User login

Bringing you the latest news, research and reviews, exclusive interviews, podcasts, quizzes, and more.

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack nav-ce-stack__large-screen')]

header[@id='header']

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

footer[@id='footer']

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

div[contains(@class, 'view-medstat-quiz-listing-panes')]

Diary of a rheumatologist who briefly became a COVID hospitalist

When the coronavirus pandemic hit New York City in early March, the Hospital for Special Surgery leadership decided that the best way to serve the city was to stop elective orthopedic procedures temporarily and use the facility to take on patients from its sister institution, NewYork–Presbyterian Hospital.

As in other institutions, it was all hands on deck. , other internal medicine subspecialists were asked to volunteer, including rheumatologists and primary care sports medicine doctors.

As a rheumatologist, it had been well over 10 years since I had last done any inpatient work. I was filled with trepidation, but I was also excited to dive in.

April 4:

Feeling very unmoored. I am in unfamiliar territory, and it’s terrifying. There are so many things that I no longer know how to do. Thankfully, the hospitalists are gracious, extremely supportive, and helpful.

My N95 doesn’t fit well. It’s never fit — not during residency or fellowship, not in any job I’ve had, and not today. The lady fit-testing me said she was sorry, but the look on her face said, “I’m sorry, but you’re going to die.”

April 7:

We don’t know how to treat coronavirus. I’ve sent some patients home, others I’ve sent to the ICU. Thank goodness for treatment algorithms from leadership, but we are sorely lacking good-quality data.

Our infectious disease doctor doesn’t think hydroxychloroquine works at all; I suspect he is right. The guidance right now is to give hydroxychloroquine and azithromycin to everyone who is sick enough to be admitted, but there are methodologic flaws in the early enthusiastic preprints, and so far, I’ve not noticed any demonstrable benefit.

The only thing that seems to be happening is that I am seeing more QT prolongation — not something I previously counseled my rheumatology patients on.

April 9:

The patients have been, with a few exceptions, alone in the room. They’re not allowed to have visitors and are required to wear masks all the time. Anyone who enters their rooms is fully covered up so you can barely see them. It’s anonymous and dehumanizing.

We’re instructed to take histories by phone in order to limit the time spent in each room. I buck this instruction; I still take histories in person because human contact seems more important now than ever.

Except maybe I should be smarter about this. One of my patients refuses any treatment, including oxygen support. She firmly believes this is a result of 5G networks — something I later discovered was a common conspiracy theory. She refused to wear a mask despite having a very bad cough. She coughed in my face a lot when we were chatting. My face with my ill-fitting N95 mask. Maybe the fit-testing lady’s eyes weren’t lying and I will die after all.

April 15:

On the days when I’m not working as a hospitalist, I am still doing remote visits with my rheumatology patients. It feels good to be doing something familiar and something I’m actually good at. But it is surreal to be faced with the quotidian on one hand and life and death on the other.

I recently saw a fairly new patient, and I still haven’t figured out if she has a rheumatic condition or if her symptoms all stem from an alcohol use disorder. In our previous visits, she could barely acknowledge that her drinking was an issue. On today’s visit, she told me she was 1½ months sober.

I don’t know her very well, but it was the happiest news I’d heard in a long time. I was so beside myself with joy that I cried, which says more about my current emotional state than anything else, really.

April 21:

On my panel of patients, I have three women with COVID-19 — all of whom lost their husbands to COVID-19, and none of whom were able to say their goodbyes. I cannot even begin to imagine what it must be like to survive this period of illness, isolation, and fear, only to be met on the other side by grief.

Rheumatology doesn’t lend itself too well to such existential concerns; I am not equipped for this. Perhaps my only advantage as a rheumatologist is that I know how to use IVIG, anakinra, and tocilizumab.

Someone on my panel was started on anakinra, and it turned his case around. Would he have gotten better without it anyway? We’ll never know for sure.

April 28:

Patients seem to be requiring prolonged intubation. We have now reached the stage where patients are alive but trached and PEGed. One of my patients had been intubated for close to 3 weeks. She was one of four people in her family who contracted the illness (they had had a dinner party before New York’s state of emergency was declared). We thought she might die once she was extubated, but she is still fighting. Unconscious, unarousable, but breathing on her own.

Will she ever wake up? We don’t know. We put the onus on her family to make decisions about placing a PEG tube in. They can only do so from a distance with imperfect information gleaned from periodic, brief FaceTime interactions — where no interaction happens at all.

May 4:

It’s my last day as a “COVID hospitalist.” When I first started, I felt like I was being helpful. Walking home in the middle of the 7 PM cheers for healthcare workers frequently left me teary eyed. As horrible as the situation was, I was proud of myself for volunteering to help and appreciative of a broken city’s gratitude toward all healthcare workers in general. Maybe I bought into the idea that, like many others around me, I am a hero.

I don’t feel like a hero, though. The stuff I saw was easy compared with the stuff that my colleagues in critical care saw. Our hospital accepted the more stable patient transfers from our sister hospitals. Patients who remained in the NewYork–Presbyterian system were sicker, with encephalitis, thrombotic complications, multiorgan failure, and cytokine release syndrome. It’s the doctors who took care of those patients who deserve to be called heroes.

No, I am no hero. But did my volunteering make a difference? It made a difference to me. The overwhelming feeling I am left with isn’t pride; it’s humility. I feel humbled that I could feel so unexpectedly touched by the lives of people that I had no idea I could feel touched by.

Postscript:

My patient Esther [name changed to hide her identity] died from COVID-19. She was MY patient — not a patient I met as a COVID hospitalist, but a patient with rheumatoid arthritis whom I cared for for years.

She had scleromalacia and multiple failed scleral grafts, which made her profoundly sad. She fought her anxiety fiercely and always with poise and panache. One way she dealt with her anxiety was that she constantly messaged me via our EHR portal. She ran everything by me and trusted me to be her rock.

The past month has been so busy that I just now noticed it had been a month since I last heard from her. I tried to call her but got her voicemail. It wasn’t until I exchanged messages with her ophthalmologist that I found out she had passed away from complications of COVID-19.

She was taking rituximab and mycophenolate. I wonder if these drugs made her sicker than she would have been otherwise; it fills me with sadness. I wonder if she was alone like my other COVID-19 patients. I wonder if she was afraid. I am sorry that I wasn’t able to say goodbye.

Karmela Kim Chan, MD, is an assistant professor at Weill Cornell Medical College and an attending physician at Hospital for Special Surgery and Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York City. Before moving to New York City, she spent 7 years in private practice in Rhode Island and was a columnist for this rheumatology publication, writing about the challenges of starting life as a full-fledged rheumatologist in a private practice.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com. This article is part of a partnership between Medscape and Hospital for Special Surgery.

When the coronavirus pandemic hit New York City in early March, the Hospital for Special Surgery leadership decided that the best way to serve the city was to stop elective orthopedic procedures temporarily and use the facility to take on patients from its sister institution, NewYork–Presbyterian Hospital.

As in other institutions, it was all hands on deck. , other internal medicine subspecialists were asked to volunteer, including rheumatologists and primary care sports medicine doctors.

As a rheumatologist, it had been well over 10 years since I had last done any inpatient work. I was filled with trepidation, but I was also excited to dive in.

April 4:

Feeling very unmoored. I am in unfamiliar territory, and it’s terrifying. There are so many things that I no longer know how to do. Thankfully, the hospitalists are gracious, extremely supportive, and helpful.

My N95 doesn’t fit well. It’s never fit — not during residency or fellowship, not in any job I’ve had, and not today. The lady fit-testing me said she was sorry, but the look on her face said, “I’m sorry, but you’re going to die.”

April 7:

We don’t know how to treat coronavirus. I’ve sent some patients home, others I’ve sent to the ICU. Thank goodness for treatment algorithms from leadership, but we are sorely lacking good-quality data.

Our infectious disease doctor doesn’t think hydroxychloroquine works at all; I suspect he is right. The guidance right now is to give hydroxychloroquine and azithromycin to everyone who is sick enough to be admitted, but there are methodologic flaws in the early enthusiastic preprints, and so far, I’ve not noticed any demonstrable benefit.

The only thing that seems to be happening is that I am seeing more QT prolongation — not something I previously counseled my rheumatology patients on.

April 9:

The patients have been, with a few exceptions, alone in the room. They’re not allowed to have visitors and are required to wear masks all the time. Anyone who enters their rooms is fully covered up so you can barely see them. It’s anonymous and dehumanizing.

We’re instructed to take histories by phone in order to limit the time spent in each room. I buck this instruction; I still take histories in person because human contact seems more important now than ever.

Except maybe I should be smarter about this. One of my patients refuses any treatment, including oxygen support. She firmly believes this is a result of 5G networks — something I later discovered was a common conspiracy theory. She refused to wear a mask despite having a very bad cough. She coughed in my face a lot when we were chatting. My face with my ill-fitting N95 mask. Maybe the fit-testing lady’s eyes weren’t lying and I will die after all.

April 15:

On the days when I’m not working as a hospitalist, I am still doing remote visits with my rheumatology patients. It feels good to be doing something familiar and something I’m actually good at. But it is surreal to be faced with the quotidian on one hand and life and death on the other.

I recently saw a fairly new patient, and I still haven’t figured out if she has a rheumatic condition or if her symptoms all stem from an alcohol use disorder. In our previous visits, she could barely acknowledge that her drinking was an issue. On today’s visit, she told me she was 1½ months sober.

I don’t know her very well, but it was the happiest news I’d heard in a long time. I was so beside myself with joy that I cried, which says more about my current emotional state than anything else, really.

April 21:

On my panel of patients, I have three women with COVID-19 — all of whom lost their husbands to COVID-19, and none of whom were able to say their goodbyes. I cannot even begin to imagine what it must be like to survive this period of illness, isolation, and fear, only to be met on the other side by grief.

Rheumatology doesn’t lend itself too well to such existential concerns; I am not equipped for this. Perhaps my only advantage as a rheumatologist is that I know how to use IVIG, anakinra, and tocilizumab.

Someone on my panel was started on anakinra, and it turned his case around. Would he have gotten better without it anyway? We’ll never know for sure.

April 28:

Patients seem to be requiring prolonged intubation. We have now reached the stage where patients are alive but trached and PEGed. One of my patients had been intubated for close to 3 weeks. She was one of four people in her family who contracted the illness (they had had a dinner party before New York’s state of emergency was declared). We thought she might die once she was extubated, but she is still fighting. Unconscious, unarousable, but breathing on her own.

Will she ever wake up? We don’t know. We put the onus on her family to make decisions about placing a PEG tube in. They can only do so from a distance with imperfect information gleaned from periodic, brief FaceTime interactions — where no interaction happens at all.

May 4:

It’s my last day as a “COVID hospitalist.” When I first started, I felt like I was being helpful. Walking home in the middle of the 7 PM cheers for healthcare workers frequently left me teary eyed. As horrible as the situation was, I was proud of myself for volunteering to help and appreciative of a broken city’s gratitude toward all healthcare workers in general. Maybe I bought into the idea that, like many others around me, I am a hero.

I don’t feel like a hero, though. The stuff I saw was easy compared with the stuff that my colleagues in critical care saw. Our hospital accepted the more stable patient transfers from our sister hospitals. Patients who remained in the NewYork–Presbyterian system were sicker, with encephalitis, thrombotic complications, multiorgan failure, and cytokine release syndrome. It’s the doctors who took care of those patients who deserve to be called heroes.

No, I am no hero. But did my volunteering make a difference? It made a difference to me. The overwhelming feeling I am left with isn’t pride; it’s humility. I feel humbled that I could feel so unexpectedly touched by the lives of people that I had no idea I could feel touched by.

Postscript:

My patient Esther [name changed to hide her identity] died from COVID-19. She was MY patient — not a patient I met as a COVID hospitalist, but a patient with rheumatoid arthritis whom I cared for for years.

She had scleromalacia and multiple failed scleral grafts, which made her profoundly sad. She fought her anxiety fiercely and always with poise and panache. One way she dealt with her anxiety was that she constantly messaged me via our EHR portal. She ran everything by me and trusted me to be her rock.

The past month has been so busy that I just now noticed it had been a month since I last heard from her. I tried to call her but got her voicemail. It wasn’t until I exchanged messages with her ophthalmologist that I found out she had passed away from complications of COVID-19.

She was taking rituximab and mycophenolate. I wonder if these drugs made her sicker than she would have been otherwise; it fills me with sadness. I wonder if she was alone like my other COVID-19 patients. I wonder if she was afraid. I am sorry that I wasn’t able to say goodbye.

Karmela Kim Chan, MD, is an assistant professor at Weill Cornell Medical College and an attending physician at Hospital for Special Surgery and Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York City. Before moving to New York City, she spent 7 years in private practice in Rhode Island and was a columnist for this rheumatology publication, writing about the challenges of starting life as a full-fledged rheumatologist in a private practice.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com. This article is part of a partnership between Medscape and Hospital for Special Surgery.

When the coronavirus pandemic hit New York City in early March, the Hospital for Special Surgery leadership decided that the best way to serve the city was to stop elective orthopedic procedures temporarily and use the facility to take on patients from its sister institution, NewYork–Presbyterian Hospital.

As in other institutions, it was all hands on deck. , other internal medicine subspecialists were asked to volunteer, including rheumatologists and primary care sports medicine doctors.

As a rheumatologist, it had been well over 10 years since I had last done any inpatient work. I was filled with trepidation, but I was also excited to dive in.

April 4:

Feeling very unmoored. I am in unfamiliar territory, and it’s terrifying. There are so many things that I no longer know how to do. Thankfully, the hospitalists are gracious, extremely supportive, and helpful.

My N95 doesn’t fit well. It’s never fit — not during residency or fellowship, not in any job I’ve had, and not today. The lady fit-testing me said she was sorry, but the look on her face said, “I’m sorry, but you’re going to die.”

April 7:

We don’t know how to treat coronavirus. I’ve sent some patients home, others I’ve sent to the ICU. Thank goodness for treatment algorithms from leadership, but we are sorely lacking good-quality data.

Our infectious disease doctor doesn’t think hydroxychloroquine works at all; I suspect he is right. The guidance right now is to give hydroxychloroquine and azithromycin to everyone who is sick enough to be admitted, but there are methodologic flaws in the early enthusiastic preprints, and so far, I’ve not noticed any demonstrable benefit.

The only thing that seems to be happening is that I am seeing more QT prolongation — not something I previously counseled my rheumatology patients on.

April 9:

The patients have been, with a few exceptions, alone in the room. They’re not allowed to have visitors and are required to wear masks all the time. Anyone who enters their rooms is fully covered up so you can barely see them. It’s anonymous and dehumanizing.

We’re instructed to take histories by phone in order to limit the time spent in each room. I buck this instruction; I still take histories in person because human contact seems more important now than ever.

Except maybe I should be smarter about this. One of my patients refuses any treatment, including oxygen support. She firmly believes this is a result of 5G networks — something I later discovered was a common conspiracy theory. She refused to wear a mask despite having a very bad cough. She coughed in my face a lot when we were chatting. My face with my ill-fitting N95 mask. Maybe the fit-testing lady’s eyes weren’t lying and I will die after all.

April 15:

On the days when I’m not working as a hospitalist, I am still doing remote visits with my rheumatology patients. It feels good to be doing something familiar and something I’m actually good at. But it is surreal to be faced with the quotidian on one hand and life and death on the other.

I recently saw a fairly new patient, and I still haven’t figured out if she has a rheumatic condition or if her symptoms all stem from an alcohol use disorder. In our previous visits, she could barely acknowledge that her drinking was an issue. On today’s visit, she told me she was 1½ months sober.

I don’t know her very well, but it was the happiest news I’d heard in a long time. I was so beside myself with joy that I cried, which says more about my current emotional state than anything else, really.

April 21:

On my panel of patients, I have three women with COVID-19 — all of whom lost their husbands to COVID-19, and none of whom were able to say their goodbyes. I cannot even begin to imagine what it must be like to survive this period of illness, isolation, and fear, only to be met on the other side by grief.

Rheumatology doesn’t lend itself too well to such existential concerns; I am not equipped for this. Perhaps my only advantage as a rheumatologist is that I know how to use IVIG, anakinra, and tocilizumab.

Someone on my panel was started on anakinra, and it turned his case around. Would he have gotten better without it anyway? We’ll never know for sure.

April 28:

Patients seem to be requiring prolonged intubation. We have now reached the stage where patients are alive but trached and PEGed. One of my patients had been intubated for close to 3 weeks. She was one of four people in her family who contracted the illness (they had had a dinner party before New York’s state of emergency was declared). We thought she might die once she was extubated, but she is still fighting. Unconscious, unarousable, but breathing on her own.

Will she ever wake up? We don’t know. We put the onus on her family to make decisions about placing a PEG tube in. They can only do so from a distance with imperfect information gleaned from periodic, brief FaceTime interactions — where no interaction happens at all.

May 4:

It’s my last day as a “COVID hospitalist.” When I first started, I felt like I was being helpful. Walking home in the middle of the 7 PM cheers for healthcare workers frequently left me teary eyed. As horrible as the situation was, I was proud of myself for volunteering to help and appreciative of a broken city’s gratitude toward all healthcare workers in general. Maybe I bought into the idea that, like many others around me, I am a hero.

I don’t feel like a hero, though. The stuff I saw was easy compared with the stuff that my colleagues in critical care saw. Our hospital accepted the more stable patient transfers from our sister hospitals. Patients who remained in the NewYork–Presbyterian system were sicker, with encephalitis, thrombotic complications, multiorgan failure, and cytokine release syndrome. It’s the doctors who took care of those patients who deserve to be called heroes.

No, I am no hero. But did my volunteering make a difference? It made a difference to me. The overwhelming feeling I am left with isn’t pride; it’s humility. I feel humbled that I could feel so unexpectedly touched by the lives of people that I had no idea I could feel touched by.

Postscript:

My patient Esther [name changed to hide her identity] died from COVID-19. She was MY patient — not a patient I met as a COVID hospitalist, but a patient with rheumatoid arthritis whom I cared for for years.

She had scleromalacia and multiple failed scleral grafts, which made her profoundly sad. She fought her anxiety fiercely and always with poise and panache. One way she dealt with her anxiety was that she constantly messaged me via our EHR portal. She ran everything by me and trusted me to be her rock.

The past month has been so busy that I just now noticed it had been a month since I last heard from her. I tried to call her but got her voicemail. It wasn’t until I exchanged messages with her ophthalmologist that I found out she had passed away from complications of COVID-19.

She was taking rituximab and mycophenolate. I wonder if these drugs made her sicker than she would have been otherwise; it fills me with sadness. I wonder if she was alone like my other COVID-19 patients. I wonder if she was afraid. I am sorry that I wasn’t able to say goodbye.

Karmela Kim Chan, MD, is an assistant professor at Weill Cornell Medical College and an attending physician at Hospital for Special Surgery and Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York City. Before moving to New York City, she spent 7 years in private practice in Rhode Island and was a columnist for this rheumatology publication, writing about the challenges of starting life as a full-fledged rheumatologist in a private practice.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com. This article is part of a partnership between Medscape and Hospital for Special Surgery.

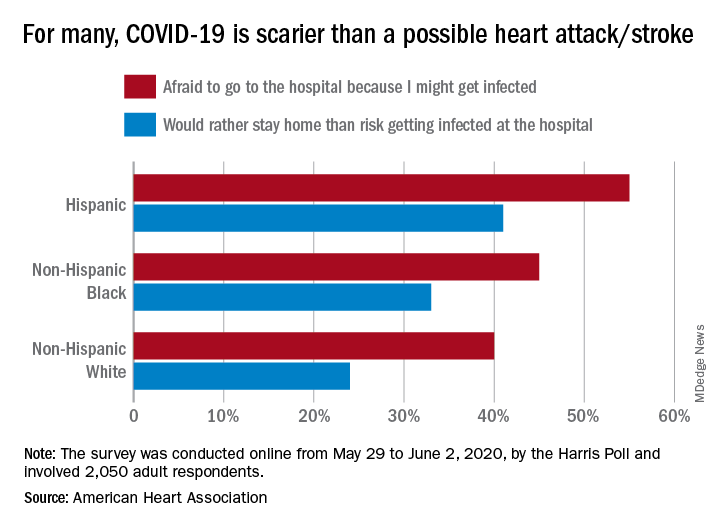

COVID-19 fears would keep most Hispanics with stroke, MI symptoms home

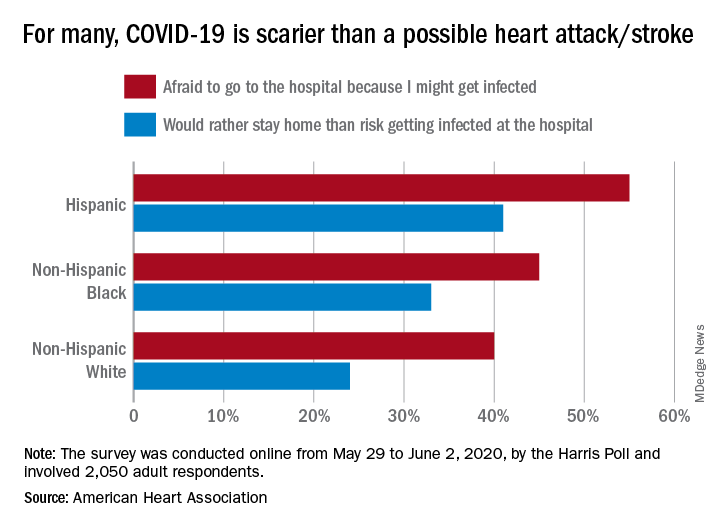

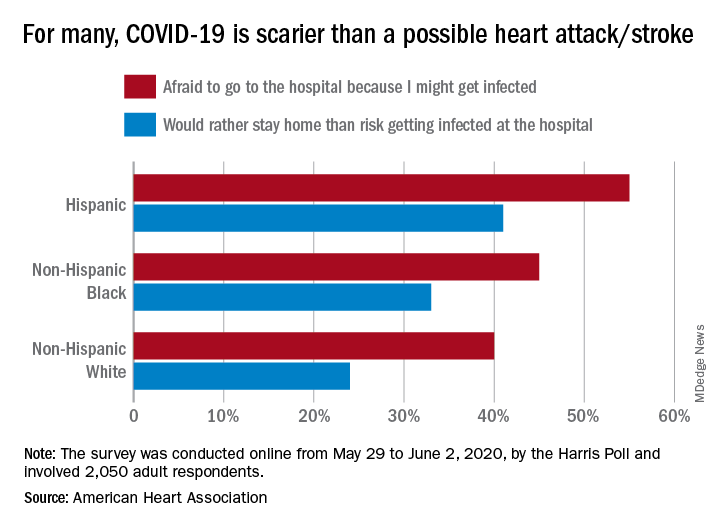

More than half of Hispanic adults would be afraid to go to a hospital for a possible heart attack or stroke because they might get infected with SARS-CoV-2, according to a new survey from the American Heart Association.

Compared with Hispanic respondents, 55% of whom said they feared COVID-19, significantly fewer Blacks (45%) and Whites (40%) would be scared to go to the hospital if they thought they were having a heart attack or stroke, the AHA said based on the survey of 2,050 adults, which was conducted May 29 to June 2, 2020, by the Harris Poll.

Hispanics also were significantly more likely to stay home if they thought they were experiencing a heart attack or stroke (41%), rather than risk getting infected at the hospital, than were Blacks (33%), who were significantly more likely than Whites (24%) to stay home, the AHA reported.

White respondents, on the other hand, were the most likely to believe (89%) that a hospital would give them the same quality of care provided to everyone else. Hispanics and Blacks had significantly lower rates, at 78% and 74%, respectively, the AHA noted.

These findings are “yet another challenge for Black and Hispanic communities, who are more likely to have underlying health conditions such as cardiovascular disease and diabetes and dying of COVID-19 at disproportionately high rates,” Rafael Ortiz, MD, American Heart Association volunteer medical expert and chief of neuro-endovascular surgery at Lenox Hill Hospital, New York, said in the AHA statement.

The survey was performed in conjunction with the AHA’s “Don’t Die of Doubt” campaign, which “reminds Americans, especially in Hispanic and Black communities, that the hospital remains the safest place to be if experiencing symptoms of a heart attack or a stroke.”

Among all the survey respondents, 57% said they would feel better if hospitals treated COVID-19 patients in a separate area. A number of other possible precautions ranked lower in helping them feel better:

- Screen all visitors, patients, and staff for COVID-19 symptoms when they enter the hospital: 39%.

- Require all patients, visitors, and staff to wear masks: 30%.

- Put increased cleaning protocols in place to disinfect multiple times per day: 23%.

- “Nothing would make me feel comfortable”: 6%.

Despite all the concerns about the risk of coronavirus infection, however, most Americans (77%) still believe that hospitals are the safest place to be in the event of a medical emergency, and 84% said that hospitals are prepared to safely treat emergencies that are not related to the pandemic, the AHA reported.

“Health care professionals know what to do even when things seem chaotic, and emergency departments have made plans behind the scenes to keep patients and healthcare workers safe even during a pandemic,” Dr. Ortiz pointed out.

More than half of Hispanic adults would be afraid to go to a hospital for a possible heart attack or stroke because they might get infected with SARS-CoV-2, according to a new survey from the American Heart Association.

Compared with Hispanic respondents, 55% of whom said they feared COVID-19, significantly fewer Blacks (45%) and Whites (40%) would be scared to go to the hospital if they thought they were having a heart attack or stroke, the AHA said based on the survey of 2,050 adults, which was conducted May 29 to June 2, 2020, by the Harris Poll.

Hispanics also were significantly more likely to stay home if they thought they were experiencing a heart attack or stroke (41%), rather than risk getting infected at the hospital, than were Blacks (33%), who were significantly more likely than Whites (24%) to stay home, the AHA reported.

White respondents, on the other hand, were the most likely to believe (89%) that a hospital would give them the same quality of care provided to everyone else. Hispanics and Blacks had significantly lower rates, at 78% and 74%, respectively, the AHA noted.

These findings are “yet another challenge for Black and Hispanic communities, who are more likely to have underlying health conditions such as cardiovascular disease and diabetes and dying of COVID-19 at disproportionately high rates,” Rafael Ortiz, MD, American Heart Association volunteer medical expert and chief of neuro-endovascular surgery at Lenox Hill Hospital, New York, said in the AHA statement.

The survey was performed in conjunction with the AHA’s “Don’t Die of Doubt” campaign, which “reminds Americans, especially in Hispanic and Black communities, that the hospital remains the safest place to be if experiencing symptoms of a heart attack or a stroke.”

Among all the survey respondents, 57% said they would feel better if hospitals treated COVID-19 patients in a separate area. A number of other possible precautions ranked lower in helping them feel better:

- Screen all visitors, patients, and staff for COVID-19 symptoms when they enter the hospital: 39%.

- Require all patients, visitors, and staff to wear masks: 30%.

- Put increased cleaning protocols in place to disinfect multiple times per day: 23%.

- “Nothing would make me feel comfortable”: 6%.

Despite all the concerns about the risk of coronavirus infection, however, most Americans (77%) still believe that hospitals are the safest place to be in the event of a medical emergency, and 84% said that hospitals are prepared to safely treat emergencies that are not related to the pandemic, the AHA reported.

“Health care professionals know what to do even when things seem chaotic, and emergency departments have made plans behind the scenes to keep patients and healthcare workers safe even during a pandemic,” Dr. Ortiz pointed out.

More than half of Hispanic adults would be afraid to go to a hospital for a possible heart attack or stroke because they might get infected with SARS-CoV-2, according to a new survey from the American Heart Association.

Compared with Hispanic respondents, 55% of whom said they feared COVID-19, significantly fewer Blacks (45%) and Whites (40%) would be scared to go to the hospital if they thought they were having a heart attack or stroke, the AHA said based on the survey of 2,050 adults, which was conducted May 29 to June 2, 2020, by the Harris Poll.

Hispanics also were significantly more likely to stay home if they thought they were experiencing a heart attack or stroke (41%), rather than risk getting infected at the hospital, than were Blacks (33%), who were significantly more likely than Whites (24%) to stay home, the AHA reported.

White respondents, on the other hand, were the most likely to believe (89%) that a hospital would give them the same quality of care provided to everyone else. Hispanics and Blacks had significantly lower rates, at 78% and 74%, respectively, the AHA noted.

These findings are “yet another challenge for Black and Hispanic communities, who are more likely to have underlying health conditions such as cardiovascular disease and diabetes and dying of COVID-19 at disproportionately high rates,” Rafael Ortiz, MD, American Heart Association volunteer medical expert and chief of neuro-endovascular surgery at Lenox Hill Hospital, New York, said in the AHA statement.

The survey was performed in conjunction with the AHA’s “Don’t Die of Doubt” campaign, which “reminds Americans, especially in Hispanic and Black communities, that the hospital remains the safest place to be if experiencing symptoms of a heart attack or a stroke.”

Among all the survey respondents, 57% said they would feel better if hospitals treated COVID-19 patients in a separate area. A number of other possible precautions ranked lower in helping them feel better:

- Screen all visitors, patients, and staff for COVID-19 symptoms when they enter the hospital: 39%.

- Require all patients, visitors, and staff to wear masks: 30%.

- Put increased cleaning protocols in place to disinfect multiple times per day: 23%.

- “Nothing would make me feel comfortable”: 6%.

Despite all the concerns about the risk of coronavirus infection, however, most Americans (77%) still believe that hospitals are the safest place to be in the event of a medical emergency, and 84% said that hospitals are prepared to safely treat emergencies that are not related to the pandemic, the AHA reported.

“Health care professionals know what to do even when things seem chaotic, and emergency departments have made plans behind the scenes to keep patients and healthcare workers safe even during a pandemic,” Dr. Ortiz pointed out.

AMA urges change after dramatic increase in illicit opioid fatalities

In the past 5 years, there has been a significant drop in the use of prescription opioids and in deaths associated with such use; but at the same time there’s been a dramatic increase in fatalities involving illicit opioids and stimulants, a new report from the American Medical Association (AMA) Opioid Task Force shows.

Although the medical community has made some important progress against the opioid epidemic, with a 37% reduction in opioid prescribing since 2013, illicit drugs are now the dominant reason why drug overdoses kill more than 70,000 people each year, the report says.

In an effort to improve the situation, the AMA Opioid Task Force is urging the removal of barriers to evidence-based care for patients who have pain and for those who have substance use disorders (SUDs). The report notes that “red tape and misguided policies are grave dangers” to these patients.

“It is critically important as we see drug overdoses increasing that we work towards reducing barriers of care for substance use abusers,” Task Force Chair Patrice A. Harris, MD, said in an interview.

“At present, the status quo is killing far too many of our loved ones and wreaking havoc in our communities,” she said.

Dr. Harris noted that “a more coordinated/integrated approach” is needed to help individuals with SUDs.

“It is vitally important that these individuals can get access to treatment. Everyone deserves the opportunity for care,” she added.

Dramatic increases

The report cites figures from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention that indicate the following regarding the period from the beginning of 2015 to the end of 2019:

- Deaths involving illicitly manufactured and fentanyl analogues increased from 5,766 to 36,509.

- Deaths involving stimulants such as increased from 4,402 to 16,279.

- Deaths involving cocaine increased from 5,496 to 15,974.

- Deaths involving heroin increased from 10,788 to 14,079.

- Deaths involving prescription opioids decreased from 12,269 to 11,904.

The report notes that deaths involving prescription opioids peaked in July 2017 at 15,003.

Some good news

In addition to the 37% reduction in opioid prescribing in recent years, the AMA lists other points of progress, such as a large increase in prescription drug monitoring program registrations. More than 1.8 million physicians and other healthcare professionals now participate in these programs.

Also, more physicians are now certified to treat opioid use disorder. More than 85,000 physicians, as well as a growing number of nurse practitioners and physician assistants, are now certified to treat patients in the office with buprenorphine. This represents an increase of more than 50,000 from 2017.

Access to naloxone is also increasing. More than 1 million naloxone prescriptions were dispensed in 2019 – nearly double the amount in 2018. This represents a 649% increase from 2017.

“We have made some good progress, but we can’t declare victory, and there are far too many barriers to getting treatment for substance use disorder,” Dr. Harris said.

“Policymakers, public health officials, and insurance companies need to come together to create a system where there are no barriers to care for people with substance use disorder and for those needing pain medications,” she added.

At present, prior authorization is often needed before these patients can receive medication. “This involves quite a bit of administration, filling in forms, making phone calls, and this is stopping people getting the care they need,” said Dr. Harris.

“This is a highly regulated environment. There are also regulations on the amount of methadone that can be prescribed and for the prescription of buprenorphine, which has to be initiated in person,” she said.

Will COVID-19 bring change?

Dr. Harris noted that some of these regulations have been relaxed during the COVID-19 crisis so that physicians could ensure that patients have continued access to medication, and she suggested that this may pave the way for the future.

“We need now to look at this carefully and have a conversation about whether these relaxations can be continued. But this would have to be evidence based. Perhaps we can use experience from the COVID-19 period to guide future policy on this,” she said.

The report highlights that despite medical society and patient advocacy, only 21 states and the District of Columbia have enacted laws that limit public and private insurers from imposing prior authorization requirements on SUD services or medications.

The Task Force urges removal of remaining prior authorizations, step therapy, and other inappropriate administrative burdens that delay or deny care for Food and Drug Administration–approved medications used as part of medication-assisted treatment for opioid use disorder.

The organization is also calling for better implementation of mental health and substance use disorder parity laws that require health insurers to provide the same level of benefits for mental health and SUD treatment and services that they do for medical/surgical care.

At present, only a few states have taken meaningful action to enact or enforce those laws, the report notes.

The Task Force also recommends the implementation of systems to track overdose and mortality trends to provide equitable public health interventions. These measures would include comprehensive, disaggregated racial and ethnic data collection related to testing, hospitalization, and mortality associated with opioids and other substances.

“We know that ending the drug overdose epidemic will not be easy, but if policymakers allow the status quo to continue, it will be impossible,” Dr. Harris said.

“ Physicians will continue to do our part. We urge policymakers to do theirs,” she added.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

In the past 5 years, there has been a significant drop in the use of prescription opioids and in deaths associated with such use; but at the same time there’s been a dramatic increase in fatalities involving illicit opioids and stimulants, a new report from the American Medical Association (AMA) Opioid Task Force shows.

Although the medical community has made some important progress against the opioid epidemic, with a 37% reduction in opioid prescribing since 2013, illicit drugs are now the dominant reason why drug overdoses kill more than 70,000 people each year, the report says.

In an effort to improve the situation, the AMA Opioid Task Force is urging the removal of barriers to evidence-based care for patients who have pain and for those who have substance use disorders (SUDs). The report notes that “red tape and misguided policies are grave dangers” to these patients.

“It is critically important as we see drug overdoses increasing that we work towards reducing barriers of care for substance use abusers,” Task Force Chair Patrice A. Harris, MD, said in an interview.

“At present, the status quo is killing far too many of our loved ones and wreaking havoc in our communities,” she said.

Dr. Harris noted that “a more coordinated/integrated approach” is needed to help individuals with SUDs.

“It is vitally important that these individuals can get access to treatment. Everyone deserves the opportunity for care,” she added.

Dramatic increases

The report cites figures from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention that indicate the following regarding the period from the beginning of 2015 to the end of 2019:

- Deaths involving illicitly manufactured and fentanyl analogues increased from 5,766 to 36,509.

- Deaths involving stimulants such as increased from 4,402 to 16,279.

- Deaths involving cocaine increased from 5,496 to 15,974.

- Deaths involving heroin increased from 10,788 to 14,079.

- Deaths involving prescription opioids decreased from 12,269 to 11,904.

The report notes that deaths involving prescription opioids peaked in July 2017 at 15,003.

Some good news

In addition to the 37% reduction in opioid prescribing in recent years, the AMA lists other points of progress, such as a large increase in prescription drug monitoring program registrations. More than 1.8 million physicians and other healthcare professionals now participate in these programs.

Also, more physicians are now certified to treat opioid use disorder. More than 85,000 physicians, as well as a growing number of nurse practitioners and physician assistants, are now certified to treat patients in the office with buprenorphine. This represents an increase of more than 50,000 from 2017.

Access to naloxone is also increasing. More than 1 million naloxone prescriptions were dispensed in 2019 – nearly double the amount in 2018. This represents a 649% increase from 2017.

“We have made some good progress, but we can’t declare victory, and there are far too many barriers to getting treatment for substance use disorder,” Dr. Harris said.

“Policymakers, public health officials, and insurance companies need to come together to create a system where there are no barriers to care for people with substance use disorder and for those needing pain medications,” she added.

At present, prior authorization is often needed before these patients can receive medication. “This involves quite a bit of administration, filling in forms, making phone calls, and this is stopping people getting the care they need,” said Dr. Harris.

“This is a highly regulated environment. There are also regulations on the amount of methadone that can be prescribed and for the prescription of buprenorphine, which has to be initiated in person,” she said.

Will COVID-19 bring change?

Dr. Harris noted that some of these regulations have been relaxed during the COVID-19 crisis so that physicians could ensure that patients have continued access to medication, and she suggested that this may pave the way for the future.

“We need now to look at this carefully and have a conversation about whether these relaxations can be continued. But this would have to be evidence based. Perhaps we can use experience from the COVID-19 period to guide future policy on this,” she said.

The report highlights that despite medical society and patient advocacy, only 21 states and the District of Columbia have enacted laws that limit public and private insurers from imposing prior authorization requirements on SUD services or medications.

The Task Force urges removal of remaining prior authorizations, step therapy, and other inappropriate administrative burdens that delay or deny care for Food and Drug Administration–approved medications used as part of medication-assisted treatment for opioid use disorder.

The organization is also calling for better implementation of mental health and substance use disorder parity laws that require health insurers to provide the same level of benefits for mental health and SUD treatment and services that they do for medical/surgical care.

At present, only a few states have taken meaningful action to enact or enforce those laws, the report notes.

The Task Force also recommends the implementation of systems to track overdose and mortality trends to provide equitable public health interventions. These measures would include comprehensive, disaggregated racial and ethnic data collection related to testing, hospitalization, and mortality associated with opioids and other substances.

“We know that ending the drug overdose epidemic will not be easy, but if policymakers allow the status quo to continue, it will be impossible,” Dr. Harris said.

“ Physicians will continue to do our part. We urge policymakers to do theirs,” she added.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

In the past 5 years, there has been a significant drop in the use of prescription opioids and in deaths associated with such use; but at the same time there’s been a dramatic increase in fatalities involving illicit opioids and stimulants, a new report from the American Medical Association (AMA) Opioid Task Force shows.

Although the medical community has made some important progress against the opioid epidemic, with a 37% reduction in opioid prescribing since 2013, illicit drugs are now the dominant reason why drug overdoses kill more than 70,000 people each year, the report says.

In an effort to improve the situation, the AMA Opioid Task Force is urging the removal of barriers to evidence-based care for patients who have pain and for those who have substance use disorders (SUDs). The report notes that “red tape and misguided policies are grave dangers” to these patients.

“It is critically important as we see drug overdoses increasing that we work towards reducing barriers of care for substance use abusers,” Task Force Chair Patrice A. Harris, MD, said in an interview.

“At present, the status quo is killing far too many of our loved ones and wreaking havoc in our communities,” she said.

Dr. Harris noted that “a more coordinated/integrated approach” is needed to help individuals with SUDs.

“It is vitally important that these individuals can get access to treatment. Everyone deserves the opportunity for care,” she added.

Dramatic increases

The report cites figures from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention that indicate the following regarding the period from the beginning of 2015 to the end of 2019:

- Deaths involving illicitly manufactured and fentanyl analogues increased from 5,766 to 36,509.

- Deaths involving stimulants such as increased from 4,402 to 16,279.

- Deaths involving cocaine increased from 5,496 to 15,974.

- Deaths involving heroin increased from 10,788 to 14,079.

- Deaths involving prescription opioids decreased from 12,269 to 11,904.

The report notes that deaths involving prescription opioids peaked in July 2017 at 15,003.

Some good news

In addition to the 37% reduction in opioid prescribing in recent years, the AMA lists other points of progress, such as a large increase in prescription drug monitoring program registrations. More than 1.8 million physicians and other healthcare professionals now participate in these programs.

Also, more physicians are now certified to treat opioid use disorder. More than 85,000 physicians, as well as a growing number of nurse practitioners and physician assistants, are now certified to treat patients in the office with buprenorphine. This represents an increase of more than 50,000 from 2017.

Access to naloxone is also increasing. More than 1 million naloxone prescriptions were dispensed in 2019 – nearly double the amount in 2018. This represents a 649% increase from 2017.

“We have made some good progress, but we can’t declare victory, and there are far too many barriers to getting treatment for substance use disorder,” Dr. Harris said.

“Policymakers, public health officials, and insurance companies need to come together to create a system where there are no barriers to care for people with substance use disorder and for those needing pain medications,” she added.

At present, prior authorization is often needed before these patients can receive medication. “This involves quite a bit of administration, filling in forms, making phone calls, and this is stopping people getting the care they need,” said Dr. Harris.

“This is a highly regulated environment. There are also regulations on the amount of methadone that can be prescribed and for the prescription of buprenorphine, which has to be initiated in person,” she said.

Will COVID-19 bring change?

Dr. Harris noted that some of these regulations have been relaxed during the COVID-19 crisis so that physicians could ensure that patients have continued access to medication, and she suggested that this may pave the way for the future.

“We need now to look at this carefully and have a conversation about whether these relaxations can be continued. But this would have to be evidence based. Perhaps we can use experience from the COVID-19 period to guide future policy on this,” she said.

The report highlights that despite medical society and patient advocacy, only 21 states and the District of Columbia have enacted laws that limit public and private insurers from imposing prior authorization requirements on SUD services or medications.

The Task Force urges removal of remaining prior authorizations, step therapy, and other inappropriate administrative burdens that delay or deny care for Food and Drug Administration–approved medications used as part of medication-assisted treatment for opioid use disorder.

The organization is also calling for better implementation of mental health and substance use disorder parity laws that require health insurers to provide the same level of benefits for mental health and SUD treatment and services that they do for medical/surgical care.

At present, only a few states have taken meaningful action to enact or enforce those laws, the report notes.

The Task Force also recommends the implementation of systems to track overdose and mortality trends to provide equitable public health interventions. These measures would include comprehensive, disaggregated racial and ethnic data collection related to testing, hospitalization, and mortality associated with opioids and other substances.

“We know that ending the drug overdose epidemic will not be easy, but if policymakers allow the status quo to continue, it will be impossible,” Dr. Harris said.

“ Physicians will continue to do our part. We urge policymakers to do theirs,” she added.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Combination therapy quells COVID-19 cytokine storm

Treatment with high-dose methylprednisolone plus tocilizumab (Actemra, Genentech) as needed was associated with faster respiratory recovery, a lower likelihood of mechanical ventilation, and fewer in-hospital deaths compared with supportive care alone among people with COVID-19 experiencing a hyperinflammatory state known as a cytokine storm.

Compared with historic controls, participants in the treatment group were 79% more likely to achieve at least a two-stage improvement in respiratory status, for example.

“COVID-19-associated cytokine storm syndrome [CSS] is an important complication of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 infection in up to 25% of the patients,” lead author Sofia Ramiro, MD, PhD, said in an interview.

Furthermore, CSS often leads to death in this population, said Dr. Ramiro, a consultant rheumatologist and senior researcher at Leiden University Medical Center and Zuyderland Medical Center in Heerlen, the Netherlands.

Results of the COVID High-Intensity Immunosuppression in Cytokine Storm Syndrome (CHIC) study were published online July 20 in Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases.

Contrary to guidance?

The World Health Organization (WHO) cautions against administering corticosteroids to some critically ill patients with COVID-19. “WHO recommends against the routine use of systemic corticosteroids for treatment of viral pneumonia,” according to an interim guidance document on the clinical management of COVID-19 published May 27.

Dr. Ramiro and colleagues make a distinction, however, noting “the risk profile of such a short course of glucocorticoid for treatment of CSS needs to be separated from preexisting chronic use of glucocorticoid for conditions like rheumatic and musculoskeletal diseases.”

Participants in the current study tolerated immunosuppressive therapy well without evidence of impaired viral clearance or bacterial superinfection, they added.

Other experts disagree with recent recommendations to use corticosteroids to treat a hyperimmune response or suspected adrenal insufficiency in the setting of refractory shock in patients with COVID-19.

Information about immunosuppressive therapy and CSS linked to COVID-19 remains anecdotal, however, Dr. Ramiro and colleagues noted.

The researchers assessed outcomes of 86 individuals with COVID-19-associated CSS treated with high-dose methylprednisolone plus/minus tocilizumab, an anti-interleukin-6 receptor monoclonal antibody. They compared them with another 86 patients with COVID-19 treated with supportive care before initiation of the combination therapy protocol.

Participants with CSS had an oxygen saturation of 94% or lower at rest or tachypnea exceeding 30 breaths per minute.

They also had at least two of the following: C-reactive protein > 100 mg/L; serum ferritin > 900 mcg/L at one occasion or a twofold increase at admission within 48 hours; or D-dimer levels > 1,500 mcg/L.

The treatment group received methylprednisolone 250 mg intravenously on day 1, followed by 80 mg intravenously on days 2-5. Investigators permitted a 2-day extension if indicated.

Those who failed to clinically improve or experienced respiratory decline could also receive intravenous tocilizumab on day 2 or after. The agent was dosed at 8 mg/kg body weight during a single infusion from day 2-5 up to a maximum of 800 mg.

In all, 37 participants received tocilizumab, including two participants who received a second dose 5 days after initial treatment.

Except for one patient in the treatment group, all participants also received antibiotic treatment and nearly 80% received chloroquine.

Mechanical ventilation and mortality

The primary outcome of at least a two-stage improvement in respiratory status on a WHO scale associated with treatment yielded a hazard ratio (HR) of 1.79. The treatment group achieved this improvement a median 7 days earlier than controls.

Mechanical ventilation to treat respiratory deterioration was 71% less likely for the treatment group versus controls (HR, 0.29).

The treatment group were also 65% less likely to die in hospital (HR, 0.35) than were controls.

The researchers also reported a significant difference in the number of deaths at day 14 in the treatment vs. control group, at 10 vs. 33 patients (P < .0001).

Glucocorticoid sufficient for many

In a sensitivity analysis excluding patients who received tocilizumab, the benefits of treatment remained statistically significant, “suggesting that a clinically relevant treatment effect can be reached by high-dose glucocorticoids alone,” the researchers noted.

This finding suggests “that the timely administration of high-dose glucocorticoids alone may provide significant benefit in more than half of the patients, and that tocilizumab is only needed in those cases that had insufficient clinical improvement on methylprednisolone alone,” they added.

“This is an important finding given the limited availability of tocilizumab in many countries and tocilizumab’s high costs.”

Complications were fairly balanced between groups. For example, bacterial infections during hospitalization were diagnosed in eight patients in the treatment group versus seven in the control group.

In addition, cardiac arrhythmias occurred in both groups, but slightly less frequently in the treatment group (P = .265), and there was a trend towards more pulmonary embolisms in the treatment group (P = .059).

Strengths and limitations

“A treatment with high-dose glucocorticoids is a convenient choice since glucocorticoids are safe, widely available, and inexpensive,” the researchers noted. “Longer follow-up, however, is needed to give final resolution about the safety and efficacy of the strategy.”

A strength of the study was “meticulous selection of those patients more likely to benefit from immunosuppressive treatment, namely patients with a CSS,” she added.

The study featured a prospective, observational design for the treatment group and retrospective analysis of the historic controls. “Methodologically, the main limitation of the study is not being a randomized controlled trial,” she noted.

“Ethically it has shown to be very rewarding to consciously decide against a randomized control trial, as we are talking about a disease that if only treated with supportive care can lead to mortality up to almost 50% from COVID-19-associated CSS,” Dr. Ramiro said.

Going forward, Dr. Ramiro plans to continue monitoring patients who experienced CSS to assess their outcome post-COVID-19 infection. “We want to focus on cardiorespiratory, functional, and quality of life outcomes,” she said. “We will also compare the outcomes between patients that have received immunosuppression with those that haven’t.”

‘Quite interesting’ results

“We desperately need better evidence to guide the management of patients hospitalized with COVID-19,” Nihar R. Desai, MD, MPH, who was not affiliated with the study, said in an interview.

“These data from the Netherlands are quite interesting and provide another signal to support the use of corticosteroids, with tocilizumab if needed, among hospitalized patients with COVID-19 to improve outcomes,” added Dr. Desai, associate professor of medicine and investigator at the Center for Outcomes Research and Evaluation, Yale University, New Haven, Conn.

“While these data are not randomized and have a relatively small sample size, we had recently seen the results of the RECOVERY trial, a UK-based randomized trial demonstrating the benefit of steroids in COVID-19,” he said.

“Taken together, these studies seem to suggest that there is a benefit with steroid therapy.” Further validation of these results is warranted, he added.

“While not a randomized clinical trial, and thus susceptible to unmeasured bias, the study adds to mounting evidence that supports targeting the excessive inflammation found in some patients with COVID-19,” Jared Radbel, MD, a pulmonologist, critical care specialist, and assistant professor of medicine at Rutgers Robert Wood Johnson Medical School, New Brunswick, N.J., said in an interview.

Dr. Radbel added that he is part of a multicenter group that has submitted a manuscript examining outcomes of critically ill patients with COVID-19 treated with tocilizumab.

Dr. Ramiro, Dr. Desai, and Dr. Radbel have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Treatment with high-dose methylprednisolone plus tocilizumab (Actemra, Genentech) as needed was associated with faster respiratory recovery, a lower likelihood of mechanical ventilation, and fewer in-hospital deaths compared with supportive care alone among people with COVID-19 experiencing a hyperinflammatory state known as a cytokine storm.

Compared with historic controls, participants in the treatment group were 79% more likely to achieve at least a two-stage improvement in respiratory status, for example.

“COVID-19-associated cytokine storm syndrome [CSS] is an important complication of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 infection in up to 25% of the patients,” lead author Sofia Ramiro, MD, PhD, said in an interview.

Furthermore, CSS often leads to death in this population, said Dr. Ramiro, a consultant rheumatologist and senior researcher at Leiden University Medical Center and Zuyderland Medical Center in Heerlen, the Netherlands.

Results of the COVID High-Intensity Immunosuppression in Cytokine Storm Syndrome (CHIC) study were published online July 20 in Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases.

Contrary to guidance?

The World Health Organization (WHO) cautions against administering corticosteroids to some critically ill patients with COVID-19. “WHO recommends against the routine use of systemic corticosteroids for treatment of viral pneumonia,” according to an interim guidance document on the clinical management of COVID-19 published May 27.

Dr. Ramiro and colleagues make a distinction, however, noting “the risk profile of such a short course of glucocorticoid for treatment of CSS needs to be separated from preexisting chronic use of glucocorticoid for conditions like rheumatic and musculoskeletal diseases.”

Participants in the current study tolerated immunosuppressive therapy well without evidence of impaired viral clearance or bacterial superinfection, they added.

Other experts disagree with recent recommendations to use corticosteroids to treat a hyperimmune response or suspected adrenal insufficiency in the setting of refractory shock in patients with COVID-19.

Information about immunosuppressive therapy and CSS linked to COVID-19 remains anecdotal, however, Dr. Ramiro and colleagues noted.

The researchers assessed outcomes of 86 individuals with COVID-19-associated CSS treated with high-dose methylprednisolone plus/minus tocilizumab, an anti-interleukin-6 receptor monoclonal antibody. They compared them with another 86 patients with COVID-19 treated with supportive care before initiation of the combination therapy protocol.

Participants with CSS had an oxygen saturation of 94% or lower at rest or tachypnea exceeding 30 breaths per minute.

They also had at least two of the following: C-reactive protein > 100 mg/L; serum ferritin > 900 mcg/L at one occasion or a twofold increase at admission within 48 hours; or D-dimer levels > 1,500 mcg/L.

The treatment group received methylprednisolone 250 mg intravenously on day 1, followed by 80 mg intravenously on days 2-5. Investigators permitted a 2-day extension if indicated.

Those who failed to clinically improve or experienced respiratory decline could also receive intravenous tocilizumab on day 2 or after. The agent was dosed at 8 mg/kg body weight during a single infusion from day 2-5 up to a maximum of 800 mg.

In all, 37 participants received tocilizumab, including two participants who received a second dose 5 days after initial treatment.

Except for one patient in the treatment group, all participants also received antibiotic treatment and nearly 80% received chloroquine.

Mechanical ventilation and mortality

The primary outcome of at least a two-stage improvement in respiratory status on a WHO scale associated with treatment yielded a hazard ratio (HR) of 1.79. The treatment group achieved this improvement a median 7 days earlier than controls.

Mechanical ventilation to treat respiratory deterioration was 71% less likely for the treatment group versus controls (HR, 0.29).

The treatment group were also 65% less likely to die in hospital (HR, 0.35) than were controls.

The researchers also reported a significant difference in the number of deaths at day 14 in the treatment vs. control group, at 10 vs. 33 patients (P < .0001).

Glucocorticoid sufficient for many

In a sensitivity analysis excluding patients who received tocilizumab, the benefits of treatment remained statistically significant, “suggesting that a clinically relevant treatment effect can be reached by high-dose glucocorticoids alone,” the researchers noted.

This finding suggests “that the timely administration of high-dose glucocorticoids alone may provide significant benefit in more than half of the patients, and that tocilizumab is only needed in those cases that had insufficient clinical improvement on methylprednisolone alone,” they added.

“This is an important finding given the limited availability of tocilizumab in many countries and tocilizumab’s high costs.”

Complications were fairly balanced between groups. For example, bacterial infections during hospitalization were diagnosed in eight patients in the treatment group versus seven in the control group.

In addition, cardiac arrhythmias occurred in both groups, but slightly less frequently in the treatment group (P = .265), and there was a trend towards more pulmonary embolisms in the treatment group (P = .059).

Strengths and limitations

“A treatment with high-dose glucocorticoids is a convenient choice since glucocorticoids are safe, widely available, and inexpensive,” the researchers noted. “Longer follow-up, however, is needed to give final resolution about the safety and efficacy of the strategy.”

A strength of the study was “meticulous selection of those patients more likely to benefit from immunosuppressive treatment, namely patients with a CSS,” she added.

The study featured a prospective, observational design for the treatment group and retrospective analysis of the historic controls. “Methodologically, the main limitation of the study is not being a randomized controlled trial,” she noted.

“Ethically it has shown to be very rewarding to consciously decide against a randomized control trial, as we are talking about a disease that if only treated with supportive care can lead to mortality up to almost 50% from COVID-19-associated CSS,” Dr. Ramiro said.

Going forward, Dr. Ramiro plans to continue monitoring patients who experienced CSS to assess their outcome post-COVID-19 infection. “We want to focus on cardiorespiratory, functional, and quality of life outcomes,” she said. “We will also compare the outcomes between patients that have received immunosuppression with those that haven’t.”

‘Quite interesting’ results

“We desperately need better evidence to guide the management of patients hospitalized with COVID-19,” Nihar R. Desai, MD, MPH, who was not affiliated with the study, said in an interview.

“These data from the Netherlands are quite interesting and provide another signal to support the use of corticosteroids, with tocilizumab if needed, among hospitalized patients with COVID-19 to improve outcomes,” added Dr. Desai, associate professor of medicine and investigator at the Center for Outcomes Research and Evaluation, Yale University, New Haven, Conn.

“While these data are not randomized and have a relatively small sample size, we had recently seen the results of the RECOVERY trial, a UK-based randomized trial demonstrating the benefit of steroids in COVID-19,” he said.

“Taken together, these studies seem to suggest that there is a benefit with steroid therapy.” Further validation of these results is warranted, he added.

“While not a randomized clinical trial, and thus susceptible to unmeasured bias, the study adds to mounting evidence that supports targeting the excessive inflammation found in some patients with COVID-19,” Jared Radbel, MD, a pulmonologist, critical care specialist, and assistant professor of medicine at Rutgers Robert Wood Johnson Medical School, New Brunswick, N.J., said in an interview.

Dr. Radbel added that he is part of a multicenter group that has submitted a manuscript examining outcomes of critically ill patients with COVID-19 treated with tocilizumab.

Dr. Ramiro, Dr. Desai, and Dr. Radbel have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Treatment with high-dose methylprednisolone plus tocilizumab (Actemra, Genentech) as needed was associated with faster respiratory recovery, a lower likelihood of mechanical ventilation, and fewer in-hospital deaths compared with supportive care alone among people with COVID-19 experiencing a hyperinflammatory state known as a cytokine storm.

Compared with historic controls, participants in the treatment group were 79% more likely to achieve at least a two-stage improvement in respiratory status, for example.

“COVID-19-associated cytokine storm syndrome [CSS] is an important complication of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 infection in up to 25% of the patients,” lead author Sofia Ramiro, MD, PhD, said in an interview.

Furthermore, CSS often leads to death in this population, said Dr. Ramiro, a consultant rheumatologist and senior researcher at Leiden University Medical Center and Zuyderland Medical Center in Heerlen, the Netherlands.

Results of the COVID High-Intensity Immunosuppression in Cytokine Storm Syndrome (CHIC) study were published online July 20 in Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases.

Contrary to guidance?

The World Health Organization (WHO) cautions against administering corticosteroids to some critically ill patients with COVID-19. “WHO recommends against the routine use of systemic corticosteroids for treatment of viral pneumonia,” according to an interim guidance document on the clinical management of COVID-19 published May 27.

Dr. Ramiro and colleagues make a distinction, however, noting “the risk profile of such a short course of glucocorticoid for treatment of CSS needs to be separated from preexisting chronic use of glucocorticoid for conditions like rheumatic and musculoskeletal diseases.”

Participants in the current study tolerated immunosuppressive therapy well without evidence of impaired viral clearance or bacterial superinfection, they added.

Other experts disagree with recent recommendations to use corticosteroids to treat a hyperimmune response or suspected adrenal insufficiency in the setting of refractory shock in patients with COVID-19.

Information about immunosuppressive therapy and CSS linked to COVID-19 remains anecdotal, however, Dr. Ramiro and colleagues noted.

The researchers assessed outcomes of 86 individuals with COVID-19-associated CSS treated with high-dose methylprednisolone plus/minus tocilizumab, an anti-interleukin-6 receptor monoclonal antibody. They compared them with another 86 patients with COVID-19 treated with supportive care before initiation of the combination therapy protocol.

Participants with CSS had an oxygen saturation of 94% or lower at rest or tachypnea exceeding 30 breaths per minute.

They also had at least two of the following: C-reactive protein > 100 mg/L; serum ferritin > 900 mcg/L at one occasion or a twofold increase at admission within 48 hours; or D-dimer levels > 1,500 mcg/L.

The treatment group received methylprednisolone 250 mg intravenously on day 1, followed by 80 mg intravenously on days 2-5. Investigators permitted a 2-day extension if indicated.

Those who failed to clinically improve or experienced respiratory decline could also receive intravenous tocilizumab on day 2 or after. The agent was dosed at 8 mg/kg body weight during a single infusion from day 2-5 up to a maximum of 800 mg.

In all, 37 participants received tocilizumab, including two participants who received a second dose 5 days after initial treatment.

Except for one patient in the treatment group, all participants also received antibiotic treatment and nearly 80% received chloroquine.

Mechanical ventilation and mortality

The primary outcome of at least a two-stage improvement in respiratory status on a WHO scale associated with treatment yielded a hazard ratio (HR) of 1.79. The treatment group achieved this improvement a median 7 days earlier than controls.

Mechanical ventilation to treat respiratory deterioration was 71% less likely for the treatment group versus controls (HR, 0.29).

The treatment group were also 65% less likely to die in hospital (HR, 0.35) than were controls.

The researchers also reported a significant difference in the number of deaths at day 14 in the treatment vs. control group, at 10 vs. 33 patients (P < .0001).

Glucocorticoid sufficient for many

In a sensitivity analysis excluding patients who received tocilizumab, the benefits of treatment remained statistically significant, “suggesting that a clinically relevant treatment effect can be reached by high-dose glucocorticoids alone,” the researchers noted.

This finding suggests “that the timely administration of high-dose glucocorticoids alone may provide significant benefit in more than half of the patients, and that tocilizumab is only needed in those cases that had insufficient clinical improvement on methylprednisolone alone,” they added.

“This is an important finding given the limited availability of tocilizumab in many countries and tocilizumab’s high costs.”

Complications were fairly balanced between groups. For example, bacterial infections during hospitalization were diagnosed in eight patients in the treatment group versus seven in the control group.

In addition, cardiac arrhythmias occurred in both groups, but slightly less frequently in the treatment group (P = .265), and there was a trend towards more pulmonary embolisms in the treatment group (P = .059).

Strengths and limitations

“A treatment with high-dose glucocorticoids is a convenient choice since glucocorticoids are safe, widely available, and inexpensive,” the researchers noted. “Longer follow-up, however, is needed to give final resolution about the safety and efficacy of the strategy.”

A strength of the study was “meticulous selection of those patients more likely to benefit from immunosuppressive treatment, namely patients with a CSS,” she added.

The study featured a prospective, observational design for the treatment group and retrospective analysis of the historic controls. “Methodologically, the main limitation of the study is not being a randomized controlled trial,” she noted.

“Ethically it has shown to be very rewarding to consciously decide against a randomized control trial, as we are talking about a disease that if only treated with supportive care can lead to mortality up to almost 50% from COVID-19-associated CSS,” Dr. Ramiro said.

Going forward, Dr. Ramiro plans to continue monitoring patients who experienced CSS to assess their outcome post-COVID-19 infection. “We want to focus on cardiorespiratory, functional, and quality of life outcomes,” she said. “We will also compare the outcomes between patients that have received immunosuppression with those that haven’t.”

‘Quite interesting’ results

“We desperately need better evidence to guide the management of patients hospitalized with COVID-19,” Nihar R. Desai, MD, MPH, who was not affiliated with the study, said in an interview.

“These data from the Netherlands are quite interesting and provide another signal to support the use of corticosteroids, with tocilizumab if needed, among hospitalized patients with COVID-19 to improve outcomes,” added Dr. Desai, associate professor of medicine and investigator at the Center for Outcomes Research and Evaluation, Yale University, New Haven, Conn.

“While these data are not randomized and have a relatively small sample size, we had recently seen the results of the RECOVERY trial, a UK-based randomized trial demonstrating the benefit of steroids in COVID-19,” he said.

“Taken together, these studies seem to suggest that there is a benefit with steroid therapy.” Further validation of these results is warranted, he added.

“While not a randomized clinical trial, and thus susceptible to unmeasured bias, the study adds to mounting evidence that supports targeting the excessive inflammation found in some patients with COVID-19,” Jared Radbel, MD, a pulmonologist, critical care specialist, and assistant professor of medicine at Rutgers Robert Wood Johnson Medical School, New Brunswick, N.J., said in an interview.

Dr. Radbel added that he is part of a multicenter group that has submitted a manuscript examining outcomes of critically ill patients with COVID-19 treated with tocilizumab.

Dr. Ramiro, Dr. Desai, and Dr. Radbel have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

One-third of outpatients with COVID-19 are unwell weeks later

, according to survey results in Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Mark W. Tenforde, MD, PhD, for the CDC-COVID-19 Response Team, and colleagues conducted a multistate telephone survey of symptomatic adults who tested positive for SARS-CoV-2. The researchers found that 35% had not returned to their usual state of wellness when they were interviewed 2-3 weeks after testing.

Among the 270 of 274 people interviewed for whom there were data on return to health, 175 (65%) reported that they had returned to baseline health an average of 7 days from the date of testing.

Among the 274 symptomatic outpatients, the median number of symptoms was seven. Fatigue (71%), cough (61%), and headache (61%) were the most commonly reported symptoms.

Prolonged illness is well described in adults hospitalized with severe COVID-19, especially among the older adult population, but little is known about other groups.

The proportion who had not returned to health differed by age: 26% of interviewees aged 18-34 years, 32% of those aged 35-49 years, and 47% of those at least 50 years old reported not having returned to their usual health (P = .010) within 14-21 days after receiving positive test results.

Among respondents aged 18-34 years who had no chronic medical condition, 19% (9 of 48) reported not having returned to their usual state of health during that time.

Public health messaging targeting younger adults, a group who might not be expected to be sick for weeks with mild disease, is particularly important, the authors wrote.

Kyle Annen, DO, medical director of transfusion services and patient blood management at Children’s Hospital Colorado and assistant professor of pathology at the University of Colorado, Denver, said in an interview that an important message is that delayed recovery (symptoms of fatigue, cough, and shortness of breath) was evident in nearly a quarter of 18- to 34-year-olds and in a third of 35- to 49-year-olds who were not sick enough to require hospitalization.