User login

UCLA Exec: Patient-Centered Approach Essential to Quality of Hospital Care

–David Feinberg, MD, MBA, president of UCLA Health System in Los Angeles

Patient satisfaction is a buzzword in HM circles, as compensation is increasingly tied to performance in keeping inpatients happy. David Feinberg, MD, MBA, president of UCLA Health System in Los Angeles, could be called a guru of patient satisfaction.

Just don’t tell him that.

“I hope I’m not seen as ‘patient satisfaction,’” he says. “I hope I’m seen as ‘patient centeredness.’ And patient satisfaction is a key piece of patient centeredness.”

Dr. Feinberg, who assumed his current role UCLA Health System in 2011, is a national voice for pushing a patient-centric model of care delivery. To wit, he will be one of the keynote speakers at HM13 next month at the Gaylord National Resort & Convention Center in National Harbor, Md. His address is fittingly titled “Healing Humankind One Patient at a Time.”

The Hospitalist spoke to Dr. Feinberg about his message to hospitalists.

Question: What do you think is the evolution of patient centeredness, as that becomes more of a focus for others?

Answer: Patient centeredness to me is the true north, and I think everything else that we’ve done that isn’t patient-centered has been a distraction. … It’s why we signed up to get into healthcare. It’s what we should be doing today and tonight, and it should guide our future tomorrow. It would be like me saying to the restaurateur, “How important is the food?”

Q: Is it something that hasn’t always been done?

A: It’s pathetic. You’re totally right. We’ve lost our way.

Q: If it’s so common-sense, how did we lose our way?

A: It really became, to me, the coin of the realm in medicine was how much the doctor made, how great their reputation was. It even got to the point of: You were a good doctor if your waiting room was packed. … I keep saying the waiting room should be for the doctors. The patient shouldn’t have to wait. You should be back in the exam room and the doctor should be waiting to see you. So we’ve got to completely change the paradigm. … It’s really the patient who’s at the top of the pyramid. And I just think we’ve lost that completely.

Q: How does a hospitalist engage quickly to ensure that they’re trying to accomplish patient centeredness and manage outcomes properly?

A: Hospitalists have a unique opportunity there, because everybody remembers when they got put in the hospital. It is a big deal when you’re hospitalized. Your family is in a vulnerable state, everybody is in a heightened sense of alertness and focus. Think about how important those four days are around education, around myths and demystifying, around beliefs and disbelief.

Check out our 6-minute feature video: "Five Reasons You Should Attend HM13"

Q: So what is the one thing you want hospitalists to take away from your address?

A: That they should join with all of us who want to heal humankind; that they are healers, above all.

Q: How do you translate “I want to be a healer” to the grind of daily work?

A: Well, I don’t think this is a grind. I think that when you’re in this healing profession, that you come here with a purpose. I think if we asked them to look at their personal statements of why they went into med school, every single one of them has something to do with, “I was sick as a kid, my grandmother got sick, I had had this doctor who was a role model, I like to help people, I was a volunteer and I met this patient.” Everyone says that. So this is different than trying to inspire the workers at Costco. These are people that, by definition, have gone and chosen this. We know they’re all smart. They could have all become investment bankers, they could have all become schoolteachers, but what they chose was to go into this field that’s about healing others, and that’s what I think we need to and what I would want them to do, is to get back in touch with themselves because I know it’s there. By definition, it’s there.

Q: Then why don’t more people just make that connection? What is the hurdle?

A: There are a lot of distractions. There are a lot of things coming your way. Worrying about your own life; doctors have lives at home. Worrying about the pressures of making a living. Some of this stuff is really, really hard. There are a million things going on. I believe, and I hope at UCLA, that we believe the strategy to make all of that stuff work is to get it right with the patient. And if you get it right with the patient, then all of that other stuff seems to fall into place and starts to make sense. The finances work out. The market share works out. The healthcare reform works out. I think it is the answer.

Richard Quinn is a freelance writer in New Jersey.

–David Feinberg, MD, MBA, president of UCLA Health System in Los Angeles

Patient satisfaction is a buzzword in HM circles, as compensation is increasingly tied to performance in keeping inpatients happy. David Feinberg, MD, MBA, president of UCLA Health System in Los Angeles, could be called a guru of patient satisfaction.

Just don’t tell him that.

“I hope I’m not seen as ‘patient satisfaction,’” he says. “I hope I’m seen as ‘patient centeredness.’ And patient satisfaction is a key piece of patient centeredness.”

Dr. Feinberg, who assumed his current role UCLA Health System in 2011, is a national voice for pushing a patient-centric model of care delivery. To wit, he will be one of the keynote speakers at HM13 next month at the Gaylord National Resort & Convention Center in National Harbor, Md. His address is fittingly titled “Healing Humankind One Patient at a Time.”

The Hospitalist spoke to Dr. Feinberg about his message to hospitalists.

Question: What do you think is the evolution of patient centeredness, as that becomes more of a focus for others?

Answer: Patient centeredness to me is the true north, and I think everything else that we’ve done that isn’t patient-centered has been a distraction. … It’s why we signed up to get into healthcare. It’s what we should be doing today and tonight, and it should guide our future tomorrow. It would be like me saying to the restaurateur, “How important is the food?”

Q: Is it something that hasn’t always been done?

A: It’s pathetic. You’re totally right. We’ve lost our way.

Q: If it’s so common-sense, how did we lose our way?

A: It really became, to me, the coin of the realm in medicine was how much the doctor made, how great their reputation was. It even got to the point of: You were a good doctor if your waiting room was packed. … I keep saying the waiting room should be for the doctors. The patient shouldn’t have to wait. You should be back in the exam room and the doctor should be waiting to see you. So we’ve got to completely change the paradigm. … It’s really the patient who’s at the top of the pyramid. And I just think we’ve lost that completely.

Q: How does a hospitalist engage quickly to ensure that they’re trying to accomplish patient centeredness and manage outcomes properly?

A: Hospitalists have a unique opportunity there, because everybody remembers when they got put in the hospital. It is a big deal when you’re hospitalized. Your family is in a vulnerable state, everybody is in a heightened sense of alertness and focus. Think about how important those four days are around education, around myths and demystifying, around beliefs and disbelief.

Check out our 6-minute feature video: "Five Reasons You Should Attend HM13"

Q: So what is the one thing you want hospitalists to take away from your address?

A: That they should join with all of us who want to heal humankind; that they are healers, above all.

Q: How do you translate “I want to be a healer” to the grind of daily work?

A: Well, I don’t think this is a grind. I think that when you’re in this healing profession, that you come here with a purpose. I think if we asked them to look at their personal statements of why they went into med school, every single one of them has something to do with, “I was sick as a kid, my grandmother got sick, I had had this doctor who was a role model, I like to help people, I was a volunteer and I met this patient.” Everyone says that. So this is different than trying to inspire the workers at Costco. These are people that, by definition, have gone and chosen this. We know they’re all smart. They could have all become investment bankers, they could have all become schoolteachers, but what they chose was to go into this field that’s about healing others, and that’s what I think we need to and what I would want them to do, is to get back in touch with themselves because I know it’s there. By definition, it’s there.

Q: Then why don’t more people just make that connection? What is the hurdle?

A: There are a lot of distractions. There are a lot of things coming your way. Worrying about your own life; doctors have lives at home. Worrying about the pressures of making a living. Some of this stuff is really, really hard. There are a million things going on. I believe, and I hope at UCLA, that we believe the strategy to make all of that stuff work is to get it right with the patient. And if you get it right with the patient, then all of that other stuff seems to fall into place and starts to make sense. The finances work out. The market share works out. The healthcare reform works out. I think it is the answer.

Richard Quinn is a freelance writer in New Jersey.

–David Feinberg, MD, MBA, president of UCLA Health System in Los Angeles

Patient satisfaction is a buzzword in HM circles, as compensation is increasingly tied to performance in keeping inpatients happy. David Feinberg, MD, MBA, president of UCLA Health System in Los Angeles, could be called a guru of patient satisfaction.

Just don’t tell him that.

“I hope I’m not seen as ‘patient satisfaction,’” he says. “I hope I’m seen as ‘patient centeredness.’ And patient satisfaction is a key piece of patient centeredness.”

Dr. Feinberg, who assumed his current role UCLA Health System in 2011, is a national voice for pushing a patient-centric model of care delivery. To wit, he will be one of the keynote speakers at HM13 next month at the Gaylord National Resort & Convention Center in National Harbor, Md. His address is fittingly titled “Healing Humankind One Patient at a Time.”

The Hospitalist spoke to Dr. Feinberg about his message to hospitalists.

Question: What do you think is the evolution of patient centeredness, as that becomes more of a focus for others?

Answer: Patient centeredness to me is the true north, and I think everything else that we’ve done that isn’t patient-centered has been a distraction. … It’s why we signed up to get into healthcare. It’s what we should be doing today and tonight, and it should guide our future tomorrow. It would be like me saying to the restaurateur, “How important is the food?”

Q: Is it something that hasn’t always been done?

A: It’s pathetic. You’re totally right. We’ve lost our way.

Q: If it’s so common-sense, how did we lose our way?

A: It really became, to me, the coin of the realm in medicine was how much the doctor made, how great their reputation was. It even got to the point of: You were a good doctor if your waiting room was packed. … I keep saying the waiting room should be for the doctors. The patient shouldn’t have to wait. You should be back in the exam room and the doctor should be waiting to see you. So we’ve got to completely change the paradigm. … It’s really the patient who’s at the top of the pyramid. And I just think we’ve lost that completely.

Q: How does a hospitalist engage quickly to ensure that they’re trying to accomplish patient centeredness and manage outcomes properly?

A: Hospitalists have a unique opportunity there, because everybody remembers when they got put in the hospital. It is a big deal when you’re hospitalized. Your family is in a vulnerable state, everybody is in a heightened sense of alertness and focus. Think about how important those four days are around education, around myths and demystifying, around beliefs and disbelief.

Check out our 6-minute feature video: "Five Reasons You Should Attend HM13"

Q: So what is the one thing you want hospitalists to take away from your address?

A: That they should join with all of us who want to heal humankind; that they are healers, above all.

Q: How do you translate “I want to be a healer” to the grind of daily work?

A: Well, I don’t think this is a grind. I think that when you’re in this healing profession, that you come here with a purpose. I think if we asked them to look at their personal statements of why they went into med school, every single one of them has something to do with, “I was sick as a kid, my grandmother got sick, I had had this doctor who was a role model, I like to help people, I was a volunteer and I met this patient.” Everyone says that. So this is different than trying to inspire the workers at Costco. These are people that, by definition, have gone and chosen this. We know they’re all smart. They could have all become investment bankers, they could have all become schoolteachers, but what they chose was to go into this field that’s about healing others, and that’s what I think we need to and what I would want them to do, is to get back in touch with themselves because I know it’s there. By definition, it’s there.

Q: Then why don’t more people just make that connection? What is the hurdle?

A: There are a lot of distractions. There are a lot of things coming your way. Worrying about your own life; doctors have lives at home. Worrying about the pressures of making a living. Some of this stuff is really, really hard. There are a million things going on. I believe, and I hope at UCLA, that we believe the strategy to make all of that stuff work is to get it right with the patient. And if you get it right with the patient, then all of that other stuff seems to fall into place and starts to make sense. The finances work out. The market share works out. The healthcare reform works out. I think it is the answer.

Richard Quinn is a freelance writer in New Jersey.

Medicare CMO Encourages Hospitalists to Become Experts in Managing Quality Patient Care

–Patrick Conway, MD, MSc, FAAP, SFHM, chief medical officer, Centers for Medicaid & Medicare Service

Patrick Conway, MD, MSc, FAAP, SFHM, chief medical officer of the Centers for Medicaid & Medicare Services (CMS), often says that physicians need to come to the proverbial table to tell CMS what they think is best. So it’s fitting that at HM13 at the Gaylord National Resort & Convention Center in National Harbor, Md., Dr. Conway will be a keynote speaker who can deliver his message of quality through teamwork to more than 2,500 hospitalists.

A pediatric hospitalist who also serves as director of the Office of Clinical Standards and Quality at the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services in Washington, D.C., Dr. Conway will paint a picture of what hospitalists can do to become the quality-improvement (QI) leaders healthcare needs in the coming years in a presentation titled “The Ideal Hospitalist in 2014 and Beyond: Active Change Agent.”

“Are hospitalists going to accept that challenge?” he asks. “I hope they are.”

This is the second year in a row that Dr. Conway will be a plenary speaker. Last year in San Diego, he told a packed room that CMS had to move from a “passive payor to an active facilitator and catalyst for quality improvement,” says Danielle Scheurer, MD, MSCR, SFHM, physician editor of The Hospitalist. Or, in his own words: “better health, better care, and lower cost.”

But many of the issues in his 2012 commentary were in flux. The Affordable Care Act (ACA), now moving through the slow process of implementation, was then still a law very much in doubt. It wasn’t until last summer that the law was upheld by a bitterly divided U.S. Supreme Court and it became clear much of the proposed reforms would move forward.

This year, he will urge hospitalists to step up their focus on patient-centered outcomes and stop questioning whether that should be the way the HM and other physicians should be judged.

“Given the changing context of payment, hospitalists are going to have to become true experts in managing the quality of care,” Dr. Conway says. “The days of you just graduating residency, seeing as many patients as you can, and you go home at the end of the day—that’s gone for hospital medicine.”

Check out our 6-minute feature video: "Five Reasons You Should Attend HM13"

Hospitalists can take charge of quality initiatives via involvement with accountable-care organizations (ACOs), health exchanges, and CMS’ value-based purchasing modifier (VBPM). In part, HM is perfectly positioned to assume leadership roles over the next few years because hospitalists already work across multiple departments.

“Hospital medicine is already ahead of a lot of specialties,” Dr. Conway says. “Hospital medicine physicians are already taking on much larger roles in their systems. I think you’re going to see an increasing trend.”

Richard Quinn is a freelance writer in New Jersey.

–Patrick Conway, MD, MSc, FAAP, SFHM, chief medical officer, Centers for Medicaid & Medicare Service

Patrick Conway, MD, MSc, FAAP, SFHM, chief medical officer of the Centers for Medicaid & Medicare Services (CMS), often says that physicians need to come to the proverbial table to tell CMS what they think is best. So it’s fitting that at HM13 at the Gaylord National Resort & Convention Center in National Harbor, Md., Dr. Conway will be a keynote speaker who can deliver his message of quality through teamwork to more than 2,500 hospitalists.

A pediatric hospitalist who also serves as director of the Office of Clinical Standards and Quality at the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services in Washington, D.C., Dr. Conway will paint a picture of what hospitalists can do to become the quality-improvement (QI) leaders healthcare needs in the coming years in a presentation titled “The Ideal Hospitalist in 2014 and Beyond: Active Change Agent.”

“Are hospitalists going to accept that challenge?” he asks. “I hope they are.”

This is the second year in a row that Dr. Conway will be a plenary speaker. Last year in San Diego, he told a packed room that CMS had to move from a “passive payor to an active facilitator and catalyst for quality improvement,” says Danielle Scheurer, MD, MSCR, SFHM, physician editor of The Hospitalist. Or, in his own words: “better health, better care, and lower cost.”

But many of the issues in his 2012 commentary were in flux. The Affordable Care Act (ACA), now moving through the slow process of implementation, was then still a law very much in doubt. It wasn’t until last summer that the law was upheld by a bitterly divided U.S. Supreme Court and it became clear much of the proposed reforms would move forward.

This year, he will urge hospitalists to step up their focus on patient-centered outcomes and stop questioning whether that should be the way the HM and other physicians should be judged.

“Given the changing context of payment, hospitalists are going to have to become true experts in managing the quality of care,” Dr. Conway says. “The days of you just graduating residency, seeing as many patients as you can, and you go home at the end of the day—that’s gone for hospital medicine.”

Check out our 6-minute feature video: "Five Reasons You Should Attend HM13"

Hospitalists can take charge of quality initiatives via involvement with accountable-care organizations (ACOs), health exchanges, and CMS’ value-based purchasing modifier (VBPM). In part, HM is perfectly positioned to assume leadership roles over the next few years because hospitalists already work across multiple departments.

“Hospital medicine is already ahead of a lot of specialties,” Dr. Conway says. “Hospital medicine physicians are already taking on much larger roles in their systems. I think you’re going to see an increasing trend.”

Richard Quinn is a freelance writer in New Jersey.

–Patrick Conway, MD, MSc, FAAP, SFHM, chief medical officer, Centers for Medicaid & Medicare Service

Patrick Conway, MD, MSc, FAAP, SFHM, chief medical officer of the Centers for Medicaid & Medicare Services (CMS), often says that physicians need to come to the proverbial table to tell CMS what they think is best. So it’s fitting that at HM13 at the Gaylord National Resort & Convention Center in National Harbor, Md., Dr. Conway will be a keynote speaker who can deliver his message of quality through teamwork to more than 2,500 hospitalists.

A pediatric hospitalist who also serves as director of the Office of Clinical Standards and Quality at the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services in Washington, D.C., Dr. Conway will paint a picture of what hospitalists can do to become the quality-improvement (QI) leaders healthcare needs in the coming years in a presentation titled “The Ideal Hospitalist in 2014 and Beyond: Active Change Agent.”

“Are hospitalists going to accept that challenge?” he asks. “I hope they are.”

This is the second year in a row that Dr. Conway will be a plenary speaker. Last year in San Diego, he told a packed room that CMS had to move from a “passive payor to an active facilitator and catalyst for quality improvement,” says Danielle Scheurer, MD, MSCR, SFHM, physician editor of The Hospitalist. Or, in his own words: “better health, better care, and lower cost.”

But many of the issues in his 2012 commentary were in flux. The Affordable Care Act (ACA), now moving through the slow process of implementation, was then still a law very much in doubt. It wasn’t until last summer that the law was upheld by a bitterly divided U.S. Supreme Court and it became clear much of the proposed reforms would move forward.

This year, he will urge hospitalists to step up their focus on patient-centered outcomes and stop questioning whether that should be the way the HM and other physicians should be judged.

“Given the changing context of payment, hospitalists are going to have to become true experts in managing the quality of care,” Dr. Conway says. “The days of you just graduating residency, seeing as many patients as you can, and you go home at the end of the day—that’s gone for hospital medicine.”

Check out our 6-minute feature video: "Five Reasons You Should Attend HM13"

Hospitalists can take charge of quality initiatives via involvement with accountable-care organizations (ACOs), health exchanges, and CMS’ value-based purchasing modifier (VBPM). In part, HM is perfectly positioned to assume leadership roles over the next few years because hospitalists already work across multiple departments.

“Hospital medicine is already ahead of a lot of specialties,” Dr. Conway says. “Hospital medicine physicians are already taking on much larger roles in their systems. I think you’re going to see an increasing trend.”

Richard Quinn is a freelance writer in New Jersey.

Educational, Networking Opportunities for Hospitalists Abound at HM13

Ask Dan Brotman, MD, FACP, SFHM, how to get the most out of the annual meeting of hospitalists and you’ll get a simple, one-word answer: Go.

“It sounds so trivial,” says Dr. Brotman, HM13 course director. “But there are a lot more hospitalists out there than we see at the meeting, and I think that [we should be] getting out the word that this is the best single opportunity that hospitalists have to network and learn about their field, not only content knowledge but also understanding where the field is going from thought leaders.”

The annual pilgrimage of hospitalists is expected to be larger than ever this year, with SHM expecting nearly 3,000 hospitalists to attend. Last year, roughly 2,700 hospitalists attended in San Diego.

But navigating a four-day maze of pre-courses, plenaries, and presentations can overwhelm even the most experienced attendee, much less a first-timer. And that’s before the annual rite that is the Research, Innovation, and Clinical Vignettes (RIV) poster competition and the Hospitalists on the Hill event that is particularly fitting this year as Capitol Hill happens to be just a few miles away.

So what’s the best advice to have the best meeting experience? Planning, planning, and a little more planning.

Ken Simone, DO, SFHM, principal of Hospitalist and Practice Solutions in Veazie, Maine, says the plethora of workshops, keynote speakers, and formalized educational offerings means attendees should “game plan” their schedule as much as possible.

“It behooves everyone to really study the offerings each day and each hour and plan their schedule accordingly,” says Dr. Simone, a Team Hospitalist member. “I typically create my schedule before I leave home for the conference.”

But don’t plan too much, he adds. Having a list of sessions to attend is important, but part of the meeting’s allure is the ability to mingle with clinical, administrative, and society leaders from around the country.

“Flexibility is the key,” he says. “Having something well planned doesn’t mean you can’t be flexible.”

Check out our 6-minute feature video: "Five Reasons You Should Attend HM13"

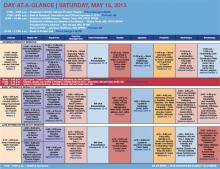

Dr. Brotman says meeting organizers take the same approach. While some topics are old favorites, SHM adds new offerings each year to adapt in real time to important trends. For example, he says, a new track this year focused on comanagement will appeal to hospitalists and subspecialists who take care of stroke patients, surgical patients, and pregnant women, among others.

The new track is in addition to the existing offerings: clinical, academic/research, rapid fire, pediatric, practice management, quality, and potpourri. The last item is in its second year and offers a break from the didactic and lecture approaches taken in nearly all of the annual meeting’s other breakout sessions. A particularly popular event is expected to be “History of Hospitals,” presented by hospitalist historian Jordan Messler, MD, SFHM.

There are two new pre-courses this year: “Bugs, Drugs and You: Infectious Disease Essentials for the Hospitalist” and “What Keeps You Awake at Night? Hot Topics in Hospitalist Practice Management.” Pre-course mainstays scheduled again this year include “ABIM Maintenance Certification,” “Medical Procedures for the Hospitalist,” and “Portable Ultrasounds for the Hospitalist.”

“As the society has gotten bigger, the meeting has gotten bigger in terms of its scope,” says Dr. Brotman, whose day job is director of the hospitalist program at Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore. “So we have Friday, Saturday, and Sunday, plus the evening activities, plus the pre-courses. One of the adjustments that we’ve made over time is that we do recognize that with a larger constituency and a larger amount of topical information that we’d like to cover, the meeting does get longer. The hope is that people can commit close to a week toward advancing their knowledge; it’s well worth the time.”

Richard Quinn is a freelance writer in New Jersey.

Ask Dan Brotman, MD, FACP, SFHM, how to get the most out of the annual meeting of hospitalists and you’ll get a simple, one-word answer: Go.

“It sounds so trivial,” says Dr. Brotman, HM13 course director. “But there are a lot more hospitalists out there than we see at the meeting, and I think that [we should be] getting out the word that this is the best single opportunity that hospitalists have to network and learn about their field, not only content knowledge but also understanding where the field is going from thought leaders.”

The annual pilgrimage of hospitalists is expected to be larger than ever this year, with SHM expecting nearly 3,000 hospitalists to attend. Last year, roughly 2,700 hospitalists attended in San Diego.

But navigating a four-day maze of pre-courses, plenaries, and presentations can overwhelm even the most experienced attendee, much less a first-timer. And that’s before the annual rite that is the Research, Innovation, and Clinical Vignettes (RIV) poster competition and the Hospitalists on the Hill event that is particularly fitting this year as Capitol Hill happens to be just a few miles away.

So what’s the best advice to have the best meeting experience? Planning, planning, and a little more planning.

Ken Simone, DO, SFHM, principal of Hospitalist and Practice Solutions in Veazie, Maine, says the plethora of workshops, keynote speakers, and formalized educational offerings means attendees should “game plan” their schedule as much as possible.

“It behooves everyone to really study the offerings each day and each hour and plan their schedule accordingly,” says Dr. Simone, a Team Hospitalist member. “I typically create my schedule before I leave home for the conference.”

But don’t plan too much, he adds. Having a list of sessions to attend is important, but part of the meeting’s allure is the ability to mingle with clinical, administrative, and society leaders from around the country.

“Flexibility is the key,” he says. “Having something well planned doesn’t mean you can’t be flexible.”

Check out our 6-minute feature video: "Five Reasons You Should Attend HM13"

Dr. Brotman says meeting organizers take the same approach. While some topics are old favorites, SHM adds new offerings each year to adapt in real time to important trends. For example, he says, a new track this year focused on comanagement will appeal to hospitalists and subspecialists who take care of stroke patients, surgical patients, and pregnant women, among others.

The new track is in addition to the existing offerings: clinical, academic/research, rapid fire, pediatric, practice management, quality, and potpourri. The last item is in its second year and offers a break from the didactic and lecture approaches taken in nearly all of the annual meeting’s other breakout sessions. A particularly popular event is expected to be “History of Hospitals,” presented by hospitalist historian Jordan Messler, MD, SFHM.

There are two new pre-courses this year: “Bugs, Drugs and You: Infectious Disease Essentials for the Hospitalist” and “What Keeps You Awake at Night? Hot Topics in Hospitalist Practice Management.” Pre-course mainstays scheduled again this year include “ABIM Maintenance Certification,” “Medical Procedures for the Hospitalist,” and “Portable Ultrasounds for the Hospitalist.”

“As the society has gotten bigger, the meeting has gotten bigger in terms of its scope,” says Dr. Brotman, whose day job is director of the hospitalist program at Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore. “So we have Friday, Saturday, and Sunday, plus the evening activities, plus the pre-courses. One of the adjustments that we’ve made over time is that we do recognize that with a larger constituency and a larger amount of topical information that we’d like to cover, the meeting does get longer. The hope is that people can commit close to a week toward advancing their knowledge; it’s well worth the time.”

Richard Quinn is a freelance writer in New Jersey.

Ask Dan Brotman, MD, FACP, SFHM, how to get the most out of the annual meeting of hospitalists and you’ll get a simple, one-word answer: Go.

“It sounds so trivial,” says Dr. Brotman, HM13 course director. “But there are a lot more hospitalists out there than we see at the meeting, and I think that [we should be] getting out the word that this is the best single opportunity that hospitalists have to network and learn about their field, not only content knowledge but also understanding where the field is going from thought leaders.”

The annual pilgrimage of hospitalists is expected to be larger than ever this year, with SHM expecting nearly 3,000 hospitalists to attend. Last year, roughly 2,700 hospitalists attended in San Diego.

But navigating a four-day maze of pre-courses, plenaries, and presentations can overwhelm even the most experienced attendee, much less a first-timer. And that’s before the annual rite that is the Research, Innovation, and Clinical Vignettes (RIV) poster competition and the Hospitalists on the Hill event that is particularly fitting this year as Capitol Hill happens to be just a few miles away.

So what’s the best advice to have the best meeting experience? Planning, planning, and a little more planning.

Ken Simone, DO, SFHM, principal of Hospitalist and Practice Solutions in Veazie, Maine, says the plethora of workshops, keynote speakers, and formalized educational offerings means attendees should “game plan” their schedule as much as possible.

“It behooves everyone to really study the offerings each day and each hour and plan their schedule accordingly,” says Dr. Simone, a Team Hospitalist member. “I typically create my schedule before I leave home for the conference.”

But don’t plan too much, he adds. Having a list of sessions to attend is important, but part of the meeting’s allure is the ability to mingle with clinical, administrative, and society leaders from around the country.

“Flexibility is the key,” he says. “Having something well planned doesn’t mean you can’t be flexible.”

Check out our 6-minute feature video: "Five Reasons You Should Attend HM13"

Dr. Brotman says meeting organizers take the same approach. While some topics are old favorites, SHM adds new offerings each year to adapt in real time to important trends. For example, he says, a new track this year focused on comanagement will appeal to hospitalists and subspecialists who take care of stroke patients, surgical patients, and pregnant women, among others.

The new track is in addition to the existing offerings: clinical, academic/research, rapid fire, pediatric, practice management, quality, and potpourri. The last item is in its second year and offers a break from the didactic and lecture approaches taken in nearly all of the annual meeting’s other breakout sessions. A particularly popular event is expected to be “History of Hospitals,” presented by hospitalist historian Jordan Messler, MD, SFHM.

There are two new pre-courses this year: “Bugs, Drugs and You: Infectious Disease Essentials for the Hospitalist” and “What Keeps You Awake at Night? Hot Topics in Hospitalist Practice Management.” Pre-course mainstays scheduled again this year include “ABIM Maintenance Certification,” “Medical Procedures for the Hospitalist,” and “Portable Ultrasounds for the Hospitalist.”

“As the society has gotten bigger, the meeting has gotten bigger in terms of its scope,” says Dr. Brotman, whose day job is director of the hospitalist program at Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore. “So we have Friday, Saturday, and Sunday, plus the evening activities, plus the pre-courses. One of the adjustments that we’ve made over time is that we do recognize that with a larger constituency and a larger amount of topical information that we’d like to cover, the meeting does get longer. The hope is that people can commit close to a week toward advancing their knowledge; it’s well worth the time.”

Richard Quinn is a freelance writer in New Jersey.

Hospitalists Gear Up to Lobby Congress on Health Care Policy

Mangla Gulati, MD, FACP, FHM, an academic hospitalist and medical director of clinical effectiveness at University of Maryland Medical Center in Baltimore, had never been involved in a lobbying trip before the waning days of last year. But then, just as members of Congress were wrestling with potential Draconian cuts to Medicare reimbursements and a $10 million slash in Medicare funding for the National Quality Forum (NQF), Dr. Gulati found herself on a daylong trip with SHM government guru Laura Allendorf and an NQF representative to make a series of in-person appeals to politicians in Washington, D.C. “When you’re a practicing physician, even though you know there’s regulation and compliance and mandates, you really don’t understand how they come to fruition and what the thought process is,” says Dr. Gulati, secretary of SHM’s Maryland chapter. “It was really interesting to see the other side of that and how people up on the Hill make a lot of decisions based on the information that’s given to them.”

The Hill she’s referring to is none other than Capitol Hill, and Dr. Gulati is making a return just a few months after her visit. And this time, she’s bringing a few hundred hospitalists with her. Hospitalists on the Hill 2013 (www.hospitalmedicine 2013.org/advocacy) is the annual trek made by SHM leadership and rank-and-file members to lobby legislators and federal staffers “on the way policies affect your practice and your patients,” SHM says on its website. This year, the showing in Washington is expected to be among the best ever, as the lobbying trip is May 16, just before HM13’s full program kicks off at the Gaylord National Resort & Convention Center in National Harbor, Md.

The all-day affair kicks off in the morning, as participants will receive briefings from SHM Public Policy Committee Chair Ron Greeno, MD, FCCP, MHM, and Allendorf, SHM’s senior advisor for advocacy and government affairs. Then comes a two-hour training course from Advocacy Associates (http://advocacyassociates.com), a boutique communications firm that helps organizations, such as SHM, tailor their message to policymakers. After that, it’s a six-hour whirlwind of meetings with home-state legislators, career administrators, and aide-de-camps that one former participant described as “almost like speed-dial dating with congressmen and -women.” Lastly, participants regroup at day’s end for a debriefing.

“I think what’s different at SHM is we go to Washington with an agenda of how we can improve patient safety and quality outcomes,” says Patrick Torcson, MD, MMM, FACP, SFHM, chair of SHM’s Performance Measurement and Reporting Committee. “We’re not there about just protecting our turf and making sure that our reimbursement stays at a reasonable level. We’ve been very clear to offer innovations about care transitions and Project BOOST, and different things that can be done to improve things like quality and service for Medicare beneficiaries.”

Check out our 6-minute feature video: "Five Reasons You Should Attend HM13"

Dr. Torcson says congressional contacts he’s made in past years “always look forward to our visits, because we really do come with an attitude of how can we help fix a broken system.”

He counts several victories as fruit of the annual trip. First, he believes the trip has “clearly educated our politicians, congressional staffers, and CMS [the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services] that the predominant model of the way patients are taken care of in the hospital is by a hospitalist.”

Second, and more granularly, SHM really gets into the weeds. Take CMS’ Quality and Resource Use Report (QRUR), which is part of the rollout of its value-based purchasing modifier (VBPM). Dr. Torcson says SHM carefully reviewed the report to register its concerns about proper attribution, fair comparisons, relevant metrics, and other issues. In turn, CMS signaled its appreciation of SHM’s due diligence and has indicated a willingness to work with SHM to address its concerns.

CMS chief medical officer Patrick Conway, MD, MSc, FAAP, SFHM, sees it from both sides of the equation. A pediatric hospitalist by training, he has been on trips to push federal officials to promulgate rules that make the most sense for HM. But in his current job, he’s often the one being pushed—and he welcomes the visits.

“We’re trying to partner up with physicians,” he says.

Dr. Conway believes lobbying trips like SHM’s are critical to informing both politicians and professionals on what physicians need or want most.

“People often think, ‘How could it matter?’ Sure, some of it will be hits and misses. But you’ll hit some key points that resonate,” he says.

Hospitalist Rick Hilger, MD, SFHM, director of resident education and adjunct associate professor of medicine at the University of Minnesota Medical School in Minneapolis, learned that lesson last year during his first Hospitalists on the Hill. A first-time member of SHM’s Public Policy Committee, he met with the legislative assistants for U.S. Sens.

Al Franken (D-Minn.) and Amy Klobuchar (D-Minn.), as well as had a face-to-face meeting with U.S. Rep. Allyson Schwartz (D-Pa.). The latter has been a staunch advocate of Medicare payment reform, sponsoring several bills—with SHM’s support—to repeal the sustainable growth rate (SGR) formula.

“It’s an investment in time, and especially for the senators and congressmen and -women from your own state, it’s more about trying to develop a relationship,” Dr. Hilger says. “I’ve already exchanged emails with the aides that I met that day concerning other healthcare issues. … I’m not sure I can completely answer for the long-term impact, but it definitely feels better than doing nothing.”

Richard Quinn is a freelance writer in New Jersey.

Mangla Gulati, MD, FACP, FHM, an academic hospitalist and medical director of clinical effectiveness at University of Maryland Medical Center in Baltimore, had never been involved in a lobbying trip before the waning days of last year. But then, just as members of Congress were wrestling with potential Draconian cuts to Medicare reimbursements and a $10 million slash in Medicare funding for the National Quality Forum (NQF), Dr. Gulati found herself on a daylong trip with SHM government guru Laura Allendorf and an NQF representative to make a series of in-person appeals to politicians in Washington, D.C. “When you’re a practicing physician, even though you know there’s regulation and compliance and mandates, you really don’t understand how they come to fruition and what the thought process is,” says Dr. Gulati, secretary of SHM’s Maryland chapter. “It was really interesting to see the other side of that and how people up on the Hill make a lot of decisions based on the information that’s given to them.”

The Hill she’s referring to is none other than Capitol Hill, and Dr. Gulati is making a return just a few months after her visit. And this time, she’s bringing a few hundred hospitalists with her. Hospitalists on the Hill 2013 (www.hospitalmedicine 2013.org/advocacy) is the annual trek made by SHM leadership and rank-and-file members to lobby legislators and federal staffers “on the way policies affect your practice and your patients,” SHM says on its website. This year, the showing in Washington is expected to be among the best ever, as the lobbying trip is May 16, just before HM13’s full program kicks off at the Gaylord National Resort & Convention Center in National Harbor, Md.

The all-day affair kicks off in the morning, as participants will receive briefings from SHM Public Policy Committee Chair Ron Greeno, MD, FCCP, MHM, and Allendorf, SHM’s senior advisor for advocacy and government affairs. Then comes a two-hour training course from Advocacy Associates (http://advocacyassociates.com), a boutique communications firm that helps organizations, such as SHM, tailor their message to policymakers. After that, it’s a six-hour whirlwind of meetings with home-state legislators, career administrators, and aide-de-camps that one former participant described as “almost like speed-dial dating with congressmen and -women.” Lastly, participants regroup at day’s end for a debriefing.

“I think what’s different at SHM is we go to Washington with an agenda of how we can improve patient safety and quality outcomes,” says Patrick Torcson, MD, MMM, FACP, SFHM, chair of SHM’s Performance Measurement and Reporting Committee. “We’re not there about just protecting our turf and making sure that our reimbursement stays at a reasonable level. We’ve been very clear to offer innovations about care transitions and Project BOOST, and different things that can be done to improve things like quality and service for Medicare beneficiaries.”

Check out our 6-minute feature video: "Five Reasons You Should Attend HM13"

Dr. Torcson says congressional contacts he’s made in past years “always look forward to our visits, because we really do come with an attitude of how can we help fix a broken system.”

He counts several victories as fruit of the annual trip. First, he believes the trip has “clearly educated our politicians, congressional staffers, and CMS [the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services] that the predominant model of the way patients are taken care of in the hospital is by a hospitalist.”

Second, and more granularly, SHM really gets into the weeds. Take CMS’ Quality and Resource Use Report (QRUR), which is part of the rollout of its value-based purchasing modifier (VBPM). Dr. Torcson says SHM carefully reviewed the report to register its concerns about proper attribution, fair comparisons, relevant metrics, and other issues. In turn, CMS signaled its appreciation of SHM’s due diligence and has indicated a willingness to work with SHM to address its concerns.

CMS chief medical officer Patrick Conway, MD, MSc, FAAP, SFHM, sees it from both sides of the equation. A pediatric hospitalist by training, he has been on trips to push federal officials to promulgate rules that make the most sense for HM. But in his current job, he’s often the one being pushed—and he welcomes the visits.

“We’re trying to partner up with physicians,” he says.

Dr. Conway believes lobbying trips like SHM’s are critical to informing both politicians and professionals on what physicians need or want most.

“People often think, ‘How could it matter?’ Sure, some of it will be hits and misses. But you’ll hit some key points that resonate,” he says.

Hospitalist Rick Hilger, MD, SFHM, director of resident education and adjunct associate professor of medicine at the University of Minnesota Medical School in Minneapolis, learned that lesson last year during his first Hospitalists on the Hill. A first-time member of SHM’s Public Policy Committee, he met with the legislative assistants for U.S. Sens.

Al Franken (D-Minn.) and Amy Klobuchar (D-Minn.), as well as had a face-to-face meeting with U.S. Rep. Allyson Schwartz (D-Pa.). The latter has been a staunch advocate of Medicare payment reform, sponsoring several bills—with SHM’s support—to repeal the sustainable growth rate (SGR) formula.

“It’s an investment in time, and especially for the senators and congressmen and -women from your own state, it’s more about trying to develop a relationship,” Dr. Hilger says. “I’ve already exchanged emails with the aides that I met that day concerning other healthcare issues. … I’m not sure I can completely answer for the long-term impact, but it definitely feels better than doing nothing.”

Richard Quinn is a freelance writer in New Jersey.

Mangla Gulati, MD, FACP, FHM, an academic hospitalist and medical director of clinical effectiveness at University of Maryland Medical Center in Baltimore, had never been involved in a lobbying trip before the waning days of last year. But then, just as members of Congress were wrestling with potential Draconian cuts to Medicare reimbursements and a $10 million slash in Medicare funding for the National Quality Forum (NQF), Dr. Gulati found herself on a daylong trip with SHM government guru Laura Allendorf and an NQF representative to make a series of in-person appeals to politicians in Washington, D.C. “When you’re a practicing physician, even though you know there’s regulation and compliance and mandates, you really don’t understand how they come to fruition and what the thought process is,” says Dr. Gulati, secretary of SHM’s Maryland chapter. “It was really interesting to see the other side of that and how people up on the Hill make a lot of decisions based on the information that’s given to them.”

The Hill she’s referring to is none other than Capitol Hill, and Dr. Gulati is making a return just a few months after her visit. And this time, she’s bringing a few hundred hospitalists with her. Hospitalists on the Hill 2013 (www.hospitalmedicine 2013.org/advocacy) is the annual trek made by SHM leadership and rank-and-file members to lobby legislators and federal staffers “on the way policies affect your practice and your patients,” SHM says on its website. This year, the showing in Washington is expected to be among the best ever, as the lobbying trip is May 16, just before HM13’s full program kicks off at the Gaylord National Resort & Convention Center in National Harbor, Md.

The all-day affair kicks off in the morning, as participants will receive briefings from SHM Public Policy Committee Chair Ron Greeno, MD, FCCP, MHM, and Allendorf, SHM’s senior advisor for advocacy and government affairs. Then comes a two-hour training course from Advocacy Associates (http://advocacyassociates.com), a boutique communications firm that helps organizations, such as SHM, tailor their message to policymakers. After that, it’s a six-hour whirlwind of meetings with home-state legislators, career administrators, and aide-de-camps that one former participant described as “almost like speed-dial dating with congressmen and -women.” Lastly, participants regroup at day’s end for a debriefing.

“I think what’s different at SHM is we go to Washington with an agenda of how we can improve patient safety and quality outcomes,” says Patrick Torcson, MD, MMM, FACP, SFHM, chair of SHM’s Performance Measurement and Reporting Committee. “We’re not there about just protecting our turf and making sure that our reimbursement stays at a reasonable level. We’ve been very clear to offer innovations about care transitions and Project BOOST, and different things that can be done to improve things like quality and service for Medicare beneficiaries.”

Check out our 6-minute feature video: "Five Reasons You Should Attend HM13"

Dr. Torcson says congressional contacts he’s made in past years “always look forward to our visits, because we really do come with an attitude of how can we help fix a broken system.”

He counts several victories as fruit of the annual trip. First, he believes the trip has “clearly educated our politicians, congressional staffers, and CMS [the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services] that the predominant model of the way patients are taken care of in the hospital is by a hospitalist.”

Second, and more granularly, SHM really gets into the weeds. Take CMS’ Quality and Resource Use Report (QRUR), which is part of the rollout of its value-based purchasing modifier (VBPM). Dr. Torcson says SHM carefully reviewed the report to register its concerns about proper attribution, fair comparisons, relevant metrics, and other issues. In turn, CMS signaled its appreciation of SHM’s due diligence and has indicated a willingness to work with SHM to address its concerns.

CMS chief medical officer Patrick Conway, MD, MSc, FAAP, SFHM, sees it from both sides of the equation. A pediatric hospitalist by training, he has been on trips to push federal officials to promulgate rules that make the most sense for HM. But in his current job, he’s often the one being pushed—and he welcomes the visits.

“We’re trying to partner up with physicians,” he says.

Dr. Conway believes lobbying trips like SHM’s are critical to informing both politicians and professionals on what physicians need or want most.

“People often think, ‘How could it matter?’ Sure, some of it will be hits and misses. But you’ll hit some key points that resonate,” he says.

Hospitalist Rick Hilger, MD, SFHM, director of resident education and adjunct associate professor of medicine at the University of Minnesota Medical School in Minneapolis, learned that lesson last year during his first Hospitalists on the Hill. A first-time member of SHM’s Public Policy Committee, he met with the legislative assistants for U.S. Sens.

Al Franken (D-Minn.) and Amy Klobuchar (D-Minn.), as well as had a face-to-face meeting with U.S. Rep. Allyson Schwartz (D-Pa.). The latter has been a staunch advocate of Medicare payment reform, sponsoring several bills—with SHM’s support—to repeal the sustainable growth rate (SGR) formula.

“It’s an investment in time, and especially for the senators and congressmen and -women from your own state, it’s more about trying to develop a relationship,” Dr. Hilger says. “I’ve already exchanged emails with the aides that I met that day concerning other healthcare issues. … I’m not sure I can completely answer for the long-term impact, but it definitely feels better than doing nothing.”

Richard Quinn is a freelance writer in New Jersey.

Continuing Medical Education (CME) Courses for Hospitalists Thrive Online

Hospitalist Lenny Feldman, MD, FACP, FAAP, SFHM, of John Hopkins School of Medicine in Baltimore, is the proverbial study in contrasts. He is the longtime editor of SHM’s Consultative & Perioperative Medicine Essentials for Hospitalists, a free continuing medical education (CME) repository more commonly known as SHMConsults (www.shmconsults.com). But in February, he helped lead “Updates in Hospital Medicine 2013: Evidence-Based Reviews on the Management of Hospitalized Patients.” That program, arranged by Canadian education provider CMEatSea (www.cmeatsea.org) and held aboard a cruise ship in the eastern Caribbean, attracted some 60 hospitalists, nurse practitioners, and physician assistants interested in earning up to 14 credits.

On the one hand, Dr. Feldman is a pioneer of free virtual CME. On the other, he is an example of the big-ticket CME events that were much more commonplace five or 10 years ago.

“It’s tough,” Dr. Feldman says. “There’s no doubt that once you’ve built that virtual infrastructure, it allows many more people access to CME than if they have to come together. But with that said, particularly at a meeting like HM13, there’s so much more to it than just the CME. The networking is a huge part of that.”

This is the current state of CME, in which ever-tightening physician budgets plus a massive pullback of pharmaceutical industry support equals a landscape of fewer and fewer big-ticket events and more and more online offerings. The expense of large-scale offerings means that many physicians look for more than just the credits available when deciding which events to attend.

For many hospitalists, of course, SHM’s annual meeting remains the best opportunity of the year for CME. Accordingly, those credits are often cited as one of the biggest lures for many of the nearly 3,000 hospitalists who are expected to convene May 16-19 at the Gaylord National Resort & Convention Center in National Harbor, Md.

“You can always get CME credits locally by attending lectures at your own institution, but so often the content of these lectures is really not something that has been vetted and put forward by hospitalists,” says HM13 course director Daniel Brotman, MD, FACP, SFHM. “I think the people who attend this meeting know where the field is going, not only because of the content that’s offered, but because of who else is there. That’s different than going to an hourlong lecture by a cardiologist at your institution on atrial fibrillation.”

—Lenny Feldman, MD, FACP, FAAP, SFHM, John Hopkins School of Medicine, Baltimore

Pharma Pullback

CME budgets typically run $3,000 to $3,500 per physician, but can range from as low as $2,000 to as high as $5,000 annually, according to rough estimates from industry leaders. Opinions are mixed on whether those budgets have been significantly reduced over the past few years, but “they’re certainly not going up,” Dr. Feldman says.

What is falling year after year is the amount of money that the pharmaceutical industry is providing to support CME, says Daniel Guinee, executive vice president of educational firm ASiM of Somerville, N.J. The drug industry funded $1.2 billion of CME in 2007, according to the Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education (ACCME). That number dropped to $736 million in 2011, the latest year for which ACCME has statistics. Guinee says many expect the total for 2012 to be approximately $600 million, then level off.

Some applaud the drop-off in industry funding as a needed correction to ensure any potential bias is eliminated. To that end, the American Medical Association’s (AMA) Council on Ethical and Judicial Affairs in 2011 adopted a policy urging the avoidance of industry funding of CME when possible. But just 42% of physicians in one study said they were willing to pay higher fees to eliminate that funding source (Arch Intern Med. 2011;171(9):840-846).

Guinee attributes much of the drug industry’s pullback in funding to companies’ uncertainty over transparency and reporting required by ACCME, the FDA, and the U.S. Department of Health & Human Services (HHS).

“The companies want to use their money as they want to,” Guinee says. “Instead of putting the money out there … as way to support medical education, they’re saying, ‘You know what? We’ll just hang on to it and spend it in other ways.’”

Check out our 6-minute feature video: "Five Reasons You Should Attend HM13"

Dr. Feldman, whose SHMConsults project has been supported by the pharmaceutical industry for seven years, says it’s unclear where future funding will come from in order to support CME. But ACCME president and chief executive officer Murray Kopelow, MD, says that while commercial support—the industry term for pharmaceutical funding—has steadily fallen, “other income” rose 221% from 2006 to 2011 for ACCME-accredited providers and ACCME–recognized, state-accredited providers. ACCME says that income can include activity registration fees, government or nonprofit foundation grants, and allocations from accredited providers’ parent organizations.

“The balance of revenue has shifted,” Dr. Kopelow says.

Education When You Need It

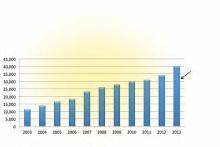

Also shifting is the nature of CME delivery. Since 2007, the number of live Internet CME activities has risen 33%, while the number of journal CME activities has risen 13%, according to ACCME figures. The number of courses in which participants physically attend is virtually static.

SHM has embraced the virtual concept and is looking to add as many online learning opportunities as feasible, says Catharine Smith, SHM’s senior director for education. That includes updates to SHMConsults and the Hospital Quality and Patient Safety Online Academy (www.hospitalmedicine.org/hqps), as well as future offerings based on core competencies. Virtual CME allows hospitalists to meet CME requirements when it is convenient for them and allows providers to set up both live events and enduring materials, Smith says.

“More online CME opportunities from SHM’s Learning Portal is about bringing quality content to hospitalists,” Smith said in a statement. “This reflects SHM’s understanding of the professional needs of hospitalists.”

She added that measuring outcomes can be easier online, as data recording in that manner is easier than during a big meeting. Then again, it’s also difficult to gauge just how well a learned lesson is then incorporated into practice.

For all its advantages, online CME shouldn’t replace all face-to-face learning, Dr. Kopelow says.

“Physicians consult colleagues and reflect on what they have learned before integrating the new information into their practice for the benefit of patients,” he adds. “It is this process that accredited CME promotes and supports. Online CME supports this process, but it does not replace the total process of continuing professional development.”

Dr. Feldman says physicians will have to decide for themselves what works for them, particularly if reduced CME spending by the drug industry continues to crimp offerings.

“There’s going to be a huge sea change there in terms of folks needing to decide where they’re going to want to spend their CME money,” he adds. “Are they going to choose some of these easier-to-use, online CME offerings if they think that going to meetings is becoming prohibitively expensive? Only time is going to tell.”

Hospitalist Lenny Feldman, MD, FACP, FAAP, SFHM, of John Hopkins School of Medicine in Baltimore, is the proverbial study in contrasts. He is the longtime editor of SHM’s Consultative & Perioperative Medicine Essentials for Hospitalists, a free continuing medical education (CME) repository more commonly known as SHMConsults (www.shmconsults.com). But in February, he helped lead “Updates in Hospital Medicine 2013: Evidence-Based Reviews on the Management of Hospitalized Patients.” That program, arranged by Canadian education provider CMEatSea (www.cmeatsea.org) and held aboard a cruise ship in the eastern Caribbean, attracted some 60 hospitalists, nurse practitioners, and physician assistants interested in earning up to 14 credits.

On the one hand, Dr. Feldman is a pioneer of free virtual CME. On the other, he is an example of the big-ticket CME events that were much more commonplace five or 10 years ago.

“It’s tough,” Dr. Feldman says. “There’s no doubt that once you’ve built that virtual infrastructure, it allows many more people access to CME than if they have to come together. But with that said, particularly at a meeting like HM13, there’s so much more to it than just the CME. The networking is a huge part of that.”

This is the current state of CME, in which ever-tightening physician budgets plus a massive pullback of pharmaceutical industry support equals a landscape of fewer and fewer big-ticket events and more and more online offerings. The expense of large-scale offerings means that many physicians look for more than just the credits available when deciding which events to attend.

For many hospitalists, of course, SHM’s annual meeting remains the best opportunity of the year for CME. Accordingly, those credits are often cited as one of the biggest lures for many of the nearly 3,000 hospitalists who are expected to convene May 16-19 at the Gaylord National Resort & Convention Center in National Harbor, Md.

“You can always get CME credits locally by attending lectures at your own institution, but so often the content of these lectures is really not something that has been vetted and put forward by hospitalists,” says HM13 course director Daniel Brotman, MD, FACP, SFHM. “I think the people who attend this meeting know where the field is going, not only because of the content that’s offered, but because of who else is there. That’s different than going to an hourlong lecture by a cardiologist at your institution on atrial fibrillation.”

—Lenny Feldman, MD, FACP, FAAP, SFHM, John Hopkins School of Medicine, Baltimore

Pharma Pullback

CME budgets typically run $3,000 to $3,500 per physician, but can range from as low as $2,000 to as high as $5,000 annually, according to rough estimates from industry leaders. Opinions are mixed on whether those budgets have been significantly reduced over the past few years, but “they’re certainly not going up,” Dr. Feldman says.

What is falling year after year is the amount of money that the pharmaceutical industry is providing to support CME, says Daniel Guinee, executive vice president of educational firm ASiM of Somerville, N.J. The drug industry funded $1.2 billion of CME in 2007, according to the Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education (ACCME). That number dropped to $736 million in 2011, the latest year for which ACCME has statistics. Guinee says many expect the total for 2012 to be approximately $600 million, then level off.

Some applaud the drop-off in industry funding as a needed correction to ensure any potential bias is eliminated. To that end, the American Medical Association’s (AMA) Council on Ethical and Judicial Affairs in 2011 adopted a policy urging the avoidance of industry funding of CME when possible. But just 42% of physicians in one study said they were willing to pay higher fees to eliminate that funding source (Arch Intern Med. 2011;171(9):840-846).

Guinee attributes much of the drug industry’s pullback in funding to companies’ uncertainty over transparency and reporting required by ACCME, the FDA, and the U.S. Department of Health & Human Services (HHS).

“The companies want to use their money as they want to,” Guinee says. “Instead of putting the money out there … as way to support medical education, they’re saying, ‘You know what? We’ll just hang on to it and spend it in other ways.’”

Check out our 6-minute feature video: "Five Reasons You Should Attend HM13"

Dr. Feldman, whose SHMConsults project has been supported by the pharmaceutical industry for seven years, says it’s unclear where future funding will come from in order to support CME. But ACCME president and chief executive officer Murray Kopelow, MD, says that while commercial support—the industry term for pharmaceutical funding—has steadily fallen, “other income” rose 221% from 2006 to 2011 for ACCME-accredited providers and ACCME–recognized, state-accredited providers. ACCME says that income can include activity registration fees, government or nonprofit foundation grants, and allocations from accredited providers’ parent organizations.

“The balance of revenue has shifted,” Dr. Kopelow says.

Education When You Need It

Also shifting is the nature of CME delivery. Since 2007, the number of live Internet CME activities has risen 33%, while the number of journal CME activities has risen 13%, according to ACCME figures. The number of courses in which participants physically attend is virtually static.

SHM has embraced the virtual concept and is looking to add as many online learning opportunities as feasible, says Catharine Smith, SHM’s senior director for education. That includes updates to SHMConsults and the Hospital Quality and Patient Safety Online Academy (www.hospitalmedicine.org/hqps), as well as future offerings based on core competencies. Virtual CME allows hospitalists to meet CME requirements when it is convenient for them and allows providers to set up both live events and enduring materials, Smith says.

“More online CME opportunities from SHM’s Learning Portal is about bringing quality content to hospitalists,” Smith said in a statement. “This reflects SHM’s understanding of the professional needs of hospitalists.”

She added that measuring outcomes can be easier online, as data recording in that manner is easier than during a big meeting. Then again, it’s also difficult to gauge just how well a learned lesson is then incorporated into practice.

For all its advantages, online CME shouldn’t replace all face-to-face learning, Dr. Kopelow says.

“Physicians consult colleagues and reflect on what they have learned before integrating the new information into their practice for the benefit of patients,” he adds. “It is this process that accredited CME promotes and supports. Online CME supports this process, but it does not replace the total process of continuing professional development.”

Dr. Feldman says physicians will have to decide for themselves what works for them, particularly if reduced CME spending by the drug industry continues to crimp offerings.

“There’s going to be a huge sea change there in terms of folks needing to decide where they’re going to want to spend their CME money,” he adds. “Are they going to choose some of these easier-to-use, online CME offerings if they think that going to meetings is becoming prohibitively expensive? Only time is going to tell.”

Hospitalist Lenny Feldman, MD, FACP, FAAP, SFHM, of John Hopkins School of Medicine in Baltimore, is the proverbial study in contrasts. He is the longtime editor of SHM’s Consultative & Perioperative Medicine Essentials for Hospitalists, a free continuing medical education (CME) repository more commonly known as SHMConsults (www.shmconsults.com). But in February, he helped lead “Updates in Hospital Medicine 2013: Evidence-Based Reviews on the Management of Hospitalized Patients.” That program, arranged by Canadian education provider CMEatSea (www.cmeatsea.org) and held aboard a cruise ship in the eastern Caribbean, attracted some 60 hospitalists, nurse practitioners, and physician assistants interested in earning up to 14 credits.

On the one hand, Dr. Feldman is a pioneer of free virtual CME. On the other, he is an example of the big-ticket CME events that were much more commonplace five or 10 years ago.

“It’s tough,” Dr. Feldman says. “There’s no doubt that once you’ve built that virtual infrastructure, it allows many more people access to CME than if they have to come together. But with that said, particularly at a meeting like HM13, there’s so much more to it than just the CME. The networking is a huge part of that.”

This is the current state of CME, in which ever-tightening physician budgets plus a massive pullback of pharmaceutical industry support equals a landscape of fewer and fewer big-ticket events and more and more online offerings. The expense of large-scale offerings means that many physicians look for more than just the credits available when deciding which events to attend.

For many hospitalists, of course, SHM’s annual meeting remains the best opportunity of the year for CME. Accordingly, those credits are often cited as one of the biggest lures for many of the nearly 3,000 hospitalists who are expected to convene May 16-19 at the Gaylord National Resort & Convention Center in National Harbor, Md.

“You can always get CME credits locally by attending lectures at your own institution, but so often the content of these lectures is really not something that has been vetted and put forward by hospitalists,” says HM13 course director Daniel Brotman, MD, FACP, SFHM. “I think the people who attend this meeting know where the field is going, not only because of the content that’s offered, but because of who else is there. That’s different than going to an hourlong lecture by a cardiologist at your institution on atrial fibrillation.”

—Lenny Feldman, MD, FACP, FAAP, SFHM, John Hopkins School of Medicine, Baltimore

Pharma Pullback

CME budgets typically run $3,000 to $3,500 per physician, but can range from as low as $2,000 to as high as $5,000 annually, according to rough estimates from industry leaders. Opinions are mixed on whether those budgets have been significantly reduced over the past few years, but “they’re certainly not going up,” Dr. Feldman says.

What is falling year after year is the amount of money that the pharmaceutical industry is providing to support CME, says Daniel Guinee, executive vice president of educational firm ASiM of Somerville, N.J. The drug industry funded $1.2 billion of CME in 2007, according to the Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education (ACCME). That number dropped to $736 million in 2011, the latest year for which ACCME has statistics. Guinee says many expect the total for 2012 to be approximately $600 million, then level off.

Some applaud the drop-off in industry funding as a needed correction to ensure any potential bias is eliminated. To that end, the American Medical Association’s (AMA) Council on Ethical and Judicial Affairs in 2011 adopted a policy urging the avoidance of industry funding of CME when possible. But just 42% of physicians in one study said they were willing to pay higher fees to eliminate that funding source (Arch Intern Med. 2011;171(9):840-846).

Guinee attributes much of the drug industry’s pullback in funding to companies’ uncertainty over transparency and reporting required by ACCME, the FDA, and the U.S. Department of Health & Human Services (HHS).

“The companies want to use their money as they want to,” Guinee says. “Instead of putting the money out there … as way to support medical education, they’re saying, ‘You know what? We’ll just hang on to it and spend it in other ways.’”

Check out our 6-minute feature video: "Five Reasons You Should Attend HM13"

Dr. Feldman, whose SHMConsults project has been supported by the pharmaceutical industry for seven years, says it’s unclear where future funding will come from in order to support CME. But ACCME president and chief executive officer Murray Kopelow, MD, says that while commercial support—the industry term for pharmaceutical funding—has steadily fallen, “other income” rose 221% from 2006 to 2011 for ACCME-accredited providers and ACCME–recognized, state-accredited providers. ACCME says that income can include activity registration fees, government or nonprofit foundation grants, and allocations from accredited providers’ parent organizations.

“The balance of revenue has shifted,” Dr. Kopelow says.

Education When You Need It

Also shifting is the nature of CME delivery. Since 2007, the number of live Internet CME activities has risen 33%, while the number of journal CME activities has risen 13%, according to ACCME figures. The number of courses in which participants physically attend is virtually static.

SHM has embraced the virtual concept and is looking to add as many online learning opportunities as feasible, says Catharine Smith, SHM’s senior director for education. That includes updates to SHMConsults and the Hospital Quality and Patient Safety Online Academy (www.hospitalmedicine.org/hqps), as well as future offerings based on core competencies. Virtual CME allows hospitalists to meet CME requirements when it is convenient for them and allows providers to set up both live events and enduring materials, Smith says.

“More online CME opportunities from SHM’s Learning Portal is about bringing quality content to hospitalists,” Smith said in a statement. “This reflects SHM’s understanding of the professional needs of hospitalists.”

She added that measuring outcomes can be easier online, as data recording in that manner is easier than during a big meeting. Then again, it’s also difficult to gauge just how well a learned lesson is then incorporated into practice.

For all its advantages, online CME shouldn’t replace all face-to-face learning, Dr. Kopelow says.

“Physicians consult colleagues and reflect on what they have learned before integrating the new information into their practice for the benefit of patients,” he adds. “It is this process that accredited CME promotes and supports. Online CME supports this process, but it does not replace the total process of continuing professional development.”

Dr. Feldman says physicians will have to decide for themselves what works for them, particularly if reduced CME spending by the drug industry continues to crimp offerings.

“There’s going to be a huge sea change there in terms of folks needing to decide where they’re going to want to spend their CME money,” he adds. “Are they going to choose some of these easier-to-use, online CME offerings if they think that going to meetings is becoming prohibitively expensive? Only time is going to tell.”

Team Hospitalist Recommends Nine Don’t-Miss Sessions at HM13

Eight educational tracks, an equal number of credit bearing pre-courses, a score of small-group forums, three plenaries, and an SHM Town Hall meeting offers a lot of professional development in a four-day span. But that’s just a sampling of what HM13 has slated May 16-19 at the Gaylord National Resort & Convention Center in National Harbor, Md., just outside Washington, D.C.

So how does one get the most value out of the conference?

“The highest-yield content is going to depend on what your background is and how to spend that time in a way that augments your knowledge, your perspective, or your exposure to like-minded colleagues in a very individual way,” says HM13 course director Daniel Brotman, MD, FACP, SFHM, director of the hospitalist program at Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore. “One of the things that’s so cool about hospital medicine is its diversity.”

But don’t take Dr. Brotman’s well-educated word for it. Here’s a list of recommendations from Team Hospitalist, the only reader-involvement group of its kind in HM, on events they would not miss this year.

The New Anticoagulants: When Should We Be Using Them?

2:45 p.m., May 17

Dr. Ma: “I’m very interested about the new anticoagulants talk. What I’m curious to see is what the speaker thinks about the survivability of these medications in our society, with so many lawyers. Pradaxa already has fallen out of favor. Let’s see what happens to Xarelto.”

How do CFOs Value Their Hospitalist Programs?

2:50 p.m., May 18

Dr. Ma: “The problem today is CFOs have to valuate their hospitalists in the setting of other specialists who also receive subsidies. There is less money to be spent on hospitalists, as other specialists vie for this allotment of savings from hospital-based value purchasing.”

Check out our 6-minute feature video: "Five Reasons You Should Attend HM13"

Mentoring/Coaching an Improvement Team: Lessons from SHM’s Mentored Implementation Programs

2:45 p.m., May 17

Dr. Perumalswami: “As a Project BOOST physician mentor in Illinois, I would highly recommend the session because the discussion will involve an inside look into valuable experience-based observations and analysis for the success of any process improvement team. The nature of teams and the culture of improvement at various sites will also be discussed. There will be a mentee side of the presentation, too, which will help other mentors of implementation programs better understand what the issues are ‘from the other side.’”

Strategies to Improve Communication with Patients and Families to Improve Care

2:45 p.m., May 17

Dr. Hale: “It is well known in pediatrics that you are treating two patients: both the child and the parents. If the family has a shared understanding of the child’s illness and there is collaboration for the care plan, there will be improved care.”

Neonatal HSV: When to Consider It, How to Evaluate for It, and How to Treat It

11 a.m., May 18

Dr. Hale: “Neonatal HSV is a devastating disease. It is essential to recognize high-risk patients to decrease morbidity and mortality for this illness. There have been recent updates in the understanding of epidemiology of this disease that can assist the provider in recognizing high-risk patients.”

Supporting Transition for Youth with Special Healthcare Needs: Coordinating Care and Preparing to Pass the Baton

4:15 p.m., May 18

Dr. Hale: “The transition of adolescents and young adults from pediatric-care teams to adult-medicine-care teams should be seamless for the sake of the patient, but often it is a blurry transition over the course of years. This session is high-yield for both pediatric and adult hospitalists.”

Getting Ready for Physician Value-Based Purchasing

9:50 a.m., May 19