User login

A young woman with enlarged lymph nodes

A previously healthy 25-year-old woman presents to her primary care physician with a “lump in the neck”—a painless, swollen area under the lower part of her left jaw that she noticed several weeks ago and that continues to enlarge. She has also noted a recent increase in fatigue, as well as the onset of generalized headaches and mild sinus congestion. Presumed by another physician to have sinusitis, she had already received a 2-week course of an antibiotic (she could not recall which antibiotic), with no improvement in her symptoms. She has been trying to lose weight and has lost 5 pounds in the last 4 months. She reports no fevers, chills, or night sweats.

She works as a special-education teacher and lives in a rural area. She has not travelled during the past year, inside or outside the United States. When she was an adolescent, she underwent tonsillectomy and had her wisdom teeth extracted. Her family has no history of hematologic dyscrasia or malignancy. She has two dogs, which are indoor pets, and she utilizes a city water supply.

1. Which of the following causes of a lump in the neck is most important to exclude?

- Viral or bacterial infection

- Lymphoma

- Oral cavity abscess

- Infectious mononucleosis

- Congenital anomaly

A lump in the neck can be broadly categorized as congenital, inflammatory, or malignant. Congenital causes include branchial cleft cyst (anterior to the sternocleidomastoid muscle) and thyroglossal duct cyst (usually in the midline between the hyoid bone and the isthmus of the thyroid gland). Other possibilities include lipoma and, less frequently, a salivary gland disorder such as sialadenitis.

A complaint of a neck lump very often correlates with the physical finding of lymphadenopathy, and a standard approach in evaluation should be undertaken, based on the mnemonic “PAAA”—ie, palpation, age, area, and associated symptoms.

Palpation. In palpation of the lymph node group, one should note the size and tactile quality of the lymph nodes and assess for abnormal temperature, tenderness, fluctuance, and mobility. In general, lymph nodes larger than 1.5 cm by 1.5 cm are more likely to be of granulomatous or neoplastic origin.1 Nodes that are tender, warm, or fluctuant are likely reactive to a local infectious process; nodes that are firm, matted, and fixed are most characteristic of malignancy; and rubbery, mobile nodes may represent either granulomatous disease or lymphoma.2

Age helps stratify the risk of malignancy as an underlying cause, which is increased in people over age 50 presenting with lymphadenopathy.1

Area. An assessment of the extent of the lymphadenopathy can guide the search either for a cause of generalized lymphadenopathy or for pathology in the anatomic area drained by the particular lymph node group, including the scalp (occipital or preauricular); external ear (posterior auricular); oral cavity (submandibular, submental); soft tissues of the face and neck (superficial cervical); upper respiratory tract and thyroid (deep cervical); and thoracic cavity and abdominal cavity (supraclavicular).

Asking the patient about occupational, environmental, and behavioral risk factors and associated signs and symptoms such as fever, rash, diaphoresis, unintentional weight loss, and splenomegaly helps to narrow the differential diagnosis. Common diagnoses to consider in the evaluation of peripheral lymphadenopathy are listed in Table 1.

A viral or bacterial upper respiratory infection is one of the most common causes of cervical lymphadenopathy, although this usually does not persist for many weeks. Mononucleosis more commonly involves the posterior cervical chain and is often accompanied by splenomegaly. Because of the prolonged presence of the lump, malignancy, including lymphoma, is the most important of the answer choices to consider and rule out in a timely fashion.

INITIAL PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

The woman appears to be well and is in no acute distress. Her oral temperature is 98.1°F (36.7°C), blood pressure 119/72 mm Hg, heart rate 86 beats per minute, and respiratory rate 18 breaths per minute.

The head and neck appear normal. The nares are patent with normal mucosa and no visible drainage. There is no tenderness during palpation of the facial sinuses. The ear canals, tympanic membranes, oropharynx, and tongue appear normal. Several firm, mobile, nontender lymph nodes about 1 cm in diameter are palpable in the left submandibular and right supraclavicular area. No other occipital, submental, axillary, or inguinal lymphadenopathy is noted. There is no overlying erythema or warmth. The cardiac examination is normal, and the lungs are clear on auscultation. The abdomen is soft, nontender, and nondistended, with no organomegaly. The skin appears normal, and the neurologic examination is normal.

INITIAL LABORATORY TESTS

Results of initial laboratory tests are as follows:

- White blood cell count 5.74 × 109/L (reference range 3.70–11.00)

- Red blood cell count 4.49 × 109/L (3.90–5.20)

- Hemoglobin 13.0 g/dL (11.5–15.5)

- Hematocrit 38.4% (36.0–46.0)

- Platelet count 210 × 109/L (150–400)

- Mean corpuscular volume 85 fL (80–100)

- Absolute neutrophil count 3.26 × 109/L (1.45–7.50)

- Blood urea nitrogen 8 mg/dL (8–25)

- Creatinine 0.65 mg/dL (0.70–1.40)

- Lactate dehydrogenase 146 U/L (100–220)

- Uric acid 4.0 mg/dL (2.0–7.0)

- Thyrotropin (thyroid-stimulating hormone) 1.86 μIU/mL (0.4–5.5).

A recent tuberculin skin test obtained as part of her employment screening was negative, and so was a test for antibody to human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), obtained recently before donating plasma. A urine pregnancy test done in the office was also negative. A peripheral blood smear showed slight toxic granulation with rare reactive lymphocytes.

2. Which test would provide the greatest diagnostic yield at this point?

- Needle aspiration biopsy of lymph node

- Excisional lymph node biopsy

- Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing for HIV

- Antistreptolysin-O (ASO) titer

Because of the persistent enlargement of the patient’s lymph nodes despite several weeks of antibiotic treatment, and because submandibular and supraclavicular nodes were involved, excisional lymph node biopsy would be the best of these choices to evaluate for malignancy. Compared with needle aspiration biopsy, it is the gold standard, preserving the nodal architecture and providing ample tissue for immunostaining and additional studies.

Needle aspiration biopsy is safe, inexpensive, and easy to do and can be useful in situations of limited resources, but it does not reliably distinguish between a reactive and a neoplastic process.1 Its collection and interpretation are highly variable and personnel-dependent, and its sensitivity for detecting lymphoma is reported to be as low as 7.1% (95% confidence interval 0.9% to 23.5%).2

An acute retroviral syndrome can cause adenopathy, especially before seroconversion is evident, but it is usually associated with an influenza-like illness and monocytosis. Although this patient had no apparent risk factors for HIV, ordering PCR testing for HIV is also an important step when the clinical situation is suggestive. In the absence of an abnormal-appearing oropharynx, tonsillar exudate, or high fever, the pretest probability of streptococcal pharyngitis is low, and an ASO titer is unlikely to be diagnostic in this case.

CASE CONTINUED: BIOPSY PERFORMED

An incisional lymph node biopsy was obtained (Figure 1).

3. Which can confirm the suspected diagnosis?

- Tissue culture

- Test for immunoglobulin (Ig) G and IgM antibodies to Toxoplasma gondii

- Serum PCR testing for T gondii

- T gondii IgG avidity testing

DIAGNOSIS OF TOXOPLASMOSIS

In this patient, acute toxoplasmosis was suspected based on recognition of the morphologic triad seen in Toxoplasma lymphadenitis— ie, follicular hyperplasia, abundance of monocytoid cells, and clusters of epithelioid lymphocytes.3,4

Detection and measurement of IgM antibodies against T gondii is the most widely used serologic test for acute toxoplasmosis and is often considered the reference standard among the most common commercially available agglutination screening assays. It has a sensitivity between 93.7% and 100% and a specificity of 97.1% to 99.2%.5 Confirmation is generally done with enzyme-linked immunoassay or chemiluminescent-based tests, which can detect lower levels of IgG and IgM.5

A positive serum IgG confirms seroconversion but by itself cannot distinguish between acute and chronic infection, although it is commonly obtained in conjunction with IgM levels.6 Since both IgG and IgM can be elevated months after initial infection, serum IgA and IgE levels can more accurately suggest the timing of infection if clarification is needed.6,7 In addition, IgG avidity testing can distinguish acute infection from chronic infection: a high avidity index suggests the acute infection occurred at least 3 to 5 months ago, whereas the avidity index may be low or zero if acute infection occurred within the past 4 weeks.7 The sensitivity of avidity testing is 91.3% to 94.4%, and the specificity 87.8% to 98.5%.7

Serum PCR testing for T gondii is useful when toxoplasmosis is suspected in patients whose immune system may not be able to mount an adequate antibody response or in patients in the hyperacute phase of infection, even before a detectable antibody response can be formed.8,9 However, because of limitations of equipment, expertise, and overall cost, this method is not universally available. Additionally, blood cultures and PCR testing or tissue culture of pathologic specimens cannot routinely be relied on for diagnosis, as often the burden of microorganisms present in these specimens is low. When positive, culture specimens may yield bradyzoites or tachyzoites, but only after considerable latency of many days to weeks.10

How people acquire acute toxoplasmosis

T gondii is an obligate intracellular protozoan parasite. Sexual replication of the organism takes place within the intestines of cats (the definitive host), with subsequent excretion of infective oocysts in feces.11 These hardy oocysts can contaminate soil or water supplies and can survive for months, depending on ambient temperature and humidity. Ingestion of oocysts can lead to infection of a variety of mammals, including sheep, pigs, chicken, and cattle.

Infection in humans can occur with consumption of raw or undercooked foods contaminated with oocysts, and inadequate hand-washing and poor kitchen hygiene substantially increase the risk of infection.12 Activities such as gardening can expose humans to oocysts in contaminated water and soil. In addition, direct contact with cat feces, such as when cleaning the litterbox, is a known exposure risk. Vertical transmission can manifest as congenital toxoplasmosis in a fetus when transmitted from an infected pregnant mother.

Eating raw or undercooked food is considered to be the greatest risk factor for acquired toxoplasmosis and is believed to be responsible for about 50% of all cases.12 However, in pooled data from 14 case-control studies, no clear risk factor for Toxoplasma infection could be identified in up to 60% of affected people, leading many experts to believe contaminated water may play a larger role in acquisition than previously surmised.12

Toxoplasma cysts have a predilection for muscle and neural tissue, resulting in myositis, myocarditis, encephalitis, and chorioretinitis. Severe systemic manifestations are seen in people with impaired T-cell immunity, such as those with HIV infection and acquired immunodeficiency syndrome; or hematologic malignancy; in recipients of solid-organ transplants; or in people taking corticosteroids or cytotoxic drugs. Congenital infection can result in stillbirth, microcephaly, developmental delay, or deafness in the developing fetus and is an important cause of infant morbidity and death worldwide.13

Infection in immunocompetent people is usually asymptomatic.14 However, up to 20% of immunocompetent patients develop symptoms that tend to be nonspecific and include muscle aches and lymphadenopathy, and these are often mistaken for an influenza-like illness.14,15 Other symptoms include malaise, fevers, night sweats, pharyngitis, abdominal pain, hepatosplenomegaly, maculopapular rash, and atypical lymphocytosis (less than 10% of peripheral blood).11 The most common physical manifestation of acute toxoplasmosis is isolated cervical lymphadenopathy, although any lymph node group can be affected.14 Lymph nodes are not fixed or matted and generally are neither tender nor suppurative.16

4. What is the correct treatment strategy for acute toxoplasmosis in this case?

- Symptomatic treatment only

- Trimethoprim 160 mg and sulfamethoxazole 800 mg daily

- Combination of atovaquone and clindamycin

- Combination pyrimethamine, sulfadiazine, and folinic acid

TREATMENT AND PROGNOSIS OF ACUTE TOXOPLASMOSIS

No antimicrobial treatment is required for most immunocompetent patients. Symptoms are self-limited and resolve within 1 to 2 months in 60% of patients.14 A substantial proportion of patients—25%—will have lingering symptoms at 2 to 4 months, and some (10%) can have mild symptoms for 6 months or longer.16

Symptomatic treatment with analgesics such as nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) is appropriate.

Immunocompromised and critically ill patients and those with ocular manifestations require combination therapy with pyrimethamine, sulfadiazine, and folinic acid.17 Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole is effective as prophylaxis against T gondii infection in immunocompromised patients at a dosage of 160 mg trimethoprim/800 mg sulfamethoxazole daily, but it is also an alternative for treatment at higher dosages (5 mg/kg trimethoprim and 25 mg/kg sulfamethoxazole twice daily).

Atovaquone and clindamycin can be used in sulfa-sensitive patients17 and also in those with latent toxoplasmosis for better penetration of tissue cysts. Corticosteroids are used as adjuncts in those with ocular involvement.

Spiramycin is the treatment of choice in pregnant women and can be given throughout the pregnancy.17,18 A recent comparative study by Hotop et al18 reported a reduction in the rate of fetal transmission (1.6% vs 4.8%) when spiramycin was given from the time of diagnosis through the 16th week of pregnancy, followed by a minimum of 4 weeks of combination therapy with pyrimethamine, sulfadiazine, and folinic acid.18

CASE CONCLUDED

Serologic testing was positive for IgM and IgG antibodies to T gondii, which suggested subacute infection. The patient received no antimicrobial therapy and her lymphadenopathy eventually resolved. Her generalized fatigue gradually resolved over the next year without antimicrobial treatment.

A thorough re-review of potential exposures was done at subsequent office visits to help elucidate how she may have acquired the infection. She recalled no recent exposure to cats or rodents, nor consumption of raw meat. We could only suppose that there may have been inadvertent exposure to oocyst-containing soil or water or to undercooked meat products. Thus, the diagnosis of acute toxoplasmosis should be kept in mind in the evaluation of lymphadenopathy, even in the absence of a clear history of exposure.

- Habermann TM, Steensma DP. Lymphadenopathy. Mayo Clin Proc 2000; 75:723–732.

- Khillan R, Sidhu G, Axiotis C, Braverman AS. Fine needle aspiration (FNA) cytology for diagnosis of cervical lymphadenopathy. Int J Hematol 2012; 95:282–284.

- Dorfman RF, Remington JS. Value of lymph-node biopsy in the diagnosis of acute acquired toxoplasmosis. N Engl J Med 1973; 289:878–881.

- Eapen M, Mathew CF, Aravindan KP. Evidence based criteria for the histopathological diagnosis of toxoplasmic lymphadenopathy. J Clin Pathol 2005; 58:1143–1146.

- Villard O, Cimon B, Franck J, et al; Network from the French National Reference Center for Toxoplasmosis. Evaluation of the usefulness of six commercial agglutination assays for serologic diagnosis of toxoplasmosis. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis 2012; 73:231–235.

- Suzuki LA, Rocha RJ, Rossi CL. Evaluation of serological markers for the immunodiagnosis of acute acquired toxoplasmosis. J Med Microbiol 2001; 50:62–70.

- Lachaud L, Calas O, Picot MC, Albaba S, Bourgeois N, Pratlong F. Value of 2 IgG avidity commercial tests used alone or in association to date toxoplasmosis contamination. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis 2009; 64:267–274.

- Rahumatullah A, Khoo BY, Noordin R. Triplex PCR using new primers for the detection of Toxoplasma gondii. Exp Parasitol 2012; 131:231–238.

- Contini C, Giuliodori M, Cultrera R, Seraceni S. Detection of clinical-stage specific molecular Toxoplasma gondii gene patterns in patients with toxoplasmic lymphadenitis. J Med Microbiol 2006; 55:771–774.

- Silveira C, Vallochi AL, Rodrigues da Silva U, et al. Toxoplasma gondii in the peripheral blood of patients with acute and chronic toxoplasmosis. Br J Ophthalmol 2011; 95:396–400.

- Montoya JG, Liesenfeld O. Toxoplasmosis. Lancet 2004; 363:1965–1976.

- Petersen E, Vesco G, Villari S, Buffolano W. What do we know about risk factors for infection in humans with Toxoplasma gondii and how can we prevent infections? Zoonoses Public Health 2010; 57:8–17.

- Feldman DM, Timms D, Borgida AF. Toxoplasmosis, parvovirus, and cytomegalovirus in pregnancy. Clin Lab Med 2010; 30:709–720.

- Weiss LM, Dubey JP. Toxoplasmosis: a history of clinical observations. Int J Parasitol 2009; 39:895–901.

- Remington JS. Toxoplasmosis in the adult. Bull NY Acad Med 1974; 50:211–227.

- McCabe RE, Brooks RG, Dorfman RF, Remington JS. Clinical spectrum in 107 cases of toxoplasmic lymphadenopathy. Rev Infect Dis 1987; 9:754–774.

- Toxoplasmosis. The Medical Letter, Drugs for Parasitic Infections. New Rochelle, NY: The Medical Letter Inc, June 1, 2010:57–58.

- Hotop A, Hlobil H, Gross U. Efficacy of rapid treatment initiation following primary Toxoplasma gondii infection during pregnancy. Clin Infect Dis 2012; 54:1545–1552.

A previously healthy 25-year-old woman presents to her primary care physician with a “lump in the neck”—a painless, swollen area under the lower part of her left jaw that she noticed several weeks ago and that continues to enlarge. She has also noted a recent increase in fatigue, as well as the onset of generalized headaches and mild sinus congestion. Presumed by another physician to have sinusitis, she had already received a 2-week course of an antibiotic (she could not recall which antibiotic), with no improvement in her symptoms. She has been trying to lose weight and has lost 5 pounds in the last 4 months. She reports no fevers, chills, or night sweats.

She works as a special-education teacher and lives in a rural area. She has not travelled during the past year, inside or outside the United States. When she was an adolescent, she underwent tonsillectomy and had her wisdom teeth extracted. Her family has no history of hematologic dyscrasia or malignancy. She has two dogs, which are indoor pets, and she utilizes a city water supply.

1. Which of the following causes of a lump in the neck is most important to exclude?

- Viral or bacterial infection

- Lymphoma

- Oral cavity abscess

- Infectious mononucleosis

- Congenital anomaly

A lump in the neck can be broadly categorized as congenital, inflammatory, or malignant. Congenital causes include branchial cleft cyst (anterior to the sternocleidomastoid muscle) and thyroglossal duct cyst (usually in the midline between the hyoid bone and the isthmus of the thyroid gland). Other possibilities include lipoma and, less frequently, a salivary gland disorder such as sialadenitis.

A complaint of a neck lump very often correlates with the physical finding of lymphadenopathy, and a standard approach in evaluation should be undertaken, based on the mnemonic “PAAA”—ie, palpation, age, area, and associated symptoms.

Palpation. In palpation of the lymph node group, one should note the size and tactile quality of the lymph nodes and assess for abnormal temperature, tenderness, fluctuance, and mobility. In general, lymph nodes larger than 1.5 cm by 1.5 cm are more likely to be of granulomatous or neoplastic origin.1 Nodes that are tender, warm, or fluctuant are likely reactive to a local infectious process; nodes that are firm, matted, and fixed are most characteristic of malignancy; and rubbery, mobile nodes may represent either granulomatous disease or lymphoma.2

Age helps stratify the risk of malignancy as an underlying cause, which is increased in people over age 50 presenting with lymphadenopathy.1

Area. An assessment of the extent of the lymphadenopathy can guide the search either for a cause of generalized lymphadenopathy or for pathology in the anatomic area drained by the particular lymph node group, including the scalp (occipital or preauricular); external ear (posterior auricular); oral cavity (submandibular, submental); soft tissues of the face and neck (superficial cervical); upper respiratory tract and thyroid (deep cervical); and thoracic cavity and abdominal cavity (supraclavicular).

Asking the patient about occupational, environmental, and behavioral risk factors and associated signs and symptoms such as fever, rash, diaphoresis, unintentional weight loss, and splenomegaly helps to narrow the differential diagnosis. Common diagnoses to consider in the evaluation of peripheral lymphadenopathy are listed in Table 1.

A viral or bacterial upper respiratory infection is one of the most common causes of cervical lymphadenopathy, although this usually does not persist for many weeks. Mononucleosis more commonly involves the posterior cervical chain and is often accompanied by splenomegaly. Because of the prolonged presence of the lump, malignancy, including lymphoma, is the most important of the answer choices to consider and rule out in a timely fashion.

INITIAL PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

The woman appears to be well and is in no acute distress. Her oral temperature is 98.1°F (36.7°C), blood pressure 119/72 mm Hg, heart rate 86 beats per minute, and respiratory rate 18 breaths per minute.

The head and neck appear normal. The nares are patent with normal mucosa and no visible drainage. There is no tenderness during palpation of the facial sinuses. The ear canals, tympanic membranes, oropharynx, and tongue appear normal. Several firm, mobile, nontender lymph nodes about 1 cm in diameter are palpable in the left submandibular and right supraclavicular area. No other occipital, submental, axillary, or inguinal lymphadenopathy is noted. There is no overlying erythema or warmth. The cardiac examination is normal, and the lungs are clear on auscultation. The abdomen is soft, nontender, and nondistended, with no organomegaly. The skin appears normal, and the neurologic examination is normal.

INITIAL LABORATORY TESTS

Results of initial laboratory tests are as follows:

- White blood cell count 5.74 × 109/L (reference range 3.70–11.00)

- Red blood cell count 4.49 × 109/L (3.90–5.20)

- Hemoglobin 13.0 g/dL (11.5–15.5)

- Hematocrit 38.4% (36.0–46.0)

- Platelet count 210 × 109/L (150–400)

- Mean corpuscular volume 85 fL (80–100)

- Absolute neutrophil count 3.26 × 109/L (1.45–7.50)

- Blood urea nitrogen 8 mg/dL (8–25)

- Creatinine 0.65 mg/dL (0.70–1.40)

- Lactate dehydrogenase 146 U/L (100–220)

- Uric acid 4.0 mg/dL (2.0–7.0)

- Thyrotropin (thyroid-stimulating hormone) 1.86 μIU/mL (0.4–5.5).

A recent tuberculin skin test obtained as part of her employment screening was negative, and so was a test for antibody to human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), obtained recently before donating plasma. A urine pregnancy test done in the office was also negative. A peripheral blood smear showed slight toxic granulation with rare reactive lymphocytes.

2. Which test would provide the greatest diagnostic yield at this point?

- Needle aspiration biopsy of lymph node

- Excisional lymph node biopsy

- Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing for HIV

- Antistreptolysin-O (ASO) titer

Because of the persistent enlargement of the patient’s lymph nodes despite several weeks of antibiotic treatment, and because submandibular and supraclavicular nodes were involved, excisional lymph node biopsy would be the best of these choices to evaluate for malignancy. Compared with needle aspiration biopsy, it is the gold standard, preserving the nodal architecture and providing ample tissue for immunostaining and additional studies.

Needle aspiration biopsy is safe, inexpensive, and easy to do and can be useful in situations of limited resources, but it does not reliably distinguish between a reactive and a neoplastic process.1 Its collection and interpretation are highly variable and personnel-dependent, and its sensitivity for detecting lymphoma is reported to be as low as 7.1% (95% confidence interval 0.9% to 23.5%).2

An acute retroviral syndrome can cause adenopathy, especially before seroconversion is evident, but it is usually associated with an influenza-like illness and monocytosis. Although this patient had no apparent risk factors for HIV, ordering PCR testing for HIV is also an important step when the clinical situation is suggestive. In the absence of an abnormal-appearing oropharynx, tonsillar exudate, or high fever, the pretest probability of streptococcal pharyngitis is low, and an ASO titer is unlikely to be diagnostic in this case.

CASE CONTINUED: BIOPSY PERFORMED

An incisional lymph node biopsy was obtained (Figure 1).

3. Which can confirm the suspected diagnosis?

- Tissue culture

- Test for immunoglobulin (Ig) G and IgM antibodies to Toxoplasma gondii

- Serum PCR testing for T gondii

- T gondii IgG avidity testing

DIAGNOSIS OF TOXOPLASMOSIS

In this patient, acute toxoplasmosis was suspected based on recognition of the morphologic triad seen in Toxoplasma lymphadenitis— ie, follicular hyperplasia, abundance of monocytoid cells, and clusters of epithelioid lymphocytes.3,4

Detection and measurement of IgM antibodies against T gondii is the most widely used serologic test for acute toxoplasmosis and is often considered the reference standard among the most common commercially available agglutination screening assays. It has a sensitivity between 93.7% and 100% and a specificity of 97.1% to 99.2%.5 Confirmation is generally done with enzyme-linked immunoassay or chemiluminescent-based tests, which can detect lower levels of IgG and IgM.5

A positive serum IgG confirms seroconversion but by itself cannot distinguish between acute and chronic infection, although it is commonly obtained in conjunction with IgM levels.6 Since both IgG and IgM can be elevated months after initial infection, serum IgA and IgE levels can more accurately suggest the timing of infection if clarification is needed.6,7 In addition, IgG avidity testing can distinguish acute infection from chronic infection: a high avidity index suggests the acute infection occurred at least 3 to 5 months ago, whereas the avidity index may be low or zero if acute infection occurred within the past 4 weeks.7 The sensitivity of avidity testing is 91.3% to 94.4%, and the specificity 87.8% to 98.5%.7

Serum PCR testing for T gondii is useful when toxoplasmosis is suspected in patients whose immune system may not be able to mount an adequate antibody response or in patients in the hyperacute phase of infection, even before a detectable antibody response can be formed.8,9 However, because of limitations of equipment, expertise, and overall cost, this method is not universally available. Additionally, blood cultures and PCR testing or tissue culture of pathologic specimens cannot routinely be relied on for diagnosis, as often the burden of microorganisms present in these specimens is low. When positive, culture specimens may yield bradyzoites or tachyzoites, but only after considerable latency of many days to weeks.10

How people acquire acute toxoplasmosis

T gondii is an obligate intracellular protozoan parasite. Sexual replication of the organism takes place within the intestines of cats (the definitive host), with subsequent excretion of infective oocysts in feces.11 These hardy oocysts can contaminate soil or water supplies and can survive for months, depending on ambient temperature and humidity. Ingestion of oocysts can lead to infection of a variety of mammals, including sheep, pigs, chicken, and cattle.

Infection in humans can occur with consumption of raw or undercooked foods contaminated with oocysts, and inadequate hand-washing and poor kitchen hygiene substantially increase the risk of infection.12 Activities such as gardening can expose humans to oocysts in contaminated water and soil. In addition, direct contact with cat feces, such as when cleaning the litterbox, is a known exposure risk. Vertical transmission can manifest as congenital toxoplasmosis in a fetus when transmitted from an infected pregnant mother.

Eating raw or undercooked food is considered to be the greatest risk factor for acquired toxoplasmosis and is believed to be responsible for about 50% of all cases.12 However, in pooled data from 14 case-control studies, no clear risk factor for Toxoplasma infection could be identified in up to 60% of affected people, leading many experts to believe contaminated water may play a larger role in acquisition than previously surmised.12

Toxoplasma cysts have a predilection for muscle and neural tissue, resulting in myositis, myocarditis, encephalitis, and chorioretinitis. Severe systemic manifestations are seen in people with impaired T-cell immunity, such as those with HIV infection and acquired immunodeficiency syndrome; or hematologic malignancy; in recipients of solid-organ transplants; or in people taking corticosteroids or cytotoxic drugs. Congenital infection can result in stillbirth, microcephaly, developmental delay, or deafness in the developing fetus and is an important cause of infant morbidity and death worldwide.13

Infection in immunocompetent people is usually asymptomatic.14 However, up to 20% of immunocompetent patients develop symptoms that tend to be nonspecific and include muscle aches and lymphadenopathy, and these are often mistaken for an influenza-like illness.14,15 Other symptoms include malaise, fevers, night sweats, pharyngitis, abdominal pain, hepatosplenomegaly, maculopapular rash, and atypical lymphocytosis (less than 10% of peripheral blood).11 The most common physical manifestation of acute toxoplasmosis is isolated cervical lymphadenopathy, although any lymph node group can be affected.14 Lymph nodes are not fixed or matted and generally are neither tender nor suppurative.16

4. What is the correct treatment strategy for acute toxoplasmosis in this case?

- Symptomatic treatment only

- Trimethoprim 160 mg and sulfamethoxazole 800 mg daily

- Combination of atovaquone and clindamycin

- Combination pyrimethamine, sulfadiazine, and folinic acid

TREATMENT AND PROGNOSIS OF ACUTE TOXOPLASMOSIS

No antimicrobial treatment is required for most immunocompetent patients. Symptoms are self-limited and resolve within 1 to 2 months in 60% of patients.14 A substantial proportion of patients—25%—will have lingering symptoms at 2 to 4 months, and some (10%) can have mild symptoms for 6 months or longer.16

Symptomatic treatment with analgesics such as nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) is appropriate.

Immunocompromised and critically ill patients and those with ocular manifestations require combination therapy with pyrimethamine, sulfadiazine, and folinic acid.17 Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole is effective as prophylaxis against T gondii infection in immunocompromised patients at a dosage of 160 mg trimethoprim/800 mg sulfamethoxazole daily, but it is also an alternative for treatment at higher dosages (5 mg/kg trimethoprim and 25 mg/kg sulfamethoxazole twice daily).

Atovaquone and clindamycin can be used in sulfa-sensitive patients17 and also in those with latent toxoplasmosis for better penetration of tissue cysts. Corticosteroids are used as adjuncts in those with ocular involvement.

Spiramycin is the treatment of choice in pregnant women and can be given throughout the pregnancy.17,18 A recent comparative study by Hotop et al18 reported a reduction in the rate of fetal transmission (1.6% vs 4.8%) when spiramycin was given from the time of diagnosis through the 16th week of pregnancy, followed by a minimum of 4 weeks of combination therapy with pyrimethamine, sulfadiazine, and folinic acid.18

CASE CONCLUDED

Serologic testing was positive for IgM and IgG antibodies to T gondii, which suggested subacute infection. The patient received no antimicrobial therapy and her lymphadenopathy eventually resolved. Her generalized fatigue gradually resolved over the next year without antimicrobial treatment.

A thorough re-review of potential exposures was done at subsequent office visits to help elucidate how she may have acquired the infection. She recalled no recent exposure to cats or rodents, nor consumption of raw meat. We could only suppose that there may have been inadvertent exposure to oocyst-containing soil or water or to undercooked meat products. Thus, the diagnosis of acute toxoplasmosis should be kept in mind in the evaluation of lymphadenopathy, even in the absence of a clear history of exposure.

A previously healthy 25-year-old woman presents to her primary care physician with a “lump in the neck”—a painless, swollen area under the lower part of her left jaw that she noticed several weeks ago and that continues to enlarge. She has also noted a recent increase in fatigue, as well as the onset of generalized headaches and mild sinus congestion. Presumed by another physician to have sinusitis, she had already received a 2-week course of an antibiotic (she could not recall which antibiotic), with no improvement in her symptoms. She has been trying to lose weight and has lost 5 pounds in the last 4 months. She reports no fevers, chills, or night sweats.

She works as a special-education teacher and lives in a rural area. She has not travelled during the past year, inside or outside the United States. When she was an adolescent, she underwent tonsillectomy and had her wisdom teeth extracted. Her family has no history of hematologic dyscrasia or malignancy. She has two dogs, which are indoor pets, and she utilizes a city water supply.

1. Which of the following causes of a lump in the neck is most important to exclude?

- Viral or bacterial infection

- Lymphoma

- Oral cavity abscess

- Infectious mononucleosis

- Congenital anomaly

A lump in the neck can be broadly categorized as congenital, inflammatory, or malignant. Congenital causes include branchial cleft cyst (anterior to the sternocleidomastoid muscle) and thyroglossal duct cyst (usually in the midline between the hyoid bone and the isthmus of the thyroid gland). Other possibilities include lipoma and, less frequently, a salivary gland disorder such as sialadenitis.

A complaint of a neck lump very often correlates with the physical finding of lymphadenopathy, and a standard approach in evaluation should be undertaken, based on the mnemonic “PAAA”—ie, palpation, age, area, and associated symptoms.

Palpation. In palpation of the lymph node group, one should note the size and tactile quality of the lymph nodes and assess for abnormal temperature, tenderness, fluctuance, and mobility. In general, lymph nodes larger than 1.5 cm by 1.5 cm are more likely to be of granulomatous or neoplastic origin.1 Nodes that are tender, warm, or fluctuant are likely reactive to a local infectious process; nodes that are firm, matted, and fixed are most characteristic of malignancy; and rubbery, mobile nodes may represent either granulomatous disease or lymphoma.2

Age helps stratify the risk of malignancy as an underlying cause, which is increased in people over age 50 presenting with lymphadenopathy.1

Area. An assessment of the extent of the lymphadenopathy can guide the search either for a cause of generalized lymphadenopathy or for pathology in the anatomic area drained by the particular lymph node group, including the scalp (occipital or preauricular); external ear (posterior auricular); oral cavity (submandibular, submental); soft tissues of the face and neck (superficial cervical); upper respiratory tract and thyroid (deep cervical); and thoracic cavity and abdominal cavity (supraclavicular).

Asking the patient about occupational, environmental, and behavioral risk factors and associated signs and symptoms such as fever, rash, diaphoresis, unintentional weight loss, and splenomegaly helps to narrow the differential diagnosis. Common diagnoses to consider in the evaluation of peripheral lymphadenopathy are listed in Table 1.

A viral or bacterial upper respiratory infection is one of the most common causes of cervical lymphadenopathy, although this usually does not persist for many weeks. Mononucleosis more commonly involves the posterior cervical chain and is often accompanied by splenomegaly. Because of the prolonged presence of the lump, malignancy, including lymphoma, is the most important of the answer choices to consider and rule out in a timely fashion.

INITIAL PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

The woman appears to be well and is in no acute distress. Her oral temperature is 98.1°F (36.7°C), blood pressure 119/72 mm Hg, heart rate 86 beats per minute, and respiratory rate 18 breaths per minute.

The head and neck appear normal. The nares are patent with normal mucosa and no visible drainage. There is no tenderness during palpation of the facial sinuses. The ear canals, tympanic membranes, oropharynx, and tongue appear normal. Several firm, mobile, nontender lymph nodes about 1 cm in diameter are palpable in the left submandibular and right supraclavicular area. No other occipital, submental, axillary, or inguinal lymphadenopathy is noted. There is no overlying erythema or warmth. The cardiac examination is normal, and the lungs are clear on auscultation. The abdomen is soft, nontender, and nondistended, with no organomegaly. The skin appears normal, and the neurologic examination is normal.

INITIAL LABORATORY TESTS

Results of initial laboratory tests are as follows:

- White blood cell count 5.74 × 109/L (reference range 3.70–11.00)

- Red blood cell count 4.49 × 109/L (3.90–5.20)

- Hemoglobin 13.0 g/dL (11.5–15.5)

- Hematocrit 38.4% (36.0–46.0)

- Platelet count 210 × 109/L (150–400)

- Mean corpuscular volume 85 fL (80–100)

- Absolute neutrophil count 3.26 × 109/L (1.45–7.50)

- Blood urea nitrogen 8 mg/dL (8–25)

- Creatinine 0.65 mg/dL (0.70–1.40)

- Lactate dehydrogenase 146 U/L (100–220)

- Uric acid 4.0 mg/dL (2.0–7.0)

- Thyrotropin (thyroid-stimulating hormone) 1.86 μIU/mL (0.4–5.5).

A recent tuberculin skin test obtained as part of her employment screening was negative, and so was a test for antibody to human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), obtained recently before donating plasma. A urine pregnancy test done in the office was also negative. A peripheral blood smear showed slight toxic granulation with rare reactive lymphocytes.

2. Which test would provide the greatest diagnostic yield at this point?

- Needle aspiration biopsy of lymph node

- Excisional lymph node biopsy

- Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing for HIV

- Antistreptolysin-O (ASO) titer

Because of the persistent enlargement of the patient’s lymph nodes despite several weeks of antibiotic treatment, and because submandibular and supraclavicular nodes were involved, excisional lymph node biopsy would be the best of these choices to evaluate for malignancy. Compared with needle aspiration biopsy, it is the gold standard, preserving the nodal architecture and providing ample tissue for immunostaining and additional studies.

Needle aspiration biopsy is safe, inexpensive, and easy to do and can be useful in situations of limited resources, but it does not reliably distinguish between a reactive and a neoplastic process.1 Its collection and interpretation are highly variable and personnel-dependent, and its sensitivity for detecting lymphoma is reported to be as low as 7.1% (95% confidence interval 0.9% to 23.5%).2

An acute retroviral syndrome can cause adenopathy, especially before seroconversion is evident, but it is usually associated with an influenza-like illness and monocytosis. Although this patient had no apparent risk factors for HIV, ordering PCR testing for HIV is also an important step when the clinical situation is suggestive. In the absence of an abnormal-appearing oropharynx, tonsillar exudate, or high fever, the pretest probability of streptococcal pharyngitis is low, and an ASO titer is unlikely to be diagnostic in this case.

CASE CONTINUED: BIOPSY PERFORMED

An incisional lymph node biopsy was obtained (Figure 1).

3. Which can confirm the suspected diagnosis?

- Tissue culture

- Test for immunoglobulin (Ig) G and IgM antibodies to Toxoplasma gondii

- Serum PCR testing for T gondii

- T gondii IgG avidity testing

DIAGNOSIS OF TOXOPLASMOSIS

In this patient, acute toxoplasmosis was suspected based on recognition of the morphologic triad seen in Toxoplasma lymphadenitis— ie, follicular hyperplasia, abundance of monocytoid cells, and clusters of epithelioid lymphocytes.3,4

Detection and measurement of IgM antibodies against T gondii is the most widely used serologic test for acute toxoplasmosis and is often considered the reference standard among the most common commercially available agglutination screening assays. It has a sensitivity between 93.7% and 100% and a specificity of 97.1% to 99.2%.5 Confirmation is generally done with enzyme-linked immunoassay or chemiluminescent-based tests, which can detect lower levels of IgG and IgM.5

A positive serum IgG confirms seroconversion but by itself cannot distinguish between acute and chronic infection, although it is commonly obtained in conjunction with IgM levels.6 Since both IgG and IgM can be elevated months after initial infection, serum IgA and IgE levels can more accurately suggest the timing of infection if clarification is needed.6,7 In addition, IgG avidity testing can distinguish acute infection from chronic infection: a high avidity index suggests the acute infection occurred at least 3 to 5 months ago, whereas the avidity index may be low or zero if acute infection occurred within the past 4 weeks.7 The sensitivity of avidity testing is 91.3% to 94.4%, and the specificity 87.8% to 98.5%.7

Serum PCR testing for T gondii is useful when toxoplasmosis is suspected in patients whose immune system may not be able to mount an adequate antibody response or in patients in the hyperacute phase of infection, even before a detectable antibody response can be formed.8,9 However, because of limitations of equipment, expertise, and overall cost, this method is not universally available. Additionally, blood cultures and PCR testing or tissue culture of pathologic specimens cannot routinely be relied on for diagnosis, as often the burden of microorganisms present in these specimens is low. When positive, culture specimens may yield bradyzoites or tachyzoites, but only after considerable latency of many days to weeks.10

How people acquire acute toxoplasmosis

T gondii is an obligate intracellular protozoan parasite. Sexual replication of the organism takes place within the intestines of cats (the definitive host), with subsequent excretion of infective oocysts in feces.11 These hardy oocysts can contaminate soil or water supplies and can survive for months, depending on ambient temperature and humidity. Ingestion of oocysts can lead to infection of a variety of mammals, including sheep, pigs, chicken, and cattle.

Infection in humans can occur with consumption of raw or undercooked foods contaminated with oocysts, and inadequate hand-washing and poor kitchen hygiene substantially increase the risk of infection.12 Activities such as gardening can expose humans to oocysts in contaminated water and soil. In addition, direct contact with cat feces, such as when cleaning the litterbox, is a known exposure risk. Vertical transmission can manifest as congenital toxoplasmosis in a fetus when transmitted from an infected pregnant mother.

Eating raw or undercooked food is considered to be the greatest risk factor for acquired toxoplasmosis and is believed to be responsible for about 50% of all cases.12 However, in pooled data from 14 case-control studies, no clear risk factor for Toxoplasma infection could be identified in up to 60% of affected people, leading many experts to believe contaminated water may play a larger role in acquisition than previously surmised.12

Toxoplasma cysts have a predilection for muscle and neural tissue, resulting in myositis, myocarditis, encephalitis, and chorioretinitis. Severe systemic manifestations are seen in people with impaired T-cell immunity, such as those with HIV infection and acquired immunodeficiency syndrome; or hematologic malignancy; in recipients of solid-organ transplants; or in people taking corticosteroids or cytotoxic drugs. Congenital infection can result in stillbirth, microcephaly, developmental delay, or deafness in the developing fetus and is an important cause of infant morbidity and death worldwide.13

Infection in immunocompetent people is usually asymptomatic.14 However, up to 20% of immunocompetent patients develop symptoms that tend to be nonspecific and include muscle aches and lymphadenopathy, and these are often mistaken for an influenza-like illness.14,15 Other symptoms include malaise, fevers, night sweats, pharyngitis, abdominal pain, hepatosplenomegaly, maculopapular rash, and atypical lymphocytosis (less than 10% of peripheral blood).11 The most common physical manifestation of acute toxoplasmosis is isolated cervical lymphadenopathy, although any lymph node group can be affected.14 Lymph nodes are not fixed or matted and generally are neither tender nor suppurative.16

4. What is the correct treatment strategy for acute toxoplasmosis in this case?

- Symptomatic treatment only

- Trimethoprim 160 mg and sulfamethoxazole 800 mg daily

- Combination of atovaquone and clindamycin

- Combination pyrimethamine, sulfadiazine, and folinic acid

TREATMENT AND PROGNOSIS OF ACUTE TOXOPLASMOSIS

No antimicrobial treatment is required for most immunocompetent patients. Symptoms are self-limited and resolve within 1 to 2 months in 60% of patients.14 A substantial proportion of patients—25%—will have lingering symptoms at 2 to 4 months, and some (10%) can have mild symptoms for 6 months or longer.16

Symptomatic treatment with analgesics such as nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) is appropriate.

Immunocompromised and critically ill patients and those with ocular manifestations require combination therapy with pyrimethamine, sulfadiazine, and folinic acid.17 Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole is effective as prophylaxis against T gondii infection in immunocompromised patients at a dosage of 160 mg trimethoprim/800 mg sulfamethoxazole daily, but it is also an alternative for treatment at higher dosages (5 mg/kg trimethoprim and 25 mg/kg sulfamethoxazole twice daily).

Atovaquone and clindamycin can be used in sulfa-sensitive patients17 and also in those with latent toxoplasmosis for better penetration of tissue cysts. Corticosteroids are used as adjuncts in those with ocular involvement.

Spiramycin is the treatment of choice in pregnant women and can be given throughout the pregnancy.17,18 A recent comparative study by Hotop et al18 reported a reduction in the rate of fetal transmission (1.6% vs 4.8%) when spiramycin was given from the time of diagnosis through the 16th week of pregnancy, followed by a minimum of 4 weeks of combination therapy with pyrimethamine, sulfadiazine, and folinic acid.18

CASE CONCLUDED

Serologic testing was positive for IgM and IgG antibodies to T gondii, which suggested subacute infection. The patient received no antimicrobial therapy and her lymphadenopathy eventually resolved. Her generalized fatigue gradually resolved over the next year without antimicrobial treatment.

A thorough re-review of potential exposures was done at subsequent office visits to help elucidate how she may have acquired the infection. She recalled no recent exposure to cats or rodents, nor consumption of raw meat. We could only suppose that there may have been inadvertent exposure to oocyst-containing soil or water or to undercooked meat products. Thus, the diagnosis of acute toxoplasmosis should be kept in mind in the evaluation of lymphadenopathy, even in the absence of a clear history of exposure.

- Habermann TM, Steensma DP. Lymphadenopathy. Mayo Clin Proc 2000; 75:723–732.

- Khillan R, Sidhu G, Axiotis C, Braverman AS. Fine needle aspiration (FNA) cytology for diagnosis of cervical lymphadenopathy. Int J Hematol 2012; 95:282–284.

- Dorfman RF, Remington JS. Value of lymph-node biopsy in the diagnosis of acute acquired toxoplasmosis. N Engl J Med 1973; 289:878–881.

- Eapen M, Mathew CF, Aravindan KP. Evidence based criteria for the histopathological diagnosis of toxoplasmic lymphadenopathy. J Clin Pathol 2005; 58:1143–1146.

- Villard O, Cimon B, Franck J, et al; Network from the French National Reference Center for Toxoplasmosis. Evaluation of the usefulness of six commercial agglutination assays for serologic diagnosis of toxoplasmosis. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis 2012; 73:231–235.

- Suzuki LA, Rocha RJ, Rossi CL. Evaluation of serological markers for the immunodiagnosis of acute acquired toxoplasmosis. J Med Microbiol 2001; 50:62–70.

- Lachaud L, Calas O, Picot MC, Albaba S, Bourgeois N, Pratlong F. Value of 2 IgG avidity commercial tests used alone or in association to date toxoplasmosis contamination. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis 2009; 64:267–274.

- Rahumatullah A, Khoo BY, Noordin R. Triplex PCR using new primers for the detection of Toxoplasma gondii. Exp Parasitol 2012; 131:231–238.

- Contini C, Giuliodori M, Cultrera R, Seraceni S. Detection of clinical-stage specific molecular Toxoplasma gondii gene patterns in patients with toxoplasmic lymphadenitis. J Med Microbiol 2006; 55:771–774.

- Silveira C, Vallochi AL, Rodrigues da Silva U, et al. Toxoplasma gondii in the peripheral blood of patients with acute and chronic toxoplasmosis. Br J Ophthalmol 2011; 95:396–400.

- Montoya JG, Liesenfeld O. Toxoplasmosis. Lancet 2004; 363:1965–1976.

- Petersen E, Vesco G, Villari S, Buffolano W. What do we know about risk factors for infection in humans with Toxoplasma gondii and how can we prevent infections? Zoonoses Public Health 2010; 57:8–17.

- Feldman DM, Timms D, Borgida AF. Toxoplasmosis, parvovirus, and cytomegalovirus in pregnancy. Clin Lab Med 2010; 30:709–720.

- Weiss LM, Dubey JP. Toxoplasmosis: a history of clinical observations. Int J Parasitol 2009; 39:895–901.

- Remington JS. Toxoplasmosis in the adult. Bull NY Acad Med 1974; 50:211–227.

- McCabe RE, Brooks RG, Dorfman RF, Remington JS. Clinical spectrum in 107 cases of toxoplasmic lymphadenopathy. Rev Infect Dis 1987; 9:754–774.

- Toxoplasmosis. The Medical Letter, Drugs for Parasitic Infections. New Rochelle, NY: The Medical Letter Inc, June 1, 2010:57–58.

- Hotop A, Hlobil H, Gross U. Efficacy of rapid treatment initiation following primary Toxoplasma gondii infection during pregnancy. Clin Infect Dis 2012; 54:1545–1552.

- Habermann TM, Steensma DP. Lymphadenopathy. Mayo Clin Proc 2000; 75:723–732.

- Khillan R, Sidhu G, Axiotis C, Braverman AS. Fine needle aspiration (FNA) cytology for diagnosis of cervical lymphadenopathy. Int J Hematol 2012; 95:282–284.

- Dorfman RF, Remington JS. Value of lymph-node biopsy in the diagnosis of acute acquired toxoplasmosis. N Engl J Med 1973; 289:878–881.

- Eapen M, Mathew CF, Aravindan KP. Evidence based criteria for the histopathological diagnosis of toxoplasmic lymphadenopathy. J Clin Pathol 2005; 58:1143–1146.

- Villard O, Cimon B, Franck J, et al; Network from the French National Reference Center for Toxoplasmosis. Evaluation of the usefulness of six commercial agglutination assays for serologic diagnosis of toxoplasmosis. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis 2012; 73:231–235.

- Suzuki LA, Rocha RJ, Rossi CL. Evaluation of serological markers for the immunodiagnosis of acute acquired toxoplasmosis. J Med Microbiol 2001; 50:62–70.

- Lachaud L, Calas O, Picot MC, Albaba S, Bourgeois N, Pratlong F. Value of 2 IgG avidity commercial tests used alone or in association to date toxoplasmosis contamination. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis 2009; 64:267–274.

- Rahumatullah A, Khoo BY, Noordin R. Triplex PCR using new primers for the detection of Toxoplasma gondii. Exp Parasitol 2012; 131:231–238.

- Contini C, Giuliodori M, Cultrera R, Seraceni S. Detection of clinical-stage specific molecular Toxoplasma gondii gene patterns in patients with toxoplasmic lymphadenitis. J Med Microbiol 2006; 55:771–774.

- Silveira C, Vallochi AL, Rodrigues da Silva U, et al. Toxoplasma gondii in the peripheral blood of patients with acute and chronic toxoplasmosis. Br J Ophthalmol 2011; 95:396–400.

- Montoya JG, Liesenfeld O. Toxoplasmosis. Lancet 2004; 363:1965–1976.

- Petersen E, Vesco G, Villari S, Buffolano W. What do we know about risk factors for infection in humans with Toxoplasma gondii and how can we prevent infections? Zoonoses Public Health 2010; 57:8–17.

- Feldman DM, Timms D, Borgida AF. Toxoplasmosis, parvovirus, and cytomegalovirus in pregnancy. Clin Lab Med 2010; 30:709–720.

- Weiss LM, Dubey JP. Toxoplasmosis: a history of clinical observations. Int J Parasitol 2009; 39:895–901.

- Remington JS. Toxoplasmosis in the adult. Bull NY Acad Med 1974; 50:211–227.

- McCabe RE, Brooks RG, Dorfman RF, Remington JS. Clinical spectrum in 107 cases of toxoplasmic lymphadenopathy. Rev Infect Dis 1987; 9:754–774.

- Toxoplasmosis. The Medical Letter, Drugs for Parasitic Infections. New Rochelle, NY: The Medical Letter Inc, June 1, 2010:57–58.

- Hotop A, Hlobil H, Gross U. Efficacy of rapid treatment initiation following primary Toxoplasma gondii infection during pregnancy. Clin Infect Dis 2012; 54:1545–1552.

A review of uncommon swelling provides useful reminders

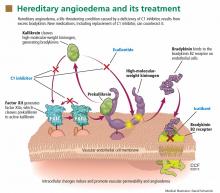

Angioedema associated with insufficient activity of circulating complement component 1 (C1) inhibitor is a rare condition that can be hereditary or acquired. The clinical characteristics of this disorder are nicely reviewed by Drs. Tse and Zuraw in this issue of the Journal. Despite the rarity of this condition, there are good reasons to spend a few minutes with this article.

Angioedema and the urticarias differ in their clinical manifestations and diagnostic and therapeutic implications. Patients who have recurrent urticaria, no matter the severity, need not be evaluated for C1 inhibitor deficiency. Some patients who have recurrent angioedema without urticaria may respond well to antiallergic therapies (eg, antihistamines, corticosteroids), and these patients also are unlikely to have C1 inhibitor deficiency. Other patients who have intermittent localized peripheral swelling (or visceral edema manifest as abdominal pain) without urticaria may not respond, and it is in these patients that a pathophysiologic mechanism other than typical allergy should be considered.

In some patients, bradykinin-mediated angioedema is due to deficient C1 inhibitor activity, in others, to angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibition. Although the biochemical site of action is different, both of these conditions result from an imbalance of protease activation and inhibition. If there is not enough C1 inhibition, there is too much kallikrein activity, which leads to excess proteolytic generation of the peptide bradykinin from kininogen. In contrast, ACE inhibitors occasionally cause angioedema by decreasing catabolism of bradykinin. In either case, bradykinin-mediated angioedema is generally clinically resistant to antiallergic therapy.

Thinking about these mechanisms reminds us of the complexity and overlap of many physiologic proteolytic cascades. Although C1 inhibitor is known as an inhibitor of C1 esterase and C4 levels are almost always low when C1 inhibitor activity is depressed, the angioedema in C1-inhibitor-deficiency states is more a result of decreased inhibition of enzymes in the coagulation cascade than in the complement cascade. Similarly, ACE-inhibitor-associated angioedema has little to do with the decreased generation of angiotensin that accounts for these drugs’ antihypertensive effect.

Generalizing these principles should make us vigilant for unpredicted adverse reactions to other newer drugs such as protease and kinase inhibitors, which may variably affect multiple biochemical pathways.

Angioedema associated with insufficient activity of circulating complement component 1 (C1) inhibitor is a rare condition that can be hereditary or acquired. The clinical characteristics of this disorder are nicely reviewed by Drs. Tse and Zuraw in this issue of the Journal. Despite the rarity of this condition, there are good reasons to spend a few minutes with this article.

Angioedema and the urticarias differ in their clinical manifestations and diagnostic and therapeutic implications. Patients who have recurrent urticaria, no matter the severity, need not be evaluated for C1 inhibitor deficiency. Some patients who have recurrent angioedema without urticaria may respond well to antiallergic therapies (eg, antihistamines, corticosteroids), and these patients also are unlikely to have C1 inhibitor deficiency. Other patients who have intermittent localized peripheral swelling (or visceral edema manifest as abdominal pain) without urticaria may not respond, and it is in these patients that a pathophysiologic mechanism other than typical allergy should be considered.

In some patients, bradykinin-mediated angioedema is due to deficient C1 inhibitor activity, in others, to angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibition. Although the biochemical site of action is different, both of these conditions result from an imbalance of protease activation and inhibition. If there is not enough C1 inhibition, there is too much kallikrein activity, which leads to excess proteolytic generation of the peptide bradykinin from kininogen. In contrast, ACE inhibitors occasionally cause angioedema by decreasing catabolism of bradykinin. In either case, bradykinin-mediated angioedema is generally clinically resistant to antiallergic therapy.

Thinking about these mechanisms reminds us of the complexity and overlap of many physiologic proteolytic cascades. Although C1 inhibitor is known as an inhibitor of C1 esterase and C4 levels are almost always low when C1 inhibitor activity is depressed, the angioedema in C1-inhibitor-deficiency states is more a result of decreased inhibition of enzymes in the coagulation cascade than in the complement cascade. Similarly, ACE-inhibitor-associated angioedema has little to do with the decreased generation of angiotensin that accounts for these drugs’ antihypertensive effect.

Generalizing these principles should make us vigilant for unpredicted adverse reactions to other newer drugs such as protease and kinase inhibitors, which may variably affect multiple biochemical pathways.

Angioedema associated with insufficient activity of circulating complement component 1 (C1) inhibitor is a rare condition that can be hereditary or acquired. The clinical characteristics of this disorder are nicely reviewed by Drs. Tse and Zuraw in this issue of the Journal. Despite the rarity of this condition, there are good reasons to spend a few minutes with this article.

Angioedema and the urticarias differ in their clinical manifestations and diagnostic and therapeutic implications. Patients who have recurrent urticaria, no matter the severity, need not be evaluated for C1 inhibitor deficiency. Some patients who have recurrent angioedema without urticaria may respond well to antiallergic therapies (eg, antihistamines, corticosteroids), and these patients also are unlikely to have C1 inhibitor deficiency. Other patients who have intermittent localized peripheral swelling (or visceral edema manifest as abdominal pain) without urticaria may not respond, and it is in these patients that a pathophysiologic mechanism other than typical allergy should be considered.

In some patients, bradykinin-mediated angioedema is due to deficient C1 inhibitor activity, in others, to angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibition. Although the biochemical site of action is different, both of these conditions result from an imbalance of protease activation and inhibition. If there is not enough C1 inhibition, there is too much kallikrein activity, which leads to excess proteolytic generation of the peptide bradykinin from kininogen. In contrast, ACE inhibitors occasionally cause angioedema by decreasing catabolism of bradykinin. In either case, bradykinin-mediated angioedema is generally clinically resistant to antiallergic therapy.

Thinking about these mechanisms reminds us of the complexity and overlap of many physiologic proteolytic cascades. Although C1 inhibitor is known as an inhibitor of C1 esterase and C4 levels are almost always low when C1 inhibitor activity is depressed, the angioedema in C1-inhibitor-deficiency states is more a result of decreased inhibition of enzymes in the coagulation cascade than in the complement cascade. Similarly, ACE-inhibitor-associated angioedema has little to do with the decreased generation of angiotensin that accounts for these drugs’ antihypertensive effect.

Generalizing these principles should make us vigilant for unpredicted adverse reactions to other newer drugs such as protease and kinase inhibitors, which may variably affect multiple biochemical pathways.

Recognizing and managing hereditary angioedema

Hereditary angioedema due to deficiency of C1 inhibitor is a rare autosomal dominant disease that can be life-threatening. It affects about 1 in 50,000 people,1 or about 6,000 people in the United States. There are no known differences in prevalence by ethnicity or sex. A form of hereditary angioedema with normal C1 inhibitor levels has also recently been identified.

Despite a growing awareness of hereditary angioedema in the medical community, repeated surveys have found an average gap of 10 years between the first appearance of symptoms and the correct diagnosis. In view of the risk of morbidity and death, recognizing this disease sooner is critical.

This article will discuss how to recognize hereditary angioedema and how to differentiate it from other forms of recurring angioedema. We will also review its acute and long-term management, with special attention to new therapies and clinical challenges.

EPISODES OF SWELLING WITHOUT HIVES

Hereditary angioedema involves recurrent episodes of nonpruritic, nonpitting, subcutaneous and submucosal edema that can affect the face, tongue, larynx, trunk, extremities, bowels, or genitals. Attacks typically follow a predictable course: swelling that increases slowly and continuously for 24 hours and then gradually subsides over the next 48 to 72 hours. Attacks that involve the oropharynx, larynx, or abdomen carry the highest risk of morbidity and death.1

The frequency and severity of attacks are highly variable and unpredictable. A few patients have no attacks, a few have two attacks per week, and most fall in between.

Hives suggests an allergic or idiopathic rather than hereditary cause and will not be discussed here in detail. A history of angioedema that was rapidly aborted by antihistamines, corticosteroids, or epinephrine also suggests an allergic rather than hereditary cause.

UNCHECKED BRADYKININ PRODUCTION

Substantial evidence indicates that hereditary angioedema results from extravasation of plasma into deeper cutaneous or mucosal compartments as a result of overproduction of the vasoactive mediator bradykinin (Figure 1).

Activated factor XII cleaves plasma prekallikrein to generate active plasma kallikrein (which, in turn, activates more factor XII).2 Once generated, plasma kallikrein cleaves high-molecular-weight kininogen, releasing bradykinin. Bradykinin binds to the B2 bradykinin receptor on endothelial cells, increasing the permeability of the endothelium.

Normally, C1 inhibitor helps control bradykinin production by inhibiting plasma kallikrein and activated factor XII. Without enough C1 inhibitor, the contact system is uninhibited and results in bradykinin being inappropriately generated.

Because the attacks of hereditary angioedema involve excessive bradykinin, they do not respond to the usual treatments for anaphylaxis and allergic angioedema (which involve mast cell degranulation), such as antihistamines, corticosteroids, and epinephrine.

TWO TYPES OF HEREDITARY ANGIOEDEMA

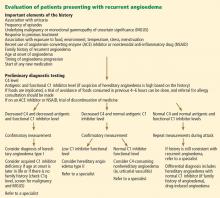

Figure 2 shows the evaluation of patients with suspected hereditary angioedema.

Hereditary angioedema due to C1 inhibitor deficiency

The classic forms of hereditary angioedema (types I and II) involve loss-of-function mutations in SERPING1—the gene that encodes for C1 inhibitor—resulting in low levels of functional C1 inhibitor.3 The mutation is inherited in an autosomal dominant pattern; however, in about 25% of cases, it appears to arise spontaneously,4 so a family history is not required for diagnosis.

Although C1 inhibitor deficiency is present from birth, the clinical disease most commonly presents for the first time when the patient is of school age. Half of patients have their first episode in the first decade of life, and another one-third first develop symptoms over the next 10 years.5

Clinically, types I and II are indistinguishable. Type I, accounting for 85% of cases,1 results from low production of C1 inhibitor. Laboratory studies reveal low antigenic and functional levels of C1 inhibitor.

In type II, the mutant C1 inhibitor protein is present but dysfunctional and unable to inhibit target proteases. On laboratory testing, the functional level of C1 inhibitor is low but its antigenic level is normal (Table 1). Function can be tested by either chromogenic assay or enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay; the former is preferred because it is more sensitive.6

Because C1 inhibitor deficiency results in chronic activation of the complement system, patients with type I or II disease usually have low C4 levels regardless of disease activity, making measuring C4 the most economical screening test. When suspicion for hereditary angioedema is high, based on the presentation and family and clinical history, measuring antigenic and functional C1 inhibitor levels and C4 simultaneously is more efficient.

Hereditary angioedema with normal C1 inhibitor levels

Hereditary angioedema with normal C1 inhibitor levels is also inherited in an autosomal dominant pattern. It is often estrogen-sensitive, making it more severe in women. Symptoms tend to develop slightly later in life than in type I or II disease.7

Angioedema with normal C1 inhibitor levels has been associated with factor XII mutations in a minority of cases, but most patients do not have a specific laboratory abnormality. Because there is no specific laboratory profile, the diagnosis is based on clinical criteria. Hereditary angioedema with normal C1 inhibitor levels should be considered in patients who have recurrent angioedema, normal C4, normal antigenic and functional C1 inhibitor levels, a lack of response to high-dose antihistamines, and either a family history of angioedema without hives or a known factor XII mutation.7 However, other forms of angioedema (allergic, drug-induced, and idiopathic) should also be considered, as C4 and C1 inhibitor levels are normal in these forms as well.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS: OTHER TYPES OF ANGIOEDEMA

Acquired C1 inhibitor deficiency

Symptoms of acquired C1 inhibitor deficiency resemble those of hereditary angioedema but typically do not emerge until the fourth decade of life or later, and patients have no family history of the condition. It is often associated with other diseases, most commonly B-cell lymphoproliferative disorders, which cause uncontrolled complement activation and consumption of C1 inhibitor.

In some patients, autoantibodies to C1 inhibitor develop, greatly reducing its effectiveness and resulting in enhanced consumption. The autoantibody is often associated with a monoclonal gammopathy of unknown significance. The presence of a C1 inhibitor autoantibody does not preclude the presence of an underlying disorder, and vice versa.

Laboratory studies reveal low C4, low C1-inhibitor antigenic and functional levels, and usually a low C1q level owing to consumption of complement. Autoantibodies to C1 inhibitor can be detected by laboratory testing.

Because of the association with autoimmune disease and malignant disorders (especially B-cell malignancy), a patient diagnosed with acquired C1 inhibitor deficiency should be further evaluated for underlying conditions.

Allergic angioedema

Allergic angioedema results from preformed antigen-specific immunoglobulin E (IgE) antibodies that stimulate mast cells to degranulate when patients are exposed to a particular allergen—most commonly food, insect venom, latex, or drugs. IgE-mediated histamine release causes swelling, as histamine is a potent vasodilator.

Symptoms often begin within 2 hours of exposure to the allergen and generally include concurrent urticaria and swelling that last less than 24 hours. Unlike in hereditary angioedema, the swelling responds to antihistamines and corticosteroids. When very severe, these symptoms may also be accompanied by bronchoconstriction and gastrointestinal symptoms, especially if the allergen is ingested.

Histamine-mediated angioedema may also be associated with exercise as part of a syndrome called exercise-induced anaphylaxis or angioedema.

Drug-induced angioedema

Drug-induced angioedema is typically associated with angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors or nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs).

Angioedema associated with ACE inhibitors is estimated to affect 0.1% to 6% of patients taking these medications, with African Americans being at significantly higher risk. Although 25% of affected patients develop symptoms of angioedema within the first month of taking the drugs, some tolerate them for as long as 10 years before the first episode.9 The swelling is not allergic or histamine-related. ACE normally degrades bradykinin; therefore, inhibiting ACE leads to accumulation of bradykinin. Because all ACE inhibitors have this effect, this class of drug should be discontinued in any patient who develops isolated angioedema.

NSAID-induced angioedema is often accompanied by other symptoms, including urticaria, rhinitis, cough, hoarseness, or breathlessness.10 The mechanism of NSAID-induced angioedema involves cyclooxygenase (COX) 1 (and to a lesser extent COX-2) inhibition. All NSAIDs (and aspirin) should be avoided in patients with recurrent angioedema. Specific COX-2 inhibitors, while theoretically capable of causing angioedema by the same mechanism, are generally well tolerated in patients who have had COX-1 inhibitor reactions.

Idiopathic angioedema

If no clear cause of recurrent angioedema (at least three episodes in a year) can be found, it is labeled idiopathic.11 Some patients with idiopathic angioedema fail to benefit from high doses of antihistamines, suggesting that the cause is bradykinin-mediated.

CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS OF HEREDITARY ANGIOEDEMA

Attacks may start at one site and progress to involve additional sites.

Prodromal symptoms may begin up to several days before an attack and include tingling, warmth, burning, or itching at the affected site; increased fatigue or malaise; nausea, abdominal distention, or gassiness; or increased hunger, particularly before an abdominal attack.5 The most characteristic prodromal symptom is erythema marginatum—a raised, serpiginous, nonpruritic rash on the trunk, arms, and legs but often sparing the face.

Abdominal attacks are easily confused with acute abdomen

Almost half of attacks involve the abdomen, and almost all patients with type I or II disease experience at least one such attack.12 Symptoms can include severe abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea. Abdominal attacks account for many emergency department visits, hospitalizations, and surgical procedures for acute abdomen; about one-third of patients with undiagnosed hereditary angioedema undergo an unnecessary surgery during an abdominal attack. Angioedema of the gastrointestinal tract can result in enough plasma extravasation and vasodilation to cause hypovolemic shock.

Eradicating Helicobacter pylori infection may alleviate abdominal attacks.13

Attacks of the extremities can be painful and disabling

Attacks of the extremities affect 96% of patients12 and can be very disfiguring and disabling. Driving or using the phone is often difficult when the hands are affected. When feet are involved, walking and standing become painful. While these symptoms rarely result in a lengthy hospitalization, they interfere with work and school and require immediate medical attention because they can progress to other parts of the body.

Laryngeal attacks are life-threatening

About half of patients with hereditary angioedema have an attack of laryngeal edema at some point in their lives.12 If not effectively managed, laryngeal angioedema can progress to asphyxiation. A survey of family history in 58 patients with hereditary angioedema suggested a 40% incidence of asphyxiation in untreated laryngeal attacks, and 25% to 30% of patients are estimated to have died of laryngeal edema before effective treatment became available.14

Symptoms of a laryngeal attack include change in voice, hoarseness, trouble swallowing, shortness of breath, and wheezing. Physicians must recognize these symptoms quickly and give effective treatment early in the attack to prevent morbidity and death.

Establishing an airway can be life-saving in the absence of effective therapy, but extensive swelling of the upper airway can make intubation extremely difficult.

Genitourinary attacks also occur

Attacks involving the scrotum and labia have been reported in up to two-thirds of patients with hereditary angioedema at some point in their lives. Attacks involving the bladder and kidneys have also been reported but are less common, affecting about 5% of patients.12 Genitourinary attacks may be triggered by local trauma, such as horseback riding or sexual intercourse, although no trigger may be evident.

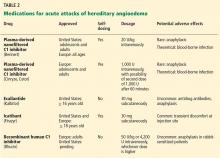

MANAGING ACUTE ATTACKS

The goals of treatment are to alleviate acute exacerbations with on-demand treatment and to reduce the number of attacks with prophylaxis. Therapy should be individualized to each patient’s needs. Treatments have advanced greatly in the last several years, and new medications for treating acute attacks and preventing attacks have shown great promise (Figure 3, Table 2).

Patients tend to have recurrent symptoms interspersed with periods of health, suggesting that attacks ought to have identifiable triggers, although in most, no trigger is evident. The most commonly identified are local trauma (including medical and dental procedures), emotional stress, and acute infection. Disease severity may be worsened by menstruation, estrogen-containing oral contraceptives, hormone replacement therapy, ACE inhibitors, and NSAIDs.

It is critical that attacks be treated with an effective medication as soon as possible. Consensus guidelines state that all patients with hereditary angioedema due to C1 inhibitor deficiency, even if they are still asymptomatic, should have access to at least one of the drugs approved for on-demand treatment.15 The guidelines further state that whenever possible, “patients should have the on-demand medicine to treat acute attacks at home and should be trained to self-administer these medicines.”15

Plasma-derived C1 inhibitors

Several plasma-derived C1 inhibitors are available (Cinryze, Berinert, Cetor). They are prepared from fractionated plasma obtained from donors, then pasteurized and nanofiltered.

Berinert and Cinryze were each found to be superior to placebo in double-blind, placebo-controlled trials: attacks usually resolved 30 to 60 minutes after intravenous injection.16,17 Berinert 20 U/kg is associated with the onset of symptom relief as early as half an hour after administration, compared with 1.5 hours with placebo. Early use (at the onset of symptoms) of a plasma-derived C1 inhibitor in a low dose (500 U) can also be effective.18,19 Efficacy appears to be consistent at all sites of attack involvement, including laryngeal edema. Safety and efficacy have been demonstrated during pregnancy and lactation and in young children and babies.20

Plasma-derived C1 inhibitors can be self-administered. The safety and efficacy of self-administration (under physician supervision) were demonstrated in a study of Cinryze and Cetor, in which attack duration, pain medication use, and graded attack severity were significantly less with self-administered therapy than with therapy in the clinic.21

A concern about plasma-derived products is the possibility of blood-borne infection, but this has not been confirmed by experience.22

Recombinant human C1 inhibitor

A recombinant human C1 inhibitor (Rhucin) has been studied in two randomized placebo-controlled trials. Although this product has a shorter half-life than the plasma-derived C1 inhibitors (3 vs more than 24 hours), the two are equipotent: 1 U of recombinant human C1 inhibitor is equivalent to 1 U of plasma-derived C1 inhibitor. Because the supply of recombinant human C1 inhibitor is elastic, dosing has been higher, which may provide more efficacy.23 Similar to plasma-derived C1 inhibitor products, the recombinant human C1 inhibitor resulted in more rapid symptom relief than with saline (66 vs 122 minutes) and in a shorter time to minimal symptoms (247−266 vs 1,210 minutes).24