User login

Bringing you the latest news, research and reviews, exclusive interviews, podcasts, quizzes, and more.

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack nav-ce-stack__large-screen')]

header[@id='header']

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

footer[@id='footer']

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

div[contains(@class, 'view-medstat-quiz-listing-panes')]

Telemedicine in primary care

How to effectively utilize this tool

By now it is well known that the COVID-19 pandemic has significantly disrupted primary care. Office visits and revenues have precipitously dropped as physicians and patients alike fear in-person visits may increase their risks of contracting the virus. However, telemedicine has emerged as a lifeline of sorts for many practices, enabling them to conduct visits and maintain contact with patients.

Telemedicine is likely to continue to serve as a tool for primary care providers to improve access to convenient, cost-effective, high-quality care after the pandemic. Another benefit of telemedicine is it can help maintain a portion of a practice’s revenue stream for physicians during uncertain times.

Indeed, the nation has seen recent progress toward telemedicine parity, which refers to the concept of reimbursing providers’ telehealth visits at the same rates as similar in-person visits.

A challenge to adopting telemedicine is that it calls for adjusting established workflows for in-person encounters. A practice cannot simply replicate in-person processes to work for telehealth. While both in-person and virtual visits require adherence to HIPAA, for example, how you actually protect patient privacy will call for different measures. Harking back to the early days of EMR implementation, one does not need to like the telemedicine platform or process, but come to terms with the fact that it is a tool that is here to stay to deliver patient care.

Treat your practice like a laboratory

Adoption may vary between practices depending on many factors, including clinicians’ comfort with technology, clinical tolerance and triage rules for nontouch encounters, state regulations, and more. Every provider group should begin experimenting with telemedicine in specific ways that make sense for them.

One physician may practice telemedicine full-time while the rest abstain, or perhaps the practice prefers to offer telemedicine services during specific hours on specific days. Don’t be afraid to start slowly when you’re trying something new – but do get started with telehealth. It will increasingly be a mainstream medium and more patients will come to expect it.

Train the entire team

Many primary care practices do not enjoy the resources of an information technology team, so all team members essentially need to learn the new skill of telemedicine usage, in addition to assisting patients. That can’t happen without staff buy-in, so it is essential that everyone from the office manager to medical assistants have the training they need to make the technology work. Juggling schedules for telehealth and in-office, activating an account through email, starting and joining a telehealth meeting, and preparing a patient for a visit are just a handful of basic tasks your staff should be trained to do to contribute to the successful integration of telehealth.

Educate and encourage patients to use telehealth

While unfamiliarity with technology may represent a roadblock for some patients, others resist telemedicine simply because no one has explained to them why it’s so important and the benefits it can hold for them. Education and communication are critical, including the sometimes painstaking work of slowly walking patients through the process of performing important functions on the telemedicine app. By providing them with some friendly coaching, patients won’t feel lost or abandoned during what for some may be an unfamiliar and frustrating process.

Manage more behavioral health

Different states and health plans incentivize primary practices for integrating behavioral health into their offerings. Rather than dismiss this addition to your own practice as too cumbersome to take on, I would recommend using telehealth to expand behavioral health care services.

If your practice is working toward a team-based, interdisciplinary approach to care delivery, behavioral health is a critical component. While other elements of this “whole person” health care may be better suited for an office visit, the vast majority of behavioral health services can be delivered virtually.

To decide if your patient may benefit from behavioral health care, the primary care provider (PCP) can conduct a screening via telehealth. Once the screening is complete, the PCP can discuss results and refer the patient to a mental health professional – all via telehealth. While patients may be reluctant to receive behavioral health treatment, perhaps because of stigma or inexperience, they may appreciate the telemedicine option as they can remain in the comfort and familiarity of their homes.

Collaborative Care is both an in-person and virtual model that allows PCP practices to offer behavioral health services in a cost effective way by utilizing a psychiatrist as a “consultant” to the practice as opposed to hiring a full-time psychiatrist. All services within the Collaborative Care Model can be offered via telehealth, and all major insurance providers reimburse primary care providers for delivering Collaborative Care.

When PCPs provide behavioral health treatment as an “extension” of the primary care service offerings, the stigma is reduced and more patients are willing to accept the care they need.

Many areas of the country suffer from a lack of access to behavioral health specialists. In rural counties, for example, the nearest therapist may be located over an hour away. By integrating behavioral telehealth services into your practice’s offerings, you can remove geographic and transportation obstacles to care for your patient population.

Doing this can lead to providing more culturally competent care. It’s important that you’re able to offer mental health services to your patients from a professional with a similar ethnic or racial background. Language barriers and cultural differences may limit a provider’s ability to treat a patient, particularly if the patient faces health disparities related to race or ethnicity. If your practice needs to look outside of your community to tap into a more diverse pool of providers to better meet your patients’ needs, telehealth makes it easier to do that.

Adopting telemedicine for consultative patient visits offers primary care a path toward restoring patient volume and hope for a postpandemic future.

Mark Stephan, MD, is chief medical officer at Equality Health, a whole-health delivery system. He practiced family medicine for 19 years, including hospital medicine and obstetrics in rural and urban settings. Dr. Stephan has no conflicts related to the content of this piece.

How to effectively utilize this tool

How to effectively utilize this tool

By now it is well known that the COVID-19 pandemic has significantly disrupted primary care. Office visits and revenues have precipitously dropped as physicians and patients alike fear in-person visits may increase their risks of contracting the virus. However, telemedicine has emerged as a lifeline of sorts for many practices, enabling them to conduct visits and maintain contact with patients.

Telemedicine is likely to continue to serve as a tool for primary care providers to improve access to convenient, cost-effective, high-quality care after the pandemic. Another benefit of telemedicine is it can help maintain a portion of a practice’s revenue stream for physicians during uncertain times.

Indeed, the nation has seen recent progress toward telemedicine parity, which refers to the concept of reimbursing providers’ telehealth visits at the same rates as similar in-person visits.

A challenge to adopting telemedicine is that it calls for adjusting established workflows for in-person encounters. A practice cannot simply replicate in-person processes to work for telehealth. While both in-person and virtual visits require adherence to HIPAA, for example, how you actually protect patient privacy will call for different measures. Harking back to the early days of EMR implementation, one does not need to like the telemedicine platform or process, but come to terms with the fact that it is a tool that is here to stay to deliver patient care.

Treat your practice like a laboratory

Adoption may vary between practices depending on many factors, including clinicians’ comfort with technology, clinical tolerance and triage rules for nontouch encounters, state regulations, and more. Every provider group should begin experimenting with telemedicine in specific ways that make sense for them.

One physician may practice telemedicine full-time while the rest abstain, or perhaps the practice prefers to offer telemedicine services during specific hours on specific days. Don’t be afraid to start slowly when you’re trying something new – but do get started with telehealth. It will increasingly be a mainstream medium and more patients will come to expect it.

Train the entire team

Many primary care practices do not enjoy the resources of an information technology team, so all team members essentially need to learn the new skill of telemedicine usage, in addition to assisting patients. That can’t happen without staff buy-in, so it is essential that everyone from the office manager to medical assistants have the training they need to make the technology work. Juggling schedules for telehealth and in-office, activating an account through email, starting and joining a telehealth meeting, and preparing a patient for a visit are just a handful of basic tasks your staff should be trained to do to contribute to the successful integration of telehealth.

Educate and encourage patients to use telehealth

While unfamiliarity with technology may represent a roadblock for some patients, others resist telemedicine simply because no one has explained to them why it’s so important and the benefits it can hold for them. Education and communication are critical, including the sometimes painstaking work of slowly walking patients through the process of performing important functions on the telemedicine app. By providing them with some friendly coaching, patients won’t feel lost or abandoned during what for some may be an unfamiliar and frustrating process.

Manage more behavioral health

Different states and health plans incentivize primary practices for integrating behavioral health into their offerings. Rather than dismiss this addition to your own practice as too cumbersome to take on, I would recommend using telehealth to expand behavioral health care services.

If your practice is working toward a team-based, interdisciplinary approach to care delivery, behavioral health is a critical component. While other elements of this “whole person” health care may be better suited for an office visit, the vast majority of behavioral health services can be delivered virtually.

To decide if your patient may benefit from behavioral health care, the primary care provider (PCP) can conduct a screening via telehealth. Once the screening is complete, the PCP can discuss results and refer the patient to a mental health professional – all via telehealth. While patients may be reluctant to receive behavioral health treatment, perhaps because of stigma or inexperience, they may appreciate the telemedicine option as they can remain in the comfort and familiarity of their homes.

Collaborative Care is both an in-person and virtual model that allows PCP practices to offer behavioral health services in a cost effective way by utilizing a psychiatrist as a “consultant” to the practice as opposed to hiring a full-time psychiatrist. All services within the Collaborative Care Model can be offered via telehealth, and all major insurance providers reimburse primary care providers for delivering Collaborative Care.

When PCPs provide behavioral health treatment as an “extension” of the primary care service offerings, the stigma is reduced and more patients are willing to accept the care they need.

Many areas of the country suffer from a lack of access to behavioral health specialists. In rural counties, for example, the nearest therapist may be located over an hour away. By integrating behavioral telehealth services into your practice’s offerings, you can remove geographic and transportation obstacles to care for your patient population.

Doing this can lead to providing more culturally competent care. It’s important that you’re able to offer mental health services to your patients from a professional with a similar ethnic or racial background. Language barriers and cultural differences may limit a provider’s ability to treat a patient, particularly if the patient faces health disparities related to race or ethnicity. If your practice needs to look outside of your community to tap into a more diverse pool of providers to better meet your patients’ needs, telehealth makes it easier to do that.

Adopting telemedicine for consultative patient visits offers primary care a path toward restoring patient volume and hope for a postpandemic future.

Mark Stephan, MD, is chief medical officer at Equality Health, a whole-health delivery system. He practiced family medicine for 19 years, including hospital medicine and obstetrics in rural and urban settings. Dr. Stephan has no conflicts related to the content of this piece.

By now it is well known that the COVID-19 pandemic has significantly disrupted primary care. Office visits and revenues have precipitously dropped as physicians and patients alike fear in-person visits may increase their risks of contracting the virus. However, telemedicine has emerged as a lifeline of sorts for many practices, enabling them to conduct visits and maintain contact with patients.

Telemedicine is likely to continue to serve as a tool for primary care providers to improve access to convenient, cost-effective, high-quality care after the pandemic. Another benefit of telemedicine is it can help maintain a portion of a practice’s revenue stream for physicians during uncertain times.

Indeed, the nation has seen recent progress toward telemedicine parity, which refers to the concept of reimbursing providers’ telehealth visits at the same rates as similar in-person visits.

A challenge to adopting telemedicine is that it calls for adjusting established workflows for in-person encounters. A practice cannot simply replicate in-person processes to work for telehealth. While both in-person and virtual visits require adherence to HIPAA, for example, how you actually protect patient privacy will call for different measures. Harking back to the early days of EMR implementation, one does not need to like the telemedicine platform or process, but come to terms with the fact that it is a tool that is here to stay to deliver patient care.

Treat your practice like a laboratory

Adoption may vary between practices depending on many factors, including clinicians’ comfort with technology, clinical tolerance and triage rules for nontouch encounters, state regulations, and more. Every provider group should begin experimenting with telemedicine in specific ways that make sense for them.

One physician may practice telemedicine full-time while the rest abstain, or perhaps the practice prefers to offer telemedicine services during specific hours on specific days. Don’t be afraid to start slowly when you’re trying something new – but do get started with telehealth. It will increasingly be a mainstream medium and more patients will come to expect it.

Train the entire team

Many primary care practices do not enjoy the resources of an information technology team, so all team members essentially need to learn the new skill of telemedicine usage, in addition to assisting patients. That can’t happen without staff buy-in, so it is essential that everyone from the office manager to medical assistants have the training they need to make the technology work. Juggling schedules for telehealth and in-office, activating an account through email, starting and joining a telehealth meeting, and preparing a patient for a visit are just a handful of basic tasks your staff should be trained to do to contribute to the successful integration of telehealth.

Educate and encourage patients to use telehealth

While unfamiliarity with technology may represent a roadblock for some patients, others resist telemedicine simply because no one has explained to them why it’s so important and the benefits it can hold for them. Education and communication are critical, including the sometimes painstaking work of slowly walking patients through the process of performing important functions on the telemedicine app. By providing them with some friendly coaching, patients won’t feel lost or abandoned during what for some may be an unfamiliar and frustrating process.

Manage more behavioral health

Different states and health plans incentivize primary practices for integrating behavioral health into their offerings. Rather than dismiss this addition to your own practice as too cumbersome to take on, I would recommend using telehealth to expand behavioral health care services.

If your practice is working toward a team-based, interdisciplinary approach to care delivery, behavioral health is a critical component. While other elements of this “whole person” health care may be better suited for an office visit, the vast majority of behavioral health services can be delivered virtually.

To decide if your patient may benefit from behavioral health care, the primary care provider (PCP) can conduct a screening via telehealth. Once the screening is complete, the PCP can discuss results and refer the patient to a mental health professional – all via telehealth. While patients may be reluctant to receive behavioral health treatment, perhaps because of stigma or inexperience, they may appreciate the telemedicine option as they can remain in the comfort and familiarity of their homes.

Collaborative Care is both an in-person and virtual model that allows PCP practices to offer behavioral health services in a cost effective way by utilizing a psychiatrist as a “consultant” to the practice as opposed to hiring a full-time psychiatrist. All services within the Collaborative Care Model can be offered via telehealth, and all major insurance providers reimburse primary care providers for delivering Collaborative Care.

When PCPs provide behavioral health treatment as an “extension” of the primary care service offerings, the stigma is reduced and more patients are willing to accept the care they need.

Many areas of the country suffer from a lack of access to behavioral health specialists. In rural counties, for example, the nearest therapist may be located over an hour away. By integrating behavioral telehealth services into your practice’s offerings, you can remove geographic and transportation obstacles to care for your patient population.

Doing this can lead to providing more culturally competent care. It’s important that you’re able to offer mental health services to your patients from a professional with a similar ethnic or racial background. Language barriers and cultural differences may limit a provider’s ability to treat a patient, particularly if the patient faces health disparities related to race or ethnicity. If your practice needs to look outside of your community to tap into a more diverse pool of providers to better meet your patients’ needs, telehealth makes it easier to do that.

Adopting telemedicine for consultative patient visits offers primary care a path toward restoring patient volume and hope for a postpandemic future.

Mark Stephan, MD, is chief medical officer at Equality Health, a whole-health delivery system. He practiced family medicine for 19 years, including hospital medicine and obstetrics in rural and urban settings. Dr. Stephan has no conflicts related to the content of this piece.

ED visits for mental health, substance use doubled in 1 decade

ED visits related to mental health conditions increased nearly twofold from 2007-2008 to 2015-2016, new research suggests.

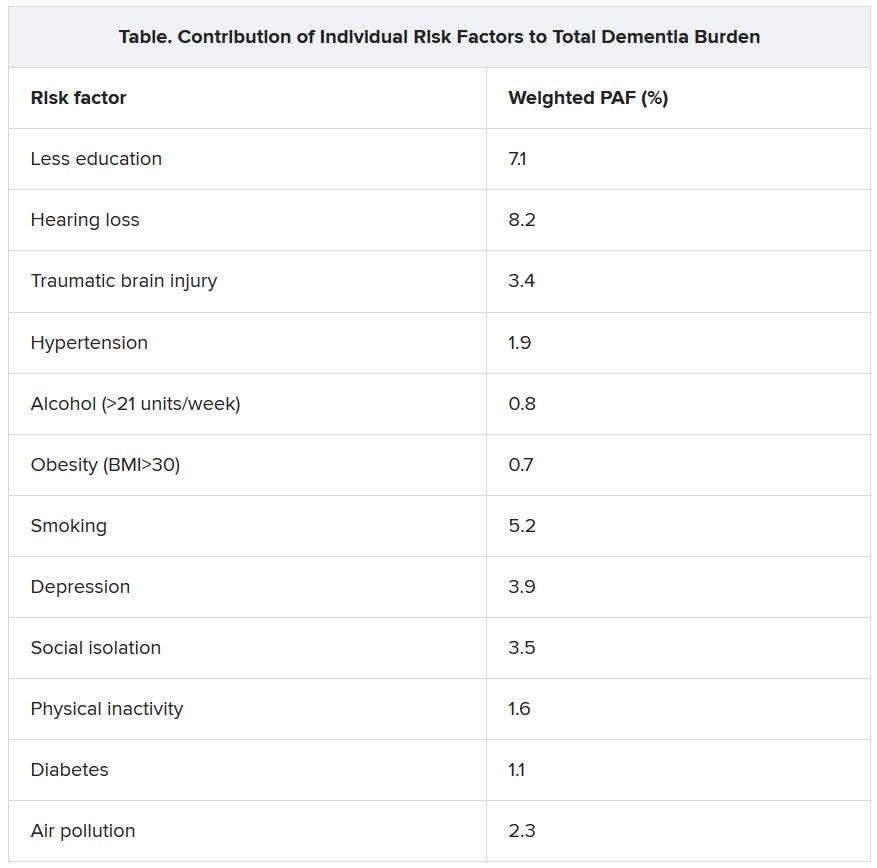

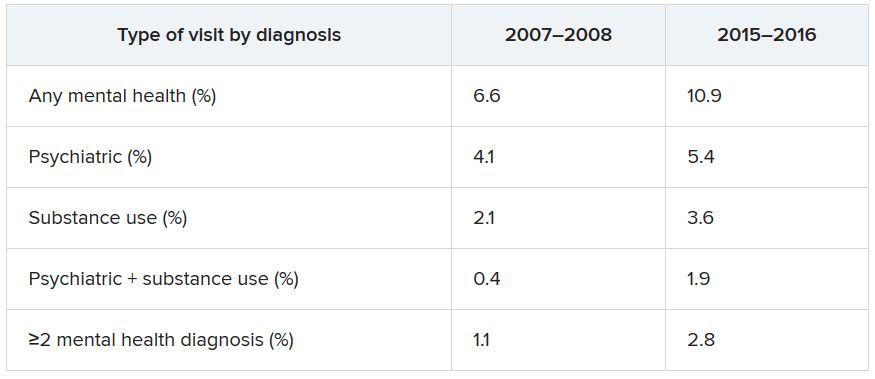

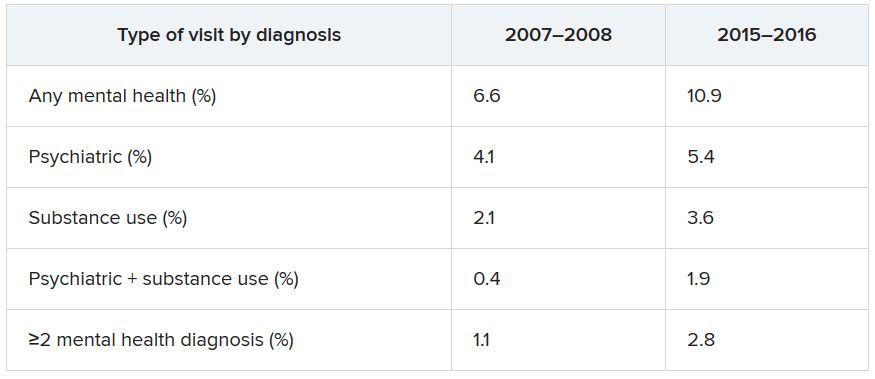

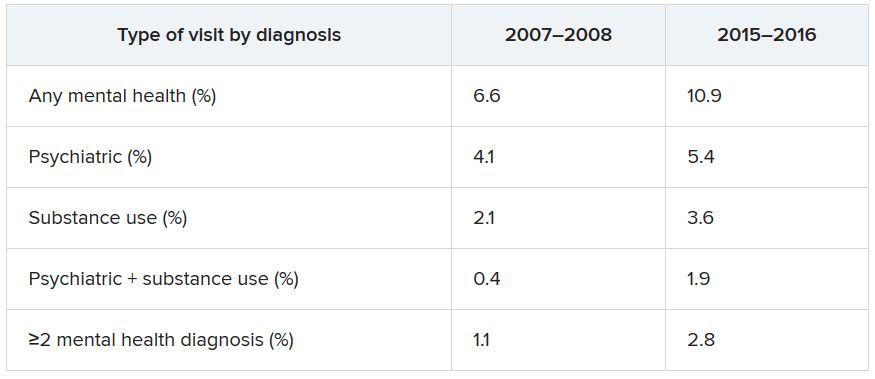

Data from the National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey (NHAMCS) showed that, over the 10-year study period, the proportion of ED visits for mental health diagnoses increased from 6.6% to 10.9%, with substance use accounting for much of the increase.

Although there have been policy efforts, such as expanding access to mental health care as part of the Affordable Care Act (ACA) of 2011, the senior author Taeho Greg Rhee, PhD, MSW, said in an interview.

“Treating mental health conditions in EDs is often considered suboptimal” because of limited time for full psychiatric assessment, lack of trained providers, and limited privacy in EDs, said Dr. Rhee of Yale University, New Haven, Conn.

The findings were published online July 28 in The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry.

“Outdated” research

Roughly one-fifth of U.S. adults experience some type of mental, behavioral, or emotional disorder annually. Moreover, the suicide rate has been steadily increasing, and there continues to be a “raging opioid epidemic,” the researchers wrote.

Despite these alarming figures, 57.4% of adults with mental illness reported in 2017 that they had not received any mental health treatment in the past year, reported the investigators.

Previous research has suggested that many adults have difficulty seeking outpatient mental health treatment and may turn to EDs instead. However, most studies of mental health ED use “are by now outdated, as they used data from years prior to the full implementation of the ACA,” the researchers noted.

“More Americans are suffering from mental illness, and given the recent policy efforts of expanding access to mental health care, we were questioning if ED visits due to mental health has changed or not,” Dr. Rhee said.

To investigate the question, the researchers conducted a cross-sectional analysis of data from the NHAMCS, a publicly available dataset provided by the National Center for Health Statistics of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

They grouped psychiatric diagnoses into five categories: mood disorders, anxiety disorders, psychosis or schizophrenia, suicide attempt or ideation, or other/unspecified. Substance use diagnoses were grouped into six categories: alcohol, amphetamine, cannabis, cocaine, opioid, or other/unspecified.

These categories were used to determine the type of disorder a patient had, whether the patient had both psychiatric and substance-related diagnoses, and whether the patient received multiple mental health diagnoses at the time of the ED visit.

Sociodemographic covariates included age, sex, race/ethnicity, and insurance coverage.

Twofold and fourfold increases

Of 100.9 million outpatient ED visits that took place between 2007 and 2016, approximately 8.4 million (8.3%) were for psychiatric or substance use–related diagnoses. Also, the visits were more likely from adults who were younger than 45 years, male, non-Hispanic White, and covered by Medicaid or other public insurance types (58.5%, 52.5%, 65.2%, and 58.6%, respectively).

The overall rate of ED visits for any mental health diagnosis nearly doubled between 2007-2008 and 2015-2016. The rate of visits in which both psychiatric and substance use–related diagnoses increased fourfold during that time span. ED visits involving at least two mental health diagnoses increased twofold.

Additional changes in the number of visits are listed below (for each, P < .001).

When these comparisons were adjusted for age, sex, and race/ethnicity, “linearly increasing trends of mental health–related ED visits were consistently found in all categories,” the authors reported. No trends were found regarding age, sex, or race/ethnicity. By contrast, mental health–related ED visits in which Medicaid was identified as the primary source of insurance nearly doubled between 2007–2008 and 2015–2016 (from 27.2% to 42.8%).

Other/unspecified psychiatric diagnoses, such as adjustment disorder and personality disorders, almost tripled between 2007-2008 and 2015-2016 (from 1,040 to 2,961 per 100,000 ED visits). ED visits for mood disorders and anxiety disorders also increased over time.

Alcohol-related ED visits were the most common substance use visits, increasing from 1,669 in 2007-2008 to 3,007 per 100,000 visits in 2015-2016. Amphetamine- and opioid-related ED visits more than doubled, and other/unspecified–related ED visits more than tripled during that time.

“One explanation why ED visits for mental health conditions have increased is that substance-related problems, which include overdose/self-injury issues, have increased over time,” Dr. Rhee noted, which “makes sense,” inasmuch as opioid, cannabis, and amphetamine use has increased across the country.

Another explanation is that, although mental health care access has been expanded through the ACA, “people, especially those with lower socioeconomic backgrounds, do not know how to get access to care and are still underserved,” he said.

“If mental health–related ED visits continue to increase in the future, there are several steps to be made. ED providers need to be better equipped with mental health care, and behavioral health should be better integrated as part of the care coordination,” said Dr. Rhee.

He added that reimbursement models across different insurance types, such as Medicare, Medicaid, and private insurance, “should consider expanding their coverage of mental health treatment in ED settings.”

“Canary in the coal mine”

Commenting on the study in an interview, Benjamin Druss, MD, MPH, professor and Rosalynn Carter Chair in Mental Health, Rollins School of Public Health, Emory University, Atlanta, called EDs the “canaries in the coal mine” for the broader health system.

The growing number of ED visits for behavioral problems “could represent both a rise in acute conditions such as substance use and lack of access to outpatient treatment,” said Dr. Druss, who was not involved with the research.

The findings “suggest the importance of strategies to effectively manage patients with behavioral conditions in ED settings and to effectively link them with high-quality outpatient care,” he noted.

Dr. Rhee has received funding from the National Institute on Aging and the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention. The other study authors and Dr. Druss report no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

ED visits related to mental health conditions increased nearly twofold from 2007-2008 to 2015-2016, new research suggests.

Data from the National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey (NHAMCS) showed that, over the 10-year study period, the proportion of ED visits for mental health diagnoses increased from 6.6% to 10.9%, with substance use accounting for much of the increase.

Although there have been policy efforts, such as expanding access to mental health care as part of the Affordable Care Act (ACA) of 2011, the senior author Taeho Greg Rhee, PhD, MSW, said in an interview.

“Treating mental health conditions in EDs is often considered suboptimal” because of limited time for full psychiatric assessment, lack of trained providers, and limited privacy in EDs, said Dr. Rhee of Yale University, New Haven, Conn.

The findings were published online July 28 in The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry.

“Outdated” research

Roughly one-fifth of U.S. adults experience some type of mental, behavioral, or emotional disorder annually. Moreover, the suicide rate has been steadily increasing, and there continues to be a “raging opioid epidemic,” the researchers wrote.

Despite these alarming figures, 57.4% of adults with mental illness reported in 2017 that they had not received any mental health treatment in the past year, reported the investigators.

Previous research has suggested that many adults have difficulty seeking outpatient mental health treatment and may turn to EDs instead. However, most studies of mental health ED use “are by now outdated, as they used data from years prior to the full implementation of the ACA,” the researchers noted.

“More Americans are suffering from mental illness, and given the recent policy efforts of expanding access to mental health care, we were questioning if ED visits due to mental health has changed or not,” Dr. Rhee said.

To investigate the question, the researchers conducted a cross-sectional analysis of data from the NHAMCS, a publicly available dataset provided by the National Center for Health Statistics of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

They grouped psychiatric diagnoses into five categories: mood disorders, anxiety disorders, psychosis or schizophrenia, suicide attempt or ideation, or other/unspecified. Substance use diagnoses were grouped into six categories: alcohol, amphetamine, cannabis, cocaine, opioid, or other/unspecified.

These categories were used to determine the type of disorder a patient had, whether the patient had both psychiatric and substance-related diagnoses, and whether the patient received multiple mental health diagnoses at the time of the ED visit.

Sociodemographic covariates included age, sex, race/ethnicity, and insurance coverage.

Twofold and fourfold increases

Of 100.9 million outpatient ED visits that took place between 2007 and 2016, approximately 8.4 million (8.3%) were for psychiatric or substance use–related diagnoses. Also, the visits were more likely from adults who were younger than 45 years, male, non-Hispanic White, and covered by Medicaid or other public insurance types (58.5%, 52.5%, 65.2%, and 58.6%, respectively).

The overall rate of ED visits for any mental health diagnosis nearly doubled between 2007-2008 and 2015-2016. The rate of visits in which both psychiatric and substance use–related diagnoses increased fourfold during that time span. ED visits involving at least two mental health diagnoses increased twofold.

Additional changes in the number of visits are listed below (for each, P < .001).

When these comparisons were adjusted for age, sex, and race/ethnicity, “linearly increasing trends of mental health–related ED visits were consistently found in all categories,” the authors reported. No trends were found regarding age, sex, or race/ethnicity. By contrast, mental health–related ED visits in which Medicaid was identified as the primary source of insurance nearly doubled between 2007–2008 and 2015–2016 (from 27.2% to 42.8%).

Other/unspecified psychiatric diagnoses, such as adjustment disorder and personality disorders, almost tripled between 2007-2008 and 2015-2016 (from 1,040 to 2,961 per 100,000 ED visits). ED visits for mood disorders and anxiety disorders also increased over time.

Alcohol-related ED visits were the most common substance use visits, increasing from 1,669 in 2007-2008 to 3,007 per 100,000 visits in 2015-2016. Amphetamine- and opioid-related ED visits more than doubled, and other/unspecified–related ED visits more than tripled during that time.

“One explanation why ED visits for mental health conditions have increased is that substance-related problems, which include overdose/self-injury issues, have increased over time,” Dr. Rhee noted, which “makes sense,” inasmuch as opioid, cannabis, and amphetamine use has increased across the country.

Another explanation is that, although mental health care access has been expanded through the ACA, “people, especially those with lower socioeconomic backgrounds, do not know how to get access to care and are still underserved,” he said.

“If mental health–related ED visits continue to increase in the future, there are several steps to be made. ED providers need to be better equipped with mental health care, and behavioral health should be better integrated as part of the care coordination,” said Dr. Rhee.

He added that reimbursement models across different insurance types, such as Medicare, Medicaid, and private insurance, “should consider expanding their coverage of mental health treatment in ED settings.”

“Canary in the coal mine”

Commenting on the study in an interview, Benjamin Druss, MD, MPH, professor and Rosalynn Carter Chair in Mental Health, Rollins School of Public Health, Emory University, Atlanta, called EDs the “canaries in the coal mine” for the broader health system.

The growing number of ED visits for behavioral problems “could represent both a rise in acute conditions such as substance use and lack of access to outpatient treatment,” said Dr. Druss, who was not involved with the research.

The findings “suggest the importance of strategies to effectively manage patients with behavioral conditions in ED settings and to effectively link them with high-quality outpatient care,” he noted.

Dr. Rhee has received funding from the National Institute on Aging and the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention. The other study authors and Dr. Druss report no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

ED visits related to mental health conditions increased nearly twofold from 2007-2008 to 2015-2016, new research suggests.

Data from the National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey (NHAMCS) showed that, over the 10-year study period, the proportion of ED visits for mental health diagnoses increased from 6.6% to 10.9%, with substance use accounting for much of the increase.

Although there have been policy efforts, such as expanding access to mental health care as part of the Affordable Care Act (ACA) of 2011, the senior author Taeho Greg Rhee, PhD, MSW, said in an interview.

“Treating mental health conditions in EDs is often considered suboptimal” because of limited time for full psychiatric assessment, lack of trained providers, and limited privacy in EDs, said Dr. Rhee of Yale University, New Haven, Conn.

The findings were published online July 28 in The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry.

“Outdated” research

Roughly one-fifth of U.S. adults experience some type of mental, behavioral, or emotional disorder annually. Moreover, the suicide rate has been steadily increasing, and there continues to be a “raging opioid epidemic,” the researchers wrote.

Despite these alarming figures, 57.4% of adults with mental illness reported in 2017 that they had not received any mental health treatment in the past year, reported the investigators.

Previous research has suggested that many adults have difficulty seeking outpatient mental health treatment and may turn to EDs instead. However, most studies of mental health ED use “are by now outdated, as they used data from years prior to the full implementation of the ACA,” the researchers noted.

“More Americans are suffering from mental illness, and given the recent policy efforts of expanding access to mental health care, we were questioning if ED visits due to mental health has changed or not,” Dr. Rhee said.

To investigate the question, the researchers conducted a cross-sectional analysis of data from the NHAMCS, a publicly available dataset provided by the National Center for Health Statistics of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

They grouped psychiatric diagnoses into five categories: mood disorders, anxiety disorders, psychosis or schizophrenia, suicide attempt or ideation, or other/unspecified. Substance use diagnoses were grouped into six categories: alcohol, amphetamine, cannabis, cocaine, opioid, or other/unspecified.

These categories were used to determine the type of disorder a patient had, whether the patient had both psychiatric and substance-related diagnoses, and whether the patient received multiple mental health diagnoses at the time of the ED visit.

Sociodemographic covariates included age, sex, race/ethnicity, and insurance coverage.

Twofold and fourfold increases

Of 100.9 million outpatient ED visits that took place between 2007 and 2016, approximately 8.4 million (8.3%) were for psychiatric or substance use–related diagnoses. Also, the visits were more likely from adults who were younger than 45 years, male, non-Hispanic White, and covered by Medicaid or other public insurance types (58.5%, 52.5%, 65.2%, and 58.6%, respectively).

The overall rate of ED visits for any mental health diagnosis nearly doubled between 2007-2008 and 2015-2016. The rate of visits in which both psychiatric and substance use–related diagnoses increased fourfold during that time span. ED visits involving at least two mental health diagnoses increased twofold.

Additional changes in the number of visits are listed below (for each, P < .001).

When these comparisons were adjusted for age, sex, and race/ethnicity, “linearly increasing trends of mental health–related ED visits were consistently found in all categories,” the authors reported. No trends were found regarding age, sex, or race/ethnicity. By contrast, mental health–related ED visits in which Medicaid was identified as the primary source of insurance nearly doubled between 2007–2008 and 2015–2016 (from 27.2% to 42.8%).

Other/unspecified psychiatric diagnoses, such as adjustment disorder and personality disorders, almost tripled between 2007-2008 and 2015-2016 (from 1,040 to 2,961 per 100,000 ED visits). ED visits for mood disorders and anxiety disorders also increased over time.

Alcohol-related ED visits were the most common substance use visits, increasing from 1,669 in 2007-2008 to 3,007 per 100,000 visits in 2015-2016. Amphetamine- and opioid-related ED visits more than doubled, and other/unspecified–related ED visits more than tripled during that time.

“One explanation why ED visits for mental health conditions have increased is that substance-related problems, which include overdose/self-injury issues, have increased over time,” Dr. Rhee noted, which “makes sense,” inasmuch as opioid, cannabis, and amphetamine use has increased across the country.

Another explanation is that, although mental health care access has been expanded through the ACA, “people, especially those with lower socioeconomic backgrounds, do not know how to get access to care and are still underserved,” he said.

“If mental health–related ED visits continue to increase in the future, there are several steps to be made. ED providers need to be better equipped with mental health care, and behavioral health should be better integrated as part of the care coordination,” said Dr. Rhee.

He added that reimbursement models across different insurance types, such as Medicare, Medicaid, and private insurance, “should consider expanding their coverage of mental health treatment in ED settings.”

“Canary in the coal mine”

Commenting on the study in an interview, Benjamin Druss, MD, MPH, professor and Rosalynn Carter Chair in Mental Health, Rollins School of Public Health, Emory University, Atlanta, called EDs the “canaries in the coal mine” for the broader health system.

The growing number of ED visits for behavioral problems “could represent both a rise in acute conditions such as substance use and lack of access to outpatient treatment,” said Dr. Druss, who was not involved with the research.

The findings “suggest the importance of strategies to effectively manage patients with behavioral conditions in ED settings and to effectively link them with high-quality outpatient care,” he noted.

Dr. Rhee has received funding from the National Institute on Aging and the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention. The other study authors and Dr. Druss report no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Many children with COVID-19 present without classic symptoms

Most children who tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 had no respiratory illness, according to data from a retrospective study of 22 patients at a single center.

To date, children account for less than 5% of COVID-19 cases in the United States, but details of the clinical presentations in children are limited, wrote Rabia Agha, MD, and colleagues of Maimonides Children’s Hospital, Brooklyn, N.Y.

In a study published in Hospital Pediatrics, the researchers reviewed data from 22 children aged 0-18 years who tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and were admitted to a single hospital over a 4-week period from March 18, 2020, to April 15, 2020.

Of four patients requiring mechanical ventilation, two had underlying pulmonary disease. The other two patients who required intubation were one with cerebral palsy and status epilepticus and one who presented in a state of cardiac arrest.

The study population ranged from 11 days to 18 years of age, but 45% were infants younger than 1 year. None of the children had a travel history that might increase their risk for SARS-CoV-2 infection; 27% had confirmed exposure to the virus.

Most of the children (82%) were hospitalized within 3 days of the onset of symptoms, and no deaths occurred during the study period. The most common symptom was fever without a source in five (23%) otherwise healthy infants aged 11-35 days. All five of these children underwent a sepsis evaluation, received empiric antibiotics, and were discharged home with negative bacterial cultures within 48-72 hours. Another 10 children had fever in combination with other symptoms.

Other presenting symptoms were respiratory (9), fatigue (6), seizures (2), and headache (1).

Most children with respiratory illness were treated with supportive therapy and antibiotics, but three of those on mechanical ventilation also were treated with remdesivir; all three were ultimately extubated.

Neurological abnormalities occurred in two patients: an 11-year-old otherwise healthy boy who presented with fever, headache, confusion, and seizure but ultimately improved without short-term sequelae; and a 12-year-old girl with cerebral palsy who developed new onset seizures and required mechanical ventilation, but ultimately improved to baseline.

Positive PCR results were identified in seven patients (32%) during the second half of the study period who were initially hospitalized for non-COVID related symptoms; four with bacterial infections, two with illnesses of unknown etiology, and one with cardiac arrest. Another two children were completely asymptomatic at the time of admission but then tested positive by PCR; one child had been admitted for routine chemotherapy and the other for social reasons, Dr. Agha and associates said.

The study findings contrast with early data from China in which respiratory illness of varying severity was the major presentation in children with COVID-19, but support a more recent meta-analysis of 551 cases, the researchers noted. The findings also highlight the value of universal testing for children.

“Our initial testing strategy was according to the federal and local guidelines that recommended PCR testing for the symptoms of fever, cough and shortness of breath, or travel to certain countries or close contact with a confirmed case,” Dr. Agha and colleagues said.

“With the implementation of our universal screening strategy of all admitted pediatric patients, we identified 9 (41%) patients with COVID-19 that would have been missed, as they did not meet the then-recommended criteria for testing,” they wrote.

The results suggest the need for broader guidelines to test pediatric patients because children presenting with other illnesses may be positive for SARS-CoV-2 as well, the researchers said.

“Testing of all hospitalized patients will not only identify cases early in the course of their admission process, but will also help prevent inadvertent exposure of other patients and health care workers, assist in cohorting infected patients, and aid in conservation of personal protective equipment,” Dr. Agha and associates concluded.

The current study is important as clinicians continue to learn about how infection with SARS-CoV-2 presents in different populations, Diana Lee, MD, of the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, said in an interview.

“Understanding how it can present in the pediatric population is important in identifying children who may have the infection and developing strategies for testing,” she said.

“I was not surprised by the finding that most children did not present with the classic symptoms of COVID-19 in adults based on other published studies and my personal clinical experience taking care of hospitalized children in New York City,” said Dr. Lee. “Studies from the U.S. and other countries have reported that fewer children experience fever, cough, and shortness of breath [compared with] adults, and that most children have a milder clinical course, though there is a small percentage of children who can have severe or critical illness,” she said.

“A multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children associated with COVID-19 has also emerged and appears to be a postinfectious process with a presentation that often differs from classic COVID-19 infection in adults,” she added.

The take-home message for clinicians is the reminder that SARS-CoV-2 infection often presents differently in children than in adults, said Dr. Lee.

“Children who present to the hospital with non-classic COVID-19 symptoms or with other diagnoses may be positive for SARS-CoV-2 on testing. Broadly testing hospitalized children for SARS-CoV-2 and instituting appropriate isolation precautions may help to protect other individuals from being exposed to the virus,” she said.

“Further research is needed to understand which individuals are contagious and how to accurately distinguish those who are infectious versus those who are not,” said Dr. Lee. “There have been individuals who persistently test positive for SARS-CoV-2 RNA (the genetic material of the virus), but were not found to have virus in their bodies that can replicate and thereby infect others,” she emphasized. “Further study is needed regarding the likelihood of household exposures in children with SARS-CoV-2 infection given that this study was done early in the epidemic in New York City when testing and contact tracing was less established,” she said.

The study received no outside funding. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose. Dr. Lee had no financial conflicts to disclose.

SOURCE: Agha R et al. Hosp Pediatr. 2020 July. doi: 10.1542/hpeds.2020-000257.

Most children who tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 had no respiratory illness, according to data from a retrospective study of 22 patients at a single center.

To date, children account for less than 5% of COVID-19 cases in the United States, but details of the clinical presentations in children are limited, wrote Rabia Agha, MD, and colleagues of Maimonides Children’s Hospital, Brooklyn, N.Y.

In a study published in Hospital Pediatrics, the researchers reviewed data from 22 children aged 0-18 years who tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and were admitted to a single hospital over a 4-week period from March 18, 2020, to April 15, 2020.

Of four patients requiring mechanical ventilation, two had underlying pulmonary disease. The other two patients who required intubation were one with cerebral palsy and status epilepticus and one who presented in a state of cardiac arrest.

The study population ranged from 11 days to 18 years of age, but 45% were infants younger than 1 year. None of the children had a travel history that might increase their risk for SARS-CoV-2 infection; 27% had confirmed exposure to the virus.

Most of the children (82%) were hospitalized within 3 days of the onset of symptoms, and no deaths occurred during the study period. The most common symptom was fever without a source in five (23%) otherwise healthy infants aged 11-35 days. All five of these children underwent a sepsis evaluation, received empiric antibiotics, and were discharged home with negative bacterial cultures within 48-72 hours. Another 10 children had fever in combination with other symptoms.

Other presenting symptoms were respiratory (9), fatigue (6), seizures (2), and headache (1).

Most children with respiratory illness were treated with supportive therapy and antibiotics, but three of those on mechanical ventilation also were treated with remdesivir; all three were ultimately extubated.

Neurological abnormalities occurred in two patients: an 11-year-old otherwise healthy boy who presented with fever, headache, confusion, and seizure but ultimately improved without short-term sequelae; and a 12-year-old girl with cerebral palsy who developed new onset seizures and required mechanical ventilation, but ultimately improved to baseline.

Positive PCR results were identified in seven patients (32%) during the second half of the study period who were initially hospitalized for non-COVID related symptoms; four with bacterial infections, two with illnesses of unknown etiology, and one with cardiac arrest. Another two children were completely asymptomatic at the time of admission but then tested positive by PCR; one child had been admitted for routine chemotherapy and the other for social reasons, Dr. Agha and associates said.

The study findings contrast with early data from China in which respiratory illness of varying severity was the major presentation in children with COVID-19, but support a more recent meta-analysis of 551 cases, the researchers noted. The findings also highlight the value of universal testing for children.

“Our initial testing strategy was according to the federal and local guidelines that recommended PCR testing for the symptoms of fever, cough and shortness of breath, or travel to certain countries or close contact with a confirmed case,” Dr. Agha and colleagues said.

“With the implementation of our universal screening strategy of all admitted pediatric patients, we identified 9 (41%) patients with COVID-19 that would have been missed, as they did not meet the then-recommended criteria for testing,” they wrote.

The results suggest the need for broader guidelines to test pediatric patients because children presenting with other illnesses may be positive for SARS-CoV-2 as well, the researchers said.

“Testing of all hospitalized patients will not only identify cases early in the course of their admission process, but will also help prevent inadvertent exposure of other patients and health care workers, assist in cohorting infected patients, and aid in conservation of personal protective equipment,” Dr. Agha and associates concluded.

The current study is important as clinicians continue to learn about how infection with SARS-CoV-2 presents in different populations, Diana Lee, MD, of the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, said in an interview.

“Understanding how it can present in the pediatric population is important in identifying children who may have the infection and developing strategies for testing,” she said.

“I was not surprised by the finding that most children did not present with the classic symptoms of COVID-19 in adults based on other published studies and my personal clinical experience taking care of hospitalized children in New York City,” said Dr. Lee. “Studies from the U.S. and other countries have reported that fewer children experience fever, cough, and shortness of breath [compared with] adults, and that most children have a milder clinical course, though there is a small percentage of children who can have severe or critical illness,” she said.

“A multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children associated with COVID-19 has also emerged and appears to be a postinfectious process with a presentation that often differs from classic COVID-19 infection in adults,” she added.

The take-home message for clinicians is the reminder that SARS-CoV-2 infection often presents differently in children than in adults, said Dr. Lee.

“Children who present to the hospital with non-classic COVID-19 symptoms or with other diagnoses may be positive for SARS-CoV-2 on testing. Broadly testing hospitalized children for SARS-CoV-2 and instituting appropriate isolation precautions may help to protect other individuals from being exposed to the virus,” she said.

“Further research is needed to understand which individuals are contagious and how to accurately distinguish those who are infectious versus those who are not,” said Dr. Lee. “There have been individuals who persistently test positive for SARS-CoV-2 RNA (the genetic material of the virus), but were not found to have virus in their bodies that can replicate and thereby infect others,” she emphasized. “Further study is needed regarding the likelihood of household exposures in children with SARS-CoV-2 infection given that this study was done early in the epidemic in New York City when testing and contact tracing was less established,” she said.

The study received no outside funding. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose. Dr. Lee had no financial conflicts to disclose.

SOURCE: Agha R et al. Hosp Pediatr. 2020 July. doi: 10.1542/hpeds.2020-000257.

Most children who tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 had no respiratory illness, according to data from a retrospective study of 22 patients at a single center.

To date, children account for less than 5% of COVID-19 cases in the United States, but details of the clinical presentations in children are limited, wrote Rabia Agha, MD, and colleagues of Maimonides Children’s Hospital, Brooklyn, N.Y.

In a study published in Hospital Pediatrics, the researchers reviewed data from 22 children aged 0-18 years who tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and were admitted to a single hospital over a 4-week period from March 18, 2020, to April 15, 2020.

Of four patients requiring mechanical ventilation, two had underlying pulmonary disease. The other two patients who required intubation were one with cerebral palsy and status epilepticus and one who presented in a state of cardiac arrest.

The study population ranged from 11 days to 18 years of age, but 45% were infants younger than 1 year. None of the children had a travel history that might increase their risk for SARS-CoV-2 infection; 27% had confirmed exposure to the virus.

Most of the children (82%) were hospitalized within 3 days of the onset of symptoms, and no deaths occurred during the study period. The most common symptom was fever without a source in five (23%) otherwise healthy infants aged 11-35 days. All five of these children underwent a sepsis evaluation, received empiric antibiotics, and were discharged home with negative bacterial cultures within 48-72 hours. Another 10 children had fever in combination with other symptoms.

Other presenting symptoms were respiratory (9), fatigue (6), seizures (2), and headache (1).

Most children with respiratory illness were treated with supportive therapy and antibiotics, but three of those on mechanical ventilation also were treated with remdesivir; all three were ultimately extubated.

Neurological abnormalities occurred in two patients: an 11-year-old otherwise healthy boy who presented with fever, headache, confusion, and seizure but ultimately improved without short-term sequelae; and a 12-year-old girl with cerebral palsy who developed new onset seizures and required mechanical ventilation, but ultimately improved to baseline.

Positive PCR results were identified in seven patients (32%) during the second half of the study period who were initially hospitalized for non-COVID related symptoms; four with bacterial infections, two with illnesses of unknown etiology, and one with cardiac arrest. Another two children were completely asymptomatic at the time of admission but then tested positive by PCR; one child had been admitted for routine chemotherapy and the other for social reasons, Dr. Agha and associates said.

The study findings contrast with early data from China in which respiratory illness of varying severity was the major presentation in children with COVID-19, but support a more recent meta-analysis of 551 cases, the researchers noted. The findings also highlight the value of universal testing for children.

“Our initial testing strategy was according to the federal and local guidelines that recommended PCR testing for the symptoms of fever, cough and shortness of breath, or travel to certain countries or close contact with a confirmed case,” Dr. Agha and colleagues said.

“With the implementation of our universal screening strategy of all admitted pediatric patients, we identified 9 (41%) patients with COVID-19 that would have been missed, as they did not meet the then-recommended criteria for testing,” they wrote.

The results suggest the need for broader guidelines to test pediatric patients because children presenting with other illnesses may be positive for SARS-CoV-2 as well, the researchers said.

“Testing of all hospitalized patients will not only identify cases early in the course of their admission process, but will also help prevent inadvertent exposure of other patients and health care workers, assist in cohorting infected patients, and aid in conservation of personal protective equipment,” Dr. Agha and associates concluded.

The current study is important as clinicians continue to learn about how infection with SARS-CoV-2 presents in different populations, Diana Lee, MD, of the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, said in an interview.

“Understanding how it can present in the pediatric population is important in identifying children who may have the infection and developing strategies for testing,” she said.

“I was not surprised by the finding that most children did not present with the classic symptoms of COVID-19 in adults based on other published studies and my personal clinical experience taking care of hospitalized children in New York City,” said Dr. Lee. “Studies from the U.S. and other countries have reported that fewer children experience fever, cough, and shortness of breath [compared with] adults, and that most children have a milder clinical course, though there is a small percentage of children who can have severe or critical illness,” she said.

“A multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children associated with COVID-19 has also emerged and appears to be a postinfectious process with a presentation that often differs from classic COVID-19 infection in adults,” she added.

The take-home message for clinicians is the reminder that SARS-CoV-2 infection often presents differently in children than in adults, said Dr. Lee.

“Children who present to the hospital with non-classic COVID-19 symptoms or with other diagnoses may be positive for SARS-CoV-2 on testing. Broadly testing hospitalized children for SARS-CoV-2 and instituting appropriate isolation precautions may help to protect other individuals from being exposed to the virus,” she said.

“Further research is needed to understand which individuals are contagious and how to accurately distinguish those who are infectious versus those who are not,” said Dr. Lee. “There have been individuals who persistently test positive for SARS-CoV-2 RNA (the genetic material of the virus), but were not found to have virus in their bodies that can replicate and thereby infect others,” she emphasized. “Further study is needed regarding the likelihood of household exposures in children with SARS-CoV-2 infection given that this study was done early in the epidemic in New York City when testing and contact tracing was less established,” she said.

The study received no outside funding. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose. Dr. Lee had no financial conflicts to disclose.

SOURCE: Agha R et al. Hosp Pediatr. 2020 July. doi: 10.1542/hpeds.2020-000257.

FROM HOSPITAL PEDIATRICS

Twelve risk factors linked to 40% of world’s dementia cases

according to an update of the Lancet Commission on Dementia Prevention, Intervention, and Care.

The original report, published in 2017, identified nine modifiable risk factors that were estimated to be responsible for one-third of dementia cases. The commission has now added three new modifiable risk factors to the list.

“We reconvened the 2017 Lancet Commission on Dementia Prevention, Intervention, and Care to identify the evidence for advances likely to have the greatest impact since our 2017 paper,” the authors wrote.

The 2020 report was presented at the virtual annual meeting of the Alzheimer’s Association International Conference (AAIC) 2020 and also was published online July 30 in the Lancet.

Alcohol, TBI, air pollution

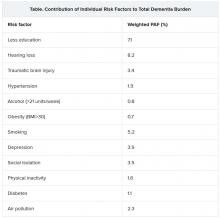

The three new risk factors that have been added in the latest update are excessive alcohol intake, traumatic brain injury (TBI), and air pollution. The original nine risk factors were not completing secondary education; hypertension; obesity; hearing loss; smoking; depression; physical inactivity; social isolation; and diabetes. Together, these 12 risk factors are estimated to account for 40% of the world’s dementia cases.

“We knew in 2017 when we published our first report with the nine risk factors that they would only be part of the story and that several other factors would likely be involved,” said lead author Gill Livingston, MD, professor, University College London (England). “We now have more published data giving enough evidence” to justify adding the three new factors to the list, she said.

The report includes the following nine recommendations for policymakers and individuals to prevent risk for dementia in the general population:

- Aim to maintain systolic blood pressure of 130 mm Hg or less in midlife from around age 40 years.

- Encourage use of hearing aids for hearing loss, and reduce hearing loss by protecting ears from high noise levels.

- Reduce exposure to air pollution and second-hand tobacco smoke.

- Prevent , particularly by targeting high-risk occupations and transport.

- Prevent alcohol misuse and limit drinking to less than 21 units per week.

- Stop smoking and support individuals to stop smoking, which the authors stress is beneficial at any age.

- Provide all children with primary and secondary education.

- Lead an active life into midlife and possibly later life.

- Reduce obesity and diabetes.

The report also summarizes the evidence supporting the three new risk factors for dementia.

TBI is usually caused by car, motorcycle, and bicycle injuries; military exposures; boxing, horse riding, and other recreational sports; firearms; and falls. The report notes that a single severe TBI is associated in humans and in mouse models with widespread hyperphosphorylated tau pathology. It also cites several nationwide studies that show that TBI is linked with a significantly increased risk for long-term dementia.

“We are not advising against partaking in sports, as playing sports is healthy. But we are urging people to take precautions to protect themselves properly,” Dr. Livingston said.

For excessive alcohol consumption, the report states that an “increasing body of evidence is emerging on alcohol’s complex relationship with cognition and dementia outcomes from a variety of sources including detailed cohorts and large-scale record-based studies.” One French study, which included more than 31 million individuals admitted to the hospital, showed that alcohol use disorders were associated with a threefold increased dementia risk. However, other studies have suggested that moderate drinking may be protective.

“We are not saying it is bad to drink, but we are saying it is bad to drink more than 21 units a week,” Dr. Livingston noted.

On air pollution, the report notes that in animal studies, airborne particulate pollutants have been found to accelerate neurodegenerative processes. Also, high nitrogen dioxide concentrations, fine ambient particulate matter from traffic exhaust, and residential wood burning have been shown in past research to be associated with increased dementia incidence.

“While we need international policy on reducing air pollution, individuals can take some action to reduce their risk,” Dr. Livingston said. For example, she suggested avoiding walking right next to busy roads and instead walking “a few streets back if possible.”

Hearing loss

The researchers assessed how much each risk factor contributes to dementia, expressed as the population-attributable fraction (PAF). Hearing loss had the greatest effect, accounting for an estimated 8.2% of dementia cases. This was followed by lower education levels in young people (7.1%) and smoking (5.2%).

Dr. Livingston noted that the evidence that hearing loss is one of the most important risk factors for dementia is very strong. New studies show that correcting hearing loss with hearing aids negates any increased risk.

Hearing loss “has both a high relative risk for dementia and is a common problem, so it contributes a significant amount to dementia cases. This is really something that we can reduce relatively easily by encouraging use of hearing aids. They need to be made more accessible, more comfortable, and more acceptable,” she said.

“This could make a huge difference in reducing dementia cases in the future,” Dr. Livingston added.

Other risk factors for which the evidence base has strengthened since the 2017 report include systolic blood pressure, social interaction, and early-life education.

Dr. Livingston noted that the SPRINT MIND trial showed that aiming for a target systolic blood pressure of 120 mm Hg reduced risk for future mild cognitive impairment. “Before, we thought under 140 was the target, but now are recommending under 130 to reduce risks of dementia,” she said.

Evidence on social interaction “has been very consistent, and we now have more certainty on this. It is now well established that increased social interaction in midlife reduces dementia in late life,” said Dr. Livingston.

On the benefits of education in the young, she noted that it has been known for some time that education for individuals younger than 11 years is important in reducing later-life dementia. However, it is now thought that education to the age of 20 also makes a difference.

“While keeping the brain active in later years has some positive effects, increasing brain activity in young people seems to be more important. This is probably because of the better plasticity of the brain in the young,” she said.

Sleep and diet

Two risk factors that have not made it onto the list are diet and sleep. “While there has also been a lot more data published on nutrition and sleep with regard to dementia in the last few years, we didn’t think the evidence stacked up enough to include these on the list of modifiable risk factors,” Dr. Livingston said.

The report cites studies that suggest that both more sleep and less sleep are associated with increased risk for dementia, which the authors thought did not make “biological sense.” In addition, other underlying factors involved in sleep, such as depression, apathy, and different sleep patterns, may be symptoms of early dementia.

More data have been published on diet and dementia, “but there isn’t any individual vitamin deficit that is associated with the condition. The evidence is quite clear on that,” Dr. Livingston said. “Global diets, such as the Mediterranean or Nordic diets, can probably make a difference, but there doesn’t seem to be any one particular element that is needed,” she noted.

“We just recommend to eat a healthy diet and stay a healthy weight. Diet is very connected to economic circumstances and so very difficult to separate out as a risk factor. We do think it is linked, but we are not convinced enough to put it in the model,” she added.

Among other key information that has become available since 2017, Dr. Livingston highlighted new data showing that dementia is more common in less privileged populations, including Black and minority ethnic groups and low- and middle-income countries.

Although dementia was traditionally considered a disease of high-income countries, that has now been shown not to be the case. “People in low- and middle-income countries are now living longer and so are developing dementia more, and they have higher rates of many of the risk factors, including smoking and low education levels. There is a huge potential for prevention in these countries,” said Dr. Livingston.

She also highlighted new evidence showing that patients with dementia do not do well when admitted to the hospital. “So we need to do more to keep them well at home,” she said.

COVID-19 advice

The report also has a section on COVID-19. It points out that patients with dementia are particularly vulnerable to the disease because of their age, multimorbidities, and difficulties in maintaining physical distancing. Death certificates from the United Kingdom indicate that dementia and Alzheimer’s disease were the most common underlying conditions (present in 25.6% of all deaths involving COVID-19).

The situation is particularly concerning in care homes. In one U.S. study, nursing home residents living with dementia made up 52% of COVID-19 cases, yet they accounted for 72% of all deaths (increased risk, 1.7), the commission reported.

The authors recommended rigorous public health measures, such as protective equipment and hygiene, not moving staff or residents between care homes, and not admitting new residents when their COVID-19 status is unknown. The report also recommends regular testing of staff in care homes and the provision of oxygen therapy at the home to avoid hospital admission.

It is also important to reduce isolation by providing the necessary equipment to relatives and offering them brief training on how to protect themselves and others from COVID-19 so that they can visit their relatives with dementia in nursing homes safely when it is allowed.

“Most comprehensive overview to date”

Alzheimer’s Research UK welcomed the new report. “This is the most comprehensive overview into dementia risk to date, building on previous work by this commission and moving our understanding forward,” Rosa Sancho, PhD, head of research at the charity, said.

“This report underlines the importance of acting at a personal and policy level to reduce dementia risk. With Alzheimer’s Research UK’s Dementia Attitudes Monitor showing just a third of people think it’s possible to reduce their risk of developing dementia, there’s clearly much to do here to increase people’s awareness of the steps they can take,” Dr. Sancho said.

She added that, although there is “no surefire way of preventing dementia,” the best way to keep a brain healthy as it ages is for an individual to stay physically and mentally active, eat a healthy balanced diet, not smoke, drink only within the recommended limits, and keep weight, cholesterol level, and blood pressure in check. “With no treatments yet able to slow or stop the onset of dementia, taking action to reduce these risks is an important part of our strategy for tackling the condition,” Dr. Sancho said.

The Lancet Commission is partnered by University College London, the Alzheimer’s Society UK, the Economic and Social Research Council, and Alzheimer’s Research UK, which funded fares, accommodation, and food for the commission meeting but had no role in the writing of the manuscript or the decision to submit it for publication.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

according to an update of the Lancet Commission on Dementia Prevention, Intervention, and Care.

The original report, published in 2017, identified nine modifiable risk factors that were estimated to be responsible for one-third of dementia cases. The commission has now added three new modifiable risk factors to the list.

“We reconvened the 2017 Lancet Commission on Dementia Prevention, Intervention, and Care to identify the evidence for advances likely to have the greatest impact since our 2017 paper,” the authors wrote.

The 2020 report was presented at the virtual annual meeting of the Alzheimer’s Association International Conference (AAIC) 2020 and also was published online July 30 in the Lancet.

Alcohol, TBI, air pollution

The three new risk factors that have been added in the latest update are excessive alcohol intake, traumatic brain injury (TBI), and air pollution. The original nine risk factors were not completing secondary education; hypertension; obesity; hearing loss; smoking; depression; physical inactivity; social isolation; and diabetes. Together, these 12 risk factors are estimated to account for 40% of the world’s dementia cases.

“We knew in 2017 when we published our first report with the nine risk factors that they would only be part of the story and that several other factors would likely be involved,” said lead author Gill Livingston, MD, professor, University College London (England). “We now have more published data giving enough evidence” to justify adding the three new factors to the list, she said.

The report includes the following nine recommendations for policymakers and individuals to prevent risk for dementia in the general population:

- Aim to maintain systolic blood pressure of 130 mm Hg or less in midlife from around age 40 years.

- Encourage use of hearing aids for hearing loss, and reduce hearing loss by protecting ears from high noise levels.

- Reduce exposure to air pollution and second-hand tobacco smoke.

- Prevent , particularly by targeting high-risk occupations and transport.

- Prevent alcohol misuse and limit drinking to less than 21 units per week.

- Stop smoking and support individuals to stop smoking, which the authors stress is beneficial at any age.

- Provide all children with primary and secondary education.

- Lead an active life into midlife and possibly later life.

- Reduce obesity and diabetes.

The report also summarizes the evidence supporting the three new risk factors for dementia.

TBI is usually caused by car, motorcycle, and bicycle injuries; military exposures; boxing, horse riding, and other recreational sports; firearms; and falls. The report notes that a single severe TBI is associated in humans and in mouse models with widespread hyperphosphorylated tau pathology. It also cites several nationwide studies that show that TBI is linked with a significantly increased risk for long-term dementia.

“We are not advising against partaking in sports, as playing sports is healthy. But we are urging people to take precautions to protect themselves properly,” Dr. Livingston said.

For excessive alcohol consumption, the report states that an “increasing body of evidence is emerging on alcohol’s complex relationship with cognition and dementia outcomes from a variety of sources including detailed cohorts and large-scale record-based studies.” One French study, which included more than 31 million individuals admitted to the hospital, showed that alcohol use disorders were associated with a threefold increased dementia risk. However, other studies have suggested that moderate drinking may be protective.

“We are not saying it is bad to drink, but we are saying it is bad to drink more than 21 units a week,” Dr. Livingston noted.

On air pollution, the report notes that in animal studies, airborne particulate pollutants have been found to accelerate neurodegenerative processes. Also, high nitrogen dioxide concentrations, fine ambient particulate matter from traffic exhaust, and residential wood burning have been shown in past research to be associated with increased dementia incidence.

“While we need international policy on reducing air pollution, individuals can take some action to reduce their risk,” Dr. Livingston said. For example, she suggested avoiding walking right next to busy roads and instead walking “a few streets back if possible.”

Hearing loss

The researchers assessed how much each risk factor contributes to dementia, expressed as the population-attributable fraction (PAF). Hearing loss had the greatest effect, accounting for an estimated 8.2% of dementia cases. This was followed by lower education levels in young people (7.1%) and smoking (5.2%).

Dr. Livingston noted that the evidence that hearing loss is one of the most important risk factors for dementia is very strong. New studies show that correcting hearing loss with hearing aids negates any increased risk.

Hearing loss “has both a high relative risk for dementia and is a common problem, so it contributes a significant amount to dementia cases. This is really something that we can reduce relatively easily by encouraging use of hearing aids. They need to be made more accessible, more comfortable, and more acceptable,” she said.

“This could make a huge difference in reducing dementia cases in the future,” Dr. Livingston added.

Other risk factors for which the evidence base has strengthened since the 2017 report include systolic blood pressure, social interaction, and early-life education.

Dr. Livingston noted that the SPRINT MIND trial showed that aiming for a target systolic blood pressure of 120 mm Hg reduced risk for future mild cognitive impairment. “Before, we thought under 140 was the target, but now are recommending under 130 to reduce risks of dementia,” she said.

Evidence on social interaction “has been very consistent, and we now have more certainty on this. It is now well established that increased social interaction in midlife reduces dementia in late life,” said Dr. Livingston.

On the benefits of education in the young, she noted that it has been known for some time that education for individuals younger than 11 years is important in reducing later-life dementia. However, it is now thought that education to the age of 20 also makes a difference.