User login

What should be the interval between bone density screenings?

In 2010, the United States Preventive Services Task Force recommended screening for osteoporosis by measuring bone mineral density in women age 65 and older and also in younger women if their fracture risk is equal to or greater than that of a 65-year-old white woman who has no additional risk factors.

But what should be the interval between screenings? The Task Force stated that evidence on the optimum screening interval is lacking, that 2 years may be the minimum interval due to precision error, but that longer intervals may be necessary to improve fracture risk prediction.1 They also cited a study showing that repeating the test up to 8 years after an initial test did not improve the ability of screening to predict fractures.2 This was recently confirmed in a study from Canada.3

GOURLAY ET AL: TEST AGAIN IN 1 TO 15 YEARS

In response to this information void, Gourlay and colleagues4 analyzed data from the Study of Osteoporotic Fractures. Because these investigators were interested in the interval between screening measurements of bone mineral density, they included only women who did not already have osteoporosis or take medication for osteoporosis. They wanted to know how long it took for 10% of women to develop osteoporosis, and found that this interval varied from 1 to 15 years depending on the initial bone density.

I did not think these results were surprising. The durations in which osteoporosis developed were similar to what one would predict from cross-sectional reference ranges. The average woman loses a little less than 1% of bone density per year after age 65. A T score of −1.0 is 22% higher than a T score of −2.5, so on average it would take more than 20 years to go from early osteopenia to osteoporosis.

AN ONGOING DEBATE ON SCREENING

The report generated a debate about the value and timing of repeated screening.5,6

In their article “More bone density testing is needed, not less,”5 Lewiecki et al criticized the Gourlay analysis because it did not include spine measurements or screen for asymptomatic vertebral fractures, and because it did not include enough clinical risk factors.5,6 They claimed that media attention suggested that dual-energy absorptiometry (DXA) was overused and expensive, citing three news reports. One of the news reports did misinterpret the Gourlay study and suggested that fewer women should be screened.7 The others, however, accurately described the findings that many women did not need to undergo DXA every 2 years.8,9

In this issue of the Cleveland Clinic Journal of Medicine, Doshi and colleagues express their opinion that the interval between bone mineral density testings should be guided by an assessment of clinical risk factors and not just T scores.10

Doshi et al are also concerned about erroneous conclusions drawn by the media. However, when I reviewed the news reports that they cited, I thought the reports were well written and conveyed the results appropriately. One report, by Alice Park,11 cautioned: “doctors need to remain flexible in advising women about when to get tested. A patient who has a normal T score but then develops cancer and loses a lot of weight, for example, may be more vulnerable to developing osteoporosis and therefore may need to get screened before the 15-year interval.”11 The other, by Gina Kolata, also explained that those taking high doses of corticosteroids for another medical condition would lose bone rapidly, but the findings “cover most normal women.”9 Neither report discouraged patients from getting screening in the first place.

Both Lewiecki et al and Doshi et al say that clinical factors should be considered, but do not specify which factors should be included in addition to the ones already evaluated by Gourlay et al (age, body mass index, estrogen use at baseline, any fracture after 50 years of age, current smoking, current or past use of oral glucocorticoids, and self-reported rheumatoid arthritis). These did not change the estimated time to develop osteoporosis for 90% of the study participants.

Furthermore, Gourlay et al had already noted that “clinicians may choose to reevaluate patients before our estimated screening intervals if there is evidence of decreased activity or mobility, weight loss, or other risk factors not considered in our analyses.”4 Thus, patients with serious diseases should undergo DXA not for screening but for monitoring disease progression, and the Gourlay study results do not apply to them.

PATIENTS ON GLUCOCORTICOIDS: A SPECIAL SUBSET

Patients who are treated with glucocorticoids deserve further discussion. Consider the example described by Doshi et al of a woman with rheumatoid arthritis, taking prednisone, with a T score of −1.4. She would have to lose about 17% of her bone density to reach a T score at the osteoporosis level. One clinical trial in patients taking glucocorticoids, most of whom had rheumatoid arthritis, reported a loss of 2% after 2 years in the placebo group,12 so it is unlikely that this patient would have bone density in the osteoporosis range for at least several years.

However, clinicians know that these patients get fractures, especially in the spine, even with a normal bone density. Therefore, vertebral fracture assessment would be more important than bone density screening in this patient. Currently, there is uncertainty about the best time to initiate treatment in patients taking these glucocortical steroids, as well as the choice of initial medication. More research about long-term benefits of treatment are especially needed in this population.

VERTEBRAL FRACTURES: NO FIRM RECOMMENDATIONS

Doshi et al state that the Gourlay study was biased towards longer screening intervals because it included women with asymptomatic vertebral fractures. This does not make sense, because women who have untreated asymptomatic fractures would not be expected to lose bone at a slower rate. This does not mean that the asymptomatic fractures are trivial.

Instead of getting more frequent bone density measurements, I think it would be more logical to evaluate vertebral fractures using radiographs or vertebral fracture assessment, but we can’t make a firm recommendation without studies of the effectiveness of screening for vertebral fractures.

WHAT ABOUT OSTEOPENIA?

Critics of the Gourlay study point out that most fractures occur in the osteopenic population. This is true, but it does not mean that bone density should be measured more frequently. The bisphosphonates are not effective at preventing a first fracture unless the T score is lower than −2.5.13 Patients who have risk factors in addition to osteopenia may have a higher risk of fracture, but it is not clear if this can be treated with medication. For example, rodeo riders have a high fracture risk, but they would not benefit from taking alendronate. In some cases, such as people who smoke or drink alcohol to excess, treating the risk factor would be more appropriate.

As Doshi et al and others have noted, the study by Gourlay et al has limitations, and of course clinical judgment must be used in implementing the findings of any study. But doctors should not order unnecessary and expensive tests, and physicians who perform bone densitometry should not recommend frequent repeat testing that does not benefit the patient.

- US Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for osteoporosis: US preventive services task force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med 2011; 154:356–364.

- Hillier TA, Stone KL, Bauer DC, et al. Evaluating the value of repeat bone mineral density measurement and prediction of fractures in older women: the study of osteoporotic fractures. Arch Intern Med 2007; 167:155–160.

- Leslie WD, Morin SN, Lix LM; Manitoba Bone Density Program. Rate of bone density change does not enhance fracture prediction in routine clinical practice. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2012; 97:1211–1218.

- Gourlay ML, Fine J P, Preisser JS, et al; Study of Osteoporotic Fractures Research Group. Bone-density testing interval and transition to osteoporosis in older women. N Engl J Med 2012; 366:225–233.

- Lewiecki EM, Laster AJ, Miller PD, Bilezikian JP. More bone density testing is needed, not less. J Bone Miner Res 2012; 27:739–742.

- Yu EW, Finkelstein JS. Bone density screening intervals for osteoporosis: one size does not fit all. JAMA 2012; 307:2591–2592.

- Frier S. Women receive bone tests too often for osteoporosis, study finds. Bloomberg News; 2012. http://www.bloomberg.com/news/2012-01-18/many-women-screened-for-osteoporosis-don-t-need-it-researchers-report.html. Accessed January 3, 2013.

- Knox R. Many older women may not need frequent bone scans. National Public Radio; 2012. http://www.npr.org/blogs/health/2012/01/19/145419138/many-older-women-may-not-need-frequent-bone-scans?ps=sh_sthdl. Accessed January 3, 2013.

- Kolata G. Patients with normal bone density can delay retests, study suggests. The New York Times; 2012. http://www.nytimes.com/2012/01/19/health/bone-density-tests-for-osteoporosis-can-wait-study-says.html. Accessed January 3, 2013.

- Doshi KB, Khan LZ, Williams SE, Licata AA. Bone mineral density testing interval and transition to osteoporosis in older women: Is a T-score enough to determine a screening interval? Cleve Clin J Med 2013; 80:234–239.

- Park A. How often do women really need bone density tests? Time Healthland; 2012. http://healthland.time.com/2012/01/19/most-women-may-be-getting-too-many-bone-density-tests/. Accessed January 3, 2013.

- Adachi JD, Saag KG, Delmas PD, et al. Two-year effects of alendronate on bone mineral density and vertebral fracture in patients receiving glucocorticoids: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled extension trial. Arthritis Rheum 2001; 44:202–211.

- Cummings SR, Black DM, Thompson DE, et al. Effect of alendronate on risk of fracture in women with low bone density but without vertebral fractures: results from the Fracture Intervention Trial. JAMA 1998; 280:2077–2082.

In 2010, the United States Preventive Services Task Force recommended screening for osteoporosis by measuring bone mineral density in women age 65 and older and also in younger women if their fracture risk is equal to or greater than that of a 65-year-old white woman who has no additional risk factors.

But what should be the interval between screenings? The Task Force stated that evidence on the optimum screening interval is lacking, that 2 years may be the minimum interval due to precision error, but that longer intervals may be necessary to improve fracture risk prediction.1 They also cited a study showing that repeating the test up to 8 years after an initial test did not improve the ability of screening to predict fractures.2 This was recently confirmed in a study from Canada.3

GOURLAY ET AL: TEST AGAIN IN 1 TO 15 YEARS

In response to this information void, Gourlay and colleagues4 analyzed data from the Study of Osteoporotic Fractures. Because these investigators were interested in the interval between screening measurements of bone mineral density, they included only women who did not already have osteoporosis or take medication for osteoporosis. They wanted to know how long it took for 10% of women to develop osteoporosis, and found that this interval varied from 1 to 15 years depending on the initial bone density.

I did not think these results were surprising. The durations in which osteoporosis developed were similar to what one would predict from cross-sectional reference ranges. The average woman loses a little less than 1% of bone density per year after age 65. A T score of −1.0 is 22% higher than a T score of −2.5, so on average it would take more than 20 years to go from early osteopenia to osteoporosis.

AN ONGOING DEBATE ON SCREENING

The report generated a debate about the value and timing of repeated screening.5,6

In their article “More bone density testing is needed, not less,”5 Lewiecki et al criticized the Gourlay analysis because it did not include spine measurements or screen for asymptomatic vertebral fractures, and because it did not include enough clinical risk factors.5,6 They claimed that media attention suggested that dual-energy absorptiometry (DXA) was overused and expensive, citing three news reports. One of the news reports did misinterpret the Gourlay study and suggested that fewer women should be screened.7 The others, however, accurately described the findings that many women did not need to undergo DXA every 2 years.8,9

In this issue of the Cleveland Clinic Journal of Medicine, Doshi and colleagues express their opinion that the interval between bone mineral density testings should be guided by an assessment of clinical risk factors and not just T scores.10

Doshi et al are also concerned about erroneous conclusions drawn by the media. However, when I reviewed the news reports that they cited, I thought the reports were well written and conveyed the results appropriately. One report, by Alice Park,11 cautioned: “doctors need to remain flexible in advising women about when to get tested. A patient who has a normal T score but then develops cancer and loses a lot of weight, for example, may be more vulnerable to developing osteoporosis and therefore may need to get screened before the 15-year interval.”11 The other, by Gina Kolata, also explained that those taking high doses of corticosteroids for another medical condition would lose bone rapidly, but the findings “cover most normal women.”9 Neither report discouraged patients from getting screening in the first place.

Both Lewiecki et al and Doshi et al say that clinical factors should be considered, but do not specify which factors should be included in addition to the ones already evaluated by Gourlay et al (age, body mass index, estrogen use at baseline, any fracture after 50 years of age, current smoking, current or past use of oral glucocorticoids, and self-reported rheumatoid arthritis). These did not change the estimated time to develop osteoporosis for 90% of the study participants.

Furthermore, Gourlay et al had already noted that “clinicians may choose to reevaluate patients before our estimated screening intervals if there is evidence of decreased activity or mobility, weight loss, or other risk factors not considered in our analyses.”4 Thus, patients with serious diseases should undergo DXA not for screening but for monitoring disease progression, and the Gourlay study results do not apply to them.

PATIENTS ON GLUCOCORTICOIDS: A SPECIAL SUBSET

Patients who are treated with glucocorticoids deserve further discussion. Consider the example described by Doshi et al of a woman with rheumatoid arthritis, taking prednisone, with a T score of −1.4. She would have to lose about 17% of her bone density to reach a T score at the osteoporosis level. One clinical trial in patients taking glucocorticoids, most of whom had rheumatoid arthritis, reported a loss of 2% after 2 years in the placebo group,12 so it is unlikely that this patient would have bone density in the osteoporosis range for at least several years.

However, clinicians know that these patients get fractures, especially in the spine, even with a normal bone density. Therefore, vertebral fracture assessment would be more important than bone density screening in this patient. Currently, there is uncertainty about the best time to initiate treatment in patients taking these glucocortical steroids, as well as the choice of initial medication. More research about long-term benefits of treatment are especially needed in this population.

VERTEBRAL FRACTURES: NO FIRM RECOMMENDATIONS

Doshi et al state that the Gourlay study was biased towards longer screening intervals because it included women with asymptomatic vertebral fractures. This does not make sense, because women who have untreated asymptomatic fractures would not be expected to lose bone at a slower rate. This does not mean that the asymptomatic fractures are trivial.

Instead of getting more frequent bone density measurements, I think it would be more logical to evaluate vertebral fractures using radiographs or vertebral fracture assessment, but we can’t make a firm recommendation without studies of the effectiveness of screening for vertebral fractures.

WHAT ABOUT OSTEOPENIA?

Critics of the Gourlay study point out that most fractures occur in the osteopenic population. This is true, but it does not mean that bone density should be measured more frequently. The bisphosphonates are not effective at preventing a first fracture unless the T score is lower than −2.5.13 Patients who have risk factors in addition to osteopenia may have a higher risk of fracture, but it is not clear if this can be treated with medication. For example, rodeo riders have a high fracture risk, but they would not benefit from taking alendronate. In some cases, such as people who smoke or drink alcohol to excess, treating the risk factor would be more appropriate.

As Doshi et al and others have noted, the study by Gourlay et al has limitations, and of course clinical judgment must be used in implementing the findings of any study. But doctors should not order unnecessary and expensive tests, and physicians who perform bone densitometry should not recommend frequent repeat testing that does not benefit the patient.

In 2010, the United States Preventive Services Task Force recommended screening for osteoporosis by measuring bone mineral density in women age 65 and older and also in younger women if their fracture risk is equal to or greater than that of a 65-year-old white woman who has no additional risk factors.

But what should be the interval between screenings? The Task Force stated that evidence on the optimum screening interval is lacking, that 2 years may be the minimum interval due to precision error, but that longer intervals may be necessary to improve fracture risk prediction.1 They also cited a study showing that repeating the test up to 8 years after an initial test did not improve the ability of screening to predict fractures.2 This was recently confirmed in a study from Canada.3

GOURLAY ET AL: TEST AGAIN IN 1 TO 15 YEARS

In response to this information void, Gourlay and colleagues4 analyzed data from the Study of Osteoporotic Fractures. Because these investigators were interested in the interval between screening measurements of bone mineral density, they included only women who did not already have osteoporosis or take medication for osteoporosis. They wanted to know how long it took for 10% of women to develop osteoporosis, and found that this interval varied from 1 to 15 years depending on the initial bone density.

I did not think these results were surprising. The durations in which osteoporosis developed were similar to what one would predict from cross-sectional reference ranges. The average woman loses a little less than 1% of bone density per year after age 65. A T score of −1.0 is 22% higher than a T score of −2.5, so on average it would take more than 20 years to go from early osteopenia to osteoporosis.

AN ONGOING DEBATE ON SCREENING

The report generated a debate about the value and timing of repeated screening.5,6

In their article “More bone density testing is needed, not less,”5 Lewiecki et al criticized the Gourlay analysis because it did not include spine measurements or screen for asymptomatic vertebral fractures, and because it did not include enough clinical risk factors.5,6 They claimed that media attention suggested that dual-energy absorptiometry (DXA) was overused and expensive, citing three news reports. One of the news reports did misinterpret the Gourlay study and suggested that fewer women should be screened.7 The others, however, accurately described the findings that many women did not need to undergo DXA every 2 years.8,9

In this issue of the Cleveland Clinic Journal of Medicine, Doshi and colleagues express their opinion that the interval between bone mineral density testings should be guided by an assessment of clinical risk factors and not just T scores.10

Doshi et al are also concerned about erroneous conclusions drawn by the media. However, when I reviewed the news reports that they cited, I thought the reports were well written and conveyed the results appropriately. One report, by Alice Park,11 cautioned: “doctors need to remain flexible in advising women about when to get tested. A patient who has a normal T score but then develops cancer and loses a lot of weight, for example, may be more vulnerable to developing osteoporosis and therefore may need to get screened before the 15-year interval.”11 The other, by Gina Kolata, also explained that those taking high doses of corticosteroids for another medical condition would lose bone rapidly, but the findings “cover most normal women.”9 Neither report discouraged patients from getting screening in the first place.

Both Lewiecki et al and Doshi et al say that clinical factors should be considered, but do not specify which factors should be included in addition to the ones already evaluated by Gourlay et al (age, body mass index, estrogen use at baseline, any fracture after 50 years of age, current smoking, current or past use of oral glucocorticoids, and self-reported rheumatoid arthritis). These did not change the estimated time to develop osteoporosis for 90% of the study participants.

Furthermore, Gourlay et al had already noted that “clinicians may choose to reevaluate patients before our estimated screening intervals if there is evidence of decreased activity or mobility, weight loss, or other risk factors not considered in our analyses.”4 Thus, patients with serious diseases should undergo DXA not for screening but for monitoring disease progression, and the Gourlay study results do not apply to them.

PATIENTS ON GLUCOCORTICOIDS: A SPECIAL SUBSET

Patients who are treated with glucocorticoids deserve further discussion. Consider the example described by Doshi et al of a woman with rheumatoid arthritis, taking prednisone, with a T score of −1.4. She would have to lose about 17% of her bone density to reach a T score at the osteoporosis level. One clinical trial in patients taking glucocorticoids, most of whom had rheumatoid arthritis, reported a loss of 2% after 2 years in the placebo group,12 so it is unlikely that this patient would have bone density in the osteoporosis range for at least several years.

However, clinicians know that these patients get fractures, especially in the spine, even with a normal bone density. Therefore, vertebral fracture assessment would be more important than bone density screening in this patient. Currently, there is uncertainty about the best time to initiate treatment in patients taking these glucocortical steroids, as well as the choice of initial medication. More research about long-term benefits of treatment are especially needed in this population.

VERTEBRAL FRACTURES: NO FIRM RECOMMENDATIONS

Doshi et al state that the Gourlay study was biased towards longer screening intervals because it included women with asymptomatic vertebral fractures. This does not make sense, because women who have untreated asymptomatic fractures would not be expected to lose bone at a slower rate. This does not mean that the asymptomatic fractures are trivial.

Instead of getting more frequent bone density measurements, I think it would be more logical to evaluate vertebral fractures using radiographs or vertebral fracture assessment, but we can’t make a firm recommendation without studies of the effectiveness of screening for vertebral fractures.

WHAT ABOUT OSTEOPENIA?

Critics of the Gourlay study point out that most fractures occur in the osteopenic population. This is true, but it does not mean that bone density should be measured more frequently. The bisphosphonates are not effective at preventing a first fracture unless the T score is lower than −2.5.13 Patients who have risk factors in addition to osteopenia may have a higher risk of fracture, but it is not clear if this can be treated with medication. For example, rodeo riders have a high fracture risk, but they would not benefit from taking alendronate. In some cases, such as people who smoke or drink alcohol to excess, treating the risk factor would be more appropriate.

As Doshi et al and others have noted, the study by Gourlay et al has limitations, and of course clinical judgment must be used in implementing the findings of any study. But doctors should not order unnecessary and expensive tests, and physicians who perform bone densitometry should not recommend frequent repeat testing that does not benefit the patient.

- US Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for osteoporosis: US preventive services task force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med 2011; 154:356–364.

- Hillier TA, Stone KL, Bauer DC, et al. Evaluating the value of repeat bone mineral density measurement and prediction of fractures in older women: the study of osteoporotic fractures. Arch Intern Med 2007; 167:155–160.

- Leslie WD, Morin SN, Lix LM; Manitoba Bone Density Program. Rate of bone density change does not enhance fracture prediction in routine clinical practice. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2012; 97:1211–1218.

- Gourlay ML, Fine J P, Preisser JS, et al; Study of Osteoporotic Fractures Research Group. Bone-density testing interval and transition to osteoporosis in older women. N Engl J Med 2012; 366:225–233.

- Lewiecki EM, Laster AJ, Miller PD, Bilezikian JP. More bone density testing is needed, not less. J Bone Miner Res 2012; 27:739–742.

- Yu EW, Finkelstein JS. Bone density screening intervals for osteoporosis: one size does not fit all. JAMA 2012; 307:2591–2592.

- Frier S. Women receive bone tests too often for osteoporosis, study finds. Bloomberg News; 2012. http://www.bloomberg.com/news/2012-01-18/many-women-screened-for-osteoporosis-don-t-need-it-researchers-report.html. Accessed January 3, 2013.

- Knox R. Many older women may not need frequent bone scans. National Public Radio; 2012. http://www.npr.org/blogs/health/2012/01/19/145419138/many-older-women-may-not-need-frequent-bone-scans?ps=sh_sthdl. Accessed January 3, 2013.

- Kolata G. Patients with normal bone density can delay retests, study suggests. The New York Times; 2012. http://www.nytimes.com/2012/01/19/health/bone-density-tests-for-osteoporosis-can-wait-study-says.html. Accessed January 3, 2013.

- Doshi KB, Khan LZ, Williams SE, Licata AA. Bone mineral density testing interval and transition to osteoporosis in older women: Is a T-score enough to determine a screening interval? Cleve Clin J Med 2013; 80:234–239.

- Park A. How often do women really need bone density tests? Time Healthland; 2012. http://healthland.time.com/2012/01/19/most-women-may-be-getting-too-many-bone-density-tests/. Accessed January 3, 2013.

- Adachi JD, Saag KG, Delmas PD, et al. Two-year effects of alendronate on bone mineral density and vertebral fracture in patients receiving glucocorticoids: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled extension trial. Arthritis Rheum 2001; 44:202–211.

- Cummings SR, Black DM, Thompson DE, et al. Effect of alendronate on risk of fracture in women with low bone density but without vertebral fractures: results from the Fracture Intervention Trial. JAMA 1998; 280:2077–2082.

- US Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for osteoporosis: US preventive services task force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med 2011; 154:356–364.

- Hillier TA, Stone KL, Bauer DC, et al. Evaluating the value of repeat bone mineral density measurement and prediction of fractures in older women: the study of osteoporotic fractures. Arch Intern Med 2007; 167:155–160.

- Leslie WD, Morin SN, Lix LM; Manitoba Bone Density Program. Rate of bone density change does not enhance fracture prediction in routine clinical practice. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2012; 97:1211–1218.

- Gourlay ML, Fine J P, Preisser JS, et al; Study of Osteoporotic Fractures Research Group. Bone-density testing interval and transition to osteoporosis in older women. N Engl J Med 2012; 366:225–233.

- Lewiecki EM, Laster AJ, Miller PD, Bilezikian JP. More bone density testing is needed, not less. J Bone Miner Res 2012; 27:739–742.

- Yu EW, Finkelstein JS. Bone density screening intervals for osteoporosis: one size does not fit all. JAMA 2012; 307:2591–2592.

- Frier S. Women receive bone tests too often for osteoporosis, study finds. Bloomberg News; 2012. http://www.bloomberg.com/news/2012-01-18/many-women-screened-for-osteoporosis-don-t-need-it-researchers-report.html. Accessed January 3, 2013.

- Knox R. Many older women may not need frequent bone scans. National Public Radio; 2012. http://www.npr.org/blogs/health/2012/01/19/145419138/many-older-women-may-not-need-frequent-bone-scans?ps=sh_sthdl. Accessed January 3, 2013.

- Kolata G. Patients with normal bone density can delay retests, study suggests. The New York Times; 2012. http://www.nytimes.com/2012/01/19/health/bone-density-tests-for-osteoporosis-can-wait-study-says.html. Accessed January 3, 2013.

- Doshi KB, Khan LZ, Williams SE, Licata AA. Bone mineral density testing interval and transition to osteoporosis in older women: Is a T-score enough to determine a screening interval? Cleve Clin J Med 2013; 80:234–239.

- Park A. How often do women really need bone density tests? Time Healthland; 2012. http://healthland.time.com/2012/01/19/most-women-may-be-getting-too-many-bone-density-tests/. Accessed January 3, 2013.

- Adachi JD, Saag KG, Delmas PD, et al. Two-year effects of alendronate on bone mineral density and vertebral fracture in patients receiving glucocorticoids: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled extension trial. Arthritis Rheum 2001; 44:202–211.

- Cummings SR, Black DM, Thompson DE, et al. Effect of alendronate on risk of fracture in women with low bone density but without vertebral fractures: results from the Fracture Intervention Trial. JAMA 1998; 280:2077–2082.

A rapidly growing crusted nodule on the lip

A 76-year-old man presented with a rapidly growing, indurated, crusted nodule on his lower lip (Figure 1). This combination—a rapidly growing nodule on a sun-exposed surface in an older patient—pointed to a diagnosis of squamous cell carcinoma, and biopsy study of the affected area confirmed this diagnosis (Figure 2). Clinical examination, computed tomography, and ultrasonography of the neck revealed no lymph node involvement; the tumor was staged as T2N0M0. Mohs microscopically controlled surgery was performed to remove the tumor with clear margins, and the patient has done well.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

Malignant melanoma, Merkel cell carcinoma, and deep fungal infection can also cause a rapidly growing crusted nodule on the lower lip, but this typically is not an initial presentation for these conditions.

Malignant melanoma

Malignant melanoma should be considered for any rapidly growing cutaneous tumor, especially on sun-damaged skin. Most melanoma lesions have variations in pigment and may contain shades of blue, brown, red, pink, and white. Amelanotic melanomas may mimic squamous cell carcinomas, but the histologic features of atypical keratinocytes in this patient ruled out that diagnosis. Biopsy of amelanotic melanoma reveals nests of melanocytes, usually associated with an in situ component in the overlying epithelium.

Merkel cell carcinoma

Merkel cell carcinoma can mimic squamous cell carcinoma or can even arise in association with squamous cell carcinoma. Histologic examination allows for differentiation. In difficult cases, cytokeratin staining with cytokeratin 20 and CAM 5.2 can clarify the diagnosis, because Merkel cell carcinomas exhibit a characteristic paranuclear dot-like pattern not evident in squamous cell carcinoma.

Deep fungal infection

Colonization by Candida organisms was noted within the overlying crust in this patient’s lesion, but fungal organisms were not noted in the epidermis or dermis. Pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia can be prominent in deep fungal infection, but the marked cytologic atypia in this case excluded deep fungal infection.

Mucosal neuroma

Mucosal neuromas are typically smooth-surfaced, soft lesions on the lip. They may be associated with multiple endocrine neoplasia syndromes. Biopsy study reveals that they are composed of delicate spindle cells that lack atypia.

SQUAMOUS CELL CARCINOMA

Squamous cell carcinoma is one of the most common types of nonmelanoma skin cancer and is associated with increased sun exposure and light skin pigmentation.1 Unlike basal cell carcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma has a considerable potential to metastasize.2–4 The current cancer staging manual of the American Joint Commission on Cancer refects recent evidence-based information on staging and prognosis.5–7 Squamous cell carcinoma of the lip carries an increased risk of metastasis,8 and an increase in the number or the size of involved lymph nodes carries a worse prognosis.9 The lower lip is most commonly involved because of increased sun exposure. The most common route for the spread of squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck is via lymphatics, so careful evaluation of the head and neck is indicated.10

STAGING OUR PATIENT’S LESION

Current staging of cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma takes into account a variety of different features. Our patient’s tumor was not associated with invasion of the maxilla, mandible, orbit, or temporal bone. This alone would have qualified the tumor as a T1 lesion, but its size of 3 cm indicated a higher risk and qualified it as a T2 lesion.

The histologic features of our patient’s lesion also indicate higher risk according to the current staging system.5 The Breslow thickness on histologic examination (measured from the granular cell layer of the epidermis to the deepest portion of the tumor) was 4 mm and the Clark’s level was IV (extension to the reticular dermis). The high-risk features and the location on the lip warrant a classification as T2 and carry a worse prognosis.

Wedge excision of the lower lip and Mohs surgery are accepted treatment options. The patient chose Mohs surgery and has done well, with excellent cosmetic and functional outcome. Radiation therapy can be useful as an adjuvant when lymph nodes are involved,11 but this was not necessary in our patient. Careful long-term follow up is warranted, as these patients are at higher risk of developing other, separate tumors.

- Schwartz RA. Squamous cell carcinoma. In:Schwartz RA, editor. Skin Cancer: Recognition and Management, 2nd ed. Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing; 2008:47–65.

- D’Souza J, Clark J. Management of the neck in metastatic cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck. Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2011; 19:99–105.

- Zbar RI, Canady JW. MOC-PSSM CME article: Nonmelanoma facial skin malignancy. Plast Reconstr Surg 2008; 121(suppl 1):1–9.

- Morselli P, Masciotra L, Pinto V, Zollino I, Brunelli G, Carinci F. Clinical parameters in T1N0M0 lower lip squamous cell carcinoma. J Craniofac Surg 2007; 18:1079–1082.

- American Joint Commission on Cancer. Cancer Staging Manual. 7th ed. http://www.cancerstaging.org. Accessed February 3, 2013.

- Lardaro T, Shea SM, Sharfman W, Liégeois N, Sober AJ. Improvements in the staging of cutaneous squamous-cell carcinoma in the 7th edition of the AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. Ann Surg Oncol 2010; 17:1979–1980.

- Cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma and other cutaneous carcinomas. In:Edge SB, Byrd DR, Compton CC, Fritz AG, Greene FL, Trotti A, editors. AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. 7th ed. New York, NY: Springer; 2010:301–314.

- Frierson HF, Cooper PH. Prognostic factors in squamous cell carcinoma of the lower lip. Hum Pathol 1986; 17:346–354.

- Civantos FJ, Moffat FL, goodwin WJ. Lymphatic mapping and sentinel lymphadenectomy for 106 head and neck lesions: contrasts between oral cavity and cutaneous malignancy. Laryngoscope 2006; 112(3 Pt 2 suppl 109):1–15.

- Rowe De, Carroll RJ, Day CL. Prognostic factors for local recurrence, metastasis, and survival rates in squamous cell carcinoma of the skin, ear, and lip. Implications for treatment modality selection. J Am Acad Dermatol 1992; 26:976–990.

- Veness MJ, Palme CE, Smith M, Cakir B, Morgan GJ, Kalnins I. Cutaneous head and neck squamous cell carcinoma metastatic to cervical lymph nodes (nonparotid): a better outcome with surgery and adjuvant radiotherapy. Laryngoscope 2003; 113:1827–1833.

A 76-year-old man presented with a rapidly growing, indurated, crusted nodule on his lower lip (Figure 1). This combination—a rapidly growing nodule on a sun-exposed surface in an older patient—pointed to a diagnosis of squamous cell carcinoma, and biopsy study of the affected area confirmed this diagnosis (Figure 2). Clinical examination, computed tomography, and ultrasonography of the neck revealed no lymph node involvement; the tumor was staged as T2N0M0. Mohs microscopically controlled surgery was performed to remove the tumor with clear margins, and the patient has done well.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

Malignant melanoma, Merkel cell carcinoma, and deep fungal infection can also cause a rapidly growing crusted nodule on the lower lip, but this typically is not an initial presentation for these conditions.

Malignant melanoma

Malignant melanoma should be considered for any rapidly growing cutaneous tumor, especially on sun-damaged skin. Most melanoma lesions have variations in pigment and may contain shades of blue, brown, red, pink, and white. Amelanotic melanomas may mimic squamous cell carcinomas, but the histologic features of atypical keratinocytes in this patient ruled out that diagnosis. Biopsy of amelanotic melanoma reveals nests of melanocytes, usually associated with an in situ component in the overlying epithelium.

Merkel cell carcinoma

Merkel cell carcinoma can mimic squamous cell carcinoma or can even arise in association with squamous cell carcinoma. Histologic examination allows for differentiation. In difficult cases, cytokeratin staining with cytokeratin 20 and CAM 5.2 can clarify the diagnosis, because Merkel cell carcinomas exhibit a characteristic paranuclear dot-like pattern not evident in squamous cell carcinoma.

Deep fungal infection

Colonization by Candida organisms was noted within the overlying crust in this patient’s lesion, but fungal organisms were not noted in the epidermis or dermis. Pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia can be prominent in deep fungal infection, but the marked cytologic atypia in this case excluded deep fungal infection.

Mucosal neuroma

Mucosal neuromas are typically smooth-surfaced, soft lesions on the lip. They may be associated with multiple endocrine neoplasia syndromes. Biopsy study reveals that they are composed of delicate spindle cells that lack atypia.

SQUAMOUS CELL CARCINOMA

Squamous cell carcinoma is one of the most common types of nonmelanoma skin cancer and is associated with increased sun exposure and light skin pigmentation.1 Unlike basal cell carcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma has a considerable potential to metastasize.2–4 The current cancer staging manual of the American Joint Commission on Cancer refects recent evidence-based information on staging and prognosis.5–7 Squamous cell carcinoma of the lip carries an increased risk of metastasis,8 and an increase in the number or the size of involved lymph nodes carries a worse prognosis.9 The lower lip is most commonly involved because of increased sun exposure. The most common route for the spread of squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck is via lymphatics, so careful evaluation of the head and neck is indicated.10

STAGING OUR PATIENT’S LESION

Current staging of cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma takes into account a variety of different features. Our patient’s tumor was not associated with invasion of the maxilla, mandible, orbit, or temporal bone. This alone would have qualified the tumor as a T1 lesion, but its size of 3 cm indicated a higher risk and qualified it as a T2 lesion.

The histologic features of our patient’s lesion also indicate higher risk according to the current staging system.5 The Breslow thickness on histologic examination (measured from the granular cell layer of the epidermis to the deepest portion of the tumor) was 4 mm and the Clark’s level was IV (extension to the reticular dermis). The high-risk features and the location on the lip warrant a classification as T2 and carry a worse prognosis.

Wedge excision of the lower lip and Mohs surgery are accepted treatment options. The patient chose Mohs surgery and has done well, with excellent cosmetic and functional outcome. Radiation therapy can be useful as an adjuvant when lymph nodes are involved,11 but this was not necessary in our patient. Careful long-term follow up is warranted, as these patients are at higher risk of developing other, separate tumors.

A 76-year-old man presented with a rapidly growing, indurated, crusted nodule on his lower lip (Figure 1). This combination—a rapidly growing nodule on a sun-exposed surface in an older patient—pointed to a diagnosis of squamous cell carcinoma, and biopsy study of the affected area confirmed this diagnosis (Figure 2). Clinical examination, computed tomography, and ultrasonography of the neck revealed no lymph node involvement; the tumor was staged as T2N0M0. Mohs microscopically controlled surgery was performed to remove the tumor with clear margins, and the patient has done well.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

Malignant melanoma, Merkel cell carcinoma, and deep fungal infection can also cause a rapidly growing crusted nodule on the lower lip, but this typically is not an initial presentation for these conditions.

Malignant melanoma

Malignant melanoma should be considered for any rapidly growing cutaneous tumor, especially on sun-damaged skin. Most melanoma lesions have variations in pigment and may contain shades of blue, brown, red, pink, and white. Amelanotic melanomas may mimic squamous cell carcinomas, but the histologic features of atypical keratinocytes in this patient ruled out that diagnosis. Biopsy of amelanotic melanoma reveals nests of melanocytes, usually associated with an in situ component in the overlying epithelium.

Merkel cell carcinoma

Merkel cell carcinoma can mimic squamous cell carcinoma or can even arise in association with squamous cell carcinoma. Histologic examination allows for differentiation. In difficult cases, cytokeratin staining with cytokeratin 20 and CAM 5.2 can clarify the diagnosis, because Merkel cell carcinomas exhibit a characteristic paranuclear dot-like pattern not evident in squamous cell carcinoma.

Deep fungal infection

Colonization by Candida organisms was noted within the overlying crust in this patient’s lesion, but fungal organisms were not noted in the epidermis or dermis. Pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia can be prominent in deep fungal infection, but the marked cytologic atypia in this case excluded deep fungal infection.

Mucosal neuroma

Mucosal neuromas are typically smooth-surfaced, soft lesions on the lip. They may be associated with multiple endocrine neoplasia syndromes. Biopsy study reveals that they are composed of delicate spindle cells that lack atypia.

SQUAMOUS CELL CARCINOMA

Squamous cell carcinoma is one of the most common types of nonmelanoma skin cancer and is associated with increased sun exposure and light skin pigmentation.1 Unlike basal cell carcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma has a considerable potential to metastasize.2–4 The current cancer staging manual of the American Joint Commission on Cancer refects recent evidence-based information on staging and prognosis.5–7 Squamous cell carcinoma of the lip carries an increased risk of metastasis,8 and an increase in the number or the size of involved lymph nodes carries a worse prognosis.9 The lower lip is most commonly involved because of increased sun exposure. The most common route for the spread of squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck is via lymphatics, so careful evaluation of the head and neck is indicated.10

STAGING OUR PATIENT’S LESION

Current staging of cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma takes into account a variety of different features. Our patient’s tumor was not associated with invasion of the maxilla, mandible, orbit, or temporal bone. This alone would have qualified the tumor as a T1 lesion, but its size of 3 cm indicated a higher risk and qualified it as a T2 lesion.

The histologic features of our patient’s lesion also indicate higher risk according to the current staging system.5 The Breslow thickness on histologic examination (measured from the granular cell layer of the epidermis to the deepest portion of the tumor) was 4 mm and the Clark’s level was IV (extension to the reticular dermis). The high-risk features and the location on the lip warrant a classification as T2 and carry a worse prognosis.

Wedge excision of the lower lip and Mohs surgery are accepted treatment options. The patient chose Mohs surgery and has done well, with excellent cosmetic and functional outcome. Radiation therapy can be useful as an adjuvant when lymph nodes are involved,11 but this was not necessary in our patient. Careful long-term follow up is warranted, as these patients are at higher risk of developing other, separate tumors.

- Schwartz RA. Squamous cell carcinoma. In:Schwartz RA, editor. Skin Cancer: Recognition and Management, 2nd ed. Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing; 2008:47–65.

- D’Souza J, Clark J. Management of the neck in metastatic cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck. Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2011; 19:99–105.

- Zbar RI, Canady JW. MOC-PSSM CME article: Nonmelanoma facial skin malignancy. Plast Reconstr Surg 2008; 121(suppl 1):1–9.

- Morselli P, Masciotra L, Pinto V, Zollino I, Brunelli G, Carinci F. Clinical parameters in T1N0M0 lower lip squamous cell carcinoma. J Craniofac Surg 2007; 18:1079–1082.

- American Joint Commission on Cancer. Cancer Staging Manual. 7th ed. http://www.cancerstaging.org. Accessed February 3, 2013.

- Lardaro T, Shea SM, Sharfman W, Liégeois N, Sober AJ. Improvements in the staging of cutaneous squamous-cell carcinoma in the 7th edition of the AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. Ann Surg Oncol 2010; 17:1979–1980.

- Cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma and other cutaneous carcinomas. In:Edge SB, Byrd DR, Compton CC, Fritz AG, Greene FL, Trotti A, editors. AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. 7th ed. New York, NY: Springer; 2010:301–314.

- Frierson HF, Cooper PH. Prognostic factors in squamous cell carcinoma of the lower lip. Hum Pathol 1986; 17:346–354.

- Civantos FJ, Moffat FL, goodwin WJ. Lymphatic mapping and sentinel lymphadenectomy for 106 head and neck lesions: contrasts between oral cavity and cutaneous malignancy. Laryngoscope 2006; 112(3 Pt 2 suppl 109):1–15.

- Rowe De, Carroll RJ, Day CL. Prognostic factors for local recurrence, metastasis, and survival rates in squamous cell carcinoma of the skin, ear, and lip. Implications for treatment modality selection. J Am Acad Dermatol 1992; 26:976–990.

- Veness MJ, Palme CE, Smith M, Cakir B, Morgan GJ, Kalnins I. Cutaneous head and neck squamous cell carcinoma metastatic to cervical lymph nodes (nonparotid): a better outcome with surgery and adjuvant radiotherapy. Laryngoscope 2003; 113:1827–1833.

- Schwartz RA. Squamous cell carcinoma. In:Schwartz RA, editor. Skin Cancer: Recognition and Management, 2nd ed. Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing; 2008:47–65.

- D’Souza J, Clark J. Management of the neck in metastatic cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck. Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2011; 19:99–105.

- Zbar RI, Canady JW. MOC-PSSM CME article: Nonmelanoma facial skin malignancy. Plast Reconstr Surg 2008; 121(suppl 1):1–9.

- Morselli P, Masciotra L, Pinto V, Zollino I, Brunelli G, Carinci F. Clinical parameters in T1N0M0 lower lip squamous cell carcinoma. J Craniofac Surg 2007; 18:1079–1082.

- American Joint Commission on Cancer. Cancer Staging Manual. 7th ed. http://www.cancerstaging.org. Accessed February 3, 2013.

- Lardaro T, Shea SM, Sharfman W, Liégeois N, Sober AJ. Improvements in the staging of cutaneous squamous-cell carcinoma in the 7th edition of the AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. Ann Surg Oncol 2010; 17:1979–1980.

- Cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma and other cutaneous carcinomas. In:Edge SB, Byrd DR, Compton CC, Fritz AG, Greene FL, Trotti A, editors. AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. 7th ed. New York, NY: Springer; 2010:301–314.

- Frierson HF, Cooper PH. Prognostic factors in squamous cell carcinoma of the lower lip. Hum Pathol 1986; 17:346–354.

- Civantos FJ, Moffat FL, goodwin WJ. Lymphatic mapping and sentinel lymphadenectomy for 106 head and neck lesions: contrasts between oral cavity and cutaneous malignancy. Laryngoscope 2006; 112(3 Pt 2 suppl 109):1–15.

- Rowe De, Carroll RJ, Day CL. Prognostic factors for local recurrence, metastasis, and survival rates in squamous cell carcinoma of the skin, ear, and lip. Implications for treatment modality selection. J Am Acad Dermatol 1992; 26:976–990.

- Veness MJ, Palme CE, Smith M, Cakir B, Morgan GJ, Kalnins I. Cutaneous head and neck squamous cell carcinoma metastatic to cervical lymph nodes (nonparotid): a better outcome with surgery and adjuvant radiotherapy. Laryngoscope 2003; 113:1827–1833.

Implications of a prominent R wave in V1

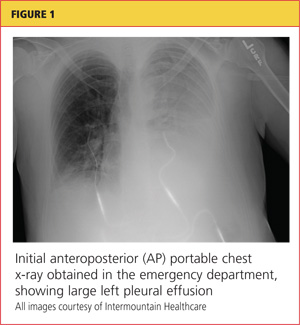

A 19-year-old woman with no significant cardiac or pulmonary history presented with exertional dyspnea, which had begun a few months earlier. Auscultation revealed a loud pulmonary component of the second heart sound and a diastolic murmur heard along the upper left sternal border. Her 12-lead electrocardiogram is shown in Figure 1.

Q: Which of the following can cause prominent R waves in lead V1?

- Normal variant in young adults

- Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome

- Posterior wall myocardial infarction

- Right ventricular hypertrophy

- All of the above

A: The correct answer is all of the above.

The patient’s electrocardiogram shows a right atrial abnormality and right ventricular hypertrophy. Right atrial enlargement is evidenced by a prominent initial P wave in V1 with an amplitude of at least 1.5 mm (0.15 mV). A P wave taller than 2.5 mm (0.25 mV) in lead II may also suggest a right atrial abnormality.1

Multiple criteria exist for the diagnosis of right ventricular hypertrophy. Tall R waves in V1 with an R/S ratio greater than 1 (ie, the R wave amplitude is more than the S wave depth) is commonly used.2 Deep S waves with an R/S ratio less than 1 in V6 is another criterion. Tall R waves of amplitude greater than 7 mm in V1 by themselves may represent right ventricular hypertrophy. Most of the electrocardiographic criteria are specific but not sensitive for this diagnosis.3

Other causes of tall R waves in V1 are given in Table 1.

Q: Which of the following diseases can present with an electrocardiographic pattern of right ventricular hypertrophy in young patients?

- Pulmonary hypertension

- Atrial septal defect

- Tetralogy of Fallot

- Pulmonary stenosis

- All of the above

A: The correct answer is all of the above.4

Our patient underwent multiple investigations. On echocardiography, her estimated right ventricular pressure was 80 mm Hg, and on cardiac catheterization her mean pulmonary arterial pressure was 55 mm Hg and her pulmonary capillary wedge pressure was 6 mm Hg. She was diagnosed with pulmonary arterial hypertension, which was the cause of her right ventricular hypertrophy. She eventually underwent bilateral lung transplantation.

- Hancock EW, Deal BJ, Mirvis DM, et al; American Heart Association Electrocardiography and Arrhythmias Committee, Council on Clinical Cardiology; American College of Cardiology Foundation; Heart Rhythm Society. AHA/ ACCF/HRS recommendations for the standardization and interpretation of the electrocardiogram: part V: electrocardiogram changes associated with cardiac chamber hypertrophy: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association Electrocardiography and Arrhythmias Committee, Council on Clinical Cardiology; the American College of Cardiology Foundation; and the Heart Rhythm Society: endorsed by the International Society for Computerized Electrocardiology. Circulation 2009; 119:e251–e261.

- Milnor WR. Electrocardiogram and vectorcardiogram in right ventricular hypertrophy and right bundle-branch block. Circulation 1957; 16:348–367.

- Lehtonen J, Sutinen S, Ikäheimo M, Pääkkö P. Electrocardiographic criteria for the diagnosis of right ventricular hypertrophy verified at autopsy. Chest 1988; 93:839–842.

- Webb G, Gatzoulis MA. Atrial septal defects in the adult: recent progress and overview. Circulation 2006; 114:1645–1653.

A 19-year-old woman with no significant cardiac or pulmonary history presented with exertional dyspnea, which had begun a few months earlier. Auscultation revealed a loud pulmonary component of the second heart sound and a diastolic murmur heard along the upper left sternal border. Her 12-lead electrocardiogram is shown in Figure 1.

Q: Which of the following can cause prominent R waves in lead V1?

- Normal variant in young adults

- Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome

- Posterior wall myocardial infarction

- Right ventricular hypertrophy

- All of the above

A: The correct answer is all of the above.

The patient’s electrocardiogram shows a right atrial abnormality and right ventricular hypertrophy. Right atrial enlargement is evidenced by a prominent initial P wave in V1 with an amplitude of at least 1.5 mm (0.15 mV). A P wave taller than 2.5 mm (0.25 mV) in lead II may also suggest a right atrial abnormality.1

Multiple criteria exist for the diagnosis of right ventricular hypertrophy. Tall R waves in V1 with an R/S ratio greater than 1 (ie, the R wave amplitude is more than the S wave depth) is commonly used.2 Deep S waves with an R/S ratio less than 1 in V6 is another criterion. Tall R waves of amplitude greater than 7 mm in V1 by themselves may represent right ventricular hypertrophy. Most of the electrocardiographic criteria are specific but not sensitive for this diagnosis.3

Other causes of tall R waves in V1 are given in Table 1.

Q: Which of the following diseases can present with an electrocardiographic pattern of right ventricular hypertrophy in young patients?

- Pulmonary hypertension

- Atrial septal defect

- Tetralogy of Fallot

- Pulmonary stenosis

- All of the above

A: The correct answer is all of the above.4

Our patient underwent multiple investigations. On echocardiography, her estimated right ventricular pressure was 80 mm Hg, and on cardiac catheterization her mean pulmonary arterial pressure was 55 mm Hg and her pulmonary capillary wedge pressure was 6 mm Hg. She was diagnosed with pulmonary arterial hypertension, which was the cause of her right ventricular hypertrophy. She eventually underwent bilateral lung transplantation.

A 19-year-old woman with no significant cardiac or pulmonary history presented with exertional dyspnea, which had begun a few months earlier. Auscultation revealed a loud pulmonary component of the second heart sound and a diastolic murmur heard along the upper left sternal border. Her 12-lead electrocardiogram is shown in Figure 1.

Q: Which of the following can cause prominent R waves in lead V1?

- Normal variant in young adults

- Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome

- Posterior wall myocardial infarction

- Right ventricular hypertrophy

- All of the above

A: The correct answer is all of the above.

The patient’s electrocardiogram shows a right atrial abnormality and right ventricular hypertrophy. Right atrial enlargement is evidenced by a prominent initial P wave in V1 with an amplitude of at least 1.5 mm (0.15 mV). A P wave taller than 2.5 mm (0.25 mV) in lead II may also suggest a right atrial abnormality.1

Multiple criteria exist for the diagnosis of right ventricular hypertrophy. Tall R waves in V1 with an R/S ratio greater than 1 (ie, the R wave amplitude is more than the S wave depth) is commonly used.2 Deep S waves with an R/S ratio less than 1 in V6 is another criterion. Tall R waves of amplitude greater than 7 mm in V1 by themselves may represent right ventricular hypertrophy. Most of the electrocardiographic criteria are specific but not sensitive for this diagnosis.3

Other causes of tall R waves in V1 are given in Table 1.

Q: Which of the following diseases can present with an electrocardiographic pattern of right ventricular hypertrophy in young patients?

- Pulmonary hypertension

- Atrial septal defect

- Tetralogy of Fallot

- Pulmonary stenosis

- All of the above

A: The correct answer is all of the above.4

Our patient underwent multiple investigations. On echocardiography, her estimated right ventricular pressure was 80 mm Hg, and on cardiac catheterization her mean pulmonary arterial pressure was 55 mm Hg and her pulmonary capillary wedge pressure was 6 mm Hg. She was diagnosed with pulmonary arterial hypertension, which was the cause of her right ventricular hypertrophy. She eventually underwent bilateral lung transplantation.

- Hancock EW, Deal BJ, Mirvis DM, et al; American Heart Association Electrocardiography and Arrhythmias Committee, Council on Clinical Cardiology; American College of Cardiology Foundation; Heart Rhythm Society. AHA/ ACCF/HRS recommendations for the standardization and interpretation of the electrocardiogram: part V: electrocardiogram changes associated with cardiac chamber hypertrophy: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association Electrocardiography and Arrhythmias Committee, Council on Clinical Cardiology; the American College of Cardiology Foundation; and the Heart Rhythm Society: endorsed by the International Society for Computerized Electrocardiology. Circulation 2009; 119:e251–e261.

- Milnor WR. Electrocardiogram and vectorcardiogram in right ventricular hypertrophy and right bundle-branch block. Circulation 1957; 16:348–367.

- Lehtonen J, Sutinen S, Ikäheimo M, Pääkkö P. Electrocardiographic criteria for the diagnosis of right ventricular hypertrophy verified at autopsy. Chest 1988; 93:839–842.

- Webb G, Gatzoulis MA. Atrial septal defects in the adult: recent progress and overview. Circulation 2006; 114:1645–1653.

- Hancock EW, Deal BJ, Mirvis DM, et al; American Heart Association Electrocardiography and Arrhythmias Committee, Council on Clinical Cardiology; American College of Cardiology Foundation; Heart Rhythm Society. AHA/ ACCF/HRS recommendations for the standardization and interpretation of the electrocardiogram: part V: electrocardiogram changes associated with cardiac chamber hypertrophy: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association Electrocardiography and Arrhythmias Committee, Council on Clinical Cardiology; the American College of Cardiology Foundation; and the Heart Rhythm Society: endorsed by the International Society for Computerized Electrocardiology. Circulation 2009; 119:e251–e261.

- Milnor WR. Electrocardiogram and vectorcardiogram in right ventricular hypertrophy and right bundle-branch block. Circulation 1957; 16:348–367.

- Lehtonen J, Sutinen S, Ikäheimo M, Pääkkö P. Electrocardiographic criteria for the diagnosis of right ventricular hypertrophy verified at autopsy. Chest 1988; 93:839–842.

- Webb G, Gatzoulis MA. Atrial septal defects in the adult: recent progress and overview. Circulation 2006; 114:1645–1653.

Resistance of man and bug

Why individual clinicians make specific decisions usually can be sorted out. But our behavior as a group is more difficult to understand and, even when there are pressing and convincing reasons to change, behavior is difficult to alter.

In this issue, Drs. Federico Perez and David Van Duin discuss the emergence of carbapenem-resistant bacteria, dubbed “superbugs” by the media. Antibiotic resistance is not new; it was reported in Staphylococcus species within several years of the introduction of penicillin.1 However, it has been increasing in prevalence and molecular complexity after years of relatively promiscuous antibiotic use. As the percentage of inpatients with immunosuppression and frailty increases in this environment of known antibiotic resistance, initial empiric antibiotic choices will by necessity include drugs likely to further promote development of resistant strains. But why do physicians still prescribe antibiotics for uncomplicated upper respiratory tract infections and asymptomatic bacteriuria, despite numerous studies and guidelines suggesting this practice has little benefit? Is it because patients expect a prescription in return for their copayment? Is it the path of least resistance? Or do physicians not accept the data showing that it is unnecessary?

Dr. Gerald Appel discusses diabetic nephropathy, an area that involves resistance of another kind, ie, the apparent resistance of physicians and patients to achieving evidence-based treatment targets. We hold controlled trials as the Holy Grail of evidence-based medicine, yet we seem to have an aversion to following guidelines based on trial-derived evidence. (I do not refer here to blind guideline adherence, ignoring individual patient characteristics.)

So how can physicians’ behavior be altered and our resistance to change be reduced? Experiments are under way, such as paying physicians based on their performance, linking patients’ insurance rates to achieving selected outcomes, and linking physician practice self-review to certification. Perhaps naively, I continue to believe that the most effective impetus to changing personal practice is the dissemination of data from high-quality trials (tempered by our accumulated experience and keeping our eyes wide open), coupled with our desire to do the best for our patients.

- Barber M. Coagulase-positive staphylococci resistant to penicillin. J Pathol Bacteriol 1947; 59:373–384.

Why individual clinicians make specific decisions usually can be sorted out. But our behavior as a group is more difficult to understand and, even when there are pressing and convincing reasons to change, behavior is difficult to alter.

In this issue, Drs. Federico Perez and David Van Duin discuss the emergence of carbapenem-resistant bacteria, dubbed “superbugs” by the media. Antibiotic resistance is not new; it was reported in Staphylococcus species within several years of the introduction of penicillin.1 However, it has been increasing in prevalence and molecular complexity after years of relatively promiscuous antibiotic use. As the percentage of inpatients with immunosuppression and frailty increases in this environment of known antibiotic resistance, initial empiric antibiotic choices will by necessity include drugs likely to further promote development of resistant strains. But why do physicians still prescribe antibiotics for uncomplicated upper respiratory tract infections and asymptomatic bacteriuria, despite numerous studies and guidelines suggesting this practice has little benefit? Is it because patients expect a prescription in return for their copayment? Is it the path of least resistance? Or do physicians not accept the data showing that it is unnecessary?

Dr. Gerald Appel discusses diabetic nephropathy, an area that involves resistance of another kind, ie, the apparent resistance of physicians and patients to achieving evidence-based treatment targets. We hold controlled trials as the Holy Grail of evidence-based medicine, yet we seem to have an aversion to following guidelines based on trial-derived evidence. (I do not refer here to blind guideline adherence, ignoring individual patient characteristics.)

So how can physicians’ behavior be altered and our resistance to change be reduced? Experiments are under way, such as paying physicians based on their performance, linking patients’ insurance rates to achieving selected outcomes, and linking physician practice self-review to certification. Perhaps naively, I continue to believe that the most effective impetus to changing personal practice is the dissemination of data from high-quality trials (tempered by our accumulated experience and keeping our eyes wide open), coupled with our desire to do the best for our patients.

Why individual clinicians make specific decisions usually can be sorted out. But our behavior as a group is more difficult to understand and, even when there are pressing and convincing reasons to change, behavior is difficult to alter.

In this issue, Drs. Federico Perez and David Van Duin discuss the emergence of carbapenem-resistant bacteria, dubbed “superbugs” by the media. Antibiotic resistance is not new; it was reported in Staphylococcus species within several years of the introduction of penicillin.1 However, it has been increasing in prevalence and molecular complexity after years of relatively promiscuous antibiotic use. As the percentage of inpatients with immunosuppression and frailty increases in this environment of known antibiotic resistance, initial empiric antibiotic choices will by necessity include drugs likely to further promote development of resistant strains. But why do physicians still prescribe antibiotics for uncomplicated upper respiratory tract infections and asymptomatic bacteriuria, despite numerous studies and guidelines suggesting this practice has little benefit? Is it because patients expect a prescription in return for their copayment? Is it the path of least resistance? Or do physicians not accept the data showing that it is unnecessary?

Dr. Gerald Appel discusses diabetic nephropathy, an area that involves resistance of another kind, ie, the apparent resistance of physicians and patients to achieving evidence-based treatment targets. We hold controlled trials as the Holy Grail of evidence-based medicine, yet we seem to have an aversion to following guidelines based on trial-derived evidence. (I do not refer here to blind guideline adherence, ignoring individual patient characteristics.)

So how can physicians’ behavior be altered and our resistance to change be reduced? Experiments are under way, such as paying physicians based on their performance, linking patients’ insurance rates to achieving selected outcomes, and linking physician practice self-review to certification. Perhaps naively, I continue to believe that the most effective impetus to changing personal practice is the dissemination of data from high-quality trials (tempered by our accumulated experience and keeping our eyes wide open), coupled with our desire to do the best for our patients.

- Barber M. Coagulase-positive staphylococci resistant to penicillin. J Pathol Bacteriol 1947; 59:373–384.

- Barber M. Coagulase-positive staphylococci resistant to penicillin. J Pathol Bacteriol 1947; 59:373–384.

Detecting and controlling diabetic nephropathy: What do we know?

Diabetes is on the rise, and so is diabetic nephropathy. In view of this epidemic, physicians should consider strategies to detect and control kidney disease in their diabetic patients.

This article will focus on kidney disease in adult-onset type 2 diabetes. Although it has different pathogenetic mechanisms than type 1 diabetes, the clinical course of the two conditions is very similar in terms of the prevalence of proteinuria after diagnosis, the progression to renal failure after the onset of proteinuria, and treatment options.1

DIABETES AND DIABETIC KIDNEY DISEASE ARE ON THE RISE

The incidence of diabetes increases with age, and with the aging of the baby boomers, its prevalence is growing dramatically. The 2005– 2008 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey estimated the prevalence as 3.7% in adults age 20 to 44, 13.7% at age 45 to 64, and 26.9% in people age 65 and older. The obesity epidemic is also contributing to the increase in diabetes in all age groups.

Diabetic kidney disease has increased in the United States from about 4 million cases 20 years ago to about 7 million in 2005–2008.2 Diabetes is the major cause of end-stage renal disease in the developed world, accounting for 40% to 50% of cases. Other major causes are hypertension (27%) and glomerulonephritis (13%).3

Physicians in nearly every field of medicine now care for patients with diabetic nephropathy. The classic presentation—a patient who has impaired vision, fluid retention with edema, and hypertension—is commonly seen in dialysis units and ophthalmology and cardiovascular clinics.

CLINICAL PROGRESSION

Early in the course of diabetic nephropathy, blood pressure is normal and microalbuminuria is not evident, but many patients have a high glomerular filtration rate (GFR), indicating temporarily “enhanced” renal function or hyperfiltration. The next stage is characterized by microalbuminuria, correlating with glomerular mesangial expansion: the GFR falls back into the normal range and blood pressure starts to increase. Finally, macroalbuminuria occurs, accompanied by rising blood pressure and a declining GFR, correlating with the histologic appearance of glomerulosclerosis and Kimmelstiel-Wilson nodules.4

Hypertension develops in 5% of patients by 10 years after type 1 diabetes is diagnosed, 33% by 20 years, and 70% by 40 years. In contrast, 40% of patients with type 2 diabetes have high blood pressure at diagnosis.

Unfortunately, in most cases, this progression is a one-way street, so it is critical to intervene to try to slow the progression early in the course of the disease process.

SCREENING FOR DIABETIC NEPHROPATHY

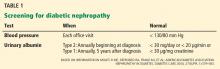

Nephropathy screening guidelines for patients with diabetes are provided in Table 1.5

Blood pressure should be monitored at each office visit (Table 1). The goal for adults with diabetes should be to reduce blood pressure to 130/80 mm Hg. Reduction beyond this level may be associated with an increased mortality rate.6 Very high blood pressure (> 180 mm Hg systolic) should be lowered slowly. Lowering blood pressure delays the progression from microalbuminuria (30–299 mg/day or 20–199 μg/min) to macroalbuminuria (> 300 mg/day or > 200 μg/min) and slows the progression to renal failure.

Urinary albumin. Proteinuria takes 5 to 10 years to develop after the onset of diabetes. Because it is possible for patients with type 2 diabetes to have had the disease for some time before being diagnosed, urinary albumin screening should be performed at diagnosis and annually thereafter. Patients with type 1 are usually diagnosed with diabetes at or near onset of disease; therefore, annual screening for urinary albumin can begin 5 years after diagnosis.5

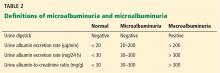

Proteinuria can be measured in different ways (Table 2). The basic screening test for clinical proteinuria is the urine dipstick, which is very sensitive to albumin and relatively insensitive to other proteins. “Trace-positive” results are common in healthy people, so proteinuria is not confirmed unless a patient has repeatedly positive results.

Microalbuminuria is important to measure, especially if it helps determine therapy. It is not detectable by the urinary dipstick, but can be measured in the following ways:

- Measurement of the albumin-creatinine ratio in a random spot collection

- 24-hour collection (creatinine should simultaneously be measured and creatinine clearance calculated)

- Timed collection (4 hours or overnight).

The first method is preferred, and any positive test result must be confirmed by repeat analyses of urinary albumin before a patient is diagnosed with microalbuminuria.

Occasionally a patient presenting with proteinuria but normal blood sugar and hemoglobin A1c will have a biopsy that reveals morphologic changes of classic diabetic nephropathy. Most such patients have a history of hyperglycemia, indicating that they actually have been diabetic.

Proteinuria—the best marker of disease progression

Proteinuria is the strongest predictor of renal outcomes. The Reduction in End Points in Noninsulin-Dependent Diabetes Mellitus With the Angiotensin II Antagonist Losartan (RENAAL) study was a randomized, placebo-controlled trial in more than 1,500 patients with type 2 diabetes to test the effects of losartan on renal outcome. Those with high albuminuria (> 3.0 g albumin/g creatinine) at baseline were five times more likely to reach a renal end point and were eight times more likely to have progression to end-stage renal disease than patients with low albuminuria (< 1.5 g/g).7 The degree of albuminuria after 6 months of treatment showed similar predictive trends, indicating that monitoring and treating proteinuria are extremely important goals.

STRATEGY 1 TO LIMIT RENAL INJURY: REDUCE BLOOD PRESSURE

Blood pressure control improves renal and cardiovascular function.

As early as 1983, Parving et al,8 in a study of only 10 insulin-dependent diabetic patients, showed strong evidence that early aggressive antihypertensive treatment improved the course of diabetic nephropathy. During the mean pretreatment period of 29 months, the GFR decreased significantly and the urinary albumin excretion rate and arterial blood pressure rose significantly. During the mean 39-month period of antihypertensive treatment with metoprolol, hydralazine, and furosemide or a thiazide, mean arterial blood pressure fell from 144/97 to 128/84 mm Hg and urinary albumin excretion from 977 to 433 μg/ min. The rate of decline in GFR slowed from 0.91 mL/min/month before treatment to 0.39 mL/min/month during treatment.

The Action in Diabetes and Vascular Disease: Preterax and Diamicron MR Controlled Evaluation (ADVANCE) trial9 enrolled more than 11,000 patients internationally with type 2 diabetes at high risk for cardiovascular events. In addition to standard therapy, blood pressure was intensively controlled in one group with a combination of the angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitor perindopril and the diuretic indapamide. The intensive-therapy group achieved blood pressures less than 140/80 mm Hg and had a mean reduction of systolic blood pressure of 5.6 mm Hg and diastolic blood pressure of 2.2 mm Hg vs controls. Despite these apparently modest reductions, the intensively controlled group had a significant 9% reduction of the primary outcome of combined macrovascular events (cardiovascular death, myocardial infarction, and stroke) and microvascular events (new or worsening nephropathy, or retinopathy).10

A meta-analysis of studies of patients with type 2 diabetes found reduced nephropathy with systolic blood pressure control to less than 130 mm Hg.11

The United Kingdom Prospective Diabetes Study (UKPDS) is a series of studies of diabetes. The original study in 1998 enrolled 5,102 patients with newly diagnosed type 2 diabetes.12 The more than 1,000 patients with hypertension were randomized to either tight blood pressure control or regular care. The intensive treatment group had a mean blood pressure reduction of 9 mm Hg systolic and 3 mm Hg diastolic, along with major reductions in all diabetes end points, diabetes deaths, microvascular disease, and stroke over a median follow-up of 8.4 years.

Continuous blood pressure control is critical

Tight blood pressure control must be maintained to have continued benefit. During the 10 years following the UKPDS, no attempts were made to maintain the previously assigned therapies. A follow-up study13 of 884 UKPDS patients found that blood pressures were the same again between the two groups 2 years after the trial was stopped, and no beneficial legacy effect from previous blood pressure control was evident on end points.

Control below 120 mm Hg systolic not needed

Blood pressure control slows kidney disease and prevents major macrovascular disease, but there is no evidence that lowering systolic blood pressure below 120 mm Hg provides additional benefit. In the Action to Control Cardiovascular Risk in Diabetes (ACCORD) trial,14 more than 10,000 patients with type 2 diabetes and existing cardiovascular disease or additional cardiovascular risk factors were randomized to a goal of systolic blood pressure less than 120 mm Hg or less than 140 mm Hg (actual mean systolic pressures were 119 vs 134 mm Hg, respectively). Over nearly 5 years, there was no difference in cardiovascular events or deaths between the two groups.15

Since 1997, six international organizations have revised their recommended blood pressure goals in diabetes mellitus and renal diseases. Randomized clinical trials and observational studies have demonstrated the importance of blood pressure control to the level of 125/75 to 140/80 mm Hg. The National Kidney Foundation, the American Diabetes Association, and the Canadian Hypertension Society have developed consensus guidelines for blood pressure control to less than 130/80 mm Hg.16–21 Table 3 summarizes blood pressure goals for patients with diabetes.

STRATEGY 2: CONTROL BLOOD SUGAR

Recommendations for blood sugar goals are more controversial.

The Diabetes Control and Complications Trial22 provided early evidence that tight blood sugar control slows the development of microalbuminuria and macroalbuminuria. The study randomized more than 1,400 patients with type 1 diabetes to either standard therapy (1 or 2 daily insulin injections) or intensive therapy (an external insulin pump or 3 or more insulin injections guided by frequent blood glucose monitoring) to keep blood glucose levels close to normal. About half the patients had mild retinopathy at baseline and the others had no retinopathy. After 6.5 years, intensive therapy was found to significantly delay the onset and slow the progression of diabetic retinopathy and nephropathy.

The Kumamoto Study23 randomized 110 patients with type 2 diabetes and either no retinopathy (primary prevention cohort) or simple retinopathy (secondary prevention cohort) to receive either multiple insulin injections or conventional insulin therapy over 8 years. Intensive therapy led to lower rates of retinopathy (7.7% vs 32% in primary prevention and 19% vs 44% in secondary prevention) and progressive nephropathy (7% vs 28% in primary prevention at 6 years and 11% vs 32% in secondary prevention).