User login

An Imposter Twice Over: A Case of IgG4-Related Disease

Immunoglobulin G4-related disease (IgG4-RD) is an immune-mediated fibroinflammatory condition that involves multiple organs and appears as syndromes that were once thought to be unrelated. This disease leads to mass lesions, fibrosis, and subsequent organ failure if allowed to progress untreated.1 Involvement of gastrointestinal (GI) organs, salivary glands, lacrimal glands, lymph, prostate, pulmonary, and vascular system have all been reported.2 Elevated IgG4 serum levels are common, but about one-third of patients with biopsy-proven IgG4-RD do not manifest this characteristic.3,4

Diagnostic confirmation is with biopsy, and all patients with symptomatic, active IgG4-RD require treatment. Glucocorticoids are first-line treatment and are utilized for relapse of symptoms. In addition to glucocorticoids, steroid-sparing medications, including rituximab, azathioprine, mycophenolate mofetil, tacrolimus, and cyclophosphamide have all been used with successful remission.5,6 Here, the authors discuss a case of IgG4-RD that presented with intrahepatic biliary obstruction (mimicking cholangiocarcinoma) and subsequent development of coronary arteritis despite treatment.

Case Presentation

In June 2015, a 57-year-old Air Force veteran presented to Eglin AFB Hospital with pruritic jaundice and acute abdominal pain. He was found to have elevated bilirubin levels (total bilirubin 10 mg/dL [normal range 0.2-1.3 mg/dL], direct bilirubin 6.6 mg/dL [normal range 0.1-0.4 mg/dL]). Alanine aminotransferase (ALT) and aspartate aminotransferase (AST) also were moderately elevated (147 U/L and 337 U/L, respectively).

Prior to this presentation, the patient had been in his usual state of health. His past medical history was notable only for minimal change kidney disease (MCD). MCD is defined as effacement of the podocyte seen on electron microscopy, which allows the passage of large amounts of protein.

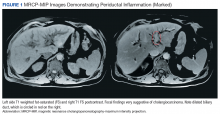

A cholangiogram showed abnormal filling into the left main intrahepatic duct and obvious obstruction at the bifurcation of the bile duct. A biliary drainage catheter was placed, and a repeat cholangiogram 2 days later showed involvement of both right and left intrahepatic ducts. The distal common bile duct appeared uninvolved as did the pancreas. Lymphadenopathy was noted at the liver hilum. Klatskin cholangiocarcinoma (type IIIB) was the presumed diagnosis. Based on these findings, tumor resection was performed 3 weeks later, including left hepatectomy, caudate lobe resection, complete bile duct resection, cholecystectomy, with reconstruction by Roux-en-Y intrahepaticojejunostomy. In addition, portal and hepatic artery lymph node dissection was completed.

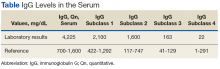

Surgical specimens were sent for pathologic evaluation and were found negative for malignancy. Patchy areas of storiform fibrosis, obliterative phlebitis, and lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate were noted. IgG4 immunostain highlighted the presence of IgG4 positive plasma cells with a peak count of 145 IgG4 positive plasma cells/hpf. About 80% of the plasma cells were positive for IgG4. Unusually dense eosinophilic infiltrate with plasma cells and regions of dense fibrosis that strongly contributed to the masslike appearance on CT imaging also were noted. Final histology confirmed the diagnosis of IgG4-RD. Elevated levels of total IgG in the serum were observed without elevation in serum IgG4 (Table).

The patient was started on prednisone 40 mg and azathioprine 150 mg daily, with subsequent taper of prednisone over the next 6 months. After prednisone was discontinued, the patient reported new symptoms of lower extremity pain, neuropathy, and swelling of his face. Laboratory results were notable for elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate. The patient was restarted on prednisone 40 mg daily. Azathioprine was replaced with a regimen of 4 doses every 6 months of IV rituximab 700 mg q week and mycophenolate mofetil (1,000 mg bid). After remission was induced, the patient was slowly weaned off prednisone again.

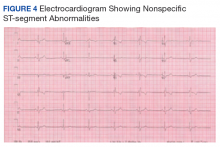

Following 6 months of successful discontinuation of prednisone and continued rituximab and mycophenolate mofetil therapy, the patient presented to the emergency department with new onset chest pain and shortness of breath. A CT angiography of the chest showed right upper and middle lobe infiltrate, and he was treated for community acquired pneumonia. Additionally, he was noted to have elevated troponin levels suggestive of myocardial infarction (MI). Initial troponin was 1.23 ng/mL (normal range < 0.015 ng/mL), which trended down over the next 18 hours. A bedside echocardiogram showed a normal left ventricular ejection fraction without wall motion abnormalities. Etiology for his acute MI was presumed to be demand ischemia from fixed atherosclerotic plaque. Further inpatient cardiac risk stratification was changed to the outpatient setting, and he was started on medical management for coronary artery disease with a beta blocker, a statin, and aspirin. He was discharged home on 10 mg prednisone daily, which was subsequently tapered over several weeks.

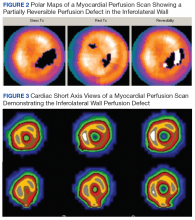

In follow-up, a Lexiscan myocardial perfusion imaging was conducted that demonstrated an inferolateral defect and associated wall motion abnormalities (Figures 2 and 3).

Discussion

IgG4-related disease has been found to be a systemic disorder. Typical characteristics include predominance in men aged > 50 years, elevated IgG4 levels, and findings on histology.1 It has been reported to involve many organs, including pancreas, liver, gallbladder, salivary glands, thyroid, and pleura of the lung.2,5

This case report begins with a presumptive diagnosis of cholangiocarcinoma, which was treated aggressively with extensive surgery. Several case reports of complex tumefactive lesions in the GI area (mostly pancreatic and biliary) have detailed IgG4-RD as both a risk factor for subsequent development of cholangiocarcinoma and as a separate entity of IgG4-related sclerosing cholangitis.7-9 It is hypothesized that the induction of IgG4- positive plasma cells has been intertwined with the development of cholangiocarcinoma. Differentiation between IgG4 reaction that is scattered around cancerous nests and IgG4 sclerosing cholangitis without malignancy is challenging. It has been documented that both elevated IgG4 levels and hilar hepatic lesions that resemble cholangiocarcinoma frequently accompany those cases of IgG4 sclerosing chlolangitis without pancreatic involvement.9 The histologic features of IgG4-RD need to be identified with multiple biopsies and cytology, and superficial biopsy from biliary mucosa cannot reliably exclude cholangiocarcinoma.

Lymphoplasmacytic aortitis and arteritis have been documented in IgG4-RD. In 2017, Barbu and colleagues described how one such case of coronary arteritis presented with typical angina and coronary catheterization revealing coronary artery stenosis.10 However, during coronary artery bypass surgery, the aorta and coronary vessels were noted to be abnormally stiff. A diffuse fibrotic tissue was identified to be causing the significant stenosis without evidence of atherosclerosis. Pathology showed typical findings of IgG4-RD, and there was a rapid response to immunosuppressive therapy. Involvement of coronary arteries has been described in a small number of cases at this time and is associated with progressive fibrotic changes resulting in an MI, aneurysms, and sudden cardiac death.2,10,11

IgG4-RD can be an extensively systemic disease. All presentations of fibrosis or vasculitis should be viewed with heightened suspicion in the future as being a facet of his IgG4-RD. Pleural involvement has been reported in 12% of cases presenting with systemic presentation, kidney involvement in 13%.2,12

Unfortunately, there is no standard laboratory parameter to date that is diagnostic for IgG4-RD. The gold standard remains confirmation of histologic findings with biopsy. According to an international consensus from 2015, 2 out of the 3 major findings need to be present: (1) dense lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate; (2) storiform fibrosis; and (3) obliterative phlebitis in veins and arteries.1,5 Most patients present with symptoms related to either tumefaction or fibrosis of an organ system.1 Peripheral eosinophilia and elevated serum IgE are often present in IgG4-RD.13 Although IgG4 values are elevated in 51% of biopsy-proven cases, flow cytometry of CD19lowCD38+CD20-CD27+ plasmablasts has been explored recently as a correlation with disease flare.3,14 These particular plasmablasts mark a stage between B cells and plasma cells and have been reported to have a sensitivity of 95% and a specificity of 82% in association with actual IgG4-RD.14 Furthermore, blood plasmablast concentrations decrease in response to glucocorticoid treatment, thereby providing a possible quantifiable value by which to measure success of IgG4 treatment.5,12

Treatment for this disease consists of immunosuppressive therapy. There is documentation of successful remission with rituximab and azathioprine, as well as methotrexate.1,5 Both 2015 consensus guidelines and a recent small single-center retrospective study support addition of second-line steroid sparing agents such as mycophenolate mofetil.5,6 For acute flairs, however, glucocorticoids with slow taper are usually utilized. In these cases, they should be tapered as soon as clinically feasible to avoid long-term adverse effects. Untreated IgG4-RD, even asymptomatic, has been shown to progress to fibrosis.5

Conclusion

IgG4-RD is a complicated disease process that requires a high index of suspicion to diagnose. In addition, for patients who are diagnosed with this condition, its ability to mimic other pathologic conditions should be taken into account with manifestation of any new illness. This case emphasizes the ability of this disease to localize in multiple organs over time and the need for lifetime surveillance in patients with IgG4-RD disease.

1. Lang D, Zwerina J, Pieringer H. IgG4-related disease: current challenges and future prospects. Ther Clin Risk Manag. 2016;12:189-199.

2. Brito-Zerón P, Ramos-Casals M, Bosch X, Stone JH. The clinical spectrum of IgG4-related disease. Autoimmun Rev. 2014;13(12):1203-1210.

3. Wallace ZS, Deshpande V, Mattoo H, et al. IgG4-related disease: clinical and laboratory features in one hundred twenty-five patients. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2015;67(9):2466-2475.

4. Carruthers MN, Khosroshahi A, Augustin T, Deshpande V, Stone JH. The diagnostic utility of serum IgG4 concentrations in IgG4-RD. Ann Rheum Dis. 2015;74(1):14-18.

5. Khosroshahi A, Wallace ZS, Crowe JL, et al; Second International Symposium on IgG4-Related Disease. International consensus guidance statement on the management and treatment of IgG4-Related disease. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2015;67(7):1688-1699.

6. Gupta N, Mathew J, Mohan H, et al. Addition of second-line steroid sparing immunosuppressants like mycophenolate mofetil improves outcome of immunoglobulin G4-related disease (IgG4-RD): a series from a tertiary care teaching hospital in South India. Rheumatol Int. 2017;38(2):203-209.

7. Lin HP, Lin KT, Ho WC, Chen CB, Kuo, CY, Lin YC. IgG4-associated cholangitis mimicking cholangiocarcinoma-report of a case. J Intern Med Taiwan. 2013;24:137-141.

8. Douhara A, Mitoro A, Otani E, et al. Cholangiocarcinoma developed in a patient with IgG4-related disease. World J Gastrointest Oncol. 2013;5(8):181-185.

9. Harada K, Nakanuma Y. Cholangiocarcinoma with respect to IgG4 reaction. Int J Hepatol. 2014;2014:803876.

10. Barbu M, Lindström U, Nordborg C, Martinsson A, Dworeck C, Jeppsson A. Sclerosing aortic and coronary arteritis due to IgG4-related disease. Ann Thorac Surg. 2017;103(6):e487-e489.

11. Kim YJ, Park YS, Koo BS, et al. Immunoglobulin G4-related disease with lymphoplasmacytic aortitis mimicking Takayasu arteritis. J Clin Rheumatol. 2011;17(8):451-452.

12. Khosroshahi A, Digumarthy SR, Gibbons FK, Deshpande V. Case 34-2015: A 36-year-old woman with a lung mass, pleural effusion and hip pain. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(18):1762-1772.

13. Della Torre E, Mattoo H, Mahajan VS, Carruthers M, Pillai S, Stone JH. Prevalence of atopy, eosinophilia and IgE elevation in IgG4-related disease. Allergy. 2014;69(2):191-206.

14. Wallace ZS, Mattoo H, Carruthers M, et al. Plasmablasts as a biomarker for IgG4-related disease, independent of serum IgG4 concentrations. Ann Rheum Dis. 2015;74(1):190-195.

Immunoglobulin G4-related disease (IgG4-RD) is an immune-mediated fibroinflammatory condition that involves multiple organs and appears as syndromes that were once thought to be unrelated. This disease leads to mass lesions, fibrosis, and subsequent organ failure if allowed to progress untreated.1 Involvement of gastrointestinal (GI) organs, salivary glands, lacrimal glands, lymph, prostate, pulmonary, and vascular system have all been reported.2 Elevated IgG4 serum levels are common, but about one-third of patients with biopsy-proven IgG4-RD do not manifest this characteristic.3,4

Diagnostic confirmation is with biopsy, and all patients with symptomatic, active IgG4-RD require treatment. Glucocorticoids are first-line treatment and are utilized for relapse of symptoms. In addition to glucocorticoids, steroid-sparing medications, including rituximab, azathioprine, mycophenolate mofetil, tacrolimus, and cyclophosphamide have all been used with successful remission.5,6 Here, the authors discuss a case of IgG4-RD that presented with intrahepatic biliary obstruction (mimicking cholangiocarcinoma) and subsequent development of coronary arteritis despite treatment.

Case Presentation

In June 2015, a 57-year-old Air Force veteran presented to Eglin AFB Hospital with pruritic jaundice and acute abdominal pain. He was found to have elevated bilirubin levels (total bilirubin 10 mg/dL [normal range 0.2-1.3 mg/dL], direct bilirubin 6.6 mg/dL [normal range 0.1-0.4 mg/dL]). Alanine aminotransferase (ALT) and aspartate aminotransferase (AST) also were moderately elevated (147 U/L and 337 U/L, respectively).

Prior to this presentation, the patient had been in his usual state of health. His past medical history was notable only for minimal change kidney disease (MCD). MCD is defined as effacement of the podocyte seen on electron microscopy, which allows the passage of large amounts of protein.

A cholangiogram showed abnormal filling into the left main intrahepatic duct and obvious obstruction at the bifurcation of the bile duct. A biliary drainage catheter was placed, and a repeat cholangiogram 2 days later showed involvement of both right and left intrahepatic ducts. The distal common bile duct appeared uninvolved as did the pancreas. Lymphadenopathy was noted at the liver hilum. Klatskin cholangiocarcinoma (type IIIB) was the presumed diagnosis. Based on these findings, tumor resection was performed 3 weeks later, including left hepatectomy, caudate lobe resection, complete bile duct resection, cholecystectomy, with reconstruction by Roux-en-Y intrahepaticojejunostomy. In addition, portal and hepatic artery lymph node dissection was completed.

Surgical specimens were sent for pathologic evaluation and were found negative for malignancy. Patchy areas of storiform fibrosis, obliterative phlebitis, and lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate were noted. IgG4 immunostain highlighted the presence of IgG4 positive plasma cells with a peak count of 145 IgG4 positive plasma cells/hpf. About 80% of the plasma cells were positive for IgG4. Unusually dense eosinophilic infiltrate with plasma cells and regions of dense fibrosis that strongly contributed to the masslike appearance on CT imaging also were noted. Final histology confirmed the diagnosis of IgG4-RD. Elevated levels of total IgG in the serum were observed without elevation in serum IgG4 (Table).

The patient was started on prednisone 40 mg and azathioprine 150 mg daily, with subsequent taper of prednisone over the next 6 months. After prednisone was discontinued, the patient reported new symptoms of lower extremity pain, neuropathy, and swelling of his face. Laboratory results were notable for elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate. The patient was restarted on prednisone 40 mg daily. Azathioprine was replaced with a regimen of 4 doses every 6 months of IV rituximab 700 mg q week and mycophenolate mofetil (1,000 mg bid). After remission was induced, the patient was slowly weaned off prednisone again.

Following 6 months of successful discontinuation of prednisone and continued rituximab and mycophenolate mofetil therapy, the patient presented to the emergency department with new onset chest pain and shortness of breath. A CT angiography of the chest showed right upper and middle lobe infiltrate, and he was treated for community acquired pneumonia. Additionally, he was noted to have elevated troponin levels suggestive of myocardial infarction (MI). Initial troponin was 1.23 ng/mL (normal range < 0.015 ng/mL), which trended down over the next 18 hours. A bedside echocardiogram showed a normal left ventricular ejection fraction without wall motion abnormalities. Etiology for his acute MI was presumed to be demand ischemia from fixed atherosclerotic plaque. Further inpatient cardiac risk stratification was changed to the outpatient setting, and he was started on medical management for coronary artery disease with a beta blocker, a statin, and aspirin. He was discharged home on 10 mg prednisone daily, which was subsequently tapered over several weeks.

In follow-up, a Lexiscan myocardial perfusion imaging was conducted that demonstrated an inferolateral defect and associated wall motion abnormalities (Figures 2 and 3).

Discussion

IgG4-related disease has been found to be a systemic disorder. Typical characteristics include predominance in men aged > 50 years, elevated IgG4 levels, and findings on histology.1 It has been reported to involve many organs, including pancreas, liver, gallbladder, salivary glands, thyroid, and pleura of the lung.2,5

This case report begins with a presumptive diagnosis of cholangiocarcinoma, which was treated aggressively with extensive surgery. Several case reports of complex tumefactive lesions in the GI area (mostly pancreatic and biliary) have detailed IgG4-RD as both a risk factor for subsequent development of cholangiocarcinoma and as a separate entity of IgG4-related sclerosing cholangitis.7-9 It is hypothesized that the induction of IgG4- positive plasma cells has been intertwined with the development of cholangiocarcinoma. Differentiation between IgG4 reaction that is scattered around cancerous nests and IgG4 sclerosing cholangitis without malignancy is challenging. It has been documented that both elevated IgG4 levels and hilar hepatic lesions that resemble cholangiocarcinoma frequently accompany those cases of IgG4 sclerosing chlolangitis without pancreatic involvement.9 The histologic features of IgG4-RD need to be identified with multiple biopsies and cytology, and superficial biopsy from biliary mucosa cannot reliably exclude cholangiocarcinoma.

Lymphoplasmacytic aortitis and arteritis have been documented in IgG4-RD. In 2017, Barbu and colleagues described how one such case of coronary arteritis presented with typical angina and coronary catheterization revealing coronary artery stenosis.10 However, during coronary artery bypass surgery, the aorta and coronary vessels were noted to be abnormally stiff. A diffuse fibrotic tissue was identified to be causing the significant stenosis without evidence of atherosclerosis. Pathology showed typical findings of IgG4-RD, and there was a rapid response to immunosuppressive therapy. Involvement of coronary arteries has been described in a small number of cases at this time and is associated with progressive fibrotic changes resulting in an MI, aneurysms, and sudden cardiac death.2,10,11

IgG4-RD can be an extensively systemic disease. All presentations of fibrosis or vasculitis should be viewed with heightened suspicion in the future as being a facet of his IgG4-RD. Pleural involvement has been reported in 12% of cases presenting with systemic presentation, kidney involvement in 13%.2,12

Unfortunately, there is no standard laboratory parameter to date that is diagnostic for IgG4-RD. The gold standard remains confirmation of histologic findings with biopsy. According to an international consensus from 2015, 2 out of the 3 major findings need to be present: (1) dense lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate; (2) storiform fibrosis; and (3) obliterative phlebitis in veins and arteries.1,5 Most patients present with symptoms related to either tumefaction or fibrosis of an organ system.1 Peripheral eosinophilia and elevated serum IgE are often present in IgG4-RD.13 Although IgG4 values are elevated in 51% of biopsy-proven cases, flow cytometry of CD19lowCD38+CD20-CD27+ plasmablasts has been explored recently as a correlation with disease flare.3,14 These particular plasmablasts mark a stage between B cells and plasma cells and have been reported to have a sensitivity of 95% and a specificity of 82% in association with actual IgG4-RD.14 Furthermore, blood plasmablast concentrations decrease in response to glucocorticoid treatment, thereby providing a possible quantifiable value by which to measure success of IgG4 treatment.5,12

Treatment for this disease consists of immunosuppressive therapy. There is documentation of successful remission with rituximab and azathioprine, as well as methotrexate.1,5 Both 2015 consensus guidelines and a recent small single-center retrospective study support addition of second-line steroid sparing agents such as mycophenolate mofetil.5,6 For acute flairs, however, glucocorticoids with slow taper are usually utilized. In these cases, they should be tapered as soon as clinically feasible to avoid long-term adverse effects. Untreated IgG4-RD, even asymptomatic, has been shown to progress to fibrosis.5

Conclusion

IgG4-RD is a complicated disease process that requires a high index of suspicion to diagnose. In addition, for patients who are diagnosed with this condition, its ability to mimic other pathologic conditions should be taken into account with manifestation of any new illness. This case emphasizes the ability of this disease to localize in multiple organs over time and the need for lifetime surveillance in patients with IgG4-RD disease.

Immunoglobulin G4-related disease (IgG4-RD) is an immune-mediated fibroinflammatory condition that involves multiple organs and appears as syndromes that were once thought to be unrelated. This disease leads to mass lesions, fibrosis, and subsequent organ failure if allowed to progress untreated.1 Involvement of gastrointestinal (GI) organs, salivary glands, lacrimal glands, lymph, prostate, pulmonary, and vascular system have all been reported.2 Elevated IgG4 serum levels are common, but about one-third of patients with biopsy-proven IgG4-RD do not manifest this characteristic.3,4

Diagnostic confirmation is with biopsy, and all patients with symptomatic, active IgG4-RD require treatment. Glucocorticoids are first-line treatment and are utilized for relapse of symptoms. In addition to glucocorticoids, steroid-sparing medications, including rituximab, azathioprine, mycophenolate mofetil, tacrolimus, and cyclophosphamide have all been used with successful remission.5,6 Here, the authors discuss a case of IgG4-RD that presented with intrahepatic biliary obstruction (mimicking cholangiocarcinoma) and subsequent development of coronary arteritis despite treatment.

Case Presentation

In June 2015, a 57-year-old Air Force veteran presented to Eglin AFB Hospital with pruritic jaundice and acute abdominal pain. He was found to have elevated bilirubin levels (total bilirubin 10 mg/dL [normal range 0.2-1.3 mg/dL], direct bilirubin 6.6 mg/dL [normal range 0.1-0.4 mg/dL]). Alanine aminotransferase (ALT) and aspartate aminotransferase (AST) also were moderately elevated (147 U/L and 337 U/L, respectively).

Prior to this presentation, the patient had been in his usual state of health. His past medical history was notable only for minimal change kidney disease (MCD). MCD is defined as effacement of the podocyte seen on electron microscopy, which allows the passage of large amounts of protein.

A cholangiogram showed abnormal filling into the left main intrahepatic duct and obvious obstruction at the bifurcation of the bile duct. A biliary drainage catheter was placed, and a repeat cholangiogram 2 days later showed involvement of both right and left intrahepatic ducts. The distal common bile duct appeared uninvolved as did the pancreas. Lymphadenopathy was noted at the liver hilum. Klatskin cholangiocarcinoma (type IIIB) was the presumed diagnosis. Based on these findings, tumor resection was performed 3 weeks later, including left hepatectomy, caudate lobe resection, complete bile duct resection, cholecystectomy, with reconstruction by Roux-en-Y intrahepaticojejunostomy. In addition, portal and hepatic artery lymph node dissection was completed.

Surgical specimens were sent for pathologic evaluation and were found negative for malignancy. Patchy areas of storiform fibrosis, obliterative phlebitis, and lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate were noted. IgG4 immunostain highlighted the presence of IgG4 positive plasma cells with a peak count of 145 IgG4 positive plasma cells/hpf. About 80% of the plasma cells were positive for IgG4. Unusually dense eosinophilic infiltrate with plasma cells and regions of dense fibrosis that strongly contributed to the masslike appearance on CT imaging also were noted. Final histology confirmed the diagnosis of IgG4-RD. Elevated levels of total IgG in the serum were observed without elevation in serum IgG4 (Table).

The patient was started on prednisone 40 mg and azathioprine 150 mg daily, with subsequent taper of prednisone over the next 6 months. After prednisone was discontinued, the patient reported new symptoms of lower extremity pain, neuropathy, and swelling of his face. Laboratory results were notable for elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate. The patient was restarted on prednisone 40 mg daily. Azathioprine was replaced with a regimen of 4 doses every 6 months of IV rituximab 700 mg q week and mycophenolate mofetil (1,000 mg bid). After remission was induced, the patient was slowly weaned off prednisone again.

Following 6 months of successful discontinuation of prednisone and continued rituximab and mycophenolate mofetil therapy, the patient presented to the emergency department with new onset chest pain and shortness of breath. A CT angiography of the chest showed right upper and middle lobe infiltrate, and he was treated for community acquired pneumonia. Additionally, he was noted to have elevated troponin levels suggestive of myocardial infarction (MI). Initial troponin was 1.23 ng/mL (normal range < 0.015 ng/mL), which trended down over the next 18 hours. A bedside echocardiogram showed a normal left ventricular ejection fraction without wall motion abnormalities. Etiology for his acute MI was presumed to be demand ischemia from fixed atherosclerotic plaque. Further inpatient cardiac risk stratification was changed to the outpatient setting, and he was started on medical management for coronary artery disease with a beta blocker, a statin, and aspirin. He was discharged home on 10 mg prednisone daily, which was subsequently tapered over several weeks.

In follow-up, a Lexiscan myocardial perfusion imaging was conducted that demonstrated an inferolateral defect and associated wall motion abnormalities (Figures 2 and 3).

Discussion

IgG4-related disease has been found to be a systemic disorder. Typical characteristics include predominance in men aged > 50 years, elevated IgG4 levels, and findings on histology.1 It has been reported to involve many organs, including pancreas, liver, gallbladder, salivary glands, thyroid, and pleura of the lung.2,5

This case report begins with a presumptive diagnosis of cholangiocarcinoma, which was treated aggressively with extensive surgery. Several case reports of complex tumefactive lesions in the GI area (mostly pancreatic and biliary) have detailed IgG4-RD as both a risk factor for subsequent development of cholangiocarcinoma and as a separate entity of IgG4-related sclerosing cholangitis.7-9 It is hypothesized that the induction of IgG4- positive plasma cells has been intertwined with the development of cholangiocarcinoma. Differentiation between IgG4 reaction that is scattered around cancerous nests and IgG4 sclerosing cholangitis without malignancy is challenging. It has been documented that both elevated IgG4 levels and hilar hepatic lesions that resemble cholangiocarcinoma frequently accompany those cases of IgG4 sclerosing chlolangitis without pancreatic involvement.9 The histologic features of IgG4-RD need to be identified with multiple biopsies and cytology, and superficial biopsy from biliary mucosa cannot reliably exclude cholangiocarcinoma.

Lymphoplasmacytic aortitis and arteritis have been documented in IgG4-RD. In 2017, Barbu and colleagues described how one such case of coronary arteritis presented with typical angina and coronary catheterization revealing coronary artery stenosis.10 However, during coronary artery bypass surgery, the aorta and coronary vessels were noted to be abnormally stiff. A diffuse fibrotic tissue was identified to be causing the significant stenosis without evidence of atherosclerosis. Pathology showed typical findings of IgG4-RD, and there was a rapid response to immunosuppressive therapy. Involvement of coronary arteries has been described in a small number of cases at this time and is associated with progressive fibrotic changes resulting in an MI, aneurysms, and sudden cardiac death.2,10,11

IgG4-RD can be an extensively systemic disease. All presentations of fibrosis or vasculitis should be viewed with heightened suspicion in the future as being a facet of his IgG4-RD. Pleural involvement has been reported in 12% of cases presenting with systemic presentation, kidney involvement in 13%.2,12

Unfortunately, there is no standard laboratory parameter to date that is diagnostic for IgG4-RD. The gold standard remains confirmation of histologic findings with biopsy. According to an international consensus from 2015, 2 out of the 3 major findings need to be present: (1) dense lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate; (2) storiform fibrosis; and (3) obliterative phlebitis in veins and arteries.1,5 Most patients present with symptoms related to either tumefaction or fibrosis of an organ system.1 Peripheral eosinophilia and elevated serum IgE are often present in IgG4-RD.13 Although IgG4 values are elevated in 51% of biopsy-proven cases, flow cytometry of CD19lowCD38+CD20-CD27+ plasmablasts has been explored recently as a correlation with disease flare.3,14 These particular plasmablasts mark a stage between B cells and plasma cells and have been reported to have a sensitivity of 95% and a specificity of 82% in association with actual IgG4-RD.14 Furthermore, blood plasmablast concentrations decrease in response to glucocorticoid treatment, thereby providing a possible quantifiable value by which to measure success of IgG4 treatment.5,12

Treatment for this disease consists of immunosuppressive therapy. There is documentation of successful remission with rituximab and azathioprine, as well as methotrexate.1,5 Both 2015 consensus guidelines and a recent small single-center retrospective study support addition of second-line steroid sparing agents such as mycophenolate mofetil.5,6 For acute flairs, however, glucocorticoids with slow taper are usually utilized. In these cases, they should be tapered as soon as clinically feasible to avoid long-term adverse effects. Untreated IgG4-RD, even asymptomatic, has been shown to progress to fibrosis.5

Conclusion

IgG4-RD is a complicated disease process that requires a high index of suspicion to diagnose. In addition, for patients who are diagnosed with this condition, its ability to mimic other pathologic conditions should be taken into account with manifestation of any new illness. This case emphasizes the ability of this disease to localize in multiple organs over time and the need for lifetime surveillance in patients with IgG4-RD disease.

1. Lang D, Zwerina J, Pieringer H. IgG4-related disease: current challenges and future prospects. Ther Clin Risk Manag. 2016;12:189-199.

2. Brito-Zerón P, Ramos-Casals M, Bosch X, Stone JH. The clinical spectrum of IgG4-related disease. Autoimmun Rev. 2014;13(12):1203-1210.

3. Wallace ZS, Deshpande V, Mattoo H, et al. IgG4-related disease: clinical and laboratory features in one hundred twenty-five patients. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2015;67(9):2466-2475.

4. Carruthers MN, Khosroshahi A, Augustin T, Deshpande V, Stone JH. The diagnostic utility of serum IgG4 concentrations in IgG4-RD. Ann Rheum Dis. 2015;74(1):14-18.

5. Khosroshahi A, Wallace ZS, Crowe JL, et al; Second International Symposium on IgG4-Related Disease. International consensus guidance statement on the management and treatment of IgG4-Related disease. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2015;67(7):1688-1699.

6. Gupta N, Mathew J, Mohan H, et al. Addition of second-line steroid sparing immunosuppressants like mycophenolate mofetil improves outcome of immunoglobulin G4-related disease (IgG4-RD): a series from a tertiary care teaching hospital in South India. Rheumatol Int. 2017;38(2):203-209.

7. Lin HP, Lin KT, Ho WC, Chen CB, Kuo, CY, Lin YC. IgG4-associated cholangitis mimicking cholangiocarcinoma-report of a case. J Intern Med Taiwan. 2013;24:137-141.

8. Douhara A, Mitoro A, Otani E, et al. Cholangiocarcinoma developed in a patient with IgG4-related disease. World J Gastrointest Oncol. 2013;5(8):181-185.

9. Harada K, Nakanuma Y. Cholangiocarcinoma with respect to IgG4 reaction. Int J Hepatol. 2014;2014:803876.

10. Barbu M, Lindström U, Nordborg C, Martinsson A, Dworeck C, Jeppsson A. Sclerosing aortic and coronary arteritis due to IgG4-related disease. Ann Thorac Surg. 2017;103(6):e487-e489.

11. Kim YJ, Park YS, Koo BS, et al. Immunoglobulin G4-related disease with lymphoplasmacytic aortitis mimicking Takayasu arteritis. J Clin Rheumatol. 2011;17(8):451-452.

12. Khosroshahi A, Digumarthy SR, Gibbons FK, Deshpande V. Case 34-2015: A 36-year-old woman with a lung mass, pleural effusion and hip pain. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(18):1762-1772.

13. Della Torre E, Mattoo H, Mahajan VS, Carruthers M, Pillai S, Stone JH. Prevalence of atopy, eosinophilia and IgE elevation in IgG4-related disease. Allergy. 2014;69(2):191-206.

14. Wallace ZS, Mattoo H, Carruthers M, et al. Plasmablasts as a biomarker for IgG4-related disease, independent of serum IgG4 concentrations. Ann Rheum Dis. 2015;74(1):190-195.

1. Lang D, Zwerina J, Pieringer H. IgG4-related disease: current challenges and future prospects. Ther Clin Risk Manag. 2016;12:189-199.

2. Brito-Zerón P, Ramos-Casals M, Bosch X, Stone JH. The clinical spectrum of IgG4-related disease. Autoimmun Rev. 2014;13(12):1203-1210.

3. Wallace ZS, Deshpande V, Mattoo H, et al. IgG4-related disease: clinical and laboratory features in one hundred twenty-five patients. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2015;67(9):2466-2475.

4. Carruthers MN, Khosroshahi A, Augustin T, Deshpande V, Stone JH. The diagnostic utility of serum IgG4 concentrations in IgG4-RD. Ann Rheum Dis. 2015;74(1):14-18.

5. Khosroshahi A, Wallace ZS, Crowe JL, et al; Second International Symposium on IgG4-Related Disease. International consensus guidance statement on the management and treatment of IgG4-Related disease. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2015;67(7):1688-1699.

6. Gupta N, Mathew J, Mohan H, et al. Addition of second-line steroid sparing immunosuppressants like mycophenolate mofetil improves outcome of immunoglobulin G4-related disease (IgG4-RD): a series from a tertiary care teaching hospital in South India. Rheumatol Int. 2017;38(2):203-209.

7. Lin HP, Lin KT, Ho WC, Chen CB, Kuo, CY, Lin YC. IgG4-associated cholangitis mimicking cholangiocarcinoma-report of a case. J Intern Med Taiwan. 2013;24:137-141.

8. Douhara A, Mitoro A, Otani E, et al. Cholangiocarcinoma developed in a patient with IgG4-related disease. World J Gastrointest Oncol. 2013;5(8):181-185.

9. Harada K, Nakanuma Y. Cholangiocarcinoma with respect to IgG4 reaction. Int J Hepatol. 2014;2014:803876.

10. Barbu M, Lindström U, Nordborg C, Martinsson A, Dworeck C, Jeppsson A. Sclerosing aortic and coronary arteritis due to IgG4-related disease. Ann Thorac Surg. 2017;103(6):e487-e489.

11. Kim YJ, Park YS, Koo BS, et al. Immunoglobulin G4-related disease with lymphoplasmacytic aortitis mimicking Takayasu arteritis. J Clin Rheumatol. 2011;17(8):451-452.

12. Khosroshahi A, Digumarthy SR, Gibbons FK, Deshpande V. Case 34-2015: A 36-year-old woman with a lung mass, pleural effusion and hip pain. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(18):1762-1772.

13. Della Torre E, Mattoo H, Mahajan VS, Carruthers M, Pillai S, Stone JH. Prevalence of atopy, eosinophilia and IgE elevation in IgG4-related disease. Allergy. 2014;69(2):191-206.

14. Wallace ZS, Mattoo H, Carruthers M, et al. Plasmablasts as a biomarker for IgG4-related disease, independent of serum IgG4 concentrations. Ann Rheum Dis. 2015;74(1):190-195.

Primary renal synovial sarcoma – a diagnostic dilemma

Soft tissue sarcomas are rare mesenchymal tumors that comprise 1% of all malignancies. Synovial sarcoma accounts for 5% to 10% of adult soft tissue sarcomas and usually occurs in close association with joint capsules, tendon sheaths, and bursa in the extremities of young and middle-aged adults.1 Synovial sarcomas have been reported in other unusual sites, including the head and neck, thoracic and abdominal wall, retroperitoneum, bone, pleura, and visceral organs such as the lung, prostate, or kidney.2 Primary renal synovial sarcoma is an extremely rare tumor accounting for <2% of all malignant renal tumors.3 To the best of our knowledge, fewer than 50 cases of primary renal synovial sarcoma have been described in the English literature.4 It presents as a diagnostic dilemma because of the dearth of specific clinical and imaging findings and is often confused with benign and malignant tumors. The differential diagnosis includes angiomyolipoma, renal cell carcinoma with sarcomatoid differentiation, metastatic sarcoma, hemangiopericytoma, malignant solitary fibrous tumor, Wilms tumor, and malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor. Hence, a combination of histomorphologic, immunohistochemical, cytogenetic, and molecular studies that show a unique chromosomal translocation t(X;18) (p11;q11) is imperative in the diagnosis of primary renal synovial sarcoma.4 In the present report, we present the case of a 38-year-old man who was diagnosed with primary renal synovial sarcoma.

Case presentation and summary

A 38-year-old man with a medical history of gastroesophageal reflux disease and Barrett’s esophagus presented to our hospital for the first time with persistent and progressive right-sided flank and abdominal pain that was aggravated after a minor trauma to the back. There was no associated hematuria or dysuria.

Of note is that he had experienced intermittent flank pain for 2 years before this transfer. He had initially been diagnosed at his local hospital close to his home by ultrasound with an angiomyolipoma of 2 × 3 cm arising from the upper pole of his right kidney, which remained stable on repeat sonograms. About 22 months after his initial presentation at his local hospital, the flank pain increased, and a computed-tomographic (CT) scan revealed a perinephric hematoma that was thought to originate from a ruptured angiomyolipoma. He subsequently underwent embolization, but his symptoms recurred soon after. He presented again to his local hospital where CT imaging revealed a significant increase in the size of the retroperitoneal mass, and findings were suggestive of a hematoma. Subsequent angiogram did not reveal active extravasation, so a biopsy was performed.

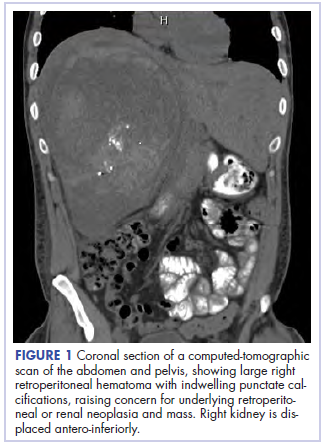

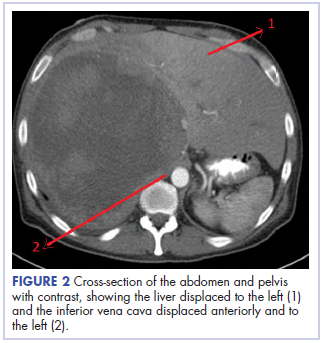

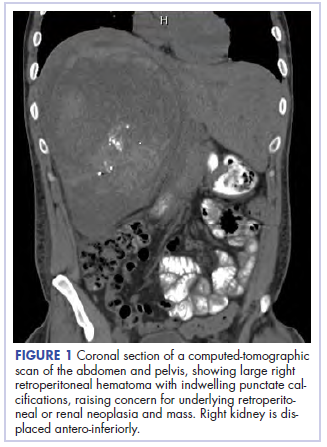

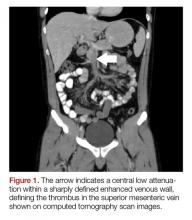

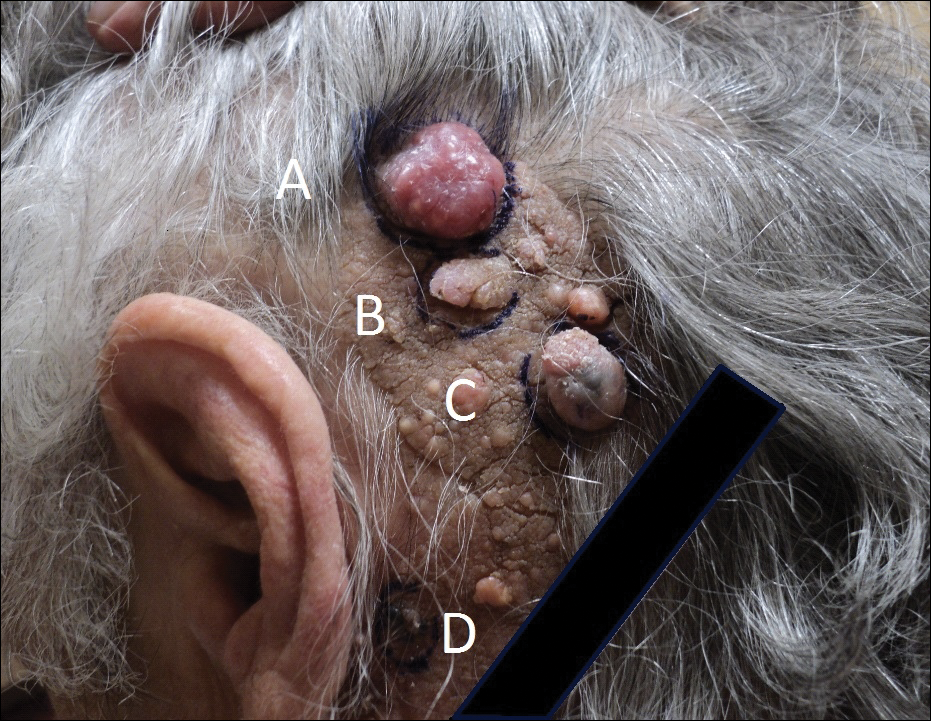

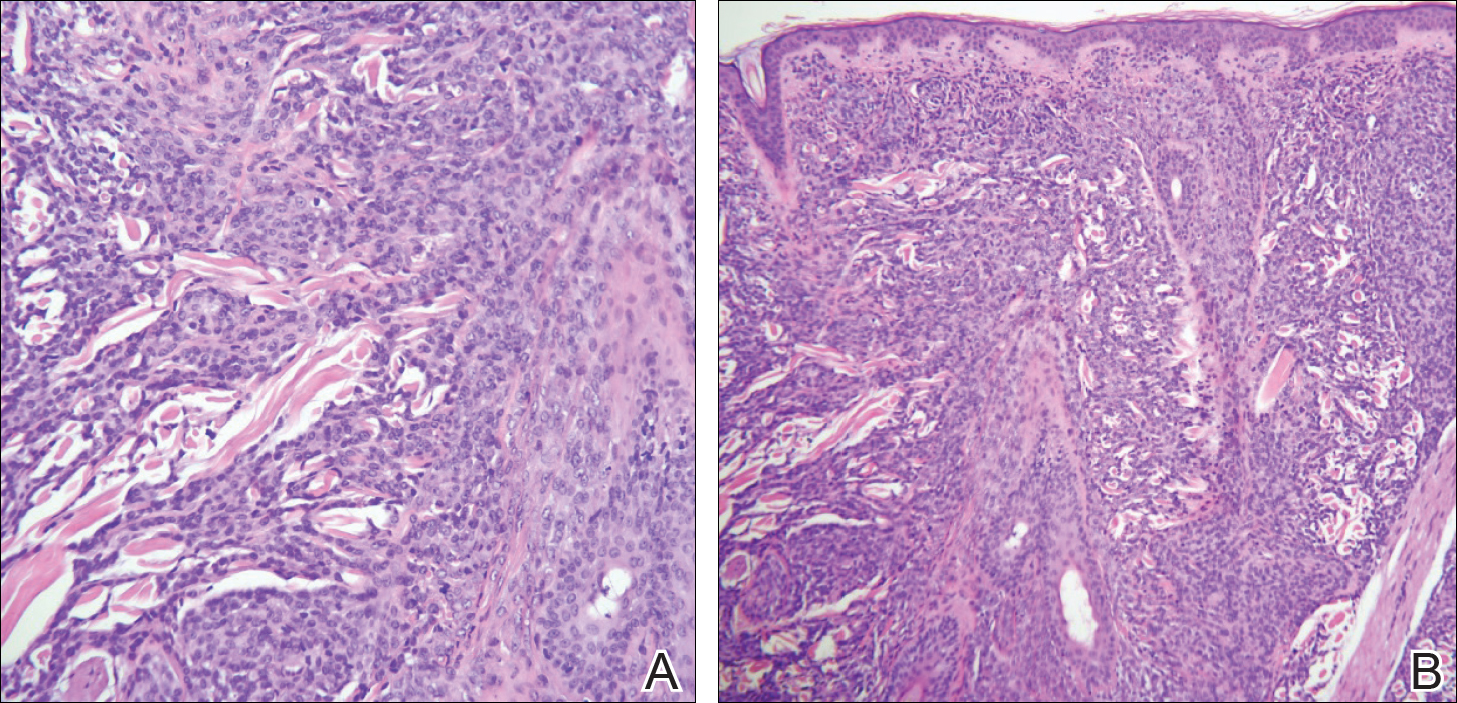

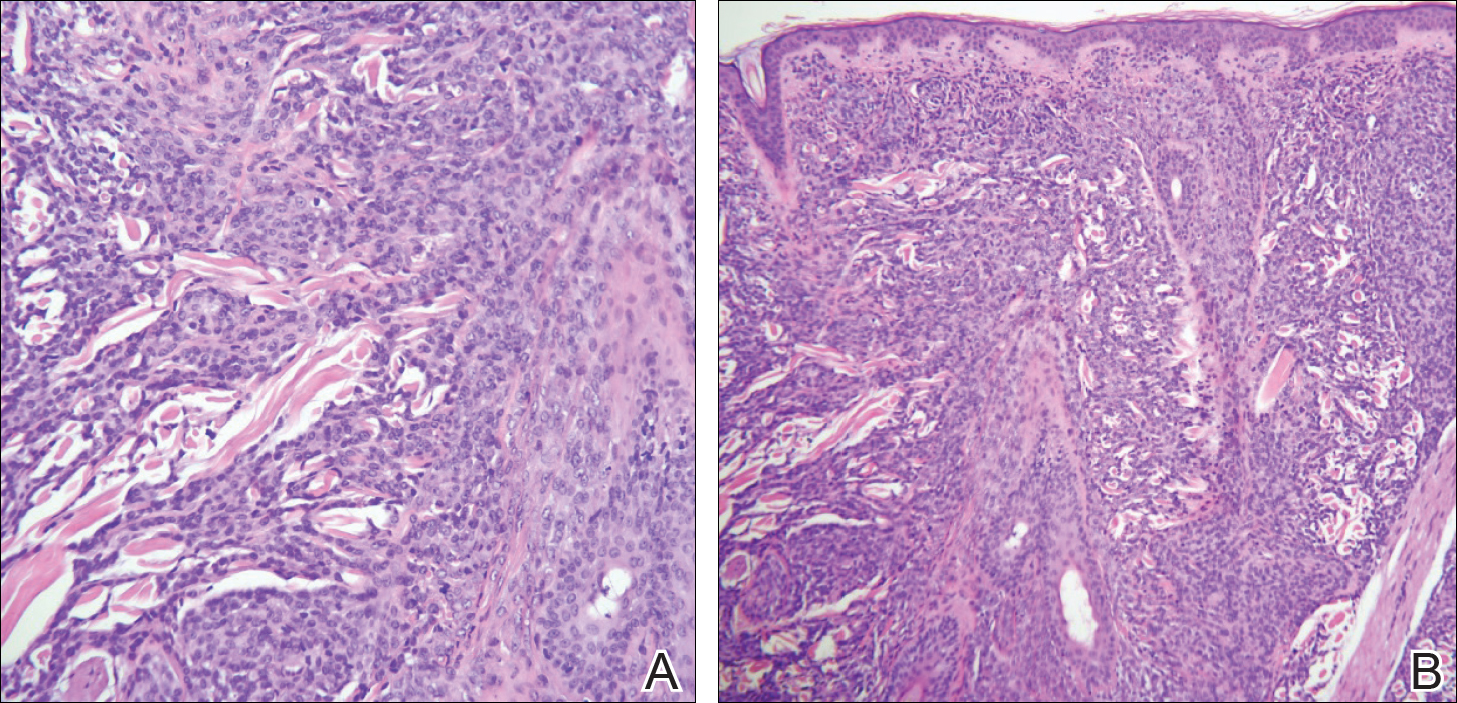

Before confirmatory pathologic evaluation could be completed, the patient presented to his local hospital again in excruciating pain. A CT scan of his abdomen and pelvis demonstrated a massive subacute on chronic hematoma in the right retroperitoneum measuring 22 × 19 × 18 cm, with calcifications originating from an upper pole right renal neoplasm. The right kidney was displaced antero-inferiorly, and the inferior vena cava was displaced anteriorly and to the left. The preliminary pathology returned with findings suggestive of sarcoma (Figures 1 and 2).

The patient was then transferred to our institution, where he was evaluated by medical and surgical oncology. A CT scan of the chest and magnetic-resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain did not reveal metastatic disease. He underwent exploratory laparotomy that involved the resection of a 22-cm retroperitoneal mass, right nephrectomy, right adrenalectomy, partial right hepatectomy, and a full thickness resection of the right postero-inferior diaphragm followed by mesh repair because of involvement by the tumor.

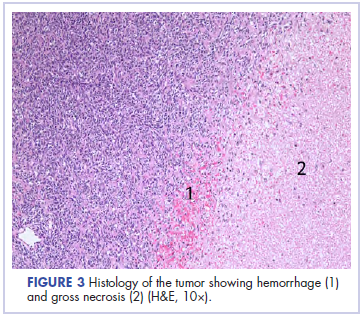

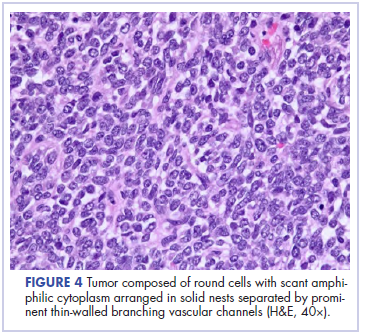

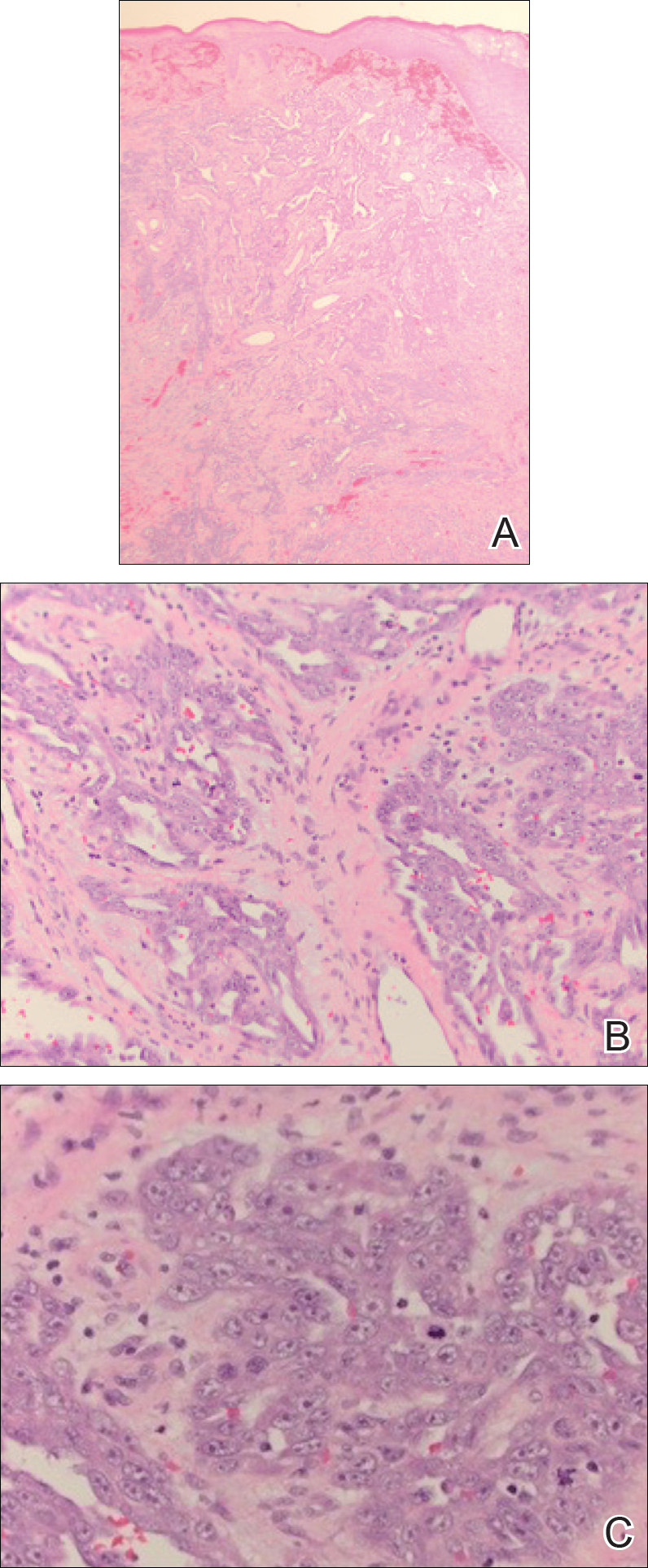

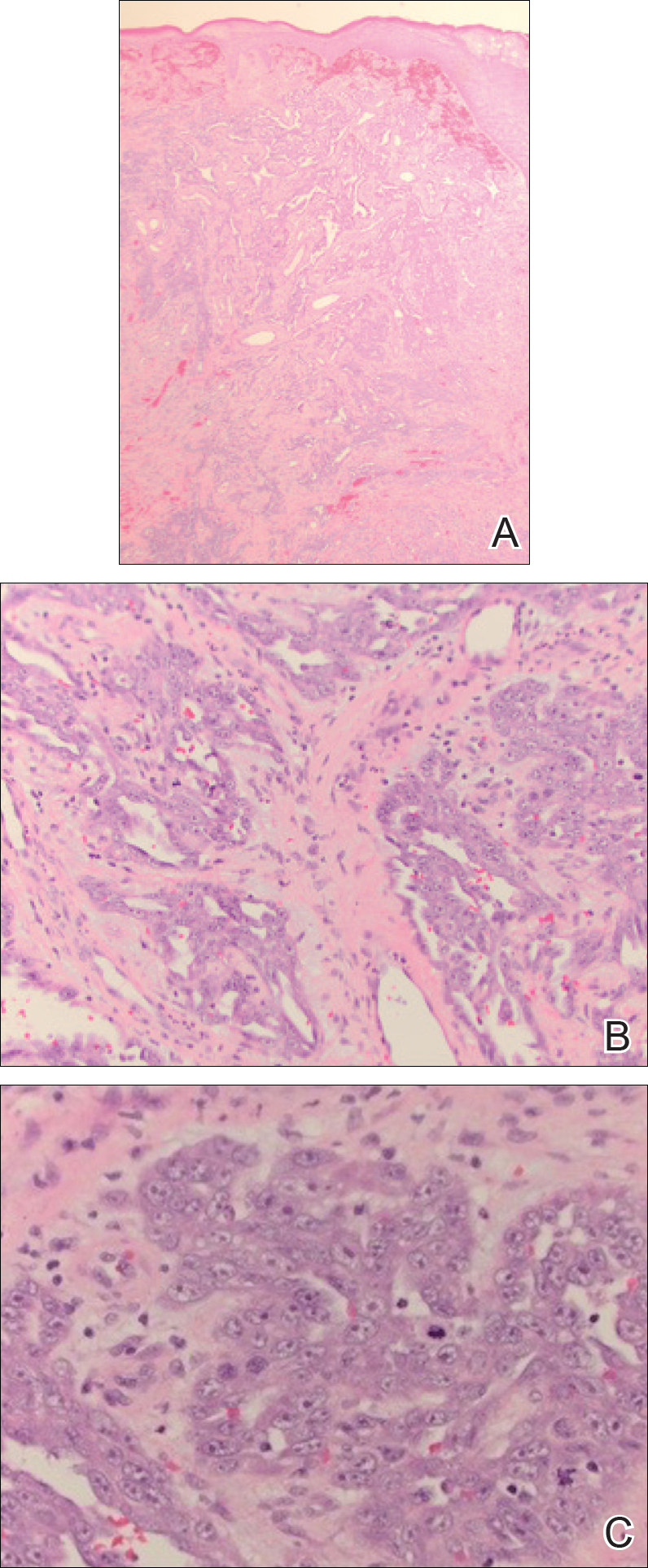

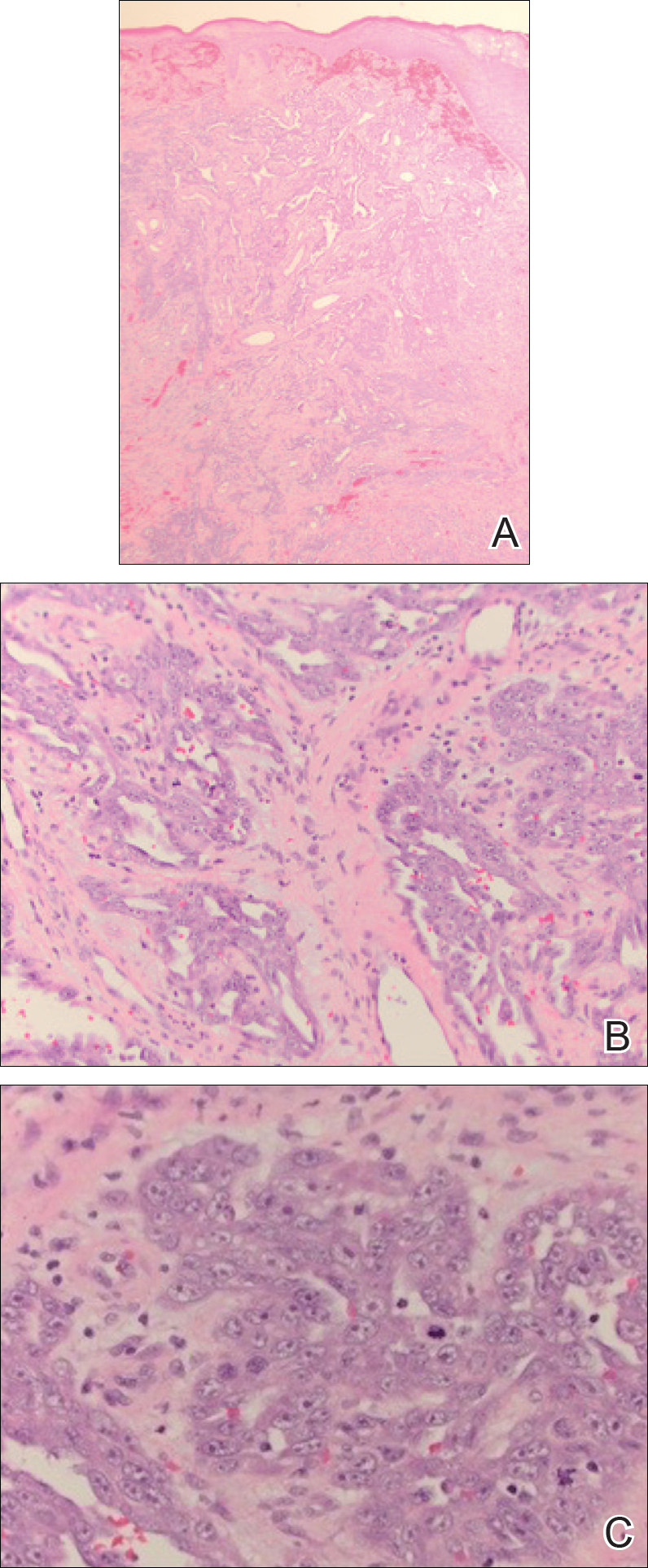

In its entirety, the specimen was a mass of 26 × 24 × 14 cm. It was sectioned to show extensively necrotic and hemorrhagic variegated white to tan-red parenchyma (Figure 3). Histology revealed a poorly differentiated malignant neoplasm composed of round cells with scant amphophilic cytoplasm arranged in solid, variably sized nests separated by prominent thin-walled branching vascular channels (Figure 4). The mitotic rate was high. It was determined to be a histologically ungraded sarcoma according to the French Federation of Comprehensive Cancer Centers system of grading soft tissue sarcomas; the margins were indeterminate. Immunohistochemistry was positive for EMA, TLE1, and negative for AE1/AE3, S100, STAT6, and Nkx2.2. Molecular pathology fluorescent in situ hybridization (FISH) analysis demonstrated positivity for SS18 gene rearrangement (SS18-SSX1 fusion).

After recovering from surgery, the patient received adjuvant chemotherapy with doxorubicin and ifosfamide. It has been almost 16 months since we first saw this patient. He was started on doxorubicin 20 mg/m2 on days 1 to 4, ifosfamide 2,500 mg on days 1 to 4, and mesna 800 mg on days 1 to 4, for a total of 6 cycles. He did well for the first 5 months, after which he developed disease recurrence in the postoperative nephrectomy bed (a biopsy showed it to be recurrent synovial sarcoma) as well as pulmonary nodules, for which he was started on trabectedin 1.5 mg/m2 every 3 weeks. Two months later, a CT scan showed an increase in the size of his retroperitoneal mass, and the treatment was changed to pazopanib 400 mg daily orally, on which he remained at the time of publication.

Discussion

Synovial sarcoma is the fourth most common type of soft tissue sarcoma, accounting for 2.5% to 10.5% of all primary soft tissue malignancies worldwide. It occurs most frequently in adolescents and young adults, with most patients presenting between the ages of 15 and 40 years. Median age of presentation is 36 years. Despite the nomenclature, synovial sarcoma does not arise in intra-articular locations but typically occurs in proximity to joints in the extremities. Synovial sarcomas are less commonly described in other sites, including the head and neck, mediastinum, intraperitoneum, retroperitoneum, lung, pleura, and kidney.4,5 Renal synovial sarcoma was first described in a published article by Argani and colleagues in 2000.5

Adult renal mesenchymal tumors are classified into benign and malignant tumors on the basis of the histologic features and clinicobiologic behavior.6,7 The benign esenchymal renal tumors include angiomyolipoma, leiomyoma, hemangioma, lymphangioma, juxtaglomerular cell tumor, renomedullary interstitial cell tumor (medullary fibroma), lipoma, solitary fibrous tumor, and schwannoma. Malignant renal tumors of mesenchymal origin include leiomyosarcoma, rhabdomyosarcoma, angiosarcoma, osteosarcoma, fibrosarcoma, malignant fibrous histiocytoma, solitary fibrous tumor, and synovial sarcoma.

Most of these tumor types cause the same nonspecific symptoms in patients – abdominal pain, flank pain, abdominal fullness, a palpable mass, and hematuria – although they can be clinically silent. The average duration of symptoms in synovial sarcoma is 2 to 4 years.8 The long duration of symptoms and initial slow growth of synovial sarcomas may give a false impression of a benign process.

A preoperative radiological diagnosis of primary renal synovial sarcoma may be suspected by analyzing the tumor’s growth patterns on CT scans.9 Renal synovial sarcomas often appear as large, well-defined soft tissue masses that can extend into the renal pelvis or into the perinephric region.9 A CT scan may identify soft tissue calcifications, especially subtle ones in areas where the tumor anatomy is complex. A CT scan may also reveal areas of hemorrhage, necrosis, or cyst formation within the tumor, and can easily confirm bone involvement. Intravenous contrast may help in differentiating the mass from adjacent muscle and neurovascular complex.9,10 On MRI, renal synovial sarcomas are often described as nonspecific heterogeneous masses, although they may also exhibit heterogeneous enhancement of hemorrhagic areas, calcifications, and air-fluid levels (known as “triple sign”) as well as septae. The triple sign may be identified as areas of low, intermediate, and high signal intensity, correlating with areas of hemorrhage, calcification, and air-fluid level.9,10 Signal intensity is about equal to that of skeletal muscle on T1-weighted MRI and higher than that of subcutaneous fat on T2-weighted MRI.

In the present case, the tumor was initially misdiagnosed as an angiomyolipoma, the most common benign tumor of the kidney. Angiomyolipomas are usually solid triphasic tumors arising from the renal cortex and are composed of 3 major elements: dysmorphic blood vessels, smooth muscle components, and adipose tissue. When angiomyolipomas are large enough, they are readily recognized by the identification of macroscopic fat within the tumor, either by CT scan or MRI.11 When they are small, they may be difficult to distinguish from a small cyst on CT because of volume averaging.

On pathology, synovial sarcoma has dual epithelial and mesenchymal differentiation. They are frequently multi-lobulated, and areas of necrosis, hemorrhage, and cyst formation are also common. There are 3 main histologic subtypes of synovial sarcoma: biphasic (20%-30%), monophasic (50%-60%), and poorly differentiated (15%-25%). Poorly differentiated synovial sarcomas are generally epithelioid in morphology, have high mitotic activity (usually 10-20 mitoses/10 high-power field; range is <5 for well differentiated, low-grade tumors), and can be confused with round cell tumors such as Ewing sarcoma. Poorly differentiated synovial sarcomas are high-grade tumors.

Immunohistochemical studies can confirm the pathological diagnosis. Synovial sarcomas usually stain positive for Bcl2, CD99/Mic2, CD56, Vim, and focally for EMA but negatively for desmin, actin, WT1, S-100, CD34, and CD31.5 Currently, the gold standard for diagnosis and hallmark for synovial sarcomas are the t (X;18) translocation and SYT-SSX gene fusion products (SYT-SSX1 in 67% and SYT-SSX2 in 33% of cases). These can be detected either by FISH or reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction. This genetic alteration is identified in more than 90% of synovial sarcomas and is highly specific.

The role of SYT-SSX gene fusion in the pathogenesis of synovial sarcoma is an active area of investigation. The fusion of SYT with SSX translates into a fusion protein that binds to the transcription activator SMARCA4 that is involved in chromatin remodeling, thus displacing both the wildtype SYT and the tumor suppressor gene SMARCB1. The modified protein complex then binds at several super-enhancer loci, unlocking suppressed genes such as Sox2, which is known to be necessary for synovial sarcoma proliferation. Alterations in SMARCB1 are involved in several cancer types, implicating this event as a driver of these malignancies.12 This results in a global alteration in chromatin remodeling that needs to be better understood to design targeted therapies.

The clinical course of synovial sarcoma, regardless of the tissue of origin, is typically poor. Multiple clinical and pathologic factors, including tumor size, location, patient age, and presence of poorly differentiated areas, are thought to have prognostic significance. A tumor size of more than 5 cm at presentation has the greatest impact on prognosis, with studies showing 5-year survival rates of 64% for patients with tumors smaller than 5 cm and 26% for patients with masses greater than 5 cm.13,14 High-grade synovial sarcoma is favored in tumors that have cystic components, hemorrhage, and fluid levels and the triple sign.

Patients with tumors in the extremities have a more favorable prognosis than those with lesions in the head and neck area or axially, a feature that likely reflects better surgical control available for extremity lesions. Patient age of less than 15 to 20 years is also associated with a better long-term prognosis.15,16 Varela-Duran and Enzinger17 reported that the presence of extensive calcifications suggests improved long-term survival, with 5-year survival rates of 82% and decreased rates of local recurrence (32%) and metastatic disease (29%). The poorly differentiated subtype is associated with a worsened prognosis, with a 5-year survival rate of 20% through 30%.18,19 Other pathologic factors associated with worsened prognosis include presence of rhabdoid cells, extensive tumor necrosis, high nuclear grade, p53 mutations, and high mitotic rate (>10 mitoses/10 high-power field). More recently, the gene fusion type SYT-SSX2 (more common in monophasic lesions) has been associated with an improved prognosis, compared with that for SYT-SSX1, and an 89% metastasis-free survival.20

Although there are no guidelines for the treatment of primary renal synovial sarcoma because of the limited number of cases reported, surgery is considered the first choice. Adjuvant chemotherapy with an anthracycline (doxorubicin or epirubicin) combined with ifosfamide has been the most frequently used regimen in published cases, especially in those in which patients have poor prognostic factors as mentioned above.

Overall, the 5-year survival rate ranges from 36% to 76%.14 The clinical course of synovial sarcoma is characterized by a high rate of local recurrence (30%-50%) and metastatic disease (41%). Most metastases occur within the first 2 to 5 years after treatment cessation. Metastases are present in 16% to 25% of patients at their initial presentation, with the most frequent metastatic site being the lung, followed by the lymph nodes (4%-18%) and bone (8%-11%).

Conclusion

Primary renal synovial sarcoma is extremely rare, and preoperative diagnosis is difficult in the absence of specific clinical or imaging findings. A high index of suspicion combined with pathologic, immunohistochemical, cytogenetic, and molecular studies is essential for accurate diagnosis and subsequent treatment planning. The differential diagnosis of renal synovial sarcoma can be extensive, and our experience with this patient illustrates the diagnostic dilemma associated with renal synovial sarcoma.

1. Majumder A, Dey S, Khandakar B, Medda S, Chandra Paul P. Primary renal synovial sarcoma: a rare tumor with an atypical presentation. Arch Iran Med. 2014;17(10):726-728.

2. Fetsch JF, Meis JM. Synovial sarcoma of the abdominal wall. Cancer. 1993;72(2):469 477.

3. Wang Z, Zhong Z, Zhu L, et al. Primary synovial sarcoma of the kidney: a case report. Oncol Lett. 2015;10(6):3542-3544.

4. Abbas M, Dämmrich ME, Braubach P, et al. Synovial sarcoma of the kidney in a young patient with a review of the literature. Rare tumors. 2014;6(2):5393

5. Argani P, Faria PA, Epstein JI, et al. Primary renal synovial sarcoma: molecular and morphologic delineation of an entity previously included among embryonal sarcomas of the kidney. Am J Surg Pathol. 2000;24(8):1087-1096.

6. Eble JN, Sauter G, Epstein JI, Sesterhenn IA, eds. World Health Organization classification of tumours: pathology and genetics of tumours of the urinary system and male genital organs. Lyon, France: IARC; 2004.

7. Tamboli P, Ro JY, Amin MB, Ligato S, Ayala AG. Benign tumors and tumor-like lesions of the adult kidney. Part II: benign mesenchymal and mixed neoplasms, and tumor-like lesions. Adv Anat Pathol. 2000;7(1):47-66.

8. Weiss SW, Goldblum JR. Malignant soft tissue tumors of uncertain type. In: Weiss SW, Goldblum JR, eds. Enzinger and Weiss’s soft tissue tumors. 4th ed. St. Louis, MO: Mosby, 2001; 1483-1565.

9. Lacovelli R, Altavilla A, Ciardi A, et al. Clinical and pathological features of primary renal synovial sarcoma: analysis of 64 cases from 11 years of medical literature. BJU Int. 2012;110(10):1449-1454.

10. Alhazzani AR, El-Sharkawy MS, Hassan H. Primary retroperitoneal synovial sarcoma in CT and MRI. Urol Ann. 2010;2(1):39-41.

11. Katabathina VS, Vikram R, Nagar AM, Tamboli P, Menias CO, Prasad SR. Mesenchymal neoplasms of the kidney in adults: imaging spectrum with radiologic-pathologic correlation. Radiographics. 2010;30(6):1525-1540.

12. Sápi Z, Papp G, Szendrői M, et al. Epigenetic regulation of SMARCB1 by miR-206, -381 and -671- 5p is evident in a variety of SMARCB1 immunonegative soft tissue sarcomas, while miR-765 appears specific for epithelioid sarcoma. A miRNA study of 223 soft tissue sarcomas. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2016;55(10):786-802.

13. Ferrari A, Gronchi A, Casanova M, et al. Synovial sarcoma: a retrospective analysis of 271 patients of all ages treated at a single institution. Cancer. 2004;101(3):627-634.

14. Rangheard AS, Vanel D, Viala J, Schwaab G, Casiraghi O, Sigal R. Synovial sarcomas of the head and neck: CT and MR imaging findings of eight patients. Am J Neuroradiol. 2001;22(5):851-857.

15. Oda Y, Hashimoto H, Tsuneyoshi M, Takeshita S. Survival in synovial sarcoma: a multivariate study of prognostic factors with special emphasis on the comparison between early death and long-term survival. Am J Surg Pathol. 1993;17(1):35-44.

16. Raney RB. Synovial sarcoma in young people: background, prognostic factors and therapeutic questions. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2005;27(4):207-211.

17. Varela-Duran J, Enzinger FM. Calcifying synovial sarcoma. Cancer. 1982;50(2):345-352.

18. Cagle LA, Mirra JM, Storm FK, Roe DJ, Eilber FR. Histologic features relating to prognosis in synovial sarcoma. Cancer. 1987;59(10):1810-1814.

19. Skytting B, Meis-Kindblom JM, Larsson O, et al. Synovial sarcoma – identification of favorable and unfavorable histologic types: a Scandinavian sarcoma group study of 104 cases. Acta Orthop Scand. 1999:70(6):543-554.

20. Murphey MD, Gibson MS, Jennings BT, Crespo-Rodríguez AM, Fanburg-Smith J, Gajewski DA. Imaging of synovial sarcoma with radiologic-pathologic correlation. Radiographics. 2006;26(5):1543-1565.

Soft tissue sarcomas are rare mesenchymal tumors that comprise 1% of all malignancies. Synovial sarcoma accounts for 5% to 10% of adult soft tissue sarcomas and usually occurs in close association with joint capsules, tendon sheaths, and bursa in the extremities of young and middle-aged adults.1 Synovial sarcomas have been reported in other unusual sites, including the head and neck, thoracic and abdominal wall, retroperitoneum, bone, pleura, and visceral organs such as the lung, prostate, or kidney.2 Primary renal synovial sarcoma is an extremely rare tumor accounting for <2% of all malignant renal tumors.3 To the best of our knowledge, fewer than 50 cases of primary renal synovial sarcoma have been described in the English literature.4 It presents as a diagnostic dilemma because of the dearth of specific clinical and imaging findings and is often confused with benign and malignant tumors. The differential diagnosis includes angiomyolipoma, renal cell carcinoma with sarcomatoid differentiation, metastatic sarcoma, hemangiopericytoma, malignant solitary fibrous tumor, Wilms tumor, and malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor. Hence, a combination of histomorphologic, immunohistochemical, cytogenetic, and molecular studies that show a unique chromosomal translocation t(X;18) (p11;q11) is imperative in the diagnosis of primary renal synovial sarcoma.4 In the present report, we present the case of a 38-year-old man who was diagnosed with primary renal synovial sarcoma.

Case presentation and summary

A 38-year-old man with a medical history of gastroesophageal reflux disease and Barrett’s esophagus presented to our hospital for the first time with persistent and progressive right-sided flank and abdominal pain that was aggravated after a minor trauma to the back. There was no associated hematuria or dysuria.

Of note is that he had experienced intermittent flank pain for 2 years before this transfer. He had initially been diagnosed at his local hospital close to his home by ultrasound with an angiomyolipoma of 2 × 3 cm arising from the upper pole of his right kidney, which remained stable on repeat sonograms. About 22 months after his initial presentation at his local hospital, the flank pain increased, and a computed-tomographic (CT) scan revealed a perinephric hematoma that was thought to originate from a ruptured angiomyolipoma. He subsequently underwent embolization, but his symptoms recurred soon after. He presented again to his local hospital where CT imaging revealed a significant increase in the size of the retroperitoneal mass, and findings were suggestive of a hematoma. Subsequent angiogram did not reveal active extravasation, so a biopsy was performed.

Before confirmatory pathologic evaluation could be completed, the patient presented to his local hospital again in excruciating pain. A CT scan of his abdomen and pelvis demonstrated a massive subacute on chronic hematoma in the right retroperitoneum measuring 22 × 19 × 18 cm, with calcifications originating from an upper pole right renal neoplasm. The right kidney was displaced antero-inferiorly, and the inferior vena cava was displaced anteriorly and to the left. The preliminary pathology returned with findings suggestive of sarcoma (Figures 1 and 2).

The patient was then transferred to our institution, where he was evaluated by medical and surgical oncology. A CT scan of the chest and magnetic-resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain did not reveal metastatic disease. He underwent exploratory laparotomy that involved the resection of a 22-cm retroperitoneal mass, right nephrectomy, right adrenalectomy, partial right hepatectomy, and a full thickness resection of the right postero-inferior diaphragm followed by mesh repair because of involvement by the tumor.

In its entirety, the specimen was a mass of 26 × 24 × 14 cm. It was sectioned to show extensively necrotic and hemorrhagic variegated white to tan-red parenchyma (Figure 3). Histology revealed a poorly differentiated malignant neoplasm composed of round cells with scant amphophilic cytoplasm arranged in solid, variably sized nests separated by prominent thin-walled branching vascular channels (Figure 4). The mitotic rate was high. It was determined to be a histologically ungraded sarcoma according to the French Federation of Comprehensive Cancer Centers system of grading soft tissue sarcomas; the margins were indeterminate. Immunohistochemistry was positive for EMA, TLE1, and negative for AE1/AE3, S100, STAT6, and Nkx2.2. Molecular pathology fluorescent in situ hybridization (FISH) analysis demonstrated positivity for SS18 gene rearrangement (SS18-SSX1 fusion).

After recovering from surgery, the patient received adjuvant chemotherapy with doxorubicin and ifosfamide. It has been almost 16 months since we first saw this patient. He was started on doxorubicin 20 mg/m2 on days 1 to 4, ifosfamide 2,500 mg on days 1 to 4, and mesna 800 mg on days 1 to 4, for a total of 6 cycles. He did well for the first 5 months, after which he developed disease recurrence in the postoperative nephrectomy bed (a biopsy showed it to be recurrent synovial sarcoma) as well as pulmonary nodules, for which he was started on trabectedin 1.5 mg/m2 every 3 weeks. Two months later, a CT scan showed an increase in the size of his retroperitoneal mass, and the treatment was changed to pazopanib 400 mg daily orally, on which he remained at the time of publication.

Discussion

Synovial sarcoma is the fourth most common type of soft tissue sarcoma, accounting for 2.5% to 10.5% of all primary soft tissue malignancies worldwide. It occurs most frequently in adolescents and young adults, with most patients presenting between the ages of 15 and 40 years. Median age of presentation is 36 years. Despite the nomenclature, synovial sarcoma does not arise in intra-articular locations but typically occurs in proximity to joints in the extremities. Synovial sarcomas are less commonly described in other sites, including the head and neck, mediastinum, intraperitoneum, retroperitoneum, lung, pleura, and kidney.4,5 Renal synovial sarcoma was first described in a published article by Argani and colleagues in 2000.5

Adult renal mesenchymal tumors are classified into benign and malignant tumors on the basis of the histologic features and clinicobiologic behavior.6,7 The benign esenchymal renal tumors include angiomyolipoma, leiomyoma, hemangioma, lymphangioma, juxtaglomerular cell tumor, renomedullary interstitial cell tumor (medullary fibroma), lipoma, solitary fibrous tumor, and schwannoma. Malignant renal tumors of mesenchymal origin include leiomyosarcoma, rhabdomyosarcoma, angiosarcoma, osteosarcoma, fibrosarcoma, malignant fibrous histiocytoma, solitary fibrous tumor, and synovial sarcoma.

Most of these tumor types cause the same nonspecific symptoms in patients – abdominal pain, flank pain, abdominal fullness, a palpable mass, and hematuria – although they can be clinically silent. The average duration of symptoms in synovial sarcoma is 2 to 4 years.8 The long duration of symptoms and initial slow growth of synovial sarcomas may give a false impression of a benign process.

A preoperative radiological diagnosis of primary renal synovial sarcoma may be suspected by analyzing the tumor’s growth patterns on CT scans.9 Renal synovial sarcomas often appear as large, well-defined soft tissue masses that can extend into the renal pelvis or into the perinephric region.9 A CT scan may identify soft tissue calcifications, especially subtle ones in areas where the tumor anatomy is complex. A CT scan may also reveal areas of hemorrhage, necrosis, or cyst formation within the tumor, and can easily confirm bone involvement. Intravenous contrast may help in differentiating the mass from adjacent muscle and neurovascular complex.9,10 On MRI, renal synovial sarcomas are often described as nonspecific heterogeneous masses, although they may also exhibit heterogeneous enhancement of hemorrhagic areas, calcifications, and air-fluid levels (known as “triple sign”) as well as septae. The triple sign may be identified as areas of low, intermediate, and high signal intensity, correlating with areas of hemorrhage, calcification, and air-fluid level.9,10 Signal intensity is about equal to that of skeletal muscle on T1-weighted MRI and higher than that of subcutaneous fat on T2-weighted MRI.

In the present case, the tumor was initially misdiagnosed as an angiomyolipoma, the most common benign tumor of the kidney. Angiomyolipomas are usually solid triphasic tumors arising from the renal cortex and are composed of 3 major elements: dysmorphic blood vessels, smooth muscle components, and adipose tissue. When angiomyolipomas are large enough, they are readily recognized by the identification of macroscopic fat within the tumor, either by CT scan or MRI.11 When they are small, they may be difficult to distinguish from a small cyst on CT because of volume averaging.

On pathology, synovial sarcoma has dual epithelial and mesenchymal differentiation. They are frequently multi-lobulated, and areas of necrosis, hemorrhage, and cyst formation are also common. There are 3 main histologic subtypes of synovial sarcoma: biphasic (20%-30%), monophasic (50%-60%), and poorly differentiated (15%-25%). Poorly differentiated synovial sarcomas are generally epithelioid in morphology, have high mitotic activity (usually 10-20 mitoses/10 high-power field; range is <5 for well differentiated, low-grade tumors), and can be confused with round cell tumors such as Ewing sarcoma. Poorly differentiated synovial sarcomas are high-grade tumors.

Immunohistochemical studies can confirm the pathological diagnosis. Synovial sarcomas usually stain positive for Bcl2, CD99/Mic2, CD56, Vim, and focally for EMA but negatively for desmin, actin, WT1, S-100, CD34, and CD31.5 Currently, the gold standard for diagnosis and hallmark for synovial sarcomas are the t (X;18) translocation and SYT-SSX gene fusion products (SYT-SSX1 in 67% and SYT-SSX2 in 33% of cases). These can be detected either by FISH or reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction. This genetic alteration is identified in more than 90% of synovial sarcomas and is highly specific.

The role of SYT-SSX gene fusion in the pathogenesis of synovial sarcoma is an active area of investigation. The fusion of SYT with SSX translates into a fusion protein that binds to the transcription activator SMARCA4 that is involved in chromatin remodeling, thus displacing both the wildtype SYT and the tumor suppressor gene SMARCB1. The modified protein complex then binds at several super-enhancer loci, unlocking suppressed genes such as Sox2, which is known to be necessary for synovial sarcoma proliferation. Alterations in SMARCB1 are involved in several cancer types, implicating this event as a driver of these malignancies.12 This results in a global alteration in chromatin remodeling that needs to be better understood to design targeted therapies.

The clinical course of synovial sarcoma, regardless of the tissue of origin, is typically poor. Multiple clinical and pathologic factors, including tumor size, location, patient age, and presence of poorly differentiated areas, are thought to have prognostic significance. A tumor size of more than 5 cm at presentation has the greatest impact on prognosis, with studies showing 5-year survival rates of 64% for patients with tumors smaller than 5 cm and 26% for patients with masses greater than 5 cm.13,14 High-grade synovial sarcoma is favored in tumors that have cystic components, hemorrhage, and fluid levels and the triple sign.

Patients with tumors in the extremities have a more favorable prognosis than those with lesions in the head and neck area or axially, a feature that likely reflects better surgical control available for extremity lesions. Patient age of less than 15 to 20 years is also associated with a better long-term prognosis.15,16 Varela-Duran and Enzinger17 reported that the presence of extensive calcifications suggests improved long-term survival, with 5-year survival rates of 82% and decreased rates of local recurrence (32%) and metastatic disease (29%). The poorly differentiated subtype is associated with a worsened prognosis, with a 5-year survival rate of 20% through 30%.18,19 Other pathologic factors associated with worsened prognosis include presence of rhabdoid cells, extensive tumor necrosis, high nuclear grade, p53 mutations, and high mitotic rate (>10 mitoses/10 high-power field). More recently, the gene fusion type SYT-SSX2 (more common in monophasic lesions) has been associated with an improved prognosis, compared with that for SYT-SSX1, and an 89% metastasis-free survival.20

Although there are no guidelines for the treatment of primary renal synovial sarcoma because of the limited number of cases reported, surgery is considered the first choice. Adjuvant chemotherapy with an anthracycline (doxorubicin or epirubicin) combined with ifosfamide has been the most frequently used regimen in published cases, especially in those in which patients have poor prognostic factors as mentioned above.

Overall, the 5-year survival rate ranges from 36% to 76%.14 The clinical course of synovial sarcoma is characterized by a high rate of local recurrence (30%-50%) and metastatic disease (41%). Most metastases occur within the first 2 to 5 years after treatment cessation. Metastases are present in 16% to 25% of patients at their initial presentation, with the most frequent metastatic site being the lung, followed by the lymph nodes (4%-18%) and bone (8%-11%).

Conclusion

Primary renal synovial sarcoma is extremely rare, and preoperative diagnosis is difficult in the absence of specific clinical or imaging findings. A high index of suspicion combined with pathologic, immunohistochemical, cytogenetic, and molecular studies is essential for accurate diagnosis and subsequent treatment planning. The differential diagnosis of renal synovial sarcoma can be extensive, and our experience with this patient illustrates the diagnostic dilemma associated with renal synovial sarcoma.

Soft tissue sarcomas are rare mesenchymal tumors that comprise 1% of all malignancies. Synovial sarcoma accounts for 5% to 10% of adult soft tissue sarcomas and usually occurs in close association with joint capsules, tendon sheaths, and bursa in the extremities of young and middle-aged adults.1 Synovial sarcomas have been reported in other unusual sites, including the head and neck, thoracic and abdominal wall, retroperitoneum, bone, pleura, and visceral organs such as the lung, prostate, or kidney.2 Primary renal synovial sarcoma is an extremely rare tumor accounting for <2% of all malignant renal tumors.3 To the best of our knowledge, fewer than 50 cases of primary renal synovial sarcoma have been described in the English literature.4 It presents as a diagnostic dilemma because of the dearth of specific clinical and imaging findings and is often confused with benign and malignant tumors. The differential diagnosis includes angiomyolipoma, renal cell carcinoma with sarcomatoid differentiation, metastatic sarcoma, hemangiopericytoma, malignant solitary fibrous tumor, Wilms tumor, and malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor. Hence, a combination of histomorphologic, immunohistochemical, cytogenetic, and molecular studies that show a unique chromosomal translocation t(X;18) (p11;q11) is imperative in the diagnosis of primary renal synovial sarcoma.4 In the present report, we present the case of a 38-year-old man who was diagnosed with primary renal synovial sarcoma.

Case presentation and summary

A 38-year-old man with a medical history of gastroesophageal reflux disease and Barrett’s esophagus presented to our hospital for the first time with persistent and progressive right-sided flank and abdominal pain that was aggravated after a minor trauma to the back. There was no associated hematuria or dysuria.

Of note is that he had experienced intermittent flank pain for 2 years before this transfer. He had initially been diagnosed at his local hospital close to his home by ultrasound with an angiomyolipoma of 2 × 3 cm arising from the upper pole of his right kidney, which remained stable on repeat sonograms. About 22 months after his initial presentation at his local hospital, the flank pain increased, and a computed-tomographic (CT) scan revealed a perinephric hematoma that was thought to originate from a ruptured angiomyolipoma. He subsequently underwent embolization, but his symptoms recurred soon after. He presented again to his local hospital where CT imaging revealed a significant increase in the size of the retroperitoneal mass, and findings were suggestive of a hematoma. Subsequent angiogram did not reveal active extravasation, so a biopsy was performed.

Before confirmatory pathologic evaluation could be completed, the patient presented to his local hospital again in excruciating pain. A CT scan of his abdomen and pelvis demonstrated a massive subacute on chronic hematoma in the right retroperitoneum measuring 22 × 19 × 18 cm, with calcifications originating from an upper pole right renal neoplasm. The right kidney was displaced antero-inferiorly, and the inferior vena cava was displaced anteriorly and to the left. The preliminary pathology returned with findings suggestive of sarcoma (Figures 1 and 2).

The patient was then transferred to our institution, where he was evaluated by medical and surgical oncology. A CT scan of the chest and magnetic-resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain did not reveal metastatic disease. He underwent exploratory laparotomy that involved the resection of a 22-cm retroperitoneal mass, right nephrectomy, right adrenalectomy, partial right hepatectomy, and a full thickness resection of the right postero-inferior diaphragm followed by mesh repair because of involvement by the tumor.

In its entirety, the specimen was a mass of 26 × 24 × 14 cm. It was sectioned to show extensively necrotic and hemorrhagic variegated white to tan-red parenchyma (Figure 3). Histology revealed a poorly differentiated malignant neoplasm composed of round cells with scant amphophilic cytoplasm arranged in solid, variably sized nests separated by prominent thin-walled branching vascular channels (Figure 4). The mitotic rate was high. It was determined to be a histologically ungraded sarcoma according to the French Federation of Comprehensive Cancer Centers system of grading soft tissue sarcomas; the margins were indeterminate. Immunohistochemistry was positive for EMA, TLE1, and negative for AE1/AE3, S100, STAT6, and Nkx2.2. Molecular pathology fluorescent in situ hybridization (FISH) analysis demonstrated positivity for SS18 gene rearrangement (SS18-SSX1 fusion).

After recovering from surgery, the patient received adjuvant chemotherapy with doxorubicin and ifosfamide. It has been almost 16 months since we first saw this patient. He was started on doxorubicin 20 mg/m2 on days 1 to 4, ifosfamide 2,500 mg on days 1 to 4, and mesna 800 mg on days 1 to 4, for a total of 6 cycles. He did well for the first 5 months, after which he developed disease recurrence in the postoperative nephrectomy bed (a biopsy showed it to be recurrent synovial sarcoma) as well as pulmonary nodules, for which he was started on trabectedin 1.5 mg/m2 every 3 weeks. Two months later, a CT scan showed an increase in the size of his retroperitoneal mass, and the treatment was changed to pazopanib 400 mg daily orally, on which he remained at the time of publication.

Discussion

Synovial sarcoma is the fourth most common type of soft tissue sarcoma, accounting for 2.5% to 10.5% of all primary soft tissue malignancies worldwide. It occurs most frequently in adolescents and young adults, with most patients presenting between the ages of 15 and 40 years. Median age of presentation is 36 years. Despite the nomenclature, synovial sarcoma does not arise in intra-articular locations but typically occurs in proximity to joints in the extremities. Synovial sarcomas are less commonly described in other sites, including the head and neck, mediastinum, intraperitoneum, retroperitoneum, lung, pleura, and kidney.4,5 Renal synovial sarcoma was first described in a published article by Argani and colleagues in 2000.5

Adult renal mesenchymal tumors are classified into benign and malignant tumors on the basis of the histologic features and clinicobiologic behavior.6,7 The benign esenchymal renal tumors include angiomyolipoma, leiomyoma, hemangioma, lymphangioma, juxtaglomerular cell tumor, renomedullary interstitial cell tumor (medullary fibroma), lipoma, solitary fibrous tumor, and schwannoma. Malignant renal tumors of mesenchymal origin include leiomyosarcoma, rhabdomyosarcoma, angiosarcoma, osteosarcoma, fibrosarcoma, malignant fibrous histiocytoma, solitary fibrous tumor, and synovial sarcoma.

Most of these tumor types cause the same nonspecific symptoms in patients – abdominal pain, flank pain, abdominal fullness, a palpable mass, and hematuria – although they can be clinically silent. The average duration of symptoms in synovial sarcoma is 2 to 4 years.8 The long duration of symptoms and initial slow growth of synovial sarcomas may give a false impression of a benign process.

A preoperative radiological diagnosis of primary renal synovial sarcoma may be suspected by analyzing the tumor’s growth patterns on CT scans.9 Renal synovial sarcomas often appear as large, well-defined soft tissue masses that can extend into the renal pelvis or into the perinephric region.9 A CT scan may identify soft tissue calcifications, especially subtle ones in areas where the tumor anatomy is complex. A CT scan may also reveal areas of hemorrhage, necrosis, or cyst formation within the tumor, and can easily confirm bone involvement. Intravenous contrast may help in differentiating the mass from adjacent muscle and neurovascular complex.9,10 On MRI, renal synovial sarcomas are often described as nonspecific heterogeneous masses, although they may also exhibit heterogeneous enhancement of hemorrhagic areas, calcifications, and air-fluid levels (known as “triple sign”) as well as septae. The triple sign may be identified as areas of low, intermediate, and high signal intensity, correlating with areas of hemorrhage, calcification, and air-fluid level.9,10 Signal intensity is about equal to that of skeletal muscle on T1-weighted MRI and higher than that of subcutaneous fat on T2-weighted MRI.

In the present case, the tumor was initially misdiagnosed as an angiomyolipoma, the most common benign tumor of the kidney. Angiomyolipomas are usually solid triphasic tumors arising from the renal cortex and are composed of 3 major elements: dysmorphic blood vessels, smooth muscle components, and adipose tissue. When angiomyolipomas are large enough, they are readily recognized by the identification of macroscopic fat within the tumor, either by CT scan or MRI.11 When they are small, they may be difficult to distinguish from a small cyst on CT because of volume averaging.

On pathology, synovial sarcoma has dual epithelial and mesenchymal differentiation. They are frequently multi-lobulated, and areas of necrosis, hemorrhage, and cyst formation are also common. There are 3 main histologic subtypes of synovial sarcoma: biphasic (20%-30%), monophasic (50%-60%), and poorly differentiated (15%-25%). Poorly differentiated synovial sarcomas are generally epithelioid in morphology, have high mitotic activity (usually 10-20 mitoses/10 high-power field; range is <5 for well differentiated, low-grade tumors), and can be confused with round cell tumors such as Ewing sarcoma. Poorly differentiated synovial sarcomas are high-grade tumors.