User login

Brodalumab in an Organ Transplant Recipient With Psoriasis

The treatment landscape for psoriasis has evolved rapidly over the last decade. Biologic therapies have demonstrated robust efficacy and acceptable safety profiles among many patients with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis. However, the use of biologics among immunocompromised patients with psoriasis rarely is discussed in the literature. As new biologics for psoriasis are being developed, a critical gap exists in the literature regarding the safety and efficacy of these medications in immunocompromised patients. Per American Academy of Dermatology–National Psoriasis Foundation guidelines, caution should be exercised when using biologics in patients with immunocompromising conditions.1 In organ transplant recipients, the potential risks of combining systemic medications used for organ transplantation and biologic treatments for psoriasis are unknown.2

In the posttransplant period, the immunosuppressive regimens for transplantation likely will improve psoriasis. However, patients with organ transplant and psoriasis still experience flares that can be challenging to treat.3 Prior treatment modalities to prevent psoriasis flares in organ transplant recipients have relied largely on topical therapies, posttransplant immunosuppressive medications (eg, cyclosporine, tacrolimus, mycophenolate mofetil) that prevent graft rejection, and systemic corticosteroids. We report a case of a 50-year-old man with a recent history of liver transplantation who presented with severe plaque psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis.

Case Report

A 50-year-old man presented to the dermatology clinic with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis that had been present for 15 years. His plaque psoriasis covered approximately 40% of the body surface area, including the scalp, trunk, arms, and legs. In addition, he had diffuse joint pain in the hands and feet; a radiograph revealed active psoriatic arthritis involving the joints of the fingers and toes.

One year prior to presentation to our dermatology clinic, the patient underwent an an orthotopic liver transplant for history of Child-Pugh class C liver cirrhosis secondary to untreated hepatitis C virus (HCV) and alcohol use that was complicated by hepatocellular carcinoma. He acquired a high-risk donor liver that was HCV positive with HCV genotype 1a. Starting 2 months after the transplant, he underwent 12 weeks of treatment for HCV with glecaprevir-pibrentasvir. Once his HCV treatment course was completed, he achieved a sustained virologic response with an undetectable viral load. To prevent transplant rejection, he was on chronic immunosuppression with tacrolimus, a calcineurin inhibitor, and mycophenolate mofetil, an inhibitor of inosine monophosphate dehydrogenase whose action leads to decreased proliferation of T cells and B cells.

The patient’s psoriasis initially was treated with triamcinolone acetonide ointment 0.1% applied twice daily to the psoriasis lesions for 1 year by another dermatologist. However, his psoriasis progressed to involve 40% of the body surface area. Following our evaluation 1 year posttransplant, the patient was started on subcutaneous brodalumab 210 mg at weeks 0, 1, and 2, then every 2 weeks thereafter. Approximately 10 weeks after initiation of brodalumab, the patient’s psoriasis was completely clear, and he was asymptomatic from psoriatic arthritis. The patient’s improvement persisted at 6 months, and his liver enzymes, including alkaline phosphatase, total bilirubin, alanine transaminase, and aspartate transaminase, continued to be within reference range. To date, there has been no evidence of posttransplant complications such as graft-vs-host disease, serious infections, or skin cancers.

Comment

Increased Risk for Infection and Malignancies in Transplant Patients

Transplant patients are on immunosuppressive regimens that increase their risk for infection and malignancies. For example, high doses of immunosuppresants predispose these patients to reactivation of viral infections, including BK and JC viruses.4 In addition, the incidence of squamous cell carcinoma is 65- to 250-fold higher in transplant patients compared to the general population.5 The risk for Merkel cell carcinoma is increased after solid organ transplantation compared to the general population.6 Importantly, transplant patients have a higher mortality from skin cancers than other types of cancers, including breast and colon cancer.7

Psoriasis in Organ Transplant Recipients

Psoriasis is a chronic, immune-mediated, inflammatory disease with a prevalence of approximately 3% in the United States.8 Approximately one-third of patients with psoriasis develop psoriatic arthritis.9 Organ transplant recipients with psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis represent a unique patient population whereby their use of chronic immunosuppressive medications to prevent graft rejection may put them at risk for developing infections and malignancies.

Special Considerations for Brodalumab

Brodalumab is an immunomodulatory biologic that binds to and inhibits IL-17RA, thereby inhibiting the actions of IL-17A, F, E, and C.2 The blockade of IL-17RA by brodalumab has been shown to result in reversal of psoriatic phenotype and gene expression patterns.10 Brodalumab was chosen as the treatment in our patient because it has a rapid onset of action, sustained efficacy, and an acceptable safety profile.11 Brodalumab is well tolerated, with approximately 60% of patients achieving clearance long-term.12 Candidal infections can occur in patients with brodalumab, but the rates are low and they are reversible with antifungal treatment.13 The increased mucocutaneous candidal infections are consistent with medications whose mechanism of action is IL-17 inhibition.14,15 The most common adverse reactions found were nasopharyngitis and headache.16 The causal link between brodalumab and suicidality has not been established.17

The use of brodalumab for psoriasis in organ transplant recipients has not been previously reported in the literature. A few case reports have been published on the successful use of etanercept and ixekizumab as biologic treatment options for psoriasis in transplant patients.18-23 In addition to choosing an appropriate biologic for psoriasis in transplant patients, transplant providers may evaluate the choice of immunosuppression regimen for the organ transplant in the context of psoriasis. In a retrospective analysis of liver transplant patients with psoriasis, Foroncewicz et al3 found cyclosporine, which was used as an antirejection immunosuppressive agent in the posttransplant period, to be more effective than tacrolimus in treating recurrent psoriasis in liver transplant recipients.

Our case illustrates one example of the successful use of brodalumab in a patient with a solid organ transplant. Our patient’s psoriasis and symptoms of psoriatic arthritis greatly improved after initiation of brodalumab. In the posttransplant period, the patient did not develop graft-vs-host disease, infections, malignancies, depression, or suicidal ideation while taking brodalumab.

Conclusion

It is important that the patient, dermatology team, and transplant team work together to navigate the challenges and relatively unknown landscape of psoriasis treatment in organ transplant recipients. As the number of organ transplant recipients continues to increase, this issue will become more clinically relevant. Case reports and future prospective studies will continue to inform us regarding the role of biologics in psoriasis treatment posttransplantation.

- Menter A, Strober BE, Kaplan DH, et al. Joint AAD-NPF guidelines of care for the management and treatment of psoriasis with biologics. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:1029-1072.

- Prussick R, Wu JJ, Armstrong AW, et al. Psoriasis in solid organ transplant patients: best practice recommendations from The Medical Board of the National Psoriasis Foundation. J Dermatol Treat. 2018;29:329-333.

- Foroncewicz B, Mucha K, Lerut J, et al. Cyclosporine is superior to tacrolimus in liver transplant recipients with recurrent psoriasis. Ann Transplant. 2014;19:427-433.

- Boukoum H, Nahdi I, Sahtout W, et al. BK and JC virus infections in healthy patients compared to kidney transplant recipients in Tunisia. Microbial Pathogenesis. 2016;97:204-208.

- Bouwes Bavinck JN, Euvrard S, Naldi L, et al. Keratotic skin lesions and other risk factors are associated with skin cancer in organ-transplant recipients: a case-control study in The Netherlands, United Kingdom, Germany, France, and Italy. J Invest Dermatol. 2007;127:1647-1656.

- Clark CA, Robbins HA, Tatalovich Z, et al. Risk of Merkel cell carcinoma after transplant. Clin Oncol. 2019;31:779-788.

- Lakhani NA, Saraiya M, Thompson TD, et al. Total body skin examination for skin cancer screening among U.S. adults from 2000 to 2010. Prev Med. 2014;61:75-80.

- Rachakonda TD, Schupp CW, Armstrong AW. Psoriasis prevalence among adults in the United States. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:512-516.

- Alinaghi F, Calov M, Kristensen LE, et al. Prevalence of psoriatic arthritis in patients with psoriasis: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational and clinical studies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:251-265.

- Russell CB, Rand H, Bigler J, et al. Gene expression profiles normalized in psoriatic skin by treatment with brodalumab, a human anti-IL-17 receptor monoclonal antibody. J Immunol. 2014;192:3828-3836.

- Foulkes AC, Warren RB. Brodalumab in psoriasis: evidence to date and clinical potential. Drugs Context. 2019;8:212570. doi:10.7573/dic.212570

- Puig L, Lebwohl M, Bachelez H, et al. Long-term efficacy and safety of brodalumab in the treatment of psoriasis: 120-week results from the randomized, double-blind, placebo- and active comparator-controlled phase 3 AMAGINE-2 trial. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82:352-359.

- Lebwohl M, Strober B, Menter A, et al. Phase 3 studies comparing brodalumab and ustekinumab in psoriasis. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:1318-1328.

- Conti HR, Shen F, Nayyar N, et al. Th17 cells and IL-17 receptor signaling are essential for mucosal host defense against oral candidiasis. J Exp Med. 2009;206:299-311.

- Puel A, Cypowyj S, Bustamante J, et al. Chronic mucocutaneous candidiasis in humans with inborn errors of interleukin-17 immunity. Science. 2011;332:65-68.

- Farahnik B, Beroukhim B, Abrouk M, et al. Brodalumab for the treatment of psoriasis: a review of Phase III trials. Dermatol Ther. 2016;6:111-124.

- Lebwohl MG, Papp KA, Marangell LB, et al. Psychiatric adverse events during treatment with brodalumab: analysis of psoriasis clinical trials. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78:81-89.

- DeSimone C, Perino F, Caldarola G, et al. Treatment of psoriasis with etanercept in immunocompromised patients: two case reports. J Int Med Res. 2016;44:67-71.

- Madankumar R, Teperman LW, Stein JA. Use of etanercept for psoriasis in a liver transplant recipient. JAAD Case Rep. 2015;1:S36-S37.

- Collazo MH, González JR, Torres EA. Etanercept therapy for psoriasis in a patient with concomitant hepatitis C and liver transplant. P R Health Sci J. 2008;27:346-347.

- Hoover WD. Etanercept therapy for severe plaque psoriasis in a patient who underwent a liver transplant. Cutis. 2007;80:211-214.

- Brokalaki EI, Voshege N, Witzke O, et al. Treatment of severe psoriasis with etanercept in a pancreas-kidney transplant recipient. Transplant Proc. 2012;44:2776-2777.

- Lora V, Graceffa D, De Felice C, et al. Treatment of severe psoriasis with ixekizumab in a liver transplant recipient with concomitant hepatitis B virus infection. Dermatol Ther. 2019;32:E12909.

The treatment landscape for psoriasis has evolved rapidly over the last decade. Biologic therapies have demonstrated robust efficacy and acceptable safety profiles among many patients with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis. However, the use of biologics among immunocompromised patients with psoriasis rarely is discussed in the literature. As new biologics for psoriasis are being developed, a critical gap exists in the literature regarding the safety and efficacy of these medications in immunocompromised patients. Per American Academy of Dermatology–National Psoriasis Foundation guidelines, caution should be exercised when using biologics in patients with immunocompromising conditions.1 In organ transplant recipients, the potential risks of combining systemic medications used for organ transplantation and biologic treatments for psoriasis are unknown.2

In the posttransplant period, the immunosuppressive regimens for transplantation likely will improve psoriasis. However, patients with organ transplant and psoriasis still experience flares that can be challenging to treat.3 Prior treatment modalities to prevent psoriasis flares in organ transplant recipients have relied largely on topical therapies, posttransplant immunosuppressive medications (eg, cyclosporine, tacrolimus, mycophenolate mofetil) that prevent graft rejection, and systemic corticosteroids. We report a case of a 50-year-old man with a recent history of liver transplantation who presented with severe plaque psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis.

Case Report

A 50-year-old man presented to the dermatology clinic with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis that had been present for 15 years. His plaque psoriasis covered approximately 40% of the body surface area, including the scalp, trunk, arms, and legs. In addition, he had diffuse joint pain in the hands and feet; a radiograph revealed active psoriatic arthritis involving the joints of the fingers and toes.

One year prior to presentation to our dermatology clinic, the patient underwent an an orthotopic liver transplant for history of Child-Pugh class C liver cirrhosis secondary to untreated hepatitis C virus (HCV) and alcohol use that was complicated by hepatocellular carcinoma. He acquired a high-risk donor liver that was HCV positive with HCV genotype 1a. Starting 2 months after the transplant, he underwent 12 weeks of treatment for HCV with glecaprevir-pibrentasvir. Once his HCV treatment course was completed, he achieved a sustained virologic response with an undetectable viral load. To prevent transplant rejection, he was on chronic immunosuppression with tacrolimus, a calcineurin inhibitor, and mycophenolate mofetil, an inhibitor of inosine monophosphate dehydrogenase whose action leads to decreased proliferation of T cells and B cells.

The patient’s psoriasis initially was treated with triamcinolone acetonide ointment 0.1% applied twice daily to the psoriasis lesions for 1 year by another dermatologist. However, his psoriasis progressed to involve 40% of the body surface area. Following our evaluation 1 year posttransplant, the patient was started on subcutaneous brodalumab 210 mg at weeks 0, 1, and 2, then every 2 weeks thereafter. Approximately 10 weeks after initiation of brodalumab, the patient’s psoriasis was completely clear, and he was asymptomatic from psoriatic arthritis. The patient’s improvement persisted at 6 months, and his liver enzymes, including alkaline phosphatase, total bilirubin, alanine transaminase, and aspartate transaminase, continued to be within reference range. To date, there has been no evidence of posttransplant complications such as graft-vs-host disease, serious infections, or skin cancers.

Comment

Increased Risk for Infection and Malignancies in Transplant Patients

Transplant patients are on immunosuppressive regimens that increase their risk for infection and malignancies. For example, high doses of immunosuppresants predispose these patients to reactivation of viral infections, including BK and JC viruses.4 In addition, the incidence of squamous cell carcinoma is 65- to 250-fold higher in transplant patients compared to the general population.5 The risk for Merkel cell carcinoma is increased after solid organ transplantation compared to the general population.6 Importantly, transplant patients have a higher mortality from skin cancers than other types of cancers, including breast and colon cancer.7

Psoriasis in Organ Transplant Recipients

Psoriasis is a chronic, immune-mediated, inflammatory disease with a prevalence of approximately 3% in the United States.8 Approximately one-third of patients with psoriasis develop psoriatic arthritis.9 Organ transplant recipients with psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis represent a unique patient population whereby their use of chronic immunosuppressive medications to prevent graft rejection may put them at risk for developing infections and malignancies.

Special Considerations for Brodalumab

Brodalumab is an immunomodulatory biologic that binds to and inhibits IL-17RA, thereby inhibiting the actions of IL-17A, F, E, and C.2 The blockade of IL-17RA by brodalumab has been shown to result in reversal of psoriatic phenotype and gene expression patterns.10 Brodalumab was chosen as the treatment in our patient because it has a rapid onset of action, sustained efficacy, and an acceptable safety profile.11 Brodalumab is well tolerated, with approximately 60% of patients achieving clearance long-term.12 Candidal infections can occur in patients with brodalumab, but the rates are low and they are reversible with antifungal treatment.13 The increased mucocutaneous candidal infections are consistent with medications whose mechanism of action is IL-17 inhibition.14,15 The most common adverse reactions found were nasopharyngitis and headache.16 The causal link between brodalumab and suicidality has not been established.17

The use of brodalumab for psoriasis in organ transplant recipients has not been previously reported in the literature. A few case reports have been published on the successful use of etanercept and ixekizumab as biologic treatment options for psoriasis in transplant patients.18-23 In addition to choosing an appropriate biologic for psoriasis in transplant patients, transplant providers may evaluate the choice of immunosuppression regimen for the organ transplant in the context of psoriasis. In a retrospective analysis of liver transplant patients with psoriasis, Foroncewicz et al3 found cyclosporine, which was used as an antirejection immunosuppressive agent in the posttransplant period, to be more effective than tacrolimus in treating recurrent psoriasis in liver transplant recipients.

Our case illustrates one example of the successful use of brodalumab in a patient with a solid organ transplant. Our patient’s psoriasis and symptoms of psoriatic arthritis greatly improved after initiation of brodalumab. In the posttransplant period, the patient did not develop graft-vs-host disease, infections, malignancies, depression, or suicidal ideation while taking brodalumab.

Conclusion

It is important that the patient, dermatology team, and transplant team work together to navigate the challenges and relatively unknown landscape of psoriasis treatment in organ transplant recipients. As the number of organ transplant recipients continues to increase, this issue will become more clinically relevant. Case reports and future prospective studies will continue to inform us regarding the role of biologics in psoriasis treatment posttransplantation.

The treatment landscape for psoriasis has evolved rapidly over the last decade. Biologic therapies have demonstrated robust efficacy and acceptable safety profiles among many patients with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis. However, the use of biologics among immunocompromised patients with psoriasis rarely is discussed in the literature. As new biologics for psoriasis are being developed, a critical gap exists in the literature regarding the safety and efficacy of these medications in immunocompromised patients. Per American Academy of Dermatology–National Psoriasis Foundation guidelines, caution should be exercised when using biologics in patients with immunocompromising conditions.1 In organ transplant recipients, the potential risks of combining systemic medications used for organ transplantation and biologic treatments for psoriasis are unknown.2

In the posttransplant period, the immunosuppressive regimens for transplantation likely will improve psoriasis. However, patients with organ transplant and psoriasis still experience flares that can be challenging to treat.3 Prior treatment modalities to prevent psoriasis flares in organ transplant recipients have relied largely on topical therapies, posttransplant immunosuppressive medications (eg, cyclosporine, tacrolimus, mycophenolate mofetil) that prevent graft rejection, and systemic corticosteroids. We report a case of a 50-year-old man with a recent history of liver transplantation who presented with severe plaque psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis.

Case Report

A 50-year-old man presented to the dermatology clinic with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis that had been present for 15 years. His plaque psoriasis covered approximately 40% of the body surface area, including the scalp, trunk, arms, and legs. In addition, he had diffuse joint pain in the hands and feet; a radiograph revealed active psoriatic arthritis involving the joints of the fingers and toes.

One year prior to presentation to our dermatology clinic, the patient underwent an an orthotopic liver transplant for history of Child-Pugh class C liver cirrhosis secondary to untreated hepatitis C virus (HCV) and alcohol use that was complicated by hepatocellular carcinoma. He acquired a high-risk donor liver that was HCV positive with HCV genotype 1a. Starting 2 months after the transplant, he underwent 12 weeks of treatment for HCV with glecaprevir-pibrentasvir. Once his HCV treatment course was completed, he achieved a sustained virologic response with an undetectable viral load. To prevent transplant rejection, he was on chronic immunosuppression with tacrolimus, a calcineurin inhibitor, and mycophenolate mofetil, an inhibitor of inosine monophosphate dehydrogenase whose action leads to decreased proliferation of T cells and B cells.

The patient’s psoriasis initially was treated with triamcinolone acetonide ointment 0.1% applied twice daily to the psoriasis lesions for 1 year by another dermatologist. However, his psoriasis progressed to involve 40% of the body surface area. Following our evaluation 1 year posttransplant, the patient was started on subcutaneous brodalumab 210 mg at weeks 0, 1, and 2, then every 2 weeks thereafter. Approximately 10 weeks after initiation of brodalumab, the patient’s psoriasis was completely clear, and he was asymptomatic from psoriatic arthritis. The patient’s improvement persisted at 6 months, and his liver enzymes, including alkaline phosphatase, total bilirubin, alanine transaminase, and aspartate transaminase, continued to be within reference range. To date, there has been no evidence of posttransplant complications such as graft-vs-host disease, serious infections, or skin cancers.

Comment

Increased Risk for Infection and Malignancies in Transplant Patients

Transplant patients are on immunosuppressive regimens that increase their risk for infection and malignancies. For example, high doses of immunosuppresants predispose these patients to reactivation of viral infections, including BK and JC viruses.4 In addition, the incidence of squamous cell carcinoma is 65- to 250-fold higher in transplant patients compared to the general population.5 The risk for Merkel cell carcinoma is increased after solid organ transplantation compared to the general population.6 Importantly, transplant patients have a higher mortality from skin cancers than other types of cancers, including breast and colon cancer.7

Psoriasis in Organ Transplant Recipients

Psoriasis is a chronic, immune-mediated, inflammatory disease with a prevalence of approximately 3% in the United States.8 Approximately one-third of patients with psoriasis develop psoriatic arthritis.9 Organ transplant recipients with psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis represent a unique patient population whereby their use of chronic immunosuppressive medications to prevent graft rejection may put them at risk for developing infections and malignancies.

Special Considerations for Brodalumab

Brodalumab is an immunomodulatory biologic that binds to and inhibits IL-17RA, thereby inhibiting the actions of IL-17A, F, E, and C.2 The blockade of IL-17RA by brodalumab has been shown to result in reversal of psoriatic phenotype and gene expression patterns.10 Brodalumab was chosen as the treatment in our patient because it has a rapid onset of action, sustained efficacy, and an acceptable safety profile.11 Brodalumab is well tolerated, with approximately 60% of patients achieving clearance long-term.12 Candidal infections can occur in patients with brodalumab, but the rates are low and they are reversible with antifungal treatment.13 The increased mucocutaneous candidal infections are consistent with medications whose mechanism of action is IL-17 inhibition.14,15 The most common adverse reactions found were nasopharyngitis and headache.16 The causal link between brodalumab and suicidality has not been established.17

The use of brodalumab for psoriasis in organ transplant recipients has not been previously reported in the literature. A few case reports have been published on the successful use of etanercept and ixekizumab as biologic treatment options for psoriasis in transplant patients.18-23 In addition to choosing an appropriate biologic for psoriasis in transplant patients, transplant providers may evaluate the choice of immunosuppression regimen for the organ transplant in the context of psoriasis. In a retrospective analysis of liver transplant patients with psoriasis, Foroncewicz et al3 found cyclosporine, which was used as an antirejection immunosuppressive agent in the posttransplant period, to be more effective than tacrolimus in treating recurrent psoriasis in liver transplant recipients.

Our case illustrates one example of the successful use of brodalumab in a patient with a solid organ transplant. Our patient’s psoriasis and symptoms of psoriatic arthritis greatly improved after initiation of brodalumab. In the posttransplant period, the patient did not develop graft-vs-host disease, infections, malignancies, depression, or suicidal ideation while taking brodalumab.

Conclusion

It is important that the patient, dermatology team, and transplant team work together to navigate the challenges and relatively unknown landscape of psoriasis treatment in organ transplant recipients. As the number of organ transplant recipients continues to increase, this issue will become more clinically relevant. Case reports and future prospective studies will continue to inform us regarding the role of biologics in psoriasis treatment posttransplantation.

- Menter A, Strober BE, Kaplan DH, et al. Joint AAD-NPF guidelines of care for the management and treatment of psoriasis with biologics. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:1029-1072.

- Prussick R, Wu JJ, Armstrong AW, et al. Psoriasis in solid organ transplant patients: best practice recommendations from The Medical Board of the National Psoriasis Foundation. J Dermatol Treat. 2018;29:329-333.

- Foroncewicz B, Mucha K, Lerut J, et al. Cyclosporine is superior to tacrolimus in liver transplant recipients with recurrent psoriasis. Ann Transplant. 2014;19:427-433.

- Boukoum H, Nahdi I, Sahtout W, et al. BK and JC virus infections in healthy patients compared to kidney transplant recipients in Tunisia. Microbial Pathogenesis. 2016;97:204-208.

- Bouwes Bavinck JN, Euvrard S, Naldi L, et al. Keratotic skin lesions and other risk factors are associated with skin cancer in organ-transplant recipients: a case-control study in The Netherlands, United Kingdom, Germany, France, and Italy. J Invest Dermatol. 2007;127:1647-1656.

- Clark CA, Robbins HA, Tatalovich Z, et al. Risk of Merkel cell carcinoma after transplant. Clin Oncol. 2019;31:779-788.

- Lakhani NA, Saraiya M, Thompson TD, et al. Total body skin examination for skin cancer screening among U.S. adults from 2000 to 2010. Prev Med. 2014;61:75-80.

- Rachakonda TD, Schupp CW, Armstrong AW. Psoriasis prevalence among adults in the United States. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:512-516.

- Alinaghi F, Calov M, Kristensen LE, et al. Prevalence of psoriatic arthritis in patients with psoriasis: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational and clinical studies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:251-265.

- Russell CB, Rand H, Bigler J, et al. Gene expression profiles normalized in psoriatic skin by treatment with brodalumab, a human anti-IL-17 receptor monoclonal antibody. J Immunol. 2014;192:3828-3836.

- Foulkes AC, Warren RB. Brodalumab in psoriasis: evidence to date and clinical potential. Drugs Context. 2019;8:212570. doi:10.7573/dic.212570

- Puig L, Lebwohl M, Bachelez H, et al. Long-term efficacy and safety of brodalumab in the treatment of psoriasis: 120-week results from the randomized, double-blind, placebo- and active comparator-controlled phase 3 AMAGINE-2 trial. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82:352-359.

- Lebwohl M, Strober B, Menter A, et al. Phase 3 studies comparing brodalumab and ustekinumab in psoriasis. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:1318-1328.

- Conti HR, Shen F, Nayyar N, et al. Th17 cells and IL-17 receptor signaling are essential for mucosal host defense against oral candidiasis. J Exp Med. 2009;206:299-311.

- Puel A, Cypowyj S, Bustamante J, et al. Chronic mucocutaneous candidiasis in humans with inborn errors of interleukin-17 immunity. Science. 2011;332:65-68.

- Farahnik B, Beroukhim B, Abrouk M, et al. Brodalumab for the treatment of psoriasis: a review of Phase III trials. Dermatol Ther. 2016;6:111-124.

- Lebwohl MG, Papp KA, Marangell LB, et al. Psychiatric adverse events during treatment with brodalumab: analysis of psoriasis clinical trials. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78:81-89.

- DeSimone C, Perino F, Caldarola G, et al. Treatment of psoriasis with etanercept in immunocompromised patients: two case reports. J Int Med Res. 2016;44:67-71.

- Madankumar R, Teperman LW, Stein JA. Use of etanercept for psoriasis in a liver transplant recipient. JAAD Case Rep. 2015;1:S36-S37.

- Collazo MH, González JR, Torres EA. Etanercept therapy for psoriasis in a patient with concomitant hepatitis C and liver transplant. P R Health Sci J. 2008;27:346-347.

- Hoover WD. Etanercept therapy for severe plaque psoriasis in a patient who underwent a liver transplant. Cutis. 2007;80:211-214.

- Brokalaki EI, Voshege N, Witzke O, et al. Treatment of severe psoriasis with etanercept in a pancreas-kidney transplant recipient. Transplant Proc. 2012;44:2776-2777.

- Lora V, Graceffa D, De Felice C, et al. Treatment of severe psoriasis with ixekizumab in a liver transplant recipient with concomitant hepatitis B virus infection. Dermatol Ther. 2019;32:E12909.

- Menter A, Strober BE, Kaplan DH, et al. Joint AAD-NPF guidelines of care for the management and treatment of psoriasis with biologics. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:1029-1072.

- Prussick R, Wu JJ, Armstrong AW, et al. Psoriasis in solid organ transplant patients: best practice recommendations from The Medical Board of the National Psoriasis Foundation. J Dermatol Treat. 2018;29:329-333.

- Foroncewicz B, Mucha K, Lerut J, et al. Cyclosporine is superior to tacrolimus in liver transplant recipients with recurrent psoriasis. Ann Transplant. 2014;19:427-433.

- Boukoum H, Nahdi I, Sahtout W, et al. BK and JC virus infections in healthy patients compared to kidney transplant recipients in Tunisia. Microbial Pathogenesis. 2016;97:204-208.

- Bouwes Bavinck JN, Euvrard S, Naldi L, et al. Keratotic skin lesions and other risk factors are associated with skin cancer in organ-transplant recipients: a case-control study in The Netherlands, United Kingdom, Germany, France, and Italy. J Invest Dermatol. 2007;127:1647-1656.

- Clark CA, Robbins HA, Tatalovich Z, et al. Risk of Merkel cell carcinoma after transplant. Clin Oncol. 2019;31:779-788.

- Lakhani NA, Saraiya M, Thompson TD, et al. Total body skin examination for skin cancer screening among U.S. adults from 2000 to 2010. Prev Med. 2014;61:75-80.

- Rachakonda TD, Schupp CW, Armstrong AW. Psoriasis prevalence among adults in the United States. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:512-516.

- Alinaghi F, Calov M, Kristensen LE, et al. Prevalence of psoriatic arthritis in patients with psoriasis: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational and clinical studies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:251-265.

- Russell CB, Rand H, Bigler J, et al. Gene expression profiles normalized in psoriatic skin by treatment with brodalumab, a human anti-IL-17 receptor monoclonal antibody. J Immunol. 2014;192:3828-3836.

- Foulkes AC, Warren RB. Brodalumab in psoriasis: evidence to date and clinical potential. Drugs Context. 2019;8:212570. doi:10.7573/dic.212570

- Puig L, Lebwohl M, Bachelez H, et al. Long-term efficacy and safety of brodalumab in the treatment of psoriasis: 120-week results from the randomized, double-blind, placebo- and active comparator-controlled phase 3 AMAGINE-2 trial. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82:352-359.

- Lebwohl M, Strober B, Menter A, et al. Phase 3 studies comparing brodalumab and ustekinumab in psoriasis. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:1318-1328.

- Conti HR, Shen F, Nayyar N, et al. Th17 cells and IL-17 receptor signaling are essential for mucosal host defense against oral candidiasis. J Exp Med. 2009;206:299-311.

- Puel A, Cypowyj S, Bustamante J, et al. Chronic mucocutaneous candidiasis in humans with inborn errors of interleukin-17 immunity. Science. 2011;332:65-68.

- Farahnik B, Beroukhim B, Abrouk M, et al. Brodalumab for the treatment of psoriasis: a review of Phase III trials. Dermatol Ther. 2016;6:111-124.

- Lebwohl MG, Papp KA, Marangell LB, et al. Psychiatric adverse events during treatment with brodalumab: analysis of psoriasis clinical trials. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78:81-89.

- DeSimone C, Perino F, Caldarola G, et al. Treatment of psoriasis with etanercept in immunocompromised patients: two case reports. J Int Med Res. 2016;44:67-71.

- Madankumar R, Teperman LW, Stein JA. Use of etanercept for psoriasis in a liver transplant recipient. JAAD Case Rep. 2015;1:S36-S37.

- Collazo MH, González JR, Torres EA. Etanercept therapy for psoriasis in a patient with concomitant hepatitis C and liver transplant. P R Health Sci J. 2008;27:346-347.

- Hoover WD. Etanercept therapy for severe plaque psoriasis in a patient who underwent a liver transplant. Cutis. 2007;80:211-214.

- Brokalaki EI, Voshege N, Witzke O, et al. Treatment of severe psoriasis with etanercept in a pancreas-kidney transplant recipient. Transplant Proc. 2012;44:2776-2777.

- Lora V, Graceffa D, De Felice C, et al. Treatment of severe psoriasis with ixekizumab in a liver transplant recipient with concomitant hepatitis B virus infection. Dermatol Ther. 2019;32:E12909.

Practice Points

- Immunocompromised patients, such as organ transplant recipients, require careful benefit-risk consideration when selecting a systemic agent for psoriasis.

- Brodalumab, an IL-17RA antagonist, was used to treat a patient with psoriasis who had undergone solid organ transplant with excellent response and good tolerability.

- Further studies are needed to evaluate the benefits and risks of using biologic treatments in patients with psoriasis who are organ transplant recipients.

Unilateral Verrucous Psoriasis

Case Report

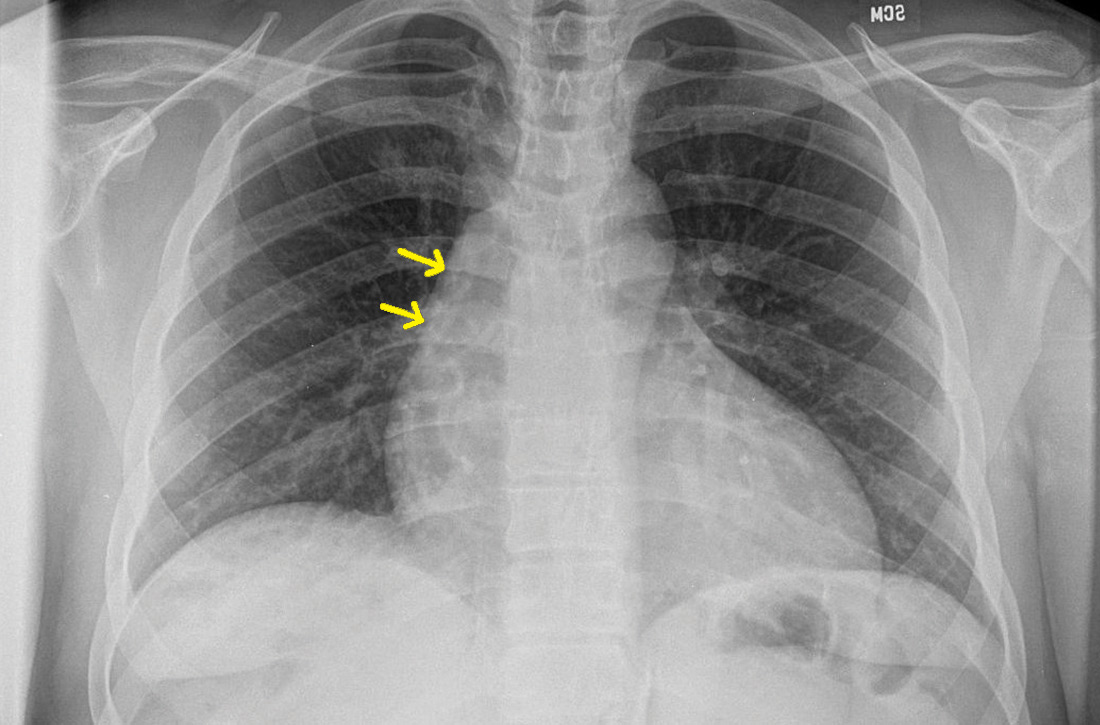

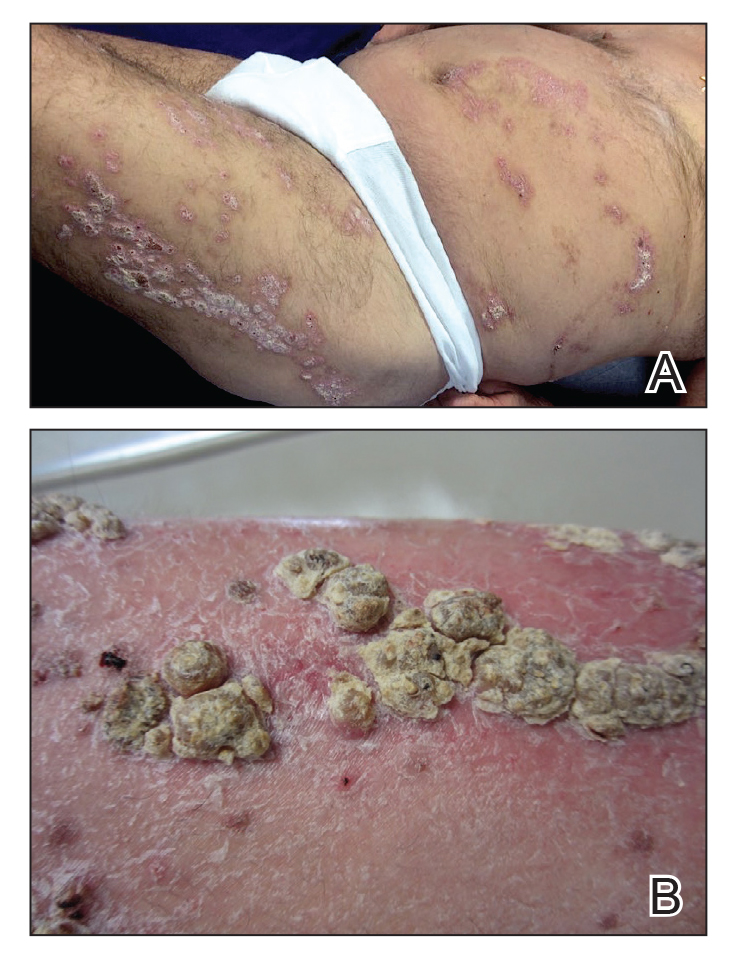

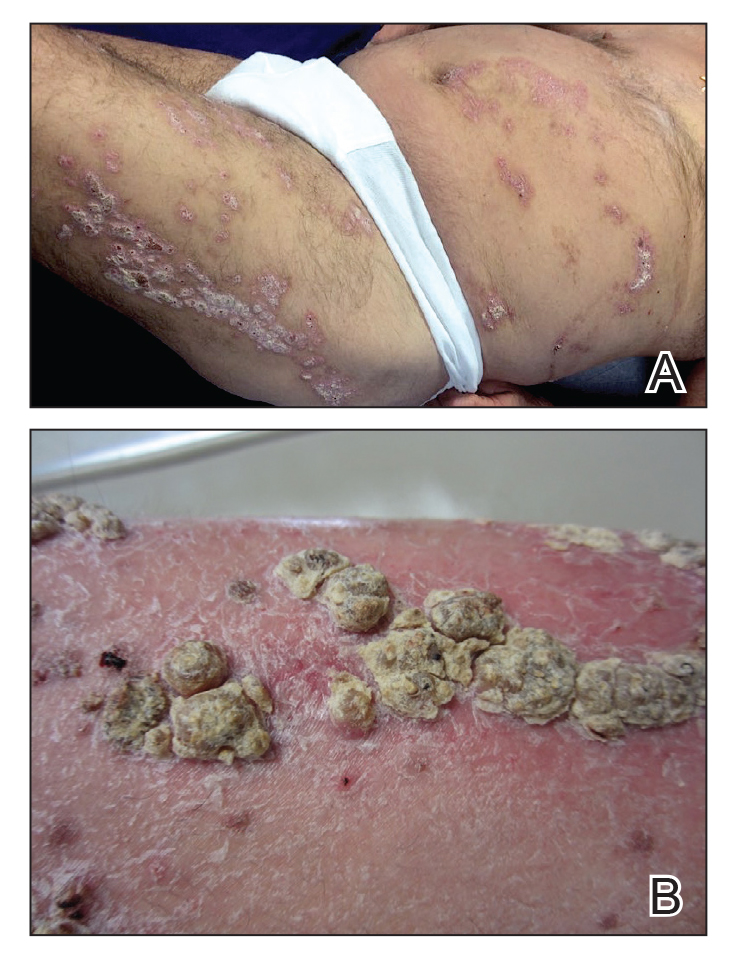

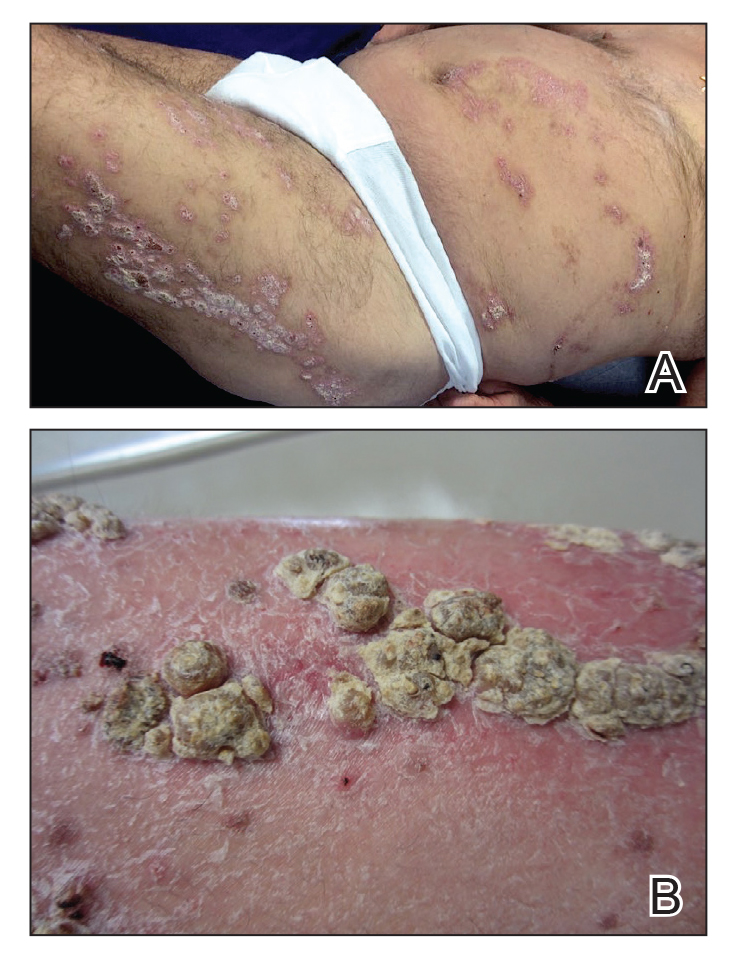

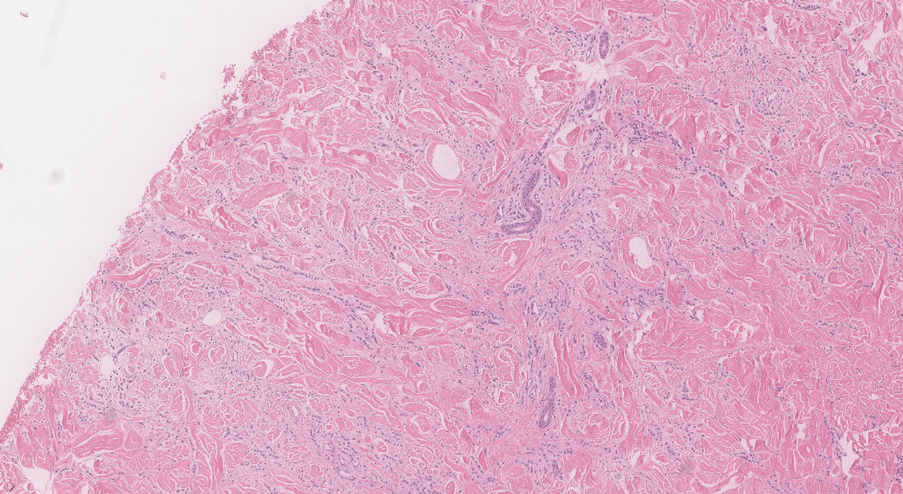

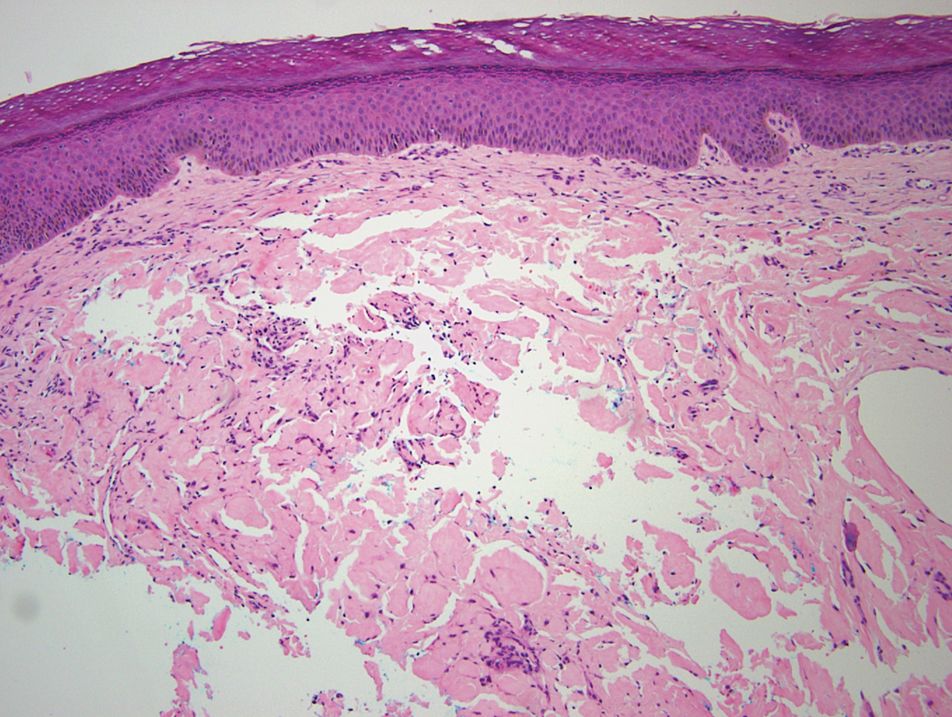

An 80-year-old man with a history of hypertension and coronary artery disease presented to the dermatology clinic with a rash characterized by multiple asymptomatic plaques with overlying verrucous nodules on the left side of the abdomen, back, and leg (Figure 1). He reported that these “growths” appeared 20 years prior to presentation, shortly after coronary artery bypass surgery with a saphenous vein graft. The patient initially was given a diagnosis of verruca vulgaris and then biopsy-proven psoriasis later that year. At that time, he refused systemic treatment and was treated instead with triamcinolone acetonide ointment, with periodic surgical removal of bothersome lesions.

At the current presentation, physical examination revealed many hyperkeratotic, yellow-gray, verrucous nodules overlying scaly, erythematous, sharply demarcated plaques, exclusively on the left side of the body, including the left side of the abdomen, back, and leg. The differential diagnosis included linear psoriasis and inflammatory linear verrucous epidermal nevus (ILVEN).

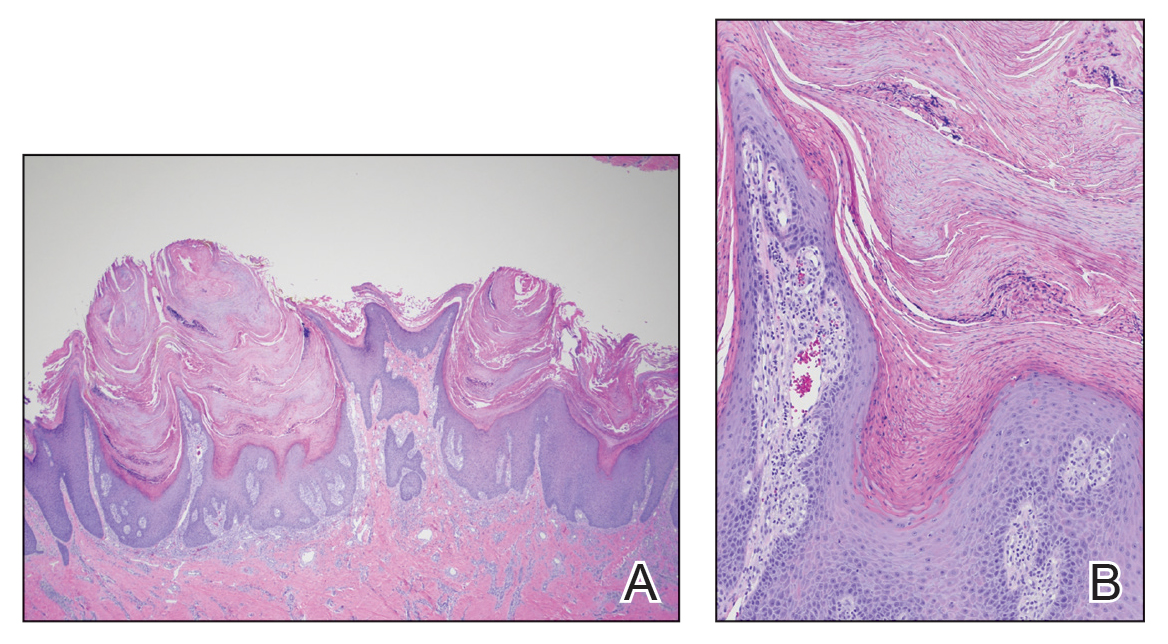

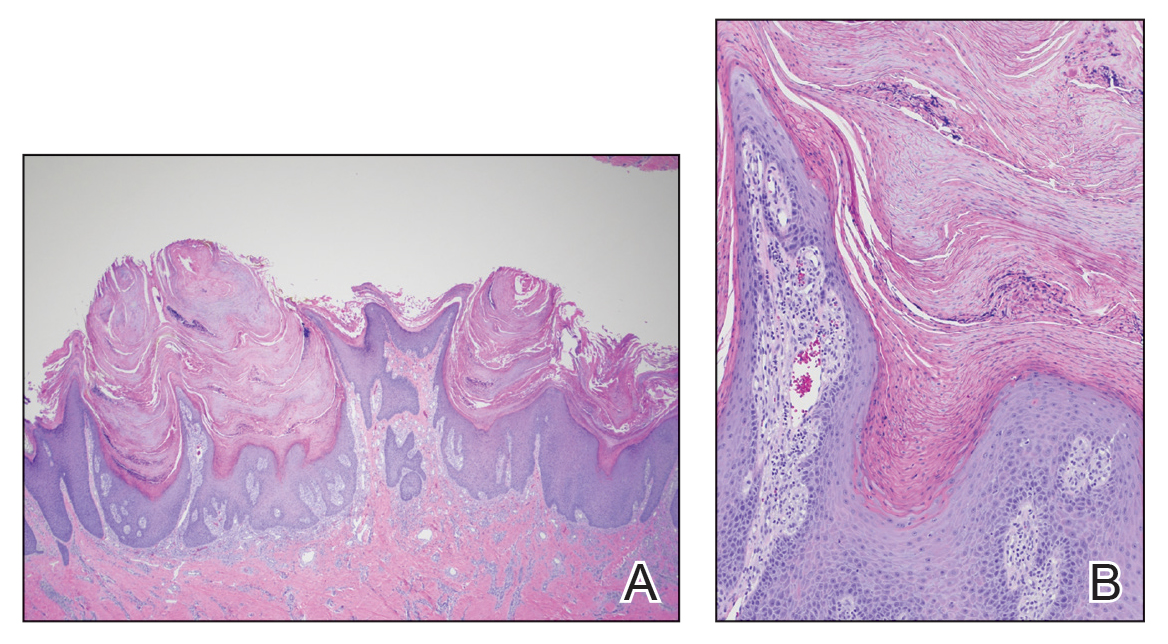

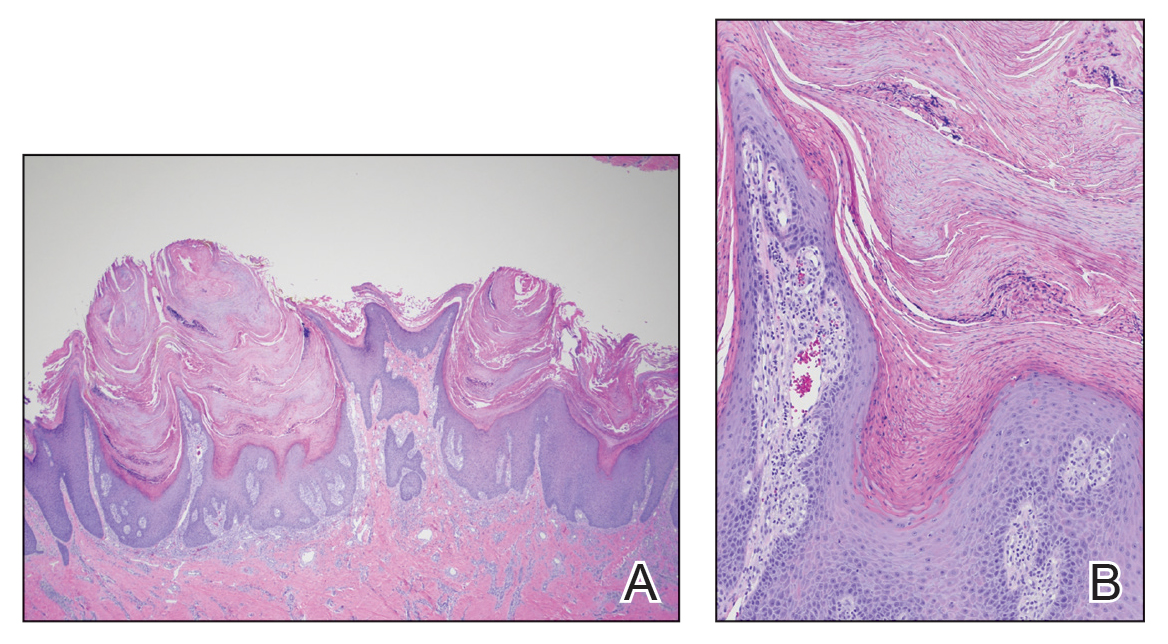

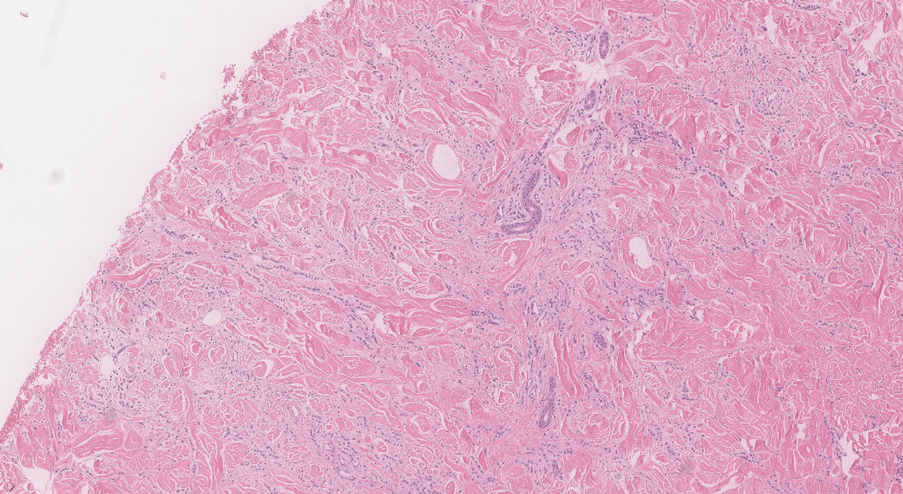

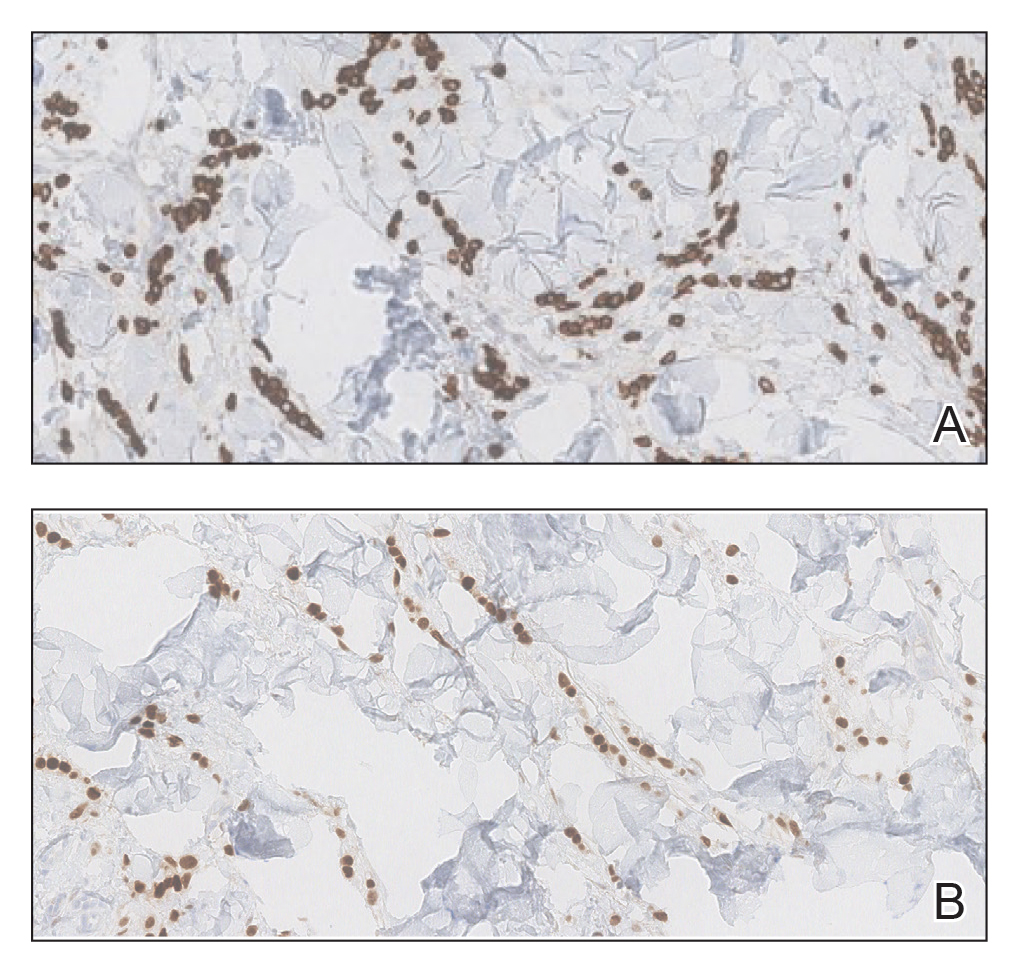

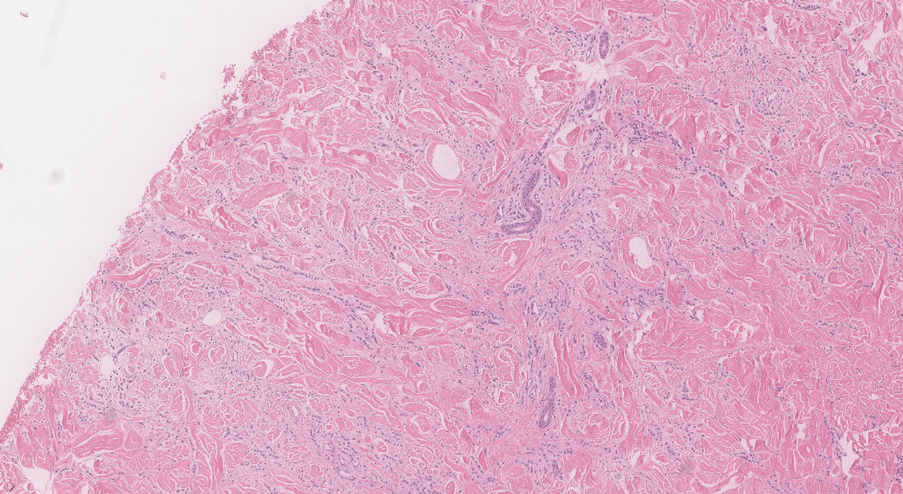

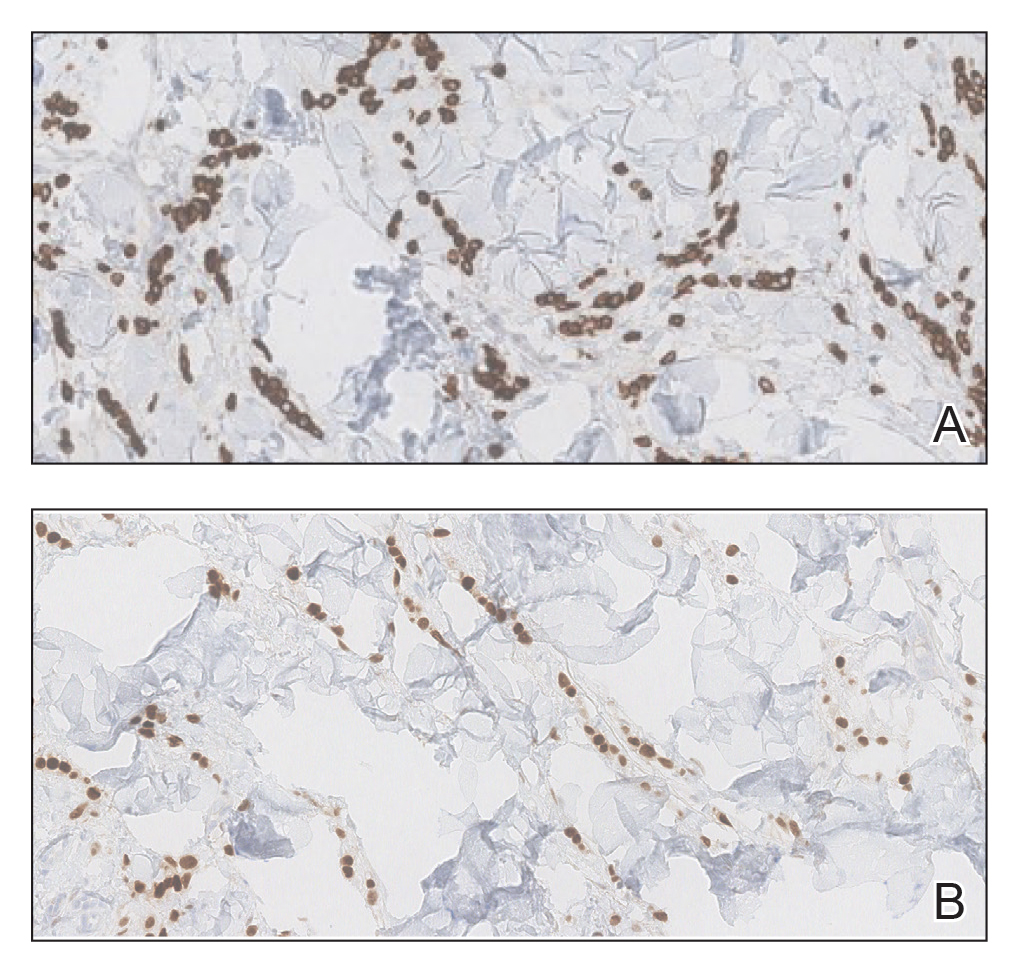

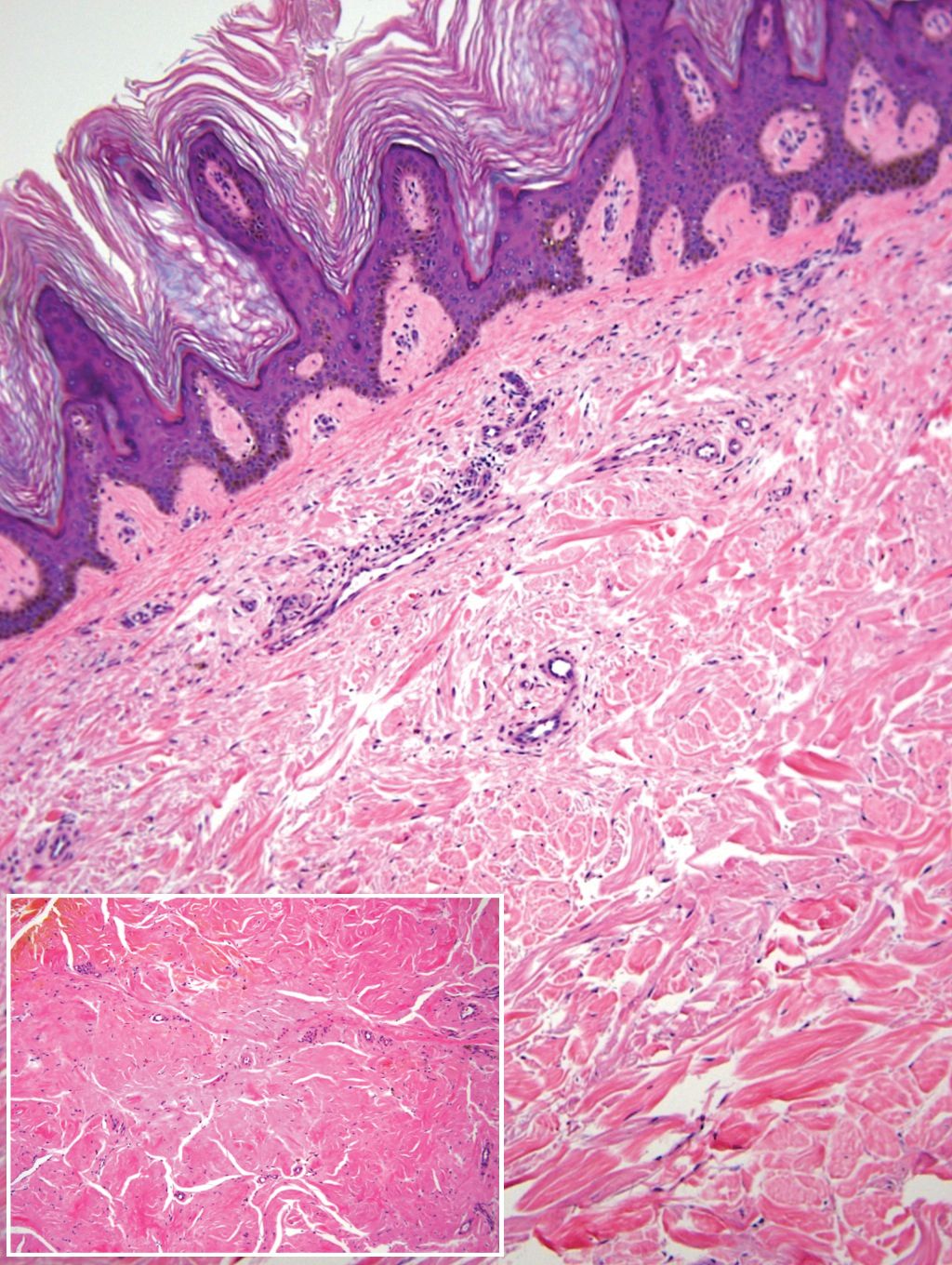

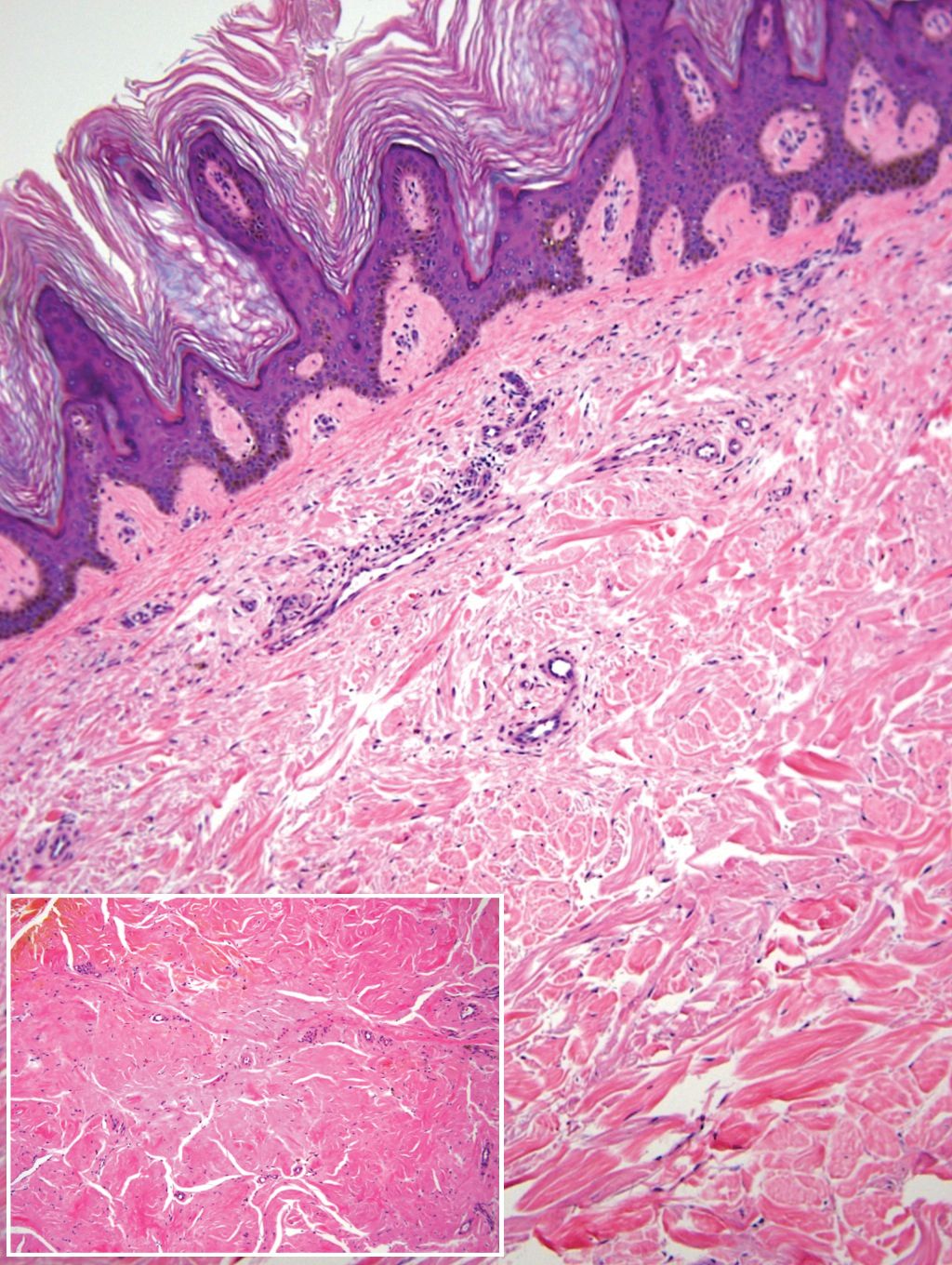

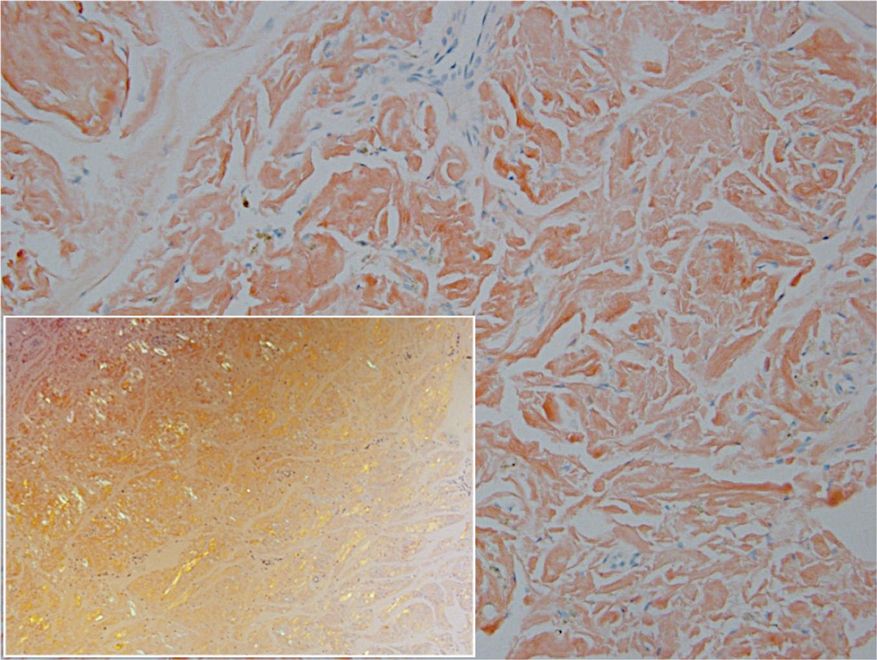

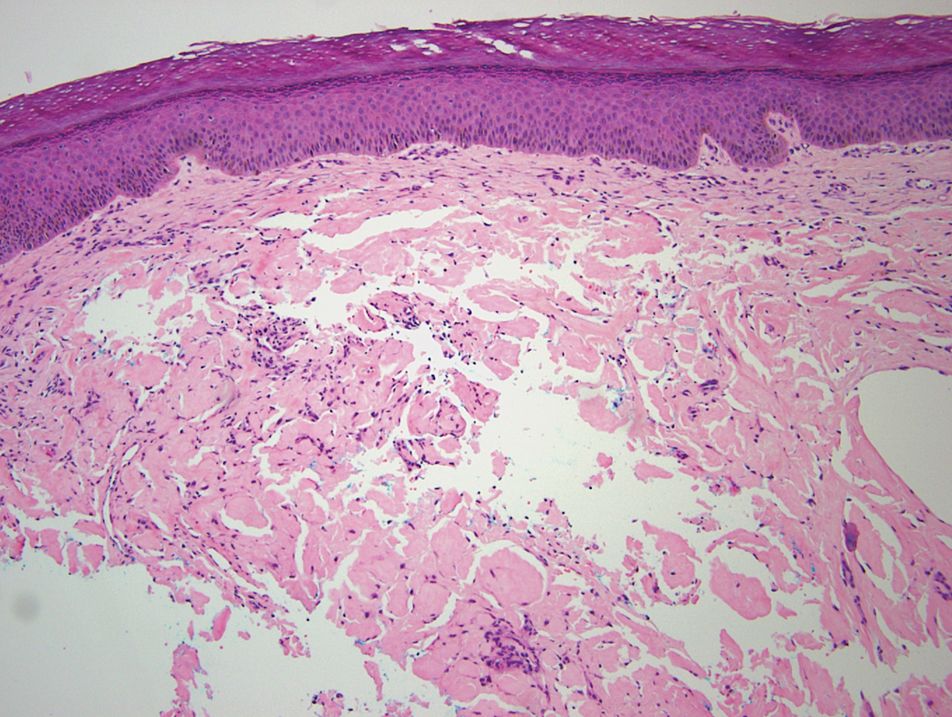

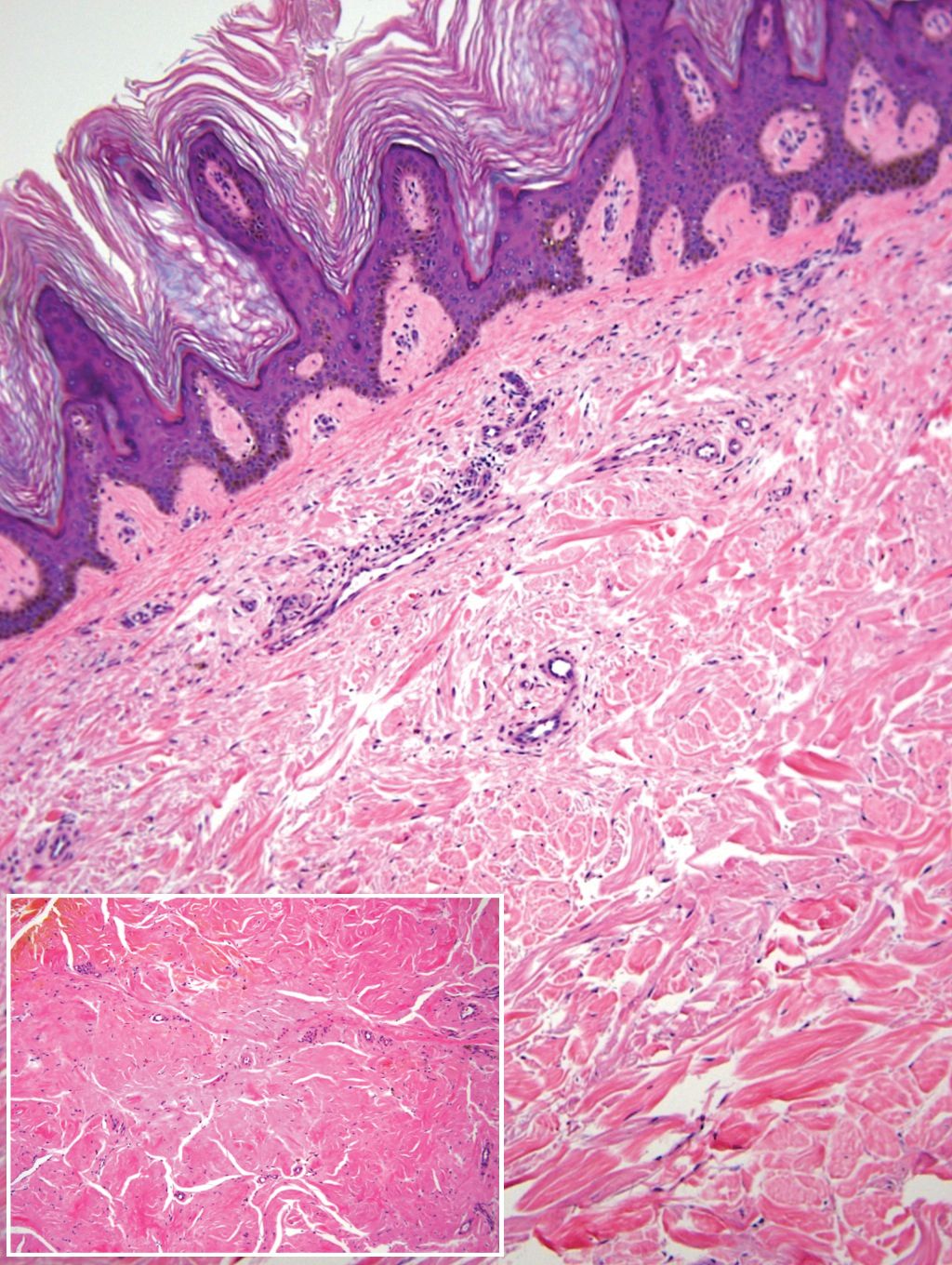

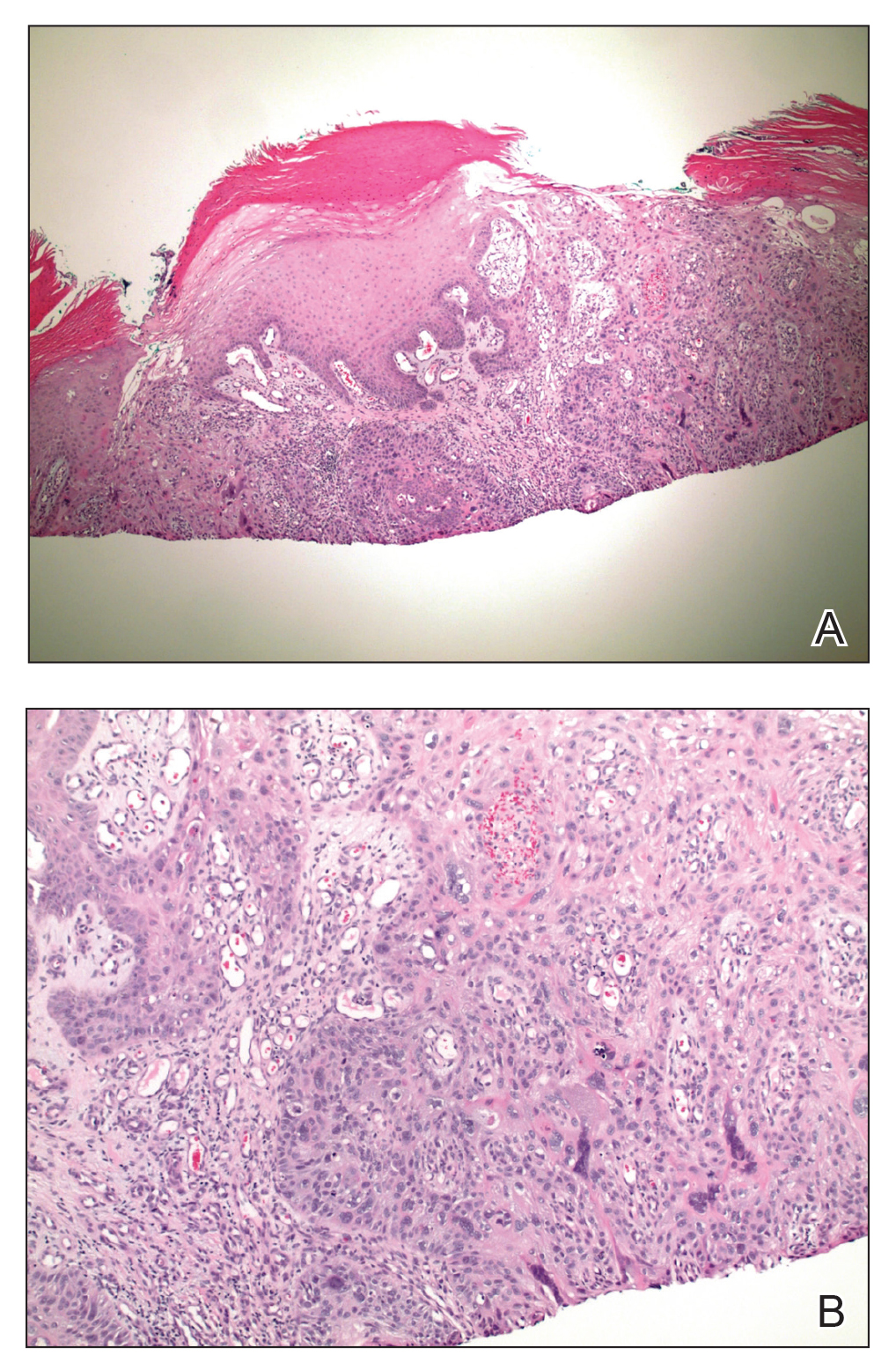

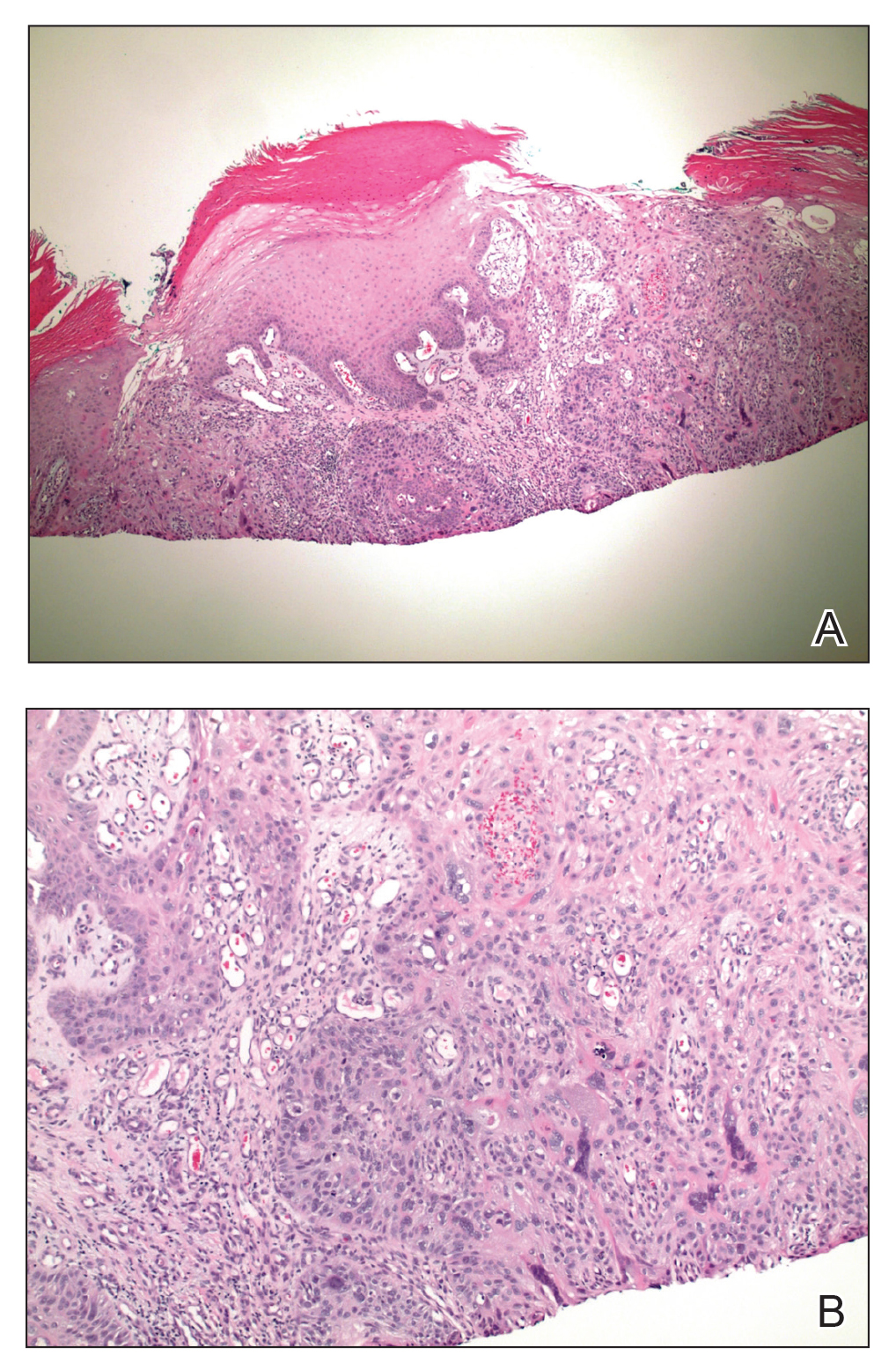

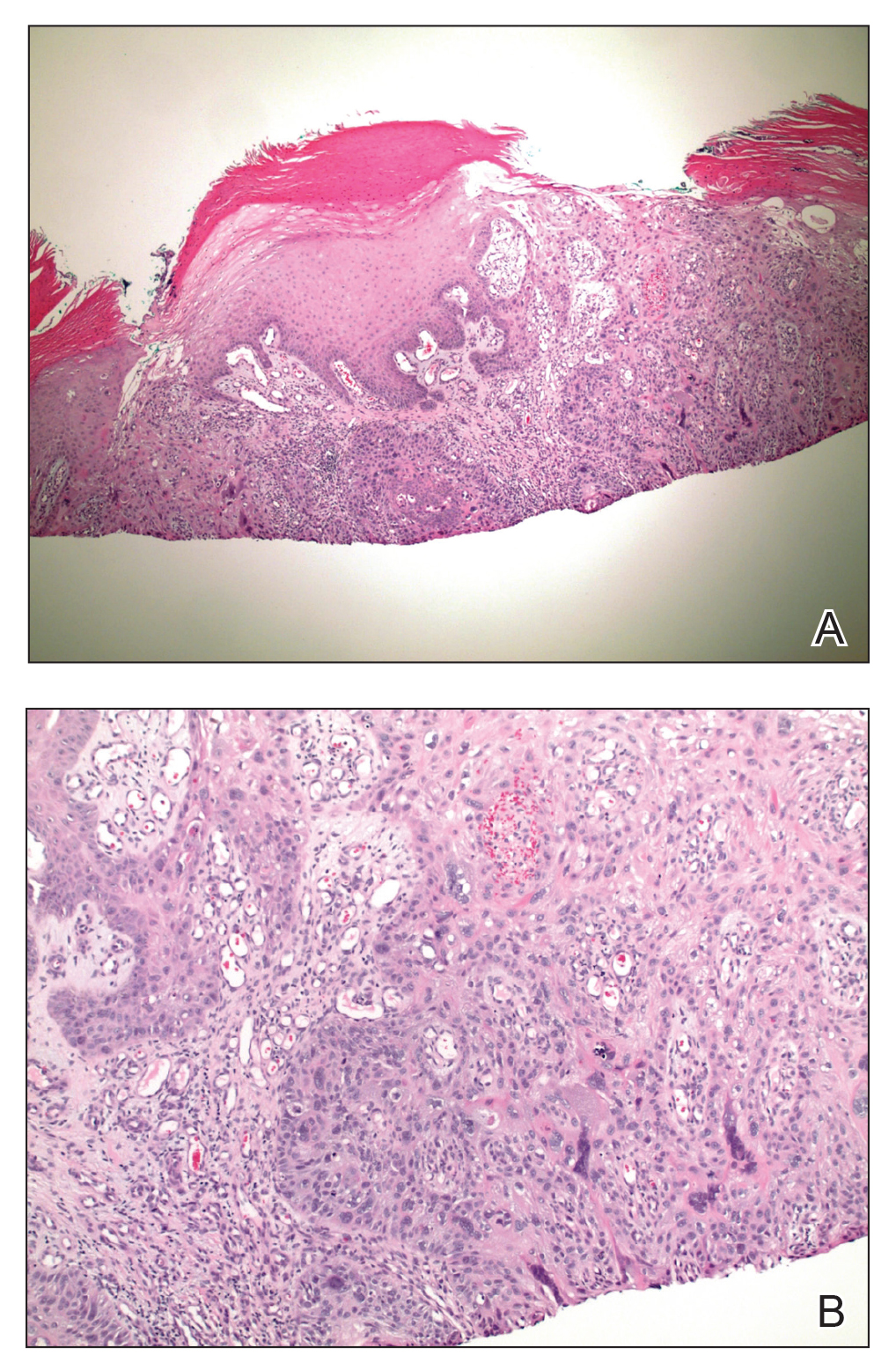

Skin biopsy showed irregular psoriasiform epidermal hyperplasia with acanthosis, hyperkeratosis, and papillomatosis, with convergence of the rete ridges, known as buttressing (Figure 2A). There were tortuous dilated blood vessels in the dermal papillae, epidermal neutrophils at the tip of the suprapapillary plates, and Munro microabscesses in the stratum corneum (Figure 2B). Koilocytes were absent, and periodic acid–Schiff staining was negative. Taken together, clinical and histologic features led to a diagnosis of unilateral verrucous psoriasis.

Comment

Presentation and Histology

Verrucous psoriasis is a variant of psoriasis that presents with wartlike clinical features and overlapping histologic features of verruca and psoriasis. It typically arises in patients with established psoriasis but can occur de novo.

Histologic features of verrucous psoriasis include epidermal hyperplasia with acanthosis, papillomatosis, and epidermal buttressing.1 It has been hypothesized that notable hyperkeratosis observed in these lesions is induced by repeat trauma to the extremities in patients with established psoriasis or by anoxia from conditions that predispose to poor circulation, such as diabetes mellitus and pulmonary disease.1,2

Pathogenesis

Most reported cases of verrucous psoriasis arose atop pre-existing psoriasis lesions.3,4 The relevance of our patient’s verrucous psoriasis to his prior coronary artery bypass surgery with saphenous vein graft is unknown; however, the distribution of lesions, timing of psoriasis onset in relation to the surgical procedure, and recent data proposing a role for neuropeptide responses to nerve injury in the development of psoriasis, taken together, provide an argument for a role for surgical trauma in the development of our patient’s condition.

Treatment

Although verrucous psoriasis presents both diagnostic and therapeutic challenges, there are some reports of improvement with topical or intralesional corticosteroids in combination with keratolytics,3 coal tar,5 and oral methotrexate.6 In addition, there are rare reports of successful treatment with biologics. A case report showed successful resolution with adalimumab,4 and a case of erythrodermic verrucous psoriasis showed moderate improvement with ustekinumab after other failed treatments.7

Differential Diagnosis

Psoriasis typically presents in a symmetric distribution, with rare reported cases of unilateral distribution. Two cases of unilateral psoriasis arising after a surgical procedure have been reported, one after mastectomy and the other after neurosurgery.8,9 Other cases of unilateral psoriasis are reported to have arisen in adolescents and young adults idiopathically.

A case of linear psoriasis arising in the distribution of the sciatic nerve in a patient with radiculopathy implicated tumor necrosis factor α, neuropeptides, and nerve growth factor released in response to compression as possible etiologic agents.10 However, none of the reported cases of linear psoriasis, or reported cases of unilateral psoriasis, exhibited verrucous features clinically or histologically. In our patient, distribution of the lesions appeared less typically blaschkoid than in linear psoriasis, and the presence of exophytic wartlike growths throughout the lesions was not characteristic of linear psoriasis.

Late-adulthood onset in this patient in addition to the absence of typical histologic features of ILVEN, including alternating orthokeratosis and parakeratosis,11 make a diagnosis of ILVEN less likely; ILVEN can be distinguished from linear psoriasis based on later age of onset and responsiveness to antipsoriatic therapy of linear psoriasis.12

Conclusion

We describe a unique presentation of an already rare variant of psoriasis that can be difficult to diagnose clinically. The unilateral distribution of lesions in this patient can create further diagnostic confusion with other entities, such as ILVEN and linear psoriasis, though it can be distinguished from those diseases based on histologic features. Our aim is that this report improves recognition of this unusual presentation of verrucous psoriasis in clinical settings and decreases delays in diagnosis and treatment.

- Khalil FK, Keehn CA, Saeed S, et al. Verrucous psoriasis: a distinctive clinicopathologic variant of psoriasis. Am J Dermatopathol. 2005;27:204-207.

- Wakamatsu K, Naniwa K, Hagiya Y, et al. Psoriasis verrucosa. J Dermatol. 2010;37:1060-1062.

- Monroe HR, Hillman JD, Chiu MW. A case of verrucous psoriasis. Dermatol Online J. 2011;17:10.

- Maejima H, Katayama C, Watarai A, et al. A case of psoriasis verrucosa successfully treated with adalimumab. J Drugs Dermatol. 2012;11:E74-E75.

- Erkek E, Bozdog˘an O. Annular verrucous psoriasis with exaggerated papillomatosis. Am J Dermatopathol. 2001;23:133-135.

- Hall L, Marks V, Tyler W. Verrucous psoriasis: a clinical and histopathologic mimicker of verruca vulgaris. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;68(4 suppl 1):AB218.

- Curtis AR, Yosipovitch G. Erythrodermic verrucous psoriasis. J Dermatolog Treat. 2012;23:215-218.

- Kim M, Jung JY, Na SY, et al. Unilateral psoriasis in a woman with ipsilateral post-mastectomy lymphedema. Ann Dermatol. 2011;23(suppl 3):S303-S305.

- Reyter I, Woodley D. Widespread unilateral plaques in a 68-year-old woman after neurosurgery. Arch Dermatol. 2004;140:1531-1536.

- Galluzzo M, Talamonti M, Di Stefani A, et al. Linear psoriasis following the typical distribution of the sciatic nerve. J Dermatol Case Rep. 2015;9:6-11.

- Sengupta S, Das JK, Gangopadhyay A. Naevoid psoriasis and ILVEN: same coin, two faces? Indian J Dermatol. 2012;57:489-491.

- Morag C, Metzker A. Inflammatory linear verrucous epidermal nevus: report of seven new cases and review of the literature. Pediatr Dermatol. 1985;3:15-18.

Case Report

An 80-year-old man with a history of hypertension and coronary artery disease presented to the dermatology clinic with a rash characterized by multiple asymptomatic plaques with overlying verrucous nodules on the left side of the abdomen, back, and leg (Figure 1). He reported that these “growths” appeared 20 years prior to presentation, shortly after coronary artery bypass surgery with a saphenous vein graft. The patient initially was given a diagnosis of verruca vulgaris and then biopsy-proven psoriasis later that year. At that time, he refused systemic treatment and was treated instead with triamcinolone acetonide ointment, with periodic surgical removal of bothersome lesions.

At the current presentation, physical examination revealed many hyperkeratotic, yellow-gray, verrucous nodules overlying scaly, erythematous, sharply demarcated plaques, exclusively on the left side of the body, including the left side of the abdomen, back, and leg. The differential diagnosis included linear psoriasis and inflammatory linear verrucous epidermal nevus (ILVEN).

Skin biopsy showed irregular psoriasiform epidermal hyperplasia with acanthosis, hyperkeratosis, and papillomatosis, with convergence of the rete ridges, known as buttressing (Figure 2A). There were tortuous dilated blood vessels in the dermal papillae, epidermal neutrophils at the tip of the suprapapillary plates, and Munro microabscesses in the stratum corneum (Figure 2B). Koilocytes were absent, and periodic acid–Schiff staining was negative. Taken together, clinical and histologic features led to a diagnosis of unilateral verrucous psoriasis.

Comment

Presentation and Histology

Verrucous psoriasis is a variant of psoriasis that presents with wartlike clinical features and overlapping histologic features of verruca and psoriasis. It typically arises in patients with established psoriasis but can occur de novo.

Histologic features of verrucous psoriasis include epidermal hyperplasia with acanthosis, papillomatosis, and epidermal buttressing.1 It has been hypothesized that notable hyperkeratosis observed in these lesions is induced by repeat trauma to the extremities in patients with established psoriasis or by anoxia from conditions that predispose to poor circulation, such as diabetes mellitus and pulmonary disease.1,2

Pathogenesis

Most reported cases of verrucous psoriasis arose atop pre-existing psoriasis lesions.3,4 The relevance of our patient’s verrucous psoriasis to his prior coronary artery bypass surgery with saphenous vein graft is unknown; however, the distribution of lesions, timing of psoriasis onset in relation to the surgical procedure, and recent data proposing a role for neuropeptide responses to nerve injury in the development of psoriasis, taken together, provide an argument for a role for surgical trauma in the development of our patient’s condition.

Treatment

Although verrucous psoriasis presents both diagnostic and therapeutic challenges, there are some reports of improvement with topical or intralesional corticosteroids in combination with keratolytics,3 coal tar,5 and oral methotrexate.6 In addition, there are rare reports of successful treatment with biologics. A case report showed successful resolution with adalimumab,4 and a case of erythrodermic verrucous psoriasis showed moderate improvement with ustekinumab after other failed treatments.7

Differential Diagnosis

Psoriasis typically presents in a symmetric distribution, with rare reported cases of unilateral distribution. Two cases of unilateral psoriasis arising after a surgical procedure have been reported, one after mastectomy and the other after neurosurgery.8,9 Other cases of unilateral psoriasis are reported to have arisen in adolescents and young adults idiopathically.

A case of linear psoriasis arising in the distribution of the sciatic nerve in a patient with radiculopathy implicated tumor necrosis factor α, neuropeptides, and nerve growth factor released in response to compression as possible etiologic agents.10 However, none of the reported cases of linear psoriasis, or reported cases of unilateral psoriasis, exhibited verrucous features clinically or histologically. In our patient, distribution of the lesions appeared less typically blaschkoid than in linear psoriasis, and the presence of exophytic wartlike growths throughout the lesions was not characteristic of linear psoriasis.

Late-adulthood onset in this patient in addition to the absence of typical histologic features of ILVEN, including alternating orthokeratosis and parakeratosis,11 make a diagnosis of ILVEN less likely; ILVEN can be distinguished from linear psoriasis based on later age of onset and responsiveness to antipsoriatic therapy of linear psoriasis.12

Conclusion

We describe a unique presentation of an already rare variant of psoriasis that can be difficult to diagnose clinically. The unilateral distribution of lesions in this patient can create further diagnostic confusion with other entities, such as ILVEN and linear psoriasis, though it can be distinguished from those diseases based on histologic features. Our aim is that this report improves recognition of this unusual presentation of verrucous psoriasis in clinical settings and decreases delays in diagnosis and treatment.

Case Report

An 80-year-old man with a history of hypertension and coronary artery disease presented to the dermatology clinic with a rash characterized by multiple asymptomatic plaques with overlying verrucous nodules on the left side of the abdomen, back, and leg (Figure 1). He reported that these “growths” appeared 20 years prior to presentation, shortly after coronary artery bypass surgery with a saphenous vein graft. The patient initially was given a diagnosis of verruca vulgaris and then biopsy-proven psoriasis later that year. At that time, he refused systemic treatment and was treated instead with triamcinolone acetonide ointment, with periodic surgical removal of bothersome lesions.

At the current presentation, physical examination revealed many hyperkeratotic, yellow-gray, verrucous nodules overlying scaly, erythematous, sharply demarcated plaques, exclusively on the left side of the body, including the left side of the abdomen, back, and leg. The differential diagnosis included linear psoriasis and inflammatory linear verrucous epidermal nevus (ILVEN).

Skin biopsy showed irregular psoriasiform epidermal hyperplasia with acanthosis, hyperkeratosis, and papillomatosis, with convergence of the rete ridges, known as buttressing (Figure 2A). There were tortuous dilated blood vessels in the dermal papillae, epidermal neutrophils at the tip of the suprapapillary plates, and Munro microabscesses in the stratum corneum (Figure 2B). Koilocytes were absent, and periodic acid–Schiff staining was negative. Taken together, clinical and histologic features led to a diagnosis of unilateral verrucous psoriasis.

Comment

Presentation and Histology

Verrucous psoriasis is a variant of psoriasis that presents with wartlike clinical features and overlapping histologic features of verruca and psoriasis. It typically arises in patients with established psoriasis but can occur de novo.

Histologic features of verrucous psoriasis include epidermal hyperplasia with acanthosis, papillomatosis, and epidermal buttressing.1 It has been hypothesized that notable hyperkeratosis observed in these lesions is induced by repeat trauma to the extremities in patients with established psoriasis or by anoxia from conditions that predispose to poor circulation, such as diabetes mellitus and pulmonary disease.1,2

Pathogenesis

Most reported cases of verrucous psoriasis arose atop pre-existing psoriasis lesions.3,4 The relevance of our patient’s verrucous psoriasis to his prior coronary artery bypass surgery with saphenous vein graft is unknown; however, the distribution of lesions, timing of psoriasis onset in relation to the surgical procedure, and recent data proposing a role for neuropeptide responses to nerve injury in the development of psoriasis, taken together, provide an argument for a role for surgical trauma in the development of our patient’s condition.

Treatment

Although verrucous psoriasis presents both diagnostic and therapeutic challenges, there are some reports of improvement with topical or intralesional corticosteroids in combination with keratolytics,3 coal tar,5 and oral methotrexate.6 In addition, there are rare reports of successful treatment with biologics. A case report showed successful resolution with adalimumab,4 and a case of erythrodermic verrucous psoriasis showed moderate improvement with ustekinumab after other failed treatments.7

Differential Diagnosis

Psoriasis typically presents in a symmetric distribution, with rare reported cases of unilateral distribution. Two cases of unilateral psoriasis arising after a surgical procedure have been reported, one after mastectomy and the other after neurosurgery.8,9 Other cases of unilateral psoriasis are reported to have arisen in adolescents and young adults idiopathically.

A case of linear psoriasis arising in the distribution of the sciatic nerve in a patient with radiculopathy implicated tumor necrosis factor α, neuropeptides, and nerve growth factor released in response to compression as possible etiologic agents.10 However, none of the reported cases of linear psoriasis, or reported cases of unilateral psoriasis, exhibited verrucous features clinically or histologically. In our patient, distribution of the lesions appeared less typically blaschkoid than in linear psoriasis, and the presence of exophytic wartlike growths throughout the lesions was not characteristic of linear psoriasis.

Late-adulthood onset in this patient in addition to the absence of typical histologic features of ILVEN, including alternating orthokeratosis and parakeratosis,11 make a diagnosis of ILVEN less likely; ILVEN can be distinguished from linear psoriasis based on later age of onset and responsiveness to antipsoriatic therapy of linear psoriasis.12

Conclusion

We describe a unique presentation of an already rare variant of psoriasis that can be difficult to diagnose clinically. The unilateral distribution of lesions in this patient can create further diagnostic confusion with other entities, such as ILVEN and linear psoriasis, though it can be distinguished from those diseases based on histologic features. Our aim is that this report improves recognition of this unusual presentation of verrucous psoriasis in clinical settings and decreases delays in diagnosis and treatment.

- Khalil FK, Keehn CA, Saeed S, et al. Verrucous psoriasis: a distinctive clinicopathologic variant of psoriasis. Am J Dermatopathol. 2005;27:204-207.

- Wakamatsu K, Naniwa K, Hagiya Y, et al. Psoriasis verrucosa. J Dermatol. 2010;37:1060-1062.

- Monroe HR, Hillman JD, Chiu MW. A case of verrucous psoriasis. Dermatol Online J. 2011;17:10.

- Maejima H, Katayama C, Watarai A, et al. A case of psoriasis verrucosa successfully treated with adalimumab. J Drugs Dermatol. 2012;11:E74-E75.

- Erkek E, Bozdog˘an O. Annular verrucous psoriasis with exaggerated papillomatosis. Am J Dermatopathol. 2001;23:133-135.

- Hall L, Marks V, Tyler W. Verrucous psoriasis: a clinical and histopathologic mimicker of verruca vulgaris. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;68(4 suppl 1):AB218.

- Curtis AR, Yosipovitch G. Erythrodermic verrucous psoriasis. J Dermatolog Treat. 2012;23:215-218.

- Kim M, Jung JY, Na SY, et al. Unilateral psoriasis in a woman with ipsilateral post-mastectomy lymphedema. Ann Dermatol. 2011;23(suppl 3):S303-S305.

- Reyter I, Woodley D. Widespread unilateral plaques in a 68-year-old woman after neurosurgery. Arch Dermatol. 2004;140:1531-1536.

- Galluzzo M, Talamonti M, Di Stefani A, et al. Linear psoriasis following the typical distribution of the sciatic nerve. J Dermatol Case Rep. 2015;9:6-11.

- Sengupta S, Das JK, Gangopadhyay A. Naevoid psoriasis and ILVEN: same coin, two faces? Indian J Dermatol. 2012;57:489-491.

- Morag C, Metzker A. Inflammatory linear verrucous epidermal nevus: report of seven new cases and review of the literature. Pediatr Dermatol. 1985;3:15-18.

- Khalil FK, Keehn CA, Saeed S, et al. Verrucous psoriasis: a distinctive clinicopathologic variant of psoriasis. Am J Dermatopathol. 2005;27:204-207.

- Wakamatsu K, Naniwa K, Hagiya Y, et al. Psoriasis verrucosa. J Dermatol. 2010;37:1060-1062.

- Monroe HR, Hillman JD, Chiu MW. A case of verrucous psoriasis. Dermatol Online J. 2011;17:10.

- Maejima H, Katayama C, Watarai A, et al. A case of psoriasis verrucosa successfully treated with adalimumab. J Drugs Dermatol. 2012;11:E74-E75.

- Erkek E, Bozdog˘an O. Annular verrucous psoriasis with exaggerated papillomatosis. Am J Dermatopathol. 2001;23:133-135.

- Hall L, Marks V, Tyler W. Verrucous psoriasis: a clinical and histopathologic mimicker of verruca vulgaris. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;68(4 suppl 1):AB218.

- Curtis AR, Yosipovitch G. Erythrodermic verrucous psoriasis. J Dermatolog Treat. 2012;23:215-218.

- Kim M, Jung JY, Na SY, et al. Unilateral psoriasis in a woman with ipsilateral post-mastectomy lymphedema. Ann Dermatol. 2011;23(suppl 3):S303-S305.

- Reyter I, Woodley D. Widespread unilateral plaques in a 68-year-old woman after neurosurgery. Arch Dermatol. 2004;140:1531-1536.

- Galluzzo M, Talamonti M, Di Stefani A, et al. Linear psoriasis following the typical distribution of the sciatic nerve. J Dermatol Case Rep. 2015;9:6-11.

- Sengupta S, Das JK, Gangopadhyay A. Naevoid psoriasis and ILVEN: same coin, two faces? Indian J Dermatol. 2012;57:489-491.

- Morag C, Metzker A. Inflammatory linear verrucous epidermal nevus: report of seven new cases and review of the literature. Pediatr Dermatol. 1985;3:15-18.

Practice Points

- Verrucous psoriasis is a rare variant of psoriasis characterized by hypertrophic verrucous papules and plaques on an erythematous base.

- Histologically, verrucous psoriasis presents with overlapping features of verruca and psoriasis.

- Although psoriasis typically presents in a symmetric distribution, unilateral psoriasis can occur either de novo in younger patients or after surgical trauma in older patients.

An Unusual Presentation of Cutaneous Metastatic Lobular Breast Carcinoma

In women, breast cancer is the leading cancer diagnosis and the second leading cause of cancer-related death,1 as well as the most common malignancy to metastasize to the skin.2 Cutaneous breast carcinoma may present as cutaneous metastasis or can occur secondary to direct tumor extension. Five percent to 10% of women with breast cancer will present clinically with metastatic cutaneous disease, most commonly as a recurrence of early-stage breast carcinoma.2

In a published meta-analysis that investigated the incidence of tumors most commonly found to metastasize to the skin, Krathen et al3 found that cutaneous metastases occurred in 24% of patients with breast cancer (N=1903). In 2 large retrospective studies from tumor registry data, breast cancer was found to be the most common tumor involving metastasis to the skin, and 3.5% of the breast cancer cases identified in the registry had cutaneous metastasis as the presenting sign (n=35) at time of diagnosis.4

We report an unusual presentation of cutaneous metastatic lobular breast carcinoma that involved diffuse cutaneous lesions and rapid progression from onset of the breast mass to development of clinically apparent metastatic skin lesions.

Case Report

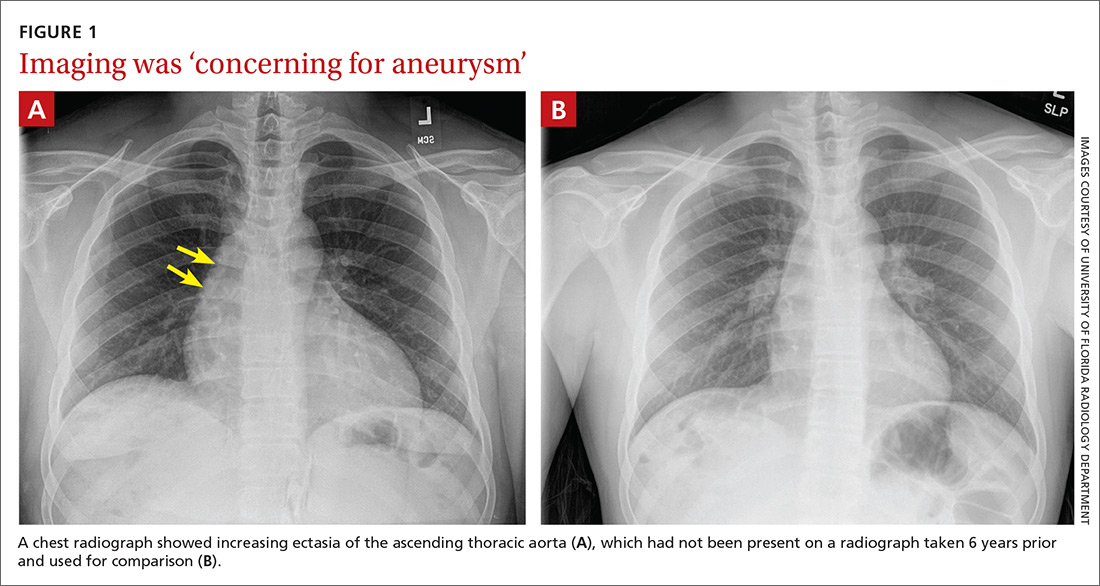

A 59-year-old woman with an unremarkable medical history presented to our dermatology clinic for evaluation of new widespread lesions that developed over a period of months. The eruption was asymptomatic and consisted of numerous bumpy lesions that reportedly started on the patient’s neck and progressively spread to involve the trunk. Physical examination revealed multiple flesh-colored, firm nodules scattered across the upper back, neck, and chest (Figure 1). Bilateral cervical and axillary lymphadenopathy also was noted. Upon questioning regarding family history of malignancy, the patient reported that her brother had been diagnosed with colon cancer. Although she was not up to date on age-appropriate malignancy screenings, she did report having a diagnostic mammogram 1 year prior that revealed a suspicious lesion on the left breast. A repeat mammogram of the left breast 6 months later was read as unremarkable.

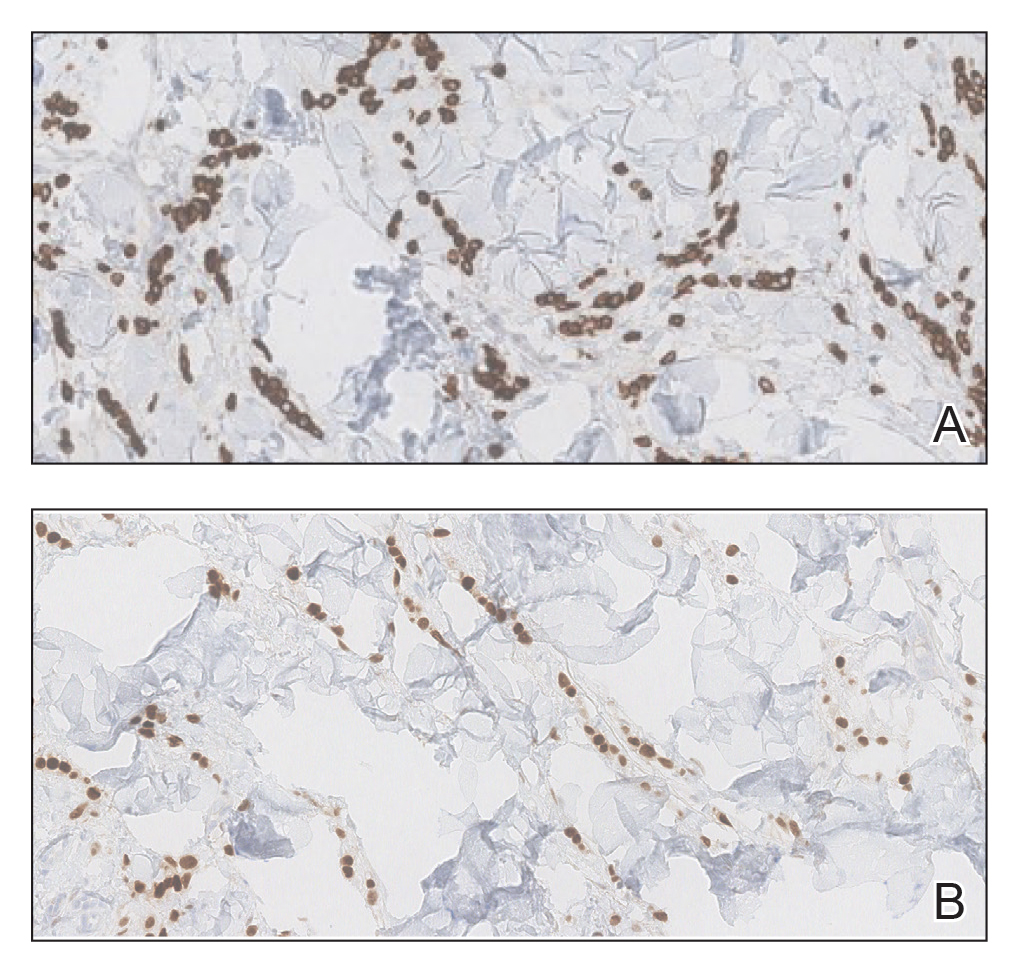

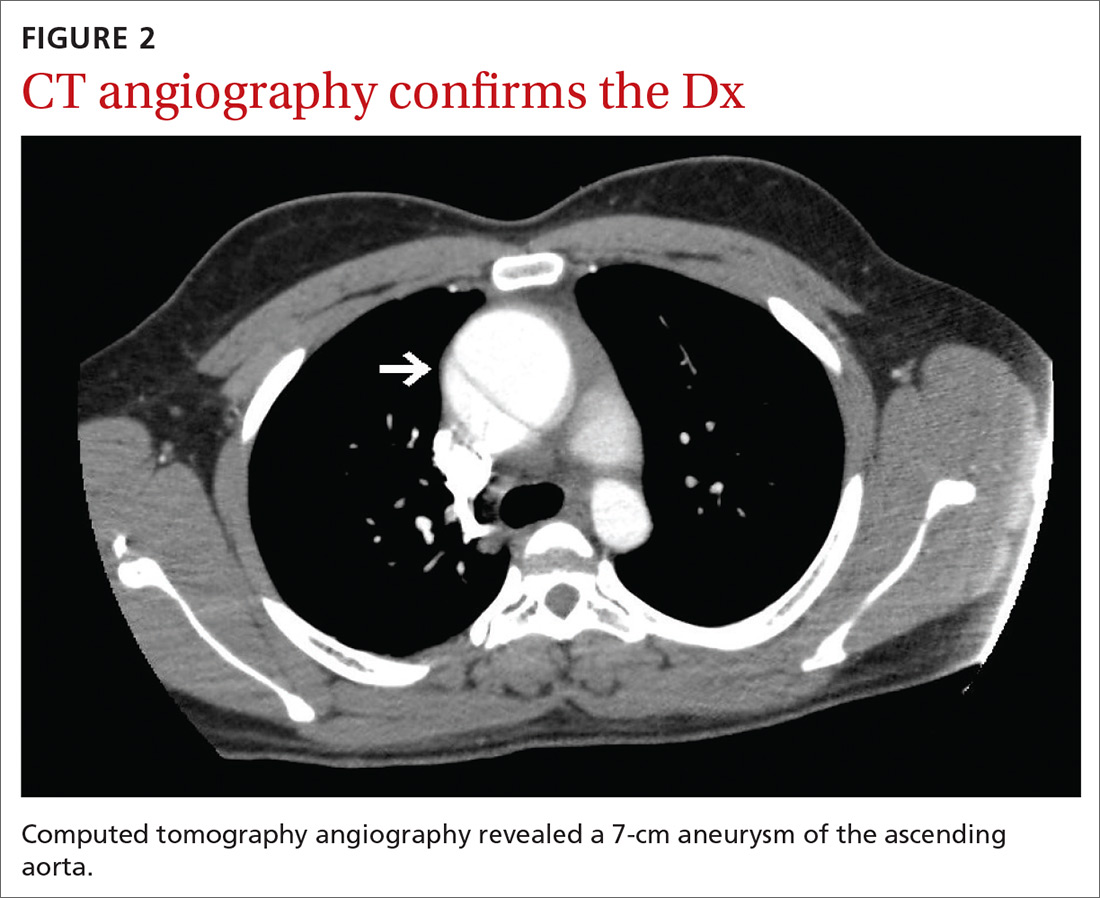

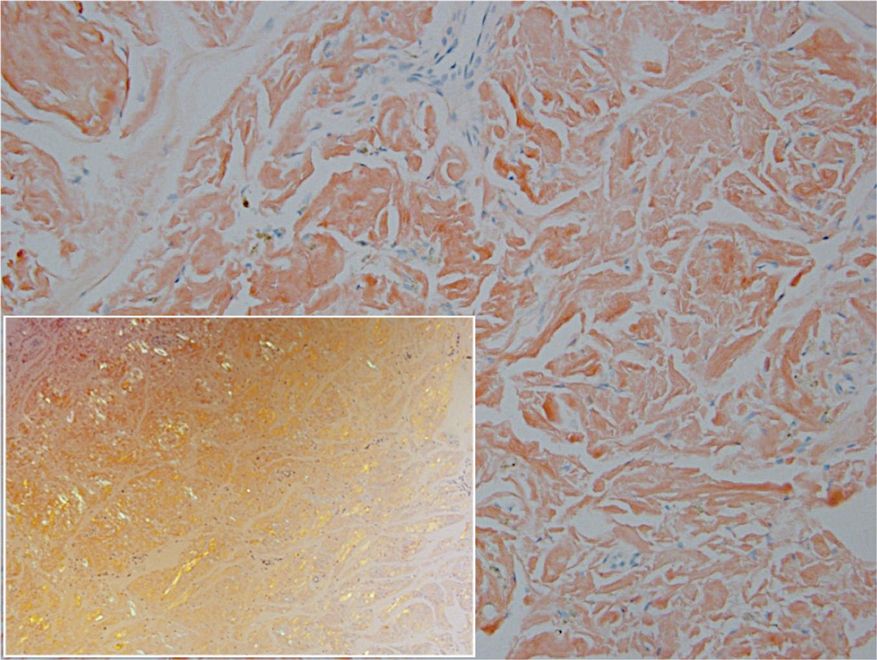

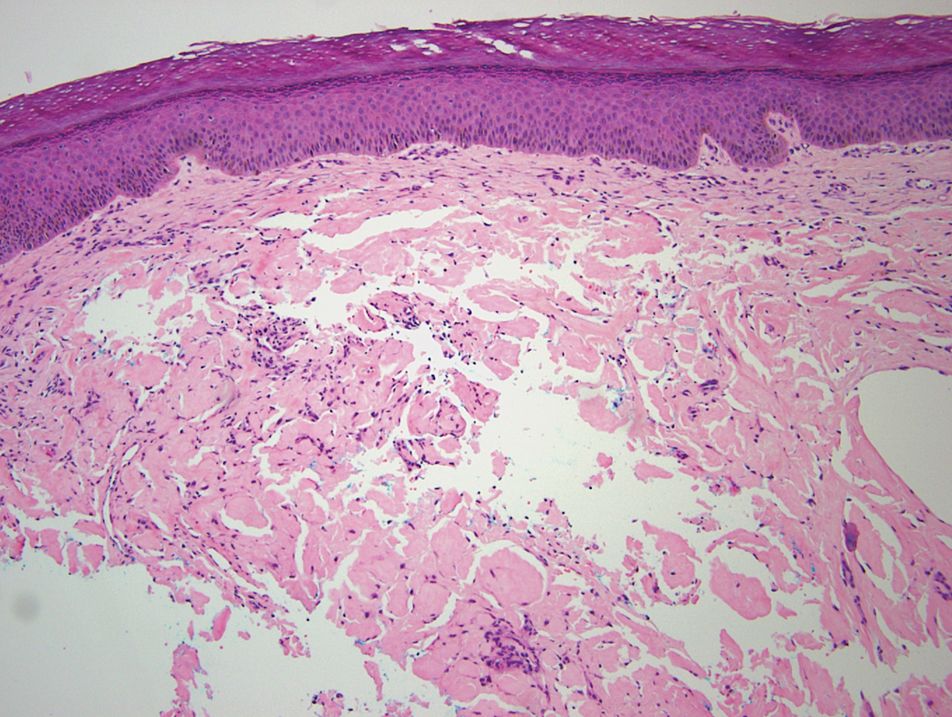

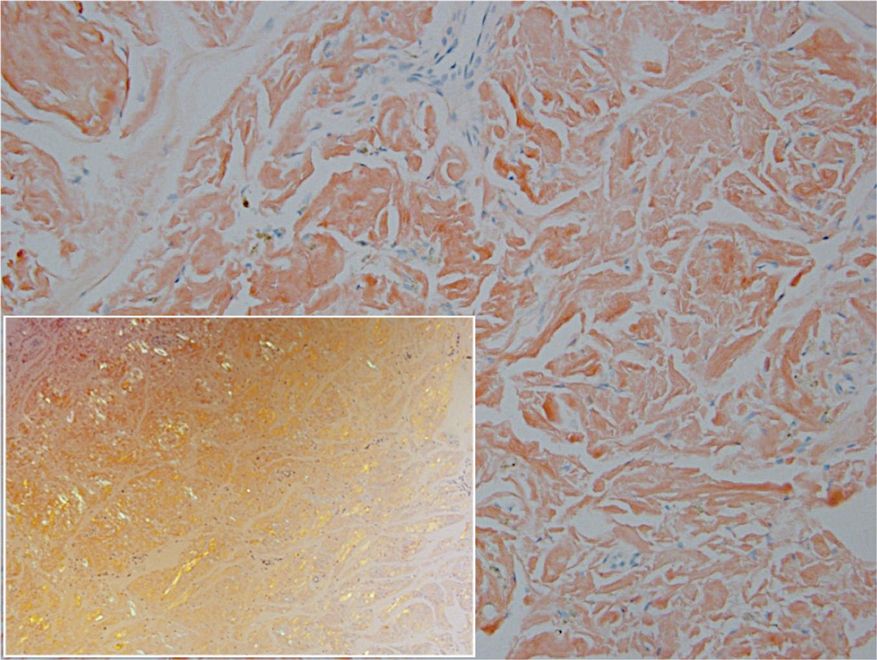

Two 3-mm representative punch biopsies were performed. Hematoxylin and eosin staining revealed a basket-weave stratum corneum with underlying epidermal atrophy. A relatively monomorphic epithelioid cell infiltrate extending from the superficial reticular dermis into the deep dermis and displaying an open chromatin pattern and pink cytoplasm was observed, as well as dermal collagen thickening. Linear, single-filing cells along with focal irregular nests and scattered cells were observed (Figure 2). Immunohistochemical staining was positive for cytokeratin 7 (Figure 3A), epithelial membrane antigen, and estrogen receptor (Figure 3B) along with gross cystic disease fluid protein 15; focal progesterone receptor positivity also was present. Cytokeratin 20, cytokeratin 5/6, carcinoembryonic antigen, p63, CDX2, paired box gene 8, thyroid transcription factor 1, and human epidermal growth factor receptor 2/neu stains were negative. Findings identified in both biopsies were consistent with metastatic cutaneous lobular breast carcinoma.

A complete blood cell count and complete metabolic panels were within normal limits, aside from a mildly elevated alkaline phosphatase level. Breast ultrasonography was unremarkable. Stereotactic breast magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) revealed a 9.4-cm mass in the upper outer quadrant of the right breast as well as enlarged lymph nodes 2.2 cm from the left axilla. A subsequent bone scan demonstrated focal activity in the left lateral fourth rib, left costochondral junction, and right anterolateral fifth rib—it was unclear whether these lesions were metastatic or secondary to trauma from a fall the patient reportedly had sustained 2 weeks prior. Lumbar MRI without gadolinium contrast revealed extensive abnormal heterogeneous signal intensity of osseous structures consistent with osseous metastasis.

Subsequent diagnostic bilateral breast ultrasonography and percutaneous left lymph node biopsy revealed pathology consistent with metastatic lobular breast carcinoma with near total effacement of the lymph node and extracapsular extension concordant with previous MRI findings. The mass in the upper outer quadrant of the right breast that previously was observed on MRI was not identifiable on this ultrasound. It was recommended that the patient pursue MRI-guided breast biopsy to have the breast lesion further characterized. She was referred to surgical oncology at a tertiary center for management; however, the patient was lost to follow-up, and there are no records available indicating the patient pursued any treatment. Although we were unable to confirm the patient’s breast lesion that previously was seen on MRI was the cause of the metastatic disease, the overall clinical picture supported metastatic lobular breast carcinoma.

Comment

Tumor metastasis to the skin accounts for approximately 2% of all skin cancers5 and typically is observed in advanced stages of cancer. In women, breast carcinoma is the most common type of cancer to exhibit this behavior.2 Invasive ductal carcinoma represents the most common histologic subtype of breast cancer overall,6,7 and breast adenocarcinomas, including lobular and ductal breast carcinomas, are the most common histologic subtypes to exhibit metastatic cutaneous lesions.8

Invasive lobular breast carcinoma represents approximately 10% of invasive breast cancer cases. Compared to invasive ductal carcinoma, there tends to be a delay in diagnosis often leading to larger tumor sizes relative to the former upon detection and with lymph node invasion. These findings may be explained by the greater difficulty of detecting invasive lobular carcinomas by mammography and clinical breast examination compared to invasive ductal carcinomas.9-11 Additionally, invasive lobular carcinomas are more likely to be positive for estrogen and progesterone receptors compared to invasive ductal carcinomas,12 which also was consistent in our case.

Cutaneous metastases of breast cancer most commonly are found on the anterior chest wall and can present as a wide spectrum of lesions, with nodules as the most common primary dermatologic manifestation.13 Cutaneous metastatic lesions commonly have been described as firm, mobile, round or oval, solitary or grouped nodules. The color of the nodules varies and may be flesh-colored, brown, blue, black, pink, and/or red-brown. The lesions often are asymptomatic but may ulcerate.2

In our case, the distribution of lesions was a unique aspect that is not typical of most cases of metastatic cutaneous breast carcinoma. The nodules appeared more scattered and involved multiple body regions, including the back, neck, and chest. Although cutaneous breast cancer metastases have been documented to extend to these body regions, a review of PubMed articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms cutaneous metastatic lobular breast carcinoma, breast carcinoma, and metastatic breast cancer suggested that it is uncommon for these multiple areas to be simultaneously affected.4,14 Rather, the more common clinical presentation of cutaneous metastatic breast carcinoma is as a solitary nodule or group of nodules localized to a single anatomic region.14

Another notable feature of our case was the rapid development of the cutaneous lesions relative to the primary tumor. This patient developed diffuse lesions over a period of several months, and given that her mammogram performed the previous year was negative for any abnormalities, one could suggest that the metastatic lesions developed less than a year from onset of the primary tumor. A previous study involving 41 patients with a known clinical primary visceral malignancy (ie, breast, lung, colon, esophageal, gastric, pancreatic, kidney, thyroid, prostate, or ovarian origin) found that it takes approximately 3 years on average for cutaneous metastases to develop from the onset of cancer diagnosis (range, 1–177 months).14 In the aforementioned study, 94% of patients had stage III or IV disease at time of skin metastasis, with the majority of those demonstrating stage IV disease. However, it also is possible that these breast tumors evaded detection or were too small to be identified on prior imaging.14 A review of our patient’s medical records did not indicate documentation of any visual or palpable breast changes prior to the onset of the clinically detected metastatic nodules.

Conclusion

Biopsy with immunohistochemical staining ultimately yielded the diagnosis of metastatic lobular breast carcinoma in our patient. Providers should be aware of the varying clinical presentations that may arise in the setting of cutaneous metastasis. When faced with lesions suspicious for cutaneous metastasis, biopsy is warranted to determine the correct diagnosis and ensure appropriate management. Upon diagnosis of cutaneous metastasis, prompt coordination with the primary care provider and appropriate referral to multidisciplinary teams is necessary. Clinical providers also should maintain a high index of suspicion when evaluating patients with cutaneous metastasis who have a history of normal malignancy screenings.

- American Cancer Society. Cancer facts & figures 2015. Accessed January 7, 2021. https://www.cancer.org/content/dam/cancer-org/research/cancer-facts-and-statistics/annual-cancer-facts-and-figures/2015/cancer-facts-and-figures-2015.pdf

- Tan AR. Cutaneous manifestations of breast cancer. Semin Oncol. 2016;43:331-334.

- Krathen RA, Orengo IF, Rosen T. Cutaneous metastasis: a meta-analysis of data. South Med J. 2003;96:164-167.

- Lookingbill DP, Spangler N, Sexton FM. Skin involvement as the presenting sign of internal carcinoma. a retrospective study of 7316 cancer patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1990;22:19-26.

- Alcaraz I, Cerroni L, Rutten A, et al. Cutaneous metastases from internal malignancies: a clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical review. Am J Dermatopathol. 2012;34:347-393.

- Li CI, Anderson BO, Daling JR, et al. Trends in incidence rates of invasive lobular and ductal breast carcinoma. JAMA. 2003;289:1421-1424.

- Li CI, Daling JR. Changes in breast cancer incidence rates in the United States by histologic subtype and race/ethnicity, 1995 to 2004. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2007;16:2773-2780.

- Lookingbill DP, Spangler N, Helm KF. Cutaneous metastases in patients with metastatic carcinoma: a retrospective study of 4020 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1993;29:228-236.

- Dixon J, Anderson R, Page D, et al. Infiltrating lobular carcioma of the breast. Histopathology. 1982;6:149-161.

- Yeatman T, Cantor AB, Smith TJ, et al. Tumor biology of infiltrating lobular carcinoma: implications for management. Ann Surg. 1995;222:549-559.

- Silverstein M, Lewinski BS, Waisman JR, et al. Infiltrating lobular carcinoma: is it different from infiltrating duct carcinoma? Cancer. 1994;73:1673-1677.

- Li CI, Uribe DJ, Daling JR. Clinical characteristics of different histologic types of breast cancer. Br J Cancer. 2005;93:1046-1052.

- Mordenti C, Peris K, Fargnoli M, et al. Cutaneous metastatic breast carcinoma. Acta Dermatovenerol. 2000;9:143-148.

- Sariya D, Ruth K, Adams-McDonnell R, et al. Clinicopathologic correlation of cutaneous metastases: experience from a cancer center. Arch Dermatol. 2007;143:613-620.

In women, breast cancer is the leading cancer diagnosis and the second leading cause of cancer-related death,1 as well as the most common malignancy to metastasize to the skin.2 Cutaneous breast carcinoma may present as cutaneous metastasis or can occur secondary to direct tumor extension. Five percent to 10% of women with breast cancer will present clinically with metastatic cutaneous disease, most commonly as a recurrence of early-stage breast carcinoma.2

In a published meta-analysis that investigated the incidence of tumors most commonly found to metastasize to the skin, Krathen et al3 found that cutaneous metastases occurred in 24% of patients with breast cancer (N=1903). In 2 large retrospective studies from tumor registry data, breast cancer was found to be the most common tumor involving metastasis to the skin, and 3.5% of the breast cancer cases identified in the registry had cutaneous metastasis as the presenting sign (n=35) at time of diagnosis.4

We report an unusual presentation of cutaneous metastatic lobular breast carcinoma that involved diffuse cutaneous lesions and rapid progression from onset of the breast mass to development of clinically apparent metastatic skin lesions.

Case Report

A 59-year-old woman with an unremarkable medical history presented to our dermatology clinic for evaluation of new widespread lesions that developed over a period of months. The eruption was asymptomatic and consisted of numerous bumpy lesions that reportedly started on the patient’s neck and progressively spread to involve the trunk. Physical examination revealed multiple flesh-colored, firm nodules scattered across the upper back, neck, and chest (Figure 1). Bilateral cervical and axillary lymphadenopathy also was noted. Upon questioning regarding family history of malignancy, the patient reported that her brother had been diagnosed with colon cancer. Although she was not up to date on age-appropriate malignancy screenings, she did report having a diagnostic mammogram 1 year prior that revealed a suspicious lesion on the left breast. A repeat mammogram of the left breast 6 months later was read as unremarkable.

Two 3-mm representative punch biopsies were performed. Hematoxylin and eosin staining revealed a basket-weave stratum corneum with underlying epidermal atrophy. A relatively monomorphic epithelioid cell infiltrate extending from the superficial reticular dermis into the deep dermis and displaying an open chromatin pattern and pink cytoplasm was observed, as well as dermal collagen thickening. Linear, single-filing cells along with focal irregular nests and scattered cells were observed (Figure 2). Immunohistochemical staining was positive for cytokeratin 7 (Figure 3A), epithelial membrane antigen, and estrogen receptor (Figure 3B) along with gross cystic disease fluid protein 15; focal progesterone receptor positivity also was present. Cytokeratin 20, cytokeratin 5/6, carcinoembryonic antigen, p63, CDX2, paired box gene 8, thyroid transcription factor 1, and human epidermal growth factor receptor 2/neu stains were negative. Findings identified in both biopsies were consistent with metastatic cutaneous lobular breast carcinoma.

A complete blood cell count and complete metabolic panels were within normal limits, aside from a mildly elevated alkaline phosphatase level. Breast ultrasonography was unremarkable. Stereotactic breast magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) revealed a 9.4-cm mass in the upper outer quadrant of the right breast as well as enlarged lymph nodes 2.2 cm from the left axilla. A subsequent bone scan demonstrated focal activity in the left lateral fourth rib, left costochondral junction, and right anterolateral fifth rib—it was unclear whether these lesions were metastatic or secondary to trauma from a fall the patient reportedly had sustained 2 weeks prior. Lumbar MRI without gadolinium contrast revealed extensive abnormal heterogeneous signal intensity of osseous structures consistent with osseous metastasis.

Subsequent diagnostic bilateral breast ultrasonography and percutaneous left lymph node biopsy revealed pathology consistent with metastatic lobular breast carcinoma with near total effacement of the lymph node and extracapsular extension concordant with previous MRI findings. The mass in the upper outer quadrant of the right breast that previously was observed on MRI was not identifiable on this ultrasound. It was recommended that the patient pursue MRI-guided breast biopsy to have the breast lesion further characterized. She was referred to surgical oncology at a tertiary center for management; however, the patient was lost to follow-up, and there are no records available indicating the patient pursued any treatment. Although we were unable to confirm the patient’s breast lesion that previously was seen on MRI was the cause of the metastatic disease, the overall clinical picture supported metastatic lobular breast carcinoma.

Comment

Tumor metastasis to the skin accounts for approximately 2% of all skin cancers5 and typically is observed in advanced stages of cancer. In women, breast carcinoma is the most common type of cancer to exhibit this behavior.2 Invasive ductal carcinoma represents the most common histologic subtype of breast cancer overall,6,7 and breast adenocarcinomas, including lobular and ductal breast carcinomas, are the most common histologic subtypes to exhibit metastatic cutaneous lesions.8

Invasive lobular breast carcinoma represents approximately 10% of invasive breast cancer cases. Compared to invasive ductal carcinoma, there tends to be a delay in diagnosis often leading to larger tumor sizes relative to the former upon detection and with lymph node invasion. These findings may be explained by the greater difficulty of detecting invasive lobular carcinomas by mammography and clinical breast examination compared to invasive ductal carcinomas.9-11 Additionally, invasive lobular carcinomas are more likely to be positive for estrogen and progesterone receptors compared to invasive ductal carcinomas,12 which also was consistent in our case.

Cutaneous metastases of breast cancer most commonly are found on the anterior chest wall and can present as a wide spectrum of lesions, with nodules as the most common primary dermatologic manifestation.13 Cutaneous metastatic lesions commonly have been described as firm, mobile, round or oval, solitary or grouped nodules. The color of the nodules varies and may be flesh-colored, brown, blue, black, pink, and/or red-brown. The lesions often are asymptomatic but may ulcerate.2

In our case, the distribution of lesions was a unique aspect that is not typical of most cases of metastatic cutaneous breast carcinoma. The nodules appeared more scattered and involved multiple body regions, including the back, neck, and chest. Although cutaneous breast cancer metastases have been documented to extend to these body regions, a review of PubMed articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms cutaneous metastatic lobular breast carcinoma, breast carcinoma, and metastatic breast cancer suggested that it is uncommon for these multiple areas to be simultaneously affected.4,14 Rather, the more common clinical presentation of cutaneous metastatic breast carcinoma is as a solitary nodule or group of nodules localized to a single anatomic region.14

Another notable feature of our case was the rapid development of the cutaneous lesions relative to the primary tumor. This patient developed diffuse lesions over a period of several months, and given that her mammogram performed the previous year was negative for any abnormalities, one could suggest that the metastatic lesions developed less than a year from onset of the primary tumor. A previous study involving 41 patients with a known clinical primary visceral malignancy (ie, breast, lung, colon, esophageal, gastric, pancreatic, kidney, thyroid, prostate, or ovarian origin) found that it takes approximately 3 years on average for cutaneous metastases to develop from the onset of cancer diagnosis (range, 1–177 months).14 In the aforementioned study, 94% of patients had stage III or IV disease at time of skin metastasis, with the majority of those demonstrating stage IV disease. However, it also is possible that these breast tumors evaded detection or were too small to be identified on prior imaging.14 A review of our patient’s medical records did not indicate documentation of any visual or palpable breast changes prior to the onset of the clinically detected metastatic nodules.

Conclusion

Biopsy with immunohistochemical staining ultimately yielded the diagnosis of metastatic lobular breast carcinoma in our patient. Providers should be aware of the varying clinical presentations that may arise in the setting of cutaneous metastasis. When faced with lesions suspicious for cutaneous metastasis, biopsy is warranted to determine the correct diagnosis and ensure appropriate management. Upon diagnosis of cutaneous metastasis, prompt coordination with the primary care provider and appropriate referral to multidisciplinary teams is necessary. Clinical providers also should maintain a high index of suspicion when evaluating patients with cutaneous metastasis who have a history of normal malignancy screenings.

In women, breast cancer is the leading cancer diagnosis and the second leading cause of cancer-related death,1 as well as the most common malignancy to metastasize to the skin.2 Cutaneous breast carcinoma may present as cutaneous metastasis or can occur secondary to direct tumor extension. Five percent to 10% of women with breast cancer will present clinically with metastatic cutaneous disease, most commonly as a recurrence of early-stage breast carcinoma.2

In a published meta-analysis that investigated the incidence of tumors most commonly found to metastasize to the skin, Krathen et al3 found that cutaneous metastases occurred in 24% of patients with breast cancer (N=1903). In 2 large retrospective studies from tumor registry data, breast cancer was found to be the most common tumor involving metastasis to the skin, and 3.5% of the breast cancer cases identified in the registry had cutaneous metastasis as the presenting sign (n=35) at time of diagnosis.4