User login

Curriculum Vitae 101

By now, if you’re a final-year resident, you should be thinking about your plans for when you finish your residency. Before you begin the job search in earnest, it’s a good idea to create or update your curriculum vitae, or CV. You might be thinking, “That’s easy. I haven’t done anything yet!” That might be the case, but in reality, you probably have done more than you realize.

Whether you are just starting out or need to freshen a rough draft, here are some recommendations for creating a CV.

Brainstorm

The first step is to capture all the things you have done. Start by taking a sheet of paper and making columns with the following headings: licensure/documents, honors and awards, presentations/publications, research activities, committees, teaching, community service, and special skills. List each of the things you’ve done in each category.

Don’t be modest. You have to sell yourself. No item is too small for consideration for your CV at this stage. Get together with other people in your residency class and brainstorm together. They might help you think of certain activities that you have not already thought about. Here are some key points to keep in mind as you brainstorm each section:

- Licensure/documents: If you haven’t obtained a license in the state where you want to practice, now is the time to do it. Make sure advanced cardiac life support (ACLS) and BLS are current. If you haven’t taken your board exam, mention that you are board-eligible and include the date you plan to take the exam.

- Honors and awards: You don’t have to receive a trophy at a fancy awards ceremony to fill out this section. Did you ever receive a letter from the department chair, program director, or clerkship director giving you a special commendation? Such recognition might be worth a mention.

- Presentations and publications: If you have been published, include the citation here. Many residents present posters at regional meetings; this information should go in your CV. Have you given a presentation for “Morning Report” or a “Morbidity and Mortality Conference”? If so, these count as presentations, too. Many residents have written Web-based materials. Cite these as well.

- Teaching: Consider all the activities you perform for medical students. Have you given the students any prepared lectures? Have you been a preceptor for their physical exam labs? Have you provided mentorship for a student? Significant time spent mentoring also should be reflected on a resident’s CV.

- Research: QI projects generally count as HM research projects.

- Committees: Think about all the meetings you’ve attended and determine if any of them count as providing services to the residency or hospital.

- Special skills: Proficiency in thoracocentesis or lumbar puncture procedures qualifies for this section. If you speak a second (or third, fourth, etc.) language, include it here.

Rough Draft = First Attempt

Now that you have gathered your information, it’s time to organize it. Web-based resources and templates are plentiful, and many can help you write the CV. If you are applying for an academic position, you will need to keep a detailed CV. If you are not applying for an academic position, it is best to keep your CV at no more than two pages in length; however, you might want to keep a comprehensive (and lengthier) version on file.

Maintain a Career Folder

Once you’ve created your first CV, you will need to develop a system to update and maintain the document. The easiest way to do this is to keep a “career folder” on your desktop or in a filing cabinet. This will help you catalog all the extra things you’ve done throughout your career.

Write notes to yourself, with the date and time spent on certain activities. Then, at regular intervals, document them on your CV. It’s best to update your CV every six months.

The career file also can be used to keep evaluations, letters from patients, or anything else that exemplifies your accomplishments at work. Having a system for organizing your achievements will help you negotiate a raise and assist with future promotions or tenure.

Cover Letter

A cover letter should be no more than three to four paragraphs in length. Keep it simple and to the point. Briefly state how you heard about the job opening and why you are interested in the job.

Take a paragraph to identify the skills and experience you have to offer the HM group. The final paragraph should be used to explain how you intend to follow up and the best way you can be reached (phone, e-mail, etc.) to arrange an interview.

Interview Tips

A well-written CV can lead to several interview offers. Here are some important tips to help you obtain that all-important job offer:

- Have a clear vision. It’s important to know what you are looking for. Having clear goals will help you know exactly the kind of job you want and avoid wasting time and energy.

- Set aside time for a phone interview. You can learn a lot about an HM program during this time; give the interviewer a chance to learn about you, too. Use this step to screen out those places you really want to visit in person.

- Show up on time. Give yourself enough time to reach your destination, park, and find the meeting location. If possible, take a test drive a day or two before.

- Remember, your appearance matters. Dress professionally in conservative business attire. Furthermore, always act professional. Avoid negative talk about past attendings or employers. If you are going out for lunch, avoid ordering alcohol.

- Write down questions to ask. This will give you more clarity and ensure that all of your questions regarding the prospective job are answered.

- Show interest in the program. Ask appropriate questions, even if you have all the information you need. Don’t leave without asking about the next steps in the hiring process.

- Talk about money last. Contrary to popular belief, it’s OK to bring up the topic of money during an interview. Just don’t make it your first—and only—question.

- Check out the town. Bring your spouse or partner to explore a prospective relocation site. Look into housing, schools, your potential commute, and recreational activities. TH

Dr. Garcia is assistant professor in the division of hospital medicine at the University of Texas Health Sciences Center at San Antonio. Dr. Patel is a hospitalist at HPMG Regions Hospital and assistant professor of medicine at the University of Minnesota in St. Paul.

Image Source: CHAGIN/ISTOCKPHOTO.COM

By now, if you’re a final-year resident, you should be thinking about your plans for when you finish your residency. Before you begin the job search in earnest, it’s a good idea to create or update your curriculum vitae, or CV. You might be thinking, “That’s easy. I haven’t done anything yet!” That might be the case, but in reality, you probably have done more than you realize.

Whether you are just starting out or need to freshen a rough draft, here are some recommendations for creating a CV.

Brainstorm

The first step is to capture all the things you have done. Start by taking a sheet of paper and making columns with the following headings: licensure/documents, honors and awards, presentations/publications, research activities, committees, teaching, community service, and special skills. List each of the things you’ve done in each category.

Don’t be modest. You have to sell yourself. No item is too small for consideration for your CV at this stage. Get together with other people in your residency class and brainstorm together. They might help you think of certain activities that you have not already thought about. Here are some key points to keep in mind as you brainstorm each section:

- Licensure/documents: If you haven’t obtained a license in the state where you want to practice, now is the time to do it. Make sure advanced cardiac life support (ACLS) and BLS are current. If you haven’t taken your board exam, mention that you are board-eligible and include the date you plan to take the exam.

- Honors and awards: You don’t have to receive a trophy at a fancy awards ceremony to fill out this section. Did you ever receive a letter from the department chair, program director, or clerkship director giving you a special commendation? Such recognition might be worth a mention.

- Presentations and publications: If you have been published, include the citation here. Many residents present posters at regional meetings; this information should go in your CV. Have you given a presentation for “Morning Report” or a “Morbidity and Mortality Conference”? If so, these count as presentations, too. Many residents have written Web-based materials. Cite these as well.

- Teaching: Consider all the activities you perform for medical students. Have you given the students any prepared lectures? Have you been a preceptor for their physical exam labs? Have you provided mentorship for a student? Significant time spent mentoring also should be reflected on a resident’s CV.

- Research: QI projects generally count as HM research projects.

- Committees: Think about all the meetings you’ve attended and determine if any of them count as providing services to the residency or hospital.

- Special skills: Proficiency in thoracocentesis or lumbar puncture procedures qualifies for this section. If you speak a second (or third, fourth, etc.) language, include it here.

Rough Draft = First Attempt

Now that you have gathered your information, it’s time to organize it. Web-based resources and templates are plentiful, and many can help you write the CV. If you are applying for an academic position, you will need to keep a detailed CV. If you are not applying for an academic position, it is best to keep your CV at no more than two pages in length; however, you might want to keep a comprehensive (and lengthier) version on file.

Maintain a Career Folder

Once you’ve created your first CV, you will need to develop a system to update and maintain the document. The easiest way to do this is to keep a “career folder” on your desktop or in a filing cabinet. This will help you catalog all the extra things you’ve done throughout your career.

Write notes to yourself, with the date and time spent on certain activities. Then, at regular intervals, document them on your CV. It’s best to update your CV every six months.

The career file also can be used to keep evaluations, letters from patients, or anything else that exemplifies your accomplishments at work. Having a system for organizing your achievements will help you negotiate a raise and assist with future promotions or tenure.

Cover Letter

A cover letter should be no more than three to four paragraphs in length. Keep it simple and to the point. Briefly state how you heard about the job opening and why you are interested in the job.

Take a paragraph to identify the skills and experience you have to offer the HM group. The final paragraph should be used to explain how you intend to follow up and the best way you can be reached (phone, e-mail, etc.) to arrange an interview.

Interview Tips

A well-written CV can lead to several interview offers. Here are some important tips to help you obtain that all-important job offer:

- Have a clear vision. It’s important to know what you are looking for. Having clear goals will help you know exactly the kind of job you want and avoid wasting time and energy.

- Set aside time for a phone interview. You can learn a lot about an HM program during this time; give the interviewer a chance to learn about you, too. Use this step to screen out those places you really want to visit in person.

- Show up on time. Give yourself enough time to reach your destination, park, and find the meeting location. If possible, take a test drive a day or two before.

- Remember, your appearance matters. Dress professionally in conservative business attire. Furthermore, always act professional. Avoid negative talk about past attendings or employers. If you are going out for lunch, avoid ordering alcohol.

- Write down questions to ask. This will give you more clarity and ensure that all of your questions regarding the prospective job are answered.

- Show interest in the program. Ask appropriate questions, even if you have all the information you need. Don’t leave without asking about the next steps in the hiring process.

- Talk about money last. Contrary to popular belief, it’s OK to bring up the topic of money during an interview. Just don’t make it your first—and only—question.

- Check out the town. Bring your spouse or partner to explore a prospective relocation site. Look into housing, schools, your potential commute, and recreational activities. TH

Dr. Garcia is assistant professor in the division of hospital medicine at the University of Texas Health Sciences Center at San Antonio. Dr. Patel is a hospitalist at HPMG Regions Hospital and assistant professor of medicine at the University of Minnesota in St. Paul.

Image Source: CHAGIN/ISTOCKPHOTO.COM

By now, if you’re a final-year resident, you should be thinking about your plans for when you finish your residency. Before you begin the job search in earnest, it’s a good idea to create or update your curriculum vitae, or CV. You might be thinking, “That’s easy. I haven’t done anything yet!” That might be the case, but in reality, you probably have done more than you realize.

Whether you are just starting out or need to freshen a rough draft, here are some recommendations for creating a CV.

Brainstorm

The first step is to capture all the things you have done. Start by taking a sheet of paper and making columns with the following headings: licensure/documents, honors and awards, presentations/publications, research activities, committees, teaching, community service, and special skills. List each of the things you’ve done in each category.

Don’t be modest. You have to sell yourself. No item is too small for consideration for your CV at this stage. Get together with other people in your residency class and brainstorm together. They might help you think of certain activities that you have not already thought about. Here are some key points to keep in mind as you brainstorm each section:

- Licensure/documents: If you haven’t obtained a license in the state where you want to practice, now is the time to do it. Make sure advanced cardiac life support (ACLS) and BLS are current. If you haven’t taken your board exam, mention that you are board-eligible and include the date you plan to take the exam.

- Honors and awards: You don’t have to receive a trophy at a fancy awards ceremony to fill out this section. Did you ever receive a letter from the department chair, program director, or clerkship director giving you a special commendation? Such recognition might be worth a mention.

- Presentations and publications: If you have been published, include the citation here. Many residents present posters at regional meetings; this information should go in your CV. Have you given a presentation for “Morning Report” or a “Morbidity and Mortality Conference”? If so, these count as presentations, too. Many residents have written Web-based materials. Cite these as well.

- Teaching: Consider all the activities you perform for medical students. Have you given the students any prepared lectures? Have you been a preceptor for their physical exam labs? Have you provided mentorship for a student? Significant time spent mentoring also should be reflected on a resident’s CV.

- Research: QI projects generally count as HM research projects.

- Committees: Think about all the meetings you’ve attended and determine if any of them count as providing services to the residency or hospital.

- Special skills: Proficiency in thoracocentesis or lumbar puncture procedures qualifies for this section. If you speak a second (or third, fourth, etc.) language, include it here.

Rough Draft = First Attempt

Now that you have gathered your information, it’s time to organize it. Web-based resources and templates are plentiful, and many can help you write the CV. If you are applying for an academic position, you will need to keep a detailed CV. If you are not applying for an academic position, it is best to keep your CV at no more than two pages in length; however, you might want to keep a comprehensive (and lengthier) version on file.

Maintain a Career Folder

Once you’ve created your first CV, you will need to develop a system to update and maintain the document. The easiest way to do this is to keep a “career folder” on your desktop or in a filing cabinet. This will help you catalog all the extra things you’ve done throughout your career.

Write notes to yourself, with the date and time spent on certain activities. Then, at regular intervals, document them on your CV. It’s best to update your CV every six months.

The career file also can be used to keep evaluations, letters from patients, or anything else that exemplifies your accomplishments at work. Having a system for organizing your achievements will help you negotiate a raise and assist with future promotions or tenure.

Cover Letter

A cover letter should be no more than three to four paragraphs in length. Keep it simple and to the point. Briefly state how you heard about the job opening and why you are interested in the job.

Take a paragraph to identify the skills and experience you have to offer the HM group. The final paragraph should be used to explain how you intend to follow up and the best way you can be reached (phone, e-mail, etc.) to arrange an interview.

Interview Tips

A well-written CV can lead to several interview offers. Here are some important tips to help you obtain that all-important job offer:

- Have a clear vision. It’s important to know what you are looking for. Having clear goals will help you know exactly the kind of job you want and avoid wasting time and energy.

- Set aside time for a phone interview. You can learn a lot about an HM program during this time; give the interviewer a chance to learn about you, too. Use this step to screen out those places you really want to visit in person.

- Show up on time. Give yourself enough time to reach your destination, park, and find the meeting location. If possible, take a test drive a day or two before.

- Remember, your appearance matters. Dress professionally in conservative business attire. Furthermore, always act professional. Avoid negative talk about past attendings or employers. If you are going out for lunch, avoid ordering alcohol.

- Write down questions to ask. This will give you more clarity and ensure that all of your questions regarding the prospective job are answered.

- Show interest in the program. Ask appropriate questions, even if you have all the information you need. Don’t leave without asking about the next steps in the hiring process.

- Talk about money last. Contrary to popular belief, it’s OK to bring up the topic of money during an interview. Just don’t make it your first—and only—question.

- Check out the town. Bring your spouse or partner to explore a prospective relocation site. Look into housing, schools, your potential commute, and recreational activities. TH

Dr. Garcia is assistant professor in the division of hospital medicine at the University of Texas Health Sciences Center at San Antonio. Dr. Patel is a hospitalist at HPMG Regions Hospital and assistant professor of medicine at the University of Minnesota in St. Paul.

Image Source: CHAGIN/ISTOCKPHOTO.COM

Market Watch

Discontinued Products

- Amoxicillin powder for oral suspension and pediatric drops for oral suspension1

- Amoxicillin powder for oral suspension (Amoxil brand usually for adults), 250mg/5mL (100mL and 150mL sizes)2

- Insulin isophane suspension (Humulin 50/50), due to limited use.3 Current patient demand and existing inventory note product availability through April 2010. There are about 3,000 patients in the U.S. who will be affected by this action.

- Phenytoin 30 mg (Dilantin Kapseals brand) are being reformulated in a new, extended-release formulation, but Kapseals will be discontinued.4

New Generics

- Tacrolimus (generic Prograf) capsules5

New Drugs, Indications, and Dosage Forms

- Asenapine tablets (Saphris) have been approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to treat adults with schizophrenia and bipolar I disorder. The most common adverse effects in trials were akathisia, oral hypoesthesia, and somnolence. The most common adverse effects that were reported in the bipolar disorder trials were somnolence, dizziness, movement disorders other than akathisia, and weight gain.6

- Colchicine 0.6 mg tablets (Colcrys) have been approved by the FDA to treat gout flares and familial Mediterranean fever.7 Colchicine has been used for many years but has not received FDA approval until recently. The FDA is re-evaluating some older drugs and drug classes. For example, the pancrelipase products fall under a similar ruling. Now that colchicine is approved, the manufacturer has shown that it meets modern standards for safety, effectiveness, quality, and labeling. Historically, physicians have administered colchicine hourly to treat acute gout flares until symptoms subsided or the patient developed adverse gastrointestinal symptoms. A dosing study determined that one 1.2-mg dose of this formulation followed by 0.6 mg one hour later was as effective as hourly dosing in patients without renal or hepatic dysfunction. This two-dose regimen was less toxic than prior dosing regimens and, therefore, it received the FDA’s approval.8

- Fentanyl buccal soluble film (Onsolis) has been approved by the FDA as an opioid for managing breakthrough cancer pain in patients 18 years and older who already are receiving and are tolerant to opioid therapy.9 It is available in 200-, 400-, 600-, 800- and 1,200-mcg strengths. A Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategies (REMS) will be available with dispensing.

- Insulin aspart injection (NovoLog) has undergone a label change. NovoLog can now be used in an insulin pump for up to six days. The infusion set should be changed at least every three days. The updated label includes information about discarding the drug if temperatures exceed 37oC (98.6oF).10

- Interferon beta-1b injection (Extavia): A new brand of interferon has been approved by the FDA for treating relapsing forms of multiple sclerosis (MS), as well as for patients who have experienced a first clinical episode of MS with magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) features consistent of the disease.11

- Morphine/naltrexone capsules (Embeda), a long-acting opioid designed to reduce drug euphoria, have been approved by the FDA to treat moderate to severe chronic pain. It was developed with the abuse-deterrent drug naltrexone, which reduces euphoria when crushed or chewed.12

- Pitavastatin 4 mg (Livalo) has been approved by the FDA to treat hypercholesterolemia and combined dyslipidemia.13 It’s a potent statin with a new base structure. Additionally, it is only minimally metabolized by the cytochrome P450 (CYP) pathway. It will be available in early 2010 in 1-, 2- and 4-mg strengths. Only time will tell whether this is truly a benefit for this new agent.

- Saxagliptin (Onglyza), a new oral dipeptidyl peptidase-4 (DPP-4) inhibitor, has been approved by the FDA to treat Type 2 diabetes mellitus as an adjunct to diet and exercise.14 It is administered once daily at a starting dose of 2.5 mg or 5 mg, without regard to meal.15 The lower dose is recommended in patients with moderate to severe renal impairment or end-stage renal disease (CrCL < 50 mL/min). The lower dose (2.5 mg) also is recommended for patients taking strong CYP3A4/5 inhibitors (e.g., ketoconazole, atazanavir, clarithromycin, indinavir, itraconazole, nefazodone, nelfinavir, ritonavir, saquinavir, or telithromycin). The most common adverse effects in clinical trials were respiratory tract infection, urinary tract infection, and headache.

Pipeline

- Roflumilast (Daxas), a phosphodiesterase 4 enzyme inhibitor, has been submitted to the FDA. It is a once-daily oral treatment for patients with symptomatic chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD).16

- Tocilizumab (Actemra), an interleukin-6 receptor-inhibiting monoclonal antibody to treat rheumatoid arthritis (RA), has been approved for use in Europe. Its manufacturer has announced that the FDA has accepted its reapplication for treating moderate to severe RA. It is available in Japan for treating RA, juvenile idiopathic arthritis, and Castleman’s disease.17

- TZP-102, an investigational oral prokinetic agent for treating diabetic gastroparesis, has received FDA fast-track status. A multinational study is under way for this ghrelin receptor agonist.18 TH

Michele B. Kaufman, PharmD, BSc, RPh, is a freelance medical writer based in New York City and a clinical pharmacist at New York Downtown Hospital.

Discontinued Products

- Amoxicillin powder for oral suspension and pediatric drops for oral suspension1

- Amoxicillin powder for oral suspension (Amoxil brand usually for adults), 250mg/5mL (100mL and 150mL sizes)2

- Insulin isophane suspension (Humulin 50/50), due to limited use.3 Current patient demand and existing inventory note product availability through April 2010. There are about 3,000 patients in the U.S. who will be affected by this action.

- Phenytoin 30 mg (Dilantin Kapseals brand) are being reformulated in a new, extended-release formulation, but Kapseals will be discontinued.4

New Generics

- Tacrolimus (generic Prograf) capsules5

New Drugs, Indications, and Dosage Forms

- Asenapine tablets (Saphris) have been approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to treat adults with schizophrenia and bipolar I disorder. The most common adverse effects in trials were akathisia, oral hypoesthesia, and somnolence. The most common adverse effects that were reported in the bipolar disorder trials were somnolence, dizziness, movement disorders other than akathisia, and weight gain.6

- Colchicine 0.6 mg tablets (Colcrys) have been approved by the FDA to treat gout flares and familial Mediterranean fever.7 Colchicine has been used for many years but has not received FDA approval until recently. The FDA is re-evaluating some older drugs and drug classes. For example, the pancrelipase products fall under a similar ruling. Now that colchicine is approved, the manufacturer has shown that it meets modern standards for safety, effectiveness, quality, and labeling. Historically, physicians have administered colchicine hourly to treat acute gout flares until symptoms subsided or the patient developed adverse gastrointestinal symptoms. A dosing study determined that one 1.2-mg dose of this formulation followed by 0.6 mg one hour later was as effective as hourly dosing in patients without renal or hepatic dysfunction. This two-dose regimen was less toxic than prior dosing regimens and, therefore, it received the FDA’s approval.8

- Fentanyl buccal soluble film (Onsolis) has been approved by the FDA as an opioid for managing breakthrough cancer pain in patients 18 years and older who already are receiving and are tolerant to opioid therapy.9 It is available in 200-, 400-, 600-, 800- and 1,200-mcg strengths. A Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategies (REMS) will be available with dispensing.

- Insulin aspart injection (NovoLog) has undergone a label change. NovoLog can now be used in an insulin pump for up to six days. The infusion set should be changed at least every three days. The updated label includes information about discarding the drug if temperatures exceed 37oC (98.6oF).10

- Interferon beta-1b injection (Extavia): A new brand of interferon has been approved by the FDA for treating relapsing forms of multiple sclerosis (MS), as well as for patients who have experienced a first clinical episode of MS with magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) features consistent of the disease.11

- Morphine/naltrexone capsules (Embeda), a long-acting opioid designed to reduce drug euphoria, have been approved by the FDA to treat moderate to severe chronic pain. It was developed with the abuse-deterrent drug naltrexone, which reduces euphoria when crushed or chewed.12

- Pitavastatin 4 mg (Livalo) has been approved by the FDA to treat hypercholesterolemia and combined dyslipidemia.13 It’s a potent statin with a new base structure. Additionally, it is only minimally metabolized by the cytochrome P450 (CYP) pathway. It will be available in early 2010 in 1-, 2- and 4-mg strengths. Only time will tell whether this is truly a benefit for this new agent.

- Saxagliptin (Onglyza), a new oral dipeptidyl peptidase-4 (DPP-4) inhibitor, has been approved by the FDA to treat Type 2 diabetes mellitus as an adjunct to diet and exercise.14 It is administered once daily at a starting dose of 2.5 mg or 5 mg, without regard to meal.15 The lower dose is recommended in patients with moderate to severe renal impairment or end-stage renal disease (CrCL < 50 mL/min). The lower dose (2.5 mg) also is recommended for patients taking strong CYP3A4/5 inhibitors (e.g., ketoconazole, atazanavir, clarithromycin, indinavir, itraconazole, nefazodone, nelfinavir, ritonavir, saquinavir, or telithromycin). The most common adverse effects in clinical trials were respiratory tract infection, urinary tract infection, and headache.

Pipeline

- Roflumilast (Daxas), a phosphodiesterase 4 enzyme inhibitor, has been submitted to the FDA. It is a once-daily oral treatment for patients with symptomatic chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD).16

- Tocilizumab (Actemra), an interleukin-6 receptor-inhibiting monoclonal antibody to treat rheumatoid arthritis (RA), has been approved for use in Europe. Its manufacturer has announced that the FDA has accepted its reapplication for treating moderate to severe RA. It is available in Japan for treating RA, juvenile idiopathic arthritis, and Castleman’s disease.17

- TZP-102, an investigational oral prokinetic agent for treating diabetic gastroparesis, has received FDA fast-track status. A multinational study is under way for this ghrelin receptor agonist.18 TH

Michele B. Kaufman, PharmD, BSc, RPh, is a freelance medical writer based in New York City and a clinical pharmacist at New York Downtown Hospital.

Discontinued Products

- Amoxicillin powder for oral suspension and pediatric drops for oral suspension1

- Amoxicillin powder for oral suspension (Amoxil brand usually for adults), 250mg/5mL (100mL and 150mL sizes)2

- Insulin isophane suspension (Humulin 50/50), due to limited use.3 Current patient demand and existing inventory note product availability through April 2010. There are about 3,000 patients in the U.S. who will be affected by this action.

- Phenytoin 30 mg (Dilantin Kapseals brand) are being reformulated in a new, extended-release formulation, but Kapseals will be discontinued.4

New Generics

- Tacrolimus (generic Prograf) capsules5

New Drugs, Indications, and Dosage Forms

- Asenapine tablets (Saphris) have been approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to treat adults with schizophrenia and bipolar I disorder. The most common adverse effects in trials were akathisia, oral hypoesthesia, and somnolence. The most common adverse effects that were reported in the bipolar disorder trials were somnolence, dizziness, movement disorders other than akathisia, and weight gain.6

- Colchicine 0.6 mg tablets (Colcrys) have been approved by the FDA to treat gout flares and familial Mediterranean fever.7 Colchicine has been used for many years but has not received FDA approval until recently. The FDA is re-evaluating some older drugs and drug classes. For example, the pancrelipase products fall under a similar ruling. Now that colchicine is approved, the manufacturer has shown that it meets modern standards for safety, effectiveness, quality, and labeling. Historically, physicians have administered colchicine hourly to treat acute gout flares until symptoms subsided or the patient developed adverse gastrointestinal symptoms. A dosing study determined that one 1.2-mg dose of this formulation followed by 0.6 mg one hour later was as effective as hourly dosing in patients without renal or hepatic dysfunction. This two-dose regimen was less toxic than prior dosing regimens and, therefore, it received the FDA’s approval.8

- Fentanyl buccal soluble film (Onsolis) has been approved by the FDA as an opioid for managing breakthrough cancer pain in patients 18 years and older who already are receiving and are tolerant to opioid therapy.9 It is available in 200-, 400-, 600-, 800- and 1,200-mcg strengths. A Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategies (REMS) will be available with dispensing.

- Insulin aspart injection (NovoLog) has undergone a label change. NovoLog can now be used in an insulin pump for up to six days. The infusion set should be changed at least every three days. The updated label includes information about discarding the drug if temperatures exceed 37oC (98.6oF).10

- Interferon beta-1b injection (Extavia): A new brand of interferon has been approved by the FDA for treating relapsing forms of multiple sclerosis (MS), as well as for patients who have experienced a first clinical episode of MS with magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) features consistent of the disease.11

- Morphine/naltrexone capsules (Embeda), a long-acting opioid designed to reduce drug euphoria, have been approved by the FDA to treat moderate to severe chronic pain. It was developed with the abuse-deterrent drug naltrexone, which reduces euphoria when crushed or chewed.12

- Pitavastatin 4 mg (Livalo) has been approved by the FDA to treat hypercholesterolemia and combined dyslipidemia.13 It’s a potent statin with a new base structure. Additionally, it is only minimally metabolized by the cytochrome P450 (CYP) pathway. It will be available in early 2010 in 1-, 2- and 4-mg strengths. Only time will tell whether this is truly a benefit for this new agent.

- Saxagliptin (Onglyza), a new oral dipeptidyl peptidase-4 (DPP-4) inhibitor, has been approved by the FDA to treat Type 2 diabetes mellitus as an adjunct to diet and exercise.14 It is administered once daily at a starting dose of 2.5 mg or 5 mg, without regard to meal.15 The lower dose is recommended in patients with moderate to severe renal impairment or end-stage renal disease (CrCL < 50 mL/min). The lower dose (2.5 mg) also is recommended for patients taking strong CYP3A4/5 inhibitors (e.g., ketoconazole, atazanavir, clarithromycin, indinavir, itraconazole, nefazodone, nelfinavir, ritonavir, saquinavir, or telithromycin). The most common adverse effects in clinical trials were respiratory tract infection, urinary tract infection, and headache.

Pipeline

- Roflumilast (Daxas), a phosphodiesterase 4 enzyme inhibitor, has been submitted to the FDA. It is a once-daily oral treatment for patients with symptomatic chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD).16

- Tocilizumab (Actemra), an interleukin-6 receptor-inhibiting monoclonal antibody to treat rheumatoid arthritis (RA), has been approved for use in Europe. Its manufacturer has announced that the FDA has accepted its reapplication for treating moderate to severe RA. It is available in Japan for treating RA, juvenile idiopathic arthritis, and Castleman’s disease.17

- TZP-102, an investigational oral prokinetic agent for treating diabetic gastroparesis, has received FDA fast-track status. A multinational study is under way for this ghrelin receptor agonist.18 TH

Michele B. Kaufman, PharmD, BSc, RPh, is a freelance medical writer based in New York City and a clinical pharmacist at New York Downtown Hospital.

What is the appropriate use of chronic medications in the perioperative setting?

Case

A 72-year-old female with multiple medical problems is admitted with a hip fracture. Surgery is scheduled in 48 hours. The patient’s home medications include aspirin, carbidopa/levodopa, celecoxib, clonidine, estradiol, ginkgo, lisinopril, NPH insulin, sulfasalazine, and prednisone 10 mg a day, which she has been taking for years. How should these and other medications be managed in the perioperative period?

Background

Perioperative management of chronic medications is a complex issue, as physicians are required to balance the beneficial and harmful effects of the individual drugs prescribed to their patients. On one hand, cessation of medications can result in decompensation of disease or withdrawal. On the other hand, continuation of drugs can alter metabolism of anesthetic agents, cause perioperative hemodynamic instability, or result in such post-operative complications as acute renal failure, bleeding, infection, and impaired wound healing.

Certain traits make it reasonable to continue medications during the perioperative period. A long elimination half-life or duration of action makes stopping some medications impractical as it takes four to five half-lives to completely clear the drug from the body; holding the drug for a few days around surgery will not appreciably affect its concentration. Stopping drugs that carry severe withdrawal symptoms can be impractical because of the need for lengthy tapers, which can delay surgery and result in decompensation of underlying disease.

Drugs with no significant interactions with anesthesia or risk of perioperative complications should be continued in order to avoid deterioration of the underlying disease. Conversely, drugs that interact with anesthesia or increase risk for complications should be stopped if this can be accomplished safely. Patient-specific factors should receive consideration, as the risk of complications has to be balanced against the danger of exacerbating the underlying disease.

Overview of the Data

The challenge in providing recommendations on perioperative medication management lies in a dearth of high-quality clinical trials. Thus, much of the information comes from case reports, expert opinion, and sound application of pharmacology.

Antiplatelet therapy: Nuances of perioperative antiplatelet therapy are beyond the scope of this review, but some general principles can be elucidated from the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association (ACC/AHA) 2007 perioperative guidelines.1 Management of antiplatelet therapy should be done in conjunction with the surgical team, as cardiovascular risk has to be weighed against bleeding risk.

Aspirin therapy should be continued in all patients with a history of coronary artery disease (CAD), balloon angioplasty, or percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI), unless the risk of bleeding complications is felt to exceed the cardioprotective benefits—for example, in some neurosurgical patients.1

Clopidogrel therapy is crucial for prevention of in-stent thrombosis (IST) following PCI because patients who experience IST suffer catastrophic myocardial infarctions with high mortality. Ideally, surgery should be delayed to permit completion of clopidogrel therapy—30 to 45 days after implantation of a bare-metal stent and 365 days after a drug-eluting stent. If surgery has to be performed sooner, guidelines recommend operating on dual antiplatelet therapy with aspirin and clopidogrel.1 Again, this course of treatment has to be balanced against the risk of hemorrhagic complications from surgery.

Both aspirin and clopidogrel irreversibly inhibit platelet aggregation. The recovery of normal coagulation involves formation of new platelets, which necessitates cessation of therapy for seven to 10 days before surgery. Platelet inhibition begins within minutes of restarting aspirin and within hours of taking clopidogrel, although attaining peak clopidogrel effect takes three to seven days, unless a loading dose is used.

Cardiovascular Drugs

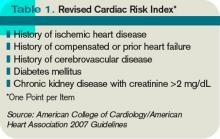

Beta-blockers in the perioperative setting are a focus of an ongoing debate beyond the scope of this review (see “What Pre-Operative Cardiac Evaluation of Patients Undergoing Intermediate-Risk Surgery Is Most Effective?,” February 2008, p. 26). Given the current evidence and the latest ACC/AHA guidelines, it is still reasonable to continue therapy in patients who are already taking them to avoid precipitating cardiovascular events by withdrawal. Patients with increased cardiac risk, demonstrated by a Revised Cardiac Risk Index (RCRI) score of ≥2 (see Table 1, p. 12), should be considered for beta-blocker therapy before surgery.1 In either case, the dose should be titrated to a heart rate <65 for optimal cardiac protection.1

Statins should be continued if the patient is taking them, especially because preoperative withdrawal has been associated with a 4.6-fold increase in troponin release and a 7.5-fold increased risk of myocardial infarction (MI) and cardiovascular death following major vascular surgery.2 Patients with increased cardiac risk— RCRI ≥1—can be considered for initiation of statin therapy before surgery, although the benefit of this intervention has not been examined in prospective studies.1

Amiodarone has an exceptionally long half-life of up to 142 days. It should be continued in the perioperative period.

Calcium channel blockers (CCBs) can be continued with no unpleasant perioperative hemodynamic effects.1 CCBs have potential cardioprotective benefits.

Clonidine withdrawal can result in severe rebound hypertension with reports of encephalopathy, stroke, and death. These effects are exacerbated by concomitant beta-blocker therapy. For this reason, if a patient is expected to be NPO for more than 12 hours, they should be converted to a clonidine patch 48-72 hours before surgery with concurrent tapering of the oral dose.3

Digoxin has a long half-life (up to 48 hours) and should be continued with monitoring of levels if there is a change in renal function.

Angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEI) and angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs) have been associated with a 50% increased risk of hypotension requiring vasopressors during induction of anesthesia.4 However, it is worth mentioning that this finding has not been corroborated in other studies. A large retrospective cohort of cardiothoracic surgical patients found a 28% increased risk of post-operative acute renal failure (ARF) with both drug classes, although another cardiothoracic report published the same year demonstrated a 50% reduction in risk with ACEIs.5,6 Although the evidence of harm is not unequivocal, perioperative blood-pressure control can be achieved with other drugs without hemodynamic or renal risk, such as CCBs, and in most cases ACEIs/ARBs should be stopped one day before surgery.

Diuretics carry a risk of volume depletion and electrolyte derangements, and should be stopped once a patient becomes NPO. Excess volume is managed with as-needed intravenous formulations.

Drugs Acting on the Central Nervous System

The majority of central nervous system (CNS)-active drugs, including antiepileptics, antipsychotics, benzodiazepines, bupropion, gabapentin, lithium, mirtazapine, selective serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs and SNRIs), tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs), and valproic acid, balance a low risk of perioperative complications against a significant potential for withdrawal and disease decompensation. Therefore, these medications should be continued.

Carbidopa/Levodopa should be continued because abrupt cessation can precipitate systemic withdrawal resembling serotonin syndrome and rapid deterioration of Parkinson’s symptoms.

Monoamine oxidase inhibitor (MAOI) therapy usually indicates refractory psychiatric illness, so these drugs should be continued to avoid decompensation. Importantly, MAOI-safe anesthesia without dextromethorphan, meperidine, epinephrine, or norepinephrine has to be used due to the risk of cardiovascular instability.7

Diabetic Drugs

Insulin therapy should be continued with adjustments. Glargine basal insulin has no peak and can be continued without changing the dose. Likewise, patients with insulin pumps can continue the usual basal rate. Short-acting insulin or such insulin mixes as 70/30 should be stopped four hours before surgery to avoid hypoglycemia. Intermediate-acting insulin (e.g., NPH) can be administered at half the usual dose the day of surgery with a perioperative 5% dextrose infusion. NPH should not be given the day of surgery if the dextrose infusion cannot be used.8

Incretins (exenatide, sitagliptin) rarely cause hypoglycemia in the absence of insulin and may be beneficial in controlling intraoperative hyperglycemia. Therefore, these medications can be continued.8

Thiazolidinediones (TZDs; pioglitazone, rosiglitazone) alter gene transcription with biological duration of action on the order of weeks and low risk of hypoglycemia, and should be continued.

Metformin carries an FDA black-box warning to discontinue therapy before any intravascular radiocontrast studies or surgical procedures due to the risk of severe lactic acidosis if renal failure develops. It should be stopped 24 hours before surgery and restarted at least 48-72 hours after. Normal renal function should be confirmed before restarting therapy.8

Sulfonylureas (glimepiride, glipizide, glyburide) carry a significant risk of hypoglycemia in a patient who is NPO; they should be stopped the night before surgery or before commencement of NPO status.

Hormones

Antithyroid drugs (methimazole, propylthiouracil) and levothyroxine should be continued, as they have no perioperative contraindications.

Oral contraceptives (OCPs), hormone replacement therapy (HRT), and raloxifene can increase the risk of DVT. The largest study on the topic was the HERS trial of postmenopausal women on estrogen/progesterone HRT. The authors reported a 4.9-fold increased risk of DVT for 90 days after surgery.9 Unfortunately, no information was provided on the types of surgery, or whether appropriate and consistent DVT prophylaxis was utilized. HERS authors also reported a 2.5-fold increased risk of DVT for at least 30 days after cessation of HRT.9

Given the data, it is reasonable to stop hormone therapy four weeks before surgery when prolonged immobilization is anticipated and patients are able to tolerate hormone withdrawal, especially if other DVT risk factors are present. If hormone therapy cannot be stopped, strong consideration should be given to higher-intensity DVT prophylaxis (e.g., chemoprophylaxis as opposed to mechanical measures) of longer duration—up to 28 days following general surgery and up to 35 days after orthopedic procedures.10

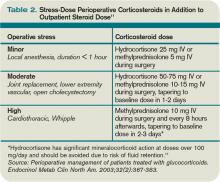

Perioperative Corticosteroids

Corticosteroid therapy in excess of prednisone 5 mg/day or equivalent for more than five days in the 30 days preceding surgery might predispose patients to acute adrenal insufficiency in the perioperative period. Surgical procedures typically result in cortisol release of 50-150 mg/day, which returns to baseline within 48 hours.11 Therefore, the recommendation is to continue a patient’s baseline steroid dose and supplement it with stress-dose steroids tailored to the severity of operative stress (see Table 2, above).

Mineralocorticoid supplementation is not necessary, because endogenous production is not suppressed by corticosteroid therapy.11 Although a recent systematic review suggests that routine stress-dose steroids might not be indicated, high-quality prospective data are needed before abandoning this strategy due to complications of acute adrenal insufficiency compared to the risk of a brief corticosteroid burst.

Non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs (NSAIDs)

Nonselective cyclooxygenase (COX) inhibitors reversibly decrease platelet aggregation only while the drug is present in the circulation and should be stopped one to three days before surgery due to risk of bleeding.

Selective COX-2 inhibitors do not significantly alter platelet aggregation and can be continued for opioid-sparing perioperative pain control.

Both COX-2-selective and nonselective inhibitors should be held if there are concerns for impaired renal function.

Disease-Modifying Antirheumatic Drugs (DMARDs) and Biological Response Modifiers (BRMs)

Methotrexate increases the risk of wound infections and dehiscence. However, this is offset by a decreased risk of post-operative disease flares with continued use. It can be continued unless the patient has medical comorbidities, advanced age, or chronic therapy with more than 10 mg/day of prednisone, in which case the drug should be stopped two weeks before surgery.12

Azathioprine, leflunomide, and sulfasalazine are renally cleared with a risk of myelosuppression; all of these medications should be stopped. Long half-life of leflunomide necessitates stopping it two weeks before surgery; azathioprine and sulfasalazine can be stopped one day in advance. The drugs can be restarted three days after surgery, assuming stable renal function.13

Anti-TNF-α (adalimumab, etanercept, infliximab), IL1 antagonist (anakinra), and anti-CD20 (rituximab) agents should be stopped one week before surgery and resumed 1-2 weeks afterward, unless risk of complications from disease flareup outweighs the concern for wound infections and dehiscence.14

Herbal Medicines

It is estimated that as much as a third of the U.S. population uses herbal medicines. These substances can result in perioperative hemodynamic instability (ephedra, ginseng, ma huang), hypoglycemia (ginseng), immunosuppression (echinacea, when taken for more than eight weeks), abnormal bleeding (garlic, ginkgo, ginseng), and prolongation of anesthesia (kava, St. John’s wort, valerian). All of these herbal medicine should be stopped one to two weeks before surgery.15,16

Back to the Case

The patient’s Carbidopa/Levodopa should be continued. Celecoxib can be continued if her renal function in stable. If aspirin is taken for a history of coronary artery disease or percutaneous coronary intervention, it should be continued, if possible. Clonidine should be continued or changed to a patch if an extended NPO period is anticipated. Ginkgo, lisinopril, and sulfasalazine should be stopped.

Hospitalization does not provide the luxury of stopping estradiol in advance, so it might be continued with chemical DVT prophylaxis for up to 35 days after surgery. The patient should receive 50-75 mg of IV hydrocortisone during surgery and an additional 25 mg the following day, in addition to her usual prednisone 10 mg/day. She can either receive half her usual NPH dose the morning of surgery with a 5% dextrose infusion in the operating room, or the NPH should be held altogether.

Bottom Line

Perioperative medication use should be tailored to each patient, balancing the risks and benefits of individual drugs. High-quality trials are needed to provide more robust clinical guidelines. TH

Dr. Levin is a hospitalist at the University of Colorado Denver.

References

- Fleisher LA, Beckman JA, Brown KA, et al. ACC/AHA 2007 Guidelines on Perioperative Cardiovascular Evaluation and Care for Noncardiac Surgery: Executive Summary: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Writing Committee to Revise the 2002 Guidelines on Perioperative Cardiovascular Evaluation for Noncardiac Surgery): Developed in Collaboration With the American Society of Echocardiography, American Society of Nuclear Cardiology, Heart Rhythm Society, Society of Cardiovascular Anesthesiologists, Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, Society for Vascular Medicine and Biology, and Society for Vascular Surgery. Circulation. 2007;116(17):1971-1996.

- Schouten O, Hoeks SE, Welten GM, et al. Effect of statin withdrawal on frequency of cardiac events after vascular surgery. Am J Cardiol. 2007;100(2):316-320.

- Spell NO III. Stopping and restarting medications in the perioperative period. Med Clin North Am. 2001;85(5):1117-1128.

- Rosenman DJ, McDonald FS, Ebbert JO, Erwin PJ, LaBella M, Montori VM. Clinical consequences of withholding versus administering renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system antagonists in the preoperative period. J Hosp Med. 2008;3(4):319-325.

- Arora P, Rajagopalam S, Ranjan R, et al. Preoperative use of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors/ angiotensin receptor blockers is associated with increased risk for acute kidney injury after cardiovascular surgery. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008;3(5):1266-1273.

- Benedetto U, Sciarretta S, Roscitano A, et al. Preoperative Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and acute kidney injury after coronary artery bypass grafting. Ann Thorac Surg. 2008;86(4):1160-1165.

- Pass SE, Simpson RW. Discontinuation and reinstitution of medications during the perioperative period. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2004;61(9):899-914.

- Kohl BA, Schwartz S. Surgery in the patient with endocrine dysfunction. Med Clin North Am. 2009;93(5):1031-1047.

- Grady D, Wenger NK, Herrington D, et al. Postmenopausal hormone therapy increases risk for venous thromboembolic disease: The Heart and Estrogen/progestin Replacement Study. Ann Intern Med. 2000;132(9):689-696.

- Hirsh J, Guyatt G, Albers GW, Harrington R, Schünemann HJ; American College of Chest Physicians. Executive summary: American College of Chest Physicians evidence-based clinical practice guidelines (8th edition). Chest. 2008;133(6 Suppl):71S-109S.

- Axelrod L. Perioperative management of patients treated with glucocorticoids. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 2003;32(2):367-383.

- Marik PE, Varon J. Requirement of perioperative stress doses of corticosteroids: a systematic review of the literature. Arch Surg. 2008;143(12):1222-1226.

- Rosandich PA, Kelley JT III, Conn DL. Perioperative management of patients with rheumatoid arthritis in the era of biologic response modifiers. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2004;16(3):192-198.

- Saag KG, Teng GG, Patkar NM, et al. American College of Rheumatology 2008 recommendations for the use of nonbiologic and biologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;59(6):762-784.

- Ang-Lee MK, Moss J, Yuan CS. Herbal medicines and perioperative care. JAMA. 2001;286(2):208-216.

- Hodges PJ, Kam PC. The peri-operative implications of herbal medicines. Anaesthesia. 2002;57(9):889-899.

Case

A 72-year-old female with multiple medical problems is admitted with a hip fracture. Surgery is scheduled in 48 hours. The patient’s home medications include aspirin, carbidopa/levodopa, celecoxib, clonidine, estradiol, ginkgo, lisinopril, NPH insulin, sulfasalazine, and prednisone 10 mg a day, which she has been taking for years. How should these and other medications be managed in the perioperative period?

Background

Perioperative management of chronic medications is a complex issue, as physicians are required to balance the beneficial and harmful effects of the individual drugs prescribed to their patients. On one hand, cessation of medications can result in decompensation of disease or withdrawal. On the other hand, continuation of drugs can alter metabolism of anesthetic agents, cause perioperative hemodynamic instability, or result in such post-operative complications as acute renal failure, bleeding, infection, and impaired wound healing.

Certain traits make it reasonable to continue medications during the perioperative period. A long elimination half-life or duration of action makes stopping some medications impractical as it takes four to five half-lives to completely clear the drug from the body; holding the drug for a few days around surgery will not appreciably affect its concentration. Stopping drugs that carry severe withdrawal symptoms can be impractical because of the need for lengthy tapers, which can delay surgery and result in decompensation of underlying disease.

Drugs with no significant interactions with anesthesia or risk of perioperative complications should be continued in order to avoid deterioration of the underlying disease. Conversely, drugs that interact with anesthesia or increase risk for complications should be stopped if this can be accomplished safely. Patient-specific factors should receive consideration, as the risk of complications has to be balanced against the danger of exacerbating the underlying disease.

Overview of the Data

The challenge in providing recommendations on perioperative medication management lies in a dearth of high-quality clinical trials. Thus, much of the information comes from case reports, expert opinion, and sound application of pharmacology.

Antiplatelet therapy: Nuances of perioperative antiplatelet therapy are beyond the scope of this review, but some general principles can be elucidated from the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association (ACC/AHA) 2007 perioperative guidelines.1 Management of antiplatelet therapy should be done in conjunction with the surgical team, as cardiovascular risk has to be weighed against bleeding risk.

Aspirin therapy should be continued in all patients with a history of coronary artery disease (CAD), balloon angioplasty, or percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI), unless the risk of bleeding complications is felt to exceed the cardioprotective benefits—for example, in some neurosurgical patients.1

Clopidogrel therapy is crucial for prevention of in-stent thrombosis (IST) following PCI because patients who experience IST suffer catastrophic myocardial infarctions with high mortality. Ideally, surgery should be delayed to permit completion of clopidogrel therapy—30 to 45 days after implantation of a bare-metal stent and 365 days after a drug-eluting stent. If surgery has to be performed sooner, guidelines recommend operating on dual antiplatelet therapy with aspirin and clopidogrel.1 Again, this course of treatment has to be balanced against the risk of hemorrhagic complications from surgery.

Both aspirin and clopidogrel irreversibly inhibit platelet aggregation. The recovery of normal coagulation involves formation of new platelets, which necessitates cessation of therapy for seven to 10 days before surgery. Platelet inhibition begins within minutes of restarting aspirin and within hours of taking clopidogrel, although attaining peak clopidogrel effect takes three to seven days, unless a loading dose is used.

Cardiovascular Drugs

Beta-blockers in the perioperative setting are a focus of an ongoing debate beyond the scope of this review (see “What Pre-Operative Cardiac Evaluation of Patients Undergoing Intermediate-Risk Surgery Is Most Effective?,” February 2008, p. 26). Given the current evidence and the latest ACC/AHA guidelines, it is still reasonable to continue therapy in patients who are already taking them to avoid precipitating cardiovascular events by withdrawal. Patients with increased cardiac risk, demonstrated by a Revised Cardiac Risk Index (RCRI) score of ≥2 (see Table 1, p. 12), should be considered for beta-blocker therapy before surgery.1 In either case, the dose should be titrated to a heart rate <65 for optimal cardiac protection.1

Statins should be continued if the patient is taking them, especially because preoperative withdrawal has been associated with a 4.6-fold increase in troponin release and a 7.5-fold increased risk of myocardial infarction (MI) and cardiovascular death following major vascular surgery.2 Patients with increased cardiac risk— RCRI ≥1—can be considered for initiation of statin therapy before surgery, although the benefit of this intervention has not been examined in prospective studies.1

Amiodarone has an exceptionally long half-life of up to 142 days. It should be continued in the perioperative period.

Calcium channel blockers (CCBs) can be continued with no unpleasant perioperative hemodynamic effects.1 CCBs have potential cardioprotective benefits.

Clonidine withdrawal can result in severe rebound hypertension with reports of encephalopathy, stroke, and death. These effects are exacerbated by concomitant beta-blocker therapy. For this reason, if a patient is expected to be NPO for more than 12 hours, they should be converted to a clonidine patch 48-72 hours before surgery with concurrent tapering of the oral dose.3

Digoxin has a long half-life (up to 48 hours) and should be continued with monitoring of levels if there is a change in renal function.

Angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEI) and angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs) have been associated with a 50% increased risk of hypotension requiring vasopressors during induction of anesthesia.4 However, it is worth mentioning that this finding has not been corroborated in other studies. A large retrospective cohort of cardiothoracic surgical patients found a 28% increased risk of post-operative acute renal failure (ARF) with both drug classes, although another cardiothoracic report published the same year demonstrated a 50% reduction in risk with ACEIs.5,6 Although the evidence of harm is not unequivocal, perioperative blood-pressure control can be achieved with other drugs without hemodynamic or renal risk, such as CCBs, and in most cases ACEIs/ARBs should be stopped one day before surgery.

Diuretics carry a risk of volume depletion and electrolyte derangements, and should be stopped once a patient becomes NPO. Excess volume is managed with as-needed intravenous formulations.

Drugs Acting on the Central Nervous System

The majority of central nervous system (CNS)-active drugs, including antiepileptics, antipsychotics, benzodiazepines, bupropion, gabapentin, lithium, mirtazapine, selective serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs and SNRIs), tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs), and valproic acid, balance a low risk of perioperative complications against a significant potential for withdrawal and disease decompensation. Therefore, these medications should be continued.

Carbidopa/Levodopa should be continued because abrupt cessation can precipitate systemic withdrawal resembling serotonin syndrome and rapid deterioration of Parkinson’s symptoms.

Monoamine oxidase inhibitor (MAOI) therapy usually indicates refractory psychiatric illness, so these drugs should be continued to avoid decompensation. Importantly, MAOI-safe anesthesia without dextromethorphan, meperidine, epinephrine, or norepinephrine has to be used due to the risk of cardiovascular instability.7

Diabetic Drugs

Insulin therapy should be continued with adjustments. Glargine basal insulin has no peak and can be continued without changing the dose. Likewise, patients with insulin pumps can continue the usual basal rate. Short-acting insulin or such insulin mixes as 70/30 should be stopped four hours before surgery to avoid hypoglycemia. Intermediate-acting insulin (e.g., NPH) can be administered at half the usual dose the day of surgery with a perioperative 5% dextrose infusion. NPH should not be given the day of surgery if the dextrose infusion cannot be used.8

Incretins (exenatide, sitagliptin) rarely cause hypoglycemia in the absence of insulin and may be beneficial in controlling intraoperative hyperglycemia. Therefore, these medications can be continued.8

Thiazolidinediones (TZDs; pioglitazone, rosiglitazone) alter gene transcription with biological duration of action on the order of weeks and low risk of hypoglycemia, and should be continued.

Metformin carries an FDA black-box warning to discontinue therapy before any intravascular radiocontrast studies or surgical procedures due to the risk of severe lactic acidosis if renal failure develops. It should be stopped 24 hours before surgery and restarted at least 48-72 hours after. Normal renal function should be confirmed before restarting therapy.8

Sulfonylureas (glimepiride, glipizide, glyburide) carry a significant risk of hypoglycemia in a patient who is NPO; they should be stopped the night before surgery or before commencement of NPO status.

Hormones

Antithyroid drugs (methimazole, propylthiouracil) and levothyroxine should be continued, as they have no perioperative contraindications.

Oral contraceptives (OCPs), hormone replacement therapy (HRT), and raloxifene can increase the risk of DVT. The largest study on the topic was the HERS trial of postmenopausal women on estrogen/progesterone HRT. The authors reported a 4.9-fold increased risk of DVT for 90 days after surgery.9 Unfortunately, no information was provided on the types of surgery, or whether appropriate and consistent DVT prophylaxis was utilized. HERS authors also reported a 2.5-fold increased risk of DVT for at least 30 days after cessation of HRT.9

Given the data, it is reasonable to stop hormone therapy four weeks before surgery when prolonged immobilization is anticipated and patients are able to tolerate hormone withdrawal, especially if other DVT risk factors are present. If hormone therapy cannot be stopped, strong consideration should be given to higher-intensity DVT prophylaxis (e.g., chemoprophylaxis as opposed to mechanical measures) of longer duration—up to 28 days following general surgery and up to 35 days after orthopedic procedures.10

Perioperative Corticosteroids

Corticosteroid therapy in excess of prednisone 5 mg/day or equivalent for more than five days in the 30 days preceding surgery might predispose patients to acute adrenal insufficiency in the perioperative period. Surgical procedures typically result in cortisol release of 50-150 mg/day, which returns to baseline within 48 hours.11 Therefore, the recommendation is to continue a patient’s baseline steroid dose and supplement it with stress-dose steroids tailored to the severity of operative stress (see Table 2, above).

Mineralocorticoid supplementation is not necessary, because endogenous production is not suppressed by corticosteroid therapy.11 Although a recent systematic review suggests that routine stress-dose steroids might not be indicated, high-quality prospective data are needed before abandoning this strategy due to complications of acute adrenal insufficiency compared to the risk of a brief corticosteroid burst.

Non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs (NSAIDs)

Nonselective cyclooxygenase (COX) inhibitors reversibly decrease platelet aggregation only while the drug is present in the circulation and should be stopped one to three days before surgery due to risk of bleeding.

Selective COX-2 inhibitors do not significantly alter platelet aggregation and can be continued for opioid-sparing perioperative pain control.

Both COX-2-selective and nonselective inhibitors should be held if there are concerns for impaired renal function.

Disease-Modifying Antirheumatic Drugs (DMARDs) and Biological Response Modifiers (BRMs)

Methotrexate increases the risk of wound infections and dehiscence. However, this is offset by a decreased risk of post-operative disease flares with continued use. It can be continued unless the patient has medical comorbidities, advanced age, or chronic therapy with more than 10 mg/day of prednisone, in which case the drug should be stopped two weeks before surgery.12

Azathioprine, leflunomide, and sulfasalazine are renally cleared with a risk of myelosuppression; all of these medications should be stopped. Long half-life of leflunomide necessitates stopping it two weeks before surgery; azathioprine and sulfasalazine can be stopped one day in advance. The drugs can be restarted three days after surgery, assuming stable renal function.13

Anti-TNF-α (adalimumab, etanercept, infliximab), IL1 antagonist (anakinra), and anti-CD20 (rituximab) agents should be stopped one week before surgery and resumed 1-2 weeks afterward, unless risk of complications from disease flareup outweighs the concern for wound infections and dehiscence.14

Herbal Medicines

It is estimated that as much as a third of the U.S. population uses herbal medicines. These substances can result in perioperative hemodynamic instability (ephedra, ginseng, ma huang), hypoglycemia (ginseng), immunosuppression (echinacea, when taken for more than eight weeks), abnormal bleeding (garlic, ginkgo, ginseng), and prolongation of anesthesia (kava, St. John’s wort, valerian). All of these herbal medicine should be stopped one to two weeks before surgery.15,16

Back to the Case

The patient’s Carbidopa/Levodopa should be continued. Celecoxib can be continued if her renal function in stable. If aspirin is taken for a history of coronary artery disease or percutaneous coronary intervention, it should be continued, if possible. Clonidine should be continued or changed to a patch if an extended NPO period is anticipated. Ginkgo, lisinopril, and sulfasalazine should be stopped.

Hospitalization does not provide the luxury of stopping estradiol in advance, so it might be continued with chemical DVT prophylaxis for up to 35 days after surgery. The patient should receive 50-75 mg of IV hydrocortisone during surgery and an additional 25 mg the following day, in addition to her usual prednisone 10 mg/day. She can either receive half her usual NPH dose the morning of surgery with a 5% dextrose infusion in the operating room, or the NPH should be held altogether.

Bottom Line

Perioperative medication use should be tailored to each patient, balancing the risks and benefits of individual drugs. High-quality trials are needed to provide more robust clinical guidelines. TH

Dr. Levin is a hospitalist at the University of Colorado Denver.

References

- Fleisher LA, Beckman JA, Brown KA, et al. ACC/AHA 2007 Guidelines on Perioperative Cardiovascular Evaluation and Care for Noncardiac Surgery: Executive Summary: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Writing Committee to Revise the 2002 Guidelines on Perioperative Cardiovascular Evaluation for Noncardiac Surgery): Developed in Collaboration With the American Society of Echocardiography, American Society of Nuclear Cardiology, Heart Rhythm Society, Society of Cardiovascular Anesthesiologists, Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, Society for Vascular Medicine and Biology, and Society for Vascular Surgery. Circulation. 2007;116(17):1971-1996.

- Schouten O, Hoeks SE, Welten GM, et al. Effect of statin withdrawal on frequency of cardiac events after vascular surgery. Am J Cardiol. 2007;100(2):316-320.

- Spell NO III. Stopping and restarting medications in the perioperative period. Med Clin North Am. 2001;85(5):1117-1128.

- Rosenman DJ, McDonald FS, Ebbert JO, Erwin PJ, LaBella M, Montori VM. Clinical consequences of withholding versus administering renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system antagonists in the preoperative period. J Hosp Med. 2008;3(4):319-325.

- Arora P, Rajagopalam S, Ranjan R, et al. Preoperative use of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors/ angiotensin receptor blockers is associated with increased risk for acute kidney injury after cardiovascular surgery. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008;3(5):1266-1273.

- Benedetto U, Sciarretta S, Roscitano A, et al. Preoperative Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and acute kidney injury after coronary artery bypass grafting. Ann Thorac Surg. 2008;86(4):1160-1165.

- Pass SE, Simpson RW. Discontinuation and reinstitution of medications during the perioperative period. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2004;61(9):899-914.

- Kohl BA, Schwartz S. Surgery in the patient with endocrine dysfunction. Med Clin North Am. 2009;93(5):1031-1047.

- Grady D, Wenger NK, Herrington D, et al. Postmenopausal hormone therapy increases risk for venous thromboembolic disease: The Heart and Estrogen/progestin Replacement Study. Ann Intern Med. 2000;132(9):689-696.

- Hirsh J, Guyatt G, Albers GW, Harrington R, Schünemann HJ; American College of Chest Physicians. Executive summary: American College of Chest Physicians evidence-based clinical practice guidelines (8th edition). Chest. 2008;133(6 Suppl):71S-109S.

- Axelrod L. Perioperative management of patients treated with glucocorticoids. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 2003;32(2):367-383.

- Marik PE, Varon J. Requirement of perioperative stress doses of corticosteroids: a systematic review of the literature. Arch Surg. 2008;143(12):1222-1226.

- Rosandich PA, Kelley JT III, Conn DL. Perioperative management of patients with rheumatoid arthritis in the era of biologic response modifiers. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2004;16(3):192-198.

- Saag KG, Teng GG, Patkar NM, et al. American College of Rheumatology 2008 recommendations for the use of nonbiologic and biologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;59(6):762-784.

- Ang-Lee MK, Moss J, Yuan CS. Herbal medicines and perioperative care. JAMA. 2001;286(2):208-216.

- Hodges PJ, Kam PC. The peri-operative implications of herbal medicines. Anaesthesia. 2002;57(9):889-899.

Case

A 72-year-old female with multiple medical problems is admitted with a hip fracture. Surgery is scheduled in 48 hours. The patient’s home medications include aspirin, carbidopa/levodopa, celecoxib, clonidine, estradiol, ginkgo, lisinopril, NPH insulin, sulfasalazine, and prednisone 10 mg a day, which she has been taking for years. How should these and other medications be managed in the perioperative period?

Background

Perioperative management of chronic medications is a complex issue, as physicians are required to balance the beneficial and harmful effects of the individual drugs prescribed to their patients. On one hand, cessation of medications can result in decompensation of disease or withdrawal. On the other hand, continuation of drugs can alter metabolism of anesthetic agents, cause perioperative hemodynamic instability, or result in such post-operative complications as acute renal failure, bleeding, infection, and impaired wound healing.

Certain traits make it reasonable to continue medications during the perioperative period. A long elimination half-life or duration of action makes stopping some medications impractical as it takes four to five half-lives to completely clear the drug from the body; holding the drug for a few days around surgery will not appreciably affect its concentration. Stopping drugs that carry severe withdrawal symptoms can be impractical because of the need for lengthy tapers, which can delay surgery and result in decompensation of underlying disease.

Drugs with no significant interactions with anesthesia or risk of perioperative complications should be continued in order to avoid deterioration of the underlying disease. Conversely, drugs that interact with anesthesia or increase risk for complications should be stopped if this can be accomplished safely. Patient-specific factors should receive consideration, as the risk of complications has to be balanced against the danger of exacerbating the underlying disease.

Overview of the Data

The challenge in providing recommendations on perioperative medication management lies in a dearth of high-quality clinical trials. Thus, much of the information comes from case reports, expert opinion, and sound application of pharmacology.

Antiplatelet therapy: Nuances of perioperative antiplatelet therapy are beyond the scope of this review, but some general principles can be elucidated from the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association (ACC/AHA) 2007 perioperative guidelines.1 Management of antiplatelet therapy should be done in conjunction with the surgical team, as cardiovascular risk has to be weighed against bleeding risk.

Aspirin therapy should be continued in all patients with a history of coronary artery disease (CAD), balloon angioplasty, or percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI), unless the risk of bleeding complications is felt to exceed the cardioprotective benefits—for example, in some neurosurgical patients.1

Clopidogrel therapy is crucial for prevention of in-stent thrombosis (IST) following PCI because patients who experience IST suffer catastrophic myocardial infarctions with high mortality. Ideally, surgery should be delayed to permit completion of clopidogrel therapy—30 to 45 days after implantation of a bare-metal stent and 365 days after a drug-eluting stent. If surgery has to be performed sooner, guidelines recommend operating on dual antiplatelet therapy with aspirin and clopidogrel.1 Again, this course of treatment has to be balanced against the risk of hemorrhagic complications from surgery.

Both aspirin and clopidogrel irreversibly inhibit platelet aggregation. The recovery of normal coagulation involves formation of new platelets, which necessitates cessation of therapy for seven to 10 days before surgery. Platelet inhibition begins within minutes of restarting aspirin and within hours of taking clopidogrel, although attaining peak clopidogrel effect takes three to seven days, unless a loading dose is used.

Cardiovascular Drugs

Beta-blockers in the perioperative setting are a focus of an ongoing debate beyond the scope of this review (see “What Pre-Operative Cardiac Evaluation of Patients Undergoing Intermediate-Risk Surgery Is Most Effective?,” February 2008, p. 26). Given the current evidence and the latest ACC/AHA guidelines, it is still reasonable to continue therapy in patients who are already taking them to avoid precipitating cardiovascular events by withdrawal. Patients with increased cardiac risk, demonstrated by a Revised Cardiac Risk Index (RCRI) score of ≥2 (see Table 1, p. 12), should be considered for beta-blocker therapy before surgery.1 In either case, the dose should be titrated to a heart rate <65 for optimal cardiac protection.1

Statins should be continued if the patient is taking them, especially because preoperative withdrawal has been associated with a 4.6-fold increase in troponin release and a 7.5-fold increased risk of myocardial infarction (MI) and cardiovascular death following major vascular surgery.2 Patients with increased cardiac risk— RCRI ≥1—can be considered for initiation of statin therapy before surgery, although the benefit of this intervention has not been examined in prospective studies.1

Amiodarone has an exceptionally long half-life of up to 142 days. It should be continued in the perioperative period.

Calcium channel blockers (CCBs) can be continued with no unpleasant perioperative hemodynamic effects.1 CCBs have potential cardioprotective benefits.