User login

Long COVID hitting some states, minorities, women harder

More than one in four adults sickened by the virus go on to have long COVID, according to a new report from the U.S. Census Bureau. Overall, nearly 15% of all American adults – more than 38 million people nationwide – have had long COVID at some point since the start of the pandemic, according to the report.

The report, based on survey data collected between March 1 and 13, defines long COVID as symptoms lasting at least 3 months that people didn’t have before getting infected with the virus.

It is the second recent look at who is most likely to face long COVID. A similar study, published in March, found that women, smokers, and those who had severe COVID-19 infections are most likely to have the disorder

The Census Bureau report found that while 27% of adults nationwide have had long COVID after getting infected with the virus, the condition has impacted some states more than others. The proportion of residents hit with long COVID ranged from a low of 18.8% in New Jersey to a high of 40.7% in West Virginia.

Other states with long COVID rates well below the national average include Alaska, Maryland, New York, and Wisconsin. At the other end of the spectrum, the states with rates well above the national average include Kentucky, Mississippi, New Mexico, Nevada, South Carolina, South Dakota, and Wyoming.

Long COVID rates also varied by age, gender, and race. People in their 50s were most at risk, with about 31% of those infected by the virus going on to have long COVID, followed by those in their 40s, at more than 29%.

Far more women (almost 33%) than men (21%) with COVID infections got long COVID. And when researchers looked at long COVID rates based on gender identity, they found that transgender adults were more than twice as likely to have long COVID than cisgender males. Bisexual adults also had much higher long COVID rates than straight, gay, or lesbian people.

Long COVID was also much more common among Hispanic adults, affecting almost 29% of those infected with the virus, than among White or Black people, who had long COVID rates similar to the national average of 27%. Asian adults had lower long COVID rates than the national average, at less than 20%.

People with disabilities were also at higher risk, with long COVID rates of almost 47%, compared with 24% among adults without disabilities.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

More than one in four adults sickened by the virus go on to have long COVID, according to a new report from the U.S. Census Bureau. Overall, nearly 15% of all American adults – more than 38 million people nationwide – have had long COVID at some point since the start of the pandemic, according to the report.

The report, based on survey data collected between March 1 and 13, defines long COVID as symptoms lasting at least 3 months that people didn’t have before getting infected with the virus.

It is the second recent look at who is most likely to face long COVID. A similar study, published in March, found that women, smokers, and those who had severe COVID-19 infections are most likely to have the disorder

The Census Bureau report found that while 27% of adults nationwide have had long COVID after getting infected with the virus, the condition has impacted some states more than others. The proportion of residents hit with long COVID ranged from a low of 18.8% in New Jersey to a high of 40.7% in West Virginia.

Other states with long COVID rates well below the national average include Alaska, Maryland, New York, and Wisconsin. At the other end of the spectrum, the states with rates well above the national average include Kentucky, Mississippi, New Mexico, Nevada, South Carolina, South Dakota, and Wyoming.

Long COVID rates also varied by age, gender, and race. People in their 50s were most at risk, with about 31% of those infected by the virus going on to have long COVID, followed by those in their 40s, at more than 29%.

Far more women (almost 33%) than men (21%) with COVID infections got long COVID. And when researchers looked at long COVID rates based on gender identity, they found that transgender adults were more than twice as likely to have long COVID than cisgender males. Bisexual adults also had much higher long COVID rates than straight, gay, or lesbian people.

Long COVID was also much more common among Hispanic adults, affecting almost 29% of those infected with the virus, than among White or Black people, who had long COVID rates similar to the national average of 27%. Asian adults had lower long COVID rates than the national average, at less than 20%.

People with disabilities were also at higher risk, with long COVID rates of almost 47%, compared with 24% among adults without disabilities.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

More than one in four adults sickened by the virus go on to have long COVID, according to a new report from the U.S. Census Bureau. Overall, nearly 15% of all American adults – more than 38 million people nationwide – have had long COVID at some point since the start of the pandemic, according to the report.

The report, based on survey data collected between March 1 and 13, defines long COVID as symptoms lasting at least 3 months that people didn’t have before getting infected with the virus.

It is the second recent look at who is most likely to face long COVID. A similar study, published in March, found that women, smokers, and those who had severe COVID-19 infections are most likely to have the disorder

The Census Bureau report found that while 27% of adults nationwide have had long COVID after getting infected with the virus, the condition has impacted some states more than others. The proportion of residents hit with long COVID ranged from a low of 18.8% in New Jersey to a high of 40.7% in West Virginia.

Other states with long COVID rates well below the national average include Alaska, Maryland, New York, and Wisconsin. At the other end of the spectrum, the states with rates well above the national average include Kentucky, Mississippi, New Mexico, Nevada, South Carolina, South Dakota, and Wyoming.

Long COVID rates also varied by age, gender, and race. People in their 50s were most at risk, with about 31% of those infected by the virus going on to have long COVID, followed by those in their 40s, at more than 29%.

Far more women (almost 33%) than men (21%) with COVID infections got long COVID. And when researchers looked at long COVID rates based on gender identity, they found that transgender adults were more than twice as likely to have long COVID than cisgender males. Bisexual adults also had much higher long COVID rates than straight, gay, or lesbian people.

Long COVID was also much more common among Hispanic adults, affecting almost 29% of those infected with the virus, than among White or Black people, who had long COVID rates similar to the national average of 27%. Asian adults had lower long COVID rates than the national average, at less than 20%.

People with disabilities were also at higher risk, with long COVID rates of almost 47%, compared with 24% among adults without disabilities.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

SARS-CoV-2 crosses placenta and infects brains of two infants: ‘This is a first’

, according to a study published online today in Pediatrics .

One of the infants died at 13 months and the other remained in hospice care at time of manuscript submission.

Lead author Merline Benny, MD, with the division of neonatology, department of pediatrics at University of Miami, and colleagues briefed reporters today ahead of the release.

“This is a first,” said senior author Shahnaz Duara, MD, medical director of the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit at Holtz Children’s Hospital, Miami, explaining it is the first study to confirm cross-placental SARS-CoV-2 transmission leading to brain injury in a newborn.

Both infants negative for the virus at birth

The two infants were admitted in the early days of the pandemic in the Delta wave to the neonatal ICU at Holtz Children’s Hospital at University of Miami/Jackson Memorial Medical Center.

Both infants tested negative for the virus at birth, but had significantly elevated SARS-CoV-2 antibodies in their blood, indicating that either antibodies crossed the placenta, or the virus crossed and the immune response was the baby’s.

Dr. Benny explained that the researchers have seen, to this point, more than 700 mother/infant pairs in whom the mother tested positive for COVID in Jackson hospital.

Most who tested positive for COVID were asymptomatic and most of the mothers and infants left the hospital without complications.

“However, (these) two babies had a very unusual clinical picture,” Dr. Benny said.

Those infants were born to mothers who became COVID positive in the second trimester and delivered a few weeks later.

Seizures started on day 1 of life

The babies began to seize from the first day of life. They had profound low tone (hypotonia) in their clinical exam, Dr. Benny explained.

“We had absolutely no good explanation for the early seizures and the degree of brain injury we saw,” Dr. Duara said.

Dr. Benny said that as their bodies grew, they had very small head circumference. Unlike some babies born with the Zika virus, these babies were not microcephalic at birth. Brain imaging on the two babies indicated significant brain atrophy, and neurodevelopment exams showed significant delay.

Discussions began with the center’s multidisciplinary team including neurologists, pathologists, neuroradiologists, and obstetricians who cared for both the mothers and the babies.

The experts examined the placentas and found some characteristic COVID changes and presence of the COVID virus. This was accompanied by increased markers for inflammation and a severe reduction in a hormone critical for placental health and brain development.

Examining the infant’s autopsy findings further raised suspicions of maternal transmission, something that had not been documented before.

Coauthor Ali G. Saad, MD, pediatric and perinatal pathology director at Miami, said, “I have seen literally thousands of brains in autopsies over the last 14 years, and this was the most dramatic case of leukoencephalopathy or loss of white matter in a patient with no significant reason. That’s what triggered the investigation.”

Mothers had very different presentations

Coauthor Michael J. Paidas, MD, with the department of obstetrics, gynecology, and reproductive sciences at Miami, pointed out that the circumstances of the two mothers, who were in their 20s, were very different.

One mother delivered at 32 weeks and had a very severe COVID presentation and spent a month in the intensive care unit. The team decided to deliver the child to save the mother, Dr. Paidas said.

In contrast, the other mother had asymptomatic COVID infection in the second trimester and delivered at full term.

He said one of the early suspicions in the babies’ presentations was hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy. “But it wasn’t lack of blood flow to the placenta that caused this,” he said. “As best we can tell, it was the viral infection.”

Instances are rare

The researchers emphasized that these instances are rare and have not been seen before or since the period of this study to their knowledge.

Dr. Duara said, “This is something we want to alert the medical community to more than the general public. We do not want the lay public to be panicked. We’re trying to understand what made these two pregnancies different, so we can direct research towards protecting vulnerable babies.”

Previous data have indicated a relatively benign status in infants who test negative for the COVID virus after birth. Dr. Benny added that COVID vaccination has been found safe in pregnancy and both vaccination and breastfeeding can help passage of antibodies to the infant and help protect the baby. Because these cases happened in the early days of the pandemic, no vaccines were available.

Dr. Paidas received funding from BioIncept to study hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy with Preimplantation Factor, is a scientific advisory board member, and has stock options. Dr. Paidas and coauthor Dr. Jayakumar are coinventors of SPIKENET, University of Miami, patent pending 2023. The other authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

, according to a study published online today in Pediatrics .

One of the infants died at 13 months and the other remained in hospice care at time of manuscript submission.

Lead author Merline Benny, MD, with the division of neonatology, department of pediatrics at University of Miami, and colleagues briefed reporters today ahead of the release.

“This is a first,” said senior author Shahnaz Duara, MD, medical director of the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit at Holtz Children’s Hospital, Miami, explaining it is the first study to confirm cross-placental SARS-CoV-2 transmission leading to brain injury in a newborn.

Both infants negative for the virus at birth

The two infants were admitted in the early days of the pandemic in the Delta wave to the neonatal ICU at Holtz Children’s Hospital at University of Miami/Jackson Memorial Medical Center.

Both infants tested negative for the virus at birth, but had significantly elevated SARS-CoV-2 antibodies in their blood, indicating that either antibodies crossed the placenta, or the virus crossed and the immune response was the baby’s.

Dr. Benny explained that the researchers have seen, to this point, more than 700 mother/infant pairs in whom the mother tested positive for COVID in Jackson hospital.

Most who tested positive for COVID were asymptomatic and most of the mothers and infants left the hospital without complications.

“However, (these) two babies had a very unusual clinical picture,” Dr. Benny said.

Those infants were born to mothers who became COVID positive in the second trimester and delivered a few weeks later.

Seizures started on day 1 of life

The babies began to seize from the first day of life. They had profound low tone (hypotonia) in their clinical exam, Dr. Benny explained.

“We had absolutely no good explanation for the early seizures and the degree of brain injury we saw,” Dr. Duara said.

Dr. Benny said that as their bodies grew, they had very small head circumference. Unlike some babies born with the Zika virus, these babies were not microcephalic at birth. Brain imaging on the two babies indicated significant brain atrophy, and neurodevelopment exams showed significant delay.

Discussions began with the center’s multidisciplinary team including neurologists, pathologists, neuroradiologists, and obstetricians who cared for both the mothers and the babies.

The experts examined the placentas and found some characteristic COVID changes and presence of the COVID virus. This was accompanied by increased markers for inflammation and a severe reduction in a hormone critical for placental health and brain development.

Examining the infant’s autopsy findings further raised suspicions of maternal transmission, something that had not been documented before.

Coauthor Ali G. Saad, MD, pediatric and perinatal pathology director at Miami, said, “I have seen literally thousands of brains in autopsies over the last 14 years, and this was the most dramatic case of leukoencephalopathy or loss of white matter in a patient with no significant reason. That’s what triggered the investigation.”

Mothers had very different presentations

Coauthor Michael J. Paidas, MD, with the department of obstetrics, gynecology, and reproductive sciences at Miami, pointed out that the circumstances of the two mothers, who were in their 20s, were very different.

One mother delivered at 32 weeks and had a very severe COVID presentation and spent a month in the intensive care unit. The team decided to deliver the child to save the mother, Dr. Paidas said.

In contrast, the other mother had asymptomatic COVID infection in the second trimester and delivered at full term.

He said one of the early suspicions in the babies’ presentations was hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy. “But it wasn’t lack of blood flow to the placenta that caused this,” he said. “As best we can tell, it was the viral infection.”

Instances are rare

The researchers emphasized that these instances are rare and have not been seen before or since the period of this study to their knowledge.

Dr. Duara said, “This is something we want to alert the medical community to more than the general public. We do not want the lay public to be panicked. We’re trying to understand what made these two pregnancies different, so we can direct research towards protecting vulnerable babies.”

Previous data have indicated a relatively benign status in infants who test negative for the COVID virus after birth. Dr. Benny added that COVID vaccination has been found safe in pregnancy and both vaccination and breastfeeding can help passage of antibodies to the infant and help protect the baby. Because these cases happened in the early days of the pandemic, no vaccines were available.

Dr. Paidas received funding from BioIncept to study hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy with Preimplantation Factor, is a scientific advisory board member, and has stock options. Dr. Paidas and coauthor Dr. Jayakumar are coinventors of SPIKENET, University of Miami, patent pending 2023. The other authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

, according to a study published online today in Pediatrics .

One of the infants died at 13 months and the other remained in hospice care at time of manuscript submission.

Lead author Merline Benny, MD, with the division of neonatology, department of pediatrics at University of Miami, and colleagues briefed reporters today ahead of the release.

“This is a first,” said senior author Shahnaz Duara, MD, medical director of the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit at Holtz Children’s Hospital, Miami, explaining it is the first study to confirm cross-placental SARS-CoV-2 transmission leading to brain injury in a newborn.

Both infants negative for the virus at birth

The two infants were admitted in the early days of the pandemic in the Delta wave to the neonatal ICU at Holtz Children’s Hospital at University of Miami/Jackson Memorial Medical Center.

Both infants tested negative for the virus at birth, but had significantly elevated SARS-CoV-2 antibodies in their blood, indicating that either antibodies crossed the placenta, or the virus crossed and the immune response was the baby’s.

Dr. Benny explained that the researchers have seen, to this point, more than 700 mother/infant pairs in whom the mother tested positive for COVID in Jackson hospital.

Most who tested positive for COVID were asymptomatic and most of the mothers and infants left the hospital without complications.

“However, (these) two babies had a very unusual clinical picture,” Dr. Benny said.

Those infants were born to mothers who became COVID positive in the second trimester and delivered a few weeks later.

Seizures started on day 1 of life

The babies began to seize from the first day of life. They had profound low tone (hypotonia) in their clinical exam, Dr. Benny explained.

“We had absolutely no good explanation for the early seizures and the degree of brain injury we saw,” Dr. Duara said.

Dr. Benny said that as their bodies grew, they had very small head circumference. Unlike some babies born with the Zika virus, these babies were not microcephalic at birth. Brain imaging on the two babies indicated significant brain atrophy, and neurodevelopment exams showed significant delay.

Discussions began with the center’s multidisciplinary team including neurologists, pathologists, neuroradiologists, and obstetricians who cared for both the mothers and the babies.

The experts examined the placentas and found some characteristic COVID changes and presence of the COVID virus. This was accompanied by increased markers for inflammation and a severe reduction in a hormone critical for placental health and brain development.

Examining the infant’s autopsy findings further raised suspicions of maternal transmission, something that had not been documented before.

Coauthor Ali G. Saad, MD, pediatric and perinatal pathology director at Miami, said, “I have seen literally thousands of brains in autopsies over the last 14 years, and this was the most dramatic case of leukoencephalopathy or loss of white matter in a patient with no significant reason. That’s what triggered the investigation.”

Mothers had very different presentations

Coauthor Michael J. Paidas, MD, with the department of obstetrics, gynecology, and reproductive sciences at Miami, pointed out that the circumstances of the two mothers, who were in their 20s, were very different.

One mother delivered at 32 weeks and had a very severe COVID presentation and spent a month in the intensive care unit. The team decided to deliver the child to save the mother, Dr. Paidas said.

In contrast, the other mother had asymptomatic COVID infection in the second trimester and delivered at full term.

He said one of the early suspicions in the babies’ presentations was hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy. “But it wasn’t lack of blood flow to the placenta that caused this,” he said. “As best we can tell, it was the viral infection.”

Instances are rare

The researchers emphasized that these instances are rare and have not been seen before or since the period of this study to their knowledge.

Dr. Duara said, “This is something we want to alert the medical community to more than the general public. We do not want the lay public to be panicked. We’re trying to understand what made these two pregnancies different, so we can direct research towards protecting vulnerable babies.”

Previous data have indicated a relatively benign status in infants who test negative for the COVID virus after birth. Dr. Benny added that COVID vaccination has been found safe in pregnancy and both vaccination and breastfeeding can help passage of antibodies to the infant and help protect the baby. Because these cases happened in the early days of the pandemic, no vaccines were available.

Dr. Paidas received funding from BioIncept to study hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy with Preimplantation Factor, is a scientific advisory board member, and has stock options. Dr. Paidas and coauthor Dr. Jayakumar are coinventors of SPIKENET, University of Miami, patent pending 2023. The other authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

FROM PEDIATRICS

High-dose prophylactic anticoagulation benefits patients with COVID-19 pneumonia

High-dose prophylactic anticoagulation or therapeutic anticoagulation reduced de novo thrombosis in patients with hypoxemic COVID-19 pneumonia, based on data from 334 adults.

Patients with hypoxemic COVID-19 pneumonia are at increased risk of thrombosis and anticoagulation-related bleeding, therefore data to identify the lowest effective anticoagulant dose are needed, wrote Vincent Labbé, MD, of Sorbonne University, Paris, and colleagues.

Previous studies of different anticoagulation strategies for noncritically ill and critically ill patients with COVID-19 pneumonia have shown contrasting results, but some institutions recommend a high-dose regimen in the wake of data showing macrovascular thrombosis in patients with COVID-19 who were treated with standard anticoagulation, the authors wrote.

However, no previously published studies have compared the effectiveness of the three anticoagulation strategies: high-dose prophylactic anticoagulation (HD-PA), standard dose prophylactic anticoagulation (SD-PA), and therapeutic anticoagulation (TA), they said.

In the open-label Anticoagulation COVID-19 (ANTICOVID) trial, published in JAMA Internal Medicine, the researchers identified consecutively hospitalized adults aged 18 years and older being treated for hypoxemic COVID-19 pneumonia in 23 centers in France between April 2021 and December 2021.

The patients were randomly assigned to SD-PA (116 patients), HD-PA (111 patients), and TA (112 patients) using low-molecular-weight heparin for 14 days, or until either hospital discharge or weaning from supplemental oxygen for 48 consecutive hours, whichever outcome occurred first. The HD-PA patients received two times the SD-PA dose. The mean age of the patients was 58.3 years, and approximately two-thirds were men; race and ethnicity data were not collected. Participants had no macrovascular thrombosis at the start of the study.

The primary outcomes were all-cause mortality and time to clinical improvement (defined as the time from randomization to a 2-point improvement on a 7-category respiratory function scale).

The secondary outcome was a combination of safety and efficacy at day 28 that included a composite of thrombosis (ischemic stroke, noncerebrovascular arterial thrombosis, deep venous thrombosis, pulmonary artery thrombosis, and central venous catheter–related deep venous thrombosis), major bleeding, or all-cause death.

For the primary outcome, results were similar among the groups; HD-PA had no significant benefit over SD-PA or TA. All-cause death rates for SD-PA, HD-PA, and TA patients were 14%, 12%, and 13%, respectively. The time to clinical improvement for the three groups was approximately 8 days, 9 days, and 8 days, respectively. Results for the primary outcome were consistent across all prespecified subgroups.

However, HD-PA was associated with a significant fourfold reduced risk of de novo thrombosis compared with SD-PA (5.5% vs. 20.2%) with no observed increase in major bleeding. TA was not associated with any significant improvement in primary or secondary outcomes compared with HD-PA or SD-PA.

The current study findings of no improvement in survival or disease resolution in patients with a higher anticoagulant dose reflects data from previous studies, the researchers wrote in their discussion. “Our study results together with those of previous RCTs support the premise that the role of microvascular thrombosis in worsening organ dysfunction may be narrower than estimated,” they said.

The findings were limited by several factors including the open-label design and the relatively small sample size, the lack of data on microvascular (vs. macrovascular) thrombosis at baseline, and the predominance of the Delta variant of COVID-19 among the study participants, which may have contributed to a lower mortality rate, the researchers noted.

However, given the significant reduction in de novo thrombosis, the results support the routine use of HD-PA in patients with severe hypoxemic COVID-19 pneumonia, they concluded.

Results inform current clinical practice

Over the course of the COVID-19 pandemic, “Patients hospitalized with COVID-19 manifested the highest risk for thromboembolic complications, especially patients in the intensive care setting,” and early reports suggested that standard prophylactic doses of anticoagulant therapy might be insufficient to prevent thrombotic events, Richard C. Becker, MD, of the University of Cincinnati, and Thomas L. Ortel, MD, of Duke University, Durham, N.C., wrote in an accompanying editorial.

“Although there have been several studies that have investigated the role of anticoagulant therapy in hospitalized patients with COVID-19, this is the first study that specifically compared a standard, prophylactic dose of low-molecular-weight heparin to a ‘high-dose’ prophylactic regimen and to a full therapeutic dose regimen,” Dr. Ortel said in an interview.

“Given the concerns about an increased thrombotic risk with prophylactic dose anticoagulation, and the potential bleeding risk associated with a full therapeutic dose of anticoagulation, this approach enabled the investigators to explore the efficacy and safety of an intermediate dose between these two extremes,” he said.

In the current study, , a finding that was not observed in other studies investigating anticoagulant therapy in hospitalized patients with severe COVID-19,” Dr. Ortel told this news organization. “Much initial concern about progression of disease in patients hospitalized with severe COVID-19 focused on the role of microvascular thrombosis, which appears to be less important in this process, or, alternatively, less responsive to anticoagulant therapy.”

The clinical takeaway from the study, Dr. Ortel said, is the decreased risk for venous thromboembolism with a high-dose prophylactic anticoagulation strategy compared with a standard-dose prophylactic regimen for patients hospitalized with hypoxemic COVID-19 pneumonia, “leading to an improved net clinical outcome.”

Looking ahead, “Additional research is needed to determine whether a higher dose of prophylactic anticoagulation would be beneficial for patients hospitalized with COVID-19 pneumonia who are not in an intensive care unit setting,” Dr. Ortel said. Studies are needed to determine whether therapeutic interventions are equally beneficial in patients with different coronavirus variants, since most patients in the current study were infected with the Delta variant, he added.

The study was supported by LEO Pharma. Dr. Labbé disclosed grants from LEO Pharma during the study and fees from AOP Health unrelated to the current study.

Dr. Becker disclosed personal fees from Novartis Data Safety Monitoring Board, Ionis Data Safety Monitoring Board, and Basking Biosciences Scientific Advisory Board unrelated to the current study. Dr. Ortel disclosed grants from the National Institutes of Health, Instrumentation Laboratory, Stago, and Siemens; contract fees from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; and honoraria from UpToDate unrelated to the current study.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

High-dose prophylactic anticoagulation or therapeutic anticoagulation reduced de novo thrombosis in patients with hypoxemic COVID-19 pneumonia, based on data from 334 adults.

Patients with hypoxemic COVID-19 pneumonia are at increased risk of thrombosis and anticoagulation-related bleeding, therefore data to identify the lowest effective anticoagulant dose are needed, wrote Vincent Labbé, MD, of Sorbonne University, Paris, and colleagues.

Previous studies of different anticoagulation strategies for noncritically ill and critically ill patients with COVID-19 pneumonia have shown contrasting results, but some institutions recommend a high-dose regimen in the wake of data showing macrovascular thrombosis in patients with COVID-19 who were treated with standard anticoagulation, the authors wrote.

However, no previously published studies have compared the effectiveness of the three anticoagulation strategies: high-dose prophylactic anticoagulation (HD-PA), standard dose prophylactic anticoagulation (SD-PA), and therapeutic anticoagulation (TA), they said.

In the open-label Anticoagulation COVID-19 (ANTICOVID) trial, published in JAMA Internal Medicine, the researchers identified consecutively hospitalized adults aged 18 years and older being treated for hypoxemic COVID-19 pneumonia in 23 centers in France between April 2021 and December 2021.

The patients were randomly assigned to SD-PA (116 patients), HD-PA (111 patients), and TA (112 patients) using low-molecular-weight heparin for 14 days, or until either hospital discharge or weaning from supplemental oxygen for 48 consecutive hours, whichever outcome occurred first. The HD-PA patients received two times the SD-PA dose. The mean age of the patients was 58.3 years, and approximately two-thirds were men; race and ethnicity data were not collected. Participants had no macrovascular thrombosis at the start of the study.

The primary outcomes were all-cause mortality and time to clinical improvement (defined as the time from randomization to a 2-point improvement on a 7-category respiratory function scale).

The secondary outcome was a combination of safety and efficacy at day 28 that included a composite of thrombosis (ischemic stroke, noncerebrovascular arterial thrombosis, deep venous thrombosis, pulmonary artery thrombosis, and central venous catheter–related deep venous thrombosis), major bleeding, or all-cause death.

For the primary outcome, results were similar among the groups; HD-PA had no significant benefit over SD-PA or TA. All-cause death rates for SD-PA, HD-PA, and TA patients were 14%, 12%, and 13%, respectively. The time to clinical improvement for the three groups was approximately 8 days, 9 days, and 8 days, respectively. Results for the primary outcome were consistent across all prespecified subgroups.

However, HD-PA was associated with a significant fourfold reduced risk of de novo thrombosis compared with SD-PA (5.5% vs. 20.2%) with no observed increase in major bleeding. TA was not associated with any significant improvement in primary or secondary outcomes compared with HD-PA or SD-PA.

The current study findings of no improvement in survival or disease resolution in patients with a higher anticoagulant dose reflects data from previous studies, the researchers wrote in their discussion. “Our study results together with those of previous RCTs support the premise that the role of microvascular thrombosis in worsening organ dysfunction may be narrower than estimated,” they said.

The findings were limited by several factors including the open-label design and the relatively small sample size, the lack of data on microvascular (vs. macrovascular) thrombosis at baseline, and the predominance of the Delta variant of COVID-19 among the study participants, which may have contributed to a lower mortality rate, the researchers noted.

However, given the significant reduction in de novo thrombosis, the results support the routine use of HD-PA in patients with severe hypoxemic COVID-19 pneumonia, they concluded.

Results inform current clinical practice

Over the course of the COVID-19 pandemic, “Patients hospitalized with COVID-19 manifested the highest risk for thromboembolic complications, especially patients in the intensive care setting,” and early reports suggested that standard prophylactic doses of anticoagulant therapy might be insufficient to prevent thrombotic events, Richard C. Becker, MD, of the University of Cincinnati, and Thomas L. Ortel, MD, of Duke University, Durham, N.C., wrote in an accompanying editorial.

“Although there have been several studies that have investigated the role of anticoagulant therapy in hospitalized patients with COVID-19, this is the first study that specifically compared a standard, prophylactic dose of low-molecular-weight heparin to a ‘high-dose’ prophylactic regimen and to a full therapeutic dose regimen,” Dr. Ortel said in an interview.

“Given the concerns about an increased thrombotic risk with prophylactic dose anticoagulation, and the potential bleeding risk associated with a full therapeutic dose of anticoagulation, this approach enabled the investigators to explore the efficacy and safety of an intermediate dose between these two extremes,” he said.

In the current study, , a finding that was not observed in other studies investigating anticoagulant therapy in hospitalized patients with severe COVID-19,” Dr. Ortel told this news organization. “Much initial concern about progression of disease in patients hospitalized with severe COVID-19 focused on the role of microvascular thrombosis, which appears to be less important in this process, or, alternatively, less responsive to anticoagulant therapy.”

The clinical takeaway from the study, Dr. Ortel said, is the decreased risk for venous thromboembolism with a high-dose prophylactic anticoagulation strategy compared with a standard-dose prophylactic regimen for patients hospitalized with hypoxemic COVID-19 pneumonia, “leading to an improved net clinical outcome.”

Looking ahead, “Additional research is needed to determine whether a higher dose of prophylactic anticoagulation would be beneficial for patients hospitalized with COVID-19 pneumonia who are not in an intensive care unit setting,” Dr. Ortel said. Studies are needed to determine whether therapeutic interventions are equally beneficial in patients with different coronavirus variants, since most patients in the current study were infected with the Delta variant, he added.

The study was supported by LEO Pharma. Dr. Labbé disclosed grants from LEO Pharma during the study and fees from AOP Health unrelated to the current study.

Dr. Becker disclosed personal fees from Novartis Data Safety Monitoring Board, Ionis Data Safety Monitoring Board, and Basking Biosciences Scientific Advisory Board unrelated to the current study. Dr. Ortel disclosed grants from the National Institutes of Health, Instrumentation Laboratory, Stago, and Siemens; contract fees from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; and honoraria from UpToDate unrelated to the current study.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

High-dose prophylactic anticoagulation or therapeutic anticoagulation reduced de novo thrombosis in patients with hypoxemic COVID-19 pneumonia, based on data from 334 adults.

Patients with hypoxemic COVID-19 pneumonia are at increased risk of thrombosis and anticoagulation-related bleeding, therefore data to identify the lowest effective anticoagulant dose are needed, wrote Vincent Labbé, MD, of Sorbonne University, Paris, and colleagues.

Previous studies of different anticoagulation strategies for noncritically ill and critically ill patients with COVID-19 pneumonia have shown contrasting results, but some institutions recommend a high-dose regimen in the wake of data showing macrovascular thrombosis in patients with COVID-19 who were treated with standard anticoagulation, the authors wrote.

However, no previously published studies have compared the effectiveness of the three anticoagulation strategies: high-dose prophylactic anticoagulation (HD-PA), standard dose prophylactic anticoagulation (SD-PA), and therapeutic anticoagulation (TA), they said.

In the open-label Anticoagulation COVID-19 (ANTICOVID) trial, published in JAMA Internal Medicine, the researchers identified consecutively hospitalized adults aged 18 years and older being treated for hypoxemic COVID-19 pneumonia in 23 centers in France between April 2021 and December 2021.

The patients were randomly assigned to SD-PA (116 patients), HD-PA (111 patients), and TA (112 patients) using low-molecular-weight heparin for 14 days, or until either hospital discharge or weaning from supplemental oxygen for 48 consecutive hours, whichever outcome occurred first. The HD-PA patients received two times the SD-PA dose. The mean age of the patients was 58.3 years, and approximately two-thirds were men; race and ethnicity data were not collected. Participants had no macrovascular thrombosis at the start of the study.

The primary outcomes were all-cause mortality and time to clinical improvement (defined as the time from randomization to a 2-point improvement on a 7-category respiratory function scale).

The secondary outcome was a combination of safety and efficacy at day 28 that included a composite of thrombosis (ischemic stroke, noncerebrovascular arterial thrombosis, deep venous thrombosis, pulmonary artery thrombosis, and central venous catheter–related deep venous thrombosis), major bleeding, or all-cause death.

For the primary outcome, results were similar among the groups; HD-PA had no significant benefit over SD-PA or TA. All-cause death rates for SD-PA, HD-PA, and TA patients were 14%, 12%, and 13%, respectively. The time to clinical improvement for the three groups was approximately 8 days, 9 days, and 8 days, respectively. Results for the primary outcome were consistent across all prespecified subgroups.

However, HD-PA was associated with a significant fourfold reduced risk of de novo thrombosis compared with SD-PA (5.5% vs. 20.2%) with no observed increase in major bleeding. TA was not associated with any significant improvement in primary or secondary outcomes compared with HD-PA or SD-PA.

The current study findings of no improvement in survival or disease resolution in patients with a higher anticoagulant dose reflects data from previous studies, the researchers wrote in their discussion. “Our study results together with those of previous RCTs support the premise that the role of microvascular thrombosis in worsening organ dysfunction may be narrower than estimated,” they said.

The findings were limited by several factors including the open-label design and the relatively small sample size, the lack of data on microvascular (vs. macrovascular) thrombosis at baseline, and the predominance of the Delta variant of COVID-19 among the study participants, which may have contributed to a lower mortality rate, the researchers noted.

However, given the significant reduction in de novo thrombosis, the results support the routine use of HD-PA in patients with severe hypoxemic COVID-19 pneumonia, they concluded.

Results inform current clinical practice

Over the course of the COVID-19 pandemic, “Patients hospitalized with COVID-19 manifested the highest risk for thromboembolic complications, especially patients in the intensive care setting,” and early reports suggested that standard prophylactic doses of anticoagulant therapy might be insufficient to prevent thrombotic events, Richard C. Becker, MD, of the University of Cincinnati, and Thomas L. Ortel, MD, of Duke University, Durham, N.C., wrote in an accompanying editorial.

“Although there have been several studies that have investigated the role of anticoagulant therapy in hospitalized patients with COVID-19, this is the first study that specifically compared a standard, prophylactic dose of low-molecular-weight heparin to a ‘high-dose’ prophylactic regimen and to a full therapeutic dose regimen,” Dr. Ortel said in an interview.

“Given the concerns about an increased thrombotic risk with prophylactic dose anticoagulation, and the potential bleeding risk associated with a full therapeutic dose of anticoagulation, this approach enabled the investigators to explore the efficacy and safety of an intermediate dose between these two extremes,” he said.

In the current study, , a finding that was not observed in other studies investigating anticoagulant therapy in hospitalized patients with severe COVID-19,” Dr. Ortel told this news organization. “Much initial concern about progression of disease in patients hospitalized with severe COVID-19 focused on the role of microvascular thrombosis, which appears to be less important in this process, or, alternatively, less responsive to anticoagulant therapy.”

The clinical takeaway from the study, Dr. Ortel said, is the decreased risk for venous thromboembolism with a high-dose prophylactic anticoagulation strategy compared with a standard-dose prophylactic regimen for patients hospitalized with hypoxemic COVID-19 pneumonia, “leading to an improved net clinical outcome.”

Looking ahead, “Additional research is needed to determine whether a higher dose of prophylactic anticoagulation would be beneficial for patients hospitalized with COVID-19 pneumonia who are not in an intensive care unit setting,” Dr. Ortel said. Studies are needed to determine whether therapeutic interventions are equally beneficial in patients with different coronavirus variants, since most patients in the current study were infected with the Delta variant, he added.

The study was supported by LEO Pharma. Dr. Labbé disclosed grants from LEO Pharma during the study and fees from AOP Health unrelated to the current study.

Dr. Becker disclosed personal fees from Novartis Data Safety Monitoring Board, Ionis Data Safety Monitoring Board, and Basking Biosciences Scientific Advisory Board unrelated to the current study. Dr. Ortel disclosed grants from the National Institutes of Health, Instrumentation Laboratory, Stago, and Siemens; contract fees from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; and honoraria from UpToDate unrelated to the current study.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

COVID led to rise in pregnancy-related deaths: New research

The rise in deaths was most pronounced among Black mothers.

In 2021, 1,205 women died from pregnancy-related causes, making the year one of the worst for maternal mortality in U.S. history, according to newly released data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Maternal mortality is defined as occurring during pregnancy, at delivery, or soon after delivery.

COVID was the driver of the increased death rate, according to a study published in the journal Obstetrics & Gynecology. The researchers noted that unvaccinated pregnant people are more likely to get severe COVID, and that prenatal and postnatal care were disrupted during the early part of the pandemic. From July 2021 to March 2023, the rate of women being vaccinated before pregnancy has risen from 22% to 70%, CDC data show.

Maternal mortality rates jumped the most among Black women, who in 2021 had a maternal mortality rate of nearly 70 deaths per 100,000 live births, which was 2.6 times the rate for White women.

Existing risks based on a mother’s age also increased from 2020 to 2021. The maternal mortality rates by age in 2021 per 100,000 live births were:

- 20.4 for women under age 25.

- 31.3 for women ages 25 to 39.

- 138.5 for women ages 40 and older.

Iffath Abbasi Hoskins, MD, FACOG, president of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, called the situation “stunning” and “preventable.”

The findings “send a resounding message that maternal health and evidence-based efforts to eliminate racial health inequities need to be, and remain, a top public health priority,” Dr. Hoskins said in a statement.

“The COVID-19 pandemic had a dramatic and tragic effect on maternal death rates, but we cannot let that fact obscure that there was – and still is – already a maternal mortality crisis to compound,” she said.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

The rise in deaths was most pronounced among Black mothers.

In 2021, 1,205 women died from pregnancy-related causes, making the year one of the worst for maternal mortality in U.S. history, according to newly released data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Maternal mortality is defined as occurring during pregnancy, at delivery, or soon after delivery.

COVID was the driver of the increased death rate, according to a study published in the journal Obstetrics & Gynecology. The researchers noted that unvaccinated pregnant people are more likely to get severe COVID, and that prenatal and postnatal care were disrupted during the early part of the pandemic. From July 2021 to March 2023, the rate of women being vaccinated before pregnancy has risen from 22% to 70%, CDC data show.

Maternal mortality rates jumped the most among Black women, who in 2021 had a maternal mortality rate of nearly 70 deaths per 100,000 live births, which was 2.6 times the rate for White women.

Existing risks based on a mother’s age also increased from 2020 to 2021. The maternal mortality rates by age in 2021 per 100,000 live births were:

- 20.4 for women under age 25.

- 31.3 for women ages 25 to 39.

- 138.5 for women ages 40 and older.

Iffath Abbasi Hoskins, MD, FACOG, president of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, called the situation “stunning” and “preventable.”

The findings “send a resounding message that maternal health and evidence-based efforts to eliminate racial health inequities need to be, and remain, a top public health priority,” Dr. Hoskins said in a statement.

“The COVID-19 pandemic had a dramatic and tragic effect on maternal death rates, but we cannot let that fact obscure that there was – and still is – already a maternal mortality crisis to compound,” she said.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

The rise in deaths was most pronounced among Black mothers.

In 2021, 1,205 women died from pregnancy-related causes, making the year one of the worst for maternal mortality in U.S. history, according to newly released data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Maternal mortality is defined as occurring during pregnancy, at delivery, or soon after delivery.

COVID was the driver of the increased death rate, according to a study published in the journal Obstetrics & Gynecology. The researchers noted that unvaccinated pregnant people are more likely to get severe COVID, and that prenatal and postnatal care were disrupted during the early part of the pandemic. From July 2021 to March 2023, the rate of women being vaccinated before pregnancy has risen from 22% to 70%, CDC data show.

Maternal mortality rates jumped the most among Black women, who in 2021 had a maternal mortality rate of nearly 70 deaths per 100,000 live births, which was 2.6 times the rate for White women.

Existing risks based on a mother’s age also increased from 2020 to 2021. The maternal mortality rates by age in 2021 per 100,000 live births were:

- 20.4 for women under age 25.

- 31.3 for women ages 25 to 39.

- 138.5 for women ages 40 and older.

Iffath Abbasi Hoskins, MD, FACOG, president of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, called the situation “stunning” and “preventable.”

The findings “send a resounding message that maternal health and evidence-based efforts to eliminate racial health inequities need to be, and remain, a top public health priority,” Dr. Hoskins said in a statement.

“The COVID-19 pandemic had a dramatic and tragic effect on maternal death rates, but we cannot let that fact obscure that there was – and still is – already a maternal mortality crisis to compound,” she said.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

COVID can mimic prostate cancer symptoms

This patient has a strong likelihood of aggressive prostate cancer, right? If that same patient also presents with severe, burning bone pain with no precipitating trauma to the area and rest and over-the-counter painkillers are not helping, you’d think, “check for metastases,” right?

That patient was me in late January 2023.

As a research scientist member of the American Urological Association, I knew enough to know I had to consult my urologist ASAP.

With the above symptoms, I’ll admit I was scared. Fortunately, if that’s the right word, I was no stranger to a rapid, dramatic spike in PSA. In 2021 I was temporarily living in a new city, and I wanted to form a relationship with a good local urologist. The urologist that I was referred to gave me a thorough consultation, including a vigorous digital rectal exam (DRE) and sent me across the street for a blood draw.

To my shock, my PSA had spiked over 2 points, to 9.9 from 7.8 a few months earlier. I freaked. Had my 3-cm tumor burst out into an aggressive cancer? Research on PubMed provided an array of studies showing what could cause PSA to suddenly rise, including a DRE performed 72 hours before the blood draw.1 A week later, my PSA was back down to its normal 7.6.

But in January 2023, I had none of those previously reported experiences that could suddenly trigger a spike in PSA, like a DRE or riding on a thin bicycle seat for a few hours before the lab visit.

The COVID effect

I went back to PubMed and found a new circumstance that could cause a surge in PSA: COVID-19. A recent study2 of 91 men with benign prostatic hypertrophy by researchers in Turkey found that PSA spiked from 0 to 5 points during the COVID infection period and up to 2 points higher 3 months after the infection had cleared. I had tested positive for COVID-19 in mid-December 2022, 4 weeks before my 9.9 PSA reading.

Using Google translate, I communicated with the team in Turkey and found out that the PSA spike can last up to 6 months.

That study helps explain why my PSA dropped over 1.5 points to 8.5 just 2 weeks after the 9.9 reading, with the expectation that it would return to its previous normal of 7.8 within 6 months of infection with SARS-CoV-2. To be safe, my urologist scheduled another PSA test in May, along with an updated multiparametric MRI, which may be followed by an in-bore MRI-guided biopsy of the 3-cm tumor if the mass has enlarged.

COVID-19 pain

What about my burning bone pain in my upper right humerus and right rotator cuff that was not precipitated by trauma or strain? A radiograph found no evidence of metastasis, thank goodness. And my research showed that several studies3 have found that COVID-19 can cause burning musculoskeletal pain, including enthesopathy, which is what I had per the radiology report. So my PSA spike and searing pain were likely consequences of the infection.

To avoid the risk for a gross misdiagnosis after a radical spike in PSA, the informed urologist should ask the patient if he has had COVID-19 in the previous 6 months. Overlooking that question could lead to the wrong diagnostic decisions about a rapid jump in PSA or unexplained bone pain.

References

1. Bossens MM et al. Eur J Cancer. 1995;31A:682-5.

2. Cinislioglu AE et al. Urology. 2022;159:16-21.

3. Ciaffi J et al. Joint Bone Spine. 2021;88:105158.

Dr. Keller is founder of the Keller Research Institute, Jacksonville, Fla. He reported serving as a research scientist for the American Urological Association, serving on the advisory board of Active Surveillance Patient’s International, and serving on the boards of numerous nonprofit organizations.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

This patient has a strong likelihood of aggressive prostate cancer, right? If that same patient also presents with severe, burning bone pain with no precipitating trauma to the area and rest and over-the-counter painkillers are not helping, you’d think, “check for metastases,” right?

That patient was me in late January 2023.

As a research scientist member of the American Urological Association, I knew enough to know I had to consult my urologist ASAP.

With the above symptoms, I’ll admit I was scared. Fortunately, if that’s the right word, I was no stranger to a rapid, dramatic spike in PSA. In 2021 I was temporarily living in a new city, and I wanted to form a relationship with a good local urologist. The urologist that I was referred to gave me a thorough consultation, including a vigorous digital rectal exam (DRE) and sent me across the street for a blood draw.

To my shock, my PSA had spiked over 2 points, to 9.9 from 7.8 a few months earlier. I freaked. Had my 3-cm tumor burst out into an aggressive cancer? Research on PubMed provided an array of studies showing what could cause PSA to suddenly rise, including a DRE performed 72 hours before the blood draw.1 A week later, my PSA was back down to its normal 7.6.

But in January 2023, I had none of those previously reported experiences that could suddenly trigger a spike in PSA, like a DRE or riding on a thin bicycle seat for a few hours before the lab visit.

The COVID effect

I went back to PubMed and found a new circumstance that could cause a surge in PSA: COVID-19. A recent study2 of 91 men with benign prostatic hypertrophy by researchers in Turkey found that PSA spiked from 0 to 5 points during the COVID infection period and up to 2 points higher 3 months after the infection had cleared. I had tested positive for COVID-19 in mid-December 2022, 4 weeks before my 9.9 PSA reading.

Using Google translate, I communicated with the team in Turkey and found out that the PSA spike can last up to 6 months.

That study helps explain why my PSA dropped over 1.5 points to 8.5 just 2 weeks after the 9.9 reading, with the expectation that it would return to its previous normal of 7.8 within 6 months of infection with SARS-CoV-2. To be safe, my urologist scheduled another PSA test in May, along with an updated multiparametric MRI, which may be followed by an in-bore MRI-guided biopsy of the 3-cm tumor if the mass has enlarged.

COVID-19 pain

What about my burning bone pain in my upper right humerus and right rotator cuff that was not precipitated by trauma or strain? A radiograph found no evidence of metastasis, thank goodness. And my research showed that several studies3 have found that COVID-19 can cause burning musculoskeletal pain, including enthesopathy, which is what I had per the radiology report. So my PSA spike and searing pain were likely consequences of the infection.

To avoid the risk for a gross misdiagnosis after a radical spike in PSA, the informed urologist should ask the patient if he has had COVID-19 in the previous 6 months. Overlooking that question could lead to the wrong diagnostic decisions about a rapid jump in PSA or unexplained bone pain.

References

1. Bossens MM et al. Eur J Cancer. 1995;31A:682-5.

2. Cinislioglu AE et al. Urology. 2022;159:16-21.

3. Ciaffi J et al. Joint Bone Spine. 2021;88:105158.

Dr. Keller is founder of the Keller Research Institute, Jacksonville, Fla. He reported serving as a research scientist for the American Urological Association, serving on the advisory board of Active Surveillance Patient’s International, and serving on the boards of numerous nonprofit organizations.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

This patient has a strong likelihood of aggressive prostate cancer, right? If that same patient also presents with severe, burning bone pain with no precipitating trauma to the area and rest and over-the-counter painkillers are not helping, you’d think, “check for metastases,” right?

That patient was me in late January 2023.

As a research scientist member of the American Urological Association, I knew enough to know I had to consult my urologist ASAP.

With the above symptoms, I’ll admit I was scared. Fortunately, if that’s the right word, I was no stranger to a rapid, dramatic spike in PSA. In 2021 I was temporarily living in a new city, and I wanted to form a relationship with a good local urologist. The urologist that I was referred to gave me a thorough consultation, including a vigorous digital rectal exam (DRE) and sent me across the street for a blood draw.

To my shock, my PSA had spiked over 2 points, to 9.9 from 7.8 a few months earlier. I freaked. Had my 3-cm tumor burst out into an aggressive cancer? Research on PubMed provided an array of studies showing what could cause PSA to suddenly rise, including a DRE performed 72 hours before the blood draw.1 A week later, my PSA was back down to its normal 7.6.

But in January 2023, I had none of those previously reported experiences that could suddenly trigger a spike in PSA, like a DRE or riding on a thin bicycle seat for a few hours before the lab visit.

The COVID effect

I went back to PubMed and found a new circumstance that could cause a surge in PSA: COVID-19. A recent study2 of 91 men with benign prostatic hypertrophy by researchers in Turkey found that PSA spiked from 0 to 5 points during the COVID infection period and up to 2 points higher 3 months after the infection had cleared. I had tested positive for COVID-19 in mid-December 2022, 4 weeks before my 9.9 PSA reading.

Using Google translate, I communicated with the team in Turkey and found out that the PSA spike can last up to 6 months.

That study helps explain why my PSA dropped over 1.5 points to 8.5 just 2 weeks after the 9.9 reading, with the expectation that it would return to its previous normal of 7.8 within 6 months of infection with SARS-CoV-2. To be safe, my urologist scheduled another PSA test in May, along with an updated multiparametric MRI, which may be followed by an in-bore MRI-guided biopsy of the 3-cm tumor if the mass has enlarged.

COVID-19 pain

What about my burning bone pain in my upper right humerus and right rotator cuff that was not precipitated by trauma or strain? A radiograph found no evidence of metastasis, thank goodness. And my research showed that several studies3 have found that COVID-19 can cause burning musculoskeletal pain, including enthesopathy, which is what I had per the radiology report. So my PSA spike and searing pain were likely consequences of the infection.

To avoid the risk for a gross misdiagnosis after a radical spike in PSA, the informed urologist should ask the patient if he has had COVID-19 in the previous 6 months. Overlooking that question could lead to the wrong diagnostic decisions about a rapid jump in PSA or unexplained bone pain.

References

1. Bossens MM et al. Eur J Cancer. 1995;31A:682-5.

2. Cinislioglu AE et al. Urology. 2022;159:16-21.

3. Ciaffi J et al. Joint Bone Spine. 2021;88:105158.

Dr. Keller is founder of the Keller Research Institute, Jacksonville, Fla. He reported serving as a research scientist for the American Urological Association, serving on the advisory board of Active Surveillance Patient’s International, and serving on the boards of numerous nonprofit organizations.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

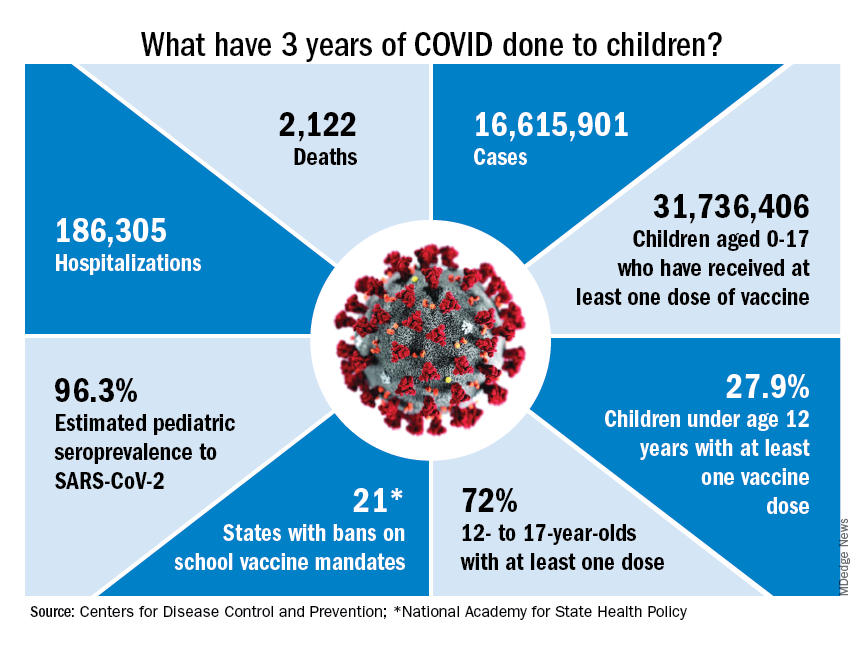

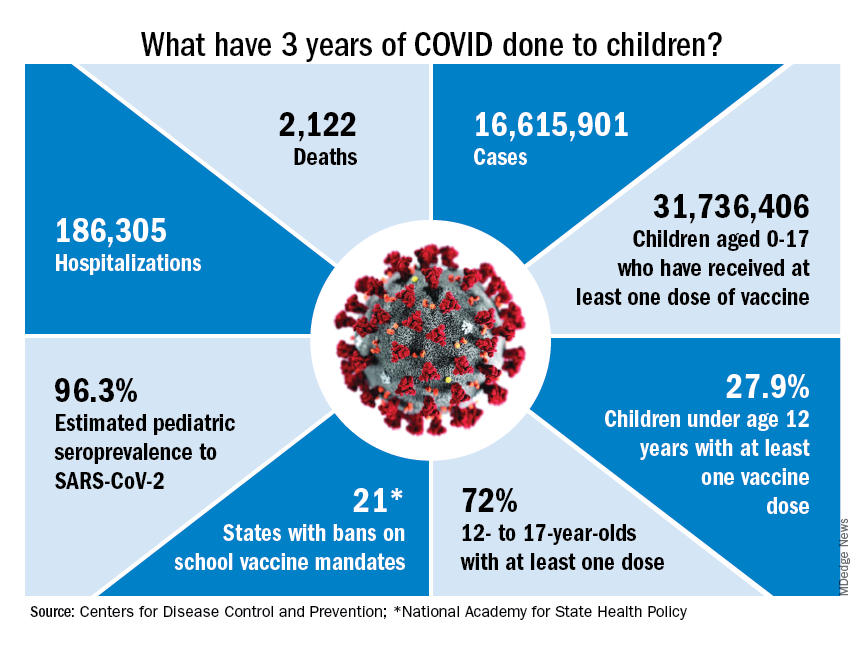

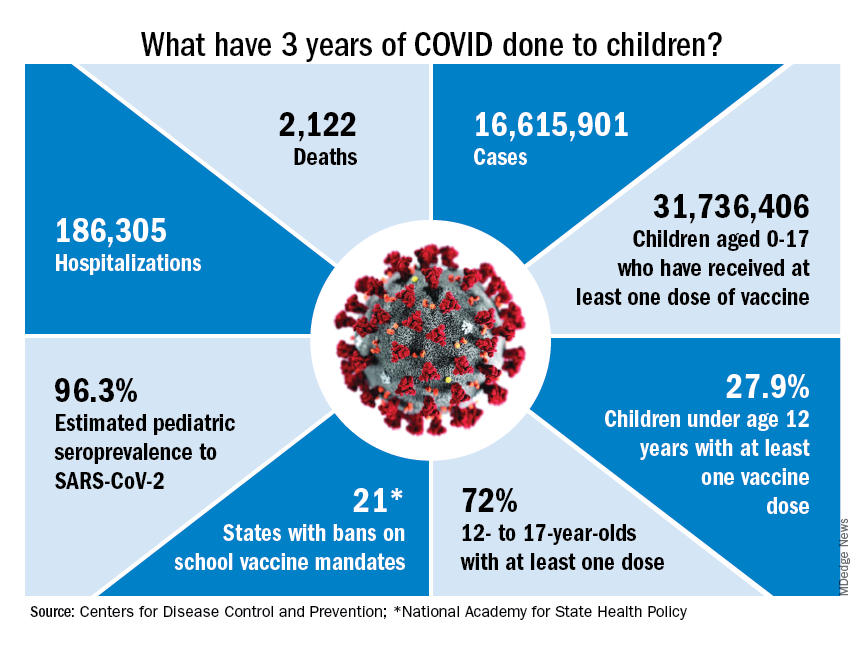

COVID-19 vaccinations lag in youngest children

Case: A 3-year-old girl presented to the emergency department after a brief seizure at home. She looked well on physical exam except for a fever of 103° F and thick rhinorrhea.

The intern on duty methodically worked through the standard list of questions. “Immunizations up to date?” she asked.

“Absolutely,” the child’s mom responded. “She’s had everything that’s recommended.”

“Including COVID-19 vaccine?” the intern prompted.

“No.” The mom responded with a shake of her head. “We don’t do that vaccine.”

That mom is not alone.

COVID-19 vaccines for children as young as 6 months were given emergency-use authorization by the Food and Drug Administration in June 2022 and in February 2023, the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices included COVID-19 vaccine on the routine childhood immunization schedule.

COVID-19 vaccines are safe in young children, and they prevent the most severe outcomes associated with infection, including hospitalization. Newly released data confirm that the COVID-19 vaccines produced by Moderna and Pfizer also provide protection against symptomatic infection for at least 4 months after completion of the monovalent primary series.

In a Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report released on Feb. 17, 2023, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported the results of a test-negative design case-control study that enrolled symptomatic children tested for SARS-CoV-2 infection through Feb. 5, 2023, as part of the Increasing Community Access to Testing (ICATT) program.1 ICATT provides SARS-CoV-2 testing to persons aged at least 3 years at pharmacy and community-based testing sites nationwide.

Two doses of monovalent Moderna vaccine (complete primary series) was 60% effective against symptomatic infection (95% confidence interval, 49%-68%) 2 weeks to 2 months after receipt of the second dose. Vaccine effectiveness dropped to 36% (95% CI, 15%-52%) 3-4 months after the second dose. Three doses of monovalent Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine (complete primary series) was 31% effective (95% CI, 7%-49%) at preventing symptomatic infection 2 weeks to 4 months after receipt of the third dose. A bivalent vaccine dose for eligible children is expected to provide more protection against currently circulating SARS-CoV-2 variants.

Despite evidence of vaccine efficacy, very few parents are opting to protect their young children with the COVID-19 vaccine. The CDC reports that, as of March 1, 2023, only 8% of children under 2 years and 10.5% of children aged 2-4 years have initiated a COVID vaccine series. The American Academy of Pediatrics has emphasized that 15.0 million children between the ages of 6 months and 4 years have not yet received their first COVID-19 vaccine dose.

While the reasons underlying low COVID-19 vaccination rates in young children are complex, themes emerge. Socioeconomic disparities contributing to low vaccination rates in young children were highlighted in another recent MMWR article.2 Through Dec. 1, 2022, vaccination coverage was lower in rural counties (3.4%) than in urban counties (10.5%). Rates were lower in Black and Hispanic children than in White and Asian children.

According to the CDC, high rates of poverty in Black and Hispanic communities may affect vaccination coverage by affecting caregivers’ access to vaccination sites or ability to leave work to take their child to be vaccinated. Pediatric care providers have repeatedly been identified by parents as a source of trusted vaccine information and a strong provider recommendation is associated with vaccination, but not all families are receiving vaccine advice. In a 2022 Kaiser Family Foundation survey, parents of young children with annual household incomes above $90,000 were more likely to talk to their pediatrician about a COVID-19 vaccine than families with lower incomes.3Vaccine hesitancy, fueled by general confusion and skepticism, is another factor contributing to low vaccination rates. Admittedly, the recommendations are complex and on March 14, 2023, the FDA again revised the emergency-use authorization for young children. Some caregivers continue to express concerns about vaccine side effects as well as the belief that the vaccine won’t prevent their child from getting sick.

Kendall Purcell, MD, a pediatrician with Norton Children’s Medical Group in Louisville, Ky., recommends COVID-19 vaccination for her patients because it reduces the risk of severe disease. That factored into her own decision to vaccinate her 4-year-old son and 1-year-old daughter, but she hasn’t been able to convince the parents of all her patients. “Some feel that COVID-19 is not as severe for children, so the risks don’t outweigh the benefits when it comes to vaccinating their children.” Back to our case: In the ED the intern reviewed the laboratory testing she had ordered. She then sat down with the mother of the 3-year-old girl to discuss the diagnosis: febrile seizure associated with COVID-19 infection. Febrile seizures are a well-recognized but uncommon complication of COVID-19 in children. In a retrospective cohort study using electronic health record data, febrile seizures occurred in 0.5% of 8,854 children aged 0-5 years with COVID-19 infection.4 About 9% of these children required critical care services. In another cohort of hospitalized children, neurologic complications occurred in 7% of children hospitalized with COVID-19.5 Febrile and nonfebrile seizures were most commonly observed.

“I really thought COVID-19 was no big deal in young kids,” the mom said. “Parents need the facts.”

The facts are these: Through Dec. 2, 2022, more than 3 million cases of COVID-19 have been reported in children aged younger than 5 years. While COVID is generally less severe in young children than older adults, it is difficult to predict which children will become seriously ill. When children are hospitalized, one in four requires intensive care. COVID-19 is now a vaccine-preventable disease, but too many children remain unprotected.

Dr. Bryant is a pediatrician specializing in infectious diseases at the University of Louisville (Ky.) and Norton Children’s Hospital, also in Louisville. She is a member of the AAP’s Committee on Infectious Diseases and one of the lead authors of the AAP’s Recommendations for Prevention and Control of Influenza in Children, 2022-2023. The opinions expressed in this article are her own. Dr. Bryant discloses that she has served as an investigator on clinical trials funded by Pfizer, Enanta, and Gilead. Email her at [email protected]. Ms. Ezell is a recent graduate from Indiana University Southeast with a Bachelor of Arts in English. They have no conflicts of interest.

References

1. Fleming-Dutra KE et al. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2023;72:177-182.

2. Murthy BP et al. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2023;72:183-9.

3. Lopes L et al. KFF COVID-19 vaccine monitor: July 2022. San Francisco: Kaiser Family Foundation, 2022.

4. Cadet K et al. J Child Neurol. 2022 Apr;37(5):410-5.

5. Antoon JW et al. Pediatrics. 2022 Nov 1;150(5):e2022058167.

Case: A 3-year-old girl presented to the emergency department after a brief seizure at home. She looked well on physical exam except for a fever of 103° F and thick rhinorrhea.

The intern on duty methodically worked through the standard list of questions. “Immunizations up to date?” she asked.

“Absolutely,” the child’s mom responded. “She’s had everything that’s recommended.”

“Including COVID-19 vaccine?” the intern prompted.

“No.” The mom responded with a shake of her head. “We don’t do that vaccine.”

That mom is not alone.

COVID-19 vaccines for children as young as 6 months were given emergency-use authorization by the Food and Drug Administration in June 2022 and in February 2023, the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices included COVID-19 vaccine on the routine childhood immunization schedule.

COVID-19 vaccines are safe in young children, and they prevent the most severe outcomes associated with infection, including hospitalization. Newly released data confirm that the COVID-19 vaccines produced by Moderna and Pfizer also provide protection against symptomatic infection for at least 4 months after completion of the monovalent primary series.

In a Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report released on Feb. 17, 2023, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported the results of a test-negative design case-control study that enrolled symptomatic children tested for SARS-CoV-2 infection through Feb. 5, 2023, as part of the Increasing Community Access to Testing (ICATT) program.1 ICATT provides SARS-CoV-2 testing to persons aged at least 3 years at pharmacy and community-based testing sites nationwide.

Two doses of monovalent Moderna vaccine (complete primary series) was 60% effective against symptomatic infection (95% confidence interval, 49%-68%) 2 weeks to 2 months after receipt of the second dose. Vaccine effectiveness dropped to 36% (95% CI, 15%-52%) 3-4 months after the second dose. Three doses of monovalent Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine (complete primary series) was 31% effective (95% CI, 7%-49%) at preventing symptomatic infection 2 weeks to 4 months after receipt of the third dose. A bivalent vaccine dose for eligible children is expected to provide more protection against currently circulating SARS-CoV-2 variants.

Despite evidence of vaccine efficacy, very few parents are opting to protect their young children with the COVID-19 vaccine. The CDC reports that, as of March 1, 2023, only 8% of children under 2 years and 10.5% of children aged 2-4 years have initiated a COVID vaccine series. The American Academy of Pediatrics has emphasized that 15.0 million children between the ages of 6 months and 4 years have not yet received their first COVID-19 vaccine dose.

While the reasons underlying low COVID-19 vaccination rates in young children are complex, themes emerge. Socioeconomic disparities contributing to low vaccination rates in young children were highlighted in another recent MMWR article.2 Through Dec. 1, 2022, vaccination coverage was lower in rural counties (3.4%) than in urban counties (10.5%). Rates were lower in Black and Hispanic children than in White and Asian children.

According to the CDC, high rates of poverty in Black and Hispanic communities may affect vaccination coverage by affecting caregivers’ access to vaccination sites or ability to leave work to take their child to be vaccinated. Pediatric care providers have repeatedly been identified by parents as a source of trusted vaccine information and a strong provider recommendation is associated with vaccination, but not all families are receiving vaccine advice. In a 2022 Kaiser Family Foundation survey, parents of young children with annual household incomes above $90,000 were more likely to talk to their pediatrician about a COVID-19 vaccine than families with lower incomes.3Vaccine hesitancy, fueled by general confusion and skepticism, is another factor contributing to low vaccination rates. Admittedly, the recommendations are complex and on March 14, 2023, the FDA again revised the emergency-use authorization for young children. Some caregivers continue to express concerns about vaccine side effects as well as the belief that the vaccine won’t prevent their child from getting sick.

Kendall Purcell, MD, a pediatrician with Norton Children’s Medical Group in Louisville, Ky., recommends COVID-19 vaccination for her patients because it reduces the risk of severe disease. That factored into her own decision to vaccinate her 4-year-old son and 1-year-old daughter, but she hasn’t been able to convince the parents of all her patients. “Some feel that COVID-19 is not as severe for children, so the risks don’t outweigh the benefits when it comes to vaccinating their children.” Back to our case: In the ED the intern reviewed the laboratory testing she had ordered. She then sat down with the mother of the 3-year-old girl to discuss the diagnosis: febrile seizure associated with COVID-19 infection. Febrile seizures are a well-recognized but uncommon complication of COVID-19 in children. In a retrospective cohort study using electronic health record data, febrile seizures occurred in 0.5% of 8,854 children aged 0-5 years with COVID-19 infection.4 About 9% of these children required critical care services. In another cohort of hospitalized children, neurologic complications occurred in 7% of children hospitalized with COVID-19.5 Febrile and nonfebrile seizures were most commonly observed.

“I really thought COVID-19 was no big deal in young kids,” the mom said. “Parents need the facts.”

The facts are these: Through Dec. 2, 2022, more than 3 million cases of COVID-19 have been reported in children aged younger than 5 years. While COVID is generally less severe in young children than older adults, it is difficult to predict which children will become seriously ill. When children are hospitalized, one in four requires intensive care. COVID-19 is now a vaccine-preventable disease, but too many children remain unprotected.

Dr. Bryant is a pediatrician specializing in infectious diseases at the University of Louisville (Ky.) and Norton Children’s Hospital, also in Louisville. She is a member of the AAP’s Committee on Infectious Diseases and one of the lead authors of the AAP’s Recommendations for Prevention and Control of Influenza in Children, 2022-2023. The opinions expressed in this article are her own. Dr. Bryant discloses that she has served as an investigator on clinical trials funded by Pfizer, Enanta, and Gilead. Email her at [email protected]. Ms. Ezell is a recent graduate from Indiana University Southeast with a Bachelor of Arts in English. They have no conflicts of interest.

References

1. Fleming-Dutra KE et al. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2023;72:177-182.

2. Murthy BP et al. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2023;72:183-9.

3. Lopes L et al. KFF COVID-19 vaccine monitor: July 2022. San Francisco: Kaiser Family Foundation, 2022.

4. Cadet K et al. J Child Neurol. 2022 Apr;37(5):410-5.

5. Antoon JW et al. Pediatrics. 2022 Nov 1;150(5):e2022058167.

Case: A 3-year-old girl presented to the emergency department after a brief seizure at home. She looked well on physical exam except for a fever of 103° F and thick rhinorrhea.

The intern on duty methodically worked through the standard list of questions. “Immunizations up to date?” she asked.

“Absolutely,” the child’s mom responded. “She’s had everything that’s recommended.”

“Including COVID-19 vaccine?” the intern prompted.

“No.” The mom responded with a shake of her head. “We don’t do that vaccine.”

That mom is not alone.

COVID-19 vaccines for children as young as 6 months were given emergency-use authorization by the Food and Drug Administration in June 2022 and in February 2023, the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices included COVID-19 vaccine on the routine childhood immunization schedule.

COVID-19 vaccines are safe in young children, and they prevent the most severe outcomes associated with infection, including hospitalization. Newly released data confirm that the COVID-19 vaccines produced by Moderna and Pfizer also provide protection against symptomatic infection for at least 4 months after completion of the monovalent primary series.

In a Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report released on Feb. 17, 2023, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported the results of a test-negative design case-control study that enrolled symptomatic children tested for SARS-CoV-2 infection through Feb. 5, 2023, as part of the Increasing Community Access to Testing (ICATT) program.1 ICATT provides SARS-CoV-2 testing to persons aged at least 3 years at pharmacy and community-based testing sites nationwide.

Two doses of monovalent Moderna vaccine (complete primary series) was 60% effective against symptomatic infection (95% confidence interval, 49%-68%) 2 weeks to 2 months after receipt of the second dose. Vaccine effectiveness dropped to 36% (95% CI, 15%-52%) 3-4 months after the second dose. Three doses of monovalent Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine (complete primary series) was 31% effective (95% CI, 7%-49%) at preventing symptomatic infection 2 weeks to 4 months after receipt of the third dose. A bivalent vaccine dose for eligible children is expected to provide more protection against currently circulating SARS-CoV-2 variants.

Despite evidence of vaccine efficacy, very few parents are opting to protect their young children with the COVID-19 vaccine. The CDC reports that, as of March 1, 2023, only 8% of children under 2 years and 10.5% of children aged 2-4 years have initiated a COVID vaccine series. The American Academy of Pediatrics has emphasized that 15.0 million children between the ages of 6 months and 4 years have not yet received their first COVID-19 vaccine dose.