User login

Hospitalists’ scope of services continues to evolve

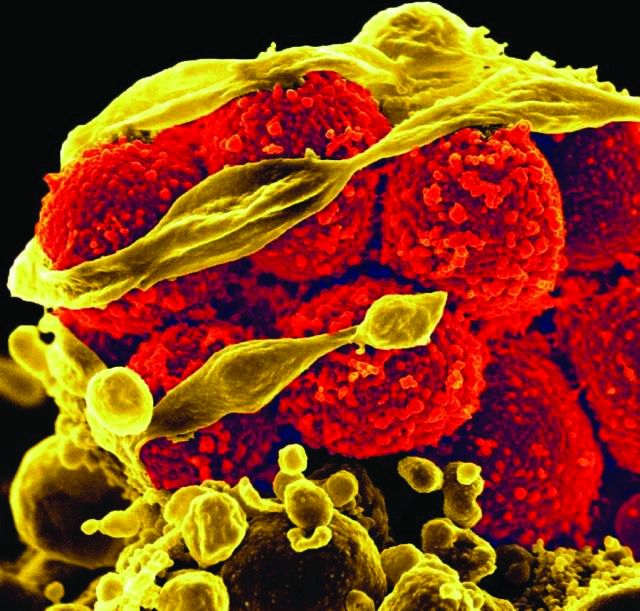

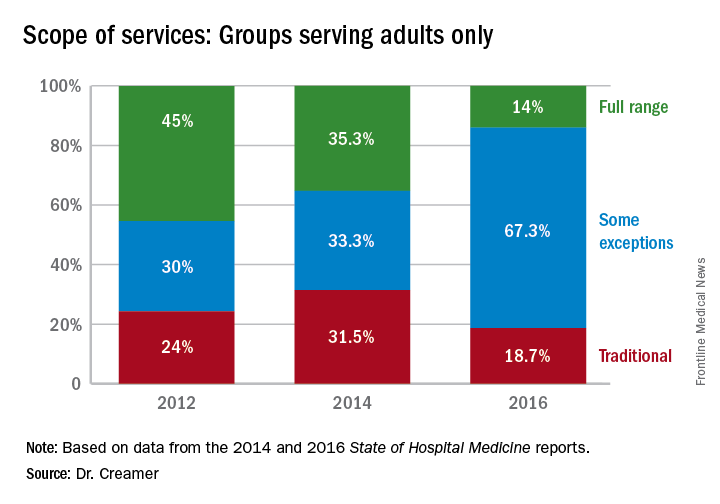

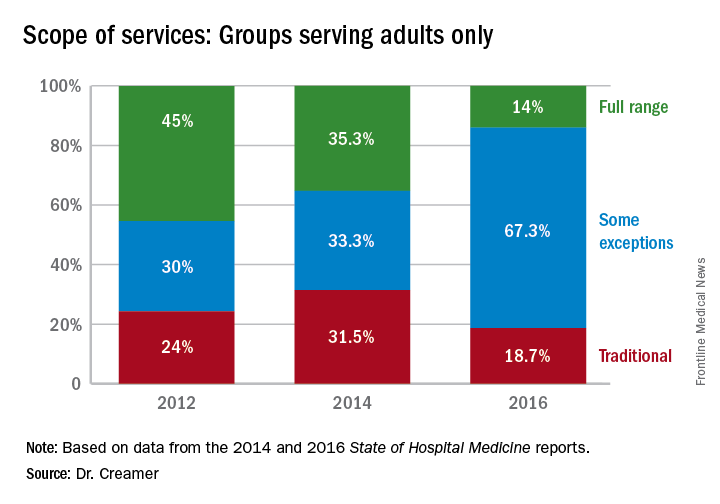

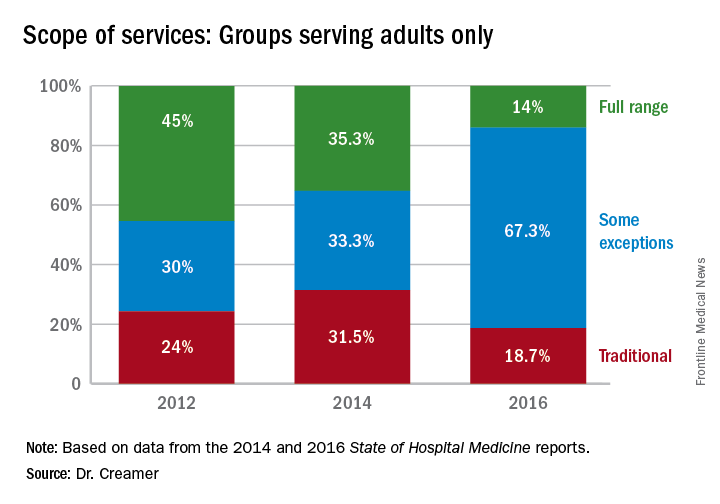

Over the course of serial iterations of the State of Hospital Medicine (SOHM) Report, SHM has presented survey data that describe the evolving role hospitalists play in patient care. The 2016 SOHM Report shows the continuation of prior trends in hospital medicine groups’ (HMGs) scope of admittance and comanagement services. Some downturns are notable among previously increased specialty services.

The SOHM Report characterizes HMGs by their general scope of admitted patients – as admitters of purely traditional internal medicine or pediatrics hospitalized patients; full-range, nearly universal admitters who admit most patients within their age designation except OB and emergency surgery patients; or traditional admitters with some exceptions (for example, limited classically surgical patients).

As adult and adult-ped HMGs make up almost 97% of survey respondents, the predominance of the “some exceptions” category seems to represent a serious trend in much of Hospital Medicine practice. This could mean that HMGs have worked out more specific arrangements as to which patients they will admit or that the definitions are more in flux. It comes at a time when concerns figure prominently in national discussions over the stretching of hospitalists by their expanding scope of care and the need for ever more coordinated care between hospitalists and specialists.

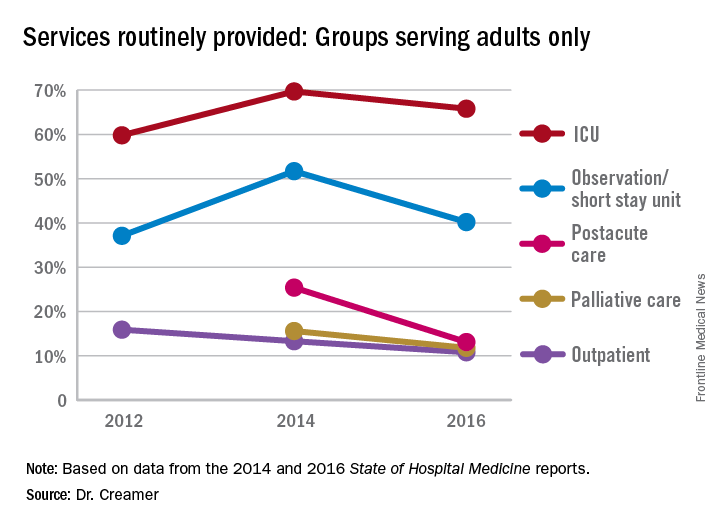

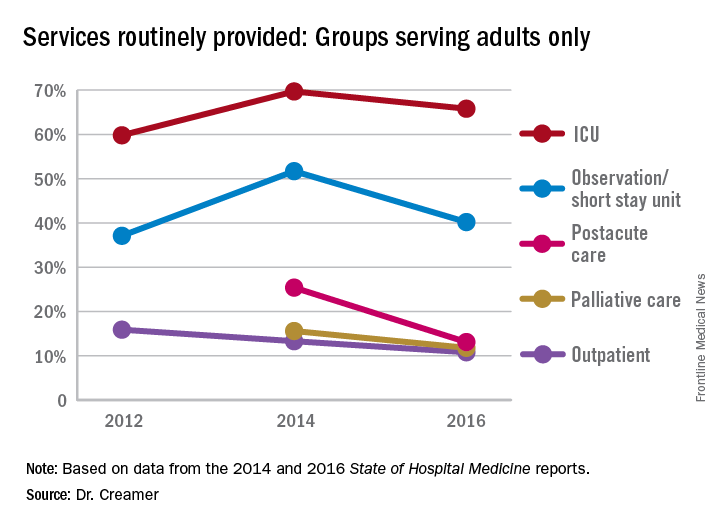

Again, with these opportunities, concerns have arisen about scope-creep and its potential deleterious effects on patient care. Hospitalists have been noted to be prodded into providing critical, geriatric, and palliative care, without specialty training in these areas.1 Interestingly, however, specialty work reported by HMGs has largely shown a downturn since 2014, when most specialty services had appeared to be on the rise.

Whether this means that there is relief from scope-creep or that it is “just a blip” will remain to be seen in future data. If HMGs are able to capture the opportunity to improve outcomes through greater involvement in postacute care, this particular area may be one to watch, despite its apparent downturn since the 2014 report.

Thus, it is as imperative as ever that HMGs participate in the State of Hospital Medicine survey.

Dr. Creamer is a member of SHM’s Practice Analysis Committee. He is a hospitalist and informaticist with the MetroHealth System in Cleveland.

References

1. Wellikson, L. Hospitalists Stretched as their Responsibilities Broaden. The Hospitalist. 2016 Nov;2016(11).

Over the course of serial iterations of the State of Hospital Medicine (SOHM) Report, SHM has presented survey data that describe the evolving role hospitalists play in patient care. The 2016 SOHM Report shows the continuation of prior trends in hospital medicine groups’ (HMGs) scope of admittance and comanagement services. Some downturns are notable among previously increased specialty services.

The SOHM Report characterizes HMGs by their general scope of admitted patients – as admitters of purely traditional internal medicine or pediatrics hospitalized patients; full-range, nearly universal admitters who admit most patients within their age designation except OB and emergency surgery patients; or traditional admitters with some exceptions (for example, limited classically surgical patients).

As adult and adult-ped HMGs make up almost 97% of survey respondents, the predominance of the “some exceptions” category seems to represent a serious trend in much of Hospital Medicine practice. This could mean that HMGs have worked out more specific arrangements as to which patients they will admit or that the definitions are more in flux. It comes at a time when concerns figure prominently in national discussions over the stretching of hospitalists by their expanding scope of care and the need for ever more coordinated care between hospitalists and specialists.

Again, with these opportunities, concerns have arisen about scope-creep and its potential deleterious effects on patient care. Hospitalists have been noted to be prodded into providing critical, geriatric, and palliative care, without specialty training in these areas.1 Interestingly, however, specialty work reported by HMGs has largely shown a downturn since 2014, when most specialty services had appeared to be on the rise.

Whether this means that there is relief from scope-creep or that it is “just a blip” will remain to be seen in future data. If HMGs are able to capture the opportunity to improve outcomes through greater involvement in postacute care, this particular area may be one to watch, despite its apparent downturn since the 2014 report.

Thus, it is as imperative as ever that HMGs participate in the State of Hospital Medicine survey.

Dr. Creamer is a member of SHM’s Practice Analysis Committee. He is a hospitalist and informaticist with the MetroHealth System in Cleveland.

References

1. Wellikson, L. Hospitalists Stretched as their Responsibilities Broaden. The Hospitalist. 2016 Nov;2016(11).

Over the course of serial iterations of the State of Hospital Medicine (SOHM) Report, SHM has presented survey data that describe the evolving role hospitalists play in patient care. The 2016 SOHM Report shows the continuation of prior trends in hospital medicine groups’ (HMGs) scope of admittance and comanagement services. Some downturns are notable among previously increased specialty services.

The SOHM Report characterizes HMGs by their general scope of admitted patients – as admitters of purely traditional internal medicine or pediatrics hospitalized patients; full-range, nearly universal admitters who admit most patients within their age designation except OB and emergency surgery patients; or traditional admitters with some exceptions (for example, limited classically surgical patients).

As adult and adult-ped HMGs make up almost 97% of survey respondents, the predominance of the “some exceptions” category seems to represent a serious trend in much of Hospital Medicine practice. This could mean that HMGs have worked out more specific arrangements as to which patients they will admit or that the definitions are more in flux. It comes at a time when concerns figure prominently in national discussions over the stretching of hospitalists by their expanding scope of care and the need for ever more coordinated care between hospitalists and specialists.

Again, with these opportunities, concerns have arisen about scope-creep and its potential deleterious effects on patient care. Hospitalists have been noted to be prodded into providing critical, geriatric, and palliative care, without specialty training in these areas.1 Interestingly, however, specialty work reported by HMGs has largely shown a downturn since 2014, when most specialty services had appeared to be on the rise.

Whether this means that there is relief from scope-creep or that it is “just a blip” will remain to be seen in future data. If HMGs are able to capture the opportunity to improve outcomes through greater involvement in postacute care, this particular area may be one to watch, despite its apparent downturn since the 2014 report.

Thus, it is as imperative as ever that HMGs participate in the State of Hospital Medicine survey.

Dr. Creamer is a member of SHM’s Practice Analysis Committee. He is a hospitalist and informaticist with the MetroHealth System in Cleveland.

References

1. Wellikson, L. Hospitalists Stretched as their Responsibilities Broaden. The Hospitalist. 2016 Nov;2016(11).

HM17 session summary: Hospitalists as leaders in patient flow and hospital throughput

Presenters

Gaby Berger, MD; Aaron Hamilton, MD, FHM; Christopher Kim, MD, SFHM; Eduardo Margo, MD; Vikas Parekh, MD, FACP, SFHM; Anneliese Schleyer, MD, SFHM; Emily Wang, MD

Session Summary

This HM17 workshop brought together academic and community hospitalists to share effective strategies for improving hospital patient flow.

This was followed by a break-out session, in which hospitalists were encouraged to further explore these and other strategies for improving patient flow.

Key takeaways for HM

- Expedited discharge: Identify patients who can be safely discharged before noon. Consider creating standard work to ensure that key steps in discharge planning process, such as completion of medication reconciliation and discharge instructions and communication with patient and families and the interdisciplinary team, occur the day prior to discharge.

- Length of stay reduction strategies: Partner with utilization management to identify and develop a strategy to actively manage patients with long length of stay. Several institutions have set up committees to review such cases and address barriers, escalating requests for resources to executive leadership as needed.

- Facilitate transfers: Develop a standard process that is streamlined and patient-centered and includes established criteria for deciding whether interhospital transfers are appropriate.

- Short Stay Units: Some hospitals have had success with hospitalist-run short stay units as a strategy to decrease length of stay in observation patients. This strategy is most ideal for patients with a predictable length of stay. If you are thinking of starting an observation unit at your hospital, consider establishing criteria and protocols to expedite care.

- Hospitalist Quarterback: Given their broad perspective and clinical knowledge, hospitalists are uniquely positioned to help manage hospital, and even system-wide, capacity in real time. Some hospitals have successfully employed this strategy in some form to improve throughput. However, hospitalists need tools to help them electronically track incoming patients, integration with utilization management resources, and support from executive leadership to be successful.

Dr. Stella is a hospitalist in Denver and an editorial board member of The Hospitalist.

Presenters

Gaby Berger, MD; Aaron Hamilton, MD, FHM; Christopher Kim, MD, SFHM; Eduardo Margo, MD; Vikas Parekh, MD, FACP, SFHM; Anneliese Schleyer, MD, SFHM; Emily Wang, MD

Session Summary

This HM17 workshop brought together academic and community hospitalists to share effective strategies for improving hospital patient flow.

This was followed by a break-out session, in which hospitalists were encouraged to further explore these and other strategies for improving patient flow.

Key takeaways for HM

- Expedited discharge: Identify patients who can be safely discharged before noon. Consider creating standard work to ensure that key steps in discharge planning process, such as completion of medication reconciliation and discharge instructions and communication with patient and families and the interdisciplinary team, occur the day prior to discharge.

- Length of stay reduction strategies: Partner with utilization management to identify and develop a strategy to actively manage patients with long length of stay. Several institutions have set up committees to review such cases and address barriers, escalating requests for resources to executive leadership as needed.

- Facilitate transfers: Develop a standard process that is streamlined and patient-centered and includes established criteria for deciding whether interhospital transfers are appropriate.

- Short Stay Units: Some hospitals have had success with hospitalist-run short stay units as a strategy to decrease length of stay in observation patients. This strategy is most ideal for patients with a predictable length of stay. If you are thinking of starting an observation unit at your hospital, consider establishing criteria and protocols to expedite care.

- Hospitalist Quarterback: Given their broad perspective and clinical knowledge, hospitalists are uniquely positioned to help manage hospital, and even system-wide, capacity in real time. Some hospitals have successfully employed this strategy in some form to improve throughput. However, hospitalists need tools to help them electronically track incoming patients, integration with utilization management resources, and support from executive leadership to be successful.

Dr. Stella is a hospitalist in Denver and an editorial board member of The Hospitalist.

Presenters

Gaby Berger, MD; Aaron Hamilton, MD, FHM; Christopher Kim, MD, SFHM; Eduardo Margo, MD; Vikas Parekh, MD, FACP, SFHM; Anneliese Schleyer, MD, SFHM; Emily Wang, MD

Session Summary

This HM17 workshop brought together academic and community hospitalists to share effective strategies for improving hospital patient flow.

This was followed by a break-out session, in which hospitalists were encouraged to further explore these and other strategies for improving patient flow.

Key takeaways for HM

- Expedited discharge: Identify patients who can be safely discharged before noon. Consider creating standard work to ensure that key steps in discharge planning process, such as completion of medication reconciliation and discharge instructions and communication with patient and families and the interdisciplinary team, occur the day prior to discharge.

- Length of stay reduction strategies: Partner with utilization management to identify and develop a strategy to actively manage patients with long length of stay. Several institutions have set up committees to review such cases and address barriers, escalating requests for resources to executive leadership as needed.

- Facilitate transfers: Develop a standard process that is streamlined and patient-centered and includes established criteria for deciding whether interhospital transfers are appropriate.

- Short Stay Units: Some hospitals have had success with hospitalist-run short stay units as a strategy to decrease length of stay in observation patients. This strategy is most ideal for patients with a predictable length of stay. If you are thinking of starting an observation unit at your hospital, consider establishing criteria and protocols to expedite care.

- Hospitalist Quarterback: Given their broad perspective and clinical knowledge, hospitalists are uniquely positioned to help manage hospital, and even system-wide, capacity in real time. Some hospitals have successfully employed this strategy in some form to improve throughput. However, hospitalists need tools to help them electronically track incoming patients, integration with utilization management resources, and support from executive leadership to be successful.

Dr. Stella is a hospitalist in Denver and an editorial board member of The Hospitalist.

Hospital isolates C. difficile carriers and rates drop

NEW ORLEANS – A Montreal hospital grappling with high Clostridium difficile infections rates launched an intervention in October 2013 to screen patients at admission and detect asymptomatic carriers, and investigators found 4.8% of 7,599 people admitted through the ED over 15 months were carriers of C. difficile.

To protect Jewish General Hospital physicians, staff and other patients from potential transmission, these patients were placed in isolation. However, because they were fairly numerous – 1 in 20 admissions – and because infectious disease (ID) experts feared a substantial backlash, these patients were put in less restrictive isolation. They were permitted to share rooms as long as the dividing curtains remained drawn, for example. In addition, clinicians could skip wearing traditional isolation hats and gowns.

The ID team at the hospital considered the intervention a success. “It is estimated we prevented 64 cases over 15 months,” Dr. Longtin said during a packed session at the annual meeting of the American Society for Microbiology.

The hospital’s C. difficile rate dropped from 6.9 per 10,000 patient-days before the screening and isolation protocol to 3.0 per 10,000 during the intervention. The difference was statically significant (P less than .001).

“Compared to other hospitals in the province, we used to be in the middle of the pack [for C. difficile infection rates], and now we are the lowest,” Dr. Longtin said.

Asymptomatic carriers were detected using rectal sampling with sterile swab and polymerase chain reaction analysis. Testing was performed 7 days a week and analyzed once daily, with results generated within 24 hours and documented in the patient chart. Only patients admitted through the ED were screened, which prompted some questions from colleagues, Dr. Longtin said. However, he defends this approach because the 30% or so of patients admitted from the ED tend to spend more days on the ward. The risk of becoming colonized increases steadily with duration of hospitalization. This occurs despite isolating patients with C. difficile infection. Initial results of the study were published in JAMA Internal Medicine (2016 Jun 1;176[6]:796-804).

Risk to health care workers

C. difficile carriers are contagious, but not as much as people with C. difficile infection, Dr. Longtin said. In one study, the microorganism was present on the skin of 61% of symptomatic carriers versus 78% of those infected (Clin Infect Dis. 2007 Oct 15;45[8]:992-8). In addition, C. difficile present on patient skin can be transferred to health care worker hands, even up to 6 weeks after resolution of associated diarrhea (Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2016 Apr;37[4]:475-7).

Prior to the intervention, C. difficile prevention at Jewish General involved guidelines that “have not really changed in the last 20 years,” Dr. Longtin said. Contact precautions around infected patients, hand hygiene, environmental cleaning, and antibiotic stewardship were the main strategies.

“Despite all these measures, we were not completely blocking dissemination of C difficile in our hospital,” Dr. Longtin said. He added that soap and water are better than alcohol for C. difficile, “but honestly not very good. Even the best hand hygiene technique is poorly effective to remove C. difficile. On the other hand – get it? – gloves are very effective. We felt we had to combine hand washing with gloves.”

Hand hygiene compliance increased from 37% to 50% during the intervention, and Dr. Longtin expected further improvements over time.

Risk to other patients

“Transmission of C. difficile cannot only be explained by infected patients in a hospital, so likely carriers also play a role,” Dr. Longtin said.

Another set of investigators found that hospital patients exposed to a carrier of C. difficile had nearly twice the risk of acquiring the infection (odds ratio, 1.79) (Gastroenterology. 2017 Apr;152[5]:1031-41.e2).

“For every patient with C. difficile infection, it’s estimated there are 5-7 C. difficile carriers, so they are numerous as well,” he said.

The bigger picture

During the study period, the C. difficile infection trends did not significantly change on the city level, further supporting the effectiveness of the carrier screen-and-isolate strategy.

There was slight increase in antibiotic use during the intervention period, Dr. Longtin said. “The only type of antibiotics that really decreased were vancomycin and metronidazole... which suggests in turn there were fewer cases of C. difficile infection.”

Long-term follow-up is ongoing, Dr. Longtin said. “We have more than 3 years of intervention. In the past year, our rate was 2.2 per 10,000 patient-days.”

Unanswered questions include the generalizability of the results “because we’re a very pro–infection control hospital,” he said. In addition, a formal cost-benefit analysis of this strategy would be worthwhile in the future.

Dr. Longtin is a consultant for AMG Medical and receives research support from Merck and BD Medical.

NEW ORLEANS – A Montreal hospital grappling with high Clostridium difficile infections rates launched an intervention in October 2013 to screen patients at admission and detect asymptomatic carriers, and investigators found 4.8% of 7,599 people admitted through the ED over 15 months were carriers of C. difficile.

To protect Jewish General Hospital physicians, staff and other patients from potential transmission, these patients were placed in isolation. However, because they were fairly numerous – 1 in 20 admissions – and because infectious disease (ID) experts feared a substantial backlash, these patients were put in less restrictive isolation. They were permitted to share rooms as long as the dividing curtains remained drawn, for example. In addition, clinicians could skip wearing traditional isolation hats and gowns.

The ID team at the hospital considered the intervention a success. “It is estimated we prevented 64 cases over 15 months,” Dr. Longtin said during a packed session at the annual meeting of the American Society for Microbiology.

The hospital’s C. difficile rate dropped from 6.9 per 10,000 patient-days before the screening and isolation protocol to 3.0 per 10,000 during the intervention. The difference was statically significant (P less than .001).

“Compared to other hospitals in the province, we used to be in the middle of the pack [for C. difficile infection rates], and now we are the lowest,” Dr. Longtin said.

Asymptomatic carriers were detected using rectal sampling with sterile swab and polymerase chain reaction analysis. Testing was performed 7 days a week and analyzed once daily, with results generated within 24 hours and documented in the patient chart. Only patients admitted through the ED were screened, which prompted some questions from colleagues, Dr. Longtin said. However, he defends this approach because the 30% or so of patients admitted from the ED tend to spend more days on the ward. The risk of becoming colonized increases steadily with duration of hospitalization. This occurs despite isolating patients with C. difficile infection. Initial results of the study were published in JAMA Internal Medicine (2016 Jun 1;176[6]:796-804).

Risk to health care workers

C. difficile carriers are contagious, but not as much as people with C. difficile infection, Dr. Longtin said. In one study, the microorganism was present on the skin of 61% of symptomatic carriers versus 78% of those infected (Clin Infect Dis. 2007 Oct 15;45[8]:992-8). In addition, C. difficile present on patient skin can be transferred to health care worker hands, even up to 6 weeks after resolution of associated diarrhea (Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2016 Apr;37[4]:475-7).

Prior to the intervention, C. difficile prevention at Jewish General involved guidelines that “have not really changed in the last 20 years,” Dr. Longtin said. Contact precautions around infected patients, hand hygiene, environmental cleaning, and antibiotic stewardship were the main strategies.

“Despite all these measures, we were not completely blocking dissemination of C difficile in our hospital,” Dr. Longtin said. He added that soap and water are better than alcohol for C. difficile, “but honestly not very good. Even the best hand hygiene technique is poorly effective to remove C. difficile. On the other hand – get it? – gloves are very effective. We felt we had to combine hand washing with gloves.”

Hand hygiene compliance increased from 37% to 50% during the intervention, and Dr. Longtin expected further improvements over time.

Risk to other patients

“Transmission of C. difficile cannot only be explained by infected patients in a hospital, so likely carriers also play a role,” Dr. Longtin said.

Another set of investigators found that hospital patients exposed to a carrier of C. difficile had nearly twice the risk of acquiring the infection (odds ratio, 1.79) (Gastroenterology. 2017 Apr;152[5]:1031-41.e2).

“For every patient with C. difficile infection, it’s estimated there are 5-7 C. difficile carriers, so they are numerous as well,” he said.

The bigger picture

During the study period, the C. difficile infection trends did not significantly change on the city level, further supporting the effectiveness of the carrier screen-and-isolate strategy.

There was slight increase in antibiotic use during the intervention period, Dr. Longtin said. “The only type of antibiotics that really decreased were vancomycin and metronidazole... which suggests in turn there were fewer cases of C. difficile infection.”

Long-term follow-up is ongoing, Dr. Longtin said. “We have more than 3 years of intervention. In the past year, our rate was 2.2 per 10,000 patient-days.”

Unanswered questions include the generalizability of the results “because we’re a very pro–infection control hospital,” he said. In addition, a formal cost-benefit analysis of this strategy would be worthwhile in the future.

Dr. Longtin is a consultant for AMG Medical and receives research support from Merck and BD Medical.

NEW ORLEANS – A Montreal hospital grappling with high Clostridium difficile infections rates launched an intervention in October 2013 to screen patients at admission and detect asymptomatic carriers, and investigators found 4.8% of 7,599 people admitted through the ED over 15 months were carriers of C. difficile.

To protect Jewish General Hospital physicians, staff and other patients from potential transmission, these patients were placed in isolation. However, because they were fairly numerous – 1 in 20 admissions – and because infectious disease (ID) experts feared a substantial backlash, these patients were put in less restrictive isolation. They were permitted to share rooms as long as the dividing curtains remained drawn, for example. In addition, clinicians could skip wearing traditional isolation hats and gowns.

The ID team at the hospital considered the intervention a success. “It is estimated we prevented 64 cases over 15 months,” Dr. Longtin said during a packed session at the annual meeting of the American Society for Microbiology.

The hospital’s C. difficile rate dropped from 6.9 per 10,000 patient-days before the screening and isolation protocol to 3.0 per 10,000 during the intervention. The difference was statically significant (P less than .001).

“Compared to other hospitals in the province, we used to be in the middle of the pack [for C. difficile infection rates], and now we are the lowest,” Dr. Longtin said.

Asymptomatic carriers were detected using rectal sampling with sterile swab and polymerase chain reaction analysis. Testing was performed 7 days a week and analyzed once daily, with results generated within 24 hours and documented in the patient chart. Only patients admitted through the ED were screened, which prompted some questions from colleagues, Dr. Longtin said. However, he defends this approach because the 30% or so of patients admitted from the ED tend to spend more days on the ward. The risk of becoming colonized increases steadily with duration of hospitalization. This occurs despite isolating patients with C. difficile infection. Initial results of the study were published in JAMA Internal Medicine (2016 Jun 1;176[6]:796-804).

Risk to health care workers

C. difficile carriers are contagious, but not as much as people with C. difficile infection, Dr. Longtin said. In one study, the microorganism was present on the skin of 61% of symptomatic carriers versus 78% of those infected (Clin Infect Dis. 2007 Oct 15;45[8]:992-8). In addition, C. difficile present on patient skin can be transferred to health care worker hands, even up to 6 weeks after resolution of associated diarrhea (Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2016 Apr;37[4]:475-7).

Prior to the intervention, C. difficile prevention at Jewish General involved guidelines that “have not really changed in the last 20 years,” Dr. Longtin said. Contact precautions around infected patients, hand hygiene, environmental cleaning, and antibiotic stewardship were the main strategies.

“Despite all these measures, we were not completely blocking dissemination of C difficile in our hospital,” Dr. Longtin said. He added that soap and water are better than alcohol for C. difficile, “but honestly not very good. Even the best hand hygiene technique is poorly effective to remove C. difficile. On the other hand – get it? – gloves are very effective. We felt we had to combine hand washing with gloves.”

Hand hygiene compliance increased from 37% to 50% during the intervention, and Dr. Longtin expected further improvements over time.

Risk to other patients

“Transmission of C. difficile cannot only be explained by infected patients in a hospital, so likely carriers also play a role,” Dr. Longtin said.

Another set of investigators found that hospital patients exposed to a carrier of C. difficile had nearly twice the risk of acquiring the infection (odds ratio, 1.79) (Gastroenterology. 2017 Apr;152[5]:1031-41.e2).

“For every patient with C. difficile infection, it’s estimated there are 5-7 C. difficile carriers, so they are numerous as well,” he said.

The bigger picture

During the study period, the C. difficile infection trends did not significantly change on the city level, further supporting the effectiveness of the carrier screen-and-isolate strategy.

There was slight increase in antibiotic use during the intervention period, Dr. Longtin said. “The only type of antibiotics that really decreased were vancomycin and metronidazole... which suggests in turn there were fewer cases of C. difficile infection.”

Long-term follow-up is ongoing, Dr. Longtin said. “We have more than 3 years of intervention. In the past year, our rate was 2.2 per 10,000 patient-days.”

Unanswered questions include the generalizability of the results “because we’re a very pro–infection control hospital,” he said. In addition, a formal cost-benefit analysis of this strategy would be worthwhile in the future.

Dr. Longtin is a consultant for AMG Medical and receives research support from Merck and BD Medical.

AT ASM MICROBE 2017

Key clinical point: Identification and isolation of asymptomatic carriers of Clostridium difficile decreased a hospital’s infection rates over time.

Major finding: (P less than .001).

Data source: A study of 7,599 people screened at admission through the ED at an acute care hospital.

Disclosures: Dr. Longtin is a consultant for AMG Medical and receives research support from Merck and BD Medical.

Idarucizumab reversed dabigatran completely and rapidly in study

One IV 5-g dose of idarucizumab completely, rapidly, and safely reversed the anticoagulant effect of dabigatran, according to final results for 503 patients in the multicenter, prospective, open-label, uncontrolled RE-VERSE AD study.

Uncontrolled bleeding stopped a median of 2.5 hours after 134 patients received idarucizumab. In a separate group of 202 patients, 197 were able to undergo urgent procedures after a median of 1.6 hours, Charles V. Pollack Jr., MD, and his associates reported at the International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis congress. The report was simultaneously published in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Idarucizumab was specifically developed to reverse the anticoagulant effect of dabigatran. Many countries have already licensed the humanized monoclonal antibody fragment based on interim results for the first 90 patients enrolled in the Reversal Effects of Idarucizumab on Active Dabigatran (RE-VERSE AD) study (NCT02104947), noted Dr. Pollack, of Thomas Jefferson University, Philadelphia.

The final RE-VERSE AD cohort included 301 patients with uncontrolled gastrointestinal, intracranial, or trauma-related bleeding and 202 patients who needed urgent procedures. Participants from both groups typically were white, in their late 70s (age range, 21-96 years), and receiving 110 mg (75-150 mg) dabigatran twice daily. The primary endpoint was maximum percentage reversal within 4 hours after patients received idarucizumab, based on diluted thrombin time and ecarin clotting time.

The median maximum percentage reversal of dabigatran was 100% (95% confidence interval, 100% to 100%) in more than 98% of patients, and the effect usually lasted 24 hours. Among patients who underwent procedures, intraprocedural hemostasis was considered normal in 93% of cases, mildly abnormal in 5% of cases, and moderately abnormal in 2% of cases, the researchers noted. Seven patients received another dose of idarucizumab after developing recurrent or postoperative bleeding.

A total of 24 patients had an adjudicated thrombotic event within 30 days after receiving idarucizumab. These events included pulmonary embolism, systemic embolism, ischemic stroke, deep vein thrombosis, and myocardial infarction. The fact that many patients did not restart anticoagulation could have contributed to these thrombotic events, the researchers asserted. They noted that idarucizumab had no procoagulant activity in studies of animals and healthy human volunteers.

About 19% of patients in both groups died within 90 days. “Patients enrolled in this study were elderly, had numerous coexisting conditions, and presented with serious index events, such as intracranial hemorrhage, multiple trauma, sepsis, acute abdomen, or open fracture,” the investigators wrote. “Most of the deaths that occurred within 5 days after enrollment appeared to be related to the severity of the index event or to coexisting conditions, such as respiratory failure or multiple organ failure, whereas deaths that occurred after 30 days were more likely to be independent events or related to coexisting conditions.”

Boehringer Ingelheim Pharmaceuticals provided funding. Dr. Pollack disclosed grant support from Boehringer Ingelheim during the course of the study and ties to Daiichi Sankyo, Portola, CSL Behring, Bristol-Myers Squibb/Pfizer, Janssen Pharma, and AstraZeneca. Eighteen coinvestigators also disclosed ties to Boehringer Ingelheim and a number of other pharmaceutical companies. Two coinvestigators had no relevant financial disclosures.

One IV 5-g dose of idarucizumab completely, rapidly, and safely reversed the anticoagulant effect of dabigatran, according to final results for 503 patients in the multicenter, prospective, open-label, uncontrolled RE-VERSE AD study.

Uncontrolled bleeding stopped a median of 2.5 hours after 134 patients received idarucizumab. In a separate group of 202 patients, 197 were able to undergo urgent procedures after a median of 1.6 hours, Charles V. Pollack Jr., MD, and his associates reported at the International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis congress. The report was simultaneously published in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Idarucizumab was specifically developed to reverse the anticoagulant effect of dabigatran. Many countries have already licensed the humanized monoclonal antibody fragment based on interim results for the first 90 patients enrolled in the Reversal Effects of Idarucizumab on Active Dabigatran (RE-VERSE AD) study (NCT02104947), noted Dr. Pollack, of Thomas Jefferson University, Philadelphia.

The final RE-VERSE AD cohort included 301 patients with uncontrolled gastrointestinal, intracranial, or trauma-related bleeding and 202 patients who needed urgent procedures. Participants from both groups typically were white, in their late 70s (age range, 21-96 years), and receiving 110 mg (75-150 mg) dabigatran twice daily. The primary endpoint was maximum percentage reversal within 4 hours after patients received idarucizumab, based on diluted thrombin time and ecarin clotting time.

The median maximum percentage reversal of dabigatran was 100% (95% confidence interval, 100% to 100%) in more than 98% of patients, and the effect usually lasted 24 hours. Among patients who underwent procedures, intraprocedural hemostasis was considered normal in 93% of cases, mildly abnormal in 5% of cases, and moderately abnormal in 2% of cases, the researchers noted. Seven patients received another dose of idarucizumab after developing recurrent or postoperative bleeding.

A total of 24 patients had an adjudicated thrombotic event within 30 days after receiving idarucizumab. These events included pulmonary embolism, systemic embolism, ischemic stroke, deep vein thrombosis, and myocardial infarction. The fact that many patients did not restart anticoagulation could have contributed to these thrombotic events, the researchers asserted. They noted that idarucizumab had no procoagulant activity in studies of animals and healthy human volunteers.

About 19% of patients in both groups died within 90 days. “Patients enrolled in this study were elderly, had numerous coexisting conditions, and presented with serious index events, such as intracranial hemorrhage, multiple trauma, sepsis, acute abdomen, or open fracture,” the investigators wrote. “Most of the deaths that occurred within 5 days after enrollment appeared to be related to the severity of the index event or to coexisting conditions, such as respiratory failure or multiple organ failure, whereas deaths that occurred after 30 days were more likely to be independent events or related to coexisting conditions.”

Boehringer Ingelheim Pharmaceuticals provided funding. Dr. Pollack disclosed grant support from Boehringer Ingelheim during the course of the study and ties to Daiichi Sankyo, Portola, CSL Behring, Bristol-Myers Squibb/Pfizer, Janssen Pharma, and AstraZeneca. Eighteen coinvestigators also disclosed ties to Boehringer Ingelheim and a number of other pharmaceutical companies. Two coinvestigators had no relevant financial disclosures.

One IV 5-g dose of idarucizumab completely, rapidly, and safely reversed the anticoagulant effect of dabigatran, according to final results for 503 patients in the multicenter, prospective, open-label, uncontrolled RE-VERSE AD study.

Uncontrolled bleeding stopped a median of 2.5 hours after 134 patients received idarucizumab. In a separate group of 202 patients, 197 were able to undergo urgent procedures after a median of 1.6 hours, Charles V. Pollack Jr., MD, and his associates reported at the International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis congress. The report was simultaneously published in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Idarucizumab was specifically developed to reverse the anticoagulant effect of dabigatran. Many countries have already licensed the humanized monoclonal antibody fragment based on interim results for the first 90 patients enrolled in the Reversal Effects of Idarucizumab on Active Dabigatran (RE-VERSE AD) study (NCT02104947), noted Dr. Pollack, of Thomas Jefferson University, Philadelphia.

The final RE-VERSE AD cohort included 301 patients with uncontrolled gastrointestinal, intracranial, or trauma-related bleeding and 202 patients who needed urgent procedures. Participants from both groups typically were white, in their late 70s (age range, 21-96 years), and receiving 110 mg (75-150 mg) dabigatran twice daily. The primary endpoint was maximum percentage reversal within 4 hours after patients received idarucizumab, based on diluted thrombin time and ecarin clotting time.

The median maximum percentage reversal of dabigatran was 100% (95% confidence interval, 100% to 100%) in more than 98% of patients, and the effect usually lasted 24 hours. Among patients who underwent procedures, intraprocedural hemostasis was considered normal in 93% of cases, mildly abnormal in 5% of cases, and moderately abnormal in 2% of cases, the researchers noted. Seven patients received another dose of idarucizumab after developing recurrent or postoperative bleeding.

A total of 24 patients had an adjudicated thrombotic event within 30 days after receiving idarucizumab. These events included pulmonary embolism, systemic embolism, ischemic stroke, deep vein thrombosis, and myocardial infarction. The fact that many patients did not restart anticoagulation could have contributed to these thrombotic events, the researchers asserted. They noted that idarucizumab had no procoagulant activity in studies of animals and healthy human volunteers.

About 19% of patients in both groups died within 90 days. “Patients enrolled in this study were elderly, had numerous coexisting conditions, and presented with serious index events, such as intracranial hemorrhage, multiple trauma, sepsis, acute abdomen, or open fracture,” the investigators wrote. “Most of the deaths that occurred within 5 days after enrollment appeared to be related to the severity of the index event or to coexisting conditions, such as respiratory failure or multiple organ failure, whereas deaths that occurred after 30 days were more likely to be independent events or related to coexisting conditions.”

Boehringer Ingelheim Pharmaceuticals provided funding. Dr. Pollack disclosed grant support from Boehringer Ingelheim during the course of the study and ties to Daiichi Sankyo, Portola, CSL Behring, Bristol-Myers Squibb/Pfizer, Janssen Pharma, and AstraZeneca. Eighteen coinvestigators also disclosed ties to Boehringer Ingelheim and a number of other pharmaceutical companies. Two coinvestigators had no relevant financial disclosures.

FROM 2017 ISTH CONGRESS

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Uncontrolled bleeding stopped a median of 2.5 hours after 134 patients received idarucizumab. In a separate group, 197 patients were able to undergo urgent procedures after a median of 1.6 hours.

Data source: A multicenter, prospective, open-label study of 503 patients (RE-VERSE AD).

Disclosures: Boehringer Ingelheim Pharmaceuticals provided funding. Dr. Pollack disclosed grant support from Boehringer Ingelheim during the course of the study and ties to Daiichi Sankyo, Portola, CSL Behring, BMS/Pfizer, Janssen Pharma, and AstraZeneca. Eighteen coinvestigators disclosed ties to Boehringer Ingelheim and a number of other pharmaceutical companies. Two coinvestigators had no relevant financial disclosures.

Ceftaroline shortens duration of MRSA bacteremia

NEW ORLEANS – Ceftaroline fosamil reduced the median duration of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) bacteremia by 2 days in Veterans Administration patients, a retrospective study showed.

Investigators identified 219 patients with MRSA within the Veterans Affairs (VA) medical system nationwide from 2011 to 2015. All patients received at least 48 hours of ceftaroline fosamil (Teflaro) therapy to treat MRSA bacteremia. “We know it has good activity against MRSA in vitro. We use it in bacteremia, but we don’t have a lot of clinical data to support or refute its use,” said Nicholas S. Britt, PharmD, a PGY2 infectious diseases resident at Barnes-Jewish Hospital in St. Louis.

“Ceftaroline was primarily used as second-line or salvage therapy … which is basically what we expected, based on how it’s used in clinical practice,” Dr. Britt said.

Treatment failures

A total of 88 of the 219 (40%) patients experienced treatment failure. This rate “seems kind of high, but, if you look at some of the other MRSA agents for bacteremia (vancomycin, for example), it usually has a treatment failure rate around 60%,” Dr. Britt said. “The outcomes were not as poor as I would expect with [patients] using it for second- and third-line therapy.”

Hospital-acquired infection (odds ratio, 2.11; P = .013), ICU admission (OR, 3.95; P less than .001) and infective endocarditis (OR, 4.77; P = .002) were significantly associated with treatment failure in a univariate analysis. “Admissions to the ICU and endocarditis were the big ones, factors you would associate with failure for most antibiotics,” Dr. Britt said. In a multivariate analysis, only ICU admission remained significantly associated with treatment failure (adjusted OR, 2.24; P = .028).

The investigators also looked at treatment failure with ceftaroline monotherapy, compared with its use in combination. There is in vitro data showing synergy when you add ceftaroline to daptomycin, vancomycin, or some of these other agents,” Dr. Britt said. However, he added, “We didn’t find any significant difference in outcomes when you added another agent.” Treatment failure with monotherapy was 35%, versus 46%, with combination treatment (P = .107).

“This could be because the sicker patients are the ones getting combination therapy.”

No observed differences by dosing

Dr. Britt and his colleagues also looked for any differences by dosing interval, “which hasn’t been evaluated extensively.”

The Food and Drug Administration labeled it for use every 12 hours, but treatment of MRSA bacteremia is an off-label use, Dr. Britt explained. Dosing every 8 hours instead improves the achievement of pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic parameters in in vitro studies. “Clinically, we’re almost always using it q8. They’re sick patients, so you don’t want to under-dose them. And ceftaroline is pretty well tolerated overall.”

“But, we didn’t really see any difference between the q8 and the q12” in terms of treatment failure. The rates were 36% and 42%, respectively, and not significantly different (P = .440). “Granted, patients who are sicker are probably going to get treated more aggressively,” Dr. Britt added.

The current research only focused on outcomes associated with ceftaroline. Going forward, Dr. Britt said, “We’re hoping to use this data to compare ceftaroline to other agents as well, probably as second-line therapy, since that’s how it’s used most often.”

Dr. Britt had no relevant financial disclosures.

NEW ORLEANS – Ceftaroline fosamil reduced the median duration of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) bacteremia by 2 days in Veterans Administration patients, a retrospective study showed.

Investigators identified 219 patients with MRSA within the Veterans Affairs (VA) medical system nationwide from 2011 to 2015. All patients received at least 48 hours of ceftaroline fosamil (Teflaro) therapy to treat MRSA bacteremia. “We know it has good activity against MRSA in vitro. We use it in bacteremia, but we don’t have a lot of clinical data to support or refute its use,” said Nicholas S. Britt, PharmD, a PGY2 infectious diseases resident at Barnes-Jewish Hospital in St. Louis.

“Ceftaroline was primarily used as second-line or salvage therapy … which is basically what we expected, based on how it’s used in clinical practice,” Dr. Britt said.

Treatment failures

A total of 88 of the 219 (40%) patients experienced treatment failure. This rate “seems kind of high, but, if you look at some of the other MRSA agents for bacteremia (vancomycin, for example), it usually has a treatment failure rate around 60%,” Dr. Britt said. “The outcomes were not as poor as I would expect with [patients] using it for second- and third-line therapy.”

Hospital-acquired infection (odds ratio, 2.11; P = .013), ICU admission (OR, 3.95; P less than .001) and infective endocarditis (OR, 4.77; P = .002) were significantly associated with treatment failure in a univariate analysis. “Admissions to the ICU and endocarditis were the big ones, factors you would associate with failure for most antibiotics,” Dr. Britt said. In a multivariate analysis, only ICU admission remained significantly associated with treatment failure (adjusted OR, 2.24; P = .028).

The investigators also looked at treatment failure with ceftaroline monotherapy, compared with its use in combination. There is in vitro data showing synergy when you add ceftaroline to daptomycin, vancomycin, or some of these other agents,” Dr. Britt said. However, he added, “We didn’t find any significant difference in outcomes when you added another agent.” Treatment failure with monotherapy was 35%, versus 46%, with combination treatment (P = .107).

“This could be because the sicker patients are the ones getting combination therapy.”

No observed differences by dosing

Dr. Britt and his colleagues also looked for any differences by dosing interval, “which hasn’t been evaluated extensively.”

The Food and Drug Administration labeled it for use every 12 hours, but treatment of MRSA bacteremia is an off-label use, Dr. Britt explained. Dosing every 8 hours instead improves the achievement of pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic parameters in in vitro studies. “Clinically, we’re almost always using it q8. They’re sick patients, so you don’t want to under-dose them. And ceftaroline is pretty well tolerated overall.”

“But, we didn’t really see any difference between the q8 and the q12” in terms of treatment failure. The rates were 36% and 42%, respectively, and not significantly different (P = .440). “Granted, patients who are sicker are probably going to get treated more aggressively,” Dr. Britt added.

The current research only focused on outcomes associated with ceftaroline. Going forward, Dr. Britt said, “We’re hoping to use this data to compare ceftaroline to other agents as well, probably as second-line therapy, since that’s how it’s used most often.”

Dr. Britt had no relevant financial disclosures.

NEW ORLEANS – Ceftaroline fosamil reduced the median duration of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) bacteremia by 2 days in Veterans Administration patients, a retrospective study showed.

Investigators identified 219 patients with MRSA within the Veterans Affairs (VA) medical system nationwide from 2011 to 2015. All patients received at least 48 hours of ceftaroline fosamil (Teflaro) therapy to treat MRSA bacteremia. “We know it has good activity against MRSA in vitro. We use it in bacteremia, but we don’t have a lot of clinical data to support or refute its use,” said Nicholas S. Britt, PharmD, a PGY2 infectious diseases resident at Barnes-Jewish Hospital in St. Louis.

“Ceftaroline was primarily used as second-line or salvage therapy … which is basically what we expected, based on how it’s used in clinical practice,” Dr. Britt said.

Treatment failures

A total of 88 of the 219 (40%) patients experienced treatment failure. This rate “seems kind of high, but, if you look at some of the other MRSA agents for bacteremia (vancomycin, for example), it usually has a treatment failure rate around 60%,” Dr. Britt said. “The outcomes were not as poor as I would expect with [patients] using it for second- and third-line therapy.”

Hospital-acquired infection (odds ratio, 2.11; P = .013), ICU admission (OR, 3.95; P less than .001) and infective endocarditis (OR, 4.77; P = .002) were significantly associated with treatment failure in a univariate analysis. “Admissions to the ICU and endocarditis were the big ones, factors you would associate with failure for most antibiotics,” Dr. Britt said. In a multivariate analysis, only ICU admission remained significantly associated with treatment failure (adjusted OR, 2.24; P = .028).

The investigators also looked at treatment failure with ceftaroline monotherapy, compared with its use in combination. There is in vitro data showing synergy when you add ceftaroline to daptomycin, vancomycin, or some of these other agents,” Dr. Britt said. However, he added, “We didn’t find any significant difference in outcomes when you added another agent.” Treatment failure with monotherapy was 35%, versus 46%, with combination treatment (P = .107).

“This could be because the sicker patients are the ones getting combination therapy.”

No observed differences by dosing

Dr. Britt and his colleagues also looked for any differences by dosing interval, “which hasn’t been evaluated extensively.”

The Food and Drug Administration labeled it for use every 12 hours, but treatment of MRSA bacteremia is an off-label use, Dr. Britt explained. Dosing every 8 hours instead improves the achievement of pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic parameters in in vitro studies. “Clinically, we’re almost always using it q8. They’re sick patients, so you don’t want to under-dose them. And ceftaroline is pretty well tolerated overall.”

“But, we didn’t really see any difference between the q8 and the q12” in terms of treatment failure. The rates were 36% and 42%, respectively, and not significantly different (P = .440). “Granted, patients who are sicker are probably going to get treated more aggressively,” Dr. Britt added.

The current research only focused on outcomes associated with ceftaroline. Going forward, Dr. Britt said, “We’re hoping to use this data to compare ceftaroline to other agents as well, probably as second-line therapy, since that’s how it’s used most often.”

Dr. Britt had no relevant financial disclosures.

AT ASM MICROBE 2017

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Median duration of MRSA bacteremia dropped from 2.79 days before to 1.18 days after initiation of ceftaroline (P less than .001).

Data source: A retrospective study of 219 hospitalized VA patients initiating ceftaroline for MRSA bacteremia.

Disclosures: Dr. Britt had no relevant financial disclosures.

Amplatzer devices outperform oral anticoagulation in atrial fib

PARIS – Percutaneous left atrial appendage closure with an Amplatzer device in patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation was associated with significantly lower rates of all-cause and cardiovascular mortality, compared with oral anticoagulation, in a large propensity score–matched observational registry study.

Left atrial appendage closure (LAAC) also bested oral anticoagulation (OAC) with warfarin or a novel oral anticoagulant (NOAC) in terms of net clinical benefit on the basis of the device therapy’s greater protection against stroke and systemic embolism coupled with a trend, albeit not statistically significant, for fewer bleeding events, Steffen Gloekler, MD, reported at the annual congress of the European Association of Percutaneous Cardiovascular Interventions.

The Watchman LAAC device, commercially available both in Europe and the United States, has previously been shown to be superior to OAC in terms of efficacy and noninferior regarding safety. But there have been no randomized trials of an Amplatzer device versus OAC. This lack of data was the impetus for Dr. Gloekler and his coinvestigators to create a meticulously propensity-matched observational registry.

Five hundred consecutive patients with AF who received an Amplatzer Cardiac Plug or its second-generation version, the Amplatzer Amulet, during 2009-2014 were tightly matched to an equal number of AF patients on OAC based on age, sex, body mass index, left ventricular ejection fraction, renal function, coronary artery disease status, hemoglobin level, CHA2DS2-VASc score, and HAS-BLED score. During a mean 2.7 years, or 2,645 patient-years, of follow-up, the composite primary efficacy endpoint, composed of stroke, systemic embolism, and cardiovascular or unexplained death occurred in 5.6% of the LAAC group, compared with 7.8% of controls in the OAC arm, for a statistically significant 30% relative risk reduction. Disabling stroke occurred in 0.7% of Amplatzer patients versus 1.5% of controls. The ischemic stroke rate was 1.5% in the device therapy group and 2% in the OAC arm.

All-cause mortality occurred in 8.3% of Amplatzer patients and 11.6% of the OAC group, for a 28% relative risk reduction. The cardiovascular death rate was 4% in the Amplatzer group, compared with 6.5% of controls, for a 36% risk reduction.

The composite safety endpoint, comprising all major procedural adverse events and major or life-threatening bleeding during follow-up, occurred in 3.6% of the Amplatzer group and 4.6% of the OAC group, for a 20% relative risk reduction that is not significant at this point because of the low number of events. Major, life-threatening, or fatal bleeding occurred in 2% of Amplatzer recipients versus 5.5% of controls, added Dr. Gloekler of University Hospital in Bern, Switzerland.

The net clinical benefit, a composite of death, bleeding, or stroke, occurred in 8.1% of the Amplatzer group, compared with 10.9% of controls, for a significant 24% reduction in relative risk in favor of device therapy.

Of note, at 2.7 years of follow-up only 55% of the OAC group were still taking an anticoagulant: 38% of the original 500 patients were on warfarin, and 17% were taking a NOAC. At that point, 8% of the Amplatzer group were on any anticoagulation therapy.

Discussion of the study focused on that low rate of medication adherence in the OAC arm. Dr. Gloekler’s response was that, after looking at the literature, he was no longer surprised by the finding that only 55% of the control group were on OAC at follow-up.

“If you look in the literature, that’s exactly the real-world adherence for OACs. Even in all four certification trials for the NOACs, the rate of discontinuation was 30% after 2 years – and these were controlled studies. Ours was observational, and it depicts a good deal of the problem with any OAC in my eyes,” Dr. Gloekler said.

Patients on warfarin in the real-world Amplatzer registry study spent on average a mere 30% of time in the therapeutic international normalized ratio range of 2-3.

“That means 70% of the time patients are higher and have an increased bleeding risk or they are lower and don’t have adequate stroke protection,” he noted.

This prompted one observer to comment, “We either have to do a better job in our clinics with OAC or we have to occlude more appendages.”

A large pivotal U.S. trial aimed at winning FDA approval for the Amplatzer Amulet for LAAC is underway. Patients with AF are being randomized to the approved Watchman or investigational Amulet at roughly 100 U.S. and 50 foreign sites.

Dr. Gloekler reported receiving research funds for the registry from the Swiss Heart Foundation and Abbott.

PARIS – Percutaneous left atrial appendage closure with an Amplatzer device in patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation was associated with significantly lower rates of all-cause and cardiovascular mortality, compared with oral anticoagulation, in a large propensity score–matched observational registry study.

Left atrial appendage closure (LAAC) also bested oral anticoagulation (OAC) with warfarin or a novel oral anticoagulant (NOAC) in terms of net clinical benefit on the basis of the device therapy’s greater protection against stroke and systemic embolism coupled with a trend, albeit not statistically significant, for fewer bleeding events, Steffen Gloekler, MD, reported at the annual congress of the European Association of Percutaneous Cardiovascular Interventions.

The Watchman LAAC device, commercially available both in Europe and the United States, has previously been shown to be superior to OAC in terms of efficacy and noninferior regarding safety. But there have been no randomized trials of an Amplatzer device versus OAC. This lack of data was the impetus for Dr. Gloekler and his coinvestigators to create a meticulously propensity-matched observational registry.

Five hundred consecutive patients with AF who received an Amplatzer Cardiac Plug or its second-generation version, the Amplatzer Amulet, during 2009-2014 were tightly matched to an equal number of AF patients on OAC based on age, sex, body mass index, left ventricular ejection fraction, renal function, coronary artery disease status, hemoglobin level, CHA2DS2-VASc score, and HAS-BLED score. During a mean 2.7 years, or 2,645 patient-years, of follow-up, the composite primary efficacy endpoint, composed of stroke, systemic embolism, and cardiovascular or unexplained death occurred in 5.6% of the LAAC group, compared with 7.8% of controls in the OAC arm, for a statistically significant 30% relative risk reduction. Disabling stroke occurred in 0.7% of Amplatzer patients versus 1.5% of controls. The ischemic stroke rate was 1.5% in the device therapy group and 2% in the OAC arm.

All-cause mortality occurred in 8.3% of Amplatzer patients and 11.6% of the OAC group, for a 28% relative risk reduction. The cardiovascular death rate was 4% in the Amplatzer group, compared with 6.5% of controls, for a 36% risk reduction.

The composite safety endpoint, comprising all major procedural adverse events and major or life-threatening bleeding during follow-up, occurred in 3.6% of the Amplatzer group and 4.6% of the OAC group, for a 20% relative risk reduction that is not significant at this point because of the low number of events. Major, life-threatening, or fatal bleeding occurred in 2% of Amplatzer recipients versus 5.5% of controls, added Dr. Gloekler of University Hospital in Bern, Switzerland.

The net clinical benefit, a composite of death, bleeding, or stroke, occurred in 8.1% of the Amplatzer group, compared with 10.9% of controls, for a significant 24% reduction in relative risk in favor of device therapy.

Of note, at 2.7 years of follow-up only 55% of the OAC group were still taking an anticoagulant: 38% of the original 500 patients were on warfarin, and 17% were taking a NOAC. At that point, 8% of the Amplatzer group were on any anticoagulation therapy.

Discussion of the study focused on that low rate of medication adherence in the OAC arm. Dr. Gloekler’s response was that, after looking at the literature, he was no longer surprised by the finding that only 55% of the control group were on OAC at follow-up.

“If you look in the literature, that’s exactly the real-world adherence for OACs. Even in all four certification trials for the NOACs, the rate of discontinuation was 30% after 2 years – and these were controlled studies. Ours was observational, and it depicts a good deal of the problem with any OAC in my eyes,” Dr. Gloekler said.

Patients on warfarin in the real-world Amplatzer registry study spent on average a mere 30% of time in the therapeutic international normalized ratio range of 2-3.

“That means 70% of the time patients are higher and have an increased bleeding risk or they are lower and don’t have adequate stroke protection,” he noted.

This prompted one observer to comment, “We either have to do a better job in our clinics with OAC or we have to occlude more appendages.”

A large pivotal U.S. trial aimed at winning FDA approval for the Amplatzer Amulet for LAAC is underway. Patients with AF are being randomized to the approved Watchman or investigational Amulet at roughly 100 U.S. and 50 foreign sites.

Dr. Gloekler reported receiving research funds for the registry from the Swiss Heart Foundation and Abbott.

PARIS – Percutaneous left atrial appendage closure with an Amplatzer device in patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation was associated with significantly lower rates of all-cause and cardiovascular mortality, compared with oral anticoagulation, in a large propensity score–matched observational registry study.

Left atrial appendage closure (LAAC) also bested oral anticoagulation (OAC) with warfarin or a novel oral anticoagulant (NOAC) in terms of net clinical benefit on the basis of the device therapy’s greater protection against stroke and systemic embolism coupled with a trend, albeit not statistically significant, for fewer bleeding events, Steffen Gloekler, MD, reported at the annual congress of the European Association of Percutaneous Cardiovascular Interventions.

The Watchman LAAC device, commercially available both in Europe and the United States, has previously been shown to be superior to OAC in terms of efficacy and noninferior regarding safety. But there have been no randomized trials of an Amplatzer device versus OAC. This lack of data was the impetus for Dr. Gloekler and his coinvestigators to create a meticulously propensity-matched observational registry.

Five hundred consecutive patients with AF who received an Amplatzer Cardiac Plug or its second-generation version, the Amplatzer Amulet, during 2009-2014 were tightly matched to an equal number of AF patients on OAC based on age, sex, body mass index, left ventricular ejection fraction, renal function, coronary artery disease status, hemoglobin level, CHA2DS2-VASc score, and HAS-BLED score. During a mean 2.7 years, or 2,645 patient-years, of follow-up, the composite primary efficacy endpoint, composed of stroke, systemic embolism, and cardiovascular or unexplained death occurred in 5.6% of the LAAC group, compared with 7.8% of controls in the OAC arm, for a statistically significant 30% relative risk reduction. Disabling stroke occurred in 0.7% of Amplatzer patients versus 1.5% of controls. The ischemic stroke rate was 1.5% in the device therapy group and 2% in the OAC arm.

All-cause mortality occurred in 8.3% of Amplatzer patients and 11.6% of the OAC group, for a 28% relative risk reduction. The cardiovascular death rate was 4% in the Amplatzer group, compared with 6.5% of controls, for a 36% risk reduction.

The composite safety endpoint, comprising all major procedural adverse events and major or life-threatening bleeding during follow-up, occurred in 3.6% of the Amplatzer group and 4.6% of the OAC group, for a 20% relative risk reduction that is not significant at this point because of the low number of events. Major, life-threatening, or fatal bleeding occurred in 2% of Amplatzer recipients versus 5.5% of controls, added Dr. Gloekler of University Hospital in Bern, Switzerland.

The net clinical benefit, a composite of death, bleeding, or stroke, occurred in 8.1% of the Amplatzer group, compared with 10.9% of controls, for a significant 24% reduction in relative risk in favor of device therapy.

Of note, at 2.7 years of follow-up only 55% of the OAC group were still taking an anticoagulant: 38% of the original 500 patients were on warfarin, and 17% were taking a NOAC. At that point, 8% of the Amplatzer group were on any anticoagulation therapy.

Discussion of the study focused on that low rate of medication adherence in the OAC arm. Dr. Gloekler’s response was that, after looking at the literature, he was no longer surprised by the finding that only 55% of the control group were on OAC at follow-up.

“If you look in the literature, that’s exactly the real-world adherence for OACs. Even in all four certification trials for the NOACs, the rate of discontinuation was 30% after 2 years – and these were controlled studies. Ours was observational, and it depicts a good deal of the problem with any OAC in my eyes,” Dr. Gloekler said.

Patients on warfarin in the real-world Amplatzer registry study spent on average a mere 30% of time in the therapeutic international normalized ratio range of 2-3.

“That means 70% of the time patients are higher and have an increased bleeding risk or they are lower and don’t have adequate stroke protection,” he noted.

This prompted one observer to comment, “We either have to do a better job in our clinics with OAC or we have to occlude more appendages.”

A large pivotal U.S. trial aimed at winning FDA approval for the Amplatzer Amulet for LAAC is underway. Patients with AF are being randomized to the approved Watchman or investigational Amulet at roughly 100 U.S. and 50 foreign sites.

Dr. Gloekler reported receiving research funds for the registry from the Swiss Heart Foundation and Abbott.

AT EUROPCR

Key clinical point:

Major finding: The primary composite efficacy endpoint of stroke, systemic embolism, or cardiovascular or unexplained death during a mean 2.7 years of follow-up occurred in 5.6% of Amplatzer device recipients, a 30% reduction, compared with the 7.8% rate in the oral anticoagulation group.

Data source: This observational registry included 500 patients with atrial fibrillation who received an Amplatzer left atrial appendage closure device and an equal number of carefully matched AF patients on oral anticoagulation.

Disclosures: The study presenter reported receiving research funds for the registry from the Swiss Heart Foundation and Abbott.

Opioid prescribing drops nationally, remains high in some counties

Opioid prescribing in the United States declined overall between 2010 and 2015, but remained stable or increased in some counties, according to a report from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The findings were published online in the CDC’s Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

“The bottom line remains: We have too many people getting too many prescriptions at too high a dose,” Anne Schuchat, MD, acting director of the CDC, said in a July 6 teleconference.

CDC researchers calculated prescribing rates from 2006 to 2015 by dividing the number of opioid prescriptions by the population estimates from the U.S. census for each year and created quartiles using morphine milligram equivalent per capita to analyze opioid distribution. Annual opioid prescribing rates increased from 72 to 81 prescriptions per 100 persons from 2006 to 2010 and remained relatively constant from 2010 to 2012 before showing a 13% decrease to 71 prescriptions per 100 persons from 2012 to 2015 (MMWR. 2017 Jul 7;66[26]:697-704. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6626a4).

But despite these overall declines, “We are now experiencing the highest overdose death rates ever recorded in the United States,” Dr. Schuchat said. Quartiles were created using MME per capita to characterize the distribution of opioids prescribed.

In the report, areas associated with higher opioid prescribing rates on a county level included small cities or towns, areas that had a higher proportion of white residents, areas with more doctors and dentists, and areas with more cases of arthritis, diabetes, or other disabilities, she said.

The findings suggest a need for more consistency among health care providers about prescription opioids, Dr. Schuchat said. “Clinical practice is all over the place, which is a sign that you need better standards; we hope the 2016 guidelines are a turning point for better prescribing,” she said.

The CDC’s guidelines on opioid prescribing were released in 2016. The guidelines recommend alternatives when possible. Clinicians should instead consider nonopioid therapy, other types of pain medication, and nondrug pain relief options, such as physical therapy and cognitive-behavioral therapy. Other concerns include the length and strength of opioid prescriptions. Even taking opioids for a few months increases the risk for addiction, Dr. Schuchat said.

“Physicians must continue to lead efforts to reverse the epidemic by using prescription drug–monitoring programs, eliminating stigma, prescribing the overdose reversal drug naloxone, and enhancing their education about safe opioid prescribing and effective pain management,” Patrice A. Harris, MD, chair of the American Medical Association Opioid Task Force, said in a statement in response to the report. “Our country must do more to provide evidence-based, comprehensive treatment for pain and for substance use disorders,” she said.

“We really encourage clinicians to look to the guidelines and the tools that are available,” Dr. Schuchat said. “We do know that internists and other primary care physicians prescribe most of the opioids, so it is important for them to be aware.” The CDC has developed a checklist and a mobile app that have been downloaded by thousands of clinicians so far, she noted. Changes in annual prescribing hold promise that practices can improve, she said.

The researchers reported no conflicts of interest.

Opioid prescribing in the United States declined overall between 2010 and 2015, but remained stable or increased in some counties, according to a report from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The findings were published online in the CDC’s Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

“The bottom line remains: We have too many people getting too many prescriptions at too high a dose,” Anne Schuchat, MD, acting director of the CDC, said in a July 6 teleconference.

CDC researchers calculated prescribing rates from 2006 to 2015 by dividing the number of opioid prescriptions by the population estimates from the U.S. census for each year and created quartiles using morphine milligram equivalent per capita to analyze opioid distribution. Annual opioid prescribing rates increased from 72 to 81 prescriptions per 100 persons from 2006 to 2010 and remained relatively constant from 2010 to 2012 before showing a 13% decrease to 71 prescriptions per 100 persons from 2012 to 2015 (MMWR. 2017 Jul 7;66[26]:697-704. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6626a4).

But despite these overall declines, “We are now experiencing the highest overdose death rates ever recorded in the United States,” Dr. Schuchat said. Quartiles were created using MME per capita to characterize the distribution of opioids prescribed.

In the report, areas associated with higher opioid prescribing rates on a county level included small cities or towns, areas that had a higher proportion of white residents, areas with more doctors and dentists, and areas with more cases of arthritis, diabetes, or other disabilities, she said.

The findings suggest a need for more consistency among health care providers about prescription opioids, Dr. Schuchat said. “Clinical practice is all over the place, which is a sign that you need better standards; we hope the 2016 guidelines are a turning point for better prescribing,” she said.

The CDC’s guidelines on opioid prescribing were released in 2016. The guidelines recommend alternatives when possible. Clinicians should instead consider nonopioid therapy, other types of pain medication, and nondrug pain relief options, such as physical therapy and cognitive-behavioral therapy. Other concerns include the length and strength of opioid prescriptions. Even taking opioids for a few months increases the risk for addiction, Dr. Schuchat said.

“Physicians must continue to lead efforts to reverse the epidemic by using prescription drug–monitoring programs, eliminating stigma, prescribing the overdose reversal drug naloxone, and enhancing their education about safe opioid prescribing and effective pain management,” Patrice A. Harris, MD, chair of the American Medical Association Opioid Task Force, said in a statement in response to the report. “Our country must do more to provide evidence-based, comprehensive treatment for pain and for substance use disorders,” she said.

“We really encourage clinicians to look to the guidelines and the tools that are available,” Dr. Schuchat said. “We do know that internists and other primary care physicians prescribe most of the opioids, so it is important for them to be aware.” The CDC has developed a checklist and a mobile app that have been downloaded by thousands of clinicians so far, she noted. Changes in annual prescribing hold promise that practices can improve, she said.

The researchers reported no conflicts of interest.

Opioid prescribing in the United States declined overall between 2010 and 2015, but remained stable or increased in some counties, according to a report from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The findings were published online in the CDC’s Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

“The bottom line remains: We have too many people getting too many prescriptions at too high a dose,” Anne Schuchat, MD, acting director of the CDC, said in a July 6 teleconference.

CDC researchers calculated prescribing rates from 2006 to 2015 by dividing the number of opioid prescriptions by the population estimates from the U.S. census for each year and created quartiles using morphine milligram equivalent per capita to analyze opioid distribution. Annual opioid prescribing rates increased from 72 to 81 prescriptions per 100 persons from 2006 to 2010 and remained relatively constant from 2010 to 2012 before showing a 13% decrease to 71 prescriptions per 100 persons from 2012 to 2015 (MMWR. 2017 Jul 7;66[26]:697-704. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6626a4).

But despite these overall declines, “We are now experiencing the highest overdose death rates ever recorded in the United States,” Dr. Schuchat said. Quartiles were created using MME per capita to characterize the distribution of opioids prescribed.

In the report, areas associated with higher opioid prescribing rates on a county level included small cities or towns, areas that had a higher proportion of white residents, areas with more doctors and dentists, and areas with more cases of arthritis, diabetes, or other disabilities, she said.

The findings suggest a need for more consistency among health care providers about prescription opioids, Dr. Schuchat said. “Clinical practice is all over the place, which is a sign that you need better standards; we hope the 2016 guidelines are a turning point for better prescribing,” she said.

The CDC’s guidelines on opioid prescribing were released in 2016. The guidelines recommend alternatives when possible. Clinicians should instead consider nonopioid therapy, other types of pain medication, and nondrug pain relief options, such as physical therapy and cognitive-behavioral therapy. Other concerns include the length and strength of opioid prescriptions. Even taking opioids for a few months increases the risk for addiction, Dr. Schuchat said.

“Physicians must continue to lead efforts to reverse the epidemic by using prescription drug–monitoring programs, eliminating stigma, prescribing the overdose reversal drug naloxone, and enhancing their education about safe opioid prescribing and effective pain management,” Patrice A. Harris, MD, chair of the American Medical Association Opioid Task Force, said in a statement in response to the report. “Our country must do more to provide evidence-based, comprehensive treatment for pain and for substance use disorders,” she said.

“We really encourage clinicians to look to the guidelines and the tools that are available,” Dr. Schuchat said. “We do know that internists and other primary care physicians prescribe most of the opioids, so it is important for them to be aware.” The CDC has developed a checklist and a mobile app that have been downloaded by thousands of clinicians so far, she noted. Changes in annual prescribing hold promise that practices can improve, she said.

The researchers reported no conflicts of interest.

FROM MMWR

Pediatrics Committee’s role amplified with subspecialty’s evolution

Editor’s note: Each month, SHM puts the spotlight on some of our most active members who are making substantial contributions to hospital medicine. For more information on how you can lend your expertise to help SHM improve the care of hospitalized patients, log on to www.hospitalmedicine.org/getinvolved.

This month, The Hospitalist spotlights Sandra Gage, MD, PhD, SFHM, associate professor of pediatrics in the section of hospital medicine at the Medical College of Wisconsin, newly appointed chair of SHM’s Pediatrics Committee, and SHM member of almost 20 years.

Why did you choose a career in pediatric hospital medicine, and how did you become an SHM member?