User login

Hospitalists Take Care Transitions Into Their Own Hands

How can hospitalists know if the care-transition plans they’ve put in place to get their discharged patients back to their PCPs are working out? For the 18-member inpatient medicine group at Aultman Hospital in Canton, Ohio, the answer is simple: Ask the PCPs.

“It’s more important than ever for the transition from one service to the next to be smooth, with a very good handoff. That’s where our hospitalist group and what we are doing comes in,” says group leader O. George Mitri, MD, FACP, FHM.

Dr. Mitri, along with Lewis Humble, MD, the group’s designated outreach champion, and Katie Wright, MSN, RN, the group’s practice administrator, visit PCPs in their offices once or twice a month. They meet with the physicians and practice managers, sharing data and exchanging stories about care transitions.

They recently held a three-hour summit in a conference room in the hospital, where PCPs were treated to dinner and discussion about transitions of care. Annually, PCPs are sent a satisfaction survey, which, like the office visits, asks if they are getting the information they need, in the format they need, and the right amount of it in order to take care of their patients post-discharge.

“We’ve taken that feedback and implemented changes at our end to better meet the needs of the patients and PCPs,” Dr. Mitri says. “It’s a lost opportunity if you’re not visiting PCPs in their offices. You lose touch.”

Changes implemented by the hospitalist group include making the admitting hospitalist for the day responsible for forwarding to PCPs any test results for discharged patients that require immediate attention, as well as revising the group’s discharge report to include a cover sheet summarizing the most pertinent information, discharge medications, and an assessment of the patient’s risk of readmission using Project BOOST’s “8Ps” risk assessment tool.

The goal is to dictate the discharge summary within 24 hours and fax it to the PCP the next business day, Wright says. The group’s rounding nurses also schedule the patient’s first medical office visit before the discharge, even if that means finding a PCP for the patient or making an appointment with a local community clinic. Patients identified as at-risk, including those with congestive heart failure (CHF) or COPD, also get a post-discharge follow-up call.

Other hospitalist groups are employing similar techniques to close the loop with PCPs for discharged patients. Bronson Internal Medicine Hospitalist Specialist Group in Kalamazoo, Mich., just hired three phone nurses to help with care transitions, using Dr. Eric Coleman’s Care Transitions model, says practice manager Joshua Hill. The nurses also call the PCPs. Paying particular attention to new heart-failure cases, they will accompany patients to follow-up appointments with PCPs and specialists and will make home visits if needed.

“For every readmission within 60 days, we also call the PCP,” Hill says.

Listen to Dr. O. George Mitri and Katie Wright discuss improving communication with PCPs

At Aultman, the hospitalists and support staff, including nurse practitioners, rounding nurses and office staff, are employed by the health system, whereas the PCPs they work with mostly belong to small, independent groups. The changes described above mostly apply to patients managed in the hospital by the hospitalists. But if the metrics—such as a decline in readmissions to 11 percent from 13 percent since they started making follow-up appointments for patients—continue to show improvements, Dr. Mitri says they might become hospital standards.

—O. George Mitri, MD, FACP, FHM

Next on the quality hit list at Aultman is a greater focus on medication safety. “How do we get what happens in the hospital to the PCP and to the patient at home? Is it a nurse visit to address what really goes on in the home, including the shoebox full of medications in the closet?” he asks.

Wright adds that the hospitalist group has started meeting with partner specialist groups in the hospital, including cardiology, neurology, and general surgery, and is working on relationships with nursing homes. That might mean another set of regular sit-down meetings to talk about how to make transitions to post-acute care work better. TH

Larry Beresford is a freelance writer in Oakland, Calif.

How can hospitalists know if the care-transition plans they’ve put in place to get their discharged patients back to their PCPs are working out? For the 18-member inpatient medicine group at Aultman Hospital in Canton, Ohio, the answer is simple: Ask the PCPs.

“It’s more important than ever for the transition from one service to the next to be smooth, with a very good handoff. That’s where our hospitalist group and what we are doing comes in,” says group leader O. George Mitri, MD, FACP, FHM.

Dr. Mitri, along with Lewis Humble, MD, the group’s designated outreach champion, and Katie Wright, MSN, RN, the group’s practice administrator, visit PCPs in their offices once or twice a month. They meet with the physicians and practice managers, sharing data and exchanging stories about care transitions.

They recently held a three-hour summit in a conference room in the hospital, where PCPs were treated to dinner and discussion about transitions of care. Annually, PCPs are sent a satisfaction survey, which, like the office visits, asks if they are getting the information they need, in the format they need, and the right amount of it in order to take care of their patients post-discharge.

“We’ve taken that feedback and implemented changes at our end to better meet the needs of the patients and PCPs,” Dr. Mitri says. “It’s a lost opportunity if you’re not visiting PCPs in their offices. You lose touch.”

Changes implemented by the hospitalist group include making the admitting hospitalist for the day responsible for forwarding to PCPs any test results for discharged patients that require immediate attention, as well as revising the group’s discharge report to include a cover sheet summarizing the most pertinent information, discharge medications, and an assessment of the patient’s risk of readmission using Project BOOST’s “8Ps” risk assessment tool.

The goal is to dictate the discharge summary within 24 hours and fax it to the PCP the next business day, Wright says. The group’s rounding nurses also schedule the patient’s first medical office visit before the discharge, even if that means finding a PCP for the patient or making an appointment with a local community clinic. Patients identified as at-risk, including those with congestive heart failure (CHF) or COPD, also get a post-discharge follow-up call.

Other hospitalist groups are employing similar techniques to close the loop with PCPs for discharged patients. Bronson Internal Medicine Hospitalist Specialist Group in Kalamazoo, Mich., just hired three phone nurses to help with care transitions, using Dr. Eric Coleman’s Care Transitions model, says practice manager Joshua Hill. The nurses also call the PCPs. Paying particular attention to new heart-failure cases, they will accompany patients to follow-up appointments with PCPs and specialists and will make home visits if needed.

“For every readmission within 60 days, we also call the PCP,” Hill says.

Listen to Dr. O. George Mitri and Katie Wright discuss improving communication with PCPs

At Aultman, the hospitalists and support staff, including nurse practitioners, rounding nurses and office staff, are employed by the health system, whereas the PCPs they work with mostly belong to small, independent groups. The changes described above mostly apply to patients managed in the hospital by the hospitalists. But if the metrics—such as a decline in readmissions to 11 percent from 13 percent since they started making follow-up appointments for patients—continue to show improvements, Dr. Mitri says they might become hospital standards.

—O. George Mitri, MD, FACP, FHM

Next on the quality hit list at Aultman is a greater focus on medication safety. “How do we get what happens in the hospital to the PCP and to the patient at home? Is it a nurse visit to address what really goes on in the home, including the shoebox full of medications in the closet?” he asks.

Wright adds that the hospitalist group has started meeting with partner specialist groups in the hospital, including cardiology, neurology, and general surgery, and is working on relationships with nursing homes. That might mean another set of regular sit-down meetings to talk about how to make transitions to post-acute care work better. TH

Larry Beresford is a freelance writer in Oakland, Calif.

How can hospitalists know if the care-transition plans they’ve put in place to get their discharged patients back to their PCPs are working out? For the 18-member inpatient medicine group at Aultman Hospital in Canton, Ohio, the answer is simple: Ask the PCPs.

“It’s more important than ever for the transition from one service to the next to be smooth, with a very good handoff. That’s where our hospitalist group and what we are doing comes in,” says group leader O. George Mitri, MD, FACP, FHM.

Dr. Mitri, along with Lewis Humble, MD, the group’s designated outreach champion, and Katie Wright, MSN, RN, the group’s practice administrator, visit PCPs in their offices once or twice a month. They meet with the physicians and practice managers, sharing data and exchanging stories about care transitions.

They recently held a three-hour summit in a conference room in the hospital, where PCPs were treated to dinner and discussion about transitions of care. Annually, PCPs are sent a satisfaction survey, which, like the office visits, asks if they are getting the information they need, in the format they need, and the right amount of it in order to take care of their patients post-discharge.

“We’ve taken that feedback and implemented changes at our end to better meet the needs of the patients and PCPs,” Dr. Mitri says. “It’s a lost opportunity if you’re not visiting PCPs in their offices. You lose touch.”

Changes implemented by the hospitalist group include making the admitting hospitalist for the day responsible for forwarding to PCPs any test results for discharged patients that require immediate attention, as well as revising the group’s discharge report to include a cover sheet summarizing the most pertinent information, discharge medications, and an assessment of the patient’s risk of readmission using Project BOOST’s “8Ps” risk assessment tool.

The goal is to dictate the discharge summary within 24 hours and fax it to the PCP the next business day, Wright says. The group’s rounding nurses also schedule the patient’s first medical office visit before the discharge, even if that means finding a PCP for the patient or making an appointment with a local community clinic. Patients identified as at-risk, including those with congestive heart failure (CHF) or COPD, also get a post-discharge follow-up call.

Other hospitalist groups are employing similar techniques to close the loop with PCPs for discharged patients. Bronson Internal Medicine Hospitalist Specialist Group in Kalamazoo, Mich., just hired three phone nurses to help with care transitions, using Dr. Eric Coleman’s Care Transitions model, says practice manager Joshua Hill. The nurses also call the PCPs. Paying particular attention to new heart-failure cases, they will accompany patients to follow-up appointments with PCPs and specialists and will make home visits if needed.

“For every readmission within 60 days, we also call the PCP,” Hill says.

Listen to Dr. O. George Mitri and Katie Wright discuss improving communication with PCPs

At Aultman, the hospitalists and support staff, including nurse practitioners, rounding nurses and office staff, are employed by the health system, whereas the PCPs they work with mostly belong to small, independent groups. The changes described above mostly apply to patients managed in the hospital by the hospitalists. But if the metrics—such as a decline in readmissions to 11 percent from 13 percent since they started making follow-up appointments for patients—continue to show improvements, Dr. Mitri says they might become hospital standards.

—O. George Mitri, MD, FACP, FHM

Next on the quality hit list at Aultman is a greater focus on medication safety. “How do we get what happens in the hospital to the PCP and to the patient at home? Is it a nurse visit to address what really goes on in the home, including the shoebox full of medications in the closet?” he asks.

Wright adds that the hospitalist group has started meeting with partner specialist groups in the hospital, including cardiology, neurology, and general surgery, and is working on relationships with nursing homes. That might mean another set of regular sit-down meetings to talk about how to make transitions to post-acute care work better. TH

Larry Beresford is a freelance writer in Oakland, Calif.

Tips and techniques for robot-assisted laparoscopic myomectomy

CASE: IS OPEN MYOMECTOMY THE BEST OPTION FOR THIS PATIENT?

In her only pregnancy, a 34-year-old patient experienced a spontaneous first-trimester loss and underwent dilation and curettage. She had noted an increase in her abdominal girth, as well as pelvic pressure, but had attributed both to the pregnancy. Three months after the pregnancy loss, however, neither had resolved. Because she hopes to conceive again and deliver a healthy infant, the patient consulted a gynecologist. After ultrasonography revealed multiple fibroids, that physician recommended open myomectomy. The patient, a Jehovah’s Witness, comes to your office for a second opinion.

On physical examination, she has a 16-weeks’ sized irregular uterus with the cervix displaced behind the pubic symphysis. T2 weighted scans from magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the pelvis in the sagittal view reveal multiple subserosal and intramural fibroids that displace, but do not involve, the uterine cavity (FIGURE 2). The MRI results confirm that the uterus extends beyond the pelvis above the sacral promontory, the fundus lies a few centimeters below the umbilicus, and there is no evidence of adenomyosis. The patient’s hemoglobin level is normal (12.2 g/dL).

What surgical approach would you recommend?

Endometrial ablation, uterine artery embolization, MRI-guided focused ultrasound, hysterectomy, and myomectomy are all treatments for symptomatic uterine fibroids. For women desiring uterine preservation and future fertility, however, myomectomy is the preferred option of many experts.

Myomectomy traditionally has been performed via an open laparotomy approach. With the rise of minimally invasive surgery in gynecology, safe endoscopic surgical approaches and techniques have evolved.

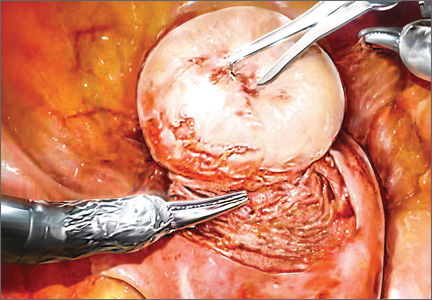

The EndoWrist technology from the da Vinci Surgical System (Intuitive Surgical, Sunnyvale, California) provides increased instrument range of motion, enabling the surgeon to mimic open surgical technique, thereby simplifying the technical challenges of conventional laparoscopic suturing and knot-tying. However, this technology does not minimize or simplify the challenges that leiomyomas can pose, including enucleation (FIGURE 1). Although it has facilitated the progression and adoption of endoscopic myomectomy, the da Vinci system requires an experienced gynecologic endoscopic surgeon.

In this article, we outline the essential steps and offer some clinical surgical pearls to make robot-assisted laparoscopic myomectomy a systematic, safe, and efficient procedure.

Benefits of the robotic approach

Compared with open abdominal myomectomy, the robot-assisted laparoscopic approach is associated with less blood loss, lower complication rates, and shorter hospitalization.1 A retrospective case study from the Cleveland Clinic confirmed these findings when investigators compared surgical outcomes between the robot-assisted laparoscopic approach, standard laparoscopy, and open myomectomy.2 In an assessment of 575 cases (393 open, 93 laparoscopic, and 89 robot-assisted laparoscopic), they found the robot-assisted laparoscopic approach to be associated with the removal of significantly larger myomas (vs standard laparoscopy), as well as lower blood loss and shorter hospitalization (vs open myomectomy).2

Related Article: The robot is gaining ground in gynecologic surgery. Should you be using it?

Comprehensive preoperative assessment is critical

Careful patient selection and thorough preoperative assessment are the cornerstones of successful robot-assisted laparoscopic myomectomy. Among the variables that should be considered in selecting patients are uterine size, the patient’s body habitus, and the quantity, size, consistency, type, and location of fibroids.

Size of the uterus, body habitus, and laxity of the abdominal wall all influence the surgeon’s ability to create the necessary operating space. Intraperitoneal space is required during myomectomy because of the need to apply traction and countertraction during enucleation of fibroids. If the necessary space cannot be obtained, a minilaparotomy technique is one alternative. This technique, described by Glasser, limits the skin incision to 3 to 6 cm in myomectomies for large fibroids that can be accessed easily anteriorly.3

Number and location of fibroids. Women with a solitary fibroid, a few dominant fibroids, or multiple pedunculated fibroids are excellent candidates for an endoscopic approach. Although there are no limits on the number of fibroids that can be removed, women with what we have termed “miliary fibroids,” or multiple fibroids disseminated throughout the entire myometrium, with very little normal myometrium, are poor surgical candidates. Not only does the presence of these fibroids leave some concern about the functional ability of the remaining myometrium in pregnancy, but it may be technically difficult to adequately resect all of the critical fibroids and reapproximate the myometrial defects.

The consistency of fibroids also affects the ease of the enucleation process during myomectomy. Due to the soft, spongy nature of degenerating fibroids and their tendency to fragment and shred when manipulated, these cases are more challenging and should not be attempted without a solid foundation of surgical experience.

MRI serves several purposes

Fibroids can be localized and identified as pedunculated, subserosal, intramural, or submucosal via MRI. Measurements and spatial orientation of the fibroids within the uterus can be formulated using T2 weighted coronal, axial, and sagittal images.

The risk of entering the uterine cavity, as well as the risk of synechiae, may be significantly greater if leiomyomas abut and distort the cavity. Surgical strategies, such as planning the location of the hysterotomy or the inclusion of other procedures (eg, hysteroscopic resection for type 0 or type 1 submucosal fibroids), can be formulated with the information provided by MRI. In cases involving multiple fibroids or intramural fibroids, in particular, MRI serves as a surgical “treasure map” or “GPS.” Preoperative MRI is also one way to offset the lack of haptic feedback during surgery to locate the myomas for removal. As we mentioned earlier, important characteristics, such as degeneration or calcification, also can be readily observed on MRI.

Most important, MRI can distinguish adenomyosis from leiomyomas. Adenomyosis can mimic leiomyomas—both clinically and on sonographic imaging—particularly when it is focal in nature. MRI can make the distinction between these two entities so that patients can be counseled appropriately.

SURGICAL TECHNIQUES

Use a uterine manipulator

This device will facilitate the enucleation process, providing another focal point for traction and countertraction. A variety of uterine manipulators are available. We use the Advincula Arch (Cooper Surgical, Trumball, Connecticut) in conjunction with the Uterine Positioning System (Cooper Surgical). The latter attaches to the operating table and to the Advincula Arch to secure the uterus in a steady position throughout the procedure.

During enucleation, the manipulator is crucial to hold the uterus within the pelvis and the field of vision and to act as countertraction as traction is applied to the fibroid.

Individualize port placement

Rather than premeasure port placement on the abdomen, we individualize it, based on a variety of characteristics, including body habitus and uterine pathology (FIGURE 3). However, we follow some basic principles:

- We insert a Veress needle through the umbilicus to achieve pneumoperitoneum

- After insufflation, we use an upper quadrant entry (right or left, depending on which side the robot patient side cart is docked) under direct visualization using a 5-mm laparoscope and optical trocar. This entry will serve as the assistant port for surgery.

- Before placing the rest of the ports under direct visualization, relative to uterine pathology, we elevate the uterus out of the pelvis. This step ensures that enough distance is placed between the camera and the instrument arms to adequately visualize and perform the surgery.

- In patients with a uterus larger than approximately 14- to 16-weeks’ size, a supraumbilical camera port often is necessary.

- We generally employ a four-arm technique using a 12-mm Xcel trocar (Ethicon Endo-Surgery, Blue Ash, Ohio) that is 150 mm in length for the camera port, three 8-mm telerobotic trocar ports, and a 5-mm Airseal trocar (SurgiQuest, Orange, Connecticut) for the assistant port. There should be at least one hand’s breadth between the ports to minimize arm collision and maximize range of motion.

- Although the 12-mm Xcel trocar comes in a variety of lengths (75–150 mm), we strongly recommend, and exclusively use, the longest length for the camera. Once the camera is docked high on the neck of the longer trocar, more space is created between the setup joints of the robotic arms, enabling greater range of motion and fewer instrument and arm collisions.

- We generally use the following wristed robotic instruments to perform myomectomy: tenaculum, monopolar scissors, and PlasmaKinetic (PK) bipolar forceps.

Inject vasopressin into the myometrium

Vasopressin causes vasospasm and uterine muscle contraction and decreases blood loss during myomectomy. It should be diluted (20 U in 50–200 mL of normal saline), introduced with a 7-inch, 22-gauge spinal needle through the anterior abdominal wall, and injected into the myometrium and serosa overlying the fibroid (VIDEO 1 and VIDEO 2).

Perform this step with care, with aspiration prior to injection, to avoid intravascular injection. Although vasopressin is safe overall, serious complications and rare cases of life-threatening hypotension, pulmonary edema, bradycardia, and cardiac arrest have been reported after the injection of as little as 3 U into the myometrium.4–7

Relative contraindications to vasopressin, such as hypertension, should be discussed with anesthesia prior to use of the drug during surgery.

Enucleate the fibroid

Although either a vertical or a horizontal-transverse incision can be made overlying the uterus, a transverse incision allows for technical optimization of wristed movements for suturing and efficient closure. Whenever possible, therefore, we favor a transverse hysterotomy.

During enucleation, keep the use of thermal energy to a minimum. The same holds true for the uterine incision, although its length can be extended as needed.

Using the wristed robotic tenaculum (or an assistant using a laparoscopic tenaculum or corkscrew), grasp and elevate the myoma away from the fixed uterus (FIGURE 1). This step is not intended to enucleate the myoma through force, but to apply traction and position the fibroid to best delineate and present the leading edge of the pseudocapsule that lies between the myoma and the myometrium. Dissection then can proceed using a “push and spread” technique, bluntly separating the natural plane between the fibroid and the myometrium. Occasionally, fibrous attachments of the pseudocapsule can be transected sharply using the bipolar forceps and monopolar scissors.

Again, we encourage the intermittent use of minimal thermal energy to facilitate this process and achieve temporary hemostasis. As the dissection progresses, the fibroid can be regrasped closer to its leading edge, causing the myoma to be rolled out (VIDEO 3 and VIDEO 4).

Close the myometrium We advocate multilayer closure with reapproximation of the myometrium and serosal edges to achieve hemostasis and prevent hematoma (VIDEO 5).

The half-life of vasopressin ranges from 20 to 40 minutes. By this point of the procedure, assuming that the use of thermal energy has been minimal, the myometrial edges should be bleeding slightly, demonstrating adequate reperfusion. The myometrial defect then can be repaired using delayed absorbable suture, such as 2-0 V-Loc 180 (Covidien, Mansfield, Massachusetts).

Barbed suture has revolutionized laparoscopy and minimally invasive surgery, eliminating the need for endoscopic knot-tying. Quill suture (Angiotech, Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada) and V-Loc suture are used safely throughout gynecology, myomectomy included.8,9 However, when the endometrial cavity has been entered, avoid using barbed suture to reapproximate this initial layer to prevent synechiae.

No closure technique has been shown to prevent uterine rupture. Uterine rupture during pregnancy is one of the most serious potential complications following myomectomy. The precise risk of rupture after laparoscopic or robot-assisted laparoscopic myomectomy has not been determined.

Parker and colleagues evaluated case reports of uterine rupture after laparoscopic myomectomy in an attempt to identify a common causal risk factor. In their review of 19 uterine ruptures, however, they were unable to identify a single plausible risk factor. Uterine rupture has occurred in cases involving three-layer closure, removal of pedunculated fibroids, removal of fibroids as small as 1 cm, and in cases where no thermal energy was used.10

Pregnancy rates and outcomes have not been well-established because of confounding variables, such as a high prevalence of infertility and difficulty with long-term follow-up. One of the largest retrospective case studies on this topic involved 872 women who underwent robot-assisted myomectomy.11 Preterm delivery was correlated with the number of myomas removed and an anterior location of the largest incision.11

Undock the robot for morcellation

We strongly recommend that fibroids be morcellated using the 5-mm laparoscope while the robot is undocked, for several reasons. First, we advocate use of the robotic camera port site for morcellation. In the umbilicus, or midline, patients generally experience less pain. And with insufflation, the camera port site is the highest point on the abdomen, allowing greater distance between the morcellator and the iliac vessels and other major structures.

Second, the 12-mm robotic camera is heavy and cumbersome, easily causing fatigue when held separately. The robotic arms and patient side cart are bulky and can be limiting, physically impeding the range of motion necessary to morcellate safely, effectively, and efficiently.

After undocking the robot, remove the midline camera port to introduce the morcellator with the aid of a 5-mm laparoscope through a lateral port. We recommend taking the patient out of a steep Trendelenberg position and placing her in minimal Trendelenberg during morcellation to keep the specimen and fragments from falling to the upper abdomen.

Perfect the art of morcellation

A number of morcellators use electrical or mechanical energy. Blades ranging in diameter from 12 to 20 mm also are available. We favor the reusable MOREsolution tissue-extraction system (Blue Endo, Lenexa, Kansas) with a disposable 20-mm blade, particularly for large or multiple myomas.

The art of morcellation can be learned (VIDEO 6 and VIDEO 7). We recommend the following strategies:

- Slower morcellation speeds cause less fragmentation but may prolong the surgery significantly when the myomas are large. For such myomas, as well as cases that involve significant calcification, we recommend morcellation speeds of at least 600 rpm.

- A beveled trocar is preferred because it allows for longer continuous morcellation along the surface of the myoma and less fragmentation and coring.

- As morcellation nears completion and the specimen begins to fragment more, use short bursts of activation with increased traction, and ask the assistant to help stabilize the end pieces. This approach will help minimize the dissemination of fragments throughout the entire abdominal and pelvic cavity.

- Reapproximate the fascia for all trocar sites larger than 10 mm to prevent incisional hernias. When you exchange the robotic camera port with the morcellator, only one port site will require fascial closure because all other trocar sites typically are 8 mm or smaller.

It is critical that you inspect and remove all fragments and debris after morcellation to prevent iatrogenic multiple peritoneal parasitic myomas. First described in 2006,12 this unusual complication, leiomyomatosis peritonealis disseminate, has been reported with greater frequency as minimally invasive surgery and morcellation have become more common. This complication is thought to arise from small fragments left behind after morcellation of a uterus or myoma. Although spontaneous cases can occur, they are rare.

Place an adhesion barrier

Myomectomy can induce the formation of significant adhesions. For that reason, as the final step before fascial closure, we recommend that an adhesion barrier be placed over any hysterotomy sites. Although they are indicated and FDA-approved only for laparotomy, we typically place Interceed (Ethicon, Cornelia, Georgia) or Seprafilm (Genzyme, Framingham, Massachusetts) over hysterotomy sites.

CODING FOR ROBOT-ASSISTED MYOMECTOMY: ADDITIONAL REIMBURSEMENT MAY NOT BE FORTHCOMING

Robot-assisted surgery is an emerging technology. As such, many health insurance companies, the American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG), and Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) editorial staff have weighed in on it. In essence, many payers have indicated that they will not provide the physician with additional reimbursement for performing a surgical procedure using robotic assistance. That is not to say that all payers will rule out additional reimbursement, although most of the larger payers have indicated that additional reimbursement is not going to happen.

Both ACOG and CPT officials have indicated that robot-assisted surgical procedures should be reported using existing CPT codes, based on the procedure and the surgical approach used, rather than coding them as an unlisted procedure. These organizations also have indicated that use of the modifier –22 on the basic laparoscopic procedure would be inappropriate because robotic assistance does not represent an unusual procedure, based on the patient’s condition.

However, if there is a chance that you can gain additional reimbursement for robotic surgery, how can you inform the payer that it was performed? The only currently accepted way to do so is to report code S2900, Surgical techniques requiring use of robotic surgical system (list separately in addition to the code for the primary procedure), in addition to the basic code for the laparoscopic approach. Code S2900 was added by CPT to the national code set in 2005 at the request of Blue Cross/Blue Shield so that the payer could track the incidence of robotic surgery. Because it is not a “regular” CPT code, S2900 was never assigned a relative value, so it is up to the surgeon to set a surgical charge for use of the robot. In doing so, the surgeon must be able to provide supporting documentation as to why additional reimbursement is being requested and on what basis the charge was calculated.

Therefore, if a robot-assisted laparoscopic myomectomy is performed, the first CPT code listed on the claim should be 58545, Laparoscopy, surgical, myomectomy, excision; 1 to 4 intramural myomas with total weight of 250 g or less and/or removal of surface myomas. An alternative would be code 58546, Laparoscopy, surgical, myomectomy, excision; 5 or more intramural myomas and/or intramural myomas with total weight greater than 250 g.

Code S2900 then would be listed second. No modifiers (such as modifier –59 [distinct procedure] or –51 [multiple procedures]) should be added to S2900 because this code does not represent either a distinct or multiple surgical procedure.

—MELANIE WITT, RN, CPC, COBGC, MA

Ms. Witt is an independent coding and documentation consultant and former program manager, department of coding and nomenclature, American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists.

CASE: RESOLVED

Because of the patient’s religious beliefs, minimal blood loss is an important goal for any surgery she undergoes. Consequently, you recommend robot-assisted laparoscopic myomectomy, and the operation is completed without complications.

TAKE-HOME MESSAGE

The success of minimally invasive myomectomy requires a careful preoperative work-up and thorough understanding of surgical dissection and suturing techniques. In combination with this knowledge, advanced surgical technology, such as robotics and barbed suture, can truly transform the way myomectomy is performed, providing both patients and physicians with additional options for the conservative management of symptomatic uterine fibroids.

KEY POINTS FOR SUCCESS WITH THE ROBOT

Select patients with care for robot-assisted laparoscopic myomectomy, and perform thorough preoperative assessment. When planning a surgical approach, keep in mind the patient’s uterine size and body habitus and the quantity, size, consistency, type, and location of fibroids.

Use preoperative magnetic resonance imaging to characterize and locate fibroids and differentiate adenomyosis from leiomyomas.

In patients with a uterus larger than approximately 14- to 16-weeks’ size, consider a supraumbilical camera port.

Although the 12-mm Xcel trocar comes in a variety of lengths (75–150 mm), use the 150-mm length for the camera port. Once the camera is docked high on the neck of the longer trocar, more space is created between the setup joints of the robotic arms, enabling greater range of motion and fewer instrument and arm collisions.

Whenever possible, perform a transverse hysterotomy, keeping the length of the incision as short as possible and minimizing use of thermal energy during enucleation of fibroids.

Do not enucleate myomas through force, but apply traction and position each fibroid in order to best delineate and pre-sent the leading edge between the myoma and the myometrium.

Use multilayer closure with reapproximation of the myometrium and serosal edges to achieve hemostasis and prevent hematoma.

Perform morcellation through a 5-mm laparoscope with the robot undocked, using the camera port site for morcellation.

Take the patient out of a steep Trendelenberg position and place her in minimal Trendelenberg during morcellation to optimize ergonomics and prevent fragments from falling into the upper

abdomen.

Inspect the abdomen and remove all fragments and debris after morcellation to help prevent leiomyomatosis peritonealis disseminate.

- Advincula AP, Xu X, Goudeau S 4th, Ransom SB. Robot-assisted laparoscopic myomectomy versus abdominal myomectomy: a comparison of short-term surgical outcomes and immediate costs. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2007;14(6):698–705.

- Barakat EE, Bedaiwy MA, Zimberg S, Nutter B, Nosseir M, Falcone T. Robotic-assisted, laparoscopic, and abdominal myomectomy: a comparison of surgical outcomes. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;117(2 Pt 1):256–265.

- Glasser MH. Minilaparotomy myomectomy: a minimally invasive alternative for the large fibroid uterus. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2005;12(3):275–283.

- Hung MH, Wang YM, Chia YY, Liu K. Intramyometrial injection of vasopressin causes bradycardia and cardiac arrest—report of two cases. Acta Anaesthesiol Taiwan. 2006;44(4):243–247.

- Tulandi T, Beique F, Kimia M. Pulmonary edema: a complication of local injection of. Fertil Steril. 1996;66(3):478–480.

- Nezhat F, Admon D Nezhat CH, Dicorpo JE, Nezhat C. Life-threatening hypotension after vasopressin injection during operative laparoscopy, followed by uneventful repeat laparoscopy. J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc. 1994;2(1):83–86.

- Riess ML, Ulrichs JG, Pagel PS, Woehlck HJ. Case report: Severe vasospasm mimics hypotension after high-dose intrauterine vasopressin. Anesth Analg. 2011;113(5):1103–1105.

- Einarsson JI, Chavan NR, Suzuki Y, Jonsdottir G, Vellinga TT, Greenberg JA. Use of bidirectional barbed suture in laparoscopic myomectomy: evaluation of perioperative outcomes, safety and efficacy. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2011;18(1):92–95.

- Angioli R, Plotti F, Montera R, et al. A new type of absorbable barbed suture for use in laparoscopic myomectomy. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2012;117(3):220–223.

- Parker WH, Einarsson J, Istre O, Dubuisson J. Risk factors for uterine rupture after laparoscopic myomectomy. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2010;17(5):551–554.

- Pitter MC, Gargiulo AR, Bonaventura LM, Lehman JS, Srouji SS. Pregnancy outcomes following robot-assisted myomectomy. Hum Reprod. 2013;28(1):99–108.

- Paul PG, Koshy AK. Multiple peritoneal parasitic myomas after laparoscopic myomectomy and morcellation. Fertil Steril. 2006;85(2):492–493.

CASE: IS OPEN MYOMECTOMY THE BEST OPTION FOR THIS PATIENT?

In her only pregnancy, a 34-year-old patient experienced a spontaneous first-trimester loss and underwent dilation and curettage. She had noted an increase in her abdominal girth, as well as pelvic pressure, but had attributed both to the pregnancy. Three months after the pregnancy loss, however, neither had resolved. Because she hopes to conceive again and deliver a healthy infant, the patient consulted a gynecologist. After ultrasonography revealed multiple fibroids, that physician recommended open myomectomy. The patient, a Jehovah’s Witness, comes to your office for a second opinion.

On physical examination, she has a 16-weeks’ sized irregular uterus with the cervix displaced behind the pubic symphysis. T2 weighted scans from magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the pelvis in the sagittal view reveal multiple subserosal and intramural fibroids that displace, but do not involve, the uterine cavity (FIGURE 2). The MRI results confirm that the uterus extends beyond the pelvis above the sacral promontory, the fundus lies a few centimeters below the umbilicus, and there is no evidence of adenomyosis. The patient’s hemoglobin level is normal (12.2 g/dL).

What surgical approach would you recommend?

Endometrial ablation, uterine artery embolization, MRI-guided focused ultrasound, hysterectomy, and myomectomy are all treatments for symptomatic uterine fibroids. For women desiring uterine preservation and future fertility, however, myomectomy is the preferred option of many experts.

Myomectomy traditionally has been performed via an open laparotomy approach. With the rise of minimally invasive surgery in gynecology, safe endoscopic surgical approaches and techniques have evolved.

The EndoWrist technology from the da Vinci Surgical System (Intuitive Surgical, Sunnyvale, California) provides increased instrument range of motion, enabling the surgeon to mimic open surgical technique, thereby simplifying the technical challenges of conventional laparoscopic suturing and knot-tying. However, this technology does not minimize or simplify the challenges that leiomyomas can pose, including enucleation (FIGURE 1). Although it has facilitated the progression and adoption of endoscopic myomectomy, the da Vinci system requires an experienced gynecologic endoscopic surgeon.

In this article, we outline the essential steps and offer some clinical surgical pearls to make robot-assisted laparoscopic myomectomy a systematic, safe, and efficient procedure.

Benefits of the robotic approach

Compared with open abdominal myomectomy, the robot-assisted laparoscopic approach is associated with less blood loss, lower complication rates, and shorter hospitalization.1 A retrospective case study from the Cleveland Clinic confirmed these findings when investigators compared surgical outcomes between the robot-assisted laparoscopic approach, standard laparoscopy, and open myomectomy.2 In an assessment of 575 cases (393 open, 93 laparoscopic, and 89 robot-assisted laparoscopic), they found the robot-assisted laparoscopic approach to be associated with the removal of significantly larger myomas (vs standard laparoscopy), as well as lower blood loss and shorter hospitalization (vs open myomectomy).2

Related Article: The robot is gaining ground in gynecologic surgery. Should you be using it?

Comprehensive preoperative assessment is critical

Careful patient selection and thorough preoperative assessment are the cornerstones of successful robot-assisted laparoscopic myomectomy. Among the variables that should be considered in selecting patients are uterine size, the patient’s body habitus, and the quantity, size, consistency, type, and location of fibroids.

Size of the uterus, body habitus, and laxity of the abdominal wall all influence the surgeon’s ability to create the necessary operating space. Intraperitoneal space is required during myomectomy because of the need to apply traction and countertraction during enucleation of fibroids. If the necessary space cannot be obtained, a minilaparotomy technique is one alternative. This technique, described by Glasser, limits the skin incision to 3 to 6 cm in myomectomies for large fibroids that can be accessed easily anteriorly.3

Number and location of fibroids. Women with a solitary fibroid, a few dominant fibroids, or multiple pedunculated fibroids are excellent candidates for an endoscopic approach. Although there are no limits on the number of fibroids that can be removed, women with what we have termed “miliary fibroids,” or multiple fibroids disseminated throughout the entire myometrium, with very little normal myometrium, are poor surgical candidates. Not only does the presence of these fibroids leave some concern about the functional ability of the remaining myometrium in pregnancy, but it may be technically difficult to adequately resect all of the critical fibroids and reapproximate the myometrial defects.

The consistency of fibroids also affects the ease of the enucleation process during myomectomy. Due to the soft, spongy nature of degenerating fibroids and their tendency to fragment and shred when manipulated, these cases are more challenging and should not be attempted without a solid foundation of surgical experience.

MRI serves several purposes

Fibroids can be localized and identified as pedunculated, subserosal, intramural, or submucosal via MRI. Measurements and spatial orientation of the fibroids within the uterus can be formulated using T2 weighted coronal, axial, and sagittal images.

The risk of entering the uterine cavity, as well as the risk of synechiae, may be significantly greater if leiomyomas abut and distort the cavity. Surgical strategies, such as planning the location of the hysterotomy or the inclusion of other procedures (eg, hysteroscopic resection for type 0 or type 1 submucosal fibroids), can be formulated with the information provided by MRI. In cases involving multiple fibroids or intramural fibroids, in particular, MRI serves as a surgical “treasure map” or “GPS.” Preoperative MRI is also one way to offset the lack of haptic feedback during surgery to locate the myomas for removal. As we mentioned earlier, important characteristics, such as degeneration or calcification, also can be readily observed on MRI.

Most important, MRI can distinguish adenomyosis from leiomyomas. Adenomyosis can mimic leiomyomas—both clinically and on sonographic imaging—particularly when it is focal in nature. MRI can make the distinction between these two entities so that patients can be counseled appropriately.

SURGICAL TECHNIQUES

Use a uterine manipulator

This device will facilitate the enucleation process, providing another focal point for traction and countertraction. A variety of uterine manipulators are available. We use the Advincula Arch (Cooper Surgical, Trumball, Connecticut) in conjunction with the Uterine Positioning System (Cooper Surgical). The latter attaches to the operating table and to the Advincula Arch to secure the uterus in a steady position throughout the procedure.

During enucleation, the manipulator is crucial to hold the uterus within the pelvis and the field of vision and to act as countertraction as traction is applied to the fibroid.

Individualize port placement

Rather than premeasure port placement on the abdomen, we individualize it, based on a variety of characteristics, including body habitus and uterine pathology (FIGURE 3). However, we follow some basic principles:

- We insert a Veress needle through the umbilicus to achieve pneumoperitoneum

- After insufflation, we use an upper quadrant entry (right or left, depending on which side the robot patient side cart is docked) under direct visualization using a 5-mm laparoscope and optical trocar. This entry will serve as the assistant port for surgery.

- Before placing the rest of the ports under direct visualization, relative to uterine pathology, we elevate the uterus out of the pelvis. This step ensures that enough distance is placed between the camera and the instrument arms to adequately visualize and perform the surgery.

- In patients with a uterus larger than approximately 14- to 16-weeks’ size, a supraumbilical camera port often is necessary.

- We generally employ a four-arm technique using a 12-mm Xcel trocar (Ethicon Endo-Surgery, Blue Ash, Ohio) that is 150 mm in length for the camera port, three 8-mm telerobotic trocar ports, and a 5-mm Airseal trocar (SurgiQuest, Orange, Connecticut) for the assistant port. There should be at least one hand’s breadth between the ports to minimize arm collision and maximize range of motion.

- Although the 12-mm Xcel trocar comes in a variety of lengths (75–150 mm), we strongly recommend, and exclusively use, the longest length for the camera. Once the camera is docked high on the neck of the longer trocar, more space is created between the setup joints of the robotic arms, enabling greater range of motion and fewer instrument and arm collisions.

- We generally use the following wristed robotic instruments to perform myomectomy: tenaculum, monopolar scissors, and PlasmaKinetic (PK) bipolar forceps.

Inject vasopressin into the myometrium

Vasopressin causes vasospasm and uterine muscle contraction and decreases blood loss during myomectomy. It should be diluted (20 U in 50–200 mL of normal saline), introduced with a 7-inch, 22-gauge spinal needle through the anterior abdominal wall, and injected into the myometrium and serosa overlying the fibroid (VIDEO 1 and VIDEO 2).

Perform this step with care, with aspiration prior to injection, to avoid intravascular injection. Although vasopressin is safe overall, serious complications and rare cases of life-threatening hypotension, pulmonary edema, bradycardia, and cardiac arrest have been reported after the injection of as little as 3 U into the myometrium.4–7

Relative contraindications to vasopressin, such as hypertension, should be discussed with anesthesia prior to use of the drug during surgery.

Enucleate the fibroid

Although either a vertical or a horizontal-transverse incision can be made overlying the uterus, a transverse incision allows for technical optimization of wristed movements for suturing and efficient closure. Whenever possible, therefore, we favor a transverse hysterotomy.

During enucleation, keep the use of thermal energy to a minimum. The same holds true for the uterine incision, although its length can be extended as needed.

Using the wristed robotic tenaculum (or an assistant using a laparoscopic tenaculum or corkscrew), grasp and elevate the myoma away from the fixed uterus (FIGURE 1). This step is not intended to enucleate the myoma through force, but to apply traction and position the fibroid to best delineate and present the leading edge of the pseudocapsule that lies between the myoma and the myometrium. Dissection then can proceed using a “push and spread” technique, bluntly separating the natural plane between the fibroid and the myometrium. Occasionally, fibrous attachments of the pseudocapsule can be transected sharply using the bipolar forceps and monopolar scissors.

Again, we encourage the intermittent use of minimal thermal energy to facilitate this process and achieve temporary hemostasis. As the dissection progresses, the fibroid can be regrasped closer to its leading edge, causing the myoma to be rolled out (VIDEO 3 and VIDEO 4).

Close the myometrium We advocate multilayer closure with reapproximation of the myometrium and serosal edges to achieve hemostasis and prevent hematoma (VIDEO 5).

The half-life of vasopressin ranges from 20 to 40 minutes. By this point of the procedure, assuming that the use of thermal energy has been minimal, the myometrial edges should be bleeding slightly, demonstrating adequate reperfusion. The myometrial defect then can be repaired using delayed absorbable suture, such as 2-0 V-Loc 180 (Covidien, Mansfield, Massachusetts).

Barbed suture has revolutionized laparoscopy and minimally invasive surgery, eliminating the need for endoscopic knot-tying. Quill suture (Angiotech, Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada) and V-Loc suture are used safely throughout gynecology, myomectomy included.8,9 However, when the endometrial cavity has been entered, avoid using barbed suture to reapproximate this initial layer to prevent synechiae.

No closure technique has been shown to prevent uterine rupture. Uterine rupture during pregnancy is one of the most serious potential complications following myomectomy. The precise risk of rupture after laparoscopic or robot-assisted laparoscopic myomectomy has not been determined.

Parker and colleagues evaluated case reports of uterine rupture after laparoscopic myomectomy in an attempt to identify a common causal risk factor. In their review of 19 uterine ruptures, however, they were unable to identify a single plausible risk factor. Uterine rupture has occurred in cases involving three-layer closure, removal of pedunculated fibroids, removal of fibroids as small as 1 cm, and in cases where no thermal energy was used.10

Pregnancy rates and outcomes have not been well-established because of confounding variables, such as a high prevalence of infertility and difficulty with long-term follow-up. One of the largest retrospective case studies on this topic involved 872 women who underwent robot-assisted myomectomy.11 Preterm delivery was correlated with the number of myomas removed and an anterior location of the largest incision.11

Undock the robot for morcellation

We strongly recommend that fibroids be morcellated using the 5-mm laparoscope while the robot is undocked, for several reasons. First, we advocate use of the robotic camera port site for morcellation. In the umbilicus, or midline, patients generally experience less pain. And with insufflation, the camera port site is the highest point on the abdomen, allowing greater distance between the morcellator and the iliac vessels and other major structures.

Second, the 12-mm robotic camera is heavy and cumbersome, easily causing fatigue when held separately. The robotic arms and patient side cart are bulky and can be limiting, physically impeding the range of motion necessary to morcellate safely, effectively, and efficiently.

After undocking the robot, remove the midline camera port to introduce the morcellator with the aid of a 5-mm laparoscope through a lateral port. We recommend taking the patient out of a steep Trendelenberg position and placing her in minimal Trendelenberg during morcellation to keep the specimen and fragments from falling to the upper abdomen.

Perfect the art of morcellation

A number of morcellators use electrical or mechanical energy. Blades ranging in diameter from 12 to 20 mm also are available. We favor the reusable MOREsolution tissue-extraction system (Blue Endo, Lenexa, Kansas) with a disposable 20-mm blade, particularly for large or multiple myomas.

The art of morcellation can be learned (VIDEO 6 and VIDEO 7). We recommend the following strategies:

- Slower morcellation speeds cause less fragmentation but may prolong the surgery significantly when the myomas are large. For such myomas, as well as cases that involve significant calcification, we recommend morcellation speeds of at least 600 rpm.

- A beveled trocar is preferred because it allows for longer continuous morcellation along the surface of the myoma and less fragmentation and coring.

- As morcellation nears completion and the specimen begins to fragment more, use short bursts of activation with increased traction, and ask the assistant to help stabilize the end pieces. This approach will help minimize the dissemination of fragments throughout the entire abdominal and pelvic cavity.

- Reapproximate the fascia for all trocar sites larger than 10 mm to prevent incisional hernias. When you exchange the robotic camera port with the morcellator, only one port site will require fascial closure because all other trocar sites typically are 8 mm or smaller.

It is critical that you inspect and remove all fragments and debris after morcellation to prevent iatrogenic multiple peritoneal parasitic myomas. First described in 2006,12 this unusual complication, leiomyomatosis peritonealis disseminate, has been reported with greater frequency as minimally invasive surgery and morcellation have become more common. This complication is thought to arise from small fragments left behind after morcellation of a uterus or myoma. Although spontaneous cases can occur, they are rare.

Place an adhesion barrier

Myomectomy can induce the formation of significant adhesions. For that reason, as the final step before fascial closure, we recommend that an adhesion barrier be placed over any hysterotomy sites. Although they are indicated and FDA-approved only for laparotomy, we typically place Interceed (Ethicon, Cornelia, Georgia) or Seprafilm (Genzyme, Framingham, Massachusetts) over hysterotomy sites.

CODING FOR ROBOT-ASSISTED MYOMECTOMY: ADDITIONAL REIMBURSEMENT MAY NOT BE FORTHCOMING

Robot-assisted surgery is an emerging technology. As such, many health insurance companies, the American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG), and Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) editorial staff have weighed in on it. In essence, many payers have indicated that they will not provide the physician with additional reimbursement for performing a surgical procedure using robotic assistance. That is not to say that all payers will rule out additional reimbursement, although most of the larger payers have indicated that additional reimbursement is not going to happen.

Both ACOG and CPT officials have indicated that robot-assisted surgical procedures should be reported using existing CPT codes, based on the procedure and the surgical approach used, rather than coding them as an unlisted procedure. These organizations also have indicated that use of the modifier –22 on the basic laparoscopic procedure would be inappropriate because robotic assistance does not represent an unusual procedure, based on the patient’s condition.

However, if there is a chance that you can gain additional reimbursement for robotic surgery, how can you inform the payer that it was performed? The only currently accepted way to do so is to report code S2900, Surgical techniques requiring use of robotic surgical system (list separately in addition to the code for the primary procedure), in addition to the basic code for the laparoscopic approach. Code S2900 was added by CPT to the national code set in 2005 at the request of Blue Cross/Blue Shield so that the payer could track the incidence of robotic surgery. Because it is not a “regular” CPT code, S2900 was never assigned a relative value, so it is up to the surgeon to set a surgical charge for use of the robot. In doing so, the surgeon must be able to provide supporting documentation as to why additional reimbursement is being requested and on what basis the charge was calculated.

Therefore, if a robot-assisted laparoscopic myomectomy is performed, the first CPT code listed on the claim should be 58545, Laparoscopy, surgical, myomectomy, excision; 1 to 4 intramural myomas with total weight of 250 g or less and/or removal of surface myomas. An alternative would be code 58546, Laparoscopy, surgical, myomectomy, excision; 5 or more intramural myomas and/or intramural myomas with total weight greater than 250 g.

Code S2900 then would be listed second. No modifiers (such as modifier –59 [distinct procedure] or –51 [multiple procedures]) should be added to S2900 because this code does not represent either a distinct or multiple surgical procedure.

—MELANIE WITT, RN, CPC, COBGC, MA

Ms. Witt is an independent coding and documentation consultant and former program manager, department of coding and nomenclature, American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists.

CASE: RESOLVED

Because of the patient’s religious beliefs, minimal blood loss is an important goal for any surgery she undergoes. Consequently, you recommend robot-assisted laparoscopic myomectomy, and the operation is completed without complications.

TAKE-HOME MESSAGE

The success of minimally invasive myomectomy requires a careful preoperative work-up and thorough understanding of surgical dissection and suturing techniques. In combination with this knowledge, advanced surgical technology, such as robotics and barbed suture, can truly transform the way myomectomy is performed, providing both patients and physicians with additional options for the conservative management of symptomatic uterine fibroids.

KEY POINTS FOR SUCCESS WITH THE ROBOT

Select patients with care for robot-assisted laparoscopic myomectomy, and perform thorough preoperative assessment. When planning a surgical approach, keep in mind the patient’s uterine size and body habitus and the quantity, size, consistency, type, and location of fibroids.

Use preoperative magnetic resonance imaging to characterize and locate fibroids and differentiate adenomyosis from leiomyomas.

In patients with a uterus larger than approximately 14- to 16-weeks’ size, consider a supraumbilical camera port.

Although the 12-mm Xcel trocar comes in a variety of lengths (75–150 mm), use the 150-mm length for the camera port. Once the camera is docked high on the neck of the longer trocar, more space is created between the setup joints of the robotic arms, enabling greater range of motion and fewer instrument and arm collisions.

Whenever possible, perform a transverse hysterotomy, keeping the length of the incision as short as possible and minimizing use of thermal energy during enucleation of fibroids.

Do not enucleate myomas through force, but apply traction and position each fibroid in order to best delineate and pre-sent the leading edge between the myoma and the myometrium.

Use multilayer closure with reapproximation of the myometrium and serosal edges to achieve hemostasis and prevent hematoma.

Perform morcellation through a 5-mm laparoscope with the robot undocked, using the camera port site for morcellation.

Take the patient out of a steep Trendelenberg position and place her in minimal Trendelenberg during morcellation to optimize ergonomics and prevent fragments from falling into the upper

abdomen.

Inspect the abdomen and remove all fragments and debris after morcellation to help prevent leiomyomatosis peritonealis disseminate.

CASE: IS OPEN MYOMECTOMY THE BEST OPTION FOR THIS PATIENT?

In her only pregnancy, a 34-year-old patient experienced a spontaneous first-trimester loss and underwent dilation and curettage. She had noted an increase in her abdominal girth, as well as pelvic pressure, but had attributed both to the pregnancy. Three months after the pregnancy loss, however, neither had resolved. Because she hopes to conceive again and deliver a healthy infant, the patient consulted a gynecologist. After ultrasonography revealed multiple fibroids, that physician recommended open myomectomy. The patient, a Jehovah’s Witness, comes to your office for a second opinion.

On physical examination, she has a 16-weeks’ sized irregular uterus with the cervix displaced behind the pubic symphysis. T2 weighted scans from magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the pelvis in the sagittal view reveal multiple subserosal and intramural fibroids that displace, but do not involve, the uterine cavity (FIGURE 2). The MRI results confirm that the uterus extends beyond the pelvis above the sacral promontory, the fundus lies a few centimeters below the umbilicus, and there is no evidence of adenomyosis. The patient’s hemoglobin level is normal (12.2 g/dL).

What surgical approach would you recommend?

Endometrial ablation, uterine artery embolization, MRI-guided focused ultrasound, hysterectomy, and myomectomy are all treatments for symptomatic uterine fibroids. For women desiring uterine preservation and future fertility, however, myomectomy is the preferred option of many experts.

Myomectomy traditionally has been performed via an open laparotomy approach. With the rise of minimally invasive surgery in gynecology, safe endoscopic surgical approaches and techniques have evolved.

The EndoWrist technology from the da Vinci Surgical System (Intuitive Surgical, Sunnyvale, California) provides increased instrument range of motion, enabling the surgeon to mimic open surgical technique, thereby simplifying the technical challenges of conventional laparoscopic suturing and knot-tying. However, this technology does not minimize or simplify the challenges that leiomyomas can pose, including enucleation (FIGURE 1). Although it has facilitated the progression and adoption of endoscopic myomectomy, the da Vinci system requires an experienced gynecologic endoscopic surgeon.

In this article, we outline the essential steps and offer some clinical surgical pearls to make robot-assisted laparoscopic myomectomy a systematic, safe, and efficient procedure.

Benefits of the robotic approach

Compared with open abdominal myomectomy, the robot-assisted laparoscopic approach is associated with less blood loss, lower complication rates, and shorter hospitalization.1 A retrospective case study from the Cleveland Clinic confirmed these findings when investigators compared surgical outcomes between the robot-assisted laparoscopic approach, standard laparoscopy, and open myomectomy.2 In an assessment of 575 cases (393 open, 93 laparoscopic, and 89 robot-assisted laparoscopic), they found the robot-assisted laparoscopic approach to be associated with the removal of significantly larger myomas (vs standard laparoscopy), as well as lower blood loss and shorter hospitalization (vs open myomectomy).2

Related Article: The robot is gaining ground in gynecologic surgery. Should you be using it?

Comprehensive preoperative assessment is critical

Careful patient selection and thorough preoperative assessment are the cornerstones of successful robot-assisted laparoscopic myomectomy. Among the variables that should be considered in selecting patients are uterine size, the patient’s body habitus, and the quantity, size, consistency, type, and location of fibroids.

Size of the uterus, body habitus, and laxity of the abdominal wall all influence the surgeon’s ability to create the necessary operating space. Intraperitoneal space is required during myomectomy because of the need to apply traction and countertraction during enucleation of fibroids. If the necessary space cannot be obtained, a minilaparotomy technique is one alternative. This technique, described by Glasser, limits the skin incision to 3 to 6 cm in myomectomies for large fibroids that can be accessed easily anteriorly.3

Number and location of fibroids. Women with a solitary fibroid, a few dominant fibroids, or multiple pedunculated fibroids are excellent candidates for an endoscopic approach. Although there are no limits on the number of fibroids that can be removed, women with what we have termed “miliary fibroids,” or multiple fibroids disseminated throughout the entire myometrium, with very little normal myometrium, are poor surgical candidates. Not only does the presence of these fibroids leave some concern about the functional ability of the remaining myometrium in pregnancy, but it may be technically difficult to adequately resect all of the critical fibroids and reapproximate the myometrial defects.

The consistency of fibroids also affects the ease of the enucleation process during myomectomy. Due to the soft, spongy nature of degenerating fibroids and their tendency to fragment and shred when manipulated, these cases are more challenging and should not be attempted without a solid foundation of surgical experience.

MRI serves several purposes

Fibroids can be localized and identified as pedunculated, subserosal, intramural, or submucosal via MRI. Measurements and spatial orientation of the fibroids within the uterus can be formulated using T2 weighted coronal, axial, and sagittal images.

The risk of entering the uterine cavity, as well as the risk of synechiae, may be significantly greater if leiomyomas abut and distort the cavity. Surgical strategies, such as planning the location of the hysterotomy or the inclusion of other procedures (eg, hysteroscopic resection for type 0 or type 1 submucosal fibroids), can be formulated with the information provided by MRI. In cases involving multiple fibroids or intramural fibroids, in particular, MRI serves as a surgical “treasure map” or “GPS.” Preoperative MRI is also one way to offset the lack of haptic feedback during surgery to locate the myomas for removal. As we mentioned earlier, important characteristics, such as degeneration or calcification, also can be readily observed on MRI.

Most important, MRI can distinguish adenomyosis from leiomyomas. Adenomyosis can mimic leiomyomas—both clinically and on sonographic imaging—particularly when it is focal in nature. MRI can make the distinction between these two entities so that patients can be counseled appropriately.

SURGICAL TECHNIQUES

Use a uterine manipulator

This device will facilitate the enucleation process, providing another focal point for traction and countertraction. A variety of uterine manipulators are available. We use the Advincula Arch (Cooper Surgical, Trumball, Connecticut) in conjunction with the Uterine Positioning System (Cooper Surgical). The latter attaches to the operating table and to the Advincula Arch to secure the uterus in a steady position throughout the procedure.

During enucleation, the manipulator is crucial to hold the uterus within the pelvis and the field of vision and to act as countertraction as traction is applied to the fibroid.

Individualize port placement

Rather than premeasure port placement on the abdomen, we individualize it, based on a variety of characteristics, including body habitus and uterine pathology (FIGURE 3). However, we follow some basic principles:

- We insert a Veress needle through the umbilicus to achieve pneumoperitoneum

- After insufflation, we use an upper quadrant entry (right or left, depending on which side the robot patient side cart is docked) under direct visualization using a 5-mm laparoscope and optical trocar. This entry will serve as the assistant port for surgery.

- Before placing the rest of the ports under direct visualization, relative to uterine pathology, we elevate the uterus out of the pelvis. This step ensures that enough distance is placed between the camera and the instrument arms to adequately visualize and perform the surgery.

- In patients with a uterus larger than approximately 14- to 16-weeks’ size, a supraumbilical camera port often is necessary.

- We generally employ a four-arm technique using a 12-mm Xcel trocar (Ethicon Endo-Surgery, Blue Ash, Ohio) that is 150 mm in length for the camera port, three 8-mm telerobotic trocar ports, and a 5-mm Airseal trocar (SurgiQuest, Orange, Connecticut) for the assistant port. There should be at least one hand’s breadth between the ports to minimize arm collision and maximize range of motion.

- Although the 12-mm Xcel trocar comes in a variety of lengths (75–150 mm), we strongly recommend, and exclusively use, the longest length for the camera. Once the camera is docked high on the neck of the longer trocar, more space is created between the setup joints of the robotic arms, enabling greater range of motion and fewer instrument and arm collisions.

- We generally use the following wristed robotic instruments to perform myomectomy: tenaculum, monopolar scissors, and PlasmaKinetic (PK) bipolar forceps.

Inject vasopressin into the myometrium

Vasopressin causes vasospasm and uterine muscle contraction and decreases blood loss during myomectomy. It should be diluted (20 U in 50–200 mL of normal saline), introduced with a 7-inch, 22-gauge spinal needle through the anterior abdominal wall, and injected into the myometrium and serosa overlying the fibroid (VIDEO 1 and VIDEO 2).

Perform this step with care, with aspiration prior to injection, to avoid intravascular injection. Although vasopressin is safe overall, serious complications and rare cases of life-threatening hypotension, pulmonary edema, bradycardia, and cardiac arrest have been reported after the injection of as little as 3 U into the myometrium.4–7

Relative contraindications to vasopressin, such as hypertension, should be discussed with anesthesia prior to use of the drug during surgery.

Enucleate the fibroid

Although either a vertical or a horizontal-transverse incision can be made overlying the uterus, a transverse incision allows for technical optimization of wristed movements for suturing and efficient closure. Whenever possible, therefore, we favor a transverse hysterotomy.

During enucleation, keep the use of thermal energy to a minimum. The same holds true for the uterine incision, although its length can be extended as needed.

Using the wristed robotic tenaculum (or an assistant using a laparoscopic tenaculum or corkscrew), grasp and elevate the myoma away from the fixed uterus (FIGURE 1). This step is not intended to enucleate the myoma through force, but to apply traction and position the fibroid to best delineate and present the leading edge of the pseudocapsule that lies between the myoma and the myometrium. Dissection then can proceed using a “push and spread” technique, bluntly separating the natural plane between the fibroid and the myometrium. Occasionally, fibrous attachments of the pseudocapsule can be transected sharply using the bipolar forceps and monopolar scissors.

Again, we encourage the intermittent use of minimal thermal energy to facilitate this process and achieve temporary hemostasis. As the dissection progresses, the fibroid can be regrasped closer to its leading edge, causing the myoma to be rolled out (VIDEO 3 and VIDEO 4).

Close the myometrium We advocate multilayer closure with reapproximation of the myometrium and serosal edges to achieve hemostasis and prevent hematoma (VIDEO 5).

The half-life of vasopressin ranges from 20 to 40 minutes. By this point of the procedure, assuming that the use of thermal energy has been minimal, the myometrial edges should be bleeding slightly, demonstrating adequate reperfusion. The myometrial defect then can be repaired using delayed absorbable suture, such as 2-0 V-Loc 180 (Covidien, Mansfield, Massachusetts).

Barbed suture has revolutionized laparoscopy and minimally invasive surgery, eliminating the need for endoscopic knot-tying. Quill suture (Angiotech, Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada) and V-Loc suture are used safely throughout gynecology, myomectomy included.8,9 However, when the endometrial cavity has been entered, avoid using barbed suture to reapproximate this initial layer to prevent synechiae.

No closure technique has been shown to prevent uterine rupture. Uterine rupture during pregnancy is one of the most serious potential complications following myomectomy. The precise risk of rupture after laparoscopic or robot-assisted laparoscopic myomectomy has not been determined.

Parker and colleagues evaluated case reports of uterine rupture after laparoscopic myomectomy in an attempt to identify a common causal risk factor. In their review of 19 uterine ruptures, however, they were unable to identify a single plausible risk factor. Uterine rupture has occurred in cases involving three-layer closure, removal of pedunculated fibroids, removal of fibroids as small as 1 cm, and in cases where no thermal energy was used.10

Pregnancy rates and outcomes have not been well-established because of confounding variables, such as a high prevalence of infertility and difficulty with long-term follow-up. One of the largest retrospective case studies on this topic involved 872 women who underwent robot-assisted myomectomy.11 Preterm delivery was correlated with the number of myomas removed and an anterior location of the largest incision.11

Undock the robot for morcellation

We strongly recommend that fibroids be morcellated using the 5-mm laparoscope while the robot is undocked, for several reasons. First, we advocate use of the robotic camera port site for morcellation. In the umbilicus, or midline, patients generally experience less pain. And with insufflation, the camera port site is the highest point on the abdomen, allowing greater distance between the morcellator and the iliac vessels and other major structures.

Second, the 12-mm robotic camera is heavy and cumbersome, easily causing fatigue when held separately. The robotic arms and patient side cart are bulky and can be limiting, physically impeding the range of motion necessary to morcellate safely, effectively, and efficiently.

After undocking the robot, remove the midline camera port to introduce the morcellator with the aid of a 5-mm laparoscope through a lateral port. We recommend taking the patient out of a steep Trendelenberg position and placing her in minimal Trendelenberg during morcellation to keep the specimen and fragments from falling to the upper abdomen.

Perfect the art of morcellation

A number of morcellators use electrical or mechanical energy. Blades ranging in diameter from 12 to 20 mm also are available. We favor the reusable MOREsolution tissue-extraction system (Blue Endo, Lenexa, Kansas) with a disposable 20-mm blade, particularly for large or multiple myomas.

The art of morcellation can be learned (VIDEO 6 and VIDEO 7). We recommend the following strategies:

- Slower morcellation speeds cause less fragmentation but may prolong the surgery significantly when the myomas are large. For such myomas, as well as cases that involve significant calcification, we recommend morcellation speeds of at least 600 rpm.

- A beveled trocar is preferred because it allows for longer continuous morcellation along the surface of the myoma and less fragmentation and coring.

- As morcellation nears completion and the specimen begins to fragment more, use short bursts of activation with increased traction, and ask the assistant to help stabilize the end pieces. This approach will help minimize the dissemination of fragments throughout the entire abdominal and pelvic cavity.

- Reapproximate the fascia for all trocar sites larger than 10 mm to prevent incisional hernias. When you exchange the robotic camera port with the morcellator, only one port site will require fascial closure because all other trocar sites typically are 8 mm or smaller.

It is critical that you inspect and remove all fragments and debris after morcellation to prevent iatrogenic multiple peritoneal parasitic myomas. First described in 2006,12 this unusual complication, leiomyomatosis peritonealis disseminate, has been reported with greater frequency as minimally invasive surgery and morcellation have become more common. This complication is thought to arise from small fragments left behind after morcellation of a uterus or myoma. Although spontaneous cases can occur, they are rare.

Place an adhesion barrier

Myomectomy can induce the formation of significant adhesions. For that reason, as the final step before fascial closure, we recommend that an adhesion barrier be placed over any hysterotomy sites. Although they are indicated and FDA-approved only for laparotomy, we typically place Interceed (Ethicon, Cornelia, Georgia) or Seprafilm (Genzyme, Framingham, Massachusetts) over hysterotomy sites.

CODING FOR ROBOT-ASSISTED MYOMECTOMY: ADDITIONAL REIMBURSEMENT MAY NOT BE FORTHCOMING

Robot-assisted surgery is an emerging technology. As such, many health insurance companies, the American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG), and Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) editorial staff have weighed in on it. In essence, many payers have indicated that they will not provide the physician with additional reimbursement for performing a surgical procedure using robotic assistance. That is not to say that all payers will rule out additional reimbursement, although most of the larger payers have indicated that additional reimbursement is not going to happen.

Both ACOG and CPT officials have indicated that robot-assisted surgical procedures should be reported using existing CPT codes, based on the procedure and the surgical approach used, rather than coding them as an unlisted procedure. These organizations also have indicated that use of the modifier –22 on the basic laparoscopic procedure would be inappropriate because robotic assistance does not represent an unusual procedure, based on the patient’s condition.