User login

New Onset of in Hospitalized Patients

A 78‐year‐old otherwise healthy man with longstanding hypertension is admitted to the hospital with pneumonia. During the second hospital day, he develops atrial fibrillation (AF) with rapid ventricular response, but his hemodynamics remain stable. He is given oral metoprolol for rate control. A transthoracic echocardiogram (TTE) shows mild concentric left ventricular hypertrophy, normal left ventricular size and function, and mild left atrial enlargement. The AF spontaneously terminates after 24 hours and does not recur during the hospitalization. What treatment and monitoring are recommended at the time of discharge for this patient's AF?

BACKGROUND

AF is a common dysrhythmia that clinicians often encounter while caring for hospitalized patients. Although many patients will have carried a diagnosis of AF prior to hospital admission, this review will pertain to patients for whom a first documented episode of AF occurs during hospitalization. These patients can be conceptually separated into 2 categories: those who have had undiagnosed AF for some time (and are now diagnosed due to continuous inpatient telemetry monitoring) and those whose AF is secondary to their acute medical illness. Although practically speaking, this distinction is not easy to make, markers of chronic AF may include left atrial enlargement and a clinical history of longstanding palpitations.

INCIDENCE

The prevalence of AF in the general population is estimated at 0.4% to 1.0%.[1, 2] Prevalence increases with advancing age. Compared to the general population, the population of hospitalized patients is inherently older and enriched for comorbidities that are known risk factors for the development of AF (such as congestive heart failure, hypertension, and obstructive sleep apnea) or are associated with paroxysmal AF (such as stroke or transient ischemic attack [TIA]). As a result, the prevalence of occult AF is necessarily higher in this population than that of a general cohort. The risk of developing AF is further increased in hospitalized patients simply by the acute illness (or postoperative state), whose associated catecholamine surge and systemic proinflammatory state are well‐known precipitants for AF.[3] AF is common after cardiac surgery (25%30%)[4, 5] and occurs in about 3% of patients undergoing major noncardiac surgery.[6]

In the setting of severe medical illness such as sepsis, the incidence of new onset AF has recently been estimated at around 6%.[7] Among patients hospitalized with stroke, 2% to 5% will have a new diagnosis of AF made by the admission electrocardiogram (ECG).[8, 9, 10] Subsequent cardiac monitoring with inpatient telemetry or Holter monitoring will detect previously undiagnosed AF in another 5% to 8% of patients admitted with stroke.[11, 12]

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

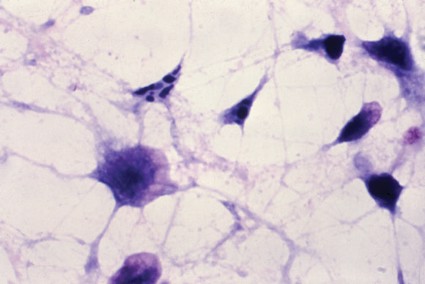

AF is a supraventricular tachyarrhythmia characterized by uncoordinated atrial activation; this chaotic atrial activation translates into atrial mechanical dysfunction. [13] Patients who develop AF may have atrial substrate, such as patchy atrial myocyte fibrosis, that increases their propensity to develop atrial dysrhythmias.[14] Other factors contributing to the likelihood of developing AF are anisotropic conduction, atrial chamber dilation, systemic inflammation, hyperadrenergic state, and atrial ischemia.[3, 15, 16, 17] Atrial flutter, on the other hand, is an organized macro‐reentrant supraventricular arrhythmia that typically rotates around the tricuspid annulus.

RISK FACTORS

Risk factors for the development of AF are well defined. The risk factors in the chronic setting remain the same as those for the development of AF in the setting of medical illness or in the postoperative state: advancing age, male gender, prior diagnosis of AF, congestive heart failure, hypertension, and obstructive sleep apnea.[1, 5, 18] Surgical procedures, due to the sympathetic surge and proinflammatory state that occur in the postoperative period, increase the risk of AF. Cardiac and thoracic procedures, which involve direct manipulation of the heart and adjacent structures, proffer the highest risk of AF.[19, 20] Although not necessarily a risk factor for the development of AF, patients with recent ischemic stroke are at high risk of harboring AF; up to 7% of patients are diagnosed with AF in the 3 months following ischemic stroke.[21]

DIAGNOSIS

In the inpatient setting, the diagnosis of AF is typically made through telemetry monitoring, which reveals irregularly spaced QRS complexes and an absence of organized atrial activity (ie, no discernible P waves or flutter waves). For patients not on a continuous cardiac monitor, the diagnosis of AF is made by 12‐lead ECG, which is triggered by patient complaint (palpitations, lightheadedness, dyspnea, or chest pain), physical exam findings, or review of vital sign measurements (ie, sudden changes in heart rate). The dysrhythmia should sustain for at least 30 seconds for a diagnosis of AF to be made.

INITIAL WORKUP

When AF is suspected (or has been diagnosed by telemetry), a 12‐lead ECG should be immediately obtained (Table 1). This will help to confirm the diagnosis of AF (as distinct from atrial flutter) and begin the investigation for underlying causes (ie, analysis of ST‐segment shifts for evidence of myocardial ischemia or pericarditis). A focused history, physical exam, and review of vital signs can quickly determine if there are any urgent indications for cardioversion, such as the development of pulmonary edema, the presence of angina pectoris, or rhythm‐related hypotension. A TTE should be obtained to assess for structural heart disease (left atrial enlargement, valvular disease, cardiac tumor) that may serve as a substrate for AF. The echocardiogram will also provide an assessment of left ventricular function, which will inform the treating physician regarding the safety of using atrioventricular (AV) nodal blocking agents, such as ‐blockers and nondihydropyridine calcium channel blockers, which may also act as negative inotropes. Although occult hyperthyroidism is a rare cause of AF,[22] a serum thyroid‐stimulating hormone test should be obtained to rule out this reversible cause. Electrolytes should be monitored and serum potassium and magnesium levels should be maintained at >4.0 mmol/L and >2.0 mEq mmol/L, respectively. Measurement of serum B‐type natriuretic peptide can be helpful in determining prognosis and likelihood of left ventricular dysfunction in patients with AF.[23, 24]

|

| Confirmatory study |

| 12‐lead electrocardiogram |

| Assessment of clinical stability |

| History (chest pain, shortness of breath, syncope/presyncope) |

| Physical exam (blood pressure, heart rate, pulmonary rales, jugular venous distension) |

| Evaluation for structural heart disease |

| Physical exam (pathologic murmurs, third heart sound, abnormal PMI, friction rub) |

| Transthoracic echocardiogram |

| Metabolic triggers |

| Serum potassium and magnesium |

| Serum thyroid stimulating hormone |

| Prognostic indicators |

| Serum brain natriuretic peptide |

| Other investigations (as guided by clinical suspicion) |

| Chest CT angiogram |

| Serum troponin |

| Blood cultures |

Other investigations should be guided by the clinical suspicion for other secondary causes. Examples include assessment for infection in the postoperative patient, ruling out myocardial infarction in patients with chest pain and risk factors for coronary artery disease, evaluating for pericarditis following cardiac surgery, and having a high suspicion for pulmonary embolism in patients with prolonged immobilization, hypercoagulable state, or recent knee/hip replacement surgery.

STRATEGIES FOR PREVENTION/SCREENING

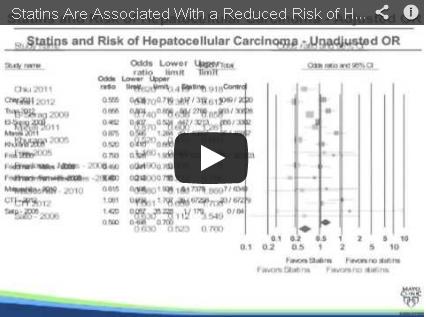

AF prevention and screening strategies are not practical for patients admitted for medical illnesses. When used for perioperative prophylaxis, however, amiodarone has been shown to clearly reduce postoperative AF (and shorten hospitalizations) after coronary artery bypass graft surgery.[4, 25] Statin use has been associated with a decrease in postoperative AF following major noncardiac surgery.[26] Patients hospitalized with acute ischemic stroke or TIA should undergo cardiac monitoring throughout their hospitalization if feasible, or for at least 24 hours.[27] Recent data indicate that either Holter monitoring or continuous cardiac telemetry are acceptable methods of screening stroke patients for underlying AF.[11]

THERAPIES

In all cases of AF, underlying causes of the dysrhythmia (such as heart failure, infection, electrolyte disturbances, and pain) should be sought and treated.

AF associated with unstable symptoms (heart failure, angina, hypotension) calls for urgent rhythm control. In this setting, cardioversion should be performed immediately; anticoagulation should be initiated concomitantly unless a contraindication to anticoagulation exists. Stable patients should be assessed for indications for elective cardioversion and acute anticoagulation. Generally speaking, it is desirable to perform transesophageal echocardiography (TEE) and cardioversion prior to discharge from the hospital in patients whose new‐onset AF has persisted, assuming that they are candidates for therapeutic anticoagulation. This is particularly true for patients who are at all symptomatic from their AF. Allowing patients to remain in AF for weeks to months will increase their risk of developing long‐standing persistent AF.

AF is a well‐recognized risk factor for the development of atrial thrombi and resultant thromboembolic events. Thrombus formation is thought to be a result of stasis of blood in the atria during AF as well as a localized hypercoagulable state in the left atrium in patients with AF.[28] Left atrial thrombus can develop in patients with AF of duration 3 days.[29] Echocardiographic evidence suggests that left atrial appendage function can be transiently depressed following cardioversion, which may help to explain the finding of increased risk of thromboembolism immediately after cardioversion.[30, 31] In fact, 98% of thromboembolic events after cardioversion occur within 10 days.[31] Studies using serial TEE show that atrial thrombi typically resolve after 3 to 4 weeks of anticoagulation.[28] These data are the basis for the recommendation that patients with AF that has lasted 48 hours or more should receive 4 weeks of therapeutic anticoagulation prior to cardioversion that is not TEE guided. Importantly, administration of antiarrhythmic agents, such as amiodarone, should be considered an attempt at rhythm control, and therefore anticoagulation should be used in the same way during antiarrhythmic drug initiation as with direct‐current cardioversion. Medications most commonly used to acutely terminate AF are ibutilide, propafenone, and flecainide.

In the inpatient setting, nonemergent cardioversion in patients who have had AF for more than 48 hours should be TEE guided, unless the onset of the arrhythmia was clearly documented and therapeutic anticoagulation was initiated within 48 hours of the onset. Patients should be receiving therapeutic anticoagulation at the time of the TEE. Contrast‐enhanced magnetic resonance imaging is a promising noninvasive option for assessing for intracardiac thrombus, but this modality has not yet been widely adopted as an acceptable alternative to TEE.[32]

Anticoagulation in the short term can be rapidly achieved using heparins (intravenous unfractionated heparin, subcutaneous enoxaparin) or the newer oral anticoagulants such as dabigatran (a thrombin inhibitor) or rivaroxaban and apixaban (factor Xa inhibitors). Importantly, should significant bleeding occur, options for reversal of these new oral anticoagulant agents are limited.[33] Vitamin K antagonists such as warfarin remain a viable option for long‐term anticoagulation, but usually require 4 to 5 days to reach peak effect; the goal international normalized ratio (INR) is 2.0 to 3.0. In patients with chronic kidney disease, the newer oral anticoagulants (dabigatran, rivaroxiban, and apixaban), as well as low molecular weight heparins, should be dose adjusted in patients with moderate renal dysfunction and avoided altogether in patients with severe renal dysfunction.

Ventricular response rate control, rather than rhythm control, is a reasonable initial strategy for patients who do not have significant symptoms from AF. Rate control can be achieved using traditional AV nodal blocking agents (‐blockers and nondihydropyridine calcium channel blockers). Initially, the use of intravenous (IV) agents is reasonable. IV metoprolol and IV diltiazem are useful because they both have a rapid onset of action, which allows for repeated bolus dosing at closely spaced intervals. Both IV agents have a 2‐ to 4‐hour half‐life. Once rate control has been achieved, the amount of IV drug required to achieve heart rate control can be tallied and converted into oral dosing. Cardiac glycosides can also be used to rate‐control AF; digitalis works by exerting a vagotonic effect via alterations in calcium handling in the AV node. Digoxin is most effective in the rate control of patients with persistent AF rather than those with recent onset AF.[34] Even in patients with persistent AF, digoxin only lowers average heart rate during rest and not during exertion/stress.[35] In patients with marginal blood pressure, digoxin can be safely used because it does not have any negative inotropic effects. In patients receiving a rate control strategy, the decision of whether to anticoagulate should be based on the risk of thromboembolic stroke as determined by clinical risk factors. In general, patients with a CHADS2 score[36] of 0 can be treated with aspirin (325 mg daily)[37] for thromboembolism prevention, and those with a score of 2 or more should receive therapeutic anticoagulation. Patients with a CHADS2 score of 1 can reasonably be treated with either regimen, and a more nuanced assessment of bleeding and stroke risk is required. The more recently described CHA2DS2‐VASc score allows for better stroke risk discrimination among patients with low CHADS2 scores (Table 2).[38]

| CHADS2 Elements | CHADS2 Score | Annual Stroke Risk |

|---|---|---|

| ||

| CHF | 0 | 1.2% |

| Hypertension | 1 | 2.8% |

| Age 75 years | 2 | 3.6% |

| Diabetes | 3 | 6.4% |

| Stroke/TIA (2 points) | 4 | 8.0% |

| 56 | 11.4% | |

| CHA2DS2‐VASc Elements | CHA2DS2‐VASc Score | Annual Stroke Risk a |

| CHF | 0 | 0.0% |

| Hypertension | 1 | 0.7% |

| Age 75 years (2 points) | 2 | 1.9% |

| Age 6574 years | 3 | 4.7% |

| Diabetes | 4 | 2.3% |

| Stroke/TIA (2) | 5 | 3.9% |

| Vascular disease | 6 | 4.5% |

| Female gender | 7 | 10.1% |

| 89 | 20% | |

Additionally, the HAS‐BLED scoring system (which incorporates hypertension, abnormal renal/liver function, stroke, bleeding history, labile INR, and drugs/alcohol) provides a convenient method for estimating a patient's risk of major bleeding with therapeutic anticoagulation.[39]

Patients who are hospitalized with acute stroke and are found to have new onset AF require special consideration in regard to the timing of anticoagulation and rate‐control strategies. Although these patients are at risk for recurrent cardioembolism during their hospitalization, they are also at increased risk of hemorrhagic conversion of their cerebral infarct. Randomized studies comparing lowmolecular‐weight heparins versus antiplatelet agents for acute cardioembolic stroke indicate no net benefit of anticoagulation in thefirst 2 weeks after stroke.[40, 41] However, anticoagulation is probably safe within 14 days for patients with minor stroke because they are at less risk of hemorrhagic conversion.[27] Therefore, a reasonable approach is to start anticoagulation immediately after TIA, 5 to 7 days after a minor stroke, and 10 to 14 days after a major stroke. Furthermore, patients with acute ischemic stroke are particularly susceptible to infarct extension from even minor degrees of blood pressure reduction,[42] and therefore their AF must be managed with this hemodynamic consideration in mind.

SHORT‐TERM SEQUELAE

Increased hospital stay length, hospital cost, and morbidity have been well described to be increased in patients with postoperative AF following cardiac surgery[5] and noncardiac surgery.[43] In a recent study of patients with severe sepsis, those who developed new onset AF had a significantly increased risk of stroke and in‐hospital mortality.[7]

LONG‐TERM THERAPIES/MONITORING

Among patients with newly diagnosed AF during a hospitalization, those with multiple major risk factors for stroke (CHADS2 score >1 or CHA2DS2VASc score >2) should receive long‐term anticoagulation, unless monitoring is performed (Holter monitor, event monitor, implantable loop recorder) and shows an absence of AF. In patients with hypertension or coronary artery disease, prescription of a ‐blocker should be considered. Outpatient clinic follow‐up with a general cardiologist or electrophysiologist is important to help guide these decisions regarding rhythm monitoring, continuation of anticoagulation, and continuation of any antiarrhythmic drugs that were prescribed.

LONG‐TERM SEQUELAE

AF has recently been shown to have adverse long‐term consequences, even in a relatively healthy cohort of patients.[44] Postoperative AF has been associated with poor neurocognitive outcomes following CABG surgery.[45] Although data are lacking with regard to the prognostic significance of AF in the setting of hospitalization, it is reasonable to presume that it is a predictor for future episodes of AF. We know that 15% to 20% of all strokes occur in patients with AF,[2] and the group of patients with a new diagnosis of AF during hospital admission is almost certainly enriched for stroke risk. This underscores the importance of either starting long‐term anticoagulation upon discharge in patients at medium‐high risk of stroke, or ensuring timely communication of a new AF diagnosis to patients' outpatient physicians so that appropriate antithrombotic drugs can be started soon after discharge.

CONCLUSIONS

AF is a common problem among patients hospitalized for medical illness or in the postoperative state. Diagnosis of the dysrhythmia and identification of any reversible causes are the key first steps in management. Oftentimes, rate and rhythm control strategies are both reasonable courses of action, although it is important to include appropriate anticoagulation as part of both approaches. Cardiology consultation can be helpful in the decision‐making process.

In the vignette described at the beginning, we have a patient with a CHADS2 score of 2 (age, hypertension) and newly diagnosed paroxysmal AF during hospitalization. The dysrhythmia was likely triggered by his medical illness, but we have no way of knowing whether he has had asymptomatic paroxysms of AF in the past. Oral anticoagulation along with a ‐blocker should be prescribed at discharge. Clinic follow‐up with a cardiologist should be arranged prior to discharge, and consideration of withdrawing anticoagulation in the future should be guided by outpatient rhythm monitoring.

Disclosure

Nothing to report.

- , , , et al. Prevalence of diagnosed atrial fibrillation in adults: national implications for rhythm management and stroke prevention: the AnTicoagulation and Risk Factors in Atrial Fibrillation (ATRIA) Study. JAMA. 2001;285:2370–2375.

- , , , , . Prevalence, age distribution, and gender of patients with atrial fibrillation. Analysis and implications. Arch Intern Med. 1995;155:469–473.

- , , , et al. Inflammation as a risk factor for atrial fibrillation. Circulation. 2003;108:3006–3010.

- , , , et al. Prophylactic Oral Amiodarone for the Prevention of Arrhythmias that Begin Early After Revascularization, Valve Replacement, or Repair: PAPABEAR: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2005;294:3093–3100.

- , , , et al. Atrial fibrillation following coronary artery bypass graft surgery: predictors, outcomes, and resource utilization. MultiCenter Study of Perioperative Ischemia Research Group. JAMA. 1996;276:300–306.

- , , , , . Incidence, predictors, and outcomes associated with postoperative atrial fibrillation after major noncardiac surgery. Am Heart J. 2012;164: 918–924.

- , , , , . Incident stroke and mortality associated with new‐onset atrial fibrillation in patients hospitalized with severe sepsis. JAMA. 2011;306:2248–2254.

- , , . Usefulness of cardiovascular investigations in stroke management: clinical relevance and economic implications. Stroke. 2007;38:1956–1958.

- , , , . Value of cardiac monitoring and echocardiography in TIA and stroke patients. Stroke. 1985;16:950–956.

- , , . Ambulatory electrocardiographic monitoring in patients with transient focal cerebral ischaemia. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1984;47:256–259.

- , , , et al. Continuous stroke unit electrocardiographic monitoring versus 24‐hour holter electrocardiography for detection of paroxysmal atrial fibrillation after stroke. Stroke. 2012;43:2689–2694.

- , , , , . Noninvasive cardiac monitoring for detecting paroxysmal atrial fibrillation or flutter after acute ischemic stroke: a systematic review. Stroke. 2007;38:2935–2940.

- , , , et al. ACC/AHA/ESC 2006 guidelines for the management of patients with atrial fibrillation: full text: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on practice guidelines and the European Society of Cardiology Committee for Practice Guidelines (Writing Committee to Revise the 2001 guidelines for the management of patients with atrial fibrillation) developed in collaboration with the European Heart Rhythm Association and the Heart Rhythm Society. Europace. 2006;8:651–745.

- , , , , , . Histological substrate of atrial biopsies in patients with lone atrial fibrillation. Circulation. 1997;96:1180–1184.

- , , . Role of inflammation in initiation and perpetuation of atrial fibrillation: a systematic review of the published data. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;50:2021–2028.

- , , , et al. Atrial fibrillation after coronary artery bypass grafting is associated with sympathetic activation. Ann Thorac Surg. 1995;60:1709–1715.

- , , , et al. Inflammation of atrium after cardiac surgery is associated with inhomogeneity of atrial conduction and atrial fibrillation. Circulation. 2005;111:2881–2888.

- , , , et al. Obstructive sleep apnea, obesity, and the risk of incident atrial fibrillation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;49:565–571.

- , , , . Mechanisms, prevention, and treatment of atrial fibrillation after cardiac surgery. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;51:793–801.

- , , , . Incidence of arrhythmias after thoracic surgery: thoracotomy versus video‐assisted thoracoscopy. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 1998;12:659–661.

- , , , et al. Delayed detection of atrial fibrillation after ischemic stroke. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2009;18:453–457.

- , , , et al. How useful is thyroid function testing in patients with recent‐onset atrial fibrillation? The Canadian Registry of Atrial Fibrillation Investigators. Arch Intern Med. 1996;156:2221–2224.

- , , , , , . Natriuretic peptide levels in atrial fibrillation: a prospective hormonal and Doppler‐echocardiographic study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2000;35:1256–1262.

- , , . Relationship between brain natriuretic peptide and recurrence of atrial fibrillation after successful electrical cardioversion: a meta‐analysis. J Int Med Res. 2011;39:1618–1624.

- , , , et al. Amiodarone prophylaxis for atrial fibrillation of high‐risk patients after coronary bypass grafting: a prospective, double‐blinded, placebo‐controlled, randomized study. Eur Heart J. 2006;27:1584–1591.

- , , , , . Statin use and postoperative atrial fibrillation after major noncardiac surgery. Heart Rhythm. 2012;9:163–169.

- , , , et al. Guidelines for the prevention of stroke in patients with stroke or transient ischemic attack: a guideline for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2011;42:227–276.

- , , , . Cardioversion of nonrheumatic atrial fibrillation. Reduced thromboembolic complications with 4 weeks of precardioversion anticoagulation are related to atrial thrombus resolution. Circulation. 1995;92:160–163.

- , , , . Left atrial appendage thrombus is not uncommon in patients with acute atrial fibrillation and a recent embolic event: a transesophageal echocardiographic study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1995;25:452–459.

- , , , et al. Impact of electrical cardioversion for atrial fibrillation on left atrial appendage function and spontaneous echo contrast: characterization by simultaneous transesophageal echocardiography. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1993;22:1359–1366.

- , , , . Pulsed Doppler evaluation of atrial mechanical function after electrical cardioversion of atrial fibrillation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1989;13:617–623.

- , , , et al. Detection and characterization of intracardiac thrombi on MR imaging. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2002;179:1539–1544.

- , , , , , . Reversal of rivaroxaban and dabigatran by prothrombin complex concentrate: a randomized, placebo‐controlled, crossover study in healthy subjects. Circulation. 2011;124:1573–1579.

- , , , et al. Conversion of atrial fibrillation to sinus rhythm and rate control by digoxin in comparison to placebo. Eur Heart J. 1997;18:643–648.

- , , , et al. The evidence regarding the drugs used for ventricular rate control. J Fam Pract. 2000;49:47–59.

- , , , , , . Validation of clinical classification schemes for predicting stroke: results from the National Registry of Atrial Fibrillation. JAMA. 2001;285:2864–2870.

- Stroke prevention in atrial fibrillation study. Final results. Circulation. 1991;84:527–539.

- , , , , . Refining clinical risk stratification for predicting stroke and thromboembolism in atrial fibrillation using a novel risk factor‐based approach: the Euro Heart Survey on atrial fibrillation. Chest. 2010;137:263–272.

- , , , , , . A novel user‐friendly score (HAS‐BLED) to assess 1‐year risk of major bleeding in patients with atrial fibrillation: the Euro Heart Survey. Chest. 2010;138:1093–1100.

- , , , . Low molecular‐weight heparin versus aspirin in patients with acute ischaemic stroke and atrial fibrillation: a double‐blind randomised study. HAEST Study Group. Heparin in Acute Embolic Stroke Trial. Lancet. 2000;355:1205–1210.

- The International Stroke Trial (IST): a randomised trial of aspirin, subcutaneous heparin, both, or neither among 19435 patients with acute ischaemic stroke. International Stroke Trial Collaborative Group. Lancet. 1997;349:1569–1581.

- , , , et al. The angiotensin‐receptor blocker candesartan for treatment of acute stroke (SCAST): a randomised, placebo‐controlled, double‐blind trial. Lancet. 2011;377:741–750.

- , , , , . Supraventricular arrhythmia in patients having noncardiac surgery: clinical correlates and effect on length of stay. Ann Intern Med. 1998;129:279–285.

- , , , et al. Risk of death and cardiovascular events in initially healthy women with new‐onset atrial fibrillation. JAMA. 2011;305:2080–2087.

- , , , et al. The impact of postoperative atrial fibrillation on neurocognitive outcome after coronary artery bypass graft surgery. Anesth Analg. 2002;94:290–295, table of contents.

A 78‐year‐old otherwise healthy man with longstanding hypertension is admitted to the hospital with pneumonia. During the second hospital day, he develops atrial fibrillation (AF) with rapid ventricular response, but his hemodynamics remain stable. He is given oral metoprolol for rate control. A transthoracic echocardiogram (TTE) shows mild concentric left ventricular hypertrophy, normal left ventricular size and function, and mild left atrial enlargement. The AF spontaneously terminates after 24 hours and does not recur during the hospitalization. What treatment and monitoring are recommended at the time of discharge for this patient's AF?

BACKGROUND

AF is a common dysrhythmia that clinicians often encounter while caring for hospitalized patients. Although many patients will have carried a diagnosis of AF prior to hospital admission, this review will pertain to patients for whom a first documented episode of AF occurs during hospitalization. These patients can be conceptually separated into 2 categories: those who have had undiagnosed AF for some time (and are now diagnosed due to continuous inpatient telemetry monitoring) and those whose AF is secondary to their acute medical illness. Although practically speaking, this distinction is not easy to make, markers of chronic AF may include left atrial enlargement and a clinical history of longstanding palpitations.

INCIDENCE

The prevalence of AF in the general population is estimated at 0.4% to 1.0%.[1, 2] Prevalence increases with advancing age. Compared to the general population, the population of hospitalized patients is inherently older and enriched for comorbidities that are known risk factors for the development of AF (such as congestive heart failure, hypertension, and obstructive sleep apnea) or are associated with paroxysmal AF (such as stroke or transient ischemic attack [TIA]). As a result, the prevalence of occult AF is necessarily higher in this population than that of a general cohort. The risk of developing AF is further increased in hospitalized patients simply by the acute illness (or postoperative state), whose associated catecholamine surge and systemic proinflammatory state are well‐known precipitants for AF.[3] AF is common after cardiac surgery (25%30%)[4, 5] and occurs in about 3% of patients undergoing major noncardiac surgery.[6]

In the setting of severe medical illness such as sepsis, the incidence of new onset AF has recently been estimated at around 6%.[7] Among patients hospitalized with stroke, 2% to 5% will have a new diagnosis of AF made by the admission electrocardiogram (ECG).[8, 9, 10] Subsequent cardiac monitoring with inpatient telemetry or Holter monitoring will detect previously undiagnosed AF in another 5% to 8% of patients admitted with stroke.[11, 12]

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

AF is a supraventricular tachyarrhythmia characterized by uncoordinated atrial activation; this chaotic atrial activation translates into atrial mechanical dysfunction. [13] Patients who develop AF may have atrial substrate, such as patchy atrial myocyte fibrosis, that increases their propensity to develop atrial dysrhythmias.[14] Other factors contributing to the likelihood of developing AF are anisotropic conduction, atrial chamber dilation, systemic inflammation, hyperadrenergic state, and atrial ischemia.[3, 15, 16, 17] Atrial flutter, on the other hand, is an organized macro‐reentrant supraventricular arrhythmia that typically rotates around the tricuspid annulus.

RISK FACTORS

Risk factors for the development of AF are well defined. The risk factors in the chronic setting remain the same as those for the development of AF in the setting of medical illness or in the postoperative state: advancing age, male gender, prior diagnosis of AF, congestive heart failure, hypertension, and obstructive sleep apnea.[1, 5, 18] Surgical procedures, due to the sympathetic surge and proinflammatory state that occur in the postoperative period, increase the risk of AF. Cardiac and thoracic procedures, which involve direct manipulation of the heart and adjacent structures, proffer the highest risk of AF.[19, 20] Although not necessarily a risk factor for the development of AF, patients with recent ischemic stroke are at high risk of harboring AF; up to 7% of patients are diagnosed with AF in the 3 months following ischemic stroke.[21]

DIAGNOSIS

In the inpatient setting, the diagnosis of AF is typically made through telemetry monitoring, which reveals irregularly spaced QRS complexes and an absence of organized atrial activity (ie, no discernible P waves or flutter waves). For patients not on a continuous cardiac monitor, the diagnosis of AF is made by 12‐lead ECG, which is triggered by patient complaint (palpitations, lightheadedness, dyspnea, or chest pain), physical exam findings, or review of vital sign measurements (ie, sudden changes in heart rate). The dysrhythmia should sustain for at least 30 seconds for a diagnosis of AF to be made.

INITIAL WORKUP

When AF is suspected (or has been diagnosed by telemetry), a 12‐lead ECG should be immediately obtained (Table 1). This will help to confirm the diagnosis of AF (as distinct from atrial flutter) and begin the investigation for underlying causes (ie, analysis of ST‐segment shifts for evidence of myocardial ischemia or pericarditis). A focused history, physical exam, and review of vital signs can quickly determine if there are any urgent indications for cardioversion, such as the development of pulmonary edema, the presence of angina pectoris, or rhythm‐related hypotension. A TTE should be obtained to assess for structural heart disease (left atrial enlargement, valvular disease, cardiac tumor) that may serve as a substrate for AF. The echocardiogram will also provide an assessment of left ventricular function, which will inform the treating physician regarding the safety of using atrioventricular (AV) nodal blocking agents, such as ‐blockers and nondihydropyridine calcium channel blockers, which may also act as negative inotropes. Although occult hyperthyroidism is a rare cause of AF,[22] a serum thyroid‐stimulating hormone test should be obtained to rule out this reversible cause. Electrolytes should be monitored and serum potassium and magnesium levels should be maintained at >4.0 mmol/L and >2.0 mEq mmol/L, respectively. Measurement of serum B‐type natriuretic peptide can be helpful in determining prognosis and likelihood of left ventricular dysfunction in patients with AF.[23, 24]

|

| Confirmatory study |

| 12‐lead electrocardiogram |

| Assessment of clinical stability |

| History (chest pain, shortness of breath, syncope/presyncope) |

| Physical exam (blood pressure, heart rate, pulmonary rales, jugular venous distension) |

| Evaluation for structural heart disease |

| Physical exam (pathologic murmurs, third heart sound, abnormal PMI, friction rub) |

| Transthoracic echocardiogram |

| Metabolic triggers |

| Serum potassium and magnesium |

| Serum thyroid stimulating hormone |

| Prognostic indicators |

| Serum brain natriuretic peptide |

| Other investigations (as guided by clinical suspicion) |

| Chest CT angiogram |

| Serum troponin |

| Blood cultures |

Other investigations should be guided by the clinical suspicion for other secondary causes. Examples include assessment for infection in the postoperative patient, ruling out myocardial infarction in patients with chest pain and risk factors for coronary artery disease, evaluating for pericarditis following cardiac surgery, and having a high suspicion for pulmonary embolism in patients with prolonged immobilization, hypercoagulable state, or recent knee/hip replacement surgery.

STRATEGIES FOR PREVENTION/SCREENING

AF prevention and screening strategies are not practical for patients admitted for medical illnesses. When used for perioperative prophylaxis, however, amiodarone has been shown to clearly reduce postoperative AF (and shorten hospitalizations) after coronary artery bypass graft surgery.[4, 25] Statin use has been associated with a decrease in postoperative AF following major noncardiac surgery.[26] Patients hospitalized with acute ischemic stroke or TIA should undergo cardiac monitoring throughout their hospitalization if feasible, or for at least 24 hours.[27] Recent data indicate that either Holter monitoring or continuous cardiac telemetry are acceptable methods of screening stroke patients for underlying AF.[11]

THERAPIES

In all cases of AF, underlying causes of the dysrhythmia (such as heart failure, infection, electrolyte disturbances, and pain) should be sought and treated.

AF associated with unstable symptoms (heart failure, angina, hypotension) calls for urgent rhythm control. In this setting, cardioversion should be performed immediately; anticoagulation should be initiated concomitantly unless a contraindication to anticoagulation exists. Stable patients should be assessed for indications for elective cardioversion and acute anticoagulation. Generally speaking, it is desirable to perform transesophageal echocardiography (TEE) and cardioversion prior to discharge from the hospital in patients whose new‐onset AF has persisted, assuming that they are candidates for therapeutic anticoagulation. This is particularly true for patients who are at all symptomatic from their AF. Allowing patients to remain in AF for weeks to months will increase their risk of developing long‐standing persistent AF.

AF is a well‐recognized risk factor for the development of atrial thrombi and resultant thromboembolic events. Thrombus formation is thought to be a result of stasis of blood in the atria during AF as well as a localized hypercoagulable state in the left atrium in patients with AF.[28] Left atrial thrombus can develop in patients with AF of duration 3 days.[29] Echocardiographic evidence suggests that left atrial appendage function can be transiently depressed following cardioversion, which may help to explain the finding of increased risk of thromboembolism immediately after cardioversion.[30, 31] In fact, 98% of thromboembolic events after cardioversion occur within 10 days.[31] Studies using serial TEE show that atrial thrombi typically resolve after 3 to 4 weeks of anticoagulation.[28] These data are the basis for the recommendation that patients with AF that has lasted 48 hours or more should receive 4 weeks of therapeutic anticoagulation prior to cardioversion that is not TEE guided. Importantly, administration of antiarrhythmic agents, such as amiodarone, should be considered an attempt at rhythm control, and therefore anticoagulation should be used in the same way during antiarrhythmic drug initiation as with direct‐current cardioversion. Medications most commonly used to acutely terminate AF are ibutilide, propafenone, and flecainide.

In the inpatient setting, nonemergent cardioversion in patients who have had AF for more than 48 hours should be TEE guided, unless the onset of the arrhythmia was clearly documented and therapeutic anticoagulation was initiated within 48 hours of the onset. Patients should be receiving therapeutic anticoagulation at the time of the TEE. Contrast‐enhanced magnetic resonance imaging is a promising noninvasive option for assessing for intracardiac thrombus, but this modality has not yet been widely adopted as an acceptable alternative to TEE.[32]

Anticoagulation in the short term can be rapidly achieved using heparins (intravenous unfractionated heparin, subcutaneous enoxaparin) or the newer oral anticoagulants such as dabigatran (a thrombin inhibitor) or rivaroxaban and apixaban (factor Xa inhibitors). Importantly, should significant bleeding occur, options for reversal of these new oral anticoagulant agents are limited.[33] Vitamin K antagonists such as warfarin remain a viable option for long‐term anticoagulation, but usually require 4 to 5 days to reach peak effect; the goal international normalized ratio (INR) is 2.0 to 3.0. In patients with chronic kidney disease, the newer oral anticoagulants (dabigatran, rivaroxiban, and apixaban), as well as low molecular weight heparins, should be dose adjusted in patients with moderate renal dysfunction and avoided altogether in patients with severe renal dysfunction.

Ventricular response rate control, rather than rhythm control, is a reasonable initial strategy for patients who do not have significant symptoms from AF. Rate control can be achieved using traditional AV nodal blocking agents (‐blockers and nondihydropyridine calcium channel blockers). Initially, the use of intravenous (IV) agents is reasonable. IV metoprolol and IV diltiazem are useful because they both have a rapid onset of action, which allows for repeated bolus dosing at closely spaced intervals. Both IV agents have a 2‐ to 4‐hour half‐life. Once rate control has been achieved, the amount of IV drug required to achieve heart rate control can be tallied and converted into oral dosing. Cardiac glycosides can also be used to rate‐control AF; digitalis works by exerting a vagotonic effect via alterations in calcium handling in the AV node. Digoxin is most effective in the rate control of patients with persistent AF rather than those with recent onset AF.[34] Even in patients with persistent AF, digoxin only lowers average heart rate during rest and not during exertion/stress.[35] In patients with marginal blood pressure, digoxin can be safely used because it does not have any negative inotropic effects. In patients receiving a rate control strategy, the decision of whether to anticoagulate should be based on the risk of thromboembolic stroke as determined by clinical risk factors. In general, patients with a CHADS2 score[36] of 0 can be treated with aspirin (325 mg daily)[37] for thromboembolism prevention, and those with a score of 2 or more should receive therapeutic anticoagulation. Patients with a CHADS2 score of 1 can reasonably be treated with either regimen, and a more nuanced assessment of bleeding and stroke risk is required. The more recently described CHA2DS2‐VASc score allows for better stroke risk discrimination among patients with low CHADS2 scores (Table 2).[38]

| CHADS2 Elements | CHADS2 Score | Annual Stroke Risk |

|---|---|---|

| ||

| CHF | 0 | 1.2% |

| Hypertension | 1 | 2.8% |

| Age 75 years | 2 | 3.6% |

| Diabetes | 3 | 6.4% |

| Stroke/TIA (2 points) | 4 | 8.0% |

| 56 | 11.4% | |

| CHA2DS2‐VASc Elements | CHA2DS2‐VASc Score | Annual Stroke Risk a |

| CHF | 0 | 0.0% |

| Hypertension | 1 | 0.7% |

| Age 75 years (2 points) | 2 | 1.9% |

| Age 6574 years | 3 | 4.7% |

| Diabetes | 4 | 2.3% |

| Stroke/TIA (2) | 5 | 3.9% |

| Vascular disease | 6 | 4.5% |

| Female gender | 7 | 10.1% |

| 89 | 20% | |

Additionally, the HAS‐BLED scoring system (which incorporates hypertension, abnormal renal/liver function, stroke, bleeding history, labile INR, and drugs/alcohol) provides a convenient method for estimating a patient's risk of major bleeding with therapeutic anticoagulation.[39]

Patients who are hospitalized with acute stroke and are found to have new onset AF require special consideration in regard to the timing of anticoagulation and rate‐control strategies. Although these patients are at risk for recurrent cardioembolism during their hospitalization, they are also at increased risk of hemorrhagic conversion of their cerebral infarct. Randomized studies comparing lowmolecular‐weight heparins versus antiplatelet agents for acute cardioembolic stroke indicate no net benefit of anticoagulation in thefirst 2 weeks after stroke.[40, 41] However, anticoagulation is probably safe within 14 days for patients with minor stroke because they are at less risk of hemorrhagic conversion.[27] Therefore, a reasonable approach is to start anticoagulation immediately after TIA, 5 to 7 days after a minor stroke, and 10 to 14 days after a major stroke. Furthermore, patients with acute ischemic stroke are particularly susceptible to infarct extension from even minor degrees of blood pressure reduction,[42] and therefore their AF must be managed with this hemodynamic consideration in mind.

SHORT‐TERM SEQUELAE

Increased hospital stay length, hospital cost, and morbidity have been well described to be increased in patients with postoperative AF following cardiac surgery[5] and noncardiac surgery.[43] In a recent study of patients with severe sepsis, those who developed new onset AF had a significantly increased risk of stroke and in‐hospital mortality.[7]

LONG‐TERM THERAPIES/MONITORING

Among patients with newly diagnosed AF during a hospitalization, those with multiple major risk factors for stroke (CHADS2 score >1 or CHA2DS2VASc score >2) should receive long‐term anticoagulation, unless monitoring is performed (Holter monitor, event monitor, implantable loop recorder) and shows an absence of AF. In patients with hypertension or coronary artery disease, prescription of a ‐blocker should be considered. Outpatient clinic follow‐up with a general cardiologist or electrophysiologist is important to help guide these decisions regarding rhythm monitoring, continuation of anticoagulation, and continuation of any antiarrhythmic drugs that were prescribed.

LONG‐TERM SEQUELAE

AF has recently been shown to have adverse long‐term consequences, even in a relatively healthy cohort of patients.[44] Postoperative AF has been associated with poor neurocognitive outcomes following CABG surgery.[45] Although data are lacking with regard to the prognostic significance of AF in the setting of hospitalization, it is reasonable to presume that it is a predictor for future episodes of AF. We know that 15% to 20% of all strokes occur in patients with AF,[2] and the group of patients with a new diagnosis of AF during hospital admission is almost certainly enriched for stroke risk. This underscores the importance of either starting long‐term anticoagulation upon discharge in patients at medium‐high risk of stroke, or ensuring timely communication of a new AF diagnosis to patients' outpatient physicians so that appropriate antithrombotic drugs can be started soon after discharge.

CONCLUSIONS

AF is a common problem among patients hospitalized for medical illness or in the postoperative state. Diagnosis of the dysrhythmia and identification of any reversible causes are the key first steps in management. Oftentimes, rate and rhythm control strategies are both reasonable courses of action, although it is important to include appropriate anticoagulation as part of both approaches. Cardiology consultation can be helpful in the decision‐making process.

In the vignette described at the beginning, we have a patient with a CHADS2 score of 2 (age, hypertension) and newly diagnosed paroxysmal AF during hospitalization. The dysrhythmia was likely triggered by his medical illness, but we have no way of knowing whether he has had asymptomatic paroxysms of AF in the past. Oral anticoagulation along with a ‐blocker should be prescribed at discharge. Clinic follow‐up with a cardiologist should be arranged prior to discharge, and consideration of withdrawing anticoagulation in the future should be guided by outpatient rhythm monitoring.

Disclosure

Nothing to report.

A 78‐year‐old otherwise healthy man with longstanding hypertension is admitted to the hospital with pneumonia. During the second hospital day, he develops atrial fibrillation (AF) with rapid ventricular response, but his hemodynamics remain stable. He is given oral metoprolol for rate control. A transthoracic echocardiogram (TTE) shows mild concentric left ventricular hypertrophy, normal left ventricular size and function, and mild left atrial enlargement. The AF spontaneously terminates after 24 hours and does not recur during the hospitalization. What treatment and monitoring are recommended at the time of discharge for this patient's AF?

BACKGROUND

AF is a common dysrhythmia that clinicians often encounter while caring for hospitalized patients. Although many patients will have carried a diagnosis of AF prior to hospital admission, this review will pertain to patients for whom a first documented episode of AF occurs during hospitalization. These patients can be conceptually separated into 2 categories: those who have had undiagnosed AF for some time (and are now diagnosed due to continuous inpatient telemetry monitoring) and those whose AF is secondary to their acute medical illness. Although practically speaking, this distinction is not easy to make, markers of chronic AF may include left atrial enlargement and a clinical history of longstanding palpitations.

INCIDENCE

The prevalence of AF in the general population is estimated at 0.4% to 1.0%.[1, 2] Prevalence increases with advancing age. Compared to the general population, the population of hospitalized patients is inherently older and enriched for comorbidities that are known risk factors for the development of AF (such as congestive heart failure, hypertension, and obstructive sleep apnea) or are associated with paroxysmal AF (such as stroke or transient ischemic attack [TIA]). As a result, the prevalence of occult AF is necessarily higher in this population than that of a general cohort. The risk of developing AF is further increased in hospitalized patients simply by the acute illness (or postoperative state), whose associated catecholamine surge and systemic proinflammatory state are well‐known precipitants for AF.[3] AF is common after cardiac surgery (25%30%)[4, 5] and occurs in about 3% of patients undergoing major noncardiac surgery.[6]

In the setting of severe medical illness such as sepsis, the incidence of new onset AF has recently been estimated at around 6%.[7] Among patients hospitalized with stroke, 2% to 5% will have a new diagnosis of AF made by the admission electrocardiogram (ECG).[8, 9, 10] Subsequent cardiac monitoring with inpatient telemetry or Holter monitoring will detect previously undiagnosed AF in another 5% to 8% of patients admitted with stroke.[11, 12]

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

AF is a supraventricular tachyarrhythmia characterized by uncoordinated atrial activation; this chaotic atrial activation translates into atrial mechanical dysfunction. [13] Patients who develop AF may have atrial substrate, such as patchy atrial myocyte fibrosis, that increases their propensity to develop atrial dysrhythmias.[14] Other factors contributing to the likelihood of developing AF are anisotropic conduction, atrial chamber dilation, systemic inflammation, hyperadrenergic state, and atrial ischemia.[3, 15, 16, 17] Atrial flutter, on the other hand, is an organized macro‐reentrant supraventricular arrhythmia that typically rotates around the tricuspid annulus.

RISK FACTORS

Risk factors for the development of AF are well defined. The risk factors in the chronic setting remain the same as those for the development of AF in the setting of medical illness or in the postoperative state: advancing age, male gender, prior diagnosis of AF, congestive heart failure, hypertension, and obstructive sleep apnea.[1, 5, 18] Surgical procedures, due to the sympathetic surge and proinflammatory state that occur in the postoperative period, increase the risk of AF. Cardiac and thoracic procedures, which involve direct manipulation of the heart and adjacent structures, proffer the highest risk of AF.[19, 20] Although not necessarily a risk factor for the development of AF, patients with recent ischemic stroke are at high risk of harboring AF; up to 7% of patients are diagnosed with AF in the 3 months following ischemic stroke.[21]

DIAGNOSIS

In the inpatient setting, the diagnosis of AF is typically made through telemetry monitoring, which reveals irregularly spaced QRS complexes and an absence of organized atrial activity (ie, no discernible P waves or flutter waves). For patients not on a continuous cardiac monitor, the diagnosis of AF is made by 12‐lead ECG, which is triggered by patient complaint (palpitations, lightheadedness, dyspnea, or chest pain), physical exam findings, or review of vital sign measurements (ie, sudden changes in heart rate). The dysrhythmia should sustain for at least 30 seconds for a diagnosis of AF to be made.

INITIAL WORKUP

When AF is suspected (or has been diagnosed by telemetry), a 12‐lead ECG should be immediately obtained (Table 1). This will help to confirm the diagnosis of AF (as distinct from atrial flutter) and begin the investigation for underlying causes (ie, analysis of ST‐segment shifts for evidence of myocardial ischemia or pericarditis). A focused history, physical exam, and review of vital signs can quickly determine if there are any urgent indications for cardioversion, such as the development of pulmonary edema, the presence of angina pectoris, or rhythm‐related hypotension. A TTE should be obtained to assess for structural heart disease (left atrial enlargement, valvular disease, cardiac tumor) that may serve as a substrate for AF. The echocardiogram will also provide an assessment of left ventricular function, which will inform the treating physician regarding the safety of using atrioventricular (AV) nodal blocking agents, such as ‐blockers and nondihydropyridine calcium channel blockers, which may also act as negative inotropes. Although occult hyperthyroidism is a rare cause of AF,[22] a serum thyroid‐stimulating hormone test should be obtained to rule out this reversible cause. Electrolytes should be monitored and serum potassium and magnesium levels should be maintained at >4.0 mmol/L and >2.0 mEq mmol/L, respectively. Measurement of serum B‐type natriuretic peptide can be helpful in determining prognosis and likelihood of left ventricular dysfunction in patients with AF.[23, 24]

|

| Confirmatory study |

| 12‐lead electrocardiogram |

| Assessment of clinical stability |

| History (chest pain, shortness of breath, syncope/presyncope) |

| Physical exam (blood pressure, heart rate, pulmonary rales, jugular venous distension) |

| Evaluation for structural heart disease |

| Physical exam (pathologic murmurs, third heart sound, abnormal PMI, friction rub) |

| Transthoracic echocardiogram |

| Metabolic triggers |

| Serum potassium and magnesium |

| Serum thyroid stimulating hormone |

| Prognostic indicators |

| Serum brain natriuretic peptide |

| Other investigations (as guided by clinical suspicion) |

| Chest CT angiogram |

| Serum troponin |

| Blood cultures |

Other investigations should be guided by the clinical suspicion for other secondary causes. Examples include assessment for infection in the postoperative patient, ruling out myocardial infarction in patients with chest pain and risk factors for coronary artery disease, evaluating for pericarditis following cardiac surgery, and having a high suspicion for pulmonary embolism in patients with prolonged immobilization, hypercoagulable state, or recent knee/hip replacement surgery.

STRATEGIES FOR PREVENTION/SCREENING

AF prevention and screening strategies are not practical for patients admitted for medical illnesses. When used for perioperative prophylaxis, however, amiodarone has been shown to clearly reduce postoperative AF (and shorten hospitalizations) after coronary artery bypass graft surgery.[4, 25] Statin use has been associated with a decrease in postoperative AF following major noncardiac surgery.[26] Patients hospitalized with acute ischemic stroke or TIA should undergo cardiac monitoring throughout their hospitalization if feasible, or for at least 24 hours.[27] Recent data indicate that either Holter monitoring or continuous cardiac telemetry are acceptable methods of screening stroke patients for underlying AF.[11]

THERAPIES

In all cases of AF, underlying causes of the dysrhythmia (such as heart failure, infection, electrolyte disturbances, and pain) should be sought and treated.

AF associated with unstable symptoms (heart failure, angina, hypotension) calls for urgent rhythm control. In this setting, cardioversion should be performed immediately; anticoagulation should be initiated concomitantly unless a contraindication to anticoagulation exists. Stable patients should be assessed for indications for elective cardioversion and acute anticoagulation. Generally speaking, it is desirable to perform transesophageal echocardiography (TEE) and cardioversion prior to discharge from the hospital in patients whose new‐onset AF has persisted, assuming that they are candidates for therapeutic anticoagulation. This is particularly true for patients who are at all symptomatic from their AF. Allowing patients to remain in AF for weeks to months will increase their risk of developing long‐standing persistent AF.

AF is a well‐recognized risk factor for the development of atrial thrombi and resultant thromboembolic events. Thrombus formation is thought to be a result of stasis of blood in the atria during AF as well as a localized hypercoagulable state in the left atrium in patients with AF.[28] Left atrial thrombus can develop in patients with AF of duration 3 days.[29] Echocardiographic evidence suggests that left atrial appendage function can be transiently depressed following cardioversion, which may help to explain the finding of increased risk of thromboembolism immediately after cardioversion.[30, 31] In fact, 98% of thromboembolic events after cardioversion occur within 10 days.[31] Studies using serial TEE show that atrial thrombi typically resolve after 3 to 4 weeks of anticoagulation.[28] These data are the basis for the recommendation that patients with AF that has lasted 48 hours or more should receive 4 weeks of therapeutic anticoagulation prior to cardioversion that is not TEE guided. Importantly, administration of antiarrhythmic agents, such as amiodarone, should be considered an attempt at rhythm control, and therefore anticoagulation should be used in the same way during antiarrhythmic drug initiation as with direct‐current cardioversion. Medications most commonly used to acutely terminate AF are ibutilide, propafenone, and flecainide.

In the inpatient setting, nonemergent cardioversion in patients who have had AF for more than 48 hours should be TEE guided, unless the onset of the arrhythmia was clearly documented and therapeutic anticoagulation was initiated within 48 hours of the onset. Patients should be receiving therapeutic anticoagulation at the time of the TEE. Contrast‐enhanced magnetic resonance imaging is a promising noninvasive option for assessing for intracardiac thrombus, but this modality has not yet been widely adopted as an acceptable alternative to TEE.[32]

Anticoagulation in the short term can be rapidly achieved using heparins (intravenous unfractionated heparin, subcutaneous enoxaparin) or the newer oral anticoagulants such as dabigatran (a thrombin inhibitor) or rivaroxaban and apixaban (factor Xa inhibitors). Importantly, should significant bleeding occur, options for reversal of these new oral anticoagulant agents are limited.[33] Vitamin K antagonists such as warfarin remain a viable option for long‐term anticoagulation, but usually require 4 to 5 days to reach peak effect; the goal international normalized ratio (INR) is 2.0 to 3.0. In patients with chronic kidney disease, the newer oral anticoagulants (dabigatran, rivaroxiban, and apixaban), as well as low molecular weight heparins, should be dose adjusted in patients with moderate renal dysfunction and avoided altogether in patients with severe renal dysfunction.

Ventricular response rate control, rather than rhythm control, is a reasonable initial strategy for patients who do not have significant symptoms from AF. Rate control can be achieved using traditional AV nodal blocking agents (‐blockers and nondihydropyridine calcium channel blockers). Initially, the use of intravenous (IV) agents is reasonable. IV metoprolol and IV diltiazem are useful because they both have a rapid onset of action, which allows for repeated bolus dosing at closely spaced intervals. Both IV agents have a 2‐ to 4‐hour half‐life. Once rate control has been achieved, the amount of IV drug required to achieve heart rate control can be tallied and converted into oral dosing. Cardiac glycosides can also be used to rate‐control AF; digitalis works by exerting a vagotonic effect via alterations in calcium handling in the AV node. Digoxin is most effective in the rate control of patients with persistent AF rather than those with recent onset AF.[34] Even in patients with persistent AF, digoxin only lowers average heart rate during rest and not during exertion/stress.[35] In patients with marginal blood pressure, digoxin can be safely used because it does not have any negative inotropic effects. In patients receiving a rate control strategy, the decision of whether to anticoagulate should be based on the risk of thromboembolic stroke as determined by clinical risk factors. In general, patients with a CHADS2 score[36] of 0 can be treated with aspirin (325 mg daily)[37] for thromboembolism prevention, and those with a score of 2 or more should receive therapeutic anticoagulation. Patients with a CHADS2 score of 1 can reasonably be treated with either regimen, and a more nuanced assessment of bleeding and stroke risk is required. The more recently described CHA2DS2‐VASc score allows for better stroke risk discrimination among patients with low CHADS2 scores (Table 2).[38]

| CHADS2 Elements | CHADS2 Score | Annual Stroke Risk |

|---|---|---|

| ||

| CHF | 0 | 1.2% |

| Hypertension | 1 | 2.8% |

| Age 75 years | 2 | 3.6% |

| Diabetes | 3 | 6.4% |

| Stroke/TIA (2 points) | 4 | 8.0% |

| 56 | 11.4% | |

| CHA2DS2‐VASc Elements | CHA2DS2‐VASc Score | Annual Stroke Risk a |

| CHF | 0 | 0.0% |

| Hypertension | 1 | 0.7% |

| Age 75 years (2 points) | 2 | 1.9% |

| Age 6574 years | 3 | 4.7% |

| Diabetes | 4 | 2.3% |

| Stroke/TIA (2) | 5 | 3.9% |

| Vascular disease | 6 | 4.5% |

| Female gender | 7 | 10.1% |

| 89 | 20% | |

Additionally, the HAS‐BLED scoring system (which incorporates hypertension, abnormal renal/liver function, stroke, bleeding history, labile INR, and drugs/alcohol) provides a convenient method for estimating a patient's risk of major bleeding with therapeutic anticoagulation.[39]

Patients who are hospitalized with acute stroke and are found to have new onset AF require special consideration in regard to the timing of anticoagulation and rate‐control strategies. Although these patients are at risk for recurrent cardioembolism during their hospitalization, they are also at increased risk of hemorrhagic conversion of their cerebral infarct. Randomized studies comparing lowmolecular‐weight heparins versus antiplatelet agents for acute cardioembolic stroke indicate no net benefit of anticoagulation in thefirst 2 weeks after stroke.[40, 41] However, anticoagulation is probably safe within 14 days for patients with minor stroke because they are at less risk of hemorrhagic conversion.[27] Therefore, a reasonable approach is to start anticoagulation immediately after TIA, 5 to 7 days after a minor stroke, and 10 to 14 days after a major stroke. Furthermore, patients with acute ischemic stroke are particularly susceptible to infarct extension from even minor degrees of blood pressure reduction,[42] and therefore their AF must be managed with this hemodynamic consideration in mind.

SHORT‐TERM SEQUELAE

Increased hospital stay length, hospital cost, and morbidity have been well described to be increased in patients with postoperative AF following cardiac surgery[5] and noncardiac surgery.[43] In a recent study of patients with severe sepsis, those who developed new onset AF had a significantly increased risk of stroke and in‐hospital mortality.[7]

LONG‐TERM THERAPIES/MONITORING

Among patients with newly diagnosed AF during a hospitalization, those with multiple major risk factors for stroke (CHADS2 score >1 or CHA2DS2VASc score >2) should receive long‐term anticoagulation, unless monitoring is performed (Holter monitor, event monitor, implantable loop recorder) and shows an absence of AF. In patients with hypertension or coronary artery disease, prescription of a ‐blocker should be considered. Outpatient clinic follow‐up with a general cardiologist or electrophysiologist is important to help guide these decisions regarding rhythm monitoring, continuation of anticoagulation, and continuation of any antiarrhythmic drugs that were prescribed.

LONG‐TERM SEQUELAE

AF has recently been shown to have adverse long‐term consequences, even in a relatively healthy cohort of patients.[44] Postoperative AF has been associated with poor neurocognitive outcomes following CABG surgery.[45] Although data are lacking with regard to the prognostic significance of AF in the setting of hospitalization, it is reasonable to presume that it is a predictor for future episodes of AF. We know that 15% to 20% of all strokes occur in patients with AF,[2] and the group of patients with a new diagnosis of AF during hospital admission is almost certainly enriched for stroke risk. This underscores the importance of either starting long‐term anticoagulation upon discharge in patients at medium‐high risk of stroke, or ensuring timely communication of a new AF diagnosis to patients' outpatient physicians so that appropriate antithrombotic drugs can be started soon after discharge.

CONCLUSIONS

AF is a common problem among patients hospitalized for medical illness or in the postoperative state. Diagnosis of the dysrhythmia and identification of any reversible causes are the key first steps in management. Oftentimes, rate and rhythm control strategies are both reasonable courses of action, although it is important to include appropriate anticoagulation as part of both approaches. Cardiology consultation can be helpful in the decision‐making process.

In the vignette described at the beginning, we have a patient with a CHADS2 score of 2 (age, hypertension) and newly diagnosed paroxysmal AF during hospitalization. The dysrhythmia was likely triggered by his medical illness, but we have no way of knowing whether he has had asymptomatic paroxysms of AF in the past. Oral anticoagulation along with a ‐blocker should be prescribed at discharge. Clinic follow‐up with a cardiologist should be arranged prior to discharge, and consideration of withdrawing anticoagulation in the future should be guided by outpatient rhythm monitoring.

Disclosure

Nothing to report.

- , , , et al. Prevalence of diagnosed atrial fibrillation in adults: national implications for rhythm management and stroke prevention: the AnTicoagulation and Risk Factors in Atrial Fibrillation (ATRIA) Study. JAMA. 2001;285:2370–2375.

- , , , , . Prevalence, age distribution, and gender of patients with atrial fibrillation. Analysis and implications. Arch Intern Med. 1995;155:469–473.

- , , , et al. Inflammation as a risk factor for atrial fibrillation. Circulation. 2003;108:3006–3010.

- , , , et al. Prophylactic Oral Amiodarone for the Prevention of Arrhythmias that Begin Early After Revascularization, Valve Replacement, or Repair: PAPABEAR: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2005;294:3093–3100.

- , , , et al. Atrial fibrillation following coronary artery bypass graft surgery: predictors, outcomes, and resource utilization. MultiCenter Study of Perioperative Ischemia Research Group. JAMA. 1996;276:300–306.

- , , , , . Incidence, predictors, and outcomes associated with postoperative atrial fibrillation after major noncardiac surgery. Am Heart J. 2012;164: 918–924.

- , , , , . Incident stroke and mortality associated with new‐onset atrial fibrillation in patients hospitalized with severe sepsis. JAMA. 2011;306:2248–2254.

- , , . Usefulness of cardiovascular investigations in stroke management: clinical relevance and economic implications. Stroke. 2007;38:1956–1958.

- , , , . Value of cardiac monitoring and echocardiography in TIA and stroke patients. Stroke. 1985;16:950–956.

- , , . Ambulatory electrocardiographic monitoring in patients with transient focal cerebral ischaemia. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1984;47:256–259.

- , , , et al. Continuous stroke unit electrocardiographic monitoring versus 24‐hour holter electrocardiography for detection of paroxysmal atrial fibrillation after stroke. Stroke. 2012;43:2689–2694.

- , , , , . Noninvasive cardiac monitoring for detecting paroxysmal atrial fibrillation or flutter after acute ischemic stroke: a systematic review. Stroke. 2007;38:2935–2940.

- , , , et al. ACC/AHA/ESC 2006 guidelines for the management of patients with atrial fibrillation: full text: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on practice guidelines and the European Society of Cardiology Committee for Practice Guidelines (Writing Committee to Revise the 2001 guidelines for the management of patients with atrial fibrillation) developed in collaboration with the European Heart Rhythm Association and the Heart Rhythm Society. Europace. 2006;8:651–745.

- , , , , , . Histological substrate of atrial biopsies in patients with lone atrial fibrillation. Circulation. 1997;96:1180–1184.

- , , . Role of inflammation in initiation and perpetuation of atrial fibrillation: a systematic review of the published data. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;50:2021–2028.

- , , , et al. Atrial fibrillation after coronary artery bypass grafting is associated with sympathetic activation. Ann Thorac Surg. 1995;60:1709–1715.

- , , , et al. Inflammation of atrium after cardiac surgery is associated with inhomogeneity of atrial conduction and atrial fibrillation. Circulation. 2005;111:2881–2888.

- , , , et al. Obstructive sleep apnea, obesity, and the risk of incident atrial fibrillation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;49:565–571.

- , , , . Mechanisms, prevention, and treatment of atrial fibrillation after cardiac surgery. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;51:793–801.

- , , , . Incidence of arrhythmias after thoracic surgery: thoracotomy versus video‐assisted thoracoscopy. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 1998;12:659–661.

- , , , et al. Delayed detection of atrial fibrillation after ischemic stroke. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2009;18:453–457.

- , , , et al. How useful is thyroid function testing in patients with recent‐onset atrial fibrillation? The Canadian Registry of Atrial Fibrillation Investigators. Arch Intern Med. 1996;156:2221–2224.

- , , , , , . Natriuretic peptide levels in atrial fibrillation: a prospective hormonal and Doppler‐echocardiographic study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2000;35:1256–1262.

- , , . Relationship between brain natriuretic peptide and recurrence of atrial fibrillation after successful electrical cardioversion: a meta‐analysis. J Int Med Res. 2011;39:1618–1624.

- , , , et al. Amiodarone prophylaxis for atrial fibrillation of high‐risk patients after coronary bypass grafting: a prospective, double‐blinded, placebo‐controlled, randomized study. Eur Heart J. 2006;27:1584–1591.

- , , , , . Statin use and postoperative atrial fibrillation after major noncardiac surgery. Heart Rhythm. 2012;9:163–169.

- , , , et al. Guidelines for the prevention of stroke in patients with stroke or transient ischemic attack: a guideline for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2011;42:227–276.

- , , , . Cardioversion of nonrheumatic atrial fibrillation. Reduced thromboembolic complications with 4 weeks of precardioversion anticoagulation are related to atrial thrombus resolution. Circulation. 1995;92:160–163.

- , , , . Left atrial appendage thrombus is not uncommon in patients with acute atrial fibrillation and a recent embolic event: a transesophageal echocardiographic study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1995;25:452–459.

- , , , et al. Impact of electrical cardioversion for atrial fibrillation on left atrial appendage function and spontaneous echo contrast: characterization by simultaneous transesophageal echocardiography. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1993;22:1359–1366.

- , , , . Pulsed Doppler evaluation of atrial mechanical function after electrical cardioversion of atrial fibrillation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1989;13:617–623.

- , , , et al. Detection and characterization of intracardiac thrombi on MR imaging. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2002;179:1539–1544.

- , , , , , . Reversal of rivaroxaban and dabigatran by prothrombin complex concentrate: a randomized, placebo‐controlled, crossover study in healthy subjects. Circulation. 2011;124:1573–1579.

- , , , et al. Conversion of atrial fibrillation to sinus rhythm and rate control by digoxin in comparison to placebo. Eur Heart J. 1997;18:643–648.

- , , , et al. The evidence regarding the drugs used for ventricular rate control. J Fam Pract. 2000;49:47–59.

- , , , , , . Validation of clinical classification schemes for predicting stroke: results from the National Registry of Atrial Fibrillation. JAMA. 2001;285:2864–2870.

- Stroke prevention in atrial fibrillation study. Final results. Circulation. 1991;84:527–539.

- , , , , . Refining clinical risk stratification for predicting stroke and thromboembolism in atrial fibrillation using a novel risk factor‐based approach: the Euro Heart Survey on atrial fibrillation. Chest. 2010;137:263–272.

- , , , , , . A novel user‐friendly score (HAS‐BLED) to assess 1‐year risk of major bleeding in patients with atrial fibrillation: the Euro Heart Survey. Chest. 2010;138:1093–1100.

- , , , . Low molecular‐weight heparin versus aspirin in patients with acute ischaemic stroke and atrial fibrillation: a double‐blind randomised study. HAEST Study Group. Heparin in Acute Embolic Stroke Trial. Lancet. 2000;355:1205–1210.

- The International Stroke Trial (IST): a randomised trial of aspirin, subcutaneous heparin, both, or neither among 19435 patients with acute ischaemic stroke. International Stroke Trial Collaborative Group. Lancet. 1997;349:1569–1581.

- , , , et al. The angiotensin‐receptor blocker candesartan for treatment of acute stroke (SCAST): a randomised, placebo‐controlled, double‐blind trial. Lancet. 2011;377:741–750.

- , , , , . Supraventricular arrhythmia in patients having noncardiac surgery: clinical correlates and effect on length of stay. Ann Intern Med. 1998;129:279–285.

- , , , et al. Risk of death and cardiovascular events in initially healthy women with new‐onset atrial fibrillation. JAMA. 2011;305:2080–2087.

- , , , et al. The impact of postoperative atrial fibrillation on neurocognitive outcome after coronary artery bypass graft surgery. Anesth Analg. 2002;94:290–295, table of contents.

- , , , et al. Prevalence of diagnosed atrial fibrillation in adults: national implications for rhythm management and stroke prevention: the AnTicoagulation and Risk Factors in Atrial Fibrillation (ATRIA) Study. JAMA. 2001;285:2370–2375.

- , , , , . Prevalence, age distribution, and gender of patients with atrial fibrillation. Analysis and implications. Arch Intern Med. 1995;155:469–473.

- , , , et al. Inflammation as a risk factor for atrial fibrillation. Circulation. 2003;108:3006–3010.

- , , , et al. Prophylactic Oral Amiodarone for the Prevention of Arrhythmias that Begin Early After Revascularization, Valve Replacement, or Repair: PAPABEAR: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2005;294:3093–3100.

- , , , et al. Atrial fibrillation following coronary artery bypass graft surgery: predictors, outcomes, and resource utilization. MultiCenter Study of Perioperative Ischemia Research Group. JAMA. 1996;276:300–306.

- , , , , . Incidence, predictors, and outcomes associated with postoperative atrial fibrillation after major noncardiac surgery. Am Heart J. 2012;164: 918–924.

- , , , , . Incident stroke and mortality associated with new‐onset atrial fibrillation in patients hospitalized with severe sepsis. JAMA. 2011;306:2248–2254.

- , , . Usefulness of cardiovascular investigations in stroke management: clinical relevance and economic implications. Stroke. 2007;38:1956–1958.

- , , , . Value of cardiac monitoring and echocardiography in TIA and stroke patients. Stroke. 1985;16:950–956.

- , , . Ambulatory electrocardiographic monitoring in patients with transient focal cerebral ischaemia. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1984;47:256–259.

- , , , et al. Continuous stroke unit electrocardiographic monitoring versus 24‐hour holter electrocardiography for detection of paroxysmal atrial fibrillation after stroke. Stroke. 2012;43:2689–2694.

- , , , , . Noninvasive cardiac monitoring for detecting paroxysmal atrial fibrillation or flutter after acute ischemic stroke: a systematic review. Stroke. 2007;38:2935–2940.

- , , , et al. ACC/AHA/ESC 2006 guidelines for the management of patients with atrial fibrillation: full text: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on practice guidelines and the European Society of Cardiology Committee for Practice Guidelines (Writing Committee to Revise the 2001 guidelines for the management of patients with atrial fibrillation) developed in collaboration with the European Heart Rhythm Association and the Heart Rhythm Society. Europace. 2006;8:651–745.

- , , , , , . Histological substrate of atrial biopsies in patients with lone atrial fibrillation. Circulation. 1997;96:1180–1184.

- , , . Role of inflammation in initiation and perpetuation of atrial fibrillation: a systematic review of the published data. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;50:2021–2028.

- , , , et al. Atrial fibrillation after coronary artery bypass grafting is associated with sympathetic activation. Ann Thorac Surg. 1995;60:1709–1715.

- , , , et al. Inflammation of atrium after cardiac surgery is associated with inhomogeneity of atrial conduction and atrial fibrillation. Circulation. 2005;111:2881–2888.

- , , , et al. Obstructive sleep apnea, obesity, and the risk of incident atrial fibrillation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;49:565–571.

- , , , . Mechanisms, prevention, and treatment of atrial fibrillation after cardiac surgery. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;51:793–801.

- , , , . Incidence of arrhythmias after thoracic surgery: thoracotomy versus video‐assisted thoracoscopy. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 1998;12:659–661.

- , , , et al. Delayed detection of atrial fibrillation after ischemic stroke. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2009;18:453–457.

- , , , et al. How useful is thyroid function testing in patients with recent‐onset atrial fibrillation? The Canadian Registry of Atrial Fibrillation Investigators. Arch Intern Med. 1996;156:2221–2224.

- , , , , , . Natriuretic peptide levels in atrial fibrillation: a prospective hormonal and Doppler‐echocardiographic study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2000;35:1256–1262.

- , , . Relationship between brain natriuretic peptide and recurrence of atrial fibrillation after successful electrical cardioversion: a meta‐analysis. J Int Med Res. 2011;39:1618–1624.