User login

What does it mean to be a trustworthy male ally?

“If you want to be trusted, be trustworthy” – Stephen Covey

A few years ago, while working in my office, a female colleague stopped by for a casual chat. During the course of the conversation, she noticed that I did not have any diplomas or certificates hanging on my office walls. Instead, there were clusters of pictures drawn by my children, family photos, and a white board with my “to-do” list. The only wall art was a print of Banksy’s “The Thinker Monkey,” which depicts a monkey with its fist to its chin similar to Rodin’s famous sculpture, “Le Penseur.”

When asked why I didn’t hang any diplomas or awards, I replied that I preferred to keep my office atmosphere light and fun, and to focus on future goals rather than past accomplishments. I could see her jaw tense. Her frustration appeared deep, but it was for reasons beyond just my self-righteous tone. She said, “You know, I appreciate your focus on future goals, but it’s a pretty privileged position to not have to worry about sharing your accomplishments publicly.”

What followed was a discussion that was generative, enlightening, uncomfortable, and necessary. I had never considered what I chose to hang (or not hang) on my office walls as a privilege, and that was exactly the point. She described numerous episodes when her accomplishments were overlooked or (worse) attributed to a male colleague because she was a woman. I began to understand that graceful self-promotion is not optional for many women in medicine, it is a necessary skill.

This is just one example of how my privilege as a male in medicine contributed to my ignorance of the gender inequities that my female coworkers have faced throughout their careers. My colleague showed a lot of grace by taking the time to help me navigate my male privilege in a constructive manner. I decided to learn more about gender inequities, and eventually determined that I was woefully inadequate as a male ally, not by refusal but by ignorance. I wanted to start earning my colleague’s trust that I would be an ally that she could count on.

Trustworthiness

I wanted to be a trustworthy ally, but what does that entail? Perhaps we can learn from medical education. Trust is a complex construct that is increasingly used as a framework for assessing medical students and residents, such as with entrustable professional activities (EPAs).1,2 Multiple studies have examined the characteristics that make a learner “trustworthy” when determining how much supervision is required.3-8 Ten Cate and Chen performed an interpretivist, narrative review to synthesize the medical education literature on learner trustworthiness in the past 15 years,9 developing five major themes that contribute to trustworthiness: Humility, Capability, Agency, Reliability, and Integrity. Let’s examine each of these through the lens of male allyship.

Humility

Humility involves knowing one’s limits, asking for help, and being receptive to feedback.9 The first thing men need to do is to put their egos in check and recognize that women do not need rescuing; they need partnership. Systemic inequities have led to men holding the majority of leadership positions and significant sociopolitical capital, and correcting these inequities is more feasible when those in leadership and positions of power contribute. Women don’t need knights in shining armor, they need collaborative activism.

Humility also means a willingness to admit fallibility and to ask for help. Men often don’t know what they don’t know (see my foibles in the opening). As David G. Smith, PhD, and W. Brad Johnson, PhD, write in their book, “Good Guys,” “There are no perfect allies. As you work to become a better ally for the women around you, you will undoubtedly make a mistake.”10 Men must accept feedback on their shortcomings as allies without feeling as though they are losing their sociopolitical standing. Allyship for women does not mean there is a devaluing of men. We must escape a “zero-sum” mindset. Mistakes are where growth happens, but only if we approach our missteps with humility.

Capability

Capability entails having the necessary knowledge, skills, and attitudes to be a strong ally. Allyship is not intuitive for most men for several reasons. Many men do not experience the same biases or systemic inequities that women do, and therefore perceive them less frequently. I want to acknowledge that men can be victims of other systemic biases such as those against one’s race, ethnicity, gender identity, sexual orientation, religion, or any number of factors. Men who face inequities for these other reasons may be more cognizant of the biases women face. Even so, allyship is a skill that few men have been explicitly taught. Even if taught, few standard or organized mechanisms for feedback on allyship capability exist. How, then, can men become capable allies?

Just like in medical education, men must become self-directed learners who seek to build capability and receive feedback on their performance as allies. Men should seek allyship training through local women-in-medicine programs or organizations, or through the increasing number of national education options such as the recent ADVANCE PHM Gender Equity Symposium. As with learning any skill, men should go to the literature, seeking knowledge from experts in the field. I recommend starting with “Good Guys: How Men Can Be Better Allies for Women in the Workplace10 or “Athena Rising: How and Why Men Should Mentor Women.”11 Both books, by Dr. Smith and Dr. Johnson, are great entry points into the gender allyship literature. Seek out other resources from local experts on gender equity and allyship. Both aforementioned books were recommended to me by a friend and gender equity expert; without her guidance I would not have known where to start.

Agency

Agency involves being proactive and engaged rather than passive or apathetic. Men must be enthusiastic allies who seek out opportunities to mentor and sponsor women rather than waiting for others to ask. Agency requires being curious and passionate about improving. Most men in medicine are not openly and explicitly misogynistic or sexist, but many are only passive when it comes to gender equity and allyship. Trustworthy allyship entails turning passive support into active change. Not sure how to start? A good first step is to ask female colleagues questions such as, “What can I do to be a better ally for you in the workplace?” or “What are some things at work that are most challenging to you, but I might not notice because I’m a man?” Curiosity is the springboard toward agency.

Reliability

Reliability means being conscientious, accountable, and doing what we say we will do. Nothing undermines trustworthiness faster than making a commitment and not following through. Allyship cannot be a show or an attempt to get public plaudits. It is a longitudinal commitment to supporting women through individual mentorship and sponsorship, and to work toward institutional and systems change.

Reliability also means taking an equitable approach to what Dr. Smith and Dr. Johnson call “office housework.” They define this as “administrative work that is necessary but undervalued, unlikely to lead to promotion, and disproportionately assigned to women.”10 In medicine, these tasks include organizing meetings, taking notes, planning social events, and remembering to celebrate colleagues’ achievements and milestones. Men should take on more of these tasks and advocate for change when the distribution of office housework in their workplace is inequitably directed toward women.

Integrity

Integrity involves honesty, professionalism, and benevolence. It is about making the morally correct choice even if there is potential risk. When men see gender inequity, they have an obligation to speak up. Whether it is overtly misogynistic behavior, subtle sexism, use of gendered language, inequitable distribution of office housework, lack of inclusivity and recognition for women, or another form of inequity, men must act with integrity and make it clear that they are partnering with women for change. Integrity means being an ally even when women are not present, and advocating that women be “at the table” for important conversations.

Beyond the individual

Allyship cannot end with individual actions; systems changes that build trustworthy institutions are necessary. Organizational leaders must approach gender conversations with humility to critically examine inequities and agency to implement meaningful changes. Workplace cultures and institutional policies should be reviewed with an eye toward system-level integrity and reliability for promoting and supporting women. Ongoing faculty and staff development programs must provide men with the knowledge, skills, and attitudes (capability) to be strong allies. We have a long history of male-dominated institutions that are unfair or (worse) unsafe for women. Many systems are designed in a way that disadvantages women. These systems must be redesigned through an equity lens to start building trust with women in medicine.

Becoming trustworthy is a process

Even the best male allies have room to improve their trustworthiness. Many men (myself included) have a LOT of room to improve, but they should not get discouraged by the amount of ground to be gained. Steady, deliberate improvement in men’s humility, capability, agency, reliability, and integrity can build the foundation of trust with female colleagues. Trust takes time. It takes effort. It takes vulnerability. It is an ongoing, developmental process that requires deliberate practice, frequent reflection, and feedback from our female colleagues.

Dr. Kinnear is associate professor of internal medicine and pediatrics in the Division of Hospital Medicine at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center and University of Cincinnati Medical Center. He is associate program director for the Med-Peds and Internal Medicine residency programs.

References

1. Ten Cate O. Nuts and bolts of entrustable professional activities. J Grad Med Educ. 2013 Mar;5(1):157-8. doi: 10.4300/JGME-D-12-00380.1.

2. Ten Cate O. Entrustment decisions: Bringing the patient into the assessment equation. Acad Med. 2017 Jun;92(6):736-8. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000001623.

3. Kennedy TJT et al. Point-of-care assessment of medical trainee competence for independent clinical work. Acad Med. 2008 Oct;83(10 Suppl):S89-92. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e318183c8b7.

4. Choo KJ et al. How do supervising physicians decide to entrust residents with unsupervised tasks? A qualitative analysis. J Hosp Med. 2014 Mar;9(3):169-75. doi: 10.1002/jhm.2150.

5. Hauer KE et al. How clinical supervisors develop trust in their trainees: A qualitative study. Med Educ. 2015 Aug;49(8):783-95. doi: 10.1111/medu.12745.

6. Sterkenburg A et al. When do supervising physicians decide to entrust residents with unsupervised tasks? Acad Med. 2010 Sep;85(9):1408-17. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181eab0ec.

7. Sheu L et al. How supervisor experience influences trust, supervision, and trainee learning: A qualitative study. Acad Med. 2017 Sep;92(9):1320-7. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000001560.

8. Pingree EW et al. Encouraging entrustment: A qualitative study of resident behaviors that promote entrustment. Acad Med. 2020 Nov;95(11):1718-25. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000003487.

9. Ten Cate O, Chen HC. The ingredients of a rich entrustment decision. Med Teach. 2020 Dec;42(12):1413-20. doi: 10.1080/0142159X.2020.1817348.

10. Smith DG, Johnson WB. Good guys: How men can be better allies for women in the workplace: Harvard Business School Publishing Corporation 2020.

11. Johnson WB, Smith D. Athena rising: How and why men should mentor women: Routledge 2016.

“If you want to be trusted, be trustworthy” – Stephen Covey

A few years ago, while working in my office, a female colleague stopped by for a casual chat. During the course of the conversation, she noticed that I did not have any diplomas or certificates hanging on my office walls. Instead, there were clusters of pictures drawn by my children, family photos, and a white board with my “to-do” list. The only wall art was a print of Banksy’s “The Thinker Monkey,” which depicts a monkey with its fist to its chin similar to Rodin’s famous sculpture, “Le Penseur.”

When asked why I didn’t hang any diplomas or awards, I replied that I preferred to keep my office atmosphere light and fun, and to focus on future goals rather than past accomplishments. I could see her jaw tense. Her frustration appeared deep, but it was for reasons beyond just my self-righteous tone. She said, “You know, I appreciate your focus on future goals, but it’s a pretty privileged position to not have to worry about sharing your accomplishments publicly.”

What followed was a discussion that was generative, enlightening, uncomfortable, and necessary. I had never considered what I chose to hang (or not hang) on my office walls as a privilege, and that was exactly the point. She described numerous episodes when her accomplishments were overlooked or (worse) attributed to a male colleague because she was a woman. I began to understand that graceful self-promotion is not optional for many women in medicine, it is a necessary skill.

This is just one example of how my privilege as a male in medicine contributed to my ignorance of the gender inequities that my female coworkers have faced throughout their careers. My colleague showed a lot of grace by taking the time to help me navigate my male privilege in a constructive manner. I decided to learn more about gender inequities, and eventually determined that I was woefully inadequate as a male ally, not by refusal but by ignorance. I wanted to start earning my colleague’s trust that I would be an ally that she could count on.

Trustworthiness

I wanted to be a trustworthy ally, but what does that entail? Perhaps we can learn from medical education. Trust is a complex construct that is increasingly used as a framework for assessing medical students and residents, such as with entrustable professional activities (EPAs).1,2 Multiple studies have examined the characteristics that make a learner “trustworthy” when determining how much supervision is required.3-8 Ten Cate and Chen performed an interpretivist, narrative review to synthesize the medical education literature on learner trustworthiness in the past 15 years,9 developing five major themes that contribute to trustworthiness: Humility, Capability, Agency, Reliability, and Integrity. Let’s examine each of these through the lens of male allyship.

Humility

Humility involves knowing one’s limits, asking for help, and being receptive to feedback.9 The first thing men need to do is to put their egos in check and recognize that women do not need rescuing; they need partnership. Systemic inequities have led to men holding the majority of leadership positions and significant sociopolitical capital, and correcting these inequities is more feasible when those in leadership and positions of power contribute. Women don’t need knights in shining armor, they need collaborative activism.

Humility also means a willingness to admit fallibility and to ask for help. Men often don’t know what they don’t know (see my foibles in the opening). As David G. Smith, PhD, and W. Brad Johnson, PhD, write in their book, “Good Guys,” “There are no perfect allies. As you work to become a better ally for the women around you, you will undoubtedly make a mistake.”10 Men must accept feedback on their shortcomings as allies without feeling as though they are losing their sociopolitical standing. Allyship for women does not mean there is a devaluing of men. We must escape a “zero-sum” mindset. Mistakes are where growth happens, but only if we approach our missteps with humility.

Capability

Capability entails having the necessary knowledge, skills, and attitudes to be a strong ally. Allyship is not intuitive for most men for several reasons. Many men do not experience the same biases or systemic inequities that women do, and therefore perceive them less frequently. I want to acknowledge that men can be victims of other systemic biases such as those against one’s race, ethnicity, gender identity, sexual orientation, religion, or any number of factors. Men who face inequities for these other reasons may be more cognizant of the biases women face. Even so, allyship is a skill that few men have been explicitly taught. Even if taught, few standard or organized mechanisms for feedback on allyship capability exist. How, then, can men become capable allies?

Just like in medical education, men must become self-directed learners who seek to build capability and receive feedback on their performance as allies. Men should seek allyship training through local women-in-medicine programs or organizations, or through the increasing number of national education options such as the recent ADVANCE PHM Gender Equity Symposium. As with learning any skill, men should go to the literature, seeking knowledge from experts in the field. I recommend starting with “Good Guys: How Men Can Be Better Allies for Women in the Workplace10 or “Athena Rising: How and Why Men Should Mentor Women.”11 Both books, by Dr. Smith and Dr. Johnson, are great entry points into the gender allyship literature. Seek out other resources from local experts on gender equity and allyship. Both aforementioned books were recommended to me by a friend and gender equity expert; without her guidance I would not have known where to start.

Agency

Agency involves being proactive and engaged rather than passive or apathetic. Men must be enthusiastic allies who seek out opportunities to mentor and sponsor women rather than waiting for others to ask. Agency requires being curious and passionate about improving. Most men in medicine are not openly and explicitly misogynistic or sexist, but many are only passive when it comes to gender equity and allyship. Trustworthy allyship entails turning passive support into active change. Not sure how to start? A good first step is to ask female colleagues questions such as, “What can I do to be a better ally for you in the workplace?” or “What are some things at work that are most challenging to you, but I might not notice because I’m a man?” Curiosity is the springboard toward agency.

Reliability

Reliability means being conscientious, accountable, and doing what we say we will do. Nothing undermines trustworthiness faster than making a commitment and not following through. Allyship cannot be a show or an attempt to get public plaudits. It is a longitudinal commitment to supporting women through individual mentorship and sponsorship, and to work toward institutional and systems change.

Reliability also means taking an equitable approach to what Dr. Smith and Dr. Johnson call “office housework.” They define this as “administrative work that is necessary but undervalued, unlikely to lead to promotion, and disproportionately assigned to women.”10 In medicine, these tasks include organizing meetings, taking notes, planning social events, and remembering to celebrate colleagues’ achievements and milestones. Men should take on more of these tasks and advocate for change when the distribution of office housework in their workplace is inequitably directed toward women.

Integrity

Integrity involves honesty, professionalism, and benevolence. It is about making the morally correct choice even if there is potential risk. When men see gender inequity, they have an obligation to speak up. Whether it is overtly misogynistic behavior, subtle sexism, use of gendered language, inequitable distribution of office housework, lack of inclusivity and recognition for women, or another form of inequity, men must act with integrity and make it clear that they are partnering with women for change. Integrity means being an ally even when women are not present, and advocating that women be “at the table” for important conversations.

Beyond the individual

Allyship cannot end with individual actions; systems changes that build trustworthy institutions are necessary. Organizational leaders must approach gender conversations with humility to critically examine inequities and agency to implement meaningful changes. Workplace cultures and institutional policies should be reviewed with an eye toward system-level integrity and reliability for promoting and supporting women. Ongoing faculty and staff development programs must provide men with the knowledge, skills, and attitudes (capability) to be strong allies. We have a long history of male-dominated institutions that are unfair or (worse) unsafe for women. Many systems are designed in a way that disadvantages women. These systems must be redesigned through an equity lens to start building trust with women in medicine.

Becoming trustworthy is a process

Even the best male allies have room to improve their trustworthiness. Many men (myself included) have a LOT of room to improve, but they should not get discouraged by the amount of ground to be gained. Steady, deliberate improvement in men’s humility, capability, agency, reliability, and integrity can build the foundation of trust with female colleagues. Trust takes time. It takes effort. It takes vulnerability. It is an ongoing, developmental process that requires deliberate practice, frequent reflection, and feedback from our female colleagues.

Dr. Kinnear is associate professor of internal medicine and pediatrics in the Division of Hospital Medicine at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center and University of Cincinnati Medical Center. He is associate program director for the Med-Peds and Internal Medicine residency programs.

References

1. Ten Cate O. Nuts and bolts of entrustable professional activities. J Grad Med Educ. 2013 Mar;5(1):157-8. doi: 10.4300/JGME-D-12-00380.1.

2. Ten Cate O. Entrustment decisions: Bringing the patient into the assessment equation. Acad Med. 2017 Jun;92(6):736-8. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000001623.

3. Kennedy TJT et al. Point-of-care assessment of medical trainee competence for independent clinical work. Acad Med. 2008 Oct;83(10 Suppl):S89-92. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e318183c8b7.

4. Choo KJ et al. How do supervising physicians decide to entrust residents with unsupervised tasks? A qualitative analysis. J Hosp Med. 2014 Mar;9(3):169-75. doi: 10.1002/jhm.2150.

5. Hauer KE et al. How clinical supervisors develop trust in their trainees: A qualitative study. Med Educ. 2015 Aug;49(8):783-95. doi: 10.1111/medu.12745.

6. Sterkenburg A et al. When do supervising physicians decide to entrust residents with unsupervised tasks? Acad Med. 2010 Sep;85(9):1408-17. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181eab0ec.

7. Sheu L et al. How supervisor experience influences trust, supervision, and trainee learning: A qualitative study. Acad Med. 2017 Sep;92(9):1320-7. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000001560.

8. Pingree EW et al. Encouraging entrustment: A qualitative study of resident behaviors that promote entrustment. Acad Med. 2020 Nov;95(11):1718-25. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000003487.

9. Ten Cate O, Chen HC. The ingredients of a rich entrustment decision. Med Teach. 2020 Dec;42(12):1413-20. doi: 10.1080/0142159X.2020.1817348.

10. Smith DG, Johnson WB. Good guys: How men can be better allies for women in the workplace: Harvard Business School Publishing Corporation 2020.

11. Johnson WB, Smith D. Athena rising: How and why men should mentor women: Routledge 2016.

“If you want to be trusted, be trustworthy” – Stephen Covey

A few years ago, while working in my office, a female colleague stopped by for a casual chat. During the course of the conversation, she noticed that I did not have any diplomas or certificates hanging on my office walls. Instead, there were clusters of pictures drawn by my children, family photos, and a white board with my “to-do” list. The only wall art was a print of Banksy’s “The Thinker Monkey,” which depicts a monkey with its fist to its chin similar to Rodin’s famous sculpture, “Le Penseur.”

When asked why I didn’t hang any diplomas or awards, I replied that I preferred to keep my office atmosphere light and fun, and to focus on future goals rather than past accomplishments. I could see her jaw tense. Her frustration appeared deep, but it was for reasons beyond just my self-righteous tone. She said, “You know, I appreciate your focus on future goals, but it’s a pretty privileged position to not have to worry about sharing your accomplishments publicly.”

What followed was a discussion that was generative, enlightening, uncomfortable, and necessary. I had never considered what I chose to hang (or not hang) on my office walls as a privilege, and that was exactly the point. She described numerous episodes when her accomplishments were overlooked or (worse) attributed to a male colleague because she was a woman. I began to understand that graceful self-promotion is not optional for many women in medicine, it is a necessary skill.

This is just one example of how my privilege as a male in medicine contributed to my ignorance of the gender inequities that my female coworkers have faced throughout their careers. My colleague showed a lot of grace by taking the time to help me navigate my male privilege in a constructive manner. I decided to learn more about gender inequities, and eventually determined that I was woefully inadequate as a male ally, not by refusal but by ignorance. I wanted to start earning my colleague’s trust that I would be an ally that she could count on.

Trustworthiness

I wanted to be a trustworthy ally, but what does that entail? Perhaps we can learn from medical education. Trust is a complex construct that is increasingly used as a framework for assessing medical students and residents, such as with entrustable professional activities (EPAs).1,2 Multiple studies have examined the characteristics that make a learner “trustworthy” when determining how much supervision is required.3-8 Ten Cate and Chen performed an interpretivist, narrative review to synthesize the medical education literature on learner trustworthiness in the past 15 years,9 developing five major themes that contribute to trustworthiness: Humility, Capability, Agency, Reliability, and Integrity. Let’s examine each of these through the lens of male allyship.

Humility

Humility involves knowing one’s limits, asking for help, and being receptive to feedback.9 The first thing men need to do is to put their egos in check and recognize that women do not need rescuing; they need partnership. Systemic inequities have led to men holding the majority of leadership positions and significant sociopolitical capital, and correcting these inequities is more feasible when those in leadership and positions of power contribute. Women don’t need knights in shining armor, they need collaborative activism.

Humility also means a willingness to admit fallibility and to ask for help. Men often don’t know what they don’t know (see my foibles in the opening). As David G. Smith, PhD, and W. Brad Johnson, PhD, write in their book, “Good Guys,” “There are no perfect allies. As you work to become a better ally for the women around you, you will undoubtedly make a mistake.”10 Men must accept feedback on their shortcomings as allies without feeling as though they are losing their sociopolitical standing. Allyship for women does not mean there is a devaluing of men. We must escape a “zero-sum” mindset. Mistakes are where growth happens, but only if we approach our missteps with humility.

Capability

Capability entails having the necessary knowledge, skills, and attitudes to be a strong ally. Allyship is not intuitive for most men for several reasons. Many men do not experience the same biases or systemic inequities that women do, and therefore perceive them less frequently. I want to acknowledge that men can be victims of other systemic biases such as those against one’s race, ethnicity, gender identity, sexual orientation, religion, or any number of factors. Men who face inequities for these other reasons may be more cognizant of the biases women face. Even so, allyship is a skill that few men have been explicitly taught. Even if taught, few standard or organized mechanisms for feedback on allyship capability exist. How, then, can men become capable allies?

Just like in medical education, men must become self-directed learners who seek to build capability and receive feedback on their performance as allies. Men should seek allyship training through local women-in-medicine programs or organizations, or through the increasing number of national education options such as the recent ADVANCE PHM Gender Equity Symposium. As with learning any skill, men should go to the literature, seeking knowledge from experts in the field. I recommend starting with “Good Guys: How Men Can Be Better Allies for Women in the Workplace10 or “Athena Rising: How and Why Men Should Mentor Women.”11 Both books, by Dr. Smith and Dr. Johnson, are great entry points into the gender allyship literature. Seek out other resources from local experts on gender equity and allyship. Both aforementioned books were recommended to me by a friend and gender equity expert; without her guidance I would not have known where to start.

Agency

Agency involves being proactive and engaged rather than passive or apathetic. Men must be enthusiastic allies who seek out opportunities to mentor and sponsor women rather than waiting for others to ask. Agency requires being curious and passionate about improving. Most men in medicine are not openly and explicitly misogynistic or sexist, but many are only passive when it comes to gender equity and allyship. Trustworthy allyship entails turning passive support into active change. Not sure how to start? A good first step is to ask female colleagues questions such as, “What can I do to be a better ally for you in the workplace?” or “What are some things at work that are most challenging to you, but I might not notice because I’m a man?” Curiosity is the springboard toward agency.

Reliability

Reliability means being conscientious, accountable, and doing what we say we will do. Nothing undermines trustworthiness faster than making a commitment and not following through. Allyship cannot be a show or an attempt to get public plaudits. It is a longitudinal commitment to supporting women through individual mentorship and sponsorship, and to work toward institutional and systems change.

Reliability also means taking an equitable approach to what Dr. Smith and Dr. Johnson call “office housework.” They define this as “administrative work that is necessary but undervalued, unlikely to lead to promotion, and disproportionately assigned to women.”10 In medicine, these tasks include organizing meetings, taking notes, planning social events, and remembering to celebrate colleagues’ achievements and milestones. Men should take on more of these tasks and advocate for change when the distribution of office housework in their workplace is inequitably directed toward women.

Integrity

Integrity involves honesty, professionalism, and benevolence. It is about making the morally correct choice even if there is potential risk. When men see gender inequity, they have an obligation to speak up. Whether it is overtly misogynistic behavior, subtle sexism, use of gendered language, inequitable distribution of office housework, lack of inclusivity and recognition for women, or another form of inequity, men must act with integrity and make it clear that they are partnering with women for change. Integrity means being an ally even when women are not present, and advocating that women be “at the table” for important conversations.

Beyond the individual

Allyship cannot end with individual actions; systems changes that build trustworthy institutions are necessary. Organizational leaders must approach gender conversations with humility to critically examine inequities and agency to implement meaningful changes. Workplace cultures and institutional policies should be reviewed with an eye toward system-level integrity and reliability for promoting and supporting women. Ongoing faculty and staff development programs must provide men with the knowledge, skills, and attitudes (capability) to be strong allies. We have a long history of male-dominated institutions that are unfair or (worse) unsafe for women. Many systems are designed in a way that disadvantages women. These systems must be redesigned through an equity lens to start building trust with women in medicine.

Becoming trustworthy is a process

Even the best male allies have room to improve their trustworthiness. Many men (myself included) have a LOT of room to improve, but they should not get discouraged by the amount of ground to be gained. Steady, deliberate improvement in men’s humility, capability, agency, reliability, and integrity can build the foundation of trust with female colleagues. Trust takes time. It takes effort. It takes vulnerability. It is an ongoing, developmental process that requires deliberate practice, frequent reflection, and feedback from our female colleagues.

Dr. Kinnear is associate professor of internal medicine and pediatrics in the Division of Hospital Medicine at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center and University of Cincinnati Medical Center. He is associate program director for the Med-Peds and Internal Medicine residency programs.

References

1. Ten Cate O. Nuts and bolts of entrustable professional activities. J Grad Med Educ. 2013 Mar;5(1):157-8. doi: 10.4300/JGME-D-12-00380.1.

2. Ten Cate O. Entrustment decisions: Bringing the patient into the assessment equation. Acad Med. 2017 Jun;92(6):736-8. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000001623.

3. Kennedy TJT et al. Point-of-care assessment of medical trainee competence for independent clinical work. Acad Med. 2008 Oct;83(10 Suppl):S89-92. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e318183c8b7.

4. Choo KJ et al. How do supervising physicians decide to entrust residents with unsupervised tasks? A qualitative analysis. J Hosp Med. 2014 Mar;9(3):169-75. doi: 10.1002/jhm.2150.

5. Hauer KE et al. How clinical supervisors develop trust in their trainees: A qualitative study. Med Educ. 2015 Aug;49(8):783-95. doi: 10.1111/medu.12745.

6. Sterkenburg A et al. When do supervising physicians decide to entrust residents with unsupervised tasks? Acad Med. 2010 Sep;85(9):1408-17. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181eab0ec.

7. Sheu L et al. How supervisor experience influences trust, supervision, and trainee learning: A qualitative study. Acad Med. 2017 Sep;92(9):1320-7. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000001560.

8. Pingree EW et al. Encouraging entrustment: A qualitative study of resident behaviors that promote entrustment. Acad Med. 2020 Nov;95(11):1718-25. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000003487.

9. Ten Cate O, Chen HC. The ingredients of a rich entrustment decision. Med Teach. 2020 Dec;42(12):1413-20. doi: 10.1080/0142159X.2020.1817348.

10. Smith DG, Johnson WB. Good guys: How men can be better allies for women in the workplace: Harvard Business School Publishing Corporation 2020.

11. Johnson WB, Smith D. Athena rising: How and why men should mentor women: Routledge 2016.

Unvaccinated people 20 times more likely to die from COVID: Texas study

During the month of September, , according to a new study from the Texas Department of State Health Services.

The data also showed that unvaccinated people were 13 times more likely to test positive for COVID-19 than people who were fully vaccinated.

“This analysis quantifies what we’ve known for months,” Jennifer Shuford, MD, the state’s chief epidemiologist, told The Dallas Morning News.

“The COVID-19 vaccines are doing an excellent job of protecting people from getting sick and from dying from COVID-19,” she said. “Vaccination remains the best way to keep yourself and the people close to you safe from this deadly disease.”

As part of the study, researchers analyzed electronic lab reports, death certificates, and state immunization records, with a particular focus on September when the contagious Delta variant surged across Texas. The research marks the state’s first statistical analysis of COVID-19 vaccinations in Texas and the effects, the newspaper reported.

The protective effect of vaccination was most noticeable among younger groups. During September, the risk of COVID-19 death was 23 times higher in unvaccinated people in their 30s and 55 times higher for unvaccinated people in their 40s.

In addition, there were fewer than 10 COVID-19 deaths in September among fully vaccinated people between ages 18-29, as compared with 339 deaths among unvaccinated people in the same age group.

Then, looking at a longer time period -- from Jan. 15 to Oct. 1 -- the researchers found that unvaccinated people were 45 times more likely to contract COVID-19 than fully vaccinated people. The protective effect of vaccination against infection was strong across all adult age groups but greatest among ages 12-17.

“All authorized COVID-19 vaccines in the United States are highly effective at protecting people from getting sick or severely ill with COVID-19, including those infected with Delta and other known variants,” the study authors wrote. “Real world data from Texas clearly shows these benefits.”

About 15.6 million people in Texas have been fully vaccinated against COVID-19 in a state of about 29 million residents, according to state data. About 66% of the population has received at least one dose, while 58% is fully vaccinated.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

During the month of September, , according to a new study from the Texas Department of State Health Services.

The data also showed that unvaccinated people were 13 times more likely to test positive for COVID-19 than people who were fully vaccinated.

“This analysis quantifies what we’ve known for months,” Jennifer Shuford, MD, the state’s chief epidemiologist, told The Dallas Morning News.

“The COVID-19 vaccines are doing an excellent job of protecting people from getting sick and from dying from COVID-19,” she said. “Vaccination remains the best way to keep yourself and the people close to you safe from this deadly disease.”

As part of the study, researchers analyzed electronic lab reports, death certificates, and state immunization records, with a particular focus on September when the contagious Delta variant surged across Texas. The research marks the state’s first statistical analysis of COVID-19 vaccinations in Texas and the effects, the newspaper reported.

The protective effect of vaccination was most noticeable among younger groups. During September, the risk of COVID-19 death was 23 times higher in unvaccinated people in their 30s and 55 times higher for unvaccinated people in their 40s.

In addition, there were fewer than 10 COVID-19 deaths in September among fully vaccinated people between ages 18-29, as compared with 339 deaths among unvaccinated people in the same age group.

Then, looking at a longer time period -- from Jan. 15 to Oct. 1 -- the researchers found that unvaccinated people were 45 times more likely to contract COVID-19 than fully vaccinated people. The protective effect of vaccination against infection was strong across all adult age groups but greatest among ages 12-17.

“All authorized COVID-19 vaccines in the United States are highly effective at protecting people from getting sick or severely ill with COVID-19, including those infected with Delta and other known variants,” the study authors wrote. “Real world data from Texas clearly shows these benefits.”

About 15.6 million people in Texas have been fully vaccinated against COVID-19 in a state of about 29 million residents, according to state data. About 66% of the population has received at least one dose, while 58% is fully vaccinated.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

During the month of September, , according to a new study from the Texas Department of State Health Services.

The data also showed that unvaccinated people were 13 times more likely to test positive for COVID-19 than people who were fully vaccinated.

“This analysis quantifies what we’ve known for months,” Jennifer Shuford, MD, the state’s chief epidemiologist, told The Dallas Morning News.

“The COVID-19 vaccines are doing an excellent job of protecting people from getting sick and from dying from COVID-19,” she said. “Vaccination remains the best way to keep yourself and the people close to you safe from this deadly disease.”

As part of the study, researchers analyzed electronic lab reports, death certificates, and state immunization records, with a particular focus on September when the contagious Delta variant surged across Texas. The research marks the state’s first statistical analysis of COVID-19 vaccinations in Texas and the effects, the newspaper reported.

The protective effect of vaccination was most noticeable among younger groups. During September, the risk of COVID-19 death was 23 times higher in unvaccinated people in their 30s and 55 times higher for unvaccinated people in their 40s.

In addition, there were fewer than 10 COVID-19 deaths in September among fully vaccinated people between ages 18-29, as compared with 339 deaths among unvaccinated people in the same age group.

Then, looking at a longer time period -- from Jan. 15 to Oct. 1 -- the researchers found that unvaccinated people were 45 times more likely to contract COVID-19 than fully vaccinated people. The protective effect of vaccination against infection was strong across all adult age groups but greatest among ages 12-17.

“All authorized COVID-19 vaccines in the United States are highly effective at protecting people from getting sick or severely ill with COVID-19, including those infected with Delta and other known variants,” the study authors wrote. “Real world data from Texas clearly shows these benefits.”

About 15.6 million people in Texas have been fully vaccinated against COVID-19 in a state of about 29 million residents, according to state data. About 66% of the population has received at least one dose, while 58% is fully vaccinated.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Children and COVID: New cases up again after dropping for 8 weeks

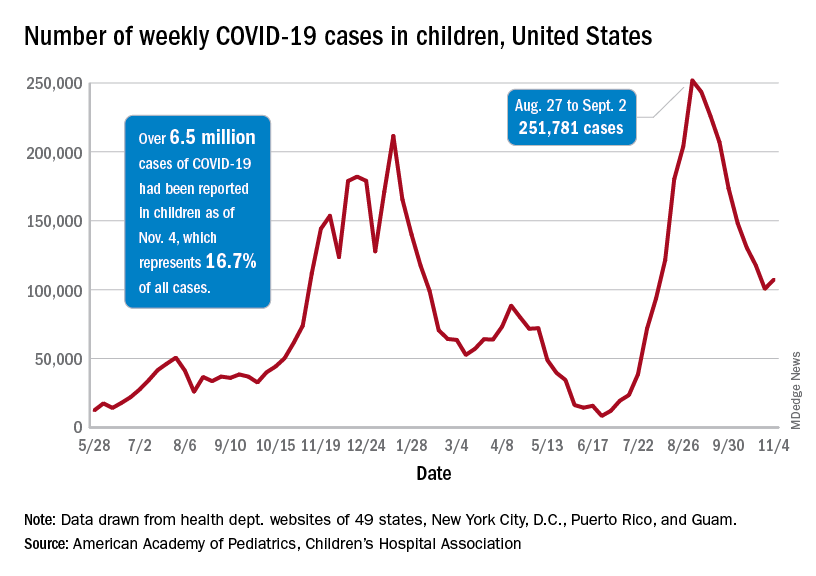

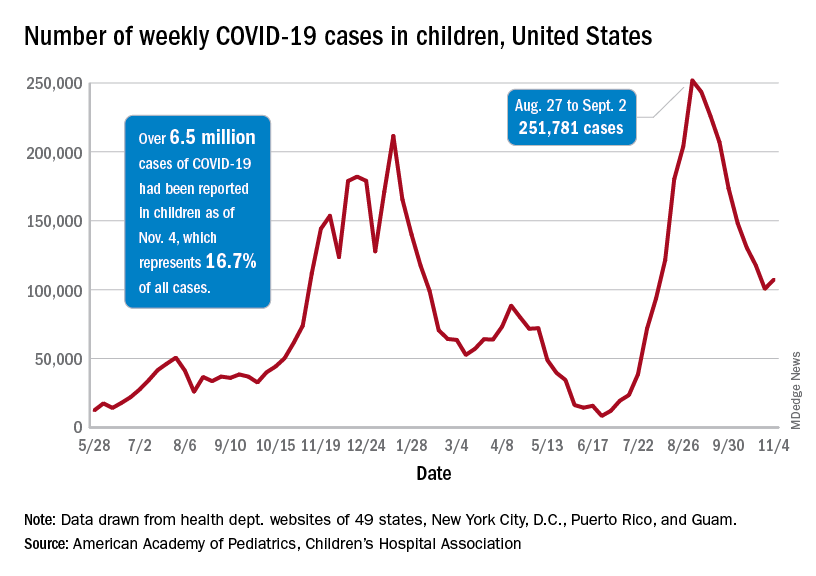

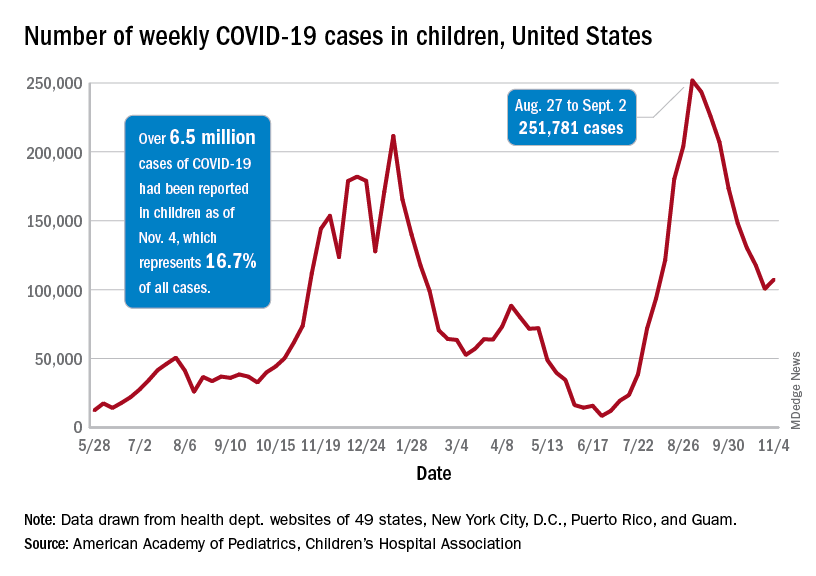

As children aged 5-11 years began to receive the first officially approved doses of COVID-19 vaccine, new pediatric cases increased after 8 consecutive weeks of declines, according to the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

Weekly cases peaked at almost 252,000 in early September and then dropped for 8 straight weeks before this latest rise, the AAP and the CHA said in their weekly COVID report, which is based on data reported by 49 states (excluding New York), the District of Columbia, New York City, Puerto Rico, and Guam.

The end of that 8-week drop, unfortunately, allowed another streak to continue: New cases have been above 100,000 for 13 consecutive weeks, the AAP and CHA noted.

The cumulative COVID count in children as of Nov. 4 was 6.5 million, the AAP/CHA said, although that figure does not fully cover Alabama, Nebraska, and Texas, which stopped public reporting over the summer. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, with input from all states and territories, puts the total through Nov. 8 at almost 5.7 million cases in children under 18 years of age, while most states define a child as someone aged 0-19 years.

As for the newest group of vaccinees, the CDC said that “updated vaccination data for 5-11 year-olds will be added to COVID Data Tracker later this week,” meaning the week of Nov. 7-13. Currently available data, however, show that almost 157,000 children under age 12 initiated vaccination in the 14 days ending Nov. 8, which was more than those aged 12-15 and 16-17 years combined (127,000).

Among those older groups, the CDC reports that 57.1% of 12- to 15-year-olds have received at least one dose and 47.9% are fully vaccinated, while 64.0% of those aged 16-17 have gotten at least one dose and 55.2% are fully vaccinated. Altogether, about 13.9 million children under age 18 have gotten at least one dose and almost 11.6 million are fully vaccinated, according to the CDC.

As children aged 5-11 years began to receive the first officially approved doses of COVID-19 vaccine, new pediatric cases increased after 8 consecutive weeks of declines, according to the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

Weekly cases peaked at almost 252,000 in early September and then dropped for 8 straight weeks before this latest rise, the AAP and the CHA said in their weekly COVID report, which is based on data reported by 49 states (excluding New York), the District of Columbia, New York City, Puerto Rico, and Guam.

The end of that 8-week drop, unfortunately, allowed another streak to continue: New cases have been above 100,000 for 13 consecutive weeks, the AAP and CHA noted.

The cumulative COVID count in children as of Nov. 4 was 6.5 million, the AAP/CHA said, although that figure does not fully cover Alabama, Nebraska, and Texas, which stopped public reporting over the summer. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, with input from all states and territories, puts the total through Nov. 8 at almost 5.7 million cases in children under 18 years of age, while most states define a child as someone aged 0-19 years.

As for the newest group of vaccinees, the CDC said that “updated vaccination data for 5-11 year-olds will be added to COVID Data Tracker later this week,” meaning the week of Nov. 7-13. Currently available data, however, show that almost 157,000 children under age 12 initiated vaccination in the 14 days ending Nov. 8, which was more than those aged 12-15 and 16-17 years combined (127,000).

Among those older groups, the CDC reports that 57.1% of 12- to 15-year-olds have received at least one dose and 47.9% are fully vaccinated, while 64.0% of those aged 16-17 have gotten at least one dose and 55.2% are fully vaccinated. Altogether, about 13.9 million children under age 18 have gotten at least one dose and almost 11.6 million are fully vaccinated, according to the CDC.

As children aged 5-11 years began to receive the first officially approved doses of COVID-19 vaccine, new pediatric cases increased after 8 consecutive weeks of declines, according to the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

Weekly cases peaked at almost 252,000 in early September and then dropped for 8 straight weeks before this latest rise, the AAP and the CHA said in their weekly COVID report, which is based on data reported by 49 states (excluding New York), the District of Columbia, New York City, Puerto Rico, and Guam.

The end of that 8-week drop, unfortunately, allowed another streak to continue: New cases have been above 100,000 for 13 consecutive weeks, the AAP and CHA noted.

The cumulative COVID count in children as of Nov. 4 was 6.5 million, the AAP/CHA said, although that figure does not fully cover Alabama, Nebraska, and Texas, which stopped public reporting over the summer. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, with input from all states and territories, puts the total through Nov. 8 at almost 5.7 million cases in children under 18 years of age, while most states define a child as someone aged 0-19 years.

As for the newest group of vaccinees, the CDC said that “updated vaccination data for 5-11 year-olds will be added to COVID Data Tracker later this week,” meaning the week of Nov. 7-13. Currently available data, however, show that almost 157,000 children under age 12 initiated vaccination in the 14 days ending Nov. 8, which was more than those aged 12-15 and 16-17 years combined (127,000).

Among those older groups, the CDC reports that 57.1% of 12- to 15-year-olds have received at least one dose and 47.9% are fully vaccinated, while 64.0% of those aged 16-17 have gotten at least one dose and 55.2% are fully vaccinated. Altogether, about 13.9 million children under age 18 have gotten at least one dose and almost 11.6 million are fully vaccinated, according to the CDC.

Severe COVID two times higher for cancer patients

A new systematic review and meta-analysis finds that unvaccinated cancer patients who contracted COVID-19 last year, were more than two times more likely – than people without cancer – to develop a case of COVID-19 so severe it required hospitalization in an intensive care unit.

“Our study provides the most precise measure to date of the effect of COVID-19 in cancer patients,” wrote researchers who were led by Paolo Boffetta, MD, MPH, a specialist in population science with the Stony Brook Cancer Center in New York.

Dr. Boffetta and colleagues also found that patients with hematologic neoplasms had a higher mortality rate from COVID-19 comparable to that of all cancers combined.

Cancer patients have long been considered to be among those patients who are at high risk of developing COVID-19, and if they contract the disease, they are at high risk of having poor outcomes. Other high-risk patients include those with hypertension, diabetes, chronic kidney disease, or COPD, or the elderly. But how high the risk of developing severe COVID-19 disease is for cancer patients hasn’t yet been documented on a wide scale.

The study, which was made available as a preprint on medRxiv on Oct. 23, is based on an analysis of COVID-19 cases that were documented in 35 reviews, meta-analyses, case reports, and studies indexed in PubMed from authors in North America, Europe, and Asia.

In this study, the pooled odds ratio for mortality for all patients with any cancer was 2.32 (95% confidence interval, 1.82-2.94; 24 studies). For ICU admission, the odds ratio was 2.39 (95% CI, 1.90-3.02; I2 0.0%; 5 studies). And, for disease severity or hospitalization, it was 2.08 (95% CI, 1.60-2.72; I2 92.1%; 15 studies). The pooled mortality odds ratio for hematologic neoplasms was 2.14 (95% CI, 1.87-2.44; I2 20.8%; 8 studies).

Their findings, which have not yet been peer reviewed, confirmed the results of a similar analysis from China published as a preprint in May 2020. The analysis included 181,323 patients (23,736 cancer patients) from 26 studies reported an odds ratio of 2.54 (95% CI, 1.47-4.42). “Cancer patients with COVID-19 have an increased likelihood of death compared to non-cancer COVID-19 patients,” Venkatesulu et al. wrote. And a systematic review and meta-analysis of five studies of 2,619 patients published in October 2020 in Medicine also found a significantly higher risk of death from COVID-19 among cancer patients (odds ratio, 2.63; 95% confidence interval, 1.14-6.06; P = .023; I2 = 26.4%).

Fakih et al., writing in the journal Hematology/Oncology and Stem Cell Therapy conducted a meta-analysis early last year finding a threefold increase for admission to the intensive care unit, an almost fourfold increase for a severe SARS-CoV-2 infection, and a fivefold increase for being intubated.

The three studies show that mortality rates were higher early in the pandemic “when diagnosis and treatment for SARS-CoV-2 might have been delayed, resulting in higher death rate,” Boffetta et al. wrote, adding that their analysis showed only a twofold increase most likely because it was a year-long analysis.

“Future studies will be able to better analyze this association for the different subtypes of cancer. Furthermore, they will eventually be able to evaluate whether the difference among vaccinated population is reduced,” Boffetta et al. wrote.

The authors noted several limitations for the study, including the fact that many of the studies included in the analysis did not include sex, age, comorbidities, and therapy. Nor were the authors able to analyze specific cancers other than hematologic neoplasms.

The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

A new systematic review and meta-analysis finds that unvaccinated cancer patients who contracted COVID-19 last year, were more than two times more likely – than people without cancer – to develop a case of COVID-19 so severe it required hospitalization in an intensive care unit.

“Our study provides the most precise measure to date of the effect of COVID-19 in cancer patients,” wrote researchers who were led by Paolo Boffetta, MD, MPH, a specialist in population science with the Stony Brook Cancer Center in New York.

Dr. Boffetta and colleagues also found that patients with hematologic neoplasms had a higher mortality rate from COVID-19 comparable to that of all cancers combined.

Cancer patients have long been considered to be among those patients who are at high risk of developing COVID-19, and if they contract the disease, they are at high risk of having poor outcomes. Other high-risk patients include those with hypertension, diabetes, chronic kidney disease, or COPD, or the elderly. But how high the risk of developing severe COVID-19 disease is for cancer patients hasn’t yet been documented on a wide scale.

The study, which was made available as a preprint on medRxiv on Oct. 23, is based on an analysis of COVID-19 cases that were documented in 35 reviews, meta-analyses, case reports, and studies indexed in PubMed from authors in North America, Europe, and Asia.

In this study, the pooled odds ratio for mortality for all patients with any cancer was 2.32 (95% confidence interval, 1.82-2.94; 24 studies). For ICU admission, the odds ratio was 2.39 (95% CI, 1.90-3.02; I2 0.0%; 5 studies). And, for disease severity or hospitalization, it was 2.08 (95% CI, 1.60-2.72; I2 92.1%; 15 studies). The pooled mortality odds ratio for hematologic neoplasms was 2.14 (95% CI, 1.87-2.44; I2 20.8%; 8 studies).

Their findings, which have not yet been peer reviewed, confirmed the results of a similar analysis from China published as a preprint in May 2020. The analysis included 181,323 patients (23,736 cancer patients) from 26 studies reported an odds ratio of 2.54 (95% CI, 1.47-4.42). “Cancer patients with COVID-19 have an increased likelihood of death compared to non-cancer COVID-19 patients,” Venkatesulu et al. wrote. And a systematic review and meta-analysis of five studies of 2,619 patients published in October 2020 in Medicine also found a significantly higher risk of death from COVID-19 among cancer patients (odds ratio, 2.63; 95% confidence interval, 1.14-6.06; P = .023; I2 = 26.4%).

Fakih et al., writing in the journal Hematology/Oncology and Stem Cell Therapy conducted a meta-analysis early last year finding a threefold increase for admission to the intensive care unit, an almost fourfold increase for a severe SARS-CoV-2 infection, and a fivefold increase for being intubated.

The three studies show that mortality rates were higher early in the pandemic “when diagnosis and treatment for SARS-CoV-2 might have been delayed, resulting in higher death rate,” Boffetta et al. wrote, adding that their analysis showed only a twofold increase most likely because it was a year-long analysis.

“Future studies will be able to better analyze this association for the different subtypes of cancer. Furthermore, they will eventually be able to evaluate whether the difference among vaccinated population is reduced,” Boffetta et al. wrote.

The authors noted several limitations for the study, including the fact that many of the studies included in the analysis did not include sex, age, comorbidities, and therapy. Nor were the authors able to analyze specific cancers other than hematologic neoplasms.

The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

A new systematic review and meta-analysis finds that unvaccinated cancer patients who contracted COVID-19 last year, were more than two times more likely – than people without cancer – to develop a case of COVID-19 so severe it required hospitalization in an intensive care unit.

“Our study provides the most precise measure to date of the effect of COVID-19 in cancer patients,” wrote researchers who were led by Paolo Boffetta, MD, MPH, a specialist in population science with the Stony Brook Cancer Center in New York.

Dr. Boffetta and colleagues also found that patients with hematologic neoplasms had a higher mortality rate from COVID-19 comparable to that of all cancers combined.

Cancer patients have long been considered to be among those patients who are at high risk of developing COVID-19, and if they contract the disease, they are at high risk of having poor outcomes. Other high-risk patients include those with hypertension, diabetes, chronic kidney disease, or COPD, or the elderly. But how high the risk of developing severe COVID-19 disease is for cancer patients hasn’t yet been documented on a wide scale.

The study, which was made available as a preprint on medRxiv on Oct. 23, is based on an analysis of COVID-19 cases that were documented in 35 reviews, meta-analyses, case reports, and studies indexed in PubMed from authors in North America, Europe, and Asia.

In this study, the pooled odds ratio for mortality for all patients with any cancer was 2.32 (95% confidence interval, 1.82-2.94; 24 studies). For ICU admission, the odds ratio was 2.39 (95% CI, 1.90-3.02; I2 0.0%; 5 studies). And, for disease severity or hospitalization, it was 2.08 (95% CI, 1.60-2.72; I2 92.1%; 15 studies). The pooled mortality odds ratio for hematologic neoplasms was 2.14 (95% CI, 1.87-2.44; I2 20.8%; 8 studies).

Their findings, which have not yet been peer reviewed, confirmed the results of a similar analysis from China published as a preprint in May 2020. The analysis included 181,323 patients (23,736 cancer patients) from 26 studies reported an odds ratio of 2.54 (95% CI, 1.47-4.42). “Cancer patients with COVID-19 have an increased likelihood of death compared to non-cancer COVID-19 patients,” Venkatesulu et al. wrote. And a systematic review and meta-analysis of five studies of 2,619 patients published in October 2020 in Medicine also found a significantly higher risk of death from COVID-19 among cancer patients (odds ratio, 2.63; 95% confidence interval, 1.14-6.06; P = .023; I2 = 26.4%).

Fakih et al., writing in the journal Hematology/Oncology and Stem Cell Therapy conducted a meta-analysis early last year finding a threefold increase for admission to the intensive care unit, an almost fourfold increase for a severe SARS-CoV-2 infection, and a fivefold increase for being intubated.

The three studies show that mortality rates were higher early in the pandemic “when diagnosis and treatment for SARS-CoV-2 might have been delayed, resulting in higher death rate,” Boffetta et al. wrote, adding that their analysis showed only a twofold increase most likely because it was a year-long analysis.

“Future studies will be able to better analyze this association for the different subtypes of cancer. Furthermore, they will eventually be able to evaluate whether the difference among vaccinated population is reduced,” Boffetta et al. wrote.

The authors noted several limitations for the study, including the fact that many of the studies included in the analysis did not include sex, age, comorbidities, and therapy. Nor were the authors able to analyze specific cancers other than hematologic neoplasms.

The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

FROM MEDRXIV

New transmission information should motivate hospitals to reexamine aerosol procedures, researchers say

Two studies published in Thorax have found that the use of continuous positive airways pressure (CPAP) or high-flow nasal oxygen (HFNO) to treat moderate to severe COVID-19 is not linked to a heightened risk of infection, as currently thought. Researchers say hospitals should use this information to re-examine aerosol procedures in regard to risk of transmission of SARS-CoV-2.

CPAP and HFNO have been thought to generate virus particles capable of contaminating the air and surfaces, necessitating additional infection control precautions such as segregating patients. However, this research demonstrates that both methods produced little measurable air or surface viral contamination. The amount of contamination was no more than with the use of supplemental oxygen and less than that produced when breathing, speaking, or coughing.

In one study, led by a team from the North Bristol NHS Trust, 25 healthy volunteers and eight hospitalized patients with COVID-19 were recruited and asked to breathe, speak, and cough in ultra-clean, laminar flow theaters followed by use of CPAP and HFNO. Aerosol emission was measured via two methodologies, simultaneously. Hospitalized patients with COVID-19 had cough recorded via the same methodology on the infectious diseases ward.

CPAP (with exhalation port filter) was found to produce less aerosol than breathing, speaking, and coughing, even with large > 50 L/min face mask leaks. Coughing was associated with the highest aerosol emissions of any recorded activity.

HFNO was associated with aerosol emission from the machine. Generated particles were small (< 1 mcm), passing from the machine through the patient and to the detector without coalescence with respiratory aerosol, and, consequently, would be unlikely to carry viral particles.

More aerosol was generated in cough from patients with COVID-19 (n = 8) than from volunteers.

In the second study, 30 hospitalized patients with COVID-19 requiring supplemental oxygen were prospectively enrolled. In this observational environmental sampling study, participants received either supplemental oxygen, CPAP, or HFNO (n = 10 in each group). A nasopharyngeal swab, three air, and three surface samples were collected from each participant and the clinical environment.

Overall, 21 of the 30 participants tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 RNA in the nasopharynx. In contrast, 4 out of 90 air samples and 6 of 90 surface samples tested positive for viral RNA, although there were an additional 10 suspected-positive samples in both air and surfaces samples.

Neither the use of CPAP nor HFNO nor coughing were associated with significantly more environmental contamination than supplemental oxygen use. Of the total positive or suspected-positive samples by viral PCR detection, only one nasopharynx sample from an HFNO patient was biologically viable in cell culture assay.

“Our findings show that the noninvasive breathing support methods do not pose a higher risk of transmitting infection, which has significant implications for the management of the patients,” said coauthor Danny McAuley, MD.

“If there isn’t a higher risk of infection transmission, current practices may be overcautious measures for certain settings, for example preventing relatives visiting the sickest patients, whilst underestimating the risk in other settings, such as coughing patients with early infection on general wards.”

Although both studies are small, the results do suggest that there is a need for an evidence-based reassessment of infection prevention and control measures for noninvasive respiratory support treatments that are currently considered aerosol generating procedures.

A version of this article first appeared on Univadis.com.

Two studies published in Thorax have found that the use of continuous positive airways pressure (CPAP) or high-flow nasal oxygen (HFNO) to treat moderate to severe COVID-19 is not linked to a heightened risk of infection, as currently thought. Researchers say hospitals should use this information to re-examine aerosol procedures in regard to risk of transmission of SARS-CoV-2.

CPAP and HFNO have been thought to generate virus particles capable of contaminating the air and surfaces, necessitating additional infection control precautions such as segregating patients. However, this research demonstrates that both methods produced little measurable air or surface viral contamination. The amount of contamination was no more than with the use of supplemental oxygen and less than that produced when breathing, speaking, or coughing.

In one study, led by a team from the North Bristol NHS Trust, 25 healthy volunteers and eight hospitalized patients with COVID-19 were recruited and asked to breathe, speak, and cough in ultra-clean, laminar flow theaters followed by use of CPAP and HFNO. Aerosol emission was measured via two methodologies, simultaneously. Hospitalized patients with COVID-19 had cough recorded via the same methodology on the infectious diseases ward.

CPAP (with exhalation port filter) was found to produce less aerosol than breathing, speaking, and coughing, even with large > 50 L/min face mask leaks. Coughing was associated with the highest aerosol emissions of any recorded activity.

HFNO was associated with aerosol emission from the machine. Generated particles were small (< 1 mcm), passing from the machine through the patient and to the detector without coalescence with respiratory aerosol, and, consequently, would be unlikely to carry viral particles.

More aerosol was generated in cough from patients with COVID-19 (n = 8) than from volunteers.

In the second study, 30 hospitalized patients with COVID-19 requiring supplemental oxygen were prospectively enrolled. In this observational environmental sampling study, participants received either supplemental oxygen, CPAP, or HFNO (n = 10 in each group). A nasopharyngeal swab, three air, and three surface samples were collected from each participant and the clinical environment.

Overall, 21 of the 30 participants tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 RNA in the nasopharynx. In contrast, 4 out of 90 air samples and 6 of 90 surface samples tested positive for viral RNA, although there were an additional 10 suspected-positive samples in both air and surfaces samples.

Neither the use of CPAP nor HFNO nor coughing were associated with significantly more environmental contamination than supplemental oxygen use. Of the total positive or suspected-positive samples by viral PCR detection, only one nasopharynx sample from an HFNO patient was biologically viable in cell culture assay.

“Our findings show that the noninvasive breathing support methods do not pose a higher risk of transmitting infection, which has significant implications for the management of the patients,” said coauthor Danny McAuley, MD.

“If there isn’t a higher risk of infection transmission, current practices may be overcautious measures for certain settings, for example preventing relatives visiting the sickest patients, whilst underestimating the risk in other settings, such as coughing patients with early infection on general wards.”

Although both studies are small, the results do suggest that there is a need for an evidence-based reassessment of infection prevention and control measures for noninvasive respiratory support treatments that are currently considered aerosol generating procedures.

A version of this article first appeared on Univadis.com.

Two studies published in Thorax have found that the use of continuous positive airways pressure (CPAP) or high-flow nasal oxygen (HFNO) to treat moderate to severe COVID-19 is not linked to a heightened risk of infection, as currently thought. Researchers say hospitals should use this information to re-examine aerosol procedures in regard to risk of transmission of SARS-CoV-2.

CPAP and HFNO have been thought to generate virus particles capable of contaminating the air and surfaces, necessitating additional infection control precautions such as segregating patients. However, this research demonstrates that both methods produced little measurable air or surface viral contamination. The amount of contamination was no more than with the use of supplemental oxygen and less than that produced when breathing, speaking, or coughing.

In one study, led by a team from the North Bristol NHS Trust, 25 healthy volunteers and eight hospitalized patients with COVID-19 were recruited and asked to breathe, speak, and cough in ultra-clean, laminar flow theaters followed by use of CPAP and HFNO. Aerosol emission was measured via two methodologies, simultaneously. Hospitalized patients with COVID-19 had cough recorded via the same methodology on the infectious diseases ward.

CPAP (with exhalation port filter) was found to produce less aerosol than breathing, speaking, and coughing, even with large > 50 L/min face mask leaks. Coughing was associated with the highest aerosol emissions of any recorded activity.

HFNO was associated with aerosol emission from the machine. Generated particles were small (< 1 mcm), passing from the machine through the patient and to the detector without coalescence with respiratory aerosol, and, consequently, would be unlikely to carry viral particles.

More aerosol was generated in cough from patients with COVID-19 (n = 8) than from volunteers.

In the second study, 30 hospitalized patients with COVID-19 requiring supplemental oxygen were prospectively enrolled. In this observational environmental sampling study, participants received either supplemental oxygen, CPAP, or HFNO (n = 10 in each group). A nasopharyngeal swab, three air, and three surface samples were collected from each participant and the clinical environment.

Overall, 21 of the 30 participants tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 RNA in the nasopharynx. In contrast, 4 out of 90 air samples and 6 of 90 surface samples tested positive for viral RNA, although there were an additional 10 suspected-positive samples in both air and surfaces samples.

Neither the use of CPAP nor HFNO nor coughing were associated with significantly more environmental contamination than supplemental oxygen use. Of the total positive or suspected-positive samples by viral PCR detection, only one nasopharynx sample from an HFNO patient was biologically viable in cell culture assay.

“Our findings show that the noninvasive breathing support methods do not pose a higher risk of transmitting infection, which has significant implications for the management of the patients,” said coauthor Danny McAuley, MD.

“If there isn’t a higher risk of infection transmission, current practices may be overcautious measures for certain settings, for example preventing relatives visiting the sickest patients, whilst underestimating the risk in other settings, such as coughing patients with early infection on general wards.”

Although both studies are small, the results do suggest that there is a need for an evidence-based reassessment of infection prevention and control measures for noninvasive respiratory support treatments that are currently considered aerosol generating procedures.

A version of this article first appeared on Univadis.com.

FROM THORAX

Hospitalist movers and shakers - November 2021

Vineet Chopra, MD, MSc, FHM, recently became chair of the Department of Medicine at the University of Colorado School of Medicine, Aurora. He had previously been the chief of the Division of Hospital Medicine at the University of Michigan Health system. He assumed his new role in October 2021.

Dr. Chopra, who specializes in research and mentorship in patient safety, helped create innovations in care delivery at the University of Michigan, including direct care hospitalist services at VA Ann Arbor Health Care and two other community hospitals.

In his safety-conscious research, Dr. Chopra focuses on preventing complications created within the hospital environment. He also is the first hospitalist to be named deputy editor of the Annals of Internal Medicine. He has written more than 250 peer-reviewed articles. Among the myriad awards he has received, Dr. Chopra recently earned the Kaiser Permanente Award for Clinical Teaching at the UM School of Medicine.

Steve Phillipson, MD, FHM, has been named regional director of hospital medicine at Aspirus Health (Wausau, Wisc.). Dr. Phillipson will oversee the hospitalist programs at 17 Aspirus hospitals in Wisconsin and Michigan.

Dr. Phillipson has worked with Aspirus since 2009, with stints in the emergency department and as a hospitalist. As Aspirus Wausau Hospital director of medicine, he chaired the facility’s COVID-19 treatment team.

Hackensack (N.J.) Meridian University Medical Center has hired Patricia (Patti) L. Fisher, MD, MHA, to be the institution’s chief medical officer. Dr. Fisher joined the medical center from Central Vermont Medical Center where she served as chief medical officer and chief safety officer, with direct oversight of hospital risk management, operations of all hospital-based services, IS services and quality including patient safety and regulatory compliance.

As a board-certified hospitalist, Dr. Fisher also served as clinical assistant professor in the Department of Family Medicine at the University of Vermont, Burlington. Dr. Fisher earned her medical degree from The University of Texas in Houston and completed residency through Forbes Family Practice Residency in Pittsburgh.

Martin Chaney, MD, has been chosen by the Maury Regional Health Board of Trustees to serve as interim chief executive officer. He was formerly the chief medical officer at MRH, which is based in Columbia, Tenn. Dr. Chaney began his new role in October, replacing Alan Watson, the CEO since 2012.

Dr. Chaney has spent 18 of his 25 years in medicine with MRH, where most recently he has focused on clinical quality, physician recruitment, and establishing and expanding the hospital medicine program.

Hyung (Harry) Cho, MD, SFHM, has been placed on Modern Healthcare’s Top 25 Innovators list for 2021, getting recognized for innovation and leadership in creating value and safety initiatives in New York City’s public health system. Dr. Cho became NYC Health + Hospitals’ first chief value officer in 2019, and his programs have created an estimated $11 million in savings per year by preventing unnecessary testing and treatment that can lead to patient harm.

A member of the Society of Hospital Medicine’s editorial advisory board, Dr. Cho is also SHM’s hospitalist liaison with the COVID-19 Real-Time Learning Network, which collaborates with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the Infectious Diseases Society of America.

Raymond Kiser, MD, a hospitalist and nephrologist at Columbus (Ind.) Regional Health, has been named the Douglas J. Leonard Caregiver of the Year. The award is given by the Indiana Hospital Association to health care workers whose care is considered exemplary by both peers and patients.

Dr. Kiser has been with CRH for 7 years, including stints as associate chief medical officer and chief of staff.

Justin Buchholz, DO, has been elevated to medical director of the hospitalist teams at Regional Medical Center (Alamosa, Colo.) and Conejos County Hospital (La Jara, Colo.). Dr. Buchholz has been a full-time hospitalist and assistant medical director at Parkview Medical Center (Pueblo, Colo.) for the past 3 years. He also worked on a part-time basis seeing patients at the Regional Medical Center.

Dr. Buchholz completed his residency at Parkview Medical Center and was named Resident of the Year in his final year with the internal medicine program.

Kenneth Mishark, MD, SFHM, a hospitalist with the Mayo Clinic Hospital (Tucson, Ariz.), will serve on the board of directors for Anigent, a drug diversion-prevention company based in Chesterfield, Mo. He will be charged with helping Anigent better serve health systems with its drug-diversion software.

Dr. Mishark is vice-chair of diversion prevention across the whole Mayo Clinic. A one-time physician in the United States Air Force, Dr. Mishark previously has been the Mayo Clinic’s Healthcare Information Coordination Committee chair.

Core Clinical Partners (Tulsa, Okla.) has announced it will join with Hillcrest HealthCare System (Tulsa, Okla.) to provide hospitalist services to Hillcrest’s eight sites across Oklahoma. The partnership will begin at four locations in December 2021, and four others in March 2022.

In expanding its services, Core Clinical Partners will create 70 new physician positions, as well as a systemwide medical director. Core will manage hospitalist operations at Hillcrest Medical Center, Hillcrest Hospital South, Hillcrest Hospital Pryor, Hillcrest Hospital Claremore, Bailey Medical Center, Hillcrest Hospital Cushing, Hillcrest Hospital Henryetta, and Tulsa Spine and Specialty Hospital.

Vineet Chopra, MD, MSc, FHM, recently became chair of the Department of Medicine at the University of Colorado School of Medicine, Aurora. He had previously been the chief of the Division of Hospital Medicine at the University of Michigan Health system. He assumed his new role in October 2021.

Dr. Chopra, who specializes in research and mentorship in patient safety, helped create innovations in care delivery at the University of Michigan, including direct care hospitalist services at VA Ann Arbor Health Care and two other community hospitals.

In his safety-conscious research, Dr. Chopra focuses on preventing complications created within the hospital environment. He also is the first hospitalist to be named deputy editor of the Annals of Internal Medicine. He has written more than 250 peer-reviewed articles. Among the myriad awards he has received, Dr. Chopra recently earned the Kaiser Permanente Award for Clinical Teaching at the UM School of Medicine.

Steve Phillipson, MD, FHM, has been named regional director of hospital medicine at Aspirus Health (Wausau, Wisc.). Dr. Phillipson will oversee the hospitalist programs at 17 Aspirus hospitals in Wisconsin and Michigan.

Dr. Phillipson has worked with Aspirus since 2009, with stints in the emergency department and as a hospitalist. As Aspirus Wausau Hospital director of medicine, he chaired the facility’s COVID-19 treatment team.

Hackensack (N.J.) Meridian University Medical Center has hired Patricia (Patti) L. Fisher, MD, MHA, to be the institution’s chief medical officer. Dr. Fisher joined the medical center from Central Vermont Medical Center where she served as chief medical officer and chief safety officer, with direct oversight of hospital risk management, operations of all hospital-based services, IS services and quality including patient safety and regulatory compliance.

As a board-certified hospitalist, Dr. Fisher also served as clinical assistant professor in the Department of Family Medicine at the University of Vermont, Burlington. Dr. Fisher earned her medical degree from The University of Texas in Houston and completed residency through Forbes Family Practice Residency in Pittsburgh.