User login

CDC: Vaccinated? You don’t need a mask indoors

the CDC announced on May 13.

“Anyone who is fully vaccinated can participate in indoor and outdoor activities, large or small, without wearing a mask or physically distancing,” CDC director Rochelle Walensky, MD, said at a press briefing. “We have all longed for this moment when we can get back to some sense of normalcy.

“This is an exciting and powerful moment,” she added, “It could only happen because of the work from so many who made sure we had the rapid administration of three safe and effective vaccines.”

Dr. Walensky cited three large studies on the effectiveness of COVID-19 vaccines against the original virus and its variants. One study from Israel found the vaccine to be 97% effective against symptomatic infection.

Those who are symptomatic should still wear masks, Dr. Walensky said, and those who are immunocompromised should talk to their doctors for further guidance. The CDC still advises travelers to wear masks while on airplanes or trains.

The COVID-19 death rates are now the lowest they have been since April 2020.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

the CDC announced on May 13.

“Anyone who is fully vaccinated can participate in indoor and outdoor activities, large or small, without wearing a mask or physically distancing,” CDC director Rochelle Walensky, MD, said at a press briefing. “We have all longed for this moment when we can get back to some sense of normalcy.

“This is an exciting and powerful moment,” she added, “It could only happen because of the work from so many who made sure we had the rapid administration of three safe and effective vaccines.”

Dr. Walensky cited three large studies on the effectiveness of COVID-19 vaccines against the original virus and its variants. One study from Israel found the vaccine to be 97% effective against symptomatic infection.

Those who are symptomatic should still wear masks, Dr. Walensky said, and those who are immunocompromised should talk to their doctors for further guidance. The CDC still advises travelers to wear masks while on airplanes or trains.

The COVID-19 death rates are now the lowest they have been since April 2020.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

the CDC announced on May 13.

“Anyone who is fully vaccinated can participate in indoor and outdoor activities, large or small, without wearing a mask or physically distancing,” CDC director Rochelle Walensky, MD, said at a press briefing. “We have all longed for this moment when we can get back to some sense of normalcy.

“This is an exciting and powerful moment,” she added, “It could only happen because of the work from so many who made sure we had the rapid administration of three safe and effective vaccines.”

Dr. Walensky cited three large studies on the effectiveness of COVID-19 vaccines against the original virus and its variants. One study from Israel found the vaccine to be 97% effective against symptomatic infection.

Those who are symptomatic should still wear masks, Dr. Walensky said, and those who are immunocompromised should talk to their doctors for further guidance. The CDC still advises travelers to wear masks while on airplanes or trains.

The COVID-19 death rates are now the lowest they have been since April 2020.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Trends in hospital medicine program operations during COVID-19

Staffing was a challenge for most groups

What a year it has been in the world of hospital medicine with all the changes, challenges, and uncertainties surrounding the COVID-19 pandemic. Some hospitalist programs were hit hard early on with an early surge, when little was known about COVID-19, and other programs have had more time to plan and adapt to later surges.

As many readers of The Hospitalist know, the Society of Hospital Medicine publishes a biennial State of Hospital Medicine (SoHM) Report – last published in September 2020 using data from 2019. The SoHM Report contains a wealth of information that many groups find useful in evaluating their programs, with topics ranging from compensation to staffing to scheduling. As some prior months’ Survey Insights columns have alluded to, with the rapid pace of change in 2020 because of the COVID-19 pandemic, the Society of Hospital Medicine made the decision to publish an addendum highlighting the myriad of adjustments and adaptations that have occurred in such a short period of time. The COVID-19 Addendum is available to all purchasers of the SoHM Report and contains data from survey responses submitted in September 2020.

Let’s take a look at what transpired in 2020, starting with staffing – no doubt a challenge for many groups. During some periods of time, patient volumes may have fallen below historical averages with stay-at-home orders, canceled procedures, and a reluctance by patients to seek medical care. In contrast, for many groups, other parts of the year were all-hands-on-deck scenarios to care for extraordinary surges in patient volume. To compound this, many hospitalist groups had physicians and staff facing quarantine or isolation requirements because of exposures or contracting COVID-19, and locums positions may have been difficult to fill because of travel restrictions and extreme demand.

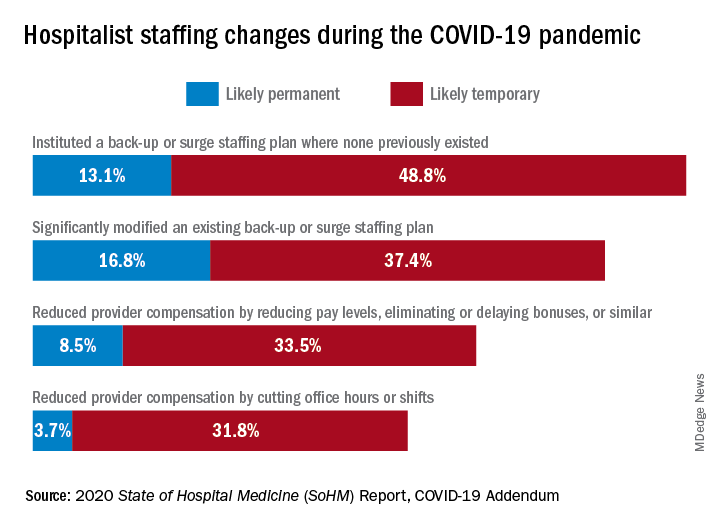

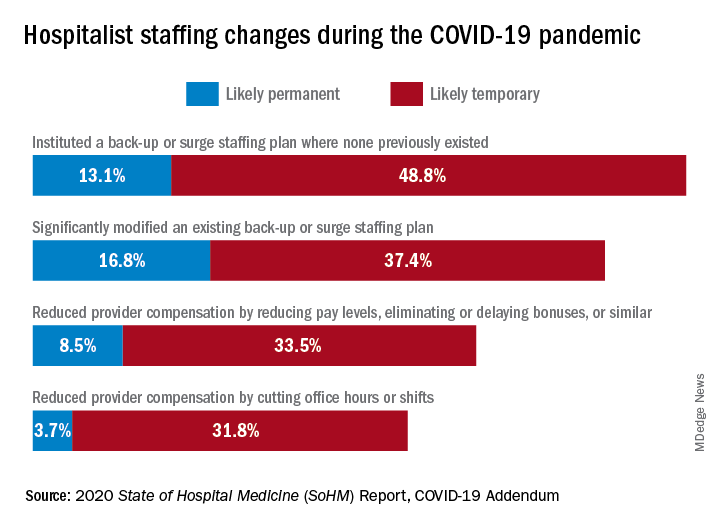

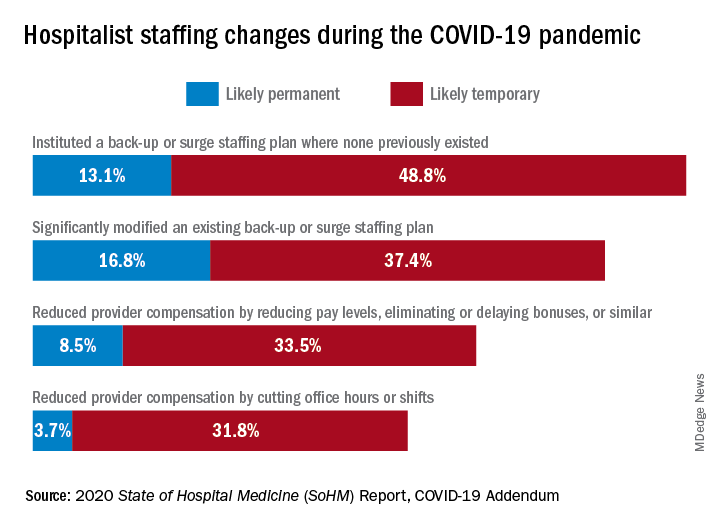

What operational changes were made in response to these staffing challenges? Perhaps one notable finding from the COVID-19 Addendum was the need for contingency planning and backup systems. From the 2020 SoHM, prior to the pandemic, 47.4% of adult hospital medicine groups had backup systems in place. In our recently published addendum, we found that 61.9% of groups instituted a backup system where none previously existed. In addition, 54.2% of groups modified their existing backup system. Some 39.6% of hospital medicine groups also utilized clinicians from other service lines to help cover service needs.

Aside from staffing, hospitals faced unprecedented financial challenges, and these effects rippled through to hospitalists. Our addendum found that 42.0% of hospitalist groups faced reductions in salary or bonuses, and 35.5% of hospital medicine groups reduced provider compensation by a reduction of work hours or shifts. I’ve personally been struck by these findings – that many hospitalists at the front-lines of COVID-19 received salary reductions, albeit temporary for many groups, during one of the most challenging years of their professional careers. Our addendum, interestingly, also found that a smaller 10.7% of groups instituted hazard pay for clinicians caring for COVID-19 patients.

So, are the changes and challenges your group faced similar to what was experienced by other hospital medicine programs? These findings and many more interesting and useful pieces of data are available in the full COVID-19 Addendum. Perhaps my biggest takeaway is that hospitalists have been perhaps the most uniquely positioned specialty to tackle the challenges of the COVID-19 pandemic. We have always been a dynamic, changing field, ready to lead and tackle change – and while change may have happened more quickly and in ways that were unforeseen just a year ago, hospitalists have undoubtedly demonstrated their strengths as leaders ready to adapt and rise to the occasion.

I am optimistic that, as we move beyond the pandemic in the coming months and years, the value that hospitalists have proven yet again will yield long-term recognition and benefits to our programs and our specialty.

Dr. Huang is a physician adviser and clinical professor of medicine in the division of hospital medicine at the University of California, San Diego. He is a member of SHM’s Practice Analysis Committee.

Staffing was a challenge for most groups

Staffing was a challenge for most groups

What a year it has been in the world of hospital medicine with all the changes, challenges, and uncertainties surrounding the COVID-19 pandemic. Some hospitalist programs were hit hard early on with an early surge, when little was known about COVID-19, and other programs have had more time to plan and adapt to later surges.

As many readers of The Hospitalist know, the Society of Hospital Medicine publishes a biennial State of Hospital Medicine (SoHM) Report – last published in September 2020 using data from 2019. The SoHM Report contains a wealth of information that many groups find useful in evaluating their programs, with topics ranging from compensation to staffing to scheduling. As some prior months’ Survey Insights columns have alluded to, with the rapid pace of change in 2020 because of the COVID-19 pandemic, the Society of Hospital Medicine made the decision to publish an addendum highlighting the myriad of adjustments and adaptations that have occurred in such a short period of time. The COVID-19 Addendum is available to all purchasers of the SoHM Report and contains data from survey responses submitted in September 2020.

Let’s take a look at what transpired in 2020, starting with staffing – no doubt a challenge for many groups. During some periods of time, patient volumes may have fallen below historical averages with stay-at-home orders, canceled procedures, and a reluctance by patients to seek medical care. In contrast, for many groups, other parts of the year were all-hands-on-deck scenarios to care for extraordinary surges in patient volume. To compound this, many hospitalist groups had physicians and staff facing quarantine or isolation requirements because of exposures or contracting COVID-19, and locums positions may have been difficult to fill because of travel restrictions and extreme demand.

What operational changes were made in response to these staffing challenges? Perhaps one notable finding from the COVID-19 Addendum was the need for contingency planning and backup systems. From the 2020 SoHM, prior to the pandemic, 47.4% of adult hospital medicine groups had backup systems in place. In our recently published addendum, we found that 61.9% of groups instituted a backup system where none previously existed. In addition, 54.2% of groups modified their existing backup system. Some 39.6% of hospital medicine groups also utilized clinicians from other service lines to help cover service needs.

Aside from staffing, hospitals faced unprecedented financial challenges, and these effects rippled through to hospitalists. Our addendum found that 42.0% of hospitalist groups faced reductions in salary or bonuses, and 35.5% of hospital medicine groups reduced provider compensation by a reduction of work hours or shifts. I’ve personally been struck by these findings – that many hospitalists at the front-lines of COVID-19 received salary reductions, albeit temporary for many groups, during one of the most challenging years of their professional careers. Our addendum, interestingly, also found that a smaller 10.7% of groups instituted hazard pay for clinicians caring for COVID-19 patients.

So, are the changes and challenges your group faced similar to what was experienced by other hospital medicine programs? These findings and many more interesting and useful pieces of data are available in the full COVID-19 Addendum. Perhaps my biggest takeaway is that hospitalists have been perhaps the most uniquely positioned specialty to tackle the challenges of the COVID-19 pandemic. We have always been a dynamic, changing field, ready to lead and tackle change – and while change may have happened more quickly and in ways that were unforeseen just a year ago, hospitalists have undoubtedly demonstrated their strengths as leaders ready to adapt and rise to the occasion.

I am optimistic that, as we move beyond the pandemic in the coming months and years, the value that hospitalists have proven yet again will yield long-term recognition and benefits to our programs and our specialty.

Dr. Huang is a physician adviser and clinical professor of medicine in the division of hospital medicine at the University of California, San Diego. He is a member of SHM’s Practice Analysis Committee.

What a year it has been in the world of hospital medicine with all the changes, challenges, and uncertainties surrounding the COVID-19 pandemic. Some hospitalist programs were hit hard early on with an early surge, when little was known about COVID-19, and other programs have had more time to plan and adapt to later surges.

As many readers of The Hospitalist know, the Society of Hospital Medicine publishes a biennial State of Hospital Medicine (SoHM) Report – last published in September 2020 using data from 2019. The SoHM Report contains a wealth of information that many groups find useful in evaluating their programs, with topics ranging from compensation to staffing to scheduling. As some prior months’ Survey Insights columns have alluded to, with the rapid pace of change in 2020 because of the COVID-19 pandemic, the Society of Hospital Medicine made the decision to publish an addendum highlighting the myriad of adjustments and adaptations that have occurred in such a short period of time. The COVID-19 Addendum is available to all purchasers of the SoHM Report and contains data from survey responses submitted in September 2020.

Let’s take a look at what transpired in 2020, starting with staffing – no doubt a challenge for many groups. During some periods of time, patient volumes may have fallen below historical averages with stay-at-home orders, canceled procedures, and a reluctance by patients to seek medical care. In contrast, for many groups, other parts of the year were all-hands-on-deck scenarios to care for extraordinary surges in patient volume. To compound this, many hospitalist groups had physicians and staff facing quarantine or isolation requirements because of exposures or contracting COVID-19, and locums positions may have been difficult to fill because of travel restrictions and extreme demand.

What operational changes were made in response to these staffing challenges? Perhaps one notable finding from the COVID-19 Addendum was the need for contingency planning and backup systems. From the 2020 SoHM, prior to the pandemic, 47.4% of adult hospital medicine groups had backup systems in place. In our recently published addendum, we found that 61.9% of groups instituted a backup system where none previously existed. In addition, 54.2% of groups modified their existing backup system. Some 39.6% of hospital medicine groups also utilized clinicians from other service lines to help cover service needs.

Aside from staffing, hospitals faced unprecedented financial challenges, and these effects rippled through to hospitalists. Our addendum found that 42.0% of hospitalist groups faced reductions in salary or bonuses, and 35.5% of hospital medicine groups reduced provider compensation by a reduction of work hours or shifts. I’ve personally been struck by these findings – that many hospitalists at the front-lines of COVID-19 received salary reductions, albeit temporary for many groups, during one of the most challenging years of their professional careers. Our addendum, interestingly, also found that a smaller 10.7% of groups instituted hazard pay for clinicians caring for COVID-19 patients.

So, are the changes and challenges your group faced similar to what was experienced by other hospital medicine programs? These findings and many more interesting and useful pieces of data are available in the full COVID-19 Addendum. Perhaps my biggest takeaway is that hospitalists have been perhaps the most uniquely positioned specialty to tackle the challenges of the COVID-19 pandemic. We have always been a dynamic, changing field, ready to lead and tackle change – and while change may have happened more quickly and in ways that were unforeseen just a year ago, hospitalists have undoubtedly demonstrated their strengths as leaders ready to adapt and rise to the occasion.

I am optimistic that, as we move beyond the pandemic in the coming months and years, the value that hospitalists have proven yet again will yield long-term recognition and benefits to our programs and our specialty.

Dr. Huang is a physician adviser and clinical professor of medicine in the division of hospital medicine at the University of California, San Diego. He is a member of SHM’s Practice Analysis Committee.

Smart prescribing strategies improve antibiotic stewardship

“Antibiotic stewardship is never easy, and sometimes it is very difficult to differentiate what is going on with a patient in the clinical setting,” said Valerie M. Vaughn, MD, of the University of Utah, Salt Lake City, at SHM Converge, the annual conference of the Society of Hospital Medicine.

“We know from studies that 20% of hospitalized patients who receive an antibiotic have an adverse drug event from that antibiotic within 30 days,” said Dr. Vaughn.

Dr. Vaughn identified several practical ways in which hospitalists can reduce antibiotic overuse, including in the management of patients hospitalized with COVID-19.

Identify asymptomatic bacteriuria

One key area in which hospitalists can improve antibiotic stewardship is in recognizing asymptomatic bacteriuria and the harms associated with treatment, Dr. Vaughn said. For example, a common scenario for hospitalists might involve and 80-year-old woman with dementia, who can provide little in the way of history, and whose chest x-ray can’t rule out an underlying infection. This patient might have a positive urine culture, but no other signs of a urinary tract infection. “We know that asymptomatic bacteriuria is very common in hospitalized patients,” especially elderly women living in nursing home settings, she noted.

In cases of asymptomatic bacteriuria, data show that antibiotic treatment does not improve outcomes, and in fact may increase the risk of subsequent UTI, said Dr. Vaughn. Elderly patients also are at increased risk for developing antibiotic-related adverse events, especially Clostridioides difficile. Asymptomatic bacteriuria is any bacteria in the urine in the absence of signs or symptoms of a UTI, even if lab tests show pyuria, nitrates, and resistant bacteria. These lab results are often associated with inappropriate antibiotic use. “The laboratory tests can’t distinguish between asymptomatic bacteriuria and a UTI, only the symptoms can,” she emphasized.

Contain treatment of community-acquired pneumonia

Another practical point for reducing antibiotics in the hospital setting is to limit treatment of community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) to 5 days when possible. Duration matters because for many diseases, shorter durations of antibiotic treatments are just as effective as longer durations based on the latest evidence. “This is a change in dogma,” from previous thinking that patients must complete a full course, and that anything less might promote antibiotic resistance, she said.

“In fact, longer antibiotic durations kill off more healthy, normal flora, select for resistant pathogens, increase the risk of C. difficile, and increase the risk of side effects,” she said.

Ultimately, the right treatment duration for pneumonia depends on several factors including patient factors, disease, clinical stability, and rate of improvement. However, a good rule of thumb is that approximately 89% of CAP patients need only 5 days of antibiotics as long as they are afebrile for 48 hours and have 1 or fewer vital sign abnormalities by day 5 of treatment. “We do need to prescribe longer durations for patients with complications,” she emphasized.

Revisit need for antibiotics at discharge

Hospitalists also can practice antibiotic stewardship by considering four points at patient discharge, said Dr. Vaughn.

First, consider whether antibiotics can be stopped. For example, antibiotics are not needed on discharge if infection is no longer the most likely diagnosis, or if the course of antibiotics has been completed, as is often the case for patients hospitalized with CAP, she noted.

Second, if the antibiotics can’t be stopped at the time of discharge, consider whether the preferred agent is being used. Third, be sure the patient is receiving the minimum duration of antibiotics, and fourth, be sure that the dose, indication, and total planned duration with start and stop dates is written in the discharge summary, said Dr. Vaughn. “This helps with communication to our outpatient providers as well as with education to the patients themselves.”

Bacterial coinfections rare in COVID-19

Dr. Vaughn concluded the session with data from a study she conducted with colleagues on the use of empiric antibacterial therapy and community-onset bacterial coinfection in hospitalized COVID-19 patients. The study included 1,667 patients at 32 hospitals in Michigan. The number of patients treated with antibiotics varied widely among hospitals, from 30% to as much as 90%, Dr. Vaughn said.

“What we found was that more than half of hospitalized patients with COVID (57%) received empiric antibiotic therapy in the first few days of hospitalization,” she said.

However, “despite all the antibiotic use, community-onset bacterial coinfections were rare,” and occurred in only 3.5% of the patients, meaning that the number needed to treat with antibiotics to prevent a single case was about 20.

Predictors of community-onset co-infections in the patients included older age, more severe disease, patients coming from nursing homes, and those with lower BMI or kidney disease, said Dr. Vaughn. She and her team also found that procalcitonin’s positive predictive value was 9.3%, but the negative predictive value was 98.3%, so these patients were extremely likely to have no coinfection.

Dr. Vaughn said that in her practice she might order procalcitonin when considering stopping antibiotics in a patient with COVID-19 and make a decision based on the negative predictive value, but she emphasized that she does not use it in the converse situation to rely on a positive value when deciding whether to start antibiotics in these patients.

Dr. Vaughn had no financial conflicts to disclose.

“Antibiotic stewardship is never easy, and sometimes it is very difficult to differentiate what is going on with a patient in the clinical setting,” said Valerie M. Vaughn, MD, of the University of Utah, Salt Lake City, at SHM Converge, the annual conference of the Society of Hospital Medicine.

“We know from studies that 20% of hospitalized patients who receive an antibiotic have an adverse drug event from that antibiotic within 30 days,” said Dr. Vaughn.

Dr. Vaughn identified several practical ways in which hospitalists can reduce antibiotic overuse, including in the management of patients hospitalized with COVID-19.

Identify asymptomatic bacteriuria

One key area in which hospitalists can improve antibiotic stewardship is in recognizing asymptomatic bacteriuria and the harms associated with treatment, Dr. Vaughn said. For example, a common scenario for hospitalists might involve and 80-year-old woman with dementia, who can provide little in the way of history, and whose chest x-ray can’t rule out an underlying infection. This patient might have a positive urine culture, but no other signs of a urinary tract infection. “We know that asymptomatic bacteriuria is very common in hospitalized patients,” especially elderly women living in nursing home settings, she noted.

In cases of asymptomatic bacteriuria, data show that antibiotic treatment does not improve outcomes, and in fact may increase the risk of subsequent UTI, said Dr. Vaughn. Elderly patients also are at increased risk for developing antibiotic-related adverse events, especially Clostridioides difficile. Asymptomatic bacteriuria is any bacteria in the urine in the absence of signs or symptoms of a UTI, even if lab tests show pyuria, nitrates, and resistant bacteria. These lab results are often associated with inappropriate antibiotic use. “The laboratory tests can’t distinguish between asymptomatic bacteriuria and a UTI, only the symptoms can,” she emphasized.

Contain treatment of community-acquired pneumonia

Another practical point for reducing antibiotics in the hospital setting is to limit treatment of community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) to 5 days when possible. Duration matters because for many diseases, shorter durations of antibiotic treatments are just as effective as longer durations based on the latest evidence. “This is a change in dogma,” from previous thinking that patients must complete a full course, and that anything less might promote antibiotic resistance, she said.

“In fact, longer antibiotic durations kill off more healthy, normal flora, select for resistant pathogens, increase the risk of C. difficile, and increase the risk of side effects,” she said.

Ultimately, the right treatment duration for pneumonia depends on several factors including patient factors, disease, clinical stability, and rate of improvement. However, a good rule of thumb is that approximately 89% of CAP patients need only 5 days of antibiotics as long as they are afebrile for 48 hours and have 1 or fewer vital sign abnormalities by day 5 of treatment. “We do need to prescribe longer durations for patients with complications,” she emphasized.

Revisit need for antibiotics at discharge

Hospitalists also can practice antibiotic stewardship by considering four points at patient discharge, said Dr. Vaughn.

First, consider whether antibiotics can be stopped. For example, antibiotics are not needed on discharge if infection is no longer the most likely diagnosis, or if the course of antibiotics has been completed, as is often the case for patients hospitalized with CAP, she noted.

Second, if the antibiotics can’t be stopped at the time of discharge, consider whether the preferred agent is being used. Third, be sure the patient is receiving the minimum duration of antibiotics, and fourth, be sure that the dose, indication, and total planned duration with start and stop dates is written in the discharge summary, said Dr. Vaughn. “This helps with communication to our outpatient providers as well as with education to the patients themselves.”

Bacterial coinfections rare in COVID-19

Dr. Vaughn concluded the session with data from a study she conducted with colleagues on the use of empiric antibacterial therapy and community-onset bacterial coinfection in hospitalized COVID-19 patients. The study included 1,667 patients at 32 hospitals in Michigan. The number of patients treated with antibiotics varied widely among hospitals, from 30% to as much as 90%, Dr. Vaughn said.

“What we found was that more than half of hospitalized patients with COVID (57%) received empiric antibiotic therapy in the first few days of hospitalization,” she said.

However, “despite all the antibiotic use, community-onset bacterial coinfections were rare,” and occurred in only 3.5% of the patients, meaning that the number needed to treat with antibiotics to prevent a single case was about 20.

Predictors of community-onset co-infections in the patients included older age, more severe disease, patients coming from nursing homes, and those with lower BMI or kidney disease, said Dr. Vaughn. She and her team also found that procalcitonin’s positive predictive value was 9.3%, but the negative predictive value was 98.3%, so these patients were extremely likely to have no coinfection.

Dr. Vaughn said that in her practice she might order procalcitonin when considering stopping antibiotics in a patient with COVID-19 and make a decision based on the negative predictive value, but she emphasized that she does not use it in the converse situation to rely on a positive value when deciding whether to start antibiotics in these patients.

Dr. Vaughn had no financial conflicts to disclose.

“Antibiotic stewardship is never easy, and sometimes it is very difficult to differentiate what is going on with a patient in the clinical setting,” said Valerie M. Vaughn, MD, of the University of Utah, Salt Lake City, at SHM Converge, the annual conference of the Society of Hospital Medicine.

“We know from studies that 20% of hospitalized patients who receive an antibiotic have an adverse drug event from that antibiotic within 30 days,” said Dr. Vaughn.

Dr. Vaughn identified several practical ways in which hospitalists can reduce antibiotic overuse, including in the management of patients hospitalized with COVID-19.

Identify asymptomatic bacteriuria

One key area in which hospitalists can improve antibiotic stewardship is in recognizing asymptomatic bacteriuria and the harms associated with treatment, Dr. Vaughn said. For example, a common scenario for hospitalists might involve and 80-year-old woman with dementia, who can provide little in the way of history, and whose chest x-ray can’t rule out an underlying infection. This patient might have a positive urine culture, but no other signs of a urinary tract infection. “We know that asymptomatic bacteriuria is very common in hospitalized patients,” especially elderly women living in nursing home settings, she noted.

In cases of asymptomatic bacteriuria, data show that antibiotic treatment does not improve outcomes, and in fact may increase the risk of subsequent UTI, said Dr. Vaughn. Elderly patients also are at increased risk for developing antibiotic-related adverse events, especially Clostridioides difficile. Asymptomatic bacteriuria is any bacteria in the urine in the absence of signs or symptoms of a UTI, even if lab tests show pyuria, nitrates, and resistant bacteria. These lab results are often associated with inappropriate antibiotic use. “The laboratory tests can’t distinguish between asymptomatic bacteriuria and a UTI, only the symptoms can,” she emphasized.

Contain treatment of community-acquired pneumonia

Another practical point for reducing antibiotics in the hospital setting is to limit treatment of community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) to 5 days when possible. Duration matters because for many diseases, shorter durations of antibiotic treatments are just as effective as longer durations based on the latest evidence. “This is a change in dogma,” from previous thinking that patients must complete a full course, and that anything less might promote antibiotic resistance, she said.

“In fact, longer antibiotic durations kill off more healthy, normal flora, select for resistant pathogens, increase the risk of C. difficile, and increase the risk of side effects,” she said.

Ultimately, the right treatment duration for pneumonia depends on several factors including patient factors, disease, clinical stability, and rate of improvement. However, a good rule of thumb is that approximately 89% of CAP patients need only 5 days of antibiotics as long as they are afebrile for 48 hours and have 1 or fewer vital sign abnormalities by day 5 of treatment. “We do need to prescribe longer durations for patients with complications,” she emphasized.

Revisit need for antibiotics at discharge

Hospitalists also can practice antibiotic stewardship by considering four points at patient discharge, said Dr. Vaughn.

First, consider whether antibiotics can be stopped. For example, antibiotics are not needed on discharge if infection is no longer the most likely diagnosis, or if the course of antibiotics has been completed, as is often the case for patients hospitalized with CAP, she noted.

Second, if the antibiotics can’t be stopped at the time of discharge, consider whether the preferred agent is being used. Third, be sure the patient is receiving the minimum duration of antibiotics, and fourth, be sure that the dose, indication, and total planned duration with start and stop dates is written in the discharge summary, said Dr. Vaughn. “This helps with communication to our outpatient providers as well as with education to the patients themselves.”

Bacterial coinfections rare in COVID-19

Dr. Vaughn concluded the session with data from a study she conducted with colleagues on the use of empiric antibacterial therapy and community-onset bacterial coinfection in hospitalized COVID-19 patients. The study included 1,667 patients at 32 hospitals in Michigan. The number of patients treated with antibiotics varied widely among hospitals, from 30% to as much as 90%, Dr. Vaughn said.

“What we found was that more than half of hospitalized patients with COVID (57%) received empiric antibiotic therapy in the first few days of hospitalization,” she said.

However, “despite all the antibiotic use, community-onset bacterial coinfections were rare,” and occurred in only 3.5% of the patients, meaning that the number needed to treat with antibiotics to prevent a single case was about 20.

Predictors of community-onset co-infections in the patients included older age, more severe disease, patients coming from nursing homes, and those with lower BMI or kidney disease, said Dr. Vaughn. She and her team also found that procalcitonin’s positive predictive value was 9.3%, but the negative predictive value was 98.3%, so these patients were extremely likely to have no coinfection.

Dr. Vaughn said that in her practice she might order procalcitonin when considering stopping antibiotics in a patient with COVID-19 and make a decision based on the negative predictive value, but she emphasized that she does not use it in the converse situation to rely on a positive value when deciding whether to start antibiotics in these patients.

Dr. Vaughn had no financial conflicts to disclose.

FROM SHM CONVERGE 2021

Mentor-mentee relationships in hospital medicine

Your mentor has been looking for someone to help lead a new project in your division, and tells you she’s been having a hard time finding someone – but that you would be great. The project isn’t something you are very interested in doing and you’re already swamped with other projects, but the mentor seems to need the help. What do you do?

Mentor-mentee relationships can be deeply beneficial, but the dynamics – in this situation and many others – can be complex. At SHM Converge, the annual conference of the Society of Hospital Medicine, panelists offered guidance on how best to navigate this terrain.

Vineet Arora, MD, MAPP, MHM, associate chief medical officer for clinical learning environment at the University of Chicago, suggested that, in the situation involving the mentor’s request to an uncertain mentee, the mentee should not give an immediate answer, but consider the pros and cons.

“It’s tough when it’s somebody who’s directly overseeing you,” she said. “If you’re really truly the best person, they’re going to want you in the job, and maybe they’ll make it work for you.” She said it would be important to find out why the mentor is having trouble finding someone, and suggested the mentee could find someone with whom to discuss it.

Calling mentoring a “team sport,” Dr. Arora described several types: the traditional mentor who helps many aspects of a mentee’s career, a “coach” who helps on a specific project or topic, a “sponsor” that can help elevate a mentee to a bigger opportunity, and a “connector” who can help a mentee begin new career relationships.

“Don’t invest in just one person,” she said. “Try to get that personal board of directors.”

She mentioned six things all mentors should do: Choose mentees carefully, establish a mentorship team, run a tight ship, head off rifts or resolve them, prepare for transitions when they take a new position and might have a new relationship with a mentee, and don’t commit “mentorship malpractice.”

Mentoring is a two-way street, with both people benefiting and learning, but mentoring can have its troubles, either through active, dysfunctional behavior that’s easy to spot, or passive behavior, such as the “bottleneck” problem when a mentor is too preoccupied with his or her own priorities to mentor well, the “country clubber” who mentors only for popularity and social capital but doesn’t do the work required, and the “world traveler” who is sought after but has little time for day-to-day mentoring.

Valerie Vaughan, MD, MSc, assistant professor of medicine at the University of Utah, described four “golden rules” of being a mentee. First, find a CAPE mentor (for capable, availability, projects of interest, and easy to get along with). Then, be respectful of a mentor’s time, communicate effectively, and be engaged and energizing.

“Mentors typically don’t get paid to mentor and so a lot of them are doing it because they find joy for doing it,” Dr. Vaughan said. “So as much as you can as a mentee, try to be the person who brings energy to the mentor-mentee relationship. It’s up to you to drive projects forward.”

Valerie Press, MD, MPH, SFHM, associate professor of medicine at the University of Chicago, offered tips for men who are mentoring women. She said that, while cross-gender mentorship is common and important, gender-based stereotypes and “unconscious assumptions” are alive and well. Women, she noted, have less access to mentorship and sponsorship, are paid less for the same work, and have high rates of attrition.

Male mentors have to meet the challenge of thinking outside of their own lived experience, combating stereotypes, and addressing these gender-based career disparities, she said.

She suggested that male mentors, for one thing, “rewrite gender scripts,” with comments such as, “This is a difficult situation, but I have confidence in you! What do you think your next move should be?” They should also “learn from each other on how to change the power dynamic,” and start and participate in conversations involving emotions, since they can be clues to what a mentee is experiencing.

When it comes to pushing for better policies, “be an upstander, not a bystander,” Dr. Press said.

“Use your organizational power and your social capital,” she said. “Use your voice to help make more equitable policies. Don’t just leave it to the women’s committee to come up with solutions to lack of lactation rooms, or paternity and maternity leave, or better daycare. These are family issues and everybody issues.”

Maylyn S. Martinez, MD, clinical associate professor of medicine at the University of Chicago, suggested that mentors for physicians from minority groups should resist the tendency to view their interests narrowly.

“Don’t assume that their interests are going to center on their gender or minority status – invite them to be on projects that have nothing to do with that,” she said. They should also not be encouraged to do projects that won’t help with career advancement any more than others would be encouraged to take on such projects.

“Be the solution,” she said. “Not the problem.”

Your mentor has been looking for someone to help lead a new project in your division, and tells you she’s been having a hard time finding someone – but that you would be great. The project isn’t something you are very interested in doing and you’re already swamped with other projects, but the mentor seems to need the help. What do you do?

Mentor-mentee relationships can be deeply beneficial, but the dynamics – in this situation and many others – can be complex. At SHM Converge, the annual conference of the Society of Hospital Medicine, panelists offered guidance on how best to navigate this terrain.

Vineet Arora, MD, MAPP, MHM, associate chief medical officer for clinical learning environment at the University of Chicago, suggested that, in the situation involving the mentor’s request to an uncertain mentee, the mentee should not give an immediate answer, but consider the pros and cons.

“It’s tough when it’s somebody who’s directly overseeing you,” she said. “If you’re really truly the best person, they’re going to want you in the job, and maybe they’ll make it work for you.” She said it would be important to find out why the mentor is having trouble finding someone, and suggested the mentee could find someone with whom to discuss it.

Calling mentoring a “team sport,” Dr. Arora described several types: the traditional mentor who helps many aspects of a mentee’s career, a “coach” who helps on a specific project or topic, a “sponsor” that can help elevate a mentee to a bigger opportunity, and a “connector” who can help a mentee begin new career relationships.

“Don’t invest in just one person,” she said. “Try to get that personal board of directors.”

She mentioned six things all mentors should do: Choose mentees carefully, establish a mentorship team, run a tight ship, head off rifts or resolve them, prepare for transitions when they take a new position and might have a new relationship with a mentee, and don’t commit “mentorship malpractice.”

Mentoring is a two-way street, with both people benefiting and learning, but mentoring can have its troubles, either through active, dysfunctional behavior that’s easy to spot, or passive behavior, such as the “bottleneck” problem when a mentor is too preoccupied with his or her own priorities to mentor well, the “country clubber” who mentors only for popularity and social capital but doesn’t do the work required, and the “world traveler” who is sought after but has little time for day-to-day mentoring.

Valerie Vaughan, MD, MSc, assistant professor of medicine at the University of Utah, described four “golden rules” of being a mentee. First, find a CAPE mentor (for capable, availability, projects of interest, and easy to get along with). Then, be respectful of a mentor’s time, communicate effectively, and be engaged and energizing.

“Mentors typically don’t get paid to mentor and so a lot of them are doing it because they find joy for doing it,” Dr. Vaughan said. “So as much as you can as a mentee, try to be the person who brings energy to the mentor-mentee relationship. It’s up to you to drive projects forward.”

Valerie Press, MD, MPH, SFHM, associate professor of medicine at the University of Chicago, offered tips for men who are mentoring women. She said that, while cross-gender mentorship is common and important, gender-based stereotypes and “unconscious assumptions” are alive and well. Women, she noted, have less access to mentorship and sponsorship, are paid less for the same work, and have high rates of attrition.

Male mentors have to meet the challenge of thinking outside of their own lived experience, combating stereotypes, and addressing these gender-based career disparities, she said.

She suggested that male mentors, for one thing, “rewrite gender scripts,” with comments such as, “This is a difficult situation, but I have confidence in you! What do you think your next move should be?” They should also “learn from each other on how to change the power dynamic,” and start and participate in conversations involving emotions, since they can be clues to what a mentee is experiencing.

When it comes to pushing for better policies, “be an upstander, not a bystander,” Dr. Press said.

“Use your organizational power and your social capital,” she said. “Use your voice to help make more equitable policies. Don’t just leave it to the women’s committee to come up with solutions to lack of lactation rooms, or paternity and maternity leave, or better daycare. These are family issues and everybody issues.”

Maylyn S. Martinez, MD, clinical associate professor of medicine at the University of Chicago, suggested that mentors for physicians from minority groups should resist the tendency to view their interests narrowly.

“Don’t assume that their interests are going to center on their gender or minority status – invite them to be on projects that have nothing to do with that,” she said. They should also not be encouraged to do projects that won’t help with career advancement any more than others would be encouraged to take on such projects.

“Be the solution,” she said. “Not the problem.”

Your mentor has been looking for someone to help lead a new project in your division, and tells you she’s been having a hard time finding someone – but that you would be great. The project isn’t something you are very interested in doing and you’re already swamped with other projects, but the mentor seems to need the help. What do you do?

Mentor-mentee relationships can be deeply beneficial, but the dynamics – in this situation and many others – can be complex. At SHM Converge, the annual conference of the Society of Hospital Medicine, panelists offered guidance on how best to navigate this terrain.

Vineet Arora, MD, MAPP, MHM, associate chief medical officer for clinical learning environment at the University of Chicago, suggested that, in the situation involving the mentor’s request to an uncertain mentee, the mentee should not give an immediate answer, but consider the pros and cons.

“It’s tough when it’s somebody who’s directly overseeing you,” she said. “If you’re really truly the best person, they’re going to want you in the job, and maybe they’ll make it work for you.” She said it would be important to find out why the mentor is having trouble finding someone, and suggested the mentee could find someone with whom to discuss it.

Calling mentoring a “team sport,” Dr. Arora described several types: the traditional mentor who helps many aspects of a mentee’s career, a “coach” who helps on a specific project or topic, a “sponsor” that can help elevate a mentee to a bigger opportunity, and a “connector” who can help a mentee begin new career relationships.

“Don’t invest in just one person,” she said. “Try to get that personal board of directors.”

She mentioned six things all mentors should do: Choose mentees carefully, establish a mentorship team, run a tight ship, head off rifts or resolve them, prepare for transitions when they take a new position and might have a new relationship with a mentee, and don’t commit “mentorship malpractice.”

Mentoring is a two-way street, with both people benefiting and learning, but mentoring can have its troubles, either through active, dysfunctional behavior that’s easy to spot, or passive behavior, such as the “bottleneck” problem when a mentor is too preoccupied with his or her own priorities to mentor well, the “country clubber” who mentors only for popularity and social capital but doesn’t do the work required, and the “world traveler” who is sought after but has little time for day-to-day mentoring.

Valerie Vaughan, MD, MSc, assistant professor of medicine at the University of Utah, described four “golden rules” of being a mentee. First, find a CAPE mentor (for capable, availability, projects of interest, and easy to get along with). Then, be respectful of a mentor’s time, communicate effectively, and be engaged and energizing.

“Mentors typically don’t get paid to mentor and so a lot of them are doing it because they find joy for doing it,” Dr. Vaughan said. “So as much as you can as a mentee, try to be the person who brings energy to the mentor-mentee relationship. It’s up to you to drive projects forward.”

Valerie Press, MD, MPH, SFHM, associate professor of medicine at the University of Chicago, offered tips for men who are mentoring women. She said that, while cross-gender mentorship is common and important, gender-based stereotypes and “unconscious assumptions” are alive and well. Women, she noted, have less access to mentorship and sponsorship, are paid less for the same work, and have high rates of attrition.

Male mentors have to meet the challenge of thinking outside of their own lived experience, combating stereotypes, and addressing these gender-based career disparities, she said.

She suggested that male mentors, for one thing, “rewrite gender scripts,” with comments such as, “This is a difficult situation, but I have confidence in you! What do you think your next move should be?” They should also “learn from each other on how to change the power dynamic,” and start and participate in conversations involving emotions, since they can be clues to what a mentee is experiencing.

When it comes to pushing for better policies, “be an upstander, not a bystander,” Dr. Press said.

“Use your organizational power and your social capital,” she said. “Use your voice to help make more equitable policies. Don’t just leave it to the women’s committee to come up with solutions to lack of lactation rooms, or paternity and maternity leave, or better daycare. These are family issues and everybody issues.”

Maylyn S. Martinez, MD, clinical associate professor of medicine at the University of Chicago, suggested that mentors for physicians from minority groups should resist the tendency to view their interests narrowly.

“Don’t assume that their interests are going to center on their gender or minority status – invite them to be on projects that have nothing to do with that,” she said. They should also not be encouraged to do projects that won’t help with career advancement any more than others would be encouraged to take on such projects.

“Be the solution,” she said. “Not the problem.”

FROM SHM CONVERGE 2021

CDC recommends use of Pfizer’s COVID vaccine in 12- to 15-year-olds

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s director Rochelle Walensky, MD, signed off on an advisory panel’s recommendation May 12 endorsing the use of the Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine in adolescents aged 12-15 years.

Earlier in the day the CDC’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices voted 14-0 in favor of the safety and effectiveness of the vaccine in younger teens.

Dr. Walensky said in an official statement.

The Food and Drug Administration on May 10 issued an emergency use authorization (EUA) for the Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine for the prevention of COVID-19 in individuals 12-15 years old. The FDA first cleared the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine through an EUA in December 2020 for those ages 16 and older. Pfizer this month also initiated steps with the FDA toward a full approval of its vaccine.

Dr. Walenksy urged parents to seriously consider vaccinating their children.

“Understandably, some parents want more information before their children receive a vaccine,” she said. “I encourage parents with questions to talk to your child’s healthcare provider or your family doctor to learn more about the vaccine.”

Vaccine “safe and effective”

Separately, the American Academy of Pediatrics issued a statement May 12 in support of vaccinating all children ages 12 and older who are eligible for the federally authorized COVID-19 vaccine.

“As a pediatrician and a parent, I have looked forward to getting my own children and patients vaccinated, and I am thrilled that those ages 12 and older can now be protected,” said AAP President Lee Savio Beers, MD, in a statement. “The data continue to show that this vaccine is safe and effective. I urge all parents to call their pediatrician to learn more about how to get their children and teens vaccinated.”

The expanded clearance for the Pfizer vaccine is seen as a critical step for allowing teens to resume activities on which they missed out during the pandemic.

“We’ve seen the harm done to children’s mental and emotional health as they’ve missed out on so many experiences during the pandemic,” Dr. Beers said. “Vaccinating children will protect them and allow them to fully engage in all of the activities – school, sports, socializing with friends and family – that are so important to their health and development.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s director Rochelle Walensky, MD, signed off on an advisory panel’s recommendation May 12 endorsing the use of the Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine in adolescents aged 12-15 years.

Earlier in the day the CDC’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices voted 14-0 in favor of the safety and effectiveness of the vaccine in younger teens.

Dr. Walensky said in an official statement.

The Food and Drug Administration on May 10 issued an emergency use authorization (EUA) for the Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine for the prevention of COVID-19 in individuals 12-15 years old. The FDA first cleared the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine through an EUA in December 2020 for those ages 16 and older. Pfizer this month also initiated steps with the FDA toward a full approval of its vaccine.

Dr. Walenksy urged parents to seriously consider vaccinating their children.

“Understandably, some parents want more information before their children receive a vaccine,” she said. “I encourage parents with questions to talk to your child’s healthcare provider or your family doctor to learn more about the vaccine.”

Vaccine “safe and effective”

Separately, the American Academy of Pediatrics issued a statement May 12 in support of vaccinating all children ages 12 and older who are eligible for the federally authorized COVID-19 vaccine.

“As a pediatrician and a parent, I have looked forward to getting my own children and patients vaccinated, and I am thrilled that those ages 12 and older can now be protected,” said AAP President Lee Savio Beers, MD, in a statement. “The data continue to show that this vaccine is safe and effective. I urge all parents to call their pediatrician to learn more about how to get their children and teens vaccinated.”

The expanded clearance for the Pfizer vaccine is seen as a critical step for allowing teens to resume activities on which they missed out during the pandemic.

“We’ve seen the harm done to children’s mental and emotional health as they’ve missed out on so many experiences during the pandemic,” Dr. Beers said. “Vaccinating children will protect them and allow them to fully engage in all of the activities – school, sports, socializing with friends and family – that are so important to their health and development.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s director Rochelle Walensky, MD, signed off on an advisory panel’s recommendation May 12 endorsing the use of the Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine in adolescents aged 12-15 years.

Earlier in the day the CDC’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices voted 14-0 in favor of the safety and effectiveness of the vaccine in younger teens.

Dr. Walensky said in an official statement.

The Food and Drug Administration on May 10 issued an emergency use authorization (EUA) for the Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine for the prevention of COVID-19 in individuals 12-15 years old. The FDA first cleared the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine through an EUA in December 2020 for those ages 16 and older. Pfizer this month also initiated steps with the FDA toward a full approval of its vaccine.

Dr. Walenksy urged parents to seriously consider vaccinating their children.

“Understandably, some parents want more information before their children receive a vaccine,” she said. “I encourage parents with questions to talk to your child’s healthcare provider or your family doctor to learn more about the vaccine.”

Vaccine “safe and effective”

Separately, the American Academy of Pediatrics issued a statement May 12 in support of vaccinating all children ages 12 and older who are eligible for the federally authorized COVID-19 vaccine.

“As a pediatrician and a parent, I have looked forward to getting my own children and patients vaccinated, and I am thrilled that those ages 12 and older can now be protected,” said AAP President Lee Savio Beers, MD, in a statement. “The data continue to show that this vaccine is safe and effective. I urge all parents to call their pediatrician to learn more about how to get their children and teens vaccinated.”

The expanded clearance for the Pfizer vaccine is seen as a critical step for allowing teens to resume activities on which they missed out during the pandemic.

“We’ve seen the harm done to children’s mental and emotional health as they’ve missed out on so many experiences during the pandemic,” Dr. Beers said. “Vaccinating children will protect them and allow them to fully engage in all of the activities – school, sports, socializing with friends and family – that are so important to their health and development.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Reassuring data on impact of mild COVID-19 on the heart

Six months after mild SARS-CoV-2 infection in a representative health care workforce, no long-term cardiovascular sequelae were detected, compared with a matched SARS-CoV-2 seronegative group.

“Mild COVID-19 left no measurable cardiovascular impact on LV structure, function, scar burden, aortic stiffness, or serum biomarkers,” the researchers reported in an article published online May 8 in JACC: Cardiovascular Imaging.

“We provide societal reassurance and support for the position that screening in asymptomatic individuals following mild disease is not indicated,” first author George Joy, MBBS, University College London, said in presenting the results at EuroCMR, the annual CMR congress of the European Association of Cardiovascular Imaging (EACVI).

Briefing comoderator Leyla Elif Sade, MD, University of Baskent, Ankara, Turkey, said, “This is the hot topic of our time because of obvious reasons and I think [this] study is quite important to avoid unnecessary further testing, surveillance testing, and to avoid a significant burden of health care costs.”

‘Alarming’ early data

Early cardiac magnetic resonance (CMR) studies in patients recovered from mild COVID-19 were “alarming,” Dr. Joy said.

As previously reported, one study showed cardiac abnormalities after mild COVID-19 in up to 78% of patients, with evidence of ongoing myocardial inflammation in 60%. The CMR findings correlated with elevations in troponin T by high-sensitivity assay (hs-TnT).

To investigate further, Dr. Joy and colleagues did a nested case-control study within the COVIDsortium, a prospective study of 731 health care workers from three London hospitals who underwent weekly symptom, polymerase chain reaction, and serology assessment over 4 months during the first wave of the pandemic.

A total of 157 (21.5%) participants seroconverted during the study period.

Six months after infection, 74 seropositive (median age, 39; 62% women) and 75 age-, sex-, and ethnicity-matched seronegative controls underwent cardiovascular phenotyping (comprehensive phantom-calibrated CMR and blood biomarkers). The analysis was blinded, using objective artificial intelligence analytics when available.

The results showed no statistically significant differences between seropositive and seronegative participants in cardiac structure (left ventricular volumes, mass, atrial area), function (ejection fraction, global longitudinal shortening, aortic distensibility), tissue characterization (T1, T2, extracellular volume fraction mapping, late gadolinium enhancement) or biomarkers (troponin, N-terminal pro–B-type natriuretic peptide).

Cardiovascular abnormalities were no more common in seropositive than seronegative otherwise healthy health care workers 6 months post mild SARS-CoV-2 infection. Measured abnormalities were “evenly distributed between both groups,” Dr. Joy said.

Therefore, it’s “important to reassure patients with mild SARS-CoV-2 infection regarding its cardiovascular effects,” Dr. Joy and colleagues concluded.

Limitations and caveats

They caution, however, that the study provides insight only into the short- to medium-term sequelae of patients aged 18-69 with mild COVID-19 who did not require hospitalization and had low numbers of comorbidities.

The study does not address the cardiovascular effects after severe COVID-19 infection requiring hospitalization or in those with multiple comorbid conditions, they noted. It also does not prove that apparently mild SARS-CoV-2 never causes chronic myocarditis.

“The study design would not distinguish between people who had sustained completely healed myocarditis and pericarditis and those in whom the heart had never been affected,” the researchers noted.

They pointed to a recent cross-sectional study of athletes 1-month post mild COVID-19 that found significant pericardial involvement (late enhancement and/or pericardial effusion), although no baseline pre-COVID-19 imaging was performed. In the current study at 6 months post infection the pericardium was normal.

The coauthors of a linked editorial say this study provides “welcome, reassuring information that in healthy individuals who experience mild infection with COVID-19, persisting evidence of cardiovascular complications is very uncommon. The results do not support cardiovascular screening in individuals with mild or asymptomatic infection with COVID-19.”

Colin Berry, PhD, and Kenneth Mangion, PhD, both from University of Glasgow, cautioned that the population is restricted to health care workers; therefore, the findings may not necessarily be generalized to a community population .

“Healthcare workers do not reflect the population of individuals most clinically affected by COVID-19 illness. The severity of acute COVID-19 infection is greatest in older individuals and those with preexisting health problems. Healthcare workers are not representative of the wider, unselected, at-risk, community population,” they pointed out.

Cardiovascular risk factors and concomitant health problems (heart and respiratory disease) may be more common in the community than in health care workers, and prior studies have highlighted their potential impact for disease pathogenesis in COVID-19.

Dr. Berry and Dr. Mangion also noted that women made up nearly two-thirds of the seropositive group. This may reflect a selection bias or may naturally reflect the fact that proportionately more women are asymptomatic or have milder forms of illness, whereas severe SARS-CoV-2 infection requiring hospitalization affects men to a greater degree.

COVIDsortium funding was donated by individuals, charitable trusts, and corporations including Goldman Sachs, Citadel and Citadel Securities, The Guy Foundation, GW Pharmaceuticals, Kusuma Trust, and Jagclif Charitable Trust, and enabled by Barts Charity with support from UCLH Charity. The authors have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Six months after mild SARS-CoV-2 infection in a representative health care workforce, no long-term cardiovascular sequelae were detected, compared with a matched SARS-CoV-2 seronegative group.

“Mild COVID-19 left no measurable cardiovascular impact on LV structure, function, scar burden, aortic stiffness, or serum biomarkers,” the researchers reported in an article published online May 8 in JACC: Cardiovascular Imaging.

“We provide societal reassurance and support for the position that screening in asymptomatic individuals following mild disease is not indicated,” first author George Joy, MBBS, University College London, said in presenting the results at EuroCMR, the annual CMR congress of the European Association of Cardiovascular Imaging (EACVI).

Briefing comoderator Leyla Elif Sade, MD, University of Baskent, Ankara, Turkey, said, “This is the hot topic of our time because of obvious reasons and I think [this] study is quite important to avoid unnecessary further testing, surveillance testing, and to avoid a significant burden of health care costs.”

‘Alarming’ early data

Early cardiac magnetic resonance (CMR) studies in patients recovered from mild COVID-19 were “alarming,” Dr. Joy said.

As previously reported, one study showed cardiac abnormalities after mild COVID-19 in up to 78% of patients, with evidence of ongoing myocardial inflammation in 60%. The CMR findings correlated with elevations in troponin T by high-sensitivity assay (hs-TnT).

To investigate further, Dr. Joy and colleagues did a nested case-control study within the COVIDsortium, a prospective study of 731 health care workers from three London hospitals who underwent weekly symptom, polymerase chain reaction, and serology assessment over 4 months during the first wave of the pandemic.

A total of 157 (21.5%) participants seroconverted during the study period.

Six months after infection, 74 seropositive (median age, 39; 62% women) and 75 age-, sex-, and ethnicity-matched seronegative controls underwent cardiovascular phenotyping (comprehensive phantom-calibrated CMR and blood biomarkers). The analysis was blinded, using objective artificial intelligence analytics when available.

The results showed no statistically significant differences between seropositive and seronegative participants in cardiac structure (left ventricular volumes, mass, atrial area), function (ejection fraction, global longitudinal shortening, aortic distensibility), tissue characterization (T1, T2, extracellular volume fraction mapping, late gadolinium enhancement) or biomarkers (troponin, N-terminal pro–B-type natriuretic peptide).

Cardiovascular abnormalities were no more common in seropositive than seronegative otherwise healthy health care workers 6 months post mild SARS-CoV-2 infection. Measured abnormalities were “evenly distributed between both groups,” Dr. Joy said.

Therefore, it’s “important to reassure patients with mild SARS-CoV-2 infection regarding its cardiovascular effects,” Dr. Joy and colleagues concluded.

Limitations and caveats

They caution, however, that the study provides insight only into the short- to medium-term sequelae of patients aged 18-69 with mild COVID-19 who did not require hospitalization and had low numbers of comorbidities.

The study does not address the cardiovascular effects after severe COVID-19 infection requiring hospitalization or in those with multiple comorbid conditions, they noted. It also does not prove that apparently mild SARS-CoV-2 never causes chronic myocarditis.

“The study design would not distinguish between people who had sustained completely healed myocarditis and pericarditis and those in whom the heart had never been affected,” the researchers noted.

They pointed to a recent cross-sectional study of athletes 1-month post mild COVID-19 that found significant pericardial involvement (late enhancement and/or pericardial effusion), although no baseline pre-COVID-19 imaging was performed. In the current study at 6 months post infection the pericardium was normal.

The coauthors of a linked editorial say this study provides “welcome, reassuring information that in healthy individuals who experience mild infection with COVID-19, persisting evidence of cardiovascular complications is very uncommon. The results do not support cardiovascular screening in individuals with mild or asymptomatic infection with COVID-19.”

Colin Berry, PhD, and Kenneth Mangion, PhD, both from University of Glasgow, cautioned that the population is restricted to health care workers; therefore, the findings may not necessarily be generalized to a community population .

“Healthcare workers do not reflect the population of individuals most clinically affected by COVID-19 illness. The severity of acute COVID-19 infection is greatest in older individuals and those with preexisting health problems. Healthcare workers are not representative of the wider, unselected, at-risk, community population,” they pointed out.

Cardiovascular risk factors and concomitant health problems (heart and respiratory disease) may be more common in the community than in health care workers, and prior studies have highlighted their potential impact for disease pathogenesis in COVID-19.

Dr. Berry and Dr. Mangion also noted that women made up nearly two-thirds of the seropositive group. This may reflect a selection bias or may naturally reflect the fact that proportionately more women are asymptomatic or have milder forms of illness, whereas severe SARS-CoV-2 infection requiring hospitalization affects men to a greater degree.

COVIDsortium funding was donated by individuals, charitable trusts, and corporations including Goldman Sachs, Citadel and Citadel Securities, The Guy Foundation, GW Pharmaceuticals, Kusuma Trust, and Jagclif Charitable Trust, and enabled by Barts Charity with support from UCLH Charity. The authors have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Six months after mild SARS-CoV-2 infection in a representative health care workforce, no long-term cardiovascular sequelae were detected, compared with a matched SARS-CoV-2 seronegative group.

“Mild COVID-19 left no measurable cardiovascular impact on LV structure, function, scar burden, aortic stiffness, or serum biomarkers,” the researchers reported in an article published online May 8 in JACC: Cardiovascular Imaging.

“We provide societal reassurance and support for the position that screening in asymptomatic individuals following mild disease is not indicated,” first author George Joy, MBBS, University College London, said in presenting the results at EuroCMR, the annual CMR congress of the European Association of Cardiovascular Imaging (EACVI).

Briefing comoderator Leyla Elif Sade, MD, University of Baskent, Ankara, Turkey, said, “This is the hot topic of our time because of obvious reasons and I think [this] study is quite important to avoid unnecessary further testing, surveillance testing, and to avoid a significant burden of health care costs.”

‘Alarming’ early data

Early cardiac magnetic resonance (CMR) studies in patients recovered from mild COVID-19 were “alarming,” Dr. Joy said.

As previously reported, one study showed cardiac abnormalities after mild COVID-19 in up to 78% of patients, with evidence of ongoing myocardial inflammation in 60%. The CMR findings correlated with elevations in troponin T by high-sensitivity assay (hs-TnT).

To investigate further, Dr. Joy and colleagues did a nested case-control study within the COVIDsortium, a prospective study of 731 health care workers from three London hospitals who underwent weekly symptom, polymerase chain reaction, and serology assessment over 4 months during the first wave of the pandemic.

A total of 157 (21.5%) participants seroconverted during the study period.

Six months after infection, 74 seropositive (median age, 39; 62% women) and 75 age-, sex-, and ethnicity-matched seronegative controls underwent cardiovascular phenotyping (comprehensive phantom-calibrated CMR and blood biomarkers). The analysis was blinded, using objective artificial intelligence analytics when available.

The results showed no statistically significant differences between seropositive and seronegative participants in cardiac structure (left ventricular volumes, mass, atrial area), function (ejection fraction, global longitudinal shortening, aortic distensibility), tissue characterization (T1, T2, extracellular volume fraction mapping, late gadolinium enhancement) or biomarkers (troponin, N-terminal pro–B-type natriuretic peptide).

Cardiovascular abnormalities were no more common in seropositive than seronegative otherwise healthy health care workers 6 months post mild SARS-CoV-2 infection. Measured abnormalities were “evenly distributed between both groups,” Dr. Joy said.

Therefore, it’s “important to reassure patients with mild SARS-CoV-2 infection regarding its cardiovascular effects,” Dr. Joy and colleagues concluded.

Limitations and caveats

They caution, however, that the study provides insight only into the short- to medium-term sequelae of patients aged 18-69 with mild COVID-19 who did not require hospitalization and had low numbers of comorbidities.

The study does not address the cardiovascular effects after severe COVID-19 infection requiring hospitalization or in those with multiple comorbid conditions, they noted. It also does not prove that apparently mild SARS-CoV-2 never causes chronic myocarditis.

“The study design would not distinguish between people who had sustained completely healed myocarditis and pericarditis and those in whom the heart had never been affected,” the researchers noted.

They pointed to a recent cross-sectional study of athletes 1-month post mild COVID-19 that found significant pericardial involvement (late enhancement and/or pericardial effusion), although no baseline pre-COVID-19 imaging was performed. In the current study at 6 months post infection the pericardium was normal.

The coauthors of a linked editorial say this study provides “welcome, reassuring information that in healthy individuals who experience mild infection with COVID-19, persisting evidence of cardiovascular complications is very uncommon. The results do not support cardiovascular screening in individuals with mild or asymptomatic infection with COVID-19.”

Colin Berry, PhD, and Kenneth Mangion, PhD, both from University of Glasgow, cautioned that the population is restricted to health care workers; therefore, the findings may not necessarily be generalized to a community population .

“Healthcare workers do not reflect the population of individuals most clinically affected by COVID-19 illness. The severity of acute COVID-19 infection is greatest in older individuals and those with preexisting health problems. Healthcare workers are not representative of the wider, unselected, at-risk, community population,” they pointed out.

Cardiovascular risk factors and concomitant health problems (heart and respiratory disease) may be more common in the community than in health care workers, and prior studies have highlighted their potential impact for disease pathogenesis in COVID-19.

Dr. Berry and Dr. Mangion also noted that women made up nearly two-thirds of the seropositive group. This may reflect a selection bias or may naturally reflect the fact that proportionately more women are asymptomatic or have milder forms of illness, whereas severe SARS-CoV-2 infection requiring hospitalization affects men to a greater degree.

COVIDsortium funding was donated by individuals, charitable trusts, and corporations including Goldman Sachs, Citadel and Citadel Securities, The Guy Foundation, GW Pharmaceuticals, Kusuma Trust, and Jagclif Charitable Trust, and enabled by Barts Charity with support from UCLH Charity. The authors have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

What to know about COVID-19 vaccines and skin reactions

The good news is that these side effects tend to be minor and vanish within a few days, Esther Freeman, MD, PhD, said in a presentation at the American Academy of Dermatology Virtual Meeting Experience.

“The reality is actually very reassuring,” Dr. Freeman said, especially in light of what is currently known about when the rashes occur and how anaphylaxis is extremely uncommon. Now, she added, dermatologists can tell patients who had reactions to their initial vaccination that “we know you had this big reaction, and we know that it was upsetting and uncomfortable. But it may not happen the second time around. And if it does, [the reaction is] probably going to be smaller.”

Dr. Freeman, associate professor of dermatology at Harvard Medical School, Boston, highlighted a study published in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology that she coauthored with dermatologists across the United States. The researchers tracked 414 cutaneous reactions to the Moderna (83%) and Pfizer (17%) COVID-19 vaccines in a group of patients, which was 90% female, 78% White, and mostly from the United States. Their average age was 44 years. The cases were reported to the AAD–International League of Dermatological Societies registry of COVID-19 cutaneous manifestations.

While most were women, “it’s a little hard to know if this is really going to end up being a true finding,” said Dr. Freeman, the registry’s principal investigator and a member of the AAD’s COVID-19 Ad Hoc Task Force. “If you think about who got vaccinated early, it was health care providers, and the American health care workforce is over 70% female. So I think there’s a little bit of bias here. There may also be a bias because women may be slightly more likely to report or go to their health care provider for a rash.”

Delayed large local reactions were the most common, accounting for 66% (175 cases) of the 267 skin reactions reported after the first Moderna vaccine dose and 30% (31 cases) of the 102 reactions reported after the second dose. These reactions represented 15% (5 cases) of the 34 skin reactions reported after the first Pfizer vaccine dose and 18% (7 cases) of the 40 reactions after the second dose.

There are two peaks with that first dose, Dr. Freeman said. “There’s a peak around day 2 or 3. And there’s another peak around day 7 or 8 with some of these reactions. Only 27% who had a reaction with the first dose had the same reaction with the second.” She added that these reactions “are not cellulitis and don’t require antibiotics.”

Other more common reactions included local injection-site reactions (swelling, erythema, and pain), urticaria (after 24 hours in almost all cases, occurring at a higher rate in patients who received the Pfizer vaccine), and morbilliform eruptions.

Dr. Freeman said that patients may experience redness and swelling in the hands and feet that can be “very uncomfortable.” She described one patient “who was having a hard time actually closing his fist, just because of the amount of swelling and redness in his hand. It did resolve, and it’s important to reassure your patients it will go away.”

According to this study, less common reports of other cutaneous findings with both vaccines included 9 reports of swelling at the site of cosmetic fillers, 8 reports of pernio/chilblains, 10 reports of varicella zoster, 4 reports of herpes simplex flares, 4 pityriasis rosea–like reactions, and 4 rashes in infants of vaccinated breastfeeding mothers.

The study noted that “patients responded well to topical corticosteroids, oral antihistamines, and/or pain-relieving medications. These reactions resolved after a median of 3-4 days.”

It’s important to understand that none of the patients developed anaphylaxis after the second dose even if they’d had a reaction to the first dose, Dr. Freeman said. “But I should point out that we’re talking about reactions that have started more than 4 hours after the vaccine. If a rash such as a urticaria specifically starts within 4 hours of vaccination, that’s in a different category. Those are considered more immediate allergic reactions, and those patients need to be seen by allergy before a second dose.”