User login

Do glucocorticoids hold promise as a treatment for PTSD?

As symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) progress, the involved person’s physical and mental health deteriorates.1 This sparks lifestyle changes that allow them to avoid re-exposure to triggering stimuli; however, it also increases their risk of social isolation. Early clinical investigation has found that patients who experience hyperarousal symptoms of overt PTSD—difficulty sleeping, emotional dyscontrol, hypervigilance, and an enhanced startle response—could benefit from the stress-reducing capacity of glucocorticoids.

Decreased glucocorticoids

After a distressing situation, norepinephrine levels rise acutely.2,3 This contributes to a protective retention of potentially threatening memories, which is how people learn to avoid danger.

Glucocorticoid secretion enhances a patient’s coping mechanisms by helping them process information in a way that diminishes retrieval of fear-evoking memories.2,3 Glucocorticoid, also called cortisol, is referred to as a “stress hormone.” Cortisol promotes emotional adaptability following a traumatic event; this action diminishes future, inappropriate retrieval of frightening memories as a physiologic mechanism to help people cope with upsetting situations.3

PTSD pathogenesis involves altered hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis function; sustained stress results in decreased levels of circulating glucocorticoid. This is a consequence of enhanced negative feedback and increased glucocorticoid receptor sensitivity, which is evidenced by results of abnormal dexamethasone suppression tests.1 Downregulation of corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH) receptors in the pituitary glands and increased CRH levels have been documented in PTSD patients.1,4 An association between high CRH levels and an increase in startle response explains the exaggerated startle response observed in patients with PTSD. Higher circulating glucocorticoid has the opposite effect4; there is an inverse relationship between the daily level of glucocorticoid and startle amplitude. A low level of circulating glucocorticoid promotes recall of frightening events that results in persistent re-experiencing of traumatic memories.2,3

Glucocorticoids in PTSD

Glucocorticoid administration reduces psychological and physiological responses to stress.3 Exogenous glucocorticoid administration affects cognition by interacting with serotonin, dopamine, and ã-aminobutyric acid by actions on the amygdala, medial prefrontal cortex, and hippocampus.2,3 Research among veterans with and without PTSD recorded a decrease in startle response after administration of a single dose of 20 mg of hydrocortisone.4 Results of a large study documented that one dose of hydrocortisone administered at >35 mg can inhibit threatening memories and improve social function.3 Hydrocortisone is linked to anxiolytic effects in healthy persons and patients with social phobia or panic disorder.3,4 Because treatment of PTSD with antidepressants and benzodiazepines often is ineffective,5 glucocorticoids may offer a new pharmacotherapy option. Glucocorticoids have been prescribed as prophylactic agents shortly after an acutely stressful event to prevent development of PTSD.4 Hydrocortisone is not FDA-approved to treat PTSD; informed consent, physician discretion, and close monitoring are emphasized.

Glucocorticoid use in mitigating PTSD symptom emergence is under investigation. Research suggests that just one acute dose of hydrocortisone might benefit patients prone to PTSD.3,4 Further study is needed to establish whether prescribing hydrocortisone is efficacious.

Disclosure

The authors report no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Jones T, Moller MD. Implications of hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis functioning in posttraumatic stress disorder. J Am Psychiatr Nurses Assoc. 2011;17(6):393-403.

2. Blundell J, Blaiss CA, Lagace DC, et al. Block of glucocorticoid synthesis during re-activation inhibits extinction of an established fear memory. Neurobiol Learn Mem. 2011;95(4):453-460.

3. Putman P, Roelofs K. Effects of single cortisol administrations on human affect reviewed: coping with stress through adaptive regulation of automatic cognitive processing. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2011;36(4):439-448.

4. Miller MW, McKinney AE, Kanter FS, et al. Hydrocortisone suppression of the fear-potentiated startle response and posttraumatic stress disorder. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2011;36(7):970-980.

5. Nin MS, Martinez LA, Pibiri F, et al. Neurosteroids reduce social isolation-induced behavioral deficits: a proposed link with neurosteroid-mediated upregulation of BDNF expression. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2011;2(73):1-12.

As symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) progress, the involved person’s physical and mental health deteriorates.1 This sparks lifestyle changes that allow them to avoid re-exposure to triggering stimuli; however, it also increases their risk of social isolation. Early clinical investigation has found that patients who experience hyperarousal symptoms of overt PTSD—difficulty sleeping, emotional dyscontrol, hypervigilance, and an enhanced startle response—could benefit from the stress-reducing capacity of glucocorticoids.

Decreased glucocorticoids

After a distressing situation, norepinephrine levels rise acutely.2,3 This contributes to a protective retention of potentially threatening memories, which is how people learn to avoid danger.

Glucocorticoid secretion enhances a patient’s coping mechanisms by helping them process information in a way that diminishes retrieval of fear-evoking memories.2,3 Glucocorticoid, also called cortisol, is referred to as a “stress hormone.” Cortisol promotes emotional adaptability following a traumatic event; this action diminishes future, inappropriate retrieval of frightening memories as a physiologic mechanism to help people cope with upsetting situations.3

PTSD pathogenesis involves altered hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis function; sustained stress results in decreased levels of circulating glucocorticoid. This is a consequence of enhanced negative feedback and increased glucocorticoid receptor sensitivity, which is evidenced by results of abnormal dexamethasone suppression tests.1 Downregulation of corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH) receptors in the pituitary glands and increased CRH levels have been documented in PTSD patients.1,4 An association between high CRH levels and an increase in startle response explains the exaggerated startle response observed in patients with PTSD. Higher circulating glucocorticoid has the opposite effect4; there is an inverse relationship between the daily level of glucocorticoid and startle amplitude. A low level of circulating glucocorticoid promotes recall of frightening events that results in persistent re-experiencing of traumatic memories.2,3

Glucocorticoids in PTSD

Glucocorticoid administration reduces psychological and physiological responses to stress.3 Exogenous glucocorticoid administration affects cognition by interacting with serotonin, dopamine, and ã-aminobutyric acid by actions on the amygdala, medial prefrontal cortex, and hippocampus.2,3 Research among veterans with and without PTSD recorded a decrease in startle response after administration of a single dose of 20 mg of hydrocortisone.4 Results of a large study documented that one dose of hydrocortisone administered at >35 mg can inhibit threatening memories and improve social function.3 Hydrocortisone is linked to anxiolytic effects in healthy persons and patients with social phobia or panic disorder.3,4 Because treatment of PTSD with antidepressants and benzodiazepines often is ineffective,5 glucocorticoids may offer a new pharmacotherapy option. Glucocorticoids have been prescribed as prophylactic agents shortly after an acutely stressful event to prevent development of PTSD.4 Hydrocortisone is not FDA-approved to treat PTSD; informed consent, physician discretion, and close monitoring are emphasized.

Glucocorticoid use in mitigating PTSD symptom emergence is under investigation. Research suggests that just one acute dose of hydrocortisone might benefit patients prone to PTSD.3,4 Further study is needed to establish whether prescribing hydrocortisone is efficacious.

Disclosure

The authors report no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

As symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) progress, the involved person’s physical and mental health deteriorates.1 This sparks lifestyle changes that allow them to avoid re-exposure to triggering stimuli; however, it also increases their risk of social isolation. Early clinical investigation has found that patients who experience hyperarousal symptoms of overt PTSD—difficulty sleeping, emotional dyscontrol, hypervigilance, and an enhanced startle response—could benefit from the stress-reducing capacity of glucocorticoids.

Decreased glucocorticoids

After a distressing situation, norepinephrine levels rise acutely.2,3 This contributes to a protective retention of potentially threatening memories, which is how people learn to avoid danger.

Glucocorticoid secretion enhances a patient’s coping mechanisms by helping them process information in a way that diminishes retrieval of fear-evoking memories.2,3 Glucocorticoid, also called cortisol, is referred to as a “stress hormone.” Cortisol promotes emotional adaptability following a traumatic event; this action diminishes future, inappropriate retrieval of frightening memories as a physiologic mechanism to help people cope with upsetting situations.3

PTSD pathogenesis involves altered hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis function; sustained stress results in decreased levels of circulating glucocorticoid. This is a consequence of enhanced negative feedback and increased glucocorticoid receptor sensitivity, which is evidenced by results of abnormal dexamethasone suppression tests.1 Downregulation of corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH) receptors in the pituitary glands and increased CRH levels have been documented in PTSD patients.1,4 An association between high CRH levels and an increase in startle response explains the exaggerated startle response observed in patients with PTSD. Higher circulating glucocorticoid has the opposite effect4; there is an inverse relationship between the daily level of glucocorticoid and startle amplitude. A low level of circulating glucocorticoid promotes recall of frightening events that results in persistent re-experiencing of traumatic memories.2,3

Glucocorticoids in PTSD

Glucocorticoid administration reduces psychological and physiological responses to stress.3 Exogenous glucocorticoid administration affects cognition by interacting with serotonin, dopamine, and ã-aminobutyric acid by actions on the amygdala, medial prefrontal cortex, and hippocampus.2,3 Research among veterans with and without PTSD recorded a decrease in startle response after administration of a single dose of 20 mg of hydrocortisone.4 Results of a large study documented that one dose of hydrocortisone administered at >35 mg can inhibit threatening memories and improve social function.3 Hydrocortisone is linked to anxiolytic effects in healthy persons and patients with social phobia or panic disorder.3,4 Because treatment of PTSD with antidepressants and benzodiazepines often is ineffective,5 glucocorticoids may offer a new pharmacotherapy option. Glucocorticoids have been prescribed as prophylactic agents shortly after an acutely stressful event to prevent development of PTSD.4 Hydrocortisone is not FDA-approved to treat PTSD; informed consent, physician discretion, and close monitoring are emphasized.

Glucocorticoid use in mitigating PTSD symptom emergence is under investigation. Research suggests that just one acute dose of hydrocortisone might benefit patients prone to PTSD.3,4 Further study is needed to establish whether prescribing hydrocortisone is efficacious.

Disclosure

The authors report no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Jones T, Moller MD. Implications of hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis functioning in posttraumatic stress disorder. J Am Psychiatr Nurses Assoc. 2011;17(6):393-403.

2. Blundell J, Blaiss CA, Lagace DC, et al. Block of glucocorticoid synthesis during re-activation inhibits extinction of an established fear memory. Neurobiol Learn Mem. 2011;95(4):453-460.

3. Putman P, Roelofs K. Effects of single cortisol administrations on human affect reviewed: coping with stress through adaptive regulation of automatic cognitive processing. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2011;36(4):439-448.

4. Miller MW, McKinney AE, Kanter FS, et al. Hydrocortisone suppression of the fear-potentiated startle response and posttraumatic stress disorder. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2011;36(7):970-980.

5. Nin MS, Martinez LA, Pibiri F, et al. Neurosteroids reduce social isolation-induced behavioral deficits: a proposed link with neurosteroid-mediated upregulation of BDNF expression. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2011;2(73):1-12.

1. Jones T, Moller MD. Implications of hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis functioning in posttraumatic stress disorder. J Am Psychiatr Nurses Assoc. 2011;17(6):393-403.

2. Blundell J, Blaiss CA, Lagace DC, et al. Block of glucocorticoid synthesis during re-activation inhibits extinction of an established fear memory. Neurobiol Learn Mem. 2011;95(4):453-460.

3. Putman P, Roelofs K. Effects of single cortisol administrations on human affect reviewed: coping with stress through adaptive regulation of automatic cognitive processing. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2011;36(4):439-448.

4. Miller MW, McKinney AE, Kanter FS, et al. Hydrocortisone suppression of the fear-potentiated startle response and posttraumatic stress disorder. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2011;36(7):970-980.

5. Nin MS, Martinez LA, Pibiri F, et al. Neurosteroids reduce social isolation-induced behavioral deficits: a proposed link with neurosteroid-mediated upregulation of BDNF expression. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2011;2(73):1-12.

Erratum

A practice recommendation in “Travelers diarrhea: Prevention, treatment, and post-trip evaluation" (J Fam Pract. 2013;62:356-361) incorrectly called for self-treatment with a fluoroquinolone (or azithromycin) and loperamide for diarrhea that is bloody or accompanied by fever. In fact, both the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the Infectious Diseases Society of America advise against the use of loperamide by travelers with fever or bloody diarrhea. The practice recommendation should have read: “Advise travelers to initiate self-treatment for travelers’ diarrhea with a fluoroquinolone (or azithromycin if in South or Southeast Asia) at the onset of diarrhea if it is bloody or accompanied by fever.”

A practice recommendation in “Travelers diarrhea: Prevention, treatment, and post-trip evaluation" (J Fam Pract. 2013;62:356-361) incorrectly called for self-treatment with a fluoroquinolone (or azithromycin) and loperamide for diarrhea that is bloody or accompanied by fever. In fact, both the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the Infectious Diseases Society of America advise against the use of loperamide by travelers with fever or bloody diarrhea. The practice recommendation should have read: “Advise travelers to initiate self-treatment for travelers’ diarrhea with a fluoroquinolone (or azithromycin if in South or Southeast Asia) at the onset of diarrhea if it is bloody or accompanied by fever.”

A practice recommendation in “Travelers diarrhea: Prevention, treatment, and post-trip evaluation" (J Fam Pract. 2013;62:356-361) incorrectly called for self-treatment with a fluoroquinolone (or azithromycin) and loperamide for diarrhea that is bloody or accompanied by fever. In fact, both the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the Infectious Diseases Society of America advise against the use of loperamide by travelers with fever or bloody diarrhea. The practice recommendation should have read: “Advise travelers to initiate self-treatment for travelers’ diarrhea with a fluoroquinolone (or azithromycin if in South or Southeast Asia) at the onset of diarrhea if it is bloody or accompanied by fever.”

Competitive Swimmer With Hip Pain

ANSWER

The radiograph demonstrates no evidence of an acute fracture or dislocation. Normal gas/stool pattern is present. Essentially, this radiograph is normal.

The patient most likely has an acute strain of her hip quadriceps or flexor. On occasion, severe enough strain injuries can cause a slight avulsion fracture within the hip at the muscle origination point. These can sometimes be evident on plain films.

ANSWER

The radiograph demonstrates no evidence of an acute fracture or dislocation. Normal gas/stool pattern is present. Essentially, this radiograph is normal.

The patient most likely has an acute strain of her hip quadriceps or flexor. On occasion, severe enough strain injuries can cause a slight avulsion fracture within the hip at the muscle origination point. These can sometimes be evident on plain films.

ANSWER

The radiograph demonstrates no evidence of an acute fracture or dislocation. Normal gas/stool pattern is present. Essentially, this radiograph is normal.

The patient most likely has an acute strain of her hip quadriceps or flexor. On occasion, severe enough strain injuries can cause a slight avulsion fracture within the hip at the muscle origination point. These can sometimes be evident on plain films.

A 17-year-old girl presents for evaluation of severe pain in her left hip. She is a competitive swimmer; earlier in the day, she was at practice doing dry land (out of the water) activities/exercises. Having completed a series of stretches and warm-up exercises, she and her teammates proceeded to do sprints. During one of these sprints, she immediately felt a “pop” in her left hip followed by severe, debilitating pain in that hip and thigh. Medical history is otherwise unremarkable. Physical exam reveals that it is extremely painful for the patient to bear weight on the affected leg. There is moderate-to-severe tenderness over the lateral hip. Some swelling is noted; no bruising is present. Distal pulses are good, and motor and sensation are intact. Radiograph of the pelvis is obtained (shown). What is your impression?

Obese, Short of Breath, and Rationing Meds

ANSWER

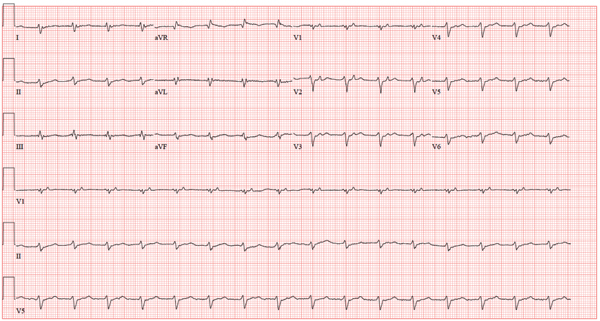

The correct interpretation is sinus rhythm with a first-degree atrioventricular (AV) block, right superior axis deviation, and low voltage QRS complexes. The measured PR interval of 360 ms is correct!

The P waves are best seen in precordial leads V1 to V3. Notice that the P waves fall between the QRS complex and the T wave. The P wave is upright and not inverted, so it is not occurring retrograde from the preceding QRS complex. The sinus node depolarizes, and a long delay occurs within the atria and AV node before conducting down the normal conduction system in the ventricles. This conduction delay is so long that the preceding beat (QRS complex) is still repolarizing (T wave) by the time the sinus node depolarizes again. Thus, the P wave is responsible for the next QRS complex after duration of 360 ms.

A right superior axis deviation, also known as an extreme right axis deviation, is evidenced by an R-wave axis of 192°. Low-voltage QRS complexes are due to the patient’s body habitus. Morbid obesity significantly diminishes the electrical vectors measured by the surface ECG electrodes.

Finally, extra credit is due if you recognize the long QTc interval as well. The maximum normal QTc adjusted for a heart rate of 100 beats/min in men is 310 ms. This ECG barely meets that criteria; in this case, the prolonged QTc interval is of no significance.

ANSWER

The correct interpretation is sinus rhythm with a first-degree atrioventricular (AV) block, right superior axis deviation, and low voltage QRS complexes. The measured PR interval of 360 ms is correct!

The P waves are best seen in precordial leads V1 to V3. Notice that the P waves fall between the QRS complex and the T wave. The P wave is upright and not inverted, so it is not occurring retrograde from the preceding QRS complex. The sinus node depolarizes, and a long delay occurs within the atria and AV node before conducting down the normal conduction system in the ventricles. This conduction delay is so long that the preceding beat (QRS complex) is still repolarizing (T wave) by the time the sinus node depolarizes again. Thus, the P wave is responsible for the next QRS complex after duration of 360 ms.

A right superior axis deviation, also known as an extreme right axis deviation, is evidenced by an R-wave axis of 192°. Low-voltage QRS complexes are due to the patient’s body habitus. Morbid obesity significantly diminishes the electrical vectors measured by the surface ECG electrodes.

Finally, extra credit is due if you recognize the long QTc interval as well. The maximum normal QTc adjusted for a heart rate of 100 beats/min in men is 310 ms. This ECG barely meets that criteria; in this case, the prolonged QTc interval is of no significance.

ANSWER

The correct interpretation is sinus rhythm with a first-degree atrioventricular (AV) block, right superior axis deviation, and low voltage QRS complexes. The measured PR interval of 360 ms is correct!

The P waves are best seen in precordial leads V1 to V3. Notice that the P waves fall between the QRS complex and the T wave. The P wave is upright and not inverted, so it is not occurring retrograde from the preceding QRS complex. The sinus node depolarizes, and a long delay occurs within the atria and AV node before conducting down the normal conduction system in the ventricles. This conduction delay is so long that the preceding beat (QRS complex) is still repolarizing (T wave) by the time the sinus node depolarizes again. Thus, the P wave is responsible for the next QRS complex after duration of 360 ms.

A right superior axis deviation, also known as an extreme right axis deviation, is evidenced by an R-wave axis of 192°. Low-voltage QRS complexes are due to the patient’s body habitus. Morbid obesity significantly diminishes the electrical vectors measured by the surface ECG electrodes.

Finally, extra credit is due if you recognize the long QTc interval as well. The maximum normal QTc adjusted for a heart rate of 100 beats/min in men is 310 ms. This ECG barely meets that criteria; in this case, the prolonged QTc interval is of no significance.

A 64-year-old man who is morbidly obese is admitted to the medical service with a two-week history of increasing shortness of breath, orthopnea, and paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea. He states that he has depleted his finances for the month and has resorted to taking his medications every other day in order to make them last until next payday. He denies chest pain but notes that he has had a lot of “heaviness” in his anterior chest for the past week and now has a persistent, nonproductive cough. His medical history is remarkable for a cardiomyopathy due to alcohol abuse, frequent pneumonias, and renal insufficiency. He has a history of sleep apnea and uses continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) at night in order to sleep. The patient is divorced, unemployed, lives alone in a subsidized apartment, and collects disability. Prior to filing for disability, he worked as a longshoreman. He is a former smoker who quit two years ago after several pulmonary infections. He attributes quitting smoking to his current weight problem. He states he has been an alcoholic for many years, and at one point consumed one bottle of whiskey per day along with one or two six-packs of beer. He has been to two alcohol rehab programs in the past five years and says he recently started drinking again when he learned his disability checks were not going to be increased. Family history is positive for coronary artery disease (mother) and diabetes (father). His parents and both of his siblings are being treated for hypertension. He has no known drug allergies. Current medications include aspirin, extended-release metoprolol, hydralazine, isosorbide mononitrate, torsemide, docusate, and senna. The review of systems is remarkable for chronic low back pain, corrective lenses, and multiple small venous ulcers on both legs that he states will “just not go away.” The physical exam reveals a morbidly obese male in mild distress. His weight is 494 lb and his height, is 70 in. His blood pressure is 120/82 mm Hg; pulse, 90 beats/min and regular; respiratory rate, 18 breaths/min; temperature, 96.8°F; and O2 saturation, 92% on room air. Pertinent physical findings include jugular venous distension to 12 cm, coarse rales in both lower lung fields, distant heart sounds without evidence of a murmur or rub, an obese abdomen without palpable organomegaly or ascites, and 3+ pitting edema in both lower extremities to the level of the knees. There are multiple old and new small, superficial venous ulcers on both lower legs. The skin is warm and pink; however, pulses are not palpable. Upon his admission, a cardiac catheterization is performed, which shows a right dominant system with angiographically normal coronary arteries, a left ventricular ejection fraction of 44%, and no evidence of valvular disease. Right heart pressures include a pulmonary artery pressure of 70/62 mm Hg with a mean of 51 mm Hg. The wedge pressure is 35 mm Hg, the transpulmonary gradient is 10, and the cardiac output is 12.5 L/min with a cardiac index of 4.4 L/min. These data are consistent with moderate-to-severe pulmonary hypertension with severely elevated left-sided filling pressures. A transthoracic echocardiogram is remarkable for elevated left ventricular end diastolic volumes with diffuse hypokinesis and an ejection fraction of 40%. The patient is also found to have a small pericardial effusion and bilateral pleural effusions. An ECG reveals the following: a ventricular rate of 98 beats/min; PR interval, 360 ms; QRS duration, 116 ms; QT/QTc interval, 24/314 ms; P axis, 54°; R axis, 192°; and T axis, 24°. As you review these measurements, you are skeptical of a PR interval of 360 ms and refer to the tracing. What is your interpretation of this ECG, and is the PR interval of 360 ms correct?

Managing Gestational Diabetes: Let’s Nip It in The Bud

One of the most common complications of pregnancy is gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM). It is defined as glucose intolerance with first onset during pregnancy.1 In 2011, the incidence of GDM in the United States was between 2% and 10% of all pregnancies. Potential complications associated with GDM include macrosomia, pre-eclampsia, preterm birth, increased risk for cesarean section, neonatal hypoglycemia, shoulder dystocia, and polyhydramnios. Women with a history of gestational diabetes have a 35% to 60% likelihood of developing type 2 diabetes over the following 10 to 20 years.2

Q: When should screening for GDM occur?

According to the American Diabetes Association’s (ADA) 2012 Clinical Practice Recommendations, a pregnant woman should be screened for undiagnosed type 2 diabetes at her first prenatal visit if she has certain risk factors.3 These include, but are not limited to, family history of diabetes, overweight/obesity, sedentary lifestyle, elevated blood pressure and/or cholesterol, impaired fasting glucose or impaired glucose tolerance, or certain ethnic backgrounds (eg, Hispanic, Native American, and non-Hispanic black).4 In 2011, the ADA revised its recommendations for GDM screening and diagnosis to be in accordance with those from the International Association of Diabetes and Pregnancy Study Groups (IADPSG), an international consensus group with representatives from multiple obstetric and diabetes organizations, including ADA.

Q: How is GDM diagnosed?

Current recommendations stipulate that women with no previous history of diabetes or prediabetes undergo one-step testing: a 75-g glucose tolerance test (GTT) at 24 to 28 weeks’ gestation.5,6 For women with a prior history of GDM, screening is recommended earlier in the pregnancy. The GTT should be performed after an overnight fast of at least eight hours.3 An elevation of any one of the values above normal reference range is consistent with the diagnosis of GDM. (Previously, the diagnostic criteria required two abnormal values.) Multiple international studies using the new criteria have estimated an increased incidence of gestational diabetes in up to 18% of pregnancies.5,6

Some organizations have not endorsed the IADPSG/ADA diagnostic criteria at this time; as a result, many practitioners continue to use two-step testing for diagnosing GDM. To do the two-step testing, a 50-g glucose load is given, followed by a blood glucose reading one hour later. If the one-hour reading is within normal range, no further testing is warranted and the patient does not have gestational diabetes. If the test is abnormal, she must undergo a fasting three-hour GTT using a 100-g glucose load.

Q: What advice should a woman get once she’s diagnosed with GDM?

As soon as a woman is diagnosed with GDM, she should be referred for a gestational diabetes education class and nutrition counseling. Specifically, she should learn what it means for her to have GDM, implications for her and her baby, and the importance of eating a healthy diet (not the proverbial concept of “eating for two”), physical activity, self-monitoring blood glucose, and adherence to any prescribed medications.

Probably the most important aspect of education is nutrition counseling. It is known that smaller meals consumed more frequently throughout the day reduce spikes in blood glucose levels. One suggestion is to eat three small meals and three low-carbohydrate (15 g) snacks each day. Meals and snacks are generally established based on fixed carbohydrate amounts. A certified diabetes educator or registered dietitian (RD) can recommend healthy meal and snack ideas that are tasty, promote satiety, and minimize spikes in glucose levels.

Q: What are the current treatment options for GDM?

During the process of receiving GDM education, the patient should be prescribed a glucometer, along with specific glucose targets. Blood glucose should be checked multiple times a day, preferably fasting and postprandial measurements. Medical practices vary in their preferred glucose targets; some individuals require tighter control than others. The ADA suggests the following targets:

• Before a meal (preprandial):

95 mg/dL or less.

• One hour after a meal (postprandial): 140 mg/dL or less.

• Two hours after a meal (postprandial): 120 mg/dL or less. 7

If blood glucose levels remain within normal range, it is possible to control gestational diabetes with dietary modification and physical activity. If readings are consistently elevated, then the patient must be started on medication. There are currently no FDA-approved oral medications to treat gestational diabetes. Glyburide is commonly used, although it is not FDA approved for this indication. More studies to establish its safety are likely needed for FDA approval.8

If pharmaceutical treatment is warranted, insulin is the safest and most effective agent. It is the only medication that is FDA approved for treatment of GDM. Levemir (insulin detemir [rDNA origin] injection) gained FDA approval for use in pregnancy in 2012, so it has become more widespread than NPH for basal insulin usage.9

Although it is usually managed by an endocrinologist or perinatologist, an experienced obstetrician could also manage GDM. Often, the patient is referred to an endocrinologist. The endocrine provider, along with the diabetes educator and RD, focus on nutrition counseling and diabetes management so the obstetrician can focus on maternal and fetal health.

Q: What is the recommended follow-up?

Since embryonic and fetal development occurs at such a rapid rate, time is of the essence for getting a patient’s blood glucose to goal. While treating diabetes in general can be challenging, this is usually not the case with GDM. Most women with GDM are motivated to take care of themselves for the well-being of their developing baby. The influence of a baby developing inside a mother is so strong that diabetic women who become pregnant often take better care of themselves than they do when they are not pregnant.

The patient’s daily responsibilities should include eating a healthy and diet checking her blood glucose levels throughout the day. These readings must be recorded. Clinic visits should occur often, with emailing of glucose readings between visits as needed. The frequency of visits varies among practices, depending on the patient’s level of glucose control and intensity of the treatment regimen.

Q: Why is postpartum testing important?

After delivery, most cases of GDM usually resolve. However, approximately 5% to 10% of women with gestational diabetes are found to have diabetes immediately after pregnancy.2 To evaluate for persistent diabetes, a two-hour GTT should be done at six weeks’ postpartum. Although an A1C can now be used to diagnose diabetes, the ADA does not recommend checking it for this purpose.3

If the two-hour GTT result is normal, a woman should be screened for diabetes every three years for the rest of her life.3 If a diagnosis of impaired fasting glucose or impaired glucose tolerance is made, then she should be tested for diabetes on an annual basis or in the interim if she develops classic symptoms of hyperglycemia.3 If diabetes is diagnosed, she should be treated accordingly as a type 2 diabetic patient.

At this time, the patient should be counseled on lifestyle interventions and consider starting metformin therapy if appropriate. Diabetes education classes are available for prediabetes. To maintain good health and prevent/delay onset of type 2 diabetes, here are some tips to follow:

• The same diet as during pregnancy does not have to be followed, although healthy eating habits are always a good idea.

• Physical activity (approximately 30 min five times a week) will help shed weight gained during pregnancy.

• Breastfeeding promotes weight loss.10

• Patients should aim for weight loss of 7% of body weight.3

• Continue annual physical exams, keeping an eye on blood pressure, weight, and cholesterol levels.

It’s reasonable for the patient to check glucose levels occasionally after delivery. If elevated readings occur, the patient can make an appointment with her primary care provider or endocrinologist.

References

1. American Association for Clinical Chemistry. A New Definition of Gestational Diabetes. www.aacc.org/publications/cln/2010/may/Pages/CoverStory2May2010.aspx. Accessed June 30, 2013.

2. National Diabetes Statistics, 2011. www.diabetes.niddk.nih.gov/dm/pubs/statistics/#Gestational. Accessed July 22, 2013.

3. American Diabetes Association. 2012 Clinical Practice Recommendations. Diabetes Care. 2012;35(suppl 1). http://professional.diabetes.org/SlideLibrary/media/4839/ADA%20Standards%20of%20Medical%20Care%202012%20FINAL.ppt. Accessed June 24, 2013.

4. American Diabetes Association. Diabetes basics: your risk. www.diabetes.org/diabetes-basics/prevention/risk-factors. Accessed August 13, 2013.

5. American Diabetes Association. Diabetes Basics: What is Gestational Diabetes? www.diabetes.org/diabetes-basics/gestational/what-is-gestational-diabetes.html. Accessed August 13, 2013.

6. Johnson K. New criteria for gestational diabetes increase diagnoses (December 5, 2011). www.medscape.com/viewarticle/754733. Accessed August 13, 2013.

7. American Diabetes Association. Diabetes basics: how to treat gestational diabetes. www.diabetes.org/diabetes-basics/gestational/how-to-treat-gestational.html. Accessed August 13, 2013.

8. Moore TR. Glyburide for the treatment of gestational diabetes: a critical appraisal. Diabetes Care. 2007;30(suppl 2). http://care.diabetesjournals.org/content/30/Supplement_2/S209.full. Accessed August 13, 2013.

9. Lowes R. Levemir assigned more reassuring pregnancy risk category (April 2, 2012). www.medscape.com/viewarticle/761349. Accessed August 13, 2013.

10. Buchanan TA, Xiang AH, Page KA. Gestational diabetes mellitus: risks and management during and after pregnancy. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2012;8(11):639-649.

One of the most common complications of pregnancy is gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM). It is defined as glucose intolerance with first onset during pregnancy.1 In 2011, the incidence of GDM in the United States was between 2% and 10% of all pregnancies. Potential complications associated with GDM include macrosomia, pre-eclampsia, preterm birth, increased risk for cesarean section, neonatal hypoglycemia, shoulder dystocia, and polyhydramnios. Women with a history of gestational diabetes have a 35% to 60% likelihood of developing type 2 diabetes over the following 10 to 20 years.2

Q: When should screening for GDM occur?

According to the American Diabetes Association’s (ADA) 2012 Clinical Practice Recommendations, a pregnant woman should be screened for undiagnosed type 2 diabetes at her first prenatal visit if she has certain risk factors.3 These include, but are not limited to, family history of diabetes, overweight/obesity, sedentary lifestyle, elevated blood pressure and/or cholesterol, impaired fasting glucose or impaired glucose tolerance, or certain ethnic backgrounds (eg, Hispanic, Native American, and non-Hispanic black).4 In 2011, the ADA revised its recommendations for GDM screening and diagnosis to be in accordance with those from the International Association of Diabetes and Pregnancy Study Groups (IADPSG), an international consensus group with representatives from multiple obstetric and diabetes organizations, including ADA.

Q: How is GDM diagnosed?

Current recommendations stipulate that women with no previous history of diabetes or prediabetes undergo one-step testing: a 75-g glucose tolerance test (GTT) at 24 to 28 weeks’ gestation.5,6 For women with a prior history of GDM, screening is recommended earlier in the pregnancy. The GTT should be performed after an overnight fast of at least eight hours.3 An elevation of any one of the values above normal reference range is consistent with the diagnosis of GDM. (Previously, the diagnostic criteria required two abnormal values.) Multiple international studies using the new criteria have estimated an increased incidence of gestational diabetes in up to 18% of pregnancies.5,6

Some organizations have not endorsed the IADPSG/ADA diagnostic criteria at this time; as a result, many practitioners continue to use two-step testing for diagnosing GDM. To do the two-step testing, a 50-g glucose load is given, followed by a blood glucose reading one hour later. If the one-hour reading is within normal range, no further testing is warranted and the patient does not have gestational diabetes. If the test is abnormal, she must undergo a fasting three-hour GTT using a 100-g glucose load.

Q: What advice should a woman get once she’s diagnosed with GDM?

As soon as a woman is diagnosed with GDM, she should be referred for a gestational diabetes education class and nutrition counseling. Specifically, she should learn what it means for her to have GDM, implications for her and her baby, and the importance of eating a healthy diet (not the proverbial concept of “eating for two”), physical activity, self-monitoring blood glucose, and adherence to any prescribed medications.

Probably the most important aspect of education is nutrition counseling. It is known that smaller meals consumed more frequently throughout the day reduce spikes in blood glucose levels. One suggestion is to eat three small meals and three low-carbohydrate (15 g) snacks each day. Meals and snacks are generally established based on fixed carbohydrate amounts. A certified diabetes educator or registered dietitian (RD) can recommend healthy meal and snack ideas that are tasty, promote satiety, and minimize spikes in glucose levels.

Q: What are the current treatment options for GDM?

During the process of receiving GDM education, the patient should be prescribed a glucometer, along with specific glucose targets. Blood glucose should be checked multiple times a day, preferably fasting and postprandial measurements. Medical practices vary in their preferred glucose targets; some individuals require tighter control than others. The ADA suggests the following targets:

• Before a meal (preprandial):

95 mg/dL or less.

• One hour after a meal (postprandial): 140 mg/dL or less.

• Two hours after a meal (postprandial): 120 mg/dL or less. 7

If blood glucose levels remain within normal range, it is possible to control gestational diabetes with dietary modification and physical activity. If readings are consistently elevated, then the patient must be started on medication. There are currently no FDA-approved oral medications to treat gestational diabetes. Glyburide is commonly used, although it is not FDA approved for this indication. More studies to establish its safety are likely needed for FDA approval.8

If pharmaceutical treatment is warranted, insulin is the safest and most effective agent. It is the only medication that is FDA approved for treatment of GDM. Levemir (insulin detemir [rDNA origin] injection) gained FDA approval for use in pregnancy in 2012, so it has become more widespread than NPH for basal insulin usage.9

Although it is usually managed by an endocrinologist or perinatologist, an experienced obstetrician could also manage GDM. Often, the patient is referred to an endocrinologist. The endocrine provider, along with the diabetes educator and RD, focus on nutrition counseling and diabetes management so the obstetrician can focus on maternal and fetal health.

Q: What is the recommended follow-up?

Since embryonic and fetal development occurs at such a rapid rate, time is of the essence for getting a patient’s blood glucose to goal. While treating diabetes in general can be challenging, this is usually not the case with GDM. Most women with GDM are motivated to take care of themselves for the well-being of their developing baby. The influence of a baby developing inside a mother is so strong that diabetic women who become pregnant often take better care of themselves than they do when they are not pregnant.

The patient’s daily responsibilities should include eating a healthy and diet checking her blood glucose levels throughout the day. These readings must be recorded. Clinic visits should occur often, with emailing of glucose readings between visits as needed. The frequency of visits varies among practices, depending on the patient’s level of glucose control and intensity of the treatment regimen.

Q: Why is postpartum testing important?

After delivery, most cases of GDM usually resolve. However, approximately 5% to 10% of women with gestational diabetes are found to have diabetes immediately after pregnancy.2 To evaluate for persistent diabetes, a two-hour GTT should be done at six weeks’ postpartum. Although an A1C can now be used to diagnose diabetes, the ADA does not recommend checking it for this purpose.3

If the two-hour GTT result is normal, a woman should be screened for diabetes every three years for the rest of her life.3 If a diagnosis of impaired fasting glucose or impaired glucose tolerance is made, then she should be tested for diabetes on an annual basis or in the interim if she develops classic symptoms of hyperglycemia.3 If diabetes is diagnosed, she should be treated accordingly as a type 2 diabetic patient.

At this time, the patient should be counseled on lifestyle interventions and consider starting metformin therapy if appropriate. Diabetes education classes are available for prediabetes. To maintain good health and prevent/delay onset of type 2 diabetes, here are some tips to follow:

• The same diet as during pregnancy does not have to be followed, although healthy eating habits are always a good idea.

• Physical activity (approximately 30 min five times a week) will help shed weight gained during pregnancy.

• Breastfeeding promotes weight loss.10

• Patients should aim for weight loss of 7% of body weight.3

• Continue annual physical exams, keeping an eye on blood pressure, weight, and cholesterol levels.

It’s reasonable for the patient to check glucose levels occasionally after delivery. If elevated readings occur, the patient can make an appointment with her primary care provider or endocrinologist.

References

1. American Association for Clinical Chemistry. A New Definition of Gestational Diabetes. www.aacc.org/publications/cln/2010/may/Pages/CoverStory2May2010.aspx. Accessed June 30, 2013.

2. National Diabetes Statistics, 2011. www.diabetes.niddk.nih.gov/dm/pubs/statistics/#Gestational. Accessed July 22, 2013.

3. American Diabetes Association. 2012 Clinical Practice Recommendations. Diabetes Care. 2012;35(suppl 1). http://professional.diabetes.org/SlideLibrary/media/4839/ADA%20Standards%20of%20Medical%20Care%202012%20FINAL.ppt. Accessed June 24, 2013.

4. American Diabetes Association. Diabetes basics: your risk. www.diabetes.org/diabetes-basics/prevention/risk-factors. Accessed August 13, 2013.

5. American Diabetes Association. Diabetes Basics: What is Gestational Diabetes? www.diabetes.org/diabetes-basics/gestational/what-is-gestational-diabetes.html. Accessed August 13, 2013.

6. Johnson K. New criteria for gestational diabetes increase diagnoses (December 5, 2011). www.medscape.com/viewarticle/754733. Accessed August 13, 2013.

7. American Diabetes Association. Diabetes basics: how to treat gestational diabetes. www.diabetes.org/diabetes-basics/gestational/how-to-treat-gestational.html. Accessed August 13, 2013.

8. Moore TR. Glyburide for the treatment of gestational diabetes: a critical appraisal. Diabetes Care. 2007;30(suppl 2). http://care.diabetesjournals.org/content/30/Supplement_2/S209.full. Accessed August 13, 2013.

9. Lowes R. Levemir assigned more reassuring pregnancy risk category (April 2, 2012). www.medscape.com/viewarticle/761349. Accessed August 13, 2013.

10. Buchanan TA, Xiang AH, Page KA. Gestational diabetes mellitus: risks and management during and after pregnancy. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2012;8(11):639-649.

One of the most common complications of pregnancy is gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM). It is defined as glucose intolerance with first onset during pregnancy.1 In 2011, the incidence of GDM in the United States was between 2% and 10% of all pregnancies. Potential complications associated with GDM include macrosomia, pre-eclampsia, preterm birth, increased risk for cesarean section, neonatal hypoglycemia, shoulder dystocia, and polyhydramnios. Women with a history of gestational diabetes have a 35% to 60% likelihood of developing type 2 diabetes over the following 10 to 20 years.2

Q: When should screening for GDM occur?

According to the American Diabetes Association’s (ADA) 2012 Clinical Practice Recommendations, a pregnant woman should be screened for undiagnosed type 2 diabetes at her first prenatal visit if she has certain risk factors.3 These include, but are not limited to, family history of diabetes, overweight/obesity, sedentary lifestyle, elevated blood pressure and/or cholesterol, impaired fasting glucose or impaired glucose tolerance, or certain ethnic backgrounds (eg, Hispanic, Native American, and non-Hispanic black).4 In 2011, the ADA revised its recommendations for GDM screening and diagnosis to be in accordance with those from the International Association of Diabetes and Pregnancy Study Groups (IADPSG), an international consensus group with representatives from multiple obstetric and diabetes organizations, including ADA.

Q: How is GDM diagnosed?

Current recommendations stipulate that women with no previous history of diabetes or prediabetes undergo one-step testing: a 75-g glucose tolerance test (GTT) at 24 to 28 weeks’ gestation.5,6 For women with a prior history of GDM, screening is recommended earlier in the pregnancy. The GTT should be performed after an overnight fast of at least eight hours.3 An elevation of any one of the values above normal reference range is consistent with the diagnosis of GDM. (Previously, the diagnostic criteria required two abnormal values.) Multiple international studies using the new criteria have estimated an increased incidence of gestational diabetes in up to 18% of pregnancies.5,6

Some organizations have not endorsed the IADPSG/ADA diagnostic criteria at this time; as a result, many practitioners continue to use two-step testing for diagnosing GDM. To do the two-step testing, a 50-g glucose load is given, followed by a blood glucose reading one hour later. If the one-hour reading is within normal range, no further testing is warranted and the patient does not have gestational diabetes. If the test is abnormal, she must undergo a fasting three-hour GTT using a 100-g glucose load.

Q: What advice should a woman get once she’s diagnosed with GDM?

As soon as a woman is diagnosed with GDM, she should be referred for a gestational diabetes education class and nutrition counseling. Specifically, she should learn what it means for her to have GDM, implications for her and her baby, and the importance of eating a healthy diet (not the proverbial concept of “eating for two”), physical activity, self-monitoring blood glucose, and adherence to any prescribed medications.

Probably the most important aspect of education is nutrition counseling. It is known that smaller meals consumed more frequently throughout the day reduce spikes in blood glucose levels. One suggestion is to eat three small meals and three low-carbohydrate (15 g) snacks each day. Meals and snacks are generally established based on fixed carbohydrate amounts. A certified diabetes educator or registered dietitian (RD) can recommend healthy meal and snack ideas that are tasty, promote satiety, and minimize spikes in glucose levels.

Q: What are the current treatment options for GDM?

During the process of receiving GDM education, the patient should be prescribed a glucometer, along with specific glucose targets. Blood glucose should be checked multiple times a day, preferably fasting and postprandial measurements. Medical practices vary in their preferred glucose targets; some individuals require tighter control than others. The ADA suggests the following targets:

• Before a meal (preprandial):

95 mg/dL or less.

• One hour after a meal (postprandial): 140 mg/dL or less.

• Two hours after a meal (postprandial): 120 mg/dL or less. 7

If blood glucose levels remain within normal range, it is possible to control gestational diabetes with dietary modification and physical activity. If readings are consistently elevated, then the patient must be started on medication. There are currently no FDA-approved oral medications to treat gestational diabetes. Glyburide is commonly used, although it is not FDA approved for this indication. More studies to establish its safety are likely needed for FDA approval.8

If pharmaceutical treatment is warranted, insulin is the safest and most effective agent. It is the only medication that is FDA approved for treatment of GDM. Levemir (insulin detemir [rDNA origin] injection) gained FDA approval for use in pregnancy in 2012, so it has become more widespread than NPH for basal insulin usage.9

Although it is usually managed by an endocrinologist or perinatologist, an experienced obstetrician could also manage GDM. Often, the patient is referred to an endocrinologist. The endocrine provider, along with the diabetes educator and RD, focus on nutrition counseling and diabetes management so the obstetrician can focus on maternal and fetal health.

Q: What is the recommended follow-up?

Since embryonic and fetal development occurs at such a rapid rate, time is of the essence for getting a patient’s blood glucose to goal. While treating diabetes in general can be challenging, this is usually not the case with GDM. Most women with GDM are motivated to take care of themselves for the well-being of their developing baby. The influence of a baby developing inside a mother is so strong that diabetic women who become pregnant often take better care of themselves than they do when they are not pregnant.

The patient’s daily responsibilities should include eating a healthy and diet checking her blood glucose levels throughout the day. These readings must be recorded. Clinic visits should occur often, with emailing of glucose readings between visits as needed. The frequency of visits varies among practices, depending on the patient’s level of glucose control and intensity of the treatment regimen.

Q: Why is postpartum testing important?

After delivery, most cases of GDM usually resolve. However, approximately 5% to 10% of women with gestational diabetes are found to have diabetes immediately after pregnancy.2 To evaluate for persistent diabetes, a two-hour GTT should be done at six weeks’ postpartum. Although an A1C can now be used to diagnose diabetes, the ADA does not recommend checking it for this purpose.3

If the two-hour GTT result is normal, a woman should be screened for diabetes every three years for the rest of her life.3 If a diagnosis of impaired fasting glucose or impaired glucose tolerance is made, then she should be tested for diabetes on an annual basis or in the interim if she develops classic symptoms of hyperglycemia.3 If diabetes is diagnosed, she should be treated accordingly as a type 2 diabetic patient.

At this time, the patient should be counseled on lifestyle interventions and consider starting metformin therapy if appropriate. Diabetes education classes are available for prediabetes. To maintain good health and prevent/delay onset of type 2 diabetes, here are some tips to follow:

• The same diet as during pregnancy does not have to be followed, although healthy eating habits are always a good idea.

• Physical activity (approximately 30 min five times a week) will help shed weight gained during pregnancy.

• Breastfeeding promotes weight loss.10

• Patients should aim for weight loss of 7% of body weight.3

• Continue annual physical exams, keeping an eye on blood pressure, weight, and cholesterol levels.

It’s reasonable for the patient to check glucose levels occasionally after delivery. If elevated readings occur, the patient can make an appointment with her primary care provider or endocrinologist.

References

1. American Association for Clinical Chemistry. A New Definition of Gestational Diabetes. www.aacc.org/publications/cln/2010/may/Pages/CoverStory2May2010.aspx. Accessed June 30, 2013.

2. National Diabetes Statistics, 2011. www.diabetes.niddk.nih.gov/dm/pubs/statistics/#Gestational. Accessed July 22, 2013.

3. American Diabetes Association. 2012 Clinical Practice Recommendations. Diabetes Care. 2012;35(suppl 1). http://professional.diabetes.org/SlideLibrary/media/4839/ADA%20Standards%20of%20Medical%20Care%202012%20FINAL.ppt. Accessed June 24, 2013.

4. American Diabetes Association. Diabetes basics: your risk. www.diabetes.org/diabetes-basics/prevention/risk-factors. Accessed August 13, 2013.

5. American Diabetes Association. Diabetes Basics: What is Gestational Diabetes? www.diabetes.org/diabetes-basics/gestational/what-is-gestational-diabetes.html. Accessed August 13, 2013.

6. Johnson K. New criteria for gestational diabetes increase diagnoses (December 5, 2011). www.medscape.com/viewarticle/754733. Accessed August 13, 2013.

7. American Diabetes Association. Diabetes basics: how to treat gestational diabetes. www.diabetes.org/diabetes-basics/gestational/how-to-treat-gestational.html. Accessed August 13, 2013.

8. Moore TR. Glyburide for the treatment of gestational diabetes: a critical appraisal. Diabetes Care. 2007;30(suppl 2). http://care.diabetesjournals.org/content/30/Supplement_2/S209.full. Accessed August 13, 2013.

9. Lowes R. Levemir assigned more reassuring pregnancy risk category (April 2, 2012). www.medscape.com/viewarticle/761349. Accessed August 13, 2013.

10. Buchanan TA, Xiang AH, Page KA. Gestational diabetes mellitus: risks and management during and after pregnancy. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2012;8(11):639-649.

Is Man Balding “Just Like Dad”?

ANSWER

The correct answer is alopecia areata (choice “d”), the causes of which are discussed below. It typically manifests with sudden-onset complete hair loss in a well-defined area or areas.

Androgenetic alopecia (choice “a”) is incorrect, since its onset is remarkably gradual and the areas it affects are patterned differently from those seen with alopecia areata.

Kerion (choice “b”) is the name of an edematous, inflamed mass in the scalp triggered by fungal infection (tinea capitis) and is almost always accompanied by broken skin and palpable lymph nodes in the area.

Lichen planopilaris (choice “c”) is lichen planus of the scalp and hair follicles, an inflammatory condition that can involve hair loss of variable size and shape, but not in the same well-defined pattern seen here.

DISCUSSION

There are dermatologists who specialize in diseases of the scalp, especially those resulting in hair loss. In addition to the differential diagnoses mentioned, they see conditions such as lupus, trichotillomania, and reactions to hair care products.

Alopecia areata (AA) seldom needs the attention of these specialists, except in atypical cases. The total hair loss in these well-defined, oval-to-round areas presents fairly acutely, with obviously excessive hair loss noted not only in the scalp but also in the comb, brush, or sink. Although AA is quite common (and thus well known to barbers and hairdressers), it is still often a total and very distressing mystery to the patient. Stress is one of the factors theorized to trigger it—but unfortunately, the more stressed the patient is about the hair loss, the worse it gets.

In the vast majority of cases, the condition resolves, the hair returns, and the grateful patient breathes a sigh of relief. Recurrences, however, are not at all uncommon. A tiny percentage of AA patients go on to lose all the hair in their scalp (alopecia totalis), and an even smaller percentage of those patients go on to lose every hair on their body, permanently (alopecia universalis).

Much has been reported about the cause, which appears to be autoimmune in nature, with an apparent hereditary predisposition. About 10% to 20% of affected patients have a positive family history of AA, and those with severe AA have a positive family history about 16% to 18% of the time.

The theory of an autoimmune basis is also strongly supported by the significantly increased incidence of other autoimmune diseases (especially thyroid disease and vitiligo) in AA patients and their families. But T-cells almost certainly play a role too: Reductions in their number are usually followed by resolution of AA, while increases have the opposite effect. Increased antibodies to various portions of the hair shaft and related structures have now been tied to AA episodes, but these may be epiphenomenal and not causative.

One constant is the perifollicular lymphocytic infiltrate surrounding anagen phase follicles of AA patients. When corticosteroids are administered (eg, by intralesional injection, orally, or systemically), it is this infiltrate that is thereby dissipated, promoting at least temporary hair regrowth. Topically applied steroid preparations are not as helpful, and no known treatment has a positive effect on the ultimate outcome.

Fortunately, most cases of AA resolve satisfactorily with minimal or no treatment. Numerous treatments have been tried for AA, including minoxidil, topical sensitizers (eg, squaric acid, dintrochlorobenzene), and several types of phototherapy. Studies of the efficacy of the various treatments is complicated by the self-limiting nature of the problem.

Predictors of potentially poor outcomes include youth, atopy, extent of involvement, and the presence of ophiasis, a term used to describe extensive involvement of the periphery of the scalp.

ANSWER

The correct answer is alopecia areata (choice “d”), the causes of which are discussed below. It typically manifests with sudden-onset complete hair loss in a well-defined area or areas.

Androgenetic alopecia (choice “a”) is incorrect, since its onset is remarkably gradual and the areas it affects are patterned differently from those seen with alopecia areata.

Kerion (choice “b”) is the name of an edematous, inflamed mass in the scalp triggered by fungal infection (tinea capitis) and is almost always accompanied by broken skin and palpable lymph nodes in the area.

Lichen planopilaris (choice “c”) is lichen planus of the scalp and hair follicles, an inflammatory condition that can involve hair loss of variable size and shape, but not in the same well-defined pattern seen here.

DISCUSSION

There are dermatologists who specialize in diseases of the scalp, especially those resulting in hair loss. In addition to the differential diagnoses mentioned, they see conditions such as lupus, trichotillomania, and reactions to hair care products.

Alopecia areata (AA) seldom needs the attention of these specialists, except in atypical cases. The total hair loss in these well-defined, oval-to-round areas presents fairly acutely, with obviously excessive hair loss noted not only in the scalp but also in the comb, brush, or sink. Although AA is quite common (and thus well known to barbers and hairdressers), it is still often a total and very distressing mystery to the patient. Stress is one of the factors theorized to trigger it—but unfortunately, the more stressed the patient is about the hair loss, the worse it gets.

In the vast majority of cases, the condition resolves, the hair returns, and the grateful patient breathes a sigh of relief. Recurrences, however, are not at all uncommon. A tiny percentage of AA patients go on to lose all the hair in their scalp (alopecia totalis), and an even smaller percentage of those patients go on to lose every hair on their body, permanently (alopecia universalis).

Much has been reported about the cause, which appears to be autoimmune in nature, with an apparent hereditary predisposition. About 10% to 20% of affected patients have a positive family history of AA, and those with severe AA have a positive family history about 16% to 18% of the time.

The theory of an autoimmune basis is also strongly supported by the significantly increased incidence of other autoimmune diseases (especially thyroid disease and vitiligo) in AA patients and their families. But T-cells almost certainly play a role too: Reductions in their number are usually followed by resolution of AA, while increases have the opposite effect. Increased antibodies to various portions of the hair shaft and related structures have now been tied to AA episodes, but these may be epiphenomenal and not causative.

One constant is the perifollicular lymphocytic infiltrate surrounding anagen phase follicles of AA patients. When corticosteroids are administered (eg, by intralesional injection, orally, or systemically), it is this infiltrate that is thereby dissipated, promoting at least temporary hair regrowth. Topically applied steroid preparations are not as helpful, and no known treatment has a positive effect on the ultimate outcome.

Fortunately, most cases of AA resolve satisfactorily with minimal or no treatment. Numerous treatments have been tried for AA, including minoxidil, topical sensitizers (eg, squaric acid, dintrochlorobenzene), and several types of phototherapy. Studies of the efficacy of the various treatments is complicated by the self-limiting nature of the problem.

Predictors of potentially poor outcomes include youth, atopy, extent of involvement, and the presence of ophiasis, a term used to describe extensive involvement of the periphery of the scalp.

ANSWER

The correct answer is alopecia areata (choice “d”), the causes of which are discussed below. It typically manifests with sudden-onset complete hair loss in a well-defined area or areas.

Androgenetic alopecia (choice “a”) is incorrect, since its onset is remarkably gradual and the areas it affects are patterned differently from those seen with alopecia areata.

Kerion (choice “b”) is the name of an edematous, inflamed mass in the scalp triggered by fungal infection (tinea capitis) and is almost always accompanied by broken skin and palpable lymph nodes in the area.

Lichen planopilaris (choice “c”) is lichen planus of the scalp and hair follicles, an inflammatory condition that can involve hair loss of variable size and shape, but not in the same well-defined pattern seen here.

DISCUSSION

There are dermatologists who specialize in diseases of the scalp, especially those resulting in hair loss. In addition to the differential diagnoses mentioned, they see conditions such as lupus, trichotillomania, and reactions to hair care products.

Alopecia areata (AA) seldom needs the attention of these specialists, except in atypical cases. The total hair loss in these well-defined, oval-to-round areas presents fairly acutely, with obviously excessive hair loss noted not only in the scalp but also in the comb, brush, or sink. Although AA is quite common (and thus well known to barbers and hairdressers), it is still often a total and very distressing mystery to the patient. Stress is one of the factors theorized to trigger it—but unfortunately, the more stressed the patient is about the hair loss, the worse it gets.

In the vast majority of cases, the condition resolves, the hair returns, and the grateful patient breathes a sigh of relief. Recurrences, however, are not at all uncommon. A tiny percentage of AA patients go on to lose all the hair in their scalp (alopecia totalis), and an even smaller percentage of those patients go on to lose every hair on their body, permanently (alopecia universalis).

Much has been reported about the cause, which appears to be autoimmune in nature, with an apparent hereditary predisposition. About 10% to 20% of affected patients have a positive family history of AA, and those with severe AA have a positive family history about 16% to 18% of the time.

The theory of an autoimmune basis is also strongly supported by the significantly increased incidence of other autoimmune diseases (especially thyroid disease and vitiligo) in AA patients and their families. But T-cells almost certainly play a role too: Reductions in their number are usually followed by resolution of AA, while increases have the opposite effect. Increased antibodies to various portions of the hair shaft and related structures have now been tied to AA episodes, but these may be epiphenomenal and not causative.

One constant is the perifollicular lymphocytic infiltrate surrounding anagen phase follicles of AA patients. When corticosteroids are administered (eg, by intralesional injection, orally, or systemically), it is this infiltrate that is thereby dissipated, promoting at least temporary hair regrowth. Topically applied steroid preparations are not as helpful, and no known treatment has a positive effect on the ultimate outcome.

Fortunately, most cases of AA resolve satisfactorily with minimal or no treatment. Numerous treatments have been tried for AA, including minoxidil, topical sensitizers (eg, squaric acid, dintrochlorobenzene), and several types of phototherapy. Studies of the efficacy of the various treatments is complicated by the self-limiting nature of the problem.

Predictors of potentially poor outcomes include youth, atopy, extent of involvement, and the presence of ophiasis, a term used to describe extensive involvement of the periphery of the scalp.

A 39-year-old man presents with a two-month history of focal hair loss that has not responded to treatment. His primary care provider prescribed first an antifungal topical cream (clotrimazole/betamethasone bid for two weeks), then an oral antibiotic (cephalexin 500 mg qid for 10 days). Neither helped. His scalp is asymptomatic in the affected area (as well as elsewhere), but the hair loss is extremely upsetting to the patient. He is convinced (and has been told by family members) that he is merely going bald “just like his father.” The onset of his hair loss was rather sudden. It began with increased hair found in his sink and shower, followed by comments from family and coworkers. One friend loaned the patient his minoxidil solution, but twice-daily application for a week failed to slow the rate of hair loss. In general, the patient’s health is excellent; he does not require any maintenance medications. Neither he nor any family members have had any serious illnesses (eg, thyroid disease, lupus, vitiligo) that he could recall. The patient’s hair loss, affecting an approximately 10 x 8–cm area, is confined to the right parietal scalp and has a sharply defined border and strikingly oval shape. The hair loss within this area is complete, with no epidermal disturbance of the involved scalp skin noted on inspection or palpation. No nodes are palpable in the surrounding head or neck. No other areas of hair loss can be seen in hair-bearing areas.

New and Noteworthy Information—September 2013

A recent case–control study provides further evidence against the Zamboni hypothesis that chronic cerebrospinal venous insufficiency is involved with multiple sclerosis (MS), researchers reported August 14 in PLOS One. The researchers randomly selected 100 patients with MS between ages 18 and 65 and 100 controls with no known history of MS or other neurologic condition. All participants underwent ultrasound imaging of the veins of the neck and the deep cerebral veins, as well as MRI of the neck veins and brain. The investigators found no evidence of reflux, stenosis, or blockage in the internal jugular veins or vertebral veins in any study participant and no evidence of reflux or cessation of flow in the deep cerebral veins in any subject.

Breastfeeding may reduce a woman’s risk of Alzheimer’s disease, according to research published online ahead of print July 23 in the Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease. Investigators collected reproductive history data from and conducted Alzheimer’s disease diagnostic interviews with a cohort of elderly British women. Analysis using Cox proportional-hazard models indicated that longer breastfeeding duration corresponded to reduced risk of Alzheimer’s disease. Women who breastfed had lower risk of Alzheimer’s disease than women who did not breastfeed. Breastfeeding practices are an important modifier of cumulative endogenous hormone exposure for mothers, according to the researchers. Future studies should consider how reproductive history leads to variation in endogenous hormone exposure and how this variation may influence the relationship between hormones and Alzheimer’s disease, the investigators concluded.

Among older adults, anemia may be associated with an increased risk of dementia, according to a study published August 6 in Neurology. Researchers studied 2,552 older adults (mean age, 76) participating in the Health, Aging, and Body Composition study and who were free of dementia at baseline. Of the total population, 392 participants had anemia at baseline. Over 11 years of follow-up, 455 participants developed dementia. An unadjusted analysis indicated that subjects with baseline anemia had an increased risk of dementia (23% vs 17%) compared with subjects without anemia. The association remained significant after adjusting for demographics, APOE ε4, baseline Modified Mini-Mental State score, comorbidities, and renal function. Additional adjustment for other anemia measures, erythropoietin, and C-reactive protein did not affect the results significantly.

The FDA has approved Trokendi XR, a once-daily extended release formulation of topiramate for the treatment of epilepsy. The agency granted a waiver for certain pediatric study requirements and a deferral for the submission of postmarketing pediatric pharmacokinetic assessments. Trokendi XR is indicated for initial monotherapy in patients ages 10 and older with partial onset or primary generalized tonic–clonic seizures. The drug also is approved as adjunctive therapy in patients ages 6 and older with partial onset or primary generalized tonic–clonic seizures, and as adjunctive therapy in patients ages 6 and older with seizures associated with Lennox–Gastaut syndrome. The product will be available in 25-, 50-, 100- and 200-mg extended-release capsules. Supernus Pharmaceuticals (Rockville, Maryland) expects to launch the product in September 2013.

The FDA has approved scored tablet and oral suspension formulations of ONFI (clobazam) CIV. ONFI is an oral antiepileptic drug of the benzodiazepine class (ie, a 1,5 benzodiazepine). The agency originally approved ONFI in 2011 as a prescription medication to treat seizures associated with Lennox–Gastaut syndrome in adults and children age 2 or older. The new oval-shaped ONFI scored tablets (10 mg and 20 mg) will replace the round, nonscored tablets and are similar in size. The new tablets contain the same ingredients as the round tablet, and the score allows patients or their caregivers to split the tablets in half. ONFI oral suspension (2.5 mg/mL) has a berry flavor. ONFI, manufactured by Lundbeck (Deerfield, Illinois), will no longer be available in a 5-mg tablet.

An incomplete circle of Willis may be more common in patients with migraine with aura than in the general population, according to research published July 26 in PLOS One. Investigators enrolled 56 migraineurs with aura, 61 migraineurs without aura, and 53 controls in an observational study. The researchers performed magnetic resonance angiography to examine subjects’ circle of Willis anatomy and measured cerebral blood flow with arterial spin–labeled perfusion MRI. An incomplete circle of Willis was significantly more common in migraineurs with aura, compared with controls (73% vs 51%). A similar trend was observed among migraineurs without aura (67% vs 51%). Compared with subjects with a complete circle of Willis, subjects with an incomplete circle had greater asymmetry in hemispheric cerebral blood flow.

Some patients with chronic pain diagnosed as fibromyalgia may have unrecognized small-fiber polyneuropathy (SFPN), according to research published online ahead of print June 7 in Pain. Investigators analyzed symptoms associated with SFPN, neurologic examinations, and pathologic and physiologic markers in 27 patients with fibromyalgia and 30 matched normal controls. Study instruments included the Michigan Neuropathy Screening Instrument (MNSI), the Utah Early Neuropathy Scale (UENS), distal-leg neurodiagnostic skin biopsies, and autonomic-function testing (AFT). Approximately 41% of skin biopsies from subjects with fibromyalgia supported a diagnosis of SFPN, compared with 3% of biopsies from control subjects. MNSI and UENS scores were higher in patients with fibromyalgia than in control subjects. Abnormal AFTs were prevalent among patients with fibromyalgia, suggesting that fibromyalgia-associated SFPN is primarily somatic, said the researchers.

High glucose levels may be a risk factor for dementia, even among persons without diabetes, according to a study published August 8 in the New England Journal of Medicine. Researchers examined 35,264 clinical measurements of glucose levels and 10,208 measurements of glycated hemoglobin levels from 2,067 participants (1,228 women) without dementia. Participants’ mean age at baseline was 76. Of the total population, 232 participants had diabetes. During a median follow-up of 6.8 years, 524 participants developed dementia (74 with diabetes). Among participants without diabetes, higher average glucose levels within the preceding five years were related to an increased risk of dementia. A glucose level of 115 mg/dL, compared with 100 mg/dL, was associated with an adjusted hazard ratio for dementia of 1.18.

A majority of Alzheimer’s disease investigators favor disclosing amyloid imaging results to participants in the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI), according to a survey published online ahead of print August 21 in Neurology. Shortly before the FDA approved the amyloid-binding radiotracer florbetapir, all ADNI investigators and personnel were asked to complete an anonymous online survey that contained fixed-choice and free-text questions. Although ADNI participants often requested amyloid imaging results, the majority of ADNI investigators (approximately 90%) did not return amyloid imaging results to the participants. Most investigators reported that if the FDA approved florbetapir, they would support the return of amyloid imaging results to participants with mild cognitive impairment and normal cognition, however. ADNI investigators emphasized the need for guidance on how to provide these results to participants.

A sudden decrease of testosterone may induce nigrostriatal pathologies in mice through a decrease in glial-derived neurotrophic factor (GDNF) mediated by inducible nitric-oxide synthase (iNOS), investigators reported in the July 19 Journal of Biological Chemistry. Levels of iNOS, glial markers, and α-synuclein were higher in the nigra of castrated male mice than in normal male mice. After castration, the level of GDNF markedly decreased in the nigra of male mice, however. Subcutaneous implantation of 5 α-dihydrotestosterone pellets reversed nigrostriatal pathologies in castrated male mice, suggesting that the male sex hormone plays a role in castration-induced nigrostriatal pathology. Castrated young male mice may be used as a simple, toxin-free, and nontransgenic animal model to study Parkinson’s disease-related nigrostriatal pathologies, thus facilitating the screening of drugs against Parkinson’s disease, said the researchers.