User login

Sunburn Purpura

To the Editor:

Chronic UV exposure has been linked to increased skin fragility and the development of purpuric lesions, a benign condition known as actinic purpura and commonly seen in elderly patients. Petechial skin changes acutely following intense sun exposure is a rare phenomenon referred to as sunburn purpura, photolocalized purpura, or solar purpura.

A 19-year-old woman presented with red and purple spots on the pretibial region of both legs extending to the thigh. One week prior to presentation she had a severe sunburn affecting most of the body, which resolved without blistering. Two days later, the spots appeared within the most severely sunburned areas of both legs. The patient reported that the lesions were mildly painful to palpation, but she was more concerned about the appearance. She denied any history of similar skin changes associated with sun exposure. The patient was otherwise healthy and denied any recent illnesses. She noted a history of mild bruising and bleeding with a resulting unremarkable workup by her primary care physician. The only medication taken was etonogestrel-ethinyl estradiol vaginal ring.

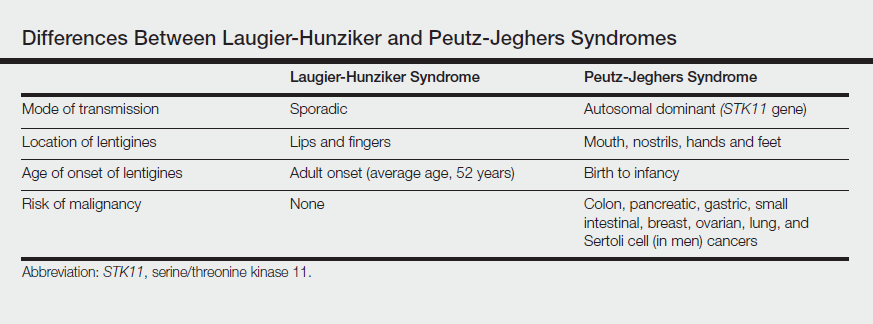

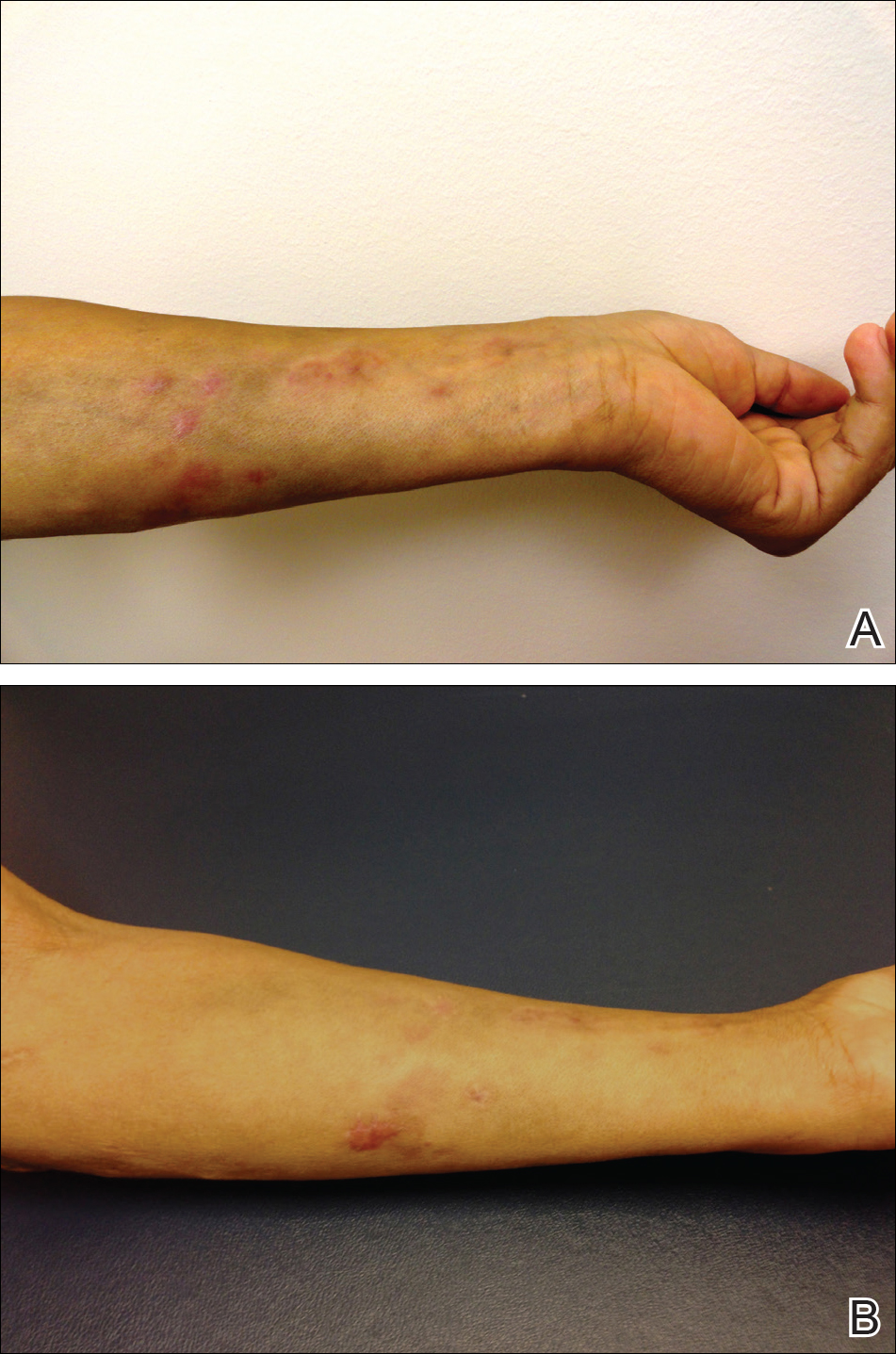

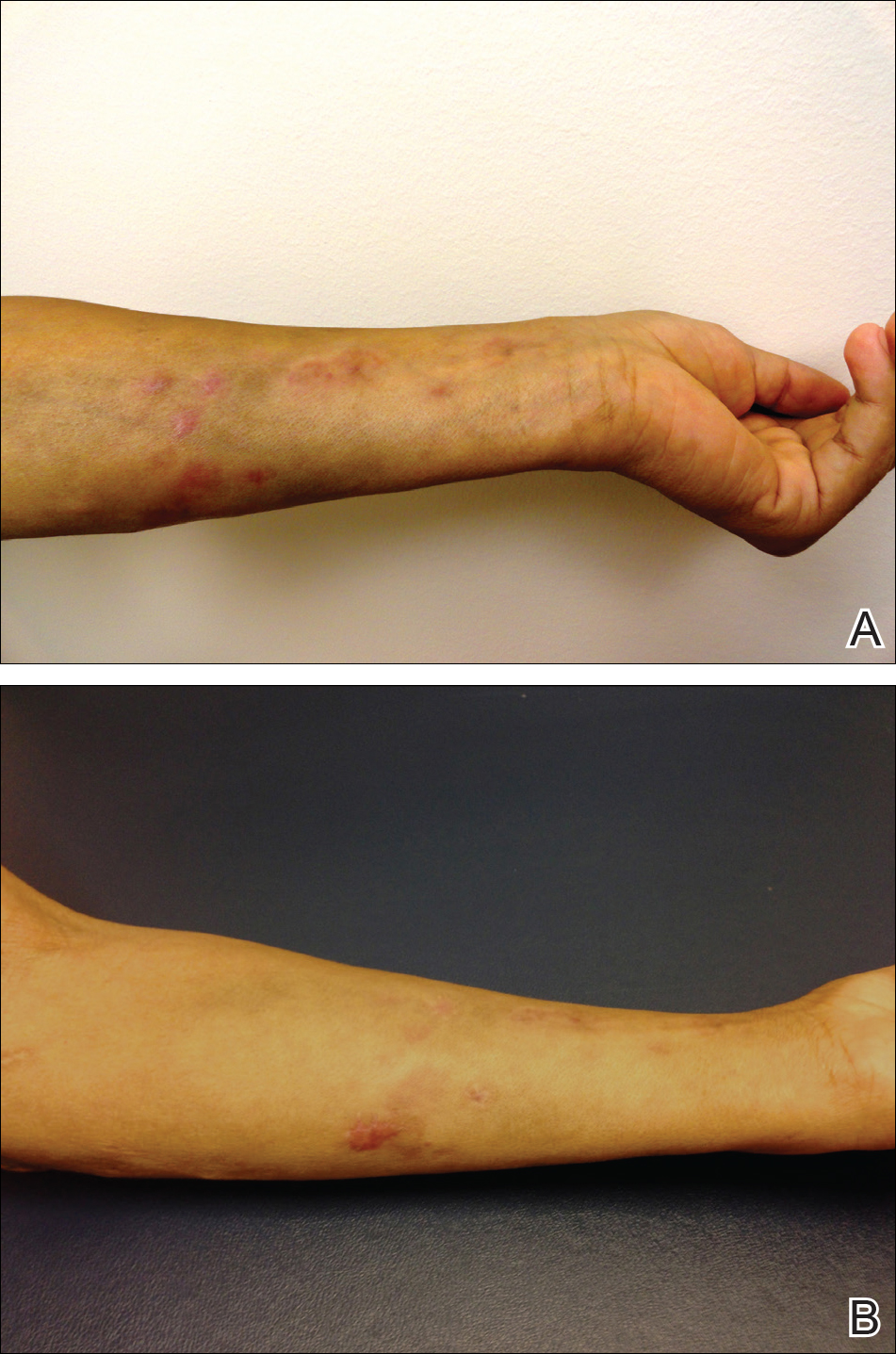

The scalp, face, arms, trunk, and legs were examined, and nonpalpable petechial changes were noted on the anterior aspect of the legs (Figure 1), with changes more prominent on the distal aspect of the legs. Mild superficial epidermal exfoliation was noted on both anterior thighs. The area of the lesions was not warm. The lesions were mildly tender to palpation. The remainder of the physical examination was unremarkable.

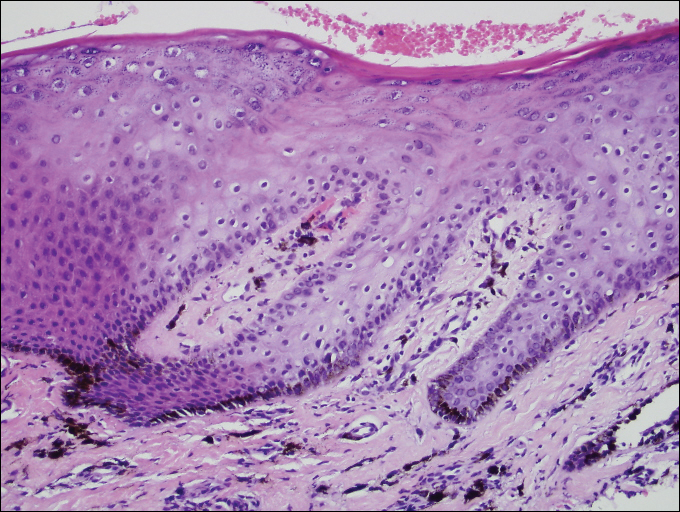

Given the timing of onset, preceding sun exposure, and the morphologic characteristics of the lesions, sunburn purpura was suspected. A punch biopsy of the anterior aspect of the left thigh was performed to rule out vasculitis. Microscopic examination revealed reactive epidermal changes with mild vascular ectasia and erythrocyte extravasation not associated with appreciable inflammation or evidence of vascular injury (Figure 2). Biopsy exposure to fluorescein-labeled antibodies directed against IgG, IgM, IgA, C3, and polyvalent immunoglobulins (IgG, IgM, and IgA) yielded no immunofluorescence. These biopsy results were consistent with sunburn purpura. Given the patient's normal platelet count, a diagnosis of idiopathic sunburn purpura was made. The patient was informed of the biopsy results and advised that the petechiae should resolve without treatment in 1 to 2 weeks, which occurred.

Sunburn purpura remains a rare phenomenon in which a petechial or purpuric rash develops acutely after intense sun exposure. We prefer the term sunburn purpura because it reflects the acuity of the phenomenon, as opposed to the previous labels solar purpura or photolocalized purpura, which also could suggest causality from chronic sun exposure. It has been proposed that sunburn purpura is a finding associated with a number of conditions rather than a unique entity.1 The following characteristics can be helpful in describing the development of sunburn purpura: delay following UV exposure, gross morphology, histologic findings, and possible associated medical conditions.1 Our case represents an important addition to the literature, as it differs from previously reported cases. Most importantly, the nonspecific biopsy findings and unremarkable laboratory findings associated with our case may represent primary or idiopathic sunburn purpura.

Previously reported cases of sunburn purpura have occurred in patients aged 10 to 66 years. It has been seen following UV exposure, vigorous exercise and high-dose aspirin, or concurrent fluoroquinolone therapy, or in the setting of erythropoietic protoporphyria, idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura, or polymorphous light eruption.2-8 When performed, histology has revealed capillaritis, solar elastosis, perivascular infiltrate, lymphocytic perivascular infiltrate with dermal edema, or leukocytoclastic vasculitis.1,2,7-9 Our patient did not have a history of erythropoietic protoporphyria, polymorphous light eruption, or idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura. She had not recently exercised, was not thrombocytopenic, and was not taking antiplatelet medications. She had no recent history of fluoroquinolone use. On histologic examination, our patient's biopsy demonstrated nonspecific petechial changes without signs of chronic UV exposure, dermal edema, vasculitis, lymphocytic infiltrate, or capillaritis.

Idiopathic sunburn purpura should only be diagnosed after other conditions are excluded. When evaluating a patient who presents with new-onset petechial rash following sun exposure, it is important to rule out vasculitis or thrombocytopenia as the cause, which is best achieved through skin biopsy and a platelet count, respectively. If there are no associated symptoms or thrombocytopenia and biopsy shows nonspecific vascular ectasia and erythrocyte extravasation, the physician should consider the diagnosis of idiopathic sunburn (solar or photolocalized) purpura. Along with regular UV protection, the physician should advise that the rash typically resolves without treatment in 1 to 2 weeks.

- Waters AJ, Sandhu DR, Green CM, et al. Solar capillaritis as a cause of solar purpura. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2009;34:E821-E824.

- Latenser BA, Hempstead RW. Exercise-associated solar purpura in an atypical location. Cutis. 1985;35:365-366.

- Rubegni P, Feci L, Pellegrino M, et al. Photolocalized purpura during levofloxacin therapy. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. 2012;28:105-107.

- Urbina F, Barrios M, Sudy E. Photolocalized purpura during ciprofloxacin therapy. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. 2006;22:111-112.

- Torinuki W, Miura T. Erythropoietic protoporphyria showing solar purpura. Dermatologica. 1983;167:220-222.

- Leung AK. Purpura associated with exposure to sunlight. J R Soc Med. 1986;79:423-424.

- Kalivas J, Kalivas L. Solar purpura appearing in a patient with polymorphous light eruption. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. 1995;11:31-32.

- Ros AM. Solar purpura--an unusual manifestation of polymorphous light eruption. Photodermatol. 1988;5:47-48.

- Guarrera M, Parodi A, Rebora A. Solar purpura is not related to polymorphous light eruption. Photodermatol. 1989;6:293-294.

To the Editor:

Chronic UV exposure has been linked to increased skin fragility and the development of purpuric lesions, a benign condition known as actinic purpura and commonly seen in elderly patients. Petechial skin changes acutely following intense sun exposure is a rare phenomenon referred to as sunburn purpura, photolocalized purpura, or solar purpura.

A 19-year-old woman presented with red and purple spots on the pretibial region of both legs extending to the thigh. One week prior to presentation she had a severe sunburn affecting most of the body, which resolved without blistering. Two days later, the spots appeared within the most severely sunburned areas of both legs. The patient reported that the lesions were mildly painful to palpation, but she was more concerned about the appearance. She denied any history of similar skin changes associated with sun exposure. The patient was otherwise healthy and denied any recent illnesses. She noted a history of mild bruising and bleeding with a resulting unremarkable workup by her primary care physician. The only medication taken was etonogestrel-ethinyl estradiol vaginal ring.

The scalp, face, arms, trunk, and legs were examined, and nonpalpable petechial changes were noted on the anterior aspect of the legs (Figure 1), with changes more prominent on the distal aspect of the legs. Mild superficial epidermal exfoliation was noted on both anterior thighs. The area of the lesions was not warm. The lesions were mildly tender to palpation. The remainder of the physical examination was unremarkable.

Given the timing of onset, preceding sun exposure, and the morphologic characteristics of the lesions, sunburn purpura was suspected. A punch biopsy of the anterior aspect of the left thigh was performed to rule out vasculitis. Microscopic examination revealed reactive epidermal changes with mild vascular ectasia and erythrocyte extravasation not associated with appreciable inflammation or evidence of vascular injury (Figure 2). Biopsy exposure to fluorescein-labeled antibodies directed against IgG, IgM, IgA, C3, and polyvalent immunoglobulins (IgG, IgM, and IgA) yielded no immunofluorescence. These biopsy results were consistent with sunburn purpura. Given the patient's normal platelet count, a diagnosis of idiopathic sunburn purpura was made. The patient was informed of the biopsy results and advised that the petechiae should resolve without treatment in 1 to 2 weeks, which occurred.

Sunburn purpura remains a rare phenomenon in which a petechial or purpuric rash develops acutely after intense sun exposure. We prefer the term sunburn purpura because it reflects the acuity of the phenomenon, as opposed to the previous labels solar purpura or photolocalized purpura, which also could suggest causality from chronic sun exposure. It has been proposed that sunburn purpura is a finding associated with a number of conditions rather than a unique entity.1 The following characteristics can be helpful in describing the development of sunburn purpura: delay following UV exposure, gross morphology, histologic findings, and possible associated medical conditions.1 Our case represents an important addition to the literature, as it differs from previously reported cases. Most importantly, the nonspecific biopsy findings and unremarkable laboratory findings associated with our case may represent primary or idiopathic sunburn purpura.

Previously reported cases of sunburn purpura have occurred in patients aged 10 to 66 years. It has been seen following UV exposure, vigorous exercise and high-dose aspirin, or concurrent fluoroquinolone therapy, or in the setting of erythropoietic protoporphyria, idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura, or polymorphous light eruption.2-8 When performed, histology has revealed capillaritis, solar elastosis, perivascular infiltrate, lymphocytic perivascular infiltrate with dermal edema, or leukocytoclastic vasculitis.1,2,7-9 Our patient did not have a history of erythropoietic protoporphyria, polymorphous light eruption, or idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura. She had not recently exercised, was not thrombocytopenic, and was not taking antiplatelet medications. She had no recent history of fluoroquinolone use. On histologic examination, our patient's biopsy demonstrated nonspecific petechial changes without signs of chronic UV exposure, dermal edema, vasculitis, lymphocytic infiltrate, or capillaritis.

Idiopathic sunburn purpura should only be diagnosed after other conditions are excluded. When evaluating a patient who presents with new-onset petechial rash following sun exposure, it is important to rule out vasculitis or thrombocytopenia as the cause, which is best achieved through skin biopsy and a platelet count, respectively. If there are no associated symptoms or thrombocytopenia and biopsy shows nonspecific vascular ectasia and erythrocyte extravasation, the physician should consider the diagnosis of idiopathic sunburn (solar or photolocalized) purpura. Along with regular UV protection, the physician should advise that the rash typically resolves without treatment in 1 to 2 weeks.

To the Editor:

Chronic UV exposure has been linked to increased skin fragility and the development of purpuric lesions, a benign condition known as actinic purpura and commonly seen in elderly patients. Petechial skin changes acutely following intense sun exposure is a rare phenomenon referred to as sunburn purpura, photolocalized purpura, or solar purpura.

A 19-year-old woman presented with red and purple spots on the pretibial region of both legs extending to the thigh. One week prior to presentation she had a severe sunburn affecting most of the body, which resolved without blistering. Two days later, the spots appeared within the most severely sunburned areas of both legs. The patient reported that the lesions were mildly painful to palpation, but she was more concerned about the appearance. She denied any history of similar skin changes associated with sun exposure. The patient was otherwise healthy and denied any recent illnesses. She noted a history of mild bruising and bleeding with a resulting unremarkable workup by her primary care physician. The only medication taken was etonogestrel-ethinyl estradiol vaginal ring.

The scalp, face, arms, trunk, and legs were examined, and nonpalpable petechial changes were noted on the anterior aspect of the legs (Figure 1), with changes more prominent on the distal aspect of the legs. Mild superficial epidermal exfoliation was noted on both anterior thighs. The area of the lesions was not warm. The lesions were mildly tender to palpation. The remainder of the physical examination was unremarkable.

Given the timing of onset, preceding sun exposure, and the morphologic characteristics of the lesions, sunburn purpura was suspected. A punch biopsy of the anterior aspect of the left thigh was performed to rule out vasculitis. Microscopic examination revealed reactive epidermal changes with mild vascular ectasia and erythrocyte extravasation not associated with appreciable inflammation or evidence of vascular injury (Figure 2). Biopsy exposure to fluorescein-labeled antibodies directed against IgG, IgM, IgA, C3, and polyvalent immunoglobulins (IgG, IgM, and IgA) yielded no immunofluorescence. These biopsy results were consistent with sunburn purpura. Given the patient's normal platelet count, a diagnosis of idiopathic sunburn purpura was made. The patient was informed of the biopsy results and advised that the petechiae should resolve without treatment in 1 to 2 weeks, which occurred.

Sunburn purpura remains a rare phenomenon in which a petechial or purpuric rash develops acutely after intense sun exposure. We prefer the term sunburn purpura because it reflects the acuity of the phenomenon, as opposed to the previous labels solar purpura or photolocalized purpura, which also could suggest causality from chronic sun exposure. It has been proposed that sunburn purpura is a finding associated with a number of conditions rather than a unique entity.1 The following characteristics can be helpful in describing the development of sunburn purpura: delay following UV exposure, gross morphology, histologic findings, and possible associated medical conditions.1 Our case represents an important addition to the literature, as it differs from previously reported cases. Most importantly, the nonspecific biopsy findings and unremarkable laboratory findings associated with our case may represent primary or idiopathic sunburn purpura.

Previously reported cases of sunburn purpura have occurred in patients aged 10 to 66 years. It has been seen following UV exposure, vigorous exercise and high-dose aspirin, or concurrent fluoroquinolone therapy, or in the setting of erythropoietic protoporphyria, idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura, or polymorphous light eruption.2-8 When performed, histology has revealed capillaritis, solar elastosis, perivascular infiltrate, lymphocytic perivascular infiltrate with dermal edema, or leukocytoclastic vasculitis.1,2,7-9 Our patient did not have a history of erythropoietic protoporphyria, polymorphous light eruption, or idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura. She had not recently exercised, was not thrombocytopenic, and was not taking antiplatelet medications. She had no recent history of fluoroquinolone use. On histologic examination, our patient's biopsy demonstrated nonspecific petechial changes without signs of chronic UV exposure, dermal edema, vasculitis, lymphocytic infiltrate, or capillaritis.

Idiopathic sunburn purpura should only be diagnosed after other conditions are excluded. When evaluating a patient who presents with new-onset petechial rash following sun exposure, it is important to rule out vasculitis or thrombocytopenia as the cause, which is best achieved through skin biopsy and a platelet count, respectively. If there are no associated symptoms or thrombocytopenia and biopsy shows nonspecific vascular ectasia and erythrocyte extravasation, the physician should consider the diagnosis of idiopathic sunburn (solar or photolocalized) purpura. Along with regular UV protection, the physician should advise that the rash typically resolves without treatment in 1 to 2 weeks.

- Waters AJ, Sandhu DR, Green CM, et al. Solar capillaritis as a cause of solar purpura. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2009;34:E821-E824.

- Latenser BA, Hempstead RW. Exercise-associated solar purpura in an atypical location. Cutis. 1985;35:365-366.

- Rubegni P, Feci L, Pellegrino M, et al. Photolocalized purpura during levofloxacin therapy. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. 2012;28:105-107.

- Urbina F, Barrios M, Sudy E. Photolocalized purpura during ciprofloxacin therapy. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. 2006;22:111-112.

- Torinuki W, Miura T. Erythropoietic protoporphyria showing solar purpura. Dermatologica. 1983;167:220-222.

- Leung AK. Purpura associated with exposure to sunlight. J R Soc Med. 1986;79:423-424.

- Kalivas J, Kalivas L. Solar purpura appearing in a patient with polymorphous light eruption. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. 1995;11:31-32.

- Ros AM. Solar purpura--an unusual manifestation of polymorphous light eruption. Photodermatol. 1988;5:47-48.

- Guarrera M, Parodi A, Rebora A. Solar purpura is not related to polymorphous light eruption. Photodermatol. 1989;6:293-294.

- Waters AJ, Sandhu DR, Green CM, et al. Solar capillaritis as a cause of solar purpura. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2009;34:E821-E824.

- Latenser BA, Hempstead RW. Exercise-associated solar purpura in an atypical location. Cutis. 1985;35:365-366.

- Rubegni P, Feci L, Pellegrino M, et al. Photolocalized purpura during levofloxacin therapy. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. 2012;28:105-107.

- Urbina F, Barrios M, Sudy E. Photolocalized purpura during ciprofloxacin therapy. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. 2006;22:111-112.

- Torinuki W, Miura T. Erythropoietic protoporphyria showing solar purpura. Dermatologica. 1983;167:220-222.

- Leung AK. Purpura associated with exposure to sunlight. J R Soc Med. 1986;79:423-424.

- Kalivas J, Kalivas L. Solar purpura appearing in a patient with polymorphous light eruption. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. 1995;11:31-32.

- Ros AM. Solar purpura--an unusual manifestation of polymorphous light eruption. Photodermatol. 1988;5:47-48.

- Guarrera M, Parodi A, Rebora A. Solar purpura is not related to polymorphous light eruption. Photodermatol. 1989;6:293-294.

Practice Points

- Petechial skin changes acutely following intense sun exposure is a rare phenomenon referred to as sunburn purpura, photolocalized purpura, or solar purpura.

- Idiopathic sunburn purpura should only be diagnosed after vasculitis and/or thrombocytopenia is ruled out, which is best achieved through skin biopsy and a platelet count, respectively.

- The rash typically resolves without treatment in 1 to 2 weeks; however, a variety of UV protection modalities and education should be offered to the patient.

Levofloxacin-Induced Purpura Annularis Telangiectodes of Majocchi

To the Editor:

Purpura annularis telangiectodes of Majocchi (PATM) is a type of pigmented purpuric dermatosis (PPD). Patients present with nonblanchable, annular, symmetric, purpuric, and telangiectatic patches, often on the legs, with histology revealing a perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate and extravasated erythrocytes.1,2 A variety of medications have been linked to the development of PPD. We describe a case of levofloxacin-induced PATM.

RELATED ARTICLE: Granulomatous Changes Associated With Pigmented Purpuric Dermatosis

A 42-year-old man presented with a rash on the arms, trunk, abdomen, and legs of 1 month’s duration. He reported no associated itching, bleeding, or pain, and no history of a similar rash. He had a history of hypothyroidism and had been taking levothyroxine for years. He had no known allergies and no history of childhood eczema, asthma, or allergic rhinitis. Notably, the rash started shortly after the patient finished a 2-week course of levofloxacin, an antibiotic he had not taken in the past. The patient resided with his wife, 3 children, and a pet dog, and no family members had the rash. Prior to presentation, the patient had tried econazole cream and then triamcinolone acetonide cream 0.5% without any clinical improvement.

A complete review of systems was unremarkable. Physical examination revealed scattered, reddish brown, annular, nonscaly patches on the back, abdomen (Figure 1), arms, and legs with nonblanching petechiae within the patches.

A punch biopsy of the left inner thigh demonstrated patchy interface dermatitis, superficial perivascular inflammation, and numerous extravasated red blood cells in the papillary dermis (Figure 2). The histologic features were compatible with the clinical impression of PATM. The patient presented for a follow-up visit 2 weeks later with no new lesions and the old lesions were rapidly fading (Figure 3).

Pigmented purpuric dermatoses are a group of conditions that have different clinical morphologies but similar histopathologic examinations.2 All PPDs are characterized by nonblanching, nonpalpable, purpuric lesions that often are bilaterally symmetrical and present on the legs.2,3 Although the precise etiology of these conditions is not known, most cases include a perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate along with the presence of extravasated erythrocytes and hemosiderin deposition in the dermis.2 Of note, PATM often is idiopathic and patients usually present with no associated comorbidities.3 The currently established PPDs include progressive pigmentary dermatosis (Schamberg disease), PATM, pigmented purpuric lichenoid dermatosis of Gougerot and Blum, lichen aureus, and eczematidlike purpura of Doucas and Kapetanakis.2,4

RELATED ARTICLE: Granulomatous Pigmented Purpuric Dermatosis

The lesions of PATM are symmetrically distributed on the bilateral legs and may be symptomatic in most cases, with severe pruritus being reported in several drug-induced PATM cases.3,5 Although the exact etiology of PPDs currently is unknown, some contributing factors that are thought to play a role include exercise, venous stasis, gravitational dependence, capillary fragility, hypertension, drugs, chemical exposure or ingestions, and contact allergy to dyes.3 Some of the drugs known to cause drug-induced PPDs fall into the class of sedatives, stimulants, antibiotics, cardiovascular drugs, vitamins, and nutritional supplements.3,6 Some medications that have been reported to cause PPDs include acetaminophen, aspirin, carbamazepine, diltiazem, furosemide, glipizide, hydralazine, infliximab, isotretinoin, lorazepam, minocycline, nitroglycerine, and sildenafil.3,7-15

Although the mechanism of drug-induced PPD is not completely understood, it is thought that the ingested substance leads to an immunologic response in the capillary endothelium, which results in a cell-mediated immune response causing vascular damage.3 The ingested substance may act as a hapten, stimulating antibody formation and immune-mediated injury, leading to the clinical presentation of nonblanching, symmetric, purpuric, telangiectatic, and atrophic patches at the site of injury.1,3

Levofloxacin is a broad-spectrum antibiotic that has activity against both gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria. It inhibits the enzymes DNA gyrase and topoisomerase IV, preventing bacteria from undergoing proper DNA synthesis.16 Our patient’s rash began shortly after a 2-week course of levofloxacin and faded within a few weeks of discontinuing the drug; the clinical presentation, time course, and histologic appearance of the lesions were consistent with the diagnosis of drug-induced PPD. Of note, solar capillaritis has been reported following a phototoxic reaction induced by levofloxacin.17 Our case differs in that our patient had annular lesions on both photoprotected and photoexposed skin.

The first-line interventions for the treatment of PPDs are nonpharmacologic, such as discontinuation of an offending drug or allergen or wearing supportive stockings if there are signs of venous stasis. Other interventions include the use of a medium- or high-potency topical corticosteroid once to twice daily to affected areas for 4 to 6 weeks.18 Some case series also have shown improvement with narrowband UVB treatment after 24 to 28 treatment sessions or with psoralen plus UVA phototherapy within 7 to 20 treatments.19,20 If the above measures are unsuccessful in resolving symptoms, other treatment alternatives may include pentoxifylline, griseofulvin, colchicine, cyclosporine, and methotrexate. The potential benefit of treatment must be weighed against the side-effect profile of these medications.2,21-24 Of note, oral rutoside (50 mg twice daily) and ascorbic acid (500 mg twice daily) were administered to 3 patients with chronic progressive pigmented purpura. At the end of the 4-week treatment period, complete clearance of skin lesions was seen in all patients with no adverse reactions noted.25

Despite these treatment options, PATM does not necessitate treatment given its benign course and often self-resolving nature.26 In cases of drug-induced PPD such as in our patient, discontinuation of the offending drug often may lead to resolution.

In summary, PATM is a PPD that has been associated with different etiologic factors. If PATM is suspected to be caused by a drug, discontinuation of the offending agent usually results in resolution of symptoms, as it did in our case with fading of lesions within a few weeks after the patient was no longer taking levofloxacin.

- Hale EK. Purpura annularis telangiectodes of Majocchi. Dermatol Online J. 2003;9:17.

- Hoesly FJ, Huerter CJ, Shehan JM. Purpura annularis telangiectodes of Majocchi: case report and review of the literature. Int J Dermatol. 2009;48:1129-1133.

- Kaplan R, Meehan SA, Leger M. A case of isotretinoin-induced purpura annularis telangiectodes of Majocchi and review of substance-induced pigmented purpuric dermatosis. JAMA Dermatol. 2014;150:182-184.

- Newton RC, Raimer SS. Pigmented purpuric eruptions. Dermatol Clin. 1985;3:165-169.

- Ratnam KV, Su WP, Peters MS. Purpura simplex (inflammatory purpura without vasculitis): a clinicopathologic study of 174 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1991;25:642-647.

- Pang BK, Su D, Ratnam KV. Drug-induced purpura simplex: clinical and histological characteristics. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 1993;22:870-872.

- Abeck D, Gross GE, Kuwert C, et al. Acetaminophen-induced progressive pigmentary purpura (Schamberg’s disease). J Am Acad Dermatol. 1992;27:123-124.

- Lipsker D, Cribier B, Heid E, et al. Cutaneous lymphoma manifesting as pigmented, purpuric capillaries [in French]. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 1999;126:321-326.

- Peterson WC Jr, Manick KP. Purpuric eruptions associated with use of carbromal and meprobamate. Arch Dermatol. 1967;95:40-42.

- Nishioka K, Katayama I, Masuzawa M, et al. Drug-induced chronic pigmented purpura. J Dermatol. 1989;16:220-222.

- Voelter WW. Pigmented purpuric dermatosis-like reaction to topical fluorouracil. Arch Dermatol. 1983;119:875-876.

- Adams BB, Gadenne AS. Glipizide-induced pigmented purpuric dermatosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;41(5, pt 2):827-829.

- Tsao H, Lerner LH. Pigmented purpuric eruption associated with injection medroxyprogesterone acetate. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;43(2, pt 1):308-310.

- Koçak AY, Akay BN, Heper AO. Sildenafil-induced pigmented purpuric dermatosis. Cutan Ocul Toxicol. 2013;32:91-92.

- Nishioka K, Sarashi C, Katayama I. Chronic pigmented purpura induced by chemical substances. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1980;5:213-218.

- Drlica K, Zhao X. DNA gyrase, topoisomerase IV, and the 4-quinolones. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 1997;61:377-392.

- Rubegni P, Feci L, Pellegrino M, et al. Photolocalized purpura during levofloxacin therapy. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. 2012;28:105-107.

- Sardana K, Sarkar R, Sehgal VN. Pigmented purpuric dermatoses: an overview. Int J Dermatol. 2004;43:482-488.

- Fathy H, Abdelgaber S. Treatment of pigmented purpuric dermatoses with narrow-band UVB: a report of six cases. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2011;25:603-606.

- Krizsa J, Hunyadi J, Dobozy A. PUVA treatment of pigmented purpuric lichenoid dermatitis (Gougerot-Blum). J Am Acad Dermatol. 1992;27(5, pt 1):778-780.

- Panda S, Malakar S, Lahiri K. Oral pentoxifylline vs topical betamethasone in Schamberg disease: a comparative randomized investigator-blinded parallel-group trial. Arch Dermatol. 2004;140:491-493.

- Tamaki K, Yasaka N, Osada A, et al. Successful treatment of pigmented purpuric dermatosis with griseofulvin. Br J Dermatol. 1995;132:159-160.

- Geller M. Benefit of colchicine in the treatment of Schamberg’s disease. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2000;85:246.

- Okada K, Ishikawa O, Miyachi Y. Purpura pigmentosa chronica successfully treated with oral cyclosporin A. Br J Dermatol. 1996;134:180-181.

- Reinhold U, Seiter S, Ugurel S, et al. Treatment of progressive pigmented purpura with oral bioflavonoids and ascorbic acid: an open pilot study in 3 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;41(2, pt 1):207-208.

- Wang A, Shuja F, Chan A, et al. Unilateral purpura annularis telangiectodes of Majocchi in an elderly male: an atypical presentation. Dermatol Online J. 2013;19:19263.

To the Editor:

Purpura annularis telangiectodes of Majocchi (PATM) is a type of pigmented purpuric dermatosis (PPD). Patients present with nonblanchable, annular, symmetric, purpuric, and telangiectatic patches, often on the legs, with histology revealing a perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate and extravasated erythrocytes.1,2 A variety of medications have been linked to the development of PPD. We describe a case of levofloxacin-induced PATM.

RELATED ARTICLE: Granulomatous Changes Associated With Pigmented Purpuric Dermatosis

A 42-year-old man presented with a rash on the arms, trunk, abdomen, and legs of 1 month’s duration. He reported no associated itching, bleeding, or pain, and no history of a similar rash. He had a history of hypothyroidism and had been taking levothyroxine for years. He had no known allergies and no history of childhood eczema, asthma, or allergic rhinitis. Notably, the rash started shortly after the patient finished a 2-week course of levofloxacin, an antibiotic he had not taken in the past. The patient resided with his wife, 3 children, and a pet dog, and no family members had the rash. Prior to presentation, the patient had tried econazole cream and then triamcinolone acetonide cream 0.5% without any clinical improvement.

A complete review of systems was unremarkable. Physical examination revealed scattered, reddish brown, annular, nonscaly patches on the back, abdomen (Figure 1), arms, and legs with nonblanching petechiae within the patches.

A punch biopsy of the left inner thigh demonstrated patchy interface dermatitis, superficial perivascular inflammation, and numerous extravasated red blood cells in the papillary dermis (Figure 2). The histologic features were compatible with the clinical impression of PATM. The patient presented for a follow-up visit 2 weeks later with no new lesions and the old lesions were rapidly fading (Figure 3).

Pigmented purpuric dermatoses are a group of conditions that have different clinical morphologies but similar histopathologic examinations.2 All PPDs are characterized by nonblanching, nonpalpable, purpuric lesions that often are bilaterally symmetrical and present on the legs.2,3 Although the precise etiology of these conditions is not known, most cases include a perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate along with the presence of extravasated erythrocytes and hemosiderin deposition in the dermis.2 Of note, PATM often is idiopathic and patients usually present with no associated comorbidities.3 The currently established PPDs include progressive pigmentary dermatosis (Schamberg disease), PATM, pigmented purpuric lichenoid dermatosis of Gougerot and Blum, lichen aureus, and eczematidlike purpura of Doucas and Kapetanakis.2,4

RELATED ARTICLE: Granulomatous Pigmented Purpuric Dermatosis

The lesions of PATM are symmetrically distributed on the bilateral legs and may be symptomatic in most cases, with severe pruritus being reported in several drug-induced PATM cases.3,5 Although the exact etiology of PPDs currently is unknown, some contributing factors that are thought to play a role include exercise, venous stasis, gravitational dependence, capillary fragility, hypertension, drugs, chemical exposure or ingestions, and contact allergy to dyes.3 Some of the drugs known to cause drug-induced PPDs fall into the class of sedatives, stimulants, antibiotics, cardiovascular drugs, vitamins, and nutritional supplements.3,6 Some medications that have been reported to cause PPDs include acetaminophen, aspirin, carbamazepine, diltiazem, furosemide, glipizide, hydralazine, infliximab, isotretinoin, lorazepam, minocycline, nitroglycerine, and sildenafil.3,7-15

Although the mechanism of drug-induced PPD is not completely understood, it is thought that the ingested substance leads to an immunologic response in the capillary endothelium, which results in a cell-mediated immune response causing vascular damage.3 The ingested substance may act as a hapten, stimulating antibody formation and immune-mediated injury, leading to the clinical presentation of nonblanching, symmetric, purpuric, telangiectatic, and atrophic patches at the site of injury.1,3

Levofloxacin is a broad-spectrum antibiotic that has activity against both gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria. It inhibits the enzymes DNA gyrase and topoisomerase IV, preventing bacteria from undergoing proper DNA synthesis.16 Our patient’s rash began shortly after a 2-week course of levofloxacin and faded within a few weeks of discontinuing the drug; the clinical presentation, time course, and histologic appearance of the lesions were consistent with the diagnosis of drug-induced PPD. Of note, solar capillaritis has been reported following a phototoxic reaction induced by levofloxacin.17 Our case differs in that our patient had annular lesions on both photoprotected and photoexposed skin.

The first-line interventions for the treatment of PPDs are nonpharmacologic, such as discontinuation of an offending drug or allergen or wearing supportive stockings if there are signs of venous stasis. Other interventions include the use of a medium- or high-potency topical corticosteroid once to twice daily to affected areas for 4 to 6 weeks.18 Some case series also have shown improvement with narrowband UVB treatment after 24 to 28 treatment sessions or with psoralen plus UVA phototherapy within 7 to 20 treatments.19,20 If the above measures are unsuccessful in resolving symptoms, other treatment alternatives may include pentoxifylline, griseofulvin, colchicine, cyclosporine, and methotrexate. The potential benefit of treatment must be weighed against the side-effect profile of these medications.2,21-24 Of note, oral rutoside (50 mg twice daily) and ascorbic acid (500 mg twice daily) were administered to 3 patients with chronic progressive pigmented purpura. At the end of the 4-week treatment period, complete clearance of skin lesions was seen in all patients with no adverse reactions noted.25

Despite these treatment options, PATM does not necessitate treatment given its benign course and often self-resolving nature.26 In cases of drug-induced PPD such as in our patient, discontinuation of the offending drug often may lead to resolution.

In summary, PATM is a PPD that has been associated with different etiologic factors. If PATM is suspected to be caused by a drug, discontinuation of the offending agent usually results in resolution of symptoms, as it did in our case with fading of lesions within a few weeks after the patient was no longer taking levofloxacin.

To the Editor:

Purpura annularis telangiectodes of Majocchi (PATM) is a type of pigmented purpuric dermatosis (PPD). Patients present with nonblanchable, annular, symmetric, purpuric, and telangiectatic patches, often on the legs, with histology revealing a perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate and extravasated erythrocytes.1,2 A variety of medications have been linked to the development of PPD. We describe a case of levofloxacin-induced PATM.

RELATED ARTICLE: Granulomatous Changes Associated With Pigmented Purpuric Dermatosis

A 42-year-old man presented with a rash on the arms, trunk, abdomen, and legs of 1 month’s duration. He reported no associated itching, bleeding, or pain, and no history of a similar rash. He had a history of hypothyroidism and had been taking levothyroxine for years. He had no known allergies and no history of childhood eczema, asthma, or allergic rhinitis. Notably, the rash started shortly after the patient finished a 2-week course of levofloxacin, an antibiotic he had not taken in the past. The patient resided with his wife, 3 children, and a pet dog, and no family members had the rash. Prior to presentation, the patient had tried econazole cream and then triamcinolone acetonide cream 0.5% without any clinical improvement.

A complete review of systems was unremarkable. Physical examination revealed scattered, reddish brown, annular, nonscaly patches on the back, abdomen (Figure 1), arms, and legs with nonblanching petechiae within the patches.

A punch biopsy of the left inner thigh demonstrated patchy interface dermatitis, superficial perivascular inflammation, and numerous extravasated red blood cells in the papillary dermis (Figure 2). The histologic features were compatible with the clinical impression of PATM. The patient presented for a follow-up visit 2 weeks later with no new lesions and the old lesions were rapidly fading (Figure 3).

Pigmented purpuric dermatoses are a group of conditions that have different clinical morphologies but similar histopathologic examinations.2 All PPDs are characterized by nonblanching, nonpalpable, purpuric lesions that often are bilaterally symmetrical and present on the legs.2,3 Although the precise etiology of these conditions is not known, most cases include a perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate along with the presence of extravasated erythrocytes and hemosiderin deposition in the dermis.2 Of note, PATM often is idiopathic and patients usually present with no associated comorbidities.3 The currently established PPDs include progressive pigmentary dermatosis (Schamberg disease), PATM, pigmented purpuric lichenoid dermatosis of Gougerot and Blum, lichen aureus, and eczematidlike purpura of Doucas and Kapetanakis.2,4

RELATED ARTICLE: Granulomatous Pigmented Purpuric Dermatosis

The lesions of PATM are symmetrically distributed on the bilateral legs and may be symptomatic in most cases, with severe pruritus being reported in several drug-induced PATM cases.3,5 Although the exact etiology of PPDs currently is unknown, some contributing factors that are thought to play a role include exercise, venous stasis, gravitational dependence, capillary fragility, hypertension, drugs, chemical exposure or ingestions, and contact allergy to dyes.3 Some of the drugs known to cause drug-induced PPDs fall into the class of sedatives, stimulants, antibiotics, cardiovascular drugs, vitamins, and nutritional supplements.3,6 Some medications that have been reported to cause PPDs include acetaminophen, aspirin, carbamazepine, diltiazem, furosemide, glipizide, hydralazine, infliximab, isotretinoin, lorazepam, minocycline, nitroglycerine, and sildenafil.3,7-15

Although the mechanism of drug-induced PPD is not completely understood, it is thought that the ingested substance leads to an immunologic response in the capillary endothelium, which results in a cell-mediated immune response causing vascular damage.3 The ingested substance may act as a hapten, stimulating antibody formation and immune-mediated injury, leading to the clinical presentation of nonblanching, symmetric, purpuric, telangiectatic, and atrophic patches at the site of injury.1,3

Levofloxacin is a broad-spectrum antibiotic that has activity against both gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria. It inhibits the enzymes DNA gyrase and topoisomerase IV, preventing bacteria from undergoing proper DNA synthesis.16 Our patient’s rash began shortly after a 2-week course of levofloxacin and faded within a few weeks of discontinuing the drug; the clinical presentation, time course, and histologic appearance of the lesions were consistent with the diagnosis of drug-induced PPD. Of note, solar capillaritis has been reported following a phototoxic reaction induced by levofloxacin.17 Our case differs in that our patient had annular lesions on both photoprotected and photoexposed skin.

The first-line interventions for the treatment of PPDs are nonpharmacologic, such as discontinuation of an offending drug or allergen or wearing supportive stockings if there are signs of venous stasis. Other interventions include the use of a medium- or high-potency topical corticosteroid once to twice daily to affected areas for 4 to 6 weeks.18 Some case series also have shown improvement with narrowband UVB treatment after 24 to 28 treatment sessions or with psoralen plus UVA phototherapy within 7 to 20 treatments.19,20 If the above measures are unsuccessful in resolving symptoms, other treatment alternatives may include pentoxifylline, griseofulvin, colchicine, cyclosporine, and methotrexate. The potential benefit of treatment must be weighed against the side-effect profile of these medications.2,21-24 Of note, oral rutoside (50 mg twice daily) and ascorbic acid (500 mg twice daily) were administered to 3 patients with chronic progressive pigmented purpura. At the end of the 4-week treatment period, complete clearance of skin lesions was seen in all patients with no adverse reactions noted.25

Despite these treatment options, PATM does not necessitate treatment given its benign course and often self-resolving nature.26 In cases of drug-induced PPD such as in our patient, discontinuation of the offending drug often may lead to resolution.

In summary, PATM is a PPD that has been associated with different etiologic factors. If PATM is suspected to be caused by a drug, discontinuation of the offending agent usually results in resolution of symptoms, as it did in our case with fading of lesions within a few weeks after the patient was no longer taking levofloxacin.

- Hale EK. Purpura annularis telangiectodes of Majocchi. Dermatol Online J. 2003;9:17.

- Hoesly FJ, Huerter CJ, Shehan JM. Purpura annularis telangiectodes of Majocchi: case report and review of the literature. Int J Dermatol. 2009;48:1129-1133.

- Kaplan R, Meehan SA, Leger M. A case of isotretinoin-induced purpura annularis telangiectodes of Majocchi and review of substance-induced pigmented purpuric dermatosis. JAMA Dermatol. 2014;150:182-184.

- Newton RC, Raimer SS. Pigmented purpuric eruptions. Dermatol Clin. 1985;3:165-169.

- Ratnam KV, Su WP, Peters MS. Purpura simplex (inflammatory purpura without vasculitis): a clinicopathologic study of 174 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1991;25:642-647.

- Pang BK, Su D, Ratnam KV. Drug-induced purpura simplex: clinical and histological characteristics. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 1993;22:870-872.

- Abeck D, Gross GE, Kuwert C, et al. Acetaminophen-induced progressive pigmentary purpura (Schamberg’s disease). J Am Acad Dermatol. 1992;27:123-124.

- Lipsker D, Cribier B, Heid E, et al. Cutaneous lymphoma manifesting as pigmented, purpuric capillaries [in French]. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 1999;126:321-326.

- Peterson WC Jr, Manick KP. Purpuric eruptions associated with use of carbromal and meprobamate. Arch Dermatol. 1967;95:40-42.

- Nishioka K, Katayama I, Masuzawa M, et al. Drug-induced chronic pigmented purpura. J Dermatol. 1989;16:220-222.

- Voelter WW. Pigmented purpuric dermatosis-like reaction to topical fluorouracil. Arch Dermatol. 1983;119:875-876.

- Adams BB, Gadenne AS. Glipizide-induced pigmented purpuric dermatosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;41(5, pt 2):827-829.

- Tsao H, Lerner LH. Pigmented purpuric eruption associated with injection medroxyprogesterone acetate. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;43(2, pt 1):308-310.

- Koçak AY, Akay BN, Heper AO. Sildenafil-induced pigmented purpuric dermatosis. Cutan Ocul Toxicol. 2013;32:91-92.

- Nishioka K, Sarashi C, Katayama I. Chronic pigmented purpura induced by chemical substances. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1980;5:213-218.

- Drlica K, Zhao X. DNA gyrase, topoisomerase IV, and the 4-quinolones. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 1997;61:377-392.

- Rubegni P, Feci L, Pellegrino M, et al. Photolocalized purpura during levofloxacin therapy. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. 2012;28:105-107.

- Sardana K, Sarkar R, Sehgal VN. Pigmented purpuric dermatoses: an overview. Int J Dermatol. 2004;43:482-488.

- Fathy H, Abdelgaber S. Treatment of pigmented purpuric dermatoses with narrow-band UVB: a report of six cases. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2011;25:603-606.

- Krizsa J, Hunyadi J, Dobozy A. PUVA treatment of pigmented purpuric lichenoid dermatitis (Gougerot-Blum). J Am Acad Dermatol. 1992;27(5, pt 1):778-780.

- Panda S, Malakar S, Lahiri K. Oral pentoxifylline vs topical betamethasone in Schamberg disease: a comparative randomized investigator-blinded parallel-group trial. Arch Dermatol. 2004;140:491-493.

- Tamaki K, Yasaka N, Osada A, et al. Successful treatment of pigmented purpuric dermatosis with griseofulvin. Br J Dermatol. 1995;132:159-160.

- Geller M. Benefit of colchicine in the treatment of Schamberg’s disease. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2000;85:246.

- Okada K, Ishikawa O, Miyachi Y. Purpura pigmentosa chronica successfully treated with oral cyclosporin A. Br J Dermatol. 1996;134:180-181.

- Reinhold U, Seiter S, Ugurel S, et al. Treatment of progressive pigmented purpura with oral bioflavonoids and ascorbic acid: an open pilot study in 3 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;41(2, pt 1):207-208.

- Wang A, Shuja F, Chan A, et al. Unilateral purpura annularis telangiectodes of Majocchi in an elderly male: an atypical presentation. Dermatol Online J. 2013;19:19263.

- Hale EK. Purpura annularis telangiectodes of Majocchi. Dermatol Online J. 2003;9:17.

- Hoesly FJ, Huerter CJ, Shehan JM. Purpura annularis telangiectodes of Majocchi: case report and review of the literature. Int J Dermatol. 2009;48:1129-1133.

- Kaplan R, Meehan SA, Leger M. A case of isotretinoin-induced purpura annularis telangiectodes of Majocchi and review of substance-induced pigmented purpuric dermatosis. JAMA Dermatol. 2014;150:182-184.

- Newton RC, Raimer SS. Pigmented purpuric eruptions. Dermatol Clin. 1985;3:165-169.

- Ratnam KV, Su WP, Peters MS. Purpura simplex (inflammatory purpura without vasculitis): a clinicopathologic study of 174 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1991;25:642-647.

- Pang BK, Su D, Ratnam KV. Drug-induced purpura simplex: clinical and histological characteristics. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 1993;22:870-872.

- Abeck D, Gross GE, Kuwert C, et al. Acetaminophen-induced progressive pigmentary purpura (Schamberg’s disease). J Am Acad Dermatol. 1992;27:123-124.

- Lipsker D, Cribier B, Heid E, et al. Cutaneous lymphoma manifesting as pigmented, purpuric capillaries [in French]. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 1999;126:321-326.

- Peterson WC Jr, Manick KP. Purpuric eruptions associated with use of carbromal and meprobamate. Arch Dermatol. 1967;95:40-42.

- Nishioka K, Katayama I, Masuzawa M, et al. Drug-induced chronic pigmented purpura. J Dermatol. 1989;16:220-222.

- Voelter WW. Pigmented purpuric dermatosis-like reaction to topical fluorouracil. Arch Dermatol. 1983;119:875-876.

- Adams BB, Gadenne AS. Glipizide-induced pigmented purpuric dermatosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;41(5, pt 2):827-829.

- Tsao H, Lerner LH. Pigmented purpuric eruption associated with injection medroxyprogesterone acetate. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;43(2, pt 1):308-310.

- Koçak AY, Akay BN, Heper AO. Sildenafil-induced pigmented purpuric dermatosis. Cutan Ocul Toxicol. 2013;32:91-92.

- Nishioka K, Sarashi C, Katayama I. Chronic pigmented purpura induced by chemical substances. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1980;5:213-218.

- Drlica K, Zhao X. DNA gyrase, topoisomerase IV, and the 4-quinolones. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 1997;61:377-392.

- Rubegni P, Feci L, Pellegrino M, et al. Photolocalized purpura during levofloxacin therapy. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. 2012;28:105-107.

- Sardana K, Sarkar R, Sehgal VN. Pigmented purpuric dermatoses: an overview. Int J Dermatol. 2004;43:482-488.

- Fathy H, Abdelgaber S. Treatment of pigmented purpuric dermatoses with narrow-band UVB: a report of six cases. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2011;25:603-606.

- Krizsa J, Hunyadi J, Dobozy A. PUVA treatment of pigmented purpuric lichenoid dermatitis (Gougerot-Blum). J Am Acad Dermatol. 1992;27(5, pt 1):778-780.

- Panda S, Malakar S, Lahiri K. Oral pentoxifylline vs topical betamethasone in Schamberg disease: a comparative randomized investigator-blinded parallel-group trial. Arch Dermatol. 2004;140:491-493.

- Tamaki K, Yasaka N, Osada A, et al. Successful treatment of pigmented purpuric dermatosis with griseofulvin. Br J Dermatol. 1995;132:159-160.

- Geller M. Benefit of colchicine in the treatment of Schamberg’s disease. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2000;85:246.

- Okada K, Ishikawa O, Miyachi Y. Purpura pigmentosa chronica successfully treated with oral cyclosporin A. Br J Dermatol. 1996;134:180-181.

- Reinhold U, Seiter S, Ugurel S, et al. Treatment of progressive pigmented purpura with oral bioflavonoids and ascorbic acid: an open pilot study in 3 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;41(2, pt 1):207-208.

- Wang A, Shuja F, Chan A, et al. Unilateral purpura annularis telangiectodes of Majocchi in an elderly male: an atypical presentation. Dermatol Online J. 2013;19:19263.

Practice Point

- Purpura annularis telangiectodes of Majocchi, a type of pigmented purpuric dermatosis, may on occasion be triggered by a medication; therefore, a careful medication history may prove to be an important part of the workup for this eruption.

Chromoblastomycosis Infection From a House Plant

To the Editor:

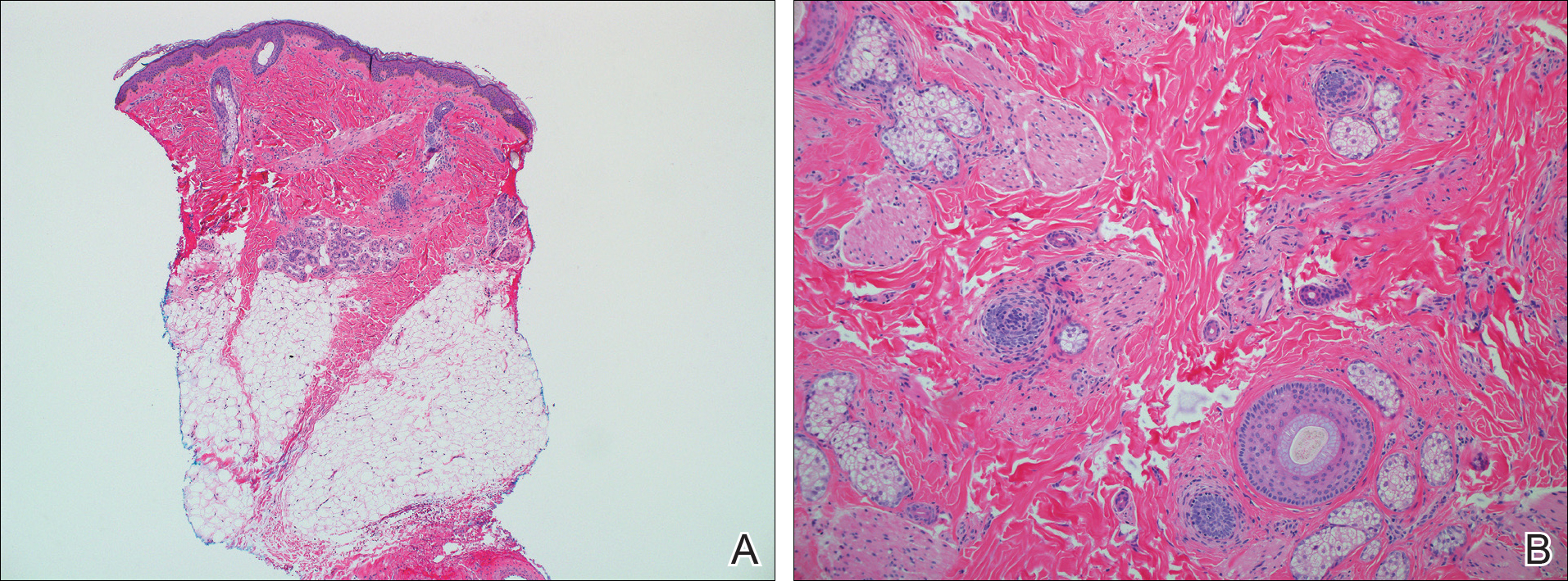

A 69-year-old woman with no history of immunodeficiency presented 1 month after a thorn from her locally grown Madagascar palm plant (Pachypodium lamerei) pierced the skin. The patient developed a painful nodule at the site on the left elbow (Figure 1). An excisional biopsy by an outside dermatologist was performed, which showed granulomatous inflammation within the dermis with epidermal hyperplasia and the presence of golden brown spherules (medlar bodies). The diagnosis was a dermal fungal infection consistent with chromoblastomycosis. A curative surgical excision was performed, and medlar bodies were seen adjacent to a polarizable foreign body consistent with plant material on histology (Figure 2). Because the lesion was localized, adjuvant medical treatment was not deemed necessary. The patient has not had any recurrence in the last 1.5 years since the resection.

The categorization of chromoblastomycosis includes a chronic fungal infection of the cutaneous and subcutaneous tissues by dematiaceous (pigmented) fungi. This definition is such that there are a multitude of organisms that can be the primary cause of this diagnosis. Generally, infection follows a traumatic permeation of the skin by a foreign body contaminated by the causative organism in agricultural workers. The most common dematiaceous pathogens are Fonsecaea pedrosoi, Phialophora verrucosa, and Cladosporium carrionii; however, the specific causative organism varies heavily on geographic location. With inoculation by a foreign body, a small papule develops at the site of the lesion. Several years after the primary infection, nodules and verrucous erythematous plaques develop in the same area, and patients present with concerns of pain and pruritus.1 Lesions usually are localized to the initial area of inoculation, generally a break in the skin by the offending foreign body, on the legs, arms, or hands, but hematogenous or lymphatic dissemination with distant transmission due to scratching also can occur. Ulceration due to secondary bacterial infection is another possible manifestation, resulting in a foul odor and less commonly lymphedema. Rarely, squamous cell carcinoma is a complication.2

RELATED ARTICLE: Fungal Foes: Presentations of Chromoblastomycosis Post–Hurricane Ike

On histopathology, thick-walled sclerotic bodies termed medlar bodies or copper pennies are pathognomonic for chromoblastomycosis and represent the fungal elements. Grossly, black dots can be seen on the skin in the affected areas from the transepidermal elimination of the fungi.1,2 However, there is no specificity for determining the causative organism in this manner, or even with culture, as it is difficult to differentiate the species morphologically. More advanced tests can help, such as polymerase chain reaction or enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay, where available.2 Hematoxylin and eosin stain also shows epidermal hyperplasia and dermal mononuclear infiltrate.

Treatment modalities include surgical excision, cryotherapy, pharmacologic treatment, and combination therapy. Localized lesions often can be resected, but more severe infections can require pharmacologic treatment. Unfortunately, there tends to be a high risk for relapse with most antifungal modalities. The combination of itraconazole and terbinafine has been shown to offer the best medical therapy with lower risk for refractoriness to treatment by producing a synergistic effect between the 2 antifungals.2,3 Many surgical treatments often are combined with oral antifungals to try to attain complete eradication in deep or extensive lesions, as seen in a case in which oral terbinafine was used prior to surgery to reduce the size of the lesion, followed by complete resection.4 With localized lesions that are resectable, a wide and deep incision often can be curative. Cryotherapy also may be coupled with surgical excision or pharmacologic therapy. Most literature suggests that cryotherapy or the use of antifungals prior to excision offers improved outcomes.2,5 Prognosis tends to be good for chromoblastomycoses, particularly with smaller lesions. Complete eradication varies greatly on the size and depth of the lesion, independent of the causative pathogen.

Our patient’s presentation with chromoblastomycosis is unique because of the source of infection, which was a plant grown from seeds in a local nursery in South Florida and then sold to the patient. The majority of chromoblastomycosis infections occur in agricultural workers, typically in tropical climates such as South and Central America, the Caribbean, and Mexico.1,2 Historically, infections in the United States have been uncommon, with the majority presenting in patients on prolonged corticosteroid therapy or with other immunosuppressive conditions.6,7

- Torres-Guerrero E, Isa-Isa R, Isa M, et al. Chromoblastomycosis. Clin Dermatol. 2012;30:403-408.

- Ameen M. Managing chromoblastomycosis. Trop Doct. 2010;40:65-67.

- Zhang J, Xi L, Lu C, et al. Successful treatment for chromoblastomycosis caused by Fonsecaea monophora: a report of three cases in Guangdong, China. Mycoses. 2009;52:176-181.

- Tamura K, Matsuyama T, Yahagi E, et al. A case of chromomycosis treated by surgical therapy combined with preceded oral administration of terbinafine to reduce the size of the lesion. Tokai J Exp Clin Med. 2012;37:6-10.

- Patel U, Chu J, Patel R, et al. Subcutaneous dematiaceous fungal infection. Dermatol Online J. 2011;17:19.

- Basílio FM, Hammerschmidt M, Mukai MM, et al. Mucormycosis and chromoblastomycosis occurring in a patient with leprosy type 2 reaction under prolonged corticosteroid and thalidomide therapy. An Bras Dermatol. 2012;87:767-771.

- Parente JN, Talhari C, Ginter-Hanselmayer G, et al. Subcutaneous phaeohyphomycosis in immunocompetent patients: two new cases caused by Exophiala jeanselmei and Cladophialophora carrionii. Mycoses. 2001;54:265-269.

To the Editor:

A 69-year-old woman with no history of immunodeficiency presented 1 month after a thorn from her locally grown Madagascar palm plant (Pachypodium lamerei) pierced the skin. The patient developed a painful nodule at the site on the left elbow (Figure 1). An excisional biopsy by an outside dermatologist was performed, which showed granulomatous inflammation within the dermis with epidermal hyperplasia and the presence of golden brown spherules (medlar bodies). The diagnosis was a dermal fungal infection consistent with chromoblastomycosis. A curative surgical excision was performed, and medlar bodies were seen adjacent to a polarizable foreign body consistent with plant material on histology (Figure 2). Because the lesion was localized, adjuvant medical treatment was not deemed necessary. The patient has not had any recurrence in the last 1.5 years since the resection.

The categorization of chromoblastomycosis includes a chronic fungal infection of the cutaneous and subcutaneous tissues by dematiaceous (pigmented) fungi. This definition is such that there are a multitude of organisms that can be the primary cause of this diagnosis. Generally, infection follows a traumatic permeation of the skin by a foreign body contaminated by the causative organism in agricultural workers. The most common dematiaceous pathogens are Fonsecaea pedrosoi, Phialophora verrucosa, and Cladosporium carrionii; however, the specific causative organism varies heavily on geographic location. With inoculation by a foreign body, a small papule develops at the site of the lesion. Several years after the primary infection, nodules and verrucous erythematous plaques develop in the same area, and patients present with concerns of pain and pruritus.1 Lesions usually are localized to the initial area of inoculation, generally a break in the skin by the offending foreign body, on the legs, arms, or hands, but hematogenous or lymphatic dissemination with distant transmission due to scratching also can occur. Ulceration due to secondary bacterial infection is another possible manifestation, resulting in a foul odor and less commonly lymphedema. Rarely, squamous cell carcinoma is a complication.2

RELATED ARTICLE: Fungal Foes: Presentations of Chromoblastomycosis Post–Hurricane Ike

On histopathology, thick-walled sclerotic bodies termed medlar bodies or copper pennies are pathognomonic for chromoblastomycosis and represent the fungal elements. Grossly, black dots can be seen on the skin in the affected areas from the transepidermal elimination of the fungi.1,2 However, there is no specificity for determining the causative organism in this manner, or even with culture, as it is difficult to differentiate the species morphologically. More advanced tests can help, such as polymerase chain reaction or enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay, where available.2 Hematoxylin and eosin stain also shows epidermal hyperplasia and dermal mononuclear infiltrate.

Treatment modalities include surgical excision, cryotherapy, pharmacologic treatment, and combination therapy. Localized lesions often can be resected, but more severe infections can require pharmacologic treatment. Unfortunately, there tends to be a high risk for relapse with most antifungal modalities. The combination of itraconazole and terbinafine has been shown to offer the best medical therapy with lower risk for refractoriness to treatment by producing a synergistic effect between the 2 antifungals.2,3 Many surgical treatments often are combined with oral antifungals to try to attain complete eradication in deep or extensive lesions, as seen in a case in which oral terbinafine was used prior to surgery to reduce the size of the lesion, followed by complete resection.4 With localized lesions that are resectable, a wide and deep incision often can be curative. Cryotherapy also may be coupled with surgical excision or pharmacologic therapy. Most literature suggests that cryotherapy or the use of antifungals prior to excision offers improved outcomes.2,5 Prognosis tends to be good for chromoblastomycoses, particularly with smaller lesions. Complete eradication varies greatly on the size and depth of the lesion, independent of the causative pathogen.

Our patient’s presentation with chromoblastomycosis is unique because of the source of infection, which was a plant grown from seeds in a local nursery in South Florida and then sold to the patient. The majority of chromoblastomycosis infections occur in agricultural workers, typically in tropical climates such as South and Central America, the Caribbean, and Mexico.1,2 Historically, infections in the United States have been uncommon, with the majority presenting in patients on prolonged corticosteroid therapy or with other immunosuppressive conditions.6,7

To the Editor:

A 69-year-old woman with no history of immunodeficiency presented 1 month after a thorn from her locally grown Madagascar palm plant (Pachypodium lamerei) pierced the skin. The patient developed a painful nodule at the site on the left elbow (Figure 1). An excisional biopsy by an outside dermatologist was performed, which showed granulomatous inflammation within the dermis with epidermal hyperplasia and the presence of golden brown spherules (medlar bodies). The diagnosis was a dermal fungal infection consistent with chromoblastomycosis. A curative surgical excision was performed, and medlar bodies were seen adjacent to a polarizable foreign body consistent with plant material on histology (Figure 2). Because the lesion was localized, adjuvant medical treatment was not deemed necessary. The patient has not had any recurrence in the last 1.5 years since the resection.

The categorization of chromoblastomycosis includes a chronic fungal infection of the cutaneous and subcutaneous tissues by dematiaceous (pigmented) fungi. This definition is such that there are a multitude of organisms that can be the primary cause of this diagnosis. Generally, infection follows a traumatic permeation of the skin by a foreign body contaminated by the causative organism in agricultural workers. The most common dematiaceous pathogens are Fonsecaea pedrosoi, Phialophora verrucosa, and Cladosporium carrionii; however, the specific causative organism varies heavily on geographic location. With inoculation by a foreign body, a small papule develops at the site of the lesion. Several years after the primary infection, nodules and verrucous erythematous plaques develop in the same area, and patients present with concerns of pain and pruritus.1 Lesions usually are localized to the initial area of inoculation, generally a break in the skin by the offending foreign body, on the legs, arms, or hands, but hematogenous or lymphatic dissemination with distant transmission due to scratching also can occur. Ulceration due to secondary bacterial infection is another possible manifestation, resulting in a foul odor and less commonly lymphedema. Rarely, squamous cell carcinoma is a complication.2

RELATED ARTICLE: Fungal Foes: Presentations of Chromoblastomycosis Post–Hurricane Ike

On histopathology, thick-walled sclerotic bodies termed medlar bodies or copper pennies are pathognomonic for chromoblastomycosis and represent the fungal elements. Grossly, black dots can be seen on the skin in the affected areas from the transepidermal elimination of the fungi.1,2 However, there is no specificity for determining the causative organism in this manner, or even with culture, as it is difficult to differentiate the species morphologically. More advanced tests can help, such as polymerase chain reaction or enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay, where available.2 Hematoxylin and eosin stain also shows epidermal hyperplasia and dermal mononuclear infiltrate.

Treatment modalities include surgical excision, cryotherapy, pharmacologic treatment, and combination therapy. Localized lesions often can be resected, but more severe infections can require pharmacologic treatment. Unfortunately, there tends to be a high risk for relapse with most antifungal modalities. The combination of itraconazole and terbinafine has been shown to offer the best medical therapy with lower risk for refractoriness to treatment by producing a synergistic effect between the 2 antifungals.2,3 Many surgical treatments often are combined with oral antifungals to try to attain complete eradication in deep or extensive lesions, as seen in a case in which oral terbinafine was used prior to surgery to reduce the size of the lesion, followed by complete resection.4 With localized lesions that are resectable, a wide and deep incision often can be curative. Cryotherapy also may be coupled with surgical excision or pharmacologic therapy. Most literature suggests that cryotherapy or the use of antifungals prior to excision offers improved outcomes.2,5 Prognosis tends to be good for chromoblastomycoses, particularly with smaller lesions. Complete eradication varies greatly on the size and depth of the lesion, independent of the causative pathogen.

Our patient’s presentation with chromoblastomycosis is unique because of the source of infection, which was a plant grown from seeds in a local nursery in South Florida and then sold to the patient. The majority of chromoblastomycosis infections occur in agricultural workers, typically in tropical climates such as South and Central America, the Caribbean, and Mexico.1,2 Historically, infections in the United States have been uncommon, with the majority presenting in patients on prolonged corticosteroid therapy or with other immunosuppressive conditions.6,7

- Torres-Guerrero E, Isa-Isa R, Isa M, et al. Chromoblastomycosis. Clin Dermatol. 2012;30:403-408.

- Ameen M. Managing chromoblastomycosis. Trop Doct. 2010;40:65-67.

- Zhang J, Xi L, Lu C, et al. Successful treatment for chromoblastomycosis caused by Fonsecaea monophora: a report of three cases in Guangdong, China. Mycoses. 2009;52:176-181.

- Tamura K, Matsuyama T, Yahagi E, et al. A case of chromomycosis treated by surgical therapy combined with preceded oral administration of terbinafine to reduce the size of the lesion. Tokai J Exp Clin Med. 2012;37:6-10.

- Patel U, Chu J, Patel R, et al. Subcutaneous dematiaceous fungal infection. Dermatol Online J. 2011;17:19.

- Basílio FM, Hammerschmidt M, Mukai MM, et al. Mucormycosis and chromoblastomycosis occurring in a patient with leprosy type 2 reaction under prolonged corticosteroid and thalidomide therapy. An Bras Dermatol. 2012;87:767-771.

- Parente JN, Talhari C, Ginter-Hanselmayer G, et al. Subcutaneous phaeohyphomycosis in immunocompetent patients: two new cases caused by Exophiala jeanselmei and Cladophialophora carrionii. Mycoses. 2001;54:265-269.

- Torres-Guerrero E, Isa-Isa R, Isa M, et al. Chromoblastomycosis. Clin Dermatol. 2012;30:403-408.

- Ameen M. Managing chromoblastomycosis. Trop Doct. 2010;40:65-67.

- Zhang J, Xi L, Lu C, et al. Successful treatment for chromoblastomycosis caused by Fonsecaea monophora: a report of three cases in Guangdong, China. Mycoses. 2009;52:176-181.

- Tamura K, Matsuyama T, Yahagi E, et al. A case of chromomycosis treated by surgical therapy combined with preceded oral administration of terbinafine to reduce the size of the lesion. Tokai J Exp Clin Med. 2012;37:6-10.

- Patel U, Chu J, Patel R, et al. Subcutaneous dematiaceous fungal infection. Dermatol Online J. 2011;17:19.

- Basílio FM, Hammerschmidt M, Mukai MM, et al. Mucormycosis and chromoblastomycosis occurring in a patient with leprosy type 2 reaction under prolonged corticosteroid and thalidomide therapy. An Bras Dermatol. 2012;87:767-771.

- Parente JN, Talhari C, Ginter-Hanselmayer G, et al. Subcutaneous phaeohyphomycosis in immunocompetent patients: two new cases caused by Exophiala jeanselmei and Cladophialophora carrionii. Mycoses. 2001;54:265-269.

Practice Points

- Chromoblastomycosis is an uncommon fungal infection that should be considered in cases of traumatic injuries to the skin.

- Biopsies of growing or nonhealing nodules will demonstrate characteristic golden brown spherules (medlar bodies).

- In localized cases, surgical excision may be curative.

Laugier-Hunziker Syndrome

To the Editor:

A 55-year-old man presented with hyperpigmented brown macules on the lips, hands, and fingertips of 6 years’ duration. The spots were persistent, asymptomatic, and had not changed in size. The patient denied a history of alopecia or dystrophic nails. He also denied a family history of similar skin findings. He had no personal history of cancer and a colonoscopy performed 5 years prior revealed no notable abnormalities. His medications included amlodipine and hydrocodone-acetaminophen. His mother died of “abdominal bleeding” at 74 years of age and his father died of a brain tumor at 64 years of age. Physical examination demonstrated numerous well-defined, dark brown macules of variable size distributed on the lower and upper mucosal lips (Figure 1A), buccal mucosa, hard palate, and gingiva, as well as the dorsal aspect of the fingers (Figure 1B) and volar aspect of the fingertips (Figure 1C).

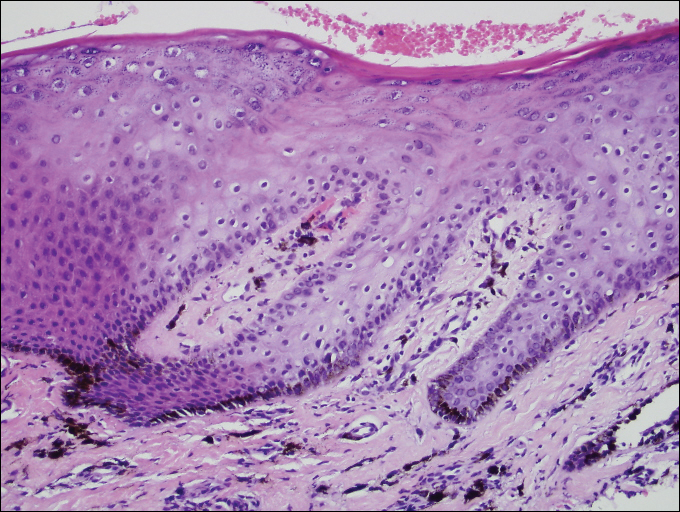

A shave biopsy of a dark brown macule from the lower lip (Figure 2) was performed. Histopathologic examination revealed pigmentation of the basal layer of the epidermis with pigment-laden cells in the dermis immediately deep to the surface epithelium. Immunoperoxidase stains showed a normal number and distribution of melanocytes.

A diagnosis of Laugier-Hunziker syndrome (LHS) was made given the age of onset; distribution of pigmentation; and lack of pathologic colonoscopic findings, personal history of cancer, or gastrointestinal tract symptoms.

Benign hyperpigmentation of the lips and fingers has been reported.1 The average age of onset of LHS is 52 years, and it typically is diagnosed in white adults.1,2 In LHS, pigmentation is most commonly distributed on the lips, especially the lower lips and oral mucosa.2 Pigmentation of the nails in the form of longitudinal melanonychia is present in approximately half of cases.2,3 There also may be pigmentation of the neck; thorax; abdomen; and acral surfaces, especially the fingertips.1-3 Rarely, pigmented macules can occur on the genitalia or sclera.1,2 Unlike Peutz-Jeghers syndrome, the diagnosis of LHS does not result from a germline mutation and carries no risk of gastrointestinal polyposis or internal malignancy.3,4 The histopathology of a pigmented macule of LHS shows a normal number and morphology of melanocytes. Epidermal basement membrane pigmentation is common, with pigment-laden macrophages evident in the papillary dermis.3

RELATED ARTICLE: Asymptomatic Lower Lip Hyperpigmentation From Laugier-Hunziker Syndrome

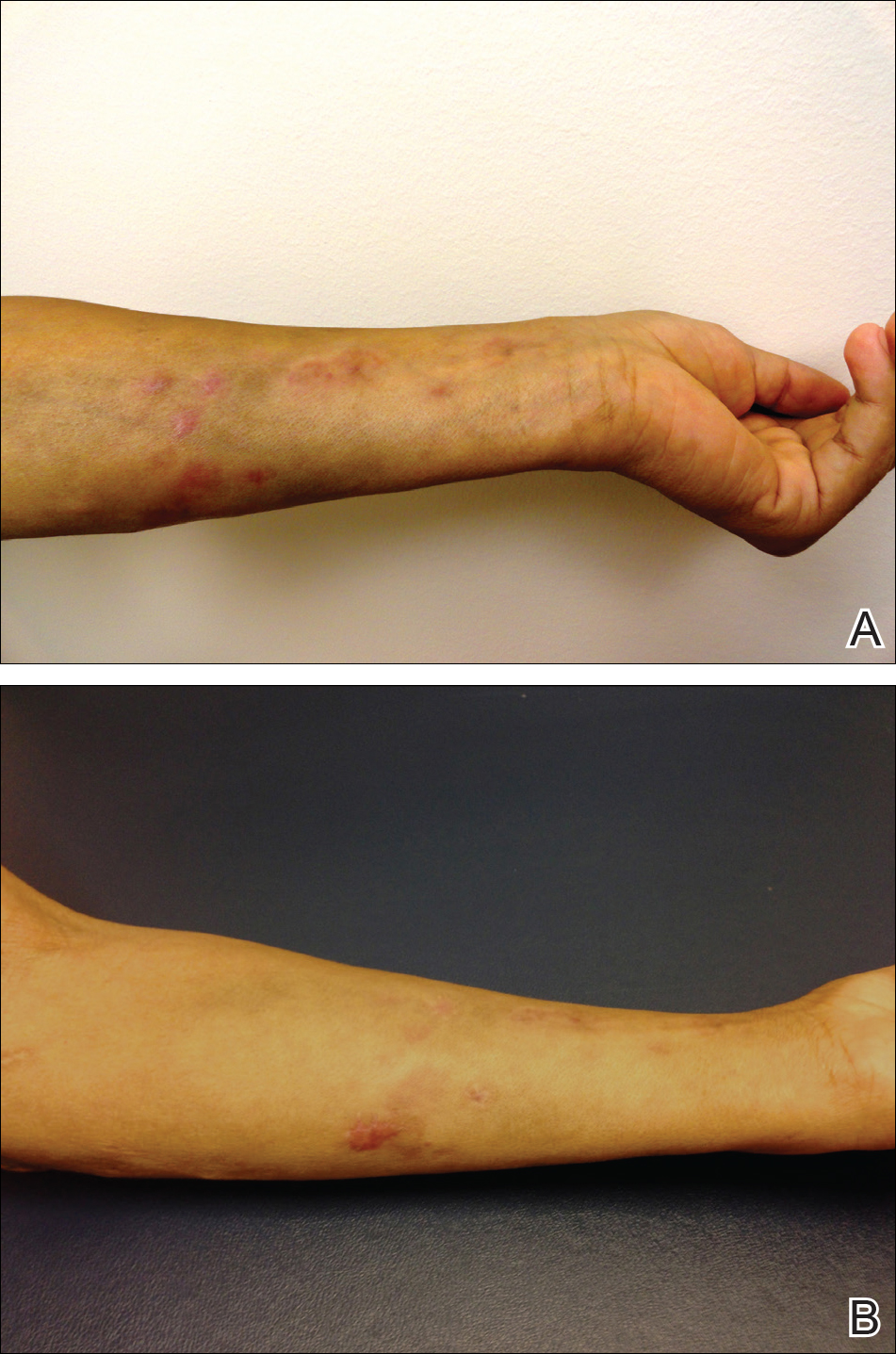

The differential diagnosis of multiple lentigines is broad and includes Peutz-Jeghers syndrome; LEOPARD (lentigines, electrocardiographic conduction abnormalities, ocular hypertelorism, pulmonary stenosis, abnormalities of genitalia, retardation of growth, deafness) syndrome; Carney complexes, including LAMB (lentigines, atrial myxoma, mucocutaneous myxoma, blue nevi) and NAME (nevi, atrial myxoma, myxoid neurofibroma, ephelide) syndromes5; primary adrenocortical insufficiency (Addison disease); and idiopathic melanoplakia.2 Peutz-Jeghers syndrome, an autosomal-dominant syndrome with mucocutaneous lentigines, has a similar clinical appearance to LHS; therefore, it is necessary to exclude this diagnosis due to its association with intestinal hamartomatous polyps and internal malignancies (Table).3,6,7

Peutz-Jeghers syndrome is characterized by mucocutaneous hyperpigmentation and intestinal hamartomatous polyposis and is associated with internal malignancies of the colon, breast, pancreas, stomach, small intestines, ovaries, lung, and Sertoli cells in men.6,7 Associated gastrointestinal tract malignancies in descending order of frequency are colon (39%), pancreatic (36%), gastric (29%), and small intestine (13%).1 It is caused by a germ line mutation of the serine/threonine kinase 11 gene, STK11. Although the appearance and distribution of the mucocutaneous lentigines is similar to individuals with LHS, by contrast the lentiginosis in individuals with Peutz-Jeghers syndrome is present from birth or develops during infancy.6 Aggressive cancer screening guidelines aid in early detection and begin at 8 years of age with a baseline colonoscopy and esophagogastroduodenoscopy; future screening is dictated by the presence or absence of polyps. If no polyps are detected at 8 years of age, a colonoscopy and esophagogastroduodenoscopy are repeated at 18 years of age and then every 3 years until 50 years of age.8

In an adult patient, the diagnosis of LHS can be made clinically and a correct diagnosis prevents frequent and unpleasant gastrointestinal tract cancer screening examinations. Lampe et al2 described a man with LHS who was incorrectly diagnosed with Peutz-Jeghers syndrome and experienced a colonic perforation as a complication of a screening colonoscopy. Their case report underscores the importance of making the correct diagnosis of LHS to avoid undertaking unnecessary aggressive cancer screening regimens.2

Although LHS is a benign condition that does not require treatment, Q-switched alexandrite or erbium:YAG laser therapy has been shown to improve the pigmentary findings associated with LHS.9,10 It has been suggested that LHS should be renamed Laugier-Hunziker pigmentation2 or mucocutaneous lentiginosis of Laugier and Hunziker1 to differentiate LHS as simply a disorder of pigmentation rather than a potentially morbid genetic defect, as in Peutz-Jeghers syndrome.

- Moore RT, Chae KA, Rhodes AR. Laugier and Hunziker pigmentation: a lentiginous proliferation of melanocytes. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;50(5 suppl):S70-S74.

- Lampe AK, Hampton PJ, Woodford-Richens K, et al. Laugier-Hunziker Syndrome: an important differential diagnosis for Peutz-Jeghers Syndrome. J Med Genet. 2003;40:E77.

- Baran R. Longitudinal melanotic streaks as a clue for Laugier-Hunziker syndrome. Arch Dermatol. 1979;115:1148-1149.

- Grimes P, Nordlund JJ, Pandya AG, et al. Increasing our understanding of pigmentary disorders. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;54(5 suppl 2):S255-S261.

- Bertherat J. Carney complex (CNC). Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2006;1:21.

- Giardiello FM, Brensinger JD, Tersemette AC, et al. Very high risk of cancer in Peutz-Jeghers Syndrome. Gastroenterology. 2000;119:1447-1453.

- Brosens LA, van Hattem WA, Jansen M, et al. Gastrointestinal polyposis syndromes. Curr Mol Med. 2007;7:29-46.

- Beggs AD, Latchford AR, Vasen HF, et al. Peutz-Jeghers syndrome: a systematic review and recommendations for management. Gut. 2010;59:975-986.

- Zuo YG, Ma DL, Jin HZ, et al. Treatment of Laugier-Hunziker syndrome with the Q-switched alexandrite laser in 22 Chinese patients. Arch Dermatol Res. 2010;302:125-130.

- Ergun S, Saruhanog˘lu A, Migliari DA, et al. Refractory pigmentation associated with Laugier-Hunziker syndrome following Er:YAG laser treatment [published online December 3, 2013]. Case Rep Dent. 2013;2013:561040.

To the Editor:

A 55-year-old man presented with hyperpigmented brown macules on the lips, hands, and fingertips of 6 years’ duration. The spots were persistent, asymptomatic, and had not changed in size. The patient denied a history of alopecia or dystrophic nails. He also denied a family history of similar skin findings. He had no personal history of cancer and a colonoscopy performed 5 years prior revealed no notable abnormalities. His medications included amlodipine and hydrocodone-acetaminophen. His mother died of “abdominal bleeding” at 74 years of age and his father died of a brain tumor at 64 years of age. Physical examination demonstrated numerous well-defined, dark brown macules of variable size distributed on the lower and upper mucosal lips (Figure 1A), buccal mucosa, hard palate, and gingiva, as well as the dorsal aspect of the fingers (Figure 1B) and volar aspect of the fingertips (Figure 1C).

A shave biopsy of a dark brown macule from the lower lip (Figure 2) was performed. Histopathologic examination revealed pigmentation of the basal layer of the epidermis with pigment-laden cells in the dermis immediately deep to the surface epithelium. Immunoperoxidase stains showed a normal number and distribution of melanocytes.

A diagnosis of Laugier-Hunziker syndrome (LHS) was made given the age of onset; distribution of pigmentation; and lack of pathologic colonoscopic findings, personal history of cancer, or gastrointestinal tract symptoms.

Benign hyperpigmentation of the lips and fingers has been reported.1 The average age of onset of LHS is 52 years, and it typically is diagnosed in white adults.1,2 In LHS, pigmentation is most commonly distributed on the lips, especially the lower lips and oral mucosa.2 Pigmentation of the nails in the form of longitudinal melanonychia is present in approximately half of cases.2,3 There also may be pigmentation of the neck; thorax; abdomen; and acral surfaces, especially the fingertips.1-3 Rarely, pigmented macules can occur on the genitalia or sclera.1,2 Unlike Peutz-Jeghers syndrome, the diagnosis of LHS does not result from a germline mutation and carries no risk of gastrointestinal polyposis or internal malignancy.3,4 The histopathology of a pigmented macule of LHS shows a normal number and morphology of melanocytes. Epidermal basement membrane pigmentation is common, with pigment-laden macrophages evident in the papillary dermis.3

RELATED ARTICLE: Asymptomatic Lower Lip Hyperpigmentation From Laugier-Hunziker Syndrome