User login

Trichodysplasia Spinulosa in the Setting of Colon Cancer

Case Report

An 82-year-old woman presented to the clinic with a rash on the face that had been present for a few months. She denied any treatment or prior occurrence. Her medical history was remarkable for non-Hodgkin lymphoma that had been successfully treated with chemotherapy 4 years prior. Additionally, she recently had been diagnosed with stage IV colon cancer. She reported that surgery had been scheduled and she would start adjuvant chemotherapy soon after.

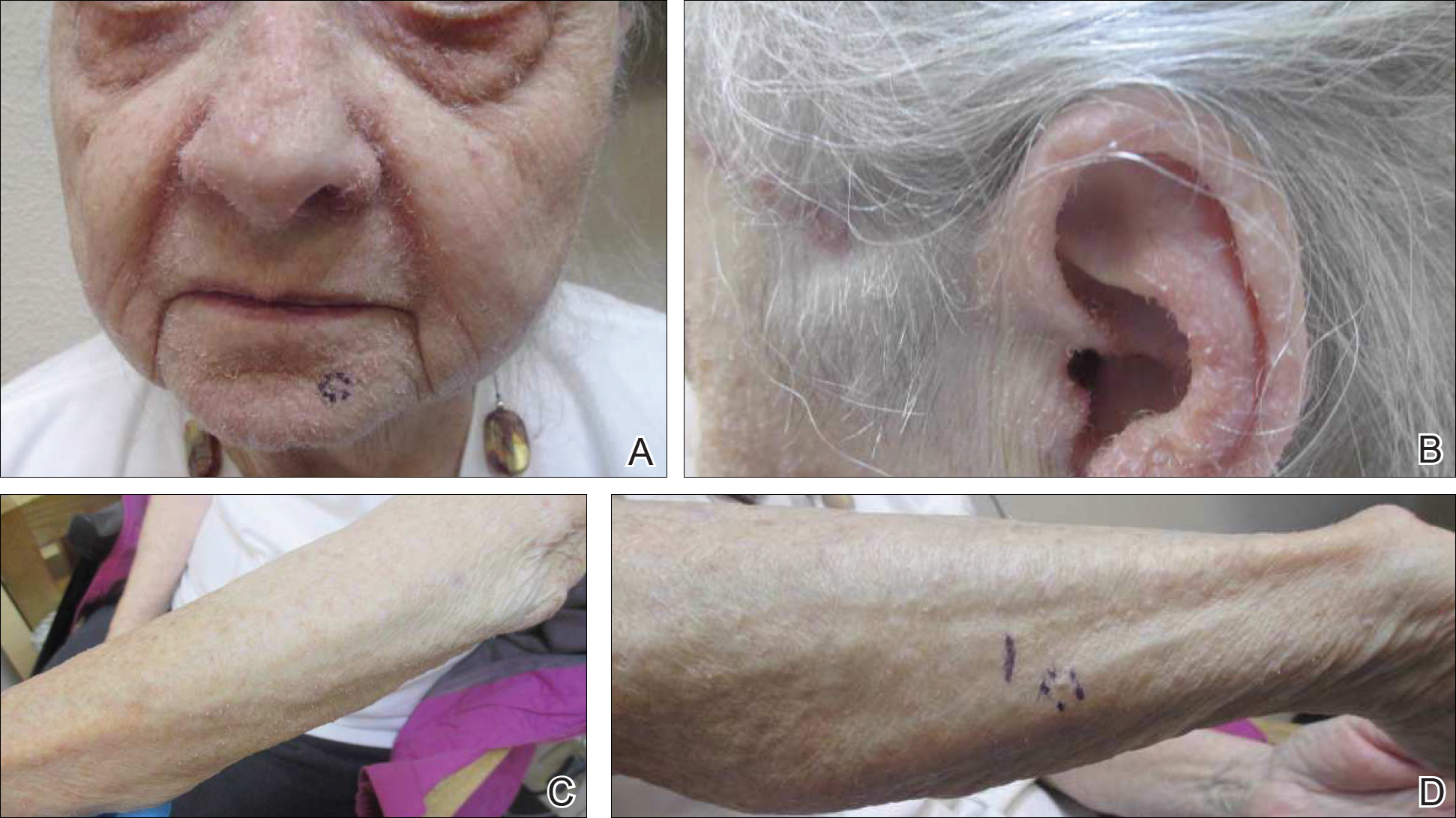

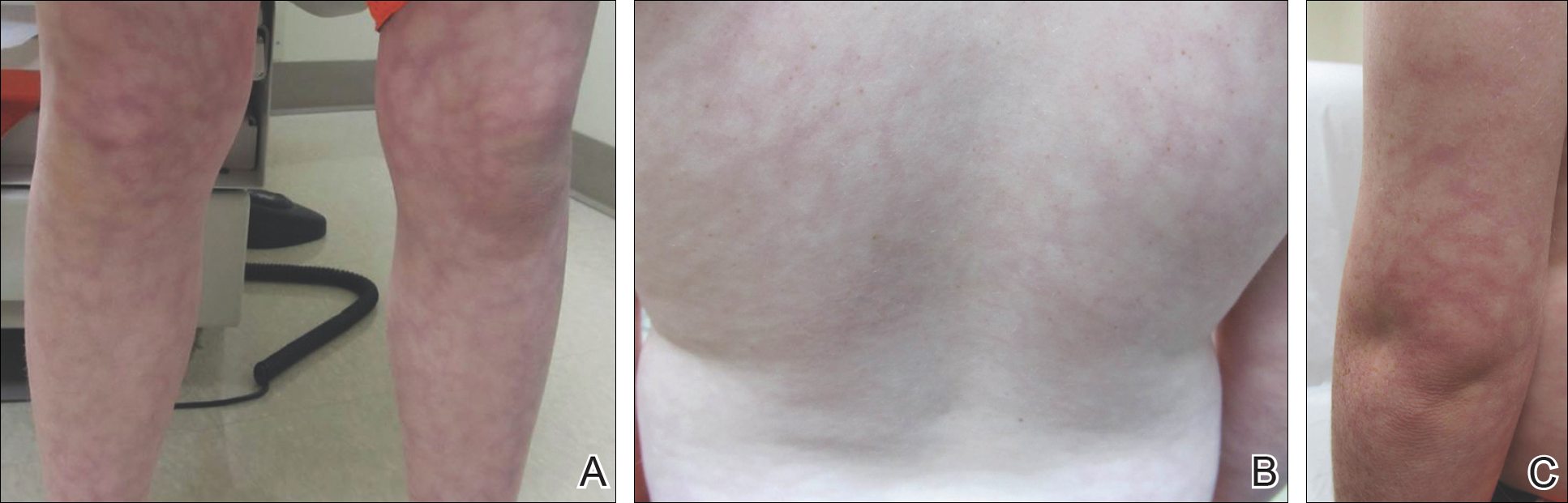

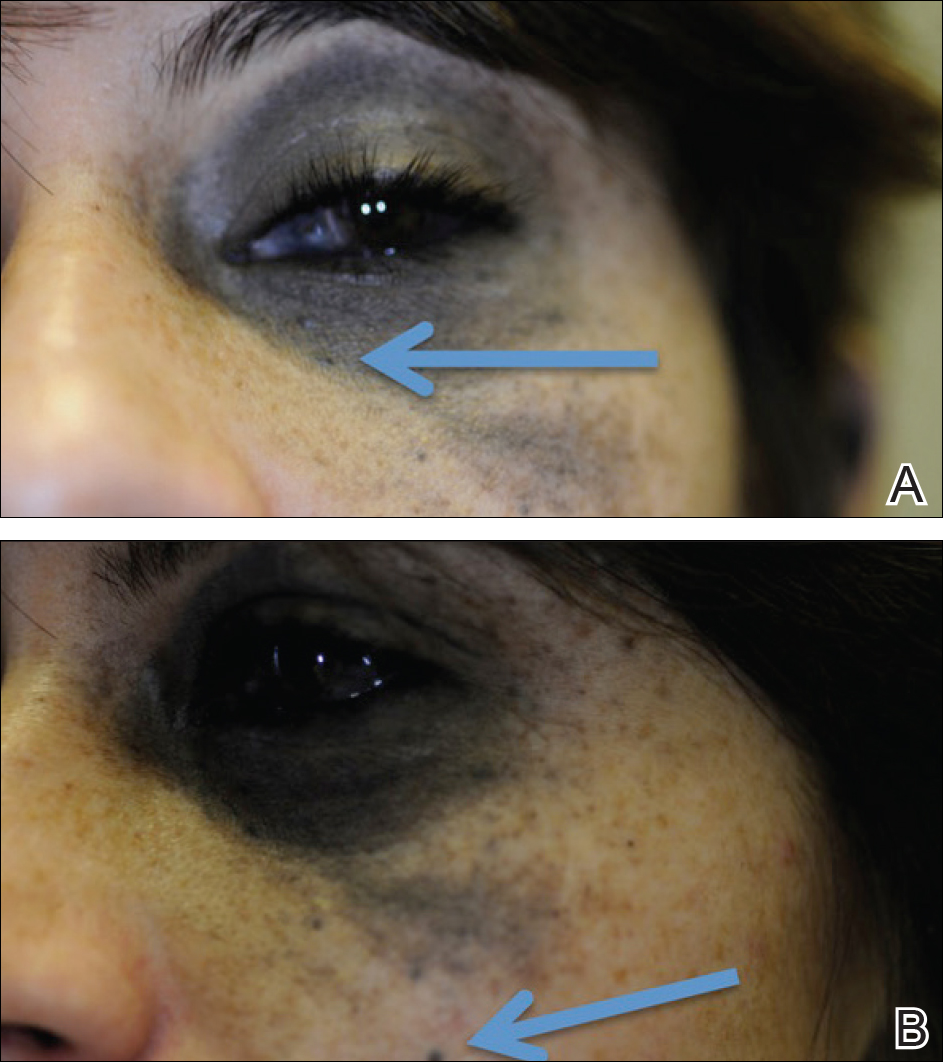

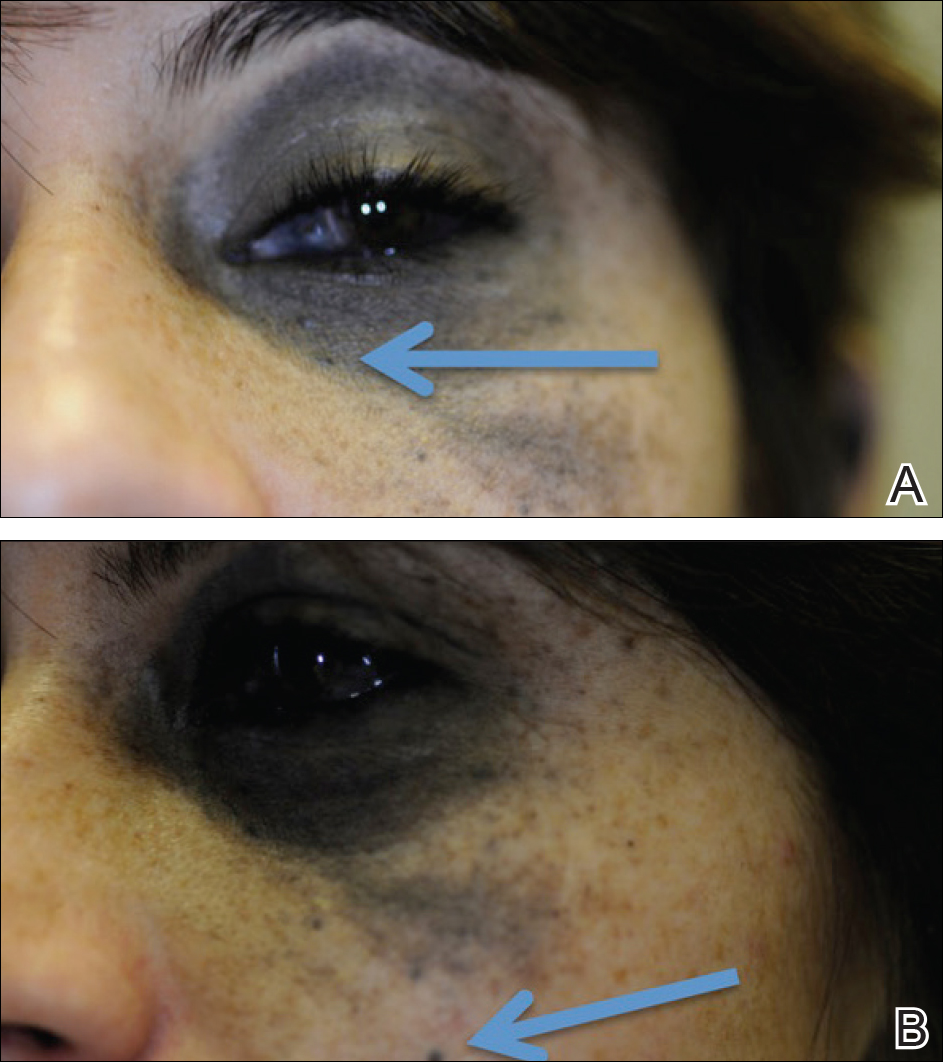

On physical examination she exhibited perioral and perinasal erythematous papules with sparing of the vermilion border. A diagnosis of perioral dermatitis was made, and she was started on topical metronidazole. At 1-month follow-up, her condition had slightly worsened and she was subsequently started on doxycycline. When she returned to the clinic again the following month, physical examination revealed agminated folliculocentric papules with central spicules on the face, nose, ears, upper extremities (Figure 1), and trunk. The differential diagnosis included multiple minute digitate hyperkeratosis, spiculosis of multiple myeloma, and trichodysplasia spinulosa (TS).

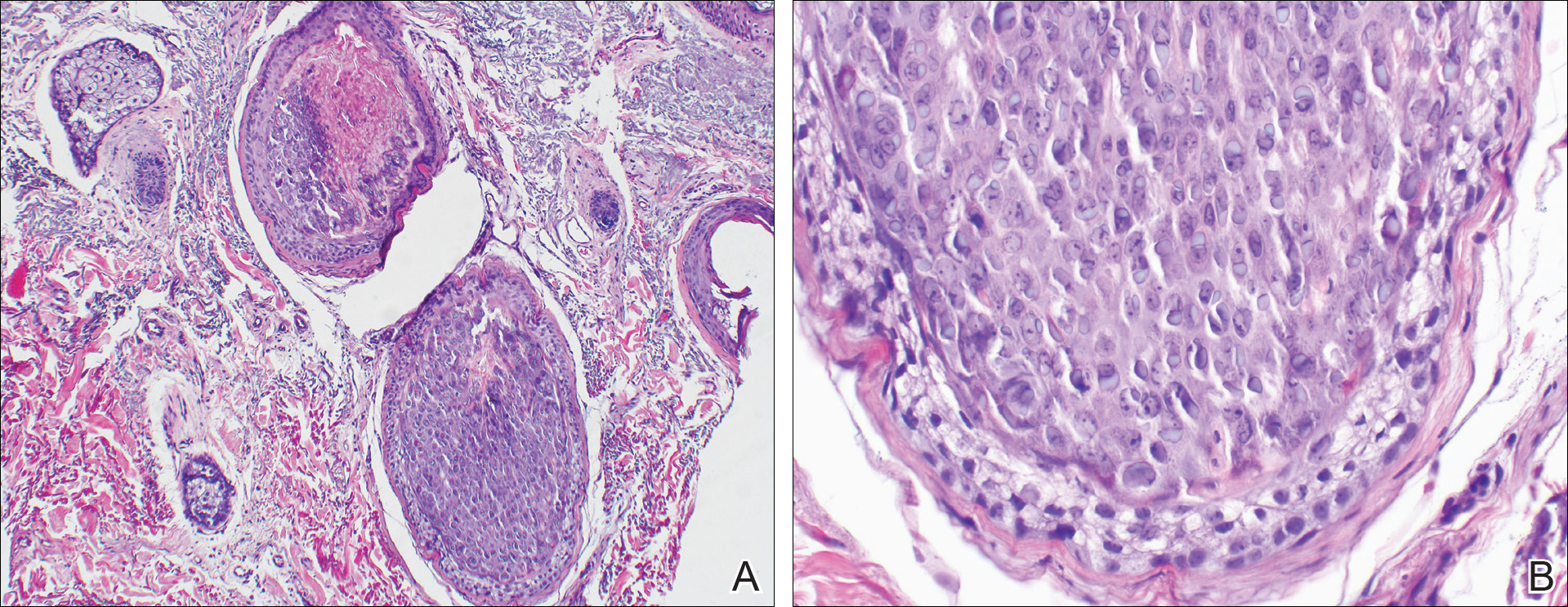

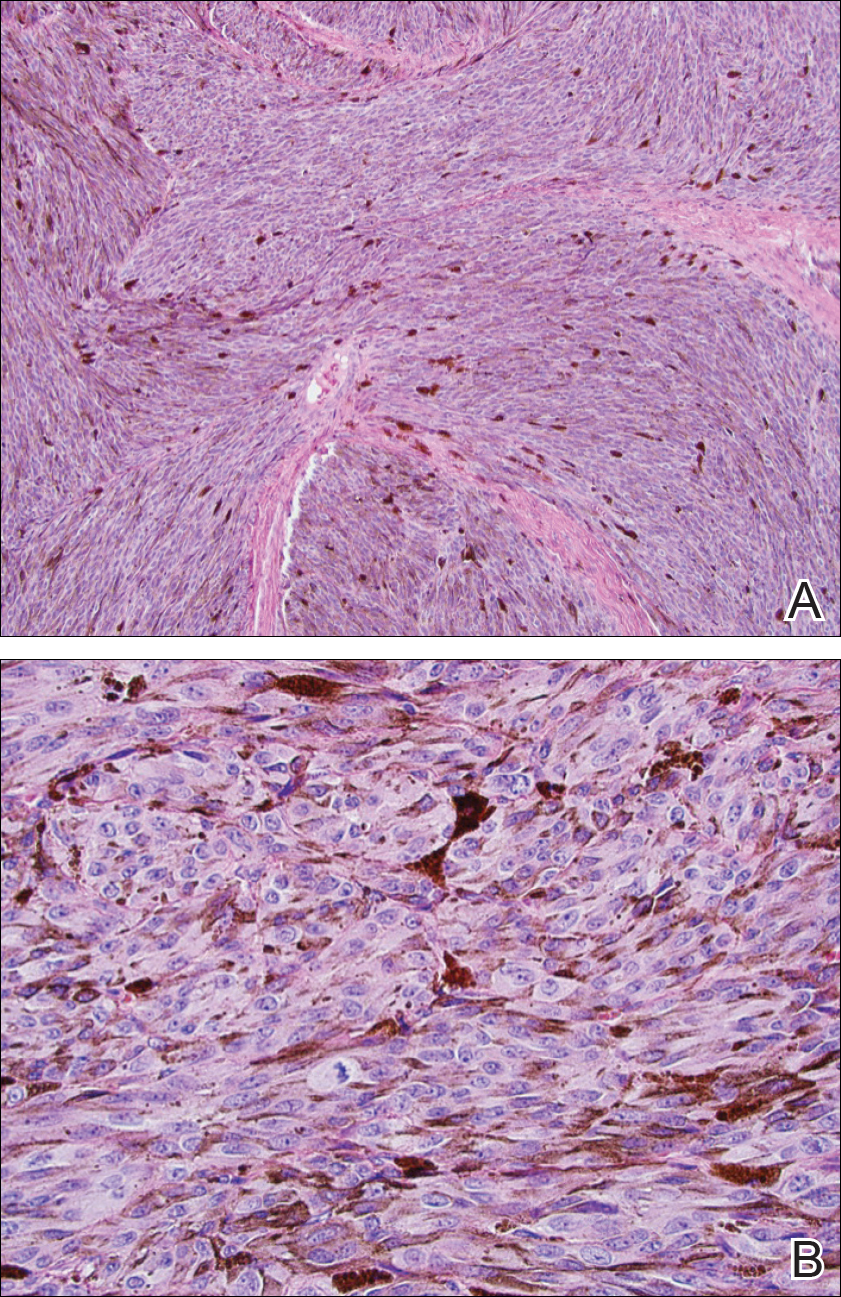

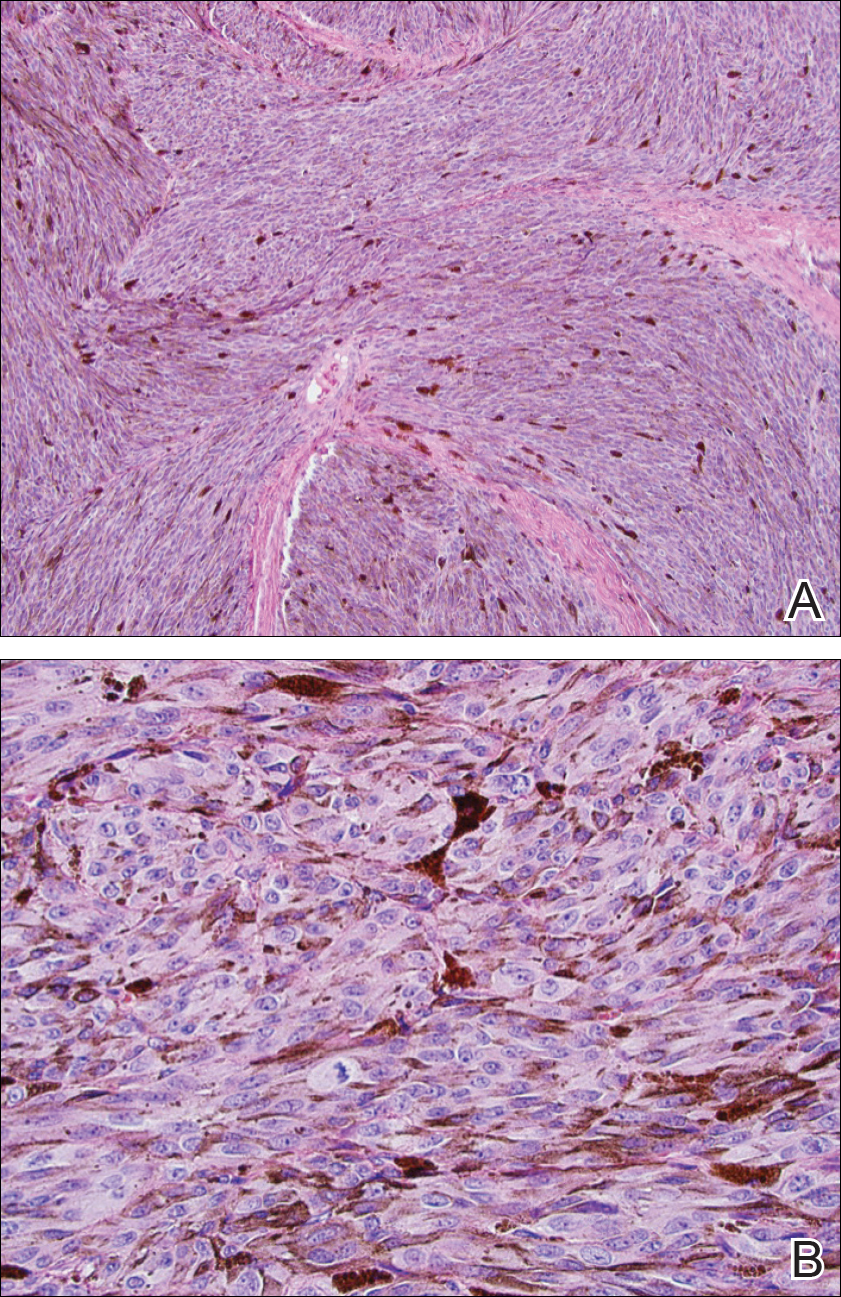

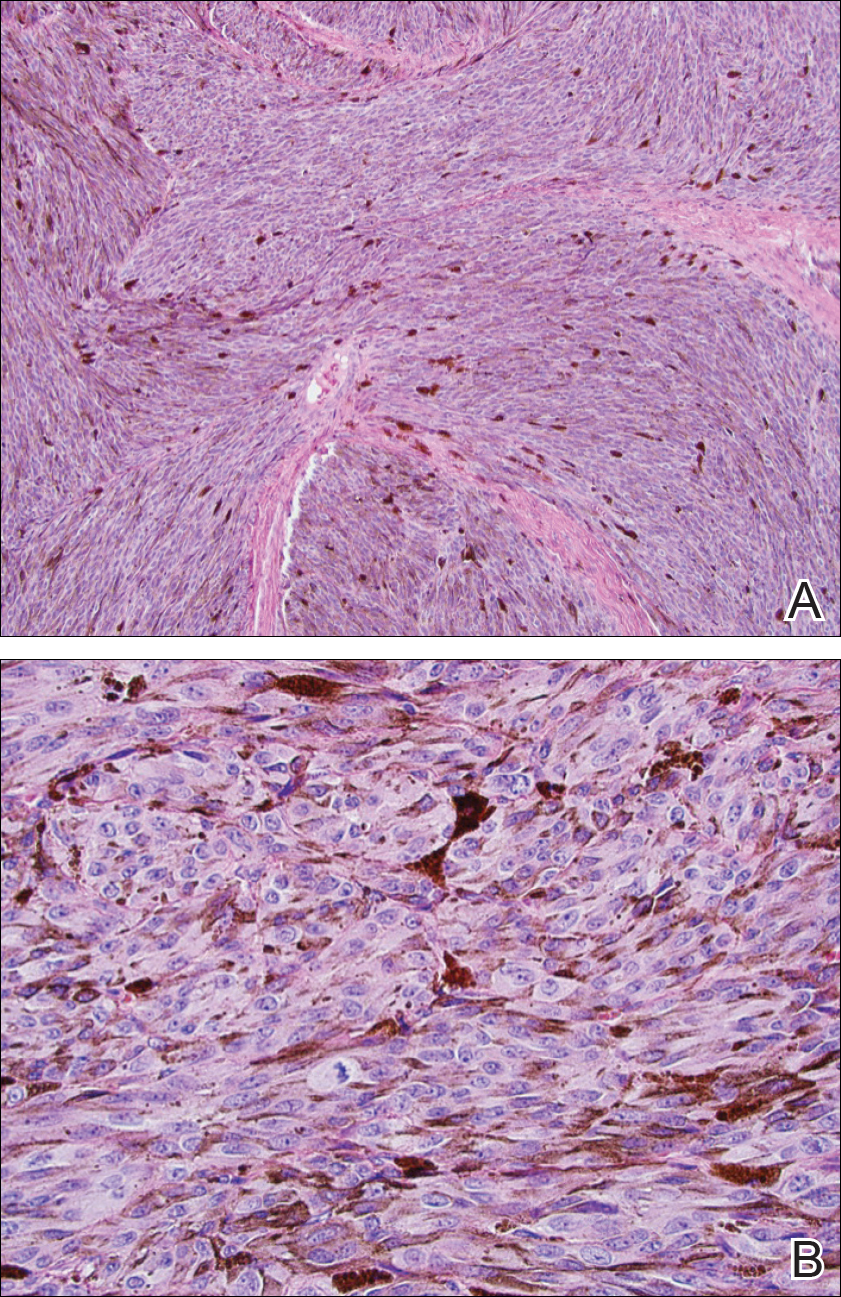

A punch biopsy of 2 separate papules on the face and upper extremity revealed dilated follicles with enlarged trichohyalin granules and dyskeratosis (Figure 2), consistent with TS. Additional testing such as electron microscopy or polymerase chain reaction was not performed to keep the patient’s medical costs down; also, the strong clinical and histopathologic evidence did not warrant further testing.

The plan was to start split-face treatment with topical acyclovir and a topical retinoid to see which agent was more effective, but the patient declined until her chemotherapy regimen had concluded. Unfortunately, the patient died 3 months later due to colon cancer.

Comment

History and Presentation

Trichodysplasia spinulosa was first recognized as hairlike hyperkeratosis.1 The name by which it is currently known was later championed by Haycox et al.2 They reported a case of a 44-year-old man who underwent a combined renal-pancreas transplant and while taking immunosuppressive medication developed erythematous papules with follicular spinous processes and progressive alopecia.2 Other synonymous terms used for this condition include pilomatrix dysplasia, cyclosporine-induced folliculodystrophy, virus-associated trichodysplasia,3 and follicular dystrophy of immunosuppression.4 Trichodysplasia spinulosa can affect both adult and pediatric immunocompromised patients, including organ transplant recipients on immunosuppressants and cancer patients on chemotherapy.3 The condition also has been reported to precede the recurrence of lymphoma.5

Etiology

The connection of TS with a viral etiology was first demonstrated in 1999, and subsequently it was confirmed to be a polyomavirus.2 The family name of Polyomaviridae possesses a Greek derivation with poly- meaning many and -oma meaning cancer.3 This name was given after the polyomavirus induced multiple tumors in mice.3,6 This viral family consists of multiple naked viruses with a surrounding icosahedral capsid containing 3 structural proteins known as VP1, VP2, and VP3. Their life cycle is characterized by early and late phases with respective early and late protein formation.3

Polyomavirus infections maintain an asymptomatic and latent course in immunocompetent patients.7 The prevalence and manifestation of these viruses change when the host’s immune system is altered. The first identified JC virus and BK virus of the same family have been found at increased frequencies in blood and lymphoid tissue during host immunosuppression.6 Moreover, the Merkel cell polyomavirus detected in Merkel cell carcinoma is well documented in the dermatologic literature.6,8

A specific polyomavirus has been implicated in the majority of TS cases and has subsequently received the name of TS polyomavirus.9 As a polyomavirus, it similarly produces capsid antigens and large/small T antigens. Among the viral protein antigens produced, the large tumor or LT antigen represents one of the most potent viral proteins. It has been postulated to inhibit the retinoblastoma family of proteins, leading to increased inner root sheath cells that allow for further viral replication.9,10

The disease presents with folliculocentric papules localized mainly on the central face and ears, which grow central keratin spines or spicules that can become 1 to 3 mm in length. Coinciding alopecia and madarosis also may be present.9

Diagnosis

Histologic examination reveals abnormal follicular maturation and distension. Additionally, increased proliferation and amount of trichohyalin is seen within the inner root sheath cells. Further testing via viral culture, polymerase chain reaction, electron microscopy, or immunohistochemical stains can confirm the diagnosis. Such testing may not be warranted in all cases given that classic clinical findings coupled with routine histopathology staining can provide enough evidence.10,11

Management

Currently, a universal successful treatment for TS does not exist. There have been anecdotal successes reported with topical medications such as cidofovir ointment 1%, acyclovir combined with 2-deoxy-D-glucose and epigallocatechin, corticosteroids, topical tacrolimus, topical retinoids, and imiquimod. Additionally, success has been seen with oral minocycline, oral retinoids, valacyclovir, and valganciclovir, with the latter showing the best results. Patients also have shown improvement after modifying their immunosuppressive treatment regimen.10,12

Conclusion

Given the previously published case of TS preceding the recurrence of lymphoma,5 we notified our patient’s oncologist of this potential risk. Her history of lymphoma and immunosuppressive treatment 4 years prior may represent the etiology of the cutaneous presentation; however, the TS with concurrent colon cancer presented prior to starting immunosuppressive therapy, suggesting that it also may have been a paraneoplastic process and not just a sign of immunosuppression. Therefore, we recommend that patients who present with TS should be evaluated for underlying malignancy if not already diagnosed.

- Linke M, Geraud C, Sauer C, et al. Follicular erythematous papules with keratotic spicules. Acta Derm Venereol . 2014;94:493-494.

- Haycox CL, Kim S, Fleckman P, et al. Trichodysplasia spinulosa—a newly described folliculocentric viral infection in an immunocompromised host. J Investig Dermatol Symp Proc. 1999;4:268-271.

- Moens U, Ludvigsen M, Van Ghelue M. Human polyomaviruses in skin diseases [published online September 12, 2011]. Patholog Res Int. 2011;2011:123491.

- Matthews MR, Wang RC, Reddick RL, et al. Viral-associated trichodysplasia spinulosa: a case with electron microscopic and molecular detection of the trichodysplasia spinulosa–associated human polyomavirus. J Cutan Pathol. 2011;38:420-431.

- Osswald SS, Kulick KB, Tomaszewski MM, et al. Viral-associated trichodysplasia in a patient with lymphoma: a case report and review. J Cutan Pathol. 2007;34:721-725.

- Dalianis T, Hirsch HH. Human polyomavirus in disease and cancer. Virology. 2013;437:63-72.

- Tsuzuki S, Fukumoto H, Mine S, et al. Detection of trichodysplasia spinulosa–associated polyomavirus in a fatal case of myocarditis in a seven-month-old girl. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2014;7:5308-5312.

- Sadeghi M, Aronen M, Chen T, et al. Merkel cell polyomavirus and trichodysplasia spinulosa–associated polyomavirus DNAs and antibodies in blood among the elderly. BMC Infect Dis. 2012;12:383.

- Van der Meijden E, Kazem S, Burgers MM, et al. Seroprevalence of trichodysplasia spinulosa-associated polyomavirus. Emerg Infect Dis. 2011;17:1355-1363.

- Krichhof MG, Shojania K, Hull MW, et al. Trichodysplasia spinulosa: rare presentation of polyomavirus infection in immunocompromised patients. J Cutan Med Surg. 2014;18:430-435.

- Rianthavorn P, Posuwan N, Payungporn S, et al. Polyomavirus reactivation in pediatric patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Tohoku J Exp Med. 2012;228:197-204.

- Wanat KA, Holler PD, Dentchev T, et al. Viral-associated trichodysplasia: characterization of a novel polyomavirus infection with therapeutic insights. Arch Dermatol. 2012;148:219-223.

Case Report

An 82-year-old woman presented to the clinic with a rash on the face that had been present for a few months. She denied any treatment or prior occurrence. Her medical history was remarkable for non-Hodgkin lymphoma that had been successfully treated with chemotherapy 4 years prior. Additionally, she recently had been diagnosed with stage IV colon cancer. She reported that surgery had been scheduled and she would start adjuvant chemotherapy soon after.

On physical examination she exhibited perioral and perinasal erythematous papules with sparing of the vermilion border. A diagnosis of perioral dermatitis was made, and she was started on topical metronidazole. At 1-month follow-up, her condition had slightly worsened and she was subsequently started on doxycycline. When she returned to the clinic again the following month, physical examination revealed agminated folliculocentric papules with central spicules on the face, nose, ears, upper extremities (Figure 1), and trunk. The differential diagnosis included multiple minute digitate hyperkeratosis, spiculosis of multiple myeloma, and trichodysplasia spinulosa (TS).

A punch biopsy of 2 separate papules on the face and upper extremity revealed dilated follicles with enlarged trichohyalin granules and dyskeratosis (Figure 2), consistent with TS. Additional testing such as electron microscopy or polymerase chain reaction was not performed to keep the patient’s medical costs down; also, the strong clinical and histopathologic evidence did not warrant further testing.

The plan was to start split-face treatment with topical acyclovir and a topical retinoid to see which agent was more effective, but the patient declined until her chemotherapy regimen had concluded. Unfortunately, the patient died 3 months later due to colon cancer.

Comment

History and Presentation

Trichodysplasia spinulosa was first recognized as hairlike hyperkeratosis.1 The name by which it is currently known was later championed by Haycox et al.2 They reported a case of a 44-year-old man who underwent a combined renal-pancreas transplant and while taking immunosuppressive medication developed erythematous papules with follicular spinous processes and progressive alopecia.2 Other synonymous terms used for this condition include pilomatrix dysplasia, cyclosporine-induced folliculodystrophy, virus-associated trichodysplasia,3 and follicular dystrophy of immunosuppression.4 Trichodysplasia spinulosa can affect both adult and pediatric immunocompromised patients, including organ transplant recipients on immunosuppressants and cancer patients on chemotherapy.3 The condition also has been reported to precede the recurrence of lymphoma.5

Etiology

The connection of TS with a viral etiology was first demonstrated in 1999, and subsequently it was confirmed to be a polyomavirus.2 The family name of Polyomaviridae possesses a Greek derivation with poly- meaning many and -oma meaning cancer.3 This name was given after the polyomavirus induced multiple tumors in mice.3,6 This viral family consists of multiple naked viruses with a surrounding icosahedral capsid containing 3 structural proteins known as VP1, VP2, and VP3. Their life cycle is characterized by early and late phases with respective early and late protein formation.3

Polyomavirus infections maintain an asymptomatic and latent course in immunocompetent patients.7 The prevalence and manifestation of these viruses change when the host’s immune system is altered. The first identified JC virus and BK virus of the same family have been found at increased frequencies in blood and lymphoid tissue during host immunosuppression.6 Moreover, the Merkel cell polyomavirus detected in Merkel cell carcinoma is well documented in the dermatologic literature.6,8

A specific polyomavirus has been implicated in the majority of TS cases and has subsequently received the name of TS polyomavirus.9 As a polyomavirus, it similarly produces capsid antigens and large/small T antigens. Among the viral protein antigens produced, the large tumor or LT antigen represents one of the most potent viral proteins. It has been postulated to inhibit the retinoblastoma family of proteins, leading to increased inner root sheath cells that allow for further viral replication.9,10

The disease presents with folliculocentric papules localized mainly on the central face and ears, which grow central keratin spines or spicules that can become 1 to 3 mm in length. Coinciding alopecia and madarosis also may be present.9

Diagnosis

Histologic examination reveals abnormal follicular maturation and distension. Additionally, increased proliferation and amount of trichohyalin is seen within the inner root sheath cells. Further testing via viral culture, polymerase chain reaction, electron microscopy, or immunohistochemical stains can confirm the diagnosis. Such testing may not be warranted in all cases given that classic clinical findings coupled with routine histopathology staining can provide enough evidence.10,11

Management

Currently, a universal successful treatment for TS does not exist. There have been anecdotal successes reported with topical medications such as cidofovir ointment 1%, acyclovir combined with 2-deoxy-D-glucose and epigallocatechin, corticosteroids, topical tacrolimus, topical retinoids, and imiquimod. Additionally, success has been seen with oral minocycline, oral retinoids, valacyclovir, and valganciclovir, with the latter showing the best results. Patients also have shown improvement after modifying their immunosuppressive treatment regimen.10,12

Conclusion

Given the previously published case of TS preceding the recurrence of lymphoma,5 we notified our patient’s oncologist of this potential risk. Her history of lymphoma and immunosuppressive treatment 4 years prior may represent the etiology of the cutaneous presentation; however, the TS with concurrent colon cancer presented prior to starting immunosuppressive therapy, suggesting that it also may have been a paraneoplastic process and not just a sign of immunosuppression. Therefore, we recommend that patients who present with TS should be evaluated for underlying malignancy if not already diagnosed.

Case Report

An 82-year-old woman presented to the clinic with a rash on the face that had been present for a few months. She denied any treatment or prior occurrence. Her medical history was remarkable for non-Hodgkin lymphoma that had been successfully treated with chemotherapy 4 years prior. Additionally, she recently had been diagnosed with stage IV colon cancer. She reported that surgery had been scheduled and she would start adjuvant chemotherapy soon after.

On physical examination she exhibited perioral and perinasal erythematous papules with sparing of the vermilion border. A diagnosis of perioral dermatitis was made, and she was started on topical metronidazole. At 1-month follow-up, her condition had slightly worsened and she was subsequently started on doxycycline. When she returned to the clinic again the following month, physical examination revealed agminated folliculocentric papules with central spicules on the face, nose, ears, upper extremities (Figure 1), and trunk. The differential diagnosis included multiple minute digitate hyperkeratosis, spiculosis of multiple myeloma, and trichodysplasia spinulosa (TS).

A punch biopsy of 2 separate papules on the face and upper extremity revealed dilated follicles with enlarged trichohyalin granules and dyskeratosis (Figure 2), consistent with TS. Additional testing such as electron microscopy or polymerase chain reaction was not performed to keep the patient’s medical costs down; also, the strong clinical and histopathologic evidence did not warrant further testing.

The plan was to start split-face treatment with topical acyclovir and a topical retinoid to see which agent was more effective, but the patient declined until her chemotherapy regimen had concluded. Unfortunately, the patient died 3 months later due to colon cancer.

Comment

History and Presentation

Trichodysplasia spinulosa was first recognized as hairlike hyperkeratosis.1 The name by which it is currently known was later championed by Haycox et al.2 They reported a case of a 44-year-old man who underwent a combined renal-pancreas transplant and while taking immunosuppressive medication developed erythematous papules with follicular spinous processes and progressive alopecia.2 Other synonymous terms used for this condition include pilomatrix dysplasia, cyclosporine-induced folliculodystrophy, virus-associated trichodysplasia,3 and follicular dystrophy of immunosuppression.4 Trichodysplasia spinulosa can affect both adult and pediatric immunocompromised patients, including organ transplant recipients on immunosuppressants and cancer patients on chemotherapy.3 The condition also has been reported to precede the recurrence of lymphoma.5

Etiology

The connection of TS with a viral etiology was first demonstrated in 1999, and subsequently it was confirmed to be a polyomavirus.2 The family name of Polyomaviridae possesses a Greek derivation with poly- meaning many and -oma meaning cancer.3 This name was given after the polyomavirus induced multiple tumors in mice.3,6 This viral family consists of multiple naked viruses with a surrounding icosahedral capsid containing 3 structural proteins known as VP1, VP2, and VP3. Their life cycle is characterized by early and late phases with respective early and late protein formation.3

Polyomavirus infections maintain an asymptomatic and latent course in immunocompetent patients.7 The prevalence and manifestation of these viruses change when the host’s immune system is altered. The first identified JC virus and BK virus of the same family have been found at increased frequencies in blood and lymphoid tissue during host immunosuppression.6 Moreover, the Merkel cell polyomavirus detected in Merkel cell carcinoma is well documented in the dermatologic literature.6,8

A specific polyomavirus has been implicated in the majority of TS cases and has subsequently received the name of TS polyomavirus.9 As a polyomavirus, it similarly produces capsid antigens and large/small T antigens. Among the viral protein antigens produced, the large tumor or LT antigen represents one of the most potent viral proteins. It has been postulated to inhibit the retinoblastoma family of proteins, leading to increased inner root sheath cells that allow for further viral replication.9,10

The disease presents with folliculocentric papules localized mainly on the central face and ears, which grow central keratin spines or spicules that can become 1 to 3 mm in length. Coinciding alopecia and madarosis also may be present.9

Diagnosis

Histologic examination reveals abnormal follicular maturation and distension. Additionally, increased proliferation and amount of trichohyalin is seen within the inner root sheath cells. Further testing via viral culture, polymerase chain reaction, electron microscopy, or immunohistochemical stains can confirm the diagnosis. Such testing may not be warranted in all cases given that classic clinical findings coupled with routine histopathology staining can provide enough evidence.10,11

Management

Currently, a universal successful treatment for TS does not exist. There have been anecdotal successes reported with topical medications such as cidofovir ointment 1%, acyclovir combined with 2-deoxy-D-glucose and epigallocatechin, corticosteroids, topical tacrolimus, topical retinoids, and imiquimod. Additionally, success has been seen with oral minocycline, oral retinoids, valacyclovir, and valganciclovir, with the latter showing the best results. Patients also have shown improvement after modifying their immunosuppressive treatment regimen.10,12

Conclusion

Given the previously published case of TS preceding the recurrence of lymphoma,5 we notified our patient’s oncologist of this potential risk. Her history of lymphoma and immunosuppressive treatment 4 years prior may represent the etiology of the cutaneous presentation; however, the TS with concurrent colon cancer presented prior to starting immunosuppressive therapy, suggesting that it also may have been a paraneoplastic process and not just a sign of immunosuppression. Therefore, we recommend that patients who present with TS should be evaluated for underlying malignancy if not already diagnosed.

- Linke M, Geraud C, Sauer C, et al. Follicular erythematous papules with keratotic spicules. Acta Derm Venereol . 2014;94:493-494.

- Haycox CL, Kim S, Fleckman P, et al. Trichodysplasia spinulosa—a newly described folliculocentric viral infection in an immunocompromised host. J Investig Dermatol Symp Proc. 1999;4:268-271.

- Moens U, Ludvigsen M, Van Ghelue M. Human polyomaviruses in skin diseases [published online September 12, 2011]. Patholog Res Int. 2011;2011:123491.

- Matthews MR, Wang RC, Reddick RL, et al. Viral-associated trichodysplasia spinulosa: a case with electron microscopic and molecular detection of the trichodysplasia spinulosa–associated human polyomavirus. J Cutan Pathol. 2011;38:420-431.

- Osswald SS, Kulick KB, Tomaszewski MM, et al. Viral-associated trichodysplasia in a patient with lymphoma: a case report and review. J Cutan Pathol. 2007;34:721-725.

- Dalianis T, Hirsch HH. Human polyomavirus in disease and cancer. Virology. 2013;437:63-72.

- Tsuzuki S, Fukumoto H, Mine S, et al. Detection of trichodysplasia spinulosa–associated polyomavirus in a fatal case of myocarditis in a seven-month-old girl. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2014;7:5308-5312.

- Sadeghi M, Aronen M, Chen T, et al. Merkel cell polyomavirus and trichodysplasia spinulosa–associated polyomavirus DNAs and antibodies in blood among the elderly. BMC Infect Dis. 2012;12:383.

- Van der Meijden E, Kazem S, Burgers MM, et al. Seroprevalence of trichodysplasia spinulosa-associated polyomavirus. Emerg Infect Dis. 2011;17:1355-1363.

- Krichhof MG, Shojania K, Hull MW, et al. Trichodysplasia spinulosa: rare presentation of polyomavirus infection in immunocompromised patients. J Cutan Med Surg. 2014;18:430-435.

- Rianthavorn P, Posuwan N, Payungporn S, et al. Polyomavirus reactivation in pediatric patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Tohoku J Exp Med. 2012;228:197-204.

- Wanat KA, Holler PD, Dentchev T, et al. Viral-associated trichodysplasia: characterization of a novel polyomavirus infection with therapeutic insights. Arch Dermatol. 2012;148:219-223.

- Linke M, Geraud C, Sauer C, et al. Follicular erythematous papules with keratotic spicules. Acta Derm Venereol . 2014;94:493-494.

- Haycox CL, Kim S, Fleckman P, et al. Trichodysplasia spinulosa—a newly described folliculocentric viral infection in an immunocompromised host. J Investig Dermatol Symp Proc. 1999;4:268-271.

- Moens U, Ludvigsen M, Van Ghelue M. Human polyomaviruses in skin diseases [published online September 12, 2011]. Patholog Res Int. 2011;2011:123491.

- Matthews MR, Wang RC, Reddick RL, et al. Viral-associated trichodysplasia spinulosa: a case with electron microscopic and molecular detection of the trichodysplasia spinulosa–associated human polyomavirus. J Cutan Pathol. 2011;38:420-431.

- Osswald SS, Kulick KB, Tomaszewski MM, et al. Viral-associated trichodysplasia in a patient with lymphoma: a case report and review. J Cutan Pathol. 2007;34:721-725.

- Dalianis T, Hirsch HH. Human polyomavirus in disease and cancer. Virology. 2013;437:63-72.

- Tsuzuki S, Fukumoto H, Mine S, et al. Detection of trichodysplasia spinulosa–associated polyomavirus in a fatal case of myocarditis in a seven-month-old girl. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2014;7:5308-5312.

- Sadeghi M, Aronen M, Chen T, et al. Merkel cell polyomavirus and trichodysplasia spinulosa–associated polyomavirus DNAs and antibodies in blood among the elderly. BMC Infect Dis. 2012;12:383.

- Van der Meijden E, Kazem S, Burgers MM, et al. Seroprevalence of trichodysplasia spinulosa-associated polyomavirus. Emerg Infect Dis. 2011;17:1355-1363.

- Krichhof MG, Shojania K, Hull MW, et al. Trichodysplasia spinulosa: rare presentation of polyomavirus infection in immunocompromised patients. J Cutan Med Surg. 2014;18:430-435.

- Rianthavorn P, Posuwan N, Payungporn S, et al. Polyomavirus reactivation in pediatric patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Tohoku J Exp Med. 2012;228:197-204.

- Wanat KA, Holler PD, Dentchev T, et al. Viral-associated trichodysplasia: characterization of a novel polyomavirus infection with therapeutic insights. Arch Dermatol. 2012;148:219-223.

Practice Points

- Rashes have a life span and can evolve with time.

- If apparent straightforward conditions do not appear to respond to standard therapy, start to think outside the box for underlying potential causes.

Nausea and vomiting • sensitivity to smell • history of hypertension and alcohol abuse • Dx?

THE CASE

A 57-year-old woman presented to a family physician with acute encephalopathy and complaints of recent gastritis. She reported a 2-month history of nausea, vomiting, decreased oral intake, and extreme sensitivity to smell. The patient had a history of hypertension, and a family member privately disclosed to the FP that she also had a history of alcohol abuse. The patient was taking lorazepam daily, as needed, for anxiety.

On initial assessment, the patient was alert, but not oriented to time or situation. She was ataxic and agitated but did not exhibit pupillary constriction or tremor. The FP sent her to the emergency department (ED).

After being assessed in the ED, the patient was admitted. Over the course of several days, she showed worsening mentation; she persistently believed she was in Chicago, her childhood home. On memory testing, she was unable to recall any of 3 objects after 5 minutes. She exhibited horizontal nystagmus and dysmetria bilaterally and continued to be ataxic, requiring 2-point assistance. Her agitation was managed nonpharmacologically.

A work-up was performed, which included laboratory testing, a urinalysis, and computed tomography (CT) of the head. A comprehensive metabolic panel, complete blood count, and thyroid stimulating hormone test were unremarkable except for electrolyte disturbances, with a sodium level of 158 mEq/L and a potassium level of 2.6 mEq/L (reference ranges: 135-145 mEq/L and 3.5-5 mEq/L, respectively).

Her blood alcohol level was zero, and not surprisingly given her use of lorazepam, a urine drug screen was positive for benzodiazepines. The urinalysis results were consistent with a urinary tract infection (UTI), for which she was treated with an antibiotic. A carbohydrate-deficient transferrin test may have been useful to establish chronic alcohol abuse, but was not ordered. The head CT was negative.

After a few days with fluids and electrolyte replacement, the patient’s electrolytes normalized.

THE DIAGNOSIS

The differential diagnosis included sepsis, metabolic encephalopathy, and alcoholic encephalopathy. Given that the patient’s urine drug screen was positive, benzodiazepine withdrawal was also considered a plausible explanation for her continued cognitive disturbances. (It was surmised that she had likely taken her last lorazepam several days prior.) However, the lack of other signs of withdrawal prompted further investigation.

Continue to: Since her encephalopathy...

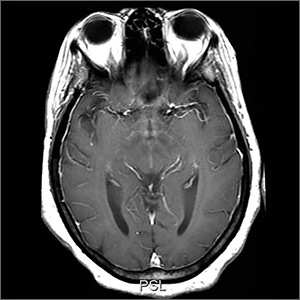

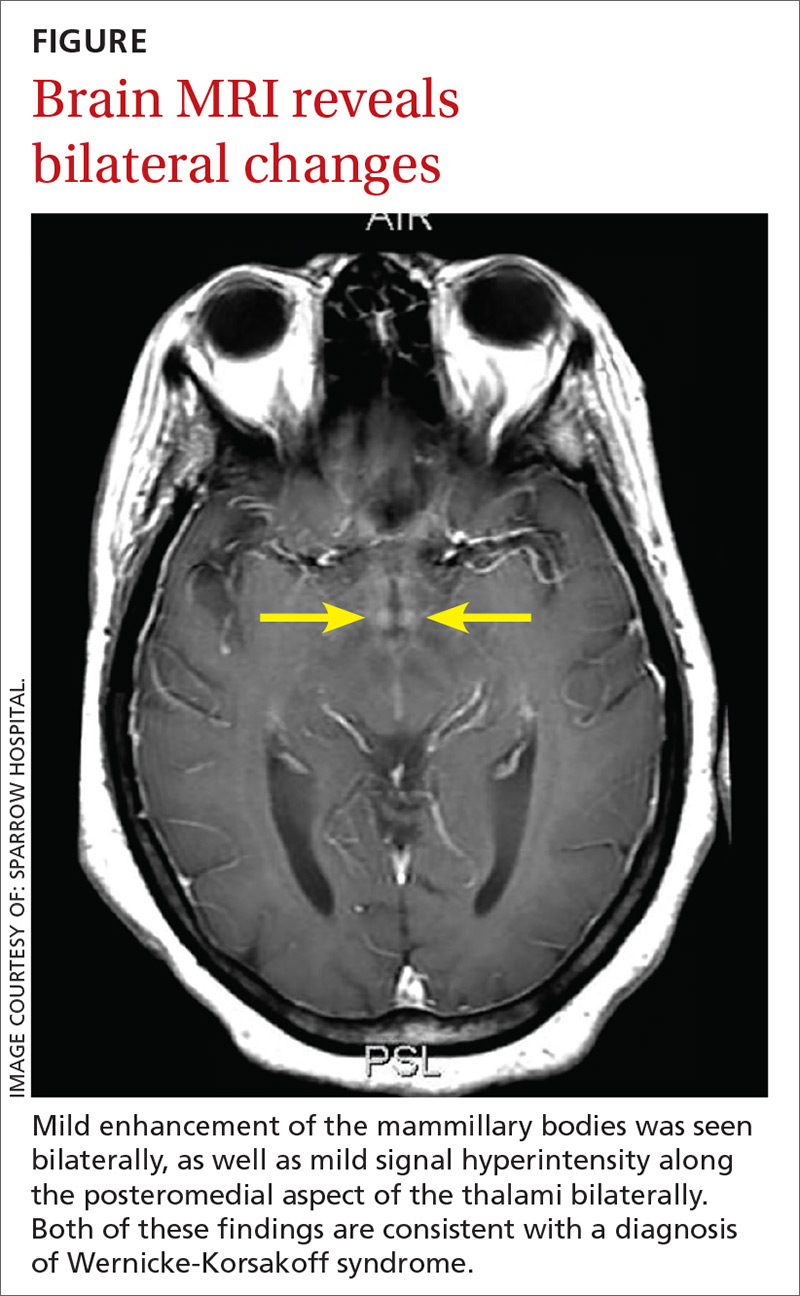

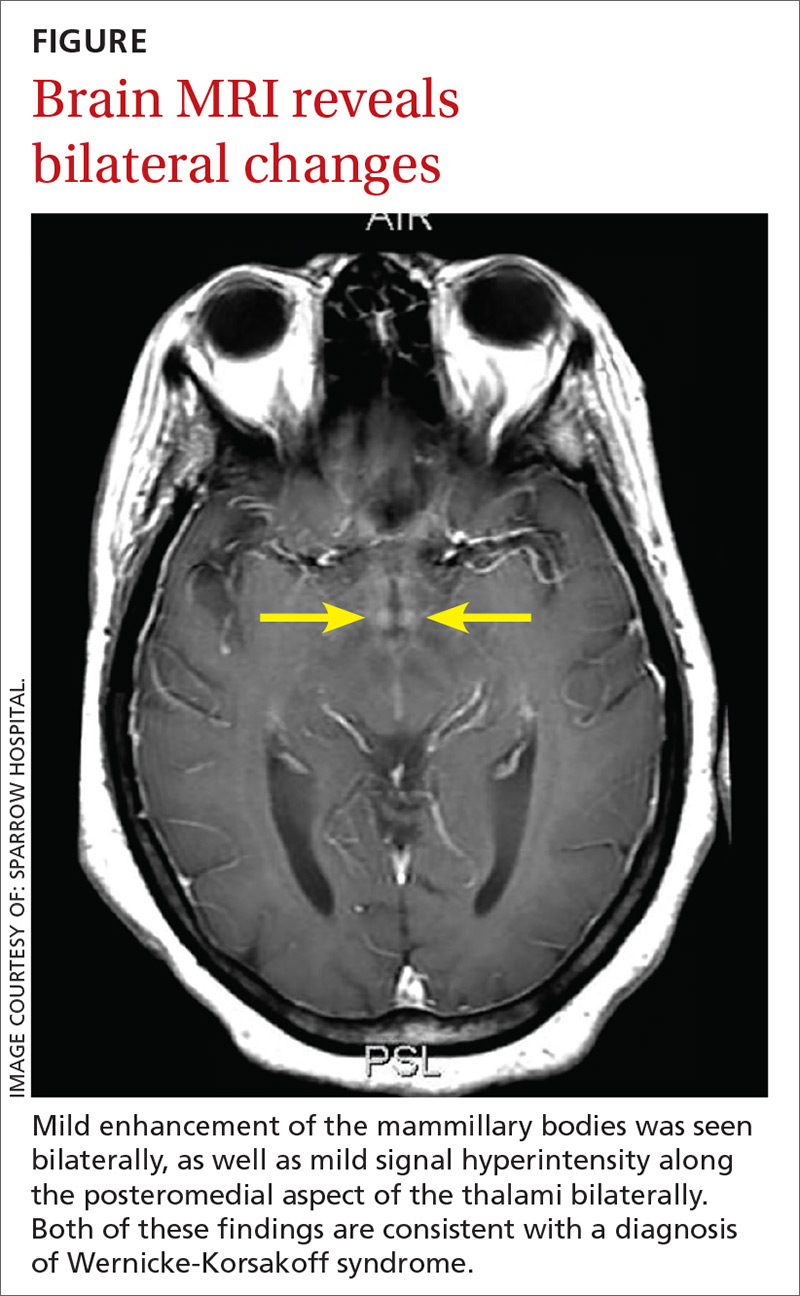

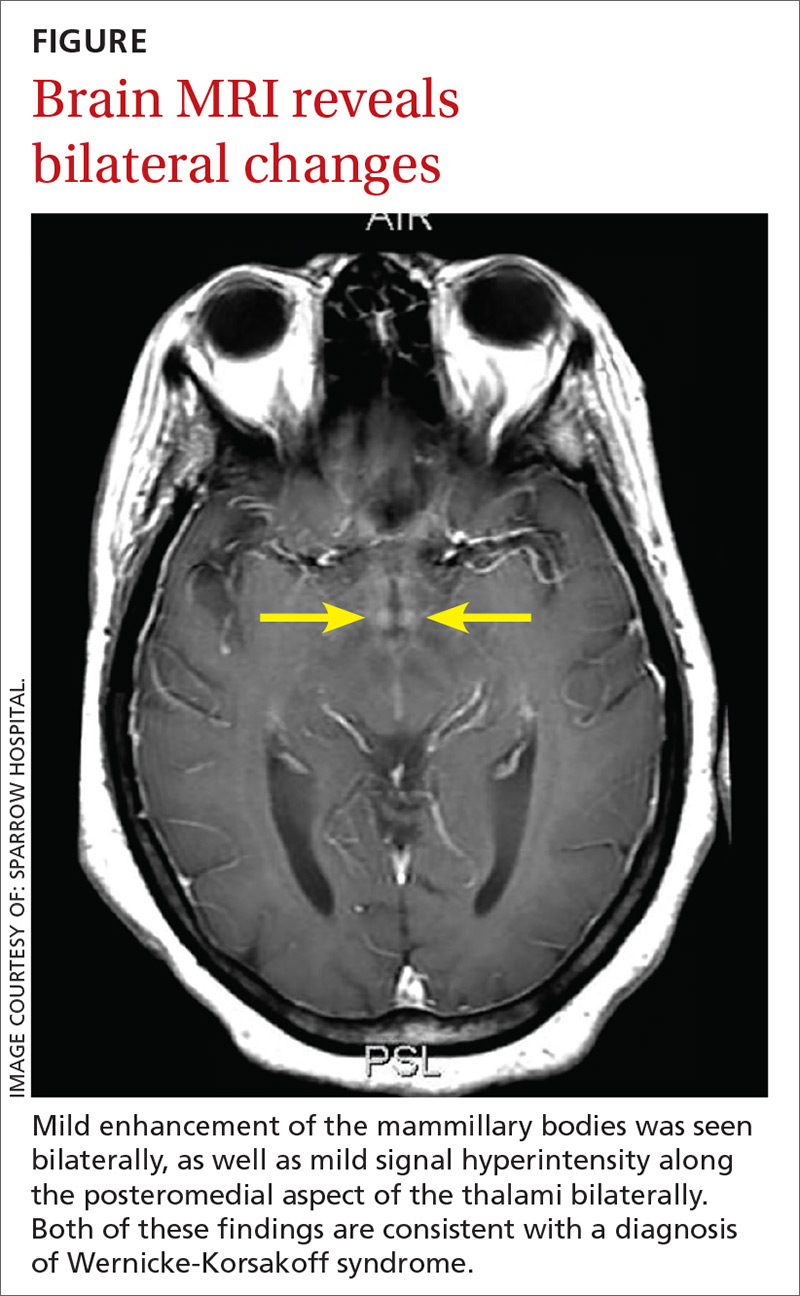

Since her encephalopathy, ataxia, and nystagmus persisted, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain was performed on Day 3 of hospitalization (FIGURE). A lumbar puncture and an electroencephalogram were also considered but were not performed because the MRI results revealed bilateral enhancement of the m

DISCUSSION

WKS is the concurrence of Wernicke’s encephalopathy (an acute, life-threatening condition marked by ataxia, confusion, and ocular signs) and Korsakoff’s psychosis (a long-term, debilitating amnestic syndrome). WKS is a neuropsychiatric disorder in which patients experience profound short-term amnesia; it is precipitated by thiamine deficiency (defined as a whole blood thiamine level <0.7 ng/ml1).The link to thiamine was confirmed during World War II, when thiamine treatment resolved symptoms in starving prisoners. If recognized early, treatment of thiamine deficiency can prevent long-term morbidity from WKS.

Etiology of thiamine deficiency

Our patient’s alcohol abuse placed her at risk for WKS, and her olfactory aversion to certain foods was a diagnostic clue. In this case, we inadvertently administered dextrose with antibiotics for the UTI prior to administering thiamine; this exacerbated the thiamine deficiency because glucose and thiamine compete for the same substrate.

Is alcohol abuse always to blame for WKS?

The quantity and type of alcohol that results in the development of WKS has not been well studied, but the Caine diagnostic criteria defines chronic alcoholism as the consumption of 80 g/d of ethanol (8 drinks/d).2 While WKS is commonly associated with alcoholism, other causative conditions may be overlooked. Other associated illnesses include acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS), cancer, hyperemesis gravidarum, prolonged total parenteral nutrition, and psychiatric illnesses such as eating disorders and schizophrenia. Procedures such as gastric bypass and dialysis can also precipitate WKS.3

Men and women are both at risk of developing WKS. A lack of consumption of thiamine-rich sources such as cereals, rice, and legumes puts patients at risk for WKS. The recommended dietary allowance of thiamine increases with age and may be higher for obese patients.4

Continue to: Suspect thiamine deficiency and obstain a thorough history

Suspect thiamine deficiency and obtain a thorough history

A high index of suspicion for thiamine deficiency is essential for diagnosis of WKS. History of alcohol use should be obtained, including quantity, frequency, pattern, duration, and time of last use. Physicians should assess nutrition and ask about vomiting and diarrhea. It is important to collaborate with the patient’s family and friends and inquire into other substance misuse.5

Since WKS targets the dorsomedial thalamus, which is responsible for olfactory processing, patients may complain of a distorted perception of smell.6 On physical examination, look for signs of protein-calorie malnutrition, including cheilitis, glossitis, and bleeding gums; signs of alcohol abuse, such as hepatomegaly; and evidence of injuries or poor self-care.5

Varied presentation leads to under- and misdiagnosis

Diagnosis of WKS can be difficult due to the varied presentation; there is a broad spectrum of clinical features. The clinical triad of mental status change, ophthalmoplegia, and gait ataxia is present in as few as 10% of cases.3 Mental status changes may include a global confusional state ranging from disorientation, apathy, anxiety, fear, and mild memory impairment to pronounced amnesia. Ophthalmoplegia can include nystagmus, ocular palsies, retinal hemorrhages, scotoma, or photophobia; and ataxia can range from a mild gait abnormality to an inability to stand.7 This varied presentation ultimately leads to underdiagnosis and misdiagnosis.

MRI findings are also varied in WKS. However, the mammillary bodies are involved in many cases, where atrophy of these structures have high specificity. The dorsomedial thalamus is associated with the reported impairment in memory and can be identified antemortem on MRI.3 There is no quantifiable evidence of how much thiamine should be used to prevent WKS. However, thiamine should be given before the administration of glucose whenever WKS is considered.

Our patient. Despite the administration of thiamine (100 mg parenterally for 5 d, followed by oral thiamine 300 mg/d indefinitely), our patient’s memory and cognition remained unchanged. She underwent intensive inpatient rehabilitation for 2 months and was eventually placed in long-term nursing care.

Continue to: THE TAKEAWAY

THE TAKEAWAY

A high index of suspicion is crucial to prevent possible long-term neurologic sequelae in WKS. Appropriate care starts at the beginning, with the patient’s story.

CORRESPONDENCE

Romith Naug, MD, 15 St. Andrew Street, Unit 601, Brockville, ON Canada K6V0B8; [email protected].

1. Doshi S, Velpandian T, Seth S, et al. Prevalence of thiamine deficiency in heart failure patients on long-term diuretic therapy. J Prac Cardiovasc Sci. 2015;1:25-29.

2. Caine D, Halliday GM, Kril JJ, et al. Operational criteria for the classification of chronic alcoholics: identification of Wernicke’s encephalopathy. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1997;62:51-60.

3. Donnino MW, Vega J, Miller J, et al. Myths and misconceptions of Wernicke’s encephalopathy: what every emergency physician should know. Ann Emerg Med. 2007;50:715-721.

4. Kerns J, Arundel C, Chawla LS. Thiamin deficiency in people with obesity. Adv Nutr. 2015;6:147-153.

5. Latt N, Dore G. Thiamine in the treatment of Wernicke encephalopathy in patients with alcohol use disorders. Intern Med J. 2014;44:911-915.

6. Wilson DA, Xu W, Sadrian B, et al. Cortical odor processing in health and disease. Prog Brain Res. 2014;208:275-305.

7. Isenberg-Grzeda E, Kutner HE, Nicolson SE. Wernicke-Korsakoff syndrome: under-recognized and under-treated. Psychosomatics. 2012;53:507-516.

THE CASE

A 57-year-old woman presented to a family physician with acute encephalopathy and complaints of recent gastritis. She reported a 2-month history of nausea, vomiting, decreased oral intake, and extreme sensitivity to smell. The patient had a history of hypertension, and a family member privately disclosed to the FP that she also had a history of alcohol abuse. The patient was taking lorazepam daily, as needed, for anxiety.

On initial assessment, the patient was alert, but not oriented to time or situation. She was ataxic and agitated but did not exhibit pupillary constriction or tremor. The FP sent her to the emergency department (ED).

After being assessed in the ED, the patient was admitted. Over the course of several days, she showed worsening mentation; she persistently believed she was in Chicago, her childhood home. On memory testing, she was unable to recall any of 3 objects after 5 minutes. She exhibited horizontal nystagmus and dysmetria bilaterally and continued to be ataxic, requiring 2-point assistance. Her agitation was managed nonpharmacologically.

A work-up was performed, which included laboratory testing, a urinalysis, and computed tomography (CT) of the head. A comprehensive metabolic panel, complete blood count, and thyroid stimulating hormone test were unremarkable except for electrolyte disturbances, with a sodium level of 158 mEq/L and a potassium level of 2.6 mEq/L (reference ranges: 135-145 mEq/L and 3.5-5 mEq/L, respectively).

Her blood alcohol level was zero, and not surprisingly given her use of lorazepam, a urine drug screen was positive for benzodiazepines. The urinalysis results were consistent with a urinary tract infection (UTI), for which she was treated with an antibiotic. A carbohydrate-deficient transferrin test may have been useful to establish chronic alcohol abuse, but was not ordered. The head CT was negative.

After a few days with fluids and electrolyte replacement, the patient’s electrolytes normalized.

THE DIAGNOSIS

The differential diagnosis included sepsis, metabolic encephalopathy, and alcoholic encephalopathy. Given that the patient’s urine drug screen was positive, benzodiazepine withdrawal was also considered a plausible explanation for her continued cognitive disturbances. (It was surmised that she had likely taken her last lorazepam several days prior.) However, the lack of other signs of withdrawal prompted further investigation.

Continue to: Since her encephalopathy...

Since her encephalopathy, ataxia, and nystagmus persisted, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain was performed on Day 3 of hospitalization (FIGURE). A lumbar puncture and an electroencephalogram were also considered but were not performed because the MRI results revealed bilateral enhancement of the m

DISCUSSION

WKS is the concurrence of Wernicke’s encephalopathy (an acute, life-threatening condition marked by ataxia, confusion, and ocular signs) and Korsakoff’s psychosis (a long-term, debilitating amnestic syndrome). WKS is a neuropsychiatric disorder in which patients experience profound short-term amnesia; it is precipitated by thiamine deficiency (defined as a whole blood thiamine level <0.7 ng/ml1).The link to thiamine was confirmed during World War II, when thiamine treatment resolved symptoms in starving prisoners. If recognized early, treatment of thiamine deficiency can prevent long-term morbidity from WKS.

Etiology of thiamine deficiency

Our patient’s alcohol abuse placed her at risk for WKS, and her olfactory aversion to certain foods was a diagnostic clue. In this case, we inadvertently administered dextrose with antibiotics for the UTI prior to administering thiamine; this exacerbated the thiamine deficiency because glucose and thiamine compete for the same substrate.

Is alcohol abuse always to blame for WKS?

The quantity and type of alcohol that results in the development of WKS has not been well studied, but the Caine diagnostic criteria defines chronic alcoholism as the consumption of 80 g/d of ethanol (8 drinks/d).2 While WKS is commonly associated with alcoholism, other causative conditions may be overlooked. Other associated illnesses include acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS), cancer, hyperemesis gravidarum, prolonged total parenteral nutrition, and psychiatric illnesses such as eating disorders and schizophrenia. Procedures such as gastric bypass and dialysis can also precipitate WKS.3

Men and women are both at risk of developing WKS. A lack of consumption of thiamine-rich sources such as cereals, rice, and legumes puts patients at risk for WKS. The recommended dietary allowance of thiamine increases with age and may be higher for obese patients.4

Continue to: Suspect thiamine deficiency and obstain a thorough history

Suspect thiamine deficiency and obtain a thorough history

A high index of suspicion for thiamine deficiency is essential for diagnosis of WKS. History of alcohol use should be obtained, including quantity, frequency, pattern, duration, and time of last use. Physicians should assess nutrition and ask about vomiting and diarrhea. It is important to collaborate with the patient’s family and friends and inquire into other substance misuse.5

Since WKS targets the dorsomedial thalamus, which is responsible for olfactory processing, patients may complain of a distorted perception of smell.6 On physical examination, look for signs of protein-calorie malnutrition, including cheilitis, glossitis, and bleeding gums; signs of alcohol abuse, such as hepatomegaly; and evidence of injuries or poor self-care.5

Varied presentation leads to under- and misdiagnosis

Diagnosis of WKS can be difficult due to the varied presentation; there is a broad spectrum of clinical features. The clinical triad of mental status change, ophthalmoplegia, and gait ataxia is present in as few as 10% of cases.3 Mental status changes may include a global confusional state ranging from disorientation, apathy, anxiety, fear, and mild memory impairment to pronounced amnesia. Ophthalmoplegia can include nystagmus, ocular palsies, retinal hemorrhages, scotoma, or photophobia; and ataxia can range from a mild gait abnormality to an inability to stand.7 This varied presentation ultimately leads to underdiagnosis and misdiagnosis.

MRI findings are also varied in WKS. However, the mammillary bodies are involved in many cases, where atrophy of these structures have high specificity. The dorsomedial thalamus is associated with the reported impairment in memory and can be identified antemortem on MRI.3 There is no quantifiable evidence of how much thiamine should be used to prevent WKS. However, thiamine should be given before the administration of glucose whenever WKS is considered.

Our patient. Despite the administration of thiamine (100 mg parenterally for 5 d, followed by oral thiamine 300 mg/d indefinitely), our patient’s memory and cognition remained unchanged. She underwent intensive inpatient rehabilitation for 2 months and was eventually placed in long-term nursing care.

Continue to: THE TAKEAWAY

THE TAKEAWAY

A high index of suspicion is crucial to prevent possible long-term neurologic sequelae in WKS. Appropriate care starts at the beginning, with the patient’s story.

CORRESPONDENCE

Romith Naug, MD, 15 St. Andrew Street, Unit 601, Brockville, ON Canada K6V0B8; [email protected].

THE CASE

A 57-year-old woman presented to a family physician with acute encephalopathy and complaints of recent gastritis. She reported a 2-month history of nausea, vomiting, decreased oral intake, and extreme sensitivity to smell. The patient had a history of hypertension, and a family member privately disclosed to the FP that she also had a history of alcohol abuse. The patient was taking lorazepam daily, as needed, for anxiety.

On initial assessment, the patient was alert, but not oriented to time or situation. She was ataxic and agitated but did not exhibit pupillary constriction or tremor. The FP sent her to the emergency department (ED).

After being assessed in the ED, the patient was admitted. Over the course of several days, she showed worsening mentation; she persistently believed she was in Chicago, her childhood home. On memory testing, she was unable to recall any of 3 objects after 5 minutes. She exhibited horizontal nystagmus and dysmetria bilaterally and continued to be ataxic, requiring 2-point assistance. Her agitation was managed nonpharmacologically.

A work-up was performed, which included laboratory testing, a urinalysis, and computed tomography (CT) of the head. A comprehensive metabolic panel, complete blood count, and thyroid stimulating hormone test were unremarkable except for electrolyte disturbances, with a sodium level of 158 mEq/L and a potassium level of 2.6 mEq/L (reference ranges: 135-145 mEq/L and 3.5-5 mEq/L, respectively).

Her blood alcohol level was zero, and not surprisingly given her use of lorazepam, a urine drug screen was positive for benzodiazepines. The urinalysis results were consistent with a urinary tract infection (UTI), for which she was treated with an antibiotic. A carbohydrate-deficient transferrin test may have been useful to establish chronic alcohol abuse, but was not ordered. The head CT was negative.

After a few days with fluids and electrolyte replacement, the patient’s electrolytes normalized.

THE DIAGNOSIS

The differential diagnosis included sepsis, metabolic encephalopathy, and alcoholic encephalopathy. Given that the patient’s urine drug screen was positive, benzodiazepine withdrawal was also considered a plausible explanation for her continued cognitive disturbances. (It was surmised that she had likely taken her last lorazepam several days prior.) However, the lack of other signs of withdrawal prompted further investigation.

Continue to: Since her encephalopathy...

Since her encephalopathy, ataxia, and nystagmus persisted, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain was performed on Day 3 of hospitalization (FIGURE). A lumbar puncture and an electroencephalogram were also considered but were not performed because the MRI results revealed bilateral enhancement of the m

DISCUSSION

WKS is the concurrence of Wernicke’s encephalopathy (an acute, life-threatening condition marked by ataxia, confusion, and ocular signs) and Korsakoff’s psychosis (a long-term, debilitating amnestic syndrome). WKS is a neuropsychiatric disorder in which patients experience profound short-term amnesia; it is precipitated by thiamine deficiency (defined as a whole blood thiamine level <0.7 ng/ml1).The link to thiamine was confirmed during World War II, when thiamine treatment resolved symptoms in starving prisoners. If recognized early, treatment of thiamine deficiency can prevent long-term morbidity from WKS.

Etiology of thiamine deficiency

Our patient’s alcohol abuse placed her at risk for WKS, and her olfactory aversion to certain foods was a diagnostic clue. In this case, we inadvertently administered dextrose with antibiotics for the UTI prior to administering thiamine; this exacerbated the thiamine deficiency because glucose and thiamine compete for the same substrate.

Is alcohol abuse always to blame for WKS?

The quantity and type of alcohol that results in the development of WKS has not been well studied, but the Caine diagnostic criteria defines chronic alcoholism as the consumption of 80 g/d of ethanol (8 drinks/d).2 While WKS is commonly associated with alcoholism, other causative conditions may be overlooked. Other associated illnesses include acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS), cancer, hyperemesis gravidarum, prolonged total parenteral nutrition, and psychiatric illnesses such as eating disorders and schizophrenia. Procedures such as gastric bypass and dialysis can also precipitate WKS.3

Men and women are both at risk of developing WKS. A lack of consumption of thiamine-rich sources such as cereals, rice, and legumes puts patients at risk for WKS. The recommended dietary allowance of thiamine increases with age and may be higher for obese patients.4

Continue to: Suspect thiamine deficiency and obstain a thorough history

Suspect thiamine deficiency and obtain a thorough history

A high index of suspicion for thiamine deficiency is essential for diagnosis of WKS. History of alcohol use should be obtained, including quantity, frequency, pattern, duration, and time of last use. Physicians should assess nutrition and ask about vomiting and diarrhea. It is important to collaborate with the patient’s family and friends and inquire into other substance misuse.5

Since WKS targets the dorsomedial thalamus, which is responsible for olfactory processing, patients may complain of a distorted perception of smell.6 On physical examination, look for signs of protein-calorie malnutrition, including cheilitis, glossitis, and bleeding gums; signs of alcohol abuse, such as hepatomegaly; and evidence of injuries or poor self-care.5

Varied presentation leads to under- and misdiagnosis

Diagnosis of WKS can be difficult due to the varied presentation; there is a broad spectrum of clinical features. The clinical triad of mental status change, ophthalmoplegia, and gait ataxia is present in as few as 10% of cases.3 Mental status changes may include a global confusional state ranging from disorientation, apathy, anxiety, fear, and mild memory impairment to pronounced amnesia. Ophthalmoplegia can include nystagmus, ocular palsies, retinal hemorrhages, scotoma, or photophobia; and ataxia can range from a mild gait abnormality to an inability to stand.7 This varied presentation ultimately leads to underdiagnosis and misdiagnosis.

MRI findings are also varied in WKS. However, the mammillary bodies are involved in many cases, where atrophy of these structures have high specificity. The dorsomedial thalamus is associated with the reported impairment in memory and can be identified antemortem on MRI.3 There is no quantifiable evidence of how much thiamine should be used to prevent WKS. However, thiamine should be given before the administration of glucose whenever WKS is considered.

Our patient. Despite the administration of thiamine (100 mg parenterally for 5 d, followed by oral thiamine 300 mg/d indefinitely), our patient’s memory and cognition remained unchanged. She underwent intensive inpatient rehabilitation for 2 months and was eventually placed in long-term nursing care.

Continue to: THE TAKEAWAY

THE TAKEAWAY

A high index of suspicion is crucial to prevent possible long-term neurologic sequelae in WKS. Appropriate care starts at the beginning, with the patient’s story.

CORRESPONDENCE

Romith Naug, MD, 15 St. Andrew Street, Unit 601, Brockville, ON Canada K6V0B8; [email protected].

1. Doshi S, Velpandian T, Seth S, et al. Prevalence of thiamine deficiency in heart failure patients on long-term diuretic therapy. J Prac Cardiovasc Sci. 2015;1:25-29.

2. Caine D, Halliday GM, Kril JJ, et al. Operational criteria for the classification of chronic alcoholics: identification of Wernicke’s encephalopathy. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1997;62:51-60.

3. Donnino MW, Vega J, Miller J, et al. Myths and misconceptions of Wernicke’s encephalopathy: what every emergency physician should know. Ann Emerg Med. 2007;50:715-721.

4. Kerns J, Arundel C, Chawla LS. Thiamin deficiency in people with obesity. Adv Nutr. 2015;6:147-153.

5. Latt N, Dore G. Thiamine in the treatment of Wernicke encephalopathy in patients with alcohol use disorders. Intern Med J. 2014;44:911-915.

6. Wilson DA, Xu W, Sadrian B, et al. Cortical odor processing in health and disease. Prog Brain Res. 2014;208:275-305.

7. Isenberg-Grzeda E, Kutner HE, Nicolson SE. Wernicke-Korsakoff syndrome: under-recognized and under-treated. Psychosomatics. 2012;53:507-516.

1. Doshi S, Velpandian T, Seth S, et al. Prevalence of thiamine deficiency in heart failure patients on long-term diuretic therapy. J Prac Cardiovasc Sci. 2015;1:25-29.

2. Caine D, Halliday GM, Kril JJ, et al. Operational criteria for the classification of chronic alcoholics: identification of Wernicke’s encephalopathy. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1997;62:51-60.

3. Donnino MW, Vega J, Miller J, et al. Myths and misconceptions of Wernicke’s encephalopathy: what every emergency physician should know. Ann Emerg Med. 2007;50:715-721.

4. Kerns J, Arundel C, Chawla LS. Thiamin deficiency in people with obesity. Adv Nutr. 2015;6:147-153.

5. Latt N, Dore G. Thiamine in the treatment of Wernicke encephalopathy in patients with alcohol use disorders. Intern Med J. 2014;44:911-915.

6. Wilson DA, Xu W, Sadrian B, et al. Cortical odor processing in health and disease. Prog Brain Res. 2014;208:275-305.

7. Isenberg-Grzeda E, Kutner HE, Nicolson SE. Wernicke-Korsakoff syndrome: under-recognized and under-treated. Psychosomatics. 2012;53:507-516.

Adult-Onset Still Disease: Persistent Pruritic Papular Rash With Unique Histopathologic Findings

Adult-onset Still disease (AOSD) is a systemic inflammatory condition that clinically manifests as spiking fevers, arthralgia, evanescent skin rash, and lymphadenopathy. 1 The most commonly used criteria for diagnosing AOSD are the Yamaguchi criteria. 2 The major criteria include high fever for more than 1 week, arthralgia for more than 2 weeks, leukocytosis, and an evanescent skin rash. The minor criteria consist of sore throat, lymphadenopathy and/or splenomegaly, liver dysfunction, and negative rheumatoid factor and antinuclear antibodies. Classically, the skin rash is described as an evanescent, salmon-colored erythema involving the extremities. Nevertheless, unusual cutaneous eruptions have been reported in AOSD, including persistent pruritic papules and plaques. 3 Importantly, this atypical rash demonstrates specific histologic findings that are not found on routine histopathology of a typical evanescent rash. We describe 2 patients with this atypical cutaneous eruption along with the unique histopathologic findings of AOSD.

Case Reports

Patient 1

A 23-year-old Chinese woman presented with periodic fevers, persistent rash, and joint pain of 2 years’ duration. Her medical history included splenectomy for hepatosplenomegaly as well as evaluation by hematology for lymphadenopathy; a cervical lymph node biopsy showed lymphoid and follicular hyperplasia.

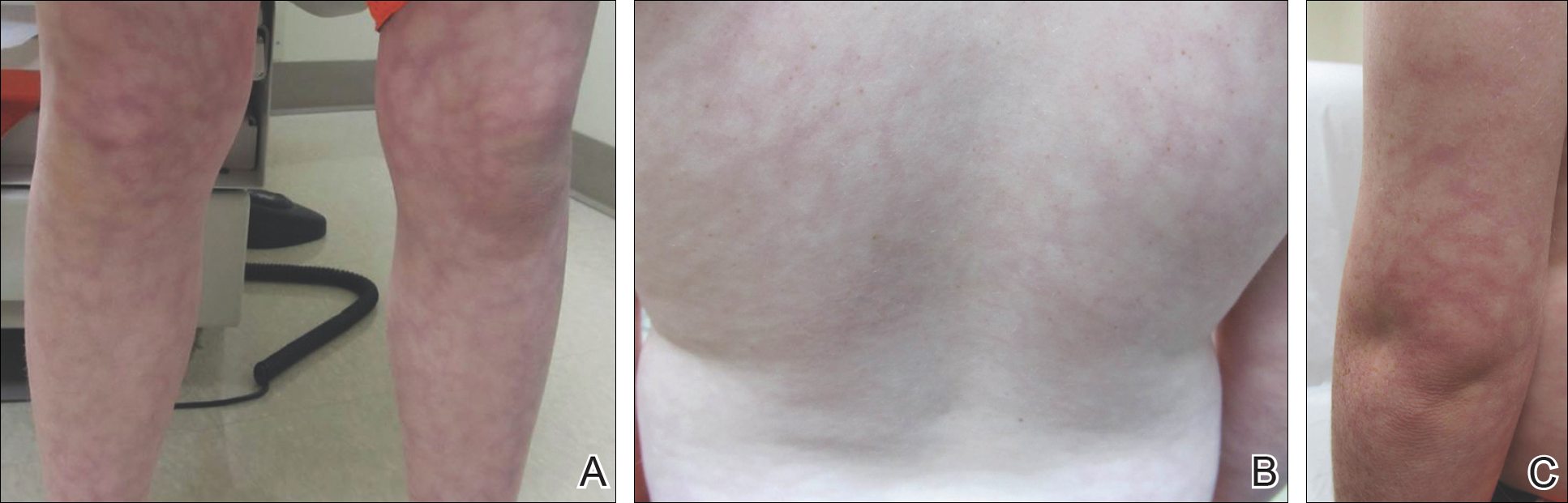

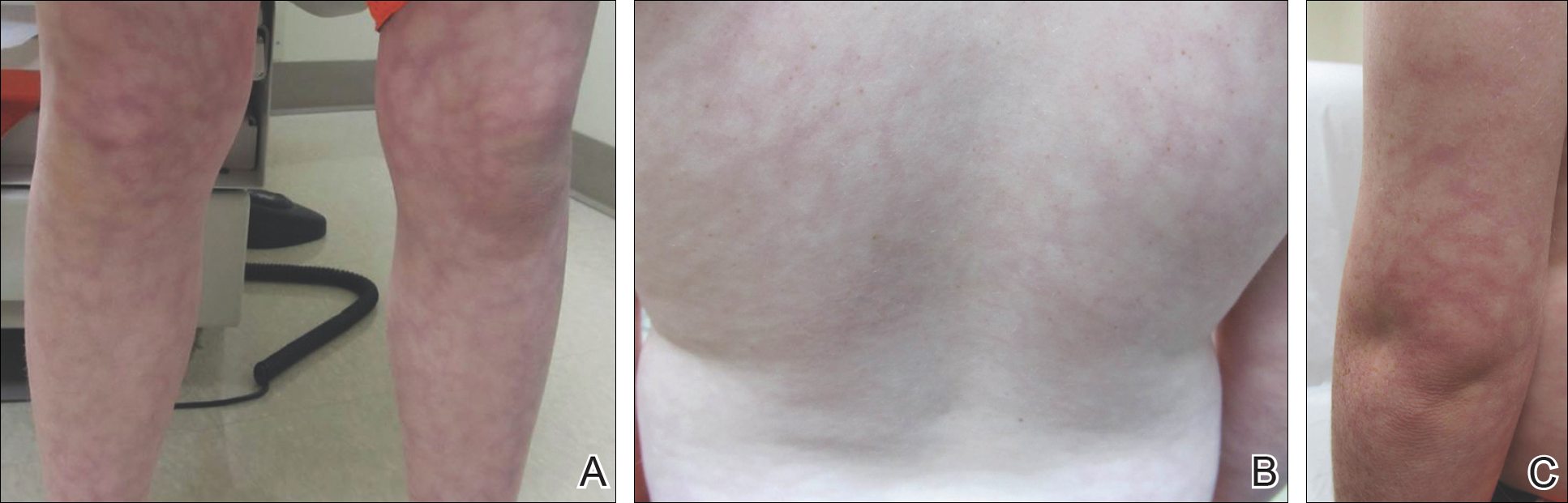

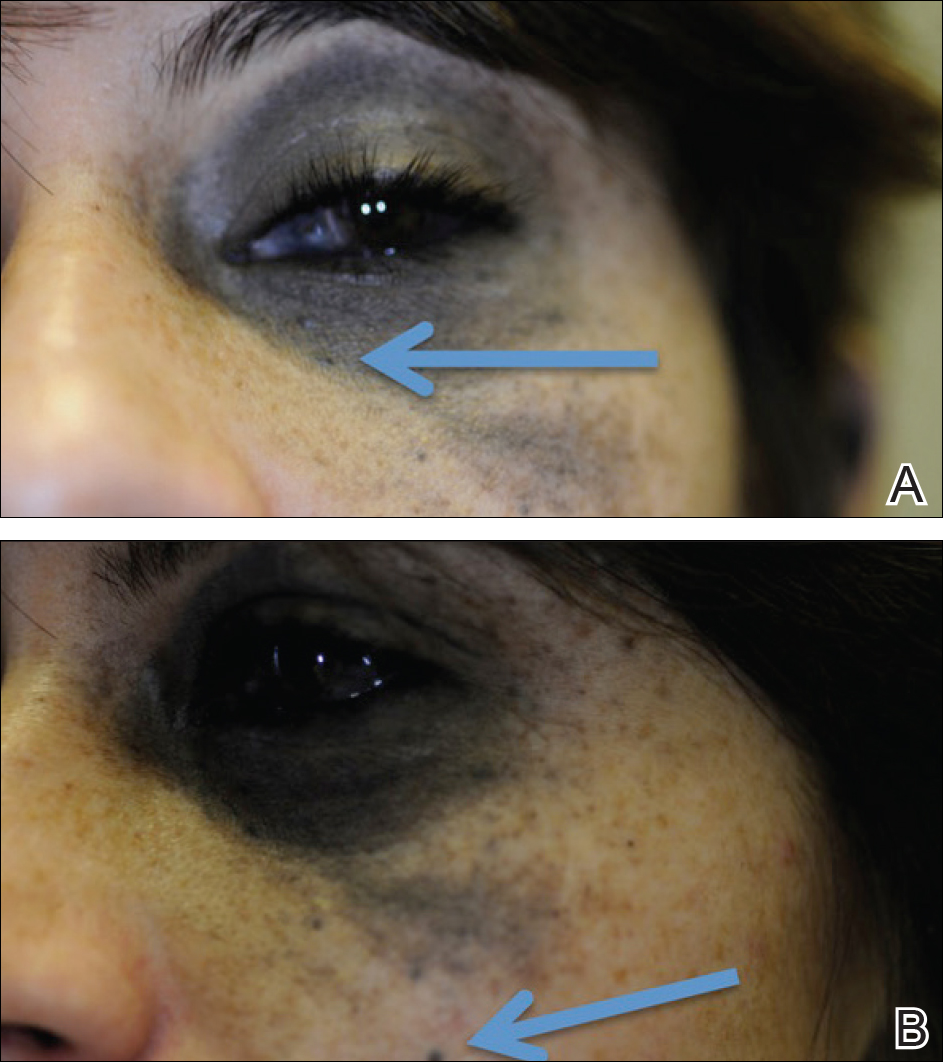

Twenty days later, the patient was referred to the dermatology department for evaluation of the persistent rash. The patient described a history of flushing of the face, severe joint pain in both arms and legs, aching muscles, and persistent sore throat. The patient did not report any history of drug ingestion. Physical examination revealed a fever (temperature, 39.2°C); swollen nontender lymph nodes in the neck, axillae, and groin; and salmon-colored and hyperpigmented patches and thin plaques over the neck, chest, abdomen, and arms (Figure 1). A splenectomy scar also was noted. Peripheral blood was collected for laboratory analyses, which revealed transaminitis and moderate hyperferritinemia (Table). An autoimmune panel was negative for rheumatoid factor, antinuclear antibodies, and antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies. The patient was admitted to the hospital, and a skin biopsy was performed. Histology showed superficial dyskeratotic keratinocytes and sparse perivascular infiltration of neutrophils in the upper dermis (Figure 2).

The patient was diagnosed with AOSD based on fulfillment of the Yamaguchi criteria.2 She was treated with methylprednisolone 60 mg daily and was discharged 14 days later. At 16-month follow-up, the patient demonstrated complete resolution of symptoms with a maintenance dose of prednisolone (7.5 mg daily).

Patient 2

A 23-year-old black woman presented to the emergency department 3 months postpartum with recurrent high fevers, worsening joint pain, and persistent itchy rash of 2 months’ duration. The patient had no history of travel, autoimmune disease, or sick contacts. She occasionally took aspirin for joint pain. Physical examination revealed a fever (temperature, 39.1°C) along with hyperpigmented patches and thin scaly hyperpigmented papules coalescing into a poorly demarcated V-shaped plaque on the upper back and posterior neck, extending to the chest in a shawl-like distribution (Figure 3). Submental lymphadenopathy was present. The spleen was not palpable.

Peripheral blood was collected for laboratory analysis and demonstrated transaminitis and a markedly high ferritin level (Table). An autoimmune panel was negative for rheumatoid factor, antinuclear antibodies, and antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies. Skin biopsy was performed and demonstrated many necrotic keratinocytes, singly and in aggregates, distributed from the spinous layer to the stratum corneum. A neutrophilic infiltrate was present in the papillary dermis (Figure 4).

The patient met the Yamaguchi criteria and was subsequently diagnosed with AOSD. She was treated with intravenous methylprednisolone 20 mg every 8 hours and was discharged 1 week later on oral prednisone 60 mg daily to be tapered over a period of months. At 2-week follow-up, the patient continued to experience rash and joint pain; oral methotrexate 10 mg weekly was added to her regimen, as well as vitamin D, calcium, and folic acid supplementation. At the next 2-week follow-up the patient noted improvement in the rash as well as the joint pain, but both still persisted. Prednisone was decreased to 50 mg daily and methotrexate was increased to 15 mg weekly. The patient continued to show improvement over the subsequent 3 months, during which prednisone was tapered to 10 mg daily and methotrexate was increased to 20 mg weekly. The patient showed resolution of symptoms at 3-month follow-up on this regimen, with plans to continue the prednisone taper and maintain methotrexate dosing.

Comment

Adult-onset Still disease is a systemic inflammatory condition that clinically manifests as spiking fevers, arthralgia, salmon-pink evanescent erythema, and lymphadenopathy.2 The condition also can cause liver dysfunction, splenomegaly, pericarditis, pleuritis, renal dysfunction, and a reactive hemophagocytic syndrome.1 Furthermore, one review of the literature described an association with delayed-onset malignancy.4 Early diagnosis is important yet challenging, as AOSD is a diagnosis of exclusion. The Yamaguchi criteria are the most widely used method of diagnosis and demonstrate more than 90% sensitivity.In addition to the Yamaguchi criteria, marked hyperferritinemia is characteristic of AOSD and can act as an indicator of disease activity.5 Interestingly, both of our patients had elevated ferritin levels, with patient 2 showing marked elevation (Table). In both patients, all major criteria were fulfilled, except the typical skin rash.

The skin rash in AOSD, classically consisting of an evanescent, salmon-pink erythema predominantly involving the extremities, has been observed in up to 87% of AOSD patients.5 The histology of the typical evanescent rash is nonspecific, characterized by a relatively sparse, perivascular, mixed inflammatory infiltrate. Notably, other skin manifestations may be found in patients with AOSD.1,2,5-16 Persistent pruritic papules and plaques are the most commonly reported nonclassical rash, presenting as erythematous, slightly scaly papules and plaques with a linear configuration typically on the trunk.2 Both of our patients presented with this atypical eruption. Importantly, the histopathology of this unique rash displays distinctive features, which can aid in early diagnosis. Findings include dyskeratotic keratinocytes in the cornified layers as well as in the epidermis, and a sparse neutrophilic and/or lymphocytic infiltrate in the papillary dermis without vasculitis. These findings were evident in both histopathologic studies of our patients (Figures 2 and 4). Although not present in our patients, dermal mucin deposition has been demonstrated in some reports.1,13,15

A 2015 review of the literature yielded 30 cases of AOSD with pruritic persistent papules and plaques.4 The study confirmed a linear, erythematous or brown rash on the back and neck in the majority of cases. Histologic findings were congruent with those reported in our 2 cases: necrotic keratinocytes in the upper epidermis with a neutrophilic infiltrate in the upper dermis without vasculitis. Most patients showed rapid resolution of the rash and symptoms with the use of prednisone, prednisolone, or intravenous pulsed methylprednisolone. Interestingly, a range of presentations were noted, including prurigo pigmentosalike urticarial papules; lichenoid papules; and dermatographismlike, dermatomyositislike, and lichen amyloidosis–like rashes.4 In our report, patient 2 presented with a rash in a dermat-omyositislike shawl distribution. It has been suggested that patients with dermatomyositislike rashes require more potent immunotherapy as compared to patients with other rash morphologies.4 The need for methotrexate in addition to a prednisone taper in the clinical course of patient 2 lends further support to this observation.

Conclusion

A clinically and pathologically distinct form of cutaneous disease—AOSD with persistent pruritic papules and plaques—was observed in our 2 patients. These histopathologic findings facilitated timely diagnosis in both patients. A range of clinical morphologies may exist in AOSD, an awareness of which is paramount. Adult-onset Still disease should be included in the differential diagnosis of a dermatomyositislike presentation in a shawl distribution. Prompt diagnosis is essential to ensure adequate therapy.

- Yamamoto T. Cutaneous manifestations associated with adult-onset Still’s disease: important diagnostic values. Rheumatol Int. 2012;32:2233-2237.

- Yamaguchi M, Ohta A, Tsunematsu T, et al. Preliminary criteria for classification of adult Still’s disease. J Rheumatol. 1992;19:424-431.

- Lee JY, Yang CC, Hsu MM. Histopathology of persistent papules and plaques in adult-onset Still’s disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;52:1003-1008.

- Sun NZ, Brezinski EA, Berliner J, et al. Updates in adult-onset Still disease: atypical cutaneous manifestations and associates with delayed malignancy [published online June 6, 2015]. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;73:294-303.

- Schwarz-Eywill M, Heilig B, Bauer H, et al. Evaluation of serum ferritin as a marker for adult Still’s disease activity. Ann Rheum Dis. 1992;51:683-685.

- Ohta A, Yamaguchi M, Tsunematsu T, et al. Adult Still’s disease: a multicenter survey of Japanese patients. J Rheumatol. 1990;17:1058-1063.

- Kaur S, Bambery P, Dhar S. Persistent dermal plaque lesions in adult onset Still’s disease. Dermatology. 1994;188:241-242.

- Lübbe J, Hofer M, Chavaz P, et al. Adult onset Still’s disease with persistent plaques. Br J Dermatol. 1999;141:710-713.

- Suzuki K, Kimura Y, Aoki M, et al. Persistent plaques and linear pigmentation in adult-onset Still’s disease. Dermatology. 2001;202:333-335.

- Fujii K, Konishi K, Kanno Y, et al. Persistent generalized erythema in adult-onset Still’s disease. Int J Dermatol. 2003;42:824-825.

- Thien Huong NT, Pitche P, Minh Hoa T, et al. Persistent pigmented plaques in adult-onset Still’s disease. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 2005;132:693-696.

- Lee JY, Yang CC, Hsu MM. Histopathology of persistent papules and plaques in adult-onset Still’s disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;52:1003-1008.

- Wolgamot G, Yoo J, Hurst S, et al. Unique histopathologic findings in a patient with adult-onset Still’s disease. Am J Dermatopathol. 2007;49:194-196.

- Fortna RR, Gudjonsson JE, Seidel G, et al. Persistent pruritic papules and plaques: a characteristic histopathologic presentation seen in a subset of patients with adult-onset and juvenile Still’s disease. J Cutan Pathol. 2010;37:932-937.

- Yang CC, Lee JY, Liu MF, et al. Adult-onset Still’s disease with persistent skin eruption and fatal respiratory failure in a Taiwanese woman. Eur J Dermatol. 2006;16:593-594.

- Azeck AG, Littlewood SM. Adult-onset Still’s disease with atypical cutaneous features. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2005;19:360-363.

Adult-onset Still disease (AOSD) is a systemic inflammatory condition that clinically manifests as spiking fevers, arthralgia, evanescent skin rash, and lymphadenopathy. 1 The most commonly used criteria for diagnosing AOSD are the Yamaguchi criteria. 2 The major criteria include high fever for more than 1 week, arthralgia for more than 2 weeks, leukocytosis, and an evanescent skin rash. The minor criteria consist of sore throat, lymphadenopathy and/or splenomegaly, liver dysfunction, and negative rheumatoid factor and antinuclear antibodies. Classically, the skin rash is described as an evanescent, salmon-colored erythema involving the extremities. Nevertheless, unusual cutaneous eruptions have been reported in AOSD, including persistent pruritic papules and plaques. 3 Importantly, this atypical rash demonstrates specific histologic findings that are not found on routine histopathology of a typical evanescent rash. We describe 2 patients with this atypical cutaneous eruption along with the unique histopathologic findings of AOSD.

Case Reports

Patient 1

A 23-year-old Chinese woman presented with periodic fevers, persistent rash, and joint pain of 2 years’ duration. Her medical history included splenectomy for hepatosplenomegaly as well as evaluation by hematology for lymphadenopathy; a cervical lymph node biopsy showed lymphoid and follicular hyperplasia.

Twenty days later, the patient was referred to the dermatology department for evaluation of the persistent rash. The patient described a history of flushing of the face, severe joint pain in both arms and legs, aching muscles, and persistent sore throat. The patient did not report any history of drug ingestion. Physical examination revealed a fever (temperature, 39.2°C); swollen nontender lymph nodes in the neck, axillae, and groin; and salmon-colored and hyperpigmented patches and thin plaques over the neck, chest, abdomen, and arms (Figure 1). A splenectomy scar also was noted. Peripheral blood was collected for laboratory analyses, which revealed transaminitis and moderate hyperferritinemia (Table). An autoimmune panel was negative for rheumatoid factor, antinuclear antibodies, and antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies. The patient was admitted to the hospital, and a skin biopsy was performed. Histology showed superficial dyskeratotic keratinocytes and sparse perivascular infiltration of neutrophils in the upper dermis (Figure 2).

The patient was diagnosed with AOSD based on fulfillment of the Yamaguchi criteria.2 She was treated with methylprednisolone 60 mg daily and was discharged 14 days later. At 16-month follow-up, the patient demonstrated complete resolution of symptoms with a maintenance dose of prednisolone (7.5 mg daily).

Patient 2

A 23-year-old black woman presented to the emergency department 3 months postpartum with recurrent high fevers, worsening joint pain, and persistent itchy rash of 2 months’ duration. The patient had no history of travel, autoimmune disease, or sick contacts. She occasionally took aspirin for joint pain. Physical examination revealed a fever (temperature, 39.1°C) along with hyperpigmented patches and thin scaly hyperpigmented papules coalescing into a poorly demarcated V-shaped plaque on the upper back and posterior neck, extending to the chest in a shawl-like distribution (Figure 3). Submental lymphadenopathy was present. The spleen was not palpable.

Peripheral blood was collected for laboratory analysis and demonstrated transaminitis and a markedly high ferritin level (Table). An autoimmune panel was negative for rheumatoid factor, antinuclear antibodies, and antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies. Skin biopsy was performed and demonstrated many necrotic keratinocytes, singly and in aggregates, distributed from the spinous layer to the stratum corneum. A neutrophilic infiltrate was present in the papillary dermis (Figure 4).

The patient met the Yamaguchi criteria and was subsequently diagnosed with AOSD. She was treated with intravenous methylprednisolone 20 mg every 8 hours and was discharged 1 week later on oral prednisone 60 mg daily to be tapered over a period of months. At 2-week follow-up, the patient continued to experience rash and joint pain; oral methotrexate 10 mg weekly was added to her regimen, as well as vitamin D, calcium, and folic acid supplementation. At the next 2-week follow-up the patient noted improvement in the rash as well as the joint pain, but both still persisted. Prednisone was decreased to 50 mg daily and methotrexate was increased to 15 mg weekly. The patient continued to show improvement over the subsequent 3 months, during which prednisone was tapered to 10 mg daily and methotrexate was increased to 20 mg weekly. The patient showed resolution of symptoms at 3-month follow-up on this regimen, with plans to continue the prednisone taper and maintain methotrexate dosing.

Comment

Adult-onset Still disease is a systemic inflammatory condition that clinically manifests as spiking fevers, arthralgia, salmon-pink evanescent erythema, and lymphadenopathy.2 The condition also can cause liver dysfunction, splenomegaly, pericarditis, pleuritis, renal dysfunction, and a reactive hemophagocytic syndrome.1 Furthermore, one review of the literature described an association with delayed-onset malignancy.4 Early diagnosis is important yet challenging, as AOSD is a diagnosis of exclusion. The Yamaguchi criteria are the most widely used method of diagnosis and demonstrate more than 90% sensitivity.In addition to the Yamaguchi criteria, marked hyperferritinemia is characteristic of AOSD and can act as an indicator of disease activity.5 Interestingly, both of our patients had elevated ferritin levels, with patient 2 showing marked elevation (Table). In both patients, all major criteria were fulfilled, except the typical skin rash.

The skin rash in AOSD, classically consisting of an evanescent, salmon-pink erythema predominantly involving the extremities, has been observed in up to 87% of AOSD patients.5 The histology of the typical evanescent rash is nonspecific, characterized by a relatively sparse, perivascular, mixed inflammatory infiltrate. Notably, other skin manifestations may be found in patients with AOSD.1,2,5-16 Persistent pruritic papules and plaques are the most commonly reported nonclassical rash, presenting as erythematous, slightly scaly papules and plaques with a linear configuration typically on the trunk.2 Both of our patients presented with this atypical eruption. Importantly, the histopathology of this unique rash displays distinctive features, which can aid in early diagnosis. Findings include dyskeratotic keratinocytes in the cornified layers as well as in the epidermis, and a sparse neutrophilic and/or lymphocytic infiltrate in the papillary dermis without vasculitis. These findings were evident in both histopathologic studies of our patients (Figures 2 and 4). Although not present in our patients, dermal mucin deposition has been demonstrated in some reports.1,13,15

A 2015 review of the literature yielded 30 cases of AOSD with pruritic persistent papules and plaques.4 The study confirmed a linear, erythematous or brown rash on the back and neck in the majority of cases. Histologic findings were congruent with those reported in our 2 cases: necrotic keratinocytes in the upper epidermis with a neutrophilic infiltrate in the upper dermis without vasculitis. Most patients showed rapid resolution of the rash and symptoms with the use of prednisone, prednisolone, or intravenous pulsed methylprednisolone. Interestingly, a range of presentations were noted, including prurigo pigmentosalike urticarial papules; lichenoid papules; and dermatographismlike, dermatomyositislike, and lichen amyloidosis–like rashes.4 In our report, patient 2 presented with a rash in a dermat-omyositislike shawl distribution. It has been suggested that patients with dermatomyositislike rashes require more potent immunotherapy as compared to patients with other rash morphologies.4 The need for methotrexate in addition to a prednisone taper in the clinical course of patient 2 lends further support to this observation.

Conclusion

A clinically and pathologically distinct form of cutaneous disease—AOSD with persistent pruritic papules and plaques—was observed in our 2 patients. These histopathologic findings facilitated timely diagnosis in both patients. A range of clinical morphologies may exist in AOSD, an awareness of which is paramount. Adult-onset Still disease should be included in the differential diagnosis of a dermatomyositislike presentation in a shawl distribution. Prompt diagnosis is essential to ensure adequate therapy.

Adult-onset Still disease (AOSD) is a systemic inflammatory condition that clinically manifests as spiking fevers, arthralgia, evanescent skin rash, and lymphadenopathy. 1 The most commonly used criteria for diagnosing AOSD are the Yamaguchi criteria. 2 The major criteria include high fever for more than 1 week, arthralgia for more than 2 weeks, leukocytosis, and an evanescent skin rash. The minor criteria consist of sore throat, lymphadenopathy and/or splenomegaly, liver dysfunction, and negative rheumatoid factor and antinuclear antibodies. Classically, the skin rash is described as an evanescent, salmon-colored erythema involving the extremities. Nevertheless, unusual cutaneous eruptions have been reported in AOSD, including persistent pruritic papules and plaques. 3 Importantly, this atypical rash demonstrates specific histologic findings that are not found on routine histopathology of a typical evanescent rash. We describe 2 patients with this atypical cutaneous eruption along with the unique histopathologic findings of AOSD.

Case Reports

Patient 1

A 23-year-old Chinese woman presented with periodic fevers, persistent rash, and joint pain of 2 years’ duration. Her medical history included splenectomy for hepatosplenomegaly as well as evaluation by hematology for lymphadenopathy; a cervical lymph node biopsy showed lymphoid and follicular hyperplasia.

Twenty days later, the patient was referred to the dermatology department for evaluation of the persistent rash. The patient described a history of flushing of the face, severe joint pain in both arms and legs, aching muscles, and persistent sore throat. The patient did not report any history of drug ingestion. Physical examination revealed a fever (temperature, 39.2°C); swollen nontender lymph nodes in the neck, axillae, and groin; and salmon-colored and hyperpigmented patches and thin plaques over the neck, chest, abdomen, and arms (Figure 1). A splenectomy scar also was noted. Peripheral blood was collected for laboratory analyses, which revealed transaminitis and moderate hyperferritinemia (Table). An autoimmune panel was negative for rheumatoid factor, antinuclear antibodies, and antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies. The patient was admitted to the hospital, and a skin biopsy was performed. Histology showed superficial dyskeratotic keratinocytes and sparse perivascular infiltration of neutrophils in the upper dermis (Figure 2).

The patient was diagnosed with AOSD based on fulfillment of the Yamaguchi criteria.2 She was treated with methylprednisolone 60 mg daily and was discharged 14 days later. At 16-month follow-up, the patient demonstrated complete resolution of symptoms with a maintenance dose of prednisolone (7.5 mg daily).

Patient 2

A 23-year-old black woman presented to the emergency department 3 months postpartum with recurrent high fevers, worsening joint pain, and persistent itchy rash of 2 months’ duration. The patient had no history of travel, autoimmune disease, or sick contacts. She occasionally took aspirin for joint pain. Physical examination revealed a fever (temperature, 39.1°C) along with hyperpigmented patches and thin scaly hyperpigmented papules coalescing into a poorly demarcated V-shaped plaque on the upper back and posterior neck, extending to the chest in a shawl-like distribution (Figure 3). Submental lymphadenopathy was present. The spleen was not palpable.

Peripheral blood was collected for laboratory analysis and demonstrated transaminitis and a markedly high ferritin level (Table). An autoimmune panel was negative for rheumatoid factor, antinuclear antibodies, and antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies. Skin biopsy was performed and demonstrated many necrotic keratinocytes, singly and in aggregates, distributed from the spinous layer to the stratum corneum. A neutrophilic infiltrate was present in the papillary dermis (Figure 4).

The patient met the Yamaguchi criteria and was subsequently diagnosed with AOSD. She was treated with intravenous methylprednisolone 20 mg every 8 hours and was discharged 1 week later on oral prednisone 60 mg daily to be tapered over a period of months. At 2-week follow-up, the patient continued to experience rash and joint pain; oral methotrexate 10 mg weekly was added to her regimen, as well as vitamin D, calcium, and folic acid supplementation. At the next 2-week follow-up the patient noted improvement in the rash as well as the joint pain, but both still persisted. Prednisone was decreased to 50 mg daily and methotrexate was increased to 15 mg weekly. The patient continued to show improvement over the subsequent 3 months, during which prednisone was tapered to 10 mg daily and methotrexate was increased to 20 mg weekly. The patient showed resolution of symptoms at 3-month follow-up on this regimen, with plans to continue the prednisone taper and maintain methotrexate dosing.

Comment

Adult-onset Still disease is a systemic inflammatory condition that clinically manifests as spiking fevers, arthralgia, salmon-pink evanescent erythema, and lymphadenopathy.2 The condition also can cause liver dysfunction, splenomegaly, pericarditis, pleuritis, renal dysfunction, and a reactive hemophagocytic syndrome.1 Furthermore, one review of the literature described an association with delayed-onset malignancy.4 Early diagnosis is important yet challenging, as AOSD is a diagnosis of exclusion. The Yamaguchi criteria are the most widely used method of diagnosis and demonstrate more than 90% sensitivity.In addition to the Yamaguchi criteria, marked hyperferritinemia is characteristic of AOSD and can act as an indicator of disease activity.5 Interestingly, both of our patients had elevated ferritin levels, with patient 2 showing marked elevation (Table). In both patients, all major criteria were fulfilled, except the typical skin rash.

The skin rash in AOSD, classically consisting of an evanescent, salmon-pink erythema predominantly involving the extremities, has been observed in up to 87% of AOSD patients.5 The histology of the typical evanescent rash is nonspecific, characterized by a relatively sparse, perivascular, mixed inflammatory infiltrate. Notably, other skin manifestations may be found in patients with AOSD.1,2,5-16 Persistent pruritic papules and plaques are the most commonly reported nonclassical rash, presenting as erythematous, slightly scaly papules and plaques with a linear configuration typically on the trunk.2 Both of our patients presented with this atypical eruption. Importantly, the histopathology of this unique rash displays distinctive features, which can aid in early diagnosis. Findings include dyskeratotic keratinocytes in the cornified layers as well as in the epidermis, and a sparse neutrophilic and/or lymphocytic infiltrate in the papillary dermis without vasculitis. These findings were evident in both histopathologic studies of our patients (Figures 2 and 4). Although not present in our patients, dermal mucin deposition has been demonstrated in some reports.1,13,15