User login

Bringing you the latest news, research and reviews, exclusive interviews, podcasts, quizzes, and more.

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack nav-ce-stack__large-screen')]

header[@id='header']

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

div[contains(@class, 'view-medstat-quiz-listing-panes')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-article-sidebar-latest-news')]

Cancer Treatment 101: A Primer for Non-Oncologists

The remaining 700,000 or so often proceed to chemotherapy either immediately or upon cancer recurrence, spread, or newly recognized metastases. “Cures” after that point are rare.

I’m speaking in generalities, understanding that each cancer and each patient is unique.

Chemotherapy

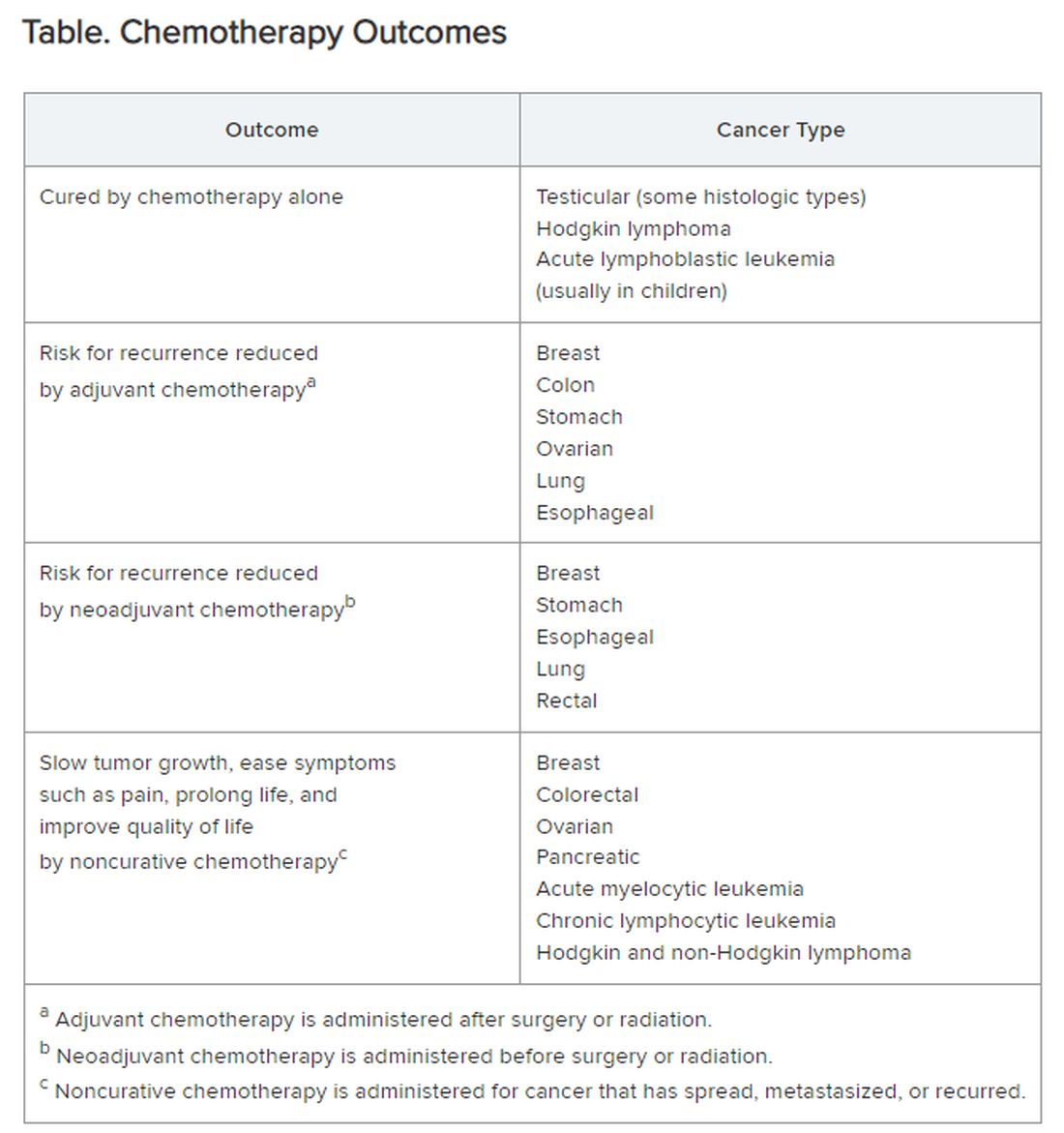

Chemotherapy alone can cure a small number of cancer types. When added to radiation or surgery, chemotherapy can help to cure a wider range of cancer types. As an add-on, chemotherapy can extend the length and quality of life for many patients with cancer. Since chemotherapy is by definition “toxic,” it can also shorten the duration or harm the quality of life and provide false hope. The Table summarizes what chemotherapy can and cannot achieve in selected cancer types.

Careful, compassionate communication between patient and physician is key. Goals and expectations must be clearly understood.

Organized chemotherapeutic efforts are further categorized as first line, second line, and third line.

First-line treatment. The initial round of recommended chemotherapy for a specific cancer. It is typically considered the most effective treatment for that type and stage of cancer on the basis of current research and clinical trials.

Second-line treatment. This is the treatment used if the first-line chemotherapy doesn’t work as desired. Reasons to switch to second-line chemo include:

- Lack of response (the tumor failed to shrink).

- Progression (the cancer may have grown or spread further).

- Adverse side effects were too severe to continue.

The drugs used in second-line chemo will typically be different from those used in first line, sometimes because cancer cells can develop resistance to chemotherapy drugs over time. Moreover, the goal of second-line chemo may differ from that of first-line therapy. Rather than chiefly aiming for a cure, second-line treatment might focus on slowing cancer growth, managing symptoms, or improving quality of life. Unfortunately, not every type of cancer has a readily available second-line option.

Third-line treatment. Third-line options come into play when both the initial course of chemo (first line) and the subsequent treatment (second line) have failed to achieve remission or control the cancer’s spread. Owing to the progressive nature of advanced cancers, patients might not be eligible or healthy enough for third-line therapy. Depending on cancer type, the patient’s general health, and response to previous treatments, third-line options could include:

- New or different chemotherapy drugs compared with prior lines.

- Surgery to debulk the tumor.

- Radiation for symptom control.

- Targeted therapy: drugs designed to target specific vulnerabilities in cancer cells.

- Immunotherapy: agents that help the body’s immune system fight cancer cells.

- Clinical trials testing new or investigational treatments, which may be applicable at any time, depending on the questions being addressed.

The goals of third-line therapy may shift from aiming for a cure to managing symptoms, improving quality of life, and potentially slowing cancer growth. The decision to pursue third-line therapy involves careful consideration by the doctor and patient, weighing the potential benefits and risks of treatment considering the individual’s overall health and specific situation.

It’s important to have realistic expectations about the potential outcomes of third-line therapy. Although remission may be unlikely, third-line therapy can still play a role in managing the disease.

Navigating advanced cancer treatment is very complex. The patient and physician must together consider detailed explanations and clarifications to set expectations and make informed decisions about care.

Interventions to Consider Earlier

In traditional clinical oncology practice, other interventions are possible, but these may not be offered until treatment has reached the third line:

- Molecular testing.

- Palliation.

- Clinical trials.

- Innovative testing to guide targeted therapy by ascertaining which agents are most likely (or not likely at all) to be effective.

I would argue that the patient’s interests are better served by considering and offering these other interventions much earlier, even before starting first-line chemotherapy.

Molecular testing. The best time for molecular testing of a new malignant tumor is typically at the time of diagnosis. Here’s why:

- Molecular testing helps identify specific genetic mutations in the cancer cells. This information can be crucial for selecting targeted therapies that are most effective against those specific mutations. Early detection allows for the most treatment options. For example, for non–small cell lung cancer, early is best because treatment and outcomes may well be changed by test results.

- Knowing the tumor’s molecular makeup can help determine whether a patient qualifies for clinical trials of new drugs designed for specific mutations.

- Some molecular markers can offer information about the tumor’s aggressiveness and potential for metastasis so that prognosis can be informed.

Molecular testing can be a valuable tool throughout a cancer patient’s journey. With genetically diverse tumors, the initial biopsy might not capture the full picture. Molecular testing of circulating tumor DNA can be used to monitor a patient’s response to treatment and detect potential mutations that might arise during treatment resistance. Retesting after metastasis can provide additional information that can aid in treatment decisions.

Palliative care. The ideal time to discuss palliative care with a patient with cancer is early in the diagnosis and treatment process. Palliative care is not the same as hospice care; it isn’t just about end-of-life. Palliative care focuses on improving a patient’s quality of life throughout cancer treatment. Palliative care specialists can address a wide range of symptoms a patient might experience from cancer or its treatment, including pain, fatigue, nausea, and anxiety.

Early discussions allow for a more comprehensive care plan. Open communication about all treatment options, including palliative care, empowers patients to make informed decisions about their care goals and preferences.

Specific situations where discussing palliative care might be appropriate are:

- Soon after a cancer diagnosis.

- If the patient experiences significant side effects from cancer treatment.

- When considering different treatment options, palliative care can complement those treatments.

- In advanced stages of cancer, to focus on comfort and quality of life.

Clinical trials. Participation in a clinical trial to explore new or investigational treatments should always be considered.

In theory, clinical trials should be an option at any time in the patient’s course. But the organized clinical trial experience may not be available or appropriate. Then, the individual becomes a de facto “clinical trial with an n of 1.” Read this brief open-access blog post at Cancer Commons to learn more about that circumstance.

Innovative testing. The best choice of chemotherapeutic or targeted therapies is often unclear. The clinician is likely to follow published guidelines, often from the National Comprehensive Cancer Network.

These are evidence based and driven by consensus of experts. But guideline-recommended therapy is not always effective, and weeks or months can pass before this ineffectiveness becomes apparent. Thus, many researchers and companies are seeking methods of testing each patient’s specific cancer to determine in advance, or very quickly, whether a particular drug is likely to be effective.

Read more about these leading innovations:

SAGE Oncotest: Entering the Next Generation of Tailored Cancer Treatment

Alibrex: A New Blood Test to Reveal Whether a Cancer Treatment is Working

PARIS Test Uses Lab-Grown Mini-Tumors to Find a Patient’s Best Treatment

Using Live Cells from Patients to Find the Right Cancer Drug

Other innovative therapies under investigation could even be agnostic to cancer type:

Treating Pancreatic Cancer: Could Metabolism — Not Genomics — Be the Key?

High-Energy Blue Light Powers a Promising New Treatment to Destroy Cancer Cells

All-Clear Follow-Up: Hydrogen Peroxide Appears to Treat Oral and Skin Lesions

Cancer is a tough nut to crack. Many people and organizations are trying very hard. So much is being learned. Some approaches will be effective. We can all hope.

Dr. Lundberg, editor in chief, Cancer Commons, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

The remaining 700,000 or so often proceed to chemotherapy either immediately or upon cancer recurrence, spread, or newly recognized metastases. “Cures” after that point are rare.

I’m speaking in generalities, understanding that each cancer and each patient is unique.

Chemotherapy

Chemotherapy alone can cure a small number of cancer types. When added to radiation or surgery, chemotherapy can help to cure a wider range of cancer types. As an add-on, chemotherapy can extend the length and quality of life for many patients with cancer. Since chemotherapy is by definition “toxic,” it can also shorten the duration or harm the quality of life and provide false hope. The Table summarizes what chemotherapy can and cannot achieve in selected cancer types.

Careful, compassionate communication between patient and physician is key. Goals and expectations must be clearly understood.

Organized chemotherapeutic efforts are further categorized as first line, second line, and third line.

First-line treatment. The initial round of recommended chemotherapy for a specific cancer. It is typically considered the most effective treatment for that type and stage of cancer on the basis of current research and clinical trials.

Second-line treatment. This is the treatment used if the first-line chemotherapy doesn’t work as desired. Reasons to switch to second-line chemo include:

- Lack of response (the tumor failed to shrink).

- Progression (the cancer may have grown or spread further).

- Adverse side effects were too severe to continue.

The drugs used in second-line chemo will typically be different from those used in first line, sometimes because cancer cells can develop resistance to chemotherapy drugs over time. Moreover, the goal of second-line chemo may differ from that of first-line therapy. Rather than chiefly aiming for a cure, second-line treatment might focus on slowing cancer growth, managing symptoms, or improving quality of life. Unfortunately, not every type of cancer has a readily available second-line option.

Third-line treatment. Third-line options come into play when both the initial course of chemo (first line) and the subsequent treatment (second line) have failed to achieve remission or control the cancer’s spread. Owing to the progressive nature of advanced cancers, patients might not be eligible or healthy enough for third-line therapy. Depending on cancer type, the patient’s general health, and response to previous treatments, third-line options could include:

- New or different chemotherapy drugs compared with prior lines.

- Surgery to debulk the tumor.

- Radiation for symptom control.

- Targeted therapy: drugs designed to target specific vulnerabilities in cancer cells.

- Immunotherapy: agents that help the body’s immune system fight cancer cells.

- Clinical trials testing new or investigational treatments, which may be applicable at any time, depending on the questions being addressed.

The goals of third-line therapy may shift from aiming for a cure to managing symptoms, improving quality of life, and potentially slowing cancer growth. The decision to pursue third-line therapy involves careful consideration by the doctor and patient, weighing the potential benefits and risks of treatment considering the individual’s overall health and specific situation.

It’s important to have realistic expectations about the potential outcomes of third-line therapy. Although remission may be unlikely, third-line therapy can still play a role in managing the disease.

Navigating advanced cancer treatment is very complex. The patient and physician must together consider detailed explanations and clarifications to set expectations and make informed decisions about care.

Interventions to Consider Earlier

In traditional clinical oncology practice, other interventions are possible, but these may not be offered until treatment has reached the third line:

- Molecular testing.

- Palliation.

- Clinical trials.

- Innovative testing to guide targeted therapy by ascertaining which agents are most likely (or not likely at all) to be effective.

I would argue that the patient’s interests are better served by considering and offering these other interventions much earlier, even before starting first-line chemotherapy.

Molecular testing. The best time for molecular testing of a new malignant tumor is typically at the time of diagnosis. Here’s why:

- Molecular testing helps identify specific genetic mutations in the cancer cells. This information can be crucial for selecting targeted therapies that are most effective against those specific mutations. Early detection allows for the most treatment options. For example, for non–small cell lung cancer, early is best because treatment and outcomes may well be changed by test results.

- Knowing the tumor’s molecular makeup can help determine whether a patient qualifies for clinical trials of new drugs designed for specific mutations.

- Some molecular markers can offer information about the tumor’s aggressiveness and potential for metastasis so that prognosis can be informed.

Molecular testing can be a valuable tool throughout a cancer patient’s journey. With genetically diverse tumors, the initial biopsy might not capture the full picture. Molecular testing of circulating tumor DNA can be used to monitor a patient’s response to treatment and detect potential mutations that might arise during treatment resistance. Retesting after metastasis can provide additional information that can aid in treatment decisions.

Palliative care. The ideal time to discuss palliative care with a patient with cancer is early in the diagnosis and treatment process. Palliative care is not the same as hospice care; it isn’t just about end-of-life. Palliative care focuses on improving a patient’s quality of life throughout cancer treatment. Palliative care specialists can address a wide range of symptoms a patient might experience from cancer or its treatment, including pain, fatigue, nausea, and anxiety.

Early discussions allow for a more comprehensive care plan. Open communication about all treatment options, including palliative care, empowers patients to make informed decisions about their care goals and preferences.

Specific situations where discussing palliative care might be appropriate are:

- Soon after a cancer diagnosis.

- If the patient experiences significant side effects from cancer treatment.

- When considering different treatment options, palliative care can complement those treatments.

- In advanced stages of cancer, to focus on comfort and quality of life.

Clinical trials. Participation in a clinical trial to explore new or investigational treatments should always be considered.

In theory, clinical trials should be an option at any time in the patient’s course. But the organized clinical trial experience may not be available or appropriate. Then, the individual becomes a de facto “clinical trial with an n of 1.” Read this brief open-access blog post at Cancer Commons to learn more about that circumstance.

Innovative testing. The best choice of chemotherapeutic or targeted therapies is often unclear. The clinician is likely to follow published guidelines, often from the National Comprehensive Cancer Network.

These are evidence based and driven by consensus of experts. But guideline-recommended therapy is not always effective, and weeks or months can pass before this ineffectiveness becomes apparent. Thus, many researchers and companies are seeking methods of testing each patient’s specific cancer to determine in advance, or very quickly, whether a particular drug is likely to be effective.

Read more about these leading innovations:

SAGE Oncotest: Entering the Next Generation of Tailored Cancer Treatment

Alibrex: A New Blood Test to Reveal Whether a Cancer Treatment is Working

PARIS Test Uses Lab-Grown Mini-Tumors to Find a Patient’s Best Treatment

Using Live Cells from Patients to Find the Right Cancer Drug

Other innovative therapies under investigation could even be agnostic to cancer type:

Treating Pancreatic Cancer: Could Metabolism — Not Genomics — Be the Key?

High-Energy Blue Light Powers a Promising New Treatment to Destroy Cancer Cells

All-Clear Follow-Up: Hydrogen Peroxide Appears to Treat Oral and Skin Lesions

Cancer is a tough nut to crack. Many people and organizations are trying very hard. So much is being learned. Some approaches will be effective. We can all hope.

Dr. Lundberg, editor in chief, Cancer Commons, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

The remaining 700,000 or so often proceed to chemotherapy either immediately or upon cancer recurrence, spread, or newly recognized metastases. “Cures” after that point are rare.

I’m speaking in generalities, understanding that each cancer and each patient is unique.

Chemotherapy

Chemotherapy alone can cure a small number of cancer types. When added to radiation or surgery, chemotherapy can help to cure a wider range of cancer types. As an add-on, chemotherapy can extend the length and quality of life for many patients with cancer. Since chemotherapy is by definition “toxic,” it can also shorten the duration or harm the quality of life and provide false hope. The Table summarizes what chemotherapy can and cannot achieve in selected cancer types.

Careful, compassionate communication between patient and physician is key. Goals and expectations must be clearly understood.

Organized chemotherapeutic efforts are further categorized as first line, second line, and third line.

First-line treatment. The initial round of recommended chemotherapy for a specific cancer. It is typically considered the most effective treatment for that type and stage of cancer on the basis of current research and clinical trials.

Second-line treatment. This is the treatment used if the first-line chemotherapy doesn’t work as desired. Reasons to switch to second-line chemo include:

- Lack of response (the tumor failed to shrink).

- Progression (the cancer may have grown or spread further).

- Adverse side effects were too severe to continue.

The drugs used in second-line chemo will typically be different from those used in first line, sometimes because cancer cells can develop resistance to chemotherapy drugs over time. Moreover, the goal of second-line chemo may differ from that of first-line therapy. Rather than chiefly aiming for a cure, second-line treatment might focus on slowing cancer growth, managing symptoms, or improving quality of life. Unfortunately, not every type of cancer has a readily available second-line option.

Third-line treatment. Third-line options come into play when both the initial course of chemo (first line) and the subsequent treatment (second line) have failed to achieve remission or control the cancer’s spread. Owing to the progressive nature of advanced cancers, patients might not be eligible or healthy enough for third-line therapy. Depending on cancer type, the patient’s general health, and response to previous treatments, third-line options could include:

- New or different chemotherapy drugs compared with prior lines.

- Surgery to debulk the tumor.

- Radiation for symptom control.

- Targeted therapy: drugs designed to target specific vulnerabilities in cancer cells.

- Immunotherapy: agents that help the body’s immune system fight cancer cells.

- Clinical trials testing new or investigational treatments, which may be applicable at any time, depending on the questions being addressed.

The goals of third-line therapy may shift from aiming for a cure to managing symptoms, improving quality of life, and potentially slowing cancer growth. The decision to pursue third-line therapy involves careful consideration by the doctor and patient, weighing the potential benefits and risks of treatment considering the individual’s overall health and specific situation.

It’s important to have realistic expectations about the potential outcomes of third-line therapy. Although remission may be unlikely, third-line therapy can still play a role in managing the disease.

Navigating advanced cancer treatment is very complex. The patient and physician must together consider detailed explanations and clarifications to set expectations and make informed decisions about care.

Interventions to Consider Earlier

In traditional clinical oncology practice, other interventions are possible, but these may not be offered until treatment has reached the third line:

- Molecular testing.

- Palliation.

- Clinical trials.

- Innovative testing to guide targeted therapy by ascertaining which agents are most likely (or not likely at all) to be effective.

I would argue that the patient’s interests are better served by considering and offering these other interventions much earlier, even before starting first-line chemotherapy.

Molecular testing. The best time for molecular testing of a new malignant tumor is typically at the time of diagnosis. Here’s why:

- Molecular testing helps identify specific genetic mutations in the cancer cells. This information can be crucial for selecting targeted therapies that are most effective against those specific mutations. Early detection allows for the most treatment options. For example, for non–small cell lung cancer, early is best because treatment and outcomes may well be changed by test results.

- Knowing the tumor’s molecular makeup can help determine whether a patient qualifies for clinical trials of new drugs designed for specific mutations.

- Some molecular markers can offer information about the tumor’s aggressiveness and potential for metastasis so that prognosis can be informed.

Molecular testing can be a valuable tool throughout a cancer patient’s journey. With genetically diverse tumors, the initial biopsy might not capture the full picture. Molecular testing of circulating tumor DNA can be used to monitor a patient’s response to treatment and detect potential mutations that might arise during treatment resistance. Retesting after metastasis can provide additional information that can aid in treatment decisions.

Palliative care. The ideal time to discuss palliative care with a patient with cancer is early in the diagnosis and treatment process. Palliative care is not the same as hospice care; it isn’t just about end-of-life. Palliative care focuses on improving a patient’s quality of life throughout cancer treatment. Palliative care specialists can address a wide range of symptoms a patient might experience from cancer or its treatment, including pain, fatigue, nausea, and anxiety.

Early discussions allow for a more comprehensive care plan. Open communication about all treatment options, including palliative care, empowers patients to make informed decisions about their care goals and preferences.

Specific situations where discussing palliative care might be appropriate are:

- Soon after a cancer diagnosis.

- If the patient experiences significant side effects from cancer treatment.

- When considering different treatment options, palliative care can complement those treatments.

- In advanced stages of cancer, to focus on comfort and quality of life.

Clinical trials. Participation in a clinical trial to explore new or investigational treatments should always be considered.

In theory, clinical trials should be an option at any time in the patient’s course. But the organized clinical trial experience may not be available or appropriate. Then, the individual becomes a de facto “clinical trial with an n of 1.” Read this brief open-access blog post at Cancer Commons to learn more about that circumstance.

Innovative testing. The best choice of chemotherapeutic or targeted therapies is often unclear. The clinician is likely to follow published guidelines, often from the National Comprehensive Cancer Network.

These are evidence based and driven by consensus of experts. But guideline-recommended therapy is not always effective, and weeks or months can pass before this ineffectiveness becomes apparent. Thus, many researchers and companies are seeking methods of testing each patient’s specific cancer to determine in advance, or very quickly, whether a particular drug is likely to be effective.

Read more about these leading innovations:

SAGE Oncotest: Entering the Next Generation of Tailored Cancer Treatment

Alibrex: A New Blood Test to Reveal Whether a Cancer Treatment is Working

PARIS Test Uses Lab-Grown Mini-Tumors to Find a Patient’s Best Treatment

Using Live Cells from Patients to Find the Right Cancer Drug

Other innovative therapies under investigation could even be agnostic to cancer type:

Treating Pancreatic Cancer: Could Metabolism — Not Genomics — Be the Key?

High-Energy Blue Light Powers a Promising New Treatment to Destroy Cancer Cells

All-Clear Follow-Up: Hydrogen Peroxide Appears to Treat Oral and Skin Lesions

Cancer is a tough nut to crack. Many people and organizations are trying very hard. So much is being learned. Some approaches will be effective. We can all hope.

Dr. Lundberg, editor in chief, Cancer Commons, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Physicians Lament Over Reliance on Relative Value Units: Survey

Most physicians oppose the way standardized relative value units (RVUs) are used to determine performance and compensation, according to Medscape’s 2024 Physicians and RVUs Report. About 6 in 10 survey respondents were unhappy with how RVUs affected them financially, while 7 in 10 said RVUs were poor measures of productivity.

The report analyzed 2024 survey data from 1005 practicing physicians who earn RVUs.

“I’m already mad that the medical field is controlled by health insurers and what they pay and authorize,” said an anesthesiologist in New York. “Then [that approach] is transferred to medical offices and hospitals, where physicians are paid by RVUs.”

Most physicians surveyed produced between 4000 and 8000 RVUs per year. Roughly one in six were high RVU generators, generating more than 10,000 annually.

In most cases, the metric influences earning potential — 42% of doctors surveyed said RVUs affect their salaries to some degree. One quarter said their salary was based entirely on RVUs. More than three fourths of physicians who received performance bonuses said they must meet RVU targets to do so.

“The current RVU system encourages unnecessary procedures, hurting patients,” said an orthopedic surgeon in Maine.

Nearly three fourths of practitioners surveyed said they occasionally to frequently felt pressure to take on more patients as a result of this system.

“I know numerous primary care doctors and specialists who have been forced to increase patient volume to meet RVU goals, and none is happy about it,” said Alok Patel, MD, a pediatric hospitalist with Stanford Hospital in Palo Alto, California. “Plus, patients are definitely not happy about being rushed.”

More than half of respondents said they occasionally or frequently felt compelled by their employer to use higher-level coding, which interferes with a physician’s ethical responsibility to the patient, said Arthur L. Caplan, PhD, a bioethicist at NYU Langone Medical Center in New York City.

“Rather than rewarding excellence or good outcomes, you’re kind of rewarding procedures and volume,” said Dr. Caplan. “It’s more than pressure; it’s expected.”

Nearly 6 in 10 physicians said that the method for calculating reimbursements was unfair. Almost half said that they weren’t happy with how their workplace uses RVUs.

A few respondents said that their RVU model, which is often based on what Dr. Patel called an “overly complicated algorithm,” did not account for the time spent on tasks or the fact that some patients miss appointments. RVUs also rely on factors outside the control of a physician, such as location and patient volume, said one doctor.

The model can also lower the level of care patients receive, Dr. Patel said.

“I know primary care doctors who work in RVU-based systems and simply cannot take the necessary time — even if it’s 30-45 minutes — to thoroughly assess a patient, when the model forces them to take on 15-minute encounters.”

Finally, over half of clinicians said alternatives to the RVU system would be more effective, and 77% suggested including qualitative data. One respondent recommended incorporating time spent doing paperwork and communicating with patients, complexity of conditions, and medication management.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Most physicians oppose the way standardized relative value units (RVUs) are used to determine performance and compensation, according to Medscape’s 2024 Physicians and RVUs Report. About 6 in 10 survey respondents were unhappy with how RVUs affected them financially, while 7 in 10 said RVUs were poor measures of productivity.

The report analyzed 2024 survey data from 1005 practicing physicians who earn RVUs.

“I’m already mad that the medical field is controlled by health insurers and what they pay and authorize,” said an anesthesiologist in New York. “Then [that approach] is transferred to medical offices and hospitals, where physicians are paid by RVUs.”

Most physicians surveyed produced between 4000 and 8000 RVUs per year. Roughly one in six were high RVU generators, generating more than 10,000 annually.

In most cases, the metric influences earning potential — 42% of doctors surveyed said RVUs affect their salaries to some degree. One quarter said their salary was based entirely on RVUs. More than three fourths of physicians who received performance bonuses said they must meet RVU targets to do so.

“The current RVU system encourages unnecessary procedures, hurting patients,” said an orthopedic surgeon in Maine.

Nearly three fourths of practitioners surveyed said they occasionally to frequently felt pressure to take on more patients as a result of this system.

“I know numerous primary care doctors and specialists who have been forced to increase patient volume to meet RVU goals, and none is happy about it,” said Alok Patel, MD, a pediatric hospitalist with Stanford Hospital in Palo Alto, California. “Plus, patients are definitely not happy about being rushed.”

More than half of respondents said they occasionally or frequently felt compelled by their employer to use higher-level coding, which interferes with a physician’s ethical responsibility to the patient, said Arthur L. Caplan, PhD, a bioethicist at NYU Langone Medical Center in New York City.

“Rather than rewarding excellence or good outcomes, you’re kind of rewarding procedures and volume,” said Dr. Caplan. “It’s more than pressure; it’s expected.”

Nearly 6 in 10 physicians said that the method for calculating reimbursements was unfair. Almost half said that they weren’t happy with how their workplace uses RVUs.

A few respondents said that their RVU model, which is often based on what Dr. Patel called an “overly complicated algorithm,” did not account for the time spent on tasks or the fact that some patients miss appointments. RVUs also rely on factors outside the control of a physician, such as location and patient volume, said one doctor.

The model can also lower the level of care patients receive, Dr. Patel said.

“I know primary care doctors who work in RVU-based systems and simply cannot take the necessary time — even if it’s 30-45 minutes — to thoroughly assess a patient, when the model forces them to take on 15-minute encounters.”

Finally, over half of clinicians said alternatives to the RVU system would be more effective, and 77% suggested including qualitative data. One respondent recommended incorporating time spent doing paperwork and communicating with patients, complexity of conditions, and medication management.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Most physicians oppose the way standardized relative value units (RVUs) are used to determine performance and compensation, according to Medscape’s 2024 Physicians and RVUs Report. About 6 in 10 survey respondents were unhappy with how RVUs affected them financially, while 7 in 10 said RVUs were poor measures of productivity.

The report analyzed 2024 survey data from 1005 practicing physicians who earn RVUs.

“I’m already mad that the medical field is controlled by health insurers and what they pay and authorize,” said an anesthesiologist in New York. “Then [that approach] is transferred to medical offices and hospitals, where physicians are paid by RVUs.”

Most physicians surveyed produced between 4000 and 8000 RVUs per year. Roughly one in six were high RVU generators, generating more than 10,000 annually.

In most cases, the metric influences earning potential — 42% of doctors surveyed said RVUs affect their salaries to some degree. One quarter said their salary was based entirely on RVUs. More than three fourths of physicians who received performance bonuses said they must meet RVU targets to do so.

“The current RVU system encourages unnecessary procedures, hurting patients,” said an orthopedic surgeon in Maine.

Nearly three fourths of practitioners surveyed said they occasionally to frequently felt pressure to take on more patients as a result of this system.

“I know numerous primary care doctors and specialists who have been forced to increase patient volume to meet RVU goals, and none is happy about it,” said Alok Patel, MD, a pediatric hospitalist with Stanford Hospital in Palo Alto, California. “Plus, patients are definitely not happy about being rushed.”

More than half of respondents said they occasionally or frequently felt compelled by their employer to use higher-level coding, which interferes with a physician’s ethical responsibility to the patient, said Arthur L. Caplan, PhD, a bioethicist at NYU Langone Medical Center in New York City.

“Rather than rewarding excellence or good outcomes, you’re kind of rewarding procedures and volume,” said Dr. Caplan. “It’s more than pressure; it’s expected.”

Nearly 6 in 10 physicians said that the method for calculating reimbursements was unfair. Almost half said that they weren’t happy with how their workplace uses RVUs.

A few respondents said that their RVU model, which is often based on what Dr. Patel called an “overly complicated algorithm,” did not account for the time spent on tasks or the fact that some patients miss appointments. RVUs also rely on factors outside the control of a physician, such as location and patient volume, said one doctor.

The model can also lower the level of care patients receive, Dr. Patel said.

“I know primary care doctors who work in RVU-based systems and simply cannot take the necessary time — even if it’s 30-45 minutes — to thoroughly assess a patient, when the model forces them to take on 15-minute encounters.”

Finally, over half of clinicians said alternatives to the RVU system would be more effective, and 77% suggested including qualitative data. One respondent recommended incorporating time spent doing paperwork and communicating with patients, complexity of conditions, and medication management.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

When Childhood Cancer Survivors Face Sexual Challenges

Childhood cancers represent a diverse group of neoplasms, and thanks to advances in treatment, survival rates have improved significantly. Today, more than 80%-85% of children diagnosed with cancer in developed countries survive into adulthood.

This increase in survival has brought new challenges, however. Compared with the general population, childhood cancer survivors (CCS) are at a notably higher risk for early mortality, developing secondary cancers, and experiencing various long-term clinical and psychosocial issues stemming from their disease or its treatment.

Long-term follow-up care for CCS is a complex and evolving field. Despite ongoing efforts to establish global and national guidelines, current evidence indicates that the care and management of these patients remain suboptimal.

The disruptions caused by cancer and its treatment can interfere with normal physiological and psychological development, leading to issues with sexual function. This aspect of health is critical as it influences not just physical well-being but also psychosocial, developmental, and emotional health.

Characteristics and Mechanisms

Sexual functioning encompasses the physiological and psychological aspects of sexual behavior, including desire, arousal, orgasm, sexual pleasure, and overall satisfaction.

As CCS reach adolescence or adulthood, they often face sexual and reproductive issues, particularly as they enter romantic relationships.

Sexual functioning is a complex process that relies on the interaction of various factors, including physiological health, psychosexual development, romantic relationships, body image, and desire.

Despite its importance, the impact of childhood cancer on sexual function is often overlooked, even though cancer and its treatments can have lifelong effects.

Sexual Function in CCS

A recent review aimed to summarize the existing research on sexual function among CCS, highlighting assessment tools, key stages of psychosexual development, common sexual problems, and the prevalence of sexual dysfunction.

The review study included 22 studies published between 2000 and 2022, comprising two qualitative, six cohort, and 14 cross-sectional studies.

Most CCS reached all key stages of psychosexual development at an average age of 29.8 years. Although some milestones were achieved later than is typical, many survivors felt they reached these stages at the appropriate time. Sexual initiation was less common among those who had undergone intensive neurotoxic treatments, such as those diagnosed with brain tumors or leukemia in childhood.

In a cross-sectional study of CCS aged 17-39 years, about one third had never engaged in sexual intercourse, 41.4% reported never experiencing sexual attraction, 44.8% were dissatisfied with their sex lives, and many rarely felt sexually attractive to others. Another study found that common issues among CCS included a lack of interest in sex (30%), difficulty enjoying sex (24%), and difficulty becoming aroused (23%). However, comparing and analyzing these problems was challenging due to the lack of standardized assessment criteria.

The prevalence of sexual dysfunction among CCS ranged from 12.3% to 46.5%. For males, the prevalence ranged from 12.3% to 54.0%, while for females, it ranged from 19.9% to 57.0%.

Factors Influencing Sexual Function

The review identified the following four categories of factors influencing sexual function in CCS: Demographic, treatment-related, psychological, and physiological.

Demographic factors: Gender, age, education level, relationship status, income level, and race all play roles in sexual function.

Female survivors reported more severe sexual dysfunction and poorer sexual health than did male survivors. Age at cancer diagnosis, age at evaluation, and the time since diagnosis were closely linked to sexual experiences. Patients diagnosed with cancer during childhood tended to report better sexual function than those diagnosed during adolescence.

Treatment-related factors: The type of cancer and intensity of treatment, along with surgical history, were significant factors. Surgeries involving the spinal cord or sympathetic nerves, as well as a history of prostate or pelvic surgery, were strongly associated with erectile dysfunction in men. In women, pelvic surgeries and treatments to the pelvic area were commonly linked to sexual dysfunction.

The association between treatment intensity and sexual function was noted across several studies, although the results were not always consistent. For example, testicular radiation above 10 Gy was positively correlated with sexual dysfunction. Women who underwent more intensive treatments were more likely to report issues in multiple areas of sexual function, while men in this group were less likely to have children.

Among female CCS, certain types of cancer, such as germ cell tumors, renal tumors, and leukemia, present a higher risk for sexual dysfunction. Women who had CNS tumors in childhood frequently reported problems like difficulty in sexual arousal, low sexual satisfaction, infrequent sexual activity, and fewer sexual partners, compared with survivors of other cancers. Survivors of acute lymphoblastic leukemia and those who underwent hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) also showed varying degrees of impaired sexual function, compared with the general population. The HSCT group showed significant testicular damage, including reduced testicular volumes, low testosterone levels, and low sperm counts.

Psychological factors: These factors, such as emotional distress, play a significant role in sexual dysfunction among CCS. Symptoms like anxiety, nervousness during sexual activity, and depression are commonly reported by those with sexual dysfunction. The connection between body image and sexual function is complex. Many CCS with sexual dysfunction express concern about how others, particularly their partners, perceived their altered body image due to cancer and its treatment.

Physiological factors: In male CCS, low serum testosterone levels and low lean muscle mass are linked to an increased risk for sexual dysfunction. Treatments involving alkylating agents or testicular radiation, and surgery or radiotherapy targeting the genitourinary organs or the hypothalamic-pituitary region, can lead to various physiological and endocrine disorders, contributing to sexual dysfunction. Despite these risks, there is a lack of research evaluating sexual function through the lens of the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis and neuroendocrine pathways.

This story was translated from Univadis Italy using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Childhood cancers represent a diverse group of neoplasms, and thanks to advances in treatment, survival rates have improved significantly. Today, more than 80%-85% of children diagnosed with cancer in developed countries survive into adulthood.

This increase in survival has brought new challenges, however. Compared with the general population, childhood cancer survivors (CCS) are at a notably higher risk for early mortality, developing secondary cancers, and experiencing various long-term clinical and psychosocial issues stemming from their disease or its treatment.

Long-term follow-up care for CCS is a complex and evolving field. Despite ongoing efforts to establish global and national guidelines, current evidence indicates that the care and management of these patients remain suboptimal.

The disruptions caused by cancer and its treatment can interfere with normal physiological and psychological development, leading to issues with sexual function. This aspect of health is critical as it influences not just physical well-being but also psychosocial, developmental, and emotional health.

Characteristics and Mechanisms

Sexual functioning encompasses the physiological and psychological aspects of sexual behavior, including desire, arousal, orgasm, sexual pleasure, and overall satisfaction.

As CCS reach adolescence or adulthood, they often face sexual and reproductive issues, particularly as they enter romantic relationships.

Sexual functioning is a complex process that relies on the interaction of various factors, including physiological health, psychosexual development, romantic relationships, body image, and desire.

Despite its importance, the impact of childhood cancer on sexual function is often overlooked, even though cancer and its treatments can have lifelong effects.

Sexual Function in CCS

A recent review aimed to summarize the existing research on sexual function among CCS, highlighting assessment tools, key stages of psychosexual development, common sexual problems, and the prevalence of sexual dysfunction.

The review study included 22 studies published between 2000 and 2022, comprising two qualitative, six cohort, and 14 cross-sectional studies.

Most CCS reached all key stages of psychosexual development at an average age of 29.8 years. Although some milestones were achieved later than is typical, many survivors felt they reached these stages at the appropriate time. Sexual initiation was less common among those who had undergone intensive neurotoxic treatments, such as those diagnosed with brain tumors or leukemia in childhood.

In a cross-sectional study of CCS aged 17-39 years, about one third had never engaged in sexual intercourse, 41.4% reported never experiencing sexual attraction, 44.8% were dissatisfied with their sex lives, and many rarely felt sexually attractive to others. Another study found that common issues among CCS included a lack of interest in sex (30%), difficulty enjoying sex (24%), and difficulty becoming aroused (23%). However, comparing and analyzing these problems was challenging due to the lack of standardized assessment criteria.

The prevalence of sexual dysfunction among CCS ranged from 12.3% to 46.5%. For males, the prevalence ranged from 12.3% to 54.0%, while for females, it ranged from 19.9% to 57.0%.

Factors Influencing Sexual Function

The review identified the following four categories of factors influencing sexual function in CCS: Demographic, treatment-related, psychological, and physiological.

Demographic factors: Gender, age, education level, relationship status, income level, and race all play roles in sexual function.

Female survivors reported more severe sexual dysfunction and poorer sexual health than did male survivors. Age at cancer diagnosis, age at evaluation, and the time since diagnosis were closely linked to sexual experiences. Patients diagnosed with cancer during childhood tended to report better sexual function than those diagnosed during adolescence.

Treatment-related factors: The type of cancer and intensity of treatment, along with surgical history, were significant factors. Surgeries involving the spinal cord or sympathetic nerves, as well as a history of prostate or pelvic surgery, were strongly associated with erectile dysfunction in men. In women, pelvic surgeries and treatments to the pelvic area were commonly linked to sexual dysfunction.

The association between treatment intensity and sexual function was noted across several studies, although the results were not always consistent. For example, testicular radiation above 10 Gy was positively correlated with sexual dysfunction. Women who underwent more intensive treatments were more likely to report issues in multiple areas of sexual function, while men in this group were less likely to have children.

Among female CCS, certain types of cancer, such as germ cell tumors, renal tumors, and leukemia, present a higher risk for sexual dysfunction. Women who had CNS tumors in childhood frequently reported problems like difficulty in sexual arousal, low sexual satisfaction, infrequent sexual activity, and fewer sexual partners, compared with survivors of other cancers. Survivors of acute lymphoblastic leukemia and those who underwent hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) also showed varying degrees of impaired sexual function, compared with the general population. The HSCT group showed significant testicular damage, including reduced testicular volumes, low testosterone levels, and low sperm counts.

Psychological factors: These factors, such as emotional distress, play a significant role in sexual dysfunction among CCS. Symptoms like anxiety, nervousness during sexual activity, and depression are commonly reported by those with sexual dysfunction. The connection between body image and sexual function is complex. Many CCS with sexual dysfunction express concern about how others, particularly their partners, perceived their altered body image due to cancer and its treatment.

Physiological factors: In male CCS, low serum testosterone levels and low lean muscle mass are linked to an increased risk for sexual dysfunction. Treatments involving alkylating agents or testicular radiation, and surgery or radiotherapy targeting the genitourinary organs or the hypothalamic-pituitary region, can lead to various physiological and endocrine disorders, contributing to sexual dysfunction. Despite these risks, there is a lack of research evaluating sexual function through the lens of the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis and neuroendocrine pathways.

This story was translated from Univadis Italy using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Childhood cancers represent a diverse group of neoplasms, and thanks to advances in treatment, survival rates have improved significantly. Today, more than 80%-85% of children diagnosed with cancer in developed countries survive into adulthood.

This increase in survival has brought new challenges, however. Compared with the general population, childhood cancer survivors (CCS) are at a notably higher risk for early mortality, developing secondary cancers, and experiencing various long-term clinical and psychosocial issues stemming from their disease or its treatment.

Long-term follow-up care for CCS is a complex and evolving field. Despite ongoing efforts to establish global and national guidelines, current evidence indicates that the care and management of these patients remain suboptimal.

The disruptions caused by cancer and its treatment can interfere with normal physiological and psychological development, leading to issues with sexual function. This aspect of health is critical as it influences not just physical well-being but also psychosocial, developmental, and emotional health.

Characteristics and Mechanisms

Sexual functioning encompasses the physiological and psychological aspects of sexual behavior, including desire, arousal, orgasm, sexual pleasure, and overall satisfaction.

As CCS reach adolescence or adulthood, they often face sexual and reproductive issues, particularly as they enter romantic relationships.

Sexual functioning is a complex process that relies on the interaction of various factors, including physiological health, psychosexual development, romantic relationships, body image, and desire.

Despite its importance, the impact of childhood cancer on sexual function is often overlooked, even though cancer and its treatments can have lifelong effects.

Sexual Function in CCS

A recent review aimed to summarize the existing research on sexual function among CCS, highlighting assessment tools, key stages of psychosexual development, common sexual problems, and the prevalence of sexual dysfunction.

The review study included 22 studies published between 2000 and 2022, comprising two qualitative, six cohort, and 14 cross-sectional studies.

Most CCS reached all key stages of psychosexual development at an average age of 29.8 years. Although some milestones were achieved later than is typical, many survivors felt they reached these stages at the appropriate time. Sexual initiation was less common among those who had undergone intensive neurotoxic treatments, such as those diagnosed with brain tumors or leukemia in childhood.

In a cross-sectional study of CCS aged 17-39 years, about one third had never engaged in sexual intercourse, 41.4% reported never experiencing sexual attraction, 44.8% were dissatisfied with their sex lives, and many rarely felt sexually attractive to others. Another study found that common issues among CCS included a lack of interest in sex (30%), difficulty enjoying sex (24%), and difficulty becoming aroused (23%). However, comparing and analyzing these problems was challenging due to the lack of standardized assessment criteria.

The prevalence of sexual dysfunction among CCS ranged from 12.3% to 46.5%. For males, the prevalence ranged from 12.3% to 54.0%, while for females, it ranged from 19.9% to 57.0%.

Factors Influencing Sexual Function

The review identified the following four categories of factors influencing sexual function in CCS: Demographic, treatment-related, psychological, and physiological.

Demographic factors: Gender, age, education level, relationship status, income level, and race all play roles in sexual function.

Female survivors reported more severe sexual dysfunction and poorer sexual health than did male survivors. Age at cancer diagnosis, age at evaluation, and the time since diagnosis were closely linked to sexual experiences. Patients diagnosed with cancer during childhood tended to report better sexual function than those diagnosed during adolescence.

Treatment-related factors: The type of cancer and intensity of treatment, along with surgical history, were significant factors. Surgeries involving the spinal cord or sympathetic nerves, as well as a history of prostate or pelvic surgery, were strongly associated with erectile dysfunction in men. In women, pelvic surgeries and treatments to the pelvic area were commonly linked to sexual dysfunction.

The association between treatment intensity and sexual function was noted across several studies, although the results were not always consistent. For example, testicular radiation above 10 Gy was positively correlated with sexual dysfunction. Women who underwent more intensive treatments were more likely to report issues in multiple areas of sexual function, while men in this group were less likely to have children.

Among female CCS, certain types of cancer, such as germ cell tumors, renal tumors, and leukemia, present a higher risk for sexual dysfunction. Women who had CNS tumors in childhood frequently reported problems like difficulty in sexual arousal, low sexual satisfaction, infrequent sexual activity, and fewer sexual partners, compared with survivors of other cancers. Survivors of acute lymphoblastic leukemia and those who underwent hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) also showed varying degrees of impaired sexual function, compared with the general population. The HSCT group showed significant testicular damage, including reduced testicular volumes, low testosterone levels, and low sperm counts.

Psychological factors: These factors, such as emotional distress, play a significant role in sexual dysfunction among CCS. Symptoms like anxiety, nervousness during sexual activity, and depression are commonly reported by those with sexual dysfunction. The connection between body image and sexual function is complex. Many CCS with sexual dysfunction express concern about how others, particularly their partners, perceived their altered body image due to cancer and its treatment.

Physiological factors: In male CCS, low serum testosterone levels and low lean muscle mass are linked to an increased risk for sexual dysfunction. Treatments involving alkylating agents or testicular radiation, and surgery or radiotherapy targeting the genitourinary organs or the hypothalamic-pituitary region, can lead to various physiological and endocrine disorders, contributing to sexual dysfunction. Despite these risks, there is a lack of research evaluating sexual function through the lens of the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis and neuroendocrine pathways.

This story was translated from Univadis Italy using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

PrEP Prescription Pickups Vary With Prescriber Specialty

Preexposure prophylaxis prescription reversals and abandonments were lower for patients seen by primary care clinicians than by other non–infectious disease clinicians, based on data from approximately 37,000 individuals.

Although preexposure prophylaxis (PrEP) has been associated with a reduced risk of HIV (human immunodeficiency virus) infection when used as prescribed, the association between PrEP prescription pickup and specialty of the prescribing clinician has not been examined, wrote Lorraine T. Dean, ScD, an epidemiologist at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, Maryland, and colleagues.

“HIV PrEP is highly effective at preventing new HIV cases, and while use is on the rise, is still used much less than it should be by people who are at risk of HIV,” Dr. Dean said in an interview. “This study is helpful in pinpointing who is at risk for not picking up PrEP and in helping us think through how to reach them so that they can be better positioned to get PrEP,” she said.

In a study published in JAMA Internal Medicine, the researchers reviewed data for PrEP care. The study population included 37,003 patients aged 18 years and older who received new insurer-approved PrEP prescriptions between 2015 and 2019. Most of the patients (77%) ranged in age from 25 to 64 years; 88% were male.

Pharmacy claims data were matched with clinician data from the US National Plan and Provider Enumeration System.

Clinicians were divided into three groups: primary care providers (PCPs), infectious disease specialists (IDs), and other specialists (defined as any clinician prescribing PrEP but not classified as a PCP or an ID specialist). The main binary outcomes were prescription reversal (defined as when a patient failed to retrieve a prescription) and abandonment (defined as when a patient neglected to pick up a prescription for 1 year).

Overall, of 24,604 patients 67% received prescriptions from PCPs, 3,571 (10%) received prescriptions from ID specialists, and 8828 (24%) received prescriptions from other specialty clinicians.

The prevalence of reversals for patients seen by PCPs, ID specialists, and other specialty clinicians was 18%, 18%, and 25%, respectively. The prevalence of abandonments by clinician group was 12%, 12%, and 20%, respectively.

In a regression analysis, patients prescribed PrEP by ID specialists had 10% lower odds of reversals and 12% lower odds of abandonments compared to those seen by PCPs (odds ratio 0.90 and 0.88, respectively). However, patients seen by other clinicians (not primary care or ID) were 33% and 54% more likely to have reversals and abandonments, respectively, compared with those seen by PCPs.

Many patients at risk for HIV first see a PCP and then are referred to a specialist, such as an ID physician, Dr. Dean said. “The patients who take the time to then follow up with a specialist may be most motivated and able to follow through with the specialist’s request, in this case, accessing their PrEP prescription,” she said. In the current study, the researchers were most surprised by how many other specialty providers are involved in PrEP care, which is very positive given the effectiveness of the medication, she noted.

“Our results suggest that a wide range of prescribers, regardless of specialty, should be equipped to prescribe PrEP as well as offer PrEP counseling,” Dr. Dean said. A key takeaway for clinicians is that PrEP should have no cost for the majority of patients in the United States, she emphasized. The absence of cost expands the population who should be interested and able to access PrEP, she said. Therefore, providers should be prepared to recommend PrEP to eligible patients, and seek training or continuing medical education for themselves so they feel equipped to prescribe and counsel patients on PrEP, she said.

“One limitation of this work is that, while it can point to what is happening, it cannot tell us why the reversals are happening; what is the reason patients prescribed by certain providers are more or less likely to get their PrEP,” Dr. Dean explained. “We have tried to do interviews with patients to understand why this might be happening, but it’s hard to find people who aren’t showing up to do something, compared to finding people who are showing up to do something,” she said. Alternatively, researchers could interview providers to understand their perspective on why differences in prescription pickups occur across specialties, she said.

Looking ahead, “a national PrEP program that includes elements of required clinician training could be beneficial, and research on how a national PrEP program could be implemented and impact HIV rates would be helpful in considering this strategy of prevention,” said Dr. Dean.

Support All Prescribers to Increase PrEP Adherence

Differences in uptake of PrEP prescriptions may be explained by the different populations seen by various specialties, Meredith Green, MD, of Indiana University School of Medicine, Indianapolis, and Lona Mody, MD, of the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, wrote in an accompanying editorial. However, the key question is how to support all prescribers and promote initiation and adherence to PrEP, they said.

Considerations include whether people at risk for HIV prefer to discuss PrEP with a clinician they already know, vs. a new specialist, but many PCPs are not familiar with the latest PrEP guidelines, they said.

“Interventions that support PrEP provision by PCPs, especially since they prescribed the largest proportion of PrEP prescriptions, can accelerate the uptake of PrEP,” the editorialists wrote.

“Supporting a diverse clinician workforce reflective of communities most impacted by HIV will remain critical, as will acknowledging and addressing HIV stigma,” they said. Educational interventions, including online programs and specialist access for complex cases, would help as well, they said. The approval of additional PrEP agents since the current study was conducted make it even more important to support PrEP prescribers and promote treatment adherence for those at risk for HIV, Dr. Green and Dr. Mody emphasized.

The study was funded by the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Dean had no financial conflicts to disclose. Dr. Green disclosed grants from Gilead and royalties from Wolters Kluwer unrelated to the current study; she also disclosed serving on the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention/Health Resources and Services Administration advisory committee on HIV, viral hepatitis, and sexually transmitted infection prevention and treatment. Dr. Mody disclosed grants from the US National Institute on Aging, Veterans Affairs, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, NanoVibronix, and UpToDate unrelated to the current study.

Preexposure prophylaxis prescription reversals and abandonments were lower for patients seen by primary care clinicians than by other non–infectious disease clinicians, based on data from approximately 37,000 individuals.

Although preexposure prophylaxis (PrEP) has been associated with a reduced risk of HIV (human immunodeficiency virus) infection when used as prescribed, the association between PrEP prescription pickup and specialty of the prescribing clinician has not been examined, wrote Lorraine T. Dean, ScD, an epidemiologist at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, Maryland, and colleagues.

“HIV PrEP is highly effective at preventing new HIV cases, and while use is on the rise, is still used much less than it should be by people who are at risk of HIV,” Dr. Dean said in an interview. “This study is helpful in pinpointing who is at risk for not picking up PrEP and in helping us think through how to reach them so that they can be better positioned to get PrEP,” she said.

In a study published in JAMA Internal Medicine, the researchers reviewed data for PrEP care. The study population included 37,003 patients aged 18 years and older who received new insurer-approved PrEP prescriptions between 2015 and 2019. Most of the patients (77%) ranged in age from 25 to 64 years; 88% were male.

Pharmacy claims data were matched with clinician data from the US National Plan and Provider Enumeration System.

Clinicians were divided into three groups: primary care providers (PCPs), infectious disease specialists (IDs), and other specialists (defined as any clinician prescribing PrEP but not classified as a PCP or an ID specialist). The main binary outcomes were prescription reversal (defined as when a patient failed to retrieve a prescription) and abandonment (defined as when a patient neglected to pick up a prescription for 1 year).

Overall, of 24,604 patients 67% received prescriptions from PCPs, 3,571 (10%) received prescriptions from ID specialists, and 8828 (24%) received prescriptions from other specialty clinicians.

The prevalence of reversals for patients seen by PCPs, ID specialists, and other specialty clinicians was 18%, 18%, and 25%, respectively. The prevalence of abandonments by clinician group was 12%, 12%, and 20%, respectively.

In a regression analysis, patients prescribed PrEP by ID specialists had 10% lower odds of reversals and 12% lower odds of abandonments compared to those seen by PCPs (odds ratio 0.90 and 0.88, respectively). However, patients seen by other clinicians (not primary care or ID) were 33% and 54% more likely to have reversals and abandonments, respectively, compared with those seen by PCPs.

Many patients at risk for HIV first see a PCP and then are referred to a specialist, such as an ID physician, Dr. Dean said. “The patients who take the time to then follow up with a specialist may be most motivated and able to follow through with the specialist’s request, in this case, accessing their PrEP prescription,” she said. In the current study, the researchers were most surprised by how many other specialty providers are involved in PrEP care, which is very positive given the effectiveness of the medication, she noted.

“Our results suggest that a wide range of prescribers, regardless of specialty, should be equipped to prescribe PrEP as well as offer PrEP counseling,” Dr. Dean said. A key takeaway for clinicians is that PrEP should have no cost for the majority of patients in the United States, she emphasized. The absence of cost expands the population who should be interested and able to access PrEP, she said. Therefore, providers should be prepared to recommend PrEP to eligible patients, and seek training or continuing medical education for themselves so they feel equipped to prescribe and counsel patients on PrEP, she said.

“One limitation of this work is that, while it can point to what is happening, it cannot tell us why the reversals are happening; what is the reason patients prescribed by certain providers are more or less likely to get their PrEP,” Dr. Dean explained. “We have tried to do interviews with patients to understand why this might be happening, but it’s hard to find people who aren’t showing up to do something, compared to finding people who are showing up to do something,” she said. Alternatively, researchers could interview providers to understand their perspective on why differences in prescription pickups occur across specialties, she said.

Looking ahead, “a national PrEP program that includes elements of required clinician training could be beneficial, and research on how a national PrEP program could be implemented and impact HIV rates would be helpful in considering this strategy of prevention,” said Dr. Dean.

Support All Prescribers to Increase PrEP Adherence

Differences in uptake of PrEP prescriptions may be explained by the different populations seen by various specialties, Meredith Green, MD, of Indiana University School of Medicine, Indianapolis, and Lona Mody, MD, of the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, wrote in an accompanying editorial. However, the key question is how to support all prescribers and promote initiation and adherence to PrEP, they said.

Considerations include whether people at risk for HIV prefer to discuss PrEP with a clinician they already know, vs. a new specialist, but many PCPs are not familiar with the latest PrEP guidelines, they said.

“Interventions that support PrEP provision by PCPs, especially since they prescribed the largest proportion of PrEP prescriptions, can accelerate the uptake of PrEP,” the editorialists wrote.

“Supporting a diverse clinician workforce reflective of communities most impacted by HIV will remain critical, as will acknowledging and addressing HIV stigma,” they said. Educational interventions, including online programs and specialist access for complex cases, would help as well, they said. The approval of additional PrEP agents since the current study was conducted make it even more important to support PrEP prescribers and promote treatment adherence for those at risk for HIV, Dr. Green and Dr. Mody emphasized.

The study was funded by the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Dean had no financial conflicts to disclose. Dr. Green disclosed grants from Gilead and royalties from Wolters Kluwer unrelated to the current study; she also disclosed serving on the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention/Health Resources and Services Administration advisory committee on HIV, viral hepatitis, and sexually transmitted infection prevention and treatment. Dr. Mody disclosed grants from the US National Institute on Aging, Veterans Affairs, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, NanoVibronix, and UpToDate unrelated to the current study.

Preexposure prophylaxis prescription reversals and abandonments were lower for patients seen by primary care clinicians than by other non–infectious disease clinicians, based on data from approximately 37,000 individuals.

Although preexposure prophylaxis (PrEP) has been associated with a reduced risk of HIV (human immunodeficiency virus) infection when used as prescribed, the association between PrEP prescription pickup and specialty of the prescribing clinician has not been examined, wrote Lorraine T. Dean, ScD, an epidemiologist at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, Maryland, and colleagues.

“HIV PrEP is highly effective at preventing new HIV cases, and while use is on the rise, is still used much less than it should be by people who are at risk of HIV,” Dr. Dean said in an interview. “This study is helpful in pinpointing who is at risk for not picking up PrEP and in helping us think through how to reach them so that they can be better positioned to get PrEP,” she said.

In a study published in JAMA Internal Medicine, the researchers reviewed data for PrEP care. The study population included 37,003 patients aged 18 years and older who received new insurer-approved PrEP prescriptions between 2015 and 2019. Most of the patients (77%) ranged in age from 25 to 64 years; 88% were male.

Pharmacy claims data were matched with clinician data from the US National Plan and Provider Enumeration System.

Clinicians were divided into three groups: primary care providers (PCPs), infectious disease specialists (IDs), and other specialists (defined as any clinician prescribing PrEP but not classified as a PCP or an ID specialist). The main binary outcomes were prescription reversal (defined as when a patient failed to retrieve a prescription) and abandonment (defined as when a patient neglected to pick up a prescription for 1 year).

Overall, of 24,604 patients 67% received prescriptions from PCPs, 3,571 (10%) received prescriptions from ID specialists, and 8828 (24%) received prescriptions from other specialty clinicians.

The prevalence of reversals for patients seen by PCPs, ID specialists, and other specialty clinicians was 18%, 18%, and 25%, respectively. The prevalence of abandonments by clinician group was 12%, 12%, and 20%, respectively.

In a regression analysis, patients prescribed PrEP by ID specialists had 10% lower odds of reversals and 12% lower odds of abandonments compared to those seen by PCPs (odds ratio 0.90 and 0.88, respectively). However, patients seen by other clinicians (not primary care or ID) were 33% and 54% more likely to have reversals and abandonments, respectively, compared with those seen by PCPs.

Many patients at risk for HIV first see a PCP and then are referred to a specialist, such as an ID physician, Dr. Dean said. “The patients who take the time to then follow up with a specialist may be most motivated and able to follow through with the specialist’s request, in this case, accessing their PrEP prescription,” she said. In the current study, the researchers were most surprised by how many other specialty providers are involved in PrEP care, which is very positive given the effectiveness of the medication, she noted.

“Our results suggest that a wide range of prescribers, regardless of specialty, should be equipped to prescribe PrEP as well as offer PrEP counseling,” Dr. Dean said. A key takeaway for clinicians is that PrEP should have no cost for the majority of patients in the United States, she emphasized. The absence of cost expands the population who should be interested and able to access PrEP, she said. Therefore, providers should be prepared to recommend PrEP to eligible patients, and seek training or continuing medical education for themselves so they feel equipped to prescribe and counsel patients on PrEP, she said.

“One limitation of this work is that, while it can point to what is happening, it cannot tell us why the reversals are happening; what is the reason patients prescribed by certain providers are more or less likely to get their PrEP,” Dr. Dean explained. “We have tried to do interviews with patients to understand why this might be happening, but it’s hard to find people who aren’t showing up to do something, compared to finding people who are showing up to do something,” she said. Alternatively, researchers could interview providers to understand their perspective on why differences in prescription pickups occur across specialties, she said.

Looking ahead, “a national PrEP program that includes elements of required clinician training could be beneficial, and research on how a national PrEP program could be implemented and impact HIV rates would be helpful in considering this strategy of prevention,” said Dr. Dean.

Support All Prescribers to Increase PrEP Adherence

Differences in uptake of PrEP prescriptions may be explained by the different populations seen by various specialties, Meredith Green, MD, of Indiana University School of Medicine, Indianapolis, and Lona Mody, MD, of the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, wrote in an accompanying editorial. However, the key question is how to support all prescribers and promote initiation and adherence to PrEP, they said.

Considerations include whether people at risk for HIV prefer to discuss PrEP with a clinician they already know, vs. a new specialist, but many PCPs are not familiar with the latest PrEP guidelines, they said.

“Interventions that support PrEP provision by PCPs, especially since they prescribed the largest proportion of PrEP prescriptions, can accelerate the uptake of PrEP,” the editorialists wrote.

“Supporting a diverse clinician workforce reflective of communities most impacted by HIV will remain critical, as will acknowledging and addressing HIV stigma,” they said. Educational interventions, including online programs and specialist access for complex cases, would help as well, they said. The approval of additional PrEP agents since the current study was conducted make it even more important to support PrEP prescribers and promote treatment adherence for those at risk for HIV, Dr. Green and Dr. Mody emphasized.

The study was funded by the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Dean had no financial conflicts to disclose. Dr. Green disclosed grants from Gilead and royalties from Wolters Kluwer unrelated to the current study; she also disclosed serving on the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention/Health Resources and Services Administration advisory committee on HIV, viral hepatitis, and sexually transmitted infection prevention and treatment. Dr. Mody disclosed grants from the US National Institute on Aging, Veterans Affairs, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, NanoVibronix, and UpToDate unrelated to the current study.

FROM JAMA INTERNAL MEDICINE

Low HPV Vaccination in the United States Is a Public Health ‘Failure’

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

I would like to briefly discuss what I consider to be a very discouraging report and one that I believe we as an oncology society and, quite frankly, as a medical community need to deal with.