. To address other miscellaneous topics such as discharge and posthospital care needs, a section was designated for the patient to check off as I have a few more questions (Use the back of the sheet).

All patients admitted to the study units were intended to receive the DD notepad and pen, which were placed on the bedside table during the room change by our custodial staff. Patients who did not receive DD notepads in the intervention group during their first hospitalization day were provided with 1 by the clinical assistants working with the hospitalists. These patients did not initially receive the notepad due to logistical reasons from temporary rotating staff who were not instructed to provide the notepads. Patients were not formally prompted to use the notepad. Hospitalists, residents, and nurses on the study units were informed about the distribution of DD notes to patients on these units; however, they were not provided with any specific instructions on how they should incorporate the DD notes into their interactions with their patients. The use of the DD notepad was left to each healthcare professional's own discretion.

Members of the study team surveyed patients who had been in the hospital for a minimum of 24 hours in the intervention and control groups twice weekly. All responses were deidentified of any personal or health information. Patients were asked to rate on a scale from 1 to 5 their use of the DD notepads, their perceived value, the circumstances in which the notepads were used, and their level of satisfaction with how their physicians communicated and answered their questions (1 = no improvement, 5 = significant improvement). For control patients, questions pertaining to DD notepads were not applicable and were therefore excluded.

Statistical Analysis

The data were analyzed in an intention‐to‐treat analysis of all 440 patients in the intervention group. Intervention and control groups were compared using 2, rank sum, and Fisher exact statistical tests, with significance assigned as P < 0.05, using SPSS software version 17.0 (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL). Our project was approved by the University of Michigan's institutional review board.

RESULTS

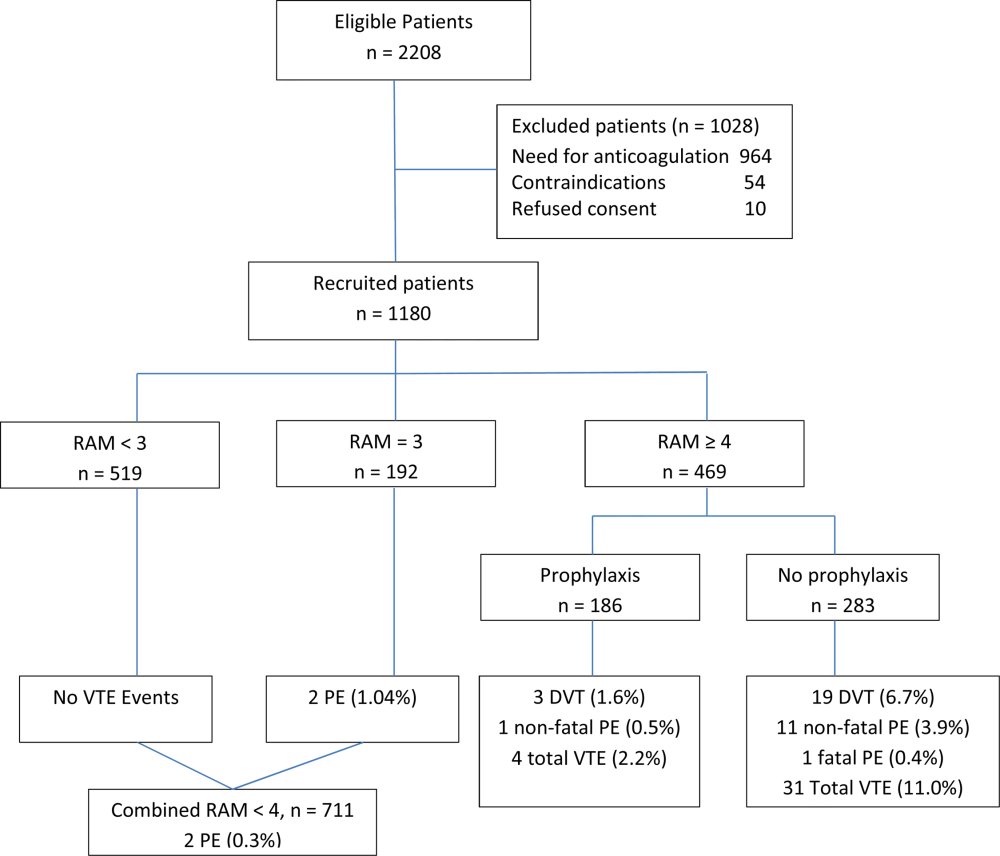

Of the 440 patients surveyed in the intervention group (1 general medicine and 1 cardiology unit), 343 (78%) received the notepads in their rooms and 207 (47%) used them (Figure 2). Not every patient in the intervention group received DD notepads due to inconsistent placement of DD notepads upon every room turnover. Of the patients admitted to the control group (1 general medicine and 1 cardiology unit), 224 were surveyed. Fifty‐four percent of the 440 patients in the intervention group reported that they took notes related to their hospital care, compared to only 22% of the 224 patients in the control group (P < 0.001). Of the patients who took notes within the intervention group (n = 207), 91% of them utilized the DD notepads.

Patients in the intervention group who received and used the DD notes (n = 207) compared to patients in the control group (n = 224) were more likely to report that their questions were answered by their physicians (4.63 vs 4.45, P < 0.001). In an intention‐to‐treat analysis of all 440 patients in the intervention group, the overall satisfaction with physician communication was not significantly different between the intervention and control groups as measured on a 5‐point Likert scale (4.55 vs 4.55, P = 0.89). However, 89% of the patients in the intervention group who used the notepads felt that DD notepads either moderately or significantly improved their communication with their providers (Figure 3).

When the 207 patients who received DD notepads were asked how they used this tool, 99% of these patients used DD to write down questions, 82% to keep track of tests and procedures, and 54% indicated that their family and friends also used the notepads during the hospital stay (Table 1). Among these patients who utilized the DD notepads, 93% reported that they would use them again in the future.

| Wrote Notes? (P < 0.001) (%) | Used DD? (%) | Use in Future? (%) | Frequency of Questions Answered (P < 0.001) | DD Improved Communication | Satisfied With Communication? (P = 0.89) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||

| Intervention (n = 440) | 54 | 91 | 93.2 | 4.63 | 3.76 | 4.55 |

| Control (n = 224) | 22 | 4.45 | 4.55 | |||

Of the 97 patients in the intervention group who did not receive a DD notepad, we asked if they would use the DD notepad if they were made aware of such a tool. Of these patients, 77% agreed that they would use DD notes if they were made available in the future, 100% of them said that they would use DD to write down questions, 97% indicated that they would write notes about tests and procedures, and 88% of them believed that their families and friends would use DD notes.

DISCUSSION

As hospitals place greater emphasis and value on patient‐centered care as part of their clinical mission, it is important to develop tools to help facilitate the doctor‐patient relationship. We found that patients who were provided the Dear Doctor notepad were more satisfied that their doctors answered their questions and felt this tool enhanced their ability to communicate with their physicians. Employing the use of a familiar tool such as the notepad to remind patients about specific issues in their interactions with their providers can be a powerful intervention. Our study demonstrated that the DD notepad was widely accepted by patients, and that almost all of them would use this tool if it were made available to them in the future.

Other tools and methods to enhance the quality of communication between patients and their healthcare providers have included using whiteboards in the patients' rooms to relay the care plan to the patients, implementing bedside rounds by the healthcare team, and multidisciplinary huddling to coordinate information to the patient.[12, 13] Studies of these communication tools have shown potential to improve teamwork, interaction, and patient care. All of these have their own merit and value, and our DD notepad should be considered an adjunct to existing methods to enhance the patient care experience. A bedside tool that is familiar in form to most patients also needs to have the feature of easy access and use. Once this barrier has been removed for the patient and their family members, tools such as the DD notepad can impact the patient‐centeredness by fostering increased and better quality dialogue between the patients, their family members, and healthcare providers.

The DD notepad represents a means of communication that may have the potential to empower patients. It is possible that through question prompts, the DD notepad stimulates the patient to be an active partner with his or her healthcare team. This may enable patients to have some sense of control and accountability of their care in a setting where they would otherwise feel overwhelmed or powerless. The 3 general categories to help patients write down their questions included diagnosis, treatment plan, and medications. In the inpatient setting, where patient‐care activities can be fast paced, and patients are unable to recall some details when speaking to the healthcare team, these notes may remind the patient to write their thoughts down so that they may be remembered for a future time. In situations where patients may not know which questions to ask, the question prompts may be particularly helpful. We did not assess whether our particular question prompts were the key elements that resulted in their perceived value, or whether simply placing a blank notepad at the bedside would also have been successful. However, the specific questions were suggested by the focus groups. Enhanced communication, focusing on the patients' understanding of their condition, and the need to pursue certain diagnostic or therapeutic interventions, may help patients to be better prepared for the next course of plan. These topics of reasons for hospitalization, treatment plan, and medication changes are also important for patients to be active participants in their care, in particular as they transition from 1 site of care to the next, and their healthcare will be delivered by different providers.

There are several limitations to our study. First, this intervention was performed at a single hospital site with only 2 clinical services (general medicine, cardiology) represented in the study groups. Although we do not have any causal reasons to believe this tool would be looked upon differently by patients on other clinical services, it is possible that patients on a different clinical unit or service may view this tool as less or more useful. Second, as the patients were not randomized to intervention, but rather based on the units to which they were admitted, it is possible that other variables, such as the experience of the unit staff, the patient's condition, and housestaff‐based service versus hospitalist‐based service may have played a role in how the patients perceived the use of DD notes. Third, patients were only surveyed if they were able to verbally communicate in English. These notes may not be as useful in hospital settings to populations with language or literacy barriers. Fourth, the logistical implementation of DD notes limited our ability to deliver the DD notepads in every patient's rooms, where only 78% of the intervention group received the DD notepads. This may be the reason that we did not find that overall satisfaction with physician communication differed between intervention and control groups. Nonetheless, we performed an intention‐to‐treat analysis to minimize any biases in our analysis. Last, although our survey of patients asked about their satisfaction in using the DD note pads, we did not compare these results with those of Press‐Ganey or HCAHPS scores of patients on the intervention group versus the control group. Additionally, lack of data about type, quality, and quantity of questions asked by a control group to see if the notepads actually improved quality of questions asked is a limitation; however, we believe our outcomes of interest were most specifically evaluated through our survey questions.

DD notes show that the majority of patients who use this tool feel a modest to significant improvement in communication with their providers. Although the quality of medical care is undoubtedly the first priority, the patients' view of their care, which includes communication, is arguably just as important. An often‐forgotten goal of hospitals and clinics is to provide service excellence along with high‐quality care. Thus, it is imperative for hospitals and their care providers to not only focus on the quality and safety of the clinical care, but also be mindful of the patient's entire experience throughout their hospital stay. Many of the categories of questions asked in the HCAHPS address the patient's experience and perspectives of hospital care. Furthermore, the role of the HCAHPS survey in the Value‐Based Purchasing rules may enhance the importance of these notepads. As the results of HCAHPS are becoming more transparent and available to the public, the impact of such results will have a greater significance to the future of the hospital's clinical mission.

CONCLUSION

DD notepads are a simple, low‐cost, patient‐centered tool that can be an effective reminder for patients to ask their healthcare providers questions related to their hospital care. Utilizing a common tool such as the notepad, redesigned for the healthcare setting, can serve to help healthcare providers interact with their patients. Patient satisfaction may be higher in patients who use the DD notepad.

Disclosures: Aaron S. Farberg, MD, and Andrew M. Lin, MD, contributed equally in every way and should be considered co‐first authors. This work was supported by a University of Michigan Fostering Innovations Grant. The authors have no conflicting financial interests.

- Committee on Quality of Health Care in America, Institute of Medicine. Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 2001.

- , , , . An evidence base for patient‐centered cancer care: a meta‐analysis of studies of observed communication between cancer specialists and their patients. Patient Educ Couns. 2009;77(3):379–383.

- . Effective physician‐patient communication and health outcomes: a review. Can Med Assoc J. 1995;152:1423–1433.

- , . Patients' understanding of their treatment plans and diagnosis at discharge. Mayo Clin Proc. 2005;80(8):991–994.

- , , , . Patients' perception of hospital care in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:1921–1931.

- Institute of Medicine of the National Academies.Best care at lower cost: the path to continuously learning health care in America. Available at: http://www.iom.edu/Reports/2012/Best‐Care‐at‐Lower‐Cost‐The‐Path‐to‐Continuously‐Learning‐Health‐Care‐in‐America.aspx. Accessed October 5, 2012.

- , . An introduction to technology for patient‐centered collaborative care. J Ambul Care Manage. 2006;29:195–198.

- , , , , , . Effect on health‐related outcome of interventions to alter the interaction between patients and practitioners: a systematic review of trials. Ann Fam Med. 2004;2(6):595–608

- , , , , . Characteristics of physicians with participatory decision‐making styles. Ann Intern Med. 1996;124(5):497–504.

- . Information‐giving consultations: the influence of patients' communicative styles and personal characteristics. Soc Sci Med. 1991:32(5):541–548.

- University of Michigan Health System.Patient care and University of Michigan Health System. Available at: http://www.uofmhealth.org/about%2Bumhs/about‐clinical‐care. Accessed August 31, 2012.

- , , , et al. It's the writing on the wall: whiteboards improve inpatient satisfaction with provider communication. Am J Med Qual. 2011;26(2):127–131

- , , , , . Patient whiteboards as a communication tool in the hospital setting: a survey of practices and recommendations. J Hosp Med. 2010;5(4):234–239.

In their seminal report Crossing the Quality Chasm, the Institute of Medicine outlined patient‐centered care as 1 of its 6 aims to improve the healthcare delivery system.[1] Patients who are more involved in their diagnosis and treatment plan are more likely to feel respected, be satisfied with their healthcare experience, and ultimately have better outcomes.[2, 3] In a study of hospitalized patients, only 42% were able to state their diagnosis at the time of discharge, suggesting that hospital providers could communicate better with patients about their hospital care.[4] Additionally, only 28% of hospitalized patients were able to list their medications, and only 37% were able to state the purpose of their medications. Although hospitals have taken great strides to improve the quality of patient care, publicly reported patient care surveys, such as the Hospital Consumer Assessment of Hospitals and Health Systems (HCAHPS), suggest that physician communication with patients could be further improved.[1, 5] Furthermore, a recent report by the Institute of Medicine stresses the need to get patients and families involved in their care.[6] Thus, hospital‐based providers should seek to enhance the quality of their communication with patients.

With greater emphasis placed on patient‐ and family‐centered care at many health systems, simple and easy‐to‐implement strategies to improve communication with patients need to be developed and tested.[7, 8] Patients who actively participate in their healthcare by asking questions of their doctor are able to control the focus of their interaction and adjust the amount of information provided.[9] Simply asking questions can have a critical impact, as 1 study found that the frequency with which patients asked questions was significantly related to the amount of information received about general and specific medical matters.[10] The notepad is a common tool for reminders and personal interactions that is used in everyday life, but has not been formalized in the hospital. We introduced Dear Doctor (DD) notes, a bedside notepad designed to prompt patient questions, with the goal of facilitating patient communication with their hospitalist physicians (Figure 1). As hospitalists provide direct and indirect care to a growing number of hospitalized patients, they are likely to be asked questions and opinions about the patients' diagnoses and plans. Furthermore, hospitalists are poised to lead institutional quality, safety, efficiency, and service improvement efforts in the inpatient setting. Becoming familiar with communication‐enhancing tools, such as the DD notes, may help hospitalists in their improvement team roles.

METHODS

Setting

We conducted a study between July 2009 and September 2009 on inpatient medical wards at a large academic medical center with 610 beds and over 44,000 annual discharges.[11] The internal medicine services served by attending physicians and residents comprise a large proportion of hospitalized patients, accounting for over 17,000 discharges per year. Each medical unit includes 32 beds.

Population

Patients over the age of 18 years admitted to a general medicine or cardiology unit and who were able to verbally communicate in English were eligible to be surveyed in the study. Patients with a length of stay <24 hours were excluded. A total of 664 patients were surveyed for inclusion in the study, 440 patients in the intervention group and 224 patients in the control group.

Intervention

The DD notepad included sample questions and informational prompts derived with input from a community focus group. The community focus group consisted of current and formerly hospitalized patients and family members who were asked by members of the study group what they thought would be important to include on a notepad provided to patients. From their answers the study team developed the DD notepad prototype. The DD notepad included 3 general categories of questions: (1) diagnosis and treatment, (2) tests and procedures, and (3) medications. To address other miscellaneous topics such as discharge and posthospital care needs, a section was designated for the patient to check off as I have a few more questions (Use the back of the sheet).

All patients admitted to the study units were intended to receive the DD notepad and pen, which were placed on the bedside table during the room change by our custodial staff. Patients who did not receive DD notepads in the intervention group during their first hospitalization day were provided with 1 by the clinical assistants working with the hospitalists. These patients did not initially receive the notepad due to logistical reasons from temporary rotating staff who were not instructed to provide the notepads. Patients were not formally prompted to use the notepad. Hospitalists, residents, and nurses on the study units were informed about the distribution of DD notes to patients on these units; however, they were not provided with any specific instructions on how they should incorporate the DD notes into their interactions with their patients. The use of the DD notepad was left to each healthcare professional's own discretion.

Members of the study team surveyed patients who had been in the hospital for a minimum of 24 hours in the intervention and control groups twice weekly. All responses were deidentified of any personal or health information. Patients were asked to rate on a scale from 1 to 5 their use of the DD notepads, their perceived value, the circumstances in which the notepads were used, and their level of satisfaction with how their physicians communicated and answered their questions (1 = no improvement, 5 = significant improvement). For control patients, questions pertaining to DD notepads were not applicable and were therefore excluded.

Statistical Analysis

The data were analyzed in an intention‐to‐treat analysis of all 440 patients in the intervention group. Intervention and control groups were compared using 2, rank sum, and Fisher exact statistical tests, with significance assigned as P < 0.05, using SPSS software version 17.0 (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL). Our project was approved by the University of Michigan's institutional review board.

RESULTS

Of the 440 patients surveyed in the intervention group (1 general medicine and 1 cardiology unit), 343 (78%) received the notepads in their rooms and 207 (47%) used them (Figure 2). Not every patient in the intervention group received DD notepads due to inconsistent placement of DD notepads upon every room turnover. Of the patients admitted to the control group (1 general medicine and 1 cardiology unit), 224 were surveyed. Fifty‐four percent of the 440 patients in the intervention group reported that they took notes related to their hospital care, compared to only 22% of the 224 patients in the control group (P < 0.001). Of the patients who took notes within the intervention group (n = 207), 91% of them utilized the DD notepads.

Patients in the intervention group who received and used the DD notes (n = 207) compared to patients in the control group (n = 224) were more likely to report that their questions were answered by their physicians (4.63 vs 4.45, P < 0.001). In an intention‐to‐treat analysis of all 440 patients in the intervention group, the overall satisfaction with physician communication was not significantly different between the intervention and control groups as measured on a 5‐point Likert scale (4.55 vs 4.55, P = 0.89). However, 89% of the patients in the intervention group who used the notepads felt that DD notepads either moderately or significantly improved their communication with their providers (Figure 3).

When the 207 patients who received DD notepads were asked how they used this tool, 99% of these patients used DD to write down questions, 82% to keep track of tests and procedures, and 54% indicated that their family and friends also used the notepads during the hospital stay (Table 1). Among these patients who utilized the DD notepads, 93% reported that they would use them again in the future.

| Wrote Notes? (P < 0.001) (%) | Used DD? (%) | Use in Future? (%) | Frequency of Questions Answered (P < 0.001) | DD Improved Communication | Satisfied With Communication? (P = 0.89) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||

| Intervention (n = 440) | 54 | 91 | 93.2 | 4.63 | 3.76 | 4.55 |

| Control (n = 224) | 22 | 4.45 | 4.55 | |||

Of the 97 patients in the intervention group who did not receive a DD notepad, we asked if they would use the DD notepad if they were made aware of such a tool. Of these patients, 77% agreed that they would use DD notes if they were made available in the future, 100% of them said that they would use DD to write down questions, 97% indicated that they would write notes about tests and procedures, and 88% of them believed that their families and friends would use DD notes.

DISCUSSION

As hospitals place greater emphasis and value on patient‐centered care as part of their clinical mission, it is important to develop tools to help facilitate the doctor‐patient relationship. We found that patients who were provided the Dear Doctor notepad were more satisfied that their doctors answered their questions and felt this tool enhanced their ability to communicate with their physicians. Employing the use of a familiar tool such as the notepad to remind patients about specific issues in their interactions with their providers can be a powerful intervention. Our study demonstrated that the DD notepad was widely accepted by patients, and that almost all of them would use this tool if it were made available to them in the future.

Other tools and methods to enhance the quality of communication between patients and their healthcare providers have included using whiteboards in the patients' rooms to relay the care plan to the patients, implementing bedside rounds by the healthcare team, and multidisciplinary huddling to coordinate information to the patient.[12, 13] Studies of these communication tools have shown potential to improve teamwork, interaction, and patient care. All of these have their own merit and value, and our DD notepad should be considered an adjunct to existing methods to enhance the patient care experience. A bedside tool that is familiar in form to most patients also needs to have the feature of easy access and use. Once this barrier has been removed for the patient and their family members, tools such as the DD notepad can impact the patient‐centeredness by fostering increased and better quality dialogue between the patients, their family members, and healthcare providers.

The DD notepad represents a means of communication that may have the potential to empower patients. It is possible that through question prompts, the DD notepad stimulates the patient to be an active partner with his or her healthcare team. This may enable patients to have some sense of control and accountability of their care in a setting where they would otherwise feel overwhelmed or powerless. The 3 general categories to help patients write down their questions included diagnosis, treatment plan, and medications. In the inpatient setting, where patient‐care activities can be fast paced, and patients are unable to recall some details when speaking to the healthcare team, these notes may remind the patient to write their thoughts down so that they may be remembered for a future time. In situations where patients may not know which questions to ask, the question prompts may be particularly helpful. We did not assess whether our particular question prompts were the key elements that resulted in their perceived value, or whether simply placing a blank notepad at the bedside would also have been successful. However, the specific questions were suggested by the focus groups. Enhanced communication, focusing on the patients' understanding of their condition, and the need to pursue certain diagnostic or therapeutic interventions, may help patients to be better prepared for the next course of plan. These topics of reasons for hospitalization, treatment plan, and medication changes are also important for patients to be active participants in their care, in particular as they transition from 1 site of care to the next, and their healthcare will be delivered by different providers.

There are several limitations to our study. First, this intervention was performed at a single hospital site with only 2 clinical services (general medicine, cardiology) represented in the study groups. Although we do not have any causal reasons to believe this tool would be looked upon differently by patients on other clinical services, it is possible that patients on a different clinical unit or service may view this tool as less or more useful. Second, as the patients were not randomized to intervention, but rather based on the units to which they were admitted, it is possible that other variables, such as the experience of the unit staff, the patient's condition, and housestaff‐based service versus hospitalist‐based service may have played a role in how the patients perceived the use of DD notes. Third, patients were only surveyed if they were able to verbally communicate in English. These notes may not be as useful in hospital settings to populations with language or literacy barriers. Fourth, the logistical implementation of DD notes limited our ability to deliver the DD notepads in every patient's rooms, where only 78% of the intervention group received the DD notepads. This may be the reason that we did not find that overall satisfaction with physician communication differed between intervention and control groups. Nonetheless, we performed an intention‐to‐treat analysis to minimize any biases in our analysis. Last, although our survey of patients asked about their satisfaction in using the DD note pads, we did not compare these results with those of Press‐Ganey or HCAHPS scores of patients on the intervention group versus the control group. Additionally, lack of data about type, quality, and quantity of questions asked by a control group to see if the notepads actually improved quality of questions asked is a limitation; however, we believe our outcomes of interest were most specifically evaluated through our survey questions.

DD notes show that the majority of patients who use this tool feel a modest to significant improvement in communication with their providers. Although the quality of medical care is undoubtedly the first priority, the patients' view of their care, which includes communication, is arguably just as important. An often‐forgotten goal of hospitals and clinics is to provide service excellence along with high‐quality care. Thus, it is imperative for hospitals and their care providers to not only focus on the quality and safety of the clinical care, but also be mindful of the patient's entire experience throughout their hospital stay. Many of the categories of questions asked in the HCAHPS address the patient's experience and perspectives of hospital care. Furthermore, the role of the HCAHPS survey in the Value‐Based Purchasing rules may enhance the importance of these notepads. As the results of HCAHPS are becoming more transparent and available to the public, the impact of such results will have a greater significance to the future of the hospital's clinical mission.

CONCLUSION

DD notepads are a simple, low‐cost, patient‐centered tool that can be an effective reminder for patients to ask their healthcare providers questions related to their hospital care. Utilizing a common tool such as the notepad, redesigned for the healthcare setting, can serve to help healthcare providers interact with their patients. Patient satisfaction may be higher in patients who use the DD notepad.

Disclosures: Aaron S. Farberg, MD, and Andrew M. Lin, MD, contributed equally in every way and should be considered co‐first authors. This work was supported by a University of Michigan Fostering Innovations Grant. The authors have no conflicting financial interests.

In their seminal report Crossing the Quality Chasm, the Institute of Medicine outlined patient‐centered care as 1 of its 6 aims to improve the healthcare delivery system.[1] Patients who are more involved in their diagnosis and treatment plan are more likely to feel respected, be satisfied with their healthcare experience, and ultimately have better outcomes.[2, 3] In a study of hospitalized patients, only 42% were able to state their diagnosis at the time of discharge, suggesting that hospital providers could communicate better with patients about their hospital care.[4] Additionally, only 28% of hospitalized patients were able to list their medications, and only 37% were able to state the purpose of their medications. Although hospitals have taken great strides to improve the quality of patient care, publicly reported patient care surveys, such as the Hospital Consumer Assessment of Hospitals and Health Systems (HCAHPS), suggest that physician communication with patients could be further improved.[1, 5] Furthermore, a recent report by the Institute of Medicine stresses the need to get patients and families involved in their care.[6] Thus, hospital‐based providers should seek to enhance the quality of their communication with patients.

With greater emphasis placed on patient‐ and family‐centered care at many health systems, simple and easy‐to‐implement strategies to improve communication with patients need to be developed and tested.[7, 8] Patients who actively participate in their healthcare by asking questions of their doctor are able to control the focus of their interaction and adjust the amount of information provided.[9] Simply asking questions can have a critical impact, as 1 study found that the frequency with which patients asked questions was significantly related to the amount of information received about general and specific medical matters.[10] The notepad is a common tool for reminders and personal interactions that is used in everyday life, but has not been formalized in the hospital. We introduced Dear Doctor (DD) notes, a bedside notepad designed to prompt patient questions, with the goal of facilitating patient communication with their hospitalist physicians (Figure 1). As hospitalists provide direct and indirect care to a growing number of hospitalized patients, they are likely to be asked questions and opinions about the patients' diagnoses and plans. Furthermore, hospitalists are poised to lead institutional quality, safety, efficiency, and service improvement efforts in the inpatient setting. Becoming familiar with communication‐enhancing tools, such as the DD notes, may help hospitalists in their improvement team roles.

METHODS

Setting

We conducted a study between July 2009 and September 2009 on inpatient medical wards at a large academic medical center with 610 beds and over 44,000 annual discharges.[11] The internal medicine services served by attending physicians and residents comprise a large proportion of hospitalized patients, accounting for over 17,000 discharges per year. Each medical unit includes 32 beds.

Population

Patients over the age of 18 years admitted to a general medicine or cardiology unit and who were able to verbally communicate in English were eligible to be surveyed in the study. Patients with a length of stay <24 hours were excluded. A total of 664 patients were surveyed for inclusion in the study, 440 patients in the intervention group and 224 patients in the control group.

Intervention

The DD notepad included sample questions and informational prompts derived with input from a community focus group. The community focus group consisted of current and formerly hospitalized patients and family members who were asked by members of the study group what they thought would be important to include on a notepad provided to patients. From their answers the study team developed the DD notepad prototype. The DD notepad included 3 general categories of questions: (1) diagnosis and treatment, (2) tests and procedures, and (3) medications. To address other miscellaneous topics such as discharge and posthospital care needs, a section was designated for the patient to check off as I have a few more questions (Use the back of the sheet).

All patients admitted to the study units were intended to receive the DD notepad and pen, which were placed on the bedside table during the room change by our custodial staff. Patients who did not receive DD notepads in the intervention group during their first hospitalization day were provided with 1 by the clinical assistants working with the hospitalists. These patients did not initially receive the notepad due to logistical reasons from temporary rotating staff who were not instructed to provide the notepads. Patients were not formally prompted to use the notepad. Hospitalists, residents, and nurses on the study units were informed about the distribution of DD notes to patients on these units; however, they were not provided with any specific instructions on how they should incorporate the DD notes into their interactions with their patients. The use of the DD notepad was left to each healthcare professional's own discretion.

Members of the study team surveyed patients who had been in the hospital for a minimum of 24 hours in the intervention and control groups twice weekly. All responses were deidentified of any personal or health information. Patients were asked to rate on a scale from 1 to 5 their use of the DD notepads, their perceived value, the circumstances in which the notepads were used, and their level of satisfaction with how their physicians communicated and answered their questions (1 = no improvement, 5 = significant improvement). For control patients, questions pertaining to DD notepads were not applicable and were therefore excluded.

Statistical Analysis

The data were analyzed in an intention‐to‐treat analysis of all 440 patients in the intervention group. Intervention and control groups were compared using 2, rank sum, and Fisher exact statistical tests, with significance assigned as P < 0.05, using SPSS software version 17.0 (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL). Our project was approved by the University of Michigan's institutional review board.

RESULTS

Of the 440 patients surveyed in the intervention group (1 general medicine and 1 cardiology unit), 343 (78%) received the notepads in their rooms and 207 (47%) used them (Figure 2). Not every patient in the intervention group received DD notepads due to inconsistent placement of DD notepads upon every room turnover. Of the patients admitted to the control group (1 general medicine and 1 cardiology unit), 224 were surveyed. Fifty‐four percent of the 440 patients in the intervention group reported that they took notes related to their hospital care, compared to only 22% of the 224 patients in the control group (P < 0.001). Of the patients who took notes within the intervention group (n = 207), 91% of them utilized the DD notepads.

Patients in the intervention group who received and used the DD notes (n = 207) compared to patients in the control group (n = 224) were more likely to report that their questions were answered by their physicians (4.63 vs 4.45, P < 0.001). In an intention‐to‐treat analysis of all 440 patients in the intervention group, the overall satisfaction with physician communication was not significantly different between the intervention and control groups as measured on a 5‐point Likert scale (4.55 vs 4.55, P = 0.89). However, 89% of the patients in the intervention group who used the notepads felt that DD notepads either moderately or significantly improved their communication with their providers (Figure 3).