User login

Psychotic and sexually deviant

CASE: Paranoid and distressed

Mr. P, age 21, is a single, white college student who presents to a psychiatric emergency room with his father at his psychotherapist’s recommendation. The psychotherapist, who has been treating Mr. P for anxiety and depression, recommended he be evaluated because of increased erratic behavior and paranoia. Mr. P reports that he has been feeling increasingly “anxious” and “paranoid” and thinks the security cameras at his college have been following him. He also describes an increased connection with God and hearing God’s voice as a commentary on his behaviors. Mr. P denies euphoria, depression, increased goal-directed activities, distractibility, increased impulsivity, or rapid speech. He is admitted voluntarily to the psychiatric unit for further evaluation.

During the hospitalization, Mr. P discloses that he has been viewing child pornography for 2 years, and during the past 6 months he has been distressed by the intensity of his sexual fantasies involving sexual contact with prepubescent girls. He also continues to experience paranoia and increased religiosity.

Mr. P says he began looking at pornography on the internet at age 14. He says he was watching “regular straight porn” and he would use it to masturbate and achieve orgasm. Mr. P began looking at child pornography at age 19. He stated that “regular porn” was no longer sufficiently arousing for him. Mr. P explains, “First, I started looking for 15- or 16-year-olds. They would work for a while [referring to sexual gratification], but then I would look for younger girls.” He says the images of younger girls are sexually arousing, typically “young girls, 8 to 10 years old” who are nude or involved in sex acts.

Mr. P denies sexual contact with prepubescent individuals and says his thoughts about such contact are “distressing.” He reports that he has viewed child pornography even when he wasn’t experiencing psychotic or mood symptoms. Mr. P’s outpatient psychotherapist reports that Mr. P first disclosed viewing child pornography and his attraction to prepubescent girls 2 years before this admission.

The authors’ observations

DSM-IV-TR diagnostic criteria for pedophilia (Table 1)1 are based on a history of sexual arousal to prepubescent individuals. A subset of sex offenders meet criteria for a paraphilia (Table 2),1 an axis I disorder, and a subset of sex offenders with paraphilia meet diagnostic criteria for pedophilia. Dunsieth et al2 found that among a sample of 113 male sex offenders, 74% had a diagnosable paraphilia, and 50% of individuals with paraphilia met criteria for pedophilia.

Table 1

DSM-IV-TR diagnostic criteria for pedophilia

| A) | Over a period of ≥6 months, recurrent, intense sexually arousing fantasies, sexual urges, or behaviors involving sexual activity with a prepubescent child or children (generally age ≤13) |

| B) | The person has acted on these sexual urges, or the sexual urges or fantasies cause marked distress or interpersonal difficulty |

| C) | The person is age ≥16 and ≥5 years older than the child or children in criterion A |

| Note: Do not include an individual in late adolescence involved in an ongoing sexual relationship with a 12- or 13-year-old | |

| Source: Reference 1 | |

DSM-IV-TR diagnostic criteria for a paraphilia

| The essential features of a paraphilia are recurrent, intense sexually arousing fantasies, sexual urges, or behaviors generally involving: | |

| A) | nonhuman objects, the suffering or humiliation of oneself or one’s partner, or children or other nonconsenting persons that occur over a period of ≥6 months |

| B) | The behavior, sexual urges, or fantasies cause clinically significant distress or impairment in social, occupational, or other important areas of functioning |

| Source: Reference 1 | |

Although most schizophrenia patients without a history of sexual offenses do not exhibit sexual deviancy, sexual content in hallucinations and delusions is common.6 Confusion about sexual identity and the boundaries of one’s body are common and may contribute to sexual deviancy.6 Psychiatric inpatients without a history of sexual offenses—including but not limited to psychotic patients—have higher rates of sexually deviant fantasies and behaviors compared with those without psychiatric illness.6 In one survey, 15% of men with schizophrenia displayed paraphilic behaviors and 20% had atypical sexual thoughts.7

Alish et al4 found that pedophilia was not necessarily linked to psychotic behavior or antisocial personality features when comparing pedophilia rates in individuals with or without schizophrenia. In a sample of 22 adolescent males who sexually molested a child at least once, axis I morbidity was common, and 55% met criteria for bipolar disorder.8

Few experts in paraphilias

A patient who endorses deviant sexual fantasies should be evaluated by a mental health professional with specialized training in paraphilias. Although paraphilias are not recognized as a subspecialty in psychiatry, diagnosing and treating patients with a paraphilia requires additional training. There is a scarcity of psychiatrists trained to evaluate and treat patients with paraphilias.

Sexual evaluation. Evaluating a patient who presents with problematic sexual behaviors includes performing a comprehensive psychiatric history with a focus on sexual history. A psychosexual history is distinct from general psychiatric evaluations because of the level of detail regarding a sexual history (Table 3). In addition to the clinical interview, objective testing to determine sexual interests may be useful in some patients (Table 4).9

Actuarial tools—risk assessment instruments based on statistically significant risk factors—are valid tools for determining the risk of sexual reoffending. There are several validated actuarial tools in the assessment of sex offender recidivism, such as the Static-99R,10 Stable-2007,11 and the Sex Offender Risk Appraisal Guide.12 However, these tools are used for sex offenders, and would not be used for individuals who have not committed a sex offense, such as Mr. P.

Table 3

Psychosexual evaluation

| Aspect of evaluation | Measures |

| Sexual behavior history | History of sexual abuse Childhood exposure to sex Masturbation history Preferred sexual partners Kinsey Scale |

| Sexual addiction or compulsion | Total Sexual Outlet measure Amount of time in sexual fantasy Financial, legal, or social cost of sexual behavior Prior treatment of sexual behavior |

| Sexual interests | Sex, age, and number of partner(s) Review of criteria for all paraphilias (exposing, voyeurism, cross-dressing, sadistic or masochistic interests) |

Objective testing to determine sexual interests

| Test | Results |

|---|---|

| Penile plethysmograph | Measures penis circumference with a mercury-in-rubber strain gauge. Used clinically by measuring circumferential changes in the penis while the patient is listening to audio or video stimuli of various sexual vignettes |

| Abel Assessment for Sexual Interests-3 | An objective method for evaluating deviant sexual interest uses noninvasive means to achieve objective measures of sexual interest. The subject’s visual response time is measured while viewing images of males and females of varying age. Visual reaction time is correlated with sexual interests |

| Source: Reference 9 | |

Medicolegal aspects of a psychosexual evaluation may include mandated reporting, confidentiality, and documentation. Mental health professionals are mandated to report to law enforcement or child welfare agencies when they observe or suspect physical, sexual, or other types of abuse in vulnerable populations such as children. In psychosexual evaluations, the evaluator is legally required to report if a patient discloses current sexual behavior with a child with a plan to continue to engage in the behavior. In Mr. P’s case, there was no duty to report because although he described viewing child pornography and had a sexual interest in prepubescent individuals, he did not report a history of engaging in handson sexual behaviors with children or impulses to do so. When an individual has engaged in sexual contact with a prepubescent individual, reporting is not mandated unless the individual continues to engage in sexual behavior with a minor. Mental health professionals are not responsible for calling the police or alerting authorities after a crime has been committed.

The relationship between viewing child pornography and pedophilia is unclear. Some child pornography viewers are pedophilic, others are sexually compulsive, and others are viewing out of curiosity and have no sexual deviance. Seto et al13 suggested that child pornography offenders show greater sexual arousal to children than to adults. Persistent child pornography use is a stronger diagnostic indicator of pedophilia than sexually offending against child victims.13 A clinician who learns that a patient is viewing child pornography should take a detailed sexual history, including a review of criteria for paraphilias. In addition, when appropriate, the clinician should perform a risk assessment to determine the patient’s risk of engaging in sexual offenses with children.

OUTCOME: Expert consultation

We start Mr. P on risperidone, 1 mg/d, to treat his paranoia and request a consultation with an expert in paraphilias to determine if Mr. P has a paraphilia and to discuss treatment options.

Mr. P’s initial diagnosis is psychotic disorder not otherwise specified. His viewing of child pornography and sexual interest in prepubescent individuals is not limited to his current mental status, and these interests persist in the absence of mood and psychotic states. Mr. P’s viewing of child pornography and sexual attraction to prepubescent girls meet the diagnostic criteria for pedophilia. During hospitalization, we educate Mr. P about his diagnoses and need for continued treatment. We refer him to a sexual disorders outpatient clinic, which continues to address his deviant sexual interests.

The authors’ observations

A meta-analysis indicates that a combination of pharmacologic and behavioral treatments coupled with close legal supervision seems to reduce the risk of repeated sexual offenses.14 Legal supervision is a general term to describe oversight of offenders in the community by supervisory boards, such as probation or parole, and tracking devices such as GPS. Currently, pedophilia treatment focuses on minimizing deviant sexual arousal through behavioral modification, cognitive-behavioral therapies, and testosterone-lowering medications, such as medroxyprogesterone or leuprolide. The decision to prescribe testosterone-lowering medication should be based on informed consent and the patient’s risk of dangerous sexual behaviors.

- Reijnen L, Bulten E, Nijman H. Demographic and personality characteristics of internet child pornography downloaders in comparison to other offenders. J Child Sex Abus. 2009;18(6):611-622.

- Hall RC, Hall RC. A profile of pedophilia: definition, characteristics of offenders, recidivism, treatment outcomes, and forensic issues. Mayo Clin Proc. 2007;82(4):457-471.

- Leuprolide • Eligard, Lupron

- Medroxyprogesterone • Cycrin, Provera

- Risperidone • Risperdal

The authors report no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 4th ed, text rev. Washington DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000.

2. Dunsieth NW, Jr, Nelson EB, Brusman-Lovins LA, et al. Psychiatric and legal features of 113 men convicted of sexual offenses. J Clin Psychiatry. 2004;65(3):293-300.

3. Wallace C, Mullen P, Burgess P, et al. Serious criminal offending and mental disorder. Case linkage study. Br J Psychiatry. 1998;172:477-484.

4. Alish Y, Birger M, Manor N, et al. Schizophrenia sex offenders: a clinical and epidemiological comparison study. Int J Law Psychiatry. 2007;30(6):459-466.

5. Smith AD, Taylor PJ. Serious sex offending against women by men with schizophrenia. Relationship of illness and psychiatric symptoms to offending. Br J Psychiatry. 1999;174:233-237.

6. Drake CR, Pathé M. Understanding sexual offending in schizophrenia. Crim Behav Ment Health. 2004;14(2):108-120.

7. Harley EW, Boardman J, Craig T. Sexual problems in schizophrenia prevalence and characteristics: a cross sectional survey. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2010;45(7):759-766.

8. Galli V, McElroy SL, Soutullo CA, et al. The psychiatric diagnoses of twenty-two adolescents who have sexually molested other children. Compr Psychiatry. 1999;40(2):85-88.

9. Abel GG, Jordan A, Hand CG, et al. Classification models of child molesters utilizing the Abel Assessment for sexual interest. Child Abuse Negl. 2001;25(5):703-718.

10. Hanson RK, Thornton D. Improving risk assessments for sex offenders: a comparison of three actuarial scales. Law Hum Behav. 2000;24(1):119-136.

11. Hanson RK, Harris AJ, Scott TL, et al. Assessing the risk of sexual offenders on community supervision: The Dynamic Supervision Project. Vol 5. Ottawa, Canada: Public Safety Canada; 2007.

12. Quinsey VL, Harris AJ, Rice ME, et al. Violent offenders: appraising and managing risk. 2nd ed. Washington DC: American Psychological Association; 2006.

13. Seto M, Cantor JM, Blanchard R. Child pornography offenses are a valid diagnostic indicator of pedophilia. J Abnorm Psychol. 2006;115(3):610-615.

14. Thibaut F, De La Barra F, Gordon H, et al. WFSBP Task Force on Sexual Disorders. The World Federation of Societies of Biological Psychiatry (WFSBP) guidelines for the biological treatment of paraphilias. World J Biol Psychiatry. 2010;11(4):604-655.

CASE: Paranoid and distressed

Mr. P, age 21, is a single, white college student who presents to a psychiatric emergency room with his father at his psychotherapist’s recommendation. The psychotherapist, who has been treating Mr. P for anxiety and depression, recommended he be evaluated because of increased erratic behavior and paranoia. Mr. P reports that he has been feeling increasingly “anxious” and “paranoid” and thinks the security cameras at his college have been following him. He also describes an increased connection with God and hearing God’s voice as a commentary on his behaviors. Mr. P denies euphoria, depression, increased goal-directed activities, distractibility, increased impulsivity, or rapid speech. He is admitted voluntarily to the psychiatric unit for further evaluation.

During the hospitalization, Mr. P discloses that he has been viewing child pornography for 2 years, and during the past 6 months he has been distressed by the intensity of his sexual fantasies involving sexual contact with prepubescent girls. He also continues to experience paranoia and increased religiosity.

Mr. P says he began looking at pornography on the internet at age 14. He says he was watching “regular straight porn” and he would use it to masturbate and achieve orgasm. Mr. P began looking at child pornography at age 19. He stated that “regular porn” was no longer sufficiently arousing for him. Mr. P explains, “First, I started looking for 15- or 16-year-olds. They would work for a while [referring to sexual gratification], but then I would look for younger girls.” He says the images of younger girls are sexually arousing, typically “young girls, 8 to 10 years old” who are nude or involved in sex acts.

Mr. P denies sexual contact with prepubescent individuals and says his thoughts about such contact are “distressing.” He reports that he has viewed child pornography even when he wasn’t experiencing psychotic or mood symptoms. Mr. P’s outpatient psychotherapist reports that Mr. P first disclosed viewing child pornography and his attraction to prepubescent girls 2 years before this admission.

The authors’ observations

DSM-IV-TR diagnostic criteria for pedophilia (Table 1)1 are based on a history of sexual arousal to prepubescent individuals. A subset of sex offenders meet criteria for a paraphilia (Table 2),1 an axis I disorder, and a subset of sex offenders with paraphilia meet diagnostic criteria for pedophilia. Dunsieth et al2 found that among a sample of 113 male sex offenders, 74% had a diagnosable paraphilia, and 50% of individuals with paraphilia met criteria for pedophilia.

Table 1

DSM-IV-TR diagnostic criteria for pedophilia

| A) | Over a period of ≥6 months, recurrent, intense sexually arousing fantasies, sexual urges, or behaviors involving sexual activity with a prepubescent child or children (generally age ≤13) |

| B) | The person has acted on these sexual urges, or the sexual urges or fantasies cause marked distress or interpersonal difficulty |

| C) | The person is age ≥16 and ≥5 years older than the child or children in criterion A |

| Note: Do not include an individual in late adolescence involved in an ongoing sexual relationship with a 12- or 13-year-old | |

| Source: Reference 1 | |

DSM-IV-TR diagnostic criteria for a paraphilia

| The essential features of a paraphilia are recurrent, intense sexually arousing fantasies, sexual urges, or behaviors generally involving: | |

| A) | nonhuman objects, the suffering or humiliation of oneself or one’s partner, or children or other nonconsenting persons that occur over a period of ≥6 months |

| B) | The behavior, sexual urges, or fantasies cause clinically significant distress or impairment in social, occupational, or other important areas of functioning |

| Source: Reference 1 | |

Although most schizophrenia patients without a history of sexual offenses do not exhibit sexual deviancy, sexual content in hallucinations and delusions is common.6 Confusion about sexual identity and the boundaries of one’s body are common and may contribute to sexual deviancy.6 Psychiatric inpatients without a history of sexual offenses—including but not limited to psychotic patients—have higher rates of sexually deviant fantasies and behaviors compared with those without psychiatric illness.6 In one survey, 15% of men with schizophrenia displayed paraphilic behaviors and 20% had atypical sexual thoughts.7

Alish et al4 found that pedophilia was not necessarily linked to psychotic behavior or antisocial personality features when comparing pedophilia rates in individuals with or without schizophrenia. In a sample of 22 adolescent males who sexually molested a child at least once, axis I morbidity was common, and 55% met criteria for bipolar disorder.8

Few experts in paraphilias

A patient who endorses deviant sexual fantasies should be evaluated by a mental health professional with specialized training in paraphilias. Although paraphilias are not recognized as a subspecialty in psychiatry, diagnosing and treating patients with a paraphilia requires additional training. There is a scarcity of psychiatrists trained to evaluate and treat patients with paraphilias.

Sexual evaluation. Evaluating a patient who presents with problematic sexual behaviors includes performing a comprehensive psychiatric history with a focus on sexual history. A psychosexual history is distinct from general psychiatric evaluations because of the level of detail regarding a sexual history (Table 3). In addition to the clinical interview, objective testing to determine sexual interests may be useful in some patients (Table 4).9

Actuarial tools—risk assessment instruments based on statistically significant risk factors—are valid tools for determining the risk of sexual reoffending. There are several validated actuarial tools in the assessment of sex offender recidivism, such as the Static-99R,10 Stable-2007,11 and the Sex Offender Risk Appraisal Guide.12 However, these tools are used for sex offenders, and would not be used for individuals who have not committed a sex offense, such as Mr. P.

Table 3

Psychosexual evaluation

| Aspect of evaluation | Measures |

| Sexual behavior history | History of sexual abuse Childhood exposure to sex Masturbation history Preferred sexual partners Kinsey Scale |

| Sexual addiction or compulsion | Total Sexual Outlet measure Amount of time in sexual fantasy Financial, legal, or social cost of sexual behavior Prior treatment of sexual behavior |

| Sexual interests | Sex, age, and number of partner(s) Review of criteria for all paraphilias (exposing, voyeurism, cross-dressing, sadistic or masochistic interests) |

Objective testing to determine sexual interests

| Test | Results |

|---|---|

| Penile plethysmograph | Measures penis circumference with a mercury-in-rubber strain gauge. Used clinically by measuring circumferential changes in the penis while the patient is listening to audio or video stimuli of various sexual vignettes |

| Abel Assessment for Sexual Interests-3 | An objective method for evaluating deviant sexual interest uses noninvasive means to achieve objective measures of sexual interest. The subject’s visual response time is measured while viewing images of males and females of varying age. Visual reaction time is correlated with sexual interests |

| Source: Reference 9 | |

Medicolegal aspects of a psychosexual evaluation may include mandated reporting, confidentiality, and documentation. Mental health professionals are mandated to report to law enforcement or child welfare agencies when they observe or suspect physical, sexual, or other types of abuse in vulnerable populations such as children. In psychosexual evaluations, the evaluator is legally required to report if a patient discloses current sexual behavior with a child with a plan to continue to engage in the behavior. In Mr. P’s case, there was no duty to report because although he described viewing child pornography and had a sexual interest in prepubescent individuals, he did not report a history of engaging in handson sexual behaviors with children or impulses to do so. When an individual has engaged in sexual contact with a prepubescent individual, reporting is not mandated unless the individual continues to engage in sexual behavior with a minor. Mental health professionals are not responsible for calling the police or alerting authorities after a crime has been committed.

The relationship between viewing child pornography and pedophilia is unclear. Some child pornography viewers are pedophilic, others are sexually compulsive, and others are viewing out of curiosity and have no sexual deviance. Seto et al13 suggested that child pornography offenders show greater sexual arousal to children than to adults. Persistent child pornography use is a stronger diagnostic indicator of pedophilia than sexually offending against child victims.13 A clinician who learns that a patient is viewing child pornography should take a detailed sexual history, including a review of criteria for paraphilias. In addition, when appropriate, the clinician should perform a risk assessment to determine the patient’s risk of engaging in sexual offenses with children.

OUTCOME: Expert consultation

We start Mr. P on risperidone, 1 mg/d, to treat his paranoia and request a consultation with an expert in paraphilias to determine if Mr. P has a paraphilia and to discuss treatment options.

Mr. P’s initial diagnosis is psychotic disorder not otherwise specified. His viewing of child pornography and sexual interest in prepubescent individuals is not limited to his current mental status, and these interests persist in the absence of mood and psychotic states. Mr. P’s viewing of child pornography and sexual attraction to prepubescent girls meet the diagnostic criteria for pedophilia. During hospitalization, we educate Mr. P about his diagnoses and need for continued treatment. We refer him to a sexual disorders outpatient clinic, which continues to address his deviant sexual interests.

The authors’ observations

A meta-analysis indicates that a combination of pharmacologic and behavioral treatments coupled with close legal supervision seems to reduce the risk of repeated sexual offenses.14 Legal supervision is a general term to describe oversight of offenders in the community by supervisory boards, such as probation or parole, and tracking devices such as GPS. Currently, pedophilia treatment focuses on minimizing deviant sexual arousal through behavioral modification, cognitive-behavioral therapies, and testosterone-lowering medications, such as medroxyprogesterone or leuprolide. The decision to prescribe testosterone-lowering medication should be based on informed consent and the patient’s risk of dangerous sexual behaviors.

- Reijnen L, Bulten E, Nijman H. Demographic and personality characteristics of internet child pornography downloaders in comparison to other offenders. J Child Sex Abus. 2009;18(6):611-622.

- Hall RC, Hall RC. A profile of pedophilia: definition, characteristics of offenders, recidivism, treatment outcomes, and forensic issues. Mayo Clin Proc. 2007;82(4):457-471.

- Leuprolide • Eligard, Lupron

- Medroxyprogesterone • Cycrin, Provera

- Risperidone • Risperdal

The authors report no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

CASE: Paranoid and distressed

Mr. P, age 21, is a single, white college student who presents to a psychiatric emergency room with his father at his psychotherapist’s recommendation. The psychotherapist, who has been treating Mr. P for anxiety and depression, recommended he be evaluated because of increased erratic behavior and paranoia. Mr. P reports that he has been feeling increasingly “anxious” and “paranoid” and thinks the security cameras at his college have been following him. He also describes an increased connection with God and hearing God’s voice as a commentary on his behaviors. Mr. P denies euphoria, depression, increased goal-directed activities, distractibility, increased impulsivity, or rapid speech. He is admitted voluntarily to the psychiatric unit for further evaluation.

During the hospitalization, Mr. P discloses that he has been viewing child pornography for 2 years, and during the past 6 months he has been distressed by the intensity of his sexual fantasies involving sexual contact with prepubescent girls. He also continues to experience paranoia and increased religiosity.

Mr. P says he began looking at pornography on the internet at age 14. He says he was watching “regular straight porn” and he would use it to masturbate and achieve orgasm. Mr. P began looking at child pornography at age 19. He stated that “regular porn” was no longer sufficiently arousing for him. Mr. P explains, “First, I started looking for 15- or 16-year-olds. They would work for a while [referring to sexual gratification], but then I would look for younger girls.” He says the images of younger girls are sexually arousing, typically “young girls, 8 to 10 years old” who are nude or involved in sex acts.

Mr. P denies sexual contact with prepubescent individuals and says his thoughts about such contact are “distressing.” He reports that he has viewed child pornography even when he wasn’t experiencing psychotic or mood symptoms. Mr. P’s outpatient psychotherapist reports that Mr. P first disclosed viewing child pornography and his attraction to prepubescent girls 2 years before this admission.

The authors’ observations

DSM-IV-TR diagnostic criteria for pedophilia (Table 1)1 are based on a history of sexual arousal to prepubescent individuals. A subset of sex offenders meet criteria for a paraphilia (Table 2),1 an axis I disorder, and a subset of sex offenders with paraphilia meet diagnostic criteria for pedophilia. Dunsieth et al2 found that among a sample of 113 male sex offenders, 74% had a diagnosable paraphilia, and 50% of individuals with paraphilia met criteria for pedophilia.

Table 1

DSM-IV-TR diagnostic criteria for pedophilia

| A) | Over a period of ≥6 months, recurrent, intense sexually arousing fantasies, sexual urges, or behaviors involving sexual activity with a prepubescent child or children (generally age ≤13) |

| B) | The person has acted on these sexual urges, or the sexual urges or fantasies cause marked distress or interpersonal difficulty |

| C) | The person is age ≥16 and ≥5 years older than the child or children in criterion A |

| Note: Do not include an individual in late adolescence involved in an ongoing sexual relationship with a 12- or 13-year-old | |

| Source: Reference 1 | |

DSM-IV-TR diagnostic criteria for a paraphilia

| The essential features of a paraphilia are recurrent, intense sexually arousing fantasies, sexual urges, or behaviors generally involving: | |

| A) | nonhuman objects, the suffering or humiliation of oneself or one’s partner, or children or other nonconsenting persons that occur over a period of ≥6 months |

| B) | The behavior, sexual urges, or fantasies cause clinically significant distress or impairment in social, occupational, or other important areas of functioning |

| Source: Reference 1 | |

Although most schizophrenia patients without a history of sexual offenses do not exhibit sexual deviancy, sexual content in hallucinations and delusions is common.6 Confusion about sexual identity and the boundaries of one’s body are common and may contribute to sexual deviancy.6 Psychiatric inpatients without a history of sexual offenses—including but not limited to psychotic patients—have higher rates of sexually deviant fantasies and behaviors compared with those without psychiatric illness.6 In one survey, 15% of men with schizophrenia displayed paraphilic behaviors and 20% had atypical sexual thoughts.7

Alish et al4 found that pedophilia was not necessarily linked to psychotic behavior or antisocial personality features when comparing pedophilia rates in individuals with or without schizophrenia. In a sample of 22 adolescent males who sexually molested a child at least once, axis I morbidity was common, and 55% met criteria for bipolar disorder.8

Few experts in paraphilias

A patient who endorses deviant sexual fantasies should be evaluated by a mental health professional with specialized training in paraphilias. Although paraphilias are not recognized as a subspecialty in psychiatry, diagnosing and treating patients with a paraphilia requires additional training. There is a scarcity of psychiatrists trained to evaluate and treat patients with paraphilias.

Sexual evaluation. Evaluating a patient who presents with problematic sexual behaviors includes performing a comprehensive psychiatric history with a focus on sexual history. A psychosexual history is distinct from general psychiatric evaluations because of the level of detail regarding a sexual history (Table 3). In addition to the clinical interview, objective testing to determine sexual interests may be useful in some patients (Table 4).9

Actuarial tools—risk assessment instruments based on statistically significant risk factors—are valid tools for determining the risk of sexual reoffending. There are several validated actuarial tools in the assessment of sex offender recidivism, such as the Static-99R,10 Stable-2007,11 and the Sex Offender Risk Appraisal Guide.12 However, these tools are used for sex offenders, and would not be used for individuals who have not committed a sex offense, such as Mr. P.

Table 3

Psychosexual evaluation

| Aspect of evaluation | Measures |

| Sexual behavior history | History of sexual abuse Childhood exposure to sex Masturbation history Preferred sexual partners Kinsey Scale |

| Sexual addiction or compulsion | Total Sexual Outlet measure Amount of time in sexual fantasy Financial, legal, or social cost of sexual behavior Prior treatment of sexual behavior |

| Sexual interests | Sex, age, and number of partner(s) Review of criteria for all paraphilias (exposing, voyeurism, cross-dressing, sadistic or masochistic interests) |

Objective testing to determine sexual interests

| Test | Results |

|---|---|

| Penile plethysmograph | Measures penis circumference with a mercury-in-rubber strain gauge. Used clinically by measuring circumferential changes in the penis while the patient is listening to audio or video stimuli of various sexual vignettes |

| Abel Assessment for Sexual Interests-3 | An objective method for evaluating deviant sexual interest uses noninvasive means to achieve objective measures of sexual interest. The subject’s visual response time is measured while viewing images of males and females of varying age. Visual reaction time is correlated with sexual interests |

| Source: Reference 9 | |

Medicolegal aspects of a psychosexual evaluation may include mandated reporting, confidentiality, and documentation. Mental health professionals are mandated to report to law enforcement or child welfare agencies when they observe or suspect physical, sexual, or other types of abuse in vulnerable populations such as children. In psychosexual evaluations, the evaluator is legally required to report if a patient discloses current sexual behavior with a child with a plan to continue to engage in the behavior. In Mr. P’s case, there was no duty to report because although he described viewing child pornography and had a sexual interest in prepubescent individuals, he did not report a history of engaging in handson sexual behaviors with children or impulses to do so. When an individual has engaged in sexual contact with a prepubescent individual, reporting is not mandated unless the individual continues to engage in sexual behavior with a minor. Mental health professionals are not responsible for calling the police or alerting authorities after a crime has been committed.

The relationship between viewing child pornography and pedophilia is unclear. Some child pornography viewers are pedophilic, others are sexually compulsive, and others are viewing out of curiosity and have no sexual deviance. Seto et al13 suggested that child pornography offenders show greater sexual arousal to children than to adults. Persistent child pornography use is a stronger diagnostic indicator of pedophilia than sexually offending against child victims.13 A clinician who learns that a patient is viewing child pornography should take a detailed sexual history, including a review of criteria for paraphilias. In addition, when appropriate, the clinician should perform a risk assessment to determine the patient’s risk of engaging in sexual offenses with children.

OUTCOME: Expert consultation

We start Mr. P on risperidone, 1 mg/d, to treat his paranoia and request a consultation with an expert in paraphilias to determine if Mr. P has a paraphilia and to discuss treatment options.

Mr. P’s initial diagnosis is psychotic disorder not otherwise specified. His viewing of child pornography and sexual interest in prepubescent individuals is not limited to his current mental status, and these interests persist in the absence of mood and psychotic states. Mr. P’s viewing of child pornography and sexual attraction to prepubescent girls meet the diagnostic criteria for pedophilia. During hospitalization, we educate Mr. P about his diagnoses and need for continued treatment. We refer him to a sexual disorders outpatient clinic, which continues to address his deviant sexual interests.

The authors’ observations

A meta-analysis indicates that a combination of pharmacologic and behavioral treatments coupled with close legal supervision seems to reduce the risk of repeated sexual offenses.14 Legal supervision is a general term to describe oversight of offenders in the community by supervisory boards, such as probation or parole, and tracking devices such as GPS. Currently, pedophilia treatment focuses on minimizing deviant sexual arousal through behavioral modification, cognitive-behavioral therapies, and testosterone-lowering medications, such as medroxyprogesterone or leuprolide. The decision to prescribe testosterone-lowering medication should be based on informed consent and the patient’s risk of dangerous sexual behaviors.

- Reijnen L, Bulten E, Nijman H. Demographic and personality characteristics of internet child pornography downloaders in comparison to other offenders. J Child Sex Abus. 2009;18(6):611-622.

- Hall RC, Hall RC. A profile of pedophilia: definition, characteristics of offenders, recidivism, treatment outcomes, and forensic issues. Mayo Clin Proc. 2007;82(4):457-471.

- Leuprolide • Eligard, Lupron

- Medroxyprogesterone • Cycrin, Provera

- Risperidone • Risperdal

The authors report no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 4th ed, text rev. Washington DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000.

2. Dunsieth NW, Jr, Nelson EB, Brusman-Lovins LA, et al. Psychiatric and legal features of 113 men convicted of sexual offenses. J Clin Psychiatry. 2004;65(3):293-300.

3. Wallace C, Mullen P, Burgess P, et al. Serious criminal offending and mental disorder. Case linkage study. Br J Psychiatry. 1998;172:477-484.

4. Alish Y, Birger M, Manor N, et al. Schizophrenia sex offenders: a clinical and epidemiological comparison study. Int J Law Psychiatry. 2007;30(6):459-466.

5. Smith AD, Taylor PJ. Serious sex offending against women by men with schizophrenia. Relationship of illness and psychiatric symptoms to offending. Br J Psychiatry. 1999;174:233-237.

6. Drake CR, Pathé M. Understanding sexual offending in schizophrenia. Crim Behav Ment Health. 2004;14(2):108-120.

7. Harley EW, Boardman J, Craig T. Sexual problems in schizophrenia prevalence and characteristics: a cross sectional survey. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2010;45(7):759-766.

8. Galli V, McElroy SL, Soutullo CA, et al. The psychiatric diagnoses of twenty-two adolescents who have sexually molested other children. Compr Psychiatry. 1999;40(2):85-88.

9. Abel GG, Jordan A, Hand CG, et al. Classification models of child molesters utilizing the Abel Assessment for sexual interest. Child Abuse Negl. 2001;25(5):703-718.

10. Hanson RK, Thornton D. Improving risk assessments for sex offenders: a comparison of three actuarial scales. Law Hum Behav. 2000;24(1):119-136.

11. Hanson RK, Harris AJ, Scott TL, et al. Assessing the risk of sexual offenders on community supervision: The Dynamic Supervision Project. Vol 5. Ottawa, Canada: Public Safety Canada; 2007.

12. Quinsey VL, Harris AJ, Rice ME, et al. Violent offenders: appraising and managing risk. 2nd ed. Washington DC: American Psychological Association; 2006.

13. Seto M, Cantor JM, Blanchard R. Child pornography offenses are a valid diagnostic indicator of pedophilia. J Abnorm Psychol. 2006;115(3):610-615.

14. Thibaut F, De La Barra F, Gordon H, et al. WFSBP Task Force on Sexual Disorders. The World Federation of Societies of Biological Psychiatry (WFSBP) guidelines for the biological treatment of paraphilias. World J Biol Psychiatry. 2010;11(4):604-655.

1. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 4th ed, text rev. Washington DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000.

2. Dunsieth NW, Jr, Nelson EB, Brusman-Lovins LA, et al. Psychiatric and legal features of 113 men convicted of sexual offenses. J Clin Psychiatry. 2004;65(3):293-300.

3. Wallace C, Mullen P, Burgess P, et al. Serious criminal offending and mental disorder. Case linkage study. Br J Psychiatry. 1998;172:477-484.

4. Alish Y, Birger M, Manor N, et al. Schizophrenia sex offenders: a clinical and epidemiological comparison study. Int J Law Psychiatry. 2007;30(6):459-466.

5. Smith AD, Taylor PJ. Serious sex offending against women by men with schizophrenia. Relationship of illness and psychiatric symptoms to offending. Br J Psychiatry. 1999;174:233-237.

6. Drake CR, Pathé M. Understanding sexual offending in schizophrenia. Crim Behav Ment Health. 2004;14(2):108-120.

7. Harley EW, Boardman J, Craig T. Sexual problems in schizophrenia prevalence and characteristics: a cross sectional survey. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2010;45(7):759-766.

8. Galli V, McElroy SL, Soutullo CA, et al. The psychiatric diagnoses of twenty-two adolescents who have sexually molested other children. Compr Psychiatry. 1999;40(2):85-88.

9. Abel GG, Jordan A, Hand CG, et al. Classification models of child molesters utilizing the Abel Assessment for sexual interest. Child Abuse Negl. 2001;25(5):703-718.

10. Hanson RK, Thornton D. Improving risk assessments for sex offenders: a comparison of three actuarial scales. Law Hum Behav. 2000;24(1):119-136.

11. Hanson RK, Harris AJ, Scott TL, et al. Assessing the risk of sexual offenders on community supervision: The Dynamic Supervision Project. Vol 5. Ottawa, Canada: Public Safety Canada; 2007.

12. Quinsey VL, Harris AJ, Rice ME, et al. Violent offenders: appraising and managing risk. 2nd ed. Washington DC: American Psychological Association; 2006.

13. Seto M, Cantor JM, Blanchard R. Child pornography offenses are a valid diagnostic indicator of pedophilia. J Abnorm Psychol. 2006;115(3):610-615.

14. Thibaut F, De La Barra F, Gordon H, et al. WFSBP Task Force on Sexual Disorders. The World Federation of Societies of Biological Psychiatry (WFSBP) guidelines for the biological treatment of paraphilias. World J Biol Psychiatry. 2010;11(4):604-655.

PSYCHIATRY UPDATE 2013

Current Psychiatry and the American Academy of Clinical Psychiatrists were pleased to host more than 550 psychiatric practitioners for this conference, led by Meeting Chair Richard Balon, MD, and Meeting Co-Chairs Donald W. Black, MD, and Nagy Youssef, MD, April 4-6, 2013 at the Swissôtel in Chicago, IL. Attendees could earn up to 18 AMA PRA Category 1 Credits™.

THURSDAY, APRIL 4, 2013

MORNING SESSIONS

Evidence-based medicine and treatment guidelines may not address complex patients with treatment-resistant depression (TRD). Andrew A. Nierenberg, MD, Massachusetts General Hospital, reviewed newer medications for TRD, including olanzapine-fluoxetine combination, ketamine, riluzole, and L-methylfolate; however, use of these medications requires careful consideration of risks and benefits.

Many FDA-approved drugs have a “black-box” warning, but still are widely used. Henry A. Nasrallah, MD, University of Cincinnati, reviewed black-box warnings for antipsychotics, antidepressants, mood stabilizers, benzodiazepines, stimulants, opiates, and hypnotics and offered strategies on how to incorporate these warnings into clinical practice.

Dr. Nierenberg discussed the outcomes of 3 published medication effectiveness studies for bipolar disorder (BD)—STEP-BD, BALANCE, and LiTMUS—and one currently underway, CHOICE. These studies examined monotherapy and combination therapy with antidepressants, anticonvulsants, antipsychotics, and psychosocial interventions.

Although there is an association between psychosis and violence, most psychotic patients are not violent. Rajiv Tandon, MD, University of Florida, reviewed modifiable and nonmodifiable risk factors for violence, key clinical questions to consider, and scales to use when assessing a patient’s risk of violence.

AFTERNOON SESSIONS

Measuring biomarkers can augment other clinical methods to help identify metabolic, structural, and functional brain changes associated with preclinical stages of cognitive disorders. James Ellison, MD, MPH, McLean Hospital, Harvard Medical School, explained how biomarkers can improve the differential diagnosis of memory impairments and aid in identifying different types of dementia.

Donald W. Black, MD, (right) receives the 2013 George Winokur Research

Award from Carol S. North, MD, for his article on pathological gambling

Case-control studies have found a strong association between schizophrenia and type II diabetes, which contributes to higher mortality among schizophrenia patients. Along with vigilant metabolic monitoring, Dr. Tandon recommended a therapeutic approach that includes changing antipsychotics, prescribing metformin, suggesting lifestyle interventions, and treating comorbid conditions.

Depressed older adults may report anxiety, hopelessness, anhedonia, or somatic symptoms, rather than sadness. Depressive symptoms may be associated with vascular disease or cognitive impairment. Dr. Ellison reviewed psychotherapeutic and pharmacologic treatments for older depressed patients.

FRIDAY, APRIL 5, 2013

MORNING SESSIONS

Many strategies exist for treating patients with TRD; adding an atypical antipsychotic has the best evidence, but there are tolerability considerations. Dr. Nierenberg suggested using a combination of treatments.

Pregnancy is inherently risky for women who take antipsychotics. In all patients of childbearing potential, take a thorough reproductive history and ask about contraception use. Marlene P. Freeman, MD, Massachusetts General Hospital, explained that psychotropics with unfavorable FDA pregnancy ratings may be among first-line choices.

George T. Grossberg, MD, (left) speaks with attendees

Clinical symptoms, cognitive deficits, psychiatric comorbidities, genetic factors, neuroimaging features, and pharmacotherapy may overlap considerably between schizophrenia and BD. Dr. Nasrallah described clinical features that differentiate the 2 disorders.

Cognitive enhancers can improve activities of daily living, behavior, and cognition in patients with Alzheimer’s disease. George T. Grossberg, MD, St. Louis University, reviewed the evidence for acetylcholinesterase inhibitors, the NMDA receptor antagonist memantine, combination therapy, and atypical antipsychotics.

Dietary consultation for older patients might help delay or decrease their risk of dementia. Patients should consume omega-3 fatty acids, whole grains, fresh fruits and vegetables, beans, legumes, and certain spices. Dr. Grossberg also suggested patients engage in physical and mental exercises, social and spiritual activities, and stress reduction, and control cardiovascular risk factors.

AFTERNOON SESSIONS

Many women experience anxiety during pregnancy, and the risk is highest during the first trimester. Dr. Freeman reviewed prevalence, diagnosis, and treatment of panic disorder, generalized anxiety disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder, and posttraumatic stress disorder during pregnancy and postpartum.

Kathleen Brady, MD, PhD, Medical University of South Carolina, explained how methylenedioxypyrovalerone, also known as bath salts, and other designer drugs are not detectable on standard urine drug screens. Agitation, tachycardia, combative behavior, hyperthermia, and hallucinations have been reported.

Kathleen Brady, MD, MPH

Alcohol abuse and depression are highly comorbid and are associated with higher suicidality, more severe symptoms, and poorer treatment response than either disorder alone. Depressive symptoms often are seen during alcohol withdrawal, and may resolve with abstinence. Dr. Brady reviewed the evidence for treating depressed alcoholics with antidepressants, medications targeting alcohol dependence such as disulfiram and naltrexone, and psychotherapy.

Ralph Aquila, MD, Columbia College of Physicians and Surgeons, discussed risk factors for and consequences of treatment nonadherence in patients with schizophrenia. Leslie L. Citrome, MD, MPH, New York Medical College, covered strategies to improve adherence, including identifying and addressing barriers to adherence for individual patients, improving the therapeutic alliance, and considering long-acting injectable antipsychotics.

SATURDAY, APRIL 6, 2013

MORNING SESSIONS

Forty-six percent of depressed patients will stop pharmacotherapy before they have a chance to respond. To minimize short-term side effects, Andrew J. Cutler, MD, Florida Clinical Research Center, suggested educating patients and slowly titrating medications; options for reducing long-term side effects or residual symptoms include switching or augmenting pharmacotherapy.

When treating patients addicted to opioids, outcome measures go beyond general health to obtaining employment and reducing criminal activity. Pharmacotherapy options include methadone maintenance therapy, oral and injectable naltrexone, and oral, sublingual, and implantable buprenorphine. Walter Ling, MD, David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA, described factors that may improve patient outcomes.

Geriatric BD is relatively common in clinical settings, but there is a lack of evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. James W. Jefferson, MD, University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health, recommended choosing a treatment based on the illness phase and balancing the benefit of certain pharmacotherapies against short- and long-term risks.

Most medications for treating alcohol dependence work by modulating functions of opioids, glutamate, GABA, and serotonin. Dr. Ling reviewed the evidence base, dosing guidelines, and clinical recommendations for disulfiram, oral and injectable naltrexone, and acamprosate, which are FDA-approved for treating alcohol dependence. He also recommended combining medications with nonpharmacologic treatments, such as 12-step programs.

Most people who die by suicide deny suicide ideation at their last mental health visit. Risk factors for suicide include family history of suicide, childhood or adult trauma, substance abuse, stressful life events, chronic illness, and psychiatric disorders. Dr. Jefferson described suicide rating and tracking scales and encouraged clinicians to document suicide risk evaluations.

AFTERNOON SESSION

Roger S. McIntyre, MD, FRCPCRobert M.A. Hirschfeld, MD, University of Texas Medical Branch, discussed how the concept of allostatic load—bodily “wear and tear” that emerges with sustained allostatic states—may help explain cognitive and physical decline associated with BD. Roger S. McIntyre, MD, FRCPC, University of Toronto, emphasized that BD is a progressive disorder and comorbidities such as metabolic problems may promote this progression. Terence A. Ketter, MD, Stanford School of Medicine, covered new developments in BD treatment, including certain second-generation antipsychotics, dopaminergic neurotransmission enhancers, mood stabilizers, adjunctive antidepressants, and adjunctive psychotherapy.

Current Psychiatry and the American Academy of Clinical Psychiatrists were pleased to host more than 550 psychiatric practitioners for this conference, led by Meeting Chair Richard Balon, MD, and Meeting Co-Chairs Donald W. Black, MD, and Nagy Youssef, MD, April 4-6, 2013 at the Swissôtel in Chicago, IL. Attendees could earn up to 18 AMA PRA Category 1 Credits™.

THURSDAY, APRIL 4, 2013

MORNING SESSIONS

Evidence-based medicine and treatment guidelines may not address complex patients with treatment-resistant depression (TRD). Andrew A. Nierenberg, MD, Massachusetts General Hospital, reviewed newer medications for TRD, including olanzapine-fluoxetine combination, ketamine, riluzole, and L-methylfolate; however, use of these medications requires careful consideration of risks and benefits.

Many FDA-approved drugs have a “black-box” warning, but still are widely used. Henry A. Nasrallah, MD, University of Cincinnati, reviewed black-box warnings for antipsychotics, antidepressants, mood stabilizers, benzodiazepines, stimulants, opiates, and hypnotics and offered strategies on how to incorporate these warnings into clinical practice.

Dr. Nierenberg discussed the outcomes of 3 published medication effectiveness studies for bipolar disorder (BD)—STEP-BD, BALANCE, and LiTMUS—and one currently underway, CHOICE. These studies examined monotherapy and combination therapy with antidepressants, anticonvulsants, antipsychotics, and psychosocial interventions.

Although there is an association between psychosis and violence, most psychotic patients are not violent. Rajiv Tandon, MD, University of Florida, reviewed modifiable and nonmodifiable risk factors for violence, key clinical questions to consider, and scales to use when assessing a patient’s risk of violence.

AFTERNOON SESSIONS

Measuring biomarkers can augment other clinical methods to help identify metabolic, structural, and functional brain changes associated with preclinical stages of cognitive disorders. James Ellison, MD, MPH, McLean Hospital, Harvard Medical School, explained how biomarkers can improve the differential diagnosis of memory impairments and aid in identifying different types of dementia.

Donald W. Black, MD, (right) receives the 2013 George Winokur Research

Award from Carol S. North, MD, for his article on pathological gambling

Case-control studies have found a strong association between schizophrenia and type II diabetes, which contributes to higher mortality among schizophrenia patients. Along with vigilant metabolic monitoring, Dr. Tandon recommended a therapeutic approach that includes changing antipsychotics, prescribing metformin, suggesting lifestyle interventions, and treating comorbid conditions.

Depressed older adults may report anxiety, hopelessness, anhedonia, or somatic symptoms, rather than sadness. Depressive symptoms may be associated with vascular disease or cognitive impairment. Dr. Ellison reviewed psychotherapeutic and pharmacologic treatments for older depressed patients.

FRIDAY, APRIL 5, 2013

MORNING SESSIONS

Many strategies exist for treating patients with TRD; adding an atypical antipsychotic has the best evidence, but there are tolerability considerations. Dr. Nierenberg suggested using a combination of treatments.

Pregnancy is inherently risky for women who take antipsychotics. In all patients of childbearing potential, take a thorough reproductive history and ask about contraception use. Marlene P. Freeman, MD, Massachusetts General Hospital, explained that psychotropics with unfavorable FDA pregnancy ratings may be among first-line choices.

George T. Grossberg, MD, (left) speaks with attendees

Clinical symptoms, cognitive deficits, psychiatric comorbidities, genetic factors, neuroimaging features, and pharmacotherapy may overlap considerably between schizophrenia and BD. Dr. Nasrallah described clinical features that differentiate the 2 disorders.

Cognitive enhancers can improve activities of daily living, behavior, and cognition in patients with Alzheimer’s disease. George T. Grossberg, MD, St. Louis University, reviewed the evidence for acetylcholinesterase inhibitors, the NMDA receptor antagonist memantine, combination therapy, and atypical antipsychotics.

Dietary consultation for older patients might help delay or decrease their risk of dementia. Patients should consume omega-3 fatty acids, whole grains, fresh fruits and vegetables, beans, legumes, and certain spices. Dr. Grossberg also suggested patients engage in physical and mental exercises, social and spiritual activities, and stress reduction, and control cardiovascular risk factors.

AFTERNOON SESSIONS

Many women experience anxiety during pregnancy, and the risk is highest during the first trimester. Dr. Freeman reviewed prevalence, diagnosis, and treatment of panic disorder, generalized anxiety disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder, and posttraumatic stress disorder during pregnancy and postpartum.

Kathleen Brady, MD, PhD, Medical University of South Carolina, explained how methylenedioxypyrovalerone, also known as bath salts, and other designer drugs are not detectable on standard urine drug screens. Agitation, tachycardia, combative behavior, hyperthermia, and hallucinations have been reported.

Kathleen Brady, MD, MPH

Alcohol abuse and depression are highly comorbid and are associated with higher suicidality, more severe symptoms, and poorer treatment response than either disorder alone. Depressive symptoms often are seen during alcohol withdrawal, and may resolve with abstinence. Dr. Brady reviewed the evidence for treating depressed alcoholics with antidepressants, medications targeting alcohol dependence such as disulfiram and naltrexone, and psychotherapy.

Ralph Aquila, MD, Columbia College of Physicians and Surgeons, discussed risk factors for and consequences of treatment nonadherence in patients with schizophrenia. Leslie L. Citrome, MD, MPH, New York Medical College, covered strategies to improve adherence, including identifying and addressing barriers to adherence for individual patients, improving the therapeutic alliance, and considering long-acting injectable antipsychotics.

SATURDAY, APRIL 6, 2013

MORNING SESSIONS

Forty-six percent of depressed patients will stop pharmacotherapy before they have a chance to respond. To minimize short-term side effects, Andrew J. Cutler, MD, Florida Clinical Research Center, suggested educating patients and slowly titrating medications; options for reducing long-term side effects or residual symptoms include switching or augmenting pharmacotherapy.

When treating patients addicted to opioids, outcome measures go beyond general health to obtaining employment and reducing criminal activity. Pharmacotherapy options include methadone maintenance therapy, oral and injectable naltrexone, and oral, sublingual, and implantable buprenorphine. Walter Ling, MD, David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA, described factors that may improve patient outcomes.

Geriatric BD is relatively common in clinical settings, but there is a lack of evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. James W. Jefferson, MD, University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health, recommended choosing a treatment based on the illness phase and balancing the benefit of certain pharmacotherapies against short- and long-term risks.

Most medications for treating alcohol dependence work by modulating functions of opioids, glutamate, GABA, and serotonin. Dr. Ling reviewed the evidence base, dosing guidelines, and clinical recommendations for disulfiram, oral and injectable naltrexone, and acamprosate, which are FDA-approved for treating alcohol dependence. He also recommended combining medications with nonpharmacologic treatments, such as 12-step programs.

Most people who die by suicide deny suicide ideation at their last mental health visit. Risk factors for suicide include family history of suicide, childhood or adult trauma, substance abuse, stressful life events, chronic illness, and psychiatric disorders. Dr. Jefferson described suicide rating and tracking scales and encouraged clinicians to document suicide risk evaluations.

AFTERNOON SESSION

Roger S. McIntyre, MD, FRCPCRobert M.A. Hirschfeld, MD, University of Texas Medical Branch, discussed how the concept of allostatic load—bodily “wear and tear” that emerges with sustained allostatic states—may help explain cognitive and physical decline associated with BD. Roger S. McIntyre, MD, FRCPC, University of Toronto, emphasized that BD is a progressive disorder and comorbidities such as metabolic problems may promote this progression. Terence A. Ketter, MD, Stanford School of Medicine, covered new developments in BD treatment, including certain second-generation antipsychotics, dopaminergic neurotransmission enhancers, mood stabilizers, adjunctive antidepressants, and adjunctive psychotherapy.

Current Psychiatry and the American Academy of Clinical Psychiatrists were pleased to host more than 550 psychiatric practitioners for this conference, led by Meeting Chair Richard Balon, MD, and Meeting Co-Chairs Donald W. Black, MD, and Nagy Youssef, MD, April 4-6, 2013 at the Swissôtel in Chicago, IL. Attendees could earn up to 18 AMA PRA Category 1 Credits™.

THURSDAY, APRIL 4, 2013

MORNING SESSIONS

Evidence-based medicine and treatment guidelines may not address complex patients with treatment-resistant depression (TRD). Andrew A. Nierenberg, MD, Massachusetts General Hospital, reviewed newer medications for TRD, including olanzapine-fluoxetine combination, ketamine, riluzole, and L-methylfolate; however, use of these medications requires careful consideration of risks and benefits.

Many FDA-approved drugs have a “black-box” warning, but still are widely used. Henry A. Nasrallah, MD, University of Cincinnati, reviewed black-box warnings for antipsychotics, antidepressants, mood stabilizers, benzodiazepines, stimulants, opiates, and hypnotics and offered strategies on how to incorporate these warnings into clinical practice.

Dr. Nierenberg discussed the outcomes of 3 published medication effectiveness studies for bipolar disorder (BD)—STEP-BD, BALANCE, and LiTMUS—and one currently underway, CHOICE. These studies examined monotherapy and combination therapy with antidepressants, anticonvulsants, antipsychotics, and psychosocial interventions.

Although there is an association between psychosis and violence, most psychotic patients are not violent. Rajiv Tandon, MD, University of Florida, reviewed modifiable and nonmodifiable risk factors for violence, key clinical questions to consider, and scales to use when assessing a patient’s risk of violence.

AFTERNOON SESSIONS

Measuring biomarkers can augment other clinical methods to help identify metabolic, structural, and functional brain changes associated with preclinical stages of cognitive disorders. James Ellison, MD, MPH, McLean Hospital, Harvard Medical School, explained how biomarkers can improve the differential diagnosis of memory impairments and aid in identifying different types of dementia.

Donald W. Black, MD, (right) receives the 2013 George Winokur Research

Award from Carol S. North, MD, for his article on pathological gambling

Case-control studies have found a strong association between schizophrenia and type II diabetes, which contributes to higher mortality among schizophrenia patients. Along with vigilant metabolic monitoring, Dr. Tandon recommended a therapeutic approach that includes changing antipsychotics, prescribing metformin, suggesting lifestyle interventions, and treating comorbid conditions.

Depressed older adults may report anxiety, hopelessness, anhedonia, or somatic symptoms, rather than sadness. Depressive symptoms may be associated with vascular disease or cognitive impairment. Dr. Ellison reviewed psychotherapeutic and pharmacologic treatments for older depressed patients.

FRIDAY, APRIL 5, 2013

MORNING SESSIONS

Many strategies exist for treating patients with TRD; adding an atypical antipsychotic has the best evidence, but there are tolerability considerations. Dr. Nierenberg suggested using a combination of treatments.

Pregnancy is inherently risky for women who take antipsychotics. In all patients of childbearing potential, take a thorough reproductive history and ask about contraception use. Marlene P. Freeman, MD, Massachusetts General Hospital, explained that psychotropics with unfavorable FDA pregnancy ratings may be among first-line choices.

George T. Grossberg, MD, (left) speaks with attendees

Clinical symptoms, cognitive deficits, psychiatric comorbidities, genetic factors, neuroimaging features, and pharmacotherapy may overlap considerably between schizophrenia and BD. Dr. Nasrallah described clinical features that differentiate the 2 disorders.

Cognitive enhancers can improve activities of daily living, behavior, and cognition in patients with Alzheimer’s disease. George T. Grossberg, MD, St. Louis University, reviewed the evidence for acetylcholinesterase inhibitors, the NMDA receptor antagonist memantine, combination therapy, and atypical antipsychotics.

Dietary consultation for older patients might help delay or decrease their risk of dementia. Patients should consume omega-3 fatty acids, whole grains, fresh fruits and vegetables, beans, legumes, and certain spices. Dr. Grossberg also suggested patients engage in physical and mental exercises, social and spiritual activities, and stress reduction, and control cardiovascular risk factors.

AFTERNOON SESSIONS

Many women experience anxiety during pregnancy, and the risk is highest during the first trimester. Dr. Freeman reviewed prevalence, diagnosis, and treatment of panic disorder, generalized anxiety disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder, and posttraumatic stress disorder during pregnancy and postpartum.

Kathleen Brady, MD, PhD, Medical University of South Carolina, explained how methylenedioxypyrovalerone, also known as bath salts, and other designer drugs are not detectable on standard urine drug screens. Agitation, tachycardia, combative behavior, hyperthermia, and hallucinations have been reported.

Kathleen Brady, MD, MPH

Alcohol abuse and depression are highly comorbid and are associated with higher suicidality, more severe symptoms, and poorer treatment response than either disorder alone. Depressive symptoms often are seen during alcohol withdrawal, and may resolve with abstinence. Dr. Brady reviewed the evidence for treating depressed alcoholics with antidepressants, medications targeting alcohol dependence such as disulfiram and naltrexone, and psychotherapy.

Ralph Aquila, MD, Columbia College of Physicians and Surgeons, discussed risk factors for and consequences of treatment nonadherence in patients with schizophrenia. Leslie L. Citrome, MD, MPH, New York Medical College, covered strategies to improve adherence, including identifying and addressing barriers to adherence for individual patients, improving the therapeutic alliance, and considering long-acting injectable antipsychotics.

SATURDAY, APRIL 6, 2013

MORNING SESSIONS

Forty-six percent of depressed patients will stop pharmacotherapy before they have a chance to respond. To minimize short-term side effects, Andrew J. Cutler, MD, Florida Clinical Research Center, suggested educating patients and slowly titrating medications; options for reducing long-term side effects or residual symptoms include switching or augmenting pharmacotherapy.

When treating patients addicted to opioids, outcome measures go beyond general health to obtaining employment and reducing criminal activity. Pharmacotherapy options include methadone maintenance therapy, oral and injectable naltrexone, and oral, sublingual, and implantable buprenorphine. Walter Ling, MD, David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA, described factors that may improve patient outcomes.

Geriatric BD is relatively common in clinical settings, but there is a lack of evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. James W. Jefferson, MD, University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health, recommended choosing a treatment based on the illness phase and balancing the benefit of certain pharmacotherapies against short- and long-term risks.

Most medications for treating alcohol dependence work by modulating functions of opioids, glutamate, GABA, and serotonin. Dr. Ling reviewed the evidence base, dosing guidelines, and clinical recommendations for disulfiram, oral and injectable naltrexone, and acamprosate, which are FDA-approved for treating alcohol dependence. He also recommended combining medications with nonpharmacologic treatments, such as 12-step programs.

Most people who die by suicide deny suicide ideation at their last mental health visit. Risk factors for suicide include family history of suicide, childhood or adult trauma, substance abuse, stressful life events, chronic illness, and psychiatric disorders. Dr. Jefferson described suicide rating and tracking scales and encouraged clinicians to document suicide risk evaluations.

AFTERNOON SESSION

Roger S. McIntyre, MD, FRCPCRobert M.A. Hirschfeld, MD, University of Texas Medical Branch, discussed how the concept of allostatic load—bodily “wear and tear” that emerges with sustained allostatic states—may help explain cognitive and physical decline associated with BD. Roger S. McIntyre, MD, FRCPC, University of Toronto, emphasized that BD is a progressive disorder and comorbidities such as metabolic problems may promote this progression. Terence A. Ketter, MD, Stanford School of Medicine, covered new developments in BD treatment, including certain second-generation antipsychotics, dopaminergic neurotransmission enhancers, mood stabilizers, adjunctive antidepressants, and adjunctive psychotherapy.

Drive Change in an ACO

From informal polls I’ve recently conducted of hospitalists, many are not even aware they are part of an accountable-care organization (ACO). And if they are aware, they might not be engaging in meaningful dialogue with ACO leaders about their role in these organizations. But, in the long term, ACOs will need to bring hospitalists to the table in order to be successful.

Are You Part of an ACO?

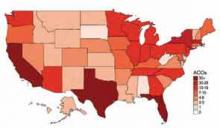

David Muhlestein, who blogs for Health Affairs, tracks the growth of ACOs around the country. He states that, as of Jan. 31, there were 428 ACOs in the U.S. (see Figure 1).1 In terms of numbers, Florida, Texas, and California lead the nation with 42, 33, and 46 ACOs, respectively. So it is likely that you are part of an ACO. If you are unsure, ask your chief medical officer or president of the medical staff.

How ACOs Work

All ACOs seek to manage a group, or population, of patients as efficiently as possible while maintaining or improving quality of care. For Medicare ACOs, the goal is to bring together hospitals and physicians in order to share savings derived from efficiencies in care. But before any savings can be shared, the Medicare ACO must demonstrate that it achieved high-quality care across four domains, totaling 33 individual quality measures. (see Table 1)

Main Flavors of ACOs

There are two types of ACOs: private ACOs and Medicare ACOs. Prior to Medicare ACOs, which were launched in January 2012, there were 150 private-sector ACOs, and this number continues to grow. Private ACOs represent a heterogeneous group in terms of reimbursement model. Some operate under shared savings programs; others use full or partial capitation, bundled payments, and/or other types of arrangements. But nearly all ACOs operate under the premise that the incentives used to make care more efficient and less costly can only be applied if measurable quality is maintained or improved. ACOs do not pay doctors or hospitals more unless high quality is demonstrated.

ACO Quality Measures and Hospitalists

Most of the 33 quality measures required by Medicare ACOs are based in ambulatory practice. These include measures related to blood pressure, immunizations, cancer, and fall-risk screening, and measures for diabetics, such as lipids and hemoglobin A1C. However, there are a few measures for which hospitalists should share in accountability, including:

- All-cause hospital readmission rate—risk-standardized;

- Ambulatory sensitive condition hospital admission rates (CHF, COPD); and

- Medication reconciliation after discharge from an inpatient facility.

Four Key Actions for Hospitalists

Hospitalists make a significant contribution to the quality and the financial performance of ACOs. In addition to the quality metrics cited above, hospitalists impact the inpatient portion of the overall population’s cost of care. Furthermore, hospitalists are vital partners in the care coordination required for an ACO to be successful.

Here are four actions I suggest taking in order for your hospitalist group to be effective as participants in an ACO:

- Have a representative from your group participate in ACO committees that address hospital utilization and related matters, such as care coordination impacting pre- and post-hospital care.

- Learn how to work with ACO case managers on care transitions, including post-discharge follow-up and information transfer.

- Understand an ACO’s approach to engagement of and coordination with post-acute-care facilities. The ability of a post-acute facility, such a skilled nursing facility, to accept patients who have complex care needs, to manage changes in condition in the facility when appropriate, and to send complete information upon transfer to the hospital are important strategies for an ACO’s success.

- Understand how an ACO reports quality and cost performance and how savings will be shared among participants.

Mindset Change

If hospitalists are part of the chain of ACO physicians and providers held accountable for the health of a population of patients, we must work more closely with the medical home/neighborhood, post-acute-care facilities, and home-care providers. The change in mindset will occur only if we have a set of tools to get the job done, such as case managers and information technology, and the appropriate incentives to support better care coordination. I encourage my fellow hospitalists to make things happen, instead of taking a passive role in this monumental transformation.

Reference

Dr. Whitcomb is medical director of healthcare quality at Baystate Medical Center in Springfield, Mass. He is a co-founder and past president of SHM. Email him at [email protected].

From informal polls I’ve recently conducted of hospitalists, many are not even aware they are part of an accountable-care organization (ACO). And if they are aware, they might not be engaging in meaningful dialogue with ACO leaders about their role in these organizations. But, in the long term, ACOs will need to bring hospitalists to the table in order to be successful.

Are You Part of an ACO?

David Muhlestein, who blogs for Health Affairs, tracks the growth of ACOs around the country. He states that, as of Jan. 31, there were 428 ACOs in the U.S. (see Figure 1).1 In terms of numbers, Florida, Texas, and California lead the nation with 42, 33, and 46 ACOs, respectively. So it is likely that you are part of an ACO. If you are unsure, ask your chief medical officer or president of the medical staff.

How ACOs Work

All ACOs seek to manage a group, or population, of patients as efficiently as possible while maintaining or improving quality of care. For Medicare ACOs, the goal is to bring together hospitals and physicians in order to share savings derived from efficiencies in care. But before any savings can be shared, the Medicare ACO must demonstrate that it achieved high-quality care across four domains, totaling 33 individual quality measures. (see Table 1)

Main Flavors of ACOs

There are two types of ACOs: private ACOs and Medicare ACOs. Prior to Medicare ACOs, which were launched in January 2012, there were 150 private-sector ACOs, and this number continues to grow. Private ACOs represent a heterogeneous group in terms of reimbursement model. Some operate under shared savings programs; others use full or partial capitation, bundled payments, and/or other types of arrangements. But nearly all ACOs operate under the premise that the incentives used to make care more efficient and less costly can only be applied if measurable quality is maintained or improved. ACOs do not pay doctors or hospitals more unless high quality is demonstrated.

ACO Quality Measures and Hospitalists

Most of the 33 quality measures required by Medicare ACOs are based in ambulatory practice. These include measures related to blood pressure, immunizations, cancer, and fall-risk screening, and measures for diabetics, such as lipids and hemoglobin A1C. However, there are a few measures for which hospitalists should share in accountability, including:

- All-cause hospital readmission rate—risk-standardized;

- Ambulatory sensitive condition hospital admission rates (CHF, COPD); and

- Medication reconciliation after discharge from an inpatient facility.

Four Key Actions for Hospitalists

Hospitalists make a significant contribution to the quality and the financial performance of ACOs. In addition to the quality metrics cited above, hospitalists impact the inpatient portion of the overall population’s cost of care. Furthermore, hospitalists are vital partners in the care coordination required for an ACO to be successful.

Here are four actions I suggest taking in order for your hospitalist group to be effective as participants in an ACO:

- Have a representative from your group participate in ACO committees that address hospital utilization and related matters, such as care coordination impacting pre- and post-hospital care.

- Learn how to work with ACO case managers on care transitions, including post-discharge follow-up and information transfer.

- Understand an ACO’s approach to engagement of and coordination with post-acute-care facilities. The ability of a post-acute facility, such a skilled nursing facility, to accept patients who have complex care needs, to manage changes in condition in the facility when appropriate, and to send complete information upon transfer to the hospital are important strategies for an ACO’s success.

- Understand how an ACO reports quality and cost performance and how savings will be shared among participants.

Mindset Change

If hospitalists are part of the chain of ACO physicians and providers held accountable for the health of a population of patients, we must work more closely with the medical home/neighborhood, post-acute-care facilities, and home-care providers. The change in mindset will occur only if we have a set of tools to get the job done, such as case managers and information technology, and the appropriate incentives to support better care coordination. I encourage my fellow hospitalists to make things happen, instead of taking a passive role in this monumental transformation.

Reference

Dr. Whitcomb is medical director of healthcare quality at Baystate Medical Center in Springfield, Mass. He is a co-founder and past president of SHM. Email him at [email protected].

From informal polls I’ve recently conducted of hospitalists, many are not even aware they are part of an accountable-care organization (ACO). And if they are aware, they might not be engaging in meaningful dialogue with ACO leaders about their role in these organizations. But, in the long term, ACOs will need to bring hospitalists to the table in order to be successful.

Are You Part of an ACO?